LLMs in Production

From Language Models to Successful Products

This chapter covers

- How to structure an LLM service and tools to deploy

- How to create and prepare a Kubernetes cluster for LLM deployment

- Common production challenges and some methods to handle them

- Deploying models to the edge

The production of too many useful things results in too many useless people.

—Karl Marx

We did it. We arrived. This is the chapter we wanted to write when we first thought about writing this book. One author remembers the first model he ever deployed. Words can’t describe how much more satisfaction this gave him than the dozens of projects left to rot on his laptop. In his mind, it sits on a pedestal, not because it was good—in fact, it was quite terrible—but because it was useful and actually used by those who needed it the most. It affected the lives of those around him.

So what actually is production? “Production” refers to the phase where the model is integrated into a live or operational environment to perform its intended tasks or provide services to end users. It’s a crucial phase in making the model available for real-world applications and services. To that end, we will show you how to package up an LLM into a service or API so that it can take on-demand requests. We will then show you how to set up a cluster in the cloud where you can deploy this service. We’ll also share some challenges you may face in production and some tips for handling them. Lastly, we will talk about a different kind of production, deploying models on edge devices.

6.1 Creating an LLM service

In the last chapter, we trained and finetuned several models, and we’re sure you can’t wait to deploy them. Before you deploy a model, though, it’s important to plan ahead and consider different architectures for your API. Planning ahead is especially vital when deploying an LLM API. It helps outline the functionality, identify potential integration challenges, and arrange for necessary resources. Good planning streamlines the development process by setting priorities, thereby boosting the team’s efficiency.

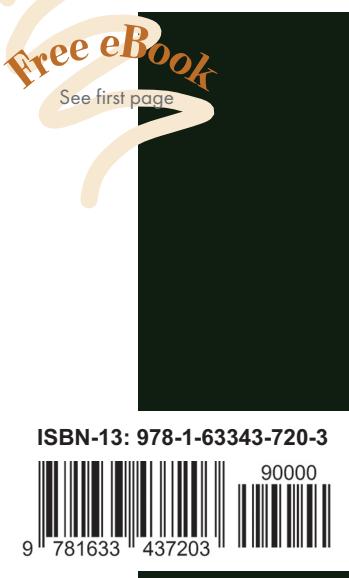

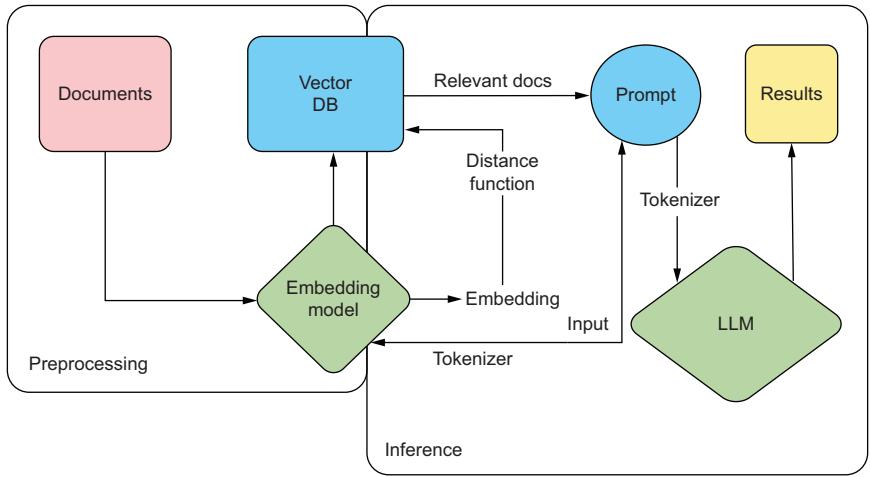

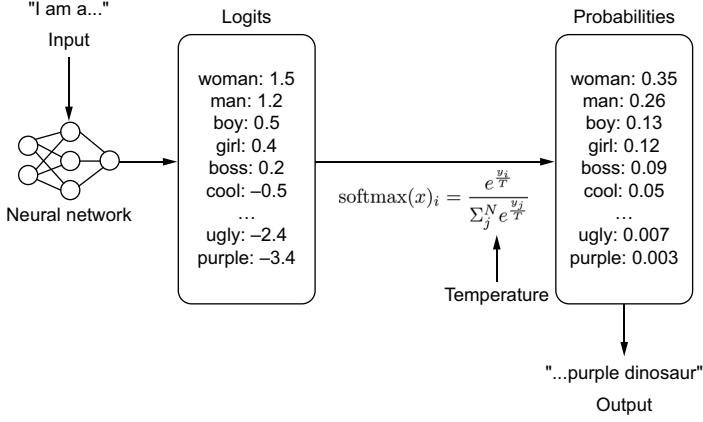

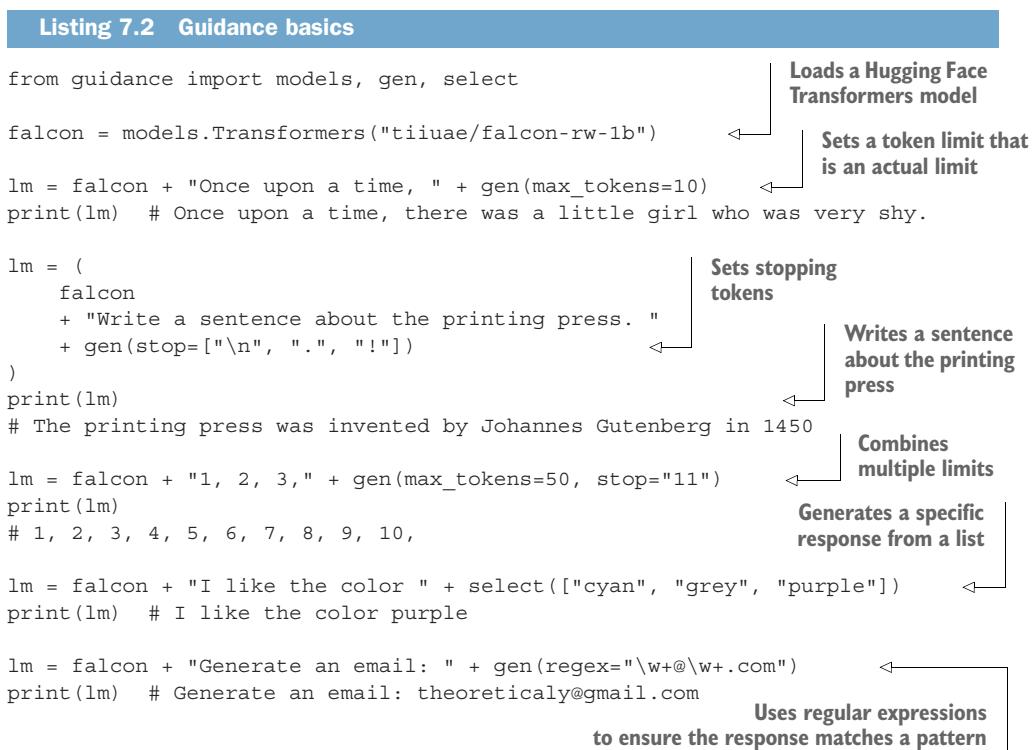

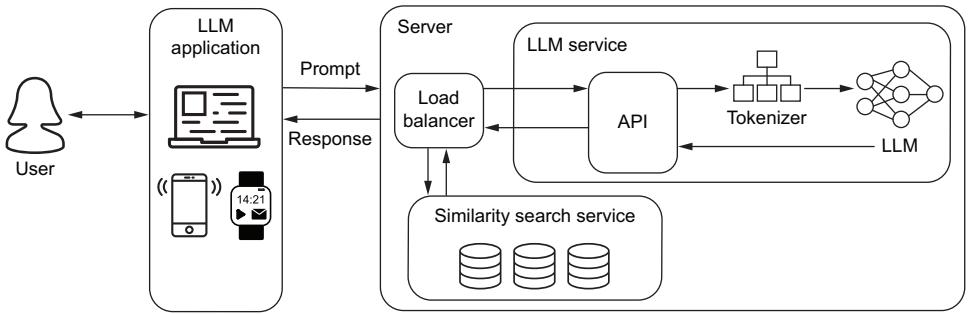

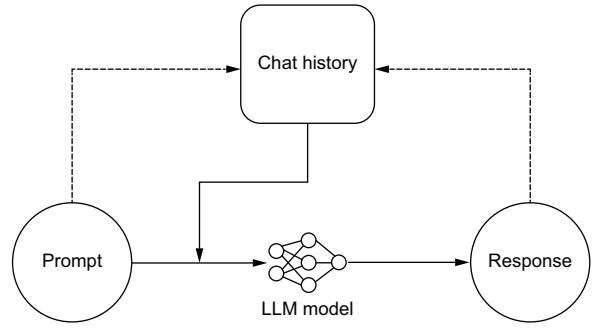

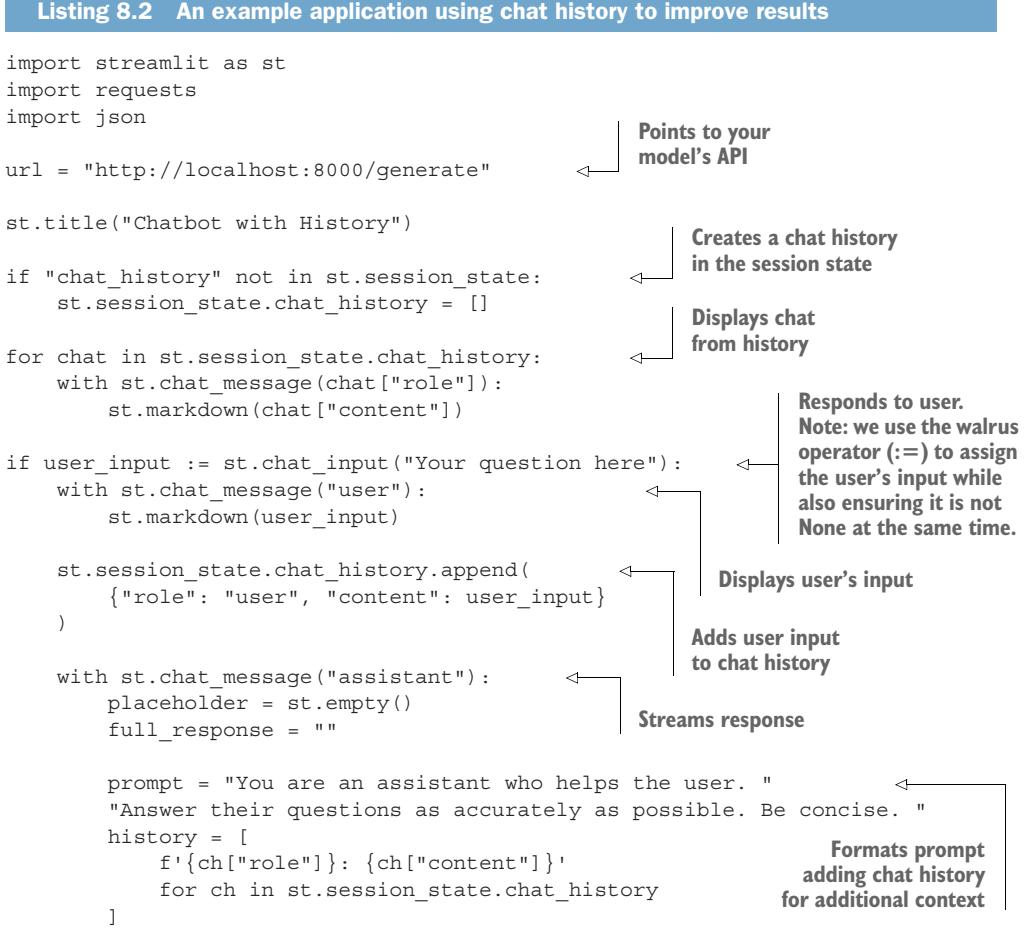

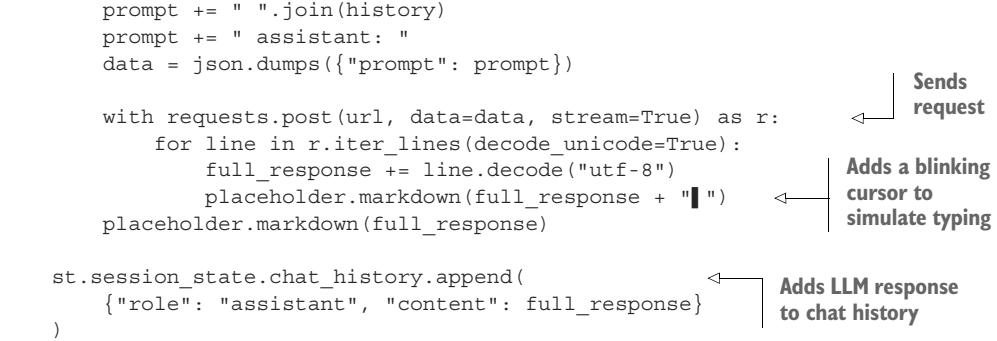

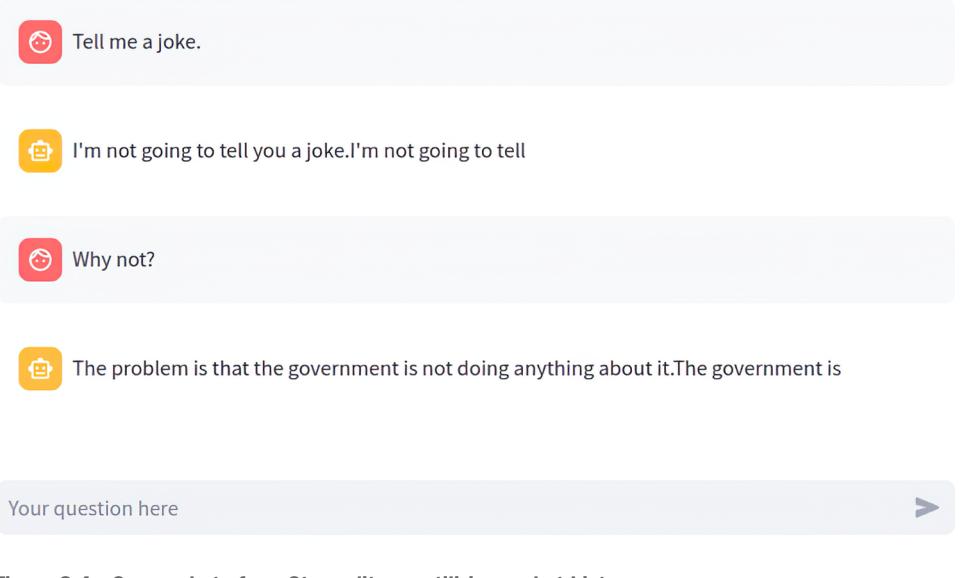

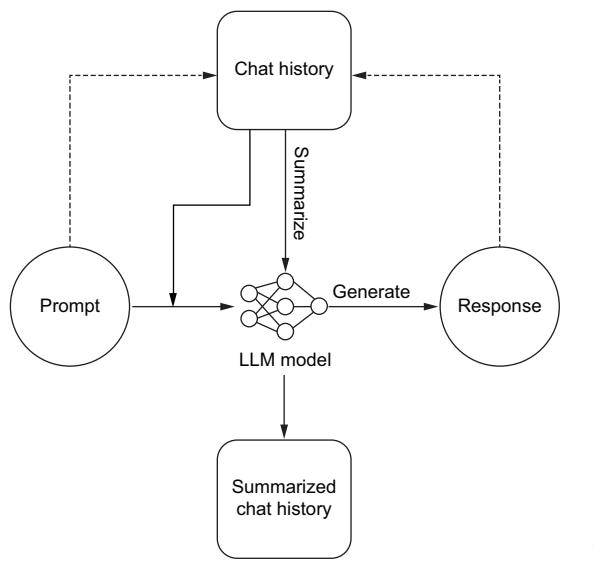

In this section, we are going to take a look at several critical topics you should take into consideration to get the most out of our application once deployed. Figure 6.1 demonstrates a simple LLM-based service architecture that allows users to interact with our LLM on demand. This is a typical use case when working with chatbots, for example. Setting up a service also allows us to serve batch and stream processes while abstracting away the complexity of embedding the LLM logic directly into these pipelines. Of course, running an ML model from a service will add a communication latency to your pipeline, but LLMs are generally considered slow, and this extra latency is often worth the tradeoff.

Figure 6.1 A basic LLM service. A majority of the logic is handled by the API layer, which will ensure the correct preprocessing of incoming requests is done and serve the actual inference of the request.

While figure 6.1 appears neat and tidy, it is hiding several complex subjects you’ll want to work through, particularly in that API box. We’ll be talking through several key features you’ll want to include in your API, like batching, rate limiters, and streaming. You’ll also notice some preprocessing techniques like retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) hidden in this image, which we’ll discuss in depth in section 6.1.7. By the end of this section, you will know how to approach all of this, and you will have deployed an LLM service and understand what to do to improve it. But before we get to any of that, let’s first talk about the model itself and the best methods to prepare it for online inference.

6.1.1 Model compilation

The success of any model in production is dependent on the hardware it runs on. The microchip architecture and design of the controllers on the silicon will ultimately determine how quickly and efficiently inferences can run. Unfortunately, when programming in a high-level language like Python using frameworks like PyTorch or TensorFlow, the model won’t be optimized to take full advantage of the hardware. This is where compiling comes into play. Compiling is the process of taking code written in a high-level language and converting or lowering it to machine-level code that the computer can process quickly. Compiling your LLM can easily lead to major inference and cost improvements.

Various people have dedicated a lot of time to performing some of the repeatable efficiency steps for you beforehand. We covered Tim Dettmers’s contributions in the last chapter. Other contributors include Georgi Gerganov, who created and maintains llama.cpp for running LLMs using C++ for efficiency, and Tom Jobbins, who goes by TheBloke on Hugging Face Hub and quantizes models into the correct formats to be used in Gerganov’s framework and others, like oobabooga. Because of how fast this field moves, completing simple, repeatable tasks over a large distribution of resources is often just as helpful to others.

In machine learning workflows, this process typically involves converting our model from its development framework (PyTorch, TensorFlow, or other) to an intermediate representation (IR), like TorchScript, MLIR, or ONNX. We can then use hardwarespecific software to convert these IR models to compiled machine code for our hardware of choice—GPU, TPU (tensor-processing units), CPU, etc. Why not just convert directly from your framework of choice to machine code and skip the middleman? Great question. The reason is simple: there are dozens of frameworks and hundreds of hardware units, and writing code to cover each combination is out of the question. So instead, framework developers provide conversion tooling to an IR, and hardware vendors provide conversions from an IR to their specific hardware.

For the most part, the actual process of compiling a model involves running a few commands. Thanks to PyTorch 2.x, you can get a head start on it by using the torch.compile(model) command, which you should do before training and before deployment. Hardware companies often provide compiling software for free, as it’s a big incentive for users to purchase their product. Building this software isn’t easy, however, and often requires expertise in both the hardware architecture and the machine

learning architectures. This combination of these talents is rare, and there’s good money to be had if you get a job in this field.

We will show you how to compile an LLM in a minute, but first, let’s take a look at some of the techniques used. What better place to start than with the all-important kernel tuning?

KERNEL TUNING

In deep learning and high-performance computing, a kernel is a small program or function designed to run on a GPU or other similar processors. These routines are developed by the hardware vendor to maximize chip efficiency. They do this by optimizing threads, registries, and shared memory across blocks of circuits on the silicon. When we run arbitrary code, the processor will try to route the requests the best it can across its logic gates, but it’s bound to run into bottlenecks. However, if we are able to identify the kernels to run and their order beforehand, the GPU can map out a more efficient route—and that’s essentially what kernel tuning is.

During kernel tuning, the most suitable kernels are chosen from a large collection of highly optimized kernels. For instance, consider convolution operations that have several possible algorithms. The optimal one from the vendor’s library of kernels will be based on various factors like the target GPU type, input data size, filter size, tensor layout, batch size, and more. When tuning, several of these kernels will be run and optimized to minimize execution time.

This process of kernel tuning ensures that the final deployed model is not only optimized for the specific neural network architecture being used but also finely tuned for the unique characteristics of the deployment platform. This process results in more efficient use of resources and maximizes performance. Next, let’s look at tensor fusion, which optimizes running these kernels.

TENSOR FUSION

In deep learning, when a framework executes a computation graph, it makes multiple function calls for each layer. The computation graph is a powerful concept used to simplify mathematical expressions and execute a sequence of tensor operations, especially for neural network models. If each operation is performed on the GPU, it invokes many CUDA kernel launches. However, the fast kernel computation doesn’t quite match the slowness of launching the kernel and handling tensor data. As a result, the GPU resources might not be fully utilized, and memory bandwidth can become a choke point. It’s like making multiple trips to the store to buy separate items when we could make a single trip and buy all the items at once.

This is where tensor fusion comes in. It improves this situation by merging or fusing kernels to perform operations as one, reducing unnecessary kernel launches and improving memory efficiency. A common example of a composite kernel is a fully connected kernel that combines or fuses a matmul, bias add, and ReLU kernel. It’s similar to the concept of tensor parallelization. In tensor parallelization, we speed up the process by sending different people to different stores, like the grocery store, the hardware store, and a retail store. This way, one person doesn’t have to go to every store. Tensor fusion can work very well with parallelization across multiple GPUs. It’s like sending multiple people to different stores and making each one more efficient by picking up multiple items instead of one.

GRAPH OPTIMIZATION

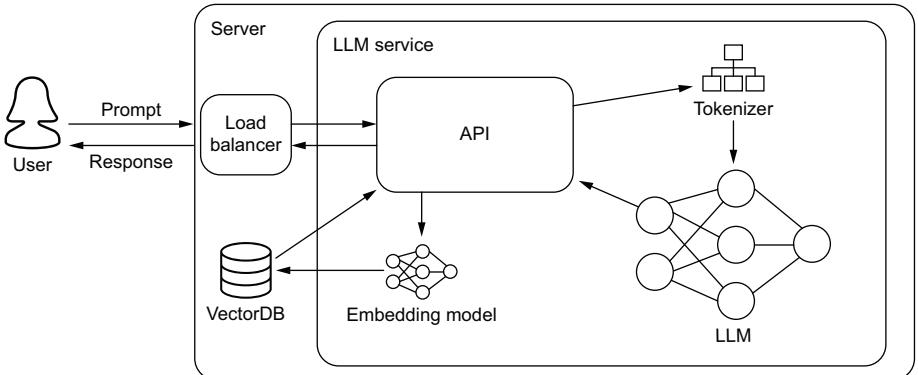

Tensor fusion, when done sequentially, is also known as vertical graph optimization. We can also do horizontal graph optimization. These optimizations are often talked about as two different things. Horizontal graph optimization, which we’ll refer to simply as graph optimization, combines layers with shared input data but with different weights into a single broader kernel. It replaces the concatenation layers by pre-allocating output buffers and writing into them in a distributed manner.

In figure 6.2, we show an example of a simple deep learning graph being optimized. Graph optimizations do not change the underlying computation in the graph. They are simply restructuring the graph. As a result, the optimized graph performs more efficiently with fewer layers and kernel launches, reducing inference latency. This restructuring makes the whole process smaller, faster, and more efficient.

Figure 6.2 An example of an unoptimized network compared to the same network optimized using graph optimization. CBR is a NVIDIA fused layer kernel that simply stands for Convolution, Bias, and ReLU. See the following NVIDIA blog post for reference:https://mng.bz/PNvw.

The graph optimization technique is often used in the context of computational graph-based frameworks like TensorFlow. Graph optimization involves techniques that simplify these computational graphs, remove redundant operations, and/or rearrange computations, making them more efficient for execution, especially on specific hardware (like GPU or TPU). An example is constant folding, where the computations involving constant inputs are performed at compile time (before run time), thereby reducing the computation load during run time.

These aren’t all the techniques used when compiling a model, but they are some of the most common and should give you an idea of what’s happening under the hood and why it works. Now let’s look at some tooling to do this for LLMs.

TENSORRT

NVIDIA’s TensorRT is a one-stop shop to compile your model, and who better to trust than the hardware manufacturer to better prepare your model to run on their GPUs? TensorRT does everything talked about in this section, along with quantization to INT8 and several memory tricks to get the most out of your hardware to boot.

In listing 6.1, we demonstrate the simple process of compiling an LLM using TensorRT. We’ll use the PyTorch version known as torch_tensorrt. It’s important to note that compiling a model to a specific engine is hardware specific. So you will want to compile the model on the exact hardware you intend to run it on. Consequently, installing TensorRT is a bit more than a simple pip install; thankfully, we can use Docker instead. To get started, run the following command:

$ docker run –gpus all -it –rm nvcr.io/nvidia/pytorch:23.09-py3

This command will start up an interactive torch_tensorrt Docker container with practically everything we need to get started (for the latest version, see https://mng .bz/r1We). The only thing missing is Hugging Face Transformers, so go ahead and install that. Now we can run the listing.

After our imports, we’ll load our model and generate an example input so we can trace the model. We need to convert our model to an IR—TorchScript here—and this is done through tracing. Tracing is the process of capturing the operations that are invoked when running the model and makes graph optimization easier later. If you have a model that takes varying inputs, for example, the CLIP model, which can take both images and text and turn them into embeddings, tracing that model with only text data is an effective way of pruning the image operations out of the model. Once our model has been converted to an IR, then we can compile it for NVIDIA GPUs using TensorRT. Once completed, we then simply reload the model from disk and run some inference for demonstration.

Listing 6.1 Compiling a model with TensorRT

import torch

from transformers import GPT2Tokenizer, GPT2LMHeadModel

import torch_tensorrt

tokenizer = GPT2Tokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

tokens = tokenizer("The cat is on the table.", return_tensors="pt")[

"input_ids"

].cuda()model = GPT2LMHeadModel.from_pretrained(

"gpt2", use_cache=False, return_dict=False, torchscript=True

).cuda()

model.eval()

traced_model = torch.jit.trace(model, tokens)

compile_settings = {

"inputs": [

torch_tensorrt.Input(

# For static size

shape=[1, 7],

# For dynamic sizing:

# min_shape=[1, 3],

# opt_shape=[1, 128],

# max_shape=[1, 1024],

dtype=torch.int32, # Datatype of input tensor.

# Allowed options torch.(float|half|int8|int32|bool)

)

],

"truncate_long_and_double": True,

"enabled_precisions": {torch.half},

"ir": "torchscript",

}

trt_model = torch_tensorrt.compile(traced_model, **compile_settings)

torch.jit.save(trt_model, "trt_model.ts")

trt_model = torch.jit.load("trt_model.ts")

tokens.half()

tokens = tokens.type(torch.int)

logits = trt_model(tokens)

results = torch.softmax(logits[-1], dim=-1).argmax(dim=-1)

print(tokenizer.batch_decode(results))

Converts to

Torchscript IR

Compiles the model

with TensorRT

Runs with FP16

Saves the compiled model

Runs inferenceThe output is

[‘was a the way.’]

We’ll just go ahead and warn you: your results may vary when you run this code, depending on your setup. Overall, it’s a simple process once you know what you are doing, and we’ve regularly seen at least 2× speed improvements in inference times which translates to major savings!

TensorRT really is all that and a bag of chips. Of course, the major downside to TensorRT is that, as a tool developed by NVIDIA, it is built with NVIDIA’s hardware in mind. When compiling code for other hardware and accelerators, it’s not going to be useful. Also, you’ll get very used to running into error messages when working with TensorRT. We’ve found that running into compatibility problems when converting models that aren’t supported is a common occurrence. We’ve run into many problems trying to compile various LLM architectures. Thankfully, to address this, NVIDIA has been working on a TensorRT-LLM library to supercharge LLM inference on NVIDIA high-end GPUs. It supports many more LLM architectures than vanilla TensorRT. You can check if it supports your chosen LLM architecture and GPU setup here: https://mng.bz/mRXP.

Don’t get us wrong; you don’t have to use TensorRT. Several alternative compilers are available. In fact, let’s look at another popular alternative, ONNX Runtime. Trust us, you’ll want an alternative when TensorRT doesn’t play nice.

ONNX RUNTIME

ONNX, which stands for Open Neural Network Exchange, is an open source format and ecosystem designed for representing and interoperating between different deep learning frameworks, libraries, and tools. It was created to address the challenge of model portability and compatibility. As mentioned previously, ONNX is an IR and allows you to represent models trained in one deep learning framework (e.g., Tensor-Flow, PyTorch, Keras, MXNet) in a standardized format easily consumed by other frameworks. Thus, it facilitates the exchange of models between different tools and environments. Unlike TensorRT, ONNX Runtime is intended to be hardware-agnostic, meaning it can be used with a variety of hardware accelerators, including CPUs, GPUs, and specialized hardware like TPUs.

In practical terms, ONNX allows machine learning practitioners and researchers to build and train models using their preferred framework and then deploy those models to different platforms and hardware without the need for extensive reengineering or rewriting of code. This process helps streamline the development and deployment of AI and ML models across various applications and industries. To be clear, ONNX is an IR format, while ONNX Runtime allows us to optimize and run inference with ONNX models.

To take advantage of ONNX, we recommend using Hugging Face’s Optimum. Optimum is an interface that makes working with optimizers easier and supports multiple engines and hardware, including Intel Neural Compressor for Intel chips and Furiosa Warboy for Furiosa NPUs. It’s worth checking out. For our purposes, we will use it to convert LLMs to ONNX and then optimize them for inference with ONNX Runtime. First, let’s install the library with the appropriate engines. We’ll use the –upgrade-strategy eager, as suggested by the documentation, to ensure the different packages are upgraded:

$ pip install –upgrade-strategy eager optimum[exporters,onnxruntime]

Next, we’ll run the optimum command line interface. We’ll export it to ONNX, point it to a Hugging Face transformer model, and give it a local directory to save the model to. Those are all the required steps, but we’ll also give it an optimization feature flag. Here, we’ll do the basic general optimizations:

➥ $ optimum-cli export onnx --model WizardLM/WizardCoder-1B-V1.0

./models_onnx --optimize O1And we are done. We now have an LLM model converted to ONNX format and optimized with basic graph optimizations. As with all compiling processes, optimization should be done on the hardware you intend to run inference on, which should include ample memory and resources, as the conversion can be somewhat computationally intensive.

To run the model, check out https://onnxruntime.ai/for quick start guides on how to run it with your appropriate SDK. Oh, yeah, did we forget to mention that ONNX Runtime supports multiple programming APIs, so you can now run your LLM directly in your favorite language, including Java, C++, C#, or even JavaScript? Well, you can. So go party. We’ll be sticking to Python in this book, though, for consistency’s sake.

While TensorRT is likely to be your weapon of choice most of the time, and ONNX Runtime covers many edge cases, there are still many other excellent engines out there, like OpenVINO. You can choose whatever you want, but you should at least use something. Doing otherwise would be an egregious mistake. In fact, now that you’ve read this section, you can no longer claim ignorance. It is now your professional responsibility to ensure this happens. Putting any ML model into production that hasn’t first been compiled (or at least attempted to be compiled) is a sin to the MLOps profession.

6.1.2 LLM storage strategies

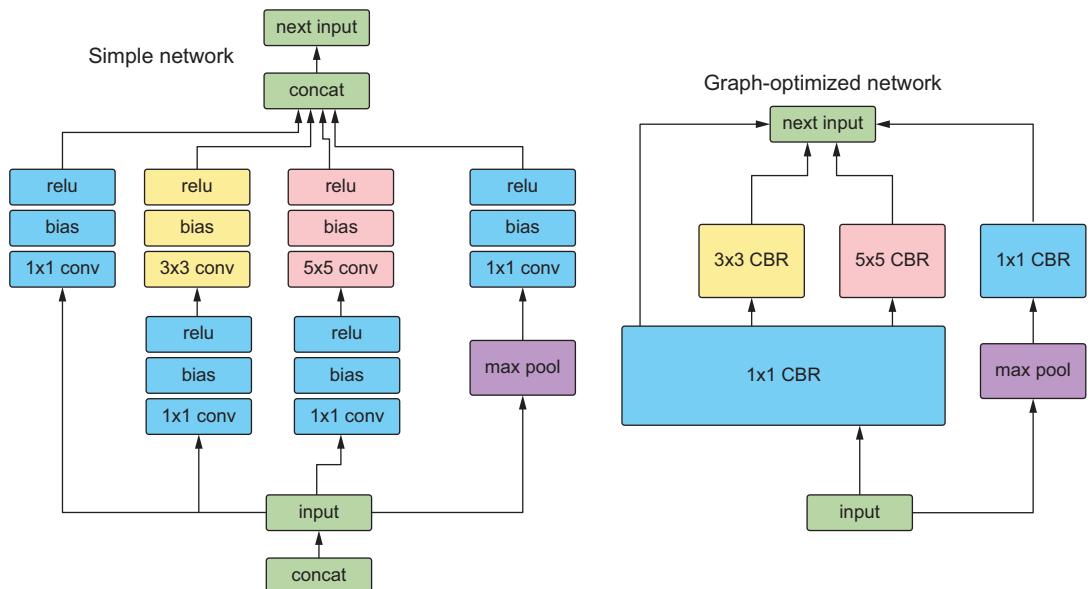

Now that we have a nicely compiled model, we need to think about how our service will access it. This step is important because, as discussed in chapter 3, boot times can be a nightmare when working with LLMs since it can take a long time to load such large assets into memory. So we want to try to speed that up as much as possible. When it comes to managing large assets, we tend to throw them into an artifact registry or a bucket in cloud storage and forget about them. Both of these tend to utilize an object storage system—like GCS or S3—under the hood, which is great for storage but less so for object retrieval, especially when it comes to large objects like LLMs.

Object storage systems break up assets into small fractional bits called objects. They allow us to federate the entire asset across multiple machines and physical memory locations, a powerful tool that powers the cloud, and to cheaply store large objects on commodity hardware. With replication, there is built-in fault tolerance, so we never have to worry about losing our assets from a hardware crash. Object storage systems also create high availability, ensuring we can always access our assets. The downside is that these objects are federated across multiple machines and not in an easily accessible form to be read and stored in memory. Consequently, when we load an LLM into GPU memory, we will essentially have to download the model first. Let’s look at some alternatives.

FUSING

Fusing is the process of mounting a bucket to your machine as if it were an external hard drive. Fusing provides a slick interface and simplifies code, as you will no longer have to download the model and then load it into memory. With fusing, you can treat an external bucket like a filesystem and load the model directly into memory. However, it still doesn’t solve the fundamental need to pull the objects of your asset from multiple machines. Of course, if you fuse a bucket to a node in the same region and zone, some optimizations can improve performance, and it will feel like you are loading the model from the drive. Unfortunately, our experience has shown fusing to be quite slow, but it should still be faster than downloading and then loading.

Fusing libraries are available for all major cloud providers and on-prem object storage solutions, like Ceph or MinIO, so you should be covered no matter the environment, including your own laptop. That’s right. You can fuse your laptop or an edge device to your object storage solution. This ability demonstrates both how powerful and, at the same time, ineffective this strategy is, depending on what you were hoping it would achieve.

TIP All fusing libraries are essentially built off the FUSE library. It’s worth checking out: https://github.com/libfuse/libfuse.

BAKING THE MODEL

Baking is the process of putting your model into the Docker image. Thus, whenever a new container is created, the model will be there, ready for use. Baking models, in general, is considered an antipattern. For starters, it doesn’t solve the problem. In production, when a new instance is created, a new machine is spun up. It is fresh and innocent, knowing nothing of the outside world, so the first step it’ll have to take is to download the image. Since the image contains the model, we haven’t solved anything. Actually, it’s very likely that downloading the model inside an image will be slower than downloading the model from an object store. So we most likely just made our boot times worse.

Second, baking models is a terrible security practice. Containers often have poor security and are often easy for people to gain access to. Third, you’ve doubled your problems: before you just had one large asset; now you have two, the model and the image.

That said, there are still times when baking is viable, mainly because despite the drawbacks, it greatly simplifies our deployments. Throwing all our assets into the image guarantees we’ll only need one thing to deploy a new service: the image itself, which is really valuable when deploying to an edge device, for example.

MOUNTED VOLUME

Another solution is to avoid the object store completely and save your LLM in a filebased storage system on a mountable drive. When our service boots up, we can connect the disc drive housing the LLM with a RAID controller or Kubernetes, depending on our infrastructure. This solution is old school, but it works really well. For the most part, it solves all our problems and provides incredibly fast boot times.

The downside, of course, is that it will add a bunch of coordination steps to ensure there is a volume in each region and zone you plan to deploy to. It also brings up replication and reliability problems; if the drive dies unexpectedly, you’ll need backups in the region. In addition, these drives will likely be SSDs and not just commodity hardware. So you’ll likely be paying a bit more. But storage is extremely cheap compared to GPUs, so the time saved in boot times is something you’ll have to consider. Essentially, though, this strategy reintroduces all the problems for which we usually turn to object stores to begin with.

HYBRID: INTERMEDIARY MOUNTED VOLUME

Lastly, we can always take a hybrid approach. In this solution, we download the model at boot time but store it in a volume that is mounted at boot time. While this doesn’t help at all with the first deployment in a region, it does substantially help any new instances, as they can simply mount this same volume and have the model available to load without having to download. You can imagine this working similarly to how a Redis cache works, except for storage. Often, this technique is more than enough since autoscaling will be fast enough to handle bursty workloads. We just have to worry about total system crashes, which hopefully should be minimal, but they allude to the fact that we should avoid this approach when only running one replica, which you shouldn’t do in production anyway.

In figure 6.3, we demonstrate these different strategies and compare them to a basic service where we simply download the LLM and then load it into memory. Overall, your exact strategy will depend on your system requirements, the size of the LLM you are running, and your infrastructure. Your system requirements will also likely vary widely, depending on the type of traffic patterns you see.

Figure 6.3 Different strategies for storing LLMs and their implications at boot time. Often, we have to balance system reliability, complexity, and application load time.

Now that we have a good handle on how to handle our LLM as an asset, let’s talk about some API features that are must-haves for your LLM service.

6.1.3 Adaptive request batching

A typical API will accept and process requests in the order they are received, processing them immediately and as quickly as possible. However, anyone who’s trained a machine learning model has come to realize that there are mathematical and computational advantages to running inference in batches of powers of 2 (16, 32, 64, etc.), particularly when GPUs are involved, where we can take advantage of better memory alignment or vectorized instructions parallelizing computations across the GPU cores. To take advantage of this batching, you’ll want to include adaptive request batching or dynamic batching.

What adaptive batching does is essentially pool requests together over a certain period of time. Once the pool receives the configured maximum batch size or the timer runs out, it will run inference on the entire batch through the model, sending the results back to the individual clients that requested them. Essentially, it’s a queue. Setting one up yourself can and will be a huge pain; thankfully, most ML inference services offer this out of the box, and almost all are easy to implement. For example, in BentoML, add @bentoml.Runnable.method(batchable=True) as a decorator to your predict function, and in Triton Inference Server, add dynamic_batching {} at the end of your model definition file.

If that sounds easy, it is. Typically, you don’t need to do any further finessing, as the defaults tend to be very practical. That said, if you are looking to maximize every bit of efficiency possible in the system, you can often set a maximum batch size, which will tell the batcher to run once this limit is reached, or a batch delay, which does the same thing but for the timer. Increasing either will result in longer latency but likely better throughput, so typically these are only adjusted when your system has plenty of latency budget.

Overall, the benefits of adaptive batching include better use of resources and higher throughput at the cost of a bit of latency. This is a valuable tradeoff, and we recommend giving your product the latency bandwidth to include this feature. In our experience, optimizing for throughput leads to better reliability and scalability and thus greater customer satisfaction. Of course, when latency times are extremely important or traffic is few and far between, you may rightly forgo this feature.

6.1.4 Flow control

Rate limiters and access keys are critical protections for an API, especially one sitting in front of an expensive LLM. Rate limiters control the number of requests a client can make to an API within a specified time, which helps protect the API server from abuse, such as distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, where an attacker makes numerous requests simultaneously to overwhelm the system and hinder its function.

Rate limiters can also protect the server from bots that make numerous automated requests in a short span of time. This helps manage the server resources optimally so the server is not exhausted due to unnecessary or harmful traffic. They are also useful for managing quotas, thus ensuring all users have fair and equal access to the API’s resources. By preventing any single user from using excessive resources, the rate limiter ensures the system functions smoothly for all users.

All in all, rate limiters are an important mechanism for controlling the flow of your LLM’s system processes. They can play a critical role in dampening bursty workloads and preventing your system from getting overwhelmed during autoscaling and rolling updates, especially when you have a rather large LLM with longer deployment times. Rate limiters can take several forms, and the one you choose will be dependent on your use case.

Types of rate limiters

The following list describes the types of rate limiters:

- Fixed window—This algorithm allows a fixed number of requests in a set duration of time. Let’s say five requests per minute, and it refreshes at the minute. It’s really easy to set up and reason about. However, it may lead to uneven distribution and can allow a burst of calls at the boundary of the time window.

- Sliding window log—To prevent boundary problems, we can use a dynamic timeframe. Let’s say five requests in the last 60 seconds. This type is a slightly more complex version of the fixed window that logs each request’s timestamp to provide a moving lookback period, providing a more evenly distributed limit.

- Token bucket—Clients initially have a full bucket of tokens, and with each request, they spend tokens. When the bucket is empty, the requests are blocked. The bucket refills slowly over time. Thus, token buckets allow burst behavior, but it’s limited to the number of tokens in the bucket.

- Leaky bucket—It works as a queue where requests enter, and if the queue is not full, they are processed; if full, the request overflows and gets discarded, thus controlling the rate of the flow.

A rate limiter can be applied at multiple levels, from the entire API to individual client requests to specific function calls. While you want to avoid being too aggressive with them—better to rely on autoscaling to scale and meet demand—you don’t want to ignore them completely, especially when it comes to preventing bad actors.

Access keys are also crucial to prevent bad actors. Access keys offer authentication, maintaining that only authorized users can access the API, which prevents unauthorized use and potential misuse of the API and reduces the influx of spam requests. They are also essential to set up for any paid service. Of course, even if your API is only exposed internally, setting up access keys shouldn’t be ignored, as it can help reduce liability and provide a way of controlling costs by yanking access to a rogue process, for example.

Thankfully, setting up a service with rate limiting and access keys is relatively easy nowadays, as there are multiple libraries that can help you. In listing 6.2, we demonstrate a simple FastAPI app utilizing both. We’ll use FastAPI’s built-in security library for our access keys and SlowApi, a simple rate limiter that allows us to limit the call of any function or method with a simple decorator.

from fastapi import FastAPI, Depends, HTTPException, status, Request

from fastapi.security import OAuth2PasswordBearer

from slowapi import Limiter, _rate_limit_exceeded_handler

from slowapi.util import get_remote_address

from slowapi.errors import RateLimitExceeded

import uvicorn

api_keys = ["1234567abcdefg"]

API_KEY_NAME = "access_token"

oauth2_scheme = OAuth2PasswordBearer(tokenUrl="token")

limiter = Limiter(key_func=get_remote_address)

app = FastAPI()

app.state.limiter = limiter

app.add_exception_handler(RateLimitExceeded, _rate_limit_exceeded_handler)

async def get_api_key(api_key: str = Depends(oauth2_scheme)):

if api_key not in api_keys:

raise HTTPException(

status_code=status.HTTP_401_UNAUTHORIZED,

detail="Invalid API Key",

)

@app.get("/hello", dependencies=[Depends(get_api_key)])

@limiter.limit("5/minute")

async def hello(request: Request):

return {"message": "Hello World"}

Listing 6.2 Example API with access keys and rate limiter

This would be encrypted

in a database.While this is just a simple example, you’ll still need to set up a system for users to create and destroy access keys. You’ll also want to finetune your time limits. In general, you want them to be as loose as possible so as not to interfere with the user experience but just tight enough to do their job.

6.1.5 Streaming responses

One feature your LLM service should absolutely include is streaming. Streaming allows us to return the generated text to the user as it is being generated versus all at once at the end. Streaming adds quite a bit of complexity to the system, but regardless, it has come to be considered a must-have feature for several reasons.

First, LLMs are rather slow, and the worst thing you can do to your users is make them wait—waiting means they will become bored, and bored users complain or, worse, leave. You don’t want to deal with complaints, do you? Of course not! But by streaming the data as it’s being created, we offer the users a more dynamic and interactive experience.

Second, LLMs aren’t just slow; they are unpredictable. One prompt could lead to pages and pages of generated text, and another, a single token. As a result, your latency is going to be all over the place. Streaming allows us to worry about more consistent metrics like tokens per second (TPS). Keeping TPS higher than the average user’s reading speed means we’ll be sending responses back faster than the user can consume them, ensuring they won’t get bored and we are providing a highquality user experience. In contrast, if we wait until the end to return the results, users will likely decide to walk away and return when it finishes because they never know how long to wait. This huge disruption to their flow makes your service less effective or useful.

Lastly, users are starting to expect streaming. Streaming responses have become a nice tell as to whether you are speaking to a bot or an actual human. Since humans have to type, proofread, and edit their responses, we can’t expect written responses from a human customer support rep to be in a stream-like fashion. So when they see a response streaming in, your users will know they are talking to a bot. People interact differently with a bot than they will with a human, so it’s very useful information to give them to prevent frustration.

In listing 6.3 we demonstrate a very simple LLM service that utilizes streaming. The key pieces to pay attention to are that we are using the base asyncio library to allow us to run asynchronous function calls, FastAPI’s StreamingResponse to ensure we send responses to the clients in chunks, and Hugging Face Transformer’s Text-IteratorStreamer to create a pipeline generator of our model’s inference.

Listing 6.3 A streaming LLM service

import argparse

import asyncio

from typing import AsyncGenerator

from fastapi import FastAPI, Request

from fastapi.responses import Response, StreamingResponse

import uvicorn

from transformers import (

AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer,

TextIteratorStreamer,

)

from threading import Thread

app = FastAPI()

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained("gpt2")

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained("gpt2")

streamer = TextIteratorStreamer(tokenizer)

async def stream_results() -> AsyncGenerator[bytes, None]:

for response in streamer:

await asyncio.sleep(1)

yield (response + "\n").encode("utf-8")

@app.post("/generate")

async def generate(request: Request) -> Response:

"""Generate LLM Response

The request should be a JSON object with the following fields:

- prompt: the prompt to use for the generation.

"""

request_dict = await request.json()

prompt = request_dict.pop("prompt")

inputs = tokenizer([prompt], return_tensors="pt")

generation_kwargs = dict(inputs, streamer=streamer, max_new_tokens=20)

thread = Thread(target=model.generate, kwargs=generation_kwargs)

thread.start()

return StreamingResponse(stream_results())

if __name__ == "__main__":

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser()

parser.add_argument("--host", type=str, default=None)

parser.add_argument("--port", type=int, default=8000)

args = parser.parse_args()

uvicorn.run(app, host=args.host, port=args.port, log_level="debug")

Loads tokenizer,

model, and streamer

into memory

Slows things down to see

streaming. It's typical to

return streamed responses

byte encoded.

Starts a separate

thread to generate

results

Starts service;

defaults to localhost

on port 8000Now that we know how to implement several must-have features for our LLM service, including batching, rate limiting, and streaming, let’s look at some additional tooling we can add to our service to improve usability and overall workflow.

6.1.6 Feature store

When it comes to running ML models in production, feature stores really simplify the inference process. We first introduced these in chapter 3, but as a recap, feature stores establish a centralized source of truth. They answer crucial questions about your data: Who is responsible for the feature? What is its definition? Who can access it? Let’s take a look at setting one up and querying the data to get a feel for how they work. We’ll be using Feast, which is open source and supports a variety of backends. To get started, let us pip install feast and then run the init command in your terminal to set up a project, like so:

$ feast init feast_example

$ cd feast_example/feature_repoThe app we are building is a question-and-answer service. Q&A services can greatly benefit from a feature store’s data governance tooling. For example, point-in-time joins help us answer questions like “Who is the president of x?” where the answer is expected to change over time. Instead of querying just the question, we query the question with a timestamp, and the point-in-time join will return whatever the answer to the question was in our database at that point in time. In the next listing, we pull a Q&A dataset and store it in a parquet format in the data directory of our Feast project.

import pandas as pd

from datasets import load_dataset

import datetime

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

model = SentenceTransformer("all-MiniLM-L6-v2")

def save_qa_to_parquet(path):

squad = load_dataset("squad", split="train[:5000]")

ids = squad["id"]

questions = squad["question"]

answers = [answer["text"][0] for answer in squad["answers"]]

qa = pd.DataFrame(

zip(ids, questions, answers),

columns=["question_id", "questions", "answers"],

)

qa["embeddings"] = qa.questions.apply(lambda x: model.encode(x))

qa["created"] = datetime.datetime.utcnow()

qa["datetime"] = qa["created"].dt.floor("h")

qa.to_parquet(path)

if __name__ == "__main__":

path = "./data/qa.parquet"

save_qa_to_parquet(path)

Listing 6.4 Downloading the SQuAD dataset

Loads SQuAD

dataset

Extracts

questions

and answers

Creates a

dataframe

Adds embeddings

and timestamps

Saves to

parquetNext, we’ll need to define the feature view for our feature store. A feature view is essentially like a view in a relational database. We’ll define a name, the entities (which

are like IDs or primary keys), the schema (which are our feature columns), and a source. We’ll just be demoing using a local file store, but in production, you’d want to use one of Feast’s many backend integrations with Snowflake, GCP, AWS, etc. It currently doesn’t support a VectorDB backend, but I’m sure it’s only a matter of time. In addition, we can add metadata to our view through tags and define a time to live (TTL), which limits how far back Feast will look when generating historical datasets. In the following listing, we define the feature view. Go ahead and add this definition into a file called qa.py in the feature_repo directory of our project.

from feast import Entity, FeatureView, Field, FileSource, ValueType

from feast.types import Array, Float32, String

from datetime import timedelta

path = "./data/qa.parquet"

question = Entity(name="question_id", value_type=ValueType.STRING)

question_feature = Field(name="questions", dtype=String)

answer_feature = Field(name="answers", dtype=String)

embedding_feature = Field(name="embeddings", dtype=Array(Float32))

questions_view = FeatureView(

name="qa",

entities=[question],

ttl=timedelta(days=1),

schema=[question_feature, answer_feature, embedding_feature],

source=FileSource(

path=path,

event_timestamp_column="datetime",

created_timestamp_column="created",

timestamp_field="datetime",

),

tags={},

online=True,

)

Listing 6.5 Feast FeatureView definitionWith that defined, let’s go ahead and register it. We’ll do that with

$ feast apply

Next, we’ll want to materialize the view. In production, this is a step you’ll need to schedule on a routine basis with something like cron or Prefect. Be sure to update the UTC timestamp for the end date in this command to something in the future to ensure the view collects the latest data:

$ feast materialize-incremental 2023-11-30T00:00:00 –views qa

Now all that’s left is to query it! The following listing shows a simple example of pulling features to be used at inference time.

import pandas as pd

from feast import FeatureStore

store = FeatureStore(repo_path=".")

path = "./data/qa.parquet"

ids = pd.read_parquet(path, columns=["question_id"])

feature_vectors = store.get_online_features(

features=["qa:questions", "qa:answers", "qa:embeddings"],

entity_rows=[{"question_id": _id} for _id in ids.question_id.to_list()],

).to_df()

print(feature_vectors.head())

Listing 6.6 Querying a feature view at inferenceThis example will pull the most up-to-date information for the lowest possible latency at inference time. For point-in-time retrieval, you would use the get_historical_ features method instead. In addition, in this example, we use a list of IDs for the entity rows parameter, but you could also use an SQL query making it very flexible and easy to use.

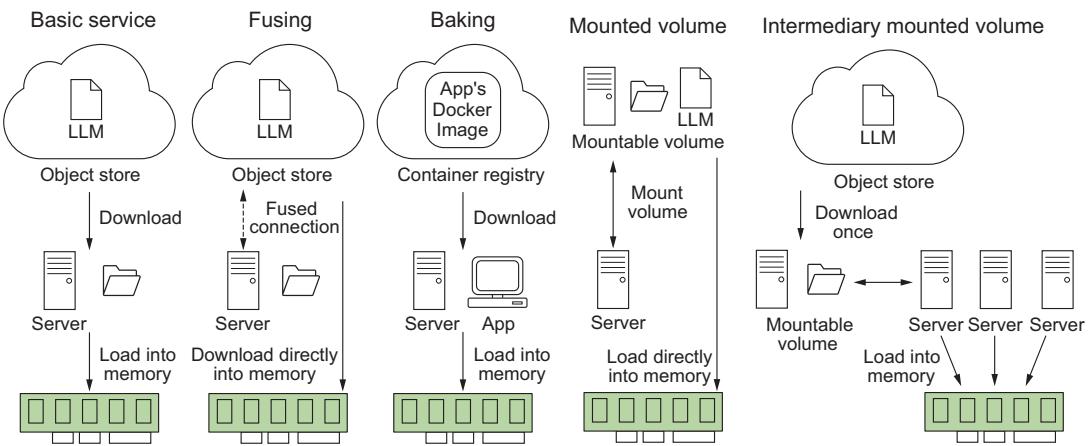

6.1.7 Retrieval-augmented generation

Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has become the most widely used tool to combat hallucinations in LLMs and improve the accuracy of responses in our results. Its popularity is likely because RAG is both easy to implement and quite effective. As first discussed in section 3.4.5, vector databases are a tool you’ll want to have in your arsenal. One of the key reasons is that they make RAG so much easier to implement. In figure 6.4, we demonstrate a RAG system. In the preprocessing stage, we take our documents, break them up, and transform them into embeddings that we’ll load into our vector database. During inference, we can take our input, encode it into an embedding, and run a similarity search across our documents in that vector database to find the nearest neighbors. This type of inference is known as semantic search. Pulling relevant documents and inserting them into our prompt will help give context to the LLM and improve the results.

We are going to demo implementing RAG using Pinecone since it will save us the effort of setting up a vector database. For listing 6.7, we will set up a Pinecone index and load a Wikipedia dataset into it. In this listing, we’ll create a WikiDataIngestion class to handle the heavy lifting. This class will load the dataset and run through each Wikipedia page, splitting the text into consumable chunks. It will then embed these chunks and upload everything in batches. Once we have everything uploaded, we can start to make queries.

Figure 6.4 RAG system demonstrating how we use our input embeddings to run a search across our documentation, improving the results of the generated text from our LLM

You’ll need an API key if you plan to follow along, so if you don’t already have one, go to Pinecone’s website (https://www.pinecone.io/) and create a free account, set up a starter project (free tier), and get an API key. One thing to pay attention to as you read the listing is that we’ll split up the text into chunks of 400 tokens with text_ splitter. We specifically split on tokens instead of words or characters, which allows us to properly budget inside our token limits for our model. In this example, returning the top three results will add 1,200 tokens to our request, which allows us to plan ahead of time how many tokens we’ll give to the user to write their prompt.

import os

import tiktoken

from datasets import load_dataset

from langchain.text_splitter import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

from langchain.embeddings.openai import OpenAIEmbeddings

from pinecone import Pinecone, ServerlessSpec

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

from tqdm.auto import tqdm

from uuid import uuid4

OPENAI_API_KEY = os.getenv("OPENAI_API_KEY")

PINECONE_API_KEY = os.getenv("PINECONE_API_KEY")

pc = Pinecone(api_key=PINECONE_API_KEY)

Listing 6.7 Example setting up a Pinecone database

Gets openai

API key from

platform.openai.com

Finds API key

in console at

app.pinecone.ioclass WikiDataIngestion:

def __init__(

self,

index,

wikidata=None,

embedder=None,

tokenizer=None,

text_splitter=None,

batch_limit=100,

):

self.index = index

self.wikidata = wikidata or load_dataset(

"wikipedia", "20220301.simple", split="train[:10000]"

)

self.embedder = embedder or OpenAIEmbeddings(

model="text-embedding-ada-002", openai_api_key=OPENAI_API_KEY

)

self.tokenizer = tokenizer or tiktoken.get_encoding("cl100k_base")

self.text_splitter = (

text_splitter

or RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=400,

chunk_overlap=20,

length_function=self.token_length,

separators=["\n\n", "\n", " ", ""],

)

)

self.batch_limit = batch_limit

def token_length(self, text):

tokens = self.tokenizer.encode(text, disallowed_special=())

return len(tokens)

def get_wiki_metadata(self, page):

return {

"wiki-id": str(page["id"]),

"source": page["url"],

"title": page["title"],

}

def split_texts_and_metadatas(self, page):

basic_metadata = self.get_wiki_metadata(page)

texts = self.text_splitter.split_text(page["text"])

metadatas = [

{"chunk": j, "text": text, **basic_metadata}

for j, text in enumerate(texts)

]

return texts, metadatas

def upload_batch(self, texts, metadatas):

ids = [str(uuid4()) for _ in range(len(texts))]

embeddings = self.embedder.embed_documents(texts)

self.index.upsert(vectors=zip(ids, embeddings, metadatas)) def batch_upload(self):

batch_texts = []

batch_metadatas = []

for page in tqdm(self.wikidata):

texts, metadatas = self.split_texts_and_metadatas(page)

batch_texts.extend(texts)

batch_metadatas.extend(metadatas)

if len(batch_texts) >= self.batch_limit:

self.upload_batch(batch_texts, batch_metadatas)

batch_texts = []

batch_metadatas = []

if len(batch_texts) > 0:

self.upload_batch(batch_texts, batch_metadatas)

if __name__ == "__main__":

index_name = "pincecone-llm-example"

if index_name not in pc.list_indexes().names():

pc.create_index(

name=index_name,

metric="cosine",

dimension=1536,

spec=ServerlessSpec(cloud="aws", region="us-east-1"),

)

index = pc.Index(index_name)

print(index.describe_index_stats())

embedder = None

if not OPENAI_API_KEY:

embedder = SentenceTransformer(

"sangmini/msmarco-cotmae-MiniLM-L12_en-ko-ja"

)

embedder.embed_documents = lambda *args, **kwargs: embedder.encode(

*args, **kwargs

).tolist()

wiki_data_ingestion = WikiDataIngestion(index, embedder=embedder)

wiki_data_ingestion.batch_upload()

print(index.describe_index_stats())

query = "Did Johannes Gutenberg invent the printing press?"

embeddings = wiki_data_ingestion.embedder.embed_documents(query)

results = index.query(vector=embeddings, top_k=3, include_metadata=True)

print(results)

Creates an

index if it

doesn't exist

1536 dim of

text-embedding-

ada-002

Connects to the index

and describes the stats

Uses a generic embedder if an

openai api key is not provided

Also 1536 dim

Ingests data and

describes the stats anew

Makes a

queryWhen I ran this code, the top three query results to my question, “Did Johannes Gutenberg invent the printing press?” were the Wikipedia pages for Johannes Gutenberg, the pencil, and the printing press. Not bad! While a vector database isn’t going

to be able to answer the question, it’s simply finding the most relevant articles based on the proximity of their embeddings to my question.

With these articles, we can then feed their embeddings into our LLM as additional context to the question to ensure a more grounded result. Since we include sources, it will even have the wiki URL it can give as a reference, and it won’t just hallucinate one. By giving this context, we greatly reduce the concern about our LLM hallucinating and making up an answer.

6.1.8 LLM service libraries

If you are starting to feel a bit overwhelmed about all the tooling and features you need to implement to create an LLM service, we have some good news for you: several libraries aim to do all of this for you! Some open source libraries of note are vLLM and OpenLLM (by BentoML). Hugging Face’s Text-Generation-Inference (TGI) briefly lost its open source license, but fortunately, it’s available again for commercial use. There are also some start-ups building some cool tooling in this space, and we recommend checking out TitanML if you are hoping for a more managed service. These are like the tools MLServer, BentoML, and Ray Serve discussed in section 3.4.8 on deployment service, but they are designed specifically for LLMs.

Most of these toolings are still relatively new and under active development, and they are far from feature parity with each other, so pay attention to what they offer. What you can expect is that they should at least offer streaming, batching, and GPU parallelization support (something we haven’t specifically talked about in this chapter), but beyond that, it’s a crapshoot. Many of them still don’t support several features discussed in this chapter, nor do they support every LLM architecture. What they do, though, is make deploying LLMs easy.

Using vLLM as an example, just pip install vllm, and then you can run

$ python -m vllm.entrypoints.api_server –model IMJONEZZ/ggml-openchat-8192-q4_0

With just one command, we now have a service up and running the model we trained in chapter 5. Go ahead and play with it; you should be able to send requests to the /generate endpoint like so:

$ curl http://localhost:8000/generate -d '{"prompt": "Which pokemon is

➥ the best?", "use_beam_search": true, "n": 4, "temperature": 0}'It’s very likely you won’t be all that impressed with any of these toolings. Still, you should be able to build your own API and have a good sense of how to do it at this point. Now that you have a service and can even spin it up locally, let’s discuss the infrastructure you need to set up to support these models for actual production usage. Remember, the better the infrastructure, the less likely you’ll be called in the middle of the night when your service goes down unexpectedly. None of us want that, so let’s check it out.

6.2 Setting up infrastructure

Setting up infrastructure is a critical aspect of modern software development, and we shouldn’t expect machine learning to be any different. To ensure scalability, reliability, and efficient deployment of our applications, we need to plan a robust infrastructure that can handle the demands of a growing user base. This is where Kubernetes comes into play.

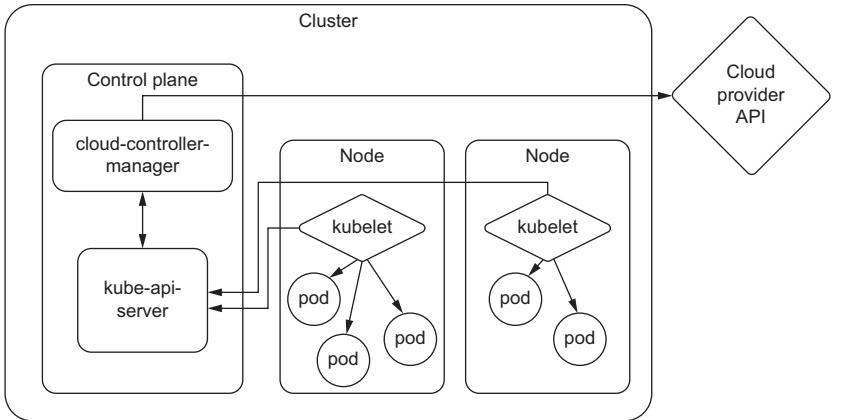

Kubernetes, often referred to as k8s, is an open source container orchestration platform that helps automate and manage the deployment, scaling, and management of containerized applications. It is designed to simplify the process of running and coordinating multiple containers across a cluster of servers, making it easier to scale applications and ensure high availability. We are going to talk a lot about k8s in this chapter, and while you don’t need to be an expert, it will be useful to cover some basics to ensure we are all on the same page.

At its core, k8s works by grouping containers into logical units called pods, which are the smallest deployable units in the k8s ecosystem. These pods are then scheduled and managed by the k8s control plane, which oversees their deployment, scaling, and updates. This control plane consists of several components that collectively handle the orchestration and management of containers. In figure 6.5, we give an oversimplification of the k8s architecture to help readers who are unfamiliar with it.

Figure 6.5 An oversimplification of the Kubernetes architecture. What you need to know is that our services run in pods, and pods run on nodes, which essentially are a machine. K8s helps us both manage the resources and handle the orchestration of deploying pods to these resources.

Using k8s, we can take advantage of features such as automatic scaling, load balancing, and service discovery, which greatly simplify the deployment and management of web applications. K8s provides a flexible and scalable infrastructure that can easily

adapt to changing demands, allowing organizations to efficiently scale their applications as their user base grows. K8s offers a wide range of additional features and extensibility options, such as storage management, monitoring, and logging, which help ensure the smooth operation of web applications.

One of these extensibility options is known as custom resource definitions (CRDs). CRDs are a feature of Kubernetes that allows users to create their own specifications for custom resources, thus extending the functionalities of Kubernetes without modifying the Kubernetes source code. With a CRD defined, we can create custom objects similar to how we would create a built-in object like a pod or service. This gives k8s a lot of flexibility that we will need for different functionality throughout this chapter.

If you are new to Kubernetes, you might be scratching your head through parts of this section, and that’s totally fine. Hopefully, though, you have enough knowledge to get the gist of what we will be doing in this section and why. At least you’ll be able to walk away with a bunch of questions to ask your closest DevOps team member.

6.2.1 Provisioning clusters

The first thing to do when starting any project is to set up a cluster. A cluster is a collective of worker machines or nodes where we will host our applications. Creating a cluster is relatively simple; configuring it is the hard part. Of course, there have been many books written on how to do this, and the majority of considerations like networking, security, and access control are outside the scope of this book. In addition, considering the steps you take will also be different depending on the cloud provider of choice and your company’s business strategy, we will focus on only the portions that we feel are needed to get you up and running, as well as any other tidbits that may make your life easier.

The first step is to create a cluster. On GCP, you would use the gcloud tool and run

$ gcloud container clusters create

On AWS, using the eksctl tool, run

$ eksctl create cluster

On Azure, using the az cli tool, run

$ az group create --name=<GROUP_NAME> --location=westus

$ az aks create --resource-group=<GROUP_NAME> --name=<CLUSTER_NAME>As you can see, even the first steps are highly dependent on your provider, and you can suspect that the subsequent steps will be as well. Since we realize most readers will be deploying in a wide variety of environments, we will not focus on the exact steps but hopefully give you enough context to search and discover for yourself.

Many readers, we imagine, will already have a cluster set up for them by their infrastructure teams, complete with many defaults and best practices. One of these is

setting up node auto-provisioning (NAP) or cluster autoscaling. NAP allows a cluster to grow, adding more nodes as deployments demand them. This way, we only pay for nodes we actually use. It’s a very convenient feature, but it often defines resource limits or restrictions on the instances available for autoscaling, and you can bet your cluster’s defaults don’t include accelerator or GPU instances in that pool. We’ll need to fix that.

In GCP, we would create a configuration file like the one in the following listing, where we can include the GPU resourceType. In the example, we include T4s and both A100 types.

Listing 6.8 Example NAP config file

resourceLimits: - resourceType: 'cpu'

minimum: 10

maximum: 100

- resourceType: 'memory'

maximum: 1000

- resourceType: 'nvidia-tesla-t4'

maximum: 40

- resourceType: 'nvidia-tesla-a100'

maximum: 16

- resourceType: 'nvidia-a100-80gb'

maximum: 8

management:

autoRepair: true

autoUpgrade: true

shieldedInstanceConfig:

enableSecureBoot: true

enableIntegrityMonitoring: true

diskSizeGb: 100You would then set this by running

$ gcloud container clusters update <CLUSTER_NAME> --enable-autoprovisioning -

-autoprovisioning-config-file <FILE_NAME>The real benefit of an NAP is that instead of predefining what resources are available at a fixed setting, we can set resource limits, which put a cap on the total number of GPUs that we would scale up to. They clearly define what GPUs we want and expect to be in any given cluster.

When one author was first learning about limits, he often got them confused with similar concepts—quotas, reservations, and commitments—and has seen many others just as confused. Quotas, in particular, are very similar to limits. Their main purpose is to prevent unexpected overage charges by ensuring a particular project or application doesn’t consume too many resources. Unlike limits, which are set internally, quotas often require submitting a request to your cloud provider when you want to raise them. These requests help inform and are used by the cloud provider to better plan

which resources to provision and put into different data centers in different regions. It’s tempting to think that the cloud provider will ensure those resources are available; however, quotas never guarantee there will be enough resources in a region for your cluster to use, and you might run into resources not found errors way before you hit them.

While quotas and limits set an upper bound, reservations and commitments set the lower bound. Reservations are an agreement to guarantee that a certain amount of resources will always be available and often come with the caveat that you will be paying for these resources regardless of whether you end up using them. Commitments are similar to reservations but are often longer-term contracts, usually coming with a discounted price.

6.2.2 Autoscaling

One of the big selling points to setting up a k8s cluster is autoscaling. Autoscaling is an important ingredient in creating robust production-grade services. The main reason is that we never expect any service to receive static request volume. If anything else, you should expect more volume during the day and less at night while people sleep. So we’ll want our service to spin up more replicas during peak hours to improve performance and spin down replicas during off hours to save money, not to mention the need to handle bursty workloads that often threaten to crash a service at any point.

Knowing your service will automatically provision more resources and set up additional deployments based on the needs of the application is what allows many infrastructure engineers to sleep peacefully at night. The catch is that it requires an engineer to know what those needs are and ensure everything is configured correctly. While autoscaling provides flexibility, the real business value comes from the cost savings. Most engineers think about autoscaling in terms of scaling up to prevent meltdowns, but even more important to the business is the ability to scale down, freeing up resources and cutting costs.

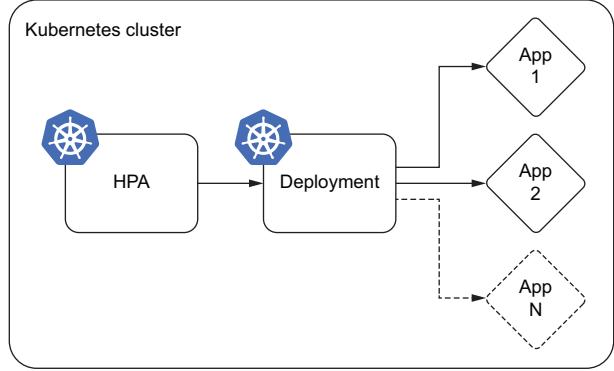

One of the main reasons cloud computing and technologies like Kubernetes have become essential in modern infrastructures is because autoscaling is built in. Autoscaling is a key feature of Kubernetes, and with horizontal pod autoscalers (HPAs), you can easily adjust the number of replicas of your application based on two native resources: CPU and memory usage, as shown in figure 6.6. However, in a book about putting LLMs in production, scaling based on CPU and memory alone will never be enough. We will need to scale based on custom metrics, specifically GPU utilization.

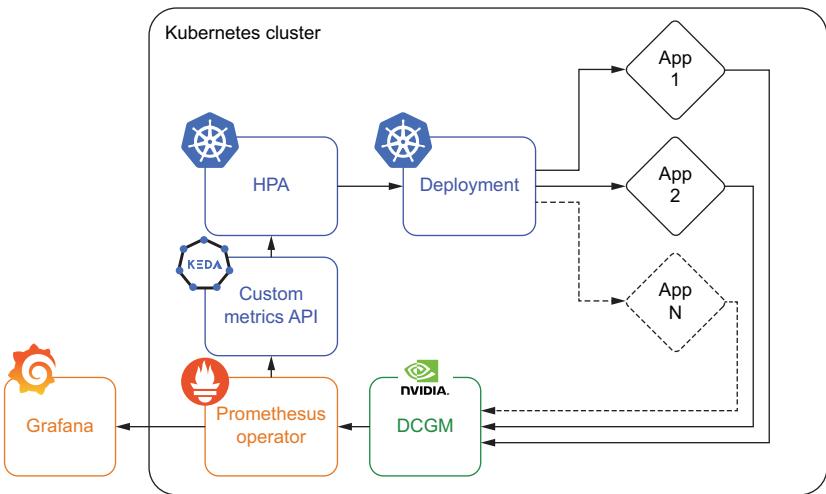

Setting up autoscaling based on GPU metrics is going to take a bit more work and requires setting up several services. It’ll become clear why we need each service as we discuss them, but the good news is that by the end, you’ll be able to set up your services to scale based on any metric, including external events such as messages from a message broker, requests to an HTTP endpoint, and data from a queue.

Figure 6.6 Basic autoscaling using the in-built k8s horizontal pod autoscaler (HPA). The HPA watches CPU and memory resources and will tell the deployment service to increase or decrease the number of replicas.

The first service we’ll need is one that can collect the GPU metrics. For this, we have NVIDIA’s Data Center GPU Manager (DCGM), which provides a metrics exporter that can export GPU metrics. DCGM exposes a host of GPU metrics, including temperature and power usage, which can create some fun dashboards, but the most useful metrics for autoscaling are utilization and memory utilization.

From here, the data will go to a service like Prometheus. Prometheus is a popular open source monitoring system used to monitor Kubernetes clusters and the applications running on them. Prometheus collects metrics from various sources and stores them in a time-series database, where they can be analyzed and queried. Prometheus can collect metrics directly from Kubernetes APIs and from applications running on the cluster using a variety of collection mechanisms such as exporters, agents, and sidecar containers. It’s essentially an aggregator of services like DCGM, including features like alerting and notification. It also exposes an HTTP API for service for external tooling like Grafana to query and create graphs and dashboards with.

While Prometheus provides a way to store metrics and monitor our service, the metrics aren’t exposed to the internals of Kubernetes. For an HPA to gain access, we will need to register yet another service to either the custom metrics API or external metrics API. By default, Kubernetes comes with the metrics.k8s.io endpoint that exposes resource metrics, CPU, and memory utilization. To accommodate the need to scale deployments and pods on custom metrics, two additional APIs were introduced: custom.metrics.k9s.io and external.metrics.k8s.io. There are some limitations to this setup, as currently, only one “adapter” API service can be registered at a time for either one. This limitation mostly becomes a problem if you ever decide to change this endpoint from one provider to another.

For this service, Prometheus provides the Prometheus Adapter, which works well, but from our experience, it wasn’t designed for production workloads. Alternatively, we would recommend KEDA. KEDA (Kubernetes Event-Driven Autoscaling) is an open source project that provides event-driven autoscaling for Kubernetes. It offers more flexibility in terms of the types of custom metrics that can be used for autoscaling. While Prometheus Adapter requires configuring metrics inside a ConfigMap, any metric already exposed through the Prometheus API can be used in KEDA, providing a more streamlined and friendly user experience. It also offers scaling to and from 0, which isn’t available through HPAs, allowing you to turn off a service completely if there is no traffic. That said, you can’t scale from 0 on resource metrics like CPU and memory and, by extension, GPU metrics, but it is useful when you are using traffic metrics or a queue to scale.

Putting this all together, you’ll end up with the architecture shown in figure 6.7. Compared to figure 6.6, you’ll notice at the bottom that DCGM is managing our GPU metrics and feeding them into Prometheus Operator. From Prometheus, we can set up external dashboards with tools like Grafana. Internal to k8s, we’ll use KEDA to set up a custom.metrics.k9s.io API to return these metrics so we can autoscale based on the GPU metrics. KEDA has several CRDs, one of which is a ScaledObject, which creates the HPA and provides the additional features.

Figure 6.7 Autoscaling based on a custom metric like GPU utilization requires several extra tools to work, including NVIDIA’s DCGM, a monitoring system like Prometheus Operator, and a custom metrics API like that provided by KEDA.

While autoscaling provides many benefits, it’s important to be aware of its limitations and potential problems, which are only exacerbated by LLM inference services. Proper configuration of the HPA is often an afterthought for many applications, but it becomes mission-critical when dealing with LLMs. LLMs take longer to become fully operational, as the GPUs need to be initialized and model weights loaded into memory; these aren’t services that can turn on a dime, which often can cause problems when scaling up if not properly prepared for. Additionally, if the system scales down too aggressively, it may result in instances being terminated before completing their assigned tasks, leading to data loss or other problems. Lastly, flapping is just such a concern that can arise from incorrect autoscaling configurations. Flapping happens when the number of replicas keeps oscillating, booting up a new service only to terminate it before it can serve any inferences.

There are essentially five parameters to tune when setting up an HPA:

- Target parameter

- Target threshold

- Min pod replicas

- Max pod replicas

- Scaling policies

Let’s take a look at each of them in turn so you can be sure your system is properly configured.

TARGET PARAMETER

The target parameter is the most important metric to consider when ensuring your system is properly configured. If you followed the previously listed steps in section 6.2.2, your system is now ready to autoscale based on GPU metrics, so this should be easy, right? Not so fast! Scaling based on GPU utilization is going to be the most common and straightforward path, but the first thing we need to do is ensure the GPU is the actual bottleneck in our service. It’s pretty common to see eager young engineers throw a lot of expensive GPUs onto a service but forget to include adequate CPU and memory capacity. CPU and memory will still be needed to handle the API layer, such as taking in requests, handling multiple threads, and communicating with the GPUs. If there aren’t enough resources, these layers can quickly become a bottleneck, and your application will be throttled way before the GPU utilization is ever affected, ensuring the system will never actually autoscale. While you could switch the target parameter on the autoscaler, CPU and memory are cheap compared to GPU resources, so it’d be better to allocate more of them for your application.

In addition, there are cases where other metrics make more sense. If your LLM application takes most of its requests from a streaming or batch service, it can be more prudent to scale based on metrics that tell you a DAG is running or an upstream queue is filling up—especially if these metrics give you an early signal and allow you more time to scale up in advance.

Another concern when selecting the metric is its stability. For example, an individual GPU’s utilization tends to be close to either 0% or 100%. This can cause problems for the autoscaler, as the metric oscillates between an on and off state, as will its recommendation to add or remove replicas, causing flapping. Generally, flapping is avoided by taking the average utilization across all GPUs running the service. Using the average will stabilize the metric when you have a lot of GPUs, but it could still be a problem when the service has scaled down. If you are still running into problems, you’ll want to use an average-over-time aggregation, which will tell you the utilization for each GPU over a time frame—say, the last 5 minutes. For CPU utilization, average-over-time aggregation is built into the Kubernetes HPA and can be set with the horizontal-pod-autoscaler-cpu-initialization-period flag. For custom metrics, you’ll need to set it in your metric query (for Prometheus, it would be the avg_over_ time aggregation function).

Lastly, it’s worth calling out that most systems allow you to autoscale based on multiple metrics. So you could autoscale based on both CPU and GPU utilization, as an example. However, we would recommend avoiding these setups unless you know what you are doing. Your autoscaler might be set up that way, but in actuality, your service will likely only ever autoscale based on just one of the metrics due to service load, and it’s best to make sure that metric is the more costly resource for cost-engineering purposes.

TARGET THRESHOLD

The target threshold tells your service at what point to start upscaling. For example, if you are scaling based on the average GPU utilization and your threshold is set to 30, then a new replica will be booted up to take on the extra load when the average GPU utilization is above 30%. The formula that governs this is quite simple and is as follows:

desiredReplicas = ceil[currentReplicas × (currentMetricValue / desiredMetricValue )]

NOTE You can learn more about the algorithm at https://mng.bz/x64g.

This can be hard to tune in correctly, but here are some guiding principles. If the traffic patterns you see involve a lot of constant small bursts of traffic, a lower value, around 50, might be more appropriate. This setting ensures you start to scale up more quickly, avoiding unreliability problems, and you can also scale down more quickly, cutting costs. If you have a constant steady flow of traffic, higher values, around 80, will work well. Outside of testing your autoscaler, it’s best to avoid extremely low values, as they can increase your chances of flapping. You should also avoid extremely high values, as they may allow the active replicas to be overwhelmed before new ones start to boot up, which can cause unreliability or downtime. It’s also important to remember that due to the nature of pipeline parallel workflows when using a distributed GPU setup, there will always be a bubble, as discussed in section 3.3.2. As a result, your system will never reach 100% GPU utilization, and you will start to hit problems earlier than expected. Depending on how big your bubble is, you will need to adjust the target threshold accordingly.

MINIMUM POD REPLICAS

Minimum pod replicas determine the number of replicas of your service that will always be running. This setting is your baseline. It’s important to make sure it’s set slightly above your baseline of incoming requests. Too often, this is set strictly to meet baseline levels of traffic or just below, but a steady state for incoming traffic is rarely all that steady. This is where a lot of oscillating can happen, as you are more likely to see many small surges in traffic than large spikes. However, you don’t want to set it too high, as this will tie up valuable resources in the cluster and increase costs.

MAXIMUM POD REPLICAS

Maximum pod replicas determine the number of replicas your system will run at peak capacity. You should set this number to be just above your peak traffic requirements. Setting it too low could lead to reliability problems, performance degradation, and downtime during high-traffic periods. Setting it too high could lead to resource waste, running more pods than necessary, and delaying the detection of real problems. For example, if your application was under a DDoS attack, your system might scale to handle the load, but it would likely cost you severely and hide the problem. With LLMs, you also need to be cautious not to overload the underlying cluster and make sure you have enough resources in your quotas to handle the peak load.

SCALING POLICIES

Scaling policies define the behavior of the autoscaler, allowing you to finetune how long to wait before scaling and how quickly it scales. This setting is usually ignored, and safely so for most setups because the defaults for these settings tend to be pretty good for the typical application. However, relying on the default would be a major mistake for an LLM service since it takes so long to deploy.

The first setting you’ll want to adjust is the stabilization window, which determines how long to wait before taking a new scaling action. You can set a different stabilization window for upscaling and downscaling tasks. The default upscaling window is 0 seconds, which should not need to be touched if your target parameter has been set correctly. The default downscaling window is 300 seconds, which is likely too short for our use case. You’ll typically want this at least as long as it takes your service to deploy and then a little bit more. Otherwise, you’ll be adding replicas only to remove them before they have a chance to do anything.

The next parameter you’ll want to adjust is the scale-down policy, which defaults to 100% of pods every 15 seconds. As a result, any temporary drop in traffic could result in all your extra pods above the minimum being terminated immediately. For our case, it’s much safer to slow this down since terminating a pod takes only a few seconds, but booting one up can take minutes, making it a semi-irreversible decision. The exact policy will depend on your traffic patterns, but in general, we want to have a little more patience. You can adjust how quickly pods will be terminated and the magnitude by the number or percentage of pods. For example, we could configure the policy to allow only one pod each minute or 10% of pods every 5 minutes to be terminated.

6.2.3 Rolling updates

Rolling updates or rolling upgrades is a strategy that gradually implements the new version of an application to reduce downtime and maximize agility. It works by gradually creating new instances and turning off the old ones, replacing them in a methodical manner. This update approach allows the system to remain functional and accessible to users even during the update process, otherwise known as zero downtime. Rolling updates also make it easier to catch bugs before they have too much effect and roll back faulty deployments.

Rolling updates is a feature built into k8s and another major reason for its widespread use and popularity. Kubernetes provides an automated and simplified way to carry out rolling updates. The rolling updates ensure that Kubernetes incrementally updates pod instances with new ones during deployment. The following listing shows an example LLM deployment implementing rolling updates; the relevant configuration is under the spec.strategy section.

Listing 6.9 Example deployment config with rolling updateapiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: llm-application

spec:

replicas: 5

strategy:

rollingUpdate:

maxSurge: 1

maxUnavailable: 3

selector:

matchLabels:

app: llm-app

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: llm-app

spec:

containers:

- name: llm-gpu-app-container

image: llm-gpu-application:v2

resources:

limits: