Learn Python Programming

Learn Python Programming

A Comprehensive, Up-to-Date, and Definitive Guide to Learning Python

Fourth Edition

Fabrizio Romano

Heinrich Kruger

Learn Python Programming

Copyright © 2024 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the author, nor Packt Publishing, and its dealers and distributors will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Early Access Publication: Learn Python Programming

Early Access Production Reference: B30992

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd.

Grosvenor House

11 St Paul’s Square

Birmingham

B3 1RB, UK

ISBN: 978-1-83588-294-8

Table of Contents

Learn Python Programming, Fourth Edition: A Comprehensive, Up-to-Date, and Definitive Guide to Learning Python

- 1 A Gentle Introduction to Python

- I. Join our book community on Discord

- A proper introduction

- Enter the Python

- About Python

- Developer productivity

- An extensive library

- Software quality

- Software integration

- Data Science

- Satisfaction and enjoyment

- V. What are the drawbacks?

- Who is using Python today?

- Tech industry

- Financial sector

- Technology and software

- Space and research

- Retail and e-Commerce

- Entertainment and media

- Education and learning platforms

- Government and non-profit

- Setting up the environment

- Installing Python

- Useful installation resources

- Installing Python on Windows

- Installing Python on macOS

- Installing Python on Linux

- The Python Console

- About virtual environments

- Your first virtual environment

- Installing third-party libraries

- The console

- How to run a Python program

- Running Python scripts

- Running the Python interactive shell

- Running Python as a service

- Running Python as a GUI application

- X. How is Python code organized?

- How do we use modules and packages?

- Python’s execution model

- Names and namespaces

- Guidelines for writing good code

- Python culture

- A note on IDEs

- A word about AI

2. 2 Built-In Data Types

- I. Everything is an object

- Immutable sequences

- V. Mutable sequences

- Set types

- Mapping types: dictionaries

- Data types

- Dates and times

- The collections module

- Final considerations

- Small value caching

- How to choose data structures

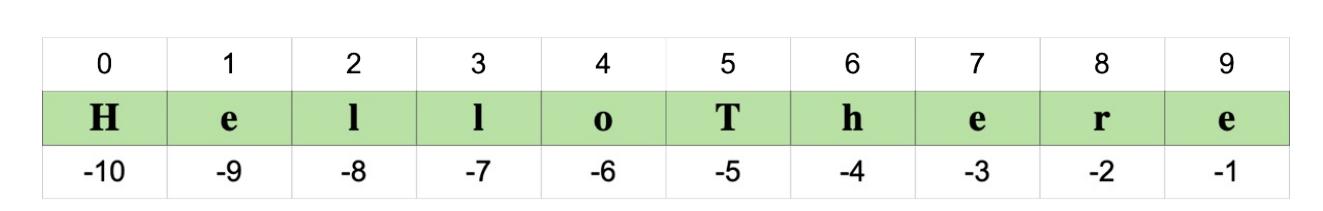

- About indexing and slicing

- About names

- X. Summary

- 3 Conditionals and Iteration

- I. Conditional programming

- The if statement

- A specialized else: elif

- Nesting if statements

- The ternary operator

- Pattern matching

- Assignment expressions

- Statements and expressions

- Using the walrus operator

- A word of warning

- Putting all this together

- V. A quick peek at the itertools module

- Infinite iterators

- Iterators terminating on the shortest input sequence

- Combinatoric generators

- 4 Functions, the Building Blocks of Code

- I. Why use functions?

- Reducing code duplication

- Splitting a complex task

- Hiding implementation details

- Improving readability

- Improving traceability

- Scopes and name resolution

- The global and nonlocal statements

- Input parameters

- Assignment to parameter names

- Changing a mutable object

- Passing arguments

- Defining parameters

- Return values

- Returning multiple values

- V. A few useful tips

- Recursive functions

- Anonymous functions

- Function attributes

- Built-in functions

- X. Documenting your code

- Importing objects

- Relative imports

- One final example

- 5 Comprehensions and Generators

- I. The map, zip, and filter functions

-

- Nested comprehensions

- Filtering a comprehension

- Dictionary comprehensions

- Set comprehensions

-

- Generator functions

- Going beyond next

- The yield from expression

- Generator expressions

- Some performance considerations

- V. Do not overdo comprehensions and generators

- Name localization

- Generation behavior in built-ins

- One last example

- 6 OOP, Decorators, and Iterators

- I. Decorators

- A decorator factory

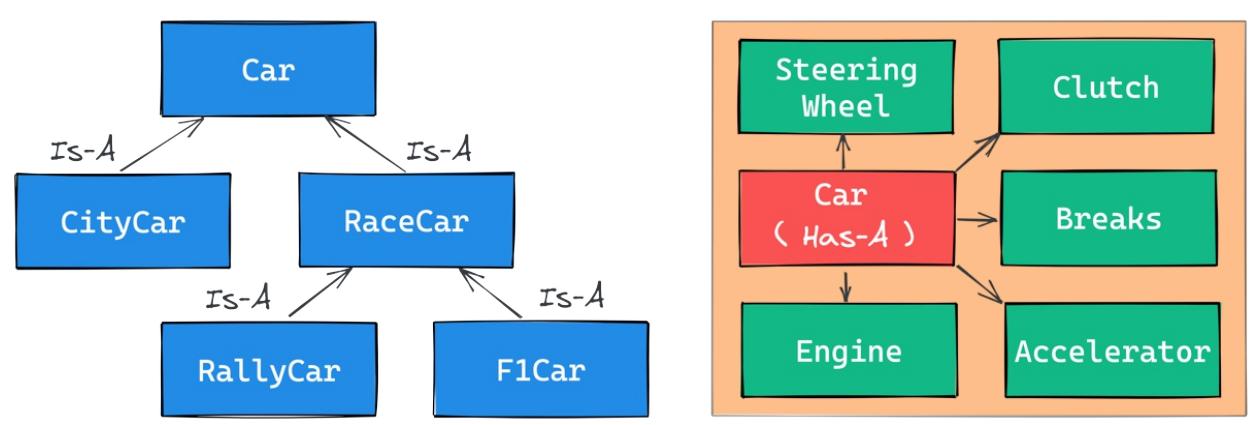

- Object-oriented programming (OOP)

- The simplest Python class

- Class and object namespaces

- Attribute shadowing

- The self argument

- Initializing an instance

- OOP is about code reuse

- Accessing a base class

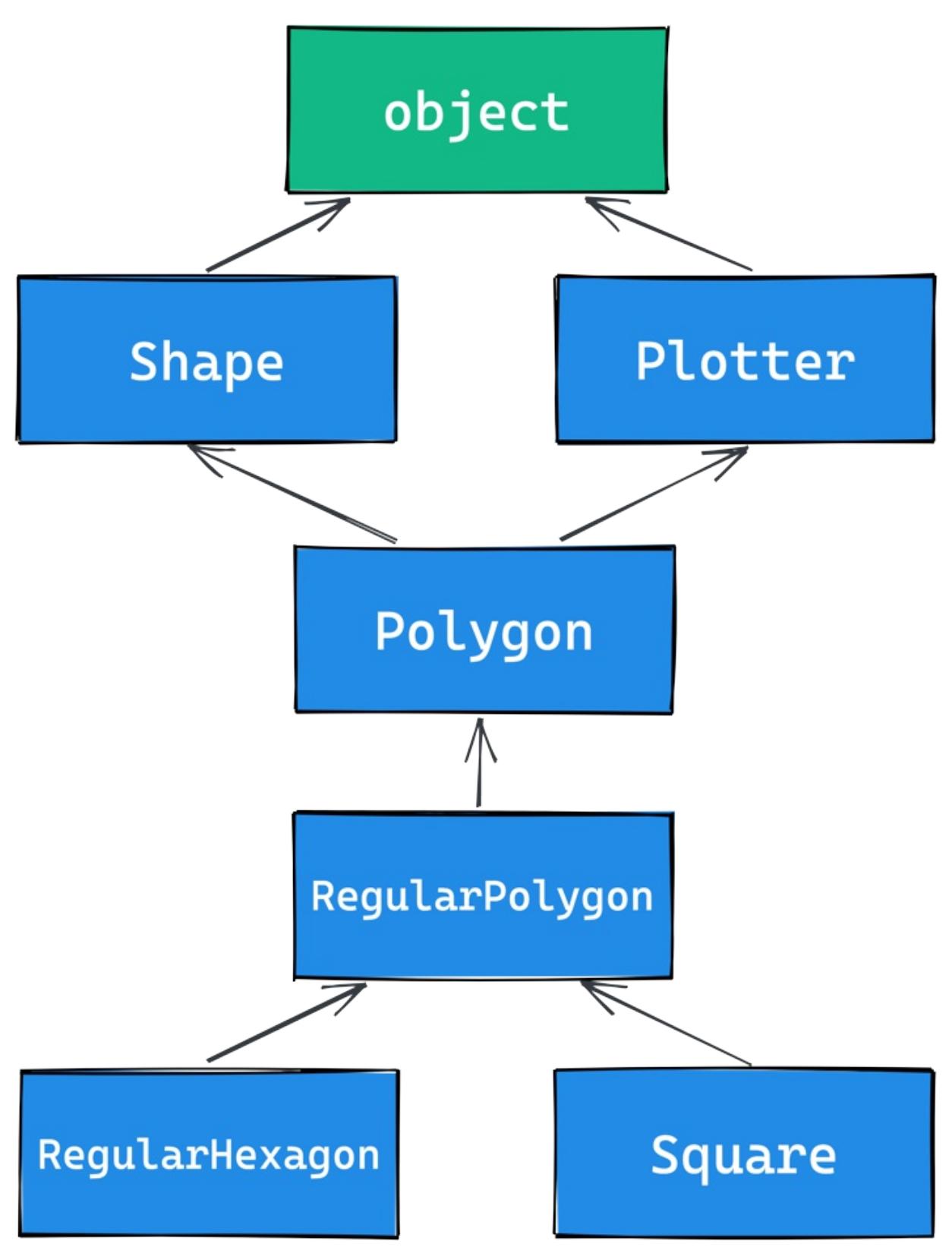

- Multiple inheritance

- Class and static methods

- Private methods and name mangling

- The property decorator

- The cached\_property decorator

- Operator overloading

- Polymorphism a brief overview

- Data classes

- Writing a custom iterator

- 7 Exceptions and Context Managers

- I. Exceptions

- Raising exceptions

- Defining your own exceptions

- Handling exceptions

- Exception Groups

- Not only for errors

- Context managers

- Class-based context managers

- Generator-based context managers

- 8 Files and Data Persistence

- I. Working with files and directories

- Opening files

- Reading and writing to a file

- Checking for file and directory existence

- Manipulating files and directories

- Temporary files and directories

- Directory content

- File and directory compression

- Data interchange formats

- Working with JSON

- I/O, streams, and requests

- Persisting data on disk

- Serializing data with pickle

- Saving data with shelve

- Saving data to a database

- V. Configuration files

- Common formats

- 9 Cryptography and Tokens

- I. The need for cryptography

- Useful guidelines

-

- Random Objects

- Token generation

- Digest comparison

- V. JSON Web Tokens

- Registered claims

- Using asymmetric (public key) algorithms

- Useful references

VII. Summary

10. 10 Testing

- I. Testing your application

- The anatomy of a test

- Testing guidelines

- Unit testing

- Testing a CSV generator

- Test-driven development

Learn Python Programming, Fourth Edition: A Comprehensive, Up-to-Date, and Definitive Guide to Learning Python

Welcome to Packt Early Access. We’re giving you an exclusive preview of this book before it goes on sale. It can take many months to write a book, but our authors have cutting-edge information to share with you today. Early Access gives you an insight into the latest developments by making chapter drafts available. The chapters may be a little rough around the edges right now, but our authors will update them over time.

You can dip in and out of this book or follow along from start to finish; Early Access is designed to be flexible. We hope you enjoy getting to know more about the process of writing a Packt book.

- Chapter 1: A Gentle Introduction to Python

- Chapter 2: Built In Data Types

- Chapter 3: Conditionals and Iterations

- Chapter 4: Functions, the Building Blocks of Code

- Chapter 5: Comprehensions and Generators

- Chapter 6: OOP, Decorators, and Iterators

- Chapter 7: Exceptions and Context Managers

- Chapter 8: Files and Data Persistence

- Chapter 9: Cryptography and Tokens

- Chapter 10: Testing

- Chapter 11: Debugging and Profiling

- Chapter 12: Introduction to Type Hinting

- Chapter 13: Data Science in Brief

- Chapter 14: Introduction to API development

- Chapter 15: CLI Applications

- Chapter 16: Packaging Python Applications

- Chapter 17: Solving Advent of Code with Python (Appendix)

A Gentle Introduction to Python

Join our book community on Discord

https://packt.link/o4zEQ

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”– Chinese proverb

According to Wikipedia, computer programming is:

“Computer programming or coding is the composition of sequences of instructions, called programs, that computers can follow to perform tasks. It involves designing and implementing algorithms, step-by-step specifications of procedures, by writing code in one or more programming languages. Programmers typically use high-level programming languages that are more easily intelligible to humans than machine code, which is directly executed by the central processing unit. Proficient programming usually requires expertise in several different subjects, including knowledge of the application domain, details of programming languages and generic code libraries, specialized algorithms, and formal logic.”

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer\_programming)

In a nutshell, computer programming, or coding, as it is sometimes known, is telling a computer to do something using a language it understands.

Computers are very powerful tools, but unfortunately, they cannot think for themselves. They need to be told everything: how to perform a task; how to evaluate a condition to decide which path to follow; how to handle data that comes from a device, such as a network or a disk; and how to react when something unforeseen happens, in the case of, say, something being broken or missing.

You can code in many different styles and languages. Is it hard? We would say yes and no. It is a bit like writing—it is something that everybody can learn. But what if you want to become a poet? Writing alone is not enough. You have to acquire a whole other set of skills, and this will involve a longer and greater effort.

In the end, it all comes down to how far you want to go down the road. Coding is not just putting together some instructions that work. It is so much more!

Good code is short, fast, elegant, easy to read and understand, simple, easy to modify and extend, easy to scale and refactor, and easy to test. It takes time to be able to write code that has all these qualities at the same time, but the good news is that you are taking the first step towards it at this very moment by reading this book. And we have no doubt you can do it. Anyone can; in fact, we all program all the time, only we are not aware of it.

Let’s say, for example, that you want to make instant coffee. You have to get a mug, the instant coffee jar, a teaspoon, water, and the kettle. Even if you are not aware of it, you are evaluating a lot of data. You are making sure that there is water in the kettle and that the kettle is plugged in, that the mug is clean, and that there is enough coffee in the jar. Then you boil the water and, maybe in the meantime, you put some coffee in the mug. When the water is ready, you pour it into the mug, and stir.

So, how is this programming?

Well, we gathered resources (the kettle, coffee, water, teaspoon, and mug) and we verified some conditions concerning them (the kettle is plugged in, the mug is clean, and there is enough coffee). Then we started two actions (boiling the water and putting coffee in the mug), and when both of them were completed, we finally ended the procedure by pouring water into the mug and stirring.

Can you see the parallel? We have just described the high-level functionality of a coffee program. It was not that hard because this is what the brain does all day long: evaluate conditions, decide to take actions, carry out tasks, repeat some of them, and stop at some point.

All you need now is to learn how to deconstruct all those actions you do automatically in real life so that a computer can actually make some sense of them. You need to learn a language as well so that the computer can be instructed.

So, this is what this book is for. We will show you one way in which you can code successfully, and we will try to do that by means of many simple but focused examples (our favorite kind).

In this chapter, we are going to cover the following:

- Python’s characteristics and ecosystem

- Guidelines on how to get up and running with Python and virtual environments

- How to run Python programs

- How to organize Python code and its execution model

A proper introduction

We love to make references to the real world when we teach coding; we believe they help people to better retain their concepts. However, now is the time to be a bit more rigorous and see what coding is from a more technical perspective.

When we write code, we are instructing a computer about the things it has to do. Where does the action happen? In many places: the computer memory, hard drives, network cables, the CPU, and so on. It is a whole world, which most of the time is the representation of a subset of the real world.

If you write a piece of software that allows people to buy clothes online, you will have to represent real people, real clothes, real brands, sizes, and so on and so forth, within the boundaries of a program.

To do this, you will need to create and handle objects in your program. A person can be an object. A car is an object. A pair of trousers is an object. Luckily, Python understands objects very well.

The two key features any object has, are properties and methods. Let us take the example of a person as an object. Typically, in a computer program, you will represent people as customers or employees. The properties that you store against them are things like a name, a Social Security number, an age, whether they have a driving license, an email, and so on. In a computer program, you store all the data needed in order to use an object for the purpose that needs to be served. If you are coding a website to sell clothes, you probably want to store the heights and weights as well as other measures of your customers so that the appropriate clothes can be suggested to them. So, properties are characteristics of an object. We use them all the time: Could you pass me that pen? —Which one? —The black one. Here, we used the color (black) property of a pen to identify it (most likely it was being kept alongside different colored pens for the distinction to be necessary).

Methods are actions that an object can perform. As a person, I have methods such as speak, walk, sleep, wake up, eat, dream, write, read, and so on. All the things that I can do could be seen as methods of the objects that represent me.

So, now that you know what objects are, that they expose methods that can be run and properties that you can inspect, you are ready to start coding. Coding, in fact, is simply about managing those objects that live in the subset of the world we’re reproducing in our software. You can create, use, reuse, and delete objects as you please.

According to the Data Model chapter on the official Python documentation (https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.xhtml):

“Objects are Python’s abstraction for data. All data in a Python program is represented by objects or by relations between objects.”

We will take a closer look at Python objects in Chapter 6, OOP, Decorators, and Iterators. For now, all we need to know is that every object in Python has an ID (or identity), a type, and a value.

Once created, the ID of an object never changes. It is a unique identifier for it, and it is used behind the scenes by Python to retrieve the object when we want to use it. The type also never changes. The type states what operations are supported by the object and the possible values that can be assigned to it. We will see Python’s most important data types in Chapter 2, Built-In Data Types. The value of some objects can change, such objects are said to be mutable. If the value cannot be changed, the object is said to be immutable.

How, then, do we use an object? We give it a name, of course! When you give an object a name, then you can use the name to retrieve the object and use it. In a more generic sense, objects, such as numbers, strings (text), and collections, are associated with a name. In other languages, the name is normally called a variable. You can see the variable as being like a box, which you can use to hold data.

Objects represent data. It is stored in databases or sent over network connections. It is what you see when you open any webpage, or work on a document. Computer programs manipulate that data to perform all sorts of actions. They regulate its flow, evaluate conditions, react to events, and much more.

To do all this, we need a language. That is what Python is for. Python is the language we will use together throughout this book to instruct the computer to do something for us.

Enter the Python

Python is the marvelous creation of Guido Van Rossum, a Dutch computer scientist and mathematician who decided to gift the world with a project he was playing around with over Christmas 1989. The language appeared to the public somewhere around 1991, and since then has evolved to be one of the leading programming languages used worldwide today.

We (the authors) started programming when we were both very young. Fabrizio started at the age of 7, on a Commodore VIC-20, which was later replaced by its bigger brother, the Commodore 64. The language it used was BASIC. Heinrich started when he learned Pascal in high school. Between us, we’ve programmed in Pascal, Assembly, C, C++, Java, JavaScript, Visual Basic, PHP, ASP, ASP .NET, C#, and plenty of others we can’t even remember; only when we landed on Python had we finally get the feeling that you go through when you find the right couch in the shop. When all of your body is yelling: Buy this one! This one is perfect!

It took us about a day to become accustomed to it. Its syntax is a bit different from what we were used to, but after getting past that initial feeling of discomfort (like having new shoes), we both just fell in love with it. Deeply. Let us see why.

About Python

Before we get into the gory details, let us get a sense of why someone would want to use Python (we recommend you read the Python page on Wikipedia to get a more detailed introduction).

In our opinion, Python epitomizes the following qualities.

Portability

Python runs everywhere, and porting a program from Linux to Windows or Mac is usually just a matter of fixing paths and settings. Python is designed for portability, and it takes care of specific operating system (OS) quirks

behind interfaces that shield you from the pain of having to write code tailored to a specific platform.

Coherence

Python is extremely logical and coherent. You can see it was designed by a brilliant computer scientist. Most of the time you can just guess how a method is called if you do not know it.

You may not realize how important this is right now, especially if you are not that experienced as a programmer, but this is a major feature. It means less cluttering in your head, as well as less skimming through the documentation, and less need for mappings in your brain when you code.

Developer productivity

According to Mark Lutz (Learning Python, 5th Edition, O’Reilly Media), a Python program is typically one-fifth to one-third the size of equivalent Java or C++ code. This means the job gets done faster. And faster is good. Faster means being able to respond more quickly to the market. Less code not only means less code to write, but also less code to read (and professional coders read much more than they write), maintain, debug, and refactor.

Another important aspect is that Python runs without the need for lengthy and time-consuming compilation and linkage steps, so there is no need to wait to see the results of your work.

An extensive library

Python has an incredibly extensive standard library (it is said to come with batteries included). If that wasn’t enough, the Python international community maintains a body of third-party libraries, tailored to specific needs, which you can access freely at the Python Package Index (PyPI). When you code in Python and realize that a certain feature is required, in most cases, there is at least one library where that feature has already been implemented.

Software quality

Python is heavily focused on readability, coherence, and quality. The language’s uniformity allows for high readability, and this is crucial nowadays, as coding is more of a collective effort than a solo endeavor. Another important aspect of Python is its intrinsic multiparadigm nature. You can use it as a scripting language, but you can also employ object-oriented, imperative, and functional programming styles—it is extremely versatile.

Software integration

Another important aspect is that Python can be extended and integrated with many other languages, which means that even when a company is using a different language as their mainstream tool, Python can come in and act as a gluing agent between complex applications that need to talk to each other in some way. This is more of an advanced topic, but in the real world, this feature is important.

Data Science

Python is among the most popular (if not the most popular) languages used in the fields of Data Science, Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence today. Knowledge of Python is therefore almost essential for those who want to have a career in these fields.

Satisfaction and enjoyment

Last, but by no means least, there is the fun of it! Working with Python is fun; we can code for eight hours and leave the office happy and satisfied, unaffected by the struggle other coders have to endure because they use languages that do not provide them with the same amount of well-designed data structures and constructs. Python makes coding fun, no doubt about it. And fun promotes motivation and productivity.

These are the major reasons why we would recommend Python to everyone. Of course, there are many other technical and advanced features that we could have mentioned, but they do not really pertain to an introductory section like this one. They will come up naturally, chapter after chapter, as we learn about Python in greater detail.

…

What are the drawbacks?

Probably, the only drawback that one could find in Python, which is not due to personal preferences, is its execution speed. Typically, Python is slower than its compiled siblings. The standard implementation of Python produces, when you run an application, a compiled version of the source code called byte code (with the extension .pyc), which is then run by the Python interpreter. The advantage of this approach is portability, which we pay for with increased runtimes because Python is not compiled down to the machine level, as other languages are.

Despite this, Python speed is rarely a problem today, hence its wide use regardless of this aspect. What happens is that, in real life, hardware cost is no longer a problem, and usually it is easy enough to gain speed by parallelizing tasks. Moreover, many programs spend a great proportion of the time waiting for I/O operations to complete; therefore, the raw execution speed is often a secondary factor to the overall performance.

It is worth noting that Python’s core developers have put great effort into speeding up operations on the most common data structures, in the last few years. This effort, in some cases very successful, has somewhat alleviated this issue.

In situations where speed really is crucial, one can switch to faster Python implementations, such as PyPy, which provides, on average, just over a four-fold speedup by implementing advanced compilation techniques (check https://pypy.org/ for reference). It is also possible to write performance-critical parts of your code in faster languages, such as C or C++, and integrate that with your Python code. Libraries such as pandas and NumPy (which are commonly used for doing data science in Python) use such techniques.

There are a few different implementations of the Python language. In this book, we will use the reference implementation, known as CPython. You can find a list of other implementations at: https://www.python.org/download/alternatives/

If that is not convincing enough, you can always consider that Python has been used to drive the backend of services such as Spotify and Instagram, where performance is a concern. From this, it can be seen that Python has done its job perfectly well.

Who is using Python today?

Python is used in many different contexts, such as system programming, web and API programming, GUI applications, gaming and robotics, rapid prototyping, system integration, data science, database applications, realtime communication, and much more. Several prestigious universities have also adopted Python as their main language in computer science courses.

Here is a list of major companies and organizations that are known to use Python in their technology stack, product development, data analysis, or automation processes:

Tech industry

Google: Uses Python for many tasks including back-end services, data analysis, and artificial intelligence (AI).

Facebook: Utilizes Python for various purposes, including infrastructure management and operational automation.

Instagram: Relies heavily on Python for its backend, making it one of the largest Django (a Python web framework) users.

Spotify: Employs Python mainly for data analysis and backend services.

Netflix: Uses Python for data analysis, operational automation, and security.

Financial sector

JP Morgan Chase: Uses Python for financial models, data analysis, and algorithmic trading.

Goldman Sachs: Employs Python for various financial models and applications.

Bloomberg: Uses Python for financial data analysis and its Bloomberg Terminal interface.

Technology and software

IBM: Utilizes Python for AI, machine learning, and cybersecurity.

Intel: Uses Python for hardware testing and development processes.

Dropbox: The desktop client is largely written in Python.

Space and research

NASA: Uses Python for various purposes, including data analysis and system integration.

CERN: Employs Python for data processing and analysis in physics experiments.

Retail and e-Commerce

Amazon: Uses Python for data analysis, product recommendations, and operational automation.

eBay: Utilizes Python for various backend services and data analysis.

Entertainment and media

Pixar: Uses Python for animation software and scripting in the animation process.

Industrial Light & Magic (ILM): Employs Python for visual effects and image processing.

Education and learning platforms

Coursera: Utilizes Python for web development and backend services.

Khan Academy: Uses Python for educational content delivery and backend services.

Government and non-profit

The United States Federal Government: Has various departments and agencies using Python for data analysis, cybersecurity, and automation.

The Raspberry Pi Foundation: Uses Python as a primary programming language for educational purposes and projects.

Setting up the environment

On our machines (MacBook Pro), this is the latest Python version:

>>> import sys

>>> print(sys.version)

3.12.2 (main, Feb 14 2024, 14:16:36) [Clang 15.0.0 (clang-1500.1.0.2.5)]So, you can see that the version is 3.12.2, which was out on the 2 nd of October 2023. The preceding text is a little bit of Python code that was typed into a console. We will talk about this in a moment.

All the examples in this book will be run using Python 3.12. If you wish to follow the examples and download the source code for this book, please make sure you are using the same version.

Installing Python

The process of installing Python on your computer depends on the operating system you have. First of all, Python is fully integrated and, most likely, already installed in almost every Linux distribution. If you have a recent version of macOS, it is likely that Python 3 is already there as well, whereas if you are using Windows, you probably need to install it.

Regardless of Python being already installed in your system, you will need to make sure that you have version 3.12 installed.

The place you want to start is the official Python website: https://www.python.org. This website hosts the official Python documentation and many other resources that you will find very useful.

Useful installation resources

The Python website hosts useful information regarding the installation of Python on various operating systems. Please refer to the relevant page for your operating system.

Windows and macOS:

For linux instead, please refer to the following links:

Installing Python on Windows

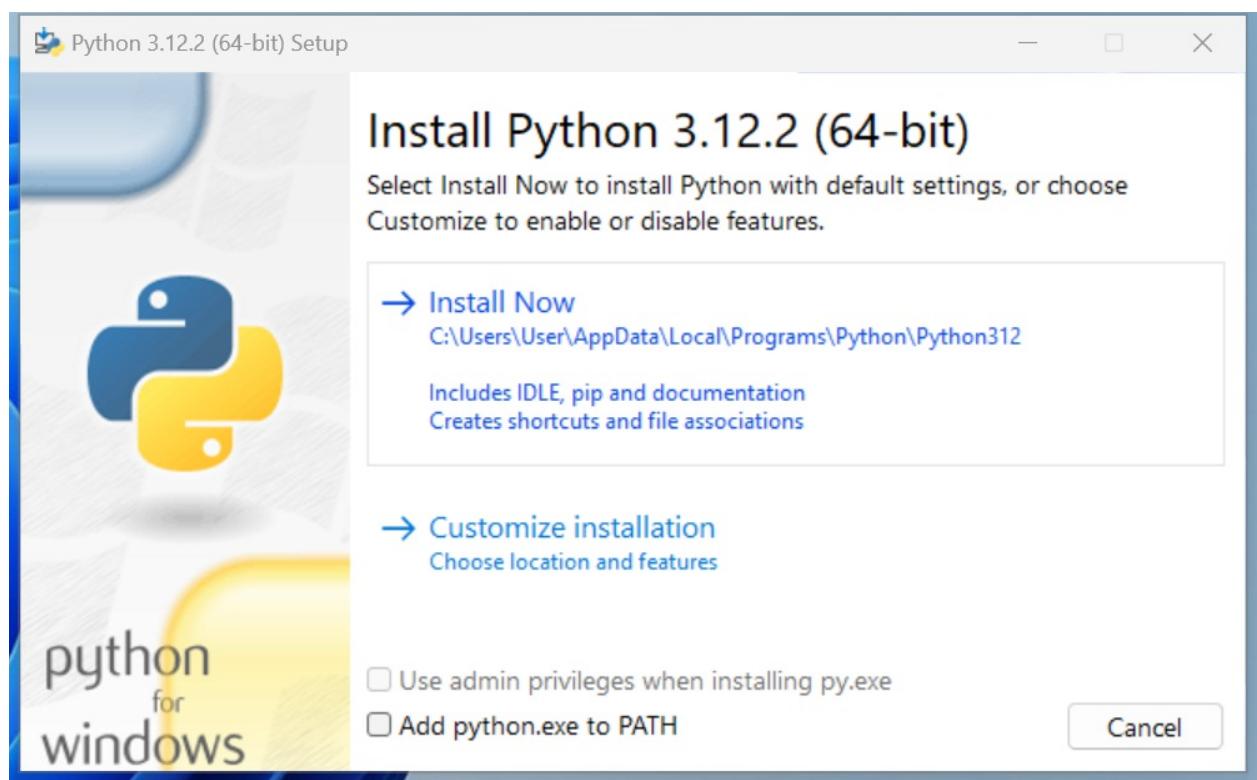

As an example, this is the procedure to install Python on Windows. Head to https://www.python.org/downloads/ and download the appropriate installer according to the CPU of your computer.

Once you have it, you can double click on it in order to start the installation.

Figure 1.1: Starting the installation process on Windows

We recommend choosing the default install, and NOT ticking the Add python.exe to PATH option to avoid clashes with other versions of Python that might be installed on your machine, potentially by other users.

For a more comprehensive set of guidelines, please refer to the link indicated in the previous paragraph.

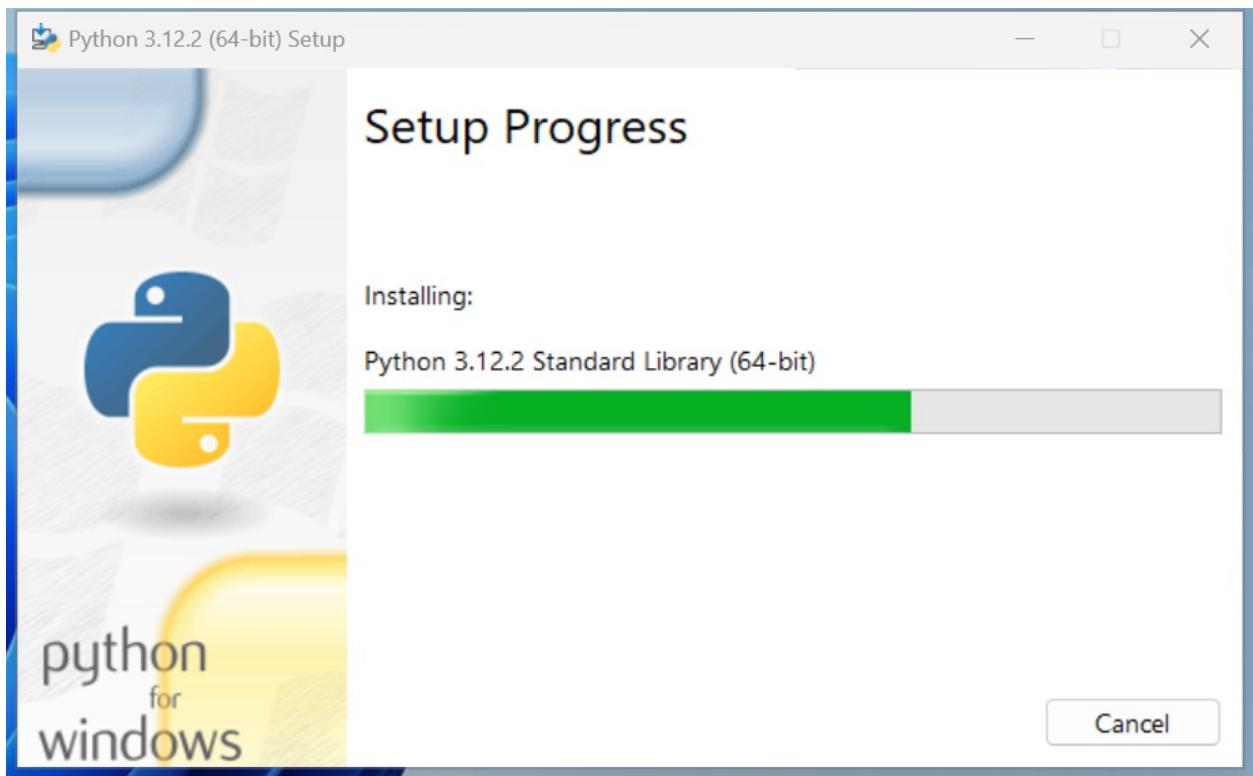

Once you click on Install Now, the installation procedure will begin.

Figure 1.2: Installation in progress

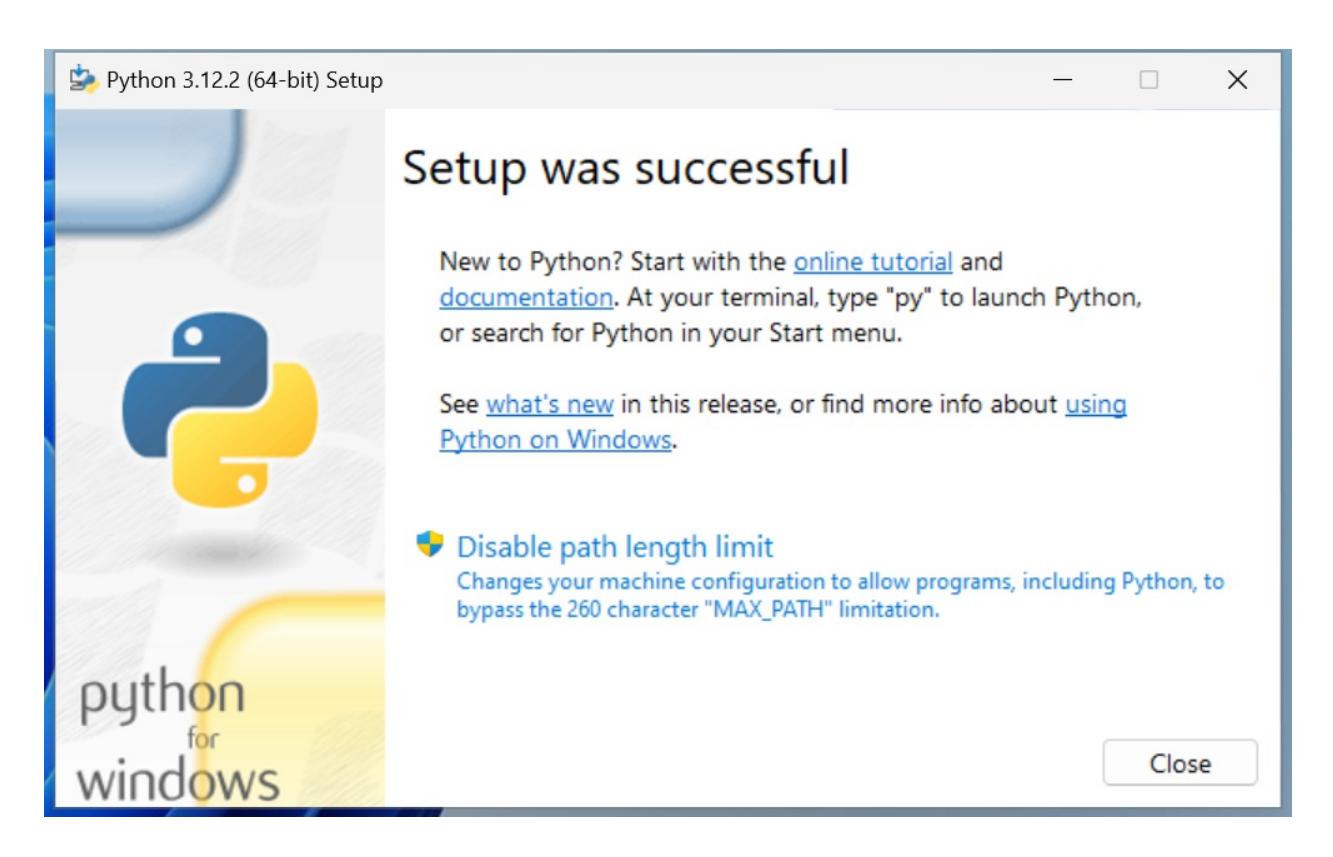

Once the installation is complete, you will land on the final screen.

Click on Close to finish the installation.

Now that Python is installed on your system, open a command prompt and run the Python interactive shell by typing py . This command will select the latest version of Python installed on your machine. At the time of writing, 3.12 is the latest available version of Python. In case you have a more recent version installed, you can specify the version with the command py -3.12 .

To open the command prompt in Windows, go to the Start menu, and type cmd in the search box, to start your terminal up. Alternatively, you can also use the Powershell.

Installing Python on macOS

On macOS, the installation procedure is similar to that of Windows. Once you have downloaded the appropriate installer for your machine, complete the installation steps, and then start a terminal by going to Applications > Utilities > Terminal.

Once in the terminal window, you can type python . If that launches the wrong version, you can try and specify either with python3 or python3.12 .

Installing Python on Linux

The process of installing Python on linux is normally a bit more complex than that for Windows or macOS. The best course of action, if you are on a linux machine, is to search the most up-to-date set of steps for your distribution online. These will likely be quite different from one distribution to another, so it is difficult to give an example that would be relevant for everyone. Please do refer to the link in the Useful Installation Resources section, for guidance.

The Python Console

We will use the term console interchangeably to indicate the Linux console, the Windows Command Prompt or the Powershell, and the macOS Terminal. We will also indicate the command-line prompt with the Linux default format, like this:

$ sudo apt-get updateIf you are not familiar with that, please take some time to learn the basics of how a console works. In a nutshell, after the $ sign, you will type your instructions. Pay attention to capitalization and spaces, as they are very important.

Whatever console you open, type python at the prompt ( py on Windows), and make sure the Python interactive shell shows up. Type exit() to quit. Keep in mind that you may have to specify python3 or python3.12 if your OS comes with other Python versions preinstalled.

We often refer to the Python interactive shell simply as the Python console.

This is roughly what you should see when you run Python (it will change in some details according to the version and OS):

$ python

Python 3.12.2 (main, Feb 14 2024, 14:16:36)

[Clang 15.0.0 (clang-1500.1.0.2.5)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>Now that Python is set up and you can run it, it is time to make sure you have the other tool that will be indispensable to follow the examples in the book: a virtual environment.

About virtual environments

When working with Python, it is very common to use virtual environments. Let us see what they are and why we need them by means of a simple example.

You install Python on your system, and you start working on a website for Client X. You create a project folder and start coding. Along the way, you also install some libraries, for example, the Django framework. Let us say the Django version you installed for Project X is 4.2.

Now, your website is so good that you get another client, Y. She wants you to build another website, so you start Project Y and, along the way, you need to install Django again. The only issue is that now the Django version is 5.0 and you cannot install it on your system because this would replace the version you installed for Project X. You do not want to risk introducing incompatibility issues, so you have two choices: either you stick with the version you have currently on your machine, or you upgrade it and make sure the first project is still fully working correctly with the new version.

Let us be honest, neither of these options is very appealing, right? Definitely not. But there is a solution: virtual environments!

Virtual environments are isolated Python environments, each of which is a folder that contains all the necessary executables to use the packages that a Python project would need (think of packages as libraries for the time being).

So, you create a virtual environment for Project X, install all the dependencies, and then you create a virtual environment for Project Y, and install all its dependencies without the slightest worry because every library you install ends up within the boundaries of the appropriate virtual environment. In our example, Project X will hold Django 4.2, while Project Y will hold Django 5.0.

It is of great importance that you never install libraries directly at the system level. Linux, for example, relies on Python for many different tasks and operations, and if you fiddle with the system installation of Python, you risk compromising the integrity of the entire system. So, take this as a rule: always create a virtual environment when you start a new project.

When it comes to creating a virtual environment on your system, there are a few different methods to carry this out. As of Python 3.5, the suggested way to create a virtual environment is to use the venv module. You can look it up on the official documentation page (https://docs.python.org/3/library/venv.xhtml) for further information.

If you are using a Debian-based distribution of Linux, for example, you will need to install the venv module before you can use it:

$ sudo apt-get install python3.12-venv

Another common way of creating virtual environments is to use the virtualenv third-party Python package. You can find it on its official website: https://virtualenv.pypa.io.

In this book, we will use the recommended technique, which leverages the venv module from the Python standard library.

Your first virtual environment

It is very easy to create a virtual environment, but according to how your system is configured and which Python version you want the virtual environment to run on, you need to run the command properly. Another thing you will need to do, when you want to work with it, is to activate it. Activating virtual environments produces some path juggling behind the scenes so that when you call the Python interpreter from that shell, you are actually calling the active virtual environment one, instead of the system one. We will show you a full example on macOS and Windows (on Linux it will be very similar to that of macOS). We will:

Open a terminal and change into the folder (directory) we use as root for our projects (our folder is code ). We

are going to create a new folder called my-project and change into it.

- Create a virtual environment called lpp4ed .

- After creating the virtual environment, we will activate it. The methods are slightly different between Linux, macOS, and Windows.

- Then, we will make sure that we are running the desired Python version (3.12.X) by running the Python interactive shell.

- Finally, we will deactivate the virtual environment.

Some developers prefer to call all virtual environments with the same name (for example, .venv ). This way they can configure tools and run scripts against any virtual environment by just knowing their location. The dot in .venv is there because in Linux/macOS, prepending a name with a dot makes that file or folder “invisible”.

These steps are all you need to start a project.

We are going to start with an example on macOS (note that you might get a slightly different result, according to your OS, Python version, and so on). In this listing, lines that start with a hash, # , are comments, spaces have been introduced for readability, and an arrow, → , indicates where the line has wrapped around due to lack of space:

fab@m1:~/code$ mkdir my-project # step 1

fab@m1:~/code$ cd my-project

fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ which python3.12 # check system python

/usr/bin/python3.12 # <-- system python3.12

fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ python3.12 -m venv lpp4ed # step 2

fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ source ./lpp4ed/bin/activate # step 3

# check python again: now using the virtual environment's one

(lpp4ed) fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ which python

/Users/fab/code/my-project/lpp4ed/bin/python

(lpp4ed) fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ python # step 4

Python 3.12.2 (main, Feb 14 2024, 14:16:36)

→ [Clang 15.0.0 (clang-1500.1.0.2.5)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> exit()

(lpp4ed) fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ deactivate # step 5

fab@m1:~/code/my-project$Each step has been marked with a comment, so you should be able to follow along quite easily.

Something to notice here is that to activate the virtual environment, we need to run the lpp4ed/bin/activate script, which needs to be sourced. When a script is sourced, it means that it is executed in the current shell, and its effects last after the execution. This is very important. Also notice how the prompt changes after we activate the virtual environment, showing its name on the left (and how it disappears when we deactivate it).

On a Windows 11 Powershell, the steps are as follows:

PS C:\Users\H\Code> mkdir my-project # step 1

PS C:\Users\H\Code> cd .\my-project\

# check installed python versions

PS C:\Users\H\Code\my-project> py --list-paths

-V:3.12 *

→ C:\Users\H\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python312\python.exe

PS C:\Users\H\Code\my-project> py -3.12 -m venv lpp4ed # step 2

PS C:\Users\H\Code\my-project> .\lpp4ed\Scripts\activate # step 3

# check python versions again: now using the virtual environment's

(lpp4ed) PS C:\Users\H\Code\my-project> py --list-paths

*

→ C:\Users\H\Code\my-project\lpp4ed\Scripts\python.exe

-V:3.12

→ C:\Users\H\AppData\Local\Programs\Python\Python312\python.exe

(lpp4ed) PS C:\Users\H\Code\my-project> python # step 4

Python 3.12.2 (tags/v3.12.2:6abddd9, Feb 6 2024, 21:26:36)

→ [MSC v.1937 64 bit (AMD64)] on win32

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more

→ information.

>>> exit()

(lpp4ed) PS C:\Users\H\Code\my-project> deactivate # step 5Notice how on Windows, after activating the virtual environment, you can either use the py command or, more directly, python .

At this point, you should be able to create and activate a virtual environment. Please try and create another one on your own. Get acquainted with this procedure—it is something that you will always be doing: we never work system-wide with Python, remember? Virtual environments are extremely important.

The source code for the book contains a dedicated folder for each chapter. When the code shown in the chapter requires third-party libraries to be installed, we will include a requirements.txt file (or an equivalent requirements folder with more than one text file inside) that you can use to install the libraries required to run that code. We suggest that when experimenting with the code for a chapter, you create a dedicated virtual environment for that chapter. This way, you will be able to get some practice in the creation of virtual environments, and the installation of third-party libraries.

Installing third-party libraries

In order to install third-party libraries, we need to use the Python Package Installer, known as pip. Chances are that it is already available to you within your virtual environment, but if not, you can learn all about it on its documentation page: https://pip.pypa.io.

The following example shows how to create a virtual environment and install a couple of third-party libraries taken from a requirements file.

fab@m1:~/code$ mkdir my-project

fab@m1:~/code$ cd my-project

fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ python3.12 -m venv lpp4ed

fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ source ./lpp4ed/bin/activate

(lpp4ed) fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ cat requirements.txt

django==5.0.3

requests==2.31.0

# the following instruction shows how to use pip to install

# requirements from a file

(lpp4ed) fab@m1:~/code/my-project$ pip install -r requirements.txt

Collecting django==5.0.3 (from -r requirements.txt (line 1))

Using cached Django-5.0.3-py3-none-any.whl.metadata (4.2 kB)

Collecting requests==2.31.0 (from -r requirements.txt (line 2))

Using cached requests-2.31.0-py3-none-any.whl.metadata (4.6 kB)

... more collecting omitted ...

Installing collected packages: ..., requests, django

Successfully installed ... django-5.0.3 requests-2.31.0

(lpp4ed) fab@m1:~/code/my-project$As you can see at the bottom of the listing, pip has installed both libraries that are in the requirements file, plus a few more. This happened because both django and requests have their own list of third-party libraries that they depend upon, and therefore pip will install them automatically for us.

Now, with the scaffolding out of the way, we are ready to talk a bit more about Python and how it can be used. Before we do that though, allow us to say a few words about the console.

The console

In this era of GUIs and touchscreen devices, it may seem a little ridiculous to have to resort to a tool such as the console, when everything is just about one click away.

But the truth is every time you remove your hand from the keyboard to grab your mouse and move the cursor over to the spot you want to click on, you’re losing time. Getting things done with the console, counter-intuitive though it may at first seem, results in higher productivity and speed. Believe us, we know—you will have to trust us on this.

Speed and productivity are important, and even though we have nothing against the mouse, being fluent with the

console is very good for another reason: when you develop code that ends up on some server, the console might be the only available tool to access the code on that server. If you make friends with it, you will never get lost when it is of utmost importance that you do not (typically, when the website is down, and you have to investigate very quickly what has happened).

If you are still not convinced, please give us the benefit of the doubt and give it a try. It is easier than you think, and you will not regret it. There is nothing more pitiful than a good developer who gets lost within an SSH connection to a server because they are used to their own custom set of tools, and only to that.

Now, let us get back to Python.

How to run a Python program

There are a few different ways in which you can run a Python program.

Running Python scripts

Python can be used as a scripting language; in fact, it always proves itself very useful. Scripts are files (usually of small dimensions) that you normally execute to do something like a task. Many developers end up having their own arsenal of tools that they fire when they need to perform a task. For example, you can have scripts to parse data in a format and render it into another one; or you can use a script to work with files and folders; you can create or modify configuration files—technically, there is not much that cannot be done in a script.

It is rather common to have scripts running at a precise time on a server. For example, if your website database needs cleaning every 24 hours (for example, to regularly clean up expired user sessions), you could set up a Cron job that fires your script at 1:00 A.M. every day.

According to Wikipedia, the software utility Cron is a time-based job scheduler in Unix-like computer operating systems. People who set up and maintain software environments use Cron (or a similar technology) to schedule jobs (commands or shell scripts) to run periodically at fixed times, dates, or intervals.

We have Python scripts to do all the menial tasks that would take us minutes or more to do manually, and at some point, we decided to automate.

Running the Python interactive shell

Another way of running Python is by calling the interactive shell. This is something we already saw when we typed python on the command line of our console.

So, open up a console, activate your virtual environment (which by now should be second nature to you, right?), and type python . You will be presented with a few lines that should look something like this:

(lpp4ed) fab@m1 ~/code/lpp4ed$ python

Python 3.12.2 (main, Feb 14 2024, 14:16:36)

[Clang 15.0.0 (clang-1500.1.0.2.5)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more

information.

>>>Those >>> are the prompt of the shell. They tell you that Python is waiting for you to type something. If you type a simple instruction, something that fits in one line, that is all you will see. However, if you type something that requires more than one line of code, the shell will change the prompt to … , giving you a visual clue that you are typing a multiline statement (or anything that would require more than one line of code).

Go on, try it out; let us do some basic math:

>>> 3 + 7

10>>> 10 / 4

2.5

>>> 2 ** 1024

179769313486231590772930519078902473361797697894230657273430081157

732675805500963132708477322407536021120113879871393357658789768814

416622492847430639474124377767893424865485276302219601246094119453

082952085005768838150682342462881473913110540827237163350510684586

298239947245938479716304835356329624224137216The last operation is showing you something incredible. We raise 2 to the power of 1024 , and Python handles this task with no trouble at all. Try to do it in Java, C++, or C#. It will not work, unless you use special libraries to handle such big numbers.

We use the interactive shell every day. It is extremely useful to debug very quickly; for example, to check if a data structure supports an operation. Or to inspect or run a piece of code.

The Django web framework provides an integration for the shell that allows you to work your way through the framework tools, to inspect the data in the database, and much more. You will find that the interactive shell soon becomes one of your dearest friends on this journey you are embarking on.

Another solution, which comes in a much nicer graphic layout, is to use the Integrated Development and Learning Environment (IDLE). It is quite a simple Integrated Development Environment (IDE), which is intended mostly for beginners. It has a slightly larger set of capabilities than the bare interactive shell you get in the console, so you may want to explore it. It comes for free in the Windows and macOS Python installers and you can easily install it on any other system. You can find more information about it on the Python website.

Guido Van Rossum named Python after the British comedy group, Monty Python, so it is rumored that the name IDLE was chosen in honor of Eric Idle, one of Monty Python’s founding members.

Running Python as a service

Apart from being run as a script, and within the boundaries of a shell, Python can be coded and run as an application. We will see examples throughout this book of this mode. We will understand more about it in a moment, when we talk about how Python code is organized and run.

Running Python as a GUI application

Python can also be run as a Graphical User Interface (GUI). There are several frameworks available, some of which are cross-platform, and some others that are platform-specific. A popular example of a GUI application library is Tkinter, which is an object-oriented layer that lives on top of Tk (Tkinter means Tk interface).

Tk is a GUI toolkit that takes desktop application development to a higher level than the conventional approach. It is the standard GUI for Tool Command Language (Tcl), but also for many other dynamic languages, and it can produce rich native applications that run seamlessly under Windows, Linux, macOS, and more.

Tkinter comes bundled with Python; therefore, it gives the programmer easy access to the GUI world.

Other widely used GUI frameworks include:

- PyQT/PySide

- wxPython

- Kivy

Describing them in detail is outside the scope of this book, but you can find all the information you need on the Python website:

https://docs.python.org/3/faq/gui.xhtml

Information can be found in the What GUI toolkits exist for Python? section. If GUIs are what you are looking for, remember to choose the one you want according to some basic principles. Make sure they:

- Offer all the features you may need to develop your project

- Run on all the platforms you may need to support

- Rely on a community that is as wide and active as possible

- Wrap graphic drivers/tools that you can easily install/access

How is Python code organized?

Let us talk a little bit about how Python code is organized. In this section, we will start to enter the proverbial rabbit hole and introduce more technical names and concepts.

Starting with the basics, how is Python code organized? Of course, you write your code into files. When you save a file with the extension .py , that file is said to be a Python module.

If you are on Windows or macOS, which typically hide file extensions from the user, we recommend that you change the configuration so that you can see the complete names of the files. This is not strictly a requirement, only a suggestion that may come in handy when discerning files from each other.

It would be impractical to save all the code that it is required for software to work within one single file. That solution works for scripts, which are usually not longer than a few hundred lines (and often they are shorter than that).

A complete Python application can be made of hundreds of thousands of lines of code, so you will have to scatter it through different modules, which is better, but not good enough. It turns out that even like this, it would still be impractical to work with the code. So, Python gives you another structure, called a package, which allows you to group modules together. A package is nothing more than a folder. In earlier versions of Python one was also required to include a special file, __init__.py . This file does not need to contain any code, and even though its presence is not mandatory anymore, there are practical reasons for which it is always a good idea to include it nonetheless.

As always, an example will make all this much clearer. We have created an illustration structure in our book project, and when we type in the console:

$ tree -v exampleWe get a tree representation of the contents of the ch1/example folder, which contains the code for the examples of this chapter. Here is what the structure of a simple application could look like:

example

├── core.py

├── run.py

└── util

├── __init__.py

├── db.py

├── maths.py

└── network.pyYou can see that within the root of this example, we have two modules, core.py and run.py , and one package, util . Within core.py , there may be the core logic of our application. On the other hand, within the run.py module, we can probably find the logic to start the application. Within the util package, we expect to find various utility tools, and in fact, we can guess that the modules there are named based on the types of tools they hold: db.py would hold tools to work with databases, maths.py would, of course, hold mathematical tools (maybe our application deals with financial data), and network.py would probably hold tools to send/receive data on networks.

As explained before, the __init__.py file is there just to tell Python that util is a package and not just a simple folder.

Had this software been organized within modules only, it would have been harder to infer its structure. We placed a module only example under the ch1/files_only folder; see it for yourself:

$ tree -v files_onlyThis shows us a completely different picture:

files_only

├── core.py

├── db.py

├── maths.py

├── network.py

└── run.pyIt is a little harder to guess what each module does, right? Now, consider that this is just a simple example, so you can guess how much harder it would be to understand a real application if we could not organize the code into packages and modules.

How do we use modules and packages?

When a developer is writing an application, it is likely that they will need to apply the same piece of logic in different parts of it. For example, when writing a parser for the data that comes from a form that a user can fill in a web page, the application will have to validate whether a certain field is holding a number or not. Regardless of how the logic for this kind of validation is written, it is likely that it will be needed for more than one field.

For example, in a poll application, where the user is asked many questions, it is likely that several of them will require a numeric answer. These might be:

- What is your age?

- How many pets do you own?

- How many children do you have?

- How many times have you been married?

It would be bad practice to copy/paste (or, said more formally, duplicate) the validation logic in every place where we expect a numeric answer. This would violate the don’t repeat yourself (DRY) principle, which states that you should never repeat the same piece of code more than once in your application. Despite the DRY principle, we feel the need here to stress the importance of this principle: you should never repeat the same piece of code more than once in your application!

There are several reasons why repeating the same piece of logic can be bad, the most important ones being:

- There could be a bug in the logic, and therefore you would have to correct it in every copy.

- You may want to amend the way you carry out the validation, and again, you would have to change it in every copy.

- You may forget to fix or amend a piece of logic because you missed it when searching for all its occurrences. This would leave wrong or inconsistent behavior in your application.

- Your code would be longer than needed for no good reason.

Python is a wonderful language and provides you with all the tools you need to apply the coding best practices. For this example, we need to be able to reuse a piece of code. To do this effectively, we need to have a construct that will hold the code for us so that we can call that construct every time we need to repeat the logic inside it. That construct exists, and it is called a function.

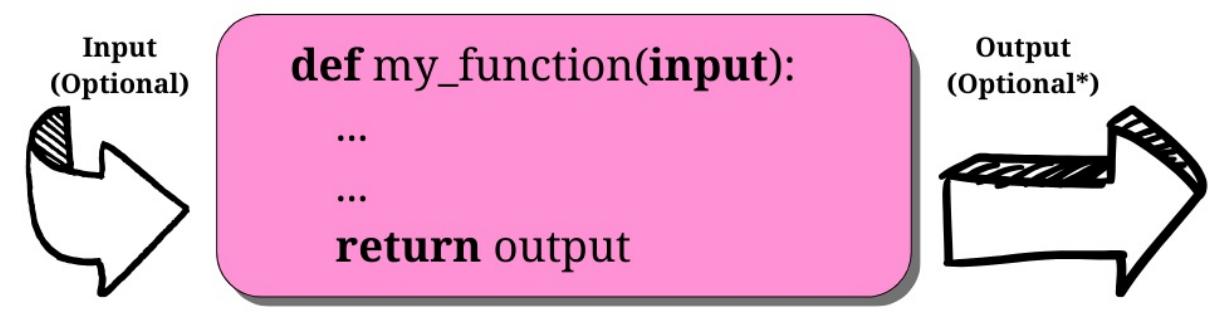

We are not going too deep into the specifics here, so please just remember that a function is a block of organized, reusable code that is used to perform a task. Functions can assume many forms and names, according to what kind of environment they belong to, but for now this is not important. Details will be seen once we are able to appreciate them, later, in the book. Functions are the building blocks of modularity in your application, and they are almost indispensable. Unless you are writing a super-simple script, functions will be used all the time. Functions will be explored in Chapter 4, Functions, the Building Blocks of Code.

Python comes with a very extensive library, as mentioned a few pages ago. Now is a good time to define what a library is: a collection of functions and objects that provide functionalities to enrich the abilities of a language. For example, within Python’s math library, a plethora of functions can be found, one of which is the factorial function, which calculates the factorial of a number.

In mathematics, the factorial of a non-negative integer number, N, denoted as N!, is defined as the product of all positive integers less than or equal to N. For example, the factorial of 5 is calculated as:

The factorial of 0 is 0! = 1, to respect the convention for an empty product.

So, if you wanted to use this function in your code, all you would have to do is to import it and call it with the right input values. Do not worry too much if input values and the concept of calling are not clear right now; please just concentrate on the import part. We use a library by importing what we need from it, which will then be used specifically. In Python, to calculate 5!, we just need the following code:

>>> from math import factorial

>>> factorial(5)

120Whatever we type in the shell, if it has a printable representation, will be printed in the console for us (in this case, the result of the function call: 120).

Let us go back to our example, the one with core.py , run.py , util , and so on. Here, the package util is our own utility library. This is our custom utility belt that holds all those reusable tools (that is, functions), which we need in our application. Some of them will deal with databases ( db.py ), some with the network ( network.py ), and some will perform mathematical calculations ( maths.py ) that are outside the scope of Python’s standard math library and, therefore, we must code them for ourselves.

We will see in detail how to import functions and use them in their dedicated chapter. Let us now talk about another important concept: Python’s execution model.

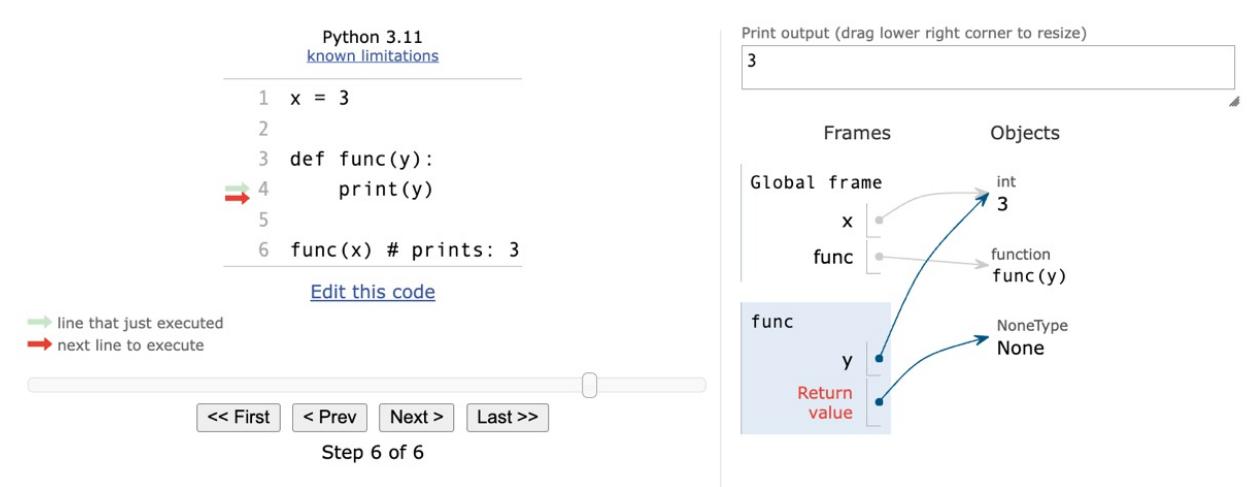

Python’s execution model

In this section, we would like to introduce you to some important concepts, such as scope, names, and namespaces. You can read all about Python’s execution model in the official language reference (https://docs.python.org/3/reference/executionmodel.xhtml), of course, but we would argue that it is quite technical and abstract, so let us give you a less formal explanation first.

Names and namespaces

Say you are looking for a book, so you go to the library and ask someone for it. They tell you something like Second Floor, Section X, Row Three. So, you go up the stairs, look for Section X, and so on. It would be very different to enter a library where all the books are piled together in random order in one big room. No floors, no sections, no rows, no order. Fetching a book would be extremely hard.

When we write code, we have the same issue: we have to try and organize it so that it will be easy for someone who has no prior knowledge about it to find what they are looking for. When software is structured correctly, it also promotes code reuse. Furthermore, disorganized software is more likely to contain scattered pieces of duplicated logic.

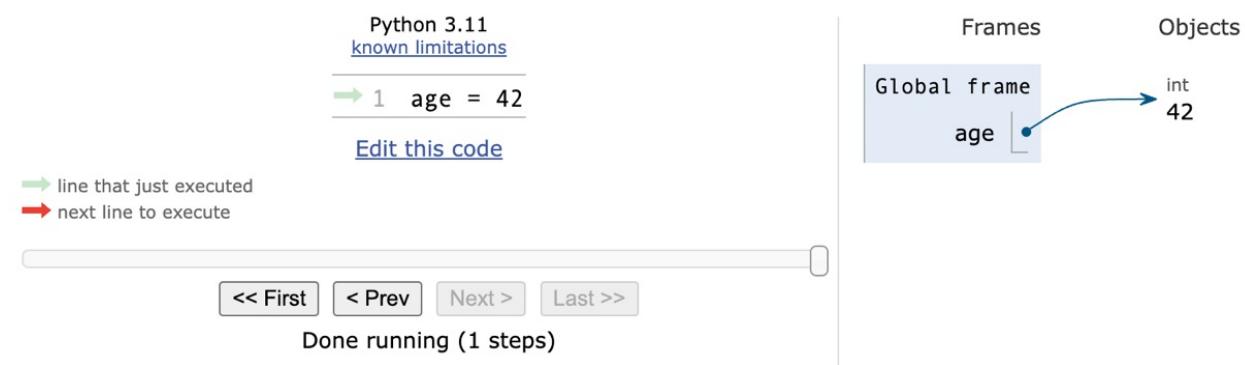

As a first example, let us take a book. We refer to a book by its title; in Python lingo, that would be a name. Python names are the closest abstraction to what other languages call variables. Names refer to objects and are introduced by name-binding operations. Let us see a quick example (again, notice that anything that follows a # is a comment):

>>> n = 3 # integer number

>>> address = "221b Baker Street, NW1 6XE, London" # Sherlock Holmes' address

>>> employee = {... 'age': 45,

... 'role': 'CTO',

... 'SSN': 'AB1234567',

... }

>>> # let us print them

>>> n

3

>>> address

'221b Baker Street, NW1 6XE, London'

>>> employee

{'age': 45, 'role': 'CTO', 'SSN': 'AB1234567'}

>>> other_name

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'other_name' is not defined

>>>Remember that each Python object has an identity, a type, and a value. We defined three objects in the preceding code; let us now examine their types and values:

- An integer number n (type: int , value: 3 )

- A string address (type: str , value: Sherlock Holmes’ address)

- A dictionary employee (type: dict , value: a dictionary object with three key/value pairs)

Fear not, we know we have not covered what a dictionary is. We will see, in Chapter 2, Built-In Data Types, that it is the king of Python data structures.

Have you noticed that the prompt changed from >>> to … when we typed in the definition of employee? That is because the definition spans over multiple lines.

So, what are n , address , and employee ? They are names, and these can be used to retrieve data from within our code. They need to be kept somewhere so that whenever we need to retrieve those objects, we can use their names to fetch them. We need some space to hold them, hence: namespaces!

A namespace is a mapping from names to objects. Examples are the set of built-in names (containing functions that are always accessible in any Python program), the global names in a module, and the local names in a function. Even the set of attributes of an object can be considered a namespace.

The beauty of namespaces is that they allow you to define and organize names with clarity, without overlapping or interference. For example, the namespace associated with the book we were looking for in the library could be used to import the book itself, like this:

from library.second_floor.section_x.row_three import bookWe start from the library namespace, and by means of the dot ( . ) operator, we walk into that namespace. Within this namespace, we look for second_floor , and again we walk into it with the . operator. We then walk into section_x , and finally, within the last namespace, row_three , we find the name we were looking for: book .

Walking through a namespace will be clearer when dealing with real code examples. For now, just keep in mind that namespaces are places where names are associated with objects.

There is another concept, closely related to that of a namespace, which we would like to mention briefly: scope.

Scopes

According to Python’s documentation:

“A scope is a textual region of a Python program, where a namespace is directly accessible.”

Directly accessible means that, when looking for an unqualified reference to a name, Python tries to find it in the namespace.

Scopes are determined statically, but at runtime, they are used dynamically. This means that by inspecting the source code, you can tell what the scope of an object is. There are four different scopes that Python makes accessible (not necessarily all of them are present at the same time, though):

- The local scope, which is the innermost one and contains the local names.

- The enclosing scope; that is, the scope of any enclosing function. It contains non-local names and non-global names.

- The global scope contains the global names.

- The built-in scope contains the built-in names. Python comes with a set of functions that you can use in an offthe-shelf fashion, such as print , all , abs , and so on. They live in the built-in scope.

The rule is the following: when we refer to a name, Python starts looking for it in the current namespace. If the name is not found, Python continues the search in the enclosing scope, and this continues until the built-in scope is searched. If a name has still not been found after searching the built-in scope, then Python raises a NameError exception, which basically means that the name has not been defined (as seen in the preceding example).

The order in which the namespaces are scanned when looking for a name is therefore local, enclosing, global, builtin (LEGB).

This is all theoretical, so let us see an example. To demonstrate local and enclosing namespaces, we will have to define a few functions. Do not worry if you are not familiar with their syntax for the moment—that will come in Chapter 4, Functions, the Building Blocks of Code. Just remember that in the following code, when you see def , it means we are defining a function:

# scopes1.py

# Local versus Global

# we define a function, called local

def local():

age = 7

print(age)

# we define age within the global scope

age = 5

# we call, or `execute` the function local

local()

print(age)In the preceding example, we define the same name age , in both the global and local scopes. When we execute this program with the following command (have you activated your virtual environment?):

$ python scopes1.pyWe see two numbers printed on the console: 7 and 5.

What happens is that the Python interpreter parses the file, top to bottom. First, it finds a couple of comment lines, which are skipped, then it parses the definition of the function local . When called, this function will do two things: it will set up a name to an object representing number 7 and will print it. The Python interpreter keeps going, and it finds another name binding. This time the binding happens in the global scope and the value is 5 . On the next line, there is a call to the function local . At this point, Python executes the function, so at this time, the binding age = 7 happens in the local scope and is printed. Finally, there is a call to the print function, which is executed and will now print 5 .

One particularly important thing to note is that the part of the code that belongs to the definition of the local function is indented by four spaces on the right. Python, in fact, defines scopes by indenting the code. You walk into a scope by indenting, and walk out of it by dedenting. Some coders use two spaces, others three, but the suggested number of spaces to use is four. It is a good measure to maximize readability. We will talk more about all the conventions you should embrace when writing Python code later.

In other languages, such as Java, C#, and C++, scopes are created by writing code within a pair of curly braces: { … } . Therefore, in Python, indenting code corresponds to opening a curly brace, while dedenting code

corresponds to closing a curly brace.

What would happen if we removed that age = 7 line? Remember the LEGB rule. Python would start looking for age in the local scope (function local ), and, not finding it, it would go to the next enclosing scope. The next one, in this case, is the global one. Therefore, we would see the number 5 printed twice on the console. Let us see what the code would look like in this case:

# scopes2.py

# Local versus Global

def local():

# age does not belong to the scope defined by the local function

# so Python will keep looking into the next enclosing scope.

# age is finally found in the global scope

print(age, 'printing from the local scope')

age = 5

print(age, 'printing from the global scope')

local()

Running scopes2.py will print this:

$ python scopes2.py

5 printing from the global scope

5 printing from the local scopeAs expected, Python prints age the first time, then when the function local is called, age is not found in its scope, so Python looks for it following the LEGB chain until age is found in the global scope. Let us see an example with an extra layer, the enclosing scope:

# scopes3.py

# Local, Enclosing and Global

def enclosing_func():

age = 13

def local():

# age does not belong to the scope defined by the local

# function so Python will keep looking into the next

# enclosing scope. This time age is found in the enclosing

# scope

print(age, 'printing from the local scope')

# calling the function local

local()

age = 5

print(age, 'printing from the global scope')

enclosing_func()

Running scopes3.py will print on the console:

$ python scopes3.py

5, 'printing from the global scope'

13, 'printing from the local scope'As you can see, the print instruction from the function local is referring to age as before. age is still not defined within the function itself, so Python starts walking scopes following the LEGB order. This time age is found in the enclosing scope.

Do not worry if this is still not perfectly clear for now. It will become clearer as we go through the examples in the book. The Classes section of the Python tutorial (https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/classes.xhtml) has an interesting paragraph about scopes and namespaces. Be sure you read it to gain a deeper understanding of the subject.

Guidelines for writing good code

Writing good code is not as easy as it seems. As we have already said, good code exhibits a long list of qualities that are difficult to combine together. Writing good code is an art. Regardless of where on the path you will be happy to settle, there is something that you can embrace that will make your code instantly better: PEP 8.

A Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP) is a document that describes a newly proposed Python feature. PEPs are also used to document processes around Python language development and to provide guidelines and information. You can find an index of all PEPs at https://www.python.org/dev/peps.

PEP 8 is perhaps the most famous of all PEPs. It lays out a simple but effective set of guidelines to define Python aesthetics so that we write beautiful, idiomatic Python code. If you take just one suggestion out of this chapter, please let it be this: use PEP 8. Embrace it. You will thank us later.

Coding today is no longer a check-in/check-out business. Rather, it is more of a social effort. Several developers collaborate on a piece of code through tools such as Git and Mercurial, and the result is code that is produced by many different hands.

Git and Mercurial are two of the most popular distributed revision control systems in use today. They are essential tools designed to help teams of developers collaborate on the same software.

These days, more than ever, we need to have a consistent way of writing code, so that readability is maximized. When all developers of a company abide by PEP 8, it is not uncommon for any of them landing on a piece of code to think they wrote it themselves (it actually happens to Fabrizio all the time, because he quickly forgets any code he writes).

This has a tremendous advantage: when you read code that you could have written yourself, you read it easily. Without conventions, every coder would structure the code the way they like most, or simply the way they were taught or are used to, and this would mean having to interpret every line according to someone else’s style. It would mean having to lose much more time just trying to understand it. Thanks to PEP 8, we can avoid this. We are such fans of it that, in our team, we will not sign off a code review if the code does not respect PEP8. So, please take the time to study it; this is very important.

Python developers can leverage several different tools to automatically format their code, according to PEP 8 guidelines. Popular such tools are black and ruff. There are also other tools, called linters, which check if the code is formatted correctly, and issue warnings to the developer with instructions on how to fix errors. Famous ones are flake8 and PyLint. We encourage you to use these tools, as they simplify the task of coding wellformatted software.

In the examples in this book, we will try to respect PEP8 as much as we can. Unfortunately, we do not have the luxury of 79 characters (which is the maximum line length suggested by PEP 8), and we will have to cut down on blank lines and other things, but we promise you we will try to lay out the code so that it is as readable as possible.

Python culture

Python has been adopted widely in the software industry. It is used by many different companies for different purposes, while also being an excellent education tool (it is excellent for that purpose due to its simplicity, making it easy to learn; it encourages good habits for writing readable code; it is platform-agnostic; and it supports modern object-oriented programming paradigms).

One of the reasons Python is so popular today is that the community around it is vast, vibrant, and full of brilliant people. Many events are organized all over the world, mostly either around Python or some of its most adopted web frameworks, such as Django.

Python’s source is open, and very often so are the minds of those who embrace it. Check out the community page on the Python website for more information and get involved!

There is another aspect to Python, which revolves around the notion of being Pythonic. It has to do with the fact that Python allows you to use some idioms that are not found elsewhere, at least not in the same form or ease of use (it can feel claustrophobic when one has to code in a language that is not Python, at times).

Anyway, over the years, this concept of being Pythonic has emerged and, the way we understand it, it is something along the lines of doing things the way they are supposed to be done in Python.

To help you understand a little bit more about Python’s culture and being Pythonic, we will show you the Zen of Python—a lovely Easter egg that is very popular. Open a Python console and type import this .

What follows is the result of that instruction:

>>> import this

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!There are two levels of reading here. One is to consider it as a set of guidelines that have been put down in a whimsical way. The other one is to keep it in mind, and read it once in a while, trying to understand how it refers to something deeper: some Python characteristics that you will have to understand deeply in order to write Python the way it is supposed to be written. Start with the fun level, and then dig deeper. Always dig deeper.

A note on IDEs

Just a few words about IDEs. To follow the examples in this book, you do not need one; any decent text editor will do fine. If you want to have more advanced features, such as syntax coloring and auto-completion, you will have to get yourself an IDE. You can find a comprehensive list of open-source IDEs (just Google “Python IDEs”) on the Python website.

Fabrizio uses Visual Studio Code, from Microsoft. It is free to use and it provides many features out of the box, which one can even expand by installing extensions.

After working for many years with several editors, including Sublime Text, this was the one that felt most productive to him.

Heinrich, on the other hand, is a hardcore Neovim user. Although it might have a steep learning curve, Neovim is a very powerful text editor that can also be extended with plugins. It also has the benefit of being compatible with its predecessor, Vim, which is installed in almost every system a software developer regularly works on.

Two important pieces of advice:

- Whatever IDE you decide to use, try to learn it well so that you can exploit its strengths, but don’t depend on it too much. Practice working with Vim (or any other text editor) once in a while; learn to be able to do some work on any platform, with any set of tools.

- Whatever text editor/IDE you use, when it comes to writing Python, indentation is four spaces. Do not use tabs, do not mix them with spaces. Use four spaces, not two, not three, not five. Just use four. The whole world works like that, and you do not want to become an outcast because you were fond of the three-spaces layout.

A word about AI