The Emotional Foundations of Personality

A Neurobiological and Evolutionary Approach

The Emotional Foundations of Personality

A Neurobiological and Evolutionary Approach

Kenneth L. Davis and Jaak Panksepp

Foreword by Mark Solms

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY New York • London

The Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology Allan N. Schore, PhD, Series Editor Daniel J. Siegel, MD, Founding Editor

The field of mental health is in a tremendously exciting period of growth and conceptual reorganization. Independent findings from a variety of scientific endeavors are converging in an interdisciplinary view of the mind and mental well-being. An interpersonal neurobiology of human development enables us to understand that the structure and function of the mind and brain are shaped by experiences, especially those involving emotional relationships.

The Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology will provide cutting-edge, multidisciplinary views that further our understanding of the complex neurobiology of the human mind. By drawing on a wide range of traditionally independent fields of research—such as neurobiology, genetics, memory, attachment, complex systems, anthropology, and evolutionary psychology these texts will offer mental health professionals a review and synthesis of scientific findings often inaccessible to clinicians. These books aim to advance our understanding of human experience by finding the unity of knowledge, or consilience, that emerges with the translation of findings from numerous domains of study into a common language and conceptual framework. The series will integrate the best of modern science with the healing art of psychotherapy.

Contents

Introduction. Personality and Basic Human Motivation: Prime Movers

- Chapter 1 The Mystery of Human Personality

- Chapter 2 Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales and the Big Five

- Chapter 3 Darwin’s Comparative “Personality” Model

- Chapter 4 William McDougall’s Comparative Psychology: Toward a Naturalistic Personality Approach

- Chapter 5 A Brief Review of Personality Since McDougall: The Need for a Bottom-Up Model of Personality

- Chapter 6 Bottom-Up and Top-Down Personality Approaches

- Chapter 7 Our Ancestral Roots: Personality Research on Great Apes

- Chapter 8 The Special Case of Our Canine Companions

- Chapter 9 Do Rats Have Personalities? Of Course They Do!

- Chapter 10 Animal Personality Summary

- Chapter 11 Preludes to the Big Five Personality Model: Different Paths Toward Understanding BrainMind States That Constitute Human Temperaments

- Chapter 12 The Big Five: The Essential Core of Cattell’s Factor Analysis

- Chapter 13 The Clarities and Confusions of the Big Five

- Chapter 14 The Earlier History of Biological Theories of Personality

- Chapter 15 Genetics and the Origins of Personality

- Chapter 16 Human Brain Imaging

- Chapter 17 Personality and the Self

- Chapter 18 Affective Neuro-Personality and Psychopathology

- Chapter 19 Fleshing Out the Complexities

- Appendix: The Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales

- References

- Index

Preface and Acknowledgments

JAAK PANKSEPP NEEDS TO BE the first words written in this book. He was the inspiration for the book. Indeed, it was his idea for me to write a book applying his years of affective neuroscience research to personality, an area that had interested him, but the ever-pressing demands on his time would not allow him the opportunity to do so on his own. He first suggested the idea at one of the “get away” seminars that Doug Watt had organized. Jaak and I had previously developed the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales, but I would likely have never embarked on such an ambitious journey without Jaak’s encouragement. As the project developed, it became a great privilege to write chapters and work with Jaak as we polished and reworked the content.

But let there be no mistake, Jaak is the central figure in this story, which really began with his insight as a gifted undergraduate psychology student that understanding emotions was the key to understanding people, both their personalities and their pathologies. As his career developed (research that spanned nearly 50 years), Jaak worked with many students and colleagues too numerous to mention to assemble what eventually amounted to a theoretical fortress of evidence (Jaak preferred to speak about evidence rather than proof) that human behavior was built upon a bedrock of emotions that had evolved over millions of years. Perhaps more than anyone else, Jaak Panksepp advanced the nearly 150-year-old Darwinian dictum that “The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.”

This son of Estonian immigrants to the United States became a tireless advocate that, like humans, other animals subjectively experience feelings and are psychologically motivated by them. Guided by their affective experiences, they are active players in their environments and not robotic

automatons. His collective research documented supporting neurochemical and neuroanatomical emotional cross-species homologies, especially between humans and other mammals that led to many therapies and novel insights into the human condition.

In Emotional Foundations, we try to tell Jaak’s story, for the first time, from a personality perspective and try to do it with less technical detail than his previous books. The story explores how affective neuroscience causal (not merely descriptive or correlational) research relates to human motivations and actions and thereby to consistently recognizable patterns of individual behavior, namely, our personalities. Our goal was to share an affective neuroscience personality narrative that would appeal to a broad audience, from those simply interested in exploring personality, to students who were looking for an approach to personality from a neuropsychology/evolutionary point of view, and to professionals—from personality theorists to psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and veterinarians interested in reading a broad “Pankseppian” interpretation of personality issues.

Sadly, Jaak did not live to see the many hours of work he put into each chapter of our book actually reach print. However, thanks to Deborah Malmud and the staff at W. W. Norton, Emotional Foundations has been refined and formatted to their standards such that Deborah Malmud can now take credit for shepherding two Jaak Panksepp books through to the public including, of course, this last book-length project.

Jaak was my teacher. He became my intellectual anchor. Writing this book was like taking a multi-year seminar with him, almost like doing a postdoc. The remarkable breadth and depth of his knowledge revealed itself in every chapter. His awesome intellect was difficult to challenge. Yet, he never belittled my efforts, and I only remember a single time he criticized me and that was for “getting too far ahead of the data.”

However, Jaak was not the only teacher who facilitated my personal journey. At Earlham College, Dr. Jerry Woolpy, known for his work socializing wolves, took me under his wing by nurturing my budding interest in cross-species studies, and he was responsible for identifying an opportunity to become one of John Paul Scott’s students at Bowling Green State University. Dr. Scott was at the peak of his eminent career in comparative animal behavior and luckily took me on as his student and was able to offer personal and financial support through most of my graduate

days. Dr. Bob Conner, who eventually became the chairman of the Bowling Green psychology department, was another of those generous intellects who somehow managed to work as hard as you did on whatever project needed his attention and served on my graduate committee. However, it was Jaak who took me on as his student after Dr. Scott retired and gave me my first real glimpse of affective neuroscience as he guided me through my dissertation on the “Opioid Control of Canine Social Behavior.”

There are a few others whose support I would like to acknowledge. Anesa Miller, Jaak’s wife, and a published poet and writer in her own right, often went beyond tolerating to even encouraging my visits to their home that on occasion dominated their weekends but which also were critical to my continuing education, as well as the rewriting and reorganizing of book chapters. Another Panksepp student, Larry Normansell, provided extensive support in developing the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales. Dave Gilmore, a good friend, who also helped collect early ANPS data as well as providing support at various times during the writing process.

My children, Matt, Jennifer, and Megan have been consistently supportive and encouraging, even providing good suggestions from time to time. Yet, it is my wife, Nancy, more than anyone else who lived through the many years of writing and rewriting Emotional Foundations. Through what must have sometimes seemed endless, she remained supportive and encouraging, often reading my latest efforts and offering helpful comments.

Ken Davis November 30, 2017

Foreword

Mark Solms

THE APPROACH TAKEN to personality in this book is revolutionary. It builds upon decades of careful research, not only concerning the development and application of the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales themselves (work which is already being extended by scientists around the world, myself included), but also concerning the monumental program of neuroscientific research upon which the Scales were based. This program of research, itself revolutionary, was conducted by Jaak Panksepp and his students (among whom Ken Davis may be prominently counted). The research builds upon earlier work conducted by such pioneers as Walter Hess and Paul Maclean, starting in the 1920s already. In fact, their work can ultimately be traced all the way back to the seminal observations of Charles Darwin, who dared to suggest that we human beings are after all just another species of animal.

To say that the approach taken to personality in this book is revolutionary is not to say that it is wild or surprising. It is common-sensical and obvious. But this can only be said in retrospect, now that the work has been done. It required the insight of Ken Davis and Jaak Panksepp to see the yawning gap in this field, and then to fill it with the evidence for the new personality assessment instrument they provide in this book. With the book now published, however, it becomes obvious to the rest of us that this is the most sensible way (by far) to classify and measure the basic building blocks of the human personality.

When I say that theirs is the only sensible way to proceed, I must add that we could not have done so before now. The knowledge that was accumulated through the research program of Jaak Panksepp mentioned above was a necessary prerequisite, before Ken Davis and he could do the obvious regarding personality. What I mean is that it is obvious that the classification

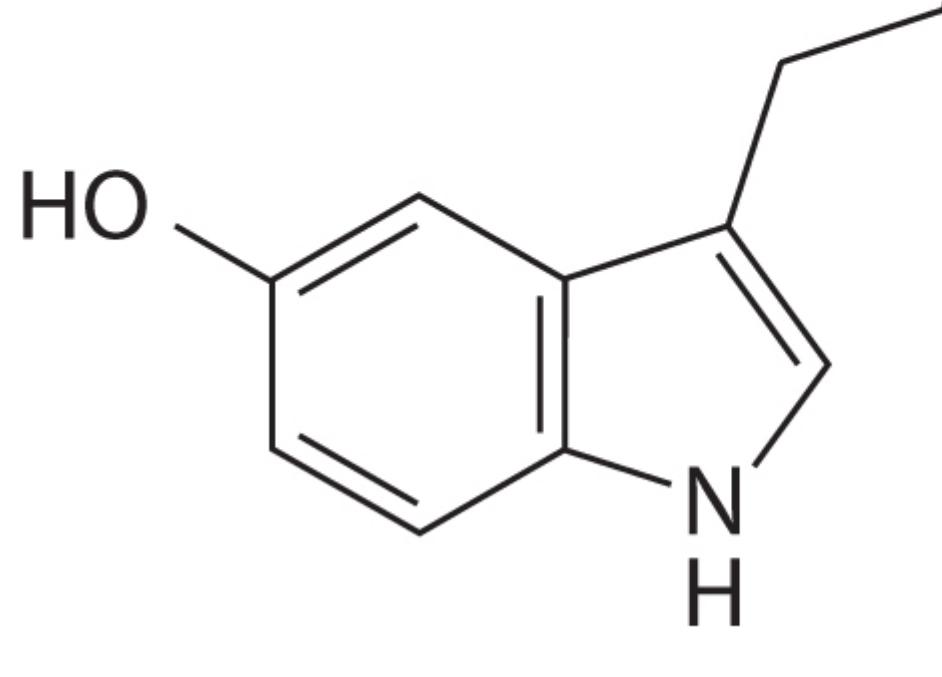

and measurement of personality must be predicated upon an identification of the “natural kinds” that constitute the actual building blocks of personality; but what are those “natural kinds?” The research upon which this book is based (research that was grounded in deep brain stimulation studies and pharmacological probes, which revealed the elementary emotional circuits of the mammalian brain, and then traced the same circuits—in the same structures, mediated by the same neurochemicals—in the human brain) provides us with nothing less than an answer to this fundamental question.

What could be more valuable for mental science than that?

It may be confidently predicted that the re-conceptualization of personality reported in this book will be followed by a revolution of equal importance (if not greater importance) in the classification and measurement of mental disorders. Just as the instruments that preceded the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales relied upon taxonomies of personality that were generated by blind statistical measures of its superficial features (or worse, culturally and linguistically mediated self conceptions of those features), so too the classification and measurement of psychiatric disorders is embarrassingly arbitrary—grounded in and confounded by the history and conventions of the discipline, rather than empirically based understanding of how the emotional brain really works.

This book heralds a new era of personality research, but there is much more to come from the approach it adopts. It shows the promise of affective neuroscience for the psychiatry, psychology and psychotherapy of the future.

The Emotional Foundations of Personality

Introduction

Personality and Basic Human Motivation: Prime Movers

But “feel” is a verb, and to say that what is felt is “a feeling” may be one of those deceptive common-sense suppositions inherent in the structure of language. . . . To feel is to do something. . . .

Feeling stands, in fact, in the midst of that vast biological field which lies between the lowliest organic activities and the rise of mind. . . . It is with the dawn of feeling that the domain of biology yields the less extensive, but still inestimably great domain of psychology.

—Susanne K. Langer, Mind: An Essay on Human Feeling

IN SEARCH OF FUNDAMENTAL CAUSES OF PERSONALITY

WHY IS IT THAT each of us can be described by a set of traits that can almost be used as a behavioral fingerprint? The fascination with knowing personality profiles has spawned a multibillion dollar personality testing industry (Economist, 2013, citing Nik Kinley, a coauthor of Talent Intelligence [Kinley & Beh-Hur 2013]). But beyond just describing our behavior, why does one person consistently behave differently than another? What actually causes our behavior? What prods us out of a state of inertia toward any particular goal-directed activity? Moreover, what would we be

like without some spark, some prod that could spur us to action—a primary mover that could motivate and guide our behavior?

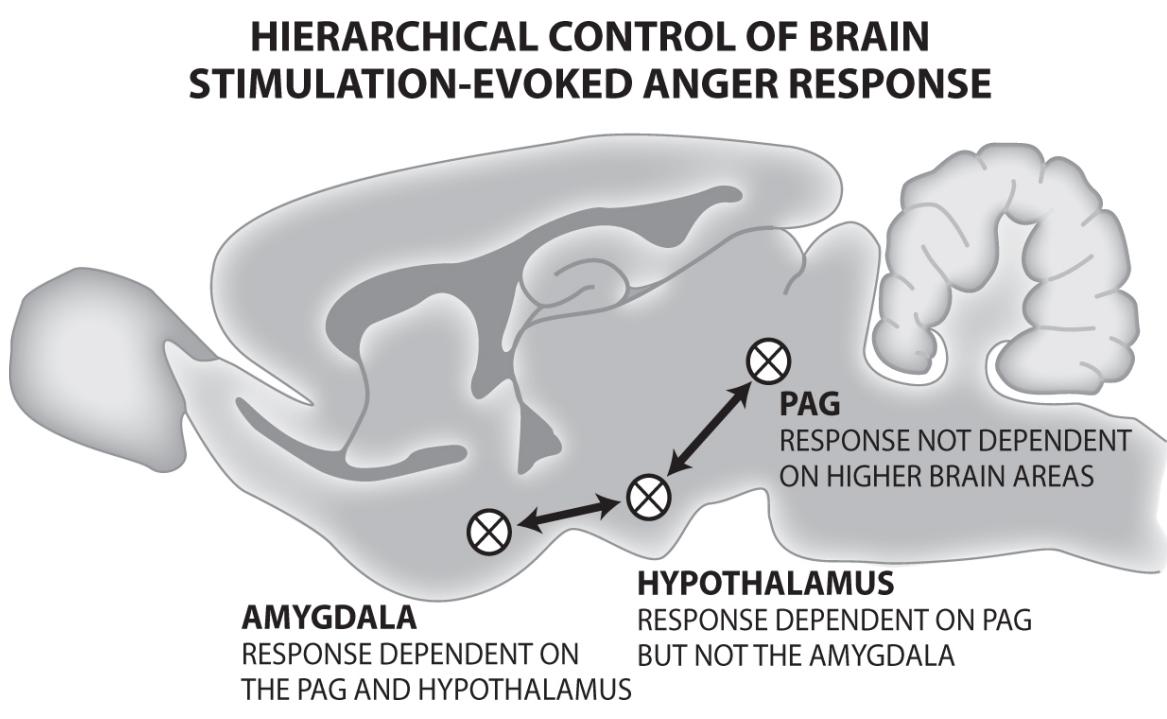

One hint regarding our prime movers comes from research showing that damage to specific emotional brain structures, with such daunting names as the medial forebrain bundle (Clark, 1938; Teitelbaum & Epstein, 1962; Coenen, Panksepp, Hurwitz, Urbach, & Mädler, 2012) and the periaqueductal gray (Bailey & Davis, 1942, 1943; Depaulis & Bandler, 1991), results in a profound loss of motivation and a condition of helplessness. Due to extreme self-neglect, including even lack of eating and drinking, these subjects require intensive care to keep them alive. It is significant that both of these brain structures are deeply embedded in evolutionarily ancient parts of the brain intimately related to primary process emotions and to motivations, because these two concepts overlap enormously.

That these brain structures are so deeply rooted in our evolutionary past suggests that Mother Nature (meaning the process of evolution) had to answer a basic motivation question early in the evolution of animal life: What would move an animal to action? It is through better understanding of these primary ancestral motivations linked to our ancestral origins that we can more fully appreciate why we feel and act the way we do.

On safari in Africa, if one is fortunate enough to observe a pride of lions, after the initial excitement of such an opportunity one is struck by how inactive the lions are most of the day. One can watch them for hours and see little else than adult lions swishing away flies and lion cubs playing with each other. Is it possible that what one observes lions doing (or not doing) most of the day until they head out for their nightly hunt is the default mammalian state, and if it were not for homeostatic motivations such as hunger and the primary emotions, we would likely lack focused goal-oriented activity?

However, beyond just describing behavior, the essential question for a discussion of personality is, What prods us to act in the ways we do? Why do human babies and puppies try to climb out of their playpens when all their physical and emotional needs seem to be generously provided through maternal care? What causes us to be so easily focused on a crying baby? What makes children expend so much energy chasing each other about with no apparent purpose?

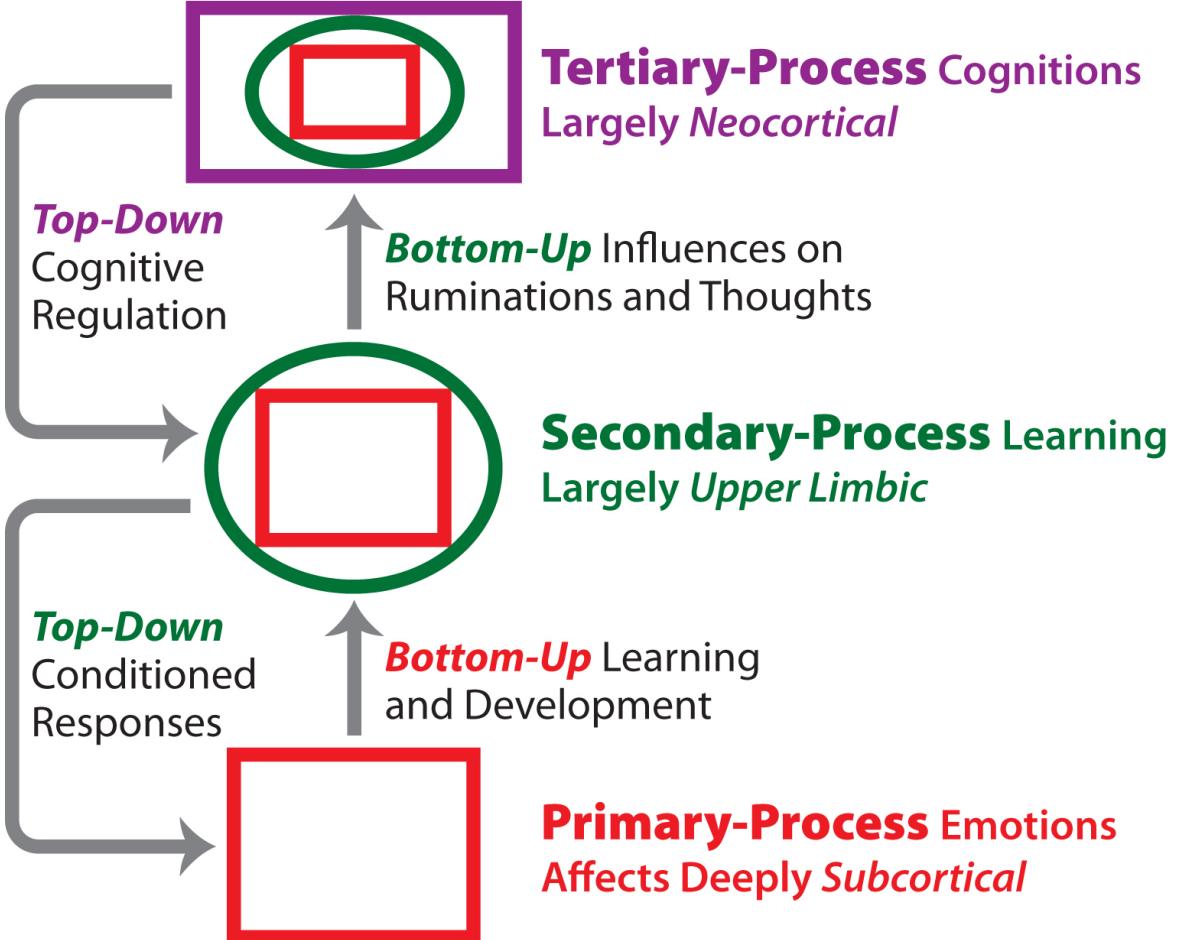

SUBCORTICAL EMOTIONAL AFFECTIVE SYSTEMS ARE CAUSAL MECHANISMS UNDERLYING PERSONALITY

It is our position throughout this book that, without an understanding of the psychobiological systems underpinning our feelings and actions, our understanding of the motivations behind our behavior is limited to obvious verbal pronouncements, and we may be restricted to just describing behavior, as linked to environmental contingencies, rather than explaining it. (Just describing rather than explaining it is what the Anglo-American behaviorists tried to convince the rest of psychology was quite enough; indeed, they at times argued that in their scheme the study of the brain was not really necessary.) For some purposes, regularly observing how caring a person is in his or her interactions toward other people may suffice, and even the observation of other animals may provide us with enough knowledge to reliably describe past behavior and perhaps predict future interactions. (In a sense this was the behaviorist perspective on what needed to be studied.) However, we are still left without an understanding about the causal mechanisms underlying this person’s gentle interactions with others. It is our premise that all the emotional affective systems that evolution (or Mother Nature, to use the most common metaphor) constructed within the subcortical brain are the primary causal mechanisms underlying our personalities that consistently guide emotional and other motivated actions. In the colorful words of the epigraph’s author, they are evolved affective designs for having “a psychical entity pushing a physical one around” (Langer, 1988, p. 4). Furthering our understanding of these prime movers will enable progress in psychology and psychiatry.

Affective neuroscience, the study of our subcortical affective Brain-Mind,1 has begun to clarify these prime movers—what Freud called the id, his supposedly unconscious foundation for the conscious mind. Now we know that this subcortical terrain of mind is not deeply unconscious (Solms & Panksepp, 2012), but it is a primal mind that can make snap decisions to various life challenges almost instantaneously without the need for reflective thought. For example, imagine yourself on a lovely day peacefully hiking through the woods. Suddenly seeing a large snake just ahead of you would generate immediate fear in most people. It is likely that the closer the snake is to you at that moment, the more intense your alarm would be. If the danger

is imminent, your subcortical brain will likely halt all your other activity and prompt you to immediately seek a safer distance, from which you may again become more reflective—at which point some would attempt to observe the snake more carefully and determine whether it is poisonous and how it behaves. That is, you will return to using your upper brain to cognitively evaluate what you are seeing.

The initial fear response is an example of a prediction, made largely by the subcortical brain, namely, that you are in danger—spotlighting an immediate survival issue. Your brain made this prediction automatically without any conscious analysis or effort on your part. As a result of this ancestral prediction, your brain concurrently created a fearful emotion and motivated a specific type of action. Regardless of how relaxed and pleasant you were feeling as you were enjoying your hike, this fearful event charged your whole being with strong emotion and set in place many bodily reactions, including the compelling urge to move away, to seek safety, without needing any intervening cognitive reflections.

This scenario is an example of an evolved response pattern—a prime mover—that helps us avoid physical harm to our bodies. This response pattern does not need to be learned. Somehow, all primates, indeed most mammals, not just humans, are instinctively afraid of snakes and have subcortical brains innately equipped to identify snakes as life-threatening dangers. From a personality perspective, once your brain has made the prediction that there is a dangerous snake in your path, it sets off a series of adaptive actions and feelings to ensure your safety and even survival. The feeling may temporally lag the action, prior to conditioning, but it is still an unconditioned flight response of our FEAR/Anxiety system (more on this below) that probably evolved as a mental heuristic, which can extend an anticipatory attitude in time and space. The brain mechanisms that generate such valenced feelings may constitute what behaviorists, without any perceived need for brain research, called reinforcements (Panksepp & Biven, 2012).

In any event, FEAR (the use of all caps indicates a formal name for an evolved emotional brain system) is an example of one of the primary movers, one of the evolved elements in the mammalian brain that can break our behavioral inertia and excite our entire being to action. As you walked along the path, you were probably not actively looking for snakes. However, your vigilant brain spied the animal and automatically set off a series of

adaptive responses that included sparking you to action. Your action was not set off by conscious intention—it was instinctive and reflexive. And it also felt like something and hence can be used as a model for those “ancestral voices” that move us out of our resting state into active coherent behavior.

This example briefly illustrated the brain’s FEAR system. A key part of this emotional system being aroused is the feeling of fear. Somehow, our subcortical brain has evolved a way for us to experience this feeling of fear as strongly aversive, even punishing, something to terminate as soon as possible. The FEAR emotion was not learned. In some manner that is yet to be fully understood, it is built in as part of our brain’s intrinsic tools for living so that the primary feeling of fear itself never fundamentally changes over the course of our entire lives, even though it can come to be regulated in space, time, and intensity as it becomes associated with various life events. FEAR also never loses its capacity to provoke an urge to act, even though at less intense levels of arousal FEAR can motivate us to “freeze” in place.

The arousal of the FEAR system alters our thoughts and perceptions as well. After seeing a dangerous snake on the trail and being intensely frightened, we will likely become more cognitively attuned to spotting snakes. We may even spot a snake when there is no snake, just a tree branch on the trail that looks a little like a snake. Likewise, our minds may fill with thoughts about venomous snakes we have read about or heard about on television, some with venom that can kill in a very short time. We may recall vague memories about how to recognize the distinctive diamond-shaped head of most poisonous snakes. We may also make plans of what to do if actually bitten by a snake and vow to come better prepared if ever hiking this trail, or any potential snake habitat, again.

Many kinds of learning can be motivated by this system, but the important point is that FEAR is an example of a prime mover, one of the archetypal emotional brain systems that strongly shape our behavior and, for our purposes here, define aspects of our personality usually measured in humans by asking appropriate questions (i.e., personality tests).

Life is full of fear-provoking situations. Importantly for a discussion of personality, some of us are more sensitive than others to these fear-provoking events. Some would feel quite apprehensive about venturing into a forest in the first place. Few have the courage to attempt rock climbing up the steep side of El Capitan at Yosemite (the fifth ever “free ascent” was completed by Jorg Verhoeven in 2014). Indeed, some would intensely dislike walking

through a strange part of town, especially at night, and especially alone. On the other hand, others of us are not so easily frightened and are much less likely to be inhibited by such challenges. It is these kinds of emotional differences that give rise to unique personalities by motivating and guiding our diverse action tendencies so consistently from day to day. These individual differences in the sensitivities of our emotional brain systems lead each of us to experience the world differently and therefore to respond differently, resulting in our recognizable individual personalities. To varying degrees, depending to a great extent on our inherited makeup, our emotions move us out of our resting state. They are the prime movers of personality.

PRIME MOVERS ALSO GUIDE LEARNING

Importantly, these instinctive emotional brain systems are not fixed and immutable. Again, using the FEAR system as an example, while the feeling of fear itself does not change, what we fear does change. Indeed, the FEAR system, like each of our brain’s emotion systems, learns spontaneously without any conscious effort on our part. The feeling of fear can be psychologically very punishing; still, fear is an important part of how we learn to adapt to a changing world. Although we have no innate fear of knives, we quickly learn knives can cut our skin and injure our bodies, but we also learn to use such tools as we need to cut into things. And, of course, we naturally learn how dangerous knives can be in the hands of a menacing individual who wants to hurt us. We can also learn less fearful responses to snakes. We can learn how ecologically beneficial snakes are in the control of rodents, and we can learn how to pin a snake’s head with a forked stick and handle it safely, and even “milk” the venom out of its fangs—a skill surely acquired more readily by those who begin life with a less arousable FEAR system. Such lack of fearfulness can be inherited, along with the variations in all the other basic emotions, as has been indicated by abundant selective breeding research in animals.

So, in addition to being our motivators and guides, emotions are also our teachers. There are other primary emotional affects, such as the pleasant, warm feelings we experience when we care for babies and help others in need. Collectively, the punishing and rewarding qualities of these primary emotional affects help us learn about the idiosyncrasies of the world. They are the rewards and punishments that help us adapt to an ever-changing

environment. Without these pleasant and unpleasant affects—the learningfacilitating function of our primary emotions, we might be locked into acting as if we continued to live in the ecological niche our ancestors evolved in. We would function like fruit flies that instinctively fly toward the light regardless of whether that light is the sun or an ultraviolet insect trap. Unlike coyotes, we would be unable to learn to avoid killing and eating sheep in areas where farmers bait coyotes with dead sheep carcasses laced with nauseating chemicals. And, unlike the proverbial fox, we would never learn to take advantage of the fact that humans have also domesticated the chicken.

Our primal emotional strengths and weaknesses endow us with the foundation of our various human personalities, beginning with an inherited base, which is adapted in many ways as we mature and learn from life experiences. We experience our emotions at various affective levels, from subtle moods shifts to full-blown RAGE or PANIC reactions. They are always ready to move us to action, and it is these ancestral emotions, evolved over millions of years, that we must learn more about to better understand why we act and feel and generally experience the world as we do. These systems are the foundations of our personality structures, but a great deal of complexity is added by learning—to a point where we can assess human personalities by simply asking the right psychological assessment questions, rather than having to focus merely on large-scale bodily behaviors, vocalizations, and various autonomic responses of our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

THE BASIC STUDY OF EMOTIONS

Jaak Panksepp, the second author, recognized early in his career that powerful emotional drivers such as desire, anger, fear, and feelings of loneliness were keys to understanding our personality differences and even the sources of some of our major psychopathologies, especially mania, excessive anger, anxiety disorders, and depression. As a result, in the mid-1960s he began his psychological research in the nascent specialty of physiological psychology, exploring the subcortical emotional systems embedded in the evolutionarily older parts of our brains—a field founded on the work of Walter Hess starting in the late 1920s, with Paul MacLean adding important observations a generation later, names we will revisit shortly. With the technical tools that were emerging to study the actual workings of the

brain, especially deep brain stimulation (DBS), Panksepp began to study the mammalian brain and its evolved emotional systems.

Panksepp first described four distinct brain emotion systems, SEEKING (a generalized form of appetitive-exploratory-foraging desire), RAGE (anger), FEAR, and PANIC (aka separation distress), weaving them into one of the first global psychobiological theories of emotions (Panksepp, 1982). However, he shortly realized that there were at least three more of these blue ribbon systems: sexual LUST, maternal CARE, and juvenile PLAY. We believe that these subcortical brain emotion systems are the tools nature has evolved to move us to action and, with the possible exception of LUST, form the emotional drivers that lie at the foundation of our personalities and psychopathologies.

Early on, personality theorists including Sigmund Freud and Gordon Allport also realized there had to be biological mechanisms underlying our personalities and psychological imbalances—“neurophysiological brain causes” in the case of Freud and “psychophysiological systems” in the case of Allport. But, as impressive as their careers were, technology had not yet provided psychological researchers with the experimental tools for studying such brain intricacies. So, despite their interest in the biological explanations of personality, both Freud and Allport chose to pursue psychological analyses along with clinical therapeutic approaches to understanding human behavior.

A great many investigators laid the foundations for and have contributed to our slowly accelerating efforts to understand emotions and other feelings, which with modern human brain imaging (functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography studies; see Chapter 16) has now reached a fever pitch. However, two pioneers, Walter Hess in the first third of the twentieth century and Paul MacLean in the second third, were especially eminent in advancing neuroscientific approaches to tease out parts of the emotional puzzles encapsulated in the subcortical regions of mammalian brains. Hess explored the technique of probing ancient areas deep in the center of the brain with DBS—tiny electric currents to reveal what areas were linked to specific emotional responses such as rage/anger. MacLean pursued an evolutionary approach to the “limbic” anatomy of the brain. He envisioned the brain to be a layered organ with more evolutionarily recent areas (neocortex) surrounding middle layers (the basal ganglia, or “limbic system,” as he called it), layered on top of even more

evolutionarily ancient areas (the upper brain stem, consisting of thalamus, hypothalamus, and midbrain), which guided the actions of the lower brain stem and spinal cord.

The “limbic” approach to emotions, although not much used by modern neuroscientists, described areas in the human brain that could be traced to “lower” mammals, from monkeys and rats to even reptiles and fish. One could actually see the work of evolutionary changes within the brain, much more than any other bodily organ. There were newer mammalian structures (cortex) layered on top of old mammalian ones (limbic system), with reptilian foundations still evident as investigators studied all species they could lay their hands on.

There were also evolutionarily more recent areas of the cortex that were indeed unique to humans, and ever since the philosopher-psychologist William James wrote his remarkable Principles of Psychology in the late nineteenth century and speculated that feelings emerged from our higher neocortical brain regions, many psychologists (even some neuroscientists who should know better) have speculated that our emotional feelings arise from cortical activities—brain regions that are critical for our ability to think. But they are wrong, even as it is clear that those higher brain regions can regulate our behaviors and thinking in ways that most other animals cannot imagine.

Panksepp blended these clinical therapeutic and neuroscientific evolutionary traditions utilizing additional neuroscience tools such as precise pharmacological methods to continue picking the lock on what some called the “black box,” a metaphor for the brain intended to suggest the futility of exploring the deeper biological causes of behavior hidden in the brain itself. Indeed, the neuroscience revolution had begun in the early twentieth century, and tantalizing questions could begin to be asked—even though all answers are provisional—questions that often suggested additional questions, many of which cannot yet be answered. In any event, many, many more generations of enthusiastic empirical brain investigators will undoubtedly be required to generate fully satisfactory answers to the secrets of human behavior and the various instinctive and learned drivers of our individual personalities.

However, in this volume we make the case that the primal brain processes that control our affective arousals, so important for constructing learning and memory, can provide a foundational understanding of our personalities. Thus, the seven blue ribbon emotions (Grade A evolutionary prizes all mammals

inherit) ——illuminated by the work of Panksepp and his colleagues (perhaps excluding LUST from the list of seven) provide an experimentally verifiable theory of shared personality foundations in both humans and other animals: they are the prime movers of our interactions with our world that shape our personalities. Even the word emotion itself suggests such an approach. The etymological roots of emotion are “out” plus “move” or “to move out”—for our purposes, to move out of a resting state into diverse and coherent adaptive behaviors that, based on millions of years of evolution, have a high probability of dealing effectively with whatever life-challenging events we are facing. Emotions provide an affectively rich action readiness, along with thought and memory facilitation, that helps structure what kind of individual we become based on both heredity and individual life trajectories.

ENCAPSULATED AFFECTIVE NEUROSCIENCE THEORY OF PERSONALITY

The affective neuroscience theory of personality proposes that we are born with various endophenotypes: primary emotional-affective personality profiles generated initially from our individual genomes. That is, our personalities arise through our endophenotypes, which are constructed from these primal emotional brain systems that provide our capacities not only to act but also to act consistently over time, without needing any conscious effort on our part, and that also promote affectively regulated patterns of learning and memory, allowing for diverse adaptations to life events.

1Our primary emotions with their built-in affects and reaction tendencies can be thought of as birthright survival systems. In urgent survival situations, they move us to react in ways that have worked effectively for countless generations of ancestors. In less urgent situations they still bias our perceptions and actions, generate both constant and coherent streams of thoughts, and add value and meaning to our experiences through the positive and negative feelings they generate. Our primary emotions begin as unconditional responses (the behaviorist term for instincts) to stimuli arising from life-challenging circumstances, but they are continuously revamped as they control and guide learning, and hence memory formations and retrievals —brain mechanisms that also operate automatically, but in those cases completely unconsciously. In addition, emotional arousals always have feeling states associated with them, which may be the first form of consciousness that emerged on the face of the earth (Panksepp, 2007a, 2009), providing a solid foundation for all the rest (Panksepp, 2015; Solms & Panksepp, 2012).

Along with learning and memories, these emotional systems guide our behavior over a lifetime in ways that are sufficiently consistent that each of us can be accurately described by personality dimensions—our personal endophenotype. Our developing endophenotype is sufficiently complex that we are not completely predictable. Yet, there is a day-to-day sameness in our behavioral interchanges with the other humans, animals, objects, and circumstances we encounter that our endophenotypes provide: a modus operandi that is recognizable to those around us such that others will remark when we are “not being ourselves,” “out of sorts,” or “just acting,” so to speak.

Why do we do anything at all, let alone in a consistent way that is recognizable to all who know us well? It is our primary-process psychobehavioral abilities, our prime movers, that arise from our subcortical brain’s primary emotional action systems that move us out of our resting state into coherent behavior patterns, which if adequately understood could be seen as our endophenotype’s optimal ways of trying to cope with life challenges, with further refinements being added by our learning mechanisms and thereby individual memories.2

These blue ribbon emotions provide a window into our deeper, some may say “true,” nature. We all experience the world through the lenses of these emotions. And understanding how strong or weak an influence each of these emotions has on our personal ways of feeling, thinking, and behaving is a good first step toward understanding ourselves. If we resolve to make needed adjustments in our lives, basing our efforts on an understanding of our deeper nature is likely to make our attempts more fruitful. In a sense, we are all survivors of the same evolutionary seas, cruising in similar boats, but in many different lakes, with slightly different patterns of affective winds in our sails. These winds are distinct personality dimensions, and a key that has been missing in personality theory is a credible cross-species neuroscientific foundation of those personality dimensions. That is why we developed the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales and have written this book.

CHAPTER 1: The Mystery of Human Personality

We need to be agnostics first and then there is some chance at arriving at a sensible system of belief.

—D. Elton Trueblood 20th-century American Quaker author and philosopher

AS YOU READ THIS BOOK, you will be exposed to a view of human personality from a distinctly new vantage. If you are a seasoned student of personality, we hope you can briefly put aside your previous training in personality theory and suspend judgment for a while, for you may appreciate a novel approach to personality contained within these pages—one that arises from the study of the primal (evolved) emotional systems of mammalian brains rather than the diverse personality traits enshrined in the study of human languages. In any case, we hope you will find the present approach fresh and challenging, for here we focus on personality, perhaps for the first time, from the perspective of the actual neurobiologically ingrained emotional systems of mammalian brains (even though there are others who have conceptually initiated such endeavors—Robert Cloninger (2004), Richard DePue (1995), and Jeffrey Gray (1982) come easily to mind).

Of course, emotionality has traditionally been seen as the foundation of personality. That is, the classic view was based on the supposition that various presumed bodily forces (humors) that control our moods were the foundation of our temperaments. According to medieval scholars of personality, some people are sanguine, basically happy and easygoing, while others are choleric, easily irritated and willing to show their anger. Some are phlegmatic, slow, ponderous, and uninteresting (basically cold fish), and yet others are melancholic, chronically sad and depressed.

Various later approaches to personality were based on clinical experiences and insights, because many of the early personality theorists were therapists and psychiatrists (see examples in Chapter 5). Their patients were primarily people with serious behavioral and/or emotional problems, so it was natural for these early personality theorists to try to distinguish their patients on the basis of temperamental differences and to assign them to diagnostic categories. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926) had compiled a taxonomy of psychological “diseases” based on medical diagnostics derived from distinct patterns of psychologically evident symptoms. One of the diagnoses Kraepelin is well known for is schizophrenia, which he originally labeled dementia praecox, or premature dementia or precocious madness, because it usually began in the late teens or early adulthood.2

If you are a therapist, physician, psychiatrist, or some other medical professional, we note that this book does not focus on using personality or personality tests to try to diagnose psychiatric problems or personality disorders, even though it may provide insights to understanding people with diverse mental problems. It is more about trying to explore the ancestral neural roots of personality, what personality means, and to gain a deeper appreciation for the individual differences that make each of us human beings on this planet not only unique but also inheritors of emotional ways of being in the world that are reflected in characteristic personalities. When extreme, such personality traits can be seen to reflect psychiatrically significant personality tendencies. As we describe in several chapters, neurogenetic findings are providing abundant support for ingrained emotional foundations for human and animal personalities. Such emerging knowledge will eventually change the way we understand human personalities as well as psychiatric disorders.

The science of psychiatry is experiencing a crisis of confidence in traditional psychiatric diagnostic categories, which was illustrated with the unveiling of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Many psychiatrists still believe that such diagnostic traditions, which arose from the way physicians learned to describe characteristic bodily disorders in the middle of the nineteenth century, are essential for progress in the field. This

transformation toward a systematic classification of mental disorders, inspired by a coterie of physicians in Germany called the Berlin Biophysics Club, aimed to establish medicine on a solid scientific foundation. However, there is a growing consensus that this might not have been the best way to proceed with the diversity of mental disorders that psychiatrists currently deal with. Recognizing that we really have no good evidence for homogeneous types of brain problems that underlie many psychiatric diagnostic labels (including autism, depression, schizophrenia, and most especially personality disorders), many favor falling back on simply using consistent symptoms, namely, fundamental psychophysiological signs (the socalled endophenotypes) that may reflect the changing activities of distinct brain circuits, as a better way to approach human personality and psychiatric problems, in ways that can be scientifically linked to distinct brain systems.

Of course, the ongoing debate on the nature of human personality and the value of diagnostics in psychiatry is by no means resolved. Disagreements and debate are bound to remain with us for a long time, especially in psychiatry, because conceptual categories provide useful ways to standardize ways to prescribe increasingly large numbers of drugs that are becoming readily available to treat the various DSM-specified psychiatric categories. Regrettably, the range in medicinal effects varies enormously, and only a few have been developed by trying to model the relevant shifts in affective states in animals (for recent summaries, see Panksepp, Wright, Döbrössy, Schlaepfer, & Coenen, 2014; Panksepp & Yovell, 2014; Panksepp, 2015, 2016).

We do not delve into this active area of debate but note that the relationship between the psychiatric profession and pharmaceutical companies has solidified to such an extent that it would take a great deal of scientific data to change established practices. Robert Whitaker’s frank critique and hard-hitting condemnation of this area of medicine (see Whitaker, 2010) has emerged from the recognition that many current mind medicines often precipitate mental/personality problems other than the ones clients started with. Indeed, medicinally induced shifts in the chemistries of mind can provoke strong “opponent processes” that gradually destabilize chemistries to such an extent that feelings of normality can no longer be achieved. We return to psychiatric issues toward the end of this book in Chapter 18. Our immediate goal is to focus on the normal variability of human personality arising from the diverse characteristics of our core emotional systems and to discuss how this knowledge can help us better understand ourselves.

It is hard to define what is psychologically normal. Obviously there are many cultural and other environmental variables that impact development, but neuroscientists are revealing that it is partly based on the emotional strengths and weaknesses we are born with—variation arising from the brain manifestations of one’s genetic heritage, which are typically further shaped by individual experiences. As we describe in this book, this perspective has been amply affirmed through the identification of many genetic predispositions for diverse personality traits. But because every baby confronts the “booming, buzzing” confusions of its surrounding social world, to borrow William James’s terms for newborn mental life, we also have to pay attention to how genes are influenced by environments. The concept of epigenesis captures the simple fact that environmentally induced influences on gene expression are as influential in the construction of stable personality as one’s hereditary endowment of genes (see Chapter 15). The stability of these early influences, as expressed in the construction of basic brain circuits that control emotional feelings—more so than other affects, for example, bodily sensory and homeostatic ones—are the very bedrock of personality development. These are what modern biological psychiatrists would call the endophenotypes of the mind—the natural affective processes that guide the individualized paths of learning and memory. Indeed, not all of the types of feelings we are born with, neither the sensory ones (sweet delights and dreadful disgusts) nor the bodily homeostatic urges experienced as hunger and thirst, are as influential as the emotional systems that exist inside our brains, conveying various basic affective feelings, the strengths and weaknesses of which constitute, we suggest, the most influential brain endophenotypes for personality development.

OUR THEORETICAL ORIENTATION

Each human being is unique. Our faces and voices easily identify us as individuals. We now know that each of us is endowed, by heredity, with our own unique genetic patterns. Even identical twins develop differences over their life-span, through epigenetic effects, as well as, of course, learning (Fraga et al., 2005). While it might initially be more obvious that our physical features are different, it is also true that each of our personalities is unique as well. However, one of the great puzzles in psychology has been how to explain the origin and development of rather stable personality similarities and differences seen across many individuals. Even though we know there are strong genetic influences on our individual traits and characteristics, the sciences of psychology and neuroscience have struggled to explain how those genetic differences emerge into personality differences (Crews, Gillette, Miller-Crews, Gore, & Skinner, 2014; Weaver et al., 2014).

A partial explanation and one of the themes of this book is that our personalities are all different because of our underlying genetically based as well as environmentally promoted emotional differences that lead each of us to perceive and react to the world differently. Our unique personalities are a reflection of how we individually experience and respond to the world. Because we cannot experience our environments directly but must rely on our brains to interpret each life event, we all experience the world in our own unique ways. In a way, each of us lives in a different world because we each perceive the world somewhat differently, although in the midst of abundant differences, there are also abiding traits we share with many others.3

Of course, none of us perceives our world directly. Our perceptions of the world are constructed by the brain. For instance, vision arises from light waves entering our eyes. However, our eyes do not directly “see” images; we perceive only a narrow part of the electromagnetic spectrum that allows us to have vision. The light-sensitive receptors in our eyes are capable of detecting only points of light energy, like pixels on a computer screen. Some of these receptors, the cones, respond to different-frequency light waves, which create a primary experience of red, green, and blue colors. However, the eye itself does not have the capacity for identifying whole images. It is primarily our visual cortex—just under the skull at the back of our heads that processes the ascending signals from the light receptors in our eyes, which through successive ascending neural refinements identifies subtler color differences, as well as features such as lines, motion, and eventually actual images. All perceptions—from color to objects—are created by brain functions that are experienced as representations of the world.

It requires yet another level of processing to give meaning to the images we eventually “see,” and it is at this level that we begin interpreting and adding affectively experienced values to images. It is at this stage of interpreting and adding value when major individual differences begin to emerge that provide each of us with foundational pillars for our various unique personalities. It is when we try to make sense of our images that we all begin to “see” the world in our own personal way. It is at this point that our emotional personality differences begin to become more apparent. For example, when we see a baby, we are not all equally attracted to the little one; some of us feel more warm and nurturing toward babies (females usually more than males). When we see a stranger, we are not all equally suspicious of or friendly toward the stranger; some of us feel more wary and anxious toward strangers. These feelings have been the most mysterious aspects of psychology, with little agreement on how they should be discussed, conceptualized, or studied. Our perspective here is that it is within the intrinsic strengths and weaknesses of our emotional feelings that we will find the major primal forces for the development of personality differences.4

As we add our affective feelings and values to life events, we simultaneously have different thoughts and memories, as well as different behavioral reactions. The fact that two people can stand side by side and yet perceive the same scene differently with different feelings, interpretations, thoughts, and actions is what adds uniqueness to our personalities. Try this exercise with a mix of friends who are willing to cooperate in a little experiment: Ask them to imagine a somewhat bedraggled person walking toward them at dusk in a lonely parking lot as they unlock their car after a long day at work. Give them some paper and ask them to write down their likely feelings and to provide a little more information about the person approaching them. Then ask your friends to share their notes with the group. If you are fortunate enough to have a variety of personalities participating in your little game, you may be amazed at the range of responses you hear. Some will likely be concerned about the health of the person or whether the person is lost or hungry. Others may express fear of the stranger, and still others may respond with some hostility toward the vagrant. In this case, perhaps you will see differences in care and kindness—flexible empathic urges on one hand and dogmatic authoritarian and punitive ones on the other. It is these differences of feelings, interpretation, thoughts, and reactions that provide windows into our basic personality differences.

THE AFFECTIVE FOUNDATIONS OF PERSONALITY

A fuller explanation of our personality differences is that these feelings, perceptions, thoughts, and behavior reactions are all wrapped up and packaged (intimately integrated) as our various instinctive emotions. Each of the many primary emotions we have inherited is basically an evolutionarily adaptive action system with intrinsic valences—various positive and negative feelings—reflecting in part that all mammals are born with the capacity to express and experience a set of primal emotions. In his 1998 text Af ective Neuroscience, Jaak Panksepp described seven of the primal emotional responses shared by all mammals, including humans. They are capitalized as SEEKING, RAGE, FEAR, LUST, CARE, PANIC, and PLAY, to highlight their primary-process inherited nature (although this does not mean that their typical activities are not modulated by living in the world– indeed, they guide a great deal of learning). Each emotion not only has its own characteristic feelings but also guides perceptual interpretations, thoughts, and behavioral reactions, both unlearned and learned. However, the strength and sensitivity of each brain emotion system, as well as the developmental learning it has guided, vary from individual to individual. So, there is substantial variation across different people in each of these basic emotion systems, part of it inherited and part of it learned. Such variations in each of these brain emotional responses promote different perceptions and reactions that map onto diverse higher-order traits and personality characteristics—from a broad and open friendliness to a narrow and obsessive neuroticism. In developing our ideas about human personality, we discarded LUST—our sexual urgencies—as perhaps a bit “too hot to handle”: important but often so personal that people may avoid frankness in rating their other personality traits. In other words, inquiring about people’s sexual interests may be just too personal, which may promote diminished frankness about other personality dimensions.

The following are brief examples of the six blue ribbon emotions we focused on in developing our new Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales (to be introduced shortly):

We all get curious and energized during new experiences, whether about new neighbors moving in next door or the excitement of buying a new car, especially our first one (all such activities entail SEEKING). We are all frustrated when we do not get the job we want and perhaps more than a little irritated when family members do not do their share of the work (we can all get enRAGEd).

Most of us are afraid of snakes and bears and no doubt would be a bit anxious if we were lost in the woods or had to walk alone through a rundown neighborhood in a strange city. The capacity for FEARfulness is built into us.

Many of us would feel especially tenderhearted and CAREing toward baby animals and might be inclined to give a little money to a homeless beggar.

We all feel loneliness and psychological pain that comes with broken relationships, especially the death of a loved one, and a similar feeling of “separation distress” when we are socially marginalized or rejected; we call this feeling PANIC/Sadness.

We all enjoy having fun with our friends and laughing at a good joke, which are all related to ancestral PLAY urges that we still share with the other mammals.

While we humans do share emotional feelings illustrated by these six examples, all are not equally expressed in our individual personalities. That is, while we all enjoy having fun with friends, some of us are much more friendly than others and more inclined to seek out opportunities for social fun. While many of us, especially females, are prone to feel tenderness toward baby animals, few of us would be moved to actually take home a baby bird that had fallen out of its nest to try to save it. So, the strength of our inclinations and reactions associated with each of these six emotions can differ dramatically across individuals. It is the variation across these six powers of the BrainMind, with their different feelings, typically exhibited in distinct life circumstances, which have been developmentally well integrated with our perceptions, thoughts, and behavioral reactions, that help constitute our diverse, often unique personalities.

Stated another way, each of the above six basic emotions arise from our inherited cerebral tools for living—arising from ancient, highly evolved brain survival systems that color and guide our perceptions and diverse responses to life events. These six brain systems are automatically, continuously, and intimately involved in our interpretations of the life situations we encounter. Our various positive and negative affective feelings are “value indicators”—they are all ancient survival mechanisms genetically passed down through millions of generations, long before modern humans or

Neanderthals walked the face of the earth, and they automatically and continuously monitor the world as we encounter it. When it comes to survival, Mother Nature (aka evolution) did not leave foundational survival issues to chance. What she did provide, with ever-increasing generosity to primates, reaching its pinnacle in our species, were higher brain tissues, namely, the most massive neocortical expansions (relative to body size), which allow us to become really smart (and all too often perplexed, indeed confused, about mental life, which is rich mixture of our affective and cognitive abilities).

It is becoming ever clearer that the lower emotional regions of the brain are very important in programming the higher reaches, namely, our various affective feeling systems govern learning processes, allowing each organism to develop cognitions that emerge in lockstep with its temperamental strengths and weaknesses. This often leads to many life situations when people simply do not understand their own motivations or the motivations of others. However, we leave this complex topic for a later time.

TOWARD A NEW PERSONALITY TEST

It is most significant that the above seven basic blue ribbon emotional brain systems are shared not only by all humans but also by all other mammals. So, your pet dogs and cats have these evolutionarily related brain emotional systems in common with humans—SEEKING, RAGE, FEAR, CARE, PANIC and PLAY. (Although, as mentioned, we focus only on six, we occasionally reflect on LUST in some later chapters.) Indeed, the subject of animal personalities is reviewed in Chapter 10. For now, we emphasize that the existence of these brain systems, which are affectively (albeit perhaps not cognitively) experienced by all animals that possess them, makes these animals sentient—creatures that experience themselves in the world. The direct evidence for the existence of experienced feelings in nonspeaking animals is the simple fact that whenever we artificially arouse those systems, as with electrical deep brain stimulation (DBS), both animals and humans experience those states. Humans can directly tell us about their feelings, while we must interrogate animals that cannot speak through their behavioral choices. They can inform us of their likes and dislikes by either voluntarily turning on brain stimulation, as for SEEKING, CARE, and PLAY systems (these evoked states are rewarding), or turning off brain stimulation, as for RAGE, FEAR, and PANIC (for overviews, see Panksepp, 1998a, 2005; Panksepp & Biven, 2012). Accordingly, we developed a new human personality inventory to monitor how these shared emotions are expressed as distinct dimensions of human temperaments—a test we call the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales (ANPS), presented more fully in Chapter 2 (for latest versions, see Davis & Panksepp, 2011 and the appendix).

Panksepp and his students have extensively studied and provided formal scientific names for these six brain systems. They are written in all capital letters to give them some separation from vernacular usages—to indicate that their meanings are not identical with their lowercase equivalents. Thus, the formal scientific names for these brains systems are SEEKING, RAGE, FEAR, CARE, PANIC, and PLAY. We have so far learned about the fundamental evolved nature of these emotional systems more by studying animal brains than human ones. The first three emotion systems, SEEKING, RAGE, and FEAR, have very ancient origins, because they can be traced back to reptiles and even fish. The other three, CARE, PANIC, and PLAY, are more uniquely mammalian and give mammals their higher social abilities (for instance, the CARE/Nurturance system may be one of the main sources of empathy; for a discussion see Panksepp & Panksepp, 2013). All six have been repeatedly shown to be linked to distinct personality differences across cultures, with early ANPS translations into German, French, Italian, Norwegian, Spanish, Turkish, and various other languages. The seventh system, sexual LUST, bridges ancient socioerotic SEEKING urges and mammalian desires to CARE for young and for the young to PLAY with each other. Clearly some females and males are more LUSTy than others, and this could also be viewed as a personality dimension, but we chose not to include it in the ANPS—as mentioned above, we were concerned that many people would not wish to reveal this aspect of their personality to strangers and suspected that if it were included, negative affective responses to such personal questions might turn people off and thereby potentially affect their responses to some of the other emotional dimensions. It is also noteworthy that we are aware of no other personality inventory that currently includes sexuality as a personality factor (nor do they evaluate homeostatic affects like hunger and thirst, which LUST may be conceptually closer to than the other emotions, because it is also controlled by bodily states, such as hormone levels).

UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONAL PRIMES MAY BE ESSENTIAL FOR UNDERSTANDING THE NEUROSCIENCE OF PERSONALITY

Before we turn to personality testing, we briefly describe these fundamental emotional systems of the brain:

The SEEKING system may have originally evolved as a generalpurpose foraging system (a “seek and find” system) energizing the search for food and other resources needed for survival. With other life goals, the function of this all important system (which probably lies at the core of our feelings of “selfhood,” a topic we return to in Chapter 17) was evolutionarily broadened to energize the exploration for resources in general.

The RAGE system responds when the loss of resources is threatened —for example, loss of food, family, or money—and prepares the body to fight to get them back if necessary. We also sometimes call it the RAGE/Anger system, as a reminder that these fundamental systems probably link up reasonably well to our vernacular use of traditional emotional labels.

The FEAR/Anxiety system identifies and predicts when dangers are imminent and prepares the body to either freeze or flee, depending on which response will be most adaptive.

The CARE/Nurturance system motivates and coordinates the caretaking and rearing of infants from the time they are totally dependent newborns throughout the long period of early childhood development (although, of course, the youngsters of others species are typically not called their children). However, the CARE system may also motivate social helping behaviors in general.

The PANIC/Sadness system is engaged, especially in youngsters, when they lose contact with their mothers—we assume this is the feeling of psychological distress/pain that all infant mammals and birds suddenly feel when they lose close contact with supportive others. It is often associated with crying in children separated from their parents, with the death of a loved one, and with social rejection in general. At times we have also called it the Grief system or the Sadness system, because many people don’t understand the implications of PANIC—the extremely agitated state young animals exhibit when they are lost or even accidentally separated from parents for even very short periods of time.

The PLAY/Joy system motivates physical social-engagement (aka “rough-and-tumble”) play in all young mammals and commonly provides an affectively positive developmental context for learning how to socially interact with others, which thereby facilitates social integration in general.

At their fundamental (primary-process) level, each of these six brain systems can be thought of as distinct instincts (unconditioned responses in behavioral parlance) consisting of highly integrated ways of being and acting in the world—survival systems that help engender and solidify abundant learning. They are all natural systems, meaning their basic brain structures and functions have been inherited and hence do not require individual learning (although the systems may be refined by being used). It has long been clear that we do not need to teach children to play or to feel panic when they have lost contact with their parents.

Of course, that does not mean that these instincts cannot be modified by life experiences and that related behavior patterns cannot be modified through learning for adaptive integration with current environmental circumstances. Indeed, these six brain systems govern much of the early learning that children spontaneously exhibit. For example, children quickly learn which of their friends play nicely and are most friendly toward them. They also learn that the dog that bit them was threatening when it growled and to fear and avoid growling dogs in the future, especially if they were nipped at. In short, the fundamental affective guidance provided by these six behavioral-emotional systems can be thought of as ancestral tools for living that we are born with. They are genetically provided “original equipment” that provide rapid, inborn (instinctual) answers to life challenges—ways of behaving and feeling that promoted survival of ancestral mammals many, many millions of years ago.

These six behavioral-emotional systems may be stronger or weaker in different species, but all exist to some extent in all mammalian species. They are essential for survival and, with learning, become ever more deeply embedded in our personalities. They are action-oriented systems that consistently bias our perceptions, thoughts, and actions; they are elaborated in our lives as stable behavioral-feeling patterns that contribute substantially to the growth of our personalities. Most people do not think of “motor” or “action-generating” systems as having any consciousness, but these systems have a feel to them that seems to be an intrinsic part of their organization. As noted earlier, artificial activation with electrical DBS in animals, just like natural activation in humans, feels good and bad in various ways. In formal animal-behavioral terms, these systems can be shown to be rewarding or punishing, and that is the only scientific measures of affective feelings we have in nonspeaking animals (Panksepp, 1998a). In this affective sense, all vertebrate species are conscious—they experience themselves in the world. Of course, this does not necessarily mean they are aware that they are experiencing—that higher level of reflective consciousness is reserved for animals that know they possess awareness (i.e., knowing one is experiencing), which is much harder to study in other animals than whether they feel positive or negative—good or bad in the vernacular.

THE NATURE OF THE PRIMAL EMOTIONAL AFFECTS

This point is very important: These six emotions engender feeling states within the brain (as does LUST), and these experiential characteristics are especially important when we talk about personality. Each emotion has an affective component that feels either good or bad. These affects, or feelings, are either pleasant or aversive, even in other animals. They help automatically inform animals, including humans, which internal conditions of the brain are rewarding, and hence support survival, and which are punishing, signaling that survival may be in jeopardy. Again, the SEEKING, CARE, and PLAY emotions are experienced as desirable feelings (rewarding affects), whereas the FEAR, RAGE, and PANIC emotions are all experienced as aversive feelings (punishing affects to use behavioristic language).

On the positive side, the SEEKING system provides us with a very special euphoric “buzz” (we humans commonly call it enthusiasm) as we explore possibilities and anticipate desired outcomes. The CARE system infuses us with a “warm glow” as we support the lives of our children and help others overcome their problems. The CARE system, along with the PANIC/Sadness system, may be especially important for engendering our feelings of empathy and sympathy when bad things happen to nearby others,

but especially to those that we love. The PLAY system fills us with “delight” as we have fun with our friends.

On the negative side, the RAGE/Anger system sparks feelings of “irritation” and directs us to “attack” whoever or whatever threatens us or our possessions. The FEAR system makes us anxious, indeed can grip us with “terror” when we sense that our life or well-being is in danger. The PANIC/Sadness system overwhelms us with “desperate helplessness,” a painful distress (that can gradually become despair) we felt when as children we lost contact with our parents, or later in life when we lose (or are suddenly locked out of) a close, sustaining relationship.

The affective tone of our personal world—the world we individually perceptually live in at an affective level—is constructed by the positive or negative valence of these affects. In other words, it is among the pleasant or aversive qualities of these emotional feelings that we often find the value of our experiences. We positively value and are attracted to situations and experiences we associate with good feelings. We avoid and place negative values on situations and experiences that feel bad. Indeed, although many animal researchers are shy about even talking about the feelings of the animals they study (often just prefering to study learning and memory, where such concepts do not seem necessary), it seems likely that the various evolved feeling-generating systems (primal emotional affects) actually directly control many of the learning and memory processes of human and animal brains. This is a complex neurochemical story that we will not address here (but for a readable synopsis, see Panksepp & Biven, 2012, chap. 6).

IN SUM

It is surprising that no personality test has tried to represent all of these brain emotional systems explicitly and equally. As we describe in the chapters that follow, during the past century many personality tests were developed. Some did represent features such as anxiety and aggressiveness, and even curiosity (sometimes called “openness to experience”), but none focused on the whole package that we describe here. Partly this is because more recent personality tests typically started from a “top-down” perspective, from the many words and concepts we use to describe one another’s temperaments. Within the complexity of words, scientists were more prone to use complex statistics to

ferret out consistent patterns among the adjectives we use to describe one another. Perhaps because an understanding of the basic brain emotional systems requires cross-species neuroscience, no one has used the full riches of our emerging understanding of the basic emotional systems of our brains, so critically important for creating our feeling of selfhood, as one critical foundation pillar for personality theory.

The ANPS that we describe in this book attempts to do that, and in so doing it allows us to better connect our increasing understanding of the brain sources of basic human emotions to the kinds of knowledge (e.g., understanding the anatomies and chemistries of these systems) that can currently be achieved by studying the brains and behaviors of other animals. In a sense, our approach is much closer to the classical medieval approaches to personality, with their four major temperamental types—sanguine (PLAYful), choleric (RAGEful), melancholic (full of that PANICy psychic pain that we commonly call sadness), and phlegmatic (the coldness of temperaments that arises perhaps from too much anxiety engendered by excessive FEAR).

Why was SEEKING not represented? Perhaps because the ancients implicitly recognized it was a universal part of mental life itself (as encapsulated in the concept of conatus, the essential force or urge underlying human effort and striving; within the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza this was the psychological “force” in every living creature to preserve its own existence (for an excellent and readable overview, see Ravven, 2013), which in its most positive form becomes the very ground of “social joy” so magnificently represented in happy-sanguine temperaments. Why was CARE not represented? Perhaps because it was more highly feminine and simply accepted as something that women are skilled at, while males are not, for the temper of those times was governed so much more by men than during our more enlightened era. And, of course, everyone knew about LUST, but for a long time few wished to talk about it openly. Before we start summarizing where we have been as humans (and at time scientists) interested in human personality, during the past century and a half of scientific psychology, we will proceed in the next chapter to our own neoclassical view of human personality as represented in the Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales (ANPS).

CHAPTER 2: Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales and the Big Five

Delgado, Roberts, and Miller (1954) have shown that cats will learn to turn a wheel to avoid the unpleasant emotion of fear produced when certain parts of the brain [hypothalamus] are stimulated. The cats act as if the sensation or feelings produced by electrically stimulating the brain are real emotions. We may anticipate that this same demonstration will eventually be made with the emotion of anger.

—John Paul Scott, Aggression

IN THIS CHAPTER we introduce the major personality model for which there is the greatest agreement among personality psychologists, the Big Five, with discrete factors for Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience. And we contrast this model with our emotional-trait-focused Affective Neuroscience Personality Scales (ANPS). This new way of looking at personality is admittedly a radical departure from the history of the field, and before continuing with that complex history, we highlight why such a radical shift is needed in order to integrate our emerging understanding of the neural infrastructure of primal emotional feelings with our understanding of human personality.

The Big Five has emerged as perhaps the most scientific personality assessment model to this point, with no preconceptions about the underlying structure of mind. It was guided by the recognition that the language of personality should map well onto our linguistic use of adjectives to describe human traits. It let the chips fall in whatever way they would, based simply on allowing a statistical analysis of our language dictate what differences existed in our personalities. Clearly, our ANPS emerged from very different premises, namely, an understanding of the subcortical brain fundamentals of our emotional-affective natures. Pausing to consider these issues, before proceeding to the history of the field, we hope will help readers appreciate not only the dynamics of science in this contentious field but also possible lasting neurobiopsychological solutions. First, however, we backtrack a bit.

TOWARD A THEORY OF PERSONALITY FOCUSED ON PRIMAL EMOTIONAL AFFECT

As we describe in Chapter 15, there are significant connections between genetics and personality. In Chapter 3, we also summarize discussions by Darwin that animals exhibit emotional personalities similar to human personalities. In Chapters 4 and 5, we review how psychological and psychoanalytic pioneers at the beginning of the twentieth century engaged in active discussions about the relations between emotions and personality. But first, in this chapter we continue to make the case that modern affective neuroscience has, for the first time, provided a coherent, evidence-based view of mammalian minds as rooted in the value/survival-coding affective circuits situated at the very basement of the brain and mind. This kind of evidence makes a strong case that our personalities are firmly grounded in the ancestral roots of our biological bodies and brains. But what is it in our neurobiology that mediates the connections between our genes and our personality traits?