AI Engineering

Building Applications with Foundation Models

CHAPTER 6 RAG and Agents

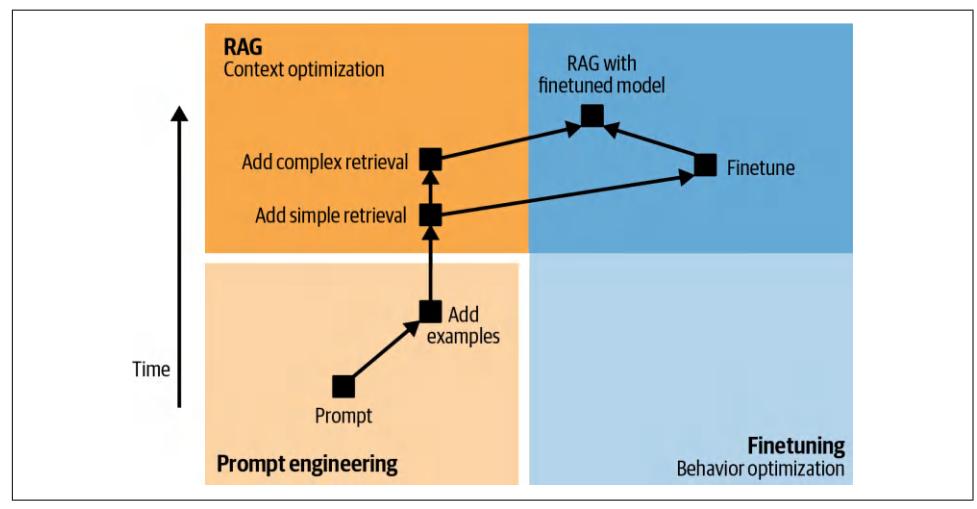

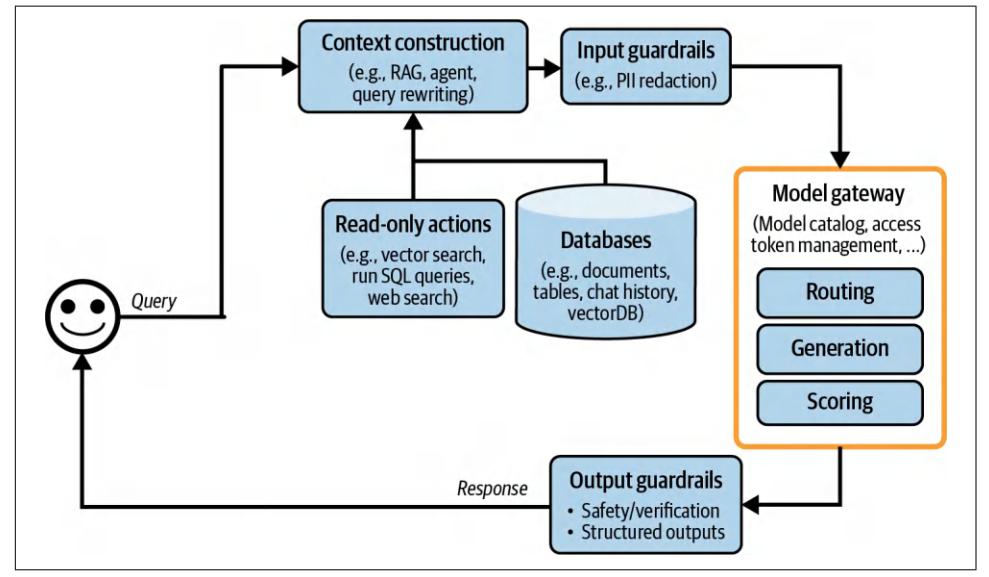

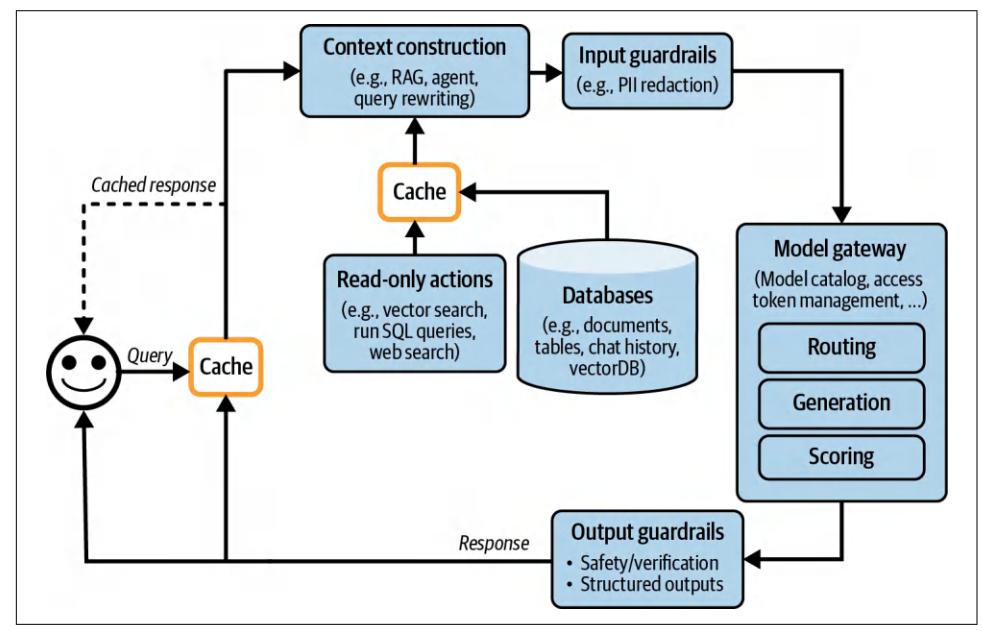

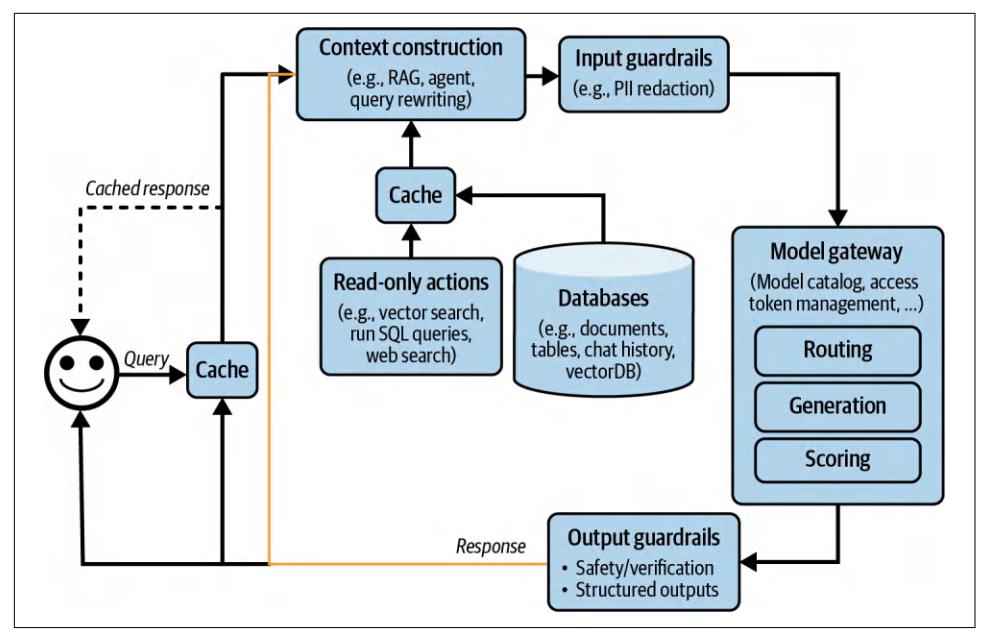

To solve a task, a model needs both the instructions on how to do it, and the neces‐ sary information to do so. Just like how a human is more likely to give a wrong answer when lacking information, AI models are more likely to make mistakes and hallucinate when they are missing context. For a given application, the model’s instructions are common to all queries, whereas context is specific to each query. The last chapter discussed how to write good instructions to the model. This chapter focuses on how to construct the relevant context for each query.

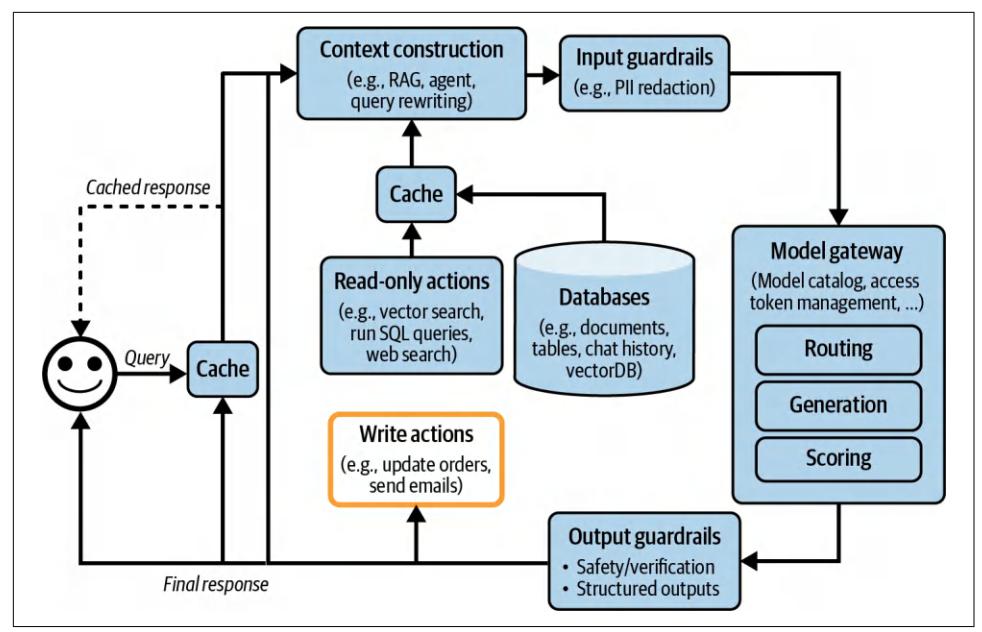

Two dominating patterns for context construction are RAG, or retrieval-augmented generation, and agents. The RAG pattern allows the model to retrieve relevant infor‐ mation from external data sources. The agentic pattern allows the model to use tools such as web search and news APIs to gather information.

While the RAG pattern is chiefly used for constructing context, the agentic pattern can do much more than that. External tools can help models address their shortcom‐ ings and expand their capabilities. Most importantly, they give models the ability to directly interact with the world, enabling them to automate many aspects of our lives.

Both RAG and agentic patterns are exciting because of the capabilities they bring to already powerful models. In a short amount of time, they’ve managed to capture the collective imagination, leading to incredible demos and products that convince many people that they are the future. This chapter will go into detail about each of these patterns, how they work, and what makes them so promising.

RAG

RAG is a technique that enhances a model’s generation by retrieving the relevant information from external memory sources. An external memory source can be an internal database, a user’s previous chat sessions, or the internet.

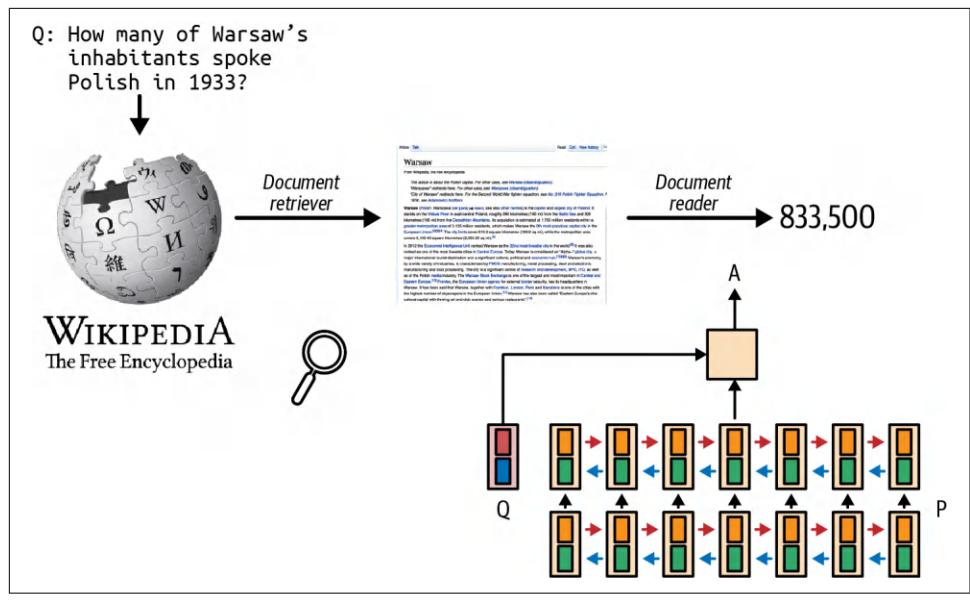

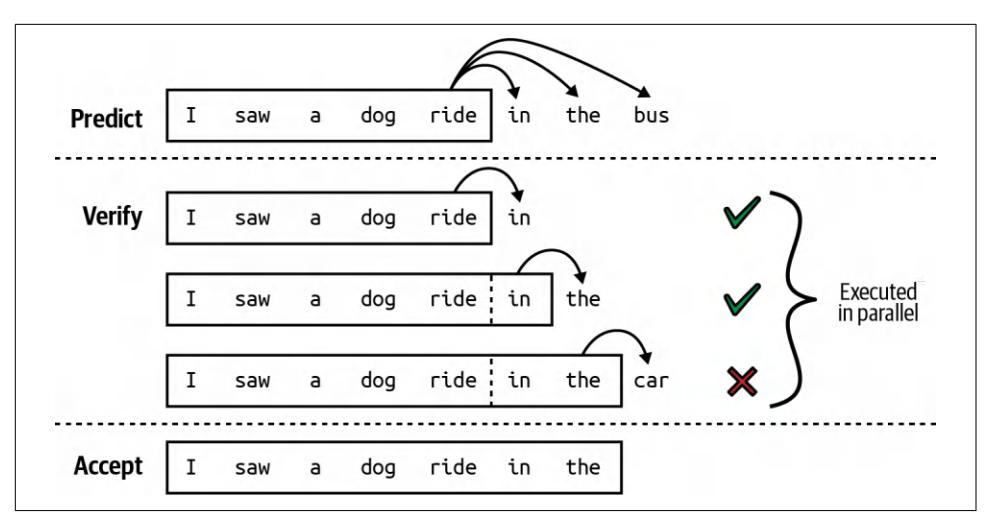

The retrieve-then-generate pattern was first introduced in “Reading Wikipedia to Answer Open-Domain Questions” (Chen et al., 2017). In this work, the system first retrieves five Wikipedia pages most relevant to a question, then a model1 uses, or reads, the information from these pages to generate an answer, as visualized in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6-1. The retrieve-then-generate pattern. The model was referred to as the docu‐ ment reader.

The term retrieval-augmented generation was coined in “Retrieval-Augmented Gen‐ eration for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks” (Lewis et al., 2020). The paper proposed RAG as a solution for knowledge-intensive tasks where all the available knowledge can’t be input into the model directly. With RAG, only the information most relevant to the query, as determined by the retriever, is retrieved and input into the model. Lewis et al. found that having access to relevant information can help the model gen‐ erate more detailed responses while reducing hallucinations.2

1 The model used was a type of recurrent neural network known as LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory). LSTM was the dominant architecture of deep learning for natural language processing (NLP) before the transformer architecture took over in 2018.

2 Around the same time, another paper, also from Facebook, “How Context Affects Language Models’ Factual Predictions” (Petroni et al., arXiv, May 2020), showed that augmenting a pre-trained language model with a retrieval system can dramatically improve the model’s performance on factual questions.

For example, given the query “Can Acme’s fancy-printer-A300 print 100pps?”, the model will be able to respond better if it’s given the specifications of fancy-printer-A300.3

You can think of RAG as a technique to construct context specific to each query, instead of using the same context for all queries. This helps with managing user data, as it allows you to include data specific to a user only in queries related to this user.

Context construction for foundation models is equivalent to feature engineering for classical ML models. They serve the same purpose: giving the model the necessary information to process an input.

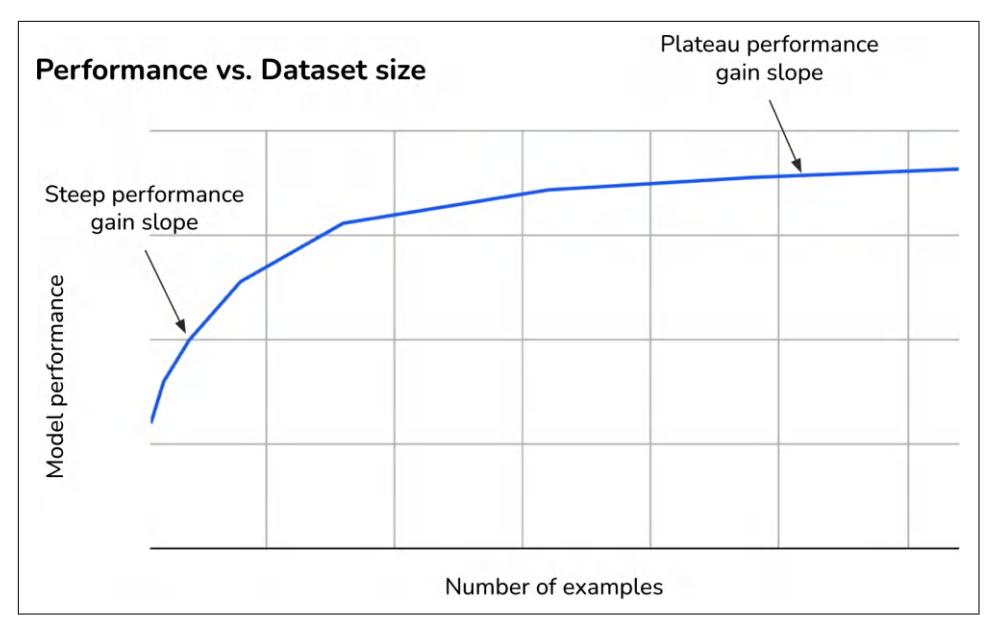

In the early days of foundation models, RAG emerged as one of the most common patterns. Its main purpose was to overcome the models’ context limitations. Many people think that a sufficiently long context will be the end of RAG. I don’t think so. First, no matter how long a model’s context length is, there will be applications that require context longer than that. After all, the amount of available data only grows over time. People generate and add new data but rarely delete data. Context length is expanding quickly, but not fast enough for the data needs of arbitrary applications.4

Second, a model that can process long context doesn’t necessarily use that context well, as discussed in “Context Length and Context Efficiency” on page 218. The longer the context, the more likely the model is to focus on the wrong part of the con‐ text. Every extra context token incurs extra cost and has the potential to add extra latency. RAG allows a model to use only the most relevant information for each query, reducing the number of input tokens while potentially increasing the model’s performance.

Efforts to expand context length are happening in parallel with efforts to make mod‐ els use context more effectively. I wouldn’t be surprised if a model provider incorpo‐ rates a retrieval-like or attention-like mechanism to help a model pick out the most salient parts of a context to use.

3 Thanks to Chetan Tekur for the example.

4 Parkinson’s Law is usually expressed as “Work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.” I have a similar theory that an application’s context expands to fill the context limit supported by the model it uses.

Anthropic suggested that for Claude models, if “your knowledge base is smaller than 200,000 tokens (about 500 pages of material), you can just include the entire knowledge base in the prompt that you give the model, with no need for RAG or similar methods” (Anthropic, 2024). It’d be amazing if other model developers pro‐ vide similar guidance for RAG versus long context for their models.

RAG Architecture

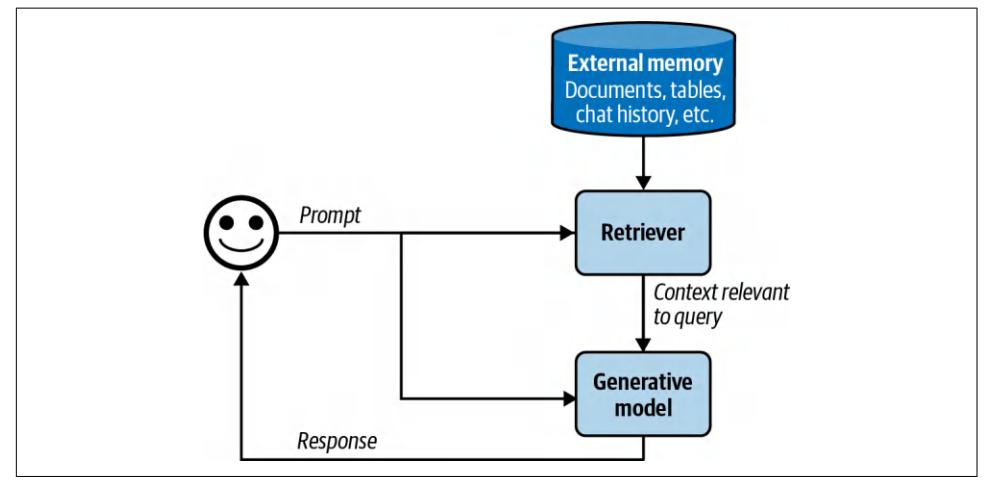

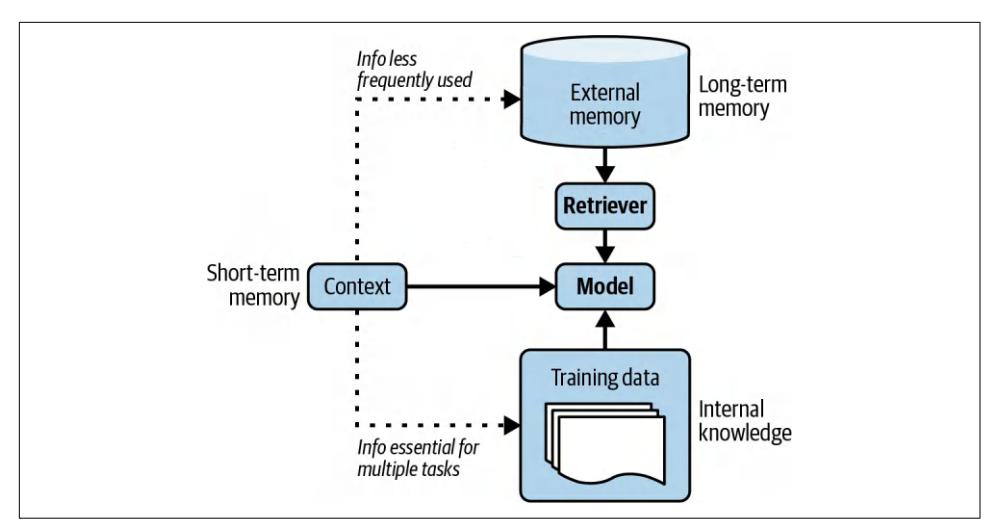

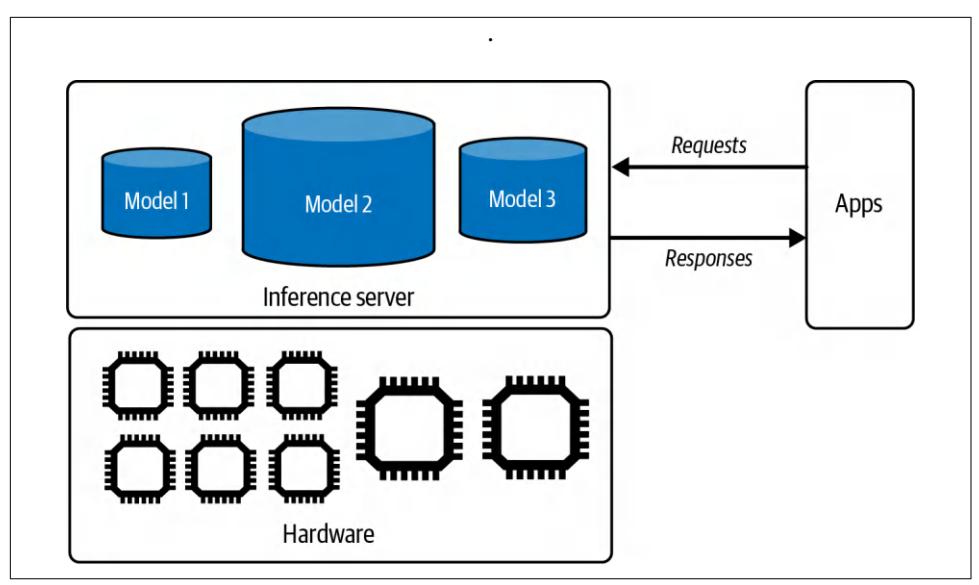

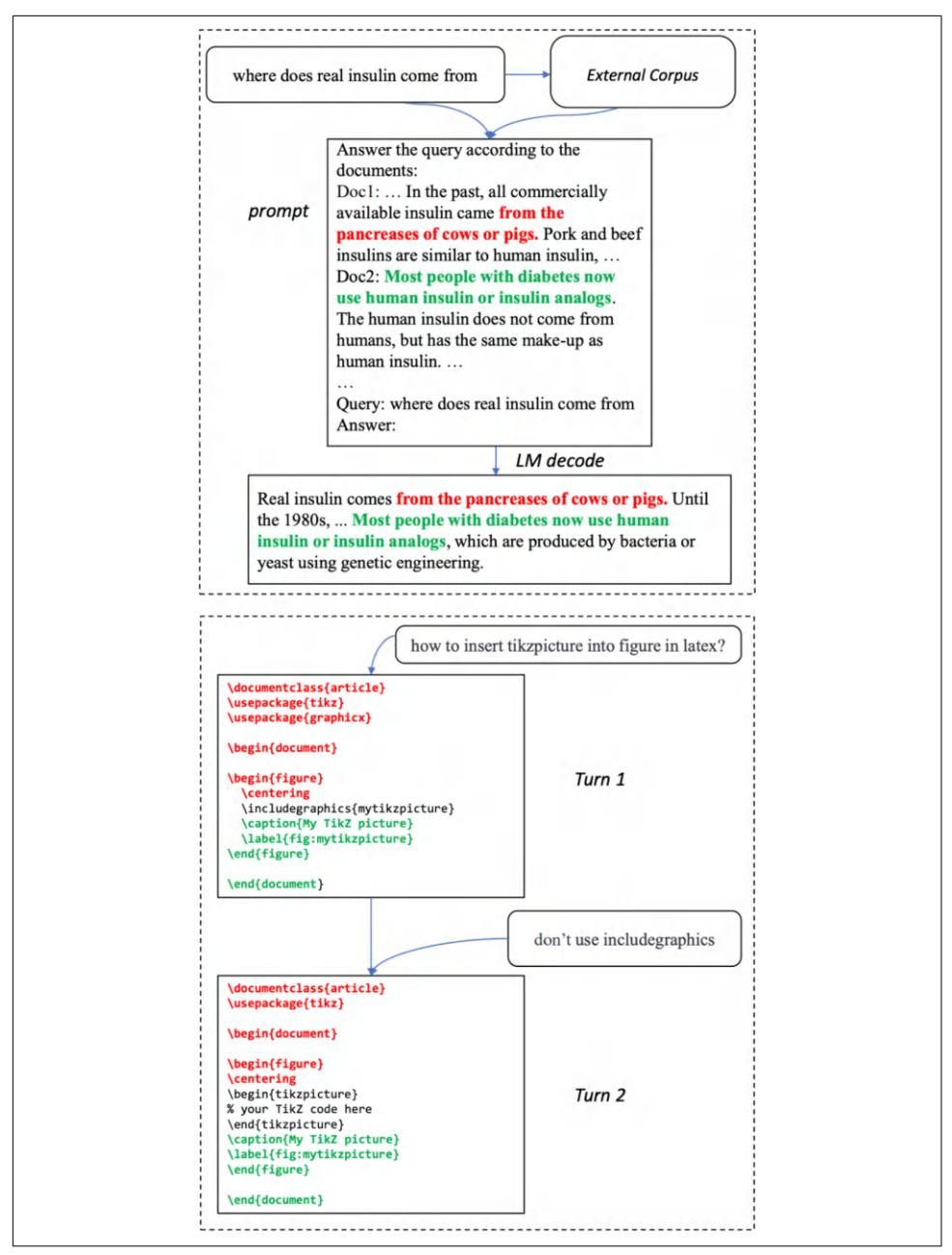

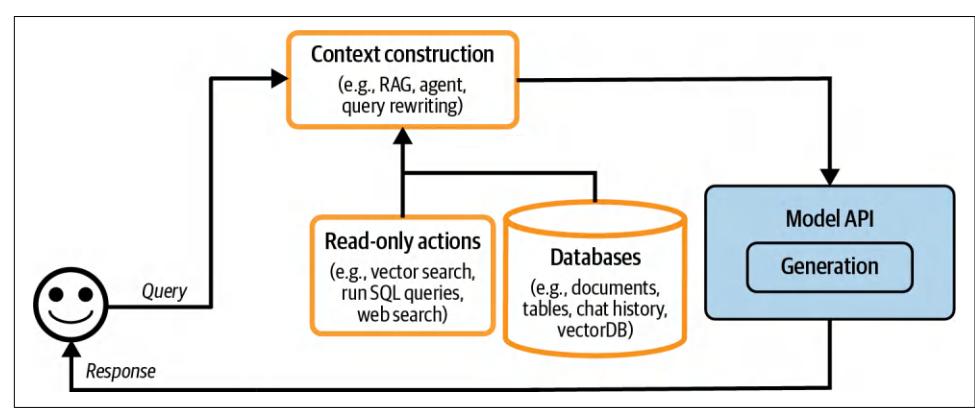

A RAG system has two components: a retriever that retrieves information from external memory sources and a generator that generates a response based on the retrieved information. Figure 6-2 shows a high-level architecture of a RAG system.

Figure 6-2. A basic RAG architecture.

In the original RAG paper, Lewis et al. trained the retriever and the generative model together. In today’s RAG systems, these two components are often trained separately, and many teams build their RAG systems using off-the-shelf retrievers and models. However, finetuning the whole RAG system end-to-end can improve its performance significantly.

The success of a RAG system depends on the quality of its retriever. A retriever has two main functions: indexing and querying. Indexing involves processing data so that it can be quickly retrieved later. Sending a query to retrieve data relevant to it is called querying. How to index data depends on how you want to retrieve it later on.

Now that we’ve covered the primary components, let’s consider an example of how a RAG system works. For simplicity, let’s assume that the external memory is a data‐ base of documents, such as a company’s memos, contracts, and meeting notes. A document can be 10 tokens or 1 million tokens. Naively retrieving whole documents can cause your context to be arbitrarily long. To avoid this, you can split each docu‐ ment into more manageable chunks. Chunking strategies will be discussed later in this chapter. For now, let’s assume that all documents have been split into workable chunks. For each query, our goal is to retrieve the data chunks most relevant to this query. Minor post-processing is often needed to join the retrieved data chunks with the user prompt to generate the final prompt. This final prompt is then fed into the generative model.

In this chapter, I use the term “document” to refer to both “docu‐ ment” and “chunk”, because technically, a chunk of a document is also a document. I do this to keep this book’s terminologies consis‐ tent with classical NLP and information retrieval (IR) terminolo‐ gies.

Retrieval Algorithms

Retrieval isn’t unique to RAG. Information retrieval is a century-old idea.5 It’s the backbone of search engines, recommender systems, log analytics, etc. Many retrieval algorithms developed for traditional retrieval systems can also be used for RAG. For instance, information retrieval is a fertile research area with a large supporting indus‐ try that can hardly be sufficiently covered within a few pages. Accordingly, this sec‐ tion will cover only the broad strokes. See this book’s GitHub repository for more indepth resources on information retrieval.

Retrieval is typically limited to one database or system, whereas search involves retrieval across various systems. This chapter uses retrieval and search interchangeably.

At its core, retrieval works by ranking documents based on their relevance to a given query. Retrieval algorithms differ based on how relevance scores are computed. I’ll start with two common retrieval mechanisms: term-based retrieval and embeddingbased retrieval.

5 Information retrieval was described as early as the 1920s in Emanuel Goldberg’s patents for a “statistical machine” to search documents stored on films. See “The History of Information Retrieval Research” (Sander‐ son and Croft, Proceedings of the IEEE, 100: Special Centennial Issue, April 2012).

Sparse Versus Dense Retrieval

In the literature, you might encounter the division of retrieval algorithms into the fol‐ lowing categories: sparse versus dense. This book, however, opted for term-based ver‐ sus embedding-based categorization.

Sparse retrievers represent data using sparse vectors. A sparse vector is a vector where the majority of the values are 0. Term-based retrieval is considered sparse, as each term can be represented using a sparse one-hot vector, a vector that is 0 everywhere except one value of 1. The vector size is the length of the vocabulary. The value of 1 is in the index corresponding to the index of the term in the vocabulary.

If we have a simple dictionary, {“food”: 0, “banana”: 1, “slug”: 2}, then the one-hot vectors of “food”, “banana”, and “slug” are [1, 0, 0], [0, 1, 0], and [0, 0, 1]. respectively.

Dense retrievers represent data using dense vectors. A dense vector is a vector where the majority of the values aren’t 0. Embedding-based retrieval is typically considered dense, as embeddings are generally dense vectors. However, there are also sparse embeddings. For example, SPLADE (Sparse Lexical and Expansion) is a retrieval algorithm that works using sparse embeddings (Formal et al., 2021). It leverages embeddings generated by BERT but uses regularization to push most embedding val‐ ues to 0. The sparsity makes embedding operations more efficient.

The sparse versus dense division causes SPLADE to be grouped together with termbased algorithms, even though SPLADE’s operations, strengths, and weaknesses are much more similar to those of dense embedding retrieval than those of term-based retrieval. Term-based versus embedding-based division avoids this miscategorization.

Term-based retrieval

Given a query, the most straightforward way to find relevant documents is with key‐ words. Some people call this approach lexical retrieval. For example, given the query “AI engineering”, the model will retrieve all the documents that contain “AI engi‐ neering”. However, this approach has two problems:

- Many documents might contain the given term, and your model might not have sufficient context space to include all of them as context. A heuristic is to include the documents that contain the term the greatest number of times. The assump‐ tion is that the more a term appears in a document, the more relevant this docu‐ ment is to this term. The number of times a term appears in a document is called term frequency (TF).

- A prompt can be long and contain many terms. Some are more important than others. For example, the prompt “Easy-to-follow recipes for Vietnamese food to cook at home” contains nine terms: easy-to-follow, recipes, for, vietnamese, food,

to, cook, at, home. You want to focus on more informative terms like vietnamese and recipes, not for and at. You need a way to identify important terms.

An intuition is that the more documents contain a term, the less informative this term is. “For” and “at” are likely to appear in most documents, hence, they are less informative. So a term’s importance is inversely proportional to the number of documents it appears in. This metric is called inverse document frequency (IDF). To compute IDF for a term, count all the documents that contain this term, then divide the total number of documents by this count. If there are 10 documents and 5 of them contain a given term, then the IDF of this term is 10 / 5 = 2. The higher a term’s IDF, the more important it is.

TF-IDF is an algorithm that combines these two metrics: term frequency (TF) and inverse document frequency (IDF). Mathematically, the TF-IDF score of document D for the query Q is computed as follows:

- Let t1 , t2 , …, tqbe the terms in the query Q.

- Given a term t, the term frequency of this term in the document D is f(t, D).

- Let N be the total number of documents, and C(t) be the number of documents that contain t. The IDF value of the term t can be written as IDF(t) = log N C(t) .

- Naively, the TF-IDF score of a document D with respect to Q is defined as Score(D, Q) = ∑i=1 q IDF(ti) × f(ti , D).

Two common term-based retrieval solutions are Elasticsearch and BM25. Elastic‐ search (Shay Banon, 2010), built on top of Lucene, uses a data structure called an inverted index. It’s a dictionary that maps from terms to documents that contain them. This dictionary allows for fast retrieval of documents given a term. The index might also store additional information such as the term frequency and the docu‐ ment count (how many documents contain this term), which are helpful for comput‐ ing TF-IDF scores. Table 6-1 illustrates an inverted index.

| learning 3 |

(1, 5), (38, 7), (42, 5) | |

|---|---|---|

| … | … | … |

Table 6-1. A simplified example of an inverted index.

Okapi BM25, the 25th generation of the Best Matching algorithm, was developed by Robertson et al. in the 1980s. Its scorer is a modification of TF-IDF. Compared to naive TF-IDF, BM25 normalizes term frequency scores by document length. Longer documents are more likely to contain a given term and have higher term frequency values.6

BM25 and its variances (BM25+, BM25F) are still widely used in the industry and serve as formidable baselines to compare against modern, more sophisticated retrieval algorithms, such as embedding-based retrieval, discussed next.7

One process I glossed over is tokenization, the process of breaking a query into indi‐ vidual terms. The simplest method is to split the query into words, treating each word as a separate term. However, this can lead to multi-word terms being broken into individual words, losing their original meaning. For example, “hot dog” would be split into “hot” and “dog”. When this happens, neither retains the meaning of the original term. One way to mitigate this issue is to treat the most common n-grams as terms. If the bigram “hot dog” is common, it’ll be treated as a term.

Additionally, you might want to convert all characters to lowercase, remove punctua‐ tion, and eliminate stop words (like “the”, “and”, “is”, etc.). Term-based retrieval sol‐ utions often handle these automatically. Classical NLP packages, such as NLTK (Natural Language Toolkit), spaCy, and Stanford’s CoreNLP, also offer tokenization functionalities.

Chapter 4 discusses measuring the lexical similarity between two texts based on their n-gram overlap. Can we retrieve documents based on the extent of their n-gram overlap with the query? Yes, we can. This approach works best when the query and the documents are of similar lengths. If the documents are much longer than the query, the likelihood of them containing the query’s n-grams increases, leading to many documents having similarly high overlap scores. This makes it difficult to dis‐ tinguish truly relevant documents from less relevant ones.

Embedding-based retrieval

Term-based retrieval computes relevance at a lexical level rather than a semantic level. As mentioned in Chapter 3, the appearance of a text doesn’t necessarily capture its meaning. This can result in returning documents irrelevant to your intent. For example, querying “transformer architecture” might return documents about the electric device or the movie Transformers. On the other hand, embedding-based retrievers aim to rank documents based on how closely their meanings align with the query. This approach is also known as semantic retrieval.

6 For those interested in learning more about BM25, I recommend this paper by the BM25 authors: “The Prob‐ abilistic Relevance Framework: BM25 and Beyond” (Robertson and Zaragoza, Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval 3 No. 4, 2009)

7 Aravind Srinivas, the CEO of Perplexity, tweeted that “Making a genuine improvement over BM25 or fulltext search is hard”.

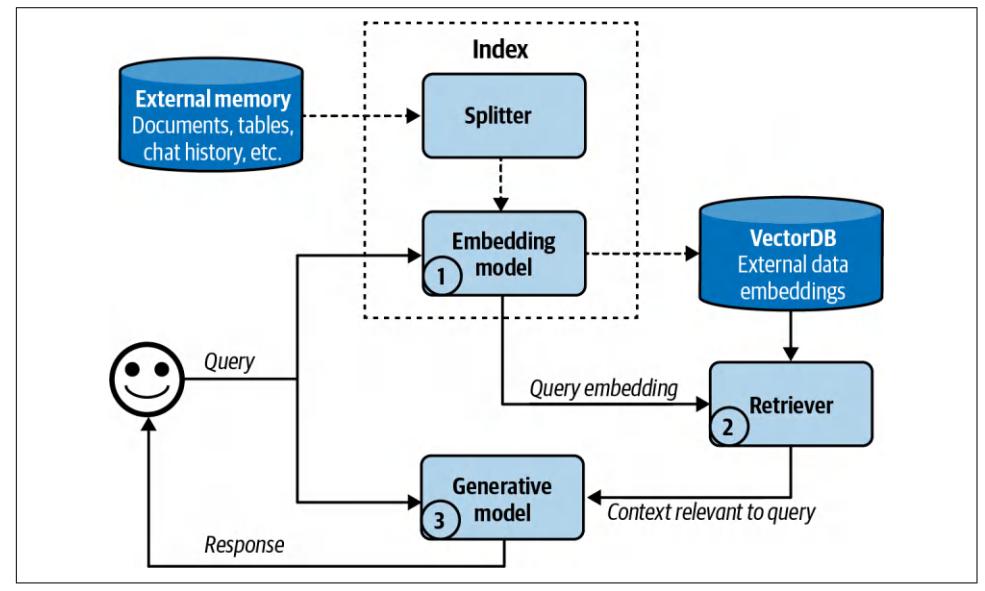

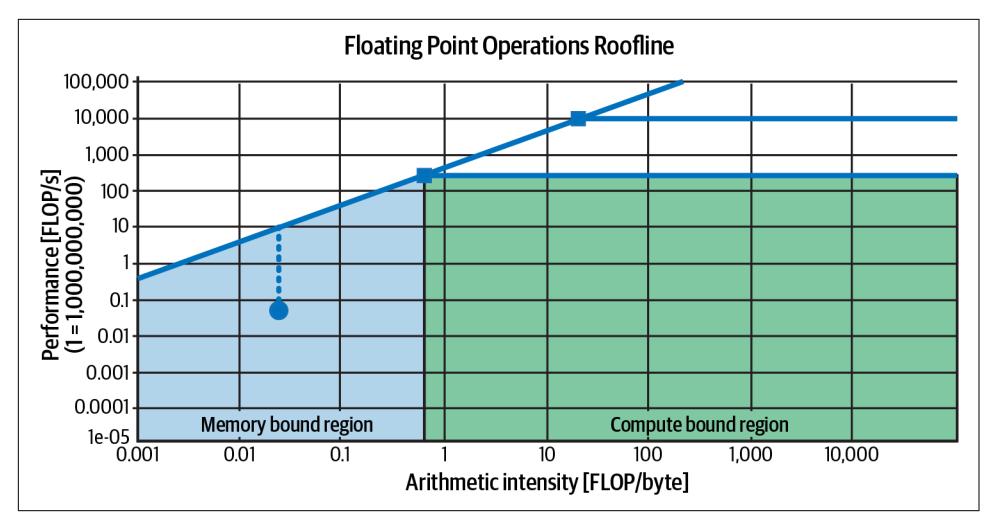

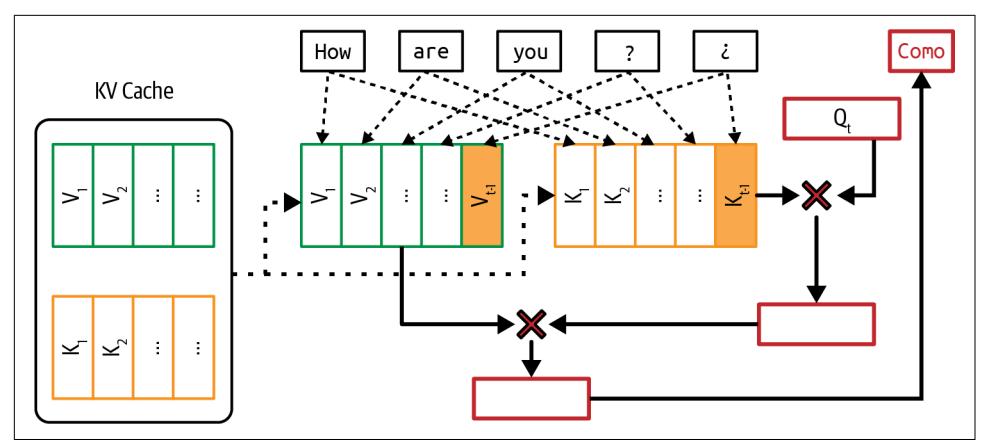

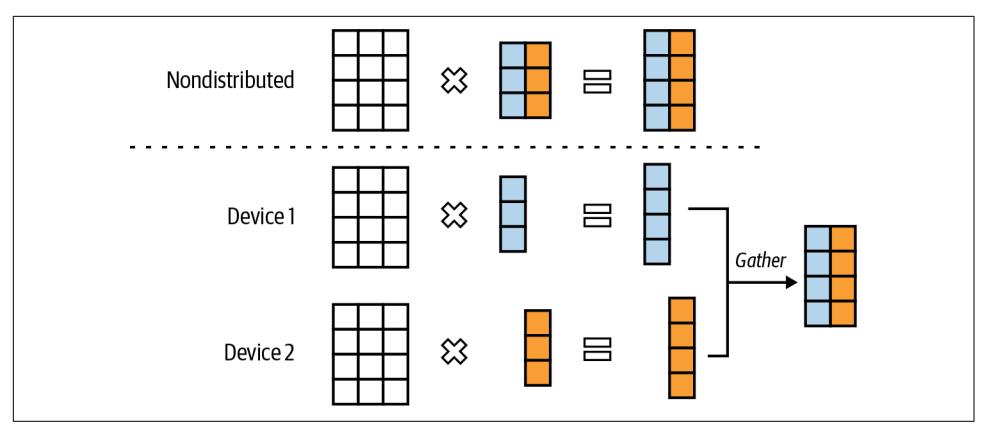

With embedding-based retrieval, indexing has an extra function: converting the orig‐ inal data chunks into embeddings. The database where the generated embeddings are stored is called a vector database. Querying then consists of two steps, as shown in Figure 6-3:

- Embedding model: convert the query into an embedding using the same embed‐ ding model used during indexing.

- Retriever: fetch k data chunks whose embeddings are closest to the query embed‐ ding, as determined by the retriever. The number of data chunks to fetch, k, depends on the use case, the generative model, and the query.

Figure 6-3. A high-level view of how an embedding-based, or semantic, retriever works.

The embedding-based retrieval workflow shown here is simplified. Real-world semantic retrieval systems might contain other components, such as a reranker to rerank all retrieved candidates, and caches to reduce latency.8

With embedding-based retrieval, we again encounter embeddings, which are dis‐ cussed in Chapter 3. As a reminder, an embedding is typically a vector that aims to preserve the important properties of the original data. An embedding-based retriever doesn’t work if the embedding model is bad.

8 A RAG retrieval workflow shares many similar steps with the traditional recommender system.

Embedding-based retrieval also introduces a new component: vector databases. A vector database stores vectors. However, storing is the easy part of a vector database. The hard part is vector search. Given a query embedding, a vector database is respon‐ sible for finding vectors in the database close to the query and returning them. Vec‐ tors have to be indexed and stored in a way that makes vector search fast and efficient.

Like many other mechanisms that generative AI applications depend on, vector search isn’t unique to generative AI. Vector search is common in any application that uses embeddings: search, recommendation, data organization, information retrieval, clustering, fraud detection, and more.

Vector search is typically framed as a nearest-neighbor search problem. For example, given a query, find the k nearest vectors. The naive solution is k-nearest neighbors (k-NN), which works as follows:

- Compute the similarity scores between the query embedding and all vectors in the database, using metrics such as cosine similarity.

- Return k vectors with the highest similarity scores.

This naive solution ensures that the results are precise, but it’s computationally heavy and slow. It should be used only for small datasets.

For large datasets, vector search is typically done using an approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) algorithm. Due to the importance of vector search, many algorithms and libraries have been developed for it. Some popular vector search libraries are FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search) (Johnson et al., 2017), Google’s ScaNN (Scal‐ able Nearest Neighbors) (Sun et al., 2020), Spotify’s Annoy (Bernhardsson, 2013), and Hnswlib (Hierarchical Navigable Small World) (Malkov and Yashunin, 2016).

Most application developers won’t implement vector search themselves, so I’ll give only a quick overview of different approaches. This overview might be helpful as you evaluate solutions.

In general, vector databases organize vectors into buckets, trees, or graphs. Vector search algorithms differ based on the heuristics they use to increase the likelihood that similar vectors are close to each other. Vectors can also be quantized (reduced precision) or made sparse. The idea is that quantized and sparse vectors are less com‐ putationally intensive to work with. For those wanting to learn more about vector search, Zilliz has an excellent series on it. Here are some significant vector search algorithms:

LSH (locality-sensitive hashing) (Indyk and Motwani, 1999)

This is a powerful and versatile algorithm that works with more than just vectors. This involves hashing similar vectors into the same buckets to speed up similarity search, trading some accuracy for efficiency. It’s implemented in FAISS and Annoy.

Product Quantization (Jégou et al., 2011)

This works by reducing each vector into a much simpler, lower-dimensional rep‐ resentation by decomposing each vector into multiple subvectors. The distances are then computed using the lower-dimensional representations, which are much faster to work with. Product quantization is a key component of FAISS and is supported by almost all popular vector search libraries.

IVF (inverted file index) (Sivic and Zisserman, 2003)

IVF uses K-means clustering to organize similar vectors into the same cluster. Depending on the number of vectors in the database, it’s typical to set the num‐ ber of clusters so that, on average, there are 100 to 10,000 vectors in each cluster. During querying, IVF finds the cluster centroids closest to the query embedding, and the vectors in these clusters become candidate neighbors. Together with product quantization, IVF forms the backbone of FAISS.

Annoy (Approximate Nearest Neighbors Oh Yeah) (Bernhardsson, 2013)

Annoy is a tree-based approach. It builds multiple binary trees, where each tree splits the vectors into clusters using random criteria, such as randomly drawing a line and splitting the vectors into two branches using this line. During a search, it traverses these trees to gather candidate neighbors. Spotify has open sourced its implementation.

There are other algorithms, such as Microsoft’s SPTAG (Space Partition Tree And Graph), and FLANN (Fast Library for Approximate Nearest Neighbors).

Even though vector databases emerged as their own category with the rise of RAG, any database that can store vectors can be called a vector database. Many traditional databases have extended or will extend to support vector storage and vector search.

Comparing retrieval algorithms

Due to the long history of retrieval, its many mature solutions make both term-based and embedding-based retrieval relatively easy to start. Each approach has its pros and cons.

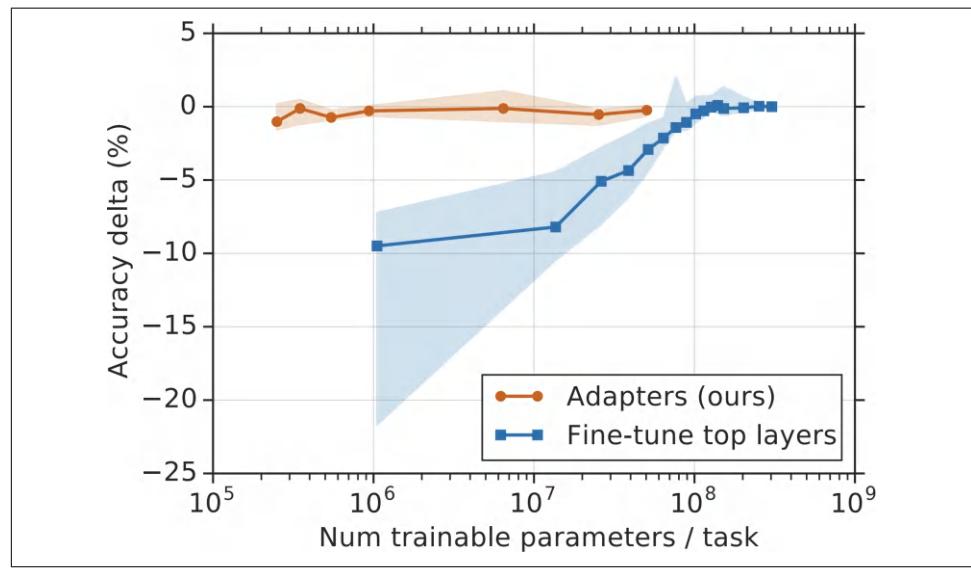

Term-based retrieval is generally much faster than embedding-based retrieval during both indexing and query. Term extraction is faster than embedding generation, and mapping from a term to the documents that contain it can be less computationally expensive than a nearest-neighbor search.

Term-based retrieval also works well out of the box. Solutions like Elasticsearch and BM25 have successfully powered many search and retrieval applications. However, its simplicity also means that it has fewer components you can tweak to improve its performance.

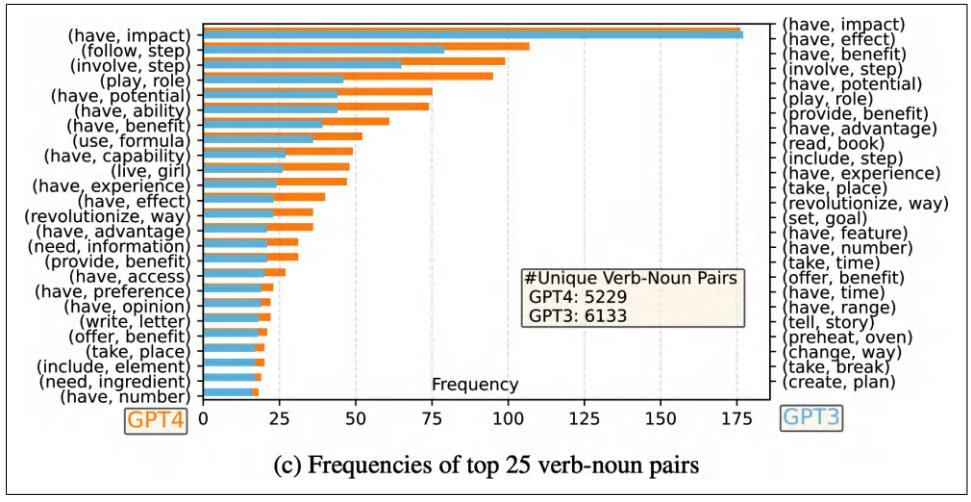

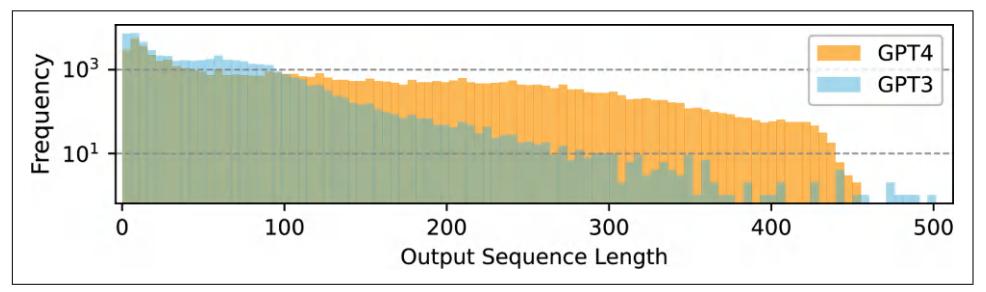

Embedding-based retrieval, on the other hand, can be significantly improved over time to outperform term-based retrieval. You can finetune the embedding model and the retriever, either separately, together, or in conjunction with the generative model. However, converting data into embeddings can obscure keywords, such as specific error codes, e.g., EADDRNOTAVAIL (99), or product names, making them harder to search later on. This limitation can be addressed by combining embedding-based retrieval with term-based retrieval, as discussed later in this chapter.

The quality of a retriever can be evaluated based on the quality of the data it retrieves. Two metrics often used by RAG evaluation frameworks are context precision and con‐ text recall, or precision and recall for short (context precision is also called context relevance):

Context precision

Out of all the documents retrieved, what percentage is relevant to the query?

Context recall

Out of all the documents that are relevant to the query, what percentage is retrieved?

To compute these metrics, you curate an evaluation set with a list of test queries and a set of documents. For each test query, you annotate each test document to be rele‐ vant or not relevant. The annotation can be done either by humans or AI judges. You then compute the precision and recall score of the retriever on this evaluation set.

In production, some RAG frameworks only support context precision, not context recall To compute context recall for a given query, you need to annotate the relevance of all documents in your database to that query. Context precision is simpler to com‐ pute. You only need to compare the retrieved documents to the query, which can be done by an AI judge.

If you care about the ranking of the retrieved documents, for example, more relevant documents should be ranked first, you can use metrics such as NDCG (nor‐ malized discounted cumulative gain), MAP (Mean Average Precision), and MRR (Mean Reciprocal Rank).

For semantic retrieval, you need to also evaluate the quality of your embeddings. As discussed in Chapter 3, embeddings can be evaluated independently—they are con‐ sidered good if more-similar documents have closer embeddings. Embeddings can also be evaluated by how well they work for specific tasks. The MTEB benchmark (Muennighoff et al., 2023) evaluates embeddings for a broad range of tasks including retrievals, classification, and clustering.

The quality of a retriever should also be evaluated in the context of the whole RAG system. Ultimately, a retriever is good if it helps the system generate high-quality answers. Evaluating outputs of generative models is discussed in Chapters 3 and 4.

Whether the performance promise of a semantic retrieval system is worth pursuing depends on how much you prioritize cost and latency, particularly during the query‐ ing phase. Since much of RAG latency comes from output generation, especially for long outputs, the added latency by query embedding generation and vector search might be minimal compared to the total RAG latency. Even so, the added latency still can impact user experience.

Another concern is cost. Generating embeddings costs money. This is especially an issue if your data changes frequently and requires frequent embedding regeneration. Imagine having to generate embeddings for 100 million documents every day! Depending on what vector databases you use, vector storage and vector search quer‐ ies can be expensive, too. It’s not uncommon to see a company’s vector database spending be one-fifth or even half of their spending on model APIs.

Table 6-2 shows a side-by-side comparison of term-based retrieval and embeddingbased retrieval.

| Performance | Typically strong performance out of the box, | |

|---|---|---|

| but hard to improve | ||

| Can retrieve wrong documents due to term | on semantics instead of terms | |

| Cost | ambiguity Much cheaper than embedding-based retrieval |

Embedding, vector storage, and vector search solutions can be expensive |

Table 6-2. Term-based retrieval and semantic retrieval by speed, performance, and cost.

With retrieval systems, you can make certain trade-offs between indexing and query‐ ing. The more detailed the index is, the more accurate the retrieval process will be, but the indexing process will be slower and more memory-consuming. Imagine building an index of potential customers. Adding more details (e.g., name, company, email, phone, interests) makes it easier to find relevant people but takes longer to build and requires more storage.

In general, a detailed index like HNSW provides high accuracy and fast query times but requires significant time and memory to build. In contrast, a simpler index like LSH is quicker and less memory-intensive to create, but it results in slower and less accurate queries.

The ANN-Benchmarks website compares different ANN algorithms on multiple datasets using four main metrics, taking into account the trade-offs between indexing and querying. These include the following:

Recall

The fraction of the nearest neighbors found by the algorithm.

Query per second (QPS)

The number of queries the algorithm can handle per second. This is crucial for high-traffic applications.

Build time

The time required to build the index. This metric is especially important if you need to frequently update your index (e.g., because your data changes).

Index size

The size of the index created by the algorithm, which is crucial for assessing its scalability and storage requirements.

Additionally, BEIR (Benchmarking IR) (Thakur et al., 2021) is an evaluation harness for retrieval. It supports retrieval systems across 14 common retrieval benchmarks.

To summarize, the quality of a RAG system should be evaluated both component by component and end to end. To do this, you should do the following things:

- Evaluate the retrieval quality.

- Evaluate the final RAG outputs.

- Evaluate the embeddings (for embedding-based retrieval).

Combining retrieval algorithms

Given the distinct advantages of different retrieval algorithms, a production retrieval system typically combines several approaches. Combining term-based retrieval and embedding-based retrieval is called hybrid search.

Different algorithms can be used in sequence. First, a cheap, less precise retriever, such as a term-based system, fetches candidates. Then, a more precise but more expensive mechanism, such as k-nearest neighbors, finds the best of these candidates. This second step is also called reranking.

For example, given the term “transformer”, you can fetch all documents that contain the word transformer, regardless of whether they are about the electric device, the neural architecture, or the movie. Then you use vector search to find among these documents those that are actually related to your transformer query. As another example, consider the query “Who’s responsible for the most sales to X?” First, you might fetch all documents associated with X using the keyword X. Then, you use vec‐ tor search to retrieve the context associated with “Who’s responsible for the most sales?”

Different algorithms can also be used in parallel as an ensemble. Remember that a retriever works by ranking documents by their relevance scores to the query. You can use multiple retrievers to fetch candidates at the same time, then combine these dif‐ ferent rankings together to generate a final ranking.

An algorithm for combining different rankings is called reciprocal rank fusion (RRF) (Cormack et al., 2009). It assigns each document a score based on its ranking by a retriever. Intuitively, if it ranks first, its score is 1/1 = 1. If it ranks second, its score is ½ = 0.5. The higher it ranks, the higher its score.

A document’s final score is the sum of its scores with respect to all retrievers. If a document is ranked first by one retriever and second by another retriever, its score is 1 + 0.5 = 1.5. This example is an oversimplification of RRF, but it shows the basics. The actual formula for a document D is more complicated, as follows:

Score(D) = ∑i=1 n 1 k + r i (D)

- n is the number of ranked lists; each rank list is produced by a retriever.

- ri(D) is the rank of the document by the retriever i.

- k is a constant to avoid division by zero and to control the influence of lowerranked documents. A typical value for k is 60.

Retrieval Optimization

Depending on the task, certain tactics can increase the chance of relevant documents being fetched. Four tactics discussed here are chunking strategy, reranking, query rewriting, and contextual retrieval.

Chunking strategy

How your data should be indexed depends on how you intend to retrieve it later. The last section covered different retrieval algorithms and their respective indexing strate‐ gies. There, the discussion was based on the assumption that documents have already been split into manageable chunks. In this section, I’ll cover different chunking strategies. This is an important consideration because the chunking strategy you use can significantly impact the performance of your retrieval system.

The simplest strategy is to chunk documents into chunks of equal length based on a certain unit. Common units are characters, words, sentences, and paragraphs. For example, you can split each document into chunks of 2,048 characters or 512 words. You can also split each document so that each chunk can contain a fixed number of sentences (such as 20 sentences) or paragraphs (such as each paragraph is its own chunk).

You can also split documents recursively using increasingly smaller units until each chunk fits within your maximum chunk size. For example, you can start by splitting a document into sections. If a section is too long, split it into paragraphs. If a paragraph is still too long, split it into sentences. This reduces the chance of related texts being arbitrarily broken off.

Specific documents might also support creative chunking strategies. For example, there are splitters developed especially for different programming languages. Q&A documents can be split by question or answer pair, where each pair makes up a chunk. Chinese texts might need to be split differently from English texts.

When a document is split into chunks without overlap, the chunks might be cut off in the middle of important context, leading to the loss of critical information. Con‐ sider the text “I left my wife a note”. If it’s split into “I left my wife” and “a note”, neither of these two chunks conveys the key information of the original text. Over‐ lapping ensures that important boundary information is included in at least one chunk. If you set the chunk size to be 2,048 characters, you can perhaps set the over‐ lapping size to be 20 characters.

The chunk size shouldn’t exceed the maximum context length of the generative model. For the embedding-based approach, the chunk size also shouldn’t exceed the embedding model’s context limit.

You can also chunk documents using tokens, determined by the generative model’s tokenizer, as a unit. Let’s say that you want to use Llama 3 as your generative model. You then first tokenize documents using Llama 3’s tokenizer. You can then split documents into chunks using tokens as the boundaries. Chunking by tokens makes it easier to work with downstream models. However, the downside of this approach is that if you switch to another generative model with a different tokenizer, you’d need to reindex your data.

Regardless of which strategy you choose, chunk sizes matter. A smaller chunk size allows for more diverse information. Smaller chunks mean that you can fit more chunks into the model’s context. If you halve the chunk size, you can fit twice as many chunks. More chunks can provide a model with a wider range of information, which can enable the model to produce a better answer.

Small chunk sizes, however, can cause the loss of important information. Imagine a document that contains important information about the topic X throughout the document, but X is only mentioned in the first half. If you split this document into two chunks, the second half of the document might not be retrieved, and the model won’t be able to use its information.

Smaller chunk sizes can also increase computational overhead. This is especially an issue for embedding-based retrieval. Halving the chunk size means that you have twice as many chunks to index and twice as many embedding vectors to generate and store. Your vector search space will be twice as big, which can reduce the query speed.

There is no universal best chunk size or overlap size. You have to experiment to find what works best for you.

Reranking

The initial document rankings generated by the retriever can be further reranked to be more accurate. Reranking is especially useful when you need to reduce the number of retrieved documents, either to fit them into your model’s context or to reduce the number of input tokens.

One common pattern for reranking is discussed in “Combining retrieval algorithms” on page 266. A cheap but less precise retriever fetches candidates, then a more precise but more expensive mechanism reranks these candidates.

Documents can also be reranked based on time, giving higher weight to more recent data. This is useful for time-sensitive applications such as news aggregation, chat with your emails (e.g., a chatbot that can answer questions about your emails), or stock market analysis.

Context reranking differs from traditional search reranking in that the exact position of items is less critical. In search, the rank (e.g., first or fifth) is crucial. In context reranking, the order of documents still matters because it affects how well a model can process them. Models might better understand documents at the beginning and end of the context, as discussed in “Context Length and Context Efficiency” on page 218. However, as long as a document is included, the impact of its order is less signif‐ icant compared to search ranking.

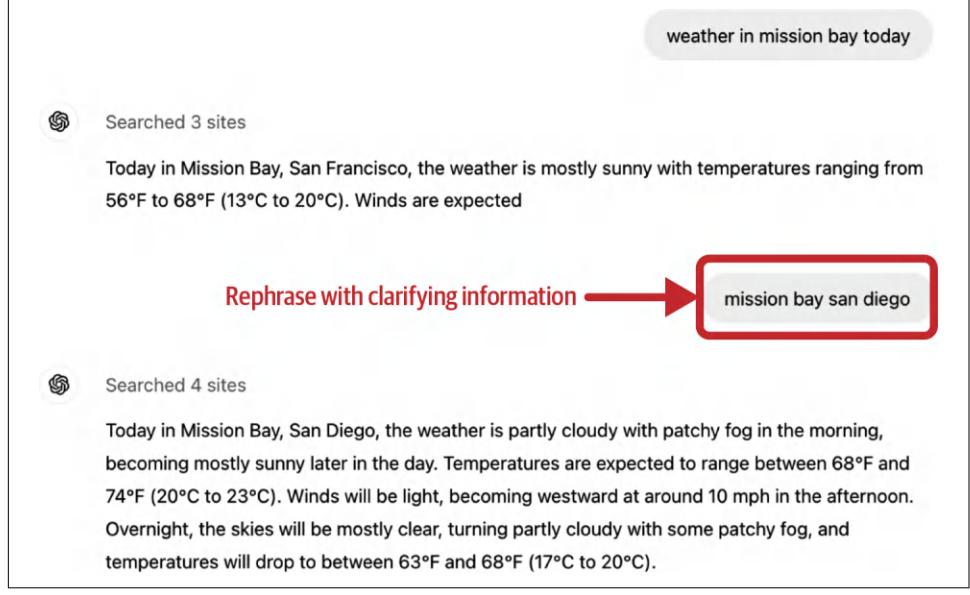

Query rewriting

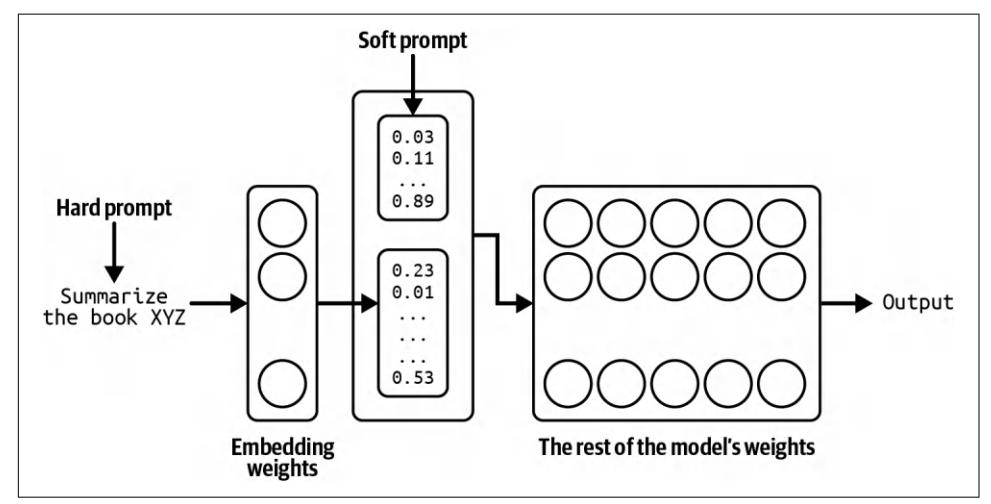

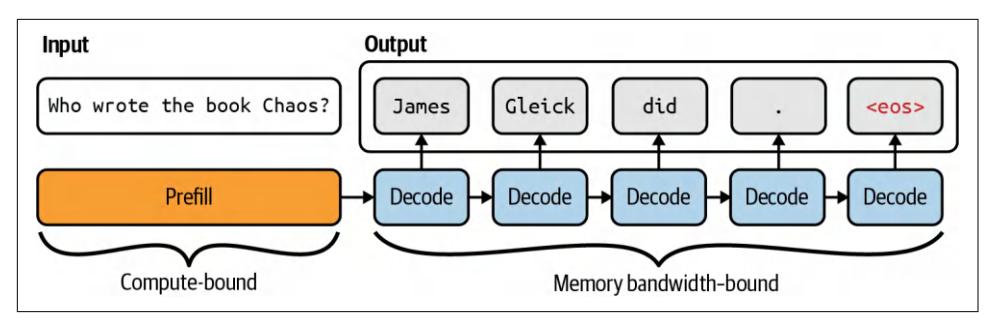

Query rewriting is also known as query reformulation, query normalization, and sometimes query expansion. Consider the following conversation:

User: When was the last time John Doe bought something from us? AI: John last bought a Fruity Fedora hat from us two weeks ago, on January 3, 2030. User: How about Emily Doe?

The last question, “How about Emily Doe?”, is ambiguous without context. If you use this query verbatim to retrieve documents, you’ll likely get irrelevant results. You need to rewrite this query to reflect what the user is actually asking. The new query should make sense on its own. In this case, the query should be rewritten to “When was the last time Emily Doe bought something from us?”

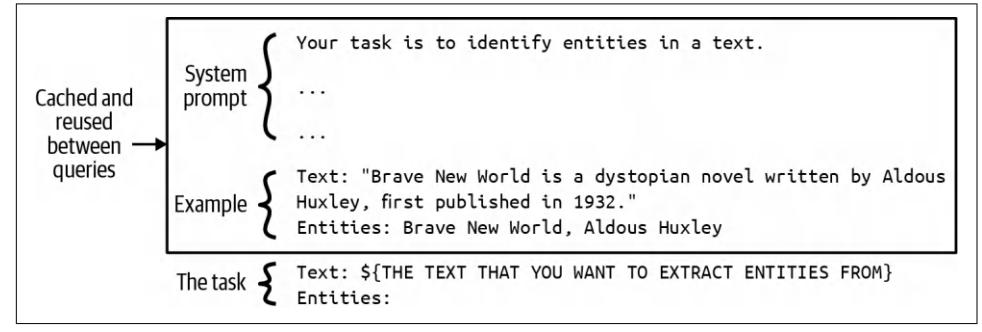

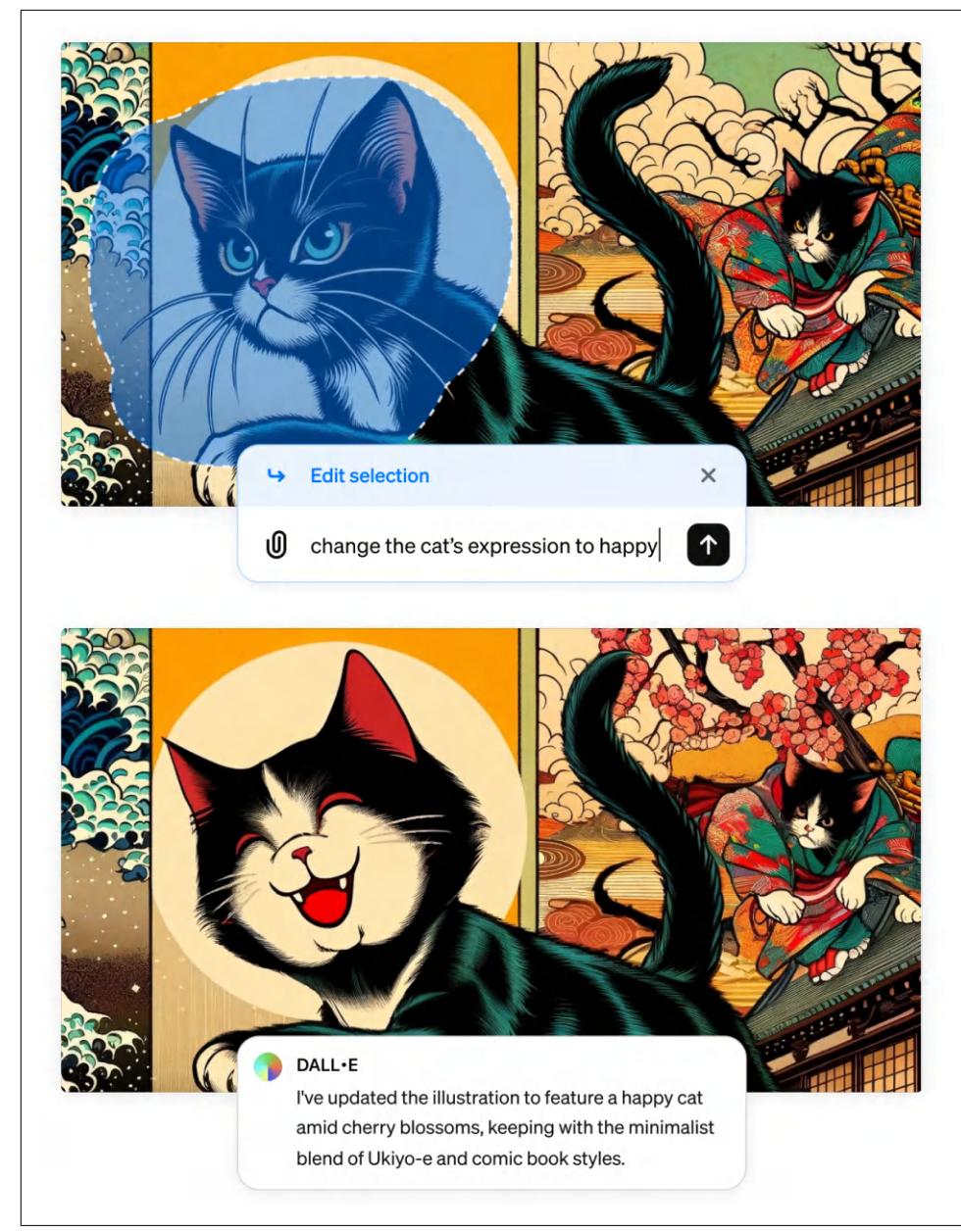

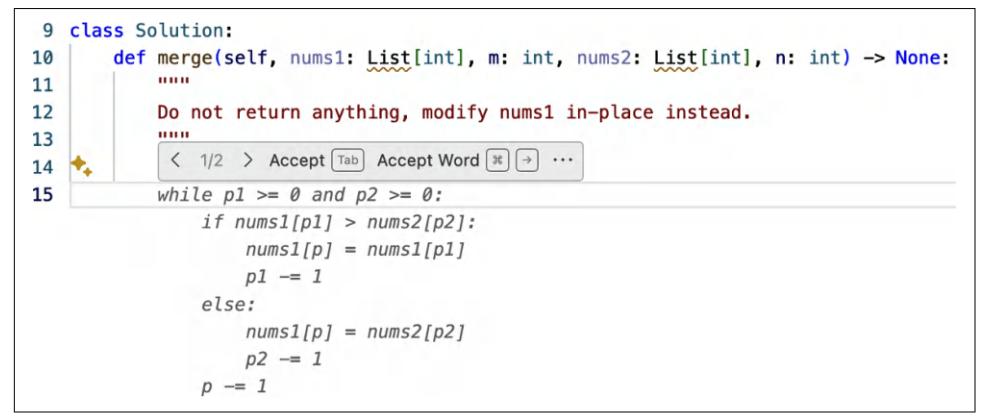

While I put query rewriting in “RAG” on page 253, query rewriting isn’t unique to RAG. In traditional search engines, query rewriting is often done using heuristics. In AI applications, query rewriting can also be done using other AI models, using a prompt similar to “Given the following conversation, rewrite the last user input to reflect what the user is actually asking”. Figure 6-4 shows how ChatGPT rewrote the query using this prompt.

Figure 6-4. You can use other generative models to rewrite queries.

Query rewriting can get complicated, especially if you need to do identity resolution or incorporate other knowledge. For example, if the user asks “How about his wife?” you will first need to query your database to find out who his wife is. If you don’t have this information, the rewriting model should acknowledge that this query isn’t solvable instead of hallucinating a name, leading to a wrong answer.

Contextual retrieval

The idea behind contextual retrieval is to augment each chunk with relevant context to make it easier to retrieve the relevant chunks. A simple technique is to augment a chunk with metadata like tags and keywords. For ecommerce, a product can be aug‐ mented by its description and reviews. Images and videos can be queried by their titles or captions.

The metadata may also include entities automatically extracted from the chunk. If your document contains specific terms like the error code EADDRNOTAVAIL (99), adding them to the document’s metadata allows the system to retrieve it by that key‐ word, even after the document has been converted into embeddings.

You can also augment each chunk with the questions it can answer. For customer support, you can augment each article with related questions. For example, the article on how to reset your password can be augmented with queries like “How to reset password?”, “I forgot my password”, “I can’t log in”, or even “Help, I can’t find my account”.9

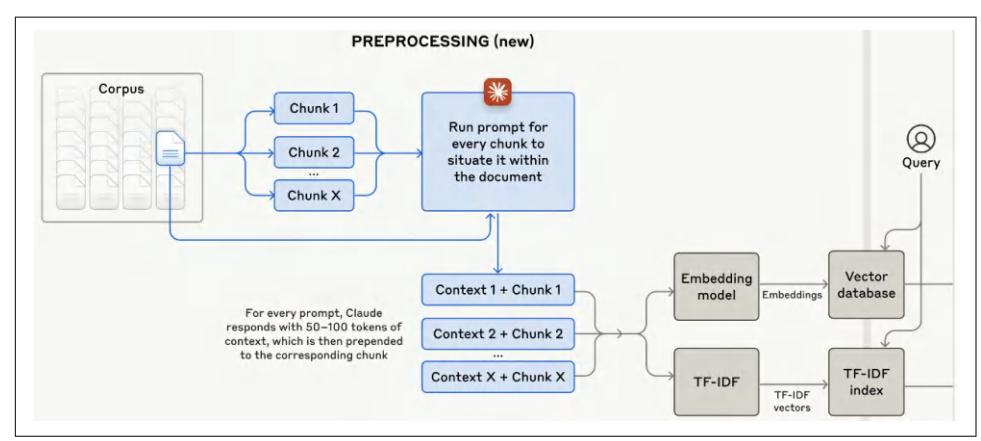

If a document is split into multiple chunks, some chunks might lack the necessary context to help the retriever understand what the chunk is about. To avoid this, you can augment each chunk with the context from the original document, such as the original document’s title and summary. Anthropic used AI models to generate a short context, usually 50-100 tokens, that explains the chunk and its relationship to the original document. Here’s the prompt Anthropic used for this purpose (Anthropic, 2024):

<document>

{{WHOLE_DOCUMENT}}

</document>

Here is the chunk we want to situate within the whole document:

<chunk>

{{CHUNK_CONTENT}}

</chunk>Please give a short succinct context to situate this chunk within the overall document for the purposes of improving search retrieval of the chunk. Answer only with the succinct context and nothing else.

9 Some teams have told me that their retrieval systems work best when the data is organized in a question-andanswer format.

The generated context for each chunk is prepended to each chunk, and the augmen‐ ted chunk is then indexed by the retrieval algorithm. Figure 6-5 visualizes the process that Anthropic follows.

Figure 6-5. Anthropic augments each chunk with a short context that situates this chunk within the original document, making it easier for the retriever to find the rele‐ vant chunks given a query. Image from “Introducing Contextual Retrieval” (Anthropic, 2024).

Evaluating Retrieval Solutions

Here are some key factors to keep in mind when evaluating a retrieval solution:

- What retrieval mechanisms does it support? Does it support hybrid search?

- If it’s a vector database, what embedding models and vector search algorithms does it support?

- How scalable is it, both in terms of data storage and query traffic? Does it work for your traffic patterns?

- How long does it take to index your data? How much data can you process (such as add/delete) in bulk at once?

- What’s its query latency for different retrieval algorithms?

- If it’s a managed solution, what’s its pricing structure? Is it based on the docu‐ ment/vector volume or on the query volume?

This list doesn’t include the functionalities typically associated with enterprise solu‐ tions such as access control, compliance, data plane and control plane separation, etc.

RAG Beyond Texts

The last section discussed text-based RAG systems where the external data sources are text documents. However, external data sources can also be multimodal and tabu‐ lar data.

Multimodal RAG

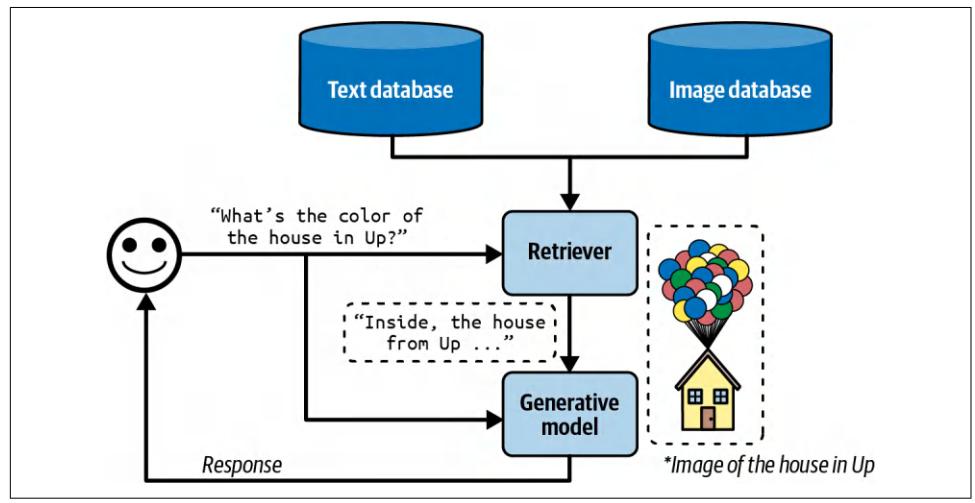

If your generator is multimodal, its contexts might be augmented not only with text documents but also with images, videos, audio, etc., from external sources. I’ll use images in the examples to keep the writing concise, but you can replace images with any other modality. Given a query, the retriever fetches both texts and images rele‐ vant to it. For example, given “What’s the color of the house in the Pixar movie Up?” the retriever can fetch a picture of the house in Up to help the model answer, as shown in Figure 6-6.

Figure 6-6. Multimodal RAG can augment a query with both text and images. (*The real image from Up is not used, for copyright reasons.)

If the images have metadata—such as titles, tags, and captions—they can be retrieved using the metadata. For example, an image is retrieved if its caption is considered rel‐ evant to the query.

If you want to retrieve images based on their content, you’ll need to have a way to compare images to queries. If queries are texts, you’ll need a multimodal embedding model that can generate embeddings for both images and texts. Let’s say you use CLIP (Radford et al., 2021) as the multimodal embedding model. The retriever works as follows:

- 1. Generate CLIP embeddings for all your data, both texts and images, and store them in a vector database.

- Given a query, generate its CLIP embedding.

- Query in the vector database for all images and texts whose embeddings are close to the query embedding.

RAG with tabular data

Most applications work not only with unstructured data like texts and images but also with tabular data. Many queries might need information from data tables to answer. The workflow for augmenting a context using tabular data is significantly different from the classic RAG workflow.

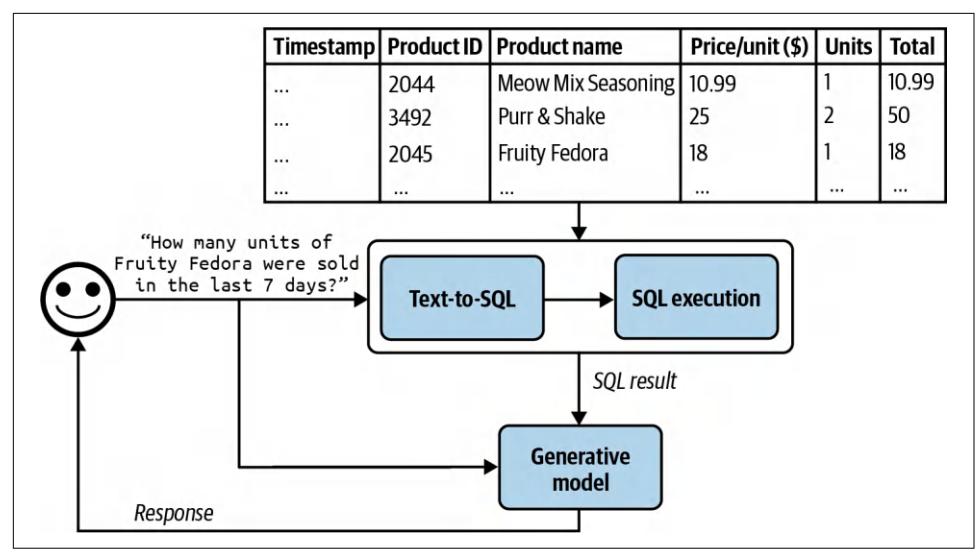

Imagine you work for an ecommerce site called Kitty Vogue that specializes in cat fashion. This store has an order table named Sales, as shown in Table 6-3.

Table 6-3. An example of an order table, Sales, for the imaginary ecommerce site Kitty Vogue.

| Order ID Timestamp Product ID Product | Unit price ($) Units Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2044 | Meow Mix Seasoning | 10.99 | 10.99 | ||

| 3497 | Purr & Shake | 25 | 50 | ||

| 2045 | Fruity Fedora | 18 | 18 | ||

To generate a response to the question “How many units of Fruity Fedora were sold in the last 7 days?”, your system needs to query this table for all orders involving Fruity Fedora and sum the number of units across all orders. Assume that this table can be queried using SQL. The SQL query might look like this:

SELECT SUM(units) AS total_units_sold

FROM Sales

WHERE product_name = 'Fruity Fedora'

AND timestamp >= DATE_SUB(CURDATE(), INTERVAL 7 DAY);The workflow is as follows, visualized in Figure 6-7. To run this workflow, your sys‐ tem must have the ability to generate and execute the SQL query:

- Text-to-SQL: based on the user query and the provided table schemas, determine what SQL query is needed. Text-to-SQL is an example of semantic parsing, as discussed in Chapter 2.

- SQL execution: execute the SQL query.

- Generation: generate a response based on the SQL result and the original user query.

Figure 6-7. A RAG system that augments context with tabular data.

For the text-to-SQL step, if there are many available tables whose schemas can’t all fit into the model context, you might need an intermediate step to predict what tables to use for each query. Text-to-SQL can be done by the same generator that generates the final response or a specialized text-to-SQL model.

In this section, we’ve discussed how tools such as retrievers and SQL executors can enable models to handle more queries and generate higher-quality responses. Would giving a model access to more tools improve its capabilities even more? Tool use is a core characteristic of the agentic pattern, which we’ll discuss in the next section.

Agents

Intelligent agents are considered by many to be the ultimate goal of AI. The classic book by Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (Prentice Hall, 1995) defines the field of artificial intelligence research as “the study and design of rational agents.”

The unprecedented capabilities of foundation models have opened the door to agentic applications that were previously unimaginable. These new capabilities make it finally possible to develop autonomous, intelligent agents to act as our assistants, coworkers, and coaches. They can help us create a website, gather data, plan a trip, do market research, manage a customer account, automate data entry, prepare us for interviews, interview our candidates, negotiate a deal, etc. The possibilities seem end‐ less, and the potential economic value of these agents is enormous.

AI-powered agents are an emerging field, with no established theo‐ retical frameworks for defining, developing, and evaluating them. This section is a best-effort attempt to build a framework from the existing literature, but it will evolve as the field does. Compared to the rest of the book, this section is more experimental.

This section will start with an overview of agents, and then continue with two aspects that determine the capabilities of an agent: tools and planning. Agents, with their new modes of operations, have new modes of failures. This section will end with a discus‐ sion on how to evaluate agents to catch these failures.

Even though agents are novel, they are built upon concepts that have already appeared in this book, including self-critique, chain-of-thought, and structured out‐ puts.

Agent Overview

The term agent has been used in many different engineering contexts, including but not limited to a software agent, intelligent agent, user agent, conversational agent, and reinforcement learning agent. So, what exactly is an agent?

An agent is anything that can perceive its environment and act upon that environ‐ ment.10 This means that an agent is characterized by the environment it operates in and the set of actions it can perform.

The environment an agent can operate in is defined by its use case. If an agent is developed to play a game (e.g., Minecraft, Go, Dota), that game is its environment. If you want an agent to scrape documents from the internet, the environment is the internet. If your agent is a cooking robot, the kitchen is its environment. A selfdriving car agent’s environment is the road system and its adjacent areas.

The set of actions an AI agent can perform is augmented by the tools it has access to. Many generative AI-powered applications you interact with daily are agents with access to tools, albeit simple ones. ChatGPT is an agent. It can search the web, exe‐ cute Python code, and generate images. RAG systems are agents, and text retrievers, image retrievers, and SQL executors are their tools.

There’s a strong dependency between an agent’s environment and its set of tools. The environment determines what tools an agent can potentially use. For example, if the environment is a chess game, the only possible actions for an agent are the valid chess moves. However, an agent’s tool inventory restricts the environment it can operate

10 Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (1995) defines an agent as anything that can be viewed as perceiv‐ ing its environment through sensors and acting upon that environment through actuators.

in. For example, if a robot’s only action is swimming, it’ll be confined to a water envi‐ ronment.

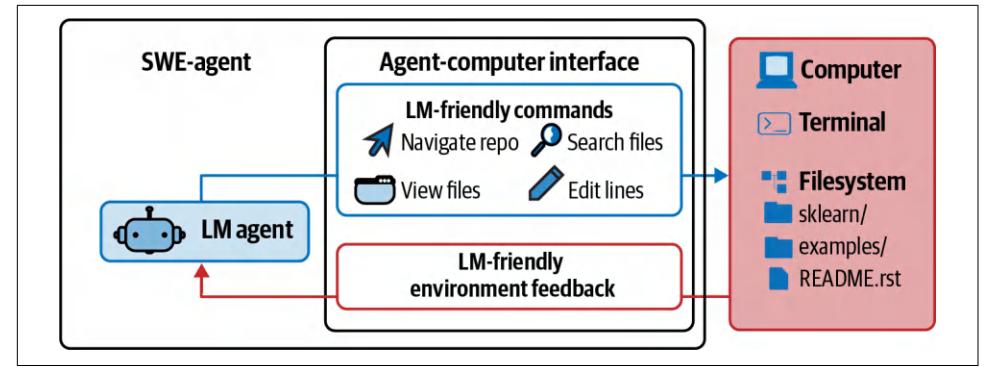

Figure 6-8 shows a visualization of SWE-agent (Yang et al., 2024), an agent built on top of GPT-4. Its environment is the computer with the terminal and the file system. Its set of actions include navigate repo, search files, view files, and edit lines.

Figure 6-8. SWE-agent (Yang et al., 2024) is a coding agent whose environment is the computer and whose actions include navigation, search, and editing. Adapted from an original image licensed under CC BY 4.0.

An AI agent is meant to accomplish tasks typically provided by the users in the inputs. In an AI agent, AI is the brain that processes the information it receives, including the task and feedback from the environment, plans a sequence of actions to achieve this task, and determines whether the task has been accomplished.

Let’s get back to the RAG system with tabular data in the Kitty Vogue example. This is a simple agent with three actions: response generation, SQL query generation, and SQL query execution. Given the query “Project the sales revenue for Fruity Fedora over the next three months”, the agent might perform the following sequence of actions:

- Reason about how to accomplish this task. It might decide that to predict future sales, it first needs the sales numbers from the last five years. Note that the agent’s reasoning is shown as its intermediate response.

- Invoke SQL query generation to generate the query to get sales numbers from the last five years.

- Invoke SQL query execution to execute this query.

- Reason about the tool outputs and how they help with sales prediction. It might decide that these numbers are insufficient to make a reliable projection, perhaps because of missing values. It then decides that it also needs information about past marketing campaigns.

- 5. Invoke SQL query generation to generate the queries for past marketing cam‐ paigns.

- Invoke SQL query execution.

- Reason that this new information is sufficient to help predict future sales. It then generates a projection.

- Reason that the task has been successfully completed.

Compared to non-agent use cases, agents typically require more powerful models for two reasons:

- Compound mistakes: an agent often needs to perform multiple steps to accom‐ plish a task, and the overall accuracy decreases as the number of steps increases. If the model’s accuracy is 95% per step, over 10 steps, the accuracy will drop to 60%, and over 100 steps, the accuracy will be only 0.6%.

- Higher stakes: with access to tools, agents are capable of performing more impactful tasks, but any failure could have more severe consequences.

A task that requires many steps can take time and money to run.11 However, if agents can be autonomous, they can save a lot of human time, making their costs worth‐ while.

Given an environment, the success of an agent in an environment depends on the tool inventory it has access to and the strength of its AI planner. Let’s start by looking into different kinds of tools a model can use.

Tools

A system doesn’t need access to external tools to be an agent. However, without external tools, the agent’s capabilities would be limited. By itself, a model can typi‐ cally perform one action—for example, an LLM can generate text, and an image gen‐ erator can generate images. External tools make an agent vastly more capable.

Tools help an agent to both perceive the environment and act upon it. Actions that allow an agent to perceive the environment are read-only actions, whereas actions that allow an agent to act upon the environment are write actions.

This section gives an overview of external tools. How tools can be used will be dis‐ cussed in “Planning” on page 281.

The set of tools an agent has access to is its tool inventory. Since an agent’s tool inventory determines what an agent can do, it’s important to think through what and

11 A complaint in the early days of agents is that agents are only good for burning through your API credits.

how many tools to give an agent. More tools give an agent more capabilities. How‐ ever, the more tools there are, the more challenging it is to understand and utilize them well. Experimentation is necessary to find the right set of tools, as discussed in “Tool selection” on page 295.

Depending on the agent’s environment, there are many possible tools. Here are three categories of tools that you might want to consider: knowledge augmentation (i.e., context construction), capability extension, and tools that let your agent act upon its environment.

Knowledge augmentation

I hope that this book, so far, has convinced you of the importance of having the rele‐ vant context for a model’s response quality. An important category of tools includes those that help augment your agent’s knowledge of your agent. Some of them have already been discussed: text retriever, image retriever, and SQL executor. Other potential tools include internal people search, an inventory API that returns the sta‐ tus of different products, Slack retrieval, an email reader, etc.

Many such tools augment a model with your organization’s private processes and information. However, tools can also give models access to public information, espe‐ cially from the internet.

Web browsing was among the earliest and most anticipated capabilities to be incor‐ porated into chatbots like ChatGPT. Web browsing prevents a model from going stale. A model goes stale when the data it was trained on becomes outdated. If the model’s training data was cut off last week, it won’t be able to answer questions that require information from this week unless this information is provided in the con‐ text. Without web browsing, a model won’t be able to tell you about the weather, news, upcoming events, stock prices, flight status, etc.

I use web browsing as an umbrella term to cover all tools that access the internet, including web browsers and specific APIs such as search APIs, news APIs, GitHub APIs, or social media APIs such as those of X, LinkedIn, and Reddit.

While web browsing allows your agent to reference up-to-date information to gener‐ ate better responses and reduce hallucinations, it can also open up your agent to the cesspools of the internet. Select your Internet APIs with care.

Capability extension

The second category of tools to consider are those that address the inherent limita‐ tions of AI models. They are easy ways to give your model a performance boost. For example, AI models are notorious for being bad at math. If you ask a model what is 199,999 divided by 292, the model will likely fail. However, this calculation is trivial if the model has access to a calculator. Instead of trying to train the model to be good at arithmetic, it’s a lot more resource-efficient to just give the model access to a tool.

Other simple tools that can significantly boost a model’s capability include a calen‐ dar, timezone converter, unit converter (e.g., from lbs to kg), and translator that can translate to and from the languages that the model isn’t good at.

More complex but powerful tools are code interpreters. Instead of training a model to understand code, you can give it access to a code interpreter so that it can execute a piece of code, return the results, or analyze the code’s failures. This capability lets your agents act as coding assistants, data analysts, and even research assistants that can write code to run experiments and report results. However, automated code exe‐ cution comes with the risk of code injection attacks, as discussed in “Defensive Prompt Engineering” on page 235. Proper security measurements are crucial to keep you and your users safe.

External tools can make a text-only or image-only model multimodal. For example, a model that can generate only texts can leverage a text-to-image model as a tool, allowing it to generate both texts and images. Given a text request, the agent’s AI planner decides whether to invoke text generation, image generation, or both. This is how ChatGPT can generate both text and images—it uses DALL-E as its image gen‐ erator. Agents can also use a code interpreter to generate charts and graphs, a LaTeX compiler to render math equations, or a browser to render web pages from HTML code.

Similarly, a model that can process only text inputs can use an image captioning tool to process images and a transcription tool to process audio. It can use an OCR (opti‐ cal character recognition) tool to read PDFs.

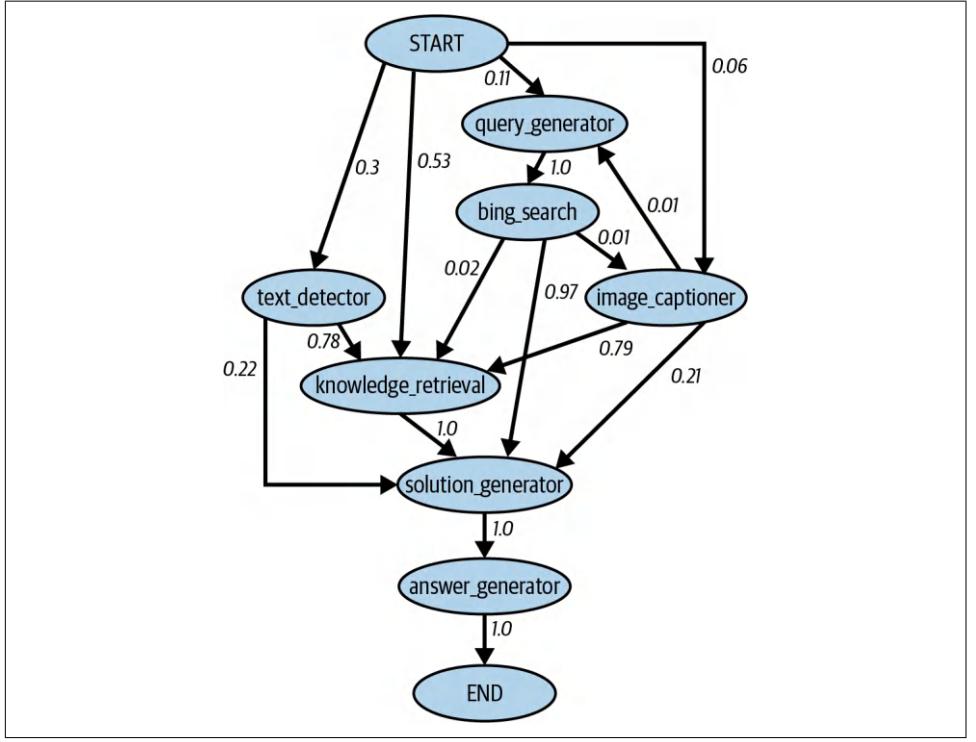

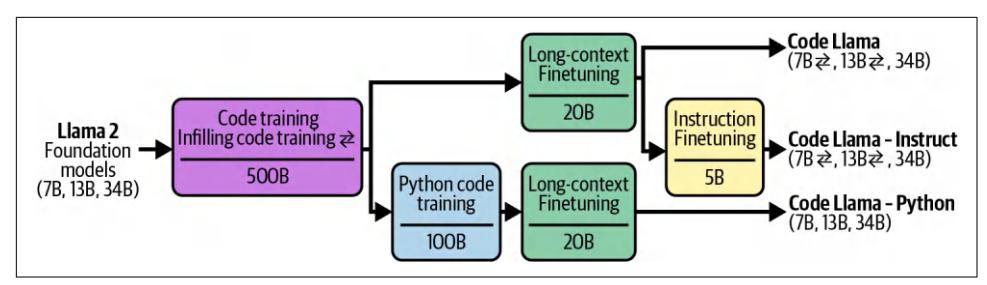

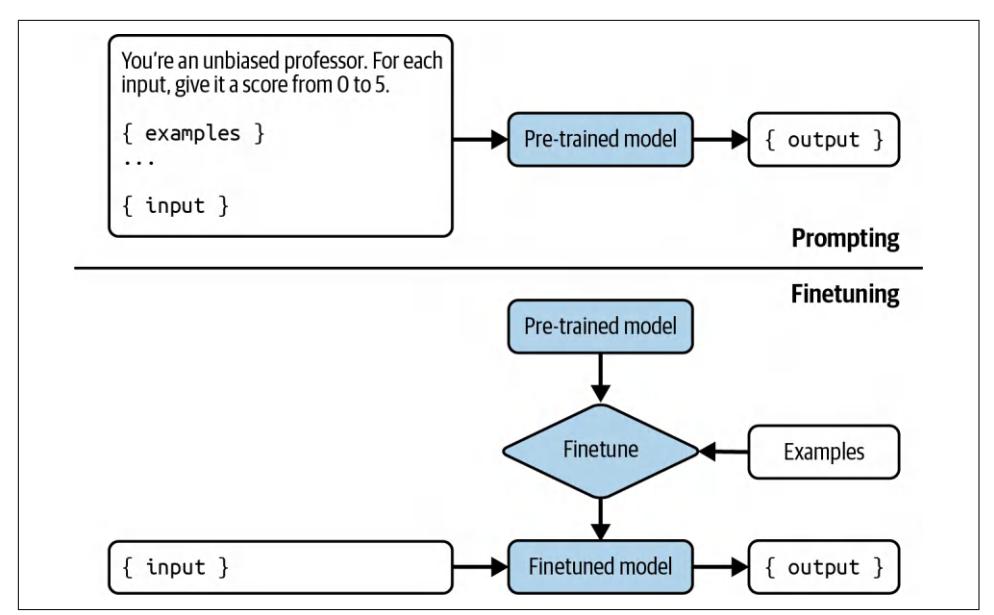

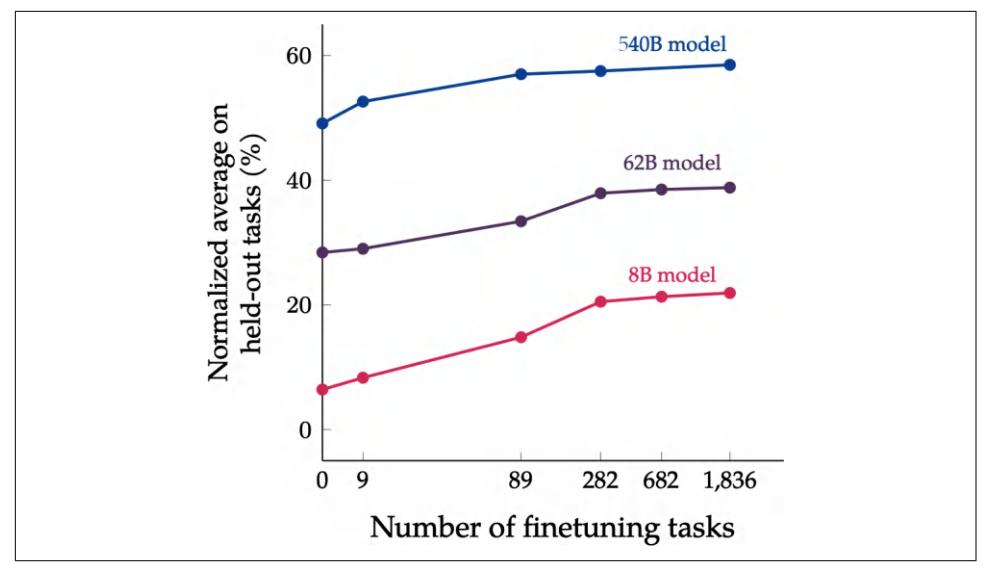

Tool use can significantly boost a model’s performance compared to just prompting or even finetuning. Chameleon (Lu et al., 2023) shows that a GPT-4-powered agent, aug‐ mented with a set of 13 tools, can outperform GPT-4 alone on several benchmarks. Examples of tools this agent used are knowledge retrieval, a query generator, an image captioner, a text detector, and Bing search.

On ScienceQA, a science question answering benchmark, Chameleon improves the best published few-shot result by 11.37%. On TabMWP (Tabular Math Word Prob‐ lems) (Lu et al., 2022), a benchmark involving tabular math questions, Chameleon improves the accuracy by 17%.

Write actions

So far, we’ve discussed read-only actions that allow a model to read from its data sources. But tools can also perform write actions, making changes to the data sources. A SQL executor can retrieve a data table (read) but can also change or delete the table

(write). An email API can read an email but can also respond to it. A banking API can retrieve your current balance but can also initiate a bank transfer.

Write actions enable a system to do more. They can enable you to automate the whole customer outreach workflow: researching potential customers, finding their contacts, drafting emails, sending first emails, reading responses, following up, extracting orders, updating your databases with new orders, etc.

However, the prospect of giving AI the ability to automatically alter our lives is frightening. Just as you shouldn’t give an intern the authority to delete your produc‐ tion database, you shouldn’t allow an unreliable AI to initiate bank transfers. Trust in the system’s capabilities and its security measures is crucial. You need to ensure that the system is protected from bad actors who might try to manipulate it into perform‐ ing harmful actions.

When I talk about autonomous AI agents to a group of people, there is often some‐ one who brings up self-driving cars. “What if someone hacks into the car to kidnap you?” While the self-driving car example seems visceral because of its physicality, an AI system can cause harm without a presence in the physical world. It can manip‐ ulate the stock market, steal copyrights, violate privacy, reinforce biases, spread mis‐ information and propaganda, and more, as discussed in “Defensive Prompt Engineering” on page 235.

These are all valid concerns, and any organization that wants to leverage AI needs to take safety and security seriously. However, this doesn’t mean that AI systems should never be given the ability to act in the real world. If we can get people to trust a machine to take us into space, I hope that one day, security measures will be suffi‐ cient for us to trust autonomous AI systems. Besides, humans can fail, too. Person‐ ally, I would trust a self-driving car more than the average stranger to drive me around.

Just as the right tools can help humans be vastly more productive—can you imagine doing business without Excel or building a skyscraper without cranes?—tools enable models to accomplish many more tasks. Many model providers already support tool use with their models, a feature often called function calling. Going forward, I would expect function calling with a wide set of tools to be common with most models.

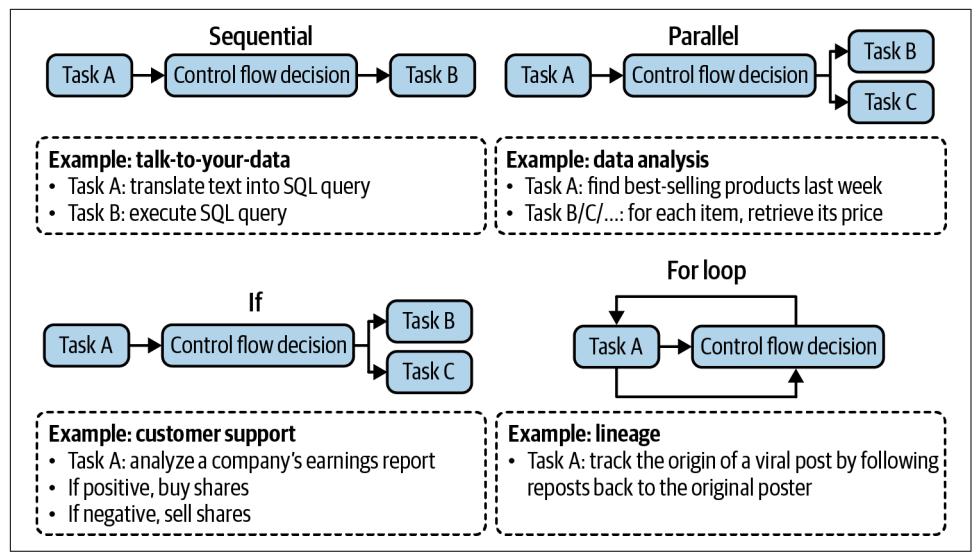

Planning

At the heart of a foundation model agent is the model responsible for solving a task. A task is defined by its goal and constraints. For example, one task is to schedule a two-week trip from San Francisco to India with a budget of $5,000. The goal is the two-week trip. The constraint is the budget.

Complex tasks require planning. The output of the planning process is a plan, which is a roadmap outlining the steps needed to accomplish a task. Effective planning typi‐ cally requires the model to understand the task, consider different options to achieve this task, and choose the most promising one.

If you’ve ever been in any planning meeting, you know that planning is hard. As an important computational problem, planning is well studied and would require sev‐ eral volumes to cover. I’ll only be able to cover the surface here.

Planning overview

Given a task, there are many possible ways to decompose it, but not all of them will lead to a successful outcome. Among the correct solutions, some are more efficient than others. Consider the query, “How many companies without revenue have raised at least $1 billion?” There are many possible ways to solve this, but as an illustration, consider the two options:

- Find all companies without revenue, then filter them by the amount raised.

- Find all companies that have raised at least $1 billion, then filter them by revenue.

The second option is more efficient. There are vastly more companies without reve‐ nue than companies that have raised $1 billion. Given only these two options, an intelligent agent should choose option 2.

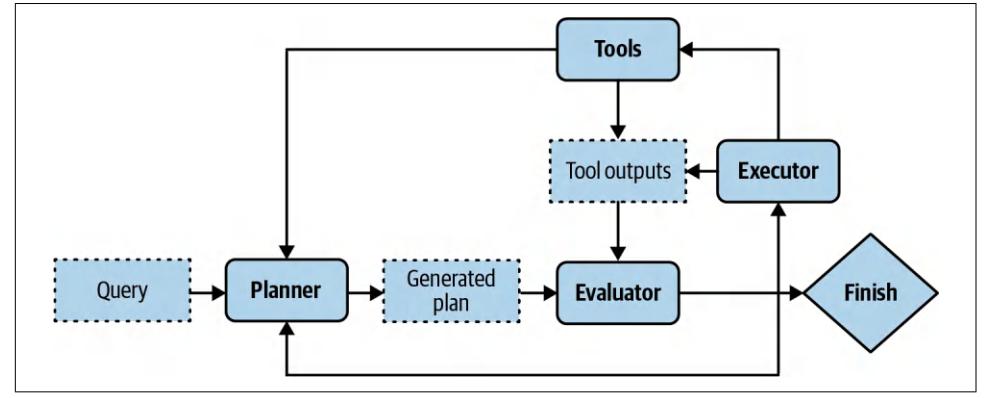

You can couple planning with execution in the same prompt. For example, you give the model a prompt, ask it to think step by step (such as with a chain-of-thought prompt), and then execute those steps all in one prompt. But what if the model comes up with a 1,000-step plan that doesn’t even accomplish the goal? Without oversight, an agent can run those steps for hours, wasting time and money on API calls, before you realize that it’s not going anywhere.

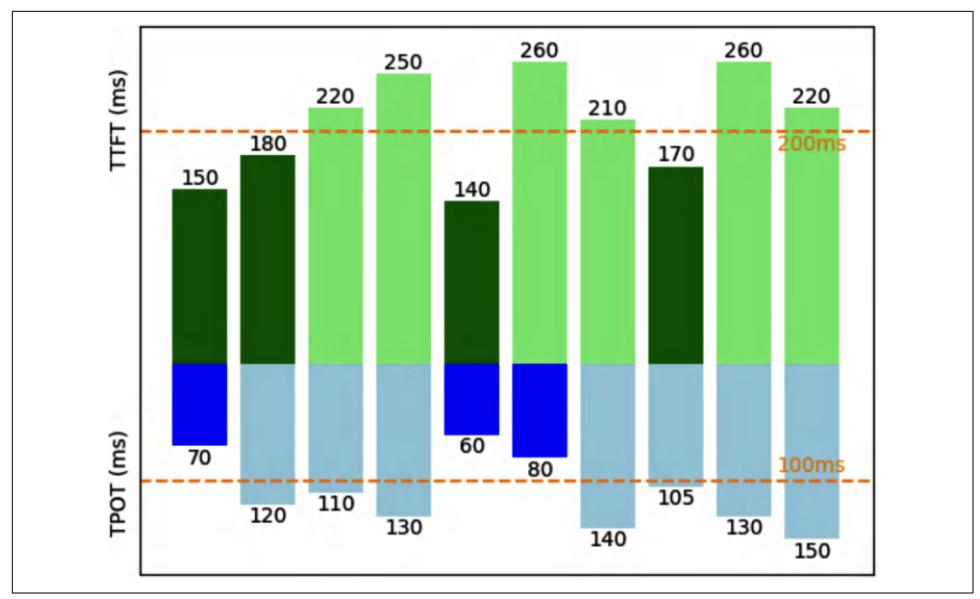

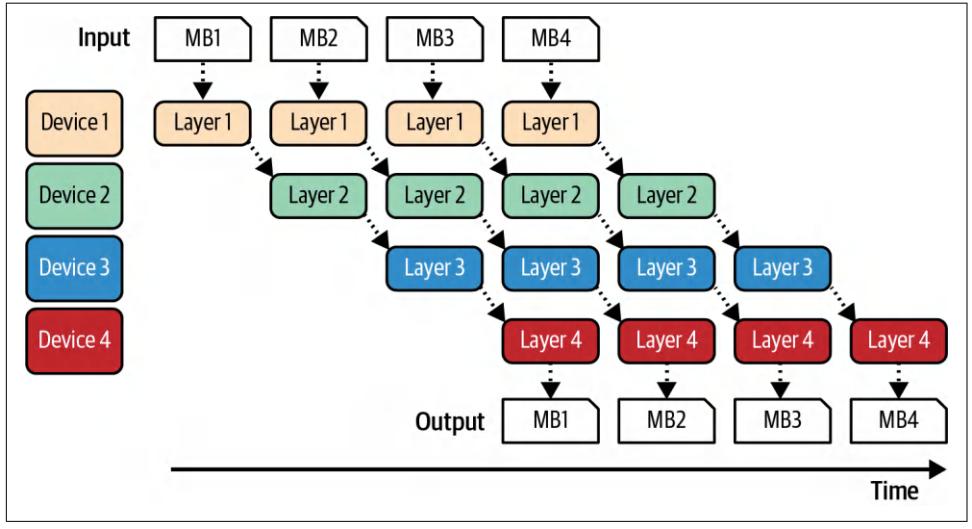

To avoid fruitless execution, planning should be decoupled from execution. You ask the agent to first generate a plan, and only after this plan is validated is it executed. The plan can be validated using heuristics. For example, one simple heuristic is to eliminate plans with invalid actions. If the generated plan requires a Google search and the agent doesn’t have access to Google Search, this plan is invalid. Another sim‐ ple heuristic might be eliminating all plans with more than X steps. A plan can also be validated using AI judges. You can ask a model to evaluate whether the plan seems reasonable or how to improve it.

If the generated plan is evaluated to be bad, you can ask the planner to generate another plan. If the generated plan is good, execute it. If the plan consists of external tools, function calling will be invoked. Outputs from executing this plan will then again need to be evaluated. Note that the generated plan doesn’t have to be an

end-to-end plan for the whole task. It can be a small plan for a subtask. The whole process looks like Figure 6-9.

Figure 6-9. Decoupling planning and execution so that only validated plans are executed.

Your system now has three components: one to generate plans, one to validate plans, and another to execute plans. If you consider each component an agent, this is a multi-agent system.12

To speed up the process, instead of generating plans sequentially, you can generate several plans in parallel and ask the evaluator to pick the most promising one. This is another latency/cost trade-off, as generating multiple plans simultaneously will incur extra costs.

Planning requires understanding the intention behind a task: what’s the user trying to do with this query? An intent classifier is often used to help agents plan. As shown in “Break Complex Tasks into Simpler Subtasks” on page 224, intent classification can be done using another prompt or a classification model trained for this task. The intent classification mechanism can be considered another agent in your multi-agent system.

Knowing the intent can help the agent pick the right tools. For example, for customer support, if the query is about billing, the agent might need access to a tool to retrieve a user’s recent payments. But if the query is about how to reset a password, the agent might need to access documentation retrieval.

12 Because most agentic workflows are sufficiently complex to involve multiple components, most agents are multi-agent.

Some queries might be out of the scope of the agent. The intent classifier should be able to classify requests as IRRELEVANT so that the agent can politely reject those instead of wasting FLOPs coming up with impossible solutions.

So far, we’ve assumed that the agent automates all three stages: generating plans, vali‐ dating plans, and executing plans. In reality, humans can be involved at any of those stages to aid with the process and mitigate risks. A human expert can provide a plan, validate a plan, or execute parts of a plan. For example, for complex tasks for which an agent has trouble generating the whole plan, a human expert can provide a highlevel plan that the agent can expand upon. If a plan involves risky operations, such as updating a database or merging a code change, the system can ask for explicit human approval before executing or let humans execute these operations. To make this pos‐ sible, you need to clearly define the level of automation an agent can have for each action.

To summarize, solving a task typically involves the following processes. Note that reflection isn’t mandatory for an agent, but it’ll significantly boost the agent’s perfor‐ mance:

- Plan generation: come up with a plan for accomplishing this task. A plan is a sequence of manageable actions, so this process is also called task decomposition.

- Reflection and error correction: evaluate the generated plan. If it’s a bad plan, gen‐ erate a new one.

- Execution: take the actions outlined in the generated plan. This often involves calling specific functions.

- Reflection and error correction: upon receiving the action outcomes, evaluate these outcomes and determine whether the goal has been accomplished. Identify and correct mistakes. If the goal is not completed, generate a new plan.

You’ve already seen some techniques for plan generation and reflection in this book. When you ask a model to “think step by step”, you’re asking it to decompose a task. When you ask a model to “verify if your answer is correct”, you’re asking it to reflect.

Foundation models as planners

An open question is how well foundation models can plan. Many researchers believe that foundation models, at least those built on top of autoregressive language models, cannot. Meta’s Chief AI Scientist Yann LeCun states unequivocally that autoregres‐ sive LLMs can’t plan (2023). In the article “Can LLMs Really Reason and Plan?” Kambhampati (2023) argues that LLMs are great at extracting knowledge but not planning. Kambhampati suggests that the papers claiming planning abilities of LLMs confuse general planning knowledge extracted from the LLMs with executable plans.

“The plans that come out of LLMs may look reasonable to the lay user, and yet lead to execution time interactions and errors.”

However, while there is a lot of anecdotal evidence that LLMs are poor planners, it’s unclear whether it’s because we don’t know how to use LLMs the right way or because LLMs, fundamentally, can’t plan.

Planning, at its core, is a search problem. You search among different paths to the goal, predict the outcome (reward) of each path, and pick the path with the most promising outcome. Often, you might determine that no path exists that can take you to the goal.

Search often requires backtracking. For example, imagine you’re at a step where there are two possible actions: A and B. After taking action A, you enter a state that’s not promising, so you need to backtrack to the previous state to take action B.

Some people argue that an autoregressive model can only generate forward actions. It can’t backtrack to generate alternate actions. Because of this, they conclude that autoregressive models can’t plan. However, this isn’t necessarily true. After executing a path with action A, if the model determines that this path doesn’t make sense, it can revise the path using action B instead, effectively backtracking. The model can also always start over and choose another path.

It’s also possible that LLMs are poor planners because they aren’t given the toolings needed to plan. To plan, it’s necessary to know not only the available actions but also the potential outcome of each action. As a simple example, let’s say you want to walk up a mountain. Your potential actions are turn right, turn left, turn around, or go straight ahead. However, if turning right will cause you to fall off the cliff, you might not want to consider this action. In technical terms, an action takes you from one state to another, and it’s necessary to know the outcome state to determine whether to take an action.

This means it’s not sufficient to prompt a model to generate only a sequence of actions like what the popular chain-of-thought prompting technique does. The paper “Reasoning with Language Model is Planning with World Model” (Hao et al., 2023) argues that an LLM, by containing so much information about the world, is capable of predicting the outcome of each action. This LLM can incorporate this outcome prediction to generate coherent plans.

Even if AI can’t plan, it can still be a part of a planner. It might be possible to aug‐ ment an LLM with a search tool and state tracking system to help it plan.

Foundation Model (FM) Versus Reinforcement Learning (RL) Planners

The agent is a core concept in RL, which is defined in Wikipedia as a field “concerned with how an intelligent agent ought to take actions in a dynamic environment in order to maximize the cumulative reward.”

RL agents and FM agents are similar in many ways. They are both characterized by their environments and possible actions. The main difference is in how their planners work. In an RL agent, the planner is trained by an RL algorithm. Training this RL planner can require a lot of time and resources. In an FM agent, the model is the planner. This model can be prompted or finetuned to improve its planning capabili‐ ties, and generally requires less time and fewer resources.

However, there’s nothing to prevent an FM agent from incorporating RL algorithms to improve its performance. I suspect that in the long run, FM agents and RL agents will merge.

Plan generation

The simplest way to turn a model into a plan generator is with prompt engineering. Imagine that you want to create an agent to help customers learn about products at Kitty Vogue. You give this agent access to three external tools: retrieve products by price, retrieve top products, and retrieve product information. Here’s an example of a prompt for plan generation. This prompt is for illustration purposes only. Production prompts are likely more complex:

SYSTEM PROMPTPropose a plan to solve the task. You have access to 5 actions: get_today_date() fetch_top_products(start_date, end_date, num_products) fetch_product_info(product_name) generate_query(task_history, tool_output) generate_response(query)

The plan must be a sequence of valid actions.

Examples Task: “Tell me about Fruity Fedora” Plan: [fetch_product_info, generate_query, generate_response] Task: “What was the best selling product last week?” Plan: [fetch_top_products, generate_query, generate_response]

Task: {USER INPUT}

Plan:There are two things to note about this example:

- The plan format used here—a list of functions whose parameters are inferred by the agent—is just one of many ways to structure the agent control flow.

- The generate_query function takes in the task’s current history and the most recent tool outputs to generate a query to be fed into the response generator. The tool output at each step is added to the task’s history.

Given the user input “What’s the price of the best-selling product last week”, a gener‐ ated plan might look like this:

- get_time() 2. fetch_top_products() 3. fetch_product_info() 4. generate_query() 5. generate_response()

You might wonder, “What about the parameters needed for each function?” The exact parameters are hard to predict in advance since they are often extracted from the previous tool outputs. If the first step, get_time(), outputs “2030-09-13”, then the agent can reason that the parameters for the next step should be called with the following parameters:

retrieve_top_products(

start_date="2030-09-07",

end_date="2030-09-13",

num_products=1

)Often, there’s insufficient information to determine the exact parameter values for a function. For example, if a user asks, “What’s the average price of best-selling prod‐ ucts?”, the answers to the following questions are unclear:

- How many best-selling products does the user want to look at?

- Does the user want the best-selling products last week, last month, or of all time?

This means that models frequently have to guess, and guesses can be wrong.

Because both the action sequence and the associated parameters are generated by AI models, they can be hallucinated. Hallucinations can cause the model to call an invalid function or call a valid function but with wrong parameters. Techniques for improving a model’s performance in general can be used to improve a model’s plan‐ ning capabilities.

Here are a few approaches to make an agent better at planning:

- Write a better system prompt with more examples.

- Give better descriptions of the tools and their parameters so that the model understands them better.

- Rewrite the functions themselves to make them simpler, such as refactoring a complex function into two simpler functions.

- Use a stronger model. In general, stronger models are better at planning.

- Finetune a model for plan generation.

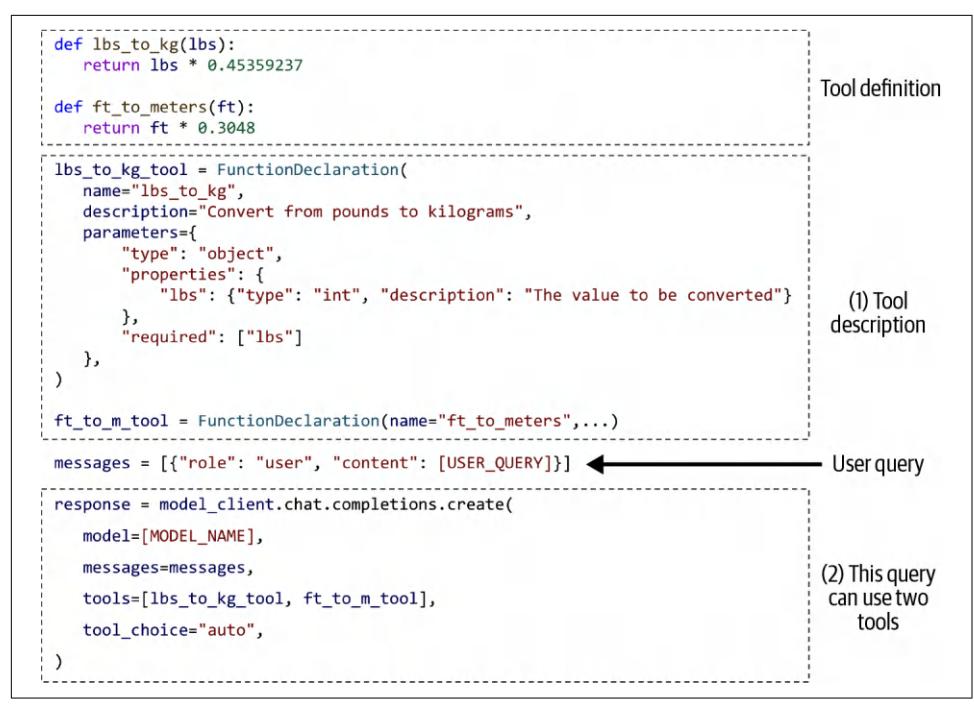

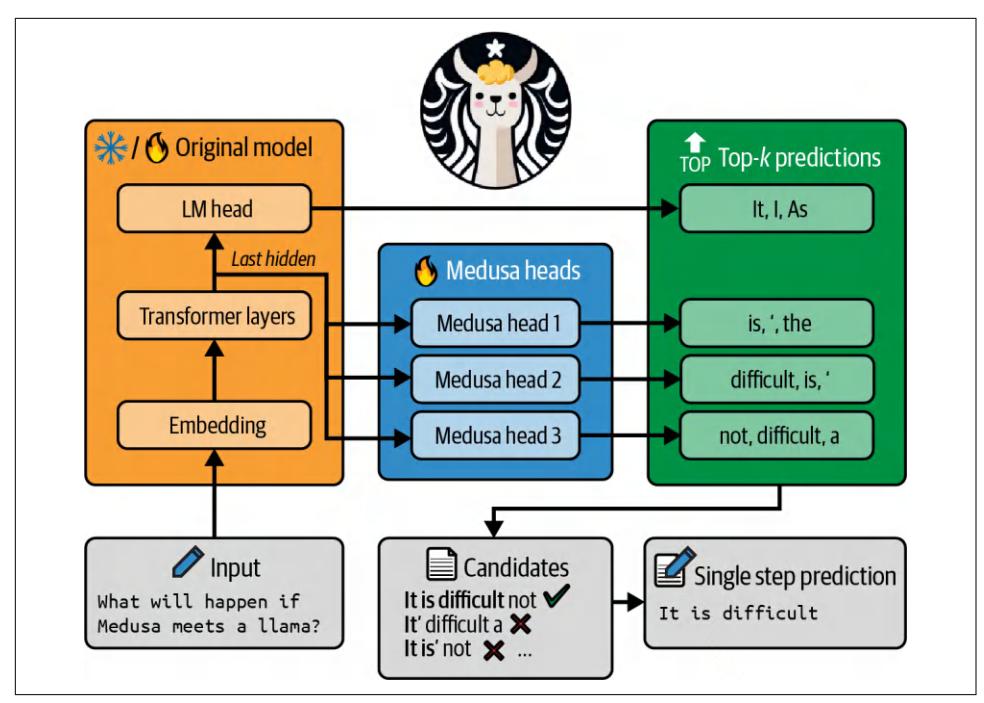

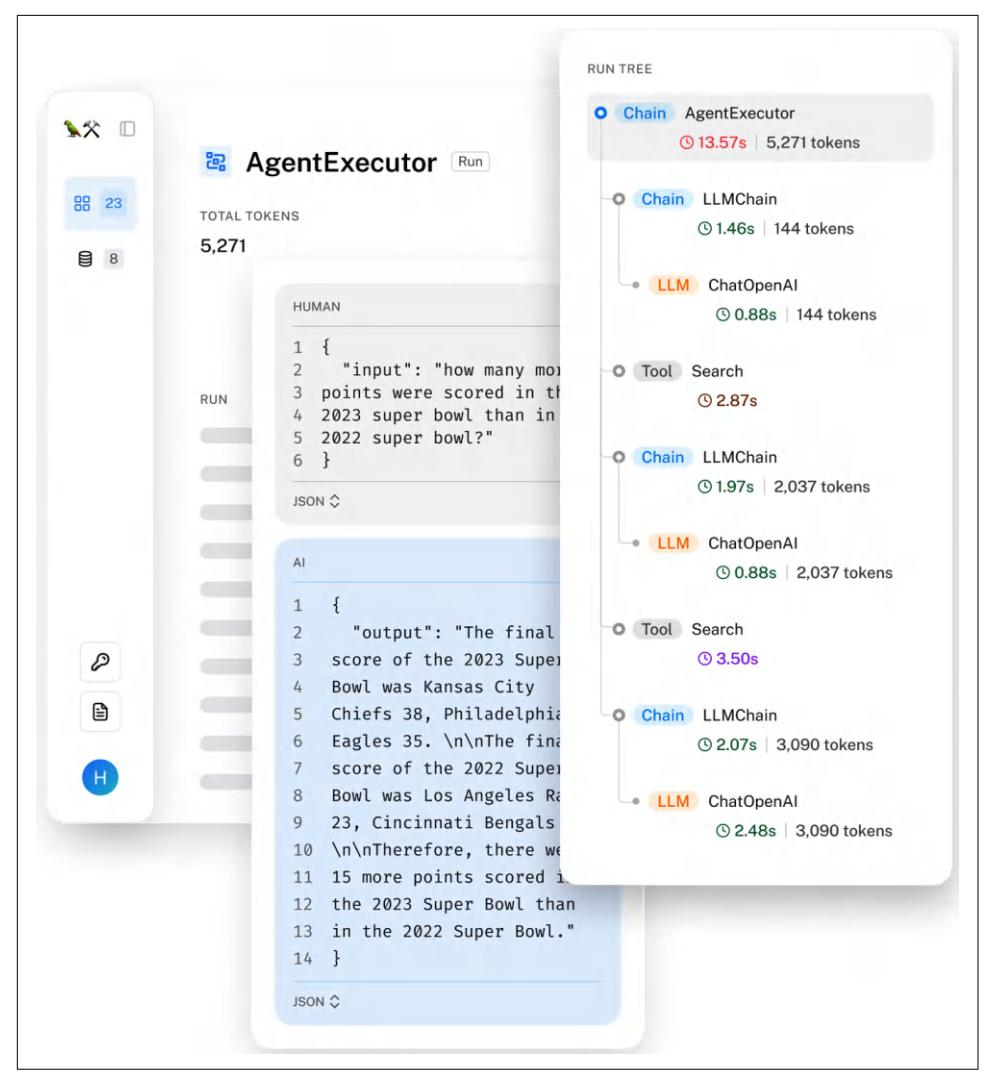

Function calling. Many model providers offer tool use for their models, effectively turning their models into agents. A tool is a function. Invoking a tool is, therefore, often called function calling. Different model APIs work differently, but in general, function calling works as follows:

- Create a tool inventory.

Declare all the tools that you might want a model to use. Each tool is described by its execution entry point (e.g., its function name), its parameters, and its doc‐ umentation (e.g., what the function does and what parameters it needs).

- Specify what tools the agent can use.

Because different queries might need different tools, many APIs let you specify a list of declared tools to be used per query. Some let you control tool use further by the following settings:

required

The model must use at least one tool.

none

The model shouldn’t use any tool.

auto

The model decides which tools to use.

Function calling is illustrated in Figure 6-10. This is written in pseudocode to make it representative of multiple APIs. To use a specific API, please refer to its documentation.

Figure 6-10. An example of a model using two simple tools.

Given a query, an agent defined as in Figure 6-10 will automatically generate what tools to use and their parameters. Some function calling APIs will make sure that only valid functions are generated, though they won’t be able to guarantee the correct parameter values.

For example, given the user query “How many kilograms are 40 pounds?”, the agent might decide that it needs the tool lbs_to_kg_tool with one parameter value of 40. The agent’s response might look like this:

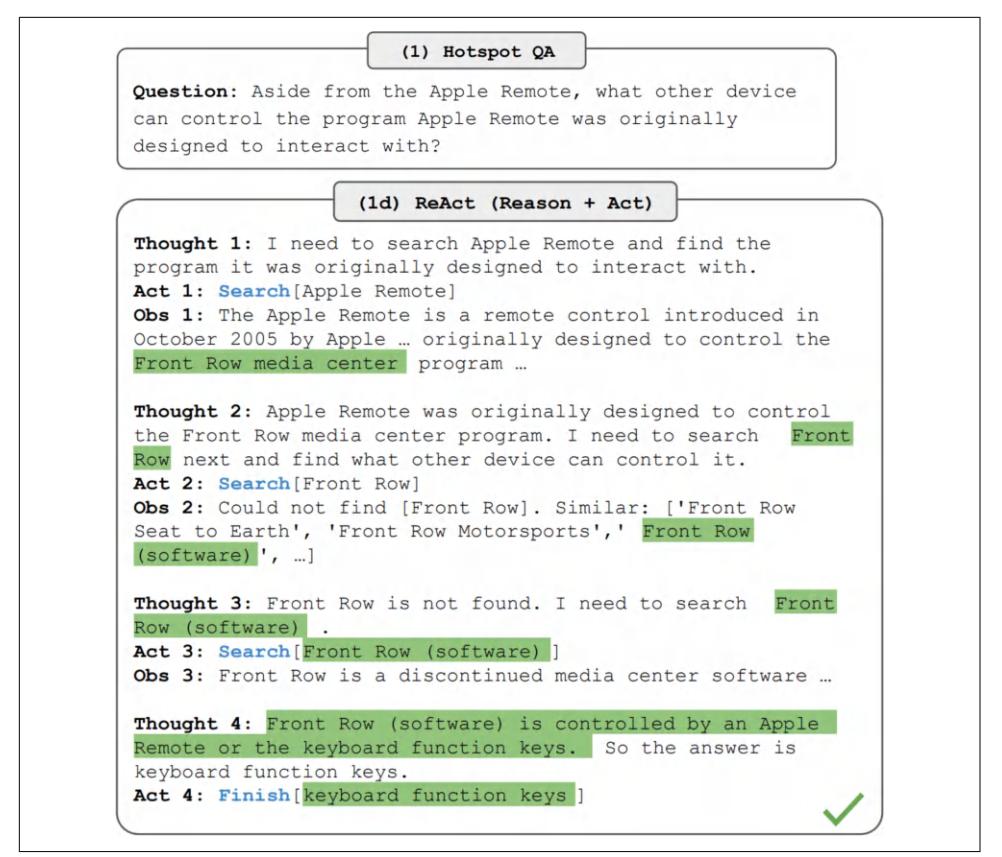

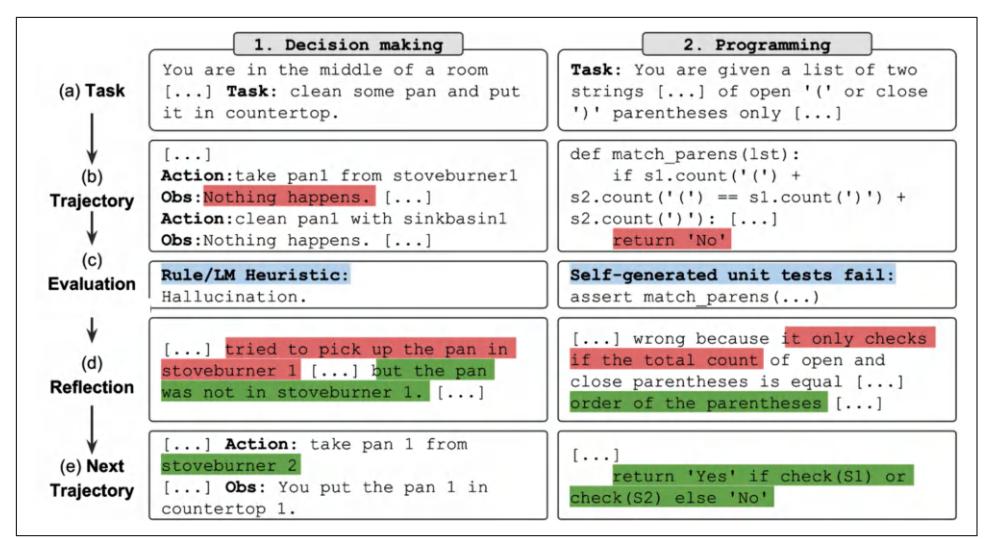

response = ModelResponse(