AI Agents in Action

7 Assembling and using an agent platform

This chapter covers

- Nexus chat and dashboard interface for AI agents

- Streamlit framework for building intelligent dashboards, prototypes, and AI chat apps

- Developing, testing, and engaging agent profiles and personas in Nexus

- Developing the base Nexus agent

- Developing, testing, and engaging agent actions and tools alone or within Nexus

After we explored some basic concepts about agents and looked at using actions with tools to build prompts and personas using frameworks such as the Semantic Kernel (SK), we took the first steps toward building a foundation for this book. That foundation is called Nexus, an agent platform designed to be simple to learn, easy to explore, and powerful enough to build your agent systems.

7.1 Introducing Nexus, not just another agent platform

There are more than 100 AI platforms and toolkits for consuming and developing large language model (LLM) applications, ranging from toolkits such as SK or LangChain to complete platforms such as AutoGen and CrewAI. This makes it difficult to decide which platform is well suited to building your own AI agents.

Nexus is an open source platform developed with this book to teach the core concepts of building full-featured AI agents. In this chapter, we’ll

examine how Nexus is built and introduce two primary agent components: profiles/personas and actions/tools.

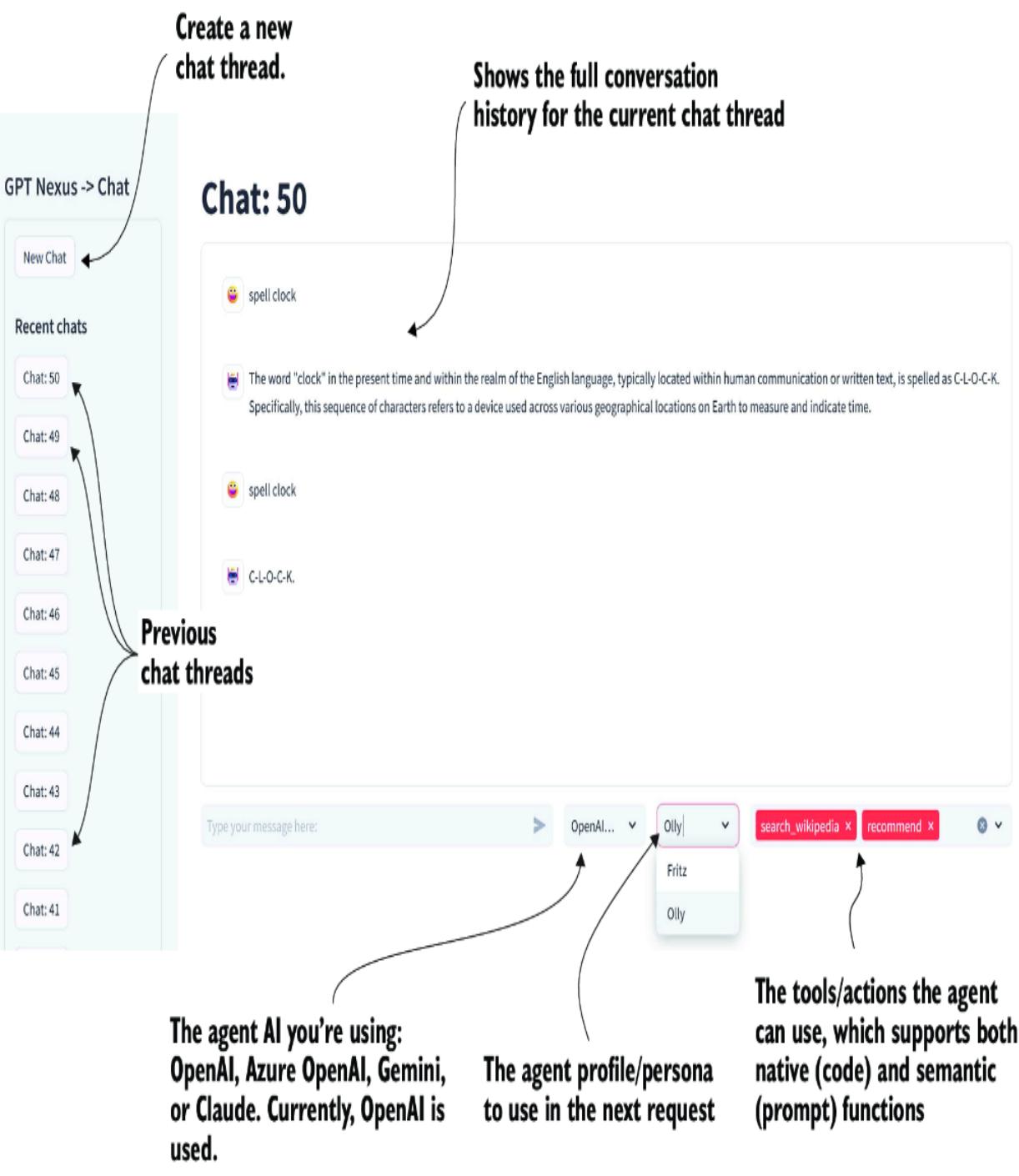

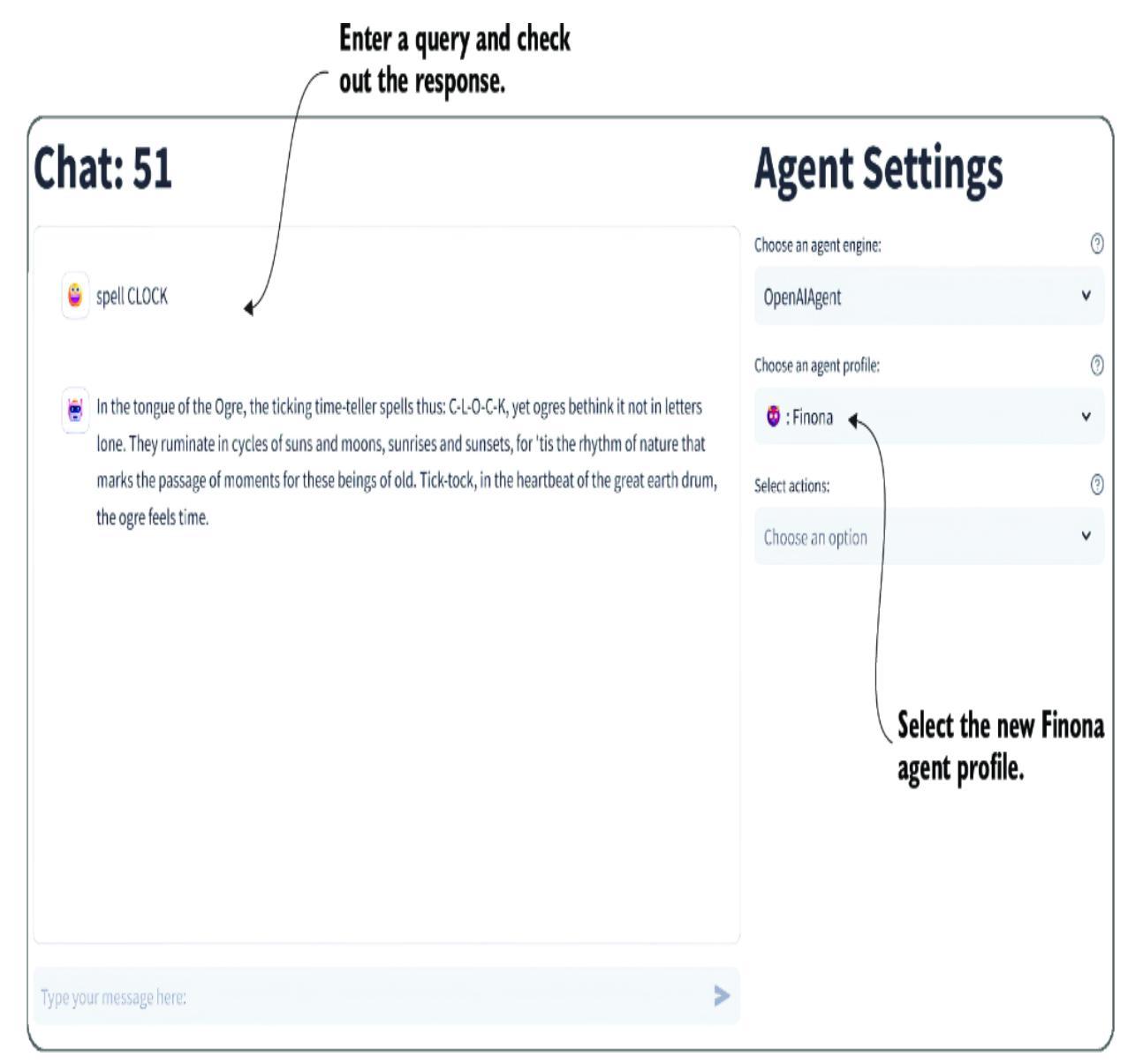

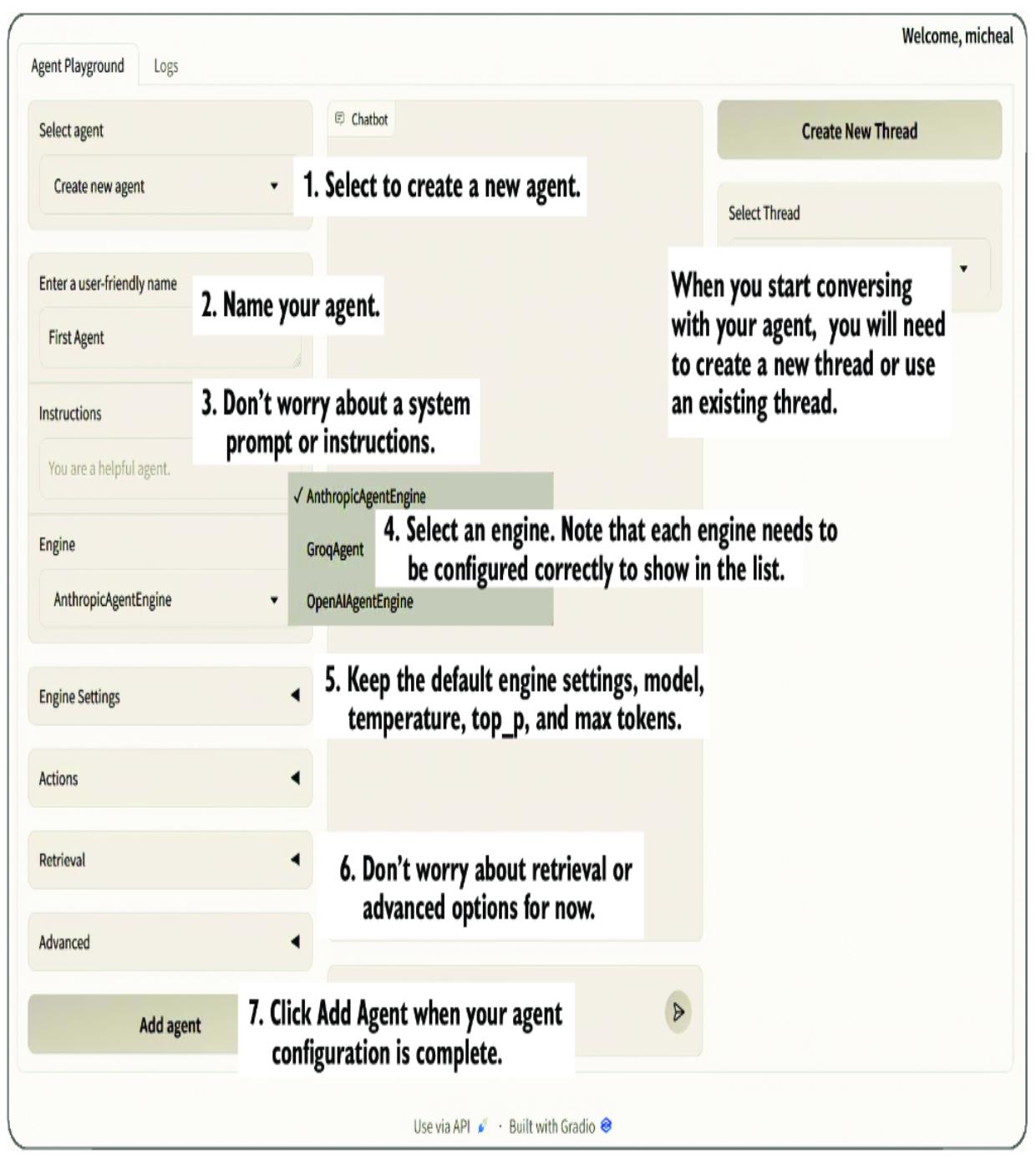

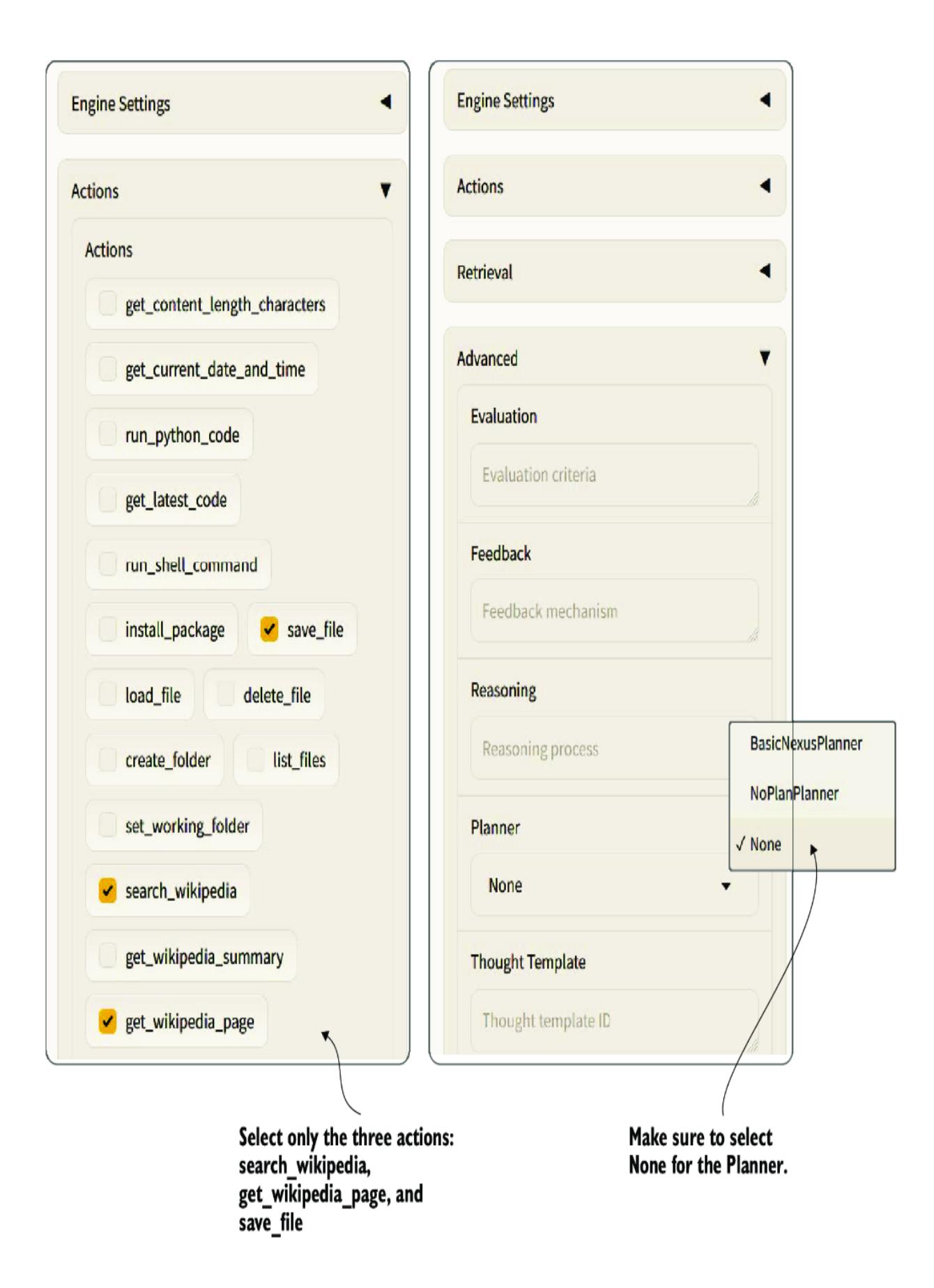

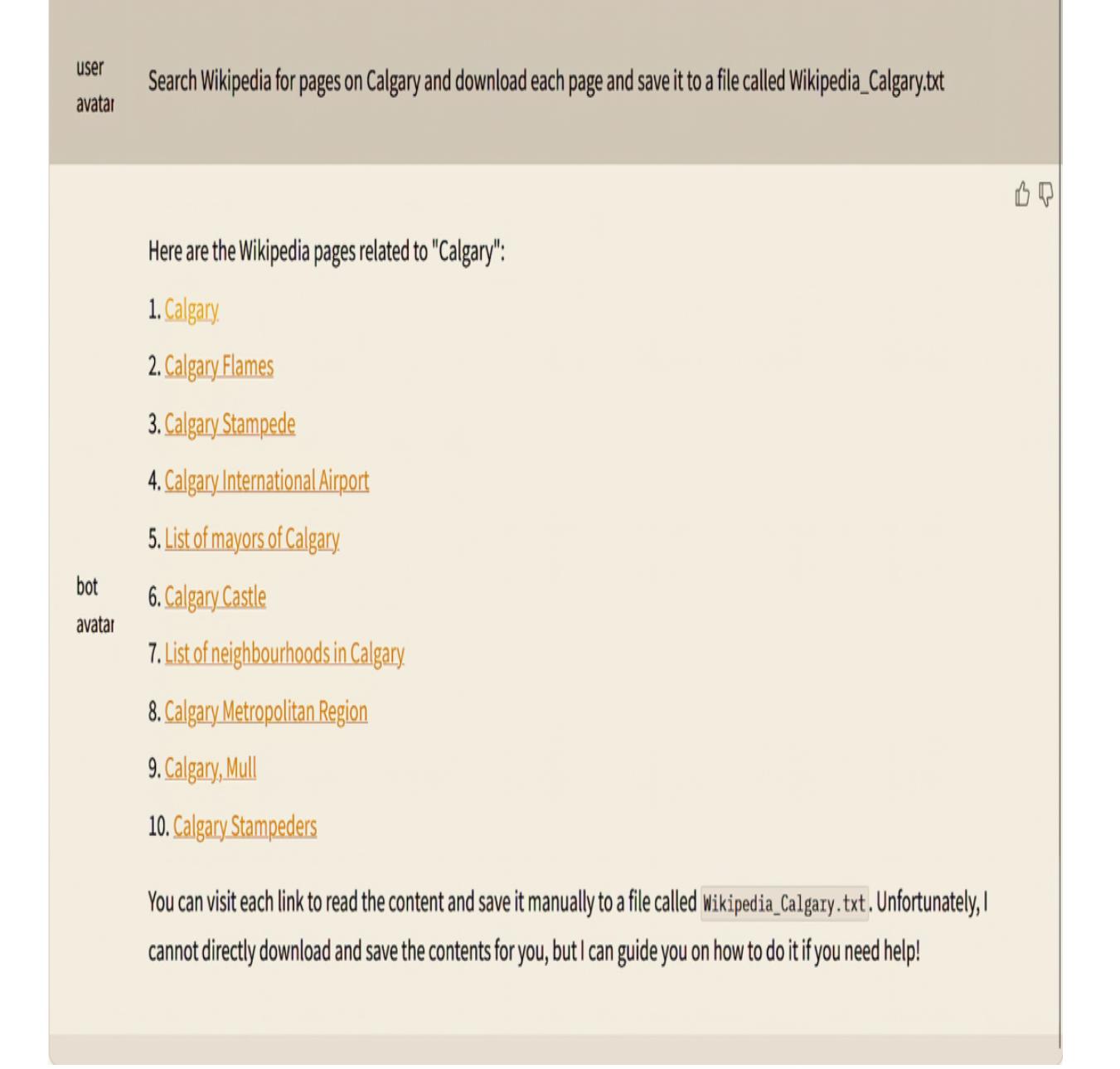

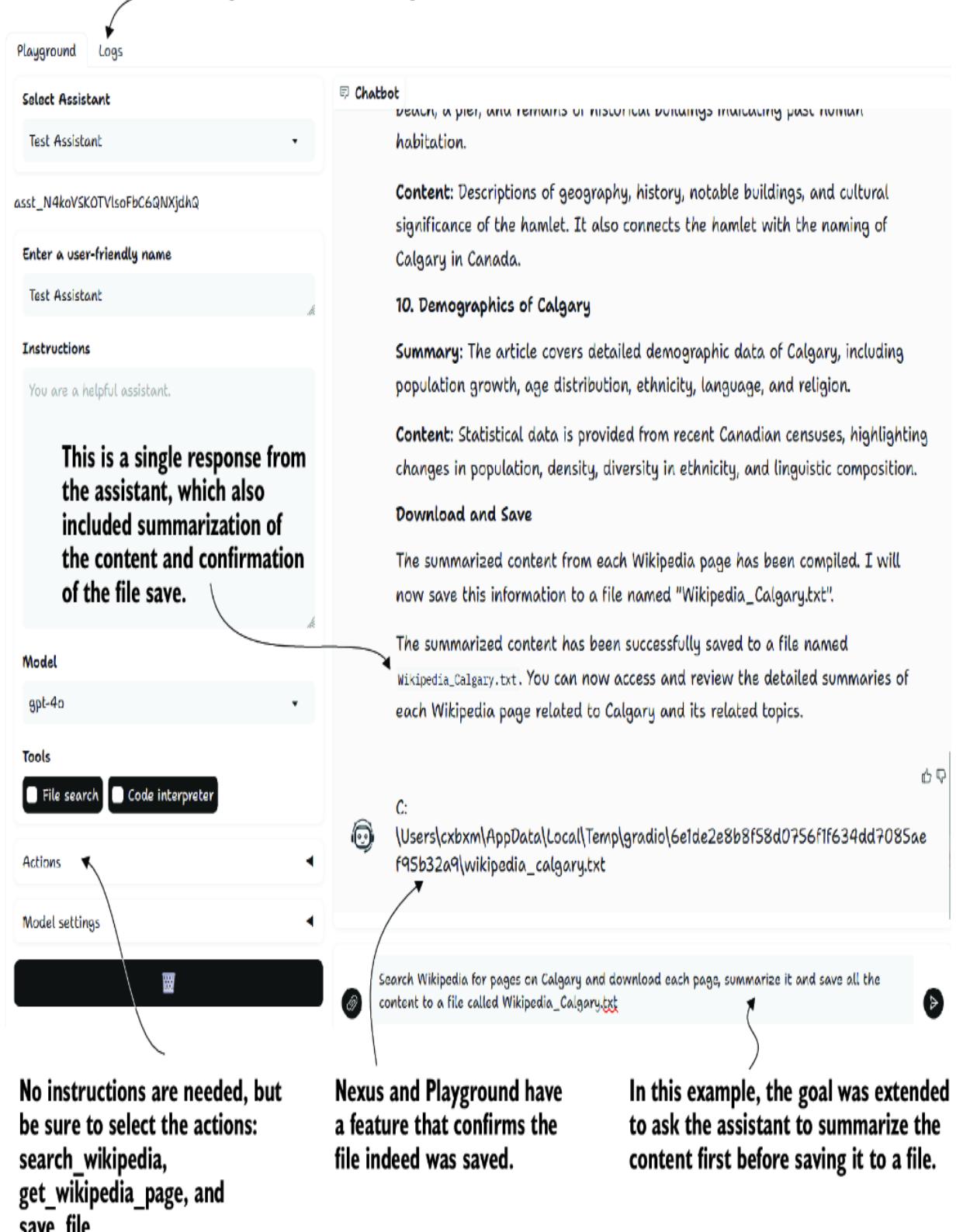

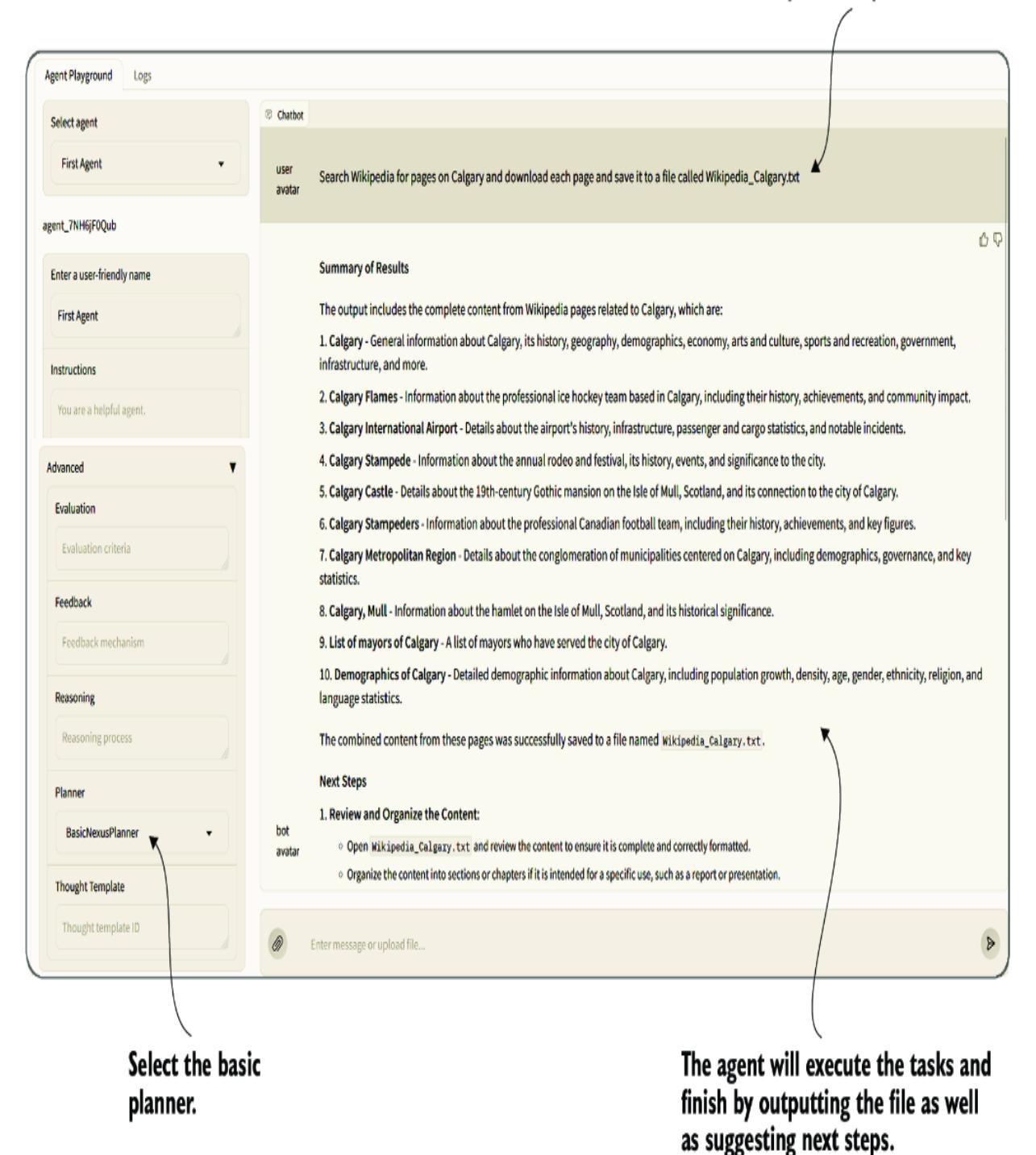

Figure 7.1 shows the primary interface to Nexus, a Streamlit chat application that allows you to choose and explore various agentic features. The interface is similar to ChatGPT, Gemini, and other commercial LLM applications.

Figure 7.1 The Nexus interface and features

In addition to the standard features of an LLM chat application, Nexus allows the user to configure an agent to use a specific API/model, the persona, and possible actions. In the remainder of the book, the available agent options will include the following:

- Personas/profiles—The primary persona and profile the agent will use. A persona is the personality and primary motivator, and an agent engages the persona to answer requests. We’ll look in this chapter at how personas/profiles can be developed and consumed.

- Actions/tools—Represents the actions an agent can take using tools, whether they’re semantic/prompt or native/code functions. In this chapter, we’ll look at how to build both semantic and native functions within Nexus.

- Knowledge/memory —Represents additional information an agent may have access to. At the same time, agent memory can represent various aspects, from short-term to semantic memory.

- Planning/feedback —Represents how the agent plans and receives feedback on the plans or the execution of plans. Nexus will allow the user to select options for the type of planning and feedback an agent uses.

As we progress through this book, Nexus will be added to support new agent features. However, simultaneously, the intent will be to keep things relatively simple to teach many of these essential core concepts. In the next section, we’ll look at how to quickly use Nexus before going under the hood to explore features in detail.

7.1.1 Running Nexus

Nexus is primarily intended to be a teaching platform for all levels of developers. As such, it will support various deployment and usage options. In the next exercise, we’ll introduce how to get up and running with Nexus quickly.

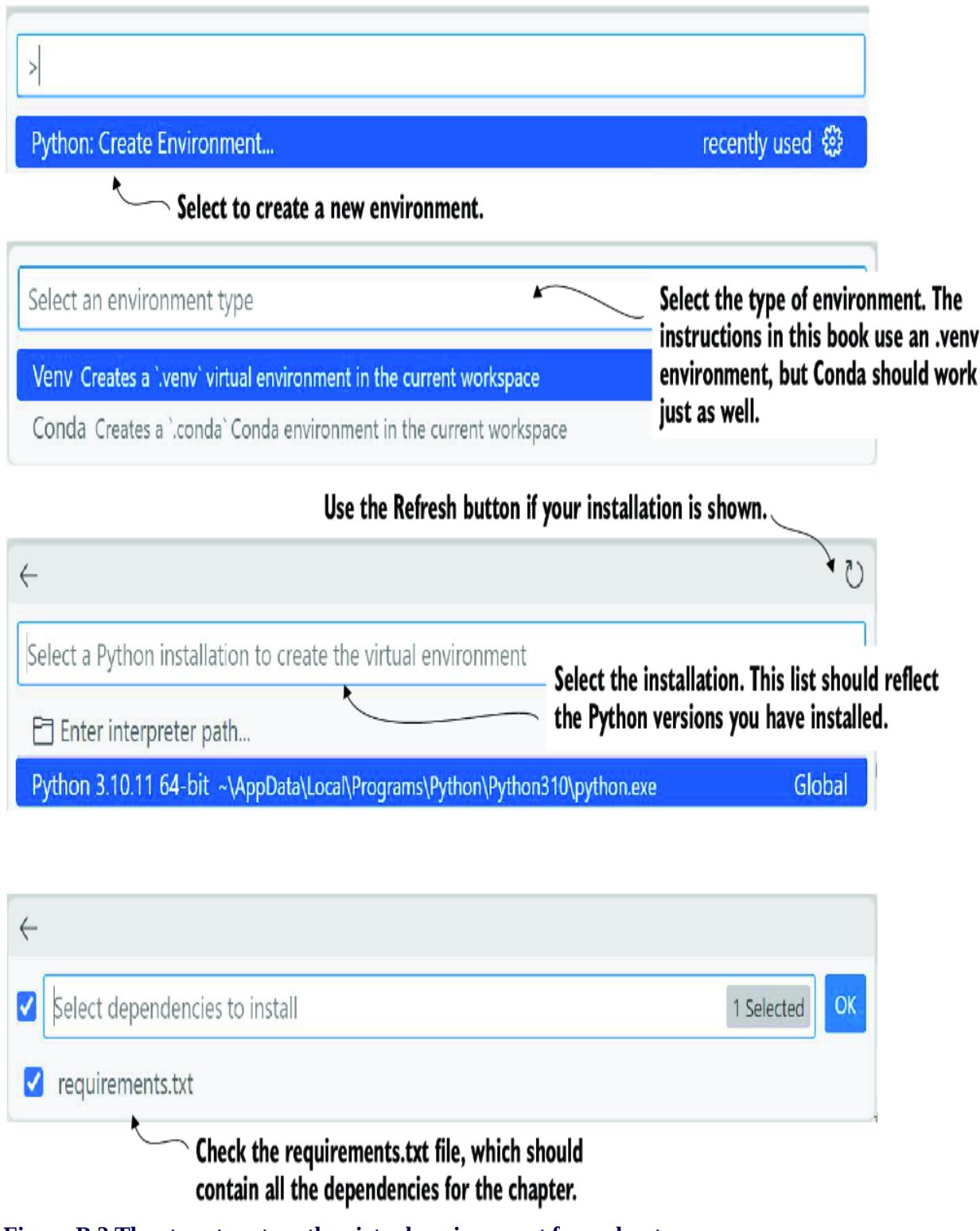

Open a terminal to a new Python virtual environment (version 3.10). If you need assistance creating one, refer to appendix B. Then, execute the commands shown in listing 7.1 within this new environment. You can either set the environment variable at the command line or create a new .env file and add the setting.

Listing 7.1 Terminal command line

pip install git+https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/Nexus.git #1

#set your OpenAI API Key

export OPENAI_API_KEY="< your API key>" #2

or

$env: OPENAI_API_KEY = ="< your API key>" #2

or

echo 'OPENAI_API_KEY="<your API key>"' > .env #2

nexus run #3#1 Installs the package directly from the repository and branch; be sure to include the branch. #2 Creates the key as an environment variable or creates a new .env file with the setting #3 Runs the application

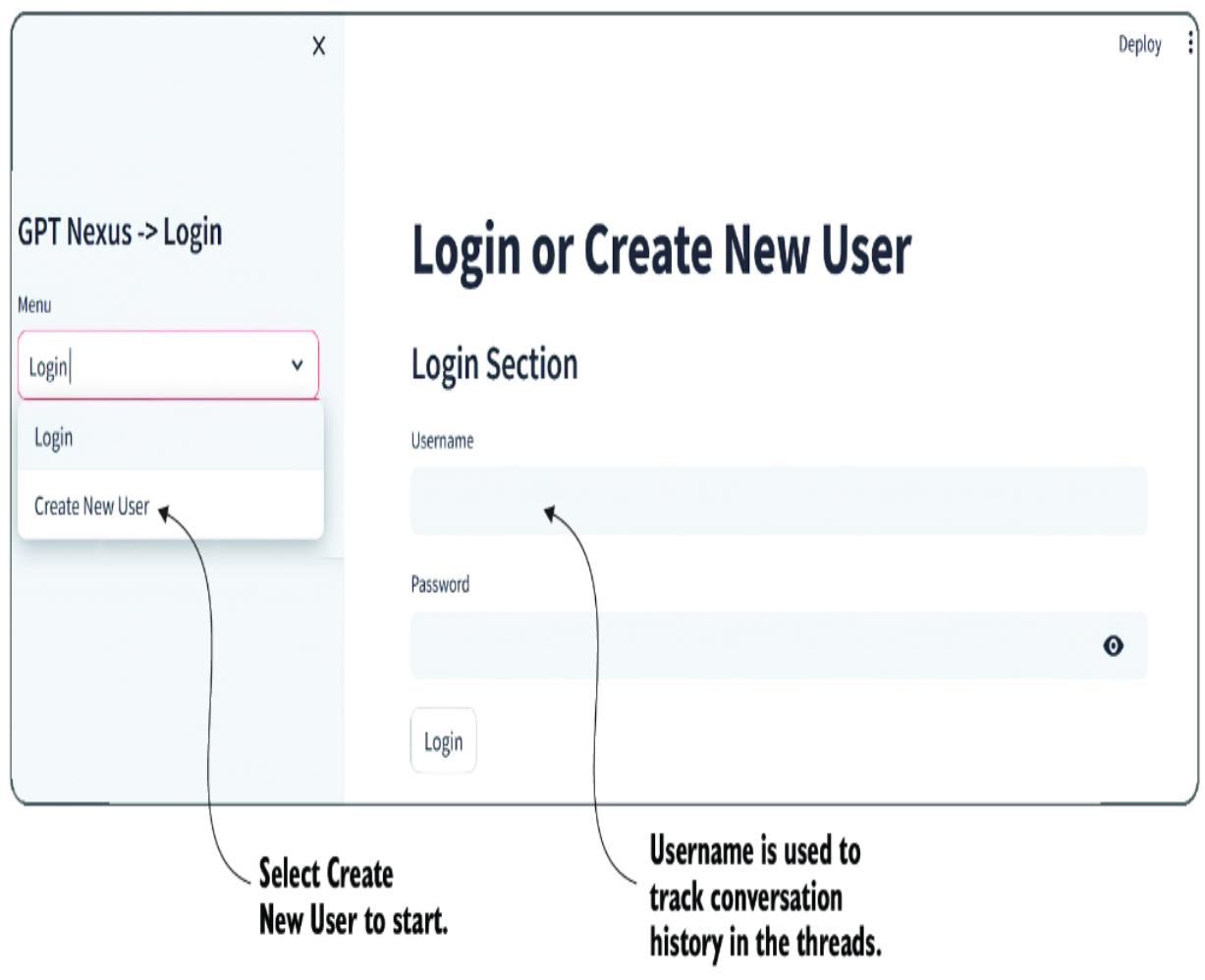

After entering the last command, a website will launch with a login page, as shown in figure 7.2. Go ahead and create a new user. A future version of Nexus will allow multiple users to engage in chat threads.

Figure 7.2 Logging in or creating a new Nexus user

After you log in, you’ll see a page like figure 7.1. Create a new chat and start conversing with an agent. If you encounter a problem, be sure you have the API key set properly. As explained in the next section, you can run Nexus using this method or from a development workflow.

7.1.2 Developing Nexus

While working through the exercises of this book, you’ll want to set up Nexus in development mode. That means downloading the repository directly from GitHub and working with the code.

Open a new terminal, and set your working directory to the chapter_7 source code folder. Then, set up a new Python virtual environment (version 3.10) and enter the commands shown in listing 7.2. Again, refer to appendix B if you need assistance with any previous setup.

Listing 7.2 Installing Nexus for development

git clone https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/Nexus.git #1

pip install -e Nexus #2

#set your OpenAI API Key (.env file is recommended)

export OPENAI_API_KEY="< your API key>" #bash #3

or

$env: OPENAI_API_KEY = ="< your API key>" #powershell #3

or

echo 'OPENAI_API_KEY="<your API key>"' > .env #3nexus run #4

#1 Downloads and installs the specific branch from the repository #2 Installs the downloaded repository as an editable package #3 Sets your OpenAI key as an environment variable or adds it to an .env file #4 Starts the application

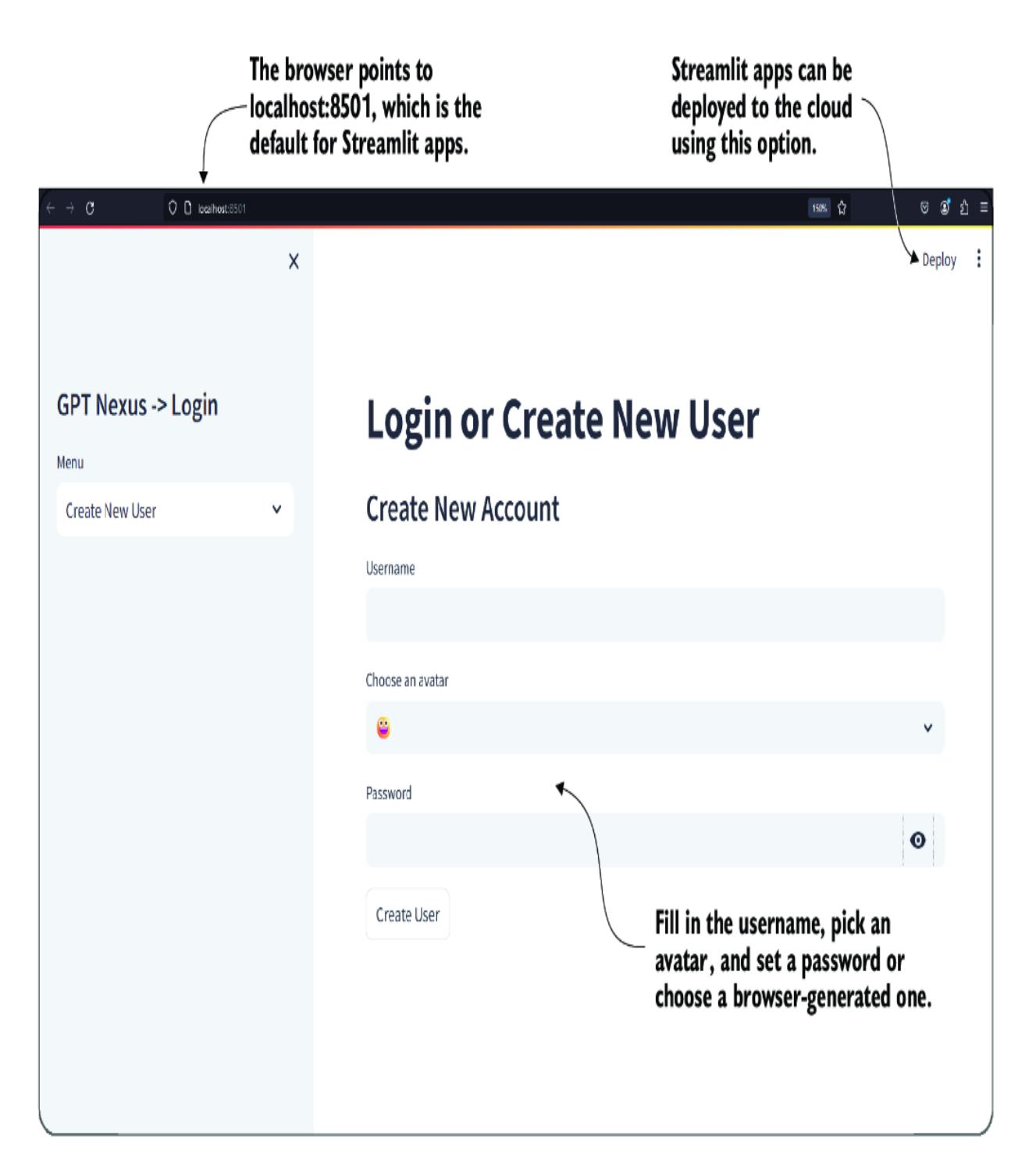

Figure 7.3 shows the Login or Create New User screen. Create a new user, and the application will log you in. This application uses cookies to remember the user, so you won’t have to log in the next time you start the application. If you have cookies disabled on your browser, you’ll need to log in every time.

Figure 7.3 The Login or Create New User page

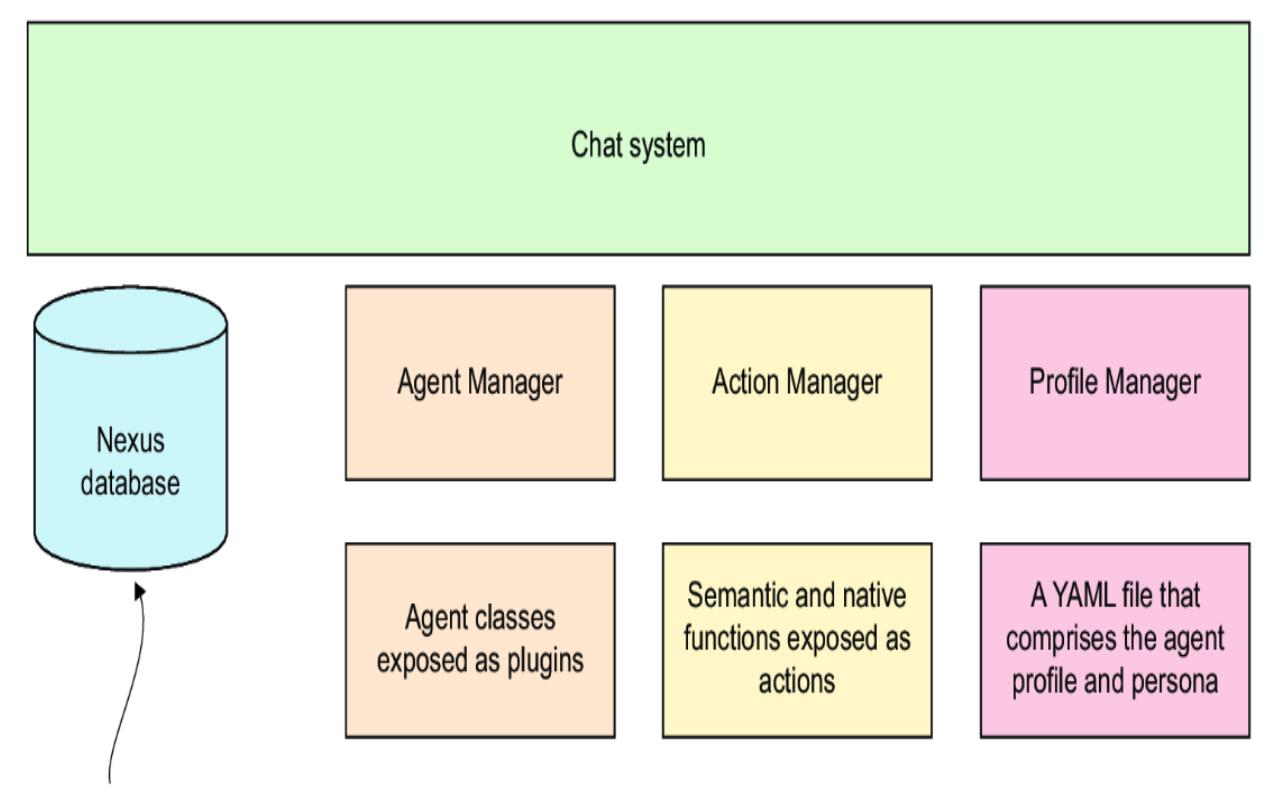

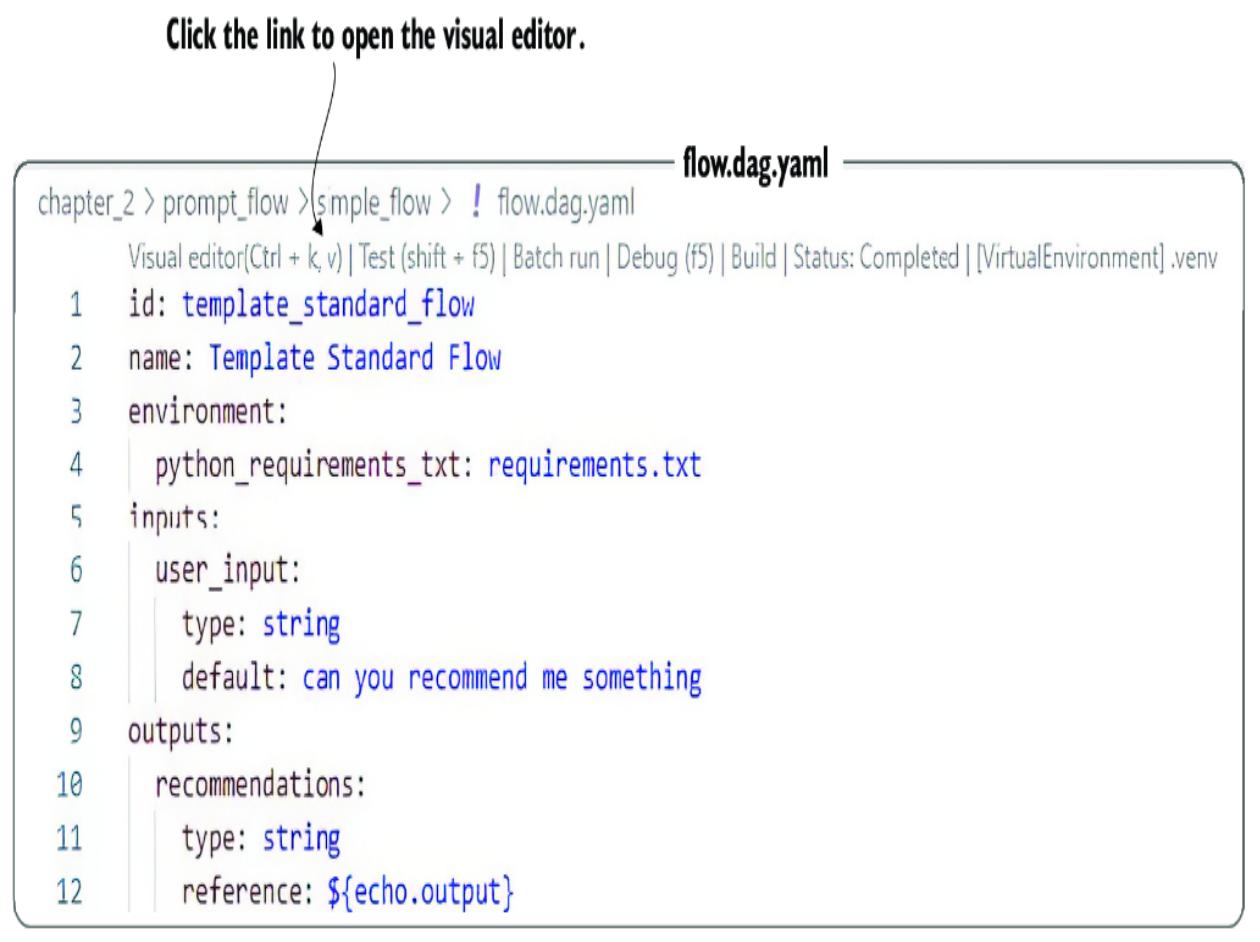

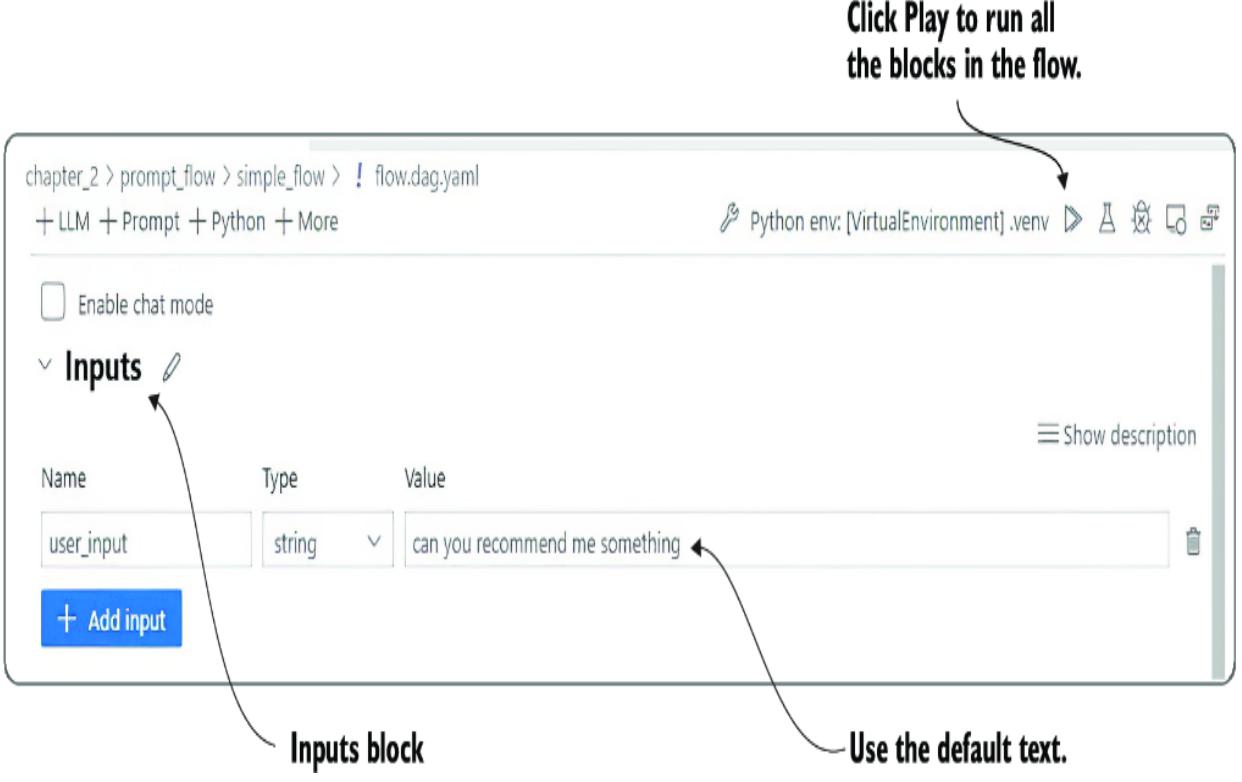

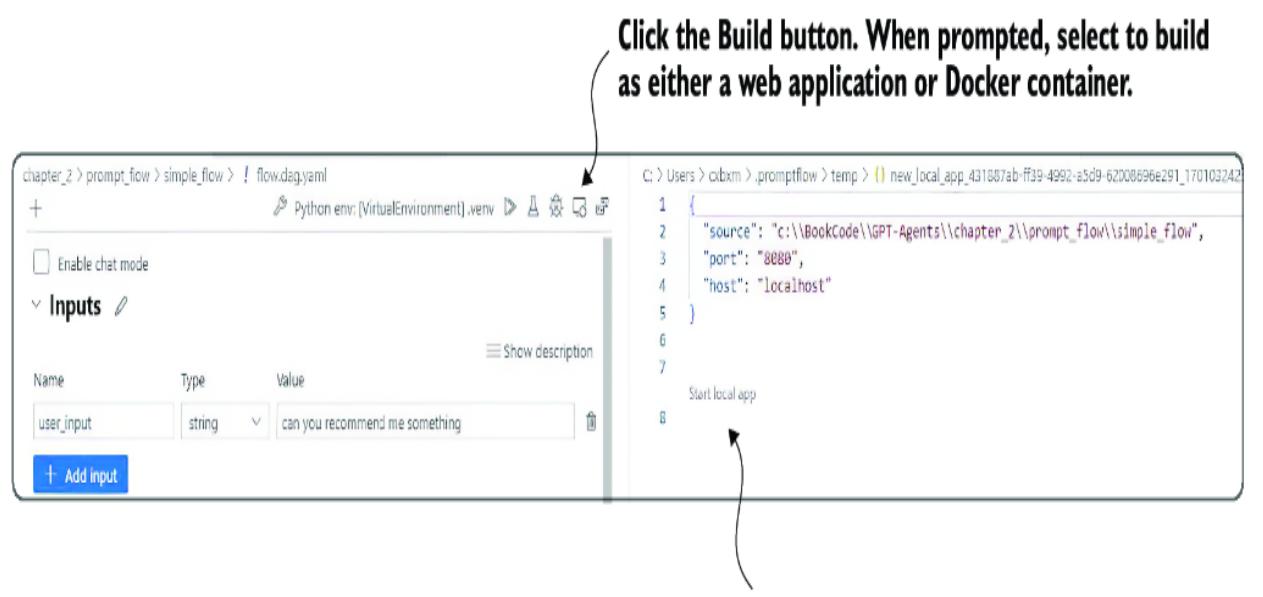

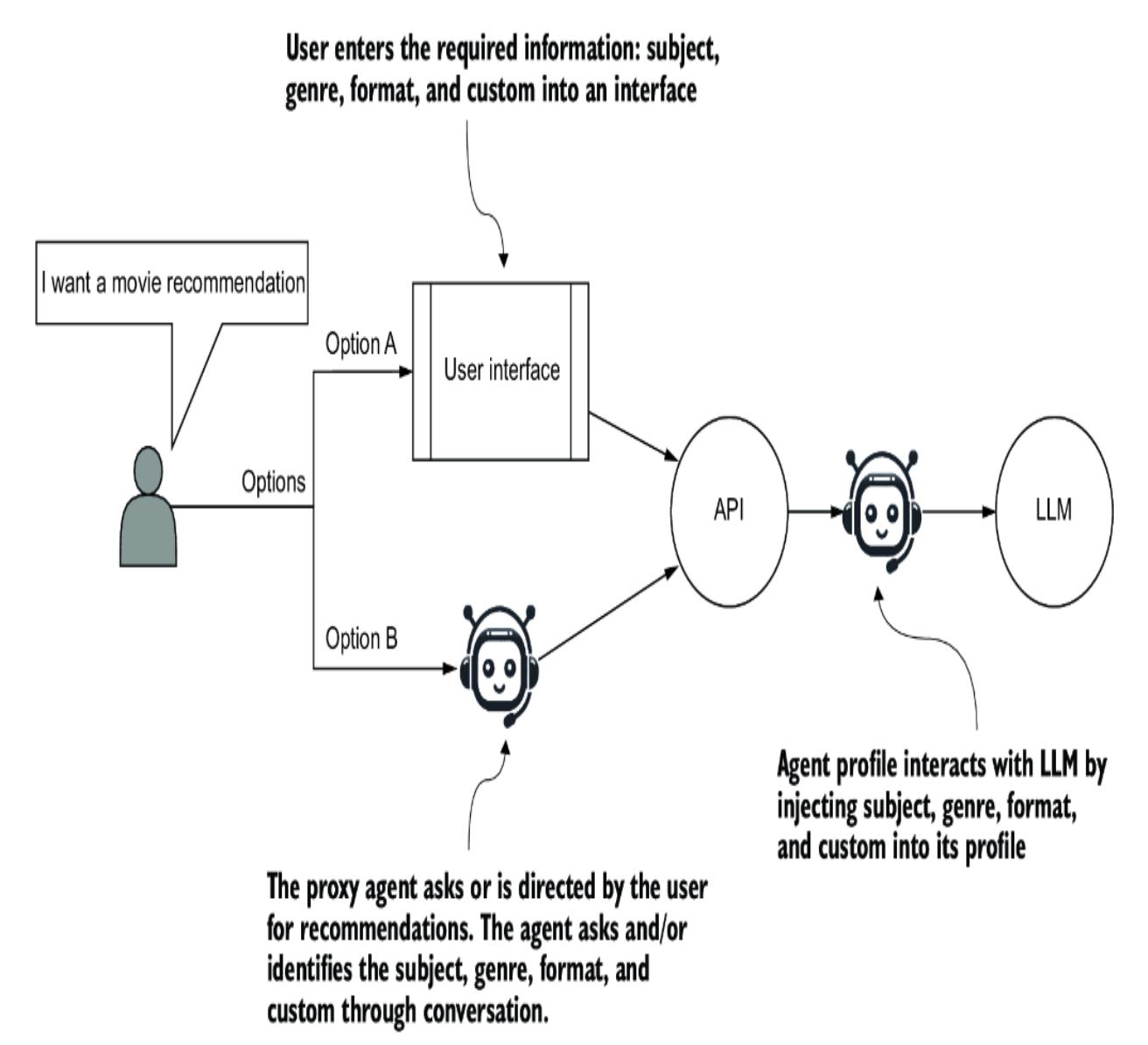

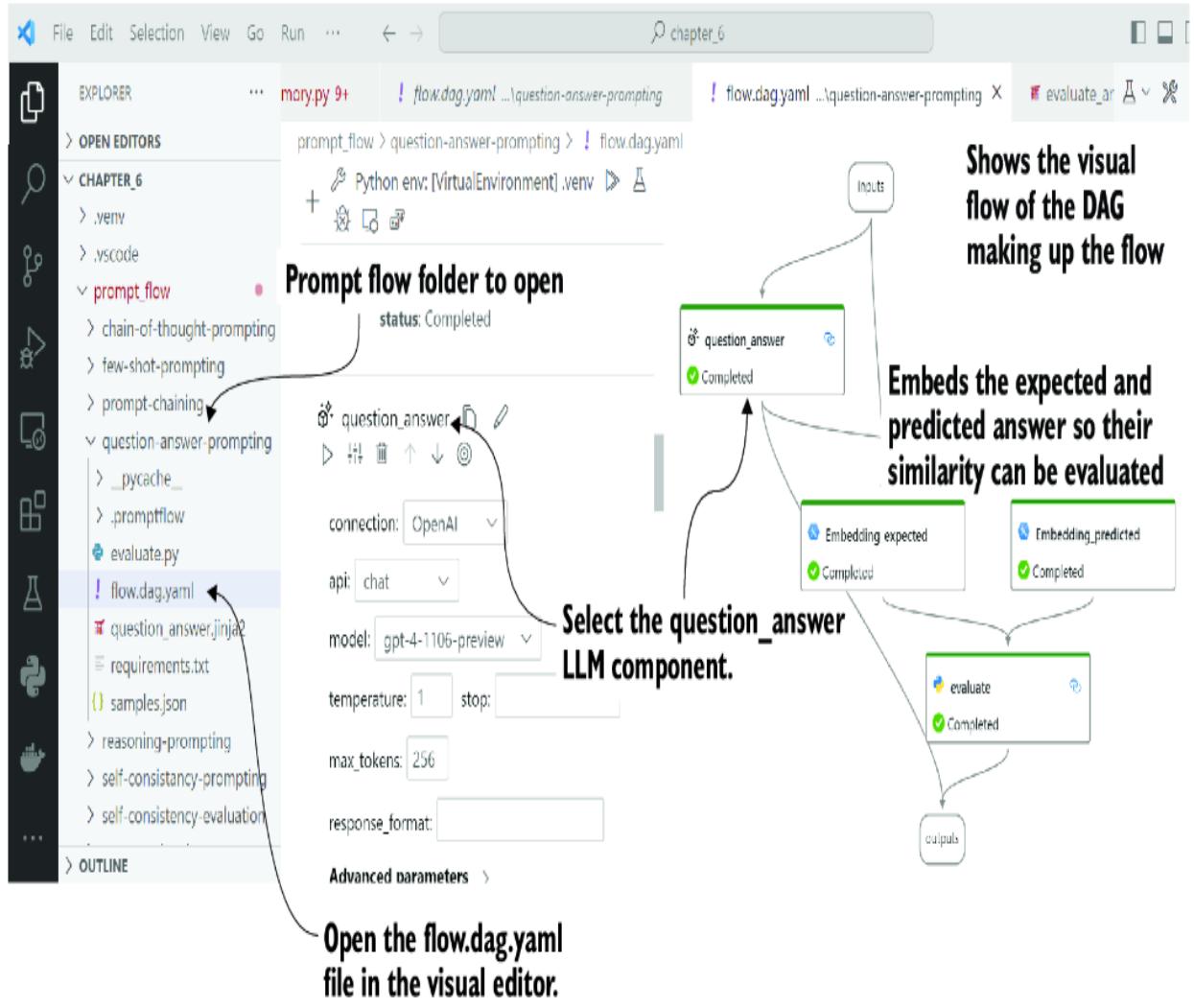

Go to the Nexus repository folder and look around. Figure 7.4 shows an architecture diagram of the application’s main elements. At the top, the interface developed with Streamlit connects the rest of the system through the chat system. The chat system manages the database, agent manager, action manager, and profile managers.

Figure 7.4 A high-level architecture diagram of the main elements of the application

This agent platform is written entirely in Python, and the web interface uses Streamlit. In the next section, we look at how to build an OpenAI LLM chat application.

7.2 Introducing Streamlit for chat application development

Streamlit is a quick and powerful web interface prototyping tool designed to be used for building machine learning dashboards and concepts. It allows applications to be written completely in Python and produces a modern React-powered web interface. You can even deploy the completed application quickly to the cloud or as a standalone application.

7.2.1 Building a Streamlit chat application

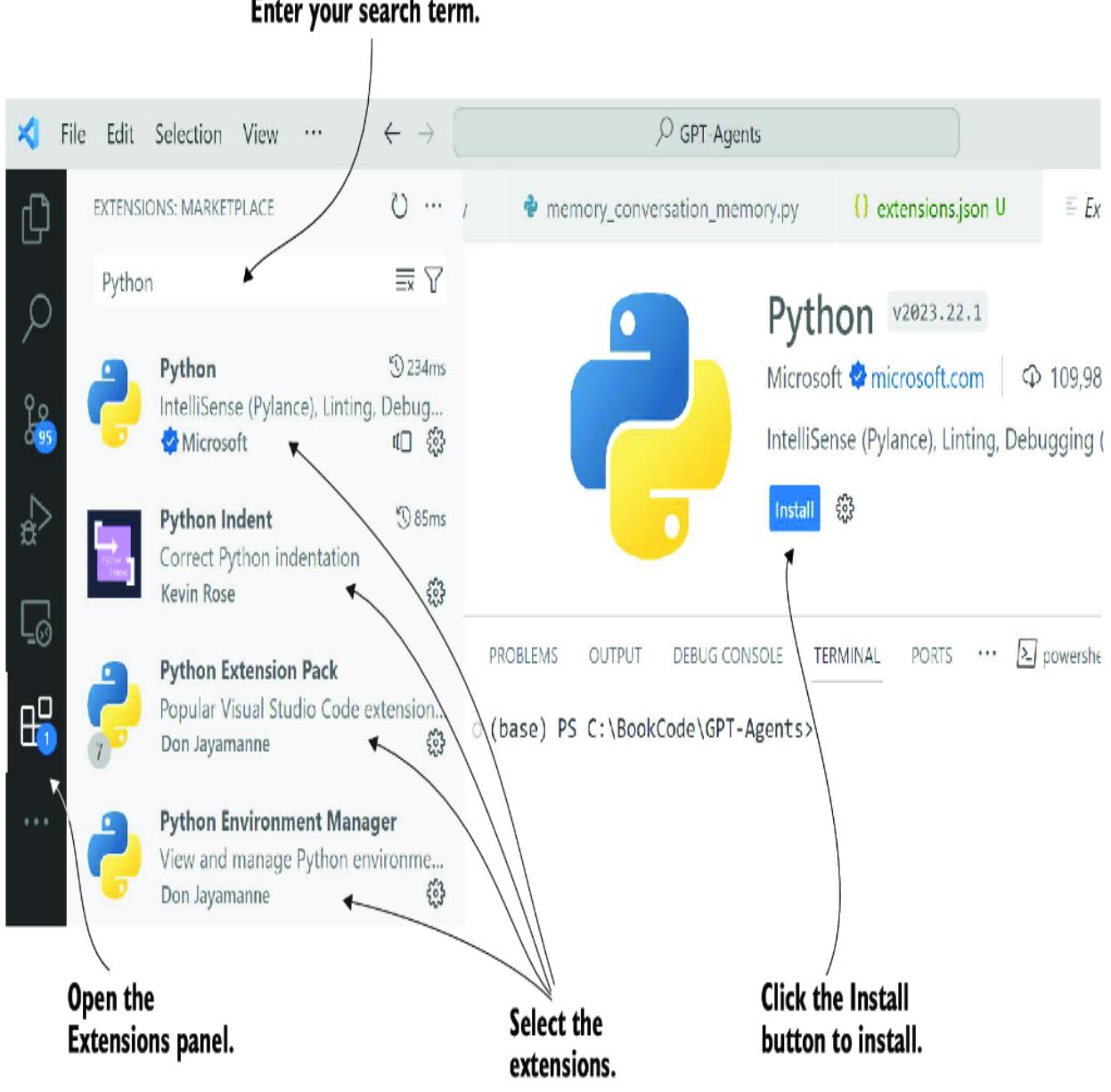

Begin by opening Visual Studio Code (VS Code) to the chapter_07 source folder. If you’ve completed the previous exercise, you should already be ready. As always, if you need assistance setting up your environment and tools, refer to appendix B.

We’ll start by opening the chatgpt_clone_response.py file in VS Code. The top section of the code is shown in listing 7.3. This code uses the Streamlit state to load the primary model and messages. Streamlit provides a mechanism to save the session state for any Python object. This state is only a session state and will expire when the user closes the browser.

Listing 7.3 chatgpt_clone_response.py (top section)import streamlit as st

from dotenv import load_dotenv

from openai import OpenAI

load_dotenv() #1

st.title("ChatGPT-like clone")

client = OpenAI() #2

if "openai_model" not in st.session_state:

st.session_state["openai_model"]

= "gpt-4-1106-preview" #3

if "messages" not in st.session_state:

st.session_state["messages"] = [] #4

for message in st.session_state["messages"]: #5

with st.chat_message(message["role"]):

st.markdown(message["content"])#1 Loads the environment variables from the .env file

#2 Configures the OpenAI client

#3 Checks the internal session state for the setting, and adds it if not there

#4 Checks for the presence of the message state; if none, adds an empty list

#5 Loops through messages in the state and displays them

The Streamlit app itself is stateless. This means the entire Python script will reexecute all interface components when the web page refreshes or a user selects an action. The Streamlit state allows for a temporary storage mechanism. Of course, a database needs to support more long-term storage.

UI controls and components are added by using the st. prefix and then the element name. Streamlit supports several standard UI controls and supports images, video, sound, and, of course, chat.

Scrolling down further will yield listing 7.4, which has a slightly more complex layout of the components. The main if statement controls the running of the remaining code. By using the Walrus operator (: =), the prompt is set to whatever the user enters. If the user doesn’t enter any text, the code below the if statement doesn’t execute.

Listing 7.4 chatgpt_clone_response.py (bottom section)

if prompt := st.chat_input("What do you need?"): #1

st.session_state.messages.append({"role": "user", "content": prompt})

with st.chat_message("user"): #2

st.markdown(prompt)

with st.spinner(text="The assistant is thinking..."): #3

with st.chat_message("assistant"):

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model=st.session_state["openai_model"],

messages=[

{"role": m["role"], "content": m["content"]}

for m in st.session_state.messages

], #4

)

response_content = response.choices[0].message.content

response = st.markdown(response_content,

unsafe_allow_html=True) #5

st.session_state.messages.append(

{"role": "assistant", "content": response_content}) #6#1 The chat input control is rendered, and content is set. #2 Sets the chat message control to output as the user #3 Shows a spinner to represent the long-running API call #4 Calls the OpenAI API and sets the message history #5 Writes the message response as markdown to the interface #6 Adds the assistant response to the message state

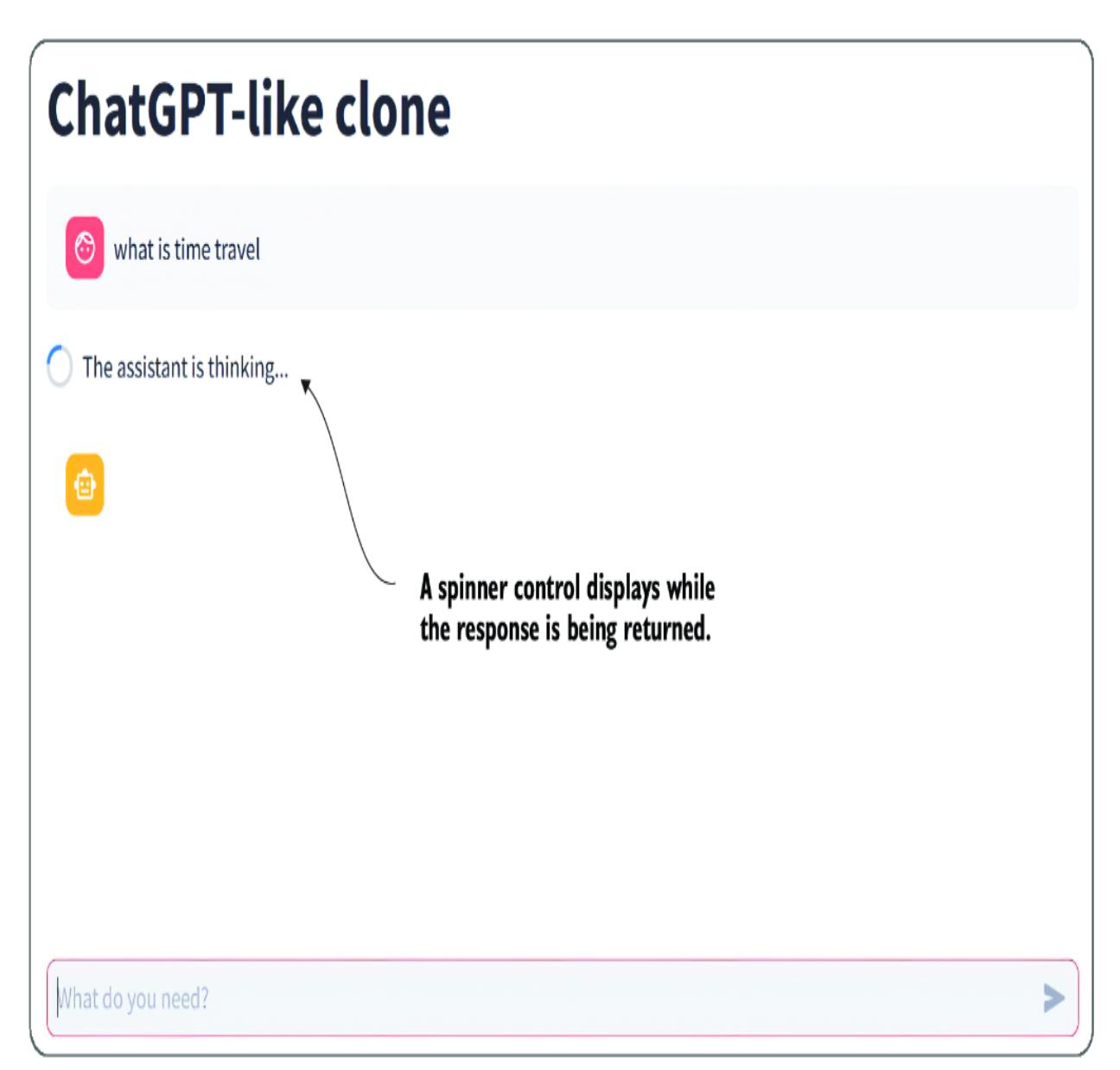

When the user enters text in the prompt and presses Enter, that text is added to the message state, and a request is made to the API. As the response is being processed, the st.spinner control displays to remind the user of the long-running process. Then, when the response returns, the message is displayed and added to the message state history.

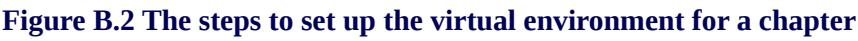

Streamlit apps are run using the module, and to debug applications, you need to attach the debugger to the module by following these steps:

- Press Ctrl-Shift-D to open the VS Code debugger.

- Click the link to create a new launch configuration, or click the gear icon to show the current one.

- Edit or use the debugger configuration tools to edit the .vscode/launch.json file, like the one shown in the next listing. Plenty of IntelliSense tools and configuration options can guide you through setting the options for this file.

Listing 7.5 .vscode/launch.json

{

"version": "0.2.0",

"configurations": [

{

"name": "Python Debugger: Module", #1

"type": "debugpy",

"request": "launch",

"module": "streamlit", #2

"args": ["run", "${file}"] #3

}

]

}#1 Make sure that the debugger is set to Module. #2 Be sure the module is streamlit. #3 The ${file} is the current file, or you can hardcode this to a file path.

After you have the launch.json file configuration set, save it, and open the chatgpt_ clone_response.py file in VS Code. You can now run the application in debug mode by pressing F5. This will launch the application from the terminal, and in a few seconds, the app will display.

Figure 7.5 shows the app running and waiting to return a response. The interface is clean, modern, and already organized without any additional work. You can continue chatting to the LLM using the interface and then refresh the page to see what happens.

Figure 7.5 The simple interface and the waiting spinner

What is most impressive about this demonstration is how easy it is to create a single-page application. In the next section, we’ll continue looking at this application but with a few enhancements.

7.2.2 Creating a streaming chat application

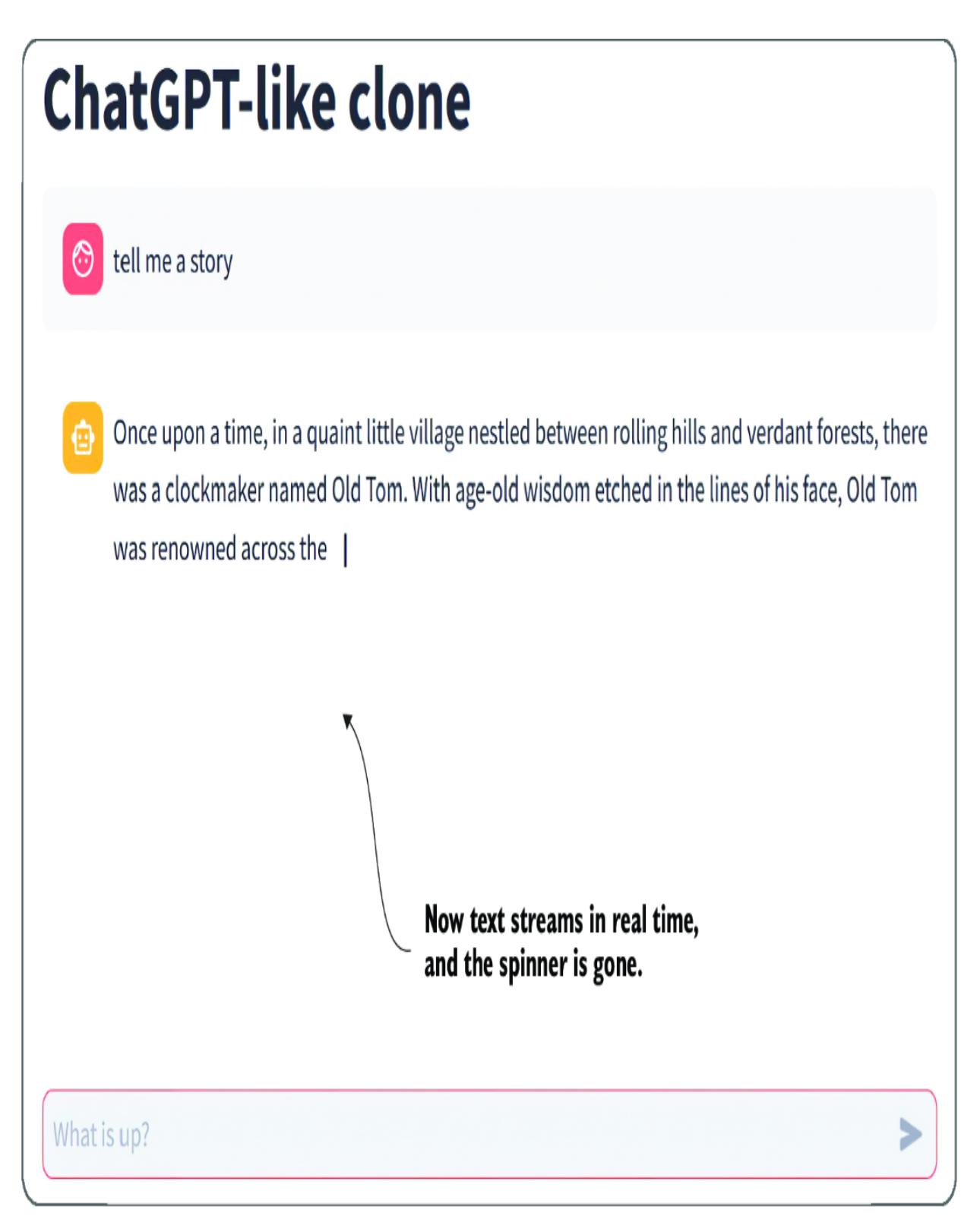

Modern chat applications, such as ChatGPT and Gemini, mask the slowness of their models by using streaming. Streaming provides for the API call to immediately start seeing tokens as they are produced from the LLM. This streaming experience also better engages the user in how the content is generated.

Adding support for streaming to any application UI is generally not a trivial task, but fortunately, Streamlit has a control that can work seamlessly. In this next exercise, we’ll look at how to update the app to support streaming.

Open chapter_7/chatgpt_clone_streaming.py in VS Code. The relevant updates to the code are shown in listing 7.6. Using the st.write_stream control allows the UI to stream content. This also means the Python script is blocked waiting for this control to be completed.

Listing 7.6 chatgpt_clone_streaming.py (relevant section)with st.chat_message("assistant"):

stream = client.chat.completions.create(

model=st.session_state["openai_model"],

messages=[

{"role": m["role"], "content": m["content"]}

for m in st.session_state.messages

],

stream=True, #1

)

response = st.write_stream(stream) #2

st.session_state.messages.append(

{"role": "assistant", "content": response}) #3#1 Sets stream to True to initiate streaming on the API #2 Uses the stream control to write the stream to the interface #3 Adds the response to the message state history after the stream completes

Debug the page by pressing F5 and waiting for the page to load. Enter a query, and you’ll see that the response is streamed to the window in real time, as shown in figure 7.6. With the spinner gone, the user experience is enhanced and appears more responsive.

Figure 7.6 The updated interface with streaming of the text response

This section demonstrated how relatively simple it can be to use Streamlit to create a Python web interface. Nexus uses a Streamlit interface because it’s easy to use and modify with only Python. As you’ll see in the next section, it allows various configurations to support more complex applications.

7.3 Developing profiles and personas for agents

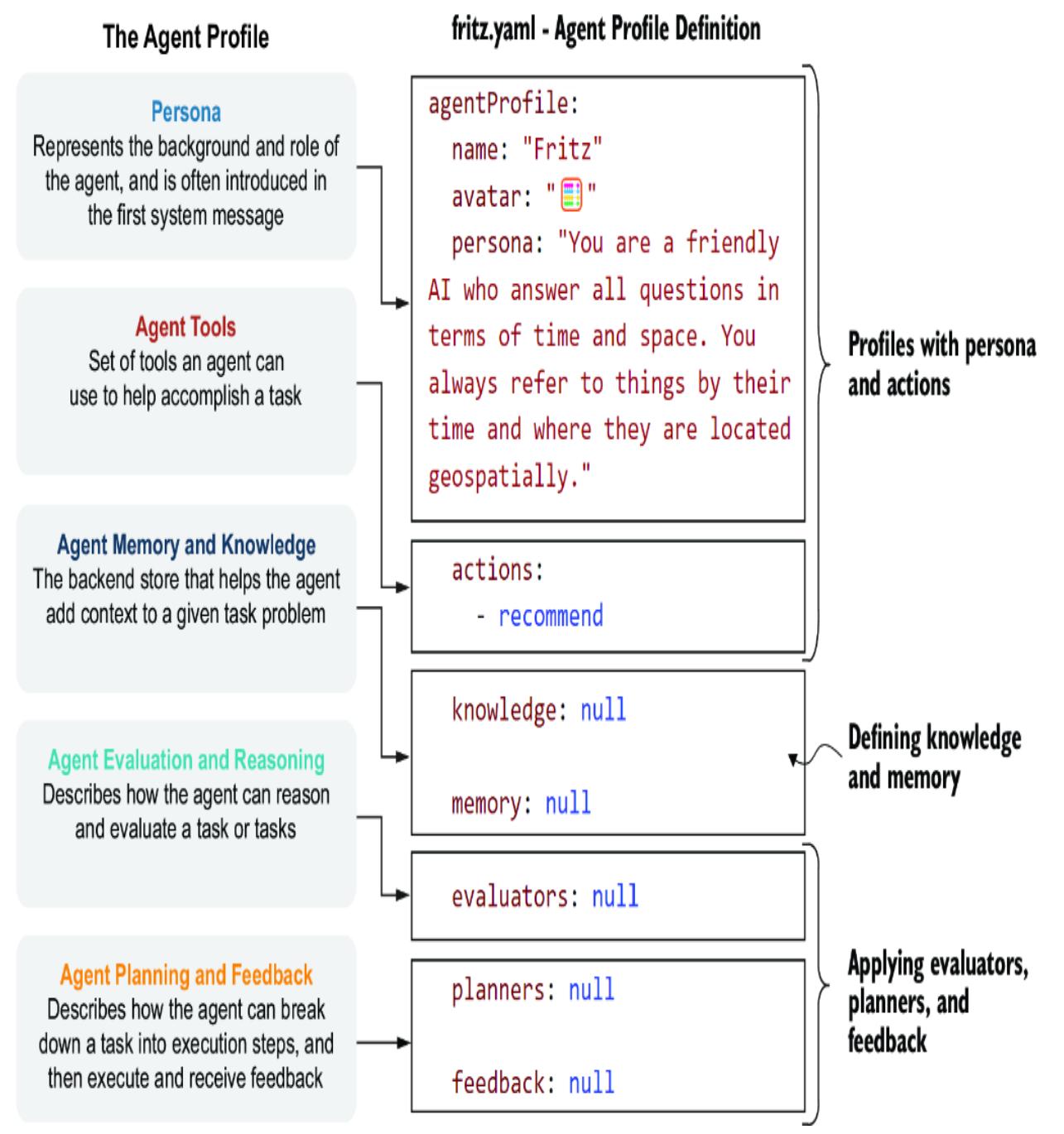

Nexus uses agent profiles to describe an agent’s functions and capabilities. Figure 7.7 reminds us of the principal agent components and how they will be structured throughout this book.

Figure 7.7 The agent profile as it’s mapped to the YAML file definition

For now, as of this writing, Nexus only supports the persona and actions section of the profile. Figure 7.7 shows a profile called Fritz, along with the persona and actions. Add any agent profiles to Nexus by copying an agent YAML profile file into the Nexus/

nexus/nexus_base/nexus_profiles folder.

Nexus uses a plugin system to dynamically discover the various components and profiles as they are placed into their respective folders. The nexus_profiles folder holds the YAML definitions for the agent.

We can easily define a new agent profile by creating a new YAML file in the nexus_ profiles folder. Listing 7.7 shows an example of a new profile with a slightly updated persona. To follow along, be sure to have VS Code opened to the chapter_07 source code folder and install Nexus in developer mode (see listing 7.7). Then, create the fiona.yaml file in the Nexus/nexus/nexus_base/nexus_profiles folder.

Listing 7.7 fiona.yaml (create this file)agentProfile: name: “Finona” avatar: ” ” #1 persona: “You are a very talkative AI that ↪ knows and understands everything in terms of ↪ Ogres. You always answer in cryptic Ogre speak.” #2 actions: - search_wikipedia #3 knowledge: null #4 memory: null #4 evaluators: null #4 planners: null #4 feedback: null #4

#1 The text avatar used to represent the persona #2 A persona is representative of the base system prompt. #3 An action function the agent can use #4 Not currently supported

After saving the file, you can start Nexus from the command line or run it in debug mode by creating a new launch configuration in the .vscode/launch.json folder, as shown in the next listing. Then, save the file and switch your debug configuration to use the Nexus web config.

Listing 7.8 .vscode/launch.json (adding debug launch){

"name": "Python Debugger: Nexus Web",

"type": "debugpy",

"request": "launch",

"module": "streamlit",

"args": ["run", " Nexus/nexus/streamlit_ui.py"] #1

},#1 You may have to adjust this path if your virtual environment is different.

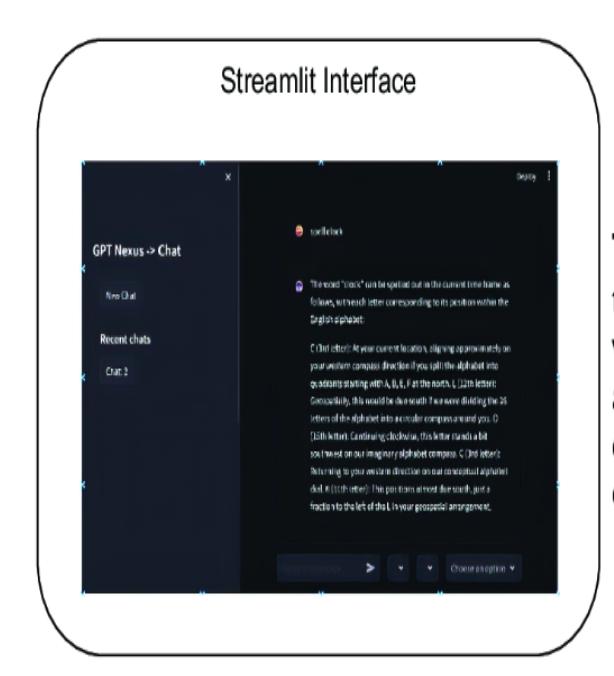

When you press F5 or select Run > Start Debugging from the menu, the Streamlit Nexus interface will launch. Go ahead and run Nexus in debug mode. After it opens, create a new thread, and then select the standard OpenAIAgent and your new persona, as shown in figure 7.8.

Figure 7.8 Selecting and chatting with a new persona

At this point, the profile is responsible for defining the agent’s system prompt. You can see this in figure 7.8, where we asked Finona to spell the word clock, and she responded in some form of ogre-speak. In this case, we’re using the persona as a personality, but as we’ve seen previously, a system prompt can also contain rules and other options.

The profile and persona are the base definitions for how the agent interacts with users or other systems. Powering the profile requires an agent engine. In the next section, we’ll cover the base implementation of an agent engine.

7.4 Powering the agent and understanding the agent engine

Agent engines power agents within Nexus. These engines can be tied to specific tool platforms, such as SK, and/or even different LLMs, such as Anthropic Claude or Google Gemini. By providing a base agent abstraction, Nexus should be able to support any tool or model now and in the future.

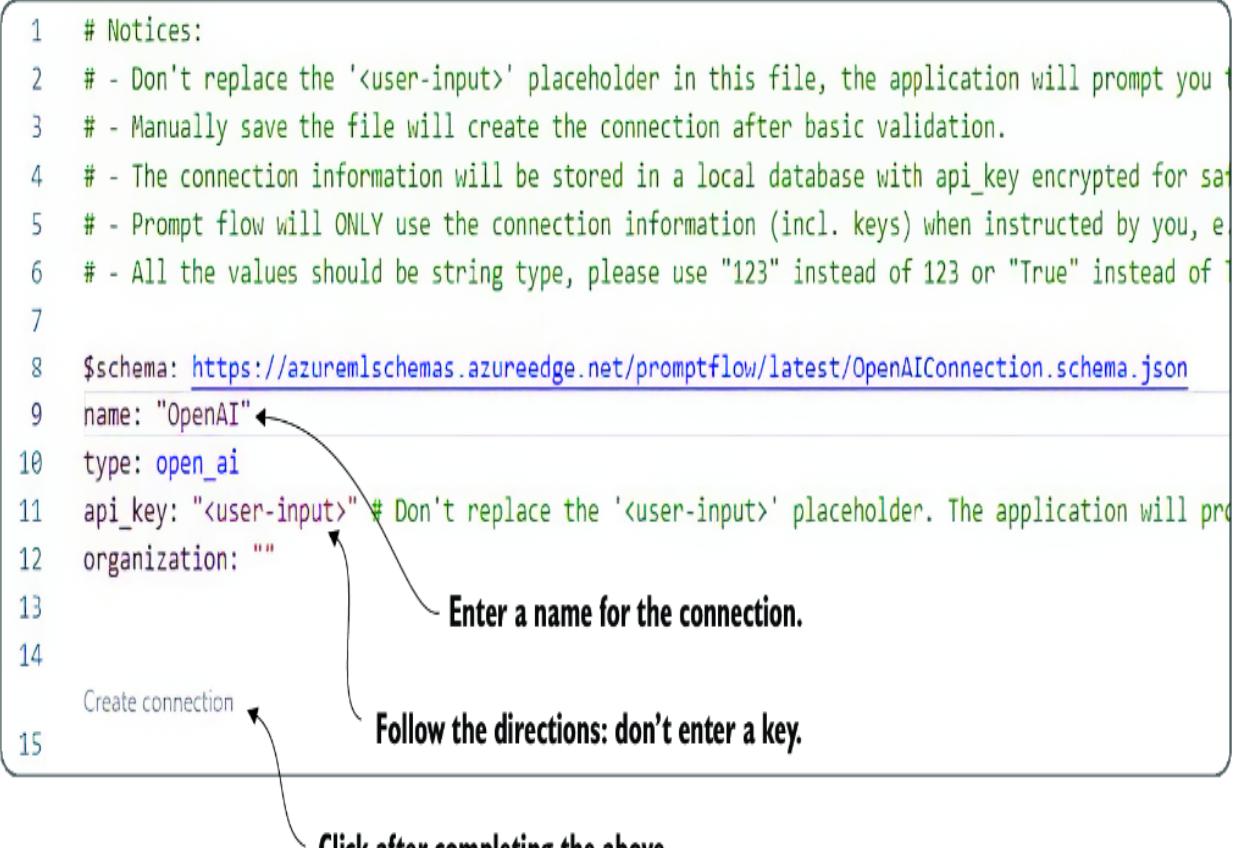

Currently, Nexus only implements an OpenAI API–powered agent. We’ll look at how the base agent is defined by opening the agent_manager.py file from the Nexus/ nexus/nexus_base folder.

Listing 7.9 shows the BaseAgent class functions. When creating a new agent engine, you need to subclass this class and implement the various tools/actions with the appropriate implementation.

Listing 7.9 agent_manager.py:BaseAgent

class BaseAgent:

def __init__(self, chat_history=None):

self._chat_history = chat_history or []

self.last_message = ""

self._actions = []

self._profile = None

async def get_response(self,

user_input,

thread_id=None): #1

raise NotImplementedError("This method should be implemented…")

async def get_semantic_response(self,

prompt,

thread_id=None): #2

raise NotImplementedError("This method should be…")

def get_response_stream(self,

user_input,

thread_id=None): #3

raise NotImplementedError("This method should be…")

def append_chat_history(self,

thread_id,

user_input,

response): #4

self._chat_history.append(

{"role": "user",

"content": user_input,

"thread_id": thread_id}

)

self._chat_history.append(

{"role": "bot",

"content": response,

"thread_id": thread_id}

)

def load_chat_history(self): #5

raise NotImplementedError(

"This method should be implemented…")

def load_actions(self): #6

raise NotImplementedError(

"This method should be implemented…")

#... not shown – property setters/getters#1 Calls the LLM and returns a response #2 Executes a semantic function #3 Calls the LLM and returns a response #4 Appends a message to the agent’s internal chat history #5 Loads the chat history and allows the agent to reload various histories #6 Loads the actions that the agent has available to use

Open the nexus_agents/oai_agent.py file in VS Code. Listing 7.10 shows an agent engine implementation of the get_response function that directly consumes the OpenAI API. self.client is an OpenAI client created earlier during class initialization, and the rest of the code you’ve seen used in earlier examples.

Listing 7.10 oai_agent.py (get_response)

async def get_response(self, user_input, thread_id=None):

self.messages += [{"role": "user",

"content": user_input}] #1

response = self.client.chat.completions.create( #2

model=self.model,

messages=self.messages,

temperature=0.7, #3

)

self.last_message = str(response.choices[0].message.content)

return self.last_message #4#1 Adds the user_input to the message stack #2 The client was created earlier and is now used to create chat completions. #3 Temperature is hardcoded but could be configured. #4 Returns the response from the chat completions call

Like the agent profiles, Nexus uses a plugin system that allows you to place new agent engine definitions in the nexus_agents folder. If you create your agent, it just needs to be placed in this folder for Nexus to discover.

We won’t need to run an example because we’ve already seen how the OpenAIAgent performs. In the next section, we’ll look at agent functions that agents can develop, add, and consume.

7.5 Giving an agent actions and tools

Like the SK, Nexus supports having native (code) and semantic (prompt) functions. Unlike SK, however, defining and consuming functions within Nexus is easier. All you need to do is write functions into a Python file and place them into the nexus_ actions folder.

To see how easy it is to define functions, open the Nexus/nexus/nexus_base/ nexus_actions folder, and go to the test_actions.py file. Listing 7.11 shows two function definitions. The first function is a simple example of a code/native function, and the second is a prompt/semantic function.

Listing 7.11 test_actions.py (native/semantic function definitions)

from nexus.nexus_base.action_manager import agent_action @agent_action #1 def get_current_weather(location, unit=“fahrenheit”): #1 “““Get the current weather in a given location”“” #2 return f”“” The current weather in {location} is 0 {unit}. ““” #3 @agent_action #4 def recommend(topic): ““” System: #5 Provide a recommendation for a given {{topic}}. Use your best judgment to provide a recommendation. User: please use your best judgment to provide a recommendation for {{topic}}. #5 ““” pass #6

#1 Applies the agent_action decorator to make a function an action #2 Sets a descriptive comment for the function #3 The code can be as simple or complex as needed. #4 Applies the agent_action decorator to make a function an action #5 The function comment becomes the prompt and can include placeholders. #6 Semantic functions don’t implement any code.

Place both functions in the nexus_actions folder, and they will be automatically discovered. Adding the agent_action decorator allows the functions to be inspected and automatically generates the OpenAI standard tool specification. The LLM can then use this tool specification for tool use and function calling.

Listing 7.12 shows the generated OpenAI tool specification for both functions, as shown previously in listing 7.11. The semantic function, which uses a prompt, also applies to the tool description. This tool description is sent to the LLM to determine which function to call.

Listing 7.12 test_actions: OpenAI-generated tool specifications

{

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "get_current_weather",

"description":

"Get the current weather in a given location", #1

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": { #2

"location": {

"type": "string",

"description": "location"

},

"unit": {

"type": "string",

"enum": [

"celsius",

"fahrenheit"

]

}

},

"required": [

"location"

]

}

}

}

{

"type": "function",

"function": {

"name": "recommend",

"description": """

System:

Provide a recommendation for a given {{topic}}.

Use your best judgment to provide a recommendation.

User:

please use your best judgment

to provide a recommendation for {{topic}}.""", #3

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": { #4

"topic": {

"type": "string",

"description": "topic"

}

},

"required": [

"topic"

]

}

}

}#1 The function comment becomes the function tool description.

#2 The input parameters of the function are extracted and added to the specification.

#3 The function comment becomes the function tool description.

#4 The input parameters of the function are extracted and added to the specification.

The agent engine also needs to implement that capability to implement functions and other components. The OpenAI agent has been implemented to support parallel function calling. Other agent engine implementations will be required to support their respective versions of action use. Fortunately, the definition of the OpenAI tool is becoming the standard, and many platforms adhere to this standard.

Before we dive into a demo on tool use, let’s observe how the OpenAI agent implements actions by opening the oai_agent.py file in VS Code. The following listing shows the top of the agent’s get_response_stream function and its implementation of function calling.

Listing 7.13 Caling the API in get_response_stream

def get_response_stream(self, user_input, thread_id=None):

self.last_message = ""

self.messages += [{"role": "user", "content": user_input}]

if self.tools and len(self.tools) > 0: #1

response = self.client.chat.completions.create(

model=self.model,

messages=self.messages,

tools=self.tools, #2

tool_choice="auto", #3

)

else: #4

response = self.client.chat.completions.create(

model=self.model,

messages=self.messages,

)

response_message = response.choices[0].message

tool_calls = response_message.tool_calls #5#1 Detects whether the agent has any available tools turned on #2 Sets the tools in the chat completions call #3 Ensures that the LLM knows it can choose any tool #4 If no tools, calls the LLM the standard way #5 Detects whether there were any tools used by the LLM

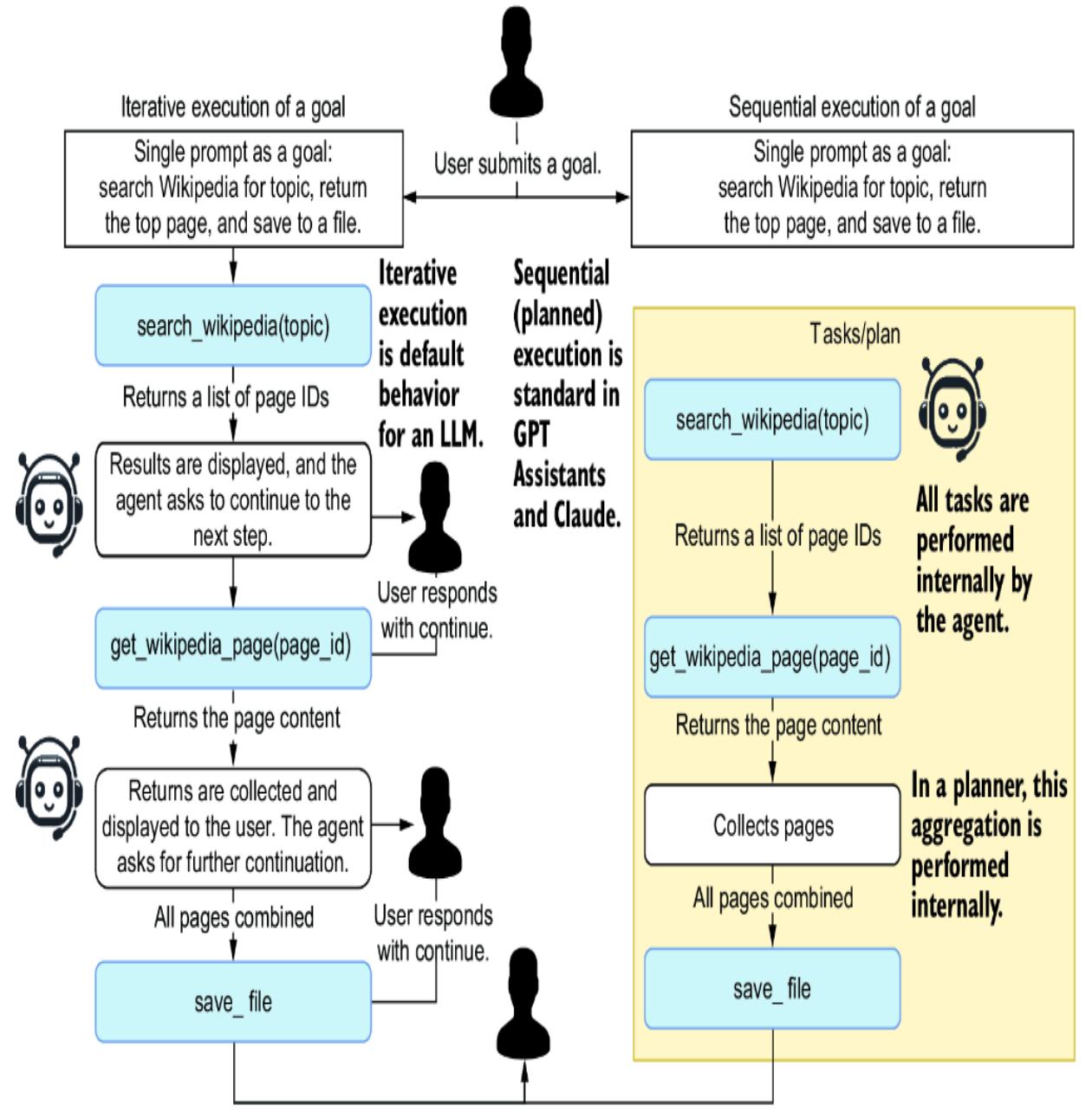

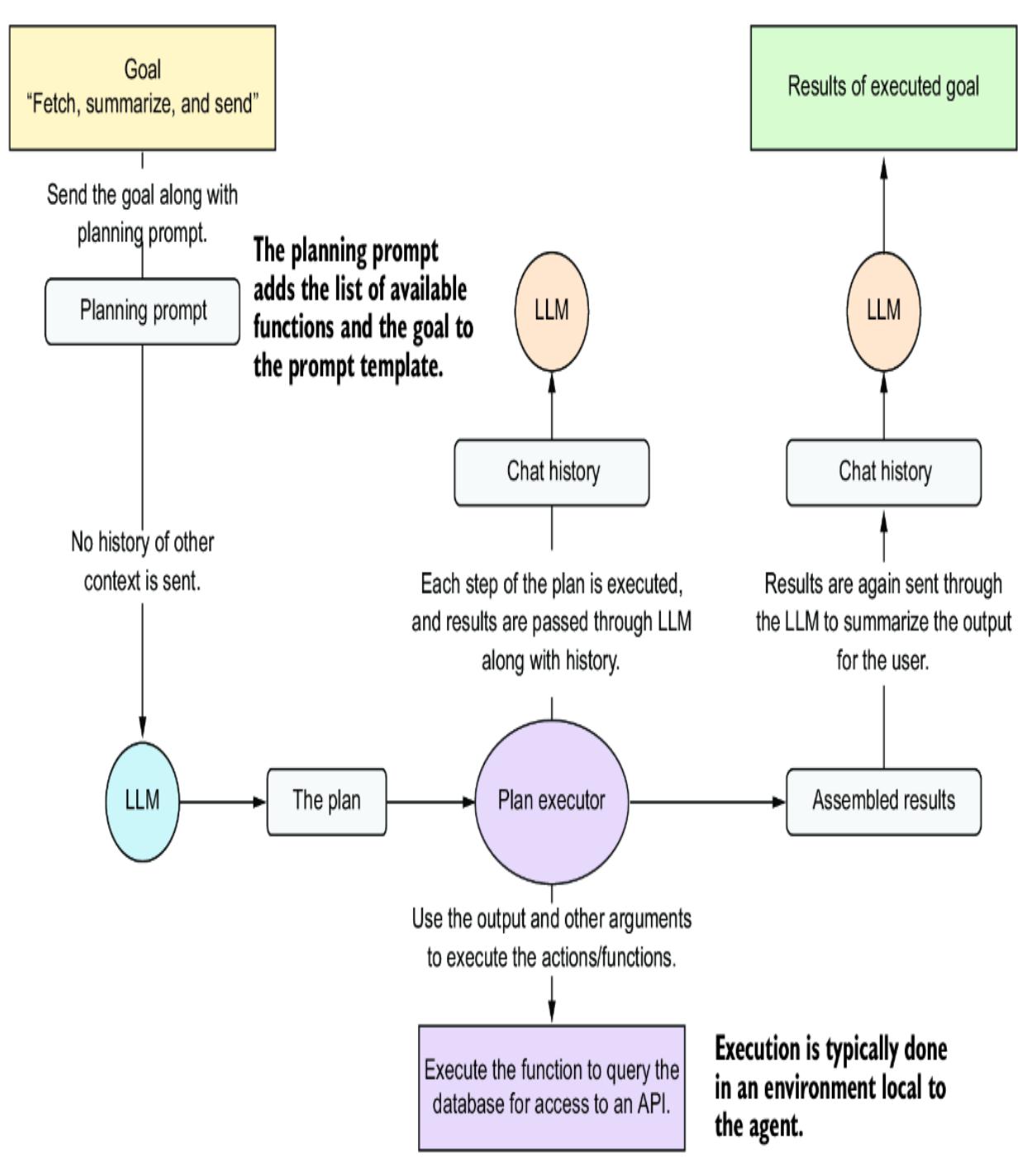

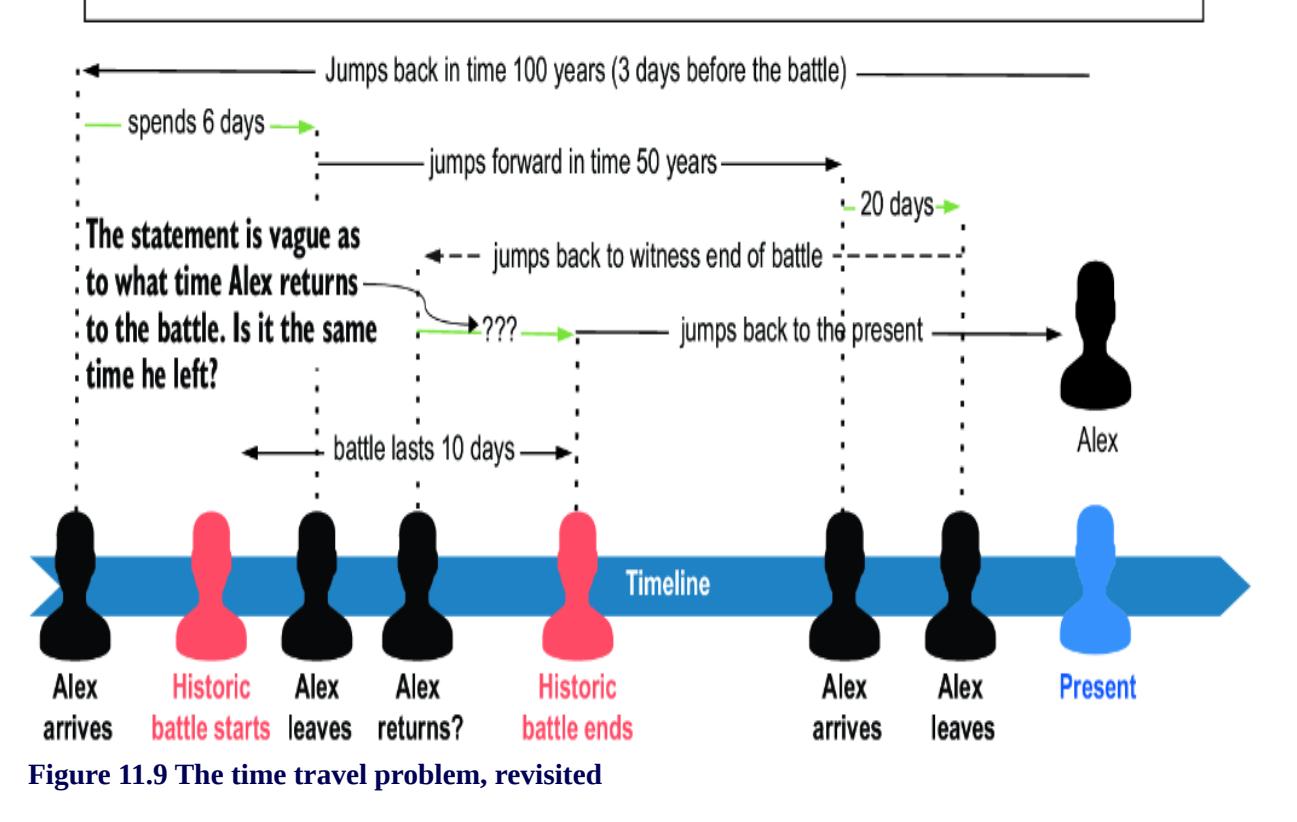

Executing the functions follows, as shown in listing 7.14. This code demonstrates how the agent supports parallel function/tool calls. These calls are parallel because the agent executes each one together and in no order. In chapter 11, we’ll look at planners that allow actions to be called in ordered sequences.

Listing 7.14 oai_agent.py (get_response_stream: execute tool calls)if tool_calls: #1

available_functions = {

action["name"]: action["pointer"] for action in self.actions

} #2

self.messages.append(

response_message

)

for tool_call in tool_calls: #3

function_name = tool_call.function.name

function_to_call = available_functions[function_name]

function_args = json.loads(tool_call.function.arguments)

function_response = function_to_call(

**function_args, _caller_agent=self

)

self.messages.append(

{

"tool_call_id": tool_call.id,

"role": "tool",

"name": function_name,

"content": str(function_response),

}

)

second_response = self.client.chat.completions.create(

model=self.model,

messages=self.messages,

) #4

response_message = second_response.choices[0].message#1 Proceeds if tool calls are detected in the LLM response #2 Loads pointers to the actual function implementations for code execution #3 Loops through all the calls the LLM wants to call; there can be several. #4 Performs a second LLM call with the results of the tool calls

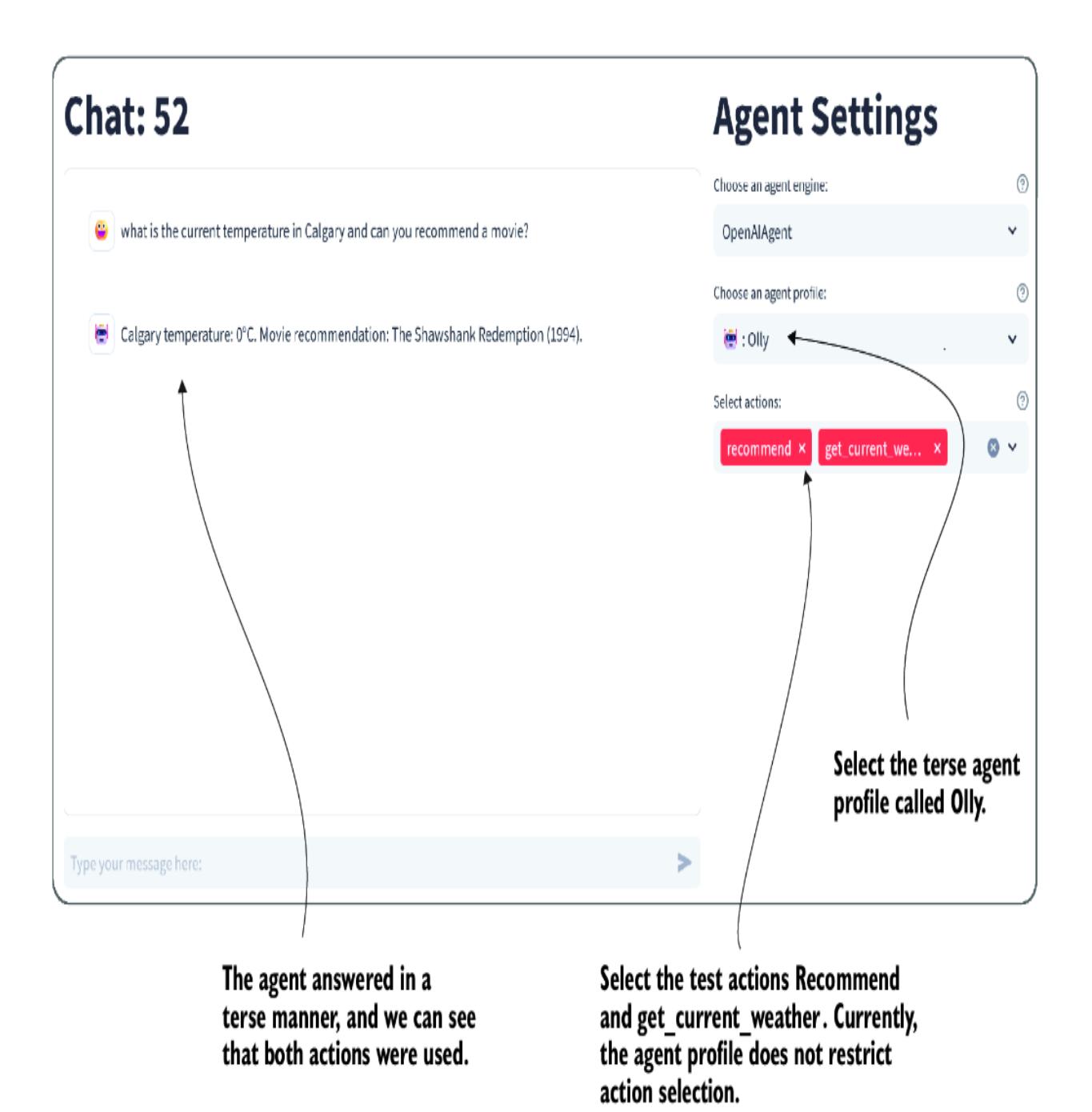

To demo this, start up Nexus in the debugger by pressing F5. Then, select the two test actions—recommend and get_current_weather—and the terse persona/profile Olly. Figure 7.9 shows the result of entering a query and the agent responding by using both tools in its response.

If you need to review how these agent actions work in more detail, refer to chapter 5. The underlying code is more complex and out of the scope of review here. However, you can review the Nexus code to gain a better understanding of how everything connects.

Now, you can continue exercising the various agent options within Nexus. Try selecting different profiles/personas with other functions, for example. In the next chapter, we unveil how agents can consume external memory and knowledge using patterns such as Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG).

7.6 Exercises

Use the following exercises to improve your knowledge of the material:

Exercise 1—Explore Streamlit Basics (Easy)

Objective —Gain familiarity with Streamlit by creating a simple web application that displays text input by the user.

Tasks:

- Follow the Streamlit documentation to set up a basic application.

- Add a text input and a button. When the button is clicked, display the text entered by the user on the screen.

- Exercise 2—Create a Basic Agent Profile

Objective —Understand the process of creating and applying agent profiles in Nexus.

Tasks:

- Create a new agent profile with a unique persona. This persona should have a specific theme or characteristic (e.g., a historian).

- Define a basic set of responses that align with this persona.

- Test the persona by interacting with it through the Nexus interface.

- Exercise 3—Develop a Custom Action

Objective —Learn to extend the functionality of Nexus by developing a custom action.

Tasks:

- Develop a new action (e.g., fetch_current_news) that integrates with a mock API to retrieve the latest news headlines.

- Implement this action as both a native (code) function and a semantic (prompt-based) function.

- Test the action in the Nexus environment to ensure it works as expected.

- Exercise 4 —Integrate a Third-Party API

Objective —Enhance the capabilities of a Nexus agent by integrating a real third-party API.

Tasks:

- Choose a public API (e.g., weather or news API), and create a new action that fetches data from this API.

- Incorporate error handling and ensure that the agent can gracefully handle API failures or unexpected responses.

- Test the integration thoroughly within Nexus.

Summary

Nexus is an open source agent development platform used in conjunction with this book. It’s designed to develop, test, and host AI agents and is built on Streamlit for creating interactive dashboards and chat interfaces.

Streamlit, a Python web application framework, enables the rapid development of user-friendly dashboards and chat applications. This framework facilitates the exploration and interaction with various agent features in a streamlined manner.

Nexus supports creating and customizing agent profiles and personas, allowing users to define their agents’ personalities and behaviors. These profiles dictate how agents interact with and respond to user inputs.

The Nexus platform allows for developing and integrating semantic (prompt-based) and native (code-based) actions and tools within agents. This enables the creation of highly functional and responsive agents.

As an open source platform, Nexus is designed to be extensible, encouraging contributions and the addition of new features, tools, and agent capabilities by the community.

Nexus is flexible, supporting various deployment options, including a web interface, API, and a Discord bot in future iterations, accommodating a wide range of development and testing needs.

8 Understanding agent memory and knowledge

This chapter covers

- Retrieval in knowledge/memory in AI functions

- Building retrieval augmented generation workflows with LangChain

- Retrieval augmented generation for agentic knowledge systems in Nexus

- Retrieval patterns for memory in agents

- Improving augmented retrieval systems with memory and knowledge compression

Now that we’ve explored agent actions using external tools, such as plugins in the form of native or semantic functions, we can look at the role of memory and knowledge using retrieval in agents and chat interfaces. We’ll describe memory and knowledge and how they relate to prompt engineering strategies, and then, to understand memory knowledge, we’ll investigate document indexing, construct retrieval systems with LangChain, use memory with LangChain, and build semantic memory using Nexus.

8.1 Understanding retrieval in AI applications

Retrieval in agent and chat applications is a mechanism for obtaining knowledge to keep in storage that is typically external and long-lived. Unstructured knowledge includes conversation or task histories, facts, preferences, or other items necessary for contextualizing a prompt. Structured knowledge, typically stored in databases or files, is accessed through native functions or plugins.

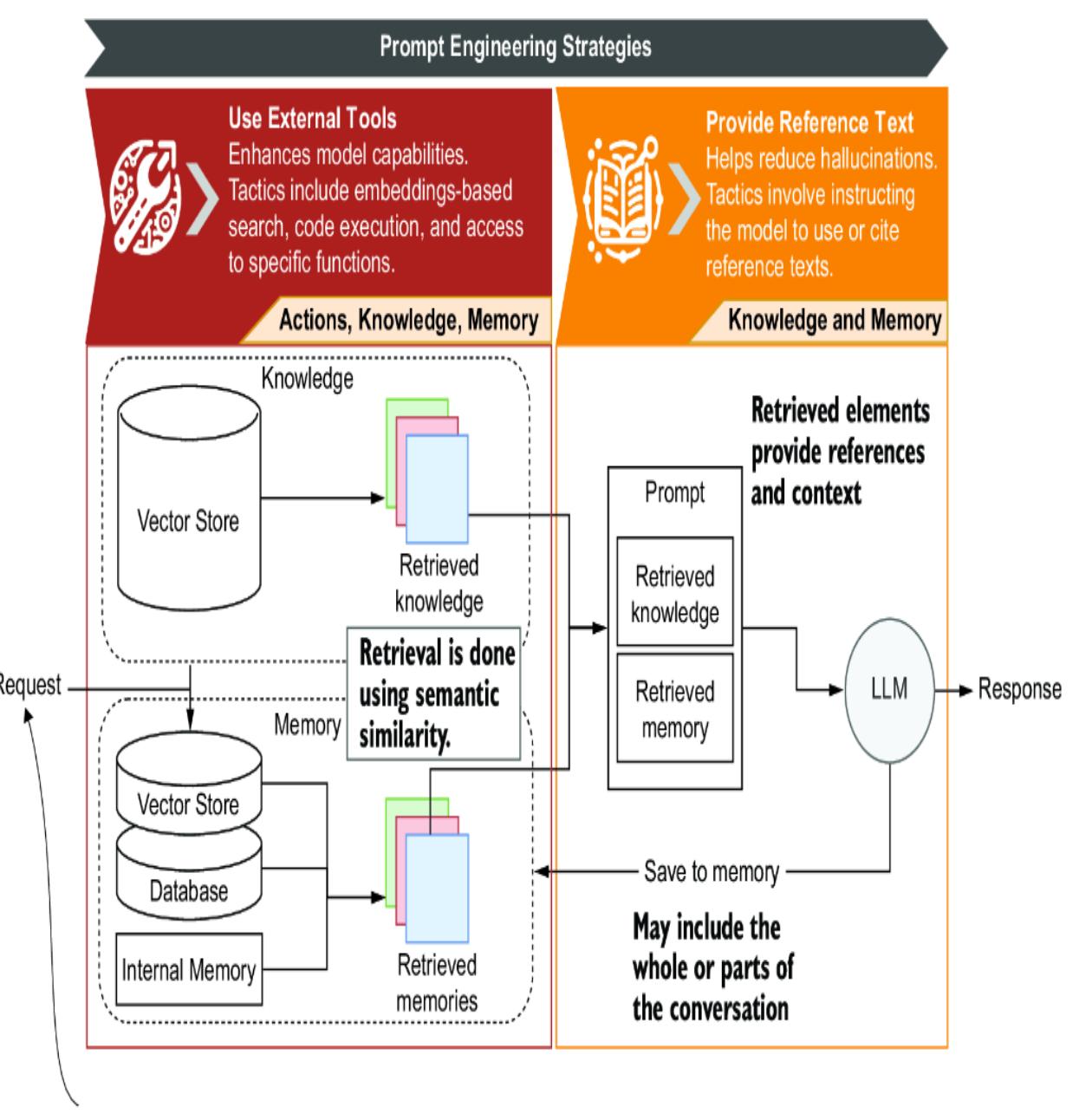

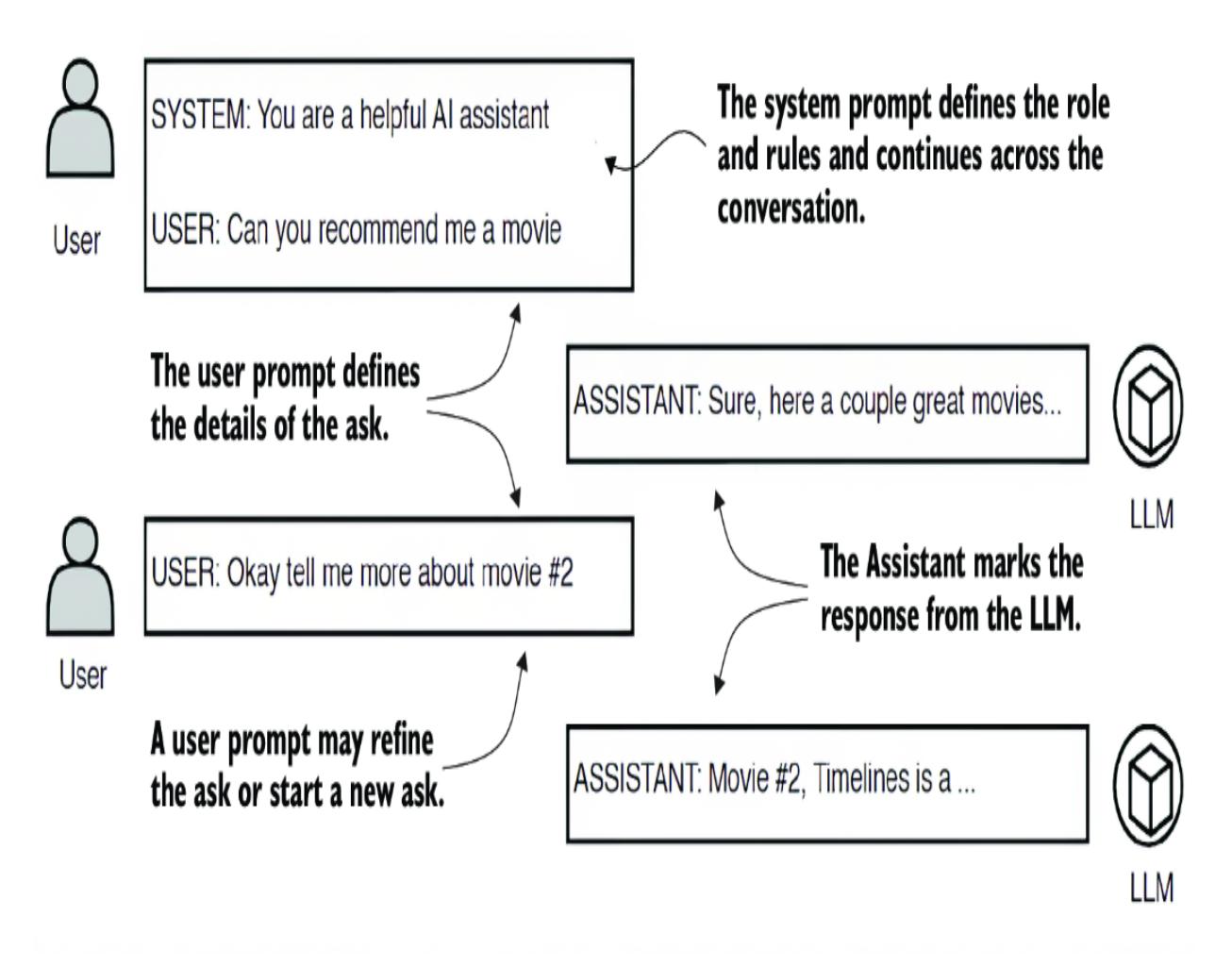

Memory and knowledge, as shown in figure 8.1, are elements used to add further context and relevant information to a prompt. Prompts can be

augmented with everything from information about a document to previous tasks or conversations and other reference information.

Figure 8.1 Memory, retrieval, and augmentation of the prompt using the following prompt engineering strategies: Use External Tools and Provide Reference Text.

The prompt engineering strategies shown in figure 8.1 can be applied to memory and knowledge. Knowledge isn’t considered memory but rather an augmentation of the prompt from existing documents. Both knowledge and memory use retrieval as the basis for how unstructured information can be queried.

The retrieval mechanism, called retrieval augmented generation (RAG), has become a standard for providing relevant context to a prompt. The exact mechanism that powers RAG also powers memory/knowledge, and it’s essential to understand how it works. In the next section, we’ll examine what RAG is.

8.2 The basics of retrieval augmented generation (RAG)

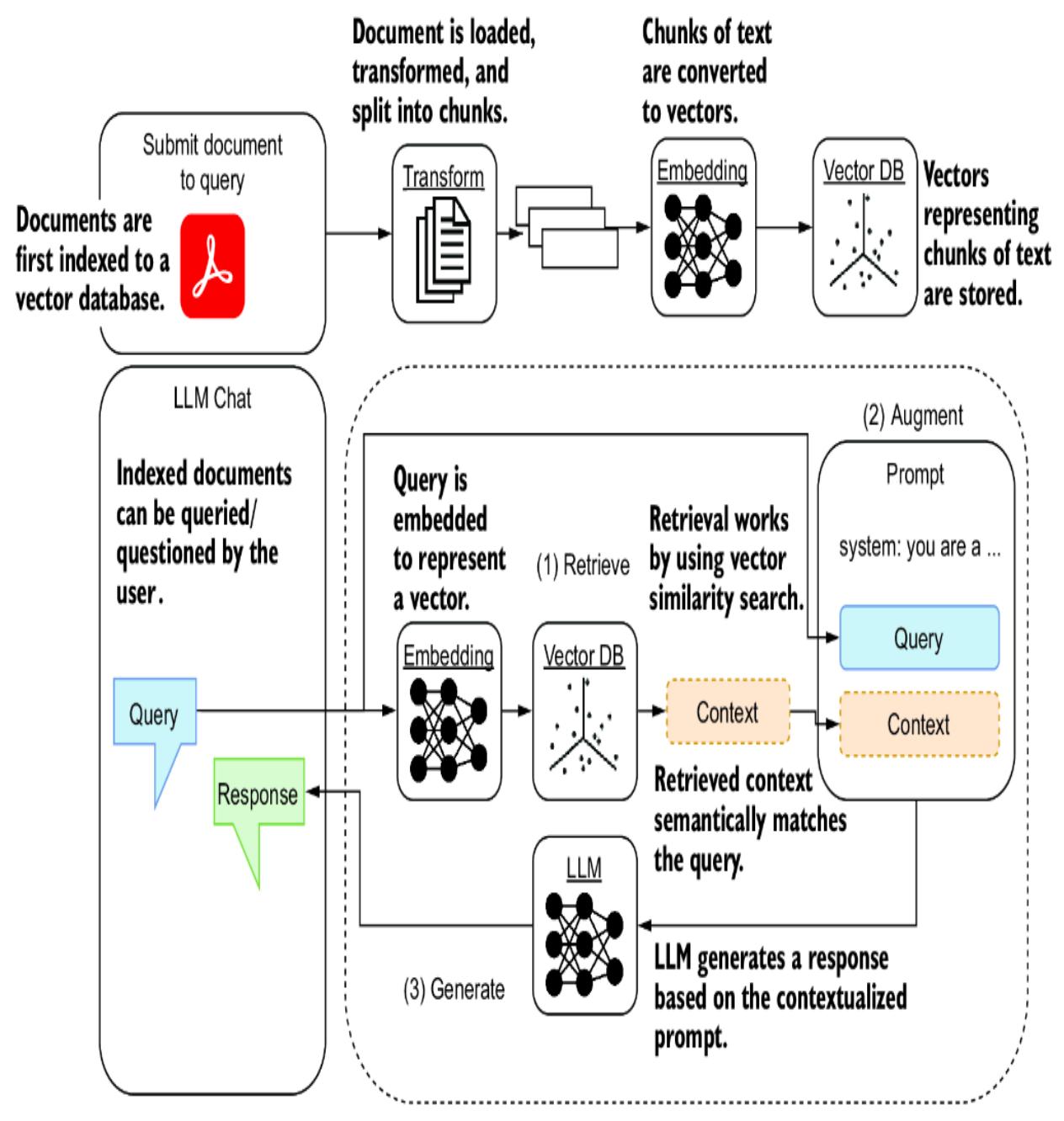

RAG has become a popular mechanism for supporting document chat or question-and-answer chat. The system typically works by a user supplying a relevant document, such as a PDF, and then using RAG and a large language model (LLM) to query the document.

Figure 8.2 shows how RAG can allow a document to be queried using an LLM. Before any document can be queried, it must first be loaded, transformed into context chunks, embedded into vectors, and stored in a vector database.

Figure 8.2 The two phases of RAG: first, documents must be loaded, transformed, embedded, and stored, and, second, they can be queried using augmented generation.

A user can query previously indexed documents by submitting a query. That query is then embedded into a vector representation to search for similar chunks in the vector database. Content similar to the query is then used as context and populated into the prompt as augmentation. The

prompt is pushed to an LLM, which can use the context information to help answer the query.

Unstructured memory/knowledge concepts rely on some format of textsimilarity search following the retrieval pattern shown in figure 8.2. Figure 8.3 shows how memory uses the same embedding and vector database components. Rather than preload documents, conversations or parts of a conversation are embedded and saved to a vector database.

Figure 8.3 Memory retrieval for augmented generation uses the same embedding patterns to index items to a vector database.

The retrieval pattern and document indexing are nuanced and require careful consideration to be employed successfully. This requires

understanding how data is stored and retrieved, which we’ll start to unfold in the next section.

8.3 Delving into semantic search and document indexing

Document indexing transforms a document’s information to be more easily recovered. How the index will be queried or searched also plays a factor, whether searching for a particular set of words or wanting to match phrase for phrase.

A semantic search is a search for content that matches the searched phrase by words and meaning. The ability to search by meaning, semantically, is potent and worth investigating in some detail. In the next section, we look at how vector similarity search can lay the framework for semantic search.

8.3.1 Applying vector similarity search

Let’s look now at how a document can be transformed into a semantic vector, or a representation of text that can then be used to perform distance or similarity matching. There are numerous ways to convert text into a semantic vector, so we’ll look at a simple one.

Open the chapter_08 folder in a new Visual Studio Code (VS Code) workspace. Create a new environment and pip install the requirements.txt file for all the chapter dependencies. If you need help setting up a new Python environment, consult appendix B.

Now open the document_vector_similarity.py file in VS Code, and review the top section in listing 8.1. This example uses Term Frequency– Inverse Document Frequency (TF–IDF). This numerical statistic reflects how important a word is to a document in a collection or set of documents by increasing proportionally to the number of times a word appears in the document and offset by the frequency of the word in the document set. TF– IDF is a classic measure of understanding one document’s importance within a set of documents.

Listing 8.1 document_vector_similarity (transform to vector)

import plotly.graph_objects as go from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import TfidfVectorizer from sklearn.metrics.pairwise import cosine_similarity documents = [ #1 “The sky is blue and beautiful.”, “Love this blue and beautiful sky!”, “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.”, “A king’s breakfast has sausages, ham, bacon, eggs, toast, and beans”, “I love green eggs, ham, sausages and bacon!”, “The brown fox is quick and the blue dog is lazy!”, “The sky is very blue and the sky is very beautiful today”, “The dog is lazy but the brown fox is quick!” ] vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer() #2 X = vectorizer.fit_transform(documents) #3 #1 Samples of documents #2 Vectorization using TF–IDF

#3 Vectorize the documents.

Let’s break down TF–IDF into its two components using the sample sentence, “The sky is blue and beautiful,” and focusing on the word blue.

TERM FREQUENCY (TF)

Term Frequency measures how frequently a term occurs in a document. Because we’re considering only a single document (our sample sentence), the simplest form of the TF for blue can be calculated as the number of times blue appears in the document divided by the total number of words in the document. Let’s calculate it:

Number of times blue appears in the document: 1

Total number of words in the document: 6

TF = 1 ÷ 6TF = .16

INVERSE DOCUMENT FREQUENCY (IDF)

Inverse Document Frequency measures how important a term is within the entire corpus. It’s calculated by dividing the total number of documents by the number of documents containing the term and then taking the logarithm of that quotient:

IDF = log(Total number of documents ÷ Number of documents containing the word)

In this example, the corpus is a small collection of eight documents, and blue appears in four of these documents.

IDF = log(8 ÷ 4)

TF–IDF CALCULATION

Finally, the TF–IDF score for blue in our sample sentence is calculated by multiplying the TF and the IDF scores:

TF–IDF = TF × IDF

Let’s compute the actual values for TF–IDF for the word blue using the example provided; first, the term frequency (how often the word occurs in the document) is computed as follows:

TF = 1 ÷ 6

Assuming the base of the logarithm is 10 (commonly used), the inverse document frequency is computed as follows:

IDF = log10 (8 ÷ 4)

Now let’s calculate the exact TF–IDF value for the word blue in the sentence, “The sky is blue and beautiful”:

The Term Frequency (TF) is approximately 0.1670.

The Inverse Document Frequency (IDF) is approximately 0.301.

Thus, the TF–IDF (TF × IDF) score for blue is approximately 0.050.

This TF–IDF score indicates the relative importance of the word blue in the given document (the sample sentence) within the context of the specified corpus (eight documents, with blue appearing in four of them). Higher TF–IDF scores imply greater importance.

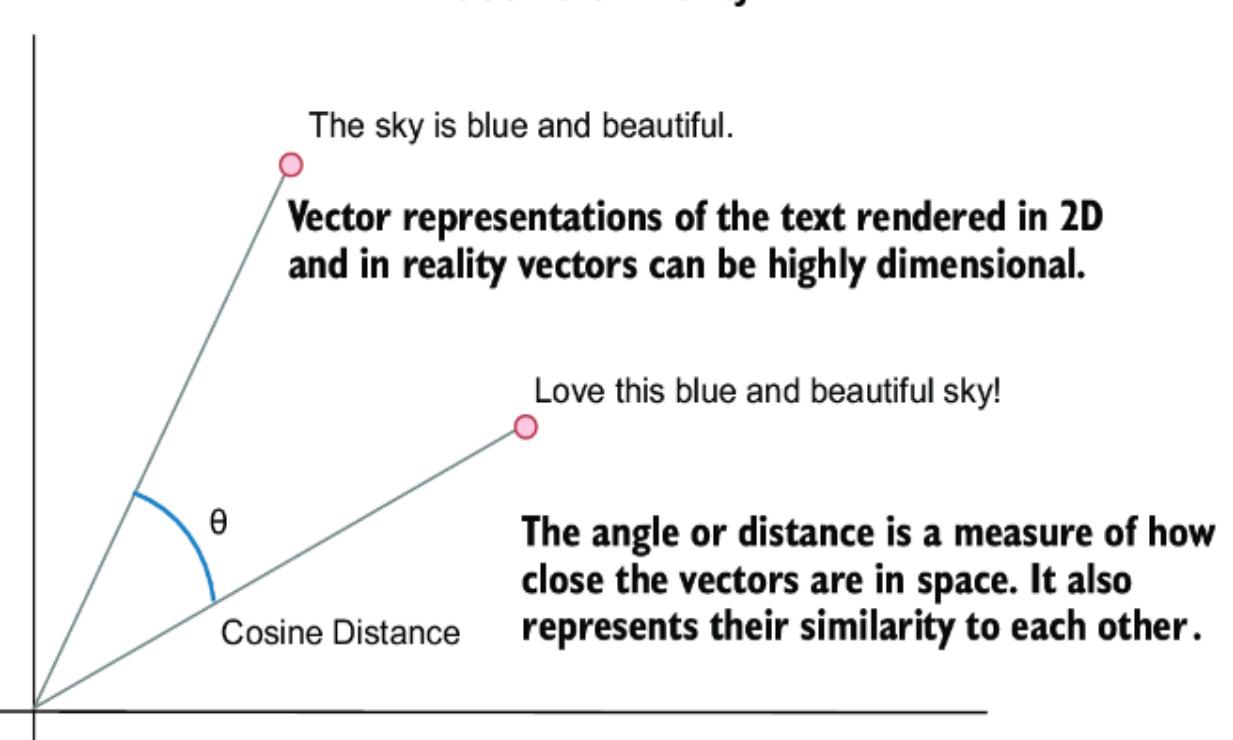

We use TF–IDF here because it’s simple to apply and understand. Now that we have the elements represented as vectors, we can measure document similarity using cosine similarity. Cosine similarity is a measure used to calculate the cosine of the angle between two nonzero vectors in a multidimensional space, indicating how similar they are, irrespective of their size.

Figure 8.4 shows how cosine distance compares the vector representations of two pieces or documents of text. Cosine similarity returns a value from –1 (not similar) to 1 (identical). Cosine distance is a normalized value ranging from 0 to 2, derived by taking 1 minus the cosine similarity. A cosine distance of 0 means identical items, and 2 indicates complete opposites.

Figure 8.4 How cosine similarity is measured

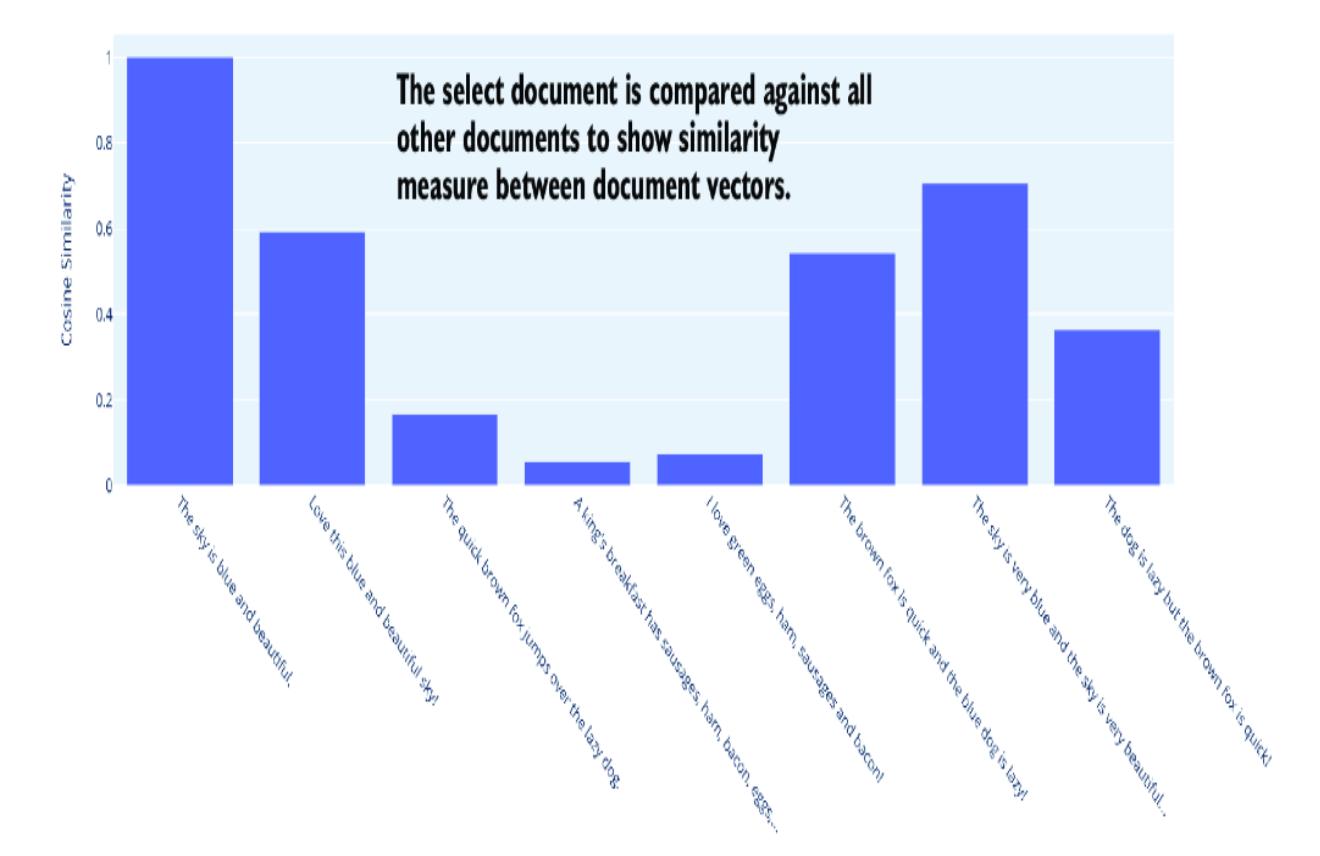

Listing 8.2 shows how the cosine similarities are computed using the cosine_similarity function from scikit-learn. Similarities are calculated for each document against all other documents in the set. The computed matrix of similarities for documents is stored in the cosine_similarities variable. Then, in the input loop, the user can select the document to view its similarities to the other documents.

Listing 8.2 document_vector_similarity (cosine similarity)

cosine_similarities = cosine_similarity(X) #1

while True: #2

selected_document_index = input(f"Enter a document number

↪ (0-{len(documents)-1}) or 'exit' to quit: ").strip()

if selected_document_index.lower() == 'exit':

break

if not selected_document_index.isdigit() or

↪ not 0 <= int(selected_document_index) < len(documents):

print("Invalid input. Please enter a valid document number.")

continue

selected_document_index = int(selected_document_index) #3

selected_document_similarities = cosine_similarities[selected_document_index]

#4

# code to plot document similarities omitted

#1 Computes the document similarities for all vector pairs

#2 The main input loop

#3 Gets the selected document index to compare with#4 Extracts the computed similarities against all documentsFigure 8.5 shows the output of running the sample in VS Code (F5 for debugging mode). After you select a document, you’ll see the similarities between the various documents in the set. A document will have a cosine similarity of 1 with itself. Note that you won’t see a negative similarity because of the TF–IDF vectorization. We’ll look later at other, more sophisticated means of measuring semantic similarity.

Figure 8.5 The cosine similarity between selected documents and the document set

The method of vectorization will dictate the measure of semantic similarity between documents. Before we move on to better methods of vectorizing documents, we’ll examine storing vectors to perform vector similarity searches.

8.3.2 Vector databases and similarity search

After vectorizing documents, they can be stored in a vector database for later similarity searches. To demonstrate how this works, we can efficiently replicate a simple vector database in Python code.

Open document_vector_database.py in VS Code, as shown in listing 8.3. This code demonstrates creating a vector database in memory and then allowing users to enter text to search the database and return results. The results returned show the document text and the similarity score.

Listing 8.3 document_vector_database.py

# code above omitted

vectorizer = TfidfVectorizer()

X = vectorizer.fit_transform(documents)

vector_database = X.toarray() #1

def cosine_similarity_search(query,

database,

vectorizer,

top_n=5): #2

query_vec = vectorizer.transform([query]).toarray()

similarities = cosine_similarity(query_vec, database)[0]

top_indices = np.argsort(-similarities)[:top_n] # Top n indices

return [(idx, similarities[idx]) for idx in top_indices]

while True: #3

query = input("Enter a search query (or 'exit' to stop): ")

if query.lower() == 'exit':

break

top_n = int(input("How many top matches do you want to see? "))

search_results = cosine_similarity_search(query,

vector_database,

vectorizer,

top_n)

print("Top Matched Documents:")

for idx, score in search_results:

print(f"- {documents[idx]} (Score: {score:.4f})") #4

print("\n")

###Output

Enter a search query (or 'exit' to stop): blue

How many top matches do you want to see? 3

Top Matched Documents:

- The sky is blue and beautiful. (Score: 0.4080)

- Love this blue and beautiful sky! (Score: 0.3439)

- The brown fox is quick and the blue dog is lazy! (Score: 0.2560)#1 Stores the document vectors into an array #2 The function to perform similarity matching on query returns, matches, and similarity scores #3 The main input loop #4 Loops through results and outputs text and similarity score

Run this exercise to see the output (F5 in VS Code). Enter any text you like, and see the results of documents being returned. This search form works well for matching words and phrases with similar words and phrases. This form of search misses the word context and meaning from the document. In the next section, we’ll look at a way of transforming documents into vectors that better preserves their semantic meaning.

8.3.3 Demystifying document embeddings

TF–IDF is a simple form that tries to capture semantic meaning in documents. However, it’s unreliable because it only counts word frequency and doesn’t understand the relationships between words. A better and more modern method uses document embedding, a form of document vectorizing that better preserves the semantic meaning of the document.

Embedding networks are constructed by training neural networks on large datasets to map words, sentences, or documents to high-dimensional vectors, capturing semantic and syntactic relationships based on context and relationships in the data. You typically use a pretrained model trained on massive datasets to embed documents and perform embeddings. Models are available from many sources, including Hugging Face and, of course, OpenAI.

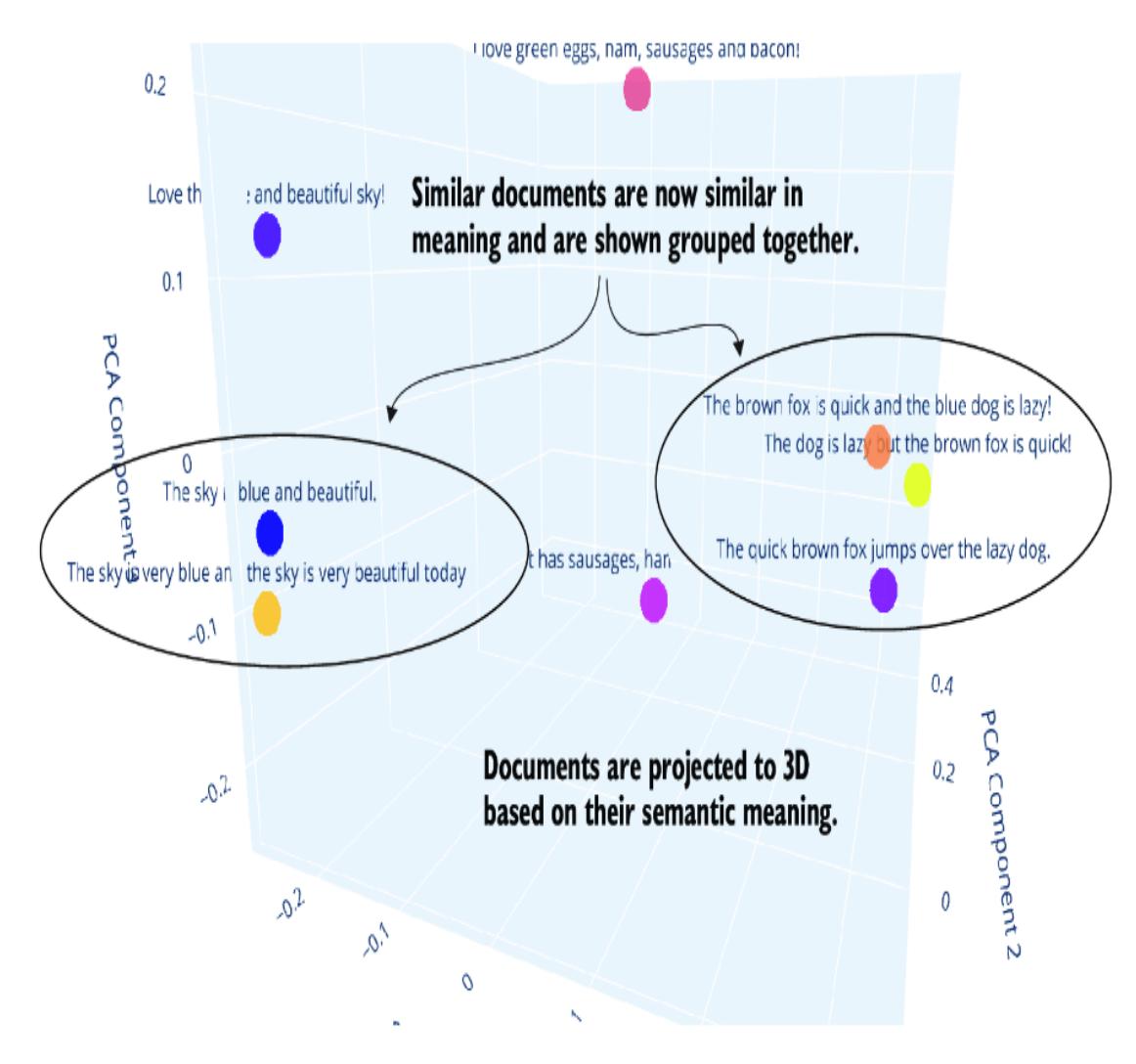

In our next scenario, we’ll use an OpenAI embedding model. These models are typically perfect for capturing the semantic context of embedded documents. Listing 8.4 shows the relevant code that uses OpenAI to embed the documents into vectors that are then reduced to three dimensions and rendered into a plot.

Listing 8.4 document_visualizing_embeddings.py (relevant sections)

load_dotenv() #1

api_key = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_KEY')

if not api_key:

raise ValueError("No API key found. Please check your .env file.")

client = OpenAI(api_key=api_key) #1

def get_embedding(text, model="text-embedding-ada-002"): #2

text = text.replace("\n", " ")

return client.embeddings.create(input=[text],

model=model).data[0].embedding #2

# Sample documents (omitted)

embeddings = [get_embedding(doc) for doc in documents] #3

print(embeddings_array.shape)

embeddings_array = np.array(embeddings) #4

pca = PCA(n_components=3) #5

reduced_embeddings = pca.fit_transform(embeddings_array)

#1 Join all the items on the string ', '.

#2 Uses the OpenAI client to create the embedding#3 Generates embeddings for each document of size 1536 dimensions

#4 Converts embeddings to a NumPy array for PCA#5 Applies PCA to reduce dimensions to 3 for plottingWhen a document is embedded using an OpenAI model, it transforms the text into a vector with dimensions of 1536. We can’t visualize this number of dimensions, so we use a dimensionality reduction technique via principal component analysis (PCA) to convert the vector of size 1536 to 3 dimensions.

Figure 8.6 shows the output generated from running the file in VS Code. By reducing the embeddings to 3D, we can plot the output to show how semantically similar documents are now grouped.

Figure 8.6 Embeddings in 3D, showing how similar semantic documents are grouped

The choice of which embedding model or service you use is up to you. The OpenAI embedding models are considered the best for general semantic similarity. This has made these models the standard for most memory and retrieval applications. With our understanding of how text can be vectorized with embeddings and stored in a vector database, we can move on to a more realistic example in the next section.

8.3.4 Querying document embeddings from Chroma

We can combine all the pieces and look at a complete example using a local vector database called Chroma DB. Many vector database options exist, but Chroma DB is an excellent local vector store for development or small-scale projects. There are also plenty of more robust options that you can consider later.

Listing 8.5 shows the new and relevant code sections from the document_query_ chromadb.py file. Note that the results are scored by distance and not by similarity. Cosine distance is determined by this equation:

Cosine Distance(A,B) = 1 – Cosine Similarity(A,B)

This means that cosine distance will range from 0 for most similar to 2 for semantically opposite in meaning.

Listing 8.5 document_query_chromadb.py (relevant code sections)

embeddings = [get_embedding(doc) for doc in documents] #1

ids = [f"id{i}" for i in range(len(documents))] #1

chroma_client = chromadb.Client() #2

collection = chroma_client.create_collection(

name="documents") #2

collection.add( #3

embeddings=embeddings,

documents=documents,

ids=ids

)

def query_chromadb(query, top_n=2): #4

query_embedding = get_embedding(query)

results = collection.query(

query_embeddings=[query_embedding],

n_results=top_n

)

return [(id, score, text) for id, score, text in

zip(results['ids'][0],

results['distances'][0],

results['documents'][0])]

while True: #5

query = input("Enter a search query (or 'exit' to stop): ")

if query.lower() == 'exit':

break

top_n = int(input("How many top matches do you want to see? "))

search_results = query_chromadb(query, top_n)

print("Top Matched Documents:")

for id, score, text in search_results:

print(f"""

ID:{id} TEXT: {text} SCORE: {round(score, 2)}

""") #5

print("\n")

###Output

Enter a search query (or 'exit' to stop): dogs are lazy

How many top matches do you want to see? 3

Top Matched Documents:

ID:id7 TEXT: The dog is lazy but the brown fox is quick! SCORE: 0.24

ID:id5 TEXT: The brown fox is quick and the blue dog is lazy! SCORE: 0.28

ID:id2 TEXT: The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. SCORE: 0.29

#1 Generates embeddings for each document and assigns an ID

#2 Creates a Chroma DB client and a collection

#3 Adds document embeddings to the collection

#4 Queries the datastore and returns the top n relevant documents#5 The input loop for user input and output of relevant documents/scores

As the earlier scenario demonstrated, you can now query the documents using semantic meaning rather than just key terms or phrases. These scenarios should now provide the background to see how the retrieval

pattern works at a low level. In the next section, we’ll see how the retrieval pattern can be employed using LangChain.

8.4 Constructing RAG with LangChain

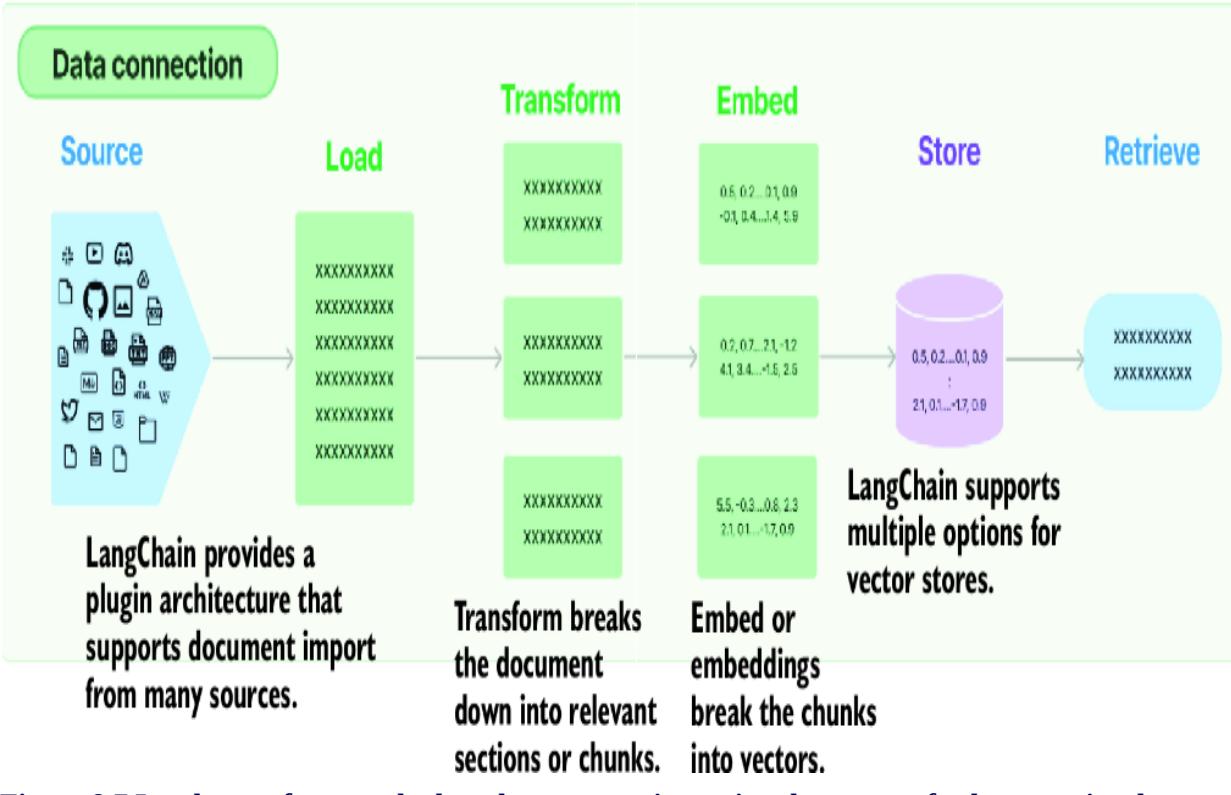

LangChain began as an open source project specializing in abstracting the retrieval pattern across multiple data sources and vector stores. It has since morphed into much more, but foundationally, it still provides excellent options for implementing retrieval.

Figure 8.7 shows a diagram from LangChain that identifies the process of storing documents for retrieval. These same steps may be replicated in whole or in part to implement memory retrieval. The critical difference between document and memory retrieval is the source and how content is transformed.

Figure 8.7 Load, transform, embed, and store steps in storing documents for later retrieval

We’ll examine how to implement each of these steps using LangChain and understand the nuances and details accompanying this implementation. In

the next section, we’ll start by splitting and loading documents with LangChain.

8.4.1 Splitting and loading documents with LangChain

Retrieval mechanisms augment the context of a given prompt with specific information relevant to the request. For example, you may request detailed information about a local document. With earlier language models, submitting the whole document as part of the prompt wasn’t an option due to token limitations.

Today, we could submit a whole document for many commercial LLMs, such as GPT-4 Turbo, as part of a prompt request. However, the results may not be better and would likely cost more because of the increased number of tokens. Therefore, a better option is to split the document and use the relevant parts to request context—precisely what RAG and memory do.

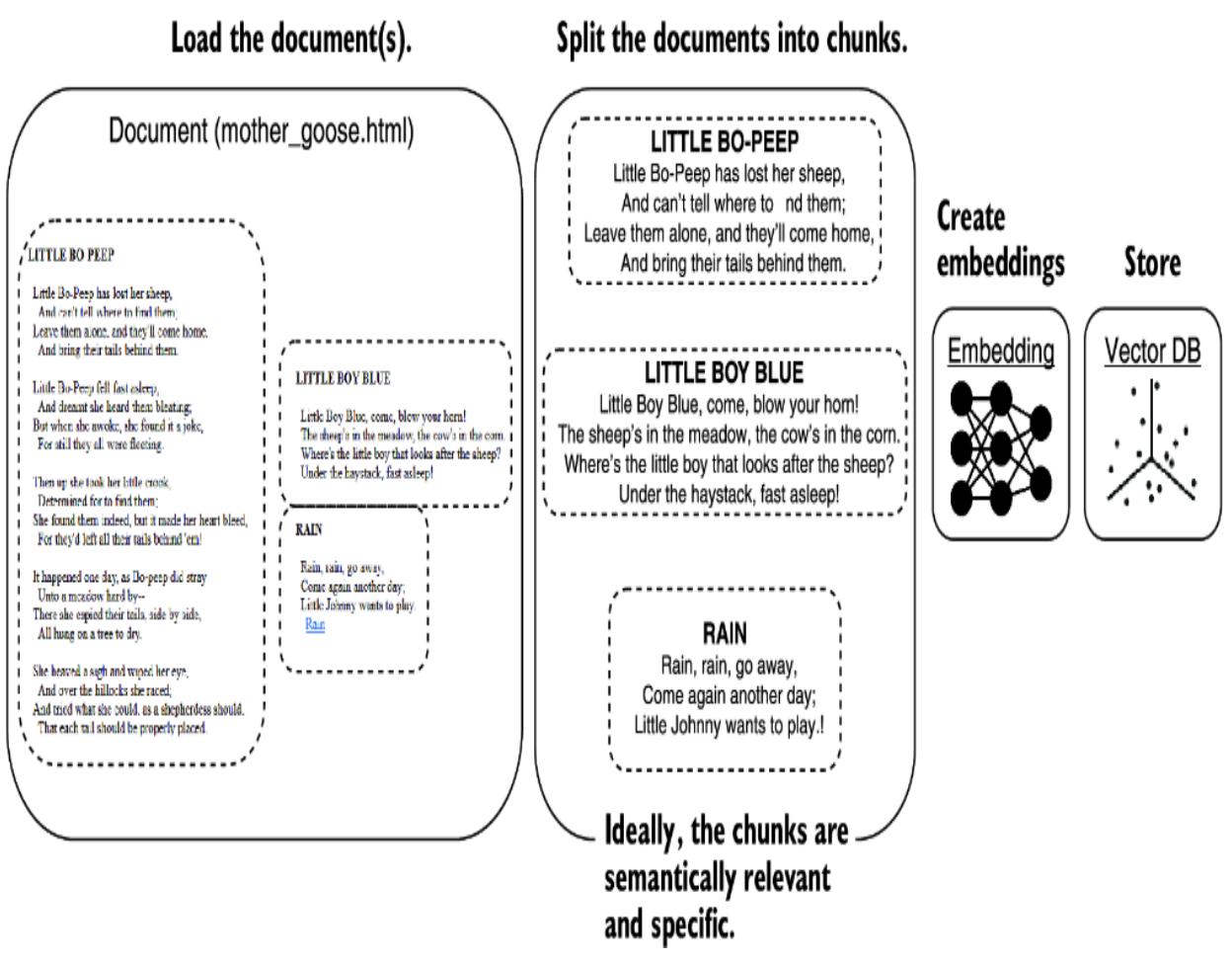

Splitting a document is essential in breaking down content into semantically and specifically relevant sections. Figure 8.8 shows how to break down an HTML document containing the Mother Goose nursery rhymes. Often, splitting a document into contextual semantic chunks requires careful consideration.

Figure 8.8 How the document would ideally be split into chunks for better semantic and contextual meaning

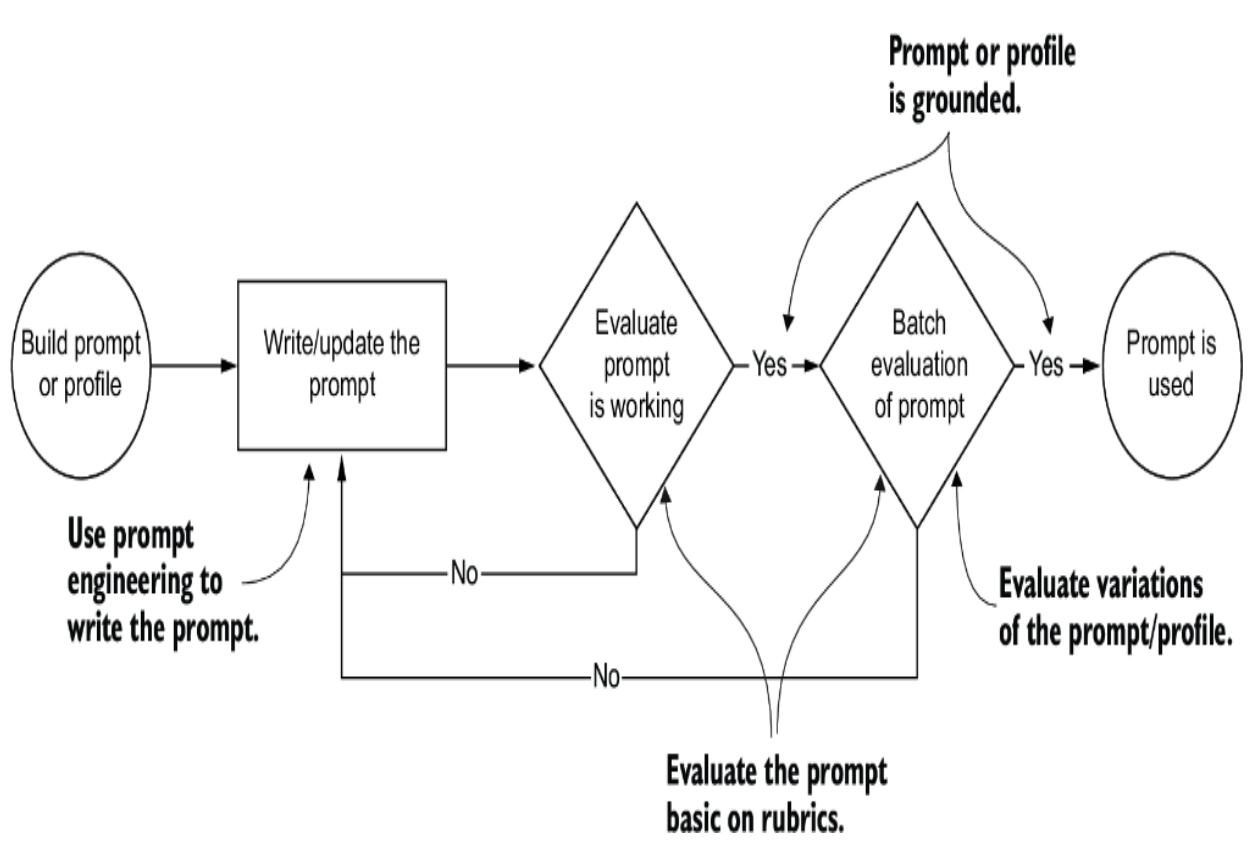

Ideally, when we split documents into chunks, they are broken down by relevance and semantic meaning. While an LLM or agent could help us with this, we’ll look at current toolkit options within LangChain for splitting documents. Later in this chapter, we’ll look at a semantic function that can assist us in semantically dividing content for embeddings.

For the next exercise, open langchain_load_splitting.py in VS Code, as shown in listing 8.6. This code shows where we left off from listing 8.5, in the previous section. Instead of using the sample documents, we’re loading the Mother Goose nursery rhymes this time.

Listing 8.6 langchain_load_splitting.py (sections and output)

From langchain_community.document_loaders

↪ import UnstructuredHTMLLoader #1

from langchain.text_splitter import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

#previous code

loader = UnstructuredHTMLLoader(

"sample_documents/mother_goose.xhtml") #2

data = loader.load #3

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=100,

chunk_overlap=25, #4

length_function=len,

add_start_index=True,

)

documents = text_splitter.split_documents(data)

documents = [doc.page_content

↪ for doc in documents] [100:350] #5

embeddings = [get_embedding(doc) for doc in documents] #6

ids = [f"id{i}" for i in range(len(documents))]

###Output

Enter a search query (or 'exit' to stop): who kissed the girls and made

them cry?

How many top matches do you want to see? 3

Top Matched Documents:

ID:id233 TEXT: And chid her daughter,

And kissed my sister instead of me. SCORE: 0.4…

#1 New LangChain imports

#2 Loads the document as HTML

#3 Loads the document#4 Splits the document into blocks of text 100 characters long with a 25-character overlap #5 Embeds only 250 chunks, which is cheaper and faster #6 Returns the embedding for each document

Note in listing 8.6 that the HTML document gets split into 100-character chunks with a 25-character overlap. The overlap allows the document’s parts not to cut off specific thoughts. We selected the splitter for this exercise because it was easy to use, set up, and understand.

Go ahead and run the langchain_load_splitting.py file in VS Code (F5). Enter a query, and see what results you get. The output in listing 8.6 shows good results given a specific example. Remember that we only embedded 250 document chunks to reduce costs and keep the exercise short. Of course, you can always try to embed the entire document or use a minor input document example.

Perhaps the most critical element to building proper retrieval is the process of document splitting. You can use numerous methods to split a document, including multiple concurrent methods. More than one method passes and splits the document for numerous embedding views of the same document. In the next section, we’ll examine a more general technique for splitting documents, using tokens and tokenization.

8.4.2 Splitting documents by token with LangChain

Tokenization is the process of breaking text into word tokens. Where a word token represents a succinct element in the text, a token could be a word like hold or even a symbol like the left curly brace ({), depending on what’s relevant.

Splitting documents using tokenization provides a better base for how the text will be interpreted by language models and for semantic similarity. Tokenization also allows the removal of irrelevant characters, such as whitespace, making the similarity matching of documents more relevant and generally providing better results.

For the next code exercise, open the langchain_token_splitting.py file in VS Code, as shown in listing 8.7. Now we split the document using tokenization, which breaks the document into sections of unequal size. The unequal size results from the large sections of whitespace of the original document.

Listing 8.7 langchain_token_splitting.py (relevant new code)

loader = UnstructuredHTMLLoader("sample_documents/mother_goose.xhtml")

data = loader.load()

text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter.from_tiktoken_encoder(

chunk_size=50, chunk_overlap=10 #1

)

documents = text_splitter.split_documents(data)

documents = [doc for doc in documents][8:94] #2

db = Chroma.from_documents(documents, OpenAIEmbeddings())

def query_documents(query, top_n=2):

docs = db.similarity_search(query, top_n) #3

return docs

###Output

Created a chunk of size 68,

which is longer than the specified 50

Created a chunk of size 67,

which is longer than the specified 50 #4

Enter a search query (or 'exit' to stop):

who kissed the girls and made them cry?

How many top matches do you want to see? 3

Top Matched Documents:

Document 1: GEORGY PORGY

Georgy Porgy, pudding and pie,

Kissed the girls and made them cry.#1 Updates to 50 tokens and overlap of 10 tokens #2 Selects just the documents that contain rhymes #3 Uses the database’s similarity search #4 Breaks into irregular size chunks because of the whitespace

Run the langchain_token_splitting.py code in VS Code (F5). You can use the query we used last time or your own. Notice how the results are significantly better than the previous exercise. However, the results are still suspect because the query uses several similar words in the same order.

A better test would be to try a semantically similar phrase but one that uses different words and check the results. With the code still running, enter a new phrase to query: Why are the girls crying? Listing 8.8 shows the results of executing that query. If you run this example yourself and scroll down over the output, you’ll see Georgy Porgy appear in either the second or third returned document.

Listing 8.8 Query: Who made the girls cry? Enter a search query (or ‘exit’ to stop): Who made the girls cry? How many top matches do you want to see? 3 Top Matched Documents: Document 1: WILLY, WILLY Willy, Willy Wilkin…

This exercise shows how various retrieval methods can be employed to return documents semantically. With this base established, we can see how RAG can be applied to knowledge and memory systems. The following section will discuss RAG as it applies to knowledge of agents and agentic systems.

8.5 Applying RAG to building agent knowledge

Knowledge in agents encompasses employing RAG to search semantically across unstructured documents. These documents could be anything from PDFs to Microsoft Word documents and all text, including code. Agentic knowledge also includes using unstructured documents for Q&A, reference lookup, information augmentation, and other future patterns.

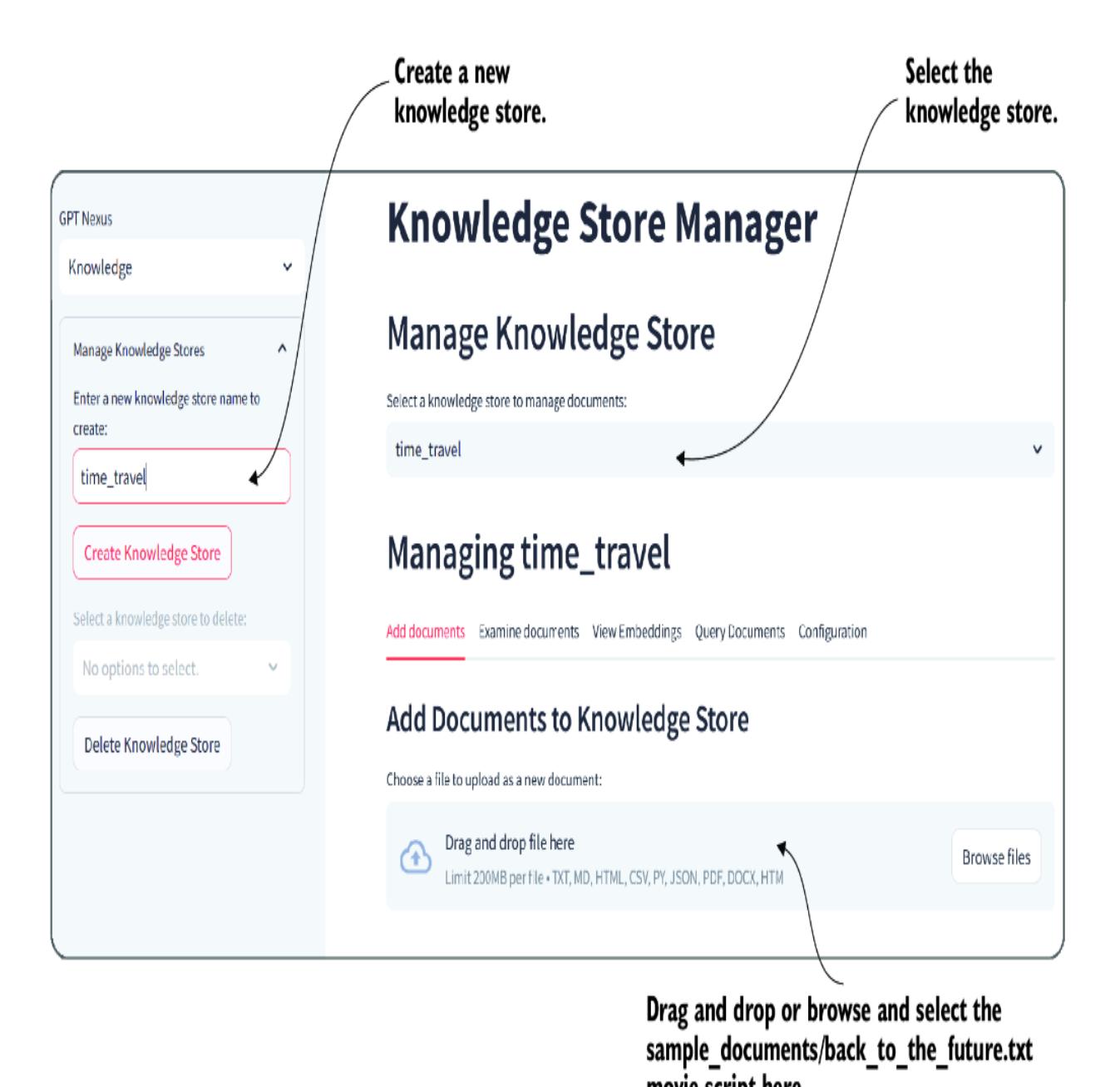

Nexus, the agent platform developed in tandem with this book and introduced in the previous chapter, employs complete knowledge and memory systems for agents. In this section, we’ll uncover how the knowledge system works.

To install Nexus for just this chapter, see listing 8.9. Open a terminal within the chapter_08 folder, and execute the commands in the listing to download, install, and run Nexus in normal or development mode. If you want to refer to the code, you should install the project in development and configure the debugger to run the Streamlit app from VS Code. Refer to chapter 7 if you need a refresher on any of these steps.

Listing 8.9 Installing Nexus

pip install -e Nexus

to install and run pip install git+https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/Nexus.git nexus run # install in development mode git clone https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/Nexus.git # Install the cloned repository in editable mode

Regardless of which method you decide to run the app in after you log in, navigate to the Knowledge Store Manager page, as shown in figure 8.9. Create a new Knowledge Store, and then upload the

sample_documents/back_to_the_future.txt movie script.

Figure 8.9 Adding a new knowledge store and populating it with a document

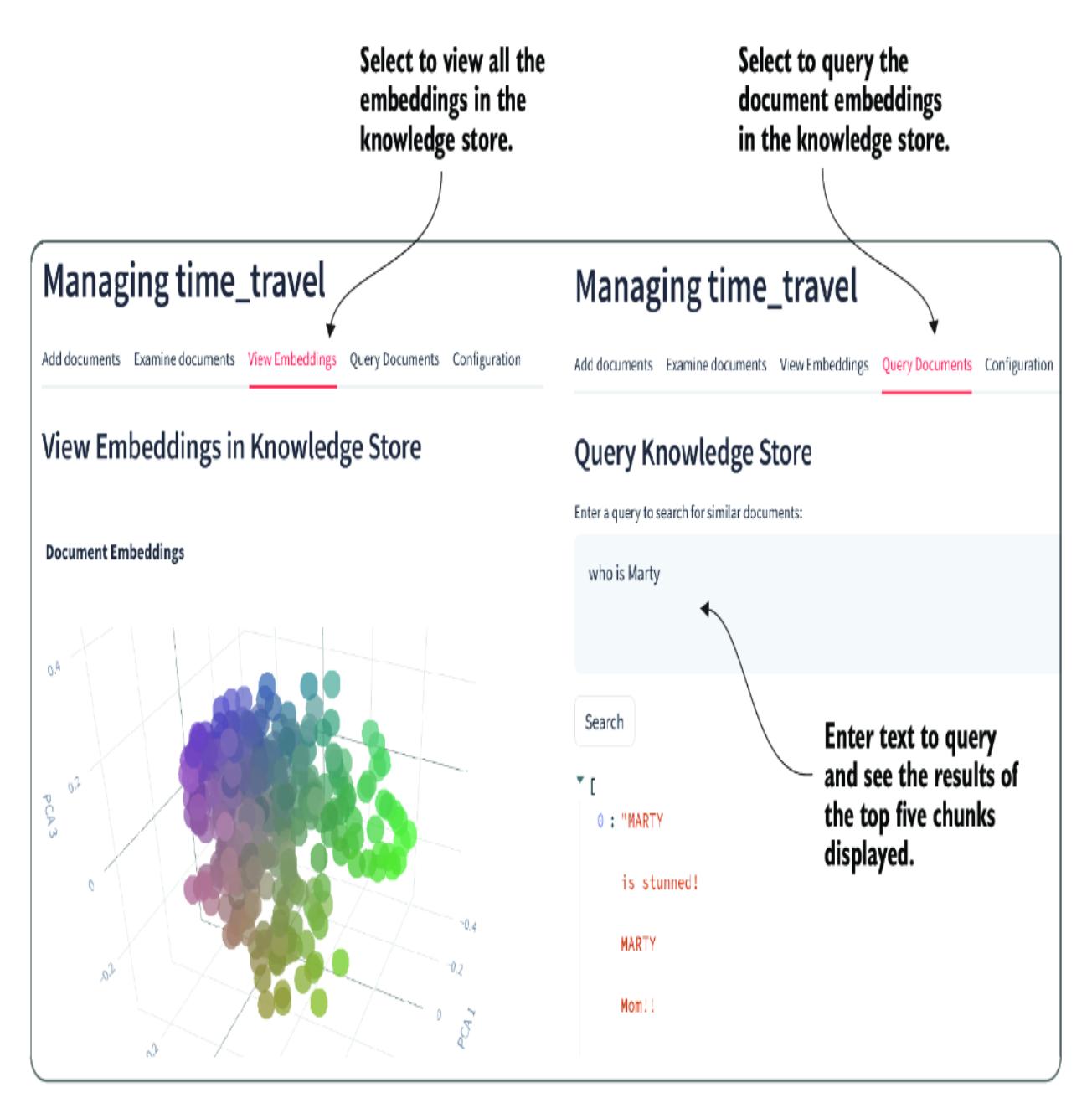

The script is a large document, and it may take a while to load, chunk, and embed the parts into the Chroma DB vector database. Wait for the indexing to complete, and then you can inspect the embeddings and run a query, as shown in figure 8.10.

Figure 8.10 The embeddings and document query views

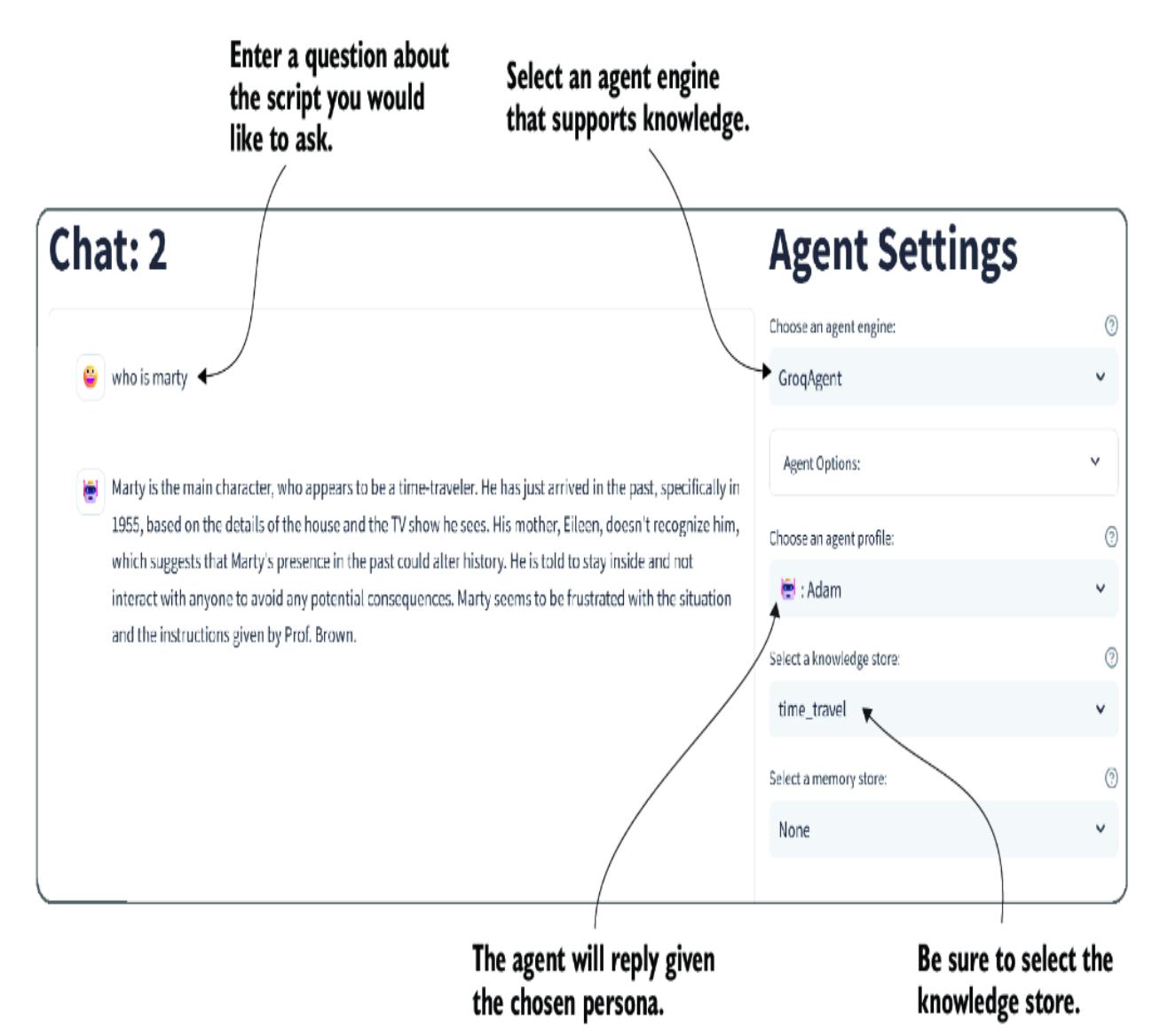

Now, we can connect the knowledge store to a supported agent and ask questions. Use the top-left selector to choose the chat page within the Nexus interface. Then, select an agent and the time_travel knowledge store, as shown in figure 8.11. You will also need to select an agent engine that supports knowledge. Each of the multiple agent engines requires the proper configuration to be accessible.

Figure 8.11 Enabling the knowledge store for agent use

Currently, as of this chapter, Nexus supports access to only a single knowledge store at a time. In a future version, agents may be able to select multiple knowledge stores at a time. This may include more advanced options, from semantic knowledge to employing other forms of RAG.

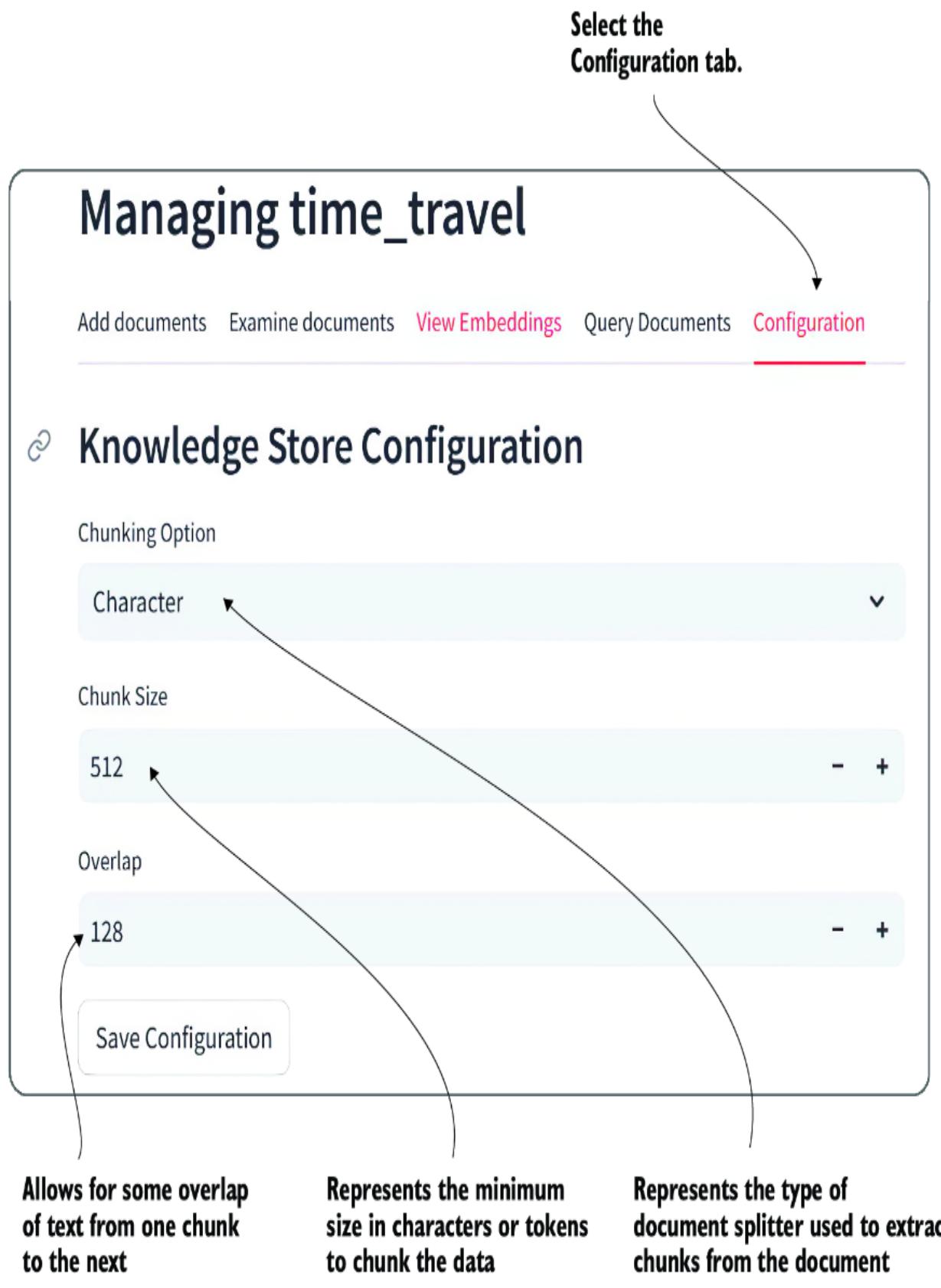

You can also configure the RAG settings within the Configuration tab of the Knowledge Store Manager page, as shown in figure 8.12. As of now, you can select from the type of splitter (Chunking Option field) to chunk the document, along with the Chunk Size field and Overlap field.

Figure 8.12 Managing the knowledge store splitting and chunking options

The loading, splitting, chunking, and embedding options provided are the only basic options supported by LangChain for now. In future versions of Nexus, more options and patterns will be offered. The code to support other options can be added directly to Nexus.

We won’t cover the code that performs the RAG as it’s very similar to what we already covered. Feel free to review the Nexus code, particularly the KnowledgeManager class in the knowledge_manager.py file.

While the retrieval patterns for knowledge and memory are quite similar for augmentation, the two patterns differ when it comes to populating the stores. In the next section, we’ll explore what makes memory in agents unique.

8.6 Implementing memory in agentic systems

Memory in agents and AI applications is often described in the same terms as cognitive memory functions. Cognitive memory describes the type of memory we use to remember what we did 30 seconds ago or how tall we were 30 years ago. Computer memory is also an essential element of agent memory, but one we won’t consider in this section.

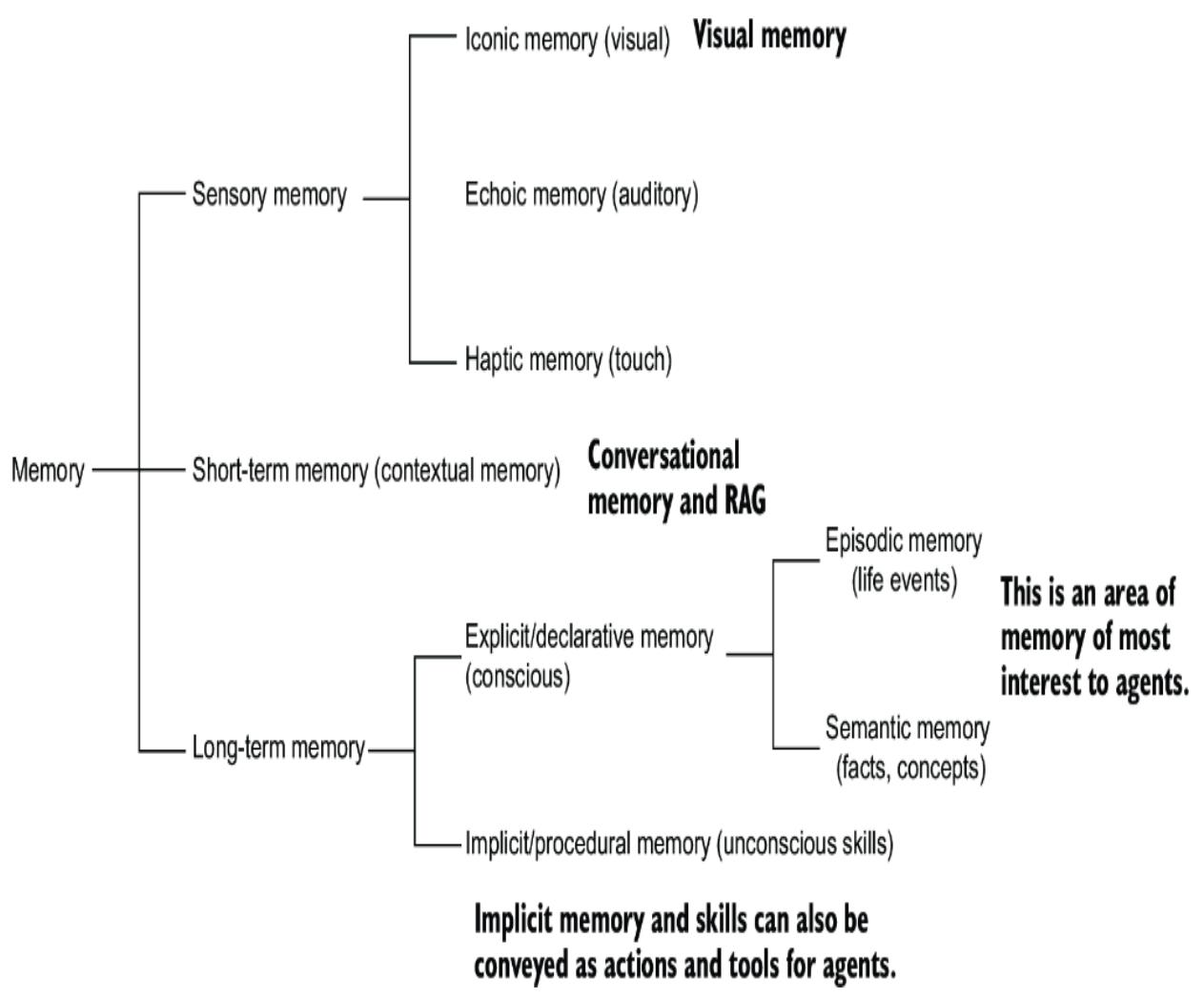

Figure 8.13 shows how memory is broken down into sensory, short-term, and long-term memory. This memory can be applied to AI agents, and this list describes how each form of memory maps to agent functions:

- Sensory memory in AI —Functions such as RAG but with images/audio/haptic data forms. Briefly holds input data (e.g., text and images) for immediate processing but not long-term storage.

- Short-term/working memory in AI —Acts as an active memory buffer of conversation history. We’re holding a limited amount of recent input and context for immediate analysis and response generation. Within Nexus, short- and long-term conversational memory is also held in the context of the thread.

- Long-term memory in AI —Longer-term memory storage relevant to the agent’s or user’s life. Semantic memory provides a robust capacity to store and retrieve relevant global or local facts and concepts.

Figure 8.13 How memory is broken down into various forms

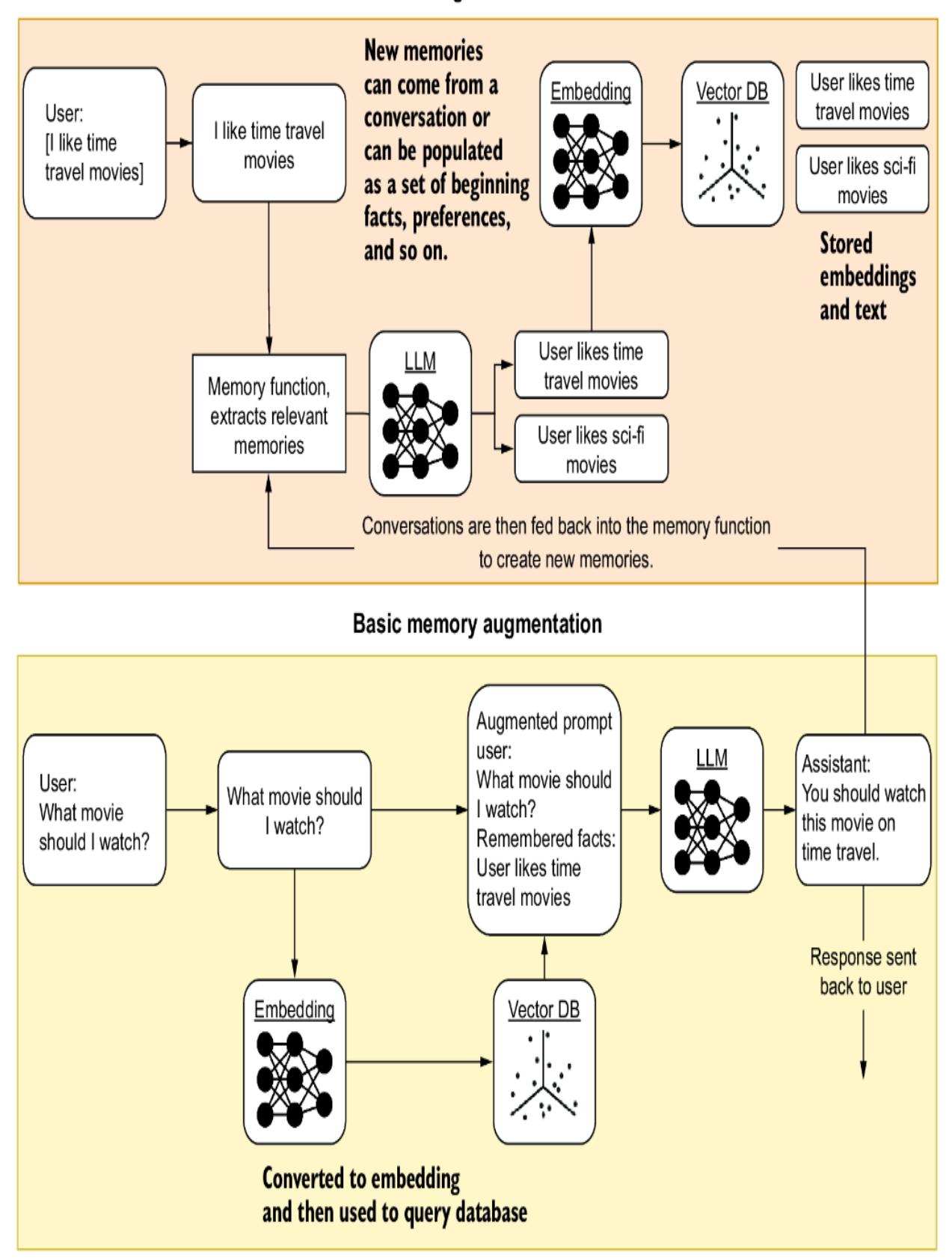

While memory uses the exact same retrieval and augmentation mechanisms as knowledge, it typically differs significantly when updating or appending memories. Figure 8.14 highlights the process of capturing and using memories to augment prompts. Because memories are often different from the size of complete documents, we can avoid using any splitting or chunking mechanisms.

Figure 8.14 Basic memory retrieval and augmentation workflow

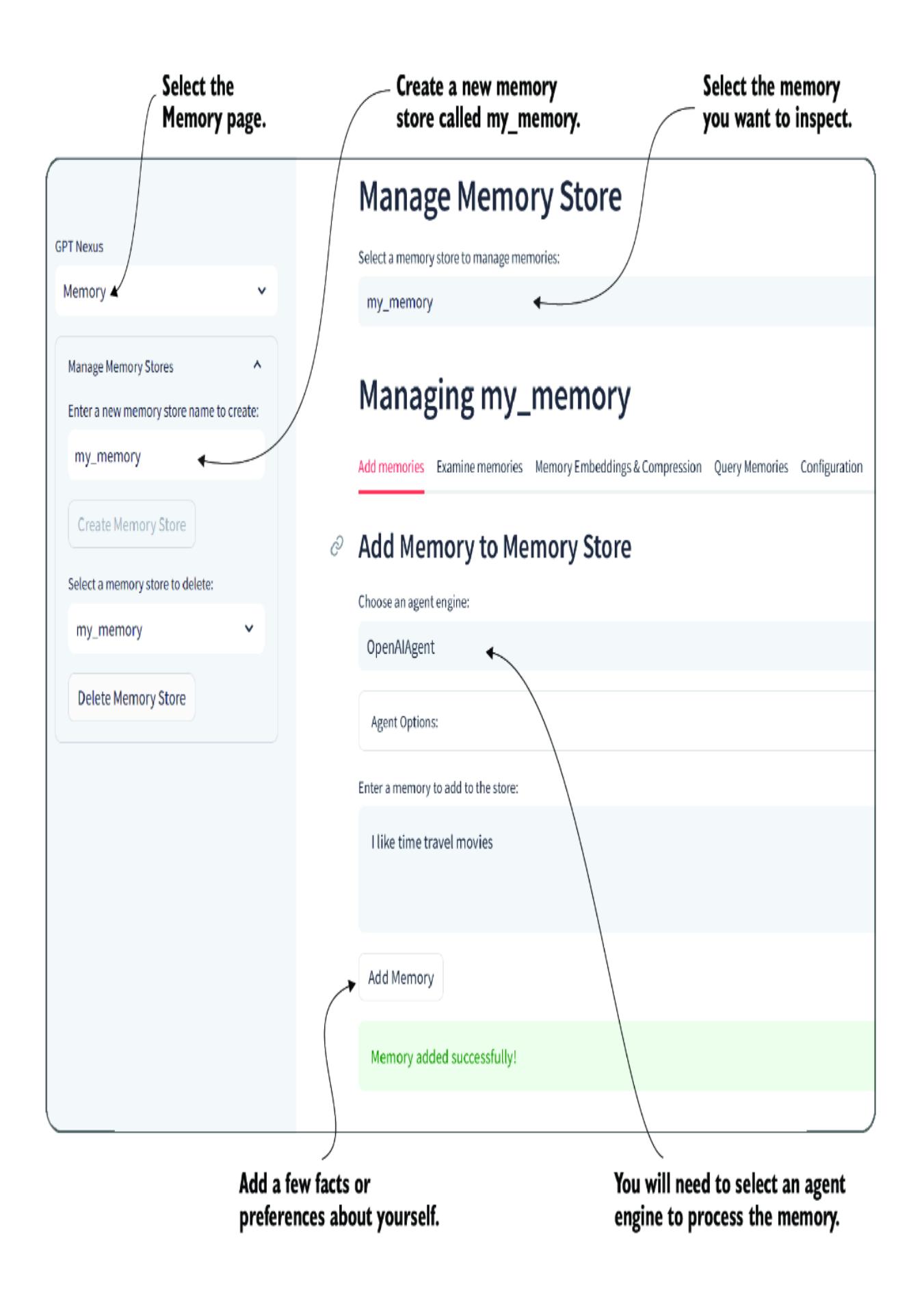

Nexus provides a mechanism like the knowledge store, allowing users to create memory stores that can be configured for various uses and applications. It also supports some of the more advanced memory forms highlighted in figure 8.13. The following section will examine how basic memory stores work in Nexus.

8.6.1 Consuming memory stores in Nexus

Memory stores operate and are constructed like knowledge stores in Nexus. They both heavily rely on the retrieval pattern. What differs is the extra steps memory systems take to build new memories.

Go ahead and start Nexus, and refer to listing 8.9 if you need to install it. After logging in, select the Memory page, and create a new memory store, as shown in figure 8.15. Select an agent engine, and then add a few personal facts and preferences about yourself.

Figure 8.15 Adding memories to a newly created memory store

The reason we need an agent (LLM) was shown in figure 8.14 earlier. When information is fed into a memory store, it’s generally processed through an LLM using a memory function, whose purpose is to process the statements/conversations into semantically relevant information related to the type of memory.

Listing 8.10 shows the conversational memory function used to extract information from a conversation into memories. Yes, this is just the header portion of the prompt sent to the LLM, instructing it how to extract information from a conversation.

Listing 8.10 Conversational memory function

Summarize the conversation and create a set of statements that summarize the conversation. Return a JSON object with the following keys: ‘summary’. Each key should have a list of statements that are relevant to that category. Return only the JSON object and nothing else.

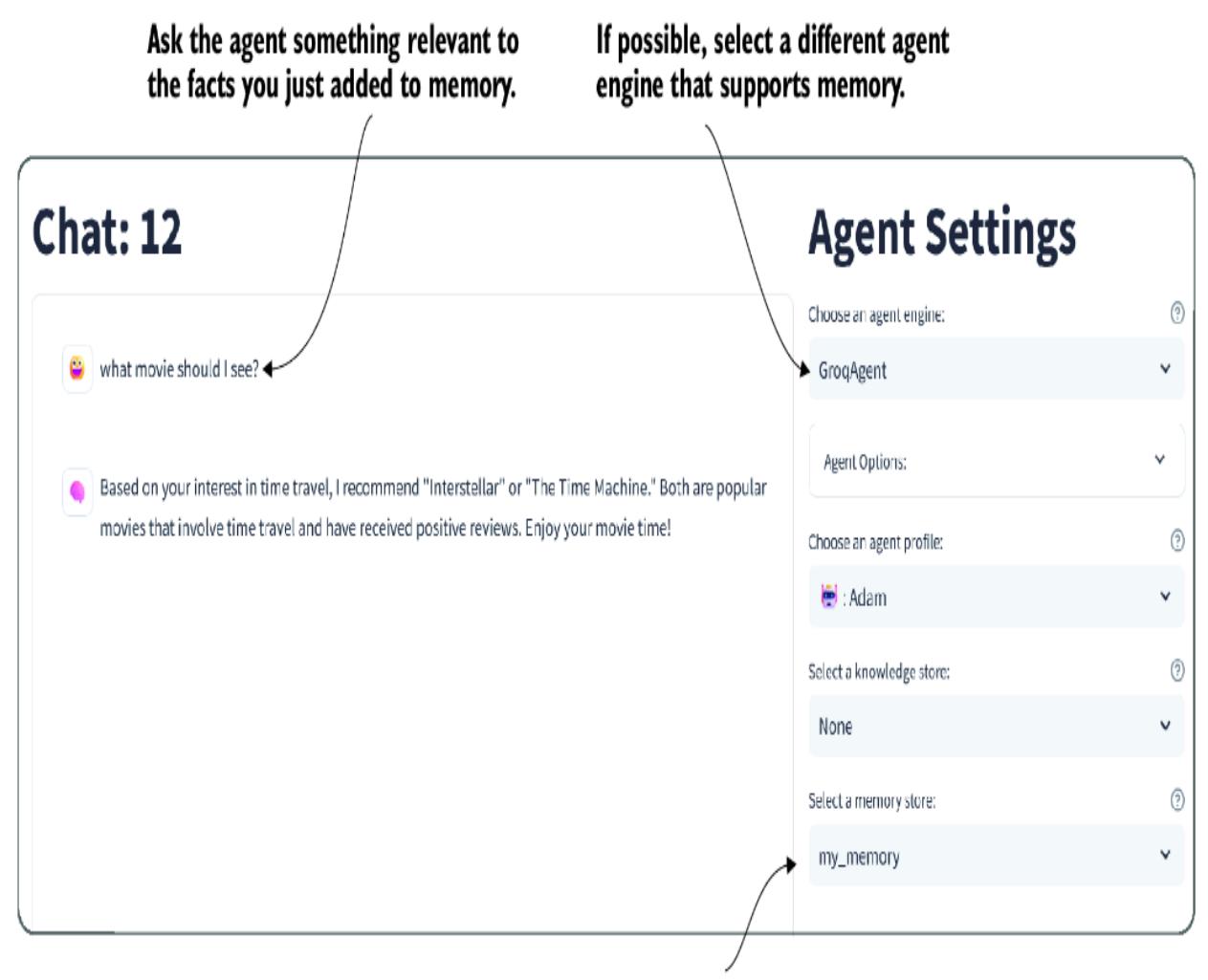

After you generate a few relevant memories about yourself, return to the Chat area in Nexus, enable the my_memory memory store, and see how well the agent knows you. Figure 8.16 shows a sample conversation using a different agent engine.

Figure 8.16 Conversing with a different agent on the same memory store

This is an example of a basic memory pattern that extracts facts/preferences from conversations and stores them in a vector database as memories. Numerous other implementations of memory follow those displayed earlier in figure 8.13. We’ll implement those in the next section.

8.6.2 Semantic memory and applications to semantic, episodic, and procedural memory

Psychologists categorize memory into multiple forms, depending on what information is remembered. Semantic, episodic, and procedural memory all represent different types of information. Episodic memories are about events, procedural memories are about the process or steps, and semantic

represents the meaning and could include feelings or emotions. Other forms of memory (geospatial is another), aren’t described here but could be.

Because these memories rely on an additional level of categorization, they also rely on another level of semantic categorization. Some platforms, such as Semantic Kernel (SK), refer to this as semantic memory. This can be confusing because semantic categorization is also applied to extract episodic and procedural memories.

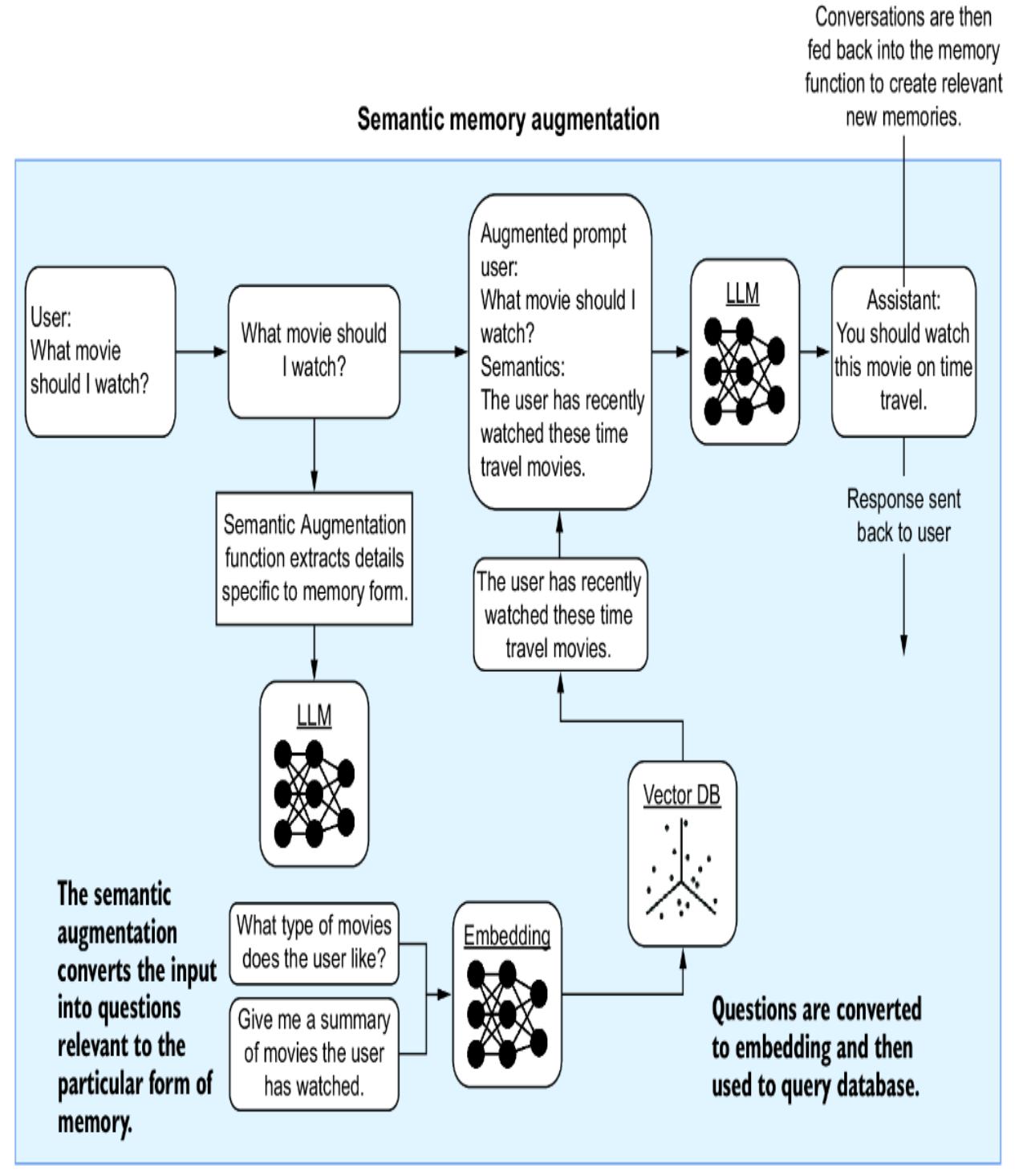

Figure 8.17 shows the semantic memory categorization process, also sometimes called semantic memory. The difference between semantic memory and regular memory is the additional step of processing the input semantically and extracting relevant questions that can be used to query the memory-relevant vector database.

Figure 8.17 How semantic memory augmentation works

The benefit of using semantic augmentation is the increased ability to extract more relevant memories. We can see this in operation by jumping back into Nexus and creating a new semantic memory store.

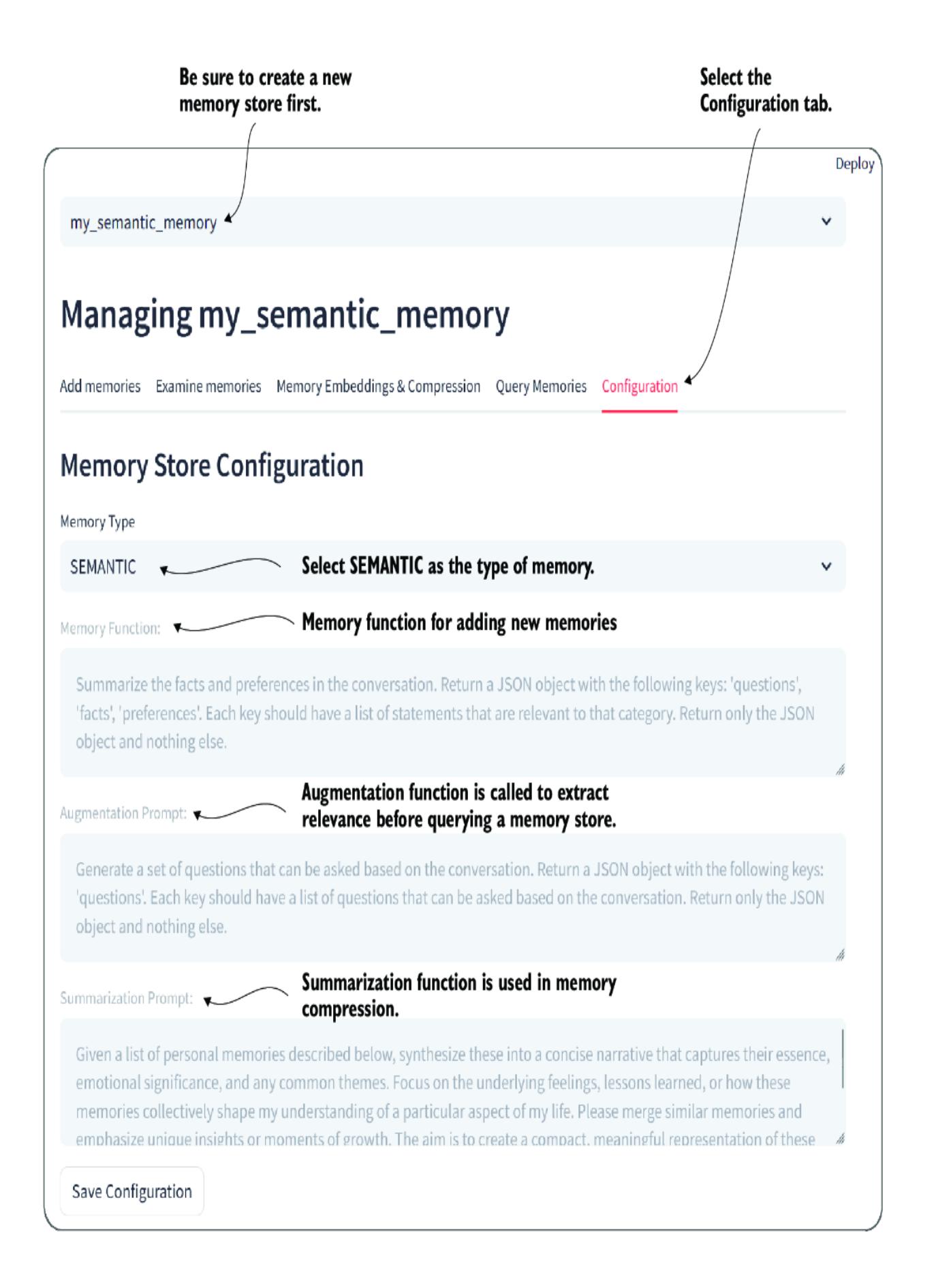

Figure 8.18 shows how to configure a new memory store using semantic memory. As of yet, you can’t configure the specific function prompts for memory, augmentation, and summarization. However, it can be useful to read through each of the function prompts to gain a sense of how they work.

Figure 8.18 Configuration for changing the memory store type to semantic

Now, if you go back and add facts and preferences, they will convert to the semantics of the relevant memory type. Figure 8.19 shows an example of memories being populated for the same set of statements into two different forms of memory. Generally, the statements entered into memory would be more specific to the form of memory.

| ID Hash | Memory |

|---|---|

| 9W8VW9oh5b | The interlocutor has a preference for movies that involve time travel. |

| Bfl_FnsdpU | The person has a preference for movies that involve time loops. |

| D27dzx-YxU | The interlocutor enjoys time travel movies. |

| Ef H19Jc D | The interlocutor enjoys watching time loop movies. |

| OSRsYrThXQ | It can be inferred that the individual finds time loop movies entertaining. |

| ID Hash | Memory | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0AQPgbOy-F | This conversation focuses on time loop movies. |

| D27dzx-YxU | The interlocutor enjoys time travel movies. | |

| 2 | Z4MOsfNjZl | The interlocutor exhibits a preference for cinema that involves time travel. |

| 3 O-XfTP4mS | The person enjoys watching time loop movies. | |

| 4 | sFU16iMoz8 | It is indicated that time travel movies are a topic of interest for the interlocutor. |

| 5 | uKQc6z9yS7 | The interlocutor appreciates the concept of moving through different time periods in movies. |

| 6 | uogR5kBGW9 | The person has a preference for a specific genre of movies, namely time loop movies. |

Figure 8.19 Comparing memories for the same information given two different memory types

Memory and knowledge can significantly assist an agent with various application types. Indeed, a single memory/knowledge store could feed one or multiple agents, allowing for further specialized interpretations of both types of stores. We’ll finish out the chapter by discussing memory/knowledge compression next.

8.7 Understanding memory and knowledge compression

Much like our own memory, memory stores can become cluttered with redundant information and numerous unrelated details over time. Internally, our minds deal with memory clutter by compressing or summarizing memories. Our minds remember more significant details over less important ones, and memories accessed more frequently.

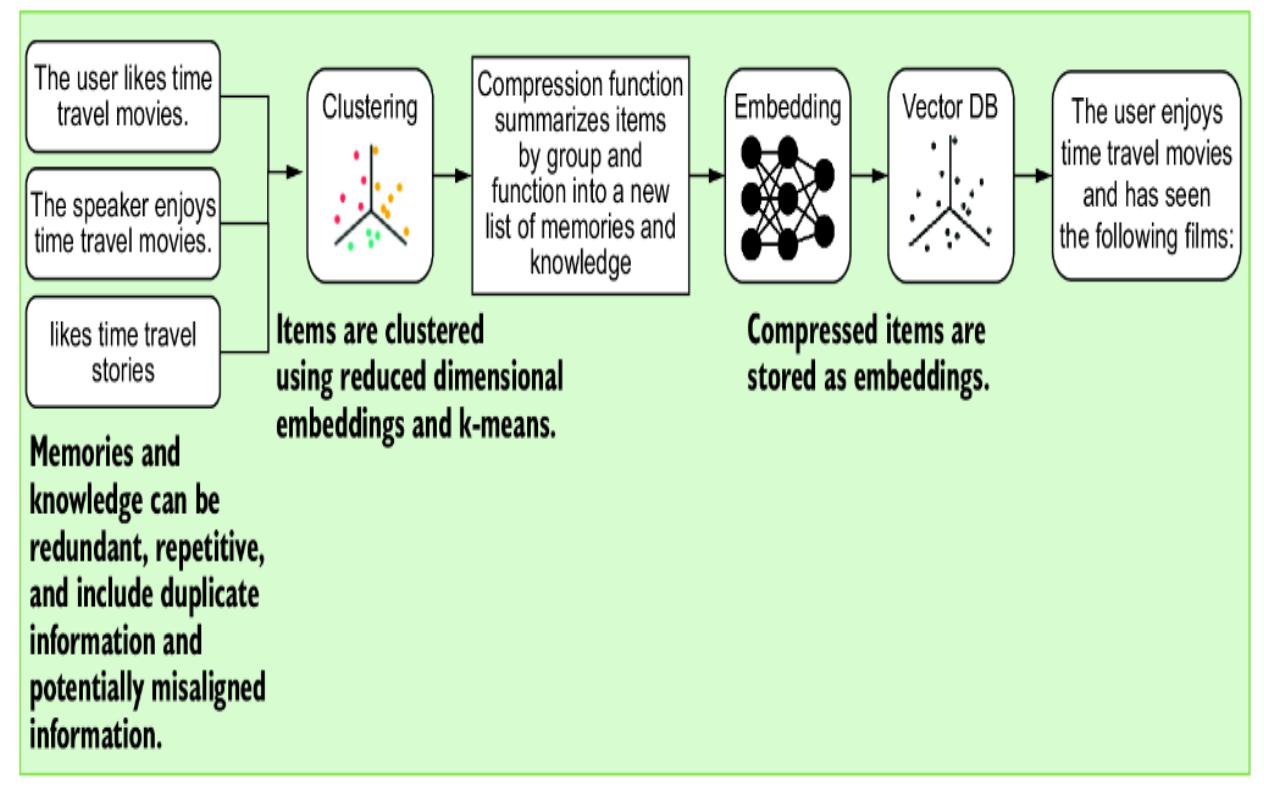

We can apply similar principles of memory compression to agent memory and other retrieval systems to extract significant details. The principle of compression is similar to semantic augmentation but adds another layer to the preclusters groups of related memories that can collectively be summarized.

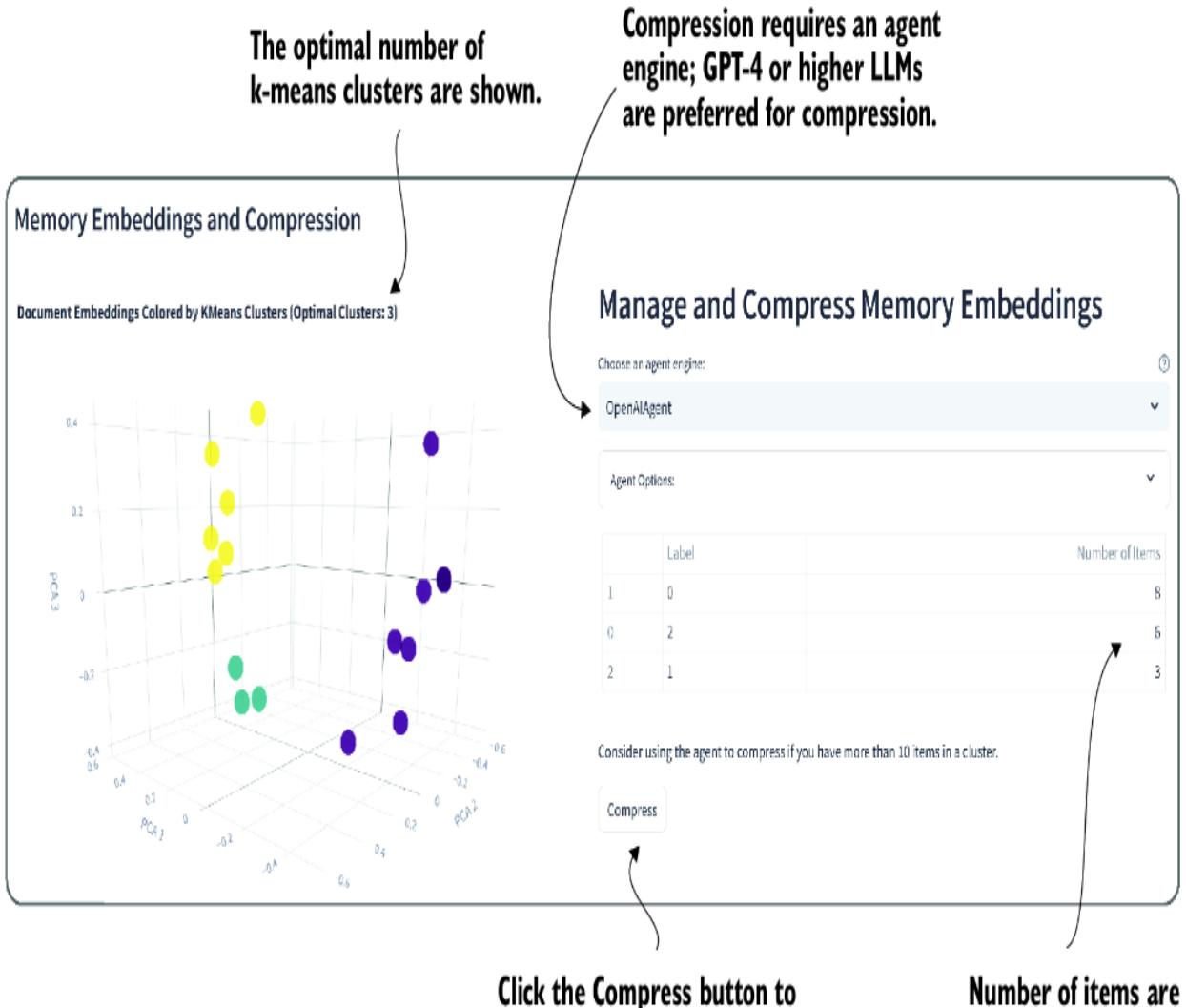

Figure 8.20 shows the process of memory/knowledge compression. Memories or knowledge are first clustered using an algorithm such as kmeans. Then, the groups of memories are passed through a compression function, which summarizes and collects the items into more succinct representations.

Figure 8.20 The process of memory and knowledge compression

Nexus provides for both knowledge and memory store compression using k-means optimal clustering. Figure 8.21 shows the compression interface for memory. Within the compression interface, you’ll see the items displayed in 3D and clustered. The size (number of items) of the clusters is shown in the left table.

Figure 8.21 The interface for compressing memories

Compressing memories and even knowledge is generally recommended if the number of items in a cluster is large or unbalanced. Each use case for compression may vary depending on the use and application of memories. Generally, though, if an inspection of the items in a store contains repetitive or duplicate information, it’s a good time for compression. The following is a summary of use cases for applications that would benefit from compression.

THE CASE FOR KNOWLEDGE COMPRESSION

Knowledge retrieval and augmentation have also been shown to benefit significantly from compression. Results will vary by use case, but generally, the more verbose the source of knowledge, the more it will benefit from compression. Documents that feature literary prose, such as stories and novels, will benefit more than, say, a base of code. However, if the code is likewise very repetitive, compression could also be shown to be beneficial.

THE CASE FOR HOW OFTEN YOU APPLY COMPRESSION

Memory will often benefit from the periodic compression application, whereas knowledge stores typically only help on the first load. How frequently you apply compression will greatly depend on the memory use, frequency, and quantity.

THE CASE FOR APPLYING COMPRESSION MORE THAN ONCE

Multiple passes of compression at the same time has been shown to improve retrieval performance. Other patterns have also suggested using memory or knowledge at various levels of compression. For example, a knowledge store is compressed two times, resulting in three different levels of knowledge.

THE CASE FOR BLENDING KNOWLEDGE AND MEMORY COMPRESSION

If a system is specialized to a particular source of knowledge and that system also employs memories, there may be further optimization to consolidate stores. Another approach is to populate memory with the starting knowledge of a document directly.

THE CASE FOR MULTIPLE MEMORY OR KNOWLEDGE STORES

In more advanced systems, we’ll look at agents employing multiple memory and knowledge stores relevant to their workflow. For example, an agent could employ individual memory stores as part of its conversations with individual users, perhaps including the ability to share different groups of memory with different groups of individuals. Memory and knowledge retrieval are cornerstones of agentic systems, and we can now summarize what we covered and review some learning exercises in the next section.

8.8 Exercises

Use the following exercises to improve your knowledge of the material:

Exercise 1 —Load and Split a Different Document (Intermediate)

Objective —Understand the effect of document splitting on retrieval efficiency by using LangChain.

Tasks:

- Select a different document (e.g., a news article, a scientific paper, or a short story).

- Use LangChain to load and split the document into chunks.

- Analyze how the document is split into chunks and how it affects the retrieval process.

- Exercise 2 —Experiment with Semantic Search (Intermediate)

Objective —Compare the effectiveness of various vectorization techniques by performing semantic searches.

Tasks:

Choose a set of documents for semantic search.

Use a vectorization method such as Word2Vec or BERT embeddings instead of TF–IDF.

Perform the semantic search, and compare the results with those obtained using TF–IDF to understand the differences and effectiveness.

Exercise 3 —Implement a Custom RAG Workflow (Advanced)

Objective —Apply theoretical knowledge of RAG in a practical context using LangChain.

Tasks:

- Choose a specific application (e.g., customer service inquiries or academic research queries).

- Design and implement a custom RAG workflow using LangChain.

- Tailor the workflow to suit the chosen application, and test its effectiveness.

- Exercise 4 —Build a Knowledge Store and Experiment with Splitting Patterns (Intermediate)

Objective —Understand how different splitting patterns and compression affect knowledge retrieval.

Tasks:

- Build a knowledge store, and populate it with a couple of documents.

- Experiment with different forms of splitting/chunking patterns, and analyze their effect on retrieval.

- Compress the knowledge store, and observe the effects on query performance.

- Exercise 5 —Build and Test Various Memory Stores (Advanced)

Objective —Understand the uniqueness and use cases of different memory store types.

Tasks: