Panpsychic Organicism: Sewall Wright’s Philosophy for Understanding Complex Genetic Systems

Panpsychic Organicism: Sewall Wright’s Philosophy for Understanding Complex Genetic Systems

DAVID M. STEFFES,

Department of the History of Science Physical Sciences, Room 628 The University of Oklahoma Norman, OK, 73019-0315 USA

E-mail: david.m.steffes-1@ou.edu

Abstract. Sewall Wright first encountered the complex systems characteristic of gene combinations while a graduate student at Harvard’s Bussey Institute from 1912 to 1915. In Mendelian breeding experiments, Wright observed a hierarchical dependence of the organism’s phenotype on dynamic networks of genetic interaction and organization. An animal’s physical traits, and thus its autonomy from surrounding environmental constraints, depended greatly on how genes behaved in certain combinations. Wright recognized that while genes are the material determinants of the animal phenotype, operating with great regularity, the special nature of genetic systems contributes to the animal phenotype a degree of spontaneity and novelty, creating unpredictable trait variations by virtue of gene interactions. As a result of his experimentation, as well as his keen interest in the philosophical literature of his day, Wright was inspired to see genetic systems as conscious, living organisms in their own right. Moreover, he decided that since genetic systems maintain ordered stability and cause unpredictable novelty in their organic wholes (the animal phenotype), it would be necessary for biologists to integrate techniques for studying causally ordered phenomena (experimental method) and chance phenomena (correlation method). From 1914 to 1921 Wright developed his ‘’method of path coefficient’’ (or ‘’path analysis’’), a new procedure drawing from both laboratory experimentation and statistical correlation in order to analyze the relative influence of specific genetic interactions on phenotype variation. In this paper I aim to show how Wright’s philosophy for understanding complex genetic systems (panpsychic organicism) logically motivated his 1914–1921 design of path analysis.

Keywords: Benjamin Moore, biometry, Bussey Institute, Henri Bergson, Karl Pearson, mathematical biology, organicism, panpyschism, path analysis, philosophy of biology, population genetics, Sewall Wright, William Castle

Introduction

Pioneering geneticist Sewall Wright (1889–1988) founded his scientific career on the special nature of complex gene systems. In order to understand these networks of interaction Wright designed his statistical technique of ‘’path analysis’’ during the 1910s, and developed his own model of organic population flux during the 1920s (which became crucial for his ‘’shifting-balance’’ theory of evolution).1 Historians of 20th century life science group these accomplishments, part statistical and part biological, under the rubric of ‘’theoretical population genetics,’’ and credit Wright as one of its founders. Yet much of the prevailing scholarship on Wright is confined specifically to the role which his population genetics served in paving the way for modern biology’s ‘’evolutionary synthesis.’’2 Few historians have examined the reasons a lab geneticist such as Wright might have had for integrating statistical and experimental biology in the 1910s.

William Provine, Wright’s biographer and seminal scholar on the origin of population genetics, laid the foundation for understanding Wright’s statistical achievement.3 Provine detailed how, after witnessing complications in Mendelian breeding experiments at Harvard, Wright recognized the existence of genetic systems and began researching their influence on animal phenotypes. According to Provine this research, accompanied by Wright’s natural ability in mathematics, culminated in the derivation of path analysis in the mid to late 1910s.4 However,

1 Wright published three articles with his refined conception of path analysis during his tenure at the USDA Animal Husbandry Division following graduate school. The first two, ‘’On the Nature of Size Factors’’ (1918) and ‘’Average Correlation Within Subgroups of a Population’‘(1917) were applications to animal breeding projects. The third, titled’‘Correlation and Causation’’ (1921), encompassed Wright’s most general treatment of the path coefficient in terms of statistical theory. Later in 1924 Wright met British biometrician R.A. Fisher and obtained a copy of Fisher’s ‘’On the Dominance Ratio’’ (1922) paper wherein Fisher discussed his statistical gene-frequency distribution model. Wright then developed his own version of the gene-frequency model based on his knowledge of genetic systems, and used it in connection with his research on Shorthorn cattle breeds to compose his ‘’shifting-balance’’ theory of evolution. He published the full exposition of his theory in his 1931 paper ‘’Evolution in Mendelian Populations,’’ graphed and restated without heavy mathematics a year later as ‘’The Roles of Mutation, Inbreeding, Crossbreeding, and Selection in Evolution’’(1932).

2 Historians of evolutionary biology have debated the level of contribution from Sewall Wright as well as population geneticists R.A. Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane to the evolutionary synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s (Mayr, 1959; Provine, 1978; Mayr and Provine, 1980; Crow, 1984; Provine, 1986; Sarkar, 1992; Smocovitis, 1996).

3 Provine, Sewall Wright and Evolutionary Biology (1986); The Origin of Theoretical Population Genetics (1971). In addition to Provine, population geneticist James F. Crow has also written several biographical articles describing Wright’s scientific contributions (1990/1992, 1982). Crow was a longtime associate and friend of Wright’s during their days at the Wisconsin Genetics Department.

4 Provine (1986, pp. 34–97).

Provine devoted only three pages of Wright’s biography to indicate that, during those same years at Harvard, Wright also adopted a new philosophical view of nature. He drew no association between Wright’s novel philosophy and Wright’s subsequent turn to statistical biology around 1914–1915.5 Provine claimed that his dismissal of philosophy as an intellectual determinant was warranted in the biography because Wright ‘’believed in a philosophical view that had no discernable effect upon his science…. Wright’s early views on philosophy therefore determined only his later views on philosophy, not his work in physiological genetics or evolutionary theory.’’6

Neglect of Wright’s philosophy has since been addressed in papers by M.J.S. Hodge (1992) and Michael Ruse (2004).7 Hodge’s comparative study of Wright and R.A. Fisher revealed that Wright’s philosophy of panpsychism did in fact influence his work in genetics and evolutionary biology. Panpsychism, the belief that nature is comprised of a hierarchy of mind-based entities, will be discussed in greater detail later. Suffice it for now to say that Hodge found a link between Wright’s panpsychism and Wright’s insistence throughout his career that natural laws are essentially ‘’statistical,’’ with nature having the capacity at all times for the spontaneous production of new patterns in form and behavior. According to Hodge, Wright’s emphasis on chance in genetics and evolutionary theory displayed his philosophical assumption that all tiers of the physico-chemical world behave freely and creatively, since they are really all composed of conscious states.8

Likewise Michael Ruse has argued more recently that Wright’s infatuation with Spencerianism (the philosophy of Herbert Spencer) impacted his 1931–1932 published model of evolution in Mendlian populations: the ‘’Shifting Balance Theory.’’ Spencerianism was a variation on the more general philosophy of organicism, which insists that the living realm of nature is structured as a hierarchy of biological wholes (or ‘’organisms’’) greater than the sum of their parts (irreducible to lower levels of organisms). Like panpsychism I will address organicism in further detail later, but it is important to note here that in

5 Provine (1986, pp. 95–97).

6 Provine (1986, p. 95). J.F. Crow’s treatment of Wright’s philosophy spans three pages of the 1990/1992 biographical article (pp. 191–193). Crow did little to connect discussion of Wright’s philosophy and science.

7 Hodge, ‘’Biology and Philosophy (Including Ideology): A Study of Fisher and Wright’’ (1992, pp. 231–93); Ruse, ‘’Adaptive Landscapes and Dynamic Equilibrium: The Spencerian Contribution to Twentieth-Century American Evolutionary Biology’’ (2004, pp. 131–150).

8 Hodge (1992, pp. 273–276).

Spencer’s version, each organism is a cohesive system of mutuallydependent parts interacting for the maintenance of the greater whole, and is therefore governed by a ‘’dynamic equilibrium.’’ According to Ruse, Sewall Wright transferred into his evolutionary genetics the Spencerian concept of ‘’dynamic equilibrium.’’ Wright asserted that interacting hereditary and environmental factors in gene populations formed a dynamic equilibrium, such that instead of atomistic populations they were ‘systems’ irreducible to either the constituent genes or the gene-bundles found in specific organisms.9

Given the scholarship by Hodge and Ruse, it now appears that Provine was wrong to conclude that Sewall Wright’s philosophy ‘’had no discernable effect upon his science.’’ On the contrary, Wright’s science and philosophy were linked through important themes like hierarchy, chance, complexity, and organic novelty. In my paper I take the thesis established by Hodge and Ruse and apply it to Provine’s over-simplified explanation of Wright’s early statistical innovation from 1914 to 1915. I argue that while experimentalism and innate mathematical ability were important for Wright’s 1914 derivation of the path coefficient method (as Provine underscored), one nevertheless has to understand Wright’s philosophical outlook at the time in order to fully appreciate Wright’s reasons for developing such a method. In Wright’s philosophy, conscious systems of activity in nature (‘living’ systems) produce both irregular and regular patterns of physical phenomena, creating spontaneous novelty along side ordered stability. To study nature’s dynamic systems and understand their simultaneous capacity for yielding stability and creativity, Wright realized in 1914 that scientists would have to integrate techniques for analyzing regular sequences (the experimental method) and irregular sequences (the correlation method). Wright’s fusing of methods from 1914 to 1921, forming ‘’path analysis,’’ was logically motivated by his view of nature.

For this article I rely on the records which Wright left behind in order to reestablish his philosophies of panpsychism and organicism (given Wright’s synthesis of the two, I call his philosophy ‘’panpsychic organicism’’). Wright’s presidential address to the American Society of Naturalists (1953), festschrift papers in honor of Charles Hartshorne

9 Ruse (2004, pp. 144–150). I gave a talk on this very subject at the 2004 annual History of Science Society Meeting in Austin, Texas, under the title ‘’Causal Connections, Nature’s Game, and Organismal Perspective.’’ I explained that for Wright, genetic populations webbed together by interacting factors were organic wholes in their own right, and worth studying as ‘’organisms’’ of different behavior (obeying different rules than traditionally understood organisms).

- and Bernard Rensch (c. 1985), and contribution to Mind in Nature (1975) all place the origin of his panpsychic organicism at Harvard from 1912 to 1914, just before his earliest statistical innovation.10 Since these papers were published late in his career, forty or more years after he claimed to have arrived at his ideas, it remains possible that Wright’s recollections were obscured over time to include inaccuracies, or that he reported inaccurately in order to achieve a certain recognition. While Wright’s testimony is not above questioning, I argue that his philosophical papers nevertheless supply a strong motive for why he initially became interested in the sort of scientific method, which he developed from 1914 to 1921. Furthermore, the credibility of Wright’s account is enhanced by the way in which his 1912–1914 genetic research and 1914–1921 statistical innovation consistently reflected his philosophical ideas. As mentioned above, his philosophy intersected with his genetic investigations on particular themes. In particular he was interested in hierarchy, complexity, and organic novelty.

Before I move on, I would like to offer general definitions for these three concepts as Wright understood them. By hierarchy, I refer to the existence of a multi-tiered nature in which each level of natural phenomena produces a set of higher level natural phenomena through its organization and behavior. The resultant phenomena of these higher levels are not governed by the rules, which govern the lower level. The higher level displays greater complexity than the lower level, yet is produced from action on that level. By complexity, I mean the existence of degrees of structural and behavioral sophistication in natural phenomena, which correspond to different hierarchical levels of nature. The sophistication of higher levels of nature is greater than that of lower levels, even though higher level orders are composed of and produced by lower levels. Finally, organic (or emergent) novelty refers to the appearance, on a particular hierarchical level, of new phenomena which result from changed activity on a hierarchical sublevel. New phenomena are said to ‘’arise from’’ or ‘’emerge out of’’ the lower level activity because no direct causal chain can be traced between a lower level entity and the new phenomena at the greater level. The new phenomena are instead due to the holistic nature of the lower level phenomena in action.

10 Wright, ‘’Psychophysical Identism,’’ (c. 1985, unpublished manuscript); ‘’Panpsychism and Science’’ (1975); ‘’Biology and the Philosophy of Science’’ (1964); ‘’Gene and Organism’’ (1953).

Nature’s Causal Connections: Wright’s Conversion from Mechanistic Determinism to Organicism

Sewall Wright was still a first year graduate student in zoology at the University of Illinois when, in the spring of 1912, he met Harvard geneticist William Ernest Castle (visiting the Illinois Agricultural College at the time). Wright had already developed a keen interest in the study of heredity from previous education at Lombard College and his summer internship at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. After hearing Castle lecture on mammalian genetics, Wright inquired into the possibility of conducting future research under Castle’s supervision at Harvard. Castle was the director of Harvard’s prestigious Bussey Institute, and he agreed to give Wright an assistantship position beginning in the fall semester of 1912.11

The Bussey Institute was exceptional because Castle advocated two brands of rigorous empiricism in Mendelian genetic research: experimental breeding and biochemical analysis. In a major ongoing project concerning mammalian coat-color and eye-color inheritance, Castle and students relied not just on the various methods of interbreeding mice, rats, rabbits, guinea pigs, and so forth, but also on the latest information from journals concerning the biochemical relationships involved in pigment production at the genotype level.12 Following Castle’s 1909 paper on the ‘’Material Basis of the Hereditary Factors,’’ the ultimate goal for students was to understand the material connection between changes at the genetic level within the animal stock and the sort of phenotype variations which they were able to observe through animal breeding.13

11 Provine (1986, pp. 26, 30–32). University of Kansas biologist J.A. Weir began an in-depth history of Harvard’s Bussey Institute, but passed away before its completion. He managed to publish a brief article on his research in Genetics (1994, v. 136, pp. 1227– 1231). Weir’s (n.d. unpublished manuscript) ‘’Genetics and Agriculture at the Bussey Institution of Harvard,’’ is now kept at the Kansas, APS, and Harvard Archives.

12 As William Provine pointed out, Castle and his students were deficient in the skills required to investigate specific genetic relationships according to gene action: ‘’Castle nor any of his students had enough background in chemistry to do original work in this field … [Harvard professor C.C.] Little said the bio-chemistry of gene action was a problem for the chemist, not the geneticist’’ (1986, pp. 91–92). Yet this fact hardly dissuaded Castle from incorporating physiological genetic research into his breeding program.

13 Castle, Studies of Inheritance in Rabbits (1909). Karen Rader has devoted particular attention to murine genetics at the Bussey Institute under Castle’s directorship, illustrating how mice as experimental subjects became the cohesive element, which united a research community (2004, 1998).

Wright invested considerable time at Harvard learning about physiological relationships while pursuing his thesis research on guinea pig coat-color and eye-color variation. He often conversed with visiting German scholar Richard Goldschmidt on the chemistry of pigmentation, as Goldschmidt’s interest in the physiology of gene mutation predisposed him for understanding Wright’s problems. Wright also read articles by American chemists Oscar Riddle and R.A. Gortner, and British chemists Huia Onslow and E.F. Armstrong, extracting information on melanin production through enzymes like tyrosinases and peroxidases. Onslow’s papers were especially useful to Wright’s understanding of recessive traits in guinea pig coat-color.14 Wright’s active interest in physiological genetics indicates that he agreed with Castle, that genes were not merely convenient mathematical abstractions but real material entities best understood in terms of causal mechanisms.

In light of this conscious emphasis in Castle’s program, it is not surprising that up to 1914 Wright adhered to a mechanist determinist philosophy of biology.15 He expected that the rules of Mendelism manifested themselves physically both at the phenotype level and the genotype level in terms of straightforward causal chains, whereby each gene matched up one-to-one with a trait, and biochemical gene effects for a particular trait accumulated to produce the phenotype variations observed in breeding experiment. Mechanistic biologists typically believed that organic wholes could be totally constructed out of their individual ‘’atomistic’’ parts, and that any changes in the organic whole are due to external agents affecting the individual parts—not internally derived from the whole.16 In the case of genetics, the organic wholes were the animal phenotype, the atomistic parts were the animal’s genes, and the ‘’external agent’’ responsible for altering the organic whole was the experimentalist himself (employing artificial selection). Such

14 Provine (1986, pp. 55–58, 91–95). Goldschmidt’s ‘visiting’ status was a side effect of the First World War. Oscar Riddle’s biochemical work was on pigeons at the University of Chicago. Ross Aiken Gortner was a biochemist at the University of Minnesota, appointed to the chair of the department in 1918. Huia Onslow’s work on melanin production in plants benefited greatly from collaboration with his wife, Muriel Wheldale Onlsow, trained in William Bateson’s laboratory at Cambridge (Canham and Canham, 2002). Edward Franklin Armstrong eventually became better known for his book on the history of chemistry (1924).

15 Wright, (c. 1985, p. 6; 1975, p. 80; 1964, p. 281). Garland Allen has shown in the case of T.H. Morgan’s experimental chromosome research at Columbia that mechanistic materialism facilitated experimental investigations into genetics during the 1910s and 1920s (1984). For a general treatment of mechanistic materialism in biology during the late 19th and early 20th century, also see Allen (1983).

16 Allen (1984, pp. 714–715).

simplicity, however, was short lived for Wright. Between roughly 1912 and 1914 Wright encountered new genetic phenomena in the labs and read of newly circulating ideas that caused him to question basic tenets of his philosophy of biology. The final stroke fell in 1914 when, after reading Karl Pearson’s The Grammar of Science, Wright saw a way of successfully harmonizing these new ideas and lab experiences through a different philosophy of biology which emphasized the importance of statistical analysis.17 What were these new experiences and ideas?

First, as an assistant to William Castle, Wright observed an experiment on the coat-color of hooded rats, which convinced him that Mendelian inheritance actually involves complex systems of genetic interaction. Over the 1912–1914 interval of the project, Wright saw that as Castle selected to isolate greater dark patches and lesser dark patches in the hooded pattern, he also unwittingly selected ulterior genetic effects. Fertility, stamina, and vigor declined while the mortality of the litters increased to the point that after a number of generations the experiment actually had to be halted because of sterility in its subjects. Wright was a proponent of the Mendelian multiple-factor model of heredity, in which numerous genes called modifiers were responsible for small variations in a given phenotypic trait. Castle’s experiment persuaded Wright that some out of the pool of genetic factors influencing coat-color in hooded rats must be interrelated with certain genetic factors influencing fertility, stamina, vigor, and mortality. He was impressed with the obvious difficulties this presented for artificial selection, which, as a mechanism applied to create phenotypic differences, was completely blind to relationships at the genotype level of the organism. This blindness to the genotype rendered artificial selection (the hand of William Castle) unable to isolate coat-color variation without indirectly selecting a tag-along variation for some other organic aspect.

The lessons of Castle’s hooded rat project carried over into Wright’s thesis research on variation in guinea pig coat-color and pattern, inspiring what Wright later said was a ‘’fascination with the frequently unpredictable effects of [gene] combinations.’’18 He realized in his

17 Wright, (c. 1985, pp. 5–8; 1975, pp. 80–82; 1964, pp. 281–283). Wright states, ‘’What really made over my thinking was reading (in 1914) Karl Pearson’s Grammar of Science…. What I derived from Pearson was a different sort of attitude toward what I then considered the absolute laws of nature. He treated them as merely condensed descriptions of how things are observed to behave, no different in kind from statistical laws…’’ (1975, p. 80).

18 Wright, ‘’The Relationship of Livestock Breeding to Theories of Evolution’’ (1978a, p. 1195).

analysis of guinea pig breeding stocks that, for example, various rosette hair patterns result from the combination of two genes which on their own would lead to completely different effects. Gene interactions were also common in hair color, exemplified by the phenomena of epistasis in albino subjects.19 In guinea pigs, the gene responsible for melanin production and the gene responsible for melanin deposit are said to be epistatic: the former gene suppresses the effect of the latter on coatcolor. If the guinea pig receives all recessive alleles for the melanin production gene then the normal effect of the melanin deposit gene (determining whether the coat is either black or brown) will be suppressed and the guinea pig will be white regardless. Furthermore, a geneticist in Wright’s position who had been observing a guinea pig population in which these two genes were present but not originally in combination would be surprised to discover, upon an opportune reshuffling of the gene combinations through breeding, that a white guinea pig could emerge from a litter of black and brown guinea pigs.

But as Wright learned from his thesis research, and from Castle’s hooded rats, the special nature of genes in combination demands that the more perceptive geneticist expect novelty in variation, expect that in the case of gene packages, there will be instances where one plus one does not equal two. By 1914, Wright’s guinea pig research was already documenting other examples of gene interaction.20 It seemed that the alleles of one gene had the power not only to suppress, but also to inhibit, modify, or complement the phenotypic expression of alleles in another gene, expanding the scope of epistasis. Moreover, the allele of a gene might have more than one effect, contributing to more than one phenotypic trait and subsequently widening the web of interrelationship as Castle’s rats had illustrated.21 Wright later recalled, ‘’From my study on gene combinations, …I recognized that an organism must never be looked upon as a mere mosaic of ’unit characters,’ each determined by a single gene, but rather as a vast network of interaction systems.’’22

During the same 1912–1914 period Wright encountered the growing philosophical literature in biology on chance and energy, reading

19 William Bateson was the first to notice the suppression of one gene’s ‘’allelomorph’’ by another gene’s ‘’allelomorph,’’ a relationship which he dubbed ‘’epistatic’’ in a 1907 issue of Science (p. 653). Anticipating Wright’s experience with guinea pigs, Bateson documented his genetic epistasis in the coat color of mice.

20 Provine (1986, pp. 83–88).

21 The genetic phenomena of two or more distinct phenotypic effects arising from the allele of one gene was later named ‘’pleiotropy’’ by C.H. Waddington in his 1939 book, Introduction to Modern Genetics (p. 162).

22 Wright (1978a, p. 1198).

Benjamin Moore’s The Nature and Origin of Life (1912) and Henri Bergson’s Creative Evolution (1911). One of Britain’s earliest biochemists, Moore followed in the line of Claude Bernard and Josiah Willard Gibbs, and anticipated Walter Cannon and L.J. Henderson by emphasizing that the ‘’living realm’’ of the universe is governed by dynamic equilibrium in energy distribution.23 He presented the physicochemical world as an assemblage of organized wholes not reducible to one material level but instead manifest in a hierarchy of atomic, molecular, colloidal, single-cellular, and multi-cellular levels. Moore viewed the difference between living nature addressed by biology and non-living nature addressed by physics and chemistry not as resting in material, for they are all manifestations of energy exchange, but instead as resting in organization, the way in which the energy is distributed in the system. He distinguished levels of complexity in energetic systems, recognizing that greater degrees of complexity yielded greater degrees of autonomy from surrounding biochemical agents in the environment. According to Moore, it is ‘’biotic energy which guides the development of the ovum, which causes such phenomena as nerve impulses, muscular contractions, and gland secretion…, it is a form of energy which arises in colloidal structure, …’’24 Moore’s hierarchical distinction highlights the fact that this energy is responsible for rules of physical behavior at the biotic level, which necessarily differ from those directing colloidal or molecular levels.

In Moore, Wright saw for the first time the philosophical doctrine of organicism applied to physical-chemistry, whereby individual units

23 Moore’s cutting-edge knowledge of physical chemistry benefited from collaborative work with Wilhelm Ostwald prior to being appointed the Johnston Chair of Biochemistry at the University of Liverpool in 1902, the first of its kind in England (Pitt 2001, pp. 16–19). Claude Bernard’s Introduction to the Study of Medicine (1865) was one of the first works to argue for a more experimental insight into the holistic ‘’balancing of forces’’ in the organic body. Bernard championed the law of the ‘’conservation of energy’’ as active within organisms, producing ‘’inner environments.’’ J.W. Gibbs’ landmark papers on the equilibrium of heterogeneous substances (1876–1878) united physics and chemistry together in its simultaneous treatment of molecular systems in gases, liquids, plastics, magnetic fields, and so forth, emphasizing their states of equilibrium. L.J. Henderson (1913, 1928) endorsed Bernard’s idea of ‘’living systems’’ while emphasizing Gibbs’ language of molecules and entropy to describe their nature. Walter Cannon’s The Wisdom of the Body (1932) continued the concept of the organism as a balanced dynamic system, advancing his idea of ‘’homeostasis’’ (Fleming, 1984). Cynthia Russett has written on the rise of organicism and dynamic equilibrium (1966, pp. 15–54). Stephen Cross and William Albury have addressed the organic analogy of Henderson and Cannon (1987).

24 Moore (1912, p. 226).

(cells, colloids, etc.) are said to synthesize a whole identity (‘’organism’‘) through an interaction which is not reducible to their individual properties.25 The system of their interaction distinguishes itself as an organismic unit hierarchically: the observer acknowledges the subject to be either the individual parts or the integrated whole, but cannot perceive both at the same time. As units they differ in their class of environments, their’‘level’’ of organization, even while being related compositionally. For the biochemist such as Moore, the trademark organismic relationship was that of water emerging from hydrogen and oxygen, or on a more complex scale cells emerging from various colloids. For the physicist it was magnetism from iron, or radioactivity from uranium or radium. For Wright, however, these examples paled in comparison to the complex relationships the biological realm had to offer: ‘’At all stages [of living nature], all parts are integrated into a harmonious functional whole. There is nothing remotely comparable, in the nonliving world, of greater size than a molecule.’’26 Wright intended for the effects of gene combination to take organismic philosophy to a new level of natural order surpassing physics and chemistry in complexity.

Wright’s reading of Moore resonated strongly with ideas he discerned in Bergson’s Creative Evolution. Bergson also capitalized on the 19th century concept of energy in arguing that the universe is truly a continuous flow of ‘’becoming;’’ that matter is action which flows ‘’downward’’ towards disorder, ‘’unmaking itself’’ as predicted by entropy, while mind is action which flows ‘’upward,’’ creating order.27 According to Bergson, matter and mind were inverse properties of one universe of action, the former following the inevitable course of the second law of thermodynamics. Conversely all organization in the world, molecular, cellular, and above, points to mind in Bergson’s perspective – it is action directed at complexity. In the interaction

25 An overview of various types of organismic philosophies around the turn of the 20th century can be found in Donna Haraway’s Crystals, Fabrics, and Fields (2004, pp. 33–63). As early as the 1880s, biologists like J.S. Haldane (1884) and Edmund Montgomery (1880) advertised its core tenets as metaphysically superior to either mechanistic determinism or vitalism, though as Hans Driesch proved with his Science and Philosophy of the Organism (1908), many biologists still struggled to abandon innate vital forces in their holistic views of nature. The 1910s brought a new concerted effort to solidify organismic philosophy in light of advances in thermodynamics and chemistry, with L.J. Hednerson (1917), J.S. Haldane (1917), and William Ritter (1919) writing more refined treatises on the special unity of the organism.

26 Wright, ‘’Genic and Organismic Selection’’ (1980, p. 826).

27 Bergson (1911, pp. 242–251); also Mind-Energy: Lectures and Essays, (1920, p. 23).

between the organism and the environment, nature appeared as an intelligently guided process.

Putting Bergson together with Moore, Wright began to see the possibility of a panpsychical worldview founded on organicism.28 Moore had depicted a world layered with organisms, ‘living’ units by virtue of their dynamic structure, and Wright realized that if Henri Bergson was correct, then the very fact that these ordered structures persist and develop within nature as opposed to dissipating demonstrates their psychical character as well. There simply was no reason to deny that ordered structures exchanging energy at the molecular, colloidal, or cellular levels were deprived of consciousness given their propensity to adapt and persist in nature as distinct from mere disorderly atoms. As one of Wright’s later colleagues at Chicago would say, perhaps only the issue of complexity in animated processes differentiates plants, dogs, and human beings as ‘’outstanding examples’’ of organicism.29 It is necessarily the case that human beings are not the only examples of nature’s psychical status, unless we intend to eliminate the hierarchical chain of self-organizing conscious entities, which give rise to our own minds (supposing a scheme of ‘something from nothing’). Complexity of structural relations, from which consciousness emerges, was the crucial distinguishing factor for what Wright qualified as biological.30

Wright’s encounters with philosophies of biology between 1912 and 1914 sparked creative thinking about how to make sense of complex genetic systems, and the ‘living’ world, which they produce. Organicism seemed more flexible than mechanical-determinism for dealing with the kind of phenomena, which he encountered in his experiments at the Bussey Institute. It explained why artificial (and analogously natural) selection could not act directly on genotype components of cells but only the phenotype of the organic whole. It explained why several genes affecting guinea pig coat-color suddenly, when placed together, give rise to a coat-color characteristic, which is typical of neither constituent genes. Mendelism proposes that organic populations are composed of genetic units and their relationships.

28 Wright, (c. 1985, p. 8; 1975, pp. 84–85). Though Wright was interested in Bergson’s equation of complexly organized nature with mind-energy, he eventually disagreed with Bergson’s vital force in nature (e´lan vital), arriving instead at the idea of nature as fundamentally psychical to begin with (only appearing ‘material’ to the mind under ordinary conditions).

29 Gerard, ‘’Organic Freedom’’ (1940, p. 412).

30 Wright, (c. 1985, pp. 7–9; 1975, pp. 81–82); ‘’Genetics and the ierarchy of Biological Science,’’ (1959, pp. 12–13).

Yet neither natural selection nor organic beings on a hierarchical level above colloidal tissue recognize genotype pools. They perceive only the organismic identity formed at the phenotype level due to the interrelationship of genes. As Wright later underscored during his tenure at Chicago, genes are the crucial link in the hierarchical chain connecting biochemical levels (from colloids all the way down to molecules) with the ‘’organic’’ levels (from cells all the way up to ecological demes and species) precisely because they manifest complexly interwoven processes which enable wide degrees of diversity.31 According to organicism it is organization, not matter, which begets life.

On the other hand panpsychism, the opinion that mind is pervasive in nature, was still much of a question mark for Wright prior to his 1914 reading of Karl Pearson’s Grammar. If Bergson was correct that mind corresponded to energies responsible for complexly organized nature, then consciousness might even be thought of as a vital force embedded in a world capable of evolving new forms out of itself. For Wright, it was still unclear whether such fantastical ontology was really necessary, and what collateral effect the elimination of materialism might have on biological studies. Not until he had acquainted himself with Pearson’s philosophy of the mind did Wright firmly establish himself on these questions, and address the relationship between the doctrines of organicism and panpsychism.

The Role of Panpsychism in Wright’s Organicism: How Pearson’s ‘’mental construct’’ Influenced Wright’s Philosophical Refinement

One of the more perplexing aspects of Wright’s philosophy of biology was its fusion of two different traditions of philosophical thinking. Panpsychism originated in the 17th century under monist philosophers Spinoza (1632–1677) and Leibniz (1646–1716). The overriding substance in the Leibnizian universe was that of mind-soul, encompassing a sea of ‘’monads’’ (individual minds) onto which God imprints sense experiences. Spinoza’s dual-aspect panpsychism, on the other hand, proposed that the universe is entirely God’s spirit expressed in parallel forms of mind and matter. As discrete manifestations of mind, human beings perceive God’s other attributes (external natural phenomena) as material entities contrasted against their own internal experience (memory, abstraction, imagination, etc.). After Spinoza and Leibniz,

31 Wright (1959, p. 959).

however, panpsychical monism remained a relatively uncommon intellectual persuasion overshadowed by mechnical philosophies of nature.32

Towards the end of the 19th century the rise of thermodynamics and the concept of energy rejuvenated the prospects of Spinoza’s ‘’dualaspect’’ panpsychism, inspiring some early 20th century scientists such as Bergson (Mind-Energy, 1920) to argue that the universe is entirely action (energy exchange) which manifests itself as both material and mental reality in everyday life. Still others like H. Wildon Carr (A Theory of Monads, 1922) returned to a Leibnizian panpsychism arguing for the complete immateriality of the universe.33 In this era Harvard psychologist William James and Bristol psychologist C.L. Morgan singled out mathematician William Kingdon Clifford as the preeminent source for resurrecting panpsychism.34 At Cambridge, Clifford designed a psycho-physical philosophy based on Spinoza’s principles but expanded it to include an intricate account of human sense experience. According to Clifford, ‘’the universe… consists entirely of mind-stuff. Some of this is woven into the complex form of human minds containing imperfect representations of the mind-stuff outside them, and of themselves also, as a mirror reflects its own image in another mirror, ad infinitum. Such an imperfect representation is called a material universe. It is a picture in the man’s mind of the real universe of mind-stuff.’‘35 Clifford added that material reality becomes known to a mind (’‘conscious’’ if human beings are involved) in terms of ejects, which he explained as the physical rearrangements of the nervous and brain system to account for images thrown outside the mind. In Clifford’s panpsychism, ’’a stream of feelings which runs parallel to, and

32 Margaret Dauler Wilson examined how Spinoza and Leibniz arrived at their philosophies in a scientific paradigm dominated by a mechanical worldview (1999).

33 In his book From Soul to Mind (1997), Edward Reed points out how concepts like energy, electricity, and other vogue topics of 19th century physics influenced philosophical discussions on the mind, fueling new psychological theories of human understanding. One of these new psycho-philosophers was G.T. Fechner, whose young field of ‘’psychophysics’‘(1860) impacted the work of William James, Wilhelm Wundt, and the German Gestaltists Koffka and Ko¨hler, introducing the principle of’‘parallelism’’ between psychical and physical realms of nature (pp. 97–129). Michael Heidelberger has recently published a book on Fechner’s psychophysical worldview (2004).

34 Richards, Darwinism and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of the Mind and Behavior (1987, pp. 377–385).

35 Clifford (1879, p. 87).

simultaneous with, a certain part of the action of the body’’ accounts for human perception of reality.36

Attending Cambridge after Clifford, and possessing a strong interest in epistemology, Karl Pearson digested Clifford’s philosophical writings on ‘’Body and Mind’’ and ‘’On the nature of things-in-themselves.’‘37 In his multiple editions of Grammar published around the turn of the 20th century, Pearson agreed with Clifford that human perception of reality is primarily founded on sense impressions which’‘psychically correspond to memory’’ such that ‘’The union of immediate sense impressions with associated stored impressions leads to the formation of ’constructs’ which we project ‘outside ourselves’ and term phenomena.’’ But Pearson went further than Clifford in emphasizing that ‘’The real world for us is such constructs, not the shadowy things-in-themselves,’’ elaborating that these constructs ‘’are the facts of science and its field is essentially the contents of the mind. It [Scientific law] is a brief description in mental shorthand of as wide a range as possible of our sense impressions.’‘38 Pearson’s emphatic tone reflected his frustration with Clifford’s unwillingness to just accept the mental construct alone as reality, instead inserting some sort of’‘shadowy’’ substance behind sense impressions giving the mind not only a ‘’type’’ to which they belong but also a ‘’regular pattern’’ to how they relate. In his distain for Clifford’s subtle objectification of nature, the positivist Pearson ranted: ‘’Herein lies the arid field of metaphysical discussion. Behind sense-impressions, and their source, the materialists place Matter; Berkley placed God; Kant, and after him Schopenhauer, placed Will; and Clifford placed Mind-stuff.’’39

Pearson and Clifford implicitly agreed on how human understanding takes place, valuing sense perception for all knowledge. Pearson was rejecting Clifford’s ontological conviction that the universe is composed of vast psychical entities which human beings register as ‘’material’’ through sense faculties, transforming them into fixed categories of natural phenomena. According to Pearson, sensations are not and

36 Clifford (1879, p. 34), italics added.

37 Clifford (1879), Pearson (1911, p. 75). In 1894 Pearson was appointed to the Chair of Applied Mathematics at University College, the position which Clifford had held until his death in 1879. Pearson also edited and published Clifford’s manuscript, The Common Sense of the Exact Sciences. Pearson’s own magnus opus, The Grammar of Science, appeared in three editions, 1892, 1900, and 1911. It is unclear from Wright’s papers which of the editions he had read in 1914.

38 Pearson (1911, p. 75), cited by Wright (c. 1985, p. 5; 1975, p. 84).

39 Pearson (1911, p. 68).

cannot be permanently tied down to entities psychical, material, or otherwise, except that through internal statistical correlation their patterns may become more predictable over time, and thus be grouped contingently. Essentially, Pearson believed in the ontological reality of only one psychical entity, his own mind, with every natural phenomenon resting contingent upon its patterns of association.40

When Sewall Wright read Grammar in 1914, however, he mistook Pearson’s argument for ‘’mental constructs’’ along with his discussion of W.K. Clifford’s ‘’mind-stuff’’ as evidence that Pearson himself supported panpsychism. Wright was moved by what he perceived to be Pearson’s endorsement of statistical analysis as the key methodology for studying a predominantly psychical universe because, in the year prior, he had also read from Bergson that all complexly organized aspects of nature (such as genetic phenomena) speak of conscious mind-energy states. Based on a skewed interpretation of Pearson, Wright began to accept that genetics (and biology generally) ought to be well suited for statistical modeling in even its most inductive cases (like experimental breeding) due to nature’s new status as a sea of interwoven mental constructs; a universe of individual minds constantly engaging one another. While Mendelian breeders sometimes mistrusted the degree to which mathematical abstraction was imposed on the study of the organism (notably William Bateson), and while Pearson’s biometricians often mistrusted the degree to which experimentalism (and with it faith in mechanical causation) was employed in the study of the organism, Wright was arriving at a position by 1914 in which there was no reason to see a fundamental divide between the two camps.41 For Wright there was no strict barrier between ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ reality, and therefore no basis for discriminating between quantitative or experimental methodology. Clifford and, in Wright’s 1914 opinion, Pearson also had suggested that mind and matter are two sides of one reality, that in effect concepts like ‘’correlation’’ and ‘’causation’’ are describing one reality.

40 According to Pearson, ‘’When an interval elapses between sense-impression and exertion, filled by cerebral activity marking the revival and combination of past sense impressions stored as impressions, we are said to think or be conscious…. Consciousness has no meaning beyond nervous systems akin to our own’’ (Pearson, 1911, cited in Wright, 1975, pp. 84–85).

41 For examples of Bateson’s disapproval of the biometrical approach see Provine (1971) and Cock (1973). R.C. Punnett, in his article on ‘’The Early Days of Genetics,’’ recalled, ‘’So came into being the School of Biometry which, as Karl Pearson remarked, would eventually reduce biology to a branch of mathematics’’ (1950, p. 2).

How had Wright misunderstood Pearson on the topic of panpsychism? In several papers delivered late in his career Wright proposed that the events which preceded his reading of Pearson’s Grammar in 1914 (i.e., the recognition of gene systems, reading of Bergson, and reading of Moore) played a major role in the sort of interpretation which he extracted from Pearson’s prescription of statistical analysis in biology.42 While no exact timeline is given for ordering the 1912–1914 ideas, reading the English translation of Bergson’s Creative Evolution (published 1911) likely laid the foundation for Wright’s interpretation by bridging a metaphysical relationship between complex organization and psychical-energies. At that point Wright probably began to loosely associate the high-level organization touted by Bergson with the integrated gene systems which he and Castle identified in the labs. Benjamin Moore’s The Nature and Origin of Life (published just after Creative Evolution, and also read by Wright in 1912) added to Bergson’s argument, associating complex biochemical structures with dynamic energy systems. In his examples Moore often emphasized cells, elaborating that ‘’The living cell consists of a combination of colloids existing in dynamic equilibrium with one another, and carrying on an exchange of energy phenomena peculiar to living matter with one another and with their environment.’’43 (Wright would easily have seen the link between holistic properties of cells and the holistic properties of genes he was encountering at Harvard, and might have concluded that such biochemical systems possess immaterial unifying principles (the mind-stuff of Clifford).

42 Wright (1975, pp. 79–88; c. 1985, pp. 1–18). Wright later testified how he had gotten caught up in the frenzy of new concept from 1912 to 1914, and confused the arguments presented by Pearson as well as Moore: ‘’I now find to my surprise on rereading Pearson and Moore for the first time after 60 years that [panpyschism] was not the conclusion of either of them’’ (p. 7). Wright added that he now saw how ‘’Pearson …fully accepted Clifford’s concept of matter and of physical phenomena, frequently using the term ’construct’ (which he credited to Clifford), but rejected his monistic concept [universal mind-stuff]’’ (1975, p. 85; c. 1985, p. 8). While the Pearson who wrote Grammar was therefore not a panpsychist, it is interesting to note that in the decade before the first edition of Grammar Pearson had been keenly interested in Spinoza, one of the fathers of panpsychism. G. Udny Yule and L.N.G. Filon later recalled in an obituary that during the 1880s, Pearson wrote a detailed review of Spinozism in the Cambridge Review and an essay on Spinozism in his book Mind (Yule and Filon, 1936, pp. 102–103). Recently Theodore Porter has shown that after Pearson rejected Christianity, his 1880s philosophical interest formed the basis of a spiritualism of nature, worshiped through science and the faculties of the mind (Porter, 2004).

43 1912, p. 198, italics added.

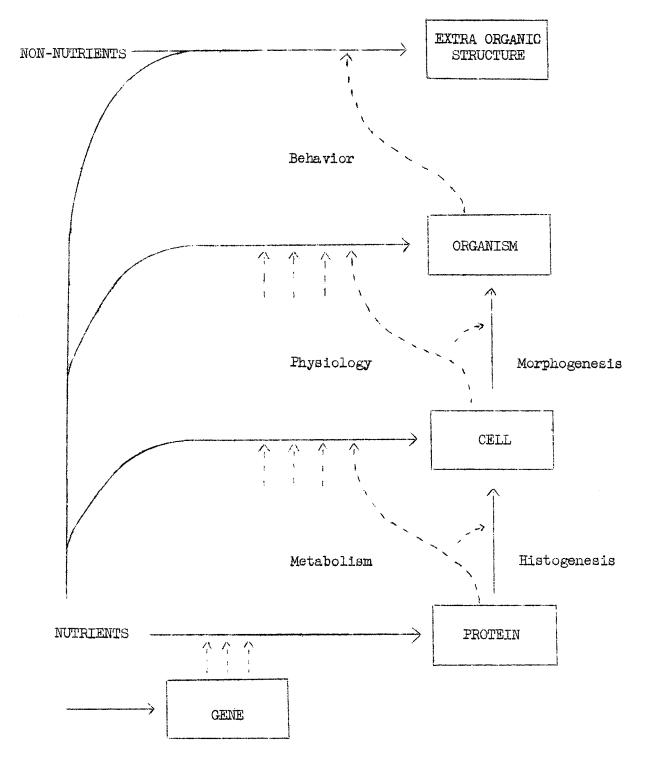

Wright also identified with Moore’s argument that even highly evolved biochemical systems possess a contingent nature resulting from their dependence on energy distribution. Following natural laws less binding to cause–effect relationship, biochemical systems instead seem guided by loose ‘’correlates,’’ quantitative patterns of behavior dependent on the matter and energy involved.44 Certainly genetics was no stranger to the contingencies offered by group factors in closely interrelated systems.45 Therefore, by the time Wright read Pearson he was already thinking in terms of complicated and contingent living systems dependent upon energy transfer, and pondering the notion that these basic biological entities possess the property of conscious mind to varying degrees. Wright stressed, however, that it was not until after Pearson’s Grammar that he became convinced that in fact all biological entities are fundamentally psychical phenomena in the first place, with each individual mind registering the other through patterns of physicality: sensations of touch, sight, sound, taste, smell, and their conversion into images, memories, abstractions, feelings, and decisions of response (Figure 1).46 Mechanist and vitalist philosophers had been wrong; the material conditions upon which physics, chemistry, and biology rely are ultimately just the language in which complex systems of consciousness interact with one another.

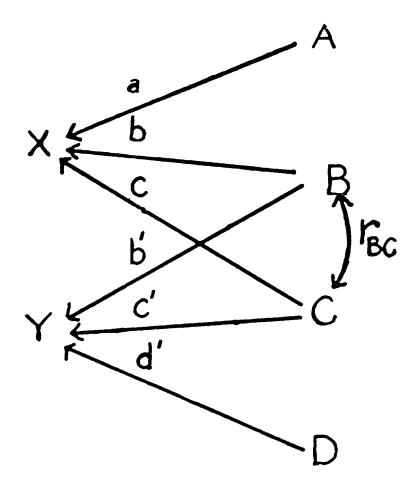

Taking Pearson’s argument for a single ‘’mental construct’’ to a whole new level, Wright deduced a world filled with vast levels of consciousness, each an organismic unity emerging from a less organized, less tightly-knit group of minds. In physical terms, this world appears to the scientific investigator as biochemical systems inside which are stacked other such systems less complex on the hierarchical scale of energy exchange. As Wright later depicted in various charts, genes are systems in cells, which are systems in ‘’organisms,’’ which themselves are systems in populations (‘’extra organic structures,’’ Figure 2).

44 Moore elaborated that ‘’The fundamental mystery [of life] lies in the existence of those entities, or things, which we call matter and energy, and in the existence of the natural laws which correlate them and cause all those things to happen which the natural philosopher observes and classifies and correlates ….’’ (1912, p. 19, italics added).

45 As Wright attested, ‘’In the biological sciences, especially, one often has to deal with group characteristics or conditions which are correlated because of a complex of interacting, uncontrollable, and often obscure causes’’(1921, p. 557).

46 Wright (1975, p. 80; c. 1985, pp. 7–8). Wright also noted that after reading Pearson, he furthered his understanding of panpsychical philosophy by reading Harvard psychologist Leonard Troland’s ‘’Psychophysics as related to the mysteries of physics and metaphysics’’(1922), which inspired him to return to W.K. Clifford’s 1879 lecture papers on the matter (c. 1985, p. 8).

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating the interaction between two fields of mind (drawn from an illustration in Wright, 1975, p. 82, 1978b, pp. 504–505). Wright explained the process as follows: ‘’if A and B represent two minds, largely private, but nevertheless capable of interacting directly or indirectly: A perceives certain regularities in its stream of consciousness which it ascribes to an external reality, B; but, as it does not enter into B’s stream of consciousness, it in general tends to consider B as merely an unconscious source of disturbance, i.e., matter. B similarly deduces matter, A, from interaction with A’s stream of consciousness. Each is aware of many such external realities and these are perceived to have interactions with each other, which can be arranged in coordination systems consisting of two dimensions of direction in addition to one of remoteness. The order of succession of events provides a fourth dimension, time. In certain cases, the behavior of external matter is of such a nature as to indicate the presence of stream of consciousness, another mind, with which varying degrees of communication become possible. In still other cases, the external reality parallels the internal so completely as to compel identification as a peripheral aspect of the observer himself, his own body’’ (Wright, 1975, pp. 82–83, with permission from University Press of America).

A conscious network of nature identifies the existence of other systems through two relationships, namely the cause–effect sort and the correlative sort. The former represents the mind’s understanding of how organismic units on the same hierarchical level of nature interact with one another, whether two or more molecules, two or more cells, two or more genes, and so forth. But these interactions often form complex networks of energy exchange from which a greater organismic unit has its existence, as for instance a sea sponge emerges from multicellular interaction, an amoeba from the interaction of single-cell components, a neural network from the interaction across synapses of single neurons, a molecule from the interaction of electrons among atoms, a gas from the interaction of molecules, and so forth. Correlative relationship represents the mind’s understanding of how organismic units on different levels (the parts and whole of one system) relate with one another.

By the end of his time at Harvard Wright realized that biology, and genetics in particular, dealt primarily with these correlative relationships.

Figure 2. Diagram illustrating a hierarchy of organismic systems in nature with complex population networks at the top tier, followed by traditionally acknowledged organisms like plants and animals, then cells, the genetic systems, and finally chemical molecules at the bottom (Wright, 1945, unpublished manuscript, p. 6, courtesy of the University of Kentucky Young Library).

It became clear that the mind identifies its organic subject matter only through its interpretation of relationships and interrelationships in nature. New means would have to be developed for measuring the complex intermingling of variables, and the overlapping effects which result in organismic phenomena. He had also cemented his belief that, beyond what could be verified by the scientific mind, nature’s vast self-regulating systems of energy exchange speak to manifold levels of consciousness: ‘’We must postulate common consciousness as arising from interactions among elementary physical entities within an atom, or among atoms and electrons within a molecule, or among molecules within a living cell as well as among cells within a multicellular organism in carrying through the concept of [psycho-physical] identism. We should again recognize that the external aspect of a stream of consciousness is not matter defined by mass and occupancy of space so much as by the association of action [energy]. We must suppose that wherever there is physical action, this is the external aspect of at least a flicker of consciousness.’’47 Wright did not yet have a platform for expressing these ideas at the end of his Harvard days or directly thereafter, at the USDA in Washington from 1915 to 1925. Finishing a thesis, securing a job, and managing the transition all took priority. With the exception of a few published book reviews, however, Wright kept mum on his philosophy even into the 1920s, 30 s, and 40 s, reserving publication on his full metaphysics until after he had established himself in quantitative genetics and evolutionary biology.48 One can only speculate as to why he did this. Perhaps he felt the need to maintain a positivist scientific rhetoric in order to have his work in genetics taken seriously, or perhaps more incentive to express his ideas emerged as some of his peers came forward with their own organismic philosophies.49

The ‘’Statistical Behavior’’ of the Organism

Wright recognized that the new attention biochemists assigned to systems of energy exchange in ‘living’ matter would force modern biologists to acknowledge two important points: first, that their job is to interpret holistic entities comprised of a great many parts and engaged in dynamic processes of interaction, and second, that because of these complex circumstances, the arrangement of the whole organic entity is always to some degree contingent, requiring statistical description. In any natural system, there will always be an element of randomness as components rearrange over time to synthesize the greater organic whole. Benjamin Moore had illustrated this point beautifully in terms of cell structure, and Wright thought Karl Pearson had already provided an appropriate philosophical treatment for handling a universe speckled with chance phenomena—except for one point. Pearson argued in

47 Wright (c. 1985, p. 10).

48 Wright published two book reviews in which he briefly touched on his philosophical ideas: a review of C.L. Morgan’s ‘’emergent’’ evolution (1935), and a review of W.J. Werkmeister’s philosophy of science (1941).

49 Many of Wright’s Chicago peers (Ralph Gerard, Ralph Lillie, and Alfred Emerson) and contemporaries (Wilfred Agar, Joseph Needham, C.H. Waddington) solidified their organicist and pan-experientialist views following A.N. Whitehead’s landmark papers at the 1925 Lowell Lectures and 1927/1928 Gifford Lectures. Whitehead’s papers formed the basis for his first two major philosophical treatises, Science and the Modern World (1925) and Process and Reality (1929). Lillie (1945), Agar (1943), and Needham (1943) later published their own books on Whiteheadian philosophy and its relation to biology.

Grammar that nature is so complex and fluid, unique at every instance, that the mind alone is capable of processing its sensible data into ‘’objects’’ and their ‘’relationships’’ because of its inherent powers of abstract correlation. He asserted that these statistical faculties were the only route to scientific knowledge; laboratory experimental methods were flawed in their reliance on the illusion of stable cause–effect relationships in nature. Furthermore, laboratory experimentation often focused on the sub-levels of organic nature, and Pearson insisted that statistical regularity was to be found at population levels. Thus, beyond vital statistics dealing with large populations little else could be known about the particulars of the organic world from a scientific standpoint.50

Wright’s later philosophical papers reveal that he had diverged from Pearson’s skepticism over nature’s deep organization, the scientific mind’s access to such organization, and hence Pearson’s negative view of experimentation. Wright insisted instead that the cause–effect relationships examined during laboratory research must be credited along with correlative relationships as useful in mentally constructing the natural world. After all, Wright trusted that beyond his mind, there were other minds existing on different hierarchical levels, manifesting themselves in other complex structural systems of matter and energy (cells and genes, for instance). The randomness associated with sensible data from nature results not because of the way the scientific mind interprets a complex and dynamic world, as Pearson thought, but because the organization and reorganization of evermore complex systems in nature requires an influx of some disorder (unused energy) for conversion to order. Wright’s belief that there was real interaction going on at the lower levels of the organic realm, combined with his ideas on energy exchange from Bergson and Moore, led him to a more favorable opinion of mechanical causation in an indeterminist world.51

50 B.J. Norten has analyzed Pearson’s epistemological thinking in several articles (1975a, b, 1978). Regarding Pearson’s rejection of objective reality, Norton finds ‘’One could not learn about underlying realities, and the postulation of a realist ontology of atoms, molecules and so on was, in his philosophy, rendered incoherent or redundant’’ (1978, p. 14). Norton underscores the influence of Ernst Mach and before that, Kantian empiricism, on Pearson’s epistemology (1975a, b). Theodore Porter’s recent book also covers Pearson’s epistemology (Porter, 2004).

51 The differences between Pearson and Wright hinged on their philosophical focus: Pearson’s philosophy was severely constrained to epistemology, rejecting the ontological reality of nature outside the scientist’s discernment of data-patterns, while Wright’s philosophy invested heavily in establishing an ontological reality (bio-chemical organicism and panpsychism) to corroborate his epistemology.

In Wright’s hierarchical view of nature, chance exists side-by-side with causal order at the level of the ‘’parts’’ within a greater organic ‘’whole.’’ Randomness does not negate the role of causal mechanisms, which Wright still trusted as responsible for structural order on each plane of nature. Systems possess a certain type of causal mechanism which he termed ‘’trigger mechanism,’’ the part of a cause–effect sequence which initiates a process wherein certain ‘’paths’’ of the sequence are traversed, and in so doing actualizes certain effects previously only potentially available within the system. Wright explained,

An organism is by its very nature a system of trigger mechanisms, which precludes merely statistical behavior. It is not …that the behavior of the whole is easily subject to indeterminacies of behavior at the quantum level. There are self-regulatory processes that usually prevent this. It is rather that the organism can act as a whole without deviation in the customary behavior of the parts of more than infinitesimal amounts.52

Wright thought that organic systems operate by their own special set of mechanical rules which neither suffer from the randomness nor directly benefit from the causal connection located in each tier of their components. These systems are emergent from their interacting components; at every level of nature organisms are ‘sealed’ from their inner systems in terms of their behavioral properties. Just as water does not suffer the properties of its gas components oxygen and hydrogen, neither does the cellular organism suffer the properties of the proteins, lipids, acids, and sugars, which interact within them. As systems they are autonomous from less complex levels of nature, though they receive their freedom from the interaction on these levels.53

Based on what he knew about energy transfer, Wright acknowledged that it was because of the interaction of parts with their respective environment that each causal system had a degree of chance in its operation (the ‘’infinitesimals’’ which Wright accepted in the organism’s function). What interested Wright, however, was another kind of contingency which he associated with the system’s autonomy, specifically

52 Wright (1953, pp. 16–17), italics added.

53 Wright hedged that ‘’Autonomy, however, is always a relative matter. Higher animals and man are far more highly integrated organisms than green plants, but are dependent on the latter with respect to energy-rich organic compounds’’(1953, p. 8). Organisms may be highly determined by their material composition, even while the complex interrelationship of these material components creates the sort of novelty, and consequently the sort of autonomy, which the organisms possess with respect to their environment.

situations where the chance results from the dynamic interaction and complex structure of the system itself (not in its parts). His guinea pig breeding projects at Harvard had shown that genetic systems often produce unexpected changes in phenotype variation through a slight shuffling in gene combinations (for instance, causing albinism in coatcolor). The genes involved were the same, but new effects emerged for the organism after its genetic network was reorganized. This other sort of ‘’statistical behavior’’ must be the unpredictable physical pattern, which is not ‘’precluded’’ by the trigger mechanisms of an organism. Therefore, even though the trigger mechanisms in a guinea pig gene system do a pretty good job of ensuring that the recognizable subject ‘guinea pig’ persists (rather than degenerates or recomposes into something other), it appeared that the gene system upon which the organismic identiy ‘guinea pig’ relied actually had in itself a ‘’statistical behavior’’ permitting it novelty of expression. This sort of chance belonged to the whole system, not to any of its component genes. Wright drew an important philosophical lesson from his Harvard breeding work, a lesson which he would reiterate later in his papers: ‘’A high degree of freedom of choice by the whole is thus consistent with apparent deterministic behavior of the parts [except infinitesimal chance, of course].’’54

Furthermore, it appeared to Wright that the more integrated an organic system (higher up the hierarchy in terms of complexity), the greater its autonomy and consequent novel expression seemed to be.55 Higher organisms appeared to achieve a ‘’statistical behavior’’ much more easily than simpler ones, and therefore bypass ordinary function in greater regularity. In some of his later philosophical papers Wright referred to ‘’switch or trigger mechanisms,’’ highlighting this capacity to bypass normal causal sequence unexpectedly.56 Though not cited in Wright’s papers, the language was that of James Clerk Maxwell. Regarding the ‘’switching’’ mechanism, Maxwell once described, ‘’There are certain cases in which a material system, when it comes to a phase in which the particular path which it is describing coincides with the envelope of all such paths, may either continue in the particular path or take to the envelope….’‘57 Wright was employing Maxwellian language to explain the indeterminism of biological systems: the’‘envelope’’ in this case was the organic whole, and as a ‘’tightly knit’’ system it

54 Wright (1975, p. 84).

55 Wright (1953, pp. 16–17).

56 Wright (1975, p. 84), italics added.

57 Maxwell to Galton, February 26, 1879, quoted from Porter (1986, p. 206).

sometimes exerted a new causal sequence rather than settling for the ‘’paths’’ on which it was operating.

As a philosopher, Wright felt convinced that these tightly knit systems of complex activity represented other minds in nature, located on hierarchic levels according to their degrees of conscious sophistication. Genes were no doubt one example of consciousness in nature. As a scientist, however, Wright did not have the liberty to acknowledge willfulness or directedness in the ‘’statistical behavior’’ of organic systems. As a scientist, Wright felt compelled to proceed under the assumption of mechanistic determinism in order to conduct proper laboratory investigation of organic phenomena. Nevertheless, Wrightthe-scientist wanted a way to quantify this ‘’statistical behavior’’ since it obviously contributed to the organism’s pattern of variation, and was especially responsible for the organism’s novelty. By the end of graduate school at Harvard, Wright was convinced that in order to render a full causal analysis of the change in guinea pig litters it would be necessary to combine efforts in breeding experimentation with efforts in statistical analysis. There had to be a new method which would take into account not only the genetic factors and chance factors in the system, but also the contribution of the organic system itself (as a whole).

Wright’s Invention of Path Analysis: What Panpsychic Organicism Contributed to Biological Method

Wright was well acquainted with the application of statistics in Mendelian breeding experiments by 1914. Summer internships from 1911 to 1912 at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York exposed Wright to the work of C.B. Davenport (CSHL director) and J.A. Harris (a visiting researcher at the CSHL), both leading American biometricians preoccupied with Mendelism.58 Studying with Castle at Harvard from 1912 to 1914 reinforced the place of statistics in genetic research, as Castle required students to learn how to use standard deviations, error measurement, and correlation coefficients in breeding analysis.

Yet it was not until 1914 that Wright began to take a personal interest in applying statistics to genetic research. That was when Wright read Karl Pearson’s Grammar, and became convinced that statistical analysis would help unravel complex genetic systems. It was

58 Provine (1986, pp. 27–30, 74–75). Both in the biography and his previous book, The Origin of Theoretical Population Genetics (1971), Provine listed C.B. Davenport, J.A. Harris, and Raymond Pearl as America’s most prominent biometricians (1986, pp. 27–29, 74–75; 1971, pp. 89, 107–110).

also the year that Castle asked Wright and another student to employ correlation tools to find the contribution of genetic factors influencing skeletal dimensions in rabbits, one of Castle’s ongoing case studies. Wright was surprised to learn that the techniques which he and his colleague had at their disposal were incapable of determining anything more than what bone variations correlated highly with other bone variations. He was also frustrated that these correlation measurements were accepted by Castle as suggestive of genetic factors affecting the entire skeletal structure (what he called ‘’general size factors’‘).59 Other geneticists, like Castle’s former student E.C. McDowell, had speculated that the correlation between bone variations might suggest’‘specific’’ size factors determining only isolated bone developments. With the available correlation methods, Wright felt there was really no way to be certain. Biometry’s regression and correlation tools were essentially descriptive and predictive devices for the purpose of discerning general characteristics of a group. When employed for studying heredity, they proved useful in describing the relative change of physical traits in a group over generations (variations in skull size, birth weight, coatcolor, etc.), but only provided suggestive information on what sort of relationships might exist at the genetic level in producing these changes.

In light of his guinea pig research Wright wanted to better understand gene actions in a causal system, but it seemed that biometry was ill suited for this end. The most sophisticated statistical techniques were developed by Karl Pearson’s program in England. Pearson’s ‘’partial correlation coefficient’’ calculated the correlation between three or more variables in population heredity, suggesting how much organic variation was due to what group of variables. Wright applied the partial correlation technique to Castle’s 1914 case study on the skeletal dimension of rabbits, using suspected genetic factors as his variables, and noticed two things: first, the partial correlation coefficient was extremely laborious to calculate, and second, after all the time put in, it merely analyzed skeletal variability into ‘’classes’’ of genetic factors.60 What the partial correlation method lacked, and what Wright considered of central importance, was any inclination

59 Provine (1986, pp. 77–80).

60 Provine (1986, pp. 77–80). It should be noted that Pearson would not have approved of the application of his partial correlation method to measure genetic contributions in heredity. Pearson denied the possibility of knowing anything about supposed microscopic mechanisms of biological change such as genes (Norton, 1975a, b, 1978).

towards revealing real causal connection in the physical system. He wanted to know what paths of influence these genetic factors had taken within the system in order to give rise to the observed organic differences.61

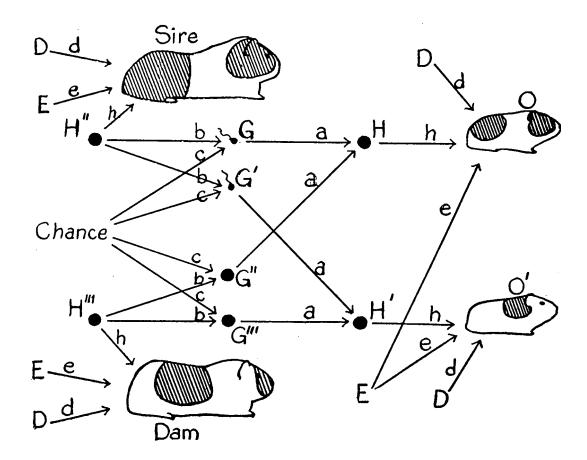

Wright held out little hope that Pearson’s biometry would soon furnish a statistical technique appropriate for analyzing the kinds of problems with which he was interested. Pearson’s biometry emphasized mathematical manipulation, the maneuvering of variables in abstract population models. Pearson had no concern for the difficulties of intertwined causal sequences faced by the geneticist. Wright therefore followed his 1914 trial of Pearson’s partial correlation coefficient with a new objective: to design a statistical technique of his own that could partition heritable variation among responsible genetic factors linked through interaction in a causal system. The major point of departure in Wright’s method was to replace random population sample data (employed by Pearson’s biometry) with a causal hypothesis ascertained from observations in experimental breeding and biochemical analysis. After deducing this hypothesis (what Wright called a ‘’qualitative scheme’‘), one would map out its branches of causal connections (literally lines of linked variables representing genetic factors and their effects), and assign to each line a coefficient of influence (Figure 3). Certain lines were given correlation coefficients adjacent to them, denoting paths of uncertain influence between variables. Other lines, however, were assigned coefficients carrying the weight of experimental research behind them; these were coefficients of causation, denoting definite influence among variables.62 When the mapping was complete, one would’‘read’’ the diagram, tracing out equations of coefficients requiring statistical correlation. These equations would yield the relative

61 Provine (1986, p. 127). Discussing Pearson’s correlation methods, Wright later remarked that ‘’It was not appreciated, however, that this approach gave no indication of the nature of the biological processes’’ (1968, p. 373). Philosopher of biology James Griesemer, who has studied Wright’s methodology, explained that ‘’Wright was dissatisfied with his application of Pearson’s partial correlation method to such data because it merely described the statistical correlations among the component variables and did not facilitate analysis of the causal determination of one variable by others through diverse paths of influence’’ (1991, p. 164).

62 Wright’s logic behind distinguishing more certain paths of influence was simple: ‘’in the world of large scale events, certain patterns tend to occur. Certain recurrent successions of events come to be recognized experimentally or otherwise, as lines of causation…’’ (1934, pp. 176–177). Consistency in the sequence of natural phenomena, observed in experimentation, indicated a more definite sort of relationship between the variables involved.

Figure 3. “Path Diagram” illustrating a causal chain of overlapping genetic factors contributing to two phenotype effects. The straight, uni-directional arrows indicate causal association and have path coefficients adjacent to them, while the curved, double-headed arrow indicates a correlative association and has a correlation coefficient assigned to it (Wright, 1920, p. 329).

degree of causal influence of variables in the system (genetic factors in the organic population). 63

Wright’s technique quantified imperceptible physical relationships, the pathways between hereditary cause and effect. He therefore named his partitioning procedure “path analysis,” and its causal measurements “path coefficients.” For Wright’s first application of path analysis he returned to the rabbit bone data from Castle’s study, assigning definite values for the growth factors to indicate their causal influence. Wright refined his analysis of the bone data after graduating Harvard in 1915, publishing his results in a 1918 issue of Genetics. Wright published other papers between 1917 and 1921 in which he formalized his technique. They included “path diagrams” to illustrate the initial mapping of the causal scheme, unidirectional and double-headed arrows to differentiate between causal and correlative pathways, and a generalized formula for calculating coefficient values (for example, a

<sup>63 Some of the best descriptions of path analysis and its benefits can be found in Ching Chun Li’s work (1954, 1975), and more recently articles by James Griesemer (1990, 1991).

<sup>64 Wright, “On the Nature of Size Factors” (1918). Wright’s other two major papers on path analysis were his inbreeding study, “Average Correlation Within Subgroups of a Population” (1917), and his most theoretical treatment of the path coefficient, “Correlation and Causation” (1921).

single path coefficient between two variables could be determined from the sum of all contributing pathways in a closed system).65 Aside from the reliance of path analysis on causal schemes vetted through experimentation, one of the more original aspects of Wright’s initial work between 1914 and 1918 was its partitioning of squared standard deviation in order to calculate the path coefficient (the ‘’partitioning of variance’’). Other than Wright, only R.A. Fisher in England had conceived of this technique, publishing his own derivation in a 1918 paper.66