Regression Modeling Strategies

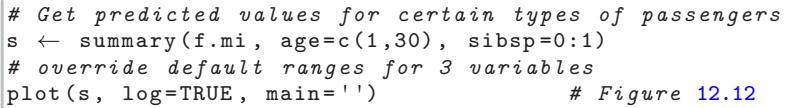

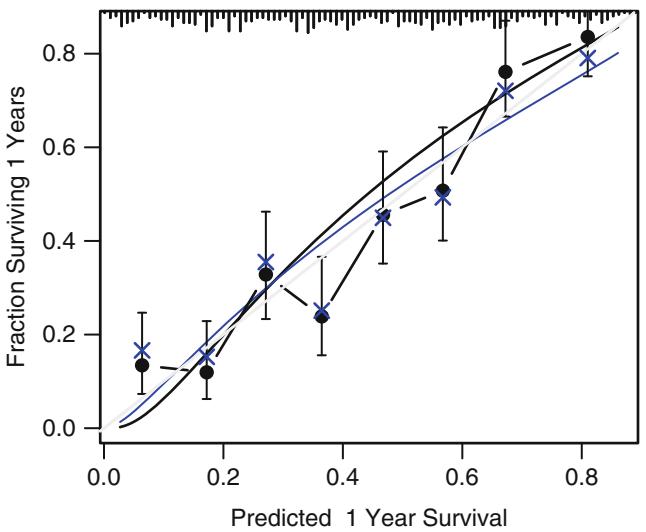

Chapter 10 Binary Logistic Regression

10.1 Model

Binary responses are commonly studied in many fields. Examples include 1 the presence or absence of a particular disease, death during surgery, or a consumer purchasing a product. Often one wishes to study how a set of predictor variables X is related to a dichotomous response variable Y . The predictors may describe such quantities as treatment assignment, dosage, risk factors, and calendar time.

For convenience we define the response to be Y = 0 or 1, with Y = 1 denoting the occurrence of the event of interest. Often a dichotomous outcome can be studied by calculating certain proportions, for example, the proportion of deaths among females and the proportion among males. However, in many situations, there are multiple descriptors, or one or more of the descriptors are continuous. Without a statistical model, studying patterns such as the relationship between age and occurrence of a disease, for example, would require the creation of arbitrary age groups to allow estimation of disease prevalence as a function of age.

Letting X denote the vector of predictors {X1, X2,…,Xk}, a first attempt at modeling the response might use the ordinary linear regression model

\[E\{Y|X\} = X\beta,\tag{10.1}\]

since the expectation of a binary variable Y is Prob{Y = 1}. However, such a model by definition cannot fit the data over the whole range of the predictors since a purely linear model E{Y |X} = Prob{Y = 1|X} = XΛ can allow Prob{Y = 1} to exceed 1 or fall below 0. The statistical model that is generally preferred for the analysis of binary responses is instead the binary logistic regression model, stated in terms of the probability that Y = 1 given X, the values of the predictors:

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

F.E. Harrell, Jr., Regression Modeling Strategies, Springer Series

in Statistics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7 10

\[\text{Prob}\{Y=1|X\} = [1 + \exp(-X\beta)]^{-1}.\tag{10.2}\]

As before, XΛ stands for Λ0 + Λ1X1 + Λ2X2 + … + ΛkXk. The binary logistic regression model was developed primarily by Cox129 and Walker and Duncan. 2 647 The regression parameters Λ are estimated by the method of maximum likelihood (see below).

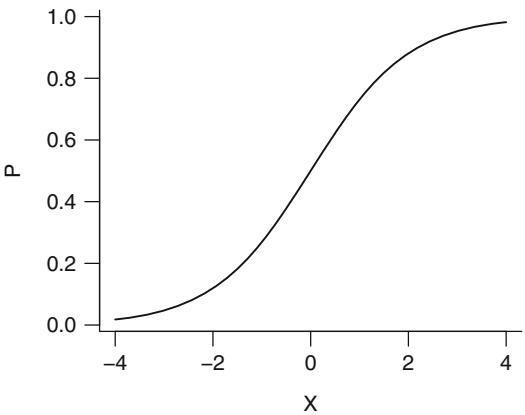

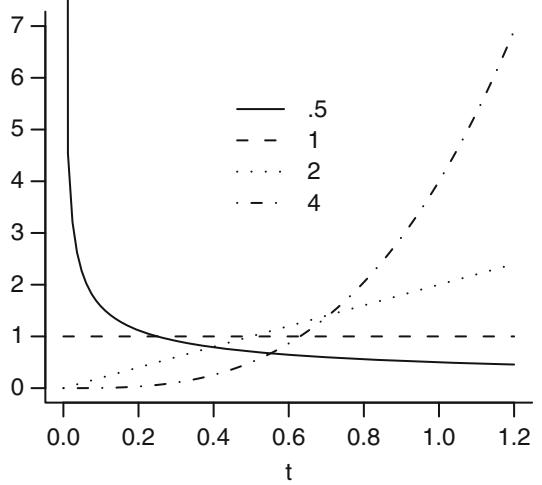

The function

\[P = [1 + \exp(-x)]^{-1} \tag{10.3}\]

is called the logistic function. This function is plotted in Figure 10.1 for x varying from ×4 to +4. This function has an unlimited range for x while P is restricted to range from 0 to 1.

Fig. 10.1 Logistic function

For future derivations it is useful to express x in terms of P. Solving the equation above for x by using

\[1 - P = \exp(-x) / [1 + \exp(-x)]\tag{10.4}\]

yields the inverse of the logistic function:

x = log[P/(1 × P)] = log[odds that Y = 1 occurs] = logit{Y = 1}. (10.5)

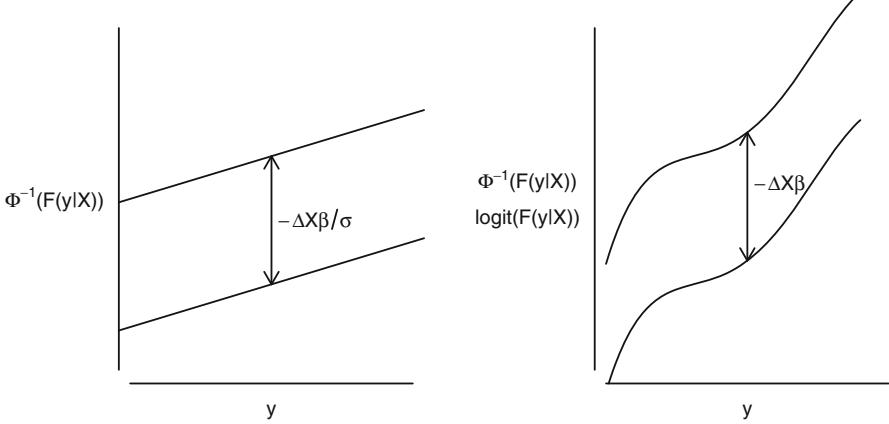

Other methods that have been used to analyze binary response data include the probit model, which writes P in terms of the cumulative normal distribution, and discriminant analysis. Probit regression, although assuming a similar shape to the logistic function for the regression relationship between XΛ and Prob{Y = 1}, involves more cumbersome calculations, and there is no natural interpretation of its regression parameters. In the past, discriminant analysis has been the predominant method since it is the simplest computationally. However, it makes more assumptions than logistic re-3 gression. The model used in discriminant analysis is stated in terms of the

distribution of X given the outcome group Y , even though one is seldom interested in the distribution of the predictors per se. The discriminant model has to be inverted using Bayes’ rule to derive the quantity of primary interest, Prob{Y = 1}. By contrast, the logistic model is a direct probability model since it is stated in terms of Prob{Y = 1|X}. Since the distribution of a binary random variable Y is completely defined by the true probability that Y = 1 and since the model makes no assumption about the distribution of the predictors, the logistic model makes no distributional assumptions whatsoever.

10.1.1 Model Assumptions and Interpretation of Parameters

Since the logistic model is a direct probability model, its only assumptions relate to the form of the regression equation. Regression assumptions are verifiable, unlike the assumption of multivariate normality made by discriminant analysis. The logistic model assumptions are most easily understood by transforming Prob{Y = 1} to make a model that is linear in XΛ:

\[\begin{split} \log \text{fit} \{ Y = 1 | X \} &= \text{logit}(P) = \log[P/(1 - P)] \\ &= X\beta, \end{split} \tag{10.6}\]

where P = Prob{Y = 1|X}. Thus the model is a linear regression model in the log odds that Y = 1 since logit(P) is a weighted sum of the Xs. If all effects are additive (i.e., no interactions are present), the model assumes that for every predictor Xj,

\[\begin{split} \text{logit} \{ Y = 1 | X \} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \dots + \beta\_j X\_j + \dots + \beta\_k X\_k \\ &= \beta\_j X\_j + C, \end{split} \tag{10.7}\]

where if all other factors are held constant, C is a constant given by

\[C = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \dots + \beta\_{j-1} X\_{j-1} + \beta\_{j+1} X\_{j+1} + \dots + \beta\_k X\_k. \tag{10.8}\]

The parameter Λj is then the change in the log odds per unit change in Xj if Xj represents a single factor that is linear and does not interact with other factors and if all other factors are held constant. Instead of writing this relationship in terms of log odds, it could just as easily be written in terms of the odds that Y = 1:

\[\text{odds}\{Y=1|X\} = \exp(X\beta),\tag{10.9}\]

and if all factors other than Xj are held constant,

\[\text{odds}\{Y=1|X\} = \exp(\beta\_j X\_j + C) = \exp(\beta\_j X\_j)\exp(C). \tag{10.10}\]

The regression parameters can also be written in terms of odds ratios. The odds that Y = 1 when Xj is increased by d, divided by the odds at Xj is

\[\begin{split} \frac{\text{odds}\{Y=1|X\_1, X\_2, \dots, X\_j+d, \dots, X\_k\}}{\text{odds}\{Y=1|X\_1, X\_2, \dots, X\_j, \dots, X\_k\}}\\ &= \frac{\exp[\beta\_j(X\_j+d)]\exp(C)}{[\exp(\beta\_j X\_j)\exp(C)]}\\ &= \exp[\beta\_j X\_j + \beta\_j d - \beta\_j X\_j] = \exp(\beta\_j d). \end{split} \tag{10.11}\]

Thus the effect of increasing Xj by d is to increase the odds that Y = 1 by a factor of exp(Λjd), or to increase the log odds that Y = 1 by an increment of Λjd. In general, the ratio of the odds of response for an individual with predictor variable values X′ compared with an individual with predictors X is

\[\begin{split} X^\*: X \text{ odds ratio} &= \exp(X^\*\beta) / \exp(X\beta) \\ &= \exp[(X^\* - X)\beta]. \end{split} \tag{10.12}\]

Now consider some special cases of the logistic multiple regression model. If there is only one predictor X and that predictor is binary, the model can be written

\[\begin{aligned} \text{logit}\{Y=1|X=0\} &= \beta\_0\\ \text{logit}\{Y=1|X=1\} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_1. \end{aligned} \tag{10.13}\]

Here Λ0 is the log odds of Y = 1 when X = 0. By subtracting the two equations above, it can be seen that Λ1 is the difference in the log odds when X = 1 as compared with X = 0, which is equivalent to the log of the ratio of the odds when X = 1 compared with the odds when X = 0. The quantity exp(Λ1) is the odds ratio for X = 1 compared with X = 0. Letting P0 = Prob{Y = 1|X = 0} and P1 = Prob{Y = 1|X = 1}, the regression parameters are interpreted by

\[\begin{split} \beta\_0 &= \text{logit}(P^0) = \log[P^0/(1-P^0)] \\ \beta\_1 &= \text{logit}(P^1) - \text{logit}(P^0) \\ &= \log[P^1/(1-P^1)] - \log[P^0/(1-P^0)] \\ &= \log\{[P^1/(1-P^1)]/[P^0/(1-P^0)]\}. \end{split} \tag{10.14}\]

Since there are only two quantities to model and two free parameters, there is no way that this two-sample model can’t fit; the model in this case is essentially fitting two cell proportions. Similarly, if there are g × 1 dummy indicator Xs representing g groups, the ANOVA-type logistic model must always fit.

If there is one continuous predictor X, the model is

\[\text{logit}\{Y=1|X\}=\beta\_0+\beta\_1X,\tag{10.15}\]

and without further modification (e.g., taking log transformation of the predictor), the model assumes a straight line in the log odds, or that an increase in X by one unit increases the odds by a factor of exp(Λ1).

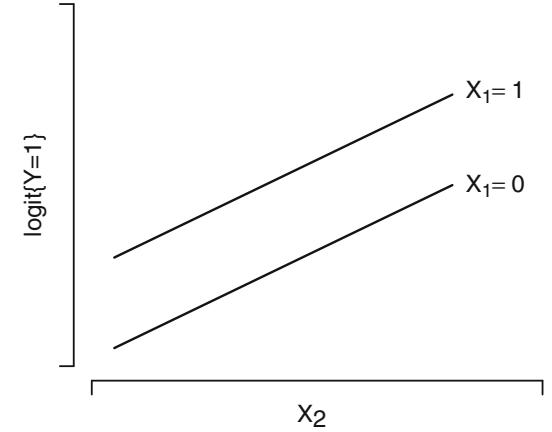

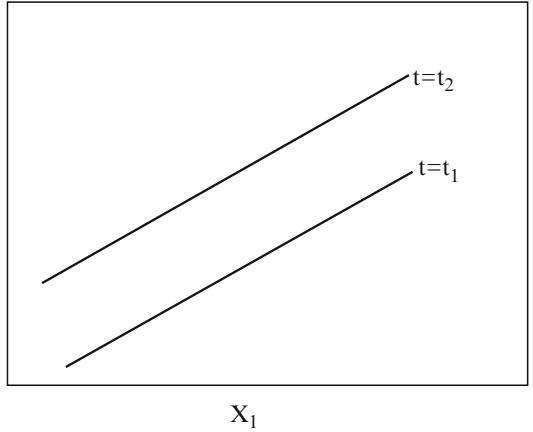

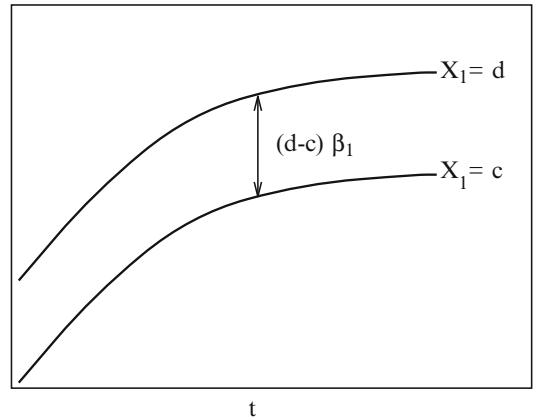

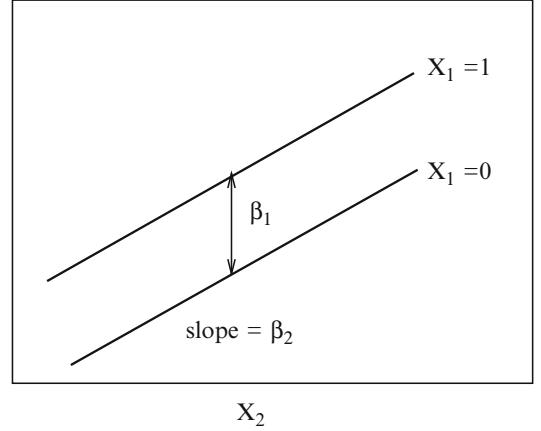

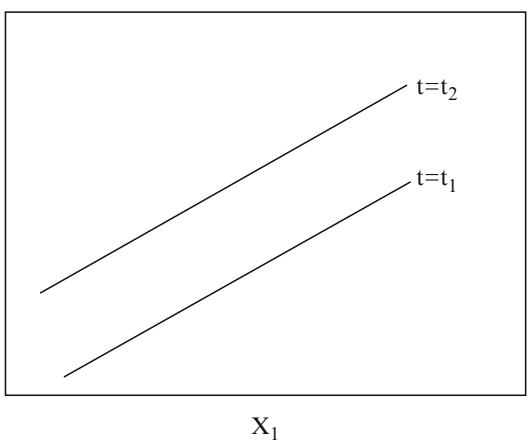

Now consider the simplest analysis of covariance model in which there are two treatments (indicated by X1 = 0 or 1) and one continuous covariable (X2). The simplest logistic model for this setup is

\[\text{logit}\{Y=1|X\} = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2,\tag{10.16}\]

which can be written also as

\[\begin{aligned} \text{logit}\{Y=1|X\_1=0, X\_2\} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_2 X\_2\\ \text{logit}\{Y=1|X\_1=1, X\_2\} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2. \end{aligned} \tag{10.17}\]

The X1 =1: X1 = 0 odds ratio is exp(Λ1), independent of X2. The odds ratio for a one-unit increase in X2 is exp(Λ2), independent of X1.

This model, with no term for a possible interaction between treatment and covariable, assumes that for each treatment the relationship between X2 and log odds is linear, and that the lines have equal slope; that is, they are parallel. Assuming linearity in X2, the only way that this model can fail is for the two slopes to differ. Thus, the only assumptions that need verification are linearity and lack of interaction between X1 and X2.

To adapt the model to allow or test for interaction, we write

\[\text{logit}\{Y=1|X\} = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2 + \beta\_3 X\_3,\tag{10.18}\]

where the derived variable X3 is defined to be X1X2. The test for lack of interaction (equal slopes) is H0 : Λ3 = 0. The model can be amplified as

\[\begin{aligned} \text{logit}\{Y=1|X\_1=0, X\_2\} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_2 X\_2\\ \text{logit}\{Y=1|X\_1=1, X\_2\} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2 + \beta\_3 X\_2\\ &= \beta\_0' + \beta\_2' X\_2, \end{aligned} \tag{10.19}\]

| Without Risk Factor | With Risk Factor | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability | Odds | Odds Probability | |

| .2 | .25 | .5 | .33 |

| .5 | 1 | 2 | .67 |

| .8 | 4 | 8 | .89 |

| .9 | 9 | 18 | .95 |

| .98 | 49 | 98 | .99 |

Table 10.1 Effect of an odds ratio of two on various risks

where Λ∗ 0 = Λ0 +Λ1 and Λ∗ 2 = Λ2 +Λ3. The model with interaction is therefore equivalent to fitting two separate logistic models with X2 as the only predictor, one model for each treatment group. Here the X1 =1: X1 = 0 odds ratio is exp(Λ1 + Λ3X2).

10.1.2 Odds Ratio, Risk Ratio, and Risk Difference

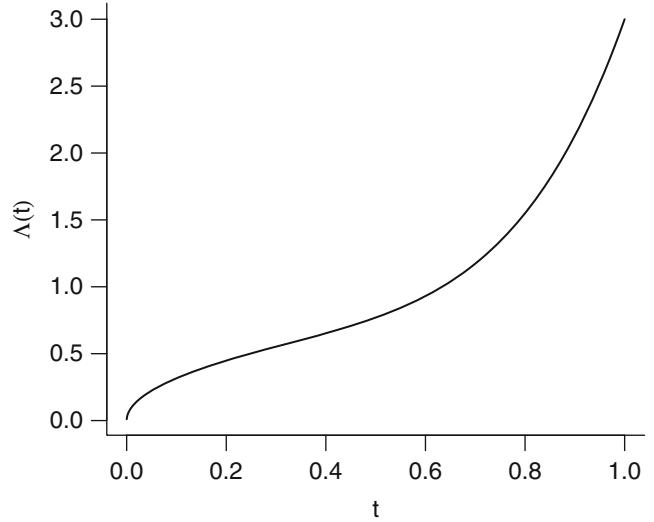

As discussed above, the logistic model quantifies the effect of a predictor in terms of an odds ratio or log odds ratio. An odds ratio is a natural description of an effect in a probability model since an odds ratio can be constant. For example, suppose that a given risk factor doubles the odds of disease. Table 10.1 shows the effect of the risk factor for various levels of initial risk.

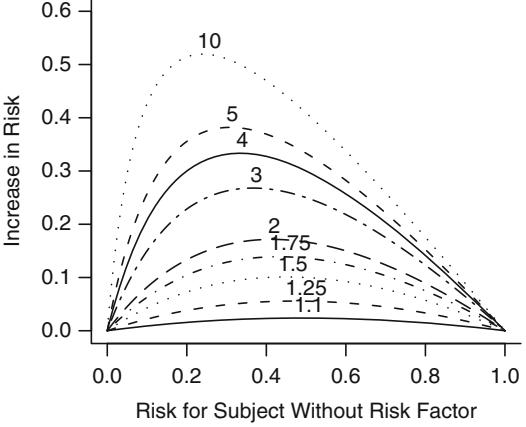

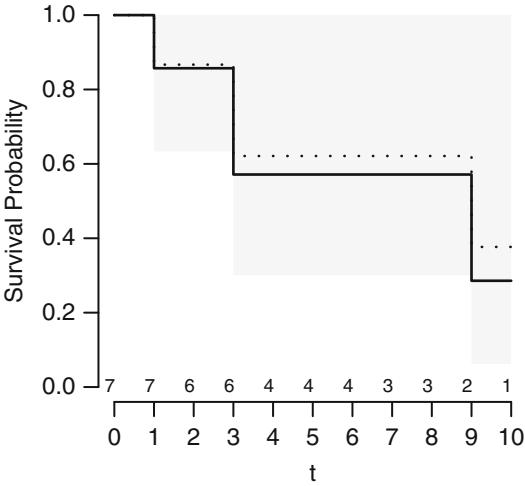

Since odds have an unlimited range, any positive odds ratio will still yield a valid probability. If one attempted to describe an effect by a risk ratio, the effect can only occur over a limited range of risk (probability). For example, a risk ratio of 2 can only apply to risks below .5; above that point the risk ratio must diminish. (Risk ratios are similar to odds ratios if the risk is small.) Risk differences have the same difficulty; the risk difference cannot be constant and must depend on the initial risk. Odds ratios, on the other hand, can describe an effect over the entire range of risk. An odds ratio can, for example, describe the effect of a treatment independently of covariables affecting risk. Figure 10.2 depicts the relationship between risk of a subject without the risk factor and the increase in risk for a variety of relative increases (odds ratios). It demonstrates how absolute risk increase is a function of the baseline risk. Risk increase will also be a function of factors that interact with the risk factor, that is, factors that modify its relative effect. Once a model is developed for estimating Prob{Y = 1|X}, this model can easily be used to estimate the absolute risk increase as a function of baseline risk factors as well as interacting factors. Let X1 be a binary risk factor and let A = {X2,…,Xp} be the other factors (which for convenience we assume do not interact with X1). Then the estimate of Prob{Y = 1|X1 = 1, A} × Prob{Y = 1|X1 = 0, A} is

Fig. 10.2 Absolute benefit as a function of risk of the event in a control subject and the relative effect (odds ratio) of the risk factor. The odds ratios are given for each curve.

Table 10.2 Example binary response data

| Females | Age: 37 39 39 42 47 48 48 52 53 55 56 57 58 58 60 64 65 68 68 70 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response: | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Males | Age: 34 38 40 40 41 43 43 43 44 46 47 48 48 50 50 52 55 60 61 61 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Response: | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

\[\begin{split} \frac{1}{1 + \exp - [\hat{\beta}\_0 + \hat{\beta}\_1 + \hat{\beta}\_2 X\_2 + \dots + \hat{\beta}\_p X\_p]} \\ - \frac{1}{1 + \exp - [\hat{\beta}\_0 + \hat{\beta}\_2 X\_2 + \dots + \hat{\beta}\_p X\_p]} \\ = \frac{1}{1 + (\frac{1 - \hat{R}}{\hat{R}}) \exp(-\hat{\beta}\_1)} - \hat{R}, \end{split} \tag{10.20}\]

where Rˆ is the estimate of the baseline risk, Prob{Y = 1|X1 = 0}. The risk difference estimate can be plotted against Rˆ or against levels of variables in A to display absolute risk increase against overall risk (Figure 10.2) or against specific subject characteristics. 4

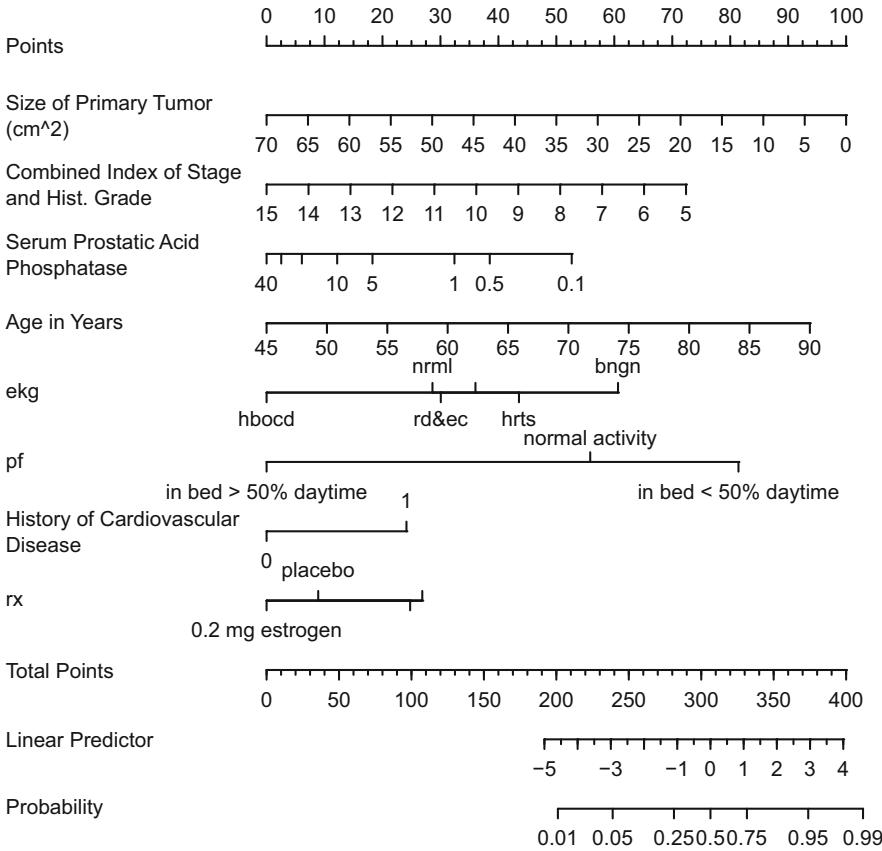

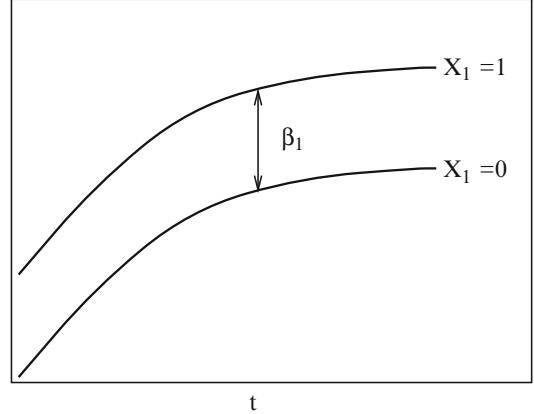

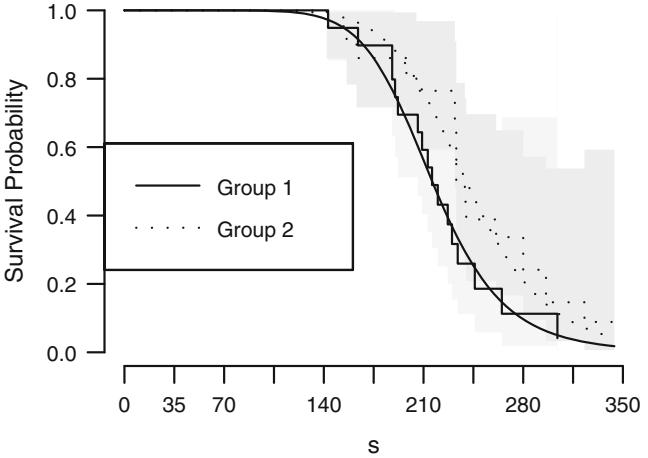

10.1.3 Detailed Example

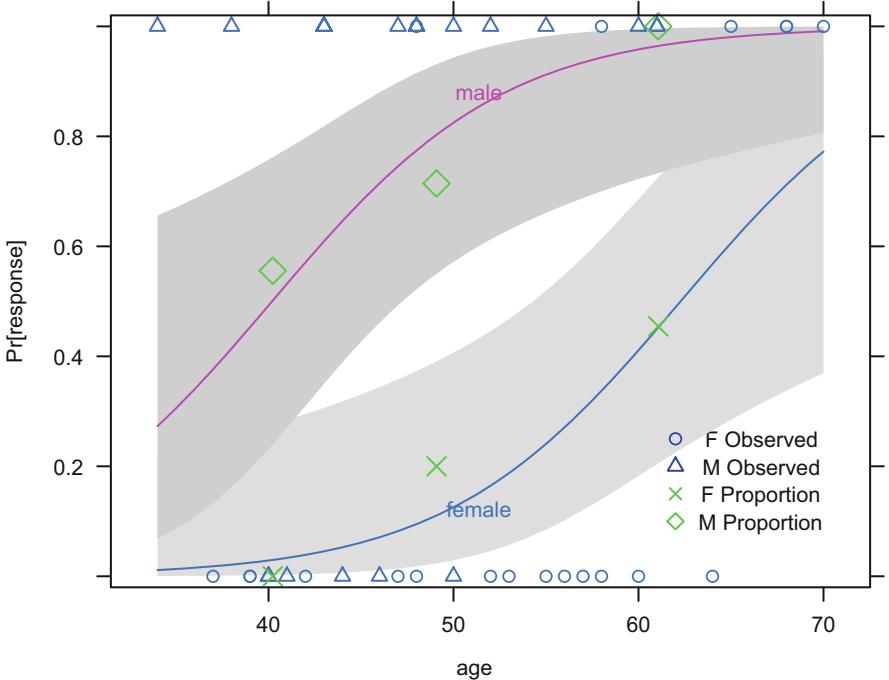

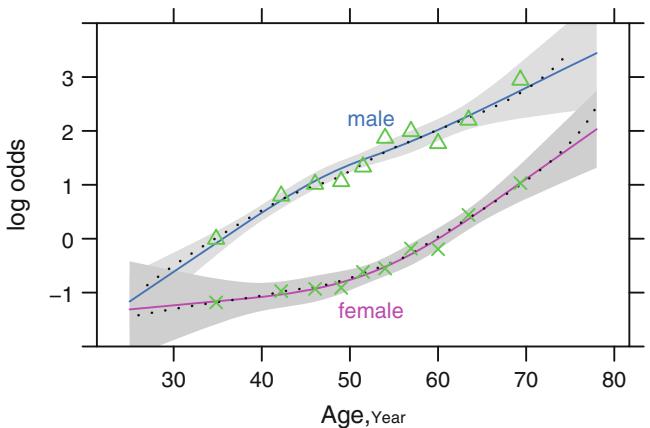

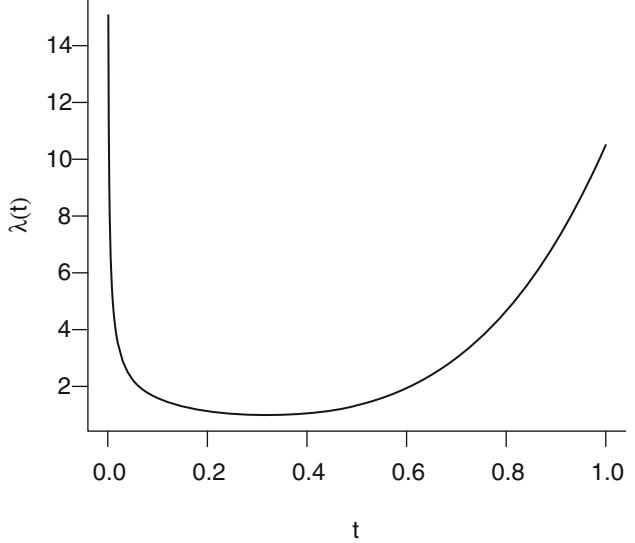

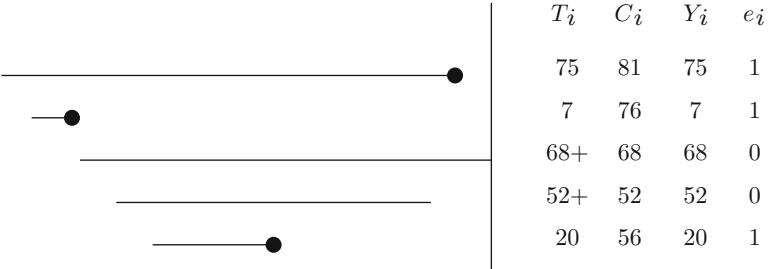

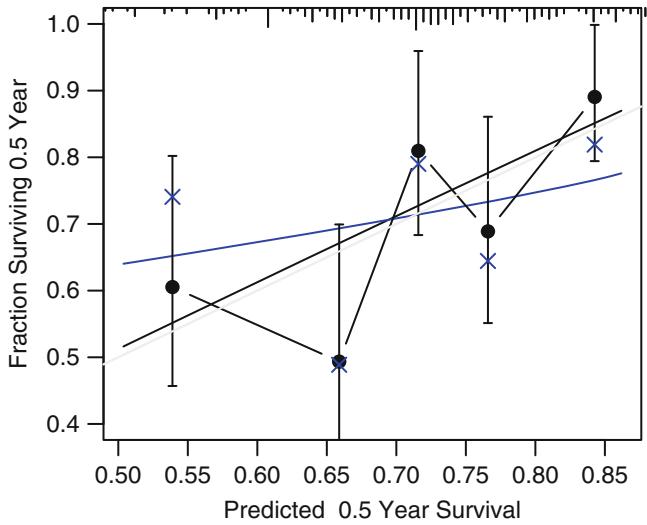

Consider the data in Table 10.2. A graph of the data, along with a fitted logistic model (described later), appears in Figure 10.3. The graph also displays proportions of responses obtained by stratifying the data by sex and age group (< 45, 45 × 54, ← 55). The age points on the abscissa for these groups are the overall mean ages in the three age intervals (40.2, 49.1, and 61.1, respectively).

require(rms)

getHdata ( sex.age.response)

d − sex.age.response

dd − datadist (d); options (datadist = ' dd ' )

f − lrm(response ← sex + age , data=d)

fasr − f # Save for later

w − function (...)

with(d, {

m − sex== ' male '

f − sex== ' female '

lpoints(age [f], response [f], pch=1)

lpoints(age [m], response [m], pch=2)

af − cut2(age , c(45,55), levels.mean =TRUE)

prop − tapply (response , list(af, sex), mean ,

na.rm=TRUE)

agem − as.numeric (row.names (prop))

lpoints(agem , prop[, ' female ' ],

pch=4, cex=1.3, col= ' green ' )

lpoints(agem , prop[, ' male ' ],

pch=5, cex=1.3, col= ' green ' )

x − rep(62, 4); y − seq(.25 , .1, length =4)

lpoints (x, y, pch=c(1, 2, 4, 5),

col=rep(c( ' blue ' , ' green ' ),each=2))

ltext(x+5, y,

c( ' F Observed ' , ' M Observed ' ,

' F Proportion ' , ' M Proportion ' ), cex=.8)

} ) # Figure 10.3

plot(Predict (f, age=seq (34, 70, length =200), sex , fun=plogis ),

ylab= ' Pr[response ] ' , ylim=c(-.02 , 1.02), addpanel =w)

ltx − function (fit) latex(fit , inline=TRUE , columns =54,

file= ' ' , after= ' $ . ' , digits =3,

size= ' Ssize ' , before= ' $X\\hat{\\beta}= ' )

ltx(f)XΛˆ = ×9.84 + 3.49[male] + 0.158 age.

Descriptive statistics for assessing the association between sex and response, age group and response, and age group and response stratified by sex are found below. Corresponding fitted logistic models, with sex coded as 0 = female, 1 = male are also given. Models were fitted first with sex as the only predictor, then with age as the (continuous) predictor, then with sex and age simultaneously. First consider the relationship between sex and response, ignoring the effect of age.

Fig. 10.3 Data, subgroup proportions, and fitted logistic model, with 0.95 pointwise confidence bands

| sex | response | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Row Pct |

0 | 1 | Total | Odds/Log | |||

| F | 14 70.00 |

6 30.00 |

20 | 6/14=.429 -.847 |

|||

| M | 6 30.00 |

14 70.00 |

20 | 14/6=2.33 .847 |

|||

| Total | 20 | 20 | 40 | ||||

| M:F odds ratio = (14/6)/(6/14) | = 5.44, log=1.695 | ||||||

| Statistics for sex ∼ response |

| Statistic | d.f. Value | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ2 | Likelihood Ratio σ2 Parameter Estimate Std Err Wald σ2 |

1 6.400 0.011 1 6.583 0.010 |

P | |

| χ0 χ1 |

×0.8473 1.6946 |

0.4880 0.6901 |

3.0152 | 6.0305 0.0141 |

Note that the estimate of Λ0, Λˆ0 is the log odds for females and that Λˆ1 is the log odds (M:F) ratio. Λˆ0 + Λˆ1 = .847, the log odds for males. The likelihood ratio test for H0 : no effect of sex on probability of response is obtained as follows.

| Log likelihood (χ1 | = 0) : ×27.727 |

|---|---|

| Log likelihood (max) | : ×24.435 |

| LR σ2(H0 : χ1 = 0) |

: ×2(×27.727 × ×24.435) = 6.584. |

(Note the agreement of the LR β2 with the contingency table likelihood ratio β2, and compare 6.584 with the Wald statistic 6.03.)

Next, consider the relationship between age and response, ignoring sex.

| age | response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | ||||

| Row Pct | 0 | 1 | Total | Odds/Log |

| <45 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 5/8=.625 |

| 61.5 | 38.4 | -.47 | ||

| 45-54 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 6/6=1 |

| 50.0 | 50.0 | 0 | ||

| 55+ | 6 | 9 | 15 | 9/6=1.5 |

| 40.0 | 60.0 | .405 | ||

| Total | 20 | 20 | 40 | |

| 55+ : <45 odds ratio = (9/6)/(5/8) | = 2.4, log=.875 |

Parameter Estimate Std Err Wald σ2 P

| χ0 | ×2.7338 | 1.8375 | 2.2134 0.1368 |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ1 | 0.0540 | 0.0358 | 2.2763 0.1314 |

The estimate of Λ1 is in rough agreement with that obtained from the frequency table. The 55+ : < 45 log odds ratio is .875, and since the respective mean ages in the 55+ and <45 age groups are 61.1 and 40.2, an estimate of the log odds ratio increase per year is .875/(61.1 × 40.2) = .875/20.9 = .042.

The likelihood ratio test for H0 : no association between age and response is obtained as follows.

Log likelihood (χ1 = 0) : ×27.727 Log likelihood (max) : ×26.511 LR σ2(H0 : χ1 = 0) : ×2(×27.727 × ×26.511) = 2.432.

(Compare 2.432 with the Wald statistic 2.28.)

Next we consider the simultaneous association of age and sex with response.

| sex=F |

|---|

| ——- |

| age Frequency |

response | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Row Pct | 0 | 1 | Total |

| <45 | 4 100.0 |

0 0.0 |

4 |

| 45-54 | 4 80.0 |

1 20.0 |

5 |

| 55+ | 6 54.6 |

5 45.4 |

11 |

| Total | 14 | 6 | 20 |

sex=M

| age Frequency |

response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Row Pct | 0 | 1 | Total | |

| <45 | 4 44.4 |

5 55.6 |

9 | |

| 45-54 | 2 28.6 |

5 71.4 |

7 | |

| 55+ | 0 0.0 |

4 100.0 |

4 | |

| Total | 6 | 14 | 20 |

A logistic model for relating sex and age simultaneously to response is given below.

Parameter Estimate Std Err Wald σ2 P

| χ0 | ×9.8429 | 3.6758 | 7.1706 0.0074 |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ1 (sex) |

3.4898 | 1.1992 | 8.4693 0.0036 |

| χ2 (age) |

0.1581 | 0.0616 | 6.5756 0.0103 |

Likelihood ratio tests are obtained from the information below.

| = 0) : ×27.727 |

|---|

| : ×19.458 |

| : ×26.511 |

| : ×24.435 |

| : ×2(×27.727 × ×19.458) = 16.538 |

| : ×2(×26.511 × ×19.458) = 14.106 |

| : ×2(×24.435 × ×19.458) = 9.954. |

The 14.1 should be compared with the Wald statistic of 8.47, and 9.954 should be compared with 6.58. The fitted logistic model is plotted separately for females and males in Figure 10.3. The fitted model is

\[\text{logit}\{\text{Response} = 1|\text{sex}, \text{age}\} = -9.84 + 3.49 \times \text{sex} + .158 \times \text{age}, \quad (10.21)\]

where as before sex = 0 for females, 1 for males. For example, for a 40-yearold female, the predicted logit is ×9.84 + .158(40) = ×3.52. The predicted probability of a response is 1/[1 + exp(3.52)] = .029. For a 40-year-old male, the predicted logit is ×9.84 + 3.49 + .158(40) = ×.03, with a probability of .492.

10.1.4 Design Formulations

The logistic multiple regression model can incorporate the same designs as can ordinary linear regression. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) model for a treatment with k levels can be formulated with k × 1 dummy variables. This logistic model is equivalent to a 2 ≤ k contingency table. An analysis of covariance logistic model is simply an ANOVA model augmented with covariables used for adjustment.

One unique design that is interesting to consider in the context of logistic models is a simultaneous comparison of multiple factors between two groups. Suppose, for example, that in a randomized trial with two treatments one wished to test whether any of 10 baseline characteristics are mal-distributed between the two groups. If the 10 factors are continuous, one could perform a two-sample Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test or a t-test for each factor (if each is normally distributed). However, this procedure would result in multiple comparison problems and would also not be able to detect the combined effect of small differences across all the factors. A better procedure would be a multivariate test. The Hotelling T 2 test is designed for just this situation. It is a k-variable extension of the one-variable unpaired t-test. The T 2 test, like discriminant analysis, assumes multivariate normality of the k factors. This assumption is especially tenuous when some of the factors are polytomous. A better alternative is the global test of no regression from the logistic model. This test is valid because it can be shown that H0 : mean X is the same for both groups (= H0 : mean X does not depend on group = H0 : mean X| group = constant) is true if and only if H0 : Prob{group|X} = constant. Thus k factors can be tested simultaneously for differences between the two groups using the binary logistic model, which has far fewer assumptions than does the Hotelling T 2 test. The logistic global test of no regression (with k d.f.) would be expected to have greater power if there is non-normality. Since the logistic model makes no assumption regarding the distribution of the descriptor variables, it can easily test for simultaneous group differences involving a mixture of continuous, binary, and nominal variables. In observational studies, such models for treatment received or exposure (propensity score models) hold great promise for adjusting for confounding.117, 380, 526, 530, 531 5

O’Brien479 has developed a general test for comparing group 1 with group 2 for a single measurement. His test detects location and scale differences by fitting a logistic model for Prob{Group 2} using X and X2 as predictors.

For a randomized study where adjustment for confounding is seldom necessary, adjusting for covariables using a binary logistic model results in increases in standard errors of regression coefficients.527 This is the opposite of what happens in linear regression where there is an unknown variance parameter that is estimated using the residual squared error. Fortunately, adjusting for covariables using logistic regression, by accounting for subject heterogeneity, will result in larger regression coefficients even for a randomized treatment variable. The increase in estimated regression coefficients more than offsets the increase in standard error284, 285, 527, 588.

10.2 Estimation

10.2.1 Maximum Likelihood Estimates

The parameters in the logistic regression model are estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method. The method is based on the same principles as the one-sample proportion example described in Section 9.1. The difference is that the general logistic model is not a single sample or a two-sample problem. The probability of response for the ith subject depends on a particular set of predictors Xi, and in fact the list of predictors may not be the same for any two subjects. Denoting the response and probability of response of the ith subject by Yi and Pi, respectively, the model states that

\[P\_i = \text{Prob}\{Y\_i = 1 | X\_i\} = \left[1 + \exp(-X\_i\beta)\right]^{-1}.\tag{10.22}\]

The likelihood of an observed response Yi given predictors Xi and the unknown parameters Λ is

\[P\_i^{Y\_i}[1 - P\_i]^{1 - Y\_i}.\tag{10.23}\]

The joint likelihood of all responses Y1, Y2,…,Yn is the product of these likelihoods for i = 1,…,n. The likelihood and log likelihood functions are rewritten by using the definition of Pi above to allow them to be recognized as a function of the unknown parameters Λ. Except in simple special cases (such as the k-sample problem in which all Xs are dummy variables), the ML estimates (MLE) of Λ cannot be written explicitly. The Newton–Raphson method described in Section 9.4 is usually used to solve iteratively for the list of values Λ that maximize the log likelihood. The MLEs are denoted by Λˆ. The inverse of the estimated observed information matrix is taken as the estimate of the variance–covariance matrix of Λˆ.

Under H0 : Λ1 = Λ2 = … = Λk = 0, the intercept parameter Λ0 can be estimated explicitly and the log likelihood under this global null hypothesis can be computed explicitly. Under the global null hypothesis, Pi = P = [1 + exp(×Λ0)]−1 and the MLE of P is Pˆ = s/n where s is the number of responses and n is the sample size. The MLE of Λ0 is Λˆ0 = logit(Pˆ). The log 6 likelihood under this null hypothesis is

\[\begin{aligned} &s\,\log(\hat{P}) + (n-s)\log(1-\hat{P})\\ &=\quad s\,\log(s/n) + (n-s)\log[(n-s)/n] \\ &=s\,\log s + (n-s)\log(n-s) - n\log(n). \end{aligned} \tag{10.24}\]

10.2.2 Estimation of Odds Ratios and Probabilities

Once Λ is estimated, one can estimate any log odds, odds, or odds ratios. The MLE of the Xj +1: Xj log odds ratio is Λˆj , and the estimate of the Xj + d : Xj log odds ratio is Λˆjd, all other predictors remaining constant (assuming the absence of interactions and nonlinearities involving Xj). For large enough samples, the MLEs are normally distributed with variances that are consistently estimated from the estimated variance–covariance matrix. Letting z denote the 1×σ/2 critical value of the standard normal distribution, a two-sided 1 × σ confidence interval for the log odds ratio for a one-unit increase in Xj is [Λˆj × zs, Λˆj + zs], where s is the estimated standard error of Λˆj . (Note that for σ = .05, i.e., for a 95% confidence interval, z = 1.96.)

A theorem in statistics states that the MLE of a function of a parameter is that same function of the MLE of the parameter. Thus the MLE of the Xj +1: Xj odds ratio is exp(Λˆj ). Also, if a 1 × σ confidence interval of a parameter Λ is [c, d] and f(u) is a one-to-one function, a 1 × σ confidence interval of f(Λ) is [f(c), f(d)]. Thus a 1×σ confidence interval for the Xj +1 : Xj odds ratio is exp[Λˆj ±zs]. Note that while the confidence interval for Λj is symmetric about Λˆj, the confidence interval for exp(Λj ) is not. By the same theorem just used, the MLE of Pi = Prob{Yi = 1|Xi} is

\[\hat{P}\_i = [1 + \exp(-X\_i \hat{\beta})]^{-1}.\tag{10.25}\]

A confidence interval for Pi could be derived by computing the standard error of Pˆi, yielding a symmetric confidence interval. However, such an interval would have the disadvantage that its endpoints could fall below zero or exceed one. A better approach uses the fact that for large samples XΛˆ is approximately normally distributed. An estimate of the variance of XΛˆ in matrix notation is XVX∗ where V is the estimated variance–covariance matrix of Λˆ (see Equation 9.51). This variance is the sum of all variances and covariances of Λˆ weighted by squares and products of the predictors. The estimated standard error of XΛˆ, s, is the square root of this variance estimate. A 1 × σ confidence interval for Pi is then 7

\[\left\{1+\exp[-(X\_i\hat{\beta}\pm zs)]\right\}^{-1}.\tag{10.26}\]

10.2.3 Minimum Sample Size Requirement

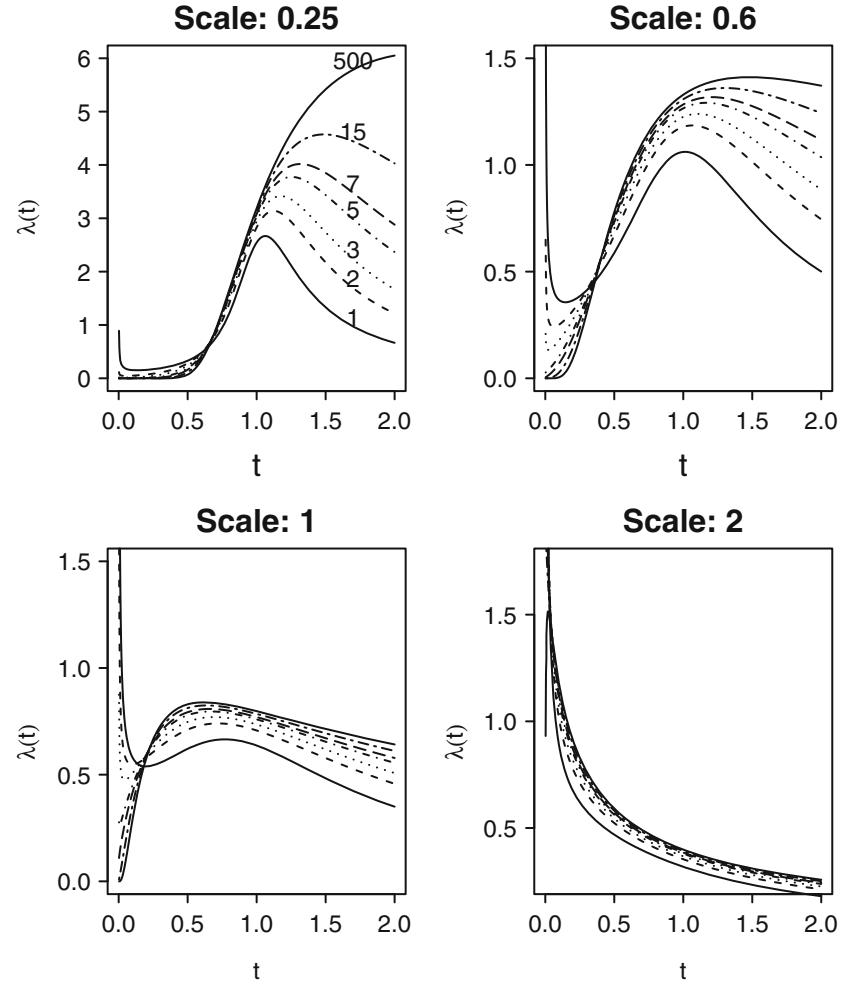

Suppose there were no covariates, so that the only parameter in the model is the intercept. What is the sample size required to allow the estimate of the intercept to be precise enough so that the predicted probability is within 0.1 of the true probability with 0.95 confidence, when the true intercept is in the neighborhood of zero? The answer is n=96. What if there were one covariate, and it was binary with a prevalence of 1 2 ? One would need 96 subjects with X = 0 and 96 with X = 1 to have an upper bound on the margin of error for estimating Prob{Y = 1|X = x} not exceed 0.1 for either value of xa.

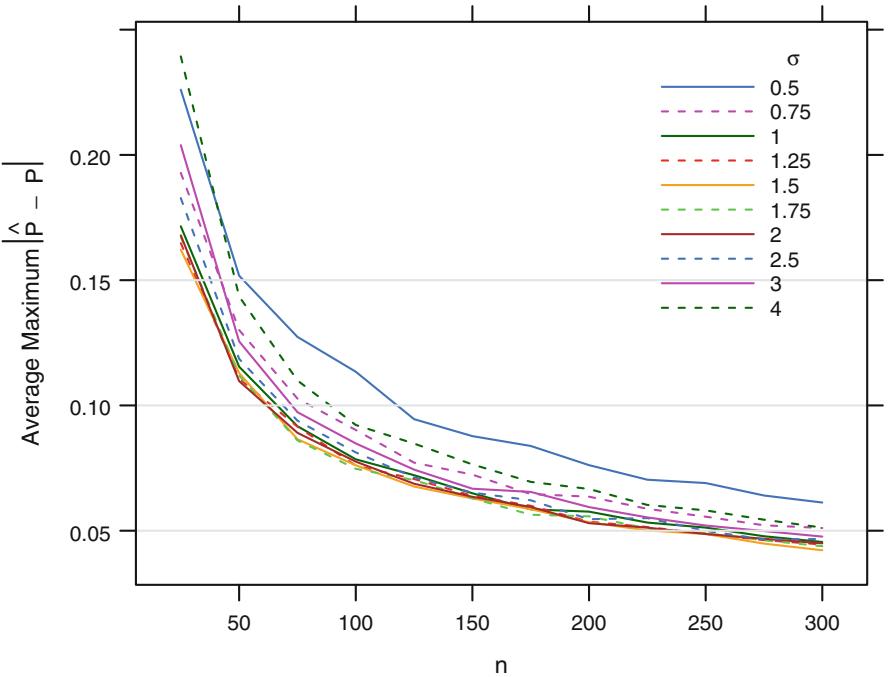

Now consider a very simple single continuous predictor case in which X has a normal distribution with mean zero and standard deviation τ, with the true Prob{Y = 1|X = x} = [1 + exp(×x)]−1. The expected number of events is n 2 b. The following simulation answers the question “What should n be so that the expected maximum absolute error (over x ≥ [×1.5, 1.5]) in Pˆ is less than χ?”

sigmas − c(.5 , .75 , 1, 1.25 , 1.5 , 1.75 , 2, 2.5 , 3, 4)

ns − seq(25, 300, by=25)

nsim − 1000

xs − seq(-1.5 , 1.5 , length =200)

pactual − plogis (xs)

dn − list(sigma =format (sigmas ), n=format (ns))

maxerr − N1 − array (NA , c(length (sigmas ), length (ns)), dn)

require(rms)

i − 0

for(s in sigmas ) {

i − i+1

j − 0

for(n in ns) {a The general formula for the sample size required to achieve a margin of error of ϵ in estimating a true probability of β at the 0.95 confidence level is n = ( 1.96 δ )2 ∼β(1×β). Set β = 1 2 (intercept=0) for the worst case.

b The R code can easily be modified for other event frequencies, or the minimum of the number of events and non-events for a dataset at hand can be compared with n 2 in this simulation. An average maximum absolute error of 0.05 corresponds roughly to a half-width of the 0.95 confidence interval of 0.1.

j − j+1

n1 − maxe − 0

for(k in 1:nsim) {

x − rnorm (n, 0, s)

P − plogis (x)

y − ifelse (runif (n) ≤ P, 1, 0)

n1 − n1 + sum(y)

beta − lrm.fit(x, y)$coefficients

phat − plogis (beta [1] + beta [2] * xs)

maxe − maxe + max(abs(phat - pactual))

}

n1 − n1/nsim

maxe − maxe/nsim

maxerr [i,j] − maxe

N1[i,j] − n1

}

}

xrange − range (xs)

simerr − llist (N1 , maxerr , sigmas , ns , nsim , xrange )

maxe − reShape( maxerr )

# Figure 10.4

xYplot (maxerr ← n, groups = sigma , data=maxe ,

ylab= expression( paste( ' Average Maximum ' ,

abs(hat(P) - P))),

type= ' l ' , lty=rep(1:2, 5), label.curve =FALSE ,

abline =list (h=c(.15 , .1 , .05), col=gray (.85 )))

Key(.8 , .68 , other =list (cex=.7 ,

title = expression(←←←←←←←←←←←sigma )))10.3 Test Statistics

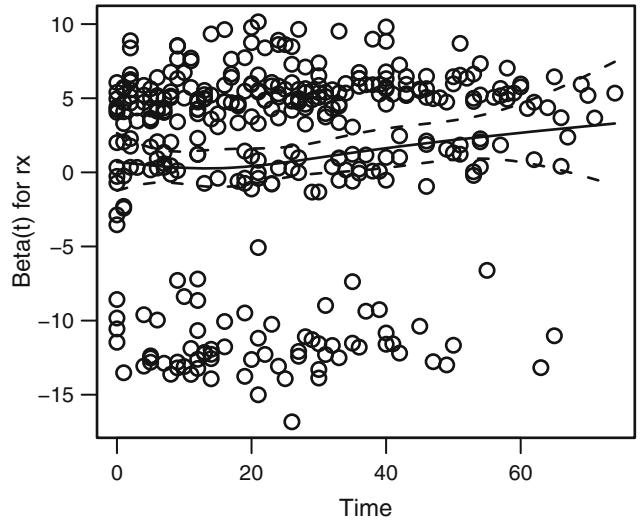

The likelihood ratio, score, and Wald statistics discussed earlier can be used to test any hypothesis in the logistic model. The likelihood ratio test is generally preferred. When true parameters are near the null values all three statistics usually agree. The Wald test has a significant drawback when the true parameter value is very far from the null value. In such case the standard error estimate becomes too large. As Λˆj increases from 0, the Wald test statistic for H0 : Λj = 0 becomes larger, but after a certain point it becomes smaller. The statistic will eventually drop to zero if Λˆj becomes infinite.278 Infinite estimates can occur in the logistic model especially when there is a binary predictor whose mean is near 0 or 1. Wald statistics are especially problematic in this case. For example, if 10 out of 20 males had a disease and 5 out of 5 females had the disease, the female : male odds ratio is infinite and so is the logistic regression coefficient for sex. If such a situation occurs, the likelihood ratio or score statistic should be used instead of the Wald statistic.

Fig. 10.4 Simulated expected maximum error in estimating probabilities for x ̸ [×1.5, 1.5] with a single normally distributed X with mean zero

For k-sample (ANOVA-type) logistic models, logistic model statistics are equivalent to contingency table β2 statistics. As exemplified in the logistic model relating sex to response described previously, the global likelihood ratio statistic for all dummy variables in a k-sample model is identical to the contingency table (k-sample binomial) likelihood ratio β2 statistic. The score statistic for this same situation turns out to be identical to the k × 1 degrees of freedom Pearson β2 for a k ≤ 2 table.

As mentioned in Section 2.6, it can be dangerous to interpret individual parameters, make pairwise treatment comparisons, or test linearity if the overall test of association for a factor represented by multiple parameters is insignificant.

10.4 Residuals

Several types of residuals can be computed for binary logistic model fits. Many of these residuals are used to examine the influence of individual observations on the fit. The partial residual can be used for directly assessing how each 8 predictor should be transformed. For the ith observation, the partial residual for the jth element of X is defined by

\[r\_{ij} = \hat{\beta}\_j X\_{ij} + \frac{Y\_i - \hat{P}\_i}{\hat{P}\_i (1 - \hat{P}\_i)},\tag{10.27}\]

where Xij is the value of the jth variable in the ith observation, Yi is the corresponding value of the response, and Pˆi is the predicted probability that Yi = 1. A smooth plot (using, e.g., loess) of Xij against rij will provide an estimate of how Xj should be transformed, adjusting for the other Xs (using their current transformations). Typically one tentatively models Xj linearly and checks the smoothed plot for linearity. A U-shaped relationship in this plot, for example, indicates that a squared term or spline function needs to 9 be added for Xj . This approach does assume additivity of predictors.

10.5 Assessment of Model Fit

As the logistic regression model makes no distributional assumptions, only the assumptions of linearity and additivity need to be verified (in addition to the usual assumptions about independence of observations and inclusion of important covariables). In ordinary linear regression there is no global test for lack of model fit unless there are replicate observations at various settings of X. This is because ordinary regression entails estimation of a separate variance parameter τ2. In logistic regression there are global tests for goodness of fit. Unfortunately, some of the most frequently used ones are inappropriate. For example, it is common to see a deviance test of goodness of fit based on the “residual”log likelihood, with P-values obtained from a β2 distribution with n × p d.f. This P-value is inappropriate since the deviance does not have an asymptotic β2 distribution, due to the facts that the number of parameters estimated is increasing at the same rate as n and the expected cell frequencies are far below five (by definition).

Hosmer and Lemeshow304 have developed a commonly used test for goodness of fit for binary logistic models based on grouping into deciles of predicted probability and performing an ordinary β2 test for the mean predicted probability against the observed fraction of events (using 8 d.f. to account for evaluating fit on the model development sample). The Hosmer–Lemeshow test is dependent on the choice of how predictions are grouped303 and it is not clear that the choice of the number of groups should be independent of n. Hosmer et al.303 have compared a number of global goodness of fit tests for binary logistic regression. They concluded that the simple unweighted sum of squares test of Copas124 as modified by le Cessie and van Houwelingen387 is as good as any. They used a normal Z-test for the sum of squared errors (n≤B, where B is the Brier index in Equation 10.35). This test takes into account the fact that one cannot obtain a β2 distribution for the sum of squares. It also takes into account the estimation of Λ. It is not yet clear for which types of lack of fit this test has reasonable power. Returning to the external validation case where uncertainty of Λ does not need to be accounted for, Stallard584 has further documented the lack of power of the original Hosmer-Lemeshow test and found more power with a logarithmic scoring rule (deviance test) and a β2 test that, unlike the simple unweighted sum of squares test, weights each squared error by dividing it by Pˆi(1×Pˆi). A scaled β2 distribution seemed to provide the best approximation to the null distribution of the test statistics.

More power for detecting lack of fit is expected to be obtained from testing specific alternatives to the model. In the model

\[\text{logit}\{Y=1|X\} = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2,\tag{10.28}\]

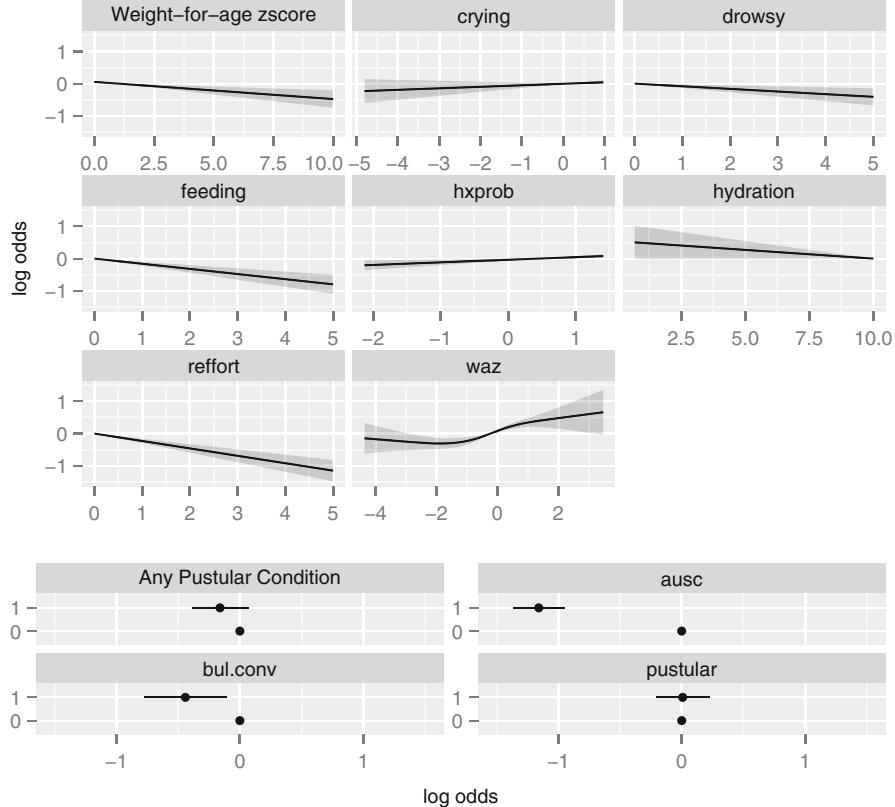

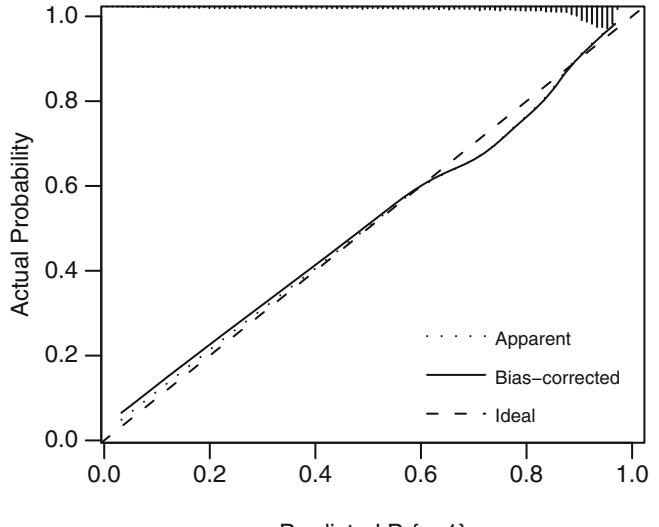

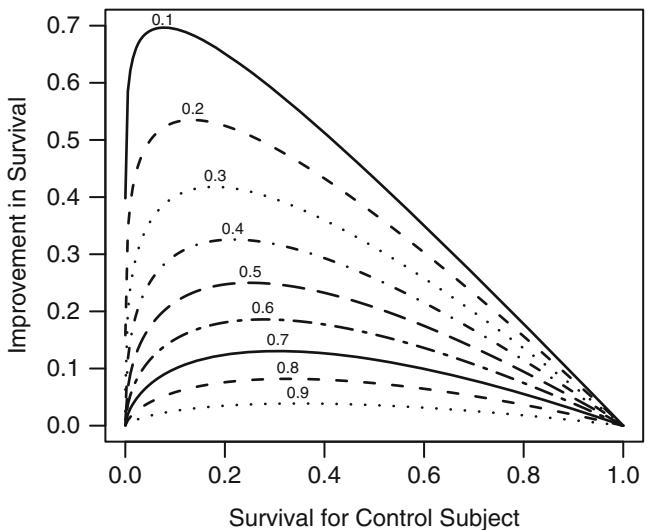

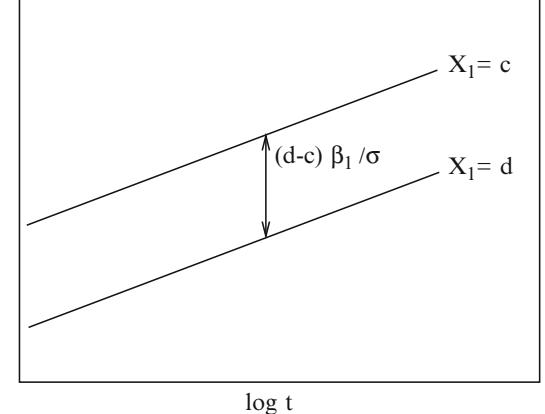

where X1 is binary and X2 is continuous, one needs to verify that the log odds is related to X1 and X2 according to Figure 10.5.

Fig. 10.5 Logistic regression assumptions for one binary and one continuous predictor

The simplest method for validating that the data are consistent with the no-interaction linear model involves stratifying the sample by X1 and quantile groups (e.g., deciles) of X2. 265 Within each stratum the proportion of responses Pˆ is computed and the log odds calculated from log[P /ˆ (1 × Pˆ)]. The number of quantile groups should be such that there are at least 20 (and perhaps many more) subjects in each X1≤X2 group. Otherwise, probabilities cannot be estimated precisely enough to allow trends to be seen above “noise” in the data. Since at least 3 X2 groups must be formed to allow assessment of linearity, the total sample size must be at least 2 ≤ 3 ≤ 20 = 120 for this method to work at all.

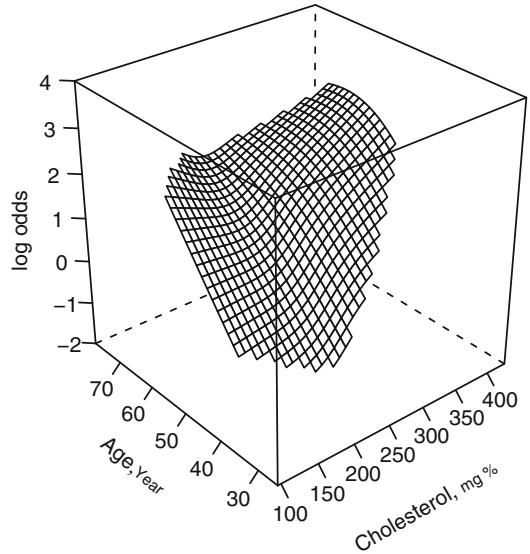

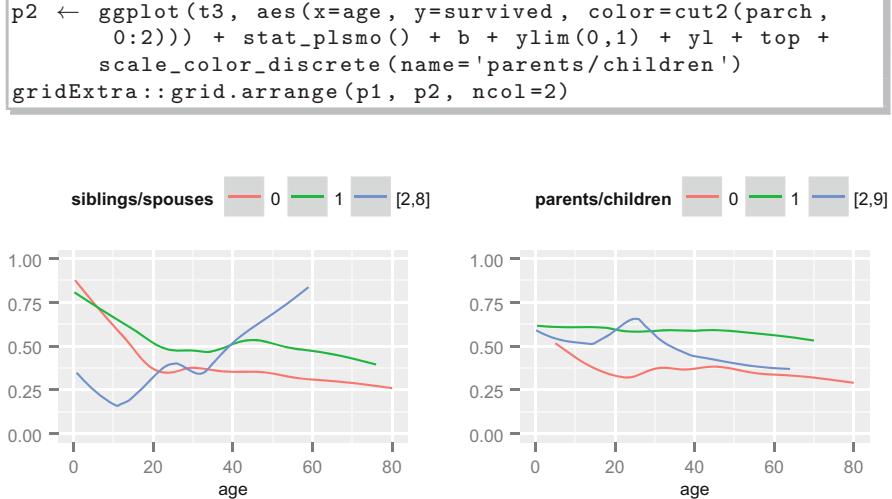

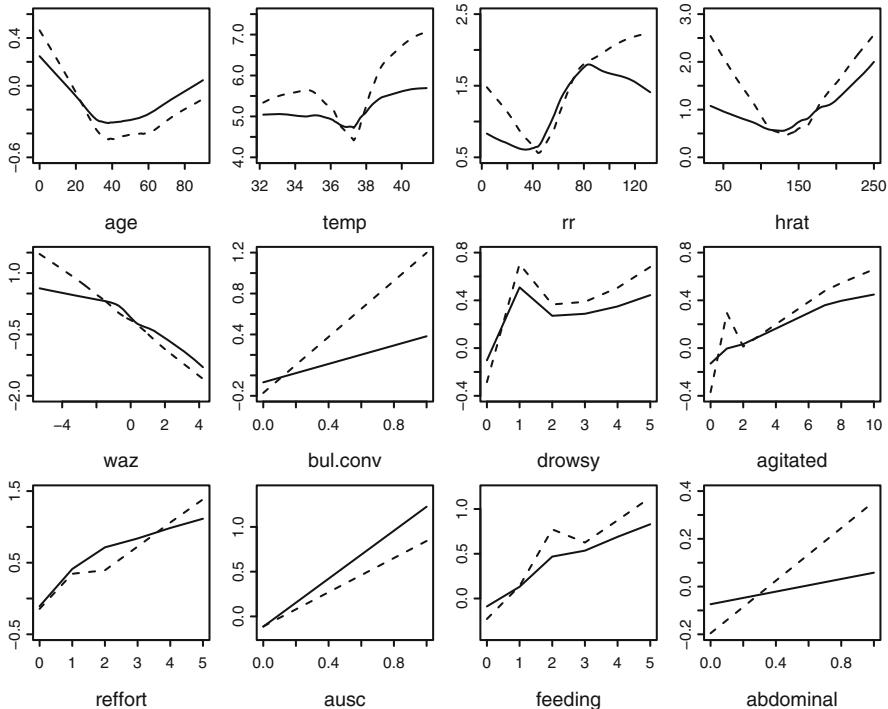

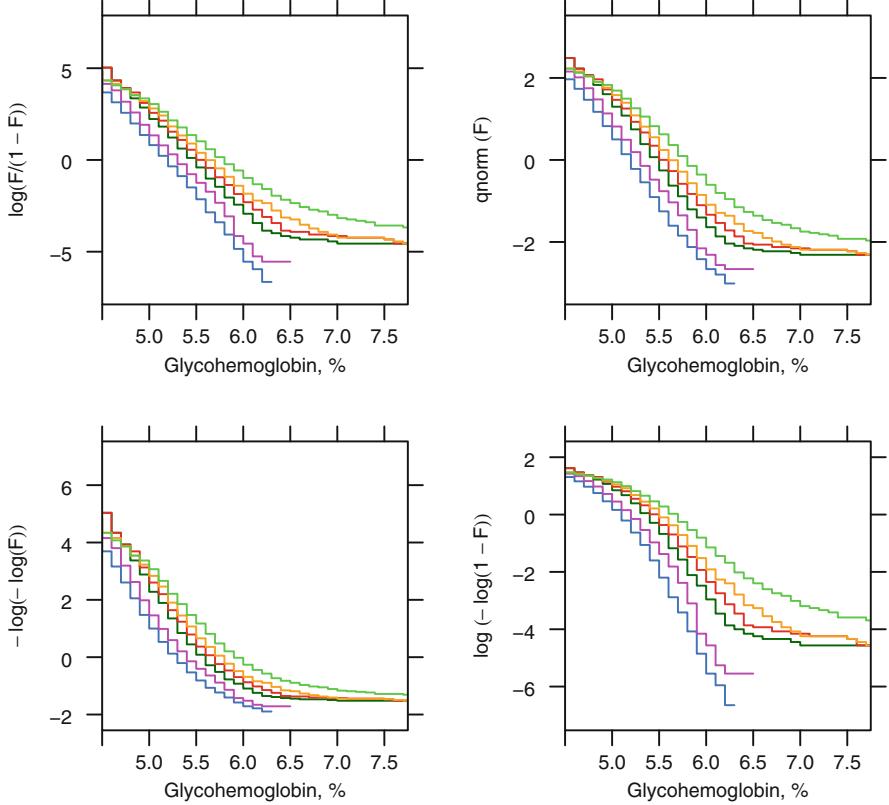

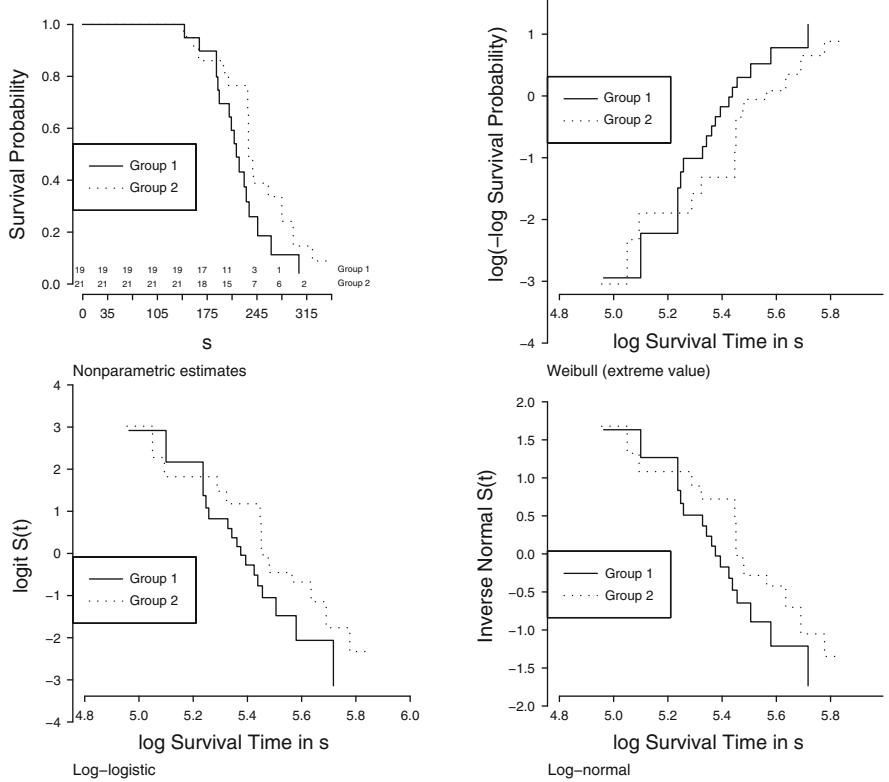

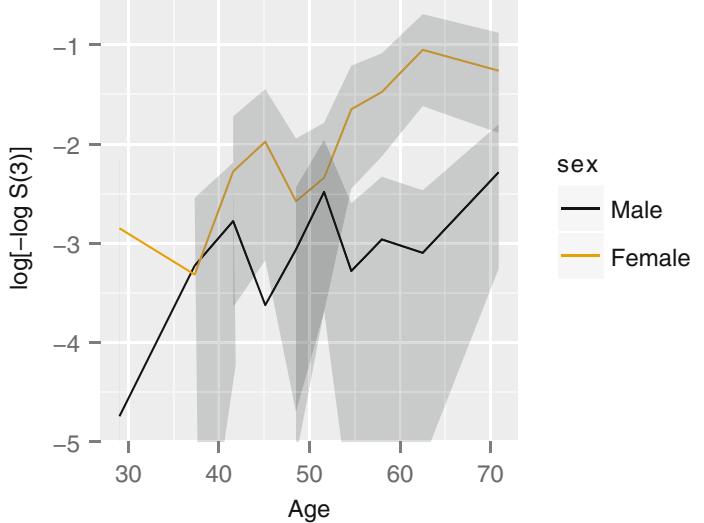

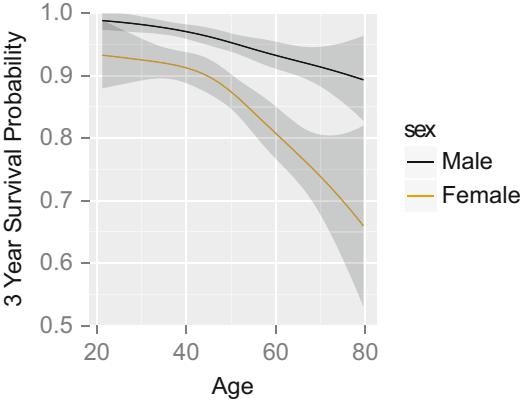

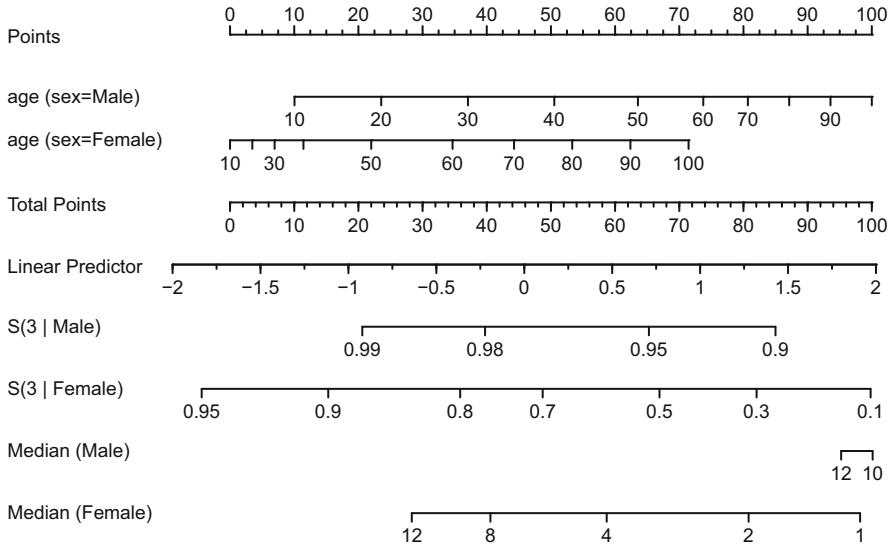

Figure 10.6 demonstrates this method for a large sample size of 3504 subjects stratified by sex and deciles of age. Linearity is apparent for males while there is evidence for slight interaction between age and sex since the age trend for females appears curved.

getHdata( acath )

acath $sex − factor (acath $sex , 0:1, c( ' male ' , ' female ' ))

dd − datadist( acath ); options(datadist= ' dd ' )

f − lrm(sigdz ← rcs(age , 4) * sex , data =acath )w − function(...)

with( acath , {

plsmo (age , sigdz , group =sex , fun=qlogis , lty= ' dotted ' ,

add=TRUE , grid=TRUE)

af − cut2 (age , g=10, levels.mean = TRUE)

prop − qlogis (tapply (sigdz , list (af , sex), mean ,

na.rm =TRUE ))

agem − as.numeric(row.names( prop ))

lpoints(agem , prop[, ' female ' ], pch=4, col= ' green ' )

lpoints(agem , prop[, ' male ' ], pch=2, col= ' green ' )

} ) # Figure 10.6

plot( Predict(f, age , sex), ylim =c(-2 ,4), addpanel=w,

label.curve = list (offset =unit (0.5 , ' cm ' )))The subgrouping method requires relatively large sample sizes and does not use continuous factors effectively. The ordering of values is not used at all between intervals, and the estimate of the relationship for a continuous variable has little resolution. Also, the method of grouping chosen (e.g., deciles vs. quintiles vs. rounding) can alter the shape of the plot.

In this dataset with only two variables, it is efficient to use a nonparametric smoother for age, separately for males and females. Nonparametric smoothers, such as loess111 used here, work well for binary response variables (see Section 2.4.7); the logit transformation is made on the smoothed 10 probability estimates. The smoothed estimates are shown in Figure 10.6.

When there are several predictors, the restricted cubic spline function is better for estimating the true relationship between X2 and logit{Y = 1} for continuous variables without assuming linearity. By fitting a model containing X2 expanded into k×1 terms, where k is the number of knots, one can obtain an estimate of the transformation of X2 as discussed in Section 2.4:

\[\begin{split} \text{logit}\{Y=1|X\} &= \hat{\beta}\_0 + \hat{\beta}\_1 X\_1 + \hat{\beta}\_2 X\_2 + \hat{\beta}\_3 X\_2' + \hat{\beta}\_4 X\_2''\\ &= \hat{\beta}\_0 + \hat{\beta}\_1 X\_1 + f(X\_2), \end{split} \tag{10.29}\]

where X∗ 2 and X∗∗ 2 are constructed spline variables (when k = 4). Plotting the estimated spline function f(X2) versus X2 will estimate how the effect of X2 should be modeled. If the sample is sufficiently large, the spline function can be fitted separately for X1 = 0 and X1 = 1, allowing detection of even unusual interaction patterns. A formal test of linearity in X2 is obtained by testing H0 : Λ3 = Λ4 = 0.

Fig. 10.6 Logit proportions of significant coronary artery disease by sex and deciles of age for n=3504 patients, with spline fits (smooth curves). Spline fits are for k = 4 knots at age= 36, 48, 56, and 68 years, and interaction between age and sex is allowed. Shaded bands are pointwise 0.95 confidence limits for predicted log odds. Smooth nonparametric estimates are shown as dotted curves. Data courtesy of the Duke Cardiovascular Disease Databank.

For testing interaction between X1 and X2, a product term (e.g., X1X2) can be added to the model and its coefficient tested. A more general simultaneous test of linearity and lack of interaction for a two-variable model in which one variable is binary (or is assumed linear) is obtained by fitting the model

\[\begin{aligned} \text{logit}\{Y=1|X\} &= \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2 + \beta\_3 X\_2' + \beta\_4 X\_2''\\ &+ \beta\_5 X\_1 X\_2 + \beta\_6 X\_1 X\_2' + \beta\_7 X\_1 X\_2'' \end{aligned} \tag{10.30}\]

and testing H0 : Λ3 = … = Λ7 = 0. This formulation allows the shape of the X2 effect to be completely different for each level of X1. There is virtually no departure from linearity and additivity that cannot be detected from this expanded model formulation. The most computationally efficient test for lack of fit is the score test (e.g., X1 and X2 are forced into a tentative model and the remaining variables are candidates). Figure 10.6 also depicts a fitted spline logistic model with k = 4, allowing for general interaction between age and sex as parameterized above. The fitted function, after expanding the restricted cubic spline function for simplicity (see Equation 2.27), is given above. Note the good agreement between the empirical estimates of log odds and the spline fits and nonparametric estimates in this large dataset.

An analysis of log likelihood for this model and various sub-models is found in Table 10.3. The β2 for global tests is corrected for the intercept and the degrees of freedom does not include the intercept.

| Model / Hypothesis | Likelihood d.f. | P | Formula | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio σ2 | ||||

| a: sex, age (linear, no interaction) | 766.0 | 2 | ||

| b: sex, age, age ∼ sex | 768.2 | 3 | ||

| c: sex, spline in age | 769.4 | 4 | ||

| d: sex, spline in age, interaction | 782.5 | 7 | ||

| H0 : no age ∼ sex interaction |

2.2 | 1 | .14 | (b × a) |

| given linearity | ||||

| H0 : age linear no interaction |

3.4 | 2 | .18 | (c × a) |

| H0 : age linear, no interaction |

16.6 | 5 | .005 | (d × a) |

| H0 : age linear, product form |

14.4 | 4 | .006 | (d × b) |

| interaction | ||||

| H0 : no interaction, allowing for |

13.1 | 3 | .004 | (d × c) |

| nonlinearity in age |

Table 10.3 LR σ2 tests for coronary artery disease risk

Table 10.4 AIC on σ2 scale by number of knots

| k | β2 Model |

AIC |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 99.23 | 97.23 |

| 3 | 112.69 | 108.69 |

| 4 | 121.30 | 115.30 |

| 5 | 123.51 | 115.51 |

| 6 | 124.41 | 114.51 |

This analysis confirms the first impression from the graph, namely, that age ≤ sex interaction is present but it is not of the form of a simple product between age and sex (change in slope). In the context of a linear age effect, there is no significant product interaction effect (P = .14). Without allowing for interaction, there is no significant nonlinear effect of age (P = .18). However, the general test of lack of fit with 5 d.f. indicates a significant departure from the linear additive model (P = .005).

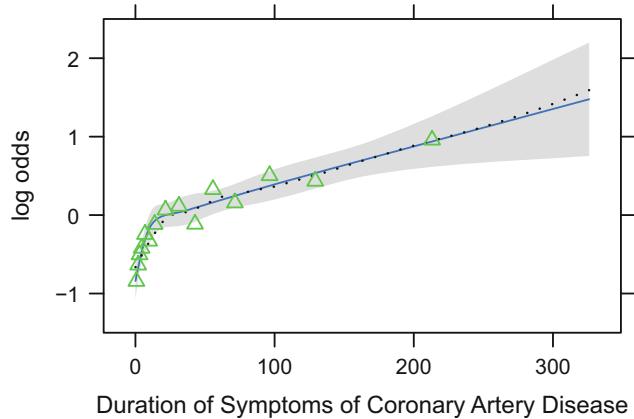

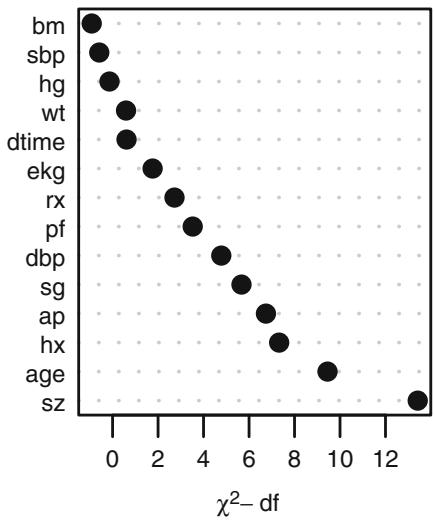

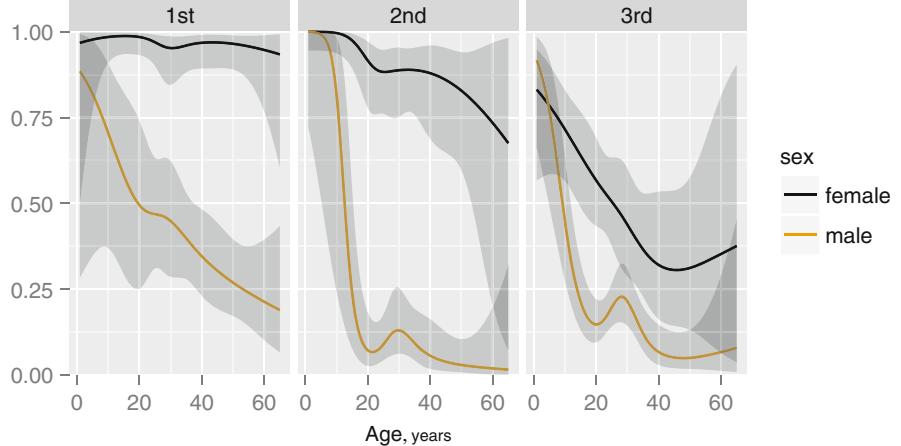

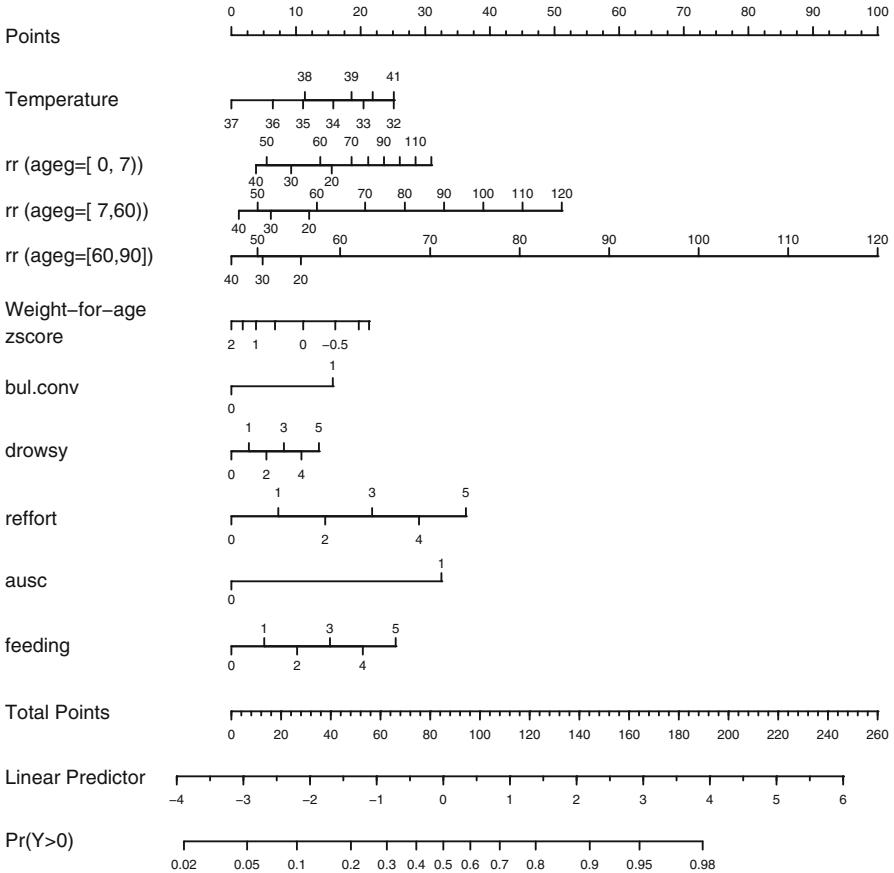

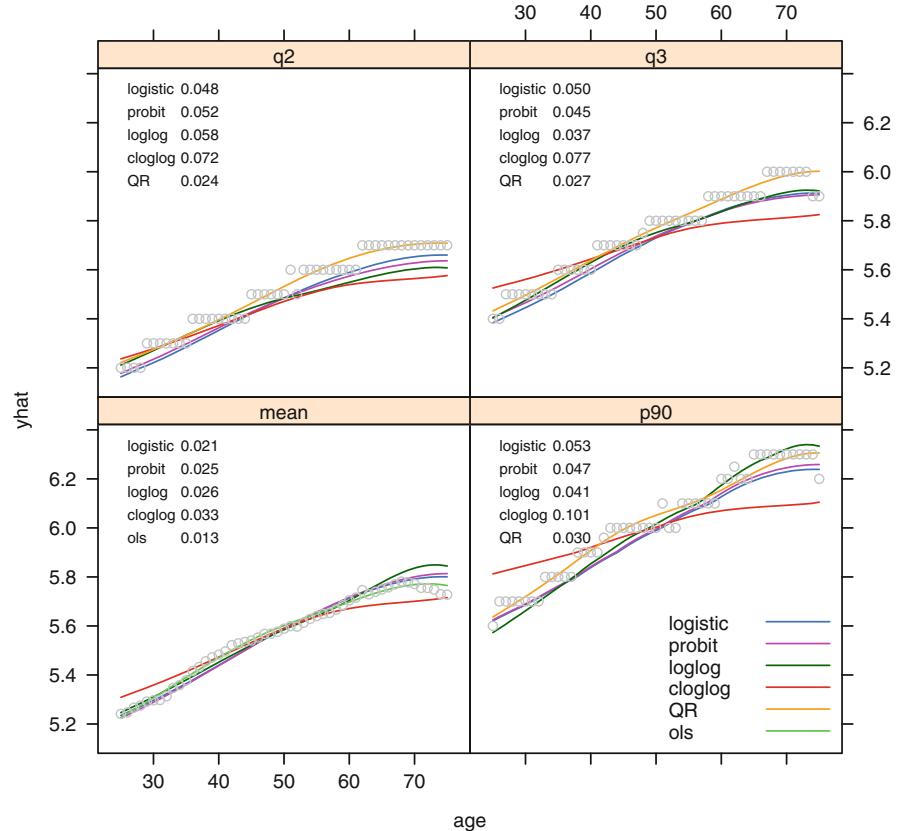

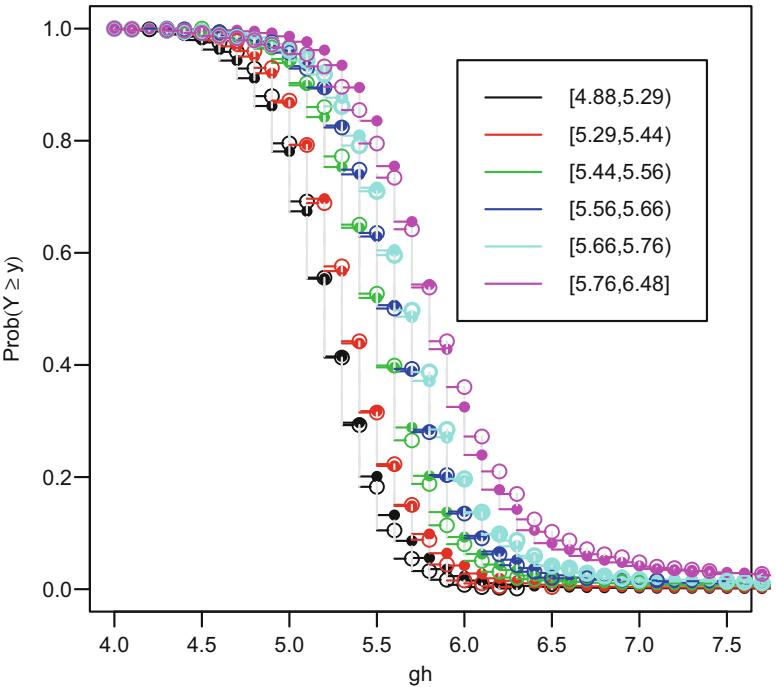

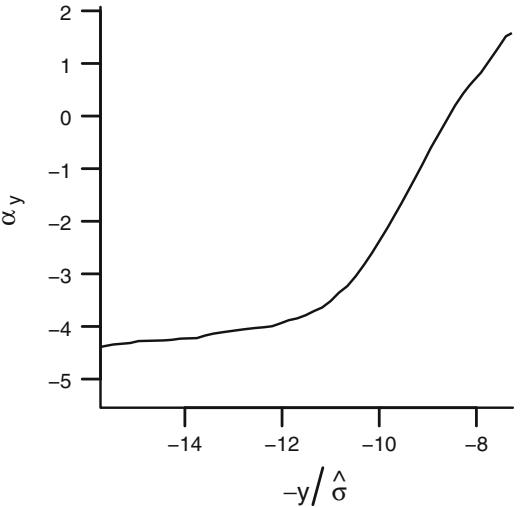

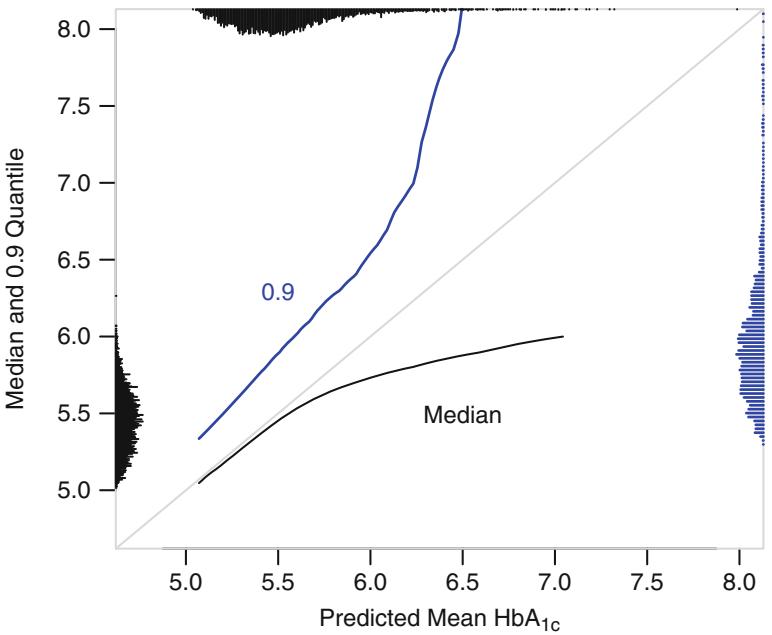

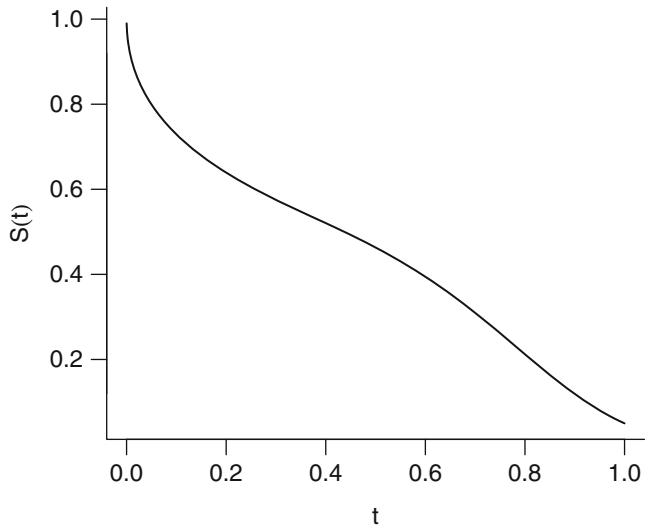

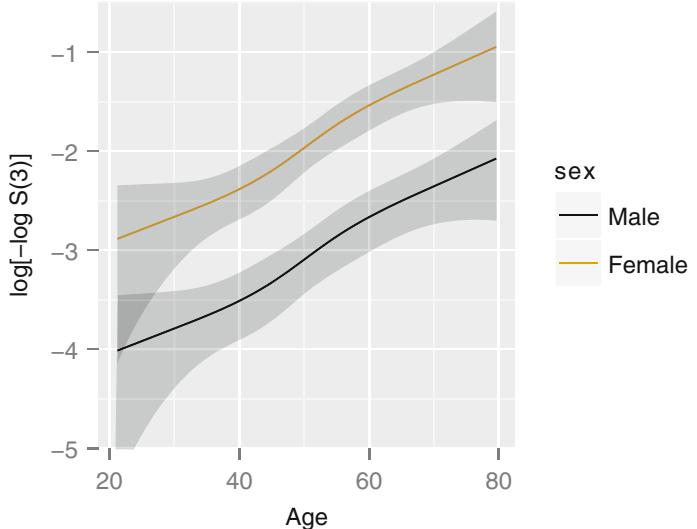

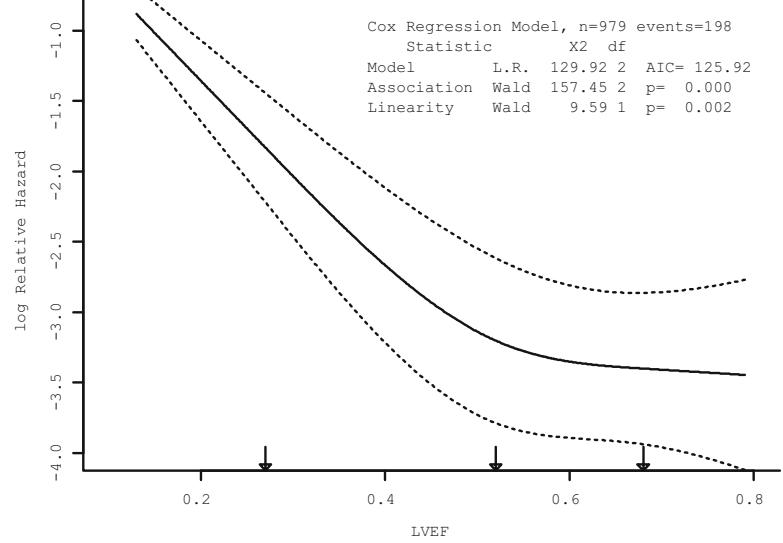

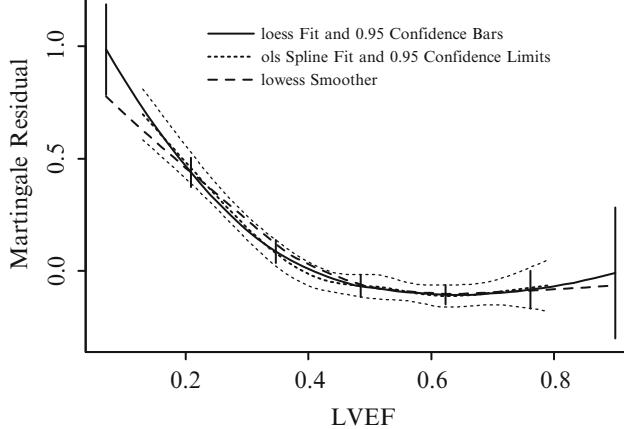

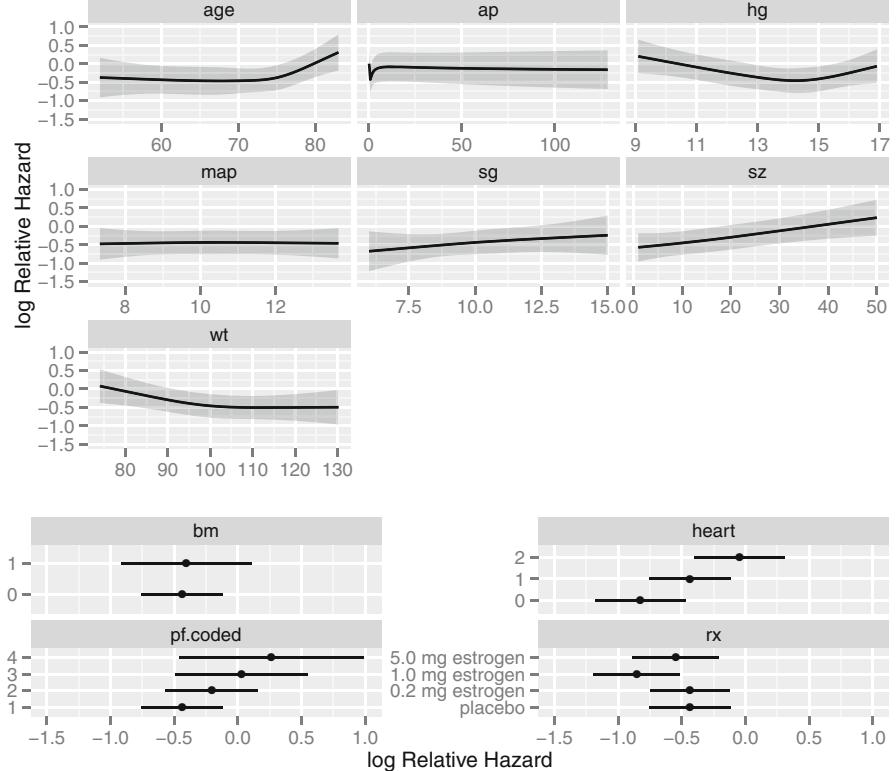

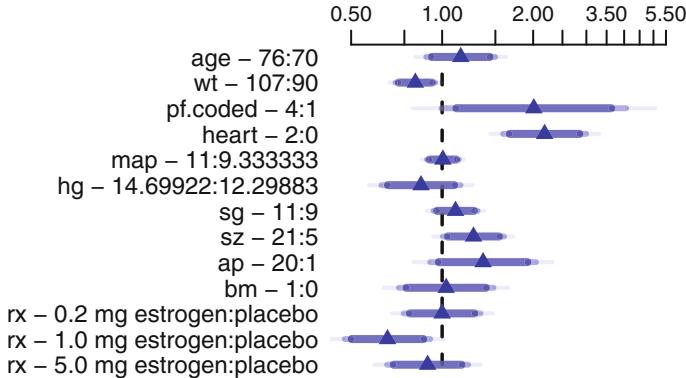

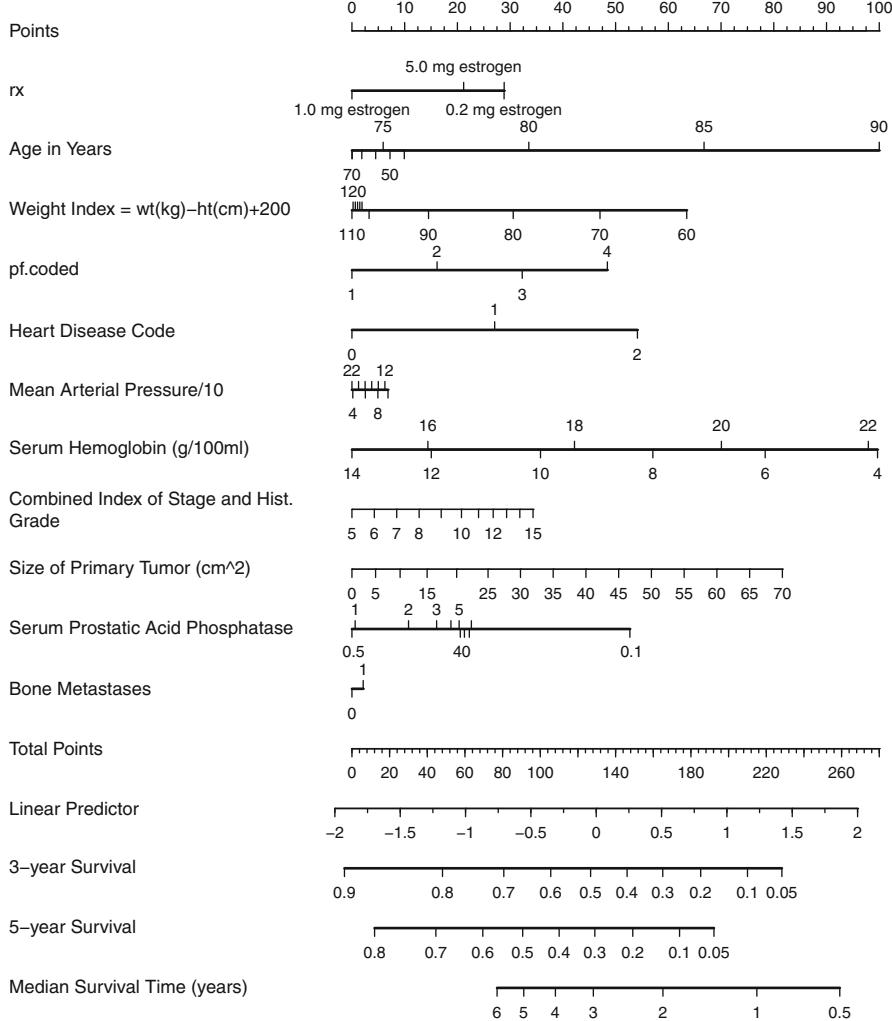

In Figure 10.7, data from 2332 patients who underwent cardiac catheterization at Duke University Medical Center and were found to have significant (← 75%) diameter narrowing of at least one major coronary artery were analyzed (the dataset is available from the Web site). The relationship between the time from the onset of symptoms of coronary artery disease (e.g., angina, myocardial infarction) to the probability that the patient has severe (threevessel disease or left main disease—tvdlm) coronary disease was of interest. There were 1129 patients with tvdlm. A logistic model was used with the duration of symptoms appearing as a restricted cubic spline function with k = 3, 4, 5, and 6 equally spaced knots in terms of quantiles between .05 and .95. The best fit for the number of parameters was chosen using Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), computed in Table 10.4 as the model likelihood ratio β2 minus twice the number of parameters in the model aside from the intercept. The linear model is denoted k = 0.

dz − subset (acath , sigdz ==1)

dd − datadist(dz)f − lrm(tvdlm ← rcs(cad.dur , 5), data =dz)

w − function(...)

with (dz , {

plsmo(cad.dur , tvdlm , fun= qlogis , add=TRUE ,

grid=TRUE , lty= ' dotted ' )

x − cut2(cad.dur , g=15, levels.mean = TRUE)

prop − qlogis (tapply (tvdlm , x, mean , na.rm =TRUE ))

xm − as.numeric( names (prop))

lpoints(xm , prop , pch=2, col= ' green ' )

} ) # Figure 10.7

plot( Predict(f, cad.dur), addpanel=w)

Fig. 10.7 Estimated relationship between duration of symptoms and the log odds of severe coronary artery disease for k = 5. Knots are marked with arrows. Solid line is spline fit; dotted line is a nonparametric loess estimate.

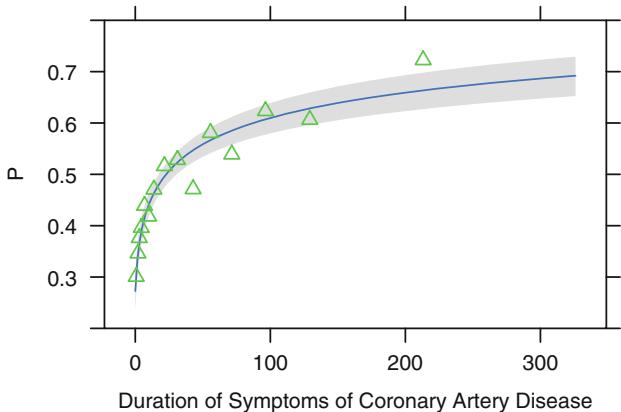

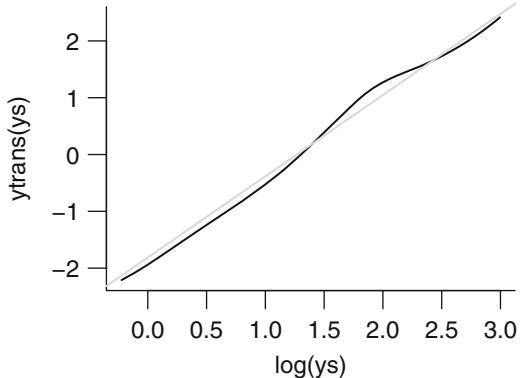

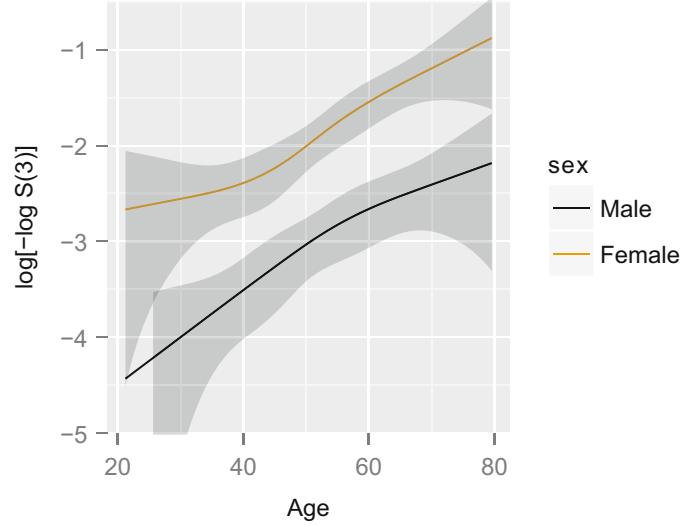

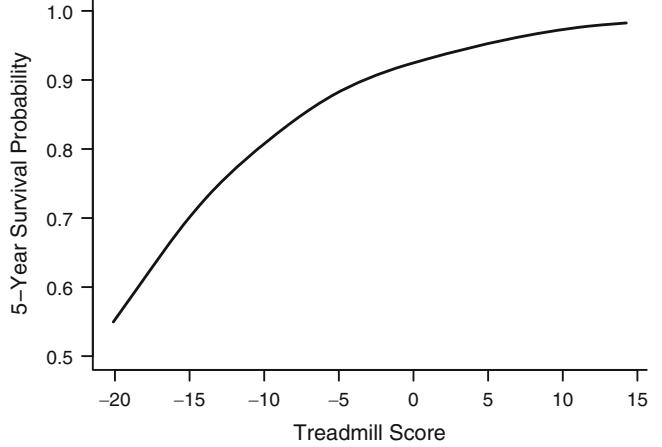

Figure 10.7 displays the spline fit for k = 5. The triangles represent subgroup estimates obtained by dividing the sample into groups of 150 patients. For example, the leftmost triangle represents the logit of the proportion of tvdlm in the 150 patients with the shortest duration of symptoms, versus the mean duration in that group. A Wald test of linearity, with 3 d.f., showed highly significant nonlinearity (β2= 23.92 with 3 d.f.). The plot of the spline transformation suggests a log transformation, and when log (duration of symptoms in months + 1) was fitted in a logistic model, the log likelihood of the model (119.33 with 1 d.f.) was virtually as good as the spline model (123.51 with 4 d.f.); the corresponding Akaike information criteria (on the β2 scale) are 117.33 and 115.51. To check for adequacy in the log transformation, a five-knot restricted cubic spline function was fitted to log10(months + 1), as displayed in Figure 10.8. There is some evidence for lack of fit on the right, but the Wald β2 for testing linearity yields P = .27.

f − lrm(tvdlm ← log10 ( cad.dur + 1), data=dz)

w − function(...)

with (dz , {

x − cut2(cad.dur , m =150, levels.mean = TRUE)

prop − tapply (tvdlm , x, mean , na.rm =TRUE)

xm − as.numeric( names (prop))

lpoints(xm , prop , pch=2, col= ' green ' )

} )

# Figure 10.8

plot( Predict(f, cad.dur , fun=plogis ), ylab= ' P ' ,

ylim =c(.2 , .8), addpanel=w)

Fig. 10.8 Fitted linear logistic model in log10(duration + 1), with subgroup estimates using groups of 150 patients. Fitted equation is logit(tvdlm) = ×.9809 + .7122 log10(months + 1).

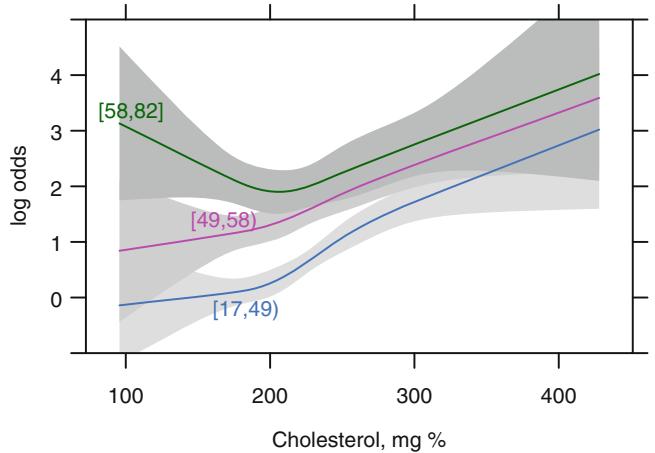

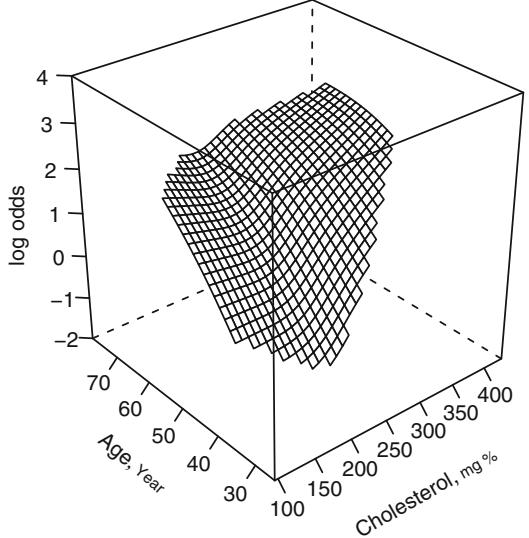

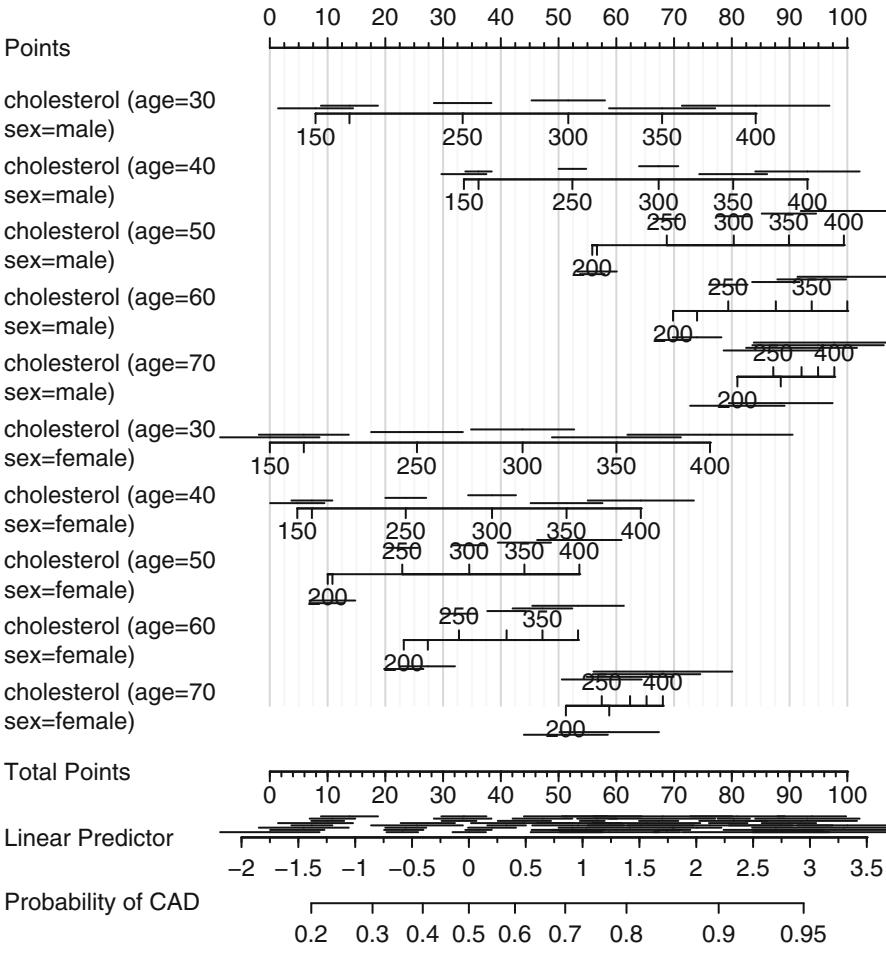

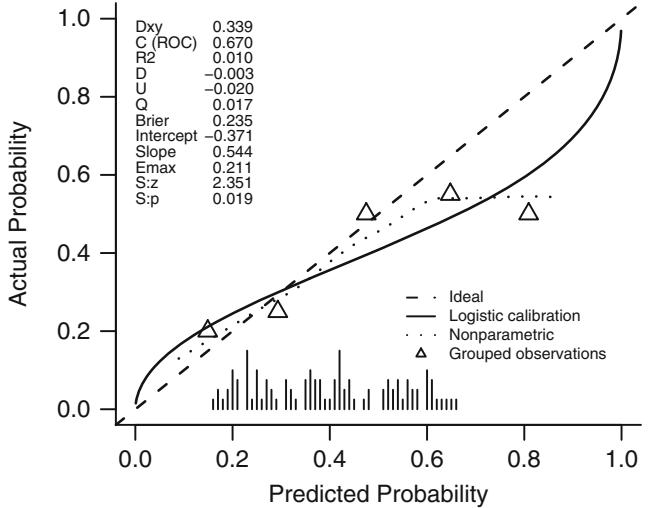

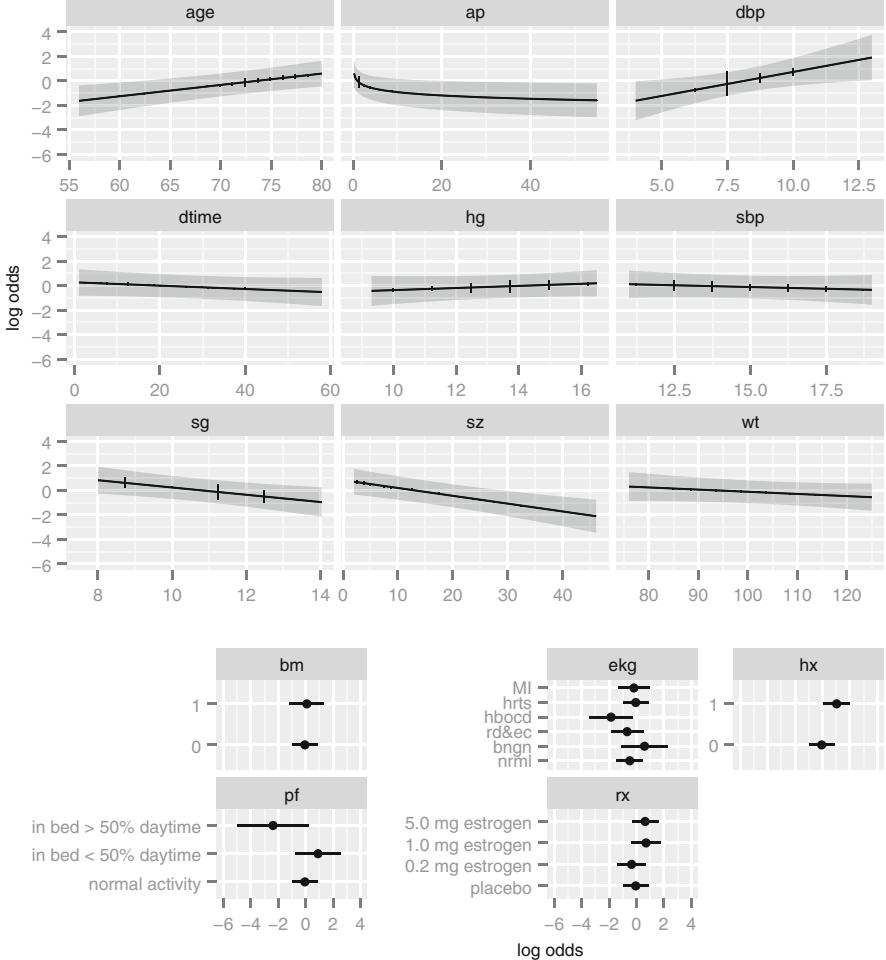

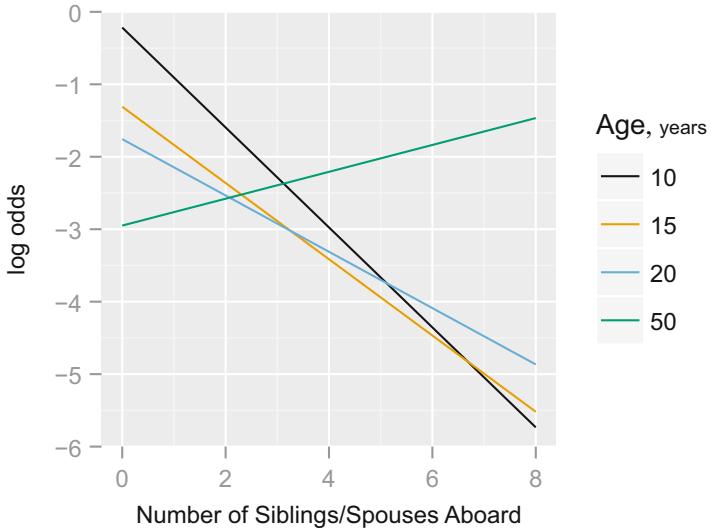

If the model contains two continuous predictors, they may both be expanded with spline functions in order to test linearity or to describe nonlinear relationships. Testing interaction is more difficult here. If X1 is continuous, one might temporarily group X1 into quantile groups. Consider the subset of 2258 (1490 with disease) of the 3504 patients used in Figure 10.6 who have serum cholesterol measured. A logistic model for predicting significant coronary disease was fitted with age in tertiles (modeled with two dummy variables), sex, age ≤ sex interaction, four-knot restricted cubic spline in cholesterol, and age tertile ≤ cholesterol interaction. Except for the sex adjustment this model is equivalent to fitting three separate spline functions in cholesterol, one for each age tertile. The fitted model is shown in Figure 10.9 for cholesterol and age tertile against logit of significant disease. Significant age ≤ cholesterol interaction is apparent from the figure and is suggested by the Wald β2 statistic (10.03) that follows. Note that the test for linearity of the interaction with respect to cholesterol is very insignificant (β2 = 2.40 on 4 d.f.), but we retain it for now. The fitted function is

acath − transform(acath ,

cholesterol = choleste ,

age.tertile = cut2 (age ,g=3),

sx = as.integer ( acath $sex) - 1)

# sx for loess , need to code as numeric

dd − datadist( acath ); options(datadist= ' dd ' )

# First model stratifies age into tertiles to get more

# empirical estimates of age x cholesterol interaction

f − lrm(sigdz ← age.tertile *(sex + rcs( cholesterol ,4)),

data=acath )

print (f, latex =TRUE)Logistic Regression Model

lrm(formula = sigdz ~ age.tertile * (sex + rcs(cholesterol, 4)), data = acath)

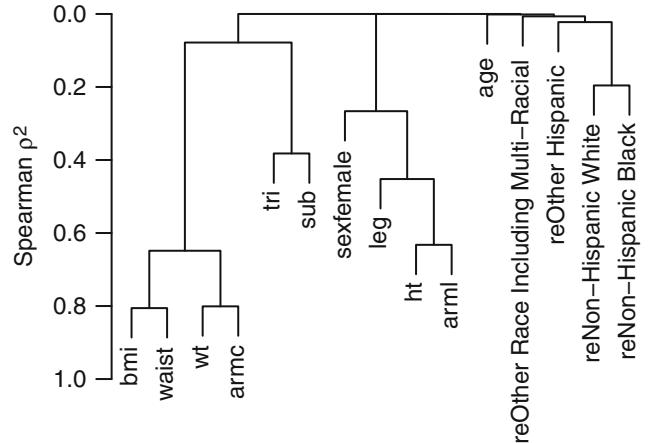

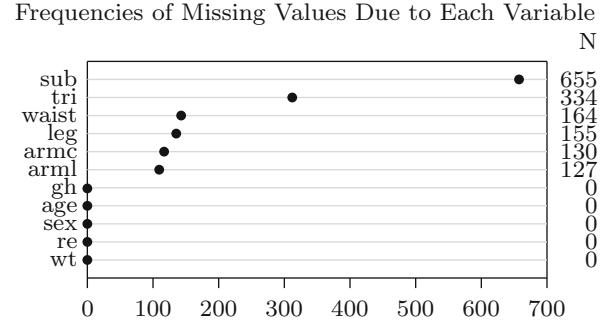

Frequencies of Missing Values Due to Each Variable

| sigdz age.tertile | sex | cholesterol | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1246 |

| Model Likelihood | Discrimination | Rank Discrim. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio Test | Indexes | Indexes | |||||

| Obs | 2258 | β2 LR |

533.52 | R2 | 0.291 | C | 0.780 |

| 0 | 768 | d.f. | 14 | g | 1.316 | Dxy | 0.560 |

| 1 | 1490 | β2) Pr(> |

< 0.0001 |

gr | 3.729 | α | 0.562 |

| α log L max αρ |

2≤10−8 | gp | 0.252 | Γa | 0.251 | ||

| Brier | 0.173 |

| Coef | S.E. | Wald Z |

Pr(> Z ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -0.4155 | 1.0987 | -0.38 | 0.7053 |

| age.tertile=[49,58) | 0.8781 | 1.7337 | 0.51 | 0.6125 |

| age.tertile=[58,82] | 4.7861 | 1.8143 | 2.64 | 0.0083 |

| sex=female | -1.6123 | 0.1751 | -9.21 | < 0.0001 |

| cholesterol | 0.0029 | 0.0060 | 0.48 | 0.6347 |

| cholesterol’ | 0.0384 | 0.0242 | 1.59 | 0.1126 |

| cholesterol” | -0.1148 | 0.0768 | -1.49 | 0.1350 |

| age.tertile=[49,58) * sex=female | -0.7900 | 0.2537 | -3.11 | 0.0018 |

| age.tertile=[58,82] * sex=female | -0.4530 | 0.2978 | -1.52 | 0.1283 |

| age.tertile=[49,58) * cholesterol | 0.0011 | 0.0095 | 0.11 | 0.9093 |

| Coef | S.E. | Wald Z |

Pr(> Z ) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age.tertile=[58,82] * cholesterol | -0.0158 | 0.0099 | -1.59 | 0.1111 |

| age.tertile=[49,58) * cholesterol’ | -0.0183 | 0.0365 | -0.50 | 0.6162 |

| age.tertile=[58,82] * cholesterol’ | 0.0127 | 0.0406 | 0.31 | 0.7550 |

| age.tertile=[49,58) * cholesterol” | 0.0582 | 0.1140 | 0.51 | 0.6095 |

| age.tertile=[58,82] * cholesterol” | -0.0092 | 0.1301 | -0.07 | 0.9436 |

ltx(f)

XΛˆ = ×0.415 + 0.878[age.tertile ≥ [49, 58)] + 4.79[age.tertile ≥ [58, 82]] × 1.61[female] + 0.00287cholesterol + 1.52≤10−6(cholesterol × 160)3 + × 4.53≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 208)3 + + 3.44 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 243)3 + × 4.28 ≤ 10−7 (cholesterol×319)3 ++[female][×0.79[age.tertile ≥ [49, 58)]×0.453[age.tertile ≥ [58, 82]]]+[age.tertile ≥ [49, 58)][0.00108cholesterol×7.23≤10−7(cholesterol× 160)3 + + 2.3≤10−6(cholesterol × 208)3 + × 1.84≤10−6(cholesterol × 243)3 + + 2.69≤10−7(cholesterol × 319)3 +] + [age.tertile ≥ [58, 82]][×0.0158cholesterol+ 5≤10−7(cholesterol × 160)3 + × 3.64≤10−7(cholesterol × 208)3 + × 5.15≤10−7 (cholesterol × 243)3 + + 3.78≤10−7(cholesterol × 319)3 +].

# Table 10.5:

latex (anova (f), file= ' ' , size= ' smaller ' ,

caption= ' Crudely categorizing age into tertiles ' ,

label = ' tab:anova-tertiles ' )yl − c(-1 ,5)

plot( Predict(f, cholesterol , age.tertile ),

adj.subtitle =FALSE , ylim=yl) # Figure 10.9| Table 10.5 | Crudely categorizing age into tertiles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ———— | – | —————————————- | – | – | – |

| σ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age.tertile (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 120.74 | 10 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 21.87 | 8 | 0.0052 |

| sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 329.54 | 3 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 9.78 | 2 | 0.0075 |

| cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 93.75 | 9 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 10.03 | 6 | 0.1235 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 9.96 | 6 | 0.1263 |

| age.tertile ∼ sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 9.78 | 2 | 0.0075 |

| age.tertile ∼ cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 10.03 | 6 | 0.1235 |

| Nonlinear | 2.62 | 4 | 0.6237 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 2.62 | 4 | 0.6237 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR | 9.96 | 6 | 0.1263 |

| TOTAL INTERACTION | 21.87 | 8 | 0.0052 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR + INTERACTION | 29.67 | 10 | 0.0010 |

| TOTAL | 410.75 | 14 < 0.0001 |

Fig. 10.9 Log odds of significant coronary artery disease modeling age with two dummy variables

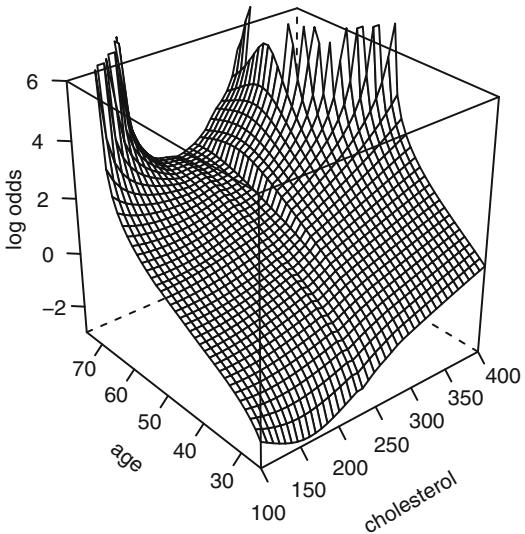

Before fitting a parametric model that allows interaction between age and cholesterol, let us use the local regression model of Cleveland et al.96 discussed in Section 2.4.7. This nonparametric smoothing method is not meant to handle binary Y , but it can still provide useful graphical displays in the binary case. Figure 10.10 depicts the fit from a local regression model predicting Y = 1 = significant coronary artery disease. Predictors are sex (modeled parametrically with a dummy variable), age, and cholesterol, the last two fitted nonparametrically. The effect of not explicitly modeling a probability is seen in the figure, as the predicted probabilities exceeded 1. Because of this we do not take the logit transformation but leave the predicted values in raw form. However, the overall shape is in agreement with Figure 10.10.

# Re-do model with continuous age

f − loess (sigdz ← age * (sx + cholesterol ), data=acath ,

parametric ="sx", drop.square ="sx")

ages − seq(25, 75, length =40)

chols − seq(100, 400, length =40)

g − expand.grid (cholesterol= chols , age=ages , sx=0)

# drop sex dimension of grid since held to 1 value

p − drop( predict(f, g))

p[p < 0.001] − 0.001

p[p > 0.999] − 0.999

zl − c(-3 , 6) # Figure 10.10

wireframe( qlogis (p) ← cholesterol *age ,

xlab=list(rot =30), ylab=list(rot=-40),

zlab=list(label= ' log odds ' , rot=90), zlim=zl ,

scales = list(arrows = FALSE), data=g)Chapter 2 discussed linear splines, which can be used to construct linear spline surfaces by adding all cross-products of the linear variables and spline terms in the model. With a sufficient number of knots for each predictor, the linear spline surface can fit a wide variety of patterns. However, it requires a large number of parameters to be estimated. For the age–sex–cholesterol example, a linear spline surface is fitted for age and cholesterol, and a sex ≤ age spline interaction is also allowed. Figure 10.11 shows a fit that placed knots at quartiles of the two continuous variablesc. The algebraic form of the fitted model is shown below.

f − lrm(sigdz ← lsp(age ,c(46 ,52 ,59)) *

(sex + lsp(cholesterol ,c(196 ,224 ,259))) ,

data=acath )

ltx(f)XΛˆ = ×1.83 + 0.0232 age + 0.0759(age × 46)+ × 0.0025(age × 52)+ +

2.27(age×59)++3.02[female]×0.0177cholesterol+0.114(cholesterol×196)+×

0.131(cholesterol×224)+ + 0.0651(cholesterol×259)+ +[female][×0.112 age+

0.0852 (age × 46)+ × 0.0302 (age × 52)+ + 0.176 (age × 59)+] + age

[0.000577 cholesterol × 0.00286 (cholesterol × 196)+ + 0.00382 (cholesterol ×

224)+ × 0.00205 (cholesterol × 259)+] + (age × 46)+[×0.000936 cholesterol +

0.00643(cholesterol×196)+×0.0115(cholesterol×224)++0.00756(cholesterol×

259)+] + (age × 52)+[0.000433 cholesterol × 0.0037 (cholesterol × 196)+ +

0.00815 (cholesterol × 224)+ × 0.00715 (cholesterol × 259)+] + (age × 59)+

[×0.0124cholesterol+0.015(cholesterol×196)+×0.0067(cholesterol×224)+ +

0.00752 (cholesterol × 259)+].

Fig. 10.10 Local regression fit for the logit of the probability of significant coronary disease vs. age and cholesterol for males, based on the loess function.

c In the wireframe plots that follow, predictions for cholesterol–age combinations for which fewer than 5 exterior points exist are not shown, so as to not extrapolate to regions not supported by at least five points beyond the data perimeter.

latex (anova (f), caption= ’ Linear spline surface ’ , file= ’ ’ , size= ’ smaller ’ , label= ’ tab:anova-lsp ’ ) # Table 10.6

perim − with(acath ,

perimeter( cholesterol , age , xinc =20, n=5))

zl − c(-2 , 4) # Figure 10.11

bplot ( Predict(f, cholesterol , age , np =40), perim =perim ,

lfun =wireframe , zlim=zl , adj.subtitle = FALSE )| Table 10.6 | Linear spline surface | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ———— | – | – | – | ———————– |

| σ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 164.17 | 24 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 42.28 | 20 | 0.0025 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 25.21 | 18 | 0.1192 |

| sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 343.80 | 5 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 23.90 | 4 | 0.0001 |

| cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 100.13 | 20 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 16.27 | 16 | 0.4341 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 16.35 | 15 | 0.3595 |

| age ∼ sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 23.90 | 4 | 0.0001 |

| Nonlinear | 12.97 | 3 | 0.0047 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 12.97 | 3 | 0.0047 |

| age ∼ cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 16.27 | 16 | 0.4341 |

| Nonlinear | 11.45 | 15 | 0.7204 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 11.45 | 15 | 0.7204 |

| f(A,B) vs. Af(B) + Bg(A) | 9.38 | 9 | 0.4033 |

| Nonlinear Interaction in age vs. Af(B) | 9.99 | 12 | 0.6167 |

| Nonlinear Interaction in cholesterol vs. Bg(A) | 10.75 | 12 | 0.5503 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR | 33.22 | 24 | 0.0995 |

| TOTAL INTERACTION | 42.28 | 20 | 0.0025 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR + INTERACTION | 49.03 | 26 | 0.0041 |

| TOTAL | 449.26 | 29 < 0.0001 |

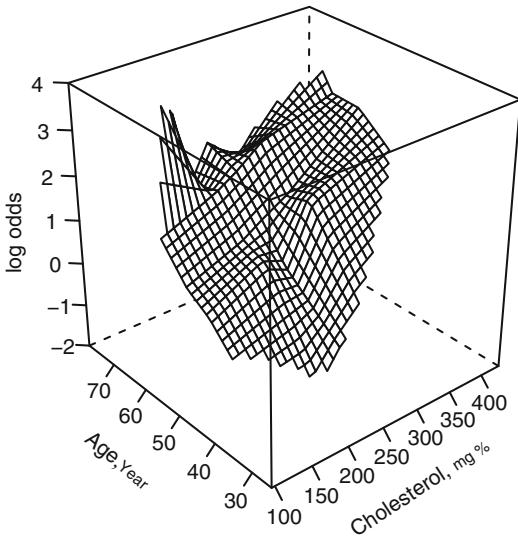

Chapter 2 also discussed a tensor spline extension of the restricted cubic spline model to fit a smooth function of two predictors, f(X1, X2). Since this function allows for general interaction between X1 and X2, the twovariable cubic spline is a powerful tool for displaying and testing interaction, assuming the sample size warrants estimating 2(k × 1) + (k × 1)2 parameters for a rectangular grid of k ≤ k knots. Unlike the linear spline surface, the cubic surface is smooth. It also requires fewer parameters in most situations. The general cubic model with k = 4 (ignoring the sex effect here) is

\[\begin{aligned} \beta\_0 &+ \beta\_1 X\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_1' + \beta\_3 X\_1'' + \beta\_4 X\_2 + \beta\_5 X\_2' + \beta\_6 X\_2'' + \beta\_7 X\_1 X\_2 \\ &+ \quad \beta\_8 X\_1 X\_2' + \beta\_9 X\_1 X\_2'' + \beta\_{10} X\_1' X\_2 + \beta\_{11} X\_1' X\_2' \\ &+ \quad \quad + \beta\_{12} X\_1' X\_2'' + \beta\_{13} X\_1'' X\_2 + \beta\_{14} X\_1'' X\_2' + \beta\_{15} X\_1'' X\_2'', \end{aligned} \tag{10.31}\]

where X∗ 1, X∗∗ 1 , X∗ 2, and X∗∗ 2 are restricted cubic spline component variables for X1 and X2 for k = 4. A general test of interaction with 9 d.f. is H0 : Λ7 = … = Λ15 = 0. A test of adequacy of a simple product form interaction is H0 : Λ8 = … = Λ15 = 0 with 8 d.f. A 13 d.f. test of linearity and additivity is H0 : Λ2 = Λ3 = Λ5 = Λ6 = Λ7 = Λ8 = Λ9 = Λ10 = Λ11 = Λ12 = Λ13 = Λ14 = Λ15 =0.

Figure 10.12 depicts the fit of this model. There is excellent agreement with Figures 10.9 and 10.11, including an increased (but probably insignificant) risk with low cholesterol for age ← 57.

f − lrm(sigdz ← rcs(age ,4)*(sex + rcs(cholesterol ,4)),

data=acath , tol=1 e-11)

ltx(f)XΛˆ = ×6.41 + 0.166age × 0.00067(age × 36)3 + + 0.00543(age × 48)3 + × 0.00727(age×56)3 + + 0.00251(age×68)3 + + 2.87[female]+ 0.00979cholesterol+ 1.96 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 160)3 + × 7.16 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 208)3 + + 6.35 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol×243)3 +×1.16≤10−6(cholesterol×319)3 ++[female][×0.109age+ 7.52≤10−5(age×36)3 ++0.00015(age×48)3 +×0.00045(age×56)3 ++0.000225(age× 68)3 +] + age[×0.00028cholesterol + 2.68≤10−9(cholesterol × 160)3 + + 3.03≤ 10−8(cholesterol × 208)3 + × 4.99 ≤ 10−8(cholesterol × 243)3 + + 1.69 ≤ 10−8 (cholesterol × 319)3 +] + age∗ [0.00341cholesterol × 4.02 ≤ 10−7(cholesterol × 160)3 ++9.71≤10−7(cholesterol×208)3 +×5.79≤10−7(cholesterol×243)3 ++8.79≤ 10−9(cholesterol×319)3 +]+ age∗∗[×0.029cholesterol+ 3.04≤10−6(cholesterol×

Fig. 10.11 Linear spline surface for males, with knots for age at 46, 52, 59 and knots for cholesterol at 196, 224, and 259 (quartiles).

160)3 + × 7.34≤10−6(cholesterol × 208)3 + + 4.36≤10−6(cholesterol × 243)3 + × 5.82≤10−8(cholesterol × 319)3 +].

latex (anova (f), caption= ' Cubic spline surface ' , file= ' ' ,

size= ' smaller ' , label= ' tab:anova-rcs ' ) #Table 10.7# Figure 10.12:

bplot ( Predict(f, cholesterol , age , np =40), perim =perim ,

lfun =wireframe , zlim=zl , adj.subtitle = FALSE )| Table 10.7 | Cubic spline surface | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ———— | – | – | – | ———————- |

| σ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| age (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 165.23 | 15 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 37.32 | 12 | 0.0002 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 21.01 | 10 | 0.0210 |

| sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 343.67 | 4 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 23.31 | 3 < 0.0001 | |

| cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 97.50 | 12 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 12.95 | 9 | 0.1649 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 13.62 | 8 | 0.0923 |

| age ∼ sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 23.31 | 3 < 0.0001 | |

| Nonlinear | 13.37 | 2 | 0.0013 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 13.37 | 2 | 0.0013 |

| age ∼ cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 12.95 | 9 | 0.1649 |

| Nonlinear | 7.27 | 8 | 0.5078 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 7.27 | 8 | 0.5078 |

| f(A,B) vs. Af(B) + Bg(A) | 5.41 | 4 | 0.2480 |

| Nonlinear Interaction in age vs. Af(B) | 6.44 | 6 | 0.3753 |

| Nonlinear Interaction in cholesterol vs. Bg(A) | 6.27 | 6 | 0.3931 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR | 29.22 | 14 | 0.0097 |

| TOTAL INTERACTION | 37.32 | 12 | 0.0002 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR + INTERACTION | 45.41 | 16 | 0.0001 |

| TOTAL | 450.88 | 19 < 0.0001 |

Statistics for testing age ≤ cholesterol components of this fit are above. None of the nonlinear interaction components is significant, but we again retain them.

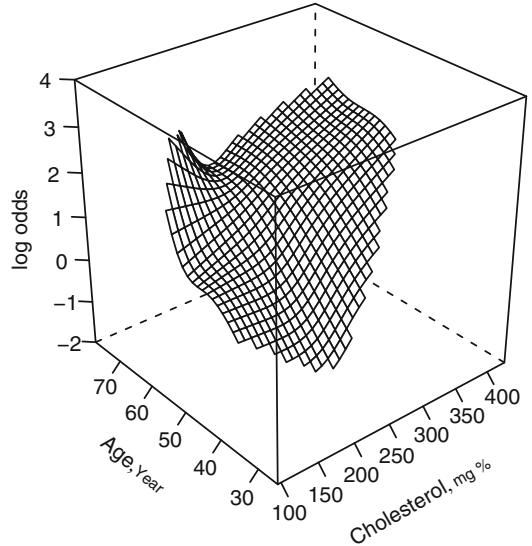

The general interaction model can be restricted to be of the form

\[f(X\_1, X\_2) = f\_1(X\_1) + f\_2(X\_2) + X\_1 g\_2(X\_2) + X\_2 g\_1(X\_1) \tag{10.32}\]

by removing the parameters Λ11, Λ12, Λ14, and Λ15 from the model. The previous table of Wald statistics included a test of adequacy of this reduced form (β2 = 5.41 on 4 d.f., P = .248). The resulting fit is in Figure 10.13.

f − lrm(sigdz ← sex*rcs(age ,4) + rcs(cholesterol ,4) +

rcs(age ,4) %ia% rcs(cholesterol ,4), data =acath )

latex (anova (f), file= ' ' , size= ' smaller ' ,

caption= ' Singly nonlinear cubic spline surface ' ,

label = ' tab:anova-ria ' ) #Table 10.8

Fig. 10.12 Restricted cubic spline surface in two variables, each with k = 4 knots

| Table 10.8 | Singly nonlinear cubic spline surface | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | – | ———— | – | ————————————— | – | – | – |

| σ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 343.42 | 4 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 24.05 | 3 < 0.0001 | |

| age (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 169.35 | 11 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 34.80 | 8 < 0.0001 | |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 16.55 | 6 | 0.0111 |

| cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 93.62 | 8 < 0.0001 | |

| All Interactions | 10.83 | 5 | 0.0548 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 10.87 | 4 | 0.0281 |

| age ∼ cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 10.83 | 5 | 0.0548 |

| Nonlinear | 3.12 | 4 | 0.5372 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 3.12 | 4 | 0.5372 |

| Nonlinear Interaction in age vs. Af(B) | 1.60 | 2 | 0.4496 |

| Nonlinear Interaction in cholesterol vs. Bg(A) | 1.64 | 2 | 0.4400 |

| sex ∼ age (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 24.05 | 3 < 0.0001 | |

| Nonlinear | 13.58 | 2 | 0.0011 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 13.58 | 2 | 0.0011 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR | 27.89 | 10 | 0.0019 |

| TOTAL INTERACTION | 34.80 | 8 < 0.0001 | |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR + INTERACTION | 45.45 | 12 < 0.0001 | |

| TOTAL | 453.10 | 15 < 0.0001 |

# Figure 10.13:

bplot ( Predict(f, cholesterol , age , np =40), perim =perim ,

lfun =wireframe , zlim=zl , adj.subtitle = FALSE )

ltx(f)Table 10.9 Linear interaction surface

| σ2 | d.f. P |

|

|---|---|---|

| age (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 167.83 | 7 < 0.0001 |

| All Interactions | 31.03 | 4 < 0.0001 |

| Nonlinear (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 14.58 | 4 0.0057 |

| sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 345.88 | 4 < 0.0001 |

| All Interactions | 22.30 | 3 0.0001 |

| cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 89.37 | 4 < 0.0001 |

| All Interactions | 7.99 | 1 0.0047 |

| Nonlinear | 10.65 | 2 0.0049 |

| age ∼ cholesterol (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 7.99 | 1 0.0047 |

| age ∼ sex (Factor+Higher Order Factors) | 22.30 | 3 0.0001 |

| Nonlinear | 12.06 | 2 0.0024 |

| Nonlinear Interaction : f(A,B) vs. AB | 12.06 | 2 0.0024 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR | 25.72 | 6 0.0003 |

| TOTAL INTERACTION | 31.03 | 4 < 0.0001 |

| TOTAL NONLINEAR + INTERACTION | 43.59 | 8 < 0.0001 |

| TOTAL | 452.75 | 11 < 0.0001 |

XΛˆ = ×7.2+2.96[female]+0.164age+7.23≤10−5(age×36)3 + ×0.000106(age× 48)3 + × 1.63≤10−5(age × 56)3 + + 4.99≤10−5(age × 68)3 + + 0.0148cholesterol + 1.21 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 160)3 + × 5.5 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 208)3 + + 5.5 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 243)3 + × 1.21≤10−6(cholesterol × 319)3 + + age[×0.00029 cholesterol+ 9.28≤10−9(cholesterol×160)3 + + 1.7≤10−8(cholesterol×208)3 + × 4.43≤10−8(cholesterol×243)3 ++1.79≤10−8(cholesterol×319)3 +]+cholesterol[2.3≤ 10−7(age × 36)3 + + 4.21≤10−7(age × 48)3 + × 1.31≤10−6(age × 56)3 + + 6.64≤ 10−7(age×68)3 +]+[female][×0.111age+8.03≤10−5(age×36)3 ++0.000135(age× 48)3 + × 0.00044(age × 56)3 + + 0.000224(age × 68)3 +].

The fit is similar to the former one except that the climb in risk for lowcholesterol older subjects is less pronounced. The test for nonlinear interaction is now more concentrated (P = .54 with 4 d.f.). Figure 10.14 accordingly depicts a fit that allows age and cholesterol to have nonlinear main effects, but restricts the interaction to be a product between (untransformed) age and cholesterol. The function agrees substantially with the previous fit.

f − lrm(sigdz ← rcs(age ,4)*sex + rcs(cholesterol ,4) +

age %ia% cholesterol , data=acath)

latex(anova (f), caption= ' Linear interaction surface ' , file= ' ' ,

size= ' smaller ' , label= ' tab:anova-lia ' ) #Table 10.9# Figure 10.14:

bplot ( Predict(f, cholesterol , age , np =40), perim =perim ,

lfun =wireframe , zlim=zl , adj.subtitle = FALSE )

f.linia − f # save linear interaction fit for later

ltx(f)

Fig. 10.13 Restricted cubic spline fit with age ∼ spline(cholesterol) and cholesterol ∼ spline(age)

XΛˆ = ×7.36+0.182age×5.18≤10−5(age×36)3 ++8.45≤10−5(age×48)3 +×2.91≤ 10−6(age × 56)3 + × 2.99≤10−5(age × 68)3 + + 2.8[female] + 0.0139cholesterol + 1.76 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 160)3 + × 4.88 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 208)3 + + 3.45 ≤ 10−6(cholesterol × 243)3 + × 3.26≤10−7(cholesterol × 319)3 + × 0.00034 age ≤ cholesterol + [female][×0.107age + 7.71≤10−5(age × 36)3 + + 0.000115(age × 48)3 + × 0.000398(age × 56)3 + + 0.000205(age × 68)3 +].

The Wald test for age ≤ cholesterol interaction yields β2 = 7.99 with 1 d.f., P = .005. These analyses favor the nonlinear model with simple product interaction in Figure 10.14 as best representing the relationships among cholesterol, age, and probability of prognostically severe coronary artery disease. A nomogram depicting this model is shown in Figure 10.21.

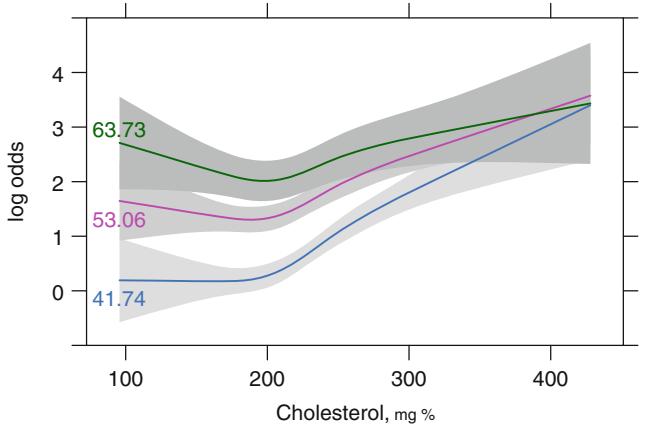

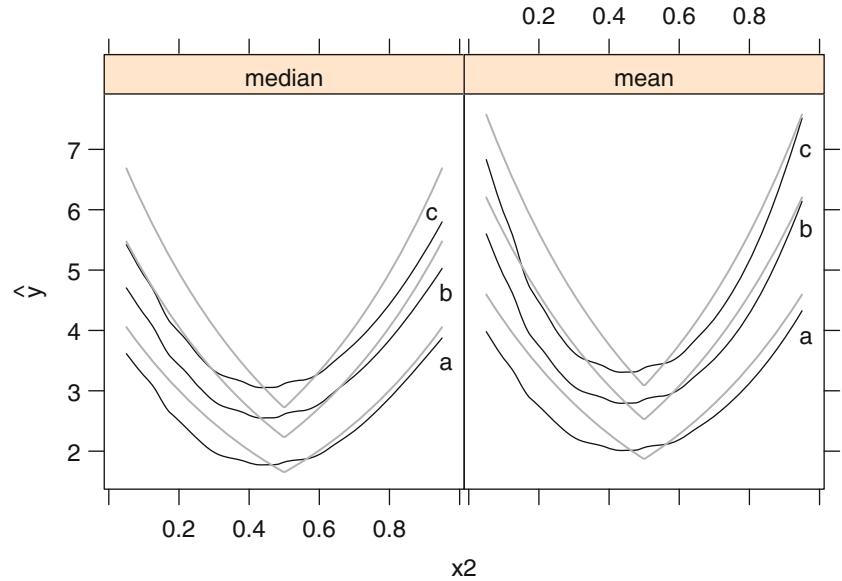

Using this simple product interaction model, Figure 10.15 displays predicted cholesterol effects at the mean age within each age tertile. Substantial agreement with Figure 10.9 is apparent.

# Make estimates of cholesterol effects for mean age in

# tertiles corresponding to initial analysis

mean.age −

with( acath ,

as.vector( tapply (age , age.tertile , mean , na.rm=TRUE)))

plot( Predict(f, cholesterol , age=round (mean.age ,2),

sex="male"),

adj.subtitle =FALSE , ylim=yl) #3 curves , Figure 10.15

Fig. 10.14 Spline fit with nonlinear effects of cholesterol and age and a simple product interaction

Fig. 10.15 Predictions from linear interaction model with mean age in tertiles indicated.

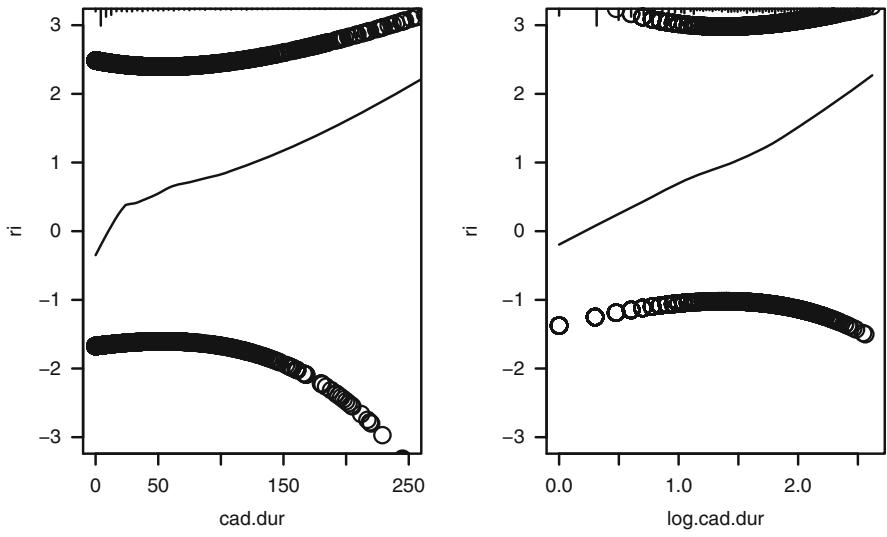

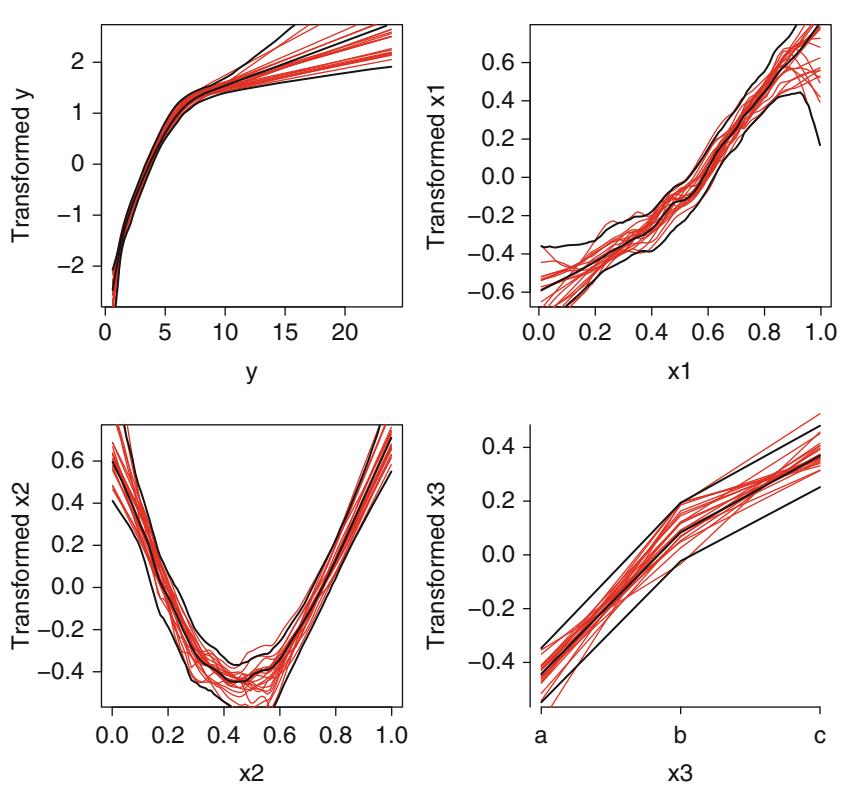

The partial residuals discussed in Section 10.4 can be used to check logistic model fit (although it may be difficult to deal with interactions). As an example, reconsider the “duration of symptoms” fit in Figure 10.7. Figure 10.16 displays “loess smoothed” and raw partial residuals for the original and log-transformed variable. The latter provides a more linear relationship, especially where the data are most dense.

| Method | Choice | Assumes | Uses Ordering | Low | Good |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Required | Additivity | of X | Variance | Resolution | |

| on X | |||||

| Stratification | Intervals | ||||

| Smoother on X1 | Bandwidth | x | x | x | |

| stratifying on X2 | (not on X2) | (if min. strat.) | (X1) | ||

| Smooth partial | Bandwidth | x | x | x | x |

| residual plot | |||||

| Spline model | Knots | x | x | x | x |

| for all Xs |

Table 10.10 Merits of Methods for Checking Logistic Model Assumptions

f − lrm(tvdlm ← cad.dur , data=dz , x=TRUE , y= TRUE)

resid (f, " partial", pl=" loess ", xlim=c(0 ,250), ylim=c(-3 ,3))

scat1d (dz$ cad.dur)

log.cad.dur − log10 (dz$ cad.dur + 1)

f − lrm(tvdlm ← log.cad.dur , data =dz , x=TRUE , y= TRUE)

resid (f, " partial", pl=" loess", ylim =c(-3 ,3))

scat1d ( log.cad.dur ) # Figure 10.16

Fig. 10.16 Partial residuals for duration and log10(duration+1). Data density shown at top of each plot.

Table 10.10 summarizes the relative merits of stratification, nonparametric smoothers, and regression splines for determining or checking binary logistic model fits.

10.6 Collinearity

The variance inflation factors (VIFs) discussed in Section 4.6 can apply to any regression fit.147, 654 These VIFs allow the analyst to isolate which variable(s) are responsible for highly correlated parameter estimates. Recall that, in general, collinearity is not a large problem compared with nonlinearity and overfitting.

10.7 Overly Influential Observations

Pregibon511 developed a number of regression diagnostics that apply to the family of regression models of which logistic regression is a member. Influence statistics based on the “leave-out-one”method use an approximation to avoid having to refit the model n times for n observations. This approximation uses the fit and covariance matrix at the last iteration and assumes that the “weights” in the weighted least squares fit can be kept constant, yielding a computationally feasible one-step estimate of the leave-out-one regression coefficients.

Hosmer and Lemeshow [305, pp. 149–170] discuss many diagnostics for logistic regression and show how the final fit can be used in any least squares program that provides diagnostics. A new dependent variable to be used in that way is

\[Z\_i = X\hat{\beta} + \frac{Y\_i - \hat{P}\_i}{V\_i},\tag{10.33}\]

where Vi = Pˆi(1×Pˆi), and Pˆi = [1+ exp ×XΛˆ] −1 is the predicted probability that Yi = 1. The Vi, i = 1, 2,…,n are used as weights in an ordinary weighted least squares fit of X against Z. This least squares fit will provide regression coefficients identical to b. The new standard errors will be off from the actual logistic model ones by a constant.

As discussed in Section 4.9, the standardized change in the regression coefficients upon leaving out each observation in turn (DFBETAS) is one of the most useful diagnostics, as these can pinpoint which observations are influential on each part of the model. After carefully modeling predictor transformations, there should be no lack of fit due to improper transformations. However, as the white blood count example in Section 4.9 indicates, it is commonly the case that extreme predictor values can still have too much influence on the estimates of coefficients involving that predictor.

In the age–sex–response example of Section 10.1.3, both DFBETAS and DFFITS identified the same influential observations. The observation given by age = 48 sex = female response = 1 was influential for both age and sex, while the observation age = 34 sex = male response = 1 was influential for age and the observation age = 50 sex = male response = 0 was influential for sex. It can readily be seen from Figure 10.3 that these points do not fit the overall trends in the data. However, as these data were simulated from a

| Females | Males | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFBETAS | DFFITS | DFBETAS | DFFITS | ||||

| Intercept | Age | Sex | Intercept | Age | Sex | ||

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.5 | -0.5 | -0.2 | 2 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.2 | -0.3 | 0.0 | 1 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -1 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -1 |

| -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -1 |

| -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| 0.7 | -0.7 | -0.8 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -0.2 | -1 |

| -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | -0.1 | -0.2 | -1 |

| -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0 |

| -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| -0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -2 |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | -1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| 0.1 | -0.2 | 0.0 | -1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1 | -0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

| -0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 |

Table 10.11 Example influence statistics

population model that is truly linear in age and additive in age and sex, the apparent influential observations are just random occurrences. It is unwise to assume that in real data all points will agree with overall trends. Removal of such points would bias the results, making the model apparently more 11 predictive than it will be prospectively. See Table 10.11.

f − update (fasr , x=TRUE , y= TRUE) which.influence (f, .4) # Table 10.11

10.8 Quantifying Predictive Ability

The test statistics discussed above allow one to test whether a factor or set of factors is related to the response. If the sample is sufficiently large, a factor that grades risk from .01 to .02 may be a significant risk factor. However, that factor is not very useful in predicting the response for an individual subject. There is controversy regarding the appropriateness of R2 from ordinary least squares in this setting.136, 424 The generalized R2 N index of Nagelkerke471 12 and Cragg and Uhler137, Maddala431, and Magee432 described in Section 9.8.3 can be useful for quantifying the predictive strength of a model:

10.8 Quantifying Predictive Ability 257

\[R\_\mathrm{N}^2 = \frac{1 - \exp(-\mathrm{LR}/n)}{1 - \exp(-L^0/n)},\tag{10.34}\]

where LR is the global log likelihood ratio statistic for testing the importance of all p predictors in the model and L0 is the ×2 log likelihood for the null model. 13

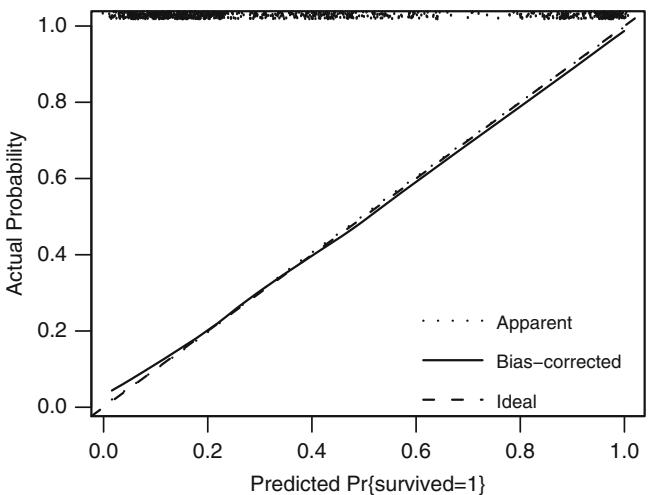

Tjur613 coined the term “coefficient of discrimination” D, defined as the average Pˆ when Y = 1 minus the average Pˆ when Y = 0, and showed how it ties in with sum of squares–based R2 measures. D has many advantages as an index of predictive powerd.

Linnet416 advocates quadratic and logarithmic probability scoring rules for measuring predictive performance for probability models. Linnet shows how to bootstrap such measures to get bias-corrected estimates and how to use bootstrapping to compare two correlated scores. The quadratic scoring rule is Brier’s score, frequently used in judging meteorologic forecasts30, 73:

\[B = \frac{1}{n} \sum\_{i=1}^{n} (\hat{P}\_i - Y\_i)^2,\tag{10.35}\]

where Pˆi is the predicted probability and Yi the corresponding observed response for the ith observation. 14

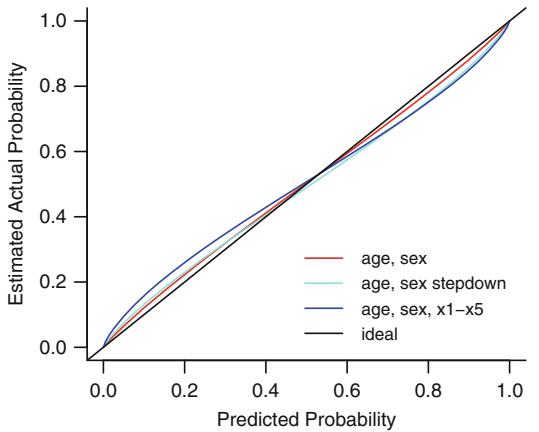

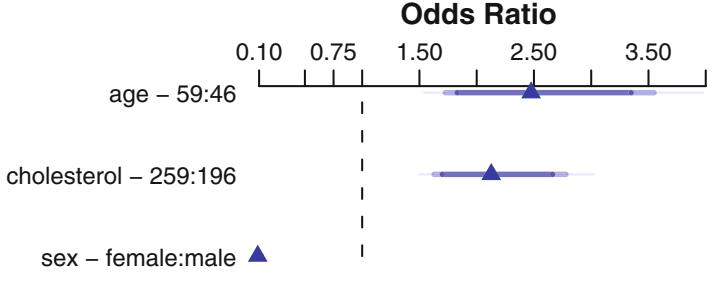

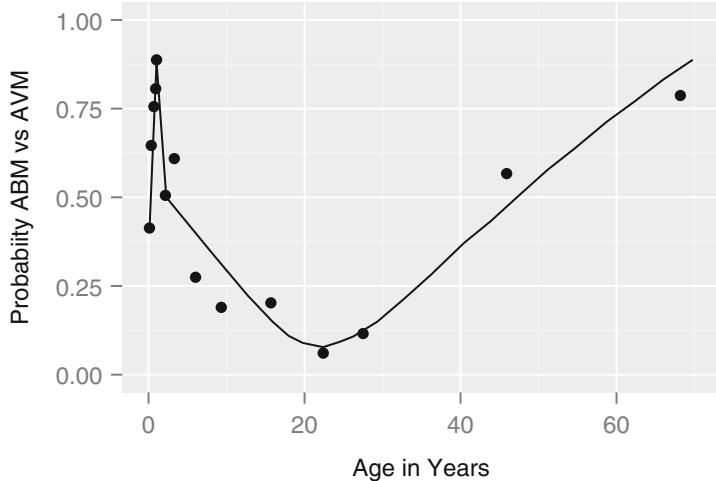

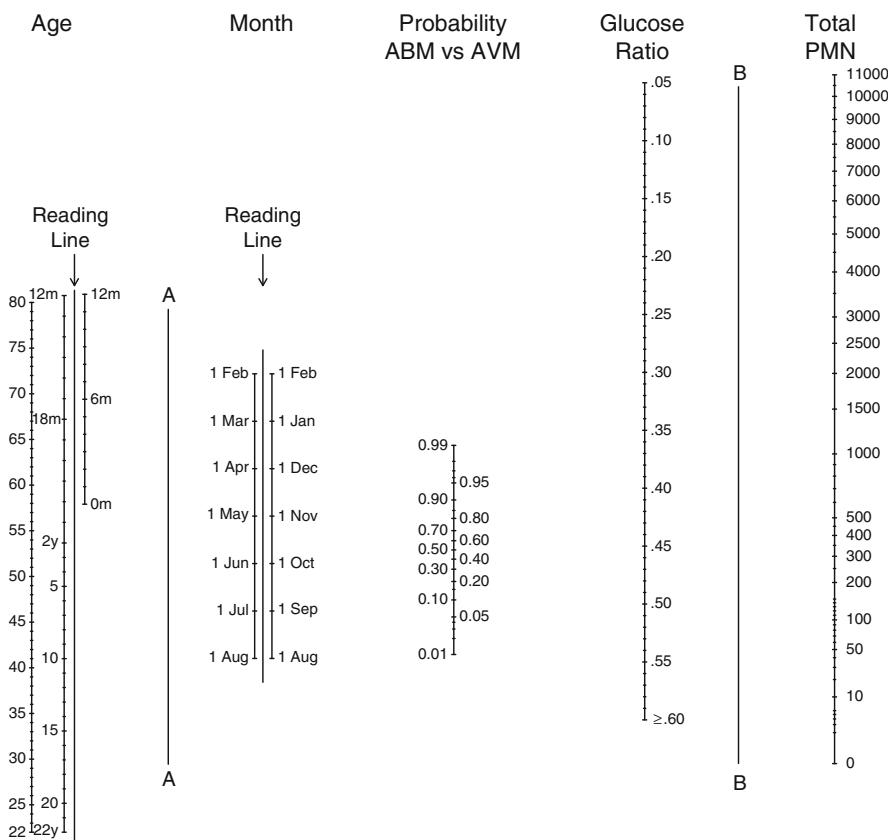

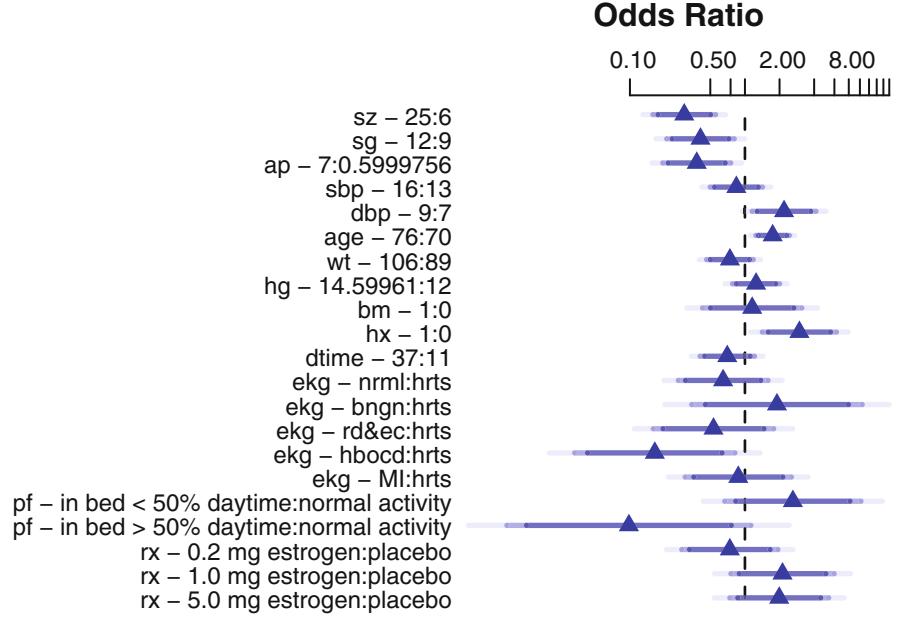

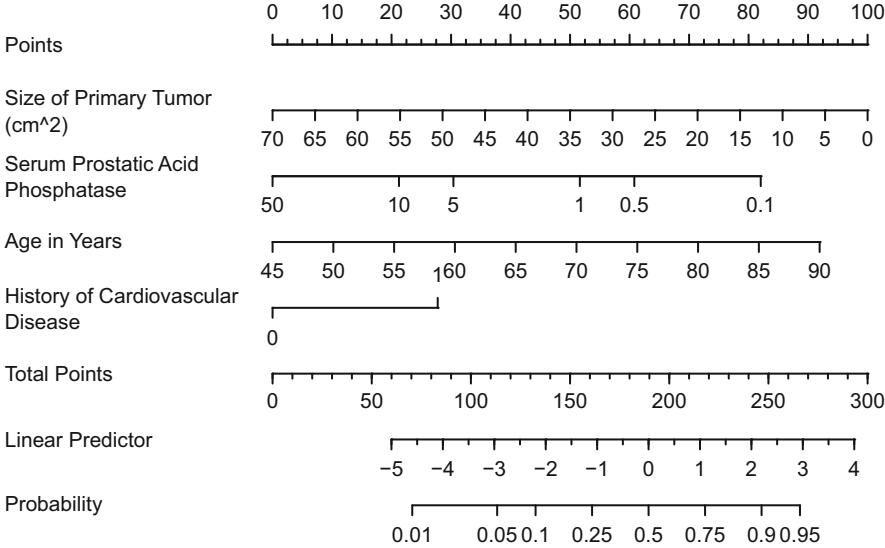

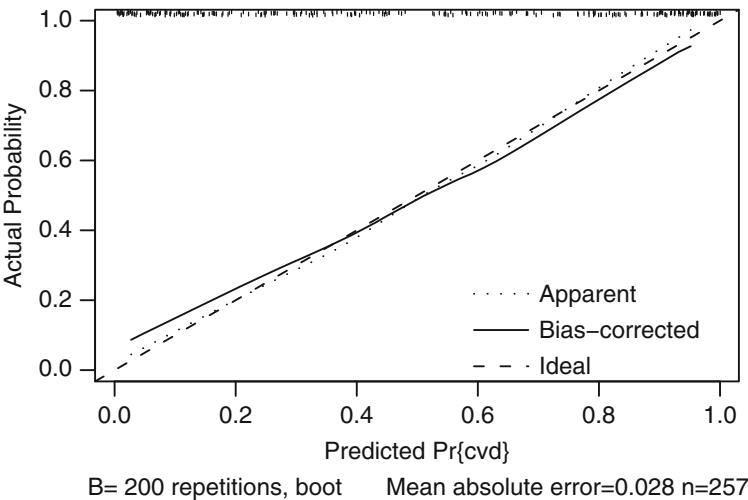

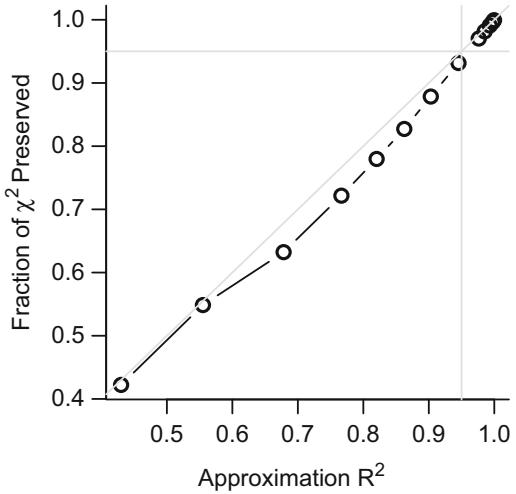

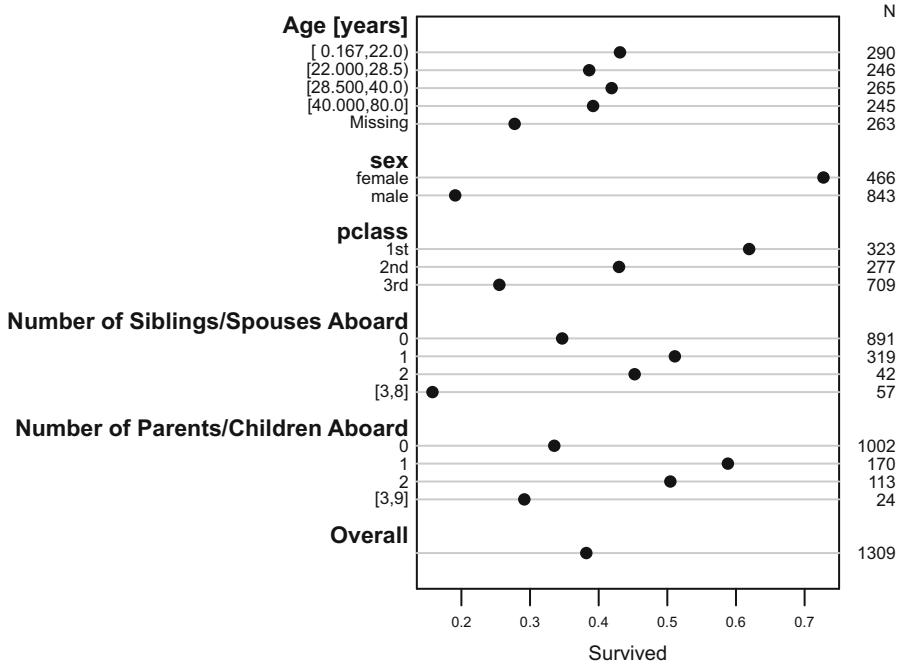

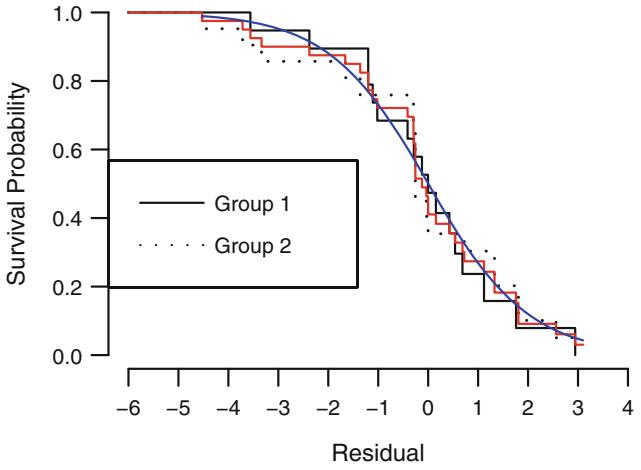

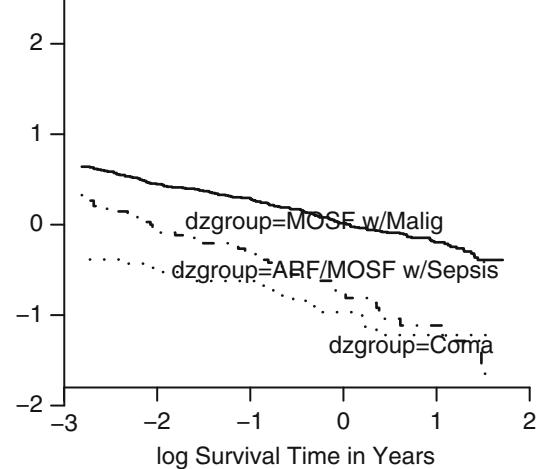

A unitless index of the strength of the rank correlation between predicted probability of response and actual response is a more interpretable measure of the fitted model’s predictive discrimination. One such index is the probability of concordance, c, between predicted probability and response. The c index, which is derived from the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney two-sample rank test, is computed by taking all possible pairs of subjects such that one subject responded and the other did not. The index is the proportion of such pairs with the responder having a higher predicted probability of response than the nonresponder.