Causal AI

Causal AI

Robert Osazuwa Ness Foreword by Lindsay Edwar ds

Manning Shelter Island

For mor e infor mation on this and other Manning titles go to manning.com .

copyright

For online infor mation and or dering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher o ers discounts on this book when or dered in quantity . For mor e infor mation, please contact

Special Sales Department

Manning P ublications Co .

20 Baldwin R oad

PO Bo x761

Shelter Island, NY 11964

Email: or ders@manning.com

©2025 by Manning P ublications Co . All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be r eproduced, stored in a r etrieval system, or transmitted, in any for m or by means electr onic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher .

Many of the designations used by manufactur ers and sellers to distinguish their pr oducts ar e claimed as trademarks. Wher e those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was awar e of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of pr eserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-fr ee paper, and we e xert our best e orts to that end. Recognizing also our r esponsibility to conserve the r esour ces of our planet, Manning books ar e printed on paper that is at least 15 per cent recycled and pr ocessed without the use of elemental chlorine.

The author and publisher have made every e ort to ensur e that the infor mation in this book was correct at pr ess time. The author and publisher do not assume and her eby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by er rors or omissions, whether such erors or omissions r esult fr om negligence, accident, or any other cause, or fr om any usage of the infor mation her ein.

Manning P ublications Co . 20 Baldwin R oad PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964

Development editor : Frances L efkowitz Technical editor : Emily McMilin Review editor : Dunja Nikitović Production editor : Kathy R ossland Copy editor : Andy Car roll Proofreader: Jason Ever ett Technical pr oofreader: Jerey Finkelstein Typesetter and cover designer : Marija T udor

ISBN 9781633439917

Printed in the United States of America

dedication

To Dad, Professor Ness

foreword

Twenty-seven lawyers in the room, anybody know ‘post hoc, ergo propter hoc?’

—President Josiah Bartlett ( The West Wing )

Post hoc er gop opter hoc is a logical fallacy r egarding causation: ૿ After it, ther efore because of it. The idea dates back at least to Aristotle (the fallacy appears in On Sophistical Refutations ). Mor e than two thousand years af ter Aristotle, W elsh economic theorist Sir Clive Granger inverted ૿post hoc er go pr opter hoc to pr ovide one of the two principles underlying what is now known as Granger Causality, namely that something cannot cause something if it happened before it.

Humans have been fascinated by the notion of causality what causes what—since their early r ecorded writing. Indeed, causal r easoning is a major distinguishing featur e of human cognition. On a practical level, the importance is obvious: one cannot contr ol something if one does not understand cause and e ect. Causal AI is the firstbook I know of that draws together the necessary theory, the technical foundations (i.e., the pack ages and libraries), and a host of r eal e xamples, to allow anyone with a decent grounding in basic pr obability theory and sof tware engineering to get started using causal AI to tackle any problem they choose.

In my own field—the application of machine lear ning to problems in biology and drug discovery—understanding causality is essential. New drugs cur rently cost $2–3B to develop, with most of this cost coming fr om the 95% failur e

rate of new drugs in clinical trials. A signi ficant pr oportion of these costs can be e xplained by failur es to understand (particularly biological) causality . Appr oximately 60% of all drug failur es can be traced back to a poor selection of drug target, and many of these poor drug tar gets ar e errors of causal attribution.

While machine lear ning and arti ficial intelligence ar e rapidly transfor ming our world, they ar e dogged by a number of technical pr oblems, including poor e xplainability, robustness, and generalizability . Causal r easoning addr esses all of these dir ectly . Of ten, one will hear AI algorithms being described as ૿black bo xes (in other wor ds, impossible to ૿peer into and e xplain). Y et, intuitively (and incr easingly backed up by r esear ch), machine lear ning models that ar e robustly pr edictive must have lear ned causality .

Models that lear n causality explicitly (such as the methods outlined in this book) will be both pr edictive and explainable. Models r egularly fail to generalize when a correlate of the true cause is used to pr edict an e ect (or output). L et us assume a chain of events: A causes B causes C. If a model, trained on this data, has lear ned to pr edict A from C, it is inher ently fragile. It will fail completely if, in a new setting, the link between A and B is somehow br oken. Again, e xplicit causal models tackle this issue dir ectly, greatly incr easing the chances that a perfor mant model will generalize well.

In this e xcellent book, R obert Ness uses vignettes drawn from business, r etail, and technology . While these ar e perfect teaching tools, r eaders should be under no illusion: The scope for these methods is vast and important, including medicine, biology, and policy -making. Understanding and modeling causality has e xtraor dinary potential to impr ove human lives. Y et, as R obert points out,

much of the knowledge r equir ed to understand and apply causal AI e ectively is distributed acr oss disciplines, including traditional statistics, Bayesian infer ence, computer science, and pr obabilistic machine lear ning. Hence, lear ning about and applying causal AI has (till now) been far mor e arduous than it should be.

Robert is also an inspir ed teacher—all the better, as this stu can be har d! I hope you enjoy Causal AI as much as I did. It is essential r eading for anyone inter ested in applying these powerful methods (cause) and, hopefully, having a positive impact in the world (e ect).

—Lindsay Edwar ds CTO at R elation, L ondon

preface

I wr ote this book because I wanted a code- first appr oach to causal infer ence that seamlessly fit with moder n deep learning. It didn’t mak e sense to me that deep lear ning was often pr esented as being at odds with causal r easoning and infer ence, so I wanted to write a book that pr oved they combine well to their mutual bene fit.

Second, I wanted to close an obvious gap. Deep generative machine lear ning methods and graphical causal infer ence have a common ancestor in pr obabilistic graphical models. There have been tr emendous advances in generative machine lear ning in r ecent years, including in the ability to synthetize r ealistic te xt, images, and video . Yet, in my view, the low-hanging fruit of connections to r elated concepts in graphical causality was lef t to r ot on the vine. Chances ar e that if you’r e reading this, you sensed this gap as well. So here we ar e.

This book evolved fr om the Causal AI workshop I run through Altdeep.ai, an educational company that runs workshops and community events devoted to advanced topics in modeling. P articipants in this causal AI workshop have included data scientists, machine lear ning engineers, and pr oduct managers fr om Google, Amazon, Meta, and other big tech companies. They’ve also included data scientists and ML e xperts fr om retailers such as Nik e, consultancies lik e Deloitte, and phar maceuticals lik e AstraZeneca. W e’ve work ed with quantitative mark eting experts trying to tak e causal appr oaches to channel attribution. W e’ve work ed with economists and molecular biologists trying to get a mor e general perspective on the causal methods popular in their domains. W e’ve work ed

with pr ofessors, post-docs, and PhD students acr oss departments looking for a code- first appr oach to lear ning causal infer ence.

I wr ote this book for all of these people, based on the r ealworld pr oblems they car e about and their feedback. If you belong to or r elate to any of these gr oups, this book is for you, too .

How is this book di erent fr om other causal infer ence books? Causal infer ence r elies mainly on thr ee dierent skill sets: the ability to tur n your domain knowledge into a causal model r endered in code, deep skills in pr obability theory, and deep skills in statistical theory and methods. This book focuses on the first skill by using libraries that enable bespok e causal modeling, and by leveraging the deep learning machinery in tools such as PyT orch to do the statistical heavy lif ting.

I hope this sounds lik e what you ar e looking for .

acknowledgments

I was very fortunate to have Emily McMilin, senior r esear ch scientist at Meta, and K evin Murphy, principal r esear ch scientist at Google AI and author of the best book on probabilistic ML, both give a car eful r eview of each chapter . Finally, Je rey Finkelstein, the most talented r esear ch engineer I’ve ever met, pr ovided a thor ough code r eview .

My colleagues at Micr osoft Resear ch, Emr e Kiciman and Amit Shar ma, pr ovided helpful advice with the DoWhy code. Fritz Ober meyer and Eli Bingham got me unstuck on Pyr o code. The book also builds on work with many collaborators, including K aren Sachs, Sara T aheri, Olga V itek, and Jer emy Zucker.

My editors F rances L efkowitz, Michael Stephens, and Andy Carroll at Manning P ublications pr ovided fr equent and invaluable edits and feedback, as did many others on the Manning team.

To all the r eviewers—A di Shavit, Alain Couniot, Camilla Montonen, Carlos A ya-Mor eno, Christian Sutton, Clemens Baader, Ger man Vidal, Guiller mo Alcántara González, Igor Vieira, Jer emy Loscheider, Jesús Juár ez, Jose San L eandro, Keith Kim, K yle P eterson, Maria Ana, Mik ael Dautr ey, Nick Decroos, P ierluigi Riti, P ietr o Alberto R ossi, Sebastian Maier, Sergio Govoni, Simone Sguazza, and Thomas Joseph Heiman —your suggestions helped mak e this a better book.

about this book

This book is for

- Machine learning engineers looking to incorporate causality into AI syste ms and build more robust predictive models

- Data scientists who are looking to expand both their causal infer ence and machine lear ning skillsets

- Resear chers who want a wholistic view of causal infer ence and how it connects to their domain of expertise without going down stats theory rabbit holes

- AI product experts looking for case studiesn business settings, especially tech and r etail

- People who want to get inon the ground floor of causal AI

Whatistherequiredmathematical andprogrammingbackground?

Rest assur ed, this book doesn’t r equir e a deep backgr ound in pr obability and statistics theory . The r elationship between causality and statistics is lik e the r elationship between engineering and math. Engineering involves a lot of math, but you need only a bit of math to lear n cor e engineering concepts. A fter lear ning those concepts and digging into an applied pr oblem, you can focus on lear ning the e xtra math you need to go deep on that pr oblem.

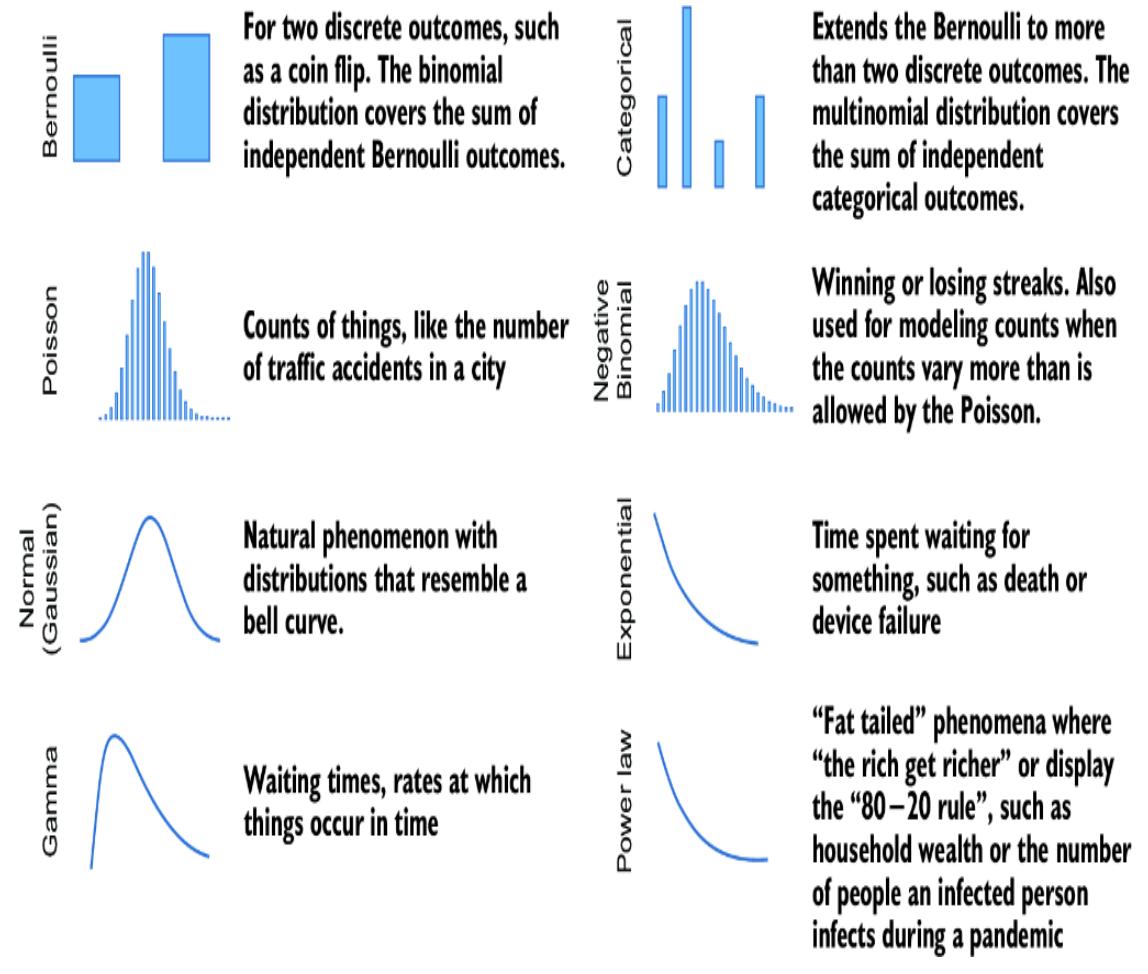

This book assumes a level of familiarity with pr obability and statistics typical of a data scientist. Speci fically, it assumes you have basic knowledge of

- Probability distributions

- Joint probability and conditional probability and how they r elate to each other (chain rule, Bayes rule)

- What it means to draw samples fr om a distribution

- Expectation, independence, and conditional independence

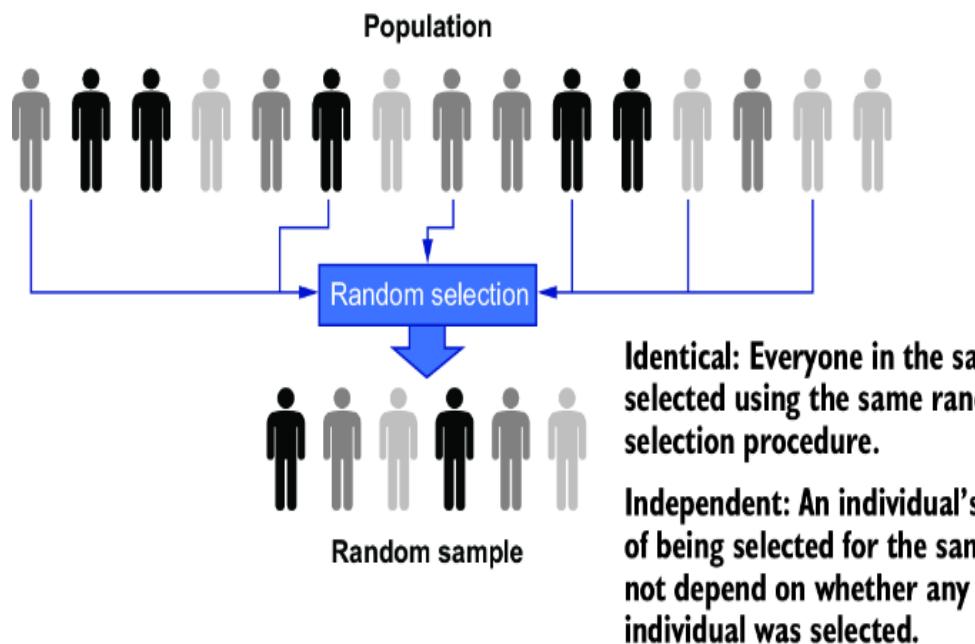

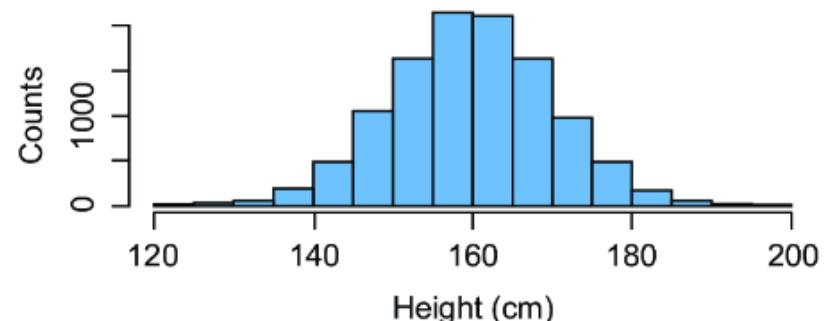

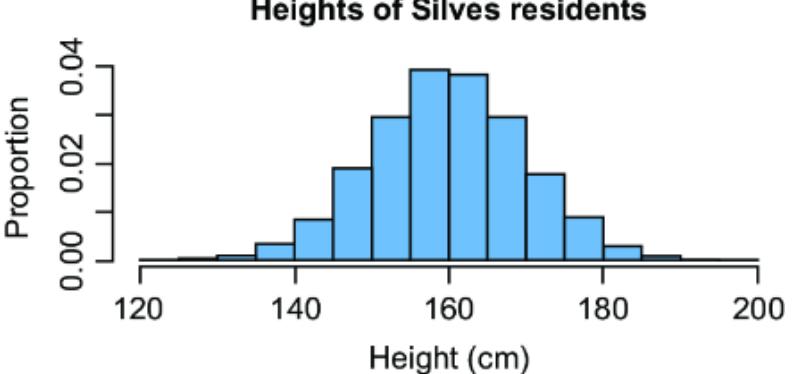

- Statistical ideas such as random samples, identically and independently sampled data, and statistical bias

Chapter 2 pr ovides a primer on these and other topics k ey to the ideas pr esented in this book for those who need refreshing.

Whatprogrammingtoolswillweuse?

This book assumes you ar e familiar with data science scripting in Python. The thr ee open sour ce Python libraries we rely on in this book ar e DoWhy, pgmpy, and Pyr o. DoWhy is a library for the open sour ce PyWhy suite of Python libraries for causal infer ence. pgmpy is a pr obabilistic graphical modeling library built on SciPy and NetworkX. Pyr o is a pr obabilistic machine lear ning library that e xtends PyTorch.

Our code- first goal is unique because, rather than going deep into the statistical theory needed to do causal infer ence, we r ely on these supporting libraries to do the statistics for us. DoWhy tries to be as end-to -end as possible in ter ms of mapping domain knowledge inputs to causal infer ence outputs. When we want to do mor e bespok e modeling, we’ll use pgmpy or Pyr o. These libraries pr ovide probabilistic infer ence algorithms that tak e car e of the estimation theory . pgmpy has graph-based infer ence algorithms that ar e extremely r eliable. Pyr o, as an e xtension of PyT orch, e xtends causal modeling to deep generative

models on high dimensional data and variational inference a cutting-edge deep lear ning–based infer ence technique.

If your backgr ound is in R or Julia, you should still find this book useful. Ther e are numer ous R and Julia pack ages that overlap in functionality with DoWhy . Graphical modeling software in these languages, such as bnlear n, can substitute for pgmpy . Similarly, the ideas we develop with Pyr o will work with similar pr obabilistic pr ogramming languages, such as PyMC. See https://altdeep.ai/p/causalaibookfor links to code notebooks r elated to the book.

Aboutthecode

In each chapter, I pr ovide a list of the Python libraries and versions you’ll need to get the code working as well as guidance in setting up your envir onment. Note that di erent versions of the same library ar e sometimes used in di erent

chapters. All the code in the book is implemented in Jupyter notebooks that ar e available online at https://altdeep.ai/p/causalaibook . The notebooks wer e all tested in Google Colab, and they include links that automatically load the notebooks in Google Colab, wher e you can run them dir ectly . This can save time and aggravation if you hit issues in setting up your envir onment. You’ll findlinks to the notebooks and other book r esour ces at https://altdeep.ai/p/causalaibook .

This book contains many e xamples of sour ce code, both in numbered listings and in-line with nor mal te xt. In both cases, sour ce code is for matted in a fixed-width font like this to separate it fr om ordinary te xt.

In many cases, the original sour ce code has been reformatted; I’ve added line br eaks and r eworked indentation to accommodate the available page space in the book. In rar e cases, even this was not enough, and listings include line-continuation mark ers (). A dditionally, comments in the sour ce code have of ten been r emoved from the listings when the code is described in the te xt. Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

You can get e xecutable snippets of code fr om the liveBook (online) version of this book at https://livebook.manning.com/book/causal-ai . The complete code for the e xamples in the book is available for download from the Manning website at https://www .manning.com/books/causal-ai and fr om https://altdeep.ai/p/causalaibook .

liveBookdiscussionforum

Purchase of Causal AI includes fr ee access to liveBook, Manning’s online r eading platfor m. Using liveBook’s exclusive discussion featur es, you can attach comments to the book globally or to speci fic sections or paragraphs. It’s a snap to mak e notes for yourself, ask and answer technical questions, and r eceive help fr om the author and other users. T o access the forum, go to https://livebook.manning.com/book/causal-ai/discussion . You can also lear n more about Manning’s forums and the rules of conduct at htps://livebook.manning.com/discussion .

Manning’s commitment to our r eaders is to pr ovide a venue where a meaningful dialogue between individual r eaders and between r eaders and the author can tak e place. It is not a commitment to any speci fic amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contribution to the forum r emains voluntary (and unpaid). W e suggest you try asking the author some challenging questions lest his inter est stray! The forum and the ar chives of pr evious discussions will be accessible fr om the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

about the cover illustration

The figure on the cover of Causal AI , titled ૿ La Religieuse, or ૿The Nun, is tak en fr om a book by L ouis Cur mer published in 1841. Each illustration is finely drawn and color ed by hand.

In those days, it was easy to identif y wher e people lived and what their trade or station in life was just by their dr ess. Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of r egional cultur e centuries ago, br ought back to life by pictur es fr om collections such as this one.

Part 1 Conceptual foundations

Part 1 lays the essential gr oundwork for understanding and building causal models. Her e, I’ll intr oduce k ey concepts from statistics, pr obabilistic modeling, generative machine learning, and Bayesian methods that will serve as our building blocks for this book’s appr oach to causal modeling. This part is all about ar ming you with the cor e concepts you need to start solving causal pr oblems with machine lear ning tools.

1Why causal AI

This chapter covers

- Defining causal AI and its bene fits

- Incorporating causality into machine lear ning models

- A simple example of applying causality to a machine learning model

Subscription str eaming platfor ms lik e Net flix ar e always looking for ways to optimize various indicators of perfor mance. One of these is their churn rate , meaning the rate at which they lose subscribers. Imagine that you ar e a machine lear ning engineer or data scientist at Net flix task ed with finding ways of r educing chur n. What ar e the types of causal questions (questions that r equir e causal thinking) you might ask with r espect to this task?

- Causal disco very—Given detailed data on who churned and who did not, can you analyze that data to find causes of the churn? Causal discov eryinvest igates what causes what.

- Estimating average treatment e ects(ATEs)—Suppose the algorithm that recommends content to the user is a cause of the churn; a better choice of algorithm might reduce churn, but by how much? The task of quantifying how much, on average, a cause drives an e ect is the ATE estimation . For example, some users could be exposed to a new version of the algorithm, and you could measur e how much this a ects churn, relative to the baseline algorithm.

Let’s go a bit deeper . The mock umentary The Oce (the American version) was one of the most popular shows on Netflix. Later, Net flix lear ned that NB CUniversal was planning to stop licensing the show to Net flix to str eam in the US, so that US str eaming of The O ce would be e xclusive to NBCUniversal’s rival str eaming platfor m, Peacock. Given the popularity of the show, chur n was certainly a ected, but by how much?

Estimating conditional average treatment e ects (CATEs) —The e ect of losing The O cewould be more pronounced for some subscriber segments than others, but what attributes define these segments? One attribute is certainly having watched the show, buther are others (demographics, other content watched,tc.). CATE estimation isthe task of quantif ying how much a cause drives an e ect for a particular segment ofthe population. Indeed, ther are likely multiple segments we could define, each with a dierent within-segment ATE. Part of the task of CATE estimation is finding distinct segments of inter est.

Suppose you had r eliable data on subscribers who quit Netflix and signed up for P eacock to continue watching The O ce. For some of these users, the r ecommendation algorithm failed to show them possible substitutes for The O ce, lik e the mock umentary Parks and Recreation . That may lead to a di erent type of question.

Counterfactual reasoning and attribution —If the algorithm had placed Parks and Recreation more prominently in those users’ dashboar ds, would theyhave stayed on with Netflix? These counterfactual questions (૿counter to the fact that the showasn’t prominent in their dashboar d) are essential for attribution (assigning a root cause and credit/blame for an outcome).

Netflix work ed with Steve Car rel (star of The Oce) and Gr eg Daniels (writer, dir ector, and pr oducer of The Oce) to create the show Space Force as Net flix original content. The show was r eleased just months befor e The Oce moved to Peacock. Suppose that this show was Net flix’s attempt to create content to r etain subscribers who wer e fans of The O ce. Consider the decisions that would go into the cr eation of such a show :

- Causal decision theory —What actors/dir ectors/writers would tempt The O cefans to stay subscribed? What themes and content?

- Causal machine learning —How could we use generative AI, such as large language models to create scripts and pilots for the show in such a way that optimizes for the objective of r educing chur n amongst fans of The Oce?

Causal inference is about br eaking down a pr oblem into these types of speci fic causal queries , and then using data to answer these queries. Causal AI is about building algorithms that automate this analysis. W e’ll tackle both of these problem ar eas in this book.

1.1WhatiscausalAI?

To understand what causal AI is, we’ll start with the basic ideas of causality and causal infer ence, and work our way up. Then we’ll r eview the kinds of pr oblems we can solve with causal AI.

Causal reasoning is a crucial element of how humans understand, e xplain, and mak e decisions about the world. Anytime we think about cause (૿Why did that happen?) or e ect (૿What will happen if I do this?), we ar e practicing causal r easoning.

In statistics and machine lear ning, we use data to lend statistical rigor to our causal r easoning. But while cause-ande ect r elationships drive the data, statistical cor relation alone is insu cient to draw causal conclusions fr om data. F or this, we must tur n to causal inference .

Statistical (non-causal) infer ence r elies on statistical assumptions. This is true even in deep lear ning, wher e assumptions ar e often called ૿inductive bias. Similarly, causal infer ence r elies on causal assumptions; causal infer ence r efers to a body of theory and practical methods that constrain statistical analysis with causal assumptions.

Causal AI refers to the automation of causal infer ence. W e can leverage machine lear ning algorithms, which have developed r obust appr oaches to automating statistical analyses and scale up to lar ge amounts of data of di erent modalities.

The goal of AI is automating r easoning tasks that until now have r equir ed human intelligence to solve. Humans r ely heavily on causal r easoning to navigate the world, and while we ar e better at causal r easoning than statistical r easoning, our cognitive biases still mak e our causal r easoning highly eror pr one. Impr oving our ability to answer causal questions has been the work of millennia of philosophers, centuries of scientists, and decades of statisticians. But now, a conver gence of statistical and computational advances has shif ted the focus fr om discourse to algorithms that we can train on data and deploy to sof tware. It is a fascinating time to lear n how to build causal AI.

KEY DEFINITIONS UNDERPINNING CA USAL AI

- Inference —Drawing conclusions from observations and data

- Assumptions —Constraints that guide infer ences

- Inductive bases —Another word for assumptions , often used to refer to assumptions implicit in the choice of machine lear ning algorithm

- Statistical model—A framework using statistical assumptions to analyze data

- Data science —An inter disciplinary field that uses statistical models along with other algorithms and techniques toxtract insights and knowledge from structur ed and unstructur ed data

- Causal inference —Techniques that use causal assumptions to guide conclusions

- Causal model—A statistical model built on causal assumptions about data generation

- Causal data science —Data science that employs causal models to e xtract causal insights

- Causal AI—Algorithms that automate causal infer ence tasks using causal models

1.2How thisbookapproachescausal inference

The goal of this book is the fusion of two powerful domains: causality and AI. By the end of this jour ney, you’ll be equipped with the skills to

- Design AI systems with causal capabilities —Harness the power of AI, but with an added layer of causal r easoning.

- Use machine learning frameworks for causal inference Utilize toolsike PyTorch and other Python libraries to seamlessly integrate causal modeling into your pr ojects.

- Build tools for automated causal decision-making Implement causal decision-making algorithms, including causal r einfor cement lear ning algorithms.

Historically, causality and AI evolved fr om dierent bodies of resear ch, they have been applied to di erent pr oblems, and they have led to e xperts with di erent skill sets, books that use di erent languages, and libraries with di erent abstractions. This book is for anyone who wants to connect these domains into one compr ehensive skill set.

There are many books on causal infer ence, including books that focus on causal infer ence in Python. The following subsections discuss some featur es that mak ethis book unique.

1.2.1 Emphasis on AI

This book focuses on causal AI. W e’ll cover not just the relevance of causal infer ence to AI, or how machine lear ning can scale up causal infer ence, but also focus on implementation. Speci fically, we’ll integrate causal models with conventional models and training pr ocedur es fr om probabilistic machine lear ning.

1.2.2 Focus on tech, retail, and business

Practical causal infer ence methods have developed fr om econometrics, public health, social sciences, and other domains wher e it is di cult to run randomized e xperiments. As a r esult, e xamples in most books tend to come fr om those domains. In contrast, this book leans heavily into e xamples from tech, r etail, and business.

1.2.3 Parallel world counterfactuals and other queries beyond causal e ects

When many think of ૿causal infer ence, they think of estimating causal e ects, namely average tr eatment e ects (ATEs) and conditional average tr eatment e ects (CA TEs). These ar e certainly important queries, but ther e are other kinds of causal queries as well. This book gives due attention to these other types.

For example, this book pr ovides in-depth coverage of the parallel worlds account of counterfactuals. In this appr oach, when some cause and some e ect occur, we imagine a parallel universe wher e the causal event was di erent. F or example, suppose you ask ed, ૿I mar ried for money and now I’m sad. W ould I have been happier had I mar ried for love? With our parallel worlds appr oach, you’d use your e xperience of mar rying for money and being sad as inputs to a causal model-based pr obabilistic simulation of your happiness in a parallel universe wher e you mar ried for love. This type of reasoning is useful in decision-making. F or example, it might help you choose a better spouse ne xt time.

Hopefully this e xample of love and r egret illustrates how fundamental this kind of ૿ what could have been thinking is to human cognition (we’ll see mor e applied e xamples in chapters 8 and 9). It ther efore makes sense to lear n how to build AI with the same capabilities. But although they’r e useful, some counterfactual infer ences ar e har d or impossible to verif y (you can’tprove you would have been happier if you had mar ried for love). Most causal infer ence books only focus on the nar row set of counterfactuals we can verif y with data and e xperiments, which misses many inter esting, cognitive science-aligned, and practical use cases of counterfactual r easoning. This book leans into those use cases.

1.2.4 An assumption of commodi fication of inference

Many causal infer ence books go deep into the statistical infer ence nuts and bolts of various causal e ect estimators. But a major tr end in the last decade of developing deep learning frameworks is the commodi fication of inference . This r efers to how libraries lik e PyT orch abstract away the dicult aspects of estimation and infer ence—if you can define your estimation/infer ence pr oblem in ter ms minimizing a di erentiable loss function, PyT orch will handle the r est. The commodi fication of infer ence fr ees up the user to focus on cr eating ever mor e nuanced and powerful models, such as models that r epresent the causal structur e of the data-generating pr ocess.

In this book, we’ll focus on leveraging frameworks for infer ence so that you can lear n a universal view of modeling techniques. Once you find the right modeling appr oach for your domain, you can use other r esour ces to go deep into any statistical algorithm of inter est.

1.2.5 Breaking down theory with code

One of the standout featur es of this book is its appr oach to advanced topics in causal infer ence theory . Many intr oductory te xts shy away fr om subjects lik e identi fication, the do -calculus, and the causal hierar chy theor em because they ar e dicult. The pr oblem is that if you want to cr eate causal-capable AI algorithms, you need an intuition for these concepts.

In this book, we’ll mak e these topics accessible by r elying on Python libraries that implement their basic abstractions and algorithms. W e’ll build intuition for these advanced topics by working with these primitives in code.

1.3Causality’sroleinmodernAI workflows

There is gr eat value in positioning ourselves to build futur e versions of AI with causal capabilities, but the topics cover ed in this book will also have an impact on applications common today . In this section, we’ll r eview how causality can enhance some of these applications.

1.3.1 Better data science

Big tech and tech-power ed retail or ganizations have recognized the signi ficance of causal infer ence, o ering premium salaries to those pr oficient in it. This is because the essence of data science—deriving actionable insights fr om data—is inher ently causal.

When a data scientist e xamines the cor relation between a featur e on an e-commer ce site and sales, they do so because they want to know whether the featur e causally drives sales.

Causal infer ence can help answer this question in several ways. F irst, it can help them design an e xperiment that will quantif y the causal e ect of the featur e on sales, especially in the case wher e a perfect randomized e xperiment is not possible. Second, if a pr oposed e xperiment is not feasible, the data scientist can use past observational data and data from related but di erent past e xperiments to infer the value of the causal e ect that would r esult fr om the pr oposed experiment without actually running it. F inally, even if the data scientist has complete fr eedom in running e xperiments, causal infer ence can help select which e xperiment to run and what variables to measur e, minimizing the opportunity cost of running wasteful or uninfor mative e xperiments.

1.3.2 Better attribution, credit assignment, and root cause analysis

Causal infer ence also supports attribution. The ૿attribution problem in mark eting is per haps best articulated by a quote credited to advertising pioneer John W anamaker:

Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half .

In other wor ds, it is di cult to know what advertisement, promotion, or other action caused a speci fic customer behavior, sales number, or other k ey business outcome. Even in online mark eting, wher e the data has gotten much richer and mor e granular than in W anamaker’s time, attribution r emains a challenge. F or example, a user may have click ed after seeing an ad, but was it that single ad view that led to the click? Or wer e they going to click anyway? P erhaps ther e was a cumulative e ect of all the nudges to click that they r eceived over multiple channels. Causal modeling addr esses the attribution pr oblem by using

formal causal logic to answer ૿ why questions, such as ૿ why did this user click?

Attribution goes by other names in other domains, such as ૿credit assignment and ૿ root cause analysis. The cor e meaning is the same; we want to understand why a particular event outcome happened. W e know what the causes ar e in general, but we want to know how much a particular cause is to blame in a given instance.

1.3.3 More robust, decomposable, and explainable models

For or ganizations that use machine lear ning to build software, incorporating causal modelling can impr ove both the pr ocess and the pr oduct. In particular, causality adds value by making machine lear ning mor e robust, decomposable, and e xplainable.

MORE ROBUST MA CHINE LEARNING

Machine lear ning models lack r obustness when di erences between the envir onment wher e the model was trained and the envir onment wher e the model is deployed cause the model to br eak down. Causality can addr ess the lack of robustness in the following ways:

- Overfitting —Overfitting occurs when learning algorithms place too much weight on spurious statistical patter ns in the training data. Causal approaches can orient machine learning models towar d learning statistical patter ns that are rooted in causal r elationships.

- Underspeci fication —Underspeci fication occurs when ther are many equivalent configurations of a model that perfor m equivalently on test data but perfor m dierently in the deployment envir onment. One sign of

underspeci fication is sensitivity to arbitrary elements of the model’s configuration, such as a random seed. Causal infer ence can tell you when acausal prediction is ૿identi fied (i.e., not ૿underspeci fied), meaning a unique answer exists given the assumptions and the data.

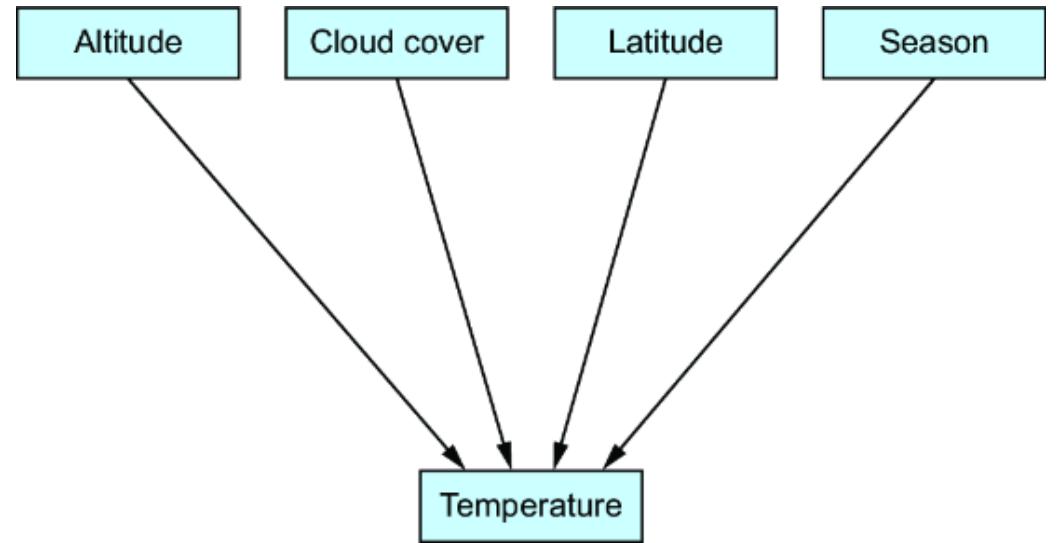

Data drift —As time passes, the characteristics of the data in the envir onment where you deploy the model dier or ૿drif t from the characteristics of the training data. Causal modeling addresses this by capturing causal invar iance underlying the data. For example, suppose you train a model that uses elevationo predict average temperatur e. If you train with data only from high-elevation cities, ithould still work well in lowelevation cities if the model successfully fit the underlying physics-based causal relationship between altitude and temperatur e.

This is why leading tech companies deploy causal machine learning techniques—they can mak e their machine lear ning services mor e robust. It is also why notable deep lear ning resear chers ar epursuing r esear ch that combines deep learning with causal r easoning.

MORE DECOMPOSABLE MA CHINE LEARNING

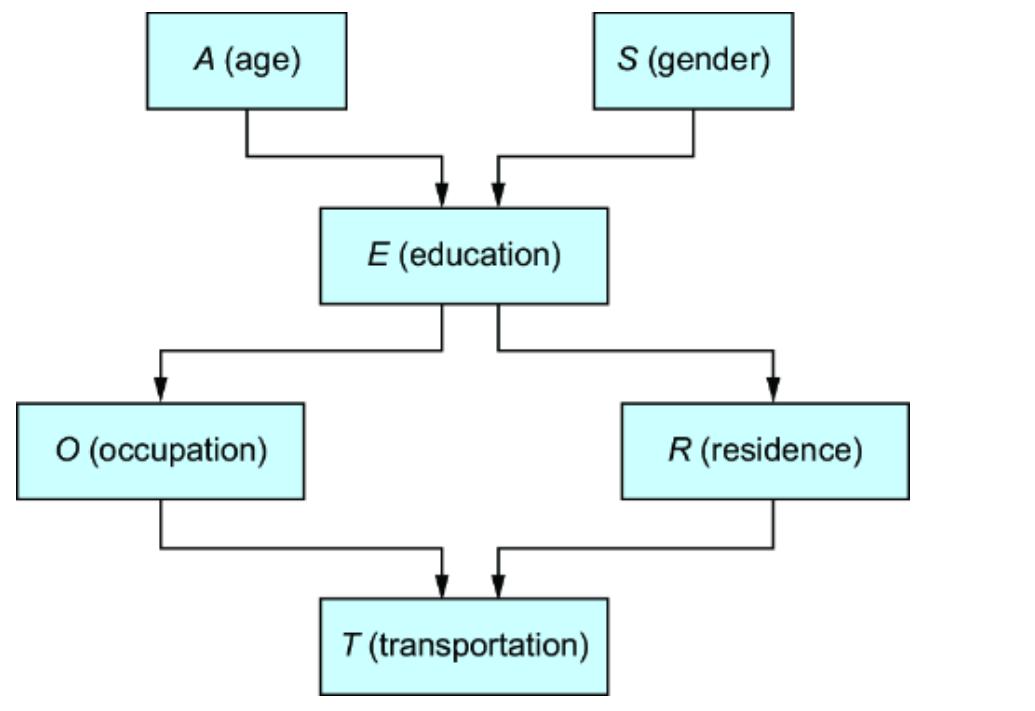

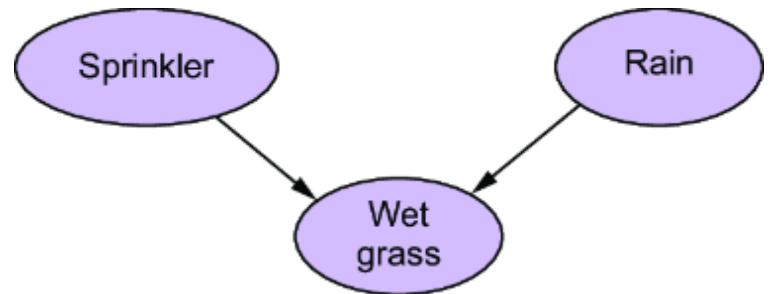

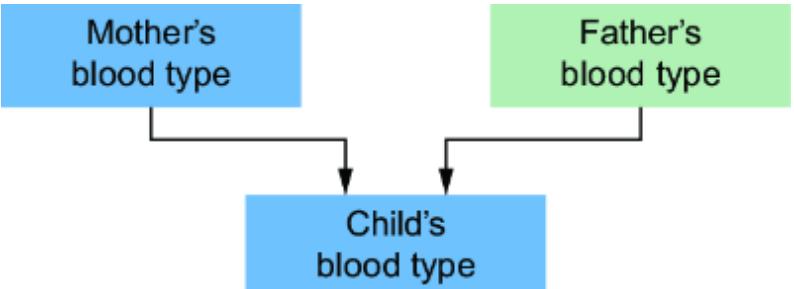

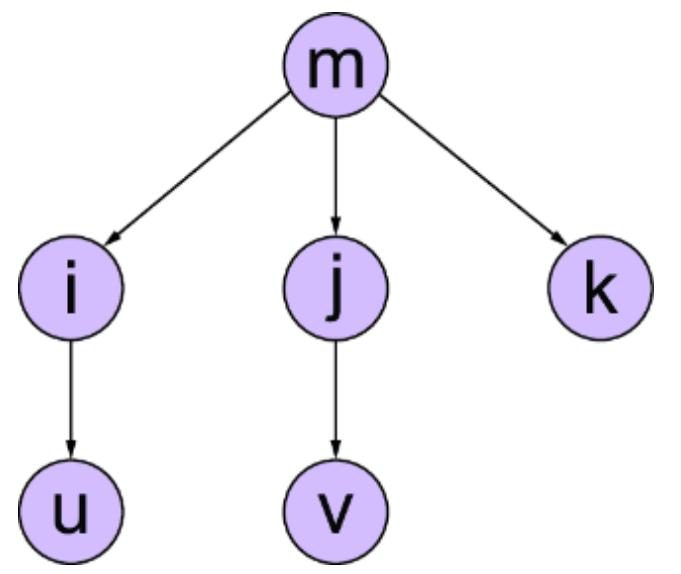

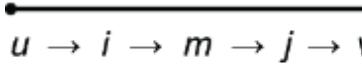

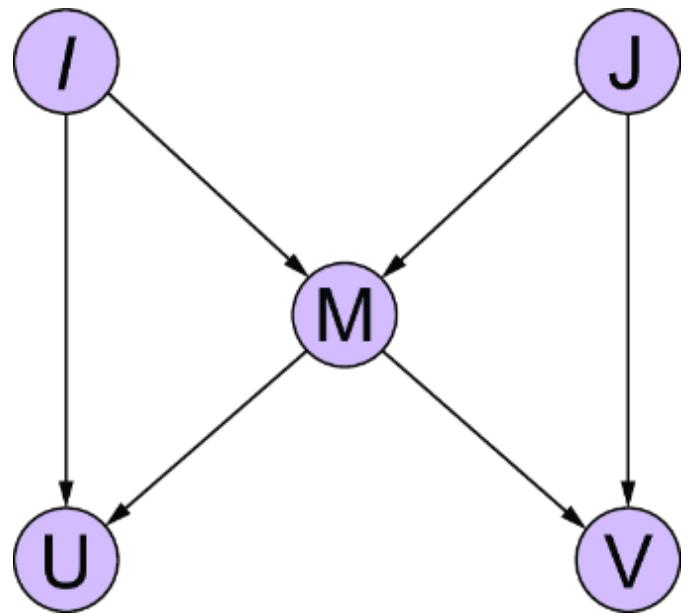

Causal models decompose into components, speci fically tuples of e ects and their dir ect causes, which I’ll de fine formally in chapter 3. T o illustrate, let’s consider a simple machine lear ning pr oblem of pr edicting whether an individual who sees a digital ad will go on to mak e a purchase.

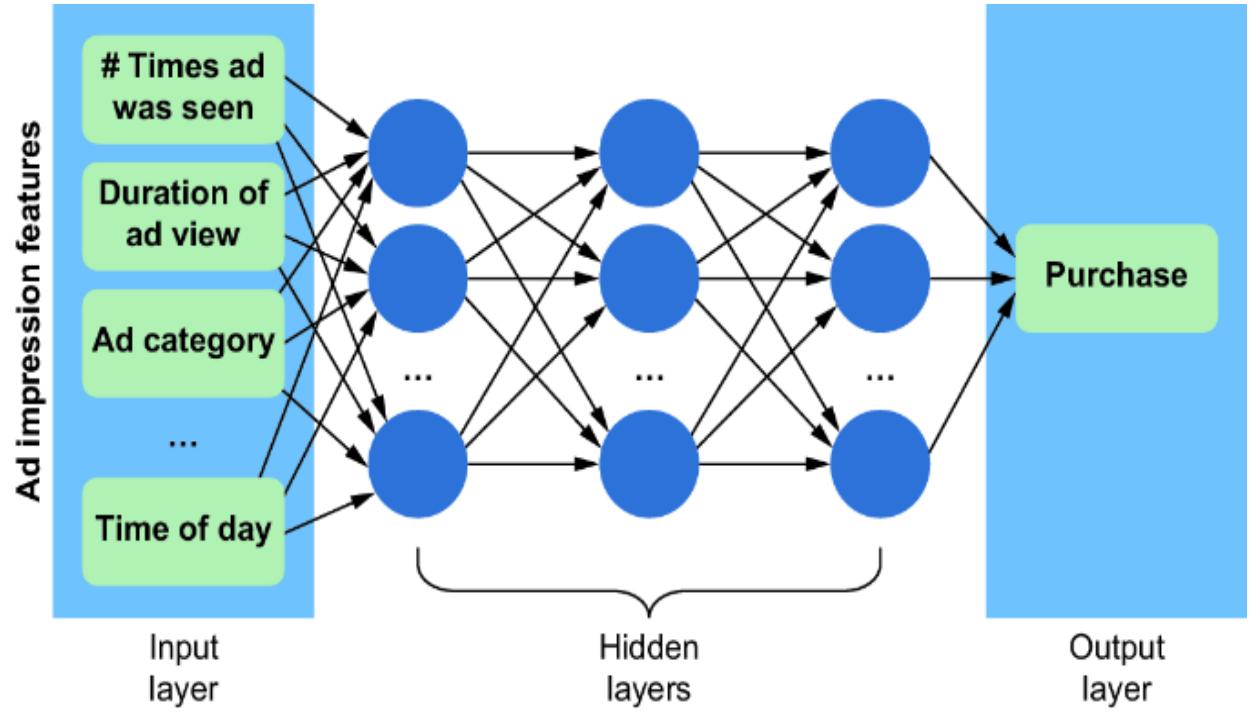

We could use various characteristics of the ad impr ession (e.g., the number of times the ad was seen, the duration of the view, the ad category, the time of day, etc.) as the

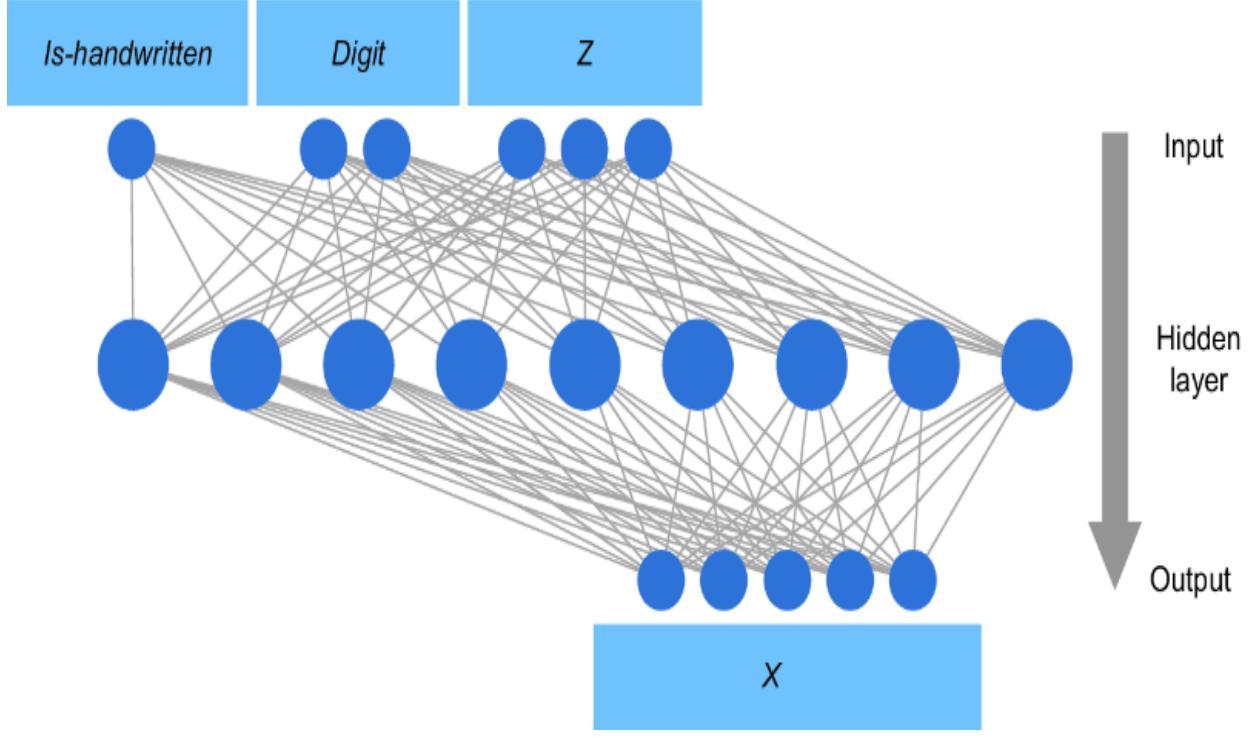

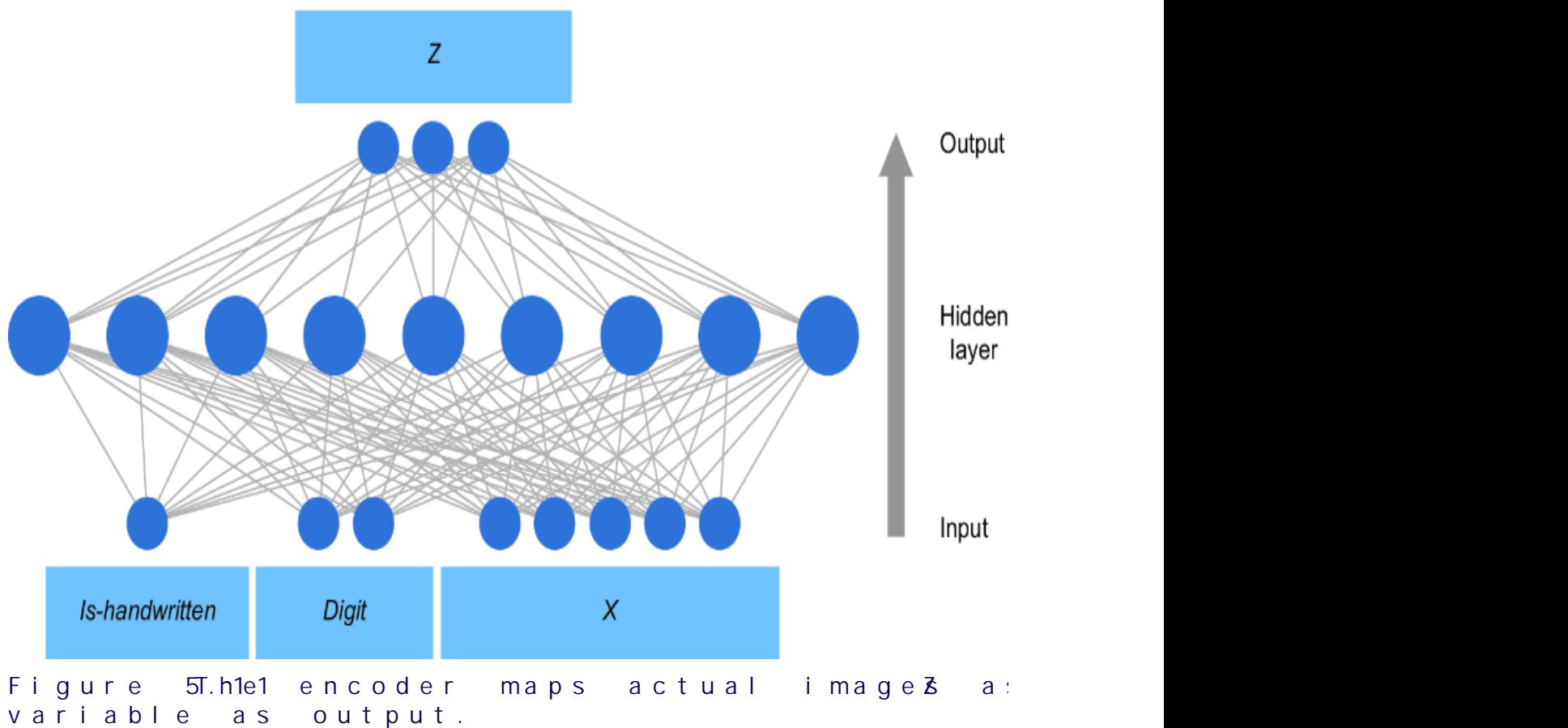

featur e vector, and pr edict the pur chase using a neural network, as depicted in figure 1.1. The weights in the hidden layers of the model ar e mutually dependent, so the model cannot be r educed to smaller independent components.

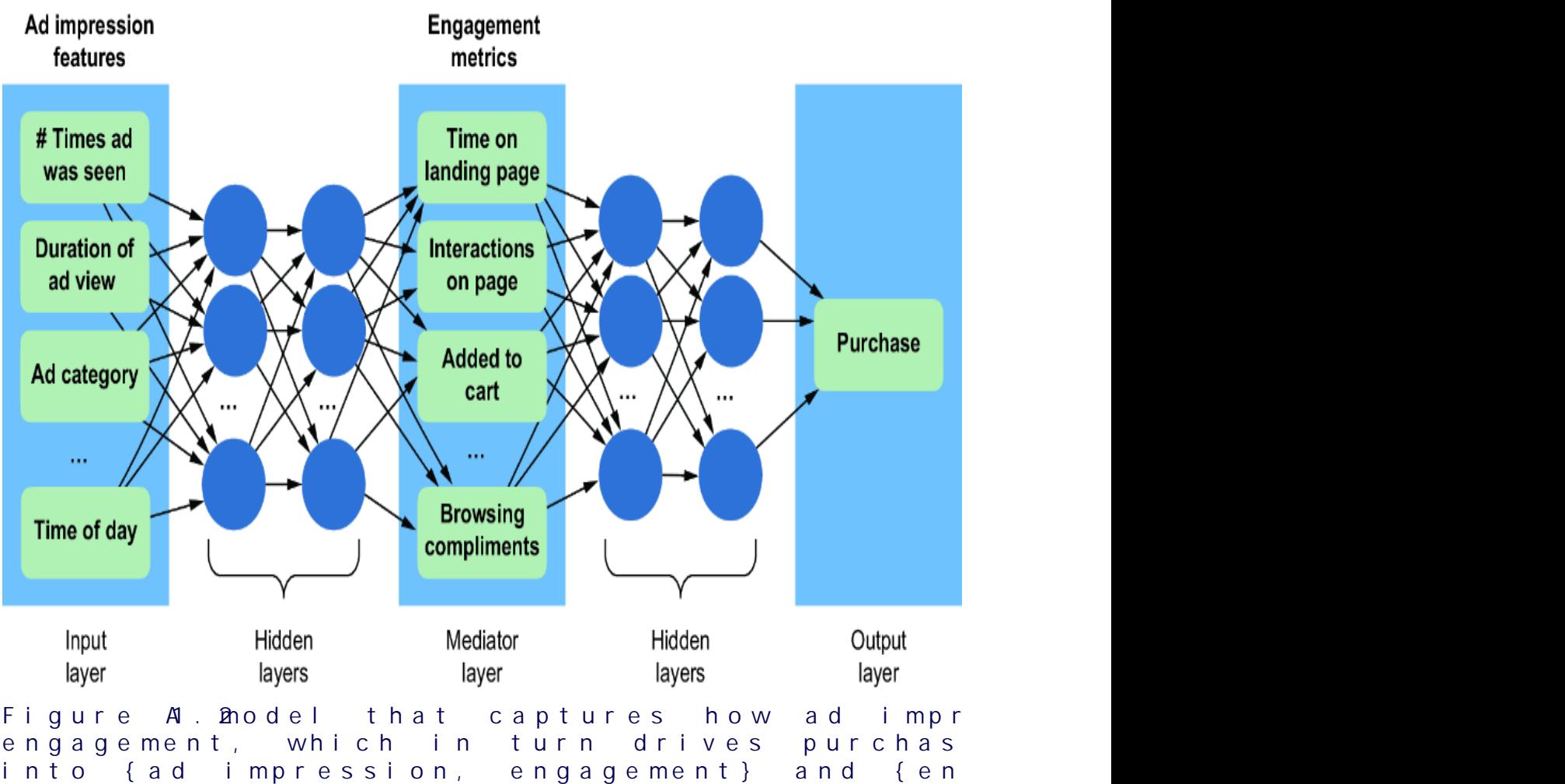

Figure 1.1 A simple multila yer perceptron neural network that uses features associated with ad impressions to predict whether a purchase will result

On the other hand, if we tak e a causal view of the pr oblem, we might r eason that an ad impr ession drives engagement, and that the engagement drives whether an individual makes a pur chase. Using engagement metrics as another featur e vector, we could instead train the model shown in figure 1.2. This model aligns with the causal structur e of the domain (i.e., ad impr essions causing engagement, and engagement causing pur chases). As such, it decomposes into two components: {ad impr ession, engagement} and {engagement, pur chase}.

There are several bene fits of this decomposability :

- Components of the model can be tested and validated independently .

- Components of the model can be executed separately, enabling more e cient use of modern cloud computing infrastructur e and enabling edge computing.

- When additi onal training data is available, only the components r elevant to the data need r etraining.

- Components of old models can be reused in new models targeting new pr oblems.

- There is less sensitivity to suboptimalodel configuration and hyperparameter settings, because

components can be optimized separately .

The components of the causal model cor respond to concepts in the domain that you ar e modeling. This leads to the ne xt benefit, e xplainability .

MORE EXPLAINABLE MA CHINE LEARNING

Many machine lear ning algorithms, particularly deep learning algorithms, can be quite ૿black bo x, meaning the inter nal workings ar e not easily interpr etable, and the process by which the model pr oduces an output for a given input is not easily e xplainable.

In contrast, causal models ar e eminently e xplainable because they dir ectly encode easy -to-understand causal relationships in the modeling domain. Indeed, causality is the core of e xplanation; e xplaining an event means describing the event’s causes and how they led to the event occur ring. Causal models pr ovide e xplanations in the language of the domain you ar e modeling (semantic e xplanations) rather than in ter ms of the model’s ar chitectur e (such as syntactic explanations of ૿ nodes and ૿activations).

Consider the e xamples in figures1.1 and 1.2. In figure 1.1, only the input featur es and output ar e interpr etable in ter ms of the domain; the inter nal workings of the hidden layers ar e not. Thus, given a particular ad impr ession, it is di cult to explain how the model ar rives at a particular pur chase outcome. In contrast, the e xample in figure 1.2 e xplicitly provides engagement to e xplain how we get fr om an ad impression to a pur chase outcome.

The connections between engagement and ad impr ession, and between pur chase and engagement, ar e still black boxes, but if we need to, we can mak e additional variables in

those black bo xes explicit. W e just need to mak e sur e we do so in a way that is aligned with our assumptions about the causal structur e of the pr oblem.

1.3.4 Fairer AI

Suppose Bob applies for a business loan. A machine lear ning algorithm pr edicts that Bob would be a bad loan candidate, so Bob is r ejected. Bob is a man, and he got ahold of the bank’s loan data, which shows that men ar e less lik ely to have their loan applications appr oved. W as this an ૿unfair outcome?

We might say the outcome is ૿unfair if, for e xample, the algorithm made that pr ediction because Bob is a man. T o be a ૿fair prediction, it would need to be for mulated fr om factors r elevant to Bob’s ability to pay back the loan, such as his cr edit history, his line of business, or his available collateral. Bob’s dilemma is another e xample of why we’d like machine lear ning to be e xplainable: so that we can analyze what factors in Bob’s application led to the algorithm’s decision.

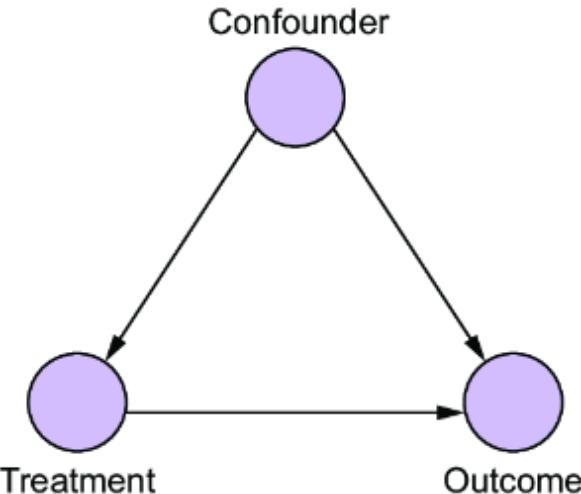

Suppose the training data came fr om a history of decisions from loan o cers, some of whom harbor ed a gender prejudice that hurt men. F or example, they might have r ead studies that show men ar e more lik ely to default in times of financial di culty . Based on those studies, they decided to deduct points fr om their rating if the applicant was a man.

Further more, suppose that when the data was collected, the bank advertised the loan pr ogram on social media. When we look at the campaign r esults, we notice that the men who responded to the ad wer e, on average, less quali fied than the women who click ed on the ad. This discr epancy might have been because the campaign was better tar geted

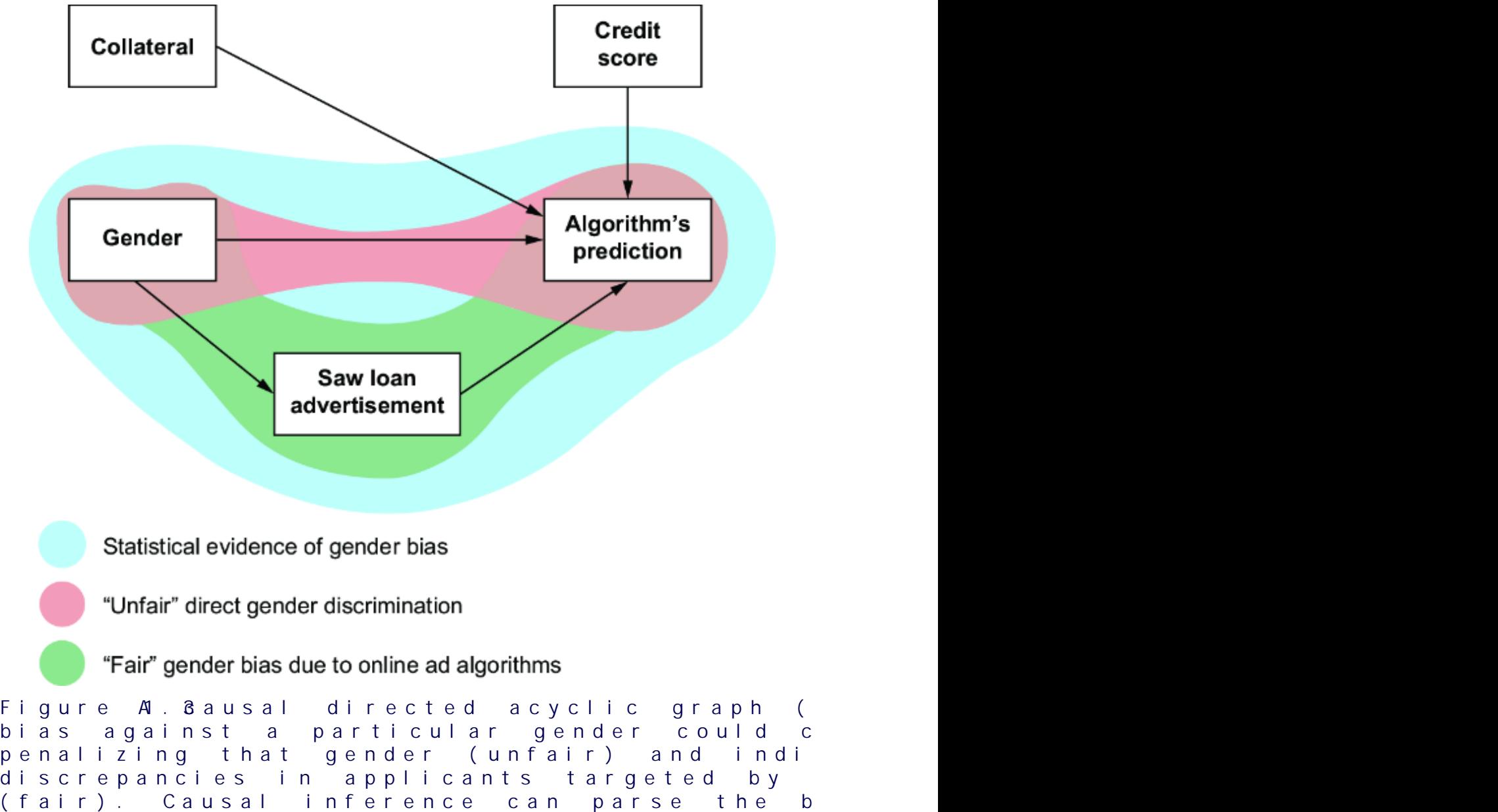

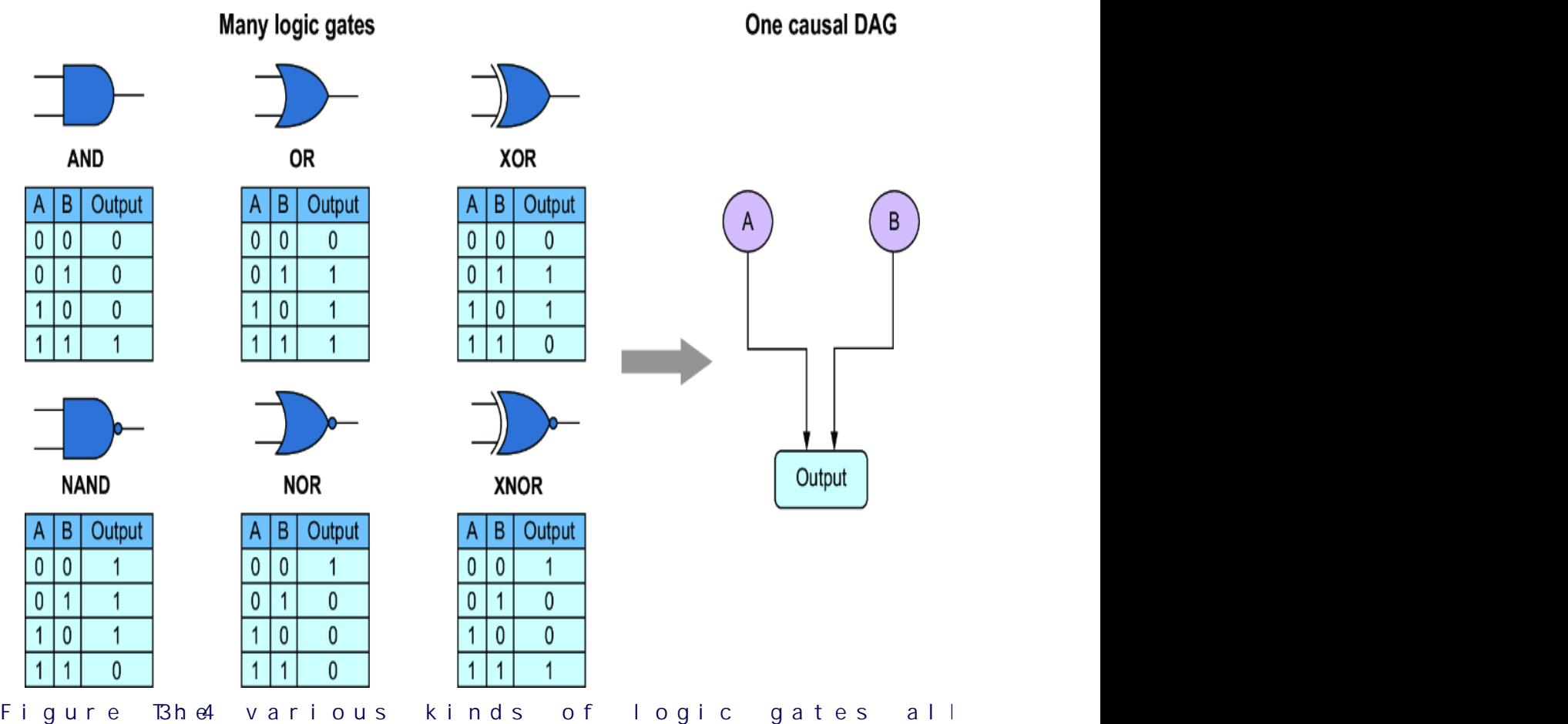

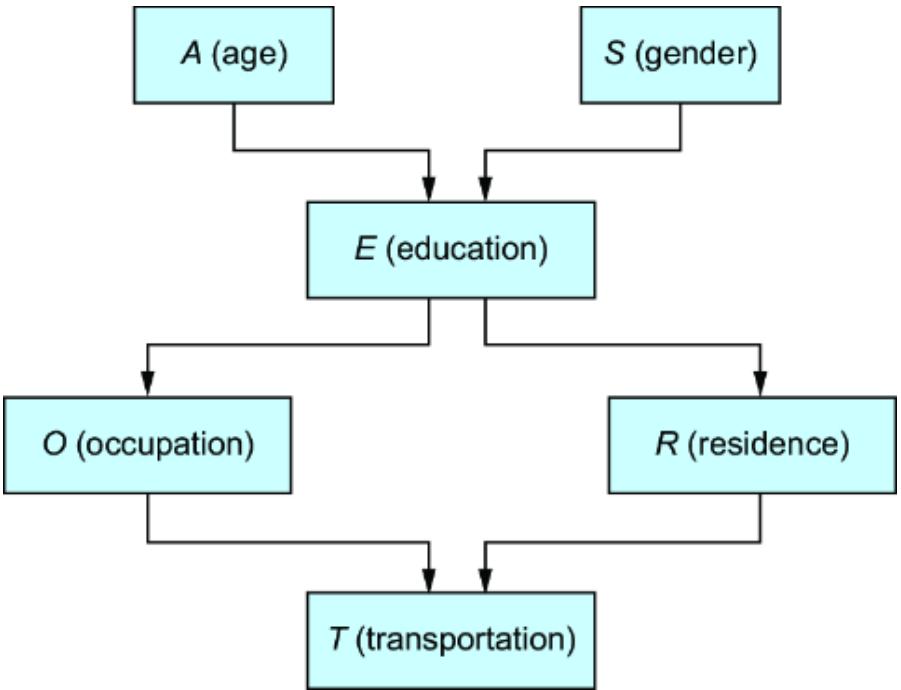

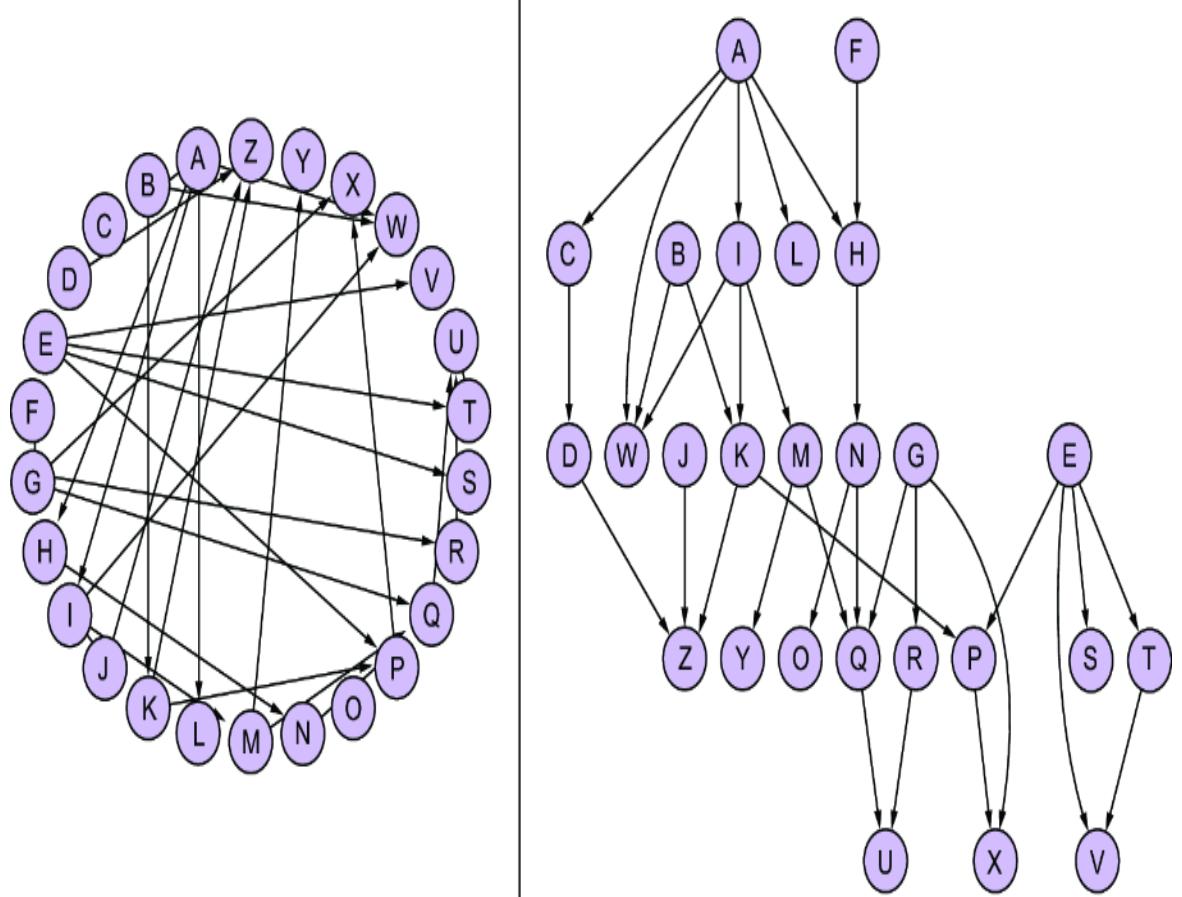

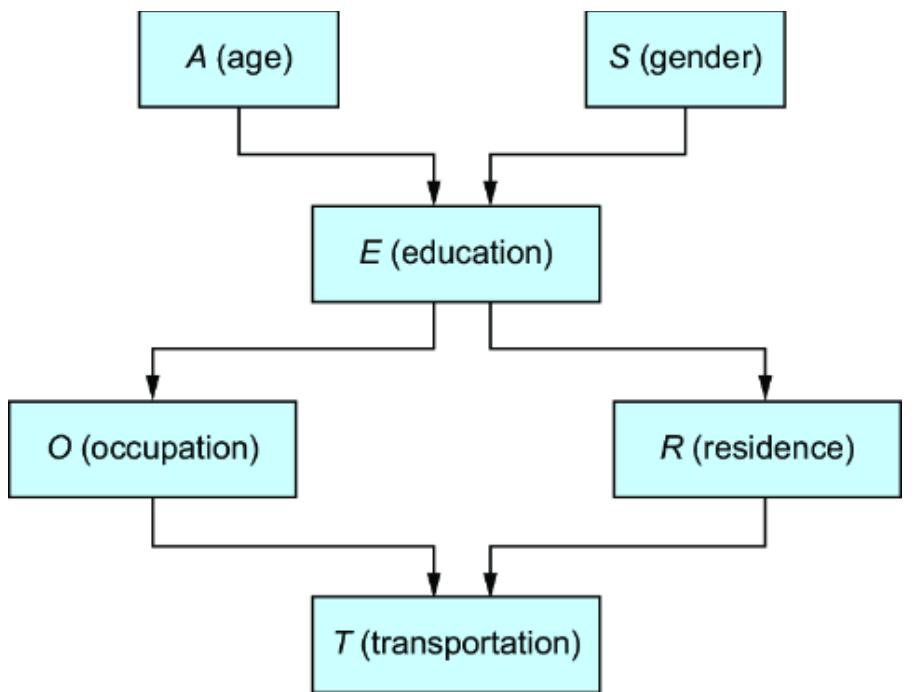

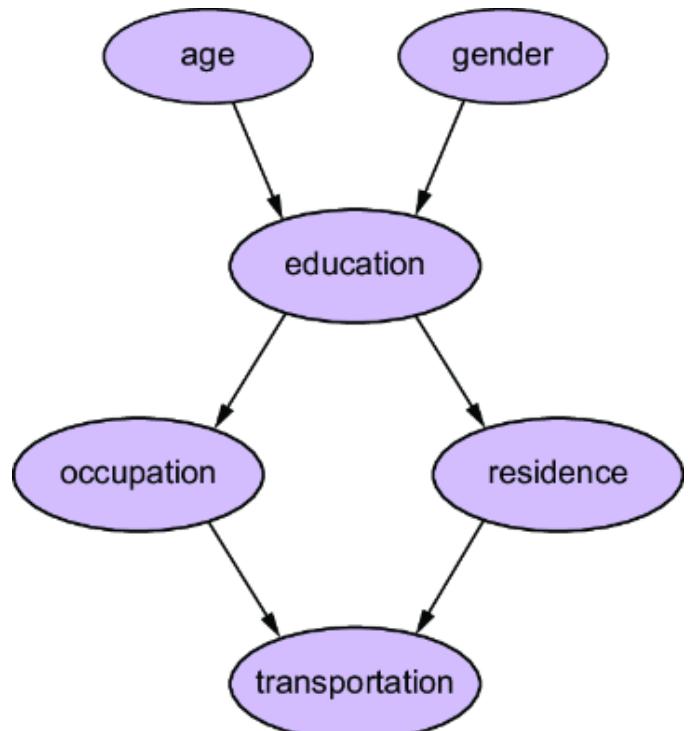

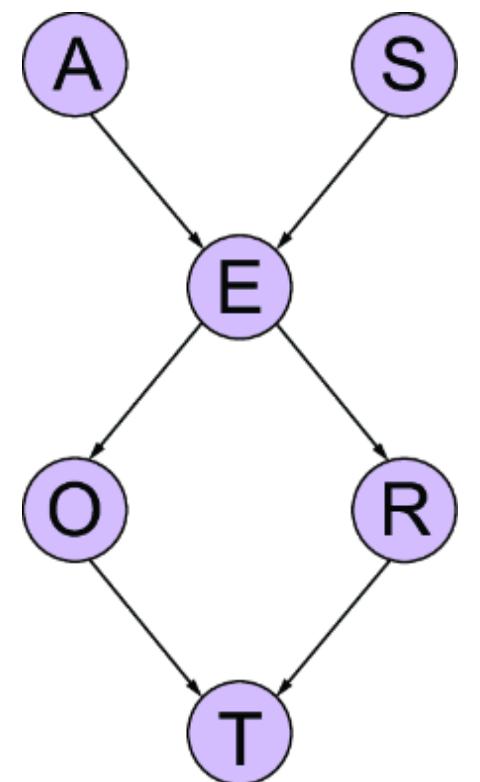

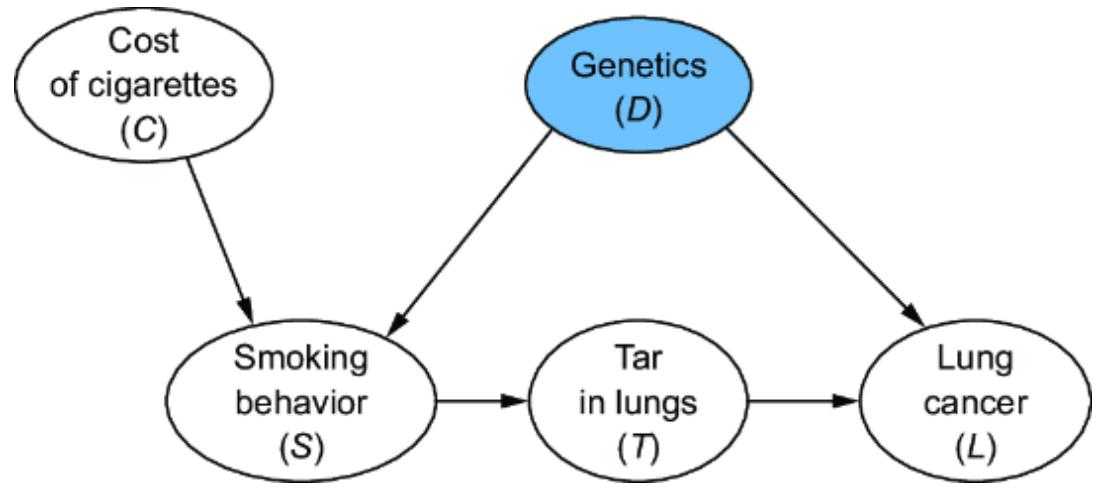

towar d women, or because the average bid price in online ad auctions was lower when the ad audience was composed of less-quali fied men. F igure 1.3 plots various factors that might influence the loan appr oval pr ocess, and it distinguishes fair from unfair causes. The factors ar e plotted in a dir ected acyclic graph (D AG), a popular and e ective way to represent causal r elationships. W e’ll use D AGs as our workhorse for causal r easoning thr oughout the book.

Thus, we have two possible sour ces of statistical bias against men in the data. One sour ce of bias is fr om the online ad that attracted men who wer e, on average, less quali fied, leading to a higher r ejection rate for men. The other sour ce of statistical bias comes fr om the pr ejudice of loan o cers. One of these sour ces of bias is ar guably ૿ fair (it’s har d to blame the bank for the tar geting behavior of digital advertising algorithms), and one of the sour ces is ૿unfair (we can blame the bank for se xist loan policies). But when we only look at the training data without this causal conte xt, all we see is statistical bias against men. The lear ning algorithm r eproduced this bias when it made its decision about Bob.

One naive solution to this pr oblem is simply to r emove gender labels fr om the training data. But even if those se xist loan ocers didn’t see an e xplicit indication of the person’s gender, they could infer it fr om elements of the application, such as the person’s name. Those loan o cers encode their prejudicial views in the for m of a statistical cor relation between those pr oxy variables for gender and loan outcome. The machine lear ning algorithm would discover this statistical patter n and use it to mak e predictions. As a r esult, you could have a situation wher e the algorithm pr oduces two dierent pr edictions for two individuals who had the same repayment risk but di ered in gender, even if gender wasn’t a dir ect input to the pr ediction. Deploying this algorithm would e ectively scale up the har m caused by those loan o cers’ pr ejudicial views.

For these r easons, we can see how many fears about the widespr ead deployment of machine lear ning algorithms ar e justi fied. Without cor rections, these algorithms could adversely impact our society by magnif ying the unfair outcomes captur ed in the data that our society pr oduces.

Causal analysis is instrumental in parsing these kinds of algorithmic fair ness issues. In this e xample, we could use causal analysis to parse the statistical bias into ૿unfair bias due to se xism and bias due to e xternal factors lik e how the digital advertising service tar gets ads. Ultimately, we could use causal modeling to build a model that only considers variables causally relevant to whether an individual can repay a loan.

It is important to note that causal infer ence alone is insucient to solve algorithmic fair ness. Causal infer ence can help parse statistical bias into what is fair and what’s not. And yet, even that depends on all parties involved agreeing on de finitions of concepts and outcomes, which is often a tall or der. To illustrate, suppose that the social media ad campaign served the loan ad to mor e men because the cost of serving an ad to men is cheaper . Thus, an ad campaign can win the online ad spot auctions with lower bids when the impr ession is coming fr om a man, and, as a result, mor een see the ad, though many of these men ar e not good matches for the loan pr ogram. W as this pr ocess unfair? Is the r esult unfair? What is the fair ness tradeo between balanced outcomes acr oss genders and pricing fair ness to advertisers? Should some advertisers have to pay more due to pricing mechanisms designed to encourage balanced outcomes? Causal analysis can’t solve these questions, but it can help understand them in technical detail.

1.4How causalityisdrivingthenext AIwave

Incorporating causal logic into machine lear ning is leading to new advances in AI. Thr ee tr ending ar eas of AI highlighted in this book ar e representation lear ning, r einfor cement

learning, and lar ge language models. These tr ends in causal AI ar e reminiscent of the early days of deep lear ning. P eople already working with neural networks when the deep learning wave was gaining momentum enjoyed first dibs on new opportunities in this space, and access to opportunities begets access to mor e opportunities. The ne xt wave of AI is still taking shape, but it is clear it will fundamentally incorporate some r epresentation of causality . The goal of this book is to help you ride that wave.

1.4.1 Causal representation learning

Many state- of-the-art deep lear ning methods attempt to learn geometric r epresentations of the objects being modeled. However, these methods struggle with lear ning causally meaningful r epresentations. F or example, consider a video of a child holding a helium- filled balloon on a string. Suppose we had a cor responding vector r epresentation of that image. If the vector r epresentation wer e causally meaningful, then manipulating the vector to r emove the child and converting the manipulated vector to a new video would r esult in a depiction of the balloon rising upwar ds. Causal r epresentation lear ning is a pr omising ar ea of deep representation lear ning that’s still in its early stages. This book pr ovides several e xamples in di erent chapters of causal models built upon deep lear ning ar chitectur es, providing an intr oduction to the fundamental ideas used in this e xciting new gr owth ar ea of causal AI.

1.4.2 Causal reinforcement learning

In canonical r einfor cement lear ning, lear ning agents ingest large amounts of data and lear n lik e Pavlov’s dog; they lear n actions that cor relate positively with good outcomes and negatively with bad outcomes. However, as we all know, correlation does not imply causation. Causal r einfor cement

learning can highlight cases wher e the action that causes a higher r eward diers fr om the action that cor relates most strongly with high r ewards. F urther, it addr esses the pr oblem of cr edit assignment (cor rectly attributing r ewards to actions) with counterfactual r easoning (i.e., asking questions like ૿how much r eward would the agent have r eceived had they been using a di erent policy?). Chapter 12 is devoted to causal r einfor cement lear ning and other ar eas of causal decision-making.

1.4.3 Large language models and foundation models

Large language models (LLMs) such as OpenAI’s GPT, Google’s Gemini, and Meta’s Llama ar e deep neural language models with many billions of parameters trained on vast amounts of te xt and other data. These models can generate highly coher ent natural language, code, and content of other modalities. They ar e foundation models, meaning they pr ovide a foundation for building mor e domain-speci fic machine lear ning models and pr oducts. These pr oducts, such as Micr osoft 365 Copilot, ar e alr eady having a tr emendous business impact.

A new ar ea of investigation and pr oduct development investigates LLMs’ ability to answer causal questions and perfor m causal analysis. Another line of investigation is using causal methods to design and train new LLMs with optimized causal capabilities. In chapter 13, we’ll e xplor e the intersection of LLMs and causality .

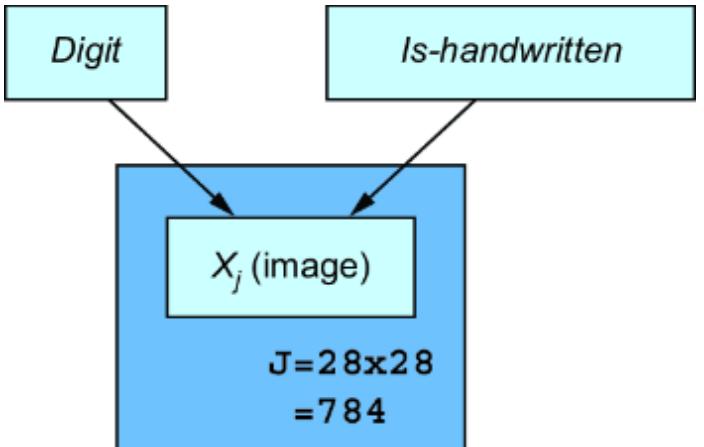

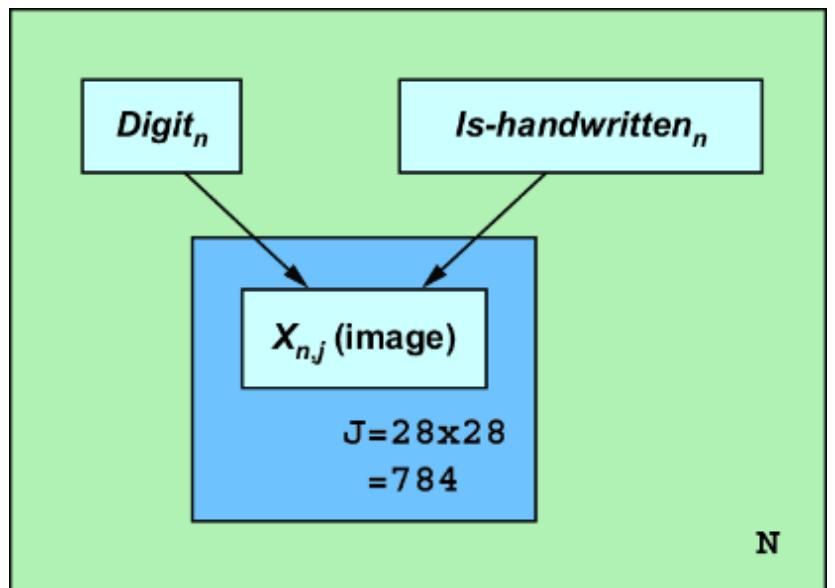

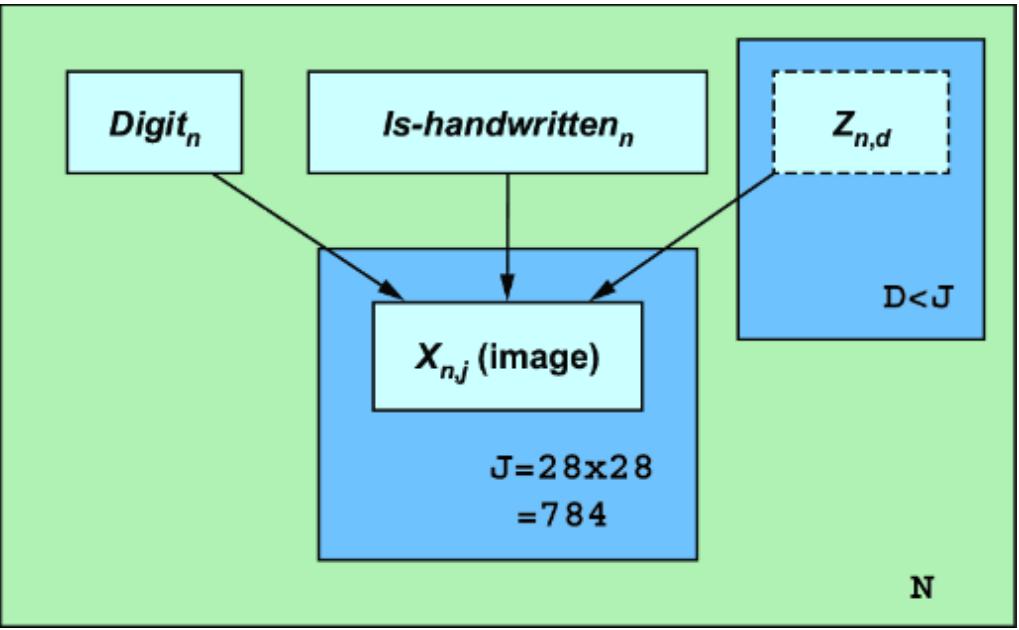

1.5Amachinelearning-themed primeroncausality

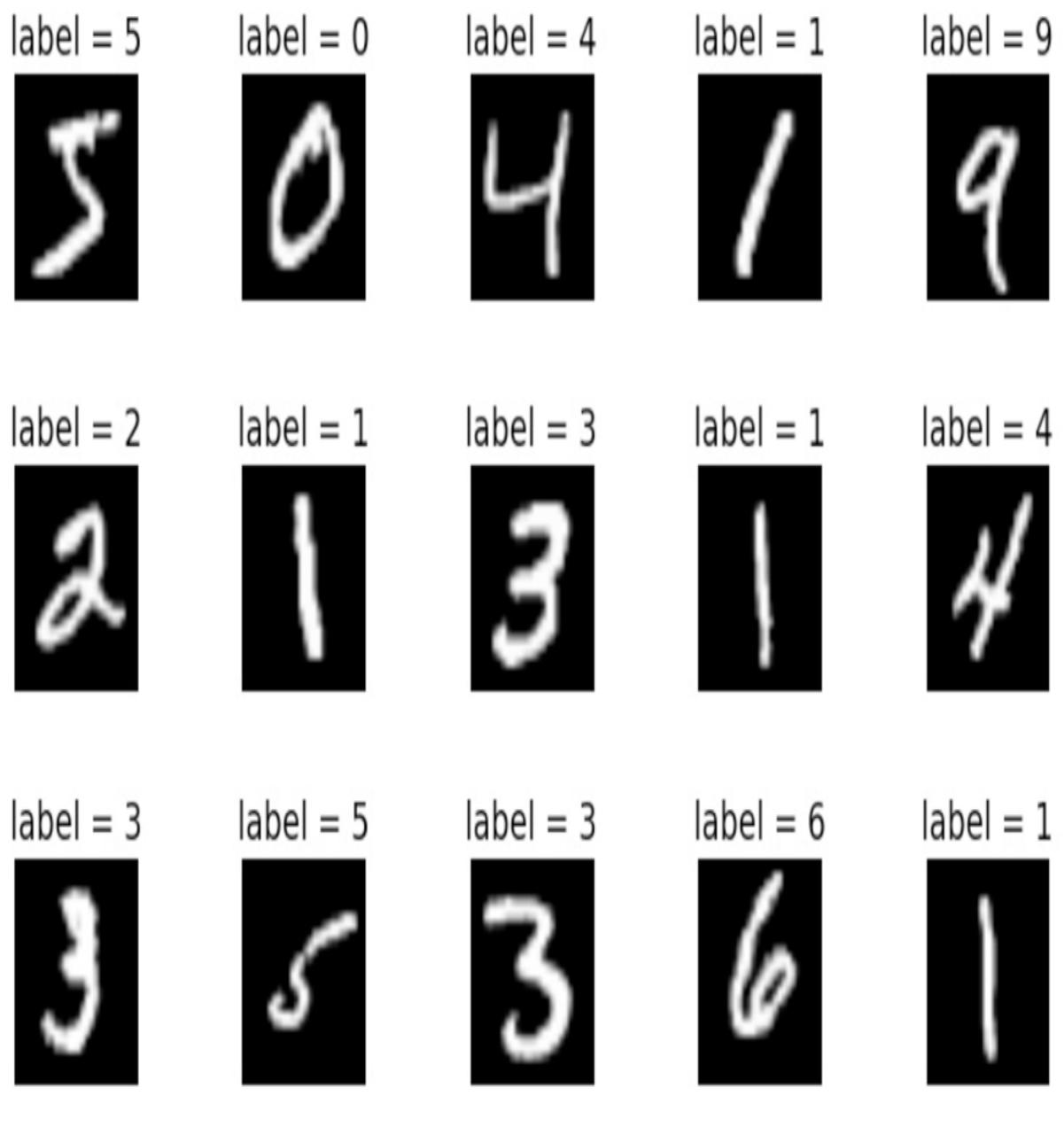

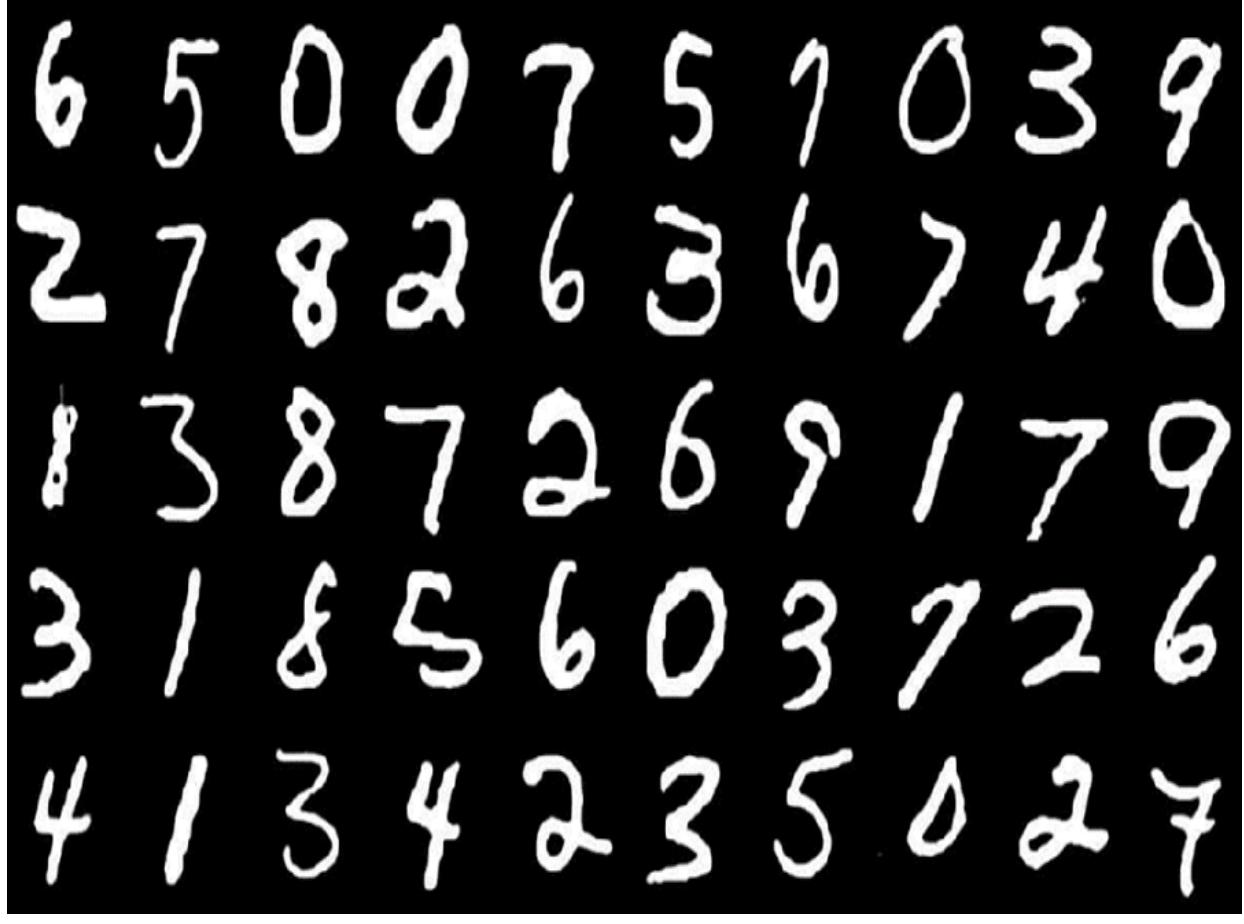

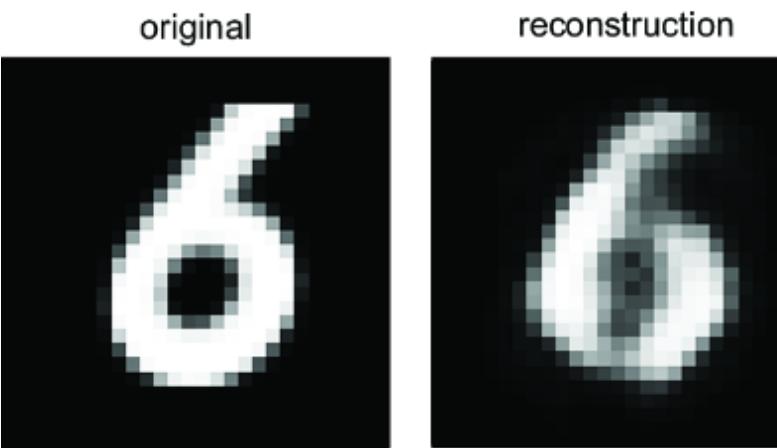

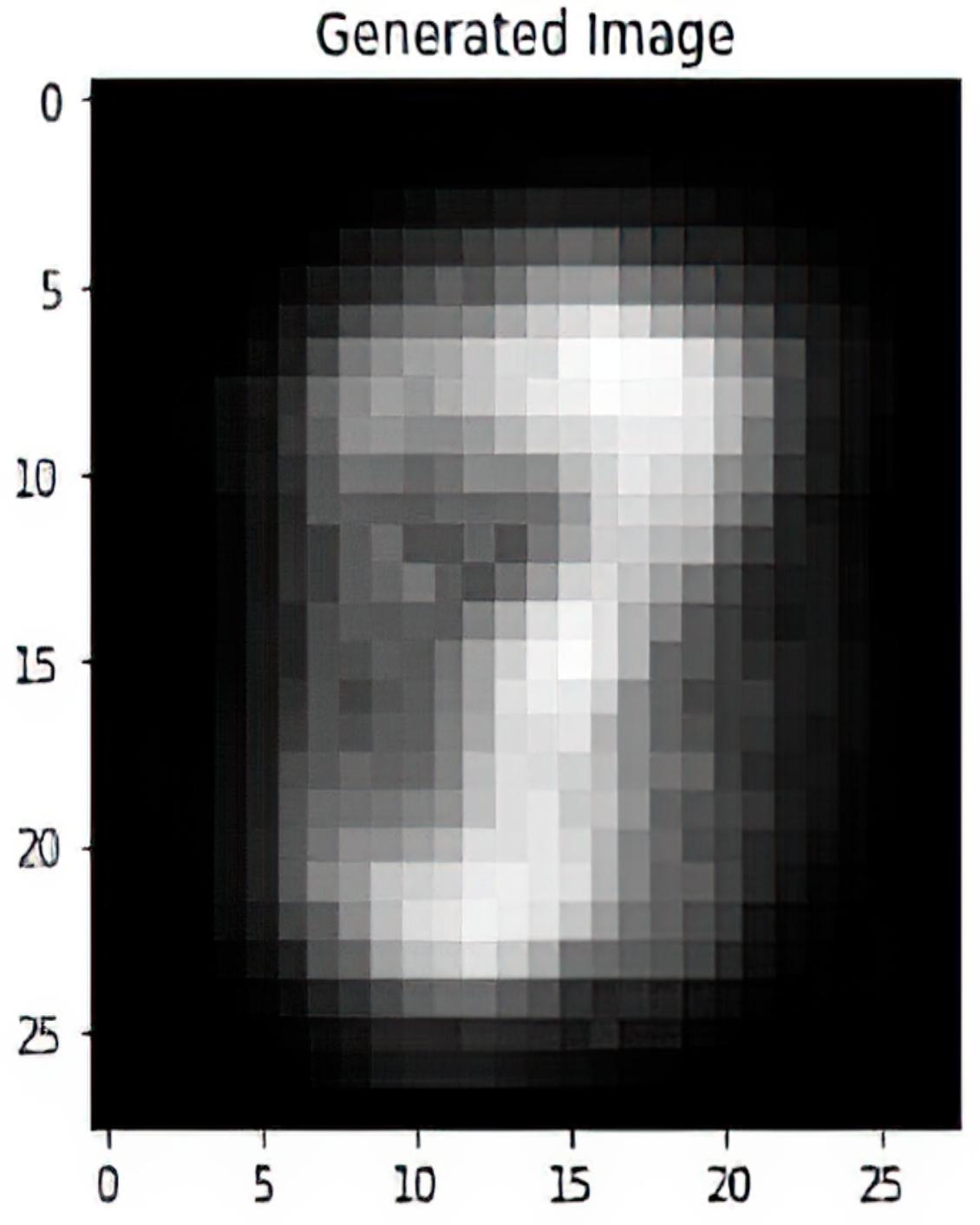

Now that you’ve seen the many ways that causal infer ence can impr ove machine lear ning, let’s look at the pr ocess of incorporating causality into AI models. T o do this, we will use a popular benchmark dataset of ten used in machine learning: the MNIST dataset of images of handwritten digits, each labeled with the actual digit r epresented in the image. Figure 1.4 illustrates multiple e xamples of the digits in MNIST.

Figure 1.4 Each image in the MNIST dataset is an image of a written digit, and each image is labeled with the digit it represents.

MNIST is essentially the ૿ Hello W orld of machine lear ning. It is primarily used to e xperiment with di erent machine learning algorithms and to compar e their rlative str engths. The basic pr ediction task is to tak e the matrix of pix els representing each image as input and r eturn the cor rect image label as output. L et’s start the pr ocess of

incorporating causal thinking into a pr obabilistic machine learning model applied to MNIST images.

1.5.1 Queries, probabilities, and statistics

First, we’ll look at the basic pr ocess without including causal infer ence. Machine lear ning can use pr obability in analyses about quantities of inter est. T o do so, a pr obabilistic machine learning model lear ns a pr obabilistic r epresentation of all the variables in that system. W e can mak e predictions and decisions with pr obabilistic machine lear ning models using a three-step pr ocess.

- Pose the question —What is the question you wanto answer?

- Write down the math—What probability (orprobability related quantity) will answer the question, given the evidence or data?

- Do the statistical inference —What statistical analysis will give you (or will estimate ) that quantity?

There is mor e for mal ter minology for these steps ( query, estimand , and estimator ) but we’ll avoid the jar gon for now . Instead, we’ll start with a simple statistical e xample pr oblem. Your step 1 might be ૿ How tall ar e Bostonians? F or step 2, you might decide that knowing the mean height (in probability ter ms, the ૿e xpected value) of everyone who lives in Boston will answer your question. Step 3 might involve randomly selecting 100 Bostonians and taking their average height; statistical theor ems guarantee that this sample average is a close estimate of the true population mean.

Let’s e xtend that work flow to modeling MNIST images.

STEP 1: POSE THE QUESTION

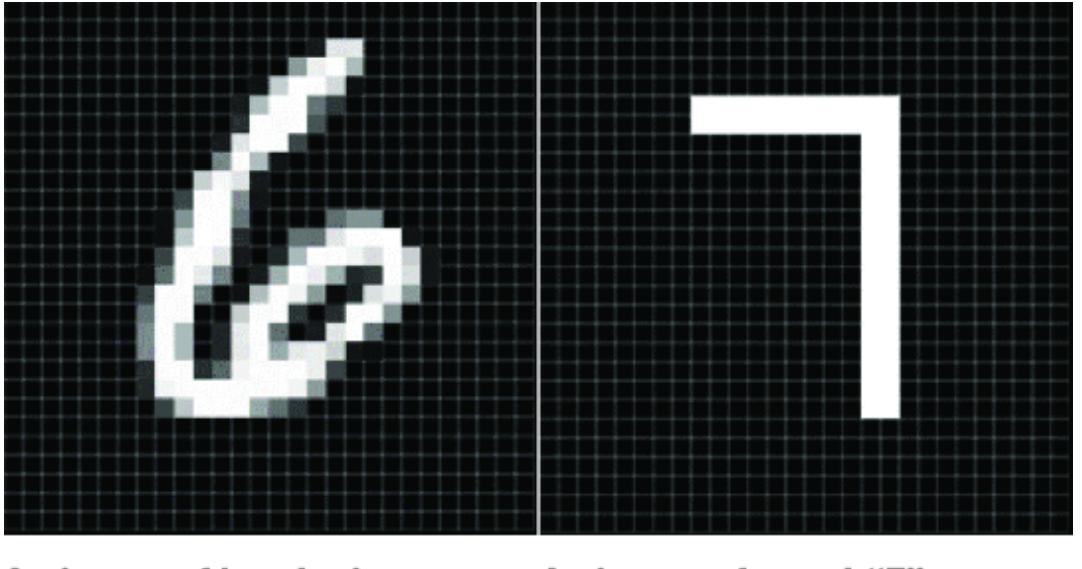

Suppose we ar e looking at the MNIST image in figure 1.5, which could be a ૿4 or could be a ૿9. In step 1, we articulate a question, such as ૿given this image, what is the digit r epresented in this image?

Figure 1.5 Is this an image of the digit 4 or 9? The canonical task of the MNIST dataset is to classify the digit label given the image. STEP 2: WRITE DOWN THE MA TH

In step 2, we want to find some pr obabilistic quantity that answers the question, given the evidence or data. In other words, we want to find something we can write down in probability math notation that can answer the question fr om step 1. F or our e xample with figure 1.5, the ૿evidence or ૿data is the image. Is the image a 4 or a 9? L et the variable I represent the image and D represent the digit. In probability notation, we can write the pr obability that the

digit is a 4, given the image, as P(D=4|I= ), where I= is shorthand for I being equal to some vector r epresentation of

the image. W e can compar e this pr obability to P(D=9|I= ), and choose the value of D that has the higher pr obability . Generalizing to all ten digits, the mathematical quantity we want in step 2 is shown in figure 1.6.

Figure 1.6 Choose the digit with the highest probability , given the image.

In plain English, this is ૿the value d that maximizes the probability that D equals d, given the image, wher e d is one of the ten digits (0–9).

STEP 3: DO THE ST ATISTICAL INFERENCE

Step 3 uses statistical analysis to assign a number to the quantity we identi fied in step 2. Ther e are any number of ways we can do this. F or example, we could train a deep neural network that tak es in the image as an input and predicts the digit as an output; we could design the neural net to assign a pr obability to D=d for every value d.

1.5.2 Causality and MNIST

So how could causality featur e in the pr evious section’s three-step analysis? Y ann L eCun is a T uring A ward winner (computer science’s equivalent of the Nobel prize) for his work on deep lear ning, and he’s dir ector of AI r esear ch at Meta. He is also one of the thr ee resear chers behind the creation of MNIST . He discusses the causal backstory of the MNIST data on his personal website, https://yann.lecun.com/e xdb/mnist/inde x.xhtml :

The MNIST database was constructed fr om NIST’s Special Database 3 and Special Database 1 which contain binary images of handwritten digits. NIST originally designated SD-3 as their training set and SD-1 as their test set. However, SD-3 is much cleaner and easier to r ecognize than SD-1. The r eason for this can be found on the fact that SD-3 was collected among Census Bur eau employees, while SD-1 was collected among high-school students. Drawing sensible conclusions fr om lear ning experiments r equir es that the r esult be independent of the choice of training set and test among the complete set of samples. Ther efore, it was necessary to build a new database by mixing NIST’s datasets.

In other wor ds, the authors mix ed the two datasets because they ar gue that if they trained a machine lear ning model solely on digits drawn by high schoolers, it would underperfor m when applied to digits drawn by bur eaucrats. However, in r eal-world settings, we want r obust models that can lear n in one scenario and pr edict in another, even when those scenarios di er. For example, we want a spam filter to keep working when the spammers switch fr om Nigerian princes to Bhutanese princesses. W e want our self -driving cars to stop even when ther e is gra ti on the stop sign.

Shuing the data lik e a deck of car ds is a luxury not easily a orded in r eal-world settings.

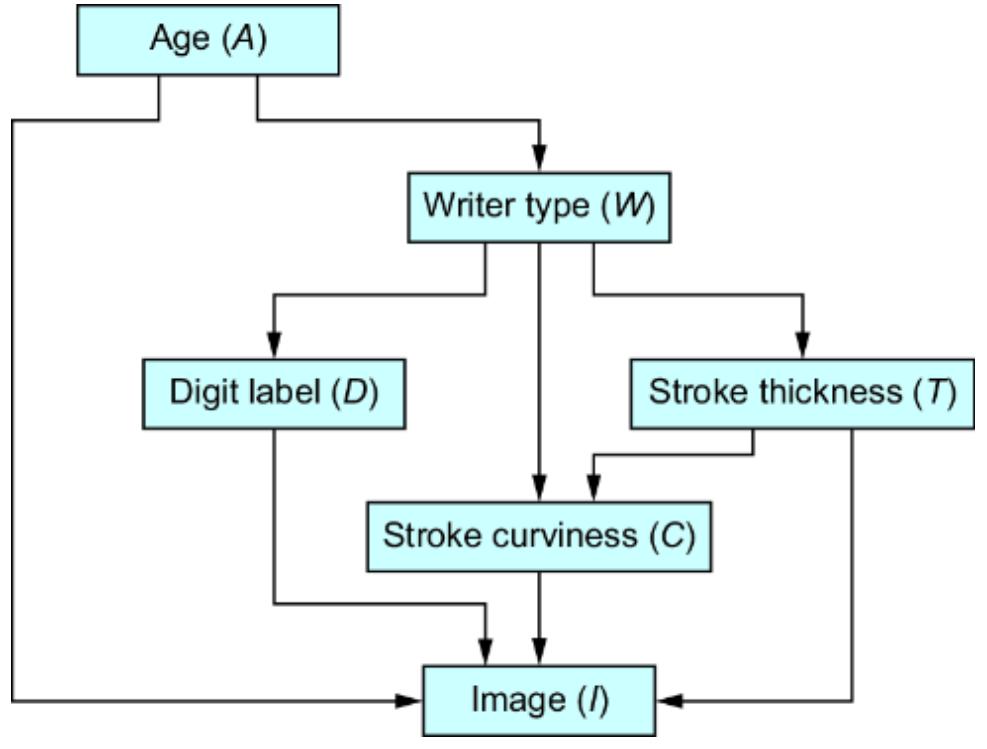

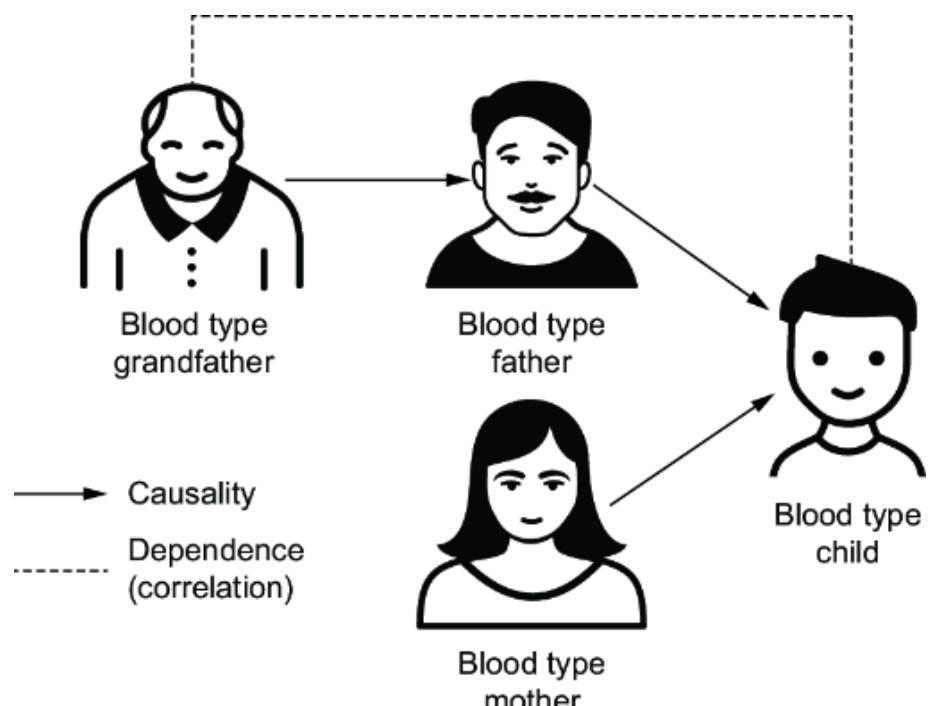

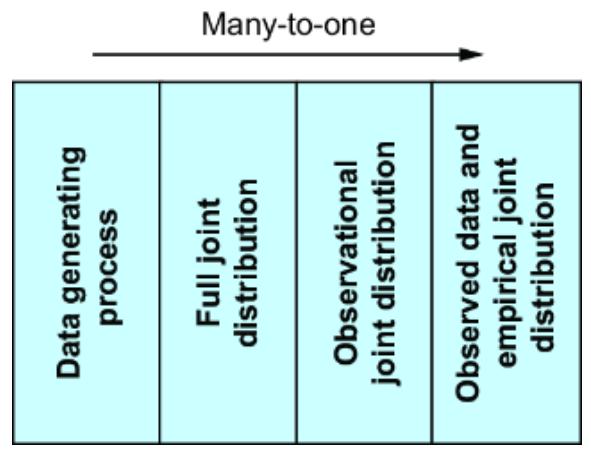

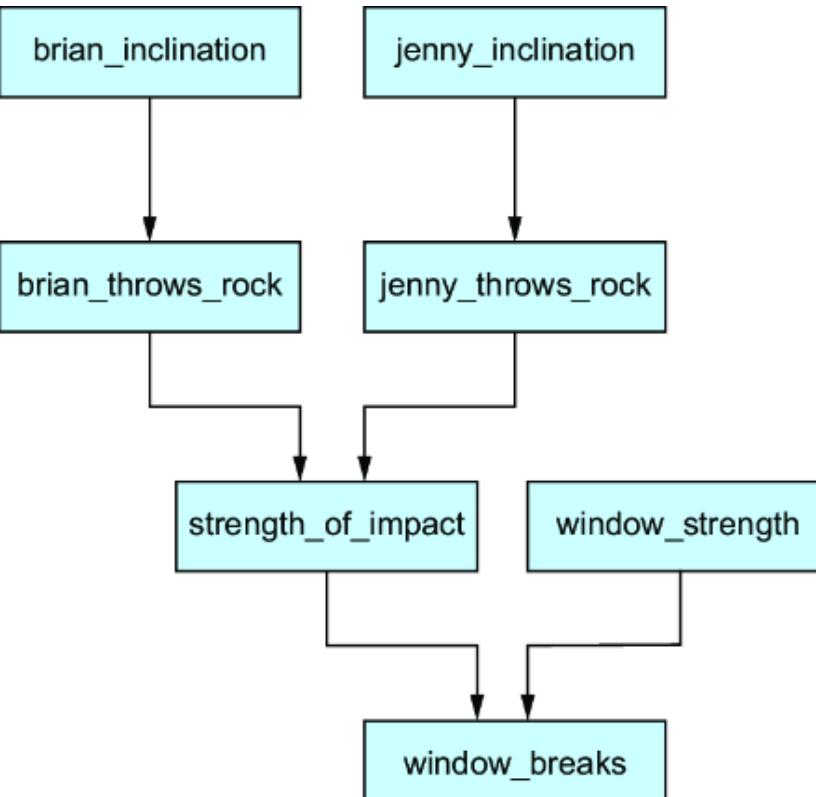

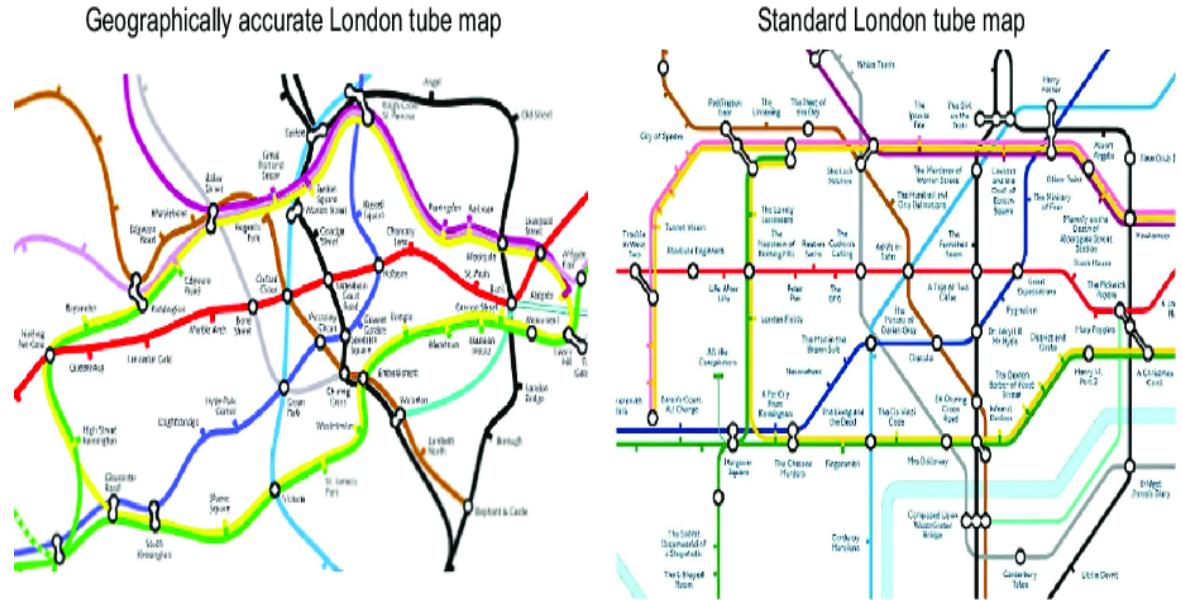

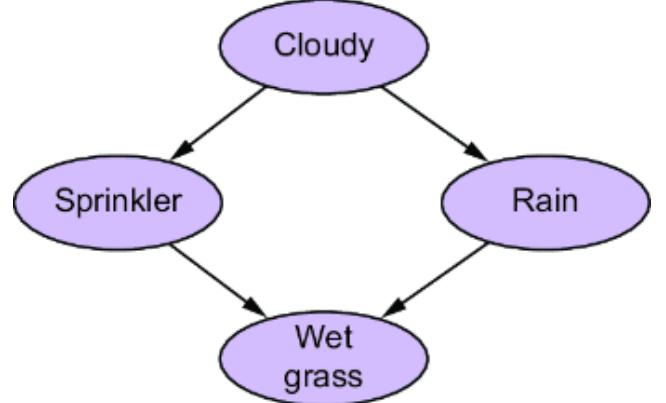

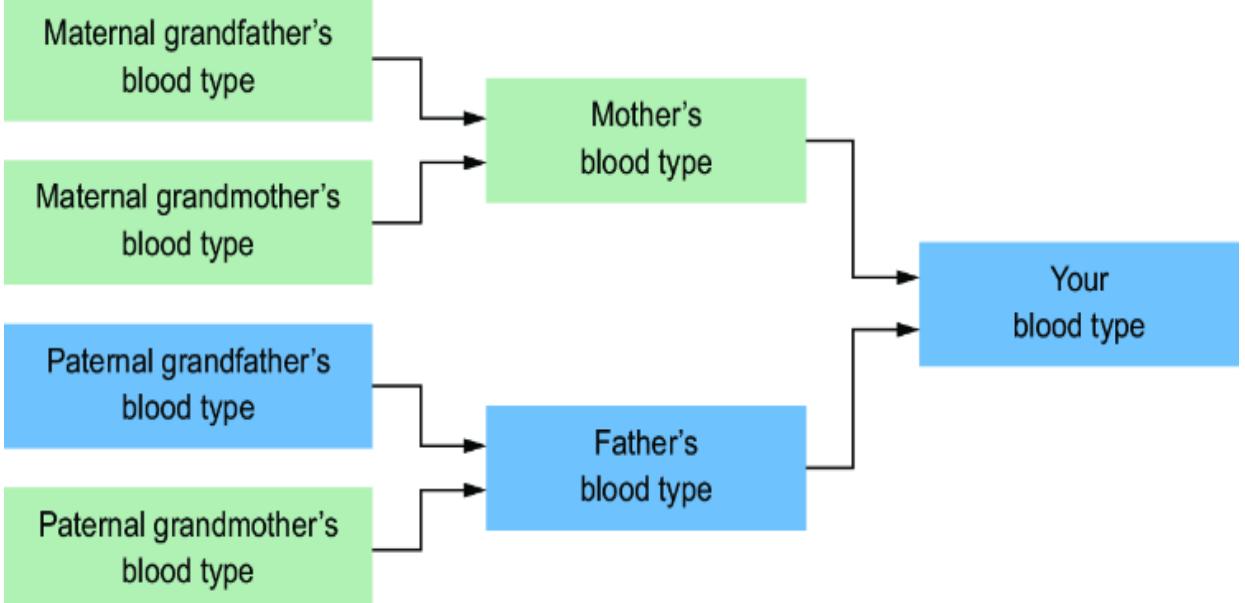

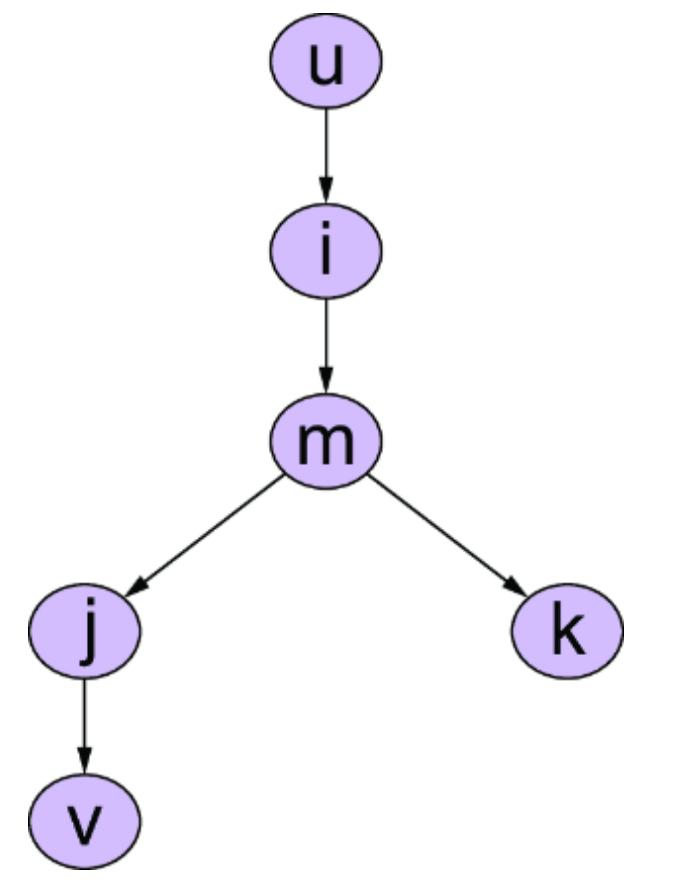

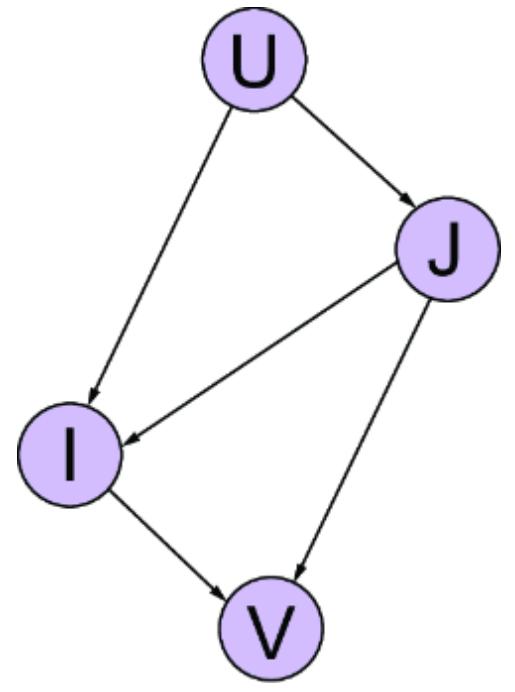

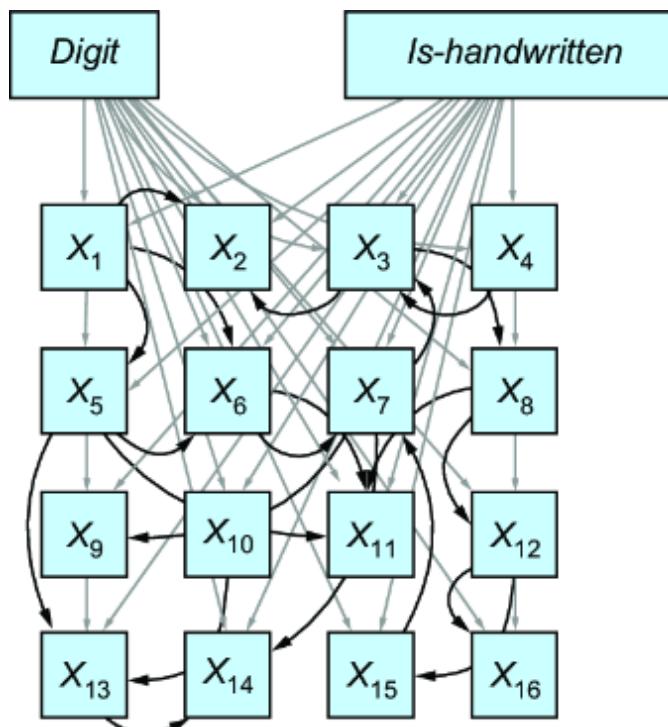

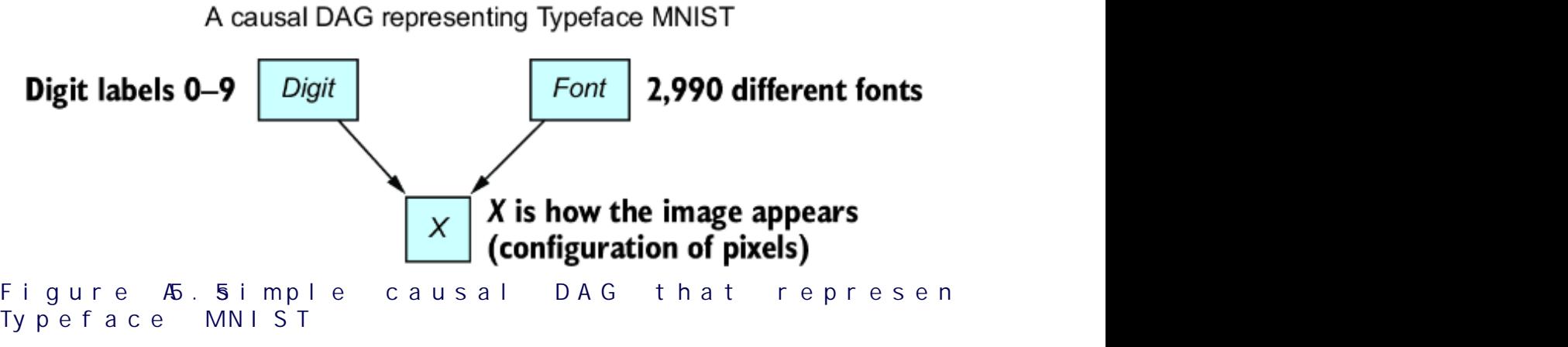

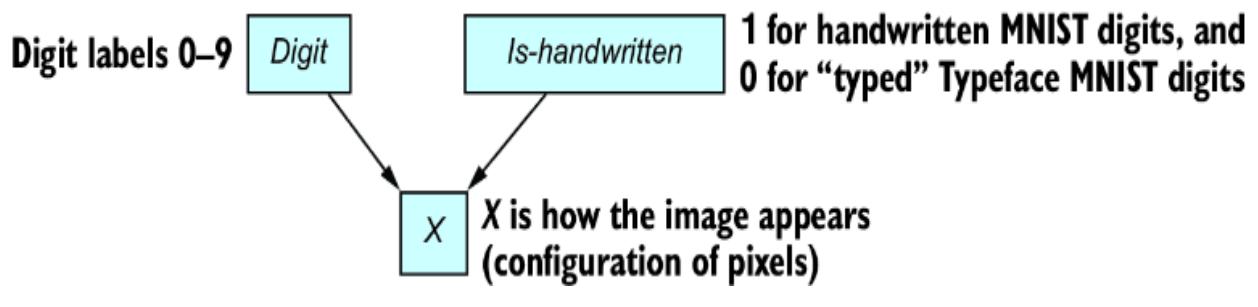

Causal modeling leverages knowledge about the causal mechanisms underlying how the digits ar e drawn that will help models generalize beyond high school students and bureaucrats in the training data to high schoolers in the test data. F igure 1.7 illustrates a causal D AG representing this system.

Figure 1.7 An example causal DAG representing the generation of MNIST images. The nodes represent objects in the data generating process, and edges correspond to causal relationships between those objects.

This particular D AG imagines that the writer deter mines the thickness and curviness of the drawn digits, and that high schoolers tend to have a di erent handwriting style than bureaucrats. The graph also assumes that the writer’s classi fication is a cause of what digits they draw . Perhaps bureaucrats write mor e 1s, 0s, and 5s, as these numbers

occur mor e f equently in census work, while high schoolers draw other digits mor e often because they do mor e long division in math classes (this is a similar idea to how, in topic models, ૿topics cause the frquency of wor ds in a document). F inally, the D AG assumes that age is a common cause of writer type and image; you have to be below a certain age to be in high school and above a certain age to be a census o cial.

A causal modeling appr oach would use this causal knowledge to train a pr edictive model that could e xtrapolate from the high school training data to the bur eaucrat test data. Such a model would generalize better to new situations where the distributions of writer type and other variables ar e dierent than in the training data.

1.5.3 Causal queries, probabilities, and statistics

At the beginning of this chapter, I discussed various types of causal questions we can pose, such as causal discovery, quantif ying causal e ects, and causal decision-making. W e can answer these and various other questions with a causal variation on our pr evious thr ee-step analysis (pose the question, write down the math, do the statistical infer ence):

- Pose the causal question —What is the question yu want to answer?

- Write down the causalmath—What probability (or expectation) will answer the causal question, given the evidence or data?

- Do the statistical inference —What statistical analysis will give you (or ૿estimate) that causal quantity?

Note that the thir d step is the same as in the original thr ee steps. The causal nuance occurs in the first and second

steps.

STEP 1: POSE THE CA USAL QUESTION

These ar e examples of some causal questions we could ask about our causal MNIST model:

- How much does the writer’s type (high schooler vs. bureaucrat) a ect the look of an image of the digit 4 with level 3 thickness? (Conditional average treatment e ect estimation is discussed in chapter 11).

- Assuming thatstroke thickness is a cause of the image, we might ask, ૿What would a 2 look like if it were as curvy as possible? (This is intervention prediction , discussed in chapter 7).

- Given an image, how would it have turned out dierently if the stroke curviness were heavier? (See counterfactual reasoning , discussed in chapters 8 and 9).

- ૿What should the stroke curviness be to get an aestheticallydea image? (Causal decision-making is discussed in chapter 12).

Let’s consider the CA TE in the first item. CA TE estimation is a common causal infer ence question applied to or dinary tabular data, but rar ely do we see it in the applied in the conte xt of an AI computer vision pr oblem.

STEP 2: WRITE DOWN THE CA USAL MATH

Causal infer ence theory tells us how to mathematically formalize our causal question. Using special causal notation, we can mathematically for malize our CA TE query as follows:

where E(.) is an e xpectation operator . We’ll r eview expectation in the ne xt chapter, but for now we can think of it as an averaging of pix els acr oss images.

The pr eceding use of subscripts is a special notation called ૿counterfactual notation that r epresents an intervention . A random assignment in an e xperiment is a r eal-world intervention, but ther e are many e xperiments we can’t run in the r eal world. F or example, it wouldn’t be feasible to run a trial wher e you randomly assign participants to either be a high school student or be a census bur eau ocial. Nonetheless, we want to know how the writer type causally impacts the images, and thus we r ely on a causal model and its ability to r epresent interventions.

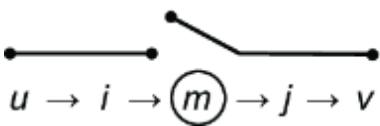

To illustrate, figure 1.8 visualizes what CA TE might look lik e. The challenge is deriving the di erential image at the right of figure 1.8. Causal infer ence theory helps us addr ess potential age-r elated ૿confounding bias in quantif ying how much writer type drives the image. F or example, the docalculus (chapter 10) is a set of graph-based rules that allows us to tak e this D AG and algorithmically derive the following equation:

\[E(I\_{W=w}|D=4, \ T=3) = \sum\_{a} E(I|W=w, A=a, D=4, \ T=3)P(A=a, D=4, \ T=3)\]

The lef t side of this equation de fines the e xpectations used in the CA TE de finition in the second step—it is a theor etical construct that captur es the hypothetical condition ૿if writer type wer e set to ‘w’. But the right side is actionable; it is composed entir ely of ter ms we could estimate using machine lear ning methods on a hypothetical version of NIST image data labeled with the writers’ ages.

Figure 1.8 Visualization of an example CA TE of writer type on an image. It is the pixel-by-pixel di erence of the expected image under one intervention ( W=“high school” ) minus the expected image under another intervention ( W=“bureaucrat” ), with both expectations conditional on being images of the digit 4 with a certain level of thickness.

STEP 3: DO THE ST ATISTICAL INFERENCE

Step 3 does the statistical estimation, and ther e are several ways we could estimate the quantities on the right side of that equation. F or example, we could use a convolutional neural network to model E(I|W =w, A=a, D=d, T=t), and build a pr obability model of the joint distribution P(A, D, T). The choice of statistical modeling appr oach involves the usual statistical trade- o s, such as ease- of-use, bias and variance, scalability to lar ge data, and parallelizability .

Other books go into gr eat detail on pr eferred statistical methods for step 3. I tak e the str ongly opinionated view that we should r ely on the ૿commodi fication of infer ence tr end

in statistical modeling and machine lear ning frameworks to handle step 3, and instead focus on honing our skills on steps 1 and 2: figuring out the right questions to ask, and representing the possible causes mathematically .

As you’ve seen in this section, our jour ney into causal AI is scaolded by a thr ee-step pr ocess, and the essence of causal thinking emer ges pr ominently in the first two steps. Step 1 invites us to frame the right causal questions, while step 2 illuminates the mathematics behind these questions. Step 3 leverages patter ns we’r e well-accustomed to in traditional statistical pr ediction and infer ence.

Using this structur ed appr oach, we’ll transition in the coming chapters fr om pur ely pr edictive machine lear ning models like the deep latent variable models you might be familiar with fr om MNIST—to causal machine lear ning models that o er deeper insights into and answers to our causal questions. F irt, we will r eview the underlying mathematics and machine lear ning foundations. Then, in part 2 of the book, we’ll delve into craf ting the right questions and articulating them mathematically for steps 1 and 2. F or step 3, we’ll har ness the power of contemporary tools lik e PyT orch and other advanced libraries to bridge the causal concepts with cutting-edge statistical lear ning algorithms.

Summary

- Causal AI seeks to augment statistical learning and probabilistic r easoning with causal logic.

- Causal infer ence helps data scientists extract more causal insights from observational data (the vast majority of data in the world) and e xperimental data.

- When data scientists can’t run experiments, causal models can simulate experiments from observational

data.

- They can use these simulations to make causal infer ences, such as estimating causal e ects, and even to prioritize inter esting e xperiments to run in r eal life.

- Causal infer ence also helps data scientists improve decision-making in their organizations through algorithmic counterfactual r easoning and attribution.

- Causal infer ence also makes machine larning more robust , decomposable , and explainable .

- Causal analysis is useful for formally analyzing fairness in predictive algorithms and for building fair er algorithms by parsing ordinary statistical bias into its causal sources.

- The commodi fication of inference is a trend in machine learning that refers to how universal modeling frameworks like PyTorch continuously automate the nuts and bolts of statistical learning and probabilistic infer ence. The trend reduces the need for the modeler to be an expert at the formal and statistical details of causal infer ence and allows them to focus on turning domain expertise into better causal models of their problem domain.

- Types of causal infer ence tasks include causal discovery , intervention prediction , causal e ect estimation , counterfactual reasoning , explanation , and attribution .

- The way we build and work with probabilistic machine learning models can be extended to causal generative models implemented in probabilistic machine larning tools such as PyT orch.

2A primer on probabilistic generative modeling

This chapter covers

- A primer on pr obability models

- Computational pr obability with the pgmpy and Pyr o libraries

- Statistics for causality : data, populations, and models

- Distinguishing between probability models and subjective Bayesianism

Chapter 1 made the case for lear ning how to code causal AI. This chapter will intr oduce some fundamentals we need to tackle causal modeling with pr obabilistic machine lear ning, which r oughly r efers to machine lear ning techniques that use pr obability to model uncertainty and simulate data. Ther e is a flexible suite of cuttingedge tools for building pr obabilistic machine lear ning models. This chapter will intr oduce the concepts fr om probability, statistics, modeling, infer ence, and even philosophy that we will need in or der to implement k ey ideas fr om causal infer ence with the pr obabilistic machine lear ning appr oach.

This chapter will not pr ovide a mathematically e xhaustive intr oduction to these ideas. I’ll focus on what is needed for the r est of this book and omit the r est. Any data scientist seeking causal infer ence e xpertise should not neglect the practical nuances of probability, statistics, machine lear ning, and computer science. See the chapter notes at https://www .altdeep.ai/p/causalaibookfor recommended r esour ces wher e you can get deeper intr oductions or review materials.

In this chapter, I’ll intr oduce two Python pr ogramming libraries for probabilistic machine lear ning:

pgmpyis a library for building probabilistic graphical models. As a traditional graphical modeling tool, it is far less flexible and

cutting-edge than Pyro but also easier to use and debug. What it does, it does well.

Pyrois a genera l probabilistic machine learning libra ry. It is quite flexible, and it leverages PyTorch’s cutting-edge gradientbased lear ning techniques.

Pyro and pgmpy ar e the general modeling libraries we’ll use in this book. Other libraries we’ll use ar e designed speci fically for causal infer ence.

2.1Primeronprobability

Let’s r eview the pr obability theory you’ll need to work with this book. W e’ll start with a few basic mathematical axioms and their logical e xtensions without yet adding any r eal-world interpr etation. Let’s begin with the concr ete idea of a simple thr ee-sided die (these exist).

2.1.1 Random variables and probability

A random variable is a variable whose possible values ar e the numerical outcomes of a random phenomenon. These values can be discr ete or continuous. In this section, we’ll focus on the discr ete case. F or example, the values of a discr ete random variable representing a thr ee-sided die r oll could be {1, 2, 3}. Alter natively, in a 0-inde xed pr ogramming language lik e Python, it might be better to use {0, 1, 2}. Similarly, a discr ete random variable representing a coin flip could have outcomes {0, 1} or {T rue, False}. F igure 2.1 illustrates thr ee-sided dice.

Figure 2.1 Three-sided dice each represent a random variable with three discrete outcomes.

The typical appr oach to notation is to write random variables with capitals lik e X, Y, and Z. For example, suppose X represents a die roll with outcomes {1, 2, 3}, and the outcome r epresents the number on the side of the die. X=1 and X=2 represent the events of r olling a 1 and 2 r espectively . If we want to abstract away the speci fic outcome with a variable, we typically use lower case. F or example, I would use ૿ X=x (e.g., X=1) to r epresent the event ૿I rolled an ’ x’! wher e x can be any value in {1, 2, 3}. See figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 X represents the outcome of a three-sided die roll. If the die roles a 2, the observed outcome is X=2.

Each outcome of a random variable has a probability value . The probability value is of ten called a probability mass for discr ete variables and a probability density for continuous variables. F or discr ete variables, pr obability values ar e between zer o and one, and summing up the pr obability values for each possible outcome yields 1. F or continuous variables, pr obability densities ar e greater than zer o, and integrating the pr obability densities over each possible outcome yields 1.

Given a random variable with outcomes {0, 1} r epresenting a coin flip, what is the pr obability value assigned to 0? What about 1? A t this point, we just know the two values ar e between zer o and one, and that they sum to one. T o go beyond that, we have to talk about how to interpret probability . First, though, let’s hash out a few mor e concepts.

2.1.2 Probability distributions and distribution functions

A probability distribution function is a function that maps the random variable outcomes to a pr obability value. F or example, if the outcome of a coin flip is 1 (heads) and the pr obability value is 0.51, the distribution function maps 1 to 0.51. I stick to the standar d notation P(X=x), as in P(X=1) = 0.51. F or longer expressions, when the random variable is obvious, I dr op the capital letter and k eep the outcome, so P(X=x) becomes P(x), and P (X=1) becomes P(1).

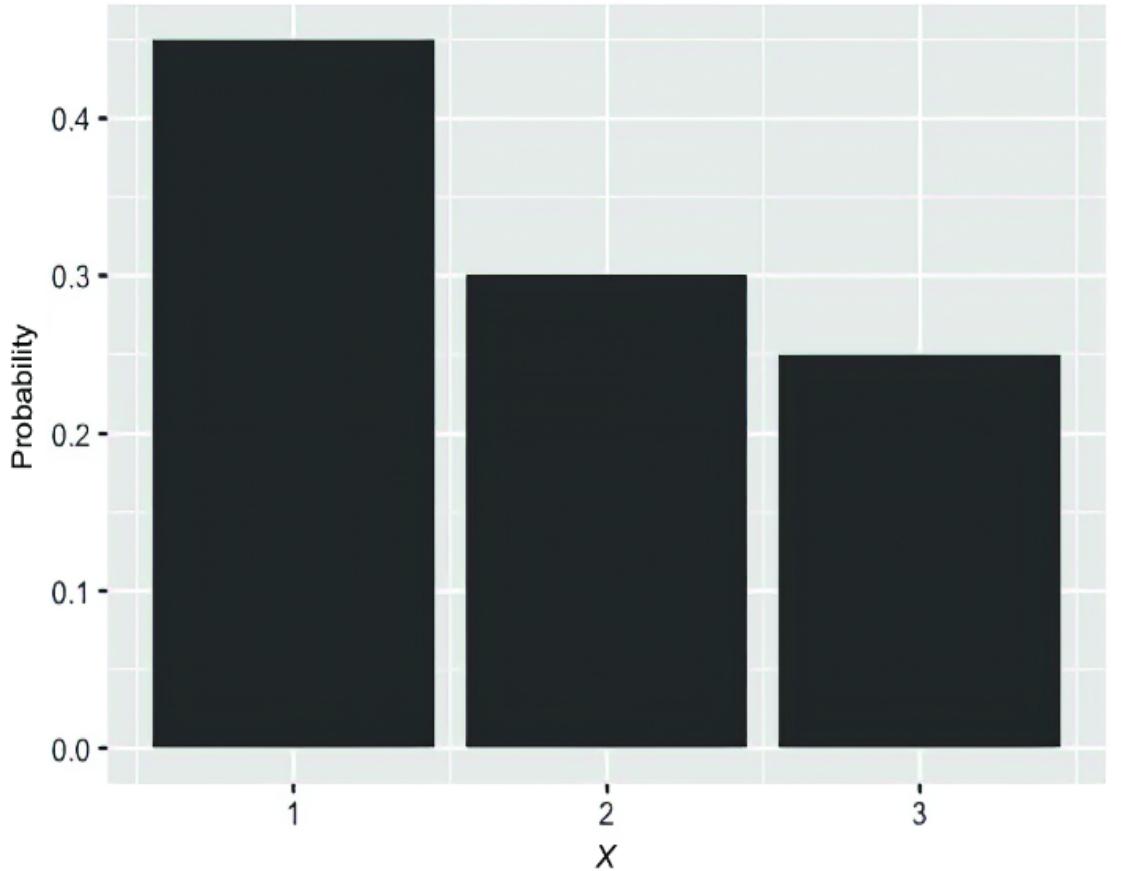

If the random variable has a finite set of discr ete outcomes, we can represent the pr obability distribution with a table. F or example, a random variable r epresenting outcomes {1, 2, 3} might look lik e figure 2.3.

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P(X) 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

Figure 2.3 A simple tabular representation of a discrete distribution

In this book, I adopt the common notation P(X) to r epresent the probability distribution over all possible outcomes of X, while P(X= x) represents the pr obability value of a speci fic outcome. T o implement a pr obability distribution as an object in pgmpy, we’ll use the DiscreteFactor class.

Listing 2.1 Implementing a discrete distribution table in pgmpy

from pgmpy.factors.discrete import DiscreteFactor dist = DiscreteFactor( variables=[“X”], #1 cardinality=[3], #2 values=[.45, .30, .25], #3 state_names= {‘X’: [‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’]} #4 )

print(dist)

#1 A list of the names of the variables in the factor #2 The cardinality (number of possible outcomes) of each variable in the factor #3 The values each variable in the factor can tak e #4 A dictionary , where the k ey is the variable name and the value is a list of the names of that variable’s outcomes

This code prints out the following:

+——+———-+ | X | phi(X) | +======+==========+ | X(1) | 0.4500 | +——+———-+ | X(2) | 0.3000 | +——+———-+ | X(3) | 0.2500 | +——+———-+

SETTING UP Y OUR ENVIRONMENT

This code was written with pgmpy version 0.1.24 and Pyr o version 1.8.6. The version of pandas used was 1.5.3.

See https://www .altdeep.ai/p/causalaibook for links to the Jupyter notebooks for each chapter, with the code and notes on setting up a working envir onment.

2.1.3 Joint probability and conditional probability

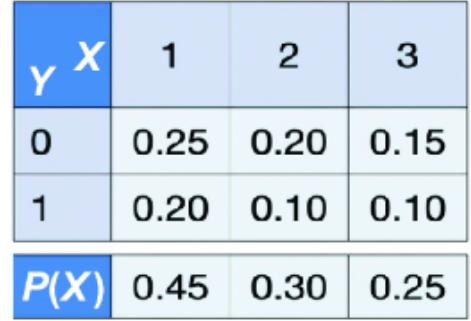

Often, we ar e inter ested in r easoning about mor e than one random variable. Suppose, in addition to the random variable X in figure 2.1, ther e was an additional random variable Y with two outcomes {0, 1}. Then ther e is a joint probability distribution function that maps each combination of X and Y to a pr obability value.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.15 |

| 1 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

Figure 2.4 A simple representation of a tabular joint probability distribution

As a table, it could look lik e figure 2.4.

The DiscreteFactor object can r epresent joint distributions as well.

Listing 2.2 Modeling a joint distribution in pgmpy

joint = DiscreteFactor( variables=[‘X’, ‘Y’], #1 cardinality=[3, 2], #2 values=[.25, .20, .20, .10, .15, .10], #3 state_names= { ‘X’: [‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’], #3 ‘Y’: [‘0’, ‘1’] #3 } ) print(joint) #4

#1 Now we have two variables instead of one. #2 X has 3 outcomes, Y has 2. #3 Now there are two variables, so we name the outcomes for both variables.

#4 You can look at the printed output to see how the values are ordered of values.

The pr eceding code prints this output:

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | phi(X,Y) | ||||||||||||

| +======+======+============+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(1) Y(0) | 0.2500 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(1) Y(1) | 0.2000 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(2) Y(0) | 0.2000 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(2) Y(1) | 0.1000 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(3) Y(0) | 0.1500 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(3) Y(1) | 0.1000 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ |

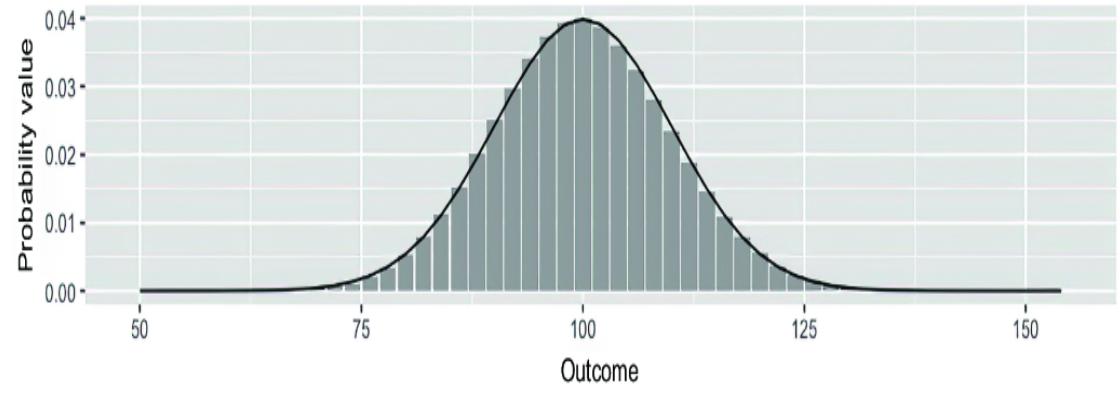

Note that the pr obability values sum to 1. F urther, when we marginalize (i.e., ૿sum over or ૿integrate over ) Y across the r ows, we recover the original distribution P(X ), (ak a the mar ginal

distribution of X ). Summing up over the r ows in figure 2.5 pr oduces the mar ginal distribution of X on the bottom.

Figure 2.5 Marginalizing over Y yields the marginal distribution of X.

The mar ginalize method will sum over the speci fied variables for us.

print(joint.marginalize(variables=[‘Y’], inplace=False) )

This prints the following output:

| +——+———-+ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | phi(X) | ||||||||

| +======+==========+ | |||||||||

| X(1) | 0.4500 | ||||||||

| +——+———-+ | |||||||||

| X(2) | 0.3000 | ||||||||

| +——+———-+ | |||||||||

| X(3) | 0.2500 | ||||||||

| +——+———-+ |

Setting the inplace argument to False gives us a new mar ginalized table rather than modif ying the original joint distribution table.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | PY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.25 0.20 0.15 0.60 | |||

| 0.20 0.10 0.10 0.40 |

Figure 2.6 Marginalizing over X yields the marginal distribution of Y.

Similarly, when we mar ginalize X over the columns, we get P(Y ). In figure 2.6, summing over the values of X in the columns gives us the mar ginal distribution of Y on the right.

print(joint.marginalize(variables=[‘X’], inplace=False))

| +——+———-+ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | phi(Y) | ||||||||

| +======+==========+ | |||||||||

| Y(0) | 0.6000 | ||||||||

| +——+———-+ | |||||||||

| Y(1) | 0.4000 | ||||||||

| +——+———-+ |

I’ll use the notation P(X, Y ) to r epresent joint distributions. I’ll use P(X=x, Y=y) to r epresent an outcome pr obability, and for shorthand, I’ll write P(x, y). F or example, in figure 2.6, P(X=1, Y= 0) = P(1, 0) = 0.25. W e can de fine a joint distribution on any number of variables; if ther e wer e thr ee variables { X, Y, Z }, I’d write the joint distribution as P(X, Y, Z ).

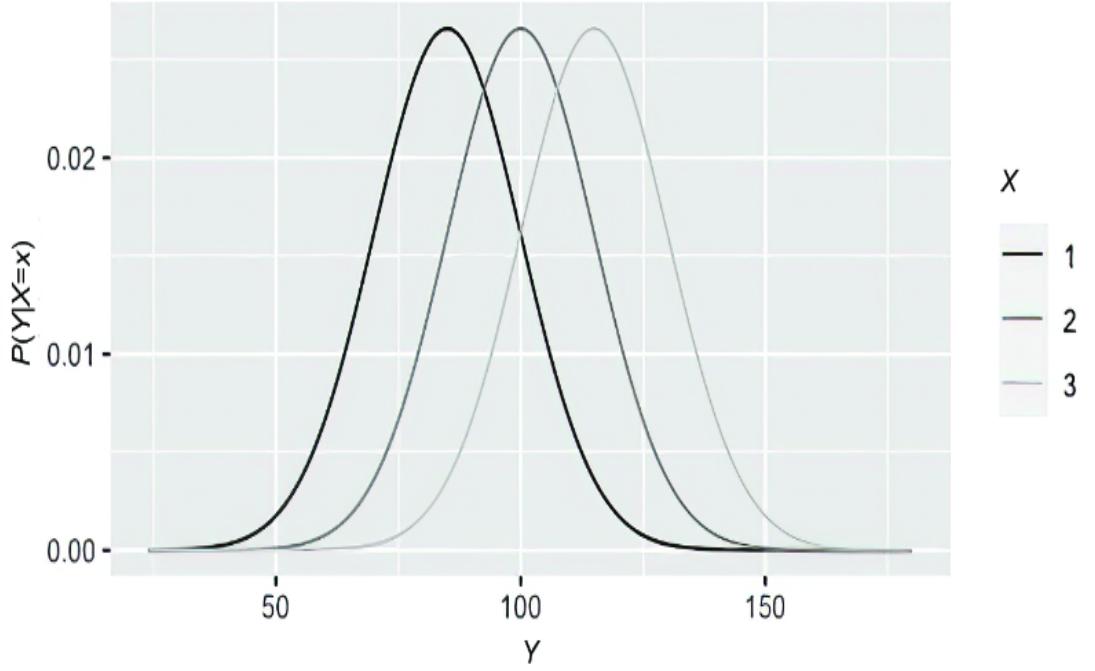

In this tabular r epresentation of the joint pr obability distribution, the number of cells incr eases e xponentially with each additional variable. Ther e are some (but not many) ૿canonical joint probability distributions (such as the multivariate nor mal distribution—I’ll show mor e examples in section 2.1.7). F or that reason, in multivariate settings, we tend to work with conditional probability distributions.

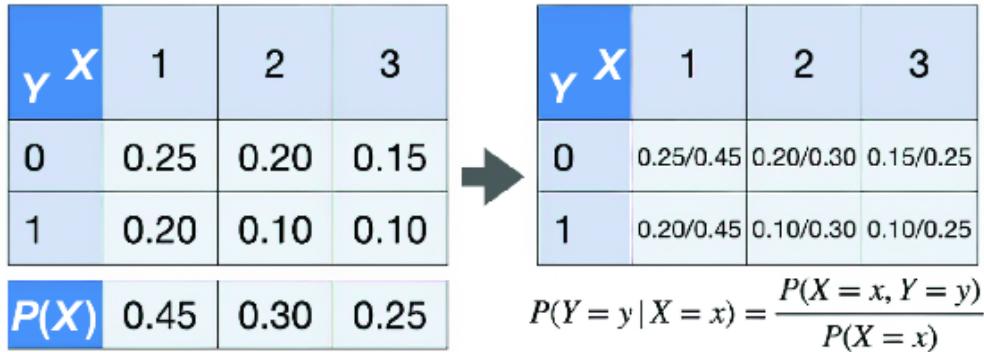

The conditional pr obability of Y, given X, is

\[P\left(Y=\mathcal{Y}|X=x\right) = \frac{P(X=x, Y=\mathcal{Y})}{P(X=x)}\]

Intuitively, P(Y |X =1) r efers to the pr obability distribution for Y conditional on X being 1. In the case of tabular r epresentations of distributions, we can derive the conditional distribution table by dividing the cells in the joint pr obability distribution table with the marginal pr obability values, as in figure 2.7. Note that the columns on the conditional pr obability table in figure 2.7 now sum to 1.

Figure 2.7 Derive the values of the conditional probability distribution by dividing the values of the joint distribution by those of the marginal distribution.

The pgmpy library allows us to do this division using the ૿/ operator :

print(joint / dist)

That line pr oduces the following output:

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | phi(X,Y) | ||||||||||||

| +======+======+============+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(1) Y(0) | 0.5556 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(1) Y(1) | 0.4444 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(2) Y(0) | 0.6667 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(2) Y(1) | 0.3333 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(3) Y(0) | 0.6000 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ | ||||||||||||||

| X(3) Y(1) | 0.4000 | |||||||||||||

| +——+——+————+ |

Also, you can dir ectly specif y a conditional pr obability distribution table with the TabularCPD class:

from pgmpy.factors.discrete.CPD import TabularCPD

PYgivenX = TabularCPD(

variable='Y', #1

variable_card=2, #2

values=[

[.25/.45, .20/.30, .15/.25], #3

[.20/.45, .10/.30, .10/.25], #3

],

evidence=['X'],

evidence_card=[3],

state_names = {

'X': ['1', '2', '3'],

'Y': ['0', '1']

})print(PYgivenX)

#1 A conditional distribution has one variable instead of ΔiscreteF actor’s list of variables. #2 variable_card is the cardinality of Y . #3 Elements of the list correspond to outcomes for Y . Elements of each list

That pr oduces the following output:

correspond to elements of X.

+——+——————–+———————+——+ | X | X(1) | X(2) | X(3) | +——+——————–+———————+——+ | Y(0) | 0.5555555555555556 | 0.6666666666666667 | 0.6 | +——+——————–+———————+——+ | Y(1) | 0.4444444444444445 | 0.33333333333333337 | 0.4 | +——+——————–+———————+——+

The variable_card argument is the car dinality of Y (meaning the number of outcomes Y can tak e), and evidence_card is the car dinality of X.

CONDITIONING AS AN OPERA TION

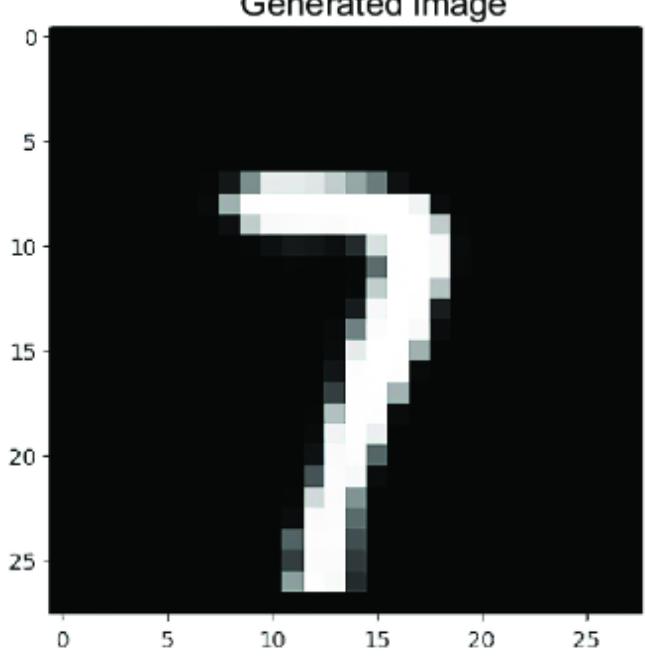

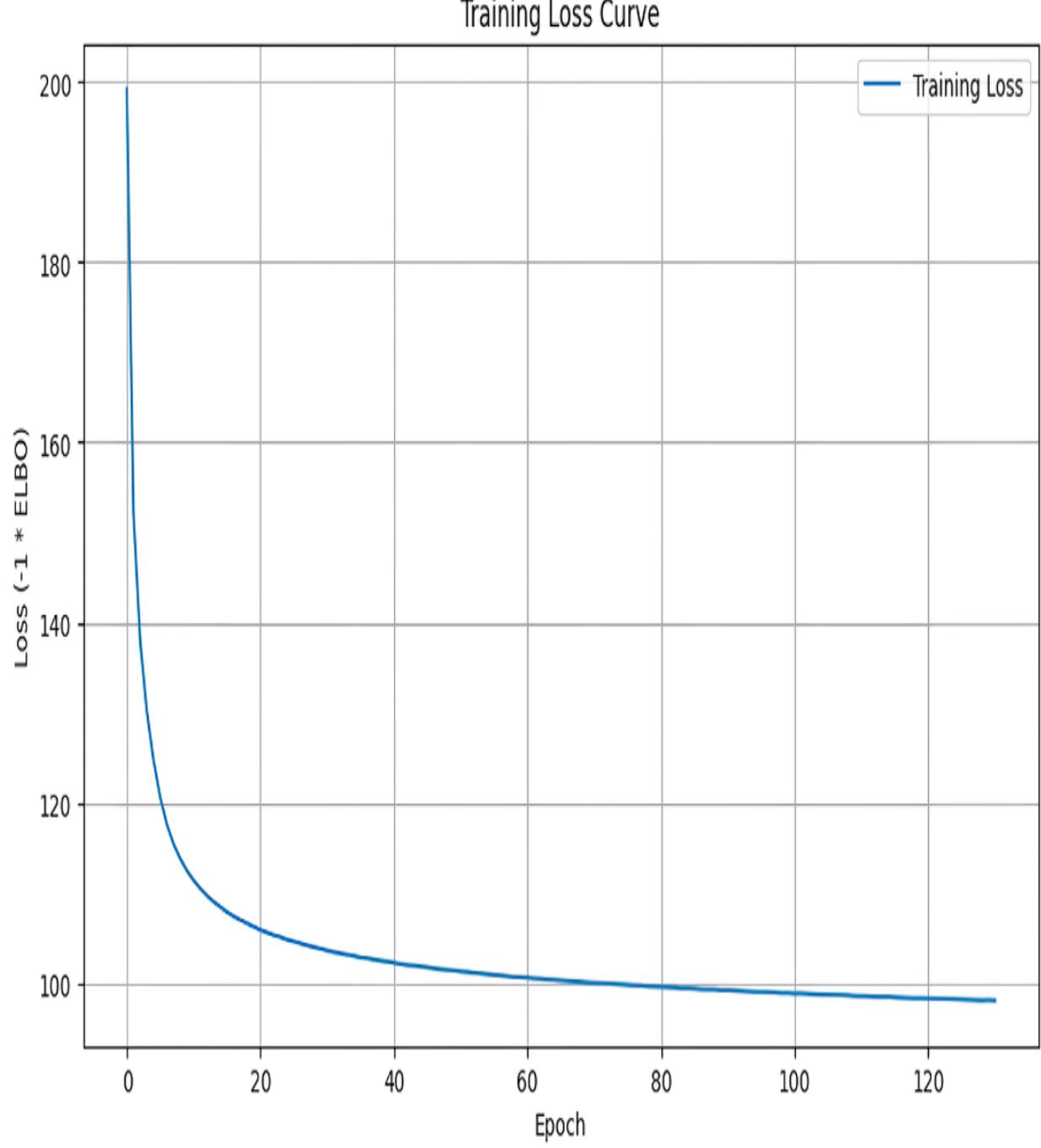

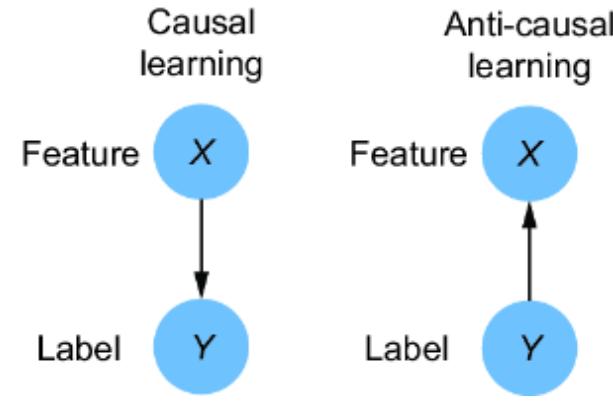

In the phrase ૿conditional pr obability, ૿conditional is an adjective. It is useful to think of ૿condition as a verb (an action). You condition a random variable lik e Y on another random variable X. For example, in figure 2.5, I can condition Yon X=1, and essentially get a new random variable with the same outcome values as Y but with a pr obability distribution equivalent to P(Y|X=1).