Causal AI

Part 4 Applications of causal inference

In part 4, we’ll turn our attention to the application of causal inference methods to practical problems. You will gain hands-on experience with causal effect estimation workflows, automated decision-making, and the integration of causality with large language models and other foundation models. By this end of this part, you’ll be able to use machine learning–based methods for causal effect estimation, as well as use causal inference methods to enhance modern machine learning applications from reinforcement learning to cutting-edge generative AI.

11 Building a causal inference workflow

This chapter covers

- Building a causal analysis workflow

- Estimating causal effects with DoWhy

- Estimating causal effects using machine learning methods

- Causal inference with causal latent variable models

In chapter 10, I introduced a causal inference workflow, and in this chapter we’ll focus on building out this workflow in full. We’ll focus on one type of query in particular—causal effects—but the workflow generalizes to all causal queries.

We’ll focus on causal effect inference, namely estimation of average treatment effects (ATEs) and conditional average treatment effects (CATEs) because they are the most popular causal queries.

In chapter 1, I mentioned ૿the commodification of inference—how modern software libraries enable us to abstract away the statistical and computational details of the inference algorithm. The first thing you’ll see in this chapter is how the DoWhy library ૿commodifies causal inference, enabling us to focus at a high level on the causal assumptions of the algorithms and whether they are appropriate for our problem.

We’ll see the phenomenon at play again in an example that uses probabilistic machine learning to do causal effect inference on a causal generative model with latent variables. Here, we’ll see how deep learning with PyTorch provides another way to commodify inference.

11.1 Step 1: Select the query

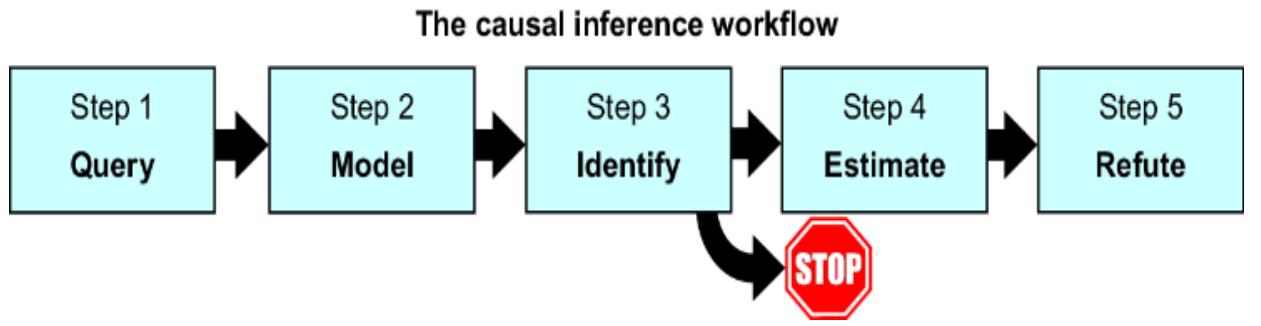

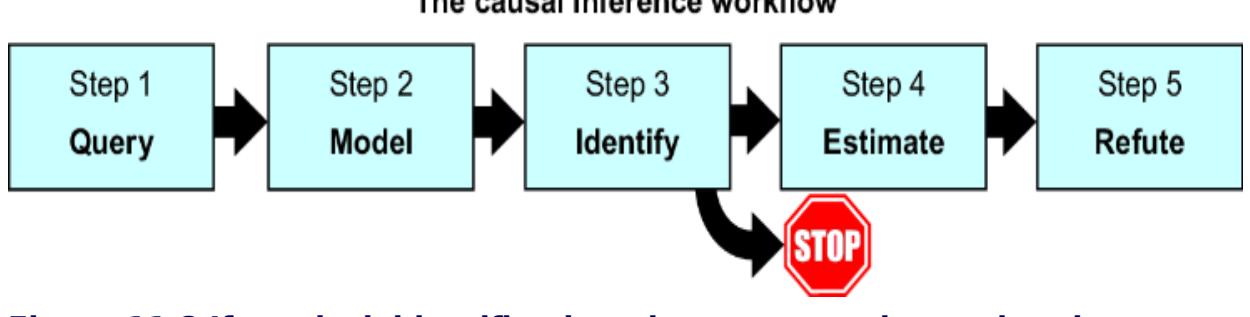

Recall the causal inference workflow from chapter 10, shown again in figure 11.1.

Figure 11.1 A workflow for a causal inference analysis

Let’s return to our online gaming example and use this workflow to answer a simple question:

How much does side-quest engagement drive in-game purchases?

We’ll call the cause of interest, Side-Quest Engagement (E), the ૿treatment variable; In-Game Purchases (I) will be the ૿outcome variable. Our query of interest is the average treatment effect (ATE):

E(IE=૿high – IE=૿low)

REFRESHER: WHY ATES AND CATES DOMINATE

Estimating ATEs and CATEs is the most popular causal effect inference task for several reasons, including the following:

- We can rely on causal effect inference techniques when randomized experiments are not feasible, ethical, or possible.

- We can use causal effect inference techniques to address practical issues with real-world experiments (e.g., post-randomization confounding, attrition, spillover, missing data, etc.).

- In an era when companies can run many different digital experiments in online applications and stores, causal effect inference techniques can help prioritize experiments, reducing opportunity costs.

Further, as we investigate our gaming data, we find data from a past experiment designed to test the effect of encouraging side-quest engagement on in-game purchases. In this experiment, all players were randomly assigned either to the treatment group or a control group. In the treatment group, the game mechanics were modified to tempt players into engaging in more side-quests, while the control group played the unmodified version of the game. We’ll define the Side-Quest Group Assignment (A) variable as whether the player was assigned to the treatment group in this experiment or the control group.

Why not just go with the estimate of the ATE produced by this experiment? This would be an estimate of E(IA=૿treatment

– IA=૿control).

This is the causal effect of the modification of game mechanics on in-game purchases. While this drives sidequest engagement, we know side-quest engagement is also driven by other potentially confounding factors. So we’ll focus on E(IE=૿high – IE=૿low).

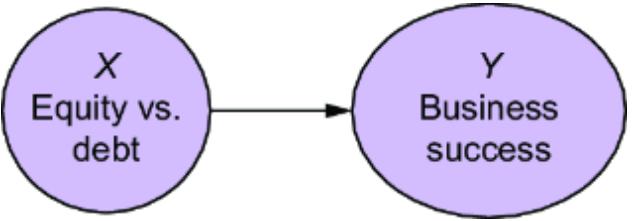

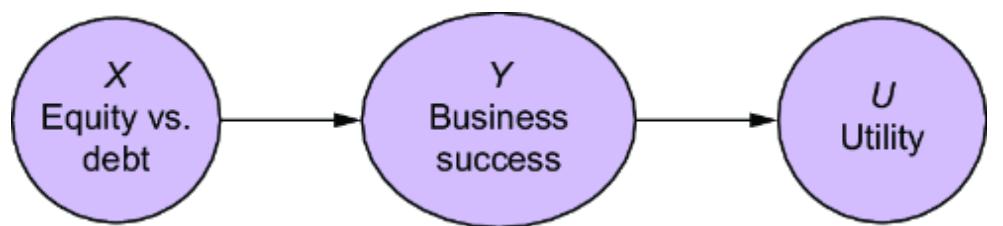

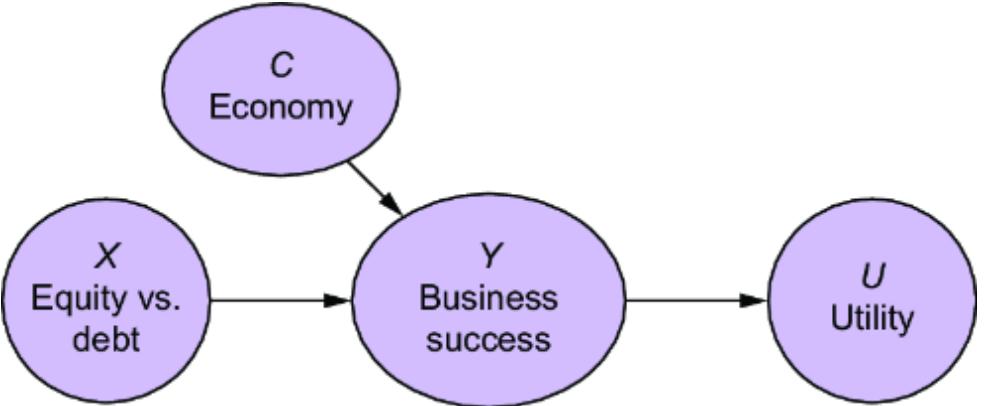

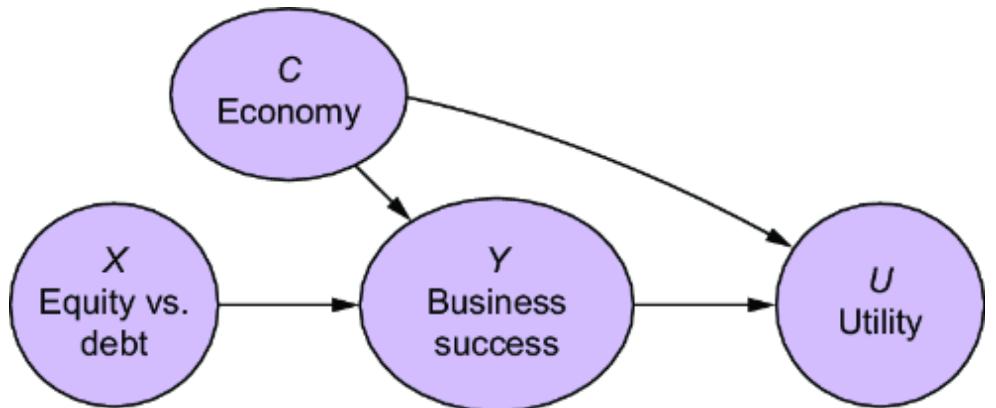

11.2 Step 2: Build the model

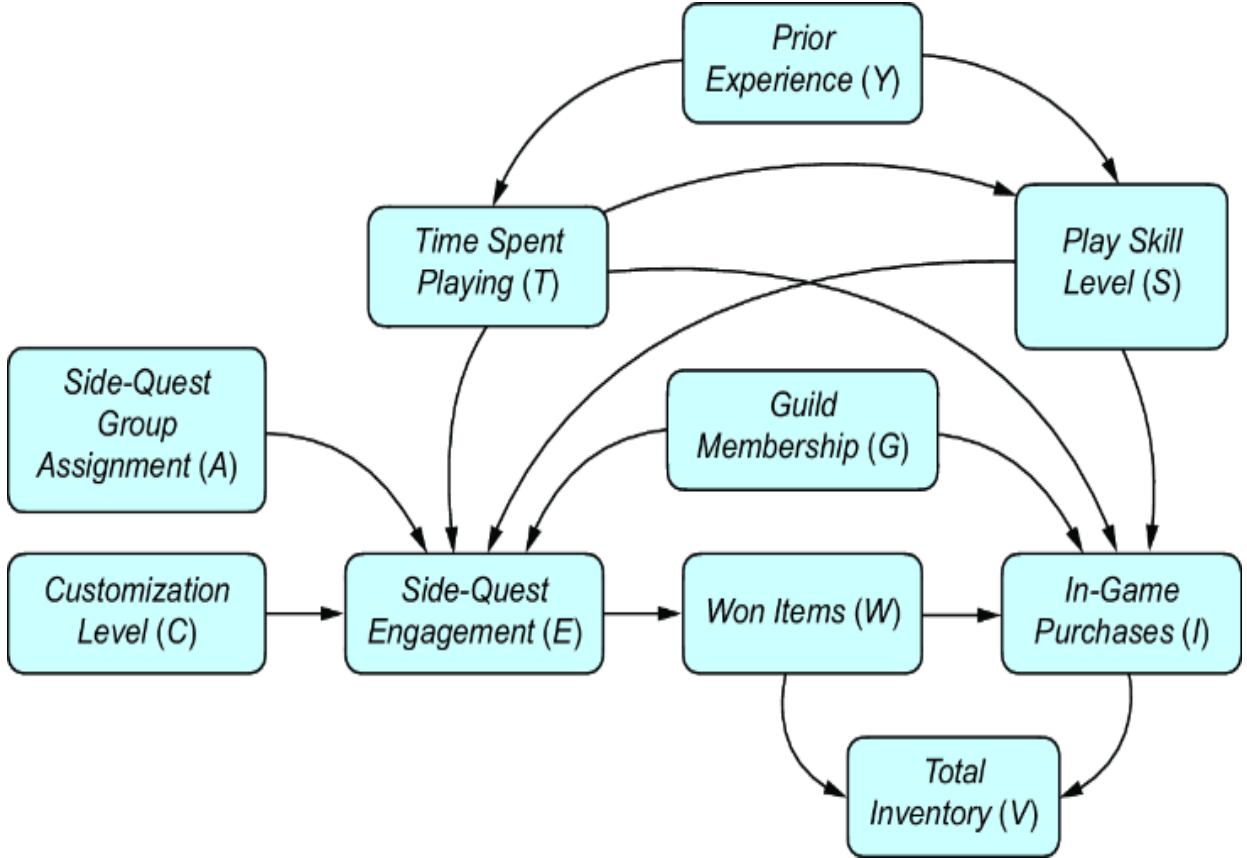

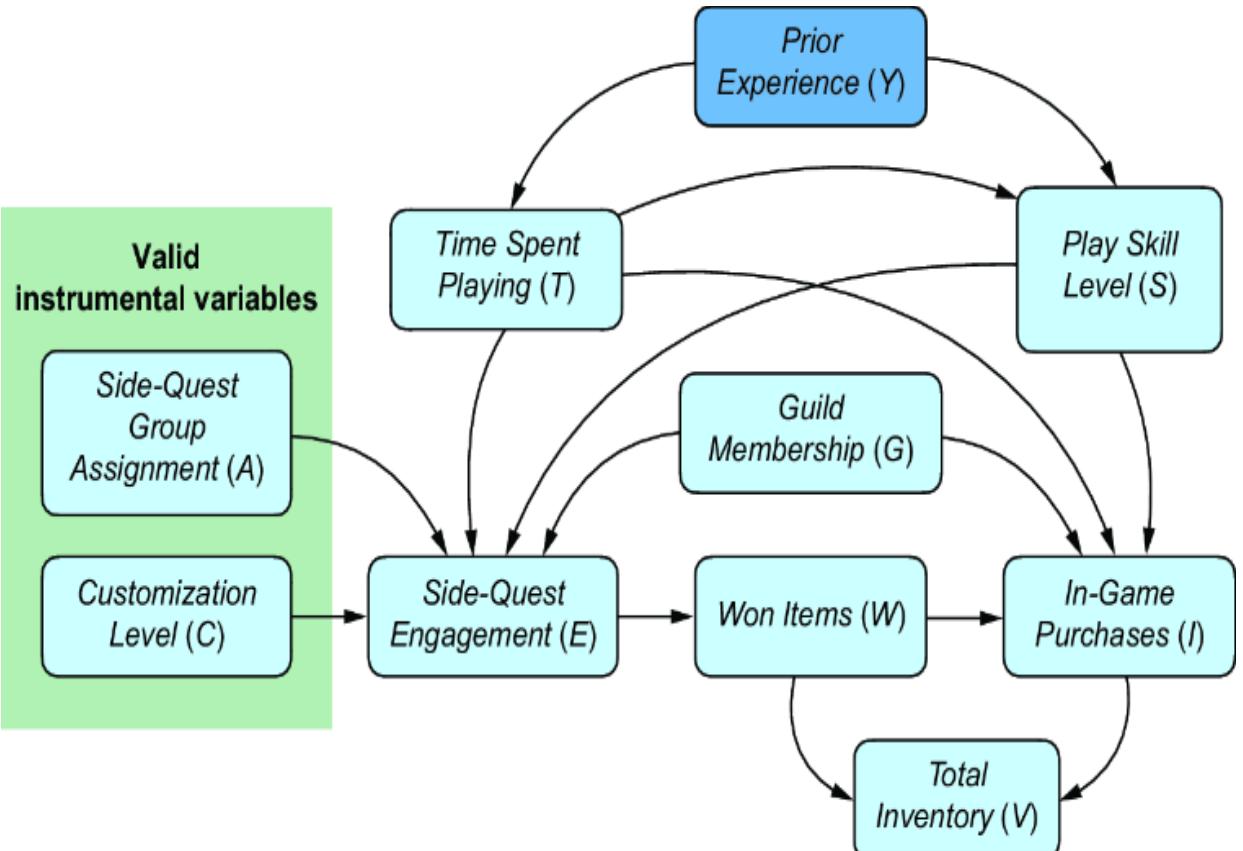

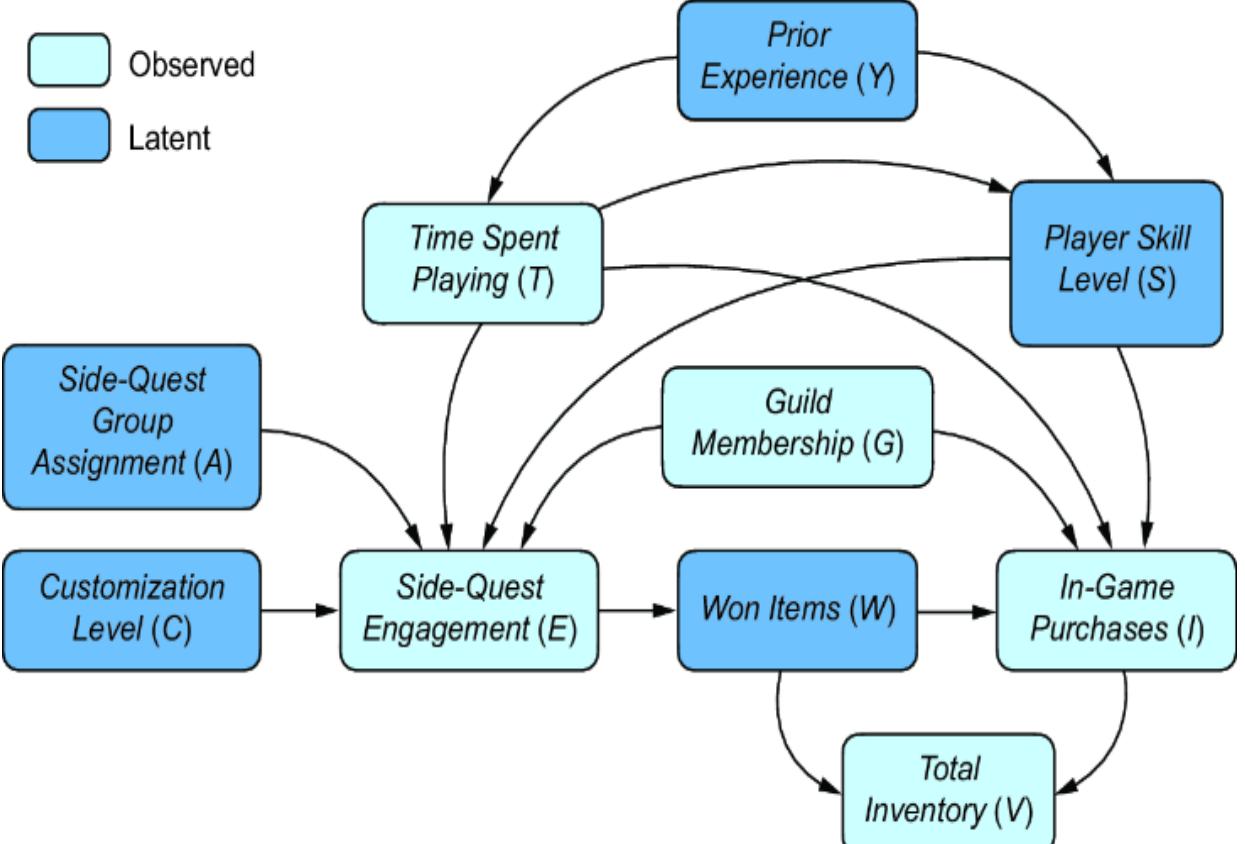

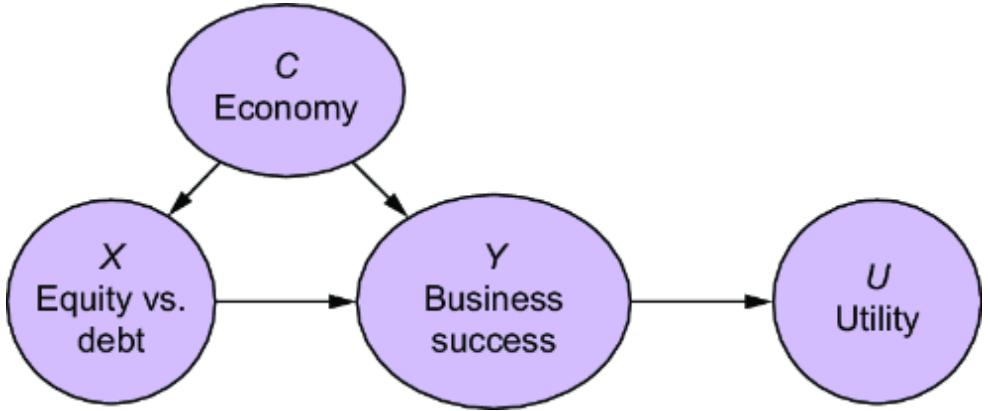

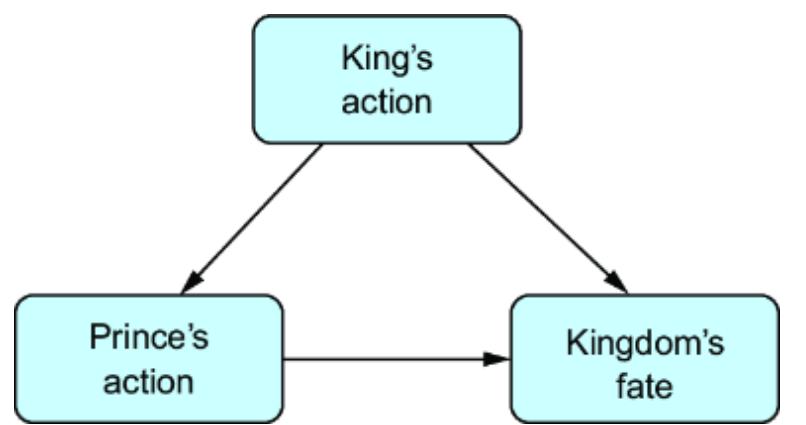

Next, we’ll build our causal model. Since we are targeting an ATE, we can stick with a DAG. Let’s suppose we build a more detailed version of our online gaming example and produce the causal DAG in figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2 An expanded version of the online gaming DAG. With respect to the causal effect of side-quest engagement on in-game purchases, we add two additional confounders and two instruments.

The expanded model adds some new variables:

- Side-Quest Group Assignment (A) —Assigned a value of 1 if a player was exposed to the mechanics that encouraged more side-quest engagement in the randomized experiment; 0 otherwise.

- Customization Level (C) —A score quantifying the player’s customizations of their character and the game environment.

- Time Spent Playing (T) —How much time the player has spent playing.

- Prior Experience (Y) —How much experience the player had prior to when they started playing the game.

- Player Skill Level (S) —A score of how well the player performs in game tasks.

- Total Inventory (V) —The amount of game items the player has accumulated.

We are interested in the ATE of Side-Quest Engagement on In-Game Purchases, so we know, based on causal sufficiency (chapter 3), that we need to add common causes for these variables. We’ve already seen Guild Membership (G ), but now we add additional common causes: Prior Experience, Time Spent Playing, and Player Skill Level. We also add Side-Quest Group Assignment and Customization Level because these might be useful instrumental variables—variables that are causes of the treatment of interest, and where the only path of causality from the variable to the outcome is via the treatment. I’ll say more about instrumental variables in the next section.

Finally, we’ll add Total Inventory. This is a collider between In-Game Purchases and Won Items. Perhaps it is common for data scientists in our company to use this as a predictor of the In-Game Purchases. But as you’ll see, we’ll want to avoid adding collider bias to causal effect estimation.

SETTING UP YOUR ENVIRONMENT

The following code was written with DoWhy 0.11 and EconML 0.15, which expects a version of NumPy before version 2.0. The specific pandas version was 1.5.3. Again, we use Graphviz for visualization, with python PyGraphviz library version 1.12. The code should work, save for visualization, if you skip the PyGraphviz installation.

First, let’s build the DAG and visualize the graph with the PyGraphviz library.

Listing 11.1 Build the causal DAG

import pygraphviz as pgv #1

from IPython.display import Image #2

causal_graph = """

digraph {

"Prior Experience" -> "Player Skill Level";

"Prior Experience" -> "Time Spent Playing";

"Time Spent Playing" -> "Player Skill Level";

"Guild Membership" -> "Side-quest Engagement";

"Guild Membership" -> "In-game Purchases";

"Player Skill Level" -> "Side-quest Engagement";

"Player Skill Level" -> "In-game Purchases";

"Time Spent Playing" -> "Side-quest Engagement";

"Time Spent Playing" -> "In-game Purchases";

"Side-quest Group Assignment" -> "Side-quest Engagement";

"Customization Level" -> "Side-quest Engagement";

"Side-quest Engagement" -> "Won Items";

"Won Items" -> "In-game Purchases";

"Won Items" -> "Total Inventory";

"In-game Purchases" -> "Total Inventory";

}

""" #3

G = pgv.AGraph(string=causal_graph) #3

G.draw('/tmp/causal_graph.png', prog='dot') #4

Image('/tmp/causal_graph.png') #5#1 Download PyGraphviz and related libraries. #2 Optional import for visualizing the DAG in a Jupyter notebook #3 Specify the DAG as a DOT language string, and load a PyGraphviz AGraph object from the string. #4 Render the graph to a PNG file. #5 Display the graph.

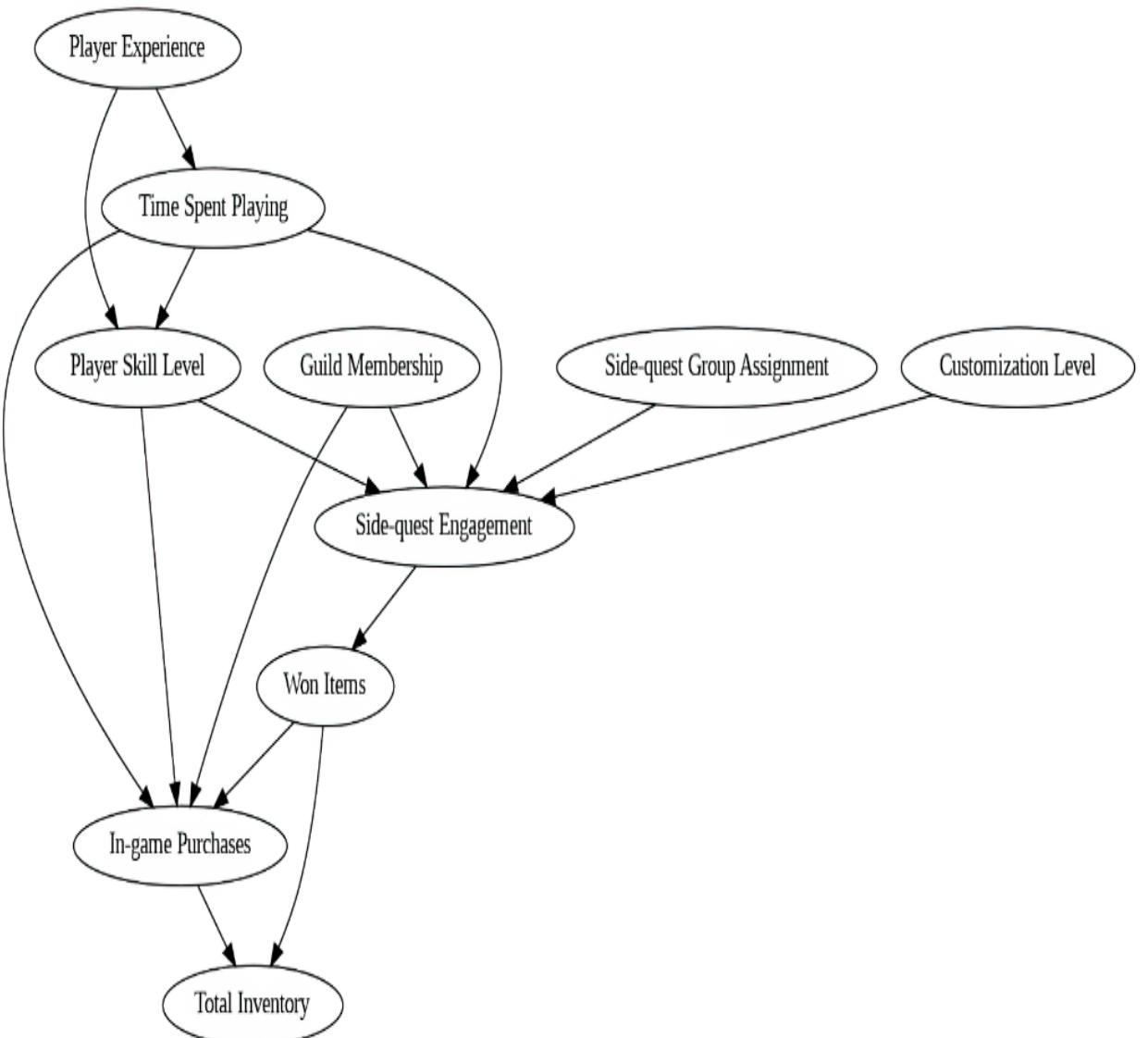

This returns the graph in figure 11.3.

Figure 11.3 Visualizing our model with the PyGraphviz library

At this stage, we can validate our model using the conditional independence testing techniques outlined in chapter 4. But keep in mind that we can also focus on the subset of assumptions we rely on for causal effect estimation to work in the ૿refutation (step 5) part of the workflow.

11.3 Step 3: Identify the estimand

Next, we’ll run identification. Our causal query is

E(IE=૿high – IE=૿low)

For simplicity, let’s recode ૿high as 1 and ૿low as 0.

E(IE=1 – IE=0)

This query is on level 2 of the causal hierarchy. We are not running an experiment; we only have observational data samples from a level 1 distribution. Our identification task is to use our level 2 query and our causal model and identify a level 1 estimand, an operation we can apply to the distribution of the variables in our data.

First, let’s download our data and see what variables are in our observational distribution.

Listing 11.2 Download and display the data

import pandas as pd

data = pd.read_csv(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/altdeep/causalML/master/datasets

↪/online_game_example_do_why.csv" #1

)

print(data.columns) #2#1 Download an online gaming dataset. #2 Print the variables.

This prints out the following set of variables:

Index([‘Guild Membership’, ‘Player Skill Level’, ‘Time Spent Playing’, ‘Side-quest Group Assignment’, ‘Customization Level’, ‘Side-quest Engagement’, ‘Won Items’, ‘In-game Purchases’, ‘Total Inventory’], dtype=‘object’)

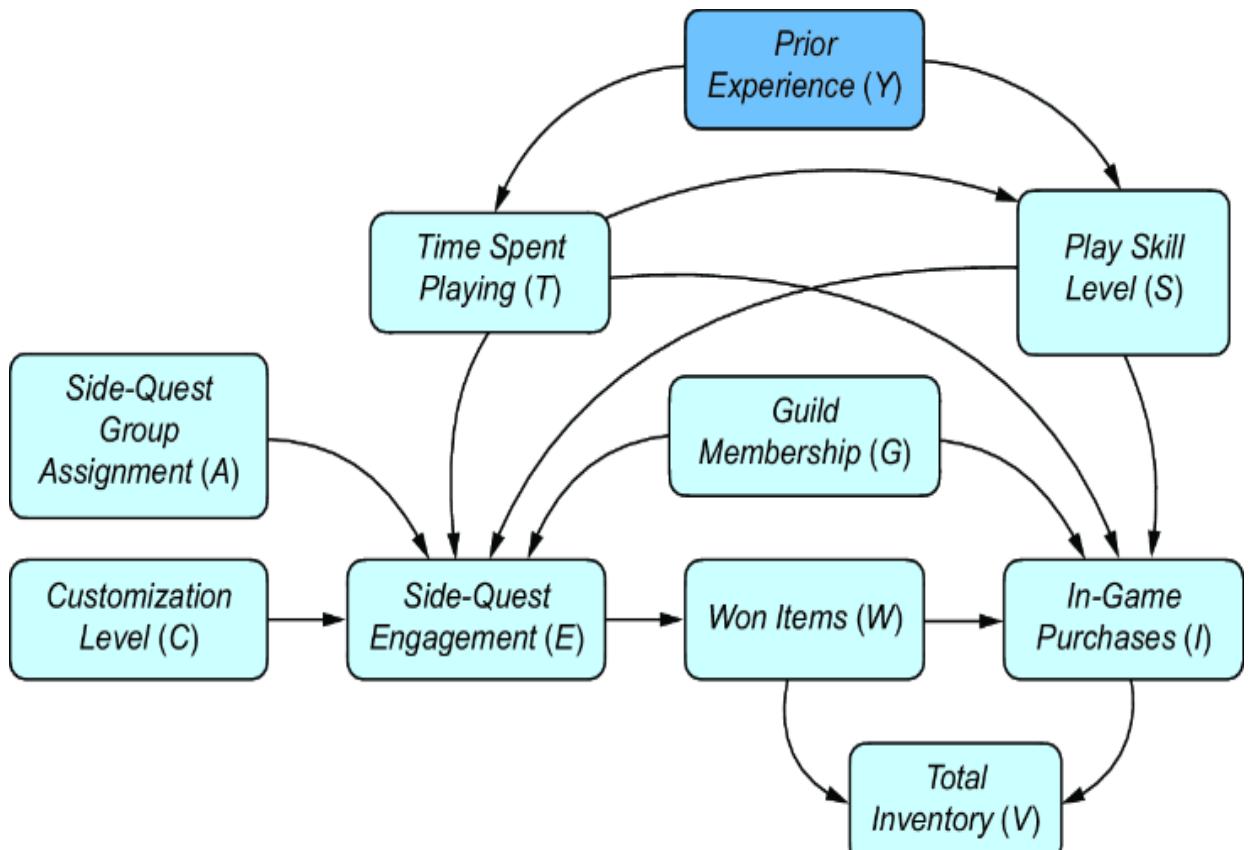

Our level 1 observational distribution includes all the variables in the DAG except Prior Experience. Thus, Prior Experience is a latent variable (figure 11.4).

Figure 11.4 Prior Experience is not observed in the data; it is a latent (unobserved) variable with respect to our DAG.

We specified the base distribution for the estimand using y0’s domain-specific language for probabilistic expressions:

Identification.from_expression(

graph=dag,

query=query,

estimand=observational_distribution

)Here, we’ll use DoWhy. With DoWhy, we specify the observational distribution by just passing in the pandas DataFrame, along with the DAG and the causal query, to the constructor of the CausalModel class.

Listing 11.3 Instantiate an instance of DoWhy’s CausalModel

from dowhy import CausalModel #1

model = CausalModel(

data=data, #2

treatment='Side-quest Engagement', #3

outcome='In-game Purchases', #3

graph=causal_graph #4

)#1 Install DoWhy and load the CausalModel class.

#2 Instantiate the CausalModel object with the data, which represents the level 1 observational distribution from which we derive the estimands.

#3 Specify the target causal query we wish to estimate, namely the causal effect of the treatment on the outcome. #4 Provide the causal DAG.

Next, the identify_effect methods will show us possible estimands we can target, given our causal model and observed variables.

Listing 11.4 Run identification in DoWhy

identified_estimand = model.identify_effect() #1 print(identified_estimand)

#1 The identify_effect method of the CausalModel class lists identified estimands.

The identified_estimand object is an object of the class IdentifiedEstimand. Printing it will list the estimands, if any, and the assumptions they entail. In our case, we have three estimands we can target:

- The backdoor adjustment estimand through the adjustment set Player Skill Level, Guild Membership, and Time Spent Playing

- The front-door adjustment estimand through the mediator Won Items

- Instrumental variable estimands through Side-Quest Group Assignment and Customization Level

GRAPHICAL IDENTIFICATION IN DOWHY

At the time of writing, DoWhy does implement graphical identification algorithms like y0, but these are experimental and are not the default identification approach. The default approach looks for commonly used estimands (e.g., backdoor, front door, instrumental variables) based on the structure of your graph. There may be identifiable estimands that the default approach misses, but these would be estimands that are not commonly used.

Let’s examine these estimands more closely.

11.3.1 The backdoor adjustment estimand

Let’s look at the printed summary for the first estimand, the backdoor adjustment estimand:

Estimand type: EstimandType.NONPARAMETRIC_ATE

### Estimand : 1

Estimand name: backdoor

Estimand expression:

d

────────────────────────(E[In-game Purchases|Time Spent Playing,Guild

d[Side-quest Engagement]Membership, Player Skill Level])

Estimand assumption 1, Unconfoundedness: If U→{Side-quest Engagement} and U→In-game P urchases then P(In-game Purchases|Side-quest Engagement,Time Spent Playing,Guild Memb ership,Player Skill Level,U) = P(In-game Purchases|Side-quest Engagement,Time Spent P laying,Guild Membership,Player Skill Level)

This printout tells us a few things:

EstimandType.NONPARAMETRIC_ATE—This means the estimand can be identified with graphical or ૿nonparametric methods, such as the do-calculus.

- Estimand name: backdoor—This is the backdoor adjustment estimand.

- Estimand expression—The mathematical expression of the estimand. Since we want the ATE, we modify the backdoor estimand to target the ATE.

- Estimand assumption 1—The causal assumptions underlying the estimand.

The last item is the most important. For each estimand, DoWhy lists the causal assumptions that must hold for valid estimation of the target causal query. In this case, the assumption is that there are no hidden (unmeasured) confounders, which DoWhy refers to as U. Estimation of a backdoor adjustment estimand assumes that all confounders are adjusted for.

Note that we do not need to observe Prior Experience to obtain a backdoor adjustment estimand. We just need to observe an adjustment set of common causes that dseparates or ૿blocks all backdoor paths.

The next estimand in the printout is an instrumental variable estimand.

11.3.2 The instrumental variable estimand

The printed summary for the second estimand, the instrumental variable estimand, is as follows (note, I shortened the variable names to acronyms so the summary fits this page):

### Estimand : 2

Estimand name: iv

Estimand expression:

⎡ -1⎤

⎢ d ⎛ d ⎞ ⎥

E⎢──────────(IGP)⋅ ───────────([SQE]) ⎥

⎣d[SQGA CL] ⎝ d[SQGA CL] ⎠ ⎦

Estimand assumption 1, As-if-random:

If U→→IGP then ¬(U →→{SQGA,CL})

Estimand assumption 2, Exclusion:

If we remove {SQGA,CL}→{SQE} then ¬({SQGA,CL}→IGP)There are two level 2 definitional requirements for a variable to be a valid instrument:

- As-if-random—Any backdoor paths between the instrument and the outcome can be blocked.

- Exclusion—The instrument is a cause of the outcome only indirectly through the treatment.

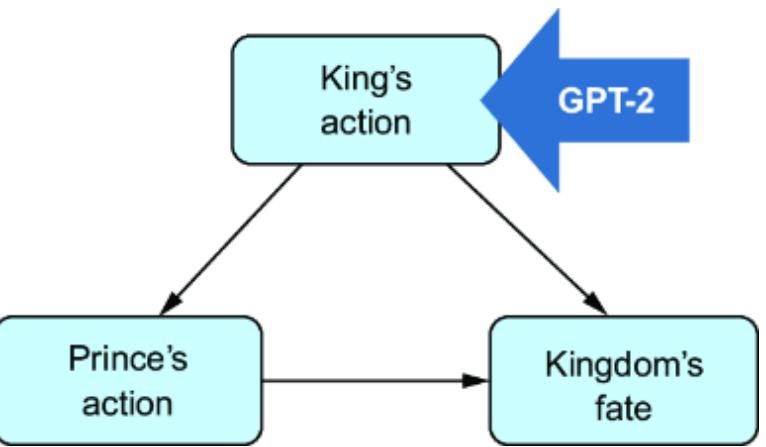

The variables in our model that satisfy these constraints are Side-Quest Group Assignment and Customization Level, as shown in figure 11.5.

Figure 11.5 Side-Quest Group Assignment and Customization Level are valid instrumental variables.

The printout of identified_estimand shows the two constraints:

- Estimand assumption 1, As-if-random—DoWhy assumes that none of the other causes of the outcome (In-Game Purchases) are also causes of either instrument. In other words, there are no backdoor paths between the instruments and the outcome.

- Estimand assumption 2, Exclusion—This says that if we remove the causal path from the instruments to the treatment (Side-quest Engagement), there would be no causal paths from the instruments to the outcome (In-Game Purchases). In other words, there are no causal paths between the instruments and the outcome that are not mediated by the treatment.

Note that DoWhy’s constraints are relatively restrictive; DoWhy prohibits the existence of backdoor paths and nontreatment-mediated causal paths between the instrument and the outcome. In practice, it would be possible to block these paths with backdoor adjustment. DoWhy is making a trade-off that favors a simpler interface.

PARAMETRIC ASSUMPTIONS FOR INSTRUMENTAL VARIABLE ESTIMATION

The level 2 graphical assumptions are not sufficient for instrumental variable identification; additional parametric assumptions are needed. DoWhy, by default, makes a linearity assumption. With a linear assumption, you can derive the ATE as a simple function of the coefficients of linear models of outcome and the treatment given the instrument. DoWhy does this by fitting linear regression models.

Next, we’ll look at the third estimand identified by DoWhy the front door estimand.

11.3.3 The front-door adjustment estimand

Let’s move on to the assumptions in the third estimand, the front-door estimand. DoWhy’s printed summary is as follows (again, I shortened the variable names to acronyms in the printout so it fits the page):

### Estimand : 3

Estimand name: frontdoor

Estimand expression:

⎡ d d ⎤

E⎢────────────(IGP)⋅───────([WI])⎥

⎣d[WI] d[SQE] ⎦

Estimand assumption 1, Full-mediation:

WI intercepts (blocks) all directed paths from SQE to IGP.

Estimand assumption 2, First-stage-unconfoundedness:

If U→{SQE} and U→{WI}

then P(WI|SQE,U) = P(WI|SQE)

Estimand assumption 3, Second-stage-unconfoundedness:

If U→{WI} and U→IGP

then P(IGP|WI, SQE, U) = P(IGP|WI, SQE)As we saw in chapter 10, the front-door estimand requires a mediator on the path from the treatment to the outcome—in our DAG, this is Won Items. The printout for identified_estimand lists three key assumptions for the frontdoor estimand:

- Full-mediation—The mediator (Won-Items) intercepts all directed paths from the treatment (Side-Quest Engagement) to the outcome (In-Game Purchases). In other words, conditioning on Won-Items would dseparate (block) all the paths of causal influence from the treatment to the outcome.

- First-stage-unconfoundedness—There are no hidden confounders between the treatment and the mediator.

- Second-stage-unconfoundedness—There are no hidden confounders between the outcome and the mediator.

With our DAG and the variables observed in the data, DoWhy has identified three estimands for the ATE of Side-Quest Engagement on In-Game Purchases. Remember, the estimand is the thing we estimate, so which estimand should we estimate?

11.3.4 Choosing estimands and reducing ૿DAG anxiety

In step 2 of the causal inference workflow, we specified our causal assumptions about the domain as a DAG (or SCM or other causal model). The subsequent steps all rely on the assumptions we make in step 2.

Errors in step 2 can lead to errors in the results of the analysis, and while we can empirically test these assumptions to some extent (e.g., using the methods in chapter 4), we cannot verify all our causal assumptions with observational data alone. This dependence on our subjective and unverified causal assumptions leads to what I call ૿DAG anxiety—a fear that if one gets any part of the causal assumptions wrong, then the output of the analysis becomes wrong. Fortunately, we don’t need to get all the assumptions right; we only need to rely on the assumptions required to identify our selected estimand.

This is what makes DoWhy’s identify_effect method so powerful. By showing us the assumptions required for each estimand it lists, we can compare these assumptions and target the estimand where we are most confident about those assumptions.

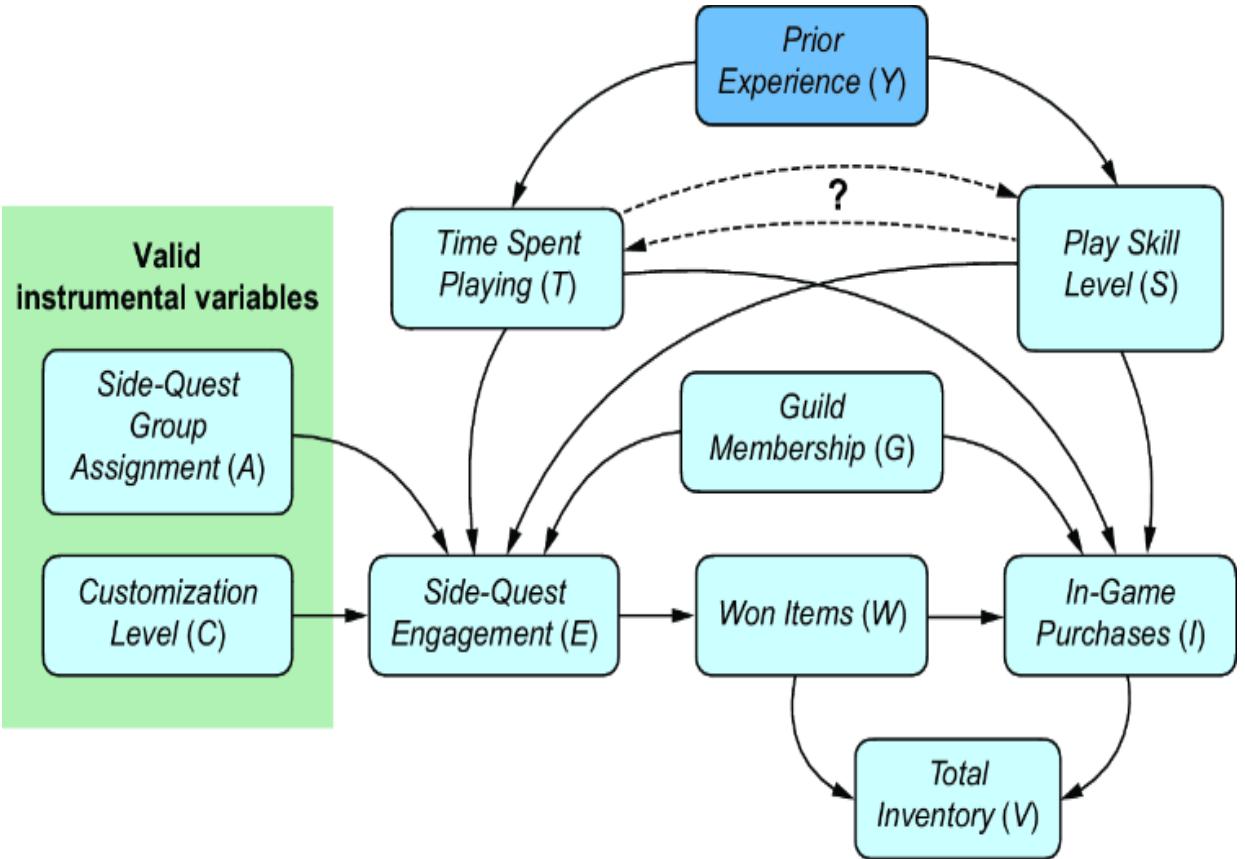

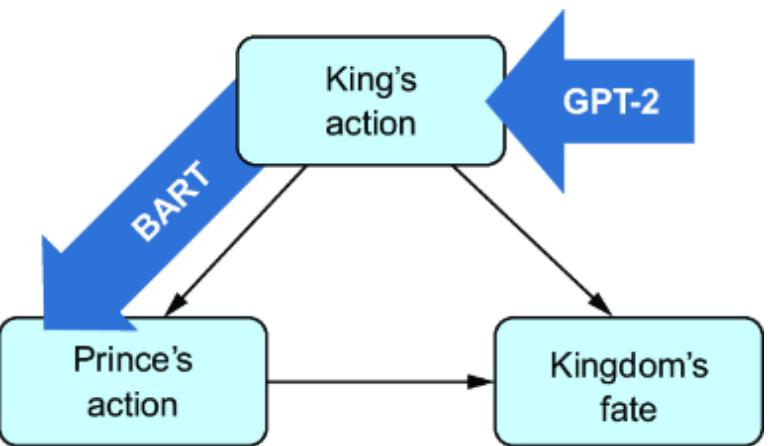

For example, the key assumption behind the backdoor adjustment estimand is that we can adjust for all sources of confounding from common causes. In our original DAG, we have an edge from Time Spent Playing to Player Skill Level. What if you weren’t sure about the direction of this edge, as illustrated in figure 11.6.

Figure 11.6 Uncertainty about the edge between Time Spent Playing and Player Skill Level doesn’t matter with respect to the backdoor adjustment estimand of the ATE of interest.

When we initially built the DAG, you might have been thinking that playing more causes skill level to increase. But now you may worry that perhaps the relationship is the other way around—that being more skilled causes you to want to spend more time playing. It doesn’t matter! At least, not with respect to the backdoor estimand for the target query—the ATE of Side-Quest Engagement on In-Game Purchases.

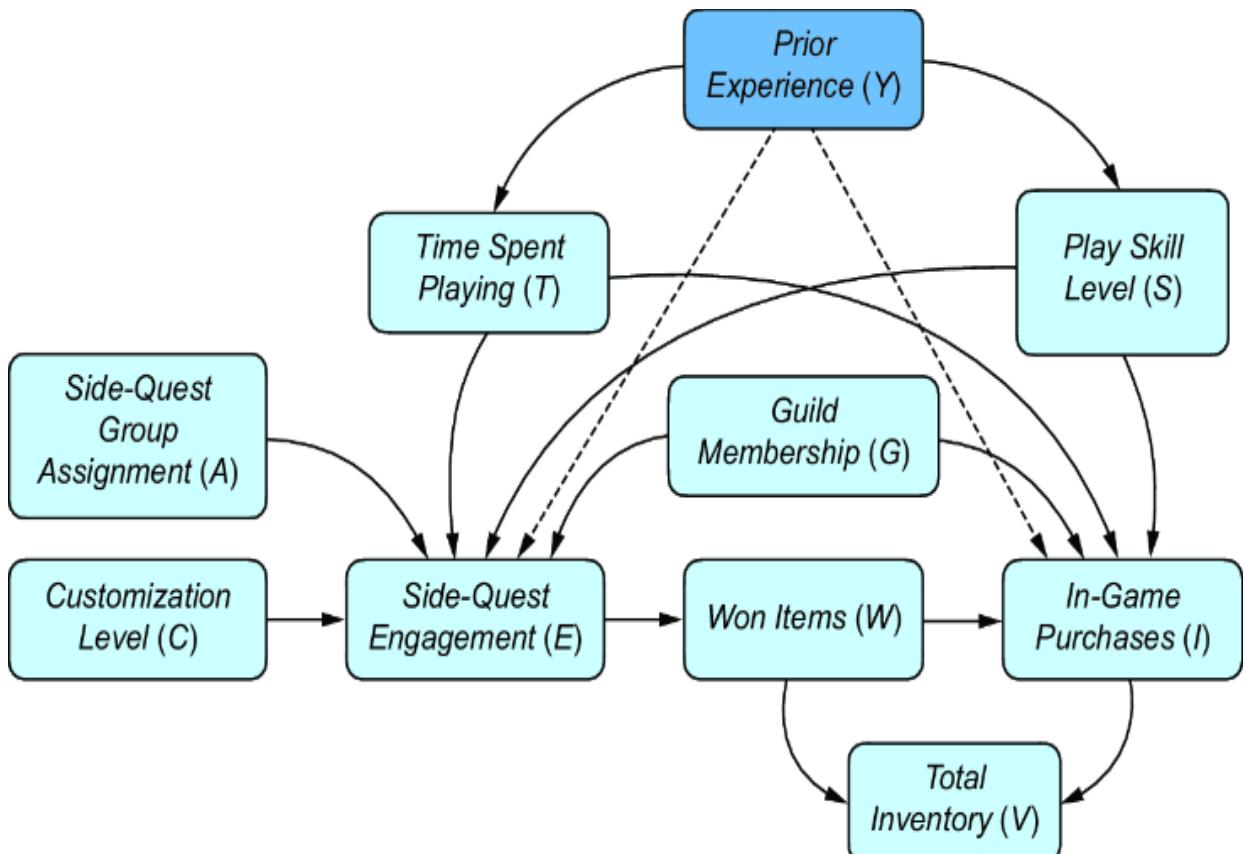

Suppose that instead you were worried that the model might have omitted edges that reflect direct influence that Prior Experience has on Side-Quest Engagement and In-Game Purchases. You worry that players might bring their habits in side-quest playing and virtual item purchasing from previous games they’ve played to the game environment you are modeling, as in figure 11.7.

Figure 11.7 Direct influence of a latent variable on the treatment and outcome would violate the assumption underpinning the backdoor adjustment estimand. If you are not confident in an estimand’s assumptions, target another.

If this is true, your backdoor adjustment estimand assumption would be violated—you would have a confounder you couldn’t adjust for, a backdoor path you couldn’t block. In this case, you’ll need to consider whether the backdoor adjustment estimand is the right estimand to target.

Fortunately, in this example, we still have two other estimands to choose from. Neither the instrumental variable estimand nor the front-door adjustment estimand rely on our ability to adjust for all common causes. As long as we’re comfortable with the assumptions for either of these estimands, we can continue.

11.3.5 When you don’t have identification

The stop sign in the causal inference workflow, shown again in figure 11.8, warns against proceeding with estimation when you don’t have identification.

Figure 11.8 If you lack identification, do not proceed to estimation. Rather, consider how to acquire data that enables identification.

Let’s consider what happens if our observational distribution only contains a subset of our initial variables, as in figure 11.9.

Figure 11.9 Player Skill Level, Won Items, Prior Experience, Side-Quest Group Assignment, and Customization Level become latent variables.

In this case, we have some problems:

- If Player Skill Level is latent, we can’t adjust for confounding from Player Skill Level and thus have no backdoor estimand.

- If Won Items is latent, we can’t identify a front-door estimand.

- If the instrumental variables are latent, we can’t target an instrumental variable estimand.

When you lack identification, you should not proceed with the next step of estimation. Rather, use the results from identification to determine what additional variables to collect—consider how you can collect new data with

- Additional confounders that would enable backdoor identification

- A mediator that would enable front-door identification

- Variables you can use as instruments

Avoid the temptation to change the DAG to get identification with your current data—you are modeling the data generating process (DGP), not the data.

However, if you do have an identified estimand, you can move on to step 4—estimation.

11.4 Step 4: Estimate the estimand

In step 4 of the causal inference workflow, we select an estimation method for whichever estimand we wish to target. In this section, we’ll walk through several estimators for each of our three estimands. Note that your results for estimation may vary slightly from those in the text, depending on modifications to the dataset and to random elements of the estimator.

In DoWhy, we do estimation using a method in the CausalModel class called estimate_effect, as in the following example.

Listing 11.5 Estimating the backdoor estimand with linear regressioncausal_estimate_reg = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand, #1

method_name="backdoor.linear_regression", #2

confidence_intervals=True #3

)#1 The estimate_effect method takes the output of the identify_effect method as input.

#2 method_name is of the form ૿[estimand].[estimator]. Here we use the linear regression estimator to estimate the backdoor estimand. #3 Return confidence intervals

The first argument is the identified_estimand object. The second argument method_name is a string of the form ” [estimand].[estimator]“, where”[estimand]” is the estimand we want to target, and “[estimator]” is the estimation method we want to use. Thus, method_name=“backdoor.linear_regression” means we want to use linear regression to estimate the backdoor estimand.

In this section, we’ll see the benefits of distinguishing identification from estimation. In step 3 of the causal inference workflow, we compared identified estimands and selected an estimand with assumptions in which we are confident. That step frees us to focus on the statistical and computational trade-offs common across data science and machine learning when we choose an estimation method in step 4. We’ll walk through these trade-offs in this section. Let’s start by looking at the linear regression estimation of the backdoor estimand.

11.4.1 Linear regression estimation of the backdoor estimand

In many causal inference texts, particularly from econometrics, the default approach to causal inference is regression—specifically, regressing the outcome on the treatment and any confounders we wish to adjust for or ૿control for. What we are doing in this case is using linear regression to estimate the backdoor estimand.

Recall that in the case where Side-Quest Engagement is continuous, the ATE would be

This is a function of x, not a point value. However, it becomes a point value when E (I E=x ) is linear—the derivative of a linear function is a constant.

So we turn to regression. The backdoor adjustment estimand identifies Guild Membership (G ), Time Spent Playing (T ), and Player Skill Level (S ) as the confounders we have to adjust for. In general, we have to sum or integrate over these variables in the backdoor adjustment estimand. But in the linear regression case, this simplifies to simply regressing I on the treatment E and the confounders G, T, and S. The coefficient estimate for E is the ATE. In the case of a binary treatment like our target ATE,

E (IE=1 – I E= 0 )

we simply treat E as a regression dummy variable. The coefficient estimates for the confounders are nuisance parameters—meaning they are necessary to estimate the ATE, but we can discard them once we have it.

To illustrate, let’s print the results of our call to estimate_method.

Listing 11.6 Print the linear regression estimation resultsprint(causal_estimate_reg)

This prints a bunch of stuff, including the following:

## Realized estimand

b: In-game Purchases~Side-quest Engagement+Guild Membership+Time Spent Playing+Player

Skill Level

Target units: ate

## Estimate

Mean value: 178.08617115757784

95.0% confidence interval: [[168.68114922 187.4911931 ]]Realized estimand shows the regression formula. Estimate shows the estimation results, the point value, and the 95% confidence interval.

Here we see why linear regression is so popular as an estimator:

- The coefficient estimate of the treatment is a point estimate of the ATE.

- We adjust for backdoor confounders by simply including them in the regression model (no summation, no integration).

- The statistical properties of the estimator (confidence intervals, p-values, etc.) are well established.

- Many people are familiar with regression and how to evaluate a regression fit.

Once we have backdoor identification, the question of whether we should use a linear regression estimator in this case involves the same considerations of whether a linear regression model is appropriate in non-causal explanatory modeling settings (e.g., is the relationship linear?).

VALID BACKDOOR ADJUSTMENT SETS: WHAT YOU CAN AND CAN’T ADJUST FOR

You do not need to adjust for all confounding from common causes. Any valid backdoor adjustment set of common causes will do. As discussed in chapter 10, a valid backdoor adjustment set any set that satisfies the backdoor criterion, meaning that it d-separates all backdoor paths. For example, Guild Membership, Time Spent Playing, and Player Skill Level are a valid adjustment set. You don’t need Prior Experience because Time Spent Playing and Player Skill Level are sufficient to d-separate the backdoor path through Prior Experience. This is fortunate for us, since Prior Experience is unobserved. Though, if it were observed, we could add it to the adjustment set—this superset would also be a valid set.

DoWhy selects a valid adjustment set when it identifies a backdoor estimand. If you write your own estimator, you’ll select your own adjustment set.

Some applied regression texts argue that you should try to adjust for or ૿control for any covariates in your data because they could be potential confounders. This is bad advice. Doing so only makes sense if you are sure the covariate is not a mediator or a collider between the treatment and outcome variables. Adjusting for a mediator will d-separate the causal path you mean to quantify with the ATE. Adjusting for a collider will add collider bias. This is a painfully common error in social science, one committed even by experts.

11.4.2 Propensity score estimators of the backdoor estimand

Propensity score methods are a collection of estimation methods for the backdoor estimand that use a quantity called the propensity score. The traditional definition of a propensity score is the probability of being exposed to the treatment conditional on the confounders. In the context of the online gaming example, this is the probability that a player has high Side-Quest Engagement given their Guild Membership, Time Spent Playing, and Player Skill Level, i.e., P (E = 1|T = t, G = g, S = s ) where t, g, and s are that player’s values for T, G, and S. In other words, it quantifies the player’s ૿propensity of being exposed to the treatment (E = 1). Typically P (E = 1|T = t, G = g, S = s ) is fit by logistic regression.

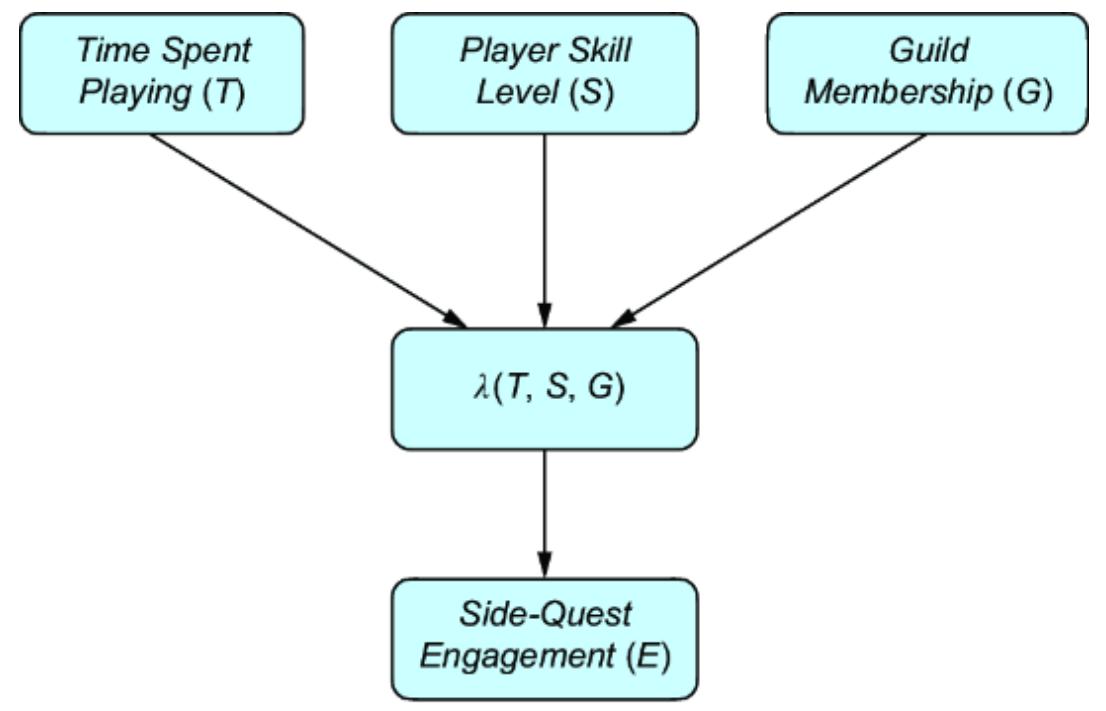

But we can take a more expansive, machine learning– friendly view of the propensity score. We can learn a propensity score function λ(…) of the backdoor adjustment set of confounders that renders those confounders conditionally independent of the treatment, as in figure 11.10.

Figure 11.10 The propensity score is a compression of the causal influence of the common causes in the backdoor adjustment set.

Here, we learn a function λ(T, S, G ) such that it effectively compresses the explanatory influence that T, S, and G have on E. The traditional function of P (E = 1|G, S, T ) compresses this influence into a probability value, but other approaches can work as well.

The utility of propensity score modeling is dimensionality reduction; now we only need to adjust for the score instead of all the confounders in the adjustment set. There are three common propensity score methods:

- Propensity score stratification

- Propensity score matching

- Propensity score weighting

These methods make different trade-offs in how they go about backdoor adjustment. Let’s examine their use in

DoWhy.

PROPENSITY SCORE STRATIFICATION

Propensity score stratification tries to break the data up into subsets (૿strata) according to propensity scores and then adjust over the strata. Note that this algorithm may take some time to run.

Listing 11.7 Propensity score stratification

causal_estimate_strat = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name="backdoor.propensity_score_stratification", #1

target_units="ate",

confidence_intervals=True

)

print(causal_estimate_strat)#1 Propensity score stratification

This produces the following results:

Estimate Mean value: 187.2931023294184 95.0% confidence interval: (180.3291962554186, 196.4556029137768)

The propensity score estimator gives us an estimate and confidence interval that differ slightly from that of the regression estimator.

PROPENSITY SCORE MATCHING

Propensity score matching tries to match individuals where treatment = 1 with individuals that have a similar propensity score but where treatment = 0 and then compare outcomes across matched pairs.

Listing 11.8 Propensity score matching

causal_estimate_match = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name="backdoor.propensity_score_matching", #1

target_units="ate",

confidence_intervals=True

)

print(causal_estimate_match)#1 Propensity score matching

This returns the following results:

## Estimate

Mean value: 199.8110290000004

95.0% confidence interval: (183.23361900000054, 210.5281390000008)Propensity score matching, despite also being a propensity score method, returns an estimate and confidence interval different from that of propensity score stratification.

PROPENSITY SCORE WEIGHTING

Propensity score weighting methods use the propensity score to calculate a weight in a class of inference algorithms called inverse probability weighting. We implement this method in DoWhy as follows.

Listing 11.9 Propensity score weighting

causal_estimate_ipw = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name="backdoor.propensity_score_weighting", #1

target_units = "ate",

method_params={"weighting_scheme":"ips_weight"}, #2

confidence_intervals=True

)

print(causal_estimate_ipw)#1 Inverse probability weighting with the propensity score #2 Parameters used to set the IPS algorithm

This returns the following:

## Estimate

Mean value: 437.79246624944926

95.0% confidence interval: (358.10472302821745, 515.2480572854872)The fact that this estimator’s result differs so dramatically from the others suggest that it is relying on statistical assumptions that don’t hold in this data.

Next, we’ll move on to a popular class of backdoor estimators that implement machine learning.

11.4.3 Backdoor estimation with machine learning

Recent developments in causal effect estimation focus on leveraging machine learning models, and most of these target the backdoor estimand. These approaches to causal effect estimation scale to large datasets and allow us to relax parametric assumptions, such as linearity. The following DoWhy code uses the sklearn and EconML libraries for these machine learning methods. DoWhy’s estimate_effects provides a wrapper to the EconML implementation of these methods.

DOUBLE MACHINE LEARNING

Double machine learning (double ML) is a backdoor estimator that uses machine learning methods to fit two predictive models: a model of the outcome, given the adjustment set of confounders, and a model of the treatment, given the adjustment set. The approach then combines these two predictive models in a final-stage estimation to create a model of the target causal effect query.

The following code performs double ML using a gradient boosting model and regularized regression model (LassoCV) from sklearn.

Listing 11.10 Double ML with DoWhy, EconML, and sklearn

from sklearn.preprocessing import PolynomialFeatures

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

featurizer = PolynomialFeatures(degree=1, include_bias=False)

gb_estimate = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name = "backdoor.econml.dml.DML", #1

control_value = 0,

treatment_value = 1,

method_params={

"init_params":{

'model_y': GradientBoostingRegressor(), #2

'model_t': GradientBoostingRegressor(), #3

'model_final': LassoCV(fit_intercept=False), #4

'featurizer': featurizer

},

"fit_params":{}

}

)

print(gb_estimate)#1 Select the double ML estimator.

#2 Use a gradient boosting model to model the outcome given the confounders.

#3 Use a gradient boosting model to model the treatment given the confounders.

#4 Use linear regression with L1 regularization (LASSO) as the final model.

This produces the following output:

Estimate Mean value: 175.7229947190752

This gives us an estimate in the ballpark of some of the other estimators.

META LEARNERS

Meta learners are another ML method for backdoor estimation. Broadly speaking, meta learners train a model (or models) of the outcome given the treatment variable and the confounders, and then account for the difference in prediction across treatment and control values of the treatment variable. They are particularly focused on highlighting heterogeneity of treatment effects across the

data. The following code shows a meta learner example called a T-learner that uses a random forest predictor.

Listing 11.11 Backdoor estimation with a meta learner

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor #1

metalearner_estimate = model.estimate_effect( #1

identified_estimand, #1

method_name="backdoor.econml.metalearners.TLearner", #1

method_params={ #1

"init_params": {'models': RandomForestRegressor()}, #1

"fit_params": {} #1

} #1

) #1print(metalearner_estimate)#1 Meta learner estimation of the backdoor estimand. This uses a Tlearner with a random forest predictor.

This returns the following output:

## Estimate

Mean value: 197.20665049459512

Effect estimates: [[ 192.6234]

[ -5.3165]

[ 133.2457]

...

[ 17.2561]

[-152.1482]

[ 264.887 ]]The values under ૿Effect estimates are the estimate of the CATE for each row of the data, conditional on the confounder values in the columns of that row.

CONFIDENCE INTERVALS WITH MACHINE LEARNING METHODS

DoWhy and EconML provide support for estimating confidence intervals for ML methods using a statistical method called nonparametric bootstrap, but this is computationally costly for large data. Cheap confidence interval estimation is one thing you give up for the flexibility and scalability of using ML methods for backdoor estimation.

11.4.4 Front-door estimation

Recall from chapter 10 that the front-door estimator for our ATE, given our Won Items mediator, is

\[P(I\_{E=e} = i) = \sum\_{w} P(W = w | E = e) \sum\_{\varepsilon} P(I = i | E = \varepsilon, W = w) P(E = \varepsilon)\]

We can estimate this by fitting two statistical models, one that predicts W given E, and one that predicts I given E and W. DoWhy does this with linear regression by default, but you also have the option of selecting different predictive models.

Listing 11.12 Front door estimation with DoWhy

causal_estimate_fd = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name="frontdoor.two_stage_regression", #1

target_units = "ate",

method_params={"weighting_scheme": "ips_weight"}, #2

confidence_intervals=True

)

print(causal_estimate_fd)#1 Select two-stage regression for the front-door estimand. #2 Specify estimator hyperparameters.

This produces the following output:

Estimate Mean value: 170.20560581290403 95.0% confidence interval: (141.53468188231938, 202.97221450388332)

The front-door estimate is similar to some of the backdoor estimators, but note that the confidence interval is skewed left.

11.4.5 Instrumental variable methods

Instrumental variable-based estimation of the ATE is straightforward in DoWhy.

Listing 11.13 Instrumental variable estimation in DoWhy

causal_estimate_iv = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name="iv.instrumental_variable", #1

method_params = {

"iv_instrument_name": "Side-quest Group Assignment" #2

},

confidence_intervals=True

)

print(causal_estimate_iv)#1 Select instrumental variable estimation. #2 Select side-quest engagement as the instrument.

This prints the following output:

Estimate Mean value: 205.82297621514252 95.0% confidence interval: (-369.04011492007703, 923.6814756173349)

Note how large the confidence interval is despite the size of the data. This indicates that this estimator, with its default assumptions, might have too much variance to be useful.

GOOD INSTRUMENTAL VARIABLES SHOULD BE “STRONG”

One requirement for good instrumental variable estimation is that the instrument is strong, meaning it has a strong causal effect on the treatment variable. If you explore this data, you’ll find Side-Quest Group Assignment is a weak instrument. Weak instruments can lead to high variance estimates of the ATE. Keep this in mind when selecting an instrument.

REGRESSION DISCONTINUITY

Regression discontinuity is an estimation method popular in econometrics. It uses a continuously valued variable related to the treatment variable, and it defines a threshold (a ૿discontinuity) in the values of that variable that partition

the data into ૿treatment and ૿control groups. It then compares observations lying closely on either side of the threshold, because those data points tend to have similar values for the confounders.

DoWhy treats regression discontinuity as an instrumental variable approach that uses continuous instruments. The rd_variable_name argument names a continuous instrument to use for thresholding, and rd_threshold_value is the threshold value. rd_bandwidth is the distance from the threshold within which confounders can be considered the same between treatment and control.

Listing 11.14 Regression discontinuity estimation with DoWhycausal_estimate_regdist = model.estimate_effect(

identified_estimand,

method_name="iv.regression_discontinuity", #1

method_params={

'rd_variable_name':'Customization Level', #2

'rd_threshold_value':0.5, #3

'rd_bandwidth': 0.15 #4

},

confidence_intervals=True,

)#1 DoWhy treats regression discontinuity as a special type of IV estimator.

#2 Use Customization Level as our instrument.

#3 The threshold value for the split (૿discontinuity) #4 The distance from the threshold within which confounders are considered the same between treatment and control values of the treatment variable

This returns the following results:

Mean value: 156.85691281931338

95.0% confidence interval: (-463.32687612531663, 940.698188663685)Again, the variance is too large for us to rely on this estimator. The instrument is likely weak, or we need to tune the arguments passed to the estimator.

CONDITIONAL AVERAGE TREATMENT EFFECT ESTIMATION AND SEGMENTATION

The conditional average treatment effect (CATE) is the ATE for a subset of the target population; i.e., we condition the ATE on specific values of covariates. DoWhy enables you to estimate the CATE as easily as the ATE.

Sometimes the goal of CATE estimation is segmentation breaking the population down into segments that have a distinct CATE from other segments. A good tool for segmentation is EconML, which enables CATEsegmentation using regression trees. EconML can segment data into groups that respond similarly to intervention on the treatment variable, and find an optimal intervention value for each group in the leaf nodes of the regression tree.

11.4.6 Comparing and selecting estimators

In chapter 1, I mentioned a phenomenon called the commodification of inference. The way DoWhy reduces estimation to merely a set of arguments passed to the estimate_effect method is an example of this phenomenon. You don’t need a detailed understanding of the estimator to get going. Once you’ve selected the estimand you wish to target, you can switch out different estimators.

ADVICE: START WITH SYNTHETIC DATA

One excellent practice is to build your workflow on synthetic data, rather than real data. Simulate a synthetic dataset that matches the size and correlation structure of your data, as well as your causal and statistical assumptions about your data. For example, you can write a causal generative model of your data, and use your data to train its parameters. Using this model as ground truth, simulate some data and derive a ground truth ATE.

You can then see if DoWhy’s estimates get close to the ground truth ATE, and if its confidence intervals contain it. You can also see how well the estimators perform under the ideal conditions where all your assumptions are true even in these conditions, the estimates will have biases and uncertainty.

Once you debug any problems that arise in these ideal conditions, you can switch out the synthetic data for real data. Then, the problems that arise are likely due to incorrect assumptions, and you can treat these by revisiting your assumptions.

My suggestion is to compare estimators after adding the next step, refutation, to the workflow. Refutation will help you stress test both the causal assumptions in the estimand and the statistical assumptions in the estimator. This enables you to make empirical comparisons of different estimators. Then, once you know what estimator you want and have seen how it performs on your data, you can do a deep dive into the statistical nuts and bolts of your chosen estimator.

11.5 Step 5: Refutation

We know that the result of our causal inference depends on our initial causal assumptions in step 2, or more specifically, the subset of those assumptions we rely on for identification in step 3. In step 4, we select an estimator that makes its own statistical assumptions. What if those causal and statistical assumptions are wrong?

We can address this in step 5 with refutation, where we actively search for evidence that our analysis is faulty. We first saw this concept in chapter 4, when we saw how to refute the causal DAG by finding statistical evidence of dependence in the data that conflicts with the conditional independence implications of the causal DAG. In section 7.6.2, we saw how to refute a model by finding cases where its predicted intervention outcomes clash with real-world intervention outcomes. Here, we implement refutation as a type of sensitivity analysis that tries to refute the various assumptions underpinning an estimate by simulating violations to those assumptions.

The CausalModel class in DoWhy has a refute_estimate method that provides a suite of refuters we can run. Each refuter provides a different attack vector for our assumptions. The refuters we run with refute_estimate perform a simulationbased statistical test; the null hypothesis is that the assumptions are not refuted, and the alternative hypothesis is that the assumptions are refuted. The tests return a pvalue. If we take a standard significance threshold of .05 and the p-value falls below this threshold, we conclude that our assumptions are refuted.

In this section, we’ll investigate a few of DoWhy’s refuters with various estimands and estimators.

11.5.1 Data size reduction

One way to test the robustness of the analysis is to reduce the size of the data and see if we obtain similar results. We are assuming our analysis has more than enough data to achieve a stable estimation. We can refute this assumption by slightly reducing the size of the data and testing whether we get a similar estimate. Let’s try this with the estimator of the front-door estimand.

Listing 11.15 Refuting the assumption of sufficient data

identified_estimand.set_identifier_method("frontdoor") #1

res_subset = model.refute_estimate(

identified_estimand, #2

causal_estimate_fd, #2

method_name="data_subset_refuter", #3

subset_fraction=0.8, #4

num_simulations=100

)

print(res_subset)#1 Not always necessary, but clarifying the estimand targeted by the estimator we want to test can help avoid errors.

#2 The refute_estimate function takes in the identified estimand and the estimator that targets the estimand.

#3 Select data_subset_refuter, which tests if the causal estimate is different when we run the analysis on a subset of the data. #4 Set the size of the subset to 80% the size of the original data.

This produces the following output (this is a random process so your results will differ slightly):

Refute: Use a subset of data Estimated effect:170.20560581290403 New effect:169.14858189323638 p value:0.82

The Estimated effect is the effect from our original analysis. New effect is the average ATE across the simulations. We want these two effects to be similar, because otherwise it would mean that our analysis is sensitive to the amount of data we have. The p-value here is above the threshold, so we failed to refute this assumption.

11.5.2 Adding a dummy confounder

One way to test our models is to add dummy common-cause confounders. If a variable is not a confounder, it has no bearing on the true ATE, so we assume that our causal effect estimation workflow will be unaffected by these variables. In truth, additional variables might add statistical noise that throws off our estimator.

The following listing attempts to refute the assumption that such noise does not affect the double ML estimator of the backdoor estimand.

Listing 11.16 Adding a dummy confounderidentified_estimand.set_identifier_method("backdoor")

res_random = model.refute_estimate( #1

identified_estimand, #1

gb_estimate, #1

method_name="random_common_cause", #1

num_simulations=100, #1

) #1

print(res_random)#1 Runs 100 simulations of the addition of a dummy confounder to the model

This returns output such as the following:

Refute: Add a random common cause Estimated effect:175.2192519976428 New effect:176.59119763647792 p value:0.30000000000000004

Again, Estimated effect is the original causal effect estimate, and New effect is the new causal effect estimate obtained after adding a random common cause to the data and rerunning the analysis. The dummy variable has no real effect, so we expect the ATE to be the same. Again, the p-value is above the significance threshold, so we failed to refute our assumptions.

11.5.3 Replacing treatment with a dummy

We can also experiment with replacing the treatment variable with a dummy variable. This is analogous to giving our causal effect inference workflow a ૿placebo, and seeing how much causality it ascribes to this fake treatment. Since this dummy variable will have no effect on the treatment, we expect the ATE to be 0.

Let’s try this with our inverse probability weighting estimator.

Listing 11.17 Replacing the treatment variable with a dummy variable

identified_estimand.set_identifier_method("backdoor")

res_placebo = model.refute_estimate(

identified_estimand, #1

causal_estimate_ipw, #1

method_name="placebo_treatment_refuter", #1

placebo_type="permute", #1

num_simulations=100 #1

)

print(res_placebo)#1 This refuter replaces the treatment variable with a dummy (placebo) variable.

This produces the following output:

Refute: Use a Placebo Treatment

Estimated effect:437.79246624944926

New effect:-531.2490111208127

p value:0.0In this case, the p-value is calculated under the null hypothesis that New effect is equal to 0. Again, a low p-value would refute our assumptions.

In this case, it would seem that our inverse probability weighting estimator was thrown off by this refuter. This result indicates that there is an issue somewhere in the joint assumptions made by the backdoor estimand and this estimator. If we then used this refuter with other backdoor estimators and they were not refuted, we would have

narrowed down the source of the issue to the statistical assumptions made by this estimator.

11.5.4 Replacing outcome with a dummy outcome

We can substitute the outcome variable with a dummy variable. The ATE in this case should be 0, because the treatment has no effect on this dummy. We’ll simulate it as a linear function of some of the confounders so the outcome still has a meaningful relationship with some of the covariates.

Let’s try this with the front door estimator.

Listing 11.18 Replacing the outcome variable with a dummy variable

import numpy as np

coefficients = np.array([100.0, 50.0])

bias = 50.0

def linear_gen(df): #1

subset = df[['guild_membership','player_skill_level']] #1

y_new = np.dot(subset.values, coefficients) + bias #1

return y_new #1

ref = model.refute_estimate( #2

identified_estimand, #2

causal_estimate_fd, #2

method_name="dummy_outcome_refuter", #2

outcome_function=linear_gen #2

) #2

res_dummy_outcome = ref[0]

print(res_dummy_outcome)

Refute: Use a Dummy Outcome

Estimated effect:0

New effect:-0.024480394297227835p value:0.86

#1 Create a function that generates a new dummy outcome variable as a linear function of the covariates. #2 Runs refute_estimate with a dummy outcome refuter

Again, the p-value is calculated under the null hypothesis that New effect equals 0, and a low p-value refutes our assumptions. In this case, our assumptions are not refuted. Next, we’ll evaluate the sensitivity of the analysis to unobserved confounding.

11.5.5 Testing robustness to unmodeled confounders

Our backdoor adjustment estimand assumes that the adjustment set blocks all backdoor paths. If there were a confounder that we failed to adjust for, that assumption is violated, and our estimate would have a confounder bias. That is not necessarily the worst thing; if we adjust for all the major confounders, bias from unknown confounders might be small and not impact our results by much. On the other hand, missing a major confounder could lead us to conclude that there is a nonzero ATE when one doesn’t exist, or conclude a positive ATE when the true ATE is negative, or vice versa. We can therefore test how robust our analysis is to the introduction of latent confounders that our model failed to capture. The hope is that the new estimate does not change drastically when we introduce some modest influence from a newly introduced confounder.

Listing 11.19 Adding an unobserved confounder

identified_estimand.set_identifier_method("backdoor")

res_unobserved = model.refute_estimate( #1

identified_estimand, #1

causal_estimate_fd, #1

method_name="add_unobserved_common_cause" #1

)print(res_unobserved)

#1 Setting up a refuter that adds an unobserved common cause

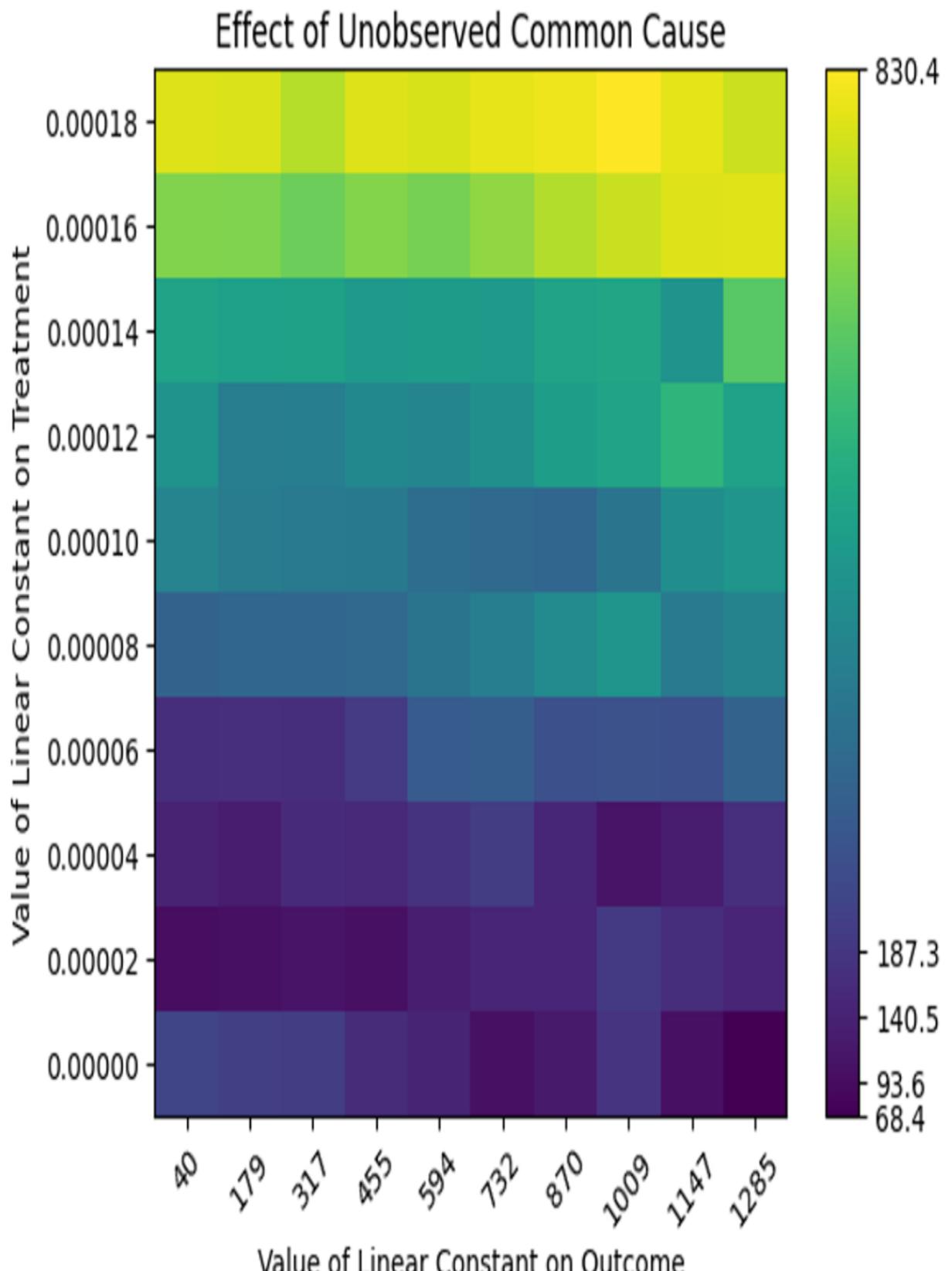

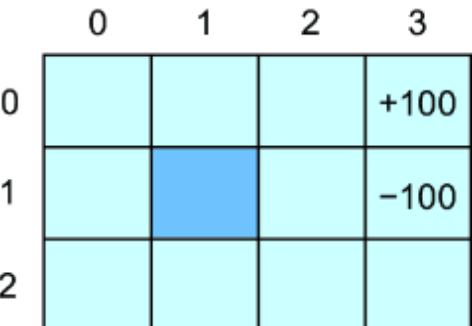

This code does not return a p-value. It produces the heatmap we see in figure 11.11, showing how quickly the estimate changes when the unobserved confounder assumption is violated. The horizontal axis shows the various levels of influence the unobserved confounder has on the outcome, and the vertical axis shows the various levels of influence

the confounder can have on the treatment. The color corresponds to the new effect estimates that result at different levels of influence.

Figure 11.11 A heatmap illustrating the effects of adding an unobserved confounder on the ATE estimate

The code also prints out the following.

Refute: Add an Unobserved Common Cause Estimated effect:187.2931023294184 New effect:(-181.5795321684548, 398.98672237350416)

Here, we see that the ATE is quite sensitive to the effect the confounder has on the treatment. Note that you can change the default parameters of the refuter to experiment with different impacts the confounder could have on the treatment and outcome.

Now that we’ve run through a full workflow in DoWhy, let’s explore how we’d build a similar workflow using the tools of probabilistic machine learning.

11.6 Causal inference with causal generative models

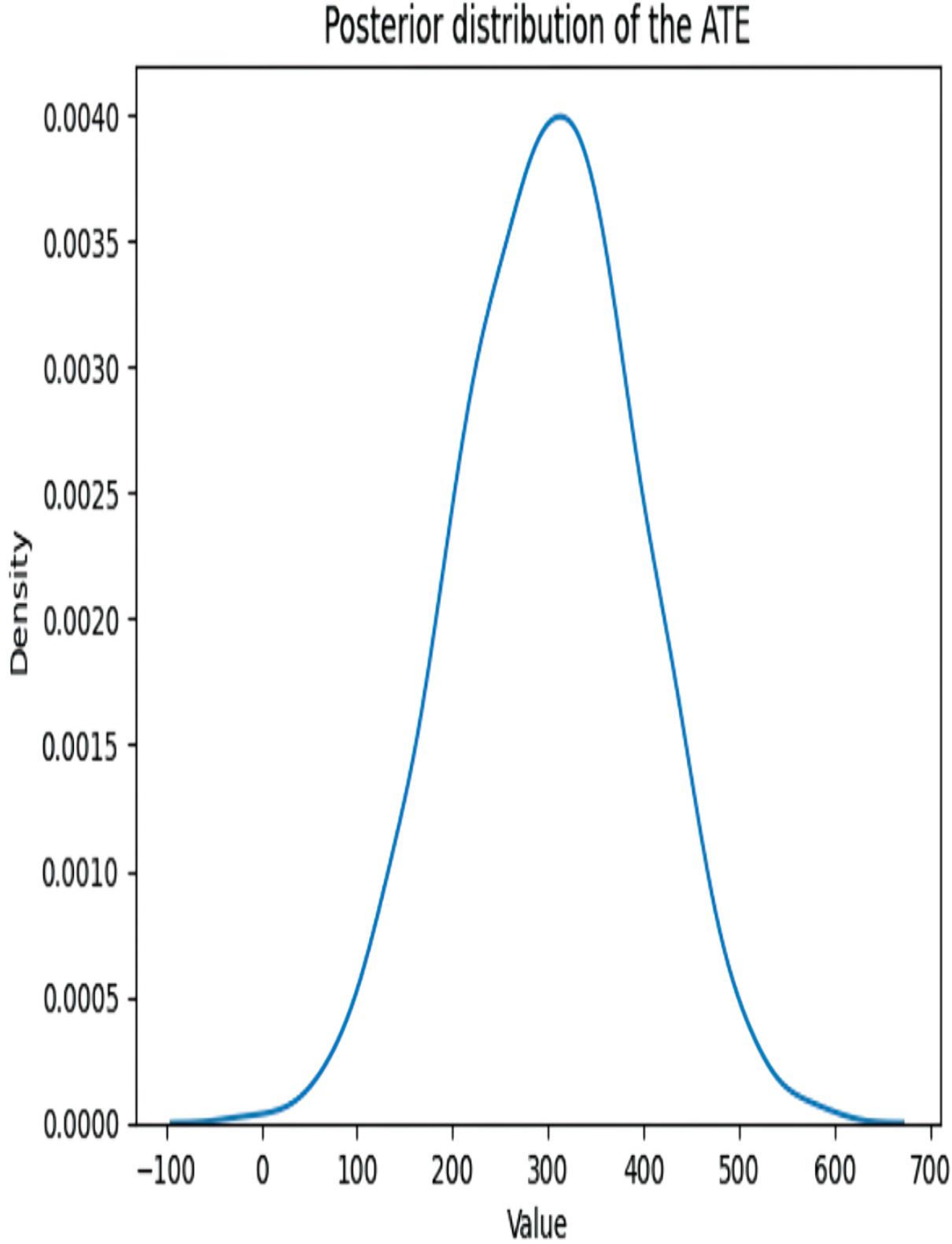

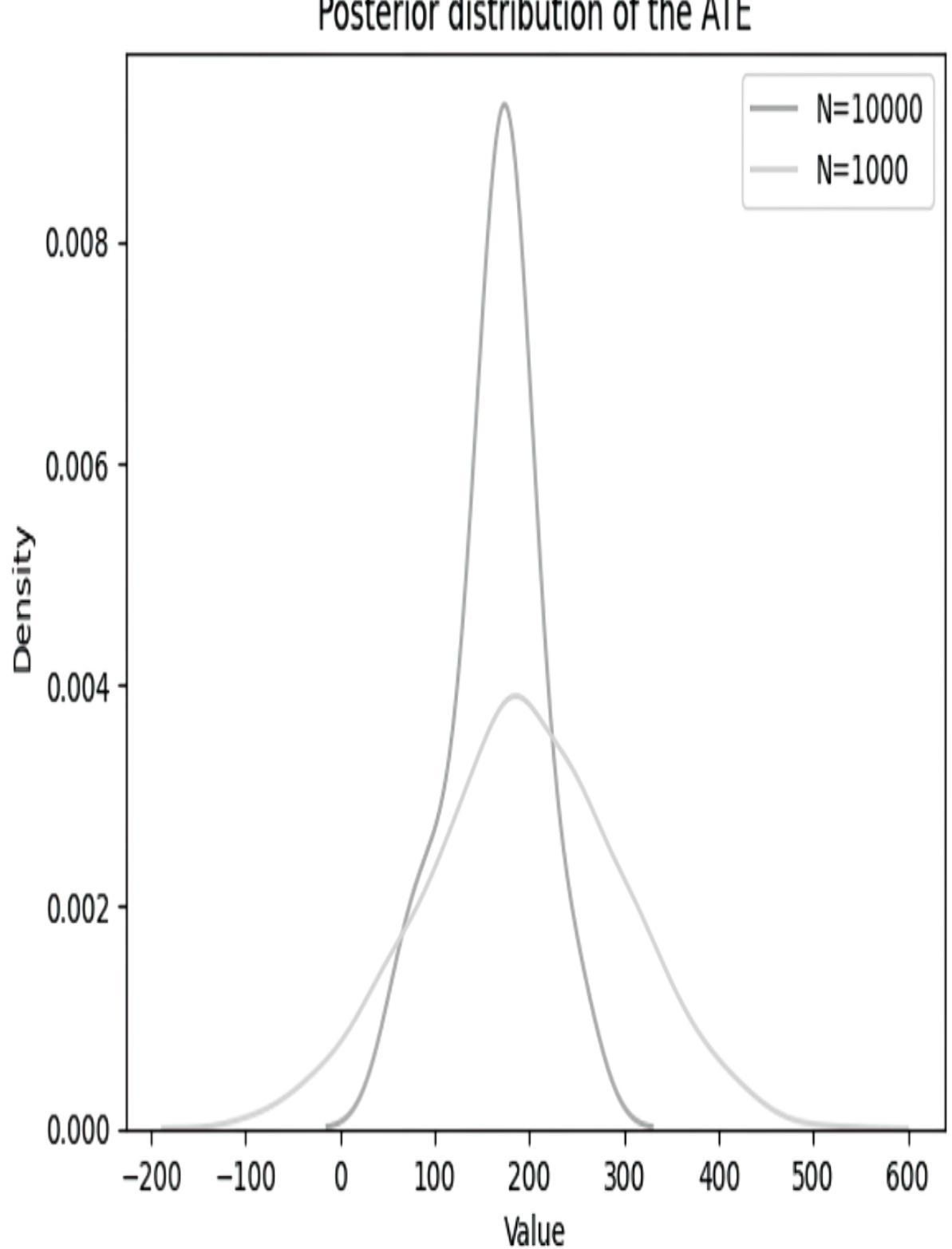

At the end of chapter 10, we calculated an ATE using the do intervention operator and a probabilistic inference algorithm. This is a powerful universal approach to doing causal inference that leverages cutting-edge probabilistic machine learning. But this wasn’t estimation. Estimation requires data. It would be estimation if we estimated the model parameters from data before running that workflow with the do function and probabilistic inference.

In this section, we’ll run through a full ATE estimation workflow that uses the do intervention operator and probabilistic inference. We used MCMC for the probabilistic inference step in chapter 10, but here we’ll use variational inference with a variational autoencoder to handle latent variables in the data. Further, we’ll use a Bayesian estimation approach, meaning we’ll assign prior probabilistic distributions to the parameters. The ATE inference step with the intervention operator will depend on sampling from the posterior distribution on parameters.

The advantage of this approach relative to using DoWhy is being able to use modern deep learning tools to work with latent variables as well as use Bayesian modeling to address uncertainty. Further, this approach will work in cases of causal identification that are not covered by DoWhy (e.g., edge cases of graphical identification, identification derived from assignment functions or prior distributions, partial identification, etc.).

This approach to ATE estimation is a specific case of a general approach to causal inference where we train a causal graphical model, transform the model in some way that reflects the causal query (e.g., with an intervention operator), and then run a probabilistic inference algorithm. Let’s review various ways we can transform a model for causal inference.

11.6.1 Transformations for causal inference

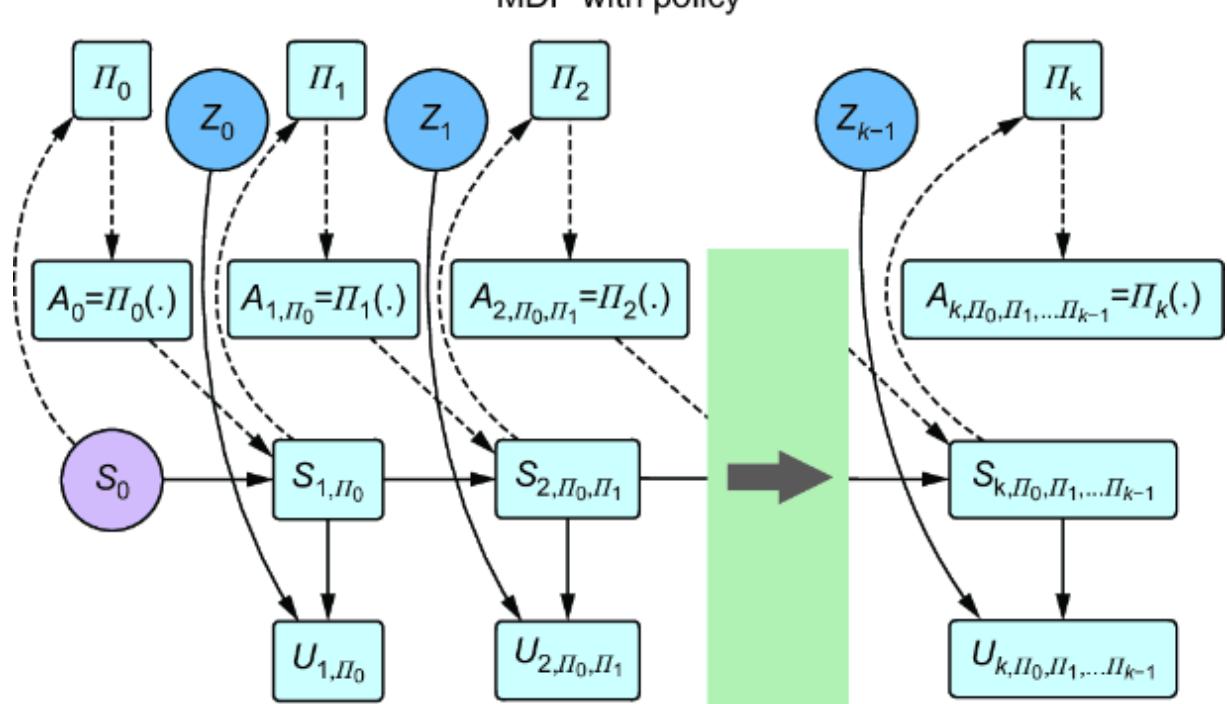

We have seen several ways of modifying a causal model such that it can readily infer a causal query. We’ll call these ૿transformations: we transform our model into a new model that targets a causal inference query. Let’s review the transformations we’ve seen so far.

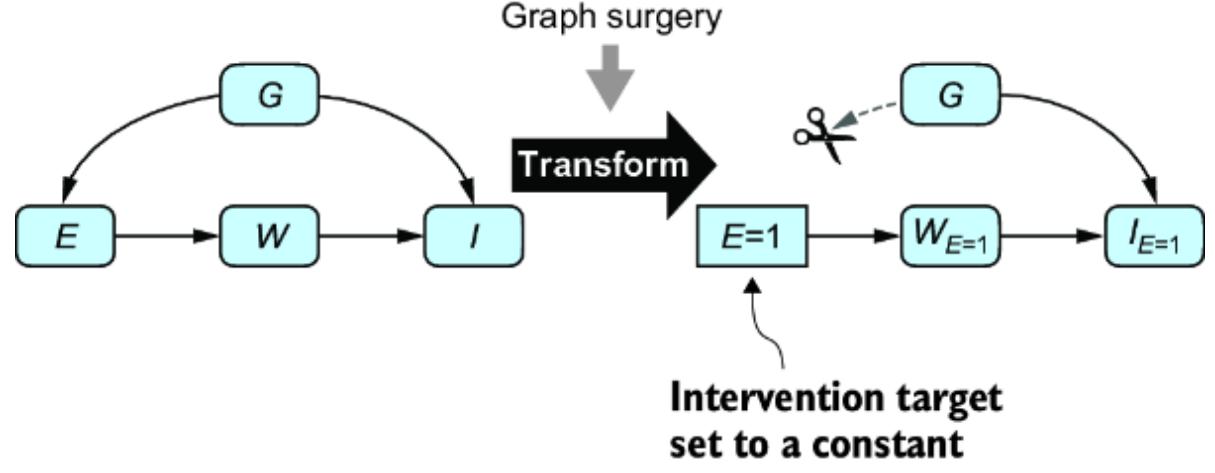

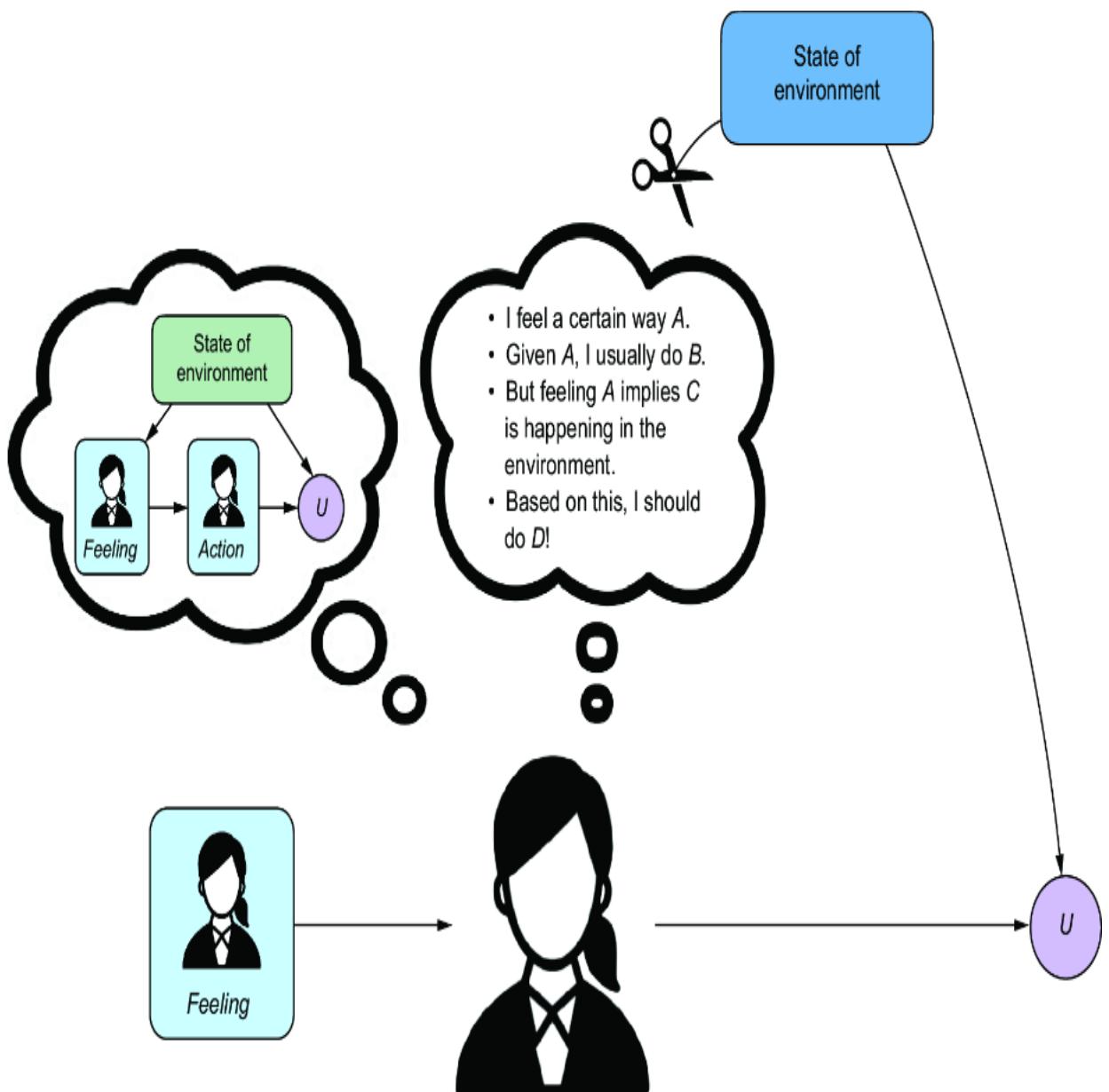

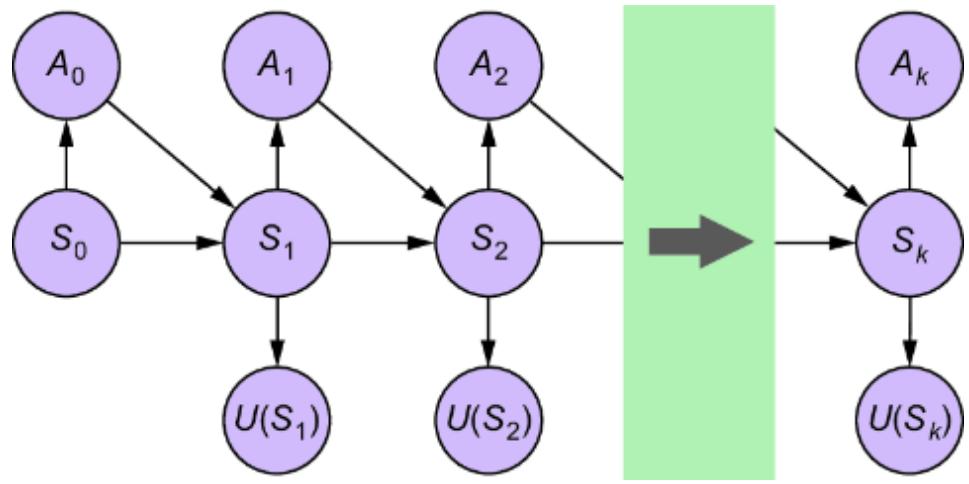

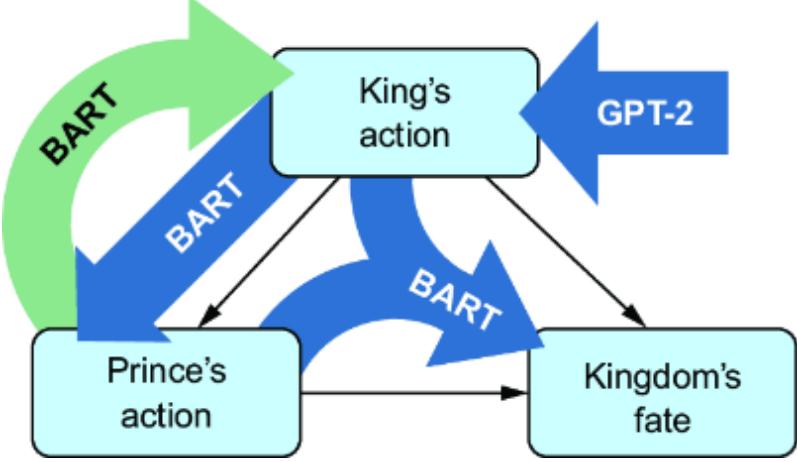

GRAPH SURGERY

One of the transformations was basic graph surgery, illustrated in figure 11.12. This operation implements an ideal intervention, setting the intervention target to a constant and severing the causal influence from the parents. This operation allows us to use our model to infer P (IE=1 ),

the ATE, and similar level 2 queries, and it’s how we have been implementing interventions in pgmpy.

Figure 11.12 Graph surgery is a transformation that implements an ideal intervention by removing incoming causal influence on the target node and setting the target node to a constant.

We implemented graph surgery in pgmpy by using the do method on the BayesianNetwork class, and then we added a hack that modified the TabularCPD object assigned to the intervention project so that the intervention value had a probability of 1.

PyMC is a probabilistic programming language similar to Pyro. It does implicit graph surgery by transforming the logic of the model. For example, PyMC might specify E, a function of G, as E = Bernoulli(“E”, p=f(G)). PyMC uses a do function to implement the intervention, as in do(model, {“E”: 1.0}). Under the hood, this function does implicit graph surgery by effectively replacing E = Bernoulli(“E”, p=f(G)) with E = 1.0.

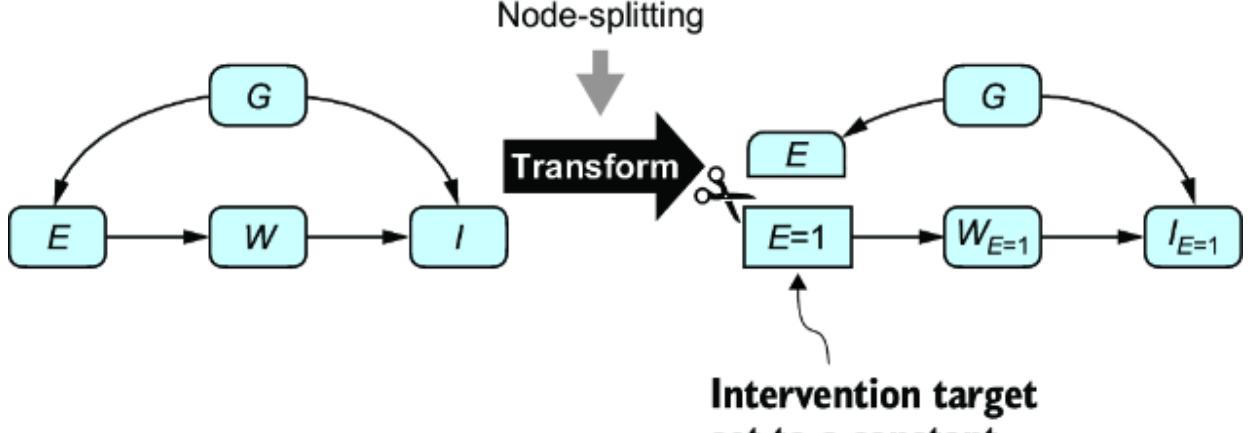

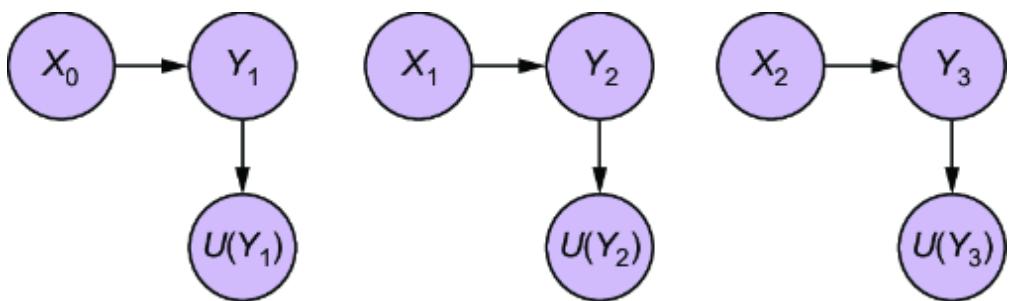

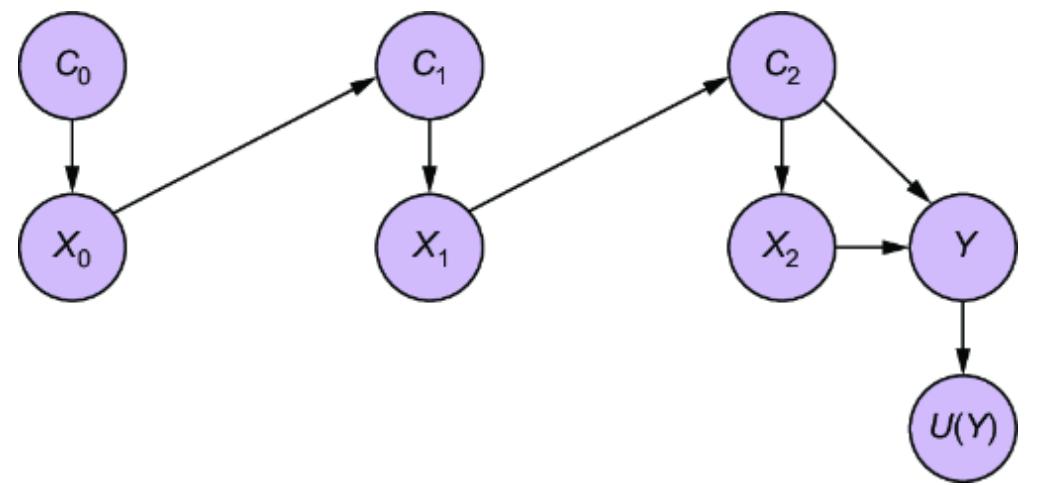

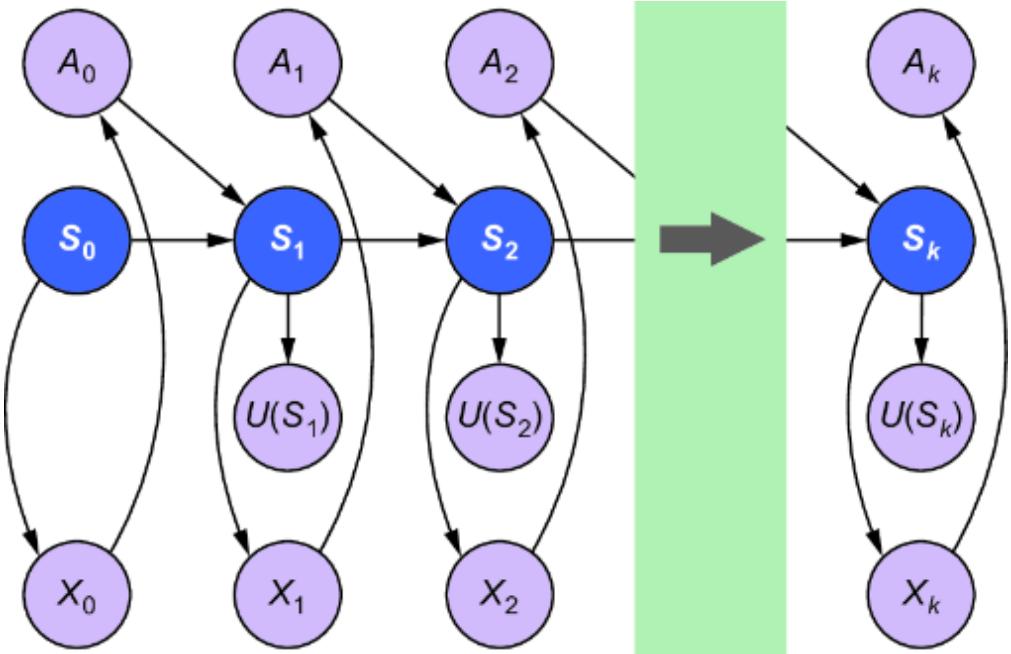

NODE-SPLITTING

In chapter 10, we discussed a slightly nuanced version of graph surgery called a node-splitting operation, illustrated in figure 11.13. Node-splitting converts the graph to a single world intervention graph, allowing us to infer level 2 queries

just as graph surgery does. It also allows us to infer level 3 queries where the factual conditions and hypothetical outcome don’t overlap, such as P (IE= 0 |E = 1) (though doing so relies on an additional ૿single world assumption, as discussed in chapter 10).

Figure 11.13 The node-splitting transform splits the intervention target into a constant that keeps the children and a random variable that keeps the parents.

Pyro’s do function implements node-splitting (though it behaves just like PyMC’s do function if you don’t target level 3 queries).

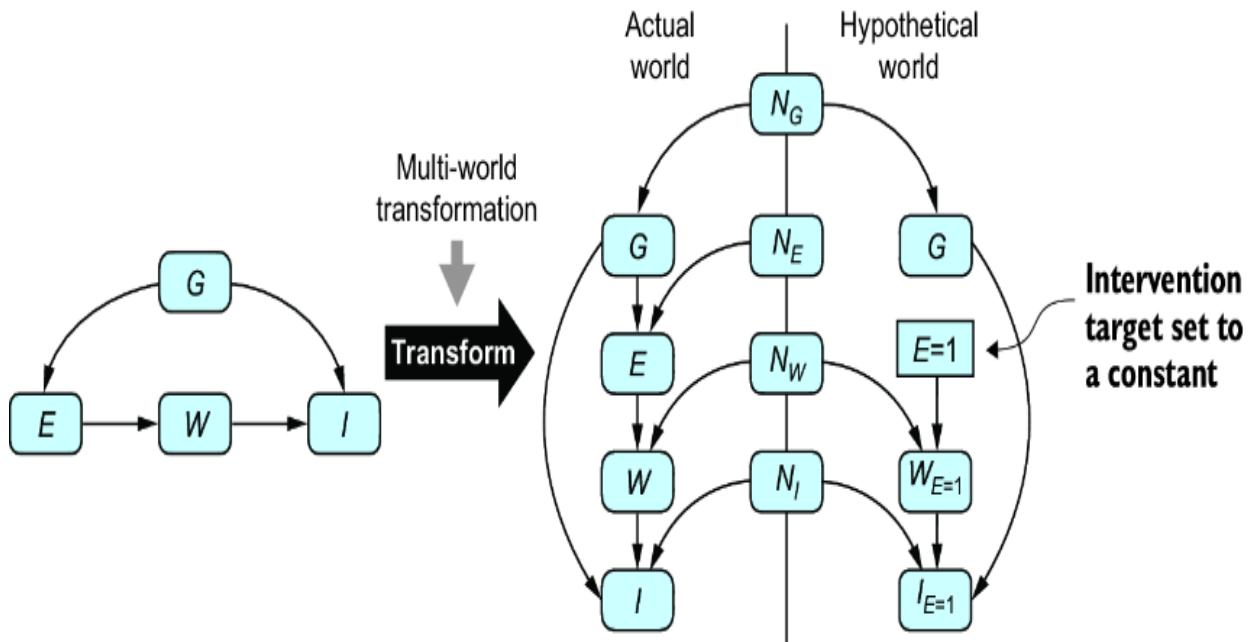

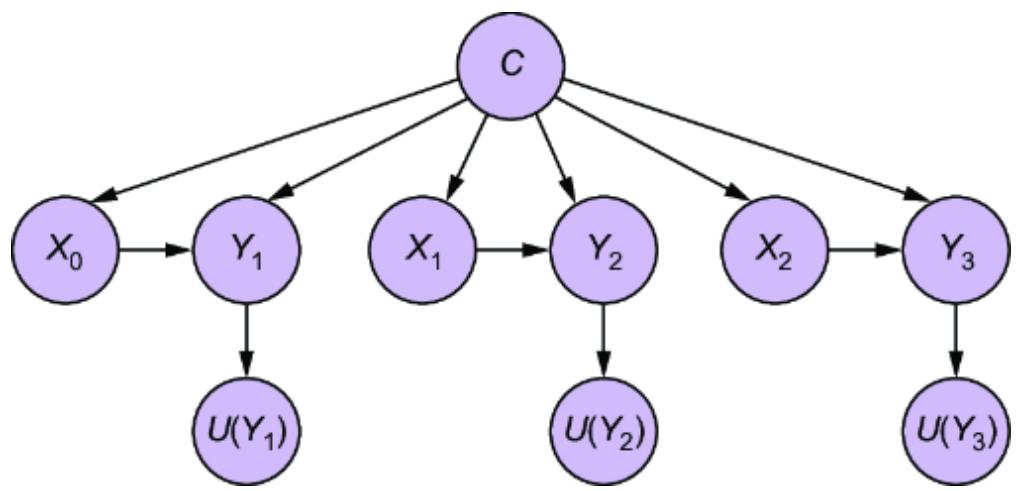

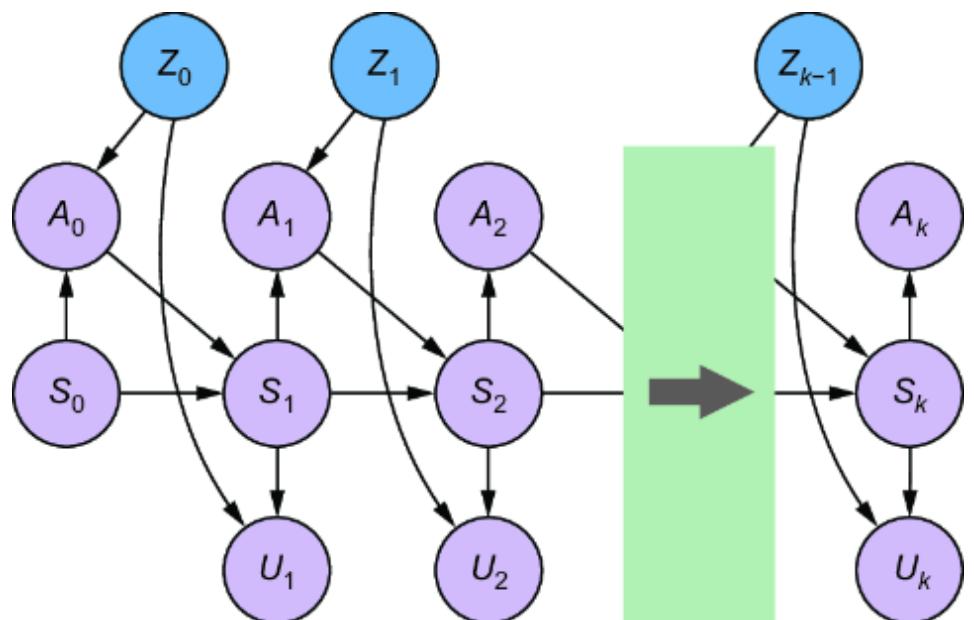

MULTI-WORLD TRANSFORMATION

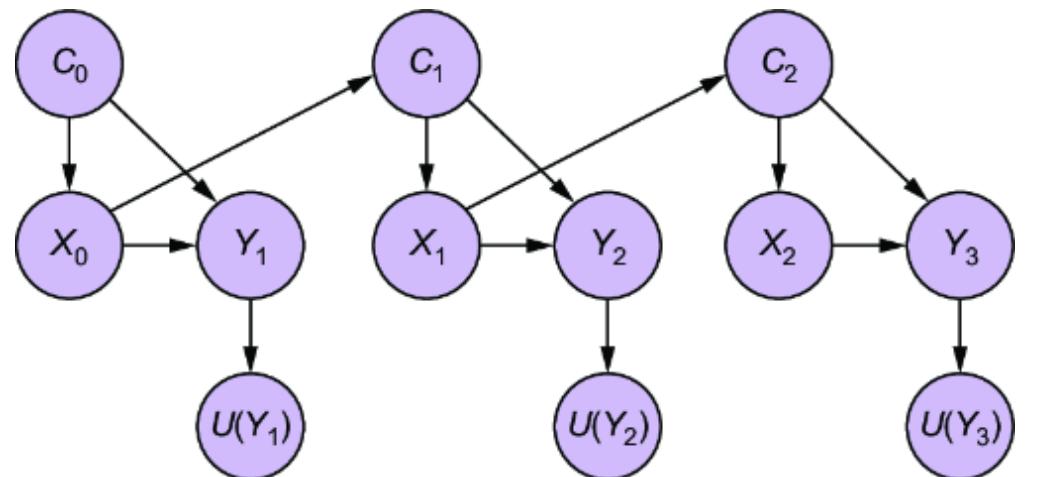

We also saw how to transform a structural causal model into a parallel world graph. Let’s call this a multi-world transformation, illustrated in figure 11.14.

Figure 11.14 Yet another transform converts the model into a parallelworld model.

We created parallel-world models by hand in chapter 9 with pgmpy and Pyro. The y0 library produces parallel world graphs from DAGs. ChiRho, the causal library that extends Pyro, has a TwinWorldCounterfactual handler that does the multi-world transformation.

TRANSFORMATION TO A COUNTERFACTUAL GRAPH

Recall that we can also transform the causal DAG to a counterfactual graph (which, in the case of a level 2 query like P (IE= 1), will simplify to the result of graph surgery). Y0 creates a counterfactual graph from your DAG and a given query. Future versions of causal probabilistic ML libraries may provide the same transformation for a Pyro/PyMC/ChiRho type model.

11.6.2 Steps for inferring a causal query with a causal generative model

Given a causal generative model and a target causal query, we have two steps to infer the target query: first, apply the transformation, and then run probabilistic inference.

We did this with the online gaming example at the end of chapter 10. We targeted P (IE= 0) and P (IE= 0 |E = 1). For each of these queries, we used the do function in Pyro to modify the model to represent the intervention E = 0. In the case of P (IE= 0 |E = 1), we also conditioned on E = 1. Then we ran an MCMC algorithm to generate samples from these distributions. We also used the probabilistic inference with parallel-world graphs to implement level 3 counterfactual inferences in chapter 9.

11.6.3 Extending inference to estimation

To extend this workflow to estimation, like the DoWhy methods in this chapter, we simply need to add a parameter estimation step to our causal graphical inference workflow:

- Estimate model parameters.

- Apply the transformation.

- Run probabilistic inference on the transformed model.

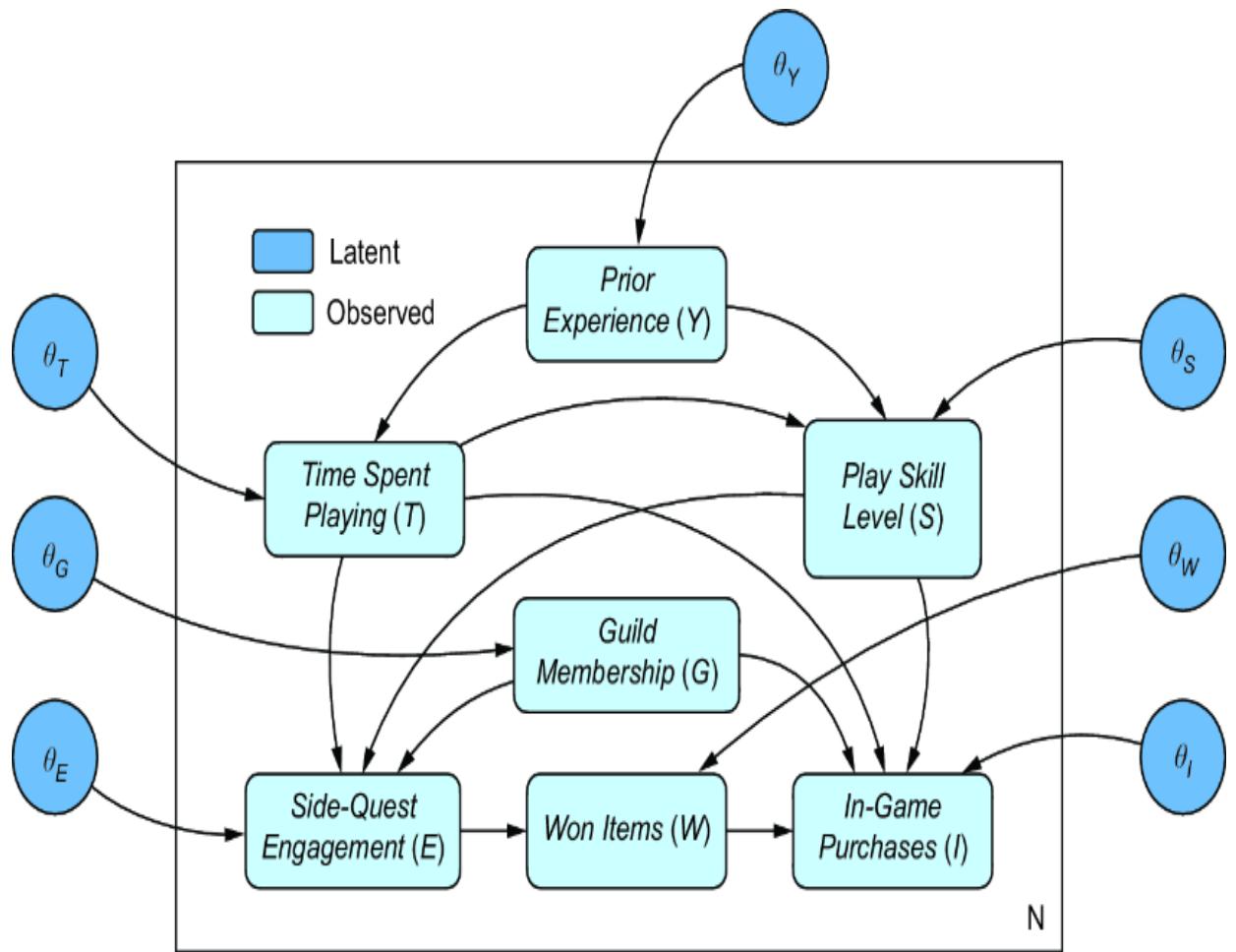

Let’s look at how to do this with the online game data. For simplicity, we’ll work with a reduced model that drops the instruments and the collider, since we won’t be using them.

We’ll model the causal Markov kernels of each node with some unique parameter vector. We can estimate the parameters any way we like, but to stay on brand with probabilistic reasoning, let’s use a Bayesian setup, treating each parameter vector as its own random variable with its

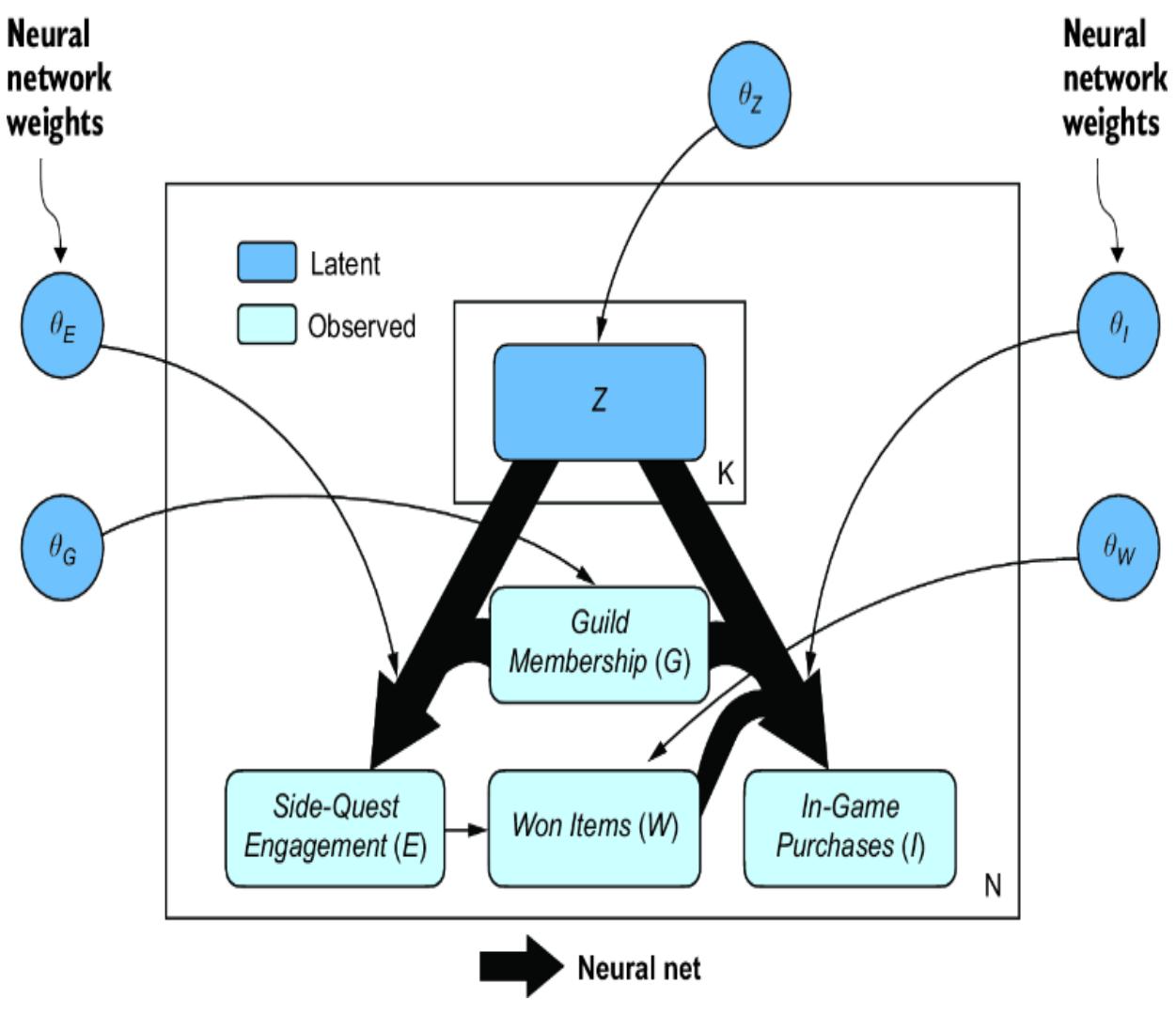

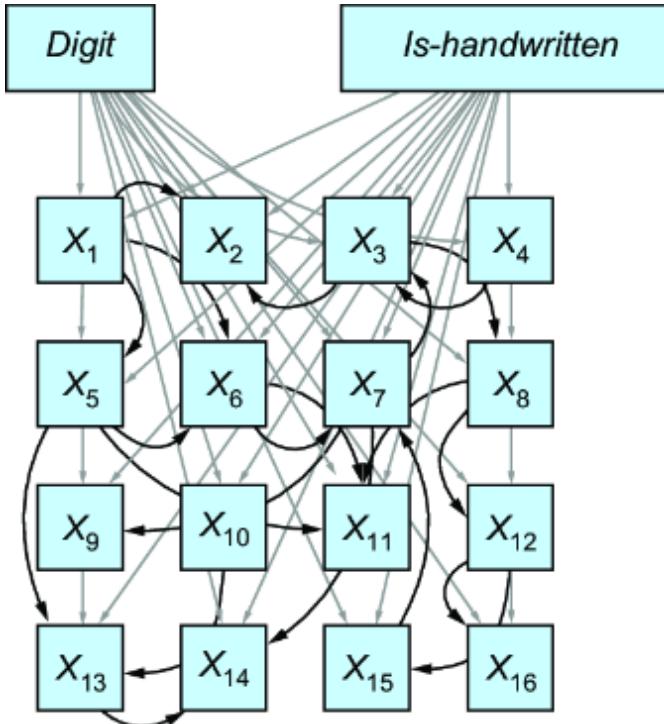

own prior probability distribution. Figure 11.15 illustrates a plate model representation of the causal DAG (we discussed plate model visualizations in chapter 2), drawing these random variables as new nodes, using Greek letters to highlight the fact that they are parameters, rather than causal components of the real world DGP.

Figure 11.15 A plate model of the causal DAG with new nodes representing parameters associated with each causal Markov kernel. There is a single plate with N identical and independent observations in the training data. θ corresponds to parameters, which are outside the plate, because the parameters are the same for each of the N data points.

In this case, Bayesian estimation will target the posterior distribution:

where each represent the N examples of E, Y, T, G, S, W, I in the data.

Estimating the θs in this case is easy. For example, in pgmpy we just run model.fit(data, estimator= BayesianEstimator, …), where ૿. . . contains arguments that specify the type of prior to assign the θs. Pgmpy uses the posterior to give us point estimates of the θs. In Pyro, we just write sample statements for the θs and use one of Pyro’s various inference algorithms to get samples from the posterior.

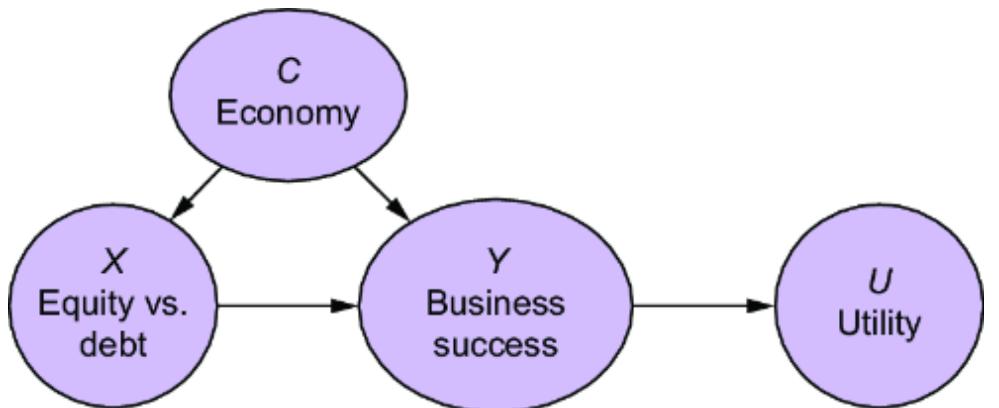

But the causal effect methods in DoWhy highlight the ability to do causal inferences when some causal variables are latent, such as confounders:

- Backdoor adjustment with some latent confounders is possible (e.g., Prior Experience) if you have a valid adjustment set (Time Spent Playing, Guild Membership, and Player Skill Level).

- If too many confounders are latent, such that you do not have backdoor adjustment, you can use other techniques, such as using instrumental variables and front-door adjustment.

So for causal generative modeling to compete with DoWhy, it needs to accommodate latent variables. Let’s consider the case where the backdoor adjustment estimand is not identified. Next, we’ll explore how we can train a latent causal generative model and then apply the transformation and probabilistic inference.

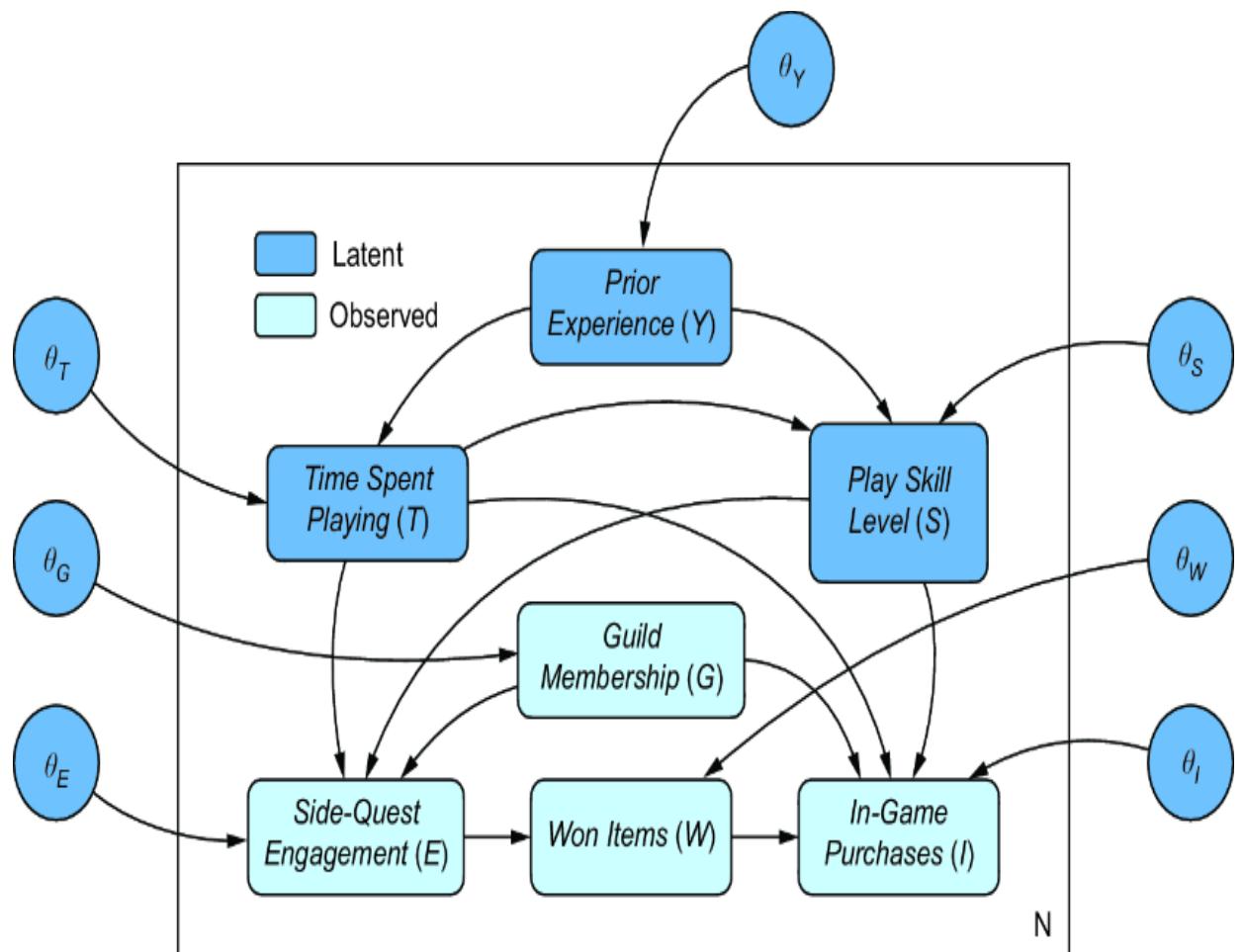

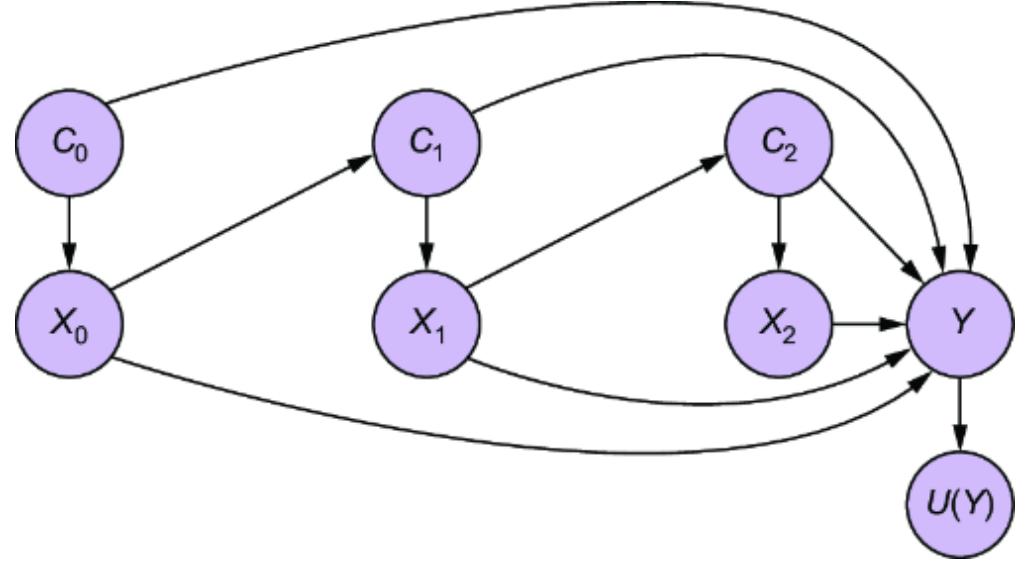

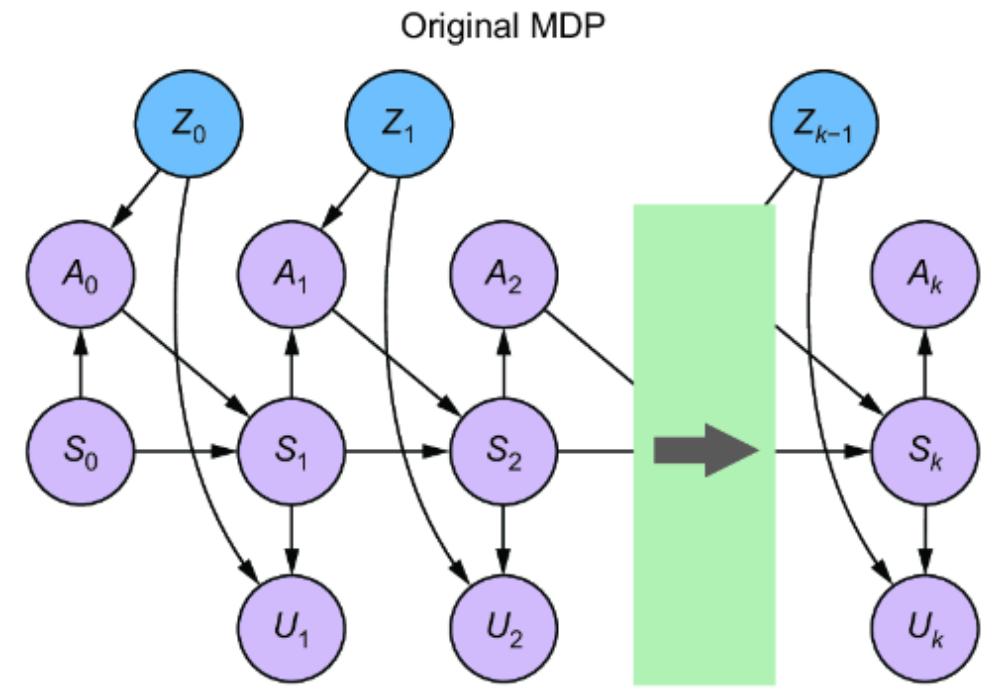

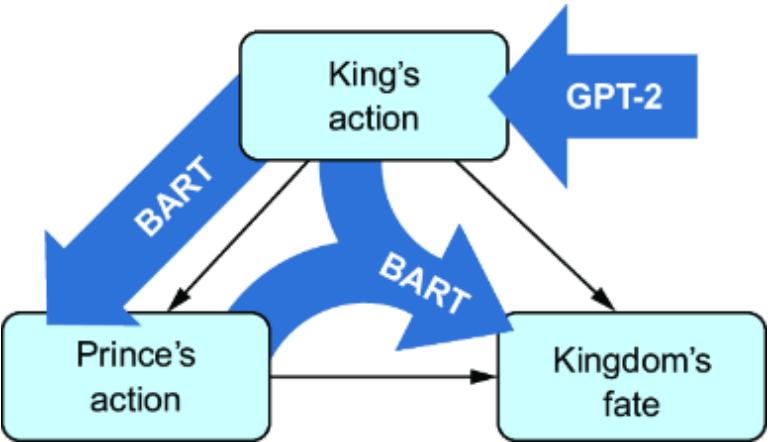

In this model, we’ll assume that Guild Membership is the only observed confounder, as in figure 11.16. In this case, we no longer have backdoor identification.

Figure 11.16 Guild Membership is the only observed confounder, so the backdoor estimand is not identified.

SETTING UP YOUR ENVIRONMENT

The following code is written with torch 2.2, pandas 1.5, and pyro-ppl 1.9. We’ll use matplotlib and seaborn for plotting.

Let’s first reload and modify the data to reflect this paucity of observed variables.

Listing 11.20 Load and reduce data to a subset of observed variables

import pandas as pd

import torch

url = ("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/altdeep/" #1

"causalML/master/datasets/online_game_ate.csv") #1

df = pd.read_csv(url) #1

df = df[["Guild Membership", "Side-quest Engagement", #2

"Won Items", "In-game Purchases"]] #2

device = torch.device("cuda" if torch.cuda.is_available() else "cpu") #3

data = { #3

col: torch.tensor(df[col].values, dtype=torch.float32).to(device) #3

for col in df.columns #3

} #3#1 Load the data.

#2 Drop everything but Guild Membership, Side-Quest Engagement, Won Items, and In-Game Purchases.

#3 Convert the data to tensors and dynamically set the device for performing tensor computations depending on the availability of a CUDA-enabled GPU.

Now we are targeting the following posterior:

\[P\left(\theta\_Y, \theta\_T, \theta\_S, \theta\_G, \theta\_E, \theta\_W, \theta\_I, \vec{Y}, \vec{T}, \vec{S} \middle| \vec{E}, \vec{G}, \vec{W}, \vec{I}\right)\]

Targeting this posterior is harder because, since the observations of are not observed, they are not available to help in inferring θY, θT, and θS. In fact, in general, θY, θT, and θS are underdetermined, meaning multiple configurations of {θY, θT, θS} would be equally likely given the data. Further, we’ll have trouble estimating with θE and θI because it will be hard to disentangle them from the other latent variables.

But it doesn’t matter! At least, not in terms of our goal of inferring P(IE=e), because we know we have identified the front-door estimand of P(IE=e). In other words, the existence of a front-door estimand proves we can infer P(IE=e) from the observed variables regardless of the lack of identifiability of some of the parameters.

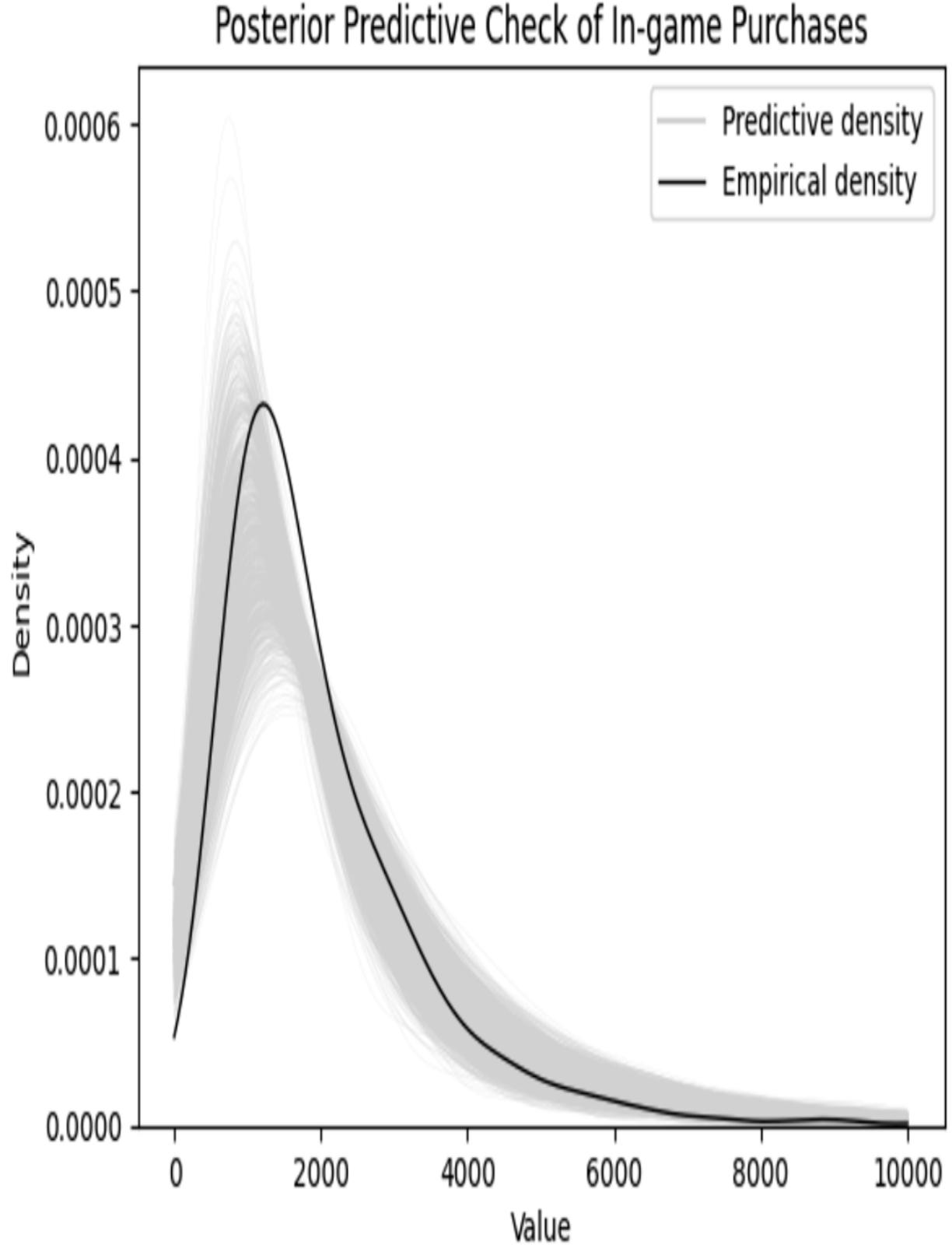

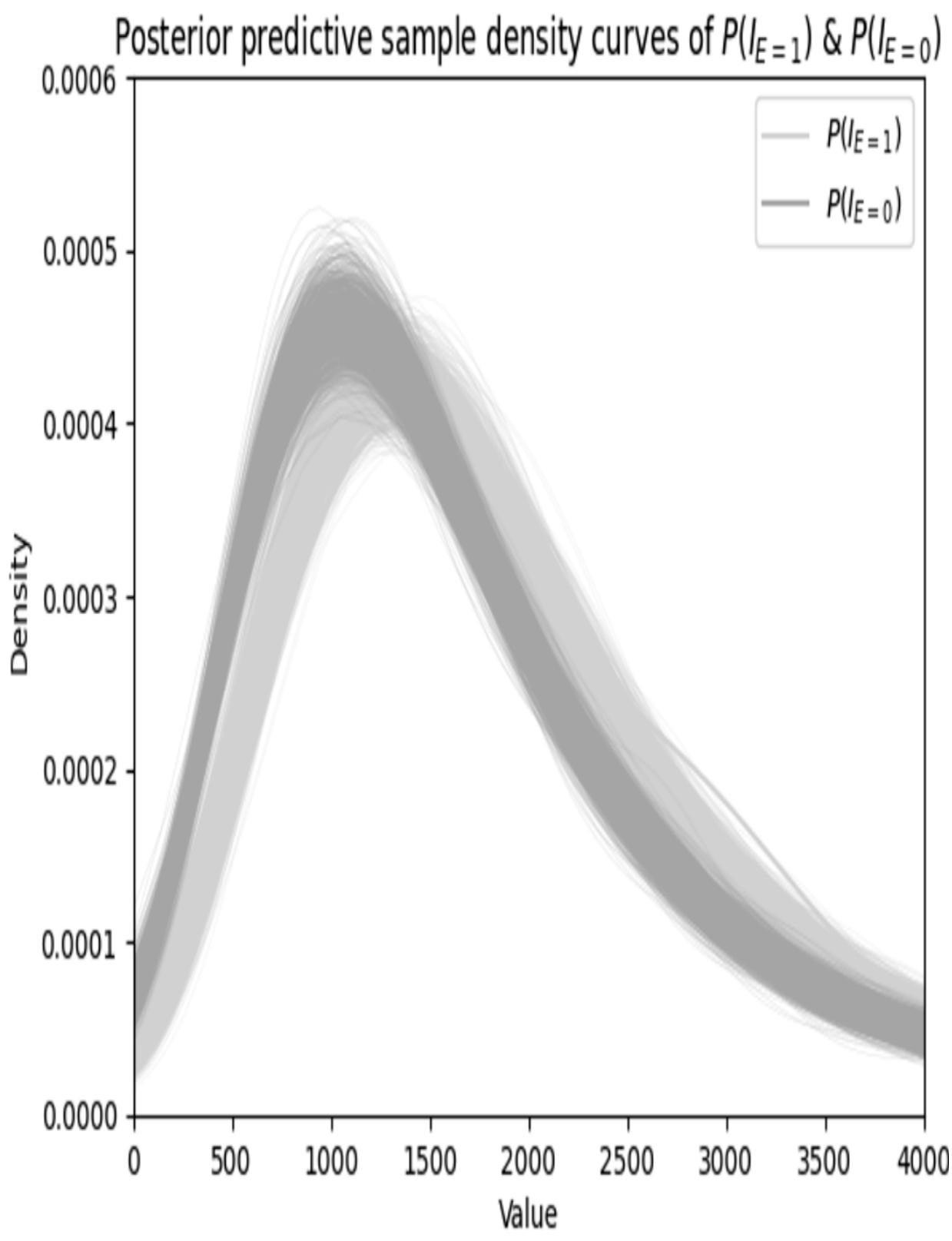

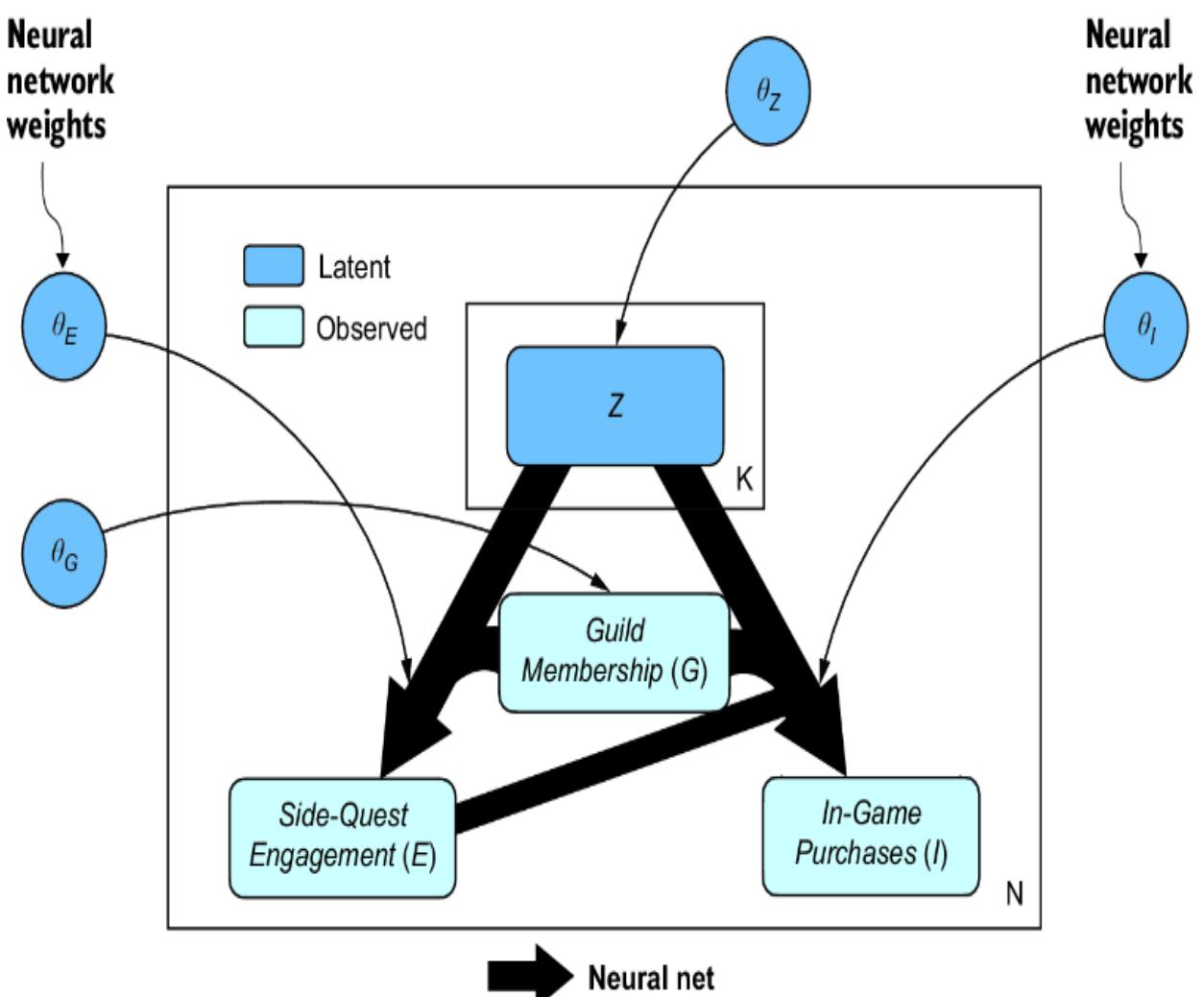

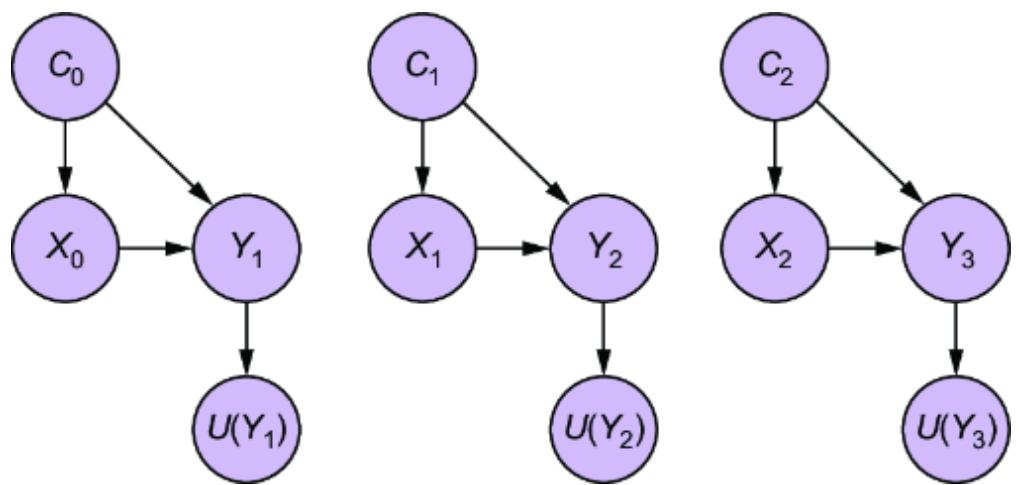

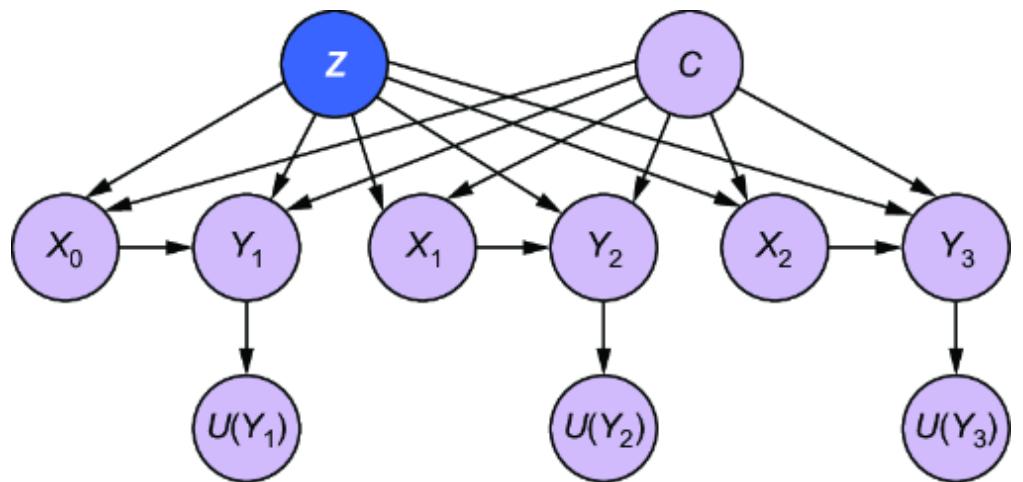

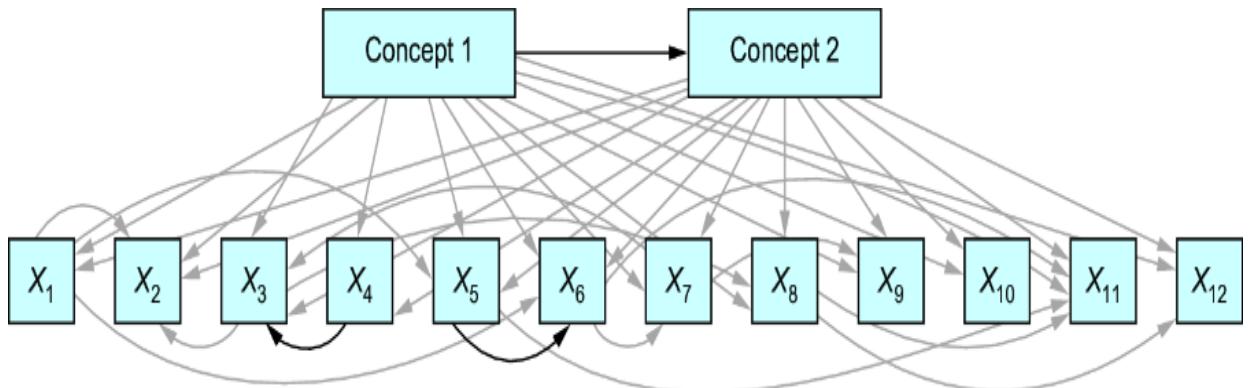

11.6.4 A VAE-inspired model for causal inference

We’ll make our modeling easier by creating proxy variables and θZ to stand in for { } and {θY, θT, θS} respectively. Collapsing the latent confounders into these proxies reduces the dimensionality of the estimation problem, and any loss of information that occurs from collapsing these variables won’t matter because we are ultimately relying on information flowing through the front door. We’ll create a causal generative model inspired by the variational autoencoder, where is a latent encoding and θE and θI become weights in decoders. This is visualized in figure 11.17.

Now our inference will target the posterior:

\[P\left(\theta\_Z, \theta\_G, \theta\_E, \theta\_W, \theta\_I, \vec{Z} \middle| \vec{E}, \,\,\vec{G}, \vec{W}, \vec{I}\right)\]

Our model will have two decoders. One decoder maps and G to E, returning a derived parameter ρ_engagement that acts as the probability that Side-Quest Engagement is high. Let’s call this network Confounders2Engagement. As shown in figure 11.17, is a vector with K elements, but we’ll set K=1 for simplicity.

Figure 11.17 VAE-inspired model where latent vector Z of length K proxies for the latent confounders in figure 11.16

Listing 11.21 Specify Confounders2Engagement neural network

import torch.nn as nn

class Confounders2Engagement(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

input_dim=1+1, #1

hidden_dim=5 #2

):

super().__init__()

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim) #3

self.f_engagement_ρ = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1) #4

self.softplus = nn.Softplus() #5

self.sigmoid = nn.Sigmoid() #6

def forward(self, input):

input = input.t()

hidden = self.softplus(self.fc1(input)) #7

ρ_engagement = self.sigmoid(self.f_engagement_ρ(hidden)) #8

ρ_engagement = ρ_engagement.t().squeeze(0)

return ρ_engagement#1 Input is confounder proxy Z concatenated with Guild Membership.

#2 Choose a hidden dimension of width 5.

#3 Linear map from input to hidden dimension

#4 Linear map from hidden dimension to In-Game Purchases location parameter

#5 Activation function for hidden layer

#6 Activation function for Side-Quest Engagement parameter

#7 From input to hidden layer

#8 From hidden layer to ρ_engagement

Next, let’s specify another neural net decoder that maps Z, W, and G to a location and scale parameter for I . Let’s call this PurchasesNetwork.

Listing 11.22 PurchasesNetwork neural network

class PurchasesNetwork(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

input_dim=1+1+1, #1

hidden_dim=5 #2

):

super().__init__()

self.f_hidden = nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim) #3

self.f_purchase_μ = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1) #4

self.f_purchase_σ = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 1) #5

self.softplus = nn.Softplus() #6

def forward(self, input):

input = input.t()

hidden = self.softplus(self.f_hidden(input)) #7

μ_purchases = self.f_purchase_μ(hidden) H #8

σ_purchases = 1e-6 + self.softplus(self.f_purchase_σ(hidden)) #9

μ_purchases = μ_purchases.t().squeeze(0)

σ_purchases = σ_purchases.t().squeeze(0)

return μ_purchases, σ_purchases#1 Input is confounder proxy Z concatenated with Guild Membership and Won Items.

#2 Choose a hidden dimension of width 5.

#3 Linear map from input to hidden dimension

#4 Linear map from hidden dimension to In-Game Purchases location parameter

#5 Linear map from hidden dimension to In-Game Purchases scale parameter

#6 Activation for hidden layer

#7 From input to hidden layer

#8 Mapping from hidden layer to location parameter for purchases #9 Mapping from hidden layer scale parameter for purchases. The 1e-6 lets us avoid scale values of 0.

Now we use both networks to specify the causal model. The model will take a dictionary of parameters called params and use them to sample the variables in the model. The Bernoulli distributions of Guild Membership and Won Items have parameters passed in a dictionary called params, with keys ρ_member representing θG, and ρ_won_engaged and ρ_won_not_engaged together representing θW. ρ_engagement, which represents the Side-Quest Engagement parameter θE, is set by the output of Confounders2Engagement, and μ_purchases and σ_purchases, which jointly represent the In-Game Purchases parameter θY, are the output of PurchaseNetwork.

The parameter set θZ is a location and scale parameter for a normal distribution. Rather than a learnable θZ, I use fixed θZ = {0, 1} and let the neural nets handle the linear transform for Z.

Listing 11.23 Specify the causal model

from pyro import sample

from pyro.distributions import Bernoulli, Normal

from torch import tensor, stack

def model(params, device=device): #1

z_dist = Normal( #2

tensor(0.0, device=device), #2

tensor(1.0, device=device)) #2

z = sample("Z", z_dist) #2

member_dist = Bernoulli(params['ρ_member']) #3

is_guild_member = sample("Guild Membership", member_dist) #3

engagement_input = stack((is_guild_member, z)).to(device) #4

ρ_engagement = confounders_2_engagement(engagement_input) #4

engage_dist = Bernoulli(ρ_engagement)

is_highly_engaged = sample("Side-quest Engagement", engage_dist) #5

p_won = ( #6

params['ρ_won_engaged'] * is_highly_engaged + #6

params['ρ_won_not_engaged'] * (1 - is_highly_engaged) #6

) #6

won_items = sample("Won Items", Bernoulli(p_won)) #6

purchase_input = stack((won_items, is_guild_member, z)).to(device) #7

μ_purchases, σ_purchases = purchases_network(purchase_input) #7

purchase_dist = Normal(μ_purchases, σ_purchases) #8

in_game_purchases = sample("In-game Purchases", purchase_dist) #8#1 The causal model

#2 A latent variable that acts as a proxy for other confounders #3 Whether someone is in a guild

#4 Use confounders_ 2_engagement to map is_guild_ member and z to a parameter for Side-Quest Engagement and In-Game Purchases.

#5 Modeling Side-Quest Engagement

#6 Modeling amount of Won Items

#7 Use purchases_network to map is_guild_member, z, and won_items to in_game_purchases.

#8 Model in_game_purchases.

This model represents a single data point. Now we need to extend the model to every example data point in the dataset. We’ll build a data_model that loads the neural networks, assigns priors to the parameters, and models the data.

Listing 11.24 Build a data model

import pyro

from pyro import render_model, plate

from pyro.distributions import Beta

from pyro import render_model

confounders_2_engagement = Confounders2Engagement().to(device) #1

purchases_network = PurchasesNetwork().to(device) #1

def data_model(data, device=device):

pyro.module("confounder_2_engagement", confounders_2_engagement) #2

pyro.module("confounder_2_purchases", purchases_network) #2

two = tensor(2., device=device)

five = tensor(5., device=device)

params = {

'ρ_member': sample('ρ_member', Beta(five, five)), #3

'ρ_won_engaged': sample('ρ_won_engaged', Beta(five, two)), #4

'ρ_won_not_engaged': sample('ρ_won_not_engaged', Beta(two, five)), #5

}

N = len(data["In-game Purchases"])

with plate("N", N): #6

model(params) #6render_model(data_model, (data, ))#1 Initialize the neural networks.

#2 pyro.module lets Pyro know about all the parameters inside the networks.

#3 Sample from prior distribution for ρ_member #4 Sample from prior distribution for ρ_won_engaged #5 Sample from prior distribution for ρ_won_not_engaged #6 The plate context manager declares N independent samples (observations) from the causal variables.

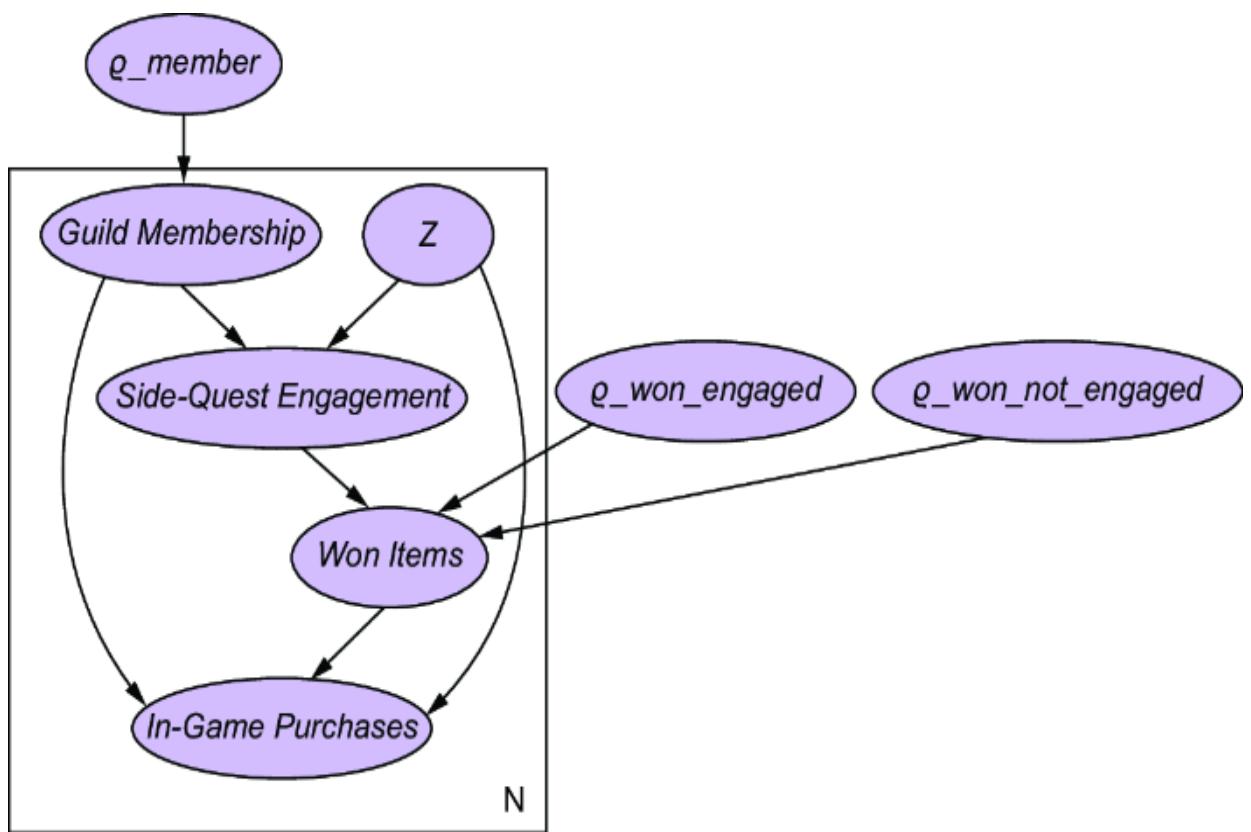

render_model lets us visualize the resulting plate model, producing figure 11.18. ρ_member, ρ_won_engaged, ρ_won_not_engaged are the parameters we wish to estimate, alongside the weights in the neural nets.

Figure 11.18 The plate model representation produced by Pyro

Now that we’ve specified the model, lets set up inference with SVI.

11.6.5 Setting up posterior inference with SVI

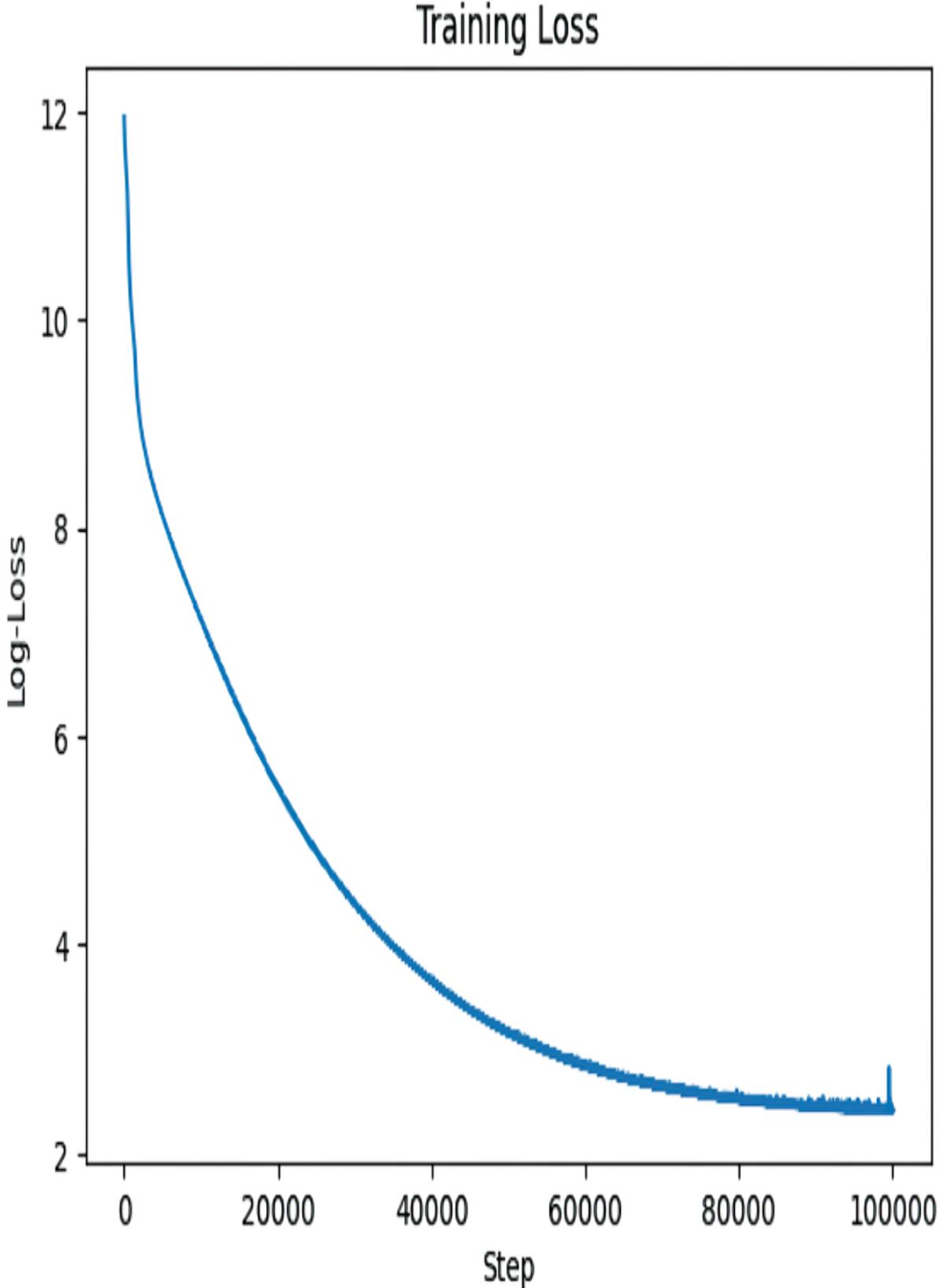

We have a data model over an underlying causal model, so we can now move on to inference. Using SVI, we need to build a guide function that represents a distribution that approximates the posterior—the guide function will have hyperparameters directly optimized during training, which will bring the approximating distribution as close as possible to the posterior.

WHY DO INFERENCE WITH SVI AND NOT MCMC?

In chapter 10, we used an MCMC inference algorithm to derive P(IE=0) and P(IE=0|E=1) from P(G, W, I, E). The θ parameters were given. Now the θ parameters are unknown, and we are using Bayesian estimation, meaning we want to infer IE=e conditional on values of those θ parameters sampled from a posterior distribution derived from training data. We do this by considering variables { , , , , } where { , , , } is a set of variables in the training data, is a latent proxy for our latent confounders, and each of these variables are vectors of length N, the size of our training data.

The challenge is the computational complexity of MCMC algorithms generally grows exponentially in the dimension of the posterior. When is a latent variable, it gets added to the posterior as another unknown along with the θs, so the shape of the posterior increases by ’s dimension, which is at least the size of the training data N. This poses a challenge when N is large. We want an inference method that works well with large data so we can leverage all that data to do cool things like use deep neural networks to help us proxy our latent confounders in a causal generative model. So here we use SVI instead of MCMC because SVI shines in high-dimensional large data settings.

The main ingredient of the guide function is an encoder that will map Side-Quest Engagement, Won Items, and In-Game Purchases to Z ; i.e., it will impute the latent values of Z.

Listing 11.25 Create an encoder for Z

class Encoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim=3, #1

z_dim=1, #2

hidden_dim=5): #3

super().__init__()

self.f_hidden = nn.Linear(input_dim, hidden_dim)

self.f_loc = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, z_dim)

self.f_scale = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, z_dim)

self.softplus = nn.Softplus()

def forward(self, input):

input = input.t()

hidden = self.softplus(self.f_hidden(input)) #4

z_loc = self.f_loc(hidden) #5

z_scale = 1e-6 + self.softplus(self.f_scale(hidden)) #6

return z_loc.t().squeeze(0), z_scale.t().squeeze(0)#1 Input dimension is 3 because it will combine Side-Quest Engagement, In-Game Purchases, and Guild Membership. #2 I use a simple univariate Z, but we could give it higher dimension with sufficient data.

#3 The width of the hidden layer is 5.

#4 Go from input to hidden layer.

#5 Mapping from hidden layer to location parameter for Z #6 Mapping from hidden layer scale parameter to Z

Now, using the encoder, we build the overall guide function. In the following guide, we’ll sample the parameters ρ_member, ρ_won_engaged, and ρ_won_not_engaged from beta distributions parameterized by constants set using param. These ૿hyperparameters are optimized during training, alongside the weights of the neural networks.

Listing 11.26 Build the guide function (approximating distribution)

from pyro import param