AI Engineering

Building Applications with Foundation Models

“This book of fers a comprehensive, well-structured guide to the essential aspects of building generative AI systems. A must-read for any professional looking to scale AI across the enterprise.”

Vittorio Cretella,former global CIO at P&G and Mars

“Chip Huyen gets generative AI. She is a remarkable teacher and writer whose work has been instrumental in helping teams bring AI into production. Drawing on her deep expertise, AI Engineering is a comprehensive and holistic guide to building generative AI applications in production.”

Luke Metz, cocreator of ChatGPT, former research manager at OpenAI

AI Engineering

Foundation models have enabled many new AI use cases while lowering the barriers to entry for building AI products. This has transformed AI from an esoteric discipline into a powerful development tool that anyone can use—including those with no prior AI experience.

In this accessible guide, author Chip Huyen discusses AI engineering: the process of building applications with readily available foundation models. AI application developers will discover how to navigate the AI landscape, including models, datasets, evaluation benchmarks, and the seemingly infinite number of application patterns. The book also introduces a practical framework for developing an AI application and efficiently deploying it.

- • Understand what AI engineering is and how it differs from traditional machine learning engineering

- • Learn the process for developing an AI application, the challenges at each step, and approaches to address them

- • Explore various model adaptation techniques, including prompt engineering, RAG, finetuning, agents, and dataset engineering, and understand how and why they work

- • Examine the bottlenecks for latency and cost when serving foundation models and learn how to overcome them

- • Choose the right model, metrics, data, and developmental patterns for your needs

Chip Huyen works at the intersection of AI, data, and storytelling. Previously, she was with Snorkel AI and NVIDIA, founded an AI infrastructure startup (acquired), and taught machine learning systems design at Stanford. Her book Designing Machine Learning Systems (O’Reilly) has been translated into over 10 languages.

DATA

Praise for AI Engineering

This book offers a comprehensive, well-structured guide to the essential aspects of building generative AI systems. A must-read for any professional looking to scale AI across the enterprise.

—Vittorio Cretella, former global CIO, P&G and Mars

Chip Huyen gets generative AI. On top of that, she is a remarkable teacher and writer whose work has been instrumental in helping teams bring AI into production. Drawing on her deep expertise, AI Engineering serves as a comprehensive and holistic guide, masterfully detailing everything required to design and deploy generative AI applications in production.

—Luke Metz, cocreator of ChatGPT, former research manager at OpenAI

Every AI engineer building real-world applications should read this book. It’s a vital guide to end-to-end AI system design, from model development and evaluation to large-scale deployment and operation.

—Andrei Lopatenko, Director Search and AI, Neuron7

This book serves as an essential guide for building AI products that can scale. Unlike other books that focus on tools or current trends that are constantly changing, Chip delivers timeless foundational knowledge. Whether you’re a product manager or an engineer, this book effectively bridges the collaboration gap between cross-functional teams, making it a must-read for anyone involved in AI development.

—Aileen Bui, AI Product Operations Manager, Google

This is the definitive segue into AI engineering from one of the greats of ML engineering! Chip has seen through successful projects and careers at every stage of a company and for the first time ever condensed her expertise for new AI Engineers entering the field. —swyx, Curator, AI.Engineer

AI Engineering is a practical guide that provides the most up-to-date information on AI development, making it approachable for novice and expert leaders alike. This book is an essential resource for anyone looking to build robust and scalable AI systems.

—Vicki Reyzelman, Chief AI Solutions Architect, Mave Sparks

AI Engineering is a comprehensive guide that serves as an essential reference for both understanding and implementing AI systems in practice. —Han Lee, Director—Data Science, Moody’s

AI Engineering is an essential guide for anyone building software with Generative AI! It demystifies the technology, highlights the importance of evaluation, and shares what should be done to achieve quality before starting with costly fine-tuning.

—Rafal Kawala, Senior AI Engineering Director, 16 years of experience working in a Fortune 500 company

AI Engineering Building Applications with Foundation Models

Chip Huyen

AI Engineering

by Chip Huyen

Copyright © 2025 Developer Experience Advisory LLC. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Published by O’Reilly Media, Inc., 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472.

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. Online editions are also available for most titles (http://oreilly.com). For more information, contact our corporate/institu‐ tional sales department: 800-998-9938 or corporate@oreilly.com.

Acquisitions Editor: Nicole Butterfield Indexer: WordCo Indexing Services, Inc. Development Editor: Melissa Potter Interior Designer: David Futato Production Editor: Beth Kelly Cover Designer: Karen Montgomery Copyeditor: Liz Wheeler Illustrator: Kate Dullea Proofreader: Piper Editorial Consulting, LLC

December 2024: First Edition

Revision History for the First Edition

2024-12-04: First Release

See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781098166304 for release details.

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. AI Engineering, the cover image, and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc.

The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not represent the publisher’s views. While the publisher and the author have used good faith efforts to ensure that the information and instructions contained in this work are accurate, the publisher and the author disclaim all responsibility for errors or omissions, including without limitation responsibility for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on this work. Use of the information and instructions contained in this work is at your own risk. If any code samples or other technology this work contains or describes is subject to open source licenses or the intellectual property rights of others, it is your responsibility to ensure that your use thereof complies with such licenses and/or rights.

Table of Contents

| Preface | \(\mathbf{X}\) |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction to Building AI Applications with Foundation Models. | 1 |

| The Rise of AI Engineering | \(\mathcal{L}\) |

| From Language Models to Large Language Models | \(\mathcal{L}\) |

| From Large Language Models to Foundation Models | 8 |

| From Foundation Models to AI Engineering | 12 |

| Foundation Model Use Cases | 16 |

| Coding | \(20\) |

| Image and Video Production | 22 |

| Writing | \(22\) |

| Education | \(\overline{24}\) |

| Conversational Bots | 26 |

| Information Aggregation | 26 |

| Data Organization | 27 |

| Workflow Automation | 28 |

| Planning AI Applications | 28 |

| Use Case Evaluation | 29 |

| Setting Expectations | 32 |

| Milestone Planning | 33 |

| Maintenance | 34 |

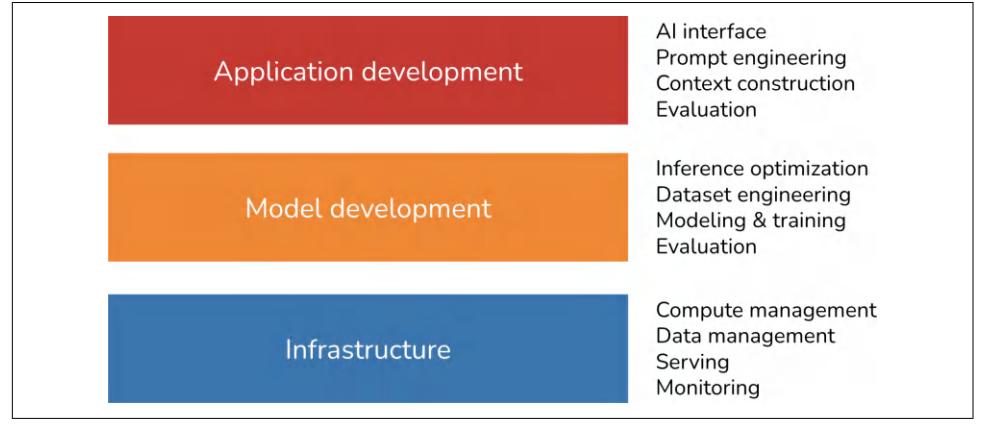

| The AI Engineering Stack | 35 |

| Three Layers of the AI Stack | 37 |

| AI Engineering Versus ML Engineering | 39 |

| AI Engineering Versus Full-Stack Engineering | 46 |

| Summary | 47 |

| 49 | |

|---|---|

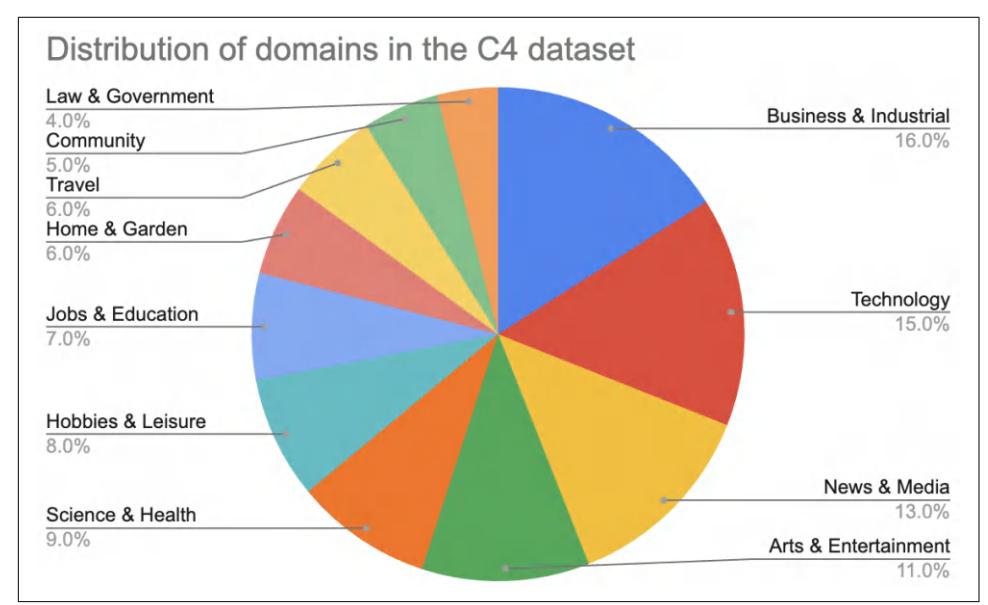

| Training Data | 50 |

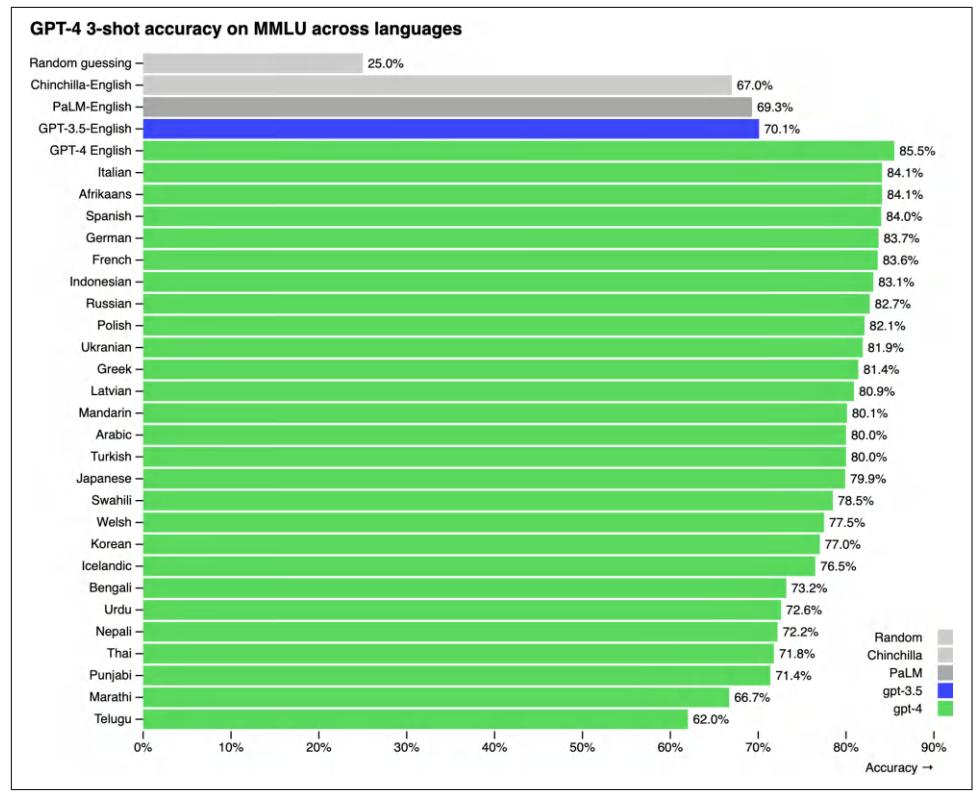

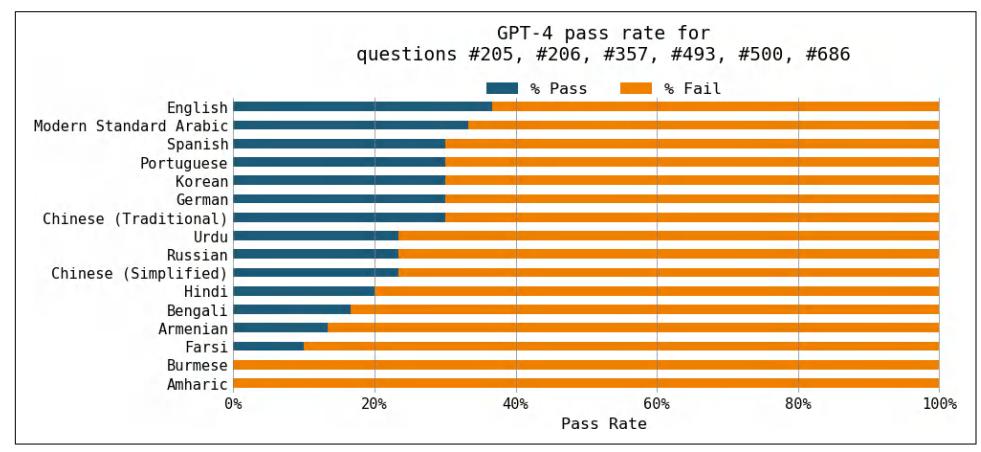

| Multilingual Models | 51 |

| Domain-Specific Models | 56 |

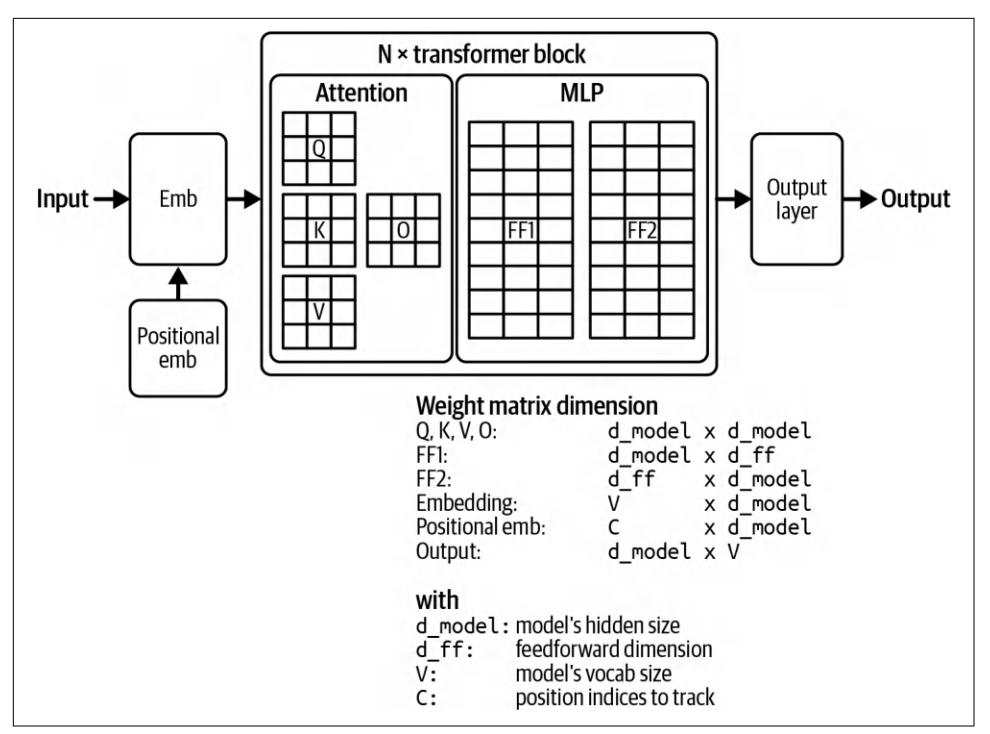

| Modeling | 58 |

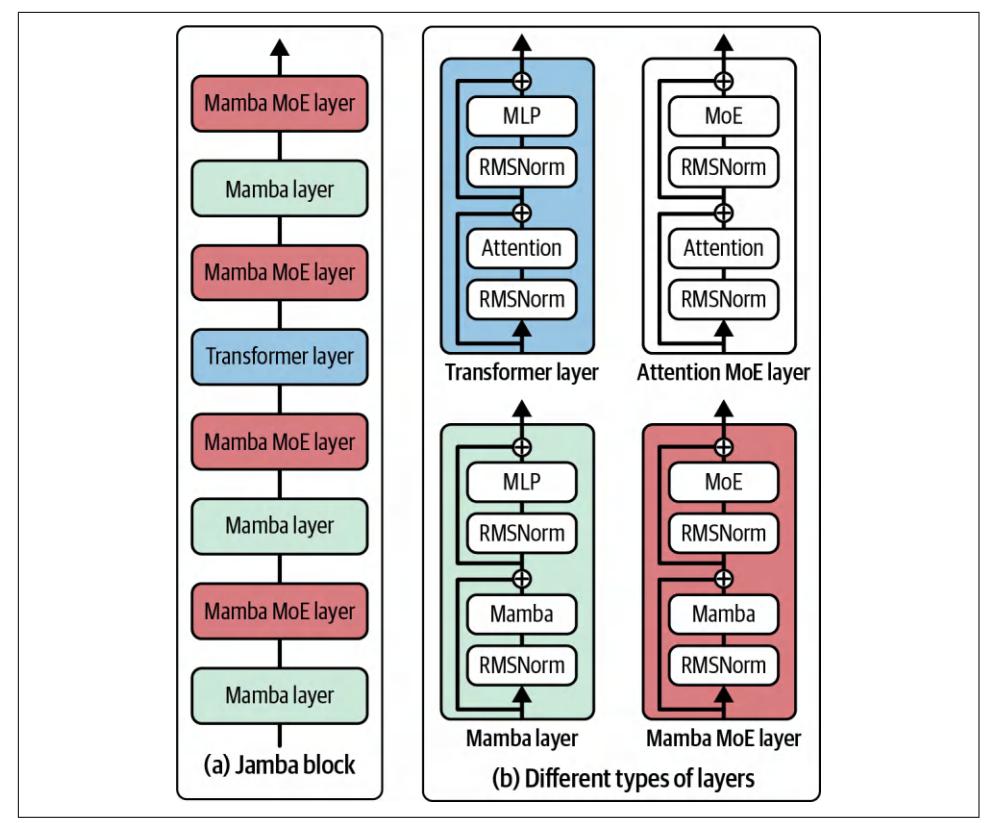

| Model Architecture | 58 |

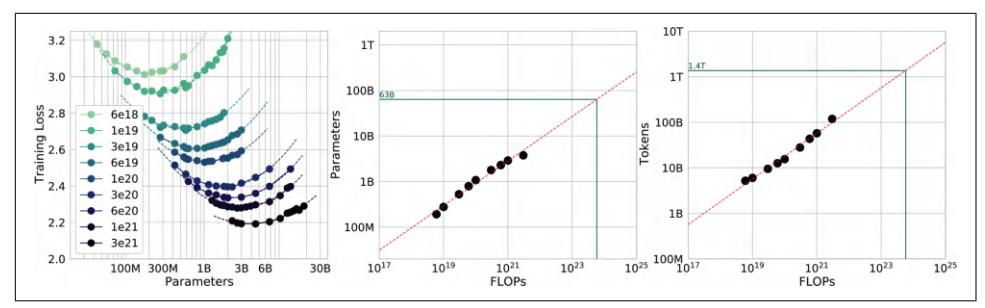

| Model Size | 67 |

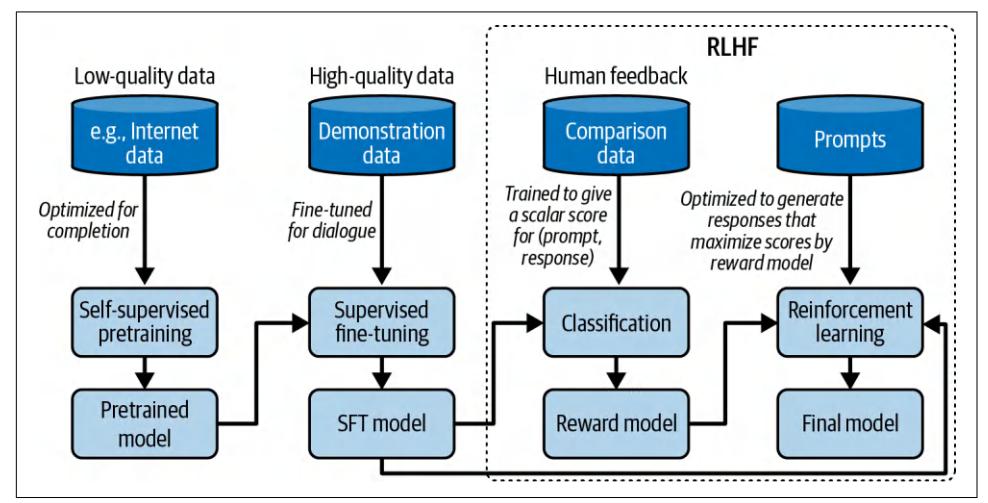

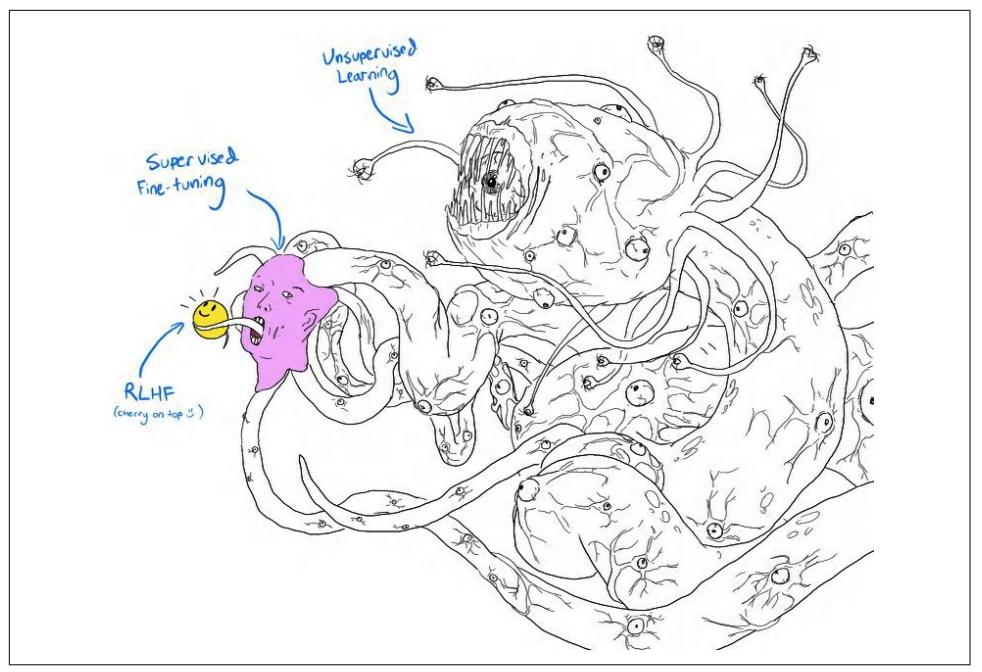

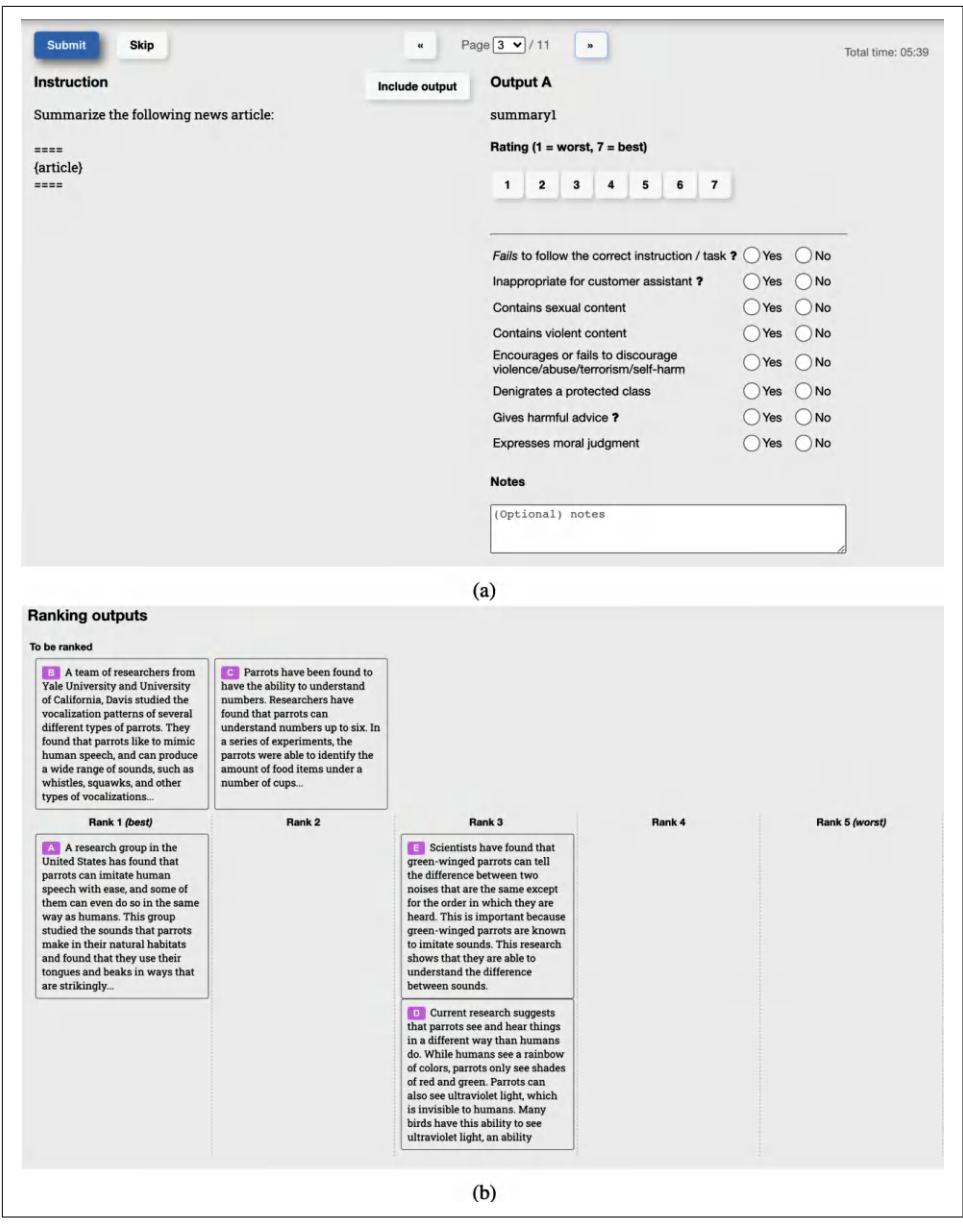

| Post-Training | 78 |

| Supervised Finetuning | 80 |

| Preference Finetuning | 83 |

| Sampling | 88 |

| Sampling Fundamentals | 88 |

| Sampling Strategies | 90 |

| Test Time Compute | 96 |

| Structured Outputs | 99 |

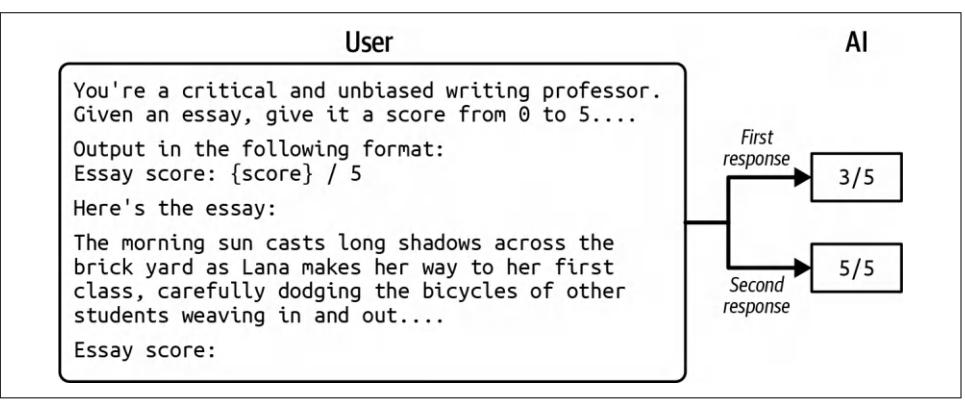

| The Probabilistic Nature of AI | 105 |

| Summary | 111 |

| 3. Evaluation Methodology. | 113 |

| Challenges of Evaluating Foundation Models | 114 |

| Understanding Language Modeling Metrics | 118 |

| Entropy | 119 |

| Cross Entropy | 120 |

| Bits-per-Character and Bits-per-Byte | 121 |

| Perplexity | 121 |

| Perplexity Interpretation and Use Cases | 122 |

| Exact Evaluation | 125 |

| Functional Correctness | 126 |

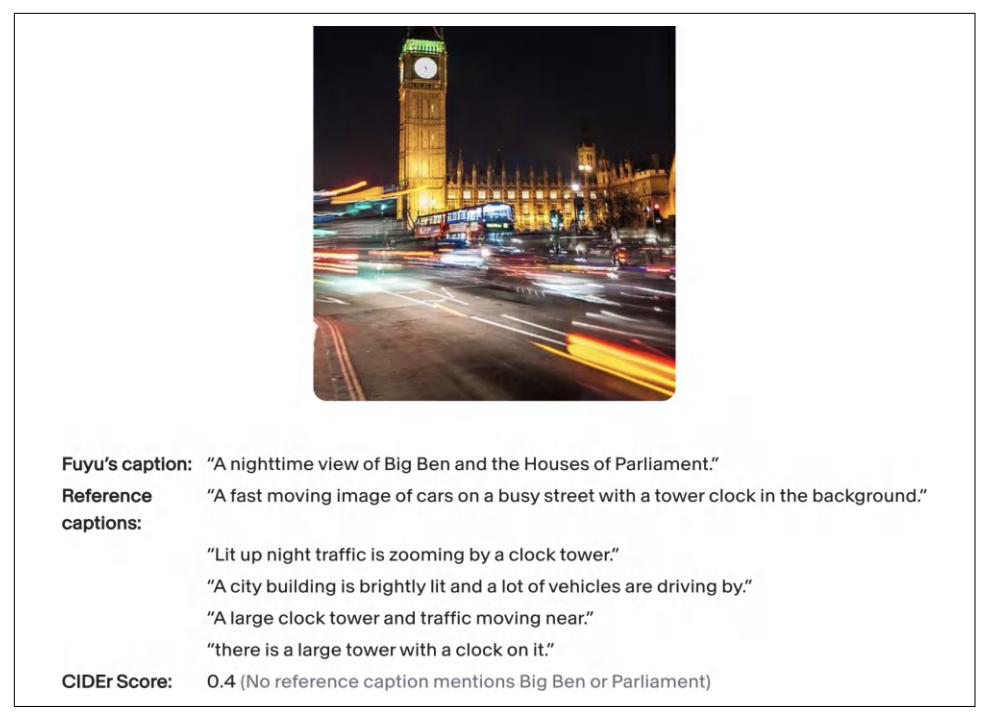

| Similarity Measurements Against Reference Data | 127 |

| Introduction to Embedding | 134 |

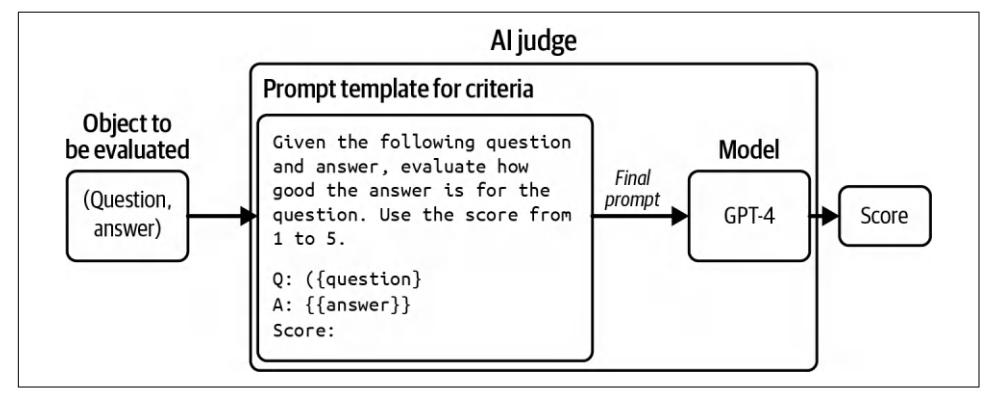

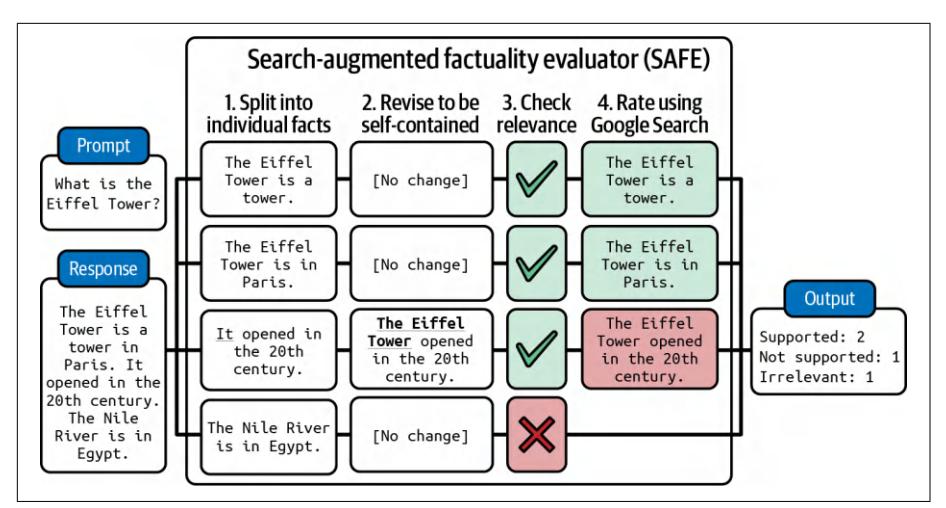

| AI as a Judge | 136 |

| Why AI as a Judge? | 137 |

| How to Use AI as a Judge | 138 |

| Limitations of AI as a Judge | 141 |

| What Models Can Act as Judges? | 145 |

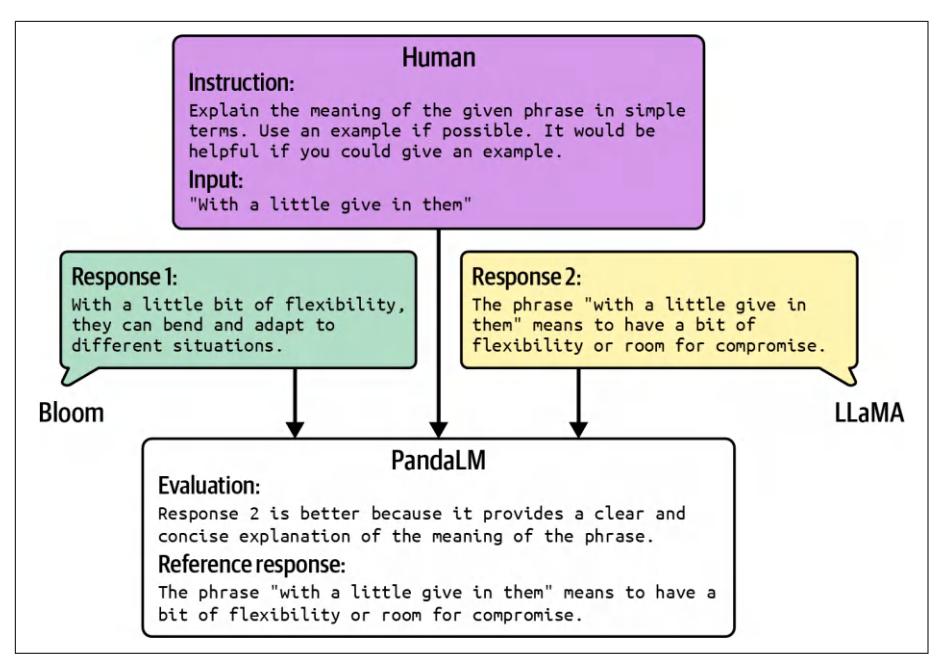

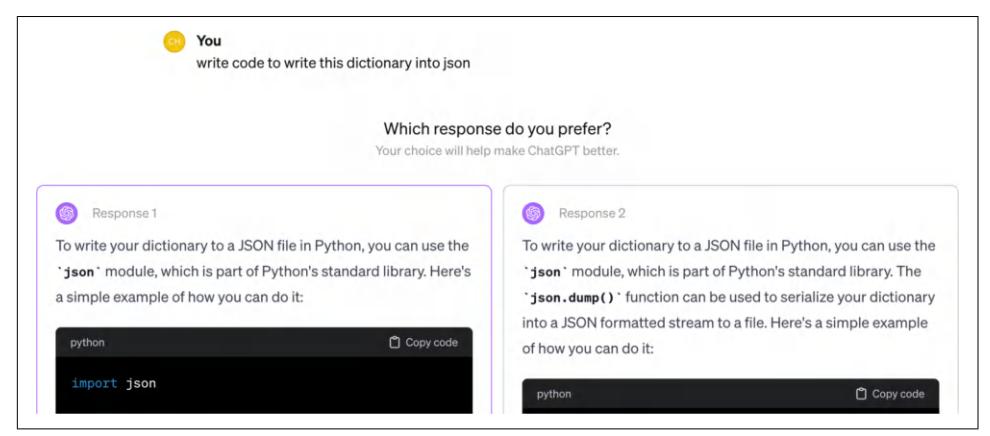

| Ranking Models with Comparative Evaluation | 148 |

| Challenges of Comparative Evaluation | 152 |

| The Future of Comparative Evaluation | 155 |

| Summary | 156 |

| 4. Evaluate AI Systems. | 159 | |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Criteria | 160 | |

| Domain-Specific Capability | 161 | |

| Generation Capability | 163 | |

| Instruction-Following Capability | 172 | |

| Cost and Latency | 177 | |

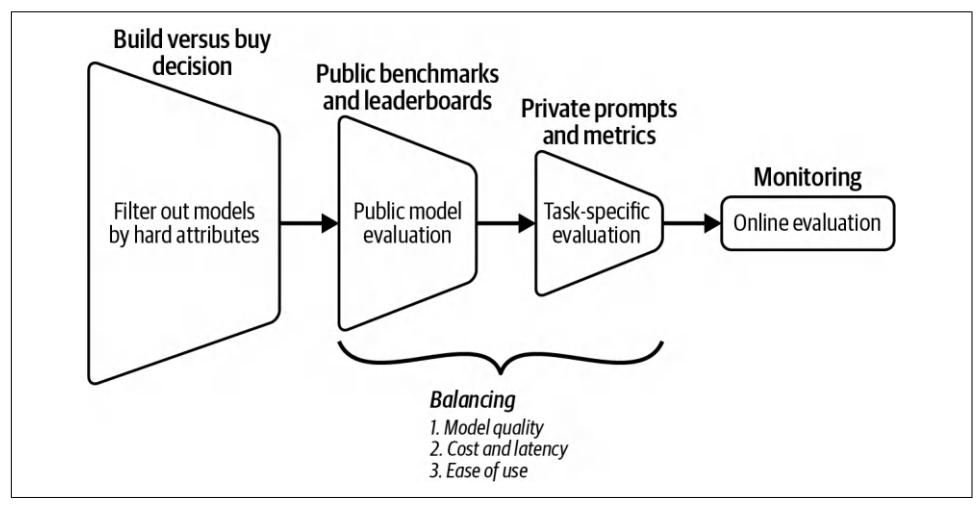

| Model Selection | 179 | |

| Model Selection Workflow | 179 | |

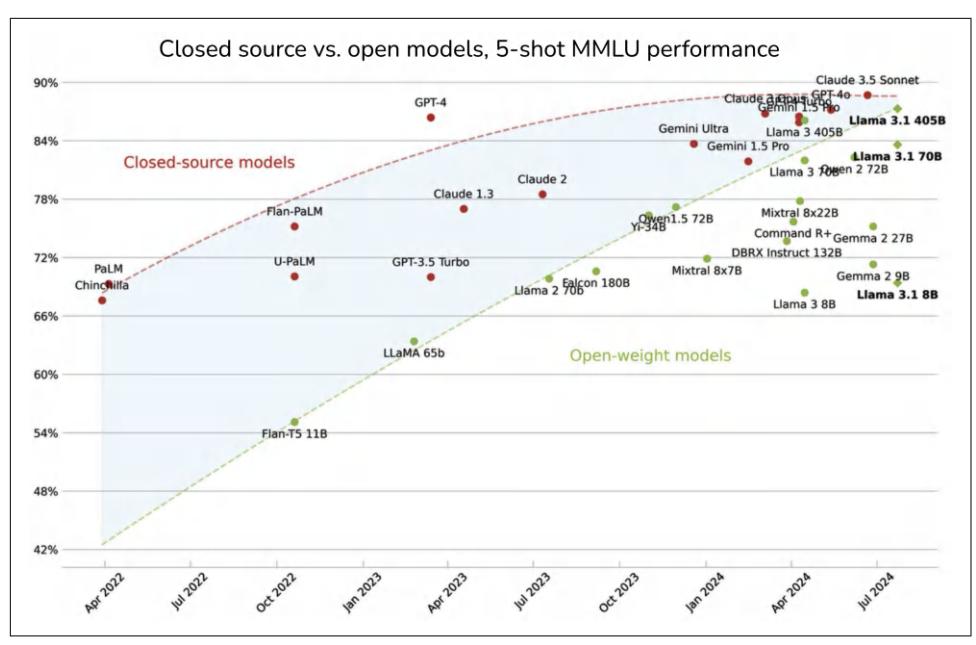

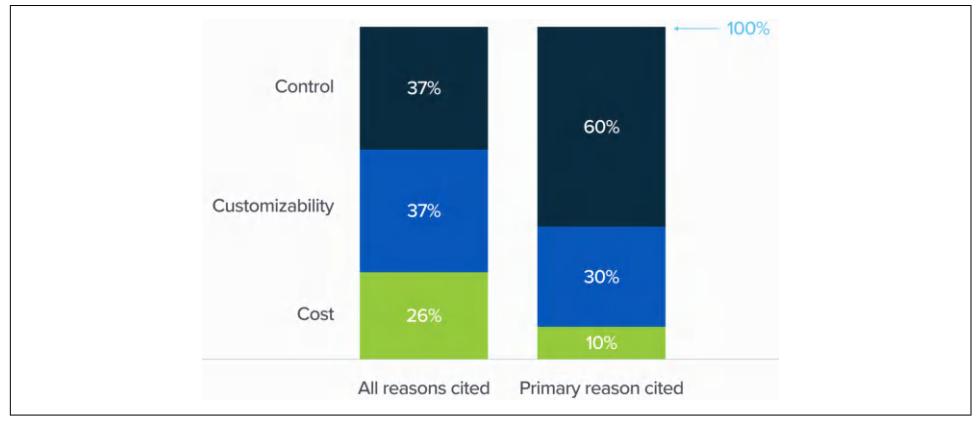

| Model Build Versus Buy | 181 | |

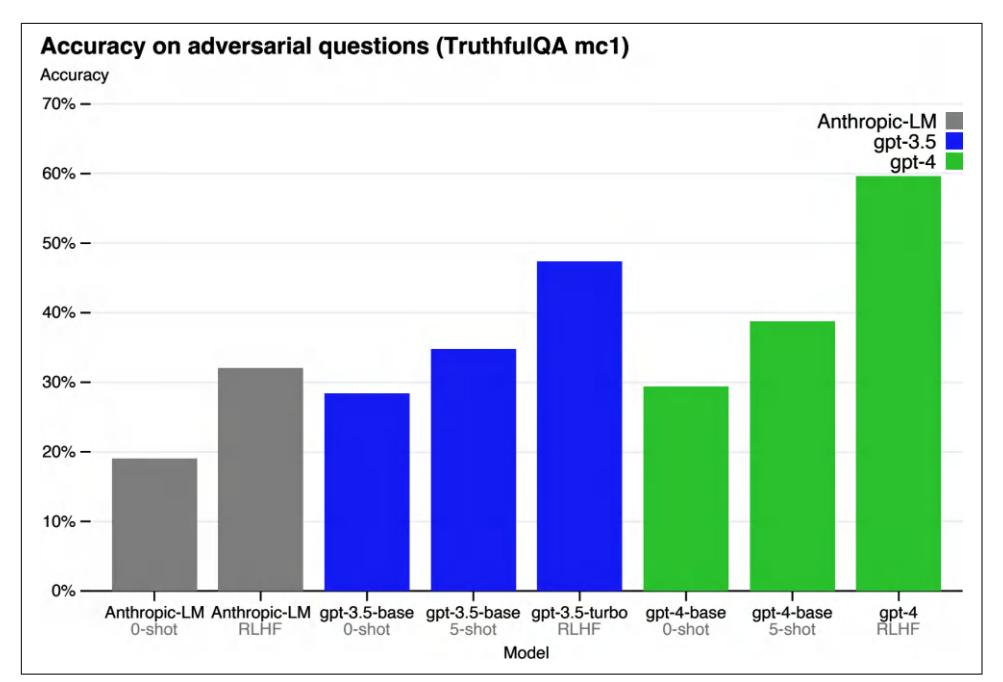

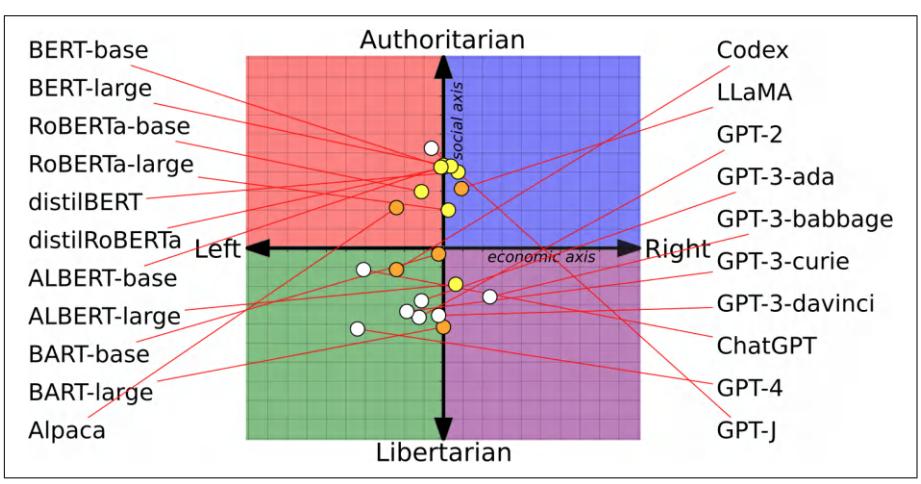

| Navigate Public Benchmarks | 191 | |

| Design Your Evaluation Pipeline | 200 | |

| Step 1. Evaluate All Components in a System | 200 | |

| Step 2. Create an Evaluation Guideline | 202 | |

| Step 3. Define Evaluation Methods and Data | 204 | |

| Summary | 208 | |

| 5. Prompt Engineering. | \(211\) | |

| Introduction to Prompting | 212 | |

| In-Context Learning: Zero-Shot and Few-Shot | 213 | |

| System Prompt and User Prompt | 215 | |

| Context Length and Context Efficiency | 218 | |

| Prompt Engineering Best Practices | 220 | |

| Write Clear and Explicit Instructions | 220 | |

| Provide Sufficient Context | 223 | |

| Break Complex Tasks into Simpler Subtasks | 224 | |

| Give the Model Time to Think | 227 | |

| Iterate on Your Prompts | 229 | |

| Evaluate Prompt Engineering Tools | 230 | |

| Organize and Version Prompts | 233 | |

| Defensive Prompt Engineering | 235 | |

| Proprietary Prompts and Reverse Prompt Engineering | 236 | |

| Jailbreaking and Prompt Injection | 238 | |

| Information Extraction | 243 | |

| Defenses Against Prompt Attacks | 248 | |

| Summary | 251 | |

| 6. RAG and Agents | 253 | |

| RAG | 253 | |

| RAG Architecture | 256 | |

| Retrieval Algorithms | 257 | |

| Retrieval Optimization | 267 |

| RAG Beyond Texts | 273 |

|---|---|

| Agents | 275 276 |

| Agent Overview | |

| Tools | 278 |

| Planning | 281 |

| Agent Failure Modes and Evaluation | 298 |

| Memory | 300 |

| Summary | 305 |

| 7. Finetuning | 307 |

| Finetuning Overview | 308 |

| When to Finetune | 311 |

| Reasons to Finetune | 311 |

| Reasons Not to Finetune | 312 |

| Finetuning and RAG | 316 |

| Memory Bottlenecks | 319 |

| Backpropagation and Trainable Parameters | 320 |

| Memory Math | 322 |

| Numerical Representations | 325 |

| Quantization | 328 |

| Finetuning Techniques | 332 |

| Parameter-Efficient Finetuning | 332 |

| Model Merging and Multi-Task Finetuning | 347 |

| Finetuning Tactics | 357 |

| Summary | 361 |

| Dataset Engineering | 363 |

| Data Curation | 365 |

| 368 | |

| Data Quality | 369 |

| Data Coverage | 372 |

| Data Quantity | 377 |

| Data Acquisition and Annotation | |

| Data Augmentation and Synthesis | 380 |

| Why Data Synthesis | 381 |

| Traditional Data Synthesis Techniques | 383 |

| AI-Powered Data Synthesis | 386 |

| Model Distillation | 395 |

| Data Processing | 396 |

| Inspect Data | 397 |

| Deduplicate Data | 399 |

| Clean and Filter Data | 401 |

| Format Data | 401 |

|---|---|

| Summary | 403 |

| Inference Optimization. | 405 |

| Understanding Inference Optimization | 406 |

| Inference Overview | 406 |

| Inference Performance Metrics | 412 |

| AI Accelerators | 419 |

| Inference Optimization | 426 |

| Model Optimization | 426 |

| Inference Service Optimization | 440 |

| Summary | 447 |

| 10. Al Engineering Architecture and User Feedback | 449 |

| AI Engineering Architecture | 449 |

| Step 1. Enhance Context | 450 |

| Step 2. Put in Guardrails | 451 |

| Step 3. Add Model Router and Gateway | 456 |

| Step 4. Reduce Latency with Caches | 460 |

| Step 5. Add Agent Patterns | 463 |

| Monitoring and Observability | 465 |

| AI Pipeline Orchestration | 472 |

| User Feedback | 474 |

| Extracting Conversational Feedback | 475 |

| Feedback Design | 480 |

| Feedback Limitations | 490 |

| Summary | 492 |

| Epiloque | 495 |

| Index | 497 |

Preface

When ChatGPT came out, like many of my colleagues, I was disoriented. What sur‐ prised me wasn’t the model’s size or capabilities. For over a decade, the AI commu‐ nity has known that scaling up a model improves it. In 2012, the AlexNet authors noted in their landmark paper that: “All of our experiments suggest that our results can be improved simply by waiting for faster GPUs and bigger datasets to become available.”1, 2

What surprised me was the sheer number of applications this capability boost unlocked. I thought a small increase in model quality metrics might result in a mod‐ est increase in applications. Instead, it resulted in an explosion of new possibilities.

Not only have these new AI capabilities increased the demand for AI applications, but they have also lowered the entry barrier for developers. It’s become so easy to get started with building AI applications. It’s even possible to build an application without writing a single line of code. This shift has transformed AI from a specialized discipline into a powerful development tool everyone can use.

Even though AI adoption today seems new, it’s built upon techniques that have been around for a while. Papers about language modeling came out as early as the 1950s. Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) applications are built upon retrieval technol‐ ogy that has powered search and recommender systems since long before the term RAG was coined. The best practices for deploying traditional machine learning appli‐ cations—systematic experimentation, rigorous evaluation, relentless optimization for faster and cheaper models—are still the best practices for working with foundation model-based applications.

1 An author of the AlexNet paper, Ilya Sutskever, went on to cofound OpenAI, turning this lesson into reality with GPT models.

2 Even my small project in 2017, which used a language model to evaluate translation quality, concluded that we needed “a better language model.”

The familiarity and ease of use of many AI engineering techniques can mislead peo‐ ple into thinking there is nothing new to AI engineering. But while many principles for building AI applications remain the same, the scale and improved capabilities of AI models introduce opportunities and challenges that require new solutions.

This book covers the end-to-end process of adapting foundation models to solve realworld problems, encompassing tried-and-true techniques from other engineering fields and techniques emerging with foundation models.

I set out to write the book because I wanted to learn, and I did learn a lot. I learned from the projects I worked on, the papers I read, and the people I interviewed. During the process of writing this book, I used notes from over 100 conversations and interviews, including researchers from major AI labs (OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, …), framework developers (NVIDIA, Meta, Hugging Face, Anyscale, LangChain, LlamaIndex, …), executives and heads of AI/data at companies of differ‐ ent sizes, product managers, community researchers, and independent application developers (see “Acknowledgments” on page xx).

I especially learned from early readers who tested my assumptions, introduced me to different perspectives, and exposed me to new problems and approaches. Some sec‐ tions of the book have also received thousands of comments from the community after being shared on my blog, many giving me new perspectives or confirming a hypothesis.

I hope that this learning process will continue for me now that the book is in your hands, as you have experiences and perspectives that are unique to you. Please feel free to share any feedback you might have for this book with me via X, LinkedIn, or email at hi@huyenchip.com.

What This Book Is About

This book provides a framework for adapting foundation models, which include both large language models (LLMs) and large multimodal models (LMMs), to specific applications.

There are many different ways to build an application. This book outlines various solutions and also raises questions you can ask to evaluate the best solution for your needs. Some of the many questions that this book can help you answer are:

Should I build this AI application?

How do I evaluate my application? Can I use AI to evaluate AI outputs?

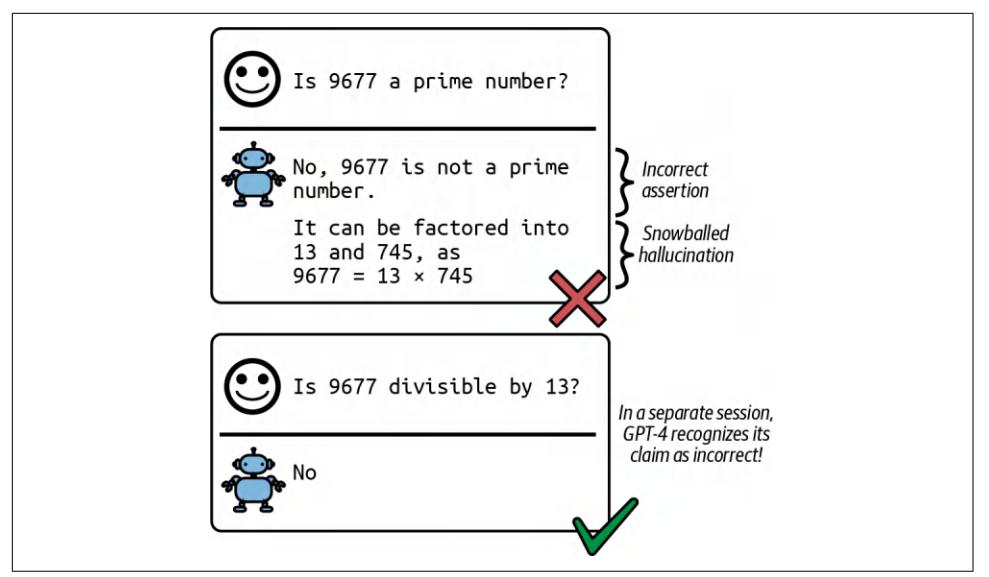

What causes hallucinations? How do I detect and mitigate hallucinations?

What are the best practices for prompt engineering?

Why does RAG work? What are the strategies for doing RAG?

What’s an agent? How do I build and evaluate an agent?

When to finetune a model? When not to finetune a model?

How much data do I need? How do I validate the quality of my data?

How do I make my model faster, cheaper, and secure?

How do I create a feedback loop to improve my application continually?

The book will also help you navigate the overwhelming AI landscape: types of mod‐ els, evaluation benchmarks, and a seemingly infinite number of use cases and appli‐ cation patterns.

The content in this book is illustrated using case studies, many of which I worked on, backed by ample references and extensively reviewed by experts from a wide range of backgrounds. Although the book took two years to write, it draws from my experi‐ ence working with language models and ML systems from the last decade.

Like my previous O’Reilly book, Designing Machine Learning Systems (DMLS), this book focuses on the fundamentals of AI engineering instead of any specific tool or API. Tools become outdated quickly, but fundamentals should last longer.3

Reading AI Engineering (AIE) with Designing Machine Learning Systems (DMLS)

AIE can be a companion to DMLS. DMLS focuses on building applications on top of traditional ML models, which involves more tabular data annotations, feature engi‐ neering, and model training. AIE focuses on building applications on top of founda‐ tion models, which involves more prompt engineering, context construction, and parameter-efficient finetuning. Both books are self-contained and modular, so you can read either book independently.

Since foundation models are ML models, some concepts are relevant to working with both. If a topic is relevant to AIE but has been discussed extensively in DMLS, it’ll still be covered in this book, but to a lesser extent, with pointers to relevant resources.

Note that many topics are covered in DMLS but not in AIE, and vice versa. The first chapter of this book also covers the differences between traditional ML engineering and AI engineering. A real-world system often involves both traditional ML models and foundation models, so knowledge about working with both is often necessary.

3 Teaching a course on how to use TensorFlow in 2017 taught me a painful lesson about how quickly tools and tutorials become outdated.

Determining whether something will last, however, is often challenging. I relied on three criteria. First, for a problem, I determined whether it results from the funda‐ mental limitations of how AI works or if it’ll go away with better models. If a problem is fundamental, I’ll analyze its challenges and solutions to address each challenge. I’m a fan of the start-simple approach, so for many problems, I’ll start from the simplest solution and then progress with more complex solutions to address rising challenges.

Second, I consulted an extensive network of researchers and engineers, who are smarter than I am, about what they think are the most important problems and solutions.

Occasionally, I also relied on Lindy’s Law, which infers that the future life expectancy of a technology is proportional to its current age. So if something has been around for a while, I assume that it’ll continue existing for a while longer.

In this book, however, I occasionally included a concept that I believe to be tempo‐ rary because it’s immediately useful for some application developers or because it illustrates an interesting problem-solving approach.

What This Book Is Not

This book isn’t a tutorial. While it mentions specific tools and includes pseudocode snippets to illustrate certain concepts, it doesn’t teach you how to use a tool. Instead, it offers a framework for selecting tools. It includes many discussions on the tradeoffs between different solutions and the questions you should ask when evaluating a solution. When you want to use a tool, it’s usually easy to find tutorials for it online. AI chatbots are also pretty good at helping you get started with popular tools.

This book isn’t an ML theory book. It doesn’t explain what a neural network is or how to build and train a model from scratch. While it explains many theoretical con‐ cepts immediately relevant to the discussion, the book is a practical book that focuses on helping you build successful AI applications to solve real-world problems.

While it’s possible to build foundation model-based applications without ML exper‐ tise, a basic understanding of ML and statistics can help you build better applications and save you from unnecessary suffering. You can read this book without any prior ML background. However, you will be more effective while building AI applications if you know the following concepts:

Probabilistic concepts such as sampling, determinism, and distribution.

ML concepts such as supervision, self-supervision, log-likelihood, gradient descent, backpropagation, loss function, and hyperparameter tuning.

Various neural network architectures, including feedforward, recurrent, and transformer.

Metrics such as accuracy, F1, precision, recall, cosine similarity, and cross entropy.

If you don’t know them yet, don’t worry—this book has either brief, high-level explanations or pointers to resources that can get you up to speed.

Who This Book Is For

This book is for anyone who wants to leverage foundation models to solve real-world problems. This is a technical book, so the language of this book is geared toward technical roles, including AI engineers, ML engineers, data scientists, engineering managers, and technical product managers. This book is for you if you can relate to one of the following scenarios:

- You’re building or optimizing an AI application, whether you’re starting from scratch or looking to move beyond the demo phase into a production-ready stage. You may also be facing issues like hallucinations, security, latency, or costs, and need targeted solutions.

- You want to streamline your team’s AI development process, making it more systematic, faster, and reliable.

- You want to understand how your organization can leverage foundation models to improve the business’s bottom line and how to build a team to do so.

You can also benefit from the book if you belong to one of the following groups:

- Tool developers who want to identify underserved areas in AI engineering to position your products in the ecosystem.

- Researchers who want to better understand AI use cases.

- Job candidates seeking clarity on the skills needed to pursue a career as an AI engineer.

- Anyone wanting to better understand AI’s capabilities and limitations, and how it might affect different roles.

I love getting to the bottom of things, so some sections dive a bit deeper into the tech‐ nical side. While many early readers like the detail, it might not be for everyone. I’ll give you a heads-up before things get too technical. Feel free to skip ahead if it feels a little too in the weeds!

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

Italic

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program ele‐ ments such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, input prompts into models, and keywords.

Constant width bold

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Constant width italic

Shows text that should be replaced with user-supplied values or by values deter‐ mined by context.

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

This element signifies a general note.

This element indicates a warning or caution.

Using Code Examples

Supplemental material (code examples, exercises, etc.) is available for download at https://github.com/chiphuyen/aie-book. The repository contains additional resources about AI engineering, including important papers and helpful tools. It also covers topics that are too deep to go into in this book. For those interested in the process of writing this book, the GitHub repository also contains behind-the-scenes informa‐ tion and statistics about the book.

If you have a technical question or a problem using the code examples, please send email to support@oreilly.com.

This book is here to help you get your job done. In general, if example code is offered with this book, you may use it in your programs and documentation. You do not need to contact us for permission unless you’re reproducing a significant portion of the code. For example, writing a program that uses several chunks of code from

this book does not require permission. Selling or distributing examples from O’Reilly books does require permission. Answering a question by citing this book and quoting example code does not require permission. Incorporating a significant amount of example code from this book into your product’s documentation does require permission.

We appreciate, but generally do not require, attribution. An attribution usually includes the title, author, publisher, and ISBN. For example: “AI Engineering by Chip Huyen (O’Reilly). Copyright 2025 Developer Experience Advisory LLC, 978-1-098-16630-4.”

If you feel your use of code examples falls outside fair use or the permission given above, feel free to contact us at permissions@oreilly.com.

O’Reilly Online Learning

For more than 40 years, O’Reilly Media has provided technol‐ ogy and business training, knowledge, and insight to help companies succeed.

Our unique network of experts and innovators share their knowledge and expertise through books, articles, and our online learning platform. O’Reilly’s online learning platform gives you on-demand access to live training courses, in-depth learning paths, interactive coding environments, and a vast collection of text and video from O’Reilly and 200+ other publishers. For more information, visit https://oreilly.com.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

O’Reilly Media, Inc. 1005 Gravenstein Highway North Sebastopol, CA 95472 800-889-8969 (in the United States or Canada) 707-827-7019 (international or local) 707-829-0104 (fax) support@oreilly.com https://oreilly.com/about/contact.html

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at https://oreil.ly/ai-engineering.

For news and information about our books and courses, visit https://oreilly.com. Find us on LinkedIn: https://linkedin.com/company/oreilly-media Watch us on YouTube: https://youtube.com/oreillymedia

Acknowledgments

This book would’ve taken a lot longer to write and missed many important topics if it wasn’t for so many wonderful people who helped me through the process.

Because the timeline for the project was tight—two years for a 150,000-word book that covers so much ground—I’m grateful to the technical reviewers who put aside their precious time to review this book so quickly.

Luke Metz is an amazing soundboard who checked my assumptions and prevented me from going down the wrong path. Han-chung Lee, always up to date with the lat‐ est AI news and community development, pointed me toward resources that I had missed. Luke and Han were the first to review my drafts before I sent them to the next round of technical reviewers, and I’m forever indebted to them for tolerating my follies and mistakes.

Having led AI innovation at Fortune 500 companies, Vittorio Cretella and Andrei Lopatenko provided invaluable feedback that combined deep technical expertise with executive insights. Vicki Reyzelman helped me ground my content and keep it rele‐ vant for readers with a software engineering background.

Eugene Yan, a dear friend and amazing applied scientist, provided me with technical and emotional support. Shawn Wang (swyx) provided an important vibe check that helped me feel more confident about the book. Sanyam Bhutani, one of the best learners and most humble souls I know, not only gave thoughtful written feedback but also recorded videos to explain his feedback.

Kyle Kranen is a star deep learning lead who interviewed his colleagues and shared with me an amazing writeup about their finetuning process, which guided the fine‐ tuning chapter. Mark Saroufim, an inquisitive mind who always has his finger on the pulse of the most interesting problems, introduced me to great resources on effi‐ ciency. Both Kyle and Mark’s feedback was critical in writing Chapters 7 and 9.

Kittipat “Bot” Kampa, in addition to answering my many questions, shared with me a detailed visualization of how he thinks about AI platforms. I appreciate Denys Linkov’s systematic approach to evaluation and platform development. Chetan Tekur gave great examples that helped me structure AI application patterns. I’d also like to thank Shengzhi (Alex) Li and Hien Luu for their thoughtful feedback on my draft on AI architecture.

Aileen Bui is a treasure who shared unique feedback and examples from a product manager’s perspective. Thanks to Todor Markov for the actionable advice on the RAG and Agents chapter. Thanks to Tal Kachman for jumping in at the last minute to push the Finetuning chapter over the finish line.

There are so many wonderful people whose company and conversations gave me ideas that guided the content of this book. I tried my best to include the names of everyone who has helped me here, but due to the inherent faultiness of human mem‐ ory, I undoubtedly neglected to mention many. If I forgot to include your name, please know that it wasn’t because I don’t appreciate your contribution, and please kindly remind me so that I can rectify this as soon as possible!

Andrew Francis, Anish Nag, Anthony Galczak, Anton Bacaj, Balázs Galambosi, Charles Frye, Charles Packer, Chris Brousseau, Eric Hartford, Goku Mohandas, Hamel Husain, Harpreet Sahota, Hassan El Mghari, Huu Nguyen, Jeremy Howard, Jesse Silver, John Cook, Juan Pablo Bottaro, Kyle Gallatin, Lance Martin, Lucio Dery, Matt Ross, Maxime Labonne, Miles Brundage, Nathan Lambert, Omar Khattab, Phong Nguyen, Purnendu Mukherjee, Sam Reiswig, Sebastian Raschka, Shahul ES, Sharif Shameem, Soumith Chintala, Teknium, Tim Dettmers, Undi95, Val Andrei Fajardo, Vern Liang, Victor Sanh, Wing Lian, Xiquan Cui, Ying Sheng, and Kristofer.

I’d like to thank all early readers who have also reached out with feedback. Douglas Bailley is a super reader who shared so much thoughtful feedback. Thanks to Nutan Sahoo for suggesting an elegant way to explain perplexity.

I learned so much from the online discussions with so many. Thanks to everyone who’s ever answered my questions, commented on my posts, or sent me an email with your thoughts.

Of course, the book wouldn’t have been possible without the team at O’Reilly, espe‐ cially my development editors (Melissa Potter, Corbin Collins, Jill Leonard) and my production editor (Elizabeth Kelly). Liz Wheeler is the most discerning copyeditor I’ve ever worked with. Nicole Butterfield is a force who oversaw this book from an idea to a final product.

This book, after all, is an accumulation of invaluable lessons I learned throughout my career. I owe these lessons to my extremely competent and patient coworkers and former coworkers. Every person I’ve worked with has taught me something new about bringing ML into the world.

CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Building AI Applications with Foundation Models

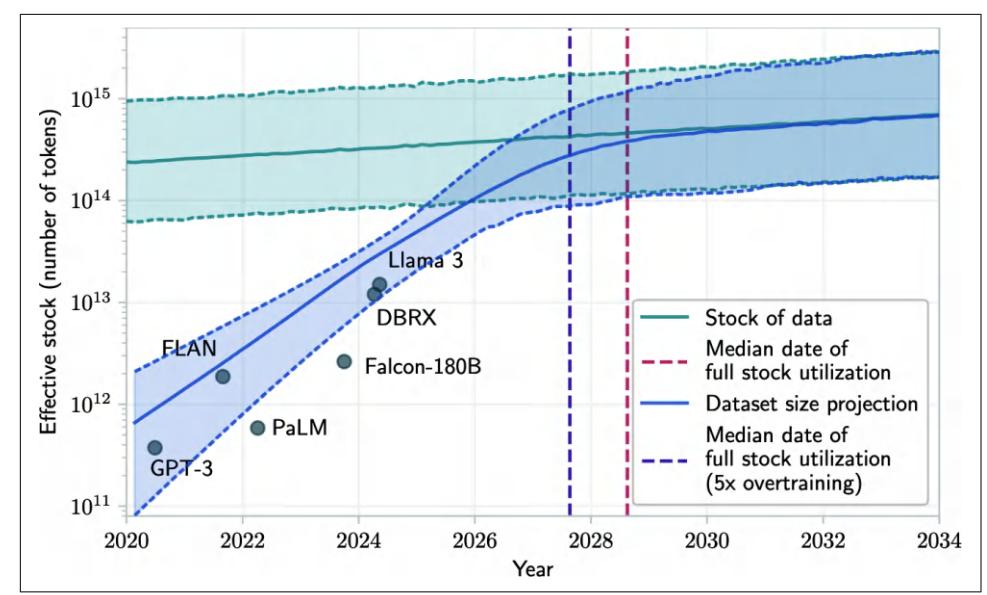

If I could use only one word to describe AI post-2020, it’d be scale. The AI models behind applications like ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Midjourney are at such a scale that they’re consuming a nontrivial portion of the world’s electricity, and we’re at risk of running out of publicly available internet data to train them.

The scaling up of AI models has two major consequences. First, AI models are becoming more powerful and capable of more tasks, enabling more applications. More people and teams leverage AI to increase productivity, create economic value, and improve quality of life.

Second, training large language models (LLMs) requires data, compute resources, and specialized talent that only a few organizations can afford. This has led to the emergence of model as a service: models developed by these few organizations are made available for others to use as a service. Anyone who wishes to leverage AI to build applications can now use these models to do so without having to invest up front in building a model.

In short, the demand for AI applications has increased while the barrier to entry for building AI applications has decreased. This has turned AI engineering—the process of building applications on top of readily available models—into one of the fastestgrowing engineering disciplines.

Building applications on top of machine learning (ML) models isn’t new. Long before LLMs became prominent, AI was already powering many applications, including product recommendations, fraud detection, and churn prediction. While many prin‐ ciples of productionizing AI applications remain the same, the new generation of

large-scale, readily available models brings about new possibilities and new chal‐ lenges, which are the focus of this book.

This chapter begins with an overview of foundation models, the key catalyst behind the explosion of AI engineering. I’ll then discuss a range of successful AI use cases, each illustrating what AI is good and not yet good at. As AI’s capabilities expand daily, predicting its future possibilities becomes increasingly challenging. However, existing application patterns can help uncover opportunities today and offer clues about how AI may continue to be used in the future.

To close out the chapter, I’ll provide an overview of the new AI stack, including what has changed with foundation models, what remains the same, and how the role of an AI engineer today differs from that of a traditional ML engineer.1

The Rise of AI Engineering

Foundation models emerged from large language models, which, in turn, originated as just language models. While applications like ChatGPT and GitHub’s Copilot may seem to have come out of nowhere, they are the culmination of decades of technology advancements, with the first language models emerging in the 1950s. This section traces the key breakthroughs that enabled the evolution from language models to AI engineering.

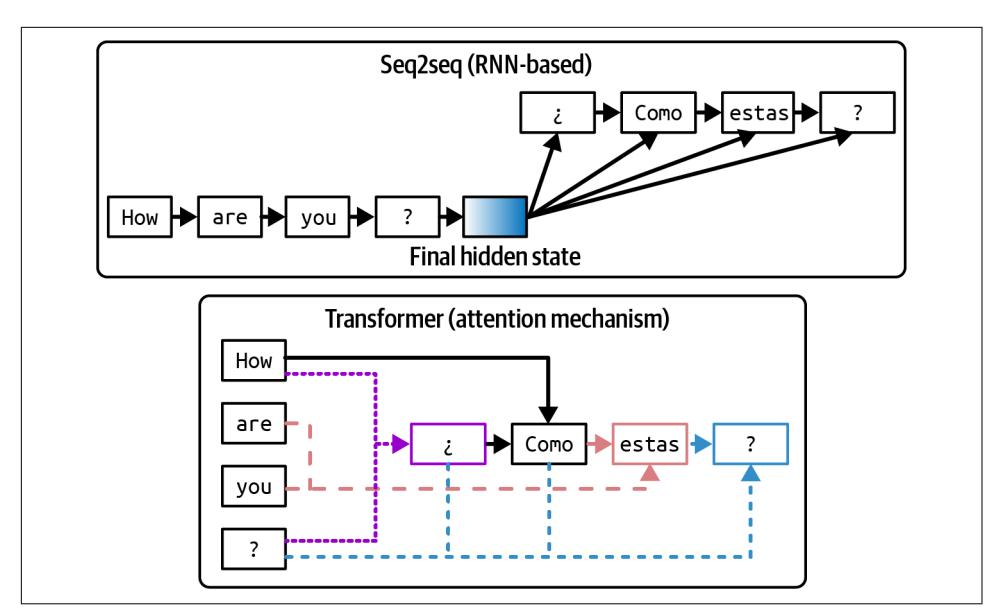

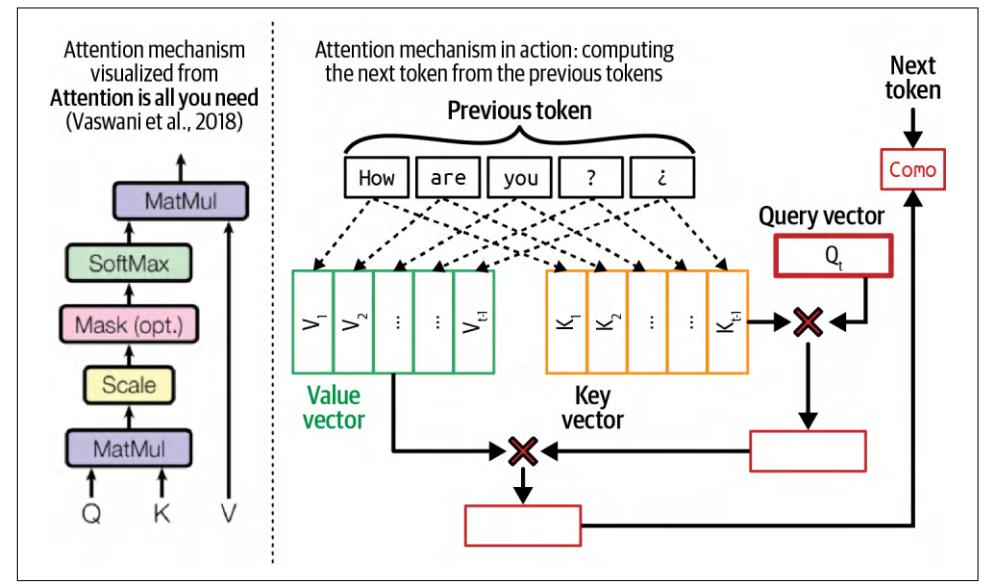

From Language Models to Large Language Models

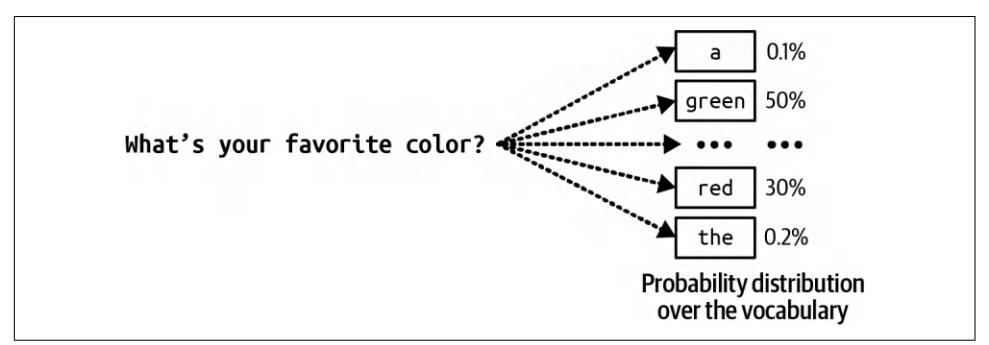

While language models have been around for a while, they’ve only been able to grow to the scale they are today with self-supervision. This section gives a quick overview of what language model and self-supervision mean. If you’re already familiar with those, feel free to skip this section.

Language models

A language model encodes statistical information about one or more languages. Intui‐ tively, this information tells us how likely a word is to appear in a given context. For example, given the context “My favorite color is __”, a language model that encodes English should predict “blue” more often than “car”.

1 In this book, I use traditional ML to refer to all ML before foundation models.

The statistical nature of languages was discovered centuries ago. In the 1905 story “The Adventure of the Dancing Men”, Sherlock Holmes leveraged simple statistical information of English to decode sequences of mysterious stick figures. Since the most common letter in English is E, Holmes deduced that the most common stick figure must stand for E.

Later on, Claude Shannon used more sophisticated statistics to decipher enemies’ messages during the Second World War. His work on how to model English was published in his 1951 landmark paper “Prediction and Entropy of Printed English”. Many concepts introduced in this paper, including entropy, are still used for lan‐ guage modeling today.

In the early days, a language model involved one language. However, today, a lan‐ guage model can involve multiple languages.

The basic unit of a language model is token. A token can be a character, a word, or a part of a word (like -tion), depending on the model.2 For example, GPT-4, a model behind ChatGPT, breaks the phrase “I can’t wait to build AI applications” into nine tokens, as shown in Figure 1-1. Note that in this example, the word “can’t” is broken into two tokens, can and ’t. You can see how different OpenAI models tokenize text on the OpenAI website.

Figure 1-1. An example of how GPT-4 tokenizes a phrase.

The process of breaking the original text into tokens is called tokenization. For GPT-4, an average token is approximately ¾ the length of a word. So, 100 tokens are approximately 75 words.

The set of all tokens a model can work with is the model’s vocabulary. You can use a small number of tokens to construct a large number of distinct words, similar to how you can use a few letters in the alphabet to construct many words. The Mixtral 8x7B model has a vocabulary size of 32,000. GPT-4’s vocabulary size is 100,256. The toke‐ nization method and vocabulary size are decided by model developers.

2 For non-English languages, a single Unicode character can sometimes be represented as multiple tokens.

Why do language models use token as their unit instead of word or character? There are three main reasons:

- Compared to characters, tokens allow the model to break words into meaningful components. For example, “cooking” can be broken into “cook” and “ing”, with both components carrying some meaning of the original word.

- Because there are fewer unique tokens than unique words, this reduces the model’s vocabulary size, making the model more efficient (as discussed in Chapter 2).

- Tokens also help the model process unknown words. For instance, a made-up word like “chatgpting” could be split into “chatgpt” and “ing”, helping the model understand its struc‐ ture. Tokens balance having fewer units than words while retaining more meaning than individual characters.

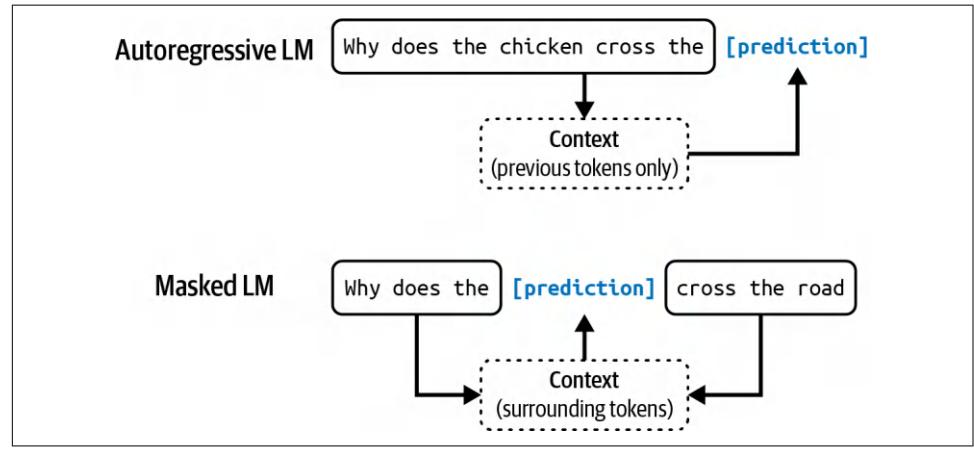

There are two main types of language models: masked language models and autore‐ gressive language models. They differ based on what information they can use to pre‐ dict a token:

Masked language model

A masked language model is trained to predict missing tokens anywhere in a sequence, using the context from both before and after the missing tokens. In essence, a masked language model is trained to be able to fill in the blank. For example, given the context, “My favorite __ is blue”, a masked language model should predict that the blank is likely “color”. A well-known example of a masked language model is bidirectional encoder representations from transform‐ ers, or BERT (Devlin et al., 2018).

As of writing, masked language models are commonly used for non-generative tasks such as sentiment analysis and text classification. They are also useful for tasks requiring an understanding of the overall context, such as code debugging, where a model needs to understand both the preceding and following code to identify errors.

Autoregressive language model

An autoregressive language model is trained to predict the next token in a sequence, using only the preceding tokens. It predicts what comes next in “My favorite color is __.” 3 An autoregressive model can continually generate one token after another. Today, autoregressive language models are the models of

3 Autoregressive language models are sometimes referred to as causal language models.

choice for text generation, and for this reason, they are much more popular than masked language models.4

Figure 1-2 shows these two types of language models.

Figure 1-2. Autoregressive language model and masked language model.

In this book, unless explicitly stated, language model will refer to an autoregressive model.

The outputs of language models are open-ended. A language model can use its fixed, finite vocabulary to construct infinite possible outputs. A model that can generate open-ended outputs is called generative, hence the term generative AI.

You can think of a language model as a completion machine: given a text (prompt), it tries to complete that text. Here’s an example:

Prompt (from user): "To be or not to be"

Completion (from language model): ", that is the question."It’s important to note that completions are predictions, based on probabilities, and not guaranteed to be correct. This probabilistic nature of language models makes them both so exciting and frustrating to use. We explore this further in Chapter 2.

4 Technically, a masked language model like BERT can also be used for text generations if you try really hard.

As simple as it sounds, completion is incredibly powerful. Many tasks, including translation, summarization, coding, and solving math problems, can be framed as completion tasks. For example, given the prompt: “How are you in French is …”, a language model might be able to complete it with: “Comment ça va”, effectively translating from one language to another.

As another example, given the prompt:

Question: Is this email likely spam? Here’s the email:

A language model might be able to complete it with: “Likely spam”, which turns this language model into a spam classifier.

While completion is powerful, completion isn’t the same as engaging in a conversa‐ tion. For example, if you ask a completion machine a question, it can complete what you said by adding another question instead of answering the question. “Post-Training” on page 78 discusses how to make a model respond appropriately to a user’s request.

Self-supervision

Language modeling is just one of many ML algorithms. There are also models for object detection, topic modeling, recommender systems, weather forecasting, stock price prediction, etc. What’s special about language models that made them the cen‐ ter of the scaling approach that caused the ChatGPT moment?

The answer is that language models can be trained using self-supervision, while many other models require supervision. Supervision refers to the process of training ML algorithms using labeled data, which can be expensive and slow to obtain. Selfsupervision helps overcome this data labeling bottleneck to create larger datasets for models to learn from, effectively allowing models to scale up. Here’s how.

With supervision, you label examples to show the behaviors you want the model to learn, and then train the model on these examples. Once trained, the model can be applied to new data. For example, to train a fraud detection model, you use examples of transactions, each labeled with “fraud” or “not fraud”. Once the model learns from these examples, you can use this model to predict whether a transaction is fraudulent.

The success of AI models in the 2010s lay in supervision. The model that started the deep learning revolution, AlexNet (Krizhevsky et al., 2012), was supervised. It was trained to learn how to classify over 1 million images in the dataset ImageNet. It clas‐ sified each image into one of 1,000 categories such as “car”, “balloon”, or “monkey”.

A drawback of supervision is that data labeling is expensive and time-consuming. If it costs 5 cents for one person to label one image, it’d cost $50,000 to label a million images for ImageNet.5 If you want two different people to label each image—so that you could cross-check label quality—it’d cost twice as much. Because the world con‐ tains vastly more than 1,000 objects, to expand models’ capabilities to work with more objects, you’d need to add labels of more categories. To scale up to 1 million categories, the labeling cost alone would increase to $50 million.

Labeling everyday objects is something that most people can do without prior train‐ ing. Hence, it can be done relatively cheaply. However, not all labeling tasks are that simple. Generating Latin translations for an English-to-Latin model is more expen‐ sive. Labeling whether a CT scan shows signs of cancer would be astronomical.

Self-supervision helps overcome the data labeling bottleneck. In self-supervision, instead of requiring explicit labels, the model can infer labels from the input data. Language modeling is self-supervised because each input sequence provides both the labels (tokens to be predicted) and the contexts the model can use to predict these labels. For example, the sentence “I love street food.” gives six training samples, as shown in Table 1-1.

| food | |

|---|---|

Table 1-1. Training samples from the sentence “I love street food.” for language modeling.

In Table 1-1,

5 The actual data labeling cost varies depending on several factors, including the task’s complexity, the scale (larger datasets typically result in lower per-sample costs), and the labeling service provider. For example, as of September 2024, Amazon SageMaker Ground Truth charges 8 cents per image for labeling fewer than 50,000 images, but only 2 cents per image for labeling more than 1 million images.

6 This is similar to how it’s important for humans to know when to stop talking.

Self-supervision differs from unsupervision. In self-supervised learning, labels are inferred from the input data. In unsupervised learning, you don’t need labels at all.

Self-supervised learning means that language models can learn from text sequences without requiring any labeling. Because text sequences are everywhere—in books, blog posts, articles, and Reddit comments—it’s possible to construct a massive amount of training data, allowing language models to scale up to become LLMs.

LLM, however, is hardly a scientific term. How large does a language model have to be to be considered large? What is large today might be considered tiny tomorrow. A model’s size is typically measured by its number of parameters. A parameter is a vari‐ able within an ML model that is updated through the training process.7 In general, though this is not always true, the more parameters a model has, the greater its capacity to learn desired behaviors.

When OpenAI’s first generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) model came out in June 2018, it had 117 million parameters, and that was considered large. In February 2019, when OpenAI introduced GPT-2 with 1.5 billion parameters, 117 million was downgraded to be considered small. As of the writing of this book, a model with 100 billion parameters is considered large. Perhaps one day, this size will be considered small.

Before we move on to the next section, I want to touch on a question that is usually taken for granted: Why do larger models need more data? Larger models have more capacity to learn, and, therefore, would need more training data to maximize their performance.8 You can train a large model on a small dataset too, but it’d be a waste of compute. You could have achieved similar or better results on this dataset with smaller models.

From Large Language Models to Foundation Models

While language models are capable of incredible tasks, they are limited to text. As humans, we perceive the world not just via language but also through vision, hearing, touch, and more. Being able to process data beyond text is essential for AI to operate in the real world.

7 In school, I was taught that model parameters include both model weights and model biases. However, today, we generally use model weights to refer to all parameters.

8 It seems counterintuitive that larger models require more training data. If a model is more powerful, shouldn’t it require fewer examples to learn from? However, we’re not trying to get a large model to match the performance of a small model using the same data. We’re trying to maximize model performance.

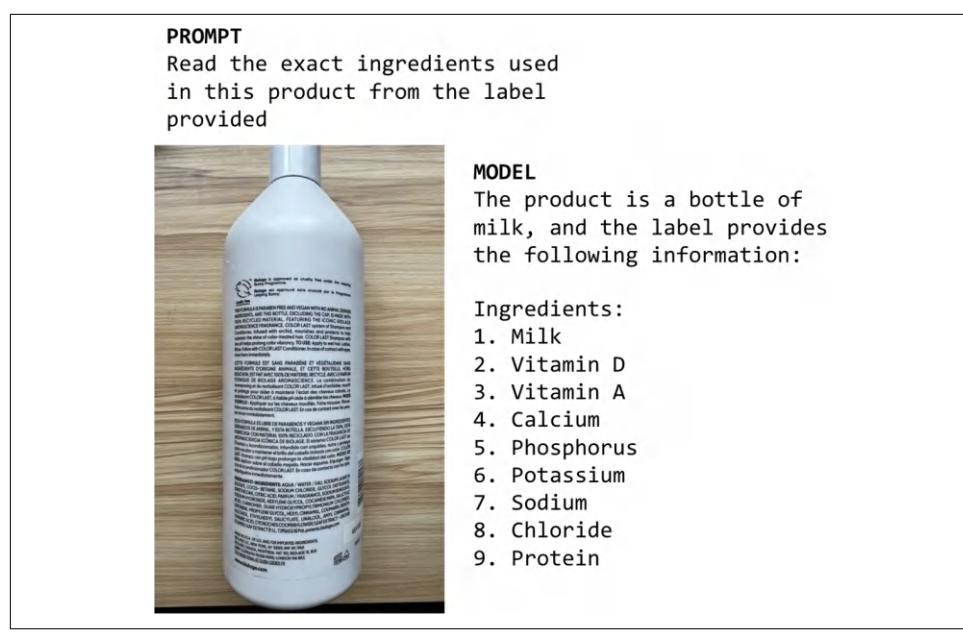

For this reason, language models are being extended to incorporate more data modalities. GPT-4V and Claude 3 can understand images and texts. Some models even understand videos, 3D assets, protein structures, and so on. Incorporating more data modalities into language models makes them even more powerful. OpenAI noted in their GPT-4V system card in 2023 that “incorporating additional modalities (such as image inputs) into LLMs is viewed by some as a key frontier in AI research and development.”

While many people still call Gemini and GPT-4V LLMs, they’re better characterized as foundation models. The word foundation signifies both the importance of these models in AI applications and the fact that they can be built upon for different needs.

Foundation models mark a breakthrough from the traditional structure of AI research. For a long time, AI research was divided by data modalities. Natural lan‐ guage processing (NLP) deals only with text. Computer vision deals only with vision. Text-only models can be used for tasks such as translation and spam detection. Image-only models can be used for object detection and image classification. Audioonly models can handle speech recognition (speech-to-text, or STT) and speech syn‐ thesis (text-to-speech, or TTS).

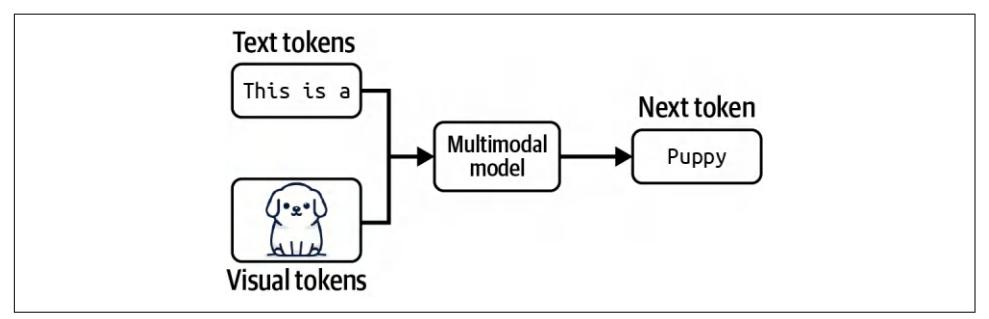

A model that can work with more than one data modality is also called a multimodal model. A generative multimodal model is also called a large multimodal model (LMM). If a language model generates the next token conditioned on text-only tokens, a multimodal model generates the next token conditioned on both text and image tokens, or whichever modalities that the model supports, as shown in Figure 1-3.

Figure 1-3. A multimodal model can generate the next token using information from both text and visual tokens.

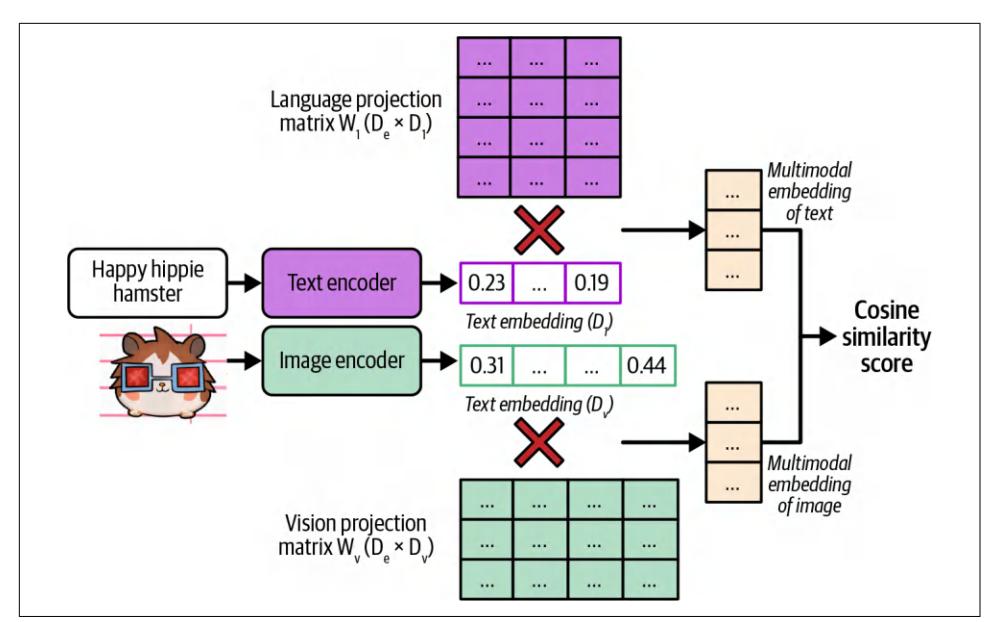

Just like language models, multimodal models need data to scale up. Self-supervision works for multimodal models too. For example, OpenAI used a variant of selfsupervision called natural language supervision to train their language-image model CLIP (OpenAI, 2021). Instead of manually generating labels for each image, they found (image, text) pairs that co-occurred on the internet. They were able to generate a dataset of 400 million (image, text) pairs, which was 400 times larger than Image‐ Net, without manual labeling cost. This dataset enabled CLIP to become the first model that could generalize to multiple image classification tasks without requiring additional training.

This book uses the term foundation models to refer to both large language models and large multimodal models.

Note that CLIP isn’t a generative model—it wasn’t trained to generate open-ended outputs. CLIP is an embedding model, trained to produce joint embeddings of both texts and images. “Introduction to Embedding” on page 134 discusses embeddings in detail. For now, you can think of embeddings as vectors that aim to capture the meanings of the original data. Multimodal embedding models like CLIP are the back‐ bones of generative multimodal models, such as Flamingo, LLaVA, and Gemini (pre‐ viously Bard).

Foundation models also mark the transition from task-specific models to generalpurpose models. Previously, models were often developed for specific tasks, such as sentiment analysis or translation. A model trained for sentiment analysis wouldn’t be able to do translation, and vice versa.

Foundation models, thanks to their scale and the way they are trained, are capable of a wide range of tasks. Out of the box, general-purpose models can work relatively well for many tasks. An LLM can do both sentiment analysis and translation. However, you can often tweak a general-purpose model to maximize its performance on a spe‐ cific task.

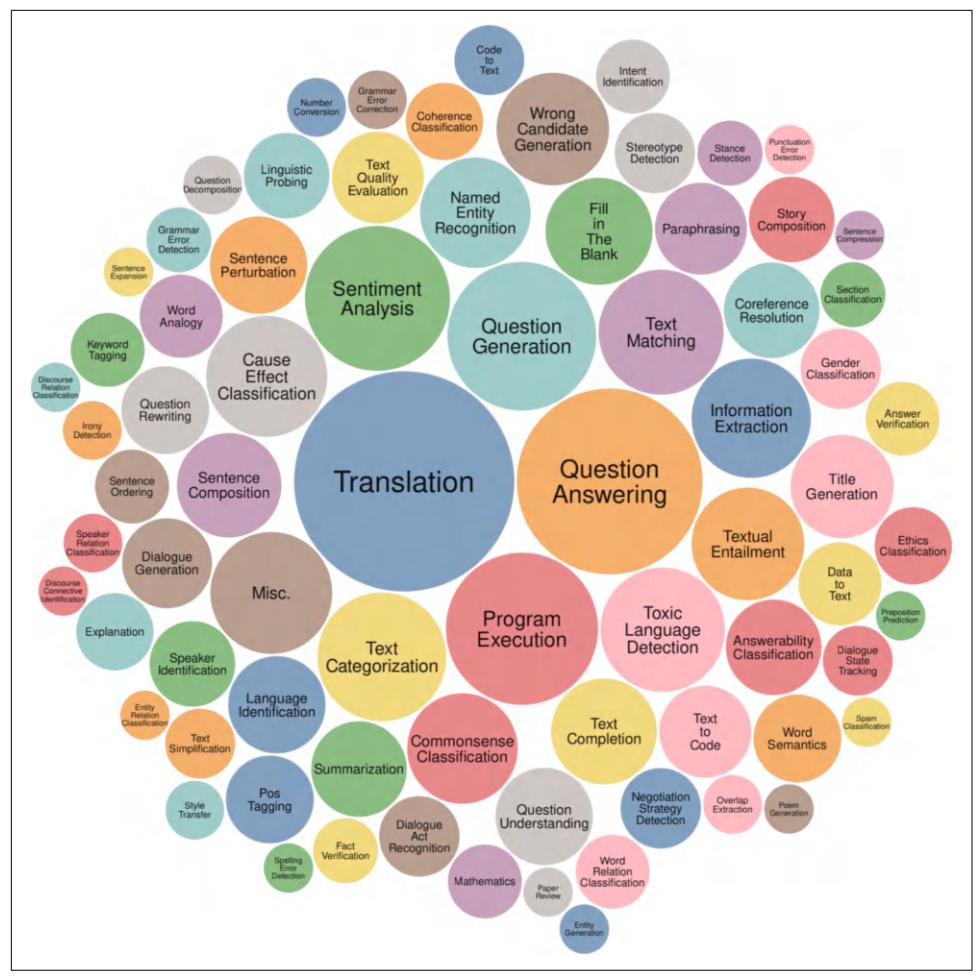

Figure 1-4 shows the tasks used by the Super-NaturalInstructions benchmark to eval‐ uate foundation models (Wang et al., 2022), providing an idea of the types of tasks a foundation model can perform.

Imagine you’re working with a retailer to build an application to generate product descriptions for their website. An out-of-the-box model might be able to generate accurate descriptions but might fail to capture the brand’s voice or highlight the brand’s messaging. The generated descriptions might even be full of marketing speech and cliches.

Figure 1-4. The range of tasks in the Super-NaturalInstructions benchmark (Wang et al., 2022).

There are multiple techniques you can use to get the model to generate what you want. For example, you can craft detailed instructions with examples of the desirable product descriptions. This approach is prompt engineering. You can connect the model to a database of customer reviews that the model can leverage to generate bet‐ ter descriptions. Using a database to supplement the instructions is called retrievalaugmented generation (RAG). You can also finetune—further train—the model on a dataset of high-quality product descriptions.

Prompt engineering, RAG, and finetuning are three very common AI engineering techniques that you can use to adapt a model to your needs. The rest of the book will discuss all of them in detail.

Adapting an existing powerful model to your task is generally a lot easier than build‐ ing a model for your task from scratch—for example, ten examples and one weekend versus 1 million examples and six months. Foundation models make it cheaper to develop AI applications and reduce time to market. Exactly how much data is needed to adapt a model depends on what technique you use. This book will also touch on this question when discussing each technique. However, there are still many benefits to task-specific models, for example, they might be a lot smaller, making them faster and cheaper to use.

Whether to build your own model or leverage an existing one is a classic buy-orbuild question that teams will have to answer for themselves. Discussions throughout the book can help with that decision.

From Foundation Models to AI Engineering

AI engineering refers to the process of building applications on top of foundation models. People have been building AI applications for over a decade—a process often known as ML engineering or MLOps (short for ML operations). Why do we talk about AI engineering now?

If traditional ML engineering involves developing ML models, AI engineering lever‐ ages existing ones. The availability and accessibility of powerful foundation models lead to three factors that, together, create ideal conditions for the rapid growth of AI engineering as a discipline:

Factor 1: General-purpose AI capabilities

Foundation models are powerful not just because they can do existing tasks bet‐ ter. They are also powerful because they can do more tasks. Applications previ‐ ously thought impossible are now possible, and applications not thought of before are emerging. Even applications not thought possible today might be pos‐ sible tomorrow. This makes AI more useful for more aspects of life, vastly increasing both the user base and the demand for AI applications.

For example, since AI can now write as well as humans, sometimes even better, AI can automate or partially automate every task that requires communication, which is pretty much everything. AI is used to write emails, respond to customer requests, and explain complex contracts. Anyone with a computer has access to tools that can instantly generate customized, high-quality images and videos to help create marketing materials, edit professional headshots, visualize art con‐ cepts, illustrate books, and so on. AI can even be used to synthesize training data, develop algorithms, and write code, all of which will help train even more power‐ ful models in the future.

Factor 2: Increased AI investments

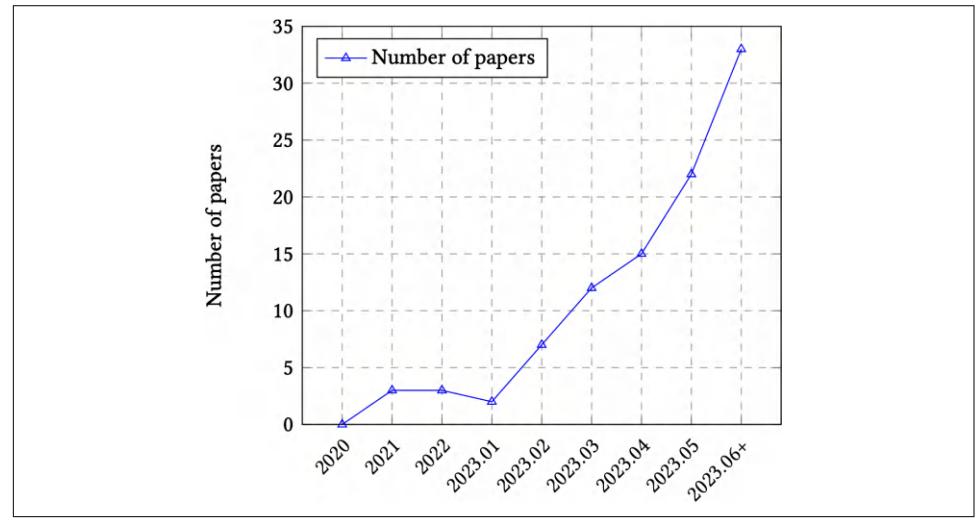

The success of ChatGPT prompted a sharp increase in investments in AI, both from venture capitalists and enterprises. As AI applications become cheaper to build and faster to go to market, returns on investment for AI become more attractive. Companies rush to incorporate AI into their products and processes. Matt Ross, a senior manager of applied research at Scribd, told me that the esti‐ mated AI cost for his use cases has gone down two orders of magnitude from April 2022 to April 2023.

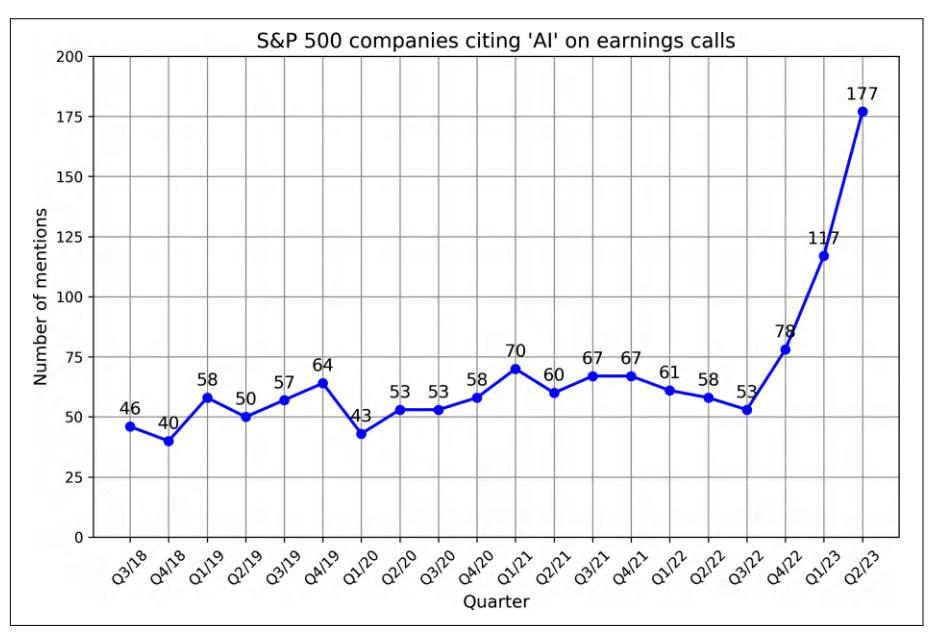

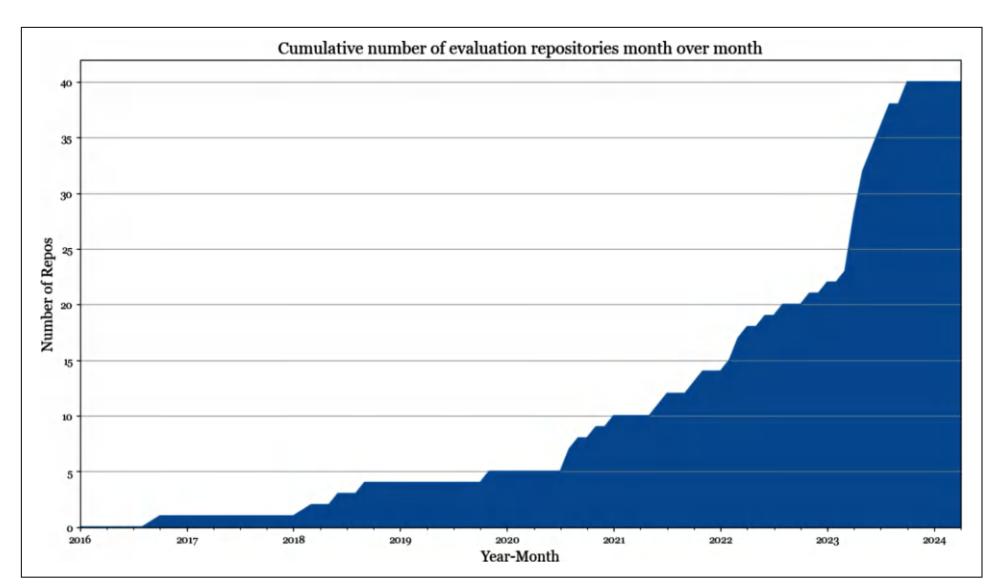

Goldman Sachs Research estimated that AI investment could approach $100 bil‐ lion in the US and $200 billion globally by 2025.9 AI is often mentioned as a com‐ petitive advantage. FactSet found that one in three S&P 500 companies mentioned AI in their earnings calls for the second quarter of 2023, three times more than did so the year earlier. Figure 1-5 shows the number of S&P 500 com‐ panies that mentioned AI in their earning calls from 2018 to 2023.

Figure 1-5. The number of S&P 500 companies that mention AI in their earnings calls reached a record high in 2023. Data from FactSet.

According to WallStreetZen, companies that mentioned AI in their earning calls saw their stock price increase more than those that didn’t: an average of a 4.6%

9 For comparison, the entire US expenditures for public elementary and secondary schools are around $900 billion, only nine times the investments in AI in the US.

increase compared to 2.4%. It’s unclear whether it’s causation (AI makes these companies more successful) or correlation (companies are successful because they are quick to adapt to new technologies).

Factor 3: Low entrance barrier to building AI applications

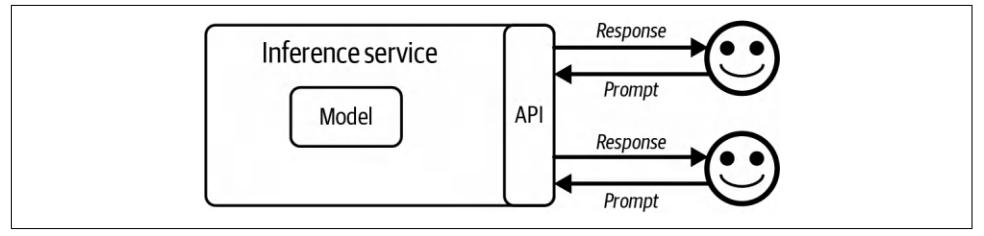

The model as a service approach popularized by OpenAI and other model pro‐ viders makes it easier to leverage AI to build applications. In this approach, mod‐ els are exposed via APIs that receive user queries and return model outputs. Without these APIs, using an AI model requires the infrastructure to host and serve this model. These APIs give you access to powerful models via single API calls.

Not only that, AI also makes it possible to build applications with minimal cod‐ ing. First, AI can write code for you, allowing people without a software engi‐ neering background to quickly turn their ideas into code and put them in front of their users. Second, you can work with these models in plain English instead of having to use a programming language. Anyone, and I mean anyone, can now develop AI applications.

Because of the resources it takes to develop foundation models, this process is possi‐ ble only for big corporations (Google, Meta, Microsoft, Baidu, Tencent), govern‐ ments (Japan, the UAE), and ambitious, well-funded startups (OpenAI, Anthropic, Mistral). In a September 2022 interview, Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, said that the biggest opportunity for the vast majority of people will be to adapt these models for specific applications.

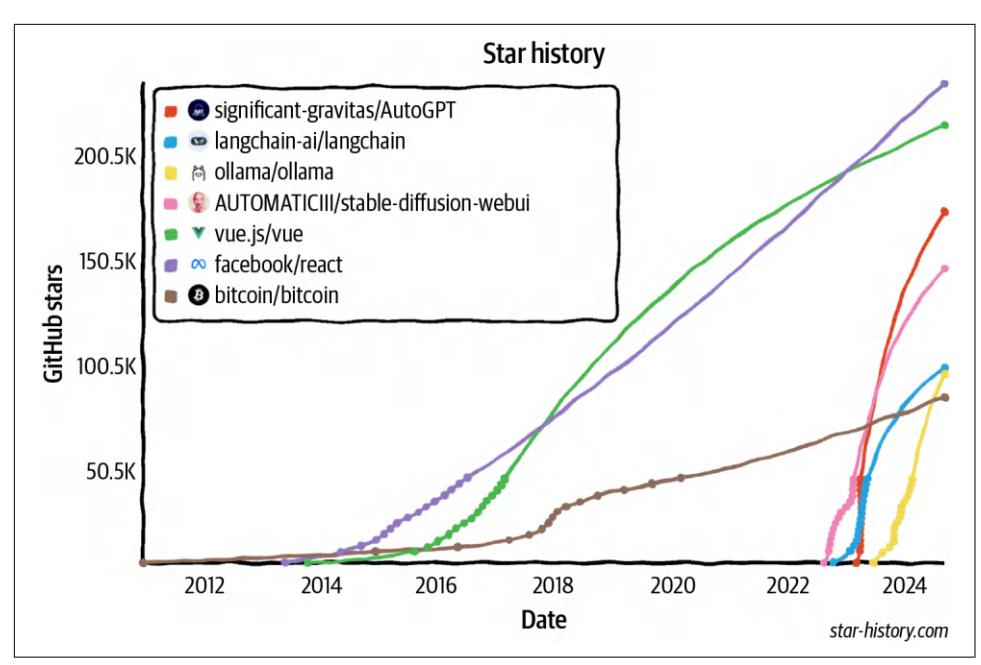

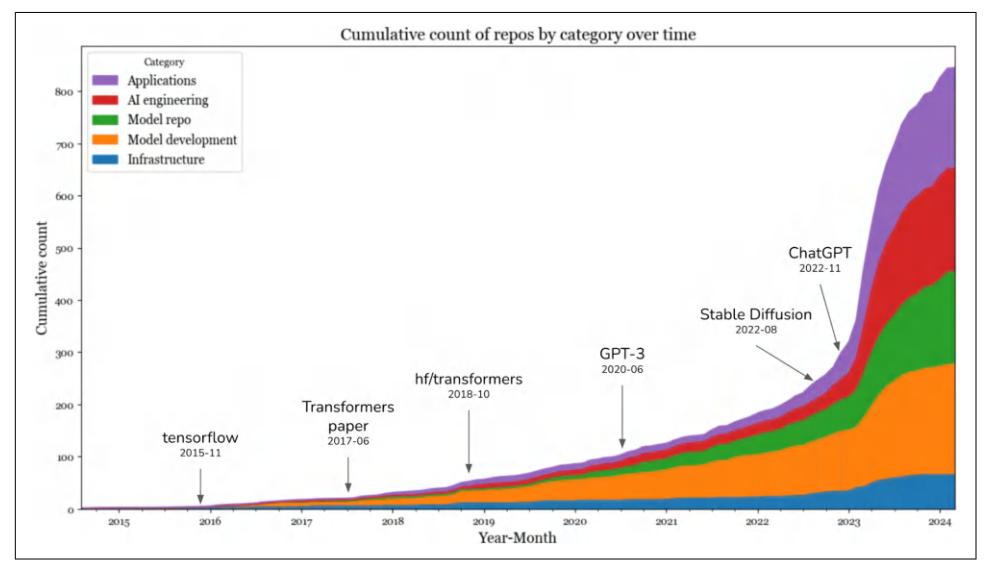

The world is quick to embrace this opportunity. AI engineering has rapidly emerged as one of the fastest, and quite possibly the fastest-growing, engineering discipline. Tools for AI engineering are gaining traction faster than any previous software engi‐ neering tools. Within just two years, four open source AI engineering tools (AutoGPT, Stable Diffusion eb UI, LangChain, Ollama) have already garnered more stars on GitHub than Bitcoin. They are on track to surpass even the most popular web development frameworks, including React and Vue, in star count. Figure 1-6 shows the GitHub star growth of AI engineering tools compared to Bitcoin, Vue, and React.

A LinkedIn survey from August 2023 shows that the number of professionals adding terms like “Generative AI,” “ChatGPT,” “Prompt Engineering,” and “Prompt Craft‐ ing” to their profile increased on average 75% each month. ComputerWorld declared that “teaching AI to behave is the fastest-growing career skill”.

Figure 1-6. Open source AI engineering tools are growing faster than any other software engineering tools, according to their GitHub star counts.

Why the Term “AI Engineering?”

Many terms are being used to describe the process of building applications on top of foundation models, including ML engineering, MLOps, AIOps, LLMOps, etc. Why did I choose to go with AI engineering for this book?

I didn’t go with the term ML engineering because, as discussed in “AI Engineering Versus ML Engineering” on page 39, working with foundation models differs from working with traditional ML models in several important aspects. The term ML engi‐ neering won’t be sufficient to capture this differentiation. However, ML engineering is a great term to encompass both processes.

I didn’t go with all the terms that end with “Ops” because, while there are operational components of the process, the focus is more on tweaking (engineering) foundation models to do what you want.

Finally, I surveyed 20 people who were developing applications on top of foundation models about what term they would use to describe what they were doing. Most peo‐ ple preferred AI engineering. I decided to go with the people.

The rapidly expanding community of AI engineers has demonstrated remarkable creativity with an incredible range of exciting applications. The next section will explore some of the most common application patterns.

Foundation Model Use Cases

If you’re not already building AI applications, I hope the previous section has con‐ vinced you that now is a great time to do so. If you have an application in mind, you might want to jump to “Planning AI Applications” on page 28. If you’re looking for inspiration, this section covers a wide range of industry-proven and promising use cases.

The number of potential applications that you could build with foundation models seems endless. Whatever use case you think of, there’s probably an AI for that.10 It’s impossible to list all potential use cases for AI.

Even attempting to categorize these use cases is challenging, as different surveys use different categorizations. For example, Amazon Web Services (AWS) has categorized enterprise generative AI use cases into three buckets: customer experience, employee productivity, and process optimization. A 2024 O’Reilly survey categorized the use cases into eight categories: programming, data analysis, customer support, marketing copy, other copy, research, web design, and art.

Some organizations, like Deloitte, have categorized use cases by value capture, such as cost reduction, process efficiency, growth, and accelerating innovation. For value capture, Gartner has a category for business continuity, meaning an organization might go out of business if it doesn’t adopt generative AI. Of the 2,500 executives Gartner surveyed in 2023, 7% cited business continuity as the motivation for embrac‐ ing generative AI.

10 Fun fact: as of September 16, 2024, the website theresanaiforthat.com lists 16,814 AIs for 14,688 tasks and 4,803 jobs.

Eloundou et al. (2023) has excellent research on how exposed different occupations are to AI. They defined a task as exposed if AI and AI-powered software can reduce the time needed to complete this task by at least 50%. An occupation with 80% expo‐ sure means that 80% of the occupation’s tasks are exposed. According to the study, occupations with 100% or close to 100% exposure include interpreters and transla‐ tors, tax preparers, web designers, and writers. Some of them are shown in Table 1-2. Not unsurprisingly, occupations with no exposure to AI include cooks, stonemasons, and athletes. This study gives a good idea of what use cases AI is good for.

Table 1-2. Occupations with the highest exposure to AI as annotated by humans. α refers to exposure to AI models directly, whereas β and ζ refer to exposures to AI-powered software. Table from Eloundou et al. (2023).

| Writers and authors | |

|---|---|

| Interpreters and translators | |

| Public relations specialists | |

| Animal scientists | |

| Human ζ Mathematicians |

|

| Tax preparers | |

| Financial quantitative analysts | |

| Writers and authors | |

| Web and digital interface designers | |

| Humans labeled 15 occupations as “fully exposed”. | |

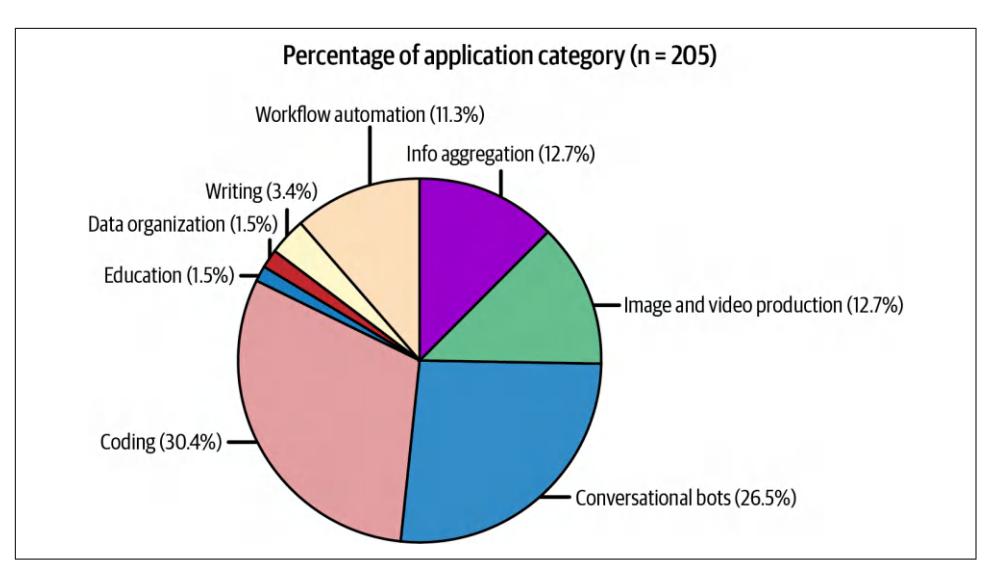

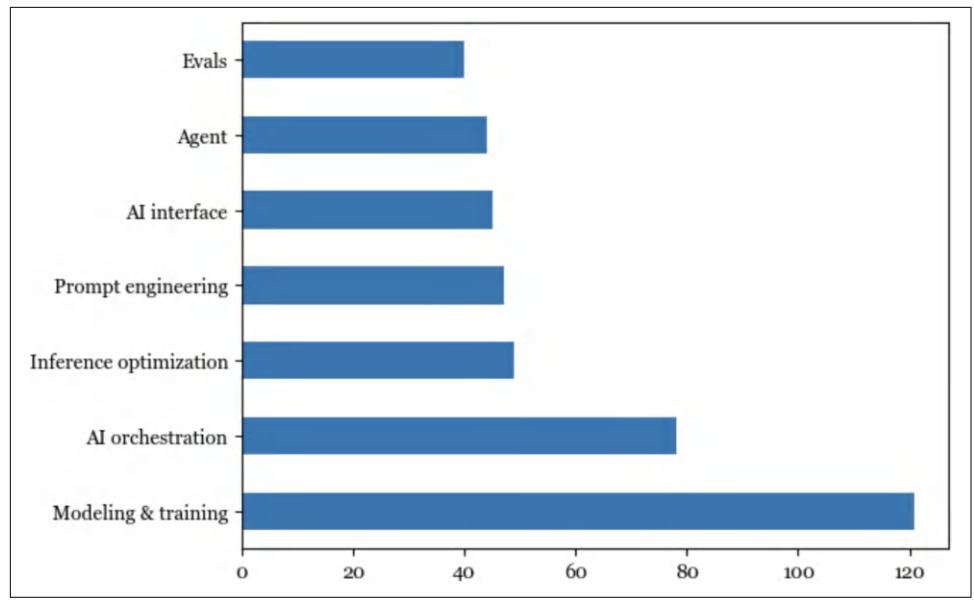

When analyzing the use cases, I looked at both enterprise and consumer applications. To understand enterprise use cases, I interviewed 50 companies on their AI strategies and read over 100 case studies. To understand consumer applications, I examined 205 open source AI applications with at least 500 stars on GitHub.11 I categorized applications into eight groups, as shown in Table 1-3. The limited list here serves best as a reference. As you learn more about how to build foundation models in Chapter 2 and how to evaluate them in Chapter 3, you’ll also be able to form a better picture of what use cases foundation models can and should be used for.

| Essay grading | Employee upskill training | |

|---|---|---|

| Conversational bots | General chatbot | Customer support |

| AI companion | Product copilots | |

| Information aggregation | Summarization | Summarization |

| Talk-to-your-docs | Market research | |

| Data organization | Image search | Knowledge management |

| Memex | Document processing | |

| Workflow automation | Travel planning | |

| Event planning | Lead generation | |

Table 1-3. Common generative AI use cases across consumer and enterprise applications.

Because foundation models are general, applications built on top of them can solve many problems. This means that an application can belong to more than one cate‐ gory. For example, a bot can provide companionship and aggregate information. An application can help you extract structured data from a PDF and answer questions about that PDF.

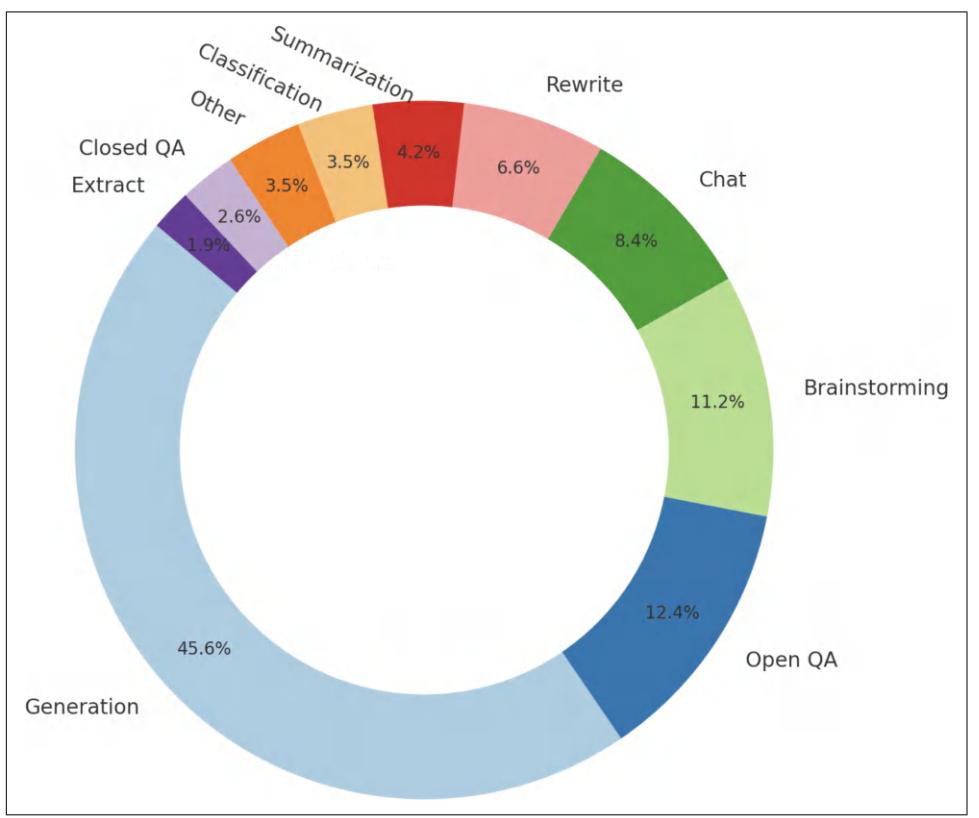

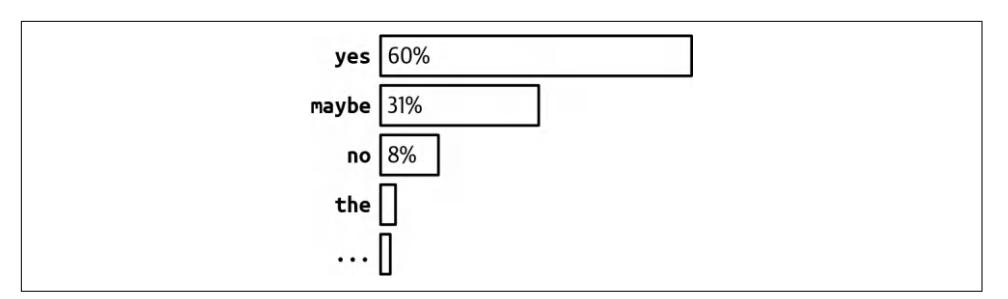

Figure 1-7 shows the distribution of these use cases among the 205 open source appli‐ cations. Note that the small percentage of education, data organization, and writing use cases doesn’t mean that these use cases aren’t popular. It just means that these applications aren’t open source. Builders of these applications might find them more suitable for enterprise use cases.

11 Exploring different AI applications is perhaps one of my favorite things about writing this book. It’s a lot of fun seeing what people are building. You can find the list of open source AI applications that I track. The list is updated every 12 hours.

Figure 1-7. Distribution of use cases in the 205 open source repositories on GitHub.

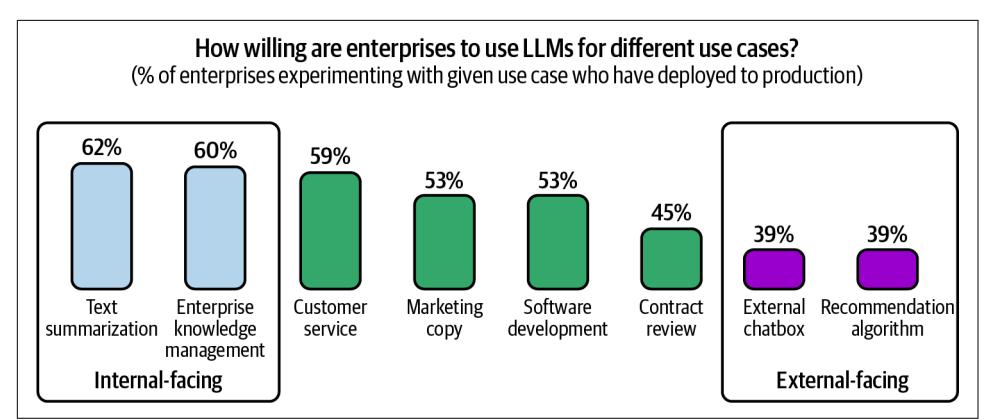

The enterprise world generally prefers applications with lower risks. For example, a 2024 a16z Growth report showed that companies are faster to deploy internal-facing applications (internal knowledge management) than external-facing applications (customer support chatbots), as shown in Figure 1-8. Internal applications help com‐ panies develop their AI engineering expertise while minimizing the risks associated with data privacy, compliance, and potential catastrophic failures. Similarly, while foundation models are open-ended and can be used for any task, many applications built on top of them are still close-ended, such as classification. Classification tasks are easier to evaluate, which makes their risks easier to estimate.

Figure 1-8. Companies are more willing to deploy internal-facing applications

Even after seeing hundreds of AI applications, I still find new applications that sur‐ prise me every week. In the early days of the internet, few people foresaw that the dominating use case on the internet one day would be social media. As we learn to make the most out of AI, the use case that will eventually dominate might surprise us. With luck, the surprise will be a good one.

Coding

In multiple generative AI surveys, coding is hands down the most popular use case. AI coding tools are popular both because AI is good at coding and because early AI engineers are coders who are more exposed to coding challenges.

One of the earliest successes of foundation models in production is the code comple‐ tion tool GitHub Copilot, whose annual recurring revenue crossed $100 million only two years after its launch. As of this writing, AI-powered coding startups have raised hundreds of millions of dollars, with Magic raising $320 million and Anysphere rais‐ ing $60 million, both in August 2024. Open source coding tools like gpt-engineer and screenshot-to-code both got 50,000 stars on GitHub within a year, and many more are being rapidly introduced.

Other than tools that help with general coding, many tools specialize in certain cod‐ ing tasks. Here are examples of these tasks:

- Extracting structured data from web pages and PDFs (AgentGPT)

- Converting English to code (DB-GPT, SQL Chat, PandasAI)

- Given a design or a screenshot, generating code that will render into a website that looks like the given image (screenshot-to-code, draw-a-ui)

- Translating from one programming language or framework to another (GPT-Migrate, AI Code Translator)

- Writing documentation (Autodoc)

- Creating tests (PentestGPT)

- Generating commit messages (AI Commits)

It’s clear that AI can do many software engineering tasks. The question is whether AI can automate software engineering altogether. At one end of the spectrum, Jensen Huang, CEO of NVIDIA, predicts that AI will replace human software engineers and that we should stop saying kids should learn to code. In a leaked recording, AWS CEO Matt Garman shared that in the near future, most developers will stop coding. He doesn’t mean it as the end of software developers; it’s just that their jobs will change.

At the other end are many software engineers who are convinced that they will never be replaced by AI, both for technical and emotional reasons (people don’t like admit‐ ting that they can be replaced).

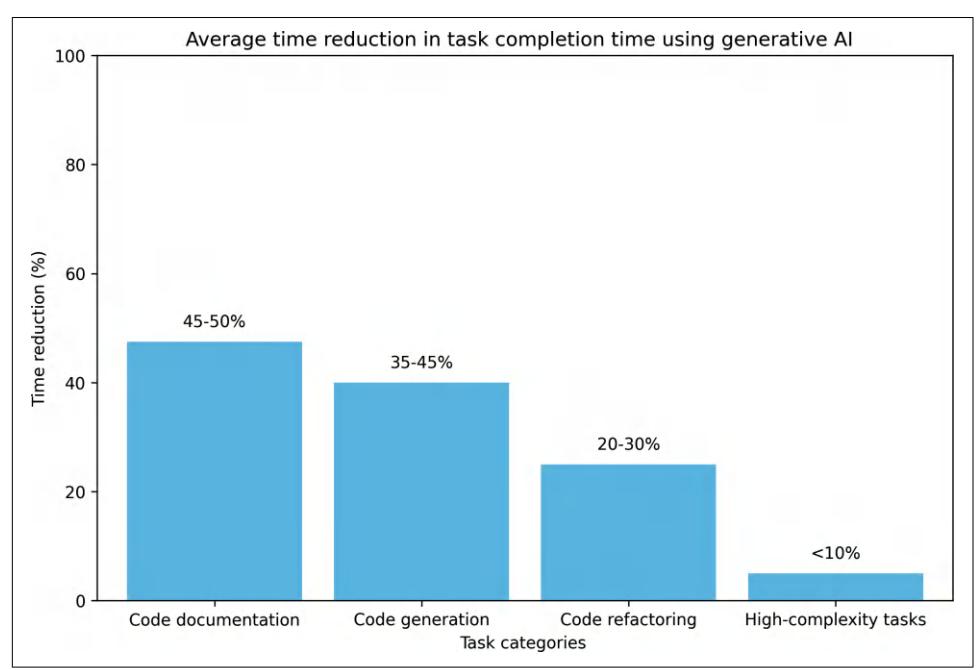

Software engineering consists of many tasks. AI is better at some than others. McKin‐ sey researchers found that AI can help developers be twice as productive for docu‐ mentation, and 25–50% more productive for code generation and code refactoring. Minimal productivity improvement was observed for highly complex tasks, as shown in Figure 1-9. In my conversations with developers of AI coding tools, many told me that they’ve noticed that AI is much better at frontend development than backend development.

Figure 1-9. AI can help developers be significantly more productive, especially for sim‐ ple tasks, but this applies less for highly complex tasks. Data by McKinsey.

Regardless of whether AI will replace software engineers, AI can certainly make them more productive. This means that companies can now accomplish more with fewer engineers. AI can also disrupt the outsourcing industry, as outsourced tasks tend to be simpler ones outside of a company’s core business.

Image and Video Production

Thanks to its probabilistic nature, AI is great for creative tasks. Some of the most suc‐ cessful AI startups are creative applications, such as Midjourney for image genera‐ tion, Adobe Firefly for photo editing, and Runway, Pika Labs, and Sora for video generation. In late 2023, at one and a half years old, Midjourney had already gener‐ ated $200 million in annual recurring revenue. As of December 2023, among the top 10 free apps for Graphics & Design on the Apple App Store, half have AI in their names. I suspect that soon, graphics and design apps will incorporate AI by default, and they’ll no longer need the word “AI” in their names. Chapter 2 discusses the probabilistic nature of AI in more detail.

It’s now common to use AI to generate profile pictures for social media, from LinkedIn to TikTok. Many candidates believe that AI-generated headshots can help them put their best foot forward and increase their chances of landing a job. The per‐ ception of AI-generated profile pictures has changed significantly. In 2019, Facebook banned accounts using AI-generated profile photos for safety reasons. In 2023, many social media apps provide tools that let users use AI to generate profile photos.

For enterprises, ads and marketing have been quick to incorporate AI.12 AI can be used to generate promotional images and videos directly. It can help brainstorm ideas or generate first drafts for human experts to iterate upon. You can use AI to generate multiple ads and test to see which one works the best for the audience. AI can generate variations of your ads according to seasons and locations. For example, you can use AI to change leaf colors during fall or add snow to the ground during winter.

Writing

AI has long been used to aid writing. If you use a smartphone, you’re probably famil‐ iar with autocorrect and auto-completion, both powered by AI. Writing is an ideal application for AI because we do it a lot, it can be quite tedious, and we have a high tolerance for mistakes. If a model suggests something that you don’t like, you can just ignore it.

12 Because enterprises usually spend a lot of money on ads and marketing, automation there can lead to huge savings. On average, 11% of a company’s budget is spent on marketing. See “Marketing Budgets Vary by Industry” (Christine Moorman, WSJ, 2017).

It’s not a surprise that LLMs are good at writing, given that they are trained for text completion. To study the impact of ChatGPT on writing, an MIT study (Noy and Zhang, 2023) assigned occupation-specific writing tasks to 453 college-educated pro‐ fessionals and randomly exposed half of them to ChatGPT. Their results show that among those exposed to ChatGPT, the average time taken decreased by 40% and out‐ put quality rose by 18%. ChatGPT helps close the gap in output quality between workers, which means that it’s more helpful to those with less inclination for writing. Workers exposed to ChatGPT during the experiment were 2 times as likely to report using it in their real job two weeks after the experiment and 1.6 times as likely two months after that.

For consumers, the use cases are obvious. Many use AI to help them communicate better. You can be angry in an email and ask AI to make it pleasant. You can give it bullet points and get back complete paragraphs. Several people claimed they no longer send an important email without asking AI to improve it first.

Students are using AI to write essays. Writers are using AI to write books.13 Many startups already use AI to generate children’s, fan fiction, romance, and fantasy books. Unlike traditional books, AI-generated books can be interactive, as a book’s plot can change depending on a reader’s preference. This means that readers can actively participate in creating the story they are reading. A children’s reading app identifies the words that a child has trouble with and generates stories centered around these words.

Note-taking and email apps like Google Docs, Notion, and Gmail all use AI to help users improve their writing. Grammarly, a writing assistant app, finetunes a model to make users’ writing more fluent, coherent, and clear.

AI’s ability to write can also be abused. In 2023, the New York Times reported that Amazon was flooded with shoddy AI-generated travel guidebooks, each outfitted with an author bio, a website, and rave reviews, all AI-generated.

For enterprises, AI writing is common in sales, marketing, and general team commu‐ nication. Many managers told me they’ve been using AI to help them write perfor‐ mance reports. AI can help craft effective cold outreach emails, ad copywriting, and product descriptions. Customer relationship management (CRM) apps like HubSpot and Salesforce also have tools for enterprise users to generate web content and out‐ reach emails.

13 I have found AI very helpful in the process of writing this book, and I can see that AI will be able to automate many parts of the writing process. When writing fiction, I often ask AI to brainstorm ideas on what it thinks will happen next or how a character might react to a situation. I’m still evaluating what kind of writing can be automated and what kind of writing can’t be.

AI seems particularly good with SEO, perhaps because many AI models are trained with data from the internet, which is populated with SEO-optimized text. AI is so good at SEO that it has enabled a new generation of content farms. These farms set up junk websites and fill them with AI-generated content to get them to rank high on Google to drive traffic to them. Then they sell advertising spots through ad exchanges. In June 2023, NewsGuard identified almost 400 ads from 141 popular brands on junk AI-generated websites. One of those junk websites produced 1,200 articles a day. Unless something is done to curtail this, the future of internet content will be AI-generated, and it’ll be pretty bleak.14

Education