Causal AI

Part 3 The causal hierarchy

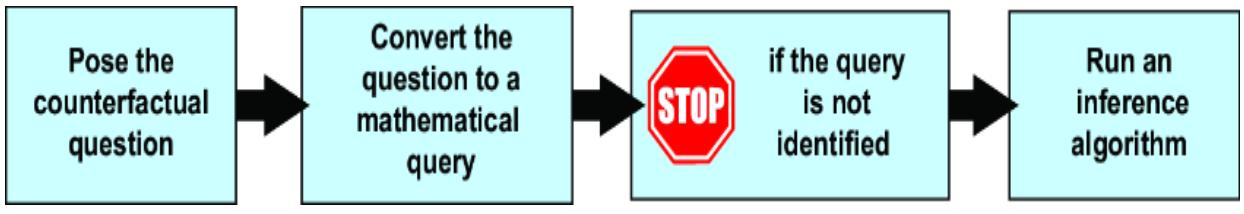

Part 3 takes a code-first deep dive into the core concepts of causal inference. Readers will explore structural causal models, interventions, multi-world counterfactual reasoning, and causal identification—where we determine what kinds of causal questions you can answer with your model and your data. This part will prepare you to take on the more challenging but rewarding aspects of causal inference, providing practical code-based tools for reasoning about ૿what if scenarios. By the end, you’ll be ready to use causal inference techniques in real-world decision-making scenarios, leveraging both generative modeling frameworks and deep learning tools.

6 Structural causal models

This chapter covers

- Converting a general causal graphical model to a structural causal model

- Mastering the key elements of SCMs

- Implementing SCMs for rule-based systems

- Building an SCM from scratch using additive models

- Combining SCMs with deep learning

In this chapter, I’ll introduce a fundamental causal modeling approach called the structural causal model (SCM). An SCM is a special case of a causal generative model that can encode causal assumptions beyond those we can capture with a DAG. If a DAG tells us what causes what, an SCM tells us both what causes what and how the causes affect the effects. We can use that extra ૿how information to make better causal inferences.

In this chapter, we’ll focus on defining and building an intuition for SCMs using examples in code. In later chapters, we’ll see examples of causal inferences that we can’t make with a DAG alone but we can make with an SCM.

6.1 From a general causal graphical model to an SCM

In the causal generative models we’ve built so far, we defined, for each node, a conditional probability distribution given the node’s direct parents, which we called a causal Markov kernel. We then fit these kernels using data. Specifically, we made a practical choice to use some parametric function class to fit these kernels. For example, we fit the parameters of a probability table using pgmpy’s TabularCPD because it let us work with pgmpy’s convenient d-separation and inference utilities. And we used a neural decoder in a VAE architecture because it solved the problem of modeling a high-dimensional variable like an image. These practical reasons have nothing to do with causality; our causal assumptions stopped at the causal DAG.

Now, with SCMs, we’ll use the parametric function class to capture additional causal assumptions beyond the causal DAG. As I said, the SCM lets us represent additional assumptions of how causes affect their effects; for example, that a change in the cause always leads to a proportional change in the effect. Indeed, a probability table or a neural network can be too flexible to capture assumptions about the ૿how of causality; with enough data they can fit anything and thus don’t imply strong assumptions. More causal assumptions enable more causal inferences, at the cost of additional risk of modeling error.

SCMs are a special case of causal graphical models (CGMs)—one with more constraints than the CGMs we’ve built so far. For clarity, I’ll use CGM to refer to the broader set of causal graphical models that are not SCMs. To make the distinction clear, let’s start by looking at how we might modify a CGM so it satisfies the constraints of an SCM.

6.1.1 Forensics case study

Imagine you are a forensic scientist working for the police. The police discover decomposed human remains consisting of a skull, pelvic bone, several ribs, and a femur. An apparent blunt force trauma injury to the skull leads the police to open a murder investigation. First, they need you to help identify the victim.

When the remains arrive in your lab, you measure and catalog the bones. From the shape of the pelvis, you can quickly tell that the remains most likely belong to an adult male. You note that the femur is 45 centimeters long. As you might suspect, there is a strong predictive relationship between femur length and an individual’s overall height. Moreover, that relationship is causal. Femur length is a cause of height. Simply put, having a long femur makes you taller, and having a short femur makes you shorter.

Indeed, when you consult your forensic text, it says that height is a linear function of femur length. It provides the following probabilistic model of height, given femur length (in males):

ny ~ N(0, 3.3)

y = 25 + 3x + ny

Here, x is femur length in centimeters, and y is height in centimeters. Of course, exact height will vary with other causal factors, and ny represents variations in height from those factors. Ny has a normal distribution with mean 0 and scale parameter 3.3 cm.

This is an example of an SCM. We’ll expand this example as we go, but the key element to focus on here is that our model is assuming the causal mechanism underpinning height (Y ) is linear. Height (Y ) is a linear function of its causes, femur length (X ) and Ny, which represents other causal determinants of height.

Linear modeling is an attractive choice because it is simple, stands on centuries of theory, and is supported by countless statistical and linear algebra software libraries. But from a causal perspective, that’s beside the point. Our SCM is not using this linear function because it is convenient. Rather, we are intentionally asserting that the relationship between the cause and the effect is linear—that for a change in femur length, there is a proportional change in height.

Let’s drill down on this example to highlight the differences between a CGM and an SCM.

6.1.2 Converting to an SCM via reparameterization

In this section, we will start by converting the type of CGM we’ve become familiar with into an SCM. Our conversion exercise will highlight those properties and make clear the technical structure of the SCM and how it differs relative to the CGMs we’ve seen so far. Note, however, that this ૿conversion is intended to build intuition; in general, you should build your SCM from scratch rather than try to shoehorn non-SCMs into SCMs, for reasons we’ll see in section 6.2.

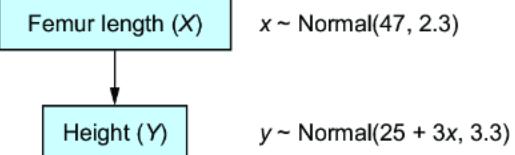

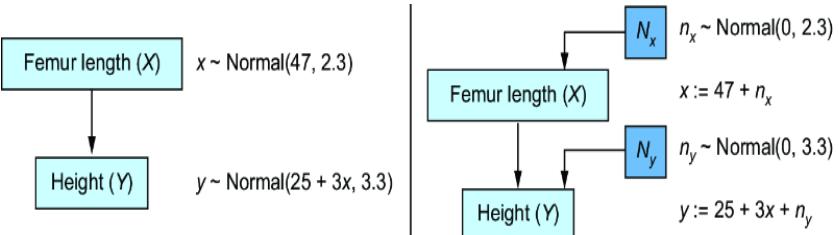

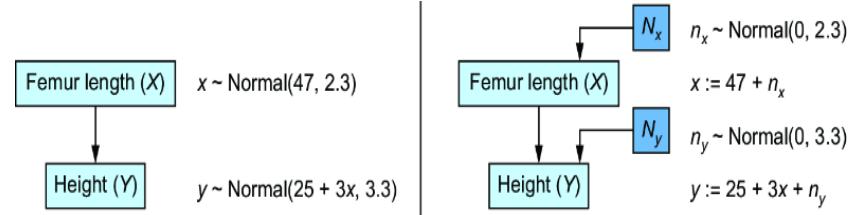

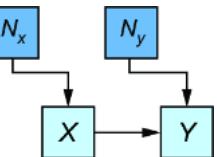

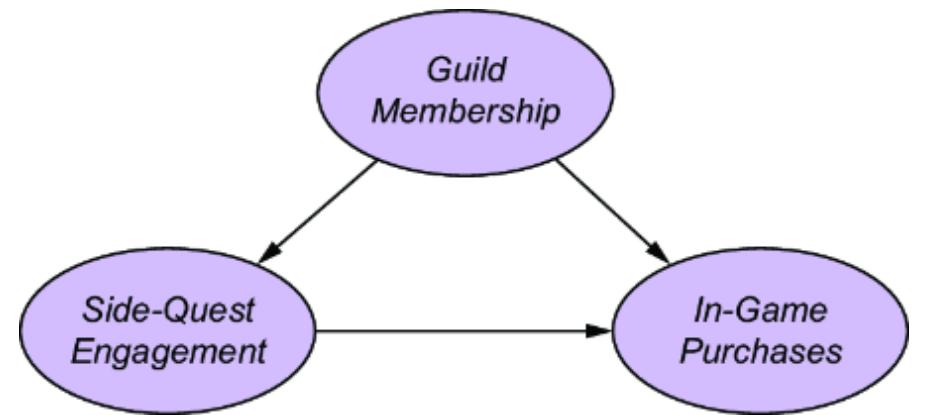

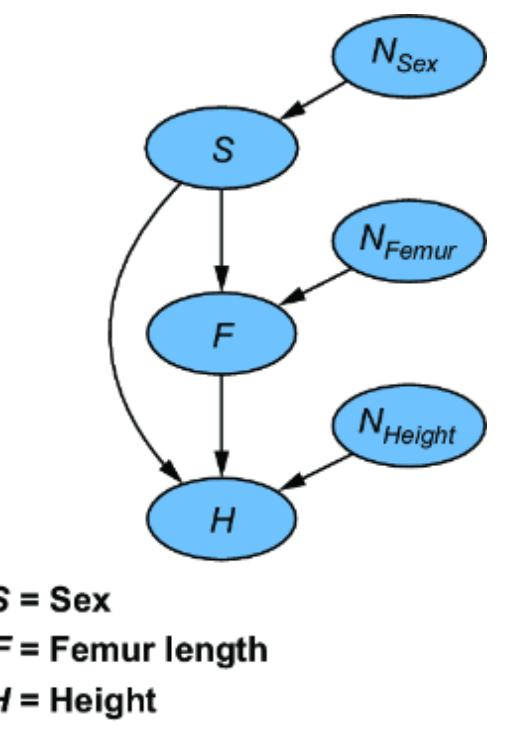

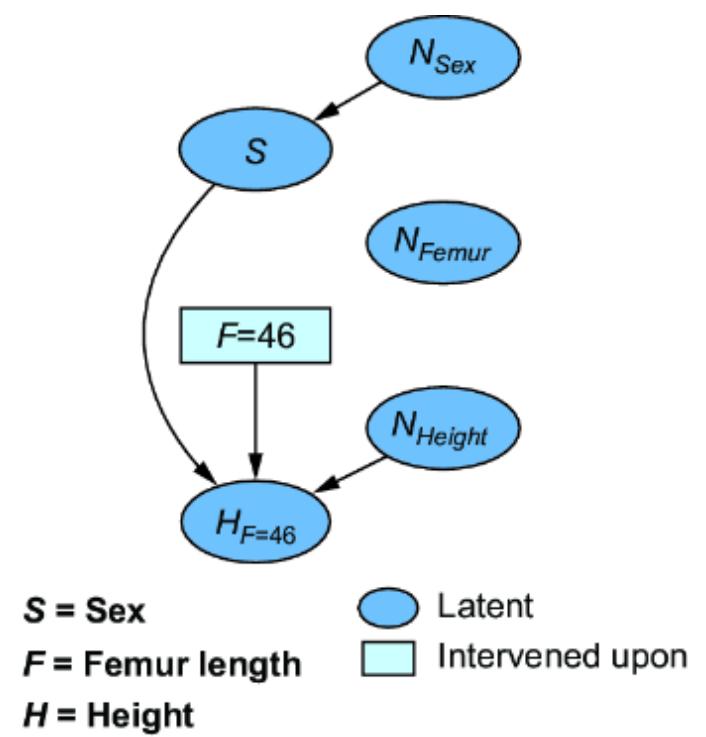

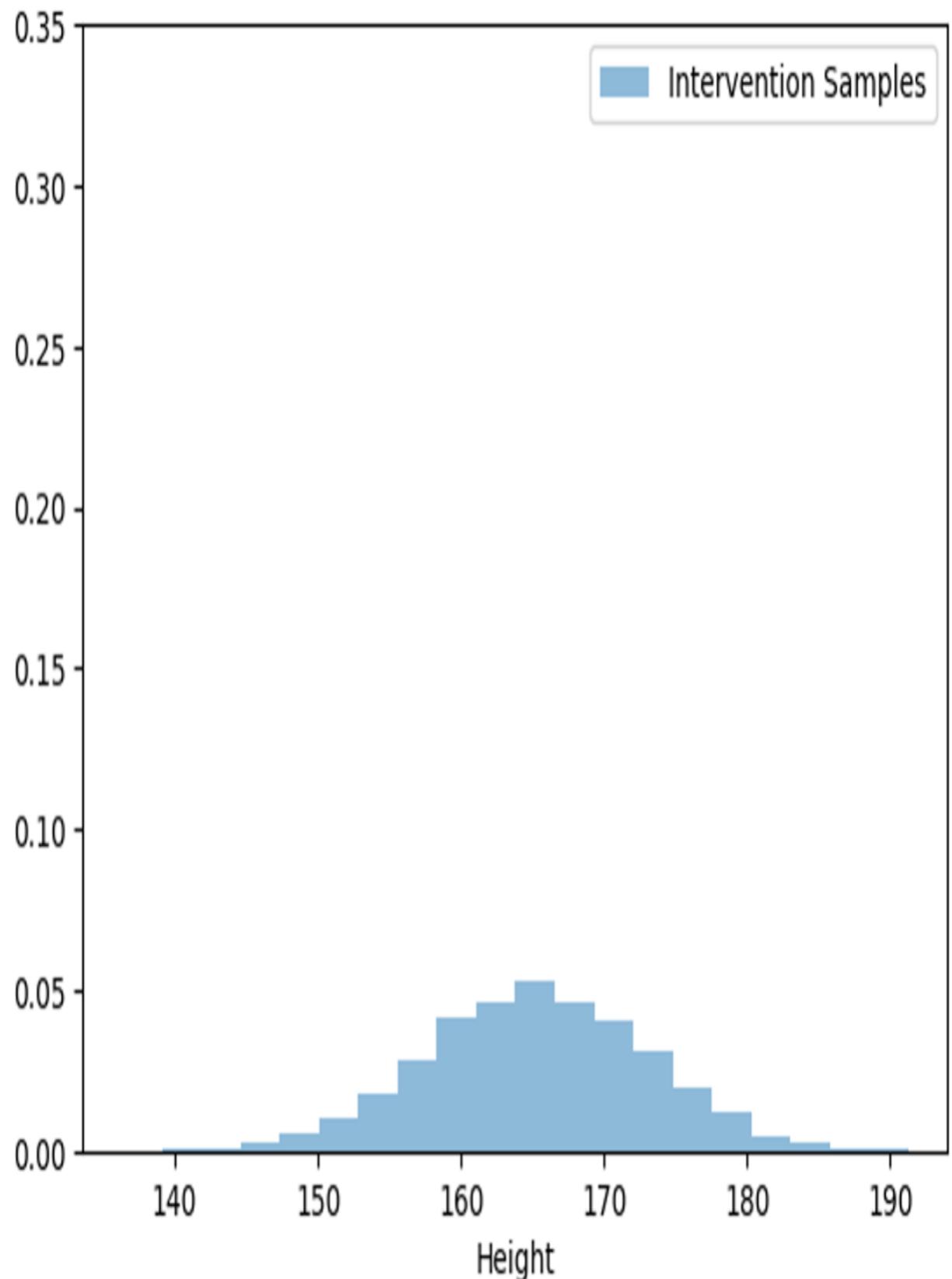

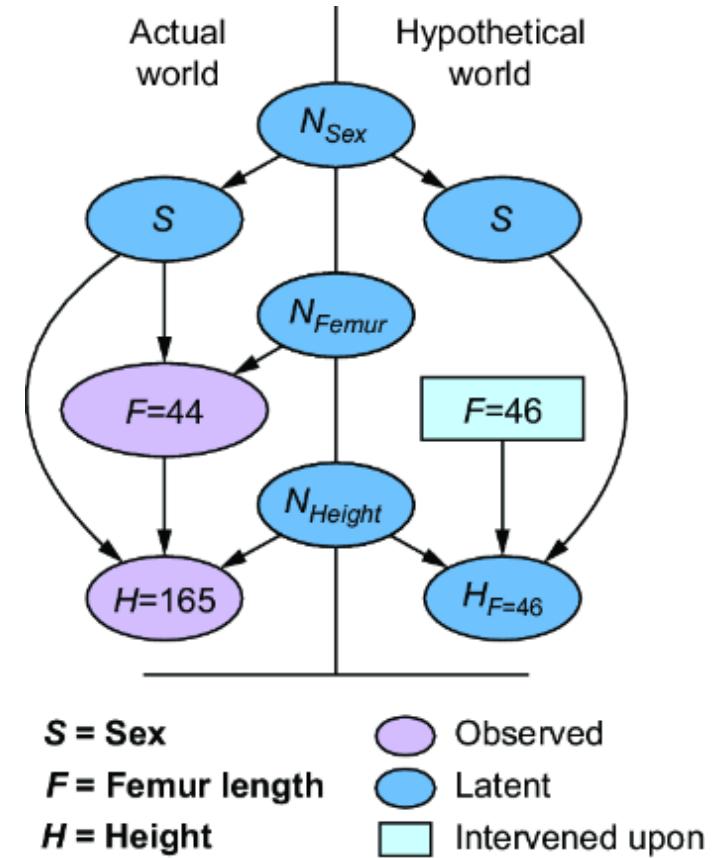

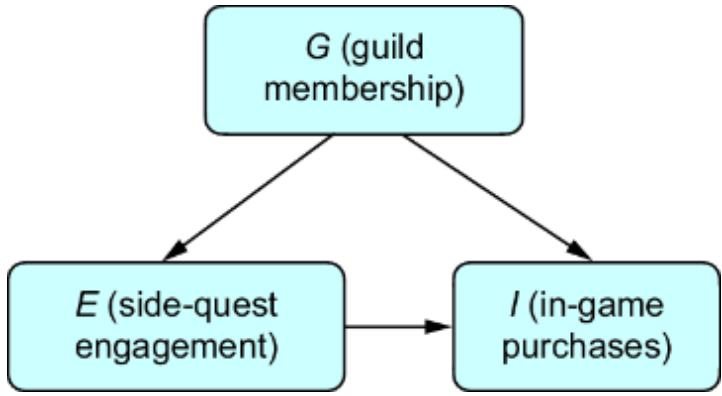

Let’s suppose our forensic SCM were a CGM. We might implement it as in figure 6.1.

Figure 6.1 A simple two-node CGM. Femur length (X) is a cause of height (Y). X has a normal distribution with a mean of 47 centimeters and a standard deviation of 2.3 centimeters. Y has a distribution with a mean of 25 + 3x centimeters and a standard deviation of 3.3 centimeters.

Recall from chapter 2 that x ~ P (X ) and y ~ P (Y |X=x ) means we generate from the probability distribution of X and conditional probability distribution of Y given X. In this case, P (X ), the distribution of femur length, represented as a normal distribution with a mean of 47 centimeters and a standard deviation of 2.3 centimeters. P (Y |X=x ) is the distribution on height given the femur length, given as a normal distribution with a mean of 25 + 3x centimeters and a standard deviation of 3.3 centimeters. We would implement this model in Pyro as follows in listing 6.1.

SETTING UP YOUR ENVIRONMENT

The code in this chapter was written using Python version 3.10, Pyro version 1.9.0, pgmpy version 0.1.25, and torch 2.3.0. See https://www.altdeep.ai/p/causalaibookfor links to the notebooks that run the code. We are also using MATLAB for some plotting; this code was tested with version 3.7.

Listing 6.1 Pyro pseudocode of the CGM in figure 6.1

from pyro.distributions import Normal

from pyro import sample

def cgm_model(): #1

x = sample("x", Normal(47., 2.3)) #1

y = sample("y", Normal(25. + 3*x, 3.3)) #1

return x, y #2#1 x and y are sampled from their causal Markov kernels, in this case normal distributions. #2 Repeatedly calling cgm_model will return samples from P(X, Y).

We are going to convert this model to an SCM using the following algorithm:

- Introduce a new latent causal parent for X called Nx and a new latent causal parent for Y called Ny with distributions P(Nx) and P(Ny).

- Make X and Y deterministic functions of Nx and Ny such that P(X, Y) in this new model is the same as in the old model.

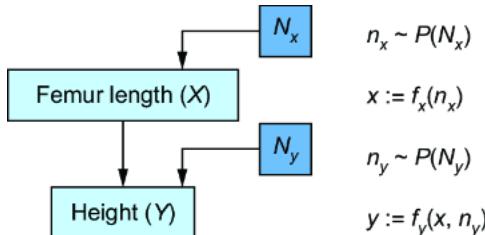

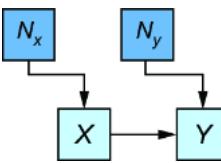

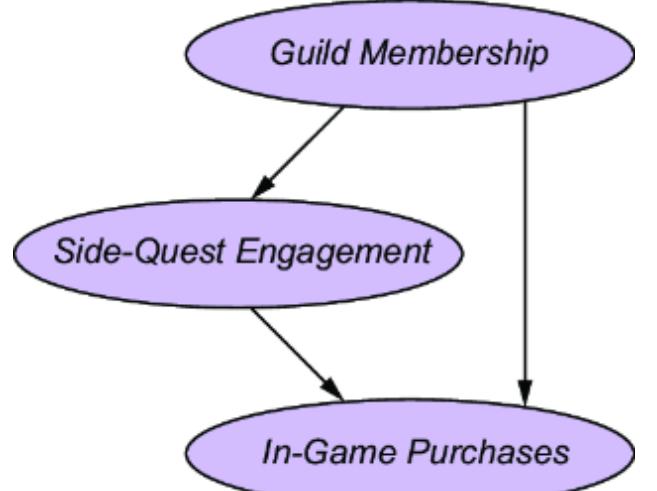

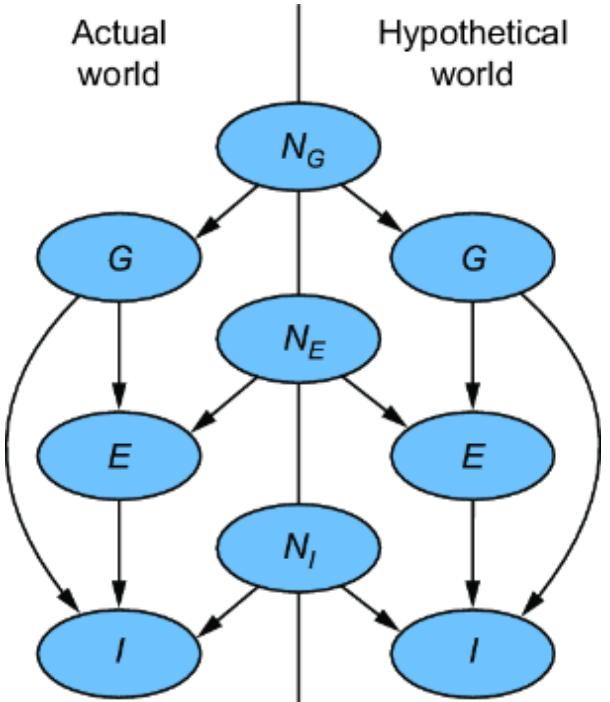

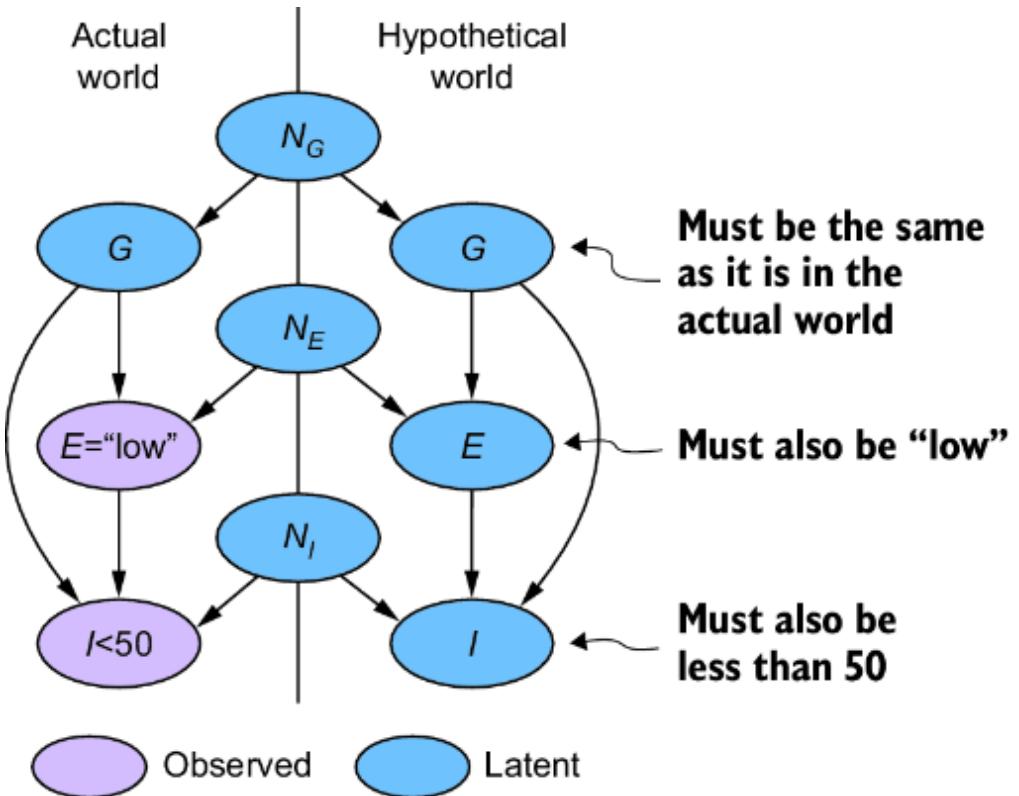

Following these instructions and adding in two new variables, we get figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2 To convert the CGM to an SCM, we introduce latent ૿exogenous parents, Nx for X and Ny for Y, and probability distributions P(Nx) and P(Ny) for these latents. We then set X and Y deterministically, given their parents, via functions fx and fy.

We have two new latent variables Nx and Ny with distributions P (Nx) and P (Ny). X and Y each have their own functions fx and fy that that deterministically set X and Y, given their parents in the graph. This difference is key; X and Y are generated in the model described in figure 6.1 but set deterministically in this new model. To emphasize this, I use the assignment operator ૿:= instead of the equal sign ૿= to emphasize that fx and fy assign the values of X and Y.

To meet our goal of converting our CGM to an SCM, we want P (X ) and P (Y |X =x ) to be the same across both models. To achieve this, we have to choose P (Nx), P (Ny), fx, and fy such that P (X ) is still Normal(47, 2.3) and P (Y |X = x ) is still Normal(25 + 3.3x, 3.3). One option

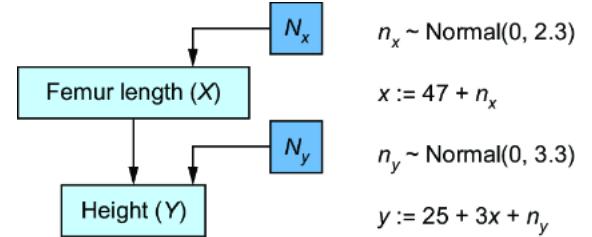

is to do a simple reparameterization. Linear functions of normally distributed random variables are also normally distributed. We can implement the model in figure 6.3.

Figure 6.3 A simple reparameterization of the original CGM produces a new SCM model with the same P(X) and P(Y|X) as the original.

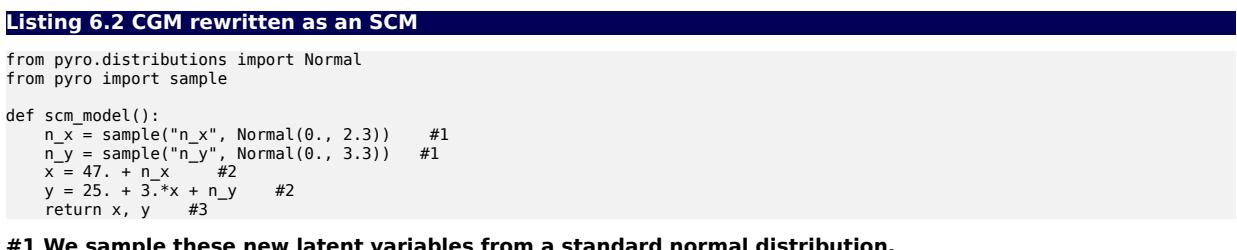

In code, we rewrite this as follows.

#1 We sample these new latent variables from a standard normal distribution. #2 X and Y are calculated deterministically as linear transformations of n_x and n_y. #3 The returned samples of P(X, Y) match the first model.

With this introduction of new exogenous variables Nx and Ny, some linear functions fx and fy, and a reparameterization, we converted the CGM to an SCM that encodes the same distribution P (X, Y ). Next, let’s look more closely at the elements we introduced.

6.1.3 Formalizing the new model

To build an SCM, we’re going to assume we’ve already built a causal DAG, as in figure 6.1. In figures 6.2 and 6.3, we see two kinds of variables: exogenous and endogenous. The endogenous variables are the original variables X and Y—we’ll define them as the variables we are modeling explicitly. These are the variables we included in our causal DAG.

The exogenous variables (also called noise variables) are our new nodes Nx and Ny. These variables represent all unmodeled causes of our endogenous variables. In our formulation, we pair each of the endogenous variable with its own exogenous variable parent; X gets new exogenous causal parent Nx, and Y gets exogenous parent Ny. We add these to our DAG for completeness as in figures 6.2 and 6.3.

In our formulation, we’ll assume exogenous variables have no parents and have no edges between one another. In other words, they are root nodes in the graph, and they are independent relative to other exogenous variables. Further, we’ll treat the exogenous variables as latent variables.

Each endogenous variable also gets its own assignment function (also called a structural assignment) fx, and fy. The assignment function deterministically sets the value of the endogenous variables X and Y given values of their parents in the causal DAG.

Assignment functions are how we capture assumptions about the ૿how of causality. For instance, to say that the causal relationship between height (Y ) and femur length (X ) is linear, we specify that fx is a linear function.

While the endogenous variables are set deterministically, the SCM generates the values of the exogenous variables from probability distributions. In our femur example, we generate values nx and ny of exogenous variables Nx and Ny from distributions P (Nx) and P (Ny), which are N (0, 2.3) and N (0, 3.3), as seen in figure 6.3.

ELEMENTS OF THE GENERATIVE SCM

- A set of endogenous variables (e.g., X, Y)—These are the variables we want to model explicitly. They are the models we build into our causal DAG.

- A set of exogenous variables (e.g., Nx and Ny)—These variables stand in for unmodeled causes of the endogenous variables. In our formulation, each endogenous variable has one corresponding latent exogenous variable.

- A set of assignment functions (e.g., fx and fy)—Each endogenous variable has an assignment function that sets its value deterministically given its parents (its corresponding exogenous variable and other endogenous variables).

- A set of exogenous variable probability distributions (e.g., P(Nx) and P(Ny))—The SCM becomes a generative model with a set of distributions on the exogenous variables. Given values generated from these distributions, the endogenous variables are set deterministically.

Let’s look at another example of an SCM, this time using discrete variables.

6.1.4 A discrete, imperative example of an SCM

Our femur example dealt with continuous variables like height and length. Let’s now return to our rock-throwing example from chapter 2 and consider a discrete case of an SCM. In this example, either Jenny or Brian or both throw a rock at window if they are inclined to do so. The window breaks depending on whether either or both Jenny and Brian throw and the strength of the windowpane.

How might we convert this model to an SCM? In fact, this model is already an SCM. We captured this with the following code.

Listing 6.3 The rock-throwing example from chapter 2 is an SCM

import pandas as pd

import random

def true_dgp(

jenny_inclination, #1

brian_inclination, #1

window_strength): #1

jenny_throws_rock = jenny_inclination > 0.5 #2

brian_throws_rock = brian_inclination > 0.5 #2

if jenny_throws_rock and brian_throws_rock: #3

strength_of_impact = 0.8 #3

elif jenny_throws_rock or brian_throws_rock: #3

strength_of_impact = 0.6 #3

else: #3

strength_of_impact = 0.0 #3

window_breaks = window_strength < strength_of_impact #4

return jenny_throws_rock, brian_throws_rock, window_breaks

generated_outcome = true_dgp(

jenny_inclination=random.uniform(0, 1), #5

brian_inclination=random.uniform(0, 1), #5

window_strength=random.uniform(0, 1) #5

)#1 The input values are instances of exogenous variables.

#2 Jenny and Brian throw the rock if so inclined. jenny_throws_rock and brian_throws_rock are endogenous variables.

#3 strength_of_impact is an endogenous variable. This entire if-then expression is the assignment function for strength of impact.

#4 window_breaks is an endogenous variable. The assignment function is lambda strength_of_impact, window_strength: strength_of_impact > window_strength. #5 Each exogenous variable has a Uniform(0, 1) distribution.

You’ll see that it satisfies the requirements of an SCM. The arguments to the true_dgp function (namely jenny_inclination, brian_inclination, window_strength) are the exogenous variables. The named variables inside the function are the endogenous variables, which are set deterministically by the exogenous variables.

Most SCMs you’ll encounter in papers and textbooks are written down as math. However, this rock-throwing example shows us the power of reasoning causally with an imperative scripting language like Python. Some causal processes are easier to write in code than in math. It is only recently that tools such as Pyro have allowed us to make sophisticated code-based SCMs.

6.1.5 Why use SCMs?

More causal assumptions mean more ability to make causal inferences. The question of whether to use an SCM instead of a regular CGM is equivalent to asking whether the additional causal assumptions encoded in the functional assignments will serve your causal inference goal.

In our femur example, our DAG says femur length causes height. Our SCM goes further and says that for every unit increase in femur length, there is a proportional increase in height. The question is whether that additional information helps us answer a causal question. One example where such a linear assumption helps make a causal inference is the use of instrumental variable estimation of causal effects, which I’ll discuss in chapter 11. This approach relies on linearity assumptions to infer causal effects in cases where the assumptions in the DAG alone are not sufficient to make the inference. Another example is where an SCM can enable us to answer counterfactual queries using an algorithm discussed in chapter 9.

Of course, if your causal inference is relying on an assumption, and that assumption is incorrect, your inference will probably be incorrect. The ૿what assumptions in a DAG are simpler than the additional ૿how assumptions in an SCM. An edge in a DAG is a true or false statement that X causes Y. An assignment function in an SCM model is a statement

about how X causes Y. The latter assumption is more nuanced and quite hard to validate, so it’s easier to get incorrect. Consider the fact that there are longstanding drugs on the market that we know work, but we don’t fully understand their mechanism of action—how they work.

GENERATIVE SCMS WITH LATENT EXOGENOUS VARIABLES

We want to use our SCMs as generative models. To that end, we treat exogenous variables (variables we don’t want to model explicitly) as latent proxies for unmodeled causes of the endogenous variables. We just need to specify probability distributions of the exogenous variables and we get a generative latent variable model.

FLEXIBLE SELECTION OF ASSIGNMENT FUNCTIONS

You’ll find that the most common applications of SCMs use linear functions as assignment functions, like we did in the femur example. However, in a generative AI setting, we certainly don’t want to constrain ourselves to linear models. We want to work with rich function classes we can write as code, optimize with automatic differentiation, and apply to high-dimensional nonlinear problems, like images. These function classes can do just as well in representing the ૿how of causality.

CONNECTION TO THE DAG

We contextualize the SCM within the DAG-based view of causality. First, we build a causal DAG as in chapters 3 and 4. Each variable in the DAG becomes an endogenous variable (a variable we want to model explicitly) in the SCM. For each endogenous variable, we add a single latent exogenous parent node to the DAG. Next, we define ૿assignment function as a function that assigns a given endogenous variable a value, given the values of its parents in the DAG. All of our DAG-based theory still applies, such as the causal Markov property and independence of mechanism.

Note that not all formulations of the SCM adhere so closely to the DAG. Some practitioners who don’t adopt a graphical view of causality still use SCM-like models (e.g., structural equation modeling in econometrics). And some variations of graphical SCMs allow us to relax acyclicity and work with cycles and feedback loops.

INDEPENDENT EXOGENOUS VARIABLES

Introducing one exogenous variable for every endogenous variable can be a nuisance; sometimes it is easier to treat a node with no parents in the original DAG as exogenous, or have the same exogenous parent for two endogenous nodes. But this approach lets us add exogenous variables in a way that maintains the d-separations entailed by the original DAG. It also allows us to make a distinction between endogenous variables we care to model explicitly, and all the exogenous causes we don’t want to model explicitly. This comes in handy when, for example, you’re building a causal image model like in chapter 5, and you don’t want to explicitly represent all the many causes of the appearance of an image.

6.1.7 Causal determinism and implications to how we model

The defining element of the SCM is that endogenous variables are set deterministically by assignment functions instead of probabilistically by drawing randomly from a distribution conditioned on causal parents. This deterministic assignment reflects the philosophical view of causal determinism, which argues that if you knew all the causal factors of an outcome, you would know the outcome with complete certainty.

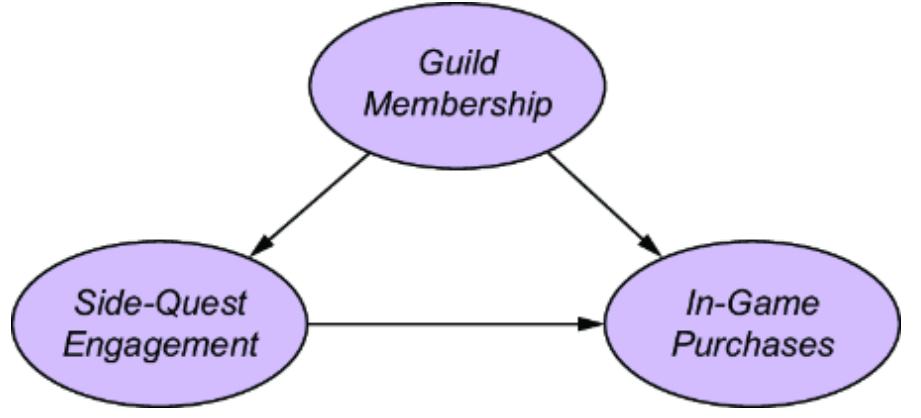

The SCM stands on this philosophical foundation. Consider again our femur-height example, shown in figure 6.4.

Figure 6.4 The original CGM samples endogenous variables from causal Markov kernels. The new model sets the endogenous variables deterministically.

In the original CGM on the left of figure 6.4, we generate values of X and Y from models of their causal Markov kernels. In the corresponding SCM on the right, the endogenous variables are set deterministically, no longer drawn from distributions. The SCM is saying that given femur length and all the other unmodeled causes of height represented by Ny, height is a certainty.

Note that despite this deterministic view, the SCM is still a probabilistic model of the joint probability distribution of the endogenous variables P(X, Y). But in comparison to the CGM on the left of figure 6.4, the SCM on the right shunts all the randomness of the model to the exogenous variable distributions. X and Y are still random variables in the SCM, because they are functions of Nx and Ny, and a function of a random variable is a random variable. But conditional on the exogenous variables, the endogenous variables are fully determined (degenerate).

The causal determinism leads to eye-opening conclusions for us as causal modelers. First, when we apply a DAG-based view of causality to a given problem, we implicitly assume the ground-truth data generating process (DGP) is an SCM. We already assumed that the ground-truth DGP had an underlying ground-truth DAG. Going a step further and assuming that each variable in that DAG is set deterministically, given all its causes (both those in and outside the DAG), is equivalent to assuming the ground-truth DGP is an SCM. The SCM might be a black box, or we might not be able to easily write it down in math or code, but it is an SCM nonetheless. That means, whether we’re using a traditional CGM or an SCM, we are modeling a ground-truth SCM.

Second, it suggests that if we were to generate from the ground-truth SCM, all the random variation in those samples would be entirely due to exogenous causes. It would not be due to an irreducible source of stochasticity like, for example, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle or butterfly effects. If such concepts drive the outcomes in your modeling domain, CGMs might not be the best choice.

Now that we know we want to model a ground-truth SCM, let’s explore why we can’t simply learn it from data.

6.2 Equivalence between SCMs

A key thing to understand about SCMs is that we can’t fully learn them from data. To see why, let’s revisit the case where we turned a CGM into an SCM. Let’s see why, in general, this can’t give us the ground-truth SCM.

6.2.1 Reparameterization is not enough

When we converted the generic CGM to the SCM, we used the fact that a linear transformation of a normally distributed random variable produces a normally distributed random variable. This ensured that the joint probability distribution of the endogenous variables was unchanged.

We could use this ૿reparameterization trick (as this technique is called in generative AI) with other distributions. When we apply the reparameterization trick, we are shunting all the uncertainty in those conditional probability distributions to the distributions of the newly introduced exogenous variables. The problem is that different ૿reparameterization tricks can lead to different SCMs with different causal assumptions, leading to different causal inferences.

REPARAMETERIZATION TRICK FOR A BERNOULLI DISTRIBUTION

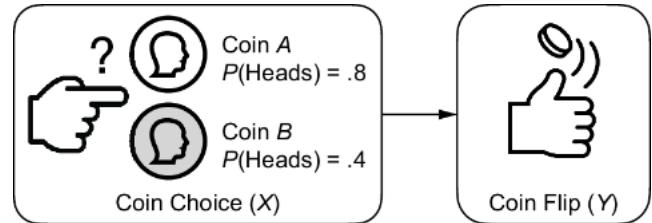

As an example, let X represent the choice of a weighted coin and Y represent the outcome of a flip of the chosen coin. Y is 1 if we flip heads and 0 if we flip tails. X takes two values, ૿coin A or ૿coin B. Coin A has a .8 chance of flipping heads, and coin B has a .4 chance of flipping heads, as shown in figure 6.5.

Figure 6.5 A simple CGM. X is a choice of one of two coins with different weights on heads and tails. Y is the outcome of the coin flip (heads or tails).

We can simulate an outcome of the flip with a variable Y sampled from a Bernoulli distribution with parameter px, where px is .8 or .4, depending on the value of x.

y ~ Bernoulli(px)

How could we apply the reparameterization trick here to make the outcome Y be the result of a deterministic process?

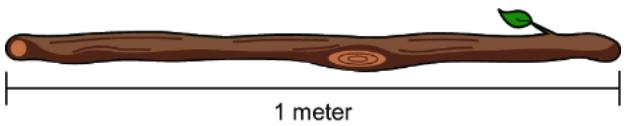

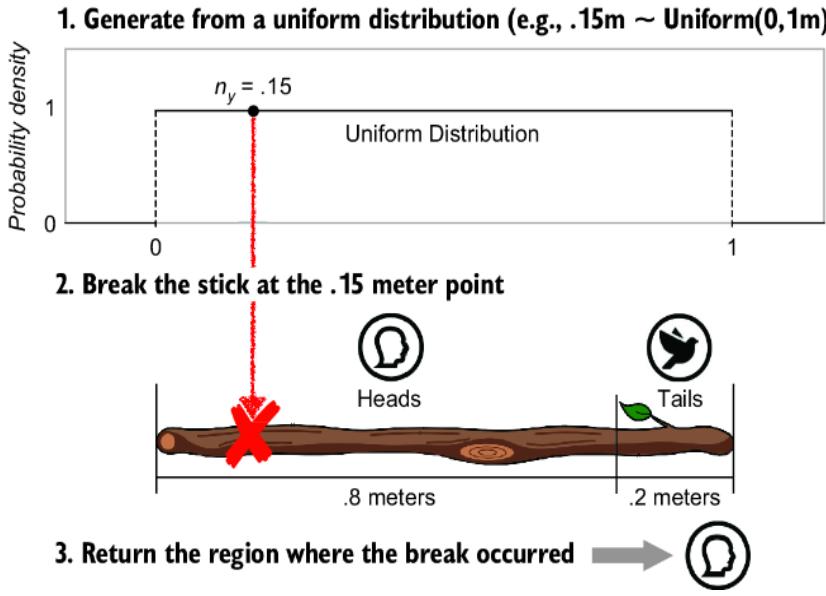

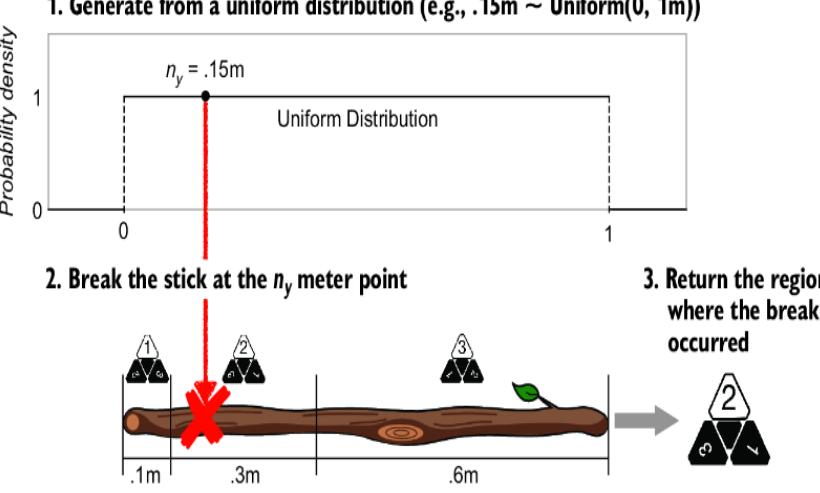

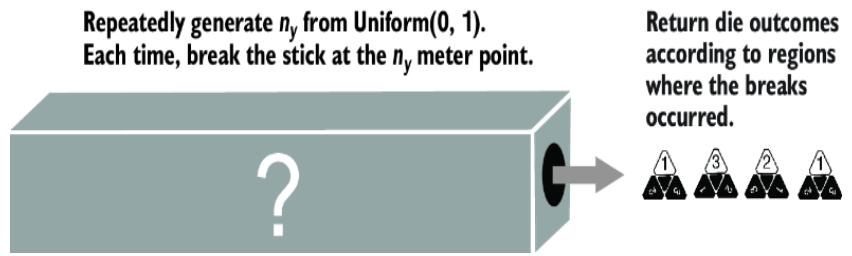

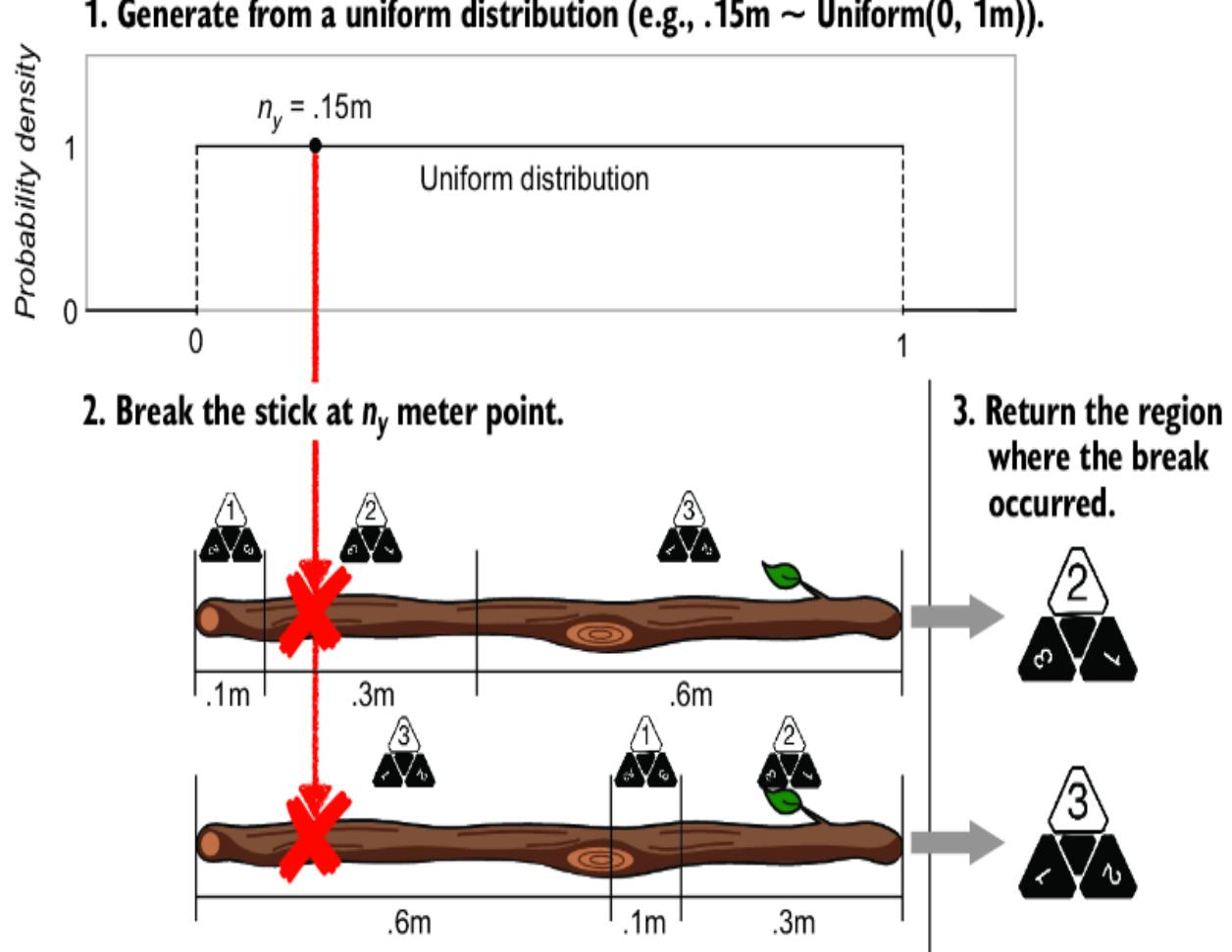

Imagine that we have a stick that’s one meter long (figure 6.6).

Figure 6.6 To turn the coin flip model into an SCM, first imagine a one meter long stick.

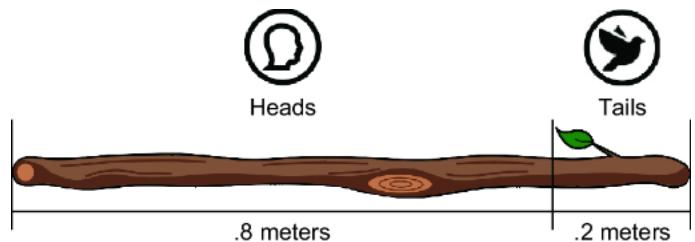

Imagine using a pocket knife to carve a mark that partitions the stick into two regions: one corresponding to ૿tails and one for ૿heads. We cut the mark at a point that makes the length of each region proportional to the probability of the corresponding outcome; the length of the heads region is px meters, and the length of the tails region is 1 – px meters. For coin A, this would be .8 meters (80 centimeters) for the heads region and .2 meters for the tails region (figure 6.7).

Figure 6.7 Divide the stick into two regions corresponding to each outcome. The length of the region is proportional to the probability of the outcome.

After marking the partition, we will now randomly select a point on the stick’s length where we will break the stick. The probability that the break will occur in a given region is equal to the probability of that region’s associated outcome (figure 6.8). The equality comes from having the length of the region correspond to the probability of the outcome. If the break point is to the left of the partition we cut with our pocket knife, y is assigned 0 (૿heads), and if the break point is to the right, y is assigned 1 (૿tails).

To randomly select a point to break the stick, we can generate from a uniform distribution. Suppose we sample .15 from a uniform(0, 1) and thus break the stick at a point .15 meters along its length, as shown in figure 6.8. The .15 falls into the ૿heads region, so we return heads. If we repeat this stick-breaking procedure many times, we’ll get samples from our target Bernoulli distribution.

In math, we can write this new model as follows:

ny ~ Uniform(0, 1)

y : = I(ny ≤ px)

where px is .8 if X is coin A, or .4 if X is coin B. Here, I(.) is the indicator function that returns 1 if ny < px and 0 otherwise.

Figure 6.8 Generate from a uniform distribution on 0 to 1 meters, break the stick at that point, and return the outcome associated with the region where the break occurred. Repeated generation of uniform variates will cause breaks in the ૿heads region 80% of the time, because its length is 80% of the full stick length.

This new model is technically an SCM, because instead of Y being generated from a Bernoulli distribution, it is set deterministically by an indicator ૿assignment function. We did a reparameterization that shunted all the randomness to an exogenous variable with a uniform distribution, and that variable is passed to the assignment function.

DIFFERENT “REPARAMETERIZATION TRICKS” LEAD TO DIFFERENT SCMS

The main reason to use SCM modeling is to have the functional assignments represent causal assumptions beyond those captured by the causal DAG. The problem with the reparameterization trick is that different reparameterization tricks applied to the same CGM will create SCMs with different assignment functions, implying different causal assumptions.

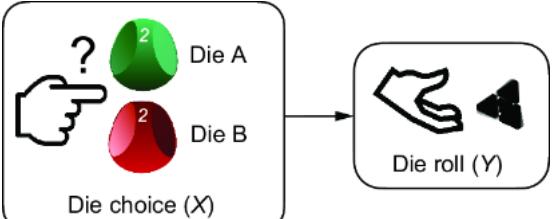

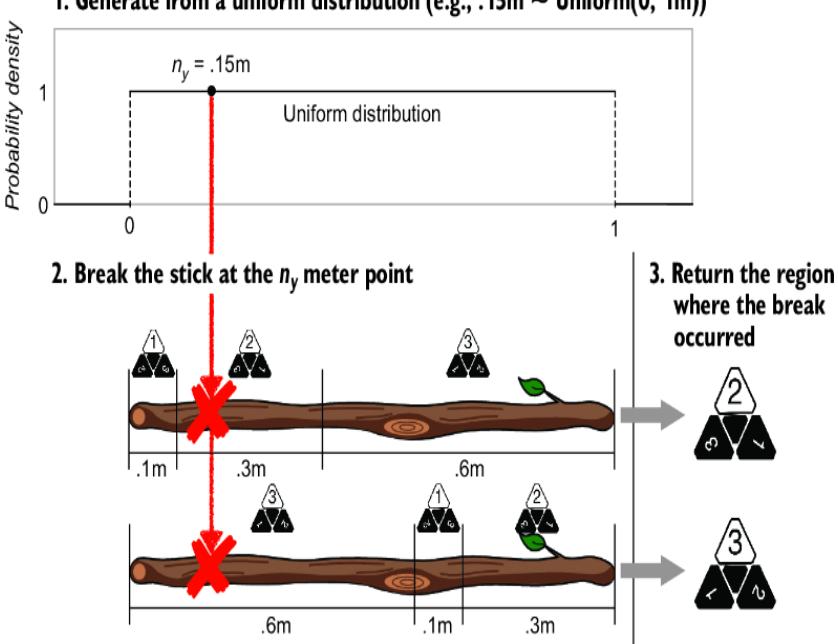

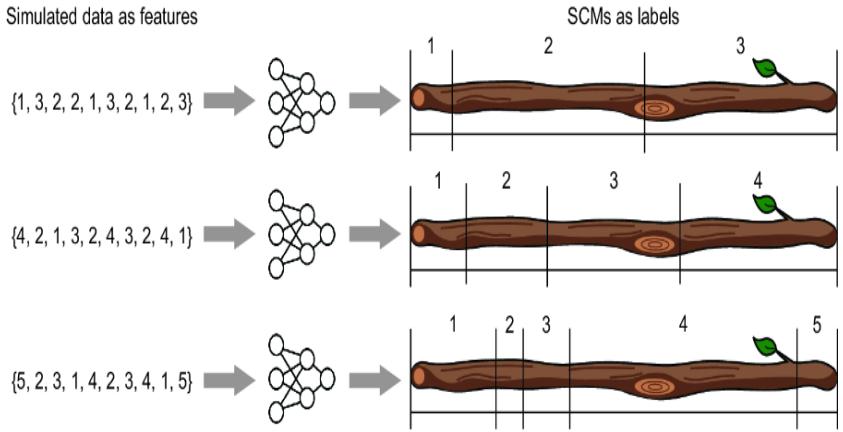

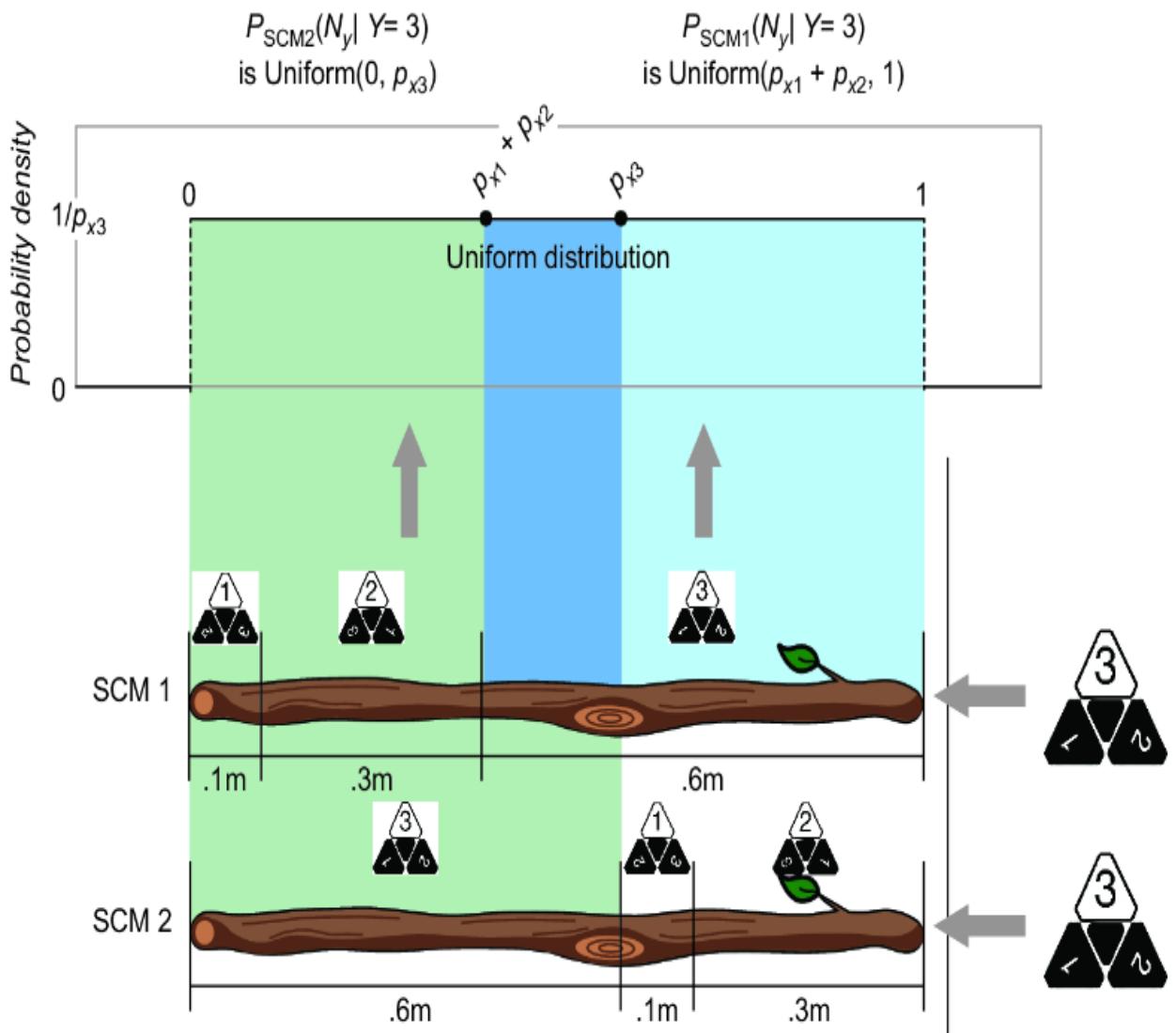

To illustrate, suppose that instead of a coin flip, Y was a three-sided die, like we saw in chapter 2 (figure 6.9). X determines which die we’ll throw; die A or die B (figure 6.10). Each die is weighted differently, so they have different probabilities of rolling a 1, 2, or 3.

Figure 6.9 Three-sided dice

Figure 6.10 Suppose we switch the model from choosing a coin (two outcomes) to choosing a three-sided die (three outcomes).

We can extend the original model from a Bernoulli distribution (which is the same as a categorical distribution with two outcomes) to a categorical distribution with three outcomes:

y ~ Categorical([px1, px2, px3])

where px1, px2, and px3 are the probabilities of rolling a 1, 2, and 3 respectively (note that one of these is redundant, since px1 = 1 – px2 – px3).

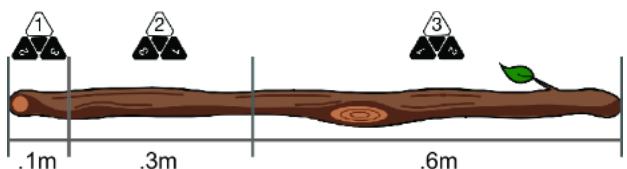

We can use the stick-based reparameterization trick here as well; we just need to extend the stick to have one more region. Suppose for die A, the probability of rolling a 1 is px1=.1, rolling a 2 is px2=.3, and rolling a 3 is px3=.6. We’ll mark our stick as in figure 6.11.

Figure 6.11 Divide the stick into three regions corresponding to outcomes of the three-sided die.

We’ll then use the same selection of a remote region using a generated uniform variate as before (figure 6.12).

Figure 6.12 The conversion to the stick-breaking SCM when Y has three outcomes

In math we’ll write this as follows:

\[n\_{\mathcal{Y}} \sim Uniform \begin{cases} n\_{\mathcal{Y}} \sim Uniform \begin{cases} 0, & 1 \end{cases} \\ 1, & p\_{x1} \\ 2, & p\_{x1} < n\_{\mathcal{Y}} \le p\_{x1} + p\_{x2} \\ 3, & p\_{x1} + p\_{x2} < n\_{\mathcal{Y}} \le 1 \end{cases}\]

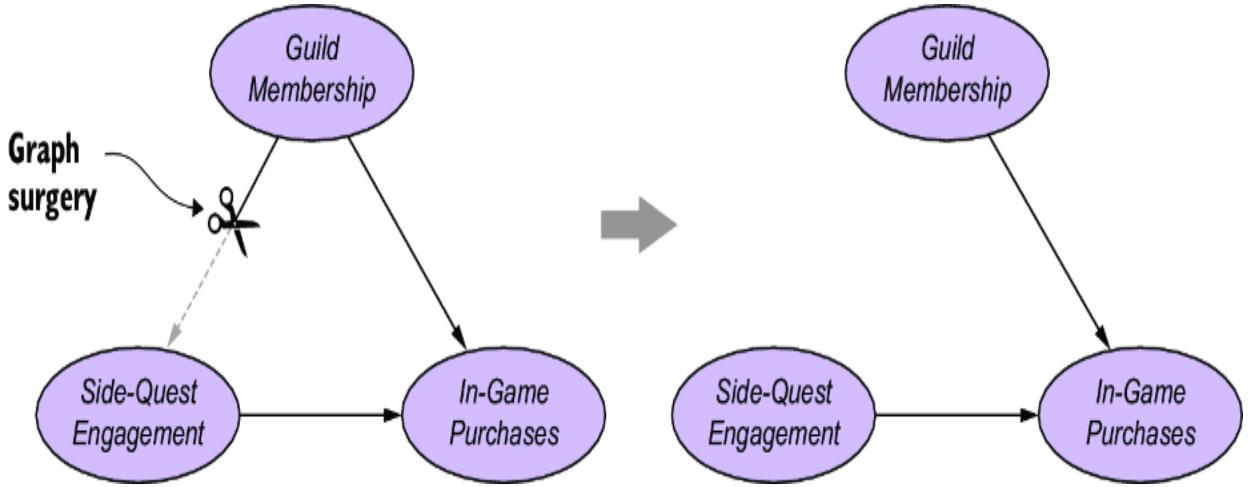

But what if we mark the stick differently, such that we change the ordering of the regions on the stick? In the second stick, the region order is 3, 1, and then 2 (figure 6.13).

Figure 6.13 Two different ways of reparameterizing a causal generative model yield two different SCMs. They encode the same joint probability distribution but different endogenous values given the same exogenous value.

In terms of the probability of each outcome (1, 2, or 3), the two sticks are equivalent—the size of the stick regions assigned to each die-roll outcome are the same on both sticks. But our causal mechanism has changed! These two sticks can return different outcomes for a given value of ny. If we randomly draw .15 and thereby break the sticks at the .15 meter point, the first stick will break in region 2, returning a 2, and the second stick will break in region 3, returning a 3.

In math, the second stick-breaking SCM has this form:

\[n\_{\mathfrak{y}} \sim Uniform\left(0, \ 1\right)\]

\[\mathfrak{y} := \begin{cases} 3, & n\_{\mathfrak{y}} \le p\_{x3} \\ 1, & p\_{x3} < n\_{\mathfrak{y}} \le p\_{x3} + p\_{x1} \\ 2, & p\_{x3} + p\_{x1} < n\_{\mathfrak{y}} \le 1 \end{cases}\]

Metaphorically speaking, imagine that in your modeling domain, the sticks are always marked a certain way, with the regions ordered in a certain way. Then there is no guarantee that a simple reparameterization trick will give you the ground-truth marking. To drive the point home, let’s look back at the reparameterization trick we performed to convert our femur-height model to an SCM (figure 6.14).

Figure 6.14 Revisiting the femur-height SCM

Suppose we create a new SCM that is the same, except that the assignment function for y now looks like this:

y := 25 + 3x – ny

Now we have a second SCM that subtracts ny instead of adding ny. A normal distribution is symmetric around its mean, so since ny has a normal distribution with mean 0, the probability values of ny and –ny are the same, so the probability distribution of Y is the same in both models. But for the same values of ny and x, the actual assigned values of y will be different. Next, we’ll examine this idea in formal detail.

6.2.2 Uniqueness and equivalence of SCMs

Given a causal DAG and a joint probability distribution on endogenous variables, there can generally be multiple SCMs consistent with that DAG and joint probability distribution. This means that we can’t rely on data alone to learn the ground-truth SCM. We’ll explore this problem of causal identifiability in depth in chapter 10. For now, let’s break this idea down using concepts we’ve seen so far.

MANY SCMS ARE CONSISTENT WITH A DAG AND CORRESPONDING DISTRIBUTIONS

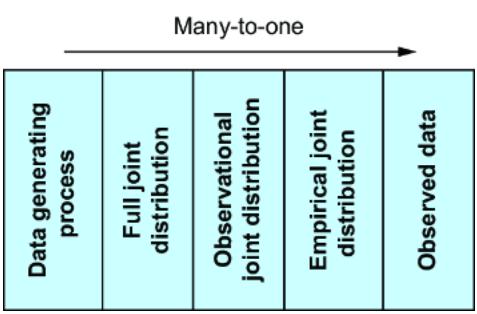

Recall the many-to-one relationships we outlined in figure 2.24, shown again here in figure 6.15.

Figure 6.15 We have many-to-one relationships as we move from the DGP to observed data.

If we can represent the underlying DGP as a ground-truth SCM, figure 6.15 becomes as shown in figure 6.16.

| SCM | Causal DAG | distribution Full joint |

ioint distribution Observational |

Empirical joint distribution |

Observed data |

|---|

Figure 6.16 Different SCMs can entail the same DAG structure and distributions. The SCMs can differ in assignment functions (and/or exogenous distributions).

In other words, given a joint distribution on a set of variables, there can be multiple causal DAGs consistent with that distribution—in chapter 4 we called these DAGs a Markov equivalence class. Further, we can have equivalence classes of SCMs—given a causal DAG and a joint distribution, there can be multiple SCMs consistent with that DAG and distribution. We saw this with how the two variants of the stick-breaking die-roll SCM are both consistent with the DAG X (die choice) → Y (die roll) and with the distributions P (X ) (probability distribution on die selection) and P (Y |X ) (probability of die roll).

THE GROUND-TRUTH SCM CAN’T BE LEARNED FROM DATA (WITHOUT CAUSAL ASSUMPTIONS)

When we were working to build a causal DAG in previous chapters, our implied objective was to reproduce the ground-truth causal DAG. Now we seek to reproduce the ground-truth SCM, as in figure 6.16.

In chapter 4, we saw that data cannot distinguish between causal DAGs in an equivalence class of DAGs. Similarly, data alone is not sufficient to recover the ground-truth SCM. Again, consider the stick-breaking SCMs we derived. We derived two marked sticks, with two different orderings of regions. Of course, there are 3 × 2 × 1 = 6 ways of ordering the three outcomes: ({1, 2, 3}, {1, 3, 2}, {2, 1, 3}, {2, 3, 2}, {3, 1, 2}, {3, 2, 1}). That’s six ways of marking the stick and thus six different possible SCMs consistent with the distributions P (X ) and P(Y |X ) (probability of die roll).

Suppose one of these marked sticks was the ground-truth SCM, and it was hidden from us in a black box, as in figure 6.17. Suppose we repeatedly ran the SCM to generate some die rolls. Based on those die rolls, could we figure out how the ground-truth stick was marked? In other words, which of the six orderings was the black box ordering?

Figure 6.17 Suppose we didn’t know which ૿marked stick was generating the observed die rolls. There would be no way of inferring the correct marked stick from the die rolls alone. More generally, SCMs cannot be learned from statistical information in the data alone.

The answer is no. More generally, because of the many-to-one relationship between SCMs and data, you cannot learn the ground-truth SCM from statistical information in the data alone.

Let that sink in for a second. I’m telling you that even with infinite data, the most cuttingedge deep learning architecture, and a bottomless compute budget, you cannot figure out the true SCM even in this trivial three-outcome stick-breaking example. In terms of statistical likelihood, each SCM is equally likely, given the data. To prefer one SCM to another in the equivalence class, you would need additional assumptions, such as that {1, 2, 3} is the most likely marking because the person marking the stick would probably mark the regions in order. That’s a fine assumption to make, as long as you are aware you are making it.

In the practice of machine learning, we are often unaware that we are making such assumptions. To illustrate, suppose you ran the following experiment. You created a bunch of stick-breaking SCMs and then simulated data from those SCMs. Then you vectorized the SCMs and used them as labels, and the simulated data as features, in a deep supervised learning training procedure focused on predicting the ૿true SCM from simulated data, as illustrated in figure 6.18.

Figure 6.18 You create many SCMs and simulate data from each of them. You could then do supervised learning of a deep net that predicted the ground-truth SCM from the simulated data. Given two SCMs of the same equivalence class, this approach would favor the SCM with attributes that appeared more often in the training data.

Suppose then you fed the trained model data actual samples of three-sided die rolls, with the goal of predicting the ground-truth SCM. That predictive model’s prediction might favor a stick with the {1, 2, 3} ordering over the equivalent {2, 3, 1} ordering. But it would only do so if the {1, 2, 3} ordering was more common in the training data.

ANALOGY TO PROGRAM INDUCTION

The problem of learning an SCM from data is related to the challenge of program induction in computer science. Suppose a program took ૿foo and ૿bar as inputs and returned ૿foobar as the output. What is the program? You might think that the program simply concatenates the inputs. But it could be anything, including one that concatenates the inputs along with the word ૿aardvark, then deletes the ૿aardvark characters, and returns the result. The ૿data (many examples of inputs to and outputs of the program) are not enough distinguish which program of all the possible programs is the correct one. For that you need additional assumptions or constraints, such as an Occam’s razor type of inductive bias that prefers the simplest program (e.g., the program with the minimum description length).

Trying to learn an SCM from data is a special case of this problem. The program’s inputs are the exogenous variable values, and the outputs are the endogenous variable values. Suppose you have the causal DAG, just not the assignment functions. The problem is that an infinite number of assignment functions could produce those outputs, given the inputs. Learning an SCM from data requires additional assumptions to constrain the assignment functions, such as constraining the function class and using Occam’s razor (e.g., model selection criterion).

Next, we’ll dive into implementing an SCM in a discrete rule-based setting.

6.3 Implementing SCMs for rule-based systems

A particularly useful application for SCMs is modeling rule-based systems. By ૿rule-based, I mean that known rules, often set by humans, determine the ૿how of causality. Games are a good example.

To illustrate, consider the Monty Hall problem—a probability-based brain teaser named after the host of a 1960’s game show with a similar setup.

6.3.1 Case study: The Monty Hall problem

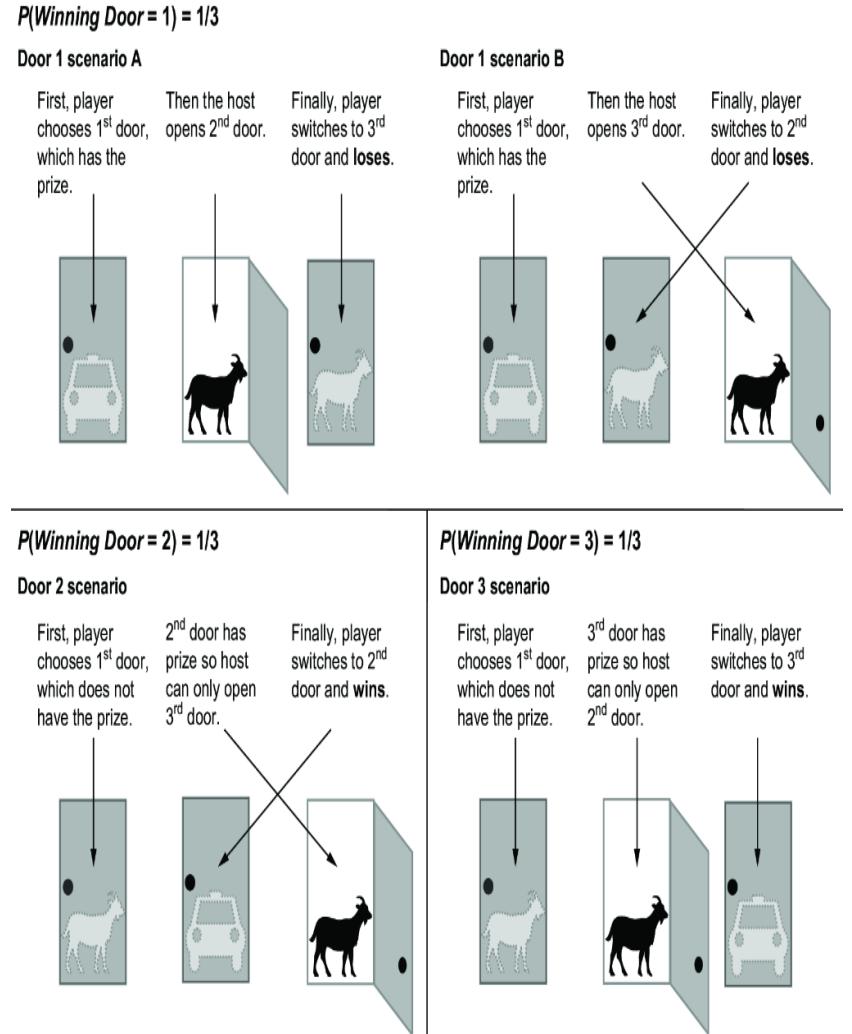

A contestant on a game show is asked to choose between three closed doors. Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. The player picks the first door. Then the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, for example the third door, which has a goat. The host then asks the contestant, ૿Do you want to switch to the second door, or do you want to stay with your original choice? The question is which is the better strategy, switching doors or staying?

The correct answer is to switch doors. This question appeared in a column in Parade magazine in 1990, with the correct answer. Thousands of readers mailed in, including many with graduate-level mathematical training, to refute the answer and say that there is no advantage to switching, that staying or switching have the same probability of winning.

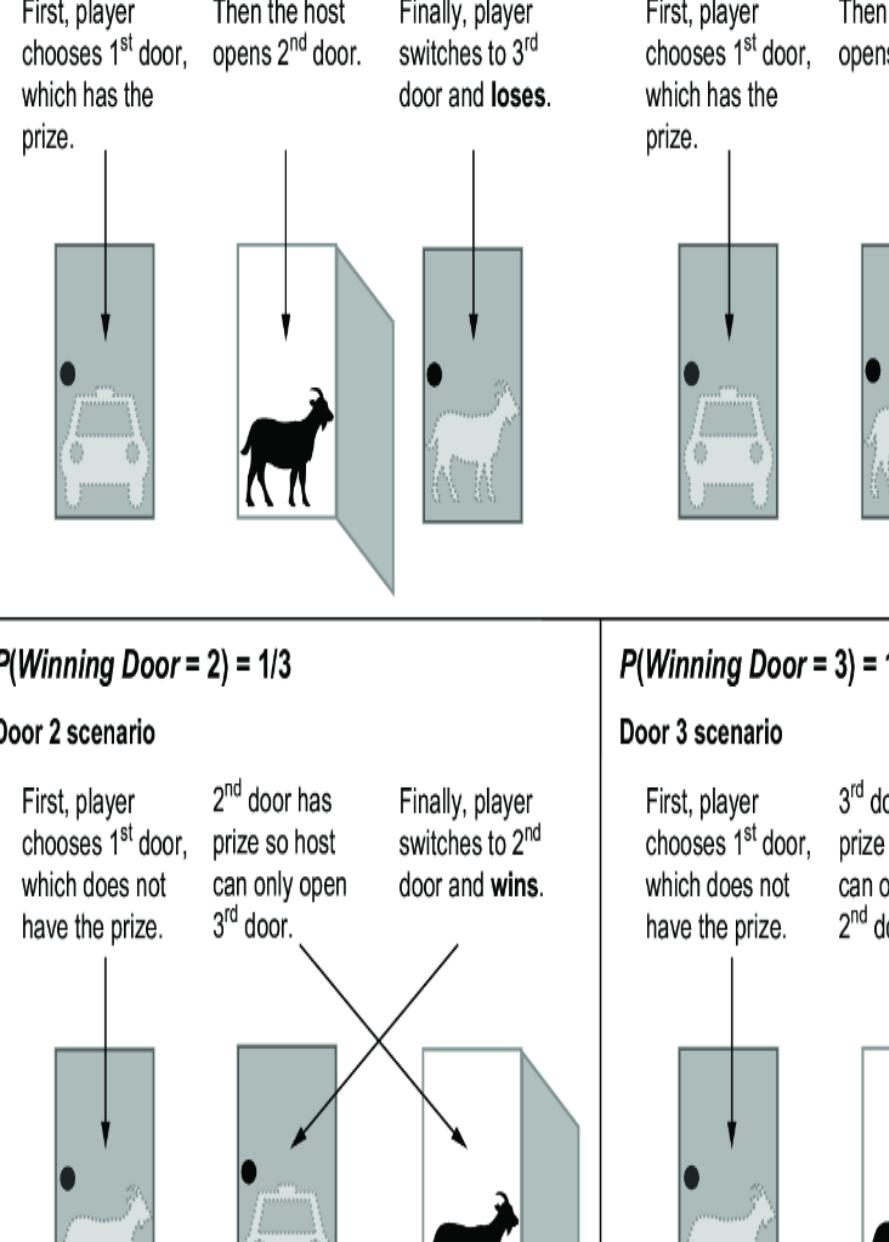

Figure 6.19 illustrates the intuition behind why switching is better. Switching doors is the correct answer because under the standard assumptions, the ૿switch strategy has a probability of two-thirds of winning the car, while the ૿stay strategy has only a one-third probability. It seems counterintuitive because each door has an equal chance of having the car when the game starts. It seems as if, once the host eliminates one door, each remaining door should have a 50-50 chance. This logic is false, because the host doesn’t

eliminate a door at random. He only eliminates a door that isn’t the player’s initial selection and that doesn’t have the car. A third of the times, those are the same door, and two-thirds of the time they are different doors; that one-third to two-thirds asymmetry is why the remaining doors don’t each have a 50-50 chance of having the car.

Figure 6.19 The Monty Hall problem. Each door has an equal probability of concealing a prize. The player chooses a door initially, the host reveals a losing door, and the player has the option to switch their initial choice. Contrary to intuition, the player should switch; if they switch, they will win two out of three times. This illustration assumes door 1 is chosen, but the results are the same regardless of the initial choice of door.

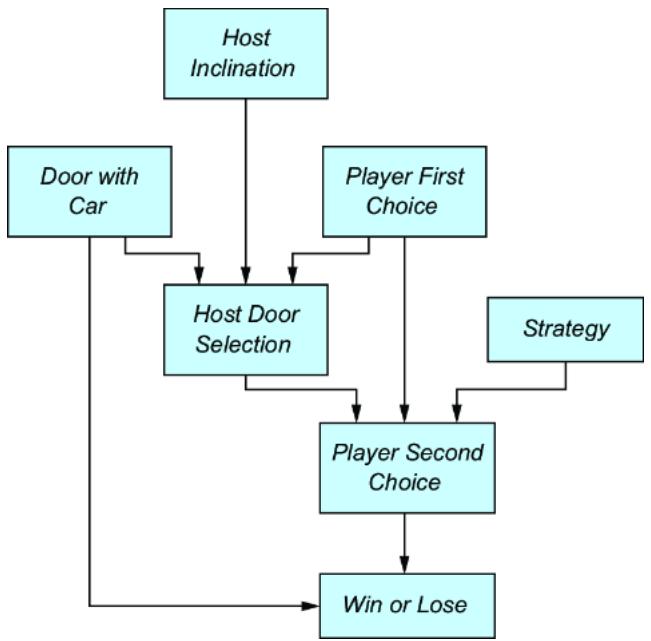

6.3.2 A causal DAG for the Monty Hall problem

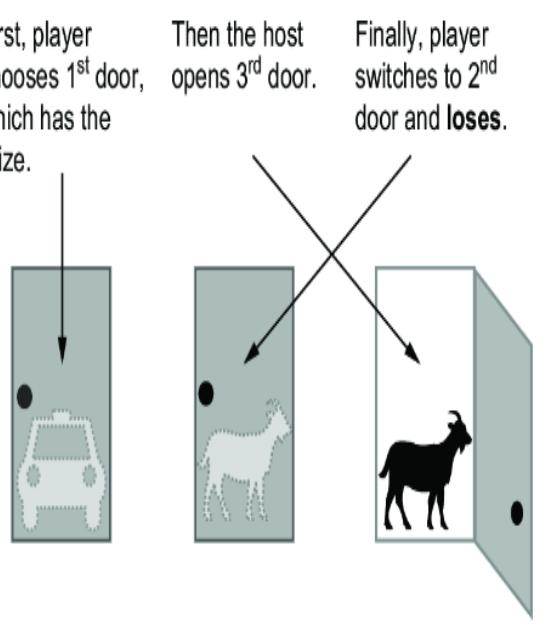

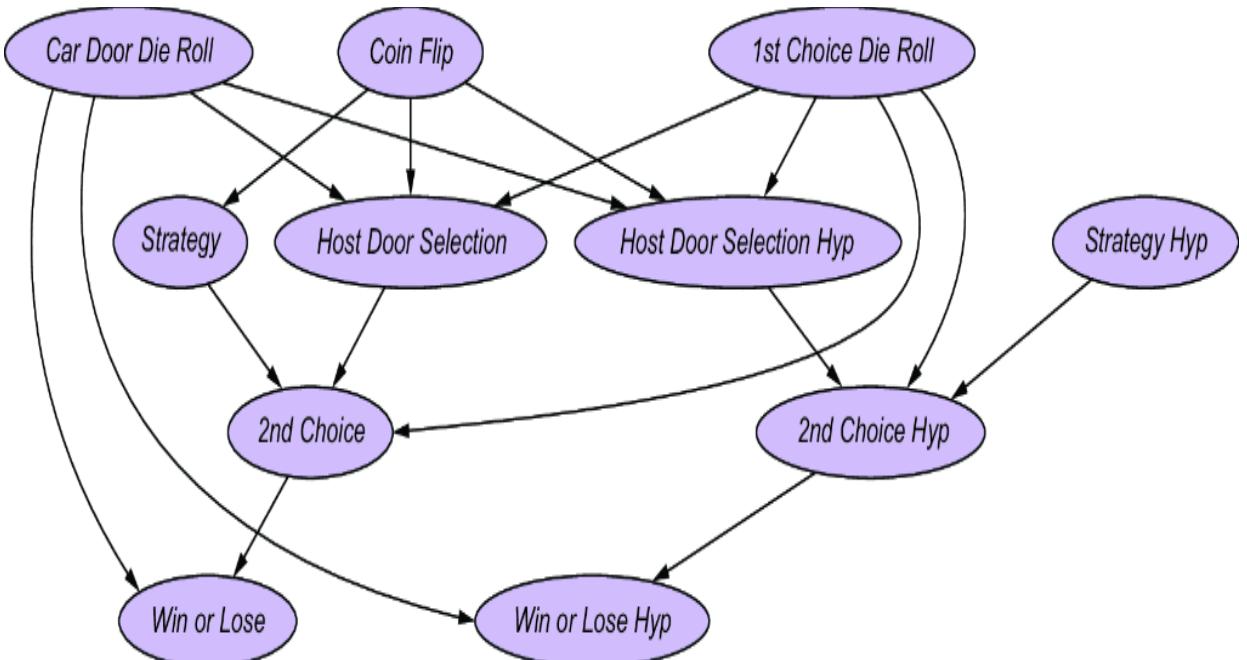

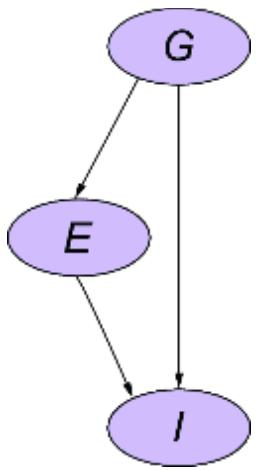

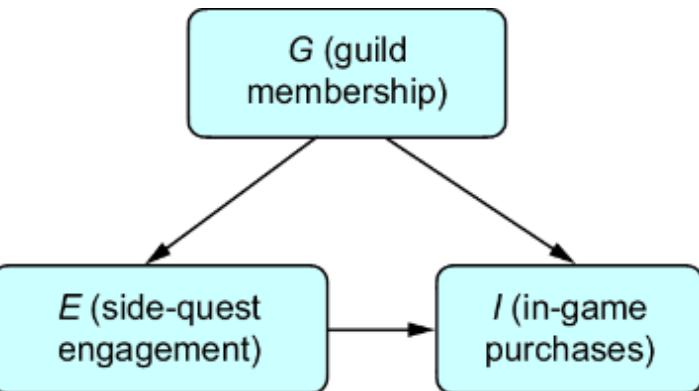

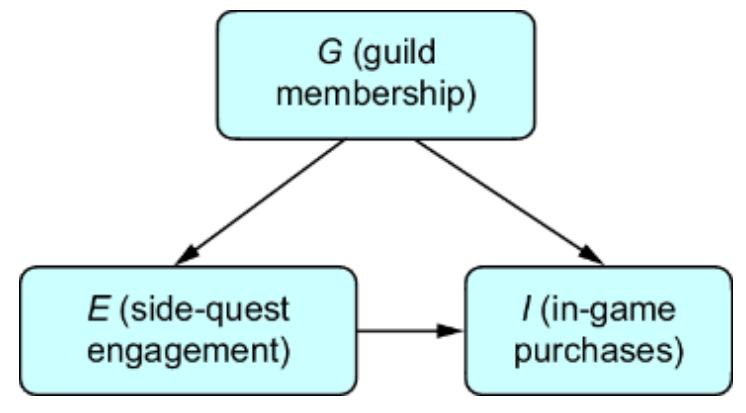

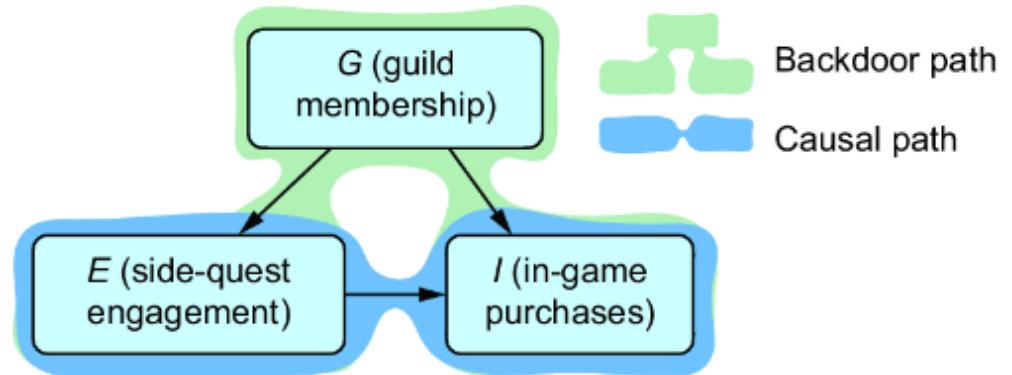

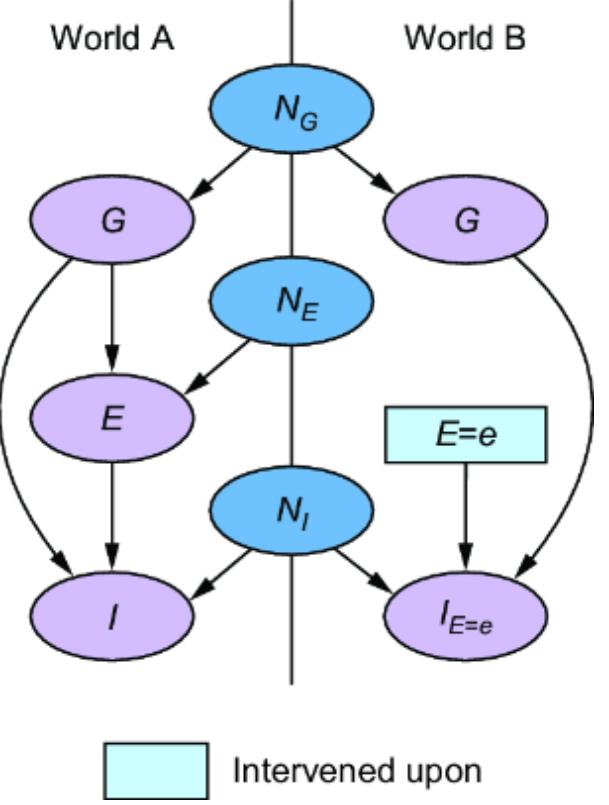

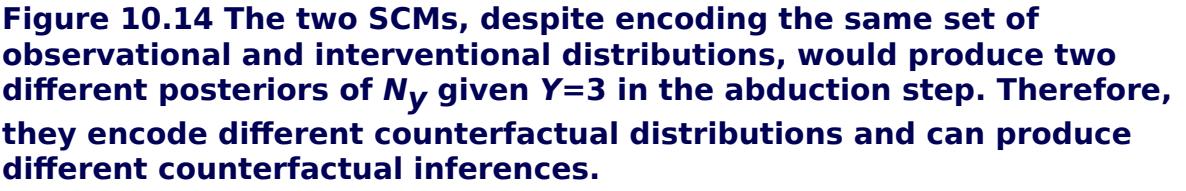

Causal modeling makes the Monty Hall problem much more intuitive. We can represent this game with the causal DAG in figure 6.20.

Figure 6.20 A causal DAG for the Monty Hall problem

The possible outcomes for each variable are as follows:

- Door with Car —Indicates the door that has the car behind it. 1st for the first door, 2nd for the second door, or 3rd for the third door.

- Player First Choice —Indicates which door the player chooses first. 1st for the first door, 2nd for the second door, or 3rd for the third door.

- Host Inclination —Suppose the host is facing the doors, such that from left to right they are ordered 1st, 2nd, and 3rd. This Host Inclination variable has two outcomes, Left and Right. When the outcome is Left, the host is inclined to choose the left-most available door; otherwise the host will be inclined to choose the right-most available door.

- Host Door Selection —The outcomes are again 1st, 2nd, and 3rd.

- Strategy —The outcomes are Switch if the strategy is to switch doors from the first choice, or Stay if the strategy is to stay with the first choice.

- Player Second Choice —Indicates which door the player chooses after being asked by the host whether they want to switch or not. The outcomes again are 1st, 2nd, and 3rd.

- Win or Lose —Indicates whether the player wins; the outcomes are Win or Lose. Winning occurs when Player Second Choice == Door with Car.

Next, we’ll see how to implement this as an SCM in pgmpy.

6.3.3 Implementing Monty Hall as an SCM with pgmpy

The rules of the game give us clear logic for the assignment functions. For example, we can represent the assignment function for Host Door Selection with table 6.1.

Table 6.1 A lookup table for Host Door Selection, given Player First Choice, Door with Car, and Host Inclination. It shows which door the host selects, given the player’s first choice, which door has the car, and the Host Inclination, which refers to whether the host will choose the left-most or right-most door in cases when the host has two doors to choose from.

| Host Inclination |

Left | Right | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Door with Car | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Player First Choice |

1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Host Door Selection |

2nd | 3rd | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 1st | 3rd | 3rd | 2nd | 3rd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 1st | 2nd |

When the door with the car and the player’s first choice are different doors, the host can only choose the remaining door. But if the door with the car and the player’s first choice are the same door, the host has two doors to choose from. He will choose the left-most door if Host Inclination is Left. For example, if Door with Car and Player First Choice are both 1st, the host must choose between the 2nd and 3rd doors. He will choose the 2nd door if Host Inclination == Left and the 3rd if Host Inclination == Right.

This logic would be straightforward to write using if-then logic with a library like Pyro. But since the rules are simple, we can use the far more constrained pgmpy library to write this function as a conditional probability table (table 6.2).

Table 6.2 We can convert the Host Door Selection lookup table (table 6.1) to a conditional probability table that we can implement as a TabularCPD object in pgmpy, where the probability of a given outcome is 0 or 1, and thus, deterministic.

| Host Inclination |

Left | Right | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Door with Car | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Player First Choice |

1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3r | |

| 1st | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Host Door |

2nd | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Selection | 3rd | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The entries in the table correspond to the probability of the Host Door Selection outcome given the values of the causes. Each probability outcome is either 0 or 1, given the causal parents, so the outcome is completely deterministic given the parents. Therefore, we can use this as our assignment function, and since it is a conditional probability table, we can implement it using the TabularCPD class in pgmpy.

Listing 6.4 Implementation of Host Door Selection assignment function in pgmpy

from pgmpy.factors.discrete.CPD import TabularCPD

f_host_door_selection = TabularCPD(

variable='Host Door Selection', #1

variable_card=3, #2

values=[ #3

[0,0,0,0,1,1,0,1,1,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,1,0], #3

[1,0,1,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,1,0,1], #3

[0,1,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,1,1,0,1,1,0,0,0,0] #3

], #3

evidence=[ #4

'Host Inclination', #4

'Door with Car', #4

'Player First Choice' #4

], #4

evidence_card=[2, 3, 3], #5

state_names={ #6

'Host Door Selection':['1st', '2nd', '3rd'], #6

'Host Inclination': ['left', 'right'], #6

'Door with Car': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd'], #6

'Player First Choice': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd'] #6

} #6

) #6#1 The name of the variable

#2 The cardinality (number of outcomes) #3 The probability table. The values match the value in table 6.2, as long as the ordering of the causal variables in the evidence argument matches the top-down ordering of causal variable names in the table. #4 The conditioning (causal) variables #5 The cardinality (number of outcomes) for each conditioning (causal) variable #6 The state names of each the variables

This code produces f_host_door_selection, a TabularCPD object we can add to a model of the class BayesianNetwork. We can then use this in a CGM as we would a more typical TabularCPD object.

Similarly, we can create a look-up table for Player Second Choice, as shown in table 6.3.

Table 6.3 A lookup table for Player Second Choice, conditional on Player First Choice, Host Door Selection, and Strategy. Player Second Choice cells are empty in the impossible cases where Player First Choice and Host Door Selection are the same.

| Strategy | Stay | Switch | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host Door Selection |

1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |||||||||||||

| Player First Choice |

1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Player Second Choice |

2nd | 3rd | 1st | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 1st |

The host will never choose the same door as the player’s first choice, so Host Door Selection and Player First Choice can never have the same value. The entries of Player Second Choice are not defined in these cases.

Expanding this to a conditional probability table gives us table 6.4. Again, the cells with impossible outcomes are left blank.

Table 6.4 The result of converting the lookup table for Player Second Choice (table 6.3) to a conditional probability table that we can implement as a TabularCPD object

| Strategy | Stay | Switch | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host Door Selection |

1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||||||||||||

| Player First Choice |

1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||

| Player | 1st | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||||

| Second | 2nd | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Choice | 3rd | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Unfortunately, we can’t leave the impossible values blank when we specify a Tabular-CPD, so in the following code, we’ll need to assign arbitrary values to these elements.

Listing 6.5 Implementation of Player Second Choice assignment function in pgmpy

from pgmpy.factors.discrete.CPD import TabularCPD

f_second_choice = TabularCPD(

variable='Player Second Choice',

variable_card=3,

values=[

[1,0,0,1,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,1,0,1,0], #1

[0,1,0,0,1,0,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1], #1

[0,0,1,0,0,1,0,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,0,0,0,0] #1

],

evidence=[

'Strategy',

'Host Door Selection',

'Player First Choice'

],

evidence_card=[2, 3, 3],

state_names={

'Player Second Choice': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd'],

'Strategy': ['stay', 'switch'],

'Host Door Selection': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd'],

'Player First Choice': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd']

}

)#1 The probability values are 0 or 1, so the assignment function is deterministic. In cases where the parent combinations are impossible, we still have to assign a value.

That gives us a second TabularCPD object. We’ll create one for each node.

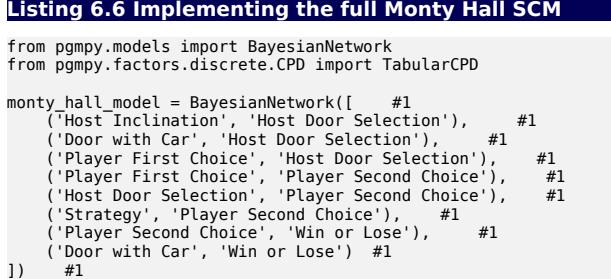

First, let’s set up the causal DAG.

#1 Build the causal DAG.

monty_hall_model is now a causal DAG. It will become an SCM after we add the exogenous variable distributions and assignment functions.

The following listing adds the exogenous variable distribution.

Listing 6.7 Create the exogenous variable distributions

p_host_inclination = TabularCPD( #1

variable='Host Inclination', #1

variable_card=2, #1

values=[[.5], [.5]], #1

state_names={'Host Inclination': ['left', 'right']} #1

) #1

p_door_with_car = TabularCPD( #2

variable='Door with Car', #2

variable_card=3, #2

values=[[1/3], [1/3], [1/3]], #2

state_names={'Door with Car': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd']} #2

) #2

p_player_first_choice = TabularCPD( #3

variable='Player First Choice', #3

variable_card=3, #3

values=[[1/3], [1/3], [1/3]], #3

state_names={'Player First Choice': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd']} #3

) #3

p_host_strategy = TabularCPD( #4

variable='Strategy', #4

variable_card=2, #4

values=[[.5], [.5]], #4

state_names={'Strategy': ['stay', 'switch']} #4

) #4#1 A CPD for the Host Inclination variable. In cases when the player chooses the door with the car, the host has a choice between the two other doors. This variable is ૿left when the host is inclined to choose the left-most door, and ૿right if the host is inclined to choose the right-most door.

#2 A CPD for the variable representing which door has the prize car. Assume each door has an equal probability of having the car.

#3 A CPD for the variable representing the player’s first door choice. Each door has an equal probability of being chosen.

#4 A CPD for the variable representing the player’s strategy. ૿Stay is the strategy of staying with the first choice, and ૿switch is the strategy of switching doors.

Having created the exogenous distributions, we’ll now create the assignment functions. We’ve already created f_host_door_selection and f_second_choice, so we’ll add f_win_or_lose the assignment function determining whether the player wins or loses.

Listing 6.8 Create the assignment functionsf_win_or_lose = TabularCPD(

variable='Win or Lose',

variable_card=2,

values=[

[1,0,0,0,1,0,0,0,1],

[0,1,1,1,0,1,1,1,0],

],

evidence=['Player Second Choice', 'Door with Car'],

evidence_card=[3, 3],

state_names={

'Win or Lose': ['win', 'lose'],

'Player Second Choice': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd'],

'Door with Car': ['1st', '2nd', '3rd']

}

)Finally, we’ll add the exogenous distribution and the assignment functions to monty_hall_model and create the SCM.

Listing 6.9 Create the SCM for the Monty Hall problem

monty_hall_model.add_cpds(

p_host_inclination,

p_door_with_car,

p_player_first_choice,

p_host_strategy,

f_host_door_selection,

f_second_choice,

f_win_or_lose

)We can run the variable elimination inference algorithm to verify the results of the algorithm. Let’s query the probability of winning, given that the player takes the ૿stay strategy.

Listing 6.10 Inferring the winning strategy

from pgmpy.inference import VariableElimination #1

infer = VariableElimination(monty_hall_model) q1 = infer.query([‘Win or Lose’], evidence={‘Strategy’: ‘stay’}) #2 print(q1) #2 q2 = infer.query([‘Win or Lose’], evidence={‘Strategy’: ‘switch’}) #3 print(q2) #3 q3 = infer.query([‘Strategy’], evidence={‘Win or Lose’: ‘win’}) #4 print(q3) #4

#1 We’ll use the inference algorithm called ૿variable elimination. #2 Print the probabilities of winning and losing when the player uses the ૿stay strategy. #3 Print the probabilities of winning and losing when the player uses the ૿switch strategy. #4 Print the probabilities that the player used a stay strategy versus a switch strategy, given that the player won.

This inference produces the following output:

| Win or Lose | +——————-+——————–+ phi(Win or Lose) |

|---|---|

| Win or Lose(win) | +===================+====================+ 0.3333 +——————-+——————–+ |

| Win or Lose(lose) | 0.6667 +——————-+——————–+ |

The probability of winning and losing under the ૿stay strategy is 1/3 and 2/3, respectively. In contrast, here’s the output for the ૿switch strategy:

| Win or Lose | +——————-+——————–+ phi(Win or Lose) +===================+====================+ |

|---|---|

| Win or Lose(win) | 0.6667 +——————-+——————–+ |

| Win or Lose(lose) | 0.3333 +——————-+——————–+ |

The probability of winning and losing under the ૿switch strategy is 2/3 and 1/3, respectively. We can also condition on a winning outcome and infer the probability that each strategy leads to that outcome.

| +——————+—————–+ Strategy |

phi(Strategy) |

|---|---|

| +==================+=================+ Strategy(stay) +——————+—————–+ |

0.3333 |

| Strategy(switch) +——————+—————–+ |

0.6667 |

These are plain vanilla non-causal probabilistic inferences—we were just validating that our SCM is capable of produce these inferences. In chapter 9, we’ll demonstrate how this SCM enables causal counterfactual inferences that simpler models can’t answer, such as ૿What would have happened had the losing player used a different strategy?

6.3.4 Exogenous variables in the rule-based system

In this Monty Hall SCM, the root nodes (nodes with no incoming edges) in the causal DAG function as the exogenous variables. This is slightly different from our formal definition of an SCM, which states that exogenous variables represent causal factors outside the system. Host Inclination meets that definition, as this was not part of the original description. Door with Car, Player First Choice, and Strategy are another matter. To remedy this, we could introduce exogenous parents to these variables, and set these variables deterministically, given these parents, as we do elsewhere in this chapter. But while modeling this in pgmpy, that’s a bit redundant.

6.3.5 Applications of SCM-modeling of rule-based systems

While the Monty Hall game is simple, do not underestimate the expressive power of incorporating rules into assignment functions. Some of the biggest achievements in AI in previous decades have been at beating expert humans in board games with simple rules. Simulation software, often based on simple rules for how a system transitions from one state to another, can model highly complex behavior. Often, we want to apply causal analysis to rule-based systems engineered by humans (who know and can rewrite those rules), such as an automated manufacturing system.

6.4 Training an SCM on data

Given a DAG, we make a choice of whether to use a CGM or an SCM. Let’s suppose we want to go with the SCM, and we want to ૿fit or ૿train this SCM on data. To do this, we choose some parameterized function class (e.g., linear functions, logistic functions, etc.) for each assignment function. That function class becomes a specific function once we’ve fit its parameters on data. Similarly, for each exogenous variable, we want to specify a canonical probability distribution, possibly with parameters we can fit on data.

In our femur-height example, all the assignment functions were linear functions and the exogenous variables were normal distributions. But with tools like Pyro, you can specify each assignment function and exogenous distribution one by one. Then you can train the parameters just as you would with a CGM. For example, instead of taking this femur-height model from the forensic textbook:

\[n\_Y \sim \mathcal{N}(0, \mathbf{3.3})\]

y = 25 + 3x + ny

you can just fit the parameters α, β, and δ of a linear model on actual forensic data:

ny ~ N (0, δ)

y = α + βx + ny

In this forensics example, we use a linear assignment function because height is proportional to femur length. Let’s consider other ways to capture how causes influence their effects.

6.4.1 What assignment functions should I choose?

The most important choice in an SCM model is your choice of function classes for the assignment functions, because these choices represent your assumptions about the ૿how of causality. You can use function classes common in math, such as linear models. You can also use code (complete with if-then statements, loops, recursion, etc.) like we did with the rock-throwing example.

Remember, you are modeling a ground-truth SCM. You are probably going to specify your assignment functions differently from those in the ground-truth SCM, but that’s fine. You don’t need your SCM to match the ground truth exactly; you just need your model to be right about the ૿how assumptions it is relying on for your causal inferences.

SCMS WITHOUT “HOW” ASSUMPTIONS ARE JUST CGMS

Suppose you built an SCM where every assignment function is a linear function. You are using a linear Gaussian assumption because your library of choice requires it (e.g., LinearGaussianCPD is pretty much your only choice for modeling continuous variables in pgmpy). However, you are not planning on relying on that linear assumption for your causal inference. In this case, while your model checks the boxes of an SCM, it is effectively a CGM with linear models of the causal Markov kernels.

Suppose, for example, that instead of a linear relationship between X and Y, X and Y followed a nonlinear S-curve, and your causal inference was sensitive to this S-curve. Imagine that the ground-truth SCM captured this with an assignment function in the form of the Hill equation (a function that arises in biochemistry and that can capture S-curves). But your SCM instead uses a logistic function fit on data. Your model, though wrong, will be sufficient to make a good causal inference if your logistic assignment function captured everything it needed to about the S-curve for your inference to work.

6.4.2 How should I model the exogenous variable distributions?

In section 6.1.3, we formulated our generative SCM in a particular way, where every node gets its own exogenous variable representing its unmodeled causes. Under that formulation, the role of the exogenous variable distribution is simply to provide sufficient variation for the SCM to model the joint distribution. This means that, assuming you have selected your assignment function classes, you can choose canonical distributions for the exogenous variables based on how well they would fit the data after parameter estimation. Some canonical distributions may fit better than others. You can contrast different choices using standard techniques for model comparison and cross-validation.

These canonical distributions can be parameterized, such as N(0, δ) in

\[n\_Y \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \mathfrak{G})\]

y = α + βx + ny

A more common approach in generative AI is to use constants in the canonical distribution and only train the parameters of the assignment function:

ny ~ N(0, 1)

y = α + βx + δ ny

Either is fine, as long as your choice captures your ૿how assumptions.

6.4.3 Additive models: A popular choice for SCM modeling

Additive models are SCM templates that use popular trainable function classes for assignment functions. They can be a great place to start in SCM modeling. We’ll look at three common types of additive models: linear Gaussian additive model (LiGAM), linear non-Gaussian additive model (LiNGAM), and the nonlinear additive noise model (ANM). These models each encapsulate a pair of constraints: one on the structure of the assignment functions, and one on the distribution of the additive exogenous variables.

Additivity makes this approach easier because there are typically unique solutions to algorithms that learn the parameters of these additive models from data. In some cases, those parameters have a direct causal interpretation. There are also myriad software libraries for training additive models on data.

Let’s demonstrate the usefulness of additive models with an example. Suppose you were a biochemist studying the synthesis of a certain protein in a biological sample. The sample has some amount of an enzyme that reacts with some precursors in the sample and synthesizes the protein you are interested in. You measure the quantity of the protein you’re interested in. Let X be the amount of enzyme, and let Y be the measured amount of the protein of interest. We’ll model this system with an SCM, which has the DAG in figure 6.21.

Figure 6.21 The amount of enzyme (X) is a cause the measured quantity of protein (Y).

We have qualitative knowledge of how causes affect effects, but we have to turn that knowledge into explicit choices of function classes for assignment functions and exogenous variable distributions. Additive models are a good place to start.

To illustrate, we’ll focus on the assignment function and exogenous variable distribution for Y, the amount of the target protein in our example. Generating from the exogenous variable, and setting Y via the assignment function, has the following notation:

ny ~ P(Ny)

y := fy(x, ny)

fy(.) denotes the assignment function for y, which takes a value of the endogenous parent X and exogenous parent Ny as inputs.

In an additive assignment function, the exogenous variable is always added to some function of endogenous parents. In our example, this means that the assignment function for Y has the following form:

y := fy(x, ny) = g(x) + ny

Here, g(.) is some trainable function of the endogenous parent(s), and ny is added to the results of that function.

For our protein Y, these models say that the measured amount of protein Y is equal to some function of the enzyme amount g (X ) plus some exogenous factors, such as noise in the measurement device. This assumption is attractive, because it lets us think of unmodeled exogenous causes as additive ૿noise. In terms of statistical signal processing, it is relatively easy to disentangle some core signal (e.g., g (x )) from additive noise.

In general, let V represent an endogenous variable in the model, VPA represent the endogenous parents of V, and Nv represent an exogenous variable.

\[\nu := f\_{\vee}(\mathsf{V}\_{\mathsf{PA}^\*} \, n\_{\vee}) = g\left(\mathsf{V}\_{\mathsf{PA}}\right) + n\_{\vee}\]

Additive SCMs have several benefits, but here we’ll focus on their benefit as a template for building SCMs. We’ll start with the simplest additive model, the linear Gaussian additive model.

6.4.4 Linear Gaussian additive model

In a linear Gaussian additive model, the assignment functions are linear functions of the parents, and the exogenous variables have a normal distribution.

In our enzyme example, Ny and Y are given as follows:

\[n\_Y \sim \mathsf{N}(\mathbf{0}, \sigma\_Y)\]

y := β0 + βxx + ny

Here, β0 is an intercept term, and βx is a coefficient for X . We are assuming that for every unit increase in the amount of enzyme X, there is a βx increase in the expected amount of the measured protein. Ny accounts for variation around that expected amount due to exogenous causal factors, and we assume it has a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and scale parameter σy. For example, we might assume that Ny is composed mostly of technical noise from the measurement device, such as dust particles that interfere with the sensors. We might know from experience with this device that this noise has a normal distribution.

In general, for variable V with a set of K parents, VPA = {Vpa,1, …, Vpa,K}:

\[\begin{aligned} n\_{\mathcal{Y}} &\sim N(0, \sigma \mathcal{y}) \\ v &:= \beta\_0 + \sum\_j \beta\_x v\_{p a, j} + n\_{\mathcal{Y}} \end{aligned}\]

This model defines parameters: β0 is an intercept term, βj is the coefficient attached to the j th parent, and σv is the scale parameter of Nv’s normal distribution.

Let’s see an example of a LiNGAM model in Pyro.

Listing 6.11 Pyro example of a linear Gaussian model

from pyro import sample

from pyro.distributions import Normal

def linear_gaussian():

n_x = sample("N_x", Normal(9., 3.))

n_y = sample("N_y", Normal(9., 3.))

x = 10. + n_x #1

y = 2. * x + n_y #2

return x, y#1 The distributions of the exogenous variables are normal (Gaussian). #2 The functional assignments are linear.

Linear Gaussian SCMs are especially popular in econometric methods used in the social sciences because the model assumptions have many attractive statistical properties. Further, in linear models, we can interpret a parent causal regressor variable’s coefficient as the causal effect (average treatment effect) of that parent on the effect (response) variable.

6.4.5 Linear non-Gaussian additive models

Linear non-Gaussian additive models (LiNGAM) are useful when the Gaussian assumption on exogenous variables is not appropriate. In our example, the amount of protein Y cannot be negative, but that can easily occur in a linear model if β0, x, or nx have low values. LiNGAM models remedy this by allowing the exogenous variable to have a non-normal distribution.

Listing 6.12 Pyro example of a LiNGAM modelfrom pyro import sample

from pyro.distributions import Gamma

def LiNGAM():

n_x = sample("N_x", Gamma(9., 1.)) #1

n_y = sample("N_y", Gamma(9., 1.)) #1

x = 10. + n_x #2

y = 2. * x + n_y #2

return x, y#1 Instead of a normal (Gaussian) distribution, the exogenous variables have a gamma distribution with the same mean and variance.

#2 These are the same assignment functions as in the linear Gaussian model.

In the preceding model, we use a gamma distribution. The lowest possible value in a gamma distribution is 0, so y cannot be negative.

6.4.6 Nonlinear additive noise models

As I’ve mentioned, the power of the SCM is the ability to choose functional assignments that reflect how causes affect their direct effects. In our hypothetical example, you are a biochemist. Could you import knowledge from biochemistry to design the assignment function? Here is what that reasoning might look like. (You don’t need to understand the biology or the math, in this example, just the logic).

There is a common mathematical assumption in enzyme modeling called mass action kinetics. In this model, T is the maximum possible amount of the target protein. The biochemical reactions happen in real time, and during that time, the amount of the target protein fluctuates before stabilizing at some equilibrium value Y. Let Y(t) and X(t) be the amount of the target protein and enzyme at a given time point. Mass action kinetics give us the following ordinary differential equation:

\[\frac{dY(t)}{d(t)} = \nu X(t)(T - Y(t)) - \alpha Y(t)\]

Here, v and α are rate parameters that characterize the rates at which different biochemical reactions occur in time. This differential equation has the following equilibrium solution,

\[Y = T \times \frac{\beta X}{1 + \beta X}\]

where Y and X are equilibrium values of Y(t) and X(t), and β = v/α.

As an enzyme biologist, you know that this equation captures something of the actual mechanism underpinning the biochemistry of this system, like physics equations such as Ohm’s law and SIR models in epidemiology. You elect to use this as your assignment function for Y:

\[Y \coloneqq T \times \frac{\beta X}{1 + \beta X} + N\_{\mathcal{Y}}\]

This is a nonlinear additive noise model (ANM). In general, ANMs have the following structure:

\[\mathsf{V} = \mathsf{g} \left( \mathsf{V}\_{\mathsf{p}\mathsf{a}} \right) + \mathsf{N}\_{\mathsf{V}}\]

In our example g (X ) = T × β X / (1 + β X ). Ny can be normal (Gaussian) or non-Gaussian.

CONNECTING DYNAMIC MODELING AND SIMULATION TO SCMS

Dynamic models describe how a system’s behavior evolves in time. The use of dynamic modeling, as you saw in the enzyme modeling example, is one approach to addressing this knowledge elicitation problem for SCMs.

In this section, I illustrated how an enzyme biologist could use a domain-specific dynamic model, specifically an ODE, to construct an SCM. An ODE is just one type of dynamic model. Another example is computer simulator models, such as the simulators used in climate modeling, power-grid modeling, and manufacturing. Simulators can also model complex social processes, such as financial markets and epidemics. Simulator software is a growing multibillion dollar market.

In simulators and other dynamic models, specifying the ૿how of causality can be easier than in SCMs. SCMs require assignment functions to explicitly capture the global behavior of the system. Dynamic models only require you to specify the rules for how things change from instant to instant. You can then see global behavior by running the simulation. The trade-off is that dynamic models can be computationally expensive to run, and it is generally difficult to train parameters of dynamic models on data or perform inferences given data as evidence. This has motivated interesting research in combining the knowledge elicitation convenience of dynamic models with the statistical and computational conveniences of SCMs.

Next, we’ll examine using regression tools to train these additive models.

6.4.7 Training additive model SCMs with regression tools

In statistics, regression modeling finds parameter values that minimize the difference between a parameterized function of a set of predictors and a response variable. Regression modeling libraries are ubiquitous, and one advantage of additive SCM models is that they can use those libraries to fit an SCM’s parameters on data. For example, parameters of additive models can be fit with standard linear and nonlinear regression parameter fitting techniques (e.g., generalized least squares). We can also leverage these tools’ regression goodness-of-fit statistics to evaluate how well the model explains the data.

Note that the predictors in a general regression model can be anything you like. Most regression modeling pedagogy encourages you to keep adding predictors that increase goodness-of-fit (e.g., adjusted R-squared) or reduce predictive error. But in an SCM, your predictors are limited to direct endogenous causes.

CAN I USE GENERALIZED LINEAR MODELS AS SCMS?

In statistical modeling, a generalized linear model (GLM) is a flexible generalization of linear regression. In a GLM, the response variable is related to a linear function of the predictors with a link function. Further, variance of the response variable can be a function of the predictors. Examples include logistic regression, Poisson regression, and gamma regression. GLMs are a fundamental statistical toolset for data scientists.

In a CGM (non-SCM), GLMs are good choices as models of causal Markov kernels. But a common question is whether GLMs can be used as assignment functions in an SCM.

Several GLMs align with the structure of additive SCMs, but it’s generally best not to think of GLMs as templates for SCMs. The functional form of assignment functions in an SCM is meant to reflect the nature of the causal relationship between a variable and its causal parents. The functional form of a GLM applies a (in some cases nonlinear) link function to a linear function of the predictors. The link function is designed to map that linear function of the predictors to the mean of a canonical distribution (e.g., normal, Poisson, gamma). It is not designed to reflect causal assumptions.

6.4.8 Beyond the additive model

If the ૿how of an assignment function requires more nuance than you can capture with an additive model, don’t constrain yourself to an additive model. Using biochemistry as an example, it is not hard to come up with scenarios where interactions between endogenous and exogenous causes would motivate a multiplicative model.

For these more complex scenarios, it starts making sense to move toward using probabilistic deep learning tools to implement an SCM.

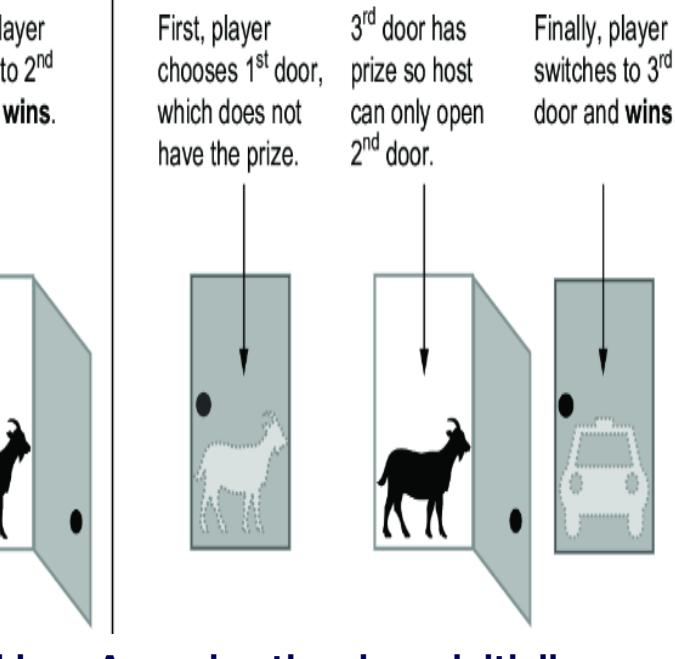

6.5 Combining SCMs with deep learning

Let’s revisit the enzyme kinetic model, where the amount of an enzyme X is a cause of the amount of a target protein Y, as in figure 6.22.

Figure 6.22 The amount of enzyme (X) is a cause of the measured quantity of protein (Y).

I said previously that, based on a dynamic mathematical model popular in the study of enzyme biology, a good candidate for an additive assignment function for Y is

\[Y \coloneqq T \times \frac{\beta X}{1 + \beta X} + N\_{\mathcal{Y}}\]

Further, suppose that we knew from experiments that T was 100 and β was .08.

Ideally, we would want to be able to reproduce these parameter values from data. Better yet, we should like to leverage the automatic differentiation-based frameworks that power modern deep learning.

6.5.1 Implementing and training an SCM with basic PyTorch

First, let’s create a PyTorch version of the enzyme model.

Listing 6.13 Implement the PyTorch enzyme model

from torch import nn

class EnzymeModel(nn.Module): #1

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.β = nn.Parameter(torch.randn(1, 1)) #2

def forward(self, x):

x = torch.mul(x, self.β) #3

x = x.log().sigmoid() #4

x = torch.mul(x, 100.) #5

return x

#1 Create the enzyme model.

#2 Initialize the parameter D�.

#3 Calculate the product of enzyme amount X and D�.

#4 Implement the function u / (u + 1) as sigmoid(log(u)), since the sigmoid and log functions are native

PyTorch transforms.

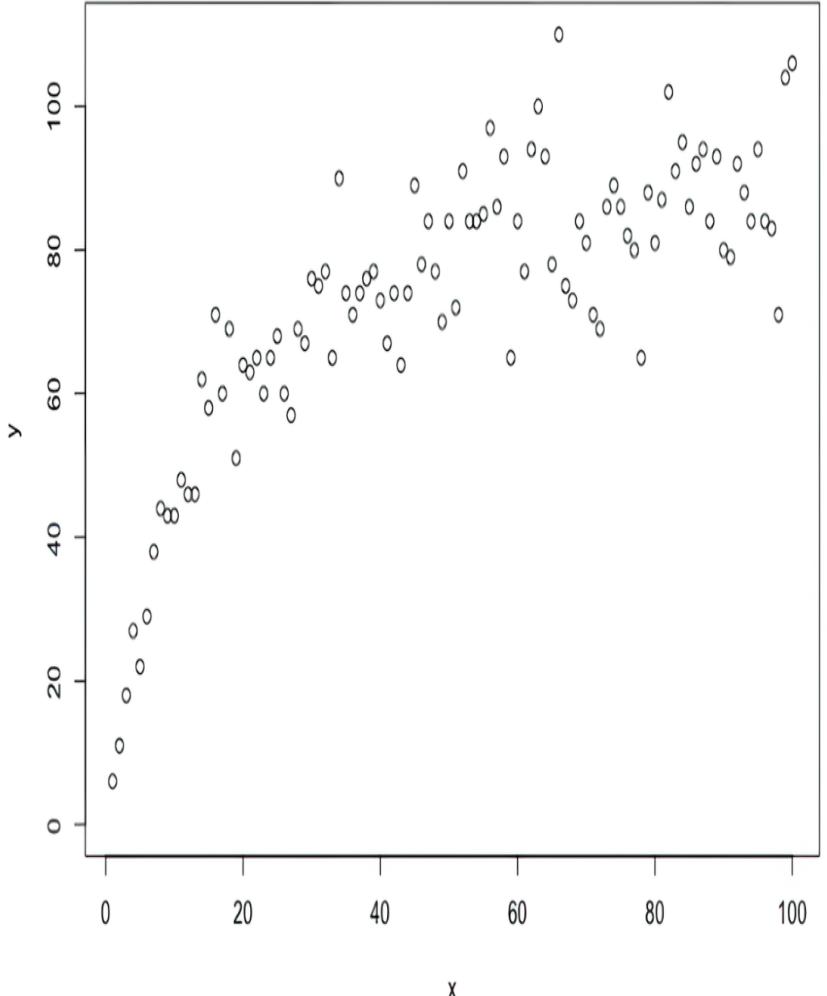

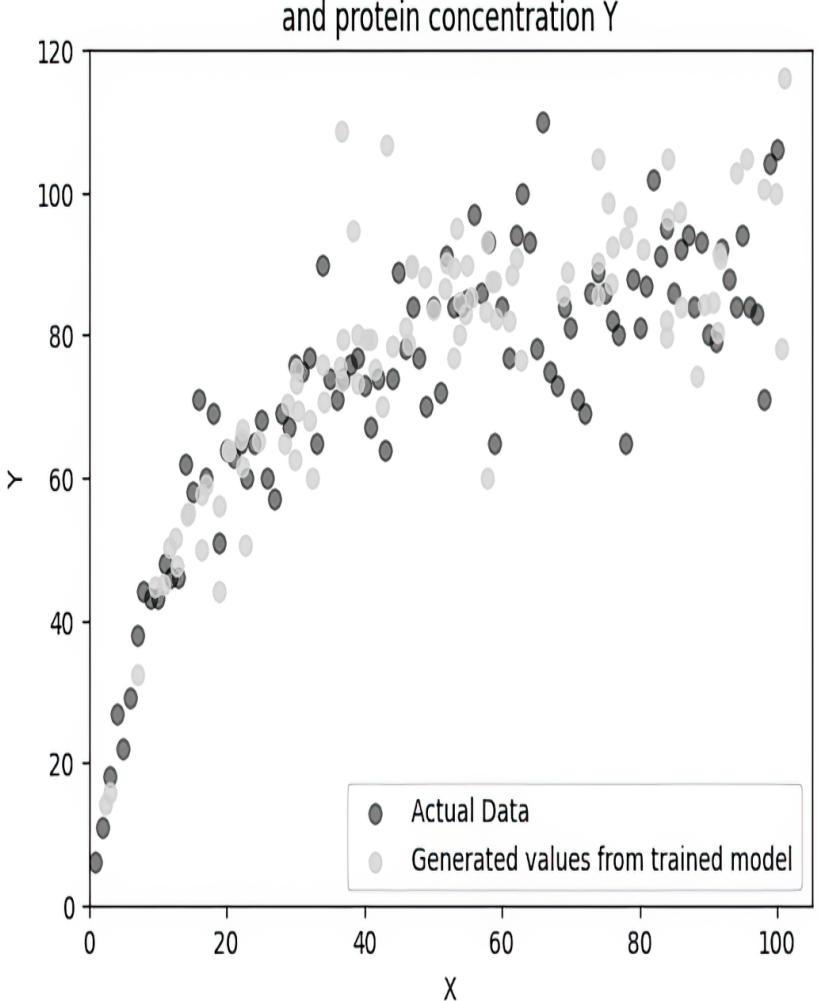

#5 Multiply by T = 100.Suppose we observed the data from this system, visualized in figure 6.23.

Figure 6.23 Exampled enzyme data. X is the amount of enzyme, and Y is the amount of target protein.

Let’s try to learn β from this data using a basic PyTorch workflow.

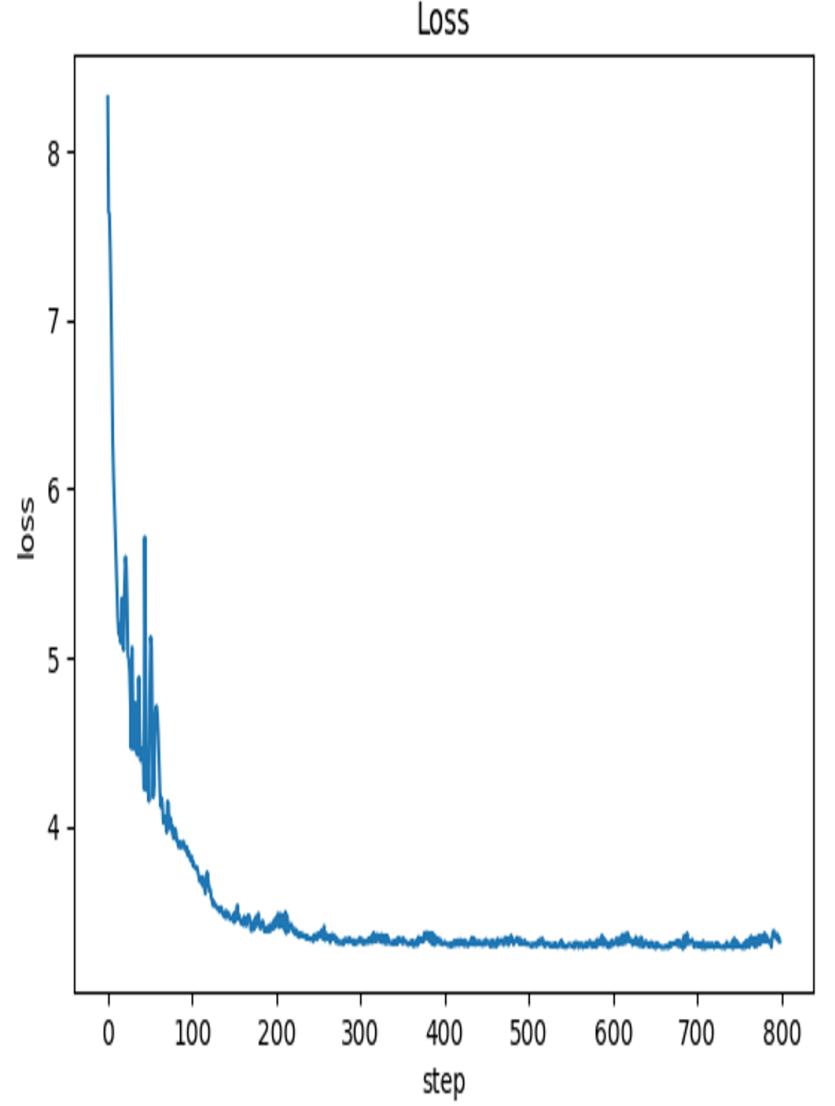

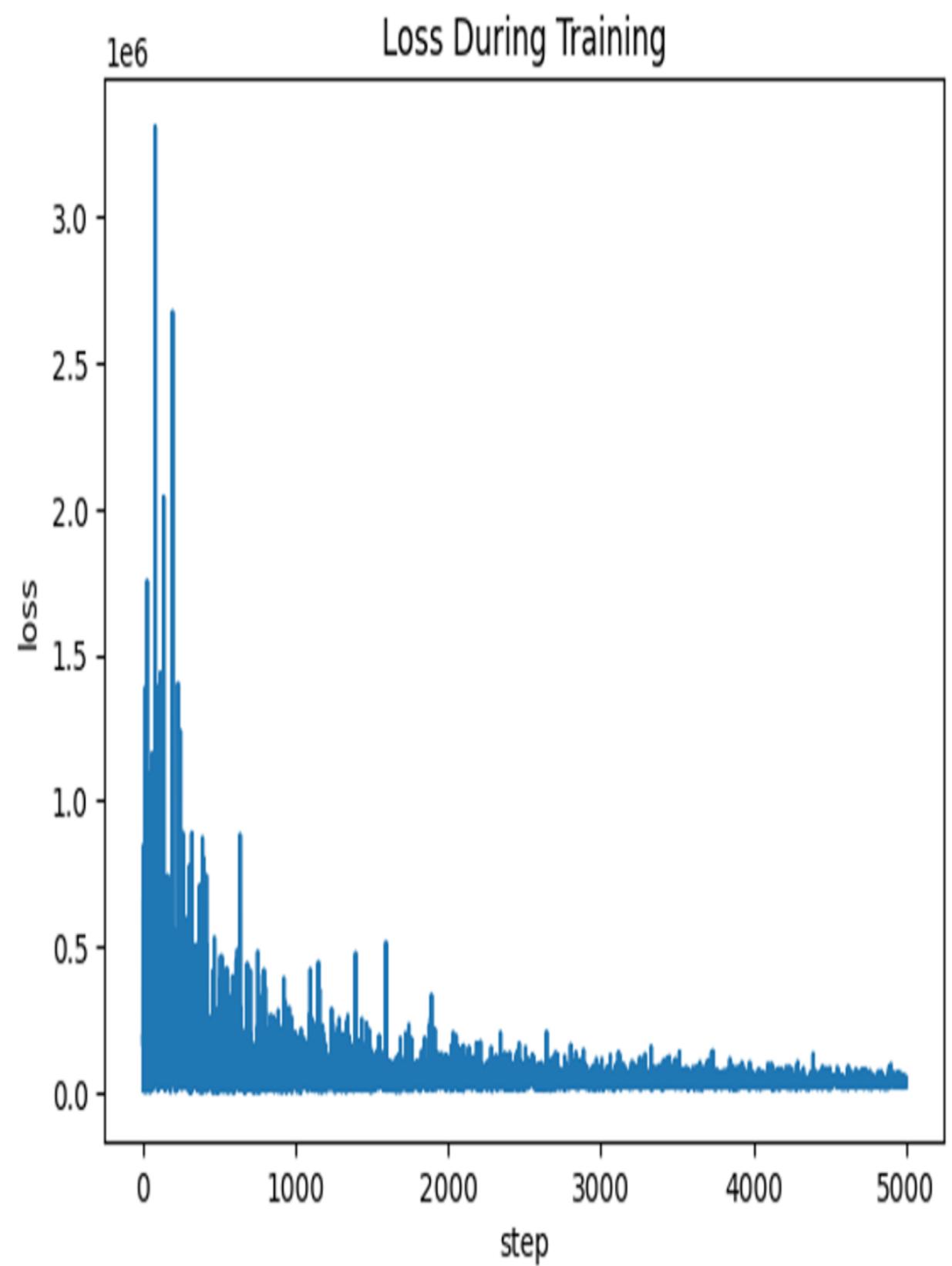

Listing 6.14 Fitting enzyme data with PyTorch import pandas as pd from torch import tensor import torch df = pd.read_csv(“https://raw.githubusercontent.com/altdeep /causalML/master/datasets/enzyme-data.csv”) #1 X = torch.tensor(df[‘x’].values).unsqueeze(1).float() #2 Y = torch.tensor(df[‘y’].values).unsqueeze(1).float() #2 def train(X, Y, model, loss_function, optim, num_epochs): #3 loss_history = [] #3 for epoch in range(num_epochs): #3 Y_pred = model(X) #3 loss = loss_function(Y_pred, Y) #3 loss.backward() #3 optim.step() #3 optim.zero_grad() #3 if epoch % 1000 == 0: #4 print(round(loss.data.item(), 6)) #4 torch.manual_seed(1) #5 enzyme_model = EnzymeModel() optim = torch.optim.Adam(enzyme_model.parameters(), lr=0.00001) #6 loss_function = nn.MSELoss() #7 train(X, Y, enzyme_model, loss_function, optim, num_epochs=60000)

#1 Load the enzyme data from GitHub. #2 Convert the data to tensors. #3 Create the training algorithm. #4 Print out losses during training. #5 Set a random seed for reproducibility. #6 Initialize an instance of the Adam optimizer. Use a low value for the learning rate because loss is very sensitive to small changes in D�. #7 Using mean squared loss error is equivalent to assuming Ny is additive and symmetric.

When I run this code with the given random seed, it produces a value of 0.1079 (you can access the value by printing enzyme_model.β.data), which only differs slightly from the ground-truth value of .08. This implementation did not represent the exogenous variable Ny explicitly, but statistics theory tells us that using the mean squared error loss function is equivalent to assuming Ny was additive and had a normal distribution. However, it also assumes that the normal distribution had constant variance, while the funnel shape in the scatterplot indicates the variance of Ny might increase with the value of X.

6.5.2 Training an SCM with probabilistic PyTorch

The problem with this basic parameter optimization approach is that the SCM should encode a distribution P (X, Y ). So we can turn to a probabilistic modeling approach to fit this model.

Listing 6.15 Bayesian estimation β in a probabilistic enzyme model

import pyro

from pyro.distributions import Beta, Normal, Uniform

from pyro.infer.mcmc import NUTS, MCMC

def g(u): #1

return u / (1 + u) #1

def model(N): #2

β = pyro.sample("β", Beta(0.5, 5.0)) #3

with pyro.plate("data", N): #4

x = pyro.sample("X", Uniform(0.0, 101.0)) #5

y = pyro.sample("Y", Normal(100.0 * g(β * x), x**.5)) #6

return x, y

conditioned_model = pyro.condition( #7

model, #7

data={"X": X.squeeze(1), "Y": Y.squeeze(1)} #7

) #7

N = X.shape[0] #8

pyro.set_rng_seed(526) #9

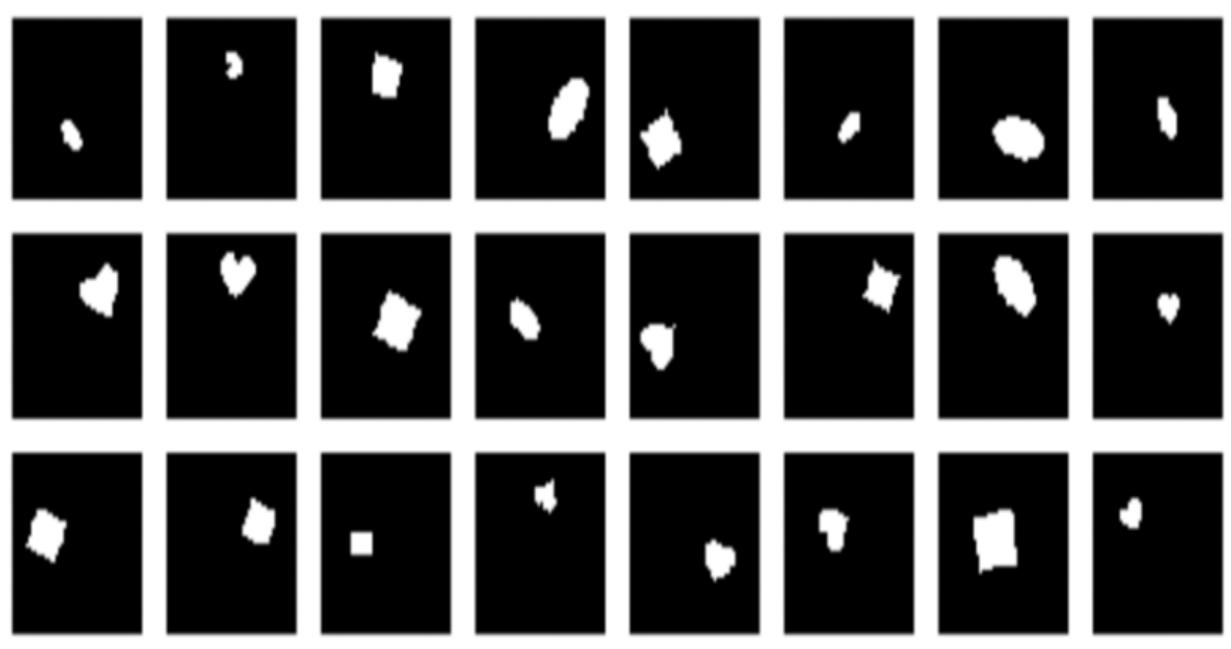

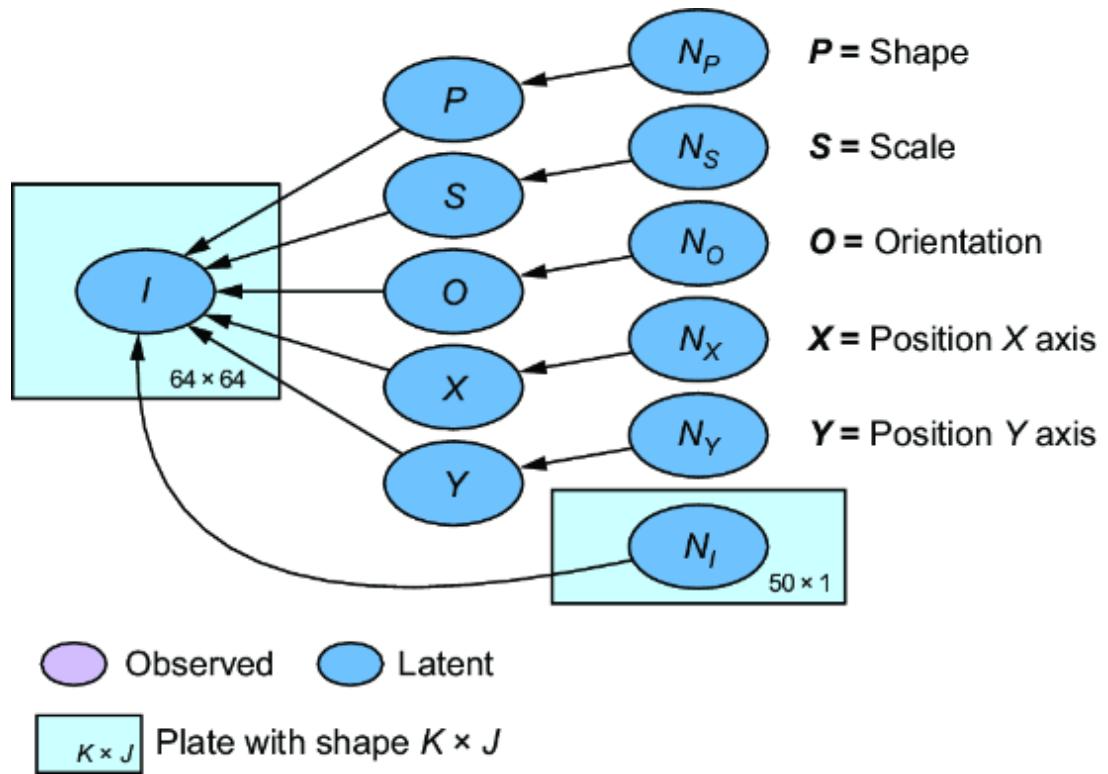

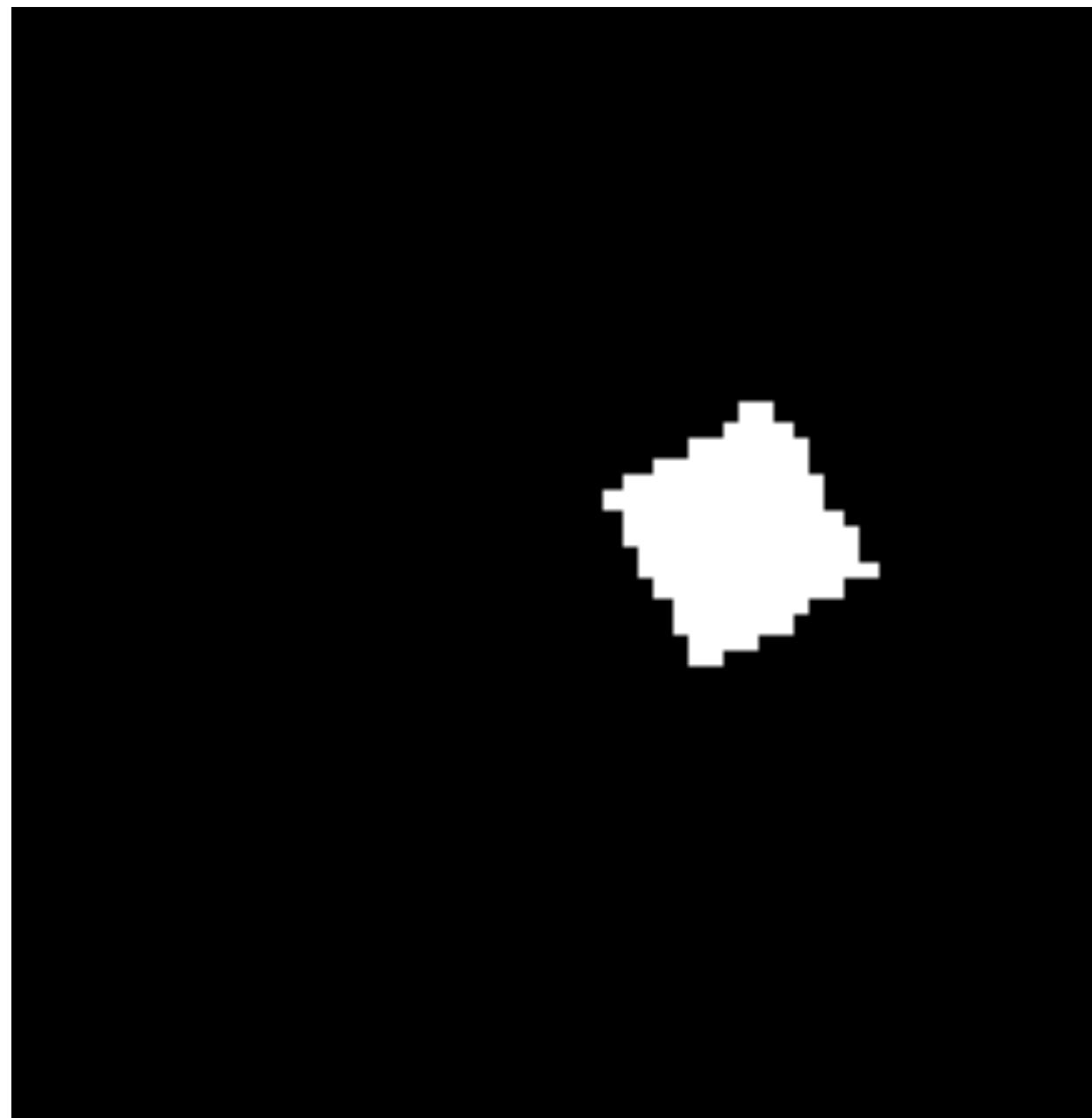

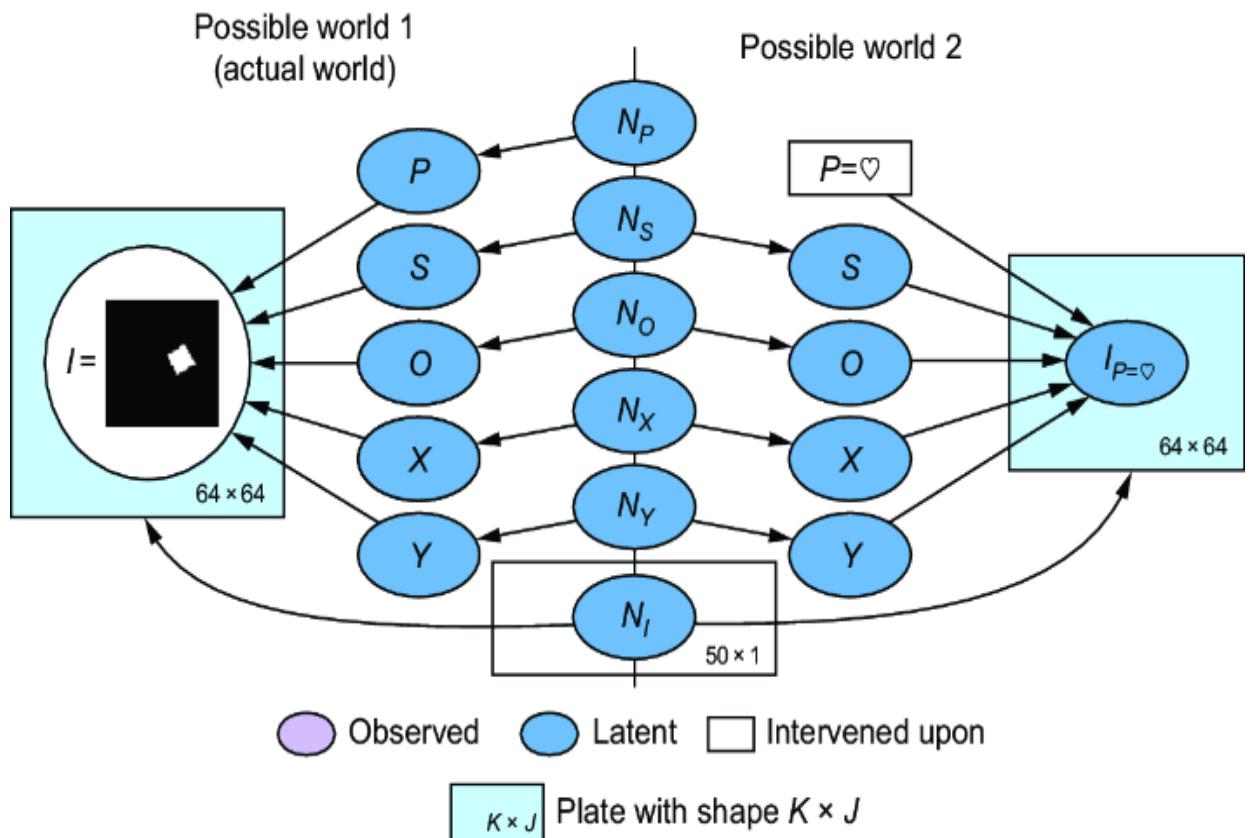

nuts_kernel = NUTS(conditioned_model, adapt_step_size=True) #10