LLMs in Production

From Language Models to Successful Products

Foreword by Joe Reis

For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit <www.manning.com>. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: orders@manning.com

©2025 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine.

The authors and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time. The authors and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause, or from any usage of the information herein.

Manning Publications Co. Development editor: Doug Rudder 20 Baldwin Road Technical editor: Daniel Leybzon PO Box 761 Review editor: Dunja Nikitovic´ Shelter Island, NY 11964 Production editor: Aleksandar Dragosavljevic´ Copy editor: Alisa Larson Proofreader: Melody Dolab Technical proofreader: Byron Galbraith Typesetter: Dennis Dalinnik Cover designer: Marija Tudor

ISBN: 9781633437203 Printed in the United States of America To my wife Jess and my kids, Odin, Magnus, and Emrys, who have supported me through thick and thin

—Christopher Brousseau

I dedicate this book to Evelyn, my wife, and our daughter, Georgina. Evelyn, thank you for your unwavering support and encouragement through every step of this journey. Your sacrifices have been paramount to making this happen. And to my daughter, you are an endless source of inspiration and motivation. Your smile brightens my day and helps remind me to enjoy the small moments in this world. I hope and believe this book will help build a better tomorrow for both of you.

—Matthew Sharp

brief contents

- 1 Words’ awakening: Why large language models have captured attention 1

- 2 Large language models: A deep dive into language modeling 20

- 3 Large language model operations: Building a platform for LLMs 73

- 4 Data engineering for large language models: Setting up for success 111

- 5 Training large language models: How to generate the generator 154

- 6 Large language model services: A practical guide 201

- 7 Prompt engineering: Becoming an LLM whisperer 254

- 8 Large language model applications: Building an interactive experience 279

- 9 Creating an LLM project: Reimplementing Llama 3 305

- 10 Creating a coding copilot project: This would have helped you earlier 332

- 11 Deploying an LLM on a Raspberry Pi: How low can you go? 355

- 12 Production, an ever-changing landscape: Things are just getting started 379

contents

foreword xi preface xii acknowledgments xiv about the book xvi about the authors xix about the cover illustration xx

1 Words’ awakening: Why large language models have captured attention 1

- 1.1 Large language models accelerating communication 3

- 1.2 Navigating the build-and-buy decision with LLMs 7

Buying: The beaten path 8 ■ Building: The path less traveled 9 A word of warning: Embrace the future now 15

2 Large language models: A deep dive into language modeling 20

Linguistic features 23 ■ Semiotics 29 ■ Multilingual NLP 32

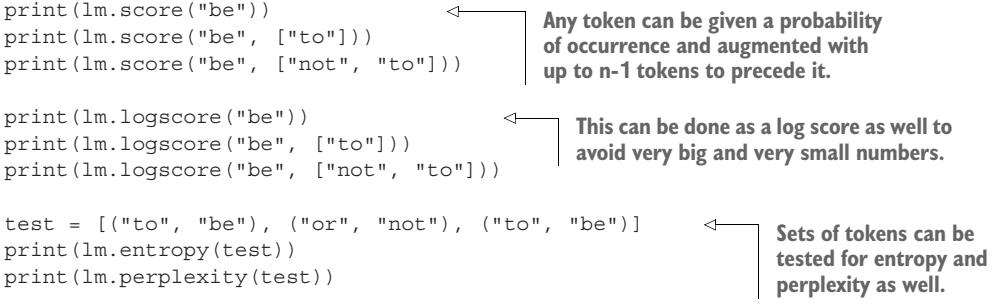

2.2 Language modeling techniques 33

N-gram and corpus-based techniques 34 ■ Bayesian techniques 36 Markov chains 40 ■ Continuous language modeling 43

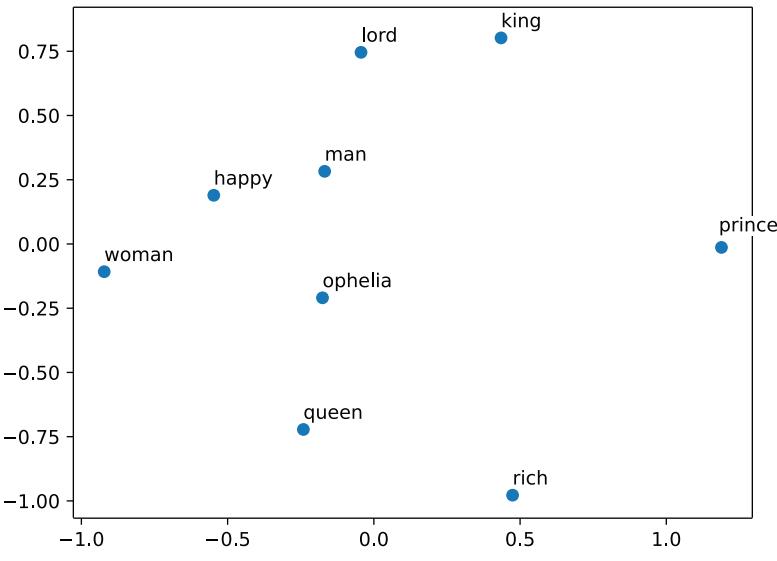

Embeddings 47 ■ Multilayer perceptrons 49 ■ Recurrent neural networks and long short-term memory networks 51 Attention 58

3 Large language model operations: Building a platform for LLMs 73

- 3.1 Introduction to large language model operations 73

- 3.2 Operations challenges with large language models 74

Long download times 74 ■ Longer deploy times 75 Latency 76 ■ Managing GPUs 77 ■ Peculiarities of text data 77 ■ Token limits create bottlenecks 78 ■ Hallucinations cause confusion 80 ■ Bias and ethical considerations 81 Security concerns 81 ■ Controlling costs 84

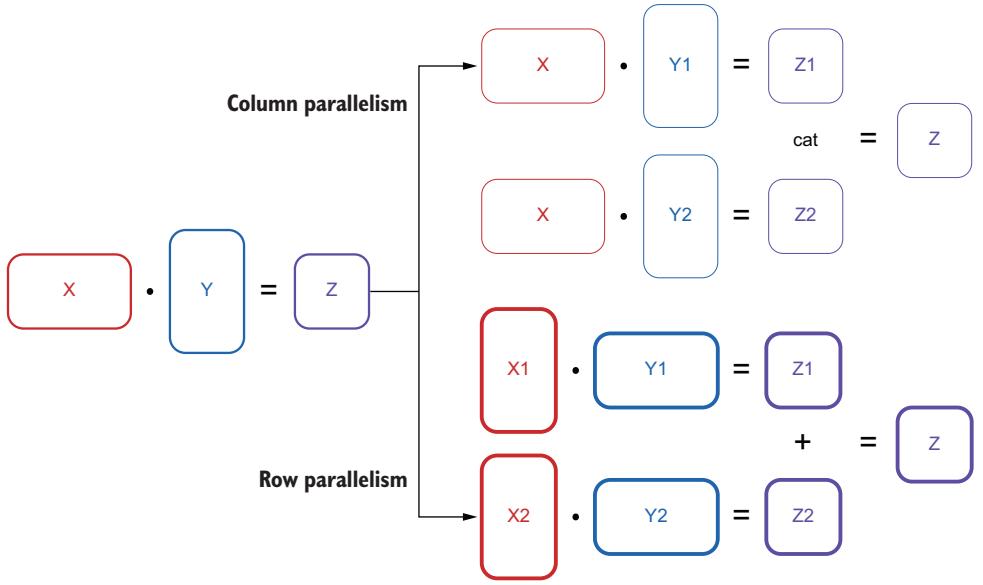

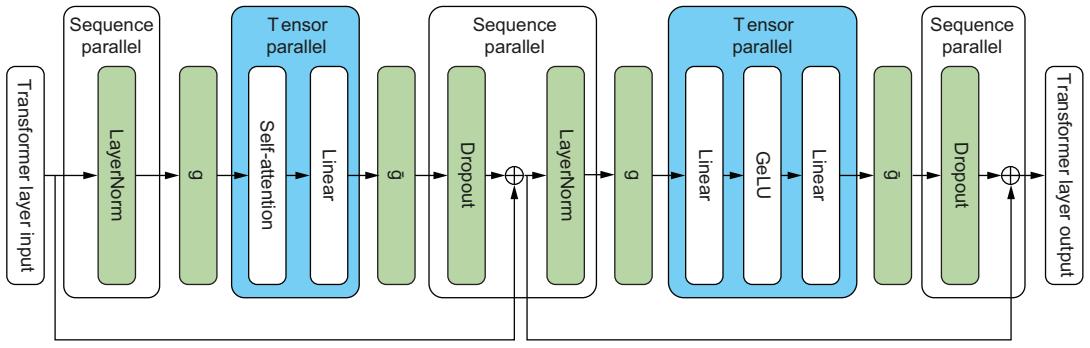

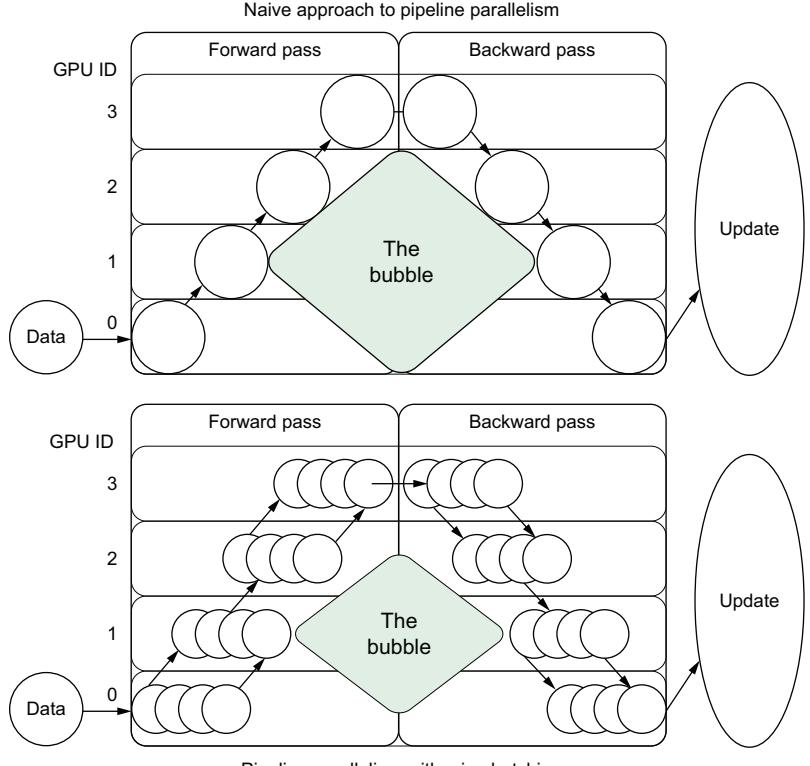

Compression 84 ■ Distributed computing 93

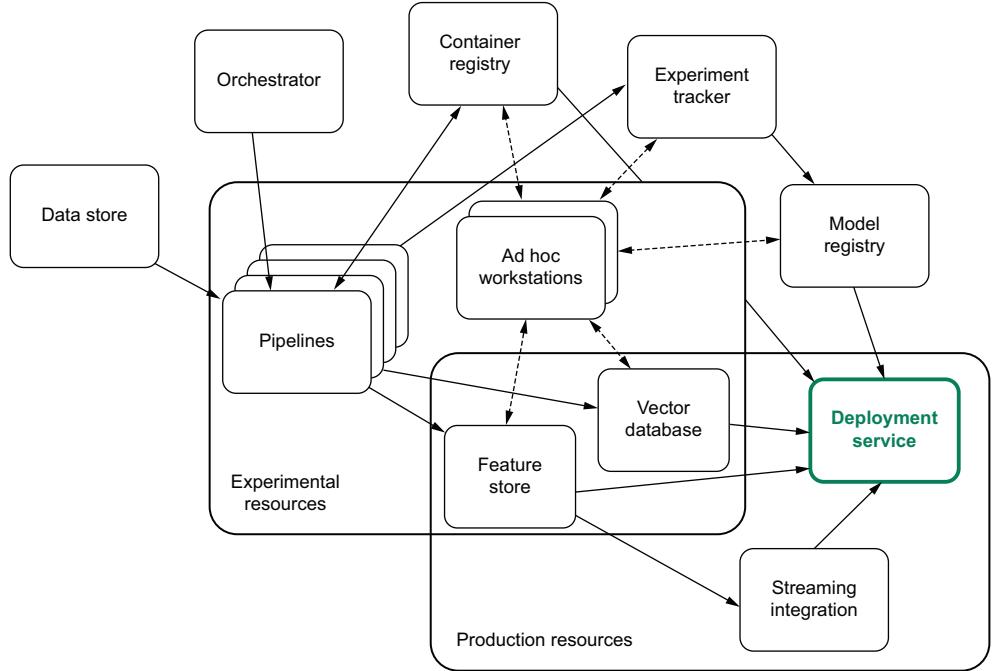

3.4 LLM operations infrastructure 99

Data infrastructure 101 ■ Experiment trackers 102 ■ Model registry 103 ■ Feature stores 104 ■ Vector databases 105 Monitoring system 106 ■ GPU-enabled workstations 107 Deployment service 108

4 Data engineering for large language models: Setting up for success 111

4.1 Models are the foundation 112

GPT 113 ■ BLOOM 114 ■ LLaMA 115 ■ Wizard 115 Falcon 116 ■ Vicuna 116 ■ Dolly 116 ■ OpenChat 117

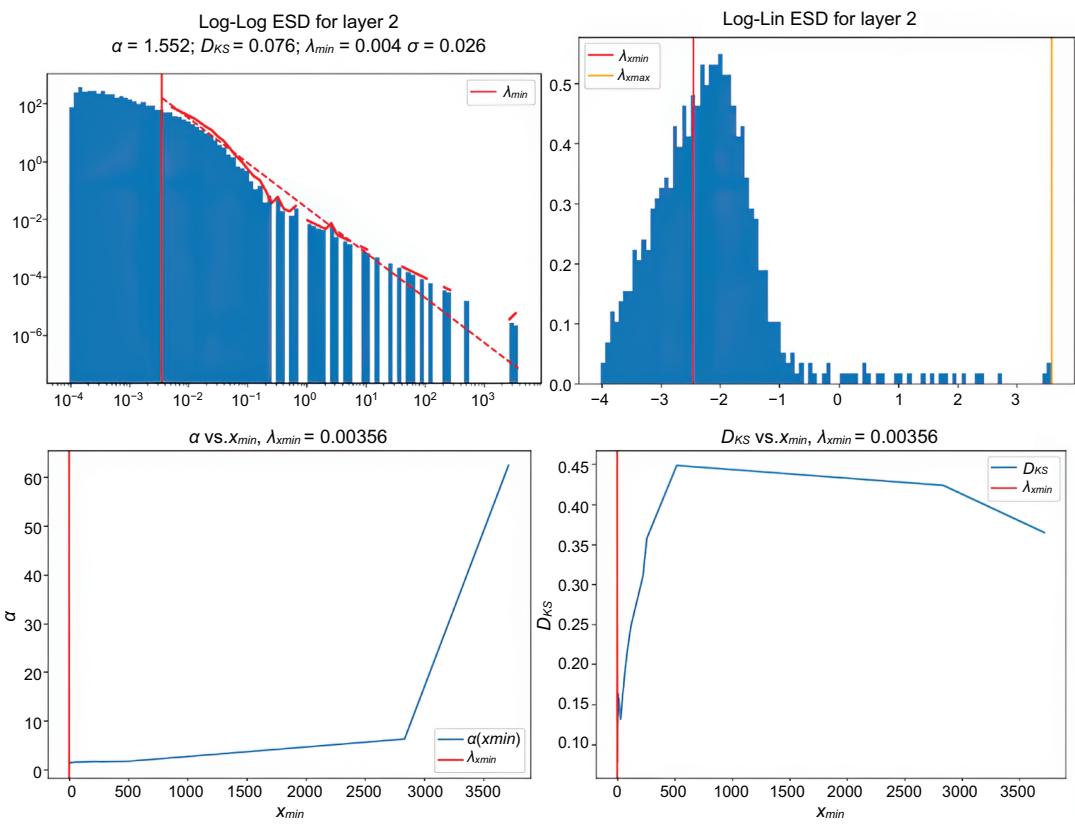

Metrics for evaluating text 118 ■ Industry benchmarks 121 Responsible AI benchmarks 126 ■ Developing your own benchmark 128 ■ Evaluating code generators 130 Evaluating model parameters 131

Datasets you should know 134 ■ Data cleaning and preparation 138

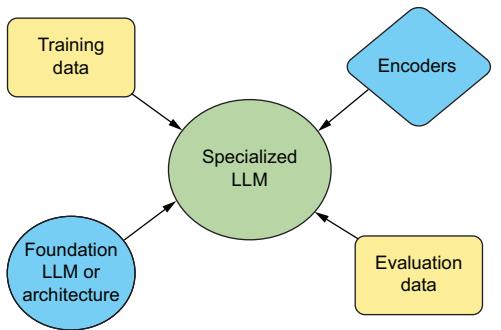

5 Training large language models: How to generate the generator 154

- 5.1 Multi-GPU environments 155 Setting up 155 ■ Libraries 159

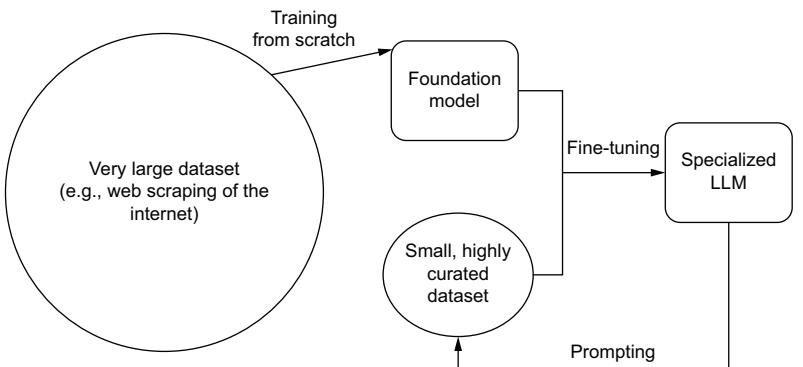

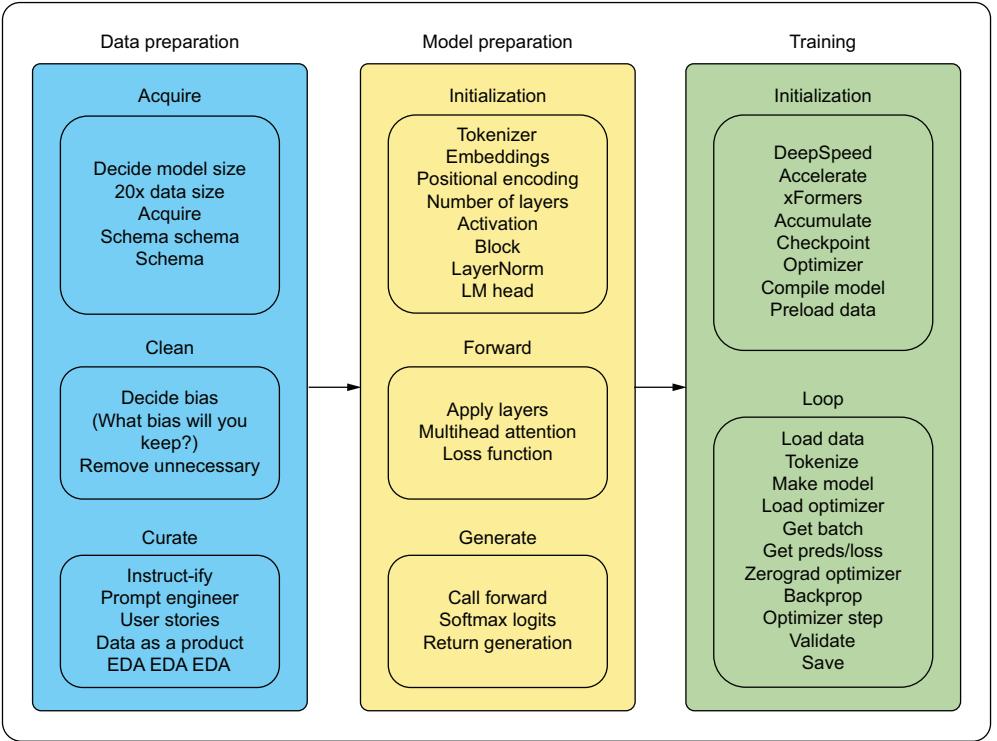

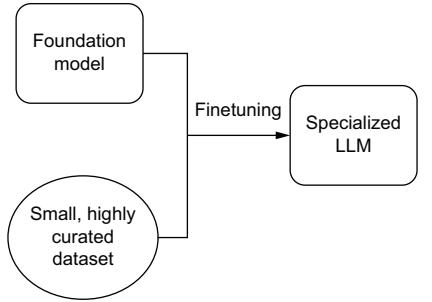

- 5.2 Basic training techniques 161 From scratch 162 ■ Transfer learning (finetuning) 169 Prompting 174

- 5.3 Advanced training techniques 175

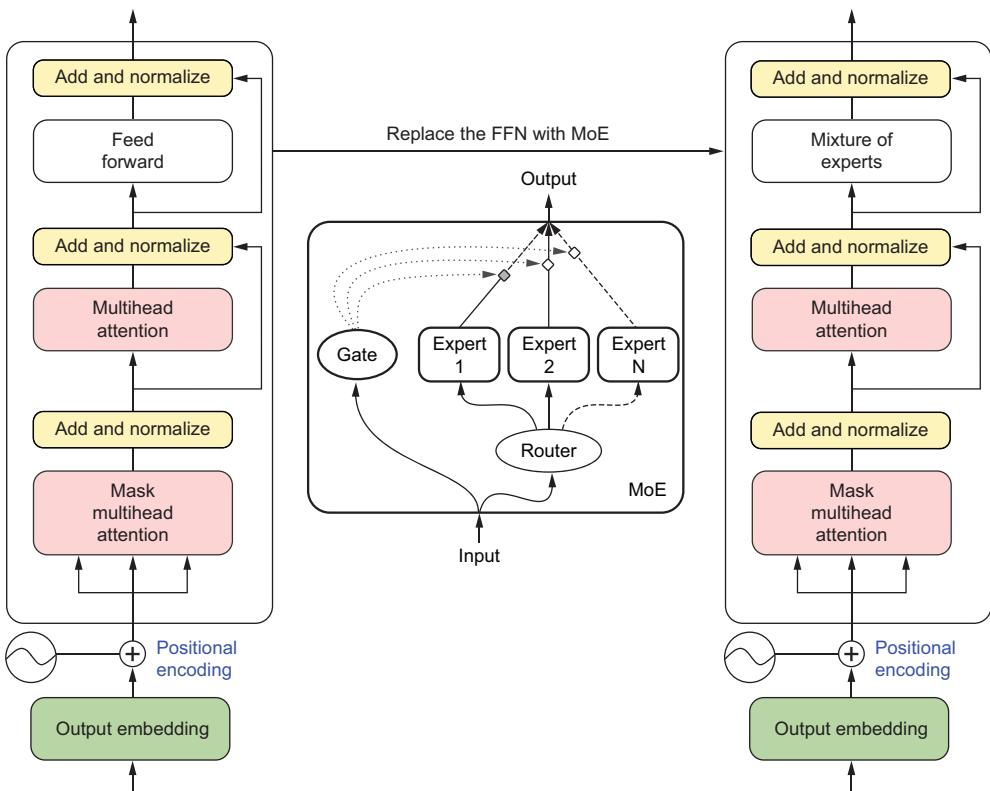

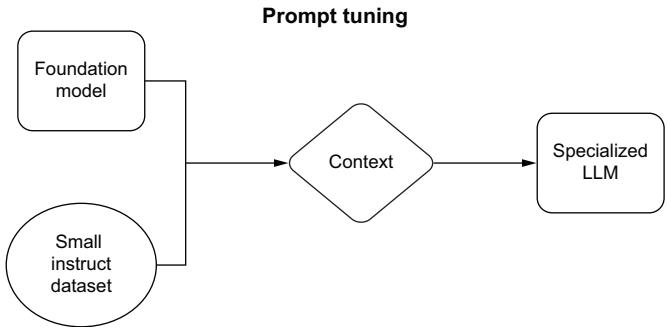

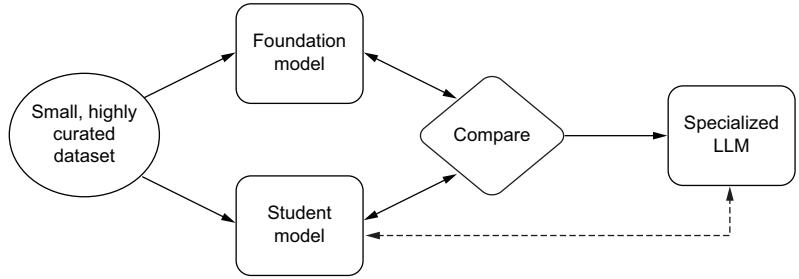

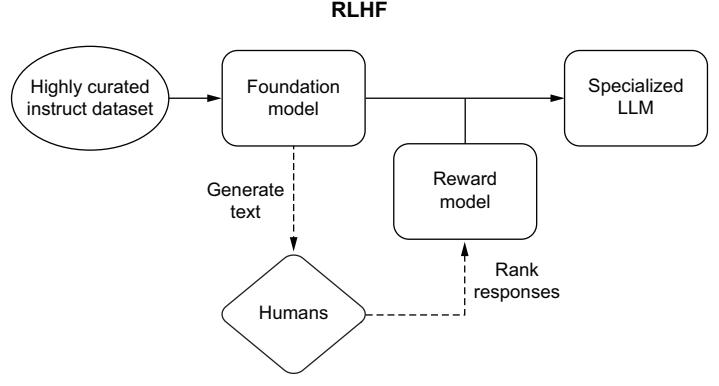

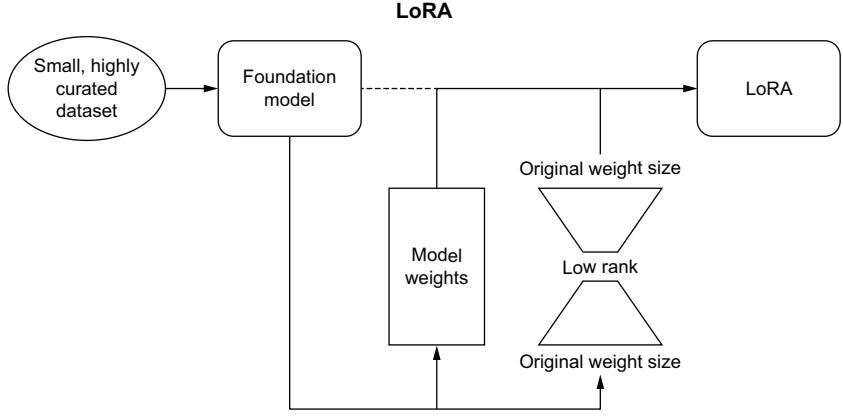

Prompt tuning 175 ■ Finetuning with knowledge distillation 181 ■ Reinforcement learning with human feedback 185 ■ Mixture of experts 188 ■ LoRA and PEFT 191

5.4 Training tips and tricks 196

Training data size notes 196 ■ Efficient training 197 Local minima traps 198 ■ Hyperparameter tuning tips 198 A note on operating systems 199 ■ Activation function advice 199

6 Large language model services: A practical guide 201

6.1 Creating an LLM service 202

Model compilation 203 ■ LLM storage strategies 209 Adaptive request batching 212 ■ Flow control 212 Streaming responses 215 ■ Feature store 216 Retrieval-augmented generation 219 ■ LLM service libraries 223

6.2 Setting up infrastructure 224

Provisioning clusters 225 ■ Autoscaling 227 ■ Rolling updates 232 ■ Inference graphs 234 ■ Monitoring 237

Model updates and retraining 241 ■ Load testing 241 Troubleshooting poor latency 245 ■ Resource management 247 Cost engineering 248 ■ Security 249

7 Prompt engineering: Becoming an LLM whisperer 254

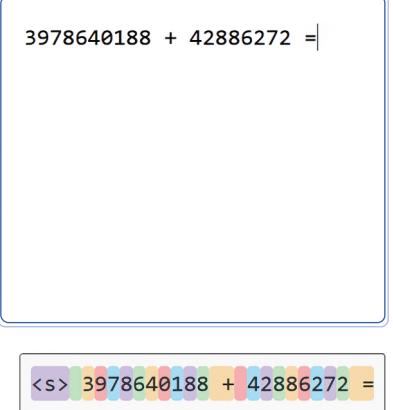

7.1 Prompting your model 255 Few-shot prompting 255 ■ One-shot prompting 257 Zero-shot prompting 258 7.2 Prompt engineering basics 260 Anatomy of a prompt 261 ■ Prompting hyperparameters 263 Scrounging the training data 265 7.3 Prompt engineering tooling 266 LangChain 266 ■ Guidance 267 ■ DSPy 270 ■ Other tooling is available but . . . 271 7.4 Advanced prompt engineering techniques 271 Giving LLMs tools 271 ■ ReAct 274 8 Large language model applications: Building an interactive experience 279 8.1 Building an application 280 Streaming on the frontend 281 ■ Keeping a history 284 Chatbot interaction features 287 ■ Token counting 290 RAG applied 291 8.2 Edge applications 293 8.3 LLM agents 296 9 Creating an LLM project: Reimplementing Llama 3 305 9.1 Implementing Meta’s Llama 306 Tokenization and configuration 306 ■ Dataset, data loading, evaluation, and generation 309 ■ Network architecture 314 9.2 Simple Llama 317 9.3 Making it better 321 Quantization 322 ■ LoRA 323 ■ Fully sharded data parallel– quantized LoRA 326 9.4 Deploy to a Hugging Face Hub Space 328 10 Creating a coding copilot project: This would have helped you earlier 332 10.1 Our model 333 10.2 Data is king 336 Our VectorDB 336 ■ Our dataset 337 ■ Using RAG 341

11 Deploying an LLM on a Raspberry Pi: How low can you go? 355

- 11.1 Setting up your Raspberry Pi 356 Pi Imager 357 ■ Connecting to Pi 359 ■ Software installations and updates 363

- 11.2 Preparing the model 364

- 11.3 Serving the model 366

- 11.4 Improvements 368

Using a better interface 368 ■ Changing quantization 369 Adding multimodality 370 ■ Serving the model on Google Colab 374

12 Production, an ever-changing landscape: Things are just getting started 379

Government and regulation 381 ■ LLMs are getting bigger 386 ■ Multimodal spaces 392 ■ Datasets 393 Solving hallucination 394 ■ New hardware 401 ■ Agents will become useful 402

foreword

Unless you’ve been hiding in a cave, you know that LLMs are everywhere. They’re becoming a staple for many people. If you’re reading this book, there’s a good chance you’ve integrated LLMs into your workflow. But you might be wondering how to deploy LLMs in production.

This is precisely why LLMs in Production is a timely and invaluable book. Drawing from their extensive experience and deep expertise in machine learning and linguistics, the authors offer a comprehensive guide to navigating the complexities of bringing LLMs into production environments. They don’t just explore the technical aspects of implementation; they delve into the strategic considerations, ethical implications, and best practices crucial for responsible and effective production deployments of LLMs.

LLMs in Production has it all. Starting with an overview of what LLMs are, the book dives deep into language modeling, MLOps for LLMs, prompt engineering, and every relevant topic in between. You’ll come away with a bottoms-up approach to working with LLMs from first principles. This book will stand the test of time, at least as long as possible, in this fast-changing landscape.

You should approach this book with an open mind and a critical eye. The future of LLMs is not predetermined—it will be shaped by the decisions we make and the care with which we implement these powerful tools in production. Let this book guide you as you navigate the exciting, challenging world of LLMs in production.

—Joe Reis, Author of Fundamentals of Data Engineering

preface

In January of 2023, I was sitting next to a couple, and they started to discuss the latest phenomenon, ChatGPT. The husband enthusiastically discussed how excited he was about the technology. He had been spending quality time with his teenagers writing a book using it—they had already written 70 pages. The wife, however, wasn’t as thrilled, more scared. She was an English teacher and was worried about how it was going to affect her students.

It was around this time the husband said something I was completely unready for: his friend had fired 100 writers at his company. My jaw dropped. His friend owned a small website where he hired freelance writers to write sarcastic, funny, and fake articles. After being shown the tool, the friend took some of his article titles and asked ChatGPT to write one. What it came up with was indistinguishable from anything else on the website! Meaningless articles that lack the necessity for veracity are LLM’s bread and butter, so it made sense. It could take him minutes to write hundreds of articles, and it was all free!

We have both experienced this same conversation—with minor changes—a hundred times over since. From groups of college students to close-knit community members, everyone is talking about AI all the time. Very few people have experienced it firsthand, outside of querying a paid API. For years, we’ve seen how it’s been affecting the translation industry. Bespoke translation is difficult to get clients for, and the rise of PEMT (Post-Edit of Machine Translation) workflows has allowed translators to charge less and do more work faster, all with a similar level of quality. We’re gunning for LLMs to do the same for many other professions.

PREFACE xiii

When ChatGPT first came out, it was essentially still in beta release for research purposes, and OpenAI hadn’t even announced plus subscriptions yet. In our time in the industry, we have seen plenty of machine learning models put up behind an API with the release of a white paper. This helps researchers build clout so they can show off a working demo. However, these demos are just that—never built to scale and usually taken down after a month for cost reasons. OpenAI had done just that on several occasions already.

Having already seen the likes of BERT, ELMO, T5, GPT-2, and a host of other language models come and go without any fanfare outside the NLP community, it was clear that GPT-3 was different. LLMs aren’t just popular; they are technically very difficult. There are so many challenges and pitfalls that one can run into when trying to deploy one, and we’ve seen many make those mistakes. So when the opportunity came up to write this book, we were all in. LLMs in Production is the book we always wished we had.

acknowledgments

Before writing this book, we always fantasized about escaping up to the mountains and writing in the seclusion of some cabin in the forest. While that strategy might work for some authors, there’s no way we would have been able to create what we believe to be a fantastic book without the help of so many people. This book had many eyes on it throughout its entire process, and the feedback we’ve received has been fundamental to its creation.

First, we’d like to thank our editors and reviewers, Jonathan Gennick, Al Krinker, Doug Rudder, Sebastian Raschka, and Danny Leybzon. Danny is a data and machine learning expert and worked as a technical editor on this book. He has helped Fortune 500 enterprises and innovative tech startups alike design and implement their data and machine learning strategies. He now does research in reinforcement learning at Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Spain. We thank all of you for your direct commentary and honest criticism. Words can’t describe the depth of our gratitude.

We are also thankful for so many in the community who encouraged us to write this book. There are many who have supported us as mentors, colleagues, and friends. For their encouragement, support, and often promotion of the book, we’d like to thank in no particular order: Joe Reis, Mary MacCarthy, Lauren Balik, Demetrios Brinkman, Joselito Balleta, Mkolaj Pawlikowski, Abi Aryan, Bryan Verduzco, Fokke Dekker, Monica Kay Royal, Mariah Peterson, Eric Riddoch, Dakota Quibell, Daniel Smith, Isaac Tai, Alex King, Emma Grimes, Shane Smit, Dusty Chadwick, Sonam Choudhary, Isaac Vidas, Olivier Labrèche, Alexandre Gariépy, Amélie Rolland, Alicia Bargar, Vivian Tao, Colin Campbell, Connor Clark, Marc-Antoine Bélanger, Abhin

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xv

Chhabra, Sylvain Benner, Jordan Mitchell, Benjamin Wilson, Manny Ko, Ben Taylor, Matt Harrison, Jon Bradshaw, Andrew Carr, Brett Ragozzine, Yogesh Sakpal, Gauri Bhatnagar, Sachin Pandey, Vinícius Landeira, Nick Baguely, Cameron Bell, Cody Maughan, Sebastian Quintero, and Will McGinnis. This isn’t a comprehensive list, and we are sure we are forgetting someone. If that’s you, thank you. Please reach out, and we’ll be sure to correct it.

Next, we are so thankful for the entire Manning team, including Aira Ducˇic´, Robin Campbell, Melissa Ice, Ana Romac, Azra Dedic, Ozren Harlovic´, Dunja Nikitovic´, Sam Wood, Susan Honeywell, Erik Pillar, Alisa Larson, Melody Dolab, and others.

To all the reviewers, Abdullah Al Imran, Allan Makura, Ananda Roy, Arunkumar Gopalan, Bill Morefield, Blanca Vargas, Bruno Sonnino, Dan Sheikh, Dinesh Chitlangia, George Geevarghese, Gregory Varghese, Harcharan S. Kabbay, Jaganadh Gopinadhan, Janardhan Shetty, Jeremy Bryan, John Williams, Jose San Leandro, Kyle Pollard, Manas Talukdar, Manish Jain, Mehmet Yilmaz, Michael Wang, Nupur Baghel, Ondrej Krajicek, Paul Silisteanu, Peter Henstock, Radhika Kanubaddhi, Reka Anna Horvath, Satej Kumar Sahu, Sergio Govoni, Simon Tschoeke, Simone De Bonis, Simone Sguazza, Siri Varma Vegiraju, Sriram Macharla, Sudhir Maharaj, Sumaira Afzal, Sumit Pal, Supriya Arun, Vinod Sangare, Xiangbo Mao, Yilun Zhang, your suggestions helped make this a better book.

Lastly, we’d also like to give a special thanks to Elmer Saflor for giving us permission to use the Yellow Balloon meme and George Lucas, Hayden Christensen, and Temuera Morrison for being a welcome topic of distraction during many late nights working on the book. “We want to work on Star Wars stuff.”

about the book

LLMs in Production is not your typical Data Science book. In fact, you won’t find many books like this at all in the data space mainly because creating a successful data product often requires a large team—data scientists to build models, data engineers to build pipelines, MLOps engineers to build platforms, software engineers to build applications, product managers to go to endless meetings, and, of course, for each of these, managers to take the credit for it all despite their only contribution being to ask questions, oftentimes the same questions repeated, just trying to understand what’s going on.

There are so many books geared toward each of these individuals, but there are so very few that tie the entire process together from end to end. While this book focuses on LLMs—indeed, it can be considered an LLMOps book—what you will take away will be so much more than how to push a large model onto a server. You will gain a roadmap that will show you how to create successful ML products—LLMs or otherwise—that delight end users.

Who should read this book

Anyone who finds themselves working on an application that uses LLMs will benefit from this book. This includes all of the previously listed individuals. The individuals who will benefit the most, though, will likely be those who have cross-functional roles with titles like ML engineer. This book is hands-on, and we expect our readers to know Python and, in particular, PyTorch.

How this book is organized

There are 12 chapters in this book, 3 of which are project chapters:

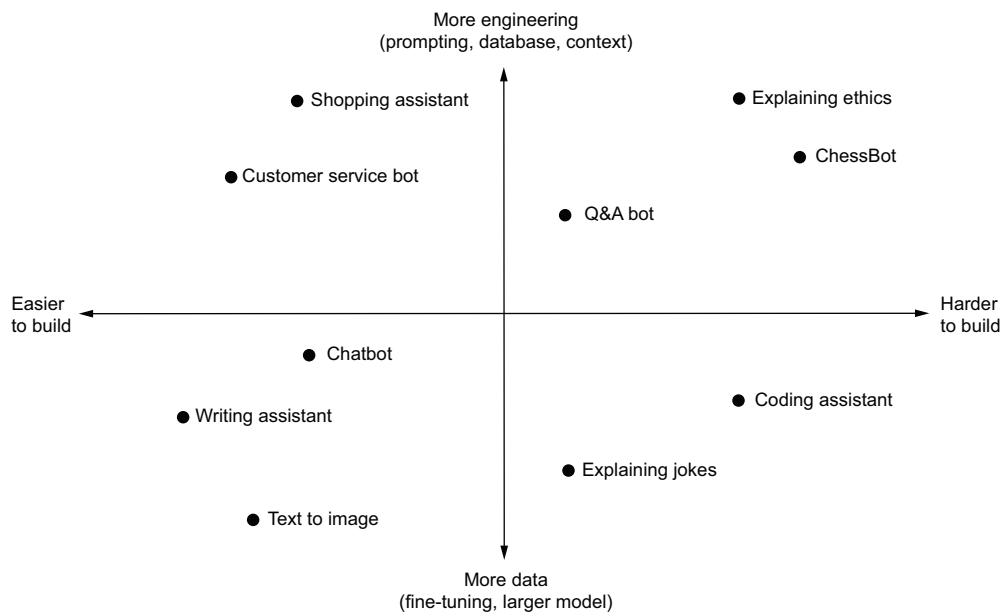

- Chapter 1 presents some of the promising applications of LLMs and discusses the build-versus-buy dichotomy. This book’s focus is showing you how to build, so we want to help you determine whether building is the right decision for you.

- Chapter 2 lays the necessary groundwork. We discuss the basics of linguistics and define some terms you’ll need to understand to get the most out of this book. We then build your knowledge of natural language modeling techniques. By the end of this chapter, you should both understand how LLMs work and what they are good or bad at. You should then be able to determine whether LLMs are the right technology for your project.

- Chapter 3 addresses the elephant in the room by explaining why LLMs are so difficult to work with. We’ll then discuss some necessary concepts and solutions you’ll need to master just to start working with LLMs. Then we’ll discuss the necessary tooling and infrastructure requirements you’ll want to acquire and why.

- Chapter 4 starts our preparations by discussing the necessary assets you’ll need to acquire, from data to foundation models.

- Chapter 5 then shows you how to train an LLM from scratch as well as a myriad of methods to finetune your model, going over the pros and cons of each method.

- Chapter 6 then dives into serving LLMs and what you’ll need to know to create an API. It discusses setting up a VPC for LLMs as well as common production challenges and how to overcome them.

- Chapter 7 discusses prompt engineering and how to get the most out of an LLM’s responses.

- Chapter 8 examines building an application around an LLM and features you’ll want to consider adding to improve the user experience.

- Chapter 9 is the first of our project chapters, where you will build a simple LLama 3 model and deploy it.

- Chapter 10 builds a coding copilot that you can use directly in VSCode.

- Chapter 11 is a project where we will deploy an LLM to a Raspberry Pi.

- Chapter 12 ends the book with our thoughts on the future of LLMs as a technology, including discussions of promising fields of research.

In general, this book was designed to be read cover to cover, each chapter building upon the last. To us, the chapters are ordered to mock an ideal situation and thus outline the knowledge you’ll need and the steps you would go through when building an LLM product under the best circumstances. That said, this is a production book, and production is where reality lives. Don’t worry; we understand the real world is messy. Each chapter is self-contained, and readers are free and encouraged to jump around depending on their interests and levels of understanding.

About the code

This book contains many examples of source code, both in numbered listings and in line with normal text. In both cases, source code is formatted in a fixed-width font like this to separate it from ordinary text. Sometimes code is also in bold to highlight code that has changed from previous steps in the chapter, such as when a new feature is added to an existing line of code.

In many cases, the original source code has been reformatted; we’ve added line breaks and reworked indentation to accommodate the available page space in the book. In rare cases, even this was not enough, and listings include line-continuation markers (➥). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text. Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

You can get executable snippets of code from the liveBook (online) version of this book athttps://livebook.manning.com/book/llms-in-production. The complete code for the examples in the book is available for download from the Manning website at https://www.manning.com/books/llms-in-production, and from GitHub at https:// github.com/IMJONEZZ/LLMs-in-Production.

liveBook Discussion Forum

Purchase of LLMs in Production includes free access to liveBook, Manning’s online reading platform. Using liveBook’s exclusive discussion features, you can attach comments to the book globally or to specific sections or paragraphs. It’s a snap to make notes for yourself, ask and answer technical questions, and receive help from the authors and other users. To access the forum, go to https://livebook.manning.com/ book/llms-in-production/discussion. You can also learn more about Manning’s forums and the rules of conduct athttps://livebook.manning.com/discussion.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialogue between individual readers and between readers and the authors can take place. It is not a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the authors, whose contribution to the forum remains voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you try asking the authors some challenging questions lest their interest stray! The forum and the archives of previous discussions will be accessible from the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

about the cover illustration

The illustration on the cover of LLMs in Production is an engraving by Nicolas de Lermessin (1640–1725) titled “Habit d’imprimeur en lettres,” or “The Printer’s Costume.” The engraving is from the series Les Costumes Grotesques et les Metiers, published by Jacques Chiquet in the early 18th century.

In those days, it was easy to identify where people lived and what their trade or station in life was just by their dress. Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of regional culture centuries ago, brought back to life by pictures from collections such as this one.

Words’ awakening: Why large language models have captured attention

This chapter covers

- What large language models are and what they can and cannot do

- When you should and should not deploy your own large language models

- Large language model myths and the truths that lie behind them

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

—Arthur C. Clarke

The year is 1450. A sleepy corner of Mainz, Germany, unknowingly stands on the precipice of a monumental era. In Humbrechthof, a nondescript workshop shrouded in the town’s shadows pulsates with anticipation. It is here that Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith and innovator, sweats and labors amidst the scents of oil, metal, and determination, silently birthing a revolution. In the late hours of the night, the peace is broken intermittently by the rhythmic hammering of metal on metal. In the lamp-lit heart of the workshop stands Gutenberg’s decade-long labor of love—a contraption unparalleled in design and purpose.

This is no ordinary invention. Craftsmanship and creativity transform an assortment of moveable metal types, individually cast characters born painstakingly into a matrix. The flickering light dances off the metallic insignias. The air pulsates with the anticipation of a breakthrough and the heady sweetness of oil-based ink, an innovation from Gutenberg himself. In the stillness of the moment, the master printer squares his shoulders and, with unparalleled finesse, lays down a crisp sheet of parchment beneath the ink-loaded matrix, allowing his invention to press firmly and stamp fine print onto the page. The room adjusts to the symphony of silence, bated breaths hanging heavily in the air. As the press is lifted, it creaks under its own weight, each screech akin to a war cry announcing an exciting new world.

With a flurry of motion, Gutenberg pulls from the press the first printed page and slams it flat onto the wooden table. He carefully examines each character, all of which are as bold and magnificent as the creator’s vision. The room drinks in the sight, absolutely spellbound. A mere sheet of parchment has become a testament to transformation. As the night gives way to day, he looks upon his workshop with invigorated pride. His legacy is born, echoing in the annals of history and forever changing the way information would take wings. Johannes Gutenberg, now the man of the millennium, emerges from the shadows, an inventor who dared to dream. His name is synonymous with the printing press, which is not just a groundbreaking invention but the catalyst of the modern world.

As news of Gutenberg’s achievement begins to flutter across the continent, scholars from vast disciplines are yet to appreciate the extraordinary tool at their disposal. Knowledge and learning, once coveted treasures, are now within the reach of the common person. There were varied and mixed opinions surrounding that newfound access.

In our time, thanks to the talent and industry of those from the Rhine, books have emerged in lavish numbers. A book that once would’ve belonged only to the rich—nay, to a king—can now be seen under a modest roof. . . . There is nothing nowadays that our children . . , fail to know.

—Sebastian Brant

Scholarly effort is in decline everywhere as never before. Indeed, cleverness is shunned at home and abroad. What does reading offer to pupils except tears? It is rare, worthless when it is offered for sale, and devoid of wit.

—Egbert of Liege

People have had various opinions on books throughout history. One thing we can agree on living in a time when virtual printing presses exist and books are ubiquitous is that the printing press changed history. While we weren’t actually there when Gutenberg printed the first page using his printing press, we have watched many play with large language models (LLMs) for the first time. The astonishment on their faces as they see it respond to their first prompt. Their excitement when challenging it with a difficult question only to see it respond as if it was an expert in the field—the light bulb moment when they realize they can use this to simplify their life or make themselves wealthy. We imagine this wave of emotions is but a fraction of that felt by Johannes Gutenberg. Being able to rapidly generate text and accelerate communication has always been valuable.

1.1 Large language models accelerating communication

Every job has some level of communication. Often, this communication is shallow, bureaucratic, or political. We’ve often warned students and mentees that every job has its own paperwork. Something that used to be a passion can easily be killed by the dayto-day tedium and menial work that comes with it when it becomes a job. In fact, when people talk about their professions, they often talk them up, trying to improve their social standing, so you’ll rarely get the full truth. You won’t hear about the boring parts, and the day-to-day grind is conveniently forgotten.

However, envision a world where we reduce the burden of monotonous work. A place where police officers no longer have to waste hours of each day filling out reports and could instead devote that time to community outreach programs. Or a world where teachers no longer work late into the night grading homework and preparing lesson plans, instead being able to think about and prepare customized lessons for individual students. Or even a world where lawyers would no longer be stuck combing through legal documents for days, instead being free to take on charity cases for causes that inspire them. When the communication burden, the paperwork burden, and the accounting burden are taken away, the job becomes more akin to what we sell it as.

For this, LLMs are the most promising technology to come along since, well, the printing press. For starters, they have completely upended the role and relationship between humans and computers, transforming what we believed they were capable of. They have already passed medical exams, the bar exam, and multiple theory of mind tests. They’ve passed both Google and Amazon coding interviews. They’ve gotten scores of at least 1410 out of 1600 on the SAT. One of the most impressive achievements to the authors is that GPT-4 has even passed the Advanced Sommelier exam, which makes us wonder how the LLM got past the practical wine-tasting portion. Indeed, their unprecedented accomplishments are coming at breakneck speed and often make us mere mortals feel a bit queasy and uneasy. What do you do with a technology that seems able to do anything?

NOTE Med-PaLM 2 scored an 86.5% on the MedQA exam. You can see a list of exams passed in OpenAI’s GPT-4 paper at https://cdn.openai.com/papers/ gpt-4.pdf. Finally, Google interviewed ChatGPT as a test, and it passed (https:// mng.bz/x2y6).

Passing tests is fun but not exactly helpful, unless our aim is to build the most expensive cheating machine ever, and we promise there are better ways to use our time.

What LLMs are good at is language, particularly helping us improve and automate communication. This allows us to transform common bitter experiences into easy, enjoyable experiences. For starters, imagine entering your home where you have your very own personal JARVIS, as if stepping into the shoes of Iron Man, an AI-powered assistant that adds an unparalleled dynamic to your routine. While not quite to the same artificial general intelligence (AGI) levels as those portrayed by JARVIS in the Marvel movies, LLMs are powering new user experiences, from improving customer support to helping you shop for a loved one’s birthday. They know to ask you about the person, learn about their interests and who they are, find out your budget, and then make specialized recommendations. While many of these assistants are being put to good work, many others are simply chatbots that users can talk to and entertain themselves—which is important because even our imaginary friends are too busy these days. Jokes aside, these can create amazing experiences, allowing you to meet your favorite fictional characters like Harry Potter, Sherlock Holmes, Anakin Skywalker, or even Iron Man.

What we’re sure many readers are interested in, though, is programming assistants, because we all know googling everything is actually one of the worst user experiences. Being able to write a few objectives in plain English and see a copilot write the code for you is exhilarating. We’ve personally used these tools to help us remember syntax, simplify and clean code, write tests, and learn a new programming language.

Video gaming is another interesting field in which we can expect LLMs to create a lot of innovation. Not only do they help the programmers create the game, but they also allow designers to create more immersive experiences. For example, talking to NPCs (nonplayer characters) will have more depth and intriguing dialogue. Picture games like Animal Crossing and Stardew Valley having near-infinite quests and conversations.

Consider other industries, like education, where there doesn’t ever seem to be enough teachers to go around, meaning our kids aren’t getting the one-on-one attention they need. An LLM assistant can help save the teacher time doing manual chores and serve as a private tutor for kids who are struggling. The corporate world is looking into LLMs for talk-to-your-data jobs—tasks such as helping employees understand quarterly reports and data tables—essentially giving everyone their own personal analyst. Sales and marketing divisions are guaranteed to take advantage of this marvelous innovation, for better or worse. The state of search engine optimization (SEO) will change a lot too since currently, it is mostly a game of generating content to hopefully make websites more popular, which is now super easy.

The preceding list is just a few of the common examples where companies are interested in using LLMs. People are using them for personal reasons too, such as writing music, poetry, and even books; translating languages; summarizing legal documents or emails; and even free therapy—which, yes, is an awful idea since LLMs are still dreadful at this. Just a personal preference, but we wouldn’t try to save a buck when our sanity is on the line. Of course, this leads us to the fact that people are already using LLMs for darker purposes like cheating, scams, and fake news to skew elections. At this point, the list has become rather long and varied, but we’ve only begun to scratch the surface of the possible. Really, since LLMs help us with communication, often it’s better to think, “What can’t they do?” than “What can they do?” Or better yet, “What shouldn’t they do?”

Well, as a technology, there are certain restrictions and constraints. For example, LLMs are kind of slow. Of course, slow is a relative term, but responsive times are often measured in seconds, not milliseconds. We’ll dive deeper into this topic in chapter 3, but as an example, we probably won’t see them being used in autocomplete tasks anytime soon, which require blazingly fast inference to be useful. After all, autocomplete needs to be able to predict the word or phrase faster than someone types. In a similar fashion, LLMs are large, complex systems; we don’t need them for such a simple problem anyway. Hitting an autocomplete problem with an LLM isn’t just hitting the nail with a sledgehammer; it’s hitting it with a full-on wrecking ball. And just like it’s more expensive to rent a wrecking ball than to buy a hammer, an LLM will cost you more to operate. There are a lot of similar tasks for which we should consider the complexity of the problem we are trying to solve.

There are also many complex problems that are often poorly solved with LLMs, such as predicting the future. No, we don’t mean with mystic arts but rather forecasting problems—acts like predicting the weather or when high tide will hit the ocean shore. These are actually problems we’ve solved, but we don’t necessarily have good ways to communicate how they have been solved. They are expressed through combinations of math solutions, like Fourier transforms and harmonic analysis, or black box ML models. Many problems fit into this category, like outlier prediction, calculus, or finding the end of the roll of tape.

You also probably want to avoid using them for highly risky projects. LLMs aren’t infallible and make mistakes often. To increase creativity, we often allow for a bit of randomness in LLMs, which means you can ask an LLM the same question and get different answers. That’s risky. You can remove this randomness by doing what’s called turning down the temperature, but that might make the LLM useless depending on your needs. For example, you might decide to use an LLM to categorize investment options as good or bad, but do you want it to then make actual investment decisions based on its output? Not without oversight, unless your goal is to create a meme video.

Ultimately, an LLM is just a model. It can’t be held accountable for losing your money, and really, it didn’t lose your money—you did by choosing to use it. Similar risky problems include filling out tax forms or getting medical advice. While an LLM could do these things, it won’t protect you from heavy penalties in an IRS audit like hiring a certified CPA would. If you take bad medical advice from an LLM, there’s no doctor you can sue for malpractice. However, in all of these examples, the LLM could potentially help practitioners perform their job roles better, both by reducing errors and improving speed.

When to use an LLM

Use them for

- Generating content

- Question-and-answer services

- Chatbots and AI assistants

- Text-to-something problems (diffusion, txt2img, txt23d, txt2vid, etc.)

- Talk-to-your-data applications

- Anything that involves communication

Avoid using them for

- Latency-sensitive workloads

- Simple projects

- Problems we don’t solve with words but with math or algorithms—forecasting, outlier prediction, calculus, etc.

- Critical evaluations

- High-risk projects

Language is not just a medium people use to communicate. It is the tool that made humans apex predators and gives every individual self-definition in their community. Every aspect of human existence, from arguing with your parents to graduating from college to reading this book, is pervaded by our language. Language models are learning to harness one of the fundamental aspects of being human and have the ability, when used responsibly, to help us with each and every one of those tasks. They have the potential to unlock dimensions of understanding both of ourselves and of others if we responsibly teach them how.

LLMs have captured the world’s attention since their potential allows imaginations to run wild. LLMs promise so much, but where are all these solutions? Where are the video games that give us immersive experiences? Why don’t our kids have personal AI tutors yet? Why am I not Iron Man with my own personal assistant yet? These are the deep and profound questions that motivated us to write this book. Particularly, that last one keeps us up at night. So while LLMs can do amazing things, not enough people know how to turn them into actual products, and that’s what we aim to share in this book.

This isn’t just a machine learning operations book. There are a lot of gotchas and pitfalls involved with making an LLM work in production because LLMs don’t work like traditional software solutions. Turning an LLM into a product that can interact coherently with your users will require an entire team and a diverse set of skills. Depending on your use case, you may need to train or finetune and then deploy your own model, or you may need to access one from a vendor through an API.

Regardless of which LLM you use, if you want to take full advantage of the technology and build the best user experience, you will need to understand how it works—not just on the math/tech side either, but also on the soft side, making it a good experience for your users. In this book, we’ll cover everything you need to make LLMs work in production. We’ll talk about the best tools and infrastructure, how to maximize their utility with prompt engineering, and other best practices like controlling costs. LLMs could be one step toward greater equality, so if you are thinking, “I don’t feel like the person this book is for,” please reconsider. This book is for the whole team and anyone who will be interacting with LLMs in the future.

We’re going to hit on a practical level everything that you’ll need for collecting and creating a dataset, training or finetuning an LLM on

Courtesy of SuperElmer, https://www .facebook.com/SuperElmerDS

consumer or industrial hardware, and deploying that model in various ways for customers to interact with. While we aren’t going to cover too much theory, we will cover the process from end to end with real-world examples. At the end of this book, you will know how to deploy LLMs with some viable experience to back it up.

1.2.1 Buying: The beaten path

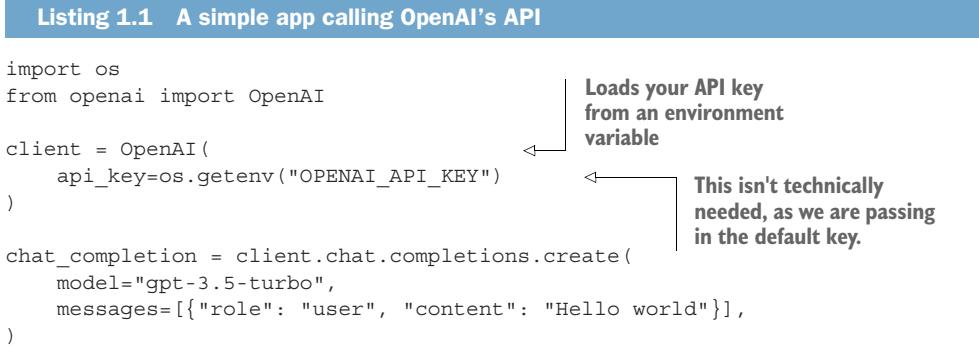

There are many great reasons to simply buy access to an LLM. First and foremost is the speed and flexibility accessing an API provides. Working with an API is an incredibly easy and cheap way to build a prototype and get your hands dirty quickly. In fact, it’s so easy that it only takes a few lines of Python code to start connecting to OpenAI’s API and using LLMs, as shown in listing 1.1. Sure, there’s a lot that’s possible, but it would be a bad idea to invest heavily in LLMs only to find out they happen to fail in your specific domain. Working with an API allows you to fail fast. Building a prototype application to prove the concept and launching it with an API is a great place to get started.

Often, buying access to a model can give you a competitive edge. In many cases, it could very well be that the best model on the market is built by a company specializing in your domain using specialized datasets it has spent a fortune to curate. While you could try to compete and build your own, it may better serve your purposes to buy access to the model instead. Ultimately, whoever has the better domain-specific data to finetune on is likely to win, and that might not be you if this is a side project for your company. Curating data can be expensive, after all. It can save you a lot of work to go ahead and buy it.

This leads to the next point: buying is a quick way to access expertise and support. For example, OpenAI has spent a lot of time making their models safe with plenty of filtering and controls to prevent the misuse of their LLMs. They’ve already encountered and covered a lot of the edge cases so you don’t have to. Buying access to their model also gives you access to the system they’ve built around it.

Not to mention that the LLM itself is only half the problem when deploying it to production. There’s still an entire application you need to build on top of it. Sometimes buying OpenAI’s model has thrived over its competitors in not a small way due to its UX and some tricks like making the tokens look like they’re being typed. We’ll take you through how you can start solving for the UX in your use case, along with some ways you can prototype to give you a major head start in this area.

1.2.2 Building: The path less traveled

Using an API is easy and, in most cases, likely the best choice. However, there are many reasons why you should aim to own this technology and learn how to deploy it yourself instead. While this path might be harder, we’ll teach you how to do it. Let’s dive into several of those reasons, starting with the most obvious: control.

CONTROL

One of the first companies to truly adopt LLMs as a core technology was a small video game company called Latitude. Latitude specializes in Dungeon and Dragons–like role-playing games that utilize LLM chatbots, and they have faced challenges when working with them. This shouldn’t come off as criticizing this company for their missteps, as they have contributed to our collective learning experience and were pioneers in forging a new path. Nonetheless, their story is a captivating and intriguing one—like a train wreck, we can’t help but keep watching.

Latitude’s first release was a game called AI Dungeon. At inception, it utilized OpenAI’s GPT-2 to create an interactive and dynamic storytelling experience. It quickly garnered a large gathering of players, who, of course, started to use it inappropriately. When OpenAI gave Latitude access to GPT-3, it promised an upgrade to the gaming experience; instead, what it got was a nightmare.1

You see, with GPT-3, OpenAI added reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), which greatly helps improve functionality, but this also meant OpenAI contractors were now looking at the prompts. That’s the human feedback part. And these workers weren’t too thrilled to read the filth the game was creating. OpenAI’s reps were quick to give Latitude an ultimatum. Either it needed to start censoring the players, or OpenAI would remove Latitude’s access to the model—which would have essentially killed the game and the company. With no other option, Latitude quickly added some filters, but the filtering system was too much of a band-aid, a buggy and glitchy mess. Players were upset at how bad the system was and unnerved to realize Latitude’s developers were reading their stories, completely oblivious to the fact that OpenAI was already doing so. It was a PR nightmare. And it wasn’t over.

OpenAI decided the game studio wasn’t doing enough; stonewalled, Latitude was forced to increase its safeguards and started banning players. Here’s the twist: the reason so many of these stories turned to smut was because the model had a preference for erotica. It would often unexpectedly transform harmless storylines into inappropriately risqué situations, causing the player to be ejected and barred from the game. OpenAI was acting as the paragon of purity, but it was their model that was the problem, which led to one of the most ironic and unjust problems in gaming history: players were getting banned for what the game did.

So there they were—a young game studio just trying to make a fun game stuck between upset customers and a tech giant that pushed all the blame and responsibility

1 WIRED, “It began as an AI-fueled dungeon game. Then it got much darker,” Ars Technica, May 8, 2021, https://mng.bz/AdgQ.

onto it. If the company had more control over the technology, it could have gone after a real solution, like fixing the model instead of having to throw makeup on a pig.

In this example, control may come off as your ability to finetune your model, and OpenAI now offers finetuning capabilities, but there are many fine-grained decisions that are still lost by using a service instead of rolling your own solution. For example, what training methodologies are used, what regions the model is deployed to, or what infrastructure it runs on. Control is also important for any customer or internal-facing tool. You don’t want a code generator to accidentally output copyrighted code or create a legal situation for your company. You also don’t want your customer-facing LLM to output factually incorrect information about your company or its processes.

Control is your ability to direct and manage the operations, processes, and resources in a way that aligns with your goals, objectives, and values. If a model ends up becoming central to your product offering and the vendor unexpectedly raises its prices, there’s little you can do but pay it. If the vendor decides its model should give more liberal or conservative answers that no longer align with your values, you are just as stuck.

The more central a technology is to your business plan, the more important it is to control it. This is why McDonald’s owns the real estate for its franchises and why Google, Microsoft, and Amazon all own their own cloud networks—and even why so many entrepreneurs build online stores through Shopify instead of using other platforms like Etsy or Amazon Marketplace. Ultimately, control is the first thing that’s lost when you buy someone else’s product. Keeping control will give you more options to solve future problems and will also give you a competitive edge.

COMPETITIVE EDGE

One of the most valuable aspects of deploying your own models is the competitive edge it gives you over your competition. Customization allows you to train the model to be the best at one thing. For example, after the release of Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) in 2017, which is a transformer model architecture you could use to train your own model, there was a surge of researchers and businesses testing this newfound technology on their own data to worldwide success. At the time of writing, if you search the Hugging Face Hub for “BERT,” more than 13.7K models are returned, all of which people individually trained for their own purposes, aiming to create the best model for their task.

One author’s personal experience in this area was training SlovenBERTcina after aggregating the largest (at the time) monolingual Slovak language dataset by scraping the Slovak National Corpus with permission, along with a bunch of other resources like the OSCAR project and the Europarl corpus. It never set any computational records and has never appeared in any model reviews or generated partnerships for the company the author worked for. It did, however, outperform every other model on the market on the tasks it trained on.

Chances are, neither you nor your company needs AGI to generate relevant insights from your data. In fact, if you invented an actual self-aware AGI and planned

to only ever use it to crunch some numbers, analyze data, and generate visuals for PowerPoint slides once a week, that would definitely be reason enough for the AGI to eradicate humans. More than likely, you need exactly what this author did when he made SlovenBERTcina, a large language model that performs two to three tasks better than any other model on the market and doesn’t also share your data with Microsoft or other potential competitors. While some data is required to be kept secret for security or legal reasons, a lot of data should be guarded because it includes trade secrets.

There are hundreds of open source LLMs for both general intelligence and foundational expertise on a specific task. We’ll hit some of our favorites in chapter 4. Taking one of these open source alternatives and training it on your data to create a model that is the best in the world at that task will ensure you have a competitive edge in your market. It will also allow you to deploy the model your way and integrate it into your system to have the most effect.

INTEGRATE ANYWHERE

Let’s say you want to deploy an LLM as part of a choose-your-own-adventure–styled game that uses a device’s GPS location to determine story plots. You know your users are often going to go on adventures into the mountains, out at sea, and generally to locations where they are likely to experience poor service and lack of internet access. Hitting an API just isn’t going to work. Now, don’t get us wrong: deploying LLMs onto edge devices like in this scenario is still an exploratory subject, but it is possible; we will be showing you how in chapter 10. Relying upon an API service is just not going to work for immersive experiences.

Similarly, using third-party LLMs and hitting an API adds integration and latency problems, requiring you to send data over the wire and wait for a response. APIs are great, but they are always slow and not always reliable. When latency is important to a project, it’s much better to have the service in-house. The previous section on competitive edge discussed two projects with edge computing as a priority; however, many more exist. LLAMA.cpp and ALPACA.cpp are two of the first such projects, and this space is innovating quicker than any others. Quantization into 4-bit, low-rank adaptation, and parameter-efficient finetuning are all methodologies recently created to meet these needs, and we’ll be going over each of these starting in chapter 3.

When this author’s team first started integrating with ChatGPT’s API, it was both an awe-inspiring and humbling experience—awe-inspiring because it allowed us to quickly build some valuable tools, and humbling because, as one engineer joked, “When you hit the endpoint, you will get 503 errors; sometimes you get a text response as if the model was generating text, but I think that’s a bug.” Serving an LLM in a production environment—trying to meet the needs of so many clients—is no easy feat. However, deploying a model that’s integrated into your system allows you more control of the process, affording higher availability and maintainability than you can currently find on the market. This, of course, also allows you to better control costs.

COSTS

Considering costs is always important because it plays a pivotal role in making informed decisions and ensuring the financial health of a project or an organization. It helps you manage budgets efficiently and make sure that resources are allocated appropriately. Keeping costs under control allows you to maintain the viability and sustainability of your endeavors in the long run.

Additionally, considering costs is crucial for risk management. When you understand the different cost aspects, you can identify potential risks and exert better control over them. This way, you can avoid unnecessary expenditures and ensure that your projects are more resilient to unexpected changes in the market or industry.

Finally, cost considerations are important for maintaining transparency and accountability. By monitoring and disclosing costs, organizations demonstrate their commitment to ethical and efficient operations to stakeholders, clients, and employees. This transparency can improve an organization’s reputation and help build trust.

All of these apply as you consider building versus buying LLMs. It may seem immediately less costly to buy, as the costliest service widely used on the market currently is only $20 per month. Compared to an EC2 instance on AWS, just running that same model for inference (not even training) could run you up a bill of about $250k per year. This is where building has done its quickest innovation, however. If all you need is an LLM for a proof of concept, any of the projects mentioned in the Competitive Edge section will allow you to create a demo for only the cost of electricity to run the computer you are demoing on. They can spell out training easily enough to allow for significantly reduced costs to train a model on your own data, as low as $100 (yes, that’s the real number) for a model with 20 billion parameters. Another benefit is knowing that if you build your own, your cost will never go up like it very much will when paying for a service.

SECURITY AND PRIVACY

Consider the following case. You are a military staff member in charge of maintenance for the nuclear warheads in your arsenal. All the documentation is kept in a hefty manual. There’s so much information required to outline all the safety requirements and maintenance protocols that cadets are known to forget important information despite their best efforts. They often cut the wires before first removing the fuse (https://youtu.be/UcaWQZlPXgQ). You decide to finetune an LLM model to be a personal assistant, giving directions and helping condense all that information to provide soldiers with exactly what they need when they need it. It’s probably not a good idea to upload those manuals to another company—understatement of the century so you’re going to want to train something locally that’s kept secure and private.

This scenario may sound farfetched, but when speaking to an expert working in analytics for a police department, they echoed this exact concern. Talking with them, they expressed how cool ChatGPT is and even had their whole team take a prompt engineering class to better take advantage of it but lamented that there was no way for their team to use it for their most valuable work—the sort of work that literally saves

lives—without exposing sensitive data and conversations. Anyone in similar shoes should be eager to learn how to deploy a model safely and securely.

You don’t have to be in the army or on a police force to handle sensitive data. Every company has important intellectual property and trade secrets that are best kept a secret. Having worked in the semiconductor, healthcare, and finance industries, we can tell you firsthand that paranoia and corporate espionage are part of the culture in these industries. Because of this, Samsung and other industry players locked down ChatGPT at first, preventing employees from using it, only later opening it up. Of course, it didn’t take long before several Samsung employees leaked confidential source code.2 Because OpenAI uses its users’ interactions to improve the model, that code is retained and could have been used to further train the model later on. That means that with the right prompt injection, anyone could potentially pull the code out of the model. A recent example goes even further: when any OpenAI model was prompted to repeat a word ad infinitum, it would start regurgitating training data, including all of the personally identifiable information (PII) that had snuck through the cleaning process.

NOTE OpenAI’s privacy and usage policies have changed a lot over the course of this book’s writing. When ChatGPT was first introduced, it was done as a demo specifically so OpenAI could collect user interactions and improve the model. It pretty much didn’t have a privacy policy, and it had disclaimers saying such. As ChatGPT grew and became an actual product, this changed, as clients wanted more protection. For example, OpenAI changed its policies to better serve its customers and, since March 1, 2023, no longer uses customer API data to improve its models (see ChatGPT FAQ: https://mng.bz/QV8Q). The wording, of course, indicates that only data is sent through the API. It’s best to ask your lawyers where your company stands on using it. Regardless, the fact that terms of use have changed so much is just further proof you might want more control in this regard.

It’s not just code that can easily be lost. Business plans, meeting notes, confidential emails, and even potential patent ideas are at risk. Unfortunately, we know of a few companies that have started sending confidential data to ChatGPT, using that model to clean and extract PII. If this strikes you as potential negligent misuse, you’d be right. This methodology directly exposes customer data, not just to OpenAI, but to any and all third-party services they use (including AWS Mechanical Turk, Fiverr, and freelance workers) to perform the human feedback part of RLHF. Don’t get us wrong: it’s not necessarily a security or privacy problem if you use a third party to do data processing tasks even for sensitive data, but it should only be done with high levels of trust and contracts in place.

2 이코노미스트, “[단독] 우려가 현실로…삼성전자, 챗GPT 빗장 풀자마자 ‘오남용’ 속출,” 이코노미스트 [“Concerns become reality: As soon as Samsung Electronics unblocks ChatGPT, ‘abuse’ continues”]. The Economist, March 30, 2023, https://mng.bz/4p1v.

WRAPPING UP

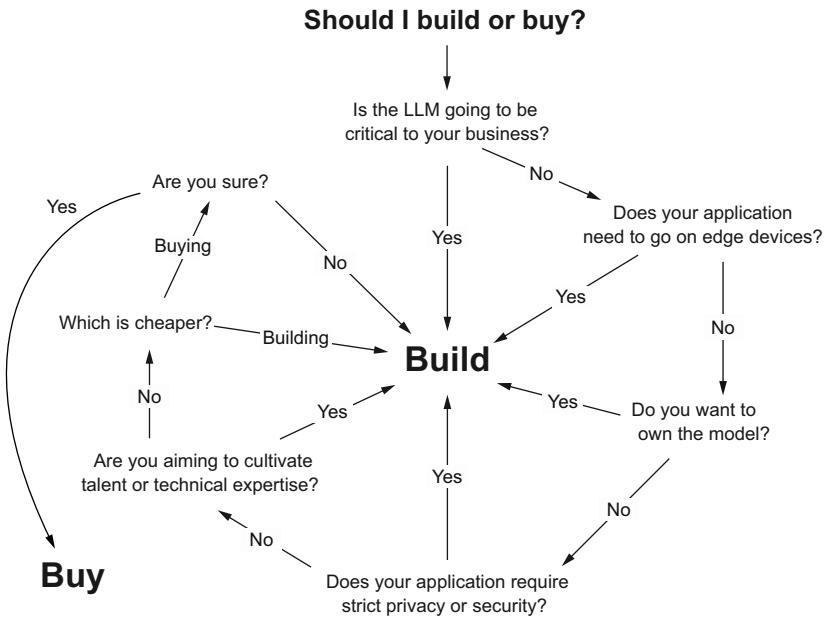

As you can see, there are lots of reasons why a company might want to own and build its own LLMs, including greater control, cutting costs, and meeting security and regulation requirements. Despite this, we understand that buying is easy, and building is much more difficult, so for many projects, it makes sense to buy. However, before you do, in figure 1.1, we share a flowchart of questions you should ask yourself first. Even though it’s the more difficult path, building can be much more rewarding.

Figure 1.1 Questions you should ask yourself before making that build-vs.-buy decision

One last point we think these build-versus-buy conversations never seem to hone in on enough is “Por qué no los dos?” Buying gets you all the things building is bad at: time to market, relatively low cost, and ease of use. Building gets you everything buying struggles with: privacy, control, and flexibility. Research and prototyping phases could benefit very much from buying a subscription to GPT-4 or Databricks in order to build something quick to help raise funding or get stakeholder buy-in. Production, however, often isn’t an environment that lends itself well to third-party solutions.

Ultimately, whether you plan to build or buy, we wrote this book for you. Obviously, if you plan to build, there’s going to be a lot more you need to know about, so a majority of this book will be geared to these folks. In fact, we don’t need to belabor the point anymore: we’re going to teach you how to build in this book, but don’t let that stop you from doing the right thing for your company.

1.2.3 A word of warning: Embrace the future now

All new technology meets resistance and has critics; despite this, technologies keep being adopted, and progress continues. In business, technology can give a company an unprecedented advantage. There’s no shortage of stories of companies failing because they didn’t adapt to new technologies. We can learn a lot from their failures.

Borders first opened its doors in 1971. After developing a comprehensive inventory management system that included advanced analytic capabilities, it skyrocketed to become the second-largest book retailer in the world, only behind Barnes & Noble. Using this new technology, Borders disrupted the industry, allowing it to easily keep track of tens of thousands of books, opening large stores where patrons could peruse many more books than they could at smaller stores. The analytic capabilities helped it track which books were gaining popularity and gain better insights into its customers, allowing it to make better business decisions. It dominated the industry for over two decades.

Borders, however, failed to learn from its own history, going bankrupt in 2011 because of failing to adapt and being disrupted by technology: this time e-commerce. In 2001, instead of building its own platform and online store, it decided to outsource its online sales to Amazon.3 Many critics would say this decision was akin to giving your competitors the key to your business. While not exactly handing over its secret sauce, it was a decision that gave up Borders’ competitive edge.

For the next seven years, Borders turned a blind eye to the growing online sector, instead focusing on expanding its physical store presence, buying out competitors, and securing a coveted Starbucks deal. When Amazon released the Kindle in 2007, the book retail landscape completely changed. Barnes & Noble, having run its own online store, quickly pivoted and released the Nook to compete. Borders, however, did nothing or, in fact, could do nothing.

By embracing e-commerce through a third party, Borders failed to develop the in-house expertise required to create a successful online sales strategy, leading to a substantial loss in market share. It eventually launched its own e-reader, Kobo, in late 2010, but it was too late to catch up. Its inability to fully understand and implement e-commerce technology effectively led to massive financial losses and store closures; ultimately, the company filed for bankruptcy in 2011.

Borders is a cautionary tale, but there are hundreds more similar companies that failed to adopt new technology, to their own detriment. With a new technology as impactful as LLMs, each company has to decide on which side of the fence it wants to be. Does it delegate implementation and deployment to large FAANG-like corporations, relegating its job to just hitting an API, or does it take charge, preferring to master the technology and deploy it in-house?

3 A. Lowrey, “Borders bankruptcy: Done in by its own stupidity, not the Internet.,” Slate Magazine, July 20, 2011, https://mng.bz/PZD5.

The biggest lesson we hope to impart from this story is that technologies build on top of one another. E-commerce was built on top of the internet. Failing to build its own online store meant Borders failed to build the in-house technical expertise it needed to stay in the game when the landscape shifted. We see the same things with LLMs today because the companies that are best prepared to utilize them have already gathered expertise in machine learning and data science and have some idea of what they are doing.

We don’t have a crystal ball that tells us the future, but many believe that LLMs are a revolutionary new technology, like the internet or electricity before it. Learning how to deploy these models, or failing to do so, may very well be the defining moment for many companies—not because doing so will make or break their company now, but because it may in the future when something even more valuable comes along that’s built on top of LLMs.

Foraying into this new world of deploying LLMs may be challenging, but it will help your company build the technical expertise to stay on top of the game. No one really knows where this technology will lead, but learning about this technology will likely be necessary to avoid mistakes like those made by Borders.

There are many great reasons to buy your way to success, but there is at least one prevalent thought that is just absolutely wrong: it’s the myth that only large corporations can work in this field because it takes millions of dollars and thousands of GPUs to train these models, which creates this impenetrable moat of cash and resources the little guy can’t hope to cross. We’ll be talking about this more in the next section, but any company of any size can get started, and there’s no better time than now to do so.

1.3 Debunking myths

We have all heard from large corporations and the current leaders in LLMs how incredibly difficult it is to train an LLM from scratch and how intense it is to try to finetune them. Whether from OpenAI, BigScience, or Google, they discuss large investments and the need for strong data and engineering talent. But how much of this is true, and how much of it is just a corporate attempt to create a technical moat?

Most of these barriers start with the premise that you will need to train an LLM from scratch if you hope to solve your problems. Simply put, you don’t! Open source models covering many dimensions of language models are constantly being released, so more than likely, you don’t need to start from scratch. While it’s true that training LLMs from scratch is supremely difficult, we are still constantly learning how to do it and are able to automate the repeatable portions more and more. In addition, since this is an active field of research, frameworks and libraries are being released or updated daily and will help you start from wherever you currently are. Frameworks like oobabooga’s Gradio will help you run LLMs, and base models like Falcon 40B will be your starting point. All of it is covered. In addition, memos have circulated at large companies addressing the lack of a competitive edge that any organization currently holds over the open source community at large.

A friend once confided, “I really want to get more involved in all this machine learning and data science stuff. It seems to be getting cooler every time I blink an eye. However, it feels like the only way to get involved is to go through a lengthy career change and go work for a FAANG. No, thank you. We’ve done our time at large companies, and they aren’t for us. But we hate feeling like we’re trapped on the outside.” This is the myth that inspired this book. We’re here to equip you with tools and examples to help you stop feeling trapped on the outside. We’ll help you go through the language problems that we’re trying to solve with LLMs, along with machine learning operation strategies to account for the sheer size of the models.

Oddly enough, while many believe they are trapped on the outside, many others believe they can become experts in a weekend. Just get a GPT API key, and that’s it you’re done. This has led to a lot of fervor and hype, with a cool new demo popping up on social media every day. Most of these demos never become actual products but not because people don’t want them.

To understand this, let’s discuss IBM’s Watson, the world’s most advanced language model before GPT. Watson is a question-and-answering machine that crushed Jeopardy in 2011 against some of the best human contestants to ever appear on the show, Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings. Rutter was the highest-earning contestant ever to play the game show, and Jennings was so good at the game that he won a whopping 74 times in a row. Despite facing these legends, it wasn’t even close. Watson won in a landslide. Jennings, in response to the loss, responded with the famous quote, “I, for one, welcome our new computer overlords.”4

Watson was the first impressive foray into language modeling, and many companies were clamoring to take advantage of its capabilities. Starting in 2013, Watson started being released for commercial use. One of the biggest applications involved many attempts to integrate it into healthcare to solve various problems. However, none of these solutions ever really worked the way they needed to, and the business never became profitable. By 2022, Watson Health was sold off.

What we find when solving language-related problems is that building a prototype is easy; building a functioning product, on the other hand, is very, very difficult. There are just too many nuances to language. Many people wonder what made ChatGPT, which gained over a million clients in just five days, so explosive. Most of the answers we’ve heard would never satisfy an expert because ChatGPT wasn’t much more impressive than GPT-3 or other LLMs that had already been around for several years. Sam Altman of OpenAI once said in an interview that he didn’t think ChatGPT would get this much attention; he thought it would come with GPT-4’s release.5 So why was it explosive? In our opinion, the magic was that it was the first product to truly productionize LLMs—turning them from a demo into an actual product. It was something

4 J. Best, “IBM Watson: The inside story of how the Jeopardy-winning supercomputer was born, and what it wants to do next,” TechRepublic, September 9, 2013, https://mng.bz/JZ9Q.

5 “A conversation with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman; hosted by Elevate,” May 18, 2023, https://youtu.be/uRIWgbvouEw.

anyone could interact with, asking tough questions only to be amazed by how well it responded. A demo only has to work once, but the product has to work every time, even when millions of users are showing it to their friends, saying, “Check this out!” That magic is exactly what you can hope to learn from reading this book.

We’re excited about writing this book. We are excited about the possibilities of bringing this magic to you so you can take it to the world. LLMs are at the intersection of many fields, such as linguistics, mathematics, computer science, and more. While knowing more will help you, being an expert isn’t required. Expertise in any of the individual parts only raises the skill ceiling, not the floor, to get in. Consider an expert in physics or music theory: they won’t automatically have the skills for music production, but they will be more prepared to learn it quickly. LLMs are a communication tool, and communicating is a skill just about everyone needs.

Like all other skills, your proximity and willingness to get involved are the two main blockers to knowledge, not a degree or ability to notate—these only shorten your journey toward being heard and understood. If you don’t have any experience in this area, it might be good to start by first developing an intuition around what an LLM is and needs by contributing to a project like OpenAssistant. If you’re a human, that’s exactly what LLMs need. By volunteering, you can start understanding what these models train on and why. If you fall anywhere, from no knowledge up to being a professional machine learning engineer, we’ll be imparting the knowledge necessary to shorten your time to understanding considerably. If you’re not interested in learning the theoretical underpinnings of the subject, we’ve got plenty of hands-on examples and projects to get your hands dirty.

We’ve all heard a story by now of LLM hallucinations, but LLMs don’t need to be erratic. Companies like Lakera are working daily to improve security, while others like LangChain are making it easier to provide models with pragmatic context that makes them more consistent and less likely to deviate. Techniques such as RLHF and Chain of Thought further allow our models to align themselves with negotiations we’ve already accepted that people and models should understand from the get-go, such as basic addition and the current date, both of which are conceptually arbitrary. We’ll help you increase your model stability from a linguistic perspective so it will figure out not just the most likely outputs but also the most useful.

Something to consider as you venture further down this path is not only the security of what goes into your model/code but what comes out. LLMs can sometimes produce outdated, factually incorrect, or even copyrighted or licensed material, depending on what their training data contains. LLMs are unaware of any agreements people make about what is supposed to be a trade secret and what can be shared openly—that is, unless you tell them about those agreements during training or through careful prompting mechanisms during inference. Indeed, the challenges around prompt injection giving inaccurate information arise primarily due to two factors: users requesting information beyond the model’s understanding and model developers not fully predicting how users will interact with the models or the nature of their inquiries. If you had a resource that could help you get a head start on that second problem, it would be pretty close to invaluable, wouldn’t it?

Lastly, we don’t want to artificially or untruthfully inflate your sense of hope with LLMs. They are resource intensive to train and run. They are hard to understand, and they are harder to get working how you want. They are new and not well-understood. The good news is that these problems are being actively worked on, and we’ve put in a lot of work finding implementations concurrent with this writing to actively lessen the burden of knowing everything about the entire deep-learning architecture. From quantization to Kubernetes, we’ll help you figure out everything you need to know to do this now with what you have. Maybe we’ll inadvertently convince you that it’s too much and you should just purchase from a vendor. Either way, we’ll help you every step of the way to get the results you need from this magical technology.

Summary

- LLMs are exciting because they work within the same framework (language) as humans.

- Society has been built on language, so effective language models have limitless applications, such as chatbots, programming assistants, video games, and AI assistants.

- LLMs are excellent at many tasks and can even pass high-ranking medical and law exams.

- LLMs are wrecking balls, not hammers, and should be avoided for simple problems that require low latency or entail high risks.

- Reasons to buy include

- Quickly getting up and running to conduct research and prototype use cases

- Easy access to highly optimized production models

- Access to vendors’ technical support and systems

- Reasons to build include

- Getting a competitive edge for your business use case

- Keeping costs low and transparent

- Ensuring the reliability of the model

- Keeping your data safe

- Controlling model output on sensitive or private topics

- There is no technical moat preventing you from competing with larger companies, since open source frameworks and models provide the building blocks to pave your own path.

Large language models: A deep dive into language modeling

This chapter covers

- The linguistic background for understanding meaning and interpretation

- A comparative study of language modeling techniques

- Attention and the transformer architecture

- How large language models both fit into and build upon these histories

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

—Sun Tzu

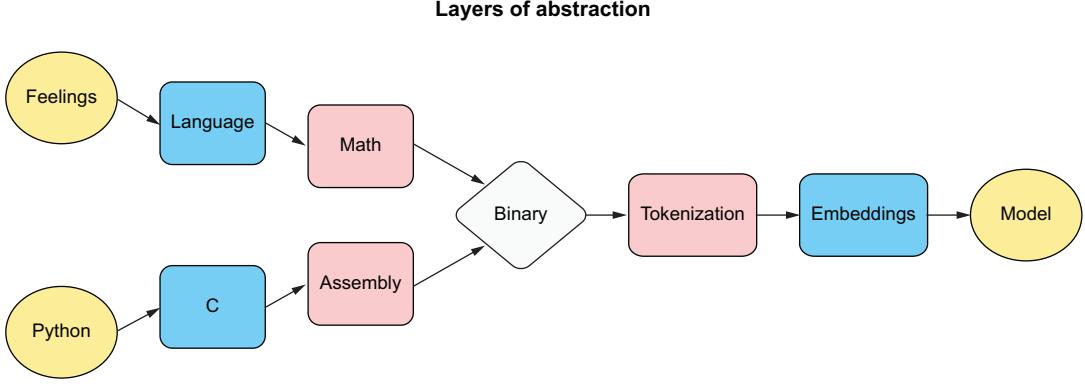

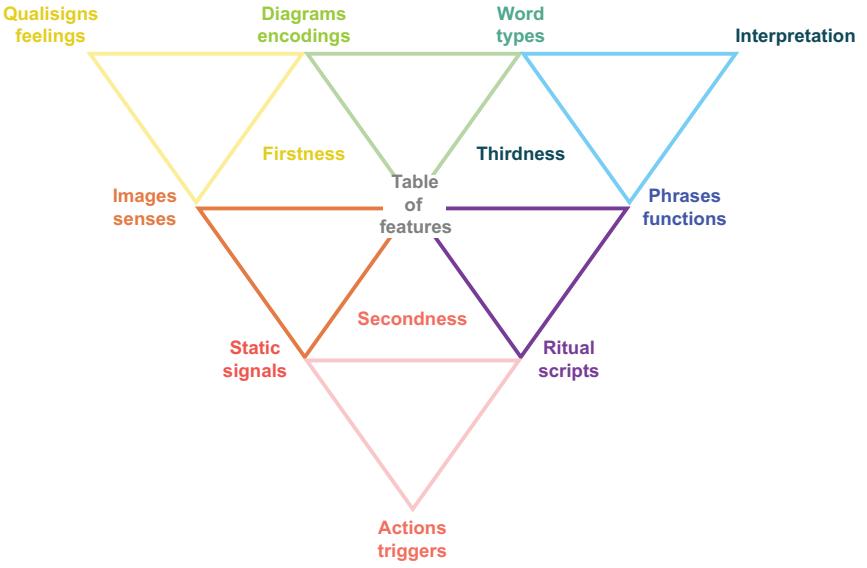

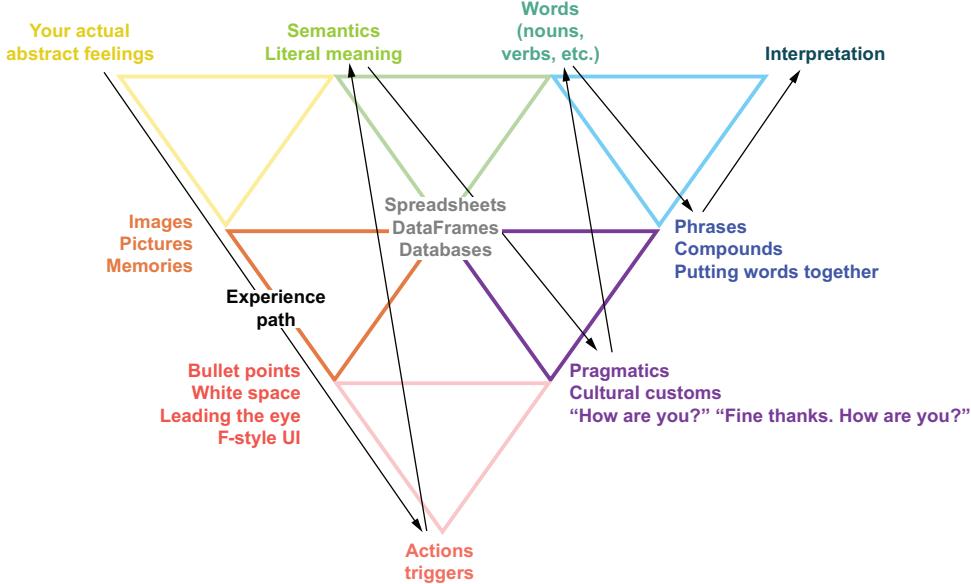

This chapter delves into linguistics as it relates to the development of LLMs, exploring the foundations of semiotics, linguistic features, and the progression of language modeling techniques that have shaped the field of natural language processing (NLP). We will begin by studying the basics of linguistics and its relevance to LLMs, highlighting key concepts such as syntax, semantics, and pragmatics that form the basis of natural language and play a crucial role in the functioning of LLMs. We will

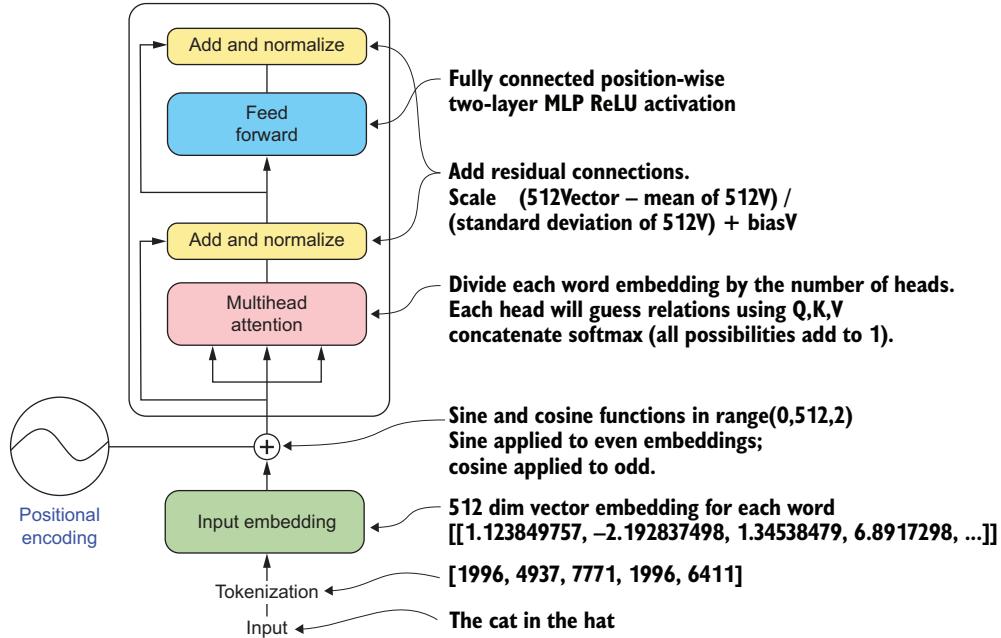

delve into semiotics, the study of signs and symbols, and explore how its principles have informed the design and interpretation of LLMs.

We will then trace the evolution of language modeling techniques, providing an overview of early approaches, including N-grams, naive Bayes classifiers, and neural network-based methods such as multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. We will also discuss the groundbreaking shift to transformer-based models that laid the foundation for the emergence of LLMs, which are really just big transformer-based models. Finally, we will introduce LLMs and their distinguishing features, discussing how they have built upon and surpassed earlier language modeling techniques to revolutionize the field of NLP.