Generative AI with LangChain

Build production-ready LLM applications and advanced agents using Python, LangChain, and LangGraph

Generative AI with LangChain

Second Edition

Build production-ready LLM applications and advanced agents using Python, LangChain, and LangGraph

Ben Auffarth Leonid Kuligin

Copyright © 2025 Packt Publishing

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles or reviews.

Every effort has been made in the preparation of this book to ensure the accuracy of the information presented. However, the information contained in this book is sold without warranty, either express or implied. Neither the authors, nor Packt Publishing or its dealers and distributors, will be held liable for any damages caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this book.

Packt Publishing has endeavored to provide trademark information about all of the companies and products mentioned in this book by the appropriate use of capitals. However, Packt Publishing cannot guarantee the accuracy of this information.

Portfolio Director: Gebin George Relationship Lead: Ali Abidi Project Manager: Prajakta Naik Content Engineer: Tanya D’cruz Technical Editor: Irfa Ansari Copy Editor: Safis Editing Indexer: Manju Arasan Proofreader: Tanya D’cruz Production Designer: Ajay Patule Growth Lead: Nimisha Dua

First published: December 2023 Second edition: May 2025

Production reference: 1190525

Published by Packt Publishing Ltd. Grosvenor House

11 St Paul’s Square

Birmingham

B3 1RB, UK.

ISBN 978-1-83702-201-4

To the mentors who guided me throughout my life—especially Tony Lindeberg, whose personal integrity and perseverance are a tremendous source of inspiration—and to my son, Nicholas, and my partner, Diane.

—Ben Auffarth

To my wife, Ksenia, whose unwavering love and optimism have been my constant support over all these years; to my mother-in-law, Tatyana, whose belief in me—even in my craziest endeavors—has been an incredible source of strength; and to my kids, Matvey and Milena: I hope you’ll read it one day.

—Leonid Kuligin

Contributors

About the reviewers

Max Tschochohei advises enterprise customers on how to realize their AI and ML ambitions on Google Cloud. As an engineering manager in Google Cloud Consulting, he leads teams of AI engineers on mission-critical customer projects. While his work spans the full range of AI products and solutions in the Google Cloud portfolio, he is particularly interested in agentic systems, machine learning operations, and healthcare applications of AI. Before joining Google in Munich, Max spent several years as a consultant, first with KPMG and later with the Boston Consulting Group. He also led the digital transformation of NTUC Enterprise, a Singapore government organization. Max holds a PhD in Economics from Coventry University.

Rany ElHousieny is an AI Solutions Architect and AI Engineering Manager with over two decades of experience in AI, NLP, and ML. Throughout his career, he has focused on the development and deployment of AI models, authoring multiple articles on AI systems architecture and ethical AI deployment. He has led groundbreaking projects at companies like Microsoft, where he spearheaded advancements in NLP and the Language Understanding Intelligent Service (LUIS). Currently, he plays a pivotal role at Clearwater Analytics, driving innovation in generative AI and AI-driven financial and investment management solutions.

Nicolas Bievre is a Machine Learning Engineer at Meta with extensive experience in AI, recommender systems, LLMs, and generative AI, applied to advertising and healthcare. He has held key AI leadership roles at Meta and PayPal, designing and implementing large-scale recommender systems used to personalize content for hundreds of millions of users. He graduated from Stanford University, where he published peer-reviewed research in leading AI and bioinformatics journals. Internationally recognized for his contributions, Nicolas has received awards such as the “Core Ads Growth Privacy” Award and the “Outre-Mer Outstanding Talent” Award. He also serves as an AI consultant to the French government and as a reviewer for top AI organizations.

Join our communities on Discord and Reddit

Have questions about the book or want to contribute to discussions on Generative AI and LLMs? Join our Discord server at https://packt.link/4Bbd9 and our Reddit channel at https://packt. link/wcYOQ to connect, share, and collaborate with like-minded AI professionals.

Discord QR Reddit QR

Preface

With Large Language Models (LLMs) now powering everything from customer service chatbots to sophisticated code generation systems, generative AI has rapidly transformed from a research lab curiosity to a production workhorse. Yet a significant gap exists between experimental prototypes and production-ready AI applications. According to industry research, while enthusiasm for generative AI is high, over 30% of projects fail to move beyond proof of concept due to reliability issues, evaluation complexity, and integration challenges. The LangChain framework has emerged as an essential bridge across this divide, providing developers with the tools to build robust, scalable, and practical LLM applications.

This book is designed to help you close that gap. It’s your practical guide to building LLM applications that actually work in production environments. We focus on real-world problems that derail most generative AI projects: inconsistent outputs, difficult debugging, fragile tool integrations, and scaling bottlenecks. Through hands-on examples and tested patterns using LangChain, LangGraph, and other tools in the growing generative AI ecosystem, you’ll learn to build systems that your organization can confidently deploy and maintain to solve real problems.

Who this book is for

This book is primarily written for software developers with basic Python knowledge who want to build production-ready applications using LLMs. You don’t need extensive machine learning expertise, but some familiarity with AI concepts will help you move more quickly through the material. By the end of the book, you’ll be confidently implementing advanced LLM architectures that would otherwise require specialized AI knowledge.

If you’re a data scientist transitioning into LLM application development, you’ll find the practical implementation patterns especially valuable, as they bridge the gap between experimental notebooks and deployable systems. The book’s structured approach to RAG implementation, evaluation frameworks, and observability practices addresses the common frustrations you’ve likely encountered when trying to scale promising prototypes into reliable services.

For technical decision-makers evaluating LLM technologies within their organizations, this book offers strategic insight into successful LLM project implementations. You’ll understand the architectural patterns that differentiate experimental systems from production-ready ones, learn to identify high-value use cases, and discover how to avoid the integration and scaling issues that cause most projects to fail. The book provides clear criteria for evaluating implementation approaches and making informed technology decisions.

What this book covers

Chapter 1, The Rise of Generative AI, From Language Models to Agents, introduces the modern LLM landscape and positions LangChain as the framework for building production-ready AI applications. You’ll learn about the practical limitations of basic LLMs and how frameworks like LangChain help with standardization and overcoming these challenges. This foundation will help you make informed decisions about which agent technologies to implement for your specific use cases.

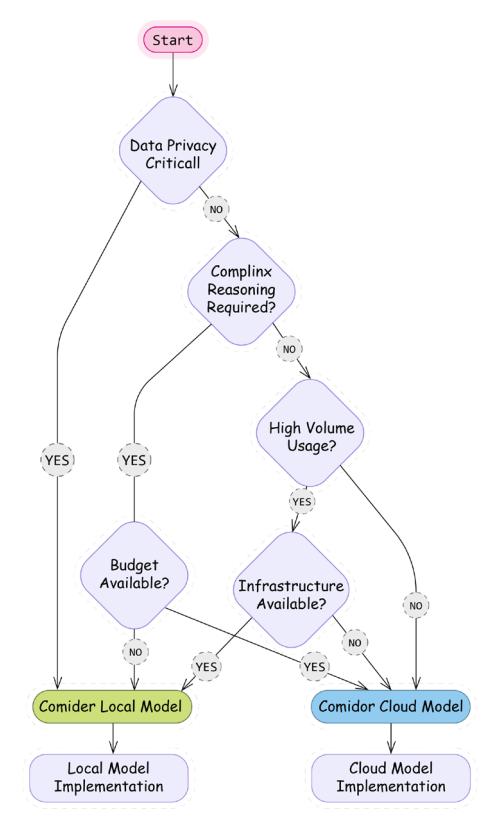

Chapter 2, First Steps with LangChain, gets you building immediately with practical, hands-on examples. You’ll set up a proper development environment, understand LangChain’s core components (model interfaces, prompts, templates, and LCEL), and create simple chains. The chapter shows you how to run both cloud-based and local models, giving you options to balance cost, privacy, and performance based on your project needs. You’ll also explore simple multimodal applications that combine text with visual understanding. These fundamentals provide the building blocks for increasingly sophisticated AI applications.

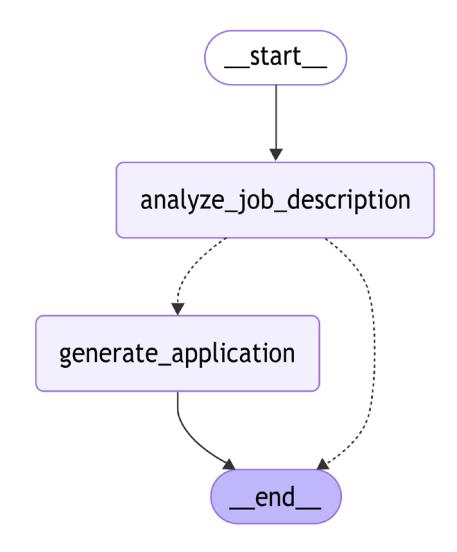

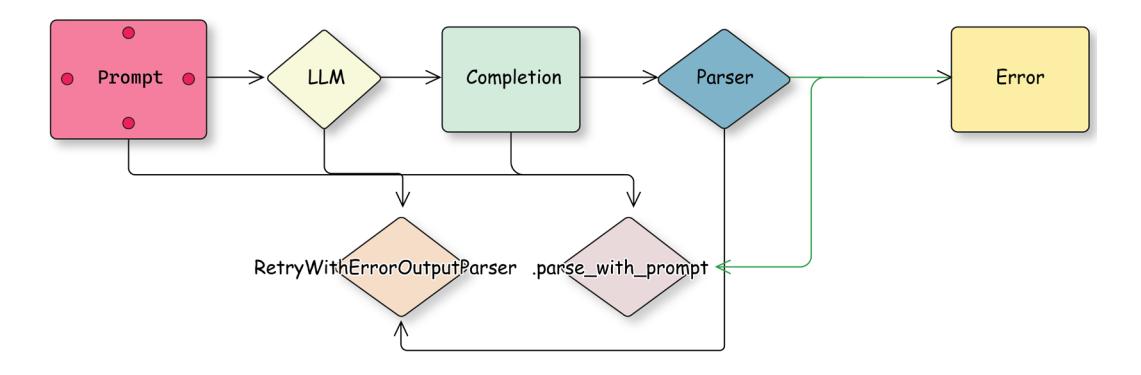

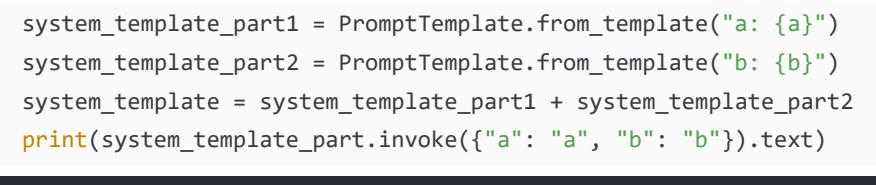

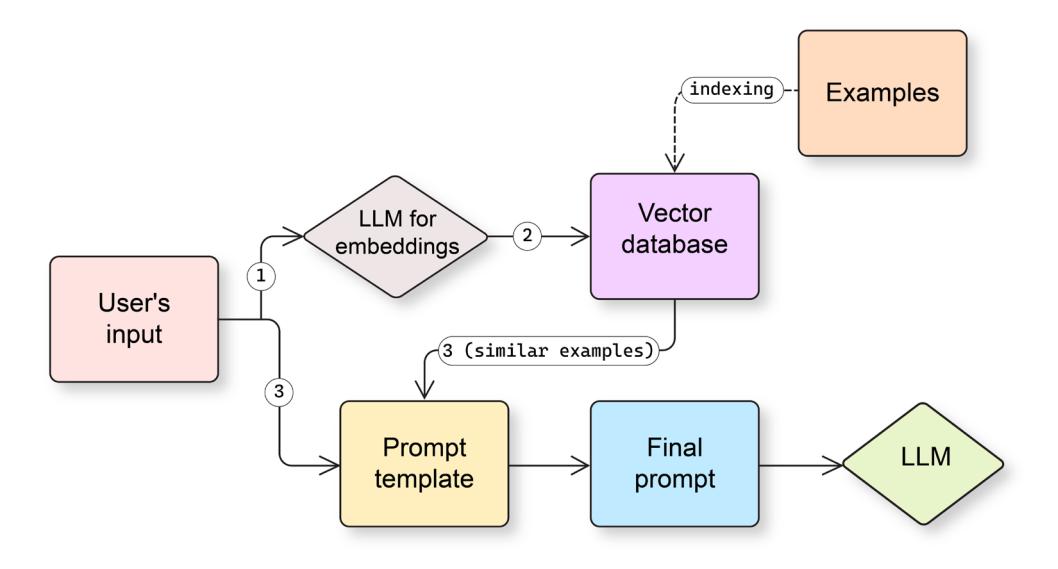

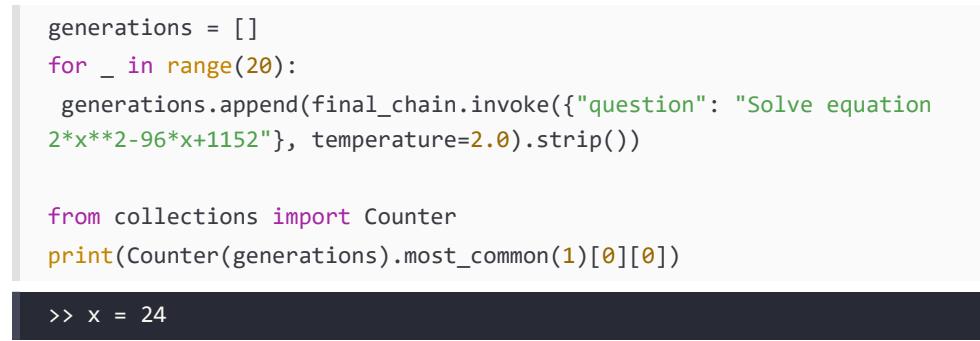

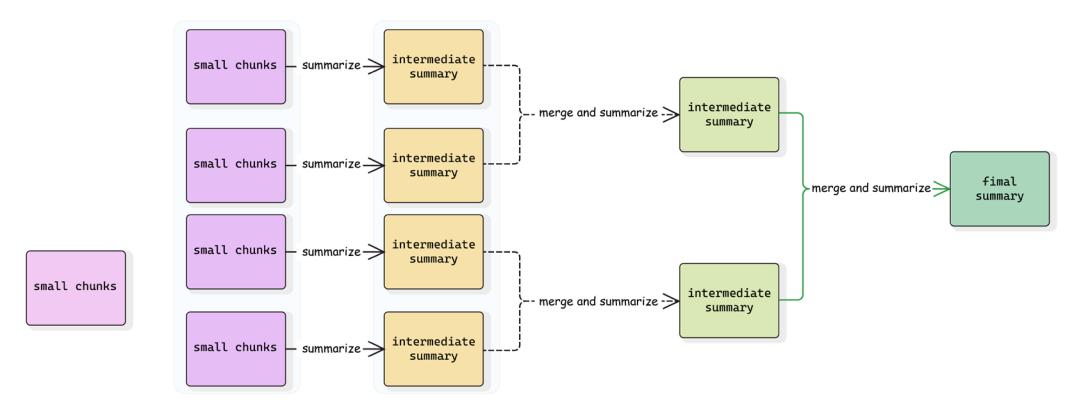

Chapter 3, Building Workflows with LangGraph, dives into creating complex workflows with LangChain and LangGraph. You’ll learn to build workflows with nodes and edges, including conditional edges for branching based on state. The chapter covers output parsing, error handling, prompt engineering techniques (zero-shot and dynamic few-shot prompting), and working with long contexts using Map-Reduce patterns. You’ll also implement memory mechanisms for managing chat history. These skills address why many LLM applications fail in real-world conditions and give you the tools to build systems that perform reliably.

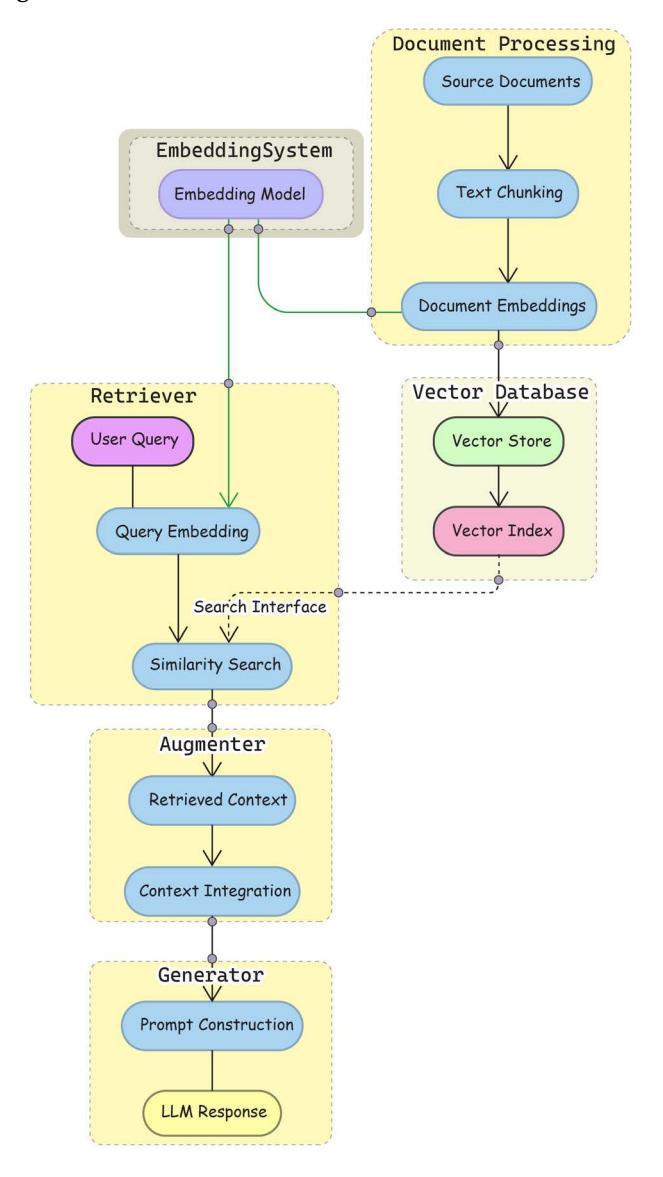

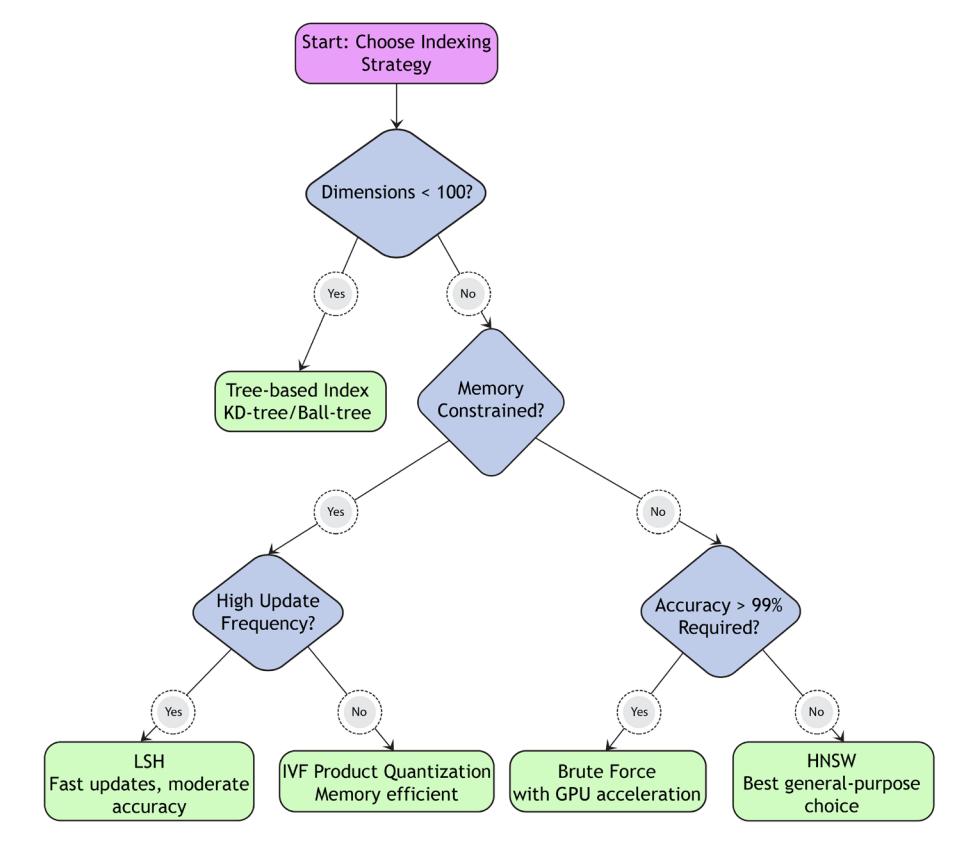

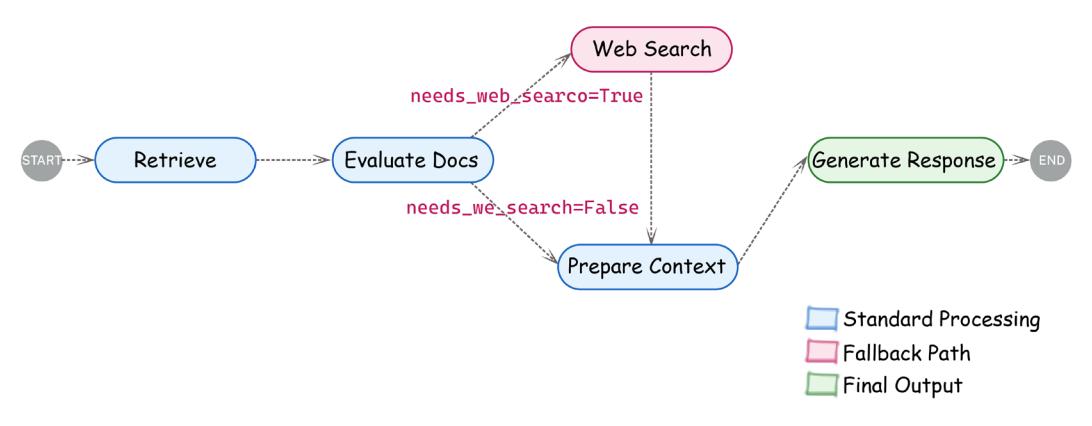

Chapter 4, Building Intelligent RAG Systems, addresses the “hallucination problem” by grounding LLMs in reliable external knowledge. You’ll master vector stores, document processing, and retrieval strategies that improve response accuracy. The chapter’s corporate documentation chatbot project demonstrates how to implement enterprise-grade RAG pipelines that maintain consistency and compliance—a capability that directly addresses data quality concerns cited in industry surveys. The troubleshooting section covers seven common RAG failure points and provides practical solutions for each.

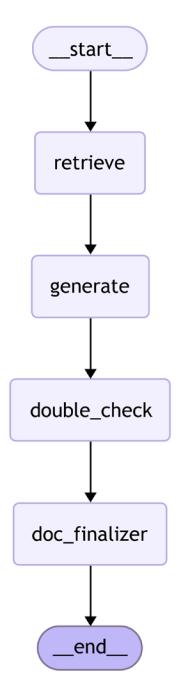

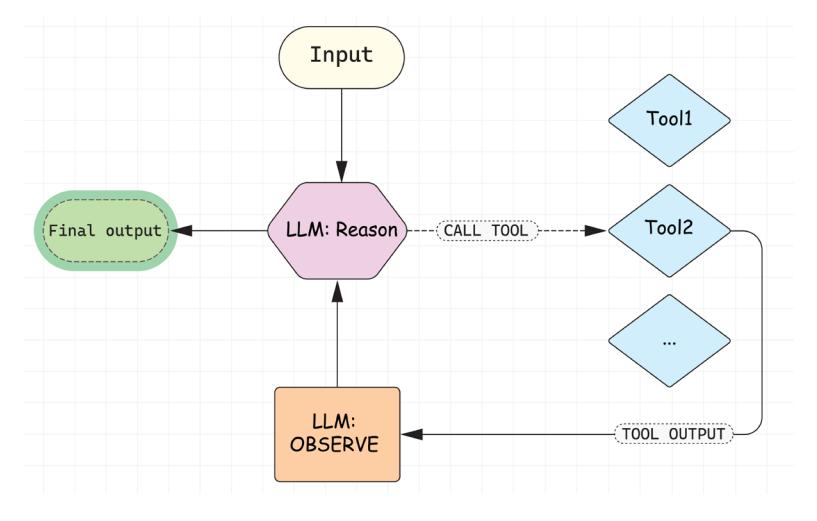

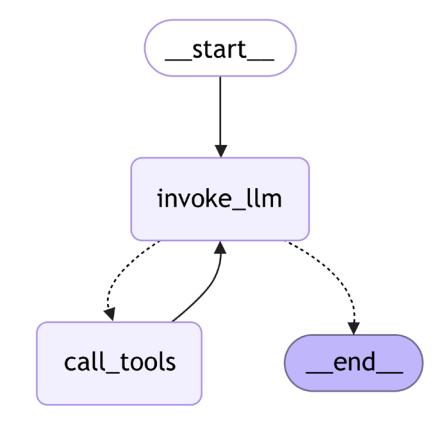

Chapter 5, Building Intelligent Agents, tackles tool use fragility—identified as a core bottleneck in agent autonomy. You’ll implement the ReACT pattern to improve agent reasoning and decision-making, develop robust custom tools, and build error-resilient tool calling processes. Through practical examples like generating structured outputs and building a research agent, you’ll understand what agents are and implement your first plan-and-solve agent with LangGraph, setting the stage for more advanced agent architectures.

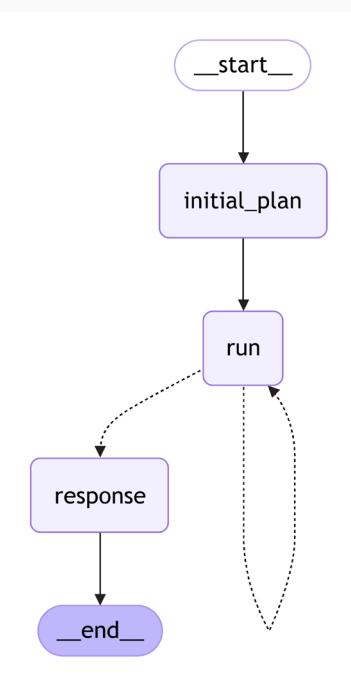

Chapter 6, Advanced Applications and Multi-Agent Systems, covers architectural patterns for agentic AI applications. You’ll explore multi-agent architectures and ways to organize communication between agents, implementing an advanced agent with self-reflection that uses tools to answer complex questions. The chapter also covers LangGraph streaming, advanced control flows, adaptive systems with humans in the loop, and the Tree-of-Thoughts pattern. You’ll learn about memory mechanisms in LangChain and LangGraph, including caches and stores, equipping you to create systems capable of tackling problems too complex for single-agent approaches—a key capability of production-ready systems.

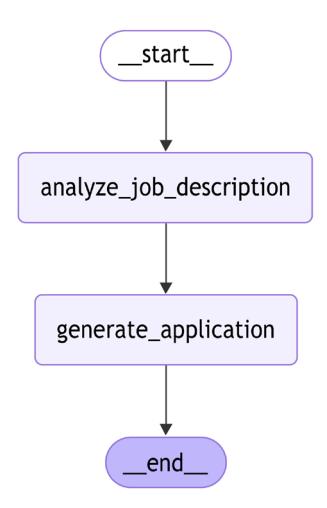

Chapter 7, Software Development and Data Analysis Agents, demonstrates how natural language has become a powerful interface for programming and data analysis. You’ll implement LLM-based solutions for code generation, code retrieval with RAG, and documentation search. These examples show how to integrate LLM agents into existing development and data workflows, illustrating how they complement rather than replace traditional programming skills.

Chapter 8, Evaluation and Testing, outlines methodologies for assessing LLM applications before production deployment. You’ll learn about system-level evaluation, evaluation-driven design, and both offline and online methods. The chapter provides practical examples for implementing correctness evaluation using exact matches and LLM-as-a-judge approaches and demonstrates tools like LangSmith for comprehensive testing and monitoring. These techniques directly increase reliability and help justify the business value of your LLM applications.

Chapter 9, Observability and Production Deployment, provides guidelines for deploying LLM applications into production, focusing on system design, scaling strategies, monitoring, and ensuring high availability. The chapter covers logging, API design, cost optimization, and redundancy strategies specific to LLMs. You’ll explore the Model Context Protocol (MCP) and learn how to implement observability practices that address the unique challenges of deploying generative AI systems. The practical deployment patterns in this chapter help you avoid common pitfalls that prevent many LLM projects from reaching production.

Chapter 10, The Future of LLM Applications, looks ahead to emerging trends, evolving architectures, and ethical considerations in generative AI. The chapter explores new technologies, market developments, potential societal impacts, and guidelines for responsible development. You’ll gain insight into how the field is likely to evolve and how to position your skills and applications for future advancements, completing your journey from basic LLM understanding to building and deploying production-ready, future-proof AI systems.

To get the most out of this book

Before diving in, it’s helpful to ensure you have a few things in place to make the most of your learning experience. This book is designed to be hands-on and practical, so having the right environment, tools, and mindset will help you follow along smoothly and get the full value from each chapter. Here’s what we recommend:

- Environment requirements: Set up a development environment with Python 3.10+ on any major operating system (Windows, macOS, or Linux). All code examples are cross-platform compatible and thoroughly tested.

- API access (optional but recommended): While we demonstrate using open-source models that can run locally, having access to commercial API providers like OpenAI, Anthropic, or other LLM providers will allow you to work with more powerful models. Many examples include both local and API-based approaches, so you can choose based on your budget and performance needs.

- Learning approach: We recommend typing the code yourself rather than copying and pasting. This hands-on practice reinforces learning and encourages experimentation. Each chapter builds on concepts introduced earlier, so working through them sequentially will give you the strongest foundation.

- Background knowledge: Basic Python proficiency is required, but no prior experience with machine learning or LLMs is necessary. We explain key concepts as they arise. If you’re already familiar with LLMs, you can focus on the implementation patterns and production-readiness aspects that distinguish this book.

| Software/Hardware covered in the book | |

|---|---|

| Python 3.10+ | |

| LangChain 0.3.1+ | |

| LangGraph 0.2.10+ | |

| Various LLM providers (Anthropic, Google, OpenAI, local models) |

You’ll find detailed guidance on environment setup in Chapter 1, along with clear explanations and step-by-step instructions to help you get started. We strongly recommend following these setup steps as outlined—given the fast-moving nature of LangChain, LangGraph and the broader ecosystem, skipping them might lead to avoidable issues down the line.

Download the example code files

The code bundle for the book is hosted on GitHub at https://github.com/benman1/generative\_ ai\_with\_langchain. We recommend typing the code yourself or using the repository as you progress through the chapters. If there’s an update to the code, it will be updated in the GitHub repository.

We also have other code bundles from our rich catalog of books and videos available at https:// github.com/PacktPublishing. Check them out!

Download the color images

We also provide a PDF file that has color images of the screenshots/diagrams used in this book. You can download it here: https://packt.link/gbp/9781837022014.

Conventions used

There are a number of text conventions used throughout this book.

CodeInText: Indicates code words in text, database table names, folder names, filenames, file extensions, pathnames, dummy URLs, user input, and Twitter handles. For example: “Let’s also restore from the initial checkpoint for thread-a. We’ll see that we start with an empty history:”

A block of code is set as follows:

checkpoint_id = checkpoints[-1].config["configurable"]["checkpoint_id"]

_ = graph.invoke(

[HumanMessage(content="test")],

config={"configurable": {"thread_id": "thread-a", "checkpoint_id":

checkpoint_id}})Any command-line input or output is written as follows:

$ pip install langchain langchain-openaiBold: Indicates a new term, an important word, or words that you see on the screen. For instance, words in menus or dialog boxes appear in the text like this. For example: ” The Google Research team introduced the Chain-of-Thought (CoT) technique early in 2022.”

Warnings or important notes appear like this.

Tips and tricks appear like this.

Get in touch

Subscribe to AI_Distilled, the go-to newsletter for AI professionals, researchers, and innovators,

Feedback from our readers is always welcome.

If you find any errors or have suggestions, please report them preferably through issues on GitHub, the discord chat, or the errata submission form on the Packt website.

For issues on GitHub, see https://github.com/benman1/generative\_ai\_with\_langchain/ issues.

If you have questions about the book’s content, or bespoke projects, feel free to contact us at ben@ chelseaai.co.uk.

General feedback: Email feedback@packtpub.com and mention the book’s title in the subject of your message. If you have questions about any aspect of this book, please email us at questions@ packtpub.com.

Errata: Although we have taken every care to ensure the accuracy of our content, mistakes do happen. If you have found a mistake in this book, we would be grateful if you reported this to us. Please visit http://www.packtpub.com/submit-errata, click Submit Errata, and fill in the form.

Piracy: If you come across any illegal copies of our works in any form on the internet, we would be grateful if you would provide us with the location address or website name. Please contact us at copyright@packtpub.com with a link to the material.

If you are interested in becoming an author: If there is a topic that you have expertise in and you are interested in either writing or contributing to a book, please visit http://authors.packtpub. com/.

Download a free PDF copy of this book

Thanks for purchasing this book!

Do you like to read on the go but are unable to carry your print books everywhere?

Is your eBook purchase not compatible with the device of your choice?

Don’t worry, now with every Packt book you get a DRM-free PDF version of that book at no cost.

Read anywhere, any place, on any device. Search, copy, and paste code from your favorite technical books directly into your application.

The perks don’t stop there, you can get exclusive access to discounts, newsletters, and great free content in your inbox daily.

Follow these simple steps to get the benefits:

- Scan the QR code or visit the link below:

https://packt.link/free-ebook/9781837022014

- Submit your proof of purchase.

- That’s it! We’ll send your free PDF and other benefits to your email directly.

Chapter 1: The Rise of Generative AI: From Language Models to Agents

The gap between experimental and production-ready agents is stark. According to LangChain’s State of Agents report, performance quality is the #1 concern among 51% of companies using agents, yet only 39.8% have implemented proper evaluation systems. Our book bridges this gap on two fronts: first, by demonstrating how LangChain and LangSmith provide robust testing and observability solutions; second, by showing how LangGraph’s state management enables complex, reliable multi-agent systems. You’ll find production-tested code patterns that leverage each tool’s strengths for enterprise-scale implementation and extend basic RAG into robust knowledge systems.

LangChain accelerates time-to-market with readily available building blocks, unified vendor APIs, and detailed tutorials. Furthermore, LangChain and LangSmith debugging and tracing functionalities simplify the analysis of complex agent behavior. Finally, LangGraph has excelled in executing its philosophy behind agentic AI – it allows a developer to give a large language model (LLM) partial control flow over the workflow (and to manage the level of how much control an LLM should have), while still making agentic workflows reliable and well-performant.

In this chapter, we’ll explore how LLMs have evolved into the foundation for agentic AI systems and how frameworks like LangChain and LangGraph transform these models into production-ready applications. We’ll also examine the modern LLM landscape, understand the limitations of raw LLMs, and introduce the core concepts of agentic applications that form the basis for the hands-on development we’ll tackle throughout this book.

In a nutshell, the following topics will be covered in this book:

- The modern LLM landscape

- From models to agentic applications

- Introducing LangChain

The modern LLM landscape

Artificial intelligence (AI) has long been a subject of fascination and research, but recent advancements in generative AI have propelled it into mainstream adoption. Unlike traditional AI systems that classify data or make predictions, generative AI can create new content—text, images, code, and more—by leveraging vast amounts of training data.

The generative AI revolution was catalyzed by the 2017 introduction of the transformer architecture, which enabled models to process text with unprecedented understanding of context and relationships. As researchers scaled these models from millions to billions of parameters, they discovered something remarkable: larger models didn’t just perform incrementally better—they exhibited entirely new emergent capabilities like few-shot learning, complex reasoning, and creative generation that weren’t explicitly programmed. Eventually, the release of ChatGPT in 2022 marked a turning point, demonstrating these capabilities to the public and sparking widespread adoption.

The landscape shifted again with the open-source revolution led by models like Llama and Mistral, democratizing access to powerful AI beyond the major tech companies. However, these advanced capabilities came with significant limitations—models couldn’t reliably use tools, reason through complex problems, or maintain context across interactions. This gap between raw model power and practical utility created the need for specialized frameworks like LangChain that transform these models from impressive text generators into functional, production-ready agents capable of solving real-world problems.

Key terminologies

Tools: External utilities or functions that AI models can use to interact with the world. Tools allow agents to perform actions like searching the web, calculating values, or accessing databases to overcome LLMs’ inherent limitations.

Memory: Systems that allow AI applications to store and retrieve information across interactions. Memory enables contextual awareness in conversations and complex workflows by tracking previous inputs, outputs, and important information.

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF): A training technique where AI models learn from direct human feedback, optimizing their performance to align with human preferences. RLHF helps create models that are more helpful, safe, and aligned with human values.

Agents: AI systems that can perceive their environment, make decisions, and take actions to accomplish goals. In LangChain, agents use LLMs to interpret tasks, choose appropriate tools, and execute multi-step processes with minimal human intervention.

| Year | Development | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| 1990s | IBM Alignment Models | Statistical machine translation |

| 2000s | Web-scale datasets | Large-scale statistical models |

| 2009 | Statistical models dominate | Large-scale text ingestion |

| 2012 | Deep learning gains traction | Neural networks outperform statistical models |

| 2016 | Neural Machine Translation (NMT) |

Seq2seq deep LSTMs replace statistical methods |

| 2017 | Transformer architecture | Self-attention revolutionizes NLP |

| 2018 | BERT and GPT-1 | Transformer-based language understanding and generation |

| 2019 | GPT-2 | Large-scale text generation, public awareness increases |

| 2020 | GPT-3 | API-based access, state-of-the-art performance |

| 2022 | ChatGPT | Mainstream adoption of LLMs |

| 2023 | Large Multimodal Models (LMMs) |

AI models process text, images, and audio |

| 2024 | OpenAI o1 | Stronger reasoning capabilities |

| —— | ————- | ———————————– |

| 2025 | DeepSeek R1 | Open-weight, large-scale AI model |

Table 1.1: A timeline of major developments in language models

The field of LLMs is rapidly evolving, with multiple models competing in terms of performance, capabilities, and accessibility. Each provider brings distinct advantages, from OpenAI’s advanced general-purpose AI to Mistral’s open-weight, high-efficiency models. Understanding the differences between these models helps practitioners make informed decisions when integrating LLMs into their applications.

Model comparison

The following points outline key factors to consider when comparing different LLMs, focusing on their accessibility, size, capabilities, and specialization:

- Open-source vs. closed-source models: Open-source models like Mistral and LLaMA provide transparency and the ability to run locally, while closed-source models like GPT-4 and Claude are accessible through APIs. Open-source LLMs can be downloaded and modified, enabling developers and researchers to investigate and build upon their architectures, though specific usage terms may apply.

- Size and capabilities: Larger models generally offer better performance but require more computational resources. This makes smaller models great for use on devices with limited computing power or memory, and can be significantly cheaper to use. Small language models (SLMs) have a relatively small number of parameters, typically using millions to a few billion parameters, as opposed to LLMs, which can have hundreds of billions or even trillions of parameters.

- Specialized models: Some LLMs are optimized for specific tasks, such as code generation (for example, Codex) or mathematical reasoning (e.g., Minerva).

The increase in the scale of language models has been a major driving force behind their impressive performance gains. However, recently there has been a shift in architecture and training methods that has led to better parameter efficiency in terms of performance.

Model scaling laws

Empirically derived scaling laws predict the performance of LLMs based on the given training budget, dataset size, and the number of parameters. If true, this means that highly powerful systems will be concentrated in the hands of Big Tech, however, we have seen a significant shift over recent months.

The KM scaling law, proposed by Kaplan et al., derived through empirical analysis and fitting of model performance with varied data sizes, model sizes, and training compute, presents power-law relationships, indicating a strong codependence between model performance and factors such as model size, dataset size, and training compute.

The Chinchilla scaling law, proposed by the Google DeepMind team, involved experiments with a wider range of model sizes and data sizes. It suggests an optimal allocation of compute budget to model size and data size, which can be determined by optimizing a specific loss function under a constraint.

However, future progress may depend more on model architecture, data cleansing, and model algorithmic innovation rather than sheer size. For example, models such as phi, first presented in Textbooks Are All You Need (2023, Gunasekar et al.), with about 1 billion parameters, showed that models can – despite a smaller scale – achieve high accuracy on evaluation benchmarks. The authors suggest that improving data quality can dramatically change the shape of scaling laws.

Further, there is a body of work on simplified model architectures, which have substantially fewer parameters and only modestly drop accuracy (for example, One Wide Feedforward is All You Need, Pessoa Pires et al., 2023). Additionally, techniques such as fine-tuning, quantization, distillation, and prompting techniques can enable smaller models to leverage the capabilities of large foundations without replicating their costs. To compensate for model limitations, tools like search engines and calculators have been incorporated into agents, and multi-step reasoning strategies, plugins, and extensions may be increasingly used to expand capabilities.

The future could see the co-existence of massive, general models with smaller and more accessible models that provide faster and cheaper training, maintenance, and inference.

Let’s now discuss a comparative overview of various LLMs, highlighting their key characteristics and differentiating factors. We’ll delve into aspects such as open-source vs. closed-source models, model size and capabilities, and specialized models. By understanding these distinctions, you can select the most suitable LLM for your specific needs and applications.

LLM provider landscape

You can access LLMs from major providers like OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic, along with a growing number of others, through their websites or APIs. As the demand for LLMs grows, numerous providers have entered the space, each offering models with unique capabilities and trade-offs. Developers need to understand the various access options available for integrating these powerful models into their applications. The choice of provider will significantly impact development experience, performance characteristics, and operational costs.

Provider Notable models Key features and strengths OpenAI GPT-4o, GPT-4.5; o1; o3-mini Strong general performance, proprietary models, advanced reasoning; multimodal reasoning across text, audio, vision, and video in real time Anthropic Claude 3.7 Sonnet; Claude 3.5 Haiku Toggle between real-time responses and extended “thinking” phases; outperforms OpenAI’s o1 in coding benchmarks Google Gemini 2.5, 2.0 (flash and pro), Gemini 1.5 Low latency and costs, large context window (up to 2M tokens), multimodal inputs and outputs, reasoning capabilities Cohere Command R, Command R Plus Retrieval-augmented generation, enterprise AI solutions Mistral AI Mistral Large; Mistral 7B Open weights, efficient inference, multilingual support AWS Titan Enterprise-scale AI models, optimized for the AWS cloud

The table below provides a comparative overview of leading LLM providers and examples of the models they offer:

| DeepSeek | R1 | Maths-first: solves Olympiad-level problems; cost effective, optimized for multilingual and programming tasks |

|---|---|---|

| Together AI |

Infrastructure for running open models |

Competitive pricing; growing marketplace of models |

Table 1.2: Comparative overview of major LLM providers and their flagship models for LangChain implementation

Other organizations develop LLMs but do not necessarily provide them through application programming interfaces (APIs) to developers. For example, Meta AI develops the very influential Llama model series, which has strong reasoning, code-generation capabilities, and is released under an open-source license.

There is a whole zoo of open-source models that you can access through Hugging Face or through other providers. You can even download these open-source models, fine-tune them, or fully train them. We’ll try this out practically starting in Chapter 2.

Once you’ve selected an appropriate model, the next crucial step is understanding how to control its behavior to suit your specific application needs. While accessing a model gives you computational capability, it’s the choice of generation parameters that transforms raw model power into tailored output for different use cases within your applications.

Now that we’ve covered the LLM provider landscape, let’s discuss another critical aspect of LLM implementation: licensing considerations. The licensing terms of different models significantly impact how you can use them in your applications.

Licensing

LLMs are available under different licensing models that impact how they can be used in practice. Open-source models like Mixtral and BERT can be freely used, modified, and integrated into applications. These models allow developers to run them locally, investigate their behavior, and build upon them for both research and commercial purposes.

In contrast, proprietary models like GPT-4 and Claude are accessible only through APIs, with their internal workings kept private. While this ensures consistent performance and regular updates, it means depending on external services and typically incurring usage costs.

Some models like Llama 2 take a middle ground, offering permissive licenses for both research and commercial use while maintaining certain usage conditions. For detailed information about specific model licenses and their implications, refer to the documentation of each model or consult the model openness framework: https://isitopen.ai/.

The model openness framework (MOF) evaluates language models based on criteria such as access to model architecture details, training methodology and hyperparameters, data sourcing and processing information, documentation around development decisions, ability to evaluate model workings, biases, and limitations, code modularity, published model card, availability of servable model, option to run locally, source code availability, and redistribution rights.

In general, open-source licenses promote wide adoption, collaboration, and innovation around the models, benefiting both research and commercial development. Proprietary licenses typically give companies exclusive control but may limit academic research progress. Non-commercial licenses often restrict commercial use while enabling research.

By making knowledge and knowledge work more accessible and adaptable, generative AI models have the potential to level the playing field and create new opportunities for people from all walks of life.

The evolution of AI has brought us to a pivotal moment where AI systems can not only process information but also take autonomous action. The next section explores the transformation from basic language models to more complex, and finally, fully agentic applications.

The information provided about AI model licensing is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Licensing terms vary significantly and evolve rapidly. Organizations should consult qualified legal counsel regarding specific licensing decisions for their AI implementations.

From models to agentic applications

As discussed so far, LLMs have been demonstrating remarkable fluency in natural language processing. However, as impressive as they are, they remain fundamentally reactive rather than proactive. They lack the ability to take independent actions, interact meaningfully with external systems, or autonomously achieve complex objectives.

To unlock the next phase of AI capabilities, we need to move beyond passive text generation and toward agentic AI—systems that can plan, reason, and take action to accomplish tasks with minimal human intervention. Before exploring the potential of agentic AI, it’s important to first understand the core limitations of LLMs that necessitate this evolution.

Limitations of traditional LLMs

Despite their advanced language capabilities, LLMs have inherent constraints that limit their effectiveness in real-world applications:

- Lack of true understanding: LLMs generate human-like text by predicting the next most likely word based on statistical patterns in training data. However, they do not understand meaning in the way humans do. This leads to hallucinations—confidently stating false information as fact—and generating plausible but incorrect, misleading, or nonsensical outputs. As Bender et al. (2021) describe, LLMs function as “stochastic parrots”—repeating patterns without genuine comprehension.

- Struggles with complex reasoning and problem-solving: While LLMs excel at retrieving and reformatting knowledge, they struggle with multi-step reasoning, logical puzzles, and mathematical problem-solving. They often fail to break down problems into sub-tasks or synthesize information across different contexts. Without explicit prompting techniques like chain-of-thought reasoning, their ability to deduce or infer remains unreliable.

- Outdated knowledge and limited external access: LLMs are trained on static datasets and do not have real-time access to current events, dynamic databases, or live information sources. This makes them unsuitable for tasks requiring up-to-date knowledge, such as financial analysis, breaking news summaries, or scientific research requiring the latest findings.

- No native tool use or action-taking abilities: LLMs operate in isolation—they cannot interact with APIs, retrieve live data, execute code, or modify external systems. This lack of tool integration makes them less effective in scenarios that require real-world actions, such as conducting web searches, automating workflows, or controlling software systems.

- Bias, ethical concerns, and reliability issues: Because LLMs learn from large datasets that may contain biases, they can unintentionally reinforce ideological, social, or cultural biases. Importantly, even with open-source models, accessing and auditing the complete training data to identify and mitigate these biases remains challenging for most practitioners. Additionally, they can generate misleading or harmful information without understanding the ethical implications of their outputs.

- Computational costs and efficiency challenges: Deploying and running LLMs at scale requires significant computational resources, making them costly and energy-intensive. Larger models can also introduce latency, slowing response times in real-time applications.

To overcome these limitations, AI systems must evolve from passive text generators into active agents that can plan, reason, and interact with their environment. This is where agentic AI comes in—integrating LLMs with tool use, decision-making mechanisms, and autonomous execution capabilities to enhance their functionality.

While frameworks like LangChain provide comprehensive solutions to LLM limitations, understanding fundamental prompt engineering techniques remains valuable. Approaches like few-shot learning, chain-of-thought, and structured prompting can significantly enhance model performance for specific tasks. Chapter 3 will cover these techniques in detail, showing how LangChain helps standardize and optimize prompting patterns while minimizing the need for custom prompt engineering in every application.

The next section explores how agentic AI extends the capabilities of traditional LLMs and unlocks new possibilities for automation, problem-solving, and intelligent decision-making.

Understanding LLM applications

LLM applications represent the bridge between raw model capability and practical business value. While LLMs possess impressive language processing abilities, they require thoughtful integration to deliver real-world solutions. These applications broadly fall into two categories: complex integrated applications and autonomous agents.

Complex integrated applications enhance human workflows by integrating LLMs into existing processes, including:

- Decision support systems that provide analysis and recommendations

- Content generation pipelines with human review

- Interactive tools that augment human capabilities

- Workflow automation with human oversight

Autonomous agents operate with minimal human intervention, further augmenting workflows through LLM integration. Examples include:

- Task automation agents that execute defined workflows

- Information gathering and analysis systems

- Multi-agent systems for complex task coordination

LangChain provides frameworks for both integrated applications and autonomous agents, offering flexible components that support various architectural choices. This book will explore both approaches, demonstrating how to build reliable, production-ready systems that match your specific requirements.

Autonomous systems of agents are potentially very powerful, and it’s therefore worthwhile exploring them a bit more.

Understanding AI agents

It is sometimes joked that AI is just a fancy word for ML, or AI is ML in a suit, as illustrated in this image; however, there’s more to it, as we’ll see.

Figure 1.1: ML in a suit. Generated by a model on replicate.com, Diffusers Stable Diffusion v2.1

An AI agent represents the bridge between raw cognitive capability and practical action. While an LLM possesses vast knowledge and processing ability, it remains fundamentally reactive without agency. AI agents transform this passive capability into active utility through structured workflows that parse requirements, analyze options, and execute actions.

Agentic AI enables autonomous systems to make decisions and act independently, with minimal human intervention. Unlike deterministic systems that follow fixed rules, agentic AI relies on patterns and likelihoods to make informed choices. It functions through a network of autonomous software components called agents, which learn from user behavior and large datasets to improve over time.

Agency in AI refers to a system’s ability to act independently to achieve goals. True agency means an AI system can perceive its environment, make decisions, act, and adapt over time by learning from interactions and feedback. The distinction between raw AI and agents parallels the difference between knowledge and expertise. Consider a brilliant researcher who understands complex theories but struggles with practical application. An agent system adds the crucial element of purposeful action, turning abstract capability into concrete results.

In the context of LLMs, agentic AI involves developing systems that act autonomously, understand context, adapt to new information, and collaborate with humans to solve complex challenges. These AI agents leverage LLMs to process information, generate responses, and execute tasks based on defined objectives.

Particularly, AI agents extend the capabilities of LLMs by integrating memory, tool use, and decision-making frameworks. These agents can:

- Retain and recall information across interactions.

- Utilize external tools, APIs, and databases.

- Plan and execute multi-step workflows.

The value of agency lies in reducing the need for constant human oversight. Instead of manually prompting an LLM for every request, an agent can proactively execute tasks, react to new data, and integrate with real-world applications.

AI agents are systems designed to act on behalf of users, leveraging LLMs alongside external tools, memory, and decision-making frameworks. The hope behind AI agents is that they can automate complex workflows, reducing human effort while increasing efficiency and accuracy. By allowing systems to act autonomously, agents promise to unlock new levels of automation in AI-driven applications. But are the hopes justified?

Despite their potential, AI agents face significant challenges:

- Reliability: Ensuring agents make correct, context-aware decisions without supervision is difficult.

- Generalization: Many agents work well in narrow domains but struggle with open-ended, multi-domain tasks.

- Lack of trust: Users must trust that agents will act responsibly, avoid unintended actions, and respect privacy constraints.

- Coordination complexity: Multi-agent systems often suffer from inefficiencies and miscommunication when executing tasks collaboratively.

Production-ready agent systems must address not just theoretical challenges but practical implementation hurdles like:

- Rate limitations and API quotas

- Token context overflow errors

- Hallucination management

- Cost optimization

LangChain and LangSmith provide robust solutions for these challenges, which we’ll explore in depth in Chapter 8 and Chapter 9. These chapters will cover how to build reliable, observable AI systems that can operate at an enterprise scale.

When developing agent-based systems, therefore, several key factors require careful consideration:

- Value generation: Agents must provide a clear utility that outweighs their costs in terms of setup, maintenance, and necessary human oversight. This often means starting with well-defined, high-value tasks where automation can demonstrably improve outcomes.

- Trust and safety: As agents take on more responsibility, establishing and maintaining user trust becomes crucial. This encompasses both technical reliability and transparent operation that allows users to understand and predict agent behavior.

- Standardization: As the agent ecosystem grows, standardized interfaces and protocols become essential for interoperability. This parallels the development of web standards that enabled the growth of internet applications.

While early AI systems focused on pattern matching and predefined templates, modern AI agents demonstrate emergent capabilities such as reasoning, problem-solving, and long-term planning. Today’s AI agents integrate LLMs with interactive environments, enabling them to function autonomously in complex domains.

The development of agent-based AI is a natural progression from statistical models to deep learning and now to reasoning-based systems. Modern AI agents leverage multimodal capabilities, reinforcement learning, and memory-augmented architectures to adapt to diverse tasks. This evolution marks a shift from predictive models to truly autonomous systems capable of dynamic decision-making.

Looking ahead, AI agents will continue to refine their ability to reason, plan, and act within structured and unstructured environments. The rise of open-weight models, combined with advances in agent-based AI, will likely drive the next wave of innovations in AI, expanding its applications across science, engineering, and everyday life.

With frameworks like LangChain, developers can build complex and agentic structured systems that overcome the limitations of raw LLMs. It offers built-in solutions for memory management, tool integration, and multi-step reasoning that align with the ecosystem model presented here. In the next section we will explore how LangChain facilitates the development of production-ready AI agents.

Introducing LangChain

LangChain exists as both an open-source framework and a venture-backed company. The framework, introduced in 2022 by Harrison Chase, streamlines the development of LLM-powered applications with support for multiple programming languages including Python, JavaScript/ TypeScript, Go, Rust, and Ruby.

The company behind the framework, LangChain, Inc., is based in San Francisco and has secured significant venture funding through multiple rounds, including a Series A in February 2024. With 11-50 employees, the company maintains and expands the framework while offering enterprise solutions for LLM application development.

While the core framework remains open source, the company provides additional enterprise features and support for commercial users. Both share the same mission: accelerating LLM application development by providing robust tools and infrastructure.

Modern LLMs are undeniably powerful, but their practical utility in production applications is constrained by several inherent limitations. Understanding these challenges is essential for appreciating why frameworks like LangChain have become indispensable tools for AI developers.

Challenges with raw LLMs

Despite their impressive capabilities, LLMs face fundamental constraints that create significant hurdles for developers building real-world applications:

- Context window limitations: LLMs process text as tokens (subword units), not complete words. For example, “LangChain” might be processed as two tokens: “Lang” and “Chain.” Every LLM has a fixed context window—the maximum number of tokens it can process at once—typically ranging from 2,000 to 128,000 tokens. This creates several practical challenges:

- Document processing: Long documents must be chunked effectively to fit within context limits

- Conversation history: Maintaining information across extended conversations requires careful memory management

- Cost management: Most providers charge based on token count, making efficient token use a business imperative

These constraints directly impact application architecture, making techniques like RAG (which we’ll explore in Chapter 4) essential for production systems.

- Limited tool orchestration: While many modern LLMs offer native tool-calling capabilities, they lack the infrastructure to discover appropriate tools, execute complex workflows, and manage tool interactions across multiple turns. Without this orchestration layer, developers must build custom solutions for each integration.

- Task coordination challenges: Managing multi-step workflows with LLMs requires structured control mechanisms. Without them, complex processes involving sequential reasoning or decision-making become difficult to implement reliably.

Tools in this context refer to functional capabilities that extend an LLM’s reach: web browsers for searching the internet, calculators for precise mathematics, coding environments for executing programs, or APIs for accessing external services and databases. Without these tools, LLMs remain confined to operating within their training knowledge, unable to perform real-world actions or access current information.

These fundamental limitations create three key challenges for developers working with raw LLM APIs, as demonstrated in the following table.

| Challenge | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Detecting hallucinations and validating outputs |

Inconsistent results that may require human verification |

| Resource | Handling context windows and | Implementation complexity and |

| Management | rate limits | potential cost overruns |

| Integration | Building connections to external | Extended development time and |

| Complexity | tools and data sources | maintenance burden |

Table 1.3: Three key developer challenges

LangChain addresses these challenges by providing a structured framework with tested solutions, simplifying AI application development and enabling more sophisticated use cases.

How LangChain enables agent development

LangChain provides the foundational infrastructure for building sophisticated AI applications through its modular architecture and composable patterns. With the evolution to version 0.3, LangChain has refined its approach to creating intelligent systems:

- Composable workflows: The LangChain Expression Language (LCEL) allows developers to break down complex tasks into modular components that can be assembled and reconfigured. This composability enables systematic reasoning through the orchestration of multiple processing steps.

- Integration ecosystem: LangChain offers battle-tested abstract interfaces for all generative AI components (LLMs, embeddings, vector databases, document loaders, search engines). This lets you build applications that can easily switch between providers without rewriting core logic.

- Unified model access: The framework provides consistent interfaces to diverse language and embedding models, allowing seamless switching between providers while maintaining application logic.

While earlier versions of LangChain handled memory management directly, version 0.3 takes a more specialized approach to application development:

- Memory and state management: For applications requiring persistent context across interactions, LangGraph now serves as the recommended solution. LangGraph maintains conversation history and application state with purpose-built persistence mechanisms.

- Agent architecture: Though LangChain contains agent implementations, LangGraph has become the preferred framework for building sophisticated agents. It provides:

- Graph-based workflow definition for complex decision paths

- Persistent state management across multiple interactions

- Streaming support for real-time feedback during processing

- Human-in-the-loop capabilities for validation and corrections

Together, LangChain and its companion projects like LangGraph and LangSmith form a comprehensive ecosystem that transforms LLMs from simple text generators into systems capable of sophisticated real-world tasks, combining strong abstractions with practical implementation patterns optimized for production use.

Exploring the LangChain architecture

LangChain’s philosophy centers on composability and modularity. Rather than treating LLMs as standalone services, LangChain views them as components that can be combined with other tools and services to create more capable systems. This approach is built on several principles:

- Modular architecture: Every component is designed to be reusable and interchangeable, allowing developers to integrate LLMs seamlessly into various applications. This modularity extends beyond LLMs to include numerous building blocks for developing complex generative AI applications.

- Support for agentic workflows: LangChain offers best-in-class APIs that allow you to develop sophisticated agents quickly. These agents can make decisions, use tools, and solve problems with minimal development overhead.

- Production readiness: The framework provides built-in capabilities for tracing, evaluation, and deployment of generative AI applications, including robust building blocks for managing memory and persistence across interactions.

- Broad vendor ecosystem: LangChain offers battle-tested abstract interfaces for all generative AI components (LLMs, embeddings, vector databases, document loaders, search engines, etc.). Vendors develop their own integrations that comply with these interfaces, allowing you to build applications on top of any third-party provider and easily switch between them.

It’s worth noting that there’ve been major changes since LangChain version 0.1 when the first edition of this book was written. While early versions attempted to handle everything, LangChain version 0.3 focuses on excelling at specific functions with companion projects handling specialized needs. LangChain manages model integration and workflows, while LangGraph handles stateful agents and LangSmith provides observability.

LangChain’s memory management, too, has gone through major changes. Memory mechanisms within the base LangChain library have been deprecated in favor of LangGraph for persistence, and while agents are present, LangGraph is the recommended approach for their creation in version 0.3. However, models and tools continue to be fundamental to LangChain’s functionality. In Chapter 3, we’ll explore LangChain and LangGraph’s memory mechanisms.

To translate model design principles into practical tools, LangChain has developed a comprehensive ecosystem of libraries, services, and applications. This ecosystem provides developers with everything they need to build, deploy, and maintain sophisticated AI applications. Let’s examine the components that make up this thriving environment and how they’ve gained adoption across the industry.

Ecosystem

LangChain has achieved impressive ecosystem metrics, demonstrating strong market adoption with over 20 million monthly downloads and powering more than 100,000 applications. Its open-source community is thriving, evidenced by 100,000+ GitHub stars and contributions from over 4,000 developers. This scale of adoption positions LangChain as a leading framework in the AI application development space, particularly for building reasoning-focused LLM applications. The framework’s modular architecture (with components like LangGraph for agent workflows and LangSmith for monitoring) has clearly resonated with developers building production AI systems across various industries.

Core libraries

- LangChain (Python): Reusable components for building LLM applications

- LangChain.js: JavaScript/TypeScript implementation of the framework

- LangGraph (Python): Tools for building LLM agents as orchestrated graphs

- LangGraph.js: JavaScript implementation for agent workflows

Platform services

- LangSmith: Platform for debugging, testing, evaluating, and monitoring LLM applications

- LangGraph: Infrastructure for deploying and scaling LangGraph agents

Applications and extensions

- ChatLangChain: Documentation assistant for answering questions about the framework

- Open Canvas: Document and chat-based UX for writing code/markdown (TypeScript)

- OpenGPTs: Open source implementation of OpenAI’s GPTs API

- Email assistant: AI tool for email management (Python)

- Social media agent: Agent for content curation and scheduling (TypeScript)

The ecosystem provides a complete solution for building reasoning-focused AI applications: from core building blocks to deployment platforms to reference implementations. This architecture allows developers to use components independently or stack them for fuller and more complete solutions.

From customer testimonials and company partnerships, LangChain is being adopted by enterprises like Rakuten, Elastic, Ally, and Adyen. Organizations report using LangChain and LangSmith to identify optimal approaches for LLM implementation, improve developer productivity, and accelerate development workflows.

LangChain also offers a full stack for AI application development:

- Build: with the composable framework

- Run: deploy with LangGraph Platform

- Manage: debug, test, and monitor with LangSmith

Based on our experience building with LangChain, here are some of its benefits we’ve found especially helpful:

- Accelerated development cycles: LangChain dramatically speeds up time-to-market with ready-made building blocks and unified APIs, eliminating weeks of integration work.

- Superior observability: The combination of LangChain and LangSmith provides unparalleled visibility into complex agent behavior, making trade-offs between cost, latency, and quality more transparent.

- Controlled agency balance: LangGraph’s approach to agentic AI is particularly powerful allowing developers to give LLMs partial control flow over workflows while maintaining reliability and performance.

- Production-ready patterns: Our implementation experience has proven that LangChain’s architecture delivers enterprise-grade solutions that effectively reduce hallucinations and improve system reliability.

- Future-proof flexibility: The framework’s vendor-agnostic design creates applications that can adapt as the LLM landscape evolves, preventing technological lock-in.

These advantages stem directly from LangChain’s architectural decisions, which prioritize modularity, observability, and deployment flexibility for real-world applications.

Modular design and dependency management

LangChain evolves rapidly, with approximately 10-40 pull requests merged daily. This fast-paced development, combined with the framework’s extensive integration ecosystem, presents unique challenges. Different integrations often require specific third-party Python packages, which can lead to dependency conflicts.

LangChain’s package architecture evolved as a direct response to scaling challenges. As the framework rapidly expanded to support hundreds of integrations, the original monolithic structure became unsustainable—forcing users to install unnecessary dependencies, creating maintenance bottlenecks, and hindering contribution accessibility. By dividing into specialized packages with lazy loading of dependencies, LangChain elegantly solved these issues while preserving a cohesive ecosystem. This architecture allows developers to import only what they need, reduces version conflicts, enables independent release cycles for stable versus experimental features, and dramatically simplifies the contribution path for community developers working on specific integrations.

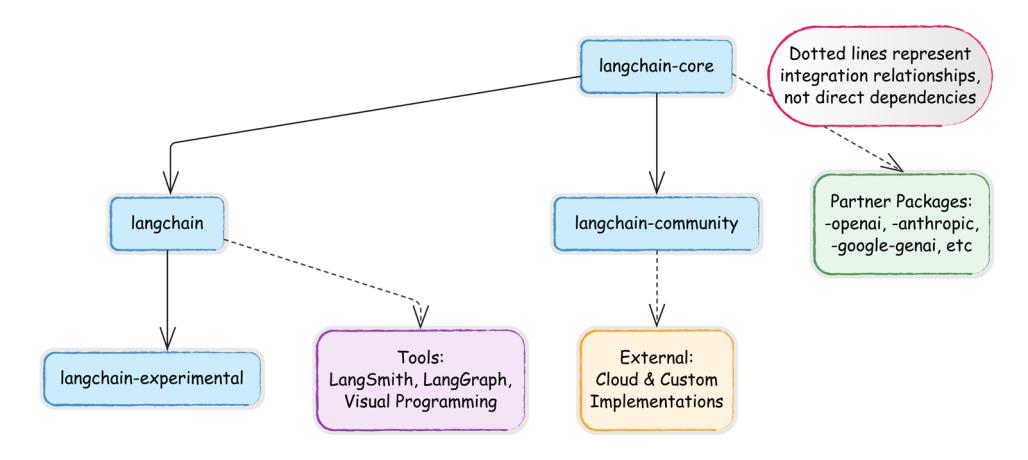

The LangChain codebase follows a well-organized structure that separates concerns while maintaining a cohesive ecosystem:

Core structure

- docs/: Documentation resources for developers

- libs/: Contains all library packages in the monorepo

Library organization

- langchain-core/: Foundational abstractions and interfaces that define the framework

- langchain/: The main implementation library with core components:

- vectorstores/: Integrations with vector databases (Pinecone, Chroma, etc.)

- chains/: Pre-built chain implementations for common workflows

Other component directories for retrievers, embeddings, etc.

- langchain-experimental/: Cutting-edge features still under development

- langchain-community: Houses third-party integrations maintained by the LangChain community. This includes most integrations for components like LLMs, vector stores, and retrievers. Dependencies are optional to maintain a lightweight package.

- Partner packages: Popular integrations are separated into dedicated packages (e.g., langchain-openai, langchain-anthropic) to enhance independent support. These packages reside outside the LangChain repository but within the GitHub “langchain-ai” organization (see <github.com/orgs/langchain-ai>). A full list is available at python.langchain. com/v0.3/docs/integrations/platforms/.

• External partner packages: Some partners maintain their integration packages independently. For example, several packages from the Google organization (github.com/ orgs/googleapis/repositories?q=langchain), such as the langchain-google-cloudsql-mssql package, are developed and maintained outside the LangChain ecosystem.

Figure 1.2: Integration ecosystem map

For full details on the dozens of available modules and packages, refer to the comprehensive LangChain API reference: https://api.python.langchain.com/. There are also hundreds of code examples demonstrating real-world use cases: https:// python.langchain.com/v0.1/docs/use\_cases/.

LangGraph, LangSmith, and companion tools

LangChain’s core functionality is extended by the following companion projects:

- LangGraph: An orchestration framework for building stateful, multi-actor applications with LLMs. While it integrates smoothly with LangChain, it can also be used independently. LangGraph facilitates complex applications with cyclic data flows and supports streaming and human-in-the-loop interactions. We’ll talk about LangGraph in more detail in Chapter 3.

- LangSmith: A platform that complements LangChain by providing robust debugging, testing, and monitoring capabilities. Developers can inspect, monitor, and evaluate their applications, ensuring continuous optimization and confident deployment.

These extensions, along with the core framework, provide a comprehensive ecosystem for developing, managing, and visualizing LLM applications, each with unique capabilities that enhance functionality and user experience.

LangChain also has an extensive array of tool integrations, which we’ll discuss in detail in Chapter 5. New integrations are added regularly, expanding the framework’s capabilities across domains.

Third-party applications and visual tools

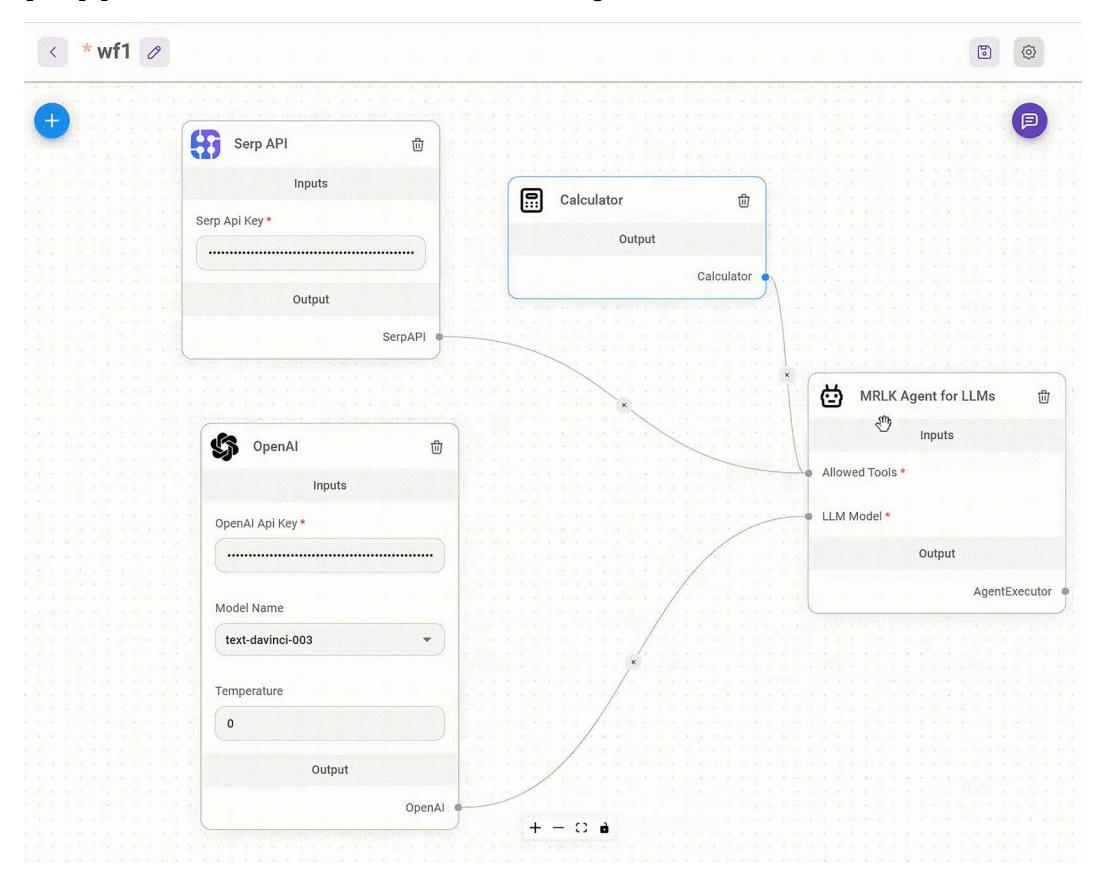

Many third-party applications have been built on top of or around LangChain. For example, LangFlow and Flowise introduce visual interfaces for LLM development, with UIs that allow for the drag-and-drop assembly of LangChain components into executable workflows. This visual approach enables rapid prototyping and experimentation, lowering the barrier to entry for complex pipeline creation, as illustrated in the following screenshot of Flowise:

Figure 1.3: Flowise UI with an agent that uses an LLM, a calculator, and a search tool (Source: https://github.com/FlowiseAI/Flowise)

In the UI above, you can see an agent connected to a search interface (Serp API), an LLM, and a calculator. LangChain and similar tools can be deployed locally using libraries like Chainlit, or on various cloud platforms, including Google Cloud.

In summary, LangChain simplifies the development of LLM applications through its modular design, extensive integrations, and supportive ecosystem. This makes it an invaluable tool for developers looking to build sophisticated AI systems without reinventing fundamental components.

Summary

This chapter introduced the modern LLM landscape and positioned LangChain as a powerful framework for building production-ready AI applications. We explored the limitations of raw LLMs and then showed how these frameworks transform models into reliable, agentic systems capable of solving complex real-world problems. We also examined the LangChain ecosystem’s architecture, including its modular components, package structure, and companion projects that support the complete development lifecycle. By understanding the relationship between LLMs and the frameworks that extend them, you’re now equipped to build applications that go beyond simple text generation.

In the next chapter, we’ll set up our development environment and take our first steps with LangChain, translating the conceptual understanding from this chapter into working code. You’ll learn how to connect to various LLM providers, create your first chains, and begin implementing the patterns that form the foundation of enterprise-grade AI applications.

Questions

- What are the three primary limitations of raw LLMs that impact production applications, and how does LangChain address each one?

- Compare and contrast open-source and closed-source LLMs in terms of deployment options, cost considerations, and use cases. When might you choose each type?

- What is the difference between a LangChain chain and a LangGraph agent? When would you choose one over the other?

- Explain how LangChain’s modular architecture supports the rapid development of AI applications. Provide an example of how this modularity might benefit an enterprise use case.

- What are the key components of the LangChain ecosystem, and how do they work together to support the development lifecycle from building to deployment to monitoring?

- How does agentic AI differ from traditional LLM applications? Describe a business scenario where an agent would provide significant advantages over a simple chain.

- What factors should you consider when selecting an LLM provider for a production application? Name at least three considerations beyond just model performance.

- How does LangChain help address common challenges like hallucinations, context limitations, and tool integration that affect all LLM applications?

- Explain how the LangChain package structure (langchain-core, langchain, langchaincommunity) affects dependency management and integration options in your applications.

- What role does LangSmith play in the development lifecycle of production LangChain applications?

Chapter 2: First Steps with LangChain

In the previous chapter, we explored LLMs and introduced LangChain as a powerful framework for building LLM-powered applications. We discussed how LLMs have revolutionized natural language processing with their ability to understand context, generate human-like text, and perform complex reasoning. While these capabilities are impressive, we also examined their limitations—hallucinations, context constraints, and lack of up-to-date knowledge.

In this chapter, we’ll move from theory to practice by building our first LangChain application. We’ll start with the fundamentals: setting up a proper development environment, understanding LangChain’s core components, and creating simple chains. From there, we’ll explore more advanced capabilities, including running local models for privacy and cost efficiency and building multimodal applications that combine text with visual understanding. By the end of this chapter, you’ll have a solid foundation in LangChain’s building blocks and be ready to create increasingly sophisticated AI applications in subsequent chapters.

To sum up, this chapter will cover the following topics:

- Setting up dependencies

- Exploring LangChain’s building blocks (model interfaces, prompts and templates, and LCEL)

- Running local models

- Multimodal AI applications

Given the rapid evolution of both LangChain and the broader AI field, we maintain up-to-date code examples and resources in our GitHub repository: https://github. com/benman1/generative\_ai\_with\_langchain.

For questions or troubleshooting help, please create an issue on GitHub or join our Discord community: https://packt.link/lang.

Setting up dependencies for this book

This book provides multiple options for running the code examples, from zero-setup cloud notebooks to local development environments. Choose the approach that best fits your experience level and preferences. Even if you are familiar with dependency management, please read these instructions since all code in this book will depend on the correct installation of the environment as outlined here.

For the quickest start with no local setup required, we provide ready-to-use online notebooks for every chapter:

- Google Colab: Run examples with free GPU access

- Kaggle Notebooks: Experiment with integrated datasets

- Gradient Notebooks: Access higher-performance compute options

All code examples you find in this book are available as online notebooks on GitHub at https:// github.com/benman1/generative\_ai\_with\_langchain.

These notebooks don’t have all dependencies pre-configured but, usually, a few install commands get you going. These tools allow you to start experimenting immediately without worrying about setup. If you prefer working locally, we recommend using conda for environment management:

- Install Miniconda if you don’t have it already.

- Download it from https://docs.conda.io/en/latest/miniconda.html.

- Create a new environment with Python 3.11:

conda create -n langchain-book python=3.11

- Activate the environment:

conda activate langchain-book

- Install Jupyter and core dependencies:

conda install jupyter

pip install langchain langchain-openai jupyter

- Launch Jupyter Notebook:

jupyter notebook

This approach provides a clean, isolated environment for working with LangChain. For experienced developers with established workflows, we also support:

- pip with venv: Instructions in the GitHub repository

- Docker containers: Dockerfiles provided in the GitHub repository

- Poetry: Configuration files available in the GitHub repository

Choose the method you’re most comfortable with but remember that all examples assume a Python 3.10+ environment with the dependencies listed in requirements.txt.

For developers, Docker, which provides isolation via containers, is a good option. The downside is that it uses a lot of disk space and is more complex than the other options. For data scientists, I’d recommend Conda or Poetry.

Conda handles intricate dependencies efficiently, although it can be excruciatingly slow in large environments. Poetry resolves dependencies well and manages environments; however, it doesn’t capture system dependencies.

All tools allow sharing and replicating dependencies from configuration files. You can find a set of instructions and the corresponding configuration files in the book’s repository at https:// github.com/benman1/generative\_ai\_with\_langchain.

Once you are finished, please make sure you have LangChain version 0.3.17 installed. You can check this with the command pip show langchain.

With the rapid pace of innovation in the LLM field, library updates are frequent. The code in this book is tested with LangChain 0.3.17, but newer versions may introduce changes. If you encounter any issues running the examples:

- Create an issue on our GitHub repository

- Join the discussion on Discord at https://packt.link/lang

- Check the errata on the book’s Packt page

This community support ensures you’ll be able to successfully implement all projects regardless of library updates.

API key setup

LangChain’s provider-agnostic approach supports a wide range of LLM providers, each with unique strengths and characteristics. Unless you use a local LLM, to use these services, you’ll need to obtain the appropriate authentication credentials.

| Provider | Environment Variable | Setup URL | Free Tier? |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenAI | OPENAI API KEY | platform.openai.com | No |

| HuggingFace | HUGGINGFACEHUB API TOKEN | Yes | |

| Anthropic | ANTHROPIC API KEY | console.anthropic.com | No |

| Google AI | GOOGLE API KEY | Yes | |

| Google VertexAI |

Application Default Credentials |

Yes (with limits) |

|

| Replicate | REPLICATE API TOKEN | replicate.com | No |

Table 2.1: API keys reference table (overview)

Most providers require an API key, while cloud providers like AWS and Google Cloud also support alternative authentication methods like Application Default Credentials (ADC). Many providers offer free tiers without requiring credit card details, making it easy to get started.

To set an API key in an environment, in Python, we can execute the following lines:

import os

<pre>os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = "<your token>"</pre>Here, OPENAI API KEY is the environment key that is appropriate for OpenAI. Setting the keys in your environment has the advantage of not needing to include them as parameters in your code every time you use a model or service integration.

You can also expose these variables in your system environment from your terminal. In Linux and macOS, you can set a system environment variable from the terminal using the export command:

export OPENAI_API_KEY=<your token>To permanently set the environment variable in Linux or macOS, you would need to add the preceding line to the ~/.bashrc or ~/.bash_profile files, and then reload the shell using the command source ~/.bashrc or source ~/.bash_profile.

For Windows users, you can set the environment variable by searching for “Environment Variables” in the system settings, editing either “User variables” or “System variables,” and adding export OPENAI_API_KEY=your_key_here.

Our choice is to create a config.py file where all API keys are stored. We then import a function from this module that loads these keys into the environment variables. This approach centralizes credential management and makes it easier to update keys when needed:

import os

OPENAI_API_KEY = "... "

# I'm omitting all other keys

def set_environment():

variable_dict = globals().items()

for key, value in variable_dict:

if "API" in key or "ID" in key:

os.environ[key] = valueIf you search for this file in the GitHub repository, you’ll notice it’s missing. This is intentional – I’ve excluded it from Git tracking using the .gitignore file. The .gitignore file tells Git which files to ignore when committing changes, which is essential for:

- Preventing sensitive credentials from being publicly exposed

- Avoiding accidental commits of personal API keys

- Protecting yourself from unauthorized usage charges

To implement this yourself, simply add config.py to your .gitignore file:

# In .gitignore

config.py

.env

**/api_keys.txt

# Other sensitive filesYou can set all your keys in the config.py file. This function, set_environment(), loads all the keys into the environment as mentioned. Anytime you want to run an application, you import the function and run it like so:

from config import set_environment

set_environment()For production environments, consider using dedicated secrets management services or environment variables injected at runtime. These approaches provide additional security while maintaining the separation between code and credentials.

While OpenAI’s models remain influential, the LLM ecosystem has rapidly diversified, offering developers multiple options for their applications. To maintain clarity, we’ll separate LLMs from the model gateways that provide access to them.

- Key LLM families

- Anthropic Claude: Excels in reasoning, long-form content processing, and vision analysis with up to 200K token context windows

- Mistral models: Powerful open-source models with strong multilingual capabilities and exceptional reasoning abilities

- Google Gemini: Advanced multimodal models with industry-leading 1M token context window and real-time information access

- OpenAI GPT-o: Leading omnimodal capabilities accepting text, audio, image, and video with enhanced reasoning

- DeepSeek models: Specialized in coding and technical reasoning with state-ofthe-art performance on programming tasks

- AI21 Labs Jurassic: Strong in academic applications and long-form content generation

- Inflection Pi: Optimized for conversational AI with exceptional emotional intelligence

- Perplexity models: Focused on accurate, cited answers for research applications

- Cohere models: Specialized for enterprise applications with strong multilingual capabilities

- Cloud provider gateways

- Amazon Bedrock: Unified API access to models from Anthropic, AI21, Cohere, Mistral, and others with AWS integration

- Azure OpenAI Service: Enterprise-grade access to OpenAI and other models with robust security and Microsoft ecosystem integration

- Google Vertex AI: Access to Gemini and other models with seamless Google Cloud integration

- Independent platforms

- Together AI: Hosts 200+ open-source models with both serverless and dedicated GPU options