Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics

Part VI

Action

34 Decision making under uncertainty

34.1 Statistical decision theory

Bayesian inference provides the optimal way to update our beliefs about hidden quantities H given observed data X = x by computing the posterior p(H|x). However, at the end of the day, we need to turn our beliefs into actions that we can perform in the world. How can we decide which action is best? This is where decision theory comes in. In this section, we give a brief introduction. For more details, see e.g., [DeG70; Ber85b; KWW22].

34.1.1 Basics

In statistical decision theory, we have an agent or decision maker, who wants to choose an action from a set of possible actions, a → A, given some observations or data x. We assume the data comes from some environment that is external to the agent; we characterize the state of this environment by a hidden or unknown variable h → H, known as the state of nature. Finally, we assume we know a loss function ω(h, a), that specifies the loss we incur if we take action a when the state of nature is h. The goal is to define a policy, also called a decision procedure, which specifies which action (decision) to take in response to each possible observation or dataset, a = ε(x), so as to minimize the expected loss, also called the risk. That is, the optimal policy is given by

\[\delta^\*(\cdot) = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{\delta} R(\delta) \tag{34.1}\]

where the risk is given by

\[R(\delta) = \mathbb{E}\left[\ell(h, \delta(\mathbf{X}))\right] \tag{34.2}\]

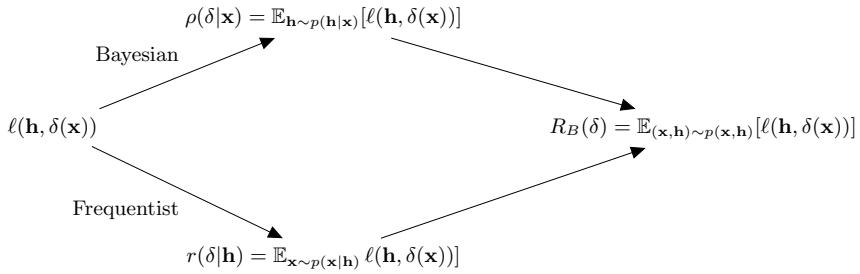

The key question is how to define the above expectation. We can use a frequentist or Bayesian approach, as we discuss below.1

1. If the state of nature corresponds to the parameters of a model, we denote them by ω = h. In this case, the action is often denoted by ωˆ = a, and the decision procedure ω is called an estimator. In statistics, it is common to assume that the dataset x comes from a known model with parameters ω, and then to use ε(ω, ωˆ) to assess the quality of the estimator. However, in machine learning, we usually focus on the accuracy of prediction of future observations, rather than predicting some inherently unknowable quantity like “nature’s parameters”. Let us assume the predictor gets access (in the future) to some (optional) context (input) variables c, and has to predict unknown (output) observations y. We make this prediction using a function yˆ = f(c). We then define the loss as ε(f, f ˆ|c) = ! ε(y, f ˆ(c))f(y|c)dy, where ε(y, yˆ) is defined in terms of observable data (e.g., 0-1 loss), and f(y|c) is nature’s unknown prediction function.

34.1.2 Frequentist decision theory

In frequentist decision theory, we treat the state of nature h as a fixed but unknown quantity, and treat the data X as random. Hence we take expectations wrt the data, which gives us the frequentist risk:

\[r(\delta|h) = \mathbb{E}\_{p(\mathbf{z}|h)}\left[\ell(h,\delta(\mathbf{z}))\right] = \int p(\mathbf{z}|h)\ell(h,\delta(\mathbf{z}))d\mathbf{z} \tag{34.3}\]

The idea is that a good estimator will have low risk across many di!erent datasets.

Unfortunately, the state of nature is not known, so the above quantity cannot be computed. There are several possible solutions to this. One idea is to put a prior distribution on h, denoted ϑ(h), and then to compute the Bayes risk, also called the integrated risk:

\[R\_{\pi}(\delta) \triangleq \mathbb{E}\_{p(h)}\left[r(\delta|h)\right] = \int \pi(h)p(x|h)\ell(h,\delta(x))\,dh\,dx\tag{34.4}\]

A decision rule that minimizes the Bayes risk is known as a Bayes estimator. (Confusingly, such an estimator does not need to be constructed using Bayesian principles; see Section 34.1.4 for a discussion.)

Of course the use of a prior might seem undesirable in the context of frequentist statistics. We can therefore use the maximum risk instead. This is defined as follows:

\[R\_{\max}(\delta) = \max\_{h} r(\delta|h) \tag{34.5}\]

Minimizing the maximum risk gives rise to a minimax estimator:

\[\delta^\* = \min\_{\delta} \max\_h r(\delta|h) \tag{34.6}\]

Minimax estimators have a certain appeal. However, computing them can be hard. And furthermore, they are very pessimistic. In fact, one can show that all minimax estimators are equivalent to Bayes estimators under a least favorable prior, since maxε Rε(ε) = maxh R(h, ε) = Rmax(ε). In most statistical situations (excluding game theoretic ones), assuming nature is an adversary is not a reasonable assumption. See [BS94, p449] for further discussion of this point.

34.1.3 Bayesian decision theory

In Bayesian decision theory, we treat the data as an observed constant, x, and the state of nature as an unknown random variable. The posterior expected loss, or posterior risk, for picking action a is defined as follows:

\[\rho\_{\pi}(a|\mathbf{z}) \triangleq \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\pi}(h|\mathbf{z})} \left[ \ell(h, a) \right] = \int \ell(h, a) p\_{\pi}(h|\mathbf{z}) dh \tag{34.7}\]

We can evaluate such a loss empirically if we have access to a holdout set of “future” data, that is not used by the estimator. We see that the decision procedure ω(X) maps the training set X to a prediction function f ˆ. This can of course be represented parameterically as ωˆ, but we evaluate performance in data space (which can be measured) rather than parameter space (which cannot).

where pε(h|x) ↑ ϑ(h)p(x|h). Similarly we can define the posterior expected loss or posterior risk for an estimator using

\[\rho\_{\pi}(\delta|\mathbf{x}) = \rho\_{\pi}(\delta(\mathbf{x})|\mathbf{x}) = \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\pi}(h|\mathbf{x})} \left[ \ell(h, \delta(\mathbf{x})) \right] \tag{34.8}\]

The optimal policy minimizes the posterior risk, and is given by

\[\delta^\*(\mathbf{x}) = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{\delta} \rho\_\pi(\delta|\mathbf{x}) = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \rho\_\pi(a|\mathbf{x}) \tag{34.9}\]

That is, we just need to compute the optimal action for each observation x.

An alternative, but equivalent, way of stating this result is as follows. Let us define a utility function U(h, a) to be the desirability of each possible action in each possible state. If we set U(h, a) = ↓ω(h, a), then the optimal policy is as follows:

\[\delta^\*(\mathbf{z}) = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \mathbb{E}\_h \left[ U(h, a) \right] \tag{34.10}\]

This is called the maximum expected utility principle.

34.1.4 Frequentist optimality of the Bayesian approach

We see that the Bayesian approach, given by Equation (34.9), which picks the best action for each individual observation x, will also optimize the Bayes risk in Equation (34.4), which picks the best policy for all possible observations. This follows from Fubini’s theorem which lets us exchange the order of integration in a double integral (this is equivalent to the law of iterated expectation):

\[R\_B(\delta) = \mathbb{E}\_{p(\mathbf{z})} \left[ \rho(\delta | \mathbf{z}) \right] = \mathbb{E}\_{p(h | \mathbf{z})p(\mathbf{z})} \left[ \ell(h, \delta(\mathbf{z})) \right] \tag{34.11}\]

\[=\mathbb{E}\_{p(h)}\left[r(\delta|h)\right] = \mathbb{E}\_{p(h)p(\mathfrak{a}|h)}\left[\ell(h,\delta(\mathfrak{x}))\right] \tag{34.12}\]

See Figure 34.1 for an illustration. The above result tells us that the Bayesian approach has optimal frequentist properties.

More generally, one can show that any admissable policy2 is a Bayes policy with respect to some, possibly improper, prior distribution, a result known as Wald’s theorem [Wal47]. (See [DR21] for a more general version of this result.) Thus we arguably lose nothing by “restricting” ourselves to the Bayesian approach (although we need to check that our modeling assumptions are adequate, a topic we discuss in Section 3.9). See [BS94, p448] for further discussion of this point.

Another advantage of the Bayesian approach is that is constructive, that is, it specifies how to create the optimal policy (estimator) given a particular dataset. By contrast, the frequentist approach allows you to use any estimator you like; it just derives the properties of this estimator across multiple datasets, but does not tell you how to create the estimator.

34.1.5 Examples of one-shot decision making problems

In the sections below, we give some common examples of one-shot decision making problems (i.e., making a single decision, not a sequence of decisions) that arise in ML applications.

2. An estimator is said to be admissible if it is not strictly dominated by any other estimator. We say that ω1 dominates ω2 if R(ω, ω1) → R(ω, ω2) for all ω. The domination is said to be strict if the inequality is strict for some ω→.

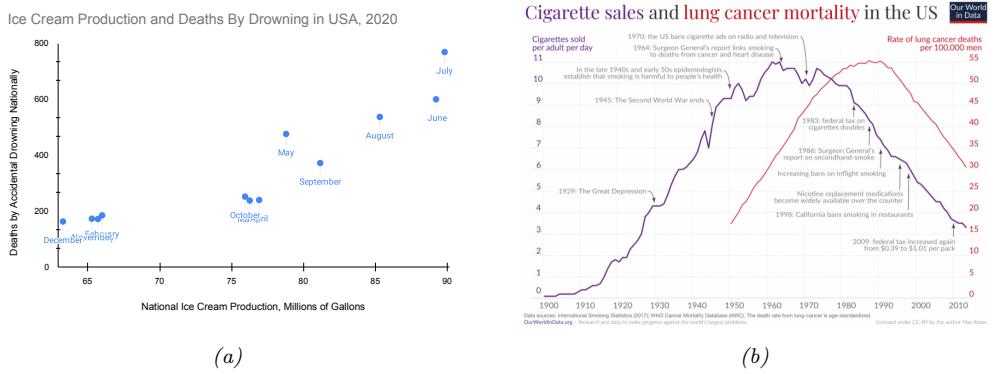

Figure 34.1: Illustration of how the Bayesian and frequentist approaches to decision making incur the same Bayes risk.

34.1.5.1 Classification

Suppose the states of nature correspond to class labels, so H = Y = {1,…,C}. Furthermore, suppose the actions also correspond to class labels, so A = Y. In this setting, a very commonly used loss function is the zero-one loss ω01(y→, yˆ), defined as follows:

\[\begin{array}{c|ccc} & \hat{y} = 0 & \hat{y} = 1 \\ \hline y^\* = 0 & 0 & 1 \\ y^\* = 1 & 1 & 0 \\ \end{array} \tag{34.13}\]

We can write this more concisely as follows:

\[\mathbb{I}\ell\_{01}(y^\*,\hat{y}) = \mathbb{I}(y^\* \neq \hat{y}) \tag{34.14}\]

In this case, the posterior expected loss is

\[\rho(\hat{y}|\mathbf{x}) = p(\hat{y} \neq y^\*|\mathbf{x}) = 1 - p(y^\* = \hat{y}|\mathbf{x}) \tag{34.15}\]

Hence the action that minimizes the expected loss is to choose the most probable label:

\[\delta(\mathbf{x}) = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} p(y|\mathbf{z}) \tag{34.16}\]

This corresponds to the mode of the posterior distribution, also known as the maximum a posteriori or MAP estimate.

We can generalize the loss function to associate di!erent costs for false positives and false negatives. We can also allow for a “reject action”, in which the decision maker abstains from classifying when it is not su”ciently confident. This is called selective prediction; see Section 19.3.3 for details.

34.1.5.2 Regression

Now suppose the hidden state of nature is a scalar h → R, and the corresponding action is also a scalar, y → R. The most common loss for continuous states and actions is the ω2 loss, also called squared error or quadratic loss, which is defined as follows:

\[\ell\_2(h, y) = (h - y)^2 \tag{34.17}\]

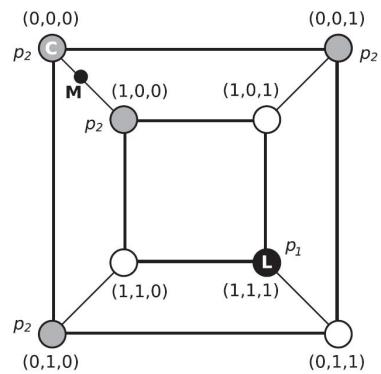

Figure 34.2: A distribution on a discrete space in which the mode (black point L, with probability p1) is untypical of most of the probability mass (gray circles, with probability p2 < p1). The small black circle labeled M (near the top left) is the posterior mean, which is not well defined in a discrete state space. C (the top left vertex) is the centroid estimator, made up of the maximizer of the posterior marginals. See text for details. From Figure 1 of [CL07]. Used with kind permission of Luis Carvalho.

In this case, the risk is given by

\[\rho(y|\mathbf{z}) = \mathbb{E}\left[ (h-y)^2 | \mathbf{z} \right] = \mathbb{E}\left[ h^2 | \mathbf{z} \right] - 2y \mathbb{E}\left[ h|\mathbf{z} \right] + y^2 \tag{34.18}\]

The optimal action must satisfy the condition that the derivative of the risk (at that point) is zero (as explained in Chapter 6). Hence the optimal action is to pick the posterior mean:

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\rho(y|x) = -2\mathbb{E}\left[h|x\right] + 2y = 0 \implies \delta(x) = \mathbb{E}\left[h|x\right] = \int h \, p(h|x) dh \tag{34.19}\]

This is often called the minimum mean squared error estimate or MMSE estimate.

34.1.5.3 Parameter estimation

Suppose the states of nature correspond to unknown parameters, so H = ! = RD. Furthermore, suppose the actions also correspond to parameters, so A = !. Finally, we assume the observed data (that is input to the policy/estimator) is a dataset, such as D = {(xn, yn) : n =1: N}. If we use quadratic loss, then the optimal action is to pick the posterior mean. If we use 0-1 loss, then the optimal action is to pick the posterior mode, i.e., the MAP estimate:

\[\delta(\mathcal{D}) = \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}} = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{\boldsymbol{\theta} \in \Theta} p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) \tag{34.20}\]

34.1.5.4 Estimating discrete parameters

The MAP estimate is the optimal estimate when the loss function is 0-1 loss, ω(ω, ωˆ) = I $ ω ↔︎= ωˆ % , as we show in Section 34.1.5.1. However, this does not give any “partial credit” for estimating some of

the components of ω correctly. An alternative is to use the Hamming loss:

\[\ell(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\hat{\theta}}) = \sum\_{d=1}^{D} \mathbb{I}\left(\theta\_d \neq \hat{\theta}\_d\right) \tag{34.21}\]

In this case, one can show that the optimal estimator is the vector of max marginals

\[\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}} = \left[ \underset{\boldsymbol{\theta}\_d}{\text{argmax}} \int\_{\boldsymbol{\theta}\_{-d}} p(\boldsymbol{\theta} | \mathcal{D}) d\boldsymbol{\theta}\_{-d} \right]\_{d=1}^{D} \tag{34.22}\]

This is also called the maximizer of posterior marginals or MPM estimate. Note that computing the max marginals involves marginalization and maximization, and thus depends on the whole distribution; this tends to be more robust than the MAP estimate [MMP87].

For example, consider a problem in which we must estimate a vector of binary variables. Figure 34.2 shows a distribution on {0, 1}3, where points are arranged such that they are connected to their nearest neighbors, as measured by Hamming distance. The black state (circle) labeled L (configuration (1,1,1)) has probability p1, and corresponds to the MAP estimate. The 4 gray states have probability p2 < p1; and the 3 white states have probability 0. Although the black state is the most probable, it is untypical of the posterior: all its nearest neighbors have probability zero, meaning it is very isolated. By contrast, the gray states, although slightly less probable, are all connected to other gray states, and together they constitute much more of the total probability mass.

In the example in Figure 34.2, we have p(ςj = 0) = 3p2 and p(ςj = 1) = p2 + p1 for j =1:3. If 2p2 > p1, the vector of max marginals is (0, 0, 0). This MPM estimate can be shown to be a centroid estimator, in the sense that it minimizes the squared distance to the posterior mean (the center of mass), yet it (usually) represents a valid configuration, unlike the actual mean (fractional estimates do not make sense for discrete problems). See [CL07] for further discussion of this point.

34.1.5.5 Structured prediction

In some problems, such as natural language processing or computer vision, the desired action is to return an output object y → Y, such as a set of labels or body poses, that not only is probable given the input x, but is also internally consistent. For example, suppose x is a sequence of phonemes and y is a sequence of words. Although x might sound more like y = “How to wreck a nice beach” on a word-by-word basis, if we take the sequence of words into account then we may find (under a language model prior) that y = “How to recognize speech” is more likely overall. (See Figure 34.3.) We can capture this kind of dependency amongst outputs, given inputs, using a structured prediction model, such as a conditional random field (see Section 4.4).

In addition to modeling dependencies in p(y|x), we may prefer certain action choices yˆ, which we capture in the loss function ω(y, yˆ). For example, referring to Figure 34.3, we may be reluctant to assume the user said yˆt=“nudist” at step t unless we are very confident of this prediction, since the cost of mis-categorizing this word may be higher than for other words.

Given a loss function, we can pick the optimal action using minimum Bayes risk decoding:

\[\hat{y} = \min\_{\hat{y} \in \mathcal{Y}} \sum\_{y \in \mathcal{Y}} p(y|x) \ell(y, \hat{y}) \tag{34.23}\]

Figure 34.3: Spectograms for three di!erent spoken sentences. The x-axis shows progression of time and the y-axis shows di!erent frequency bands. The energy of the signal in di!erent bands is shown as intensity in grayscale values with progression of time. (A) and (B) show spectrograms of the same sentence “How to recognize speech with this new display” spoken by two di!erent speakers, male and female. Although the frequency characterization is similar, the formant frequencies are much more clearly defined in the speech of the female speaker. (C) shows the spectrogram of the utterance “How to wreck a nice beach with this nudist play” spoken by the same female speaker as in (B). (A) and (B) are not identical even though they are composed of the same words. (B) and (C) are similar to each other even though they are not the same sentences. From Figure 1.2 of [Gan07]. Used with kind permission of Madhavi Ganapathiraju.

We can approximate the expectation empirically by sampling M solutions ym ↘ p(y|x) from the posterior predictive distribution. (Ideally these are diverse from each other.) We use the same set of M samples to approximate the minimization to get

\[\hat{\mathfrak{y}} \approx \min\_{\mathbf{y}^j, i \in \{1, \dots, M\}} \sum\_{j \in \{1, \dots, M\}} p(\mathbf{y}^j | \mathbf{x}) \ell(\mathbf{y}^j, \mathbf{y}^i) \tag{34.24}\]

This is called empirical MBR [Pre+17a], who applied it to computer vision problems. A similar approach was adopted in [Fre+22], who applied it to neural machine translation.

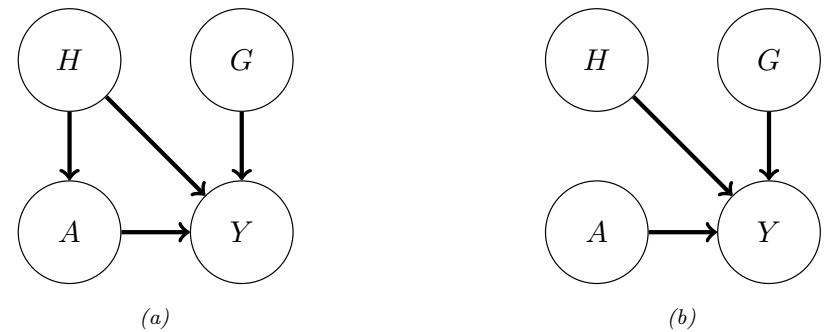

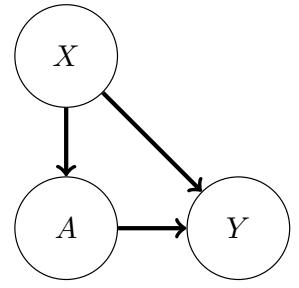

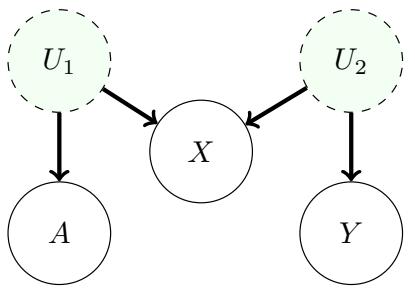

34.1.5.6 Fairness

Models trained with ML are increasingly being used to high-stakes applications, such as deciding whether someone should be released from prison or not, etc. In such applications, it is important that we focus not only on accuracy, but also on fairness. A variety of definitions for what is meant by fairness have been proposed (see e.g., [VR18]), many of which entail conflicting goals [Kle18]. Below we mention a few common definitions, which can all be interpreted decision theoretically.

We consider a binary classification problem with true label Y , predicted label Yˆ and sensitive attribute S (such as gender or race). The concept of equal opportunity requires equal true positive rates across subgroups, i.e., p(Yˆ = 1|Y = 1, S = 0) = p(Yˆ = 1|Y = 1, S = 1). The concept of equal

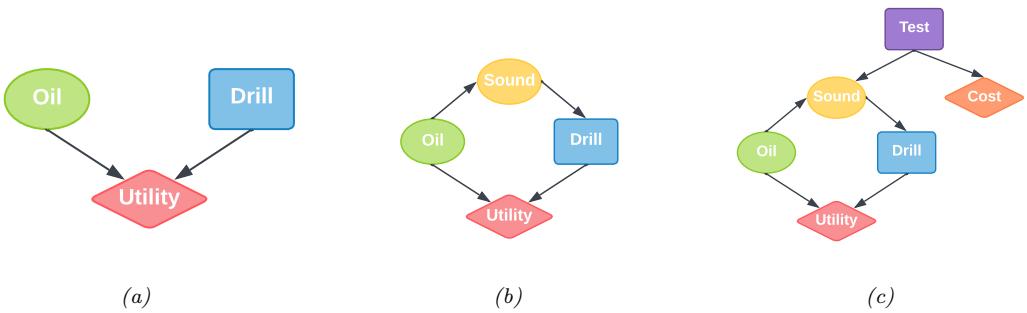

Figure 34.4: Influence diagrams for the oil wildcatter problem. Ovals are random variables (chance nodes), squares are decision (action) nodes, diamonds are utility (value) nodes. (a) Basic model. (b) An extension in which we have an information arc from the Sound chance node to the Drill decision node. (c) An extension in which we get to decide whether to perform a test or not, as well as whether to drill or not.

odds requires equal true positive rates across subgroups, and also equal false positive rates across subgroups, i.e., p(Yˆ = 1|Y = 0, S = 0) = p(Yˆ = 1|Y = 0, S = 1). The concept of statistical parity requires positive predictions to be una!ected by the value of the protected attribute, regardless of the true label, i.e., p(Yˆ = 1|S = 0) = p(Yˆ |S = 1).

For more details on this topic, see e.g., [KR19].

34.2 Decision (influence) diagrams

When dealing with structured multi-stage decision problems, it is useful to use a graphical notation called an influence diagram [HM81; KM08], also called a decision diagram. This extends directed probabilistic graphical models (Chapter 4) by adding decision nodes (also called action nodes), represented by rectangles, and utility nodes (also called value nodes), represented by diamonds. The original random variables are called chance nodes, and are represented by ovals, as usual.

34.2.1 Example: oil wildcatter

As an example (from [Rai68]), consider creating a model for the decision problem faced by an oil “wildcatter”, which is a person who drills wildcat wells, which are exploration wells drilled in areas not known to be oil fields.

Suppose you have to decide whether to drill an oil well or not at a given location. You have two possible actions: d = 1 means drill, d = 0 means don’t drill. You assume there are 3 states of nature: o = 0 means the well is dry, o = 1 means it is wet (has some oil), and o = 2 means it is soaking (has a lot of oil). We can represent this as a decision diagram as shown in Figure 34.4(a).

Suppose your prior beliefs are p(o) = [0.5, 0.3, 0.2], and your utility function U(d, o) is specified by the following table:

| o = 0 |

o = 1 |

o = 2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| d = 0 |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| d = 1 |

↓70 | 50 | 200 |

We see that if you don’t drill, you incur no costs, but also make no money. If you drill a dry well, you lose $70; if you drill a wet well, you gain $50; and if you drill a soaking well, you gain $200.

What action should you take if you have no information beyond your prior knowledge? Your prior expected utility for taking action d is

\[\text{EU}(d) = \sum\_{o=0}^{2} p(o)U(d, o) \tag{34.25}\]

We find EU(d = 0) = 0 and EU(d = 1) = 20 and hence the maximum expected utility is

\[\text{MEU} = \max\{\text{EU}(d=0), \text{EU}(d=1)\} = \max\{0, 20\} = 20 \tag{34.26}\]

Thus the optimal action is to drill, d→ = 1.

34.2.2 Information arcs

Now let us consider a slight extension to the model, in which you have access to a measurement (called a “sounding”), which is a noisy indicator about the state of the oil well. Hence we add an O ⇐ S arc to the model. In addition, we assume that the outcome of the sounding test will be available before we decide whether to drill or not; hence we add an information arc from S to D. This is illustrated in Figure 34.4(b). Note that the utility depends on the action and the true state of the world, but not the measurement.

We assume the sounding variable can be in one of 3 states: s = 0 is a di!use reflection pattern, suggesting no oil; s = 1 is an open reflection pattern, suggesting some oil; and s = 2 is a closed reflection pattern, indicating lots of oil. Since S is caused by O, we add an O ⇐ S arc to our model. Let us model the reliability of our sensor using the following conditional distribution for p(S|O):

| s = 0 |

s = 1 |

s = 2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| o = 0 |

0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| o = 1 |

0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| o = 2 |

0.1 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

Suppose the sounding observation is s. The posterior expected utility of performing action d is

\[\text{EU}(d|s) = \sum\_{o=0}^{2} p(o|s)U(o,d)\tag{34.27}\]

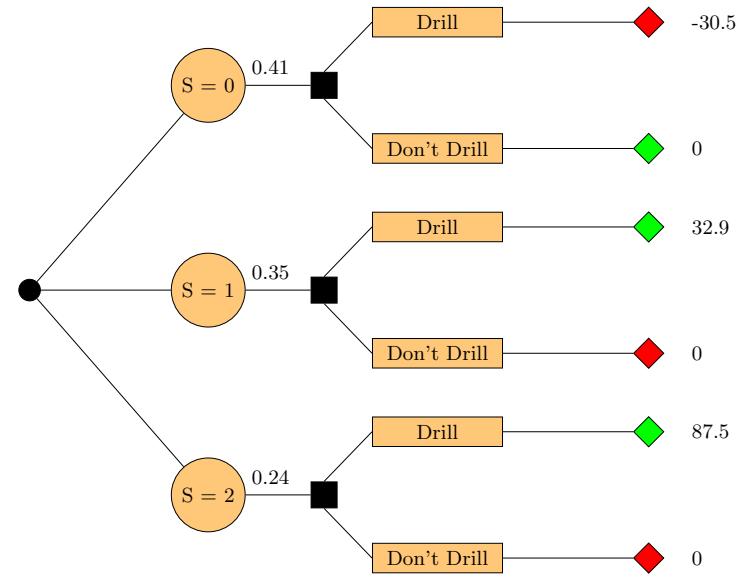

We need to compute this for each possible observation, s → {0, 1, 2}, and each possible action, d → {0, 1}. If s = 0, we find the posterior over the oil state is p(o|s = 0) = [0.732, 0.219, 0.049], and hence EU(d = 0|s = 0) = 0 and EU(d = 1|s = 0) = ↓30.5. If s = 1, we similarly find EU(d = 0|s = 1) = 0 and EU(d = 1|s = 1) = 32.9. If s = 2, we find EU(d = 0|s = 2) = 0 and EU(d = 1|s = 2) = 87.5. Hence the optimal policy d→(s) is as follows: if s = 0, choose d = 0 and get $0; if s = 1, choose d = 1 and get $32.9; and if s = 2, choose d = 1 and get $87.5.

The maximum expected utility of the wildcatter, before seeing the experimental sounding, can be computed using

\[\text{MEU} = \sum\_{s} p(s) \text{EU}(d^\*(s)|s) \tag{34.28}\]

Figure 34.5: Decision tree for the oil wildcatter problem. Black circles are chance variables, black squares are decision nodes, diamonds are the resulting utilities. Green leaf nodes have higher utility than red leaf nodes.

where prior marginal on the outcome of the test is p(s) = ) o p(o)p(s|o) = [0.41, 0.35, 0.24]. Hence the MEU is

MEU = 0.41 ⇒ 0+0.35 ⇒ 32.9+0.24 ⇒ 87.5 = 32.2 (34.29)

These numbers can be summarized in the decision tree shown in Figure 34.5.

34.2.3 Value of information

Now suppose you can choose whether to do the test or not. This can be modelled as shown in Figure 34.4(c), where we add a new test node T. If T = 1, we do the test, and S can enter states {0, 1, 2}, determined by O, exactly as above. If T = 0, we don’t do the test, and S enters a special unknown state. There is also some cost associated with performing the test.

Is it worth doing the test? This depends on how much our MEU changes if we know the outcome of the test (namely the state of S). If you don’t do the test, we have MEU = 20 from Equation (34.26). If you do the test, you have MEU = 32.2 from Equation (34.29). So the improvement in utility if you do the test (and act optimally on its outcome) is $12.2. This is called the value of perfect information (VPI). So we should do the test as long as it costs less than $12.2.

In terms of graphical models, the VPI of a variable S can be determined by computing the MEU for the base influence diagram, G, in Figure 34.4(b), and then computing the MEU for the same influence diagram where we add information arcs from S to the action node, and then computing the di!erence. In other words,

\[\text{VPI} = \text{MEU}(\mathcal{G} + S \to D) - \text{MEU}(\mathcal{G}) \tag{34.30}\]

where D is the decision node and S is the variable we are measuring. This will tell us whether it is worth adding obtaining measurement S.

34.2.4 Computing the optimal policy

In general, given an influence diagram, we can compute the optimal policy automatically by modifiying the variable elimination algorithm (Section 9.5), as explained in [LN01; KM08]. The basic idea is to work backwards from the final action, computing the optimal decision at each step, assuming all following actions are chosen optimally. When the influence diagram has a simple chain structure, as in a Markov decision process (Section 34.5), the result is equivalent to Bellman’s equation (Section 34.5.5).

34.3 A/B testing

Suppose you are trying to decide which version of a product is likely to sell more, or which version of a drug is likely to work better. Let us call the versions you are choosing between A and B; sometimes version A is called the control, and version B is called the treatment. (Sometimes the di!erent actions are called “arms”.)

A very common approach to such problems is to use an A/B test, in which you try both actions out for a while, by randomly assigning a di!erent action to di!erent subsets of the population, and then you measure the resulting accumulated reward from each action, and you pick the winner. (This is sometimes called a “test and roll” approach, since you test which method is best, and then roll it out for the rest of the population.)

A key problem in A/B testing is to come up with a decision rule, or policy, for deciding which action is best, after obtaining potentially noisy results during the test phase. Another problem is to choose how many people to assign to the treatment, n1, and how many to the control, n0. The fundamental tradeo! is that using larger values of n1 and n0 will help you collect more data and hence be more confident in picking the best action, but this incurs an opportunity cost, because the testing phase involves performing actions that may not result in the highest reward. (This is an example of the exploration-exploitation tradeo!, which we discuss more in Section 34.4.3.) In this section, we give a simple Bayesian decision theoretic analysis of this problem, following the presentation of [FB19].3 More details on A/B testing can be found in [KTX20].

34.3.1 A Bayesian approach

We assume the i’th reward for action j is given by Yij ↘ N (µj , φ2 j ) for i =1: nj and j =0:1, where j = 0 corresponds to the control (action A), j = 1 corresponds to the treatment (action B), and nj is the number of samples you collect from group j. The parameters µj are the expected reward for action j; our goal is to estimate these parameters. (For simplicity, we assume the φ2 j are known.)

We will adopt a Bayesian approach, which is well suited to sequential decision problems. For simplicity, we will use Gaussian priors for the unknowns, µj ↘ N (mj , ↼ 2 j ), where mj is the prior mean reward for action j, and ↼j is our confidence in this prior. We assume the prior parameters are known. (In practice we can use an empirical Bayes approach, as we discuss in Section 34.3.2.)

3. For a similar set of results in the time-discounted setting, see https://chris-said.io/2020/01/10/ optimizing-sample-sizes-in-ab-testing-part-I.

34.3.1.1 Optimal policy

Initially we assume the sample size of the experiment (i.e., the values n1 for the treatment and n0 for the control) are known. Our goal is to compute the optimal policy or decision rule ϑ(y1, y0), which specifies which action to deploy, where yj = (y1j ,…,ynj ,j ) is the data from action j.

The optimal policy is simple: choose the action with the greater expected posterior expected reward:

\[\pi^\*(\boldsymbol{y}\_1, \boldsymbol{y}\_0) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } \mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{\mu}\_1 | \boldsymbol{y}\_1\right] \ge \mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{\mu}\_0 | \boldsymbol{y}\_0\right] \\ 0 & \text{if } \mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{\mu}\_1 | \boldsymbol{y}\_1\right] < \mathbb{E}\left[\boldsymbol{\mu}\_0 | \boldsymbol{y}\_0\right] \end{cases} \tag{34.31}\]

All that remains is to compute the posterior. over the unknown parameters, µj . Applying Bayes’ rule for Gaussians (Equation (2.121)), we find that the corresponding posterior is given by

\[p(\mu\_j | \mathbf{y}\_j, n\_j) = \mathcal{N}(\mu\_j | \hat{m}\_j, \hat{\tau}\_j^2) \tag{34.32}\]

\[1/\ \hat{\tau}\_j^2 = n\_j/\sigma\_j^2 + 1/\tau\_j^2\tag{34.33}\]

\[ \hat{m}\_j \mid \hat{\tau}\_j^2 = n\_j \overline{y}\_j / \sigma\_j^2 + m\_j / \tau\_j^2 \tag{34.34} \]

We see that the posterior precision (inverse variance) is a weighted sum of the prior precision plus nj units of measurement precision. We also see that the posterior precision weighted mean is a sum of the prior precision weighted mean and the measurement precision weighted mean.

Given the posterior, we can plug m ↭ j into Equation (34.31). In the fully symmetric case, where n1 = n0, m1 = m0 = m, ↼1 = ↼0 = ↼ , and φ1 = φ0 = φ, we find that the optimal policy is to simply “pick the winner”, which is the arm with higher empirical performance:

\[\pi^\*(y\_1, y\_0) = \mathbb{I}\left(\frac{m}{\tau^2} + \frac{\overline{y}\_1}{\sigma^2} > \frac{m}{\tau^2} + \frac{\overline{y}\_0}{\sigma^2}\right) = \mathbb{I}\left(\overline{y}\_1 > \overline{y}\_0\right) \tag{34.35}\]

However, when the problem is asymmetric, we need to take into account the di!erent sample sizes and/or di!erent prior beliefs.

34.3.1.2 Optimal sample size

We now discuss how to compute the optimal sample size for each arm of the experiment, i.e, the values n0 and n1. We assume the total population size is N, and we cannot reuse people from the testing phase,

The prior expected reward in the testing phase is given by

\[\mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{test}}\right] = n\_0 m\_0 + n\_1 m\_1 \tag{34.36}\]

The expected reward in the roll phase depends on the decision rule ϑ(y1, y0) that we use:

\[\mathbb{E}\_{\pi} \left[ R\_{\text{coll}} \right] = \int\_{\mu\_1} \int\_{\mu\_0} \int\_{\mathbf{y}\_1} \int\_{\mathbf{y}\_0} \left( N - n\_1 - n\_0 \right) \left( \pi(\mathbf{y}\_1, \mathbf{y}\_0) \mu\_1 + (1 - \pi(\mathbf{y}\_1, \mathbf{y}\_0)) \mu\_0 \right) \tag{34.37}\]

\[0 \times p(\mathfrak{y}\_0|\mu\_0)p(\mathfrak{y}\_1|\mu\_1)p(\mu\_0)p(\mu\_1)d\mathfrak{y}\_0d\mathfrak{y}\_1d\mu\_0d\mu\_1 \tag{34.38}\]

For ϑ = ϑ→ one can show that this equals

\[\mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{roll}}\right] \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \mathbb{E}\_{\pi \ast} \left[R\_{\text{roll}}\right] = \left(N - n\_1 - n\_0\right) \left(m\_1 + e\Phi(\frac{e}{v}) + v\phi(\frac{e}{v})\right) \tag{34.39}\]

where ↽ is the Gaussian pdf, ” is the Gaussian cdf, e = m0 ↓ m1 and

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{\tau\_1^4}{\tau\_1^2 + \sigma\_1^2/n\_1} + \frac{\tau\_0^4}{\tau\_0^2 + \sigma\_0^2/n\_0}}\tag{34.40}\]

In the fully symmetric case, Equation (34.39) simplifies to

\[\mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{coll}}\right] = \underbrace{(N-2n)m}\_{R\_a} + \underbrace{(N-2n)\frac{\sqrt{2}\tau^2}{\sqrt{\pi}\sqrt{2\tau^2 + \frac{2}{n}\sigma^2}}}\_{R\_b} \tag{34.41}\]

This has an intuitive interpretation. The first term, Ra, is the prior reward we expect to get before we learn anything about the arms. The second term, Rb, is the reward we expect to see by virtue of picking the optimal action to deploy.

Let us we write Rb = (N ↓ 2n)Ri, where Ri is the incremental gain. We see that the incremental gain increases with n, because we are more likely to pick the correct action with a larger sample size; however, this gain can only be accrued for a smaller number of people, as shown by the N ↓ 2n prefactor. (This is a consequence of the explore-exploit tradeo!.)

The total expected reward is given by adding Equation (34.36) and Equation (34.41):

\[\mathbb{E}\left[R\right] = \mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{test}}\right] + \mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{roll}}\right] = Nm + (N - 2n)\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}\tau^2}{\sqrt{\pi}\sqrt{2\tau^2 + \frac{2}{n}\sigma^2}}\right) \tag{34.42}\]

(The equation for the nonsymmetric case is given in [FB19].)

We can maximize the expected reward in Equation (34.42) to find the optimal sample size for the testing phase, which (from symmetry) satisfies n→ 1 = n→ 2 = n→, and from d dn↑ E [R]=0 satisfies

\[m^\* = \sqrt{\frac{N}{4}u^2 + \left(\frac{3}{4}u^2\right)^2} - \frac{3}{4}u^2 \le \sqrt{N}\frac{\sigma}{2\tau} \tag{34.43}\]

where u2 = ϖ2 ϱ2 . Thus we see that the optimal sample size n→ increases as the observation noise φ increases, since we need to collect more data to be confident of the right decision. However, the optimal sample size decreases with ↼ , since a prior belief that the e!ect size ε = µ1 ↓ µ0 will be large implies we expect to need less data to reach a confident conclusion.

34.3.1.3 Regret

Given a policy, it is natural to wonder how good it is. We define the regret of a policy to be the di!erence between the expected reward given perfect information (PI) about the true best action

and the expected reward due to our policy. Minimizing regret is equivalent to making the expected reward of our policy equal to the best possible reward (which may be high or low, depending on the problem).

An oracle with perfect information about which µj is bigger would pick the highest scoring action, and hence get an expected reward of NE [max(µ1, µ2)]. Since we assume µj ↘ N (m, ↼ 2), we have

\[\mathbb{E}\left[R|PI\right] = N\left(m + \frac{\tau}{\sqrt{\pi}}\right) \tag{34.44}\]

Therefore the regret from the optimal policy is given by

\[\mathbb{E}\left[R|PI\right] - \left(\mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{test}}|\pi^\*\right] + \mathbb{E}\left[R\_{\text{coll}}|\pi^\*\right]\right) = N\frac{\tau}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left(1 - \frac{\tau}{\sqrt{\tau^2 + \frac{\sigma^2}{n^\*}}}\right) + \frac{2n^\*\tau^2}{\sqrt{\pi}\sqrt{\tau^2 + \frac{\sigma^2}{n^\*}}}\tag{34.45}\]

One can show that the regret is O( ⇓ N), which is optimal for this problem when using a time horizon (population size) of N [AG13].

34.3.1.4 Expected error rate

Sometimes the goal is posed as best arm identification, which means identifying whether µ1 > µ0 or not. That is, if we define ε = µ1 ↓ µ0, we want to know if ε > 0 or ε < 0. This is naturally phrased as a hypothesis test. However, this is arguably the wrong objective, since it is usually not worth spending money on collecting a large sample size to be confident that ε > 0 (say) if the magnitude of ε is small. Instead, it makes more sense to optimize total expected reward, using the method in Section 34.3.1.1.

Nevertheless, we may want to know the probability that we have picked the wrong arm if we use the policy from Section 34.3.1.1. In the symmetric case, this is given by the following:

\[\Pr(\pi(y\_1, y\_0) = 1 | \mu\_1 < \mu\_0) = \Pr(Y\_1 - Y\_0 > 0 | \mu\_1 < \mu\_0) = 1 - \Phi\left(\frac{\mu\_1 - \mu\_0}{\sigma \sqrt{\frac{1}{n\_1} + \frac{1}{n\_0}}}\right) \tag{34.46}\]

The above expression assumed that µj are known. Since they are not known, we can compute the expected error rate using E [Pr(ϑ(y1, y0)=1|µ1 < µ0)]. By symmetry, the quantity E [Pr(ϑ(y1, y0)=0|µ1 > µ0)] is the same. One can show that both quantities are given by

\[\text{Prob. error} = \frac{1}{4} - \frac{1}{2\pi} \arctan\left(\frac{\sqrt{2}\tau}{\sigma} \sqrt{\frac{n\_1 n\_0}{n\_1 + n\_0}}\right) \tag{34.47}\]

As expected, the error rate decreases with the sample size n1 and n0, increases with observation noise φ, and decreases with variance of the e!ect size ↼ . Thus a policy that minimizes the classification error will also maximize expected reward, but it may pick an overly large sample size, since it does not take into account the magnitude of ε.

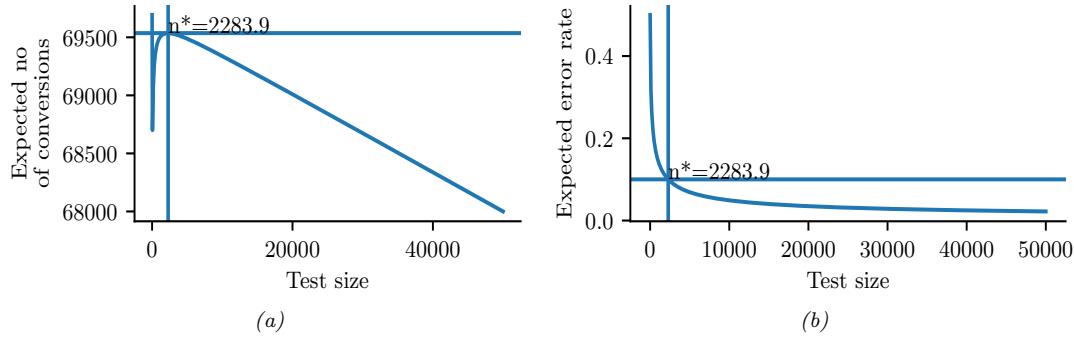

Figure 34.6: Total expected profit (a) and error rate (b) as a function of the sample size used for website testing. Generated by ab\_test\_demo.ipynb.

34.3.2 Example

In this section, we give a simple example of the above framework. Suppose our goal is to do website testing, where have two di!erent versions of a webpage that we want to compare in terms of their click through rate. The observed data is now binary, yij ↘ Ber(µj ), so it is natural to use a beta prior, µj ↘ Beta(⇀, ⇁) (see Section 3.4.1). However, in this case the optimal sample size and decision rule is harder to compute (see [FB19; Sta+17] for details). As a simple approximation, we can assume yij ↘ N (µj , φ2), where µj ↘ N (m, ↼ 2), m = ς ς+φ , ↼ 2 = ςφ (ς+φ)2(ς+φ+1) , and φ2 = m(1 ↓ m).

To set the Gaussian prior, [FB19] used empirical data from about 2000 prior A/B tests. For each test, they observed the number of times the page was served with each of the two variations, as well as the total number of times a user clicked on each version. Given this data, they used a hierarchical Bayesian model to infer µj ↘ N (m = 0.68, ↼ = 0.03). This prior implies that the expected e!ect size is quite small, E [|µ1 ↓ µ0|] = 0.023. (This is consistent with the results in [Aze+20], who found that most changes made to the Microsoft Bing EXP platform had negligible e!ect, although there were occasionally some “big hits”.)

With this prior, and assuming a population of N = 100, 000, Equation (34.43) says that the optimal number of trials to run is n→ 1 = n→ 0 = 2284. The expected reward (number of clicks or conversions) in the testing phase is E [Rtest] = 3106, and in the deployment phase E [Rroll] = 66, 430, for a total reward of 69, 536. The expected error rate is 10%.

In Figure 34.6a, we plot the expected reward vs the size of the test phase n. We see that the reward increases sharply with n to the global maximum at n→ = 2284, and then drops o! more slowly. This indicates that it is better to have a slightly larger test than one that is too small by the same amount. (However, when using a heavy tailed model, [Aze+20] finds that it is better to do lots of smaller tests.)

In Figure 34.6b, we plot the probability of picking the wrong action vs n. We see that tests that are larger than optimal only reduce this error rate marginally. Consequently, if you want to make the misclassification rate low, you may need a large sample size, particularly if µ1 ↓ µ0 is small, since then it will be hard to detect the true best action. However, it is also less important to identify the best action in this case, since both actions have very similar expected reward. This explains why classical methods for A/B testing based on frequentist statistics, which use hypothesis testing

methods to determine if A is better than B, may often recommend sample sizes that are much larger than necessary. (See [FB19] and references therein for further discussion.)

34.4 Contextual bandits

34.4.1 Types of bandit

In a multi-armed bandit problem (MAB) there is an agent (decision maker) that can choose an action from some policy at ↘ ϑt at each step, after which it receives a reward sampled from the environment, rt ↘ pR(at), with expected value R(s, a) = E [R|a]. 4

We can think of this in terms of an agent at a casino who is faced with multiple slot machines, each of which pays out rewards at a di!erent rate. A slot machine is sometimes called a onearmed bandit, so a set of K such machines is called a multi-armed bandit; each di!erent action corresponds to pulling the arm of a di!erent slot machine, at → {1,…,K}. The goal is to quickly figure out which machine pays out the most money, and then to keep playing that one until you become as rich as possible.

We can extend this model by defining a contextual bandit, in which the input to the policy at each step is a randomly chosen state or context st → S. The states evolve over time according to some arbitrary process, st ↘ p(st|s1:t↓1), independent of the actions of the agent. The policy now has the form at ↘ ϑt(at|st), and the reward function now has the form rt ↘ pR(rt|st, at), with expected value R(s, a) = E [R|s, a]. At each step, the agent can use the observed data, D1:t where Dt = (st, at, rt), to update its policy, to maximize expected reward.

In the finite horizon formulation of (contextual) bandits, the goal is to maximize the expected cumulative reward:

\[J \triangleq \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \mathbb{E}\_{p\_R(r\_t|s\_t, a\_t)\pi\_t(a\_t|s\_t)p(s\_t|s\_{1:t-1})}[r\_t] = \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \mathbb{E}\left[r\_t\right] \tag{34.48}\]

4. This is known as a stochastic bandit. It is also possible to allow the reward, and possibly the state, to be chosen in an adversarial manner, where nature tries to minimize the reward of the agent. This is known as an adversarial bandit.

(Note that the reward is accrued at each step, even while the agent updates its policy; this is sometimes called “earning while learning”.) In the infinite horizon formulation, where T = ↖, the cumulative reward may be infinite. To prevent J from being unbounded, we introduce a discount factor 0 < γ < 1, so that

\[J \triangleq \sum\_{t=1}^{\infty} \gamma^{t-1} \mathbb{E}\left[r\_t\right] \tag{34.49}\]

The quantity 1 ↓ γ can be interpreted as the probability that the agent is terminated at any moment in time (in which case it will cease to accumulate reward).

Another way to write this is as follows:

\[J = \sum\_{t=1}^{\infty} \gamma^{t-1} \mathbb{E}\left[r\_t\right] = \sum\_{t=1}^{\infty} \gamma^{t-1} \mathbb{E}\left[\sum\_{a=1}^{K} R\_a(s\_t, a\_t)\right] \tag{34.50}\]

where we define

\[R\_a(s\_t, a\_t) = \begin{cases} R(s\_t, a) & \text{if } a\_t = a \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \tag{34.51}\]

Thus we conceptually evaluate the reward for all arms, but only the one that was actually chosen (namely at) gives a non-zero value to the agent, namely rt.

There are many extensions of the basic bandit problem. A natural one is to allow the agent to perform multiple plays, choosing M ⇔ K distinct arms at once. Let at be the corresponding action vector which specifies the identity of the chosen arms. Then we define the reward to be

\[r\_t = \sum\_{a=1}^{K} R\_a(s\_t, \mathbf{a}\_t) \tag{34.52}\]

where

\[R\_a(s\_t, \mathbf{a}\_t) = \begin{cases} R(s\_t, a) & \text{if } a \in \mathbf{a}\_t \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \tag{34.53}\]

This is useful for modeling resource allocation problems.

Another variant is known as a restless bandit [Whi88]. This is the same as the multiple play formulation, except we additionally assume that each arm has its own state vector sa t associated with it, which evolves according to some stochastic process, regardless of whether arm a was chosen or not. We then define

\[r\_t = \sum\_{a=1}^{K} R\_a(s\_t^a, \mathbf{a}\_t) \tag{34.54}\]

where sa t ↘ p(sa t |sa 1:t↓1) is some arbitrary distribution, often assumed to be Markovian. (The fact that the states associated with each arm evolve even if the arm is not picked is what gives rise to the term “restless”.) This can be used to model serial dependence between the rewards given by each arm.

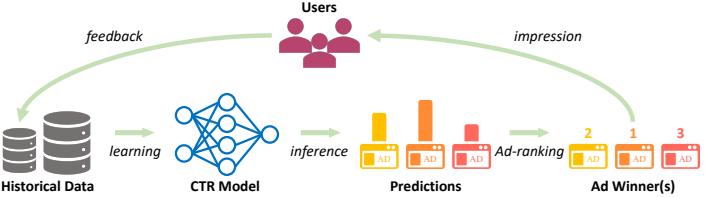

Figure 34.7: Illustration of the feedback problem in online advertising and recommendation systems. The click through rate (CTR) model is used to decide what ads to show, which a!ects what data is collected, which a!ects how the model learns. From Figure 1–2 of [Du+21]. Used with kind permission of Chao Du.

34.4.2 Applications

Contextual bandits have many applications. For example, consider an online advertising system. In this case, the state st represents features of the web page that the user is currently looking at, and the action at represents the identity of the ad which the system chooses to show. Since the relevance of the ad depends on the page, the reward function has the form R(st, at), and hence the problem is contextual. The goal is to maximize the expected reward, which is equivalent to the expected number of times people click on ads; this is known as the click through rate or CTR. (See e.g., [Gra+10; Li+10; McM+13; Aga+14; Du+21; YZ22] for more information about this application.)

Another application of contextual bandits arises in clinical trials [VBW15]. In this case, the state st are features of the current patient we are treating, and the action at is the treatment the doctor chooses to give them (e.g., a new drug or a placebo). Our goal is to maximize expected reward, i.e., the expected number of people who get cured. (An alternative goal is to determine which treatment is best as quickly as possible, rather than maximizing expected reward; this variant is known as best-arm identification [ABM10].)

34.4.3 Exploration-exploitation tradeo!

The fundamental di”culty in solving bandit problems is known as the exploration-exploitation tradeo!. This refers to the fact that the agent needs to try multiple state/action combinations (this is known as exploration) in order to collect enough data so it can reliably learn the reward function R(s, a); it can then exploit its knowledge by picking the predicted best action for each state. If the agent starts exploiting an incorrect model too early, it will collect suboptimal data, and will get stuck in a negative feedback loop, as illustrated in Figure 34.7. This is di!erent from supervised learning, where the data is drawn iid from a fixed distribution (see e.g., [Jeu+19] for details).

We discuss some solutions to the exploration-exploitation problem below.

34.4.4 The optimal solution

In this section, we discuss the optimal solution to the exploration-exploitation tradeo!. Let us denote the posterior over the parameters of the reward function by bt = p(ω|ht), where ht = {s1:t↓1, a1:t↓1, r1:t↓1} is the history of observations; this is known as the belief state or information state. It is a finite su”cient statistic for the history ht. The belief state can be

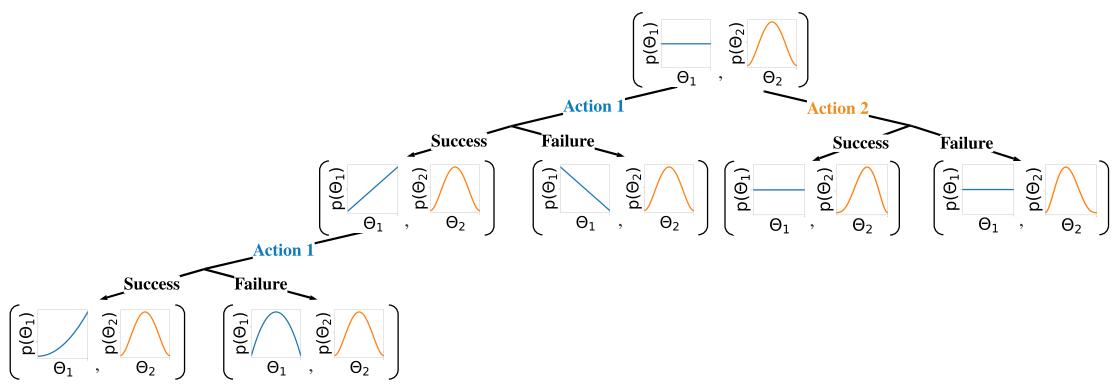

Figure 34.8: Illustration of sequential belief updating for a two-armed beta-Bernoulli bandit. The prior for the reward for action 1 is the (blue) uniform distribution Beta(1, 1); the prior for the reward for action 2 is the (orange) unimodal distribution Beta(2, 2). We update the parameters of the belief state based on the chosen action, and based on whether the observed reward is success (1) or failure (0).

updated deterministically using Bayes’ rule:

\[\mathbf{b}\_{t} = \text{BayesRule}(\mathbf{b}\_{t-1}, a\_t, r\_t) \tag{34.55}\]

For example, consider a context-free Bernoulli bandit, where pR(r|a) = Ber(r|µa), and µa = pR(r = 1|a) = R(a) is the expected reward for taking action a. Suppose we use a factored beta prior

\[p\_0(\theta) = \prod\_a \text{Beta}(\mu\_a | \alpha\_0^a, \beta\_0^a) \tag{34.56}\]

where ω = (µ1,…,µK). We can compute the posterior in closed form, as we discuss in Section 3.4.1. In particular, we find

\[p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}\_t) = \prod\_a \text{Beta}(\mu\_a | \underbrace{\alpha\_0^a + N\_t^0(a)}\_{\alpha\_t^a}, \underbrace{\beta\_0^a + N\_t^1(a)}\_{\beta\_t^a}) \tag{34.57}\]

where

\[N\_t^r(a) = \sum\_{s=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{I}(a\_s = a, r\_s = r) \tag{34.58}\]

This is illustrated in Figure 34.8 for a two-armed Bernoulli bandit.

We can use a similar method for a Gaussian bandit, where pR(r|a) = N (r|µa, φ2 a), using results from Section 3.4.3. In the case of contextual bandits, the problem becomes more complicated. If we assume a linear regression bandit, pR(r|s, a; ω) = N (r|ε(s, a) Tω, φ2), we can use Bayesian linear regression to compute p(ω|Dt) in closed form, as we discuss in Section 15.2. If we assume a logistic regression bandit, pR(r|s, a; ω) = Ber(r|φ(ε(s, a) Tω)), we can use Bayesian logistic regression to compute p(ω|Dt), as we discuss in Section 15.3.5. If we have a neural bandit of the form pR(r|s, a; ω) = GLM(r|f(s, a; ω)) for some nonlinear function f, then posterior inference becomes more challenging, as we discuss in Chapter 17. However, standard techniques, such as the extended Kalman filter (Section 17.5.2) can be applied. (For a way to scale this approach to large DNNs, see the “subspace neural bandit” approach of [DMKM22].)

Regardless of the algorithmic details, we can represent the belief state update as follows:

\[p(\mathbf{b}\_t | \mathbf{b}\_{t-1}, a\_t, r\_t) = \mathbb{I}\left(\mathbf{b}\_t = \text{BayesRule}(\mathbf{b}\_{t-1}, a\_t, r\_t)\right) \tag{34.59}\]

The observed reward at each step is then predicted to be

\[p(r\_t|\mathbf{b}\_t) = \int p\_R(r\_t|s\_t, a\_t; \theta) p(\theta|\mathbf{b}\_t) d\theta \tag{34.60}\]

We see that this is a special form of a (controlled) Markov decision process (Section 34.5) known as a belief-state MDP.

In the special case of context-free bandits with a finite number of arms, the optimal policy of this belief state MDP can be computed using dynamic programming (see Section 34.6); the result can be represented as a table of action probabilities, ϑt(a1,…,aK), for each step; this is known as the Gittins index [Git89]. However, computing the optimal policy for general contextual bandits is intractable [PT87], so we have to resort to approximations, as we discuss below.

34.4.5 Upper confidence bounds (UCBs)

The optimal solution to explore-exploit is intractable. However, an intuitively sensible approach is based on the principle known as “optimism in the face of uncertainty”. The principle selects actions greedily, but based on optimistic estimates of their rewards. The most important class of strategies with this principle are collectively called upper confidence bound or UCB methods.

To use a UCB strategy, the agent maintains an optimistic reward function estimate R˜t, so that R˜t(st, a) ⇑ R(st, a) for all a with high probability, and then chooses the greedy action accordingly:

\[a\_t = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_a \tilde{R}\_t(s\_t, a) \tag{34.61}\]

UCB can be viewed a form of exploration bonus, where the optimistic estimate encourages exploration. Typically, the amount of optimism, R˜t ↓ R, decreases over time so that the agent gradually reduces exploration. With properly constructed optimistic reward estimates, the UCB strategy has been shown to achieve near-optimal regret in many variants of bandits [LS19]. (We discuss regret in Section 34.4.7.)

The optimistic function R˜ can be obtained in di!erent ways, sometimes in closed forms, as we discuss below.

34.4.5.1 Frequentist approach

One approach is to use a concentration inequality [BLM16] to derive a high-probability upper bound of the estimation error: |Rˆt(s, a) ↓ Rt(s, a)| ⇔ εt(s, a), where Rˆt is a usual estimate of R (often the MLE), and εt is a properly selected function. An optimistic reward is then obtained by setting R˜t(s, a) = Rˆt(s, a) + εt(s, a).

As an example, consider again the context-free Bernoulli bandit, R(a) ↘ Ber(µ(a)). The MLE Rˆt(a)=ˆµt(a) is given by the empirical average of observed rewards whenever action a was taken:

\[ \hat{\mu}\_t(a) = \frac{N\_t^1(a)}{N\_t(a)} = \frac{N\_t^1(a)}{N\_t^0(a) + N\_t^1(a)}\tag{34.62} \]

where Nr t (a) is the number of times (up to step t ↓ 1) that action a has been tried and the observed reward was r, and Nt(a) is the total number of times action a has been tried:

\[N\_t(a) = \sum\_{s=1}^{t-1} \mathbb{I}\left(a\_t = a\right) \tag{34.63}\]

Then the Cherno!-Hoe!ding inequality [BLM16] leads to εt(a) = c/Nt(a) for some proper constant c, so

\[ \bar{R}\_t(a) = \hat{\mu}\_t(a) + \frac{c}{\sqrt{N\_t(a)}} \tag{34.64} \]

34.4.5.2 Bayesian approach

We may also derive R˜ from Bayesian inference. If we use a beta prior, we can compute the posterior in closed form, as shown in Equation (34.57). The posterior mean is µˆt(a) = E [µ(a)|ht] = ςa t ςa t +φa t . From Equation (3.17), the posterior standard deviation is approximately

\[ \hat{\sigma}\_t(a) = \sqrt{\mathcal{V}[\mu(a)|h\_t]} \approx \sqrt{\frac{\hat{\mu}\_t(a)(1-\hat{\mu}\_t(a))}{N\_t(a)}}\tag{34.65} \]

We can use similar techniques for a Gaussian bandit, where pR(R|a, ω) = N (R|µa, φ2 a), µa is the expected reward, and φ2 a the variance. If we use a conjugate prior, we can compute p(µa, φa|Dt) in closed form (see Section 3.4.3). Using an uninformative version of the conjugate prior, we find E [µa|ht] = µˆt(a), which is just the empirical mean of rewards for action a. The uncertainty in this estimate is the standard error of the mean, given by Equation (3.133), i.e., V [µa|ht] = φˆt(a)/ Nt(a), where φˆt(a) is the empirical standard deviation of the rewards for action a.

This approach can also be extended to contextual bandits, modulo the di”culty of computing the belief state.

Once we have computed the mean and posterior standard deviation, we define the optimistic reward estimate as

\[ \hat{R}\_t(a) = \hat{\mu}\_t(a) + c\hat{\sigma}\_t(a) \tag{34.66} \]

for some constant c that controls how greedy the policy is. We see that this is similar to the frequentist method based on concentration inequalities, but is more general.

34.4.5.3 Example

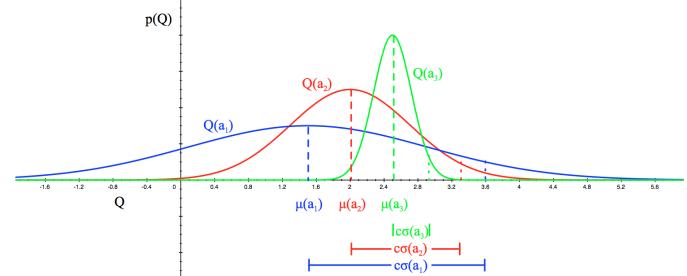

Figure 34.9 illustrates the UCB principle for a Gaussian bandit. We assume there are 3 actions, and we represent p(R(a)|Dt) using a Gaussian. We show the posterior means Q(a) = µ(a) with a vertical dotted line, and the scaled posterior standard deviations cφ(a) as a horizontal solid line.

Figure 34.9: Illustration of the reward distribution Q(a) for 3 di!erent actions, and the corresponding lower and upper confidence bounds. From [Sil18]. Used with kind permission of David Silver.

34.4.6 Thompson sampling

A common alternative to UCB is to use Thompson sampling [Tho33], also called probability matching [Sco10]. In this approach, we define the policy at step t to be ϑt(a|st, ht) = pa, where pa is the probability that a is the optimal action. This can be computed using

\[p\_a = \Pr(a = a\_\* | s\_t, h\_t) = \int \mathbb{I}\left(a = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{a'} R(s\_t, a'; \theta)\right) p(\theta | h\_t) d\theta \tag{34.67}\]

If the posterior is uncertain, the agent will sample many di!erent actions, automatically resulting in exploration. As the uncertainty decreases, it will start to exploit its knowledge.

To see how we can implement this method, note that we can compute the expression in Equation (34.67) by using a single Monte Carlo sample ω˜t ↘ p(ω|ht). We then plug in this parameter into our reward model, and greedily pick the best action:

\[a\_t = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{a'} R(s\_t, a'; \tilde{\theta}\_t) \tag{34.68}\]

This sample-then-exploit approach will choose actions with exactly the desired probability, since

\[p\_a = \int \mathbb{I}\left(a = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{a'} R(s\_t, a'; \tilde{\theta}\_t)\right) p(\tilde{\theta}\_t | h\_t) = \Pr\_{\theta\_t \sim p(\theta | h\_t)}\left(a = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_{a'} R(s\_t, a'; \tilde{\theta}\_t)\right) \tag{34.69}\]

Despite its simplicity, this approach can be shown to achieve optimal (logarithmic) regret (see e.g., [Rus+18] for a survey). In addition, it is very easy to implement, and hence is widely used in practice [Gra+10; Sco10; CL11].

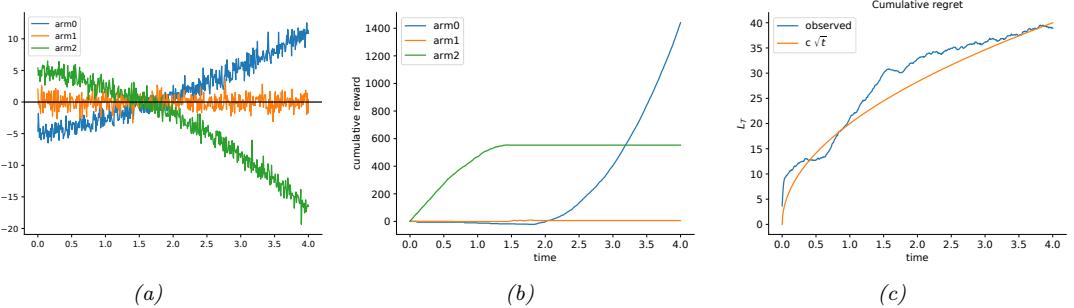

In Figure 34.10, we give a simple example of Thompson sampling applied to a linear regression bandit. The context has the form st = (1, t, t2). The true reward function has the form R(st, a) = wT ast. The weights per arm are chosen as follows: w0 = (↓5, 2, 0.5), w1 = (0, 0, 0), w2 = (5, ↓1.5, ↓1). Thus we see that arm 0 is initially worse (large negative bias) but gets better over time (positive slope), arm 1 is useless, and arm 2 is initially better (large positive bias) but gets worse over time. The observation noise is the same for all arms, φ2 = 1. See Figure 34.10(a) for a plot of the reward function.

We use a conjugate Gaussian-gamma prior and perform exact Bayesian updating. Thompson sampling quickly discovers that arm 1 is useless. Initially it pulls arm 2 more, but it adapts to the non-stationary nature of the problem and switches over to arm 0, as shown in Figure 34.10(b).

Figure 34.10: Illustration of Thompson sampling applied to a linear-Gaussian contextual bandit. The context has the form st = (1, t, t2). (a) True reward for each arm vs time. (b) Cumulative reward per arm vs time. (c) Cumulative regret vs time. Generated by thompson\_sampling\_linear\_gaussian.ipynb.

34.4.7 Regret

We have discussed several methods for solving the exploration-exploitation tradeo!. It is useful to quantify the degree of suboptimality of these methods. A common approach is to compute the regret, which is defined as the di!erence between the expected reward under the agent’s policy and the oracle policy ϑ→, which knows the true reward function. (Note that the oracle policy will in general be better than the Bayes optimal policy, which we disucssed in Section 34.4.4.)

Specifically, let ϑt be the agent’s policy at time t. Then the per-step regret at t is defined as

\[l\_t \triangleq \mathbb{E}\_{p(s\_t)} \left[ R(s\_t, \pi\_\*(s\_t)) \right] - \mathbb{E}\_{\pi\_t(a\_t|s\_t)p(s\_t)} \left[ R(s\_t, a\_t) \right] \tag{34.70}\]

If we only care about the final performance of the best discovered arm, as in most optimization problems, it is enough to look at the simple regret at the last step, namely lT . Optimizing simple regret results in a problem known as pure exploration [BMS11], since there is no need to exploit the information during the learning process. However, it is more common to focus on the cumulative regret, also called the total regret or just the regret, which is defined as

\[L\_T \triangleq \mathbb{E}\left[\sum\_{t=1}^T l\_t\right] \tag{34.71}\]

Here the expectation is with respect to randomness in determining ϑt, which depends on earlier states, actions and rewards, as well as other potential sources of randomness.

Under the typical assumption that rewards are bounded, LT is at most linear in T. If the agent’s policy converges to the optimal policy as T increases, then the regret is sublinear: LT = o(T). In general, the slower LT grows, the more e”cient the agent is in trading o! exploration and exploitation.

To understand its growth rate, it is helpful to consider again a simple context-free bandit, where R→ = argmaxa R(a) is the optimal reward. The total regret in the first T steps can be written as

\[L\_T = \mathbb{E}\left[\sum\_{t=1}^T R\_\* - R(a\_t)\right] = \sum\_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \mathbb{E}\left[N\_{T+1}(a)\right] (R\_\* - R(a)) = \sum\_{a \in \mathcal{A}} \mathbb{E}\left[N\_{T+1}(a)\right] \Delta\_a \tag{34.72}\]

where NT +1(a) is the total number of times the agent picks action a up to step T, and #a = R→↓R(a) is the reward gap. If the agent under-explores and converges to choosing a suboptimal action (say, aˆ), then a linear regret is su!ered with a per-step regret of #aˆ. On the other hand, if the agent over-explores, then Nt(a) will be too large for suboptimal actions, and the agent also su!ers a linear regret.

Fortunately, it is possible to achieve sublinear regrets, using some of the methods discussed above, such as UCB and Thompson sampling. For example, one can show that Thompson sampling has O( ⇓KT log T) regret [RR14]. This is shown empirically in Figure 34.10(c).

In fact, both UCB and Thompson sampling are optimal, in the sense that their regrets are essentially not improvable; that is, they match regret lower bounds. To establish such a lower bound, note that the agent needs to collect enough data to distinguish di!erent reward distributions, before identifying the optimal action. Typically, the deviation of the reward estimate from the true reward decays at the rate of 1/ ⇓ N, where N is the sample size (see e.g., Equation (3.133)). Therefore, if two reward distributions are similar, distinguishing them becomes harder and requires more samples. (For example, consider the case of a bandit with Gaussian rewards with slightly di!erent means and large variance, as shown in Figure 34.9.)

The following fundamental result is proved by [LR85] for the asymptotic regret (under certain mild assumptions not given here):

\[\liminf\_{T \to \infty} L\_T \ge \log T \sum\_{a:\Delta\_a > 0} \frac{\Delta\_a}{D\_{\text{KL}}(p\_R(a) \parallel p\_R(a\_\*))}\tag{34.73}\]

Thus, we see that the best we can achieve is logarithmic growth in the total regret. Similar lower bounds have also been obtained for various bandits variants.

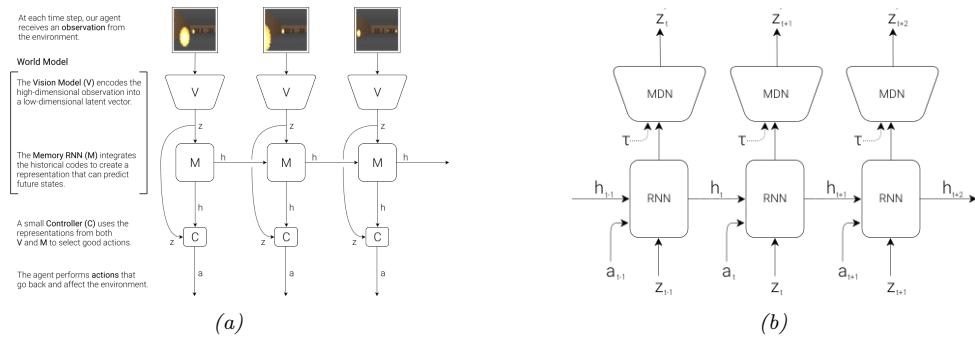

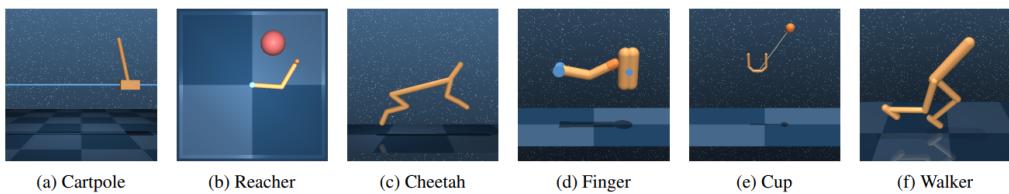

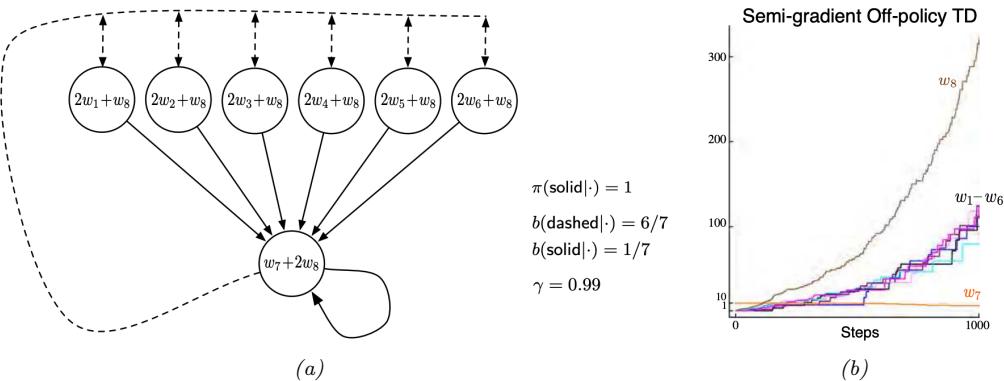

34.5 Markov decision problems

In this section, we generalize the discussion of contextual bandits by allowing the state of nature to change depending on the actions chosen by the agent. The resulting model is called a Markov decision process or MDP, as we explain in detail below. This model forms the foundation of reinforcement learning, which we discuss in Chapter 35.

34.5.1 Basics

A Markov decision process [Put94] can be used to model the interaction of an agent and an environment. It is often described by a tuple ∝S, A, p, pR, p0′, where S is a set of environment states, A a set of actions the agent can take, p a transition model, pR a reward model, and p0 the initial state distribution. The interaction starts at time t = 0, where the initial state s0 ↘ p0. Then, at time t ⇑ 0, the agent observes the environment state st → S, and follows a policy ϑ to take an action at → A. In response, the environment emits a real-valued reward signal rt → R and enters a new state st+1 → S. The policy is in general stochastic, with ϑ(a|s) being the probability of choosing action a in state s. We use ϑ(s) to denote the conditional probability over A if the policy is stochastic, or the action it chooses if it is deterministic. The process at every step is called a transition; at time t, it consists of the tuple (st, at, rt, st+1), where at ↘ ϑ(st), st+1 ↘ p(st, at), and rt ↘ pR(st, at, st+1). Hence, under policy ϑ, the probability of generating a trajectory ϑ of length T

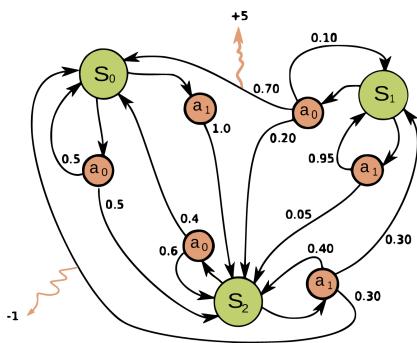

Figure 34.11: Illustration of an MDP as a finite state machine (FSM). The MDP has three discrete states (green cirlces), two discrete actions (orange circles), and two non-zero rewards (orange arrows). The numbers on the black edges represent state transition probabilities, e.g., p(s↑ = s0|a = a0, s↑ = s1)=0.7; most state transitions are impossible (probability 0), so the graph is sparse. The numbers on the yellow wiggly edges represent expected rewards, e.g., R(s = s1, a = a0, s↑ = s0) = +5; state transitions with zero reward are not annotated. From https: // en. wikipedia. org/ wiki/ Markov\_ decision\_ process . Used with kind permission of Wikipedia author waldoalvarez.

can be written explicitly as

\[p(\boldsymbol{\pi}) = p\_0(s\_0) \prod\_{t=0}^{T-1} \pi(a\_t|s\_t) p(s\_{t+1}|s\_t, a\_t) p\_R(r\_t|s\_t, a\_t, s\_{t+1}) \tag{34.74}\]

It is useful to define the reward function from the reward model pR, as the average immediate reward of taking action a in state s, with the next state marginalized:

\[R(s, a) \triangleq \mathbb{E}\_{p(s'|s, a)} \left[ \mathbb{E}\_{p\_R(r|s, a, s')} \left[ r \right] \right] \tag{34.75}\]

Eliminating the dependence on next states does not lead to loss of generality in the following discussions, as our subject of interest is the total (additive) expected reward along the trajectory. For this reason, we often use the tuple ∝S, A, p, R, p0′ to describe an MDP.

In general, the state and action sets of an MDP can be discrete or continuous. When both sets are finite, we can represent these functions as lookup tables; this is known as a tabular representation. In this case, we can represent the MDP as a finite state machine, which is a graph where nodes correspond to states, and edges correspond to actions and the resulting rewards and next states. Figure 34.11 gives a simple example of an MDP with 3 states and 2 actions.

The field of control theory, which is very closely related to RL, uses slightly di!erent terminology. In particular, the environment is called the plant, and the agent is called the controller. States are denoted by xt → X ∞ RD, actions are denoted by ut → U ∞ RK, and rewards are denoted by costs ct → R. Apart from this notational di!erence, the fields of RL and control theory are very similar (see e.g., [Son98; Rec19; Ber19]), although control theory tends to focus on provably optimal methods (by making strong modeling assumptions, such as linearity), whereas RL tends to tackle harder problems with heuristic methods, for which optimality guarantees are often hard to obtain.

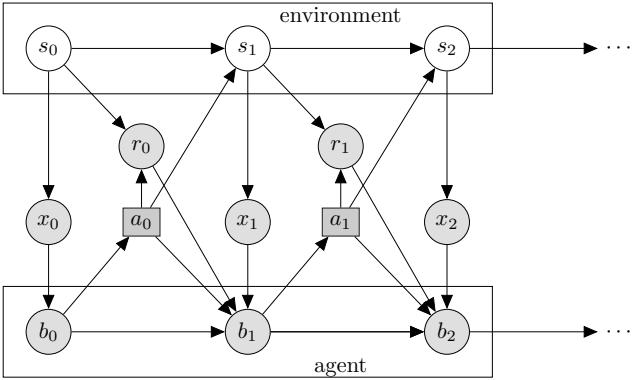

Figure 34.12: Illustration of a partially observable Markov decision process (POMDP) with hidden environment state st which generates the observation xt, controlled by an agent with internal belief state bt which generates the action at. The reward rt depends on st and at. Nodes in this graph represent random variables (circles) and decision variables (squares).

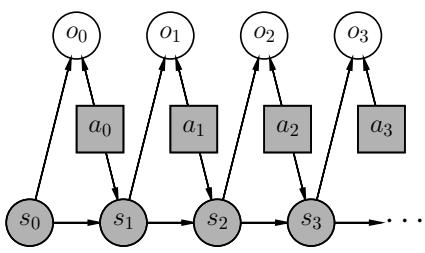

34.5.2 Partially observed MDPs

An important generalization of the MDP framework relaxes the assumption that the agent sees the hidden world state st directly; instead we assume it only sees a potentially noisy observation generated from the hidden state, ot ↘ p(·|st, at). The resulting model is called a partially observable Markov decision process or POMDP (pronounced “pom-dee-pee”). Now the agent’s policy is a mapping from all the available data to actions, at ↘ ϑ(ht), where ht = (a1, o1,…,at↓1, ot) is the past history of observations and actions, plus the current observation. See Figure 34.12 for an illustration. MDPs are a special case where ot = st.

In general, POMDPs are much harder to solve than MDPs (see e.g., [KLC98]). The optimal solution is to compute the belief state bt = p(st|ht), and then to define the corresponding belief state MDP, in which the transition dynamics is a deterministic update given by Bayes rule, and the observation model averages out the hidden state st. However, solving this belief state MDP is computationally intractable. A common approximation is to use the last several observed inputs, say ot↓k:t, in lieu of the full history, and then to treat this as a fully observed MDP. Various other approximations are discussed in [Mur00b].

34.5.3 Episodes and returns

The Markov decision process describes how a trajectory ϑ = (s0, a0, r0, s1, a1, r1,…) is stochastically generated. If the agent can potentially interact with the environment forever, we call it a continuing task. Alternatively, the agent is in an episodic task, if its interaction terminates once the system enters a terminal state or absorbing state; s is absorbing if the next state from s is always s with 0 reward. After entering a terminal state, we may start a new epsiode from a new initial state s0 ↘ p0. The episode length is in general random. For example, the amount of time a robot takes to reach its goal may be quite variable, depending on the decisions it makes, and the randomness in the environment. Note that we can convert an episodic MDP to a continuing MDP by redefining the

transition model in absorbing states to be the initial-state distribution p0. Finally, if the trajectory length T in an episodic task is fixed and known, it is called a finite horizon problem.

Let ϑ be a trajectory of length T, where T may be ↖ if the task is continuing. We define the return for the state at time t to be the sum of expected rewards obtained going forwards, where each reward is multiplied by a discount factor γ → [0, 1]:

\[G\_t \triangleq r\_t + \gamma r\_{t+1} + \gamma^2 r\_{t+2} + \dots + \gamma^{T-t-1} r\_{T-1} \tag{34.76}\]

\[\hat{r} = \sum\_{k=0}^{T-t-1} \gamma^k r\_{t+k} = \sum\_{j=t}^{T-1} \gamma^{j-t} r\_j \tag{34.77}\]

Gt is sometimes called the reward-to-go. For episodic tasks that terminate at time T, we define Gt = 0 for t ⇑ T. Clearly, the return satisfies the following recursive relationship:

\[G\_t = r\_t + \gamma (r\_{t+1} + \gamma r\_{t+2} + \dotsb) = r\_t + \gamma G\_{t+1} \tag{34.78}\]

The discount factor γ plays two roles. First, it ensures the return is finite even if T = ↖ (i.e., infinite horizon), provided we use γ < 1 and the rewards rt are bounded. Second, it puts more weight on short-term rewards, which generally has the e!ect of encouraging the agent to achieve its goals more quickly (see Section 34.5.5.1 for an example). However, if γ is too small, the agent will become too greedy. In the extreme case where γ = 0, the agent is completely myopic, and only tries to maximize its immediate reward. In general, the discount factor reflects the assumption that there is a probability of 1 ↓ γ that the interaction will end at the next step. For finite horizon problems, where T is known, we can set γ = 1, since we know the life time of the agent a priori.5

34.5.4 Value functions

Let ϑ be a given policy. We define the state-value function, or value function for short, as follows (with Eε [·] indicating that actions are selected by ϑ):

\[V\_{\pi}(s) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \mathbb{E}\_{\pi} \left[ G\_0 | s\_0 = s \right] = \mathbb{E}\_{\pi} \left[ \sum\_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t r\_t | s\_0 = s \right] \tag{34.79}\]

This is the expected return obtained if we start in state s and follow ϑ to choose actions in a continuing task (i.e., T = ↖).

Similarly, we define the action-value function, also known as the Q-function, as follows:

\[Q\_{\pi}(s, a) \triangleq \mathbb{E}\_{\pi} \left[ G\_0 | s\_0 = s, a\_0 = a \right] = \mathbb{E}\_{\pi} \left[ \sum\_{t=0}^{\infty} \gamma^t r\_t | s\_0 = s, a\_0 = a \right] \tag{34.80}\]

This quantity represents the expected return obtained if we start by taking action a in state s, and then follow ϑ to choose actions thereafter.

Finally, we define the advantage function as follows:

\[A\_{\pi}(s, a) \triangleq Q\_{\pi}(s, a) - V\_{\pi}(s) \tag{34.81}\]

5. We may also use ϑ = 1 for continuing tasks, targeting the (undiscounted) average reward criterion [Put94].

This tells us the benefit of picking action a in state s then switching to policy ϑ, relative to the baseline return of always following ϑ. Note that Aε(s, a) can be both positive and negative, and Eε(a|s) [Aε(s, a)] = 0 due to a useful equality: Vε(s) = Eε(a|s) [Qε(s, a)].

34.5.5 Optimal value functions and policies

Suppose ϑ→ is a policy such that Vε↑ ⇑ Vε for all s → S and all policy ϑ, then it is an optimal policy. There can be multiple optimal policies for the same MDP, but by definition their value functions must be the same, and are denoted by V→ and Q→, respectively. We call V→ the optimal state-value function, and Q→ the optimal action-value function. Furthermore, any finite MDP must have at least one deterministic optimal policy [Put94].

A fundamental result about the optimal value function is Bellman’s optimality equations:

\[V\_\*(s) = \max\_a R(s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}\_{p(s'|s, a)} \left[ V\_\*(s') \right] \tag{34.82}\]

\[Q\_\*(s, a) = R(s, a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}\_{p(s'|s, a)} \left[ \max\_{a'} Q\_\*(s', a') \right] \tag{34.83}\]

Conversely, the optimal value functions are the only solutions that satisfy the equations. In other words, although the value function is defined as the expectation of a sum of infinitely many rewards, it can be characterized by a recursive equation that involves only one-step transition and reward models of the MDP. Such a recursion play a central role in many RL algorithms we will see later in this chapter. Given a value function (V or Q), the discrepancy between the right- and left-hand sides of Equations (34.82) and (34.83) are called Bellman error or Bellman residual.

Furthermore, given the optimal value function, we can derive an optimal policy using

\[\pi\_\*(s) = \operatorname\*{argmax}\_a Q\_\*(s, a) \tag{34.84}\]

\[=\operatorname\*{argmax}\_{a}\left[R(s,a) + \gamma \mathbb{E}\_{p(s'|s,a)}\left[V\_{\*}(s')\right]\right] \tag{34.85}\]

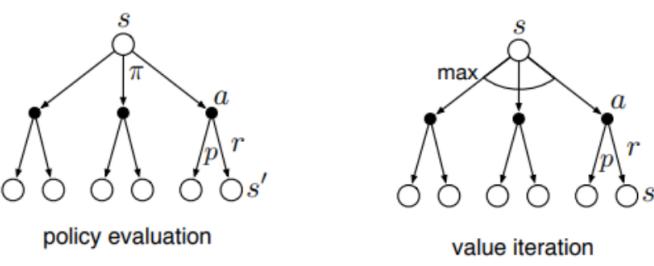

Following such an optimal policy ensures the agent achieves maximum expected return starting from any state. The problem of solving for V→, Q→ or ϑ→ is called policy optimization. In contrast, solving for Vε or Qε for a given policy ϑ is called policy evaluation, which constitutes an important subclass of RL problems as will be discussed in later sections. For policy evaluation, we have similar Bellman equations, which simply replace maxa{·} in Equations (34.82) and (34.83) with Eε(a|s) [·].

In Equations (34.84) and (34.85), as in the Bellman optimality equations, we must take a maximum over all actions in A, and the maximizing action is called the greedy action with respect to the value functions, Q→ or V→. Finding greedy actions is computationally easy if A is a small finite set. For high dimensional continuous spaces, we can treat a as a sequence of actions, and optimize one dimension at a time [Met+17], or use gradient-free optimizers such as cross-entropy method (Section 6.7.5), as used in the QT-Opt method [Kal+18a]. Recently, CAQL (continuous action Q-learning, [Ryu+20]) proposed to use mixed integer programming to solve the argmax problem, leveraging the ReLU structure of the Q-network. We can also amortize the cost of this optimization by training a policy a→ = ϑ→(s) after learning the optimal Q-function.

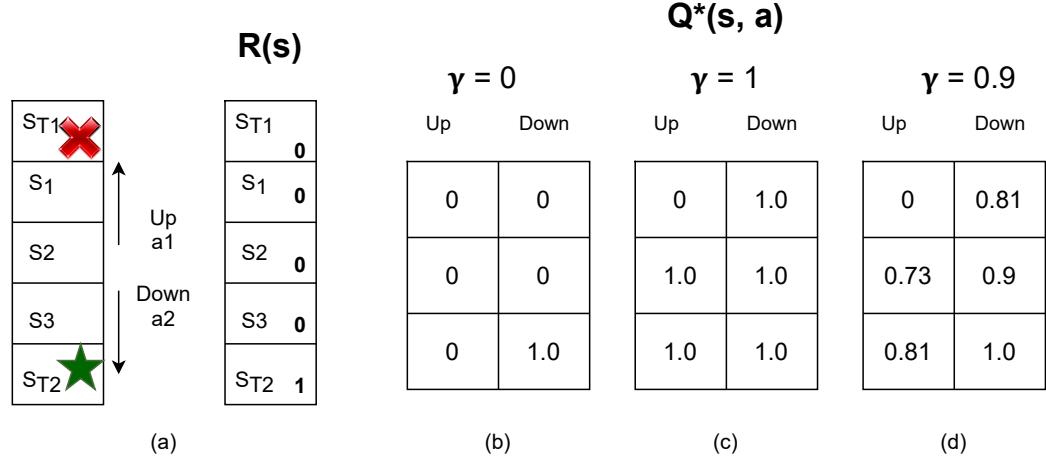

Figure 34.13: Left: illustration of a simple MDP corresponding to a 1d grid world of 3 non-absorbing states and 2 actions. Right: optimal Q-functions for di!erent values of ω. Adapted from Figures 3.1, 3.2, 3.4 of [GK19].

34.5.5.1 Example

In this section, we show a simple example, to make concepts like value functions more concrete. Consider the 1d grid world shown in Figure 34.13(a). There are 5 possible states, among them ST1 and ST2 are absorbing states, since the interaction ends once the agent enters them. There are 2 actions, ∈ and ∋. The reward function is zero everywhere except at the goal state, ST2, which gives a reward of 1 upon entering. Thus the optimal action in every state is to move down.

Figure 34.13(b) shows the Q→ function for γ = 0. Note that we only show the function for non-absorbing states, as the optimal Q-values are 0 in absorbing states by definition. We see that Q→(s3, ∋)=1.0, since the agent will get a reward of 1.0 on the next step if it moves down from s3; however, Q→(s, a)=0 for all other state-action pairs, since they do not provide nonzero immediate reward. This optimal Q-function reflects the fact that using γ = 0 is completely myopic, and ignores the future.

Figure 34.13(c) shows Q→ when γ = 1. In this case, we care about all future rewards equally. Thus Q→(s, a)=1 for all state-action pairs, since the agent can always reach the goal eventually. This is infinitely far-sighted. However, it does not give the agent any short-term guidance on how to behave. For example, in s2, it is not clear if it is should go up or down, since both actions will eventually reach the goal with identical Q→-values.

Figure 34.13(d) shows Q→ when γ = 0.9. This reflects a preference for near-term rewards, while also taking future reward into account. This encourages the agent to seek the shortest path to the goal, which is usually what we desire. A proper choice of γ is up to the agent designer, just like the design of the reward function, and has to reflect the desired behavior of the agent.

34.6 Planning in an MDP

In this section, we discuss how to compute an optimal policy when the MDP model is known. This problem is called planning, in contrast to the learning problem where the models are unknown, which is tackled using reinforcement learning (see Chapter 35). The planning algorithms we discuss are based on dynamic programming (DP) and linear programming (LP).

For simplicity, in this section, we assume discrete state and action sets with γ < 1. However, exact calculation of optimal policies often depends polynomially on the sizes of S and A, and is intractable, for example, when the state space is a Cartesian product of several finite sets. This challenge is known as the curse of dimensionality. Therefore, approximations are typically needed, such as using parametric or nonparametric representations of the value function or policy, both for computational tractability and for extending the methods to handle MDPs with general state and action sets. In this case, we have approximate dynamic programming (ADP) and approximate linear programming (ALP) algorithms (see e.g., [Ber19]).

34.6.1 Value iteration

A popular and e!ective DP method for solving an MDP is value iteration (VI). Starting from an initial value function estimate V0, the algorithm iteratively updates the estimate by

\[V\_{k+1}(s) = \max\_{a} \left[ R(s, a) + \gamma \sum\_{s'} p(s'|s, a) V\_k(s') \right] \tag{34.86}\]

Note that the update rule, sometimes called a Bellman backup, is exactly the right-hand side of the Bellman optimality equation Equation (34.82), with the unknown V→ replaced by the current estimate Vk. A fundamental property of Equation (34.86) is that the update is a contraction: it can be verified that

\[\max\_{s} \left| V\_{k+1}(s) - V\_{\*}(s) \right| \le \gamma \max\_{s} \left| V\_{k}(s) - V\_{\*}(s) \right| \tag{34.87}\]

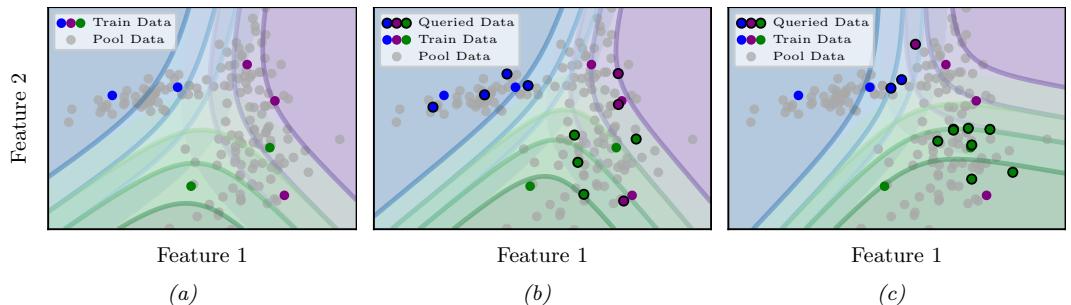

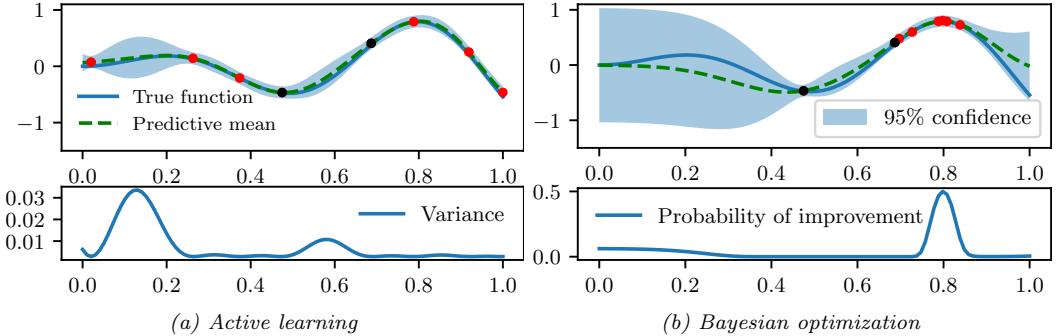

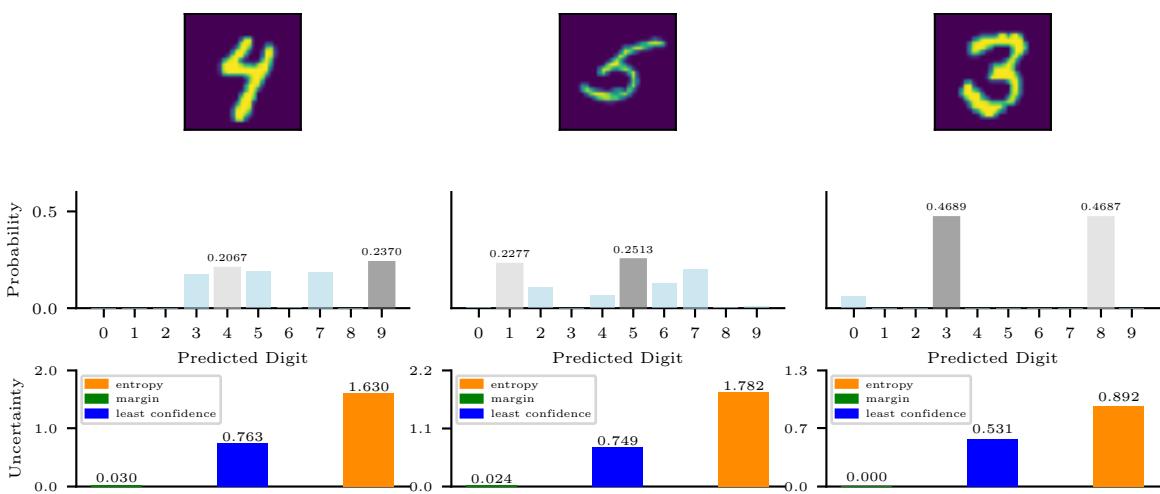

In other words, every iteration will reduce the maximum value function error by a constant factor. It follows immediately that Vk will converge to V→, after which an optimal policy can be extracted using Equation (34.85). In practice, we can often terminate VI when Vk is close enough to V→, since the resulting greedy policy wrt Vk will be near optimal. Value iteration can be adapted to learn the optimal action-value function Q→.