Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction

Part III

Deep Neural Networks

13 Neural Networks for Tabular Data

13.1 Introduction

In Part II, we discussed linear models for regression and classification. In particular, in Chapter 10, we discussed logistic regression, which, in the binary case, corresponds to the model p(y|x, w) = Ber(y|ω(wTx)), and in the multiclass case corresponds to the model p(y|x,W) = Cat(y|softmax(Wx)). In Chapter 11, we discussed linear regression, which corresponds to the model p(y|x, w) = N (y|wTx, ω2). And in Chapter 12, we discussed generalized linear models, which generalizes these models to other kinds of output distributions, such as Poisson. However, all these models make the strong assumption that the input-output mapping is linear.

A simple way of increasing the flexibility of such models is to perform a feature transformation, by replacing x with ω(x). For example, we can use a polynomial transform, which in 1d is given by ω(x) = [1, x, x2, x3,…], as we discussed in Section 1.2.2.2. This is sometimes called basis function expansion. The model now becomes

\[f(x; \theta) = \mathbf{W}\phi(x) + b\]

This is still linear in the parameters ε = (W, b), which makes model fitting easy (since the negative log-likelihood is convex). However, having to specify the feature transformation by hand is very limiting.

A natural extension is to endow the feature extractor with its own parameters, ε2, to get

\[f(x; \theta) = \mathbf{W}\phi(x; \theta\_2) + \mathbf{b} \tag{13.2}\]

where ε = (ε1, ε2) and ε1 = (W, b). We can obviously repeat this process recursively, to create more and more complex functions. If we compose L functions, we get

\[f(x; \theta) = f\_L(f\_{L-1}(\cdots(f\_1(x))\cdots))\tag{13.3}\]

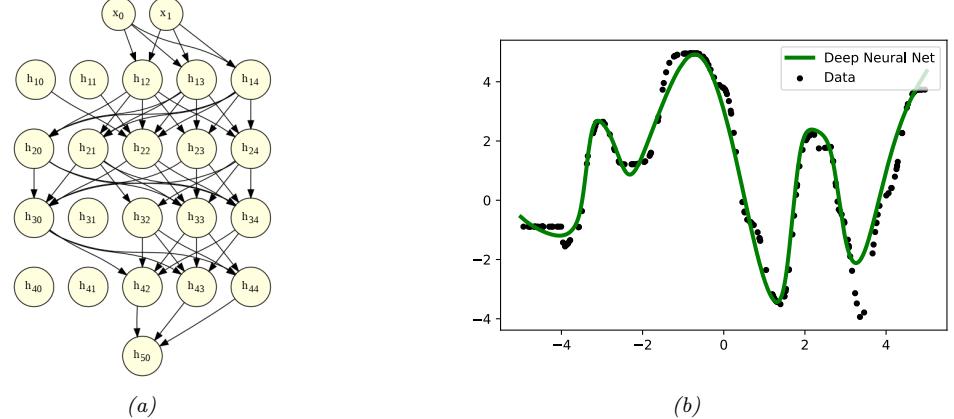

where fω(x) = f(x; εω) is the function at layer ε. This is the key idea behind deep neural networks or DNNs.

The term “DNN” actually encompasses a larger family of models, in which we compose di!erentiable functions into any kind of DAG (directed acyclic graph), mapping input to output. Equation (13.3) is the simplest example where the DAG is a chain. This is known as a feedforward neural network (FFNN) or multilayer perceptron (MLP).

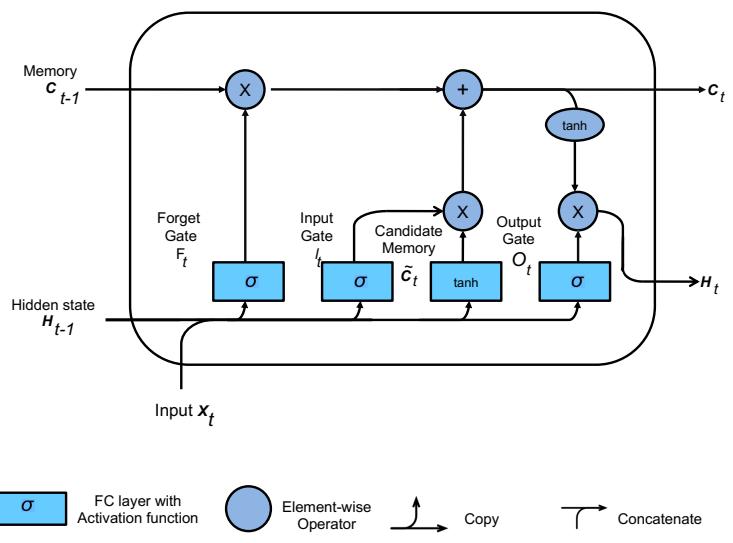

An MLP assumes that the input is a fixed-dimensional vector, say x → RD. It is common to call such data “structured data” or “tabular data”, since the data is often stored in an N ↑ D design

| x1 | x2 | y |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

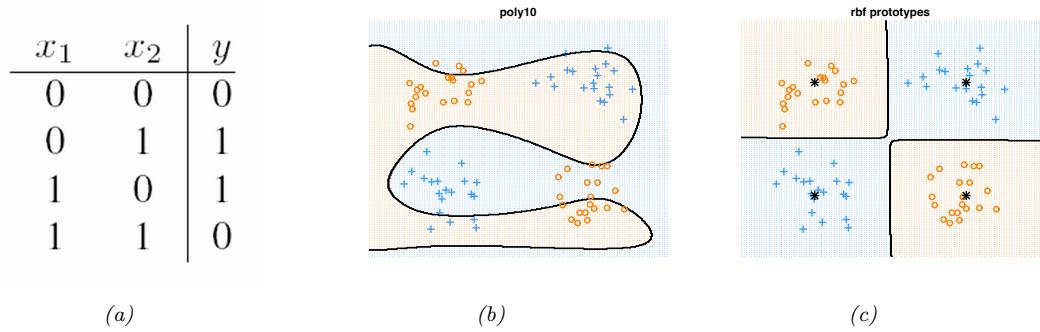

Table 13.1: Truth table for the XOR (exclusive OR) function, y = x1 ↭ x2.

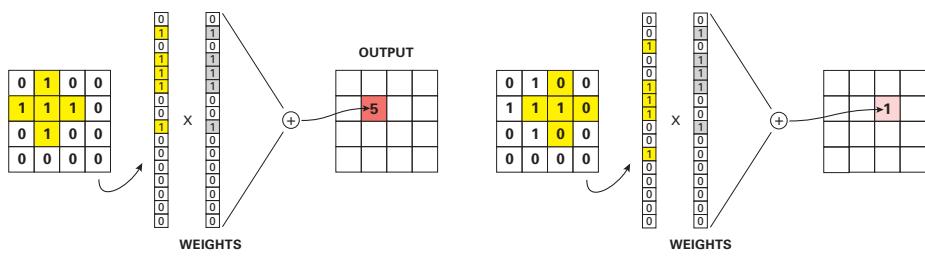

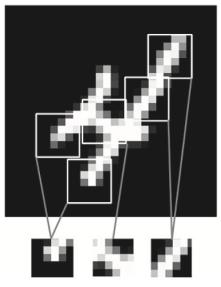

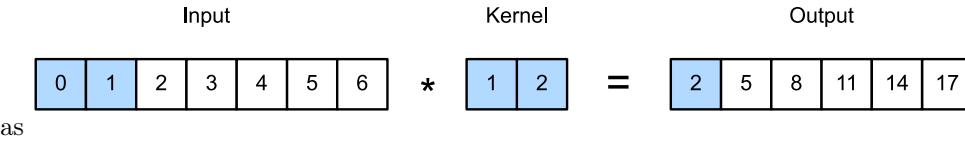

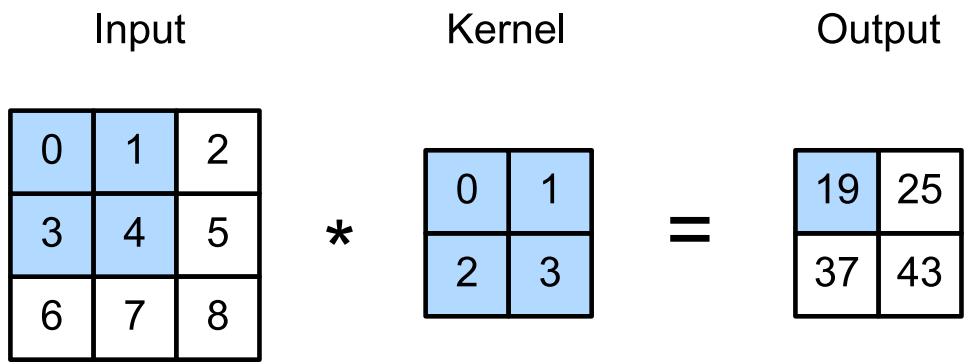

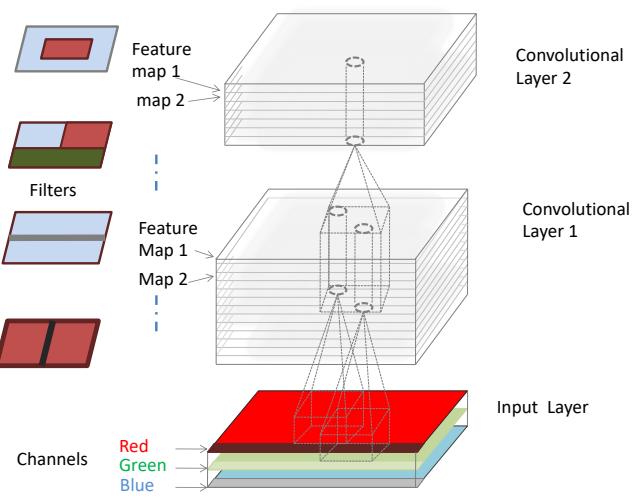

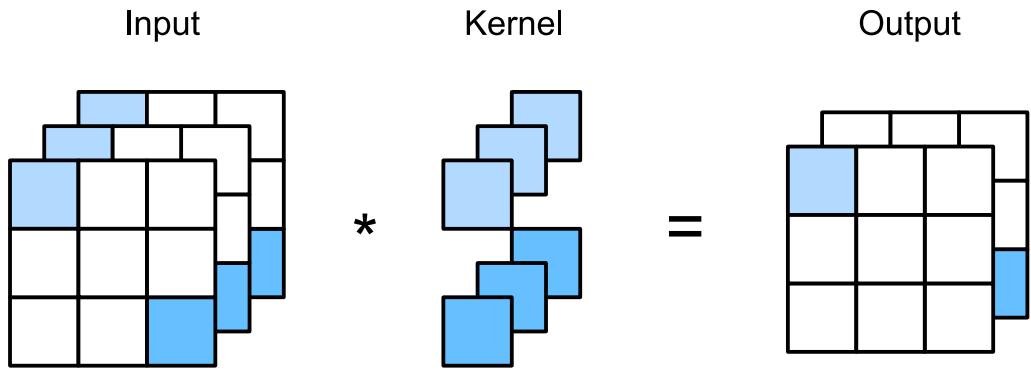

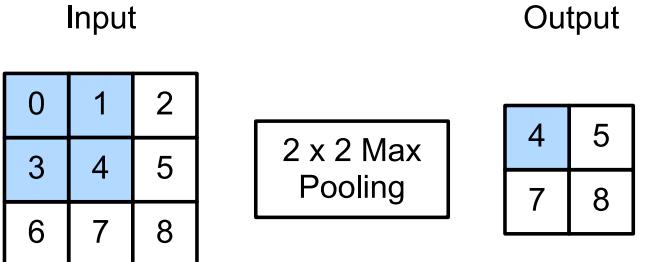

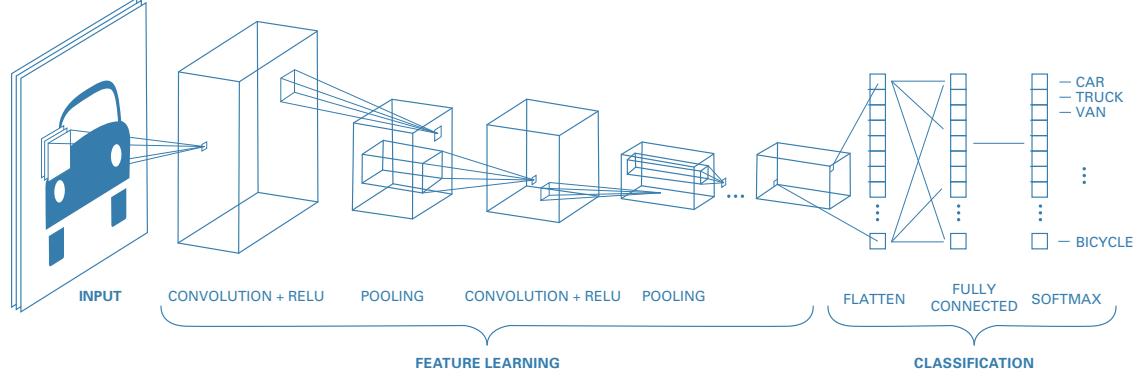

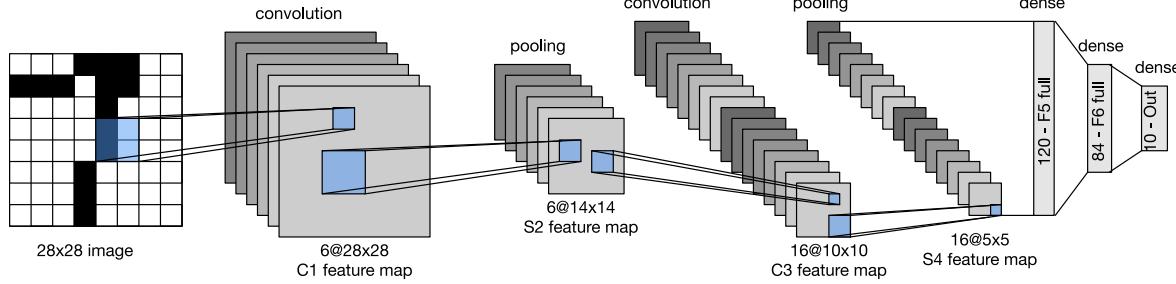

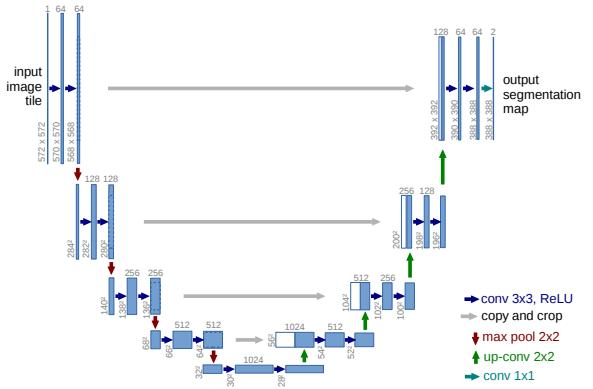

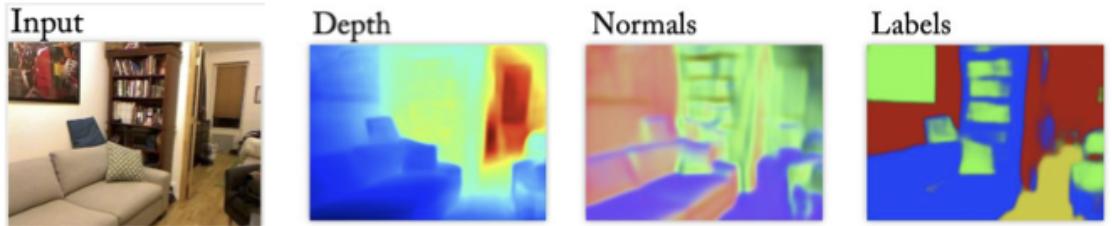

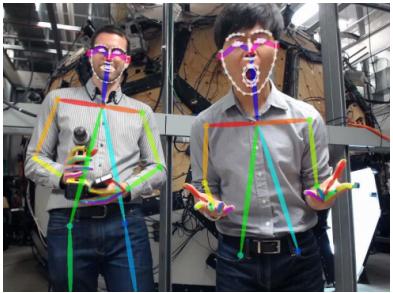

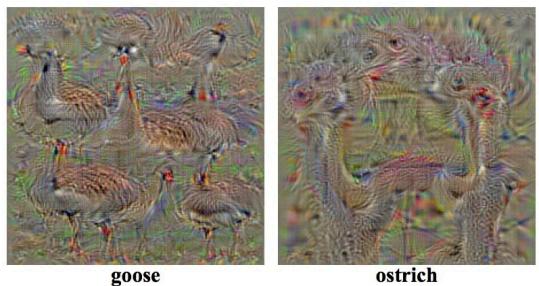

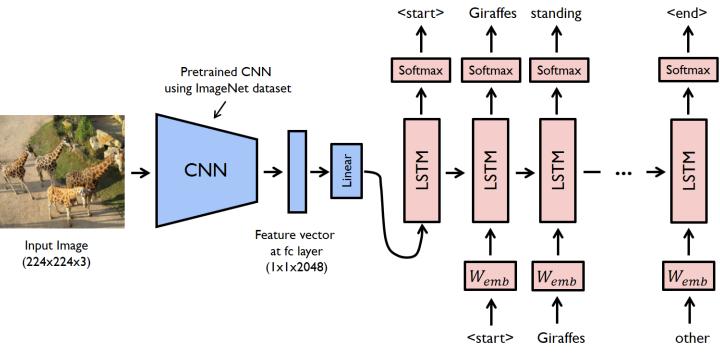

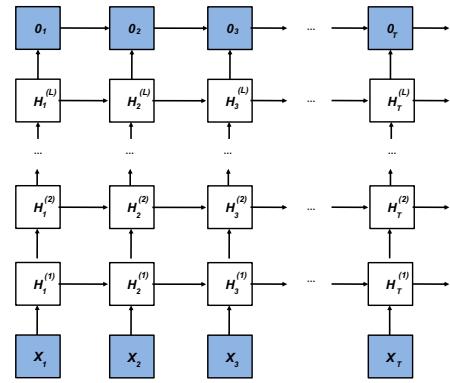

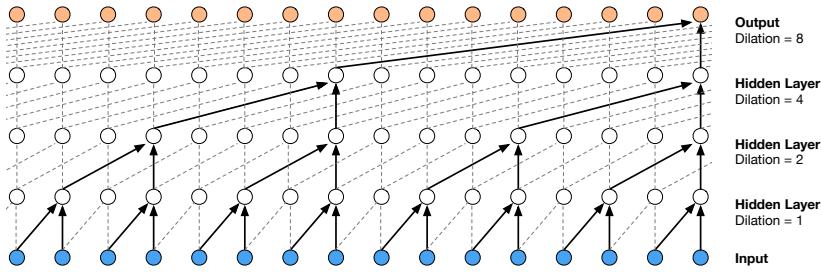

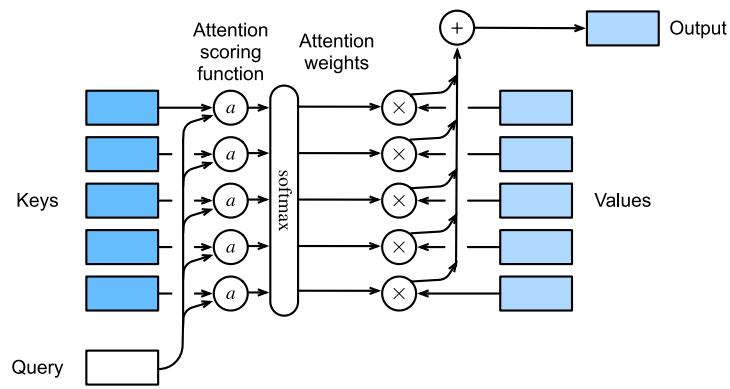

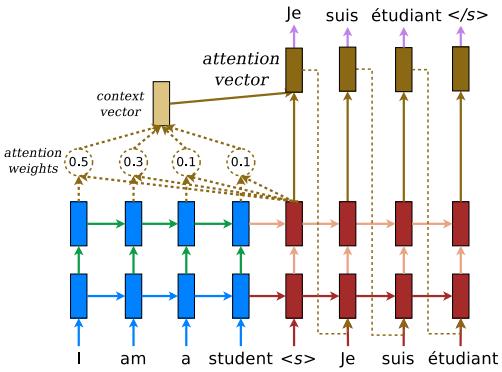

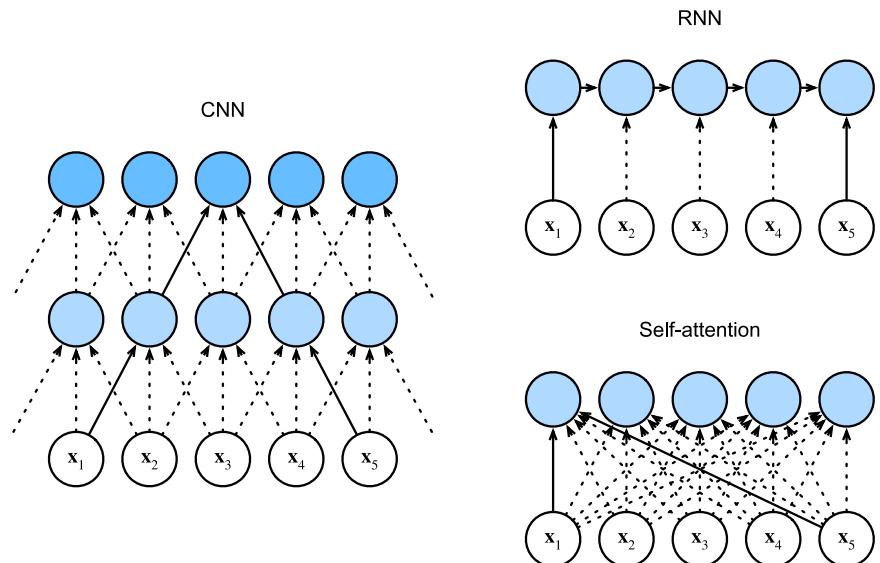

matrix, where each column (feature) has a specific meaning, such as height, weight, age, etc. In later chapters, we discuss other kinds of DNNs that are more suited to “unstructured data” such as images and text, where the input data is variable sized, and each individual element (e.g., pixel or word) is often meaningless on its own.1 In particular, in Chapter 14, we discuss convolutional neural networks (CNN), which are designed to work with images; in Chapter 15, we discuss recurrent neural networks (RNN) and transformers, which are designed to work with sequences; and in Chapter 23, we discuss graph neural networks (GNN), which are designed to work with graphs.

Although DNNs can work well, there are often a lot of engineering details that need to be addressed to get good performance. Some of these details are discussed in the supplementary material to this book, available at probml.ai. There are also various other books that cover this topic in more depth (e.g., [Zha+20; Cho21; Gér19; GBC16; Raf22]), as well as a multitude of online courses. For a more theoretical treatment, see e.g., [Ber+21; Cal20; Aro+21; RY21].

13.2 Multilayer perceptrons (MLPs)

In Section 10.2.5, we explained that a perceptron is a deterministic version of logistic regression. Specifically, it is a mapping of the following form:

\[f(\mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = \mathbb{I}\left(\mathbf{w}^{\mathsf{T}}\mathbf{z} + b \geq 0\right) = H(\mathbf{w}^{\mathsf{T}}\mathbf{z} + b) \tag{13.4}\]

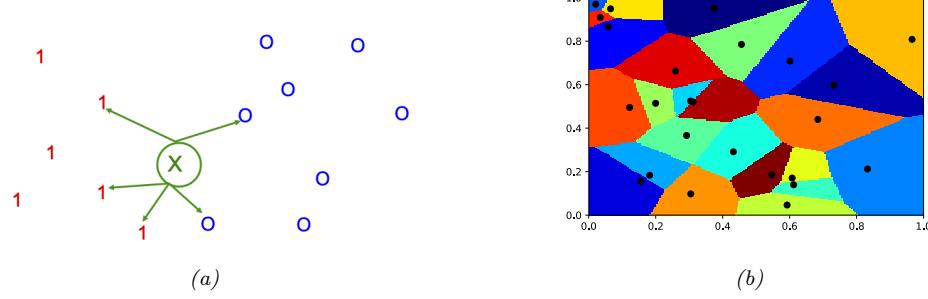

where H(a) is the heaviside step function, also known as a linear threshold function. Since the decision boundaries represented by perceptrons are linear, they are very limited in what they can represent. In 1969, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert published a famous book called Perceptrons [MP69] in which they gave numerous examples of pattern recognition problems which perceptrons cannot solve. We give a specific example below, before discussing how to solve the problem.

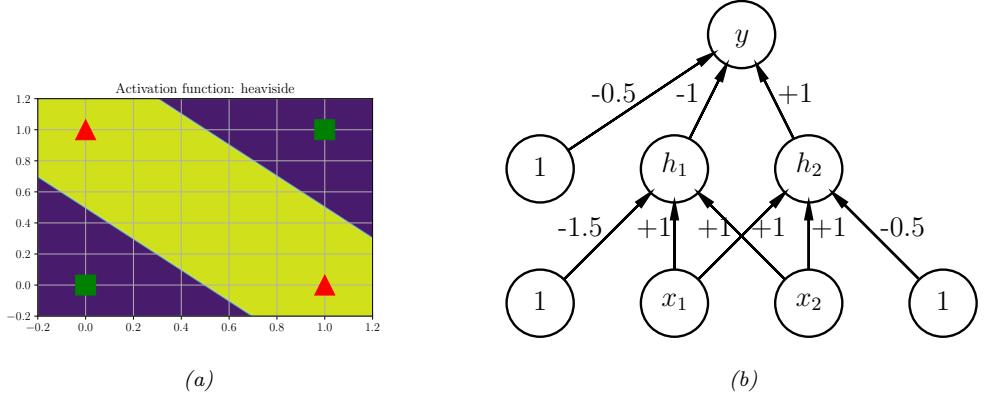

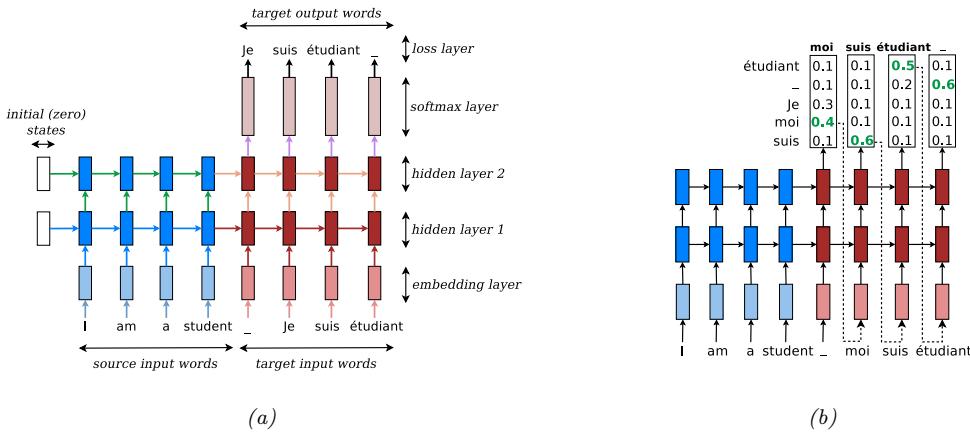

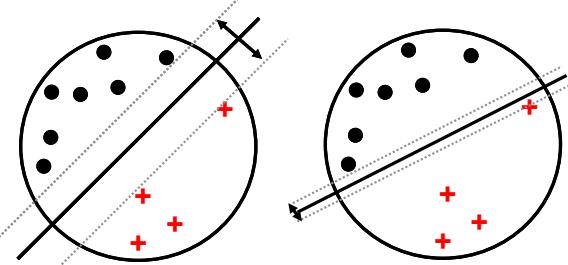

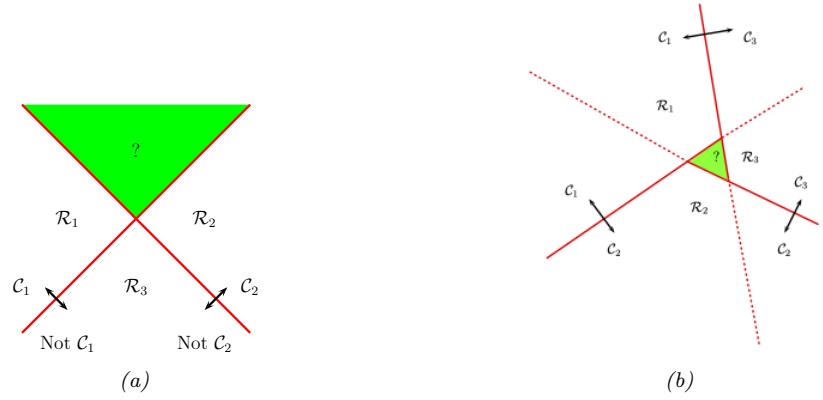

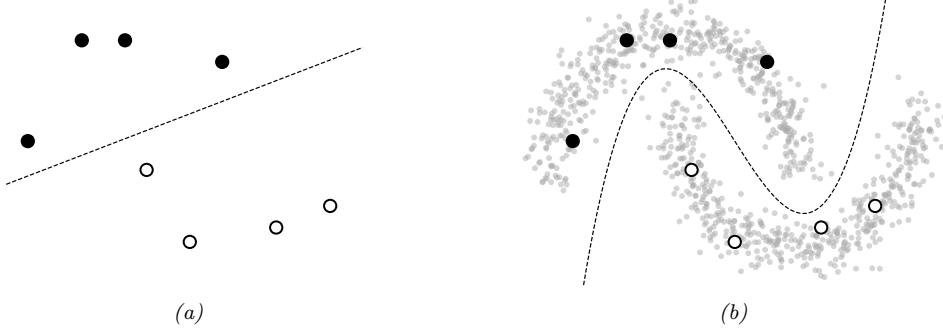

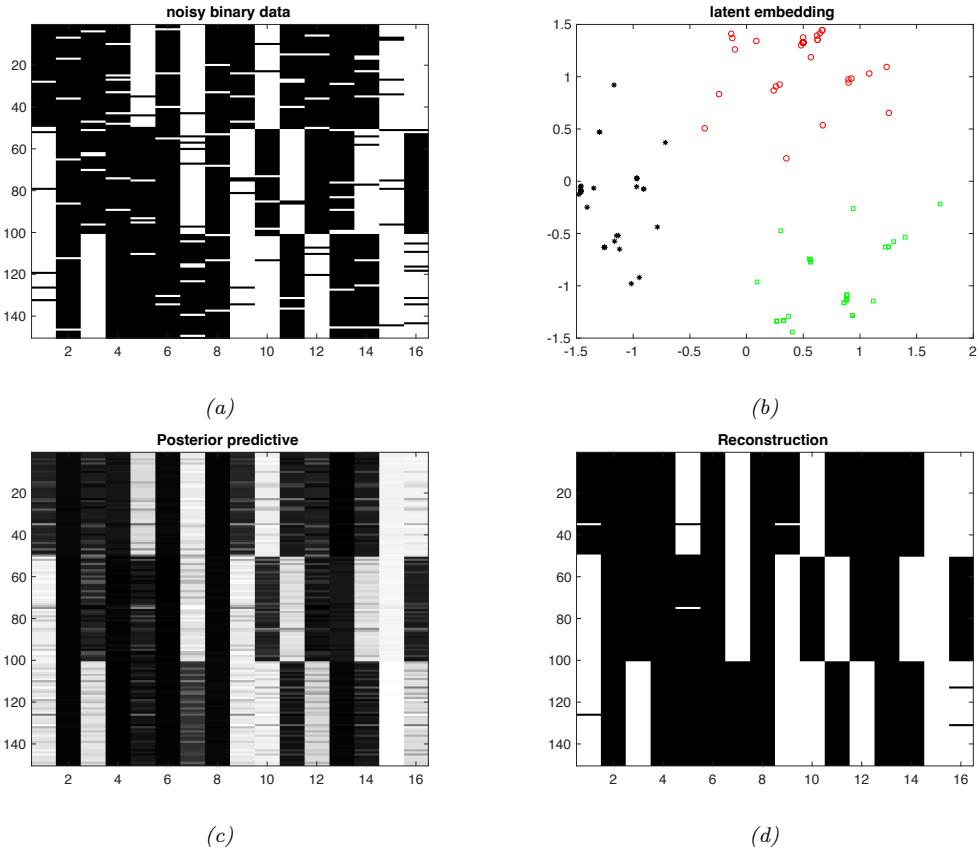

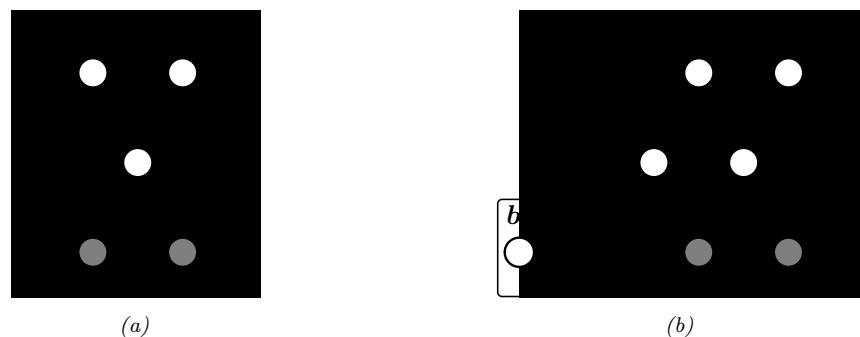

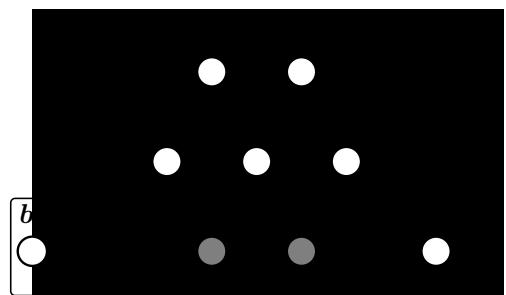

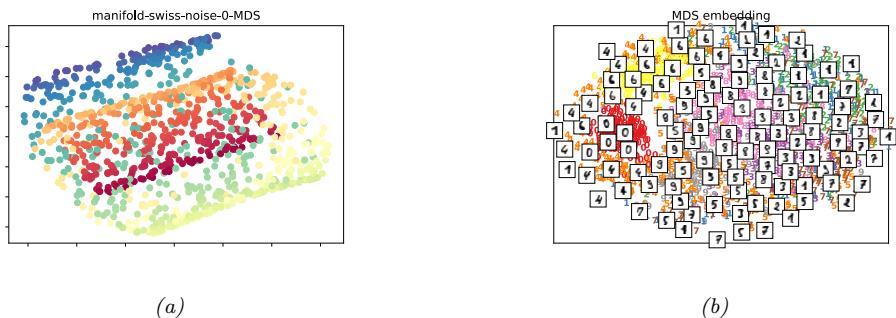

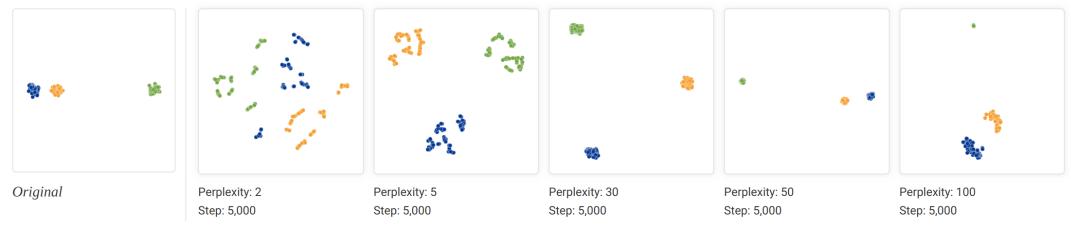

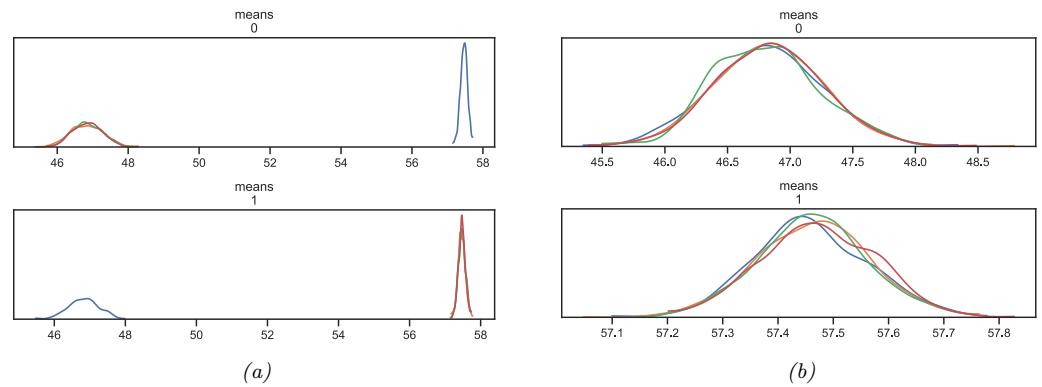

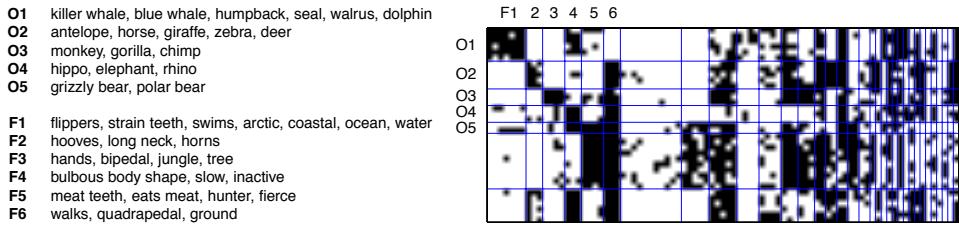

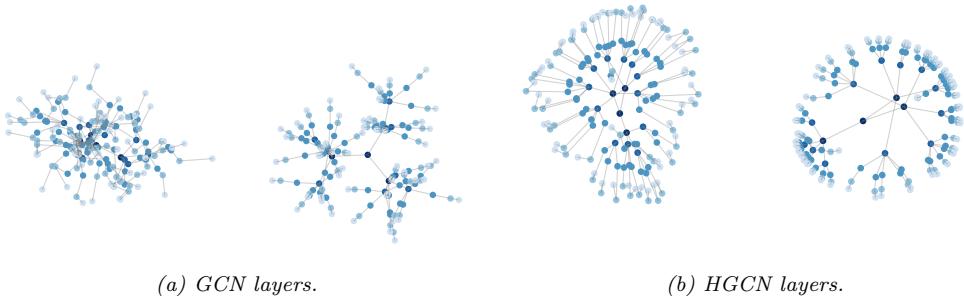

Figure 13.1: (a) Illustration of the fact that the XOR function is not linearly separable, but can be separated by the two layer model using Heaviside activation functions. Adapted from Figure 10.6 of [Gér19]. Generated by xor\_heaviside.ipynb. (b) A neural net with one hidden layer, whose weights have been manually constructed to implement the XOR function. h1 is the AND function and h2 is the OR function. The bias terms are implemented using weights from constant nodes with the value 1.

13.2.1 The XOR problem

One of the most famous examples from the Perceptrons book is the XOR problem. Here the goal is to learn a function that computes the exclusive OR of its two binary inputs. The truth table for this function is given in Table 13.1. We visualize this function in Figure 13.1a. It is clear that the data is not linearly separable, so a perceptron cannot represent this mapping.

However, we can overcome this problem by stacking multiple perceptrons on top of each other. This is called a multilayer perceptron (MLP). For example, to solve the XOR problem, we can use the MLP shown in Figure 13.1b. This consists of 3 perceptrons, denoted h1, h2 and y. The nodes marked x are inputs, and the nodes marked 1 are constant terms. The nodes h1 and h2 are called hidden units, since their values are not observed in the training data.

The first hidden unit computes h1 = x1 ↔︎ x2 by using appropriately set weights. (Here ↔︎ is the AND operation.) In particular, it has inputs from x1 and x2, both weighted by 1.0, but has a bias term of -1.5 (this is implemented by a “wire” with weight -1.5 coming from a dummy node whose value is fixed to 1). Thus h1 will fire i! x1 and x2 are both on, since then

\[\mathbf{w}\_1^\mathsf{T}\mathbf{z} - b\_1 = [1.0, 1.0]^\mathsf{T}[1, 1] - 1.5 = 0.5 > 0\tag{13.5}\]

1. The term “unstructured data” is a bit misleading, since images and text do have structure. For example, neighboring pixels in an image are highly correlated, as are neighboring words in a sentence. Indeed, it is precisely this structure that is exploited (assumed) by CNNs and RNNs. By contrast, MLPs make no assumptions about their inputs. This is useful for applications such as tabular data, where the structure (dependencies between the columns) is usually not obvious, and thus needs to be learned. We can also apply MLPs to images and text, as we will see, but performance will usually be worse compared to specialized models, such as as CNNs and RNNs. (There are some exceptions, such as the MLP-mixer model of [Tol+21], which is an unstructured model that can learn to perform well on image and text data, but such models need massive datasets to overcome their lack of inductive bias.)

Similarly, the second hidden unit computes h2 = x1 ↘ x2, where ↘ is the OR operation, and the third computes the output y = h1 ↔︎ h2, where h = ¬h is the NOT (logical negation) operation. Thus y computes

\[y = f(x\_1, x\_2) = \overline{(x\_1 \land x\_2)} \land (x\_1 \lor x\_2) \tag{13.6}\]

This is equivalent to the XOR function.

By generalizing this example, we can show that an MLP can represent any logical function. However, we obviously want to avoid having to specify the weights and biases by hand. In the rest of this chapter, we discuss ways to learn these parameters from data.

13.2.2 Di!erentiable MLPs

The MLP we discussed in Section 13.2.1 was defined as a stack of perceptrons, each of which involved the non-di!erentiable Heaviside function. This makes such models di”cult to train, which is why they were never widely used. However, suppose we replace the Heaviside function H : R ≃ {0, 1} with a di!erentiable activation function ϑ : R ≃ R. More precisely, we define the hidden units zl at each layer l to be a linear transformation of the hidden units at the previous layer passed elementwise through this activation function:

\[\mathbf{z}\_{l} = f\_{l}(\mathbf{z}\_{l-1}) = \varphi\_{l} \left( \mathbf{b}\_{l} + \mathbf{W}\_{l} \mathbf{z}\_{l-1} \right) \tag{13.7}\]

or, in scalar form,

\[z\_{kl} = \varphi\_l \left( b\_{kl} + \sum\_{j=1}^{K\_{l-1}} w\_{lkj} z\_{jl-1} \right) \tag{13.8}\]

The quantity that is passed to the activation function is called the pre-activations:

\[\mathbf{a}\_l = \mathbf{b}\_l + \mathbf{W}\_l \mathbf{z}\_{l-1} \tag{13.9}\]

so zl = ϑl(al).

If we now compose L of these functions together, as in Equation (13.3), then we can compute the gradient of the output wrt the parameters in each layer using the chain rule, also known as backpropagation, as we explain in Section 13.3. (This is true for any kind of di!erentiable activation function, although some kinds work better than others, as we discuss in Section 13.2.3.) We can then pass the gradient to an optimizer, and thus minimize some training objective, as we discuss in Section 13.4. For this reason, the term “MLP” almost always refers to this di!erentiable form of the model, rather than the historical version with non-di!erentiable linear threshold units.

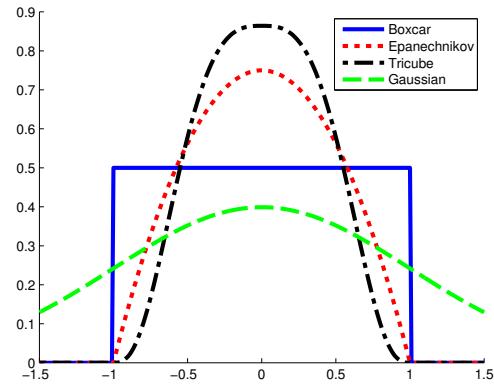

13.2.3 Activation functions

We are free to use any kind of di!erentiable activation function we like at each layer. However, if we use a linear activation function, ϑω(a) = cωa, then the whole model reduces to a regular linear model. To see this, note that Equation (13.3) becomes

\[f(x; \theta) = \mathbf{W}\_L c\_L(\mathbf{W}\_{L-1} c\_{L-1}(\cdots(\mathbf{W}\_1 x) \cdots)) \propto \mathbf{W}\_L \mathbf{W}\_{L-1} \cdots \mathbf{W}\_1 x = \mathbf{W}' x \tag{13.10}\]

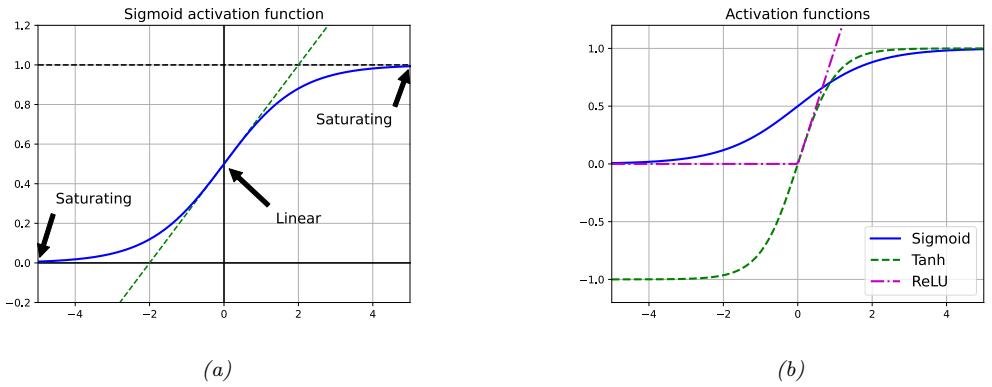

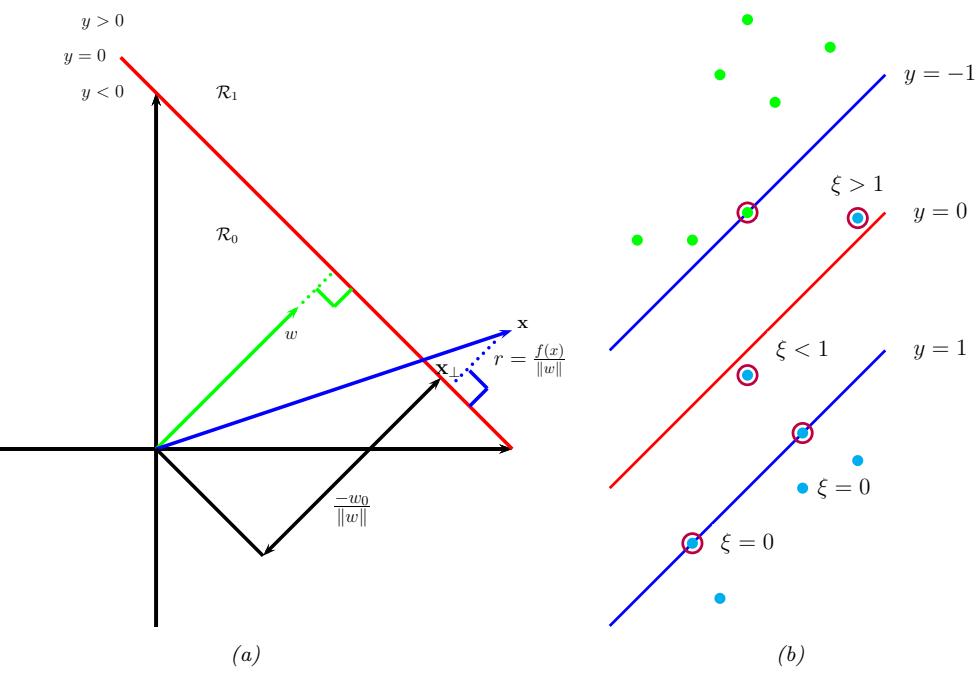

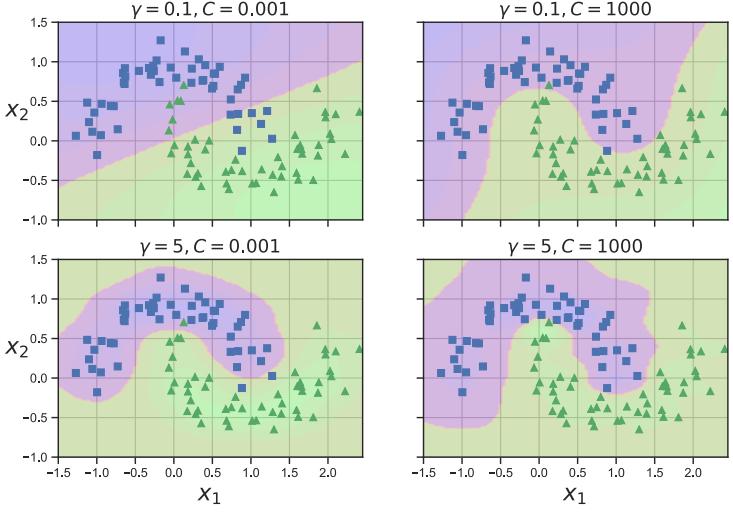

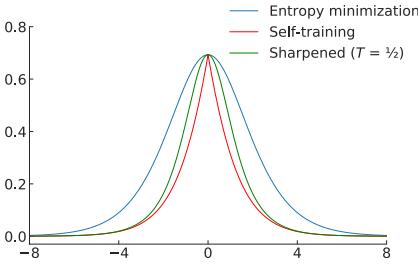

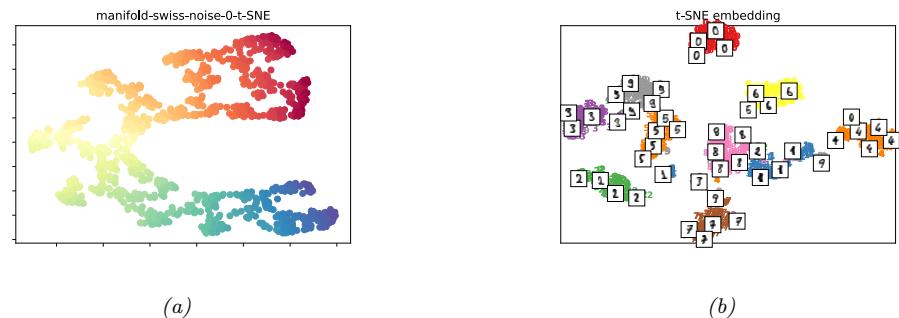

Figure 13.2: (a) Illustration of how the sigmoid function is linear for inputs near 0, but saturates for large positive and negative inputs. Adapted from 11.1 of [Gér19]. (b) Plots of some neural network activation functions. Generated by activation\_fun\_plot.ipynb.

where we dropped the bias terms for notational simplicity. For this reason, it is important to use nonlinear activation functions.

In the early days of neural networks, a common choice was to use a sigmoid (logistic) function, which can be seen as a smooth approximation to the Heaviside function used in a perceptron:

\[ \sigma(a) = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-a}} \tag{13.11} \]

However, as shown in Figure 13.2a, the sigmoid function saturates at 1 for large positive inputs, and at 0 for large negative inputs. Another common choice is the tanh function, which has a similar shape, but saturates at -1 and +1. See Figure 13.2b.

In the saturated regimes, the gradient of the output wrt the input will be close to zero, so any gradient signal from higher layers will not be able to propagate back to earlier layers. This is called the vanishing gradient problem, and it makes it hard to train the model using gradient descent (see Section 13.4.2 for details). One of the keys to being able to train very deep models is to use non-saturating activation functions. Several di!erent functions have been proposed. The most common is rectified linear unit or ReLU, proposed in [GBB11; KSH12]. This is defined as

\[\text{ReLU}(a) = \max(a, 0) = a \mathbb{I}\left(a > 0\right) \tag{13.12}\]

The ReLU function simply “turns o!” negative inputs, and passes positive inputs unchanged: see Figure 13.2b for a plot, and Section 13.4.3 for more details.

When neural networks are used to represent functions defined on a continuous input space such as points in time, f(t), or in 3d space, f(x, y, z) — they are often called neural implicit representations or coordinated based representations of the underlying signal. In such cases, it is often important to capture high frequencies to represent the signal faithfully. Unfortunately MLPs have an intrinsic bias to low frequency functions [Tan+20; RML22]. One simple solution is to use a sine function, sin(a), as the nonlinearity, instead of ReLU, as explained in [Sit+20].2

2. For some simple illustrations of the surprising power of the sine activation function for learning functions

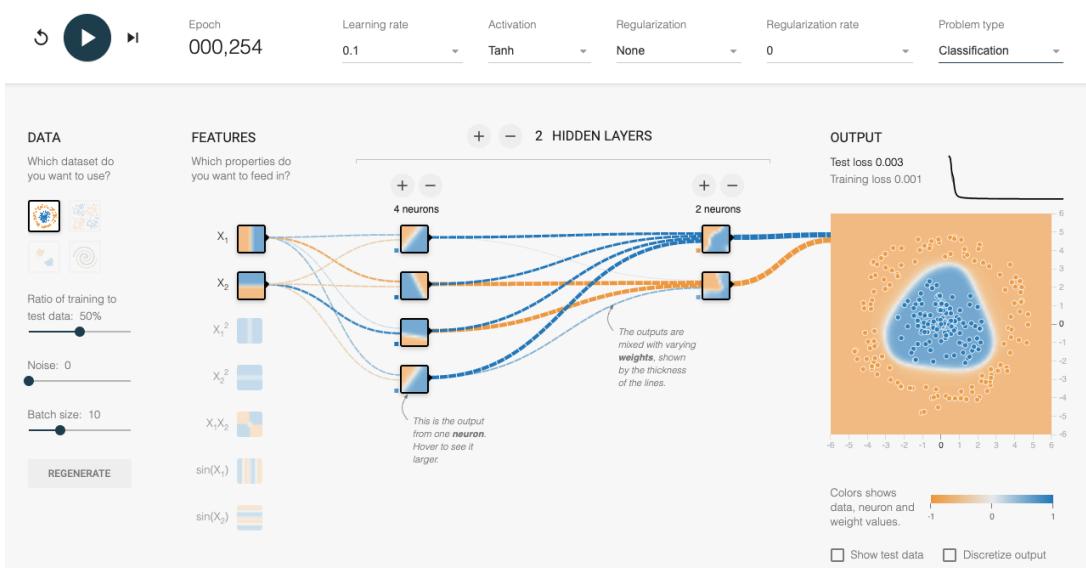

Figure 13.3: An MLP with 2 hidden layers applied to a set of 2d points from 2 classes, shown in the top left corner. The visualizations associated with each hidden unit show the decision boundary at that part of the network. The final output is shown on the right. The input is x → R2, the first layer activations are z1 → R4, the second layer activations are z2 → R2, and the final logit is a3 → R, which is converted to a probability using the sigmoid function. This is a screenshot from the interactive demo at http: // playground. tensorflow. org .

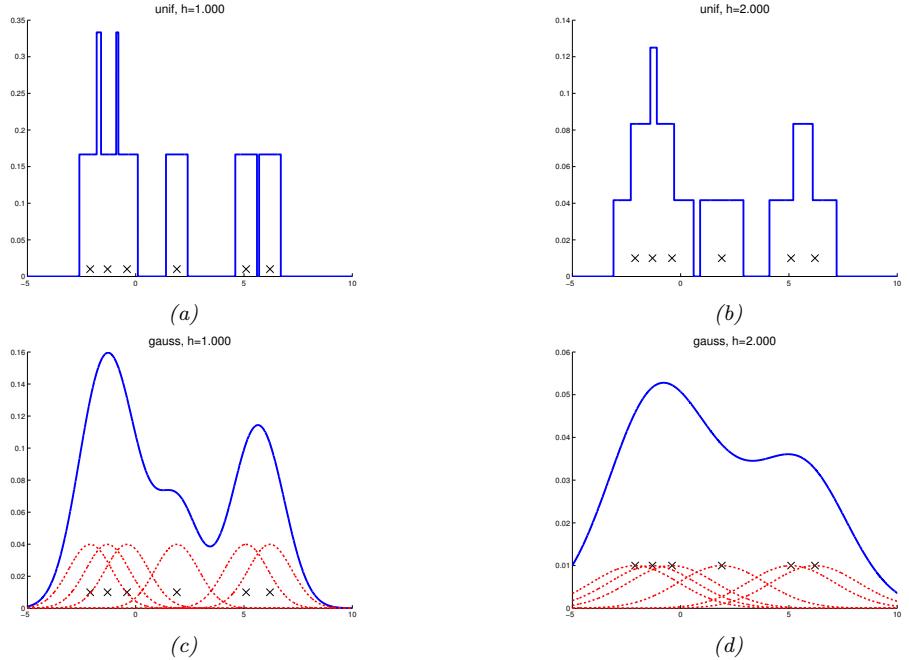

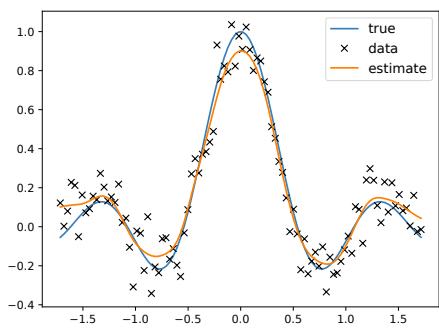

13.2.4 Example models

MLPs can be used to perform classification and regression for many kinds of data. We give some examples below.

13.2.4.1 MLP for classifying 2d data into 2 categories

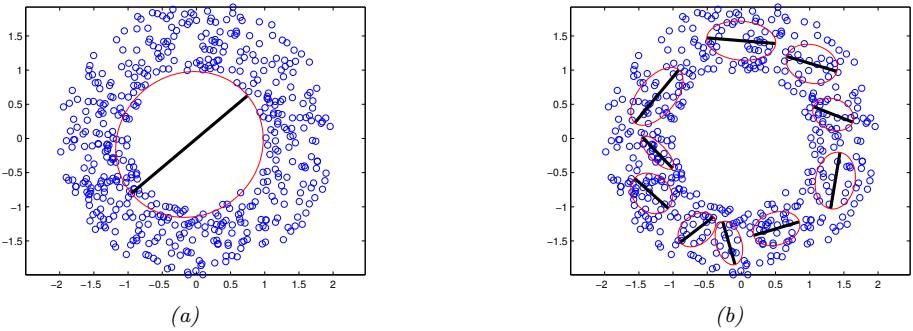

Figure 13.3 gives an illustration of an MLP with two hidden layers applied to a 2d input vector, corresponding to points in the plane, coming from two concentric circles. This model has the following form:

\[p(y|x; \theta) = \text{Ber}(y|\sigma(a\_3))\tag{13.13}\]

\[a\_3 = w\_3^\top \mathbf{z}\_2 + b\_3 \tag{13.14}\]

\[\mathbf{z}\_2 = \varphi(\mathbf{W}\_2 \mathbf{z}\_1 + \mathbf{b}\_2) \tag{13.15}\]

\[\mathbf{z}\_1 = \varphi(\mathbf{W}\_1 \mathbf{z} + \mathbf{b}\_1) \tag{13.16}\]

Here a3 is the final logit score, which is converted to a probability via the sigmoid (logistic) function. The value a3 is computed by taking a linear combination of the 2 hidden units in layer 2, using

on low dimensional input spaces, see https://nipunbatra.github.io/blog/posts/siren-paper.html and https: //nipunbatra.github.io/blog/posts/siren-paper.html.

| _________________________________________________________________ Layer (type) |

Output Shape | Param # |

|---|---|---|

| ================================================================= flatten (Flatten) |

(None, 784) | 0 |

| _________________________________________________________________ dense (Dense) |

(None, 128) | 100480 |

| _________________________________________________________________ dense_1 (Dense) |

(None, 128) | 16512 |

| _________________________________________________________________ dense_2 (Dense) |

(None, 10) | 1290 |

| ================================================================= Total params: 118,282 Trainable params: 118,282 Non-trainable params: 0 |

Model: “sequential”

Table 13.2: Structure of the MLP used for MNIST classification. Note that 100, 480 = (784 + 1) ↑ 128, and 16, 512 = (128 + 1) ↑ 128. mlp\_mnist\_tf.ipynb.

a3 = wT 3 z2 + b3. In turn, layer 2 is computed by taking a nonlinear combination of the 4 hidden units in layer 1, using z2 = ϑ(W2z1+b2). Finally, layer 1 is computed by taking a nonlinear combination of the 2 input units, using z1 = ϑ(W1x+b1). By adjusting the parameters, ε = (W1, b1,W2, b2, w3, b3), to minimize the negative log likelihood, we can fit the training data very well, despite the highly nonlinear nature of the decision boundary. (You can find an interactive version of this figure at http://playground.tensorflow.org.)

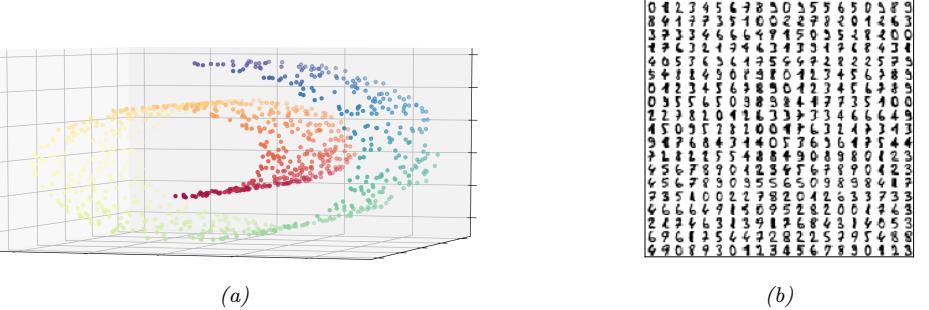

13.2.4.2 MLP for image classification

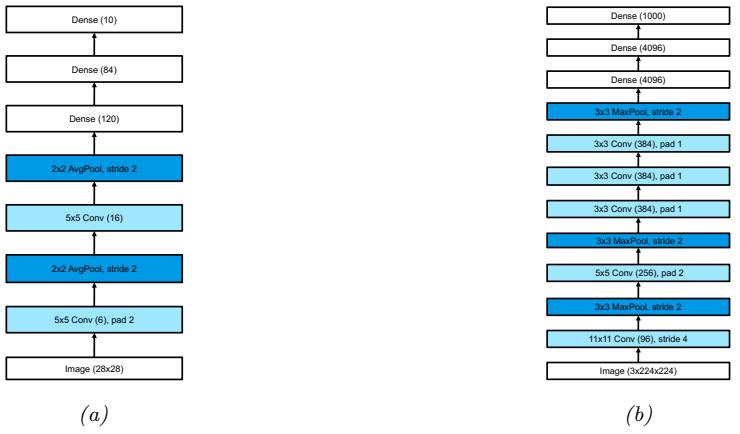

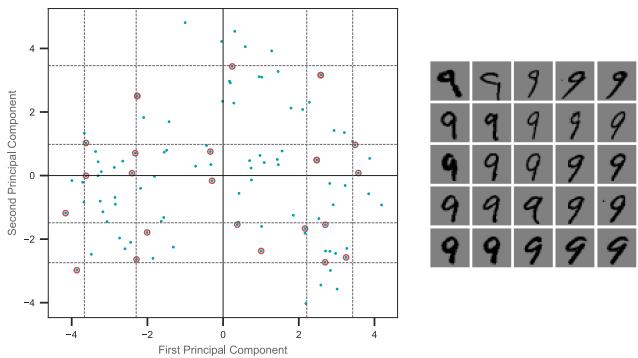

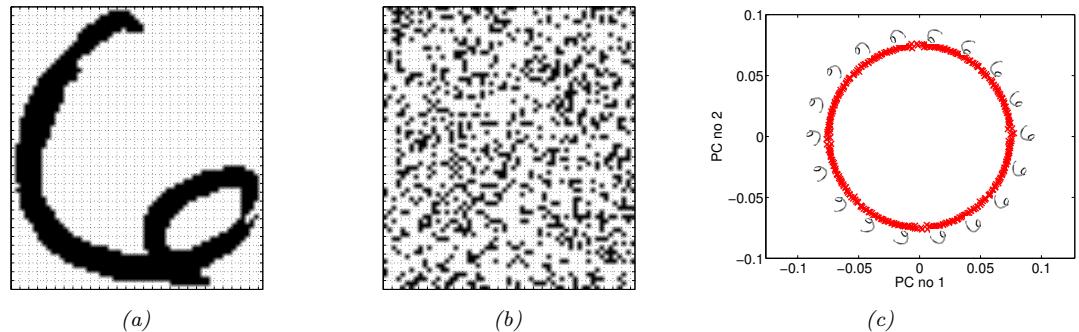

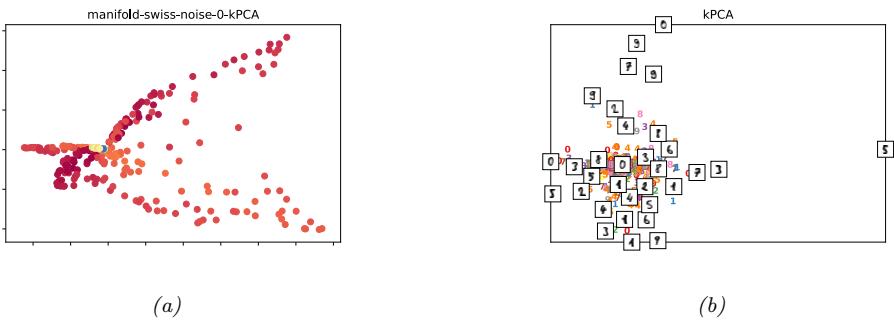

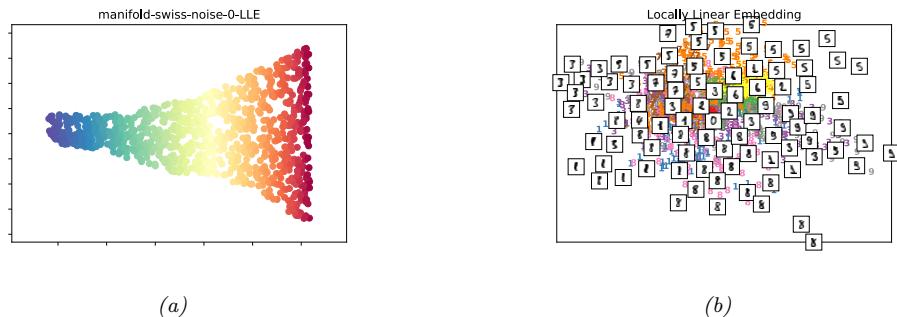

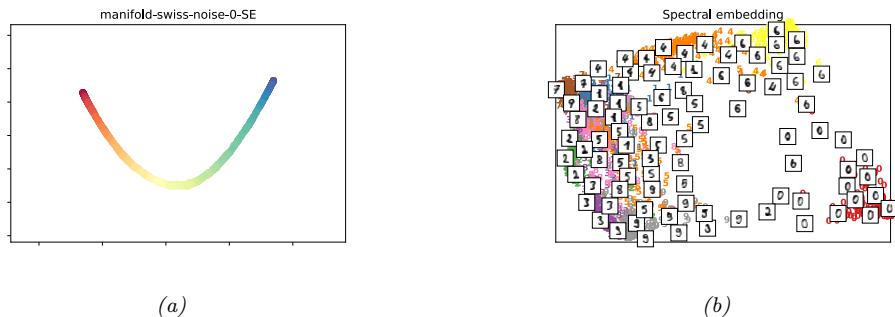

To apply an MLP to image classification, we need to “flatten” the 2d input into 1d vector. We can then use a feedforward architecture similar to the one described in Section 13.2.4.1. For example, consider building an MLP to classifiy MNIST digits (Section 3.5.2). These are 28 ↑ 28 = 784 dimensional. If we use 2 hidden layers with 128 units each, followed by a final 10 way softmax layer, we get the model shown in Table 13.2.

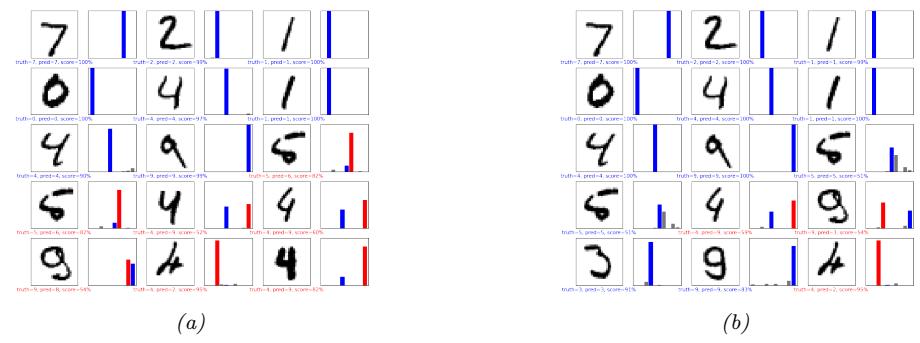

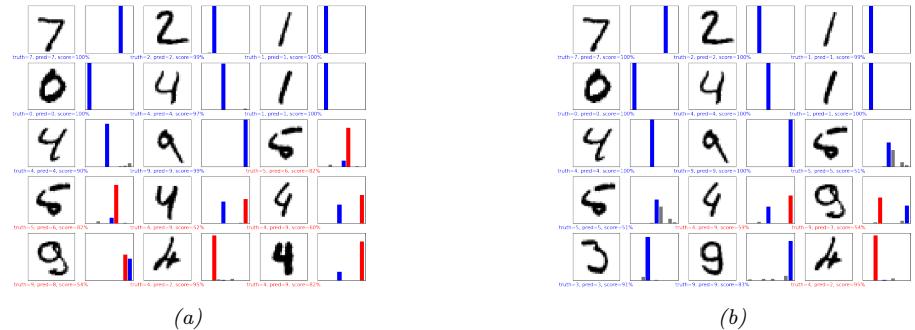

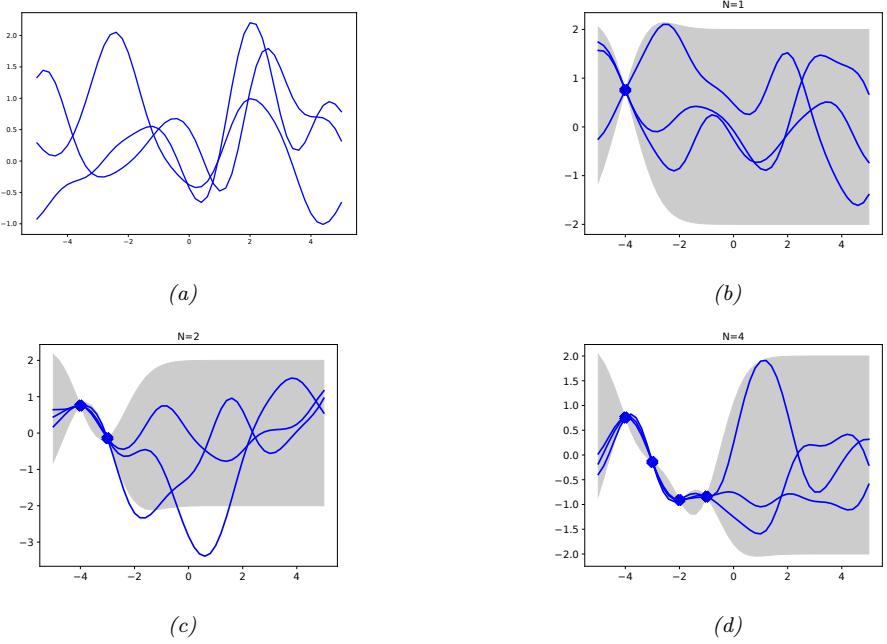

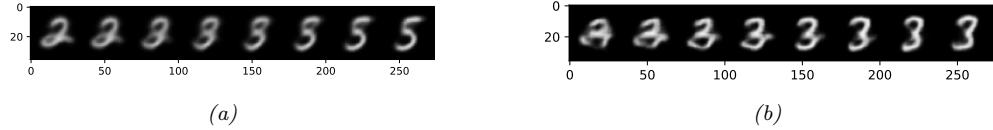

We show some predictions from this model in Figure 13.4. We train it for just two “epochs” (passes over the dataset), but already the model is doing quite well, with a test set accuracy of 97.1%. Furthermore, the errors seem sensible, e.g., 9 is mistaken as a 3. Training for more epochs can further improve test accuracy.

In Chapter 14 we discuss a di!erent kind of model, called a convolutional neural network, which is better suited to images. This gets even better performance and uses fewer parameters, by exploiting prior knowledge about the spatial structure of images. By contrast, with an MLP, we can randomly shu#e (permute) the pixels without a!ecting the output (assuming we use the same random permutation for all inputs).

Figure 13.4: Results of applying an MLP (with 2 hidden layers with 128 units and 1 output layer with 10 units) to some MNIST images (cherry picked to include some errors). Red is incorrect, blue is correct. (a) After 1 epoch of training. (b) After 2 epochs. Generated by mlp\_mnist\_tf.ipynb.

13.2.4.3 MLP for text classification

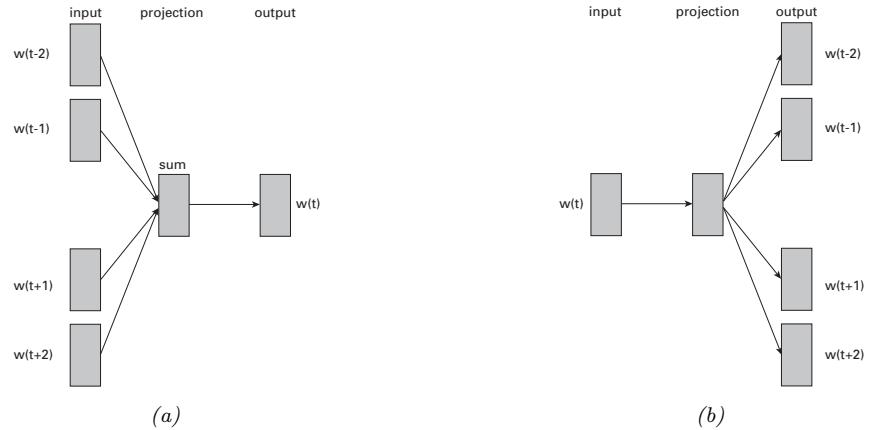

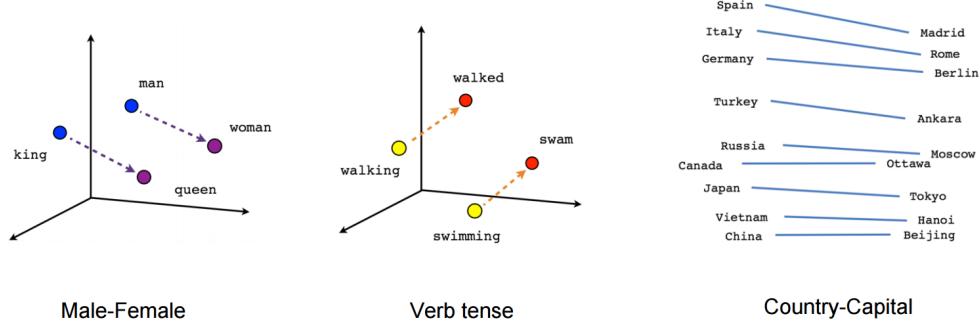

To apply MLPs to text classification, we need to convert the variable-length sequence of words v1,…, vT (where each vt is a one-hot vector of length V , where V is the vocabulary size) into a fixed dimensional vector x. The easiest way to do this is as follows. First we treat the input as an unordered bag of words (Section 1.5.4.1), {vt}. The first layer of the model is a E ↑ V embedding matrix W1, which converts each sparse V -dimensional vector to a dense E-dimensional embedding, et = W1vt (see Section 20.5 for more details on word embeddings). Next we convert this set of T E-dimensional embeddings into a fixed-sized vector using global average pooling, e = 1 T (T t=1 et. This can then be passed as input to an MLP. For example, if we use a single hidden layer, and a logistic output (for binary classification), we get

\[p(y|x; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = \text{Ber}(y|\sigma(\boldsymbol{w}\_3^\mathsf{T}\boldsymbol{h} + b\_3))\tag{13.17}\]

\[h = \varphi(\mathbf{W}\_2 \overline{\mathbf{e}} + \mathbf{b}\_2) \tag{13.18}\]

\[\overline{\mathbf{e}} = \frac{1}{T} \sum\_{t=1}^{T} \mathbf{e}\_t \tag{13.19}\]

\[\mathbf{e}\_t = \mathbf{W}\_1 \mathbf{v}\_t\tag{13.20}\]

If we use a vocabulary size of V = 10, 000, an embedding size of E = 16, and a hidden layer of size 16, we get the model shown in Table 13.3. If we apply this to the IMDB movie review sentiment classification dataset discussed in Section 1.5.2.1, we get 86% on the validation set.

We see from Table 13.3 that the model has a lot of parameters, which can result in overfitting, since the IMDB training set only has 25k examples. However, we also see that most of the parameters are in the embedding matrix, so instead of learning these in a supervised way, we can perform unsupervised pre-training of word embedding models, as we discuss in Section 20.5. If the embedding matrix W1 is fixed, we just have to fine-tune the parameters in layers 2 and 3 for this specific labeled task, which requires much less data. (See also Chapter 19, where we discuss general techniques for training with limited labeled data.)

Model: “sequential”

| _________________________________________________________________ Layer (type) |

Output Shape | Param # |

|---|---|---|

| ================================================================= embedding (Embedding) |

(None, None, 16) | 160000 |

| _________________________________________________________________ global_average_pooling1d (Gl (None, 16) _________________________________________________________________ |

0 | |

| dense (Dense) _________________________________________________________________ |

(None, 16) | 272 |

| dense_1 (Dense) ================================================================= |

(None, 1) | 17 |

| Total params: 160,289 Trainable params: 160,289 Non-trainable params: 0 |

Table 13.3: Structure of the MLP used for IMDB review classification. We use a vocabulary size of V = 10, 000, an embedding size of E = 16, and a hidden layer of size 16. The embedding matrix W1 has size 10, 000 ↑ 16, the hidden layer (labeled “dense”) has a weight matrix W2 of size 16 ↑ 16 and bias b2 of size 16 (note that 16 ↑ 16 + 16 = 272), and the final layer (labeled “dense_1”) has a weight vector w3 of size 16 and a bias b3 of size 1. The global average pooling layer has no free parameters. mlp\_imdb\_tf.ipynb.

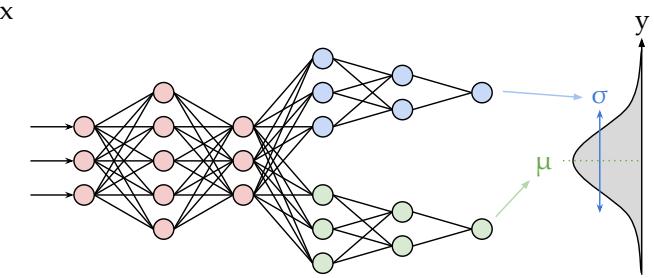

Figure 13.5: Illustration of an MLP with a shared “backbone” and two output “heads”, one for predicting the mean and one for predicting the variance. From https: // brendanhasz. github. io/ 2019/ 07/ 23/ bayesian-density-net. html . Used with kind permission of Brendan Hasz.

13.2.4.4 MLP for heteroskedastic regression

We can also use MLPs for regression. Figure 13.5 shows how we can make a model for heteroskedastic nonlinear regression. (The term “heteroskedastic” just means that the predicted output variance is input-dependent, as discussed in Section 2.6.3.) This function has two outputs which compute fµ(x) = E [y|x, ε] and fε(x) = )V [y|x, ε]. We can share most of the layers (and hence parameters) between these two functions by using a common “backbone” and two output “heads”, as shown in Figure 13.5. For the µ head, we use a linear activation, ϑ(a) = a. For the ω head, we use a softplus

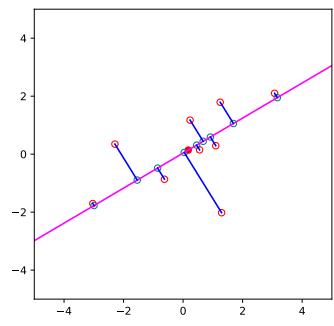

Figure 13.6: Illustration of predictions from an MLP fit using MLE to a 1d regression dataset with growing noise. (a) Output variance is input-dependent, as in Figure 13.5. (b) Mean is computed using same model as in (a), but output variance is treated as a fixed parameter ω2, which is estimated by MLE after training, as in Section 11.2.3.6. Generated by mlp\_1d\_regression\_hetero\_tfp.ipynb.

activation, ϑ(a) = ω+(a) = log(1 + ea). If we use linear heads and a nonlinear backbone, the overall model is given by

\[p(y|\mathbf{z},\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \mathcal{N}\left(y|\mathbf{w}\_{\mu}^{\mathsf{T}}f(\boldsymbol{x};\boldsymbol{w}\_{\text{shared}}), \sigma\_{+}(\boldsymbol{w}\_{\sigma}^{\mathsf{T}}f(\boldsymbol{x};\boldsymbol{w}\_{\text{shared}}))\right) \tag{13.21}\]

Figure 13.6 shows the advantage of this kind of model on a dataset where the mean grows linearly over time, with seasonal oscillations, and the variance increases quadratically. (This is a simple example of a stochastic volatility model; it can be used to model financial data, as well as the global temperature of the earth, which (due to climate change) is increasing in mean and in variance.) We see that a regression model where the output variance ω2 is treated as a fixed (input-independent) parameter will sometimes be underconfident, since it needs to adjust to the overall noise level, and cannot adapt to the noise level at each point in input space.

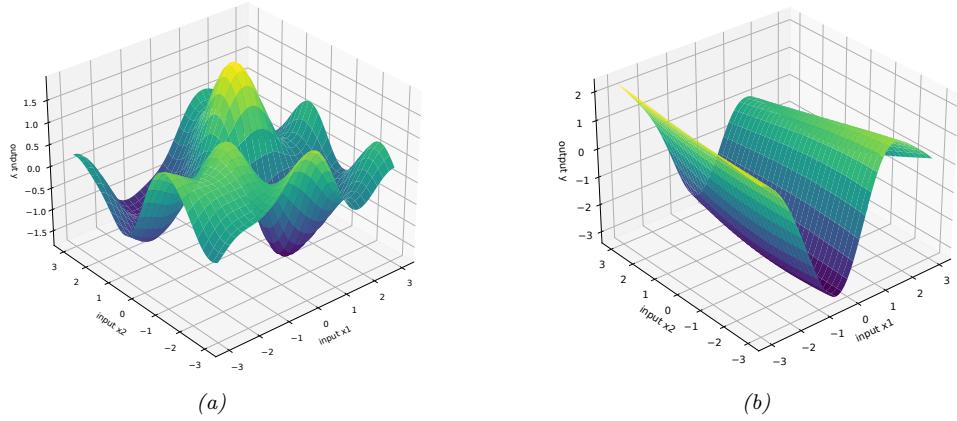

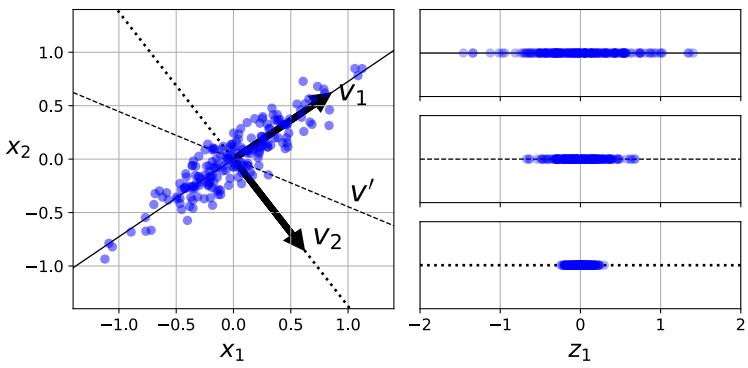

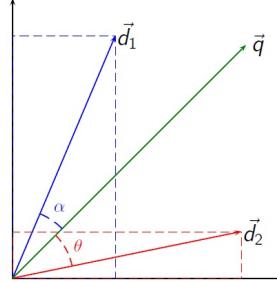

13.2.5 The importance of depth

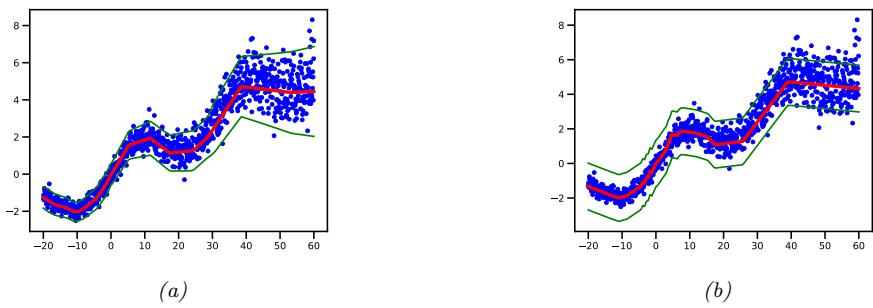

One can show that an MLP with one hidden layer is a universal function approximator, meaning it can model any suitably smooth function, given enough hidden units, to any desired level of accuracy [HSW89; Cyb89; Hor91]. Intuitively, the reason for this is that each hidden unit can specify a half plane, and a su”ciently large combination of these can “carve up” any region of space, to which we can associate any response (this is easiest to see when using piecewise linear activation functions, as shown in Figure 13.7).

However, various arguments, both experimental and theoretical (e.g., [Has87; Mon+14; Rag+17; Pog+17]), have shown that deep networks work better than shallow ones. The reason is that later layers can leverage the features that are learned by earlier layers; that is, the function is defined in a compositional or hierarchical way. For example, suppose we want to classify DNA strings, and the positive class is associated with the string *AA??CGCG??AA*, where ? is a wildcard denoting any single character, and * is a wildcard denoting any sequence of characters (possibly of length 0). Although we could fit this with a single hidden layer model, intuitively it will be easier to learn if the model first learns to detect the AA and CG “motifs” using the hidden units in layer 1, and then uses

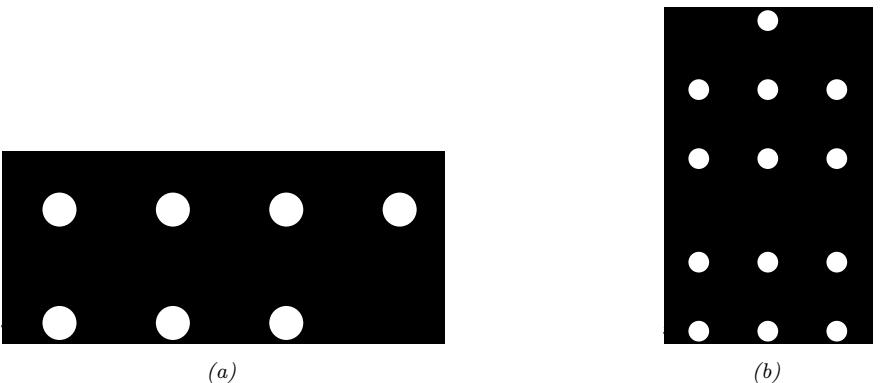

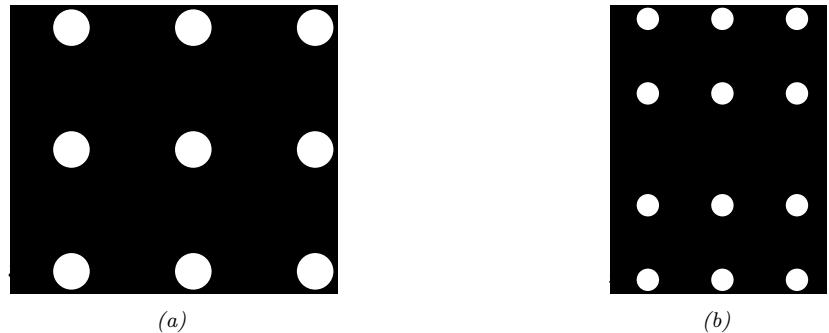

Figure 13.7: A decomposition of R2 into a finite set of linear decision regions produced by an MLP with ReLU activations with (a) one hidden layer of 25 hidden units and (b) two hidden layers. From Figure 1 of [HAB19]. Used with kind permission of Maksym Andriuschenko.

these features to define a simple linear classifier in layer 2, analogously to how we solved the XOR problem in Section 13.2.1.

13.2.6 The “deep learning revolution”

Although the ideas behind DNNs date back several decades, it was not until the 2010s that they started to become very widely used. The first area to adopt these methods was the field of automatic speech recognition (ASR), based on breakthrough results in [Dah+11]. This approach rapidly became the standard paradigm, and was widely adopted in academia and industry [Hin+12].

However, the moment that got the most attention was when [KSH12] showed that deep CNNs could significantly improve performance on the challenging ImageNet image classification benchmark, reducing the error rate from 26% to 16% in a single year (see Figure 1.14b); this was a huge jump compared to the previous rate of progress of about 2% reduction per year.

The “explosion” in the usage of DNNs has several contributing factors. One is the availability of cheap GPUs (graphics processing units); these were originally developed to speed up image rendering for video games, but they can also massively reduce the time it takes to fit large CNNs, which involve similar kinds of matrix-vector computations. Another is the growth in large labeled datasets, which enables us to fit complex function approximators with many parameters without overfitting. (For example, ImageNet has 1.3M labeled images, and is used to fit models that have millions of parameters.) Indeed, if deep learning systems are viewed as “rockets”, then large datasets have been called the fuel.3

Motivated by the outstanding empirical success of DNNs, various companies started to become interested in this technology. This had led to the development of high quality open-source software libraries, such as Tensorflow (made by Google), PyTorch (made by Facebook), and MXNet (made by Amazon). These libraries support automatic di!erentiation (see Section 13.3) and scalable gradient-based optimization (see Section 8.4) of complex di!erentiable functions. We will use some

3. This popular analogy is due to Andrew Ng, who mentioned it in a keynote talk at the GPU Technology Conference (GTC) in 2015. His slides are available at https://bit.ly/38RTxzH.

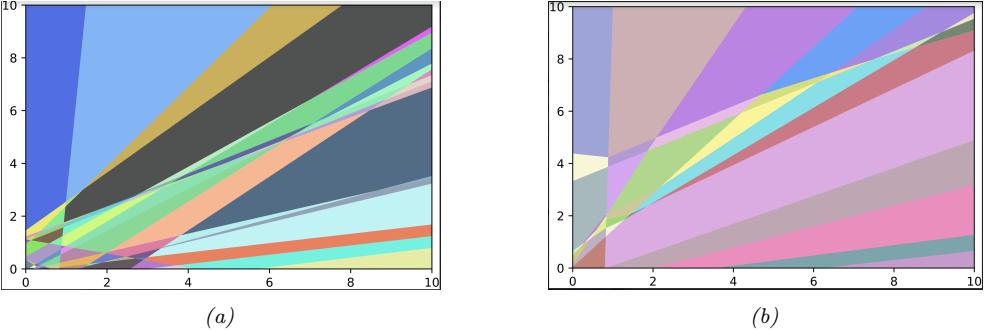

Figure 13.8: Illustration of two neurons connected together in a “circuit”. The output axon of the left neuron makes a synaptic connection with the dendrites of the cell on the right. Electrical charges, in the form of ion flows, allow the cells to communicate. From https: // en. wikipedia. org/ wiki/ Neuron . Used with kind permission of Wikipedia author BruceBlaus.

of these libraries in various places throughout the book to implement a variety of models, not just DNNs.4

More details on the history of the “deep learning revolution” can be found in e.g., [Sej18; Met21].

13.2.7 Connections with biology

In this section, we discuss the connections between the kinds of neural networks we have discussed above, known as artificial neural networks or ANNs, and real neural networks. The details on how real biological brains work are quite complex (see e.g., [Kan+12]), but we can give a simple “cartoon”.

We start by considering a model of a single neuron. To a first approximation, we can say that whether neuron k fires, denoted by hk → {0, 1}, depends on the activity of its inputs, denoted by x → RD, as well as the strength of the incoming connections, which we denote by wk → RD. We can compute a weighted sum of the inputs using ak = wT kx. These weights can be viewed as “wires” connecting the inputs xd to neuron hk; these are analogous to dendrites in a real neuron (see Figure 13.8). This weighted sum is then compared to a threshold, bk, and if the activation exceeds the threshold, the neuron fires; this is analogous to the neuron emitting an electrical output or action potential. Thus we can model the behavior of the neuron using hk(x) = H(wT kx ↗ bk), where H(a) = I(a > 0) is the Heaviside function. This is called the McCulloch-Pitts model of the neuron, and was proposed in 1943 [MP43].

We can combine multiple such neurons together to make an ANN. The result has sometimes been

4. Note, however, that some have argued (see e.g., [BI19]) that current libraries are too inflexible, and put too much emphasis on methods based on dense matrix-vector multiplication, as opposed to more general algorithmic primitives.

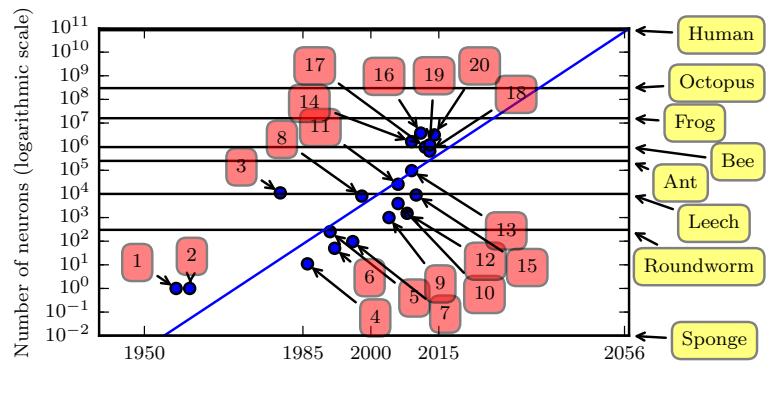

Figure 13.9: Plot of neural network sizes over time. Models 1, 2, 3 and 4 correspond to the perceptron [Ros58], the adaptive linear unit [WH60] the neocognitron [Fuk80], and the first MLP trained by backprop [RHW86]. Approximate number of neurons for some living organisms are shown on the right scale (the sponge has 0 neurons), based on https: // en. wikipedia. org/ wiki/ List\_ of\_ animals\_ by\_ number\_ of\_ neurons . From Figure 1.11 of [GBC16]. Used with kind permission of Ian Goodfellow.

viewed as a model of the brain. However, ANNs di!ers from biological brains in many ways, including the following:

- Most ANNs use backpropagation to modify the strength of their connections (see Section 13.3). However, real brains do not use backprop, since there is no way to send information backwards along an axon [Ben+15b; BS16; KH19]. Instead, they use local update rules for adjusting synaptic strengths.

- Most ANNs are strictly feedforward, but real brains have many feedback connections. It is believed that this feedback acts like a prior, which can be combined with bottom up likelihoods from the sensory system to compute a posterior over hidden states of the world, which can then be used for optimal decision making (see e.g., [Doy+07]).

- Most ANNs use simplified neurons consisting of a weighted sum passed through a nonlinearity, but real biological neurons have complex dendritic tree structures (see Figure 13.8), with complex spatio-temporal dynamics.

- Most ANNs are smaller in size and number of connections than biological brains (see Figure 13.9). Of course, ANNs are getting larger every week, fueled by various new hardware accelerators, such as GPUs and TPUs (tensor processing units), etc. However, even if ANNs match biological brains in terms of number of units, the comparison is misleading since the processing capability of a biological neuron is much higher than an artificial neuron (see point above).

- Most ANNs are designed to model a single function, such as mapping an image to a label, or a sequence of words to another sequence of words. By contrast, biological brains are very complex systems, composed of multiple specialized interacting modules, which implement di!erent kinds of functions or behaviors such as perception, control, memory, language, etc (see e.g., [Sha88; Kan+12]).

Of course, there are e!orts to make realistic models of biological brains (e.g., the Blue Brain Project [Mar06; Yon19]). However, an interesting question is whether studying the brain at this level of detail is useful for “solving AI”. It is commonly believed that the low level details of biological brains do not matter if our goal is to build “intelligent machines”, just as aeroplanes do not flap their wings. However, presumably “AIs” will follow similar “laws of intelligence” to intelligent biological agents, just as planes and birds follow the same laws of aerodynamics.

Unfortunately, we do not yet know what the “laws of intelligence” are, or indeed if there even are such laws. In this book we make the assumption that any intelligent agent should follow the basic principles of information processing and Bayesian decision theory, which is known to be the optimal way to make decisions under uncertainty (see Section 5.1).

In practice, the optimal Bayesian approach is often computationally intractable. In the natural world, biological agents have evolved various algorithmic “shortcuts” to the optimal solution; this can explain many of the heuristics that people use in everyday reasoning [KST82; GTA00; Gri20]. As the tasks we want our machines to solve become harder, we may be able to gain insights from neuroscience and cognitive science for how to solve such tasks in an approximate way (see e.g., [SC16; MWK16; Has+17; Lak+17; HG21]). However, we should also bear in mind that AI/ML systems are increasingly used for safety-critical applications, in which we might want and expect the machine to do better than a human. In such cases, we may want more than just heuristic solutions that often work; instead we may want provably reliable methods, similar to other engineering fields (see Section 1.6.3 for further discussion).

13.3 Backpropagation

13.3.1 Forward vs reverse mode di!erentiation

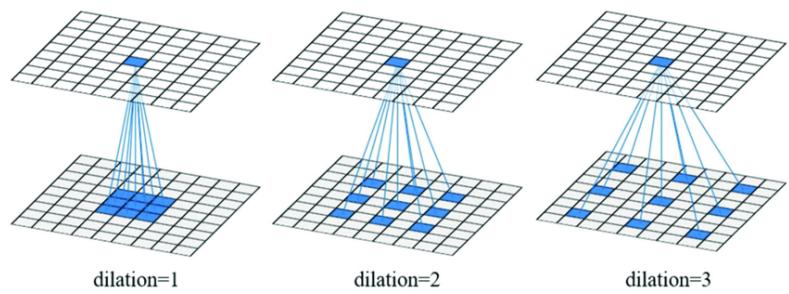

Consider a mapping of the form o = f(x), where x → Rn and o → Rm. We assume that f is defined as a composition of functions:

\[f = f\_4 \circ f\_3 \circ f\_2 \circ f\_1 \tag{13.22}\]

5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Backpropagation#History

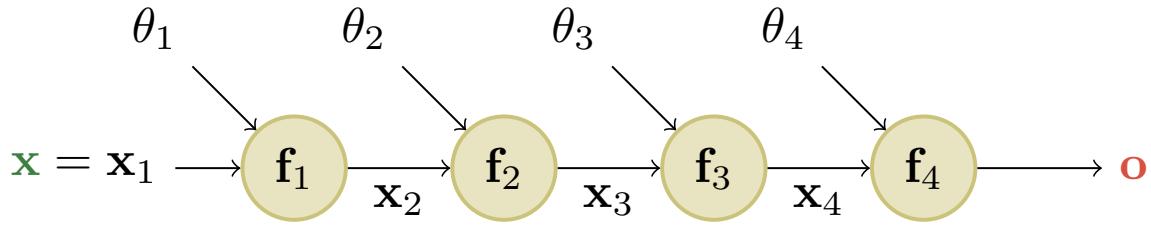

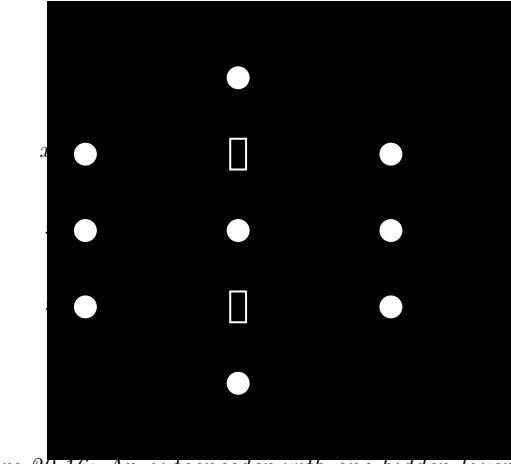

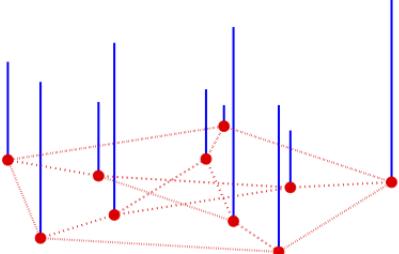

Figure 13.10: A simple linear-chain feedforward model with 4 layers. Here x is the input and o is the output. From [Blo20].

where f1 : Rn ≃ Rm1 , f2 : Rm1 ≃ Rm2 , f3 : Rm2 ≃ Rm3 , and f4 : Rm3 ≃ Rm. The intermediate steps needed to compute o = f(x) are x2 = f1(x), x3 = f2(x2), x4 = f3(x3), and o = f4(x4).

We can compute the Jacobian Jf (x) = ϑo ϑx → Rm↓n using the chain rule:

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_4} \frac{\partial x\_4}{\partial x\_3} \frac{\partial x\_3}{\partial x\_2} \frac{\partial x\_2}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial f\_4(x\_4)}{\partial x\_4} \frac{\partial f\_3(x\_3)}{\partial x\_3} \frac{\partial f\_2(x\_2)}{\partial x\_2} \frac{\partial f\_1(x)}{\partial x} \tag{13.23}\]

\[\mathbf{J}\_1 = \mathbf{J}\_{f\_4}(x\_4)\mathbf{J}\_{f\_3}(x\_3)\mathbf{J}\_{f\_2}(x\_2)\mathbf{J}\_{f\_1}(x) \tag{13.24}\]

We now discuss how to compute the Jacobian Jf (x) e”ciently. Recall that

\[\mathbf{J}\_f(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{x})}{\partial \mathbf{z}} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial f\_1}{\partial x\_1} & \cdots & \frac{\partial f\_1}{\partial x\_n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial f\_m}{\partial x\_1} & \cdots & \frac{\partial f\_m}{\partial x\_n} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla f\_1(\mathbf{z})^\mathsf{T} \\ \vdots \\ \nabla f\_m(\mathbf{z})^\mathsf{T} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x\_1}, \cdots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x\_n} \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n} \tag{13.25}\]

where ⇑fi(x) T → R1↓n is the i’th row (for i =1: m) and ϑf ϑxj → Rm is the j’th column (for j =1: n). Note that, in our notation, when m = 1, the gradient, denoted ⇑f(x), has the same shape as x. It is therefore a column vector, while Jf (x) is a row vector. In this case, we therefore technically have ⇑f(x) = Jf (x) T.

We can extract the i’th row from Jf (x) by using a vector Jacobian product (VJP) of the form eT i Jf (x), where ei → Rm is the unit basis vector. Similarly, we can extract the j’th column from Jf (x) by using a Jacobian vector product (JVP) of the form Jf (x)ej , where ej → Rn. This shows that the computation of Jf (x) reduces to either n JVPs or m VJPs.

If n<m, it is more e”cient to compute Jf (x) for each column j =1: n by using JVPs in a right-to-left manner. The right multiplication with a column vector v is

\[\mathbf{J}\_f(x)v = \underbrace{\mathbf{J}\_{f\_4}(x\_4)}\_{m \times m\_3} \underbrace{\mathbf{J}\_{f\_3}(x\_3)}\_{m\_3 \times m\_2} \underbrace{\mathbf{J}\_{f\_2}(x\_2)}\_{m\_2 \times m\_1} \underbrace{v}\_{m \times 1} \tag{13.26}\]

This can be computed using forward mode di!erentiation; see Algorithm 13.1 for the pseudocode. Assuming m = 1 and n = m1 = m2 = m3, the cost of computing Jf (x) is O(n2).

If n>m (e.g., if the output is a scalar), it is more e”cient to compute Jf (x) for each row i =1: m by using VJPs in a left-to-right manner. The left multiplication with a row vector uT is

\[u^{\sf T} \mathbf{J}\_f(x) = \underbrace{u^{\sf T}}\_{1 \times m} \underbrace{\mathbf{J}\_{f\_4}(x\_4)}\_{m \times m\_3} \underbrace{\mathbf{J}\_{f\_3}(x\_3)}\_{m\_3 \times m\_2} \underbrace{\mathbf{J}\_{f\_2}(x\_2)}\_{m\_2 \times m\_1} \mathbf{J}\_{f\_1}(x\_1) \tag{13.27}\]

Algorithm 13.1: Foward mode di!erentiation

1 x1 := x vj := ej → Rn for j =1: n for k =1: K do xk+1 = fk(xk) vj := Jfk (xk)vj for j =1: n Return o = xK+1, [Jf (x)]:,j = vj for j =1: n

This can be done using reverse mode di!erentiation; see Algorithm 13.2 for the pseudocode. Assuming m = 1 and n = m1 = m2 = m3, the cost of computing Jf (x) is O(n2).

Algorithm 13.2: Reverse mode di!erentiation 1 x1 := x 2 for k =1: K do 3 xk+1 = fk(xk) 4 ui := ei → Rm for i =1: m 5 for k = K : 1 do 6 uT i := uT i Jfk (xk) for i =1: m 7 Return o = xK+1, [Jf (x)]i,: = uT i for i =1: m

Both Algorithms 13.1 and 13.2 can be adapted to compute JVPs and VJPs against any collection of input vectors, by accepting {vj}j=1,…,n and {ui}i=1,…,m as respective inputs. Initializing these vectors to the standard basis is useful specifically for producing the complete Jacobian as output.

13.3.2 Reverse mode di!erentiation for multilayer perceptrons

In the previous section, we considered a simple linear-chain feedforward model where each layer does not have any learnable parameters. In this section, each layer can now have (optional) parameters ε1,…, ε4. See Figure 13.10 for an illustration. We focus on the case where the mapping has the form L : Rn ≃ R, so the output is a scalar. For example, consider ε2 loss for a MLP with one hidden layer:

\[\mathcal{L}((x, y), \theta) = \frac{1}{2} ||y - \mathbf{W}\_2 \varphi(\mathbf{W}\_1 x)||\_2^2 \tag{13.28}\]

we can represent this as the following feedforward model:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbf{f}\_4 \diamond \mathbf{f}\_3 \diamond \mathbf{f}\_2 \diamond \mathbf{f}\_1 \tag{13.29}\]

\[x\_2 = f\_1(x, \theta\_1) = \mathbf{W}\_1 x \tag{13.30}\]

\[x\_3 = f\_2(x\_2, \emptyset) = \varphi(x\_2) \tag{13.31}\]

\[x\_4 = f\_3(x\_3, \theta\_3) = \mathbf{W}\_2 x\_3 \tag{13.32}\]

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathbf{f}\_4(x\_4, y) = \frac{1}{2}||x\_4 - y||^2 \tag{13.33}\]

We use the notation fk(xk, εk) to denote the function at layer k, where xk is the previous output and εk are the optional parameters for this layer.

In this example, the final layer returns a scalar, since it corresponds to a loss function L → R. Therefore it is more e”cient to use reverse mode di!erentation to compute the gradient vectors.

We first discuss how to compute the gradient of the scalar output wrt the parameters in each layer. We can easily compute the gradient wrt the predictions in the final layer ϑL ϑx4 . For the gradient wrt the parameters in the earlier layers, we can use the chain rule to get

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_4}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \tag{13.34}\]

\[ \begin{array}{ccccc} \partial\theta\_3 & \partial x\_4 \,\partial\theta\_3 & & & \\ \partial\mathcal{L} & \\_\partial\mathcal{L} & \partial x\_4 \,\partial x\_3 & & \\ & & & & \\ \end{array} \tag{12.25} \]

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta\_2} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial x\_4} \frac{\partial x\_4}{\partial x\_3} \frac{\partial x\_3}{\partial \theta\_2} \tag{13.35}\]

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\_{1}} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}\_{4}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{x}\_{4}}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}\_{3}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{x}\_{3}}{\partial \boldsymbol{x}\_{2}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{x}\_{2}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\_{1}} \tag{13.36}\]

where each ϑL ϑεk = (⇑εk L) T is a dk-dimensional gradient row vector, where dk is the number of parameters in layer k. We see that these can be computed recursively, by multiplying the gradient row vector at layer k by the Jacobian ϑxk ϑxk→1 which is an nk ↑ nk→1 matrix, where nk is the number of hidden units in layer k. See Algorithm 13.3 for the pseudocode.

This algorithm computes the gradient of the loss wrt the parameters at each layer. It also computes the gradient of the loss wrt the input, ⇑xL → Rn, where n is the dimensionality of the input. This latter quantity is not needed for parameter learning, but can be useful for generating inputs to a model (see Section 14.6 for some applications).

All that remains is to specify how to compute the vector Jacobian product (VJP) of all supported layers. The details of this depend on the form of the function at each layer. We discuss some examples below.

13.3.3 Vector-Jacobian product for common layers

Recall that the Jacobian for a layer of the form f : Rn ≃ Rm. is defined by

\[\mathbf{J}\_{f}(\mathbf{z}) = \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{z})}{\partial \mathbf{z}} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial f\_{1}}{\partial x\_{1}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial f\_{1}}{\partial x\_{n}} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \frac{\partial f\_{m}}{\partial x\_{1}} & \cdots & \frac{\partial f\_{m}}{\partial x\_{n}} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \nabla f\_{1}(\mathbf{z})^{\mathsf{T}} \\ \vdots \\ \nabla f\_{m}(\mathbf{z})^{\mathsf{T}} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x\_{1}}, \cdots, \frac{\partial f}{\partial x\_{n}} \end{pmatrix} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n} \tag{13.37}\]

where ⇑fi(x) T → Rn is the i’th row (for i =1: m) and ϑf ϑxj → Rm is the j’th column (for j =1: n). In this section, we describe how to compute the VJP uTJf (x) for common layers.

Algorithm 13.3: Backpropagation for an MLP with K layers

1 // Forward pass 2 x1 := x 3 for k =1: K do 4 xk+1 = fk(xk, εk) 5 // Backward pass 6 uK+1 := 1 7 for k = K : 1 do 8 gk := uT k+1 ϑfk(xk,εk) ϑεk 9 uT k := uT k+1 ϑfk(xk,εk) ϑxk 10 // Output 11 Return L = xK+1, ⇑xL = u1, {⇑εk L = gk : k =1: K}

13.3.3.1 Cross entropy layer

Consider a cross-entropy loss layer taking logits x and target labels y as input, and returning a scalar:

\[z = f(\mathbf{z}) = \text{CrossEntropyWithLogits}(y, \mathbf{z}) = -\sum\_{c} y\_c \log(\text{softmax}(\mathbf{z})\_c) = -\sum\_{c} y\_c \log p\_c \quad (13.38)\]

where p = softmax(x) = exc !C c↑=1 exc↑ are the predicted class probabilites, and y is the true distribution over labels (often a one-hot vector). The Jacobian wrt the input is

\[\mathbf{J} = \frac{\partial z}{\partial x} = (\mathbf{p} - \mathbf{y})^{\mathsf{T}} \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times C} \tag{13.39}\]

To see this, assume the target label is class c. We have

\[z = f(x) = -\log(p\_c) = -\log\left(\frac{e^{x\_c}}{\sum\_j e^{x\_j}}\right) = \log\left(\sum\_j e^{x\_j}\right) - x\_c \tag{13.40}\]

Hence

\[\frac{\partial z}{\partial x\_i} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x\_i} \log \sum\_j e^{x\_j} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x\_i} x\_c = \frac{e^{x\_i}}{\sum\_j e^{x\_j}} - \frac{\partial}{\partial x\_i} x\_c = p\_i - \mathbb{I}\left(i = c\right) \tag{13.41}\]

If we define y = [I(i = c)], we recover Equation (13.39). Note that the Jacobian of this layer is a row vector, since the output is a scalar.

13.3.3.2 Elementwise nonlinearity

Consider a layer that applies an elementwise nonlinearity, z = f(x) = ϑ(x), so zi = ϑ(xi). The (i, j) element of the Jacobian is given by

\[\frac{\partial z\_i}{\partial x\_j} = \begin{cases} \varphi'(x\_i) & \text{if } i = j \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} \tag{13.42}\]

where ϑ↑ (a) = d daϑ(a). In other words, the Jacobian wrt the input is

\[\mathbf{J} = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \text{diag}(\varphi'(x))\tag{13.43}\]

For an arbitrary vector u, we can compute uTJ by elementwise multiplication of the diagonal elements of J with u. For example, if

\[ \varphi(a) = \text{ReLU}(a) = \max(a, 0) \tag{13.44} \]

we have

\[\varphi'(a) = \begin{cases} 0 & a < 0 \\ 1 & a > 0 \end{cases} \tag{13.45}\]

The subderivative (Section 8.1.4.1) at a = 0 is any value in [0, 1]. It is often taken to be 0. Hence

\[\text{ReLU}'(a) = H(a) \tag{13.46}\]

where H is the Heaviside step function.

13.3.3.3 Linear layer

Now consider a linear layer, z = f(x,W) = Wx, where W → Rm↓n, so x → Rn and z → Rm. We can compute the Jacobian wrt the input vector, J = ϑz ϑx → Rm↓n, as follows. Note that

\[z\_i = \sum\_{k=1}^{n} W\_{ik} x\_k \tag{13.47}\]

So the (i, j) entry of the Jacobian will be

\[\frac{\partial z\_i}{\partial x\_j} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x\_j} \sum\_{k=1}^n W\_{ik} x\_k = \sum\_{k=1}^n W\_{ik} \frac{\partial}{\partial x\_j} x\_k = W\_{ij} \tag{13.48}\]

since ϑ ϑxj xk = I(k = j). Hence the Jacobian wrt the input is

\[\mathbf{J} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial x} = \mathbf{W} \tag{13.49}\]

The VJP between uT → R1↓m and J → Rm↓n is

\[\mathbf{u}^{\mathsf{T}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial x} = \mathbf{u}^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{1 \times n} \tag{13.50}\]

Now consider the Jacobian wrt the weight matrix, J = ϑz ϑW. This can be represented as a m↑(m↑n) matrix, which is complex to deal with. So instead, let us focus on taking the gradient wrt a single weight, Wij . This is easier to compute, since ϑz ϑWij is a vector. To compute this, note that

\[z\_k = \sum\_{l=1}^{n} W\_{kl} x\_l \tag{13.51}\]

\[\frac{\partial z\_k}{\partial W\_{ij}} = \sum\_{l=1}^n x\_l \frac{\partial}{\partial W\_{ij}} W\_{kl} = \sum\_{l=1}^n x\_l \mathbb{I}\left(i = k \text{ and } j = l\right) \tag{13.52}\]

Hence

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial W\_{ij}} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & \cdots & 0 & x\_j & 0 & \cdots & 0 \end{pmatrix}^{\mathsf{T}} \tag{13.53}\]

where the non-zero entry occurs in location i. The VJP between uT → R1↓m and ϑz ϑW → Rm↓(m↓n) can be represented as a matrix of shape 1 ↑ (m ↑ n). Note that

\[\mathbf{u}^{\mathsf{T}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial W\_{ij}} = \sum\_{k=1}^{m} u\_k \frac{\partial z\_k}{\partial W\_{ij}} = u\_i x\_j \tag{13.54}\]

Therefore

\[\left[\mathbf{u}^{\mathsf{T}}\frac{\partial\mathbf{z}}{\partial\mathbf{W}}\right]\_{1,:} = \mathbf{u}\mathbf{z}^{\mathsf{T}} \in \mathbb{R}^{m \times n} \tag{13.55}\]

13.3.3.4 Putting it all together

For an exercise that puts this all together, see Exercise 13.1.

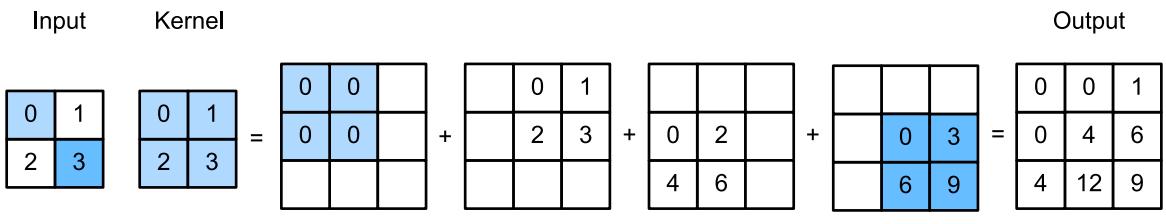

13.3.4 Computation graphs

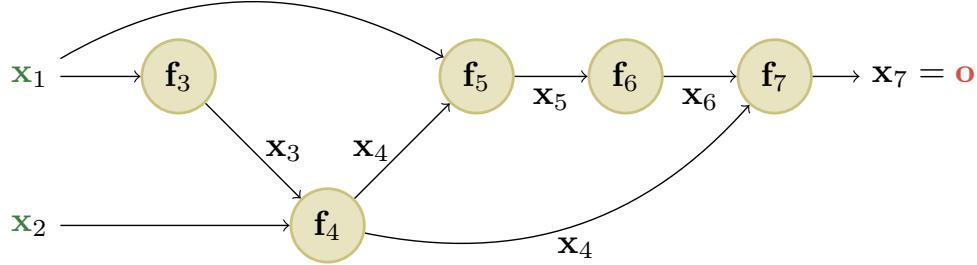

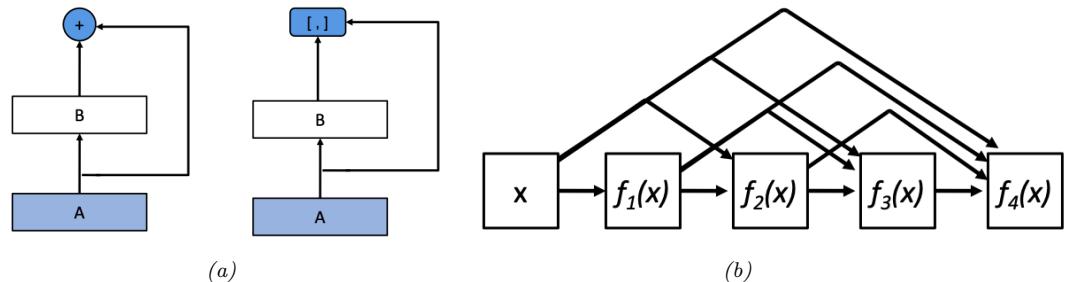

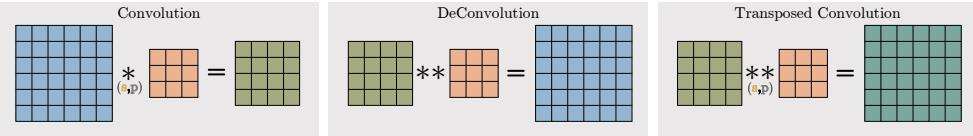

MLPs are a simple kind of DNN in which each layer feeds directly into the next, forming a chain structure, as shown in Figure 13.10. However, modern DNNs can combine di!erentiable components in much more complex ways, to create a computation graph, analogous to how programmers combine elementary functions to make more complex ones. (Indeed, some have suggested that “deep learning” be called “di!erentiable programming”.) The only restriction is that the resulting computation graph corresponds to a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where each node is a di!erentiable function of all its inputs.

For example, consider the function

\[f(x\_1, x\_2) = x\_2 e^{x\_1} \sqrt{x\_1 + x\_2 e^{x\_1}} \tag{13.56}\]

Figure 13.11: An example of a computation graph with 2 (scalar) inputs and 1 (scalar) output. From [Blo20].

We can compute this using the DAG in Figure 13.11, with the following intermediate functions:

\[x\_3 = f\_3(x\_1) = e^{x\_1} \tag{13.57}\]

\[x\_4 = f\_4(x\_2, x\_3) = x\_2 x\_3 \tag{13.58}\]

\[x\_5 = f\_5(x\_1, x\_4) = x\_1 + x\_4 \tag{13.59}\]

\[x\_6 = f\_6(x\_5) = \sqrt{x\_5} \tag{13.60}\]

\[x\_7 = f\_7(x\_4, x\_6) = x\_4 x\_6 \tag{13.61}\]

Note that we have numbered the nodes in topological order (parents before children). During the backward pass, since the graph is no longer a chain, we may need to sum gradients along multiple paths. For example, since x4 influences x5 and x7, we have

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_4} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_5} \frac{\partial x\_5}{\partial x\_4} + \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_7} \frac{\partial x\_7}{\partial x\_4} \tag{13.62}\]

We can avoid repeated computation by working in reverse topological order. For example,

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_7} = \frac{\partial x\_7}{\partial x\_7} = \mathbf{I}\_m \tag{13.63}\]

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial \mathbf{o}} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial \mathbf{o}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_7}{\partial \mathbf{x}\_8} \tag{13.64}\]

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_6}{\partial \mathbf{a}} &= \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_7}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_6}{\partial \mathbf{a}}\\ \frac{\partial \mathbf{a}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} &= \frac{\partial \mathbf{a}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_6}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \end{aligned} \tag{13.65}\]

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial \mathbf{\bar{x}}\_5}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_6} &= \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_6}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_6} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_5}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_5} \\ \frac{\partial \mathbf{\bar{o}}}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_2} &= \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_5}{\partial \mathbf{z}} + \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_7}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \end{aligned} \tag{13.60}\]

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{U}}{\partial \mathbf{x}\_4} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_5}{\partial \mathbf{x}\_5} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_4}{\partial \mathbf{x}\_4} + \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_5}{\partial \mathbf{x}\_7} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_4}{\partial \mathbf{x}\_4} \tag{13.66}\]

In general, we use

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_j} = \sum\_{k \in \text{Ch}(j)} \frac{\partial \mathbf{o}}{\partial x\_k} \frac{\partial \mathbf{x}\_k}{\partial x\_j} \tag{13.67}\]

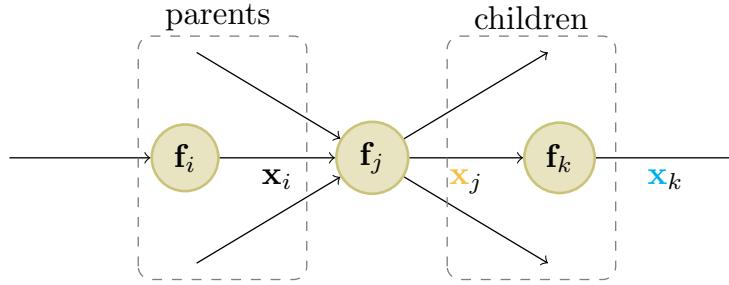

where the sum is over all children k of node j, as shown in Figure 13.12. The ϑo ϑxk gradient vector has already been computed for each child k; this quantity is called the adjoint. This gets multiplied by the Jacobian ϑxk ϑxj of each child.

Figure 13.12: Notation for automatic di!erentiation at node j in a computation graph. From [Blo20].

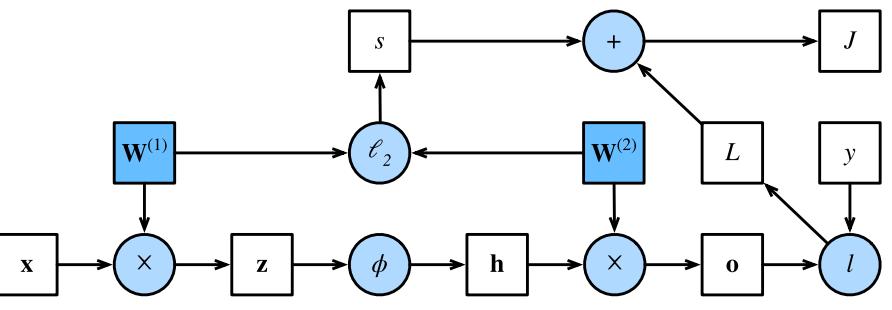

Figure 13.13: Computation graph for an MLP with input x, hidden layer h, output o, loss function L = ε(o, y), an ε2 regularizer s on the weights, and total loss J = L + s. From Figure 4.7.1 of [Zha+20]. Used with kind permission of Aston Zhang.

The computation graph can be computed ahead of time, by using an API to define a static graph. (This is how Tensorflow 1 worked.) Alternatively, the graph can be computed “just in time”, by tracing the execution of the function on an input argument. (This is how Tensorflow eager mode works, as well as JAX and PyTorch.) The latter approach makes it easier to work with a dynamic graph, whose shape can change depending on the values computed by the function.

Figure 13.13 shows a computation graph corresponding to an MLP with one hidden layer with weight decay. More precisely, the model computes the linear pre-activations z = W(1)x, the hidden activations h = ϱ(z), the linear outputs o = W(2)h, the loss L = ε(o, y), the regularizer s = ϖ 2 (||W(1)||2 F + ||W(2)||2 F ), and the total loss J = L + s.

13.4 Training neural networks

In this section, we discuss how to fit DNNs to data. The standard approach is to use maximum likelihood estimation, by minimizing the NLL:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = -\log p(\mathcal{D}|\boldsymbol{\theta}) = -\sum\_{n=1}^{N} \log p(y\_n|\boldsymbol{x}\_n; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \tag{13.68}\]

It is also common to add a regularizer (such as the negative log prior), as we discuss in Section 13.5.

In principle we can just use the backprop algorithm (Section 13.3) to compute the gradient of this loss and pass it to an o!-the-shelf optimizer, such as those discussed in Chapter 8. (The Adam optimizer of Section 8.4.6.3 is a popular choice, due to its ability to scale to large datasets (by virtue of being an SGD-type algorithm), and to converge fairly quickly (by virtue of using diagonal preconditioning and momentum).) However, in practice this may not work well. In this section, we discuss various problems that may arise, as well as some solutions. For more details on the practicalities of training DNNs, see various other books, such as [HG20; Zha+20; Gér19].

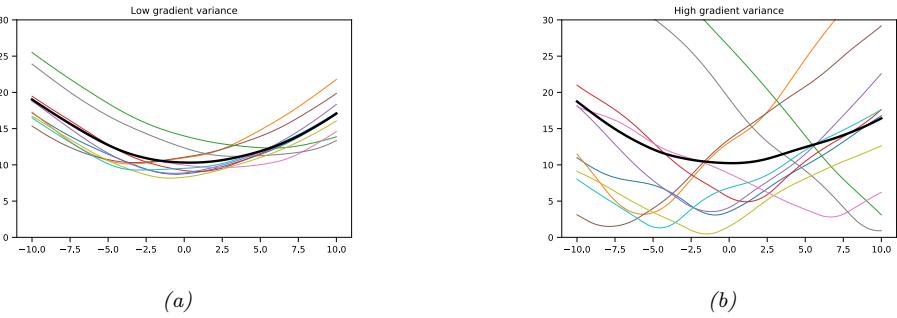

In addition to practical issues, there are important theoretical issues. In particular, we note that the DNN loss is not a convex objective, so in general we will not be able to find the global optimum. Nevertheless, SGD can often find suprisingly good solutions. The research into why this is the case is still being conducted; see [Bah+20] for a recent review of some of this work.

13.4.1 Tuning the learning rate

It is important to tune the learning rate (step size), to ensure convergence to a good solution. We discuss this issue in Section 8.4.3.

13.4.2 Vanishing and exploding gradients

When training very deep models, the gradient tends to become either very small (this is called the vanishing gradient problem) or very large (this is called the exploding gradient problem), because the error signal is being passed through a series of layers which either amplify or diminish it [Hoc+01]. (Similar problems arise in RNNs on long sequences, as we explain in Section 15.2.6.)

To explain the problem in more detail, consider the gradient of the loss wrt a node at layer l:

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_{l}} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_{l+1}} \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}\_{l+1}}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_{l}} = \mathbf{J}\_{l} g\_{l+1} \tag{13.69}\]

where Jl = ϑzl+1 ϑzl is the Jacobian matrix, and gl+1 = ϑL ϑzl+1 is the gradient at the next layer. If Jl is constant across layers, it is clear that the contribution of the gradient from the final layer, gL, to layer l will be JL→l gL. Thus the behavior of the system depends on the eigenvectors of J.

Although J is a real-valued matrix, it is not (in general) symmetric, so its eigenvalues and eigenvectors can be complex-valued, with the imaginary components corresponding to oscillatory behavior. Let ς be the spectral radius of J, which is the maximum of the absolute values of the eigenvalues. If this is greater than 1, the gradient can explode; if this is less than 1, the gradient can vanish. (Similarly, the spectral radius of W, connecting zl to zl+1, determines the stability of the dynamical system when run in forwards mode.)

The exploding gradient problem can be ameliorated by gradient clipping, in which we cap the magnitude of the gradient if it becomes too large, i.e., we use

\[\mathbf{g}' = \min(1, \frac{c}{||\mathbf{g}||}) \mathbf{g} \tag{13.70}\]

This way, the norm of g↑ can never exceed c, but the vector is always in the same direction as g.

However, the vanishing gradient problem is more di”cult to solve. There are various solutions, such as the following:

| Name | Definition | Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sigmoid | 1 ω(a) = 1+e→a |

[0, 1] |

|

| Hyperbolic tangent |

tanh(a)=2ω(2a) ↗ 1 |

[↗1, 1] |

|

| Softplus | ea) ω+(a) = log(1 + |

[0, ↖] |

[GBB11] |

| Rectified linear unit |

ReLU(a) = max(a, 0) |

[0, ↖] |

[GBB11; KSH12] |

| Leaky ReLU |

max(a, 0) + φ min(a, 0) |

[↗↖, ↖] |

[MHN13] |

| Exponential linear unit |

min(φ(ea ↗ max(a, 0) + 1), 0) |

[↗↖, ↖] |

[CUH16] |

| Swish | aω(a) | [↗↖, ↖] |

[RZL17] |

| GELU | a!(a) | [↗↖, ↖] |

[HG16] |

Table 13.4: List of some popular activation functions for neural networks.

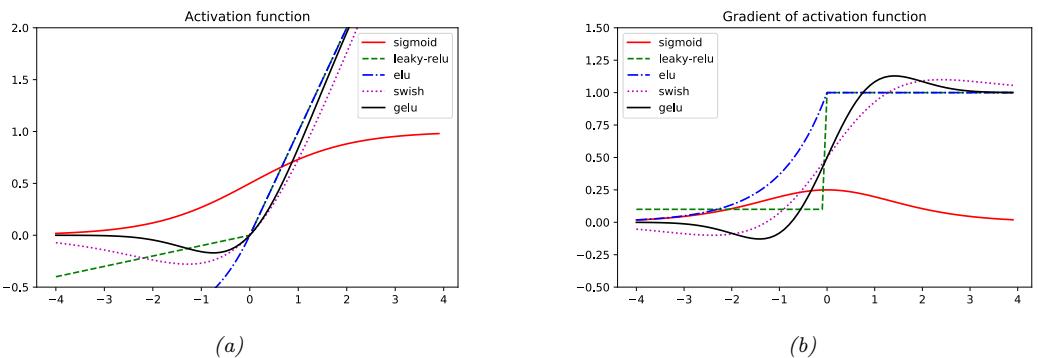

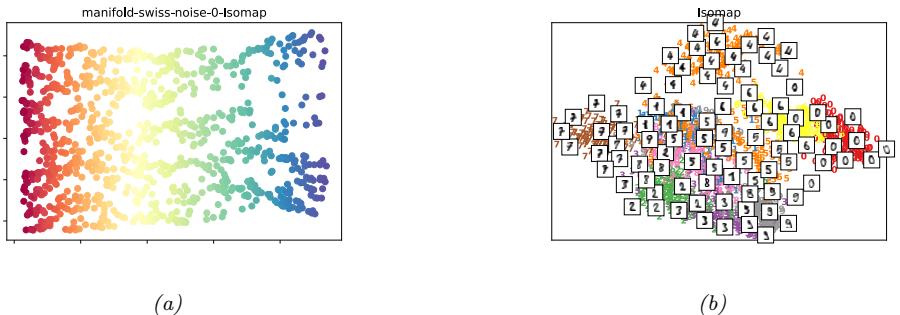

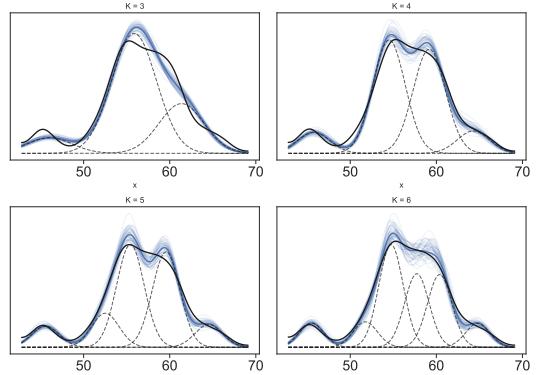

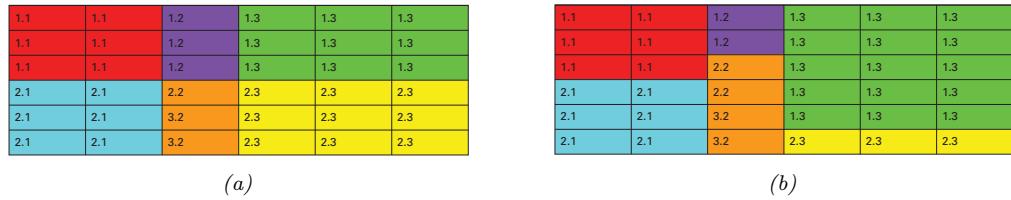

Figure 13.14: (a) Some popular activation functions. (b) Plot of their gradients. Generated by activation\_fun\_deriv\_jax.ipynb.

- Modify the the activation functions at each layer to prevent the gradient from becoming too large or too small; see Section 13.4.3.

- Modify the architecture so that the updates are additive rather than multiplicative; see Section 13.4.4.

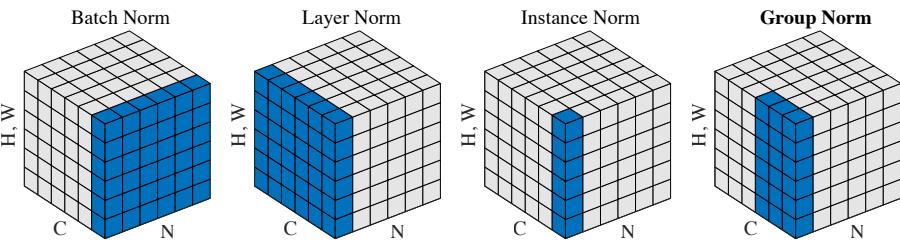

- Modify the architecture to standardize the activations at each layer, so that the distribution of activations over the dataset remains constant during training; see Section 14.2.4.1.

- Carefully choose the initial values of the parameters; see Section 13.4.5.

13.4.3 Non-saturating activation functions

In Section 13.2.3, we mentioned that the sigmoid activation function saturates at 0 for large negative inputs, and at 1 for large positive inputs. It turns out that the gradient signal in these regimes is 0, preventing backpropagation from working.

To see why the gradient vanishes, consider a layer which computes z = ω(Wx), where the activation

function is sigmoidal:

\[ \varphi(a) = \sigma(a) = \frac{1}{1 + \exp(-a)}\tag{13.71} \]

If the weights are initialized to be large (positive or negative), then it becomes very easy for a = Wx to take on large values, and hence for z to saturate near 0 or 1, since the sigmoid saturates, as shown in Figure 13.14a.

Now let us consider how gradients propagate through this layer. The derivative of the activation function (elementwise) is given by

\[ \varphi'(a) = \sigma(a)(1 - \sigma(a))\tag{13.72} \]

See Figure 13.14b for a plot. By the chain rule, we can compute the Jacobian for this layer wrt the inputs by multiplying the Jacobian for the sigmoid nonlinearity, z = ω(a), using Equation (13.43), with the Jacobian for the linear layer, a = Wx, using Equation (13.49), to get

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial \mathbf{z}} = \text{diag}(\mathbf{z}(1-\mathbf{z})^{\mathsf{T}})\mathbf{W} \tag{13.73}\]

Hence, if z is near 0 or 1, the gradients wrt the inputs will go to 0.

Similarly, the Jacobian of this layer wrt the parameters can be computed by multiplying Equation (13.43) with Equation (13.55) to get

\[\frac{\partial z}{\partial \mathbf{W}} = z(1 - z)\mathbf{z}^{\mathsf{T}} \tag{13.74}\]

Hence, if z is near 0 or 1, the gradients wrt the parameters will go to 0.

One of the keys to being able to train very deep models is to use non-saturating activation functions. Several di!erent functions have been proposed: see Table 13.4 for a summary.

13.4.3.1 ReLU

The most common is rectified linear unit or ReLU, proposed in [GBB11; KSH12]. This is defined as

\[\text{ReLU}(a) = \max(a, 0) = a \mathbb{I}(a > 0) \tag{13.75}\]

The ReLU function simply “turns o!” negative inputs, and passes positive inputs unchanged. The gradient has the following form:

\[\text{ReLU}'(a) = \mathbb{I}\left(a > 0\right) \tag{13.76}\]

Now suppose we use this in a layer to compute z = ReLU(Wx). Using the results from Section 13.3.3, we can show that the Jacobian for this layer wrt the inputs has the form

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial \mathbf{z}} = \mathbf{W}^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbb{I}(\mathbf{z} > \mathbf{0}) \tag{13.77}\]

and wrt the parameters has the form

\[\frac{\partial \mathbf{z}}{\partial \mathbf{W}} = \mathbb{I}\left(\mathbf{z} > \mathbf{0}\right)\mathbf{z}^{\mathrm{T}}\tag{13.78}\]

Hence the gradient will not vanish, as long as z is positive.

Unfortunately, when using ReLU, if the weights are initialized to be large and negative, then it becomes very easy for (some components of) a = Wx to take on large negative values, and hence for z to go to 0. This will cause the gradient for the weights to go to 0. The algorithm will never be able to escape this situation, so the hidden units (components of z) will stay permanently o!. This is called the “dead ReLU” problem [Lu+19].

13.4.3.2 Non-saturating ReLU

The problem of dead ReLU’s can be solved by using non-saturating variants of ReLU. One alternate is the leaky ReLU, proposed in [MHN13]. This is defined as

\[\text{LReLU}(a; \alpha) = \max(\alpha a, a) \tag{13.79}\]

where 0 < φ < 1. The slope of this function is 1 for positive inputs, and φ for negative inputs, thus ensuring there is some signal passed back to earlier layers, even when the input is negative. See Figure 13.14b for a plot. If we allow the parameter φ to be learned, rather than fixed, the leaky ReLU is called parametric ReLU [He+15].

Another popular choice is the ELU, proposed in [CUH16]. This is defined by

\[\text{ELU}(a;\alpha) = \begin{cases} \alpha(e^a - 1) & \text{if } a \le 0 \\ a & \text{if } a > 0 \end{cases} \tag{13.80}\]

This has the advantage over leaky ReLU of being a smooth function.6 See Figure 13.14 for plot.

A slight variant of ELU, known as SELU (self-normalizing ELU), was proposed in [Kla+17]. This has the form

\[\text{SELU}(a;\alpha,\lambda) = \lambda \text{ELU}(a;\alpha) \tag{13.81}\]

Surprisingly, they prove that by setting φ and ς to carefully chosen values, this activation function is guaranteed to ensure that the output of each layer is standardized (provided the input is also standardized), even without the use of techniques such as batchnorm (Section 14.2.4.1). This can help with model fitting.

13.4.3.3 Other choices

As an alternative to manually discovering good activation functions, we can use blackbox optimization methods to search over the space of functional forms. Such an approach was used in [RZL17], where they discovered a function they call swish that seems to do well on some image classification benchmarks. It is defined by

\[\text{swish}(a;\beta) = a\sigma(\beta a) \tag{13.82}\]

6. ELU only has a continuous first derivative if ω = 1.

(The same function, under the name SiLU (for Sigmoid Linear Unit), was independently proposed in [HG16].) See Figure 13.14 for plot.

Another popular activation function is GELU, which stands for “Gaussian Error Linear Unit” [HG16]. This is defined as follows:

\[\text{GELU}(a) = a\Phi(a) \tag{13.83}\]

where !(a) is the cdf of a standard normal:

\[\Phi(a) = \Pr(\mathcal{N}(0, 1) \le a) = \frac{1}{2} \left( 1 + \text{erf}(a/\sqrt{2}) \right) \tag{13.84}\]

We see from Figure 13.14 that this is not a convex or monontonic function, unlike most other activation functions.

We can think of GELU as a “soft” version of ReLU, since it replaces the step function I(a > 0) with the Gaussian cdf, !(a). Alternatively, the GELU can be motivated as an adaptive version of dropout (Section 13.5.4), where we multiply the input by a binary scalar mask, m ∝ Ber(!(a)), where the probability of being dropped is given by 1 ↗ !(a). Thus the expected output is

\[\mathbb{E}[a] = \Phi(a) \times a + (1 - \Phi(a)) \times 0 = a\Phi(a) \tag{13.85}\]

We can approximate GELU using swish with a particular parameter setting, namely

\[\text{GELU}(a) \approx a \sigma (1.702a) \tag{13.86}\]

The SmelU activation function proposed in [SLC20] is another smooth version of ReLU but which results in more reproducibility in terms of training runs, due to enhanced robustness to numerical issues.

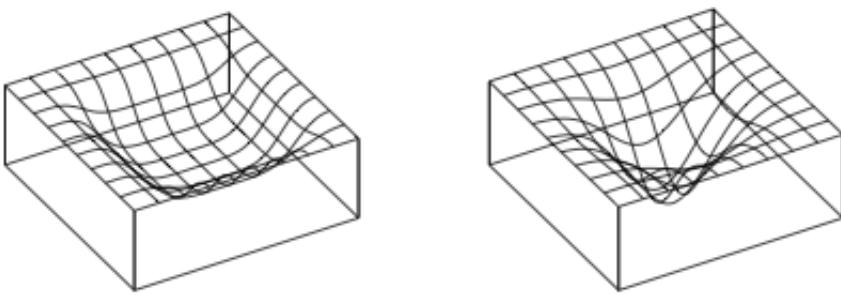

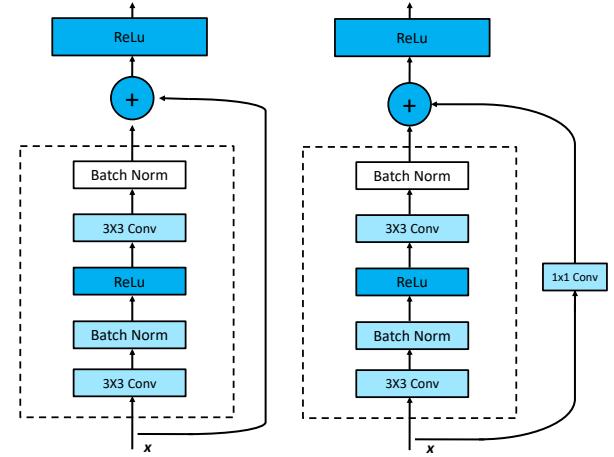

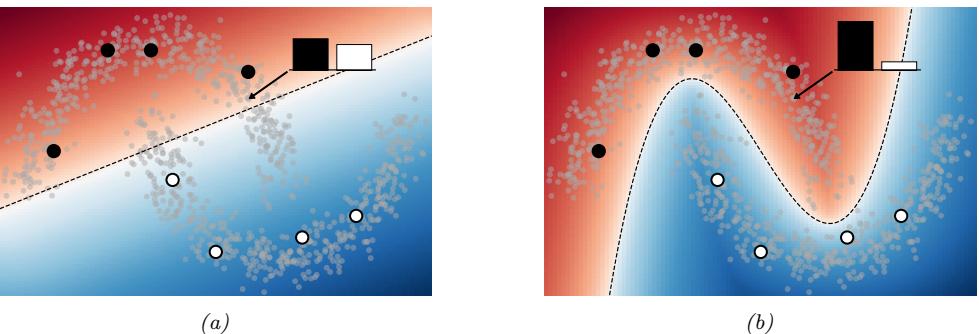

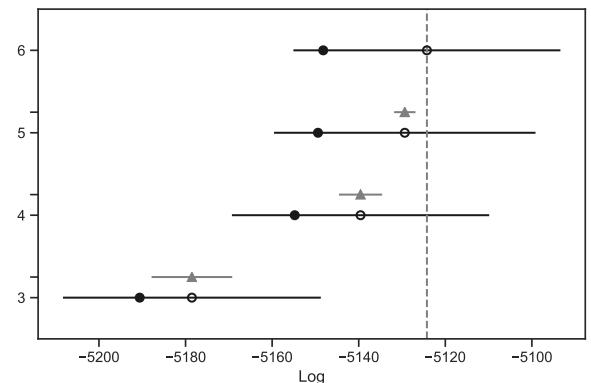

13.4.4 Residual connections

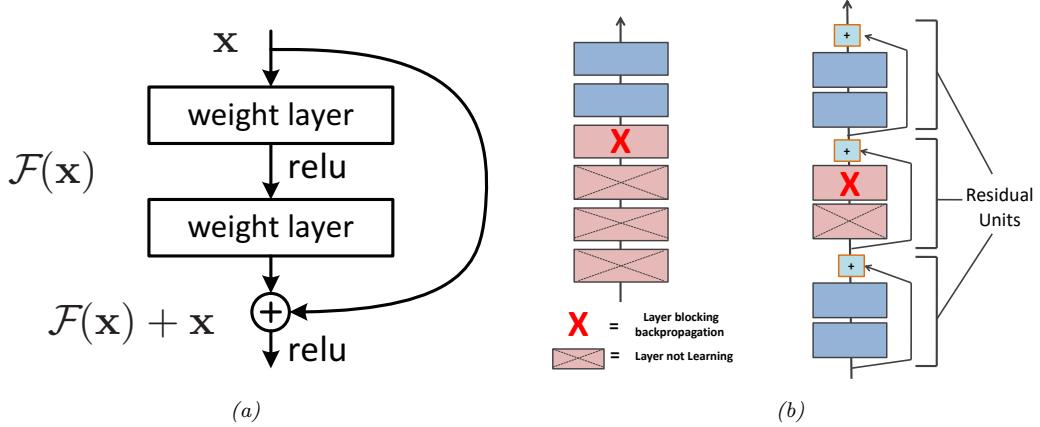

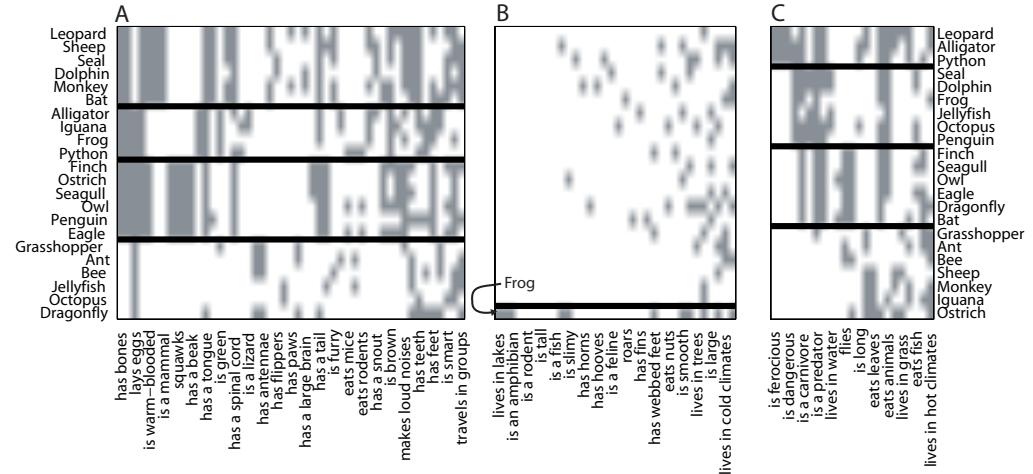

One solution to the vanishing gradient problem for DNNs is to use a residual network or ResNet [He+16a]. This is a feedforward model in which each layer has the form of a residual block, defined by

\[\mathcal{F}\_l'(x) = \mathcal{F}\_l(x) + x \tag{13.87}\]

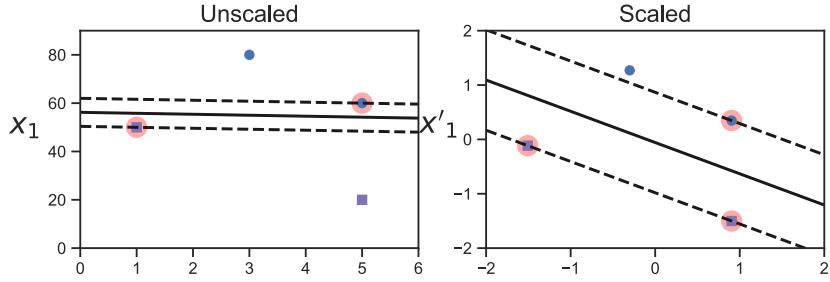

where Fl is a standard shallow nonlinear mapping (e.g., linear-activation-linear). The inner Fl function computes the residual term or delta that needs to be added to the input x to generate the desired output; it is often easier to learn to generate a small perturbation to the input than to directly predict the output. (Residual connections are usually used in conjunction with CNNs, as discussed in Section 14.3.4, but can also be used in MLPs.)

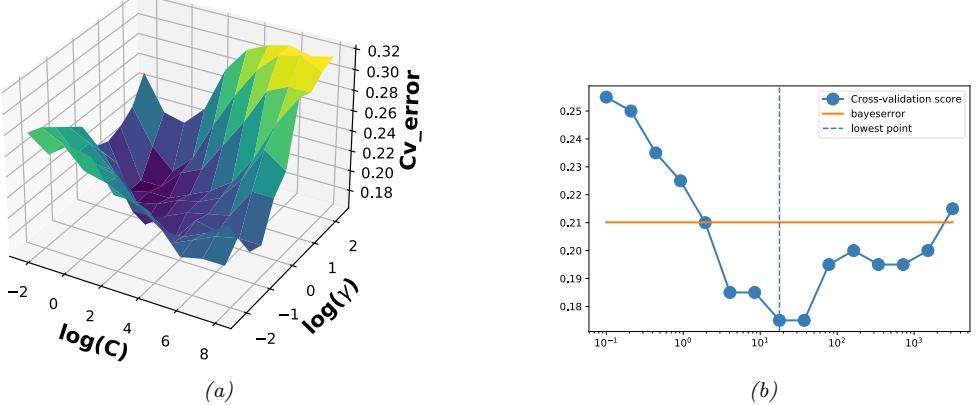

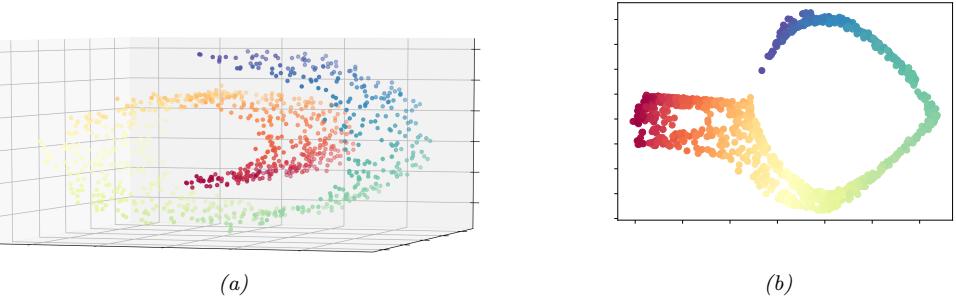

A model with residual connections has the same number of parameters as a model without residual connections, but it is easier to train. The reason is that gradients can flow directly from the output to earlier layers, as sketched in Figure 13.15b. To see this, note that the activations at the output layer can be derived in terms of any previous layer l using

\[\mathbf{z}\_{L} = \mathbf{z}\_{l} + \sum\_{i=l}^{L-1} \mathcal{F}\_{i}(\mathbf{z}\_{i}; \boldsymbol{\theta}\_{i}). \tag{13.88}\]

Figure 13.15: (a) Illustration of a residual block. (b) Illustration of why adding residual connections can help when training a very deep model. Adapted from Figure 14.16 of [Gér19].

We can therefore compute the gradient of the loss wrt the parameters of the l’th layer as follows:

\[\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}\_l}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{a}} \tag{13.89}\]

\[\begin{split} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\_{l}}{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{l}} &= \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\_{l}}{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{l}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{l}}{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{L}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{L}}{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{l}} \\ &= \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{l}}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\_{l}} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{L}} \frac{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{L}}{\partial \boldsymbol{z}\_{l}} \end{split} \tag{13.90}\]

\[\mathcal{L} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}\_l}{\partial \boldsymbol{\theta}\_l} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_L} \left( \mathbf{1} + \sum\_{i=l}^{L-1} \frac{\partial \mathcal{F}\_i(\mathbf{z}\_i; \boldsymbol{\theta}\_i)}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_l} \right) \tag{13.91}\]

\[\mathbf{H} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{z}\_l}{\partial \theta\_l} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \mathbf{z}\_L} + \text{other terms} \tag{13.92}\]

Thus we see that the gradient at layer l depends directly on the gradient at layer L in a way that is independent of the depth of the network.

13.4.5 Parameter initialization

Since the objective function for DNN training is non-convex, the way that we initialize the parameters of a DNN can play a big role on what kind of solution we end up with, as well as how easy the function is to train (i.e., how well information can flow forwards and backwards through the model). In the rest of this section, we present some common heuristic methods that are used for initializing parameters.

13.4.5.1 Heuristic initialization schemes

In [GB10], they show that sampling parameters from a standard normal with fixed variance can result in exploding activations or gradients. To see why, consider a linear unit with no activation

function given by oi = (nin j=1 wijxj ; suppose wij ∝ N (0, ω2), and E [xj ] = 0 and V [xj ] = ↽2, where we assume xj are independent of wij . The mean and variance of the output is given by

\[\mathbb{E}\left[o\_{i}\right] = \sum\_{j=1}^{n\_{\text{in}}} \mathbb{E}\left[w\_{ij}x\_{j}\right] = \sum\_{j=1}^{n\_{\text{in}}} \mathbb{E}\left[w\_{ij}\right] \mathbb{E}\left[x\_{j}\right] = 0 \tag{13.93}\]

\[\mathbb{E}\left[o\_i\right] = \mathbb{E}\left[o\_i^2\right] - \left(\mathbb{E}\left[o\_i\right]\right)^2 = \sum\_{j=1}^{n\_{\text{in}}} \mathbb{E}\left[w\_{ij}^2 x\_j^2\right] - 0 = \sum\_{j=1}^{n\_{\text{in}}} \mathbb{E}\left[w\_{ij}^2\right] \mathbb{E}\left[x\_j^2\right] = n\_{\text{in}} \sigma^2 \gamma^2 \tag{13.94}\]

To keep the output variance from blowing up, we need to ensure ninω2 = 1 (or some other constant), where nin is the fan-in of a unit (number of incoming connections).

Now consider the backwards pass. By analogous reasoning, we see that the variance of the gradients can blow up unless noutω2 = 1, where nout is the fan-out of a unit (number of outgoing connections). To satisfy both requirements at once, we set 1 2 (nin + nout)ω2 = 1, or equivalently

\[ \sigma^2 = \frac{2}{n\_{\rm in} + n\_{\rm out}} \tag{13.95} \]

This is known as Xavier initialization or Glorot initialization, named after the first author of [GB10].

A special case arises if we use ω2 = 1/nin; this is known as LeCun initialization, named after Yann LeCun, who proposed it in the 1990s. This is equivalent to Glorot initialization when nin = nout. If we use ω2 = 2/nin, the method is called He initialization, named after Kaiming He, who proposed it in [He+15].

Note that it is not necessary to use a Gaussian distribution. Indeed, the above derivation just worked in terms of the first two moments (mean and variance), and made no assumptions about Gaussianity. For example, suppose we sample weights from a uniform distribution, wij ∝ Unif(↗a, a). The mean is 0, and the variance is ω2 = a2/3. Hence we should set a = 6 nin+nout .

Although the above derivation assumes a linear output unit, the technique works well empirically even for nonlinear units. The best choice of initialization method depends on which activation function you use. For linear, tanh, logistic, and softmax, Glorot is recommended. For ReLU and variants, He is recommended. For SELU, LeCun is recommended. See e.g., [Gér19] for more heuristics, and e.g., [HDR19] for some theory.

13.4.5.2 Data-driven initializations

We can also adopt a data-driven approach to parameter initialization. For example, [MM16] proposed a simple but e!ective scheme known as layer-sequential unit-variance (LSUV) initialization, which works as follows. First we initialize the weights of each (fully connected or convolutional) layer with orthonormal matrices, as proposed in [SMG14]. (This can be achieved by drawing from w ∝ N (0, I), reshaping to w to a matrix W, and then computing an orthonormal basis using QR or SVD decomposition.) Then, for each layer l, we compute the variance vl of the activations across a minibatch; we then rescale using Wl := Wl/ ⇔vl. This scheme can be viewed as an orthonormal initialization combined with batch normalization performed only on the first mini-batch. This is faster than full batch normalization, but can sometimes work just as well.

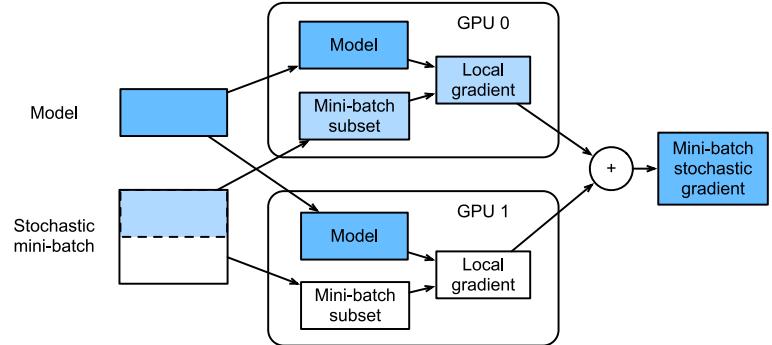

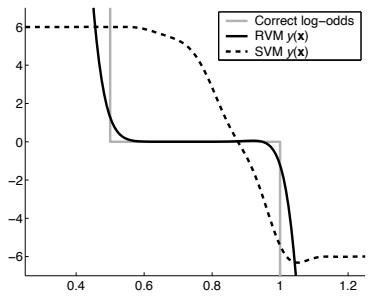

Figure 13.16: Calculation of minibatch stochastic gradient using data parallelism and two GPUs. From Figure 12.5.2 of [Zha+20]. Used with kind permission of Aston Zhang.

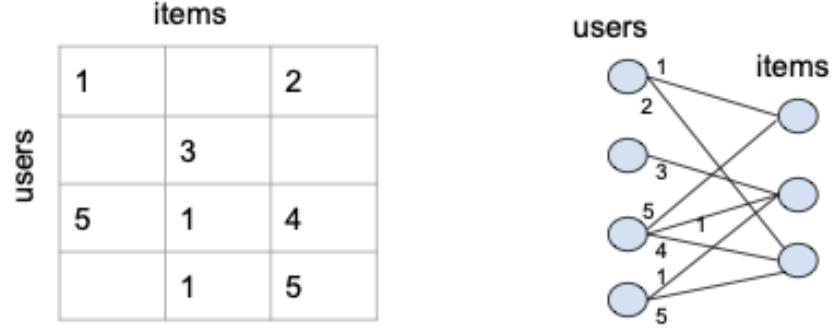

13.4.6 Parallel training

It can be quite slow to train large models on large datasets. One way to speed this process up is to use specialized hardware, such as graphics processing units (GPUs) and tensor processing units (TPUs), which are very e”cient at performing matrix-matrix multiplication. If we have multiple GPUs, we can sometimes further speed things up. There are two main approaches: model parallelism, in which we partition the model between machines, and data parallelism, in which each machine has its own copy of the model, and applies it to a di!erent set of data.

Model parallelism can be quite complicated, since it requires tight communication between machines to ensure they compute the correct answer. We will not discuss this further. Data parallelism is generally much simpler, since it is embarassingly parallel. To use this to speed up training, at each training step t, we do the following: 1) we partition the minibatch across the K machines to get Dk t ; 2) each machine k computes its own gradient, gk t = ⇑εL(ε; Dk t ); 3) we collect all the local gradients on a central machine (e.g., device 0) and sum them using gt = (K k=1 gk t ; 4) we broadcast the summed gradient back to all devices, so g˜k t = gt; 5) each machine updates its own copy of the parameters using εk t := εk t ↗ ⇀tg˜k t . See Figure 13.16 for an illustration and multi\_gpu\_training\_jax.ipynb for some sample code.

Note that steps 3 and 4 are usually combined into one atomic step; this is known as an all-reduce operation (where we use sum to reduce the set of (gradient) vectors into one). If each machine blocks until receiving the centrally aggregated gradient, gt, the method is known as synchronous training. This will give the same results as training with one machine (with a larger batchsize), only faster (assuming we ignore any batch normalization layers). If we let each machine update its parameters using its own local gradient estimate, and not wait for the broadcast to/from the other machines, the method is called asynchronous training. This is not guaranteed to work, since the di!erent machines may get out of step, and hence will be updating di!erent versions of the parameters; this approach has therefore been called hogwild training [Niu+11]. However, if the updates are sparse, so each machine “touches” a di!erent part of the parameter vector, one can prove that hogwild training behaves like standard synchronous SGD.

13.5 Regularization

In Section 13.4 we discussed computational issues associated with training (large) neural networks. In this section, we discuss statistical issues. In particular, we focus on ways to avoid overfitting. This is crucial, since large neural networks can easily have millions of parameters.

13.5.1 Early stopping

Perhaps the simplest way to prevent overfitting is called early stopping, which refers to the heuristic of stopping the training procedure when the error on the validation set starts to increase (see Figure 4.8 for an example). This method works because we are restricting the ability of the optimization algorithm to transfer information from the training examples to the parameters, as explained in [AS19].

13.5.2 Weight decay

A common approach to reduce overfitting is to impose a prior on the parameters, and then use MAP estimation. It is standard to use a Gaussian prior for the weights N (w|0, φ2I) and biases, N (b|0, ↼2I). This is equivalent to ε2 regularization of the objective. In the neural networks literature, this is called weight decay, since it encourages small weights, and hence simpler models, as in ridge regression (Section 11.3).

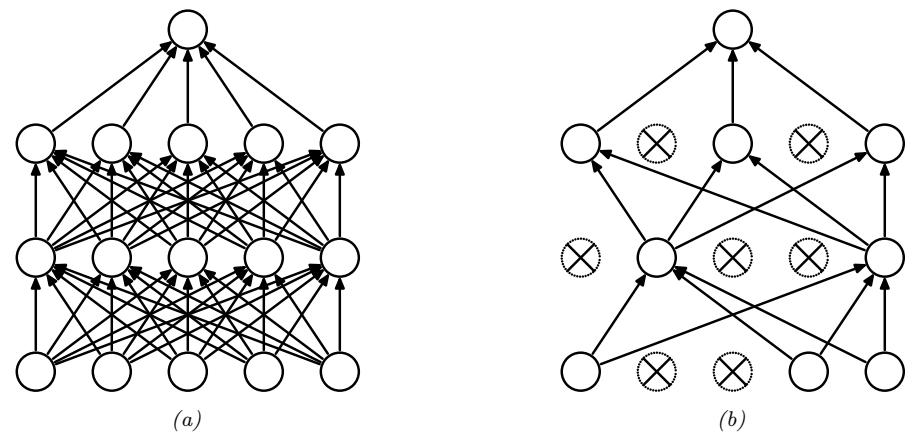

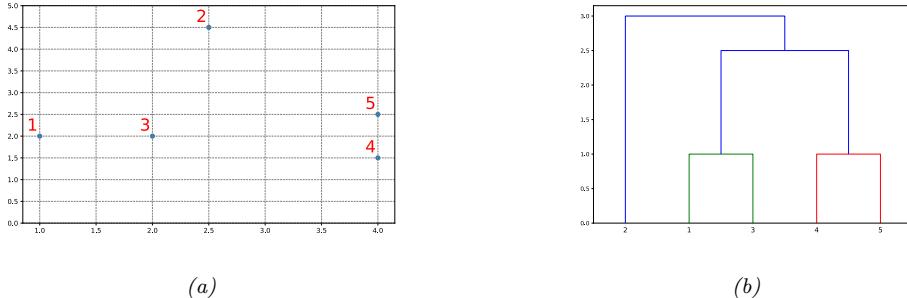

13.5.3 Sparse DNNs

Since there are many weights in a neural network, it is often helpful to encourage sparsity. This allows us to perform model compression, which can save memory and time. To do this, we can use ε1 regularization (as in Section 11.4), or ARD (as in Section 11.7.7), or several other methods (see e.g., [Hoe+21; Bha+20] for recent reviews). As a simple example, Figure 13.17 shows a 5 layer MLP which has been fit to some 1d regression data using an ε1 regularizer on the weights. We see that the resulting graph topology is sparse.

Despite the intuitive appeal of sparse topology, in practice these methods are not widely used, since modern GPUs are optimized for dense matrix multiplication, and there are few computational benefits to sparse weight matrices. However, if we use methods that encourage group sparsity, we can prune out whole layers of the model. This results in block sparse weight matrices, which can result in speedups and memory savings (see e.g., [Sca+17; Wen+16; MAV17; LUW17]).

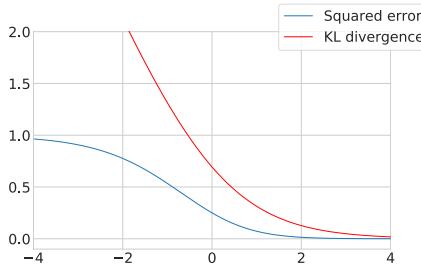

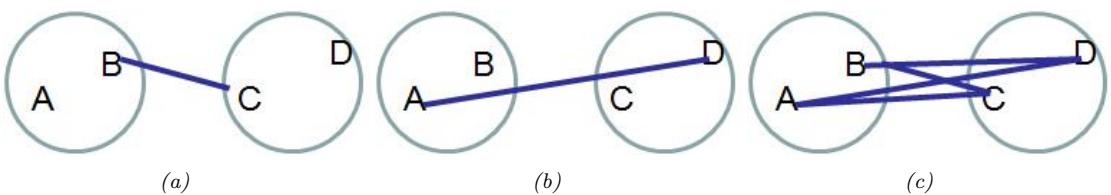

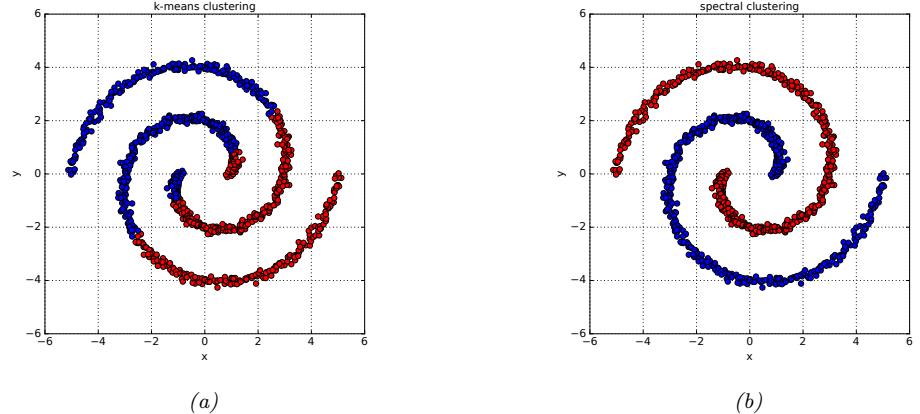

13.5.4 Dropout

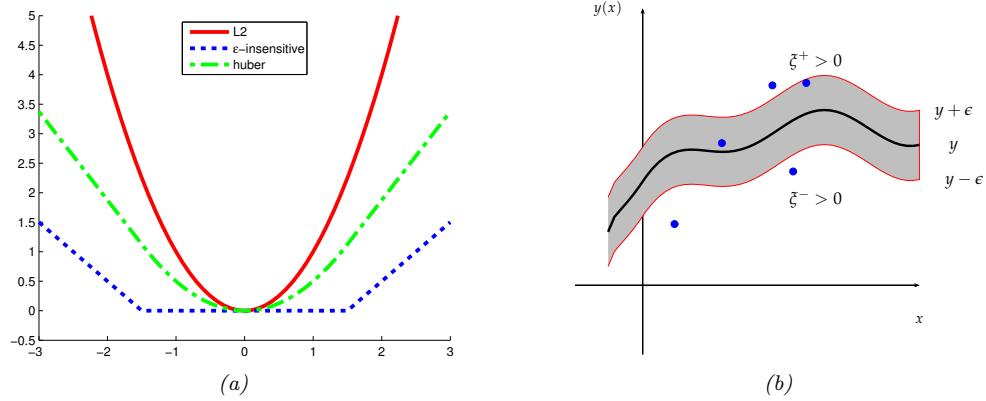

Suppose that we randomly (on a per-example basis) turn o! all the outgoing connections from each neuron with probability p, as illustrated in Figure 13.18. This technique is known as dropout [Sri+14].

Dropout can dramatically reduce overfitting and is very widely used. Intuitively, the reason dropout works well is that it prevents complex co-adaptation of the hidden units. In other words, each unit must learn to perform well even if some of the other units are missing at random. This prevents the

Figure 13.17: (a) A deep but sparse neural network. The connections are pruned using ε1 regularization. At each level, nodes numbered 0 are clamped to 1, so their outgoing weights correspond to the o!set/bias terms. (b) Predictions made by the model on the training set. Generated by sparse\_mlp.ipynb.

Figure 13.18: Illustration of dropout. (a) A standard neural net with 2 hidden layers. (b) An example of a thinned net produced by applying dropout with p0 = 0.5. Units that have been dropped out are marked with an x. From Figure 1 of [Sri+14]. Used with kind permission of Geo! Hinton.

units from learning complex, but fragile, dependencies on each other.7 A more formal explanation, in terms of Gaussian scale mixture priors, can be found in [NHLS19].

We can view dropout as estimating a noisy version of the weights, ⇁lji = wlji,li, where ,li ∝ Ber(1 ↗ p) is a Bernoulli noise term. (So if we sample ,li = 0, then all of the weights going out of unit i in layer l ↗ 1 into any j in layer l will be set to 0.) At test time, we usually turn the noise o!.

7. Geo! Hinton, who invented dropout, said he was inspired by a talk on sexual reproduction, which encourages genes to be individually useful (or at most depend on a small number of other genes), even when combined with random other genes.

To ensure the weights have the same expectation at test time as they did during training (so the input activation to the neurons is the same, on average), at test time we should use wlij = ⇁ljiE [,li]. For Bernoulli noise, we have E [,] = 1 ↗ p, so we should multiply the weights by the keep probability, 1 ↗ p, before making predictions.

We can, however, use dropout at test time if we wish. The result is an ensemble of networks, each with slightly di!erent sparse graph structures. This is called Monte Carlo dropout [GG16; KG17], and has the form

\[p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{z}, \mathcal{D}) \approx \frac{1}{S} \sum\_{s=1}^{S} p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{z}, \hat{\mathbf{W}}\epsilon^{s} + \hat{\mathbf{b}}) \tag{13.96}\]

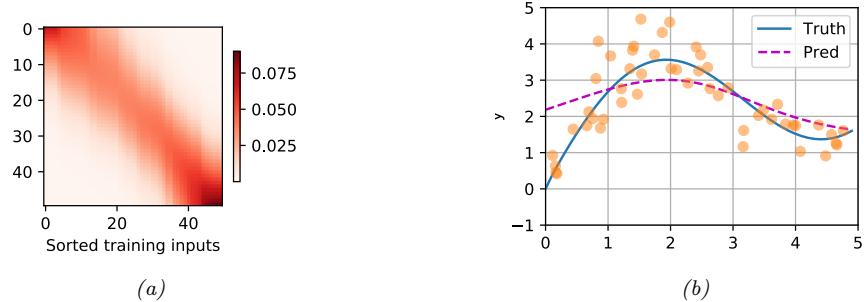

where S is the number of samples, and we write Wˆ ,s to indicate that we are multiplying all the estimated weight matrices by a sampled noise vector. This can sometimes provide a good approximation to the Bayesian posterior predictive distribution p(y|x, D), especially if the noise rate is optimized [GHK17].

13.5.5 Bayesian neural networks

Modern DNNs are usually trained using a (penalized) maximum likelihood objective to find a single setting of parameters. However, with large models, there are often many more parameters than data points, so there may be multiple possible models which fit the training data equally well, yet which generalize in di!erent ways. It is often useful to capture the induced uncertainty in the posterior predictive distribution. This can be done by marginalizing out the parameters by computing

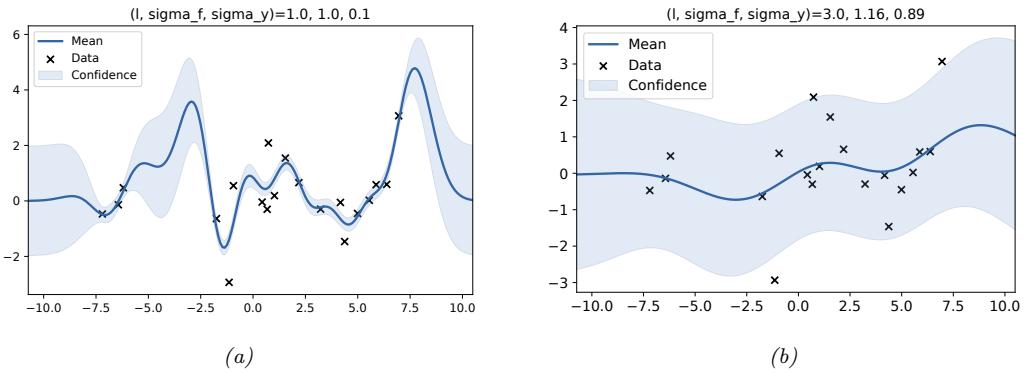

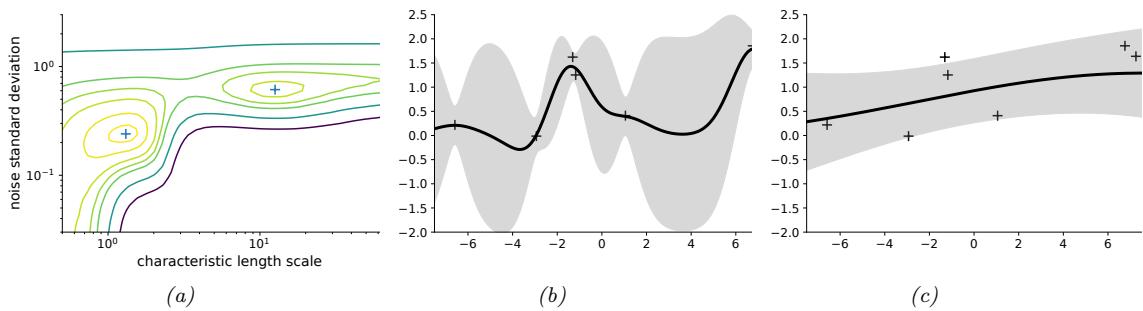

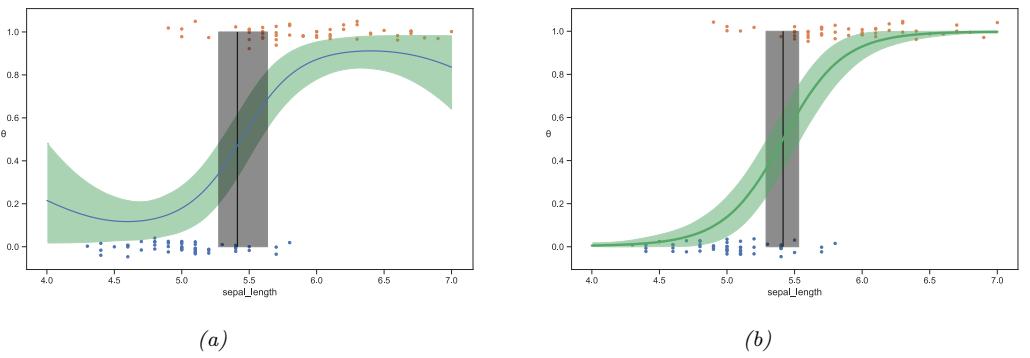

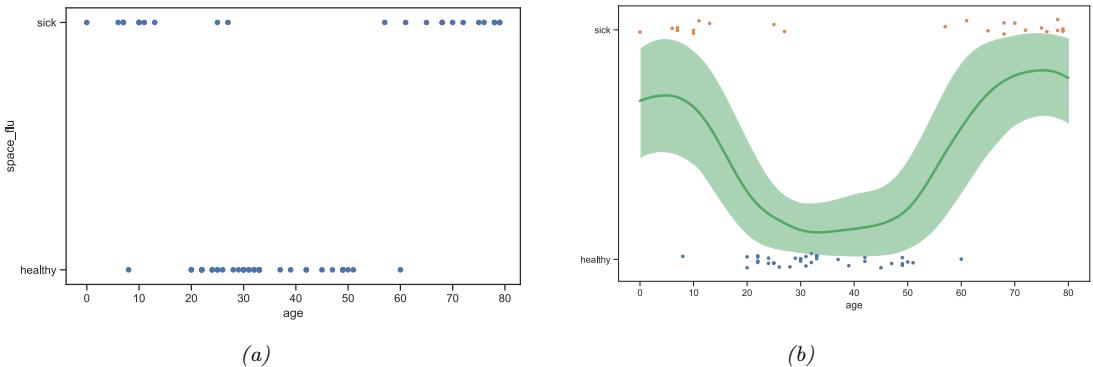

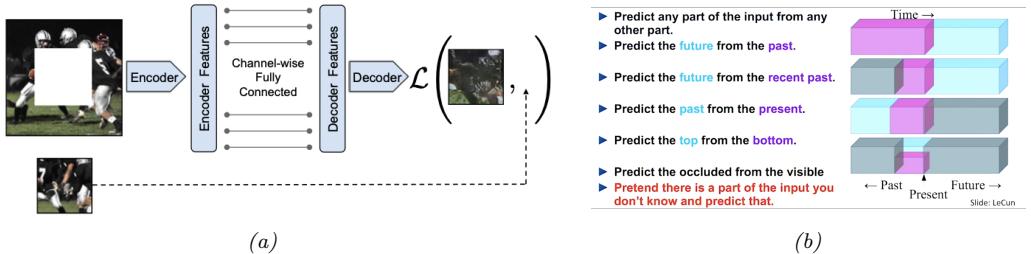

\[p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{z}, \mathcal{D}) = \int p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{z}, \boldsymbol{\theta}) p(\boldsymbol{\theta}|\mathcal{D}) d\boldsymbol{\theta} \tag{13.97}\]