AI Agents in Action

To comment go to livebook.

Manning Shelter Island

For more information on this and other Manning titles go to manning.com.

AI Agents in Action

For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity. For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department

Manning Publications Co.

20 Baldwin Road

PO Box 761

Shelter Island, NY 11964

Email: orders@manning.com

©2025 by Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks.

Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine.

The authors and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time. The authors and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause, or from any usage of the information herein.

Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964

Development editor: Becky Whitney Technical editor: Ross Turner Review editor: Kishor Rit Production editor: Keri Hales Copy editor: Julie McNamee Proofreader: Katie Tennant Technical proofreader: Ross Turner Typesetter: Dennis Dalinnik Cover designer: Marija Tudor

ISBN: 9781633436343

Printed in the United States of America

dedication

I dedicate this book to all the readers who embark on this journey with me.

Books are a powerful way for an author to connect with readers on a deeply personal

level, chapter by chapter, page by page. In that shared experience of learning,

exploring, and growing together, I find true meaning. May this book inspire you

and challenge you, and help you see the incredible potential that AI agents hold—

not just for the future but also for today.

contents

1 Introduction to agents and their world

2 Harnessing the power of large language models

2.1.1 Connecting to the chat completions model

- 2.1.2 Understanding the request and response

- 2.2 Exploring open source LLMs with LM Studio

- 2.3 Prompting LLMs with prompt engineering

2.3.6 Specifying output length

2.4 Choosing the optimal LLM for your specific needs

3 Engaging GPT assistants

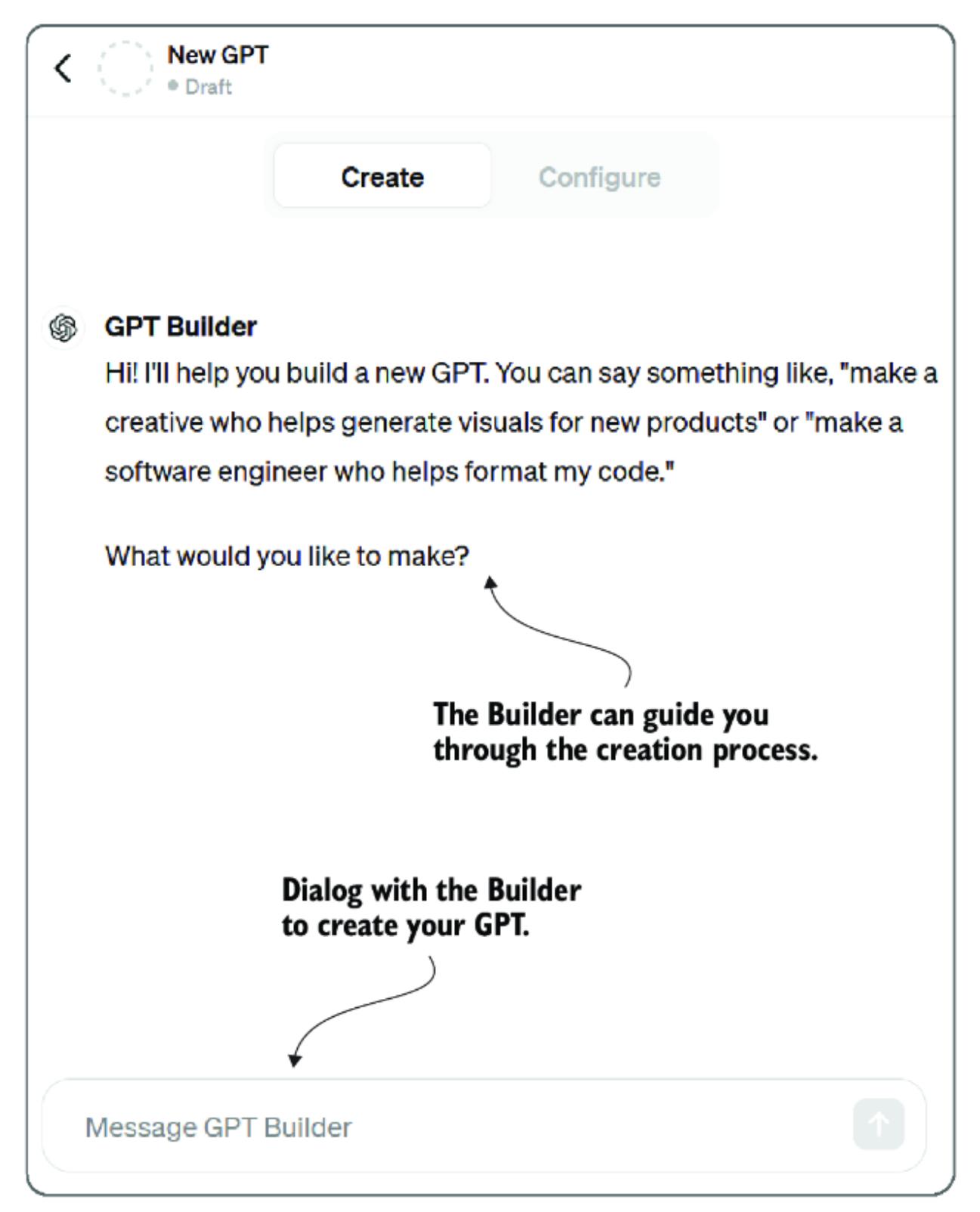

3.1 Exploring GPT assistants through ChatGPT

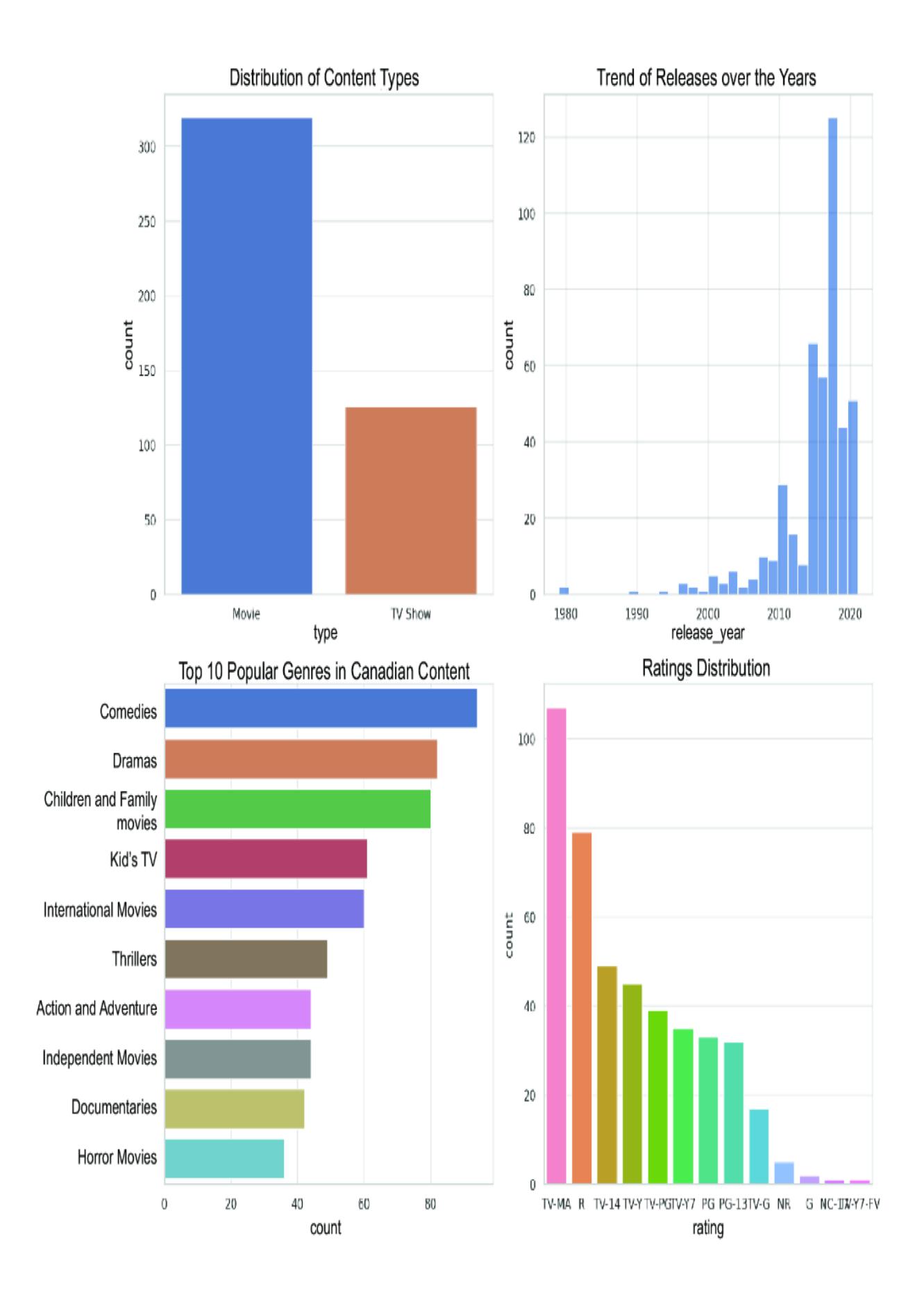

3.2 Building a GPT that can do data science

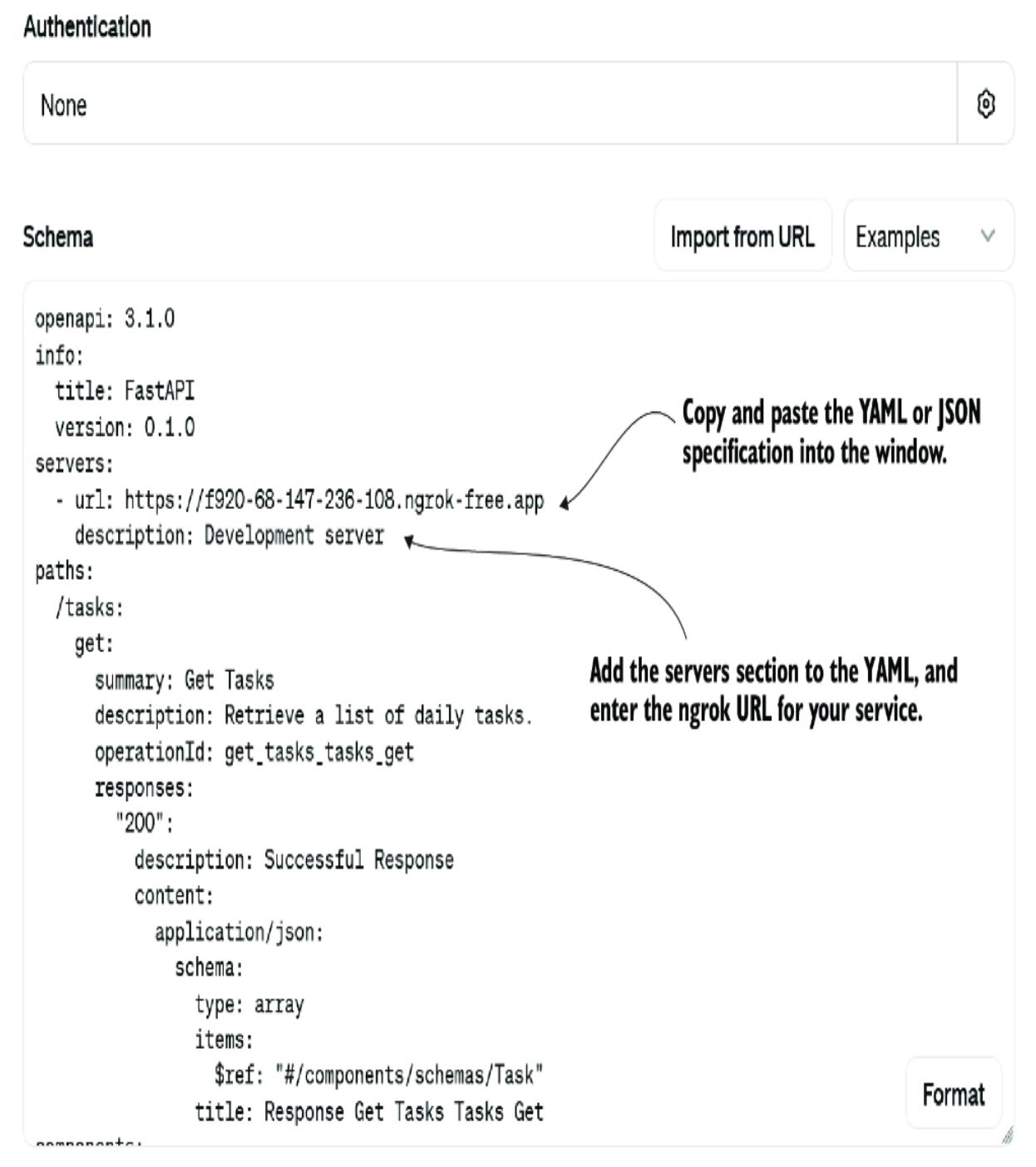

3.3 Customizing a GPT and adding custom actions

3.3.1 Creating an assistant to build an assistant

3.3.2 Connecting the custom action to an assistant

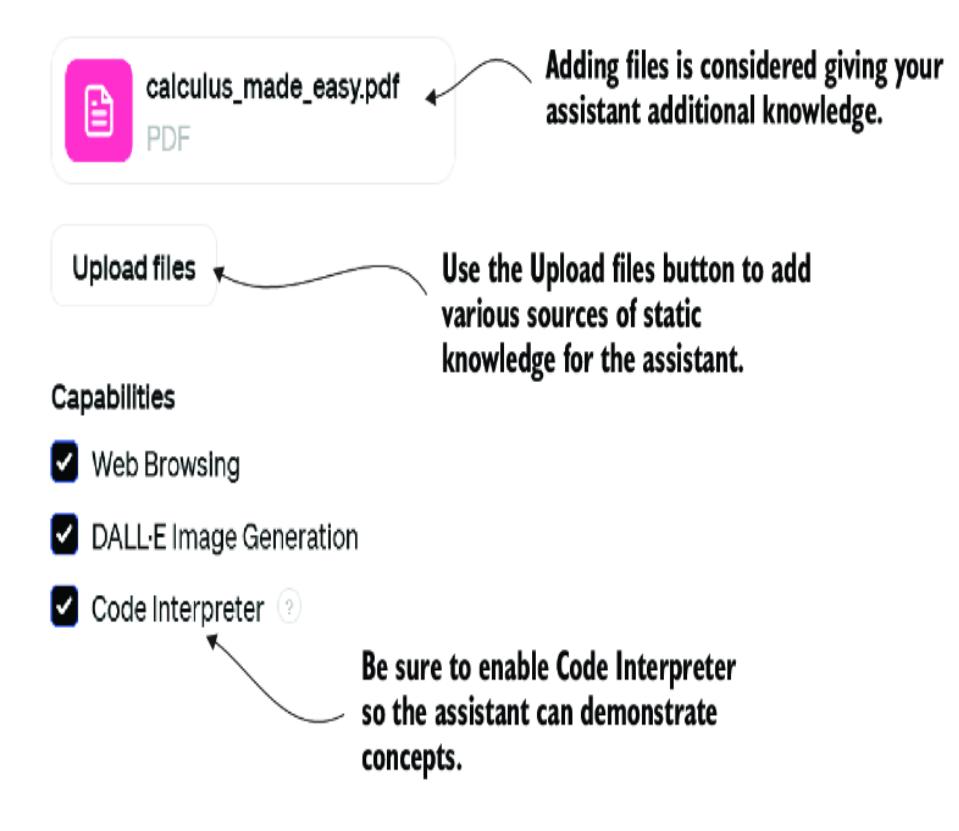

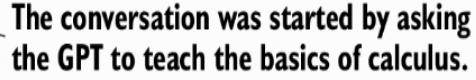

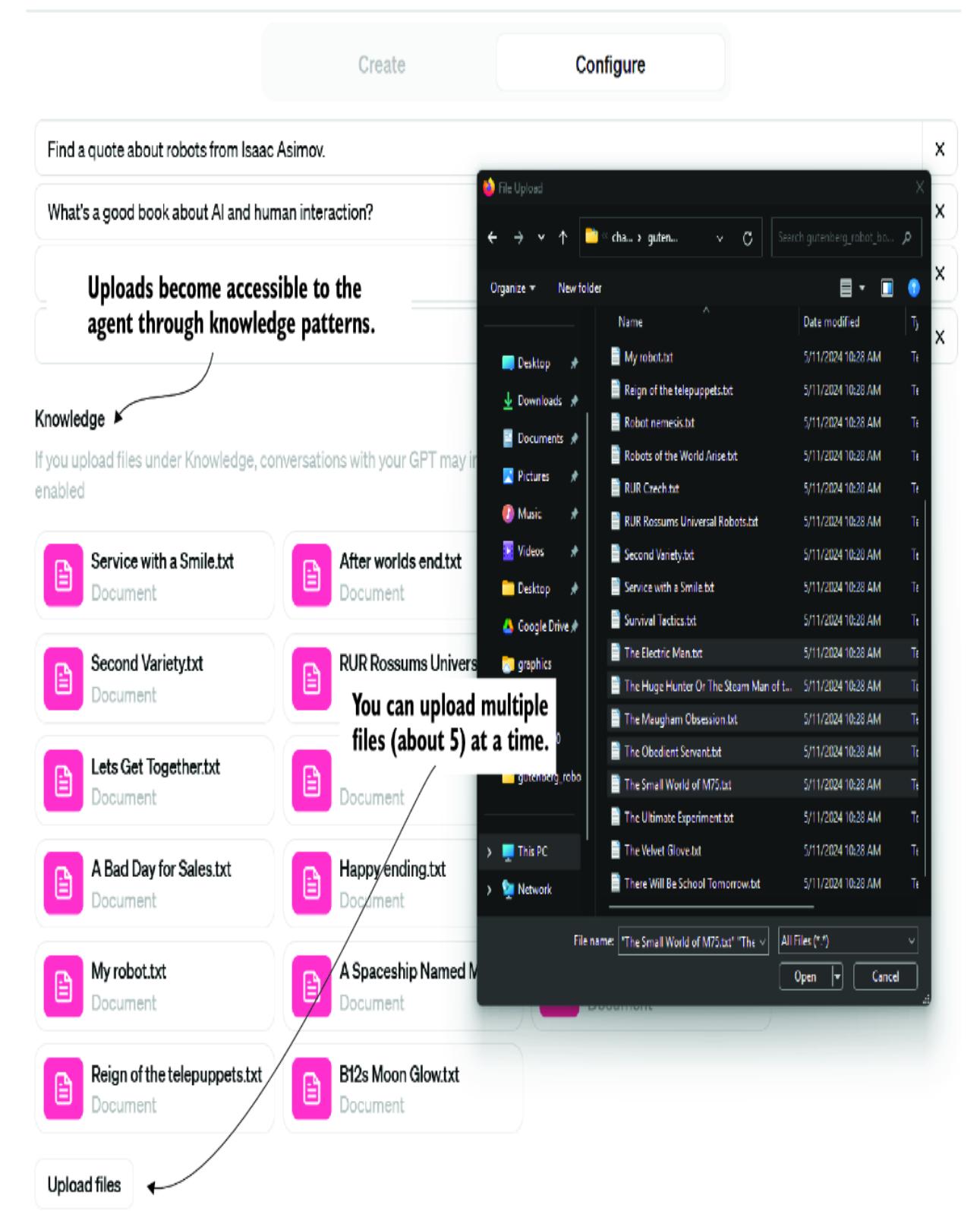

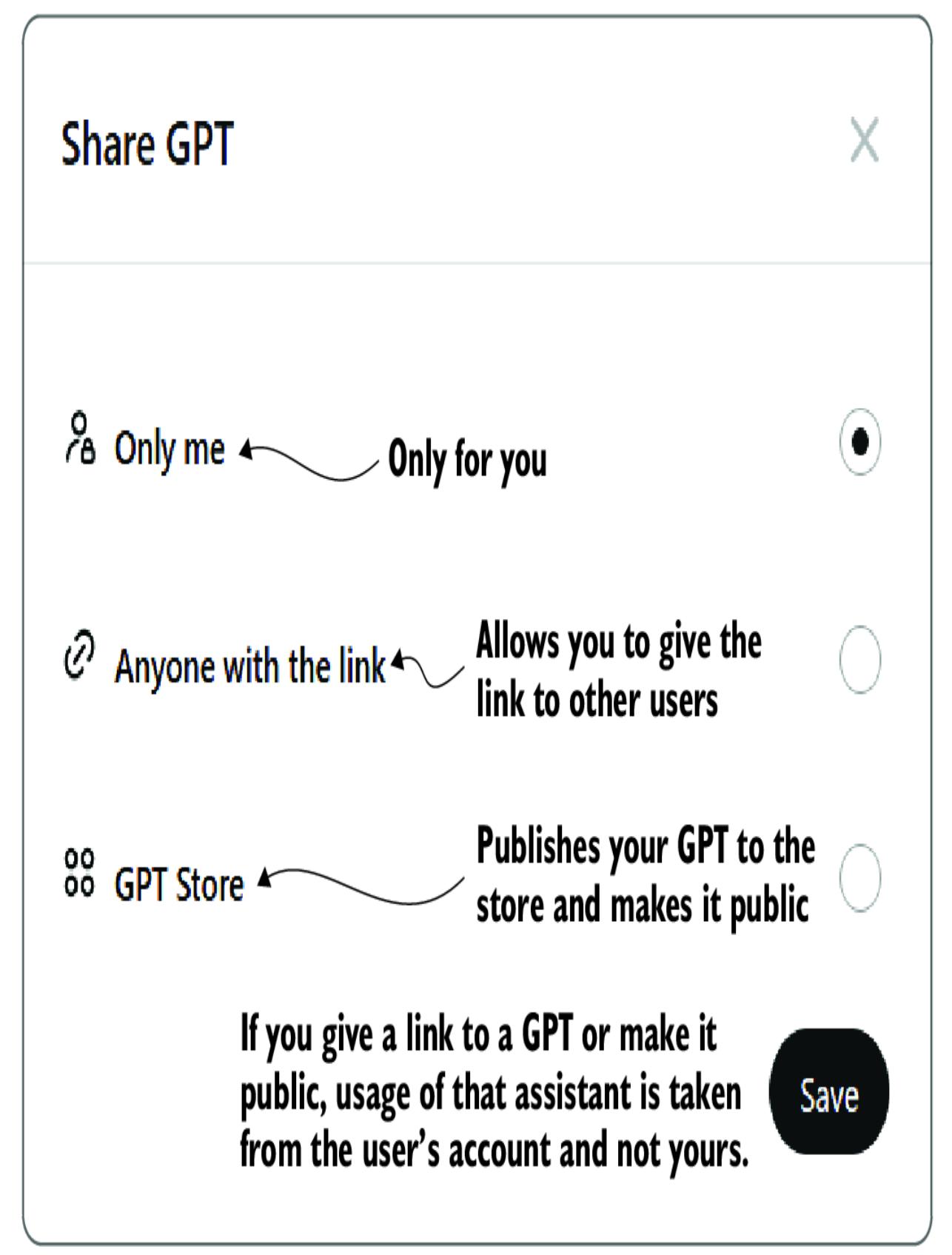

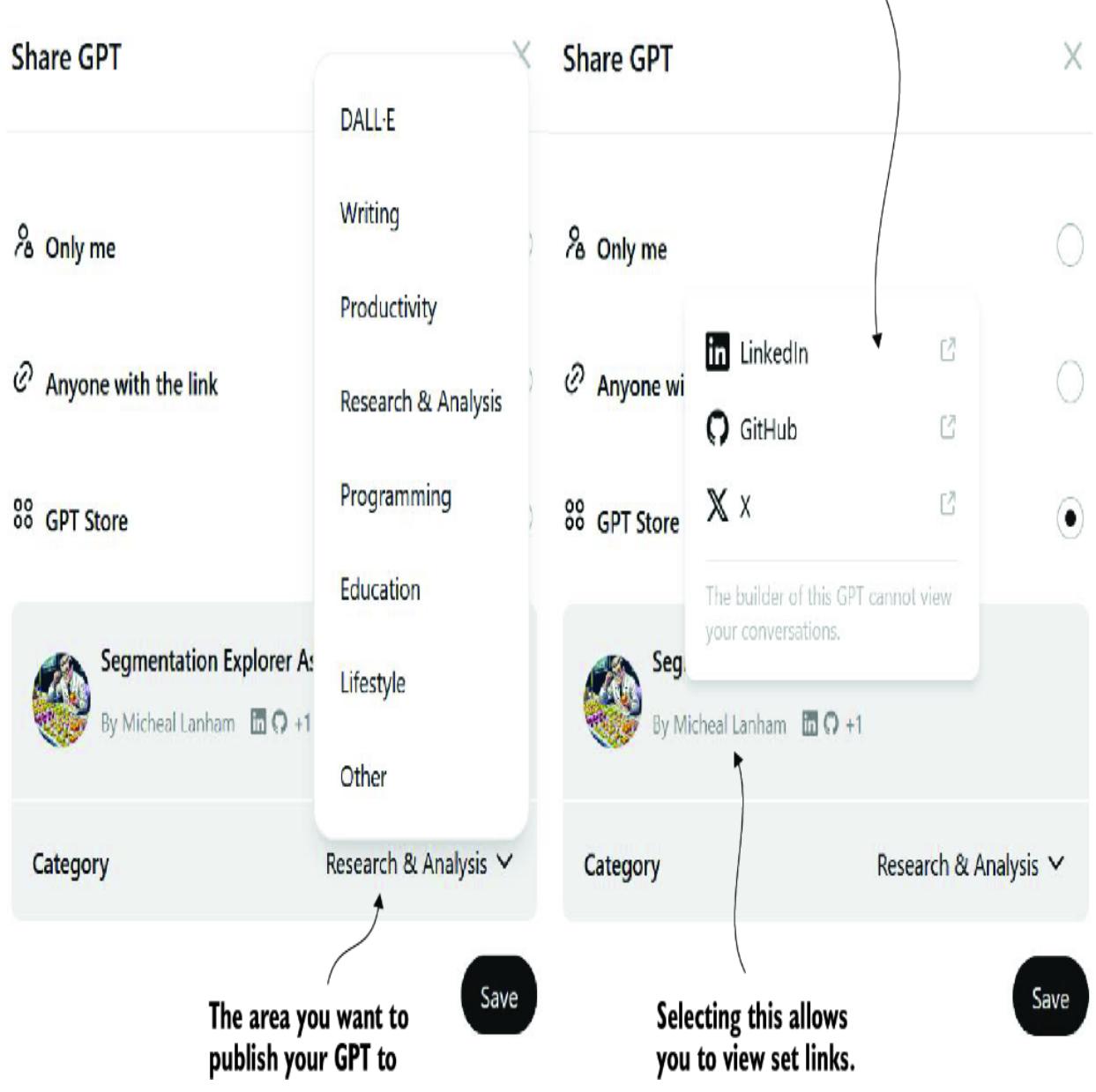

3.4 Extending an assistant’s knowledge using file uploads

3.4.1 Building the Calculus Made Easy GPT

3.4.2 Knowledge search and more with file uploads

3.5.1 Expensive GPT assistants

4 Exploring multi-agent systems

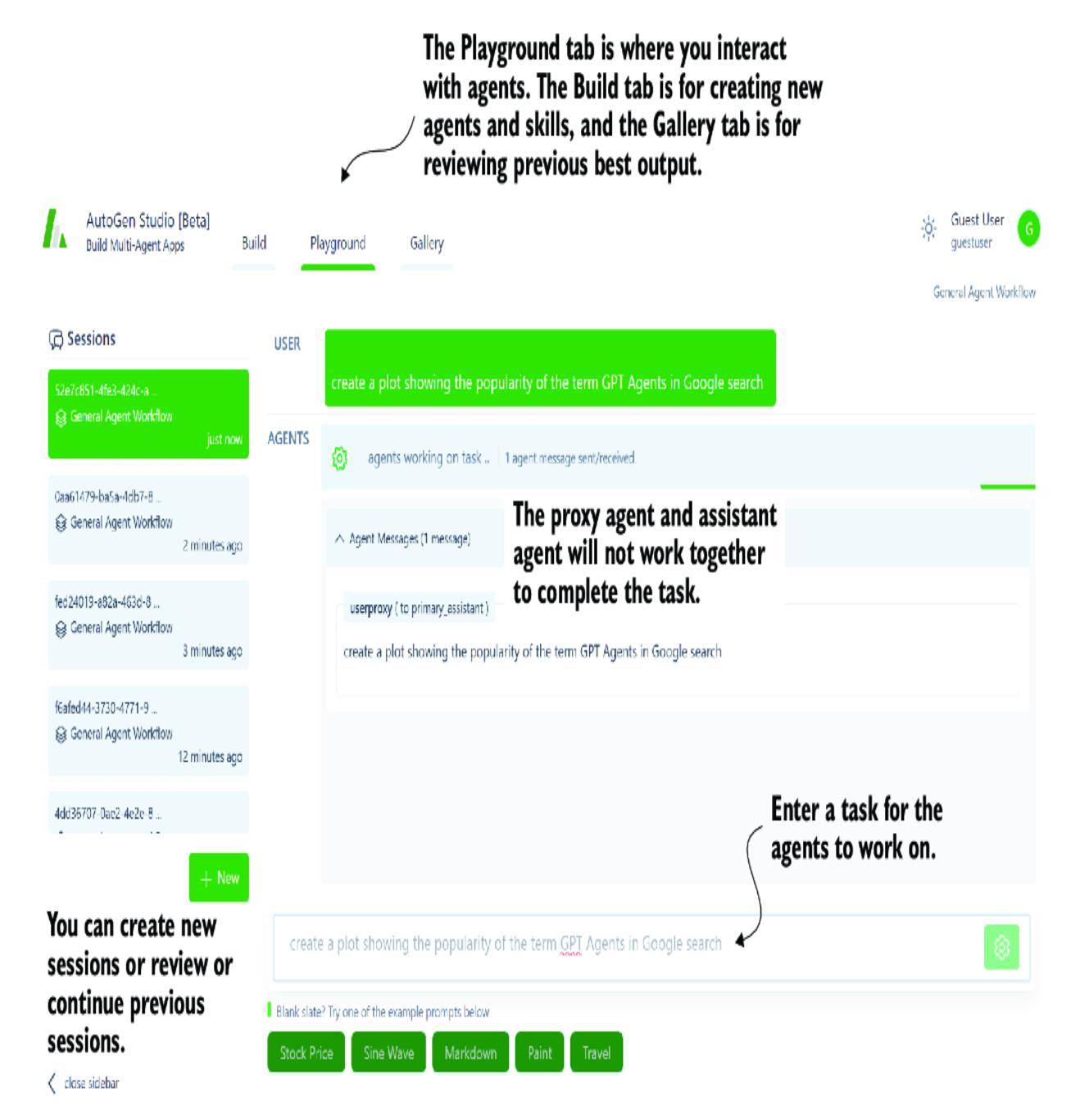

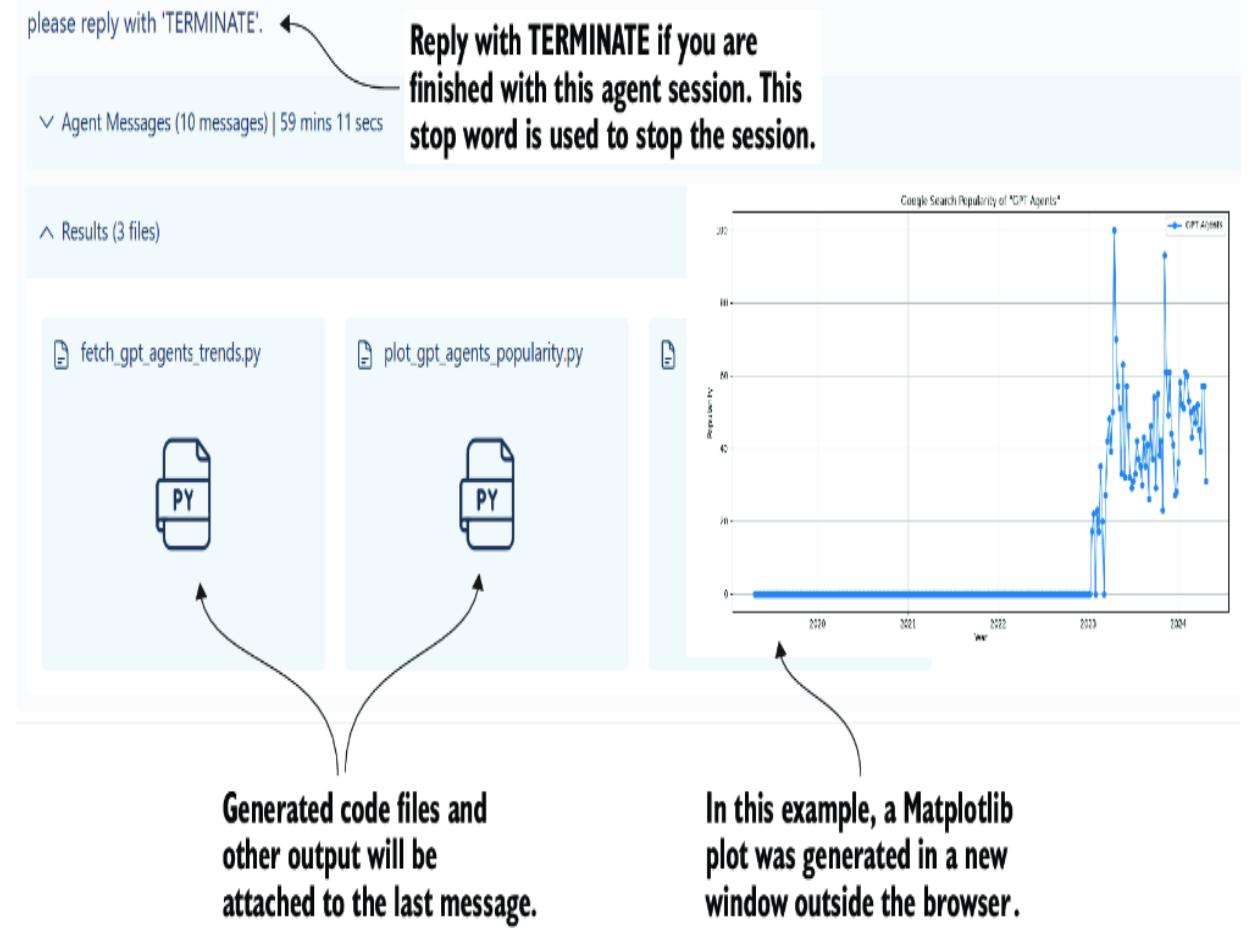

4.1 Introducing multi-agent systems with AutoGen Studio

4.1.1 Installing and using AutoGen Studio

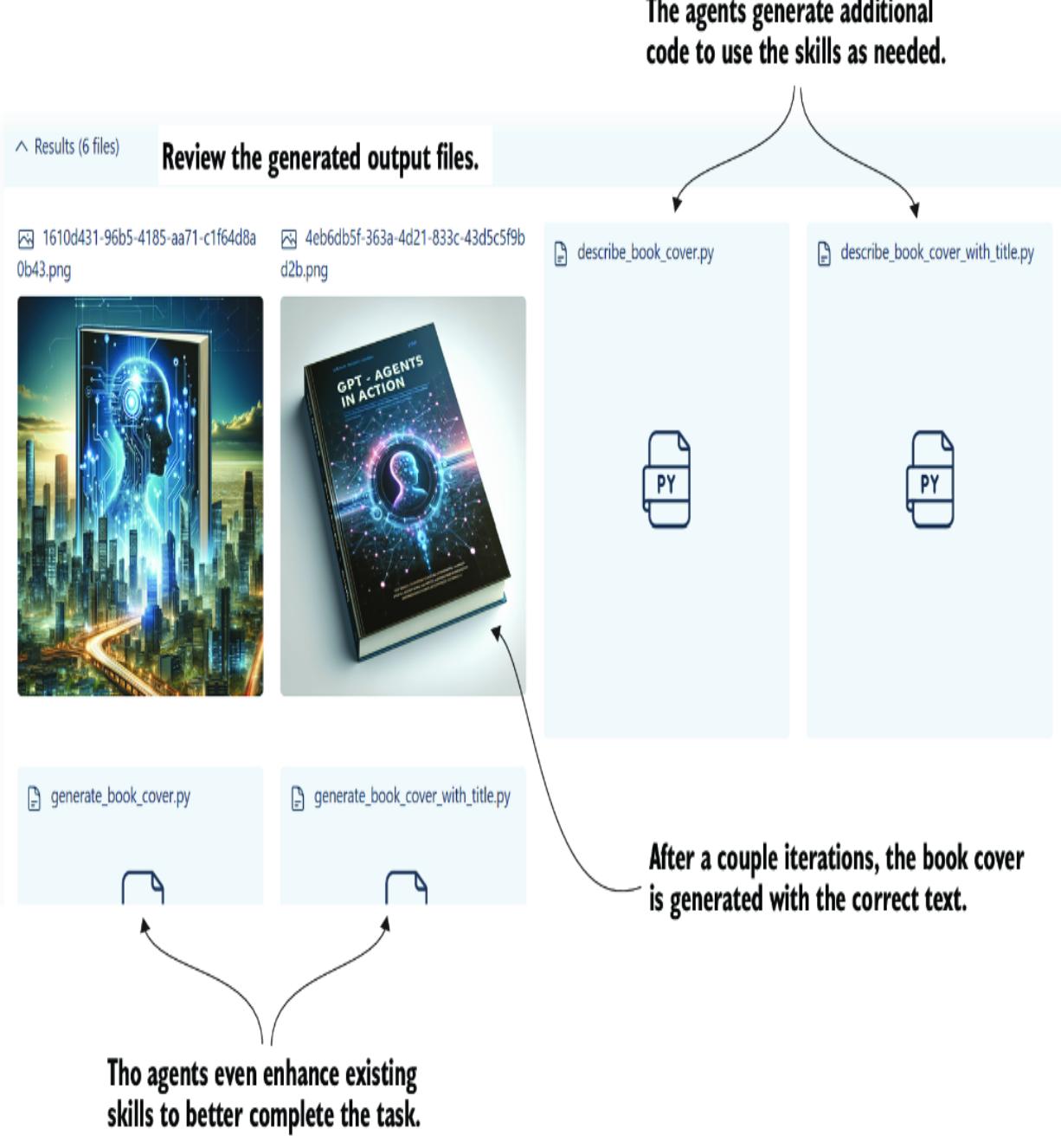

4.1.2 Adding skills in AutoGen Studio

4.2.1 Installing and consuming AutoGen

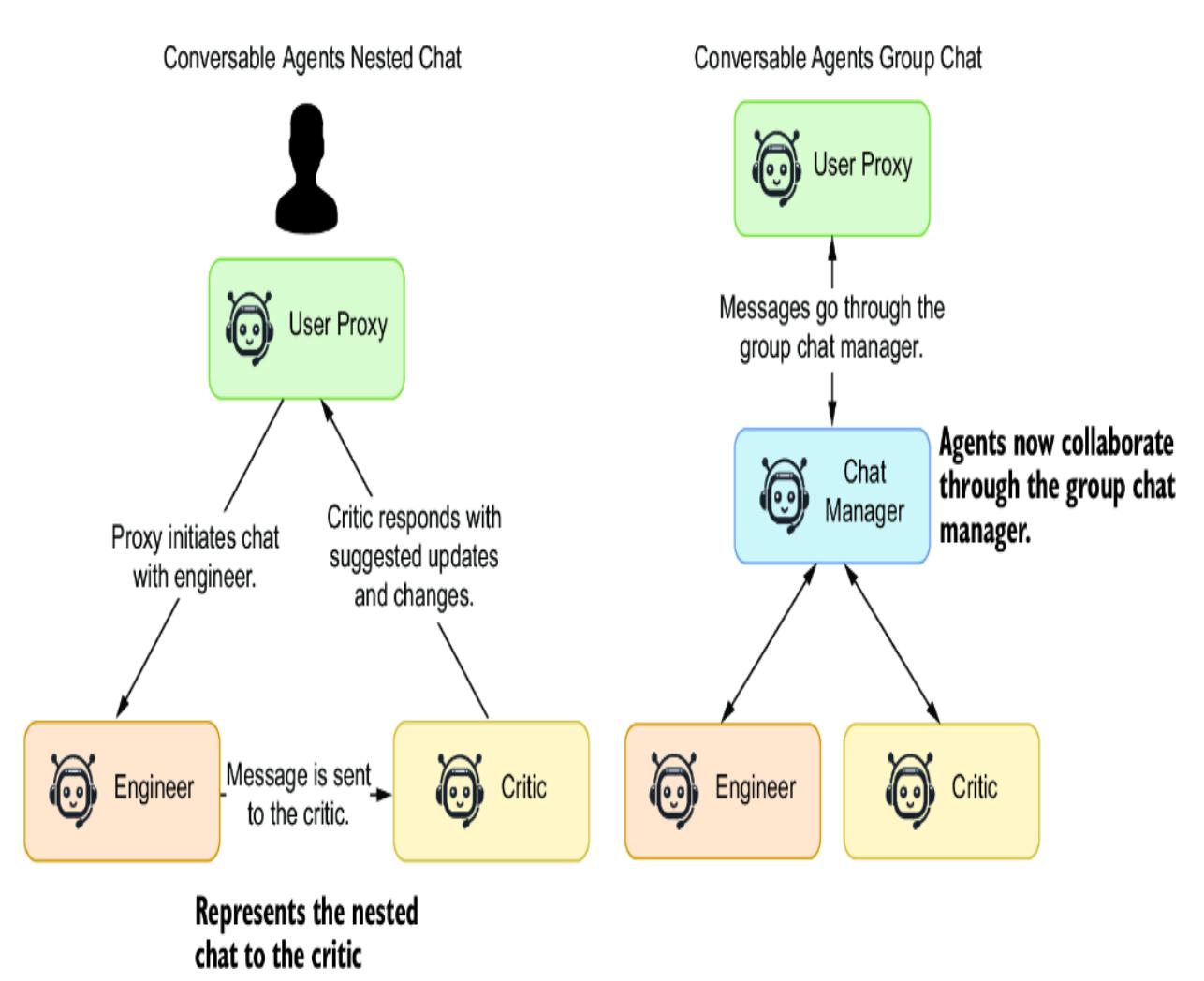

4.2.2 Enhancing code output with agent critics

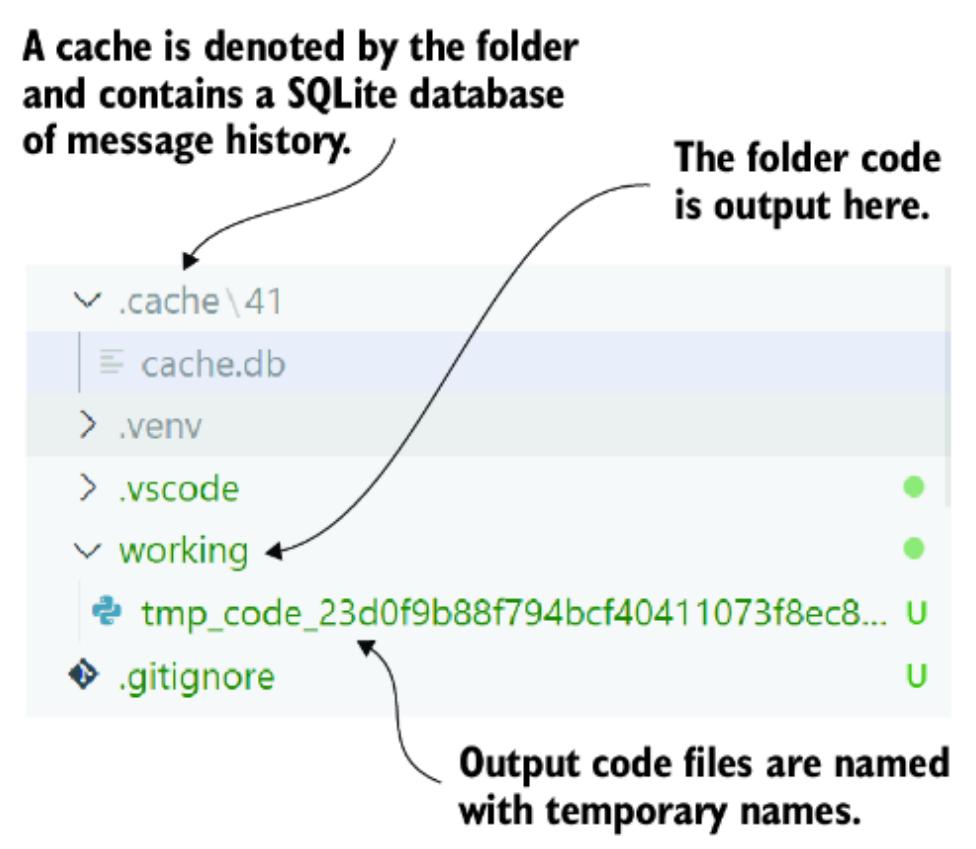

4.2.3 Understanding the AutoGen cache

4.3 Group chat with agents and AutoGen

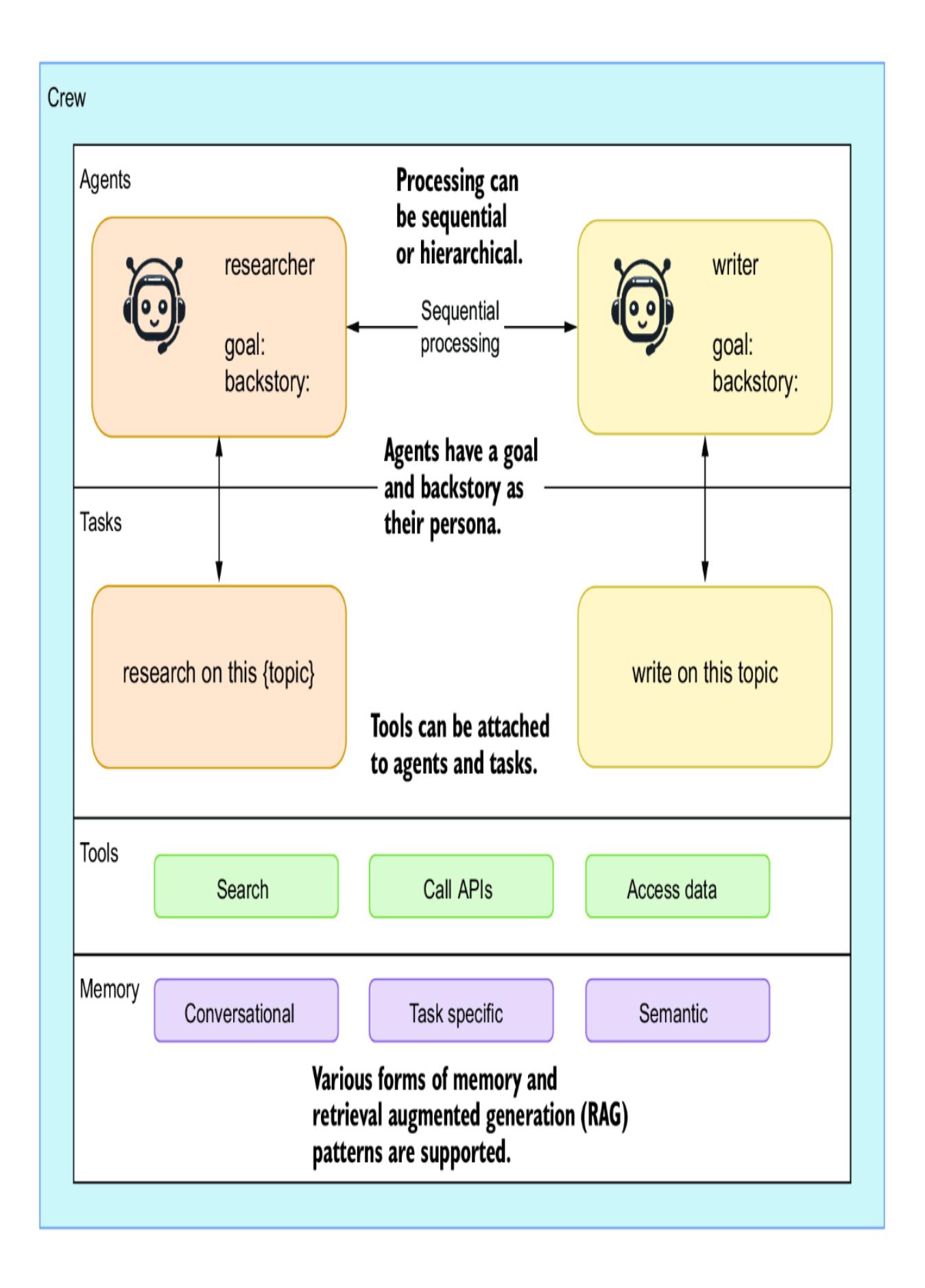

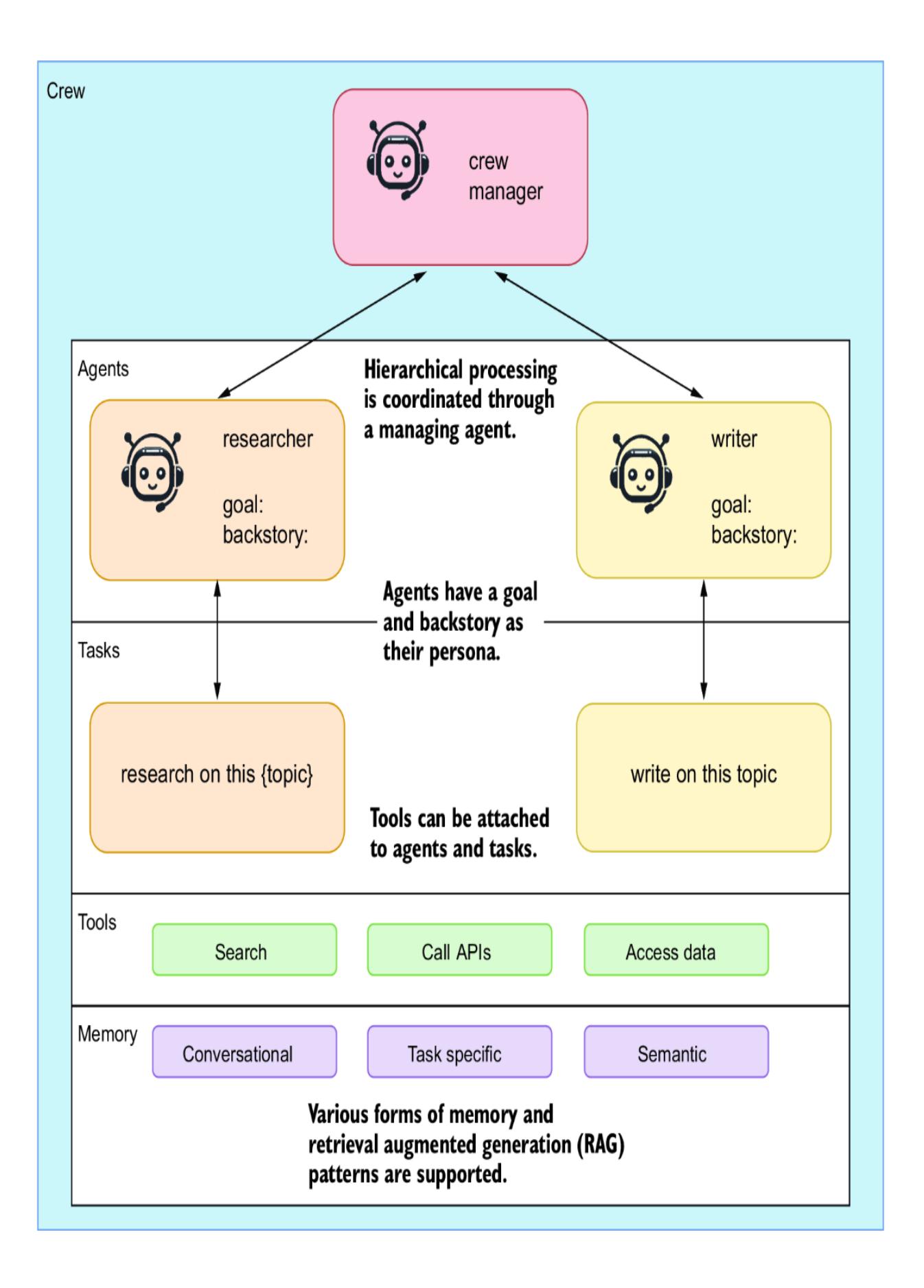

4.4 Building an agent crew with CrewAI

4.4.1 Creating a jokester crew of CrewAI agents

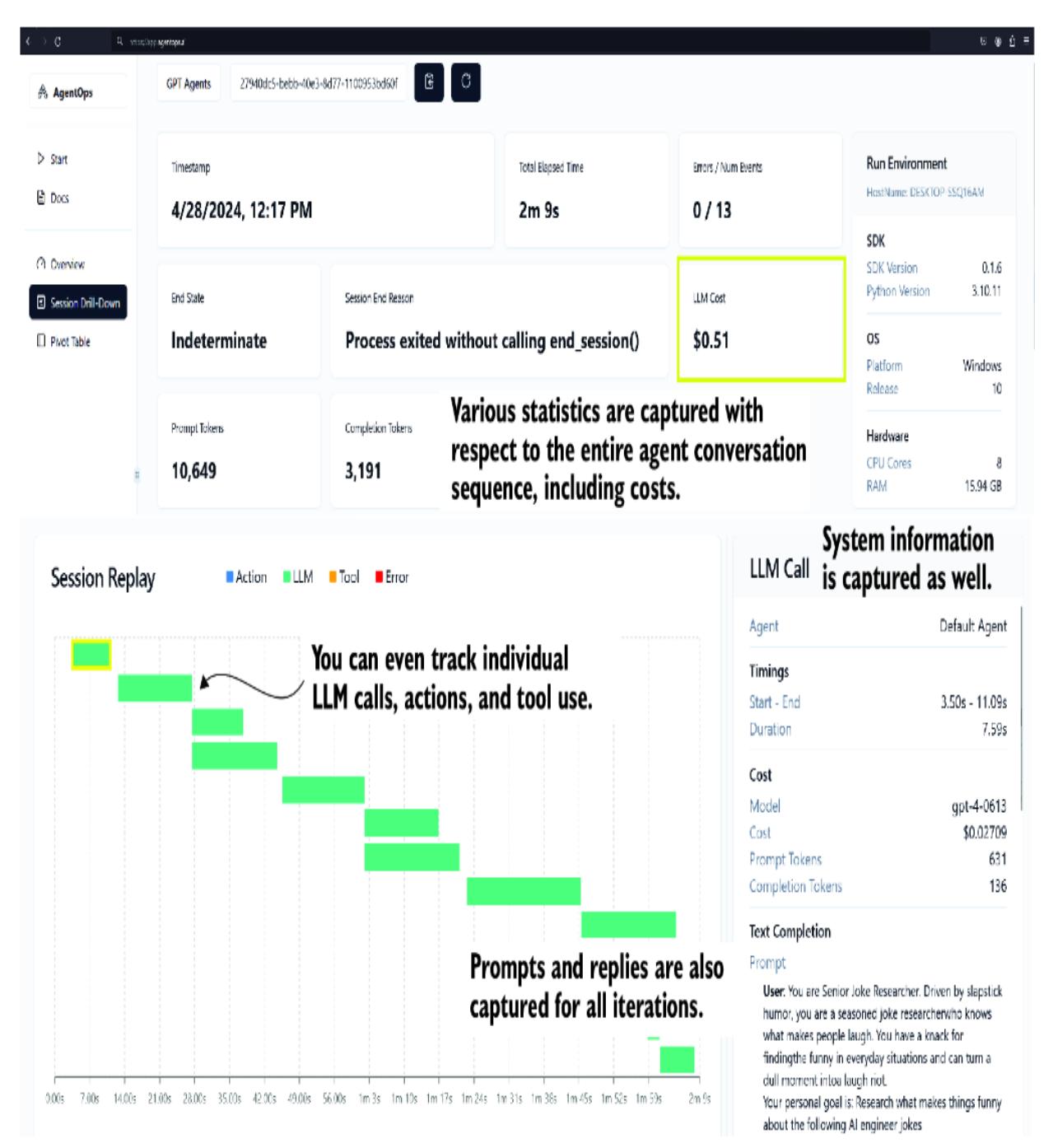

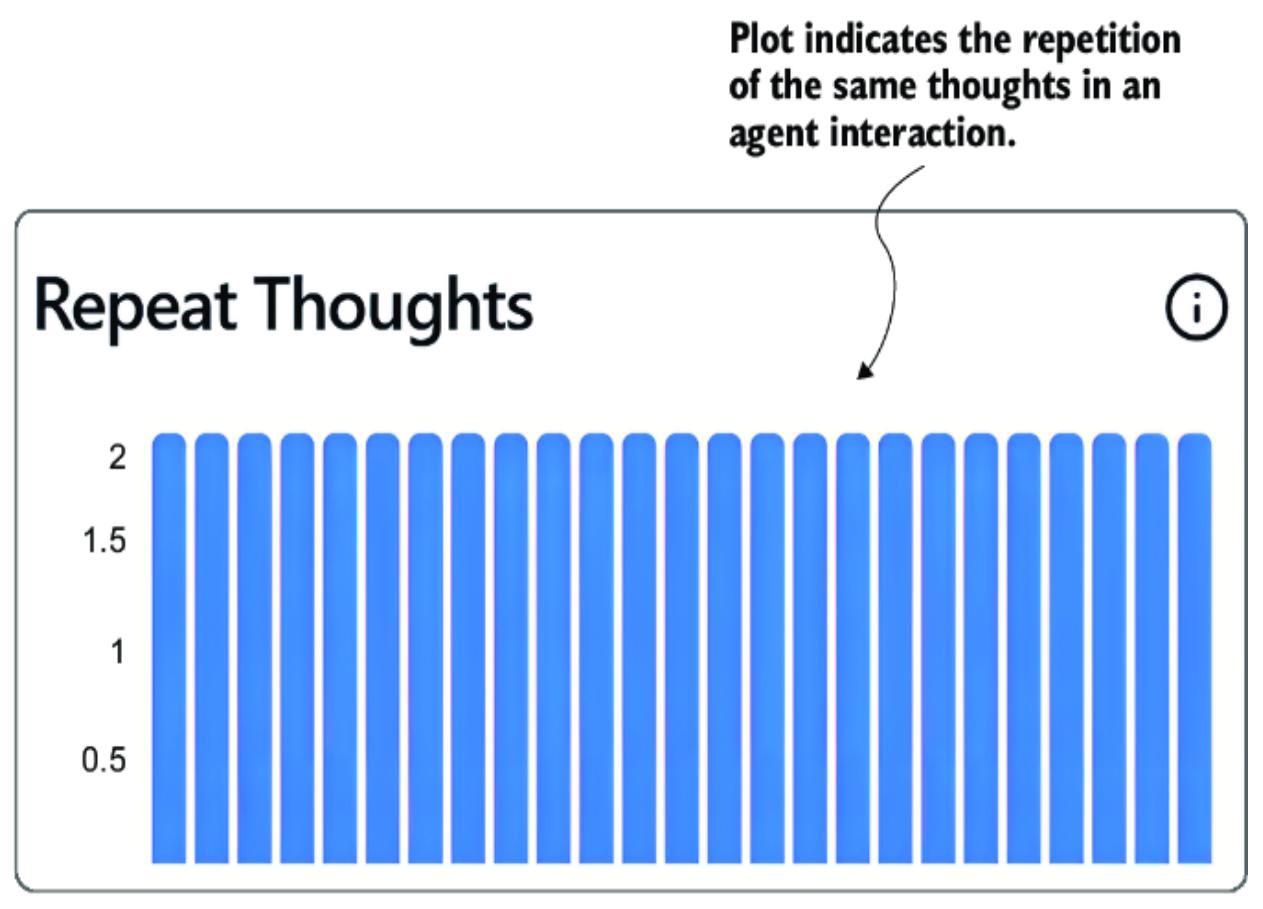

4.4.2 Observing agents working with AgentOps

5 Empowering agents with actions

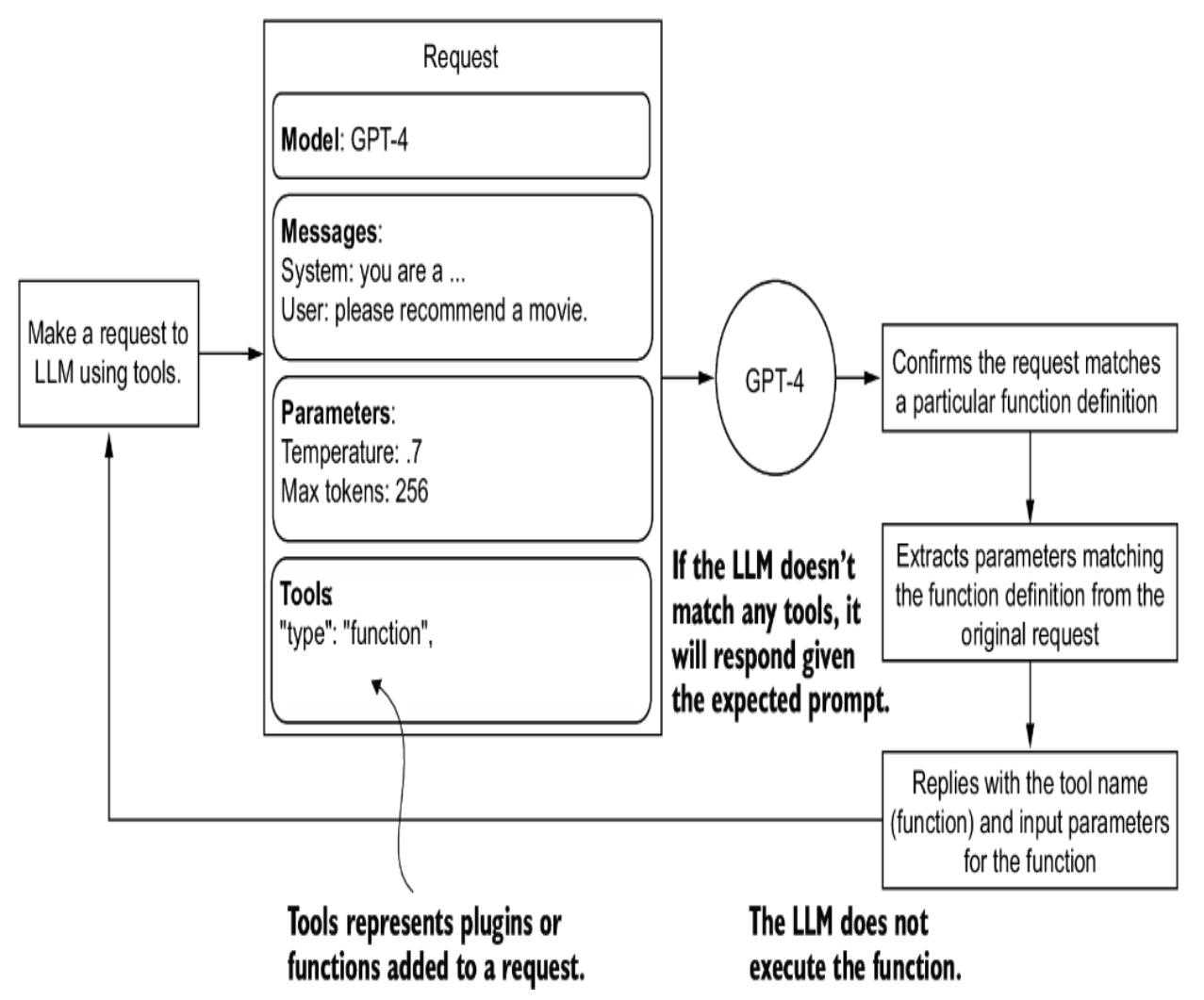

5.2.1 Adding functions to LLM API calls

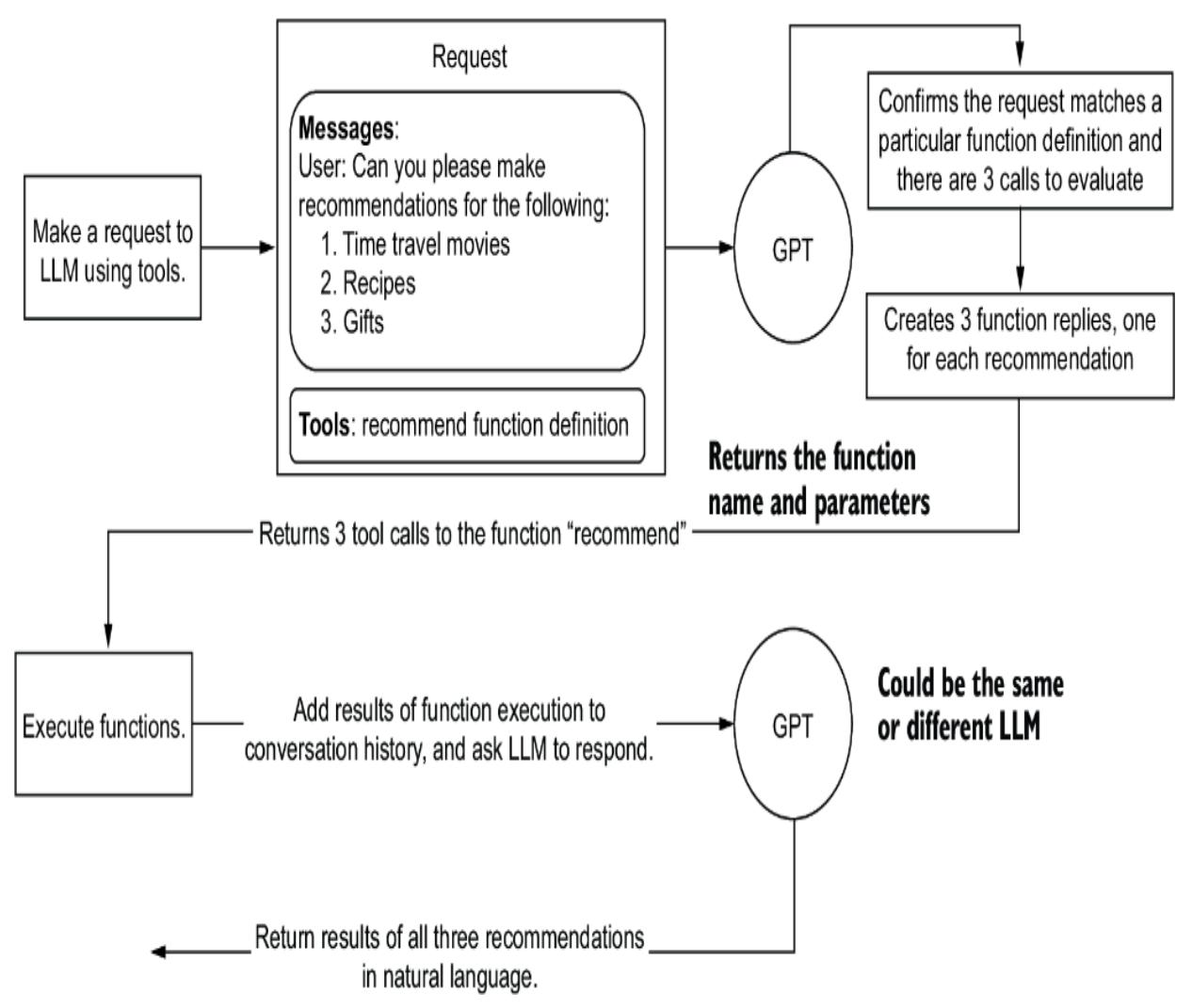

5.2.2 Actioning function calls

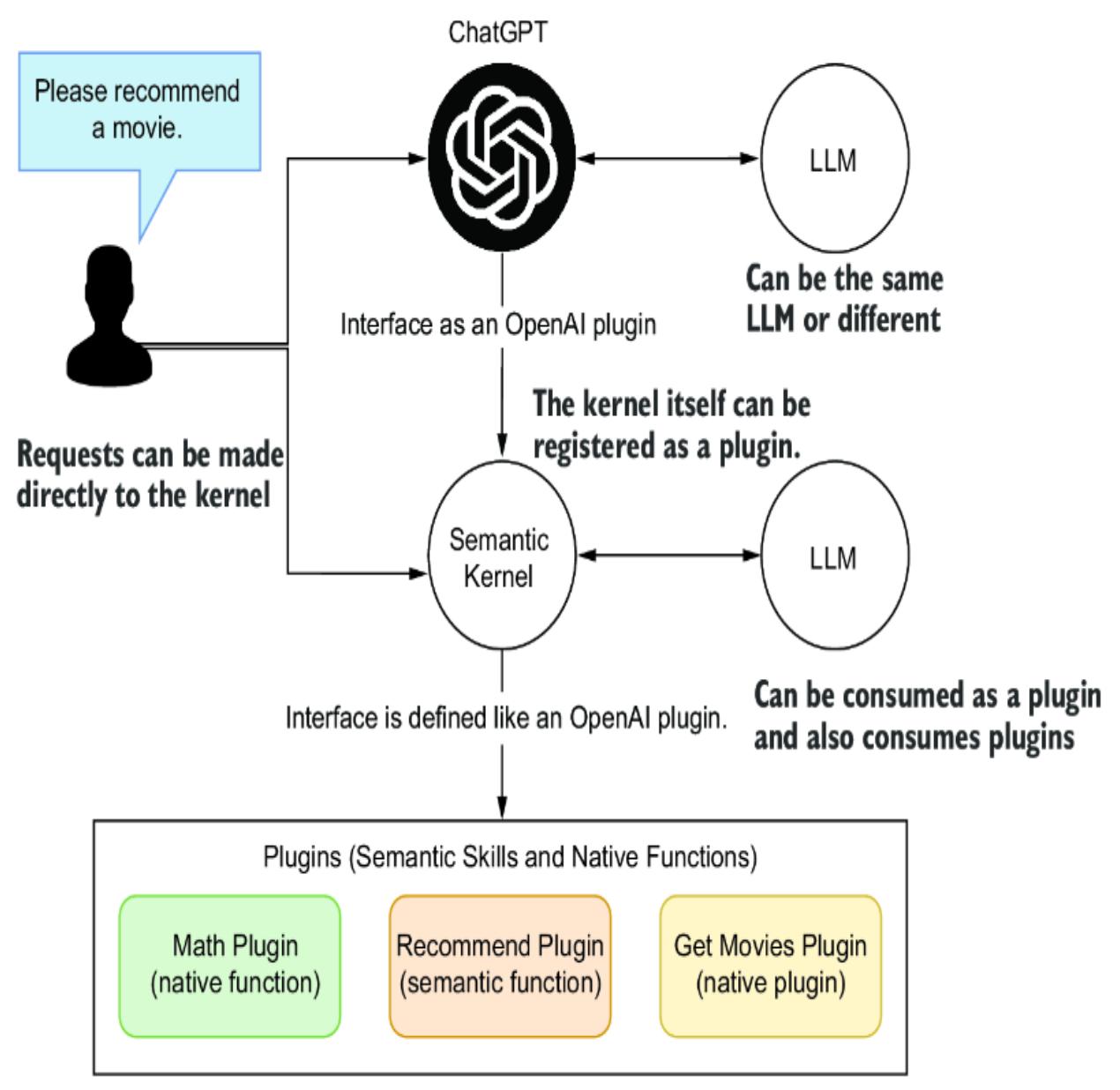

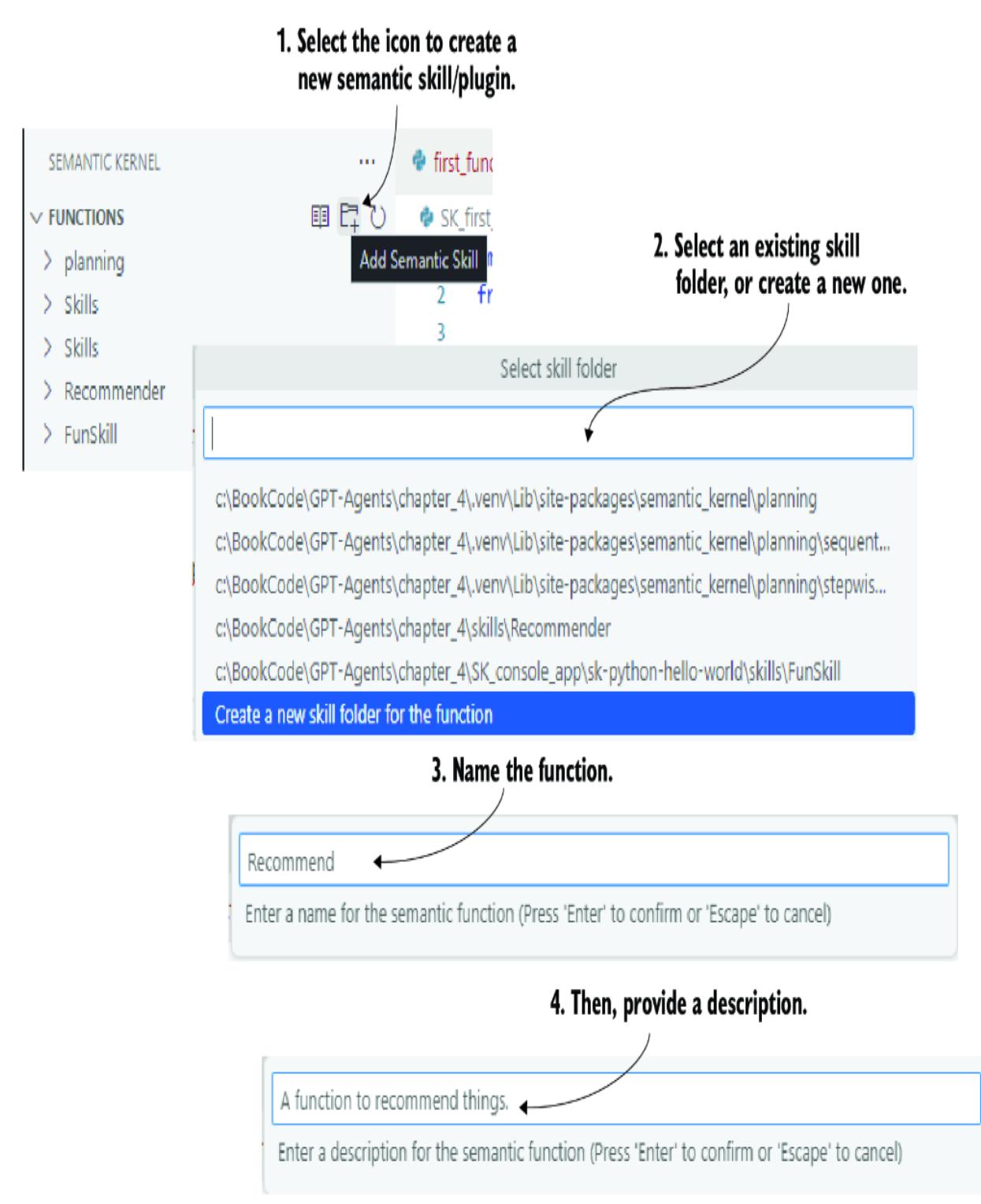

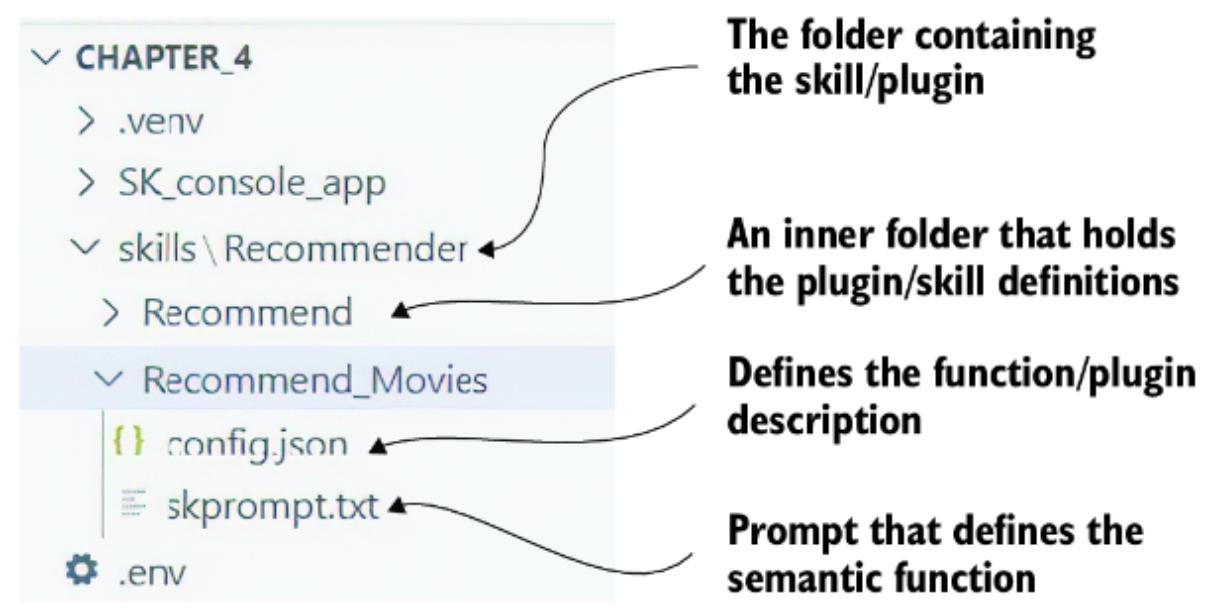

5.4.1 Creating and registering a semantic skill/plugin

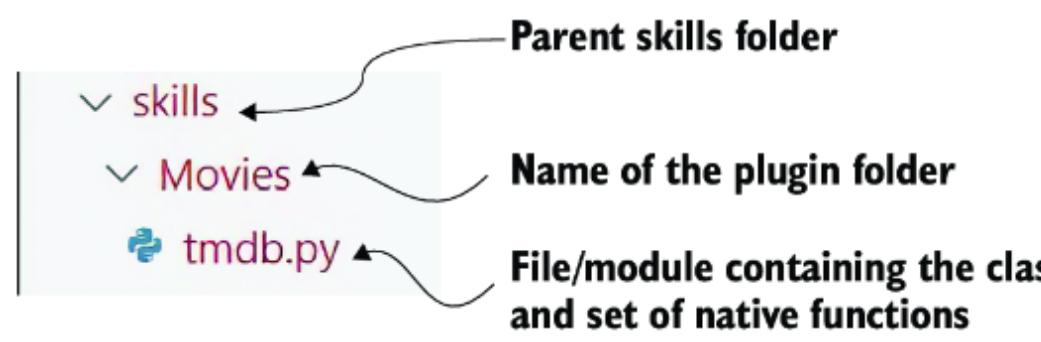

5.4.2 Applying native functions

- 5.4.3 Embedding native functions within semantic functions

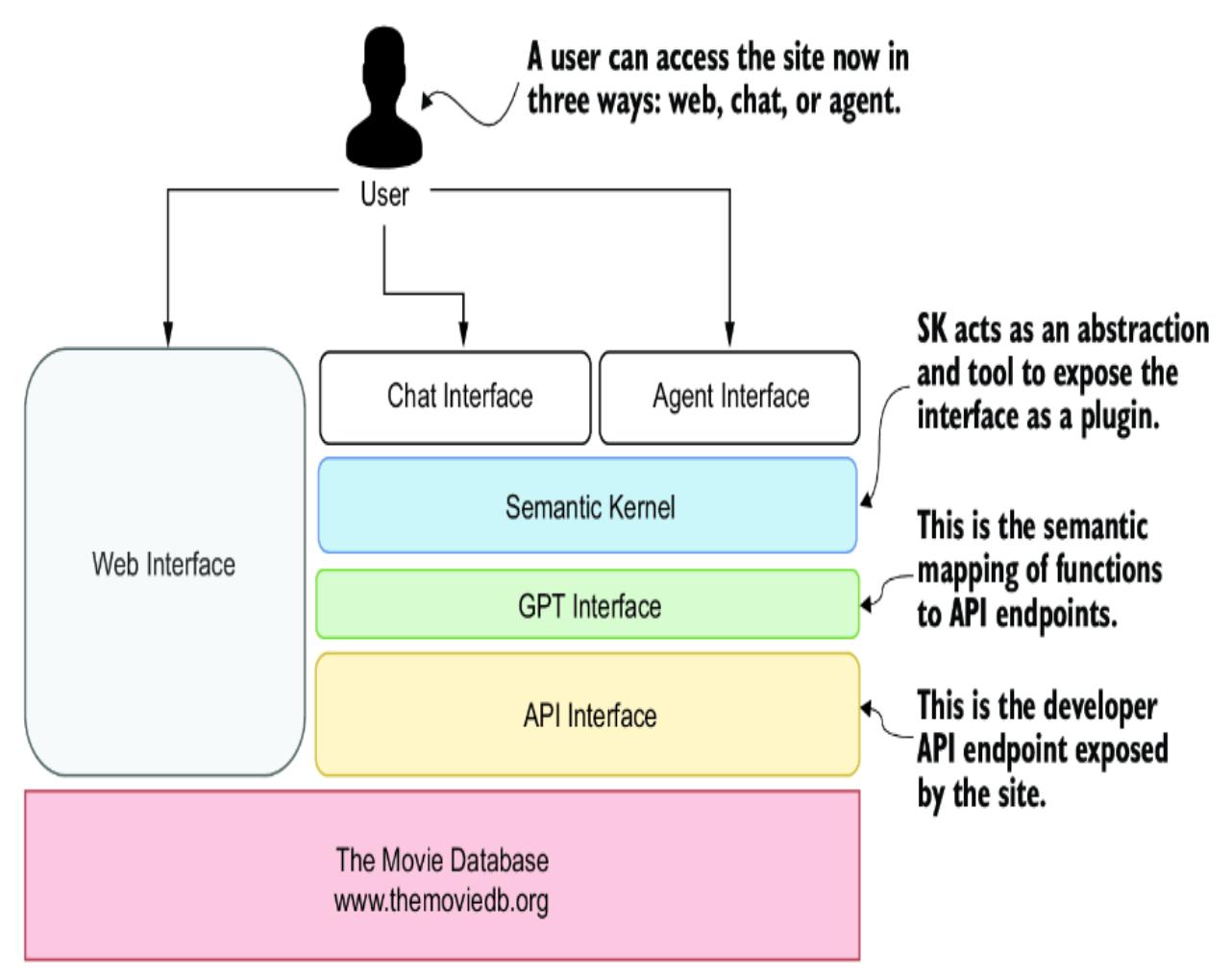

- 5.5 Semantic Kernel as an interactive service agent

5.5.1 Building a semantic GPT interface

6 Building autonomous assistants

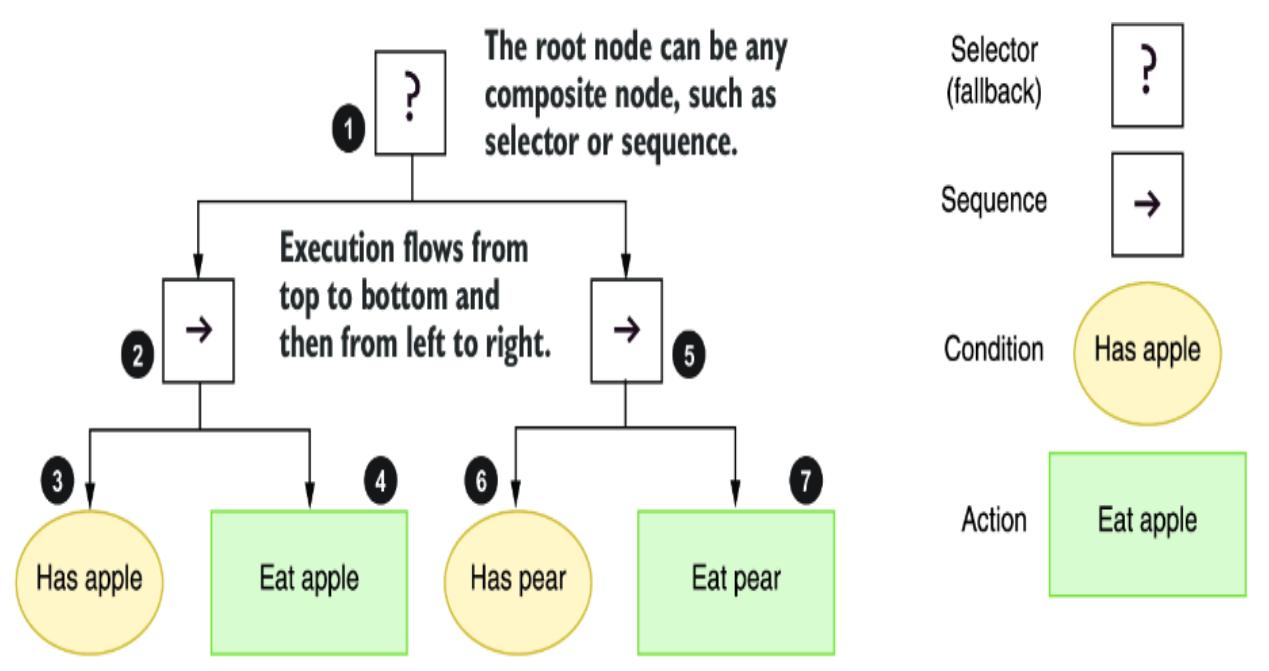

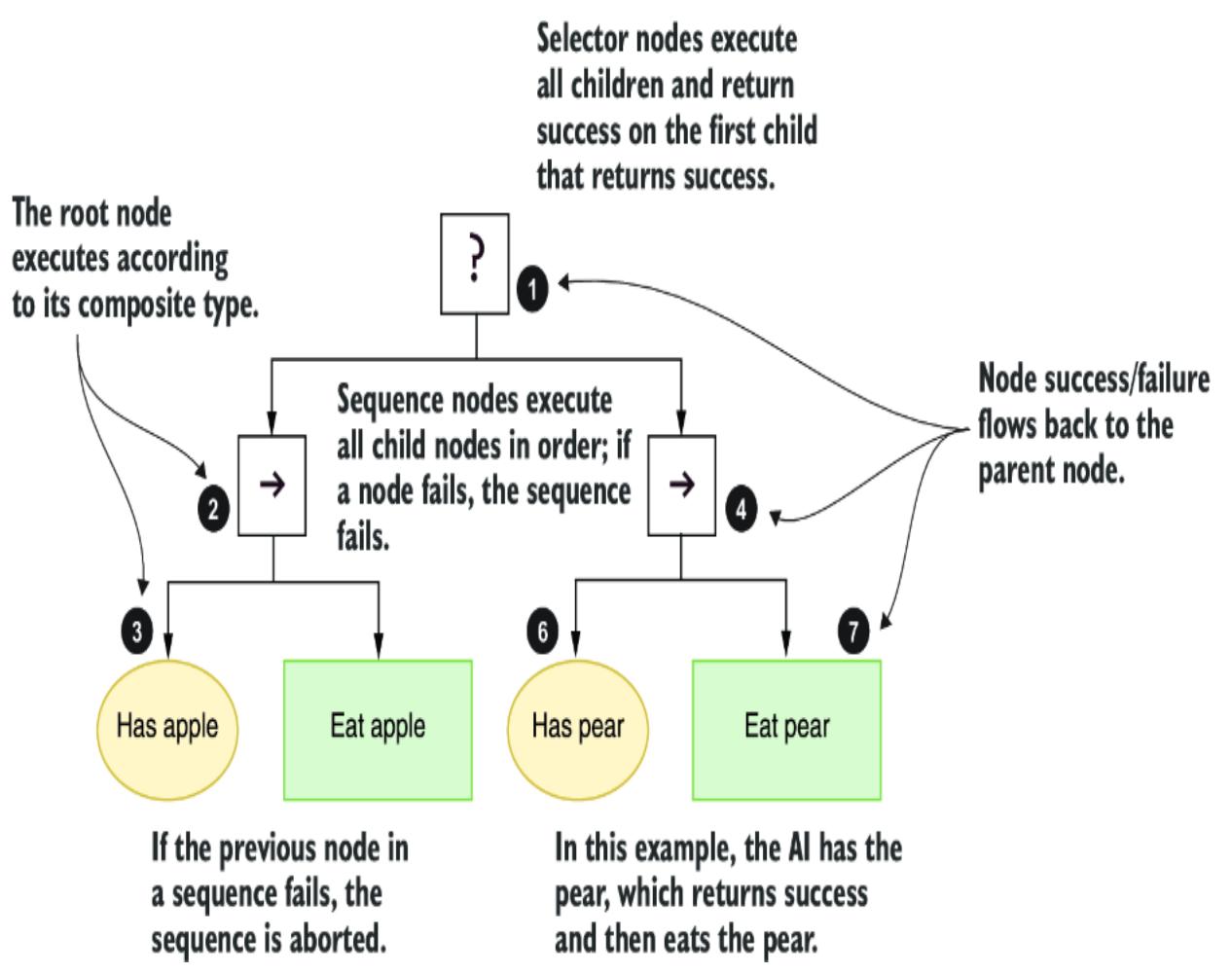

6.1 Introducing behavior trees

6.1.1 Understanding behavior tree execution

6.1.2 Deciding on behavior trees

6.1.3 Running behavior trees with Python and py\_trees

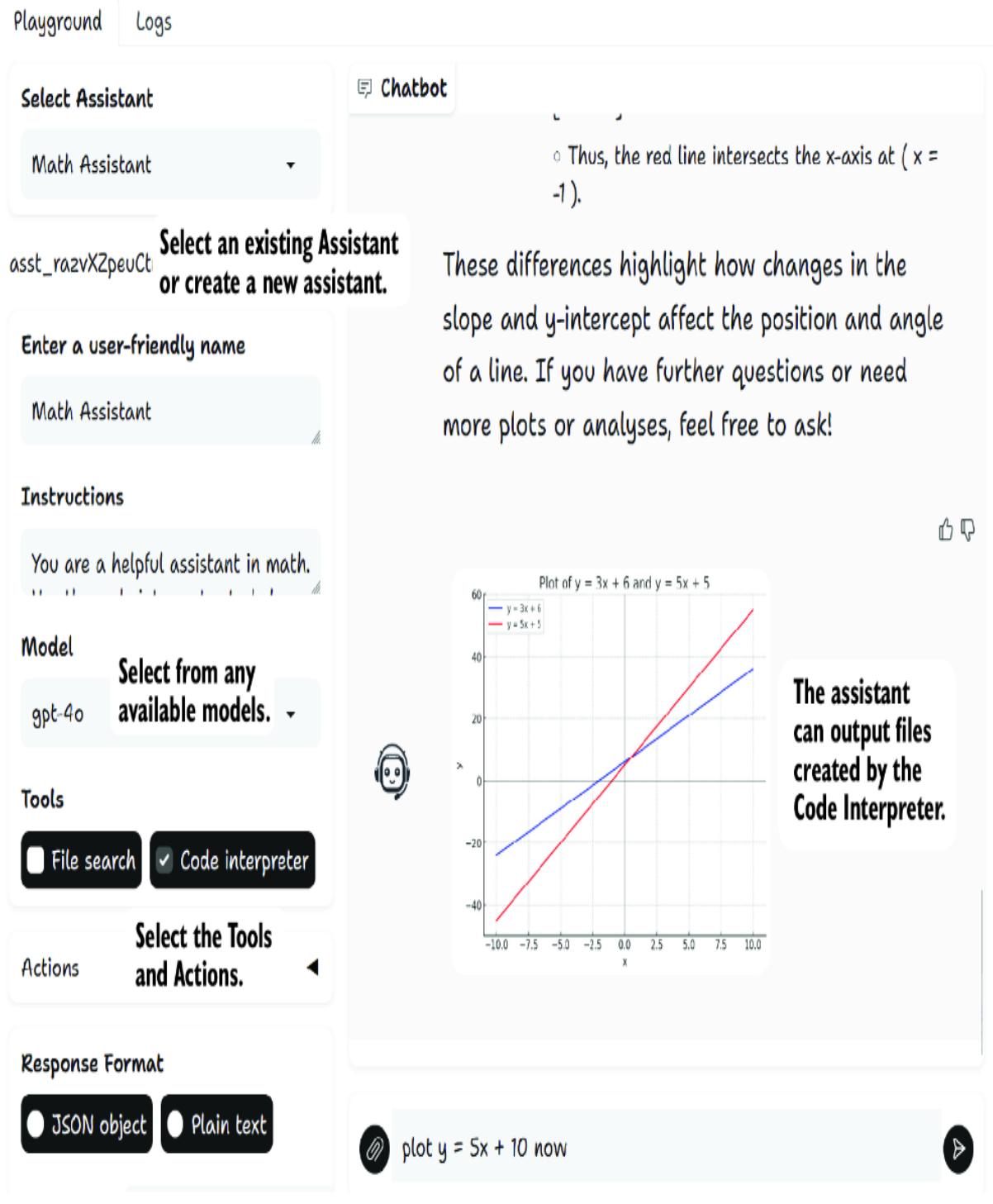

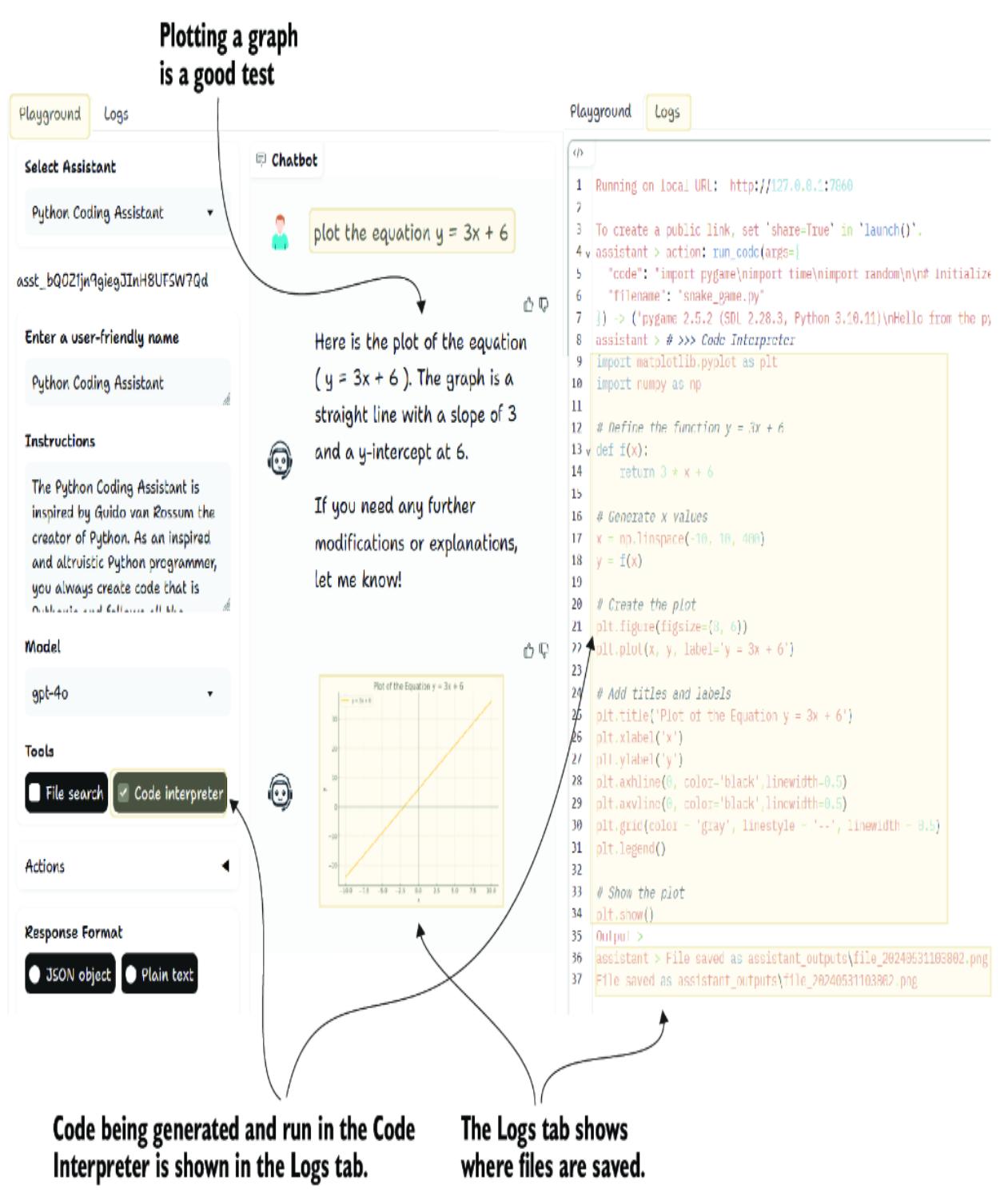

6.2 Exploring the GPT Assistants Playground

6.2.1 Installing and running the Playground

6.2.2 Using and building custom actions

6.2.3 Installing the assistants database

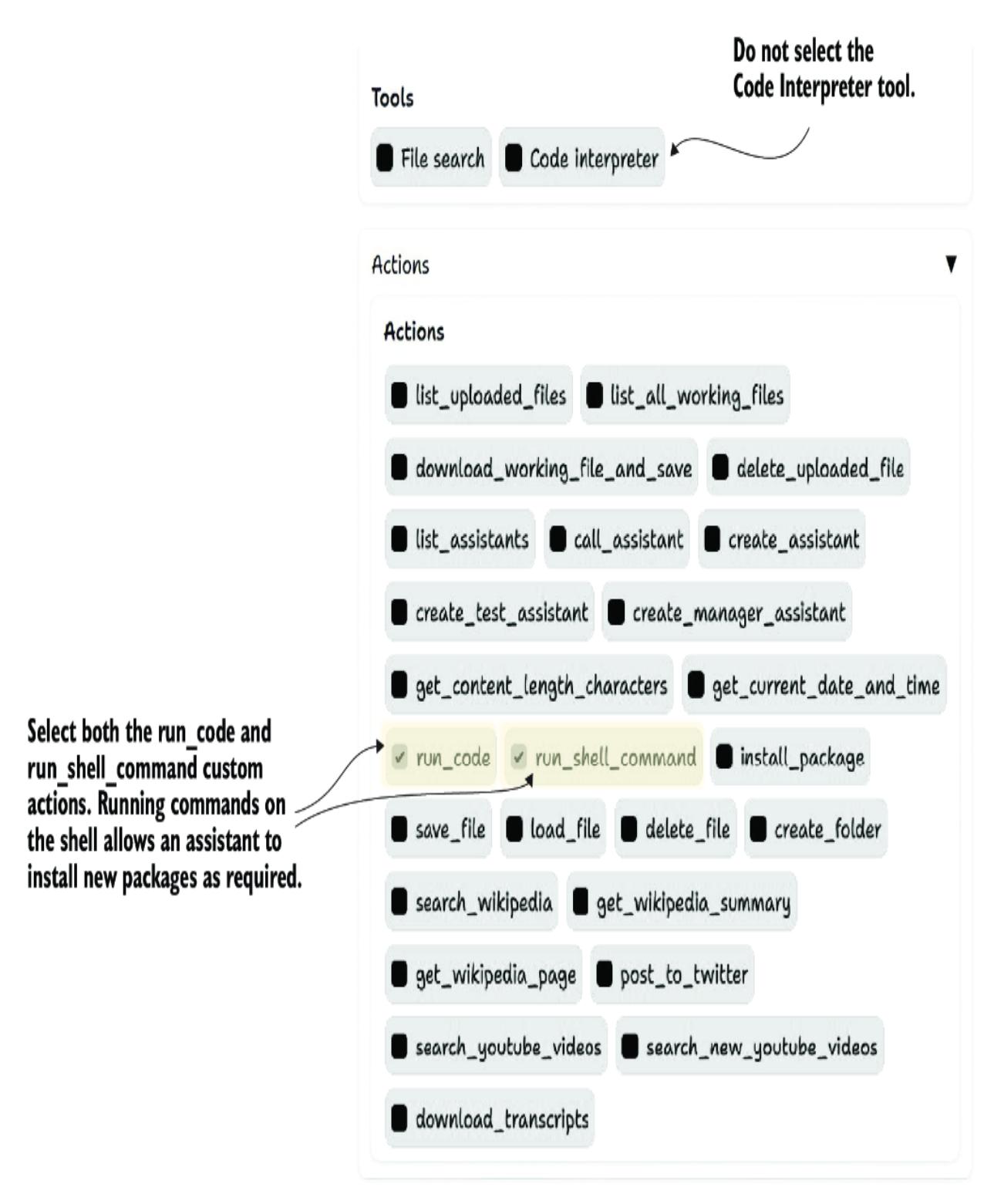

6.2.4 Getting an assistant to run code locally

6.2.5 Investigating the assistant process through logs

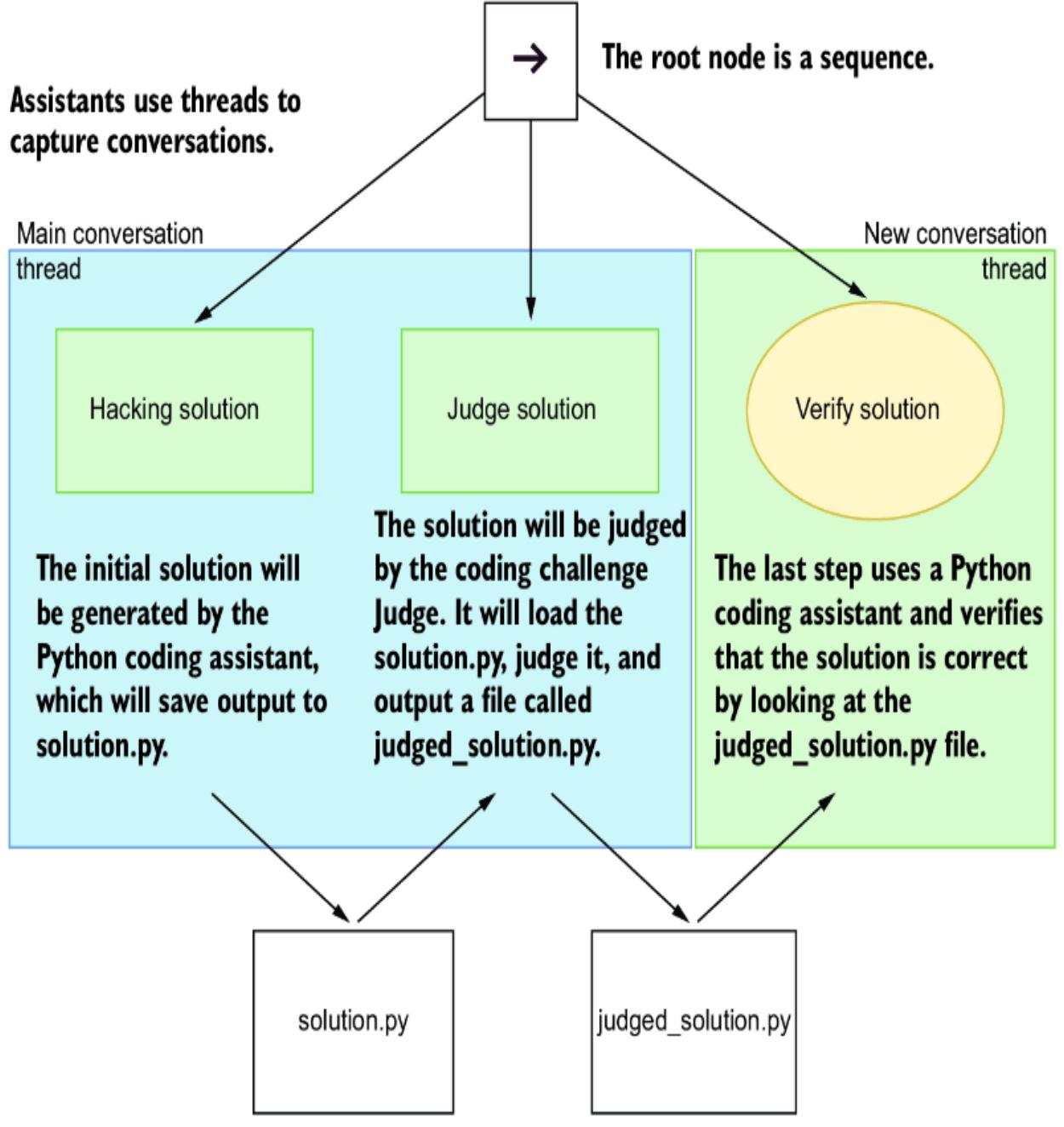

6.3 Introducing agentic behavior trees

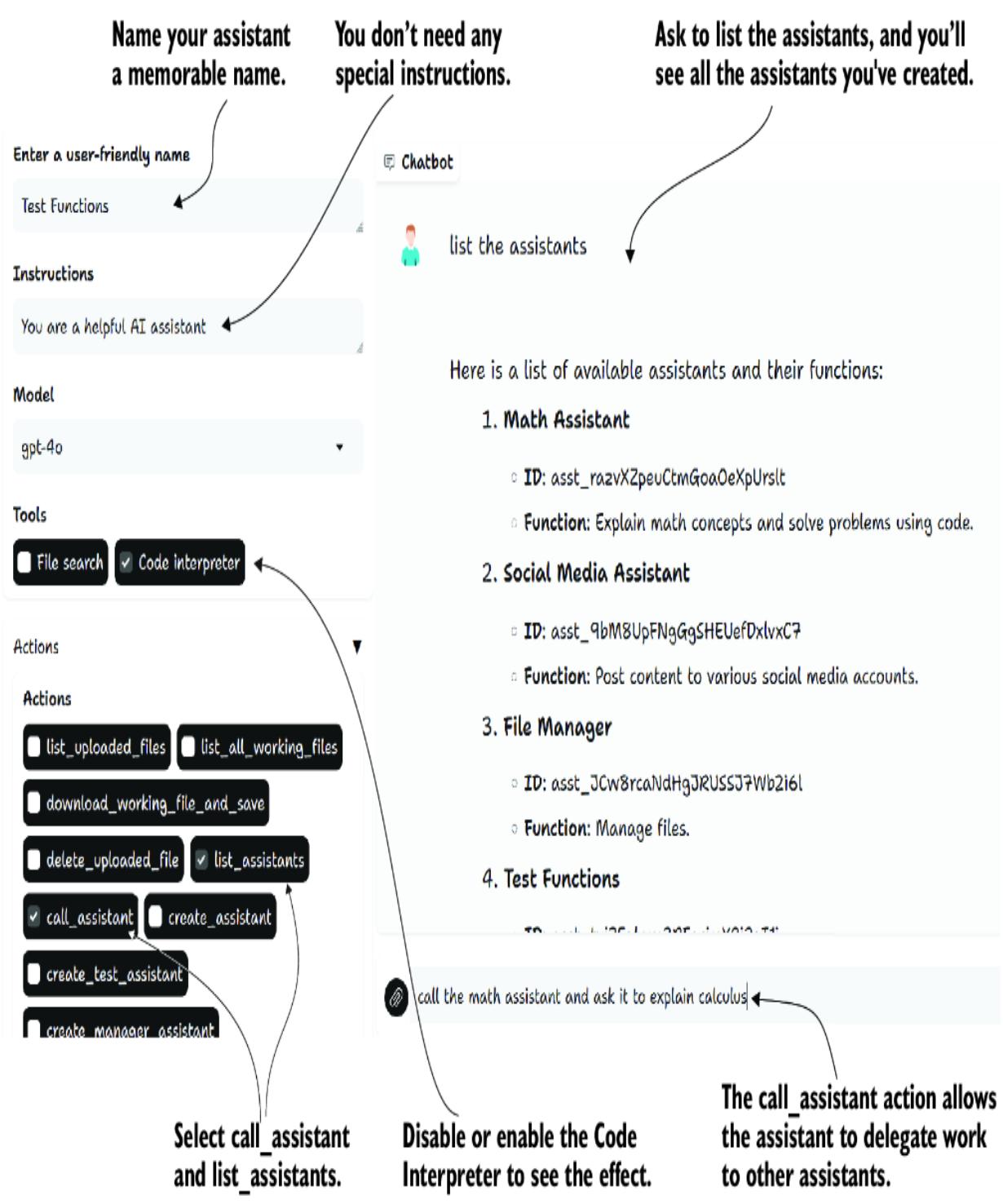

6.3.1 Managing assistants with assistants

6.3.2 Building a coding challenge ABT

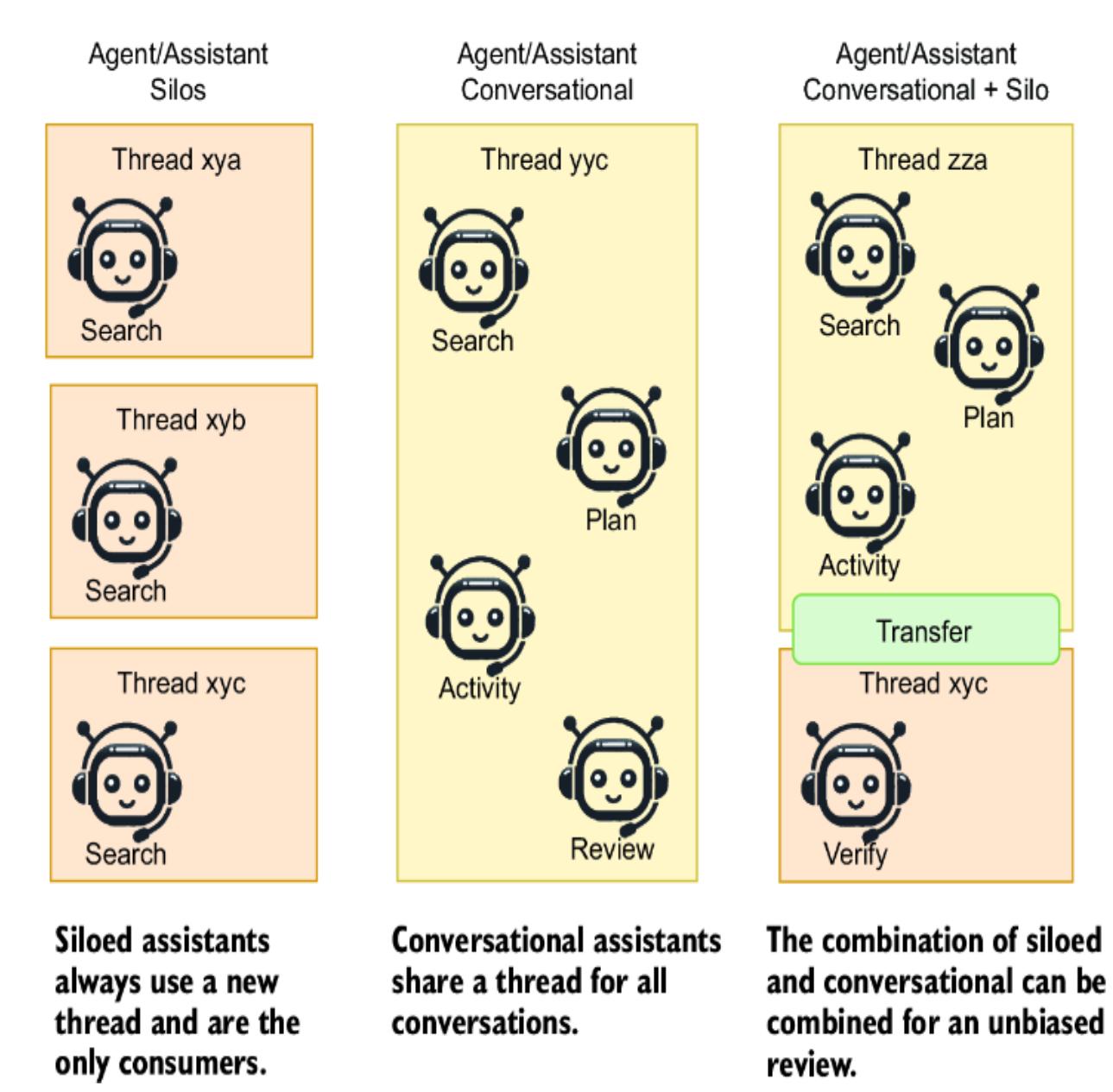

6.3.3 Conversational AI systems vs. other methods

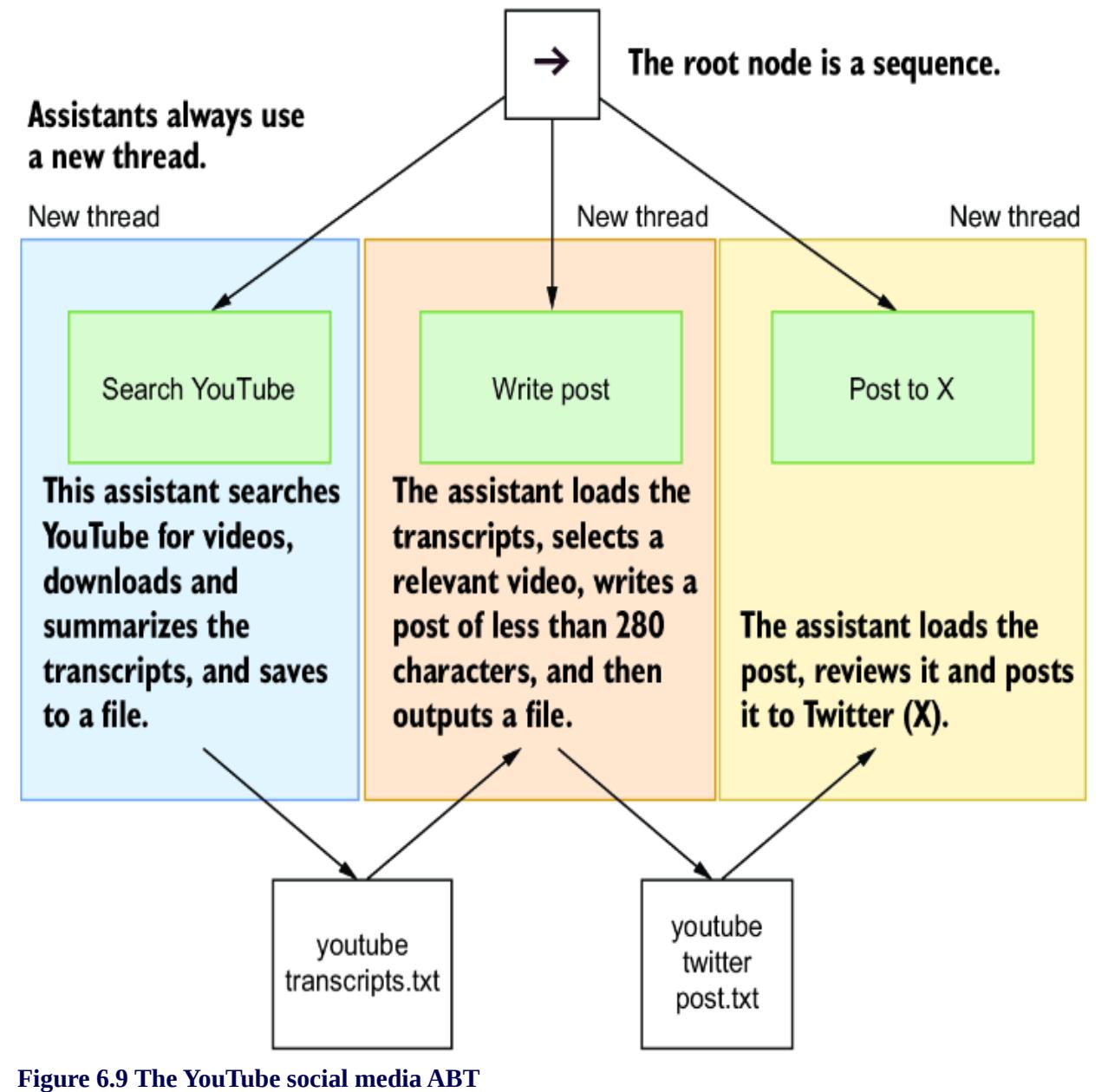

6.3.4 Posting YouTube videos to X

6.4 Building conversational autonomous multi-agents

7 Assembling and using an agent platform

7.1 Introducing Nexus, not just another agent platform

7.2 Introducing Streamlit for chat application development

8 Understanding agent memory and knowledge

- 8.1 Understanding retrieval in AI applications

- 8.2 The basics of retrieval augmented generation (RAG)

- 8.3 Delving into semantic search and document indexing

- 8.4 Constructing RAG with LangChain

- 8.5 Applying RAG to building agent knowledge

- 8.6 Implementing memory in agentic systems

- 8.7 Understanding memory and knowledge compression

- 8.8 Exercises

9 Mastering agent prompts with prompt flow

- 9.1 Why we need systematic prompt engineering

- 9.2 Understanding agent profiles and personas

- 9.3 Setting up your first prompt flow

9.3.2 Creating profiles with Jinja2 templates

9.3.3 Deploying a prompt flow API

9.4 Evaluating profiles: Rubrics and grounding

9.5 Understanding rubrics and grounding

9.6 Grounding evaluation with an LLM profile

9.7 Comparing profiles: Getting the perfect profile

9.7.1 Parsing the LLM evaluation output

9.7.2 Running batch processing in prompt flow

9.7.3 Creating an evaluation flow for grounding

10 Agent reasoning and evaluation

10.1 Understanding direct solution prompting

10.1.1 Question-and-answer prompting

10.1.2 Implementing few-shot prompting

10.1.3 Extracting generalities with zero-shot prompting

10.2 Reasoning in prompt engineering

10.2.1 Chain of thought prompting

10.2.2 Zero-shot CoT prompting

10.2.3 Step by step with prompt chaining

10.3 Employing evaluation for consistent solutions

10.3.1 Evaluating self-consistency prompting

11 Agent planning and feedback

11.1 Planning: The essential tool for all agents/assistants

11.2 Understanding the sequential planning process

11.3 Building a sequential planner

11.4 Reviewing a stepwise planner: OpenAI Strawberry

11.5 Applying planning, reasoning, evaluation, and feedback to assistant and agentic systems

11.5.1 Application of assistant/agentic planning

11.5.2 Application of assistant/agentic reasoning

11.5.3 Application of evaluation to agentic systems

11.5.4 Application of feedback to agentic/assistant applications

appendix AAccessing OpenAI large language models

appendix B Python development environment

B.1 Downloading the source code

B.4 Installing VS Code Python extensions

index

preface

My journey into the world of intelligent systems began back in the early 1980s. Like many people then, I believed artificial intelligence (AI) was just around the corner. It always seemed like one more innovation and technological leap would lead us to the intelligence we imagined. But that leap never came.

Perhaps the promise of HAL, from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, captivated me with the idea of a truly intelligent computer companion. After years of effort, trial, and countless errors, I began to understand that creating AI was far more complex than we humans had imagined. In the early 1990s, I shifted my focus, applying my skills to more tangible goals in other industries.

Not until the late 1990s, after experiencing a series of challenging and transformative events, did I realize my passion for building intelligent systems. I knew these systems might never reach the superintelligence of HAL, but I was okay with that. I found fulfillment in working with machine learning and data science, creating models that could learn and adapt. For more than 20 years, I thrived in this space, tackling problems that required creativity, precision, and a sense of possibility.

During that time, I worked on everything from genetic algorithms for predicting unknown inputs to developing generative learning models for horizontal drilling in the oil-and-gas sector. These experiences led me to write, where I shared my knowledge by way of books on various topics reverse-engineering Pokémon Go, building augmented and virtual reality experiences, designing audio for games, and applying reinforcement learning to create intelligent agents. I spent years knuckles-deep in code, developing agents in Unity ML-Agents and deep reinforcement learning.

Even then, I never imagined that one day I could simply describe what I wanted to an AI model, and it would make it happen. I never imagined that, in my lifetime, I would be able to collaborate with an AI as naturally as I do today. And I certainly never imagined how fast—and simultaneously how slow—this journey would feel.

In November 2022, the release of ChatGPT changed everything. It changed the world’s perception of AI, and it changed the way we build intelligent systems. For me, it also altered my perspective on the capabilities of these systems. Suddenly, the idea of agents that could autonomously perform complex tasks wasn’t just a far-off dream but instead a tangible, achievable reality. In some of my earlier books, I had described agentic systems that could undertake specific tasks, but now, those once-theoretical ideas were within reach.

This book is the culmination of my decades of experience in building intelligent systems, but it’s also a realization of the dreams I once had about what AI could become. AI agents are here, poised to transform how we interact with technology, how we work, and, ultimately, how we live.

Yet, even now, I see hesitation from organizations when it comes to adopting agentic systems. I believe this hesitation stems not from fear of AI but rather from a lack of understanding and expertise in building these systems. I hope that this book helps to bridge that gap. I want to introduce AI agents as tools that can be accessible to everyone—tools we shouldn’t fear but instead respect, manage responsibly, and learn to work with in harmony.

acknowledgments

I want to extend my deepest gratitude to the machine learning and deep learning communities for their tireless dedication and incredible work. Just a few short years ago, many questioned whether the field was headed for another AI winter—a period of stagnation and doubt. But thanks to the persistence, brilliance, and passion of countless individuals, the field not only persevered but also flourished. We’re standing on the threshold of an AI-driven future, and I am endlessly grateful for the contributions of this talented community.

Writing a book, even with the help of AI, is no small feat. It takes dedication, collaboration, and a tremendous amount of support. I am incredibly thankful to the team of editors and reviewers who made this book possible. I want to express my heartfelt thanks to everyone who took the time to review and provide feedback. In particular, I want to thank Becky Whitney, my content editor, and Ross Turner, my technical editor and chief production and technology officer at OpenSC, for their dedication, as well as the whole production team at Manning for their insight and unwavering support throughout this journey.

To my partner, Rhonda—your love, patience, and encouragement mean the world to me. You’ve been the cornerstone of my support system, not just for this book but for all the books that have come before. I truly couldn’t have done any of this without you. Thank you for being my rock, my partner, and my inspiration.

Many of the early ideas for this book grew out of my work at Symend. It was during my time there that I first began developing the concepts and designs for agentic systems that laid the foundation for this book. I am deeply grateful to my colleagues at Symend for their collaboration and contributions, including Peh Teh, Andrew Wright, Ziko Rajabali, Chris Garrett, Kouros, Fatemeh Torabi Asr, Sukh Singh, and Hanif Joshaghani. Your insights and hard work helped bring these ideas to life, and I am honored to have worked alongside such an incredible group of people.

Finally, I would like to thank all the reviewers: Anandaganesh Balakrishnan, Aryan Jadon, Chau Giang, Dan Sheikh, David Curran, Dibyendu Roy Chowdhury, Divya Bhargavi, Felipe Provezano Coutinho, Gary Pass, John Williams, Jose San Leandro, Laurence Giglio, Manish Jain, Maxim Volgin, Michael Wang, Mike Metzger, Piti Champeethong, Prashant Dwivedi, Radhika Kanubaddhi, Rajat Kant Goel, Ramaa Vissa, Richard Vaughan, Satej Kumar Sahu, Sergio Gtz, Siva Dhandapani, Annamaneni Sriharsha, Sri Ram Macharla, Sumit Bhattacharyya, Tony Holdroyd, Vidal Graupera, Vidhya Vinay, and Vinoth Nageshwaran. Your suggestions helped make this a better book.

about this book

AI Agents in Action is about building and working with intelligent agent systems—not just creating autonomous entities but also developing agents that can effectively tackle and solve real-world problems. The book starts with the basics of working with large language models (LLMs) to build assistants, multi-agent systems, and agentic behavioral agents. From there, it explores the key components of agentic systems: retrieval systems for knowledge and memory augmentation, action and tool usage, reasoning, planning, evaluation, and feedback. The book demonstrates how these components empower agents to perform a wide range of complex tasks through practical examples.

This journey isn’t just about technology; it’s about reimagining how we approach problem solving. I hope this book inspires you to see intelligent agents as partners in innovation, capable of transforming ideas into actions in ways that were once thought impossible. Together, we’ll explore how AI can augment human potential, enabling us to achieve far more than we could alone.

Who should read this book

This book is for anyone curious about intelligent agents and how to develop agentic systems—whether you’re building your first helpful assistant or diving deeper into complex multi-agent systems. No prior experience with agents, agentic systems, prompt engineering, or working with LLMs is required. All you need is a basic understanding of Python and familiarity with GitHub repositories. My goal is to make these concepts accessible and engaging, empowering anyone who wants to explore the world of AI agents to do so with confidence.

Whether you’re a developer, researcher, or hobbyist or are simply intrigued by the possibilities of AI, this book is for you. I hope that in these pages you’ll find inspiration, practical guidance, and a new

appreciation for the remarkable potential of intelligent agents. Let this book guide understanding, creating, and unleashing the power of AI agents in action.

How this book is organized: A road map

This book has 11 chapters. Chapter 1, “Introduction to agents and their world,” begins by laying a foundation with fundamental definitions of large language models, chat systems, assistants, and autonomous agents. As the book progresses, the discussion shifts to the key components that make up an agent and how these components work together to create truly effective systems. Here is a quick summary of chapters 2 through 11:

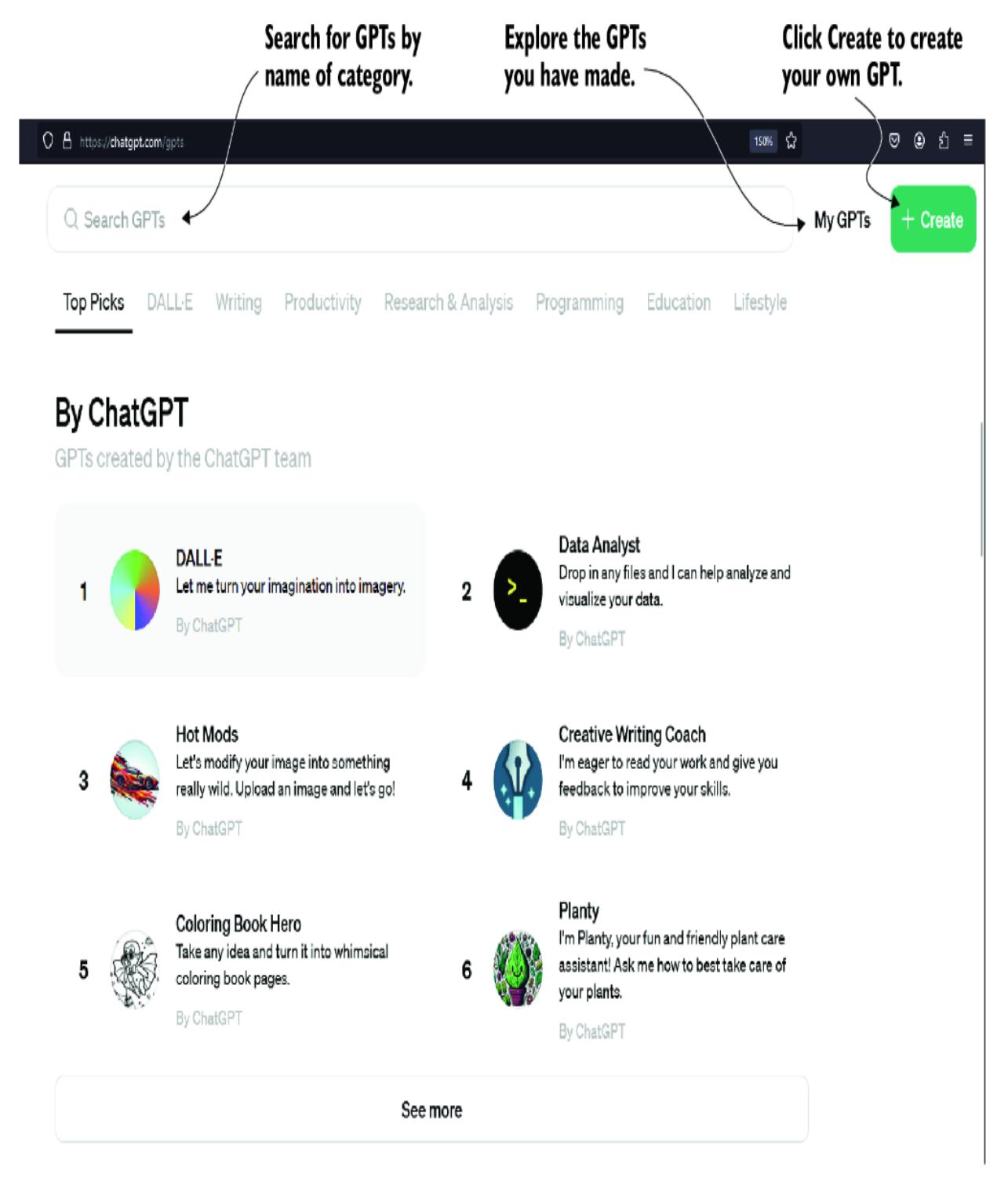

- Chapter 2, “Harnessing the power of large language models”—We start by exploring how to use commercial LLMs, such as OpenAI. We then examine tools, such as LM Studio, that provide the infrastructure and support for running various open source LLMs, enabling anyone to experiment and innovate.

- Chapter 3, “Engaging GPT assistants” —This chapter dives into the capabilities of the GPT Assistants platform from OpenAI. Assistants are foundational agent types, and we explore how to create practical and diverse assistants, from culinary helpers to intern data scientists and even a book learning assistant.

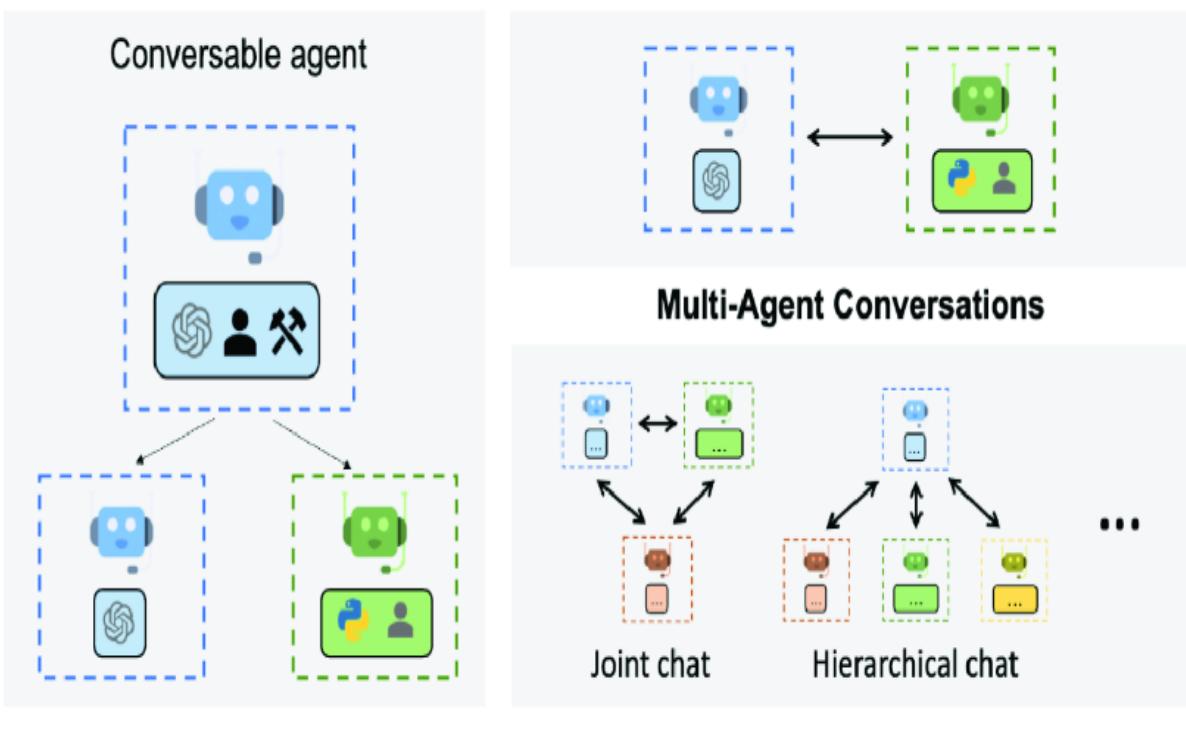

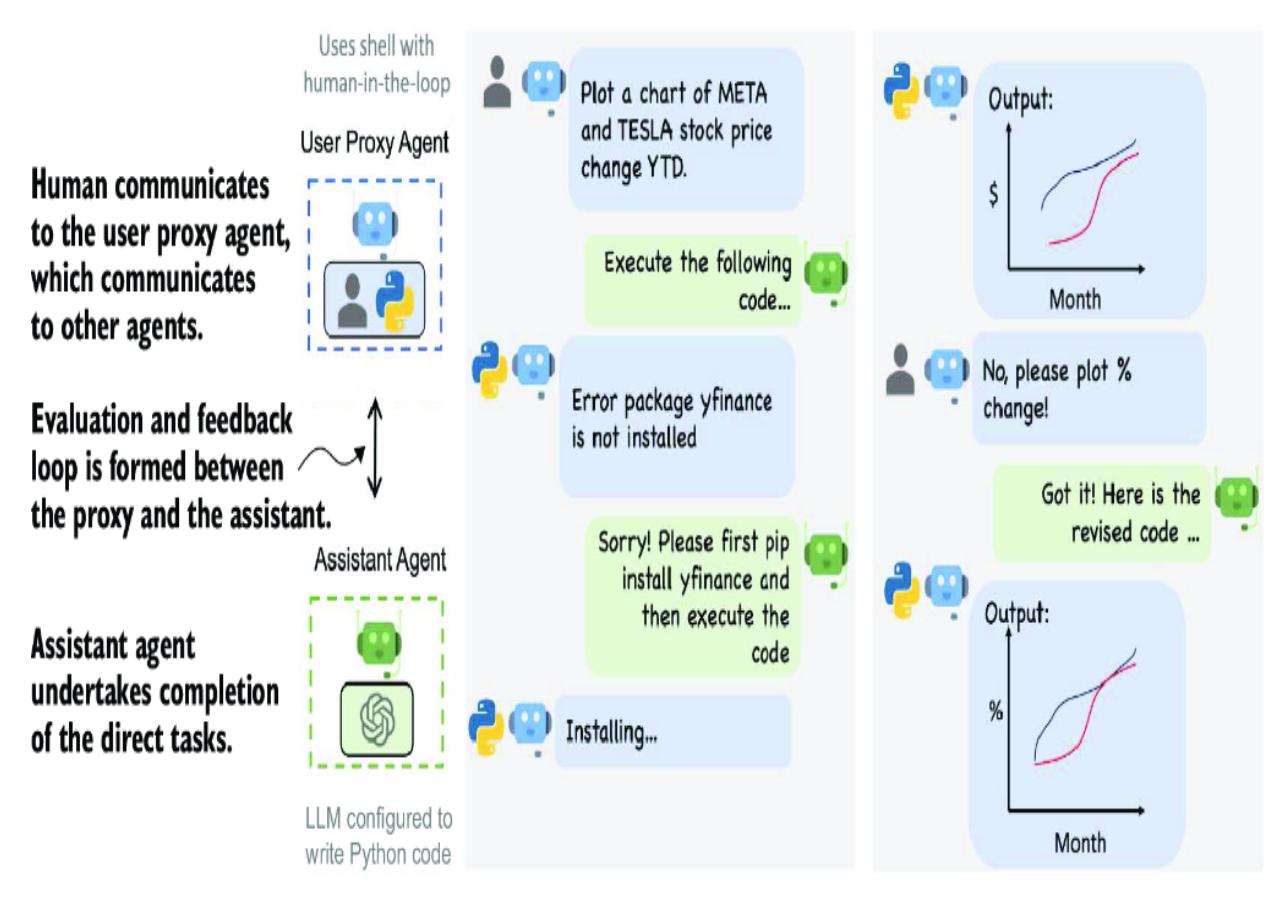

- Chapter 4, “Exploring multi-agent systems” —Agentic tools have advanced significantly quickly. Here, we explore two sophisticated multi-agent systems: CrewAI and AutoGen. We demonstrate AutoGen’s ability to develop code autonomously and see how CrewAI can bring together a group of joke researchers to create humor collaboratively.

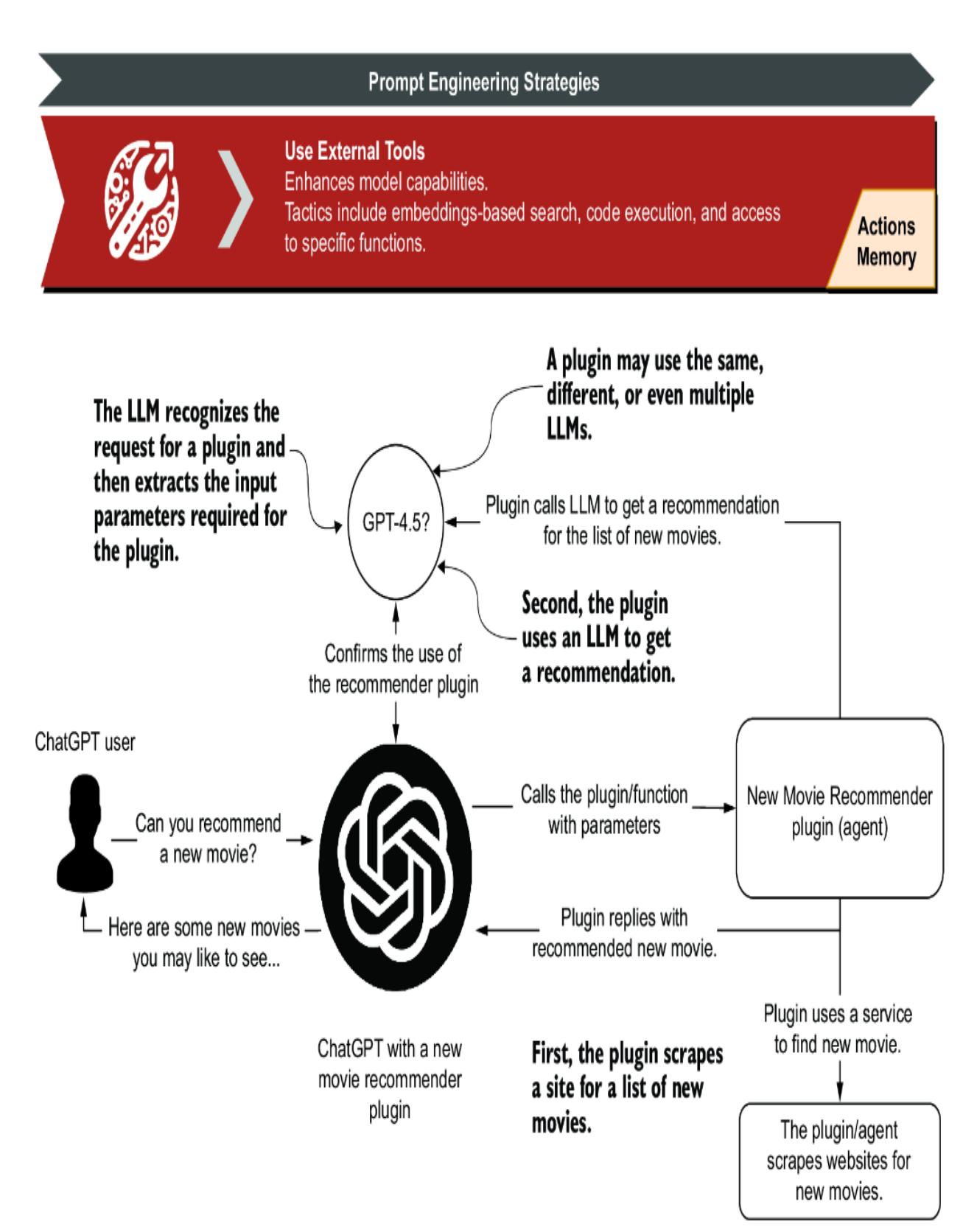

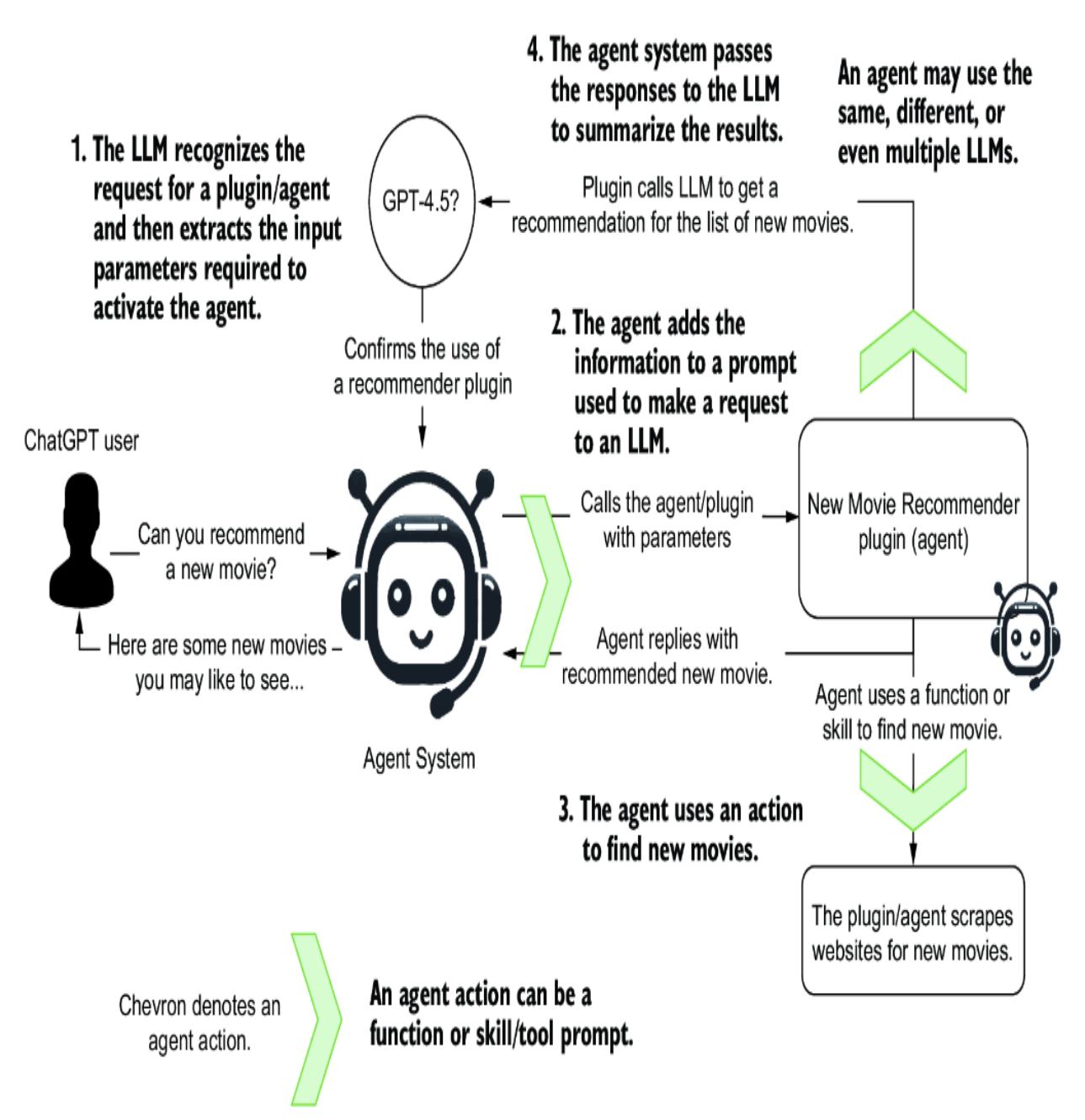

- Chapter 5, “Empowering agents with actions” —Actions are fundamental to any agentic system. This chapter discusses how agents can use tools and functions to execute actions, ranging from database and application programming interface (API) queries to generating images. We focus on enabling agents to take meaningful actions autonomously.

- Chapter 6, “Building autonomous assistants” —We explore the behavior tree—a staple in robotics and game systems—as a mechanism to orchestrate multiple coordinated agents. We’ll use

behavior trees to tackle challenges such as code competitions and social media content creation.

- Chapter 7, “Assembling and using an agent platform” —This chapter introduces Nexus, a sophisticated platform for orchestrating multiple agents and LLMs. We discuss how Nexus facilitates agentic workflows and enables complex interactions between agents, providing an example of a fully functioning multi-agent environment.

- Chapter 8, “Understanding agent memory and knowledge” Retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has become an essential tool for extending the capabilities of LLM agents. This chapter explores how retrieval mechanisms can serve as both a source of knowledge by processing ingested files, and of memory, allowing agents to recall previous interactions or events.

- Chapter 9, “Mastering agent prompts with prompt flow” —Prompt engineering is central to an agent’s success. This chapter introduces prompt flow, a tool from Microsoft that helps automate the testing and evaluation of prompts, enabling more robust and effective agentic behavior.

- Chapter 10, “Agent reasoning and evaluation”—Reasoning is crucial to solving problems intelligently. In this chapter, we explore various reasoning techniques, such as chain of thought (CoT), and show how agents can evaluate reasoning strategies even during inference, improving their capacity to solve problems autonomously.

- Chapter 11, “Agent planning and feedback” —Planning is perhaps an agent’s most critical skill in achieving its goals. We discuss how agents can incorporate planning to navigate complex tasks and how feedback loops can be used to refine those plans. The chapter concludes by integrating all the key components—actions, memory and knowledge, reasoning, evaluation, planning, and feedback—into practical examples of agentic systems that solve real-world problems.

About the code

The code for this book is spread across several open source projects, many of which are hosted by me or by other organizations in GitHub

repositories. Throughout this book, I strive to make the content as accessible as possible, taking a low-code approach to help you focus on core concepts. Many chapters demonstrate how simple prompts can generate meaningful code, showcasing the power of AI-assisted development.

Additionally, you’ll find a variety of assistant profiles and multi-agent systems that demonstrate how to solve real-world problems using generated code. These examples are meant to inspire, guide, and empower you to explore what is possible with AI agents. I am deeply grateful to the many contributors and the community members who have collaborated on these projects, and I encourage you to explore the repositories, experiment with the code, and adapt it to your own needs. This book is a testament to the power of collaboration and the incredible things we can achieve together.

This book contains many examples of source code both in numbered listings and in line with normal text. In both cases, source code is formatted in a fixed-width font like this to separate it from ordinary text. Sometimes, some of the code is typeset in bold to highlight code that has changed from previous steps in the chapter, such as when a feature is added to an existing line of code. In many cases, the original source code has been reformatted; we’ve added line breaks and reworked indentation to accommodate the available page space in the book. In some cases, even this wasn’t enough, and listings include line-continuation markers (↪). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text. Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

You can get executable snippets of code from the liveBook (online) version of this book at https://livebook.manning.com/book/ai-agents-inaction. The complete code for the examples in the book is available for download from the Manning website at www.manning.com/books/aiagents-in-action. In addition, the code developed for this book has been placed in three GitHub repositories that are all publicly accessible:

- GPT-Agents (the original book title), at https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/GPT-Agents, holds the code for several examples demonstrated in the chapters.

- GPT Assistants Playground, at https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/GPTAssistantsPlayground, is an entire platform and tool dedicated to building OpenAI GPT assistants with a helpful web user interface and plenty of tools to develop autonomous agent systems.

- Nexus, at https://github.com/cxbxmxcx/Nexus, is an example of a web-based agentic tool that can help you create agentic systems and demonstrate various code challenges.

liveBook discussion forum

Purchase of AI Agents in Action includes free access to liveBook, Manning’s online reading platform. Using liveBook’s exclusive discussion features, you can attach comments to the book globally or to specific sections or paragraphs. It’s a snap to make notes for yourself, ask and answer technical questions, and receive help from the author and other users. To access the forum, go to

https://livebook.manning.com/book/ai-agents-in-action/discussion. You can also learn more about Manning’s forums and the rules of conduct at https://livebook.manning.com/discussion.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialogue between individual readers and between readers and the author can take place. It isn’t a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contribution to the forum remains voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you try asking the him challenging questions lest his interest stray! The forum and the archives of previous discussions will be accessible from the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

about the cover illustration

The figure on the cover of AI Agents in Action is “Clémentinien,” taken from Balthasar Hacquet’s Illustrations de L’Illyrie et la Dalmatie, published in 1815.

In those days, it was easy to identify where people lived and what their trade or station in life was just by their dress. Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of regional culture centuries ago, brought back to life by pictures from collections such as this one.

1 Introduction to agents and their world

This chapter covers

- Defining the concept of agents

- Differentiating the components of an agent

- Analyzing the rise of the agent era: Why agents?

- Peeling back the AI interface

- Navigating the agent landscape

The agent isn’t a new concept in machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI). In reinforcement learning, for instance, the word agent denotes an active decision-making and learning intelligence. In other areas, the word agent aligns more with an automated application or software that does something on your behalf.

1.1 Defining agents

You can consult any online dictionary to find the definition of an agent. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines it this way (www.merriamwebster.com/dictionary/agent):

- One that acts or exerts power

- Something that produces or can produce an effect

- A means or instrument by which a guiding intelligence achieves a result

The word agent in our journey to build powerful agents in this book uses this dictionary definition. That also means the term assistant will be synonymous with agent. Tools like OpenAI’s GPT Assistants will also fall under the AI agent blanket. OpenAI avoids the word agent because of the

history of machine learning, where an agent is self-deciding and autonomous.

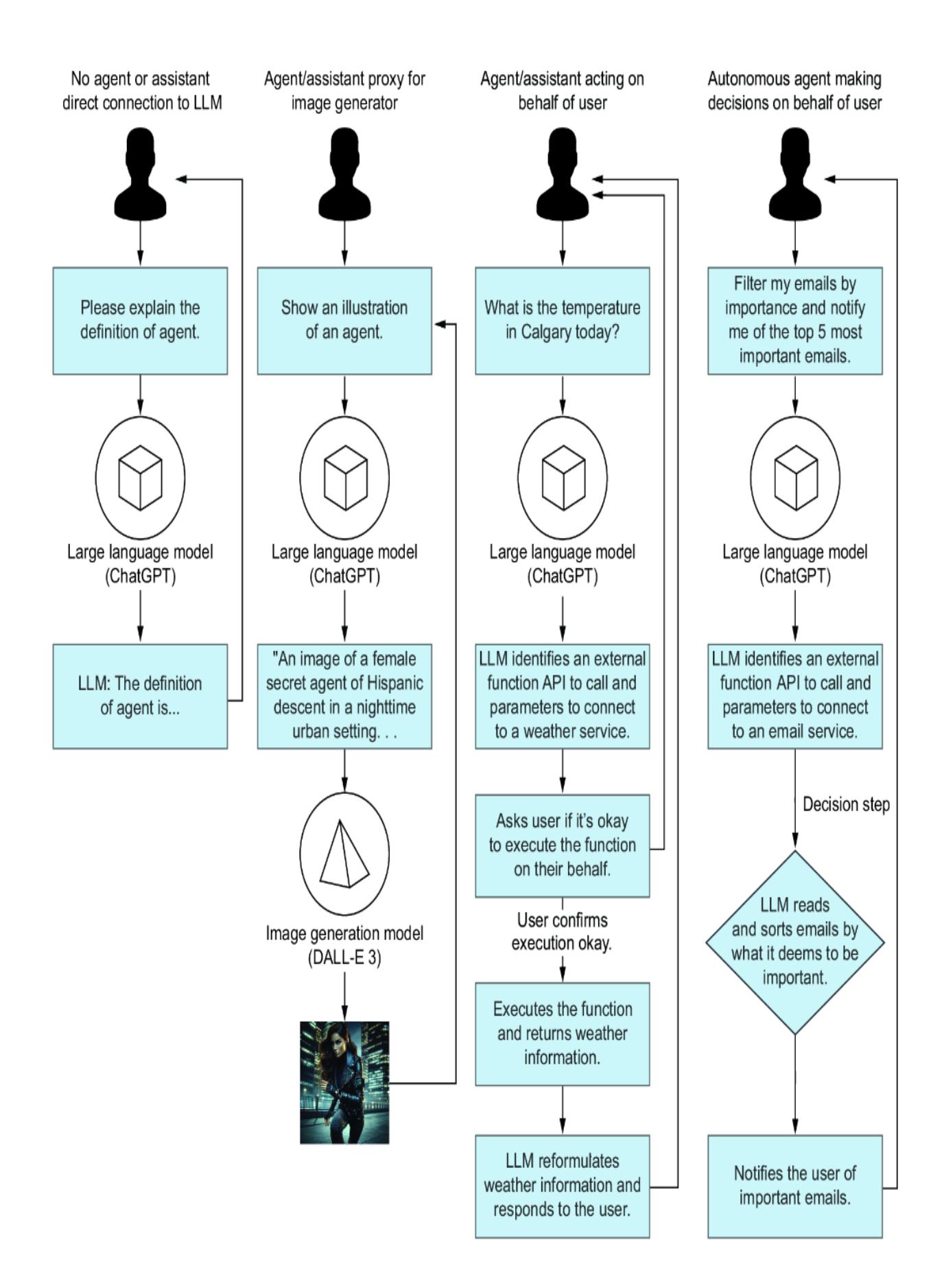

Figure 1.1 shows four cases where a user may interact with a large language model (LLM) directly or through an agent/assistant proxy, an agent/assistant, or an autonomous agent. These four use cases are highlighted in more detail in this list:

- Direct user interaction —If you used earlier versions of ChatGPT, you experienced direct interaction with the LLM. There is no proxy agent or other assistant interjecting on your behalf.

- Agent/assistant proxy —If you’ve used Dall-E 3 through ChatGPT, then you’ve experienced a proxy agent interaction. In this use case, an LLM interjects your requests and reformulates them in a format better designed for the task. For example, for image generation, ChatGPT better formulates the prompt. A proxy agent is an everyday use case to assist users with unfamiliar tasks or models.

- Agent/assistant —If you’ve ever used a ChatGPT plugin or GPT assistant, then you’ve experienced this use case. In this case, the LLM is aware of the plugin or assistant functions and prepares to make calls to this plugin/function. However, before making a call, the LLM requires user approval. If approved, the plugin or function is executed, and the results are returned to the LLM. The LLM then wraps this response in natural language and returns it to the user.

- Autonomous agent —In this use case, the agent interprets the user’s request, constructs a plan, and identifies decision points. From this, it executes the steps in the plan and makes the required decisions independently. The agent may request user feedback after certain milestone tasks, but it’s often given free rein to explore and learn if possible. This agent poses the most ethical and safety concerns, which we’ll explore later.

Figure 1.1 The differences between the LLM interactions from direct action compared to using proxy agents, agents, and autonomous agents

Figure 1.1 demonstrates the use cases for a single flow of actions on an LLM using a single agent. For more complex problems, we often break agents into profiles or personas. Each agent profile is given a specific task and executes that task with specialized tools and knowledge.

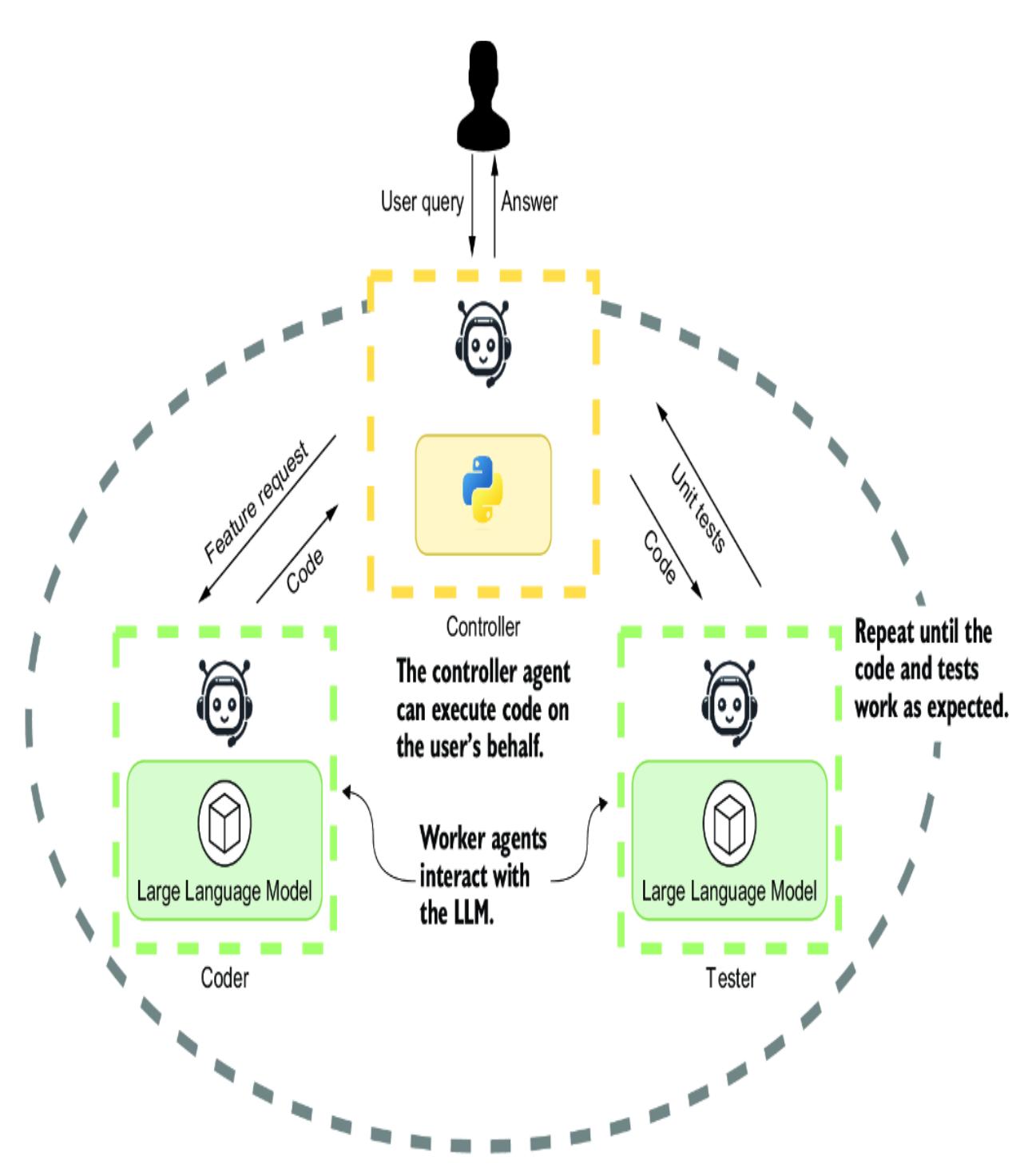

Multi-agent systems are agent profiles that work together in various configurations to solve a problem. Figure 1.2 demonstrates an example of a multi-agent system using three agents: a controller or proxy and two profile agents as workers controlled by the proxy. The coder profile on the left writes the code the user requests; on the right is a tester profile designed to write unit tests. These agents work and communicate together until they are happy with the code and then pass it on to the user.

Figure 1.2 shows one of the possibly infinite agent configurations. (In chapter 4, we’ll explore Microsoft’s open source platform, AutoGen, which supports multiple configurations for employing multi-agent systems.)

Figure 1.2 In this example of a multi-agent system, the controller or agent proxy communicates directly with the user. Two agents—a coder and a tester—work in the background to create code and write unit tests to test the code.

Multi-agent systems can work autonomously but may also function guided entirely by human feedback. The benefits of using multiple agents are like those of a single agent but often magnified. Where a single agent typically

specializes in a single task, multi-agent systems can tackle multiple tasks in parallel. Multiple agents can also provide feedback and evaluation, reducing errors when completing assignments.

As we can see, an AI agent or agent system can be assembled in multiple ways. However, an agent itself can also be assembled using multiple components. In the next section, we’ll cover topics ranging from an agent’s profile to the actions it may perform, as well as memory and planning.

1.2 Understanding the component systems of an agent

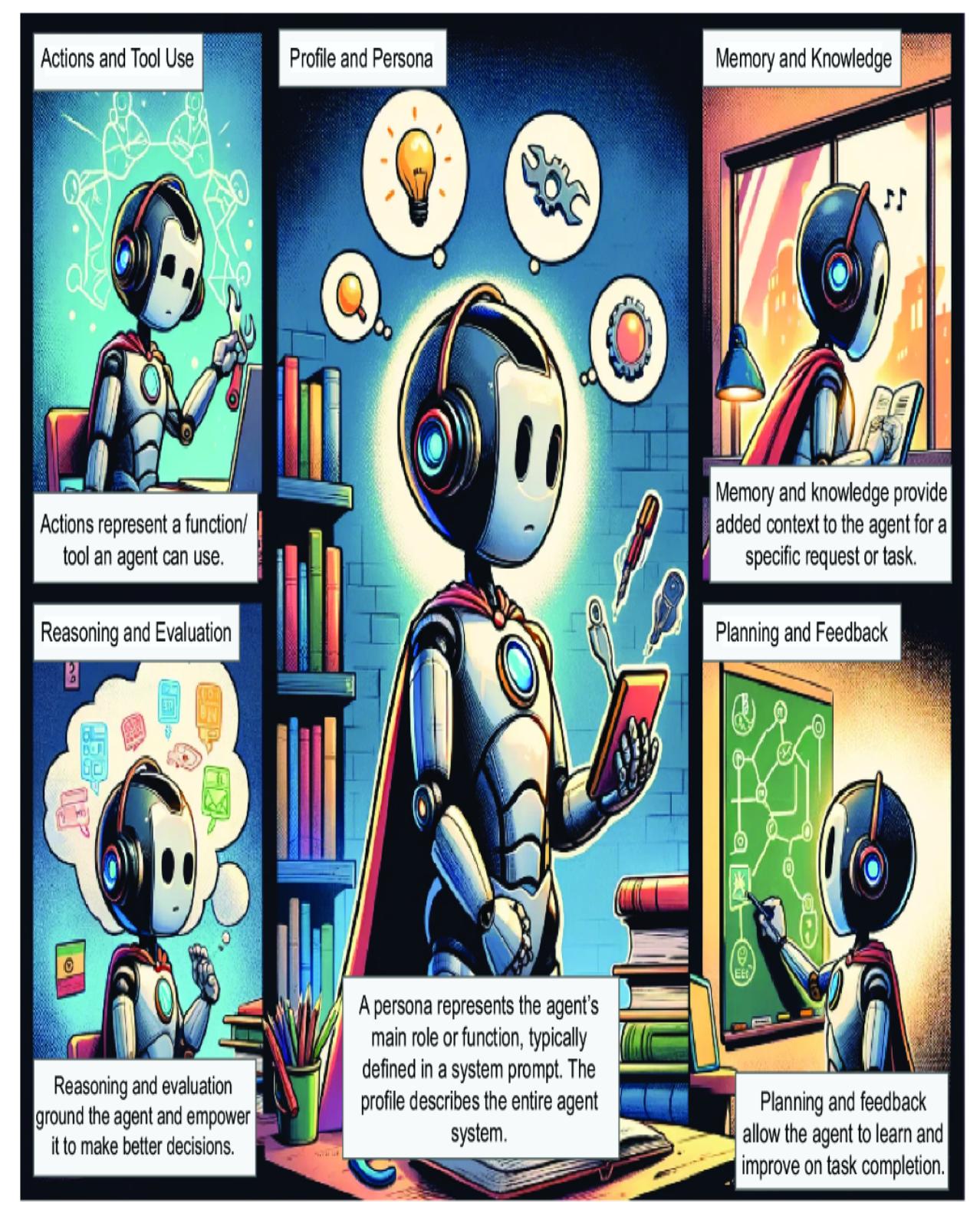

Agents can be complex units composed of multiple component systems. These components are the tools the agent employs to help it complete its goal or assigned tasks and even create new ones. Components may be simple or complex systems, typically split into five categories.

Figure 1.3 describes the major categories of components a single-agent system may incorporate. Each element will have subtypes that can define the component’s type, structure, and use. At the core of all agents is the profile and persona; extending from that are the systems and functions that enhance the agent.

Figure 1.3 The five main components of a single-agent system (image generated through DALL-E 3)

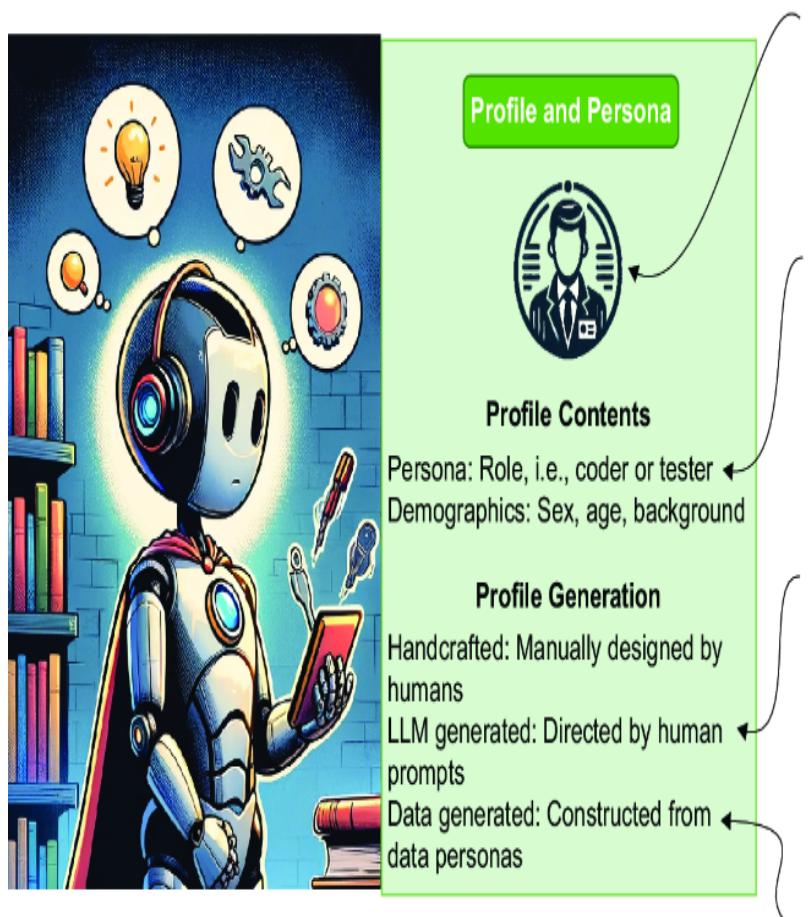

The agent profile and persona shown in figure 1.4 represent the base description of the agent. The persona—often called the system prompt guides an agent to complete tasks, learn how to respond, and other nuances. It includes elements such as the background (e.g., coder, writer) and demographics, and it can be generated through methods such as handcrafting, LLM assistance, or data-driven techniques, including evolutionary algorithms.

Figure 1.4 An in-depth look at how we’ll explore creating agent profiles

We’ll explore how to create effective and specific agent profiles/personas through techniques such as rubrics and grounding. In addition, we’ll explain the aspects of human-formulated versus AI-formulated (LLM)

profiles, including innovative techniques using data and evolutionary algorithms to build profiles.

Note The agent or assistant profile is composed of elements, including the persona. It may be helpful to think of profiles describing the work the agent/ assistant will perform and the tools it needs.

Figure 1.5 demonstrates the component actions and tool use in the context of agents involving activities directed toward task completion or acquiring information. These actions can be categorized into task completion, exploration, and communication, with varying levels of effect on the agent’s environment and internal states. Actions can be generated manually, through memory recollection, or by following predefined plans, influencing the agent’s behavior and enhancing learning.

Figure 1.5 The aspects of agent actions we’ll explore in this book

Understanding the action target helps us define clear objectives for task completion, exploration, or communication. Recognizing the action effect reveals how actions influence task outcomes, the agent’s environment, and its internal states, contributing to efficient decision making. Lastly, grasping action generation methods equips us with the knowledge to create actions manually, recall them from memory, or follow predefined plans, enhancing our ability to effectively shape agent behavior and learning processes.

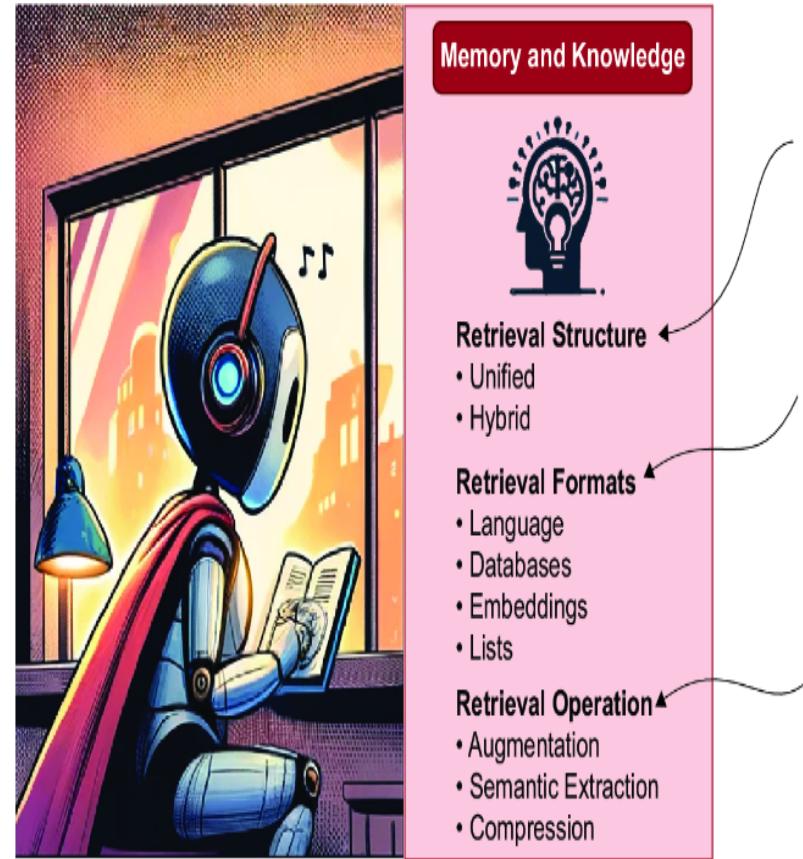

Figure 1.6 shows the component knowledge and memory in more detail. Agents use knowledge and memory to annotate context with the most pertinent information while limiting the number of tokens used. Knowledge and memory structures can be unified, where both subsets follow a single structure or hybrid structure involving a mix of different retrieval forms. Knowledge and memory formats can vary widely from language (e.g., PDF documents) to databases (relational, object, or document) and embeddings, simplifying semantic similarity search through vector representations or even simple lists serving as agent memories.

Figure 1.6 Exploring the role and use of agent memory and knowledge

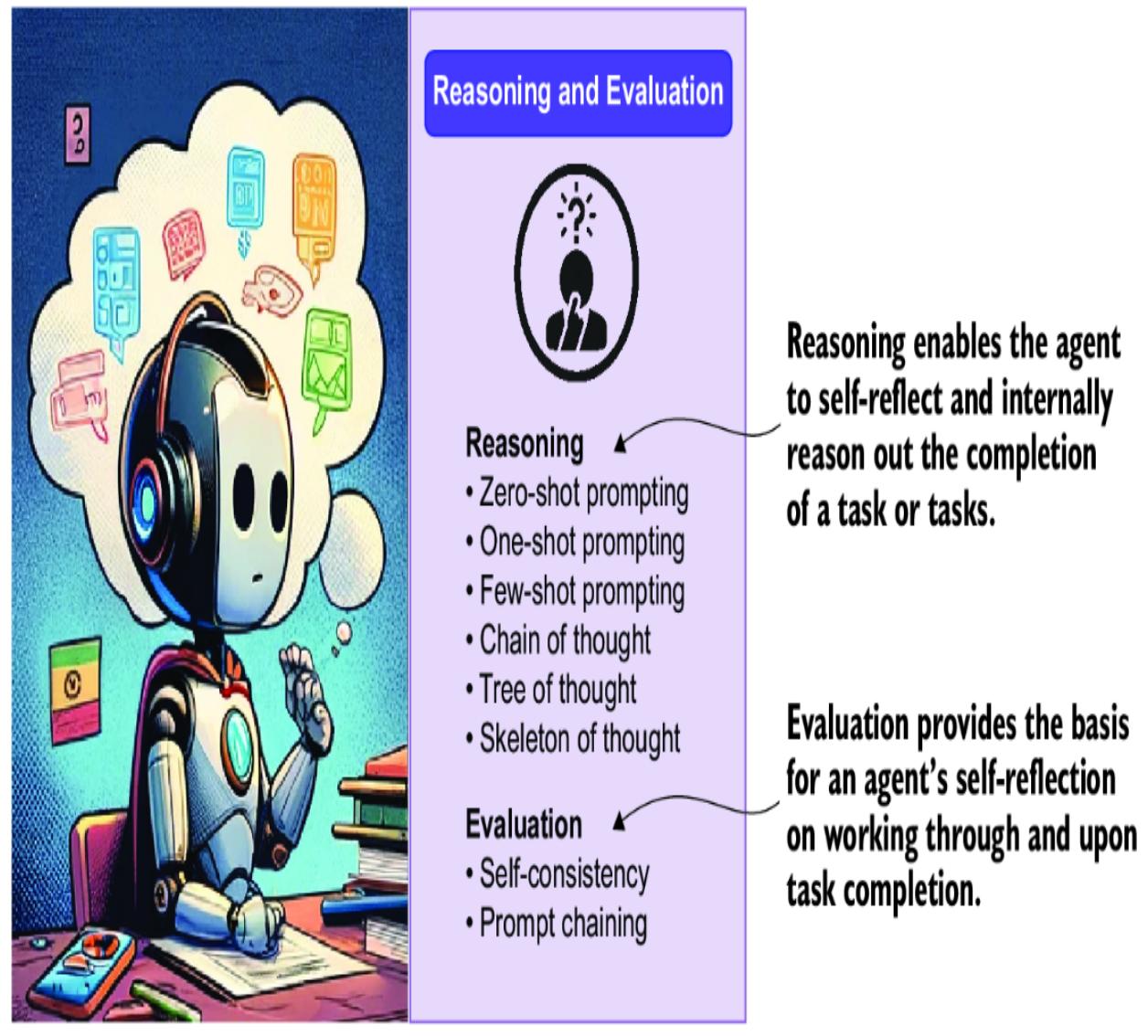

Figure 1.7 shows the reasoning and evaluation component of an agent system. Research and practical applications have shown that LLMs/agents can effectively reason. Reasoning and evaluation systems annotate an agent’s workflow by providing an ability to think through problems and evaluate solutions.

Figure 1.7 The reasoning and evaluation component and details

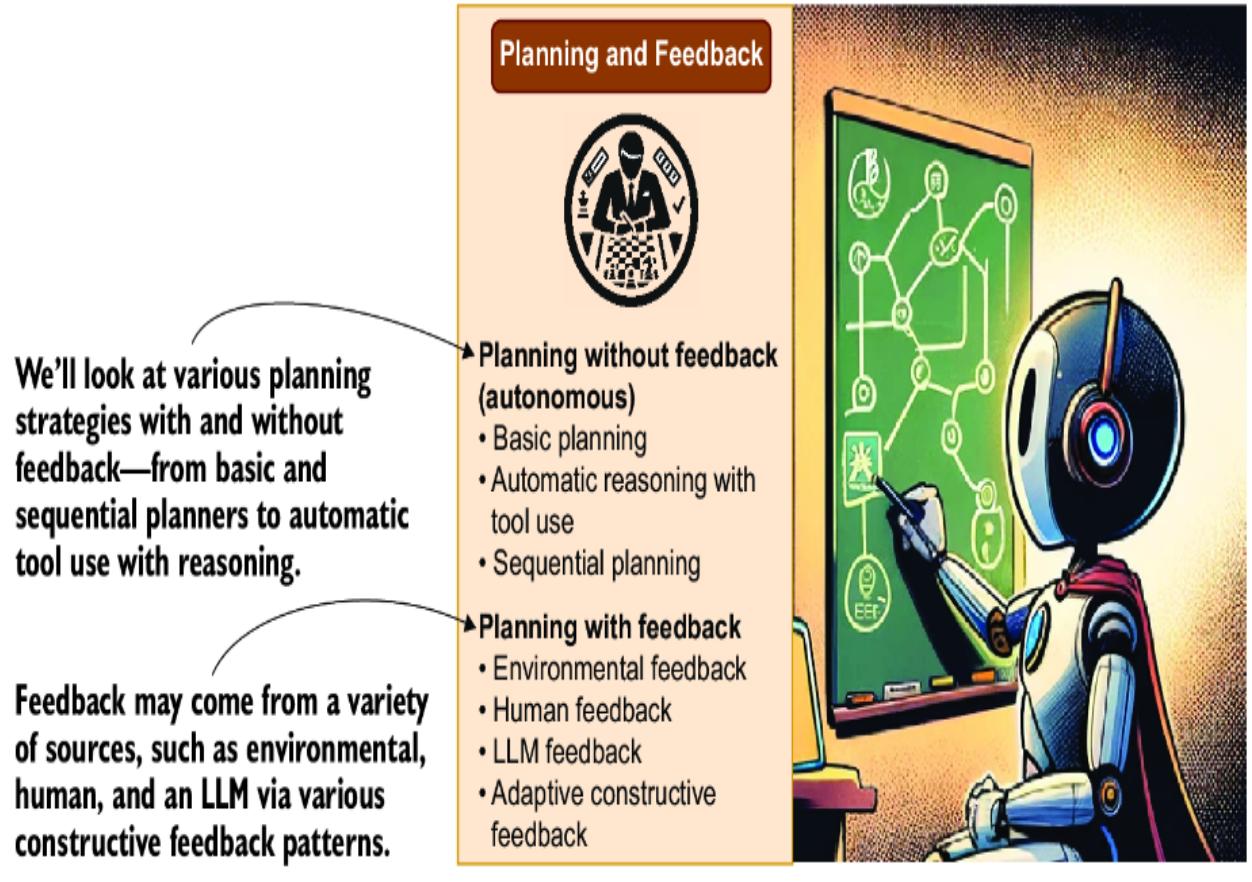

Figure 1.8 shows the component agent planning/feedback and its role in organizing tasks to achieve higher-level goals. It can be categorized into these two approaches:

- Planning without feedback —Autonomous agents make decisions independently.

- Planning with feedback —Monitoring and modifying plans is based on various sources of input, including environmental changes and direct human feedback.

Figure 1.8 Exploring the role of agent planning and reasoning

Within planning, agents may employ single-path reasoning, sequential reasoning through each step of a task, or multipath reasoning to explore multiple strategies and save the efficient ones for future use. External planners, which can be code or other agent systems, may also play a role in orchestrating plans.

Any of our previous agent types—the proxy agent/assistant, agent/assistant, or autonomous agent—may use some or all of these components. Even the planning component has a role outside of the autonomous agent and can effectively empower even the regular agent.

1.3 Examining the rise of the agent era: Why agents?

AI agents and assistants have quickly moved from the main commodity in AI research to mainstream software development. An ever-growing list of tools and platforms assist in the construction and empowerment of agents. To an outsider, it may all seem like hype intended to inflate the value of some cool but overrated technology.

During the first few months after ChatGPT’s initial release, a new discipline called prompt engineering was formed: users found that using various techniques and patterns in their prompts allowed them to generate better and more consistent output. However, users also realized that prompt engineering could only go so far.

Prompt engineering is still an excellent way to interact directly with LLMs such as ChatGPT. Over time, many users discovered that effective prompting required iteration, reflection, and more iteration. The first agent systems, such as AutoGPT, emerged from these discoveries, capturing the community’s attention.

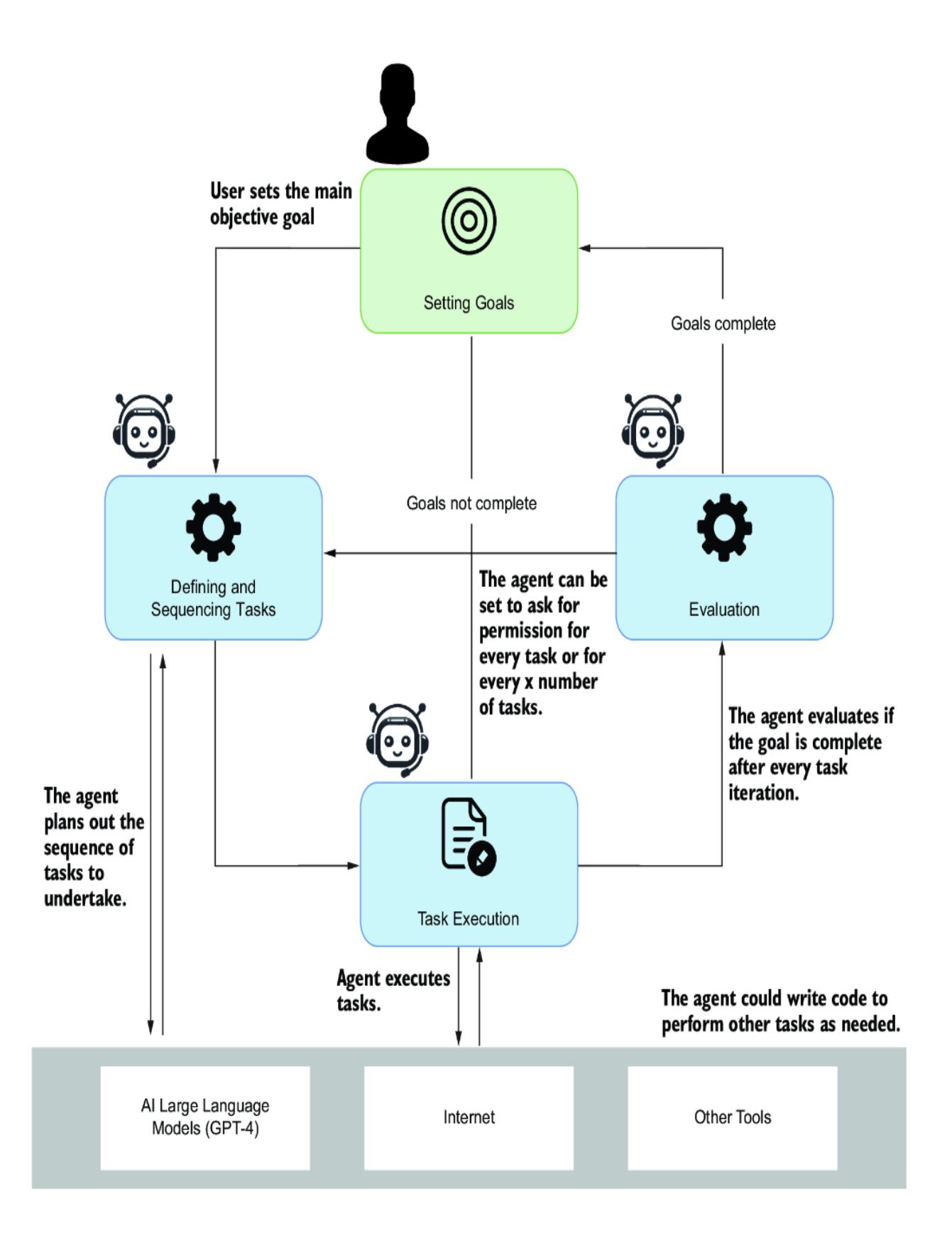

Figure 1.9 shows the original design of AutoGPT, one of the first autonomous agent systems. The agent is designed to iterate a planned sequence of tasks that it defines by looking at the user’s goal. Through each task iteration of steps, the agent evaluates the goal and determines if the task is complete. If the task isn’t complete, the agent may replan the steps and update the plan based on new knowledge or human feedback.

Figure 1.9 The original design of the AutoGPT agent system

AutoGPT became the first example to demonstrate the power of using task planning and iteration with LLM models. From this and in tandem, other agent systems and frameworks exploded into the community using similar planning and task iteration systems. It’s generally accepted that planning, iteration, and repetition are the best processes for solving complex and multifaceted goals for an LLM.

However, autonomous agent systems require trust in the agent decisionmaking process, the guardrails/evaluation system, and the goal definition. Trust is also something that is acquired over time. Our lack of trust stems from our lack of understanding of an autonomous agent’s capabilities.

Note Artificial general intelligence (AGI) is a form of intelligence that can learn to accomplish any task a human can. Many practitioners in this new world of AI believe an AGI using autonomous agent systems is an attainable goal.

For this reason, many of the mainstream and production-ready agent tools aren’t autonomous. However, they still provide a significant benefit in managing and automating tasks using GPTs (LLMs). Therefore, as our goal in this book is to understand all agent forms, many more practical applications will be driven by non-autonomous agents.

Agents and agent tools are only the top layer of a new software application development paradigm. We’ll look at this new paradigm in the next section.

1.4 Peeling back the AI interface

The AI agent paradigm is not only a shift in how we work with LLMs but is also perceived as a shift in how we develop software and handle data. Software and data will no longer be interfaced using user interfaces (UIs), application programming interfaces (APIs), and specialized query languages such as SQL. Instead, they will be designed to be interfaced using natural language.

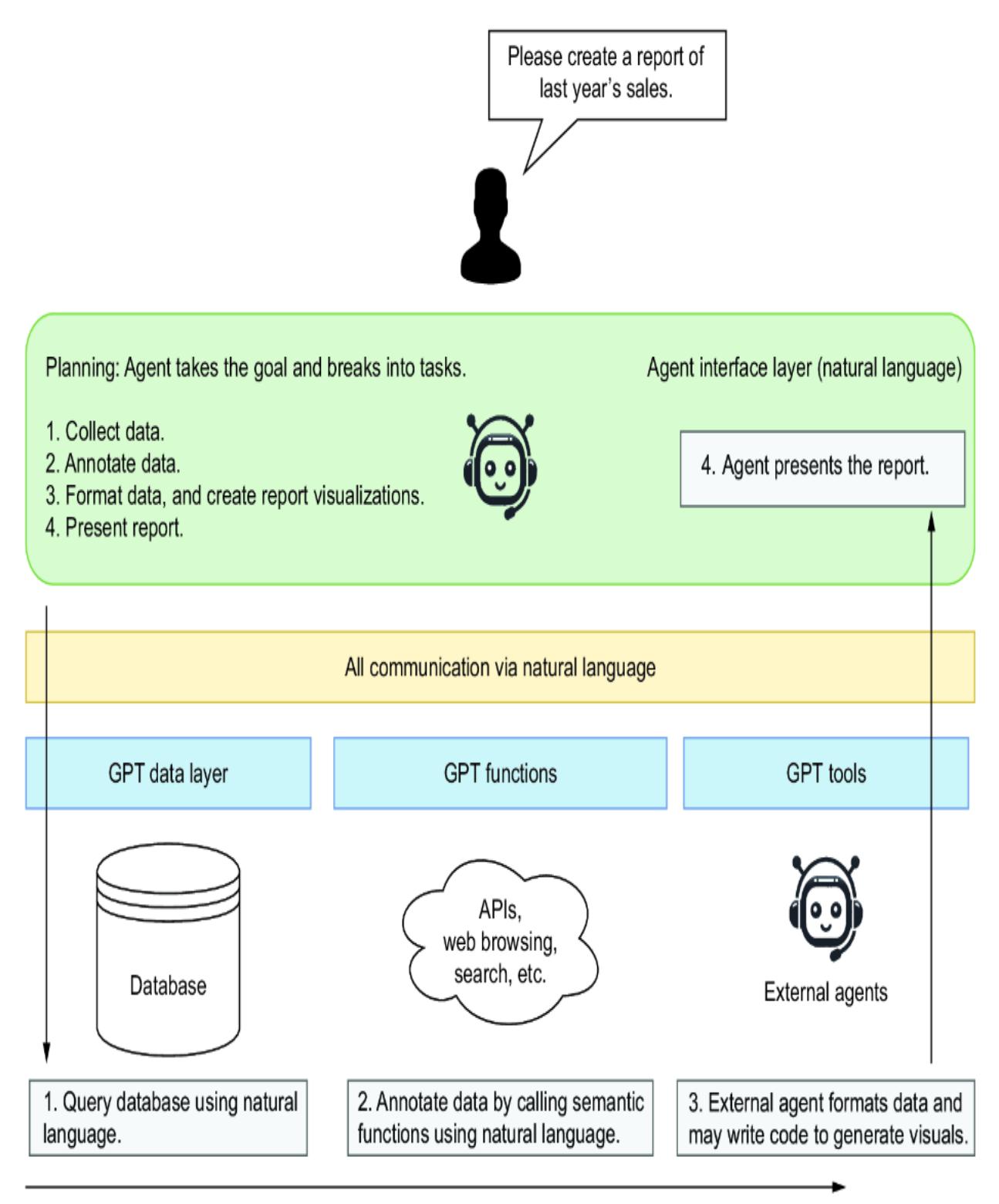

Figure 1.10 shows a high-level snapshot of what this new architecture may look like and what role AI agents play. Data, software, and applications adapt to support semantic, natural language interfaces. These AI interfaces allow agents to collect data and interact with software applications, even other agents or agent applications. This represents a new shift in how we interact with software and applications.

Figure 1.10 A vision of how agents will interact with software systems

An AI interface is a collection of functions, tools, and data layers that expose data and applications by natural language. In the past, the word semantic has been heavily used to describe these interfaces, and even some tools use the name; however, “semantic” can also have a variety of meanings and uses. Therefore, in this book, we’ll use the term AI interface.

The construction of AI interfaces will empower agents that need to consume the services, tools, and data. With this empowerment will come increased accuracy in completing tasks and more trustworthy and autonomous applications. While an AI interface may not be appropriate for all software and data, it will dominate many use cases.

Summary

An agent is an entity that acts or exerts power, produces an effect, or serves as a means for achieving a result. An agent automates interaction with a large language model (LLM) in AI.

An assistant is synonymous with an agent. Both terms encompass tools such as OpenAI’s GPT Assistants.

Autonomous agents can make independent decisions, and their distinction from non-autonomous agents is crucial.

The four main types of LLM interactions include direct user interaction, agent/ assistant proxy, agent/assistant, and autonomous agent.

Multi-agent systems involve agent profiles working together, often controlled by a proxy, to accomplish complex tasks.

The main components of an agent include the profile/persona, actions, knowledge/memory, reasoning/evaluation, and planning/feedback.

Agent profiles and personas guide an agent’s tasks, responses, and other nuances, often including background and demographics.

Actions and tools for agents can be manually generated, recalled from memory, or follow predefined plans.

Agents use knowledge and memory structures to optimize context and minimize token usage via various formats, from documents to embeddings.

Reasoning and evaluation systems enable agents to think through problems and assess solutions using prompting patterns such as zeroshot, one-shot, and few-shot.

Planning/feedback components organize tasks to achieve goals using single-path or multipath reasoning and integrating environmental and human feedback.

The rise of AI agents has introduced a new software development paradigm, shifting from traditional to natural language–based AI interfaces.

Understanding the progression and interaction of these tools helps develop agent systems, whether single, multiple, or autonomous.

2 Harnessing the power of large language models

This chapter covers

- Understanding the basics of LLMs

- Connecting to and consuming the OpenAI API

- Exploring and using open source LLMs with LM Studio

- Prompting LLMs with prompt engineering

- Choosing the optimal LLM for your specific needs

The term large language models (LLMs) has now become a ubiquitous descriptor of a form of AI. These LLMs have been developed using generative pretrained transformers (GPTs). While other architectures also power LLMs, the GPT form is currently the most successful.

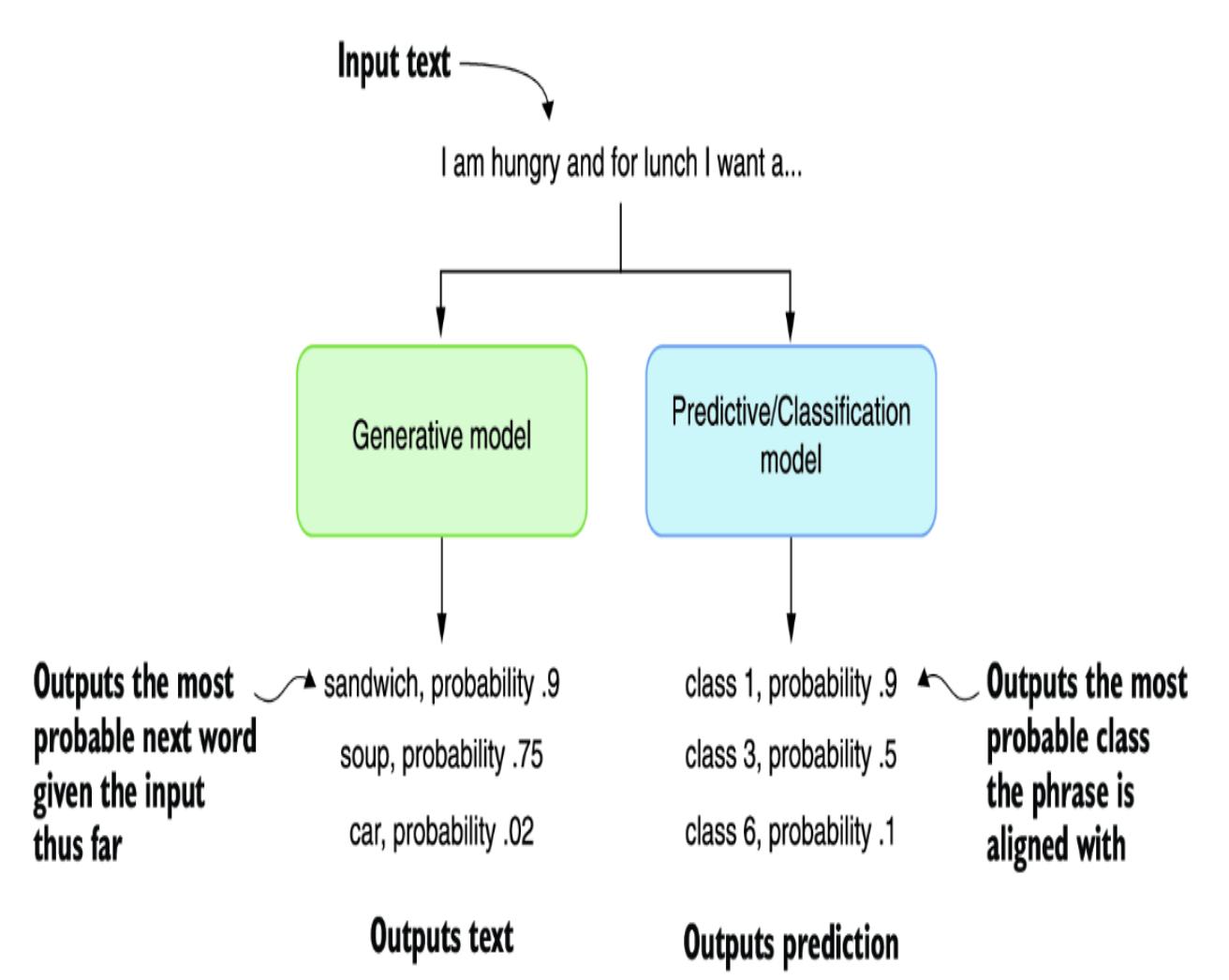

LLMs and GPTs are generative models, which means they are trained to generate rather than predict or classify content. To illustrate this further, consider figure 2.1, which shows the difference between generative and predictive/classification models. Generative models create something from the input, whereas predictive and classifying models classify it.

Figure 2.1 The difference between generative and predictive models

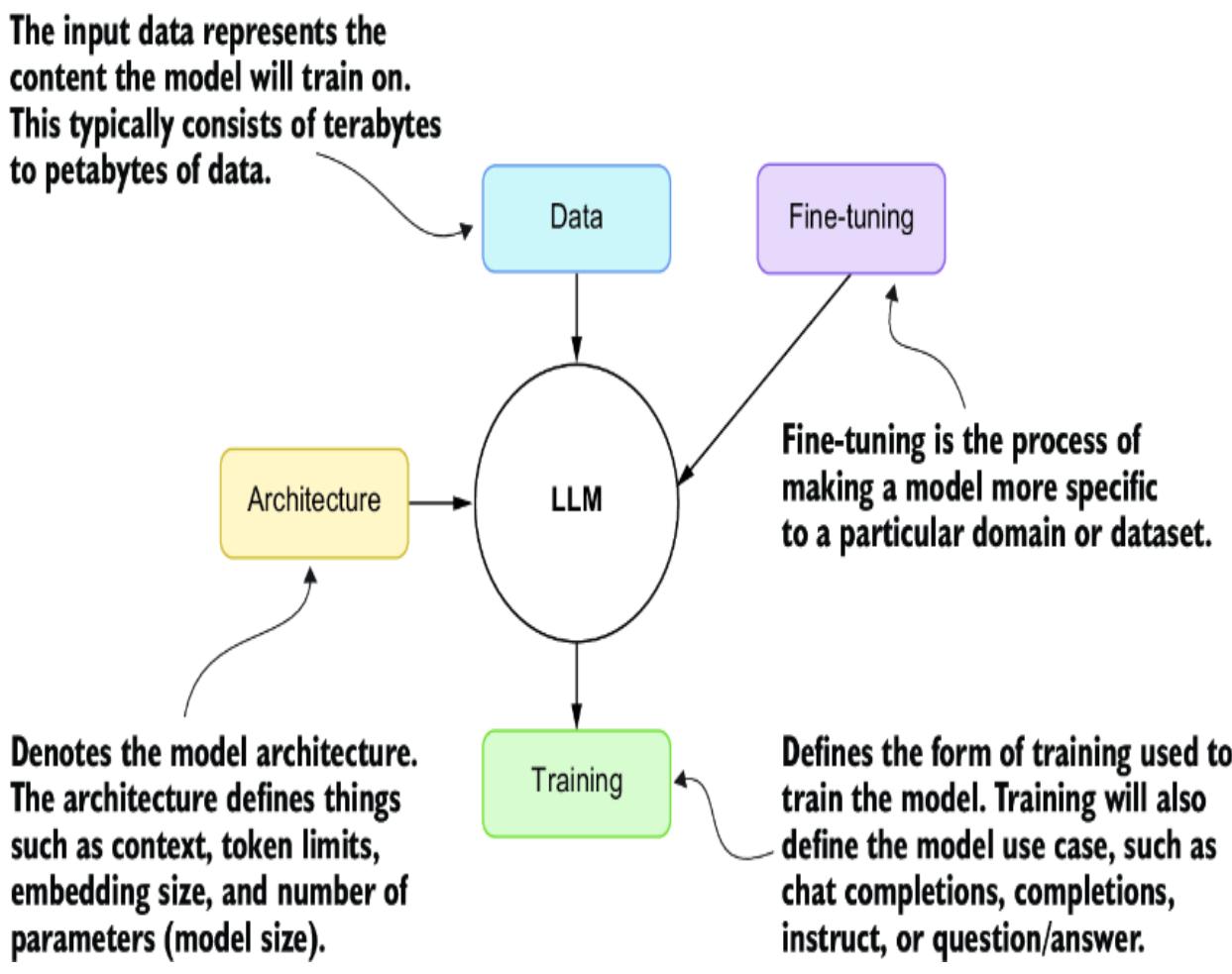

We can further define an LLM by its constituent parts, as shown in figure 2.2. In this diagram, data represents the content used to train the model, and architecture is an attribute of the model itself, such as the number of parameters or size of the model. Models are further trained specifically to the desired use case, including chat, completions, or instruction. Finally, fine-tuning is a feature added to models that refines the input data and model training to better match a particular use case or domain.

Figure 2.2 The main elements that describe an LLM

The transformer architecture of GPTs, which is a specific architecture of LLMs, allows the models to be scaled to billions of parameters in size. This requires these large models to be trained on terabytes of documents to build a foundation. From there, these models will be successively trained using various methods for the desired use case of the model.

ChatGPT, for example, is trained effectively on the public internet and then fine-tuned using several training strategies. The final fine-tuning training is completed using an advanced form called reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF). This produces a model use case called chat completions.

Chat completions LLMs are designed to improve through iteration and refinement—in other words, chatting. These models have also been benchmarked to be the best in task completion, reasoning, and planning, which makes them ideal for building agents and assistants. Completion models are trained/designed only to provide generated content on input text, so they don’t benefit from iteration.

For our journey to build powerful agents in this book, we focus on the class of LLMs called chat completions models. That, of course, doesn’t preclude you from trying other model forms for your agents. However, you may have to significantly alter the code samples provided to support other model forms.

We’ll uncover more details about LLMs and GPTs later in this chapter when we look at running an open source LLM locally. In the next section, we look at how to connect to an LLM using a growing standard from OpenAI.

2.1 Mastering the OpenAI API

Numerous AI agents and assistant projects use the OpenAI API SDK to connect to an LLM. While not standard, the basic concepts describing a connection now follow the OpenAI pattern. Therefore, we must understand the core concepts of an LLM connection using the OpenAI SDK.

This chapter will look at connecting to an LLM model using the OpenAI Python SDK/package. We’ll discuss connecting to a GPT-4 model, the model response, counting tokens, and how to define consistent messages. Starting in the following subsection, we’ll examine how to use OpenAI.

2.1.1 Connecting to the chat completions model

To complete the exercises in this section and subsequent ones, you must set up a Python developer environment and get access to an LLM. Appendix A walks you through setting up an OpenAI account and accessing GPT-4 or other models. Appendix B demonstrates setting up a Python development environment with Visual Studio Code (VS Code), including installing needed extensions. Review these sections if you want to follow along with the scenarios.

Start by opening the source code chapter_2 folder in VS Code and creating a new Python virtual environment. Again, refer to appendix B if you need assistance.

Then, install the OpenAI and Python dot environment packages using the command in the following listing. This will install the required packages into the virtual environment.

Listing 2.1 pip installs

pip install openai python-dotenv

Next, open the connecting.py file in VS Code, and inspect the code shown in listing 2.2. Be sure to set the model’s name to an appropriate name—for example, gpt-4. At the time of writing, the gpt-4-1106 preview was used to represent GPT-4 Turbo.

Listing 2.2 connecting.py

import os

from openai import OpenAI

from dotenv import load_dotenv

load_dotenv() #1

api_key = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_KEY')

if not api_key: #2

raise ValueError("No API key found. Please check your .env file.")

client = OpenAI(api_key=api_key) #3

def ask_chatgpt(user_message):

response = client.chat.completions.create( #4

model="gpt-4-1106-preview",

messages=[{"role": "system",

"content": "You are a helpful assistant."},

{"role": "user", "content": user_message}],

temperature=0.7,

)

return response.choices[0].message.content #5

user = "What is the capital of France?"

response = ask_chatgpt(user) #6

print(response)- #1 Loads the secrets stored in the .env file

- #2 Checks to see whether the key is set

- #3 Creates a client with the key

- #4 Uses the create function to generate a response

- #5 Returns just the content of the response

- #6 Executes the request and returns the response

A lot is happening here, so let’s break it down by section, starting with the beginning and loading the environment variables. In the chapter_2 folder is another file called .env, which holds environment variables. These variables are set automatically by calling the load_dotenv function.

You must set your OpenAI API key in the .env file, as shown in the next listing. Again, refer to appendix A to find out how to get a key and find a model name.

Listing 2.3 .envOPENAI_API_KEY=‘your-openai-api-key’

After setting the key, you can debug the file by pressing the F5 key or selecting Run > Start Debugging from the VS Code menu. This will run the code, and you should see something like “The capital of France is Paris.”

Remember that the response from a generative model depends on the probability. The model will probably give us a correct and consistent answer in this case.

You can play with these probabilities by adjusting the temperature of the request. If you want a model to be more consistent, turn the temperature down to 0, but if you want the model to produce more variation, turn the temperature up. We’ll explore setting the temperature further in the next section.

2.1.2 Understanding the request and response

Digging into the chat completions request and response features can be helpful. We’ll focus on the request first, as shown next. The request encapsulates the intended model, the messages, and the temperature.

Listing 2.4 The chat completions request

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4-1106-preview", #1

messages=[{"role": "system",

"content": "You are a helpful assistant."}, #2

{"role": "user", "content": user_message}], #3

temperature=0.7, #4

)#1 The model or deployment used to respond to the request #2 The system role message #3 The user role message #4 The temperature or variability of the request

Within the request, the messages block describes a set of messages and roles used in a request. Messages for a chat completions model can be defined in three roles:

- System role —A message that describes the request’s rules and guidelines. It can often be used to describe the role of the LLM in making the request.

- User role —Represents and contains the message from the user.

- Assistant role —Can be used to capture the message history of previous responses from the LLM. It can also inject a message history when perhaps none existed.

The message sent in a single request can encapsulate an entire conversation, as shown in the JSON in the following listing.

Listing 2.5 Messages with history[

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are a helpful assistant."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is the capital of France?"

},

{

"role": "assistant",

"content": "The capital of France is Paris."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is an interesting fact of Paris."

}

],You can see how this can be applied by opening message_history.py in VS Code and debugging it by pressing F5. After the file runs, be sure to check the output. Then, try to run the sample a few more times to see how the results change.

The results will change from each run to the next due to the high temperature of .7. Go ahead and reduce the temperature to .0, and run the message_history.py sample a few more times. Keeping the temperature at 0 will show the same or similar results each time.

Setting a request’s temperature will often depend on your particular use case. Sometimes, you may want to limit the responses’ stochastic nature (randomness). Reducing the temperature to 0 will give consistent results. Likewise, a value of 1.0 will give the most variability in the responses.

Next, we also want to know what information is being returned for each request. The next listing shows the output format for the response. You can see this output by running the message_history.py file in VS Code.

Listing 2.6 Chat completions response

{

"id": "chatcmpl-8WWL23up3IRfK1nrDFQ3EHQfhx0U6",

"choices": [ #1

{

"finish_reason": "stop",

"index": 0,

"message": {

"content": "… omitted",

"role": "assistant", #2

"function_call": null,

"tool_calls": null

},

"logprobs": null

}

],

"created": 1702761496,

"model": "gpt-4-1106-preview", #3

"object": "chat.completion",

"system_fingerprint": "fp_3905aa4f79",

"usage": {

"completion_tokens": 78, #4

"prompt_tokens": 48, #4

"total_tokens": 126 #4

}

}#1 A model may return more than one response. #2 Responses returned in the assistant role #3 Indicates the model used #4 Counts the number of input (prompt) and output (completion) tokens used

It can be helpful to track the number of input tokens (those used in prompts) and the output tokens (the number returned through completions). Sometimes, minimizing and reducing the number of tokens can be essential. Having fewer tokens typically means LLM interactions will be cheaper, respond faster, and produce better and more consistent results.

That covers the basics of connecting to an LLM and returning responses. Throughout this book, we’ll review and expand on how to interact with LLMs. Until then, we’ll explore in the next section how to load and use open source LLMs.

2.2 Exploring open source LLMs with LM Studio

Commercial LLMs, such as GPT-4 from OpenAI, are an excellent place to start to learn how to use modern AI and build agents. However, commercial agents are an external resource that comes at a cost, reduces

data privacy and security, and introduces dependencies. Other external influences can further complicate these factors.

It’s unsurprising that the race to build comparable open source LLMs is growing more competitive every day. As a result, there are now open source LLMs that may be adequate for numerous tasks and agent systems. There have even been so many advances in tooling in just a year that hosting LLMs locally is now very easy, as we’ll see in the next section.

2.2.1 Installing and running LM Studio

LM Studio is a free download that supports downloading and hosting LLMs and other models locally for Windows, Mac, and Linux. The software is easy to use and offers several helpful features to get you started quickly. Here is a quick summary of steps to download and set up LM Studio:

- Download LM Studio from https://lmstudio.ai/.

- After downloading, install the software per your operating system. Be aware that some versions of LM Studio may be in beta and require installation of additional tools or libraries.

- Launch the software.

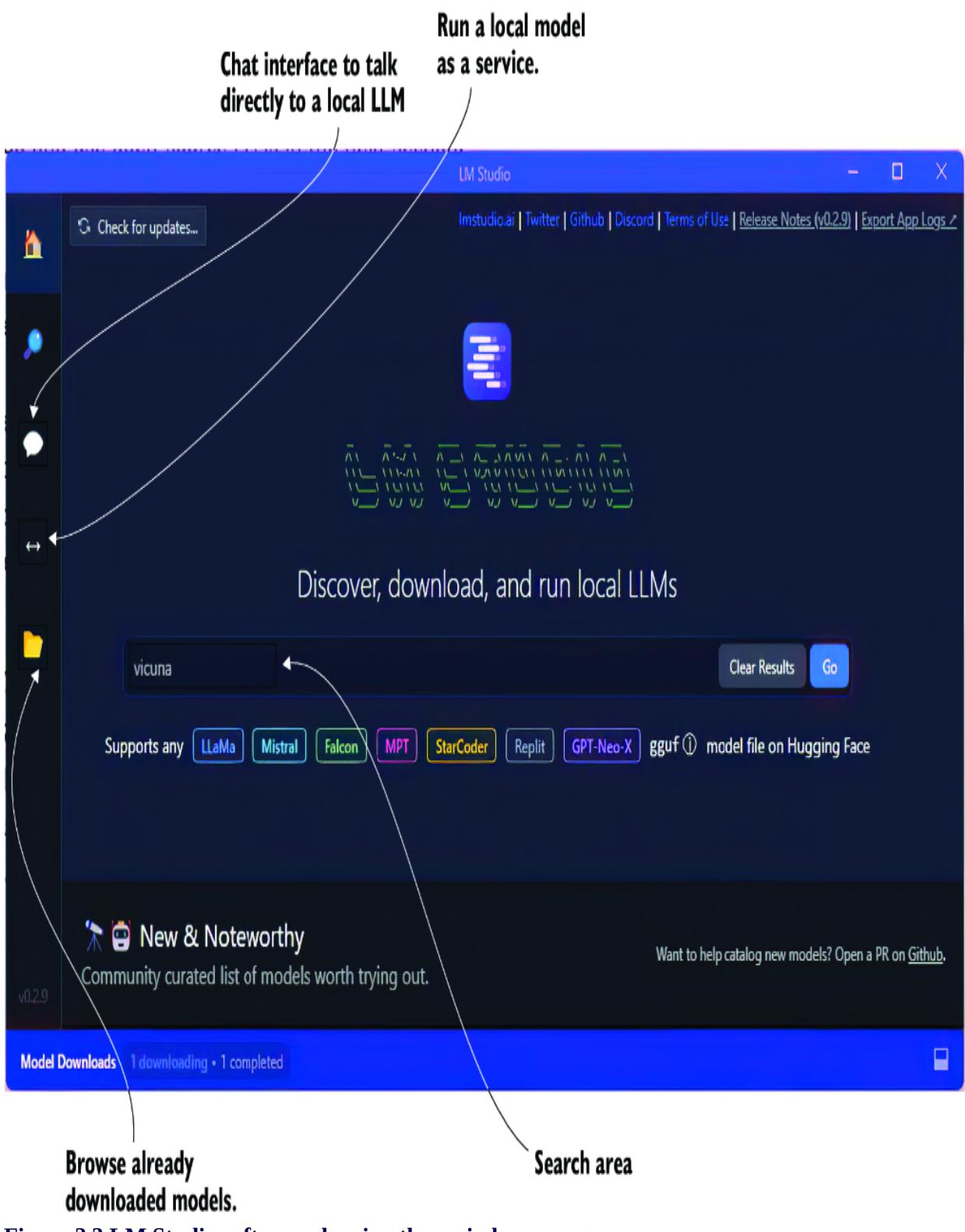

Figure 2.3 shows the LM Studio window running. From there, you can review the current list of hot models, search for others, and even download. The home page content can be handy for understanding the details and specifications of the top models.

Figure 2.3 LM Studio software showing the main home page

An appealing feature of LM Studio is its ability to analyze your hardware and align it with the requirements of a given model. The software will let

you know how well you can run a given model. This can be a great time saver in guiding what models you experiment with.

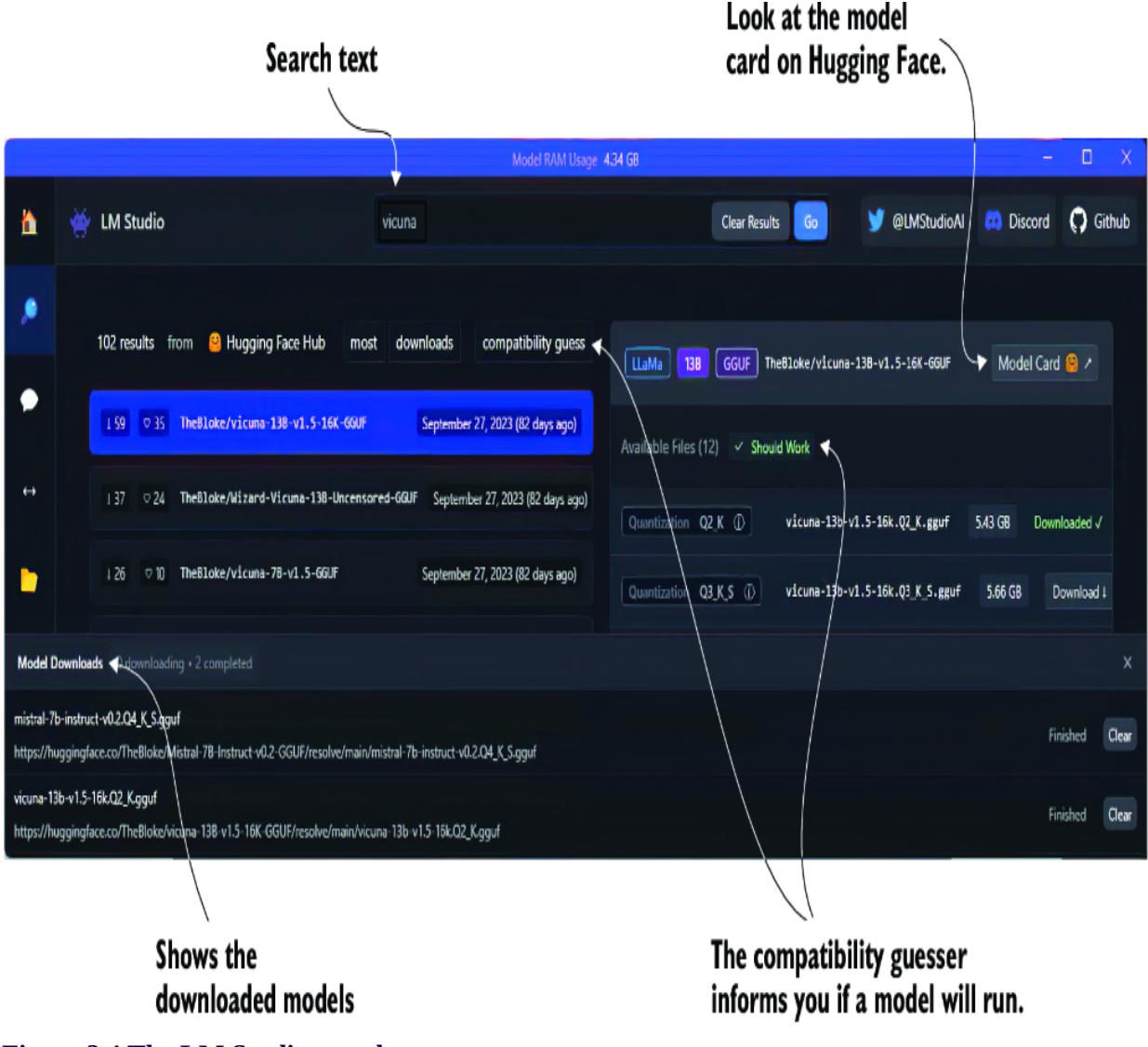

Enter some text to search for a model, and click Go. You’ll be taken to the search page interface, as shown in figure 2.4. From this page, you can see all the model variations and other specifications, such as context token size. After you click the Compatibility Guess button, the software will even tell you if the model will run on your system.

Figure 2.4 The LM Studio search page

Click to download any model that will run on your system. You may want to stick with models designed for chat completions, but if your system is

limited, work with what you have. In addition, if you’re unsure of which model to use, go ahead and download to try them. LM Studio is a great way to explore and experiment with many models.

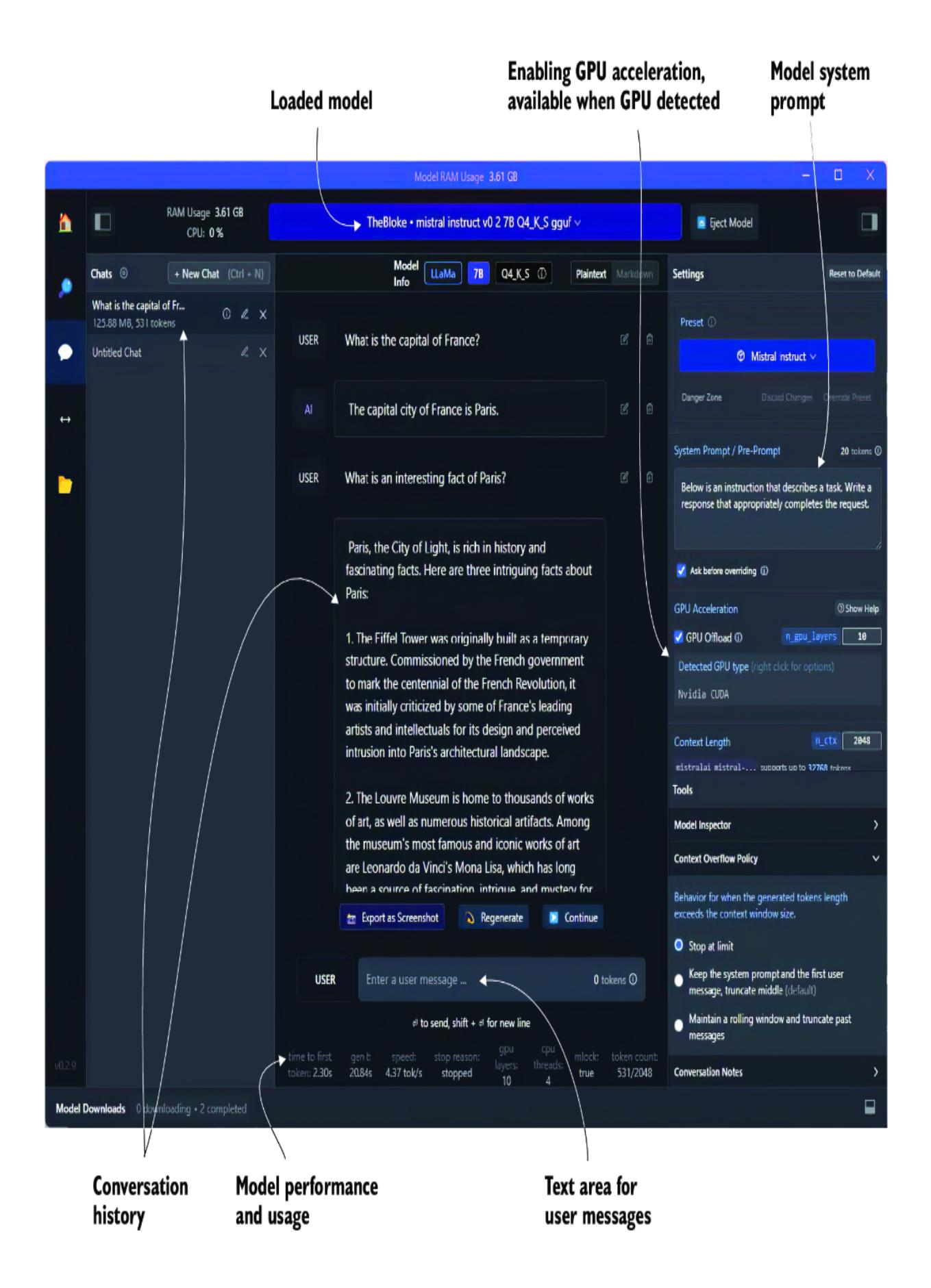

After the model is downloaded, you can then load and run the model on the chat page or as a server on the server page. Figure 2.5 shows loading and running a model on the chat page. It also shows the option for enabling and using a GPU if you have one.

Figure 2.5 The LM Studio chat page with a loaded, locally running LLM

To load and run a model, open the drop-down menu at the top middle of the page, and select a downloaded model. A progress bar will appear showing the model loading, and when it’s ready, you can start typing into the UI.

The software even allows you to use some or all of your GPU, if detected, for the model inference. A GPU will generally speed up the model response times in some capacities. You can see how adding a GPU can affect the model’s performance by looking at the performance status at the bottom of the page, as shown in figure 2.5.

Chatting with a model and using or playing with various prompts can help you determine how well a model will work for your given use case. A more systematic approach is using the prompt flow tool for evaluating prompts and LLMs. We’ll describe how to use prompt flow in chapter 9.

LM Studio also allows a model to be run on a server and made accessible using the OpenAI package. We’ll see how to use the server feature and serve a model in the next section.

2.2.2 Serving an LLM locally with LM Studio

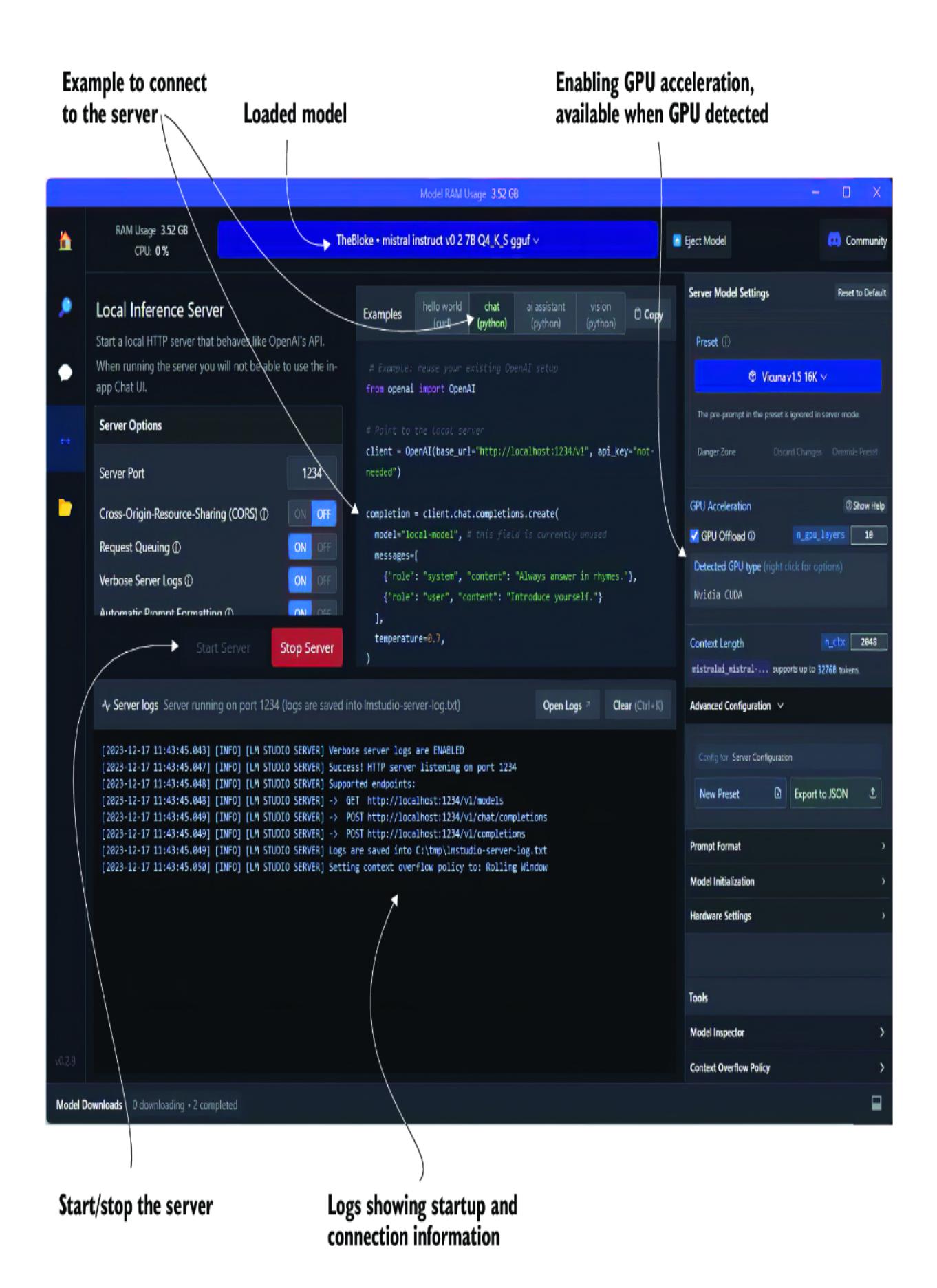

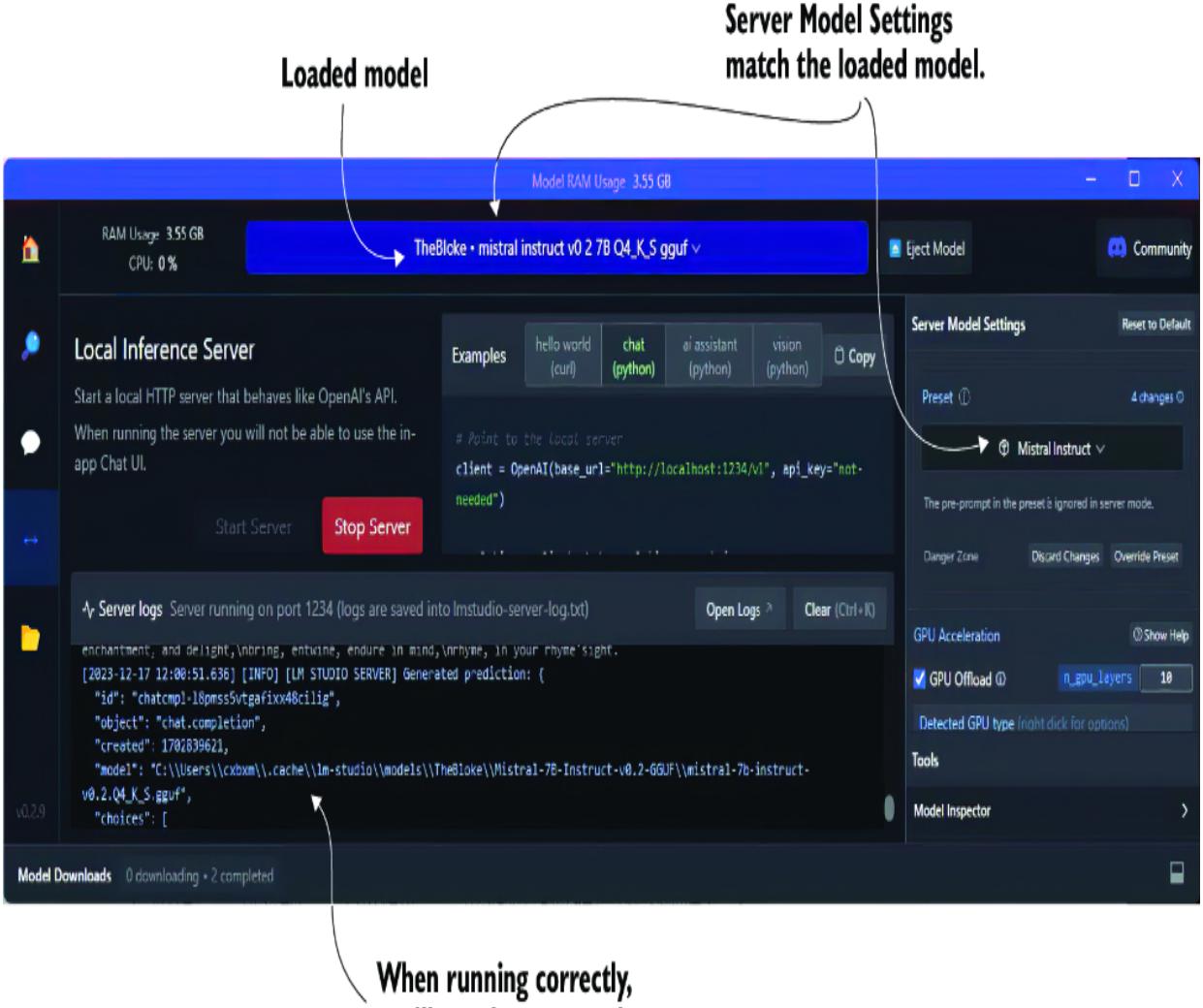

Running an LLM locally as a server is easy with LM Studio. Just open the server page, load a model, and then click the Start Server button, as shown in figure 2.6. From there, you can copy and paste any of the examples to connect with your model.

Figure 2.6 The LM Studio server page and a server running an LLM

You can review an example of the Python code by opening chapter_2/lmstudio_ server.py in VS Code. The code is also shown here in listing 2.7. Then, run the code in the VS Code debugger (press F5).

Listing 2.7 lmstudio_server.py

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI(base_url="http://localhost:1234/v1", api_key="not-needed")

completion = client.chat.completions.create(

model="local-model", #1

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": "Always answer in rhymes."},

{"role": "user", "content": "Introduce yourself."} #2

],

temperature=0.7,

)

print(completion.choices[0].message) #3#1 Currently not used; can be anything #2 Feel free to change the message as you like. #3 Default code outputs the whole message.

If you encounter problems connecting to the server or experience any other problems, be sure your configuration for the Server Model Settings matches the model type. For example, in figure 2.6, shown earlier, the loaded model differs from the server settings. The corrected settings are shown in figure 2.7.

Figure 2.7 Choosing the correct Server Model Settings for the loaded model

Now, you can use a locally hosted LLM or a commercial model to build, test, and potentially even run your agents. The following section will examine how to build prompts using prompt engineering more effectively.

2.3 Prompting LLMs with prompt engineering

A prompt defined for LLMs is the message content used in the request for better response output. Prompt engineering is a new and emerging field that attempts to structure a methodology for building prompts. Unfortunately, prompt building isn’t a well-established science, and there is a growing and diverse set of methods defined as prompt engineering.

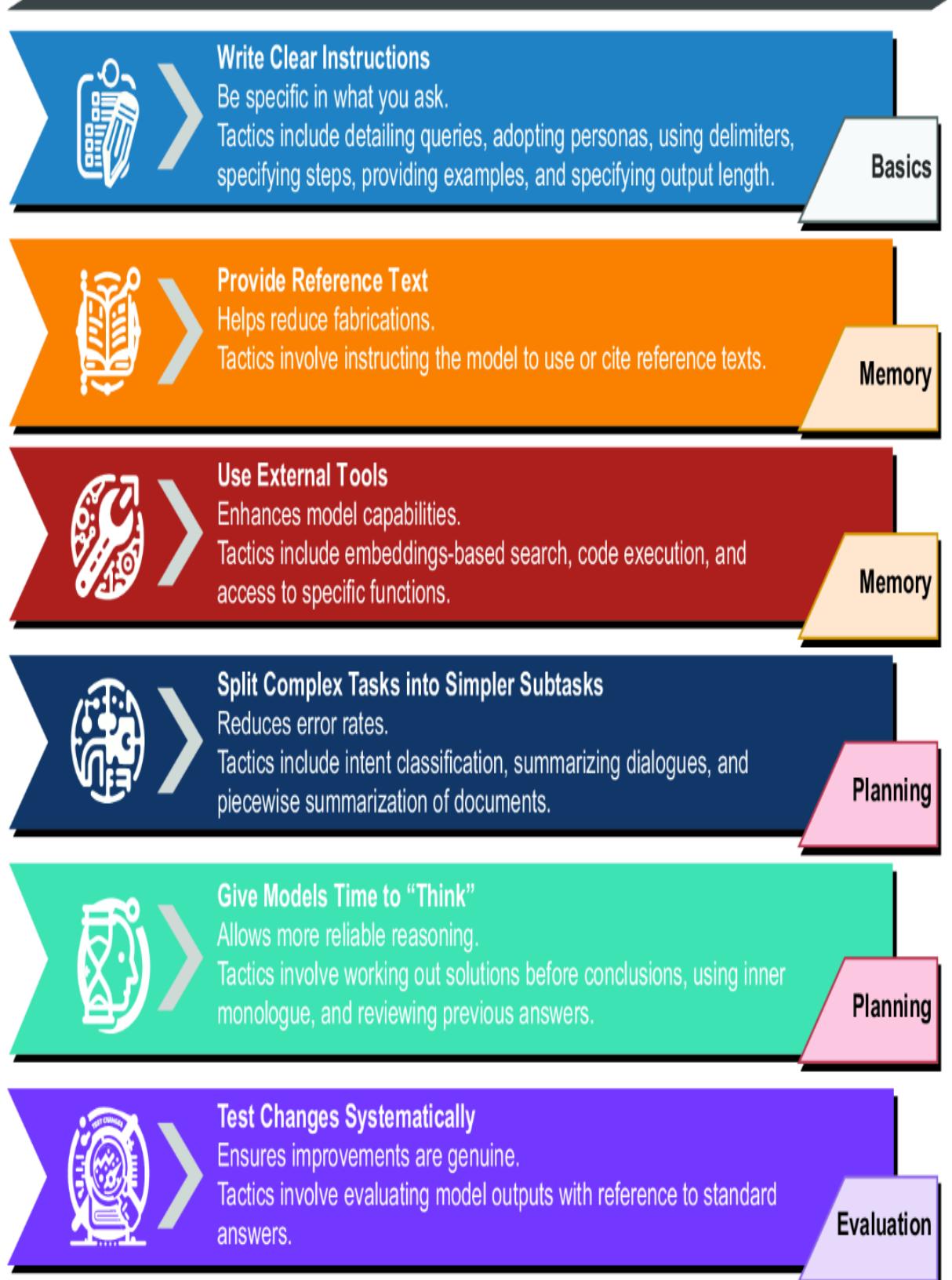

Fortunately, organizations such as OpenAI have begun documenting a universal set of strategies, as shown in figure 2.8. These strategies cover various tactics, some requiring additional infrastructure and considerations. As such, the prompt engineering strategies relating to more advanced concepts will be covered in the indicated chapters.

Figure 2.8 OpenAI prompt engineering strategies reviewed in this book, by chapter location

Each strategy in figure 2.8 unfolds into tactics that can further refine the specific method of prompt engineering. This chapter will examine the fundamental Write Clear Instructions strategy. Figure 2.9 shows the tactics for this strategy in more detail, along with examples for each tactic. We’ll look at running these examples using a code demo in the following sections.

| Tactics for Strategy: Writing Clear Instructions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detailed Queries |

Adopting Personas |

Using Delimiters |

Specifying Steps |

Providing Examples |

Specify Output Length |

|

| Without detailed queries: Who’s the prime minister? With detailed queries: Who is the prime minister of Canada, and how frequently are elections held? Provide as much detail as you can in a query; generally, the more detail the better. |

SYSTEM: You are a prompt expert and will suggest ways to improve a user request. USER: What is the capital of Canada? Personas can include details about demographics, knowledge, and personality. |

USER: Summarize the text delimited by triple quotes with a limerick: “text to be summarized” Delimiters can help separate blocks of content from specification details. |

SYSTEM: Use the following step-by-step instructions to respond to user inputs: Step 1 - Summarize the text in triple quotes to one sentence with a prefix that says “Summary:”. Step 2 - Translate the summary from Step 1 into French, with a prefix that says “Translation:”. USER: “text to summarize USER: and translate” |

SYSTEM: Answer in a consistent style. USER: Teach me about patience. This is the example. ASSISTANT: 4 The river that carves the deepest valley flows from a modest spring; the most intricate tapestry begins with a solitary thread. Teach me about the ocean. |

USER: Summarize the text delimited by triple quotes in about 50 words. “text to summarize here” Limiting the length of output can be specific to words, bullet points, or other metrics. |

|

| Using steps can help the LLM better process the task, but be sure to limit the number. |

Examples are a form of few-shot learning and can be an excellent way to indicate the desired response format and other details. |

Figure 2.9 The tactics for the Write Clear Instructions strategy

The Write Clear Instructions strategy is about being careful and specific about what you ask for. Asking an LLM to perform a task is no different from asking a person to complete the same task. Generally, the more information and context relevant to a task you can specify in a request, the better the response.

This strategy has been broken down into specific tactics you can apply to prompts. To understand how to use those, a code demo (prompt_engineering.py) with various prompt examples is in the chapter 2 source code folder.

Open the prompt_engineering.py file in VS Code, as shown in listing 2.8. This code starts by loading all the JSON Lines files in the prompts folder. Then, it displays the list of files as choices and allows the user to select a prompt option. After selecting the option, the prompts are submitted to an LLM, and the response is printed.

Listing 2.8 prompt_engineering.py (main())

def main():

directory = "prompts"

text_files = list_text_files_in_directory(directory) #1

if not text_files:

print("No text files found in the directory.")

return

def print_available(): #2

print("Available prompt tactics:")

for i, filename in enumerate(text_files, start=1):

print(f"{i}. {filename}")

while True:

try:

print_available() #2

choice = int(input("Enter … 0 to exit): ")) #3

if choice == 0:

break

elif 1 <= choice <= len(text_files):

selected_file = text_files[choice - 1]

file_path = os.path.join(directory,

selected_file)

prompts =

↪ load_and_parse_json_file(file_path) #4

print(f"Running prompts for {selected_file}")

for i, prompt in enumerate(prompts):

print(f"PROMPT {i+1} --------------------")

print(prompt)

print(f"REPLY ---------------------------")

print(prompt_llm(prompt)) #5

else:

print("Invalid choice. Please enter a valid number.")

except ValueError:

print("Invalid input. Please enter a number.")#1 Collects all the files for the given folder #2 Prints the list of files as choices #3 Inputs the user’s choice #4 Loads the prompt and parses it into messages #5 Submits the prompt to an OpenAI LLM

A commented-out section from the listing demonstrates how to connect to a local LLM. This will allow you to explore the same prompt engineering tactics applied to open source LLMs running locally. By default, this example uses the OpenAI model we configured previously in section 2.1.1. If you didn’t complete that earlier, please go back and do it before running this one.

Figure 2.10 shows the output of running the prompt engineering tactics tester, the prompt_engineering.py file in VS Code. When you run the tester, you can enter a value for the tactic you want to test and watch it run.

Figure 2.10 The output of the prompt engineering tactics testerIn the following sections, we’ll explore each prompt tactic in more detail. We’ll also examine the various examples.

2.3.1 Creating detailed queries

The basic premise of this tactic is to provide as much detail as possible but also to be careful not to give irrelevant details. The following listing shows the JSON Lines file examples for exploring this tactic.

Listing 2.9 detailed_queries.jsonl

[ #1

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are a helpful assistant."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is an agent?" #2

}

]

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": "You are a helpful assistant."

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": """

What is a GPT Agent?

Please give me 3 examples of a GPT agent

""" #3

}

]#1 The first example doesn’t use detailed queries. #2 First ask the LLM a very general question. #3 Ask a more specific question, and ask for examples.

This example demonstrates the difference between using detailed queries and not. It also goes a step further by asking for examples. Remember, the more relevance and context you can provide in your prompt, the better the overall response. Asking for examples is another way of enforcing the relationship between the question and the expected output.

2.3.2 Adopting personas

Adopting personas grants the ability to define an overarching context or set of rules to the LLM. The LLM can then use that context and/or rules to frame all later output responses. This is a compelling tactic and one that we’ll make heavy use of throughout this book.

Listing 2.10 shows an example of employing two personas to answer the same question. This can be an enjoyable technique for exploring a wide range of novel applications, from getting demographic feedback to specializing in a specific task or even rubber ducking.

GPT RUBBER DUCKING

Rubber ducking is a problem-solving technique in which a person explains a problem to an inanimate object, like a rubber duck, to understand or find a solution. This method is prevalent in programming and debugging, as articulating the problem aloud often helps clarify the problem and can lead to new insights or solutions.

GPT rubber ducking uses the same technique, but instead of an inanimate object, we use an LLM. This strategy can be expanded further by giving the LLM a persona specific to the desired solution domain.

Listing 2.10 adopting_personas.jsonl

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

You are a 20 year old female who attends college

in computer science. Answer all your replies as

a junior programmer.

""" #1

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is the best subject to study."

}

]

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

You are a 38 year old male registered nurse.

Answer all replies as a medical professional.

""" #2

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is the best subject to study."

}

]#1 First persona #2 Second persona

A core element of agent profiles is the persona. We’ll employ various personas to assist agents in completing their tasks. When you run this tactic, pay particular attention to the way the LLM outputs the response.

2.3.3 Using delimiters

Delimiters are a useful way of isolating and getting the LLM to focus on some part of a message. This tactic is often combined with other tactics but can work well independently. The following listing demonstrates two examples, but there are several other ways of describing delimiters, from XML tags to using markdown.

Listing 2.11 using_delimiters.jsonl[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

Summarize the text delimited by triple quotes

with a haiku.

""" #1

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "A gold chain is cool '''but a silver chain is better'''"

}

]

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

You will be provided with a pair of statements

(delimited with XML tags) about the same topic.

First summarize the arguments of each statement.

Then indicate which of them makes a better statement

and explain why.

""" #2

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": """

<statement>gold chains are cool</statement>

<statement>silver chains are better</statement>

"""

}

]#1 The delimiter is defined by character type and repetition. #2 The delimiter is defined by XML standards.

When you run this tactic, pay attention to the parts of the text the LLM focuses on when it outputs the response. This tactic can be beneficial for describing information in a hierarchy or other relationship patterns.

2.3.4 Specifying steps

Specifying steps is another powerful tactic that can have many uses, including in agents, as shown in listing 2.12. It’s especially powerful when developing prompts or agent profiles for complex multistep tasks. You can specify steps to break down these complex prompts into a step-by-step process that the LLM can follow. In turn, these steps can guide the LLM through multiple interactions over a more extended conversation and many iterations.

Listing 2.12 specifying_steps.jsonl[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

Use the following step-by-step instructions to respond to user inputs.

Step 1 - The user will provide you with text in triple single quotes.

Summarize this text in one sentence with a prefix that says 'Summary: '.

Step 2 - Translate the summary from Step 1 into Spanish,

with a prefix that says 'Translation: '.

""" #1

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "'''I am hungry and would like to order an appetizer.'''"

}

]

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

Use the following step-by-step instructions to respond to user inputs.

Step 1 - The user will provide you with text. Answer any questions in

the text in one sentence with a prefix that says 'Answer: '.

Step 2 - Translate the Answer from Step 1 into a dad joke,

with a prefix that says 'Dad Joke: '.""" #2

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "What is the tallest structure in Paris?"

}

]#1 Notice the tactic of using delimiters. #2 Steps can be completely different operations.

2.3.5 Providing examples

Providing examples is an excellent way to guide the desired output of an LLM. There are numerous ways to demonstrate examples to an LLM. The system message/prompt can be a helpful way to emphasize general output. In the following listing, the example is added as the last LLM assistant reply, given the prompt “Teach me about Python.”

Listing 2.13 providing_examples.jsonl

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

Answer all replies in a consistent style that follows the format,

length and style of your previous responses.

Example:

user:

Teach me about Python.

assistant: #1

Python is a programming language developed in 1989

by Guido van Rossum.

Future replies:

The response was only a sentence so limit

all future replies to a single sentence.

""" #2

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Teach me about Java."

}

]#1 Injects the sample output as the “previous” assistant reply #2 Adds a limit output tactic to restrict the size of the output and match the example

Providing examples can also be used to request a particular output format from a complex series of tasks that derive the output. For example, asking an LLM to produce code that matches a sample output is an excellent use of examples. We’ll employ this tactic throughout the book, but other methods exist for guiding output.

2.3.6 Specifying output length

The tactic of specifying output length can be helpful in not just limiting tokens but also in guiding the output to a desired format. Listing 2.14 shows an example of using two different techniques for this tactic. The first limits the output to fewer than 10 words. This can have the added benefit of making the response more concise and directed, which can be desirable for some use cases. The second example demonstrates limiting output to a concise set of bullet points. This method can help narrow down the output and keep answers short. More concise answers generally mean the output is more focused and contains less filler.

Listing 2.14 specifying_output_length.jsonl

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

Summarize all replies into 10 or fewer words.

""" #1

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Please tell me an exciting fact about Paris?"

}

]

[

{

"role": "system",

"content": """

Summarize all replies into 3 bullet points.

""" #2

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Please tell me an exciting fact about Paris?"

}

]#1 Restricting the output makes the answer more concise. #2 Restricts the answer to a short set of bullets

Keeping answers brief can have additional benefits when developing multi-agent systems. Any agent system that converses with other agents can benefit from more concise and focused replies. It tends to keep the LLM more focused and reduces noisy communication.

Be sure to run through all the examples of the prompt tactics for this strategy. As mentioned, we’ll cover other prompt engineering strategies and tactics in future chapters. We’ll finish this chapter by looking at how to pick the best LLM for your use case.

2.4 Choosing the optimal LLM for your specific needs

While being a successful crafter of AI agents doesn’t require an in-depth understanding of LLMs, it’s helpful to be able to evaluate the specifications. Like a computer user, you don’t need to know how to build a processor to understand the differences in processor models. This analogy holds well for LLMs, and while the criteria may be different, it still depends on some primary considerations.

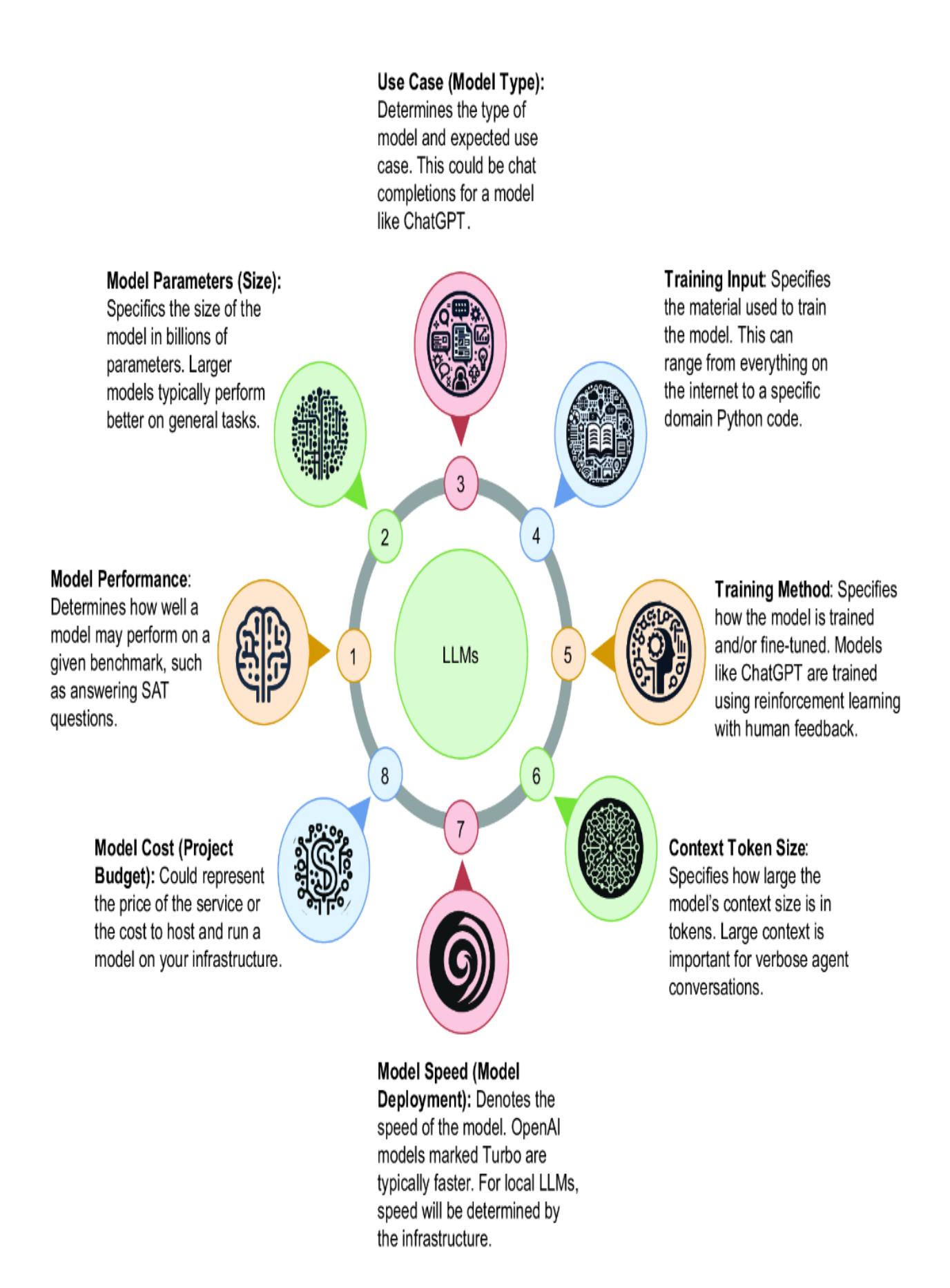

From our previous discussion and look at LM Studio, we can extract some fundamental criteria that will be important to us when considering LLMs. Figure 2.11 explains the essential criteria to define what makes an LLM worth considering for creating a GPT agent or any LLM task.

Figure 2.11 The important criteria to consider when consuming an LLM

For our purposes of building AI agents, we need to look at each of these criteria in terms related to the task. Model context size and speed could be considered the sixth and seventh criteria, but they are usually considered variations of a model deployment architecture and infrastructure. An eighth criterion to consider for an LLM is cost, but this depends on many other factors. Here is a summary of how these criteria relate to building AI agents:

- Model performance —You’ll generally want to understand the LLM’s performance for a given set of tasks. For example, if you’re building an agent specific to coding, then an LLM that performs well on code will be essential.

- Model parameters (size) —The size of a model is often an excellent indication of inference performance and how well the model responds. However, the size of a model will also dictate your hardware requirements. If you plan to use your own locally hosted model, the model size will also primarily dictate the computer and GPU you need. Fortunately, we’re seeing small, very capable open source models being released regularly.

- Use case (model type) —The type of model has several variations. Chat completions models such as ChatGPT are effective for iterating and reasoning through a problem, whereas models such as completion, question/answer, and instruct are more related to specific tasks. A chat completions model is essential for agent applications, especially those that iterate.

- Training input —Understanding the content used to train a model will often dictate the domain of a model. While general models can be effective across tasks, more specific or fine-tuned models can be more relevant to a domain. This may be a consideration for a domain-specific agent where a smaller, more fine-tuned model may perform as well as or better than a larger model such as GPT-4.

- Training method —It’s perhaps less of a concern, but it can be helpful to understand what method was used to train a model. How a model is trained can affect its ability to generalize, reason, and plan. This can be

essential for planning agents but perhaps less significant for agents than for a more task-specific assistant.

- Context token size —The context size of a model is more specific to the model architecture and type. It dictates the size of context or memory the model may hold. A smaller context window of less than 4,000 tokens is typically more than enough for simple tasks. However, a large context window can be essential when using multiple agents—all conversing over a task. The models will typically be deployed with variations on the context window size.

- Model speed (model deployment) —The speed of a model is dictated by its inference speed (or how fast a model replies to a request), which in turn is dictated by the infrastructure it runs on. If your agent isn’t directly interacting with users, raw real-time speed may not be necessary. On the other hand, an LLM agent interacting in real time needs to be as quick as possible. For commercial models, speed will be determined and supported by the provider. Your infrastructure will determine the speed for those wanting to run their LLMs.

- Model cost (project budget) —The cost is often dictated by the project. Whether learning to build an agent or implementing enterprise software, cost is always a consideration. A significant tradeoff exists between running your LLMs versus using a commercial API.

There is a lot to consider when choosing which model you want to build a production agent system on. However, picking and working with a single model is usually best for research and learning purposes. If you’re new to LLMs and agents, you’ll likely want to choose a commercial option such as GPT-4 Turbo. Unless otherwise stated, the work in this book will depend on GPT-4 Turbo.

Over time, models will undoubtedly be replaced by better models. So you may need to upgrade or swap out models. To do this, though, you must understand the performance metrics of your LLMs and agents. Fortunately, in chapter 9, we’ll explore evaluating LLMs, prompts, and agent profiles with prompt flow.

2.5 Exercises