Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics

Part IV

Generation

20 Generative models: an overview

20.1 Introduction

A generative model is a joint probability distribution p(x), for x → X . In some cases, the model may be conditioned on inputs or covariates c → C, which gives rise to a conditional generative model of the form p(x|c).

There are many kinds of generative models. We give a brief summary in Section 20.2, and go into more detail in subsequent chapters. See also [Tom22] for a recent book on this topic that goes into more depth.

20.2 Types of generative model

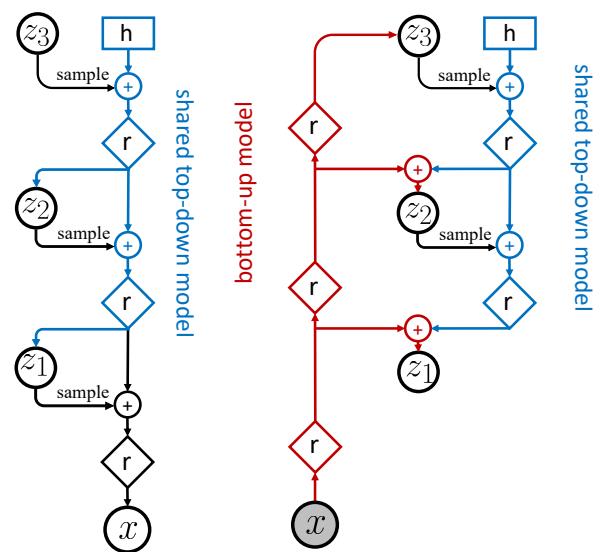

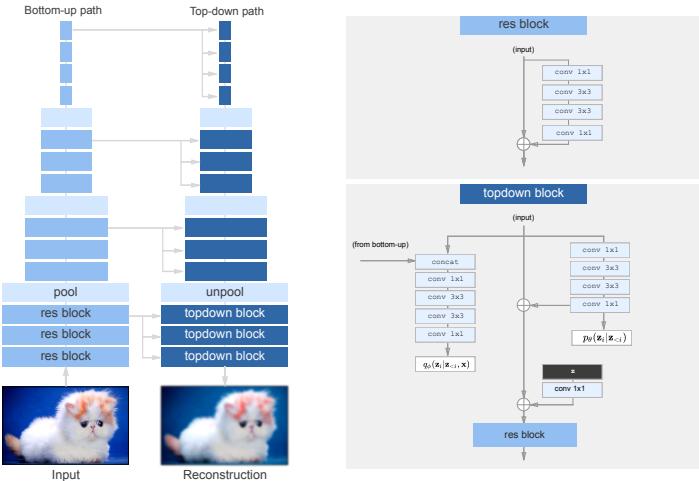

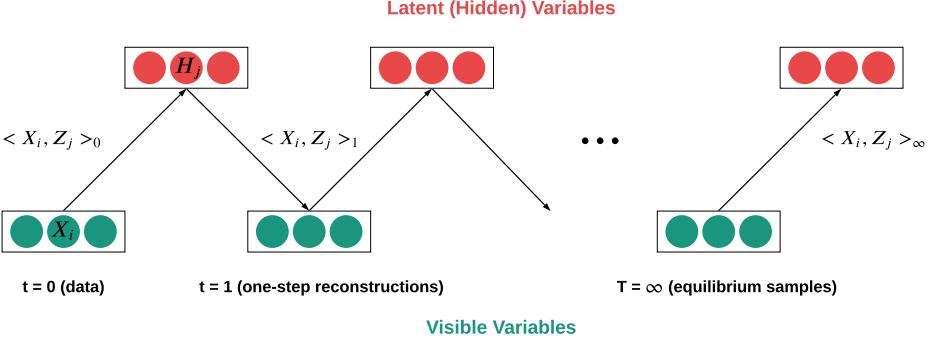

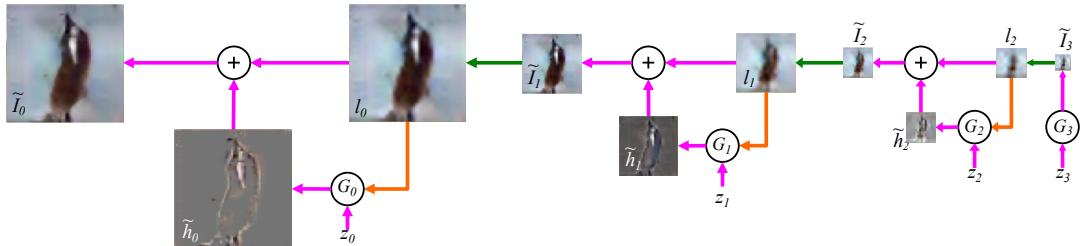

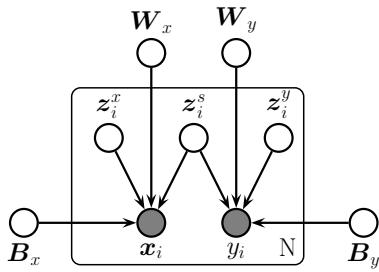

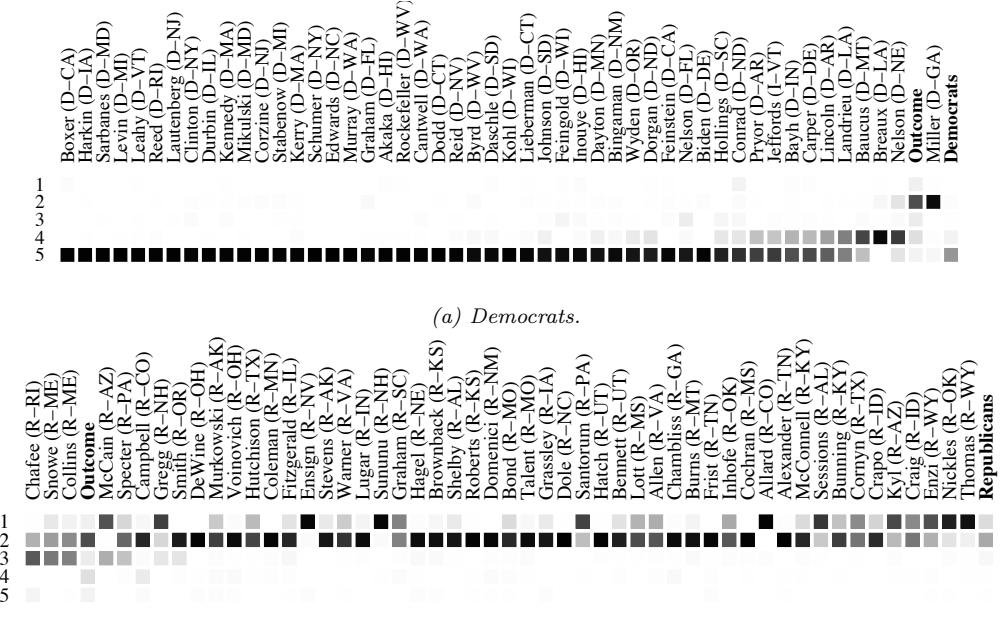

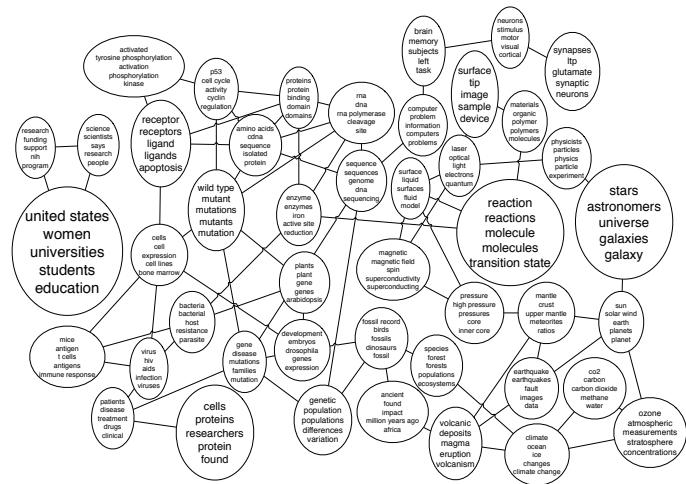

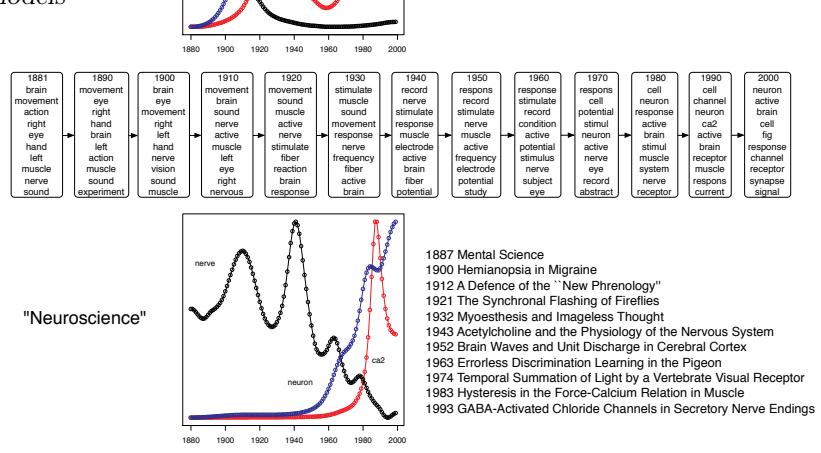

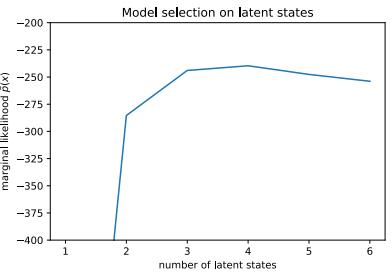

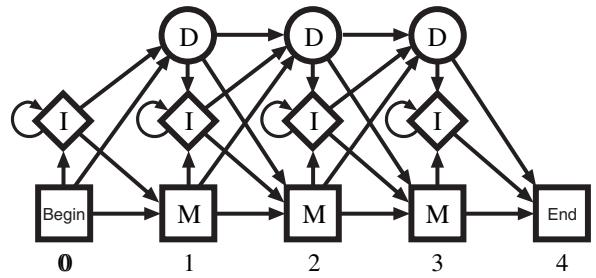

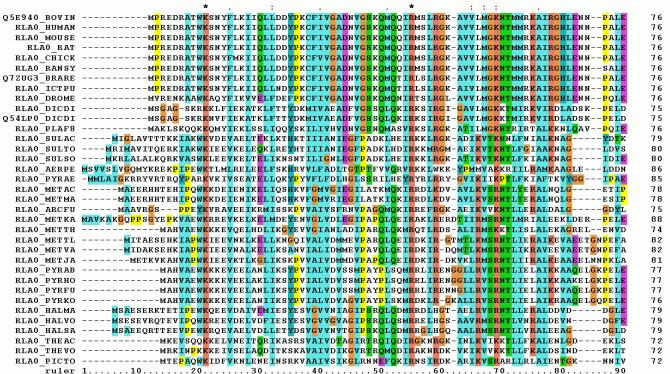

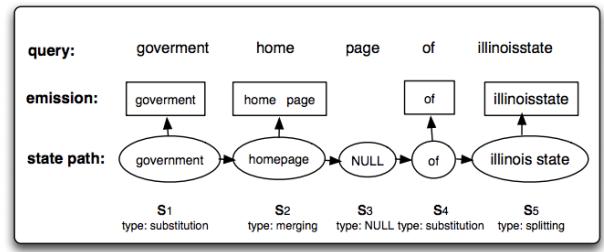

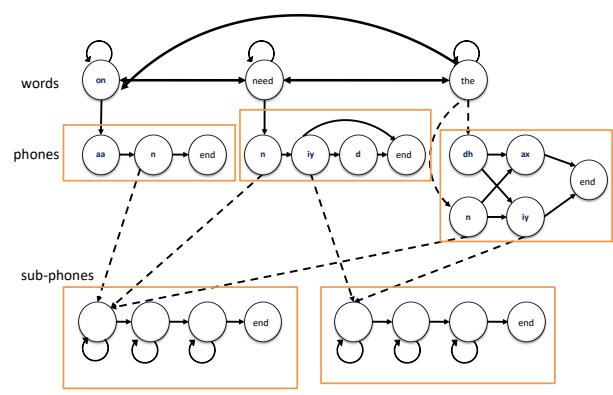

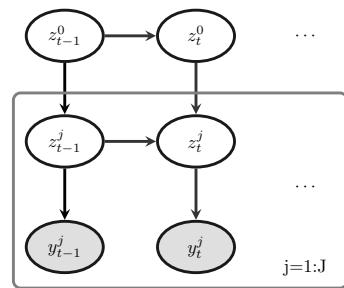

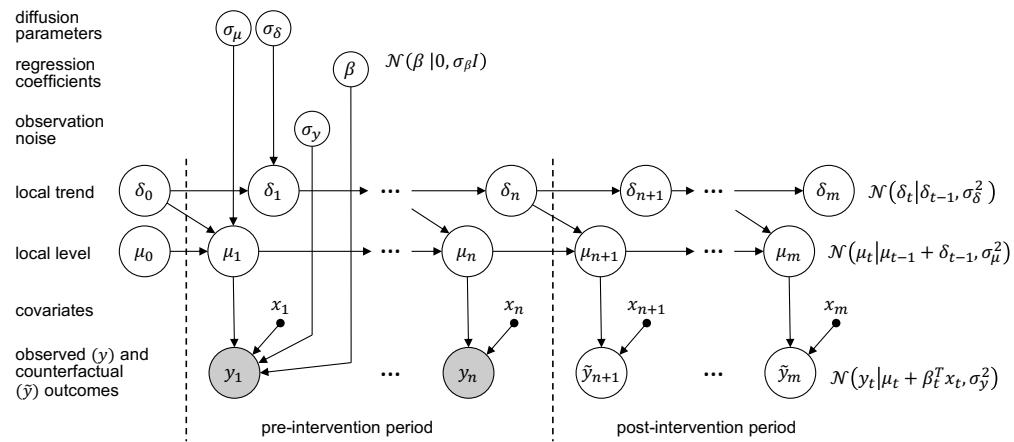

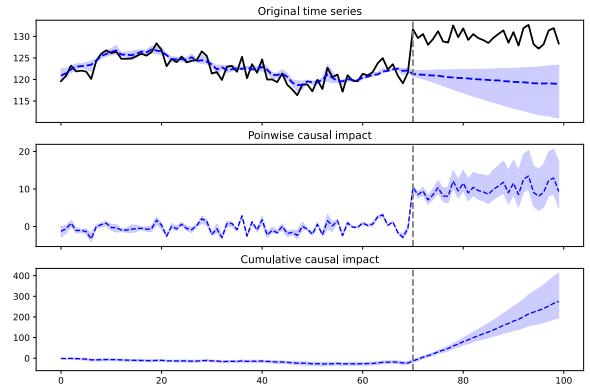

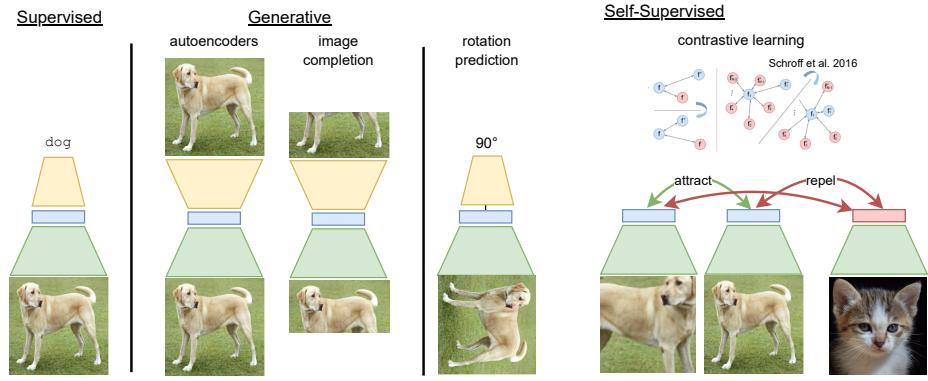

There are many kinds of generative model, some of which we list in Table 20.1. At a high level, we can distinguish between deep generative models (DGM) — which use deep neural networks to learn a complex mapping from a single latent vector z to the observed data x — and more “classical” probabilistic graphical models (PGM), that map a set of interconnected latent variables z1,…, zL to the observed variables x1,…, xD using simpler, often linear, mappings. Of course, many hybrids are possible. For example, PGMs can use neural networks, and DGMs can use structured state spaces. We discuss PGMs in general terms in Chapter 4, and give examples in Chapter 28, Chapter 29, Chapter 30. In this part of the book, we mostly focus on DGMs.

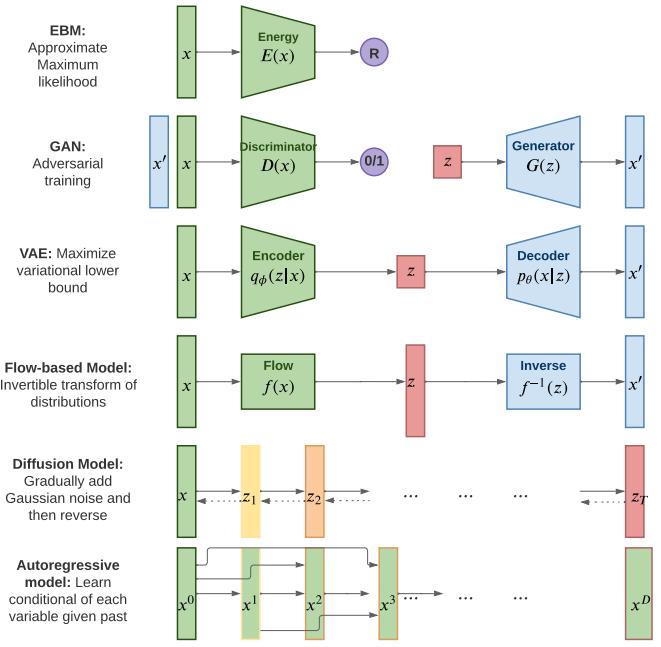

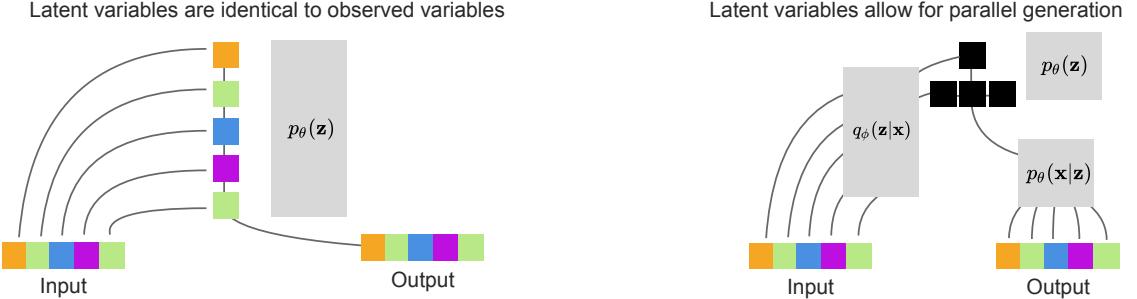

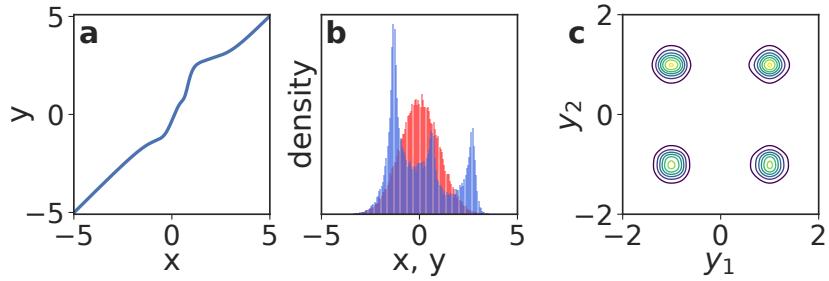

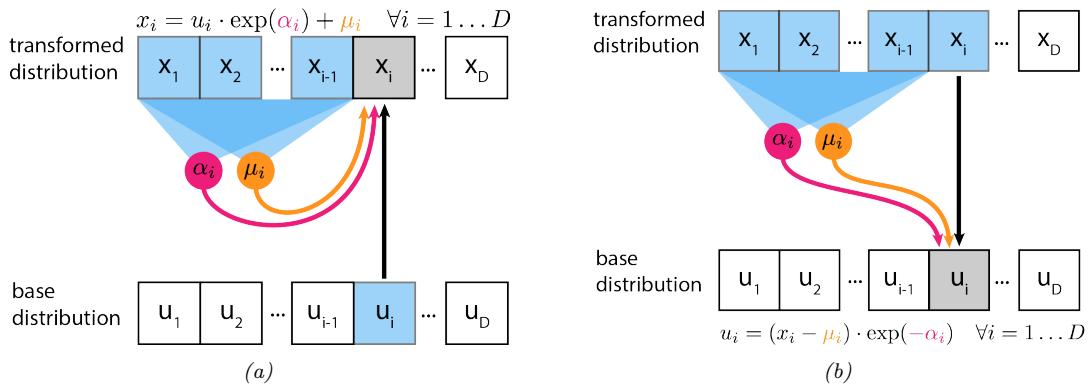

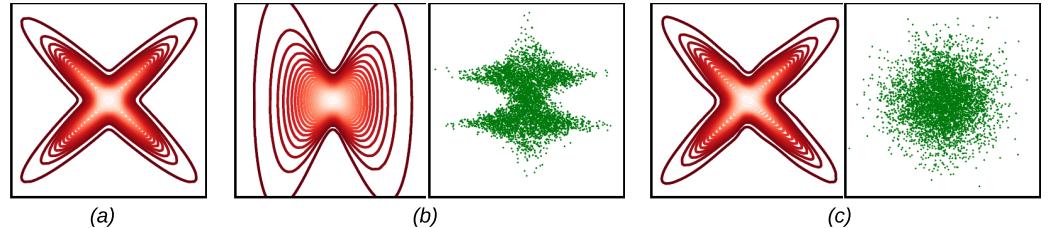

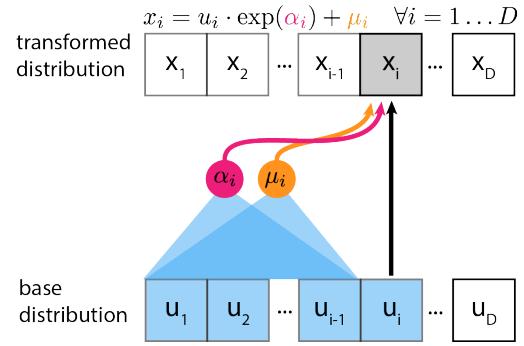

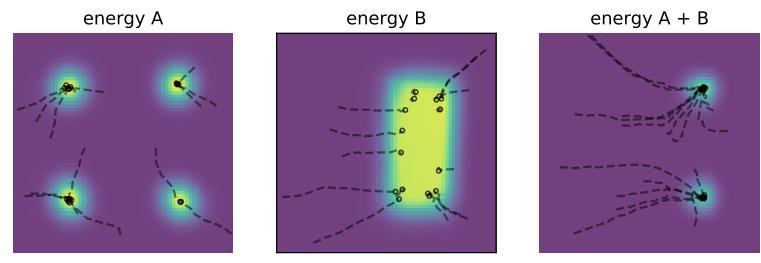

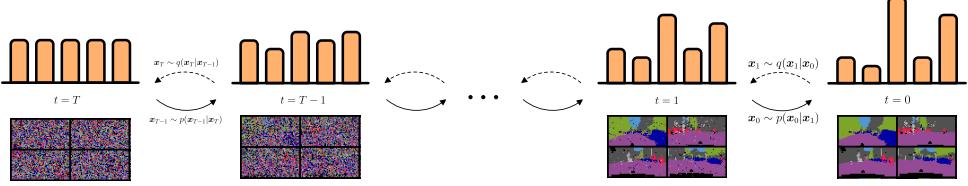

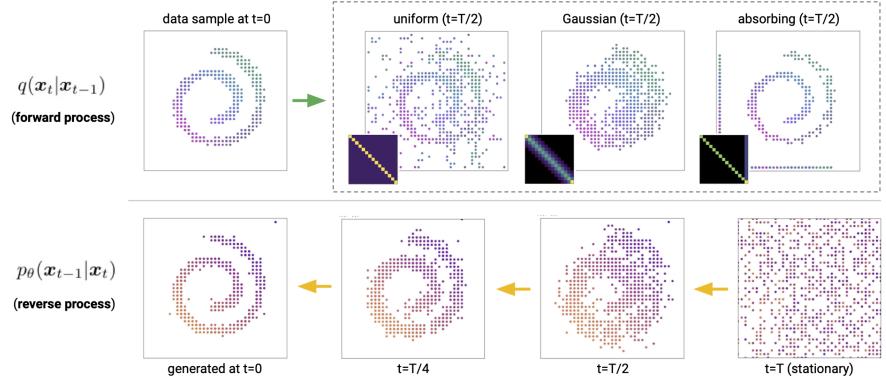

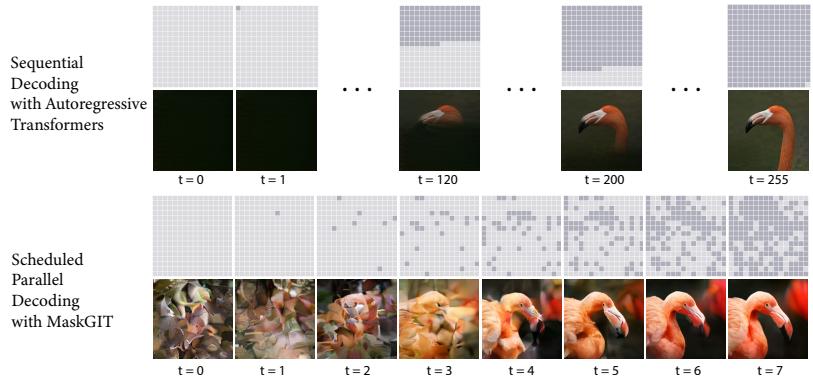

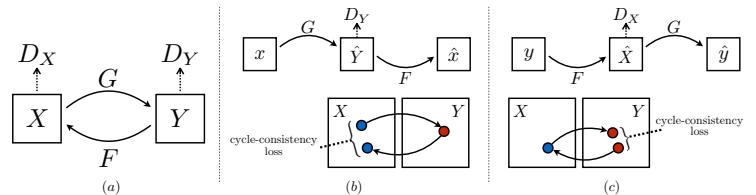

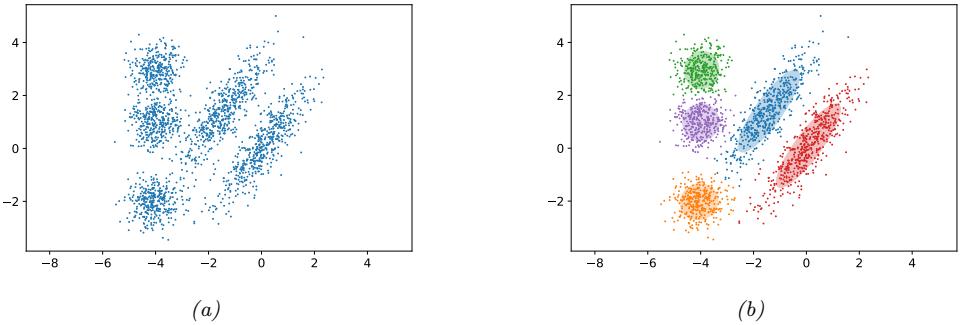

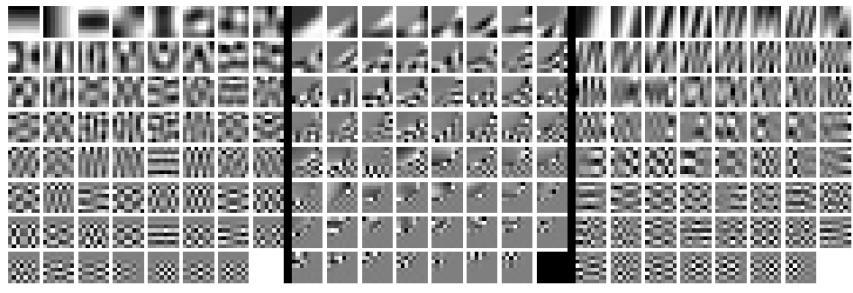

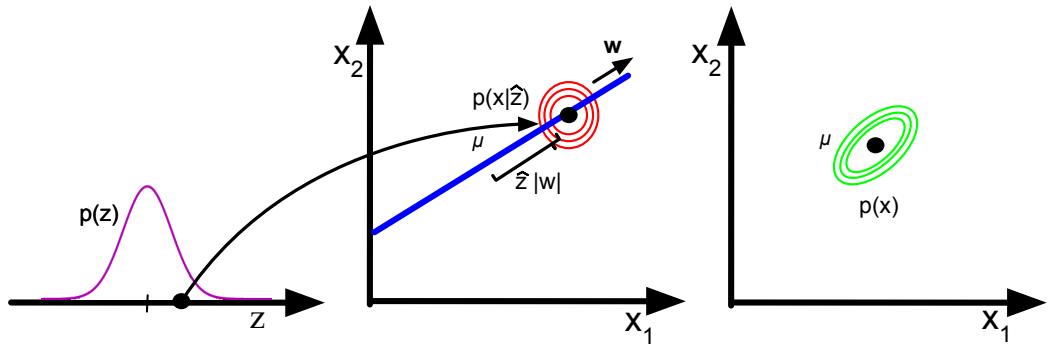

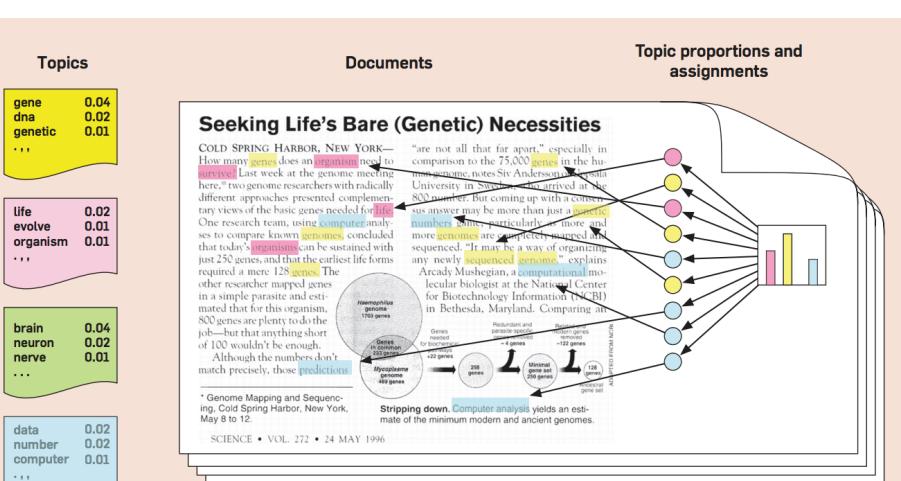

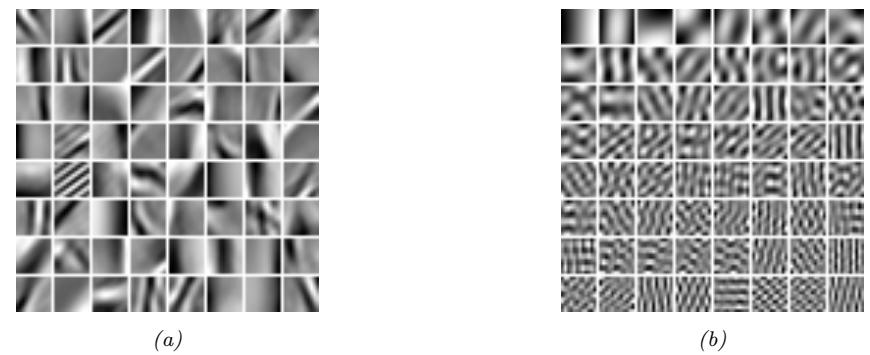

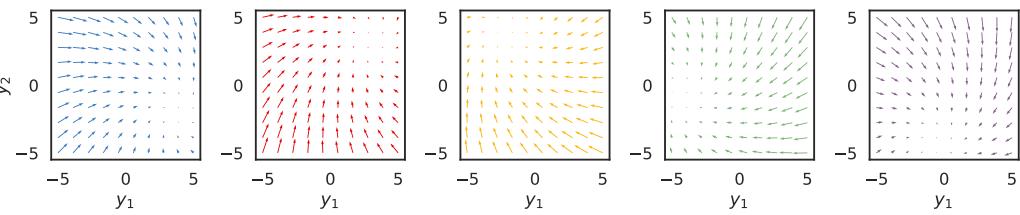

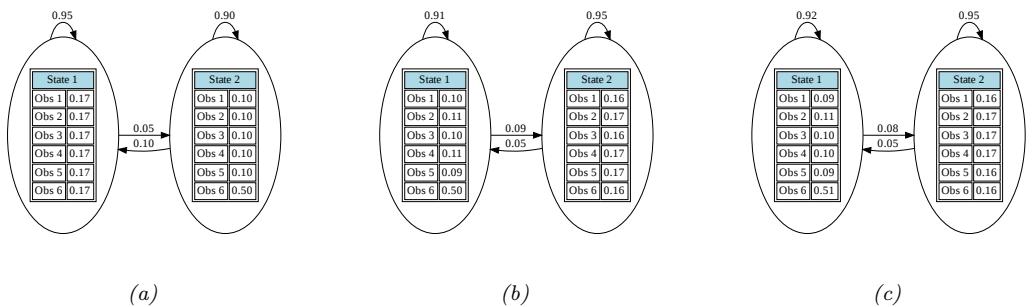

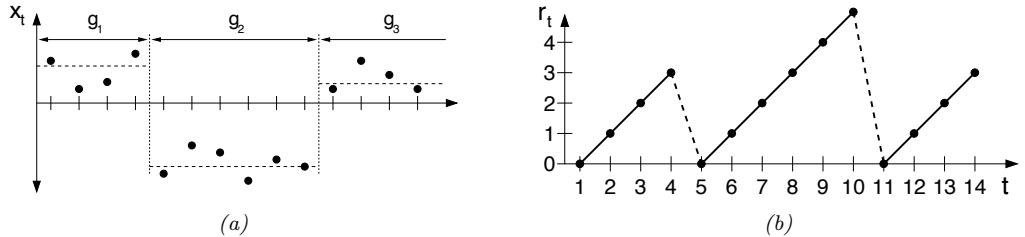

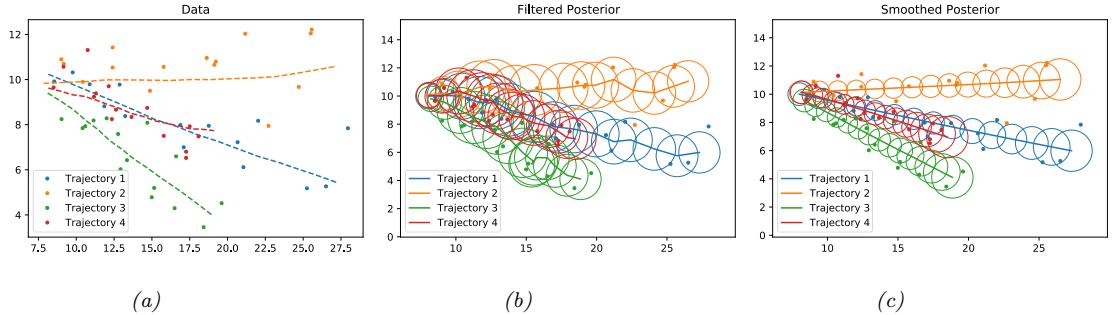

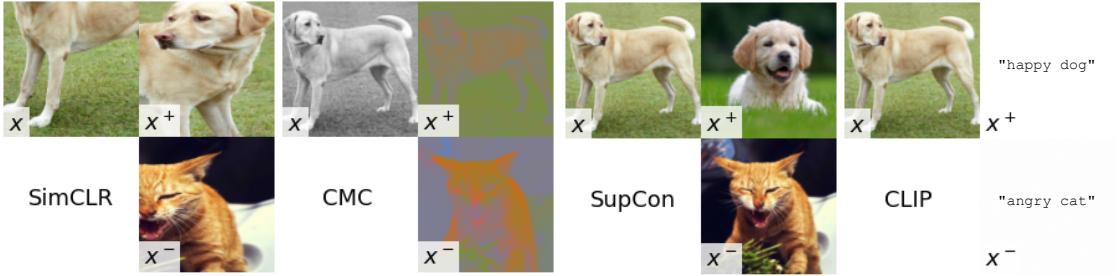

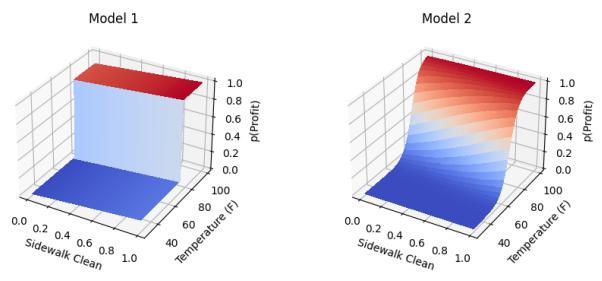

The main kinds of DGM are: variational autoencoders (VAE), autoregressive models (ARM), normalizing flows, di!usion models, energy based models (EBM), and generative adversarial networks (GAN). We can categorize these models in terms of the following criteria (see Figure 20.1 for a visual summary):

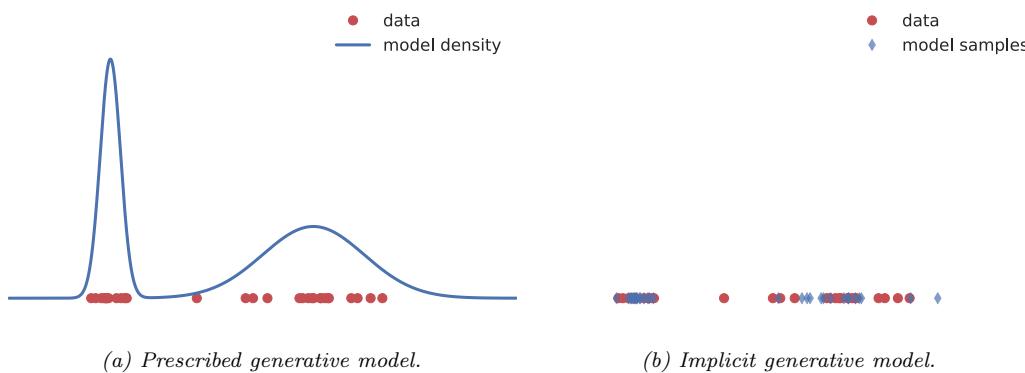

- Density: does the model support pointwise evaluation of the probability density function p(x), and if so, is this fast or slow, exact, approximate or a bound, etc? For implicit models, such as GANs, there is no well-defined density p(x). For other models, we can only compute a lower bound on the density (VAEs), or an approximation to the density (EBMs, UPGMs).

- Sampling: does the model support generating new samples, x ↑ p(x), and if so, is this fast or slow, exact or approximate? Directed PGMs, VAEs, and GANs all support fast sampling. However, undirected PGMs, EBMs, ARM, di!usion, and flows are slow for sampling.

- Training: what kind of method is used for parameter estimation? For some models (such as AR, flows and directed PGMs), we can perform exact maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), although

| Model | Chapter | Density | Sampling | Training | Latents | Architecture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGM-D | Section 4.2 | Exact, fast | Fast | MLE | Optional | Sparse DAG |

| PGM-U | Section 4.3 | Approx, slow | Slow | MLE-A | Optional | Sparse graph |

| VAE | Chapter 21 | LB, fast | Fast | MLE-LB | RL | Encoder-Decoder |

| ARM | Chapter 22 | Exact, fast | Slow | MLE | None | Sequential |

| Flows | Chapter 23 | Exact, slow/fast | Slow | MLE | RD | Invertible |

| EBM | Chapter 24 | Approx, slow | Slow | MLE-A | Optional | Discriminative |

| Di!usion | Chapter 25 | LB | Slow | MLE-LB | RD | Encoder-Decoder |

| GAN | Chapter 26 | NA | Fast | Min-max | RL | Generator-Discriminator |

Table 20.1: Characteristics of common kinds of generative model. Here D is the dimensionality of the observed x, and L is the dimensionality of the latent z, if present. (We usually assume L → D, although overcomplete representations can have L ↑ D.) Abbreviations: Approx = approximate, ARM = autoregressive model, EBM = energy based model, GAN = generative adversarial network, MLE = maximum likelihood estimation, MLE-A = MLE (approximate), MLE-LB = MLE (lower bound), NA = not available, PGM = probabilistic graphical model, PGM-D = directed PGM, PGM-U = undirected PGM, VAE = variational autoencoder.

Figure 20.1: Summary of various kinds of deep generative models. Here x is the observed data, z is the latent code, and x→ is a sample from the model. AR models do not have a latent code z. For di!usion models and flow models, the size of z is the same as x. For AR models, xd is the d’th dimension of x. R represents real-valued output, 0/1 represents binary output. Adapted from Figure 1 of [Wen21].

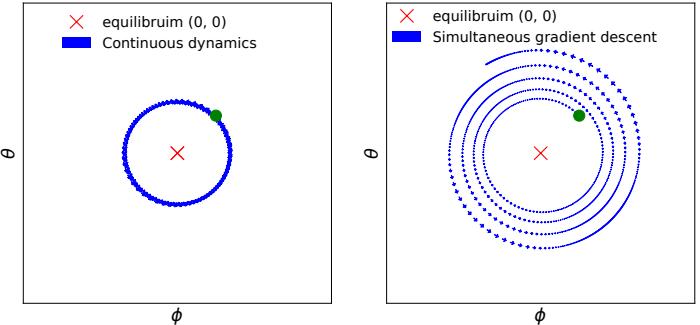

the objective is usually non-convex, so we can only reach a local optimum. For other models, we cannot tractably compute the likelihood. In the case of VAEs, we maximize a lower bound on the likelihood; in the case of EBMs and UGMs, we maximize an approximation to the likelihood. For GANs we have to use min-max training, which can be unstable, and there is no clear objective function to monitor.

- Latents: does the model use a latent vector z to generate x or not, and if so, is it the same size as x or is it a potentially compressed representation? For example, ARMs do not use latents; flows and di!usion use latents, but they are not compressed.1 Graphical models, including EBMs, may or may not use latents.

- Architecture: what kind of neural network should we use, and are there restrictions? For flows, we are restricted to using invertible neural networks where each layer has a tractable Jacobian. For EBMs, we can use any model we like. The other models have di!erent restrictions.

20.3 Goals of generative modeling

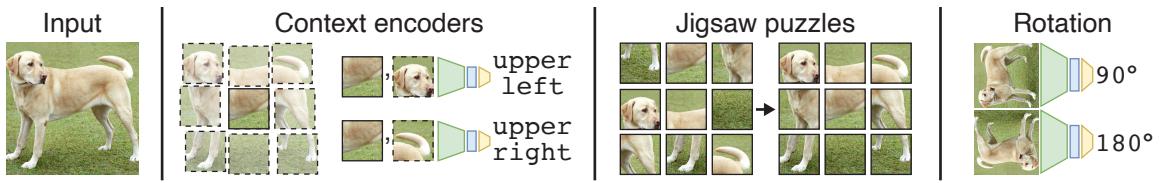

There are several di!erent kinds of tasks that we can use generative models for, as we discuss below.

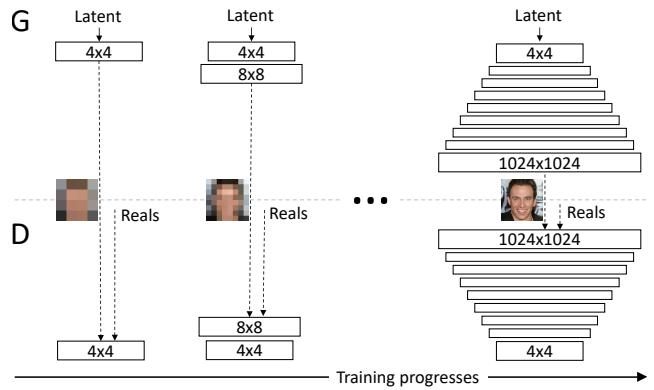

20.3.1 Generating data

One of the main goals of generative models is to generate (create) new data samples. This is sometimes called generative AI (see e.g., [GBGM23] for a recent survey). For example, if we fit a model p(x) to images of faces, we can sample new faces from it, as illustrated in Figure 25.10. 2 Similar methods can be used to create samples of text, audio, etc. When this technology is abused to make fake content, they are called deep fakes (see e.g., [Ngu+19]). Generative models can also be used to create synthetic data for training discriminative models (see e.g., [Wil+20; Jor+22]).

To control what is generated, it is useful to use a conditional generative model of the form p(x|c). Here are some examples:

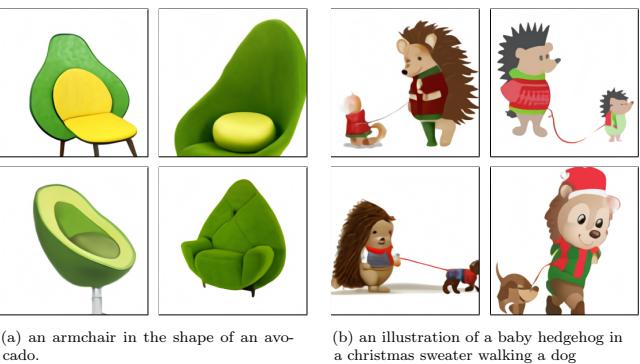

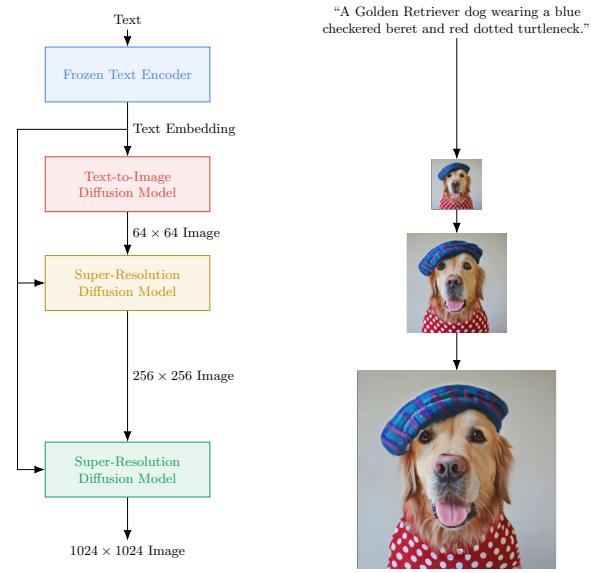

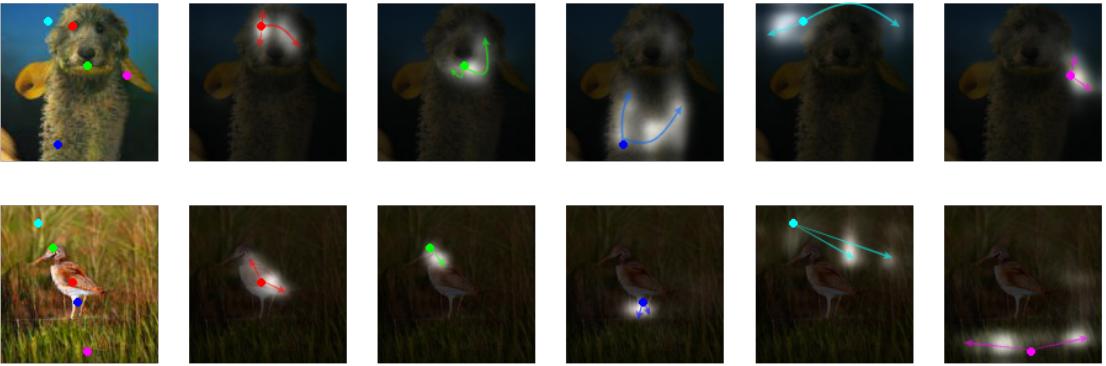

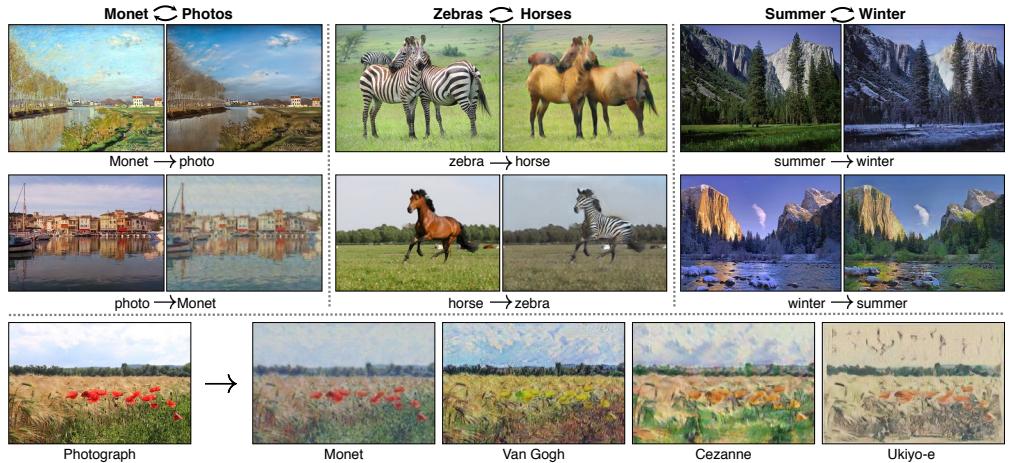

- c = text prompt, x = image. This is a text-to-image model (see Figure 20.2, Figure 20.3 and Figure 22.6 for examples).

- c = image, x = text. This is an image-to-text model, which is useful for image captioning.

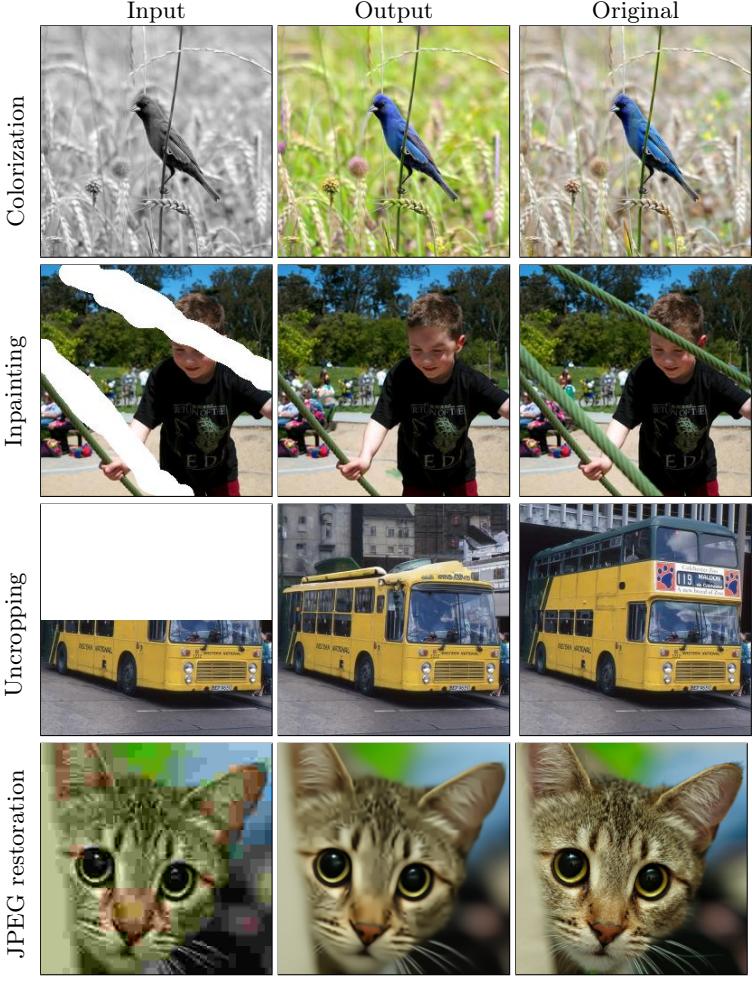

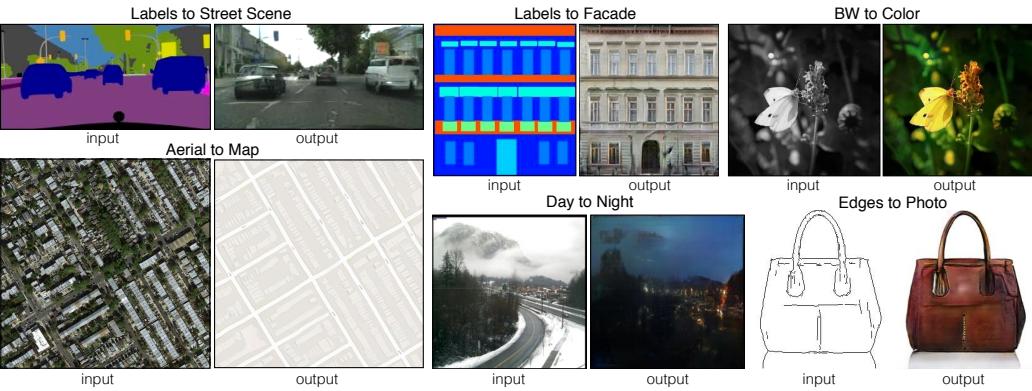

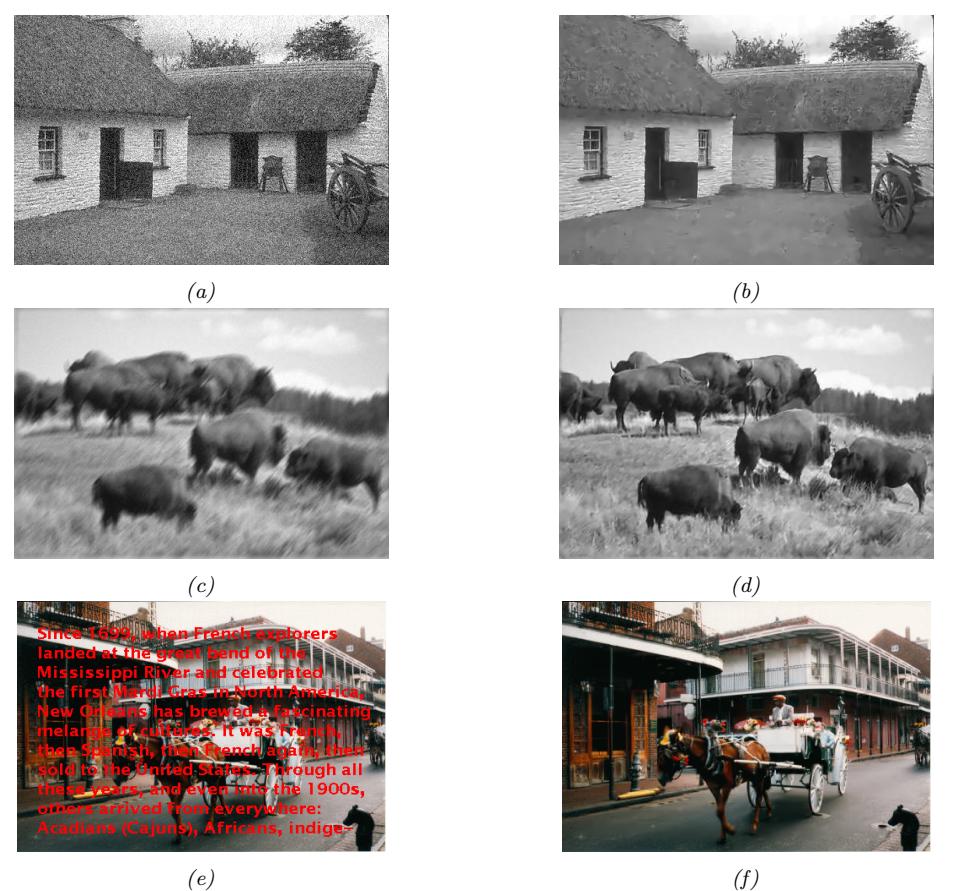

- c = image, x = image. This is an image-to-image model, and can be used for image colorization, inpainting, uncropping, JPEG artefact restoration, etc. See Figure 20.4 for examples.

- c = sequence of sounds, x = sequence of words. This is a speech-to-text model, which is useful for automatic speech recognition (ASR).

- c = sequence of English words, x = sequence of French words. This is a sequence-to-sequence model, which is useful for machine translation.

1. Flow models define a latent vector z that has the same size as x, although the internal deterministic computation may use vectors that are larger or smaller than the input (see e.g., the DenseFlow paper [GGS21]).

2. These images were made with a technique called score-based generative modeling (Section 25.3), although similar results can be obtained using many other techniques. See for example https://this-person-does-not-exist.com/en which shows results from a GAN model (Chapter 26).

(a) Teddy bears swimming at the Olympics 400m Butterfly event.

(b) A cute corgi lives in a house made out of sushi.

(c) A cute sloth holding a small treasure chest. A bright golden glow is coming from the chest.

Figure 20.2: Some 1024 ↓ 1024 images generated from text prompts by the Imagen di!usion model (Section 25.6.4). From Figure 1 of [Sah+22b]. Used with kind permission of William Chan.

Figure 20.3: Some images generated from the Parti transformer model (Section 22.4.2) in response to a text prompt. We show results from models of increasing size (350M, 750M, 3B, 20B). Multiple samples are generated, and the highest ranked one is shown. From Figure 10 of [Yu+22]. Used with kind permission of Jiahui Yu.

• c = initial prompt, x = continuation of the text. This is another sequence-to-sequence model, which is useful for automatic text generation (see Figure 22.5 for an example).

Note that, in the conditional case, we sometimes denote the inputs by x and the outputs by y. In this case the model has the familiar form p(y|x). In the special case that y denotes a low dimensional quantity, such as a integer class label, y → {1,…,C}, we get a predictive (discriminative) model. The main di!erence between a discriminative model and a conditional generative model is this: in a discriminative model, we assume there is one correct output, whereas in a conditional generative model, we assume there may be multiple correct outputs. This makes it harder to evaluate generative models, as we discuss in Section 20.4.

Figure 20.4: Illustration of some image-to-image tasks using the Palette conditional di!usion model (Section 25.6.4). From Figure 1 of [Sah+22a]. Used with kind permission of Chitwan Saharia.

20.3.2 Density estimation

The task of density estimation refers to evaluating the probability of an observed data vector, i.e., computing p(x). This can be useful for outlier detection (Section 19.3.2), data compression (Section 5.4), generative classifiers, model comparison, etc.

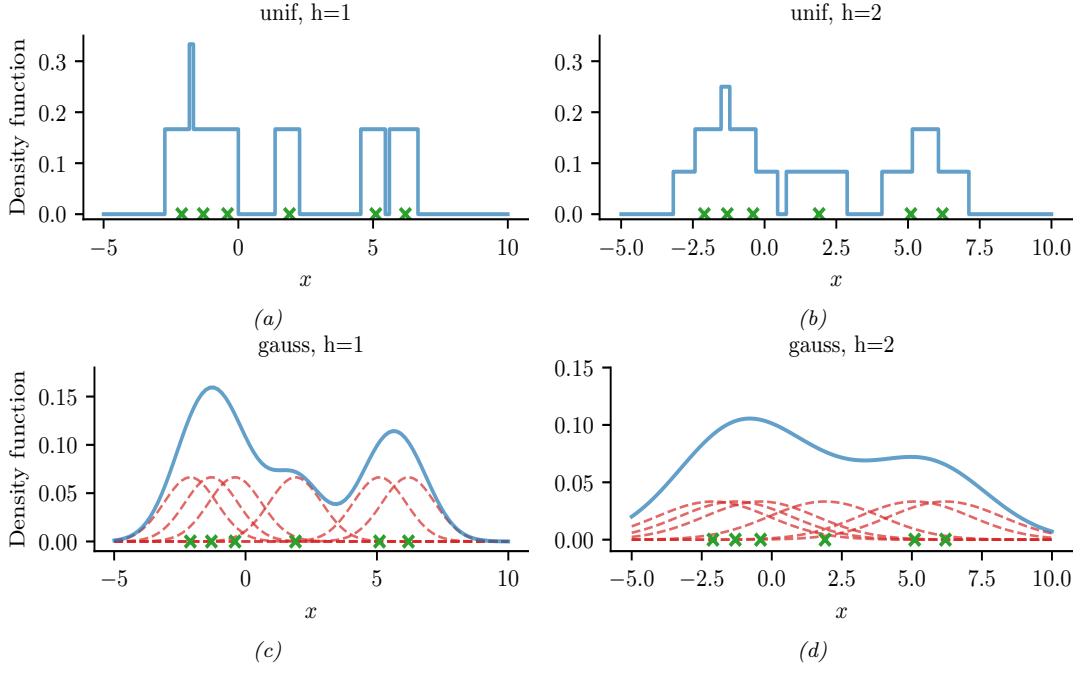

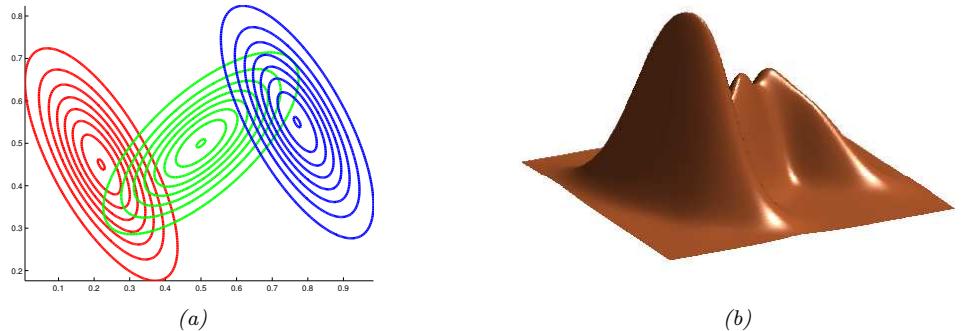

A simple approach to this problem, which works in low dimensions, is to use kernel density

Figure 20.5: A nonparametric (Parzen) density estimator in 1d estimated from 6 datapoints, denoted by x. Top row: uniform kernel. Bottom row: Gaussian kernel. Left column: bandwidth parameter h = 1. Right column: bandwidth parameter h = 2. Adapted from http: // en. wikipedia. org/ wiki/ Kernel\_ density\_ estimation . Generated by parzen\_window\_demo.ipynb.

estimation or KDE, which has the form

\[p(\mathbf{z}|\mathcal{D}) = \frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \mathcal{K}\_h \left(\mathbf{z} - \mathbf{z}\_n\right) \tag{20.1}\]

Here D = {x1,…, xN } is the data, and Kh is a density kernel with bandwidth h, which is a function K : R ↔︎ R+ such that ” K(x)dx = 1 and ” xK(x)dx = 0. We give a 1d example of this in Figure 20.5: in the top row, we use a uniform (boxcar) kernel, and in the bottom row, we use a Gaussian kernel.

In higher dimensions, KDE su!ers from the curse of dimensionality (see e.g., [AHK01]), and we need to use parametric density models pω(x) of some kind.

20.3.3 Imputation

The task of imputation refers to “filling in” missing values of a data vector or data matrix. For example, suppose X is an N ↗ D matrix of data (think of a spreadsheet) in which some entries, call them Xm, may be missing, while the rest, Xo, are observed. A simple way to fill in the missing data is to use the mean value of each feature, E [xd]; this is called mean value imputation, and is

| Input | Output | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | A | B | C | |

| 6 | 6 | NA | 6 | 6 | 7.5 | |

| NA | 6 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 0 | |

| NA | 6 | NA | 9 | 6 | 7.5 | |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |

| 9 | 8 | 7.5 | 9 | 8 | 7.5 |

Figure 20.6: Missing data imputation. Left: input data: NA means “not available” (missing), and the bottom row (in red) shows the mean of each column. Right: output data, where NA values are replaced by the mean.

illustrated in Figure 20.6. However, this ignores dependencies between the variables within each row, and does not return any measure of uncertainty.

We can generalize this by fitting a generative model to the observed data, p(Xo), and then computing samples from p(Xm|Xo). This is called multiple imputation. We can fit the model to partially observed data using methods such as EM (Section 6.5.3). (See e.g., [ZFY24] for a recent approach using EM and di!usion models (Chapter 25).) A generative model can also be used to fill in more complex data types, such as in-painting occluded pixels in an image (see Figure 20.4).

See Section 3.11 for a more general discussion of missing data.

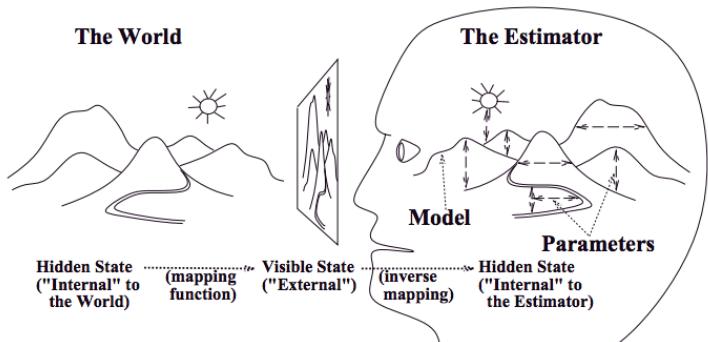

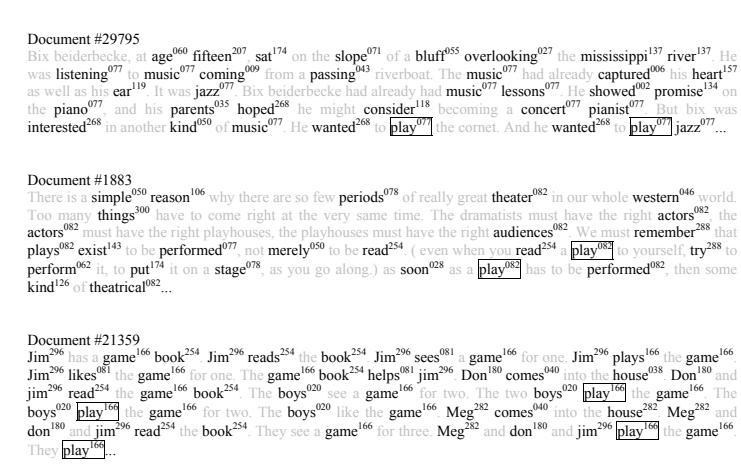

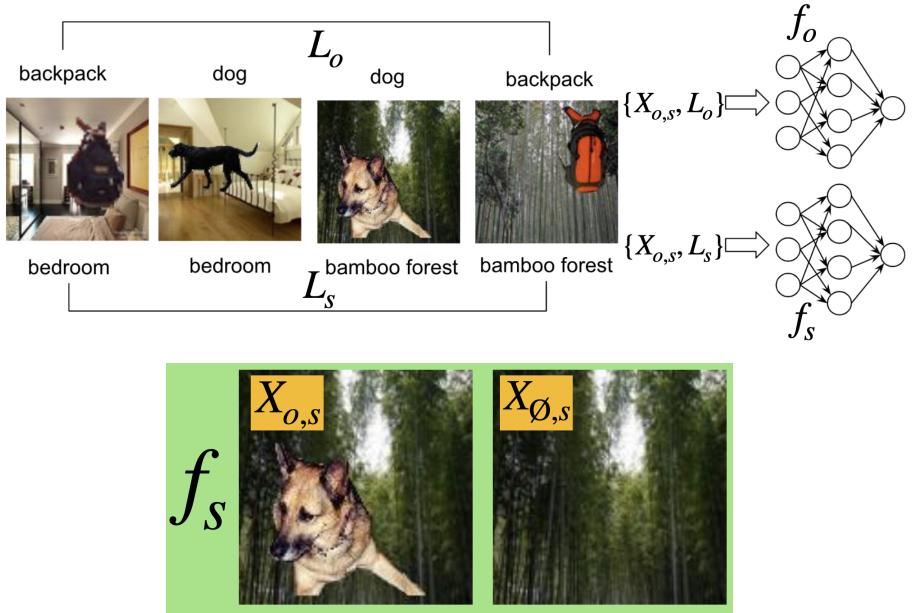

20.3.4 Structure discovery

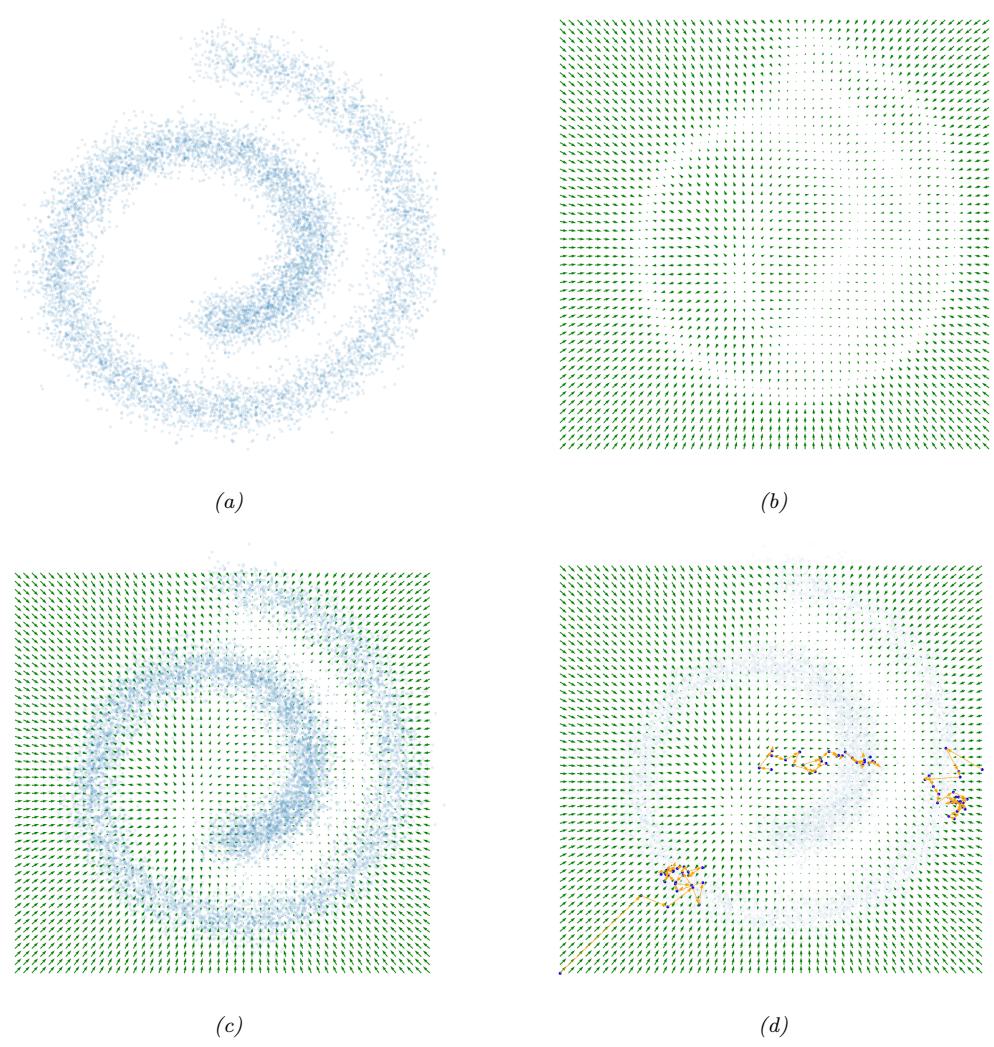

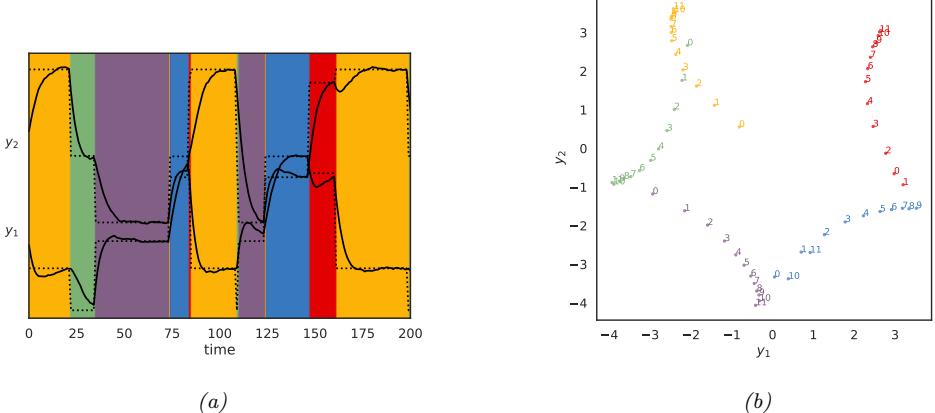

Some kinds of generative models have latent variables z, which are assumed to be the “causes” that generated the observed data x. We can use Bayes’ rule to invert the model to compute p(z|x) ↘ p(z)p(x|z). This can be useful for discovering latent, low-dimensional patterns in the data.

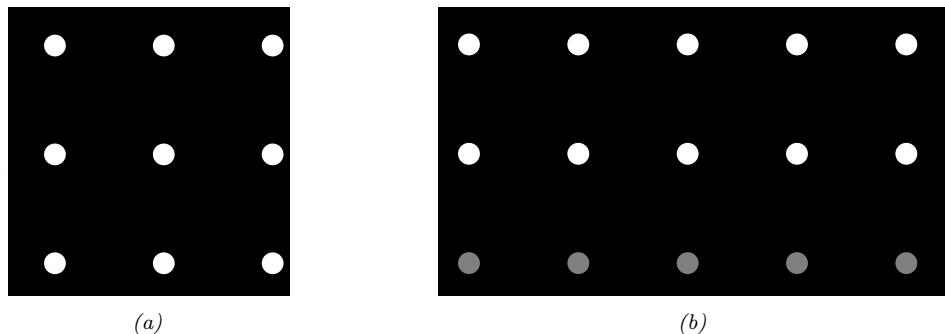

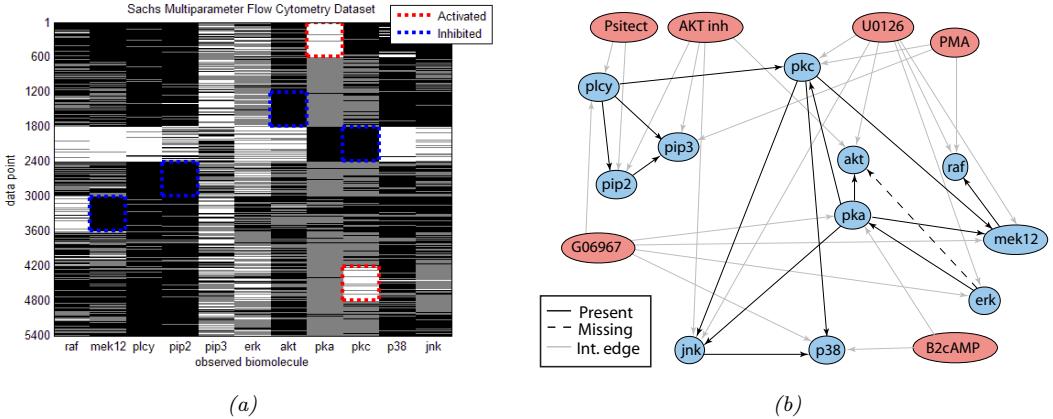

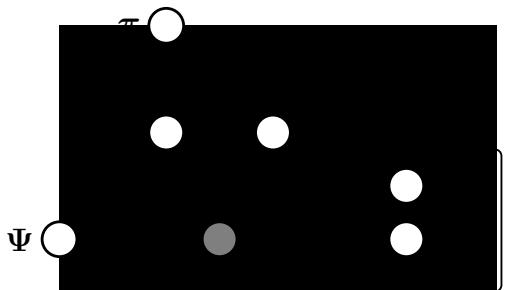

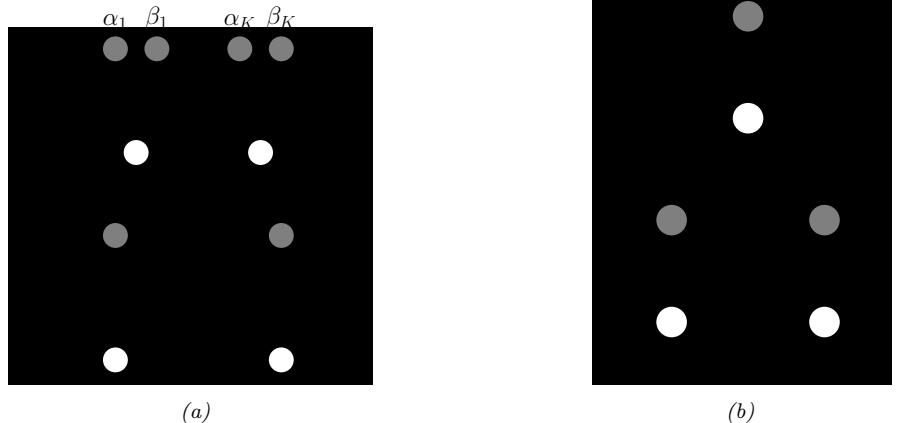

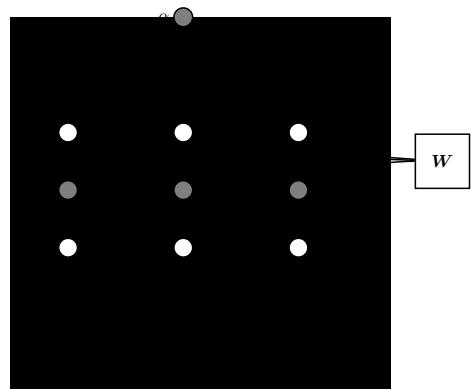

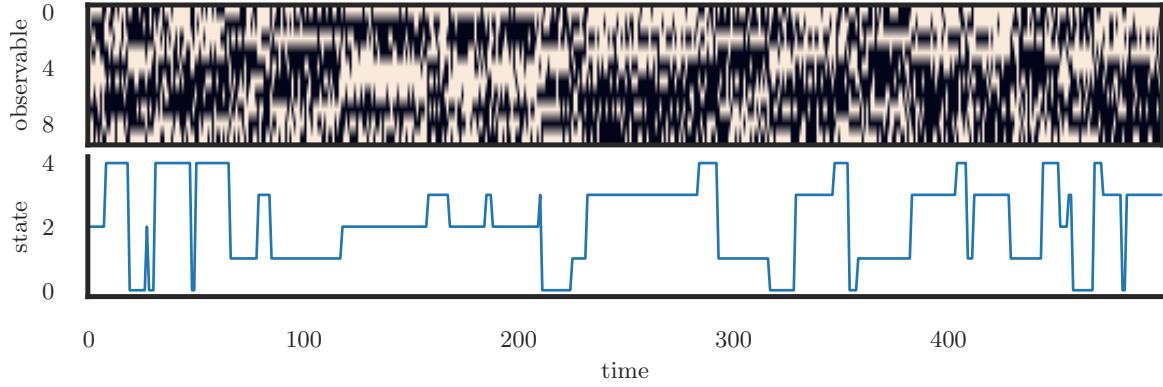

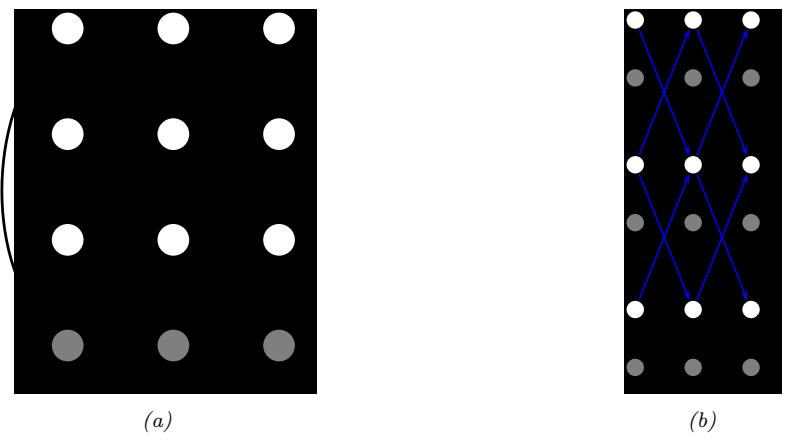

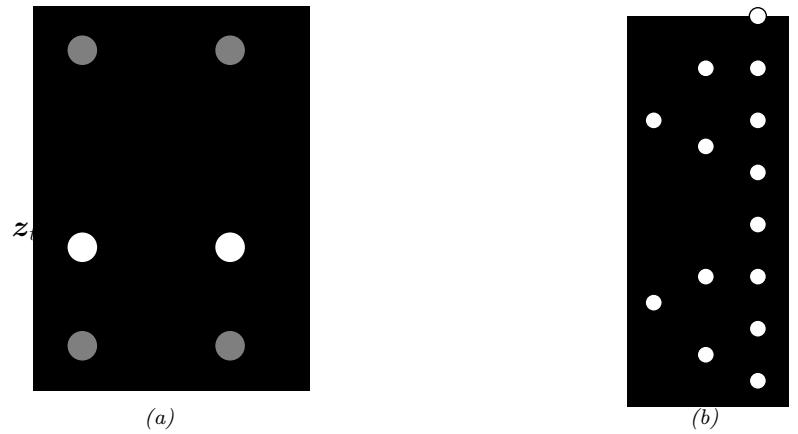

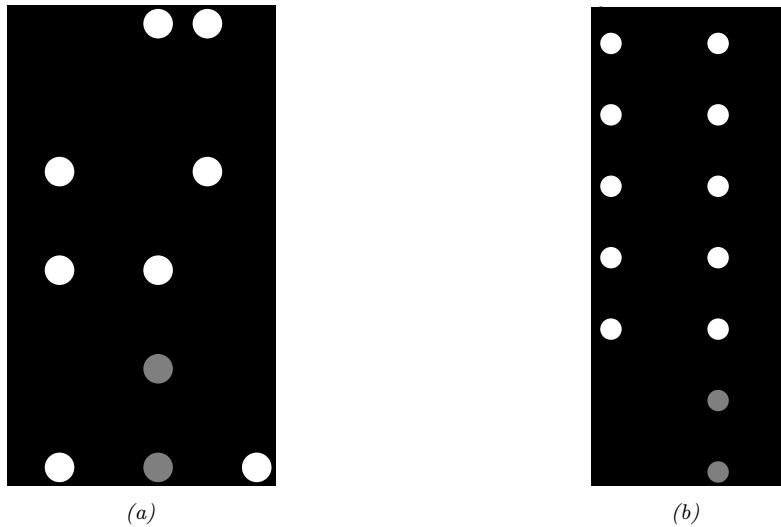

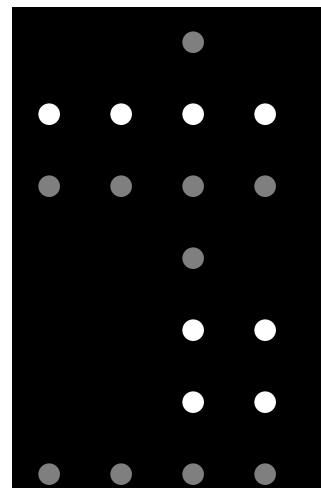

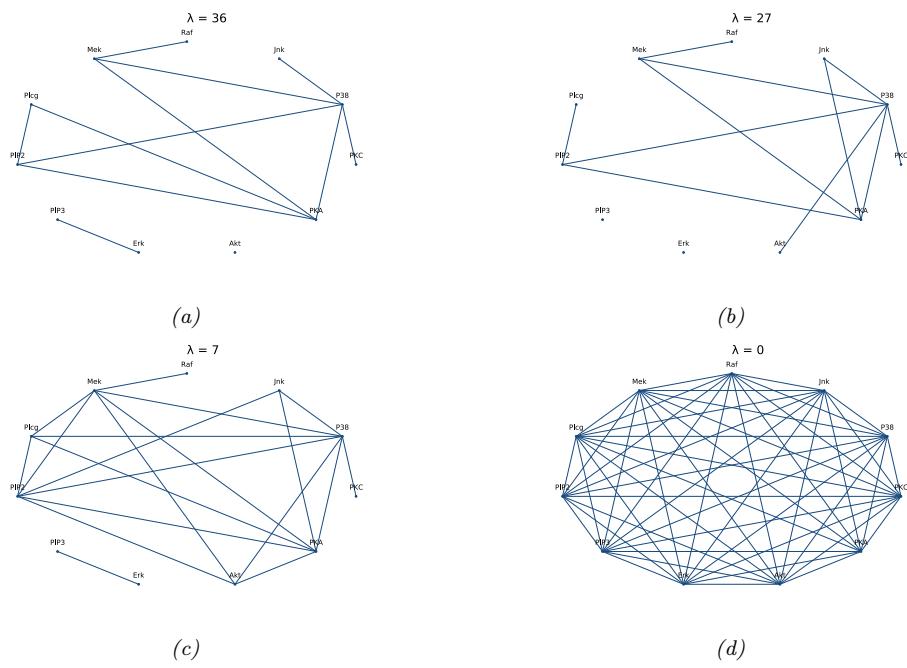

For example, suppose we perturb various proteins in a cell and measure the resulting phosphorylation state using a technique known as flow cytometry, as in [Sac+05]. An example of such a dataset is shown in Figure 20.7(a). Each row represents a data sample xn ↑ p(·|an, z), where x → R11 is a vector of outputs (phosphorylations), a → {0, 1}6 is a vector of input actions (perturbations) and z is the unknown cellular signaling network structure. We can infer the graph structure p(z|D) using graphical model structure learning techniques (see Section 30.3). In particular, we can use the dynamic programming method described in [EM07] to get the result shown in Figure 20.7(b). Here

Figure 20.7: (a) A design matrix consisting of 5400 datapoints (rows) measuring the state (using flow cytometry) of 11 proteins (columns) under di!erent experimental conditions. The data has been discretized into 3 states: low (black), medium (grey), and high (white). Some proteins were explicitly controlled using activating or inhibiting chemicals. (b) A directed graphical model representing dependencies between various proteins (blue circles) and various experimental interventions (pink ovals), which was inferred from this data. We plot all edges for which p(Gij = 1|D) > 0.5. Dotted edges are believed to exist in nature but were not discovered by the algorithm (1 false negative). Solid edges are true positives. The light colored edges represent the e!ects of intervention. From Figure 6d of [EM07].

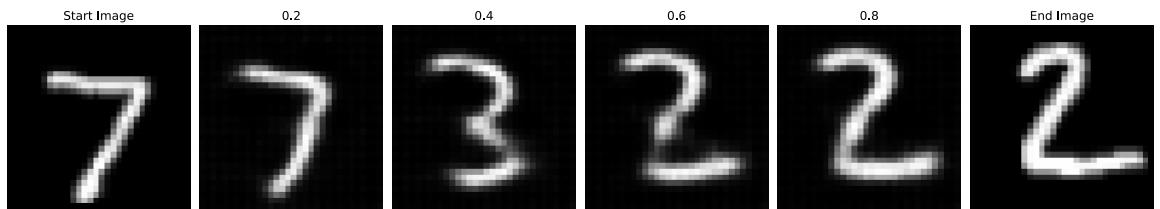

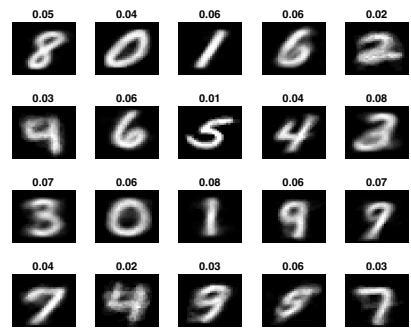

Figure 20.8: Interpolation between two MNIST images in the latent space of a ω-VAE (with ω = 0.5). Generated by mnist\_vae\_ae\_comparison.ipynb.

we plot the median graph, which includes all edges for which p(zij = 1|D) > 0.5. (For a more recent approach to this problem, see e.g., [Bro+20b].)

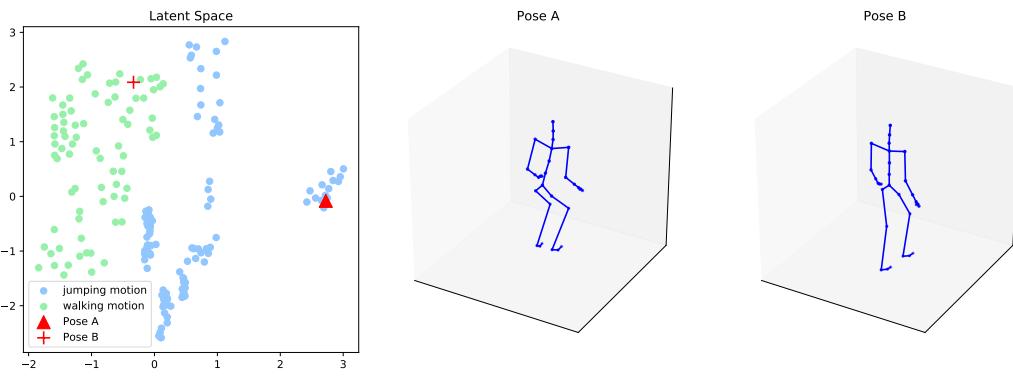

20.3.5 Latent space interpolation

One of the most interesting abilities of certain latent variable models is the ability to generate samples that have certain desired properties by interpolating between existing datapoints in latent space. To explain how this works, let x1 and x2 be two inputs (e.g., images), and let z1 = e(x1) and z2 = e(x2) be their latent encodings. (The method used for computing these will depend on the type of model; we discuss the details in later chapters.) We can regard z1 and z2 as two “anchors” in

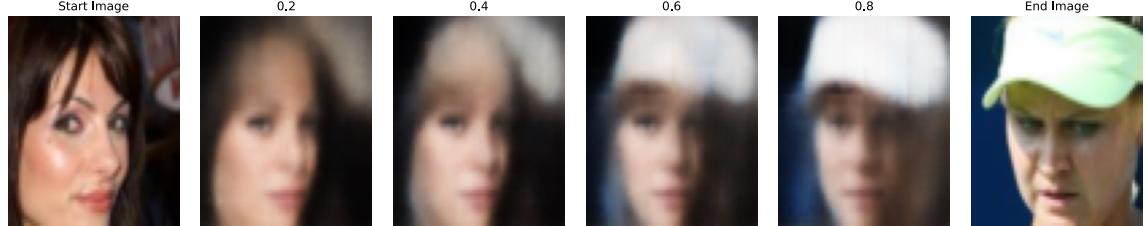

Figure 20.9: Interpolation between two CelebA images in the latent space of a ω-VAE (with ω = 0.5). Generated by celeba\_vae\_ae\_comparison.ipynb.

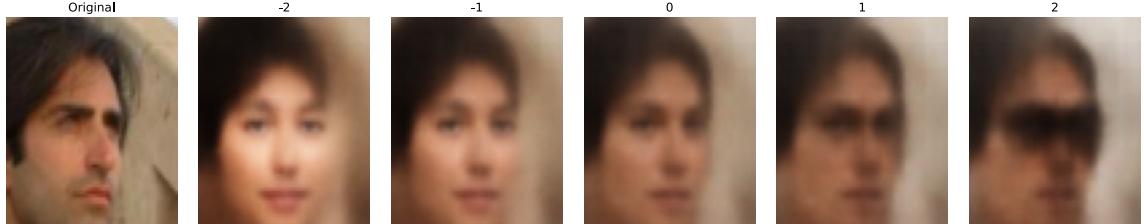

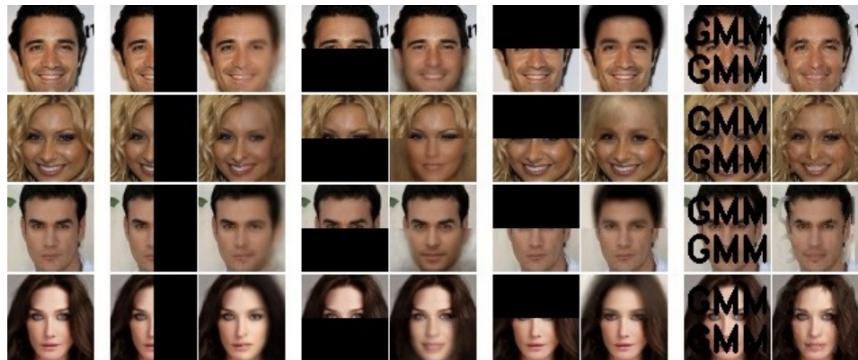

Figure 20.10: Arithmetic in the latent space of a ω-VAE (with ω = 0.5). The first column is an input image, with embedding z. Subsequent columns show the decoding of z + s!, where s ↔︎ {↗2, ↗1, 0, 1, 2} and ! = z+ ↗ z↑ is the di!erence in the average embeddings of images with or without a certain attribute (here, wearing sunglasses). Generated by celeba\_vae\_ae\_comparison.ipynb.

latent space. We can now generate new images that interpolate between these points by computing z = ωz1 + (1 ↓ ω)z2, where 0 ≃ ω ≃ 1, and then decoding by computing x→ = d(z), where d() is the decoder. This is called latent space interpolation, and will generate data that combines semantic features from both x1 and x2. (The justification for taking a linear interpolation is that the learned manifold often has approximately zero curvature, as shown in [SKTF18]. However, sometimes it is better to use nonlinear interpolation [Whi16; MB21; Fad+20].)

We can see an example of this process in Figure 20.8, where we use a ε-VAE model (Section 21.3.1) fit to the MNIST dataset. We see that the model is able to produce plausible interpolations between the digit 7 and the digit 2. As a more interesting example, we can fit a ε-VAE to the CelebA dataset [Liu+15].3 The results are shown in Figure 20.9, and look reasonable. (We can get much better quality if we use a larger model trained on more data for a longer amount of time.)

It is also possible to perform interpolation in the latent space of text models, as illustrated in Figure 21.7.

20.3.6 Latent space arithmetic

In some cases, we can go beyond interpolation, and can perform latent space arithmetic, in which we can increase or decrease the amount of a desired “semantic factor of variation”. This was first

3. CelebA contains about 200k images of famous celebrities. The images are also annotated with 40 attributes. We reduce the resolution of the images to 64 → 64, as is conventional.

shown in the word2vec model [Mik+13], but it also is possible in other latent variable models. For example, consider our VAE model fit to the CelebA dataset, which has faces of celebrities and some corresponding attributes. Let X+ i be a set of images which have attribute i, and X↑ i be a set of images which do not have this attribute. Let Z+ i and Z↑ i be the corresponding embeddings, and z+ i and z↑ i be the average of these embeddings. We define the o!set vector as !i = z+ i ↓ z↑ i . If we add some positive multiple of !i to a new point z, we increase the amount of the attribute i; if we subtract some multiple of !i, we decrease the amount of the attribute i [Whi16].

We give an example of this in Figure 20.10. We consider the attribute of wearing sunglasses. The j’th reconstruction is computed using xˆj = d(z + sj!), where z = e(x) is the encoding of the original image, and sj is a scale factor. When sj > 0 we add sunglasses to the face. When sj < 0 we remove sunglasses; but this also has the side e!ect of making the face look younger and more female, possibly a result of dataset bias.

20.3.7 Generative design

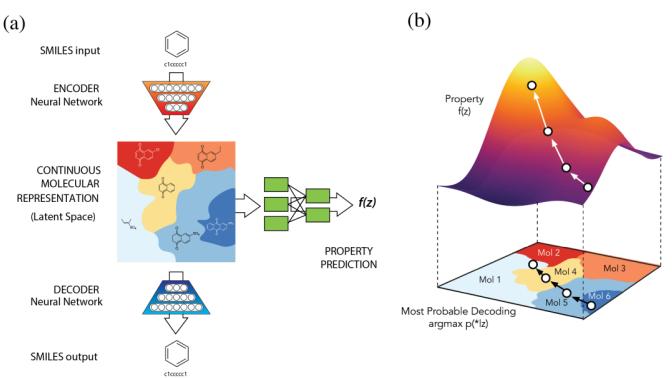

Another interesting use case for (deep) generative models is generative design, in which we use the model to generate candidate objects, such as molecules, which have desired properties (see e.g., [RNA22]). One approach is to fit a VAE to unlabeled samples, and then to perform Bayesian optimization (Section 6.6) in its latent space, as discussed in Section 21.3.5.2.

20.3.8 Model-based reinforcement learning

We discuss reinforcement learning (RL) in Chapter 35. The main success stories of RL to date have been in computer games, where simulators exist and data is abundant. However, in other areas, such as robotics, data is expensive to acquire. In this case, it can be useful to learn a generative “world model”, so the agent can do planning and learning “in its head”. See Section 35.4 for more details.

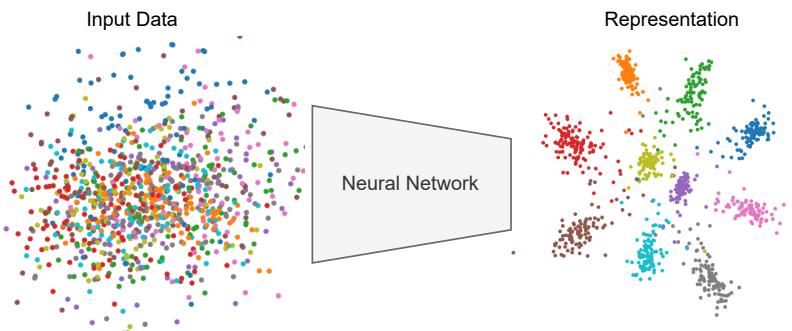

20.3.9 Representation learning

Representation learning refers to learning (possibly uninterpretable) latent factors z that generate the observed data x. The primary goal is for these features to be used in “downstream” supervised tasks. This is discussed in Chapter 32.

20.3.10 Data compression

Models which can assign high probability to frequently occuring data vectors (e.g., images, sentences), and low probability to rare vectors, can be used for data compression, since we can assign shorter codes to the more common items. Indeed, the optimal coding length for a vector x from some stochastic source p(x) is l(x) = ↓ log p(x), as proved by Shannon. See Section 5.4 for details.

20.4 Evaluating generative models

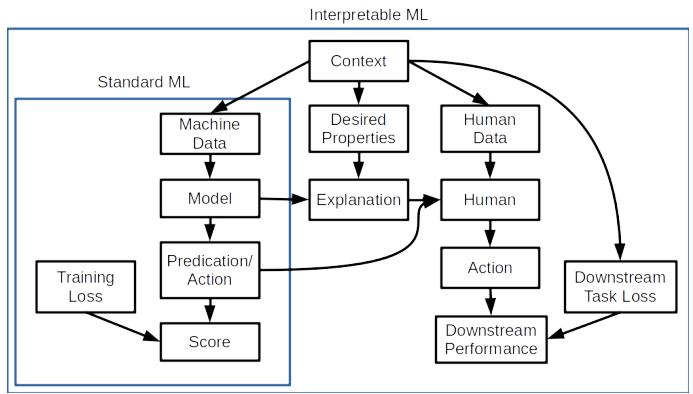

This section is written by Mihaela Rosca, Shakir Mohamed, and Balaji Lakshminarayanan.

Evaluating generative models requires metrics which capture

• sample quality — are samples generated by the model a part of the data distribution?

- sample diversity are samples from the model distribution capturing all modes of the data distribution?

- generalization is the model generalizing beyond the training data?

There is no known metric which meets all these requirements, but various metrics have been proposed to capture di!erent aspects of the learned distribution, some of which we discuss below.

20.4.1 Likelihood-based evaluation

A standard way to measure how close a model q is to a true distribution p is in terms of the KL divergence (Section 5.1):

\[D\_{\mathbb{KL}}\left(p \parallel q\right) = \int p(\mathbf{z}) \log \frac{p(\mathbf{z})}{q(\mathbf{z})} = -\mathbb{H}\left(p\right) + \mathbb{H}\_{\text{ce}}\left(p, q\right) \tag{20.2}\]

where H (p) is a constant, and Hce (p, q) is the cross entropy. If we approximate p(x) by the empirical distribution, we can evaluate the cross entropy in terms of the empirical negative log likelihood on the dataset:

\[\text{NLL} = -\frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \log q(\mathbf{z}\_n) \tag{20.3}\]

Usually we care about negative log likelihood on a held-out test set.4

20.4.1.1 Computing the log-likelihood

For models of discrete data, such as language models, it is easy to compute the (negative) log likelihood. However, it is common to measure performance using a quantity called perplexity, which is defined as 2H, where H = NLL is the cross entropy or negative log likelihood.

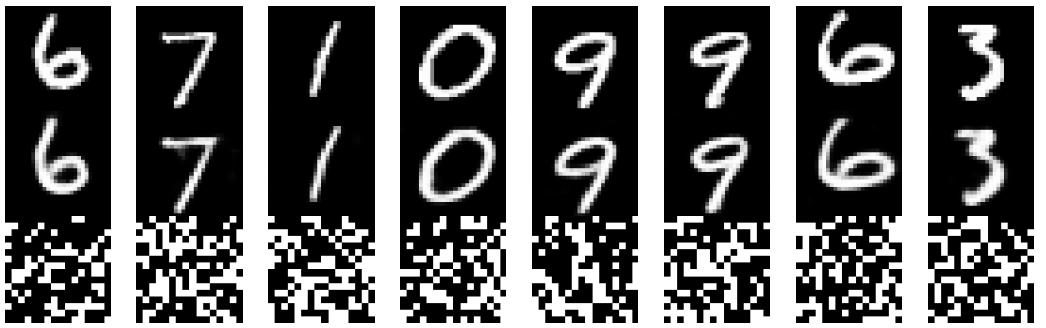

For image and audio models, one complication is that the model is usually a continuous distribution p(x) ⇒ 0 but the data is usually discrete (e.g., x → {0,…, 255}D if we use one byte per pixel). Consequently the average log likelihood can be arbitrary large, since the pdf can be bigger than 1. To avoid this it is standard pratice to use uniform dequantization [TOB16], in which we add uniform random noise to the discrete data, and then treat it as continuous-valued data. This gives a lower bound on the average log likelihood of the discrete model on the original data.

To see this, let z be a continuous latent variable, and x be a vector of binary observations computed by rounding, so p(x|z) = ϑ(x ↓ round(z)), computed elementwise. We have p(x) = ” p(x|z)p(z)dz. Let q(z|x) be a probabilistic inverse of x, that is, it has support only on values where p(x|z)=1. In this case, Jensen’s inequality gives

\[\log p(\mathbf{z}) \ge \mathbb{E}\_{q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) + \log p(\mathbf{z}) - \log q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \right] \tag{20.4}\]

\[=\mathbb{E}\_{q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})}\left[\log p(\mathbf{z}) - \log q(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})\right] \tag{20.5}\]

Thus if we model the density of z ↑ q(z|x), which is a dequantized version of x, we will get a lower bound on p(x).

4. In some applications, we report bits per dimension, which is the log likelihood using log base 2, divided by the dimensionality of x. To compute this metric, recall that log2 L = loge L loge 2 , and hence bpd = NLL loge(2) 1 |x| .

20.4.1.2 Likelihood can be hard to compute

Unfortunately, for many models, computing the likelihood can be computationally expensive, since it requires knowing the normalization constant of the probability model. One solution is to use variational inference (Chapter 10), which provides a way to e”ciently compute lower (and sometimes upper) bounds on the log likelihood. Another solution is to use annealed importance sampling (Section 11.5.4.1), which provides a way to estimate the log likelihood using Monte Carlo sampling. However, in the case of implicit generative models, such as GANs (Chapter 26), the likelihood is not even defined, so we need to find evaluation metrics that do not rely on likelihood.

20.4.2 Distances and divergences in feature space

Due to the challenges associated with comparing distributions in high dimensional spaces, and the desire to compare distributions in a semantically meaningful way, it is common to use domain-specific perceptual distance metrics, that measure how similar data vectors are to each other or to the training data. However, most metrics used to evaluate generative models do not directly compare raw data (e.g., pixels) but use a neural network to obtain features from the raw data and compare

the feature distribution obtained from model samples with the feature distribution obtained from the dataset. The neural network used to obtain features can be trained solely for the purpose of evaluation, or can be pretrained; a common choice is to use a pretrained classifier (see e.g., [Sal+16; Heu+17b; Bin+18; Kyn+19; SSG18a]).

The Inception score [Sal+16] measures the average KL divergence between the marginal distribution of class labels obtained from the samples pω(y) = ” pdisc(y|x)pω(x)dx (where the integral is approximated by sampling images x from a fixed dataset) and the distribution p(y|x) induced by samples from the model, x ↑ pω(x). (The term comes from the “Inception” model [Sze+15b] that is often used to define pdisc(y|x).) This leads to the following score:

\[\text{IS} = \exp\left[\mathbf{E}\_{p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})} D\_{\text{KL}}\left(p\_{\text{disc}}(Y|\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(Y)\right)\right] \tag{20.9}\]

To understand this, let us rewrite the log score as follows:

\[\log(\text{IS}) = \mathbb{H}(p\_{\theta}(Y)) - \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})} \left[ \mathbb{H}(p\_{\text{disc}}(Y|\mathbf{z})) \right] \tag{20.10}\]

Thus we see that a high scoring model will be equally likely to generate samples from all classes, thus maximizing the entropy of pω(Y ), while also ensuring that each individual sample is easy to classify, thus minimizing the entropy of pdisc(Y |x).

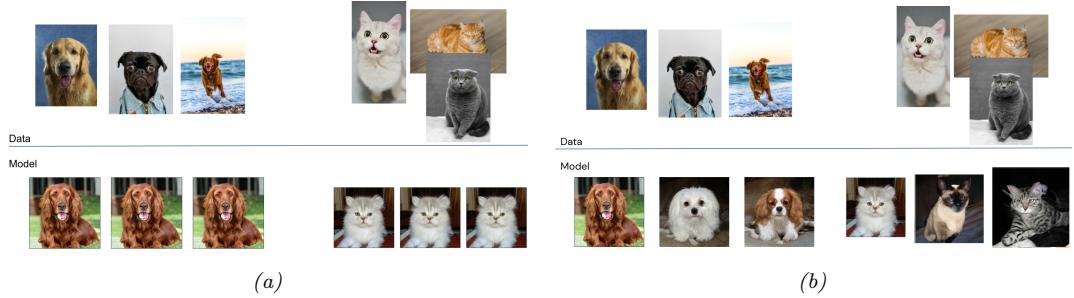

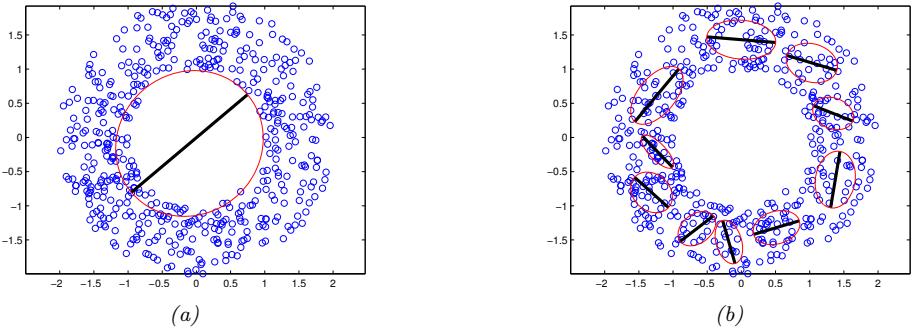

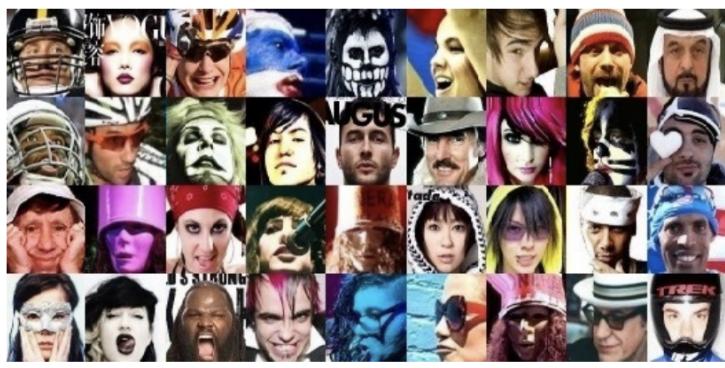

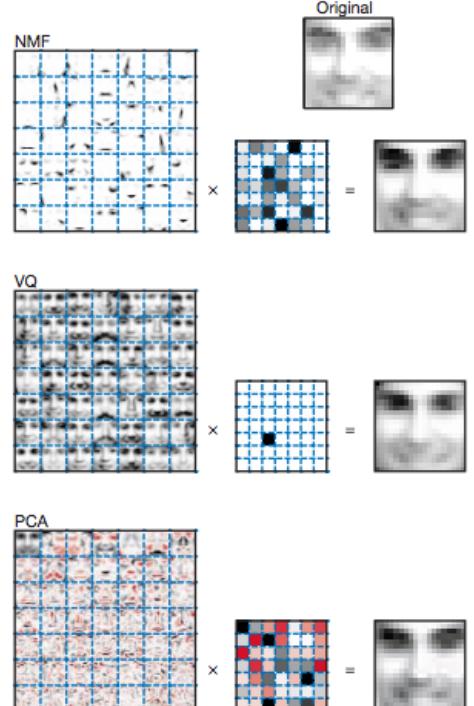

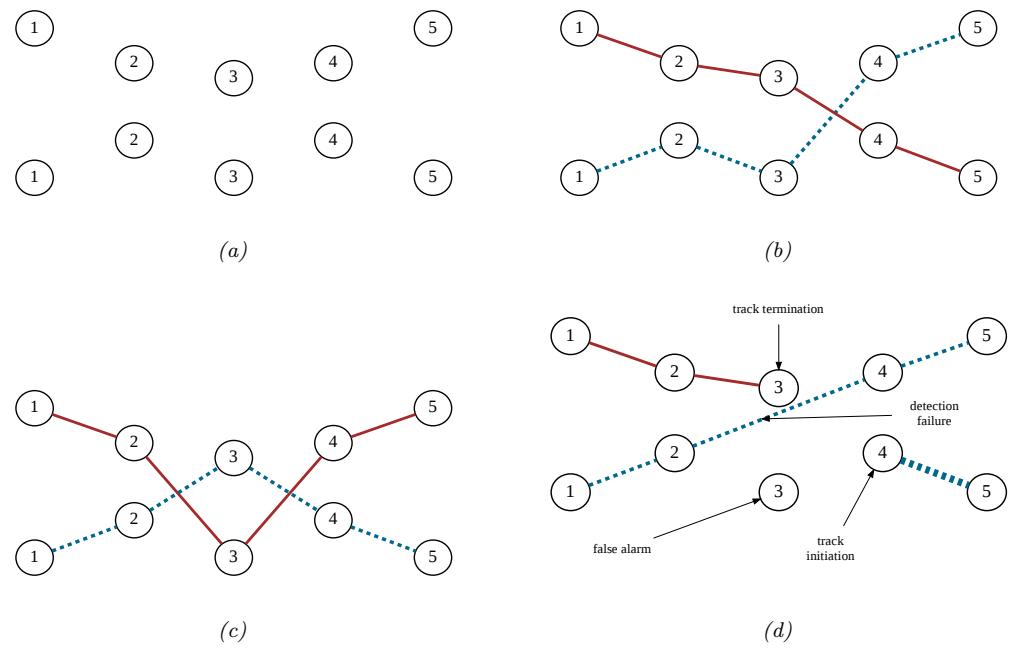

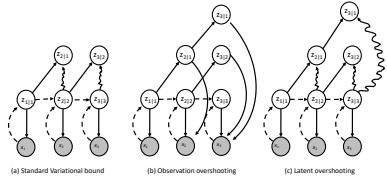

The Inception score solely relies on class labels, and thus does not measure overfitting or sample diversity outside the predefined dataset classes. For example, a model which generates one perfect example per class would get a perfect Inception score, despite not capturing the variety of examples inside a class, as shown in Figure 20.11a. To address this drawback, the Fréchet Inception distance or FID score [Heu+17b] measures the Fréchet distance between two Gaussian distributions on sets of features of a pre-trained classifier. One Gaussian is obtained by passing model samples through a pretrained classifier, and the other by passing dataset samples through the same classifier. If we assume that the mean and covariance obtained from model features are µm and “m and those from the data are µd and”d, then the FID is

\[\text{FID} = \|\mu\_m - \mu\_d\|\_2^2 + \text{tr}\left(\Sigma\_d + \Sigma\_m - 2(\Sigma\_d \Sigma\_m)^{1/2}\right) \tag{20.11}\]

Since it uses features instead of class logits, the Fréchet distance captures more than modes captured by class labels, as shown in Figure 20.11b. Unlike the Inception score, a lower score is better since we want the two distributions to be as close as possible.

Unfortunately, the Fréchet distance has been shown to have a high bias, with results varying widely based on the number of samples used to compute the score. To mitigate this issue, the kernel Inception distance has been introduced [Bin+18], which measures the squared MMD (Section 2.7.3) between the features obtained from the data and features obtained from model samples.

20.4.3 Precision and recall metrics

Since the FID only measures the distance between the data and model distributions, it is di”cult to use it as a diagnostic tool: a bad (high) FID can indicate that the model is not able to generate high quality data, or that it puts too much mass around the data distribution, or that the model only captures a subset of the data (e.g., in Figure 26.6). Trying to disentangle between these two failure modes has been the motivation to seek individual precision (sample quality) and recall (sample

Figure 20.11: (a) Model samples with good (high) inception score are visually realistic. (b) Model samples with good (low) FID score are visually realistic and diverse.

diversity) metrics in the context of generative models [LPO17; Kyn+19]. (The diversity question is especially important in the context of GANs, where mode collapse (Section 26.3.3) can be an issue.)

A common approach is to use nearest neighbors in the feature space of a pretrained classifier to define precision and recall [Kyn+19]. To formalize this, let us define

\[f\_k(\phi, \Phi) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } \exists \phi' \in \Phi s.t. \left\| |\phi - \phi'| \right\|\_2^2 \le \left\| \phi' - \text{NN}\_k(\phi', \Phi) \right\|\_2^2\\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \tag{20.12}\]

where ! is a set of feature vectors and NNk(ϱ→ , !) is a function returning the k’th nearest neighbor of ϱ→ in !. We now define precision and recall as follows:

\[\text{precision}(\Phi\_{model}, \Phi\_{data}) = \frac{1}{|\Phi\_{model}|} \sum\_{\phi \in \Phi\_{model}} f\_k(\phi, \Phi\_{data});\tag{20.13}\]

\[\text{recall}(\Phi\_{model}, \Phi\_{data}) = \frac{1}{|\Phi\_{data}|} \sum\_{\phi \in \Phi\_{data}} f\_k(\phi, \Phi\_{model});\tag{20.14}\]

Precision and recall are always between 0 and 1. Intuitively, the precision metric measures whether samples are as close to data as data is to other data examples, while recall measures whether data is as close to model samples as model samples are to other samples. The parameter k controls how lenient the metrics will be — the higher k, the higher both precision and recall will be. As in classification, precision and recall in generative models can be used to construct a trade-o! curve between di!erent models which allows practitioners to make an informed decision regarding which model they want to use.

20.4.4 Statistical tests

Statistical tests have long been used to determine whether two sets of samples have been generated from the same distribution; these types of statistical tests are called two sample tests. Let us define the null hypothesis as the statement that both set of samples are from the same distribution. We then compute a statistic from the data and compare it to a threshold, and based on this we decide whether to reject the null hypothesis. In the context of evaluating implicit generative models

such as GANs, statistics based on classifiers [Saj+18] and the MMD [Liu+20b] have been used. For use in scenarios with high dimensional input spaces, which are ubiquitous in the era of deep learning, two sample tests have been adapted to use learned features instead of raw data.

Like all other evaluation metrics for generative models, statistical tests have their own advantages and disadvantages: while users can specify Type 1 error — the chance they allow that the null hypothesis is wrongly rejected — statistical tests tend to be computationally expensive and thus cannot be used to monitor progress in training; hence they are best used to compare fully trained models.

20.4.5 Challenges with using pretrained classifiers

While popular and convenient, evaluation metrics that rely on pretrained classifiers (such as IS, FID, nearest neighbors in feature space, and statistical tests in feature space) have significant drawbacks. One might not have a pretrained classifier available for the dataset at hand, so classifiers trained on other datasets are used. Given the well known challenges with neural network generalization (see Section 17.4), the features of a classifier trained on images from one dataset might not be reliable enough to provide a fine grained signal of quality for samples obtained from a model trained on a di!erent dataset. If the generative model is trained on the same dataset as the pre-trained classifier but the model is not capturing the data distribution perfectly, we are presenting the pre-trained classifier with out-of-distribution data and relying on its features to obtain score to evaluate our models. Far from being purely theoretical concerns, these issues have been studied extensively and have been shown to a!ect evaluation in practice [RV19; BS18].

20.4.6 Using model samples to train classifiers

Instead of using pretrained classifiers to evaluate samples, one can train a classifier on samples from conditional generative models, and then see how good these classifiers are at classifying data. For example, does adding synthetic (sampled) data to the real data help? This is closer to a reliable evaluation of generative model samples, since ultimately, the performance of generative models is dependent on the downstream task they are trained for. If used for semisupervised learning, one should assess how much adding samples to a classifier dataset helps with test accuracy. If used for model based reinforcement learning, one should assess how much the generative model helps with agent performance. For examples of this approach, see e.g., [SSM18; SSA18; RV19; SS20b; Jor+22].

20.4.7 Assessing overfitting

Many of the metrics discussed so far capture the sample quality and diversity, but do not capture overfitting to the training data. To capture overfitting, often a visual inspection is performed: a set of samples is generated from the model and for each sample its closest K nearest neighbors in the feature space of a pretrained classifier are obtained from the dataset. While this approach requires manually assessing samples, it is a simple way to test whether a model is simply memorizing the data. We show an example in Figure 20.12: since the model sample in the top left is quite di!erent than its neighbors from the dataset (remaining images), we can conclude the sample is not simply memorised from the dataset. Similarly, sample diversity can be measured by approximating the support of the learned distribution by looking for similar samples in a large sample pool — as in the pigeonhole principle — but it is expensive and often requires manual human assessment[AZ17].

Figure 20.12: Illustration of nearest neighbors in feature space: in the top left we have the query sample generated using BigGAN, and the rest of the images are its nearest neighbors from the dataset. The nearest neighbors search is done in the feature space of a pretrained classifier. From Figure 13 of [BDS18]. Used with kind permission of Andy Brock.

For likelihood-based models — such as variational autoencoders (Chapter 21), autoregressive models (Chapter 22), and normalizing flows (Chapter 23) — we can assess memorization by seeing how much the log-likelihood of a model changes when a sample is included in the model’s training set or not [BW21].

20.4.8 Human evaluation

One approach to evaluate generative models is to use human evaluation, by presenting samples from the model alongside samples from the data distribution, and ask human raters to compare the quality of the samples [Zho+19b]. Human evaluation is a suitable metric if the model is used to create art or other data for human display, or if reliable automated metrics are hard to obtain. However, human evaluation can be di”cult to standardize, hard to automate, and can be expensive or cumbersome to set up.

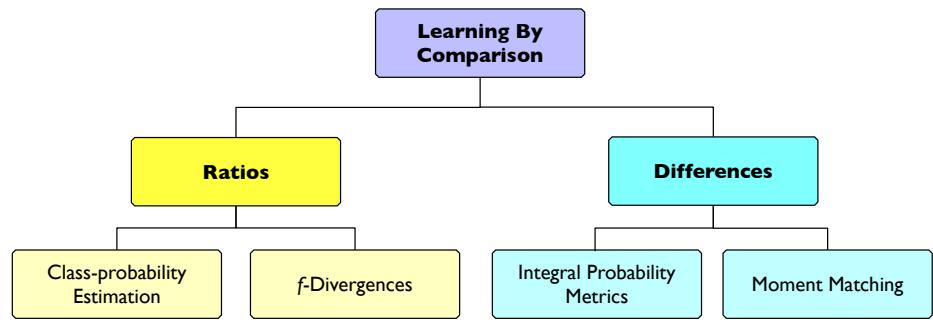

20.5 Training objectives5

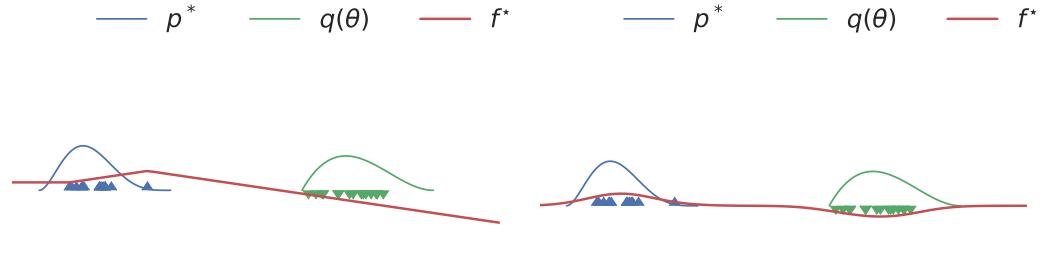

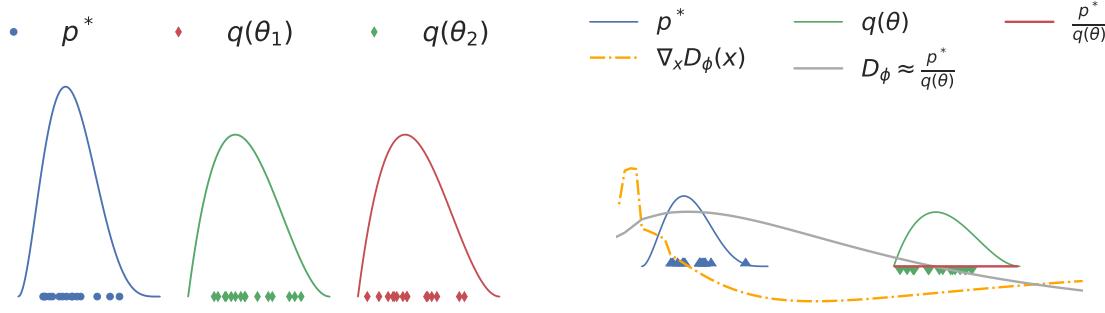

So far we have not discussed how to train generative models. Most of the book adopts an approach based on (regularized) maximum likelihood estimation, or some approximation thereof (see the “Training” column of Table 20.1). In MLE, the training objective is to maximize Ep(x) [log q(x)] = ↓DKL (p ⇐ q) + const, where p is the target distribution (usually approximated by the empirical data distribution) and q is the model distribution which we are learning. However, this objective can have some fundamental flaws when modeling high dimensional continuous distributions, where x → RD. In particular, suppose the target distribution p lies on a low-dimensional manifold, meaning that p(x) > 0 only for x → M where M = Rd→ is a low-dimensional subspace with dimension d↔︎ which is

5. This section was newly added in September 2024.

less than the ambient dimension D. (This is called the manifold hypothesis, and is a reasonable assumption for many natural distributions, such as the set of natural images.) By contrast, the likelihood objective assumes that p(x) is defined over the entire ambient space, RD, in order for the above expectation to be well defined. If p is not defined on the full space, maximizing likelihood is no longer a good objective, since there can be many distributions q that assign infinite likelihood to the manifold M, while not matching p. (This is because M is “too thin” relative to RD.) (A simple example is when p is a mixture of two delta functions, and q is a GMM; in this case, the variance of each mixture component will go to 0, to approximate the two “spikes”. This drives the likelihood to infinity, but q may still assign wrong mixture weights to each component.) See [LG+23; LG+24] for an extensive discussion of this point.

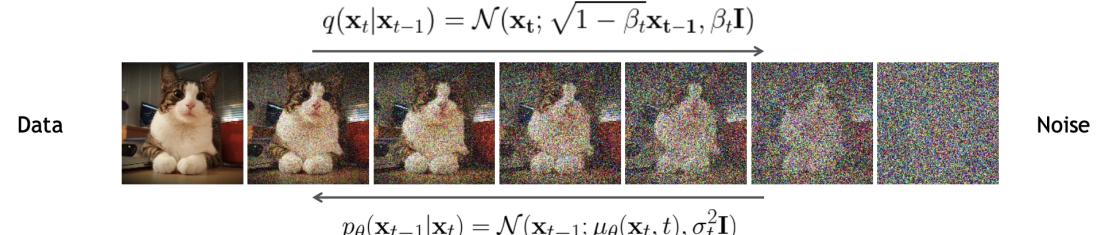

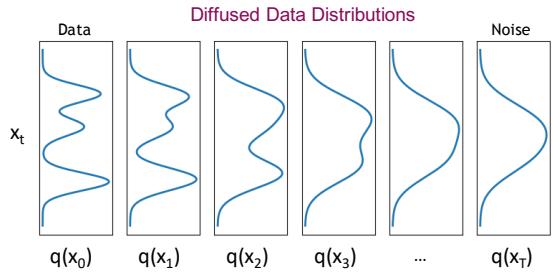

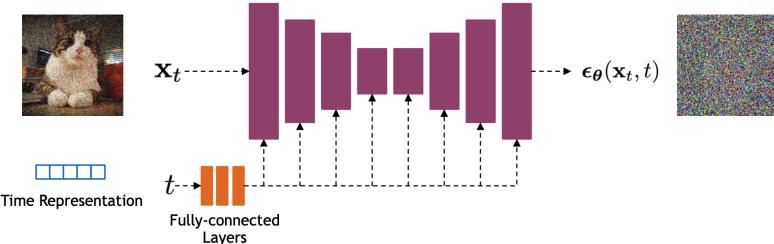

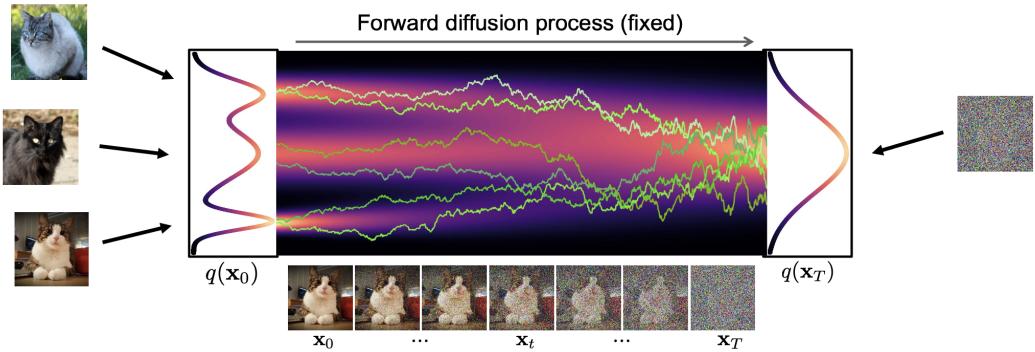

There are three main types of solution to this problem. The first is to add noise to the data vectors, so they “fill the space”. This ensures that both p and q both have support over all D dimensions. One approach to this is to use di!usion models, which add noise at many di!erent levels (see Chapter 25). Another approach is to replace the KL with the spread KL divergence [Zha+20c], which is defined as DKLε(p||q) = DKL(pε||qε), where pε = p ↭ N (·|0, ς2ID) and qε = q ↭ N (·|0, ς2ID) are smoothed versions of the distribution obtained by convolving with a Gaussian. This ensures the KL is always finite. We can then optimize the modified KL using a latent variable model of the form q(x) = N (x|gω(z), ς2I), where g : Rd ↔︎ RD is a deterministic decoder and z ↑ N (0, Id) is a low-dimensional stochastic latent variable. After training, we can “turn o!” the noise from the decoder, so that q has the same support as the manifold of p; this is known as the delta-VAE [Zha+20c]. See Chapter 21 for more details on VAEs, and [Tra+23] for related approaches based on smoothed likelihoods.

The second type of solution is to use support-agnostic training objectives rather than KL. Formally, we need to use divergences between probability distributions which “metrize weak convergence” (see [LG+24] for an explanation). Examples include Wasserstein distances (Section 6.8.2.4) and maximum mean discrepancy (Section 2.7.3). Methods of this type, known as generative adversarial networks, are discussed in Chapter 26.

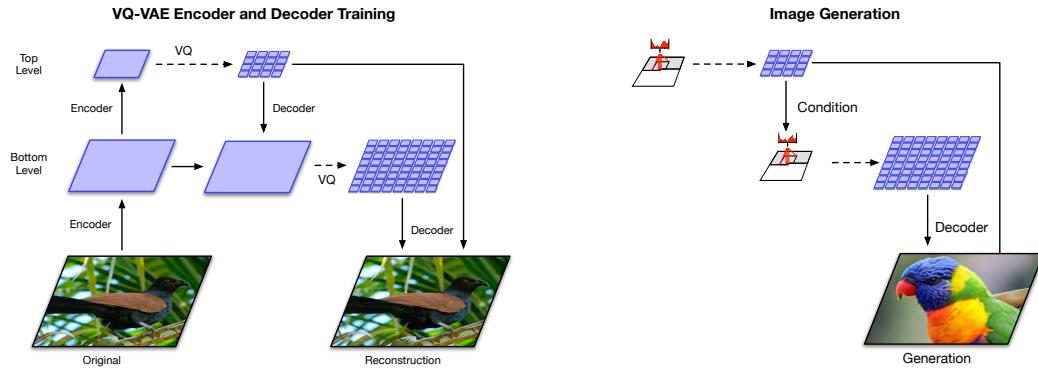

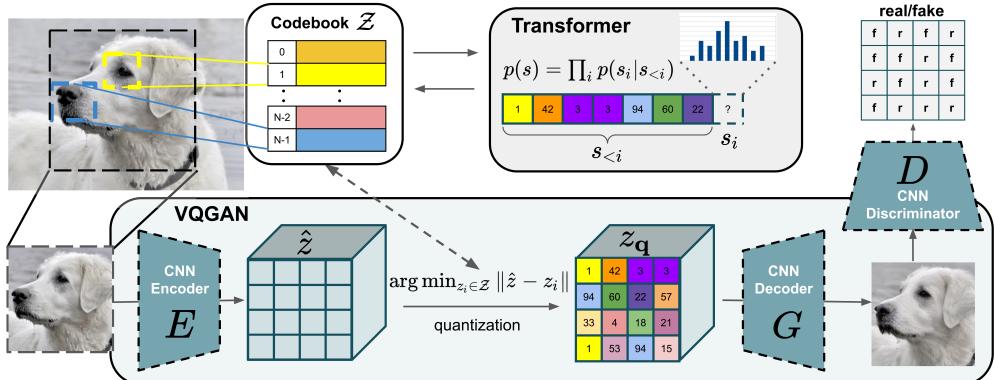

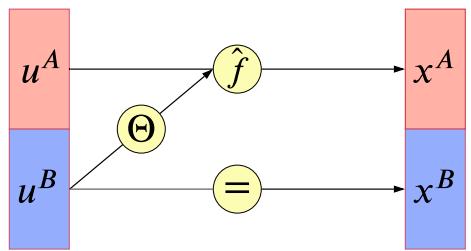

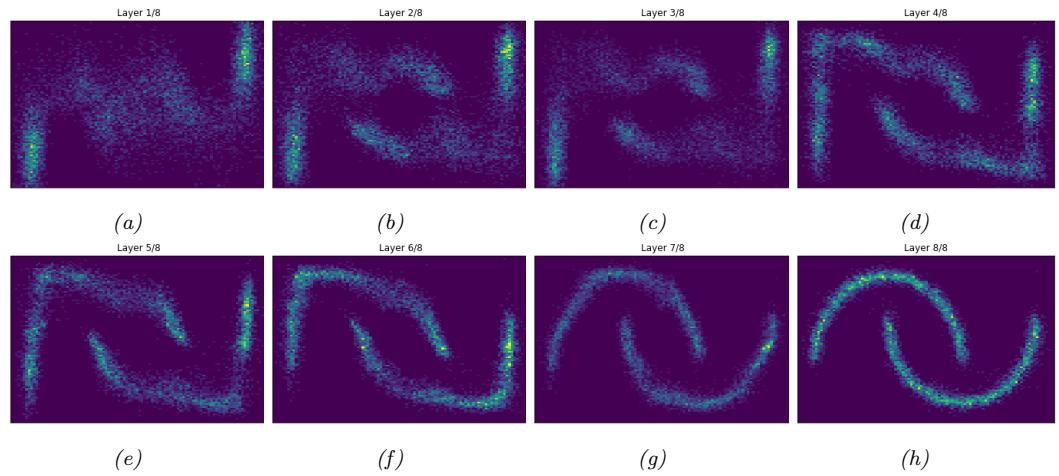

The third type of solution is to use two-step methods [LG+23]. In the first step, we learn the underlying latent manifold using a method such as a (regularized) autoencoder (see Section 21.2.3). This learns a (deterministic) encoder z = fε(x) and a decoder x = gω1 (z), where z → Rd for d ↖ D. The objective is to minimize the reconstruction error of the target distribution: L(ω, ε1) = Ep(x) $ ||x ↓ gω1 (fε(x))||2 2 % . In the second step, we learn a density model qω2 (z), using pε→ (z) = push-through(p(x), fε→ ) as the target distribution. This second stage is relatively easy, since the target distribution is a low-dimensional distribution with full support in Rd, making it safe to use standard MLE methods. Finally, we define the generative model q(x) by composing the stochastic latent prior, z ↑ qω2 , with the deterministic decoder, x = gω1 (z), similar to the delta-VAE. In [LG+24], they prove that this two-step approach optimizes (an upper bound on) the Wasserstein distance between q and p. Furthermore, the approach is easy to implement, and popular in practice. For example, it is used by latent di!usion models (Section 25.5.4), VQ-VAE models (Section 21.6), and certain kinds of (variational) autoencoders (e.g., [Gho+19b] fit a regularized deterministic AE in stage 1, and a GMM in stage 2, and [DW19] fit two VAEs, one per stage),

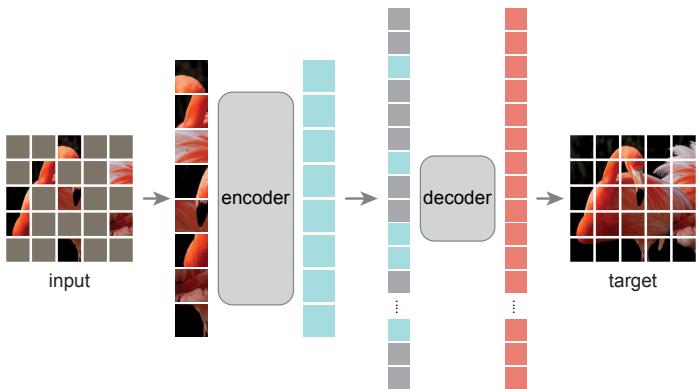

21 Variational autoencoders

21.1 Introduction

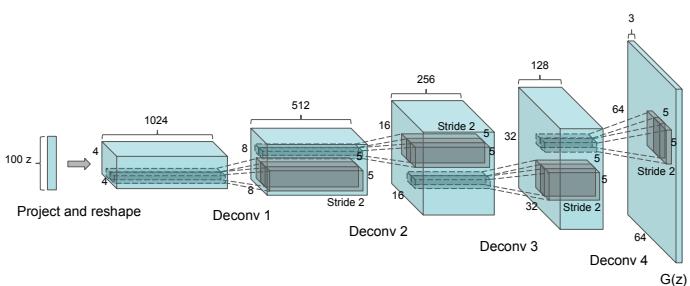

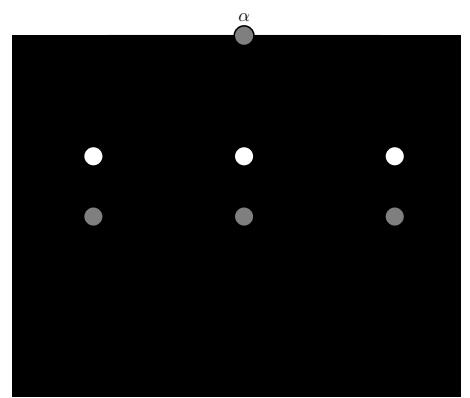

In this chapter, we discuss generative models of the form

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{z} & \sim p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \\ \mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z} & \sim \text{Exp}\text{fam}(\mathbf{z}|d\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})) \end{aligned} \tag{21.1}\]

where \(p(\mathbf{z})\) is some kind of prior on the latent code \(\mathbf{z}\) , \(d\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})\) is a deep neural network, known as the **decoder**, and **Exfam( \(x \| \boldsymbol{\eta}\) ) is an exponential family distribution, such as a Gaussian or product of Bernoulli. This is called a deep latent variable model or **DLVM. When the prior is Gaussian

Posterior inference (i.e., computing pω(z|x)) is computationally intractable, as is computing the marginal likelihood

(as is often the case), this model is called a deep latent Gaussian model or DLGM.

\[p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) = \int p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \, d\mathbf{z} \tag{21.3}\]

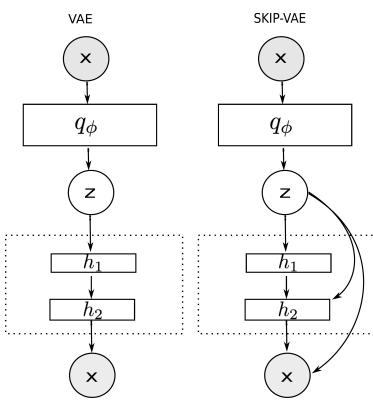

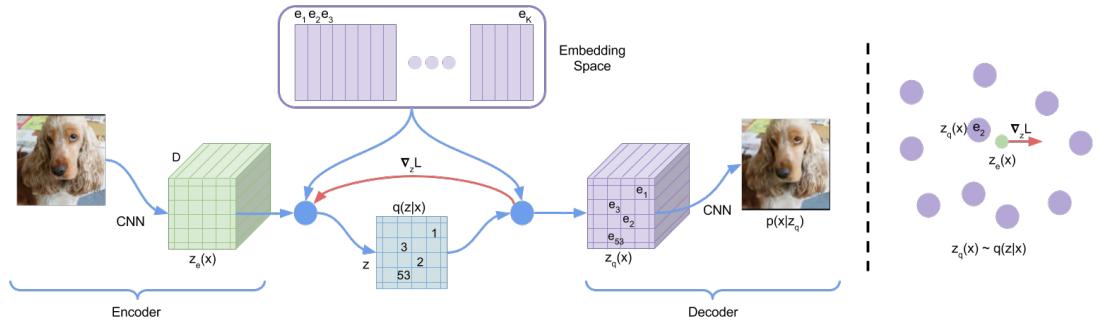

Hence we need to resort to approximate inference. For most of this chapter, we will use amortized inference, which we discussed in Section 10.1.5. This trains another model, qε(z|x), called the recognition network or inference network, simultaneously with the generative model to do approximate posterior inference. This combination is called a variational autoencoder or VAE [KW14; RMW14b; KW19a], since it can be thought of as a probabilistic version of a deterministic autoencoder, discussed in Section 16.3.3.

In this chapter, we introduce the basic VAE, as well as some extensions. Note that the literature on VAE-like methods is vast1, so we will only discuss a small subset of the ideas that have been explored.

21.2 VAE basics

In this section, we discuss the basics of variational autoencoders.

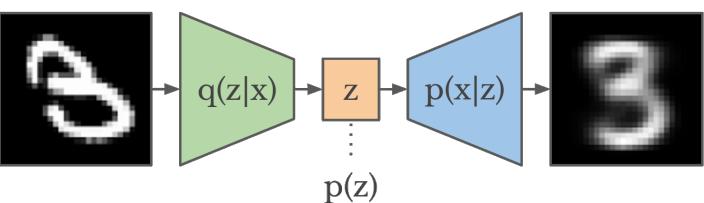

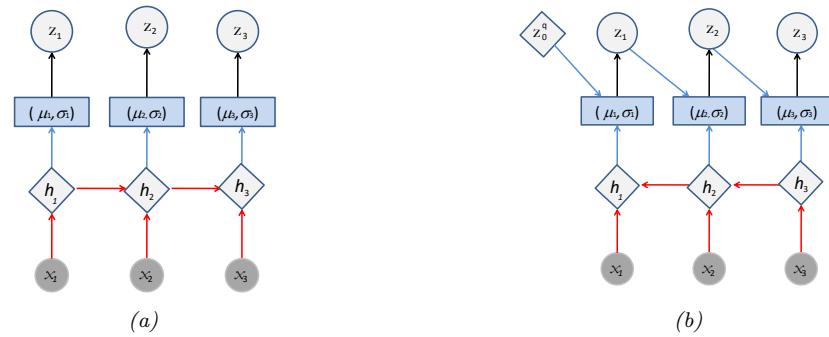

Figure 21.1: Schematic illustration of a VAE. From a figure in [Haf18]. Used with kind permission of Danijar Hafner.

21.2.1 Modeling assumptions

In the simplest setting, a VAE defines a generative model of the form

\[p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) = p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \tag{21.4}\]

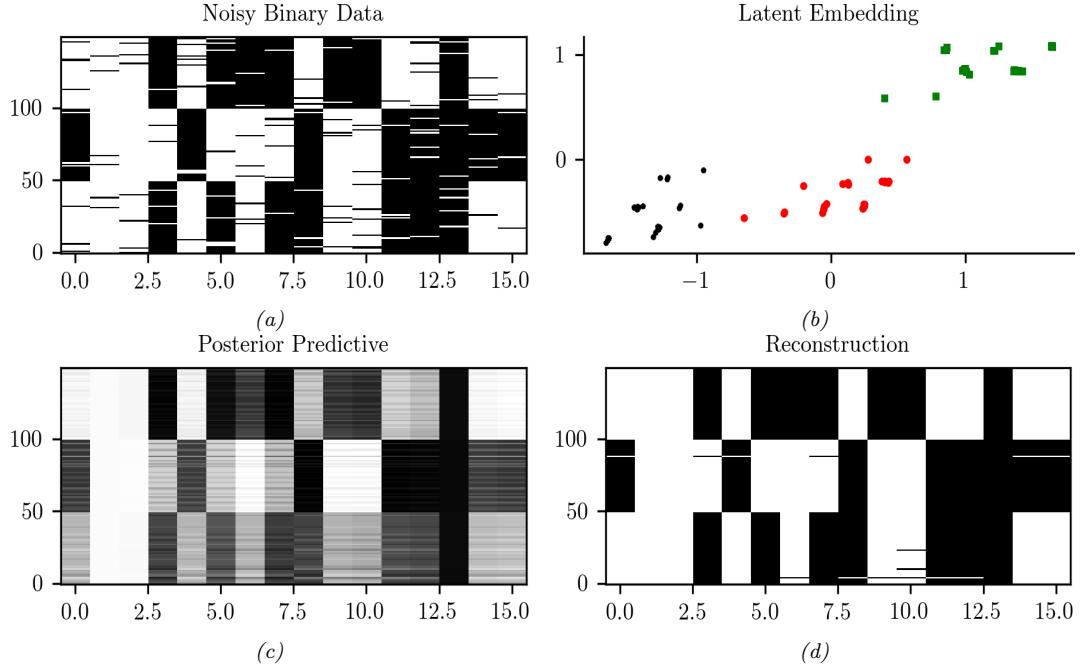

where pω(z) is usually a Gaussian, and pω(x|z) is usually a product of exponential family distributions (e.g., Gaussians or Bernoullis), with parameters computed by a neural network decoder, dω(z). For example, for binary observations, we can use

\[p\_{\theta}(x|\mathbf{z}) = \prod\_{d=1}^{D} \text{Ber}(x\_d | \sigma(d\mathfrak{g}(\mathbf{z})) \tag{21.5}\]

In addition, a VAE fits a recognition model

\[q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}) = q(\mathbf{z}|e\_{\phi}(\mathbf{x})) \approx p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}) \tag{21.6}\]

to perform approximate posterior inference. Here qε(z|x) is usually a Gaussian, with parameters computed by a neural network encoder eε(x):

\[q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}|\mu, \text{diag}(\exp(\mathcal{E}))) \tag{21.7}\]

\[e\_{\phi}(\mu, \ell) = e\_{\phi}(x) \tag{21.8}\]

where ϖ = log ϱ. The model can be thought of as encoding the input x into a stochastic latent bottleneck z and then decoding it to approximately reconstruct the input, as shown in Figure 21.1.

The idea of training an inference network to “invert” a generative network, rather than running an optimization algorithm to infer the latent code, is called amortized inference, and is discussed in Section 10.1.5. This idea was first proposed in the Helmholtz machine [Day+95]. However, that paper did not present a single unified objective function for inference and generation, but instead used the wake-sleep (Section 10.6) method for training. By contrast, the VAE optimizes a variational lower bound on the log-likelihood, which means that convergence to a locally optimal MLE of the parameters is guaranteed.

We can use other approaches to fitting the DLGM (see e.g., [Hof17; DF19]). However, learning an inference network to fit the DLGM is often faster and can have some regularization benefits (see e.g., [KP20]).2

1. For example, the website https://github.com/matthewvowels1/Awesome-VAEs lists over 900 papers.

2. Combining a generative model with an inference model in this way results in what has been called a “monference”,

21.2.2 Model fitting

We can fit a VAE using amortized stochastic variational inference, as we discuss in Section 10.2.1.6. For example, suppose we use a VAE with a diagonal Bernoulli likelihood model, and a full covariance Gaussian as our variational posterior. Then we can use the methods discussed in Section 10.2.1.2 to derive the fitting algorithm. See Algorithm 21.1 for the corresponding pseudocode.

Algorithm 21.1: Fitting a VAE with Bernoulli likelihood and full covariance Gaussian posterior. Based on Algorithm 2 of [KW19a].

1 Initialize ε, ω

2 repeat

3 Sample x ↑ pD

4 Sample ς ↑ q0

5 (µ, log ϱ,L→

) = eε(x)

6 M = np.triu(np.ones(K), ↓1)

7 L = M↙ L→ + diag(ϱ)

8 z = Lς + µ

9 pω = dω(z)

10 Llogqz = ↓*K

k=1 $ 1

2 ϖ2

k + 1

2 log(2φ) + log ςk

%

// from qε(z|x) in Equation (10.47)

11 Llogpz = ↓*K

k=1 $ 1

2 z2

k + 1

2 log(2φ)

%

// from pω(z) in Equation (10.48)

12 Llogpx = ↓*D

d=1 [xd log pd + (1 ↓ xd) log(1 ↓ pd)] // from pω(x|z)

13 L = Llogpx + Llogpz ↓ Llogqz

14 Update ε := ε ↓ ↼∝ωL

15 Update ω := ω ↓ ↼∝εL

16 until converged21.2.3 Comparison of VAEs and autoencoders

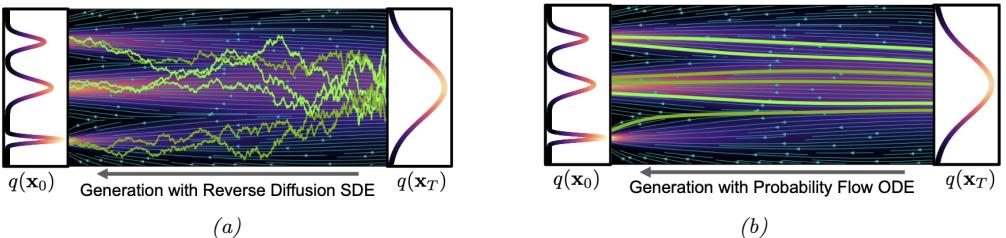

VAEs are very similar to deterministic autoencoders (AE). There are 2 main di!erences: in the AE, the objective is the log likelihood of the reconstruction without any KL term; and in addition, the encoding is deterministic, so the encoder network just needs to compute E [z|x] and not V [z|x]. In view of these similarities, one can use the same codebase to implement both methods. However, it is natural to wonder what the benefits and potential drawbacks of the VAE are compared to the deterministic AE.

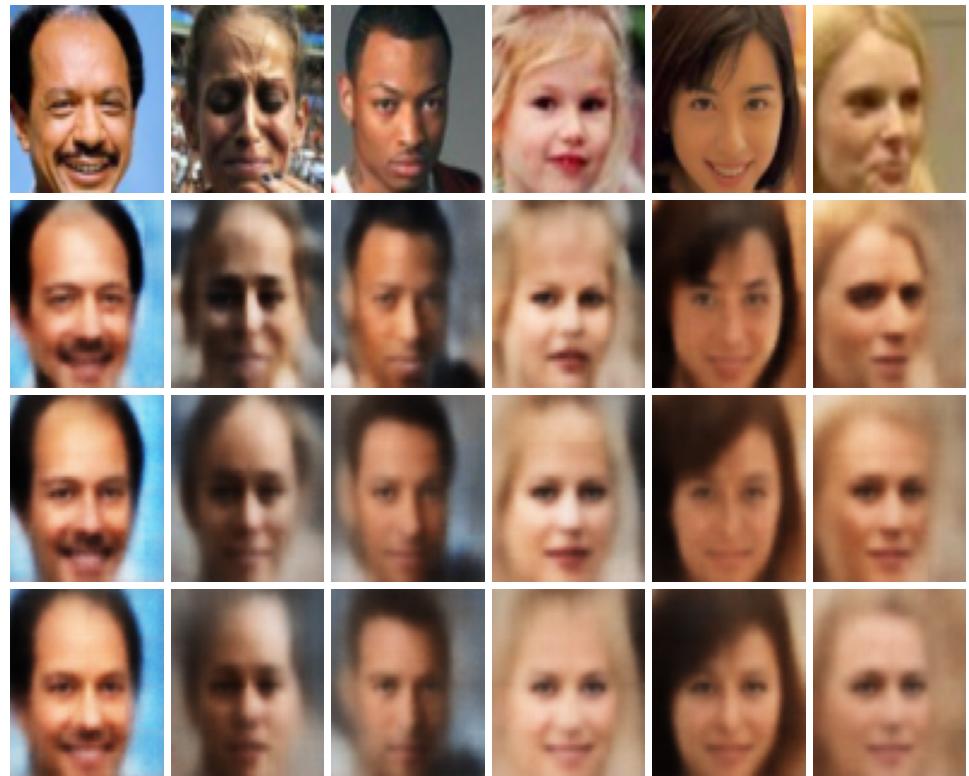

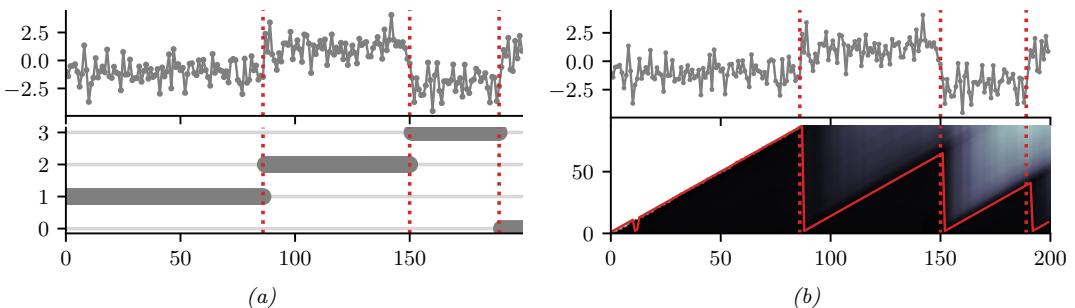

We shall answer this question by fitting both models to the CelebA dataset. Both models have the same convolutional structure with the following number of hidden channels per convolutional layer in the encoder: (32, 64, 128, 256, 512). The spatial size of each layer is as follows: (32, 16, 8, 4, 2). The final 2 ↗ 2 ↗ 512 convolutional layer then gets reshaped and passed through a linear layer to generate the mean and (marginal) variance of the stochastic latent vector, which has size 256. The structure

i.e., model-inference hybrid. See the blog by Jacob Andreas, http://blog.jacobandreas.net/monference.html, for further discussion.

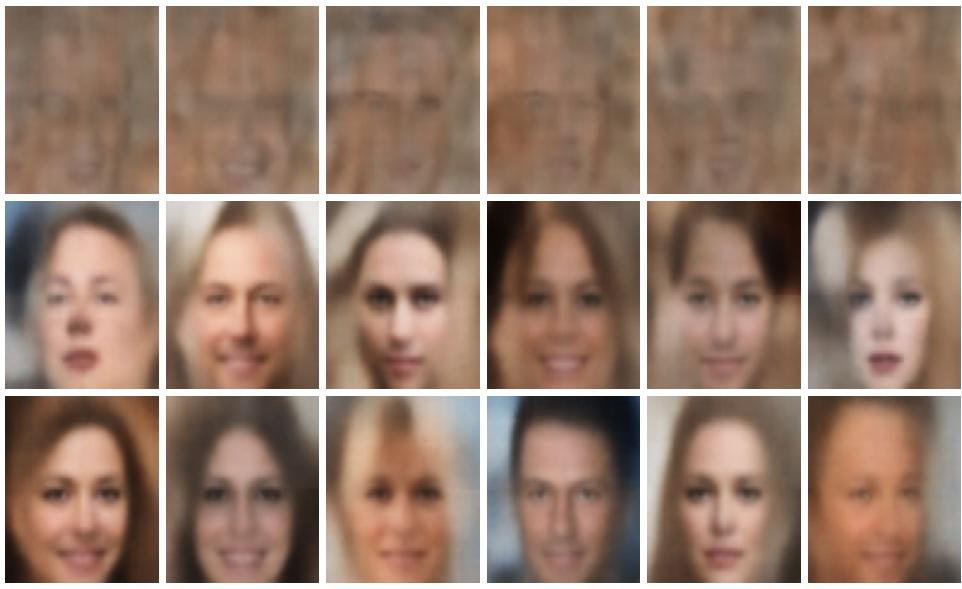

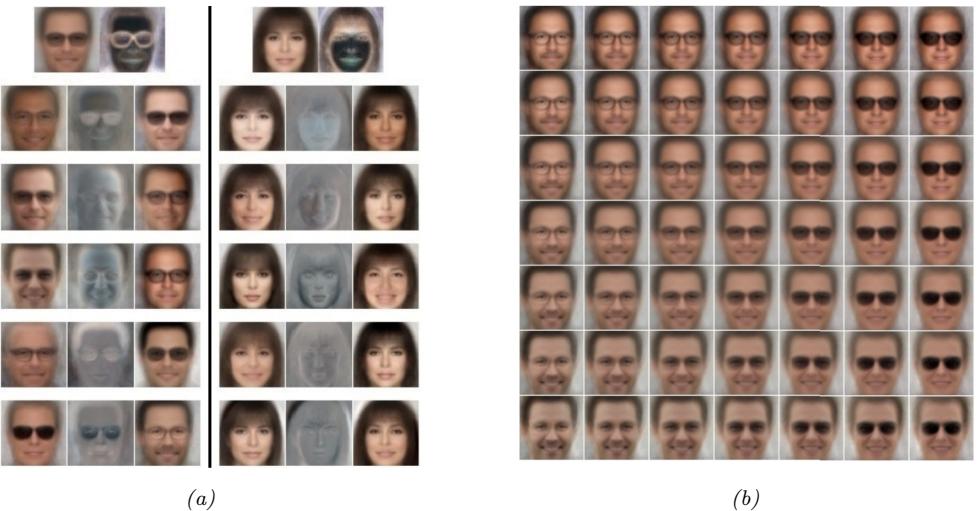

Figure 21.2: Illustration of unconditional image generation using (V)AEs trained on CelebA. Row 1: deterministic autoencoder. Row 2: ω-VAE with ω = 0.5. Row 3: VAE (with ω = 1). Generated by celeba\_vae\_ae\_comparison.ipynb.

of the decoder is the mirror image of the encoder. Each model is trained for 5 epochs with a batch size of 256, which takes about 20 minutes on a GPU.

The main advantage of a VAE over a deterministic autoencoder is that it defines a proper generative model, that can create sensible-looking novel images by decoding prior samples z ↑ N (0, I). By contrast, an autoencoder only knows how to decode latent codes derived from the training set, so does poorly when fed random inputs. This is illustrated in Figure 21.2.

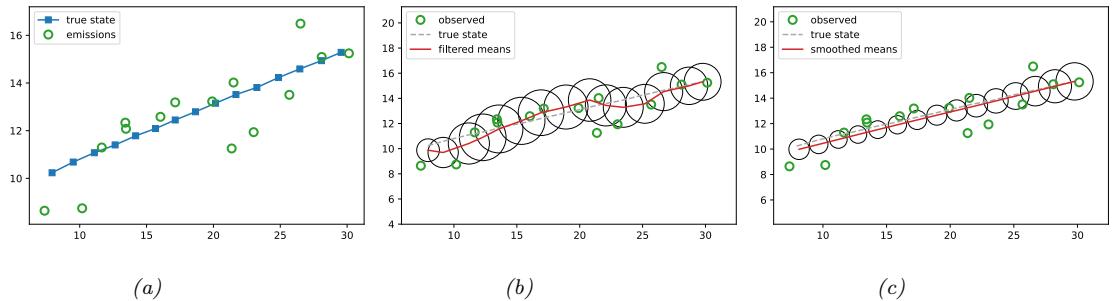

We can also use both models to reconstruct a given input image. In Figure 21.3, we see that both AE and VAE can reconstruct the input images reasonably well, although the VAE reconstructions are somewhat blurry, for reasons we discuss in Section 21.3.1. We can reduce the amount of blurriness by scaling down the KL penalty term by a factor of ε; this is known as the ε-VAE, and is discussed in more detail in Section 21.3.1.

21.2.4 VAEs optimize in an augmented space

In this section, we derive several alternative expressions for the ELBO which shed light on how VAEs work.

First, let us define the joint generative distribution

\[p\_{\theta}(x, z) = p\_{\theta}(z) p\_{\theta}(x|z) \tag{21.9}\]

Figure 21.3: Illustration of image reconstruction using (V)AEs trained and applied to CelebA. Row 1: original images. Row 2: deterministic autoencoder. Row 3: ω-VAE with ω = 0.5. Row 4: VAE (with ω = 1). Generated by celeba\_vae\_ae\_comparison.ipynb.

from which we can derive the generative data marginal

\[p\_{\theta}(x) = \int\_{x} p\_{\theta}(x, z) dz \tag{21.10}\]

and the generative posterior

\[p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}) = p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) / p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \tag{21.11}\]

Let us also define the joint inference distribution

\[q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z}) = p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z})q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})\tag{21.12}\]

where

\[p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z}) = \frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \delta(\mathbf{z}\_n - \mathbf{z}) \tag{21.13}\]

is the empirical distribution. From this we can derive the inference latent marginal, also called the aggregated posterior:

\[q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z}) = \int\_{\mathbf{z}} q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) d\mathbf{z} \tag{21.14}\]

and the inference likelihood

\[q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) = q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})/q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z})\tag{21.15}\]

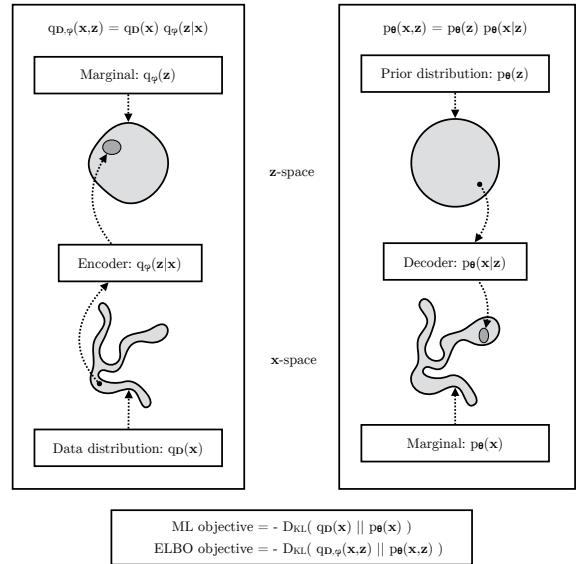

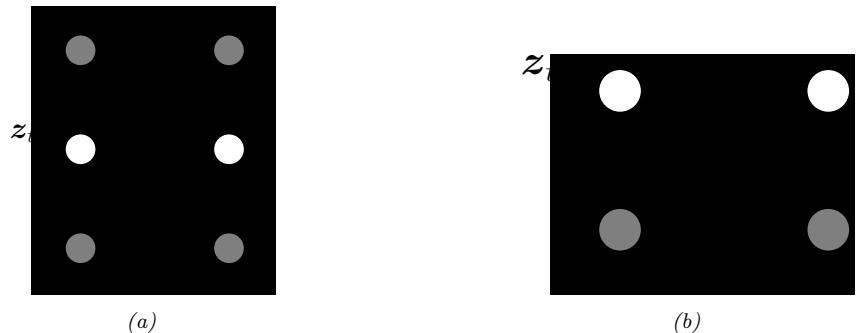

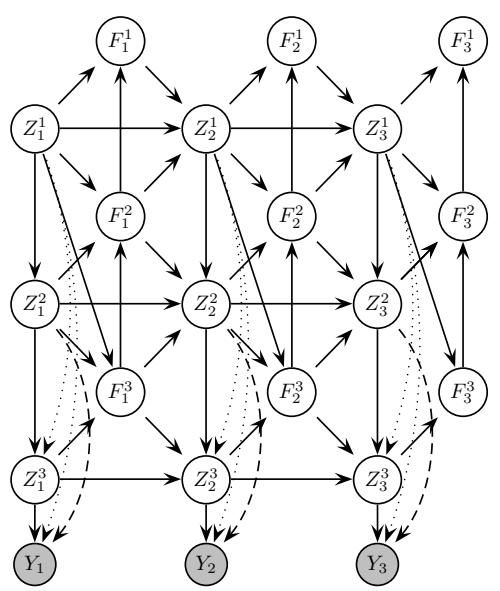

See Figure 21.4 for a visual illustration.

Having defined our terms, we can now derive various alternative versions of the ELBO, following [ZSE19]. First note that the ELBO averaged over all the data is given by

\[\mathbb{E}\left(\boldsymbol{\theta},\phi|\mathcal{D}\right) = \mathbb{E}\_{\mathsf{p}\boldsymbol{\varphi}\left(\mathbf{z}\right)}\left[\mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\boldsymbol{\Phi}}\left(\mathbf{z}\mid\mathbf{z}\right)}\left[\log p\_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{z}\mid\mathbf{z})\right]\right] - \mathbb{E}\_{\mathsf{p}\boldsymbol{\varphi}\left(\mathbf{z}\right)}\left[D\_{\mathbb{KL}}\left(q\_{\boldsymbol{\Phi}}(\mathbf{z}\mid\mathbf{z})\parallel p\_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{z})\right)\right] \tag{21.16}\]

\[=\mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})}\left[\log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) + \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) - \log q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})\right] \tag{21.17}\]

\[=\mathbb{E}\_{q\mathcal{D},\phi(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})}\left[\log\frac{p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})}{q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})}+\log p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z})\right] \tag{21.18}\]

\[\hat{\rho} = -D\_{\rm KL} \left( q\_{\mathcal{D}, \phi}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) \right) + \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z}) \right] \tag{21.19}\]

If we define c = to mean equal up to additive constants, we can rewrite the above as

\[\text{KL}(\theta, \phi | \mathcal{D}) \stackrel{c}{=} -D\_{\text{KL}}\left(q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z})\right) \tag{21.20}\]

\[\stackrel{c}{=} -D\_{\text{KL}}\left(p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})\right) - \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}\left(\mathbf{z}\right)}\left[D\_{\text{KL}}\left(q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})\right)\right] \tag{21.21}\]

Thus maximizing the ELBO requires minimizing the two KL terms. The first KL term is minimized by MLE, and the second KL term is minimized by fitting the true posterior. Thus if the posterior family is limited, there may be a conflict between these objectives.

Finally, we note that the ELBO can also be written as

\[\operatorname{KL}(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\phi} | \mathcal{D}) \stackrel{c}{=} -D\_{\operatorname{KL}}\left(q\_{\mathcal{D}, \boldsymbol{\phi}}(\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{z})\right) - \operatorname{E}\_{q\_{\mathcal{D}, \boldsymbol{\phi}}(\mathbf{z})} \left[D\_{\operatorname{KL}}\left(q\_{\boldsymbol{\phi}}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})\right)\right] \tag{21.22}\]

We see from Equation (21.22) that VAEs are trying to minimize the di!erence between the inference marginal and generative prior, DKL (qε(z) ⇐ pω(z)), while simultaneously minimizing reconstruction error, DKL (qε(x|z) ⇐ pω(x|z)) Since x is typically of much higher dimensionality than z, the latter term usually dominates. Consequently, if there is a conflict between these two objectives (e.g., due to limited modeling power), the VAE will favor reconstruction accuracy over posterior inference. Thus the learned posterior may not be a very good approximation to the true posterior (see [ZSE19] for further discussion).

21.3 VAE generalizations

In this section, we discuss some variants of the basic VAE model.

Figure 21.4: The maximum likelihood (ML) objective can be viewed as the minimization of DKL (pD(x) ↘ pω(x)). (Note: in the figure, pD(x) is denoted by qD(x).) The ELBO objective is minimization of DKL (qD,ε(x, z) ↘ pω(x, z)), which upper bounds DKL (qD(x) ↘ pω(x)). From Figure 2.4 of [KW19a]. Used with kind permission of Durk Kingma.

21.3.1 φ-VAE

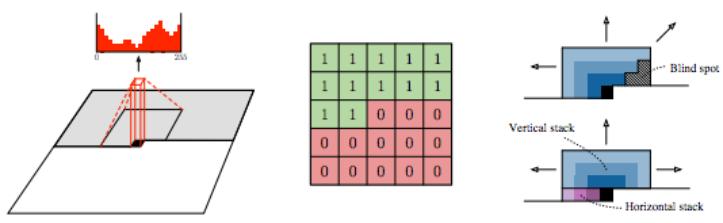

It is often the case that VAEs generate somewhat blurry images, as illustrated in Figure 21.3, Figure 21.2 and Figure 20.9. This is not the case for models that optimize the exact likelihood, such as pixelCNNs (Section 22.3.2) and flow models (Chapter 23). To see why VAEs are di!erent, consider the common case where the decoder is a Gaussian with fixed variance, so

\[\log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) = -\frac{1}{2\sigma^{2}}||\mathbf{z} - d\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})||\_{2}^{2} + \text{const} \tag{21.23}\]

Let eε(x) = E [qε(z|x)] be the encoding of x, and X (z) = {x : eε(x) = z} be the set of inputs that get mapped to z. For a fixed inference network, the optimal setting of the generator parameters, when using squared reconstruction loss, is to ensure dω(z) = E [x : x → X (z)]. Thus the decoder should predict the average of all inputs x that map to that z, resulting in blurry images.

We can solve this problem by increasing the expressive power of the posterior approximation (avoiding the merging of distinct inputs into the same latent code), or of the generator (by adding back information that is missing from the latent code), or both. However, an even simpler solution is to reduce the penalty on the KL term, making the model closer to a deterministic autoencoder:

\[\mathcal{L}\_{\beta}(\theta,\phi|x) = \underbrace{-\mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \right]}\_{\mathcal{L}\_{E}} + \beta \underbrace{D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|x) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \right)}\_{\mathcal{L}\_{R}} \tag{21.24}\]

where LE is the reconstruction error (negative log likelihood), and LR is the KL regularizer. This is

called the ε-VAE objective [Hig+17a]. If we set ε = 1, we recover the objective used in standard VAEs; if we set ε = 0, we recover the objective used in standard autoencoders.

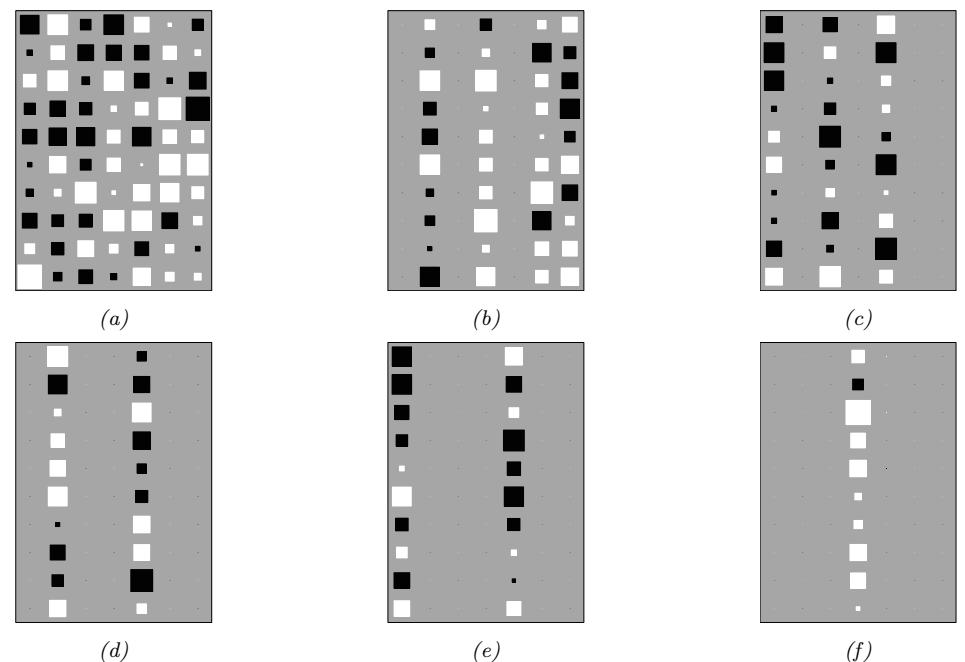

By varying ε from 0 to infinity, we can reach di!erent points on the rate distortion curve, as discussed in Section 5.4.2. These points make di!erent tradeo!s between reconstruction error (distortion) and how much information is stored in the latents about the input (rate of the corresponding code). By using ε < 1, we store more bits about each input, and hence can reconstruct images in a less blurry way. If we use ε > 1, we get a more compressed representation.

21.3.1.1 Disentangled representations

One advantage of using ε > 1 is that it encourages the learning of a latent representation that is “disentangled”. Intuitively this means that each latent dimension represents a di!erent factor of variation in the input. This is often formalized in terms of the total correlation (Section 5.3.5.1), which is defined as follows:

\[\text{TC}(\mathbf{z}) = \sum\_{k} \mathbb{H}(z\_k) - \mathbb{H}(\mathbf{z}) = D\_{\text{KL}}\left(p(\mathbf{z}) \parallel \prod\_{k} p\_k(z\_k)\right) \tag{21.25}\]

This is zero i! the components of z are all mutually independent, and hence disentangled. In [AS18], they prove that using ε > 1 will decrease the TC.

Unfortunately, in [Loc+18] they prove that nonlinear latent variable models are unidentifiable, and therefore for any disentangled representation, there is an equivalent fully entangled representation with exactly the same likelihood. Thus it is not possible to recover the correct latent representation without choosing the appropriate inductive bias, via the encoder, decoder, prior, dataset, or learning algorithm, i.e., merely adjusting ε is not su”cient. See Section 32.4.1 for more discussion.

21.3.1.2 Connection with information bottleneck

In this section, we show that the ε-VAE is an unsupervised version of the information bottleneck (IB) objective from Section 5.6. If the input is x, the hidden bottleneck is z, and the target outputs are x˜, then the unsupervised IB objective becomes

\[\mathcal{L}\_{\text{UIB}} = \beta \, \mathbb{I}(\mathbf{z}; \mathbf{z}) - \mathbb{I}(\mathbf{z}; \mathbf{\bar{z}}) \tag{21.26}\]

\[=\beta \mathbb{E}\_{p(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log \frac{p(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})}{p(\mathbf{z})p(\mathbf{z})} \right] - \mathbb{E}\_{p(\mathbf{z},\hat{\mathbf{z}})} \left[ \log \frac{p(\mathbf{z},\hat{\mathbf{z}})}{p(\mathbf{z})p(\hat{\mathbf{z}})} \right] \tag{21.27}\]

where

\[p(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}) = p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z}) p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \tag{21.28}\]

\[p(\mathbf{z}, \tilde{\mathbf{z}}) = \int p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z}) p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) p(\tilde{\mathbf{z}}|\mathbf{z}) d\mathbf{z} \tag{21.29}\]

Intuitively, the objective in Equation (21.26) means we should pick a representation z that can predict x˜ reliably, while not memorizing too much information about the input x. The tradeo! parameter is controlled by ε.

From Equation (5.181), we have the following variational upper bound on this unsupervised objective:

\[\mathcal{L}\_{\text{UVIB}} = -\mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\mathcal{D},\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \right] + \beta \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z})} \left[ D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \right) \right] \tag{21.30}\]

which matches Equation (21.24) when averaged over x.

21.3.2 InfoVAE

In Section 21.2.4, we discussed some drawbacks of the standard ELBO objective for training VAEs, namely the tendency to ignore the latent code when the decoder is powerful (Section 21.4), and the tendency to learn a poor posterior approximation due to the mismatch between the KL terms in data space and latent space (Section 21.2.4). We can fix these problems to some degree by using a generalized objective of the following form:

\[\operatorname{KL}(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \phi | \boldsymbol{x}) = -\lambda D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \right) - \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})} \left[ D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{z}) \right) \right] + \alpha \operatorname{I}\_{q}(\mathbf{z}; \mathbf{z}) \tag{21.31}\]

where ↽ ⇒ 0 controls how much we weight the mutual information Iq(x; z) between x and z, and ω ⇒ 0 controls the tradeo! between z-space KL and x-space KL. This is called the InfoVAE objective [ZSE19]. If we set ↽ = 0 and ω = 1, we recover the standard ELBO, as shown in Equation (21.22).

Unfortunately, the objective in Equation (21.31) cannot be computed as written, because of the intractable MI term:

\[\mathbb{E}\_{q}(\mathbf{z};\mathbf{z}) = \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log \frac{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})}{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})} \right] = -\mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z},\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log \frac{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})}{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})} \right] \tag{21.32}\]

However, using the fact that qε(x|z) = pD(x)qε(z|x)/qε(z), we can rewrite the objective as follows:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z})} \left[ -\lambda \log \frac{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})}{p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})} - \log \frac{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})}{p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})} - \alpha \log \frac{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})}{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})} \right] \tag{21.33}\]

\[\mathbf{E} = \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z})} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) - \log \frac{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})^{\lambda + \alpha - 1} p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathbf{z})}{p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})^{\lambda} q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})^{\alpha - 1}} \right] \tag{21.34}\]

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{E} &= \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathfrak{a})} \left[ \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\Phi}(\mathfrak{z}|\mathfrak{a})} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{z}|\mathfrak{z}) \right] \right] - (1 - \alpha) \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathfrak{a})} \left[ D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathfrak{z}|\mathfrak{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{z}) \right) \right] \\ &- (\alpha + \lambda - 1) D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathfrak{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{z}) \right) - \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathfrak{a})} \left[ \log p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathfrak{x}) \right] \end{aligned} \tag{21.35}\]

where the last term is a constant we can ignore. The first two terms can be optimized using the reparameterization trick. Unfortunately, the last term requires computing qε(z) = ” x qε(x, z)dx, which is intractable. Fortunately, we can easily sample from this distribution, by sampling x ↑ pD(x) and z ↑ qε(z|x). Thus qε(z) is an implicit probability model, similar to a GAN (see Chapter 26).

As long as we use a strict divergence, meaning D(q, p)=0 i! q = p, then one can show that this does not a!ect the optimality of the procedure. In particular, proposition 2 of [ZSE19] tells us the following:

Theorem 1. Let X and Z be continuous spaces, and ↽ < 1 (to bound the MI) and ω > 0. For any fixed value of Iq(x; z), the approximate InfoVAE loss, with any strict divergence D(qε(z), pω(z)), is globally optimized if pω(x) = pD(x) and qε(z|x) = pω(z|x).

21.3.2.1 Connection with MMD VAE

If we set ↽ = 1, the InfoVAE objective simplifies to

\[\mathbf{L} \stackrel{\circ}{=} \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathfrak{x})} \left[ \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathfrak{z}|\mathfrak{x})} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{x}|\mathfrak{z}) \right] \right] - \lambda D\_{\mathbb{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathfrak{z}) \parallel p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{z}) \right) \tag{21.36}\]

The MMD VAE3 replaces the KL divergence in the above term with the (squared) maximum mean discrepancy or MMD divergence defined in Section 2.7.3. (This is valid based on the above theorem.) The advantage of this approach over standard InfoVAE is that the resulting objective is tractable. In particular, if we set ω = 1 and swap the sign we get

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbb{E}\_{p\_{\mathcal{D}}(\mathfrak{x})} \left[ \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathfrak{z}|\mathfrak{x})} \left[ -\log p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{x}|\mathfrak{z}) \right] \right] + \text{MMD}(q\_{\phi}(\mathfrak{z}), p\_{\theta}(\mathfrak{z})) \tag{21.37}\]

As we discuss in Section 2.7.3, we can compute the MMD as follows:

\[\text{MMD}(p,q) = \mathbb{E}\_{p(\mathbf{z}), p(\mathbf{z}')} \left[ \mathbb{K}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}') \right] + \mathbb{E}\_{q(\mathbf{z}), q(\mathbf{z}')} \left[ \mathbb{K}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}') \right] - 2\mathbb{E}\_{p(\mathbf{z}), q(\mathbf{z}')} \left[ \mathbb{K}(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{z}') \right] \tag{21.38}\]

where K() is some kernel function, such as the RBF kernel, K(z, z→ ) = exp(↓ 1 2ε2 ||z↓z→ ||2 2). Intuitively the MMD measures the similarity (in latent space) between samples from the prior and samples from the aggregated posterior.

In practice, we can implement the MMD objective by using the posterior predicted mean zn = eε(xn) for all B samples in the current minibatch, and comparing this to B random samples from the N (0, I) prior.

If we use a Gaussian decoder with fixed variance, the negative log likelihood is just a squared error term:

\[-\log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}) = ||\mathbf{z} - d\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z})||\_{2}^{2} \tag{21.39}\]

Thus the entire model is deterministic, and just predicts the means in latent space and visible space.

21.3.2.2 Connection with φ-VAEs

If we set ↽ = 0 and ω = 1, we get back the original ELBO. If ω > 0 is freely chosen, but we use ↽ = 1 ↓ ω, we get the ε-VAE.

21.3.2.3 Connection with adversarial autoencoders

If we set ↽ = 1 and ω = 1, and D is chosen to be the Jensen-Shannon divergence (which can be minimized by training a binary discriminator, as explained in Section 26.2.2), then we get a model known as an adversarial autoencoder [Mak+15a].

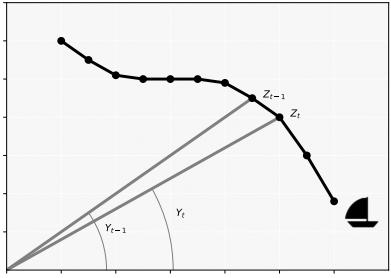

21.3.3 Multimodal VAEs

It is possible to extend VAEs to create joint distributions over di!erent kinds of variables, such as images and text. This is sometimes called a multimodal VAE or MVAE. Let us assume there are

3. Proposed in https://ermongroup.github.io/blog/a-tutorial-on-mmd-variational-autoencoders/.

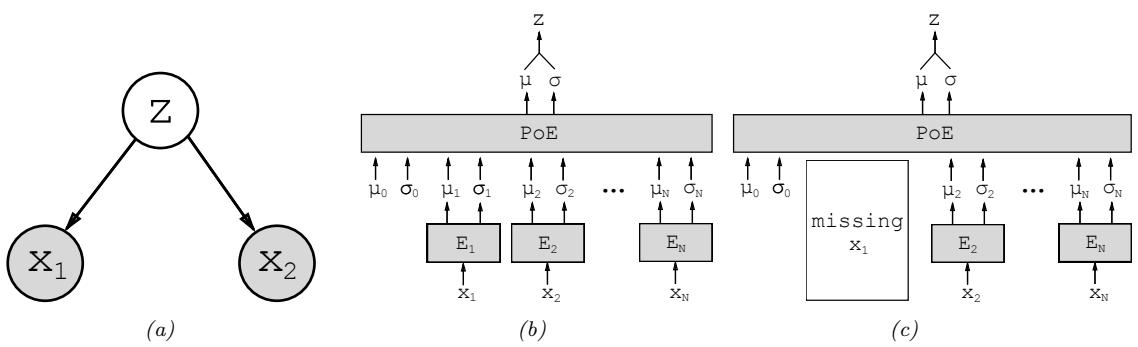

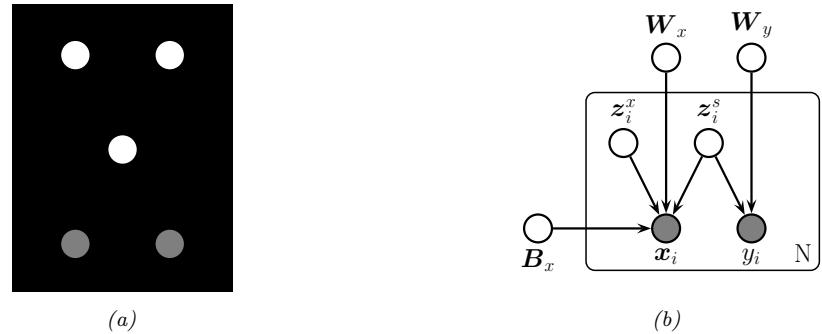

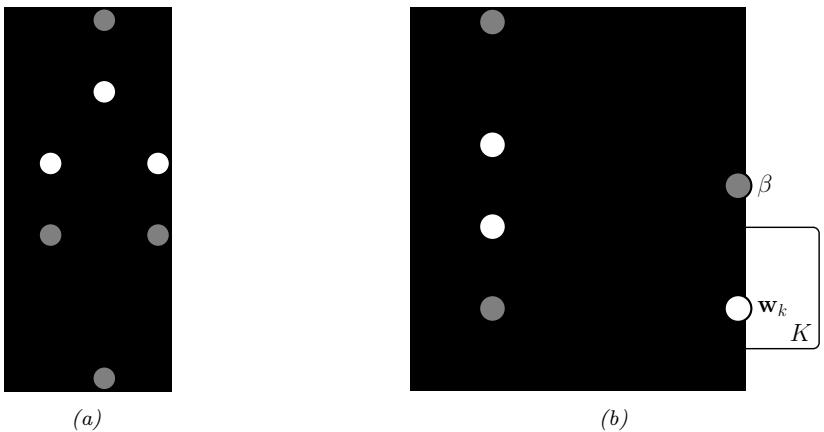

Figure 21.5: Illustration of multi-modal VAE. (a) The generative model with N = 2 modalities. (b) The product of experts (PoE) inference network is derived from N individual Gaussian experts Ei. µ0 and ε0 are parameters of the prior. (c) If a modality is missing, we omit its contribution to the posterior. From Figure 1 of [WG18]. Used with kind permission of Mike Wu.

M modalities. We assume they are conditionally independent given the latent code, and hence the generative model has the form

\[p\_{\theta}(x\_1, \ldots, x\_M, z) = p(z) \prod\_{m=1}^{M} p\_{\theta}(x\_m|z) \tag{21.40}\]

where we treat p(z) as a fixed prior. See Figure 21.5(a) for an illustration.

The standard ELBO is given by

\[\mathbb{E}(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \phi | \mathbf{X}) = \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{X})} \left[ \sum\_{m} \log p\_{\theta}(\boldsymbol{x}\_{m} | \mathbf{z}) \right] - D\_{\text{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{X}) \parallel p(\mathbf{z}) \right) \tag{21.41}\]

where X = (x1,…, xM) is the observed data. However, the di!erent likelihood terms p(xm|z) may have di!erent dynamic ranges (e.g., Gaussian pdf for pixels, and categorical pmf for text), so we introduce weight terms ωm ⇒ 0 for each likelihood. In addition, let ε ⇒ 0 control the amount of KL regularization. This gives us a weighted version of the ELBO, as follows:

\[\mathbb{E}\left(\theta,\phi|\mathbf{X}\right) = \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{X})} \left[ \sum\_{m} \lambda\_{m} \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}\_{m}|\mathbf{z}) \right] - \beta D\_{\text{KL}}\left(q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{X}) \parallel p(\mathbf{z})\right) \tag{21.42}\]

Often we don’t have a lot of paired (aligned) data from all M modalities. For example, we may have a lot of images (modality 1), and a lot of text (modality 2), but very few (image, text) pairs. So it is useful to generalize the loss so it fits the marginal distributions of subsets of the features. Let Om = 1 if modality m is observed (i.e., xm is known), and let Om = 0 if it is missing or unobserved. Let X = {xm : Om = 1} be the visible features. We now use the following objective:

\[\mathbb{E}(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \phi | \mathbf{X}) = \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{X})} \left[ \sum\_{m: O\_m = 1} \lambda\_m \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}\_m | \mathbf{z}) \right] - \beta D\_{\mathbf{KL}} \left( q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z} | \mathbf{X}) \parallel p(\mathbf{z}) \right) \tag{21.43}\]

The key problem is how to compute the posterior qε(z|X) given di!erent subsets of features. In general this can be hard, since the inference network is a discriminative model that assumes all inputs are available. For example, if it is trained on (image, text) pairs, qε(z|x1, x2), how can we compute the posterior just given an image, qε(z|x1), or just given text, qε(z|x2)? (This issue arises in general with VAE when we have missing inputs.)

Fortunately, based on our conditional independence assumption between the modalities, we can compute the optimal form for qε(z|X) given set of inputs by computing the exact posterior under the model, which is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{X}) = \frac{p(\mathbf{z})p(\mathbf{z}\_1, \dots, \mathbf{z}\_M|\mathbf{z})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_1, \dots, \mathbf{z}\_M)} = \frac{p(\mathbf{z})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_1, \dots, \mathbf{z}\_M)} \prod\_{m=1}^M p(\mathbf{z}\_m|\mathbf{z}) \tag{21.44}\]

\[=\frac{p(\mathbf{z})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_1,\ldots,\mathbf{z}\_M)}\prod\_{m=1}^M \frac{p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}\_m)p(\mathbf{x}\_m)}{p(\mathbf{z})}\tag{21.45}\]

\[\propto p(\mathbf{z}) \prod\_{m=1}^{M} \frac{p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z}\_m)}{p(\mathbf{z})} \approx p(\mathbf{z}) \prod\_{m=1}^{M} \bar{q}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}\_m) \tag{21.46}\]

This can be viewed as a product of experts (Section 24.1.1), where each q˜(z|xm) is an “expert” for the m’th modality, and p(z) is the prior. We can compute the above posterior for any subset of modalities for which we have data by modifying the product over m. If we use Gaussian distributions for the prior p(z) = N (z|µ0, #↑1 0 ) and marginal posterior ratio q˜(z|xm) = N (z|µm, #↑1 m ), then we can compute the product of Gaussians using the result from Equation (2.154):

\[\prod\_{m=0}^{M} \mathcal{N}(z|\mu\_m, \Lambda\_m^{-1}) \propto \mathcal{N}(z|\mu, \Sigma), \quad \Sigma = (\sum\_m \Lambda\_m)^{-1}, \ \mu = \Sigma(\sum\_m \Lambda\_m \mu\_m) \tag{21.47}\]

Thus the overall posterior precision is the sum of individual expert posterior precisions, and the overall posterior mean is the precision weighted average of the individual expert posterior means. See Figure 21.5(b) for an illustration. For a linear Gaussian (factor analysis) model, we can ensure q(z|xm) = p(z|xm), in which case the above solution is the exact posterior [WN18], but in general it will be an approximation.

We need to train the individual expert recognition models q(z|xm) as well as the joint model q(z|X), so the model knows what to do with fully observed as well as partially observed inputs at test time. In [Ved+18], they propose a somewhat complex “triple ELBO” objective. In [WG18], they propose the simpler approach of optimizing the ELBO for the fully observed feature vector, all the marginals, and a set of J randomly chosen joint modalities:

\[\text{KL}(\theta, \phi | \mathbf{X}) = \text{L}(\theta, \phi | (\langle x\_1, \dots, x\_M \rangle) + \sum\_{m=1}^{M} \text{L}(\theta, \phi | x\_m) + \sum\_{j \in \mathcal{J}} \text{L}(\theta, \phi | \mathbf{X}\_j) \tag{21.48}\]

This generalizes nicely to the semi-supervised setting, in which we only have a few aligned (“labeled”) examples from the joint, but have many unaligned (“unlabeled”) examples from the individual marginals. See Figure 21.5(c) for an illustration.

Note that the above scheme can only handle the case of a fixed number of missingness patterns; we can generalize to allow for arbitrary missingness as discussed in [CNW20]. (See also Section 3.11 for a more general discussion of missing data.)

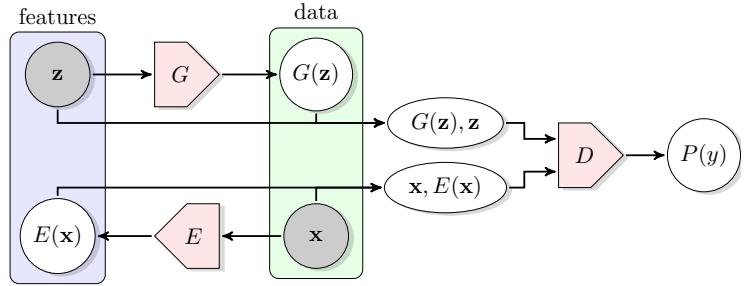

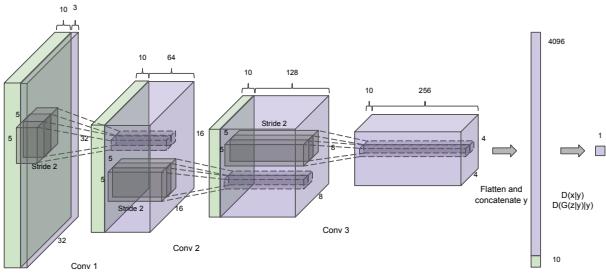

21.3.4 Semisupervised VAEs

In this section, we discuss how to extend VAEs to the semi-supervised learning setting in which we have both labeled data, DL = {(xn, yn)}, and unlabeled data, DU = {(xn)}. We focus on the M2 model, proposed in [Kin+14a].

The generative model has the following form:

\[p\_{\theta}(x,y) = p\_{\theta}(y)p\_{\theta}(x|y) = p\_{\theta}(y) \int p\_{\theta}(x|y,z)p\_{\theta}(z)dz\tag{21.49}\]

where z is a latent variable, pω(z) = N (z|0, I) is the latent prior, pω(y) = Cat(y|↼) the label prior, and pω(x|y, z) = p(x|fω(y, z)) is the likelihood, such as a Gaussian, with parameters computed by f (a deep neural network). The main innovation of this approach is to assume that data is generated according to both a latent class variable y as well as the continuous latent variable z. The class variable y is observed for labeled data and unobserved for unlabled data.

To compute the likelihood for the labeled data, pω(x, y), we need to marginalize over z, which we can do by using an inference network of the form

\[q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|y,\mathbf{z}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}|\mu\_{\phi}(y,\mathbf{z}), \text{diag}(\sigma\_{\phi}(y,\mathbf{z})) \tag{21.50}\]

We then use the following variational lower bound

\[\log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}, y) \ge \mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}, y)} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|y, \mathbf{z}) + \log p\_{\theta}(y) + \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) - \log q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}, y) \right] = -\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{x}, y) \tag{21.51}\]

as is standard for VAEs (see Section 21.2). The only di!erence is that we observe two kinds of data: x and y.

To compute the likelihood for the unlabeled data, pω(x), we need to marginalize over z and y, which we can do by using an inference network of the form

\[q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}, y|\mathbf{z}) = q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{z})q\_{\phi}(y|\mathbf{z})\tag{21.52}\]

\[q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}|\mu\_{\phi}(\mathbf{x}), \text{diag}(\sigma\_{\phi}(\mathbf{x})) \tag{21.53}\]

\[q\_{\phi}(y|\mathbf{z}) = \text{Cat}(y|\pi\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z})) \tag{21.54}\]

Note that qε(y|x) acts like a discriminative classifier, that imputes the missing labels. We then use the following variational lower bound:

\[\log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) \ge \underbrace{\mathbb{E}\_{q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}, y|\mathbf{z})} \left[ \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}|y, \mathbf{z}) + \log p\_{\theta}(y) + \log p\_{\theta}(\mathbf{z}) - \log q\_{\phi}(\mathbf{z}, y|\mathbf{z}) \right]}\_{\text{(21.55)}} \tag{21.55}\]

\[\mathcal{L} = -\sum\_{y} q\_{\phi}(y|\mathbf{z})\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{z}, y) + \mathbb{H}\left(q\_{\phi}(y|\mathbf{z})\right) = -\mathcal{U}(\mathbf{z})\tag{21.56}\]

Note that the discriminative classifier qε(y|x) is only used to compute the log-likelihood of the unlabeled data, which is undesirable. We can therefore add an extra classification loss on the supervised data, to get the following overall objective function:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \mathbb{E}\_{(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) \sim \mathcal{D}\_{L}} \left[ \mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) \right] + \mathbb{E}\_{\mathbf{z} \sim \mathcal{D}\_{U}} \left[ \mathcal{U}(\boldsymbol{x}) \right] + \alpha \mathbb{E}\_{(\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}) \sim \mathcal{D}\_{L}} \left[ -\log q\_{\boldsymbol{\phi}}(\boldsymbol{y}|\boldsymbol{x}) \right] \tag{21.57}\]

where DL is the labeled data, DU is the unlabeled data, and ↽ is a hyperparameter that controls the relative weight of generative and discriminative learning.

y y y y y

1 2 3 Nmax-1 Nmax

’ ’ ’

GMM, softmax sample τ

GMM, softmax sample τ

GMM, softmax sample τ

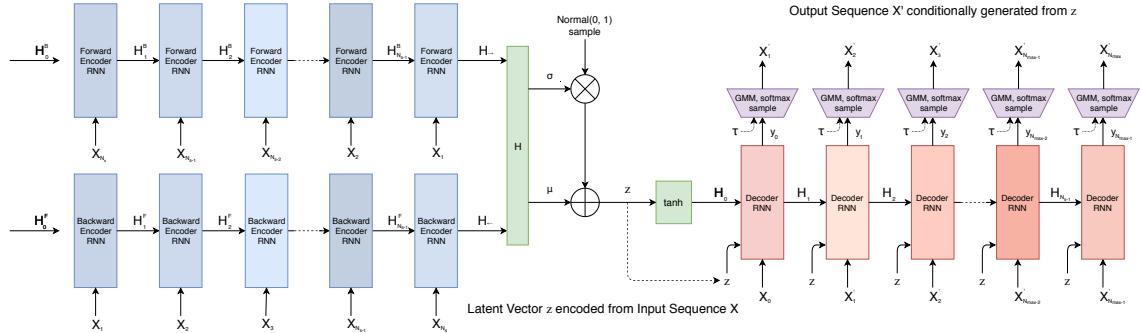

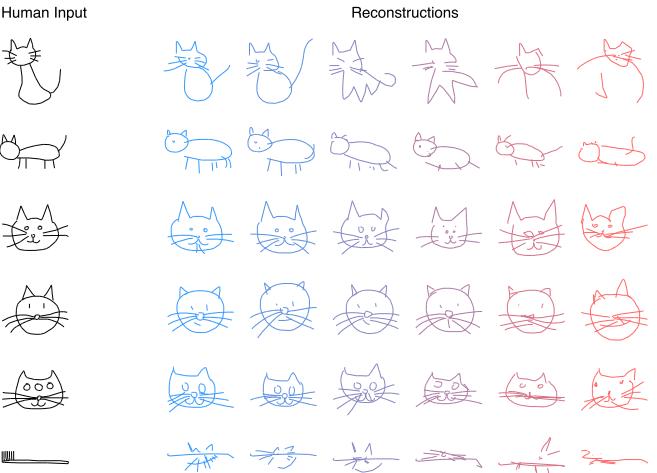

h Backward Encoder h← 0 Backward Encoder Backward Encoder Backward Encoder Backward Encoder N(0, I) sample Output Sequence S’ conditionally generated from z B h 1 B h 2 B hNs-1 B S1 S2 S3 SNmax-1 ’ ’ ’ ’ SNmax ’ Figure 21.6: Illustration of a VAE with a bidirectional RNN encoder and a unidirectional RNN decoder. The output generator can use a GMM and/or softmax distribution. From Figure 2 of [HE18]. Used with kind permission of David Ha.

GMM, softmax sample

GMM, softmax sample τ

’

τ

σ

S S h Ns Ns-1 SNs-2 S2 S1 21.3.5 VAEs with sequential encoders/decoders

RNN

RNN

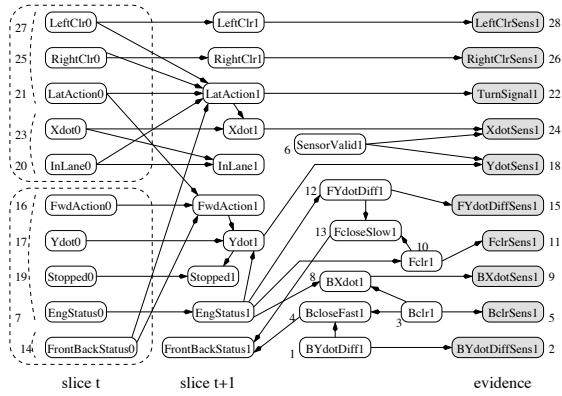

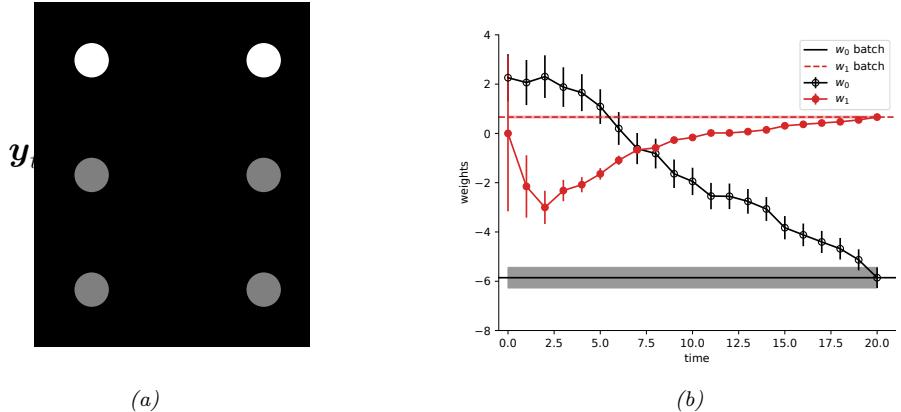

Decoder RNN Decoder RNN Decoder RNN Decoder RNN z Decoder RNN Forward Encoder RNN Forward Encoder RNN Forward Encoder RNN Forward Encoder RNN Forward Encoder RNN z tanh z z z z Latent Vector z encoded from Input Sequence S S1 S2 S3 SNs-1 SNs h h→ 0 F h 1 F h 2 F hNs-1 F S0 S1 S2 SNmax-2 SNmax-1 h 0 h 1 h 2 hNs-1 μ In this section, we discuss VAEs for sequential data, such as text and biosequences, in which the data x is a variable-length sequence, but we have a fixed-sized latent variable z → RK. (We consider the more general case in which z is a variable-length sequence of latents — known as sequential VAE or dynamic VAE — in Section 29.13.) All we have to do is modify the decoder p(x|z) and encoder q(z|x) to work with sequences.

21.3.5.1 Models

RNN

RNN

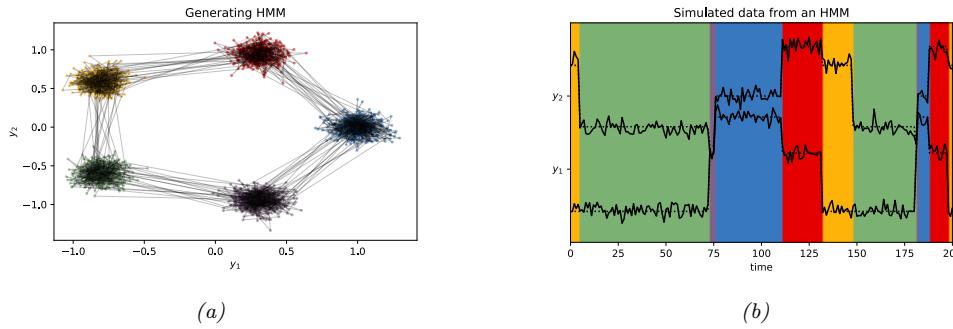

RNN

If we use an RNN for the encoder and decoder of a VAE, we get a model which is called a VAE-RNN, as proposed in [Bow+16a]. In more detail, the generative model is p(z, x1:T ) = p(z)RNN(x1:T |z), where z can be injected as the initial state of the RNN, or as an input to every time step. The inference model is q(z|x1:T ) = N (z|µ(h), “(h)), where h = [h↘ T , h≃ 1 ] is the output of a bidirectional RNN applied to x1:T . See Figure 21.6 for an illustration.

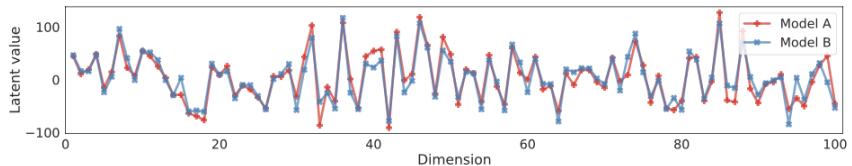

More recently, people have tried to combine transformers with VAEs. For example, in the Optimus model of [Li+20], they use a BERT model for the encoder. In more detail, the encoder q(z|x) is derived from the embedding vector associated with a dummy token corresponding to the “class label” which is appended to the input sequence x. The decoder is a standard autoregressive model (similar to GPT), with one additional input, namely the latent vector z. They consider two ways of injecting the latent vector. The simplest approach is to add z to the embedding layer of every token in the decoding step, by defining h→ i = hi + Wz, where hi → RH is the original embedding for the i’th token, and W → RH⇐K is a decoding matrix, where K is the size of the latent vector. However, they get better results in their experiments by letting all the layers of the decoder attend to the latent code z. An easy way to do this is to define the memory vector hm = Wz, where W → RLH⇐K, where L is the number of layers in the decoder, and then to append hm → RL⇐H to all the other embeddings at each layer.

An alternative approach, known as transformer VAE, was proposed in [Gre20]. This model uses a funnel transformer [Dai+20b] as the encoder, and the T5 [Raf+20a] conditional transformer for

he was silent for a long moment .

he was silent for a moment .

it was quiet for a moment .

it was dark and cold .

there was a pause .

it was my turn .

i went to the store to buy some groceries .

i store to buy some groceries .

i were to buy any groceries .

horses are to buy any groceries .

horses are to buy any animal .

horses the favorite any animal .

horses the favorite favorite animal .

horses are my favorite animal .(a)

(b)

Figure 21.7: (a) Samples from the latent space of a VAE text model, as we interpolate between two sentences (on first and last line). Note that the intermediate sentences are grammatical, and semantically related to their neighbors. From Table 8 of [Bow+16b]. (b) Same as (a), but now using a deterministic autoencoder (with the same RNN encoder and decoder). From Table 1 of [Bow+16b]. Used with kind permission of Sam Bowman.

the decoder. In addition, it uses an MMD VAE (Section 21.3.2.1) to avoid posterior collapse.

21.3.5.2 Applications

In this section, we discuss some applications of VAEs to sequence data.

Text