The Quick Python Book

Naomi Ceder Foreword by Luciano Ramalho

The Zen of Python (PEP 20)

by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one—and preferably only one—obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than **right** now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea—let's do more of those!Praise for the Third Edition

Naomi’s book epitomizes what it is to be Pythonic: beautiful is better than ugly, simple is better than complex, and readability counts.

—From the Foreword by Nicholas Tollervey, Python Software Foundation

Leads you from a basic knowledge of Python to its most interesting features, always using accessible language.

— Eros Pedrini, everis

Unleash your Pythonic powers with this book and start coding real-world applications fast. — Carlos Fernandez Manzano, Aguas de Murcia

The complete and definitive book to start learning Python.

— Christos Paisios, e-Travel

Excellent starter for beginners in Python.

—Ruslan Vidert, Yandex

When time is precious, this is THE book to learn Python quickly and efficiently.

— Aaron Jensen, Shoot the Moon Products

This book is concise yet comprehensive and provides the tools to quickly solve real-world problems using Python!

—Negmat Mullodzhanov, Wavemaker

The definitive place to start introducing you to code on Python! —Felipe E. Vildoso-Castillo, University of Chile

The Quick Python Book, Fourth Edition

Naomi Ceder

Foreword by Luciano Ramalho

For online information and ordering of this and other Manning books, please visit www.manning.com. The publisher offers discounts on this book when ordered in quantity.

For more information, please contact

Special Sales Department Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964 Email: orders@manning.com

© 2025 Manning Publications Co. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of the publisher.

Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in the book, and Manning Publications was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial caps or all caps.

Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, it is Manning’s policy to have the books we publish printed on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end. Recognizing also our responsibility to conserve the resources of our planet, Manning books are printed on paper that is at least 15 percent recycled and processed without the use of elemental chlorine. ∞

The author and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the information in this book was correct at press time. The author and publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause, or from any usage of the information herein.

Manning Publications Co. 20 Baldwin Road PO Box 761 Shelter Island, NY 11964

Development editor: Doug Rudder Technical editor: Kenneth W. Alger Review editor: Dunja NikitoviÊ Production editor: Kathy Rossland Copy editor: Kari Lucke Proofreader: Katie Tennant Typesetter: Tamara ŠveliÊ SabljiÊ Cover designer: Marija Tudor

ISBN 9781633436336 Printed in the United States of America To my friends past, present, and future in the global Python community, with gratitude for your love, acceptance, and support

foreword

I read the first edition of The Quick Python Book by Daryl Harms and Kenneth McDonald in late 1999. At the time there were only a handful of books about Python, and I believe I had them all. The Quick Python Book was the best book-length Python tutorial in the market. It offered a gentle learning curve and lots of practical advice, and it went beyond small snippets to discuss how to organize complete Python modules and programs.

All the qualities I mentioned remain, enhanced by new examples and insights by Naomi Ceder, who took over as the main author in the second edition.

The most important quality of The Quick Python Book has always been the practical context around the technical details. The labs at the end of the chapters and the chapter-length case study are about the creation and evolution of complete, useful programs.

In this fourth edition, Naomi complemented coverage of new Python features with two major changes. The first is using interactive notebooks on Google’s Colaboratory. That allows readers to jump right into coding and experimenting without installing anything on their computers. It also helps them get comfortable with the most popular coding environment for data science and AI: Jupyter notebooks.

The second major change is in the labs. Naomi now compares her solutions with AI-generated code by the Colaboratory and GitHub Copilot. She shows the pros and cons of using those AI assistants, discusses their effects on the coding workflow, and advises on how to write prompts to get the best results.

Updating and improving this excellent book over the last 15 years is only one of Naomi’s many contributions to Python. She has devoted countless hours of volunteer time to the Python Software Foundation and the wider Python international community.

Thousands of Python books later, this is still the best book-length Python tutorial that I know about. Thank you, Naomi, for keeping it fresh and ever more relevant in the 21st century!

—Luciano Ramalho Pythonista since 1998 and author of Fluent Python

preface

Since I wrote the third edition of this book, more than five years have passed, and in that time we’ve been through some changes—including a pandemic and various crises but also the continued growth of data science and machine learning, the rise of AI-assisted code (AI everything, it seems), and of course the continued growth of Python, which is now one of the most used coding languages on the planet.

I’ve been coding in Python for almost 25 years now, far longer than in any other language I’ve ever used. I’ve used Python for system administration, web applications, database management, and data analysis over those years, but most important, I’ve come to use Python just to help myself think about a problem more clearly.

Based on my earlier experience, I would have expected that by now I would have been lured away by some other language that was faster, cooler, sexier, whatever. I think there are two reasons that didn’t happen. First, while other languages have come along, none has helped me do what I needed to do quite as effectively as Python. Even after all these years, the more I use Python and the more I understand it, the more I feel the quality of my programming improves and matures.

The second reason I’m still around is the Python community. It’s one of the most welcoming, inclusive, active, and friendly communities I’ve seen, embracing scientists, quants, web developers, systems people, and data scientists on every continent. It’s been a joy and honor to work with members of this community, and I encourage everyone to join in.

Writing this book has shown me again how time passes and things change. While we’re still on Python 3, today’s Python 3 has evolved considerably even from the Python 3.6 of the last edition of this book. Things that were never dreamed of are now features of the language, and even the old nemesis of multicore processing, the GIL, is on the verge of workable solutions.

As the language has changed, so too have the ways people use Python. Although my goal has always been to keep the best bits of the previous edition, there have been a fair number of additions, deletions, and reorganizations that I hope make this edition both useful and timely. I’ve tried to keep the style clear, low-key, and also accessible to the many Python coders around the world whose first language is not English.

For me, the aim of this book is to share the positive experiences I’ve gotten from coding in Python by introducing people to Python 3, the latest and, in my opinion, greatest version of Python to date. May your journey be as satisfying as mine has been.

acknowledgments

I want to thank David Fugate of LaunchBooks for getting me into this book in the first place and for all of the support and advice he has provided over the years. I can’t imagine having a better agent and friend. I also need to thank Jonathan Gennick of Manning for pushing the idea of doing a fourth edition of this book and supporting me in my efforts to make it as good as the first three. I also thank every person at Manning who worked on this project, with special thanks to Marjan Bace for his support, Doug Rudder for guidance in the development phases, Kathy Rossland for getting the book (and me) through the production process, Kari Lucke for her patience in copy editing, and Katie Tennant for proofreading. Likewise, hearty thanks go to the many reviewers whose insights and feedback were of immense help, especially Ken Alger, the technical editor for this edition of the book. Ken has taught, written about, and presented on various Python topics. In 2017, he served on the board of directors of the Django Software Foundation. Ken has worked with Python off and on since the mid-1990s, helping several industries automate tasks using Python.

Thanks as well go to the many others who provided valuable feedback, including all the reviewers: Aaron S. Bush, Advait Patel, Alfonso Harding, Anders Persson, Anuj Tyagi, Arian Ahmdinejad, Asaad Saad, Cay Horstmann, Chalamayya Batchu, Christian Sutton, Daivid Morgan, Dane Hillard, Darrin Bishop, Felipe Provezano Coutinho, Gajendra Babu Thokala, Ganesh Harke, Glen Mules, Greg Wagner, Harshita Asnani, Heather Ward, Ian Brierley, James Bishop, James Brett, James McCorrie, Jim Mason, Jose Apablaza, Juan Gomez, Justin Reiser, Ken Youens-Clark, Kiran Kumar Gunturu, Laurence Baldwin, Lav Kumar, Lev Veyde, Monisha Athi Kesavan Premalatha, Nicolas Chartier, Peter Van Caeneghem, Raghunath Mysore, Raz Pavel, Rich Hilliar, Robert F. Scheyder, Steve Grey-Wilson, Tanvir Kaur, Vatche Jabagchourian, Venkatesh Rajagopal, and William Jamir. Your suggestions helped make this a better book.

I have to thank the authors of the first edition, Daryl Harms and Kenneth MacDonald, for writing a book so sound that it has remained in print well beyond the average lifespan of most tech books, giving me a chance to do the second, third, and now fourth edition, as well as everyone who bought and gave positive reviews to the previous editions. I hope this version carries on the successful and long-lived tradition of the first three editions.

Thanks also go to Luciano Ramalho for the kindness with which he wrote the foreword to this edition, as well as for our years of friendship and the many years he has spent sharing his vast Python knowledge with communities in Brazil and throughout the world. Muito obrigada, meu amigo. I also owe thanks to the global Python community, an unfailing source of support, wisdom, friendship, and joy over the years. To borrow the quote one more time from Brett Cannon, “I came for the language, but I stayed for the community.” Thank you all, my friends.

Most important, as always, I thank my wife, Becky, who both encouraged me to take on this project and supported me through the entire process. I really couldn’t have done it without her.

about this book

The Quick Python Book, Fourth Edition, is intended for people who already have experience in one or more programming languages and want to learn the basics of Python 3 as quickly and directly as possible. Although some basic concepts are covered, there’s no attempt to teach fundamental programming skills in this book, and the basic concepts of flow control, object-oriented programming (OOP), file access, exception handling, and the like are assumed. This book may also be of service to users of earlier versions of Python who want a concise reference for Python 3.

Who should read this book

This book is intended for readers who know how to write some code and understand basic programming concepts. They might be coming from another programming language, they might still be learning Python and wanting to level up their knowledge, or they might be looking to update and refresh their knowledge. This book provides a compact and accessible view of the Python landscape at the level of the features that are used to get 90% of the work done.

How this book is organized: A road map

Part 1 introduces Python and explains how to use Python via Google’s Colaboratory and how to obtain the source code Jupyter notebooks from the book’s GitHub repository. It also includes a very general survey of the language, which will be most useful for experienced programmers looking for a high-level view of Python:

Chapter 1 discusses the strengths and weaknesses of Python and shows why Python is a good choice of programming language for many situations.

- Chapter 2 covers how to use Python via Google’s Colaboratory and how to obtain the source code as Jupyter notebooks from the book’s GitHub repository.

- Chapter 3 is a short overview of the Python language. It provides a basic idea of the philosophy, syntax, semantics, and capabilities of the language.

Part 2 is the heart of the book. It covers the ingredients necessary for obtaining a working knowledge of Python as a general-purpose programming language. The chapters are designed to allow readers who are beginning to learn Python to work their way through sequentially, picking up knowledge of the key points of the language. These chapters also contain some more advanced sections, allowing you to return to find in one place all the necessary information about a construct or topic:

- Chapter 4 starts with the basics of Python. It introduces Python variables, expressions, strings, and numbers. It also introduces Python’s block-structured syntax.

- Chapters 5, 6, and 7 describe the five powerful built-in Python data types: lists, tuples, sets, strings, and dictionaries.

- Chapter 8 introduces Python’s control flow syntax and use (loops, if-else statements, and the new match-case statement).

- Chapter 9 describes function definition in Python along with its flexible parameter-passing capabilities.

- Chapter 10 describes Python modules, which provide an easy mechanism for segmenting the program namespace.

- Chapter 11 covers creating standalone Python programs, or scripts, and running them on Windows, macOS, and Linux platforms. The chapter also covers the support available for command-line options, arguments, and I/O redirection.

- Chapter 12 describes how to work with and navigate through the files and directories of the filesystem. It shows how to write code that’s as independent as possible of the actual operating system you’re working on.

- Chapter 13 introduces the mechanisms for reading and writing files in Python, including the basic capability to read and write strings (or byte streams), the mechanism available for reading binary records, and the ability to read and write arbitrary Python objects.

- Chapter 14 discusses the use of exceptions, the error-handling mechanism used by Python. It doesn’t assume that you have any previous knowledge of exceptions, although if you’ve previously used them in C++ or Java, you’ll find them familiar.

Part 3 introduces advanced language features of Python—elements of the language that aren’t essential to its use but that can certainly be a great help to a serious Python programmer:

- Chapter 15 introduces Python’s support for writing object-oriented programs.

- Chapter 16 discusses the regular expression capabilities available for Python.

- Chapter 17 introduces more advanced OOP techniques, including the use of Python’s special method attributes mechanism, metaclasses, and abstract base classes.

- Chapter 18 introduces the package concept in Python for structuring the code of large projects.

- Chapter 19 is a brief survey of the standard library. It also includes a discussion of where to find other modules and how to install them.

Part 4 describes more advanced or specialized topics that are beyond the strict syntax of the language. You may read these chapters or not, depending on your needs.

- Chapter 20 dives deeper into manipulating files in Python.

- Chapter 21 covers strategies for reading, cleaning, and writing various types of data files.

- Chapter 22 surveys the process, issues, and tools involved in fetching data over the network.

- Chapter 23 discusses how Python accesses relational and NoSQL databases.

- Chapter 24 is a brief introduction to using Python, Jupyter notebooks, and pandas to explore datasets.

- The case study walks you through using Python to fetch data, clean it, and then graph it. The project combines several features of the language discussed in the chapters, and it gives you a chance to see a project worked through from beginning to end.

- The appendix contains a guide to obtaining and accessing Python’s full documentation, the Pythonic style guide, PEP 8, and “The Zen of Python,” a slightly wry summary of the philosophy behind Python.

A suggested plan if you’re new to Python programming and want to skip straight to the language is to start by reading chapter 3 to obtain an overall perspective and then work through the chapters in part 2 that are applicable. Enter in the interactive examples as they are introduced to immediately reinforce the concepts. You can also easily go beyond the examples in the text to answer questions about anything that may be unclear. This has the potential to amplify the speed of your learning and the level of your comprehension. If you aren’t familiar with OOP or don’t need it for your application, skip most of chapter 15.

Those who are familiar with Python should also start with chapter 3. It’s a good review and introduces differences between Python and what may be more familiar. It’s also a reasonable test of whether you’re ready to move on to the advanced chapters in parts 3 and 4 of this book.

It’s possible that some readers, although new to Python, will have enough experience with other programming languages to be able to pick up the bulk of what they need to get going by reading chapter 3 and by browsing the Python standard library modules listed in chapter 19 and the documentation for the Python standard library.

About the code

The code samples in this book are deliberately kept as simple as possible, because they aren’t intended to be reusable parts that can be plugged into your code. Instead, the code samples are stripped down so that you can focus on the principle being illustrated.

This book is based on Python 3.13, including some features not yet supported on Colaboratory (which is on Python 3.11 at the time of writing), and all examples should work on any subsequent version of Python 3. Other than the newest features, the examples also work on Python 3.9 and later, but I strongly recommend using the most current version you can; there are no advantages to using the earlier versions, and each version has several subtle improvements over the earlier ones.

In keeping with the idea of ease of use, the code examples are presented as Jupyter notebook cells that you can run in Google Colaboratory or with any other Jupyter server. Where possible, you should enter and experiment with these samples as much as you can.

The Jupyter notebooks with the code for the examples and the answers to most of the Quick Check and Try This exercises in this book are available from the publisher’s website at <www.manning.com/books/the-quick-python-book-fourth-edition>. You can also find all of the code in a GitHub repository athttps://github.com/nceder/qpb4e.

You can get executable snippets of code from the liveBook (online) version of this book at https://livebook.manning.com/book/the-quick-python-book-fourth-edition.

This book contains many examples of source code both in numbered listings and in line with normal text. In both cases, source code is formatted in a fixed-width font like this to separate it from ordinary text. The output of the code when run is also in bold.

In many cases, the original source code has been reformatted; we’ve added line breaks and reworked indentation to accommodate the available page space in the book. In some cases, even this was not enough, and listings include line-continuation markers (➥). Additionally, comments in the source code have often been removed from the listings when the code is described in the text. Code annotations accompany many of the listings, highlighting important concepts.

In some cases, a longer code sample is needed, and these cases are identified in the text as file listings. You can download these files from the source code repository or save the listings as files with names matching those used in the text and run them as standalone scripts.

liveBook discussion forum

Purchase of The Quick Python Book, Fourth Edition, includes free access to liveBook, Manning’s online reading platform. Using liveBook’s exclusive discussion features, you can attach comments to the book globally or to specific sections or paragraphs. It’s a snap to make notes for yourself, ask and answer technical questions, and receive help from the author and other users. To access the forum, go to https://livebook.manning .com/book/the-quick-python-book-fourth-edition/discussion. You can also learn more about Manning’s forums and the rules of conduct at https://livebook.manning .com/book/discussion.

Manning’s commitment to our readers is to provide a venue where a meaningful dialogue between individual readers and between readers and the author can take place. It is not a commitment to any specific amount of participation on the part of the author, whose contribution to the forum remains voluntary (and unpaid). We suggest you try asking the author some challenging questions lest their interest stray! The forum and the archives of previous discussions will be accessible from the publisher’s website as long as the book is in print.

about the cover illustration

The figure on the cover of The Quick Python Book, Fourth Edition, is “Bavaroise” or “Woman from Bavaria,” taken from a 19th-century edition of Sylvain Maréchal’s fourvolume compendium, Costumes Civils Actuels de Tous les Peuples Connus. Each illustration is finely drawn and colored by hand.

In those days, it was easy to identify where people lived and what their trade or station in life was just by their dress. Manning celebrates the inventiveness and initiative of the computer business with book covers based on the rich diversity of regional culture centuries ago, brought back to life by pictures from collections such as this one.

Part 1

Starting out

These first three chapters tell you a little bit about Python, its strengths and weaknesses, and why you should consider learning Python. In chapter 2 you see how to run Python using Google Colaboratory, how to access the book’s example code repository on GitHub, and how to write a simple program. Chapter 3 is a quick, high-level survey of Python’s syntax and features. If you’re looking for the quickest possible introduction to Python, start with chapter 3.

1 About Python

This chapter covers

- Why use Python?

- What Python does well

- What Python is improving

This book is intended to help people get a solid general understanding of Python as quickly as possible, avoiding getting bogged down in advanced topics but covering the essentials to write and read Python code. In particular, this book is intended for people who are coming to Python from other languages and for those who know a bit of Python but are looking to level up their skills as Python continues to gain popularity, particularly in areas like data science, machine learning, and the sciences. While no prior knowledge of Python is needed, some knowledge and experience with programming is necessary to get the most out of this book.

After introducing Python and offering some advice on getting started with a Python environment, the book provides a quick summary of Python’s syntax, followed by chapters that build from the built-in data types up through creating functions, classes, and packages, as well as some more advanced features and a case study in handling data.

With the rise of AI tools based on large language models (LLMs), it is now possible to generate increasing amounts of usable code if (and that’s a big “if”) one has enough knowledge of coding to guide the process intelligently. While this book is not a tutorial on AI and its use in code generation, the coding problems posed at the end of each chapter, starting with chapter 5, provide examples of AI responses to the same questions along with a brief discussion of what the AI got right (and wrong). This will help build an understanding of how to use AI tools to generate code that actually works.

1.1 Why should I use Python?

Hundreds of programming languages are available today, from mature languages like C and C++, to newer entries like Rust, Go, and C#, to enterprise juggernauts like Java, to the more web-oriented JavaScript and Typescript. This abundance of choice makes deciding on a programming language difficult. Although no one language is the right choice for every possible situation, I think that Python is a good choice for a large number of programming problems, and it’s also a good choice if you’re learning to program. Millions of programmers around the world use Python, and the number grows every year.

Python continues to attract new users for a variety of reasons. It’s a true cross-platform language, running equally well on Windows, Linux/UNIX, and iOS platforms, as well as others, ranging from supercomputers to mobile devices. It can be used to develop small applications and rapid prototypes, but it scales well to permit the development of large programs. It comes with a powerful and easy-to-use graphical user interface (GUI) toolkit, web programming libraries, and more. Python has also become a vital tool for scientific computing and for data science, machine learning, and work with AI. And it’s free.

1.2 What Python does well

Python is a modern programming language developed by Guido van Rossum in the 1990s (and named after a famous comedic troupe). Although Python isn’t perfect for every application, its strengths make it a good choice for many situations.

1.2.1 Python is easy to use

Programmers familiar with traditional languages will find it easy to learn Python. All of the familiar constructs—loops, conditional statements, arrays, and so forth—are included, but many are easier to use in Python. Here are a few of the reasons why:

Types are associated with objects, not variables. A variable can be assigned a value of any type, and a list can contain objects of many types. This also means that type casting usually isn’t necessary and that your code isn’t locked into the straitjacket of predeclared types. But while types are not required for variables, Python does allow type hints that allow developers to check that their code is consistent in the type of object used for parameters, return values, etc.; we’ll talk a little bit about type hints later in the book.

- Python typically operates at a much higher level of abstraction. This is partly the result of the way the language is built and partly the result of an extensive standard code library that comes with the Python distribution. A program to download a web page can be written in two or three lines!

- Syntax rules are very simple. Although becoming an expert Pythonista takes time and effort, even beginners can absorb enough Python syntax to write useful code quickly.

Python is well suited for rapid application development. It isn’t unusual for coding an application in Python to take one-fifth the time it would in C or Java and to take as little as one-fifth the number of lines of the equivalent C program. This depends on the particular application, of course; for a numerical algorithm performing mostly integer arithmetic in for loops, there would be much less of a productivity gain. For the average application, the productivity gain can be significant.

1.2.2 Python is expressive

Python is a very expressive language. Expressive in this context means that a single line of Python code can do more than a single line of code in most other languages. The advantages of a more expressive language are obvious: the fewer lines of code you have to write, the faster you can complete the project. The fewer lines of code there are, the easier the program will be to maintain and debug.

To get an idea of how Python’s expressiveness can simplify code, consider swapping the values of two variables, var1 and var2. In a language like Java, this requires three lines of code and an extra variable:

int temp = var1;

var1 = var2;

var2 = temp;The variable temp is needed to save the value of var1 when var2 is put into it, and then that saved value is put into var2. The process isn’t terribly complex, but reading those three lines and understanding that a swap has taken place takes a certain amount of overhead, even for experienced coders.

By contrast, Python lets you make the same swap in one line and in a way that makes it obvious that a swap of values has occurred:

var2, var1 = var1, var2Of course, this is a very simple example, but you can find the same advantages throughout the language.

1.2.3 Python is readable

Another advantage of Python is that it’s easy to read. You might think that a programming language needs to be read only by a computer, but humans have to read your code as well: whoever debugs your code (quite possibly you), whoever maintains your code (could be you again), and whoever might want to modify your code in the future. In all of those situations, the easier the code is to read and understand, the better it is.

The easier code is to understand, the easier it is to debug, maintain, and modify. Python’s main advantage in this department is its use of indentation. Unlike most languages, Python insists that blocks of code be indented. Although this strikes some people as odd, it has the benefit that your code is always formatted in a very easy-to-read style.

The following are two short programs, one written in Perl and one in Python. Both take two equal-size lists of numbers and return the pairwise sum of those lists. I think the Python code is more readable than the Perl code; it’s visually cleaner and contains fewer inscrutable symbols:

# Perl version.

sub pairwise_sum {

my($arg1, $arg2) = @_;

my @result;

for(0 .. $#$arg1) {

push(@result, $arg1->[$_] + $arg2->[$_]);

}

return(\@result);

}

# Python version.

def pairwise_sum(list1, list2):

result = []

for i in range(len(list1)):

result.append(list1[i] + list2[i])

return resultBoth pieces of code do the same thing, but the Python code wins in terms of readability. (There are other ways to do this in Perl, of course, some of which are much more concise—but, in my opinion, are harder to read than the one shown.)

1.2.4 Python is complete: “Batteries included”

Another advantage of Python is its “batteries included” philosophy when it comes to libraries. The idea is that when you install Python, you should have everything you need to do real work without the need to install additional libraries. This is why the Python standard library comes with modules for handling email, web pages, databases, operating-system calls, GUI development, and more.

For example, with Python, you can write a web server to share the files in a directory with just two lines of code:

import http.server

http.server.test(HandlerClass=http.server.SimpleHTTPRequestHandler)There’s no need to install libraries to handle network connections and HTTP; it’s already in Python, right out of the box.

1.2.5 Python has a rich ecosystem of third-party libraries

While Python is “batteries included,” there are still many situations where one needs to go beyond even a well-stocked standard library—a specialized task, a new data format, more complex applications, and so on. Here Python has really come to the forefront over the past decade. In many areas, from web applications and APIs to data handling and visualization, to machine learning and data science and more, Python has one of the richest ecosystems of packages, libraries, and frameworks of any current language. It’s very unlikely that you’ll find yourself in a situation where there are no Python packages to meet your needs.

1.2.6 Python is cross-platform

Python is also an excellent cross-platform language. Python runs on many platforms, including Windows, Mac, Linux, UNIX, and others. Because it’s interpreted, the same code can run on any platform that has a Python interpreter, and almost all current platforms have one. There are even versions of Python that run on Java (Jython), .NET (IronPython), and microcontrollers (MicroPython and CircuitPython), giving you even more possible platforms that run Python.

1.2.7 Python is free

Python is also free. Python was originally, and continues to be, developed under the open source model, and it’s freely available. You can download and install practically any version of Python and use it to develop software for commercial or personal applications, and you don’t need to pay a dime.

Although attitudes are changing, some people are still leery of free software because of concerns about a lack of support, fearing such software lacks the clout of paying customers. But Python is used by many established companies as a key part of their business; Google, Bloomberg, NVIDIA, and Capital One are just a few examples. These companies and many others know Python for what it is: a very stable, reliable, and well-supported product with an active and knowledgeable user community. You’ll get an answer to even the most difficult Python question more quickly in various Python internet forums than you will on most tech-support phone lines, and the Python answer will be free and correct.

Python and open source software

Not only is Python free but its source code is also freely available, and you’re free to modify, improve, and extend it if you want. Because the source code is freely available, you have the ability to go in yourself and change it (or to hire someone to go in and do so for you). You rarely have this option at any reasonable cost with proprietary software.

If this is your first foray into the world of open source software, you should understand that you’re not only free to use and modify Python but also able (and encouraged) to contribute to it and improve it. Depending on your circumstances, interests, and skills, those contributions might be financial, as in a donation to the Python Software Foundation, or they may involve participating in one of the special interest groups, testing and giving feedback on releases of the Python core or one of the auxiliary modules, or contributing some of what you or your company develops back to the community. The level of contribution (if any) is, of course, up to you; but if you’re able to give back, definitely consider doing so. Something of significant value is being created here, and you have an opportunity to add to it.

Python has a lot going for it: expressiveness, readability, rich included libraries, and cross-platform capabilities. Also, it’s open source. What’s the catch?

1.3 What Python is improving

Although Python has many advantages, no language can do everything, so Python isn’t the perfect solution for all your needs. While Python is improving in all of the following areas, to decide whether it is the right language for your situation, you also need to consider these areas where Python doesn’t do as well.

1.3.1 Python is getting faster

A possible drawback with Python is its speed of execution. It isn’t a fully compiled language. Instead, it’s first compiled to an internal bytecode form, which is then executed by a Python interpreter. There are some tasks, such as string parsing using regular expressions, for which Python has efficient implementations and is as fast as, or faster than, any C program you’re likely to write. Nevertheless, most of the time, using Python results in slower programs than in a language like C. But you should keep this in perspective. Modern computers have so much computing power that, for the vast majority of applications, the speed of the program isn’t as important as the speed of development, and Python programs can typically be written much more quickly than others. In addition, it’s easy to extend Python with modules written in C or C++, which can be used to run the CPU-intensive portions of a program.

Python’s core developers are also hard at work creating new versions of Python that are more efficient, load and run faster, and take better advantage of multiple processor cores. This work has already yielded significant improvements in performance, and the work will continue in the future, so if you have a performance-critical application, you may want to consider carefully if Python will do the job—but don’t write it off immediately.

1.3.2 Python doesn’t enforce variable types at compile time

Unlike in some languages, Python’s variables don’t work like containers; instead, they’re more like labels that refer to various objects: integers, strings, class instances, whatever. That means that although those objects themselves have types, the variables referring to them aren’t bound to those particular types. It’s possible (if not necessarily desirable) to use the variable x to refer to a string in one line and an integer in another (note: output of the code is in bold):

x = "2"

x

'2'

Output of x is the string '2'.x = int(x)

x

2

Output of x is now the integer 2.The fact that Python associates types with objects and not with variables means that the interpreter doesn’t help you catch variable type mismatches. If you intend a variable count to hold an integer, Python won’t complain if you assign the string “two” to it. Traditional coders count this as a disadvantage, because you lose an additional free check on your code.

In response to this concern, Python has added syntax and tools to allow coders to specify the desired type of the object a variable refers to, as well as function parameters, return values, and the like. With these type hints, as they are called, various tools can flag any inconsistencies in the types of objects before runtime. In smaller programs, type errors usually aren’t hard to find and fix even without type hints, and in any case, Python’s testing features makes avoiding type errors manageable. Many Python programmers feel that the flexibility of dynamic typing more than outweighs any advantage mandatory variable typing might offer.

1.3.3 Python is improving mobile support

In the past decade, the numbers and types of mobile devices have exploded, and smartphones, tablets, phablets, Chromebooks, and more are everywhere, running on a variety of operating systems. Python isn’t a strong player in this space, but various projects are working on the problem, developing toolkits and frameworks that allow writing apps for both iOS and Android platforms. This situation is improving, but as of this writing, using Python to write and distribute commercial mobile apps is a bit of a pain.

1.3.4 Python is improving support for multiple processors

Multiple-core processors are everywhere now, producing significant increases in performance in many situations. However, the standard implementation of Python isn’t designed to use multiple cores, due to a feature called the global interpreter lock. As mentioned in the context of speed, Python’s development team is currently working on ways to make Python work more seamlessly and efficiently with multiple processor cores, and the development of multicore Python will continue over the next several years.

Summary

- Python is a modern, high-level language with dynamic typing and simple, consistent syntax and semantics.

- Python is multiplatform, highly modular, and suited for both rapid development and large-scale programming.

- It’s reasonably fast and can be easily extended with C or C++ modules for higher speeds.

- Python has built-in advanced features, such as persistent object storage, advanced hash tables, expandable class syntax, and universal comparison functions.

- Python includes a wide range of libraries, such as numeric processing, image manipulation, user interfaces, and web scripting.

- It’s supported by a dynamic community.

2 Getting started

This chapter covers

- Available Python options

- Getting started with Colaboratory

- Accessing the GitHub repository for this book

- Writing a simple program and handling errors

- Using the help() and dir() functions

- AI tools for generating Python code

This chapter gives you a quick survey of the many options for installing and using Python and guides you through getting up and running with Google Colaboratory, a web-hosted Python environment. Combined with the code for each chapter, available in a GitHub repository at https://github.com/nceder/qpb4e, Colaboratory is one of the quickest and easiest ways to get up and running with Python so that you can test out the code examples in the text and work through the lab exercises throughout the book.

2.1 Paradox of choice: Which Python?

As Python has matured, particularly over the past 10 years, the number of options for running Python has exploded. After a brief survey of the versions, sources, devices, environments, and tools in the Python ecosystem, we’ll look at our recommended solution, Google Colaboratory, and how to use it to run the sample code snippets in this book and write the code for the lab exercises in most of the chapters.

2.1.1 Python versions

For many years, Python had a somewhat variable release cycle, with new versions being released when the core developers felt there were enough new features to be worth it. From Python 3.1 in 2009 to 3.8 in 2018, new versions were released roughly every 18 months. As Python’s popularity continued to grow, a quicker and more regular cadence for new releases became the goal. So, beginning with version 3.9, the decision was made (recorded in PEP 602: Annual Release Cycle for Python) to move to an annual release cycle, with a release every October.

The current release schedule for Python means that after the October 2024 release of version 3.13, version 3.14 will come out in October 2025, and so on. As of this writing, Python 3.13 is the most current version, having been released in October 2024. Since the features of 3.13 have already been frozen, I have included the new features of 3.13 and I have tested the code on both 3.12 and 3.13.

Choosing a Python version

Having a new version of Python come out every year is a good thing for releasing new features, but it’s not always the most convenient thing for anyone who needs to test and deploy a new version of the language. Because of this, versions of Python are officially supported for a total of five years: the first two years with full releases and then three years with source code only with releases of security fixes.

While it’s usually preferable to have the latest version, any supported version (3.9 or later as of this writing) should be fine to use with this book. If you have an earlier version, there will be a few new features that you won’t have, but you can still do a lot of work without upgrading.

2.1.2 Sources of Python

The classic way to get Python is by downloading and installing a version from the Python Sofware Foundation’s website at https://www.python.org/downloads/. There you can find installers for several operating systems and platforms and versions going back to the very beginnings of Python, over 30 years ago. It’s possible, however, that the exact version you need or want isn’t on python.org. You can also get a data science–oriented distribution of Python from Anaconda at https://www.anaconda.com/download/, or you may be able to use the app store or package manager of your operating system to install Python. If you are into the technical details, you can also fork the source code repository on GitHub and download and compile the source yourself. The choice depends on your preferences and your situation, and since the solution I recommend doesn’t require a local install, you can wait to make that decision until you know Python a bit better.

2.1.3 Devices, platforms, and operating systems

You can run Python on a wide variety of devices and on many operating systems. While in the early days, a server or desktop computer was the norm, today Python runs on many processors, from embedded devices and single board computers to phones and tablets, to Chromebooks, laptops, and desktops, to virtual machines and containers, to server clusters, and so on. While the most common implementation of Python is based on the C language, there are versions that are written in and run on Java, in the browser based on WASM, or even in applications like Excel.

2.1.4 Environments and tools

There are also a number of ways that you can run and develop code in Python. It’s possible to run the Python interpreter from a command line and interact using either the built-in shell or an enhanced shell like IPython and to write code in the text editor of your choice. You can also use education-oriented IDEs like IDLE (provided with Python), Mu, or Thonny, or you can opt for more advanced Python IDEs like VSCode, Wingware, or PyCharm. Of course, in all of those categories there are too many other fine options to list.

Another option for using and writing Python combines features of the IPython shell with a web interface and is called Jupyter. Jupyter runs on a server and is accessed via browser, and its web interface allows you to combine text (formatted using Markdown) with cells for executing code in a “notebook.” The combination has proven to be so useful that Jupyter notebooks are increasingly popular for teaching, data exploration and data science, AI experimentation, and many other uses. While you can run your own Jupyter server locally, it’s even more convenient to use a server hosted in the cloud, which brings us to my recommendation for this book.

2.2 Colaboratory: Jupyter notebooks in the cloud

As mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, for this book I recommend using Jupyter notebooks, specifically, the hosted version of Jupyter from Google, Colaboratory. Using Colaboratory means that you don’t need to worry about installing (or updating) Python, and you can take advantage of Jupyter’s friendly interface, which is becoming increasingly popular, particularly for data science.

Another advantage of Colaboratory is that you can launch a session with one of the code notebooks from this book’s source repository on GitHub with a single click, and you can access it on virtually any device that has a modern web browser.

For that reason, in this book, I’ll present sample code and problem solutions in Jupyter notebooks. Of course, the code will still work in other environments, and I’ll provide text files of the code as well, but unless stated otherwise, you can assume that the code presented is in notebook form.

2.2.1 Getting the source notebooks

The simplest way to get started with Colaboratory and this book is by accessing a notebook in the GitHub repository. If you are not familiar with GitHub, it’s a very popular online version control service based on the version control tool Git. To access the notebooks in the repository, you don’t need to know how to use Git, nor do you need to have an account on GitHub—just following the links given here will get you started.

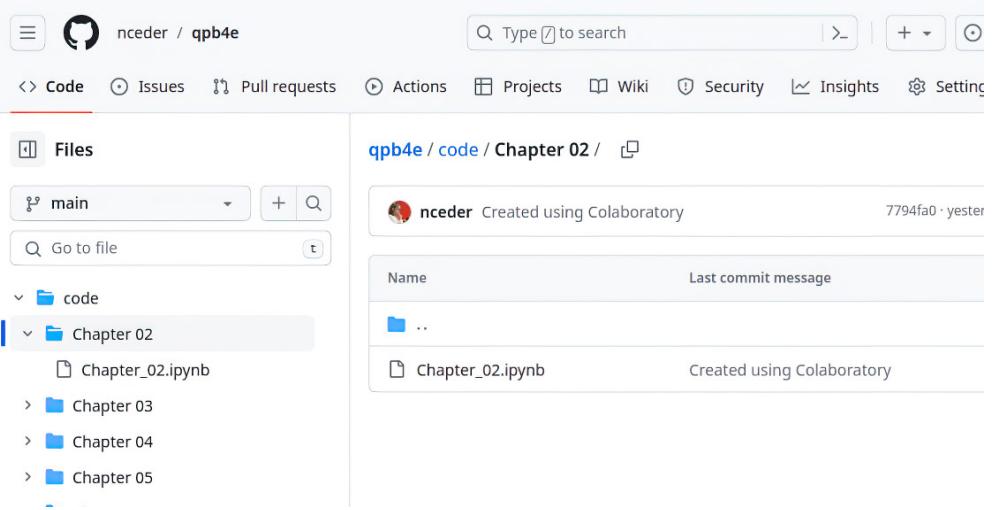

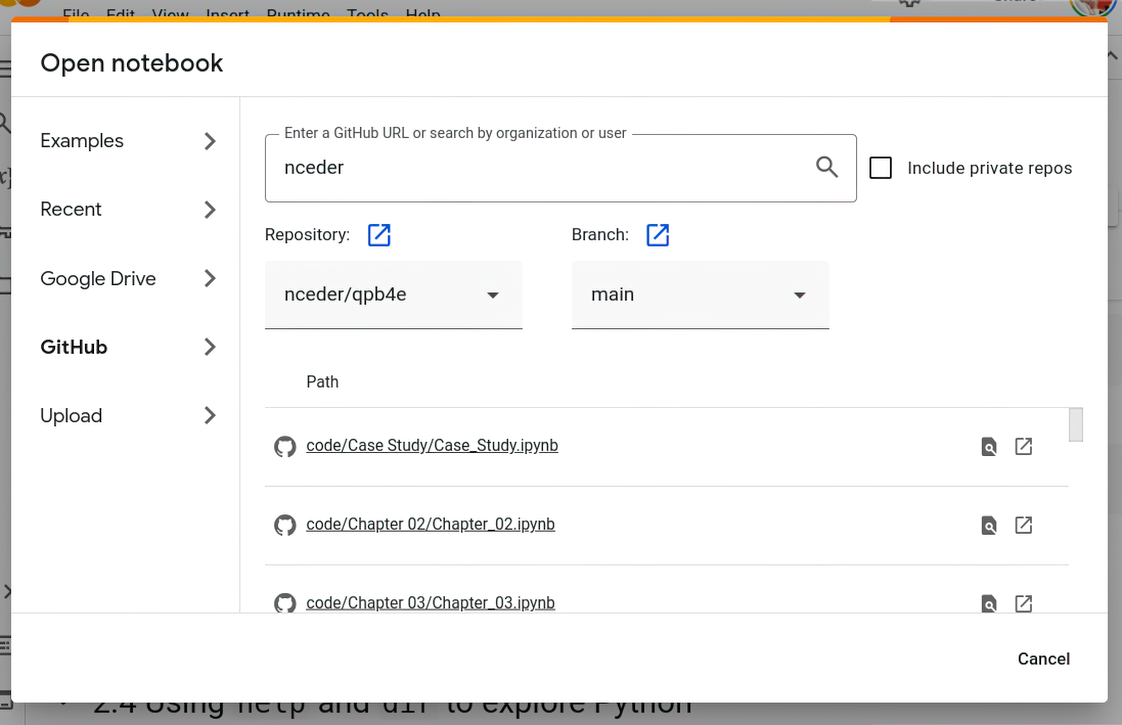

You can find the GitHub repository at https://github.com/nceder/qpb4e/tree/ main; the notebooks for each chapter are in separate directories inside the code directory. To get started, let’s find and open the notebook for chapter 2 (this chapter). If you look in the Chapter 02 directory, you will find a notebook file called Chapter_02.ipynb (direct link athttps://mng.bz/gaDG). You should see a page similar to the one shown in figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 GitHub repository, showing Chapter_02 notebook

2.2.2 Getting started with Colaboratory

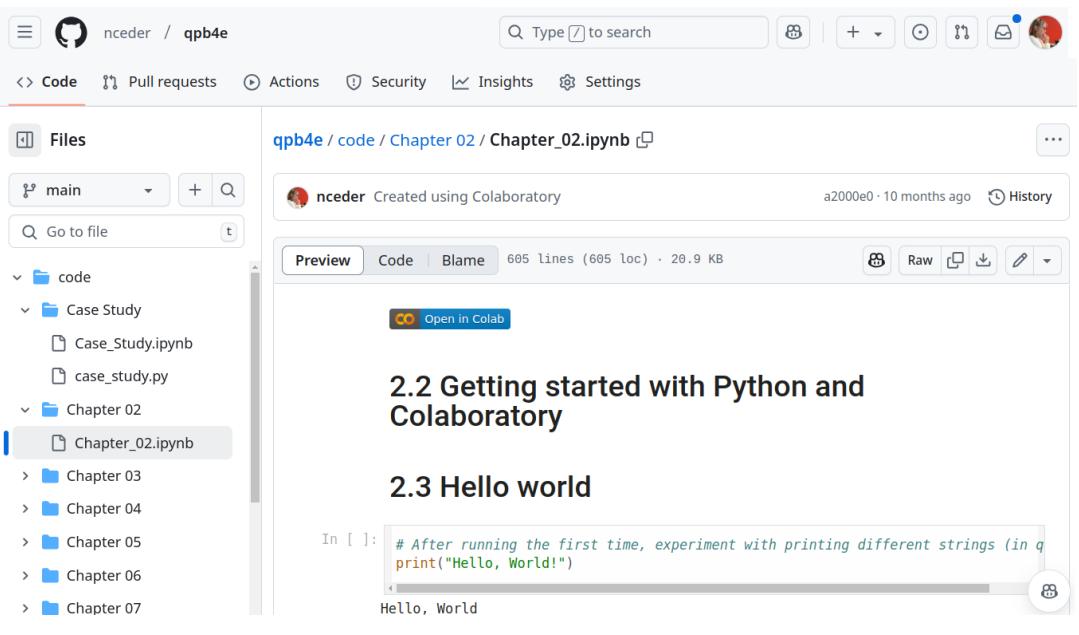

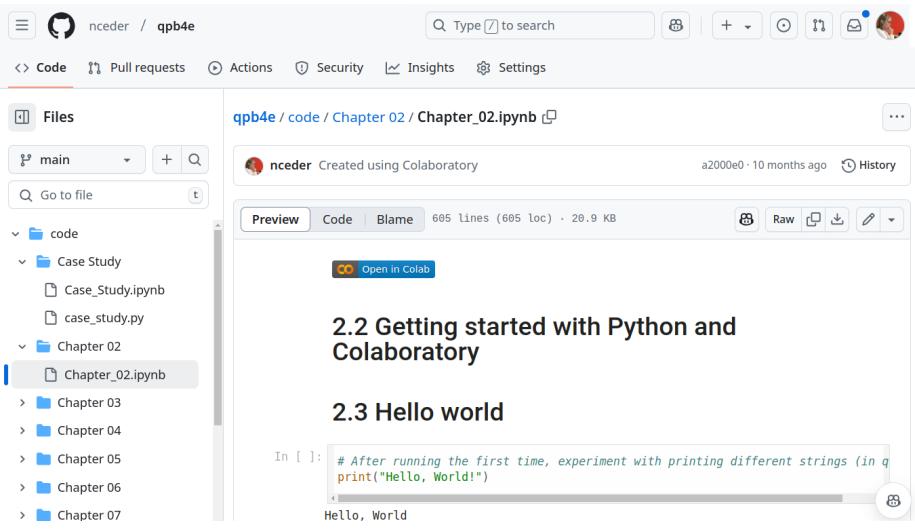

If you click the Chapter_02.ipynb file, you can view its contents using GitHub’s viewer (as shown in figure 2.2), and at the top of the code window (right above 2.2 Getting Started with Python and Colaboratory), you should also see a blue button link Open in Colab.

Figure 2.2 Chapter_02.ipynb notebook viewed in GitHub

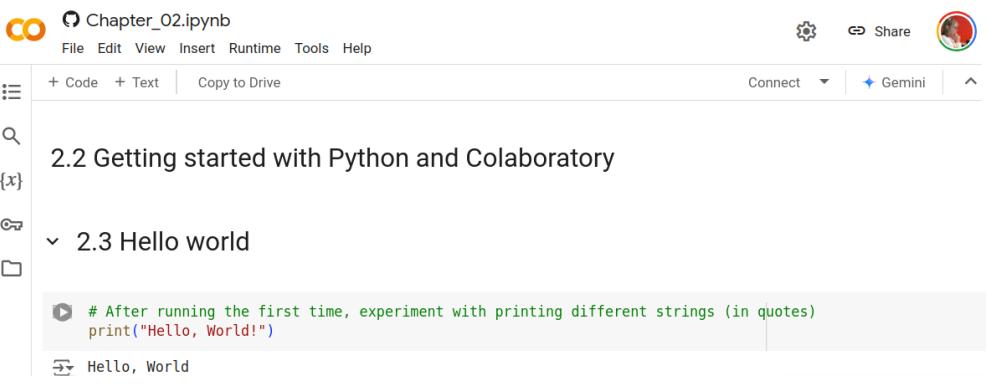

If you click that link, it will open that notebook in a Colaboratory session where you can edit, run, and experiment with the code, as shown in figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Chapter_02.ipynb notebook open in Colaboratory

As with GitHub, you don’t need a Google account to access Colaboratory, but to run code and use all of the features, including the ability to save sessions and files, logging in with a Google account is required.

Logging into colaboratory first

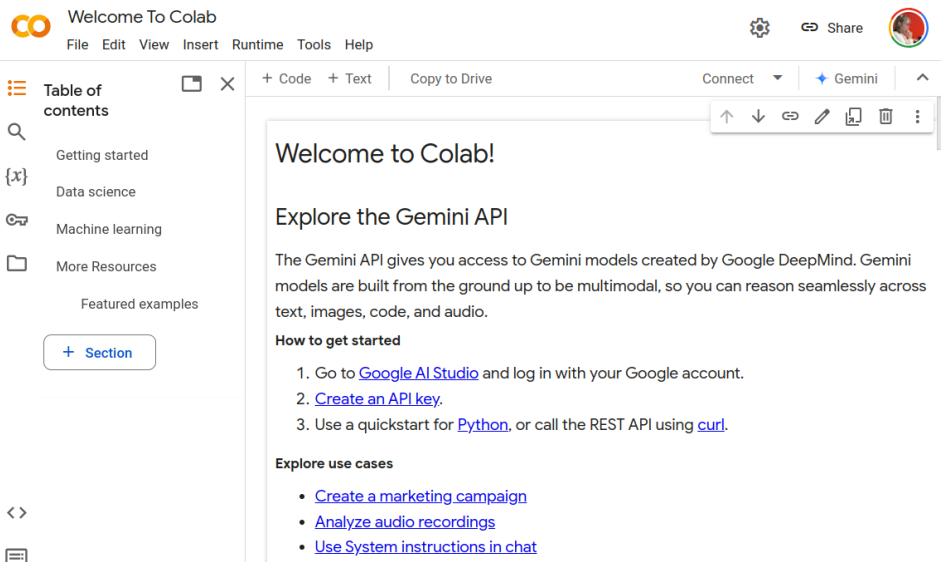

You can also access Colaboratory directly by using your browser to open https://colab .research.google.com/. This will open Colaboratory with a “Welcome to Colab” notebook (as shown in figure 2.4) that explains some of the platform’s features. If you are unfamiliar with Jupyter notebooks, there are some links at the bottom of this notebook to other notebooks that explain how Colaboratory’s version of Jupyter notebooks works. If you find yourself a bit confused at first, those resources can help.

Figure 2.4 Opening Colaboratory

To open a file for this book, you would select the File menu under Welcome to Colab at the upper left of the window and select the Open notebook option. To illustrate how it works, again let’s look at the notebook for this chapter.

Enter https://github.com/nceder/qpb4e where it asks for a GitHub URL, and click the search icon at the end of the line, as shown in figure 2.5. The paths to all of the notebooks will appear below, and you should then click code/Chapter 02/Chapter_02 .ipynb to open the notebook for chapter 2.

2.2.3 Colaboratory’s Python version

The good news about using Colaboratory is that you don’t have to worry about installing and maintaining a Python environment, and the Jupyter notebooks are accessible from almost any device with a standard web browser. One minor downside of using Colaboratory is that the version of Python that it runs may be a few months behind the latest version, which means that a few of the very newest features of Python may not be available. However, Colaboratory’s ease of access and use far outweighs this slight drawback.

Figure 2.5 Opening a notebook from the GitHub repository

2.3 Writing and running code in Colaboratory

A Jupyter notebook consists of two types of cells: text cells and code cells. The text cells are meant to contain text, which can be formatted using the Markdown text formatting language (there’s a guide to Colaboratory’s flavor of Markdown at https://mng .bz/eyjq). If you double-click a text cell or right-click and select Edit, the cell will be opened in edit mode, and the text and formatting can be changed. To save the changes and go back to text mode, you can use either Ctrl-Enter or you can right-click the cell and choose Select. Any changes you make to the source notebooks will not be changed in the GitHub repository, nor will they be saved in Colaboratory unless you are logged in with a Google account.

The code cells are for code that can be executed and are always in edit mode. To execute the code, you can either use Ctrl-Enter or you can right-click the cell and click Run the Focused Cell. You can also click the little triangle in a circle that appears to the left of the cell when you hover your mouse over the cell. The first time you run code from a notebook loaded from GitHub, you may see a warning that the code is being loaded from GitHub. This is normal, and it’s fine to click the Run Anyway choice to execute the code. If there is any output from the execution of the code, it will appear in the area immediately below the cell. We’ll see how all of this works as we run our first bit of code next.

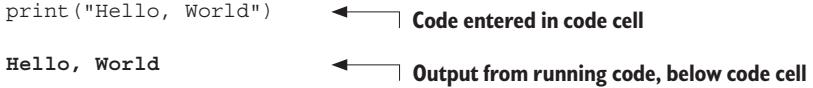

2.3.1 Hello, World

Let’s start with the traditional Hello, World program, which is a one-liner in Python:

Here, the code for the print() function, along with the string “Hello, World” as its parameter, has already been entered into the first code cell of the chapter 2 notebook. To run it, as mentioned earlier, you can use Ctrl-Enter and the output, “Hello, World” will be printed below the cell. If you are new to Jupyter notebooks (or to Python), feel free to experiment a bit with the print function or other commands in this code cell.

Note that throughout this book, I will show the code that is entered into a code cell in Jupyter (or a Python shell prompt in some other environment) using a normal-weight monospace font and the output as a monospace bold font. For comparison, the previous code and output should look something like figure 2.6 in Colaboratory.

Figure 2.6 Text cells, code cell, and output

2.3.2 Dealing with errors in Jupyter

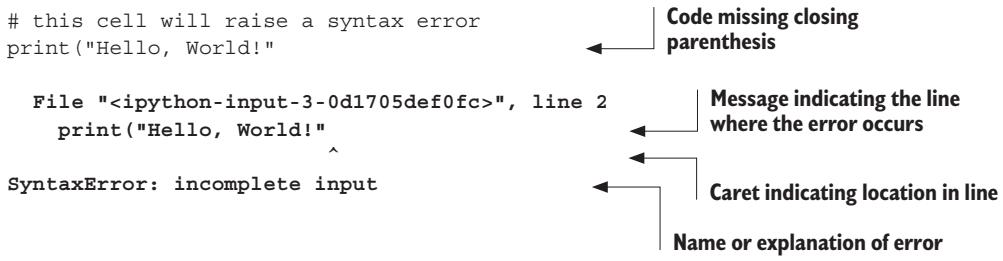

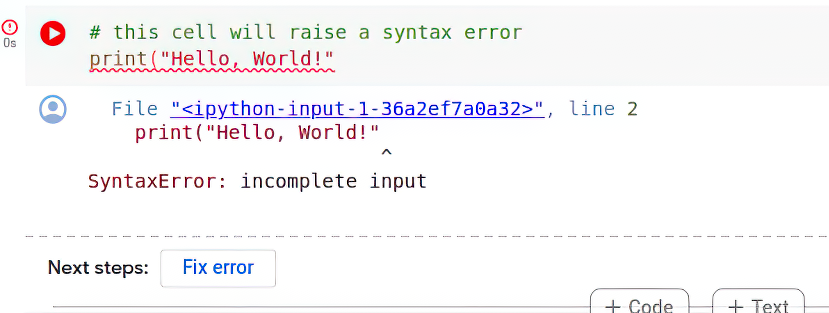

Errors are something all coders have to deal with in virtually every piece of code we write. If there is an error while running code in a code cell, Jupyter prints Python’s error message below the cell where the output would go. Code error messages have been famously difficult to understand, but the latest versions of Python have improved the clarity and usefulness of error messages:

In this case, the code deliberately has a syntax error—the closing parenthesis has been omitted. Python reports the message and the line where it occurs, puts a caret (^) under the error’s location in the line, and finally names the problem “incomplete input.”

A nice feature of Colaboratory is that below the Python error message it may offer an option to attempt to fix the error automatically, with a Next Steps: section and a Fix Error button, as shown in figure 2.7. In this case, clicking the Fix Error button will enter the fix in the previous code cell and allow the user to either accept or reject it.

Figure 2.7 Error with Fix error option

It’s a good idea to examine the suggested fix carefully. While for a simple error like this the suggestion is sound, the more complex the code, the more chance there is that the fix won’t be reliable.

2.4 Using help and dir to explore Python

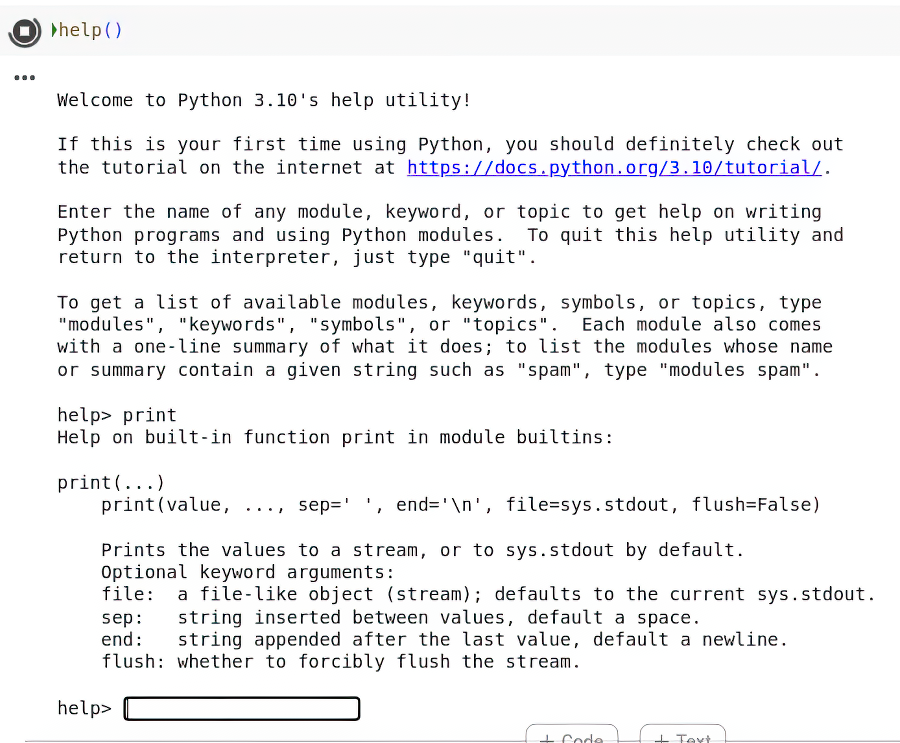

There are a couple of handy tools that can help you explore Python. The first is the help() function, which has two modes. You can execute help() in a code cell to enter the help system, where you can get help on modules, keywords, or topics. When you’re in the help system, you see a help> prompt, and you can enter a module name, such as print or some other topic, to read Python’s documentation on that topic. When you want to leave the help system, just press Enter, with no other input. Figure 2.8 shows the result of entering help()and then entering print into the input box. The help for the print function is displayed, and a new help> prompt and input box appear below it.

Figure 2.8 Using help() for the print function

Usually, it’s more convenient to use help() in a more targeted way. Entering a type or variable name as a parameter for help() gives you an immediate display of that object’s documentation and exits:

x = 2

help(x)Help on int object:

class int(object)

| int(x=0) -> integer

| int(x, base=10) -> integer

|

| Convert a number or string to an integer, or return 0 if no arguments

| are given. If x is a number, return x.__int__(). For floating point

| numbers, this truncates towards zero.

|

| If x is not a number or if base is given, then x must be a string,

| bytes, or bytearray instance representing an integer literal in the...

(continues with the documentation for an int...)Using help() in this way is handy for checking the exact syntax of a method or the behavior of an object.

The help() function is part of the pydoc library, which has several options for accessing the documentation built into Python libraries. Because every Python installation comes with complete documentation, you can have all the official documentation at your fingertips, even if you aren’t online. See the appendix for more information on accessing Python’s documentation.

The other useful function is dir(), which lists the objects in a particular namespace. Used with no parameters, it lists the current global namespace, but it can also list objects for a module or even a type:

dir()['In',

'Out',

'_',

'__',

'___',

'__builtin__',

'__builtins__',

'__doc__',

'__loader__',

'__name__',

'__package__',

'__spec__',

'_dh',

'_i',

'_i1',

'_i2',

'_ih',

'_ii',

'_iii',

'_oh',

'exit',

'get_ipython',

'quit',

'x']dir(int)

['__abs__',

'__add__',

'__and__',

'__bool__',

'__ceil__',

'__class__',

'__delattr__',

'__dir__',

'__divmod__',

'__doc__',

'__eq__',

'__float__',

'__floor__',

'__floordiv__',

'__format__',

'__ge__',

'__getattribute__',

... (continues with more items... ]dir() is useful for finding out what methods and data are defined, for reminding yourself at a glance of all the members that belong to an object or module, and for debugging, because you can see what is defined where.

2.5 Using AI tools to write Python code

The rise of large language model–based tools, such as ChatGPT, CoPilot, and many others, is beginning to revolutionize how we write software. It is now possible to have these tools generate working code in response to a text prompt. Note, however, that while it is possible, it is not yet always reliable. I am one of many who believe that human understanding is the vital ingredient for good code but that experience using AI tools to generate code will be increasingly helpful in the future.

With that in mind, we will use some of these tools to generate code for the solutions for the lab exercises in this book, and we will discuss and evaluate the AI-generated solutions. This will give you a feel for what is possible, how to create prompts, and what the potential drawbacks are.

2.5.1 Benefits of AI tools

It’s undeniable that AI code generation has developed to the point that it has several advantages. First, it’s fast. Even fairly large chunks of code can be generated in less than a minute, so even if you spend some time crafting and entering a good prompt for the chatbot to work from, the overall amount of time you need to spend to get a fair bit of code is definitely less than what even a lightning-fast human can achieve.

Second, the code tends to be free of all of the little glitches we humans have in typing in code—a chatbot will probably spell things correctly, use punctuation correctly, etc.

But—and this is a significant “but”—there are some drawbacks to consider.

2.5.2 Negatives of using AI tools

One thing to consider is that AI bots use a lot of resources. In this age of concern for the climate and environment, many will be worried about the resource (particularly energy and water) consumption of machines behind these coding tools. One can only hope that future developments will reduce that consumption to sustainable levels.

Second, using an AI bot for coding means that you are by definition sharing your code and using other’s code, and the most common mechanisms for that sharing are weak in terms of protecting privacy and intellectual property.

Third, not all of the AI code generators are free, and as companies decide to recover the costs of the resources consumed by their machines, it’s likely that fewer will remain free of charge for basic users.

Finally, while the code produced is surprisingly good, it’s far from perfect. The bugs and inefficiencies in AI-generated code are not always obvious and can take a trained eye to spot. Putting AI-generated code into production without careful review and testing is at least as dangerous as uncritically using a junior developer’s code.

While none of these drawbacks are dealbreakers, they are all things that responsible organizations and developers need to consider before deciding to use generated code.

2.5.3 AI options

The most convenient AI code generator is the one offered in Colaboratory, which is currently free of charge for most users. For comparison, we will also discuss solutions generated by GitHub Copilot, which works best with Microsoft’s VSCode IDE and a local version of Python. Copilot also requires a $10 monthly subscription fee as of this writing. Given that you need to install Python and VSCode on your machine and pay the subscription, it may not be worth the trouble for the code examples and problems in this book. There are also other options, such as Codeium, that offer a free tier and work better with VSCode than with Colaboratory. Personally, if I were writing production code, I would prefer Copilot, but any of them can work for experimentation, and using an AI tool is purely optional—the results I obtained are all shared in the text and in the source notebooks.

Summary

- Python is available across a wide variety of operating systems, hardware platforms, and user interfaces.

- For ease of use and maintenance, Google Colaboratory is recommended for use with the Jupyter notebooks of example code for this book.

- You can access both the GitHub repository and Colaboratory without an account, but more features may be available with an account.

- Jupyter notebooks consist of two types of cells: formattable text cells and cells for executable code.

- Errors are usually reported in the same area as output below code cells.

- The help() and dir() functions can be useful in learning more about Python.

- AI tools can be used to generate Python code, and we will use and critique a couple of those tools when we discuss the solutions to the lab exercises later.

3 The quick Python overview

This chapter covers

- Surveying Python

- Using built-in data types

- Controlling program flow

- Creating modules

- Using object-oriented programming

The purpose of this chapter is to give you a basic feeling for the syntax, semantics, capabilities, and philosophy of the Python language. It has been designed to provide an initial perspective or conceptual framework to which you’ll be able to add details as you encounter them in the rest of the book.

On an initial read, you needn’t be concerned about working through and understanding the details of the code segments. You’ll be doing fine if you pick up a bit of an idea about what’s being done. The subsequent chapters walk you through the specifics of these features and don’t assume previous knowledge. You can always return to this chapter and work through the examples in the appropriate sections as a review after you’ve read the later chapters.

3.1 Python synopsis

Python has several built-in data types, such as integers, floats, complex numbers, strings, lists, tuples, dictionaries, and file objects. These data types can be manipulated using language operators, built-in functions, library functions, or a data type’s own methods.

Programmers can also define their own classes and instantiate their own class instances. These class instances can be manipulated by programmer-defined methods, as well as by the language operators and built-in functions for which the programmer has defined the appropriate special method attributes.

NOTE The Python documentation and this book use the term “object” to refer to instances of any Python data type, not just what many other languages would call “class instances.” This is because all Python objects are instances of one class or another.

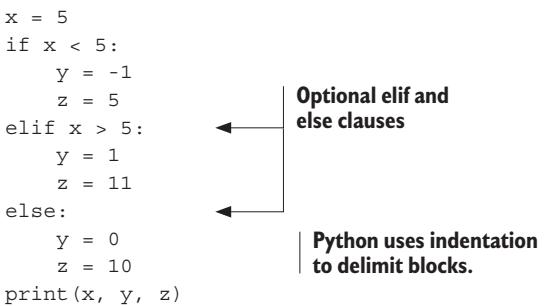

Python provides conditional and iterative control flow through an if-elif-else construct along with while and for loops and a new structural pattern-matching match-case feature. It allows function definition with flexible argument-passing options. Exceptions (errors) can be raised by using the raise statement, and they can be caught and handled by using the try-except-else-finally construct.

Variables (or identifiers) don’t have to be declared and can refer to any built-in data type, user-defined object, function, or module.

3.2 Built-in data types

Python has several built-in data types, from scalars, such as numbers and Booleans, to more complex structures, such as lists, dictionaries, and files.

NOTE In the examples, code is in normal monospace and output is in bold monospace type.

3.2.1 Numbers

Python’s four number types are integers, floats, complex numbers, and Booleans:

- Integers — 1, –3, 42, 355, 888888888888888, –7777777777 (integers aren’t limited in size except by available memory)

- Floats — 3.0, 31e12, –6e-4

- Complex numbers — 3 + 2j, –4 2j, 4.2 + 6.3j

- Booleans — True, False

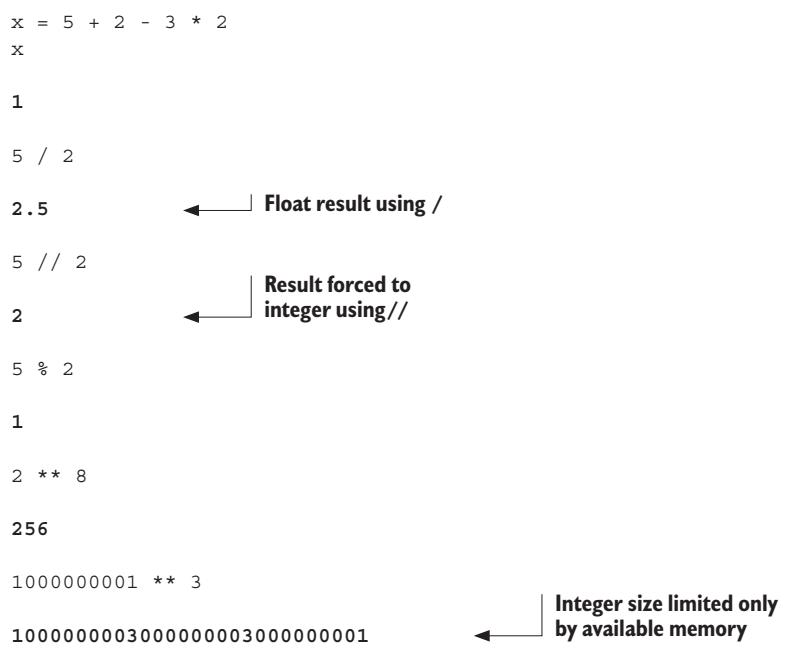

You can manipulate them by using the arithmetic operators: + (addition), – (subtraction), * (multiplication), / (division), // (division with truncation to integer), ** (exponentiation), and % (modulus).

The following examples use integers:

Division of integers with / results in a float, and division of integers with // results in truncation to an integer. Note that integers are of unlimited size; they grow as large as you need them to, limited only by the memory available. The following examples work with floats, which are based on the doubles in C:

x = 4.3 ** 2.4

x33.137847377716483.5e30 * 2.77e45 9.695e+751000000001.0 ** 3 1.000000003e+27These examples use complex numbers:

(3+2j) ** (2+3j)(0.6817665190890336-2.1207457766159625j)x = (3+2j) * (4+9j) # x assigned to a complex number

x (-6+35j)

x.real -6.0Complex numbers consist of both a real element and an imaginary element, suffixed with j. In the preceding code, variable x is assigned to a complex number. You can obtain its “real” part by using the attribute notation x.real and obtain the “imaginary” part with x.imag.

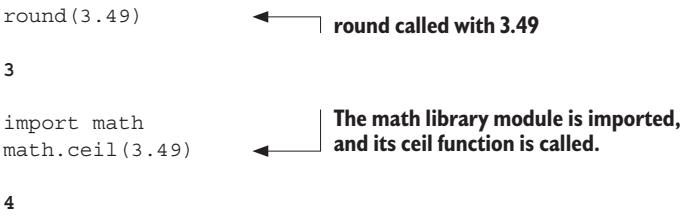

Several built-in functions can operate on numbers. In addition, the library module cmath contains functions for complex numbers, and the library module math contains functions for the other three types:

Built-in functions are always available and are called by using a standard functioncalling syntax. In the preceding code, round is called with a float as its input argument.

The functions in library modules are made available via the import statement. In the previous code, the math library module is imported, and its ceil function is called using attribute notation: module.function(arguments).

The following examples use Booleans:

x = False

xFalsenot xTruey = True * 2 # Boolean treated as integer 1

y2Other than their representation as True and False, Booleans behave like the numbers 1 (True) and 0 (False).

3.2.2 Lists

Python has a powerful built-in list type:

[]

[1]

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12]

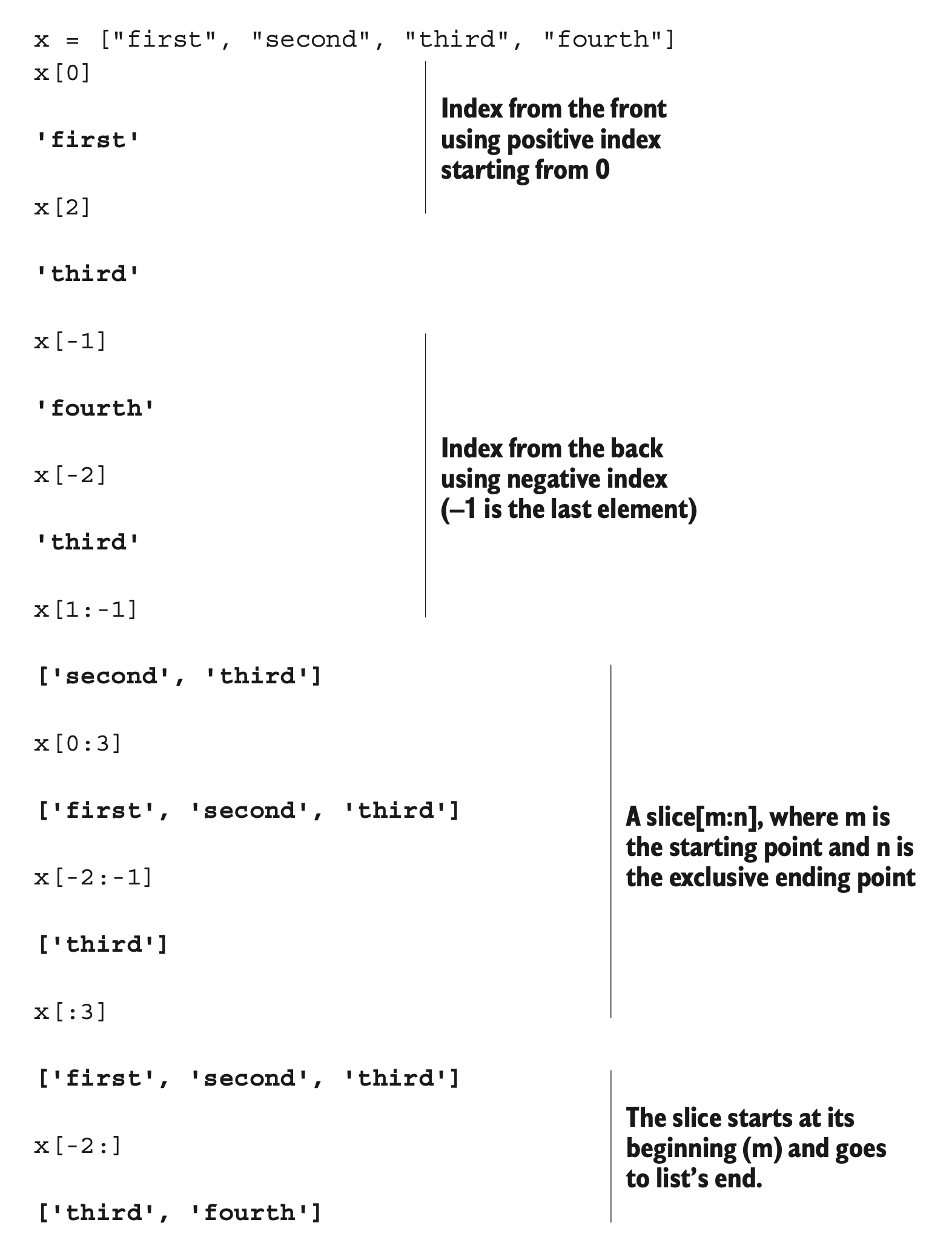

[1, "two", 3, 4.0, ["a", "b"], (5,6)] # A list ist contains ints, float, string, list, and tuple.A list can contain a mixture of other types as its elements, including strings, tuples, lists, dictionaries, functions, file objects, and any type of number. A list can be indexed from its beginning or end. You can also refer to a subsegment, or slice, of a list by using slice notation:

Lists can be accessed by index from the front using positive indices (starting with 0 as the first element). Index from the back using negative indices (starting with –1 as the last element). Obtain a slice using [m:n], where m is the inclusive starting point and n is the exclusive ending point (see table 3.1). An [:n] slice starts at a list’s beginning, and an [m:] slice goes to its end.

Table 3.1 List indices| x= | [ | “first” , | “second” , | “third” , | “fourth” | ] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive indices | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Negative indices | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 |

You can use this notation to add, remove, and replace elements in a list or to obtain an element or a new list that’s a slice from it:

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

x[1] = "two"

x[8:9] = []

x[1, 'two', 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]x[5:7] = [6.0, 6.5, 7.0] # The size of x increases by 1.

x[1, 'two', 3, 4, 5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 8]x[5:] [6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 8]The size of the list increases or decreases if the new slice is bigger or smaller than the slice it’s replacing.

Some built-in functions (len, max, and min), some operators (in, +, and *), the del statement, and the list methods (append, count, extend, index, insert, pop, remove, reverse, and sort) operate on lists:

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

len(x)9[-1, 0] + x # + and * each create a new list.[-1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]x.reverse() # reverse() method called by using x.reverse()

x[9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1] The operators + and * each create a new list, leaving the original unchanged. A list’s methods are called by using attribute notation on the list itself: x.method (arguments).

Some of these operations repeat functionality that can be performed with slice notation, but they improve code readability.

3.2.3 Tuples

Tuples are similar to lists but are immutable—that is, they can’t be modified after they’ve been created. The operators (in, +, and *) and built-in functions (len, max, and min) operate on them the same way as they do on lists because none of them modify the original. Index and slice notation work the same way for obtaining elements or slices but can’t be used to add, remove, or replace elements. Also, there are only two tuple methods: count and index. An important purpose of tuples is for use as keys for dictionaries. They’re also more efficient to use when you don’t need modifiability:

()

(1,)

(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12) # One-element tuple with comma

(1, "two", 3, 4.0, ["a", "b"], (5, 6)) # Different types in one listA one-element tuple needs a comma. A tuple, like a list, can contain a mixture of other types as its elements, including strings, tuples, lists, dictionaries, functions, file objects, and any type of number.

A list can be converted to a tuple by using the built-in function tuple:

x = [1, 2, 3, 4]

tuple(x)(1, 2, 3, 4)Conversely, a tuple can be converted to a list by using the built-in function list:

x = (1, 2, 3, 4)

list(x)[1, 2, 3, 4]3.2.4 Strings

String processing is one of Python’s strengths. There are many options for delimiting strings:

"A string in double quotes can contain 'single quote' characters."

'A string in single quotes can contain "double quote" characters.'

'''\tA string which starts with a tab; ends with a newline character.\n'''

"""This is a triple double quoted string - triple quoted strings (single

or double quoted) are only kind that can contain real newlines."""Strings can be delimited by single (' '), double (" "), triple single (''' '''), or triple double (""" """) quotations and can contain tab (\t) and newline (\n) characters.

Strings are also immutable. The operators and functions that work with them return new strings derived from the original. The operators (in, +, and *) and built-in functions (len, max, and min) operate on strings as they do on lists and tuples. Index and slice notation works the same way for obtaining elements or slices but can’t be used to add, remove, or replace elements.

Strings have several methods to work with their contents, and the re library module also contains functions for working with strings:

x = "live and let \t \tlive"

x.split()['live', 'and', 'let', 'live']x.replace(" let \t \tlive", "enjoy life")'live and enjoy life'import re # re module used to replace all spaces

regexpr = re.compile(r'[\t ]+')

regexpr.sub(" ", x)'live and let live'The re module provides regular expression functionality. It provides more sophisticated pattern extraction and replacement capabilities than the string module.

The print function outputs strings. Other Python data types can be easily converted to strings and formatted:

e = 2.718

x = [1, "two", 3, 4.0, ["a", "b"], (5, 6)]

print("The constant e is:", e, "and the list x is:", x) # list is automatically converted to string by print(). The constant e is: 2.718 and the list x is: [1, 'two', 3, 4.0,['a', 'b'], (5, 6)] print(f"the value of e is: {e}") # f in front of a string creates an "f-string" with values in { }.the value of e is: 2.718Objects are automatically converted to string representations for printing. The % operator provides formatting capability similar to that of C’s sprintf.

3.2.5 Dictionaries

Python’s built-in dictionary data type provides associative array functionality implemented by using hash tables. The built-in len function returns the number of key-value pairs in a dictionary. The del statement can be used to delete a key-value pair. As is the case for lists, several dictionary methods (clear, copy, get, items, keys, update, and values) are available:

x = {1: "one", 2: "two"}

x["first"] = "one" # Sets the value of a new key, "first", to "one"

x[("Delorme", "Ryan", 1995)] = (1, 2, 3) # Keys can be numbers, strings, tuples, or other immutable types.

list(x.keys())[1, 2, 'first', ('Delorme', 'Ryan', 1995)]x[1]'one'x.get(1, "not available")'one'x.get(4, "not available") # get returns "not available" when a key isn't in a dictionary.'not available'Keys must be of an immutable type, including numbers, strings, and tuples. Values can be any kind of object, including mutable types, such as lists and dictionaries. If you try to access the value of a key that isn’t in the dictionary, a KeyError exception is raised. To avoid this error, the dictionary method get optionally returns a user-definable value when a key isn’t in a dictionary.

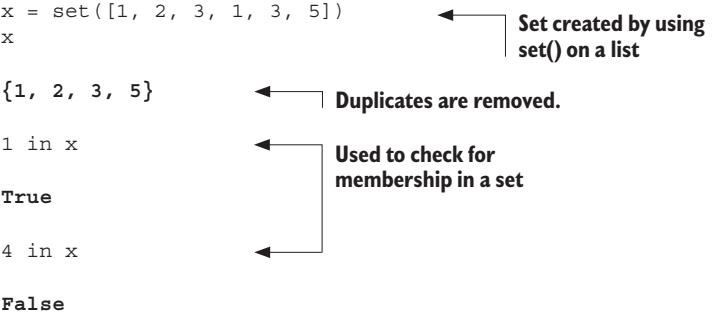

3.2.6 Sets, frozensets

A set in Python is an unordered collection of objects, used in situations where membership and uniqueness in the set are the main things you need to know about that object. Sets behave as collections of dictionary keys without any associated values:

You can create a set by using set on a sequence, like a list. When a sequence is made into a set, duplicates are removed. The in keyword is used to check for membership of an object in a set.

A frozenset is a set that is immutable. That means that after the set has been created with code like x = frozenset([1, 2, 3, 1, 3, 5]), it cannot be changed, so no elements can be added removed.

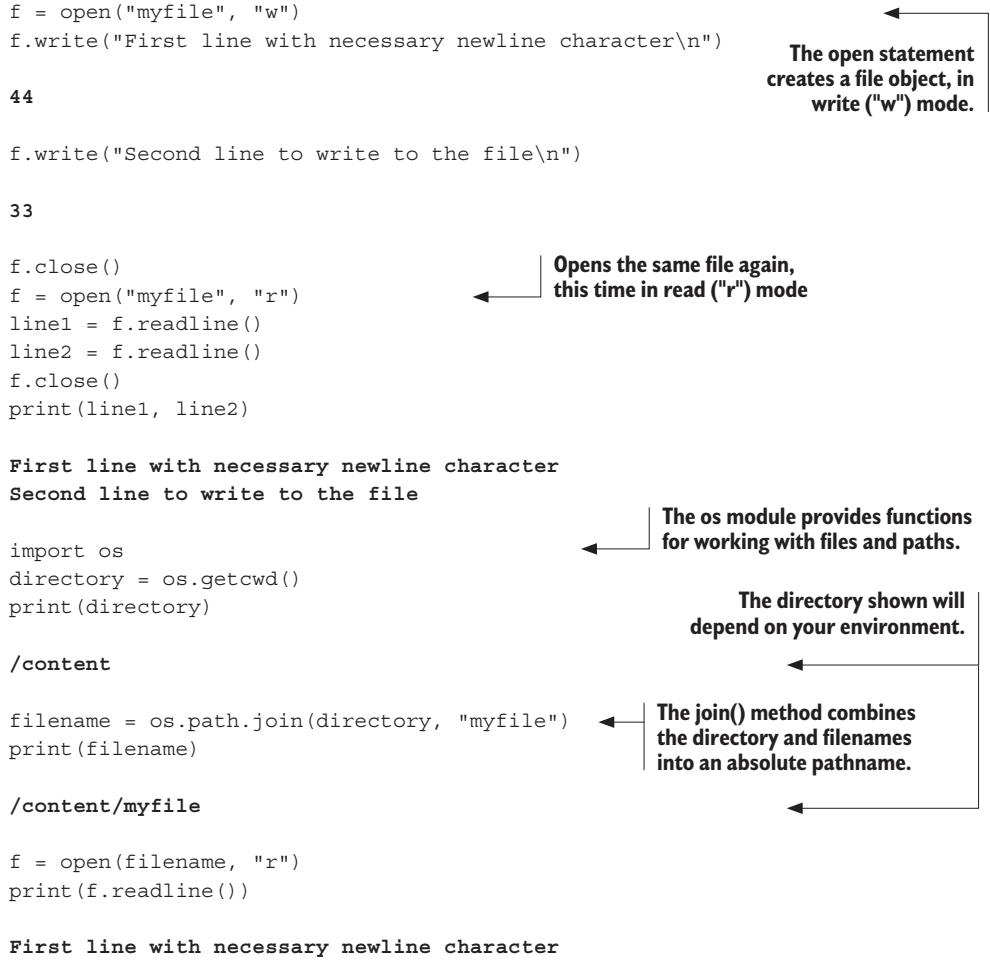

3.2.7 File objects

A file is accessed through a Python file object:

f.close()f = open("myfile", "w")

f.write("First line with necessary newline character\n")

#> 44

f.write("Second line to write to the file\n")

#> 33

f.close()

f = open("myfile", "r")

line1 = f.readline()

line2 = f.readline()

f.close()

print(line1, line2)

#> First line with necessary newline character

#> Second line to write to the file

import os

directory = os.getcwd()

print(directory)

#> /content

filename = os.path.join(directory, "myfile")

print(filename)

#> /content/myfile

f = open(filename, "r")

print(f.readline())

#> First line with necessary newline character

f.close()The open statement creates a file object. Here, the file myfile in the current working directory is being opened in write (“w”) mode. After writing two lines to it and closing it, you open the same file again—this time in read (“r”) mode. The os module provides several functions for moving around the filesystem and working with the pathnames of files and directories. Here, you move to another directory. But by referring to the file by an absolute pathname, you’re still able to access it.

Several other input/output capabilities are available. As we’ll see later, you can use the built-in input function to prompt and obtain a string from the user. The sys library module allows access to stdin, stdout, and stderr. The struct library module provides support for reading and writing files that were generated by, or are to be used by, C programs. The Pickle library module delivers data persistence through the ability to easily read and write the Python data types to and from files.

3.3 Type hints in Python

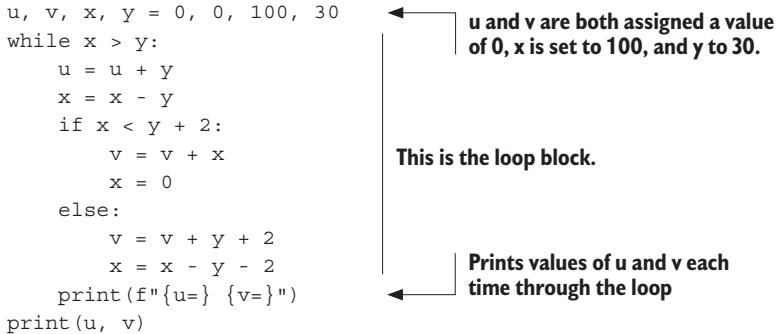

Unlike many programming languages, Python by design does not use typed variables and return values. While this makes the language more flexible and readable, it means that in many cases the type of an object referred to by a variable, or needed as a parameter, or returned by a function or method is not always immediately obvious. While inadvertently mixing incompatible types of objects will cause a runtime exception in Python, it will not raise an error at compile time. Particularly for large projects, there are many times when having the types of objects more explicitly available would be useful. For this, Python has added type hints.