Introduction to Statistical Learning

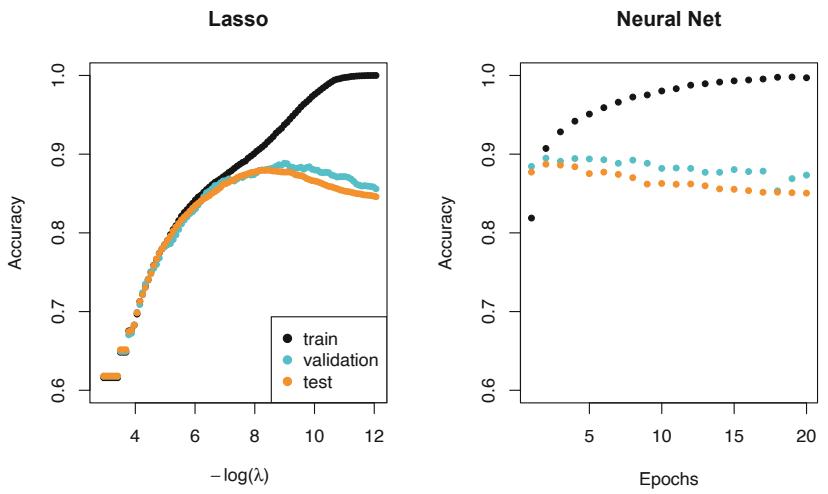

with Applications in Python

7 Moving Beyond Linearity

So far in this book, we have mostly focused on linear models. Linear models are relatively simple to describe and implement, and have advantages over other approaches in terms of interpretation and inference. However, standard linear regression can have signifcant limitations in terms of predictive power. This is because the linearity assumption is almost always an approximation, and sometimes a poor one. In Chapter 6 we see that we can improve upon least squares using ridge regression, the lasso, principal components regression, and other techniques. In that setting, the improvement is obtained by reducing the complexity of the linear model, and hence the variance of the estimates. But we are still using a linear model, which can only be improved so far! In this chapter we relax the linearity assumption while still attempting to maintain as much interpretability as possible. We do this by examining very simple extensions of linear models like polynomial regression and step functions, as well as more sophisticated approaches such as splines, local regression, and generalized additive models.

- Polynomial regression extends the linear model by adding extra predictors, obtained by raising each of the original predictors to a power. For example, a cubic regression uses three variables, X, X2, and X3, as predictors. This approach provides a simple way to provide a nonlinear ft to data.

- Step functions cut the range of a variable into K distinct regions in order to produce a qualitative variable. This has the efect of ftting a piecewise constant function.

- Regression splines are more fexible than polynomials and step functions, and in fact are an extension of the two. They involve dividing the range of X into K distinct regions. Within each region, a polynomial function is ft to the data. However, these polynomials are

© Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

constrained so that they join smoothly at the region boundaries, or knots. Provided that the interval is divided into enough regions, this can produce an extremely fexible ft.

- Smoothing splines are similar to regression splines, but arise in a slightly diferent situation. Smoothing splines result from minimizing a residual sum of squares criterion subject to a smoothness penalty.

- Local regression is similar to splines, but difers in an important way. The regions are allowed to overlap, and indeed they do so in a very smooth way.

- Generalized additive models allow us to extend the methods above to deal with multiple predictors.

In Sections 7.1–7.6, we present a number of approaches for modeling the relationship between a response Y and a single predictor X in a fexible way. In Section 7.7, we show that these approaches can be seamlessly integrated in order to model a response Y as a function of several predictors X1,…,Xp.

7.1 Polynomial Regression

Historically, the standard way to extend linear regression to settings in which the relationship between the predictors and the response is nonlinear has been to replace the standard linear model

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 x\_i + \epsilon\_i\]

with a polynomial function

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 x\_i + \beta\_2 x\_i^2 + \beta\_3 x\_i^3 + \dots + \beta\_d x\_i^d + \epsilon\_i,\tag{7.1}\]

where ϵi is the error term. This approach is known as polynomial regression, polynomial regression and in fact we saw an example of this method in Section 3.3.2. For large enough degree d, a polynomial regression allows us to produce an extremely non-linear curve. Notice that the coefcients in (7.1) can be easily estimated using least squares linear regression because this is just a standard linear model with predictors xi, x2 i , x3 i ,…,xd i . Generally speaking, it is unusual to use d greater than 3 or 4 because for large values of d, the polynomial curve can become overly fexible and can take on some very strange shapes. This is especially true near the boundary of the X variable.

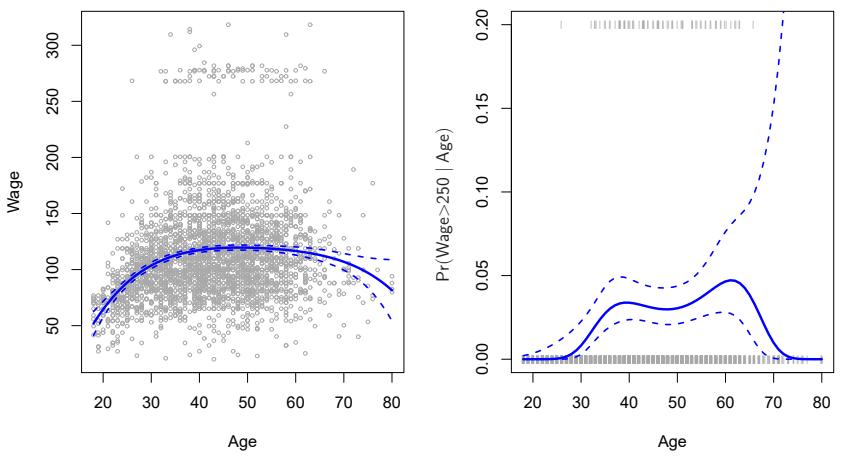

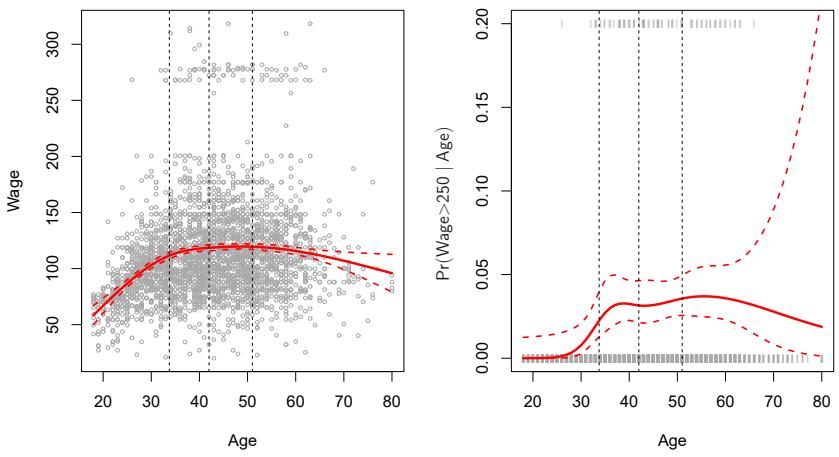

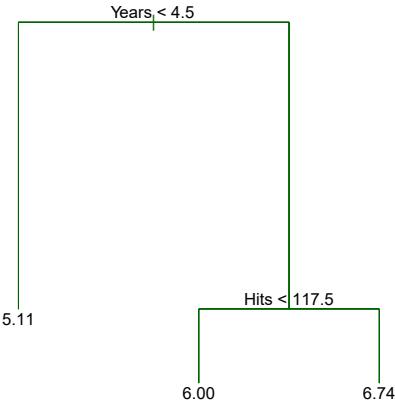

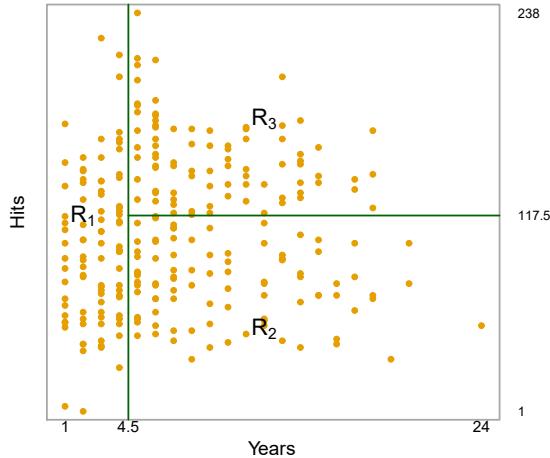

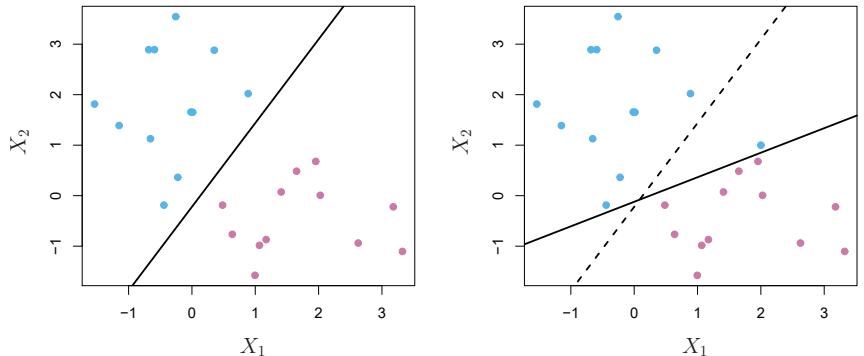

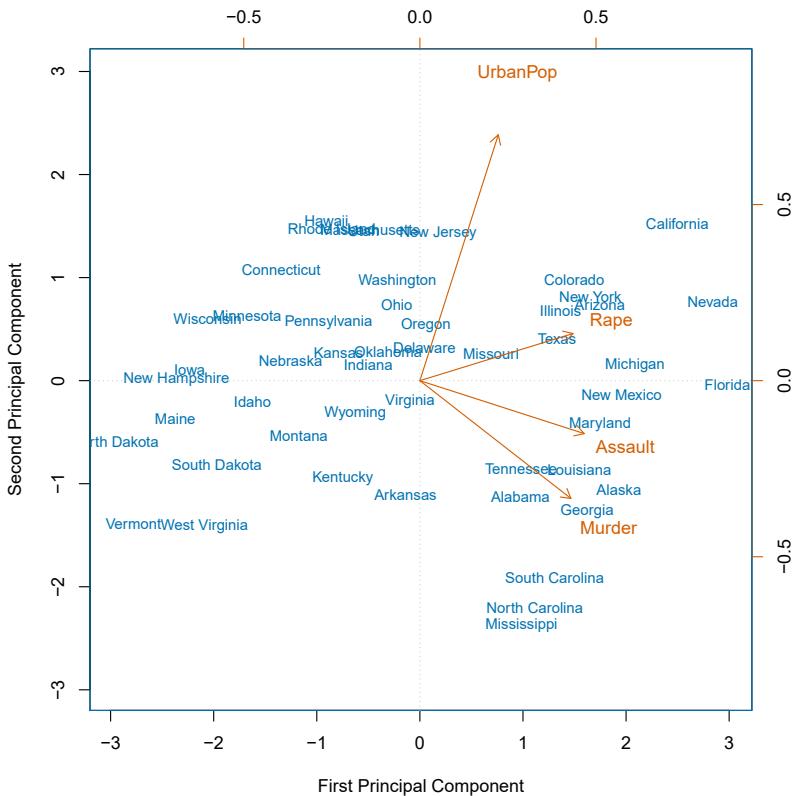

The left-hand panel in Figure 7.1 is a plot of wage against age for the Wage data set, which contains income and demographic information for males who reside in the central Atlantic region of the United States. We see the results of ftting a degree-4 polynomial using least squares (solid blue curve). Even though this is a linear regression model like any other, the individual coefcients are not of particular interest. Instead, we look at the entire ftted function across a grid of 63 values for age from 18 to 80 in order to understand the relationship between age and wage.

Degree−4 Polynomial

FIGURE 7.1. The Wage data. Left: The solid blue curve is a degree-4 polynomial of wage (in thousands of dollars) as a function of age, ft by least squares. The dashed curves indicate an estimated 95 % confdence interval. Right: We model the binary event wage>250 using logistic regression, again with a degree-4 polynomial. The ftted posterior probability of wage exceeding $250,000 is shown in blue, along with an estimated 95 % confdence interval.

In Figure 7.1, a pair of dashed curves accompanies the ft; these are (2×) standard error curves. Let’s see how these arise. Suppose we have computed the ft at a particular value of age, x0:

\[ \hat{f}(x\_0) = \hat{\beta}\_0 + \hat{\beta}\_1 x\_0 + \hat{\beta}\_2 x\_0^2 + \hat{\beta}\_3 x\_0^3 + \hat{\beta}\_4 x\_0^4. \tag{7.2} \]

What is the variance of the ft, i.e. Var ˆf(x0)? Least squares returns variance estimates for each of the ftted coefcients βˆj , as well as the covariances between pairs of coefcient estimates. We can use these to compute the estimated variance of ˆf(x0). 1 The estimated pointwise standard error of ˆf(x0) is the square-root of this variance. This computation is repeated at each reference point x0, and we plot the ftted curve, as well as twice the standard error on either side of the ftted curve. We plot twice the standard error because, for normally distributed error terms, this quantity corresponds to an approximate 95 % confdence interval.

It seems like the wages in Figure 7.1 are from two distinct populations: there appears to be a high earners group earning more than $250,000 per annum, as well as a low earners group. We can treat wage as a binary variable by splitting it into these two groups. Logistic regression can then be used to predict this binary response, using polynomial functions of age

1If Cˆ is the 5 × 5 covariance matrix of the βˆj , and if ℓT 0 = (1, x0, x2 0, x3 0, x4 0), then Var[f ˆ(x0)] = ℓT 0 Cˆ ℓ0.

292 7. Moving Beyond Linearity

as predictors. In other words, we ft the model

\[\Pr(y\_i > 250 | x\_i) = \frac{\exp(\beta\_0 + \beta\_1 x\_i + \beta\_2 x\_i^2 + \dots + \beta\_d x\_i^d)}{1 + \exp(\beta\_0 + \beta\_1 x\_i + \beta\_2 x\_i^2 + \dots + \beta\_d x\_i^d)}. \tag{7.3}\]

The result is shown in the right-hand panel of Figure 7.1. The gray marks on the top and bottom of the panel indicate the ages of the high earners and the low earners. The solid blue curve indicates the ftted probabilities of being a high earner, as a function of age. The estimated 95 % confdence interval is shown as well. We see that here the confdence intervals are fairly wide, especially on the right-hand side. Although the sample size for this data set is substantial (n = 3,000), there are only 79 high earners, which results in a high variance in the estimated coefcients and consequently wide confdence intervals.

7.2 Step Functions

Using polynomial functions of the features as predictors in a linear model imposes a global structure on the non-linear function of X. We can instead use step functions in order to avoid imposing such a global structure. Here step we break the range of X function into bins, and ft a diferent constant in each bin. This amounts to converting a continuous variable into an ordered categorical variable. ordered

In greater detail, we create cutpoints c1, c2,…,cK in the range of X, and then construct K + 1 new variables

categorical variable

\[\begin{array}{lcl}C\_0(X) &=& I(X < c\_1), \\ C\_1(X) &=& I(c\_1 \le X < c\_2), \\ C\_2(X) &=& I(c\_2 \le X < c\_3), \\ &\vdots & \\ C\_{K-1}(X) &=& I(c\_{K-1} \le X < c\_K), \\ C\_K(X) &=& I(c\_K \le X), \end{array} \tag{7.4}\]

where I(·) is an indicator function that returns a 1 if the condition is true, indicator function and returns a 0 otherwise. For example, I(cK ≤ X) equals 1 if cK ≤ X, and equals 0 otherwise. These are sometimes called dummy variables. Notice that for any value of X, C0(X) + C1(X) + ··· + CK(X)=1, since X must be in exactly one of the K + 1 intervals. We then use least squares to ft a linear model using C1(X), C2(X),…,CK(X) as predictors2:

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 C\_1(x\_i) + \beta\_2 C\_2(x\_i) + \dots + \beta\_K C\_K(x\_i) + \epsilon\_i. \tag{7.5}\]

For a given value of X, at most one of C1, C2,…,CK can be non-zero. Note that when X<c1, all of the predictors in (7.5) are zero, so β0 can

2We exclude C0(X) as a predictor in (7.5) because it is redundant with the intercept. This is similar to the fact that we need only two dummy variables to code a qualitative variable with three levels, provided that the model will contain an intercept. The decision to exclude C0(X) instead of some other Ck(X) in (7.5) is arbitrary. Alternatively, we could include C0(X), C1(X),…,CK(X), and exclude the intercept.

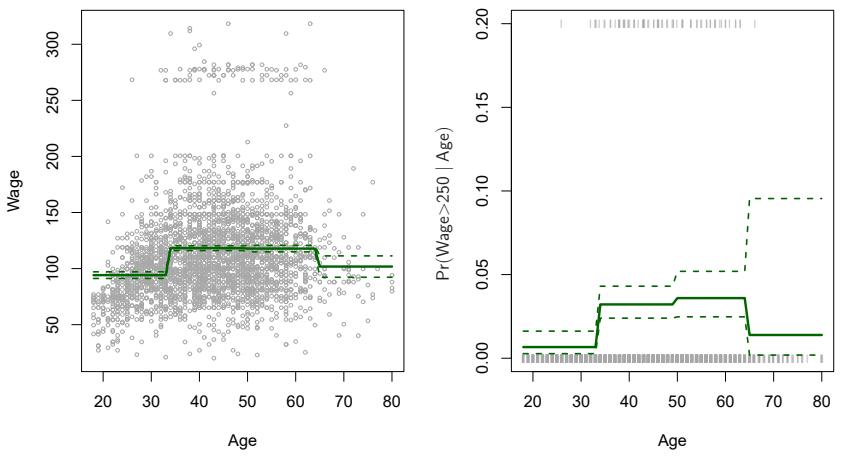

Piecewise Constant

FIGURE 7.2. The Wage data. Left: The solid curve displays the ftted value from a least squares regression of wage (in thousands of dollars) using step functions of age. The dashed curves indicate an estimated 95 % confdence interval. Right: We model the binary event wage>250 using logistic regression, again using step functions of age. The ftted posterior probability of wage exceeding $250,000 is shown, along with an estimated 95 % confdence interval.

be interpreted as the mean value of Y for X<c1. By comparison, (7.5) predicts a response of β0+βj for cj ≤ X<cj+1, so βj represents the average increase in the response for X in cj ≤ X<cj+1 relative to X<c1.

An example of ftting step functions to the Wage data from Figure 7.1 is shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 7.2. We also ft the logistic regression model

\[\Pr(y\_i > 250 | x\_i) = \frac{\exp(\beta\_0 + \beta\_1 C\_1(x\_i) + \dots + \beta\_K C\_K(x\_i))}{1 + \exp(\beta\_0 + \beta\_1 C\_1(x\_i) + \dots + \beta\_K C\_K(x\_i))} \tag{7.6}\]

in order to predict the probability that an individual is a high earner on the basis of age. The right-hand panel of Figure 7.2 displays the ftted posterior probabilities obtained using this approach.

Unfortunately, unless there are natural breakpoints in the predictors, piecewise-constant functions can miss the action. For example, in the lefthand panel of Figure 7.2, the frst bin clearly misses the increasing trend of wage with age. Nevertheless, step function approaches are very popular in biostatistics and epidemiology, among other disciplines. For example, 5-year age groups are often used to defne the bins.

7.3 Basis Functions

Polynomial and piecewise-constant regression models are in fact special cases of a basis function approach. The idea is to have at hand a fam- basis

function

ily of functions or transformations that can be applied to a variable X: b1(X), b2(X),…,bK(X). Instead of ftting a linear model in X, we ft the model

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 b\_1(x\_i) + \beta\_2 b\_2(x\_i) + \beta\_3 b\_3(x\_i) + \dots + \beta\_K b\_K(x\_i) + \epsilon\_i. \tag{7.7}\]

Note that the basis functions b1(·), b2(·),…,bK(·) are fxed and known. (In other words, we choose the functions ahead of time.) For polynomial regression, the basis functions are bj (xi) = xj i , and for piecewise constant functions they are bj (xi) = I(cj ≤ xi < cj+1). We can think of (7.7) as a standard linear model with predictors b1(xi), b2(xi),…,bK(xi). Hence, we can use least squares to estimate the unknown regression coefcients in (7.7). Importantly, this means that all of the inference tools for linear models that are discussed in Chapter 3, such as standard errors for the coefcient estimates and F-statistics for the model’s overall signifcance, are available in this setting.

Thus far we have considered the use of polynomial functions and piecewise constant functions for our basis functions; however, many alternatives are possible. For instance, we can use wavelets or Fourier series to construct basis functions. In the next section, we investigate a very common choice for a basis function: regression splines. regression

spline

7.4 Regression Splines

Now we discuss a fexible class of basis functions that extends upon the polynomial regression and piecewise constant regression approaches that we have just seen.

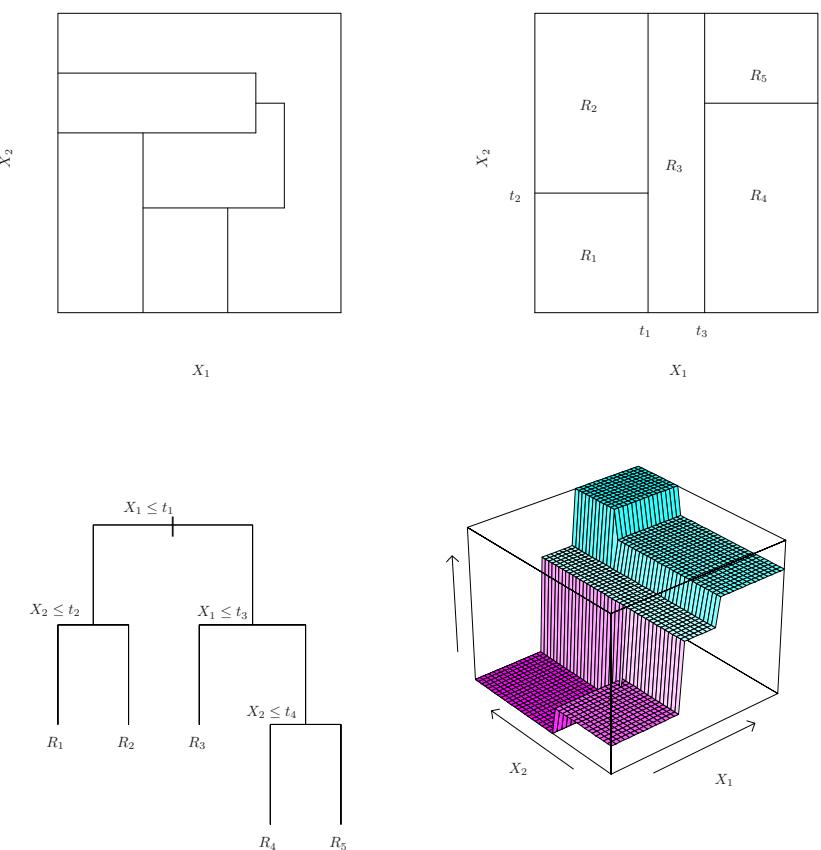

7.4.1 Piecewise Polynomials

Instead of ftting a high-degree polynomial over the entire range of X, piecewise polynomial regression involves ftting separate low-degree polynomials piecewise over diferent regions of X. For example, a piecewise cubic polynomial works by ftting a cubic regression model of the form

polynomial regression

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 x\_i + \beta\_2 x\_i^2 + \beta\_3 x\_i^3 + \epsilon\_i,\tag{7.8}\]

where the coefcients β0, β1, β2, and β3 difer in diferent parts of the range

of X. The points where the coefcients change are called knots. knot For example, a piecewise cubic with no knots is just a standard cubic polynomial, as in (7.1) with d = 3. A piecewise cubic polynomial with a single knot at a point c takes the form

\[y\_i = \begin{cases} \beta\_{01} + \beta\_{11}x\_i + \beta\_{21}x\_i^2 + \beta\_{31}x\_i^3 + \epsilon\_i & \text{if } x\_i < c\\ \beta\_{02} + \beta\_{12}x\_i + \beta\_{22}x\_i^2 + \beta\_{32}x\_i^3 + \epsilon\_i & \text{if } x\_i \ge c. \end{cases}\]

In other words, we ft two diferent polynomial functions to the data, one on the subset of the observations with xi < c, and one on the subset of the observations with xi ≥ c. The frst polynomial function has coefcients

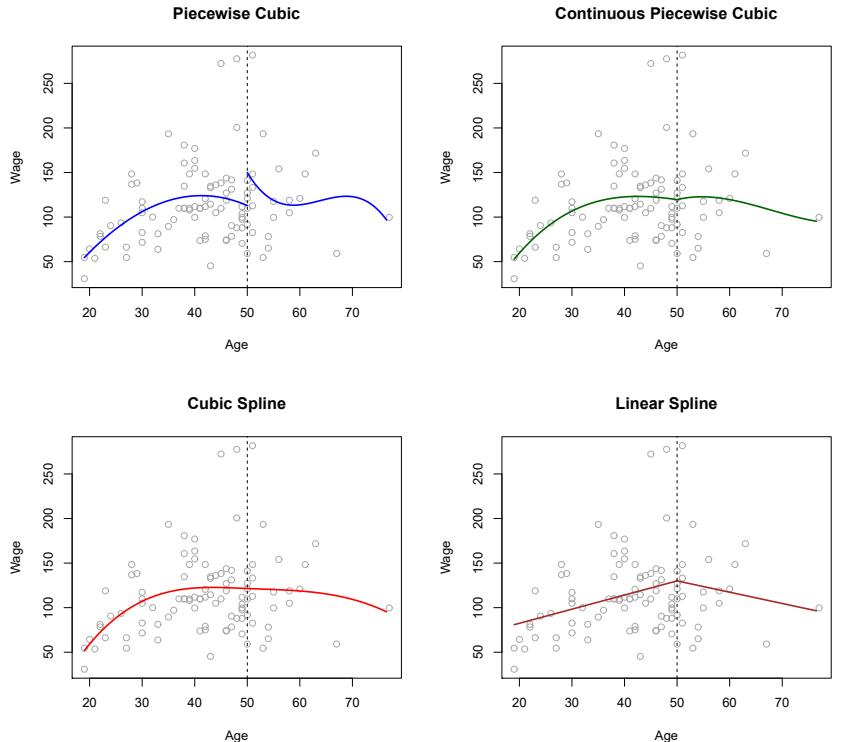

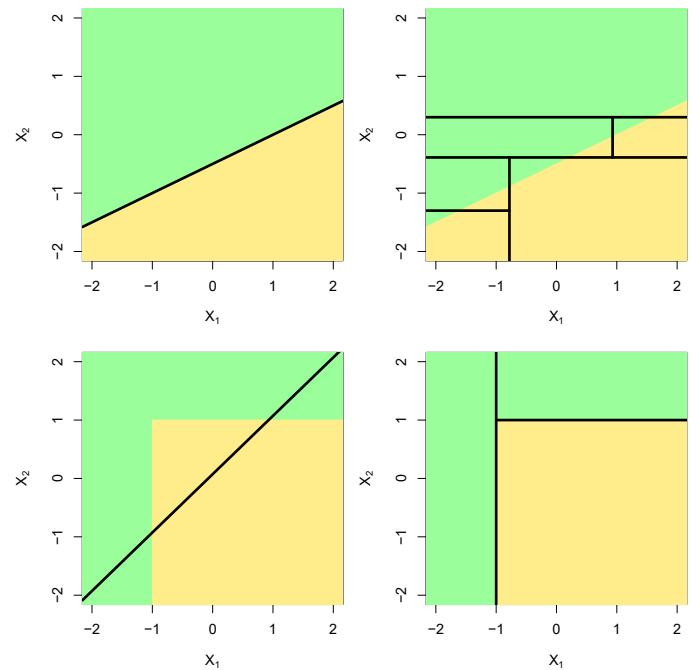

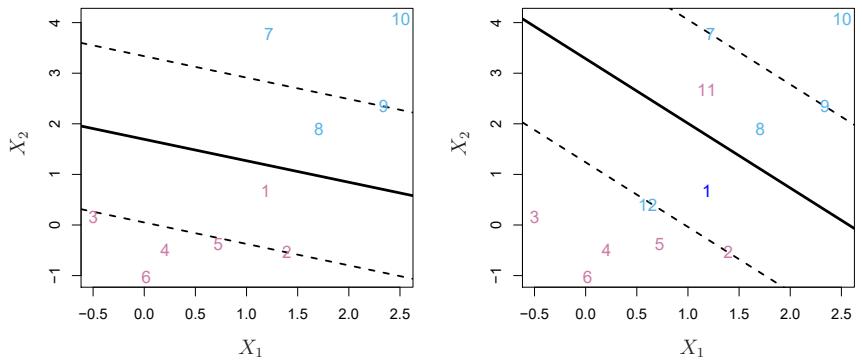

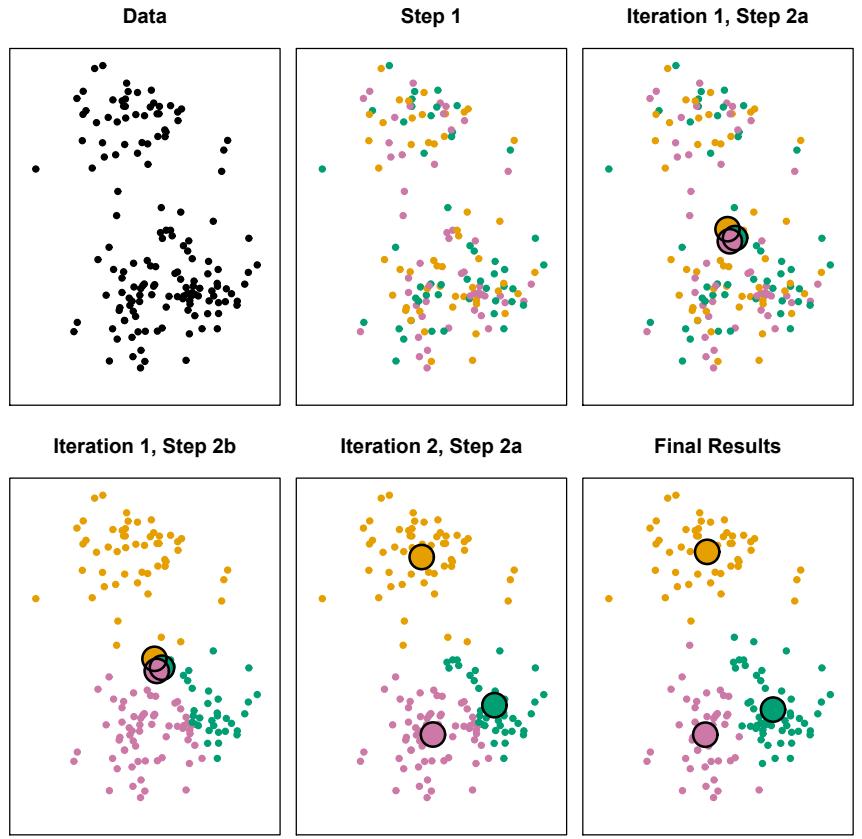

FIGURE 7.3. Various piecewise polynomials are ft to a subset of the Wage data, with a knot at age=50. Top Left: The cubic polynomials are unconstrained. Top Right: The cubic polynomials are constrained to be continuous at age=50. Bottom Left: The cubic polynomials are constrained to be continuous, and to have continuous frst and second derivatives. Bottom Right: A linear spline is shown, which is constrained to be continuous.

β01, β11, β21, and β31, and the second has coefcients β02, β12, β22, and β32. Each of these polynomial functions can be ft using least squares applied to simple functions of the original predictor.

Using more knots leads to a more fexible piecewise polynomial. In general, if we place K diferent knots throughout the range of X, then we will end up ftting K + 1 diferent cubic polynomials. Note that we do not need to use a cubic polynomial. For example, we can instead ft piecewise linear functions. In fact, our piecewise constant functions of Section 7.2 are piecewise polynomials of degree 0!

The top left panel of Figure 7.3 shows a piecewise cubic polynomial ft to a subset of the Wage data, with a single knot at age=50. We immediately see a problem: the function is discontinuous and looks ridiculous! Since each polynomial has four parameters, we are using a total of eight degrees of freedom in ftting this piecewise polynomial model. degrees of

freedom

7.4.2 Constraints and Splines

The top left panel of Figure 7.3 looks wrong because the ftted curve is just too fexible. To remedy this problem, we can ft a piecewise polynomial under the constraint that the ftted curve must be continuous. In other words, there cannot be a jump when age=50. The top right plot in Figure 7.3 shows the resulting ft. This looks better than the top left plot, but the Vshaped join looks unnatural.

In the lower left plot, we have added two additional constraints: now both the frst and second derivatives of the piecewise polynomials are continuous derivative at age=50. In other words, we are requiring that the piecewise polynomial be not only continuous when age=50, but also very smooth. Each constraint that we impose on the piecewise cubic polynomials efectively frees up one degree of freedom, by reducing the complexity of the resulting piecewise polynomial ft. So in the top left plot, we are using eight degrees of freedom, but in the bottom left plot we imposed three constraints (continuity, continuity of the frst derivative, and continuity of the second derivative) and so are left with fve degrees of freedom. The curve in the bottom left plot is called a cubic spline. 3 In general, a cubic spline with K knots uses cubic spline a total of 4 + K degrees of freedom.

In Figure 7.3, the lower right plot is a linear spline, which is continuous linear spline at age=50. The general defnition of a degree-d spline is that it is a piecewise degree-d polynomial, with continuity in derivatives up to degree d − 1 at each knot. Therefore, a linear spline is obtained by ftting a line in each region of the predictor space defned by the knots, requiring continuity at each knot.

In Figure 7.3, there is a single knot at age=50. Of course, we could add more knots, and impose continuity at each.

7.4.3 The Spline Basis Representation

The regression splines that we just saw in the previous section may have seemed somewhat complex: how can we ft a piecewise degree-d polynomial under the constraint that it (and possibly its frst d − 1 derivatives) be continuous? It turns out that we can use the basis model (7.7) to represent a regression spline. A cubic spline with K knots can be modeled as

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 b\_1(x\_i) + \beta\_2 b\_2(x\_i) + \dots + \beta\_{K+3} b\_{K+3}(x\_i) + \epsilon\_i,\tag{7.9}\]

for an appropriate choice of basis functions b1, b2,…,bK+3. The model (7.9) can then be ft using least squares.

Just as there were several ways to represent polynomials, there are also many equivalent ways to represent cubic splines using diferent choices of basis functions in (7.9). The most direct way to represent a cubic spline using (7.9) is to start of with a basis for a cubic polynomial—namely, x, x2, and x3—and then add one truncated power basis function per knot. truncated

power basis

3Cubic splines are popular because most human eyes cannot detect the discontinuity at the knots.

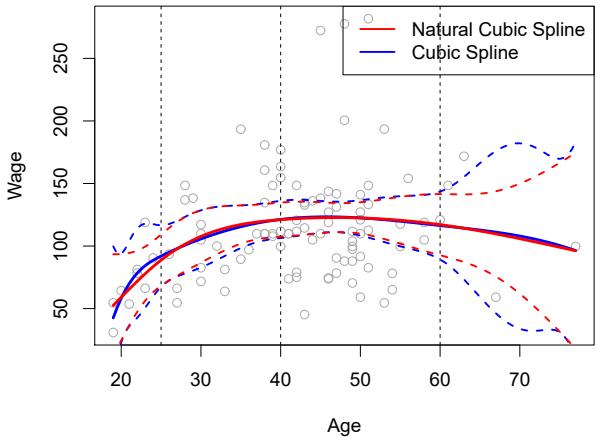

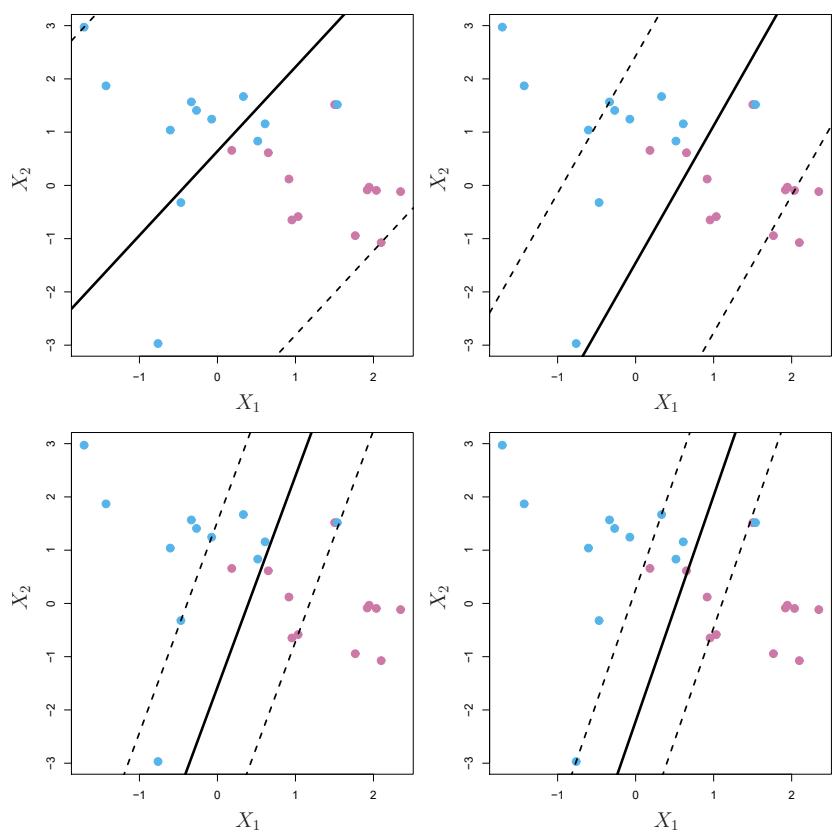

FIGURE 7.4. A cubic spline and a natural cubic spline, with three knots, ft to a subset of the Wage data. The dashed lines denote the knot locations.

A truncated power basis function is defned as

\[h(x,\xi) = (x-\xi)\_+^3 = \begin{cases} \ (x-\xi)^3 & \text{if } x > \xi \\ & 0 \quad \text{otherwise}, \end{cases} \tag{7.10}\]

where ξ is the knot. One can show that adding a term of the form β4h(x, ξ) to the model (7.8) for a cubic polynomial will lead to a discontinuity in only the third derivative at ξ; the function will remain continuous, with continuous frst and second derivatives, at each of the knots.

In other words, in order to ft a cubic spline to a data set with K knots, we perform least squares regression with an intercept and 3 + K predictors, of the form X, X2, X3, h(X, ξ1), h(X, ξ2),…,h(X, ξK), where ξ1,…, ξK are the knots. This amounts to estimating a total of K + 4 regression coefcients; for this reason, ftting a cubic spline with K knots uses K+4 degrees of freedom.

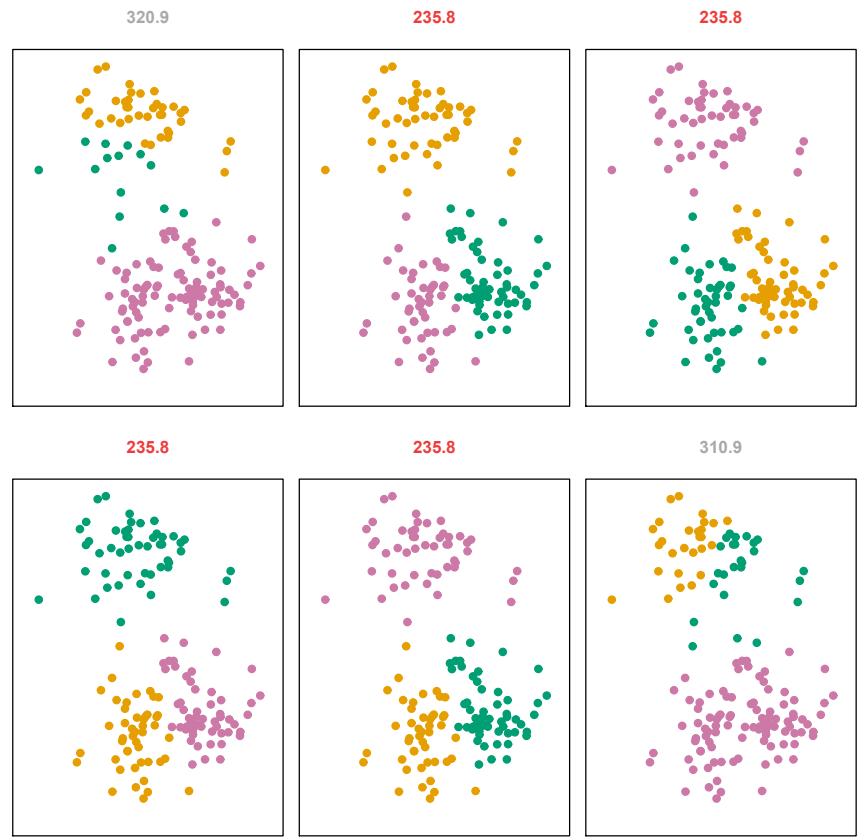

Unfortunately, splines can have high variance at the outer range of the predictors—that is, when X takes on either a very small or very large value. Figure 7.4 shows a ft to the Wage data with three knots. We see that the confdence bands in the boundary region appear fairly wild. A natural spline is a regression spline with additional boundary constraints: the natural spline function is required to be linear at the boundary (in the region where X is smaller than the smallest knot, or larger than the largest knot). This additional constraint means that natural splines generally produce more stable estimates at the boundaries. In Figure 7.4, a natural cubic spline is also displayed as a red line. Note that the corresponding confdence intervals are narrower.

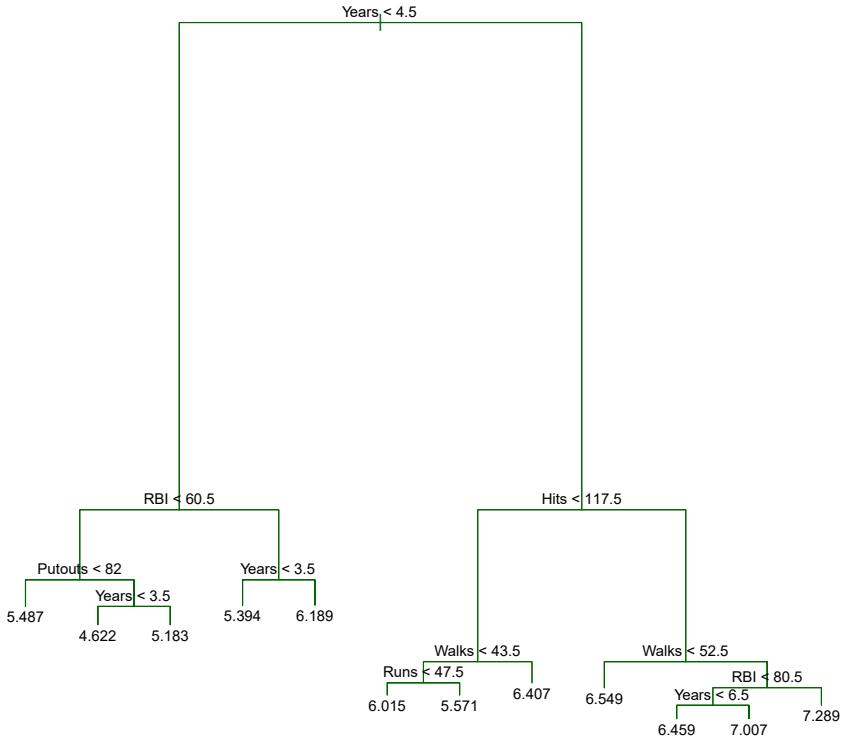

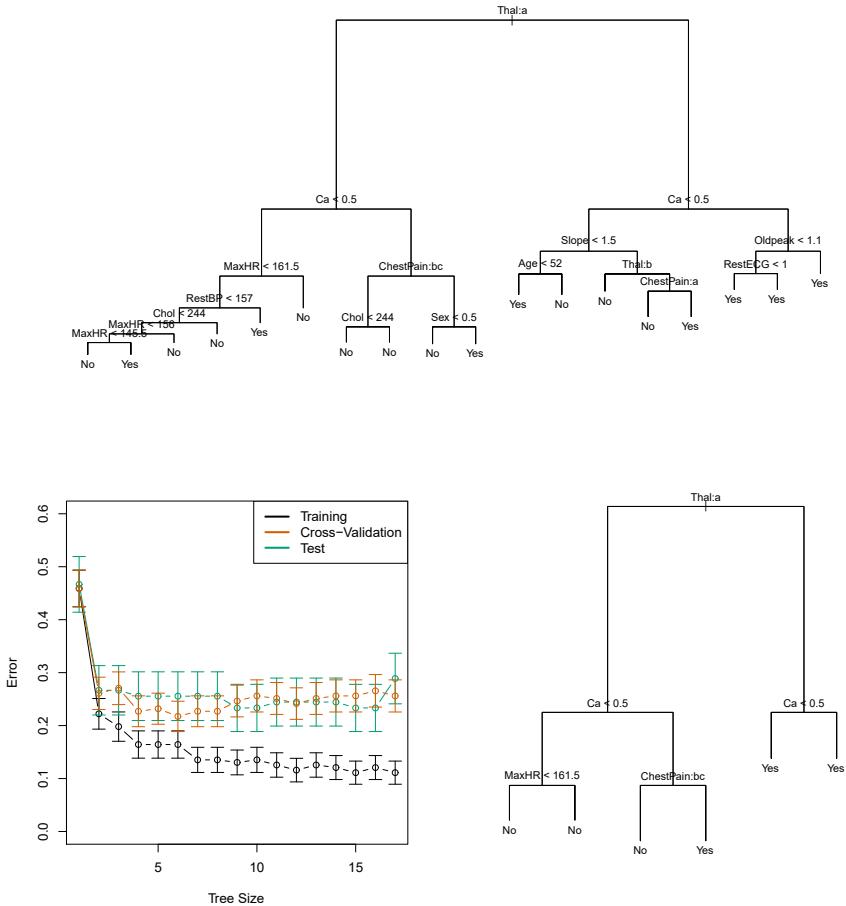

7.4.4 Choosing the Number and Locations of the Knots

When we ft a spline, where should we place the knots? The regression spline is most fexible in regions that contain a lot of knots, because in those regions the polynomial coefcients can change rapidly. Hence, one

Natural Cubic Spline

FIGURE 7.5. A natural cubic spline function with four degrees of freedom is ft to the Wage data. Left: A spline is ft to wage (in thousands of dollars) as a function of age. Right: Logistic regression is used to model the binary event wage>250 as a function of age. The ftted posterior probability of wage exceeding $250,000 is shown. The dashed lines denote the knot locations.

option is to place more knots in places where we feel the function might vary most rapidly, and to place fewer knots where it seems more stable. While this option can work well, in practice it is common to place knots in a uniform fashion. One way to do this is to specify the desired degrees of freedom, and then have the software automatically place the corresponding number of knots at uniform quantiles of the data.

Figure 7.5 shows an example on the Wage data. As in Figure 7.4, we have ft a natural cubic spline with three knots, except this time the knot locations were chosen automatically as the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of age. This was specifed by requesting four degrees of freedom. The argument by which four degrees of freedom leads to three interior knots is somewhat technical.4

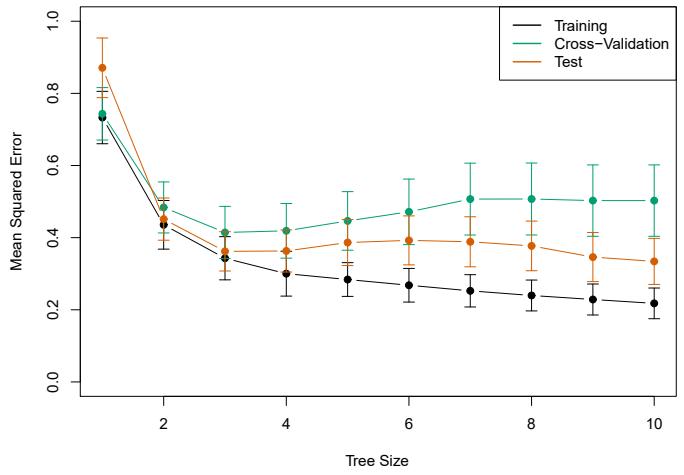

How many knots should we use, or equivalently how many degrees of freedom should our spline contain? One option is to try out diferent numbers of knots and see which produces the best looking curve. A somewhat more objective approach is to use cross-validation, as discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. With this method, we remove a portion of the data (say 10 %), ft a spline with a certain number of knots to the remaining data, and then use the spline to make predictions for the held-out portion. We repeat this process multiple times until each observation has been left out once, and

4There are actually fve knots, including the two boundary knots. A cubic spline with fve knots has nine degrees of freedom. But natural cubic splines have two additional natural constraints at each boundary to enforce linearity, resulting in 9 − 4=5 degrees of freedom. Since this includes a constant, which is absorbed in the intercept, we count it as four degrees of freedom.

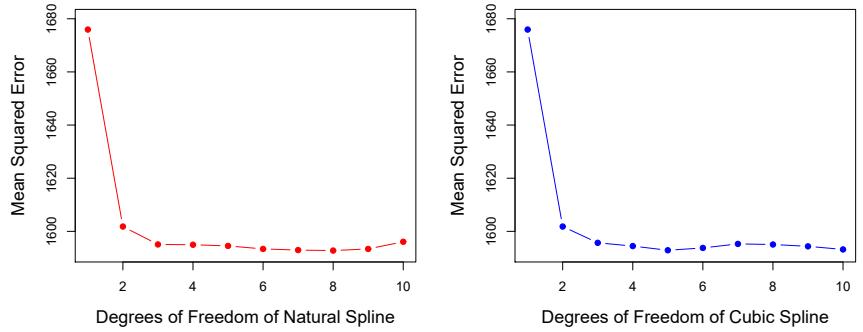

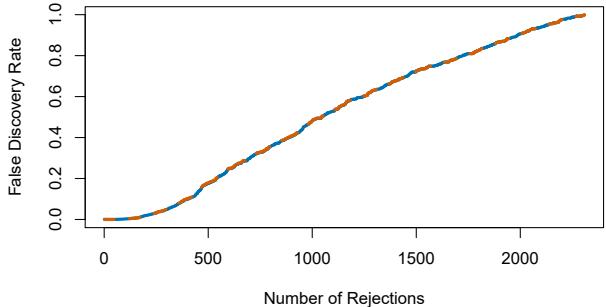

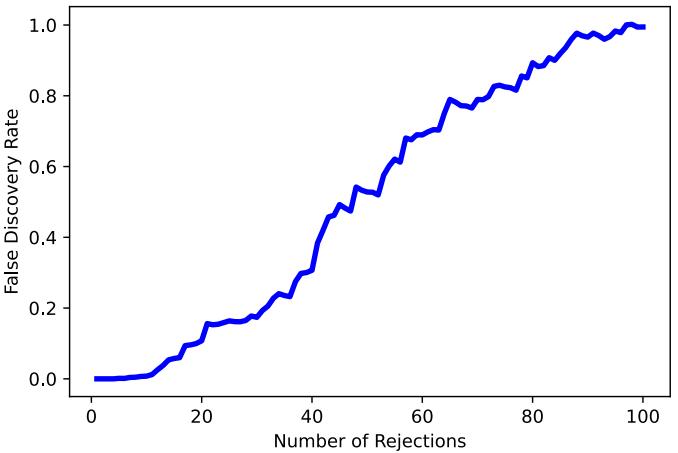

FIGURE 7.6. Ten-fold cross-validated mean squared errors for selecting the degrees of freedom when ftting splines to the Wage data. The response is wage and the predictor age. Left: A natural cubic spline. Right: A cubic spline.

then compute the overall cross-validated RSS. This procedure can be repeated for diferent numbers of knots K. Then the value of K giving the smallest RSS is chosen.

Figure 7.6 shows ten-fold cross-validated mean squared errors for splines with various degrees of freedom ft to the Wage data. The left-hand panel corresponds to a natural cubic spline and the right-hand panel to a cubic spline. The two methods produce almost identical results, with clear evidence that a one-degree ft (a linear regression) is not adequate. Both curves fatten out quickly, and it seems that three degrees of freedom for the natural spline and four degrees of freedom for the cubic spline are quite adequate.

In Section 7.7 we ft additive spline models simultaneously on several variables at a time. This could potentially require the selection of degrees of freedom for each variable. In cases like this we typically adopt a more pragmatic approach and set the degrees of freedom to a fxed number, say four, for all terms.

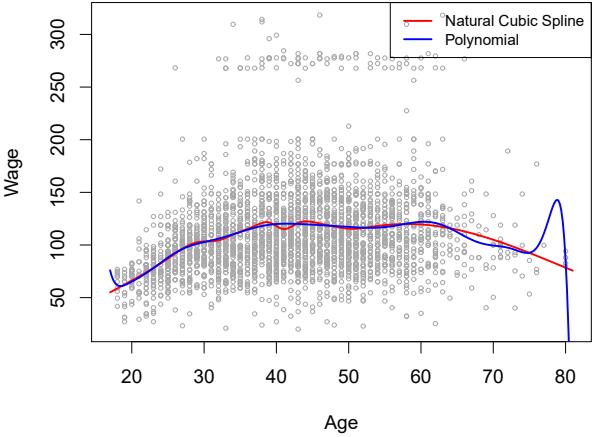

7.4.5 Comparison to Polynomial Regression

Figure 7.7 compares a natural cubic spline with 15 degrees of freedom to a degree-15 polynomial on the Wage data set. The extra fexibility in the polynomial produces undesirable results at the boundaries, while the natural cubic spline still provides a reasonable ft to the data. Regression splines often give superior results to polynomial regression. This is because unlike polynomials, which must use a high degree (exponent in the highest monomial term, e.g. X15) to produce fexible fts, splines introduce fexibility by increasing the number of knots but keeping the degree fxed. Generally, this approach produces more stable estimates. Splines also allow us to place more knots, and hence fexibility, over regions where the function f seems to be changing rapidly, and fewer knots where f appears more stable.

FIGURE 7.7. On the Wage data set, a natural cubic spline with 15 degrees of freedom is compared to a degree-15 polynomial. Polynomials can show wild behavior, especially near the tails.

7.5 Smoothing Splines

In the last section we discussed regression splines, which we create by specifying a set of knots, producing a sequence of basis functions, and then using least squares to estimate the spline coefcients. We now introduce a somewhat diferent approach that also produces a spline.

7.5.1 An Overview of Smoothing Splines

In ftting a smooth curve to a set of data, what we really want to do is fnd some function, say g(x), that fts the observed data well: that is, we want RSS = #n i=1(yi − g(xi))2 to be small. However, there is a problem with this approach. If we don’t put any constraints on g(xi), then we can always make RSS zero simply by choosing g such that it interpolates all of the yi. Such a function would woefully overft the data—it would be far too fexible. What we really want is a function g that makes RSS small, but that is also smooth.

How might we ensure that g is smooth? There are a number of ways to do this. A natural approach is to fnd the function g that minimizes

\[\sum\_{i=1}^{n} (y\_i - g(x\_i))^2 + \lambda \int g''(t)^2 dt\tag{7.11}\]

where λ is a nonnegative tuning parameter. The function g that minimizes

(7.11) is known as a smoothing spline. smoothing What does ( spline 7.11) mean? Equation 7.11 takes the “Loss+Penalty” formulation that we encounter in the context of ridge regression and the lasso in Chapter 6. The term #n i=1(yi − g(xi))2 is a loss function that encour- loss function ages g to ft the data well, and the term λ & g′′(t)2dt is a penalty term that penalizes the variability in g. The notation g′′(t) indicates the second derivative of the function g. The frst derivative g′ (t) measures the slope

of a function at t, and the second derivative corresponds to the amount by which the slope is changing. Hence, broadly speaking, the second derivative of a function is a measure of its roughness: it is large in absolute value if g(t) is very wiggly near t, and it is close to zero otherwise. (The second derivative of a straight line is zero; note that a line is perfectly smooth.) The & notation is an integral, which we can think of as a summation over the range of t. In other words, & g′′(t)2dt is simply a measure of the total change in the function g′ (t), over its entire range. If g is very smooth, then g′ (t) will be close to constant and & g′′(t)2dt will take on a small value. Conversely, if g is jumpy and variable then g′ (t) will vary signifcantly and & g′′(t)2dt will take on a large value. Therefore, in (7.11), λ & g′′(t)2dt encourages g to be smooth. The larger the value of λ, the smoother g will be.

When λ = 0, then the penalty term in (7.11) has no efect, and so the function g will be very jumpy and will exactly interpolate the training observations. When λ → ∞, g will be perfectly smooth—it will just be a straight line that passes as closely as possible to the training points. In fact, in this case, g will be the linear least squares line, since the loss function in (7.11) amounts to minimizing the residual sum of squares. For an intermediate value of λ, g will approximate the training observations but will be somewhat smooth. We see that λ controls the bias-variance trade-of of the smoothing spline.

The function g(x) that minimizes (7.11) can be shown to have some special properties: it is a piecewise cubic polynomial with knots at the unique values of x1,…,xn, and continuous frst and second derivatives at each knot. Furthermore, it is linear in the region outside of the extreme knots. In other words, the function g(x) that minimizes (7.11) is a natural cubic spline with knots at x1,…,xn! However, it is not the same natural cubic spline that one would get if one applied the basis function approach described in Section 7.4.3 with knots at x1,…,xn—rather, it is a shrunken version of such a natural cubic spline, where the value of the tuning parameter λ in (7.11) controls the level of shrinkage.

7.5.2 Choosing the Smoothing Parameter λ

We have seen that a smoothing spline is simply a natural cubic spline with knots at every unique value of xi. It might seem that a smoothing spline will have far too many degrees of freedom, since a knot at each data point allows a great deal of fexibility. But the tuning parameter λ controls the roughness of the smoothing spline, and hence the efective degrees of freedom. It is possible to show that as λ increases from 0 to ∞, the efective efective degrees of freedom, which we write dfλ, decrease from n to 2.

degrees of freedom

In the context of smoothing splines, why do we discuss efective degrees of freedom instead of degrees of freedom? Usually degrees of freedom refer to the number of free parameters, such as the number of coefcients ft in a polynomial or cubic spline. Although a smoothing spline has n parameters and hence n nominal degrees of freedom, these n parameters are heavily constrained or shrunk down. Hence dfλ is a measure of the fexibility of the smoothing spline—the higher it is, the more fexible (and the lower-bias but higher-variance) the smoothing spline. The defnition of efective degrees of freedom is somewhat technical. We can write

\[ \hat{\mathbf{g}}\_{\lambda} = \mathbf{S}\_{\lambda} \mathbf{y},\tag{7.12} \]

where gˆλ is the solution to (7.11) for a particular choice of λ—that is, it is an n-vector containing the ftted values of the smoothing spline at the training points x1,…,xn. Equation 7.12 indicates that the vector of ftted values when applying a smoothing spline to the data can be written as a n × n matrix Sλ (for which there is a formula) times the response vector y. Then the efective degrees of freedom is defned to be

\[df\_{\lambda} = \sum\_{i=1}^{n} \{ \mathbf{S}\_{\lambda} \}\_{ii},\tag{7.13}\]

the sum of the diagonal elements of the matrix Sλ.

In ftting a smoothing spline, we do not need to select the number or location of the knots—there will be a knot at each training observation, x1,…,xn. Instead, we have another problem: we need to choose the value of λ. It should come as no surprise that one possible solution to this problem is cross-validation. In other words, we can fnd the value of λ that makes the cross-validated RSS as small as possible. It turns out that the leaveone-out cross-validation error (LOOCV) can be computed very efciently for smoothing splines, with essentially the same cost as computing a single ft, using the following formula:

\[\text{RSS}\_{cv}(\lambda) = \sum\_{i=1}^{n} (y\_i - \hat{g}\_{\lambda}^{(-i)}(x\_i))^2 = \sum\_{i=1}^{n} \left[ \frac{y\_i - \hat{g}\_{\lambda}(x\_i)}{1 - \{\mathbf{S}\_{\lambda}\}\_{ii}} \right]^2 \cdot \mathbf{1}\]

The notation gˆ (−i) λ (xi) indicates the ftted value for this smoothing spline evaluated at xi, where the ft uses all of the training observations except for the ith observation (xi, yi). In contrast, gˆλ(xi) indicates the smoothing spline function ft to all of the training observations and evaluated at xi. This remarkable formula says that we can compute each of these leaveone-out fts using only gˆλ, the original ft to all of the data We have a very similar formula (5.2) on page 205 in Chapter 5 for least squares linear regression. Using (5.2), we can very quickly perform LOOCV for the regression splines discussed earlier in this chapter, as well as for least squares regression using arbitrary basis functions.

We have a very similar formula (5.2) on page 205 in Chapter 5 for least squares linear regression. Using (5.2), we can very quickly perform LOOCV for the regression splines discussed earlier in this chapter, as well as for least squares regression using arbitrary basis functions.

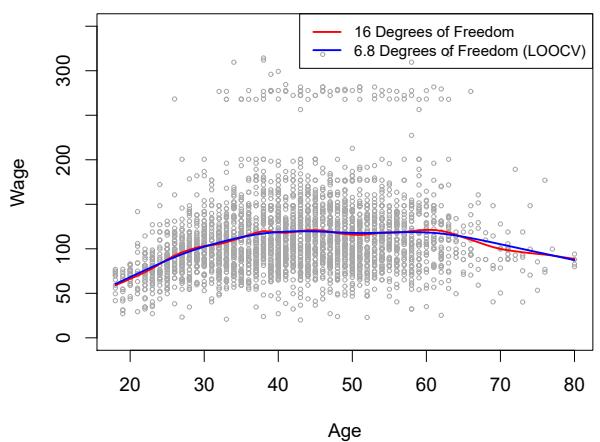

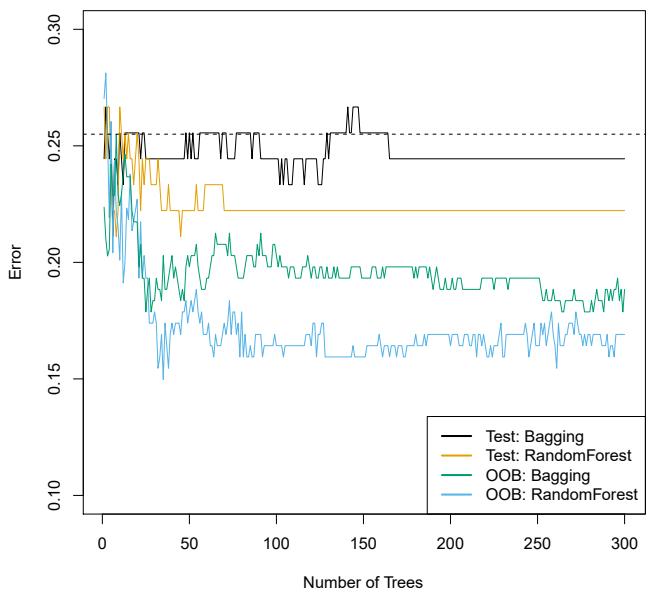

Figure 7.8 shows the results from ftting a smoothing spline to the Wage data. The red curve indicates the ft obtained from pre-specifying that we would like a smoothing spline with 16 efective degrees of freedom. The blue curve is the smoothing spline obtained when λ is chosen using LOOCV; in this case, the value of λ chosen results in 6.8 efective degrees of freedom (computed using (7.13)). For this data, there is little discernible diference between the two smoothing splines, beyond the fact that the one with 16 degrees of freedom seems slightly wigglier. Since there is little diference between the two fts, the smoothing spline ft with 6.8 degrees of freedom

5The exact formulas for computing gˆ(xi) and Sλ are very technical; however, efcient algorithms are available for computing these quantities.

Smoothing Spline

FIGURE 7.8. Smoothing spline fts to the Wage data. The red curve results from specifying 16 efective degrees of freedom. For the blue curve, λ was found automatically by leave-one-out cross-validation, which resulted in 6.8 efective degrees of freedom.

is preferable, since in general simpler models are better unless the data provides evidence in support of a more complex model.

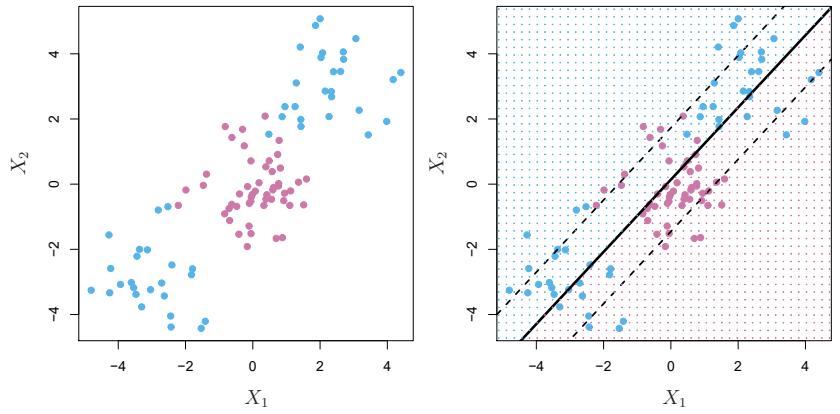

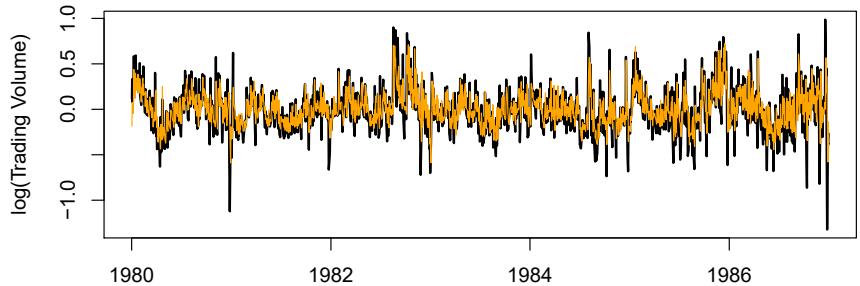

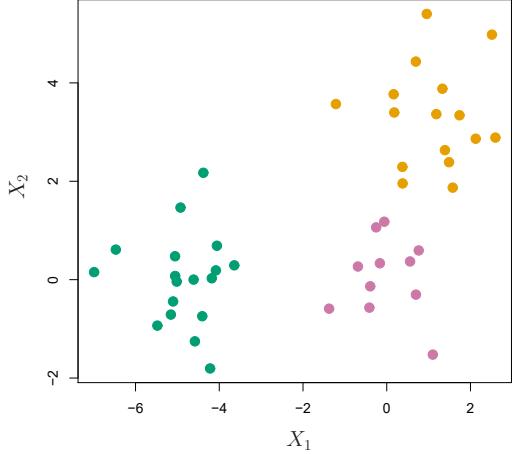

7.6 Local Regression

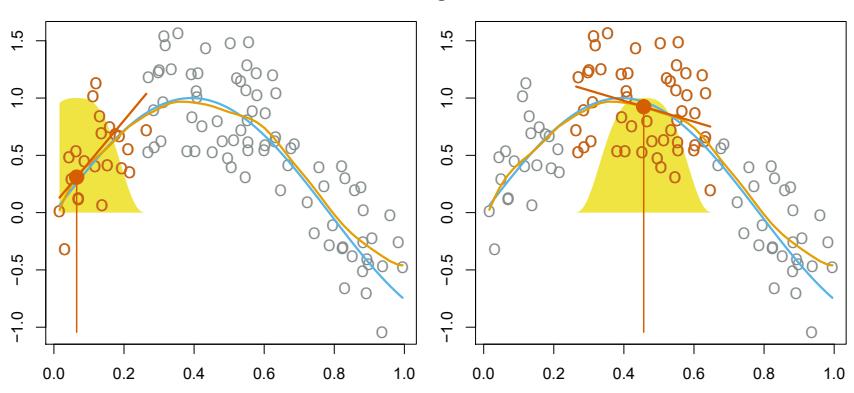

Local regression is a diferent approach for ftting fexible non-linear func- local regression tions, which involves computing the ft at a target point x0 using only the nearby training observations. Figure 7.9 illustrates the idea on some simulated data, with one target point near 0.4, and another near the boundary at 0.05. In this fgure the blue line represents the function f(x) from which the data were generated, and the light orange line corresponds to the local regression estimate ˆf(x). Local regression is described in Algorithm 7.1.

Note that in Step 3 of Algorithm 7.1, the weights Ki0 will difer for each value of x0. In other words, in order to obtain the local regression ft at a new point, we need to ft a new weighted least squares regression model by minimizing (7.14) for a new set of weights. Local regression is sometimes referred to as a memory-based procedure, because like nearest-neighbors, we need all the training data each time we wish to compute a prediction. We will avoid getting into the technical details of local regression here—there are books written on the topic.

In order to perform local regression, there are a number of choices to be made, such as how to defne the weighting function K, and whether to ft a linear, constant, or quadratic regression in Step 3. (Equation 7.14 corresponds to a linear regression.) While all of these choices make some diference, the most important choice is the span s, which is the proportion of points used to compute the local regression at x0, as defned in Step 1 above. The span plays a role like that of the tuning parameter λ in smooth-

Local Regression

FIGURE 7.9. Local regression illustrated on some simulated data, where the blue curve represents f(x) from which the data were generated, and the light orange curve corresponds to the local regression estimate ˆf(x). The orange colored points are local to the target point x0, represented by the orange vertical line. The yellow bell-shape superimposed on the plot indicates weights assigned to each point, decreasing to zero with distance from the target point. The ft ˆf(x0) at x0 is obtained by ftting a weighted linear regression (orange line segment), and using the ftted value at x0 (orange solid dot) as the estimate ˆf(x0).

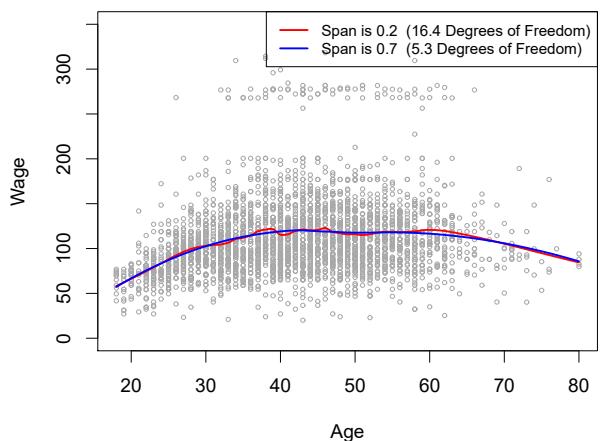

ing splines: it controls the fexibility of the non-linear ft. The smaller the value of s, the more local and wiggly will be our ft; alternatively, a very large value of s will lead to a global ft to the data using all of the training observations. We can again use cross-validation to choose s, or we can specify it directly. Figure 7.10 displays local linear regression fts on the Wage data, using two values of s: 0.7 and 0.2. As expected, the ft obtained using s = 0.7 is smoother than that obtained using s = 0.2.

The idea of local regression can be generalized in many diferent ways. In a setting with multiple features X1, X2,…,Xp, one very useful generalization involves ftting a multiple linear regression model that is global in some variables, but local in another, such as time. Such varying coefcient models are a useful way of adapting a model to the most recently gathered varying data. Local regression also generalizes very naturally when we want to ft models that are local in a pair of variables X1 and X2, rather than one. We can simply use two-dimensional neighborhoods, and ft bivariate linear regression models using the observations that are near each target point in two-dimensional space. Theoretically the same approach can be implemented in higher dimensions, using linear regressions ft to p-dimensional neighborhoods. However, local regression can perform poorly if p is much larger than about 3 or 4 because there will generally be very few training observations close to x0. Nearest-neighbors regression, discussed in Chapter 3, sufers from a similar problem in high dimensions.

coefcient model

Algorithm 7.1 Local Regression At X = x0

- Gather the fraction s = k/n of training points whose xi are closest to x0.

- Assign a weight Ki0 = K(xi, x0) to each point in this neighborhood, so that the point furthest from x0 has weight zero, and the closest has the highest weight. All but these k nearest neighbors get weight zero.

- Fit a weighted least squares regression of the yi on the xi using the aforementioned weights, by fnding βˆ0 and βˆ1 that minimize

\[\sum\_{i=1}^{n} K\_{i0} (y\_i - \beta\_0 - \beta\_1 x\_i)^2. \tag{7.14}\]

- The ftted value at x0 is given by ˆf(x0) = βˆ0 + βˆ1x0.

Local Linear Regression

FIGURE 7.10. Local linear fts to the Wage data. The span specifes the fraction of the data used to compute the ft at each target point.

7.7 Generalized Additive Models

In Sections 7.1–7.6, we present a number of approaches for fexibly predicting a response Y on the basis of a single predictor X. These approaches can be seen as extensions of simple linear regression. Here we explore the problem of fexibly predicting Y on the basis of several predictors, X1,…,Xp. This amounts to an extension of multiple linear regression.

Generalized additive models (GAMs) provide a general framework for generalized extending a standard linear model by allowing non-linear functions of each of the variables, while maintaining additivity. Just like linear models, GAMs can be applied with both quantitative and qualitative responses. We frst additivity

additive model

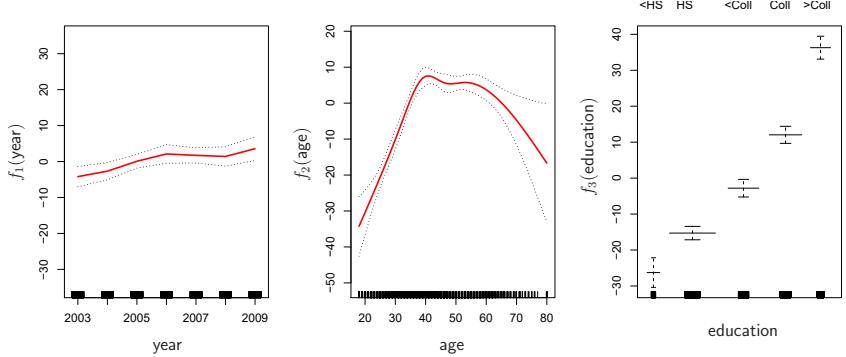

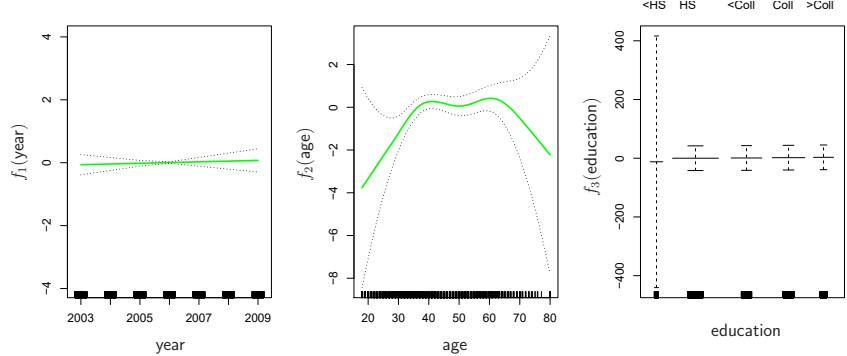

FIGURE 7.11. For the Wage data, plots of the relationship between each feature and the response, wage, in the ftted model (7.16). Each plot displays the ftted function and pointwise standard errors. The frst two functions are natural splines in year and age, with four and fve degrees of freedom, respectively. The third function is a step function, ft to the qualitative variable education.

examine GAMs for a quantitative response in Section 7.7.1, and then for a qualitative response in Section 7.7.2.

7.7.1 GAMs for Regression Problems

A natural way to extend the multiple linear regression model

\[y\_i = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 x\_{i1} + \beta\_2 x\_{i2} + \dots + \beta\_p x\_{ip} + \epsilon\_i\]

in order to allow for non-linear relationships between each feature and the response is to replace each linear component βjxij with a (smooth) nonlinear function fj (xij ). We would then write the model as

\[\begin{aligned} y\_i &= \beta\_0 + \sum\_{j=1}^p f\_j(x\_{ij}) + \epsilon\_i \\ &= \beta\_0 + f\_1(x\_{i1}) + f\_2(x\_{i2}) + \dots + f\_p(x\_{ip}) + \epsilon\_i. \end{aligned} \tag{7.15}\]

This is an example of a GAM. It is called an additive model because we calculate a separate fj for each Xj , and then add together all of their contributions.

In Sections 7.1–7.6, we discuss many methods for ftting functions to a single variable. The beauty of GAMs is that we can use these methods as building blocks for ftting an additive model. In fact, for most of the methods that we have seen so far in this chapter, this can be done fairly trivially. Take, for example, natural splines, and consider the task of ftting the model

\[\text{wage} = \beta\_0 + f\_1(\text{year}) + f\_2(\text{age}) + f\_3(\text{education}) + \epsilon \tag{7.16}\]

on the Wage data. Here year and age are quantitative variables, while the variable education is qualitative with fve levels: <HS, HS, <Coll, Coll, >Coll, referring to the amount of high school or college education that an individual has completed. We ft the frst two functions using natural splines. We

FIGURE 7.12. Details are as in Figure 7.11, but now f1 and f2 are smoothing splines with four and fve degrees of freedom, respectively.

ft the third function using a separate constant for each level, via the usual dummy variable approach of Section 3.3.1.

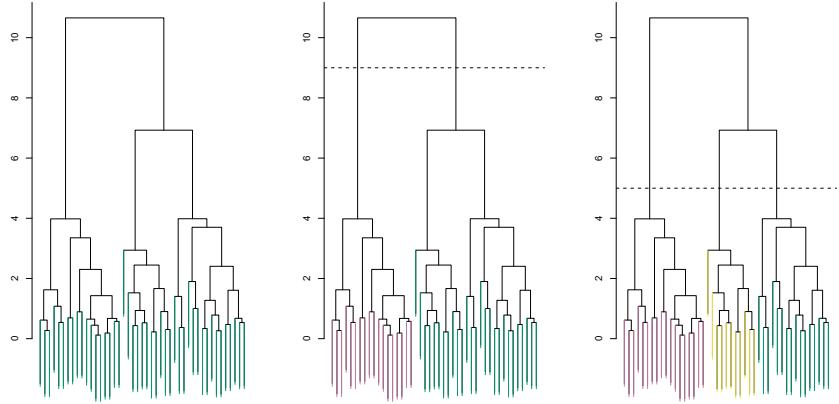

Figure 7.11 shows the results of ftting the model (7.16) using least squares. This is easy to do, since as discussed in Section 7.4, natural splines can be constructed using an appropriately chosen set of basis functions. Hence the entire model is just a big regression onto spline basis variables and dummy variables, all packed into one big regression matrix.

Figure 7.11 can be easily interpreted. The left-hand panel indicates that holding age and education fxed, wage tends to increase slightly with year; this may be due to infation. The center panel indicates that holding education and year fxed, wage tends to be highest for intermediate values of age, and lowest for the very young and very old. The right-hand panel indicates that holding year and age fxed, wage tends to increase with education: the more educated a person is, the higher their salary, on average. All of these fndings are intuitive.

Figure 7.12 shows a similar triple of plots, but this time f1 and f2 are smoothing splines with four and fve degrees of freedom, respectively. Fitting a GAM with a smoothing spline is not quite as simple as ftting a GAM with a natural spline, since in the case of smoothing splines, least squares cannot be used. However, standard software such as the Python package pygam can be used to ft GAMs using smoothing splines, via an approach pygam known as backftting. This method fts a model involving multiple predic- backftting tors by repeatedly updating the ft for each predictor in turn, holding the others fxed. The beauty of this approach is that each time we update a function, we simply apply the ftting method for that variable to a partial residual. 6

The ftted functions in Figures 7.11 and 7.12 look rather similar. In most situations, the diferences in the GAMs obtained using smoothing splines versus natural splines are small.

6A partial residual for X3, for example, has the form ri = yi −f1(xi1)−f2(xi2). If we know f1 and f2, then we can ft f3 by treating this residual as a response in a non-linear regression on X3.

We do not have to use splines as the building blocks for GAMs: we can just as well use local regression, polynomial regression, or any combination of the approaches seen earlier in this chapter in order to create a GAM. GAMs are investigated in further detail in the lab at the end of this chapter.

Pros and Cons of GAMs

Before we move on, let us summarize the advantages and limitations of a GAM.

- ▲ GAMs allow us to ft a non-linear fj to each Xj , so that we can automatically model non-linear relationships that standard linear regression will miss. This means that we do not need to manually try out many diferent transformations on each variable individually.

- ▲ The non-linear fts can potentially make more accurate predictions for the response Y .

- ▲ Because the model is additive, we can examine the efect of each Xj on Y individually while holding all of the other variables fxed.

- ▲ The smoothness of the function fj for the variable Xj can be summarized via degrees of freedom.

- ◆ The main limitation of GAMs is that the model is restricted to be additive. With many variables, important interactions can be missed. However, as with linear regression, we can manually add interaction terms to the GAM model by including additional predictors of the form Xj × Xk. In addition we can add low-dimensional interaction functions of the form fjk(Xj , Xk) into the model; such terms can be ft using two-dimensional smoothers such as local regression, or two-dimensional splines (not covered here).

For fully general models, we have to look for even more fexible approaches such as random forests and boosting, described in Chapter 8. GAMs provide a useful compromise between linear and fully nonparametric models.

7.7.2 GAMs for Classifcation Problems

GAMs can also be used in situations where Y is qualitative. For simplicity, here we assume Y takes on values 0 or 1, and let p(X) = Pr(Y = 1|X) be the conditional probability (given the predictors) that the response equals one. Recall the logistic regression model (4.6):

\[\log\left(\frac{p(X)}{1 - p(X)}\right) = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \beta\_2 X\_2 + \dots + \beta\_p X\_p. \tag{7.17}\]

The left-hand side is the log of the odds of P(Y = 1|X) versus P(Y = 0|X), which (7.17) represents as a linear function of the predictors. A natural way to extend (7.17) to allow for non-linear relationships is to use the model

\[\log\left(\frac{p(X)}{1 - p(X)}\right) = \beta\_0 + f\_1(X\_1) + f\_2(X\_2) + \dots + f\_p(X\_p). \tag{7.18}\]

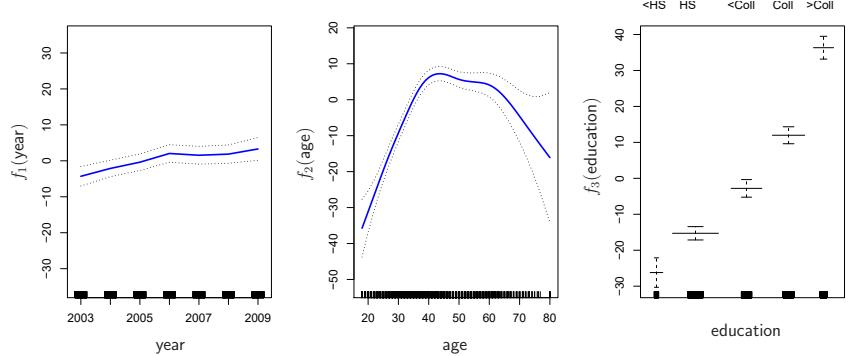

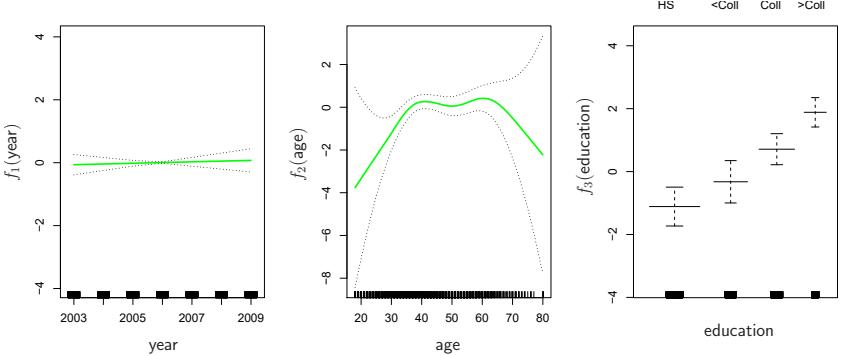

FIGURE 7.13. For the Wage data, the logistic regression GAM given in (7.19) is ft to the binary response I(wage>250). Each plot displays the ftted function and pointwise standard errors. The frst function is linear in year, the second function a smoothing spline with fve degrees of freedom in age, and the third a step function for education. There are very wide standard errors for the frst level <HS of education.

Equation 7.18 is a logistic regression GAM. It has all the same pros and cons as discussed in the previous section for quantitative responses.

We ft a GAM to the Wage data in order to predict the probability that an individual’s income exceeds $250,000 per year. The GAM that we ft takes the form

\[\log\left(\frac{p(X)}{1-p(X)}\right) = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 \times \text{year} + f\_2(\text{age}) + f\_3(\text{education}), \quad (7.19)\]

where

\[p(X) = \Pr(\text{wage} > 250 | \text{year}, \text{age}, \text{education}).\]

Once again f2 is ft using a smoothing spline with fve degrees of freedom, and f3 is ft as a step function, by creating dummy variables for each of the levels of education. The resulting ft is shown in Figure 7.13. The last panel looks suspicious, with very wide confdence intervals for level <HS. In fact, no response values equal one for that category: no individuals with less than a high school education make more than $250,000 per year. Hence we reft the GAM, excluding the individuals with less than a high school education. The resulting model is shown in Figure 7.14. As in Figures 7.11 and 7.12, all three panels have similar vertical scales. This allows us to visually assess the relative contributions of each of the variables. We observe that age and education have a much larger efect than year on the probability of being a high earner.

7.8 Lab: Non-Linear Modeling

In this lab, we demonstrate some of the nonlinear models discussed in this chapter. We use the Wage data as a running example, and show that many of the complex non-linear ftting procedures discussed can easily be implemented in Python.

FIGURE 7.14. The same model is ft as in Figure 7.13, this time excluding the observations for which education is <HS. Now we see that increased education tends to be associated with higher salaries.

As usual, we start with some of our standard imports.

In [1]: import numpy as np, pandas as pd

from matplotlib.pyplot import subplots

import statsmodels.api as sm

from ISLP import load_data

from ISLP.models import (summarize,

poly,

ModelSpec as MS)

from statsmodels.stats.anova import anova_lmWe again collect the new imports needed for this lab. Many of these are developed specifcally for the ISLP package.

In [2]: from pygam import (s as s_gam,

l as l_gam,

f as f_gam,

LinearGAM,

LogisticGAM)

from ISLP.transforms import (BSpline,

NaturalSpline)

from ISLP.models import bs, ns

from ISLP.pygam import (approx_lam,

degrees_of_freedom,

plot as plot_gam,

anova as anova_gam)7.8.1 Polynomial Regression and Step Functions

We start by demonstrating how Figure 7.1 can be reproduced. Let’s begin by loading the data.

In [3]: Wage = load_data(‘Wage’) y = Wage[‘wage’] age = Wage[‘age’]

Throughout most of this lab, our response is Wage[‘wage’], which we have stored as y above. As in Section 3.6.6, we will use the poly() function to create a model matrix that will ft a 4th degree polynomial in age.

In [4]: poly_age = MS([poly('age', degree=4)]).fit(Wage)

M = sm.OLS(y, poly_age.transform(Wage)).fit()

summarize(M)Out[4]: coef std err t P>|t|

intercept 111.7036 0.729 153.283 0.000

poly(age, degree=4)[0] 447.0679 39.915 11.201 0.000

poly(age, degree=4)[1] -478.3158 39.915 -11.983 0.000

poly(age, degree=4)[2] 125.5217 39.915 3.145 0.002

poly(age, degree=4)[3] -77.9112 39.915 -1.952 0.051This polynomial is constructed using the function poly(), which creates a special transformer Poly() (using sklearn terminology for feature transformer transformations such as PCA() seen in Section 6.5.3) which allows for easy evaluation of the polynomial at new data points. Here poly() is referred to as a helper function, and sets up the transformation; Poly() is the ac- helper tual workhorse that computes the transformation. See also the discussion of transformations on page 118.

In the code above, the frst line executes the fit() method using the dataframe Wage. This recomputes and stores as attributes any parameters needed by Poly() on the training data, and these will be used on all subsequent evaluations of the transform() method. For example, it is used on the second line, as well as in the plotting function developed below.

We now create a grid of values for age at which we want predictions.

In [5]: age_grid = np.linspace(age.min(),

age.max(),

100)

age_df = pd.DataFrame({'age': age_grid})Finally, we wish to plot the data and add the ft from the fourth-degree polynomial. As we will make several similar plots below, we frst write a function to create all the ingredients and produce the plot. Our function takes in a model specifcation (here a basis specifed by a transform), as well as a grid of age values. The function produces a ftted curve as well as 95% confdence bands. By using an argument for basis we can produce and plot the results with several diferent transforms, such as the splines we will see shortly.

In [6]: def plot_wage_fit(age_df,basis,

title):

X = basis.transform(Wage)

Xnew = basis.transform(age_df)

M = sm.OLS(y, X).fit()

preds = M.get_prediction(Xnew)

bands = preds.conf_int(alpha=0.05)

fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

ax.scatter(age,

y,facecolor='gray',

alpha=0.5)

for val, ls in zip([preds.predicted_mean ,

bands[:,0],

bands[:,1]],

['b','r--','r--']):

ax.plot(age_df.values, val, ls, linewidth=3)

ax.set_title(title, fontsize=20)

ax.set_xlabel('Age', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('Wage', fontsize=20);

return axWe include an argument alpha to ax.scatter() to add some transparency to the points. This provides a visual indication of density. Notice the use of the zip() function in the for loop above (see Section 2.3.8). We have three lines to plot, each with diferent colors and line types. Here zip() conveniently bundles these together as iterators in the loop.7

iterator We now plot the ft of the fourth-degree polynomial using this function.

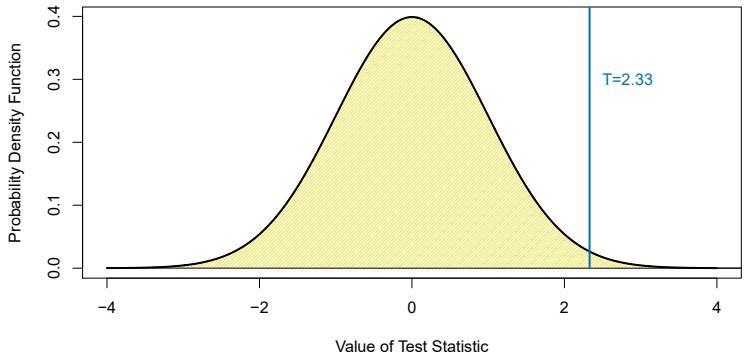

In [7]: plot_wage_fit(age_df,poly_age,

'Degree-4 Polynomial');With polynomial regression we must decide on the degree of the polynomial to use. Sometimes we just wing it, and decide to use second or third degree polynomials, simply to obtain a nonlinear ft. But we can make such a decision in a more systematic way. One way to do this is through hypothesis tests, which we demonstrate here. We now ft a series of models ranging from linear (degree-one) to degree-fve polynomials, and look to determine the simplest model that is sufcient to explain the relationship between wage and age. We use the anova_lm() function, which performs a series of ANOVA tests. An analysis of variance or ANOVA tests the null hypothesis analysis of variance that a model M1 is sufcient to explain the data against the alternative hypothesis that a more complex model M2 is required. The determination is based on an F-test. To perform the test, the models M1 and M2 must be nested: the space spanned by the predictors in M1 must be a subspace of the space spanned by the predictors in M2. In this case, we ft fve different polynomial models and sequentially compare the simpler model to the more complex model.

In [8]: models = [MS([poly('age', degree=d)])

for d in range(1, 6)]

Xs = [model.fit_transform(Wage) for model in models]

anova_lm(*[sm.OLS(y, X_).fit()

for X_ in Xs])| Out[8]: | df_resid | ssr | df_diff | ss_diff | F | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2998.0 | 5.022e+06 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| 1 | 2997.0 | 4.793e+06 | 1.0 | 228786.010 | 143.593 | 2.364e-32 | |

| 2 | 2996.0 | 4.778e+06 | 1.0 | 15755.694 | 9.889 | 1.679e-03 | |

| 3 | 2995.0 | 4.772e+06 | 1.0 | 6070.152 | 3.810 | 5.105e-02 |

7In Python speak, an “iterator” is an object with a fnite number of values, that can be iterated on, as in a loop.

4 2994.0 4.770e+06 1.0 1282.563 0.805 3.697e-01

Notice the * in the anova_lm() line above. This function takes a variable number of non-keyword arguments, in this case ftted models. When these models are provided as a list (as is done here), it must be prefxed by *.

The p-value comparing the linear models[0] to the quadratic models[1] is essentially zero, indicating that a linear ft is not sufcient.8 Similarly the p-value comparing the quadratic models[1] to the cubic models[2] is very low (0.0017), so the quadratic ft is also insufcient. The p-value comparing the cubic and degree-four polynomials, models[2] and models[3], is approximately 5%, while the degree-fve polynomial models[4] seems unnecessary because its p-value is 0.37. Hence, either a cubic or a quartic polynomial appear to provide a reasonable ft to the data, but lower- or higher-order models are not justifed.

In this case, instead of using the anova() function, we could have obtained these p-values more succinctly by exploiting the fact that poly() creates orthogonal polynomials.

In [9]: summarize(M)Out[9]: coef std err t P>|t|

intercept 111.7036 0.729 153.283 0.000

poly(age, degree=4)[0] 447.0679 39.915 11.201 0.000

poly(age, degree=4)[1] -478.3158 39.915 -11.983 0.000

poly(age, degree=4)[2] 125.5217 39.915 3.145 0.002

poly(age, degree=4)[3] -77.9112 39.915 -1.952 0.051Notice that the p-values are the same, and in fact the square of the t-statistics are equal to the F-statistics from the anova_lm() function; for example:

In [10]: (-11.983)**2

Out[10]: 143.59228

However, the ANOVA method works whether or not we used orthogonal polynomials, provided the models are nested. For example, we can use anova_lm() to compare the following three models, which all have a linear term in education and a polynomial in age of diferent degrees:

In [11]: models = [MS(['education', poly('age', degree=d)])

for d in range(1, 4)]

XEs = [model.fit_transform(Wage)

for model in models]

anova_lm(*[sm.OLS(y, X_).fit() for X_ in XEs])| Out[11]: | df_resid | ssr | df_diff | ss_diff | F | Pr(>F) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2997.0 | 3.902e+06 | 0.0 | NaN | NaN | NaN | |

| 1 | 2996.0 | 3.759e+06 | 1.0 | 142862.701 | 113.992 | 3.838e-26 | |

| 2 | 2995.0 | 3.754e+06 | 1.0 | 5926.207 | 4.729 | 2.974e-02 |

8Indexing starting at zero is confusing for the polynomial degree example, since models[1] is quadratic rather than linear!

As an alternative to using hypothesis tests and ANOVA, we could choose the polynomial degree using cross-validation, as discussed in Chapter 5.

Next we consider the task of predicting whether an individual earns more than $250,000 per year. We proceed much as before, except that frst we create the appropriate response vector, and then apply the glm() function using the binomial family in order to ft a polynomial logistic regression model.

In [12]: X = poly_age.transform(Wage)

high_earn = Wage['high_earn'] = y > 250 # shorthand

glm = sm.GLM(y > 250,

X,

family=sm.families.Binomial())

B = glm.fit()

summarize(B)Out[12]: coef std err z P>|z| intercept -4.3012 0.345 -12.457 0.000 poly(age, degree=4)[0] 71.9642 26.133 2.754 0.006 poly(age, degree=4)[1] -85.7729 35.929 -2.387 0.017 poly(age, degree=4)[2] 34.1626 19.697 1.734 0.083 poly(age, degree=4)[3] -47.4008 24.105 -1.966 0.049

Once again, we make predictions using the get_prediction() method.

In [13]: newX = poly_age.transform(age_df)

preds = B.get_prediction(newX)

bands = preds.conf_int(alpha=0.05)We now plot the estimated relationship.

In [14]: fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

rng = np.random.default_rng(0)

ax.scatter(age +

0.2 * rng.uniform(size=y.shape[0]),

np.where(high_earn, 0.198, 0.002),

fc='gray',

marker='|')

for val, ls in zip([preds.predicted_mean ,

bands[:,0],

bands[:,1]],

['b','r--','r--']):

ax.plot(age_df.values, val, ls, linewidth=3)

ax.set_title('Degree-4 Polynomial', fontsize=20)

ax.set_xlabel('Age', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylim([0,0.2])

ax.set_ylabel('P(Wage > 250)', fontsize=20);We have drawn the age values corresponding to the observations with wage values above 250 as gray marks on the top of the plot, and those with wage values below 250 are shown as gray marks on the bottom of the plot. We added a small amount of noise to jitter the age values a bit so that observations with the same age value do not cover each other up. This type

of plot is often called a rug plot. rug plot In order to ft a step function, as discussed in Section 7.2, we frst use the pd.qcut() function to discretize age based on quantiles. Then we use pd.qcut()

pd.get_dummies() to create the columns of the model matrix for this catedummies() gorical variable. Note that this function will include all columns for a given categorical, rather than the usual approach which drops one of the levels.

pd.get_

| In [15]: | cut_age = pd.qcut(age, 4) summarize(sm.OLS(y, pd.get_dummies(cut_age)).fit()) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Out[15]: | coef | std err |

t | P> t | ||||

| (17.999, 33.75] |

94.1584 | 1.478 | 63.692 | 0.0 | ||||

| (33.75, 42.0] |

116.6608 | 1.470 | 79.385 | 0.0 | ||||

| (42.0, 51.0] |

119.1887 | 1.416 | 84.147 | 0.0 | ||||

| (51.0, 80.0] |

116.5717 | 1.559 | 74.751 | 0.0 |

Here pd.qcut() automatically picked the cutpoints based on the quantiles 25%, 50% and 75%, which results in four regions. We could also have specifed our own quantiles directly instead of the argument 4. For cuts not based on quantiles we would use the pd.cut() function. The function pd.cut() pd.qcut() (and pd.cut()) returns an ordered categorical variable. The regression model then creates a set of dummy variables for use in the regression. Since age is the only variable in the model, the value $94,158.40 is the average salary for those under 33.75 years of age, and the other coefcients are the average salary for those in the other age groups. We can produce predictions and plots just as we did in the case of the polynomial ft.

7.8.2 Splines

In order to ft regression splines, we use transforms from the ISLP package. The actual spline evaluation functions are in the scipy.interpolate package; we have simply wrapped them as transforms similar to Poly() and PCA().

In Section 7.4, we saw that regression splines can be ft by constructing an appropriate matrix of basis functions. The BSpline() function generates BSpline() the entire matrix of basis functions for splines with the specifed set of knots. By default, the B-splines produced are cubic. To change the degree, use the argument degree.

In [16]: bs_ = BSpline(internal_knots=[25,40,60], intercept=True).fit(age)

bs_age = bs_.transform(age)

bs_age.shapeOut[16]: (3000, 7)

This results in a seven-column matrix, which is what is expected for a cubicspline basis with 3 interior knots. We can form this same matrix using the bs() object, which facilitates adding this to a model-matrix builder (as in poly() versus its workhorse Poly()) described in Section 7.8.1.

We now ft a cubic spline model to the Wage data.

In [17]: bs_age = MS([bs('age', internal_knots=[25,40,60])])

Xbs = bs_age.fit_transform(Wage)

M = sm.OLS(y, Xbs).fit()

summarize(M)316 7. Moving Beyond Linearity

Out[17]: coef std err ...

intercept 60.494 9.460 ...

bs(age, internal_knots=[25, 40, 60])[0] 3.980 12.538 ...

bs(age, internal_knots=[25, 40, 60])[1] 44.631 9.626 ...

bs(age, internal_knots=[25, 40, 60])[2] 62.839 10.755 ...

bs(age, internal_knots=[25, 40, 60])[3] 55.991 10.706 ...

bs(age, internal_knots=[25, 40, 60])[4] 50.688 14.402 ...

bs(age, internal_knots=[25, 40, 60])[5] 16.606 19.126 ...The column names are a little cumbersome, and have caused us to truncate the printed summary. They can be set on construction using the name argument as follows.

In [18]: bs_age = MS([bs('age',

internal_knots=[25,40,60],

name='bs(age)')])

Xbs = bs_age.fit_transform(Wage)

M = sm.OLS(y, Xbs).fit()

summarize(M)| Out[18]: | coef | std err |

t | P> t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 60.494 | 9.460 | 6.394 | 0.000 | ||

| bs(age, | knots)[0] | 3.981 | 12.538 | 0.317 | 0.751 | |

| bs(age, | knots)[1] | 44.631 | 9.626 | 4.636 | 0.000 | |

| bs(age, | knots)[2] | 62.839 | 10.755 | 5.843 | 0.000 | |

| bs(age, | knots)[3] | 55.991 | 10.706 | 5.230 | 0.000 | |

| bs(age, | knots)[4] | 50.688 | 14.402 | 3.520 | 0.000 | |

| bs(age, | knots)[5] | 16.606 | 19.126 | 0.868 | 0.385 | |

Notice that there are 6 spline coefcients rather than 7. This is because, by default, bs() assumes intercept=False, since we typically have an overall intercept in the model. So it generates the spline basis with the given knots, and then discards one of the basis functions to account for the intercept.

We could also use the df (degrees of freedom) option to specify the complexity of the spline. We see above that with 3 knots, the spline basis has 6 columns or degrees of freedom. When we specify df=6 rather than the actual knots, bs() will produce a spline with 3 knots chosen at uniform quantiles of the training data. We can see these chosen knots most easily using Bspline() directly:

In [19]: BSpline(df=6).fit(age).internal_knots_Out[19]: array([33.75, 42.0, 51.0])When asking for six degrees of freedom, the transform chooses knots at ages 33.75, 42.0, and 51.0, which correspond to the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles of age.

When using B-splines we need not limit ourselves to cubic polynomials (i.e. degree=3). For instance, using degree=0 results in piecewise constant functions, as in our example with pd.qcut() above.

In [20]: bs_age0 = MS([bs(‘age’,

df=3,

degree=0)]).fit(Wage)

Xbs0 = bs_age0.transform(Wage)

summarize(sm.OLS(y, Xbs0).fit())| Out[20]: | coef | std err |

t | P> t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 94.158 | 1.478 | 63.687 | 0.0 | |||

| bs(age, | df=3, | degree=0)[0] | 22.349 | 2.152 | 10.388 | 0.0 | |

| bs(age, | df=3, | degree=0)[1] | 24.808 | 2.044 | 12.137 | 0.0 | |

| bs(age, | df=3, | degree=0)[2] | 22.781 | 2.087 | 10.917 | 0.0 |

This ft should be compared with cell [15] where we use qcut() to create four bins by cutting at the 25%, 50% and 75% quantiles of age. Since we specifed df=3 for degree-zero splines here, there will also be knots at the same three quantiles. Although the coefcients appear diferent, we see that this is a result of the diferent coding. For example, the frst coefcient is identical in both cases, and is the mean response in the frst bin. For the second coefcient, we have 94.158 + 22.349 = 116.507 ≈ 116.611, the latter being the mean in the second bin in cell [15]. Here the intercept is coded by a column of ones, so the second, third and fourth coefcients are increments for those bins. Why is the sum not exactly the same? It turns out that the qcut() uses ≤, while bs() uses < when deciding bin membership.

In order to ft a natural spline, we use the NaturalSpline() transform Natural with the corresponding helper Spline() ns(). Here we ft a natural spline with fve degrees of freedom (excluding the intercept) and plot the results.

In [21]: ns_age = MS([ns('age', df=5)]).fit(Wage)

M_ns = sm.OLS(y, ns_age.transform(Wage)).fit()

summarize(M_ns)| Out[21]: | coef | std err |

t | P> t | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 60.475 | 4.708 | 12.844 | 0.000 | ||

| ns(age, | df=5)[0] | 61.527 | 4.709 | 13.065 | 0.000 | |

| ns(age, | df=5)[1] | 55.691 | 5.717 | 9.741 | 0.000 | |

| ns(age, | df=5)[2] | 46.818 | 4.948 | 9.463 | 0.000 | |

| ns(age, | df=5)[3] | 83.204 | 11.918 | 6.982 | 0.000 | |

| ns(age, | df=5)[4] | 6.877 | 9.484 | 0.725 | 0.468 | |

We now plot the natural spline using our plotting function.

In [22]: plot_wage_fit(age_df,

ns_age, ‘Natural spline, df=5’);

7.8.3 Smoothing Splines and GAMs

A smoothing spline is a special case of a GAM with squared-error loss and a single feature. To ft GAMs in Python we will use the pygam package pygam which can be installed via pip install pygam. The estimator LinearGAM() LinearGAM() uses squared-error loss. The GAM is specifed by associating each column of a model matrix with a particular smoothing operation: s for smoothing spline; l for linear, and f for factor or categorical variables. The argument 0 passed to s below indicates that this smoother will apply to the frst column of a feature matrix. Below, we pass it a matrix with a single column: X_age. The argument lam is the penalty parameter λ as discussed in Section 7.5.2.

In [23]: X_age = np.asarray(age).reshape((-1,1))

gam = LinearGAM(s_gam(0, lam=0.6))

gam.fit(X_age, y)318 7. Moving Beyond Linearity

Out[23]: LinearGAM(callbacks=[Deviance(), Diffs()], fit_intercept=True,

max_iter=100, scale=None, terms=s(0) + intercept, tol=0.0001,

verbose=False)The pygam library generally expects a matrix of features so we reshape age to be a matrix (a two-dimensional array) instead of a vector (i.e. a onedimensional array). The -1 in the call to the reshape() method tells numpy to impute the size of that dimension based on the remaining entries of the shape tuple.

Let’s investigate how the ft changes with the smoothing parameter lam. The function np.logspace() is similar to np.linspace() but spaces points np.logspace() evenly on the log-scale. Below we vary lam from 10−2 to 106.

In [24]: fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

ax.scatter(age, y, facecolor='gray', alpha=0.5)

for lam in np.logspace(-2, 6, 5):

gam = LinearGAM(s_gam(0, lam=lam)).fit(X_age, y)

ax.plot(age_grid,

gam.predict(age_grid),

label='{:.1e}'.format(lam),

linewidth=3)

ax.set_xlabel('Age', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('Wage', fontsize=20);

ax.legend(title='$\lambda$');The pygam package can perform a search for an optimal smoothing parameter.

In [25]: gam_opt = gam.gridsearch(X_age, y)

ax.plot(age_grid,

gam_opt.predict(age_grid),

label='Grid search',

linewidth=4)

ax.legend()

figAlternatively, we can fx the degrees of freedom of the smoothing spline using a function included in the ISLP.pygam package. Below we fnd a value of λ that gives us roughly four degrees of freedom. We note here that these degrees of freedom include the unpenalized intercept and linear term of the smoothing spline, hence there are at least two degrees of freedom.

In [26]: age_term = gam.terms[0]

lam_4 = approx_lam(X_age, age_term, 4)

age_term.lam = lam_4

degrees_of_freedom(X_age, age_term)Out[26]: 4.000000100004728

Let’s vary the degrees of freedom in a similar plot to above. We choose the degrees of freedom as the desired degrees of freedom plus one to account for the fact that these smoothing splines always have an intercept term. Hence, a value of one for df is just a linear ft.

In [27]: fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

ax.scatter(X_age,

y,facecolor='gray',

alpha=0.3)

for df in [1,3,4,8,15]:

lam = approx_lam(X_age, age_term, df+1)

age_term.lam = lam

gam.fit(X_age, y)

ax.plot(age_grid,

gam.predict(age_grid),

label='{:d}'.format(df),

linewidth=4)

ax.set_xlabel('Age', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('Wage', fontsize=20);

ax.legend(title='Degrees of freedom');Additive Models with Several Terms

The strength of generalized additive models lies in their ability to ft multivariate regression models with more fexibility than linear models. We demonstrate two approaches: the frst in a more manual fashion using natural splines and piecewise constant functions, and the second using the pygam package and smoothing splines.

We now ft a GAM by hand to predict wage using natural spline functions of year and age, treating education as a qualitative predictor, as in (7.16). Since this is just a big linear regression model using an appropriate choice of basis functions, we can simply do this using the sm.OLS() function.

We will build the model matrix in a more manual fashion here, since we wish to access the pieces separately when constructing partial dependence plots.

In [28]: ns_age = NaturalSpline(df=4).fit(age)

ns_year = NaturalSpline(df=5).fit(Wage['year'])

Xs = [ns_age.transform(age),

ns_year.transform(Wage['year']),

pd.get_dummies(Wage['education']).values]

X_bh = np.hstack(Xs)

gam_bh = sm.OLS(y, X_bh).fit()Here the function NaturalSpline() is the workhorse supporting the ns() helper function. We chose to use all columns of the indicator matrix for the categorical variable education, making an intercept redundant. Finally, we stacked the three component matrices horizontally to form the model matrix X_bh.

We now show how to construct partial dependence plots for each of the terms in our rudimentary GAM. We can do this by hand, given grids for age and year. We simply predict with new X matrices, fxing all but one of the features at a time.

In [29]: age_grid = np.linspace(age.min(),

age.max(),

100)

X_age_bh = X_bh.copy()[:100]

X_age_bh[:] = X_bh[:].mean(0)[None,:]

X_age_bh[:,:4] = ns_age.transform(age_grid)

preds = gam_bh.get_prediction(X_age_bh)

bounds_age = preds.conf_int(alpha=0.05)320 7. Moving Beyond Linearity

partial_age = preds.predicted_mean

center = partial_age.mean()

partial_age -= center

bounds_age -= center

fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

ax.plot(age_grid, partial_age, 'b', linewidth=3)

ax.plot(age_grid, bounds_age[:,0], 'r--', linewidth=3)

ax.plot(age_grid, bounds_age[:,1], 'r--', linewidth=3)

ax.set_xlabel('Age')

ax.set_ylabel('Effect on wage')

ax.set_title('Partial dependence of age on wage', fontsize=20);Let’s explain in some detail what we did above. The idea is to create a new prediction matrix, where all but the columns belonging to age are constant (and set to their training-data means). The four columns for age are flled in with the natural spline basis evaluated at the 100 values in age_grid.

- We made a grid of length 100 in age, and created a matrix X_age_bh with 100 rows and the same number of columns as X_bh.

- We replaced every row of this matrix with the column means of the original.

- We then replace just the frst four columns representing age with the natural spline basis computed at the values in age_grid.

The remaining steps should by now be familiar.

We also look at the efect of year on wage; the process is the same.

In [30]: year_grid = np.linspace(2003, 2009, 100)year_grid = np.linspace(Wage['year'].min(),

Wage['year'].max(),

100)

X_year_bh = X_bh.copy()[:100]

X_year_bh[:] = X_bh[:].mean(0)[None,:]

X_year_bh[:,4:9] = ns_year.transform(year_grid)

preds = gam_bh.get_prediction(X_year_bh)

bounds_year = preds.conf_int(alpha=0.05)

partial_year = preds.predicted_mean

center = partial_year.mean()

partial_year -= center

bounds_year -= center

fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

ax.plot(year_grid, partial_year , 'b', linewidth=3)

ax.plot(year_grid, bounds_year[:,0], 'r--', linewidth=3)

ax.plot(year_grid, bounds_year[:,1], 'r--', linewidth=3)

ax.set_xlabel('Year')

ax.set_ylabel('Effect on wage')

ax.set_title('Partial dependence of year on wage', fontsize=20);We now ft the model (7.16) using smoothing splines rather than natural splines. All of the terms in (7.16) are ft simultaneously, taking each other into account to explain the response. The pygam package only works with matrices, so we must convert the categorical series education to its array representation, which can be found with the cat.codes attribute of education. As year only has 7 unique values, we use only seven basis functions for it.

In [31]: gam_full = LinearGAM(s_gam(0) +

s_gam(1, n_splines=7) +

f_gam(2, lam=0))

Xgam = np.column_stack([age,

Wage['year'],

Wage['education'].cat.codes])

gam_full = gam_full.fit(Xgam, y)The two s_gam() terms result in smoothing spline fts, and use a default value for λ (lam=0.6), which is somewhat arbitrary. For the categorical term education, specifed using a f_gam() term, we specify lam=0 to avoid any shrinkage. We produce the partial dependence plot in age to see the efect of these choices.

The values for the plot are generated by the pygam package. We provide a plot_gam() function for partial-dependence plots in ISLP.pygam, which plot_gam() makes this job easier than in our last example with natural splines.

In [32]: fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

plot_gam(gam_full, 0, ax=ax)

ax.set_xlabel('Age')

ax.set_ylabel('Effect on wage')

ax.set_title('Partial dependence of age on wage - default lam=0.6',

fontsize=20);We see that the function is somewhat wiggly. It is more natural to specify the df than a value for lam. We reft a GAM using four degrees of freedom each for age and year. Recall that the addition of one below takes into account the intercept of the smoothing spline.

In [33]: age_term = gam_full.terms[0]

age_term.lam = approx_lam(Xgam, age_term, df=4+1)

year_term = gam_full.terms[1]

year_term.lam = approx_lam(Xgam, year_term, df=4+1)

gam_full = gam_full.fit(Xgam, y)Note that updating age_term.lam above updates it in gam_full.terms[0] as well! Likewise for year_term.lam.

Repeating the plot for age, we see that it is much smoother. We also produce the plot for year.

In [34]: fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8,8))

plot_gam(gam_full,

1,

ax=ax)

ax.set_xlabel('Year')

ax.set_ylabel('Effect on wage')

ax.set_title('Partial dependence of year on wage', fontsize=20)Finally we plot education, which is categorical. The partial dependence plot is diferent, and more suitable for the set of ftted constants for each level of this variable.

In [35]: fig, ax = subplots(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plot_gam(gam_full, 2)

ax.set_xlabel('Education')

ax.set_ylabel('Effect on wage')322 7. Moving Beyond Linearity

ax.set_title('Partial dependence of wage on education',

fontsize=20);

ax.set_xticklabels(Wage['education'].cat.categories, fontsize=8);ANOVA Tests for Additive Models

In all of our models, the function of year looks rather linear. We can perform a series of ANOVA tests in order to determine which of these three models is best: a GAM that excludes year (M1), a GAM that uses a linear function of year (M2), or a GAM that uses a spline function of year (M3).

In [36]: gam_0 = LinearGAM(age_term + f_gam(2, lam=0))

gam_0.fit(Xgam, y)

gam_linear = LinearGAM(age_term +

l_gam(1, lam=0) +

f_gam(2, lam=0))

gam_linear.fit(Xgam, y)Out[36]: LinearGAM(callbacks=[Deviance(), Diffs()], fit_intercept=True,

max_iter=100, scale=None, terms=s(0) + l(1) + f(2) + intercept,

tol=0.0001, verbose=False)Notice our use of age_term in the expressions above. We do this because earlier we set the value for lam in this term to achieve four degrees of freedom.

To directly assess the efect of year we run an ANOVA on the three models ft above.

In [37]: anova_gam(gam_0, gam_linear, gam_full)Out[37]:

| deviance | df | deviance_diff | df_diff | F | pvalue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3714362.366 | 2991.004 | NaN | NaN | NaN | NaN |

| 1 | 3696745.823 | 2990.005 | 17616.543 | 0.999 | 14.265 | 0.002 |

| 2 | 3693142.930 | 2987.007 | 3602.894 | 2.998 | 0.972 | 0.436 |