Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics

Probabilistic Machine Learning

Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning

Francis Bach, editor

A complete list of titles can be found online at https://mitpress.mit.edu/search-result-list/ ?series=adaptive-computation-and-machine-learning-series.

Probabilistic Machine Learning Advanced Topics

Kevin P. Murphy

The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

© 2023 Kevin P. Murphy

This work is subject to a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license.

Subject to such license, all rights are reserved.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Murphy, Kevin P., author.

Title: Probabilistic machine learning : advanced topics / Kevin P. Murphy. Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2023] | Series: Adaptive computation and machine learning series | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2022045222 (print) | LCCN 2022045223 (ebook) | ISBN 9780262048439 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780262376006 (epub) | ISBN 9780262375993 (pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Machine learning. | Probabilities. Classification: LCC Q325.5 .M873 2023 (print) | LCC Q325.5 (ebook) | DDC 006.3/1015192–dc23/eng20230111 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022045222 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022045223

This book is dedicated to my wife Margaret, who has been the love of my life for 20+ years.

Brief Contents

I Fundamentals 3

- 2 Probability 5

- 3 Statistics 63

- 4 Graphical models 143

- 5 Information theory 219

- 6 Optimization 261

II Inference 343

III Prediction 573

IV Generation 771

V Discovery 925

VI Action 1103

Contents

Preface xxxi

I Fundamentals 3

2 Probability 5

| 2.1 | Introduction | 5 |

|---|---|---|

| 2.1.1 | Probability space 5 |

|

| 2.1.2 | Discrete random variables 5 |

|

| 2.1.3 | Continuous random variables 6 |

|

| 2.1.4 | Probability axioms 7 |

|

| 2.1.5 | Conditional probability 7 |

|

| 2.1.6 | Bayes’ rule 8 |

|

| 2.2 | Some common probability distributions 8 |

|

| 2.2.1 | Discrete distributions 9 |

|

| 2.2.2 | Continuous distributions on R 10 |

|

| 2.2.3 | Continuous distributions on R+ 13 |

|

| 2.2.4 | Continuous distributions on [0, 1] 17 |

|

| 2.2.5 | Multivariate continuous distributions 17 |

|

| 2.3 | Gaussian joint distributions 22 |

|

| 2.3.1 | The multivariate normal 22 |

|

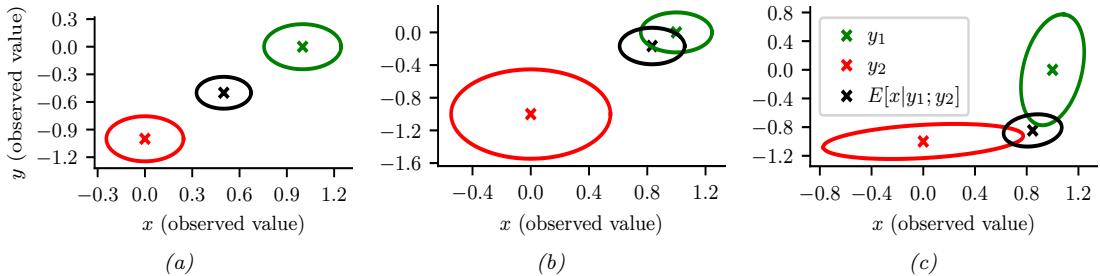

| 2.3.2 | Linear Gaussian systems 28 |

|

| 2.3.3 | A general calculus for linear Gaussian systems 30 |

|

| 2.4 | The exponential family 33 |

|

| 2.4.1 | Definition 34 |

|

| 2.4.2 | Examples 34 |

|

| 2.4.3 | Log partition function is cumulant generating function 39 |

|

| 2.4.4 | Canonical (natural) vs mean (moment) parameters 41 |

|

| 2.4.5 | MLE for the exponential family 42 |

|

| 2.4.6 | Exponential dispersion family 43 |

|

| 2.4.7 | Maximum entropy derivation of the exponential family 43 |

|

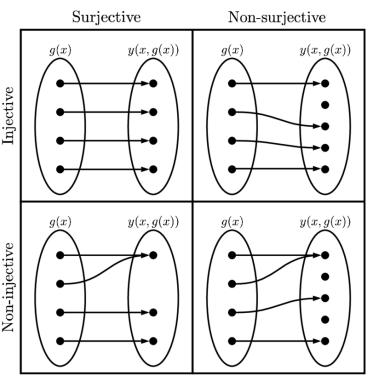

| 2.5 | Transformations of random variables 44 |

|

| 2.5.1 | Invertible transformations (bijections) 44 |

|

| 2.5.2 | Monte Carlo approximation 45 |

|

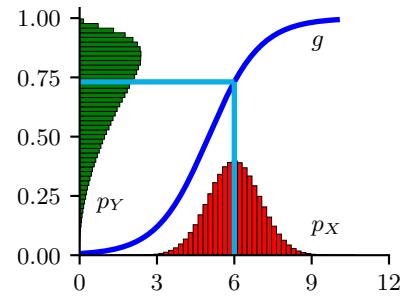

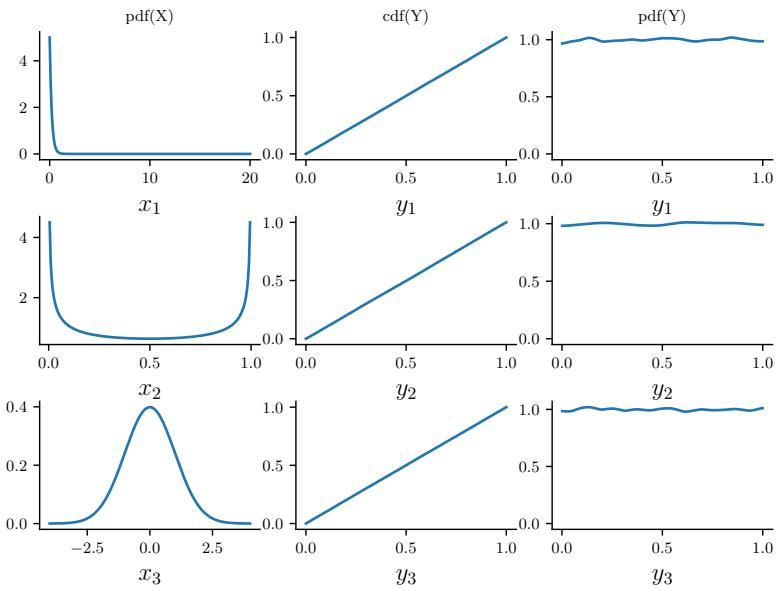

| 2.5.3 | Probability integral transform 45 |

|

| 2.6 | Markov chains 46 |

|

| 2.6.1 | Parameterization 47 |

|

| 2.6.2 | Application: language modeling 49 |

|

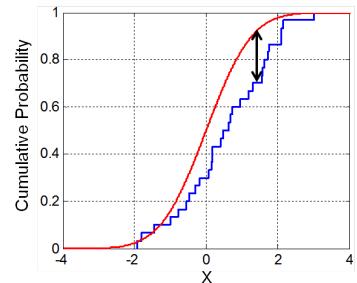

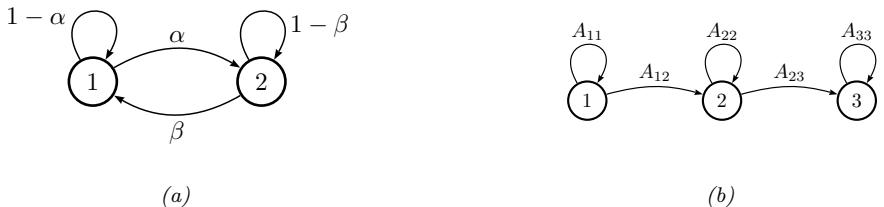

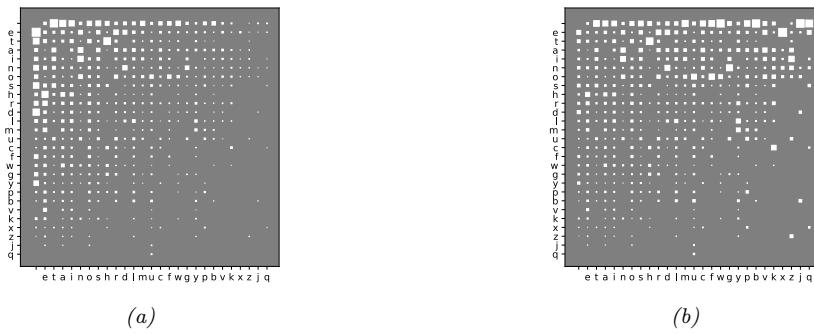

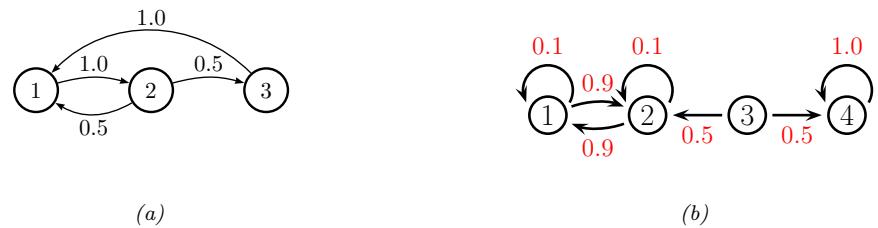

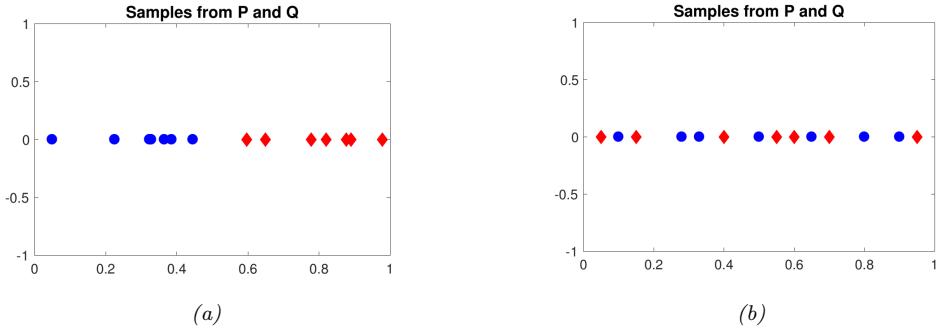

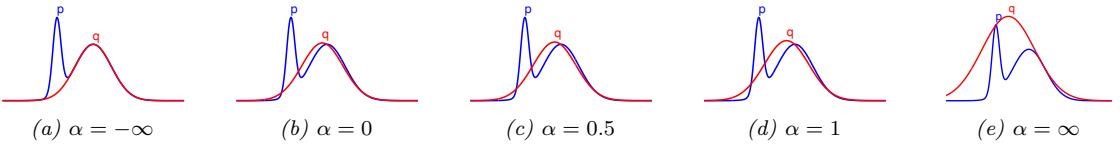

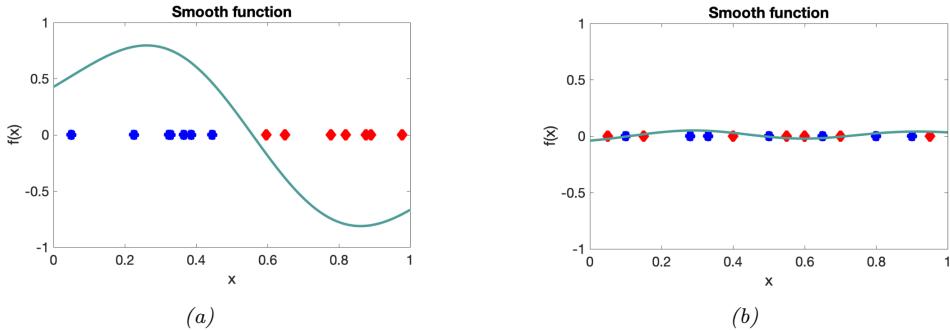

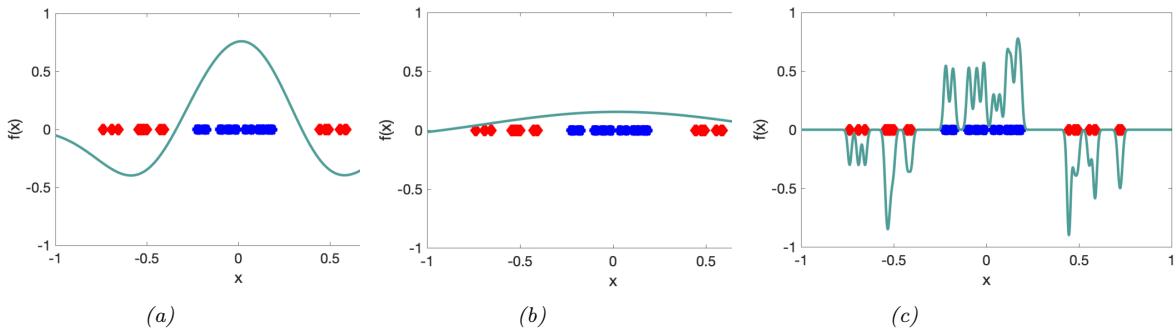

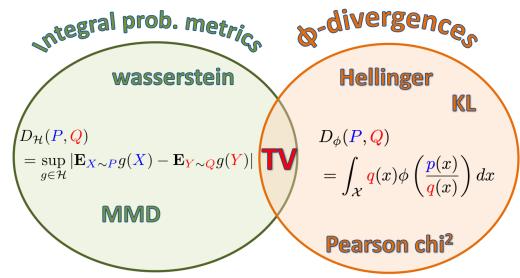

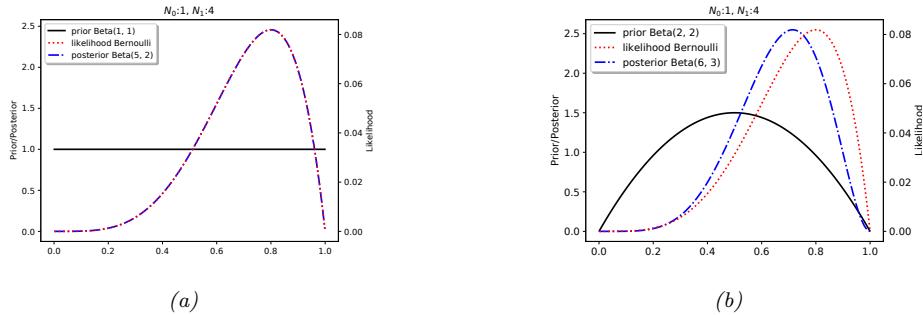

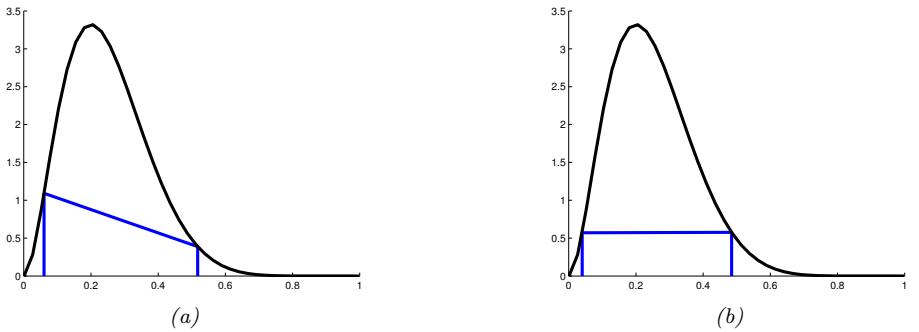

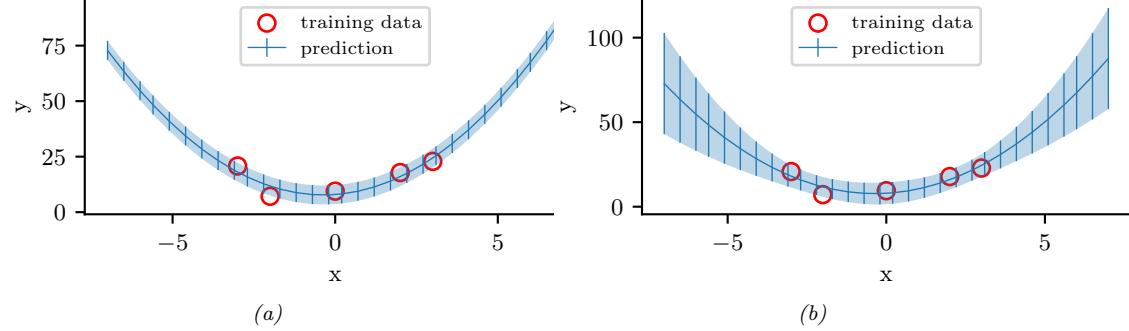

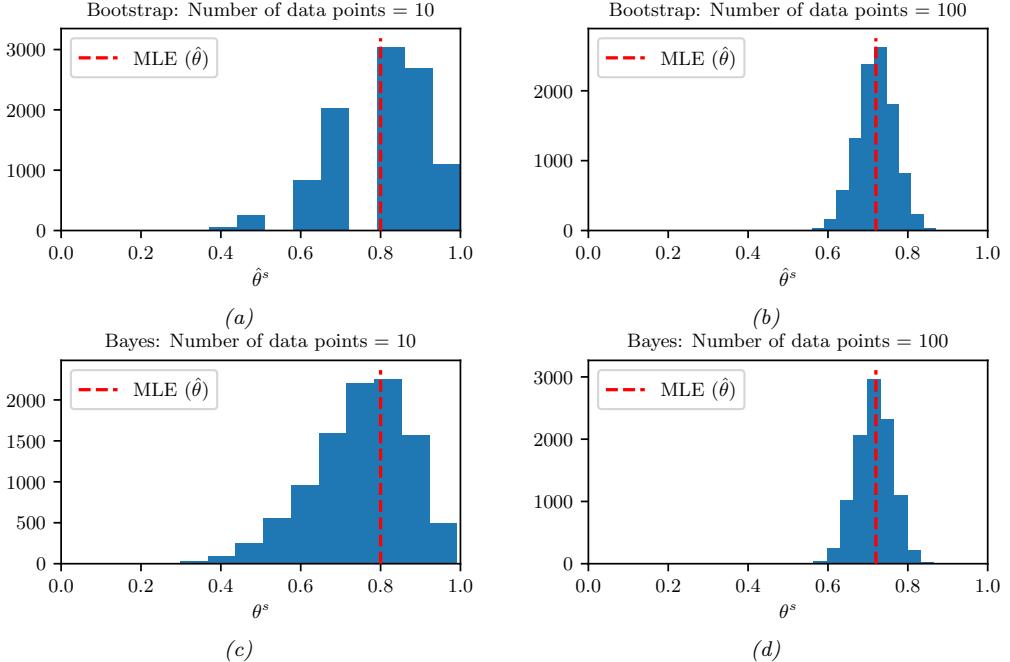

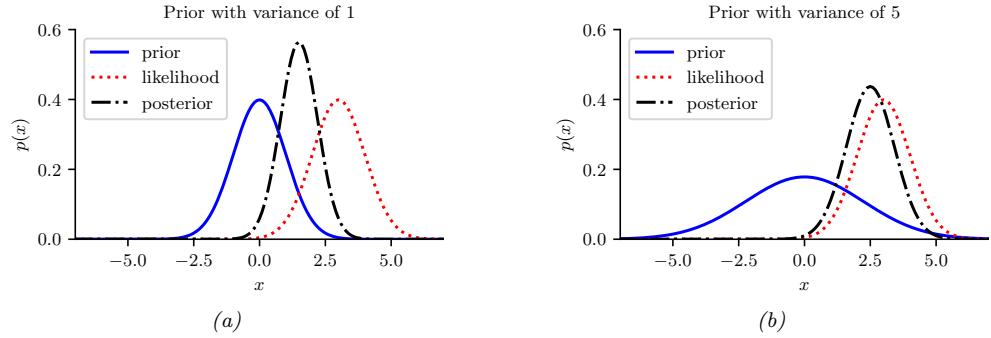

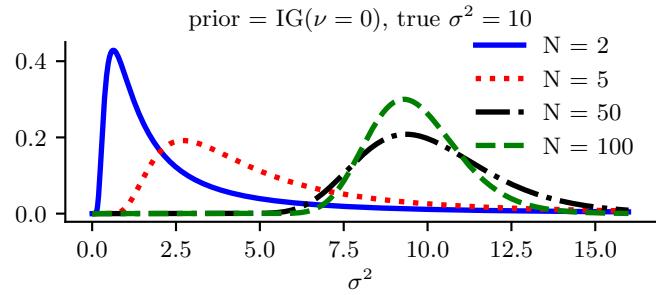

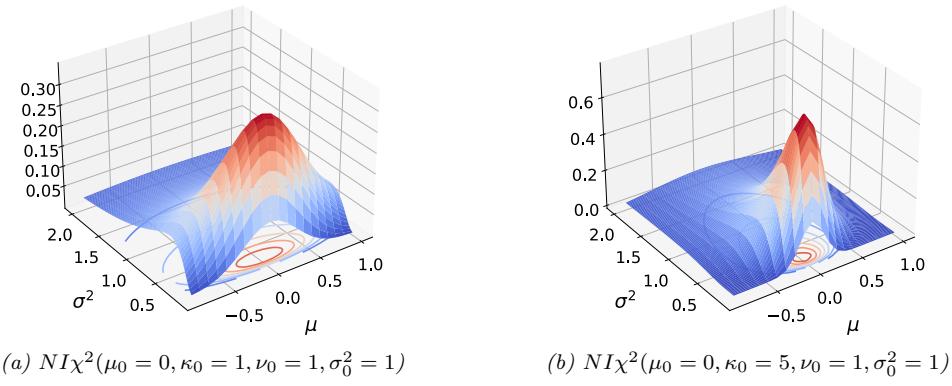

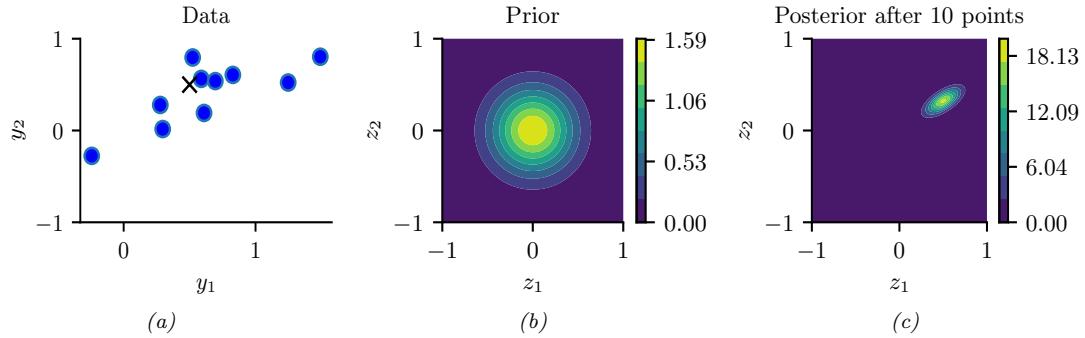

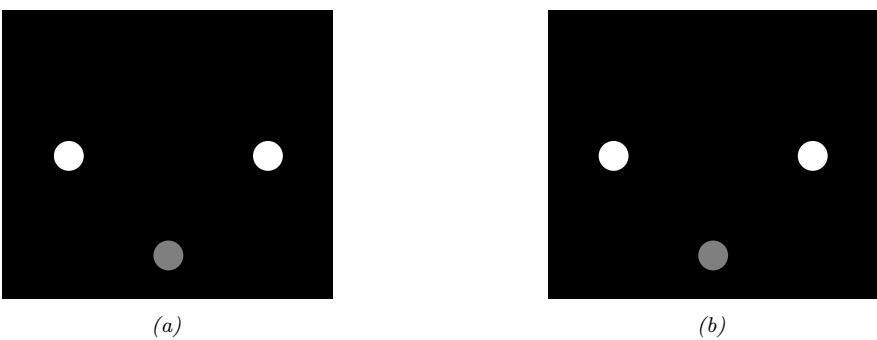

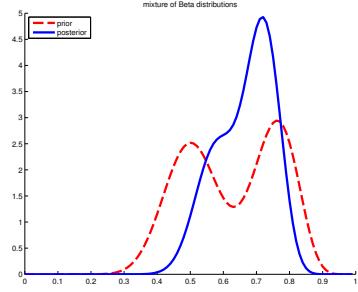

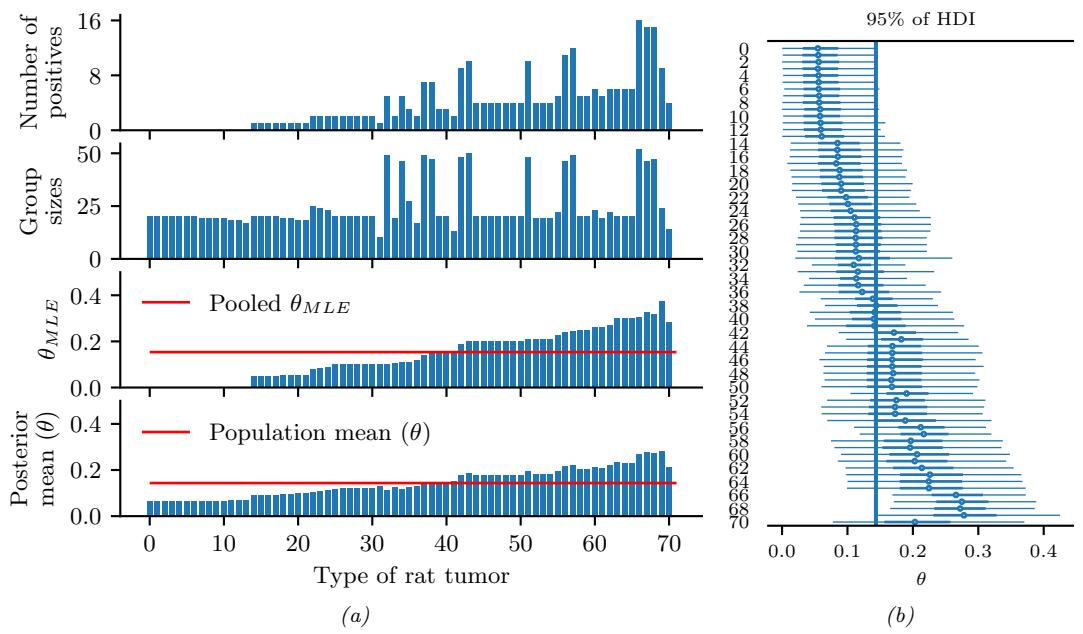

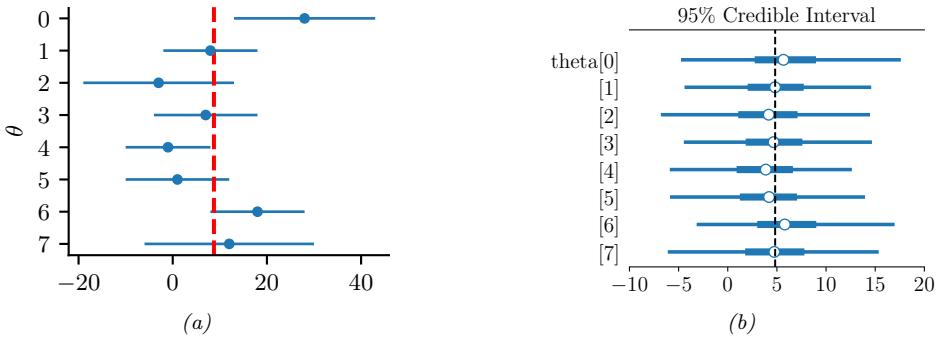

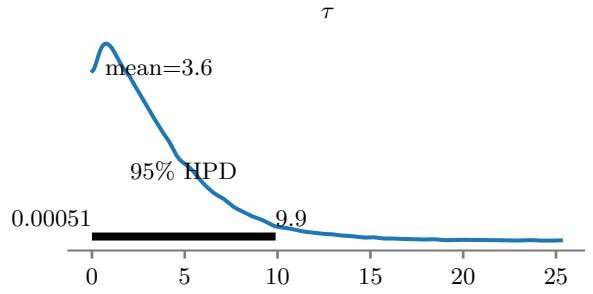

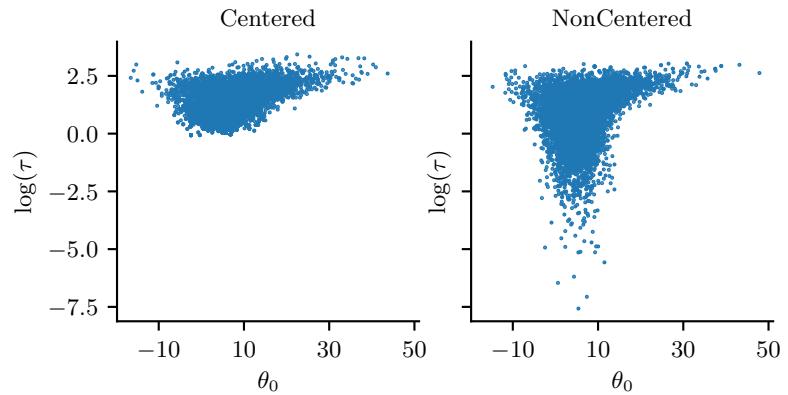

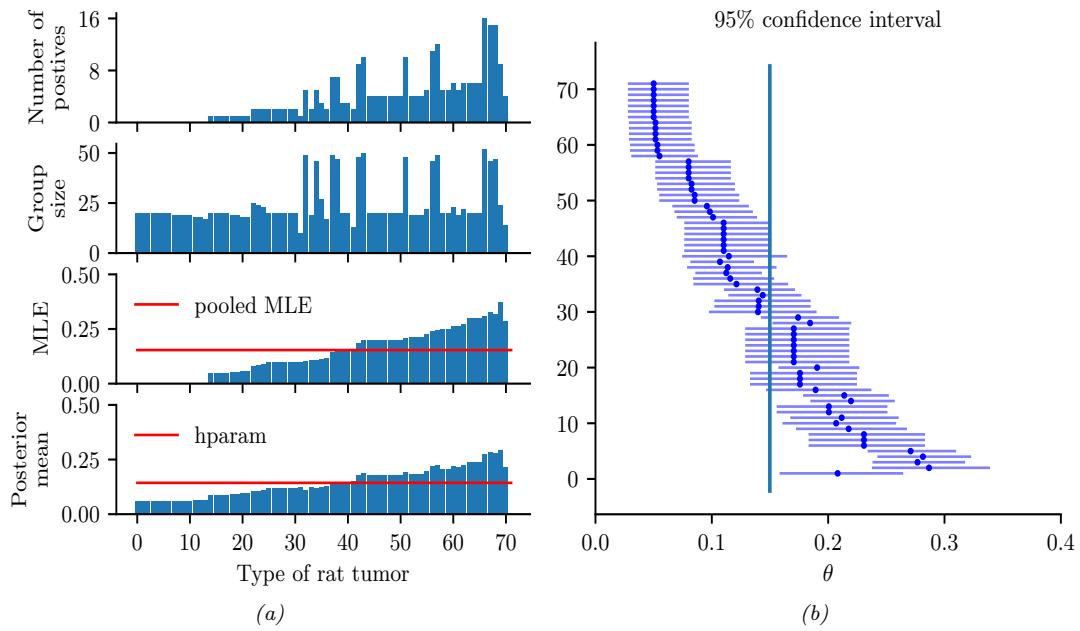

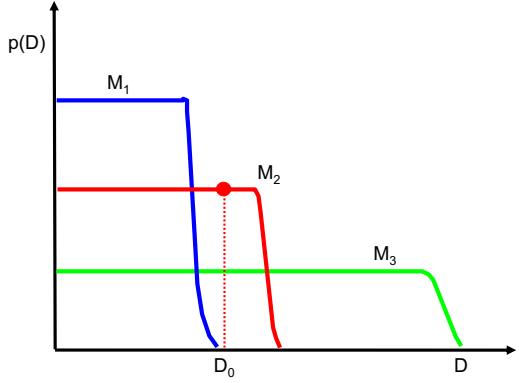

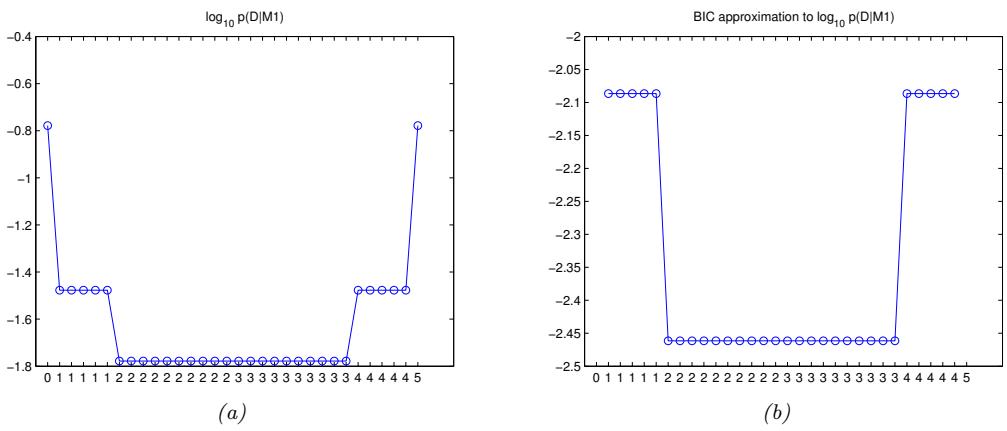

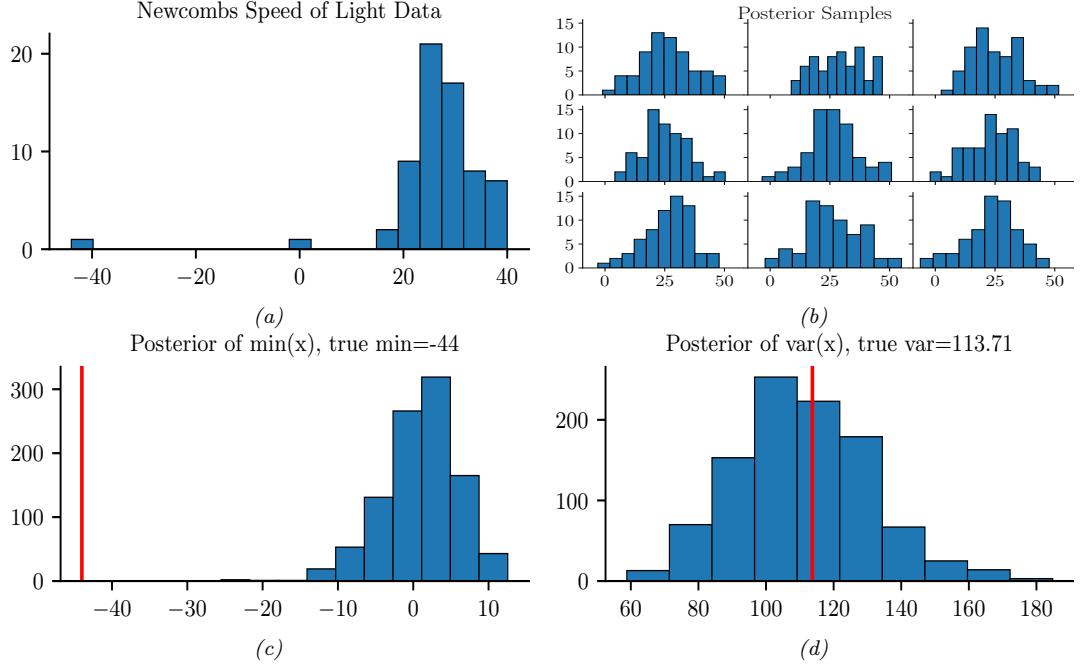

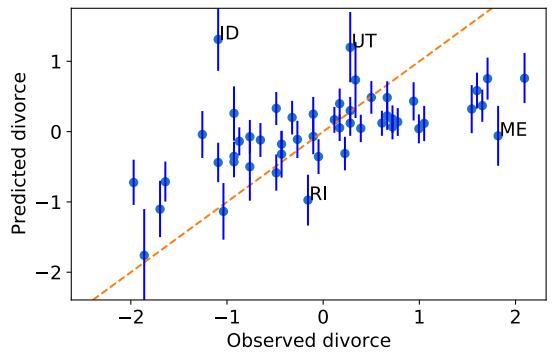

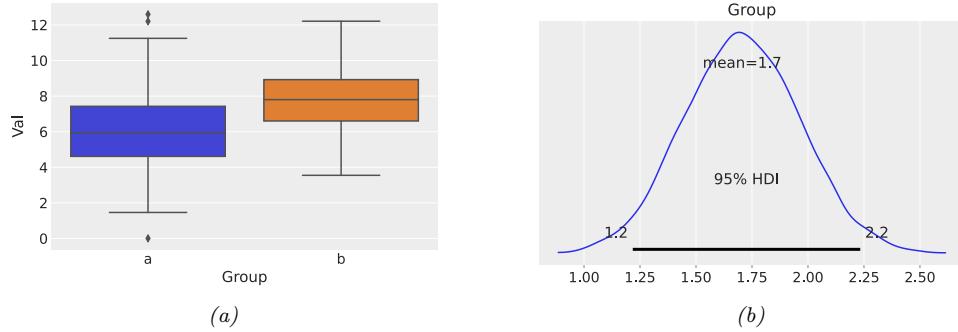

2.6.3 Parameter estimation 49 2.6.4 Stationary distribution of a Markov chain 51 2.7 Divergence measures between probability distributions 55 2.7.1 f-divergence 55 2.7.2 Integral probability metrics 57 2.7.3 Maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) 58 2.7.4 Total variation distance 61 2.7.5 Density ratio estimation using binary classifiers 61 3 Statistics 63 3.1 Introduction 63 3.2 Bayesian statistics 63 3.2.1 Tossing coins 64 3.2.2 Modeling more complex data 70 3.2.3 Selecting the prior 71 3.2.4 Computational issues 71 3.2.5 Exchangeability and de Finetti’s theorem 72 3.3 Frequentist statistics 72 3.3.1 Sampling distributions 73 3.3.2 Bootstrap approximation of the sampling distribution 73 3.3.3 Asymptotic normality of the sampling distribution of the MLE 75 3.3.4 Fisher information matrix 75 3.3.5 Counterintuitive properties of frequentist statistics 80 3.3.6 Why isn’t everyone a Bayesian? 82 3.4 Conjugate priors 83 3.4.1 The binomial model 84 3.4.2 The multinomial model 84 3.4.3 The univariate Gaussian model 85 3.4.4 The multivariate Gaussian model 90 3.4.5 The exponential family model 96 3.4.6 Beyond conjugate priors 99 3.5 Noninformative priors 102 3.5.1 Maximum entropy priors 102 3.5.2 Je!reys priors 103 3.5.3 Invariant priors 106 3.5.4 Reference priors 107 3.6 Hierarchical priors 108 3.6.1 A hierarchical binomial model 108 3.6.2 A hierarchical Gaussian model 111 3.6.3 Hierarchical conditional models 114 3.7 Empirical Bayes 114 3.7.1 EB for the hierarchical binomial model 115 3.7.2 EB for the hierarchical Gaussian model 116 3.7.3 EB for Markov models (n-gram smoothing) 116 3.7.4 EB for non-conjugate models 118 3.8 Model selection 118 3.8.1 Bayesian model selection 119 3.8.2 Bayes model averaging 121 3.8.3 Estimating the marginal likelihood 121 3.8.4 Connection between cross validation and marginal likelihood 122 3.8.5 Conditional marginal likelihood 123 3.8.6 Bayesian leave-one-out (LOO) estimate 124 3.8.7 Information criteria 125 3.9 Model checking 128 3.9.1 Posterior predictive checks 128

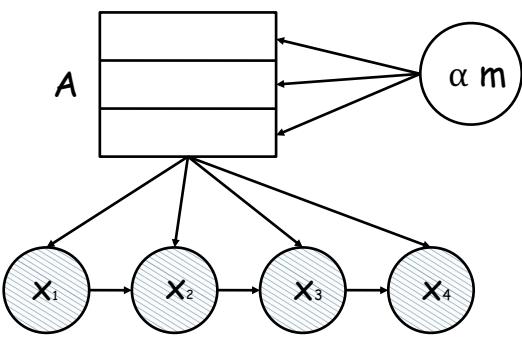

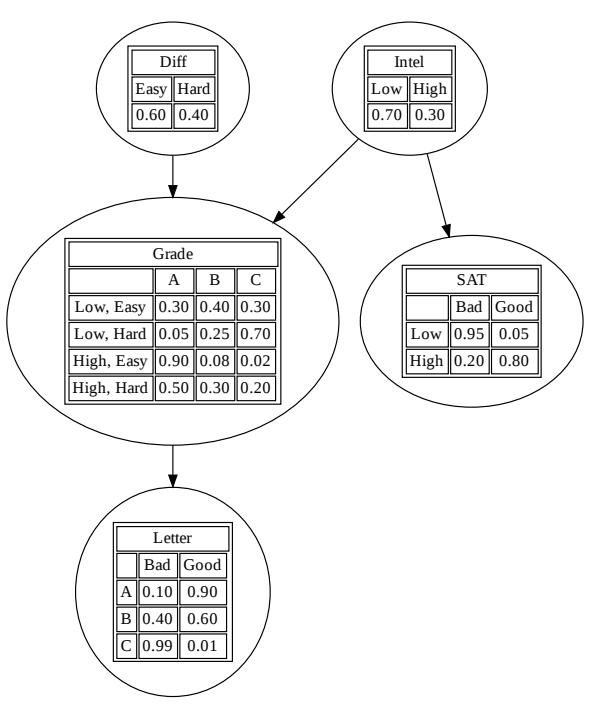

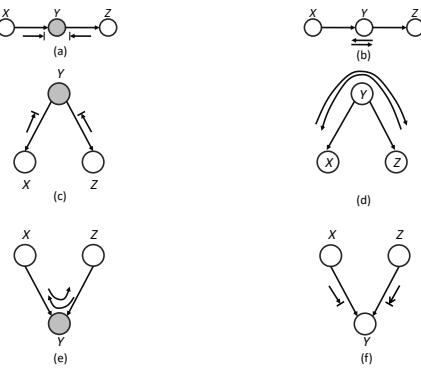

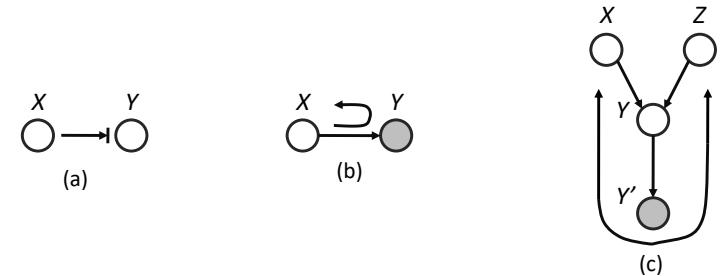

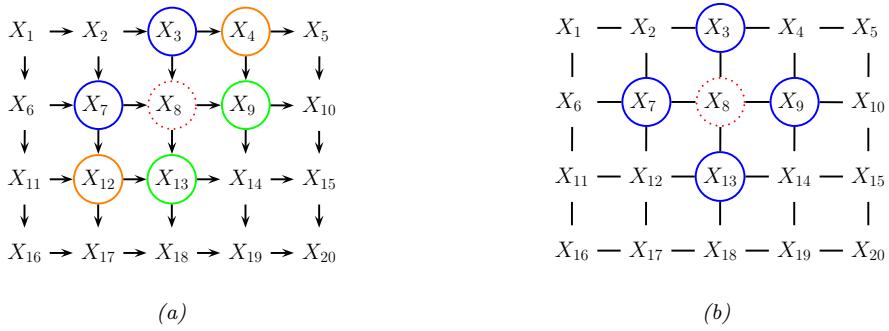

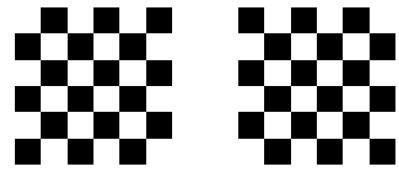

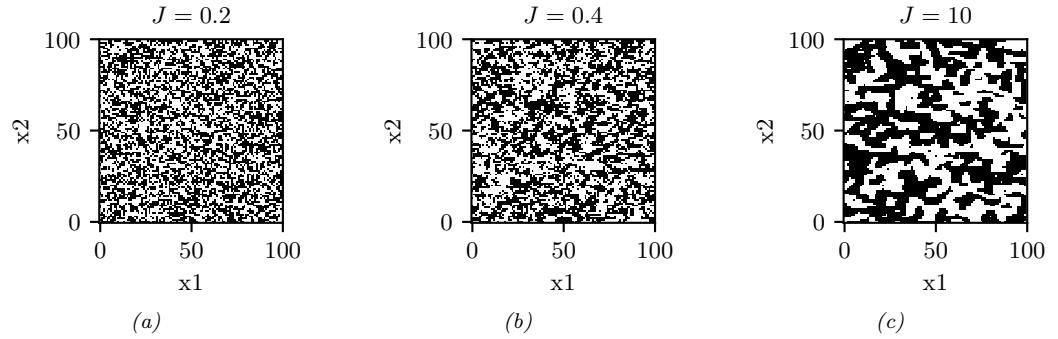

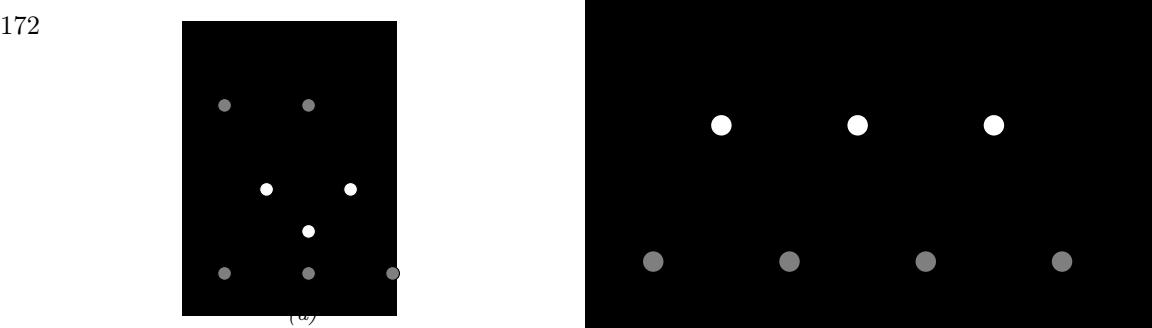

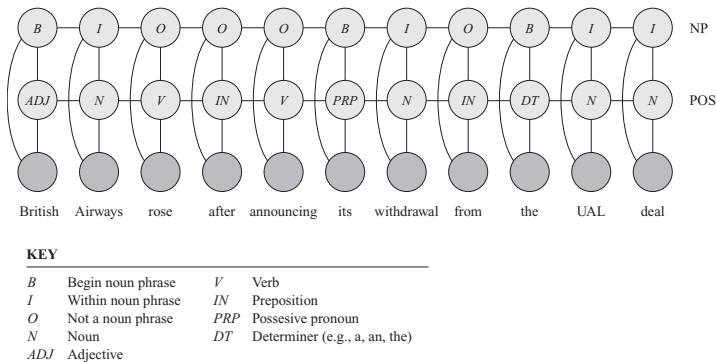

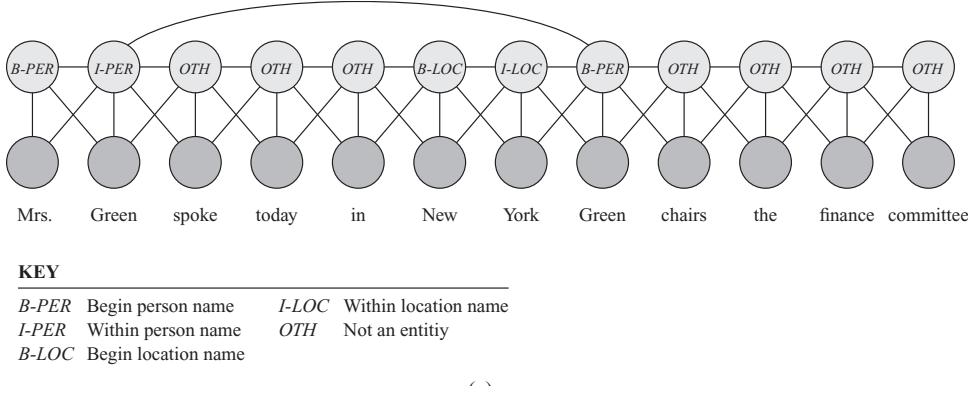

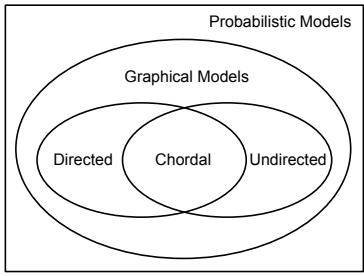

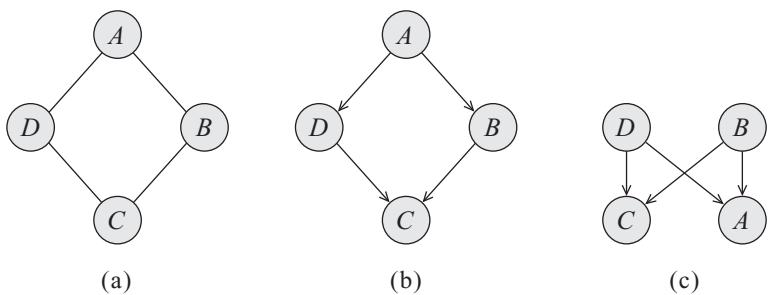

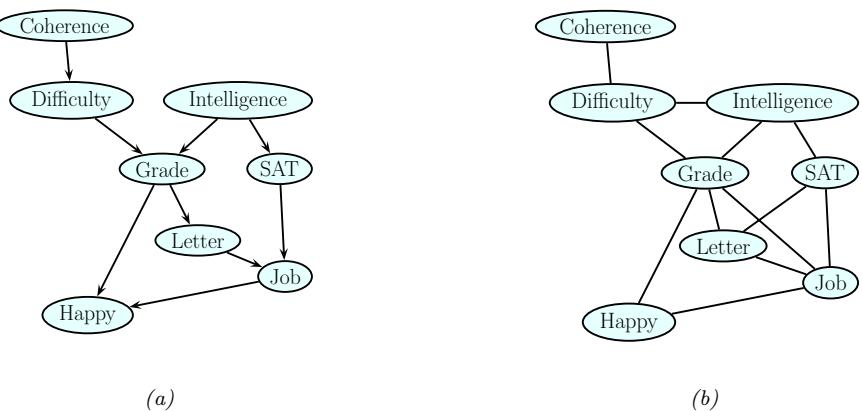

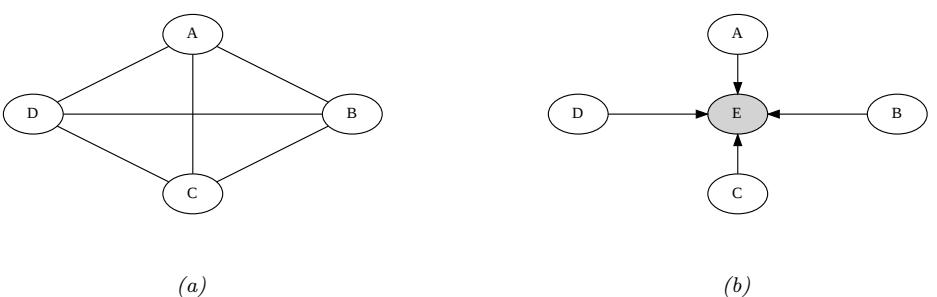

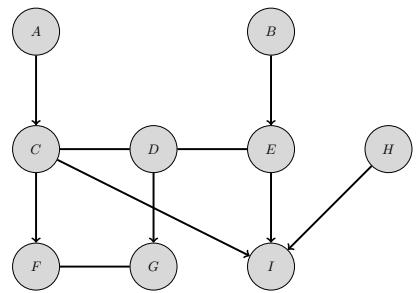

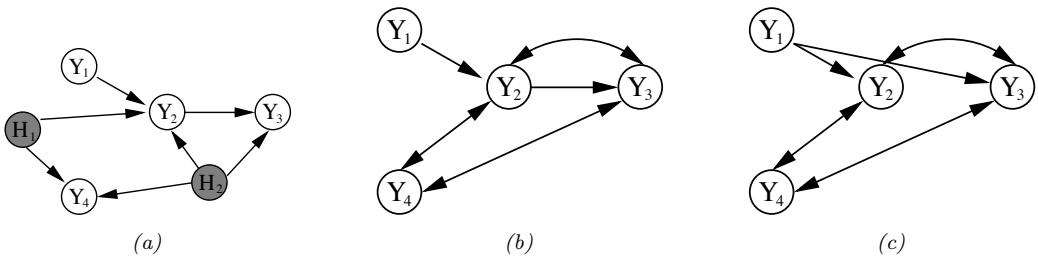

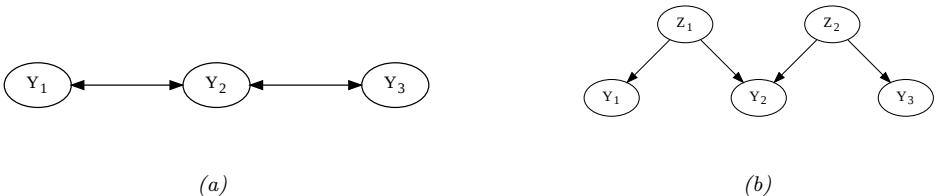

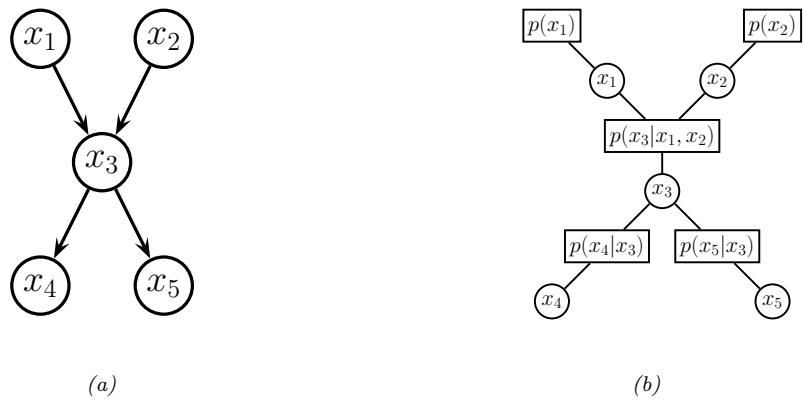

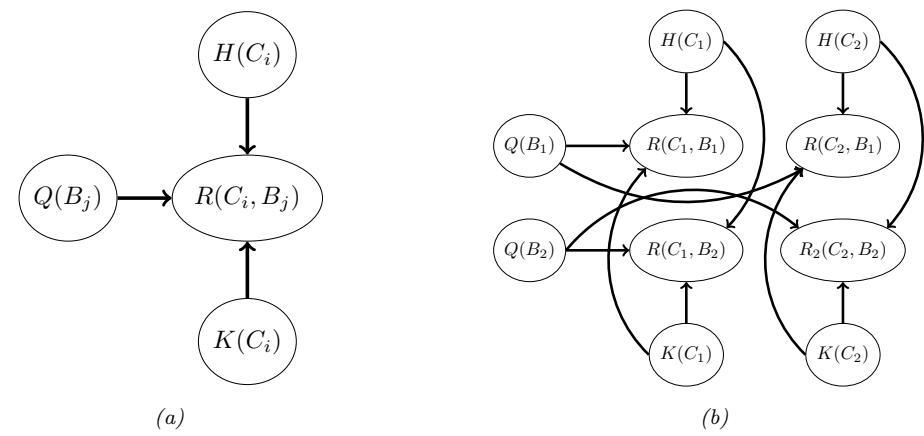

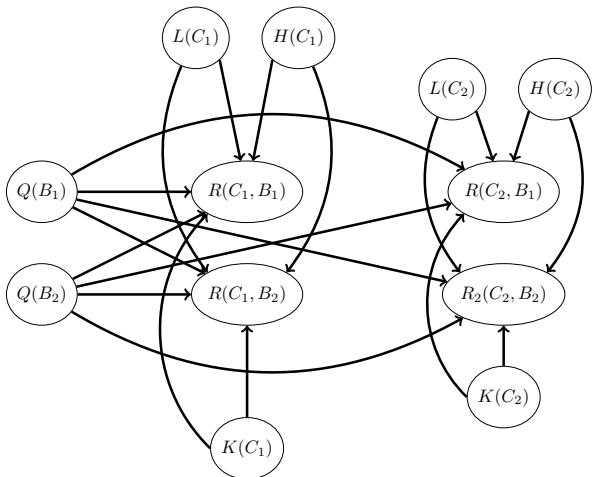

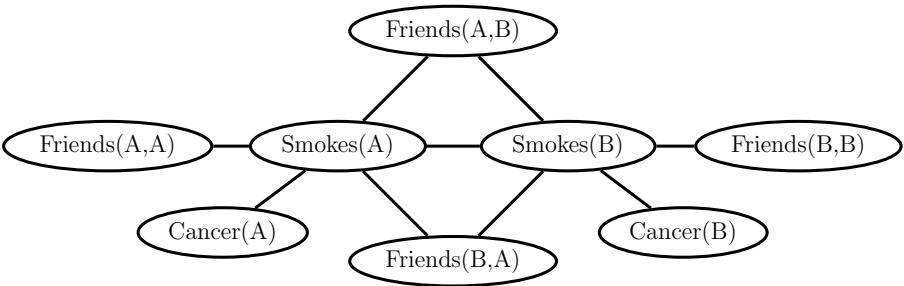

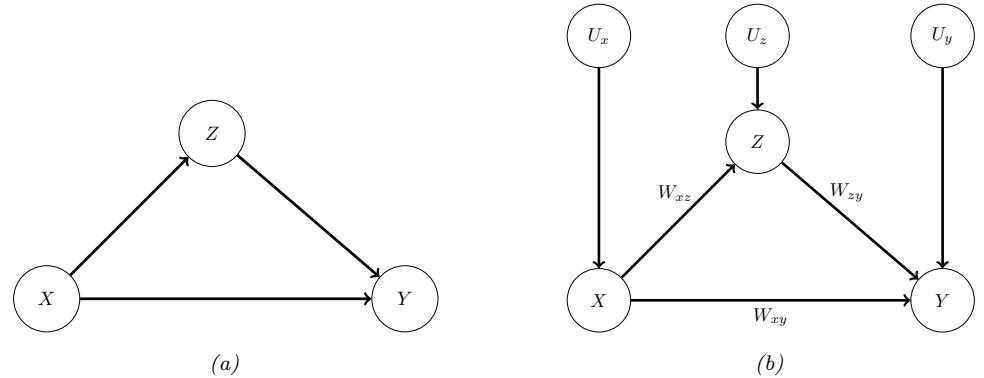

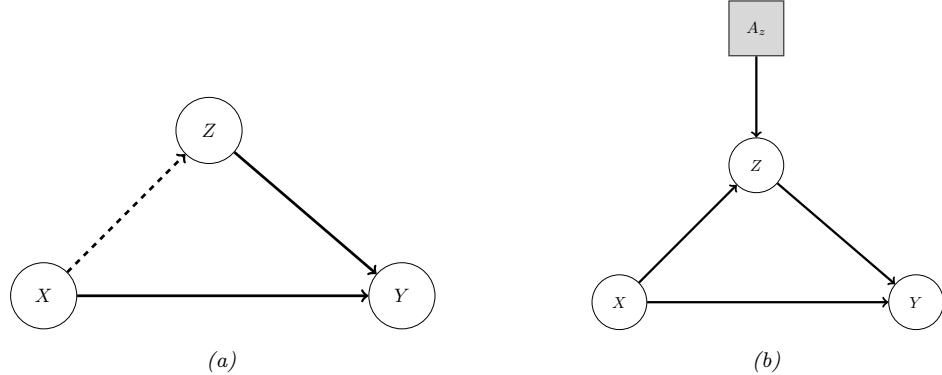

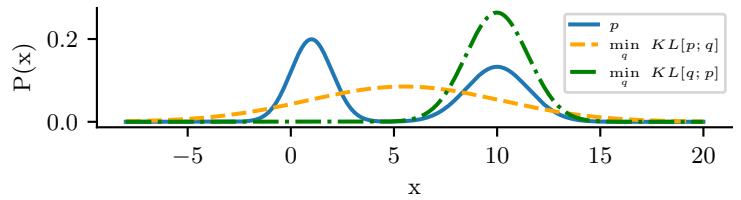

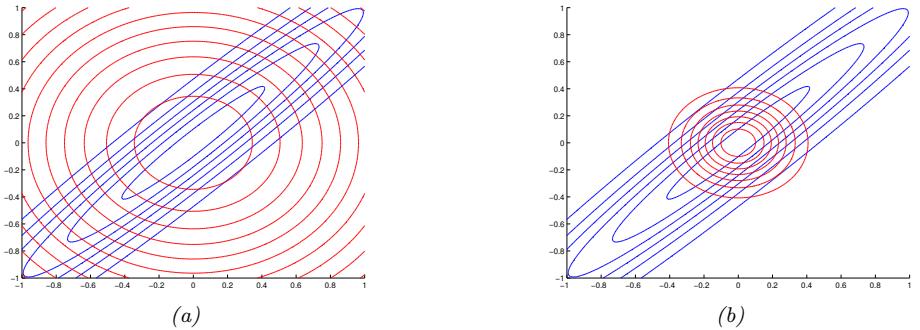

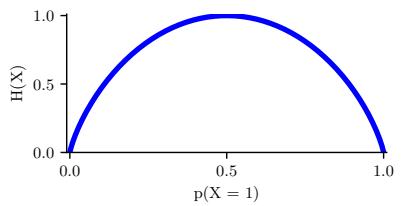

3.10 Hypothesis testing 131 3.10.1 Frequentist approach 131 3.10.2 Bayesian approach 132 3.10.3 Common statistical tests correspond to inference in linear models 136 3.11 Missing data 141 4 Graphical models 143 4.1 Introduction 143 4.2 Directed graphical models (Bayes nets) 143 4.2.1 Representing the joint distribution 143 4.2.2 Examples 144 4.2.3 Gaussian Bayes nets 148 4.2.4 Conditional independence properties 149 4.2.5 Generation (sampling) 154 4.2.6 Inference 155 4.2.7 Learning 155 4.2.8 Plate notation 161 4.3 Undirected graphical models (Markov random fields) 164 4.3.1 Representing the joint distribution 165 4.3.2 Fully visible MRFs (Ising, Potts, Hopfield, etc.) 166 4.3.3 MRFs with latent variables (Boltzmann machines, etc.) 172 4.3.4 Maximum entropy models 174 4.3.5 Gaussian MRFs 177 4.3.6 Conditional independence properties 179 4.3.7 Generation (sampling) 181 4.3.8 Inference 182 4.3.9 Learning 182 4.4 Conditional random fields (CRFs) 186 4.4.1 1d CRFs 187 4.4.2 2d CRFs 190 4.4.3 Parameter estimation 193 4.4.4 Other approaches to structured prediction 194 4.5 Comparing directed and undirected PGMs 194 4.5.1 CI properties 194 4.5.2 Converting between a directed and undirected model 196 4.5.3 Conditional directed vs undirected PGMs and the label bias problem 197 4.5.4 Combining directed and undirected graphs 198 4.5.5 Comparing directed and undirected Gaussian PGMs 200 4.6 PGM extensions 202 4.6.1 Factor graphs 202 4.6.2 Probabilistic circuits 205 4.6.3 Directed relational PGMs 206 4.6.4 Undirected relational PGMs 208 4.6.5 Open-universe probability models 211 4.6.6 Programs as probability models 211 4.7 Structural causal models 212 4.7.1 Example: causal impact of education on wealth 213 4.7.2 Structural equation models 214 4.7.3 Do operator and augmented DAGs 214 4.7.4 Counterfactuals 215 5 Information theory 219 5.1 KL divergence 219 5.1.1 Desiderata 220 5.1.2 The KL divergence uniquely satisfies the desiderata 221 5.1.3 Thinking about KL 224 5.1.4 Minimizing KL 225

- 5.1.5 Properties of KL 228

- 5.1.6 KL divergence and MLE 230

- 5.1.7 KL divergence and Bayesian inference 231

- 5.1.8 KL divergence and exponential families 232

- 5.1.9 Approximating KL divergence using the Fisher information matrix 233

- 5.1.10 Bregman divergence 233

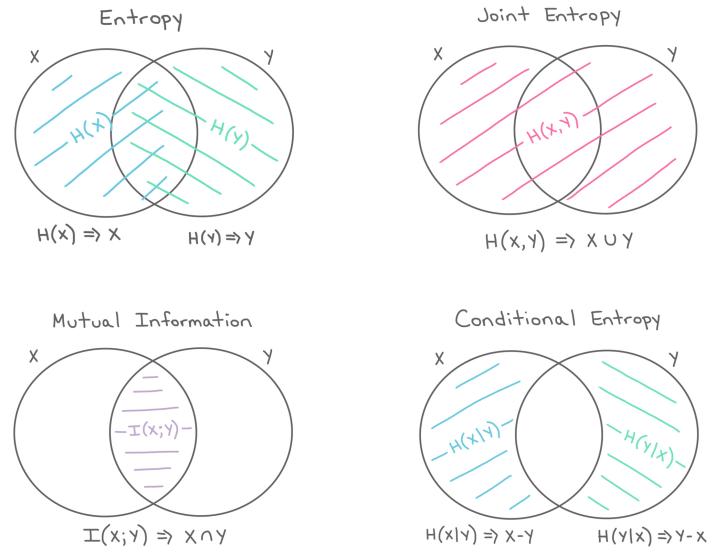

- 5.2 Entropy 234

- 5.2.1 Definition 235

- 5.2.2 Di

235

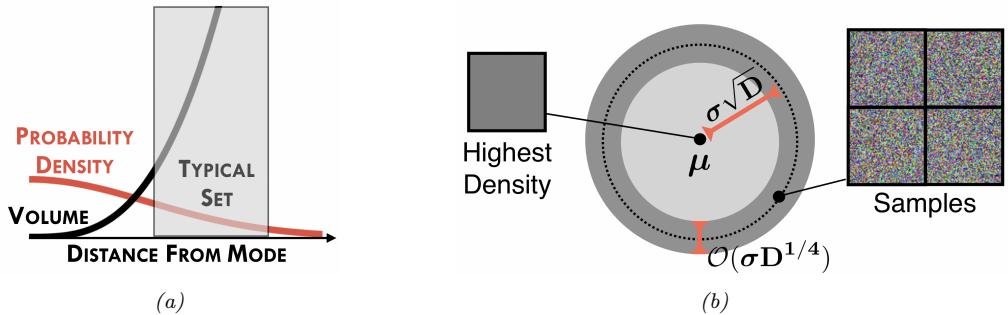

235 - 5.2.3 Typical sets 236

- 5.2.4 Cross entropy and perplexity 237

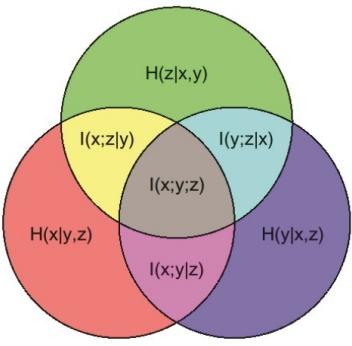

- 5.3 Mutual information 238

- 5.4 Data compression (source coding) 247

- 5.5 Error-correcting codes (channel coding) 251

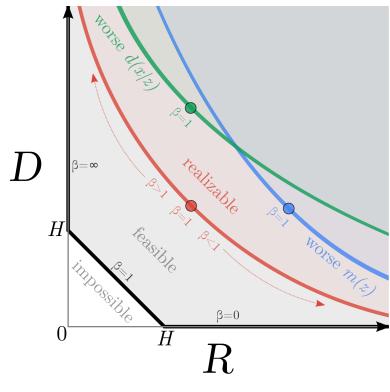

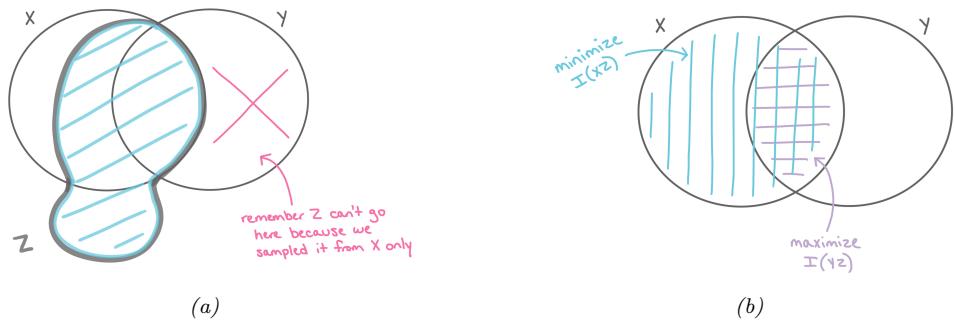

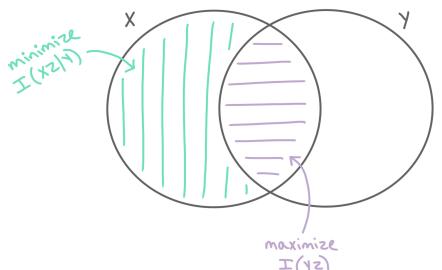

- 5.6 The information bottleneck 252

- 5.7 Algorithmic information theory 256

- 5.7.1 Kolmogorov complexity 256

- 5.7.2 Solomono! induction 257

- 5.7.1 Kolmogorov complexity 256

6 Optimization 261

- 6.1 Introduction 261 6.2 Automatic di!erentiation 261 6.2.1 Di

261 6.2.2 Di

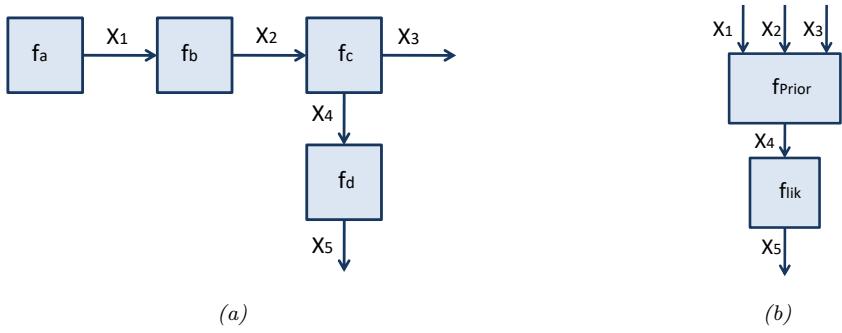

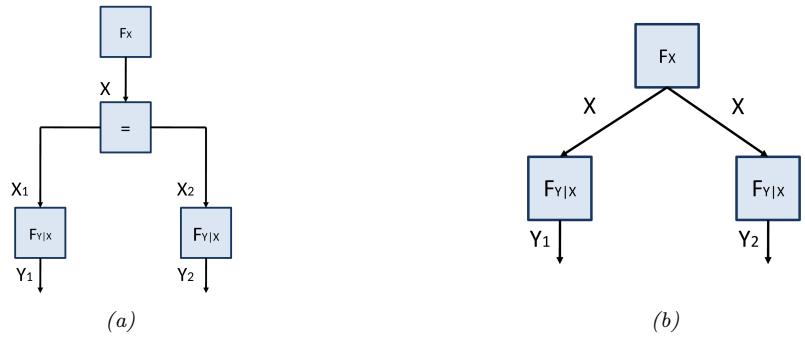

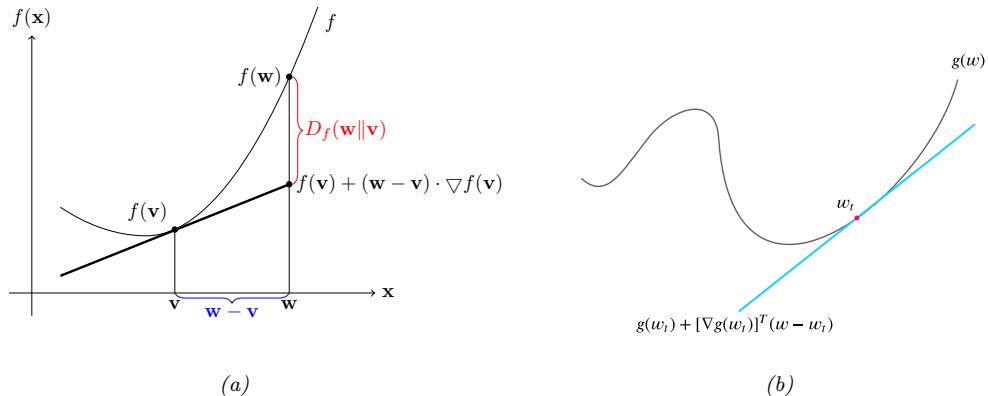

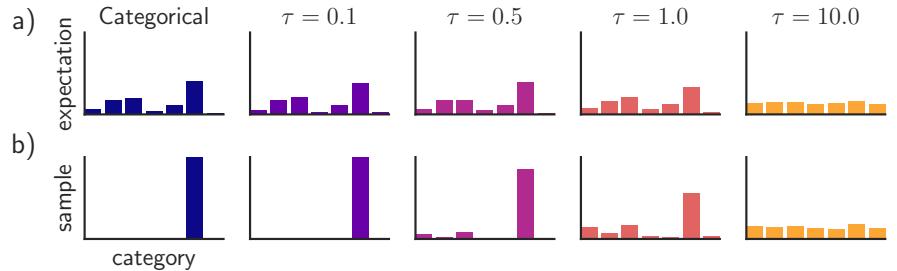

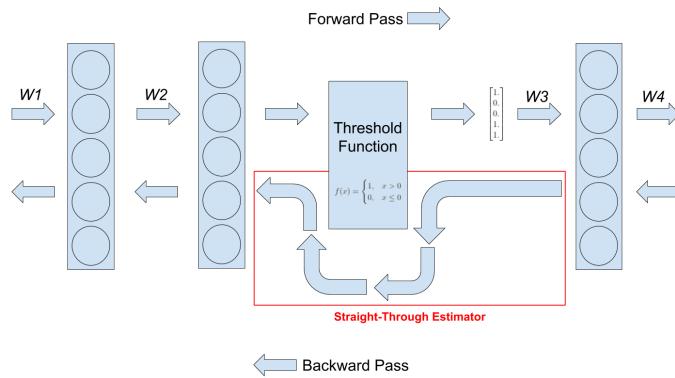

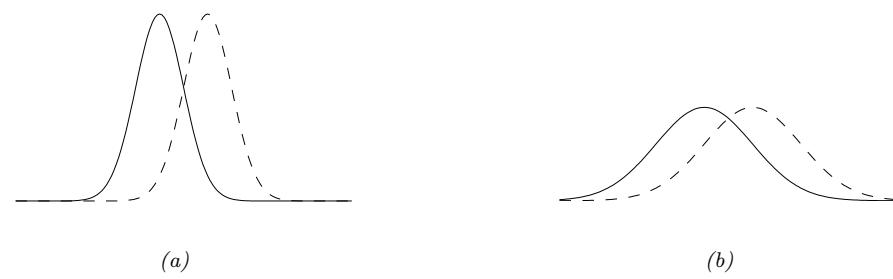

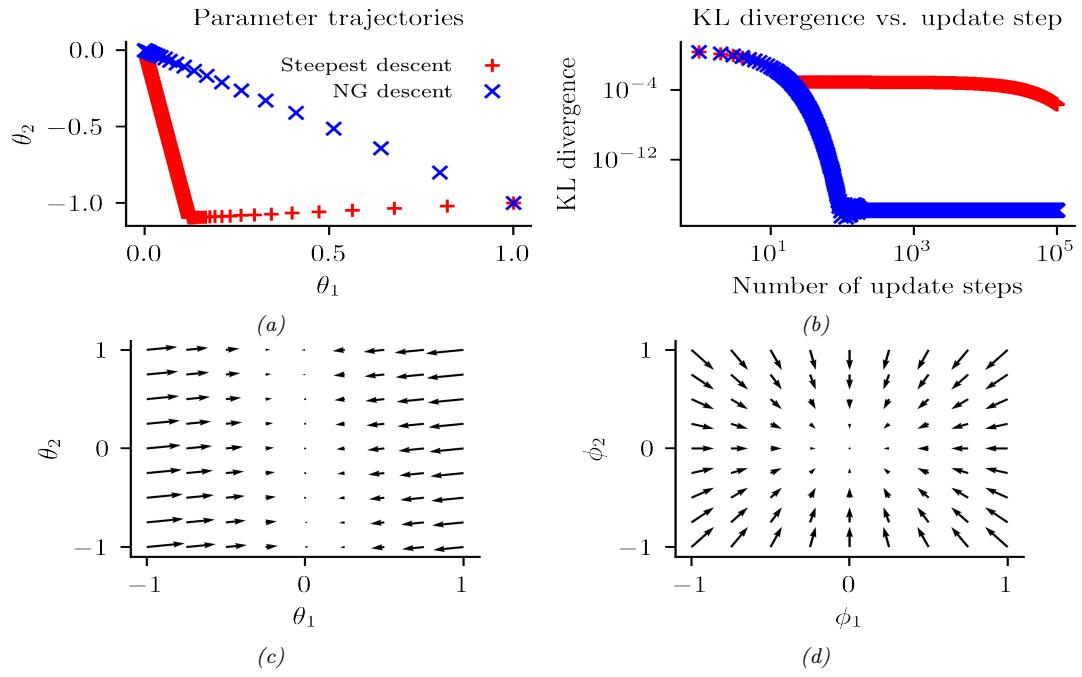

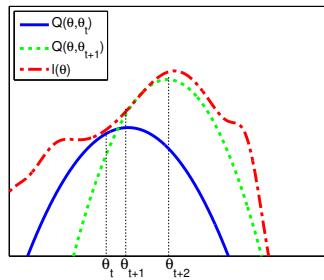

261 6.2.2 Di 266 6.3 Stochastic optimization 271 6.3.1 Stochastic gradient descent 271 6.3.2 SGD for optimizing a finite-sum objective 273 6.3.3 SGD for optimizing the parameters of a distribution 273 6.3.4 Score function estimator (REINFORCE) 274 6.3.5 Reparameterization trick 275 6.3.6 Gumbel softmax trick 277 6.3.7 Stochastic computation graphs 278 6.3.8 Straight-through estimator 279 6.4 Natural gradient descent 279 6.4.1 Defining the natural gradient 280 6.4.2 Interpretations of NGD 281 6.4.3 Benefits of NGD 282 6.4.4 Approximating the natural gradient 282 6.4.5 Natural gradients for the exponential family 284 6.5 Bound optimization (MM) algorithms 287 6.5.1 The general algorithm 287

266 6.3 Stochastic optimization 271 6.3.1 Stochastic gradient descent 271 6.3.2 SGD for optimizing a finite-sum objective 273 6.3.3 SGD for optimizing the parameters of a distribution 273 6.3.4 Score function estimator (REINFORCE) 274 6.3.5 Reparameterization trick 275 6.3.6 Gumbel softmax trick 277 6.3.7 Stochastic computation graphs 278 6.3.8 Straight-through estimator 279 6.4 Natural gradient descent 279 6.4.1 Defining the natural gradient 280 6.4.2 Interpretations of NGD 281 6.4.3 Benefits of NGD 282 6.4.4 Approximating the natural gradient 282 6.4.5 Natural gradients for the exponential family 284 6.5 Bound optimization (MM) algorithms 287 6.5.1 The general algorithm 287

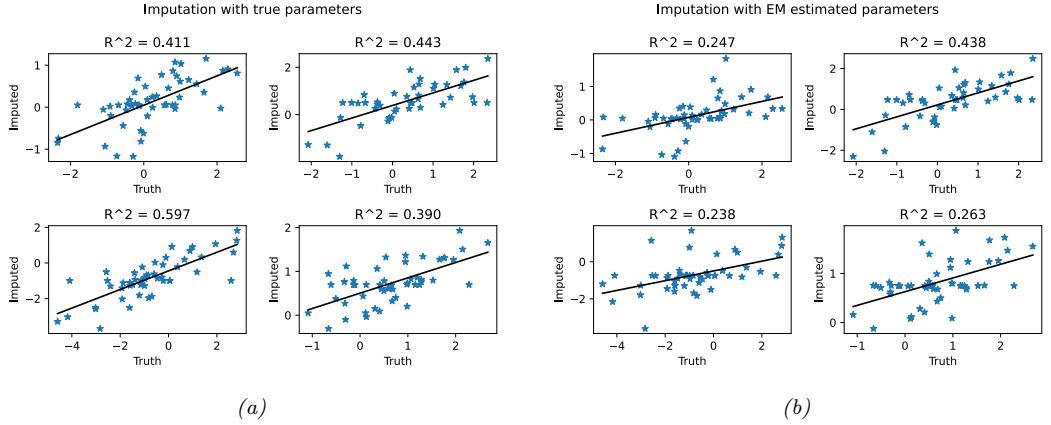

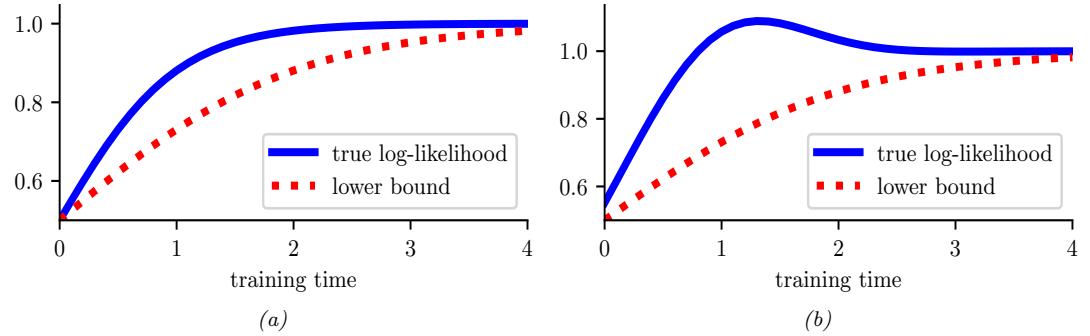

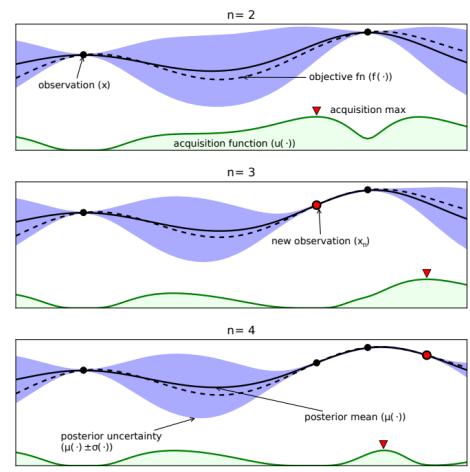

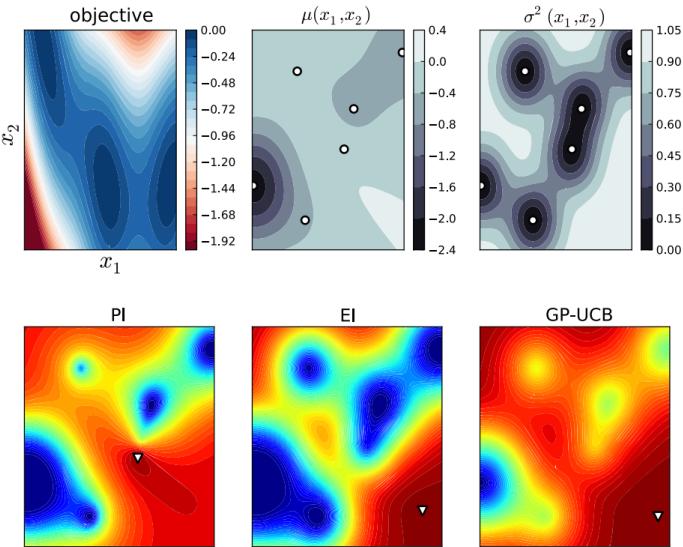

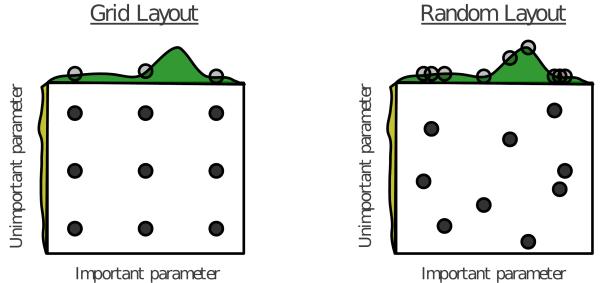

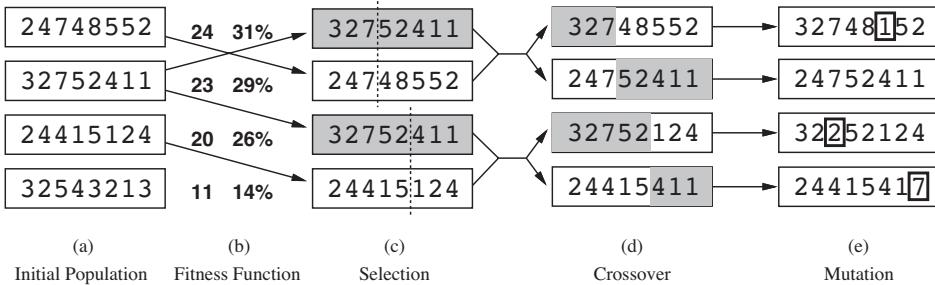

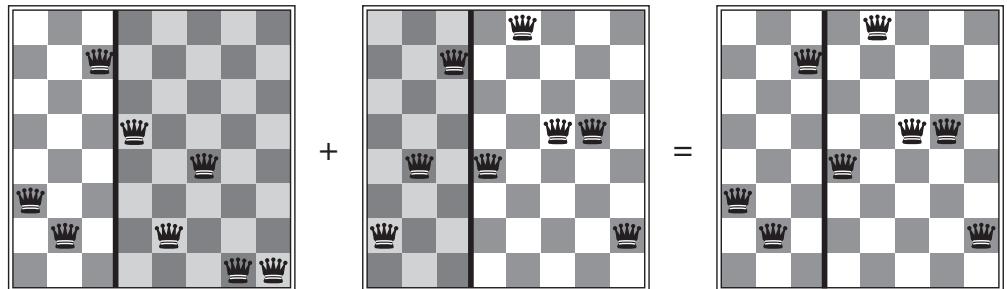

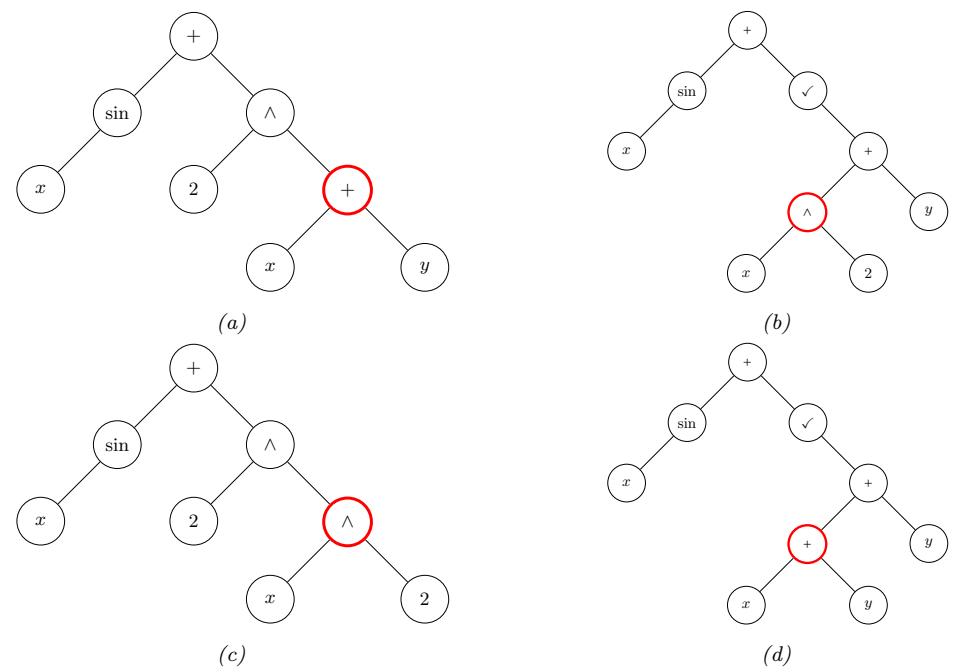

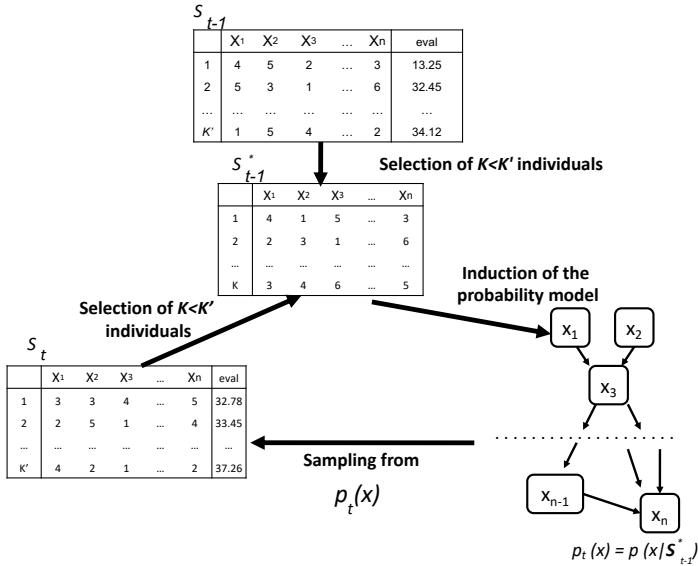

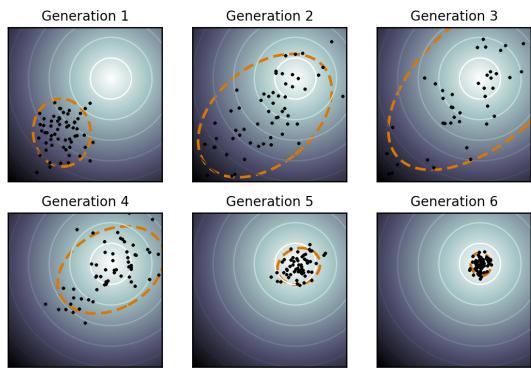

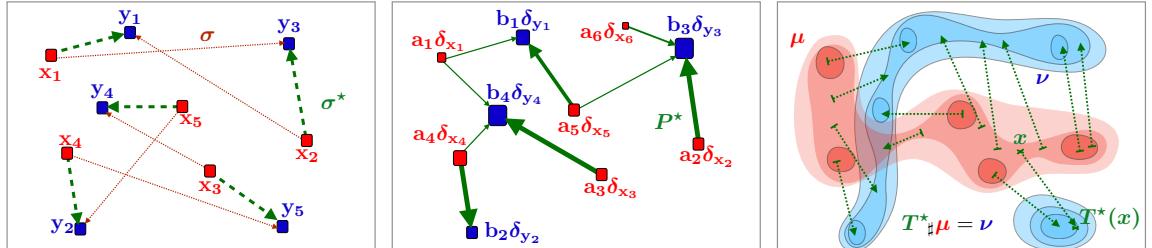

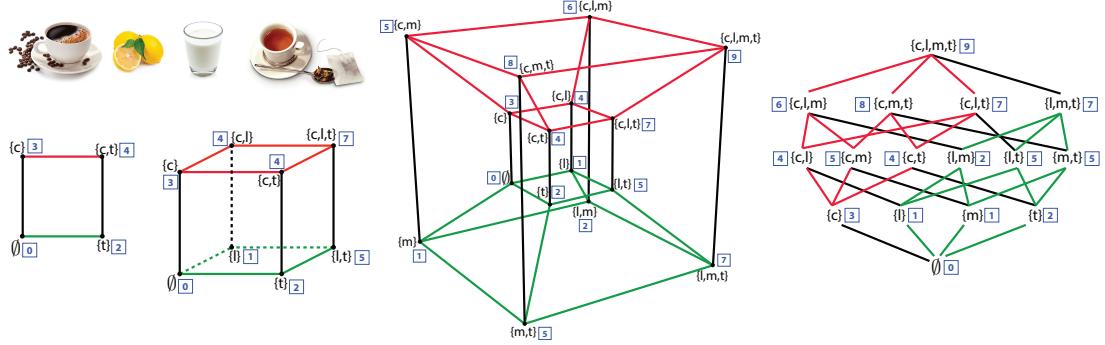

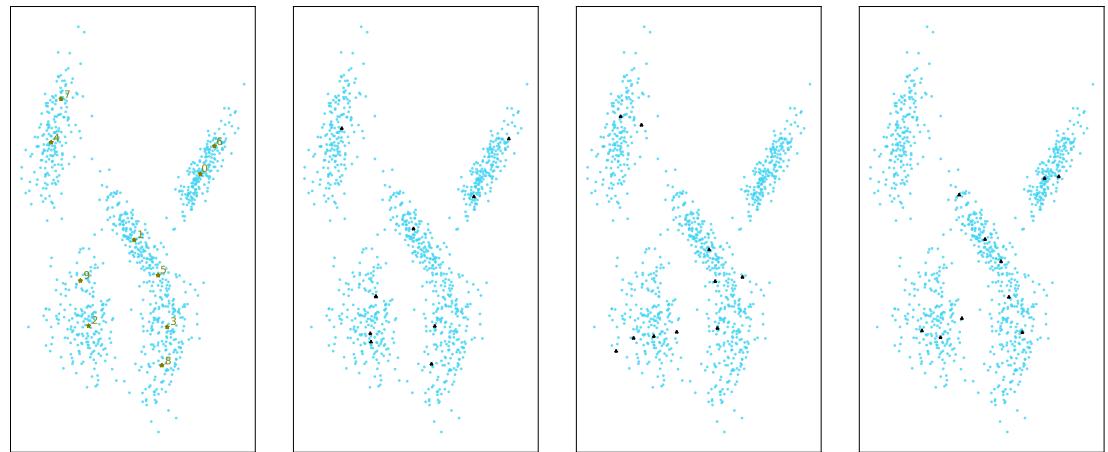

6.5.4 Example: EM for an MVN with missing data 291 6.5.5 Example: robust linear regression using Student likelihood 293 6.5.6 Extensions to EM 295 6.6 Bayesian optimization 297 6.6.1 Sequential model-based optimization 298 6.6.2 Surrogate functions 298 6.6.3 Acquisition functions 300 6.6.4 Other issues 303 6.7 Derivative-free optimization 304 6.7.1 Local search 304 6.7.2 Simulated annealing 307 6.7.3 Evolutionary algorithms 307 6.7.4 Estimation of distribution (EDA) algorithms 310 6.7.5 Cross-entropy method 312 6.7.6 Evolutionary strategies 312 6.7.7 LLMs for DFO 314 6.8 Optimal transport 314 6.8.1 Warm-up: matching optimally two families of points 314 6.8.2 From optimal matchings to Kantorovich and Monge formulations 316 6.8.3 Solving optimal transport 318 6.9 Submodular optimization 322 6.9.1 Intuition, examples, and background 323 6.9.2 Submodular basic definitions 325 6.9.3 Example submodular functions 327 6.9.4 Submodular optimization 329 6.9.5 Applications of submodularity in machine learning and AI 333 6.9.6 Sketching, coresets, distillation, and data subset and feature selection 334 6.9.7 Combinatorial information functions 337 6.9.8 Clustering, data partitioning, and parallel machine learning 339 6.9.9 Active and semi-supervised learning 339 6.9.10 Probabilistic modeling 340 6.9.11 Structured norms and loss functions 341 6.9.12 Conclusions 342

II Inference 343

7 Inference algorithms: an overview 345

8 Gaussian filtering and smoothing 359

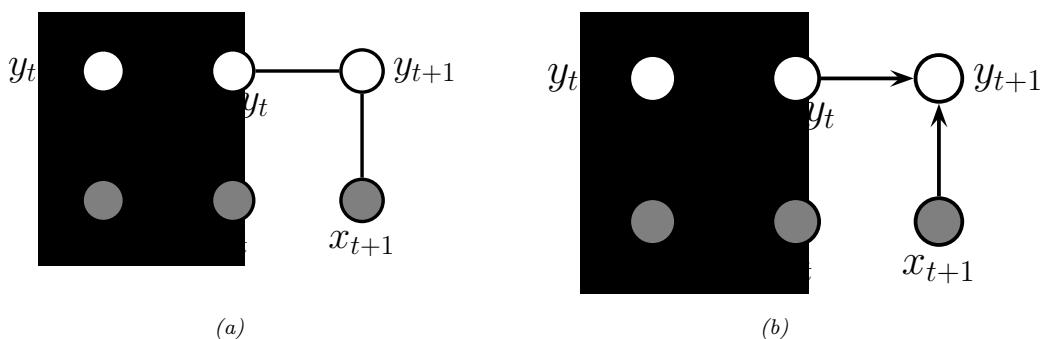

8.1 Introduction 359 8.1.1 Inferential goals 359

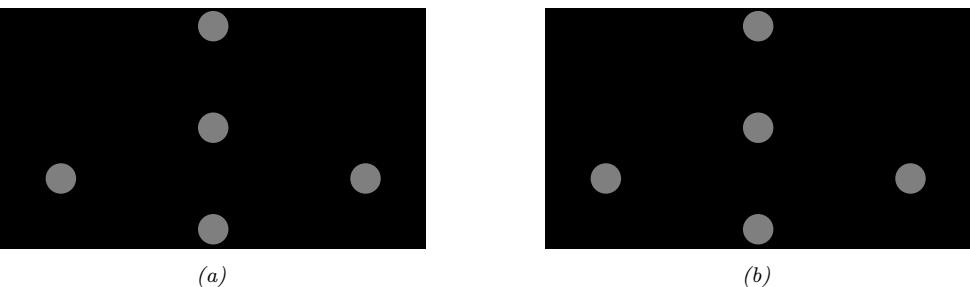

8.1.2 Bayesian filtering equations 361 8.1.3 Bayesian smoothing equations 362 8.1.4 The Gaussian ansatz 363 8.2 Inference for linear-Gaussian SSMs 363 8.2.1 Examples 364 8.2.2 The Kalman filter 365 8.2.3 The Kalman (RTS) smoother 370 8.2.4 Information form filtering and smoothing 372 8.3 Inference based on local linearization 375 8.3.1 Taylor series expansion 375 8.3.2 The extended Kalman filter (EKF) 376 8.3.3 The extended Kalman smoother (EKS) 379 8.4 Inference based on the unscented transform 379 8.4.1 The unscented transform 381 8.4.2 The unscented Kalman filter (UKF) 382 8.4.3 The unscented Kalman smoother (UKS) 382 8.5 Other variants of the Kalman filter 383 8.5.1 General Gaussian filtering 383 8.5.2 Conditional moment Gaussian filtering 386 8.5.3 Iterated filters and smoothers 387 8.5.4 Ensemble Kalman filter 388 8.5.5 Robust Kalman filters 390 8.5.6 Dual EKF 390 8.5.7 Normalizing flow KFs 390 8.6 Assumed density filtering 391 8.6.1 Connection with Gaussian filtering 392 8.6.2 ADF for SLDS (Gaussian sum filter) 393 8.6.3 ADF for online logistic regression 394 8.6.4 ADF for online DNNs 398 8.7 Other inference methods for SSMs 398 8.7.1 Grid-based approximations 398 8.7.2 Expectation propagation 398 8.7.3 Variational inference 399 8.7.4 MCMC 399 8.7.5 Particle filtering 400 9 Message passing algorithms 401 9.1 Introduction 401 9.2 Belief propagation on chains 401 9.2.1 Hidden Markov Models 402 9.2.2 The forwards algorithm 403 9.2.3 The forwards-backwards algorithm 404 9.2.4 Forwards filtering backwards smoothing 407 9.2.5 Time and space complexity 408 9.2.6 The Viterbi algorithm 409 9.2.7 Forwards filtering backwards sampling 412 9.3 Belief propagation on trees 412 9.3.1 Directed vs undirected trees 412 9.3.2 Sum-product algorithm 414 9.3.3 Max-product algorithm 415 9.4 Loopy belief propagation 417 9.4.1 Loopy BP for pairwise undirected graphs 418 9.4.2 Loopy BP for factor graphs 418 9.4.3 Gaussian belief propagation 419 9.4.4 Convergence 421 9.4.5 Accuracy 423

9.4.6 Generalized belief propagation 424 9.4.7 Convex BP 424 9.4.8 Application: error correcting codes 424 9.4.9 Application: a“nity propagation 426 9.4.10 Emulating BP with graph neural nets 427 9.5 The variable elimination (VE) algorithm 428 9.5.1 Derivation of the algorithm 428 9.5.2 Computational complexity of VE 430 9.5.3 Picking a good elimination order 432 9.5.4 Computational complexity of exact inference 432 9.5.5 Drawbacks of VE 433 9.6 The junction tree algorithm (JTA) 434 9.7 Inference as optimization 435 9.7.1 Inference as backpropagation 435 9.7.2 Perturb and MAP 436 10 Variational inference 439 10.1 Introduction 439 10.1.1 The variational objective 439 10.1.2 Form of the variational posterior 441 10.1.3 Parameter estimation using variational EM 442 10.1.4 Stochastic VI 444 10.1.5 Amortized VI 444 10.1.6 Semi-amortized inference 445 10.2 Gradient-based VI 445 10.2.1 Reparameterized VI 446 10.2.2 Automatic di!erentiation VI 452 10.2.3 Blackbox variational inference 454 10.3 Coordinate ascent VI 455 10.3.1 Derivation of CAVI algorithm 456 10.3.2 Example: CAVI for the Ising model 458 10.3.3 Variational Bayes 459 10.3.4 Example: VB for a univariate Gaussian 460 10.3.5 Variational Bayes EM 463 10.3.6 Example: VBEM for a GMM 464 10.3.7 Variational message passing (VMP) 470 10.3.8 Autoconj 471 10.4 More accurate variational posteriors 471 10.4.1 Structured mean field 471 10.4.2 Hierarchical (auxiliary variable) posteriors 471 10.4.3 Normalizing flow posteriors 472 10.4.4 Implicit posteriors 472 10.4.5 Combining VI with MCMC inference 472 10.5 Tighter bounds 473 10.5.1 Multi-sample ELBO (IWAE bound) 473 10.5.2 The thermodynamic variational objective (TVO) 474 10.5.3 Minimizing the evidence upper bound 474 10.6 Wake-sleep algorithm 475 10.6.1 Wake phase 475 10.6.2 Sleep phase 476 10.6.3 Daydream phase 477 10.6.4 Summary of algorithm 477 10.7 Expectation propagation (EP) 478 10.7.1 Algorithm 478 10.7.2 Example 480 10.7.3 EP as generalized ADF 480

| 10.7.4 | Optimization issues 481 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 10.7.5 | Power EP and ω-divergence 481 |

||

| 10.7.6 | Stochastic EP 481 |

||

| 11 Monte Carlo methods 483 |

|||

| 11.1 | Introduction | 483 | |

| 11.2 | Monte Carlo integration 483 |

||

| 11.2.1 | Example: estimating ε by Monte Carlo integration 484 |

||

| 11.2.2 | Accuracy of Monte Carlo integration 484 |

||

| 11.3 | Generating random samples from simple distributions 486 |

||

| 11.3.1 | Sampling using the inverse cdf 486 |

||

| 11.3.2 | Sampling from a Gaussian (Box-Muller method) 487 |

||

| 11.4 | Rejection sampling 487 |

||

| 11.4.1 | Basic idea 488 |

||

| 11.4.2 | Example 489 |

||

| 11.4.3 | Adaptive rejection sampling 489 |

||

| 11.4.4 | Rejection sampling in high dimensions 490 |

||

| 11.5 | Importance sampling 490 |

||

| 11.5.1 | Direct importance sampling 491 |

||

| 11.5.2 | Self-normalized importance sampling 491 |

||

| 11.5.3 | Choosing the proposal 492 |

||

| 11.5.4 | Annealed importance sampling (AIS) 492 |

||

| 11.6 | Controlling Monte Carlo variance 494 |

||

| 11.6.1 | Common random numbers 494 |

||

| 11.6.2 | Rao-Blackwellization 494 |

||

| 11.6.3 | Control variates 495 |

||

| 11.6.4 | Antithetic sampling 496 |

||

| 11.6.5 | Quasi-Monte Carlo (QMC) 497 |

||

| 12 Markov chain Monte Carlo 499 |

|||

| 12.1 | Introduction | 499 | |

| 12.2 | Metropolis-Hastings algorithm 500 |

||

| 12.2.1 | Basic idea 500 |

||

| 12.2.2 | Why MH works 501 |

||

| 12.2.3 | Proposal distributions 502 |

||

| 12.2.4 | Initialization 505 |

||

| 12.3 | Gibbs sampling 505 |

||

| 12.3.1 | Basic idea 505 |

||

| 12.3.2 | Gibbs sampling is a special case of MH 506 |

||

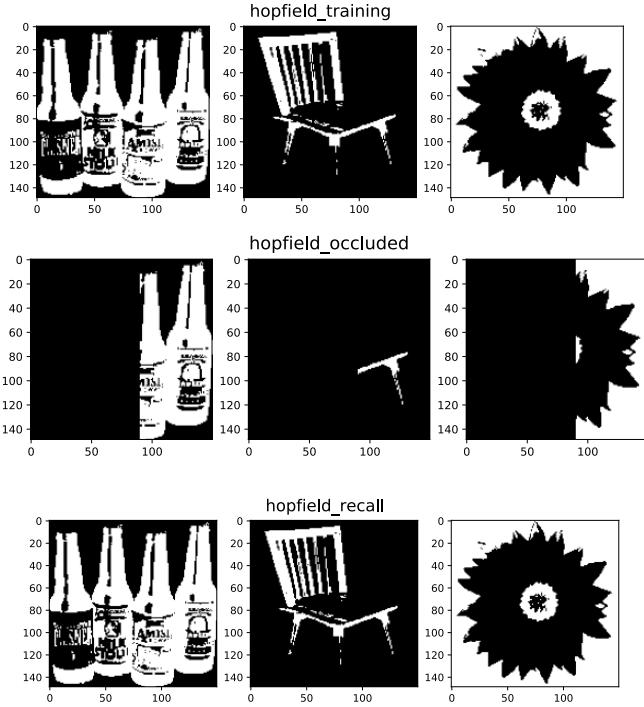

| 12.3.3 | Example: Gibbs sampling for Ising models 506 |

||

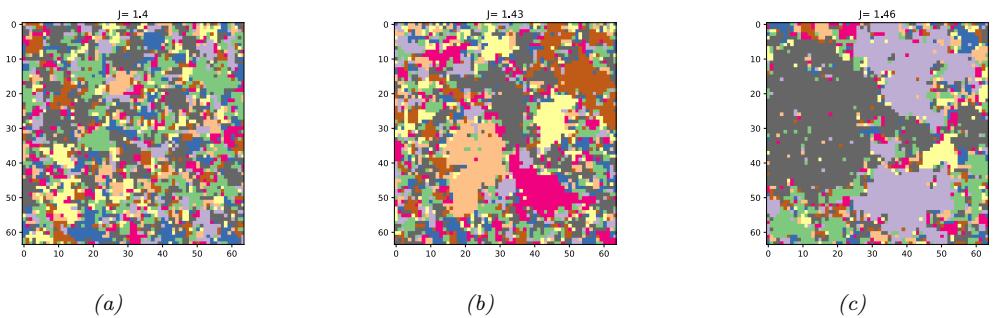

| 12.3.4 | Example: Gibbs sampling for Potts models 508 |

||

| 12.3.5 | Example: Gibbs sampling for GMMs 508 |

||

| 12.3.6 | Metropolis within Gibbs 510 |

||

| 12.3.7 | Blocked Gibbs sampling 511 |

||

| 12.3.8 | Collapsed Gibbs sampling 512 |

||

| 12.4 | Auxiliary variable MCMC 513 |

||

| 12.4.1 | Slice sampling 514 |

||

| 12.4.2 | Swendsen-Wang 515 |

||

| 12.5 | Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) 517 |

||

| 12.5.1 | Hamiltonian mechanics 517 |

||

| 12.5.2 | Integrating Hamilton’s equations 518 |

||

| 12.5.3 | The HMC algorithm 519 |

||

| 12.5.4 | Tuning HMC 520 |

||

| 12.5.5 | Riemann manifold HMC 521 |

||

| 12.5.6 | Langevin Monte Carlo (MALA) 521 |

||

| 12.5.7 | Connection between SGD and Langevin sampling 522 |

||

| 12.5.8 | Applying HMC to constrained parameters 523 |

||

| 12.5.9 | Speeding up HMC 524 |

|

|---|---|---|

| 12.6 | MCMC convergence 524 |

|

| 12.6.1 | Mixing rates of Markov chains 525 |

|

| 12.6.2 | Practical convergence diagnostics 526 |

|

| 12.6.3 | E!ective sample size 529 |

|

| 12.6.4 | Improving speed of convergence 531 |

|

| 12.6.5 | Non-centered parameterizations and Neal’s funnel 532 |

|

| 12.7 | Stochastic gradient MCMC 533 |

|

| 12.7.1 | Stochastic gradient Langevin dynamics (SGLD) 533 |

|

| 12.7.2 | Preconditionining 534 |

|

| 12.7.3 | Reducing the variance of the gradient estimate 534 |

|

| 12.7.4 | SG-HMC 535 |

|

| 12.7.5 | Underdamped Langevin dynamics 535 |

|

| 12.8 | Reversible jump (transdimensional) MCMC 536 |

|

| 12.8.1 | Basic idea 536 |

|

| 12.8.2 | Example 537 |

|

| 12.8.3 | Discussion 539 |

|

| 12.9 | Annealing methods 539 |

|

| 12.9.1 | Simulated annealing 540 |

|

| 12.9.2 | Parallel tempering 542 |

|

| 13 Sequential Monte Carlo 543 |

||

| 13.1 | Introduction | 543 |

| 13.1.1 | Problem statement 543 |

|

| 13.1.2 | Particle filtering for state-space models 543 |

|

| 13.1.3 | SMC samplers for static parameter estimation 545 |

|

| 13.2 | Particle filtering 545 |

|

| 13.2.1 | Importance sampling 545 |

|

| 13.2.2 | Sequential importance sampling 547 |

|

| 13.2.3 | Sequential importance sampling with resampling 548 |

|

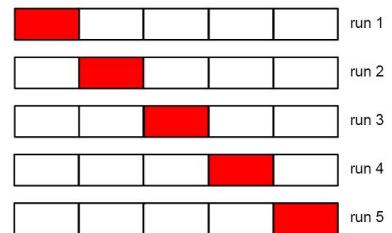

| 13.2.4 | Resampling methods 551 |

|

| 13.2.5 | Adaptive resampling 553 |

|

| 13.3 | Proposal distributions 553 |

|

| 13.3.1 | Locally optimal proposal 554 |

|

| 13.3.2 | Proposals based on the extended and unscented Kalman filter 555 |

|

| 13.3.3 | Proposals based on the Laplace approximation 555 |

|

| 13.3.4 | Proposals based on SMC (nested SMC) 557 |

|

| 13.4 | Rao-Blackwellized particle filtering (RBPF) 557 |

|

| 13.4.1 | Mixture of Kalman filters 557 |

|

| 13.4.2 | Example: tracking a maneuvering object 559 |

|

| 13.4.3 | Example: FastSLAM 560 |

|

| 13.5 | Extensions of the particle filter 563 |

|

| 13.6 | SMC samplers | 563 |

| 13.6.1 | Ingredients of an SMC sampler 564 |

|

| 13.6.2 | Likelihood tempering (geometric path) 565 |

|

| 13.6.3 | Data tempering 567 |

|

| 13.6.4 | Sampling rare events and extrema 568 |

|

| 13.6.5 | SMC-ABC and likelihood-free inference 569 |

|

| 13.6.6 | SMC2 569 |

|

| 13.6.7 | Variational filtering SMC 569 |

|

| 13.6.8 | Variational smoothing SMC 570 |

III Prediction 573

14 Predictive models: an overview 575

| 14.1 | Introduction | 575 |

|---|---|---|

| 14.1.1 | Types of model 575 |

|

| 14.1.2 | Model fitting using ERM, MLE, and MAP 576 |

|

| 14.1.3 | Model fitting using Bayes, VI, and generalized Bayes 577 |

|

| 14.2 | Evaluating predictive models 578 |

|

| 14.2.1 | Proper scoring rules 578 |

|

| 14.2.2 | Calibration 578 |

|

| 14.2.3 | Beyond evaluating marginal probabilities 582 |

|

| 14.3 | Conformal prediction 585 |

|

| 14.3.1 | Conformalizing classification 587 |

|

| 14.3.2 | Conformalizing regression 587 |

|

| 14.3.3 | Conformalizing Bayes 588 |

|

| 14.3.4 | What do we do if we don’t have a calibration set? 589 |

|

| 14.3.5 | General conformal prediction/ decision problems 589 |

|

| 15 Generalized linear models 591 |

||

| 15.1 | Introduction | 591 |

| 15.1.1 | Some popular GLMs 591 |

|

| 15.1.2 | GLMs with noncanonical link functions 594 |

|

| 15.1.3 | Maximum likelihood estimation 595 |

|

| 15.1.4 | Bayesian inference 595 |

|

| 15.2 | Linear regression 596 |

|

| 15.2.1 | Ordinary least squares 596 |

|

| 15.2.2 | Conjugate priors 597 |

|

| 15.2.3 | Uninformative priors 599 |

|

| 15.2.4 | Informative priors 601 |

|

| 15.2.5 | Spike and slab prior 603 |

|

| 15.2.6 | Laplace prior (Bayesian lasso) 604 |

|

| 15.2.7 | Horseshoe prior 605 |

|

| 15.2.8 | Automatic relevancy determination 606 |

|

| 15.2.9 | Multivariate linear regression 608 |

|

| 15.3 | Logistic regression 610 |

|

| 15.3.1 | Binary logistic regression 610 |

|

| 15.3.2 | Multinomial logistic regression 611 |

|

| 15.3.3 | Dealing with class imbalance and the long tail 612 |

|

| 15.3.4 | Parameter priors 612 |

|

| 15.3.5 | Laplace approximation to the posterior 613 |

|

| 15.3.6 | Approximating the posterior predictive distribution 615 |

|

| 15.3.7 | MCMC inference 617 |

|

| 15.3.8 | Other approximate inference methods 618 |

|

| 15.3.9 | Case study: is Berkeley admissions biased against women? 619 |

|

| 15.4 | Probit regression 621 |

|

| 15.4.1 | Latent variable interpretation 621 |

|

| 15.4.2 | Maximum likelihood estimation 622 |

|

| 15.4.3 | Bayesian inference 624 |

|

| 15.4.4 | Ordinal probit regression 624 |

|

| 15.4.5 | Multinomial probit models 625 |

|

| 15.5 | Multilevel (hierarchical) GLMs 625 |

|

| 15.5.1 | Generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) 626 |

|

| 15.5.2 | Example: radon regression 626 |

|

| 16 Deep neural networks 631 |

||

| 16.1 | Introduction | 631 |

| 16.2 | Building blocks of di!erentiable circuits 632 |

- 16.2.1 Linear layers 632

- 16.2.2 Nonlinearities 632

- 16.2.3 Convolutional layers 633

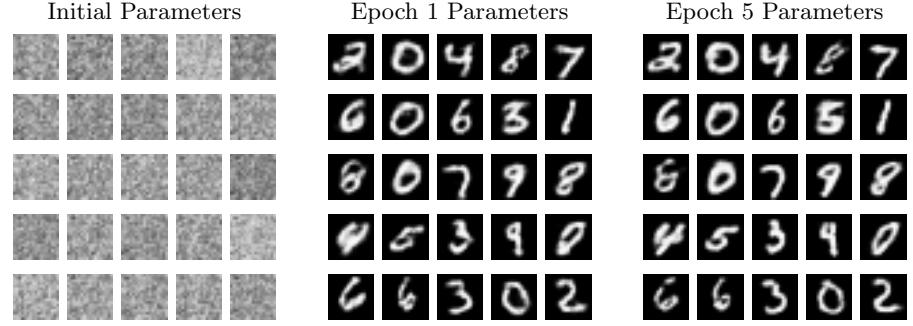

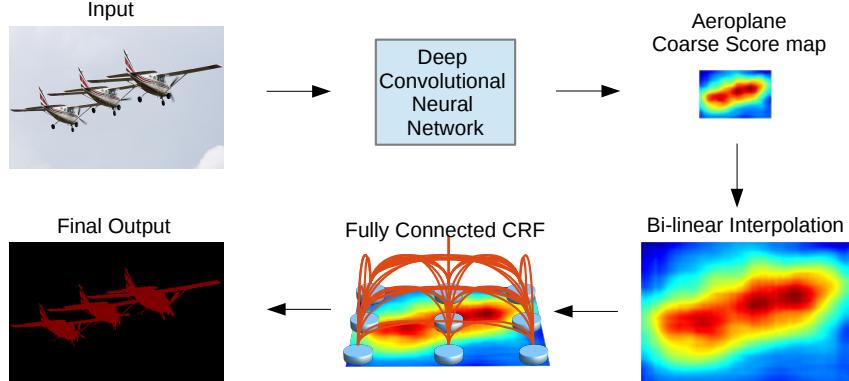

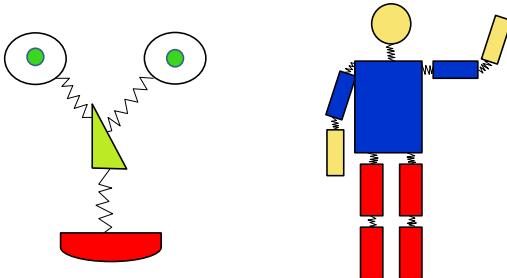

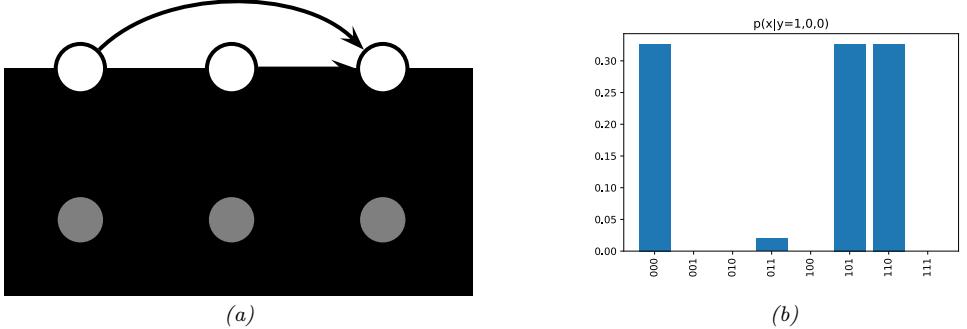

- 16.2.4 Residual (skip) connections 635 16.2.5 Normalization layers 635 16.2.6 Dropout layers 636 16.2.7 Attention layers 636 16.2.8 Recurrent layers 639 16.2.9 Multiplicative layers 639 16.2.10 Implicit layers 640 16.3 Canonical examples of neural networks 641 16.3.1 Multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) 641 16.3.2 Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) 642 16.3.3 Autoencoders 642 16.3.4 Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) 644 16.3.5 Transformers 645 16.3.6 Graph neural networks (GNNs) 646 17 Bayesian neural networks 647 17.1 Introduction 647 17.2 Priors for BNNs 647 17.2.1 Gaussian priors 648 17.2.2 Sparsity-promoting priors 650 17.2.3 Learning the prior 650 17.2.4 Priors in function space 650 17.2.5 Architectural priors 651 17.3 Posteriors for BNNs 651 17.3.1 Monte Carlo dropout 651 17.3.2 Laplace approximation 652 17.3.3 Variational inference 653 17.3.4 Expectation propagation 654 17.3.5 Last layer methods 654 17.3.6 SNGP 655 17.3.7 MCMC methods 655 17.3.8 Methods based on the SGD trajectory 656 17.3.9 Deep ensembles 657 17.3.10 Approximating the posterior predictive distribution 661 17.3.11 Tempered and cold posteriors 664 17.4 Generalization in Bayesian deep learning 665 17.4.1 Sharp vs flat minima 665 17.4.2 Mode connectivity and the loss landscape 666 17.4.3 E

667 17.4.4 The hypothesis space of DNNs 668 17.4.5 PAC-Bayes 669 17.4.6 Out-of-distribution generalization for BNNs 670 17.4.7 Model selection for BNNs 671 17.5 Online inference 672 17.5.1 Sequential Laplace for DNNs 672 17.5.2 Extended Kalman filtering for DNNs 673 17.5.3 Assumed density filtering for DNNs 675 17.5.4 Online variational inference for DNNs 676 17.6 Hierarchical Bayesian neural networks 677 17.6.1 Example: multimoons classification 678 18 Gaussian processes 681 18.1 Introduction 681 18.1.1 GPs: what and why? 681 18.2 Mercer kernels 683

667 17.4.4 The hypothesis space of DNNs 668 17.4.5 PAC-Bayes 669 17.4.6 Out-of-distribution generalization for BNNs 670 17.4.7 Model selection for BNNs 671 17.5 Online inference 672 17.5.1 Sequential Laplace for DNNs 672 17.5.2 Extended Kalman filtering for DNNs 673 17.5.3 Assumed density filtering for DNNs 675 17.5.4 Online variational inference for DNNs 676 17.6 Hierarchical Bayesian neural networks 677 17.6.1 Example: multimoons classification 678 18 Gaussian processes 681 18.1 Introduction 681 18.1.1 GPs: what and why? 681 18.2 Mercer kernels 683

18.2.3 Kernels for nonvectorial (structured) inputs 690 18.2.4 Making new kernels from old 690 18.2.5 Mercer’s theorem 691 18.2.6 Approximating kernels with random features 692 18.3 GPs with Gaussian likelihoods 693 18.3.1 Predictions using noise-free observations 693 18.3.2 Predictions using noisy observations 694 18.3.3 Weight space vs function space 695 18.3.4 Semiparametric GPs 696 18.3.5 Marginal likelihood 697 18.3.6 Computational and numerical issues 697 18.3.7 Kernel ridge regression 698 18.4 GPs with non-Gaussian likelihoods 701 18.4.1 Binary classification 702 18.4.2 Multiclass classification 703 18.4.3 GPs for Poisson regression (Cox process) 703 18.4.4 Other likelihoods 704 18.5 Scaling GP inference to large datasets 704 18.5.1 Subset of data 705 18.5.2 Nyström approximation 706 18.5.3 Inducing point methods 707 18.5.4 Sparse variational methods 710 18.5.5 Exploiting parallelization and structure via kernel matrix multiplies 714 18.5.6 Converting a GP to an SSM 716 18.6 Learning the kernel 717 18.6.1 Empirical Bayes for the kernel parameters 717 18.6.2 Bayesian inference for the kernel parameters 720 18.6.3 Multiple kernel learning for additive kernels 721 18.6.4 Automatic search for compositional kernels 722 18.6.5 Spectral mixture kernel learning 725 18.6.6 Deep kernel learning 726 18.7 GPs and DNNs 728 18.7.1 Kernels derived from infinitely wide DNNs (NN-GP) 729 18.7.2 Neural tangent kernel (NTK) 731 18.7.3 Deep GPs 731 18.8 Gaussian processes for time series forecasting 732 18.8.1 Example: Mauna Loa 732 19 Beyond the iid assumption 735 19.1 Introduction 735 19.2 Distribution shift 735 19.2.1 Motivating examples 735 19.2.2 A causal view of distribution shift 737 19.2.3 The four main types of distribution shift 738 19.2.4 Selection bias 740 19.3 Detecting distribution shifts 740 19.3.1 Detecting shifts using two-sample testing 741 19.3.2 Detecting single out-of-distribution (OOD) inputs 741 19.3.3 Selective prediction 744 19.3.4 Open set and open world recognition 745 19.4 Robustness to distribution shifts 745 19.4.1 Data augmentation 746 19.4.2 Distributionally robust optimization 746 19.5 Adapting to distribution shifts 746 19.5.1 Supervised adaptation using transfer learning 746 19.5.2 Weighted ERM for covariate shift 748

IV Generation 771

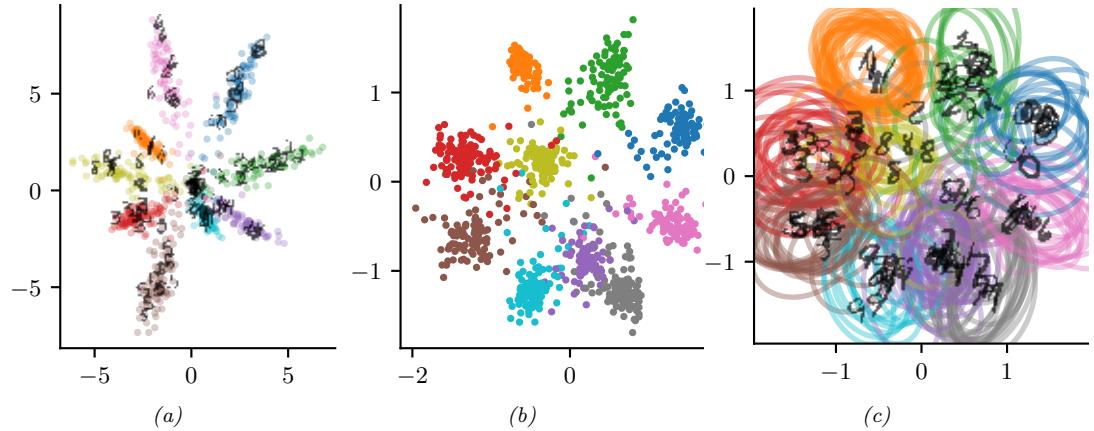

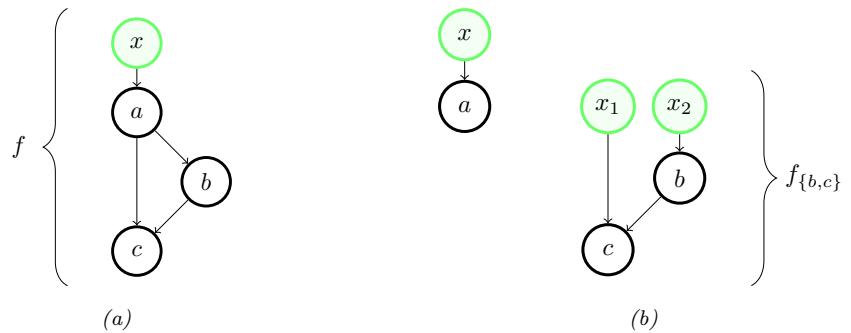

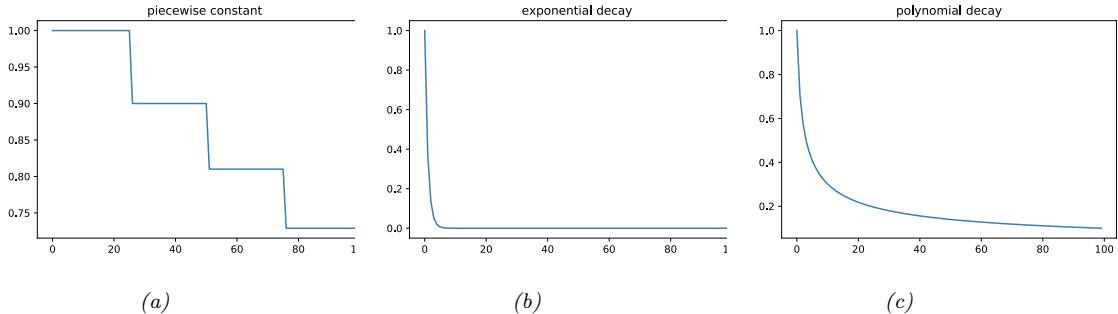

20 Generative models: an overview 773 20.1 Introduction 773 20.2 Types of generative model 773 20.3 Goals of generative modeling 775 20.3.1 Generating data 775 20.3.2 Density estimation 777 20.3.3 Imputation 778 20.3.4 Structure discovery 779 20.3.5 Latent space interpolation 780 20.3.6 Latent space arithmetic 781 20.3.7 Generative design 782 20.3.8 Model-based reinforcement learning 782 20.3.9 Representation learning 782 20.3.10 Data compression 782 20.4 Evaluating generative models 782 20.4.1 Likelihood-based evaluation 783 20.4.2 Distances and divergences in feature space 784 20.4.3 Precision and recall metrics 785 20.4.4 Statistical tests 786 20.4.5 Challenges with using pretrained classifiers 787 20.4.6 Using model samples to train classifiers 787 20.4.7 Assessing overfitting 787 20.4.8 Human evaluation 788 20.5 Training objectives 788 21 Variational autoencoders 791

21.1 Introduction 791

- 21.2 VAE basics 791

| 21.3 | VAE generalizations 796 |

|---|---|

| 21.3.1 ϑ-VAE 797 |

|

| 21.3.2 InfoVAE 799 |

|

| 21.3.3 Multimodal VAEs 800 |

|

| 21.3.4 Semisupervised VAEs 803 |

|

| 21.3.5 VAEs with sequential encoders/decoders 804 |

|

| 21.4 | Avoiding posterior collapse 806 |

| 21.4.1 KL annealing 807 |

|

| 21.4.2 Lower bounding the rate 808 |

|

| 21.4.3 Free bits 808 |

|

| 21.4.4 Adding skip connections 808 |

|

| 21.4.5 Improved variational inference 808 |

|

| 21.4.6 Alternative objectives 809 |

|

| 21.5 | VAEs with hierarchical structure 809 |

| 21.5.1 Bottom-up vs top-down inference 810 |

|

| 21.5.2 Example: very deep VAE 811 |

|

| 21.5.3 Connection with autoregressive models 812 |

|

| 21.5.4 Variational pruning 814 |

|

| 21.5.5 Other optimization di”culties 814 |

|

| 21.6 | Vector quantization VAE 815 |

| 21.6.1 Autoencoder with binary code 815 |

|

| 21.6.2 VQ-VAE model 815 |

|

| 21.6.3 Learning the prior 817 |

|

| 21.6.4 Hierarchical extension (VQ-VAE-2) 817 |

|

| 21.6.5 Discrete VAE 818 |

|

| 21.6.6 VQ-GAN 819 |

|

| 22 Autoregressive models 821 |

|

| 22.1 | Introduction 821 |

| 22.2 | Neural autoregressive density estimators (NADE) 822 |

| 22.3 | Causal CNNs 822 |

| 22.3.1 1d causal CNN (convolutional Markov models) 823 |

|

| 22.3.2 2d causal CNN (PixelCNN) 823 |

|

| 22.4 | Transformers 824 |

| 22.4.1 Text generation (GPT, etc.) 825 |

|

| 22.4.2 Image generation (DALL-E, etc.) 826 |

|

| 22.4.3 Other applications 828 |

|

| 22.5 | Large Language Models (LLMs) 828 |

| 23 Normalizing flows 829 |

|

| 23.1 | Introduction 829 |

| 23.1.1 Preliminaries 829 |

|

| 23.1.2 How to train a flow model 831 |

|

| 23.2 | Constructing flows 832 |

| 23.2.1 A”ne flows 832 |

|

| 23.2.2 Elementwise flows 832 |

|

| 23.2.3 Coupling flows 835 |

|

| 23.2.4 Autoregressive flows 836 |

|

| 23.2.5 Residual flows 842 |

|

| 23.2.6 Continuous-time flows 844 |

|

| 23.3 | Applications 846 |

| 23.3.1 Density estimation 846 |

|

| 23.3.2 Generative modeling 846 |

|

| 23.3.3 Inference 847 |

|

| 24 Energy-based models 849 |

| 24.1.1 Example: products of experts (PoE) 849 |

||

|---|---|---|

| 24.1.2 Computational di”culties 850 |

||

| 24.2 | Maximum likelihood training 850 |

|

| 24.2.1 Gradient-based MCMC methods 852 |

||

| 24.2.2 Contrastive divergence 852 |

||

| 24.3 | Score matching (SM) 855 |

|

| 24.3.1 Basic score matching 856 |

||

| 24.3.2 Denoising score matching (DSM) 857 |

||

| 24.3.3 Sliced score matching (SSM) 858 |

||

| 24.3.4 Connection to contrastive divergence 859 |

||

| 24.3.5 Score-based generative models 860 |

||

| 24.4 | Noise contrastive estimation 860 |

|

| 24.4.1 Connection to score matching 862 |

||

| 24.5 | Other methods 862 |

|

| 24.5.1 Minimizing Di!erences/Derivatives of KL Divergences 863 |

||

| 24.5.2 Minimizing the Stein discrepancy 863 |

||

| 24.5.3 Adversarial training 864 |

||

| 25 Di!usion models 867 |

||

| 25.1 | Introduction 867 |

|

| 25.2 | Denoising di!usion probabilistic models (DDPMs) 867 |

|

| 25.2.1 Encoder (forwards di!usion) 868 |

||

| 25.2.2 Decoder (reverse di!usion) 869 |

||

| 25.2.3 Model fitting 870 |

||

| 25.2.4 Learning the noise schedule 872 |

||

| 25.2.5 Example: image generation 873 |

||

| 25.3 | Score-based generative models (SGMs) 874 |

|

| 25.3.1 Example 874 |

||

| 25.3.2 Adding noise at multiple scales 874 |

||

| 25.3.3 Equivalence to DDPM 876 |

||

| 25.4 | Continuous time models using di!erential equations 877 |

|

| 25.4.1 Forwards di!usion SDE 877 |

||

| 25.4.2 Forwards di!usion ODE 878 |

||

| 25.4.3 Reverse di!usion SDE 879 |

||

| 25.4.4 Reverse di!usion ODE 880 |

||

| 25.4.5 Comparison of the SDE and ODE approach 881 |

||

| 25.4.6 Example 881 |

||

| 25.4.7 Flow matching 881 |

||

| 25.5 | Speeding up di!usion models 882 |

|

| 25.5.1 DDIM sampler 882 |

||

| 25.5.2 Non-Gaussian decoder networks 883 |

||

| 25.5.3 Distillation 883 |

||

| 25.5.4 Latent space di!usion 884 |

||

| 25.6 | Conditional generation 885 |

|

| 25.6.1 Conditional di!usion model 885 |

||

| 25.6.2 Classifier guidance 886 |

||

| 25.6.3 Classifier-free guidance 886 |

||

| 25.6.4 Generating high resolution images 886 |

||

| 25.7 | Di!usion for discrete state spaces 887 |

|

| 25.7.1 Discrete Denoising Di!usion Probabilistic Models 887 |

||

| 25.7.2 Choice of Markov transition matrices for the forward processes |

889 | |

| 25.7.3 Parameterization of the reverse process 890 |

||

| 25.7.4 Noise schedules 890 |

||

| 25.7.5 Connections to other probabilistic models for discrete sequences |

890 | |

| 26 Generative adversarial networks 893 |

||

| 26.2 | Learning by comparison 894 |

|

|---|---|---|

| 26.2.1 | Guiding principles 895 |

|

| 26.2.2 | Density ratio estimation using binary classifiers 896 |

|

| 26.2.3 | Bounds on f-divergences 898 |

|

| 26.2.4 | Integral probability metrics 900 |

|

| 26.2.5 | Moment matching 902 |

|

| 26.2.6 | On density ratios and di!erences 902 |

|

| 26.3 | Generative adversarial networks 904 |

|

| 26.3.1 | From learning principles to loss functions 904 |

|

| 26.3.2 | Gradient descent 905 |

|

| 26.3.3 | Challenges with GAN training 907 |

|

| 26.3.4 | Improving GAN optimization 908 |

|

| 26.3.5 | Convergence of GAN training 908 |

|

| 26.4 | Conditional GANs 912 |

|

| 26.5 | Inference with GANs 913 |

|

| 26.6 | Neural architectures in GANs 914 |

|

| 26.6.1 | The importance of discriminator architectures 914 |

|

| 26.6.2 | Architectural inductive biases 915 |

|

| 26.6.3 | Attention in GANs 915 |

|

| 26.6.4 | Progressive generation 916 |

|

| 26.6.5 | Regularization 917 |

|

| 26.6.6 | Scaling up GAN models 918 |

|

| 26.7 | Applications | 918 |

| 26.7.1 | GANs for image generation 918 |

|

| 26.7.2 | Video generation 921 |

|

| 26.7.3 | Audio generation 922 |

|

| 26.7.4 | Text generation 922 |

|

| 26.7.5 | Imitation learning 923 |

|

| 26.7.6 | Domain adaptation 924 |

|

| 26.7.7 | Design, art and creativity 924 |

V Discovery 925

27 Discovery methods: an overview 927

- 27.1 Introduction 927

- 27.2 Overview of Part V 928

28 Latent factor models 929

- 28.1 Introduction 929

- 28.2 Mixture models 929

- 28.3 Factor analysis 940

- 28.3.1 Factor analysis: the basics 940

- 28.3.2 Probabilistic PCA 944

- 28.3.3 Mixture of factor analyzers 946

- 28.3.4 Factor analysis models for paired data 953

- 28.3.5 Factor analysis with exponential family likelihoods 956

- 28.3.6 Factor analysis with DNN likelihoods (VAEs) 957

- 28.3.7 Factor analysis with GP likelihoods (GP-LVM) 958

- 28.4 LFMs with non-Gaussian priors 959

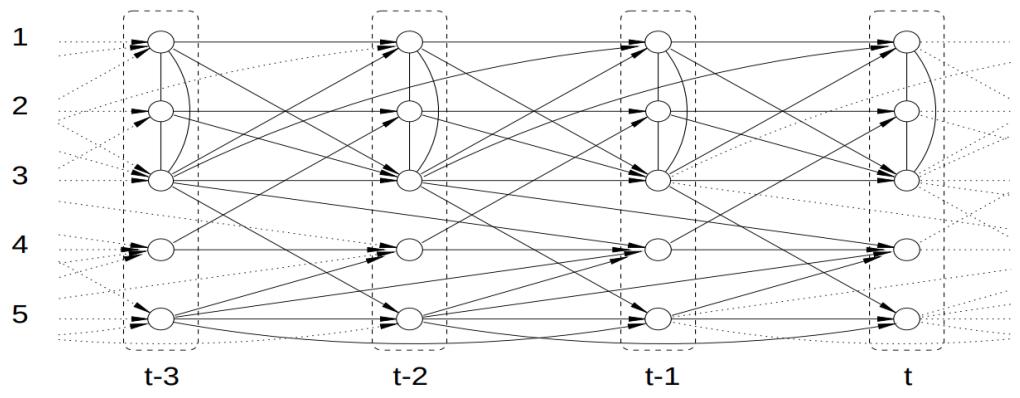

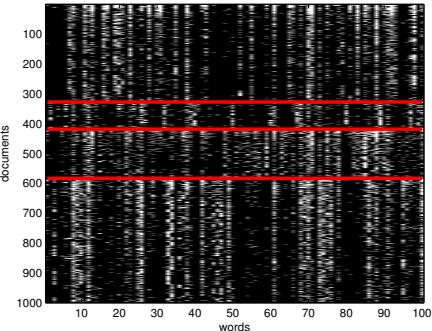

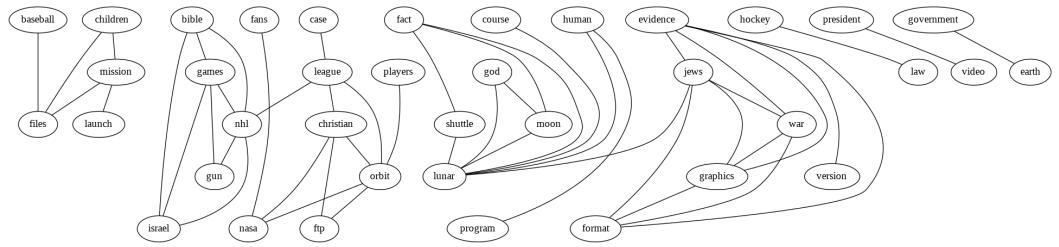

28.4.1 Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) 960 28.4.2 Multinomial PCA 962 28.5 Topic models 963 28.5.1 Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) 963 28.5.2 Correlated topic model 967 28.5.3 Dynamic topic model 967 28.5.4 LDA-HMM 969 28.6 Independent components analysis (ICA) 971 28.6.1 Noiseless ICA model 972 28.6.2 The need for non-Gaussian priors 973 28.6.3 Maximum likelihood estimation 975 28.6.4 Alternatives to MLE 975 28.6.5 Sparse coding 977 28.6.6 Nonlinear ICA 978 29 State-space models 979 29.1 Introduction 979 29.2 Hidden Markov models (HMMs) 980 29.2.1 Conditional independence properties 980 29.2.2 State transition model 980 29.2.3 Discrete likelihoods 981 29.2.4 Gaussian likelihoods 982 29.2.5 Autoregressive likelihoods 982 29.2.6 Neural network likelihoods 983 29.3 HMMs: applications 984 29.3.1 Time series segmentation 984 29.3.2 Protein sequence alignment 986 29.3.3 Spelling correction 988 29.4 HMMs: parameter learning 990 29.4.1 The Baum-Welch (EM) algorithm 990 29.4.2 Parameter estimation using SGD 993 29.4.3 Parameter estimation using spectral methods 994 29.4.4 Bayesian HMMs 995 29.5 HMMs: generalizations 997 29.5.1 Hidden semi-Markov model (HSMM) 997 29.5.2 Hierarchical HMMs 999 29.5.3 Factorial HMMs 1001 29.5.4 Coupled HMMs 1002 29.5.5 Dynamic Bayes nets (DBN) 1003 29.5.6 Changepoint detection 1003 29.6 Linear dynamical systems (LDSs) 1006 29.6.1 Conditional independence properties 1006 29.6.2 Parameterization 1006 29.7 LDS: applications 1007 29.7.1 Object tracking and state estimation 1007 29.7.2 Online Bayesian linear regression (recursive least squares) 1008 29.7.3 Adaptive filtering 1010 29.7.4 Time series forecasting 1010 29.8 LDS: parameter learning 1011 29.8.1 EM for LDS 1011 29.8.2 Subspace identification methods 1013 29.8.3 Ensuring stability of the dynamical system 1013 29.8.4 Bayesian LDS 1014 29.8.5 Online parameter learning for SSMs 1015 29.9 Switching linear dynamical systems (SLDSs) 1015 29.9.1 Parameterization 1015

29.9.2 Posterior inference 1015 29.9.3 Application: Multitarget tracking 1016 29.10 Nonlinear SSMs 1020 29.10.1 Example: object tracking and state estimation 1020 29.10.2 Posterior inference 1021 29.11 Non-Gaussian SSMs 1021 29.11.1 Example: spike train modeling 1021 29.11.2 Example: stochastic volatility models 1022 29.11.3 Posterior inference 1023 29.12 Structural time series models 1023 29.12.1 Introduction 1023 29.12.2 Structural building blocks 1024 29.12.3 Model fitting 1026 29.12.4 Forecasting 1027 29.12.5 Examples 1027 29.12.6 Causal impact of a time series intervention 1031 29.12.7 Prophet 1035 29.12.8 Neural forecasting methods 1035 29.13 Deep SSMs 1036 29.13.1 Deep Markov models 1037 29.13.2 Recurrent SSM 1038 29.13.3 Improving multistep predictions 1039 29.13.4 Variational RNNs 1040

30 Graph learning 1043

31 Nonparametric Bayesian models 1047

31.1 Introduction 1047

32 Representation learning 1049

33 Interpretability 1073

VI Action 1103

| 34 Decision making under uncertainty 1105 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 34.1 | Statistical decision theory 1105 |

||

| 34.1.1 | Basics 1105 |

||

| 34.1.2 | Frequentist decision theory 1106 |

||

| 34.1.3 | Bayesian decision theory 1106 |

||

| 34.1.4 | Frequentist optimality of the Bayesian approach 1107 |

||

| 34.1.5 | Examples of one-shot decision making problems 1107 |

||

| 34.2 | Decision (influence) diagrams 1112 |

||

| 34.2.1 | Example: oil wildcatter 1112 |

||

| 34.2.2 | Information arcs 1113 |

||

| 34.2.3 | Value of information 1114 |

||

| 34.2.4 | Computing the optimal policy 1115 |

||

| 34.3 | A/B testing | 1115 | |

| 34.3.1 | A Bayesian approach 1115 |

||

| 34.3.2 | Example 1119 |

||

| 34.4 | Contextual bandits 1120 |

||

| 34.4.1 | Types of bandit 1120 |

||

| 34.4.2 | Applications 1122 |

||

| 34.4.3 | Exploration-exploitation tradeo! 1122 |

||

| 34.4.4 | The optimal solution 1122 |

||

| 34.4.5 | Upper confidence bounds (UCBs) 1124 |

||

| 34.4.6 | Thompson sampling 1126 |

||

| 34.4.7 | Regret 1127 |

||

| 34.5 | Markov decision problems 1128 |

||

| 34.5.1 | Basics 1128 |

||

| 34.5.2 | Partially observed MDPs 1130 |

||

| 34.5.3 | Episodes and returns 1130 |

||

| 34.5.4 | Value functions 1131 |

||

| 34.5.5 | Optimal value functions and policies 1132 |

||

| 34.6 | Planning in an MDP 1134 |

||

| 34.6.1 | Value iteration 1134 |

||

| 34.6.2 | Policy iteration 1135 |

||

| 34.6.3 | Linear programming 1136 |

||

| 34.7 | Active learning 1137 |

||

| 34.7.1 | Active learning scenarios 1138 |

||

| 34.7.2 | Relationship to other forms of sequential decision making | 1138 | |

| 34.7.3 | Acquisition strategies 1139 |

||

| 34.7.4 | Batch active learning 1141 |

||

| 35 Reinforcement learning 1145 |

|||

| 35.1 | Introduction | 1145 | |

| 35.1.1 | Overview of methods 1145 |

||

| 35.1.2 | Value-based methods 1147 |

||

| 35.1.3 | Policy search methods 1147 |

||

| 35.1.4 | Model-based RL 1147 |

35.1.5 Exploration-exploitation tradeo! 1148 35.2 Value-based RL 1150 35.2.1 Monte Carlo RL 1150 35.2.2 Temporal di 1150 35.2.3 TD learning with eligibility traces 1151 35.2.4 SARSA: on-policy TD control 1152 35.2.5 Q-learning: o!-policy TD control 1153 35.2.6 Deep Q-network (DQN) 1154 35.3 Policy-based RL 1156 35.3.1 The policy gradient theorem 1157 35.3.2 REINFORCE 1158 35.3.3 Actor-critic methods 1158 35.3.4 Bound optimization methods 1160 35.3.5 Deterministic policy gradient methods 1162 35.3.6 Gradient-free methods 1163 35.4 Model-based RL 1164 35.4.1 Model predictive control (MPC) 1164 35.4.2 Combining model-based and model-free 1166 35.4.3 MBRL using Gaussian processes 1166 35.4.4 MBRL using DNNs 1168 35.4.5 MBRL using latent-variable models 1168 35.4.6 Robustness to model errors 1171 35.5 O

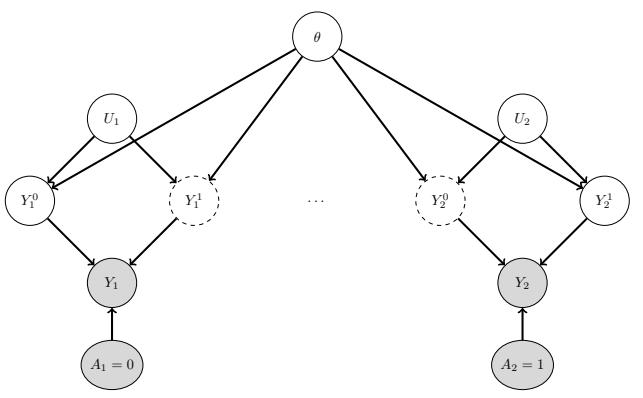

1150 35.2.3 TD learning with eligibility traces 1151 35.2.4 SARSA: on-policy TD control 1152 35.2.5 Q-learning: o!-policy TD control 1153 35.2.6 Deep Q-network (DQN) 1154 35.3 Policy-based RL 1156 35.3.1 The policy gradient theorem 1157 35.3.2 REINFORCE 1158 35.3.3 Actor-critic methods 1158 35.3.4 Bound optimization methods 1160 35.3.5 Deterministic policy gradient methods 1162 35.3.6 Gradient-free methods 1163 35.4 Model-based RL 1164 35.4.1 Model predictive control (MPC) 1164 35.4.2 Combining model-based and model-free 1166 35.4.3 MBRL using Gaussian processes 1166 35.4.4 MBRL using DNNs 1168 35.4.5 MBRL using latent-variable models 1168 35.4.6 Robustness to model errors 1171 35.5 O 1171 35.5.1 Basic techniques 1171 35.5.2 The curse of horizon 1175 35.5.3 The deadly triad 1176 35.5.4 Some common o!-policy methods 1177 35.6 Control as inference 1177 35.6.1 Maximum entropy reinforcement learning 1178 35.6.2 Other approaches 1180 35.6.3 Imitation learning 1182 36 Causality 1185 36.1 Introduction 1185 36.2 Causal formalism 1187 36.2.1 Structural causal models 1187 36.2.2 Causal DAGs 1188 36.2.3 Identification 1190 36.2.4 Counterfactuals and the causal hierarchy 1192 36.3 Randomized control trials 1194 36.4 Confounder adjustment 1195 36.4.1 Causal estimand, statistical estimand, and identification 1195 36.4.2 ATE estimation with observed confounders 1198 36.4.3 Uncertainty quantification 1203 36.4.4 Matching 1203 36.4.5 Practical considerations and procedures 1204 36.4.6 Summary and practical advice 1207 36.5 Instrumental variable strategies 1208 36.5.1 Additive unobserved confounding 1210 36.5.2 Instrument monotonicity and local average treatment e!ect 1212 36.5.3 Two stage least squares 1215 36.6 Di

1171 35.5.1 Basic techniques 1171 35.5.2 The curse of horizon 1175 35.5.3 The deadly triad 1176 35.5.4 Some common o!-policy methods 1177 35.6 Control as inference 1177 35.6.1 Maximum entropy reinforcement learning 1178 35.6.2 Other approaches 1180 35.6.3 Imitation learning 1182 36 Causality 1185 36.1 Introduction 1185 36.2 Causal formalism 1187 36.2.1 Structural causal models 1187 36.2.2 Causal DAGs 1188 36.2.3 Identification 1190 36.2.4 Counterfactuals and the causal hierarchy 1192 36.3 Randomized control trials 1194 36.4 Confounder adjustment 1195 36.4.1 Causal estimand, statistical estimand, and identification 1195 36.4.2 ATE estimation with observed confounders 1198 36.4.3 Uncertainty quantification 1203 36.4.4 Matching 1203 36.4.5 Practical considerations and procedures 1204 36.4.6 Summary and practical advice 1207 36.5 Instrumental variable strategies 1208 36.5.1 Additive unobserved confounding 1210 36.5.2 Instrument monotonicity and local average treatment e!ect 1212 36.5.3 Two stage least squares 1215 36.6 Di !erences 1216 36.6.1 Estimation 1219 36.7 Credibility checks 1219 36.7.1 Placebo checks 1220 36.7.2 Sensitivity analysis to unobserved confounding 1221

!erences 1216 36.6.1 Estimation 1219 36.7 Credibility checks 1219 36.7.1 Placebo checks 1220 36.7.2 Sensitivity analysis to unobserved confounding 1221

36.8 The do-calculus 1228 36.8.1 The three rules 1228 36.8.2 Revisiting backdoor adjustment 1229 36.8.3 Frontdoor adjustment 1230 36.9 Further reading 1232

Index 1235

Bibliography 1253

Preface

I am writing a longer [book] than usual because there is not enough time to write a short one. (Blaise Pascal, paraphrased.)

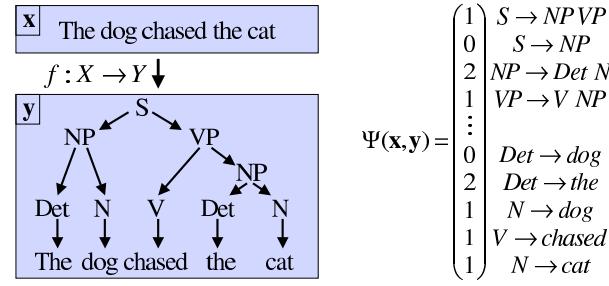

This book is a sequel to [Mur22]. and provides a deeper dive into various topics in machine learning (ML). The previous book mostly focused on techniques for learning functions of the form f : X → Y, where f is some nonlinear model, such as a deep neural network, X is the set of possible inputs (typically X = RD), and Y = {1,…,C} represents the set of labels for classification problems or Y = R for regression problems. Judea Pearl, a well known AI researcher, has called this kind of ML a form of “glorified curve fitting” (quoted in [Har18]).

In this book, we expand the scope of ML to encompass more challenging problems. For example, we consider training and testing under di!erent distributions; we consider generation of high dimensional outputs, such as images, text, and graphs, so the output space is, say, Y = R3→256→256 for image generation or Y = {1,…,K}T for text generation (this is sometimes called generative AI); we discuss methods for discovering “insights” about data, based on latent variable models; and we discuss how to use probabilistic models for causal inference and decision making under uncertainty.

We assume the reader has some prior exposure to ML and other relevant mathematical topics (e.g., probability, statistics, linear algebra, optimization). This background material can be found in the prequel to this book, [Mur22], as well several other good books (e.g., [Lin+21b; DFO20]).

Python code (mostly in JAX) to reproduce nearly all of the figures can be found online. In particular, if a figure caption says “Generated by gauss_plot_2d.ipynb”, then you can find the corresponding Jupyter notebook at probml.github.io/notebooks#gauss\_plot\_2d.ipynb. Clicking on the figure link in the pdf version of the book will take you to this list of notebooks. Clicking on the notebook link will open it inside Google Colab, which will let you easily reproduce the figure for yourself, and modify the underlying source code to gain a deeper understanding of the methods. (Colab gives you access to a free GPU, which is useful for some of the more computationally heavy demos.)

In addition to the online code, probml.github.io/supp contains some additional supplementary online content which was excluded from the main book for space reasons. For exercises (and solutions) related to the topics in this book, see [Gut22].

Other contributors

I would also like to thank the following people who helped in various other ways:

• Many people who helped make or improve the figures, including: Aman Atman, Vibhuti Bansal, Shobhit Belwal, Aadesh Desai, Vishal Ghoniya, Anand Hegde, Ankita Kumari Jain, Madhav Kanda, Aleyna Kara, Rohit Khoiwal, Taksh Panchal, Dhruv Patel, Prey Patel, Nitish Sharma, Hetvi Shastri, Mahmoud Soliman, and Gautam Vashishtha. A special shout out to Zeel B Patel

and Karm Patel for their significant e!orts in improving the figure quality.

- Participants in the Google Summer of Code (GSOC) for 2021, including Ming Liang Ang, Aleyna Kara, Gerardo Duran-Martin, Srikar Reddy Jilugu, Drishti Patel, and co-mentor Mahmoud Soliman.

- Participants in the Google Summer of Code (GSOC) for 2022, including Peter Chang, Giles Harper-Donnelly, Xinglong Li, Zeel B Patel, Karm Patel, Qingyao Sun, and co-mentors Nipun Batra and Scott Linderman.

- Many other people who contributed code (see autogenerated list at https://github.com/probml/ pyprobml#acknowledgements).

- Many people who proofread parts of the book, including: Aalto Seminar students, Bill Behrman, Kay Brodersen, Peter Chang, Krzysztof Choromanski, Adrien Corenflos, Tom Dietterich, Gerardo Duran-Martin, Lehman Krunoslav, Ruiqi Gao, Amir Globerson, Giles Harper-Donnelly, Ravin Kumar, Junpeng Lao, Stephen Mandt, Norm Matlo!, Simon Prince, Rif Saurous, Erik Sudderth, Donna Vakalis, Hal Varian, Chris Williams, Raymond Yeh, and others listed at https://github. com/probml/pml2-book/issues?q=is:issue. A special shout out to John Fearns who proofread almost all the math, and the MIT Press editor who ensured I use “Oxford commas” in all the right places.

About the cover

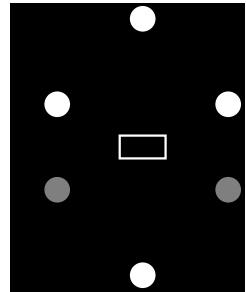

The cover illustrates a variational autoencoder (Chapter 21) being used to map from a 2d Gaussian to image space.

Changelog

All changes listed at https://github.com/probml/pml2-book/issues?q=is%3Aissue+is%3Aclosed.

• August, 2023. First printing.

1 Introduction

“Intelligence is not just about pattern recognition and function approximation. It’s about modeling the world”. — Josh Tenenbaum, NeurIPS 2021.

Much of current machine learning focuses on the task of mapping inputs to outputs (i.e., approximating functions of the form f : X → Y), often using “deep learning” (see e.g., [LBH15; Sch14; Sej20; BLH21]). Judea Pearl, a well known AI researcher, has called this “glorified curve fitting” (quoted in [Har18]). This is a little unfair, since when X and/or Y are high-dimensional spaces — such as images, sentences, graphs, or sequences of decisions/actions — then the term “curve fitting” is rather misleading, since one-dimensional intuitions often do not work in higher-dimensional settings (see e.g., [BPL21]). Nevertheless, the quote gets at what many feel is lacking in current attempts to “solve AI” using machine learning techniques, namely that they are too focused on prediction of observable patterns, and not focused enough on “understanding” the underlying latent structure behind these patterns.

Gaining a “deep understanding” of the structure behind the observed data is necessary for advancing science, as well as for certain applications, such as healthcare (see e.g., [DD22]), where identifying the root causes or mechanisms behind various diseases is the key to developing cures. In addition, such “deep understanding” is necessary in order to develop robust and e!cient systems. By “robust” we mean methods that work well even if there are unexpected changes to the data distribution to which the system is applied, which is an important concern in many areas, such as robotics (see e.g., [Roy+21]). By “e”cient” we generally mean data or statistically e”cient, i.e., methods that can learn quickly from small amounts of data (cf., [Lu+23]). This is important since data can be limited in some domains, such as healthcare and robotics, even though it is abundant in other domains, such as language and vision, due to the ability to scrape the internet. We are also interested in computationally e”cient methods, although this is a secondary concern as computing power continues to grow. (We also note that this trend has been instrumental to much of the recent progress in AI, as noted in [Sut19].)

To develop robust and e”cient systems, this book adopts a model-based approach, in which we try to learn parsimonious representations of the underlying “data generating process” (DGP) given samples from one or more datasets (c.f., [Lak+17; Win+19; Sch20; Ben+21a; Cun22; MTS22]). This is in fact similar to the scientific method, where we try to explain (features of) the observations by developing theories or models. One way to formalize this process is in terms of Bayesian inference applied to probabilistic models, as argued in [Jay03; Box80; GS13]. We discuss inference algorithms in detail in Part II of the book.1 But before we get there, in Part I we cover some relevant background

1. Note that, in the deep learning community, the term “inference” means applying a function to some inputs to

material that will be needed. (This part can be skipped by readers who are already familiar with these basics.)

Once we have a set of inference methods in our toolbox (some of which may be as simple as computing a maximum likelihood estimate using an optimization method, such as stochastic gradient descent) we can turn our focus to discussing di!erent kinds of models. The choice of model depends on our task, the kind and amount of data we have, and our metric(s) of success. We will broadly consider four main kinds of task: prediction (e.g., classification and regression), generation (e.g., of images or text), discovery (of “meaningful structure” in data), and control (optimal decision making). We give more details below.

In Part III, we discuss models for prediction. These models are conditional distributions of the form p(y|x), where x ↑ X is some input (often high dimensional), and y ↑ Y is the desired output (often low dimensional). In this part of the book, we assume there is one right answer that we want to predict, although we may be uncertain about it.

In Part IV, we discuss models for generation. These models are distributions of the form p(x) or p(x|c), where c are optional conditioning inputs, and where there may be multiple valid outputs. For example, given a text prompt c, we may want to generate a diverse set of images x that “match” the caption. Evaluating such models is harder than in the prediction setting, since it is less clear what the desired output should be.

In Part V, we discuss latent variable models, which are joint models of the form p(z, x) = p(z)p(x|z), where z is the hidden state and x are the observations that are assumed to be generated from z. The goal is to compute p(z|x), in order to uncover some (hopefully meaningful/useful) underlying state or patterns in the observed data. We also consider methods for trying to discover patterns learned implicitly by predictive models of the form p(y|x), without relying on an explicit generative model of the data.

Finally, in Part VI, we discuss models and algorithms which can be used to make decisions under uncertainty. This naturally leads into the very important topic of causality, with which we close the book.

In view of the broad scope of the book, we cannot go into detail on every topic. However, we have attempted to cover all the basics. In some cases, we also provide a “deeper dive” into the research frontier (as of 2022). We hope that by bringing all these topics together, you will find it easier to make connections between all these seemingly disparate areas, and can thereby deepen your understanding of the field of machine learning.

compute the output. This is unrelated to Bayesian inference, which is concerned with the much harder task of inverting a function, and working backwards from observed outputs to possible hidden inputs (causes). The latter is more closely related to what the deep learning community calls “training”.

Part I Fundamentals

2 Probability

2.1 Introduction

In this section, we formally define what we mean by probability, following the presentation of [Cha21, Ch. 2]. Other good introductions to this topic can be found in e.g., [GS97; BT08; Bet18; DFO20].

2.1.1 Probability space

We define a probability space to be a triple (!, F, P), where ! is the sample space, which is the set of possible outcomes from an experiment; F is the event space, which is the set of all possible subsets of !; and P is the probability measure, which is a mapping from an event E ↓ ! to a number in [0, 1] (i.e., P : F → [0, 1]), which satisfies certain consistency requirements, which we discuss in Section 2.1.4.

2.1.2 Discrete random variables

The simplest setting is where the outcomes of the experiment constitute a countable set. For example, consider throwing a 3-sided die, where the faces are labeled “A”, “B”, and “C”. (We choose 3 sides instead of 6 for brevity.) The sample space is ! = {A, B, C}, which represents all the possible outcomes of the “experiment”. The event space is the set of all possible subsets of the sample space, so F = {↔︎, {A}, {B}, {C}, {A, B}, {A, C}, {B,C}, {A, B, C}}. An event is an element of the event space. For example, the event E1 = {A, B} represents outcomes where the die shows face A or B, and event E2 = {C} represents the outcome where the die shows face C.

Once we have defined the event space, we need to specify the probability measure, which provides a way to compute the “size” or “weight” of each set in the event space. In the 3-sided die example, suppose we define the probability of each outcome (atomic event) as P[{A}] = 2 6 , P[{B}] = 1 6 , and P[{C}] = 3 6 . We can derive the probability of other events by adding up the measures for each outcome, e.g., P[{A, B}] = 2 6 + 1 6 = 1 2 . We formalize this in Section 2.1.4.

To simplify notation, we will assign a number to each possible outcome in the sample space. This can be done by defining a random variable or rv, which is a function X : ! → R that maps an outcome ω ↑ ! to a number X(ω) on the real line. For example, we can define the random variable X for our 3-sided die using X(A)=1, X(B)=2, X(C)=3. As another example, consider an experiment where we flip a fair coin twice. The sample space is ! = {ω1 = (H, H), ω2 = (H, T), ω3 = (T,H), ω4 = (T,T)}, where H stands for head, and T for tail. Let X be the random variable that represents the number of heads. Then we have X(ω1)=2, X(ω2)=1, X(ω3)=1, and X(ω4)=0.

We define the set of possible values of the random variable to be its state space, denoted X(!) = X . We define the probability of any given state using

\[p\_X(a) = \mathbb{P}[X = a] = \mathbb{P}[X^{-1}(a)] \tag{2.1}\]

where X↑1(a) = {ω ↑ !|X(ω) = a} is the pre-image of a. Here pX is called the probability mass function or pmf for random variable X. In the example where we flip a fair coin twice, the pmf is pX(0) = P[{(T,T)}] = 1 4 , pX(1) = P[{(T,H),(H, T)}] = 2 4 , and pX(2) = P[{(H, H)}] = 1 4 . The pmf can be represented by a histogram, or some parametric function (see Section 2.2.1). We call pX the probability distribution for rv X. We will often drop the X subscript from pX where it is clear from context.

2.1.3 Continuous random variables

We can also consider experiments with continuous outcomes. In this case, we assume the sample space is a subset of the reals, ! ↓ R, and we define each continuous random variable to be the identify function, X(ω) = ω.

For example, consider measuring the duration of some event (in seconds). We define the sample space to be ! = {t : 0 ↗ t ↗ Tmax}. Since this is an uncountable set, we cannot define all possible subsets by enumeration, unlike the discrete case. Instead, we need to define event space in terms of a Borel sigma-field, also called a Borel sigma-algebra. We say that F is a ε-field if (1) ↔︎ ↑ F and ! ↑ F; (2) F is closed under complement, so if E ↑ F then Ec ↑ F; and (3) F is closed under countable unions and intersections, meaning that ↘↓ i=1Ei ↑ F and ≃↓ i=1Ei ↑ F, provided E1, E2,… ↑ F. Finally, we say that B is a Borel ε-field if it is a ε-field generated from semi-closed intervals of the form (⇐⇒, b] = {x : ⇐⇒ < x ↗ b}. By taking unions, intersections and complements of these intervals, we can see that B contains the following sets:

\[\{(a,b), [a,b], (a,b], [a,b], \{b\}, \ -\infty \le a \le b \le \infty\tag{2.2}\]

In our duration example, we can further restrict the event space to only contain intervals whose lower bound is 0 and whose upper bound is ↗ Tmax.

To define the probability measure, we assign a weighting function pX(x) ⇑ 0 for each x ↑ ! known as a probability density function or pdf. See Section 2.2.2 for a list of common pdf’s. We can then derive the probability of an event E = [a, b] using

\[\mathbb{P}([a,b]) = \int\_{E} d\mathbb{P} = \int\_{a}^{b} p(x) dx \tag{2.3}\]

We can also define the cumulative distribution function or cdf for random variable X as follows:

\[P\_X(x) \triangleq \mathbb{P}[X \le x] = \int\_{-\infty}^{x} p\_X(x') dx' \tag{2.4}\]

From this we can compute the probability of an interval using

\[\mathbb{P}([a,b]) = p(a \le X \le b) = P\_X(b) - P\_X(a) \tag{2.5}\]

The term “probability distribution” could refer to the pdf pX or the cdf PX or even the probabiliy measure P.

We can generalize the above definitions to multidimensional spaces, ! ↓ Rn, as well as more complex sample spaces, such as functions.

2.1.4 Probability axioms

The probability law associated with the event space must follow the axioms of probability, also called the Kolmogorov axioms, which are as follows:1

- Non-negativity: P[E] ⇑ 0 for any E ↓ !.

- Normalization: P[!] = 1.

- Additivity: for any countable sequence of pairwise disjoint sets {E1, E2,…, }, we have

\[\mathbb{P}\left[\cup\_{i=1}^{\infty} E\_i\right] = \sum\_{i=1}^{\infty} \mathbb{P}[E\_i] \tag{2.6}\]

In the finite case, where we just have two disjoint sets, E1 and E2, this becomes

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cup E\_2] = \mathbb{P}[E\_1] + \mathbb{P}[E\_2] \tag{2.7}\]

This corresponds to the probability of event E1 or E2, assuming they are mutually exclusive (disjoint sets).

From these axioms, we can derive the complement rule:

\[\mathbb{P}[E^c] = 1 - \mathbb{P}[E] \tag{2.8}\]

where Ec = ! E is the complement of E. (This follows since P[!] = 1 = P[E ↘ Ec] = P[E] + P[Ec].) We can also show that P[E] ↗ 1 (proof by contradiction), and P[↔︎]=0 (which follows from first corollary with E = !).

We can also show the following result, known as the addition rule:

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cup E\_2] = \mathbb{P}[E\_1] + \mathbb{P}[E\_2] - \mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cap E\_2] \tag{2.9}\]

This holds for any pair of events, even if they are not disjoint.

2.1.5 Conditional probability

Consider two events E1 and E2. If P[E2] ⇓= 0, we define the conditional probability of E1 given E2 as

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1|E\_2] \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \frac{\mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cap E\_2]}{\mathbb{P}[E\_2]} \tag{2.10}\]

From this, we can get the multiplication rule:

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cap E\_2] = \mathbb{P}[E\_1|E\_2]\mathbb{P}[E\_2] = \mathbb{P}[E\_2|E\_1]\mathbb{P}[E\_1] \tag{2.11}\]

1. These laws can be shown to follow from a more basic set of assumptions about reasoning under uncertainty, a result known as Cox’s theorem [Cox46; Cox61].

Conditional probability measures how likely an event E1 is given that event E2 has happened. However, if the events are unrelated, the probability will not change. Formally, We say that E1 and E2 are independent events if

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cap E\_2] = \mathbb{P}[E\_1]\mathbb{P}[E\_2] \tag{2.12}\]

If both P[E1] > 0 and P[E2] > 0, this is equivalent to requiring that P[E1|E2] = P[E1] or equivalently, P[E2|E1] = P[E2]. Similarly, we say that E1 and E2 are conditionally independent given E3 if

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1 \cap E\_2 | E\_3] = \mathbb{P}[E\_1 | E\_3] \mathbb{P}[E\_2 | E\_3] \tag{2.13}\]

From the definition of conditional probability, we can derive the law of total probability, which states the following: if {A1,…,An} is a partition of the sample space !, then for any event B ↓ !, we have

\[\mathbb{P}[B] = \sum\_{i=1}^{n} \mathbb{P}[B|A\_i] \mathbb{P}[A\_i] \tag{2.14}\]

2.1.6 Bayes’ rule

From the definition of conditional probability, we can derive Bayes’ rule, also called Bayes’ theorem, which says that, for any two events E1 and E2 such that P[E1] > 0 and P[E2] > 0, we have

\[\mathbb{P}[E\_1|E\_2] = \frac{\mathbb{P}[E\_2|E\_1]\mathbb{P}[E\_1]}{\mathbb{P}[E\_2]} \tag{2.15}\]

For a discrete random variable X with K possible states, we can write Bayes’ rule as follows, using the law of total probability:

\[p(X=k|E) = \frac{p(E|X=k)p(X=k)}{p(E)} = \frac{p(E|X=k)p(X=k)}{\sum\_{k'=1}^{K} p(E|X=k')p(X=k')}\tag{2.16}\]

Here p(X = k) is the prior probability, p(E|X = k) is the likelihood, p(X = k|E) is the posterior probability, and p(E) is a normalization constant, known as the marginal likelihood.

Similarly, for a continuous random variable X, we can write Bayes’ rule as follows:

\[p(X=x|E) = \frac{p(E|X=x)p(X=x)}{p(E)} = \frac{p(E|X=x)p(X=x)}{\int p(E|X=x')p(X=x')dx'} \tag{2.17}\]

2.2 Some common probability distributions

There are a wide variety of probability distributions that are used for various kinds of models. We summarize some of the more commonly used ones in the sections below. See Supplementary Chapter 2 for more information, and https://ben18785.shinyapps.io/distribution-zoo/ for an interactive visualization.

2.2.1 Discrete distributions

In this section, we discuss some discrete distributions defined on subsets of the (non-negative) integers.

2.2.1.1 Bernoulli and binomial distributions

Let x ↑ {0, 1,…,N}. The binomial distribution is defined by

\[\operatorname{Bin}(x|N,\mu) \triangleq \binom{N}{x} \mu^x (1-\mu)^{N-x} \tag{2.18}\]

where ’N k ( ↭ N! (N↑k)!k! is the number of ways to choose k items from N (this is known as the binomial coe!cient, and is pronounced “N choose k”).

If N = 1, so x ↑ {0, 1}, the binomial distribution reduces to the Bernoulli distribution:

\[\text{Ber}(x|\mu) = \begin{cases} 1 - \mu & \text{if } x = 0 \\ \mu & \text{if } x = 1 \end{cases} \tag{2.19}\]

where µ = E [x] = p(x = 1) is the mean.

2.2.1.2 Categorical and multinomial distributions

If the variable is discrete-valued, x ↑ {1,…,K}, we can use the categorical distribution:

\[\text{Cat}(x|\theta) \triangleq \prod\_{k=1}^{K} \theta\_k^{\mathbb{I}(x=k)} \tag{2.20}\]

Alternatively, we can represent the K-valued variable x with the one-hot binary vector x, which lets us write

\[\text{Cat}(x|\theta) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \prod\_{k=1}^{K} \theta\_k^{x\_k} \tag{2.21}\]

If the k’th element of x counts the number of times the value k is seen in N = #K k=1 xk trials, then we get the multinomial distribution:

\[\mathcal{M}(\mathbf{x}|N,\boldsymbol{\theta}) \triangleq \binom{N}{x\_1 \dots x\_K} \prod\_{k=1}^K \theta\_k^{x\_k} \tag{2.22}\]

where the multinomial coe!cient is defined as

\[\binom{N}{k\_1 \dots k\_m} \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \frac{N!}{k\_1! \dots k\_m!} \tag{2.23}\]

2.2.1.3 Poisson distribution

Suppose X ↑ {0, 1, 2,…}. We say that a random variable has a Poisson distribution with parameter ϖ > 0, written X ⇔ Poi(ϖ), if its pmf (probability mass function) is

\[\text{Poi}(x|\lambda) = e^{-\lambda} \frac{\lambda^x}{x!} \tag{2.24}\]

where ϖ is the mean (and variance) of x.

2.2.1.4 Negative binomial distribution

Suppose we have an “urn” with N balls, R of which are red and B of which are blue. Suppose we perform sampling with replacement until we get n ⇑ 1 balls. Let X be the number of these that are blue. It can be shown that X ⇔ Bin(n, p), where p = B/N is the fraction of blue balls; thus X follows the binomial distribution, discussed in Section 2.2.1.1.

Now suppose we consider drawing a red ball a “failure”, and drawing a blue ball a “success”. Suppose we keep drawing balls until we observe r failures. Let X be the resulting number of successes (blue balls); it can be shown that X ⇔ NegBinom(r, p), which is the negative binomial distribution defined by

\[\text{NegBinom}(x|r, p) \triangleq \binom{x+r-1}{x} (1-p)^r p^x \tag{2.25}\]

for x ↑ {0, 1, 2,…}. (If r is real-valued, we replace ’x+r↑1 x ( with !(x+r) x!!(r) , exploiting the fact that (x ⇐ 1)! = “(x).)

This distribution has the following moments:

\[\mathbb{E}\left[x\right] = \frac{p\left[r\right]}{1-p}, \; \mathbb{V}\left[x\right] = \frac{p\left[r\right]}{(1-p)^2} \tag{2.26}\]

This two parameter family has more modeling flexibility than the Poisson distribution, since it can represent the mean and variance separately. This is useful, e.g., for modeling “contagious” events, which have positively correlated occurrences, causing a larger variance than if the occurrences were independent. In fact, the Poisson distribution is a special case of the negative binomial, since it can be shown that Poi(ϖ) = limr↗↓ NegBinom(r, ω 1+ω ). Another special case is when r = 1; this is called the geometric distribution.

2.2.2 Continuous distributions on R

In this section, we discuss some univariate distributions defined on the reals, p(x) for x ↑ R.

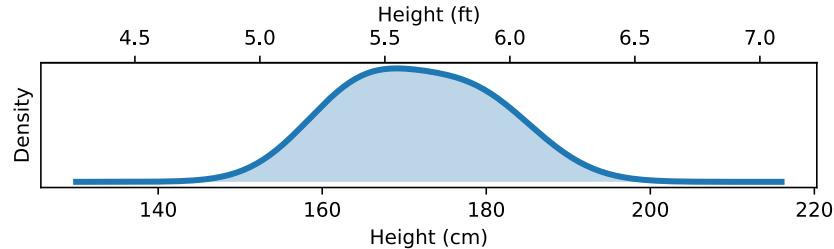

2.2.2.1 Gaussian (Normal)

The most widely used univariate distribution is the Gaussian distribution, also called the normal distribution. (See [Mur22, Sec 2.6.4] for a discussion of these names.) The pdf (probability density function) of the Gaussian is given by

\[\mathcal{N}(x|\mu, \sigma^2) \triangleq \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} \ e^{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(x-\mu)^2} \tag{2.27}\]

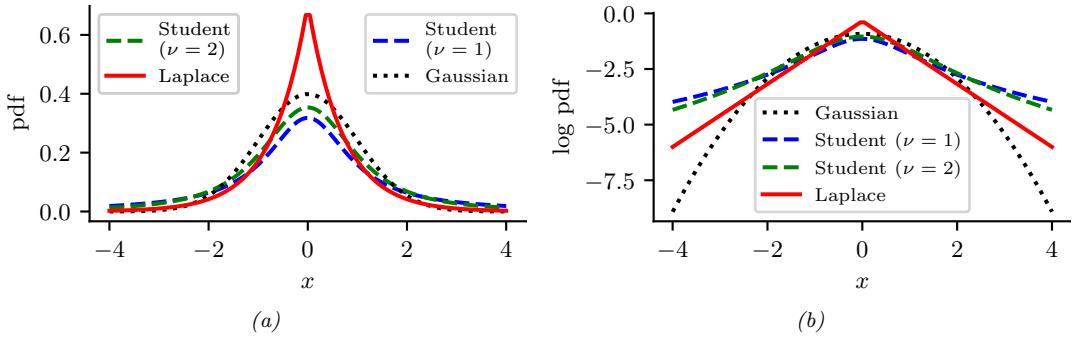

Figure 2.1: (a) The pdf ’s for a N (0, 1), T1(0, 1) and Laplace(0, 1/ →2). The mean is 0 and the variance is 1 for both the Gaussian and Laplace. The mean and variance of the Student distribution is undefined when ω = 1. (b) Log of these pdf ’s. Note that the Student distribution is not log-concave for any parameter value, unlike the Laplace distribution. Nevertheless, both are unimodal. Generated by student\_laplace\_pdf\_plot.ipynb.

where ↖ 2ϱε2 is the normalization constant needed to ensure the density integrates to 1. The parameter µ encodes the mean of the distribution, which is also equal to the mode. The parameter ε2 encodes the variance. Sometimes we talk about the precision of a Gaussian, by which we mean the inverse variance: ϖ = 1/ε2. A high precision means a narrow distribution (low variance) centered on µ.

The cumulative distribution function or cdf of the Gaussian is defined as

\[\Phi(x;\mu,\sigma^2) \triangleq \int\_{-\infty}^{x} \mathcal{N}(z|\mu,\sigma^2) dz \tag{2.28}\]

If µ = 0 and ε = 1 (known as the standard normal distribution), we just write #(x).

2.2.2.2 Half-normal

For some problems, we want a distribution over non-negative reals. One way to create such a distribution is to define Y = |X|, where X ⇔ N (0, ε2). The induced distribution for Y is called the half-normal distribution, which has the pdf

\[\mathcal{N}\_{+}(y|\sigma) \triangleq 2\mathcal{N}(y|0, \sigma^{2}) = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sigma\sqrt{\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{y^{2}}{2\sigma^{2}}\right) \quad y \ge 0 \tag{2.29}\]

This can be thought of as the N (0, ε2) distribution “folded over” onto itself.

2.2.2.3 Student t-distribution

One problem with the Gaussian distribution is that it is sensitive to outliers, since the probability decays exponentially fast with the (squared) distance from the center. A more robust distribution is the Student t-distribution, which we shall call the Student distribution for short. Its pdf is as

follows:

\[\mathcal{T}\_{\nu}(x|\mu,\sigma^2) = \frac{1}{Z} \left[ 1 + \frac{1}{\nu} \left( \frac{x-\mu}{\sigma} \right)^2 \right]^{-\left(\frac{\nu+1}{2}\right)} \tag{2.30}\]

\[Z = \frac{\sqrt{\nu \pi \sigma^2} \Gamma(\frac{\nu}{2})}{\Gamma(\frac{\nu+1}{2})} = \sqrt{\nu} \sigma B(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{\nu}{2}) \tag{2.31}\]

where µ is the mean, ε > 0 is the scale parameter (not the standard deviation), and ς > 0 is called the degrees of freedom (although a better term would be the degree of normality [Kru13], since large values of ς make the distribution act like a Gaussian). Here “(a) is the gamma function defined by

\[ \Gamma(a) \triangleq \int\_0^\infty x^{a-1} e^{-x} dx\tag{2.32} \]

and B(a, b) is the beta function, defined by

\[B(a,b) \triangleq \frac{\Gamma(a)\Gamma(b)}{\Gamma(a+b)}\tag{2.33}\]

2.2.2.4 Cauchy distribution

If ς = 1, the Student distribution is known as the Cauchy or Lorentz distribution. Its pdf is defined by

\[\mathcal{L}(x|\mu,\gamma) = \frac{1}{Z} \left[ 1 + \left(\frac{x-\mu}{\gamma}\right)^2 \right]^{-1} \tag{2.34}\]

where Z = φ↼( 1 2 , 1 2 ) = φϱ. This distribution is notable for having such heavy tails that the integral that defines the mean does not converge.

The half Cauchy distribution is a version of the Cauchy (with mean 0) that is “folded over” on itself, so all its probability density is on the positive reals. Thus it has the form

\[\mathcal{L}\_{+}(x|\gamma) \triangleq \frac{2}{\pi \gamma} \left[ 1 + \left(\frac{x}{\gamma}\right)^{2} \right]^{-1} \tag{2.35}\]

2.2.2.5 Laplace distribution

Another distribution with heavy tails is the Laplace distribution, also known as the double sided exponential distribution. This has the following pdf:

\[\text{Laplace}(x|\mu, b) \triangleq \frac{1}{2b} \exp\left(-\frac{|x-\mu|}{b}\right) \tag{2.36}\]

Here µ is a location parameter and b > 0 is a scale parameter. See Figure 2.1 for a plot.

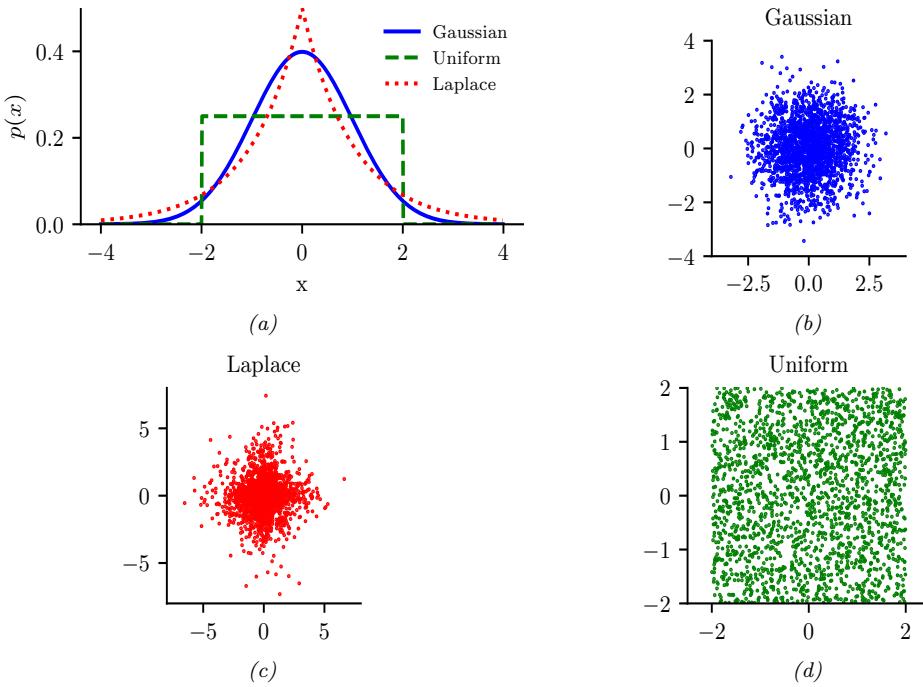

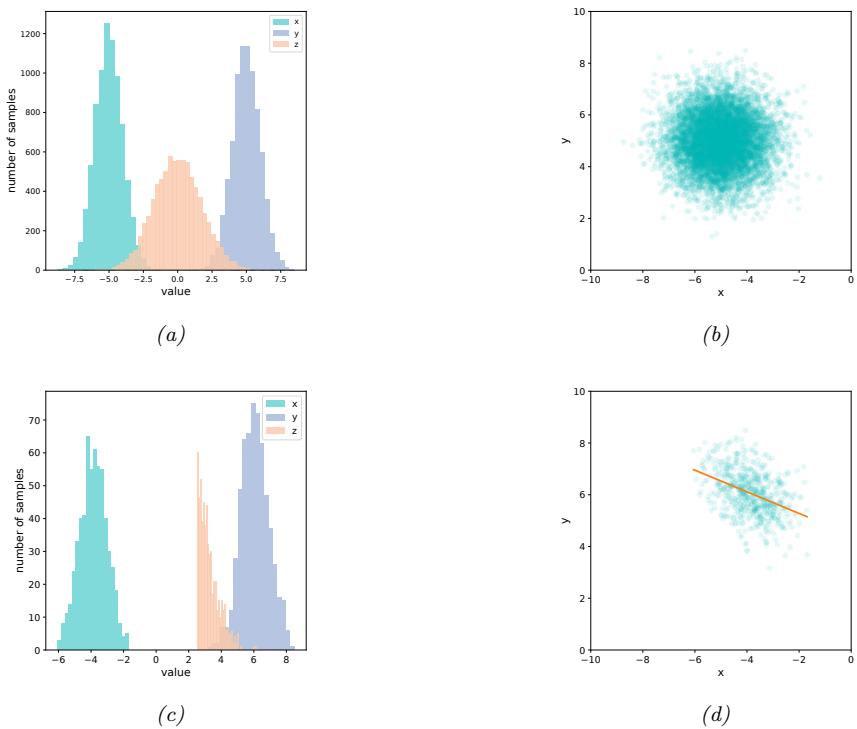

Figure 2.2: Illustration of Gaussian (blue), sub-Gaussian (uniform, green), and super-Gaussian (Laplace, red) distributions in 1d and 2d. Generated by sub\_super\_gauss\_plot.ipynb.

2.2.2.6 Sub-Gaussian and super-Gaussian distributions

There are two main variants of the Gaussian distribution, known as super-Gaussian or leptokurtic (“Lepto” is Greek for “narrow”) and sub-Gaussian or platykurtic (“Platy” is Greek for “broad”). These distributions di!er in terms of their kurtosis, which is a measure of how heavy or light their tails are (i.e., how fast the density dies o! to zero away from its mean). More precisely, the kurtosis is defined as

\[\text{kurt}(z) \triangleq \frac{\mu\_4}{\sigma^4} = \frac{\mathbb{E}\left[ (Z - \mu)^4 \right]}{(\mathbb{E}\left[ (Z - \mu)^2 \right])^2} \tag{2.37}\]

where ε is the standard deviation, and µ4 is the 4th central moment. (Thus µ1 = µ is the mean, and µ2 = ε2 is the variance.) For a standard Gaussian, the kurtosis is 3, so some authors define the excess kurtosis as the kurtosis minus 3.

A super-Gaussian distribution (e.g., the Laplace) has positive excess kurtosis, and hence heavier tails than the Gaussian. A sub-Gaussian distribution, such as the uniform, has negative excess kurtosis, and hence lighter tails than the Gaussian. See Figure 2.2 for an illustration.

2.2.3 Continuous distributions on R+

In this section, we discuss some univariate distributions defined on the positive reals, p(x) for x ↑ R+.

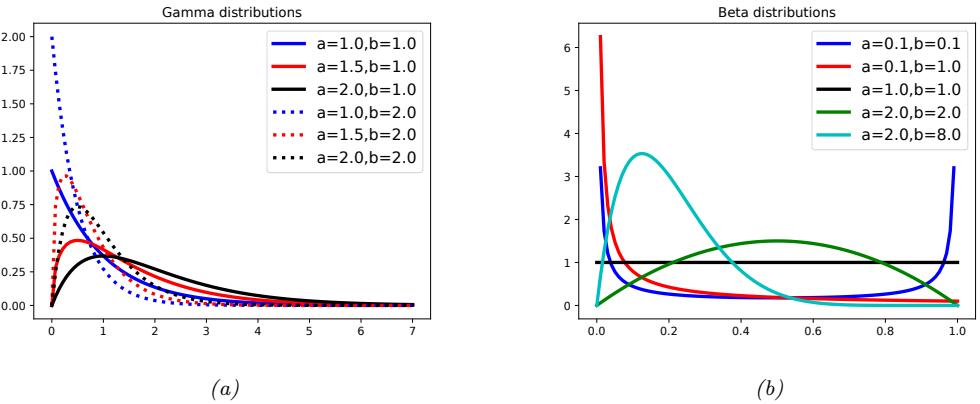

Figure 2.3: (a) Some gamma distributions. If a ↑ 1, the mode is at 0; otherwise the mode is away from 0. As we increase the rate b, we reduce the horizontal scale, thus squeezing everything leftwards and upwards. Generated by gamma\_dist\_plot.ipynb. (b) Some beta distributions. If a < 1, we get a “spike” on the left, and if b < 1, we get a “spike” on the right. If a = b = 1, the distribution is uniform. If a > 1 and b > 1, the distribution is unimodal. Generated by beta\_dist\_plot.ipynb.

2.2.3.1 Gamma distribution

The gamma distribution is a flexible distribution for positive real valued rv’s, x > 0. It is defined in terms of two parameters, called the shape a > 0 and the rate b > 0:

\[\text{Ga}(x|\text{shape}=a, \text{rate}=b) \triangleq \frac{b^a}{\Gamma(a)} x^{a-1} e^{-xb} \tag{2.38}\]

Sometimes the distribution is parameterized in terms of the rate a and the scale s = 1/b:

\[\text{Ga}(x|\text{shape}=a,\text{scale}=s) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \frac{1}{s^a \Gamma(a)} x^{a-1} e^{-x/s} \tag{2.39}\]

See Figure 2.3a for an illustration.

2.2.3.2 Exponential distribution

The exponential distribution is a special case of the gamma distribution and is defined by

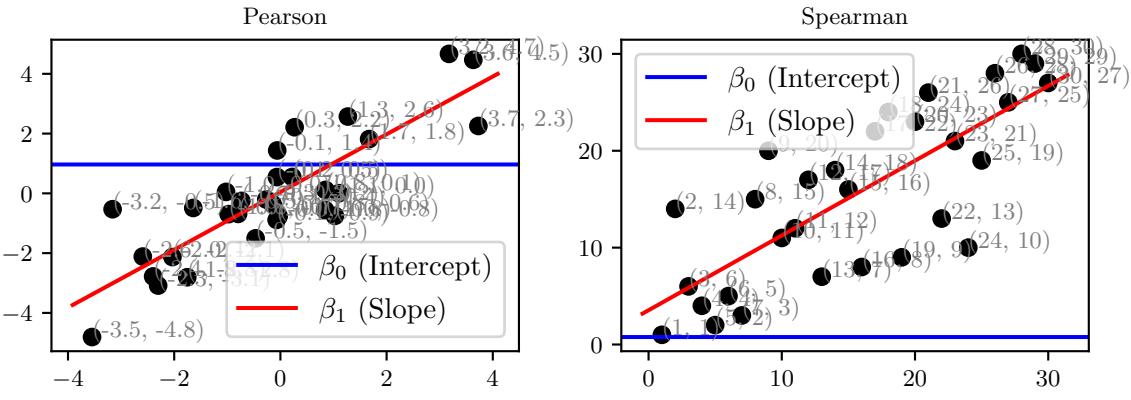

\[\text{Expon}(x|\lambda) \triangleq \text{Ga}(x|\text{shape}=1, \text{rate}=\lambda) \tag{2.40}\]