Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics

Part II

Inference

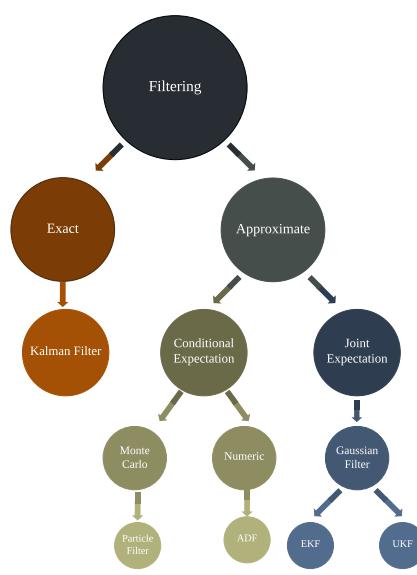

7 Inference algorithms: an overview

7.1 Introduction

In the probabilistic approach to machine learning, all unknown quantities — be they predictions about the future, hidden states of a system, or parameters of a model — are treated as random variables, and endowed with probability distributions. The process of inference corresponds to computing the posterior distribution over these quantities, conditioning on whatever data is available.

In more detail, let ω represent the unknown variables, and D represent the known variables. Given a likelihood p(D|ω) and a prior p(ω), we can compute the posterior p(ω|D) using Bayes’ rule:

\[p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) = \frac{p(\boldsymbol{\theta})p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta})}{p(\mathcal{D})} \tag{7.1}\]

The main computational bottleneck is computing the normalization constant in the denominator, which requires solving the following high dimensional integral:

\[p(\mathcal{D}) = \int p(\mathcal{D}|\theta)p(\theta)d\theta \tag{7.2}\]

This is needed to convert the unnormalized joint probability of some parameter value, p(ω, D), to a normalized probability, p(ω|D), which takes into account all the other plausible values that ω could have.

Once we have the posterior, we can use it to compute posterior expectations of some function of the unknown variables, i.e.,

\[\mathbb{E}\left[g(\theta)|\mathcal{D}\right] = \int g(\theta)p(\theta|\mathcal{D})d\theta\tag{7.3}\]

By defining g in the appropriate way, we can compute many quantities of interest, such as the following:

\[\text{mean: } g(\theta) = \theta\]

\[\text{covariance: } g(\theta) = (\theta - \mathbb{E}\left[\theta | \mathcal{D}\right])(\theta - \mathbb{E}\left[\theta | \mathcal{D}\right])^{\mathsf{T}} \tag{7.5}\]

\[\text{marginals: } g(\theta) = p(\theta\_1 = \theta\_1^\* | \theta\_{2:D}) \tag{7.6}\]

\[\text{preactive: } g(\theta) = p(\mathbf{y}\_{N+1}|\theta) \tag{7.7}\]

\[\text{expected loss: } g(\theta) = \ell(\theta, a) \tag{7.8}\]

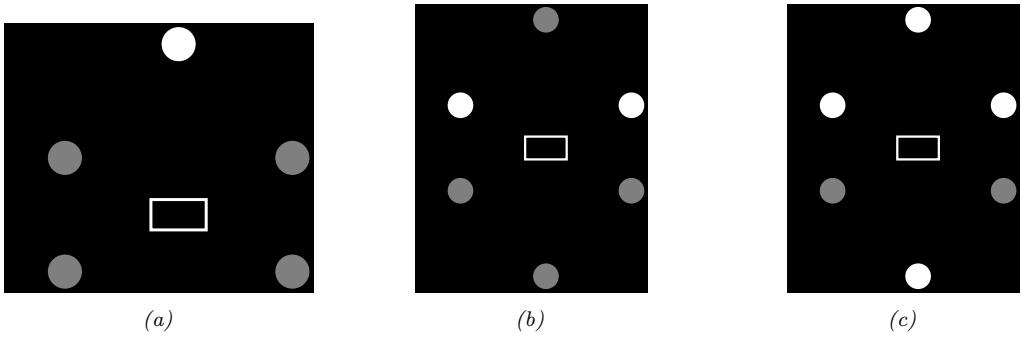

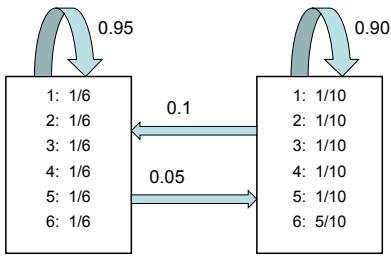

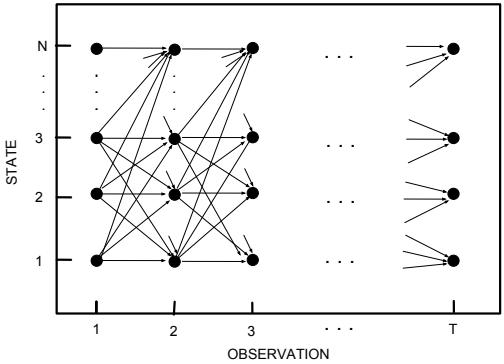

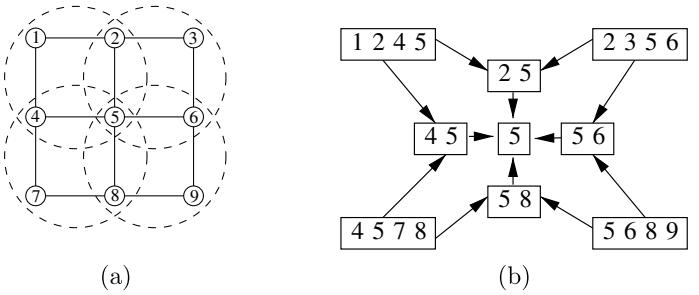

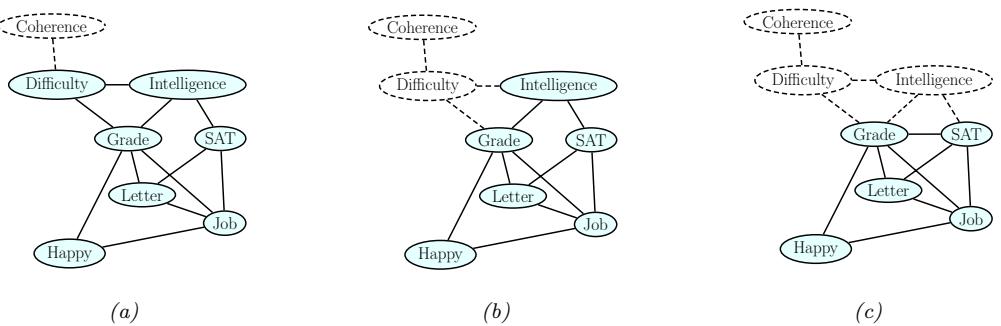

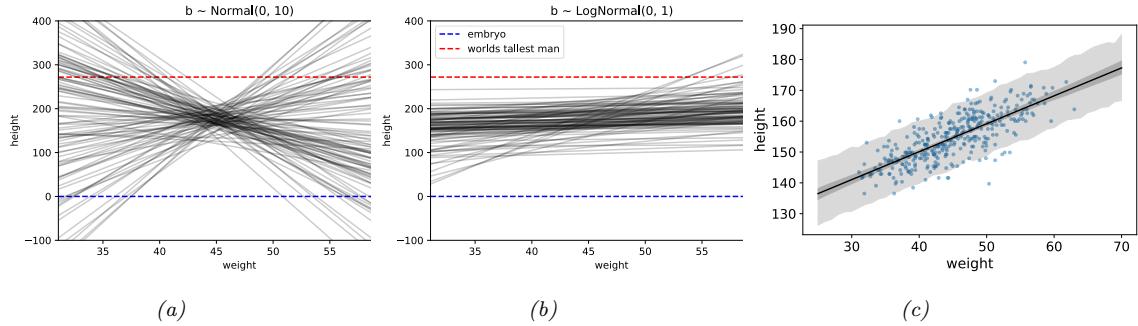

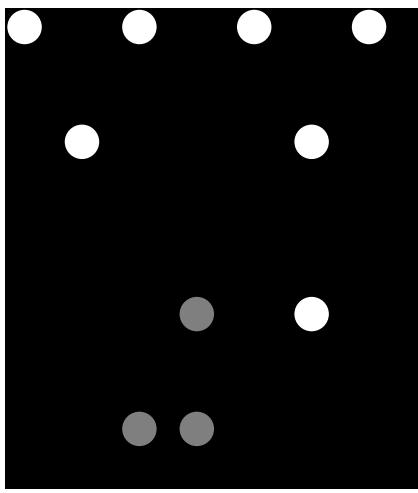

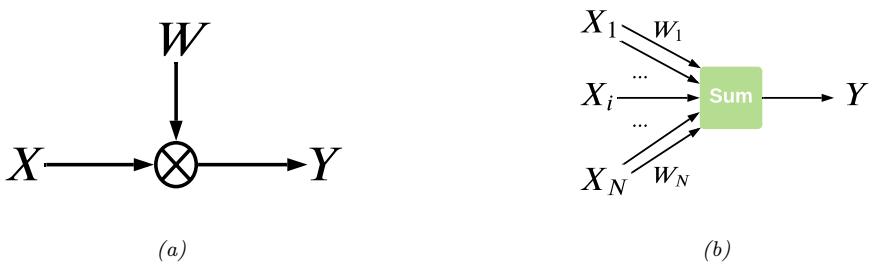

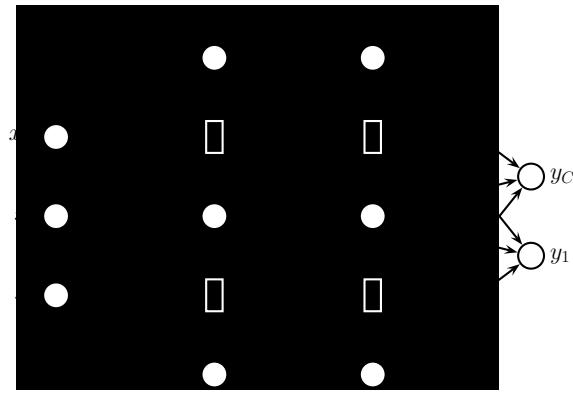

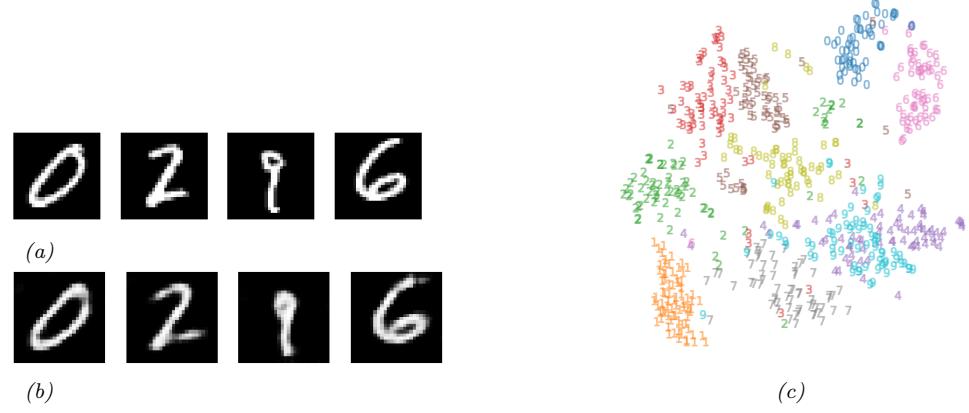

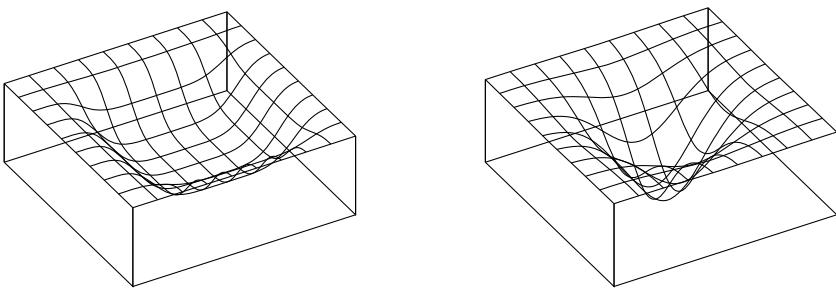

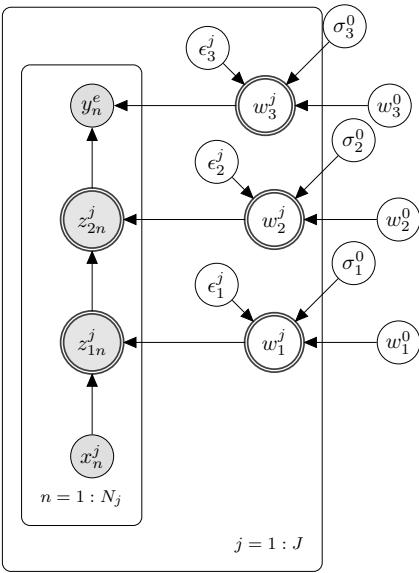

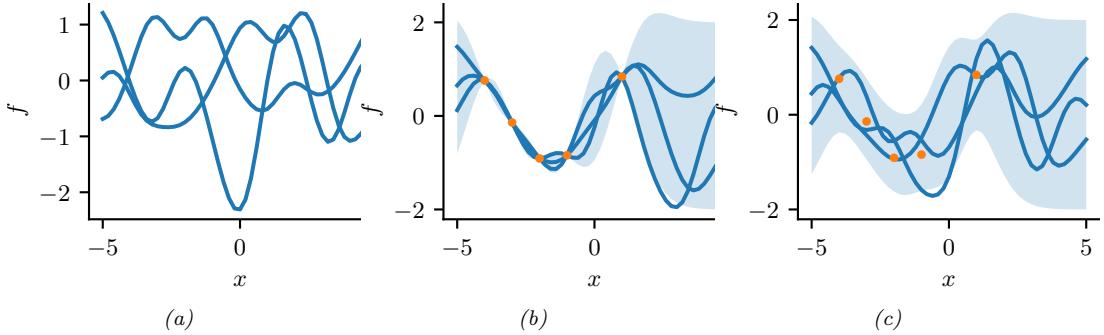

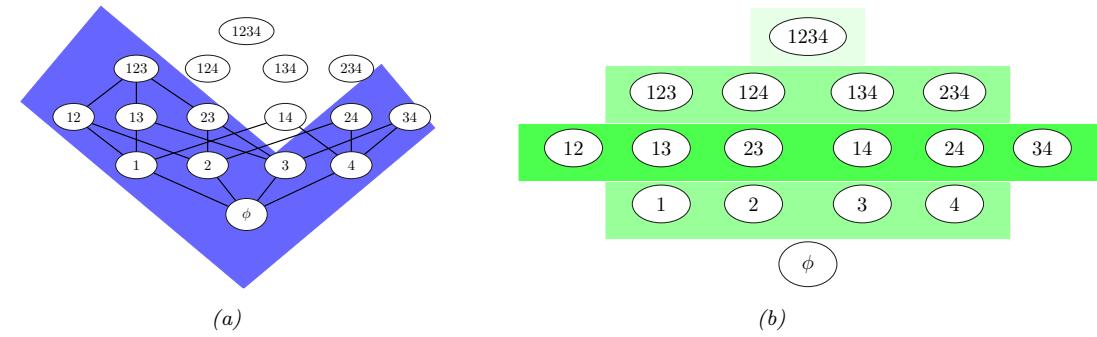

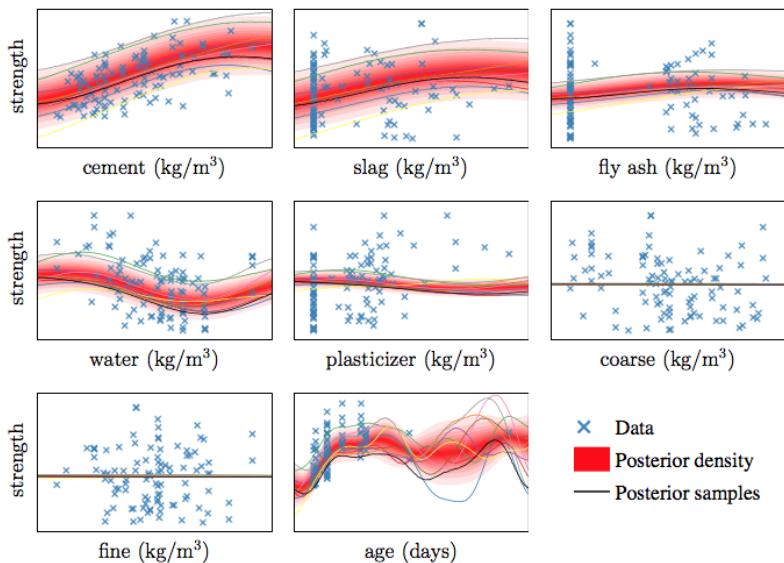

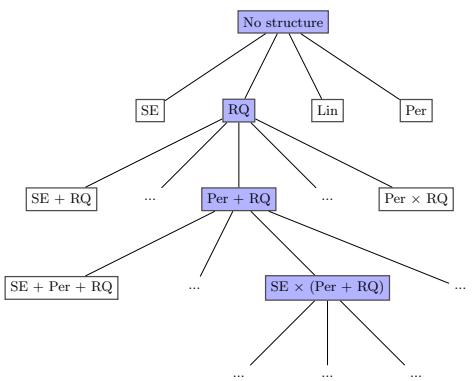

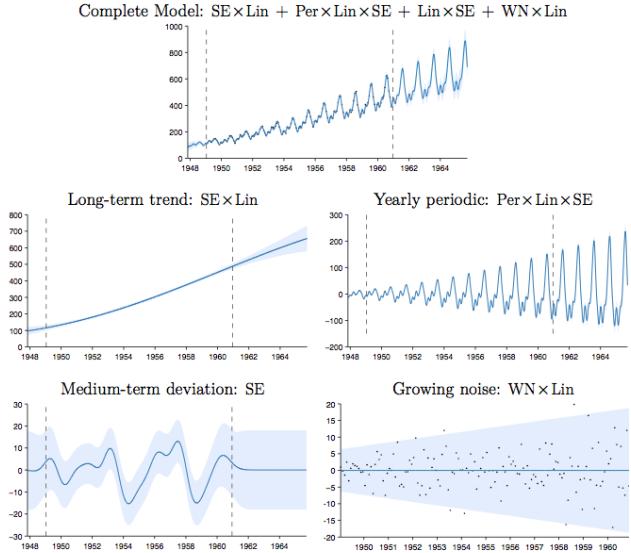

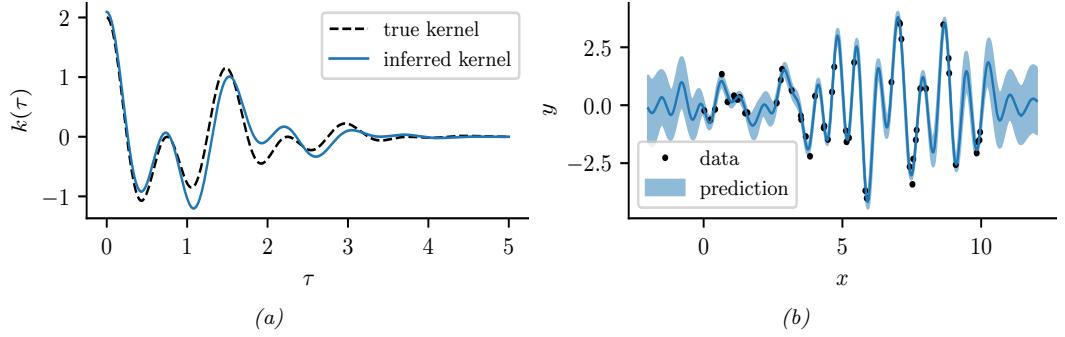

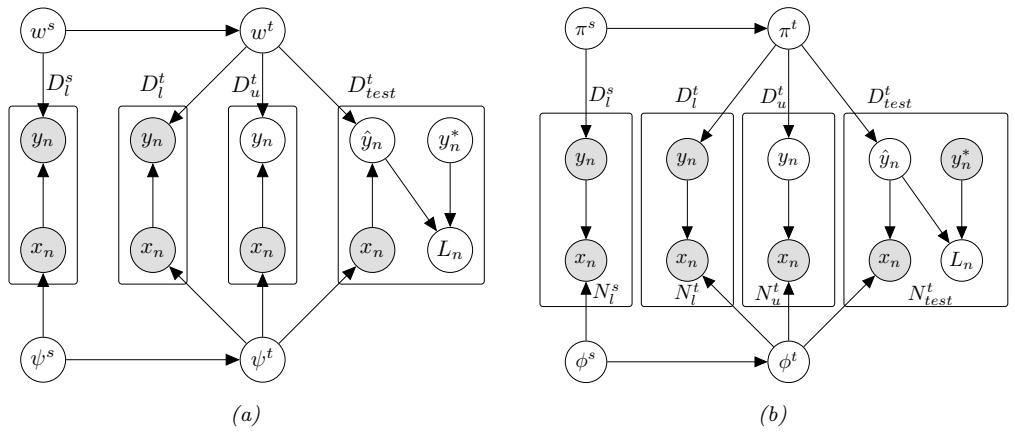

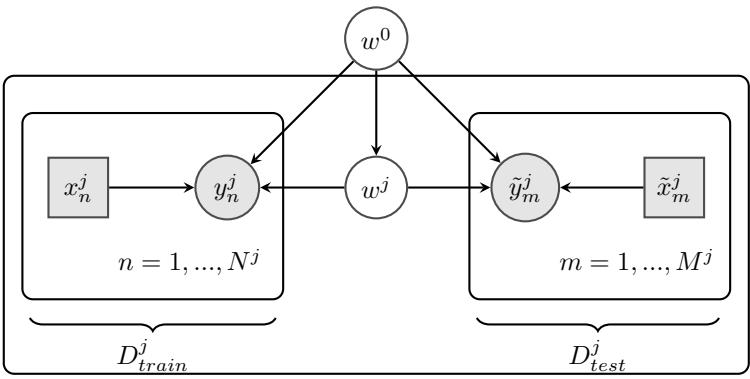

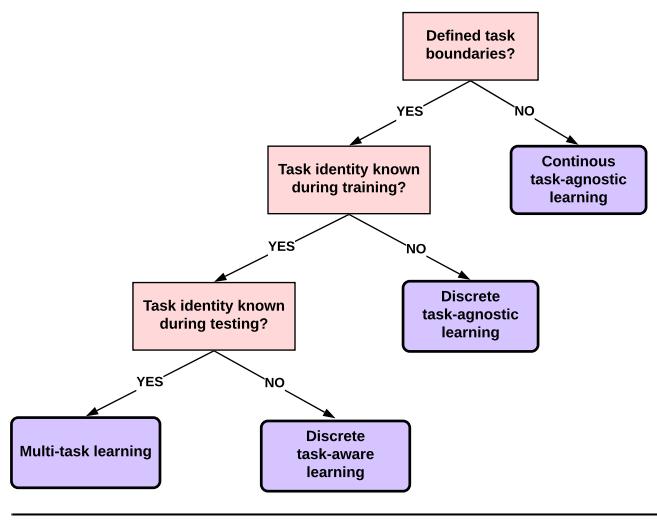

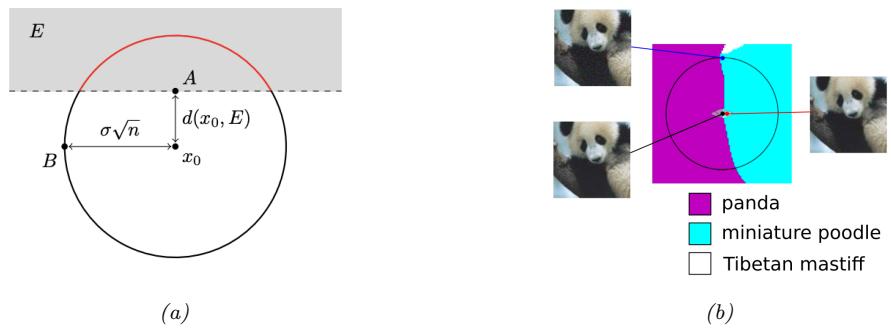

Figure 7.1: Graphical models with (a) global hidden variables for representing the Bayesian discriminative model p(y1:N , ωy|x1:N ) = p(ωy) !N n=1 p(yn|xn; ωy); (b) local hidden variables for representing the generative model p(x1:N , z1:N |ω) = !N n=1 p(zn|ωz)p(xn|zn, ωx); (c) local and global hidden variables for representing the Bayesian generative model p(x1:N , z1:N , ω) = p(ωz)p(ωx) !N n=1 p(zn|ωz)p(xn|zn, ωx). Shaded nodes are assumed to be known (observed), unshaded nodes are hidden.

where yN+1 is the next observation after seeing the N examples in D, and the posterior expected loss is computing using loss function ε and action a (see Section 34.1.3). Finally, if we define g(ω) = p(D|ω, M) for model M, we can also phrase the marginal likelihood (Section 3.8.3) as an expectation wrt the prior:

\[\mathbb{E}\left[g(\theta)|M\right] = \int g(\theta)p(\theta|M)d\theta = \int p(\mathcal{D}|\theta,M)p(\theta|M)d\theta = p(\mathcal{D}|M) \tag{7.9}\]

Thus we see that integration (and computing expectations) is at the heart of Bayesian inference, whereas di!erentiation is at the heart of optimization.

In this chapter, we give a high level summary of algorithmic techniques for computing (approximate) posteriors, and/or their corresponding expectations. We will give more details in the following chapters. Note that most of these methods are independent of the specific model. This allows problem solvers to focus on creating the best model possible for the task, and then relying on some inference engine to do the rest of the work — this latter process is sometimes called “turning the Bayesian crank”. For more details on Bayesian computation, see e.g., [Gel+14a; MKL21; MFR20].

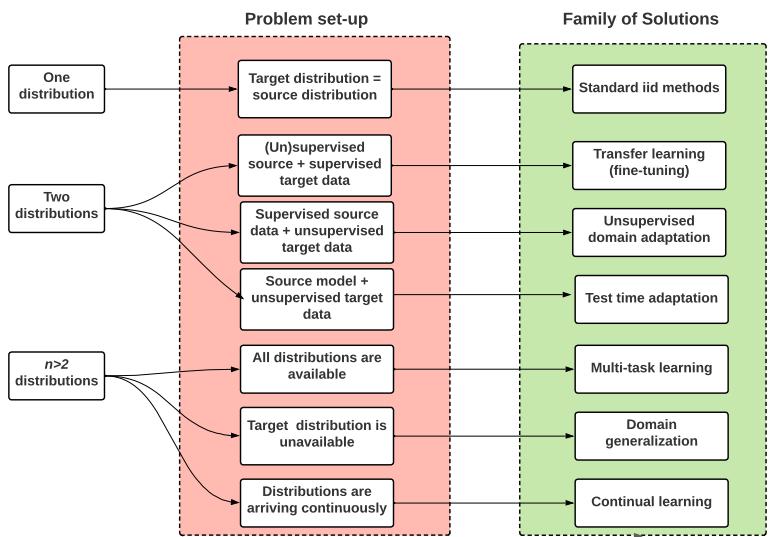

7.2 Common inference patterns

There are kinds of posterior we may want to compute, but we can identify 3 main patterns, as we discuss below. These give rise to di!erent types of inference algorithm, as we will see in later chapters.

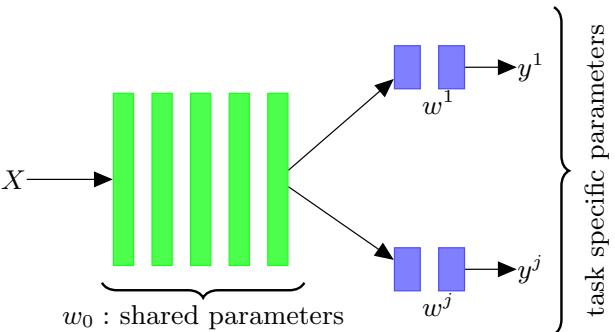

7.2.1 Global latents

The first pattern arises when we need to perform inference in models which have global latent variables, such as parameters of a model ω, which are shared across all N observed training cases. This is shown in Figure 7.1a, and corresponds to the usual setting for supervised or discriminative

learning, where the joint distribution has the form

\[p(\mathbf{y}\_{1:N}, \boldsymbol{\theta} | \boldsymbol{x}\_{1:N}) = p(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \left[ \prod\_{n=1}^{N} p(\mathbf{y}\_n | \boldsymbol{x}\_n, \boldsymbol{\theta}) \right] \tag{7.10}\]

The goal is to compute the posterior p(ω|x1:N , y1:N ). Most of the Bayesian supervised learning models discussed in Part III follow this pattern.

7.2.2 Local latents

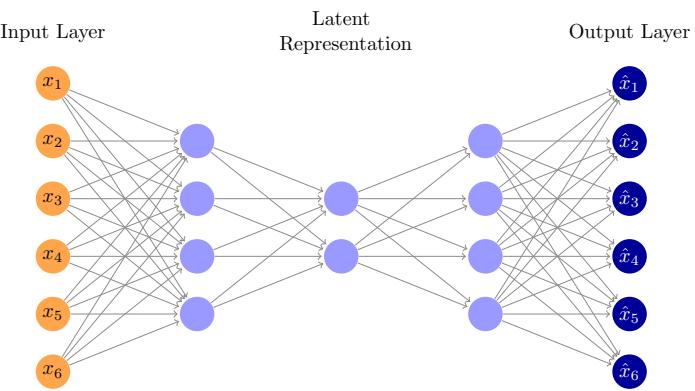

The second pattern arises when we need to perform inference in models which have local latent variables, such as hidden states z1:N ; we assume the model parameters ω are known. This is shown in Figure 7.1b. Now the joint distribution has the form

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{1:N}, \mathbf{z}\_{1:N} | \boldsymbol{\theta}) = \left[ \prod\_{n=1}^{N} p(\mathbf{z}\_n | \mathbf{z}\_n, \boldsymbol{\theta}\_x) p(\mathbf{z}\_n | \boldsymbol{\theta}\_z) \right] \tag{7.11}\]

The goal is to compute p(zn|xn, ω) for each n. This is the setting we consider for most of the PGM inference methods in Chapter 9.

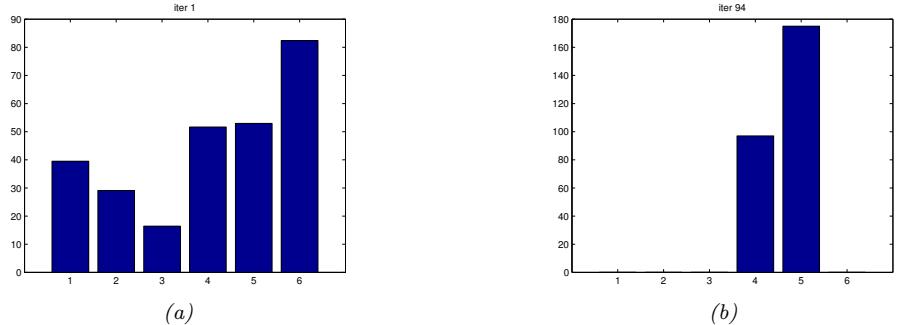

If the parameters are not known (which is the case for most latent variable models, such as mixture models), we may choose to estimate them by some method (e.g., maximum likelihood), and then plug in this point estimate. The advantage of this approach is that, conditional on ω, all the latent variables are conditionally independent, so we can perform inference in parallel across the data. This lets us use methods such as expectation maximization (Section 6.5.3), in which we infer p(zn|xn, ωt) in the E step for all n simultaneously, and then update ωt in the M step. If the inference of zn cannot be done exactly, we can use variational inference, a combination known as variational EM (Section 6.5.6.1).

Alternatively, we can use a minibatch approximation to the likelihood, marginalizing out zn for each example in the minibatch to get

\[\log p(\mathcal{D}\_t | \theta\_t) = \sum\_{n \in \mathcal{D}\_t} \log \left[ \sum\_{\mathbf{z}\_n} p(\mathbf{z}\_n, \mathbf{z}\_n | \theta\_t) \right] \tag{7.12}\]

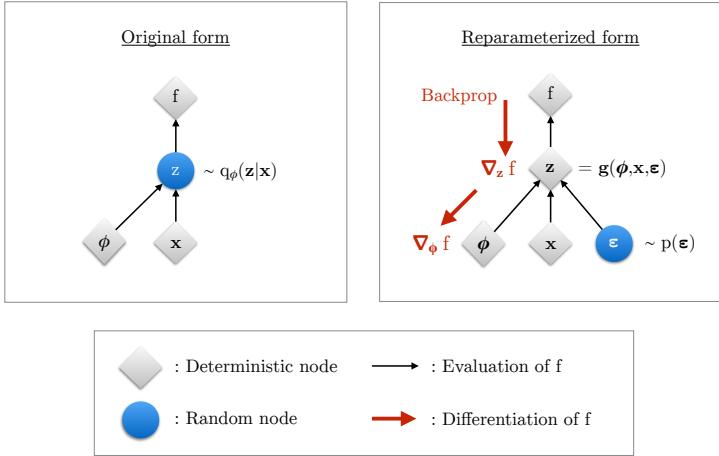

where Dt is the minibatch at step t. If the marginalization cannot be done exactly, we can use variational inference, a combination known as stochastic variational inference or SVI (Section 10.1.4). We can also learn an inference network qω(z|x; ω) to perform the inference for us, rather than running an inference engine for each example n in each batch t; the cost of learning ε can be amortized across the batches. This is called amortized SVI (see Section 10.1.5).

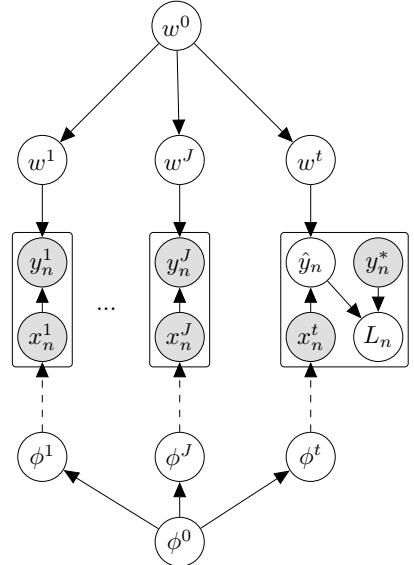

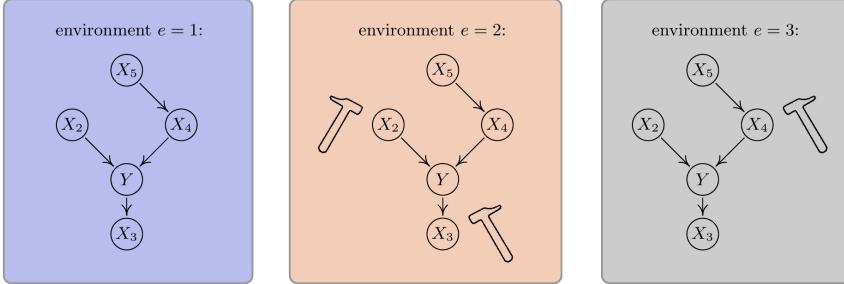

7.2.3 Global and local latents

The third pattern arises when we need to perform inference in models which have local and global latent variables. This is shown in Figure 7.1c, and corresponds to the following joint distribution:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{1:N}, \mathbf{z}\_{1:N}, \boldsymbol{\theta}) = p(\boldsymbol{\theta}\_x) p(\boldsymbol{\theta}\_z) \left[ \prod\_{n=1}^N p(\mathbf{z}\_n | \mathbf{z}\_n, \boldsymbol{\theta}\_x) p(\mathbf{z}\_n | \boldsymbol{\theta}\_z) \right] \tag{7.13}\]

This is essentially a Bayesian version of the latent variable model in Figure 7.1b, where now we model uncertainty in both the local variables zn and the shared global variables ω. This approach is less common in the ML community, since it is often assumed that the uncertainty in the parameters ω is negligible compared to the uncertainty in the local variables zn. The reason for this is that the parameters are “informed” by all N data cases, whereas each local latent zn is only informed by a single datapoint, namely xn. Nevertheless, there are advantages to being “fully Bayesian”, and modeling uncertainty in both local and global variables. We will see some examples of this later in the book.

7.3 Exact inference algorithms

In some cases, we can perform example posterior inference in a tractable manner. In particular, if the prior is conjugate to the likelihood, the posterior will be analytically tractable. In general, this will be the case when the prior and likelihood are from the same exponential family (Section 2.4). In particular, if the unknown variables are represented by ω, then we assume

\[p(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \propto \exp(\boldsymbol{\lambda}\_0^\mathsf{T} \boldsymbol{\tau}(\boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{7.14}\]

\[p(y\_i|\theta) \propto \exp(\tilde{\lambda}\_i(y\_i)^\mathsf{T}\mathcal{T}(\theta))\tag{7.15}\]

where T (ω) are the su”cient statistics, and ϑ are the natural parameters. We can then compute the posterior by just adding the natural parameters:

\[p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{y}\_{1:N}) = \exp(\boldsymbol{\lambda}\_{\*}^{\mathsf{T}}\mathcal{T}(\boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{7.16}\]

\[ \lambda\_\* = \lambda\_0 + \sum\_{n=1}^N \bar{\lambda}\_n(y\_n) \tag{7.17} \]

See Section 3.4 for details.

Another setting where we can compute the posterior exactly arises when the D unknown variables are all discrete, each with K states; in this case, the integral for the normalizing constant becomes a sum with KD terms. In many cases, KD will be too large to be tractable. However, if the distribution satisfies certain conditional independence properties, as expressed by a probabilistic graphical model (PGM), then we can write the joint as a product of local terms (see Chapter 4). This lets us use dynamic programming to make the computation tractable (see Chapter 9).

7.4 Approximate inference algorithms

For most probability models, we will not be able to compute marginals or posteriors exactly, so we must resort to using approximate inference. There are many di!erent algorithms, which trade o! speed, accuracy, simplicity, and generality. We briefly discuss some of these algorithms below, and give more detail in the following chapters. (See also [Alq22; MFR20] for a review of various methods.)

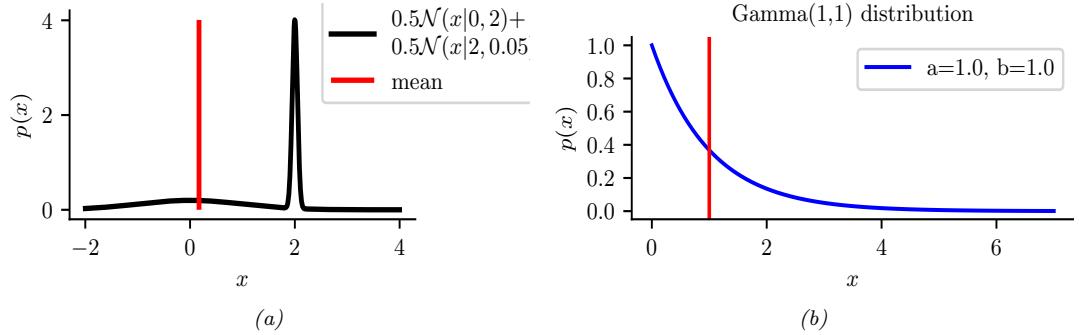

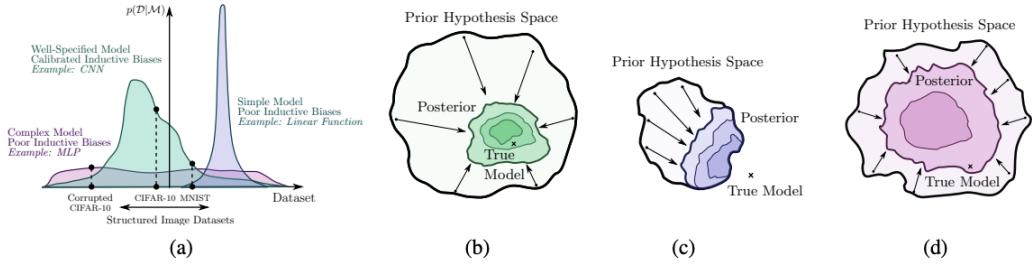

Figure 7.2: Two distributions in which the mode (highest point) is untypical of the distribution; the mean (vertical red line) is a better summary. (a) A bimodal distribution. Generated by bimodal\_dist\_plot.ipynb. (b) A skewed Ga(1, 1) distribution. Generated by gamma\_dist\_plot.ipynb.

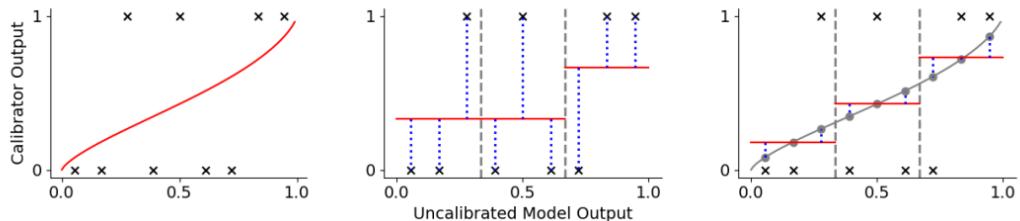

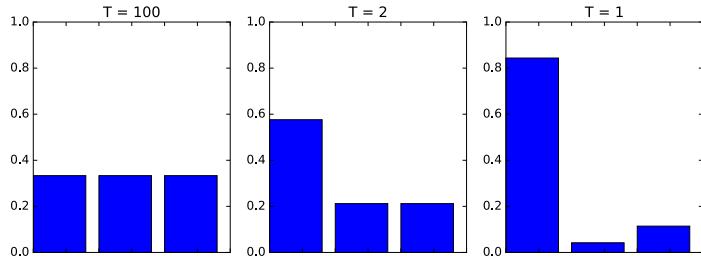

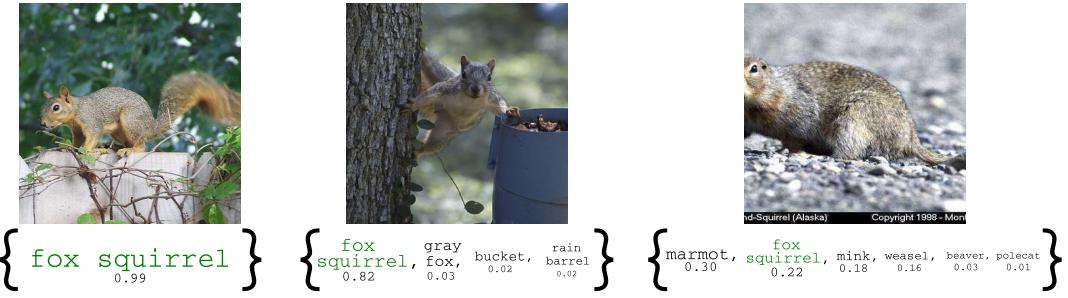

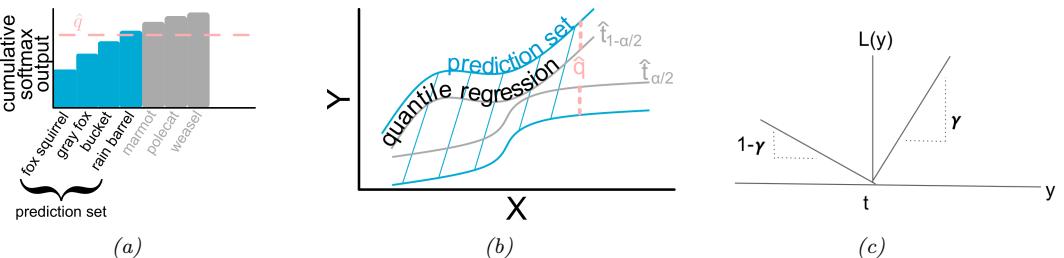

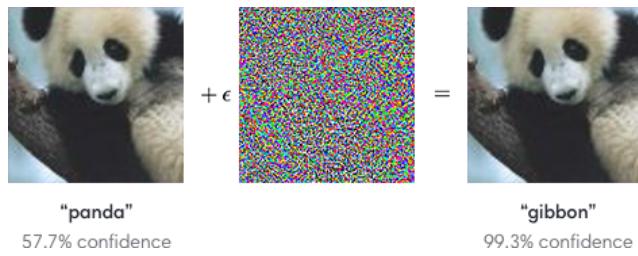

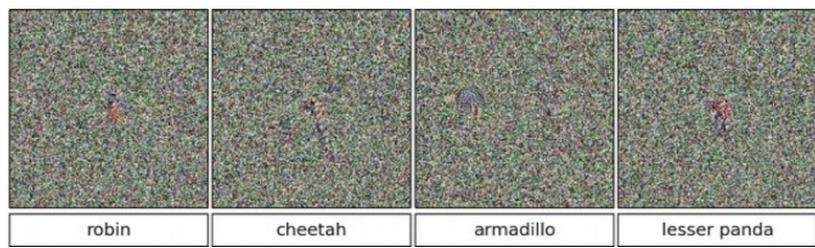

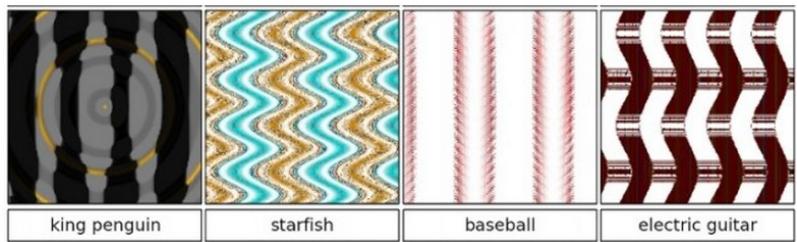

7.4.1 The MAP approximation and its problems

The simplest approximate inference method is to compute the MAP estimate

\[\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}} = \operatorname{argmax} p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) = \operatorname{argmax} \log p(\boldsymbol{\theta}) + \log p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta}) \tag{7.18}\]

and then to assume that the posterior puts 100% of its probability on this single value:

\[p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) \approx \delta(\boldsymbol{\theta} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}) \tag{7.19}\]

The advantage of this approach is that we can compute the MAP estimate using a variety of optimization algorithms, which we discuss in Chapter 6. However, the MAP estimate also has various drawbacks, some of which we discuss below.

7.4.1.1 The MAP estimate gives no measure of uncertainty

In many statistical applications (especially in science) it is important to know how much one can trust a given parameter estimate. Obviously a point estimate does not convey any notion of uncertainty. Although it is possible to derive frequentist notions of uncertainty from a point estimate (see Section 3.3.1), it is arguably much more natural to just compute the posterior, from which we can derive useful quantities such as the standard error (see Section 3.2.1.6) and credible regions (see Section 3.2.1.7).

In the context of prediction (which is the main focus in machine learning), we saw in Section 3.2.2 that plugging in a point estimate can underestimate the predictive uncertainty, which can result in predictions which are not just wrong, but confidently wrong. It is generally considered very important for a predictive model to “know what it does not know”, and the Bayesian approach is a good strategy for achieving this goal.

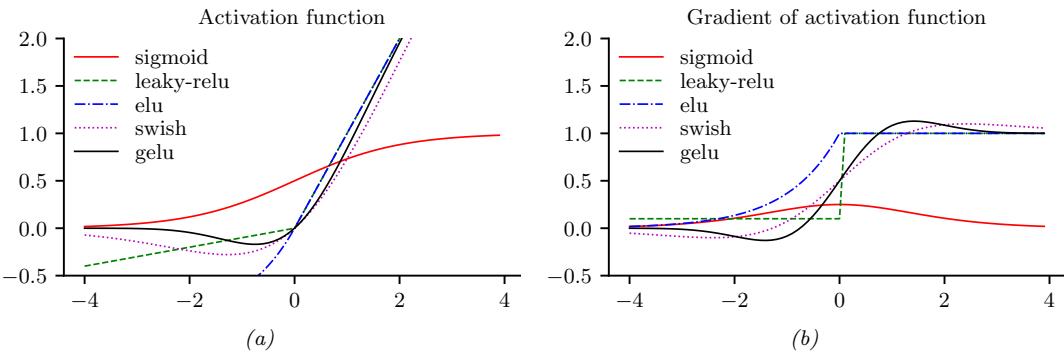

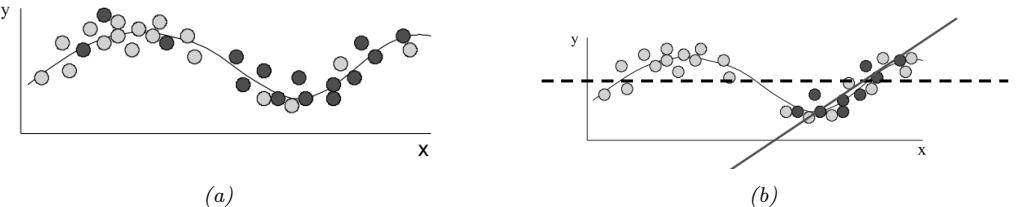

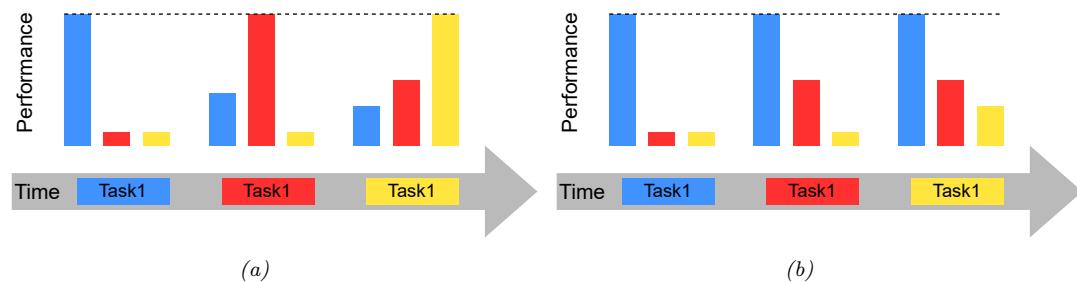

7.4.1.2 The MAP estimate is often untypical of the posterior

In some cases, we may not be interested in uncertainty, and instead we just want a single summary of the posterior. However, the mode of a posterior distribution is often a very poor choice as a

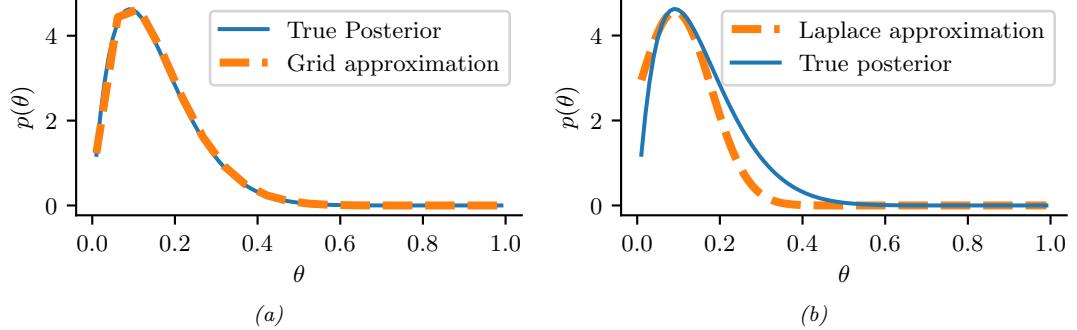

Figure 7.3: Approximating the posterior of a beta-Bernoulli model. (a) Grid approximation using 20 grid points. (b) Laplace approximation. Generated by laplace\_approx\_beta\_binom.ipynb.

summary statistic, since the mode is usually quite untypical of the distribution, unlike the mean or median. This is illustrated in Figure 7.2(a) for a 1d continuous space, where we see that the mode is an isolated peak (black line), far from most of the probability mass. By contrast, the mean (red line) is near the middle of the distribution.

Another example is shown in Figure 7.2(b): here the mode is 0, but the mean is non-zero. Such skewed distributions often arise when inferring variance parameters, especially in hierarchical models. In such cases the MAP estimate (and hence the MLE) is obviously a very bad estimate.

7.4.1.3 The MAP estimate is not invariant to reparameterization

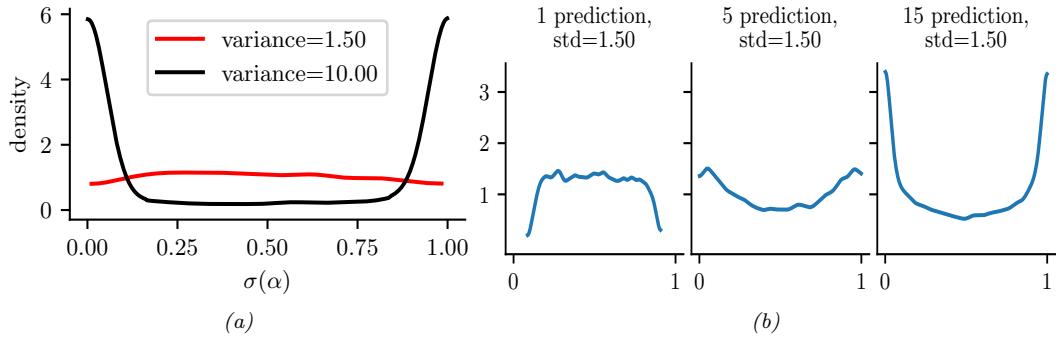

A more subtle problem with MAP estimation is that the result we get depends on how we parameterize the probability distribution, which is not very desirable. For example, when representing a Bernoulli distribution, we should be able to parameterize it in terms of probability of success, or in terms of the log-odds (logit), without that a!ecting our beliefs.

For example, let xˆ = argmaxx px(x) be the MAP estimate for x. Now let y = f(x) be a transformation of x. In general it is not the case that yˆ = argmaxy py(y) is given by f(xˆ). For example, let x ↔︎ N (6, 1) and y = f(x), where f(x) = 1 1+exp(↓x+5) . We can use the change of variables (Section 2.5.1) to conclude py(y) = px(f ↓1(y))| df→1(y) dy |. Alternatively we can use a Monte Carlo approximation. The result is shown in Figure 2.12. We see that the original Gaussian for p(x) has become “squashed” by the sigmoid nonlinearity. In particular, we see that the mode of the transformed distribution is not equal to the transform of the original mode.

We have seen that the MAP estimate depends on the parameterization. The MLE does not su!er from this since the likelihood is a function, not a probability density. Bayesian inference does not su!er from this problem either, since the change of measure is taken into account when integrating over the parameter space.

7.4.2 Grid approximation

If we want to capture uncertainty, we need to allow for the fact that ω may have a range of possible values, each with non-zero probability. The simplest way to capture this property is to partition the

space of possible values into a finite set of regions, call them r1,…, rK, each representing a region of parameter space of volume ! centered on ωk. This is called a grid approximation. The probability of being in each region is given by p(ω ↗ rk|D) ↓ pk!, where

\[p\_k = \frac{\tilde{p}\_k}{\sum\_{k'=1}^K \tilde{p}\_{k'}} \tag{7.20}\]

\[ \bar{p}\_k = p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta}\_k)p(\boldsymbol{\theta}\_k) \tag{7.21} \]

As K increases, we decrease the size of each grid cell. Thus the denominator is just a simple numerical approximation of the integral

\[p(\mathcal{D}) = \int p(\mathcal{D}|\theta)p(\theta)d\theta \approx \sum\_{k=1}^{K} \Delta \bar{p}\_k \tag{7.22}\]

As a simple example, we will use the problem of approximating the posterior of a beta-Bernoulli model. Specifically, the goal is to approximate

\[p(\theta|\mathcal{D}) \propto \left[ \prod\_{n=1}^{N} \text{Ber}(y\_n|\theta) \right] \text{Beta}(1, 1) \tag{7.23}\]

where D consists of 10 heads and 1 tail (so the total number of observations is N = 11), with a uniform prior. Although we can compute this posterior exactly using the method discussed in Section 3.4.1, this serves as a useful pedagogical example since we can compare the approximation to the exact answer. Also, since the target distribution is just 1d, it is easy to visualize the results.

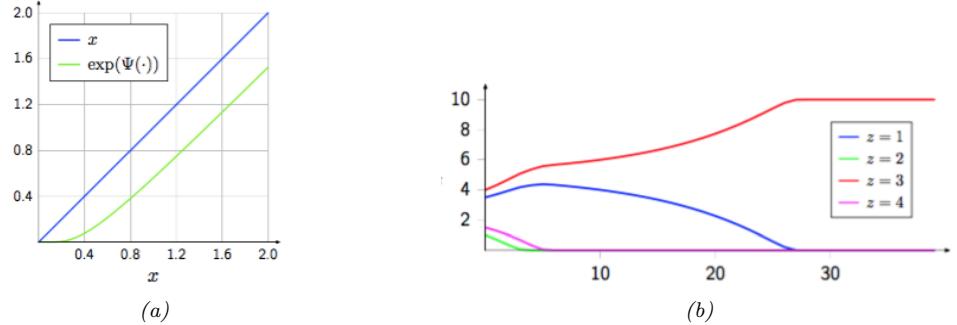

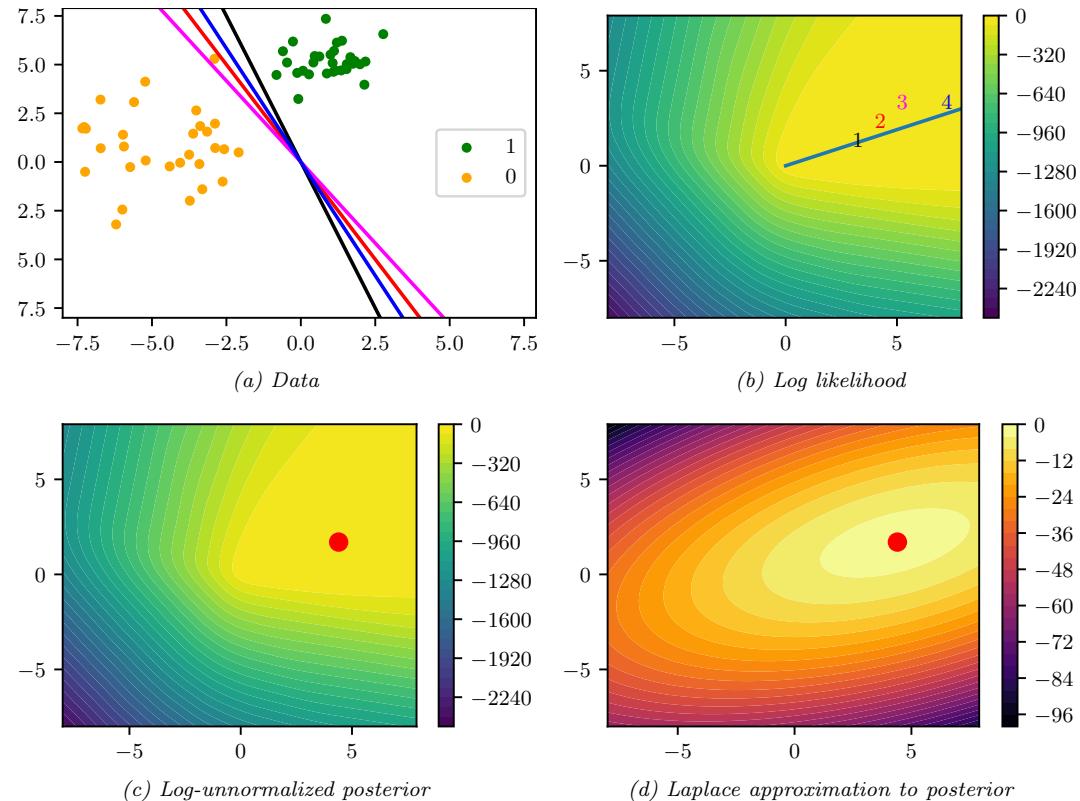

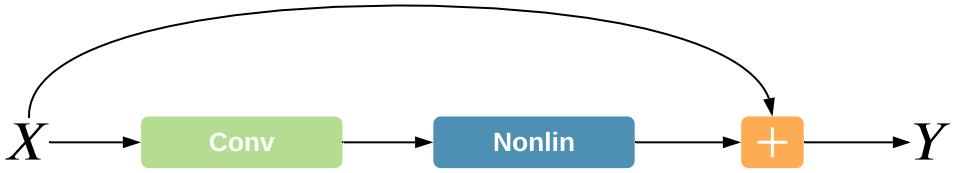

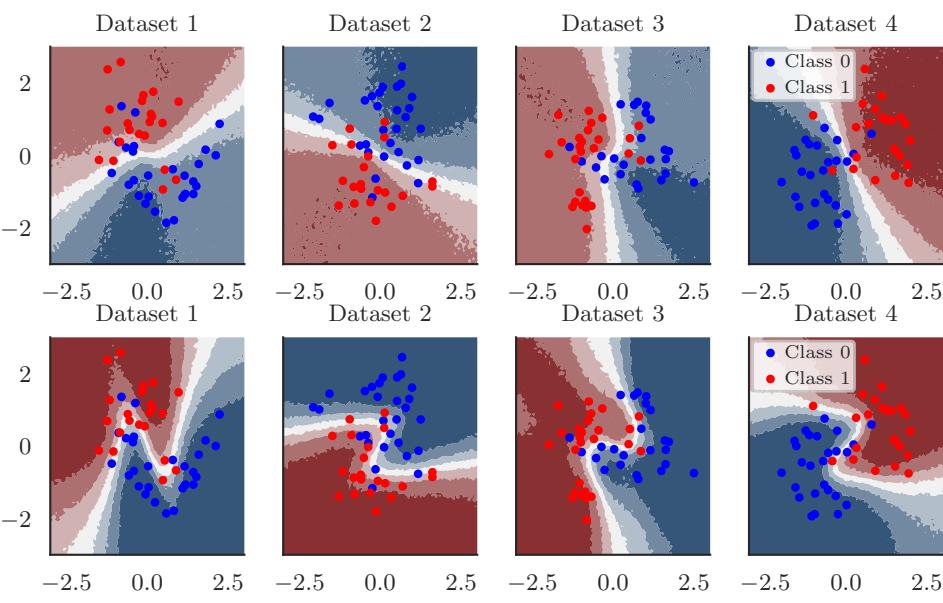

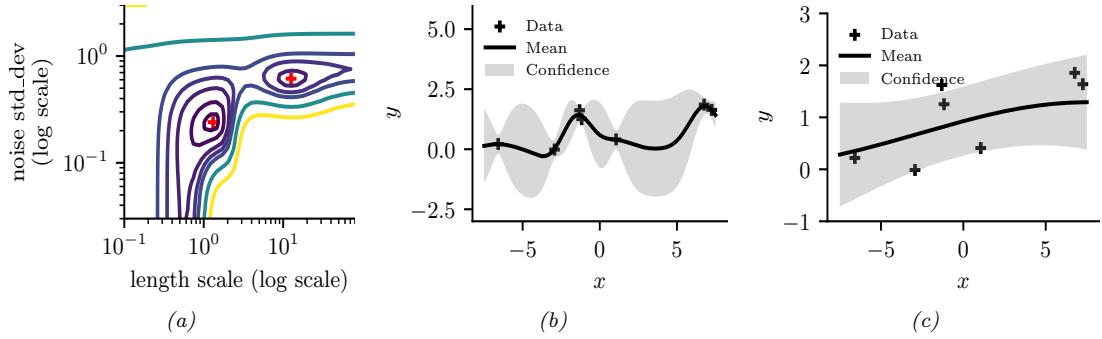

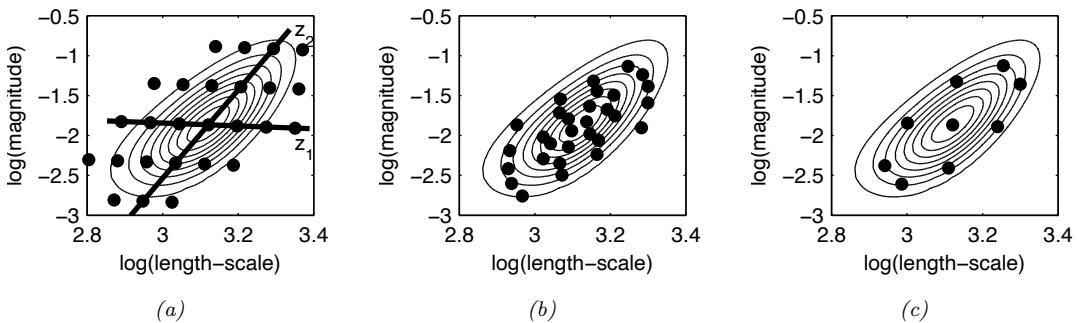

In Figure 7.3a, we illustrate the grid approximation applied to our 1d problem. We see that it is easily able to capture the skewed posterior (due to the use of an imbalanced sample of 10 heads and 1 tail). Unfortunately, this approach does not scale to problems in more than 2 or 3 dimensions, because the number of grid points grows exponentially with the number of dimensions.

7.4.3 Laplace (quadratic) approximation

In this section, we discuss a simple way to approximate the posterior using a multivariate Gaussian; this known as a Laplace approximation or quadratic approximation (see e.g., [TK86; RMC09]).

Suppose we write the posterior as follows:

\[p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) = \frac{1}{Z}e^{-\mathcal{E}(\boldsymbol{\theta})} \tag{7.24}\]

where E(ω) = → log p(ω, D) is called an energy function, and Z = p(D) is the normalization constant. Performing a Taylor series expansion around the mode ωˆ (i.e., the lowest energy state) we get

\[\mathcal{E}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \approx \mathcal{E}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}) + (\boldsymbol{\theta} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}})^{\mathsf{T}} \boldsymbol{g} + \frac{1}{2} (\boldsymbol{\theta} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}})^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbf{H} (\boldsymbol{\theta} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}) \tag{7.25}\]

where g is the gradient at the mode, and H is the Hessian. Since ωˆ is the mode, the gradient term is

zero. Hence

\[\hat{p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \mathcal{D}) = e^{-\mathcal{E}(\boldsymbol{\theta})} \exp\left[ -\frac{1}{2} (\boldsymbol{\theta} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}})^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbf{H}(\boldsymbol{\theta} - \hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}) \right] \tag{7.26}\]

\[\hat{p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) = \frac{1}{Z}\hat{p}(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \mathcal{D}) = \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\theta}, \mathbf{H}^{-1})\tag{7.27}\]

\[Z = e^{-\mathcal{E}(\dot{\hat{\theta}})} (2\pi)^{D/2} |\mathbf{H}|^{-\frac{1}{2}} \tag{7.28}\]

The last line follows from normalization constant of the multivariate Gaussian.

The Laplace approximation is easy to apply, since we can leverage existing optimization algorithms to compute the MAP estimate, and then we just have to compute the Hessian at the mode. (In high dimensional spaces, we can use a diagonal approximation.)

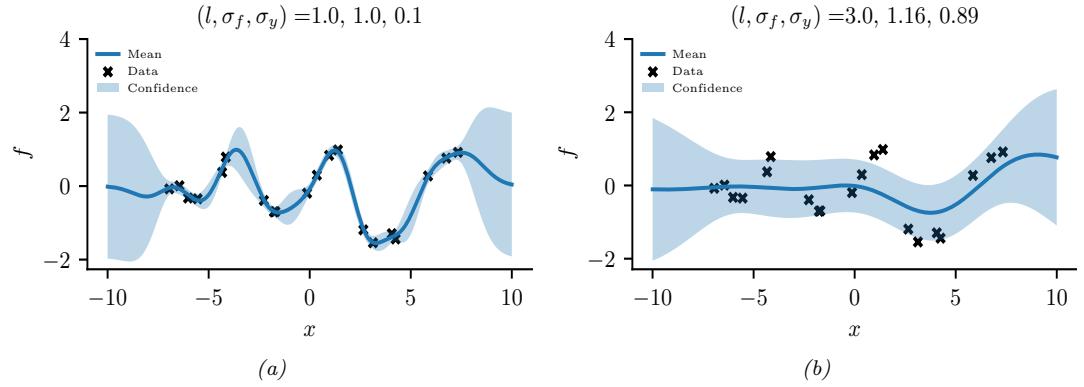

In Figure 7.3b, we illustrate this method applied to our 1d problem. Unfortunately we see that it is not a particularly good approximation. This is because the posterior is skewed, whereas a Gaussian is symmetric. In addition, the parameter of interest lies in the constrained interval ω ↗ [0, 1], whereas the Gaussian assumes an unconstrained space, ω ↗ RD. Fortunately, we can solve this latter problem by using a change of variable. For example, in this case we can apply the Laplace approximation to ϱ = logit(ω). This is a common trick to simplify the job of inference.

See Section 15.3.5 for an application of Laplace approximation to Bayesian logistic regression, Section 17.3.2 for an application of Laplace approximation to Bayesian neural networks, and Section 4.3.5.3 for an application to Gaussian Markov random fields.

7.4.4 Variational inference

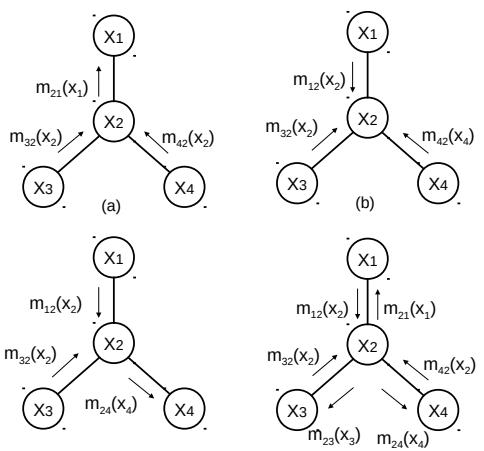

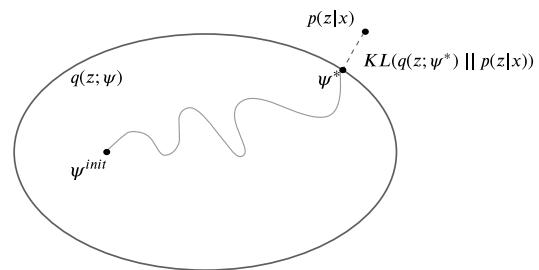

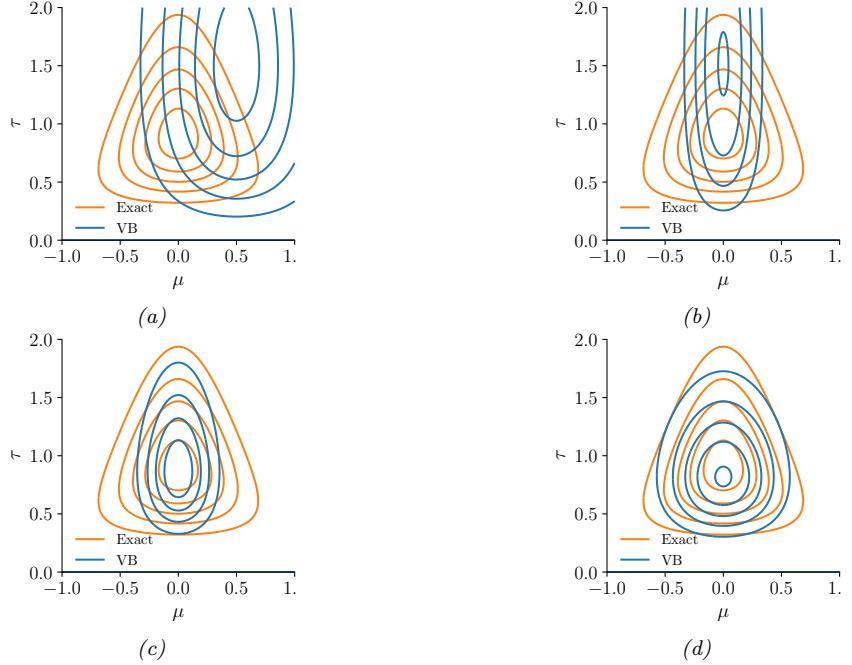

In Section 7.4.3, we discussed the Laplace approximation, which uses an optimization procedure to find the MAP estimate, and then approximates the curvature of the posterior at that point based on the Hessian. In this section, we discuss variational inference (VI), also called variational Bayes (VB). This is another optimization-based approach to posterior inference, but which has much more modeling flexibility (and thus can give a much more accurate approximation).

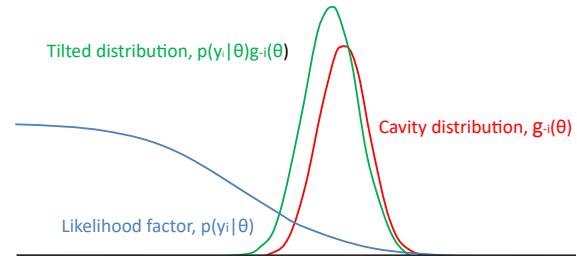

VI attempts to approximate an intractable probability distribution, such as p(ω|D), with one that is tractable, q(ω), so as to minimize some discrepancy D between the distributions:

\[q^\* = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{q \in \mathcal{Q}} D(q, p) \tag{7.29}\]

where Q is some tractable family of distributions (e.g., fully factorized distributions). Rather than optimizing over functions q, we typically optimize over the parameters of the function q; we denote these variational parameters by ϖ.

It is common to use the KL divergence (Section 5.1) as the discrepancy measure, which is given by

\[D(q, p) = D\_{\mathbb{KL}}\left(q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi}) \parallel p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D})\right) = \int q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi}) \log \frac{q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi})}{p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D})} d\boldsymbol{\theta} \tag{7.30}\]

where p(ω|D) = p(D|ω)p(ω)/p(D). The inference problem then reduces to the following optimization

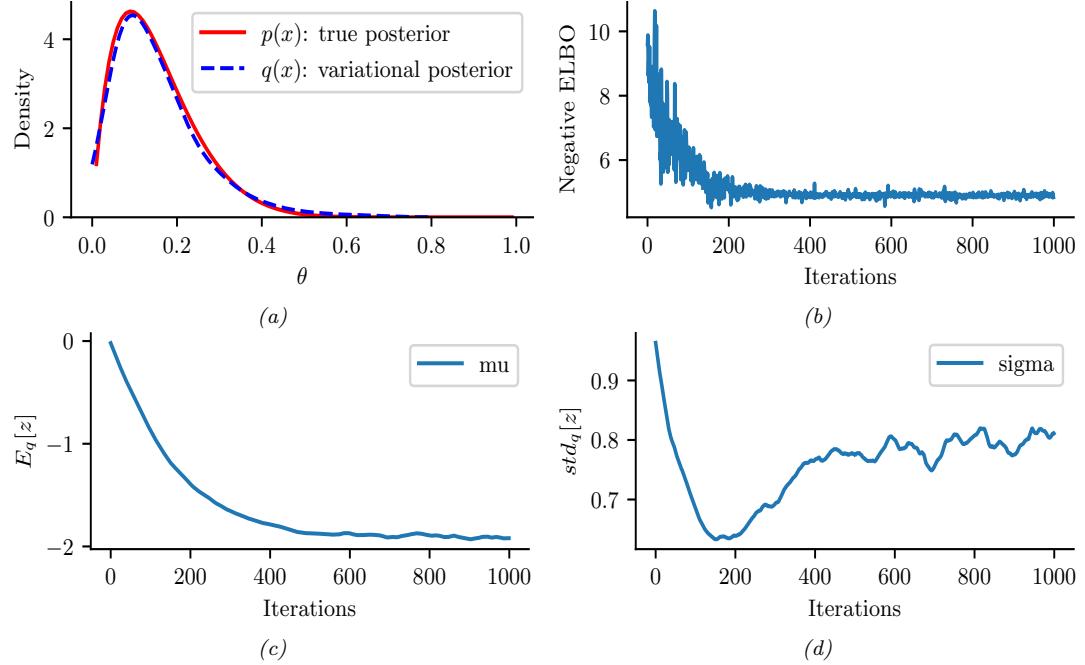

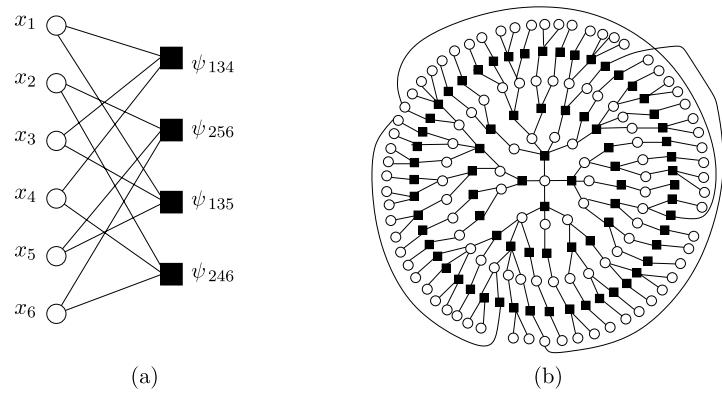

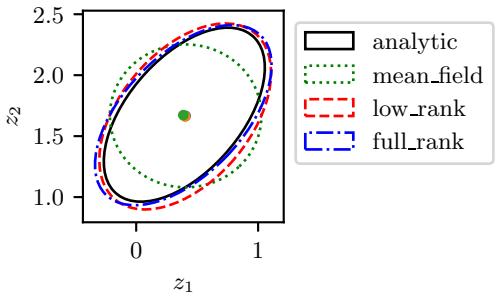

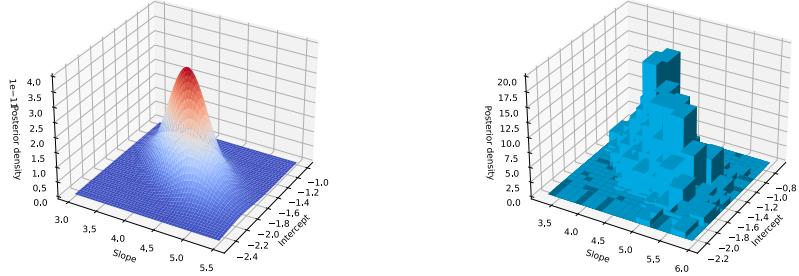

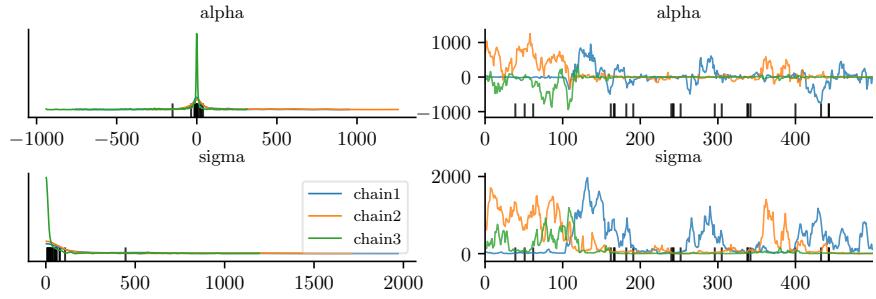

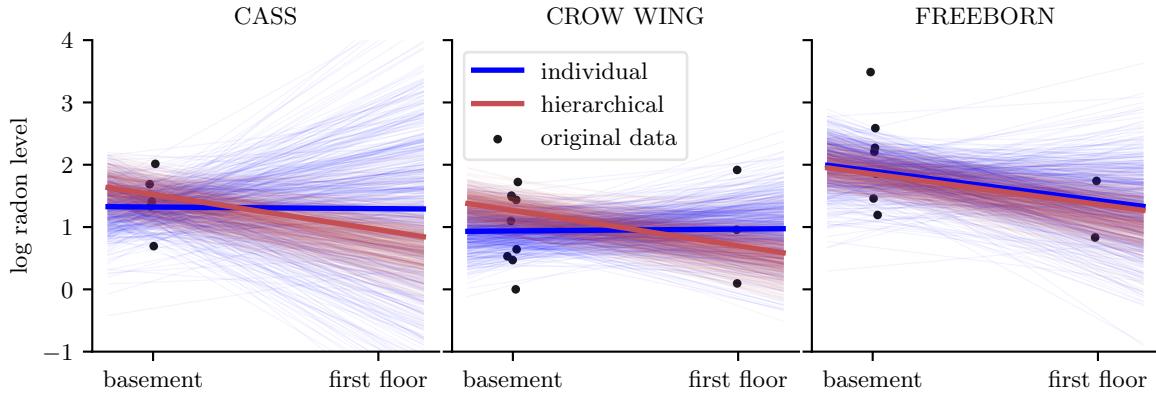

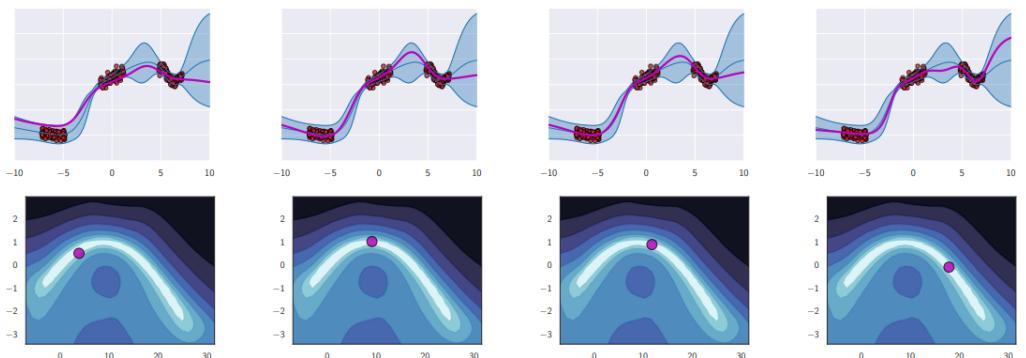

Figure 7.4: ADVI applied to the beta-Bernoulli model. (a) Approximate vs true posterior. (b) Negative ELBO over time. (c) Variational µ parameter over time. (d) Variational ω parameter over time. Generated by advi\_beta\_binom.ipynb.

problem:

\[\psi^\* = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{\psi} D\_{\text{KL}}\left(q(\theta|\psi) \parallel p(\theta|\mathcal{D})\right) \tag{7.31}\]

\[\mathbb{E}\_{\theta} = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{\boldsymbol{\Psi}} \mathbb{E}\_{q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\Psi})} \left[ \log q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi}) - \log \left( \frac{p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta})p(\boldsymbol{\theta})}{p(\mathcal{D})} \right) \right] \tag{7.32}\]

\[\Psi = \operatorname\*{argmin}\_{\boldsymbol{\Psi}} \underbrace{\mathbb{E}\_{q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\Psi})} \left[ -\log p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta}) - \log p(\boldsymbol{\theta}) + \log q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi}) \right]}\_{-L(\boldsymbol{\psi})} + \log p(\mathcal{D}) \tag{7.33}\]

Note that log p(D) is independent of ϖ, so we can ignore it when fitting the approximate posterior, and just focus on maximizing the term

\[\mathbb{E}(\psi) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \mathbb{E}\_{q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi})} \left[ \log p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta}) + \log p(\boldsymbol{\theta}) - \log q(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\boldsymbol{\psi}) \right] \tag{7.34}\]

Since we have DKL (q ↘ p) ≃ 0, we have #(ϖ) ⇐ log p(D). The quantity log p(D), which is the log marginal likelihood, is also called the evidence. Hence #(ϖ) is known as the evidence lower bound or ELBO. By maximizing this bound, we are making the variational posterior closer to the true posterior. (See Section 10.1 for details.)

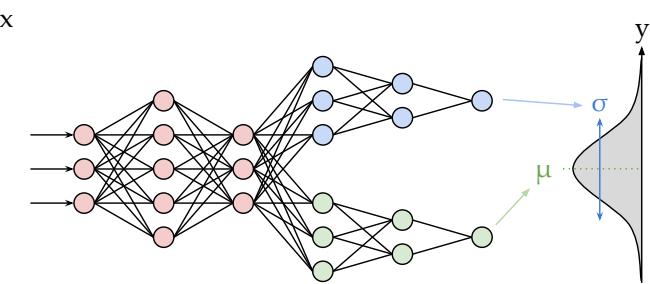

We can choose any kind of approximate posterior that we like. For example, we may use a Gaussian, q(ω|ϖ) = N (ω|µ, !). This is di!erent from the Laplace approximation, since in VI, we optimize

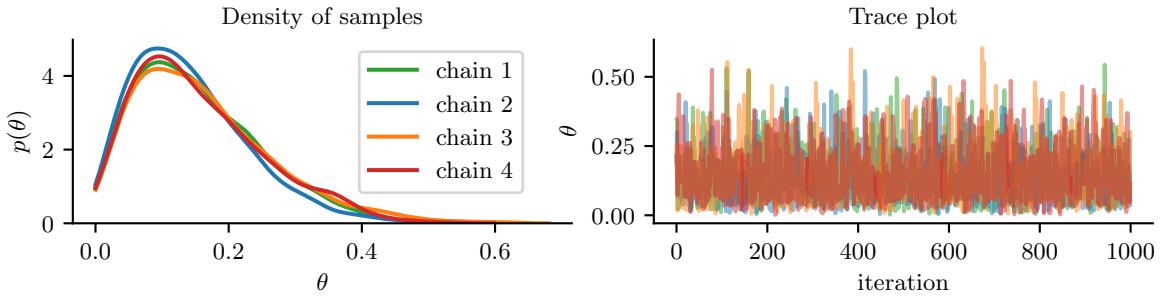

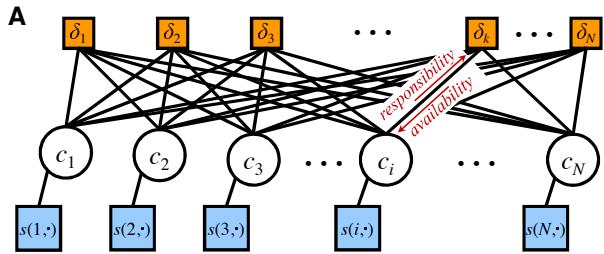

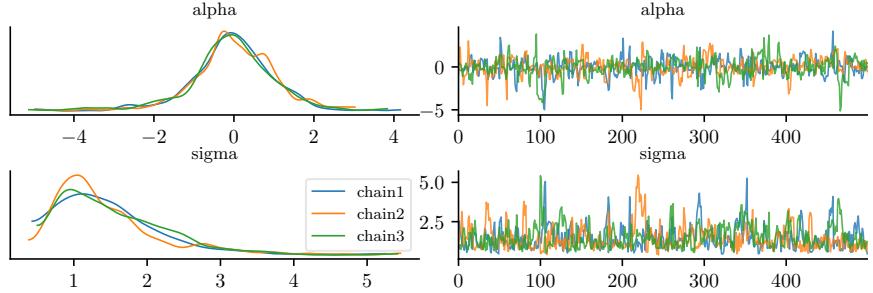

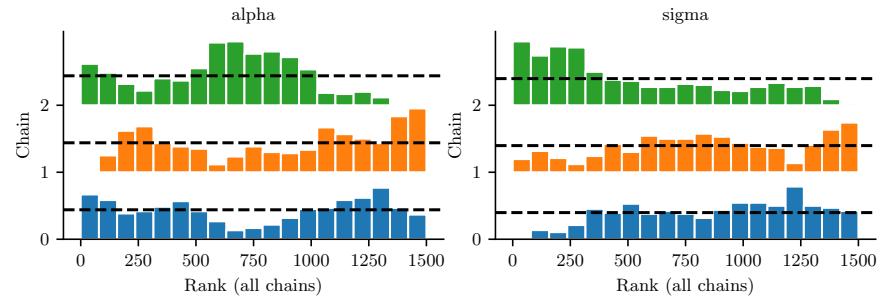

Figure 7.5: Approximating the posterior of a beta-Bernoulli model using MCMC. (a) Kernel density estimate derived from samples from 4 independent chains. (b) Trace plot of the chains as they generate posterior samples. Generated by hmc\_beta\_binom.ipynb.

!, rather than equating it to the Hessian. If ! is diagonal, we are assuming the posterior is fully factorized; this is called a mean field approximation.

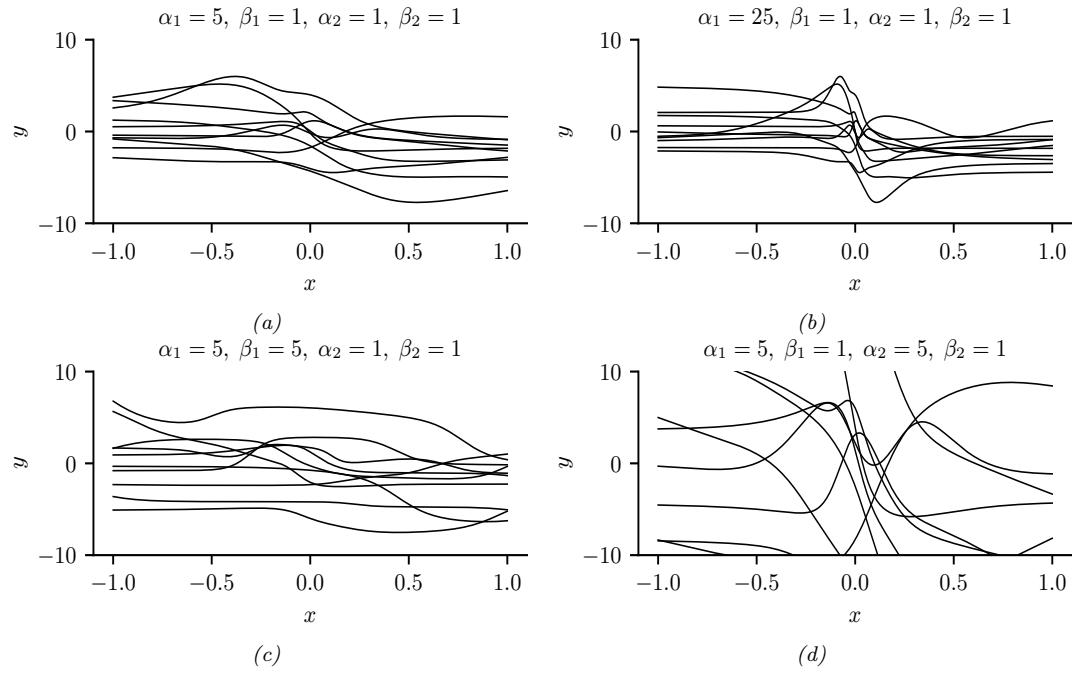

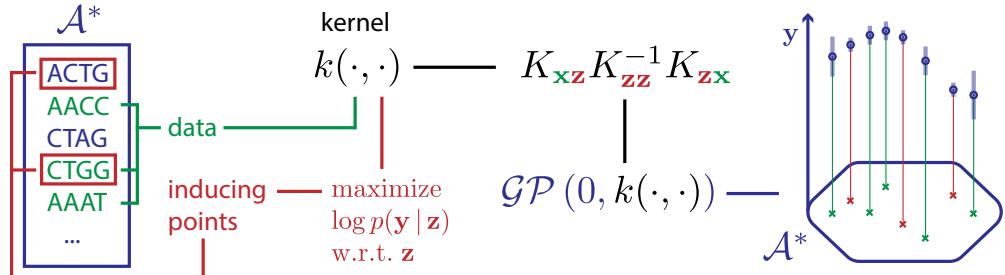

A Gaussian approximation is not always suitable for all parameters. For example, in our 1d example we have the constraint that ω ↗ [0, 1]. We could use a variational approximation of the form q(ω|ϖ) = Beta(ω|a, b), where ϖ = (a, b). However choosing a suitable form of variational distribution requires some level of expertise. To create a more easily applicable, or “turn-key”, method, that works on a wide range of models, we can use a method called automatic di!erentiation variational inference or ADVI [Kuc+16]. This uses the change of variables method to convert the parameters to an unconstrained form, and then computes a Gaussian variational approximation. The method also uses automatic di!erentiation to derive the Jacobian term needed to compute the density of the transformed variables. See Section 10.2.2 for details.

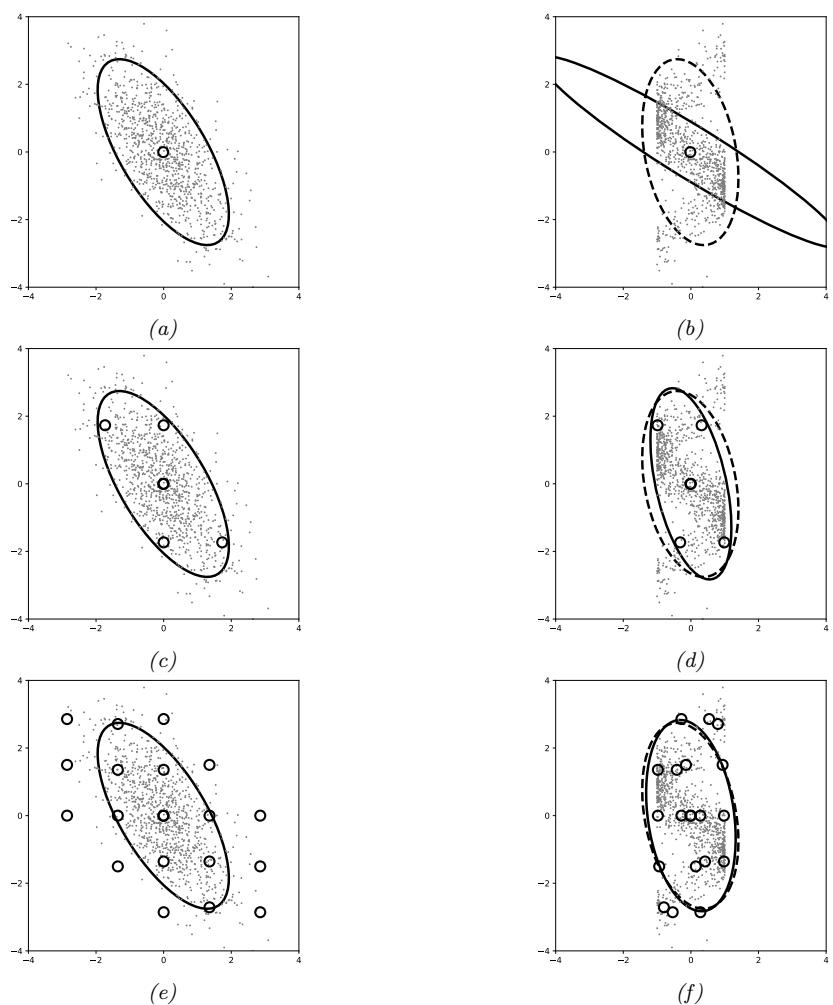

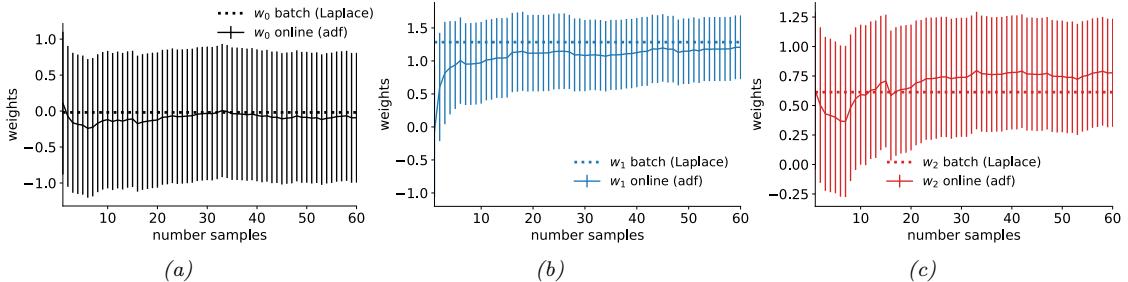

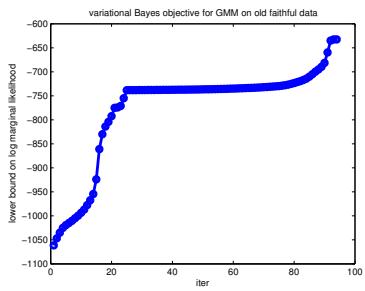

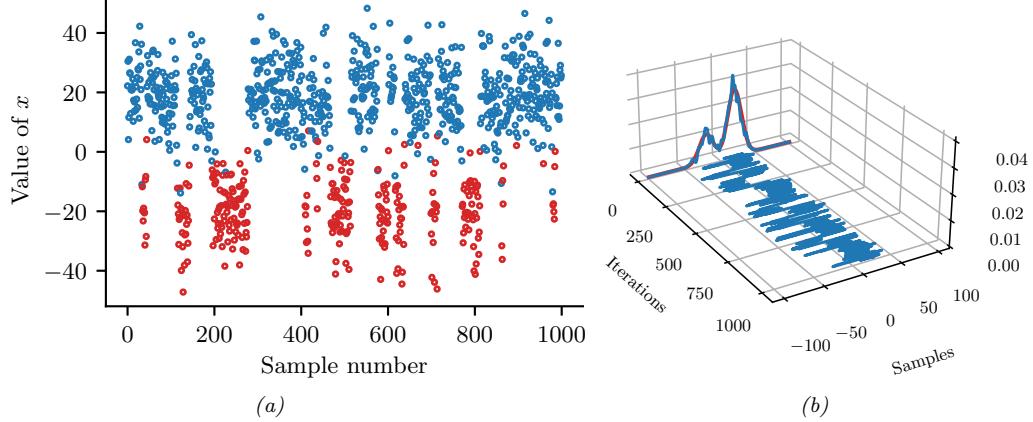

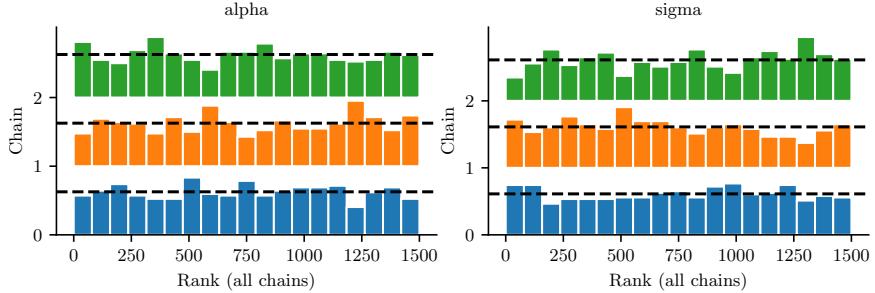

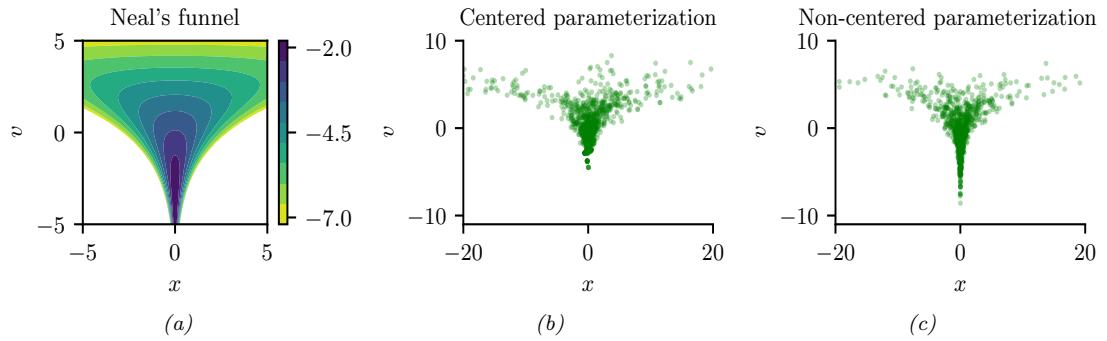

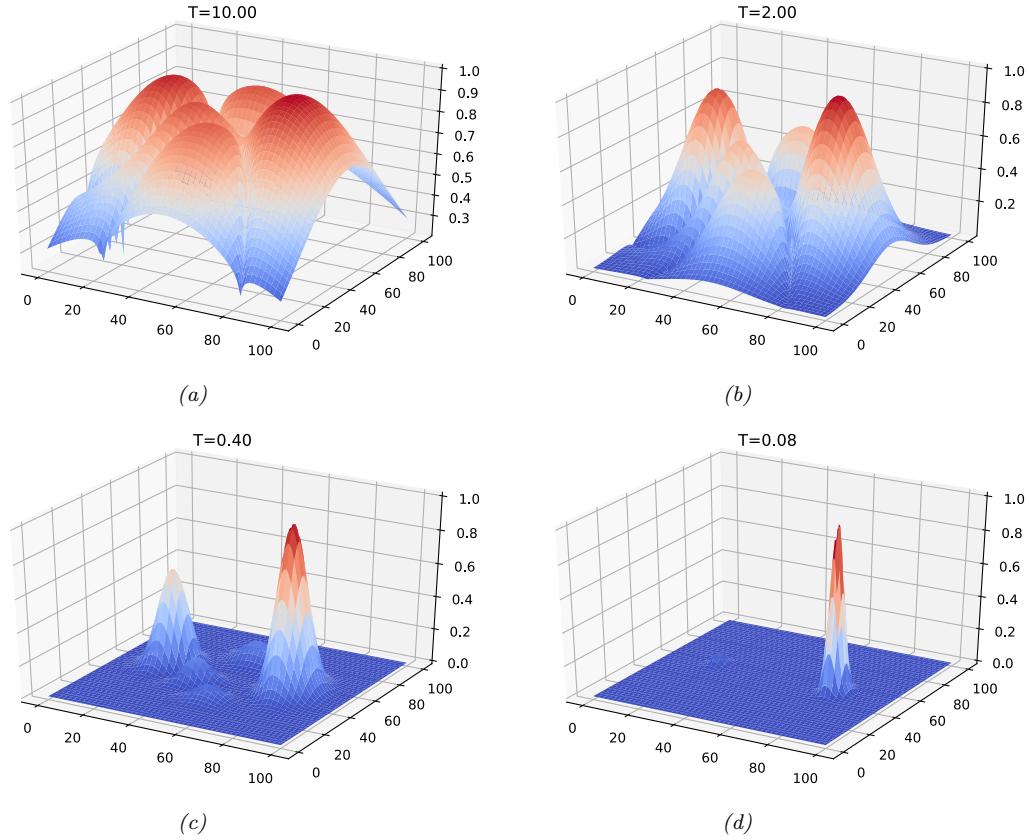

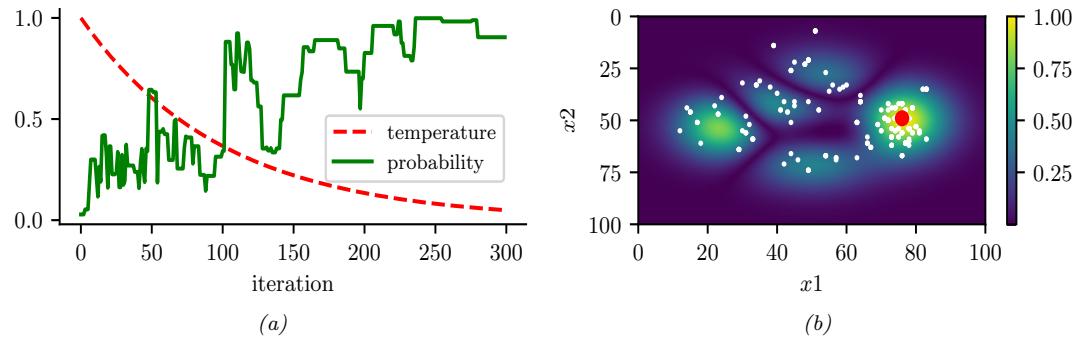

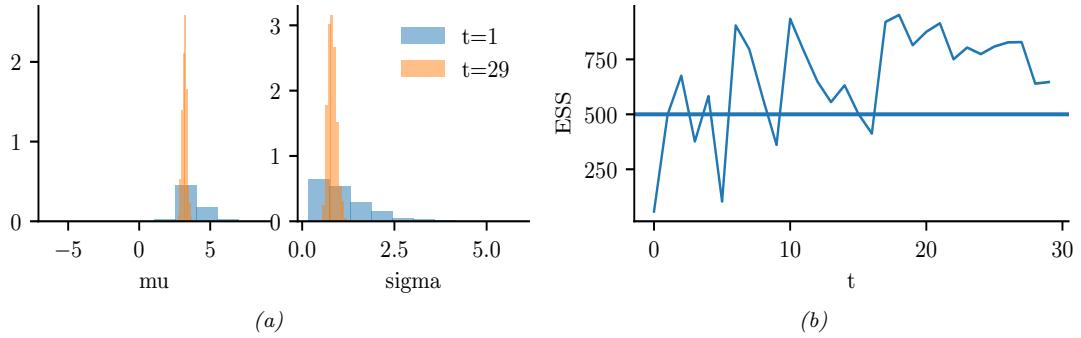

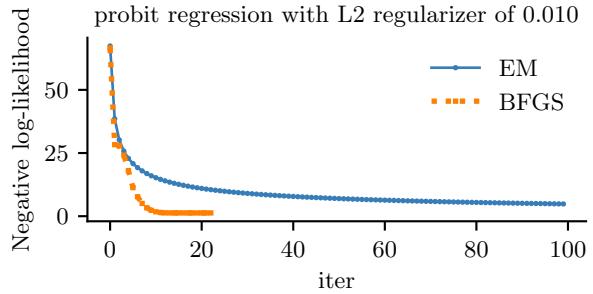

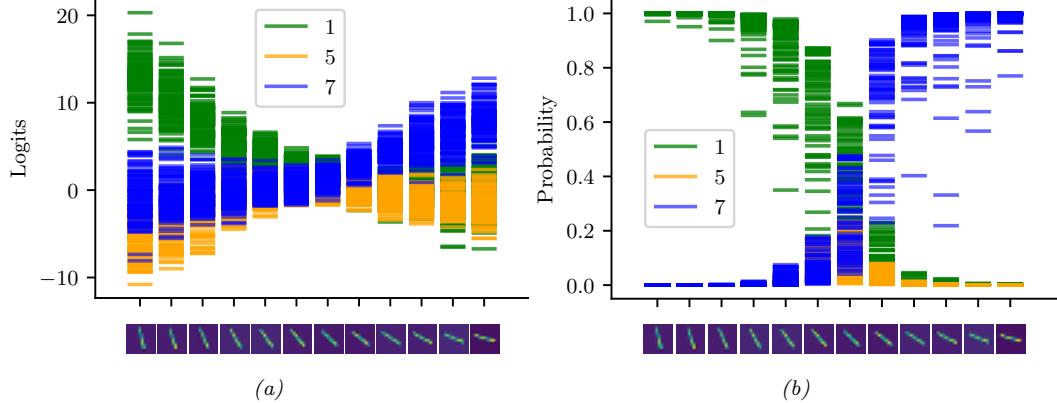

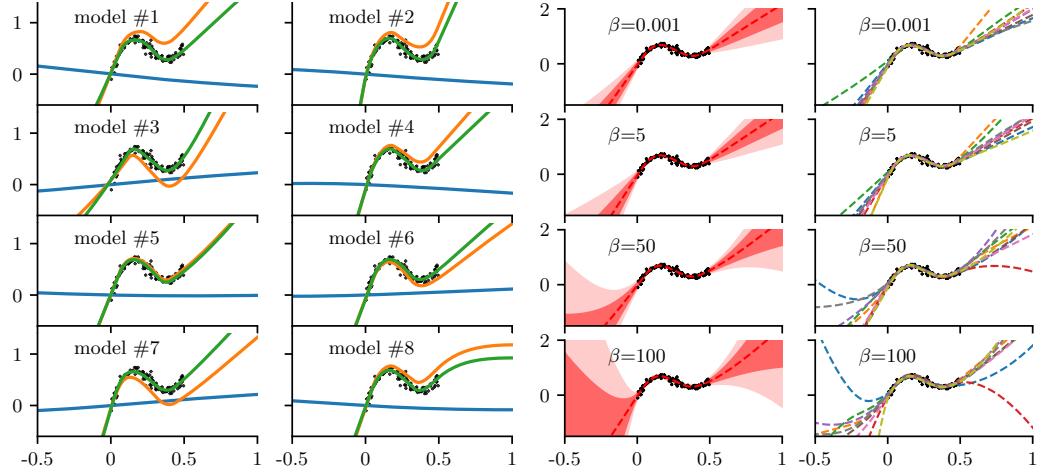

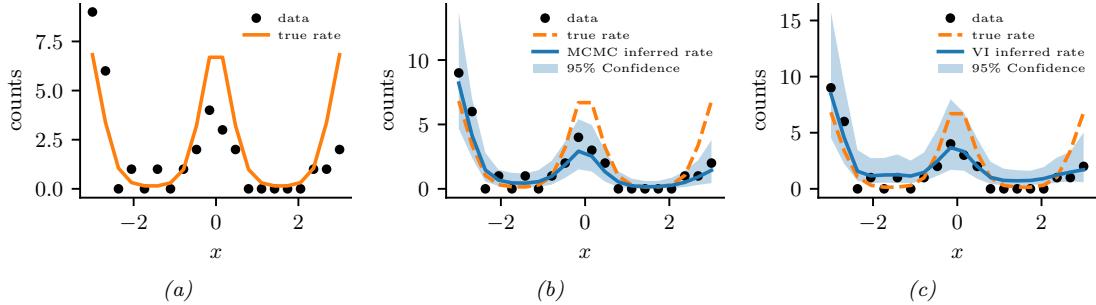

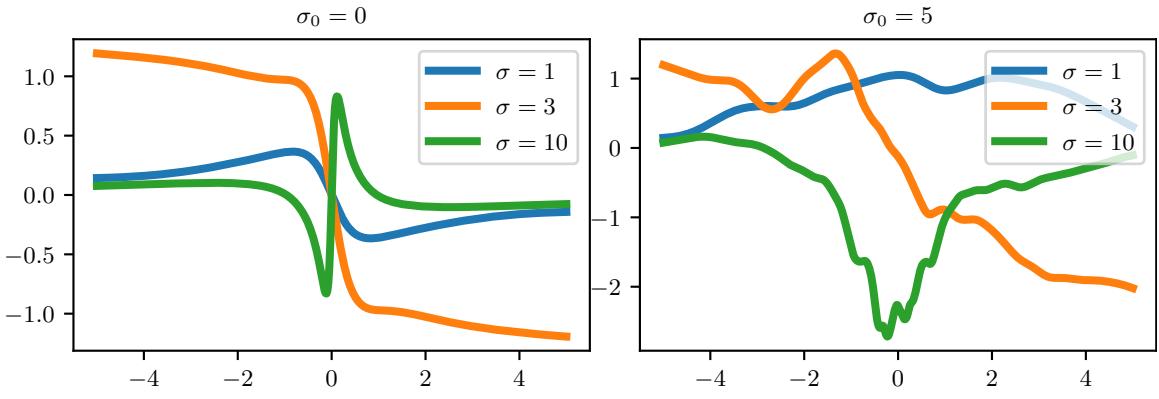

We now apply ADVI to our 1d beta-Bernoulli model. Let ω = ς(z), where we replace p(ω|D) with q(z|ϖ) = N (z|µ, ς), where ϖ = (µ, ς). We optimize a stochastic approximation to the ELBO using SGD. The results are shown in Figure 7.4 and seem reasonable.

7.4.5 Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)

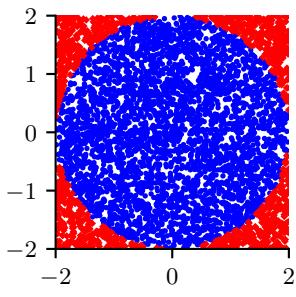

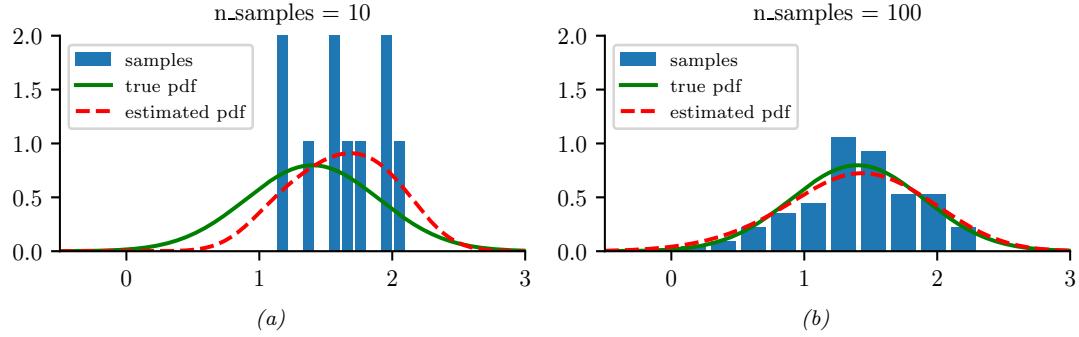

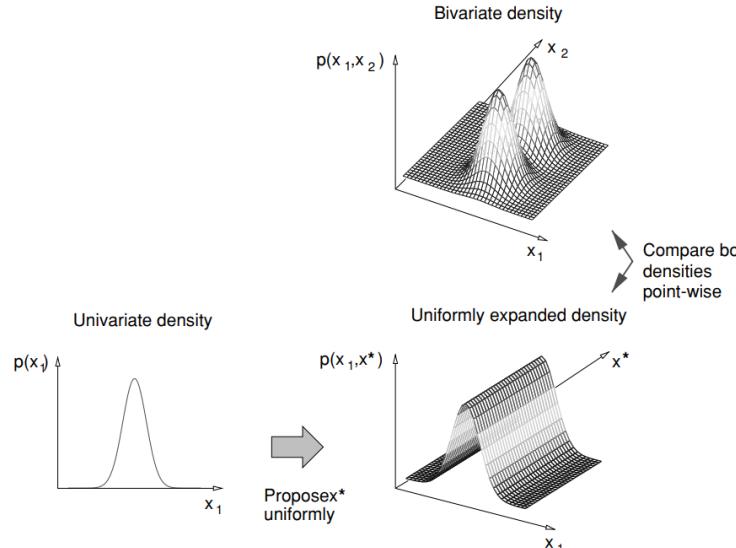

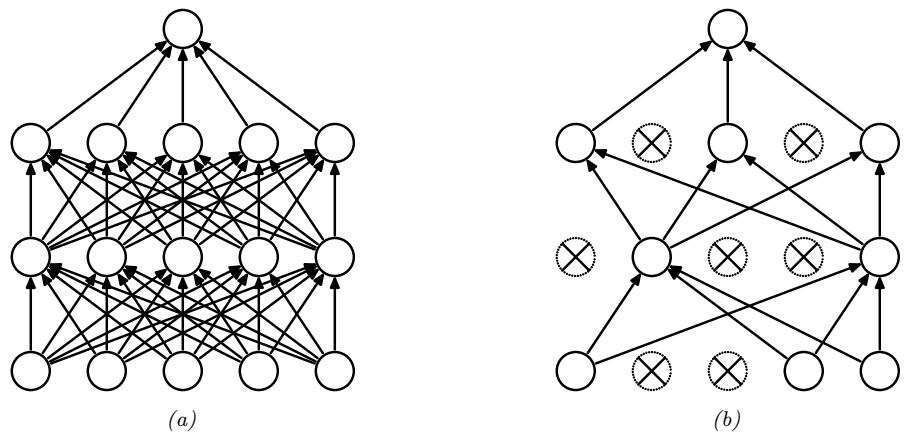

Although VI is fast, it can give a biased approximation to the posterior, since it is restricted to a specific function form q ↗ Q. A more flexible approach is to use a non-parametric approximation in terms of a set of samples, q(ω) ↓ 1 S &S s=1 ϑ(ω → ωs). This is called a Monte Carlo approximation. The key issue is how to create the posterior samples ωs ↔︎ p(ω|D) e”ciently, without having to evaluate the normalization constant p(D) = / p(ω, D)dω.

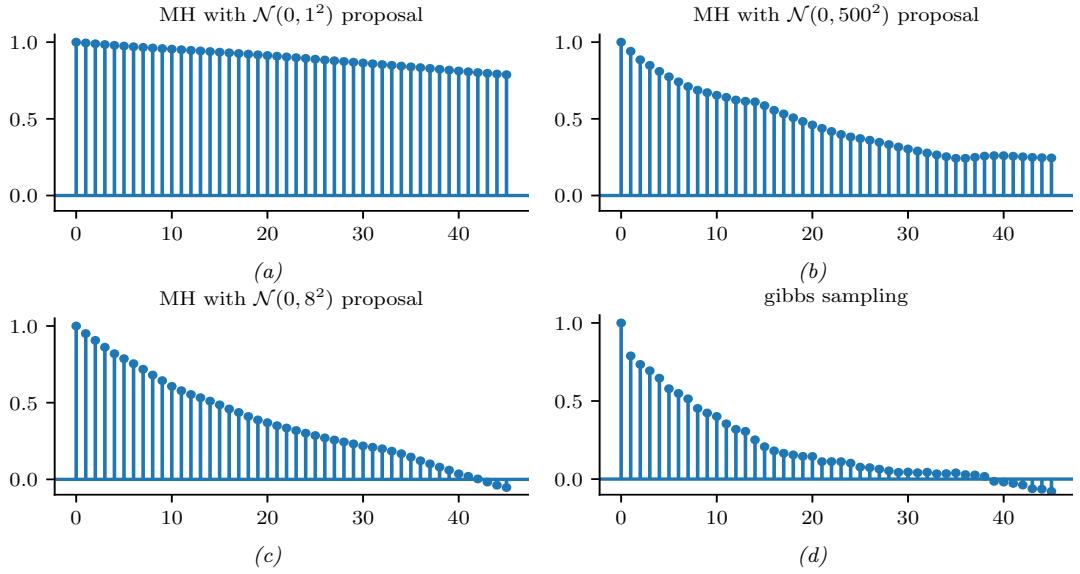

For low dimensional problems, we can use methods such as importance sampling, which we discuss in Section 11.5. However, for high dimensional problems, it is more common to use Markov chain Monte Carlo or MCMC. We give the details in Chapter 12, but give a brief introduction here.

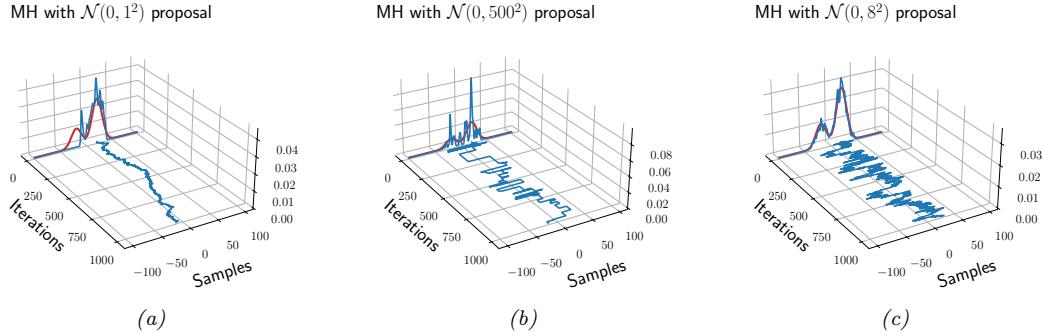

The most common kind of MCMC is known as the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm. The basic idea behind MH is as follows: we start at a random point in parameter space, and then perform a random walk, by sampling new states (parameters) from a proposal distribution q(ω↔︎ |ω). If q is chosen carefully, the resulting Markov chain distribution will satisfy the property that the fraction of

time we visit each point in space is proportional to the posterior probability. The key point is that to decide whether to move to a newly proposed point ω↔︎ or to stay in the current point ω, we only need to evaluate the unnormalized density ratio

\[\frac{p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D})}{p(\boldsymbol{\theta}'|\mathcal{D})} = \frac{p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta})p(\boldsymbol{\theta})/p(\mathcal{D})}{p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta}')p(\boldsymbol{\theta}')/p(\mathcal{D})} = \frac{p(\mathcal{D},\boldsymbol{\theta})}{p(\mathcal{D},\boldsymbol{\theta}')}\tag{7.35}\]

This avoids the need to compute the normalization constant p(D). (In practice we usually work with log probabilities, instead of joint probabilities, to avoid numerical issues.)

We see that the input to the algorithm is just a function that computes the log joint density, log p(ω, D), as well as a proposal distribution q(ω↔︎ |ω) for deciding which states to visit next. It is common to use a Gaussian distribution for the proposal, q(ω↔︎ |ω) = N (ω↔︎ |ω, ςI); this is called the random walk Metropolis algorithm. However, this can be very ine”cient, since it is blindly walking through the space, in the hopes of finding higher probability regions.

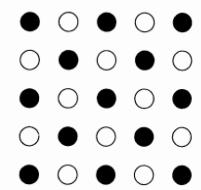

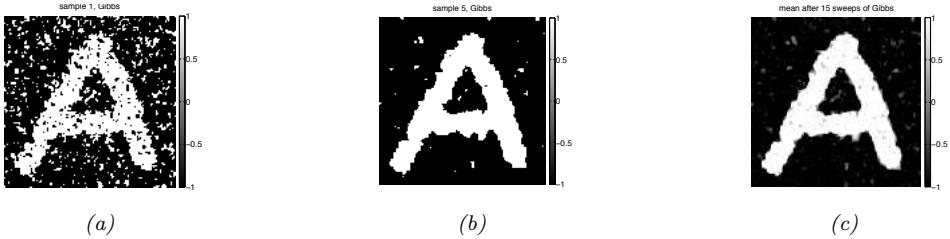

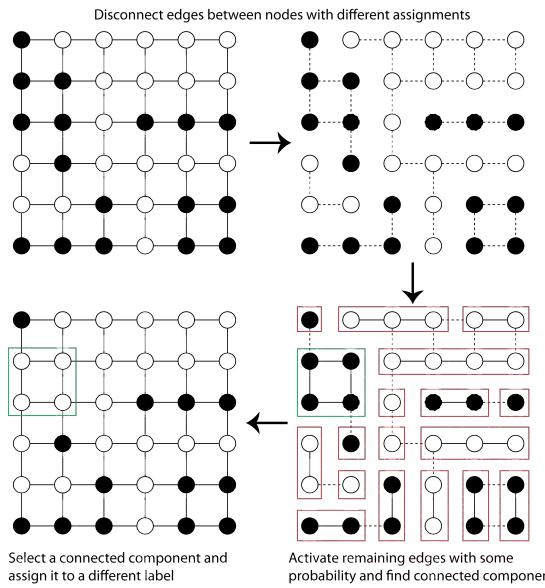

In models that have conditional independence structure, it is often easy to compute the full conditionals p(ωd|ω↓d, D) for each variable d, one at a time, and then sample from them. This is like a stochastic analog of coordinate ascent, and is called Gibbs sampling (see Section 12.3 for details).

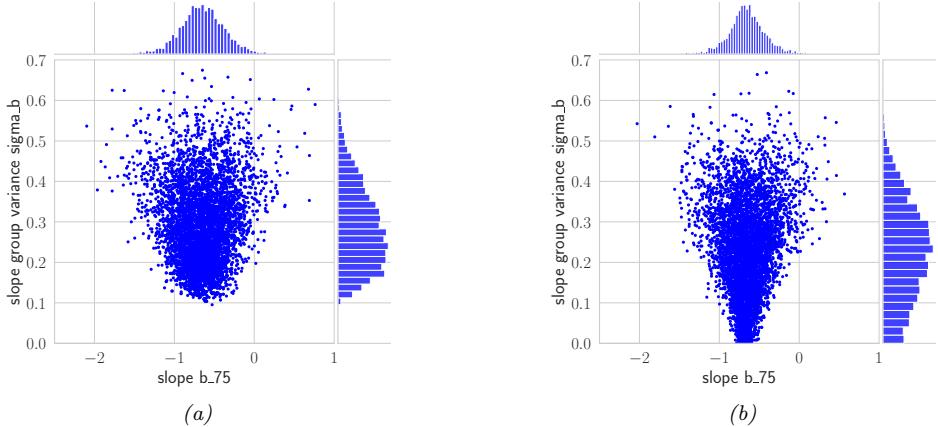

For models where all unknown variables are continuous, we can often compute the gradient of the log joint, ⇒ε log p(ω, D). We can use this gradient information to guide the proposals into regions of space with higher probability. This approach is called Hamiltonian Monte Carlo or HMC, and is one of the most widely used MCMC algorithms due to its speed. For details, see Section 12.5.

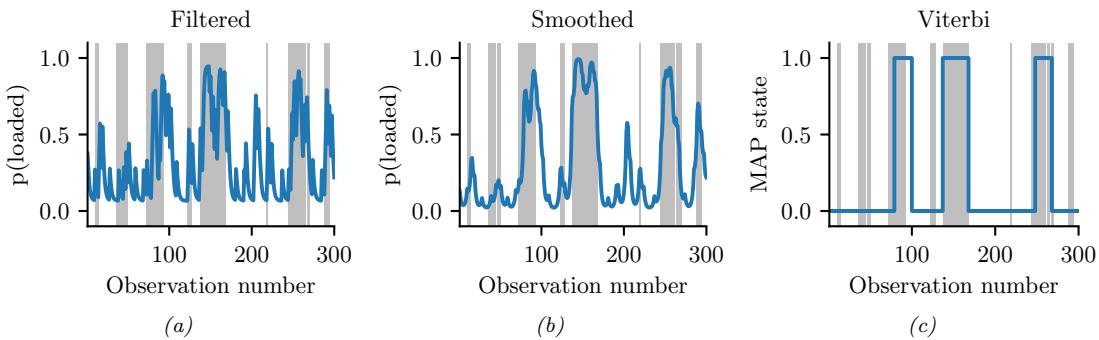

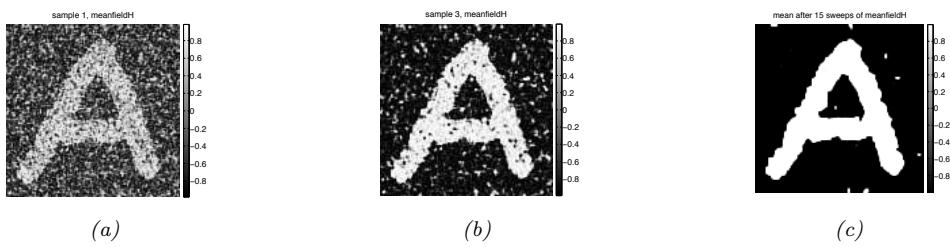

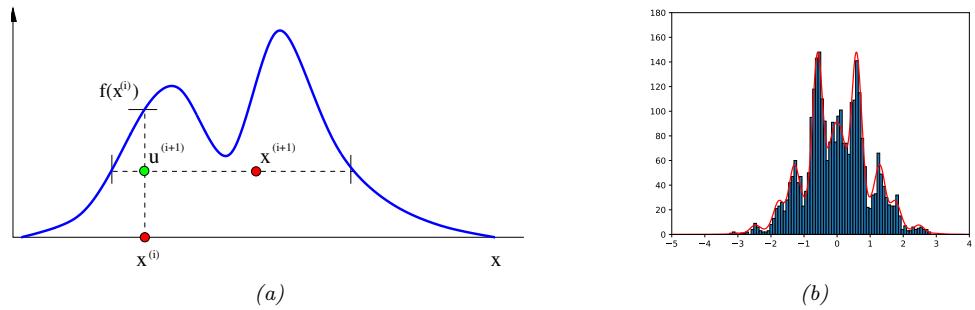

We apply HMC to our beta-Bernoulli model in Figure 7.5. (We use a logit transformation for the parameter.) In panel b, we show samples generated by the algorithm from 4 parallel Markov chains. We see that they oscillate around the true posterior, as desired. In panel a, we compute a kernel density estimate from the posterior samples from each chain; we see that the result is a good approximation to the true posterior in Figure 7.3.

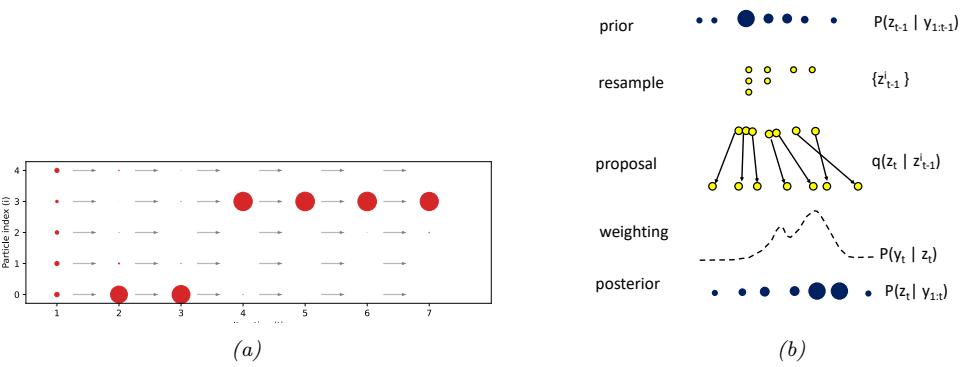

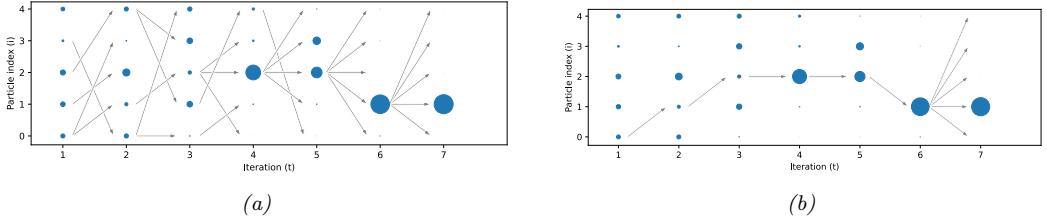

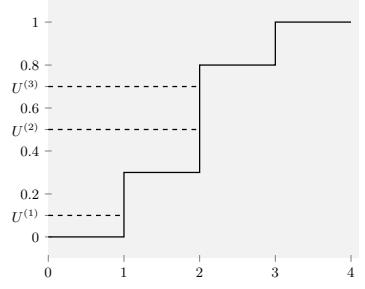

7.4.6 Sequential Monte Carlo

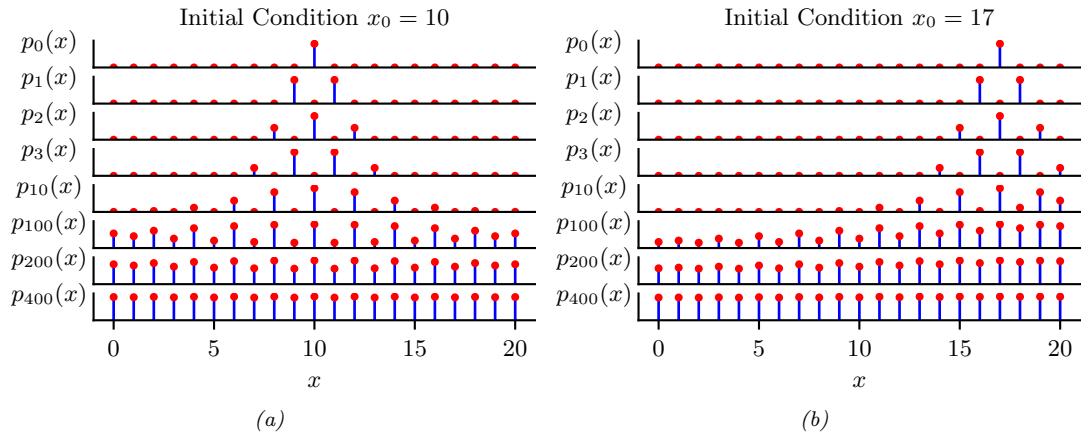

MCMC is like a stochastic local search algorithm, in that it makes moves through the state space of the posterior distribution, comparing the current value to proposed neighboring values. An alternative approach is to use perform inference using a sequence of di!erent distributions, from simpler to more complex, with the final distribution being equal to the target posterior. This is called sequential Monte Carlo or SMC. This approach, which is more similar to tree search than local search, has various advantages over MCMC, which we discuss in Chapter 13.

A common application of SMC is to sequential Bayesian inference, in which we recursively compute (i.e., in an online fashion) the posterior p(ωt|D1:t), where D1:t = {(xn, yn) : n =1: t} is all the data we have seen so far. This sequence of distributions converges to the full batch posterior p(ω|D) once all the data has been seen. However, the approach can also be used when the data is arriving in a continual, unending stream, as in state-space models (see Chapter 29). The application of SMC to such dynamical models is known as particle filtering. See Section 13.2 for details.

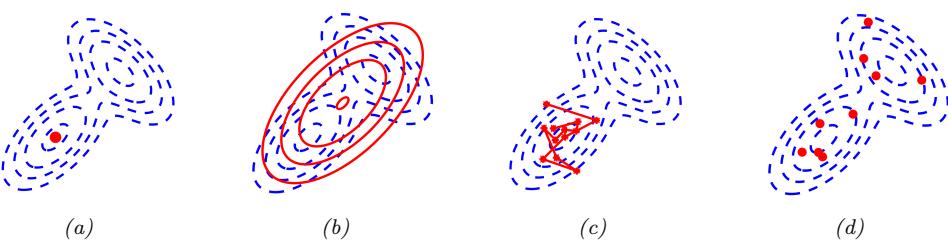

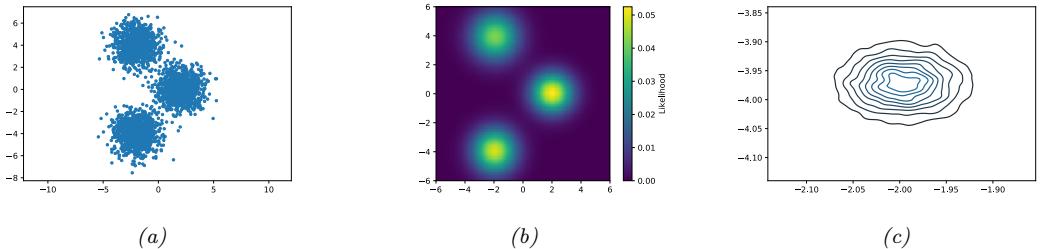

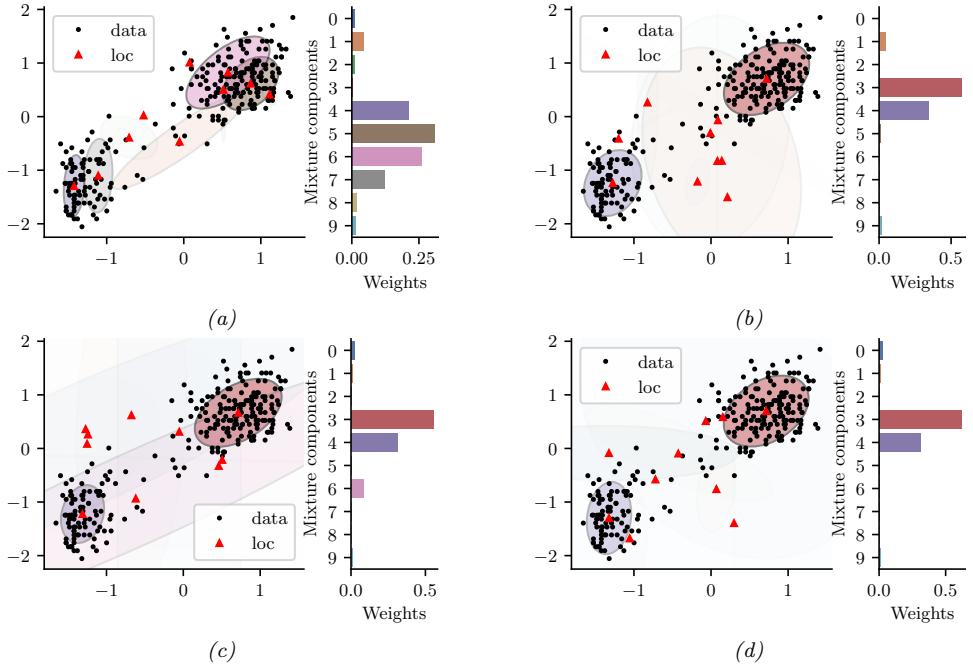

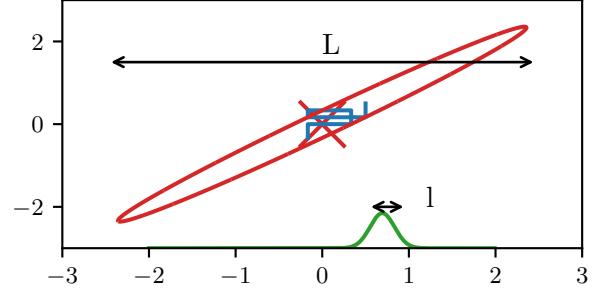

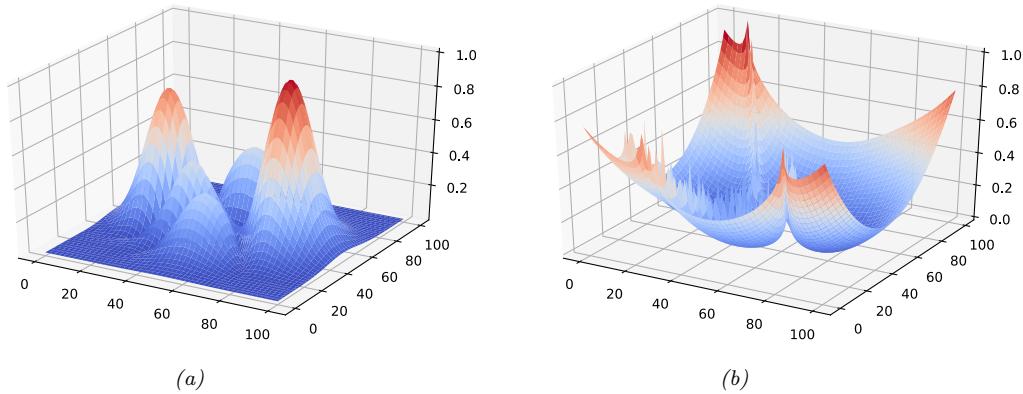

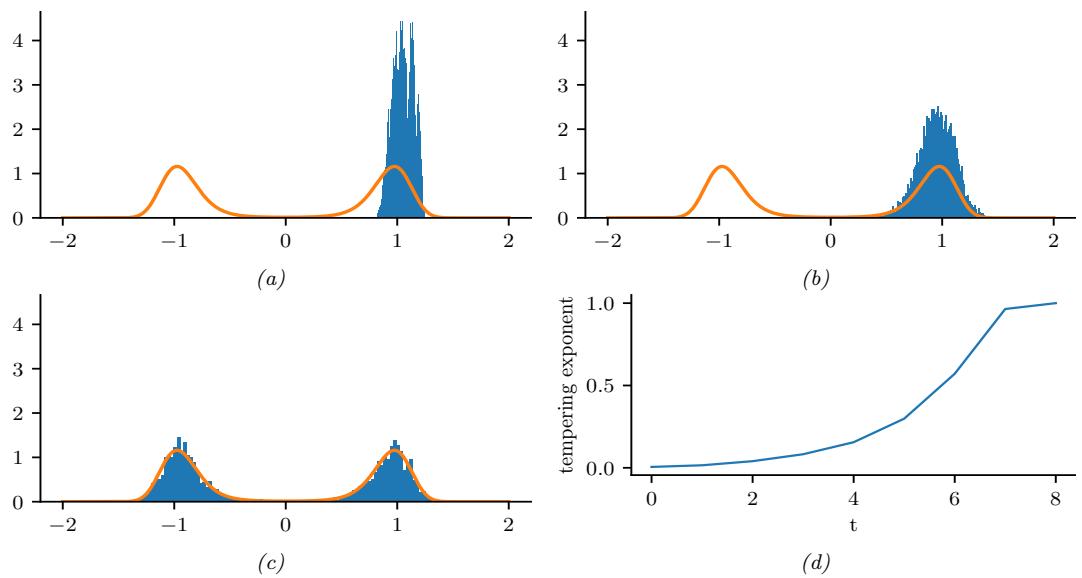

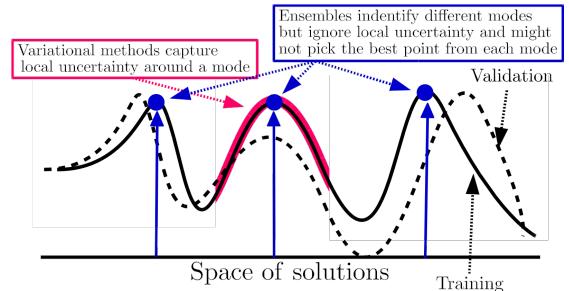

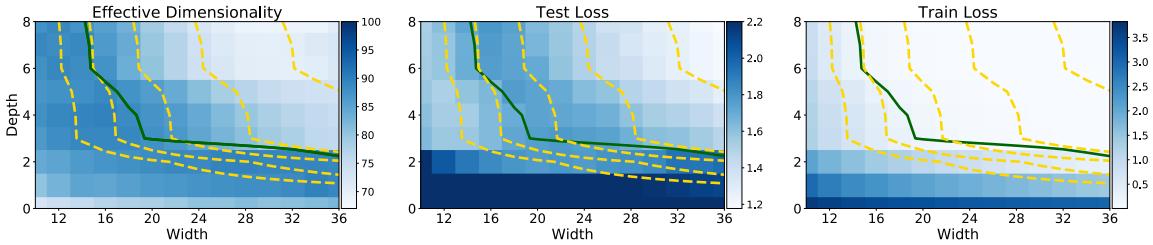

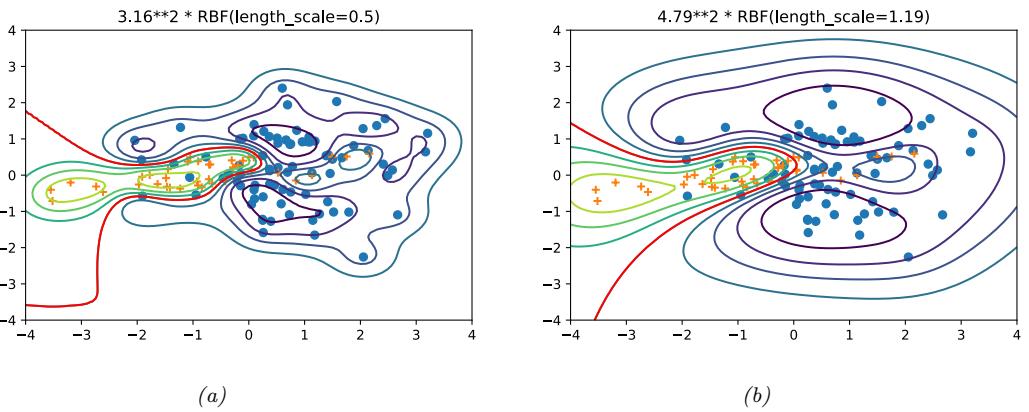

Figure 7.6: Di!erent approximations to a bimodal 2d distribution. (a) Local MAP estimate. (b) Parametric Gaussian approximation. (c) Correlated samples from near one mode. (d) Independent samples from the distribution. Adapted from Figure 2 of [PY14]. Used with kind permission of George Panadreou.

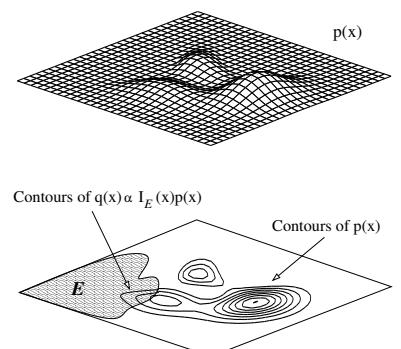

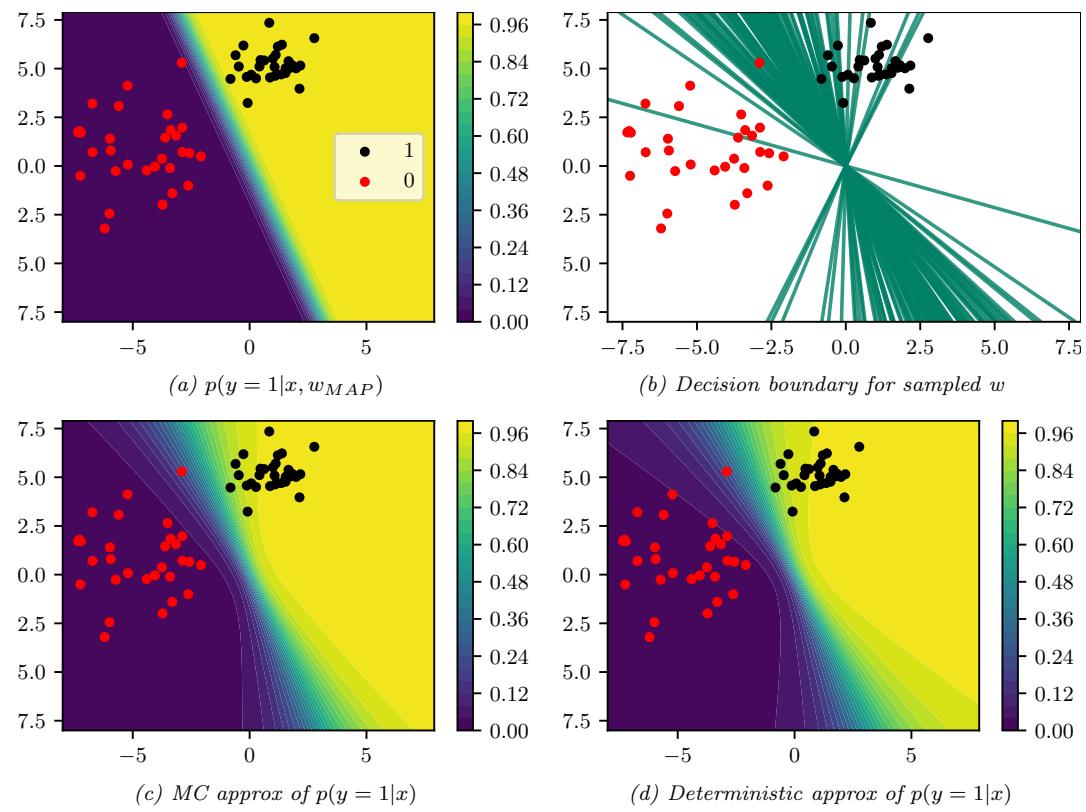

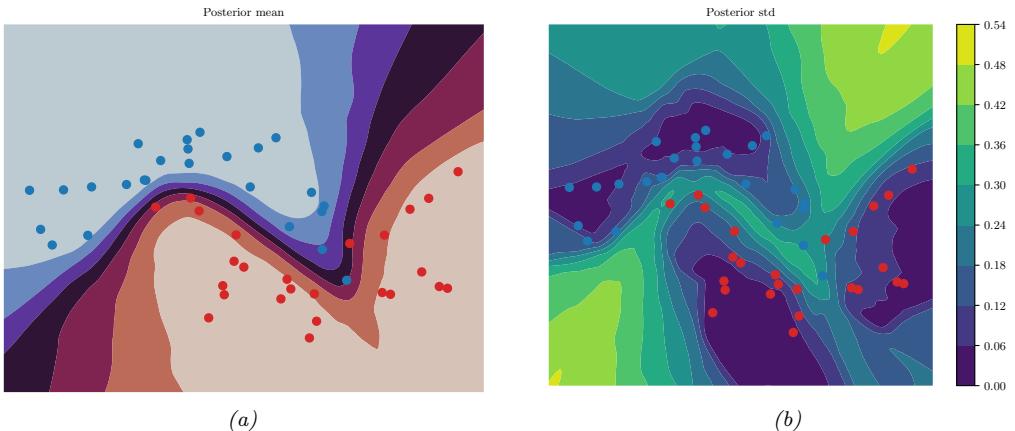

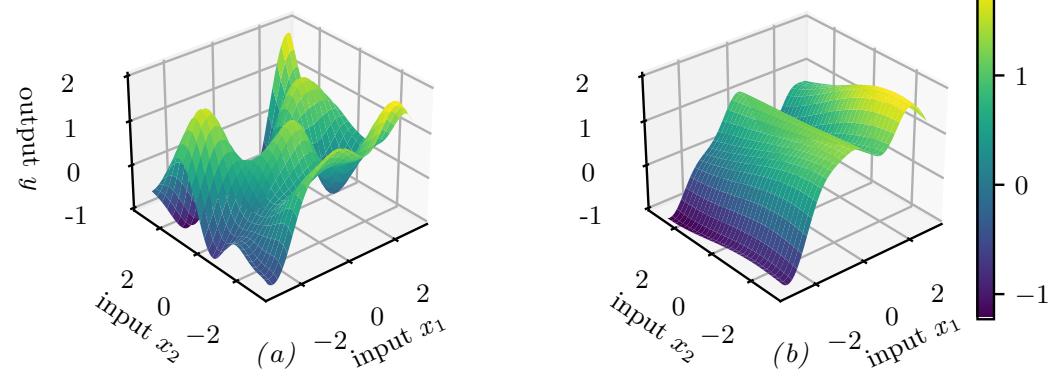

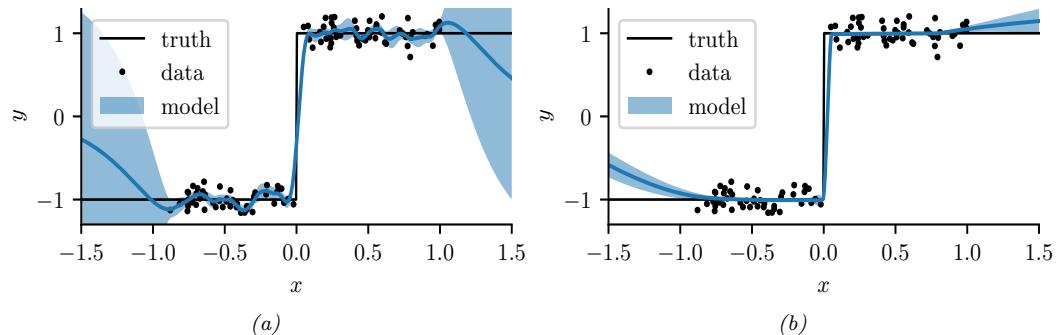

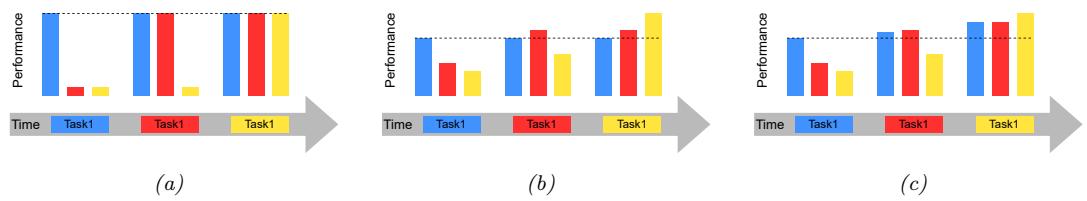

7.4.7 Challenging posteriors

In many applications, the posterior can be high dimensional and multimodal. Approximating such distributions can be quite challenging. In Figure 7.6, we give a simple 2d example. We compare MAP estimation (which does not capture any uncertainty), a Gaussian parametric approximation such as the Laplace approximation or variational inference (see panel b), and a nonparametric approximation in terms of samples. If the samples are generated from MCMC, they are serially correlated, and may only explore a local model (see panel c). However, ideally we can draw independent samples from the entire support of the distribution, as shown in panel d. We may also be able to fit a local parametric approximation around each such sample (see Section 17.3.9.1), to get a semi-parametric approximation to the posterior.

7.5 Evaluating approximate inference algorithms

There are many di!erent approximate inference algorithms, each of which make di!erent tradeo!s between speed, accuracy, generality, simplicity, etc. This makes it hard to compare them on an equal footing.

One approach is to evaluate the accuracy of the approximation q(ω) by comparing to the “true” posterior p(ω|D), computed o$ine with an “exact” method. We are usually interested in accuracy vs speed tradeo!s, which we can compute by evaluating DKL (p(ω|D) ↘ qt(ω)), where qt(ω) is the approximate posterior after t units of compute time. Of course, we could use other measures of distributional similarity, such as Wasserstein distance.

Unfortunately, it is usually impossible to compute the true posterior p(ω|D). A simple alternative is to evaluate the quality in terms of its prediction abilities on out of sample observed data, similar to cross validation. More generally, we can compare the expected loss or Bayesian risk (Section 34.1.3) of di!erent posteriors, as proposed in [KPS98; KPS99]:

\[R = \mathbb{E}\_{p^\*(x,y)}\left[\ell(y, q(y|x, \mathcal{D}))\right] \text{ where } q(y|x, \mathcal{D}) = \int p(y|x, \theta)q(\theta|\mathcal{D})d\theta \tag{7.36}\]

where ε(y, q(y)) is some loss function, such as log-loss. Alternatively, we can measure performance of the posterior when it is used in some downstream task, such as continual or active learning, as proposed in [Far22].

For some specialized methods for assessing variational inference, see [Yao+18b; Hug+20], and for Monte Carlo methods, see [CGR06; CTM17; GAR16].

8 Gaussian filtering and smoothing

8.1 Introduction

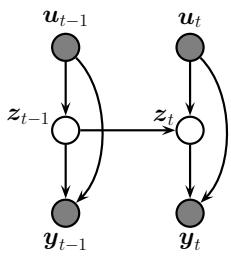

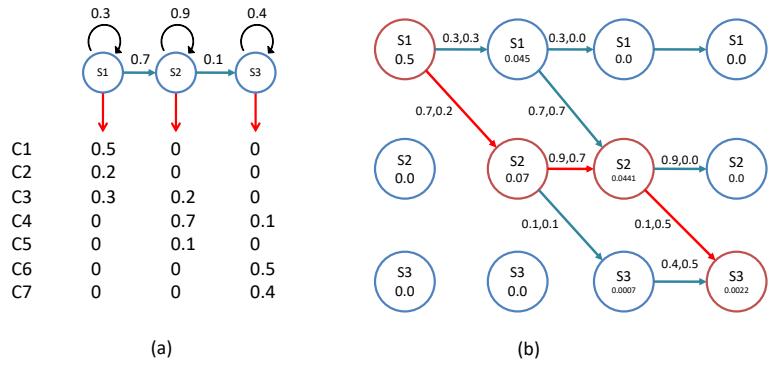

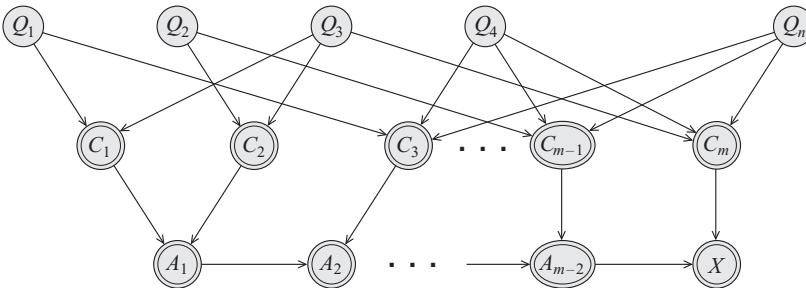

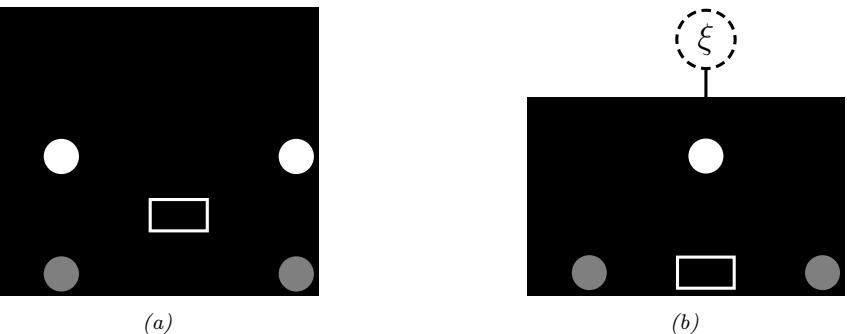

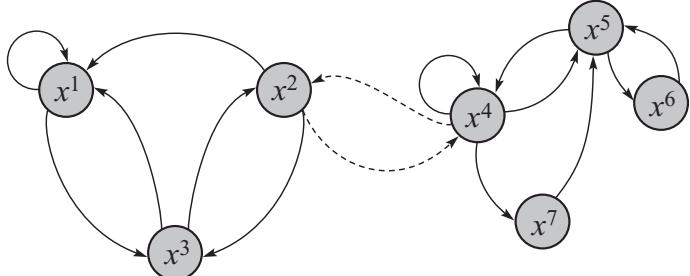

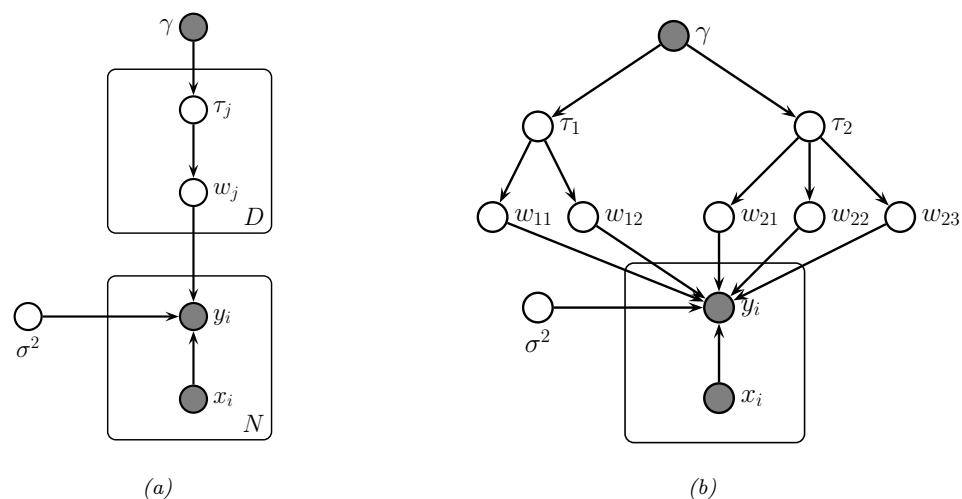

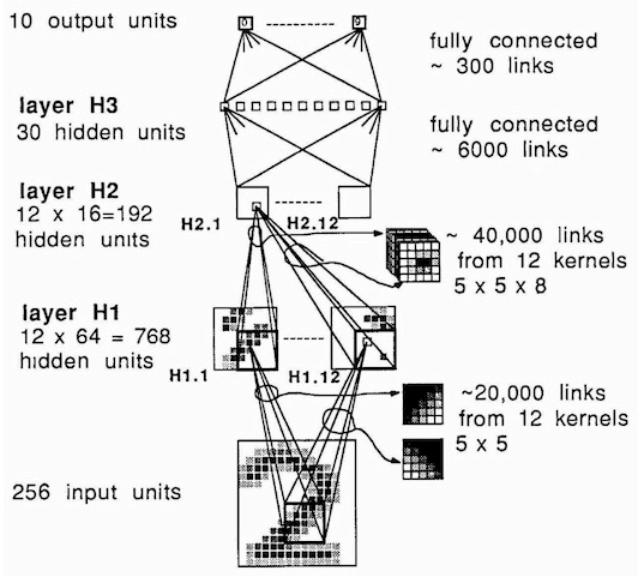

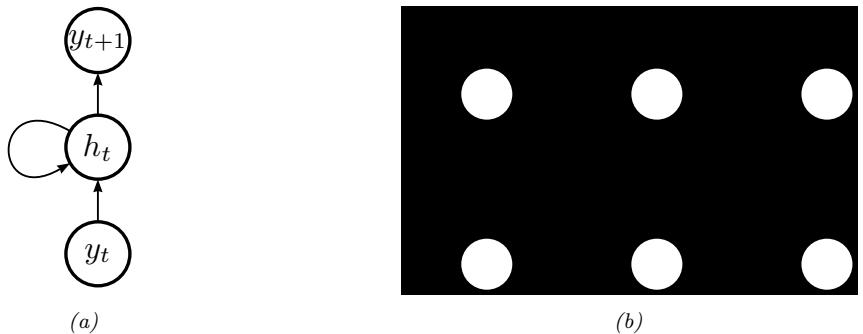

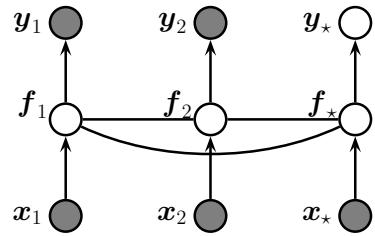

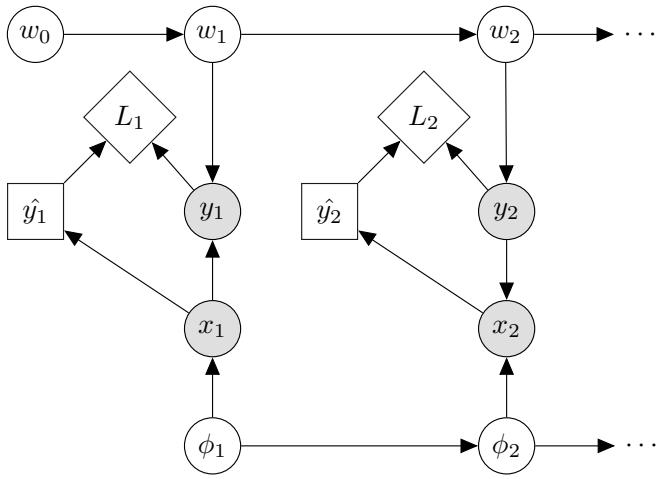

In this chapter, we consider the task of posterior inference in state-space models (SSMs). We discuss SSMs in more detail in Chapter 29, but we can think of them as latent variable sequence models with the conditional independencies shown by the chain-structured graphical model Figure 8.1. The corresponding joint distribution has the form

\[p(\mathbf{y}\_{1:T}, \mathbf{z}\_{1:T} | \mathbf{u}\_{1:T}) = \left[ p(\mathbf{z}\_1 | \mathbf{u}\_1) \prod\_{t=2}^{T} p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_t) \right] \left[ \prod\_{t=1}^{T} p(\mathbf{y}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{u}\_t) \right] \tag{8.1}\]

where zt are the hidden variables at time t, yt are the observations (outputs), and ut are the optional inputs. The term p(zt|zt↓1,ut) is called the dynamics model or transition model, p(yt|zt,ut) is called the observation model or measurement model, and p(z1|u1) is the prior or initial state distribution.1

8.1.1 Inferential goals

Given the sequence of observations, and a known model, one of the main tasks with SSMs is to perform posterior inference about the hidden states; this is also called state estimation.

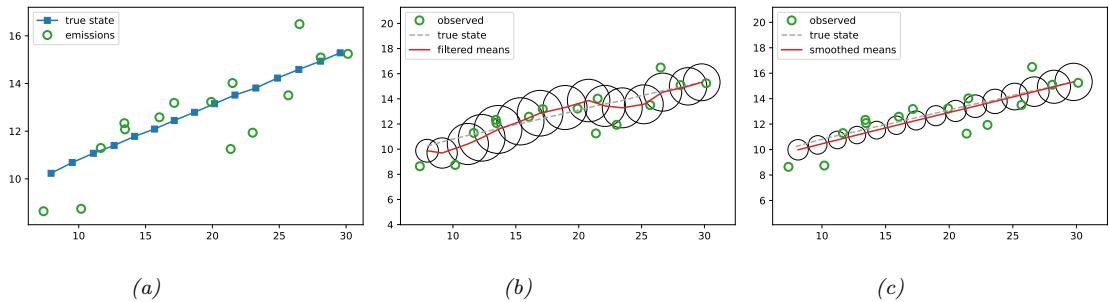

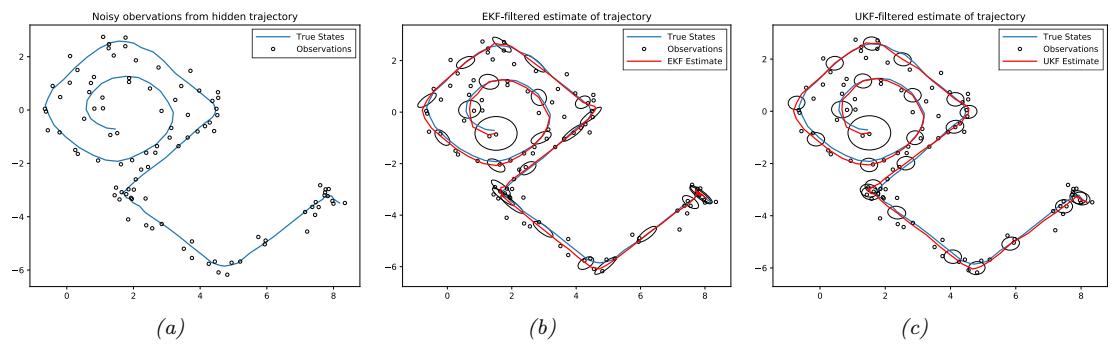

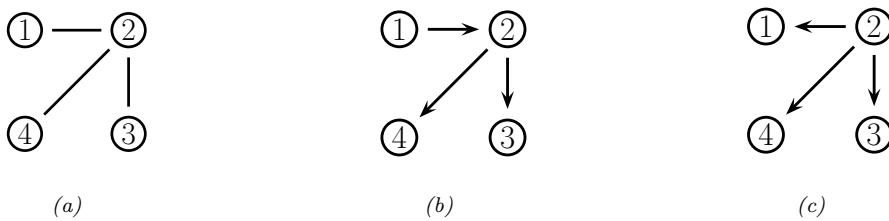

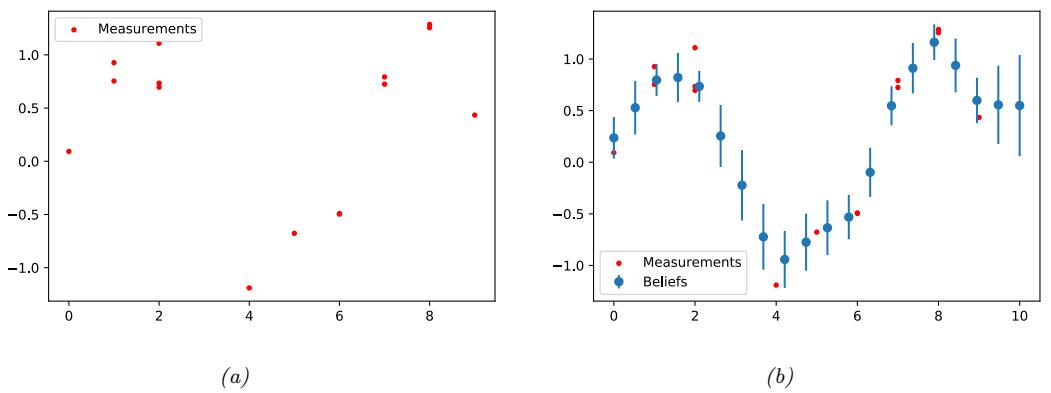

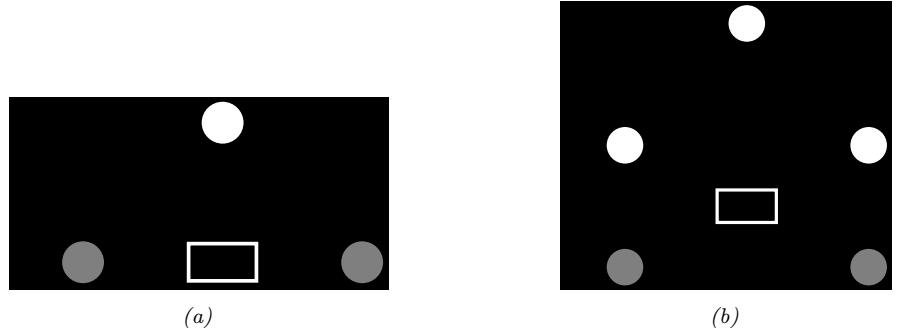

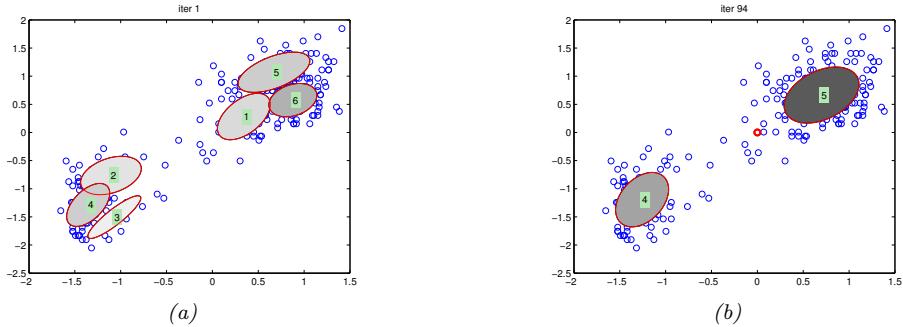

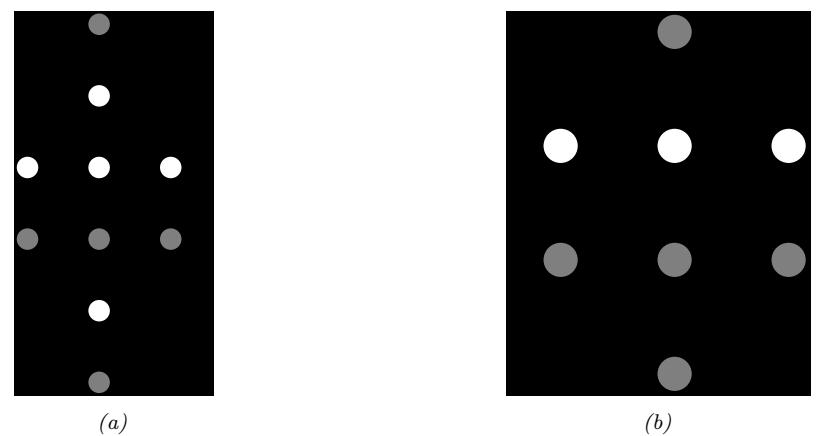

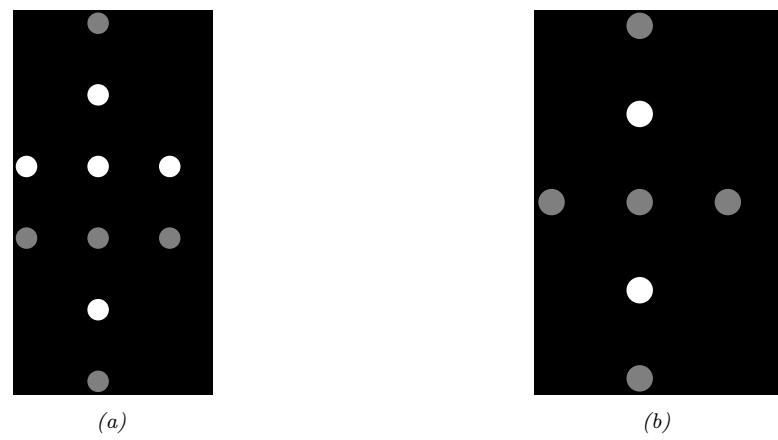

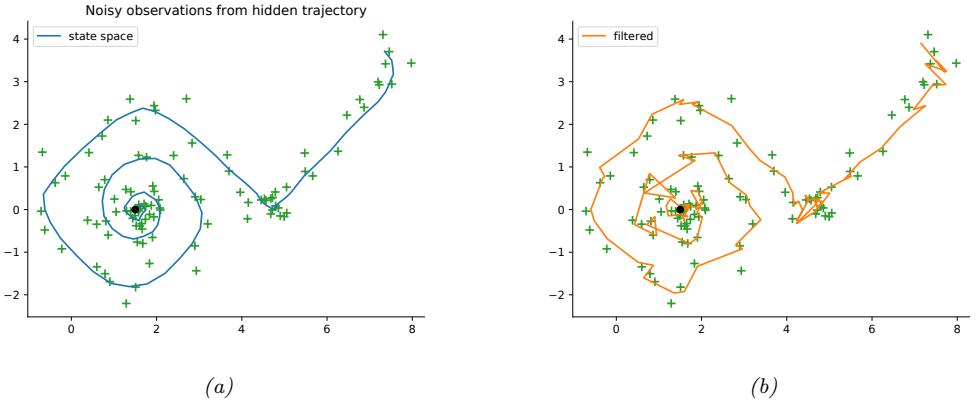

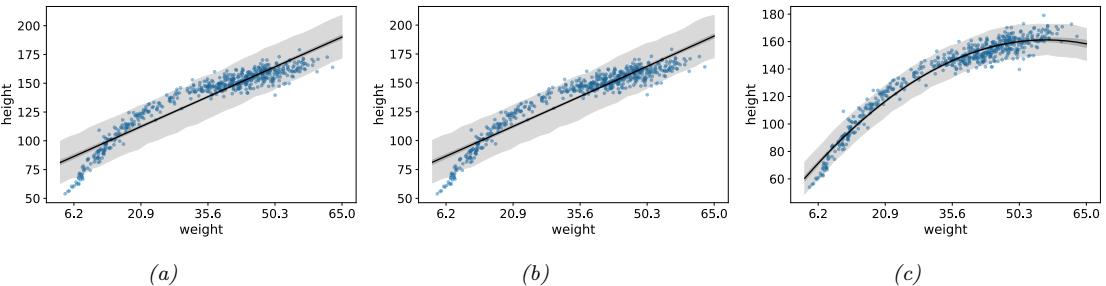

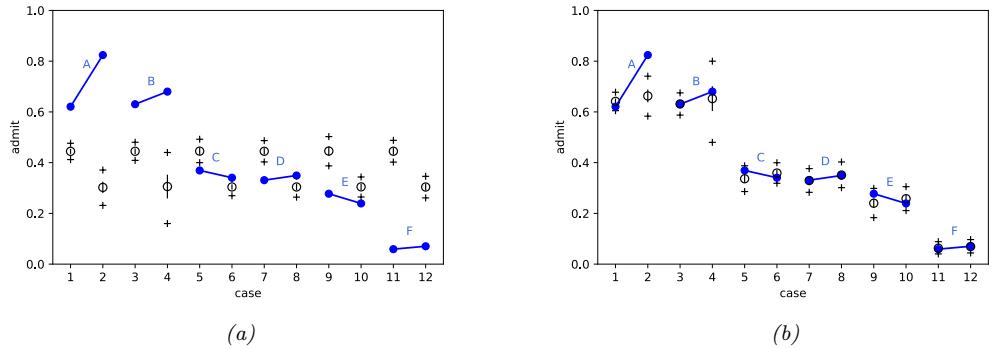

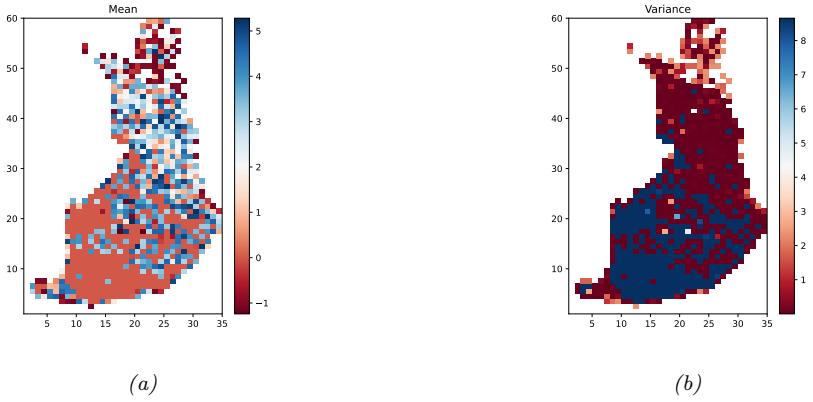

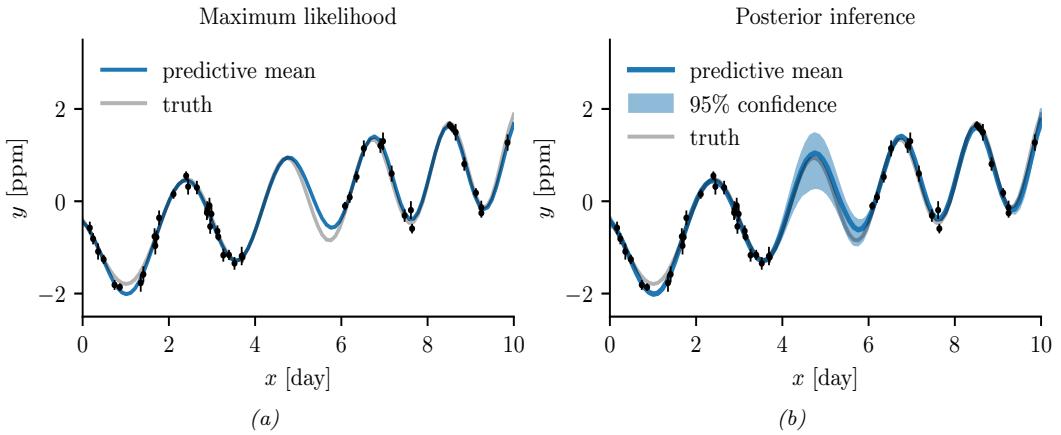

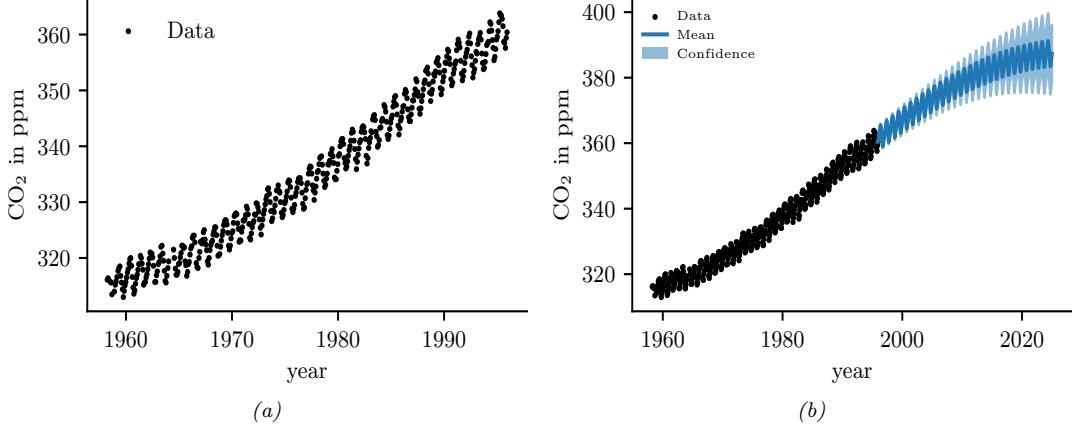

For example, consider an airplane flying in the sky. (For simplicity, we assume the world is 2d, not 3d.) We would like to estimate its location and velocity zt ↗ R4 given noisy sensor measurements of its location yt ↗ R2, as illustrated in Figure 8.2(a). (We ignore the inputs ut for simplicity.)

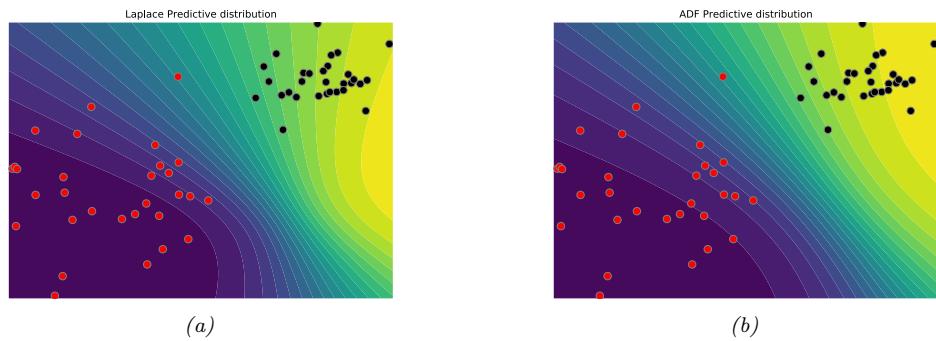

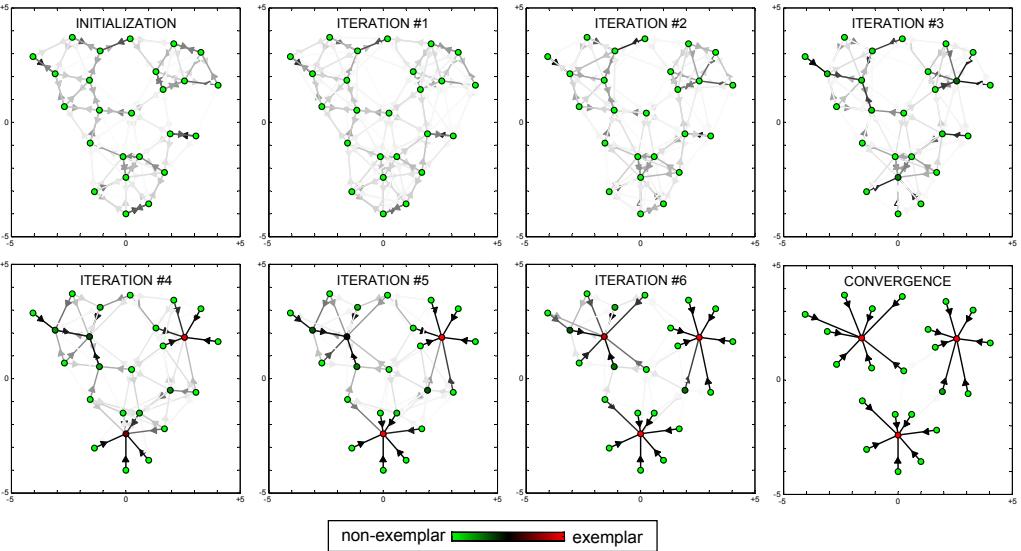

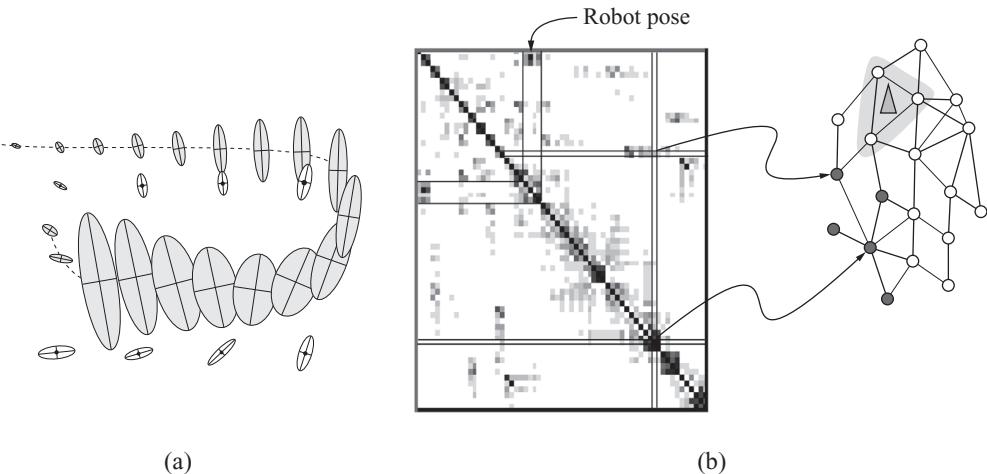

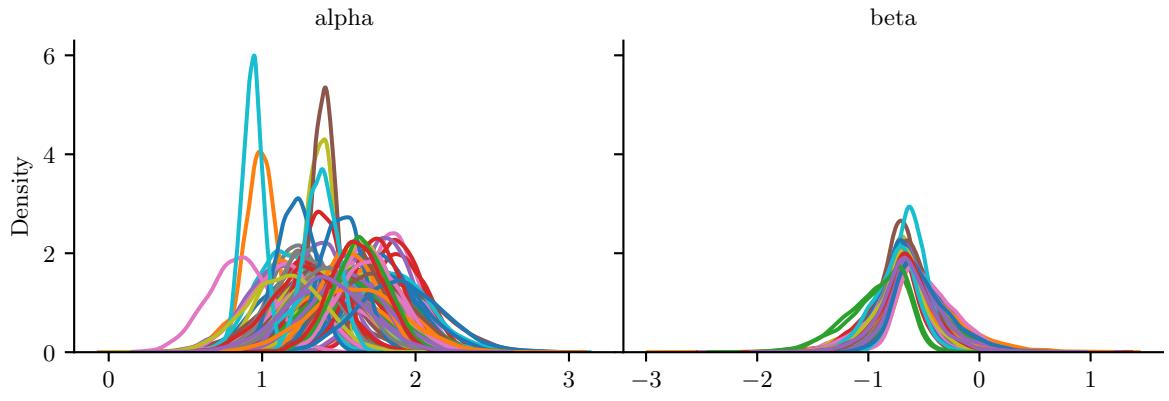

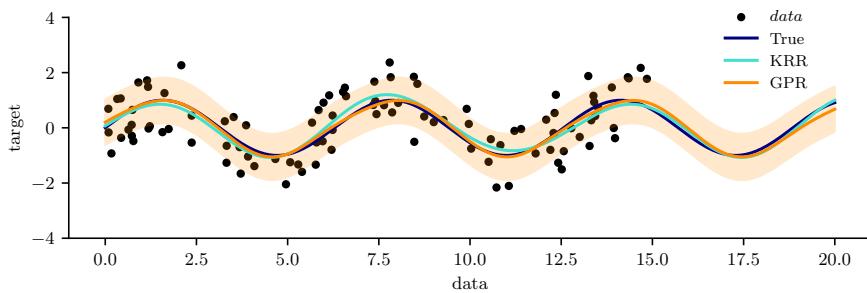

We discuss a suitable SSM for this problem, that embodies Newton’s laws of motion, in Section 8.2.1.1. We can use the model to compute the belief state p(zt|y1:t); this is called Bayesian filtering. If we represent the belief state using a Gaussian, then we can use the Kalman filter to solve this task, as we discuss in Section 8.2.2. In Figure 8.2(b) we show the results of this algorithm. The green dots are the noisy observations, the red line shows the posterior mean estimate of the location, and the black circles show the posterior covariance. (The posterior over the velocity is not shown.) We see that the estimated trajectory is less noisy than the raw data, since it incorporates prior knowledge about how the data was generated.

Another task of interest is the smoothing problem where we want to compute p(zt|y1:T ) using an o$ine dataset. We can compute these quantities using the Kalman smoother described in

1. In some cases, the initial state distribution is denoted by p(z0), and then we derive p(z1|u1) by passing p(z0) through the dynamics model. In this case, the joint distribution represents p(y1:T , z0:T |u1:T ).

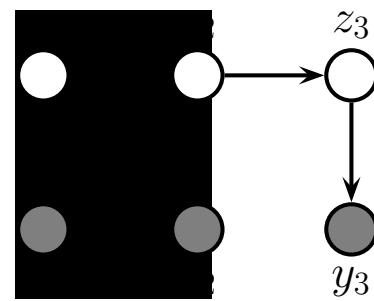

Figure 8.1: A state-space model represented as a graphical model. zt are the hidden variables at time t, yt are the observations (outputs), and ut are the optional inputs.

Figure 8.2: Illustration of Kalman filtering and smoothing for a linear dynamical system. (a) Observations (green cirles) are generated by an object moving to the right (true location denoted by blue squares). (b) Results of online Kalman filtering. Circles are 95% confidence ellipses, whose center is the posterior mean, and whose shape is derived from the posterior covariance. (c) Same as (b), but using o”ine Kalman smoothing. The MSE in the trajectory for filtering is 3.13, and for smoothing is 1.71. Generated by kf\_tracking\_script.ipynb.

Section 8.2.3. In Figure 8.2(c) we show the result of this algorithm. We see that the resulting estimate is smoother compared to filtering, and that the posterior uncertainty is reduced (as visualized by the smaller confidence ellipses).

To understand this behavior intuitively, consider a detective trying to figure out who committed a crime. As they move through the crime scene, their uncertainty is high until he finds the key clue; then they have an “aha” moment, the uncertainty is reduced, and all the previously confusing observations are, in hindsight, easy to explain. Thus we see that, given all the data (including finding the clue), it is much easier to infer the state of the world.

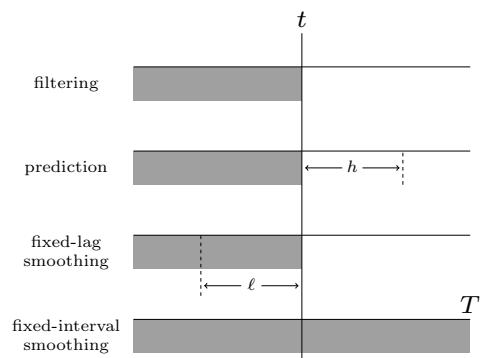

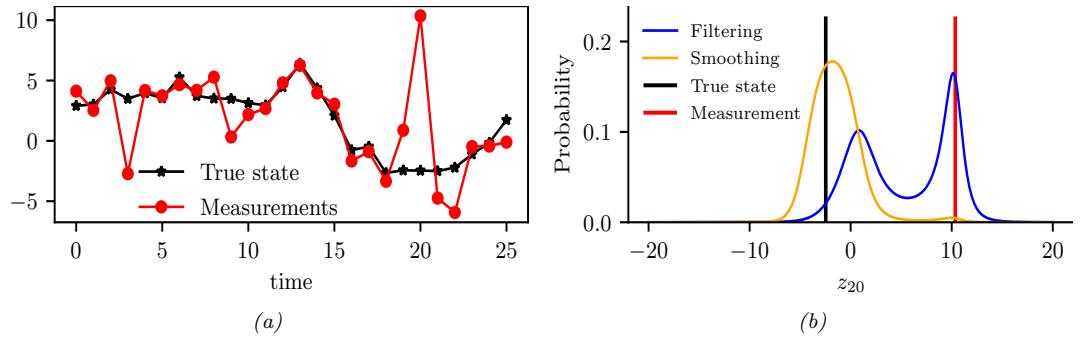

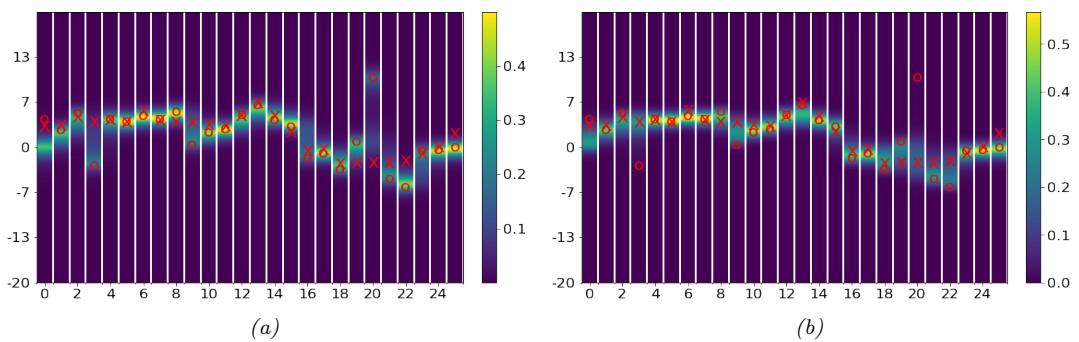

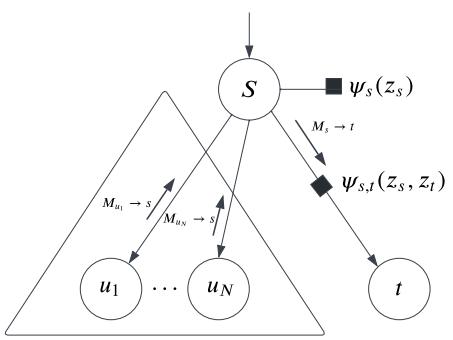

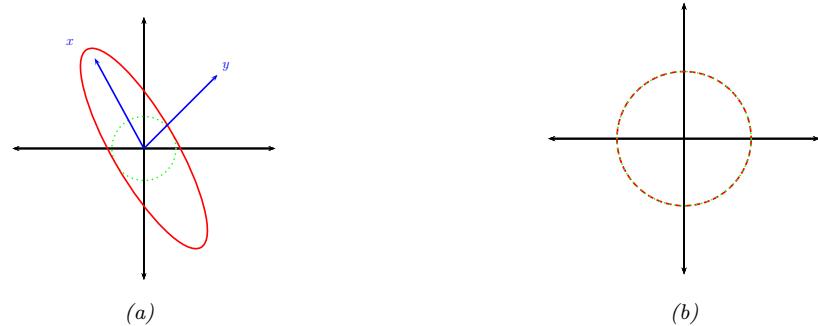

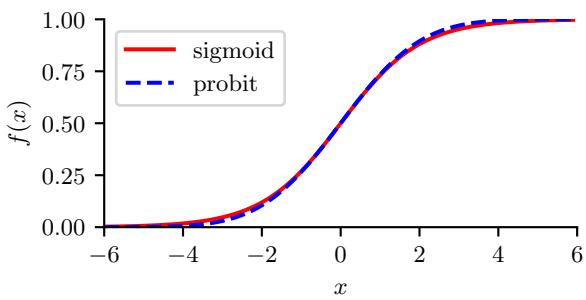

A disadvantage of the smoothing method is that we have to wait until all the data has been observed before we start performing inference, so it cannot be used for online or realtime problems. Fixed lag smoothing is a useful compromise between online and o$ine estimation; it involves computing p(zt↓ω|y1:t), where ε > 0 is called the lag. This gives better performance than filtering, but incurs a slight delay. By changing the size of the lag, we can trade o! accuracy vs delay. See Figure 8.3 for an illustration.

Figure 8.3: The main kinds of inference for state-space models. The shaded region is the interval for which we have data. The arrow represents the time step at which we want to perform inference. t is the current time, T is the sequence length, ε is the lag, and h is the prediction horizon. Used with kind permission of Peter Chang.

In addition to infering the latent state, we may want to predict future observations. We can compute the observed predictive distribution h steps into the future as follows:

\[p(\mathbf{y}\_{t+h}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) = \sum\_{\mathbf{z}\_{t+h}} p(\mathbf{y}\_{t+h}|\mathbf{z}\_{t+h}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+h}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) \tag{8.2}\]

where the hidden state predictive distribution is obtained by pushing the current belief state through the dynamics model

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+h}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) = \sum\_{\mathbf{z}\_{t:t+h-1}} p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+2}|\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}) \cdots p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+h}|\mathbf{z}\_{t+h-1}) \tag{8.3}\]

(When the states are continuous, we need to replace the sums with integrals.)

8.1.2 Bayesian filtering equations

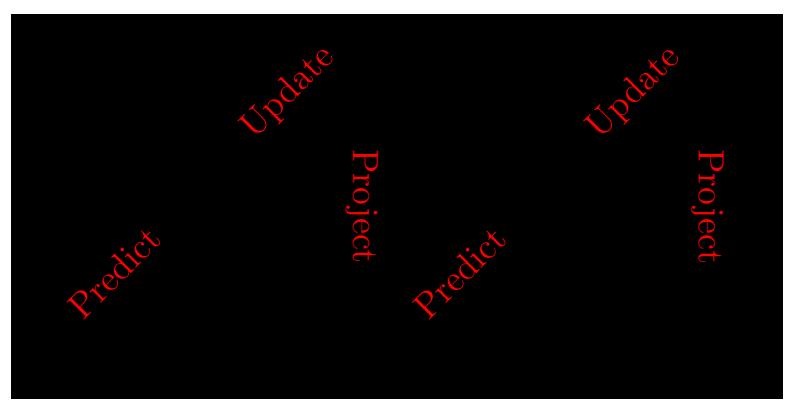

The Bayes filter is an algorithm for recursively computing the belief state p(zt|y1:t) given the prior belief from the previous step, p(zt↓1|y1:t↓1), the new observation yt, and the model. This can be done using sequential Bayesian updating, and requires a constant amount of computation per time step (independent of t). For a dynamical model, this reduces to the predict-update cycle described below.

The prediction step is just the Chapman-Kolmogorov equation:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = \int p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) d\mathbf{z}\_{t-1} \tag{8.4}\]

The prediction step computes the one-step-ahead predictive distribution for the latent state, which

updates the posterior from the previous time step into the prior for the current step.2

The update step is just Bayes’ rule:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) = \frac{1}{Z\_t} p(\mathbf{y}\_t|\mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) \tag{8.5}\]

where the normalization constant is

\[Z\_t = \int p(y\_t|\mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) d\mathbf{z}\_t = p(y\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) \tag{8.6}\]

We can use the normalization constants to compute the log likelihood of the sequence as follows:

\[\log p(\mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \log p(\mathbf{y}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \log Z\_t \tag{8.7}\]

where we define p(y1|y0) = p(y1). This quantity is useful for computing the MLE of the parameters.

8.1.3 Bayesian smoothing equations

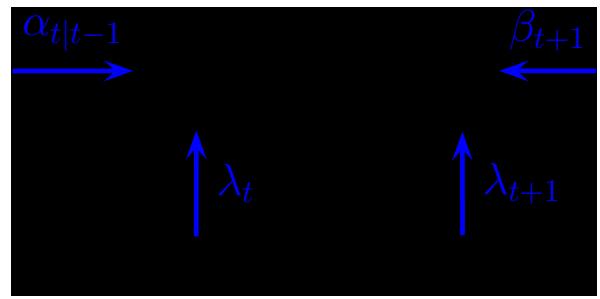

In the o$ine setting, we want to compute p(zt|y1:T ), which is the belief about the hidden state at time t given all the data, both past and future. This is called (fixed interval) smoothing. We first perform the forwards or filtering pass, and then compute the smoothed belief states by working backwards, from right (time t = T) to left (t = 1), as we explain below. Hence this method is also called forwards filtering backwards smoothing or FFBS.

Suppose, by induction, that we have already computed p(zt+1|y1:T ). We can convert this into a joint smoothed distribution over two consecutive time steps using

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, y\_{1:T}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:T}) \tag{8.8}\]

To derive the first term, note that from the Markov properties of the model, and Bayes’ rule, we have

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:t}, \mathbf{y}\_{t+T:T}) \tag{8.9}\]

\[\mathbf{y} = \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t})} \tag{8.10}\]

\[\dot{\mathbf{y}} = \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{z}\_t)p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t})} \tag{8.11}\]

Thus the joint distribution over two consecutive time steps is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, y\_{1:t}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:T}) = \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:T})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:t})} \tag{8.12}\]

2. The prediction step is not needed at t = 1 if p(z1) is provided as input to the model. However, if we just provide p(z0), we need to compute p(z1|y1:0) = p(z1) by applying the prediction step.

from which we get the new smoothed marginal distribution:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) \int \left[ \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{z}\_t)p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:T})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t})} \right] d\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} \tag{8.13}\]

\[=\int p(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:T})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t})} d\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} \tag{8.14}\]

Intuitively we can interpret this as follows: we start with the two-slice filtered distribution, p(zt, zt+1|y1:t), and then we divide out the old p(zt+1|y1:t) and multiply in the new p(zt+1|y1:T ), and then marginalize out zt+1.

8.1.4 The Gaussian ansatz

In general, computing the integrals required to implement Bayesian filtering and smoothing is intractable. However, there are two notable exceptions: if the state space is discrete, as in an HMM, we can represent the belief states as discrete distributions (histograms), which we can update using the forwards-backwards algorithm, as discussed in Section 9.2; and if the SSM is a linear-Gaussian model, then we can represent the belief states by Gaussians, which we can update using the Kalman filter and smoother, which we discuss in Section 8.2.2 and Section 8.2.3. In the nonlinear and/or non-Gaussian setting, we can still use a Gaussian to represent an approximate belief state, as we discuss in Section 8.3, Section 8.4, Section 8.5 and Section 8.6. We discuss some non-Gaussian approximations in Section 8.7.

For most of this chapter, we assume the SSM can be written as a nonlinear model subject to additive Gaussian noise:

\[\begin{aligned} z\_t &= f(z\_{t-1}, u\_t) + \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{Q}\_t) \\ y\_t &= h(z\_t, u\_t) + \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{0}, \mathbf{R}\_t) \end{aligned} \tag{8.15}\]

where f is the transition or dynamics function, and h is the observation function. In some cases, we will further assume that these functions are linear.

8.2 Inference for linear-Gaussian SSMs

In this section, we discuss inference in SSMs where all the distributions are linear Gaussian. This is called a linear Gaussian state space model (LG-SSM) or a linear dynamical system (LDS). We discuss such models in detail in Section 29.6, but in brief they have the following form:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_t) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{F}\_t \mathbf{z}\_{t-1} + \mathbf{B}\_t \mathbf{u}\_t + \mathbf{b}\_t, \mathbf{Q}\_t) \tag{8.16}\]

\[p(y\_t|\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{u}\_t) = \mathcal{N}(y\_t|\mathbf{H}\_t\mathbf{z}\_t + \mathbf{D}\_t\mathbf{u}\_t + \mathbf{d}\_t, \mathbf{R}\_t) \tag{8.17}\]

where zt ↗ RNz is the hidden state, yt ↗ RNy is the observation, and ut ↗ RNu is the input. (We have allowed the parameters to be time-varying, for later extensions that we will consider.) We often assume the means of the process noise and observation noise (i.e., the bias or o!set terms) are zero, so bt = 0 and dt = 0. In addition, we often have no inputs, so Bt = Dt = 0. In this case, the model

simplifies to the following:3

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{F}\_t\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{Q}\_t) \tag{8.18}\]

\[p(y\_t|\mathbf{z}\_t) = \mathcal{N}(y\_t|\mathbf{H}\_t\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{R}\_t) \tag{8.19}\]

See Figure 8.1 for the graphical model.4

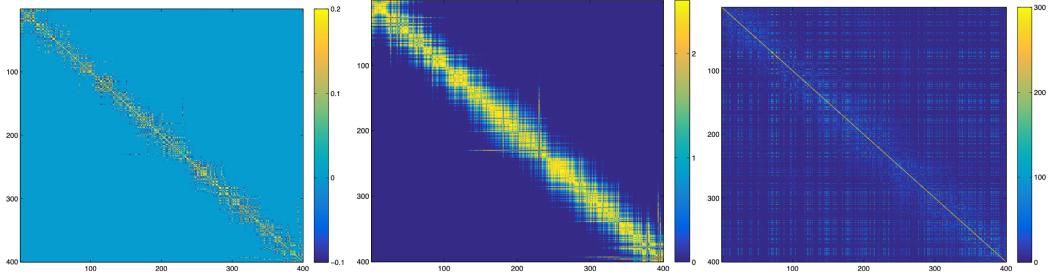

Note that an LG-SSM is just a special case of a Gaussian Bayes net (Section 4.2.3), so the entire joint distribution p(y1:T , z1:T |u1:T ) is a large multivariate Gaussian with NyNzT dimensions. However, it has a special structure that makes it computationally tractable to use, as we show below. In particular, we will discuss the Kalman filter and Kalman smoother, that can perform exact filtering and smoothing in O(T N3 z ) time.

8.2.1 Examples

Before diving into the theory, we give some motivating examples.

8.2.1.1 Tracking and state estimation

A common application of LG-SSMs is for tracking objects, such as airplanes or animals, from noisy measurements, such as radar or cameras. For example, suppose we want to track an object moving in 2d. (We discuss this example in more detail in Section 29.7.1.) The hidden state zt encodes the location, (xt1, xt2), and the velocity, (x˙ t1, x˙ t1), of the moving object. The observation yt is a noisy version of the location. (The velocity is not observed but can be inferred from the change in location.) We assume that we obtain measurements with a sampling period of !. The new location is the old location plus ! times the velocity, plus noise added to all terms:

\[\mathbf{z}\_{t} = \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & \Delta & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & \Delta \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}}\_{\mathbf{F}} \mathbf{z}\_{t-1} + \mathbf{q}\_{t} \tag{8.20}\]

where qt ↔︎ N (0, Qt). The observation extracts the location and adds noise:

\[\mathbf{y}\_t = \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}}\_{\mathbf{H}} \mathbf{z}\_t + \mathbf{r}\_t \tag{8.21}\]

where rt ↔︎ N (0, Rt).

Our goal is to use this model to estimate the unknown location (and velocity) of the object given the noisy observations. In particular, in the filtering problem, we want to compute p(zt|y1:t) in

3. Our notation is similar to [SS23], except he writes p(xk|xk→1) = N (xk|Ak→1xk→1, Qk→1) instead of p(zt|zt→1) = N (zt|Ftzt→1, Qt), and p(yk|xk) = N (yk|Hkxk, Rk) instead of p(yt|zt) = N (yt|Htzt, Rt).

4. Note that, for some problems, the evolution of certain components of the state vector is deterministic, in which case the corresponding noise terms must be zero. To avoid singular covariance matrices, we can replace the dynamics noise wt → N (0, Qt) with Gtw˜ t, where w˜ t → N (0, Q˜ t), where Q˜ t is a smaller Nq ↑ Nq psd matrix, and Gt is a Ny ↑ Nq. In this case, the covariance of the noise becomes Qt = GtQ˜ tGT t .

a recursive fashion. Figure 8.2(b) illustrates filtering for the linear Gaussian SSM applied to the noisy tracking data in Figure 8.2(a) (shown by the green dots). The filtered estimates are computed using the Kalman filter algorithm described in Section 8.2.2. The red line shows the posterior mean estimate of the location, and the black circles show the posterior covariance. We see that the estimated trajectory is less noisy than the raw data, since it incorporates prior knowledge about how the data was generated.

Another task of interest is the smoothing problem where we want to compute p(zt|y1:T ) using an o$ine dataset. Figure 8.2(c) illustrates smoothing for the LG-SSM, implemented using the Kalman smoothing algorithm described in Section 8.2.3. We see that the resulting estimate is smoother, and that the posterior uncertainty is reduced (as visualized by the smaller confidence ellipses).

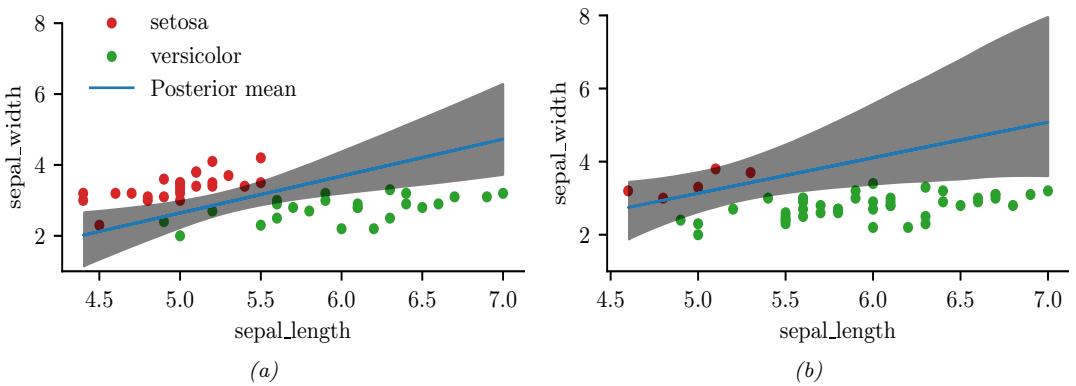

8.2.1.2 Online Bayesian linear regression (recursive least squares)

In Section 29.7.2 we discuss how to use the Kalman filter to recursively compute the exact posterior p(w|D1:t) for a linear regression model in an online fashion. This is known as the recursive least squares algorithm. The basic idea is to treat the latent state to be the parameter values, zt = w, and to define the non-stationary observation model as p(yt|zt) = N (yt|xT t zt, ς2), and the dynamics model as p(zt|zt↓1) = N (zt|zt↓1, 0I).

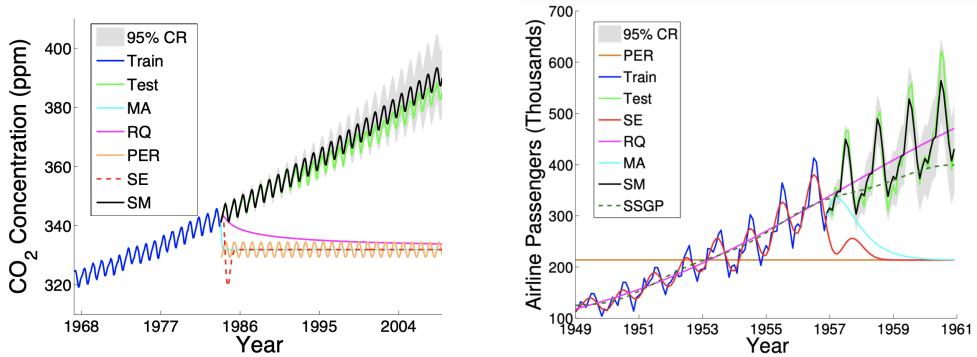

8.2.1.3 Time series forecasting

In Section 29.12, we discuss how to use Kalman filtering to perform time series forecasting.

8.2.2 The Kalman filter

The Kalman filter (KF) is an algorithm for exact Bayesian filtering for linear Gaussian state space models. The resulting algorithm is the Gaussian analog of the HMM filter in Section 9.2.2. The belief state at time t is now given by p(zt|y1:t) = N (zt|µt|t, !t|t), where we use the notation µt|t↑ and !t|t↑ to represent the posterior mean and covariance given y1:t↑ . 5 Since everything is Gaussian, we can perform the prediction and update steps in closed form, as we explain below (see Section 8.2.2.4 for the derivation).

8.2.2.1 Predict step

The one-step-ahead prediction for the hidden state, also called the time update step, is given by the following:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1}) \tag{8.22}\]

\[ \mu\_{t|t-1} = \mathbf{F}\_t \mu\_{t-1|t-1} + \mathbf{B}\_t u\_t + \mathbf{b}\_t \tag{8.23} \]

\[\mathbf{E}\_{t|t-1} = \mathbf{F}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t-1|t-1} \mathbf{F}\_t^\top + \mathbf{Q}\_t \tag{8.24}\]

5. We represent the mean and covariance of the filtered belief state by µt|t and !t|t, but some authors use the notation mt and Pt instead. We represent the mean and covariance of the smoothed belief state by µt|T and !t|T , but some authors use the notation ms t and Ps t instead. Finally, we represent the mean and covariance of the one-step-ahead posterior predictive distribution, p(zt|y1:t→1), by µt|t→1 and !t|t→1, whereas some authors use m→ t and P→ t instead.

8.2.2.2 Update step

The update step (also called the measurement update step) can be computed using Bayes’ rule, as follows:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t}) = N(\mathbf{z}\_t | \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t}) \tag{8.25}\]

\[ \hat{y}\_t = \mathbf{H}\_t \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1} + \mathbf{D}\_t \mathbf{u}\_t + \mathbf{d}\_t \tag{8.26} \]

\[\mathbf{S}\_{t} = \mathbf{H}\_{t} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} + \mathbf{R}\_{t} \tag{8.27}\]

\[\mathbf{K}\_t = \mathbf{E}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{S}\_t^{-1} \tag{8.28}\]

\[ \mu\_{t|t} = \mu\_{t|t-1} + \mathbf{K}\_t (y\_t - \hat{y}\_t) \tag{8.29} \]

\[ \Sigma\_{t|t} = \Sigma\_{t|t-1} - \mathbf{K}\_t \mathbf{H}\_t \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \tag{8.30} \]

\[\mathbf{K} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} - \mathbf{K}\_t \mathbf{S}\_t \mathbf{K}\_t^\top \tag{8.31}\]

where Kt is the Kalman gain matrix. Note that yˆt is the expected observation, so et = yt → yˆt is the residual error, also called the innovation term. The covariance of the observation is denoted by St, and the cross covariance bwteen the observation and state is denoted by Ct = !t|t↓1HT t . In practice, to compute the Kalman gain, we do not use Kt = CtS↓1 t , but instead we solve the linear system KtSt = Ct. 6

To understand the update step intuitively, note that the update for the latent mean, µt|t = µt|t↓1 + Ktet, is the predicted new latent mean plus a correction factor, which is Kt times the error signal et. If Ht = I, then Kt = !t|t↓1S↓1 t ; in the scalar case, this becomes kt = “t|t↓1/St, which is the ratio between the variance of the prior (from the dynamics model) and the variance of the measurement, which we can interpret as an inverse signal to noise ratio. If we have a strong prior and/or very noisy sensors, |Kt| will be small, and we will place little weight on the correction term. Conversely, if we have a weak prior and/or high precision sensors, then |Kt| will be large, and we will place a lot of weight on the correction term. Similarly, the new covariance is the old covariance minus a positive definite matrix, which depends on how informative the measurement is.

Note that, by using the matrix inversion lemma, the Kalman gain matrix can also be written as

\[\mathbf{K}\_{t} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} (\mathbf{H}\_{t} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} + \mathbf{R}\_{t})^{-1} = (\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1}^{-1} + \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbf{R}\_{t}^{-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t})^{-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbf{R}\_{t}^{-1} \tag{8.32}\]

This is useful if R↓1 t is precomputed (e.g., if it is constant over time) and Ny ⇑ Nz. In addition, in Equation (8.97), we give the information form of the filter, which shows that the posterior precision has the form !↓1 t = !↓1 t|t↓1 + HT t R↓1 t Ht, so we can also write the gain matrix as Kt = !tHT t R↓1 t .

8.2.2.3 Posterior predictive

The one-step-ahead posterior predictive density for the observations can be computed as follows. (We ignore inputs and bias terms, for notational brevity.) First we compute the one-step-ahead predictive density for latent states:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = \int p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t-1}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1} | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) d\mathbf{z}\_{t-1} \tag{8.33}\]

\[=\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{F}\_t\mu\_{t-1\mid t-1}, \mathbf{F}\_t\Sigma\_{t-1\mid t-1}\mathbf{F}\_t^\top + \mathbf{Q}\_t) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mu\_{t\mid t-1}, \Sigma\_{t\mid t-1})\tag{8.34}\]

6. Equivalently we have ST t KT t = CT t , so we can compute Kt in JAX using K = jnp.linalg.lstq(S.T, C.T)[0].T. Then we convert this to a prediction about observations by marginalizing out zt:

\[p(y\_t|y\_{1:t-1}) = \int p(y\_t, z\_t|y\_{1:t-1})dz\_t = \int p(y\_t|z\_t)p(z\_t|y\_{1:t-1})dz\_t = \mathcal{N}(y\_t|\dot{y}\_t, \mathbf{S}\_t) \tag{8.35}\]

This can also be used to compute the log-likelihood of the observations: The normalization constant of the new posterior can be computed as follows:

\[\log p(\mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \log p(\mathbf{y}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \log Z\_t \tag{8.36}\]

where we define p(y1|y0) = p(y1). This is just a sum of the log probabilities of the one-step-ahead measurement predictions, and is a measure of how “surprised” the model is at each step.

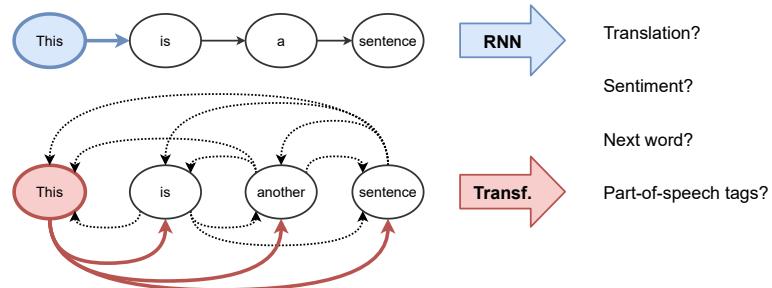

We can generalize the prediction step to predict observations K steps into the future by first forecasting K steps in latent space, and then “grounding” the final state into predicted observations. (This is in contrast to an RNN (Section 16.3.4), which requires generating observations at each step, in order to update future hidden states.)

8.2.2.4 Derivation

In this section we derive the Kalman filter equations, following [SS23, Sec 6.3]. The results are a straightforward application of the rules for manipulating linear Gaussian systems, discussed in Section 2.3.2.

First we derive the prediction step. From Equation (2.120), the joint predictive distribution for states is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t-1}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1} | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) \tag{8.37}\]

\[\mathbf{y}^{\*} = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_{t}|\mathbf{F}\_{t}\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{Q}\_{t})\mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}|\boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t-1|t-1}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t-1|t-1})\tag{8.38}\]

\[=\mathcal{N}\left(\begin{pmatrix}\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}\\\mathbf{z}\_{t}\end{pmatrix}|\mu',\Sigma'\right)\tag{8.39}\]

where

\[\boldsymbol{\mu}' = \begin{pmatrix} \mu\_{t-1|t-1} \\ \mathbf{F}\_t \mu\_{t-1|t-1} \end{pmatrix}, \ \boldsymbol{\Sigma}' = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t-1|t-1} & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t-1|t-1} \mathbf{F}\_t^\top \\ \mathbf{F}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t-1|t-1} & \mathbf{F}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t-1|t-1} \mathbf{F}\_t^\top + \mathbf{Q}\_t \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.40}\]

Hence the marginal predictive distribution for states is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mathbf{F}\_t\mu\_{t-1\mid t-1}, \mathbf{F}\_t\Sigma\_{t-1\mid t-1}\mathbf{F}\_t^\top + \mathbf{Q}\_t) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t|\mu\_{t\mid t-1}, \Sigma\_{t\mid t-1}) \tag{8.41}\]

Now we derive the measurement update step. The joint distribution for state and observation is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t, y\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) = p(\mathbf{y}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}) \tag{8.42}\]

\[=\mathcal{N}(y\_t|\mathbf{H}\_t\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{R}\_t)\mathcal{N}(z\_t|\boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1})\tag{8.43}\]

\[\mathbf{y}^{\prime} = \mathcal{N}\left( \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{z}\_{t} \\ \mathbf{y}\_{t} \end{pmatrix} \big| \boldsymbol{\mu}^{\prime\prime}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^{\prime\prime} \right) \tag{8.44}\]

where

\[\boldsymbol{\mu}^{\prime\prime} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1} \\ \mathbf{H}\_{t}\boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1} \end{pmatrix}, \ \boldsymbol{\Sigma}^{\prime\prime} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\top} \\ \mathbf{H}\_{t}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} & \mathbf{H}\_{t}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1}^{-1}\mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\top} + \mathbf{R}\_{t} \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.45}\]

Finally, we convert this joint into a conditional using Equation (2.78) as follows:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_t, y\_{1:t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mu\_{t|t}, \Sigma\_{t|t}) \tag{8.46}\]

\[ \mu\_{t|t} = \mu\_{t|t-1} + \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathsf{T} (\mathbf{H}\_t \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathsf{T} + \mathbf{R}\_t)^{-1} [y\_t - \mathbf{H}\_t \mu\_{t|t-1}] \tag{8.47} \]

\[\mathbf{y} = \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1} + \mathbf{K}\_t[\mathbf{y}\_t - \mathbf{H}\_t \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t-1}] \tag{8.48}\]

\[ \Sigma\_{t|t} = \Sigma\_{t|t-1} - \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathsf{T} (\mathbf{H}\_t \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathsf{T} + \mathbf{R}\_t)^{-1} \mathbf{H}\_t \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \tag{8.49} \]

\[\mathbf{x} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} - \mathbf{K}\_t \mathbf{H}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \tag{8.50}\]

where

\[\mathbf{S}\_t = \mathbf{H}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_t^\top + \mathbf{R}\_t \tag{8.51}\]

\[\mathbf{K}\_{t} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t-1} \mathbf{H}\_{t}^{\mathrm{T}} \mathbf{S}\_{t}^{-1} \tag{8.52}\]

8.2.2.5 Abstract formulation

We can represent the Kalman filter equations much more compactly by defining various functions that create and manipulate jointly Gaussian systems, as in Section 2.3.2. In particular, suppose we have the following linear Gaussian system:

\[p(\mathbf{z}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathfrak{p}, \mathfrak{P}) \tag{8.53}\]

\[p(y|\mathbf{z}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{A}\mathbf{z} + \mathbf{b}, \boldsymbol{\Omega})\tag{8.54}\]

Then the joint is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}, \mathbf{y}) = \mathcal{N}\left(\left(\frac{\check{\boldsymbol{\mu}}}{\overline{\boldsymbol{\mu}}}\right), \begin{pmatrix} \check{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}} & \mathbf{C} \\ \mathbf{C}^{\mathsf{T}} & \mathbf{S} \end{pmatrix}\right) = \mathcal{N}\left(\left(\mathbf{A}\,\check{\boldsymbol{\mu}} + \mathbf{b}\right), \begin{pmatrix} \check{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}} & \check{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\,\mathbf{A}^{\mathsf{T}} \\ \mathbf{A}\,\check{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}} & \mathbf{A}\,\check{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\,\mathbf{A}^{\mathsf{T}} + \boldsymbol{\Omega} \end{pmatrix}\right) \tag{8.55}\]

and the posterior is given by

\[p(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{y}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}|\,\hat{\boldsymbol{\mu}}, \hat{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}) = \mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{z}|\,\check{\boldsymbol{\mu}} + \mathbf{K}(\boldsymbol{y} - \overline{\boldsymbol{\mu}}), \check{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}} - \mathbf{K}\mathbf{S}\mathbf{K}^{\mathsf{T}}\right) \tag{8.56}\]

where K = CS↓1. See Algorithm 8.1 for the pseudocode.

We can now apply these functions to derive Kalman filtering as follows. In the prediction step, we compute

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t-1}) = \mathcal{N}\left( \begin{pmatrix} \mu\_{t-1|t-1} \\ \mu\_{t|t-1} \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} \Sigma\_{t-1|t-1} & \Sigma\_{t-1,t|t-1} \\ \Sigma\_{t,t-1|t-1} & \Sigma\_{t|t-1} \end{pmatrix} \right) \tag{8.57}\]

\[\mathbf{u}\_t(\mu\_{t|t-1}, \Sigma\_{t|t-1}, \Sigma\_{t-1,t|t}) = \mathbf{LinGaussJoint}(\mu\_{t-1|t-1}, \Sigma\_{t-1|t-1}, \mathbf{F}\_t, \mathbf{B}\_t \mathbf{u}\_t + \mathbf{b}\_t, \mathbf{Q}\_t) \tag{8.58}\]

Algorithm 8.1: Functions for a linear Gaussian system.

1 def LinGaussJoint( ↭µ, ↭ !, A, b, “) : 2 µ = A ↭µ +b 3 S =” + A ↭ ! AT 4 C =↭ ! AT 5 Return (µ, S, C) 6 def GaussCondition( ↭µ, ↭ !, µ, S, C, y) : 7 K = CS↓1 8 ↫µ=↭µ +K(y → µ) 9 ↫ !=↭ ! →KSKT 10 ε = log N (y|µ, S) 11 Return ( ↫µ, ↫ !, ε)

from which we get the marginal distribution

\[p(z\_t | y\_{1:t-1}) = \mathcal{N}(\mu\_{t|t-1}, \Sigma\_{t|t-1}) \tag{8.59}\]

In the update step, we compute the joint distribution

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t, y\_t | y\_{1:t-1}) = \mathcal{N}\left( \begin{pmatrix} \mu\_{t \mid t-1} \\ \overline{\mu}\_t \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} \Sigma\_{t \mid t-1} & \mathbf{C}\_t \\ \mathbf{C}\_t^\top & \mathbf{S}\_t \end{pmatrix} \right) \tag{8.60}\]

\[(\hat{y}\_t, \mathbf{S}\_t, \mathbf{C}\_t) = \text{Lin}\text{Gauss}\text{Joint}(\mu\_{t|t-1}, \Sigma\_{t|t-1}, \mathbf{H}\_t, \mathbf{D}\_t u\_t + \mathbf{d}\_t, \mathbf{R}\_t) \tag{8.61}\]

We then condition this on the observations to get the posterior distribution

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_t, y\_{1:t-1}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t}) = N(\mu\_{t|t}, \Sigma\_{t|t}) \tag{8.62}\]

\[(\mu\_{t|t}, \Sigma\_{t|t}, \ell\_t) = \mathbf{GuessCondition}(\mu\_{t|t-1}, \Sigma\_{t|t-1}, \hat{y}\_t, \mathbf{S}\_t, \mathbf{C}\_t, y\_t) \tag{8.63}\]

The overall KF algorithm is shown in Algorithm 8.2.

Algorithm 8.2: Kalman filter.

def KF(F1:T , B1:T , b1:T , Q1:T , H1:T , D1:T , d1:T , R1:T ,u1:T , y1:T , µ0|0, !0|0) : foreach t =1: T do // Predict: (µt|t↓1, !t|t↓1, →) = LinGaussJoint(µt↓1|t↓1, !t↓1|t↓1, Ft, Btut + bt, Qt) // Update: (µ, S, C) = LinGaussJoint(µt|t↓1, !t|t↓1, Ht, Dtut + dt, Rt) (µt|t, !t|t, εt) = GaussCondition(µt|t↓1, !t|t↓1, µ, S, C, y) Return (µt|t, !t|t)T t=1, &T t=1 εt

8.2.2.6 Numerical issues

In practice, the Kalman filter can encounter numerical issues. One solution is to use the information filter, which recursively updates the natural parameters of the Gaussian, #t|t = !↓1 t|t and ϱt|t = #tµt|t, instead of the mean and covariance (see Section 8.2.4). Another solution is the square root filter, which works with the Cholesky or QR decomposition of !t|t, which is much more numerically stable than directly updating !t|t. These techniques can be combined to create the square root information filter (SRIF) [May79]. (According to [Bie06], the SRIF was developed in 1969 for use in JPL’s Mariner 10 mission to Venus.) In [Tol22] they present an approach which uses QR decompositions instead of matrix inversions, which can also be more stable.

8.2.2.7 Continuous-time version

The Kalman filter can be extended to work with continuous time dynamical systems; the resulting method is called the Kalman Bucy filter. See [SS19, p208] for details. q

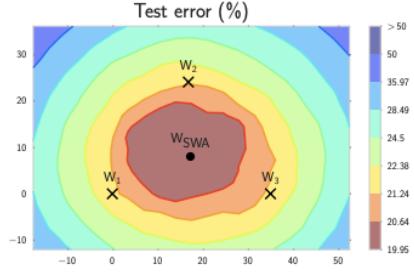

8.2.3 The Kalman (RTS) smoother

In Section 8.2.2, we described the Kalman filter, which sequentially computes p(zt|y1:t) for each t. This is useful for online inference problems, such as tracking. However, in an o$ine setting, we can wait until all the data has arrived, and then compute p(zt|y1:T ). By conditioning on past and future data, our uncertainty will be significantly reduced. This is illustrated in Figure 8.2(c), where we see that the posterior covariance ellipsoids are smaller for the smoothed trajectory than for the filtered trajectory.

We now explain how to compute the smoothed estimates, using an algorithm called the RTS smoother or RTSS, named after its inventors, Rauch, Tung, and Striebel [RTS65]. It is also known as the Kalman smoothing algorithm. The algorithm is the linear-Gaussian analog to the forwards-filtering backwards-smoothing algorithm for HMMs in Section 9.2.4.

8.2.3.1 Algorithm

In this section, we state the Kalman smoother algorithm. We give the derivation in Section 8.2.3.2. The key update equations are as follows: From this, we can extract the smoothed marginal

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|T}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|T}) \tag{8.64}\]

\[ \mu\_{t+1|t} = \mathbf{F}\_t \mu\_{t|t} \tag{8.65} \]

\[\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t} = \mathbf{F}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} \mathbf{F}\_t^\top + \mathbf{Q}\_{t+1} \tag{8.66}\]

\[\mathbf{J}\_t = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} \mathbf{F}\_t^\top \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t}^{-1} \tag{8.67}\]

\[ \mu\_{t|T} = \mu\_{t|t} + \mathbf{J}\_t (\mu\_{t+1|T} - \mu\_{t+1|t}) \tag{8.68} \]

\[\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|T} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} + \mathbf{J}\_t (\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|T} - \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t}) \mathbf{J}\_t^T \tag{8.69}\]

8.2.3.2 Derivation

In this section, we derive the RTS smoother, following [SS23, Sec 12.2]. As in the derivation of the Kalman filter in Section 8.2.2.4, we make heavy use of the rules for manipulating linear Gaussian

systems, discussed in Section 2.3.2.

The joint filtered distribution for two consecutive time slices is

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:t}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{F}\_t \mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{Q}\_{t+1}) \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t}) \tag{8.70}\]

\[=N\left(\left(\begin{array}{c}\mathbf{z}\_{t}\\\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}\end{array}\right)|\mathbf{m}\_{1},\mathbf{V}\_{1}\right)\tag{8.71}\]

where

\[\boldsymbol{\mu}\_{1} = \begin{pmatrix} \mu\_{t|t} \\ \mathbf{F}\_{t}\mu\_{t|t} \end{pmatrix}, \ \mathbf{V}\_{1} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t}\mathbf{F}\_{t}^{\top} \\ \mathbf{F}\_{t}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} & \mathbf{F}\_{t}\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t}\mathbf{F}\_{t}^{\top} + \mathbf{Q}\_{t+1} \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.72}\]

By the Markov property for the hidden states we have

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:t}, \mathbf{y}\_{t+1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) \tag{8.73}\]

and hence by conditioning the joint distribution p(zt, zt+1|y1:t) on the future state we get

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{m}\_2, \mathbf{V}\_2) \tag{8.74}\]

\[ \mu\_{t+1|t} = \mathbf{F}\_t \mu\_{t|t} \tag{8.75} \]

\[\mathbf{E}\_{t+1|t} = \mathbf{F}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} \mathbf{F}\_t^\top + \mathbf{Q}\_{t+1} \tag{8.76}\]

\[\mathbf{J}\_t = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t}^{-1} \tag{8.77}\]

\[m\_2 = \mu\_{t|t} + \mathbf{J}\_t(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} - \mu\_{t+1|t}) \tag{8.78}\]

\[\mathbf{V}\_2 = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} - \mathbf{J}\_t \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t} \mathbf{J}\_t^\top \tag{8.79}\]

where Jt is the backwards Kalman gain matrix.

\[\mathbf{J}\_t = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t, t+1|t} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t}^{-1} \tag{8.80}\]

where !t,t+1|t = !t|tFT t is the cross covariance term in the upper right block of V1.

The joint distribution of two consecutive time slices given all the data is

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) \tag{8.81}\]

\[\mathbf{y} = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{m}\_2(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}), \mathbf{V}\_2) \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t+1|T}, \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|T}) \tag{8.82}\]

\[\mathbf{y} = \mathcal{N}\left(\begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} \\ \mathbf{z}\_t \end{pmatrix} \, \big|\, m\_3, \mathbf{V}\_3\right) \tag{8.83}\]

where

\[\boldsymbol{\mu}\_{3} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t+1|T} \\ \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t|t} + \mathbf{J}\_{t}(\boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t+1|T} - \boldsymbol{\mu}\_{t+1|t}) \end{pmatrix}, \ \mathbf{V}\_{3} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|T} & \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|T} \mathbf{J}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} \\ \mathbf{J}\_{t} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|T} & \mathbf{J}\_{t} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|T} \mathbf{J}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} + \mathbf{V}\_{2} \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.84}\]

From this, we can extract p(zt|y1:T ), with the mean and covariance given by Equation (8.68) and Equation (8.69).

8.2.3.3 Two-filter smoothing

Note that the backwards pass of the Kalman smoother does not need access to the observations, y1:T , but does need access to the filtered belief states from the forwards pass, p(zt|y1:t) = N (zt|µt|t, !t|t). There is an alternative version of the algorithm, known as two-filter smoothing [FP69; Kit04], in which we compute the forwards pass as usual, and then separately compute backwards messages p(yt+1:T |zt) ↑ N (zt|µb t|t, !b t|t), similar to the backwards filtering algorithm in HMMs (Section 9.2.3).

However, these backwards messages are conditional likelihoods, not posteriors, which can cause numerical problems. For example, consider t = T; in this case, we need to set the initial covariance matrix to be !b T = ⇓I, so that the backwards message has no e!ect on the filtered posterior (since there is no evidence beyond step T). This problem can be resolved by working in information form. An alternative approach is to generalize the two-filter smoothing equations to ensure the likelihoods are normalizable by multiplying them by artificial distributions [BDM10].

In general, the RTS smoother is preferred to the two-filter smoother, since it is more numerically stable, and it is easier to generalize it to the nonlinear case.

8.2.3.4 Time and space complexity

In general, the Kalman smoothing algorithm takes O(N3 y + N2 z + NyNz) per step, where there are T steps. This can be slow when applied to long sequences. In [SGF21], they describe how to reduce this to O(log T) steps using a parallel prefix scan operator that can be run e”ciently on GPUs. In addition, we can reduce the space from O(T), to O(log T) using the same algorithm as in Section 9.2.5.

8.2.3.5 Forwards filtering backwards sampling

To draw posterior samples from the LG-SSM, we can leverage the following result:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}, \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}\_t | \bar{\mu}\_t, \bar{\Sigma}\_t) \tag{8.85}\]

\[ \tilde{\mu}\_t = \mu\_{t|t} + \mathbf{J}\_t (\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} - \mathbf{F}\_t \mu\_{t|t}) \tag{8.86} \]

\[\tilde{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\_{t} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} - \mathbf{J}\_{t} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t} \mathbf{J}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} - \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} \mathbf{F}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t+1|t} \mathbf{J}\_{t}^{\mathsf{T}} \tag{8.87}\]

\[\mathbf{I} = \boldsymbol{\Sigma}\_{t|t} (\mathbf{I} - \mathbf{F}\_t^{\mathrm{T}} \mathbf{J}\_t^{\mathrm{T}}) \tag{8.88}\]

where Jt is the backwards Kalman gain defined in Equation (8.67).

8.2.4 Information form filtering and smoothing

This section is written by Giles Harper-Donnelly.

In this section, we derive the Kalman filter and smoother algorithms in information form. We will see that this is the “dual” of Kalman filtering/smoothing in moment form. In particular, while computing marginals in moment form is easy, computing conditionals is hard (requires a matrix inverse). Conversely, for information form, computing marginals is hard, but computing conditionals is easy.

8.2.4.1 Filtering: algorithm

The predict step has a similar structure to the update step in moment form. We start with the prior p(zt↓1|y1:t↓1,u1:t↓1) = Nc(zt↓1|ϱt↓1|t↓1, #t↓1|t↓1) and then compute

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t}) = \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_t | \eta\_{t|t-1}, \mathbf{A}\_{t|t-1}) \tag{8.89}\]

\[\mathbf{M}\_t = \mathbf{A}\_{t-1|t-1} + \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t \tag{8.90}\]

\[\mathbf{J}\_t = \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t \mathbf{M}\_t^{-1} \tag{8.91}\]

\[\mathbf{A}\_{t|t-1} = \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} - \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t (\mathbf{A}\_{t-1|t-1} + \mathbf{F}\_t^{\mathrm{T}} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t)^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t^{\mathrm{T}} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \tag{8.92}\]

\[\mathbf{Q} = \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} - \mathbf{J}\_t \mathbf{F}\_t^T \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \tag{8.93}\]

\[\mathbf{Q} = \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} - \mathbf{J}\_t \mathbf{M}\_t \mathbf{J}\_t^{\mathsf{T}} \tag{8.94}\]

\[ \eta\_{t|t-1} = \mathbf{J}\_t \eta\_{t-1|t-1} + \boldsymbol{\Lambda}\_{t|t-1} (\mathbf{B}\_t \boldsymbol{u}\_t + \mathbf{b}\_t), \tag{8.95} \]

where Jt is analogous to the Kalman gain matrix in moment form Equation (8.28). From the matrix inversion lemma, Equation (2.93), we see that Equation (8.92) is the inverse of the predicted covariance !t|t↓1 given in Equation (8.24).

The update step in information form is as follows:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t}) = \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_t | \boldsymbol{\eta}\_{t|t}, \mathbf{A}\_{t|t}) \tag{8.96}\]

\[\mathbf{A}\_{t|t} = \mathbf{A}\_{t|t-1} + \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathrm{T} \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{H}\_t \tag{8.97}\]

\[ \eta\_{t|t} = \eta\_{t|t-1} + \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} (y\_t - \mathbf{D}\_t u\_t - d\_t). \tag{8.98} \]

8.2.4.2 Filtering: derivation

For the predict step, we first derive the joint distribution over hidden states at t, t → 1:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1} | \mathbf{y}\_{1:t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t-1}) \tag{8.99}\]

\[=\boldsymbol{\mathcal{N}}\_{c}(\mathbf{z}\_{t}, \boldsymbol{|\mathbf{Q}|}^{-1}(\mathbf{F}\_{t}\mathbf{z}\_{t-1} + \mathbf{B}\_{t}\boldsymbol{u}\_{t} + \mathbf{b}\_{t}), \mathbf{Q}\_{t}^{-1})\tag{8.100}\]

\[\times \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_{t-1}, |\boldsymbol{\eta}\_{t-1|t-1}, \mathbf{A}\_{t-1|t-1}) \tag{8.101}\]

\[=\mathcal{N}\_c(z\_{t-1}, z\_t | \eta\_{t-1,t|t}, \Lambda\_{t-1,t|t}) \tag{8.102}\]

where

\[\eta\_{t-1,t|t-1} = \begin{pmatrix} \eta\_{t-1|t-1} - \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} (\mathbf{B}\_t u\_t + b\_t) \\ \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} (\mathbf{B}\_t u\_t + b\_t) \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.103}\]

\[ \boldsymbol{\Lambda}\_{t-1,t|t-1} = \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{A}\_{t-1|t-1} + \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t & -\mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \\ -\mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t & \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.104} \]

The information form predicted parameters ϱt|t↓1, #t|t↓1 can then be derived using the marginalisation formulae in Section 2.3.1.4.

For the update step, we start with the joint distribution over the hidden state and the observation

at t:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t, y\_t | y\_{1:t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t}) = p(y\_t | \mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{u}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t-1}, \mathbf{u}\_{1:t-1}) \tag{8.105}\]

\[\mathbf{y} = \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{y}\_t, |\mathbf{R}\_t^{-1}(\mathbf{H}\_t z\_t + \mathbf{D} u\_t + \mathbf{d}\_t), \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1}) \mathcal{N}\_c(z\_t | \eta\_{t|t-1}, \mathbf{A}\_{t|t-1}) \tag{8.106}\]

\[=\mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{y}|\eta\_{\mathbf{z},\mathbf{y}|t}, \mathbf{A}\_{\mathbf{z},\mathbf{y}|t})\tag{8.107}\]

where

\[\eta\_{x,y|t} = \begin{pmatrix} \eta\_{t|t-1} - \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathrm{T} \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} (\mathbf{D}\_t u\_t + \mathbf{d}\_t) \\ \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} (\mathbf{D}\_t u\_t + \mathbf{d}\_t) \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.108}\]

\[\mathbf{A}\_{\mathbf{z},\mathbf{y}|t} = \begin{pmatrix} \mathbf{A}\_{t|t-1} + \mathbf{H}\_t^\mathrm{T} \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{H}\_t & -\mathbf{H}\_t^\mathrm{T} \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} \\ -\mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{H}\_t & \mathbf{R}\_t^{-1} \end{pmatrix} \tag{8.109}\]

The information form filtered parameters ϱt|t, #t|t are then derived using the conditional formulae in 2.3.1.4.

8.2.4.3 Smoothing: algorithm

The smoothing equations are as follows:

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | \mathbf{y}\_{1:T}) = \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_t | \boldsymbol{\eta}\_{t|T}, \boldsymbol{\Lambda}\_{t|T}) \tag{8.110}\]

\[\mathbf{U}\_t = \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} + \boldsymbol{\Lambda}\_{t+1|T} - \boldsymbol{\Lambda}\_{t+1|t} \tag{8.111}\]

\[\mathbf{L}\_t = \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{U}\_t^{-1} \tag{8.112}\]

\[\mathbf{A}\_{t|T} = \mathbf{A}\_{t|t} + \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t - \mathbf{L}\_t \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F} \tag{8.113}\]

\[=\mathbf{A}\_{t|t} + \mathbf{F}\_t^\mathrm{T} \mathbf{Q}\_t^{-1} \mathbf{F}\_t - \mathbf{L}\_t \mathbf{U}\_t \mathbf{L}\_t^\mathrm{T} \tag{8.114}\]

\[ \eta\_{t|T} = \eta\_{t|t} + \mathbf{L}\_t (\eta\_{t+1|T} - \eta\_{t+1|t}).\tag{8.115} \]

The parameters ϱt|t and #t|t are the filtered values from Equations (8.98) and (8.97) respectively. Similarly, ϱt+1|t and #t+1|t are the predicted parameters from Equations (8.95) and (8.92). The matrix Lt is the information form analog to the backwards Kalman gain matrix in Equation (8.67).

8.2.4.4 Smoothing: derivation

From the generic forwards-filtering backwards-smoothing equation, Equation (8.14), we have

\[p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:T}) = p(\mathbf{z}\_t | y\_{1:t}) \int \left[ \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \mathbf{z}\_t) p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:T})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | y\_{1:t})} \right] d\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} \tag{8.116}\]

\[=\int p(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t}) \frac{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:T})}{p(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}|\mathbf{y}\_{1:t})} d\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} \tag{8.117}\]

\[\mathcal{N} = \int \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \eta\_{t, t+1|t}, \Lambda\_{t, t+1|t}) \frac{\mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \eta\_{t+1|T}, \Lambda\_{t+1|T})}{\mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \eta\_{t+1|t}, \Lambda\_{t+1|t})} d\mathbf{z}\_{t+1} \tag{8.118}\]

\[\mathcal{I}\_t = \int \mathcal{N}\_c(\mathbf{z}\_t, \mathbf{z}\_{t+1} | \eta\_{t, t+1 \mid T}, \Lambda\_{t, t+1 \mid T}) d\mathbf{z}\_{t+1}. \tag{8.119}\]

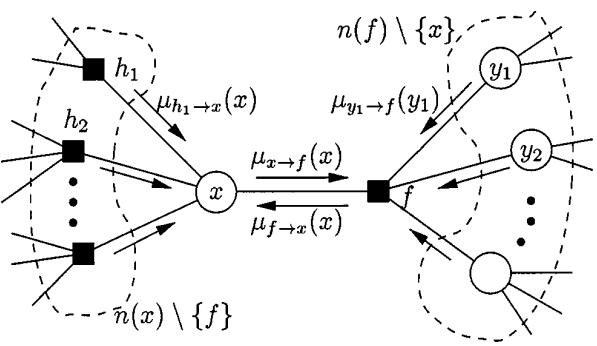

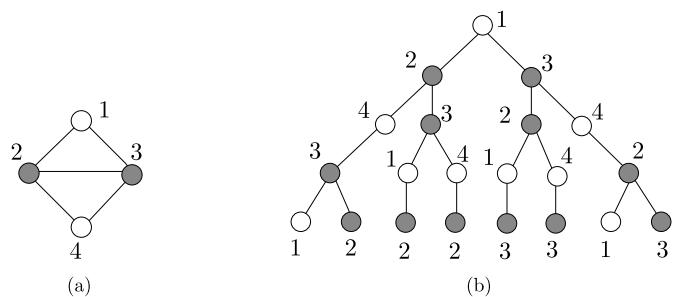

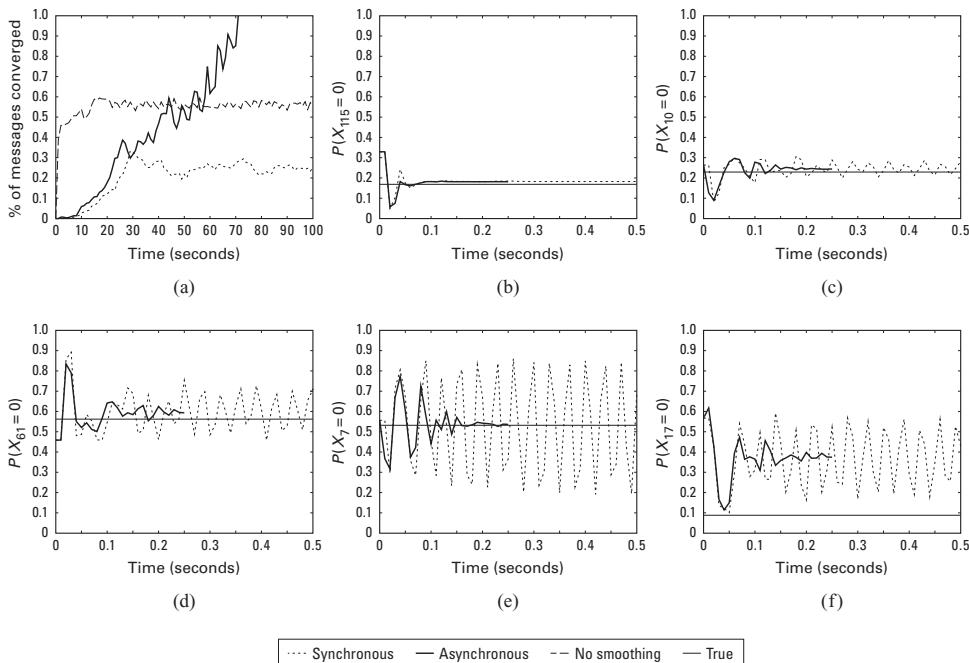

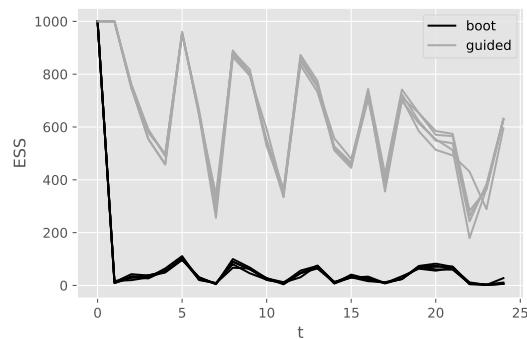

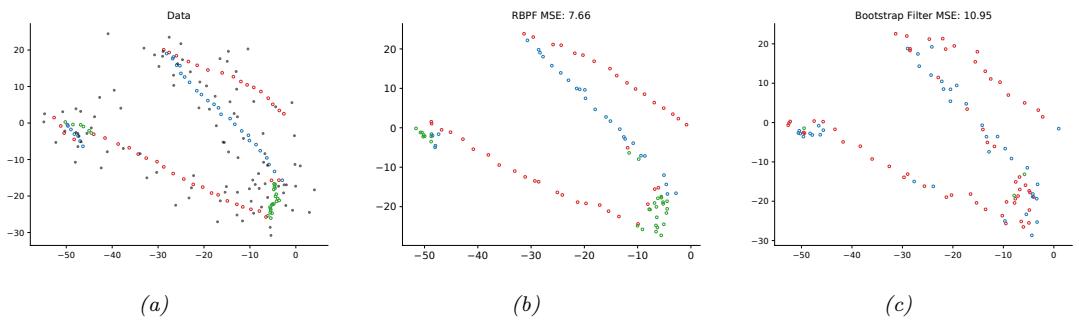

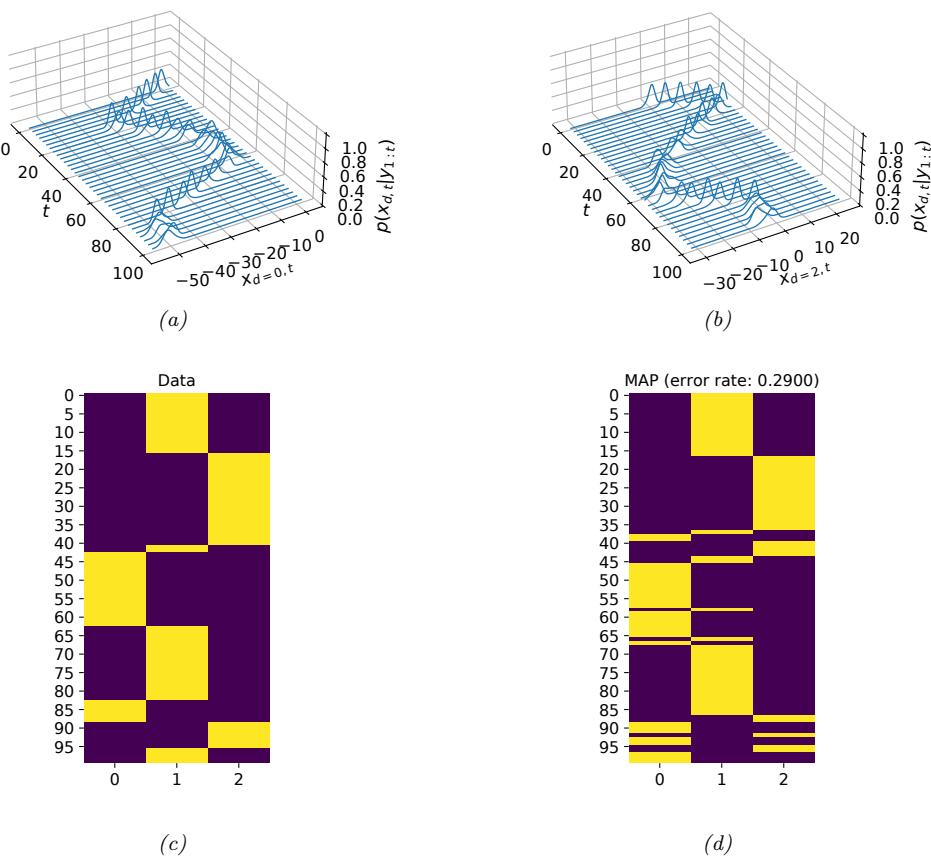

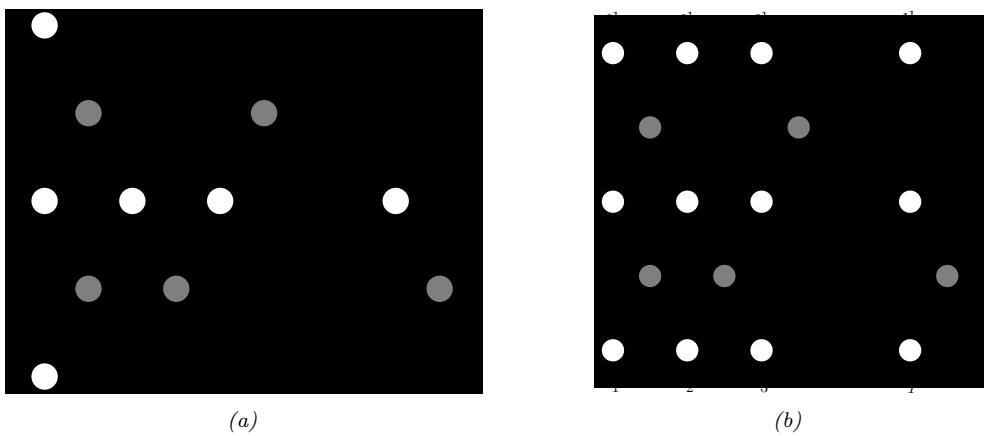

The parameters of the joint filtering predictive distribution, p(zt, zt+1|y1:t), take precisely the same form as those in the filtering derivation described in Section 8.2.4.2: