Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction

Probabilistic Machine Learning

Adaptive Computation and Machine Learning

Thomas Dietterich, Editor

Christopher Bishop, David Heckerman, Michael Jordan, and Michael Kearns, Associate Editors

Bioinformatics: The Machine Learning Approach, Pierre Baldi and Søren Brunak Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, Richard S. Sutton and Andrew G. Barto Graphical Models for Machine Learning and Digital Communication, Brendan J. Frey Learning in Graphical Models, Michael I. Jordan Causation, Prediction, and Search, second edition, Peter Spirtes, Clark Glymour, and Richard Scheines Principles of Data Mining, David Hand, Heikki Mannila, and Padhraic Smyth Bioinformatics: The Machine Learning Approach, second edition, Pierre Baldi and Søren Brunak Learning Kernel Classifiers: Theory and Algorithms, Ralf Herbrich Learning with Kernels: Support Vector Machines, Regularization, Optimization, and Beyond, Bernhard Schölkopf and Alexander J. Smola Introduction to Machine Learning, Ethem Alpaydin Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning, Carl Edward Rasmussen and Christopher K.I. Williams Semi-Supervised Learning, Olivier Chapelle, Bernhard Schölkopf, and Alexander Zien, Eds. The Minimum Description Length Principle, Peter D. Grünwald Introduction to Statistical Relational Learning, Lise Getoor and Ben Taskar, Eds. Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques, Daphne Koller and Nir Friedman Introduction to Machine Learning, second edition, Ethem Alpaydin Boosting: Foundations and Algorithms, Robert E. Schapire and Yoav Freund Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective, Kevin P. Murphy Foundations of Machine Learning, Mehryar Mohri, Afshin Rostami, and Ameet Talwalker Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction, Kevin P. Murphy

Probabilistic Machine Learning An Introduction

Kevin P. Murphy

The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England

© 2022 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

This work is subject to a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license.

Subject to such license, all rights are reserved.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Murphy, Kevin P., author. Title: Probabilistic machine learning : an introduction / Kevin P. Murphy. Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] Series: Adaptive computation and machine learning series Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2021027430 | ISBN 9780262046824 (hardcover) Subjects: LCSH: Machine learning. | Probabilities. Classification: LCC Q325.5 .M872 2022 | DDC 006.3/1–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021027430

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to my mother, Brigid Murphy, who introduced me to the joy of learning and teaching.

Brief Contents

1 Introduction 1

I Foundations 31

II Linear Models 321

III Deep Neural Networks 423

IV Nonparametric Models 545

V Beyond Supervised Learning 625

19 Learning with Fewer Labeled Examples 627

- 20 Dimensionality Reduction 657

- 21 Clustering 715

- 22 Recommender Systems 741

- 23 Graph Embeddings \* 753

- A Notation 773

Contents

Preface xxvii

1 Introduction 1

I Foundations 31

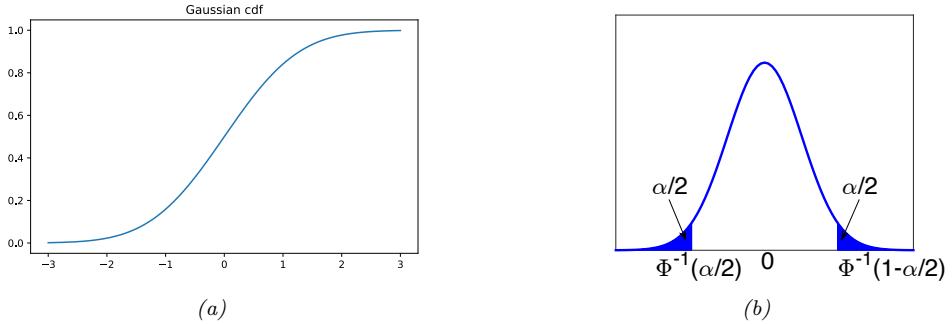

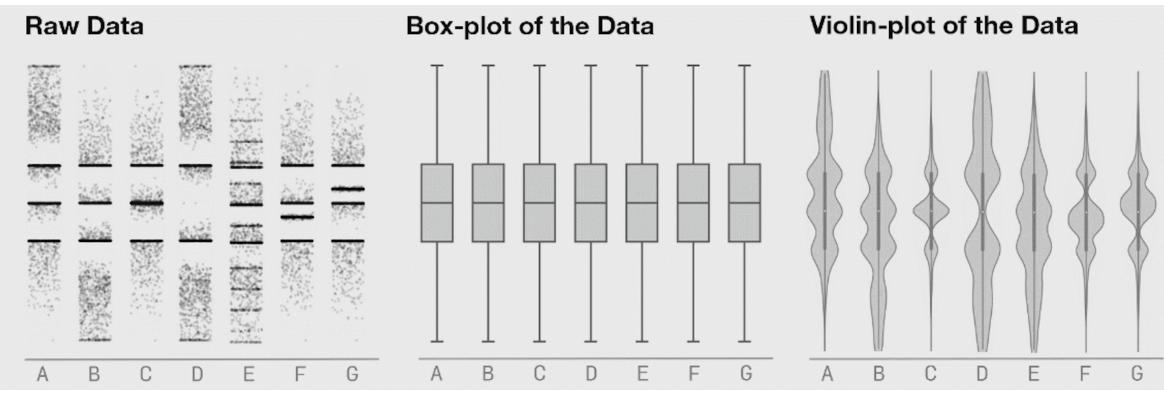

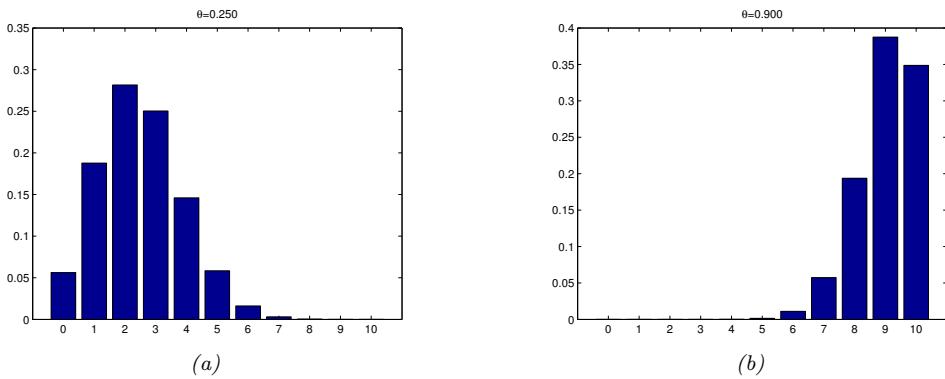

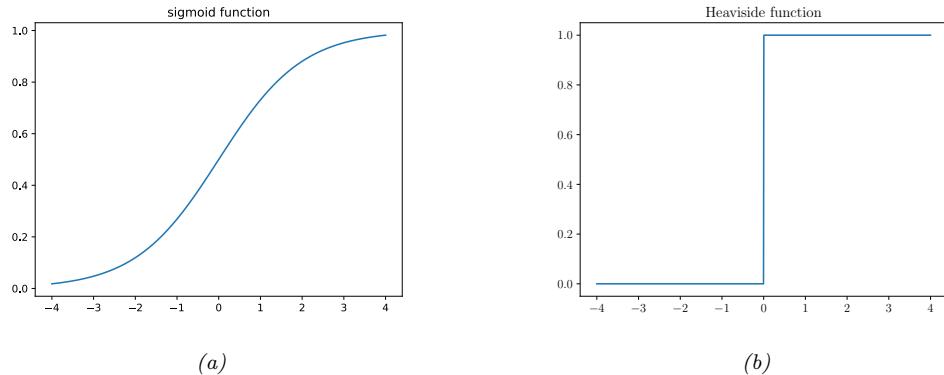

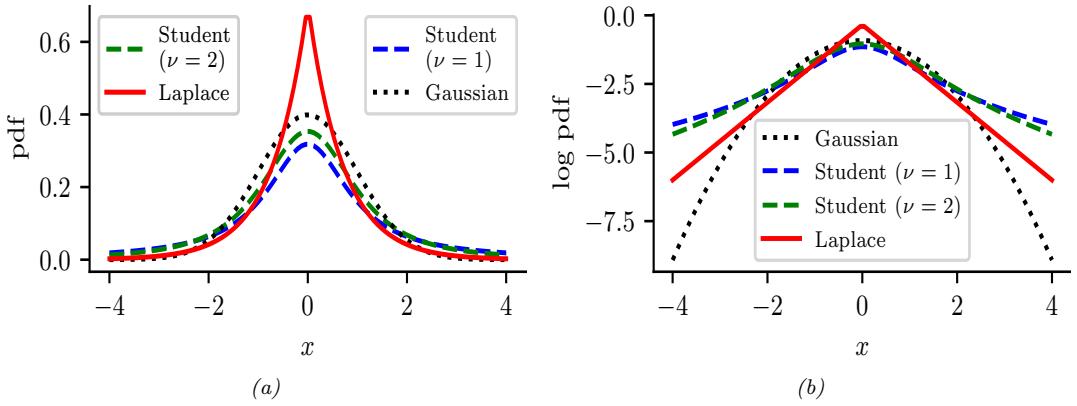

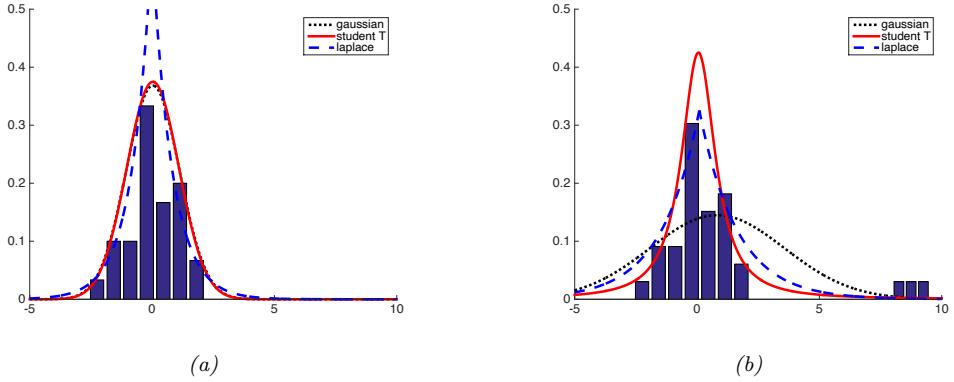

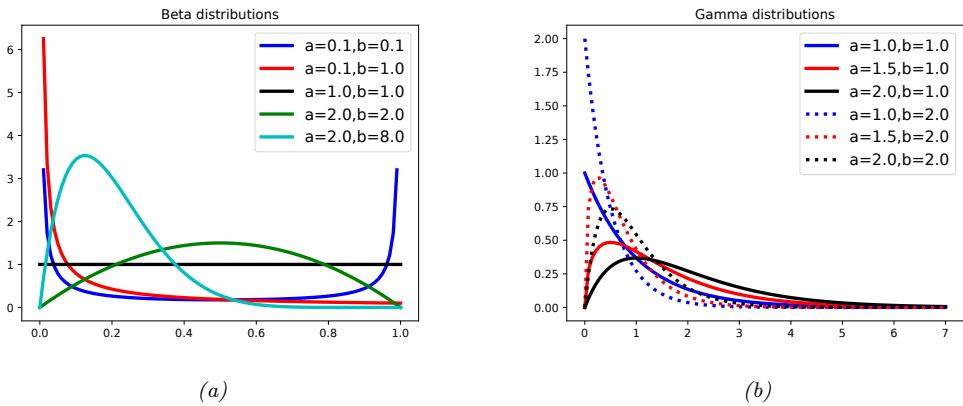

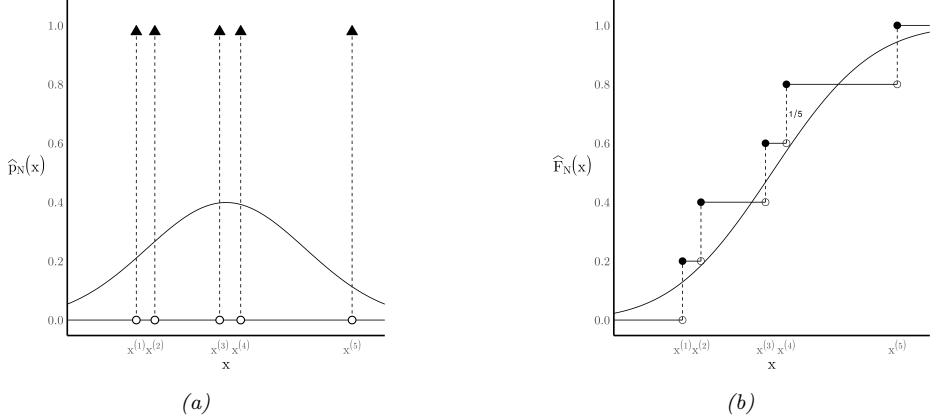

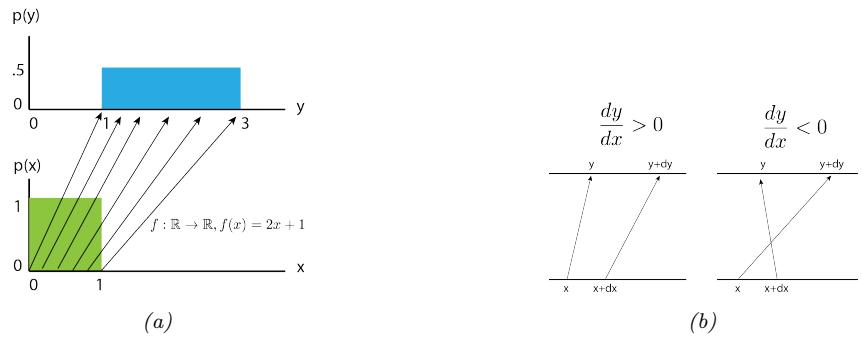

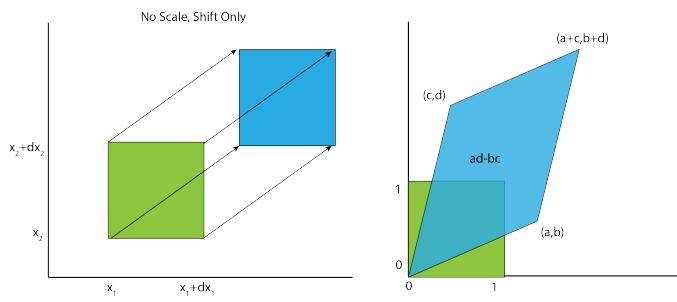

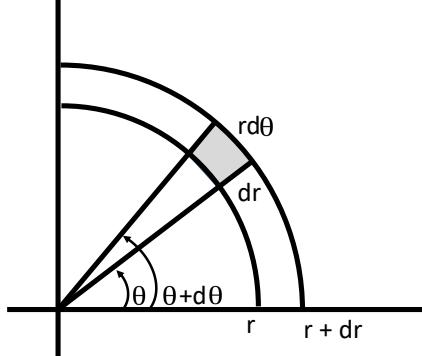

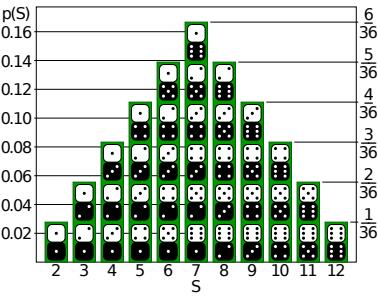

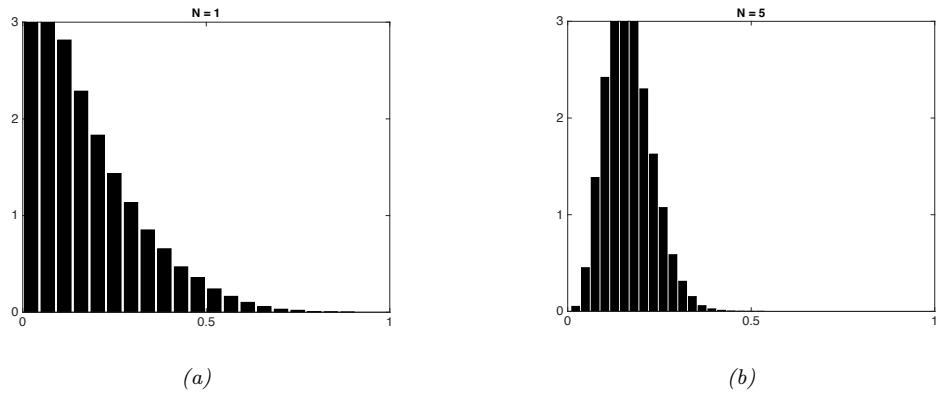

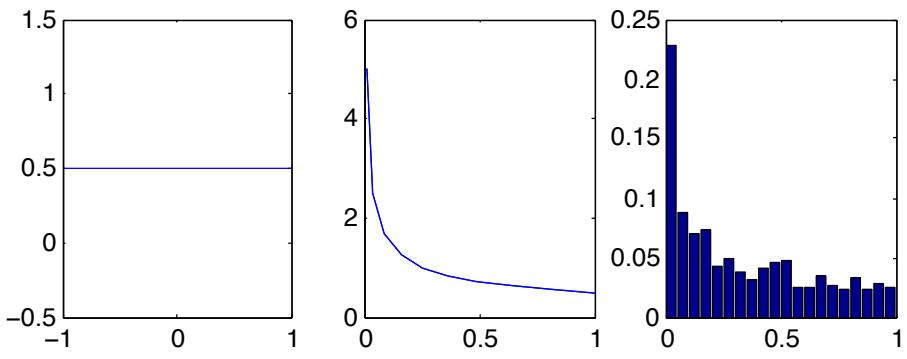

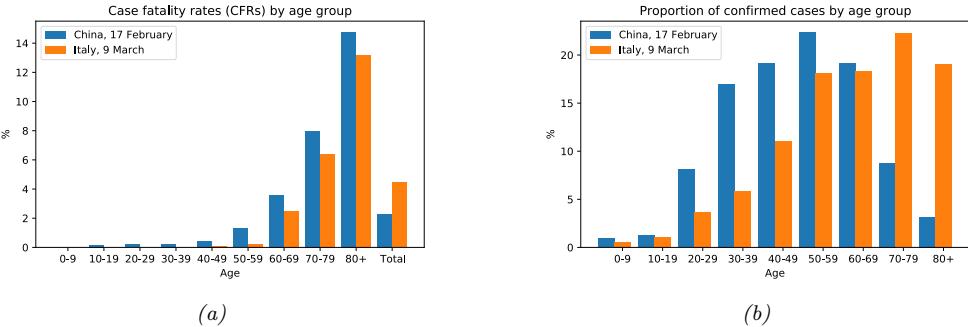

2.1.2 Types of uncertainty 33 2.1.3 Probability as an extension of logic 34 2.2 Random variables 35 2.2.1 Discrete random variables 35 2.2.2 Continuous random variables 36 2.2.3 Sets of related random variables 38 2.2.4 Independence and conditional independence 39 2.2.5 Moments of a distribution 40 2.2.6 Limitations of summary statistics \* 43 2.3 Bayes’ rule 44 2.3.1 Example: Testing for COVID-19 46 2.3.2 Example: The Monty Hall problem 47 2.3.3 Inverse problems \* 49 2.4 Bernoulli and binomial distributions 49 2.4.1 Definition 49 2.4.2 Sigmoid (logistic) function 50 2.4.3 Binary logistic regression 52 2.5 Categorical and multinomial distributions 53 2.5.1 Definition 53 2.5.2 Softmax function 54 2.5.3 Multiclass logistic regression 55 2.5.4 Log-sum-exp trick 56 2.6 Univariate Gaussian (normal) distribution 57 2.6.1 Cumulative distribution function 57 2.6.2 Probability density function 58 2.6.3 Regression 59 2.6.4 Why is the Gaussian distribution so widely used? 60 2.6.5 Dirac delta function as a limiting case 60 2.6.6 Truncated Gaussian distribution 61 2.7 Some other common univariate distributions \* 61 2.7.1 Student t distribution 61 2.7.2 Cauchy distribution 63 2.7.3 Laplace distribution 63 2.7.4 Beta distribution 63 2.7.5 Gamma distribution 64 2.7.6 Empirical distribution 65 2.8 Transformations of random variables \* 66 2.8.1 Discrete case 66 2.8.2 Continuous case 67 2.8.3 Invertible transformations (bijections) 67 2.8.4 Moments of a linear transformation 69 2.8.5 The convolution theorem 70 2.8.6 Central limit theorem 72 2.8.7 Monte Carlo approximation 73

| 3 | Probability: | Multivariate Models 77 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1 | Joint | distributions for multiple random variables 77 |

||||

| 3.1.1 | Covariance 77 |

|||||

| 3.1.2 | Correlation 78 |

|||||

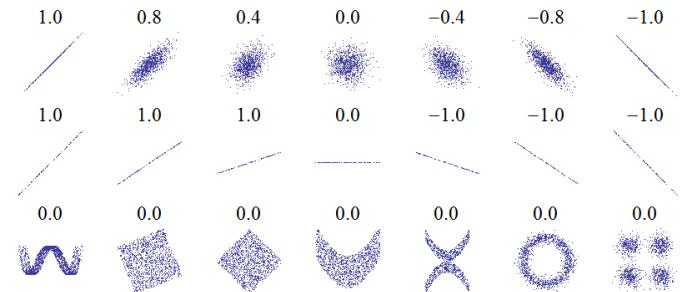

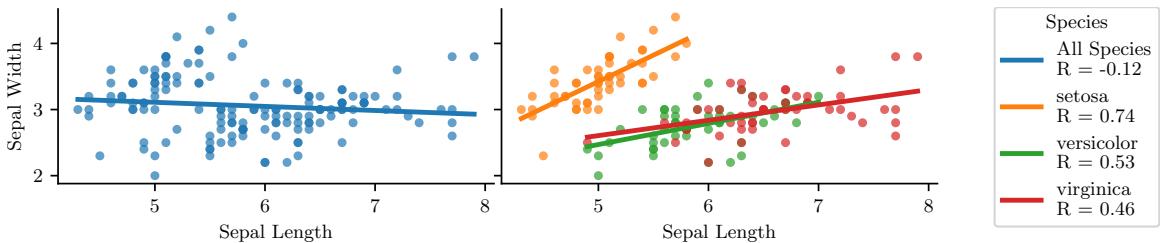

| 3.1.3 | Uncorrelated does not imply independent 79 |

|||||

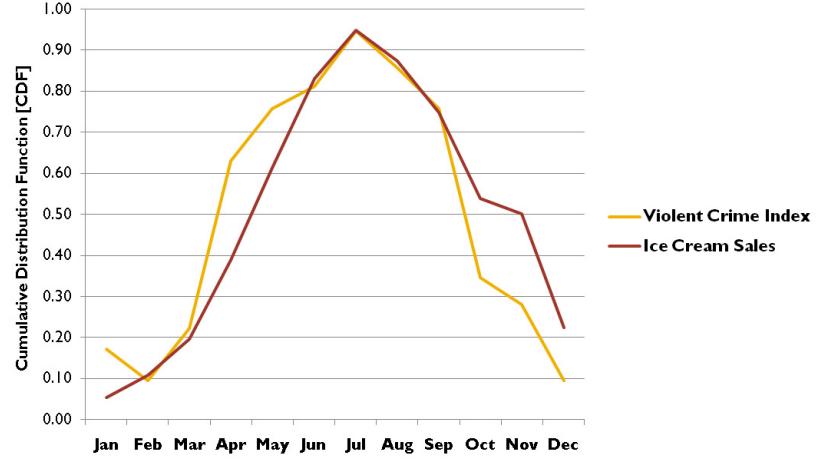

| 3.1.4 | Correlation does not imply causation 79 |

|||||

| 3.1.5 | Simpson’s paradox 80 |

|||||

| 3.2 | The | multivariate Gaussian (normal) distribution 80 |

||||

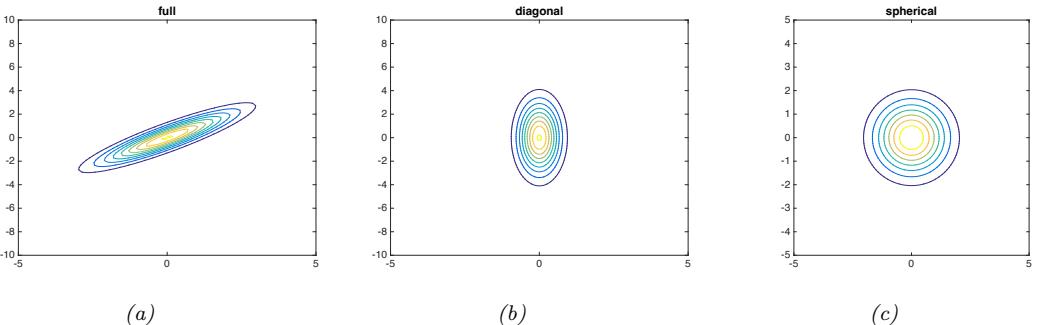

| 3.2.1 | Definition 81 |

|||||

| 3.2.2 | Mahalanobis distance 83 |

|||||

| 3.2.3 | Marginals and conditionals of an MVN * 84 |

|||||

| 3.2.4 | Example: conditioning a 2d Gaussian 85 |

|||||

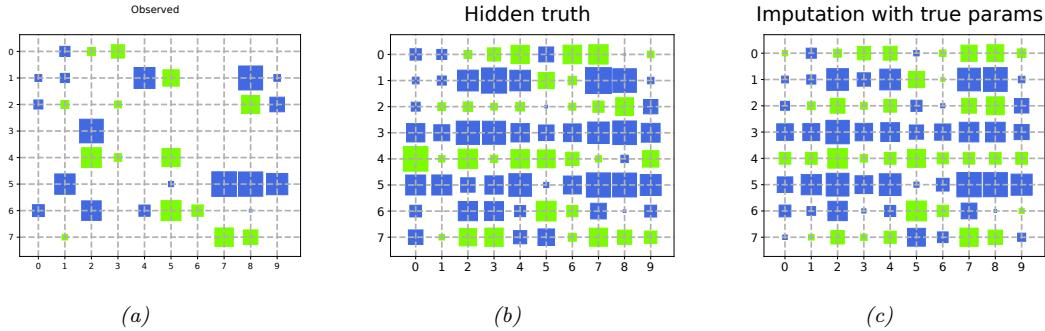

| 3.2.5 | Example: Imputing missing values * 85 |

|||||

| 3.3 | Linear | Gaussian systems * 86 |

||||

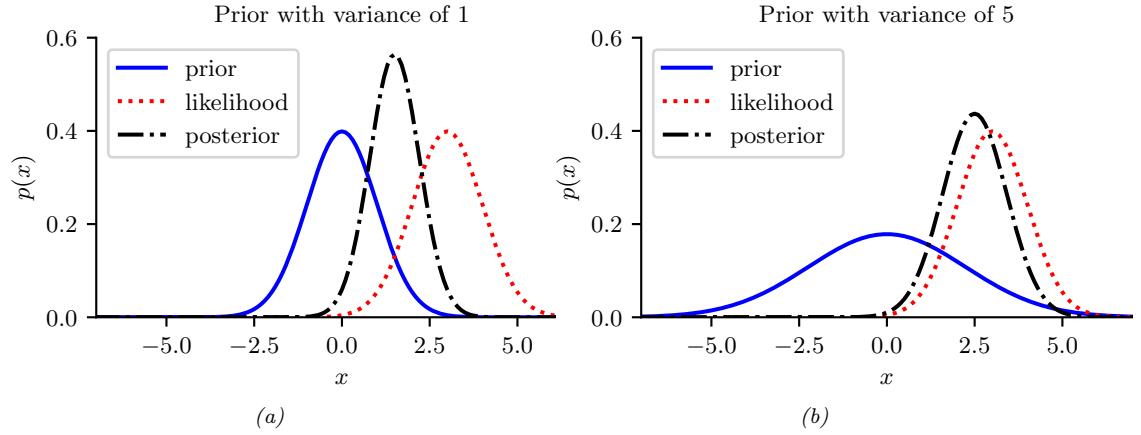

| 3.3.1 | Bayes rule for Gaussians 87 |

|||||

| 3.3.2 | Derivation * 87 |

|||||

| 3.3.3 | Example: Inferring an unknown scalar 88 |

|||||

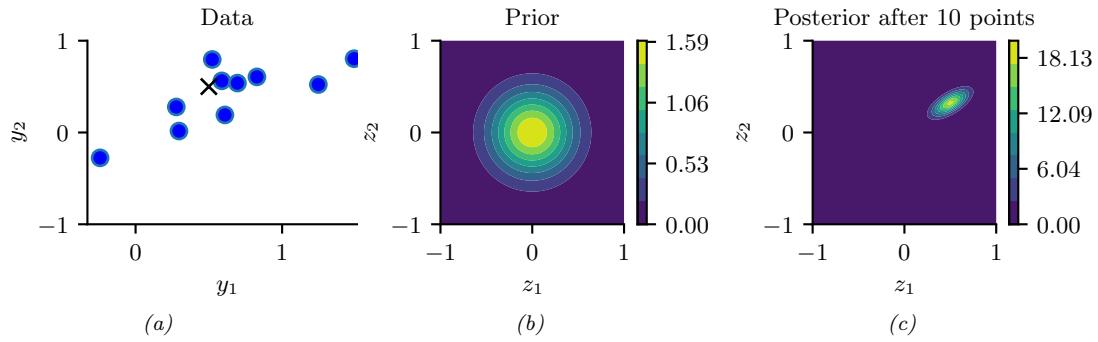

| 3.3.4 | Example: inferring an unknown vector 90 |

|||||

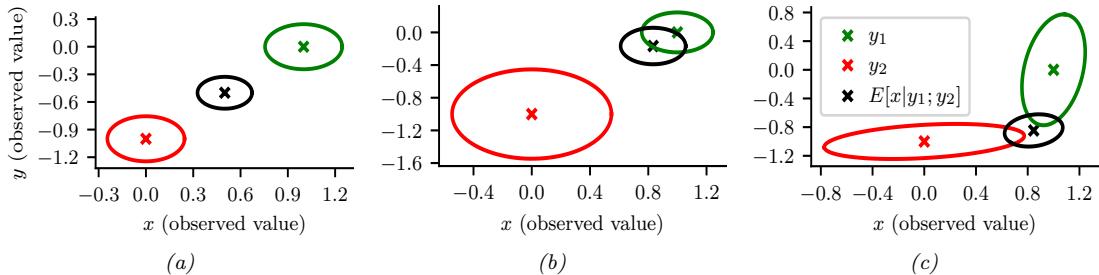

| 3.3.5 | Example: sensor fusion 92 |

|||||

| 3.4 | The | exponential family * 93 |

||||

| 3.4.1 | Definition 93 |

|||||

| 3.4.2 | Example 94 |

|||||

| 3.4.3 | Log partition function is cumulant generating function 95 |

|||||

| 3.4.4 | Maximum entropy derivation of the exponential family 95 |

|||||

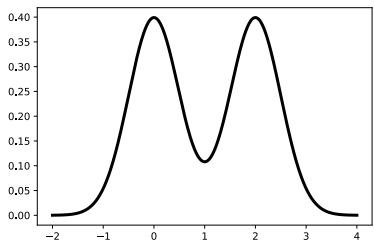

| 3.5 | Mixture | models 96 |

||||

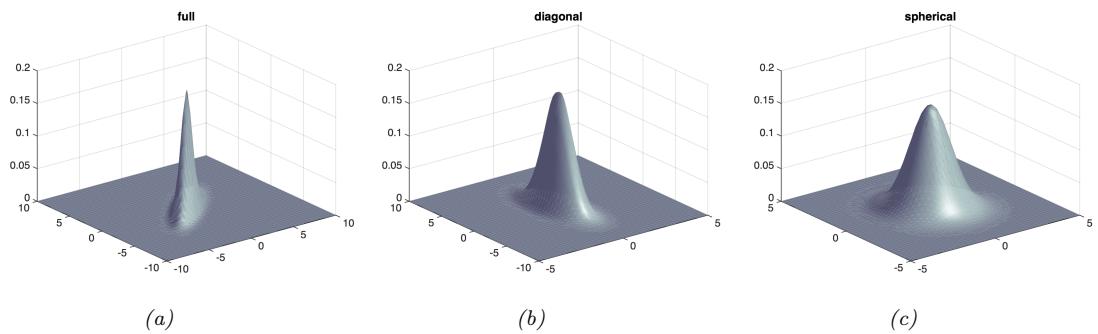

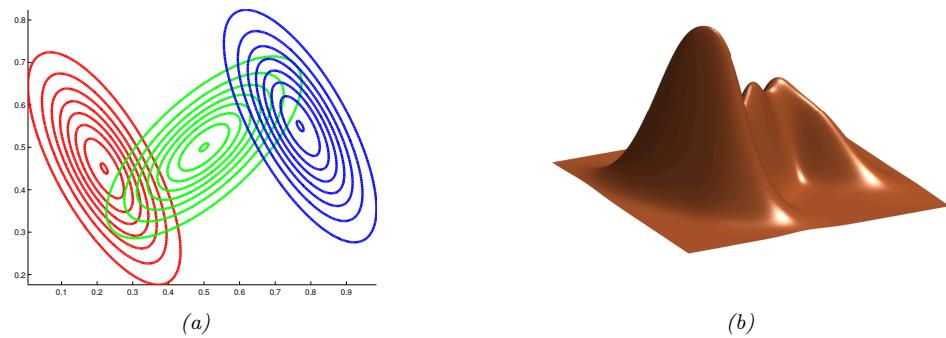

| 3.5.1 | Gaussian mixture models 97 |

|||||

| 3.5.2 | Bernoulli mixture models 98 |

|||||

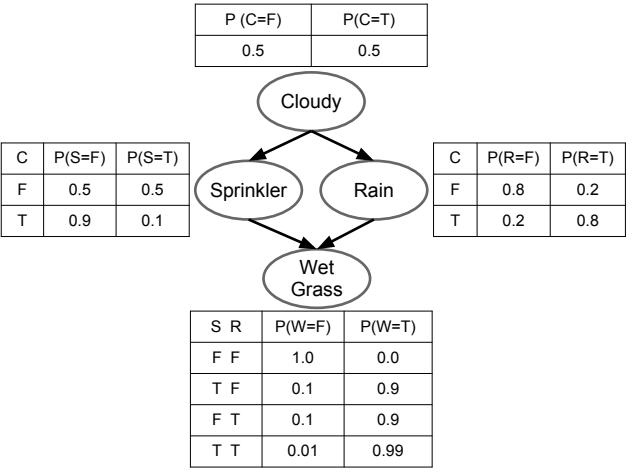

| 3.6 | Probabilistic | graphical models * 99 |

||||

| 3.6.1 | Representation 100 |

|||||

| 3.6.2 | Inference 102 |

|||||

| 3.6.3 | Learning 102 |

|||||

| 3.7 | Exercises | 103 | ||||

| 4 | Statistics | 107 | ||||

| 4.1 4.2 |

Introduction Maximum |

107 likelihood estimation (MLE) 107 |

||||

| 4.2.1 | Definition 107 |

|||||

| 4.2.2 | Justification for MLE 108 |

|||||

| 4.2.3 | Example: MLE for the Bernoulli distribution 110 |

|||||

| 4.2.4 | Example: MLE for the categorical distribution 111 |

|||||

| 4.2.5 | Example: MLE for the univariate Gaussian 111 |

|||||

| 4.2.6 | Example: MLE for the multivariate Gaussian 112 |

|||||

| 4.2.7 | Example: MLE for linear regression 114 |

|||||

| 4.3 | Empirical | risk minimization (ERM) 115 |

||||

| 4.3.1 | Example: minimizing the misclassification rate 116 |

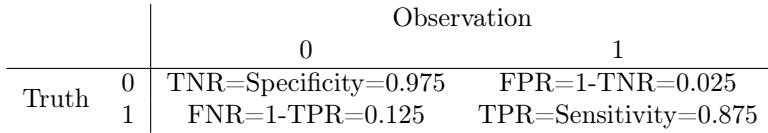

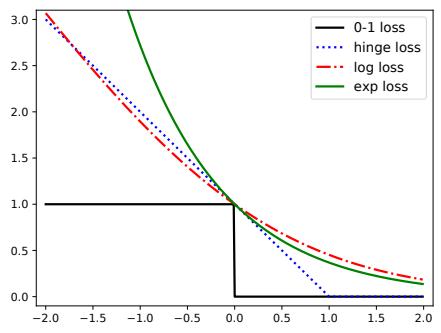

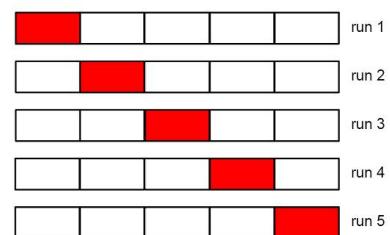

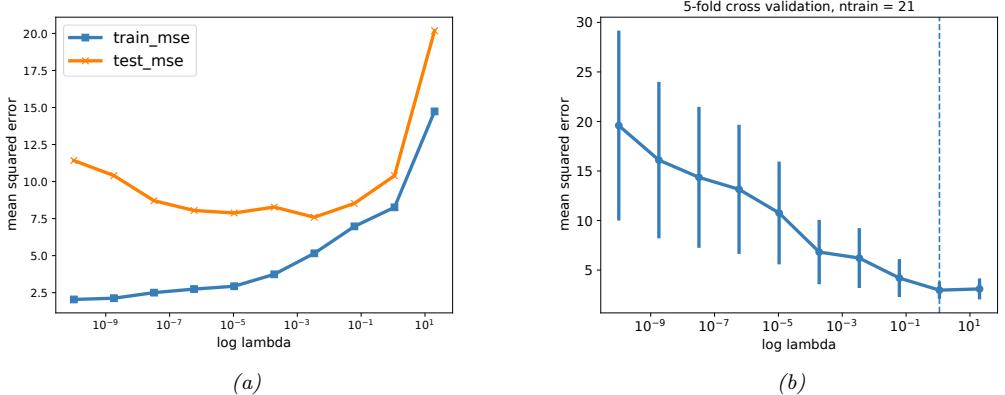

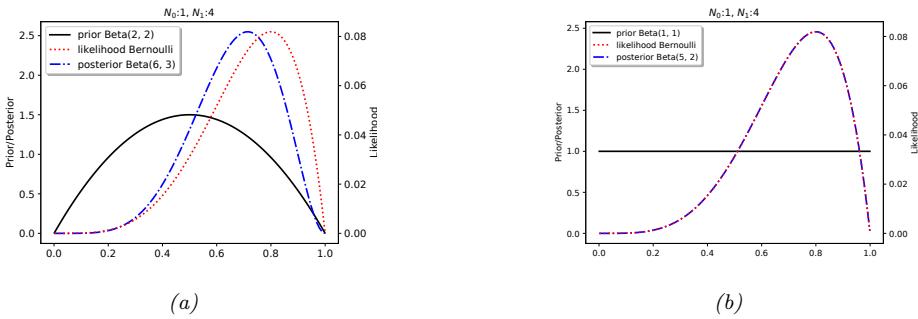

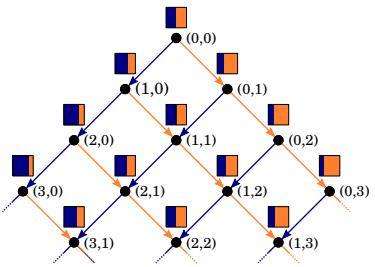

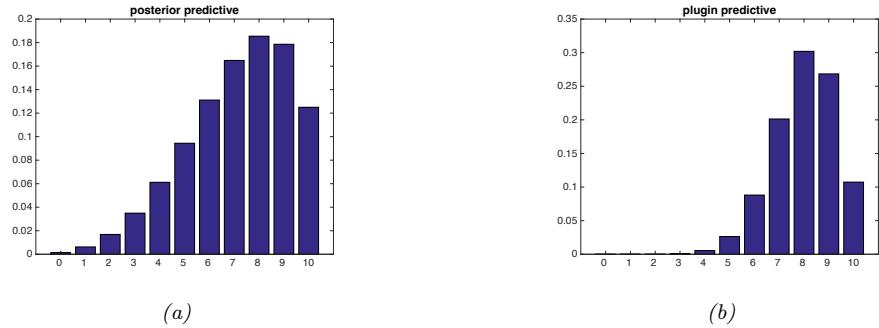

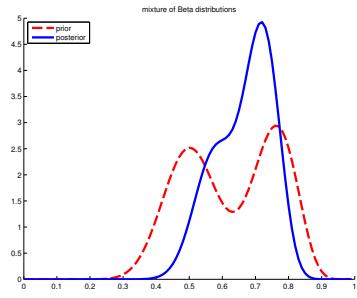

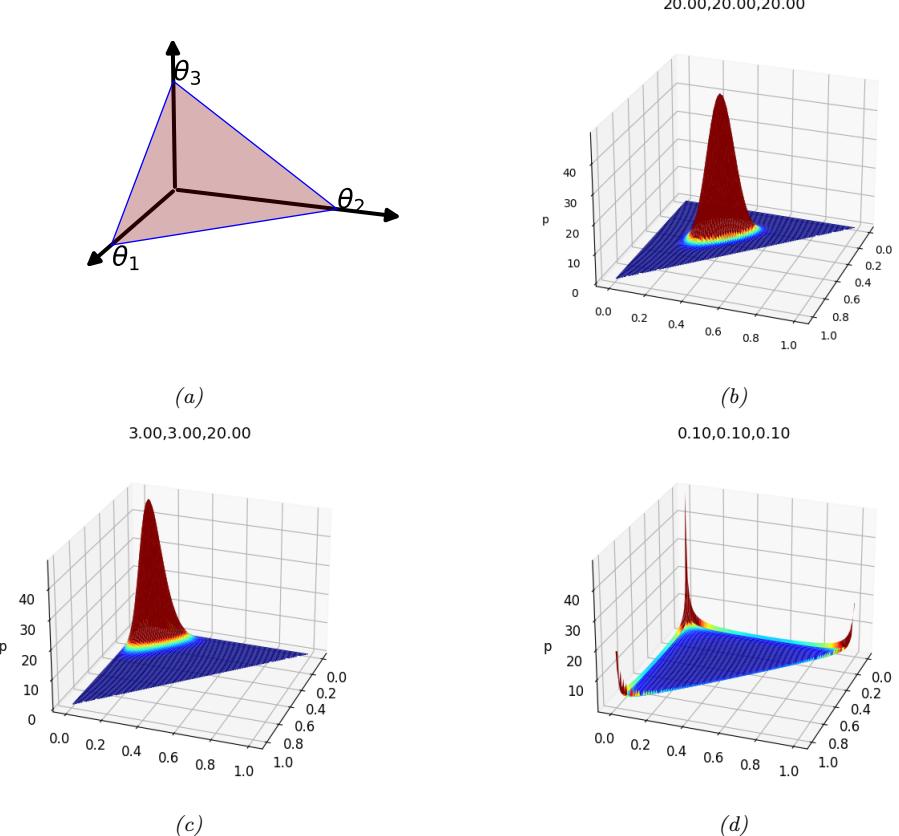

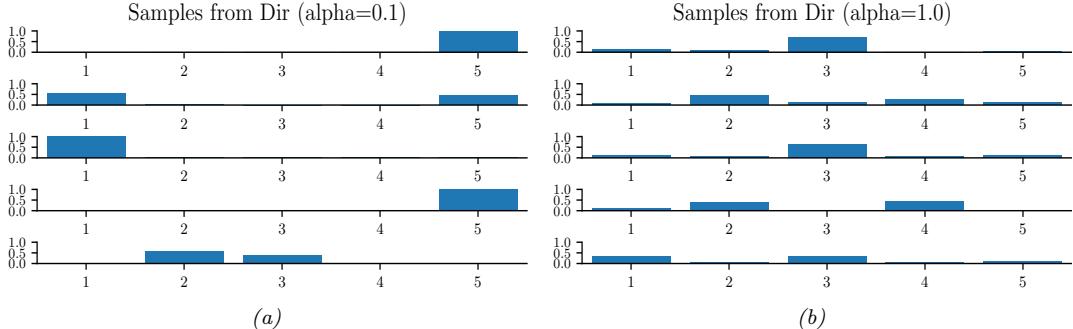

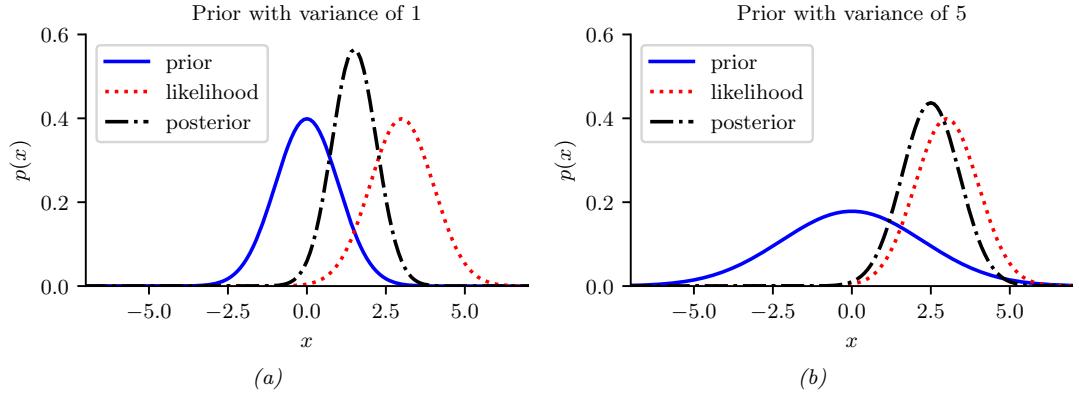

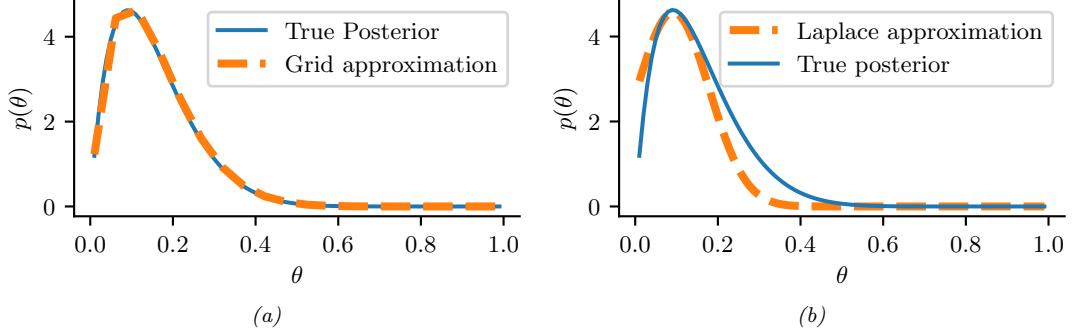

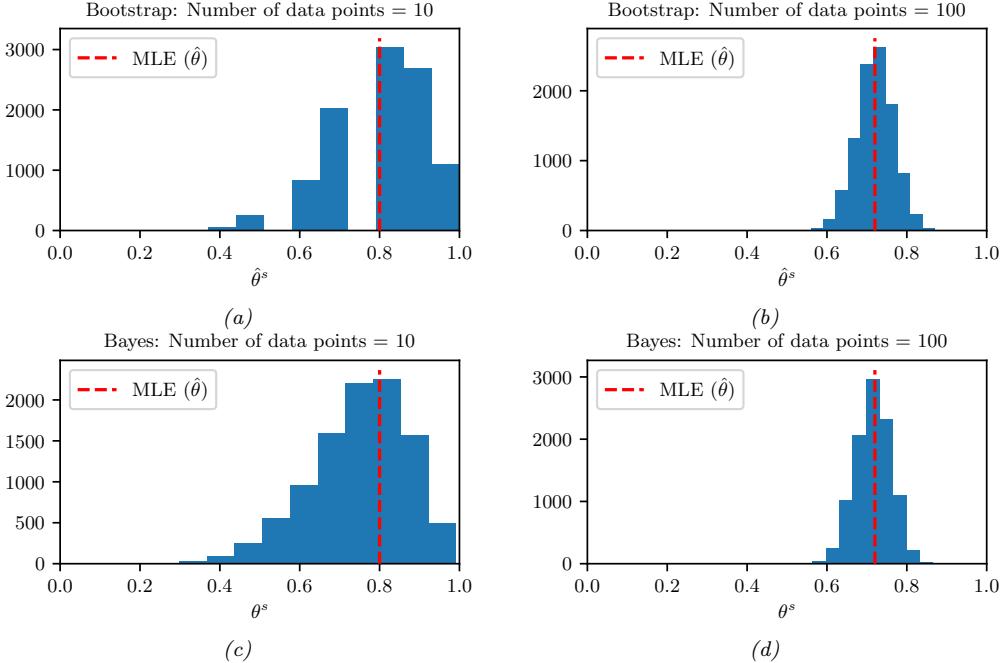

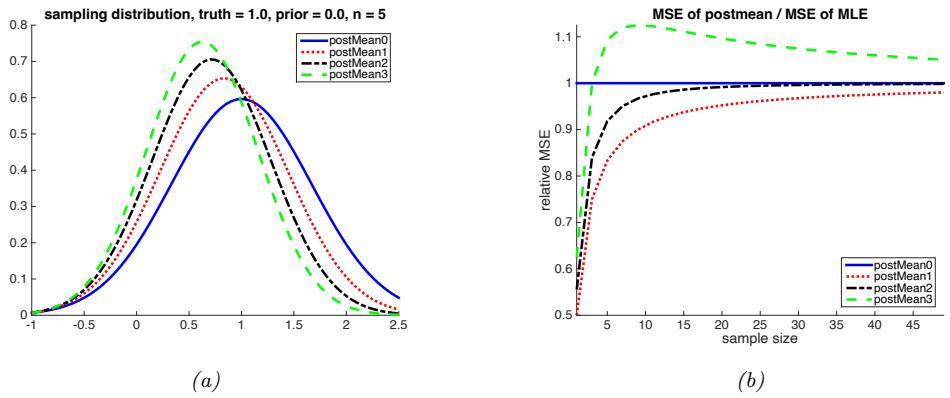

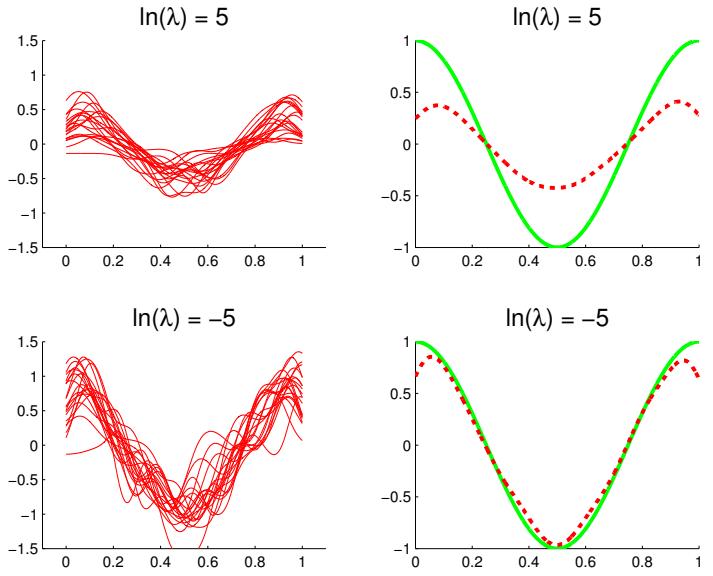

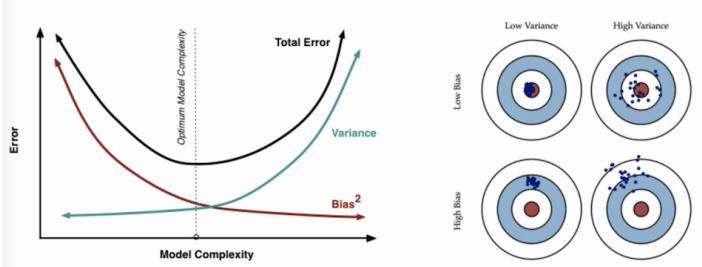

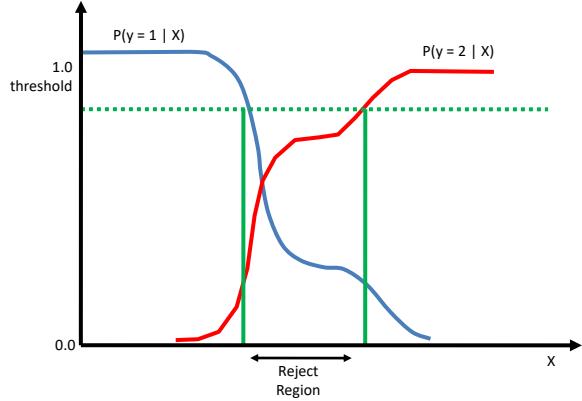

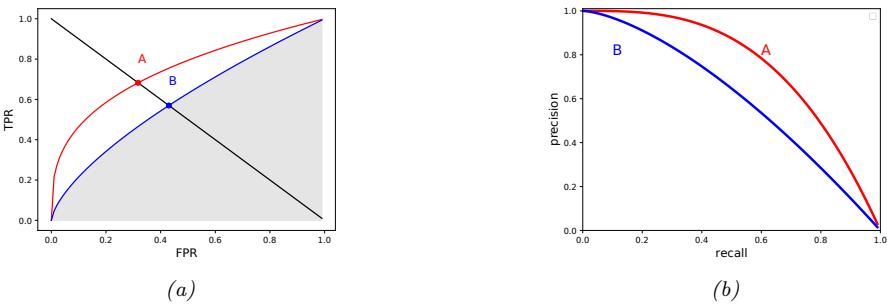

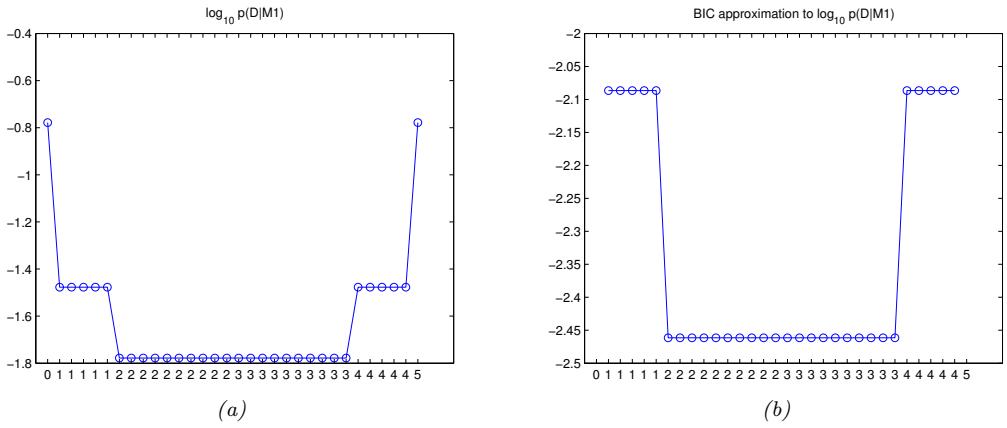

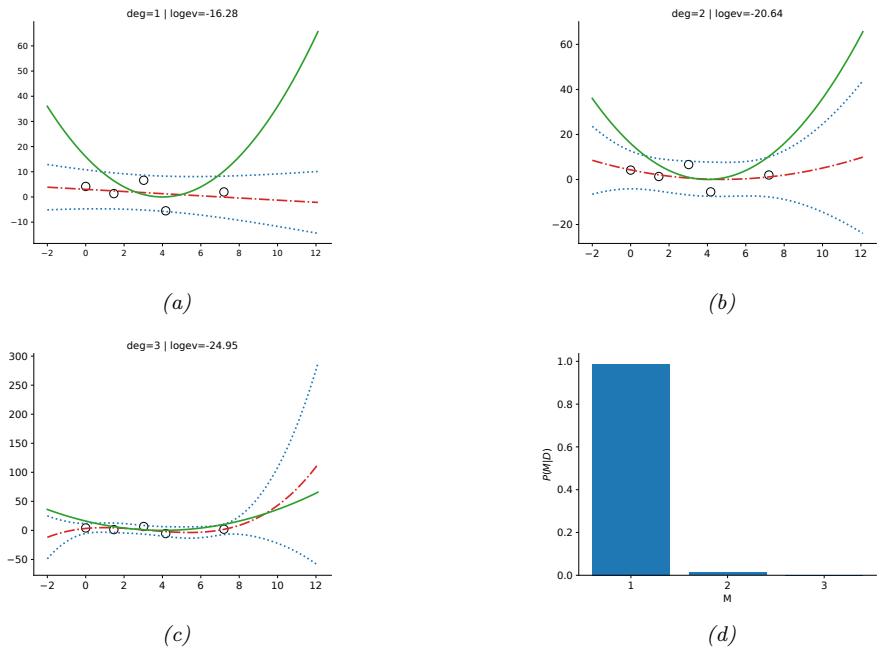

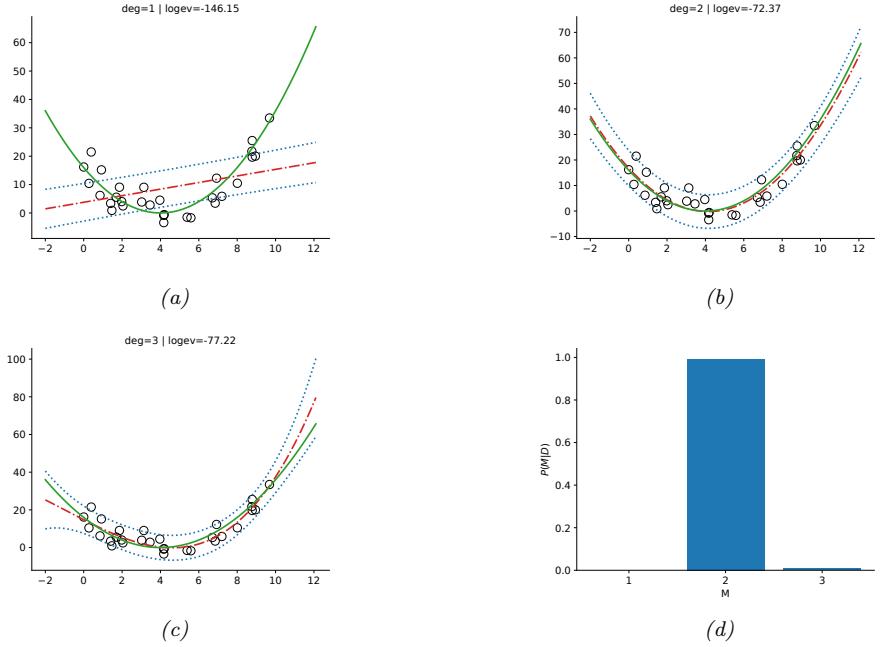

4.3.2 Surrogate loss 116 4.4 Other estimation methods \* 117 4.4.1 The method of moments 117 4.4.2 Online (recursive) estimation 119 4.5 Regularization 120 4.5.1 Example: MAP estimation for the Bernoulli distribution 121 4.5.2 Example: MAP estimation for the multivariate Gaussian \* 122 4.5.3 Example: weight decay 123 4.5.4 Picking the regularizer using a validation set 124 4.5.5 Cross-validation 125 4.5.6 Early stopping 126 4.5.7 Using more data 127 4.6 Bayesian statistics \* 129 4.6.1 Conjugate priors 129 4.6.2 The beta-binomial model 130 4.6.3 The Dirichlet-multinomial model 137 4.6.4 The Gaussian-Gaussian model 141 4.6.5 Beyond conjugate priors 144 4.6.6 Credible intervals 146 4.6.7 Bayesian machine learning 147 4.6.8 Computational issues 151 4.7 Frequentist statistics \* 154 4.7.1 Sampling distributions 154 4.7.2 Gaussian approximation of the sampling distribution of the MLE 155 4.7.3 Bootstrap approximation of the sampling distribution of any estimator 156 4.7.4 Confidence intervals 157 4.7.5 Caution: Confidence intervals are not credible 158 4.7.6 The bias-variance tradeo! 159 4.8 Exercises 164 5 Decision Theory 167 5.1 Bayesian decision theory 167 5.1.1 Basics 167 5.1.2 Classification problems 169 5.1.3 ROC curves 171 5.1.4 Precision-recall curves 174 5.1.5 Regression problems 176 5.1.6 Probabilistic prediction problems 177 5.2 Choosing the “right” model 179 5.2.1 Bayesian hypothesis testing 179 5.2.2 Bayesian model selection 181 5.2.3 Occam’s razor 183 5.2.4 Connection between cross validation and marginal likelihood 184 5.2.5 Information criteria 185 5.2.6 Posterior inference over e 187

187

- 5.3 Frequentist decision theory 189

- 5.4 Empirical risk minimization 193

- 5.5 Frequentist hypothesis testing \* 198

- 5.6 Exercises 204

6 Information Theory 207

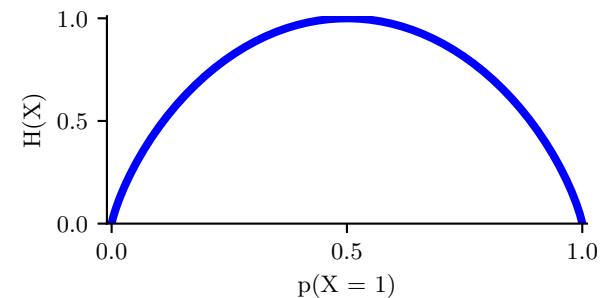

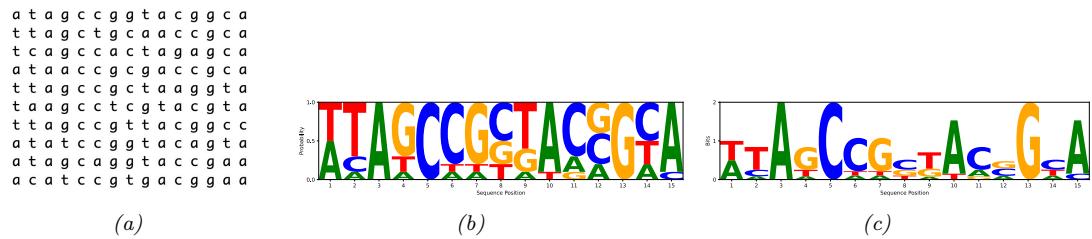

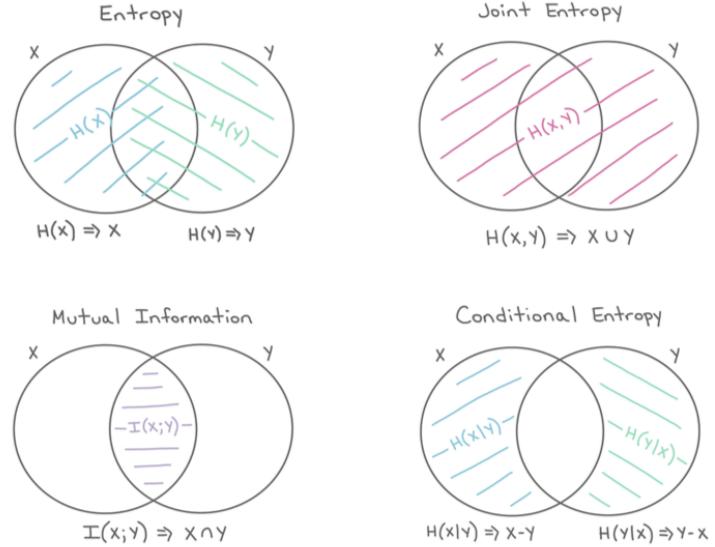

| 6.1 | Entropy | 207 |

|---|---|---|

| 6.1.1 | Entropy for discrete random variables 207 |

|

| 6.1.2 | Cross entropy 209 |

|

| 6.1.3 | Joint entropy 209 |

|

| 6.1.4 | Conditional entropy 210 |

|

| 6.1.5 | Perplexity 211 |

|

| 6.1.6 | Di!erential entropy for continuous random variables * 212 |

|

| 6.2 | Relative | entropy (KL divergence) * 213 |

| 6.2.1 | Definition 213 |

|

| 6.2.2 | Interpretation 214 |

|

| 6.2.3 | Example: KL divergence between two Gaussians 214 |

|

| 6.2.4 | Non-negativity of KL 214 |

|

| 6.2.5 | KL divergence and MLE 215 |

|

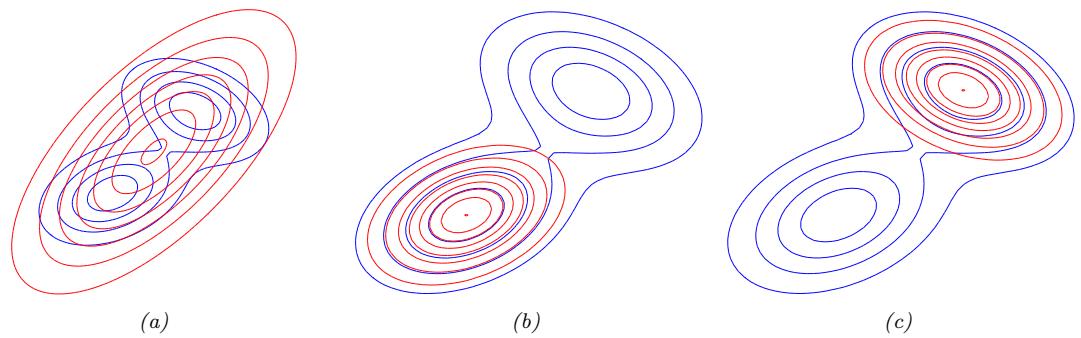

| 6.2.6 | Forward vs reverse KL 216 |

|

| 6.3 | Mutual | information * 217 |

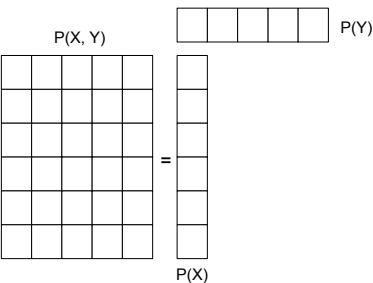

| 6.3.1 | Definition 217 |

|

| 6.3.2 | Interpretation 218 |

|

| 6.3.3 | Example 218 |

|

| 6.3.4 | Conditional mutual information 219 |

|

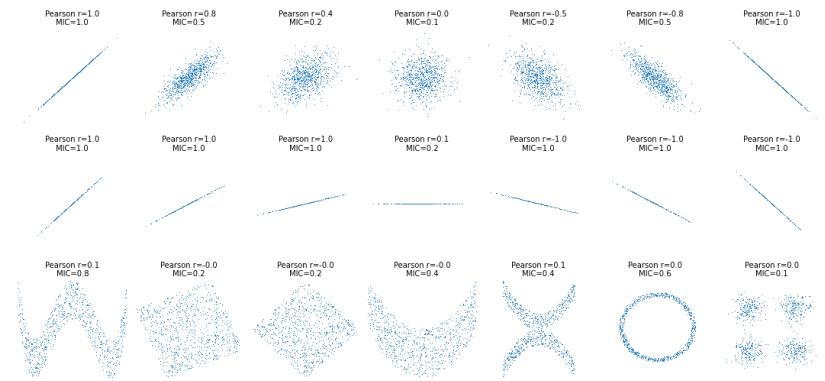

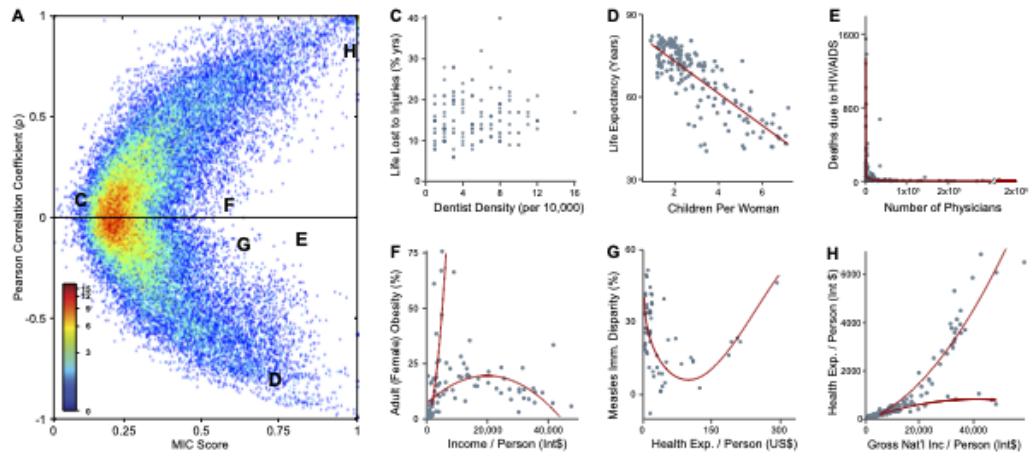

| 6.3.5 | MI as a “generalized correlation coe”cient” 220 |

|

| 6.3.6 | Normalized mutual information 221 |

|

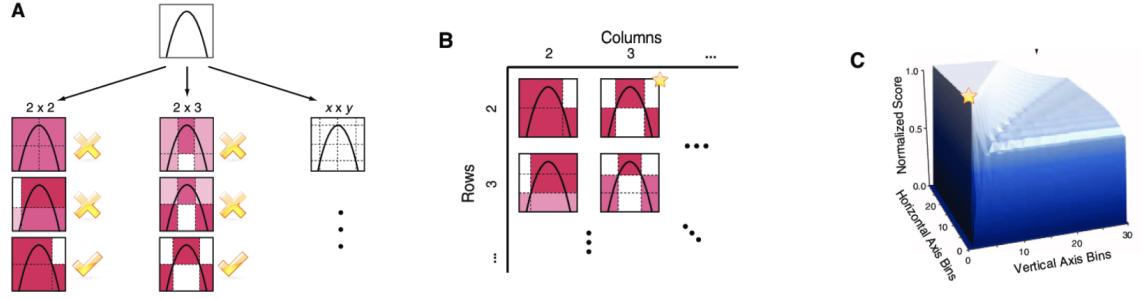

| 6.3.7 | Maximal information coe”cient 221 |

|

| 6.3.8 | Data processing inequality 223 |

|

| 6.3.9 | Su”cient Statistics 224 |

|

| 6.3.10 | Fano’s inequality * 225 |

|

| 6.4 | Exercises | 226 |

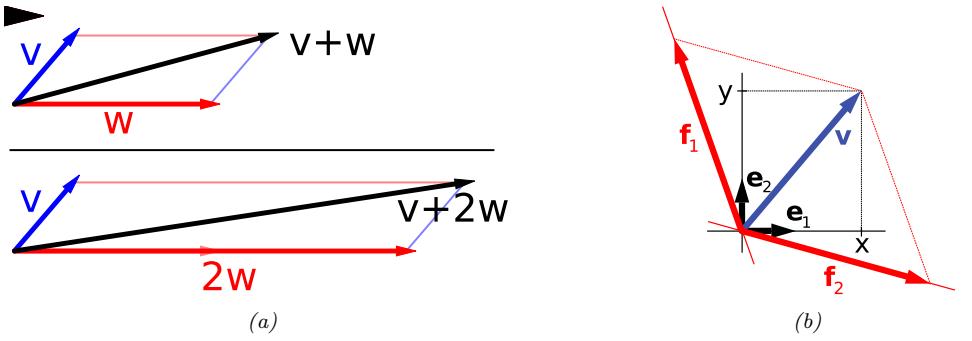

| 7 | Linear | Algebra | 229 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.1 | Introduction | 229 | |

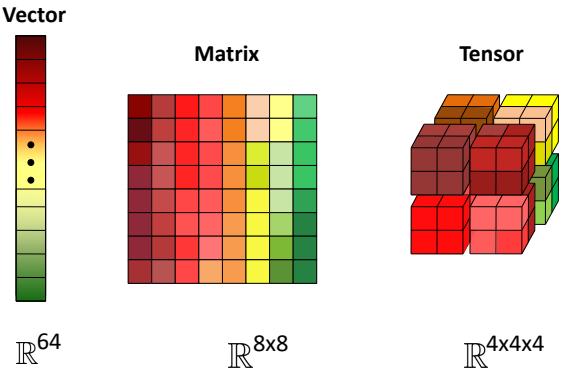

| 7.1.1 | Notation 229 |

||

| 7.1.2 | Vector spaces 232 |

||

| 7.1.3 | Norms of a vector and matrix 234 |

||

| 7.1.4 | Properties of a matrix 236 |

||

| 7.1.5 | Special types of matrices 239 |

||

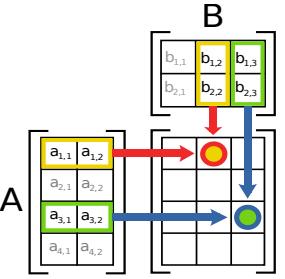

| 7.2 | Matrix | multiplication 242 |

|

| 7.2.1 | Vector–vector products 242 |

||

| 7.2.2 | Matrix–vector products 243 |

||

| 7.2.3 | Matrix–matrix products 243 |

||

| 7.2.4 | Application: manipulating data matrices 245 |

||

| 7.2.5 | Kronecker products * 248 |

||

| 7.2.6 | Einstein summation * 248 |

||

| 7.3 | Matrix | inversion 249 |

|

| 7.3.1 | The inverse of a square matrix 249 |

||

| 7.3.2 | Schur complements * 250 |

||

| 7.3.3 | The matrix inversion lemma * 251 |

||

| 7.3.4 | Matrix determinant lemma * 251 |

||

| 7.3.5 | Application: deriving the conditionals of an MVN * 252 |

||

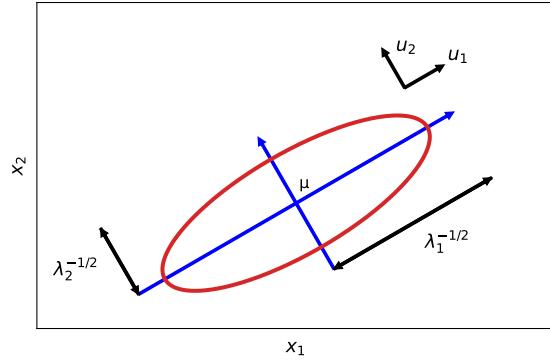

| 7.4 | Eigenvalue | decomposition (EVD) 253 |

|

| 7.4.1 | Basics 253 |

||

| 7.4.2 | Diagonalization 254 |

||

| 7.4.3 | Eigenvalues and eigenvectors of symmetric matrices 255 |

||

| 7.4.4 | Geometry of quadratic forms 256 |

||

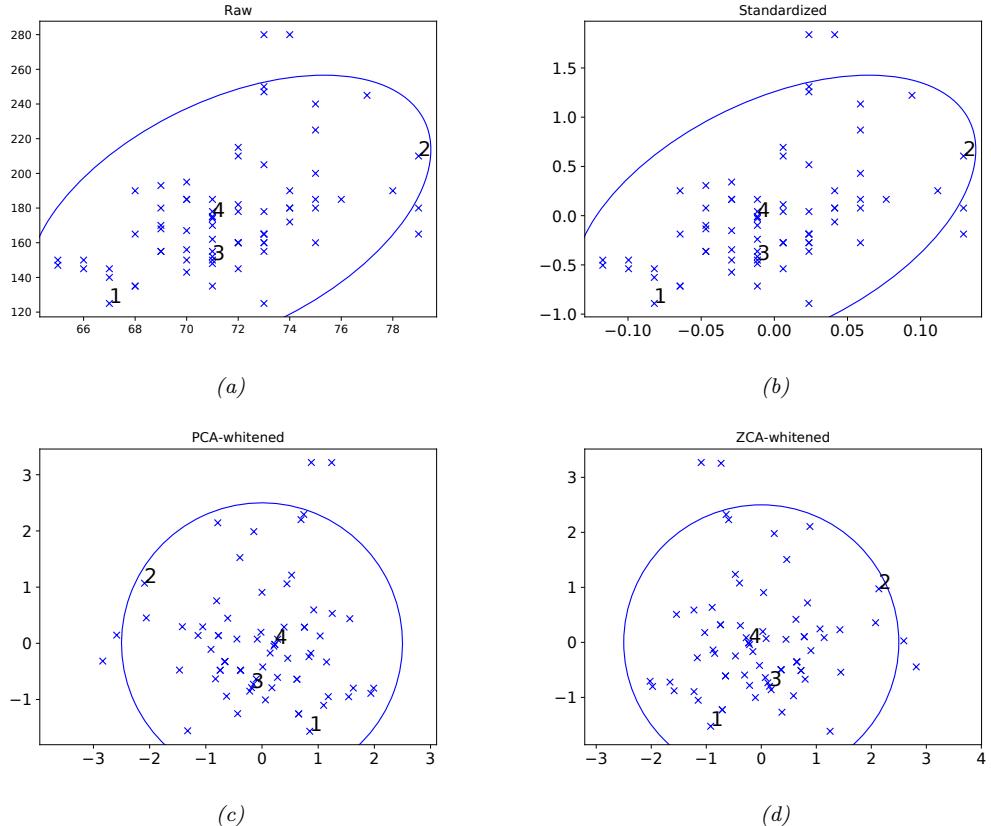

| 7.4.5 | Standardizing and whitening data 256 |

||

| 7.4.6 | Power method 258 |

||

| 7.4.7 | Deflation 259 |

||

| 7.4.8 | Eigenvectors optimize quadratic forms 259 |

||

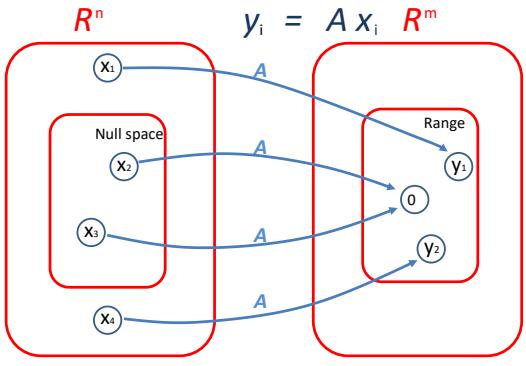

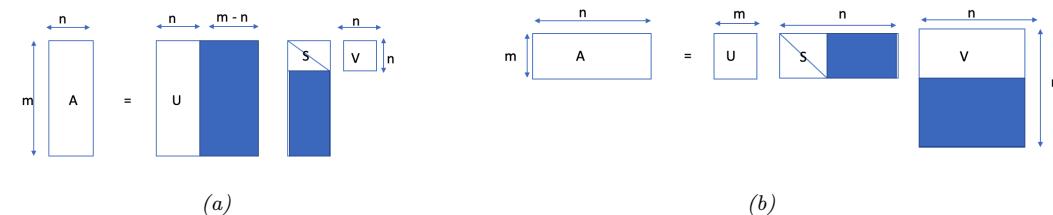

| 7.5 | Singular | value decomposition (SVD) 259 |

|

| 7.5.1 | Basics 259 |

||

| 7.5.2 | Connection between SVD and EVD 260 |

||

| 7.5.3 | Pseudo inverse 261 |

||

| 7.5.4 | SVD and the range and null space of a matrix * 262 |

||

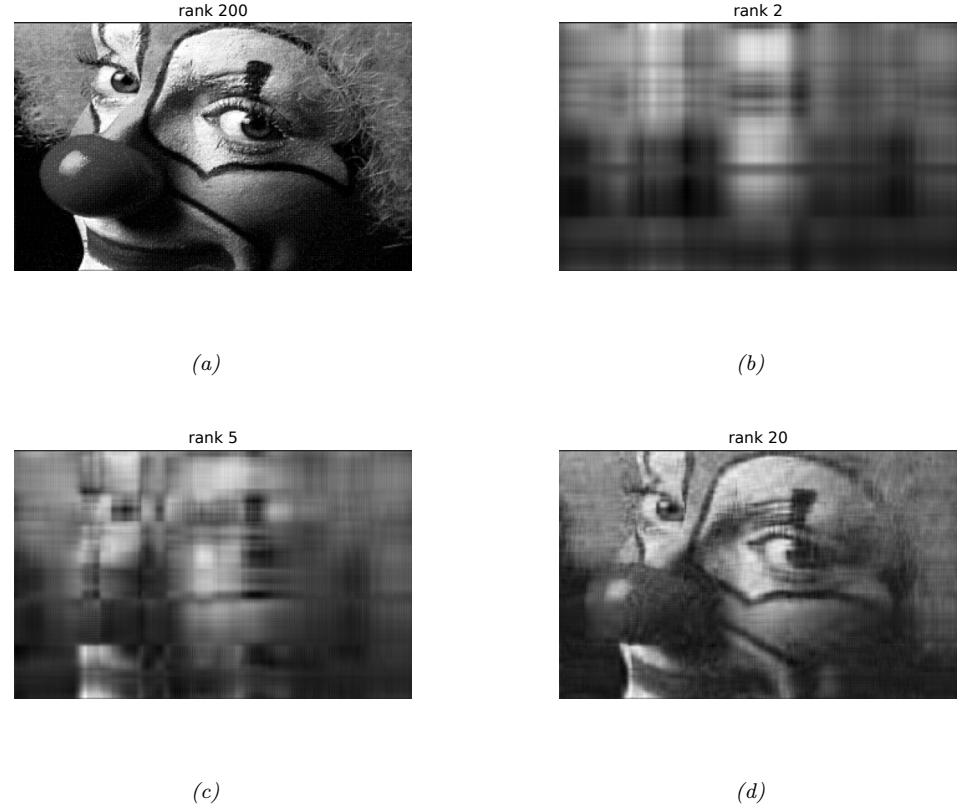

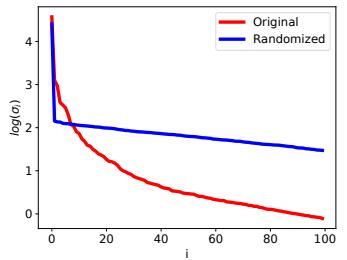

| 7.5.5 | Truncated SVD 264 |

||

| 7.6 | Other | matrix decompositions * 264 |

|

| 7.6.1 | LU factorization 264 |

||

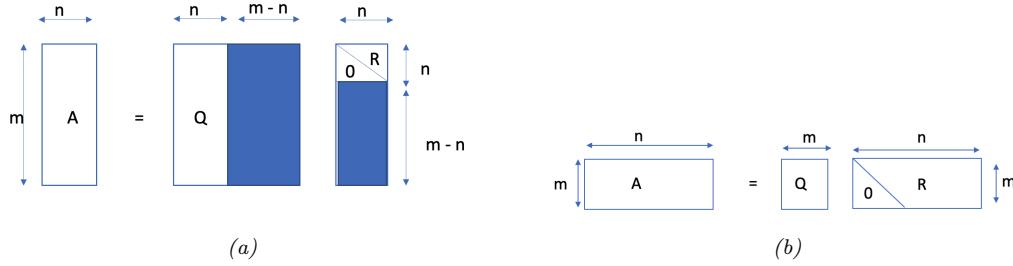

| 7.6.2 | QR decomposition 265 |

||

| 7.6.3 | Cholesky decomposition 266 |

||

| 7.7 | Solving | systems of linear equations * 266 |

|

| 7.7.1 | Solving square systems 267 |

||

| 7.7.2 | Solving underconstrained systems (least norm estimation) 267 |

||

| 7.7.3 | Solving overconstrained systems (least squares estimation) 268 |

||

| 7.8 | Matrix | calculus 269 |

|

| 7.8.1 | Derivatives 269 |

| 7.8.2 | Gradients 270 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.8.3 | Directional derivative 270 |

||

| 7.8.4 | Total derivative * 271 |

||

| 7.8.5 | Jacobian 271 |

||

| 7.8.6 | Hessian 272 |

||

| 7.8.7 | Gradients of commonly used functions 272 |

||

| 7.9 | Exercises | 274 | |

| 8 | Optimization | 275 | |

| 8.1 | Introduction | 275 | |

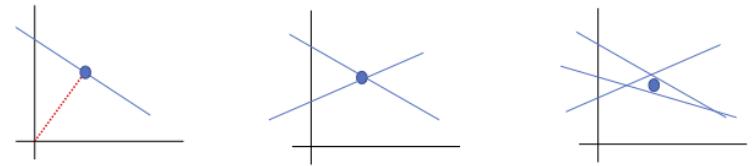

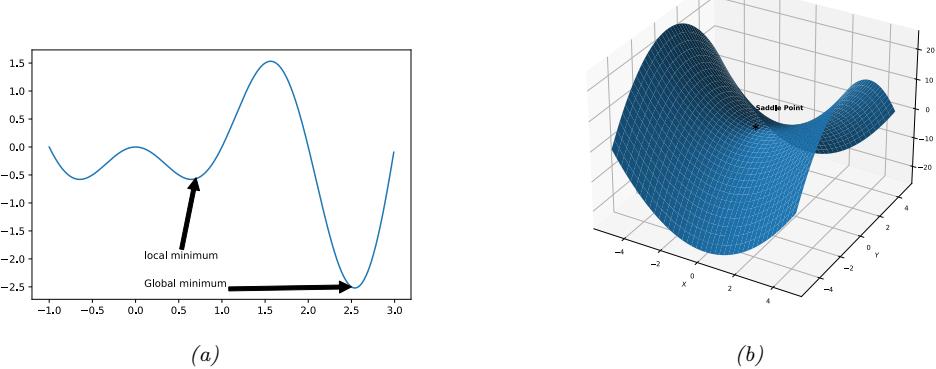

| 8.1.1 | Local vs global optimization 275 |

||

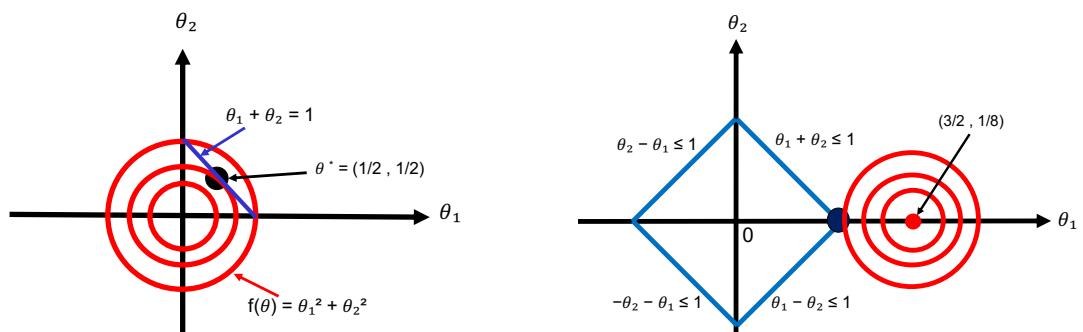

| 8.1.2 | Constrained vs unconstrained optimization 277 |

||

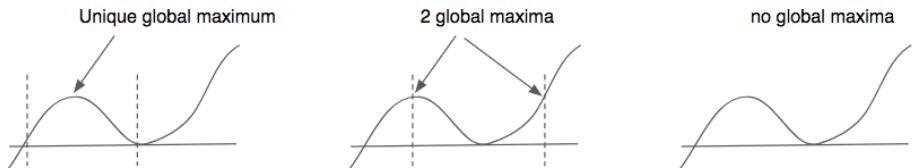

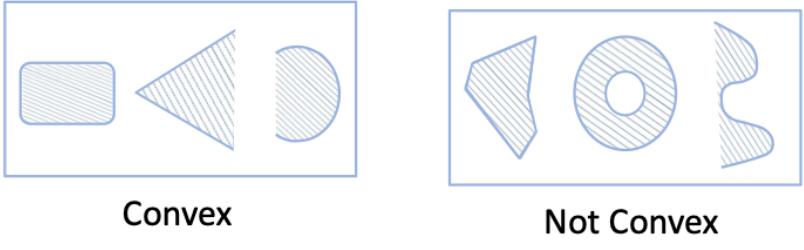

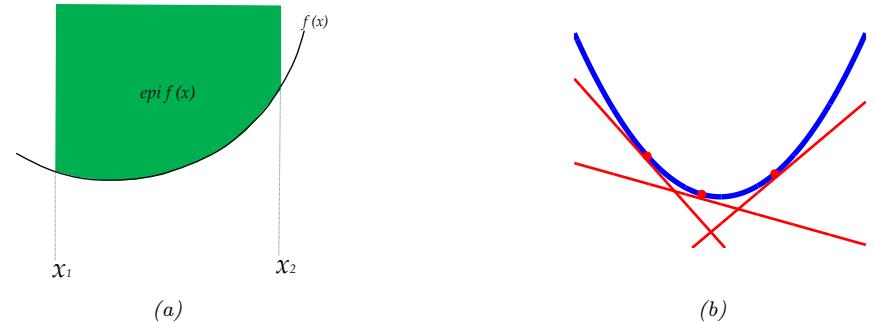

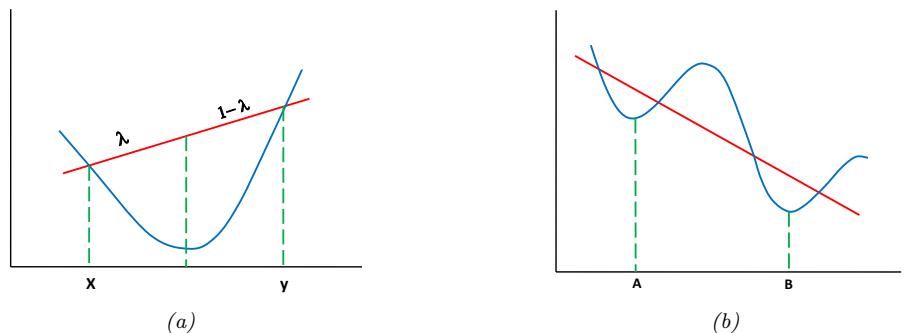

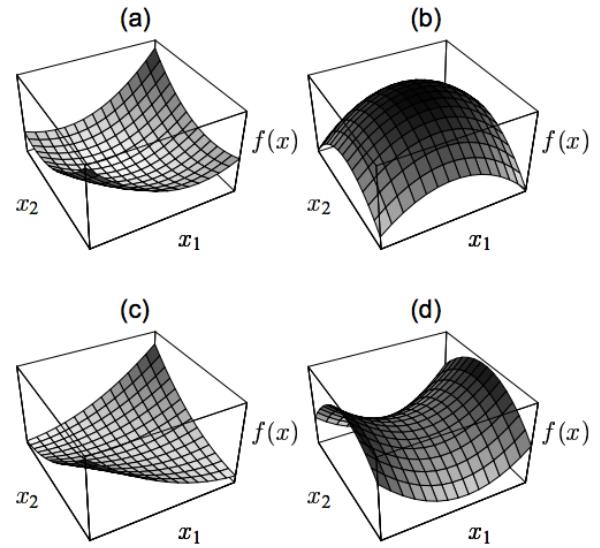

| 8.1.3 | Convex vs nonconvex optimization 277 |

||

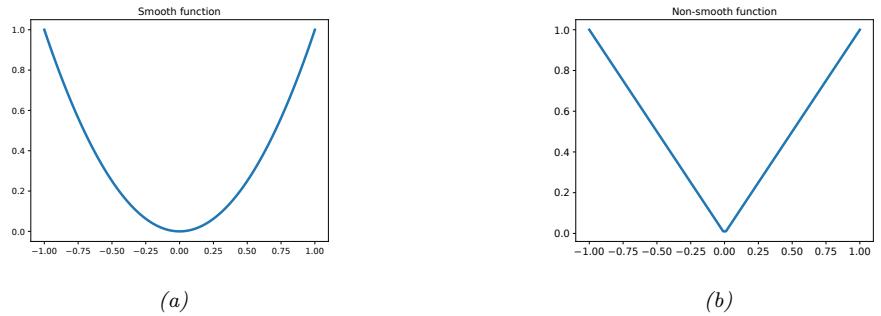

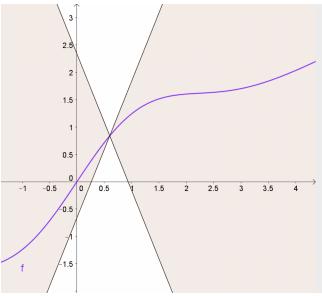

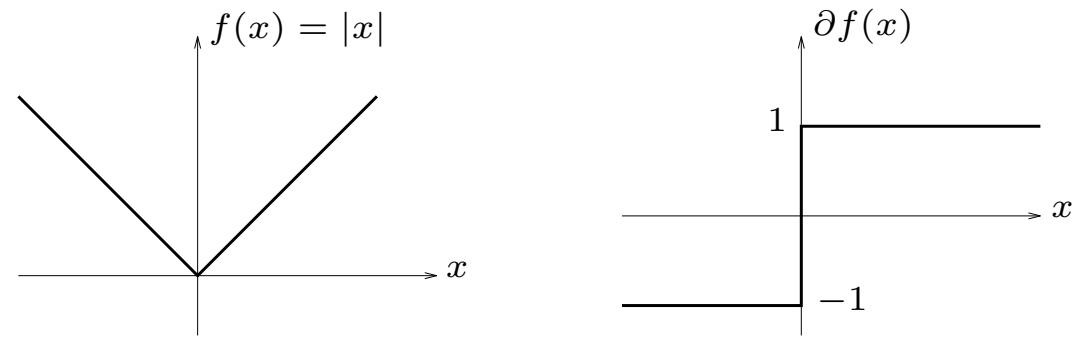

| 8.1.4 | Smooth vs nonsmooth optimization 281 |

||

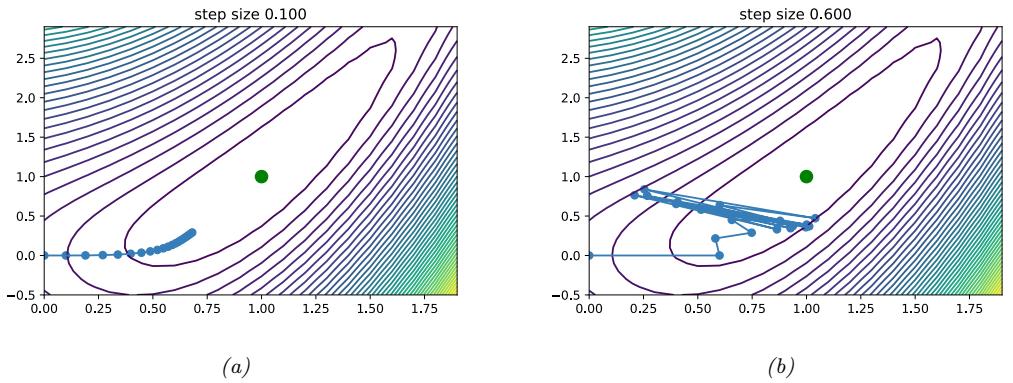

| 8.2 | First-order | methods 282 |

|

| 8.2.1 | Descent direction 284 |

||

| 8.2.2 | Step size (learning rate) 284 |

||

| 8.2.3 | Convergence rates 286 |

||

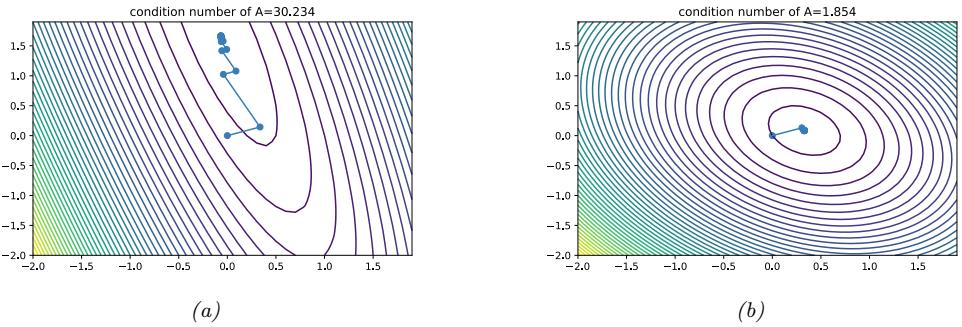

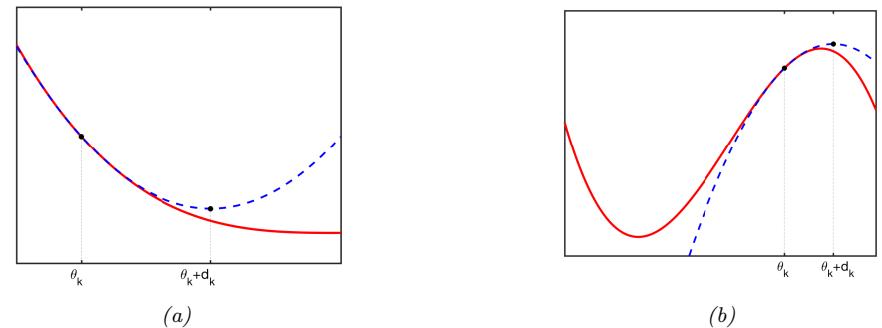

| 8.2.4 | Momentum methods 287 |

||

| 8.3 | Second-order | methods 289 |

|

| 8.3.1 | Newton’s method 289 |

||

| 8.3.2 | BFGS and other quasi-Newton methods 290 |

||

| 8.3.3 | Trust region methods 291 |

||

| 8.4 | Stochastic | gradient descent 292 |

|

| 8.4.1 | Application to finite sum problems 293 |

||

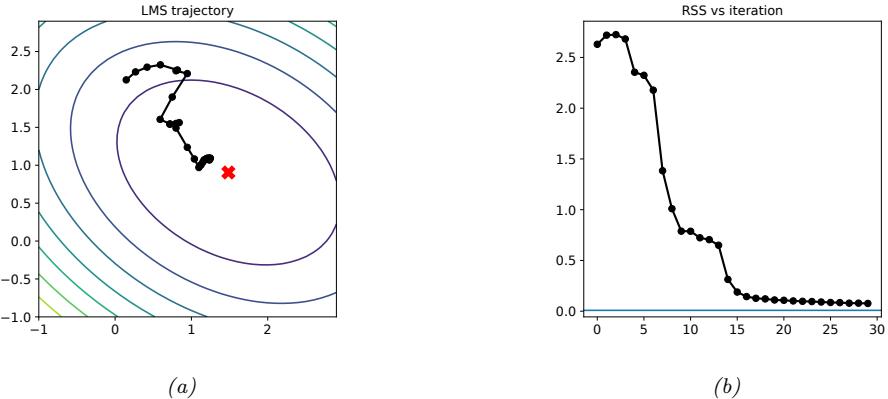

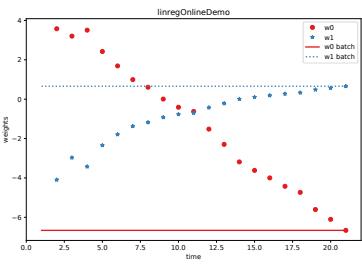

| 8.4.2 | Example: SGD for fitting linear regression 293 |

||

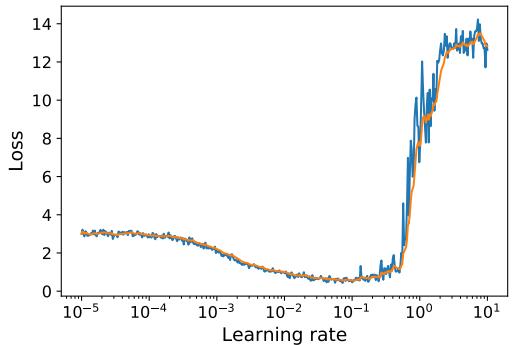

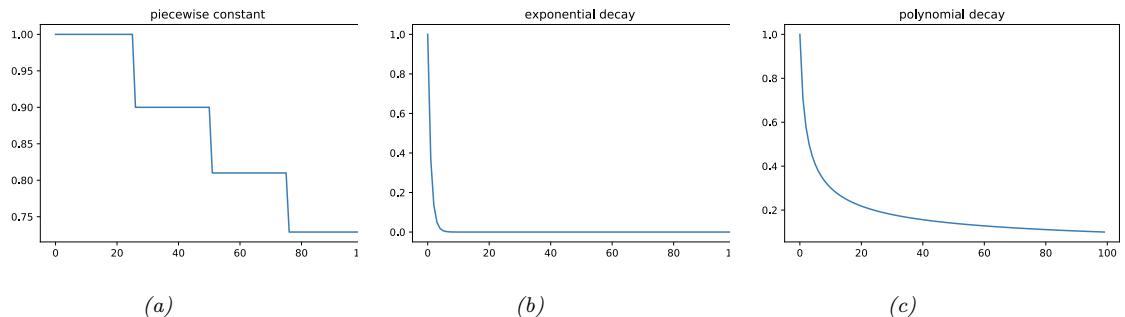

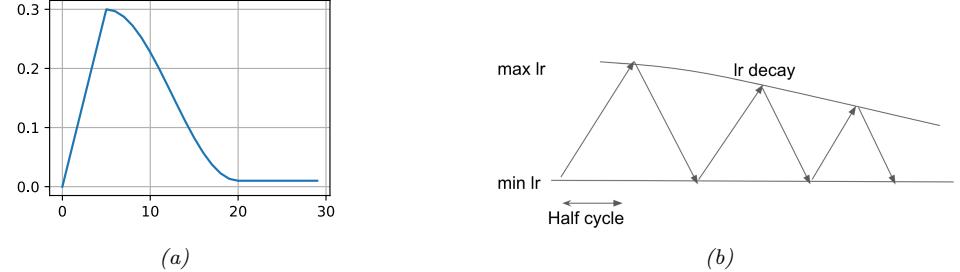

| 8.4.3 | Choosing the step size (learning rate) 294 |

||

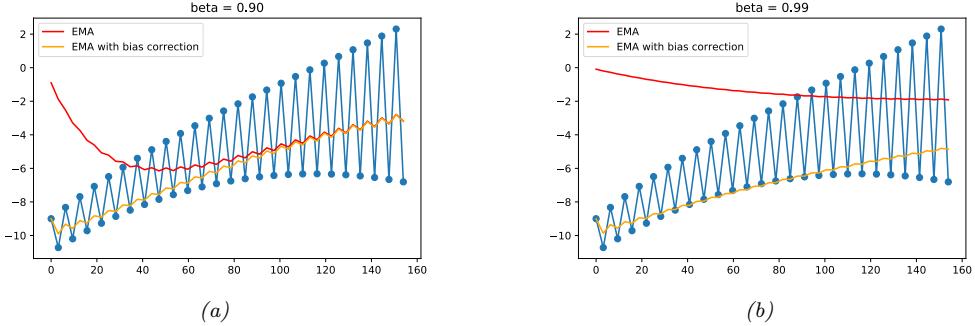

| 8.4.4 | Iterate averaging 297 |

||

| 8.4.5 | Variance reduction * 297 |

||

| 8.4.6 | Preconditioned SGD 298 |

||

| 8.5 | Constrained | optimization 302 |

|

| 8.5.1 | Lagrange multipliers 302 |

||

| 8.5.2 | The KKT conditions 304 |

||

| 8.5.3 | Linear programming 305 |

||

| 8.5.4 | Quadratic programming 306 |

||

| 8.5.5 | Mixed integer linear programming * 307 |

||

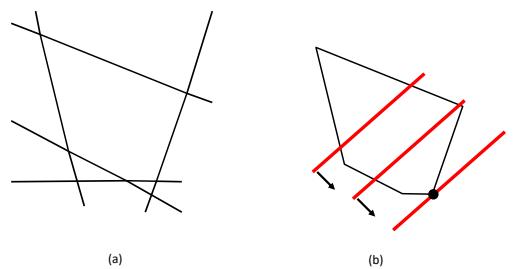

| 8.6 | Proximal | gradient method * 308 |

|

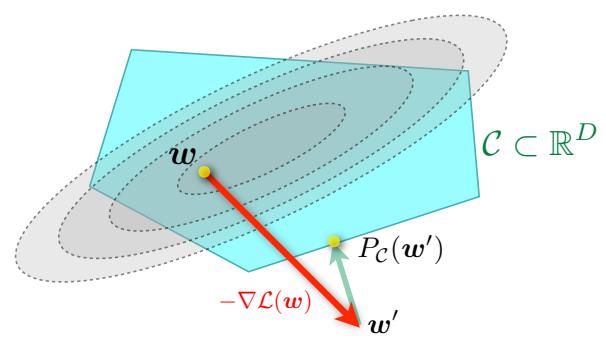

| 8.6.1 | Projected gradient descent 308 |

||

| 8.6.2 | Proximal operator for ω1-norm regularizer 310 |

||

| 8.6.3 | Proximal operator for quantization 311 |

||

| 8.6.4 | Incremental (online) proximal methods 311 |

||

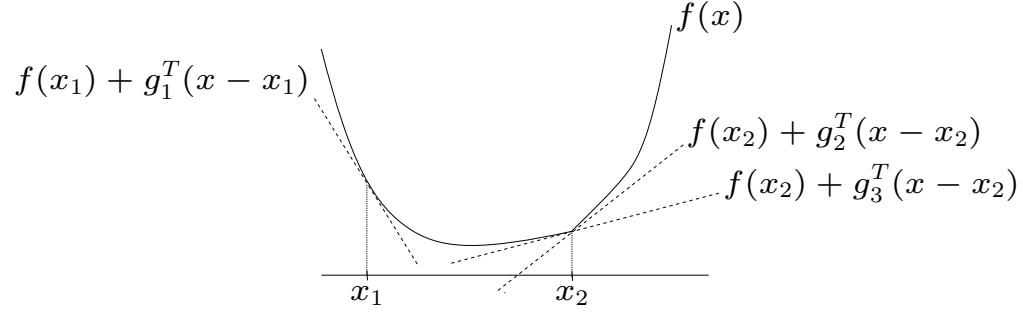

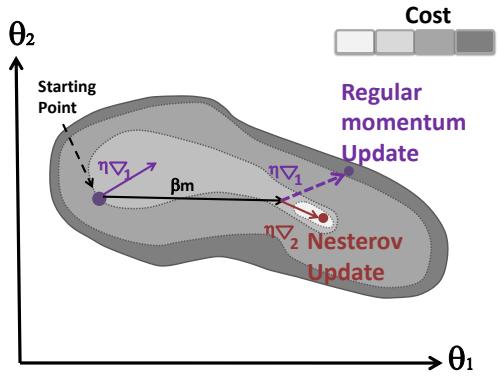

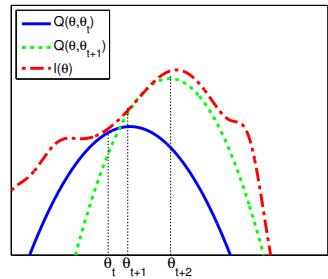

| 8.7 | Bound | optimization * 312 |

|

| 8.7.1 | The general algorithm 312 |

||

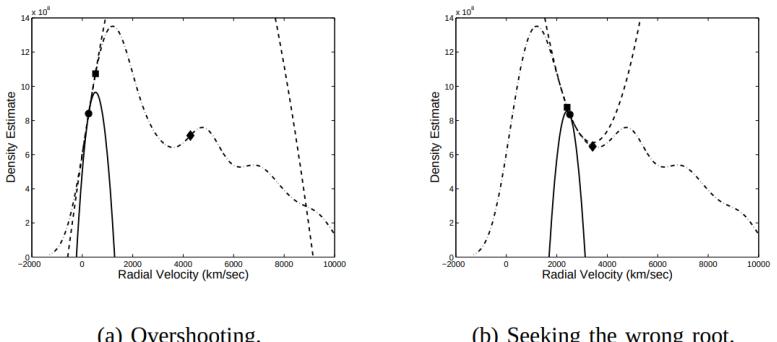

| 8.7.2 | The EM algorithm 312 |

||

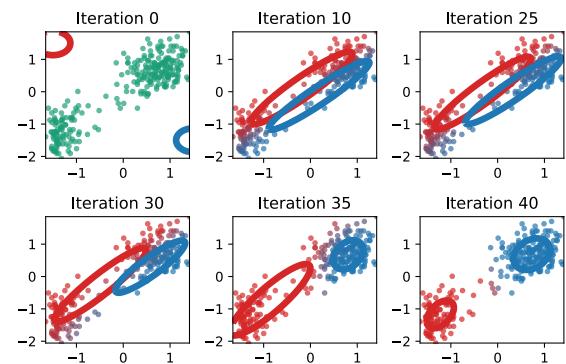

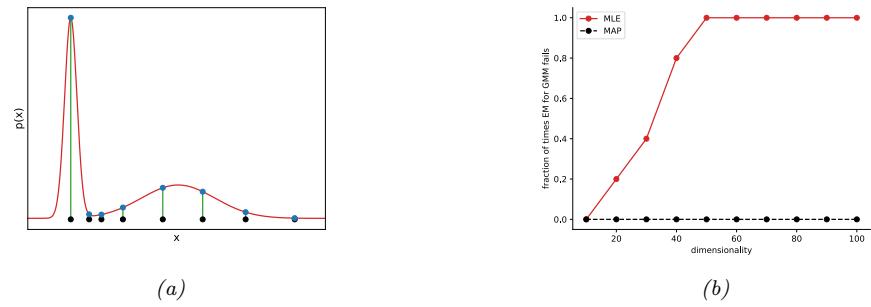

| 8.7.3 | Example: EM for a GMM 315 |

II Linear Models 321

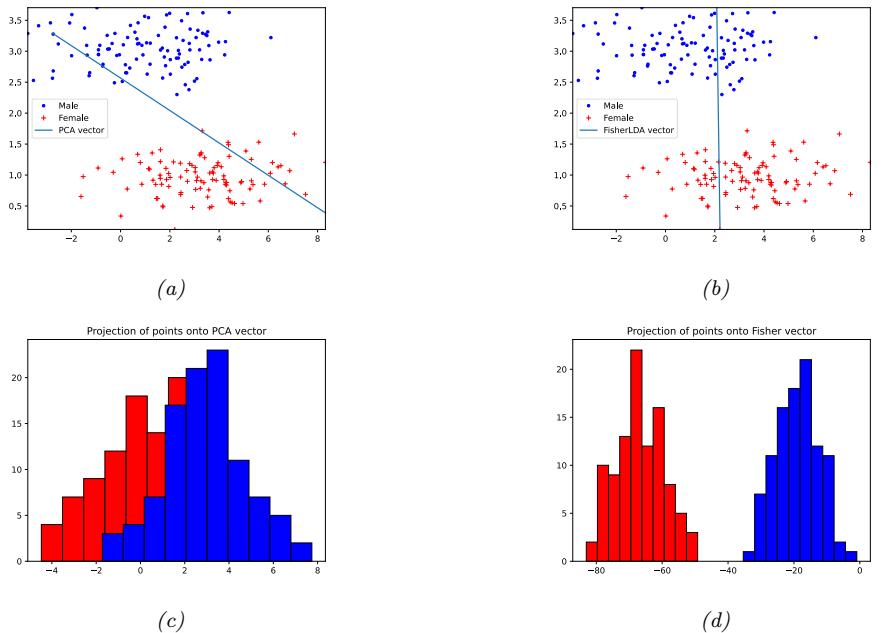

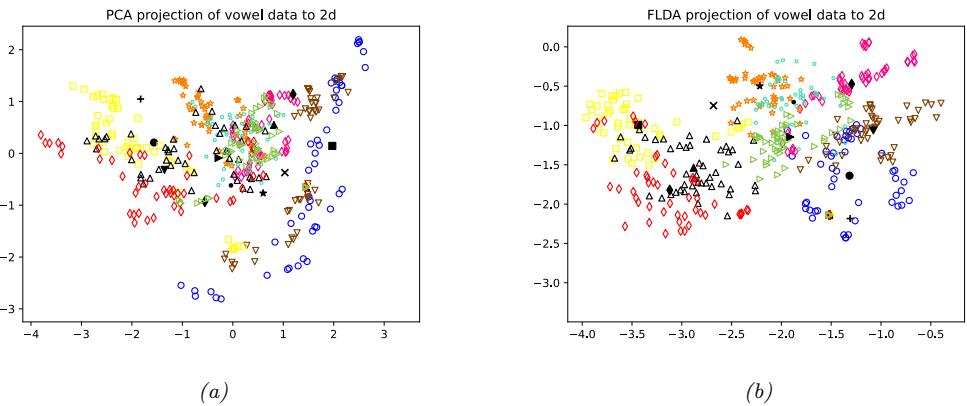

9 Linear Discriminant Analysis 323

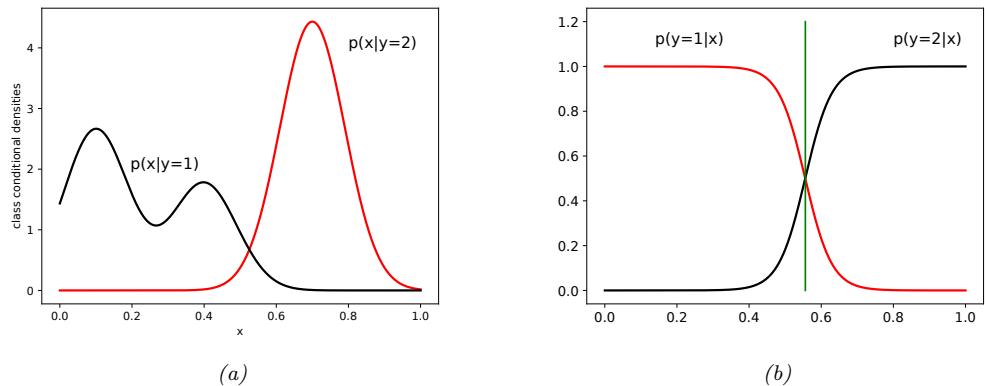

10 Logistic Regression 339

| CONTENTS | xvii |

|---|---|

| 10.3.8 Handling large numbers of classes 358 |

|

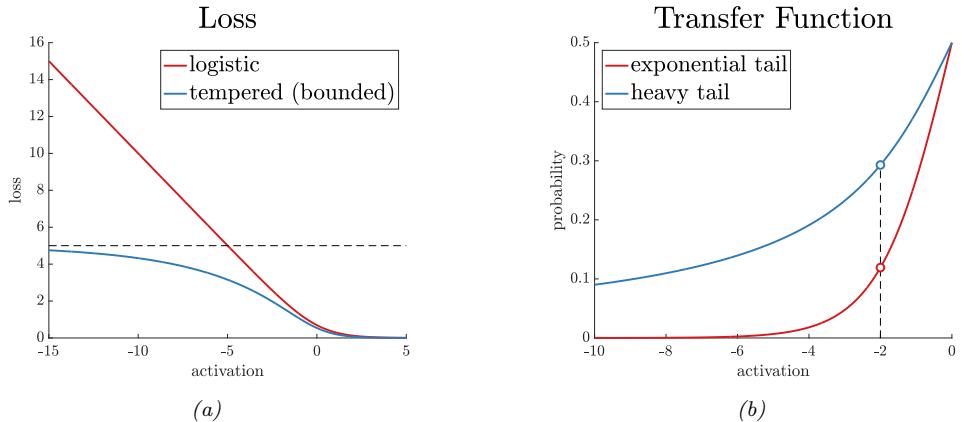

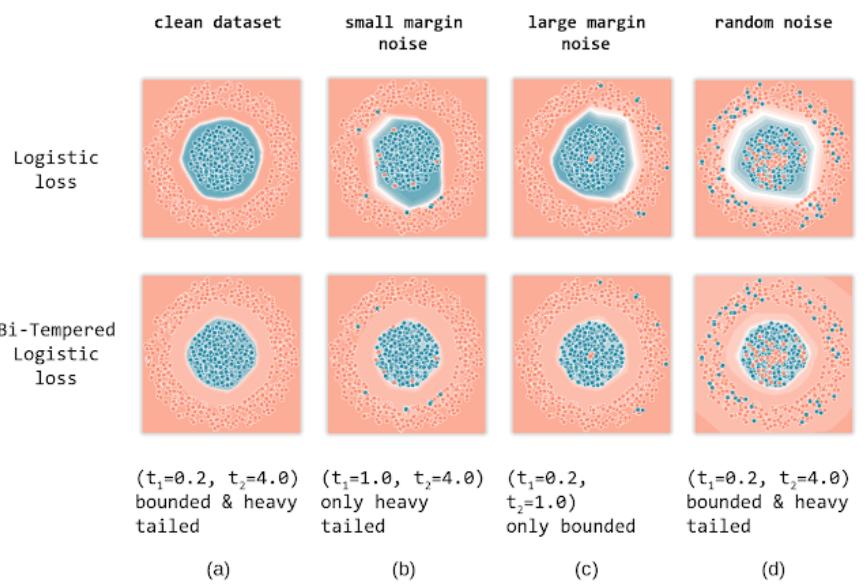

| 10.4 Robust logistic regression * 360 |

|

| 10.4.1 Mixture model for the likelihood 360 |

|

| 10.4.2 Bi-tempered loss 361 |

|

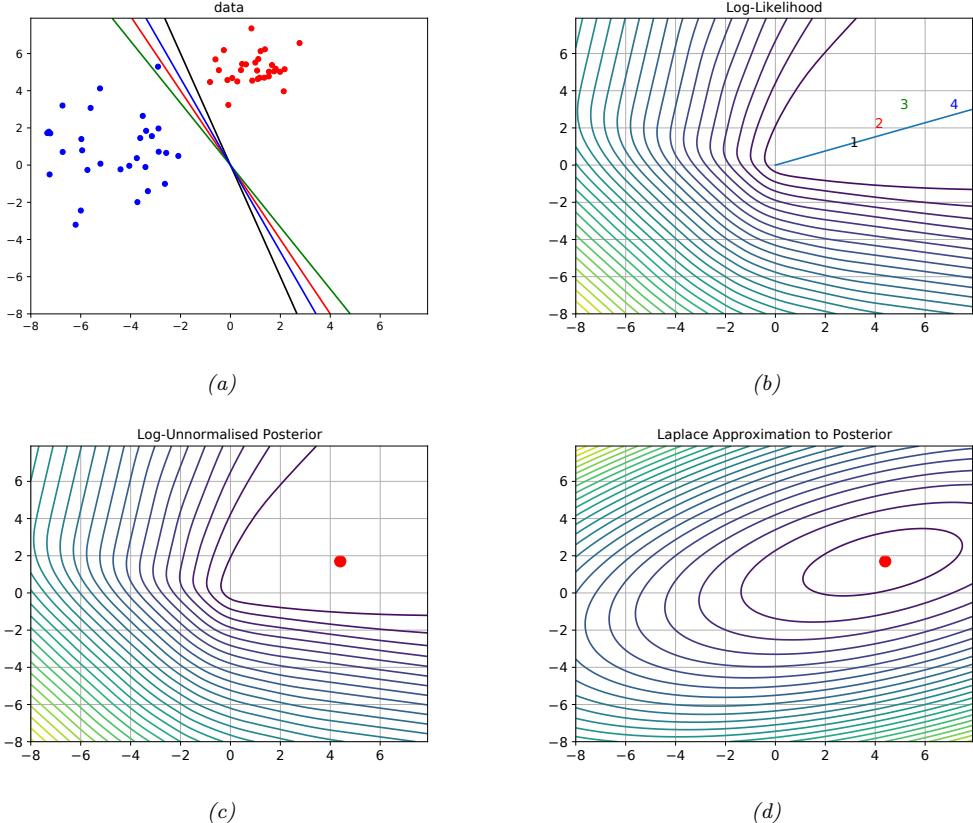

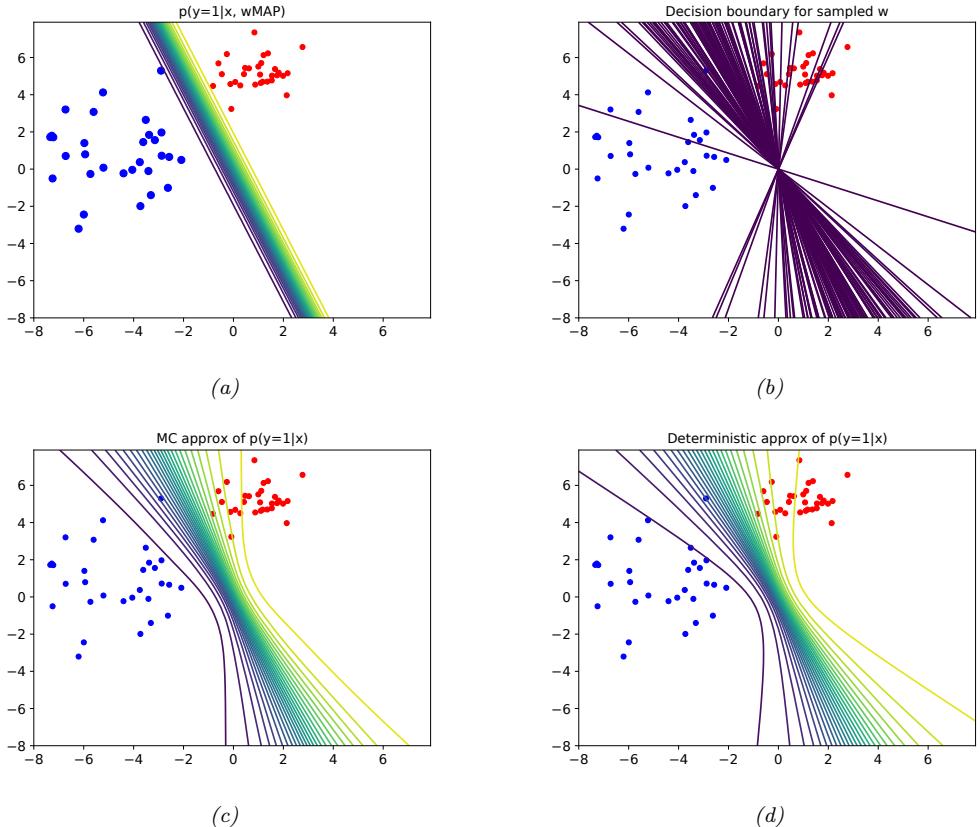

| 10.5 Bayesian logistic regression * 363 |

|

| 10.5.1 Laplace approximation 363 |

|

| 10.5.2 Approximating the posterior predictive 366 |

|

| 10.6 Exercises 367 |

|

| 11 Linear Regression 371 |

|

| 11.1 Introduction 371 |

|

| 11.2 Least squares linear regression 371 |

|

| 11.2.1 Terminology 371 |

|

| 11.2.2 Least squares estimation 372 |

11.2.2 Least squares estimation 372 11.2.3 Other approaches to computing the MLE 376

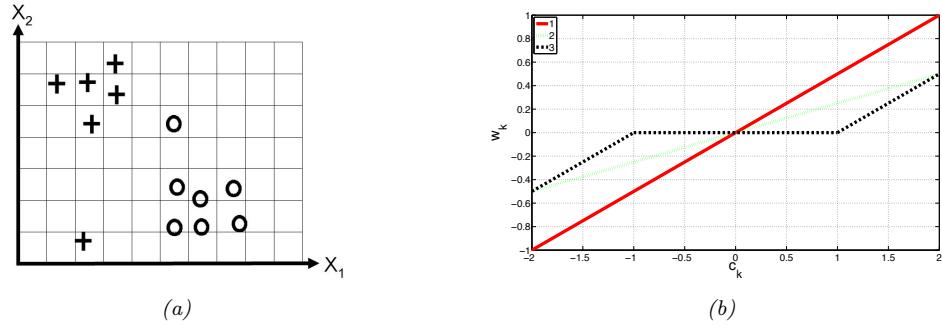

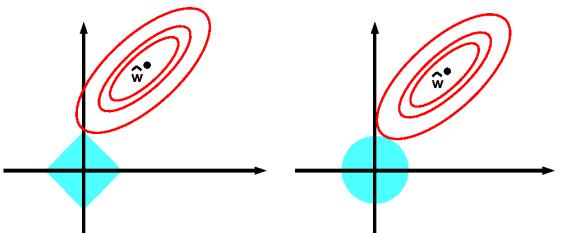

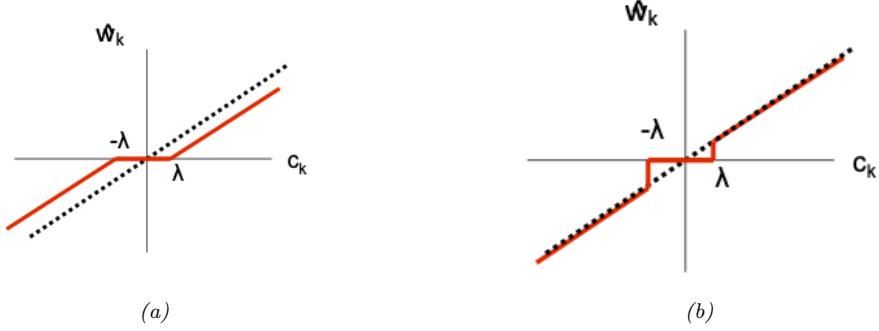

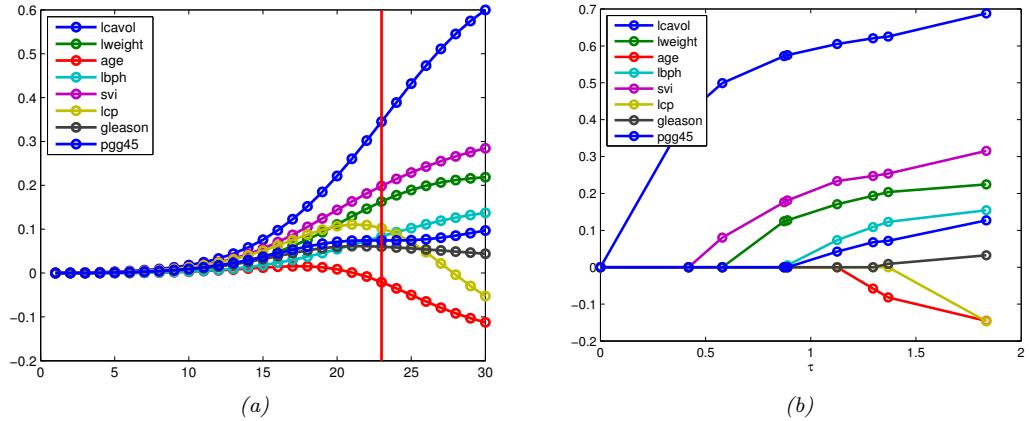

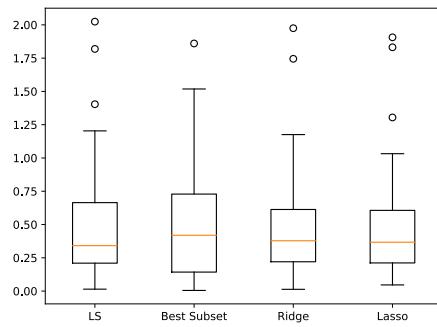

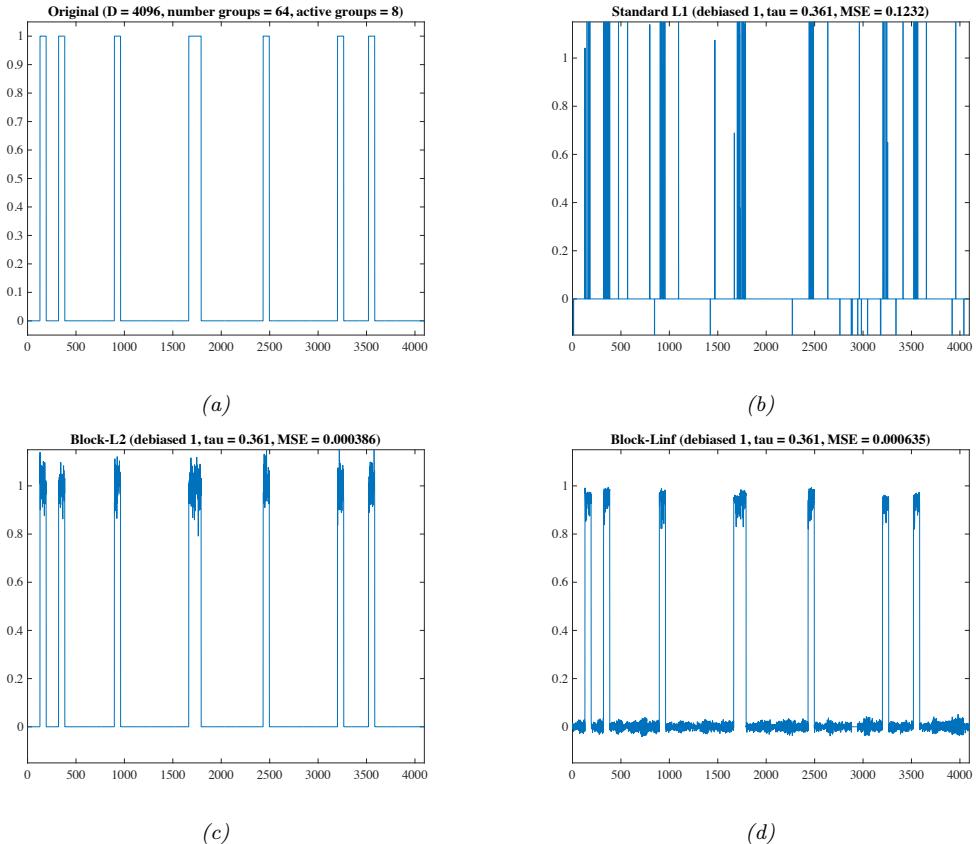

11.4 Lasso regression 385

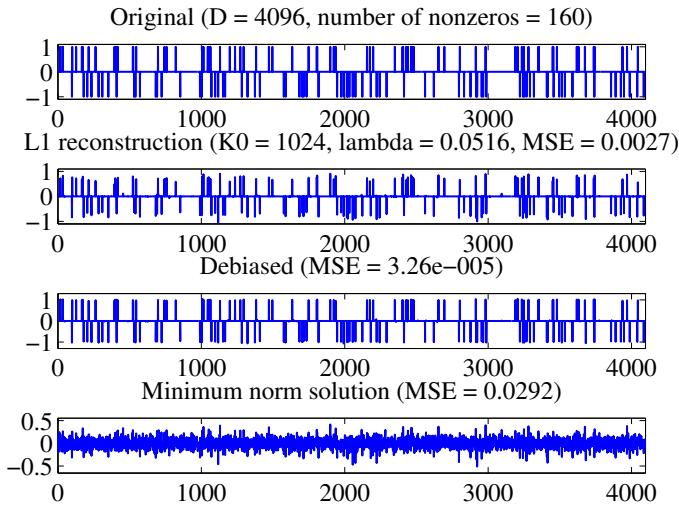

- 11.4.1 MAP estimation with a Laplace prior (ω1 regularization) 385

- 11.4.2 Why does ω1 regularization yield sparse solutions? 386

- 11.4.3 Hard vs soft thresholding 387

- 11.4.4 Regularization path 389

- 11.4.5 Comparison of least squares, lasso, ridge and subset selection 390

- 11.4.6 Variable selection consistency 392

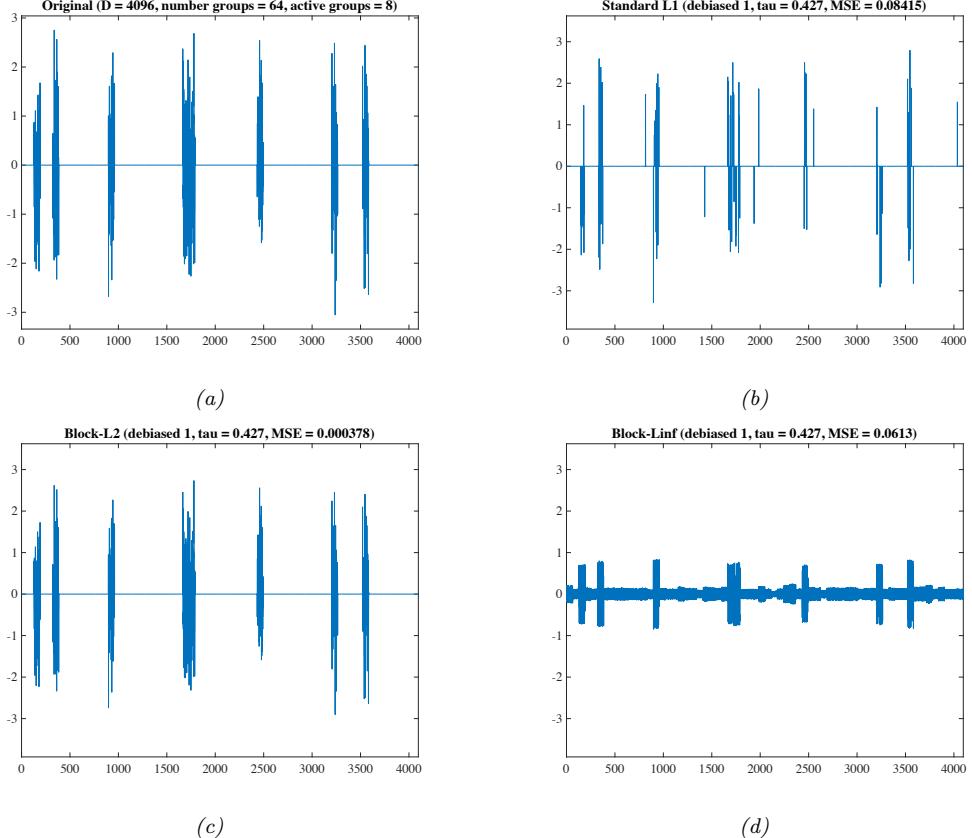

- 11.4.7 Group lasso 393

- 11.4.8 Elastic net (ridge and lasso combined) 396

- 11.4.9 Optimization algorithms 397

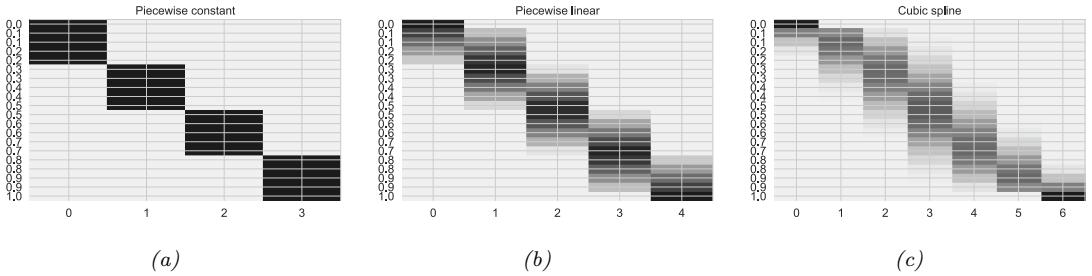

11.5 Regression splines \* 399

- 11.5.1 B-spline basis functions 399

- 11.5.2 Fitting a linear model using a spline basis 401

- 11.5.3 Smoothing splines 401

- 11.5.4 Generalized additive models 401

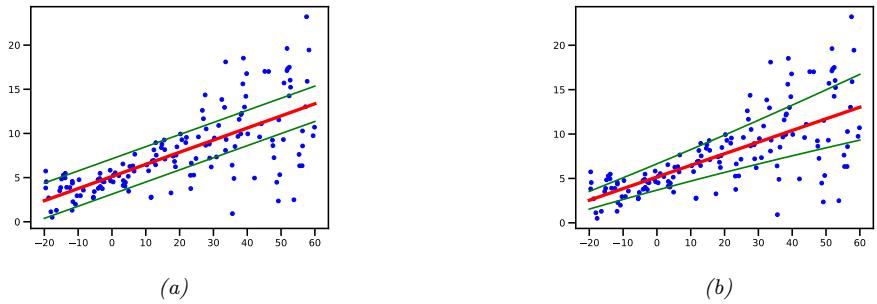

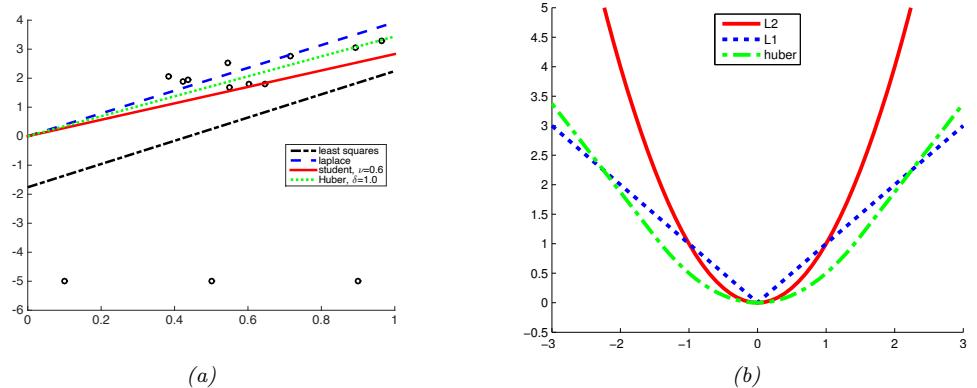

- 11.6 Robust linear regression \* 402

- 11.6.1 Laplace likelihood 402

- 11.6.2 Student-t likelihood 404

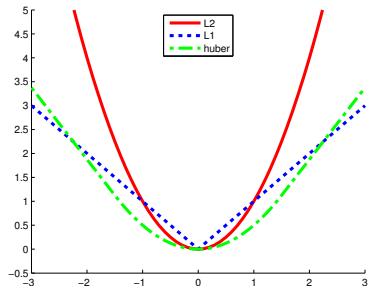

- 11.6.3 Huber loss 404

- 11.6.4 RANSAC 404

- 11.7 Bayesian linear regression \* 405

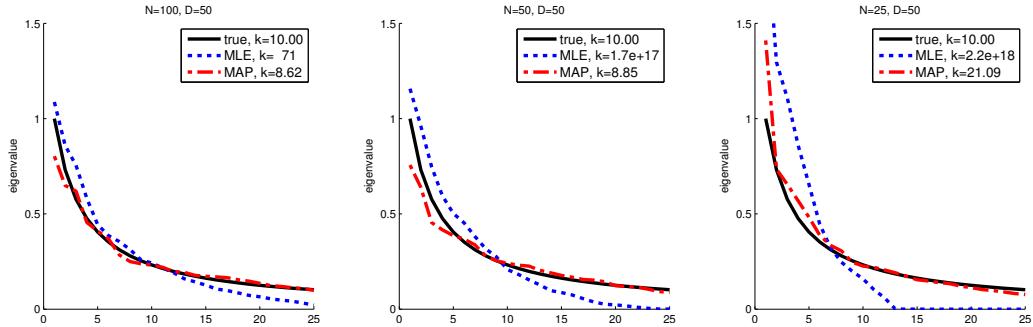

- 11.7.5 The advantage of centering 408 11.7.6 Dealing with multicollinearity 409 11.7.7 Automatic relevancy determination (ARD) \* 410 11.8 Exercises 411 12 Generalized Linear Models \* 415 12.1 Introduction 415 12.2 Examples 415

III Deep Neural Networks 423

13 Neural Networks for Tabular Data 425

- 13.1 Introduction 425 13.2 Multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) 426 13.2.1 The XOR problem 427 13.2.2 Di

428 13.2.3 Activation functions 428 13.2.4 Example models 430 13.2.5 The importance of depth 434 13.2.6 The “deep learning revolution” 435 13.2.7 Connections with biology 436 13.3 Backpropagation 438 13.3.1 Forward vs reverse mode di!erentiation 438 13.3.2 Reverse mode di

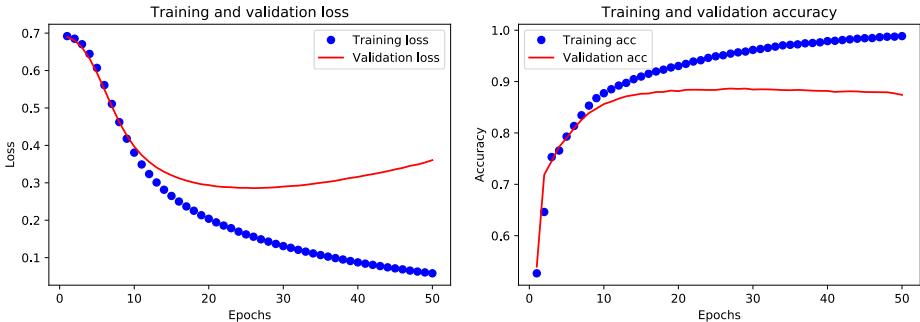

428 13.2.3 Activation functions 428 13.2.4 Example models 430 13.2.5 The importance of depth 434 13.2.6 The “deep learning revolution” 435 13.2.7 Connections with biology 436 13.3 Backpropagation 438 13.3.1 Forward vs reverse mode di!erentiation 438 13.3.2 Reverse mode di 440 13.3.3 Vector-Jacobian product for common layers 441 13.3.4 Computation graphs 444 13.4 Training neural networks 446 13.4.1 Tuning the learning rate 447 13.4.2 Vanishing and exploding gradients 447 13.4.3 Non-saturating activation functions 448 13.4.4 Residual connections 451 13.4.5 Parameter initialization 452 13.4.6 Parallel training 454 13.5 Regularization 455 13.5.1 Early stopping 455 13.5.2 Weight decay 455 13.5.3 Sparse DNNs 455

440 13.3.3 Vector-Jacobian product for common layers 441 13.3.4 Computation graphs 444 13.4 Training neural networks 446 13.4.1 Tuning the learning rate 447 13.4.2 Vanishing and exploding gradients 447 13.4.3 Non-saturating activation functions 448 13.4.4 Residual connections 451 13.4.5 Parameter initialization 452 13.4.6 Parallel training 454 13.5 Regularization 455 13.5.1 Early stopping 455 13.5.2 Weight decay 455 13.5.3 Sparse DNNs 455

- 13.5.4 Dropout 455

13.5.5 Bayesian neural networks 457 13.5.6 Regularization e 457 13.5.7 Over-parameterized models 459 13.6 Other kinds of feedforward networks \* 459 13.6.1 Radial basis function networks 459 13.6.2 Mixtures of experts 461 13.7 Exercises 463 14 Neural Networks for Images 467 14.1 Introduction 467 14.2 Common layers 468 14.2.1 Convolutional layers 468 14.2.2 Pooling layers 475 14.2.3 Putting it all together 476 14.2.4 Normalization layers 476 14.3 Common architectures for image classification 479 14.3.1 LeNet 479 14.3.2 AlexNet 481 14.3.3 GoogLeNet (Inception) 482 14.3.4 ResNet 483 14.3.5 DenseNet 484 14.3.6 Neural architecture search 485 14.4 Other forms of convolution \* 486 14.4.1 Dilated convolution 486 14.4.2 Transposed convolution 486 14.4.3 Depthwise separable convolution 488 14.5 Solving other discriminative vision tasks with CNNs \* 488 14.5.1 Image tagging 488 14.5.2 Object detection 489 14.5.3 Instance segmentation 490 14.5.4 Semantic segmentation 491 14.5.5 Human pose estimation 492 14.6 Generating images by inverting CNNs \* 493 14.6.1 Converting a trained classifier into a generative model 493 14.6.2 Image priors 494 14.6.3 Visualizing the features learned by a CNN 495 14.6.4 Deep Dream 496 14.6.5 Neural style transfer 497 15 Neural Networks for Sequences 503 15.1 Introduction 503 15.2 Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) 503 15.2.1 Vec2Seq (sequence generation) 503 15.2.2 Seq2Vec (sequence classification) 505 15.2.3 Seq2Seq (sequence translation) 507

457 13.5.7 Over-parameterized models 459 13.6 Other kinds of feedforward networks \* 459 13.6.1 Radial basis function networks 459 13.6.2 Mixtures of experts 461 13.7 Exercises 463 14 Neural Networks for Images 467 14.1 Introduction 467 14.2 Common layers 468 14.2.1 Convolutional layers 468 14.2.2 Pooling layers 475 14.2.3 Putting it all together 476 14.2.4 Normalization layers 476 14.3 Common architectures for image classification 479 14.3.1 LeNet 479 14.3.2 AlexNet 481 14.3.3 GoogLeNet (Inception) 482 14.3.4 ResNet 483 14.3.5 DenseNet 484 14.3.6 Neural architecture search 485 14.4 Other forms of convolution \* 486 14.4.1 Dilated convolution 486 14.4.2 Transposed convolution 486 14.4.3 Depthwise separable convolution 488 14.5 Solving other discriminative vision tasks with CNNs \* 488 14.5.1 Image tagging 488 14.5.2 Object detection 489 14.5.3 Instance segmentation 490 14.5.4 Semantic segmentation 491 14.5.5 Human pose estimation 492 14.6 Generating images by inverting CNNs \* 493 14.6.1 Converting a trained classifier into a generative model 493 14.6.2 Image priors 494 14.6.3 Visualizing the features learned by a CNN 495 14.6.4 Deep Dream 496 14.6.5 Neural style transfer 497 15 Neural Networks for Sequences 503 15.1 Introduction 503 15.2 Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) 503 15.2.1 Vec2Seq (sequence generation) 503 15.2.2 Seq2Vec (sequence classification) 505 15.2.3 Seq2Seq (sequence translation) 507

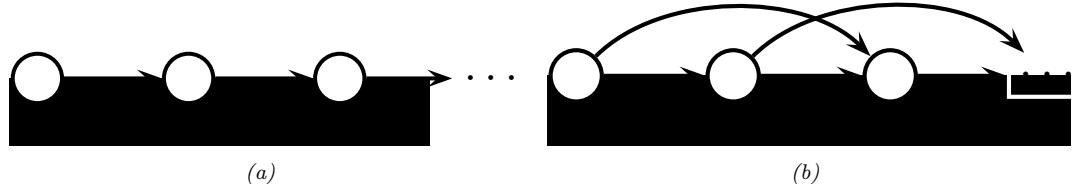

15.2.4 Teacher forcing 509 15.2.5 Backpropagation through time 510 15.2.6 Vanishing and exploding gradients 511 15.2.7 Gating and long term memory 512 15.2.8 Beam search 515 15.3 1d CNNs 516 15.3.1 1d CNNs for sequence classification 516 15.3.2 Causal 1d CNNs for sequence generation 517 15.4 Attention 518 15.4.1 Attention as soft dictionary lookup 519 15.4.2 Kernel regression as non-parametric attention 520 15.4.3 Parametric attention 521 15.4.4 Seq2Seq with attention 522 15.4.5 Seq2vec with attention (text classification) 523 15.4.6 Seq+Seq2Vec with attention (text pair classification) 523 15.4.7 Soft vs hard attention 525 15.5 Transformers 526 15.5.1 Self-attention 526 15.5.2 Multi-headed attention 527 15.5.3 Positional encoding 528 15.5.4 Putting it all together 529 15.5.5 Comparing transformers, CNNs and RNNs 531 15.5.6 Transformers for images \* 532 15.5.7 Other transformer variants \* 533 15.6 E”cient transformers \* 533 15.6.1 Fixed non-learnable localized attention patterns 534 15.6.2 Learnable sparse attention patterns 535 15.6.3 Memory and recurrence methods 535 15.6.4 Low-rank and kernel methods 535 15.7 Language models and unsupervised representation learning 537 15.7.1 Non-generative language models 538 15.7.2 Generative (causal) Large Language Models (LLMs) 542

IV Nonparametric Models 545

16 Exemplar-based Methods 547

| 16.1 | K nearest neighbor (KNN) classification 547 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 16.1.1 | Example 548 |

||

| 16.1.2 | The curse of dimensionality 548 |

||

| 16.1.3 | Reducing the speed and memory requirements 550 |

||

| 16.1.4 | Open set recognition 550 |

||

| 16.2 | Learning distance metrics 551 |

||

| 16.2.1 | Linear and convex methods 552 |

||

| 16.2.2 | Deep metric learning 554 |

| 16.2.3 | Classification losses 554 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 16.2.4 | Ranking losses 555 |

||

| 16.2.5 | Speeding up ranking loss optimization 556 |

||

| 16.2.6 | Other training tricks for DML 559 |

||

| 16.3 | Kernel | density estimation (KDE) 560 |

|

| 16.3.1 | Density kernels 560 |

||

| 16.3.2 | Parzen window density estimator 561 |

||

| 16.3.3 | How to choose the bandwidth parameter 562 |

||

| 16.3.4 | From KDE to KNN classification 563 |

||

| 16.3.5 | Kernel regression 563 |

||

| 17 | Kernel | Methods | * 567 |

| 17.1 | Mercer | kernels 567 |

|

| 17.1.1 | Mercer’s theorem 568 |

||

| 17.1.2 | Some popular Mercer kernels 569 |

||

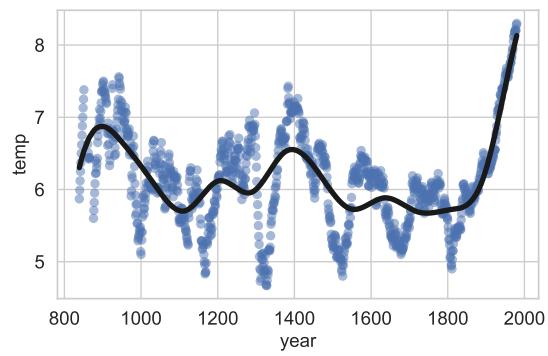

| 17.2 | Gaussian | processes 574 |

|

| 17.2.1 | Noise-free observations 574 |

||

| 17.2.2 | Noisy observations 575 |

||

| 17.2.3 | Comparison to kernel regression 576 |

||

| 17.2.4 | Weight space vs function space 577 |

||

| 17.2.5 | Numerical issues 577 |

||

| 17.2.6 | Estimating the kernel 578 |

||

| 17.2.7 | GPs for classification 581 |

||

| 17.2.8 | Connections with deep learning 582 |

||

| 17.2.9 | Scaling GPs to large datasets 582 |

||

| 17.3 | Support | vector machines (SVMs) 585 |

|

| 17.3.1 | Large margin classifiers 585 |

||

| 17.3.2 | The dual problem 587 |

||

| 17.3.3 | Soft margin classifiers 589 |

||

| 17.3.4 | The kernel trick 590 |

||

| 17.3.5 | Converting SVM outputs into probabilities 591 |

||

| 17.3.6 | Connection with logistic regression 591 |

||

| 17.3.7 | Multi-class classification with SVMs 592 |

||

| 17.3.8 | How to choose the regularizer C 593 |

||

| 17.3.9 | Kernel ridge regression 594 |

||

| 17.3.10 | SVMs for regression 595 |

||

| 17.4 | Sparse | vector machines 597 |

|

| 17.4.1 | Relevance vector machines (RVMs) 598 |

||

| 17.4.2 | Comparison of sparse and dense kernel methods 598 |

||

| 17.5 | Exercises | 601 | |

| 18 | Trees, | Forests, | Bagging, and Boosting 603 |

| 18.1 | Classification | and regression trees (CART) 603 |

|

| 18.1.1 | Model definition 603 |

||

| 18.1.2 | Model fitting 605 |

||

18.1.3 Regularization 606 18.1.4 Handling missing input features 606 18.1.5 Pros and cons 606 18.2 Ensemble learning 608 18.2.1 Stacking 608 18.2.2 Ensembling is not Bayes model averaging 609 18.3 Bagging 609 18.4 Random forests 610 18.5 Boosting 611 18.5.1 Forward stagewise additive modeling 612 18.5.2 Quadratic loss and least squares boosting 612 18.5.3 Exponential loss and AdaBoost 613 18.5.4 LogitBoost 616 18.5.5 Gradient boosting 616 18.6 Interpreting tree ensembles 620 18.6.1 Feature importance 621 18.6.2 Partial dependency plots 623 V Beyond Supervised Learning 625 19 Learning with Fewer Labeled Examples 627 19.1 Data augmentation 627 19.1.1 Examples 627 19.1.2 Theoretical justification 628 19.2 Transfer learning 628

- 19.2.1 Fine-tuning 629

- 19.2.2 Adapters 630

- 19.2.3 Supervised pre-training 631

- 19.2.4 Unsupervised pre-training (self-supervised learning) 632

- 19.2.5 Domain adaptation 637

- 19.3 Semi-supervised learning 638

- 19.4 Active learning 650

- 19.5 Meta-learning 651 19.5.1 Model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) 652

| 19.6 | Few-shot learning 653 |

|

|---|---|---|

| 19.6.1 Matching networks 653 |

||

| 19.7 | Weakly supervised learning 655 |

|

| 19.8 | Exercises 655 |

|

| 20 | Dimensionality Reduction 657 |

|

| 20.1 | Principal components analysis (PCA) 657 |

|

| 20.1.1 Examples 657 |

||

| 20.1.2 Derivation of the algorithm 659 |

||

| 20.1.3 Computational issues 662 |

||

| 20.1.4 Choosing the number of latent dimensions 664 |

||

| 20.2 | Factor analysis * 666 |

|

| 20.2.1 Generative model 667 |

||

| 20.2.2 Probabilistic PCA 668 |

||

| 20.2.3 EM algorithm for FA/PPCA 669 |

||

| 20.2.4 Unidentifiability of the parameters 671 |

||

| 20.2.5 Nonlinear factor analysis 673 |

||

| 20.2.6 Mixtures of factor analyzers 674 |

||

| 20.2.7 Exponential family factor analysis 675 |

||

| 20.2.8 Factor analysis models for paired data 677 |

||

| 20.3 | Autoencoders 679 |

|

| 20.3.1 Bottleneck autoencoders 680 |

||

| 20.3.2 Denoising autoencoders 681 |

||

| 20.3.3 Contractive autoencoders 682 |

||

| 20.3.4 Sparse autoencoders 683 |

||

| 20.3.5 Variational autoencoders 683 |

||

| 20.4 | Manifold learning * 689 |

|

| 20.4.1 What are manifolds? 689 |

||

| 20.4.2 The manifold hypothesis 689 |

||

| 20.4.3 Approaches to manifold learning 690 |

||

| 20.4.4 Multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) 691 |

||

| 20.4.5 Isomap 694 |

||

| 20.4.6 Kernel PCA 695 |

||

| 20.4.7 Maximum variance unfolding (MVU) 697 |

||

| 20.4.8 Local linear embedding (LLE) 697 |

||

| 20.4.9 Laplacian eigenmaps 699 |

||

| 20.4.10 t-SNE 701 |

||

| 20.5 | Word embeddings 705 |

|

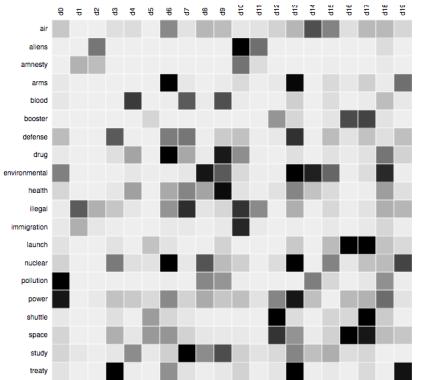

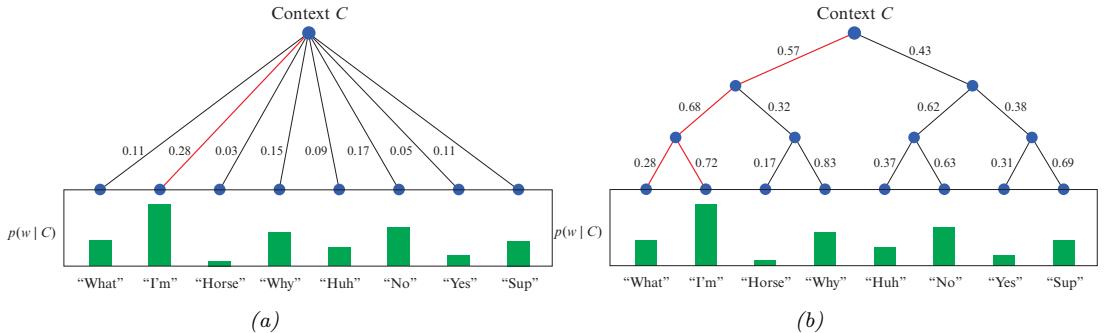

| 20.5.1 Latent semantic analysis / indexing 705 |

||

| 20.5.2 Word2vec 707 |

||

| 20.5.3 GloVE 710 |

||

| 20.5.4 Word analogies 710 |

||

| 20.5.5 RAND-WALK model of word embeddings 711 |

||

| 20.5.6 Contextual word embeddings 712 |

||

| 20.6 | Exercises 712 |

|

| 21 | Clustering | 715 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21.1 | Introduction | 715 | |

| 21.1.1 | Evaluating the output of clustering methods 715 |

||

| 21.2 | Hierarchical | agglomerative clustering 717 |

|

| 21.2.1 | The algorithm 718 |

||

| 21.2.2 | Example 720 |

||

| 21.2.3 | Extensions 721 |

||

| 21.3 | K means |

clustering 722 |

|

| 21.3.1 | The algorithm 722 |

||

| 21.3.2 | Examples 722 |

||

| 21.3.3 | Vector quantization 724 |

||

| 21.3.4 | The K-means++ algorithm 725 |

||

| 21.3.5 | The K-medoids algorithm 725 |

||

| 21.3.6 | Speedup tricks 726 |

||

| 21.3.7 | Choosing the number of clusters K 726 |

||

| 21.4 | Clustering | using mixture models 729 |

|

| 21.4.1 | Mixtures of Gaussians 730 |

||

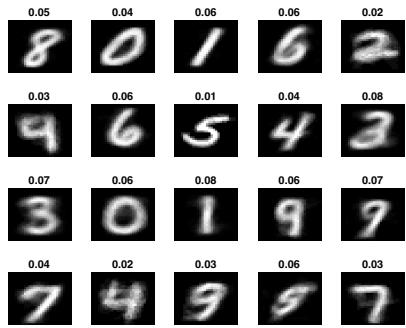

| 21.4.2 | Mixtures of Bernoullis 733 |

||

| 21.5 | Spectral | clustering * 734 |

|

| 21.5.1 | Normalized cuts 734 |

||

| 21.5.2 | Eigenvectors of the graph Laplacian encode the clustering 735 |

||

| 21.5.3 | Example 736 |

||

| 21.5.4 | Connection with other methods 737 |

||

| 21.6 | Biclustering | * 737 |

|

| 21.6.1 | Basic biclustering 738 |

||

| 21.6.2 | Nested partition models (Crosscat) 738 |

||

| 22 | Recommender | Systems 741 |

|

| 22.1 | Explicit | feedback 741 |

|

| 22.1.1 | Datasets 741 |

||

| 22.1.2 | Collaborative filtering 742 |

||

| 22.1.3 | Matrix factorization 743 |

||

| 22.1.4 | Autoencoders 745 |

||

| 22.2 | Implicit | feedback 747 |

|

| 22.2.1 | Bayesian personalized ranking 747 |

||

| 22.2.2 | Factorization machines 748 |

||

| 22.2.3 | Neural matrix factorization 749 |

||

| 22.3 | Leveraging | side information 749 |

|

| 22.4 | Exploration-exploitation tradeo! 750 |

||

| 23 | Graph | Embeddings * 753 |

|

| 23.1 | Introduction | 753 | |

| 23.2 | Graph | Embedding as an Encoder/Decoder Problem 754 |

|

| 23.3 | Shallow | graph embeddings 756 |

|

| 23.3.1 | Unsupervised embeddings 757 |

| 23.3.2 Distance-based: Euclidean methods 757 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 23.3.3 Distance-based: non-Euclidean methods 758 |

|||

| 23.3.4 Outer product-based: Matrix factorization methods 758 |

|||

| 23.3.5 Outer product-based: Skip-gram methods 759 |

|||

| 23.3.6 Supervised embeddings 761 |

|||

| 23.4 | Graph Neural Networks 762 |

||

| 23.4.1 Message passing GNNs 762 |

|||

| 23.4.2 Spectral Graph Convolutions 763 |

|||

| 23.4.3 Spatial Graph Convolutions 763 |

|||

| 23.4.4 Non-Euclidean Graph Convolutions 765 |

|||

| 23.5 | Deep graph embeddings 765 |

||

| 23.5.1 Unsupervised embeddings 766 |

|||

| 23.5.2 Semi-supervised embeddings 768 |

|||

| 23.6 | Applications 769 |

||

| 23.6.1 Unsupervised applications 769 |

|||

| 23.6.2 Supervised applications 771 |

|||

| A | Notation 773 |

||

| A.1 | Introduction 773 |

||

| A.2 | Common mathematical symbols 773 |

||

| A.3 | Functions 774 |

||

| A.3.1 Common functions of one argument 774 |

|||

| A.3.2 Common functions of two arguments 774 |

|||

| A.3.3 Common functions of > 2 arguments 774 |

|||

| A.4 | Linear algebra 775 |

||

| A.4.1 General notation 775 |

|||

| A.4.2 Vectors 775 |

|||

| A.4.3 Matrices 775 |

|||

| A.4.4 Matrix calculus 776 |

|||

| A.5 | Optimization 776 |

||

| A.6 | Probability 777 |

||

| A.7 | Information theory 777 |

||

| A.8 | Statistics and machine learning 778 |

||

| A.8.1 Supervised learning 778 |

|||

| A.8.2 Unsupervised learning and generative models 778 |

|||

| A.8.3 Bayesian inference 778 |

|||

| A.9 | Abbreviations 779 |

||

| Index | 781 | ||

Bibliography 798

Preface

In 2012, I published a 1200-page book called Machine Learning: A Probabilistic Perspective, which provided a fairly comprehensive coverage of the field of machine learning (ML) at that time, under the unifying lens of probabilistic modeling. The book was well received, and won the De Groot prize in 2013.

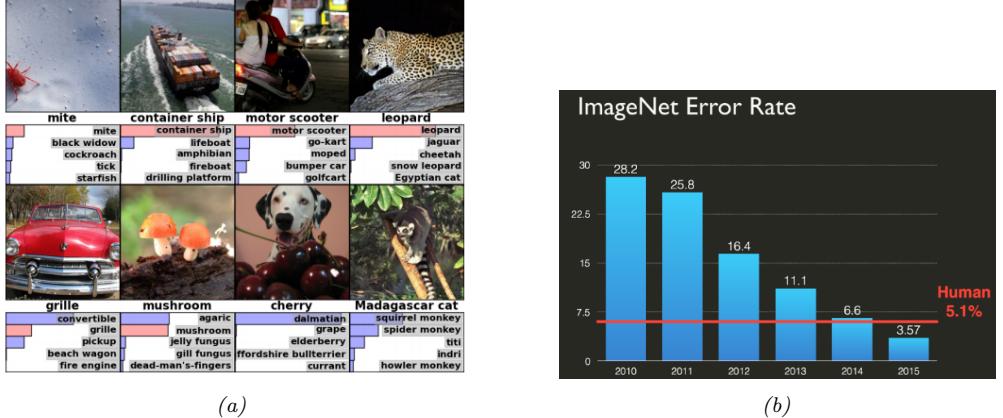

The year 2012 is also generally considered the start of the “deep learning revolution”. The term “deep learning” refers to a branch of ML that is based on neural networks (DNNs), which are nonlinear functions with many layers of processing (hence the term “deep”). Although this basic technology had been around for many years, it was in 2012 when [KSH12] used DNNs to win the ImageNet image classification challenge by such a large margin that it caught the attention of the wider community. Related advances on other hard problems, such as speech recognition, appeared around the same time (see e.g., [Cir+10; Cir+11; Hin+12]). These breakthroughs were enabled by advances in hardware technology (in particular, the repurposing of fast graphics processing units (GPUs) from video games to ML), data collection technology (in particular, the use of crowd sourcing tools, such as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform, to collect large labeled datasets, such as ImageNet), as well as various new algorithmic ideas, some of which we cover in this book.

Since 2012, the field of deep learning has exploded, with new advances coming at an increasing pace. Interest in the field has also grown rapidly, fueled by the commercial success of the technology, and the breadth of applications to which it can be applied. Therefore, in 2018, I decided to write a second edition of my book, to attempt to summarize some of this progress.

By March 2020, my draft of the second edition had swollen to about 1600 pages, and I still had many topics left to cover. As a result, MIT Press told me I would need to split the book into two volumes. Then the COVID-19 pandemic struck. I decided to pivot away from book writing, and to help develop the risk score algorithm for Google’s exposure notification app [MKS21] as well as to assist with various forecasting projects [Wah+22]. However, by the Fall of 2020, I decided to return to working on the book.

To make up for lost time, I asked several colleagues to help me finish by writing various sections (see acknowledgements below). The result of all this is two new books, “Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction”, which you are currently reading, and “Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics”, which is the sequel to this book [Mur23]. Together these two books attempt to present a fairly broad coverage of the field of ML c. 2021, using the same unifying lens of probabilistic modeling and Bayesian decision theory that I used in the 2012 book.

Nearly all of the content from the 2012 book has been retained, but it is now split fairly evenly

between the two new books. In addition, each new book has lots of fresh material, covering topics from deep learning, as well as advances in other parts of the field, such as generative models, variational inference and reinforcement learning.

To make this introductory book more self-contained and useful for students, I have added some background material, on topics such as optimization and linear algebra, that was omitted from the 2012 book due to lack of space. Advanced material, that can be skipped during an introductory level course, is denoted by * in the section or chapter title. Exercises can be found at the end of some chapters. Solutions to exercises marked with † are available to qualified instructors by contacting MIT Press; solutions to all other exercises can be found online at https://probml.github.io/ pml-book/book1.html, along with additional teaching material (e.g., figures and slides).

Another major change is that all of the software now uses Python instead of Matlab. (In the future, we may create a Julia version of the code.) The new code leverages standard Python libraries, such as NumPy, Scikit-learn, JAX, PyTorch, TensorFlow, PyMC, etc.

If a figure caption says “Generated by iris_plot.ipynb”, then you can find the corresponding Jupyter notebook at probml.github.io/notebooks#iris\_plot.ipynb. Clicking on the figure link in the pdf version of the book will take you to this list of notebooks. Clicking on the notebook link will open it inside Google Colab, which will let you easily reproduce the figure for yourself, and modify the underlying source code to gain a deeper understanding of the methods. (Colab gives you access to a free GPU, which is useful for some of the more computationally heavy demos.)

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for helping me with the book:

- Zico Kolter (CMU), who helped write parts of Chapter 7 (Linear Algebra).

- Frederik Kunstner, Si Yi Meng, Aaron Mishkin, Sharan Vaswani, and Mark Schmidt who helped write parts of Chapter 8 (Optimization).

- Mathieu Blondel (Google), who helped write Section 13.3 (Backpropagation).

- Krzysztof Choromanski (Google), who wrote Section 15.6 (E”cient transformers \* ).

- Colin Ra!el (UNC), who helped write Section 19.2 (Transfer learning) and Section 19.3 (Semisupervised learning).

- Bryan Perozzi (Google), Sami Abu-El-Haija (USC) and Ines Chami, who helped write Chapter 23 (Graph Embeddings \* ).

- John Fearns and Peter Cerno for carefully proofreading the book.

- Many members of the github community for finding typos, etc (see https://github.com/probml/ pml-book/issues?q=is:issue for a list of issues).

- The 4 anonymous reviewers solicited by MIT Press.

- Mahmoud Soliman for writing all the magic plumbing code that connects latex, colab, github, etc, and for teaching me about GCP and TPUs.

- The 2021 cohort of Google Summer of Code students who worked on code for the book: Aleyna Kara, Srikar Jilugu, Drishti Patel, Ming Liang Ang, Gerardo Durán-Martín. (See https:// probml.github.io/pml-book/gsoc/gsoc2021.html for a summary of their contributions.)

- Zeel B Patel, Karm Patel, Nitish Sharma, Ankita Kumari Jain and Nipun Batra for help improving the figures and code after the book first came out.

- Many members of the github community for their code contributions (see https://github.com/

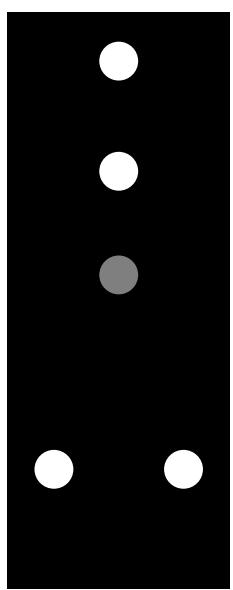

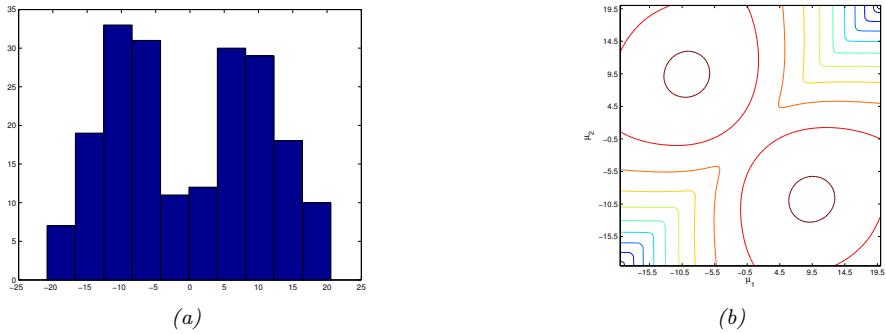

About the cover

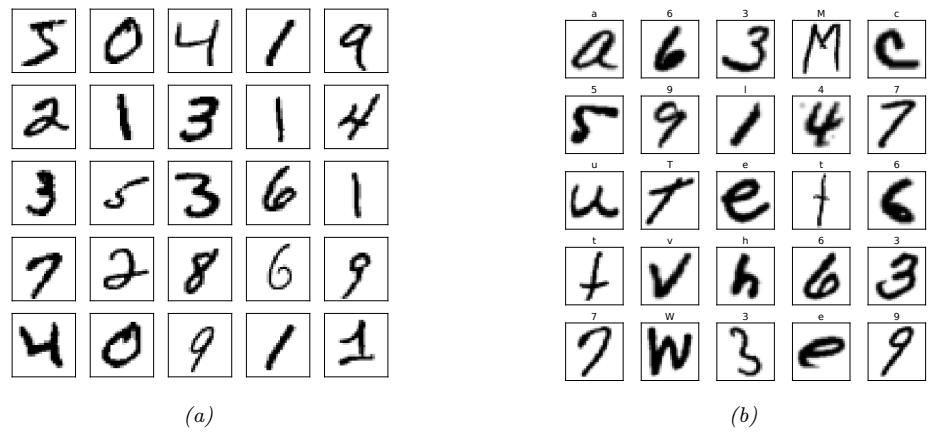

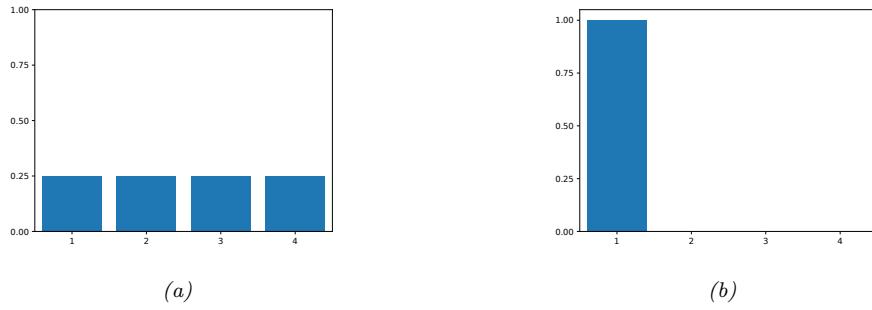

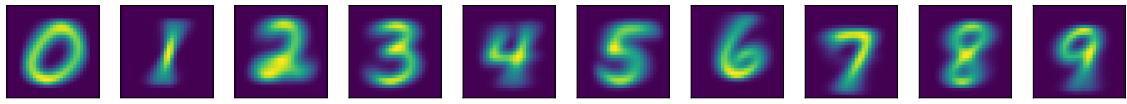

The cover illustrates a neural network (Chapter 13) being used to classify a hand-written digit x into one of 10 class labels y → {0, 1,…, 9}. The histogram on the right is the output of the model, and corresponds to the conditional probability distribution p(y|x). 1

Changelog

All changes listed at https://github.com/probml/pml-book/issues?q=is%3Aissue+is%3Aclosed.

- March, 2022. First printing.

- April, 2023. Second printing.

- January, 2025. Third printing.

1. There is an error in the illustration on the front cover — it has 11 bins instead of 10. (If your version has 10 bins, then you have the third printing or newer.)

1 Introduction

1.1 What is machine learning?

A popular definition of machine learning or ML, due to Tom Mitchell [Mit97], is as follows:

A computer program is said to learn from experience E with respect to some class of tasks T, and performance measure P, if its performance at tasks in T, as measured by P, improves with experience E.

Thus there are many di!erent kinds of machine learning, depending on the nature of the tasks T we wish the system to learn, the nature of the performance measure P we use to evaluate the system, and the nature of the training signal or experience E we give it.

In this book, we will cover the most common types of ML, but from a probabilistic perspective. Roughly speaking, this means that we treat all unknown quantities (e.g., predictions about the future value of some quantity of interest, such as tomorrow’s temperature, or the parameters of some model) as random variables, that are endowed with probability distributions which describe a weighted set of possible values the variable may have. (See Chapter 2 for a quick refresher on the basics of probability, if necessary.)

There are two main reasons we adopt a probabilistic approach. First, it is the optimal approach to decision making under uncertainty, as we explain in Section 5.1. Second, probabilistic modeling is the language used by most other areas of science and engineering, and thus provides a unifying framework between these fields. As Shakir Mohamed, a researcher at DeepMind, put it:1

Almost all of machine learning can be viewed in probabilistic terms, making probabilistic thinking fundamental. It is, of course, not the only view. But it is through this view that we can connect what we do in machine learning to every other computational science, whether that be in stochastic optimisation, control theory, operations research, econometrics, information theory, statistical physics or bio-statistics. For this reason alone, mastery of probabilistic thinking is essential.

1.2 Supervised learning

The most common form of ML is supervised learning. In this problem, the task T is to learn a mapping f from inputs x → X to outputs y → Y. The inputs x are also called the features,

1. Source: Slide 2 of https://bit.ly/3pyHyPn

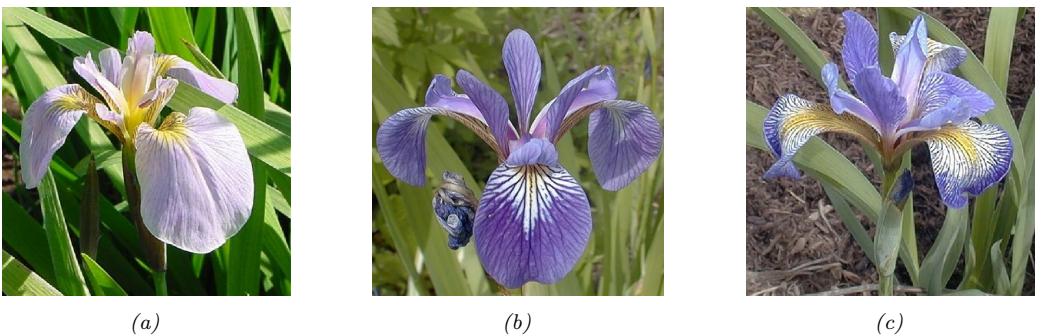

Figure 1.1: Three types of Iris flowers: Setosa, Versicolor and Virginica. Used with kind permission of Dennis Kramb and SIGNA.

| index | sl | sw | pl | pw | label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 1.4 | 0.2 | Setosa |

| 1 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 1.4 | 0.2 | Setosa |

| ··· | |||||

| 50 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 1.4 | Versicolor |

| ··· | |||||

| 149 | 5.9 | 3.0 | 5.1 | 1.8 | Virginica |

Table 1.1: A subset of the Iris design matrix. The features are: sepal length, sepal width, petal length, petal width. There are 50 examples of each class.

covariates, or predictors; this is often a fixed-dimensional vector of numbers, such as the height and weight of a person, or the pixels in an image. In this case, X = RD, where D is the dimensionality of the vector (i.e., the number of input features). The output y is also known as the label, target, or response. 2 The experience E is given in the form of a set of N input-output pairs D = {(xn, yn)}N n=1, known as the training set. (N is called the sample size.) The performance measure P depends on the type of output we are predicting, as we discuss below.

1.2.1 Classification

In classification problems, the output space is a set of C unordered and mutually exclusive labels known as classes, Y = {1, 2,…,C}. The problem of predicting the class label given an input is also called pattern recognition. (If there are just two classes, often denoted by y → {0, 1} or y → {↑1, +1}, it is called binary classification.)

1.2.1.1 Example: classifying Iris flowers

As an example, consider the problem of classifying Iris flowers into their 3 subspecies, Setosa, Versicolor and Virginica. Figure 1.1 shows one example of each of these classes.

2. Sometimes (e.g., in the statsmodels Python package) x are called the exogenous variables and y are called the endogenous variables.

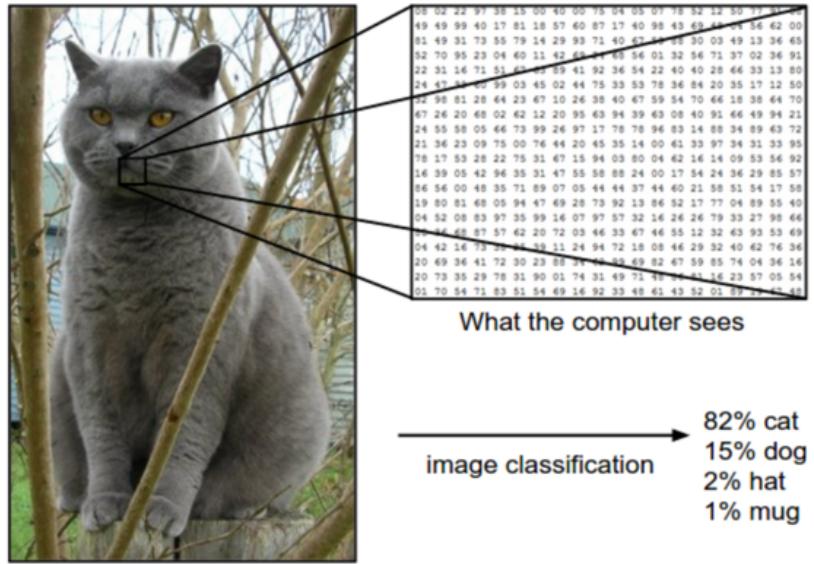

Figure 1.2: Illustration of the image classification problem. From https: // cs231n. github. io/ . Used with kind permission of Andrej Karpathy.

In image classification, the input space X is the set of images, which is a very high-dimensional space: for a color image with C = 3 channels (e.g., RGB) and D1 ↓ D2 pixels, we have X = RD, where D = C ↓ D1 ↓ D2. (In practice we represent each pixel intensity with an integer, typically from the range {0, 1,…, 255}, but we assume real valued inputs for notational simplicity.) Learning a mapping f : X ↔︎ Y from images to labels is quite challenging, as illustrated in Figure 1.2. However, it can be tackled using certain kinds of functions, such as a convolutional neural network or CNN, which we discuss in Section 14.1.

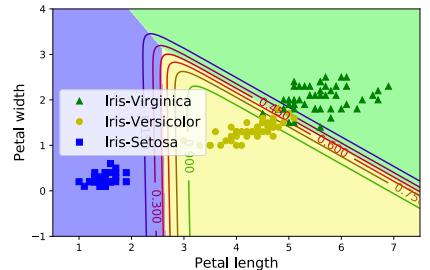

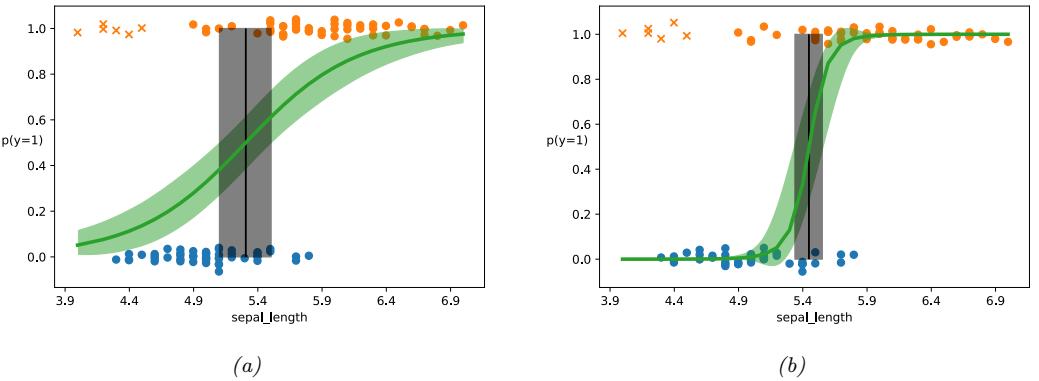

Fortunately for us, some botanists have already identified 4 simple, but highly informative, numeric features — sepal length, sepal width, petal length, petal width — which can be used to distinguish the three kinds of Iris flowers. In this section, we will use this much lower-dimensional input space, X = R4, for simplicity. The Iris dataset is a collection of 150 labeled examples of Iris flowers, 50 of each type, described by these 4 features. It is widely used as an example, because it is small and simple to understand. (We will discuss larger and more complex datasets later in the book.)

When we have small datasets of features, it is common to store them in an N ↓ D matrix, in which each row represents an example, and each column represents a feature. This is known as a design matrix; see Table 1.1 for an example.3

The Iris dataset is an example of tabular data. When the inputs are of variable size (e.g., sequences of words, or social networks), rather than fixed-length vectors, the data is usually stored

3. This particular design matrix has N = 150 rows and D = 4 columns, and hence has a tall and skinny shape, since N → D. By contrast, some datasets (e.g., genomics) have more features than examples, D → N; their design matrices are short and fat. The term “big data” usually means that N is large, whereas the term “wide data” means that D is large (relative to N).

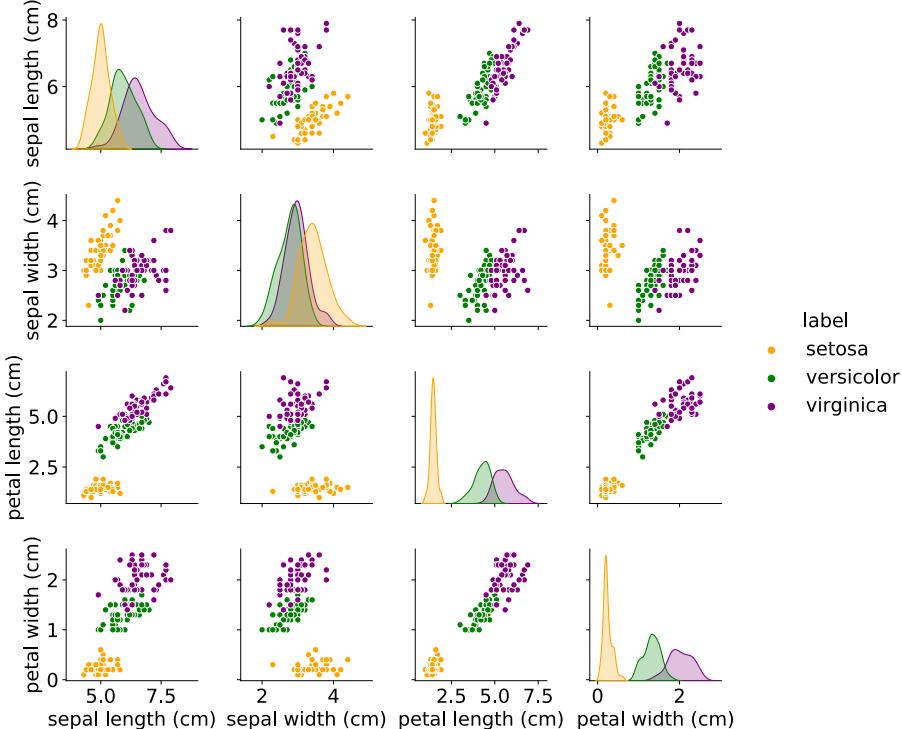

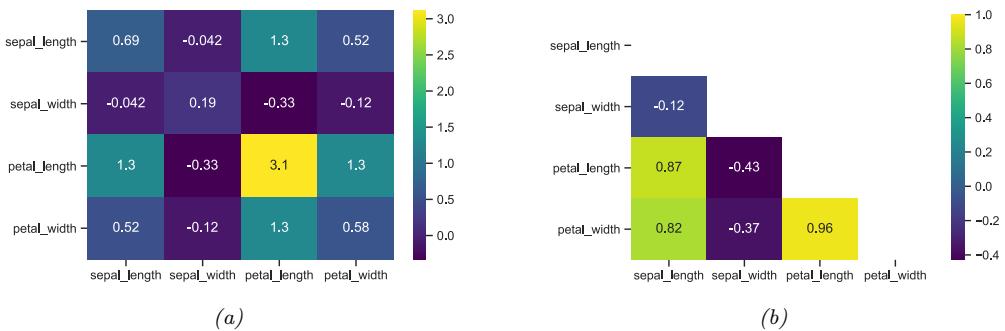

Figure 1.3: Visualization of the Iris data as a pairwise scatter plot. On the diagonal we plot the marginal distribution of each feature for each class. The o!-diagonals contain scatterplots of all possible pairs of features. Generated by iris\_plot.ipynb

in some other format rather than in a design matrix. However, such data is often converted to a fixed-sized feature representation (a process known as featurization), thus implicitly creating a design matrix for further processing. We give an example of this in Section 1.5.4.1, where we discuss the “bag of words” representation for sequence data.

1.2.1.2 Exploratory data analysis

Before tackling a problem with ML, it is usually a good idea to perform exploratory data analysis, to see if there are any obvious patterns (which might give hints on what method to choose), or any obvious problems with the data (e.g., label noise or outliers).

For tabular data with a small number of features, it is common to make a pair plot, in which panel (i, j) shows a scatter plot of variables i and j, and the diagonal entries (i, i) show the marginal density of variable i; all plots are optionally color coded by class label — see Figure 1.3 for an example.

For higher-dimensional data, it is common to first perform dimensionality reduction, and then

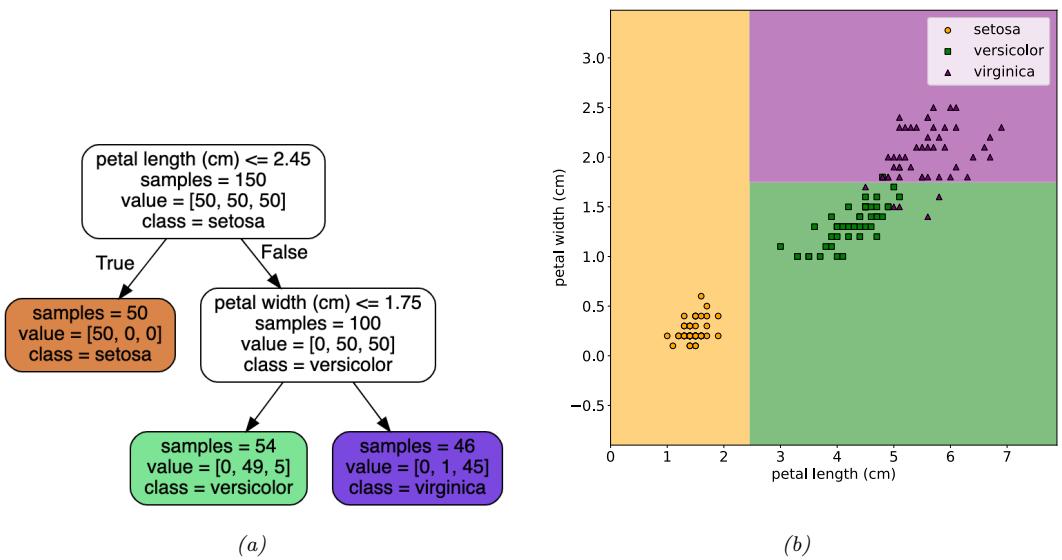

Figure 1.4: Example of a decision tree of depth 2 applied to the Iris data, using just the petal length and petal width features. Leaf nodes are color coded according to the predicted class. The number of training samples that pass from the root to a node is shown inside each box; we show how many values of each class fall into this node. This vector of counts can be normalized to get a distribution over class labels for each node. We can then pick the majority class. Adapted from Figures 6.1 and 6.2 of [Gér19]. Generated by iris\_dtree.ipynb.

to visualize the data in 2d or 3d. We discuss methods for dimensionality reduction in Chapter 20.

1.2.1.3 Learning a classifier

From Figure 1.3, we can see that the Setosa class is easy to distinguish from the other two classes. For example, suppose we create the following decision rule:

\[f(x; \theta) = \begin{cases} \text{Setosa if petal length} < 2.45\\ \text{Versicolor or Viginica otherwise} \end{cases} \tag{1.1}\]

This is a very simple example of a classifier, in which we have partitioned the input space into two regions, defined by the one-dimensional (1d) decision boundary at xpetal length = 2.45. Points lying to the left of this boundary are classified as Setosa; points to the right are either Versicolor or Virginica.

We see that this rule perfectly classifies the Setosa examples, but not the Virginica and Versicolor ones. To improve performance, we can recursively partition the space, by splitting regions in which the classifier makes errors. For example, we can add another decision rule, to be applied to inputs that fail the first test, to check if the petal width is below 1.75cm (in which case we predict Versicolor) or above (in which case we predict Virginica). We can arrange these nested rules into a tree structure,

| Estimate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Setosa | Versicolor | Virginica | ||

| Setosa | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Truth | Versicolor | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Virginica | 10 | 10 | 0 |

Table 1.2: Hypothetical asymmetric loss matrix for Iris classification.

called a decision tree, as shown in Figure 1.4a This induces the 2d decision surface shown in Figure 1.4b.

We can represent the tree by storing, for each internal node, the feature index that is used, as well as the corresponding threshold value. We denote all these parameters by ω. We discuss how to learn these parameters in Section 18.1.

1.2.1.4 Empirical risk minimization

The goal of supervised learning is to automatically come up with classification models such as the one shown in Figure 1.4a, so as to reliably predict the labels for any given input. A common way to measure performance on this task is in terms of the misclassification rate on the training set:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \triangleq \frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \mathbb{I}\left(y\_n \neq f(\mathbf{z}\_n; \boldsymbol{\theta})\right) \tag{1.2}\]

where I(e) is the binary indicator function, which returns 1 i! (if and only if) the condition e is true, and returns 0 otherwise, i.e.,

\[\mathbb{I}(e) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if } e \text{ is true} \\ 0 & \text{if } e \text{ is false} \end{cases} \tag{1.3}\]

This assumes all errors are equal. However it may be the case that some errors are more costly than others. For example, suppose we are foraging in the wilderness and we find some Iris flowers. Furthermore, suppose that Setosa and Versicolor are tasty, but Virginica is poisonous. In this case, we might use the asymmetric loss function ω(y, yˆ) shown in Table 1.2.

We can then define empirical risk to be the average loss of the predictor on the training set:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \triangleq \frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \ell(y\_n, f(\boldsymbol{x}\_n; \boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{1.4}\]

We see that the misclassification rate Equation (1.2) is equal to the empirical risk when we use zero-one loss for comparing the true label with the prediction:

\[\ell\_{01}(y,\hat{y}) = \mathbb{I}\left(y \neq \hat{y}\right) \tag{1.5}\]

See Section 5.1 for more details.

One way to define the problem of model fitting or training is to find a setting of the parameters that minimizes the empirical risk on the training set:

\[\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}} = \underset{\boldsymbol{\theta}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = \underset{\boldsymbol{\theta}}{\operatorname{argmin}} \frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \ell(y\_n, f(\boldsymbol{x}\_n; \boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{1.6}\]

This is called empirical risk minimization.

However, our true goal is to minimize the expected loss on future data that we have not yet seen. That is, we want to generalize, rather than just do well on the training set. We discuss this important point in Section 1.2.3.

1.2.1.5 Uncertainty

[We must avoid] false confidence bred from an ignorance of the probabilistic nature of the world, from a desire to see black and white where we should rightly see gray. — Immanuel Kant, as paraphrased by Maria Konnikova [Kon20].

In many cases, we will not be able to perfectly predict the exact output given the input, due to lack of knowledge of the input-output mapping (this is called epistemic uncertainty or model uncertainty), and/or due to intrinsic (irreducible) stochasticity in the mapping (this is called aleatoric uncertainty or data uncertainty).

Representing uncertainty in our prediction can be important for various applications. For example, let us return to our poisonous flower example, whose loss matrix is shown in Table 1.2. If we predict the flower is Virginica with high probability, then we should not eat the flower. Alternatively, we may be able to perform an information gathering action, such as performing a diagnostic test, to reduce our uncertainty. For more information about how to make optimal decisions in the presence of uncertainty, see Section 5.1.

We can capture our uncertainty using the following conditional probability distribution:

\[p(y = c | \mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = f\_c(\mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) \tag{1.7}\]

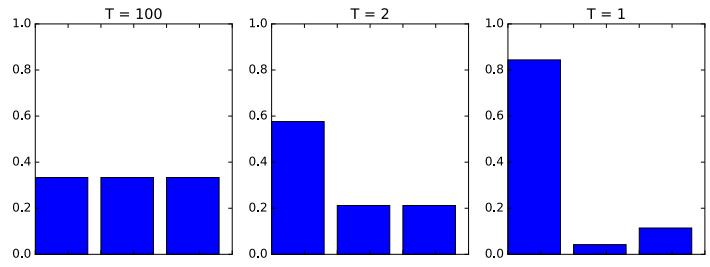

where f : X ↔︎ [0, 1]C maps inputs to a probability distribution over the C possible output labels. Since fc(x; ω) returns the probability of class label c, we require 0 ↘ fc ↘ 1 for each c, and $C c=1 fc = 1. To avoid this restriction, it is common to instead require the model to return unnormalized logprobabilities. We can then convert these to probabilities using the softmax function, which is defined as follows

\[\text{softmax}(\mathbf{a}) \triangleq \left[ \frac{e^{a\_1}}{\sum\_{c'=1}^{C} e^{a\_{c'}}}, \dots, \frac{e^{a\_C}}{\sum\_{c'=1}^{C} e^{a\_{c'}}} \right] \tag{1.8}\]

This maps RC to [0, 1]C , and satisfies the constraints that 0 ↘ softmax(a)c ↘ 1 and $C c=1 softmax(a)c = 1. The inputs to the softmax, a = f(x; ω), are called logits. See Section 2.5.2 for details. We thus define the overall model as follows:

\[p(y = c | \mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = \text{softmax}\_{\mathbf{c}}(f(\mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{1.9}\]

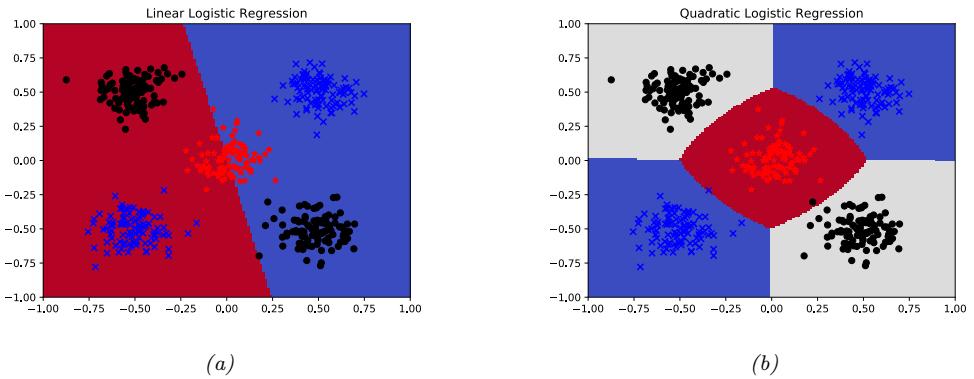

A common special case of this arises when f is an a!ne function of the form

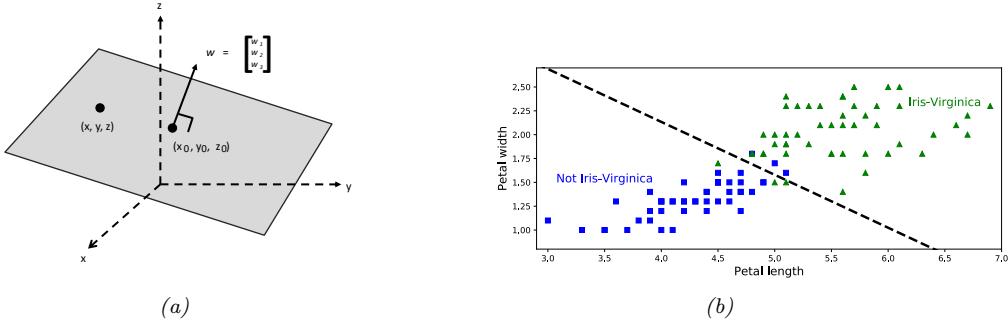

\[f(\mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = b + \mathbf{w}^{\mathsf{T}} \mathbf{z} = b + w\_1 x\_1 + w\_2 x\_2 + \dots + w\_D x\_D \tag{1.10}\]

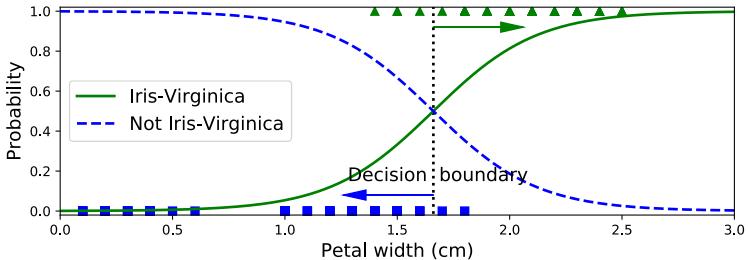

where ω = (b, w) are the parameters of the model. This model is called logistic regression, and will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.

In statistics, the w parameters are usually called regression coe!cients (and are typically denoted by ε) and b is called the intercept. In ML, the parameters w are called the weights and b is called the bias. This terminology arises from electrical engineering, where we view the function f as a circuit which takes in x and returns f(x). Each input is fed to the circuit on “wires”, which have weights w. The circuit computes the weighted sum of its inputs, and adds a constant bias or o!set term b. (This use of the term “bias” should not be confused with the statistical concept of bias discussed in Section 4.7.6.1.)

To reduce notational clutter, it is common to absorb the bias term b into the weights w by defining w˜ = [b, w1,…,wD] and defining x˜ = [1, x1,…,xD], so that

\[ \bar{w}^{\mathsf{T}}\bar{x} = b + w^{\mathsf{T}}x\tag{1.11} \]

This converts the a”ne function into a linear function. We will usually assume that this has been done, so we can just write the prediction function as follows:

\[f(x; w) = w^{\top} x\]

1.2.1.6 Maximum likelihood estimation

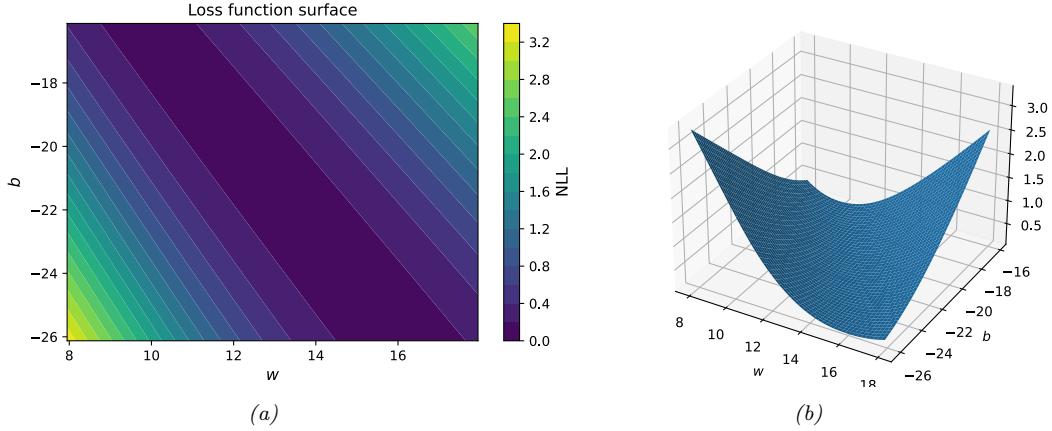

When fitting probabilistic models, it is common to use the negative log probability as our loss function:

\[\ell(y, f(x; \theta)) = -\log p(y|f(x; \theta)) \tag{1.13}\]

The reasons for this are explained in Section 5.1.6.1, but the intuition is that a good model (with low loss) is one that assigns a high probability to the true output y for each corresponding input x. The average negative log probability of the training set is given by

\[\text{NLL}(\theta) = -\frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \log p(y\_n | f(x\_n; \theta)) \tag{1.14}\]

This is called the negative log likelihood. If we minimize this, we can compute the maximum likelihood estimate or MLE:

\[\hat{\theta}\_{\text{mle}} = \underset{\theta}{\text{argmin}} \,\text{NLL}(\theta) \tag{1.15}\]

This is a very common way to fit models to data, as we will see.

1.2.2 Regression

Now suppose that we want to predict a real-valued quantity y → R instead of a class label y → {1,…,C}; this is known as regression. For example, in the case of Iris flowers, y might be the degree of toxicity if the flower is eaten, or the average height of the plant.

Regression is very similar to classification. However, since the output is real-valued, we need to use a di!erent loss function. For regression, the most common choice is to use quadratic loss, or ω2 loss:

\[\ell\_2(y, \hat{y}) = (y - \hat{y})^2 \tag{1.16}\]

This penalizes large residuals y ↑ yˆ more than small ones.4 The empirical risk when using quadratic loss is equal to the mean squared error or MSE:

\[\text{MSE}(\theta) = \frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} (y\_n - f(x\_n; \theta))^2 \tag{1.17}\]

Based on the discussion in Section 1.2.1.5, we should also model the uncertainty in our prediction. In regression problems, it is common to assume the output distribution is a Gaussian or normal. As we explain in Section 2.6, this distribution is defined by

\[\mathcal{N}(y|\mu,\sigma^2) \stackrel{\Delta}{=} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} e^{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2}(y-\mu)^2} \tag{1.18}\]

where µ is the mean, ε2 is the variance, and ≃ 2ϑε2 is the normalization constant needed to ensure the density integrates to 1. In the context of regression, we can make the mean depend on the inputs by defining µ = f(xn; ω). We therefore get the following conditional probability distribution:

\[p(y\_n|x\_n; \theta) = \mathcal{N}(y\_n|f(x\_n; \theta), \sigma^2) \tag{1.19}\]

If we assume that the variance ε2 is fixed (for simplicity), the corresponding average (per-sample) negative log likelihood becomes

\[\text{NLL}(\boldsymbol{\theta}) = -\frac{1}{N} \sum\_{n=1}^{N} \log \left[ \left( \frac{1}{2\pi\sigma^2} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} \exp \left( -\frac{1}{2\sigma^2} (y\_n - f(\boldsymbol{x}\_n; \boldsymbol{\theta}))^2 \right) \right] \tag{1.20}\]

\[\hat{\sigma} = \frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \text{MSE}(\hat{\theta}) + \text{const} \tag{1.21}\]

We see that the NLL is proportional to the MSE. Hence computing the maximum likelihood estimate of the parameters will result in minimizing the squared error, which seems like a sensible approach to model fitting.

1.2.2.1 Linear regression

As an example of a regression model, consider the 1d data in Figure 1.5a. We can fit this data using a simple linear regression model of the form

\[f(x; \theta) = b + wx \tag{1.22}\]

4. If the data has outliers, the quadratic penalty can be too severe. In such cases, it can be better to use ω1 loss instead, which is more robust. See Section 11.6 for details.

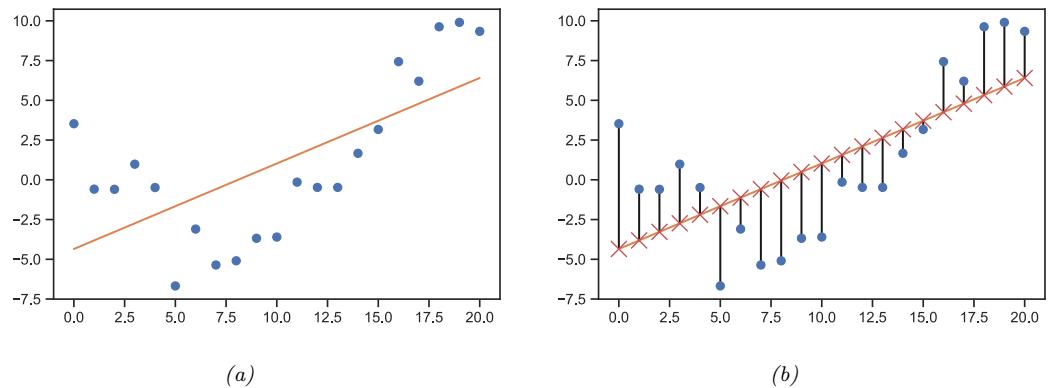

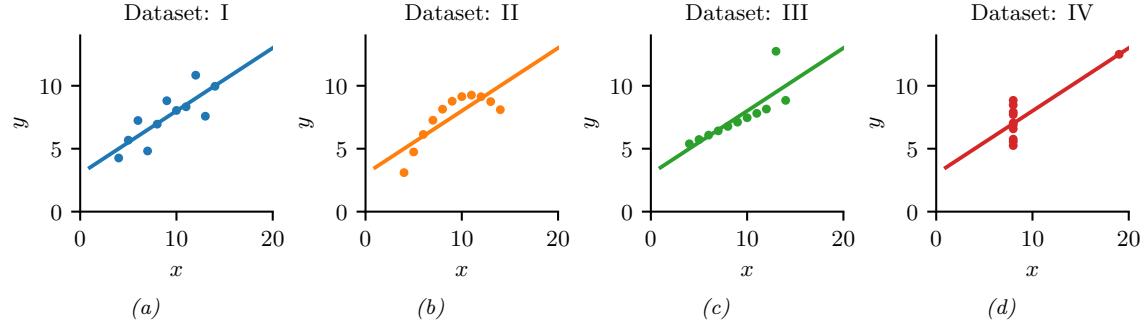

Figure 1.5: (a) Linear regression on some 1d data. (b) The vertical lines denote the residuals between the observed output value for each input (blue circle) and its predicted value (red cross). The goal of least squares regression is to pick a line that minimizes the sum of squared residuals. Generated by linreg\_residuals\_plot.ipynb.

where w is the slope, b is the o”set, and ω = (w, b) are all the parameters of the model. By adjusting ω, we can minimize the sum of squared errors, shown by the vertical lines in Figure 1.5b. until we find the least squares solution

\[\hat{\boldsymbol{\theta}} = \underset{\boldsymbol{\theta}}{\text{argmin}} \,\text{MSE}(\boldsymbol{\theta})\tag{1.23}\]

See Section 11.2.2.1 for details.

If we have multiple input features, we can write

\[f(\mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = b + w\_1 x\_1 + \dots + w\_D x\_D = b + \mathbf{w}^\mathsf{T} \mathbf{z} \tag{1.24}\]

where ω = (w, b). This is called multiple linear regression.

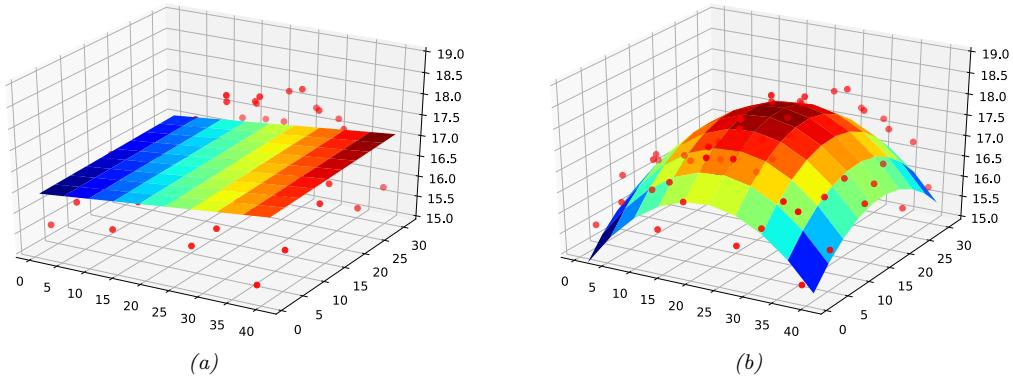

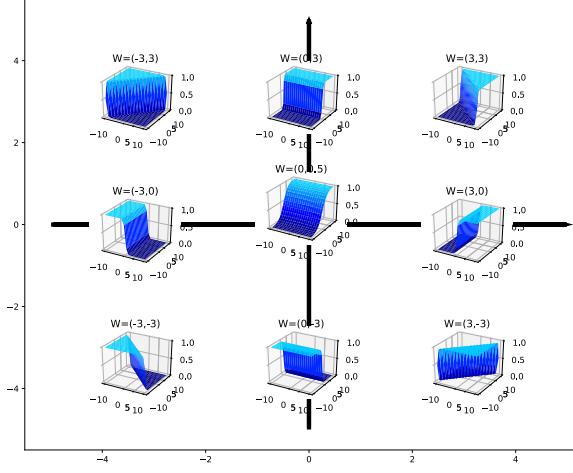

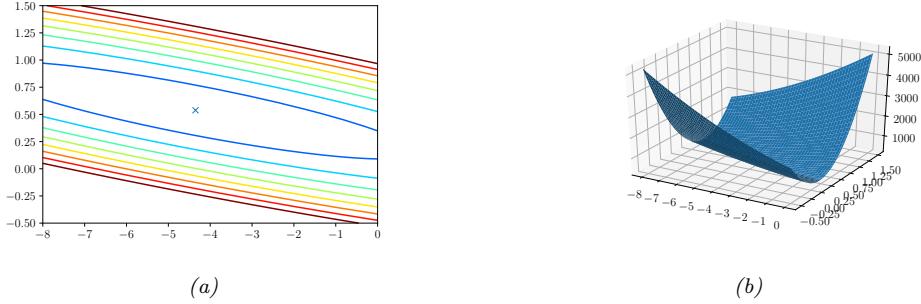

For example, consider the task of predicting temperature as a function of 2d location in a room. Figure 1.6(a) plots the results of a linear model of the following form:

\[f(x; \theta) = b + w\_1 x\_1 + w\_2 x\_2 \tag{1.25}\]

We can extend this model to use D > 2 input features (such as time of day), but then it becomes harder to visualize.

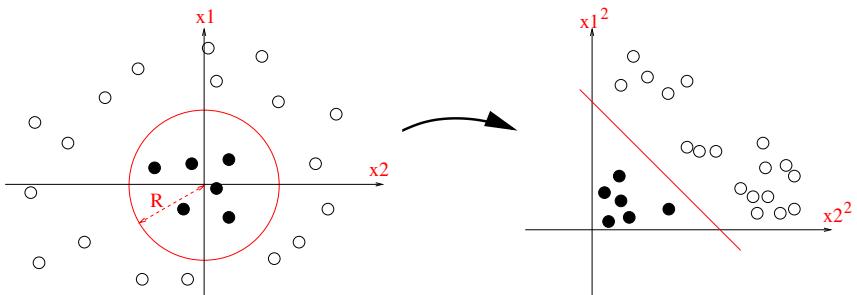

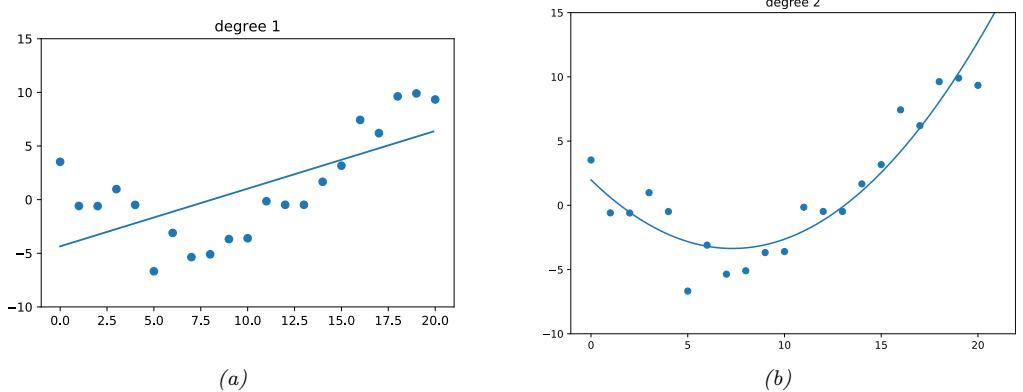

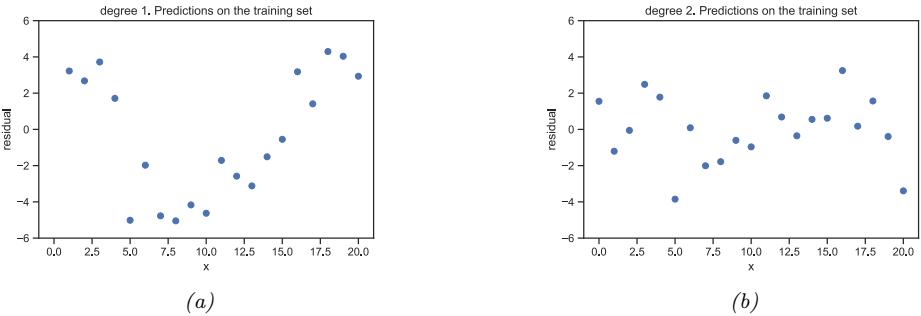

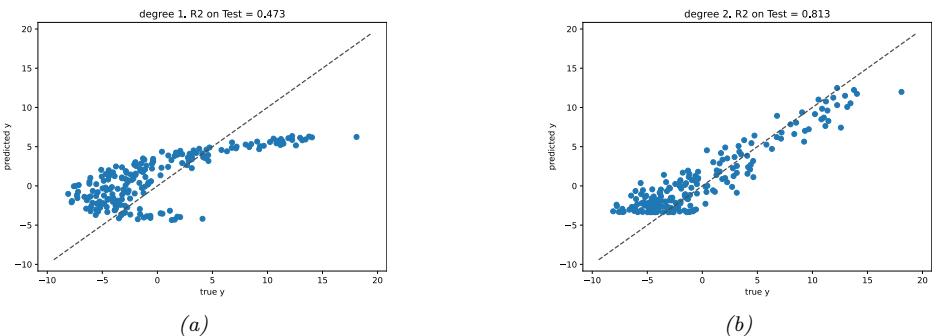

1.2.2.2 Polynomial regression

The linear model in Figure 1.5a is obviously not a very good fit to the data. We can improve the fit by using a polynomial regression model of degree D. This has the form f(x; w) = wTϑ(x), where ϑ(x) is a feature vector derived from the input, which has the following form:

\[\phi(x) = [1, x, x^2, \dots, x^D] \tag{1.26}\]

Figure 1.6: Linear and polynomial regression applied to 2d data. Vertical axis is temperature, horizontal axes are location within a room. Data was collected by some remote sensing motes at Intel’s lab in Berkeley, CA (data courtesy of Romain Thibaux). (a) The fitted plane has the form ˆf(x) = w0 + w1x1 + w2x2. (b) Temperature data is fitted with a quadratic of the form ˆf(x) = w0 + w1x1 + w2x2 + w3x2 1 + w4x2 2. Generated by linreg\_2d\_surface\_demo.ipynb.

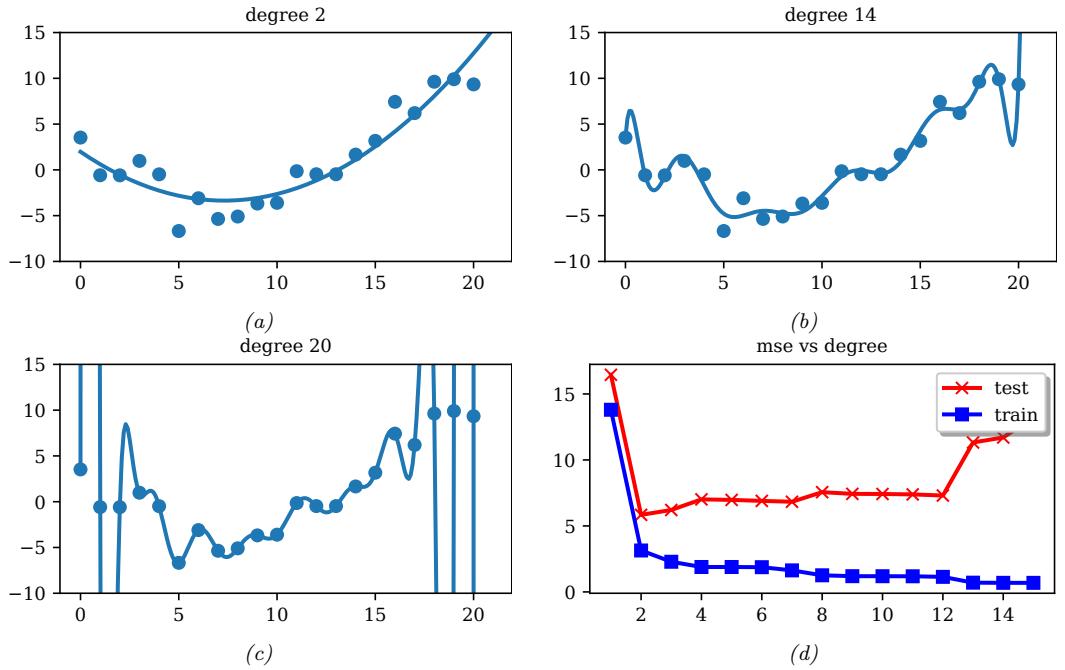

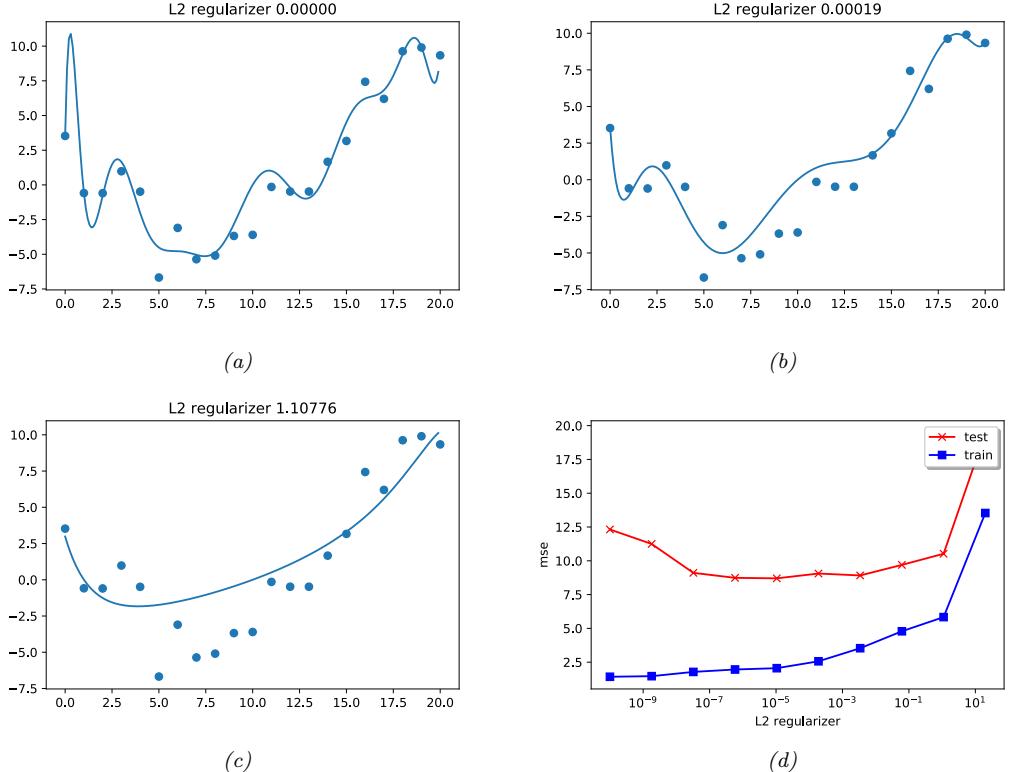

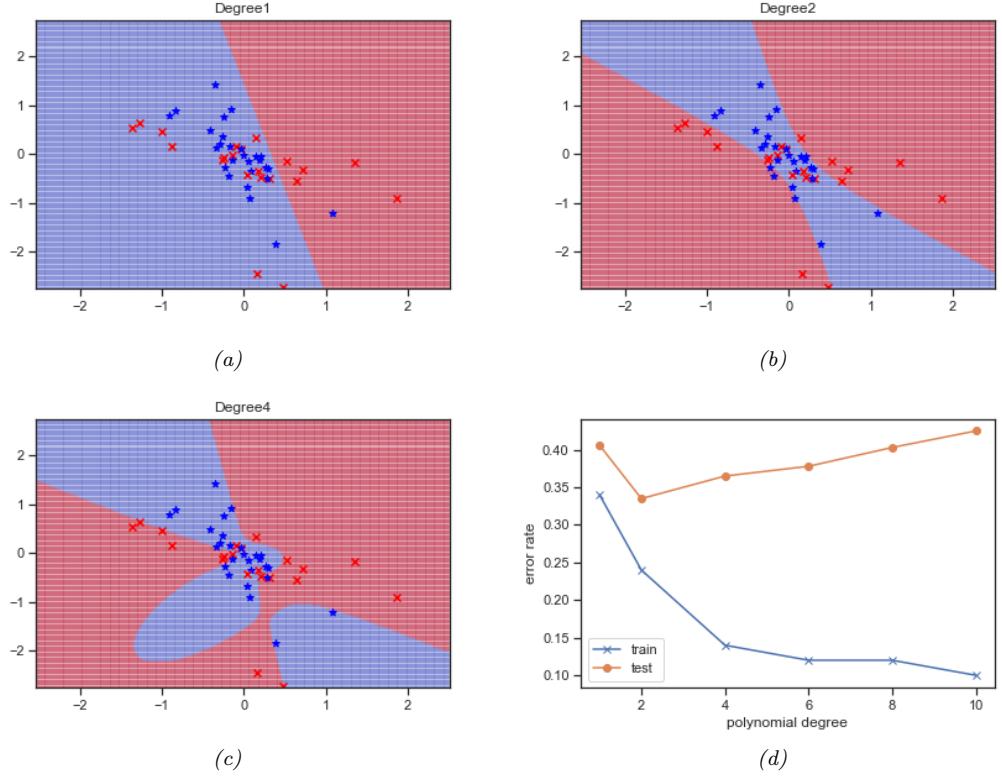

Figure 1.7: (a-c) Polynomials of degrees 2, 14 and 20 fit to 21 datapoints (the same data as in Figure 1.5). (d) MSE vs degree. Generated by linreg\_poly\_vs\_degree.ipynb.

This is a simple example of feature preprocessing, also called feature engineering.

In Figure 1.7a, we see that using D = 2 results in a much better fit. We can keep increasing D, and hence the number of parameters in the model, until D = N ↑ 1; in this case, we have one parameter per data point, so we can perfectly interpolate the data. The resulting model will have 0 MSE, as shown in Figure 1.7c. However, intuitively the resulting function will not be a good predictor for future inputs, since it is too “wiggly”. We discuss this in more detail in Section 1.2.3.

We can also apply polynomial regression to multi-dimensional inputs. For example, Figure 1.6(b) plots the predictions for the temperature model after performing a quadratic expansion of the inputs

\[f(\mathbf{z}; \mathbf{w}) = w\_0 + w\_1 x\_1 + w\_2 x\_2 + w\_3 x\_1^2 + w\_4 x\_2^2 \tag{1.27}\]

The quadratic shape is a better fit to the data than the linear model in Figure 1.6(a), since it captures the fact that the middle of the room is hotter. We can also add cross terms, such as x1x2, to capture interaction e!ects. See Section 1.5.3.2 for details.

Note that the above models still use a prediction function that is a linear function of the parameters w, even though it is a nonlinear function of the original input x. The reason this is important is that a linear model induces an MSE loss function MSE(ω) that has a unique global optimum, as we explain in Section 11.2.2.1.

1.2.2.3 Deep neural networks

In Section 1.2.2.2, we manually specified the transformation of the input features, namely polynomial expansion, ϑ(x) = [1, x1, x2, x2 1, x2 2,…]. We can create much more powerful models by learning to do such nonlinear feature extraction automatically. If we let ϑ(x) have its own set of parameters, say V, then the overall model has the form

\[f(x; w, \mathbf{V}) = w^{\top} \phi(x; \mathbf{V}) \tag{1.28}\]

We can recursively decompose the feature extractor ϑ(x; V) into a composition of simpler functions. The resulting model then becomes a stack of L nested functions:

\[f(\mathbf{z}; \boldsymbol{\theta}) = f\_L(f\_{L-1}(\cdots(f\_1(\mathbf{z}))\cdots))\tag{1.29}\]

where fω(x) = f(x; ωω) is the function at layer ω. The final layer is linear and has the form fL(x) = wT Lx, so f(x; ω) = wT Lf1:L→1(x), where f1:L→1(x) = fL→1(···(f1(x))···) is the learned feature extractor. This is the key idea behind deep neural networks or DNNs, which includes common variants such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for images, and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) for sequences. See Part III for details.

1.2.3 Overfitting and generalization

We can rewrite the empirical risk in Equation (1.4) in the following equivalent way:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}; \mathcal{D}\_{\text{train}}) = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}\_{\text{train}}|} \sum\_{(\mathfrak{x}, \mathfrak{y}) \in \mathcal{D}\_{\text{train}}} \ell(\mathfrak{y}, f(\mathfrak{x}; \boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{1.30}\]

where |Dtrain| is the size of the training set Dtrain. This formulation is useful because it makes explicit which dataset the loss is being evaluated on.

1.2. Supervised learning 13

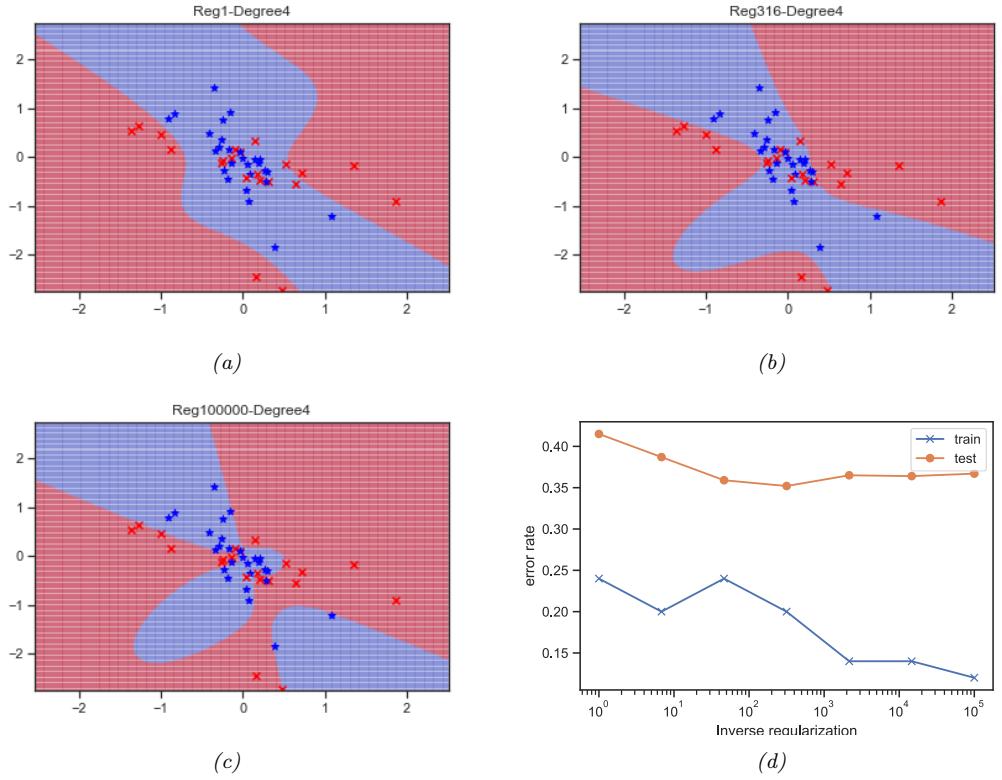

With a suitably flexible model, we can drive the training loss to zero (assuming no label noise), by simply memorizing the correct output for each input. For example, Figure 1.7(c) perfectly interpolates the training data (modulo the last point on the right). But what we care about is prediction accuracy on new data, which may not be part of the training set. A model that perfectly fits the training data, but which is too complex, is said to su!er from overfitting.

To detect if a model is overfitting, let us assume (for now) that we have access to the true (but unknown) distribution p↓(x, y) used to generate the training set. Then, instead of computing the empirical risk we compute the theoretical expected loss or population risk

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta; p^\*) \triangleq \mathbb{E}\_{p^\*(x, y)} \left[ \ell(y, f(x; \theta)) \right] \tag{1.31}\]

The di!erence L(ω; p↓) ↑ L(ω; Dtrain) is called the generalization gap. If a model has a large generalization gap (i.e., low empirical risk but high population risk), it is a sign that it is overfitting.

In practice we don’t know p↓. However, we can partition the data we do have into two subsets, known as the training set and the test set. Then we can approximate the population risk using the test risk:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}; \mathcal{D}\_{\text{test}}) \stackrel{\scriptstyle \Delta}{=} \frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}\_{\text{test}}|} \sum\_{(\mathfrak{x}, \mathfrak{y}) \in \mathcal{D}\_{\text{test}}} \ell(\boldsymbol{y}, f(\boldsymbol{x}; \boldsymbol{\theta})) \tag{1.32}\]

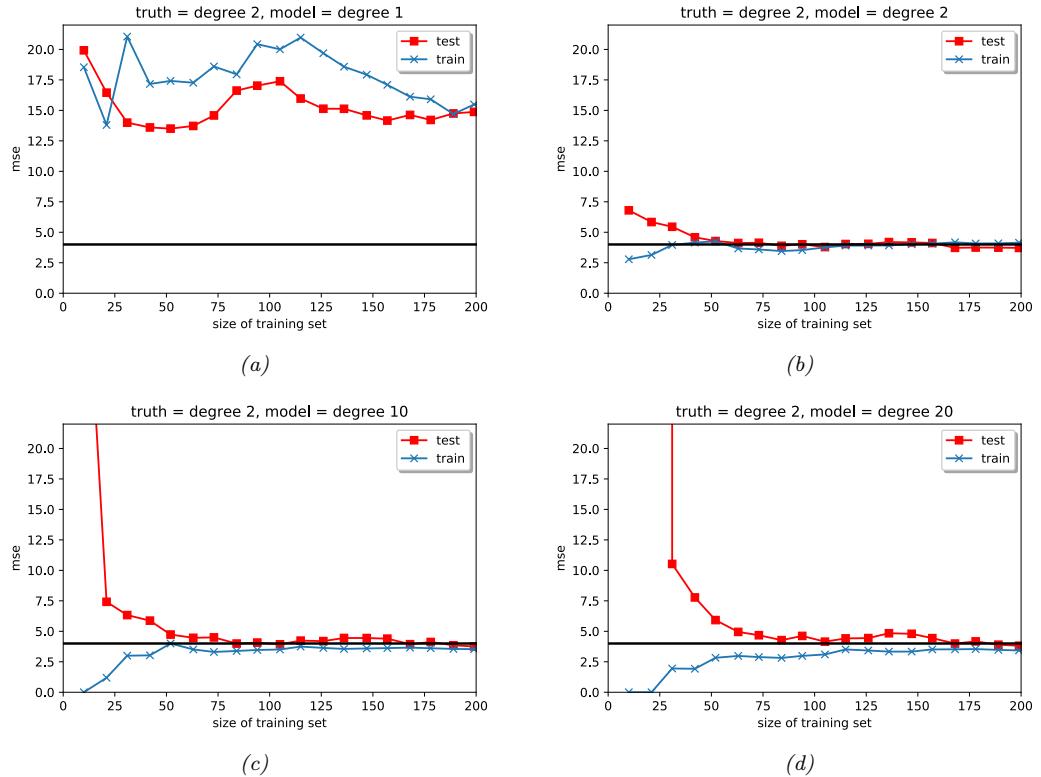

As an example, in Figure 1.7d, we plot the training error and test error for polynomial regression as a function of degree D. We see that the training error goes to 0 as the model becomes more complex. However, the test error has a characteristic U-shaped curve: on the left, where D = 1, the model is underfitting; on the right, where D ⇐ 1, the model is overfitting; and when D = 2, the model complexity is “just right”.

How can we pick a model of the right complexity? If we use the training set to evaluate di!erent models, we will always pick the most complex model, since that will have the most degrees of freedom, and hence will have minimum loss. So instead we should pick the model with minimum test loss.

In practice, we need to partition the data into three sets, namely the training set, the test set and a validation set; the latter is used for model selection, and we just use the test set to estimate future performance (the population risk), i.e., the test set is not used for model fitting or model selection. See Section 4.5.4 for further details.

1.2.4 No free lunch theorem

All models are wrong, but some models are useful. — George Box [BD87, p424].5

Given the large variety of models in the literature, it is natural to wonder which one is best. Unfortunately, there is no single best model that works optimally for all kinds of problems — this is sometimes called the no free lunch theorem [Wol96]. The reason is that a set of assumptions (also called inductive bias) that works well in one domain may work poorly in another. The best way to pick a suitable model is based on domain knowledge, and/or trial and error (i.e., using model selection techniques such as cross validation (Section 4.5.4) or Bayesian methods (Section 5.2.2 and Section 5.2.6). For this reason, it is important to have many models and algorithmic techniques in one’s toolbox to choose from.

5. George Box is a retired statistics professor at the University of Wisconsin.

1.3 Unsupervised learning

In supervised learning, we assume that each input example x in the training set has an associated set of output targets y, and our goal is to learn the input-output mapping. Although this is useful, and can be di”cult, supervised learning is essentially just “glorified curve fitting” [Pea18].

An arguably much more interesting task is to try to “make sense of” data, as opposed to just learning a mapping. That is, we just get observed “inputs” D = {xn : n =1: N} without any corresponding “outputs” yn. This is called unsupervised learning.

From a probabilistic perspective, we can view the task of unsupervised learning as fitting an unconditional model of the form p(x), which can generate new data x, whereas supervised learning involves fitting a conditional model, p(y|x), which specifies (a distribution over) outputs given inputs.6

Unsupervised learning avoids the need to collect large labeled datasets for training, which can often be time consuming and expensive (think of asking doctors to label medical images).

Unsupervised learning also avoids the need to learn how to partition the world into often arbitrary categories. For example, consider the task of labeling when an action, such as “drinking” or “sipping”, occurs in a video. Is it when the person picks up the glass, or when the glass first touches the mouth, or when the liquid pours out? What if they pour out some liquid, then pause, then pour again — is that two actions or one? Humans will often disagree on such issues [Idr+17], which means the task is not well defined. It is therefore not reasonable to expect machines to learn such mappings.7

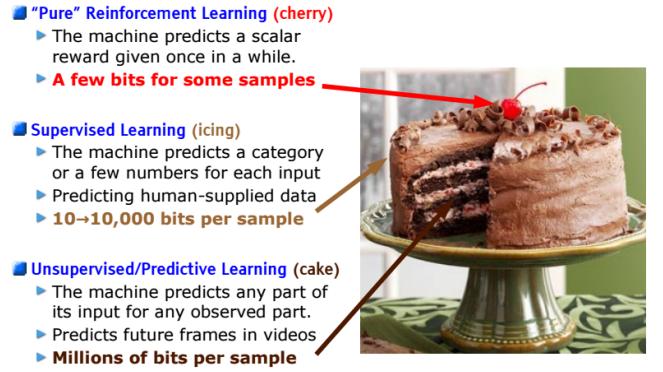

Finally, unsupervised learning forces the model to “explain” the high-dimensional inputs, rather than just the low-dimensional outputs. This allows us to learn richer models of “how the world works”. As Geo! Hinton, who is a famous professor of ML at the University of Toronto, has said:

When we’re learning to see, nobody’s telling us what the right answers are — we just look. Every so often, your mother says “that’s a dog”, but that’s very little information. You’d be lucky if you got a few bits of information — even one bit per second — that way. The brain’s visual system has O(1014) neural connections. And you only live for O(109) seconds. So it’s no use learning one bit per second. You need more like O(105) bits per second. And there’s only one place you can get that much information: from the input itself. — Geo!rey Hinton, 1996 (quoted in [Gor06]).

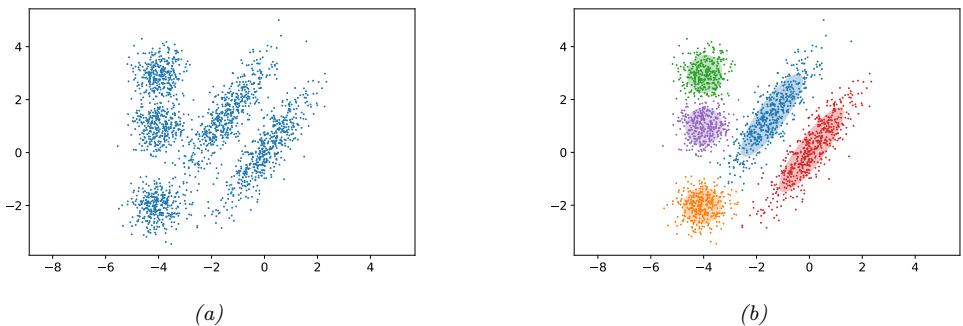

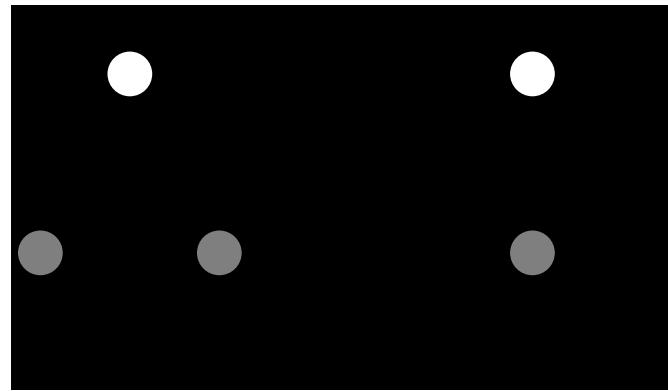

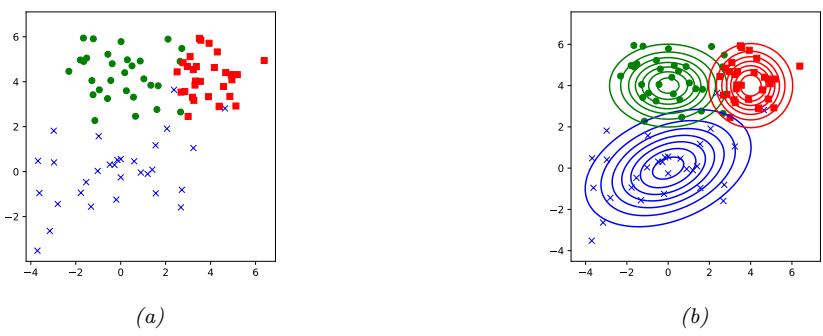

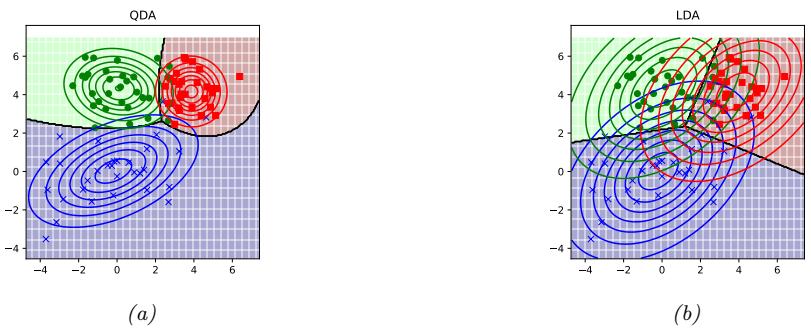

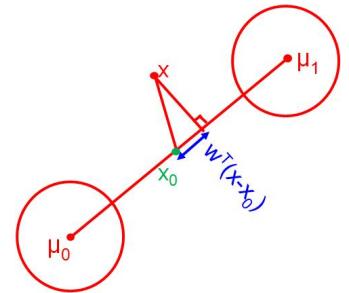

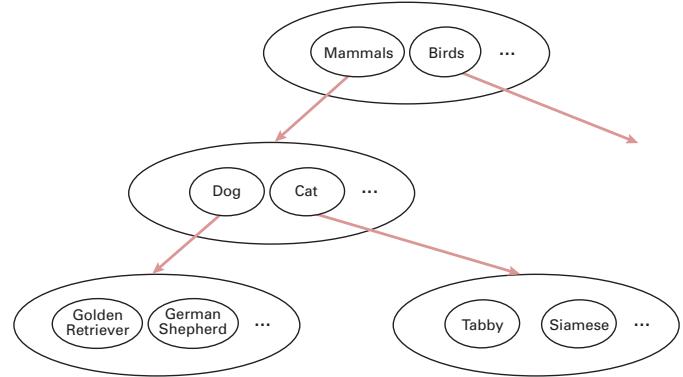

1.3.1 Clustering

A simple example of unsupervised learning is the problem of finding clusters in data. The goal is to partition the input into regions that contain “similar” points. As an example, consider a 2d version of the Iris dataset. In Figure 1.8a, we show the points without any class labels. Intuitively there are at least two clusters in the data, one in the bottom left and one in the top right. Furthermore, if we assume that a “good” set of clusters should be fairly compact, then we might want to split the top right into (at least) two subclusters. The resulting partition into three clusters is shown in Figure 1.8b. (Note that there is no correct number of clusters; instead, we need to consider the

6. In the statistics community, it is common to use x to denote exogenous variables that are not modeled, but are simply given as inputs. Therefore an unconditional model would be denoted p(y) rather than p(x).

7. A more reasonable approach is to try to capture the probability distribution over labels produced by a “crowd” of annotators (see e.g., [Dum+18; Aro+19]). This embraces the fact that there can be multiple “correct” labels for a given input due to the ambiguity of the task itself.

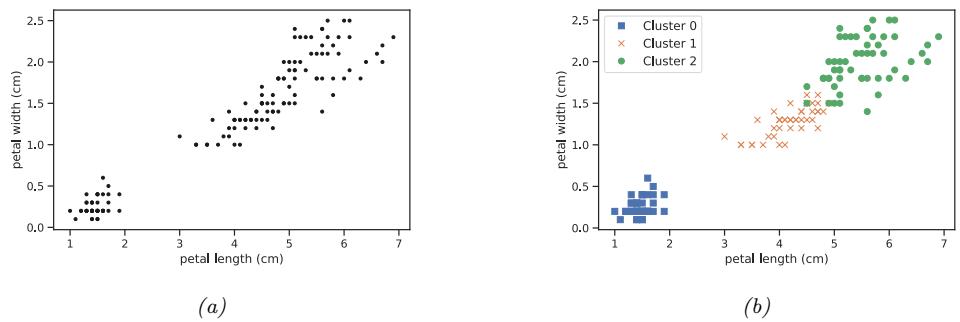

Figure 1.8: (a) A scatterplot of the petal features from the iris dataset. (b) The result of unsupervised clustering using K = 3. Generated by iris\_kmeans.ipynb.

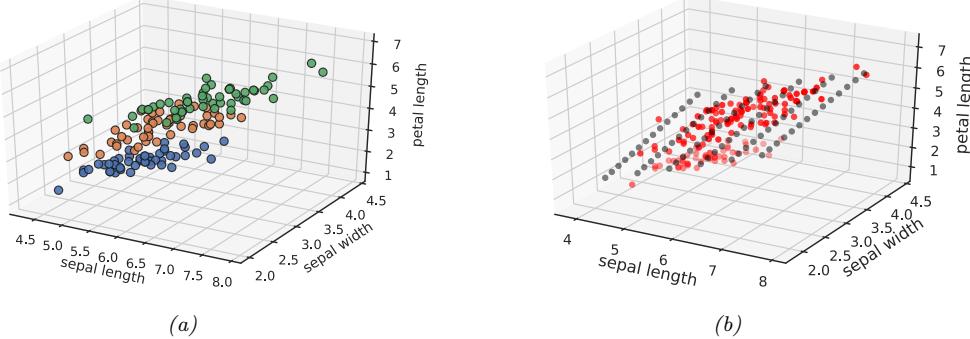

Figure 1.9: (a) Scatterplot of iris data (first 3 features). Points are color coded by class. (b) We fit a 2d linear subspace to the 3d data using PCA. The class labels are ignored. Red dots are the original data, black dots are points generated from the model using xˆ = Wz + µ, where z are latent points on the underlying inferred 2d linear manifold. Generated by iris\_pca.ipynb.

tradeo! between model complexity and fit to the data. We discuss ways to make this tradeo! in Section 21.3.7.)

1.3.2 Discovering latent “factors of variation”

When dealing with high-dimensional data, it is often useful to reduce the dimensionality by projecting it to a lower dimensional subspace which captures the “essence” of the data. One approach to this problem is to assume that each observed high-dimensional output xn → RD was generated by a set of hidden or unobserved low-dimensional latent factors zn → RK. We can represent the model diagrammatically as follows: zn ↔︎ xn, where the arrow represents causation. Since we don’t know the latent factors zn, we often assume a simple prior probability model for p(zn) such as a Gaussian, which says that each factor is a random K-dimensional vector. If the data is real-valued, we can use a Gaussian likelihood as well.

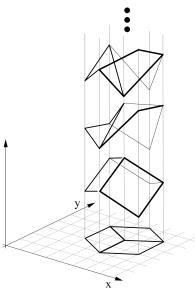

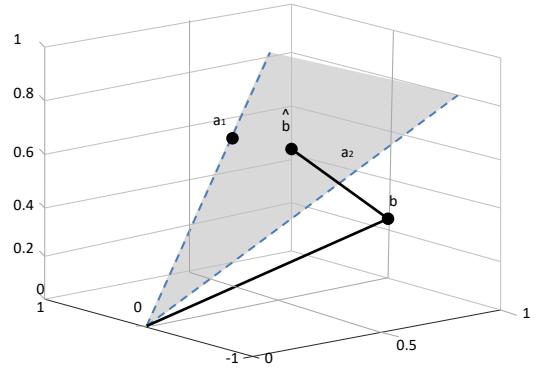

The simplest example is when we use a linear model, p(xn|zn; ω) = N (xn|Wzn + µ, !). The resulting model is called factor analysis (FA). It is similar to linear regression, except we only observe the outputs xn, and not the inputs zn. In the special case that ! = ε2I, this reduces to a model called probabilistic principal components analysis (PCA), which we will explain in Section 20.1. In Figure 1.9, we give an illustration of how this method can find a 2d linear subspace when applied to some simple 3d data.

Of course, assuming a linear mapping from zn to xn is very restrictive. However, we can create nonlinear extensions by defining p(xn|zn; ω) = N (xn|f(zn; ω), ε2I), where f(z; ω) is a nonlinear model, such as a deep neural network. It becomes much harder to fit such a model (i.e., to estimate the parameters ω), because the inputs to the neural net have to be inferred, as well as the parameters of the model. However, there are various approximate methods, such as the variational autoencoder which can be applied (see Section 20.3.5).

1.3.3 Self-supervised learning

A recently popular approach to unsupervised learning is known as self-supervised learning. In this approach, we create proxy supervised tasks from unlabeled data. For example, we might try to learn to predict a color image from a grayscale image, or to mask out words in a sentence and then try to predict them given the surrounding context. The hope is that the resulting predictor xˆ1 = f(x2; ω), where x2 is the observed input and xˆ1 is the predicted output, will learn useful features from the data, that can then be used in standard, downstream supervised tasks. This avoids the hard problem of trying to infer the “true latent factors” z behind the observed data, and instead relies on standard supervised learning methods. We discuss this approach in more detail in Section 19.2.

1.3.4 Evaluating unsupervised learning

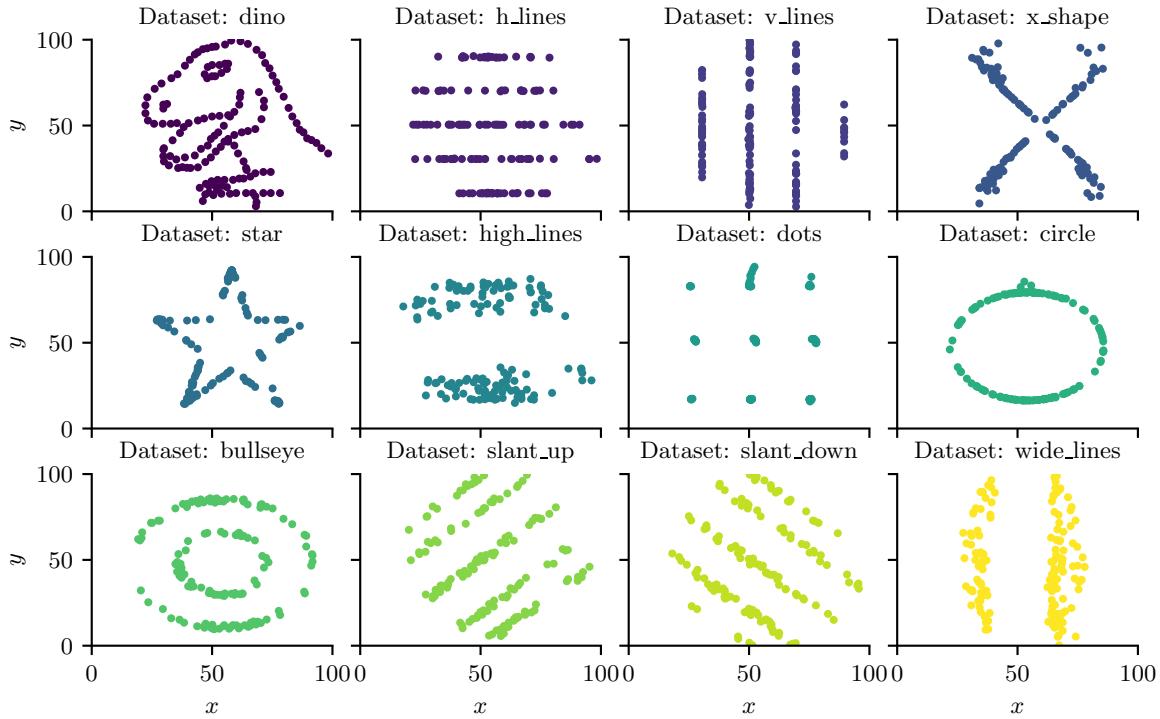

Although unsupervised learning is appealing, it is very hard to evaluate the quality of the output of an unsupervised learning method, because there is no ground truth to compare to [TOB16].

A common method for evaluating unsupervised models is to measure the probability assigned by the model to unseen test examples. We can do this by computing the (unconditional) negative log likelihood of the data:

\[\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\theta}; \mathcal{D}) = -\frac{1}{|\mathcal{D}|} \sum\_{\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathcal{D}} \log p(\boldsymbol{x}|\boldsymbol{\theta}) \tag{1.33}\]

This treats the problem of unsupervised learning as one of density estimation. The idea is that a good model will not be “surprised” by actual data samples (i.e., will assign them high probability). Furthermore, since probabilities must sum to 1.0, if the model assigns high probability to regions of data space where the data samples come from, it implicitly assigns low probability to the regions where the data does not come from. Thus the model has learned to capture the typical patterns in the data. This can be used inside of a data compression algorithm.

Unfortunately, density estimation is di”cult, especially in high dimensions. Furthermore, a model that assigns high probability to the data may not have learned useful high-level patterns (after all, the model could just memorize all the training examples).

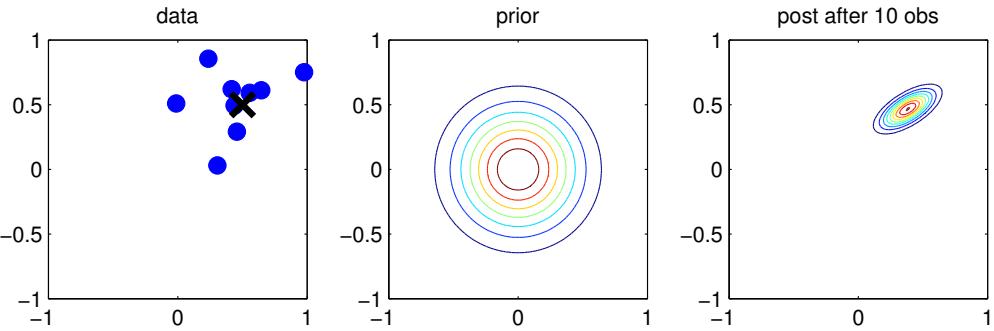

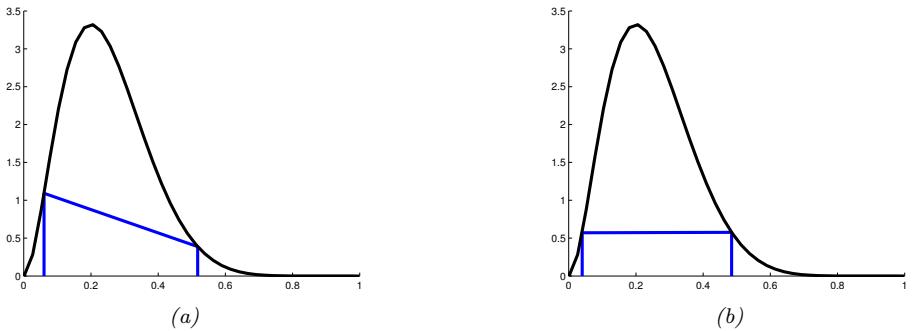

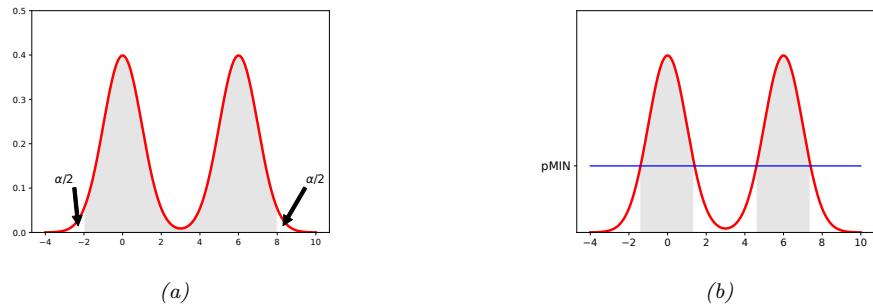

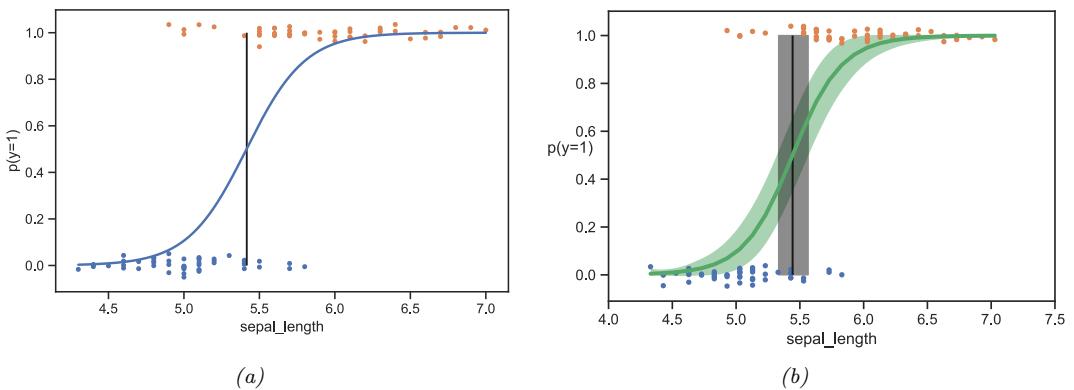

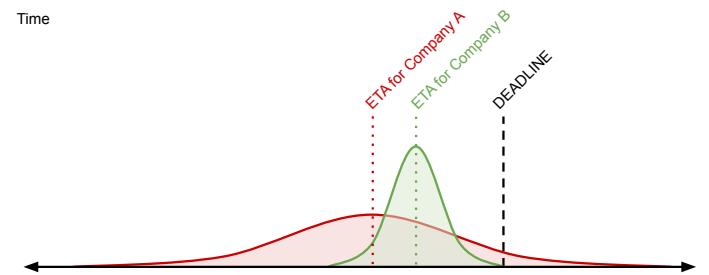

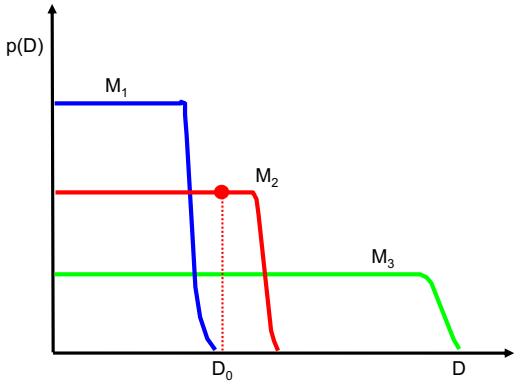

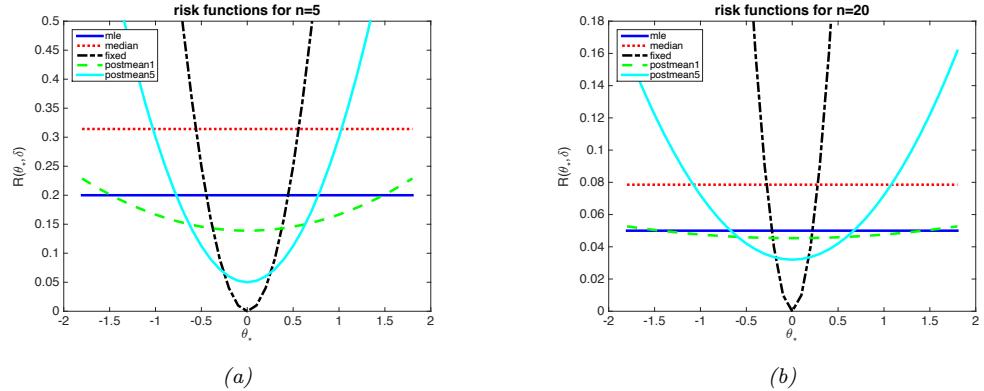

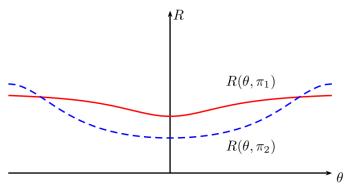

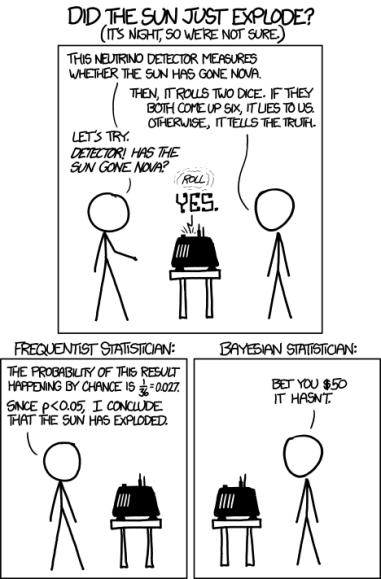

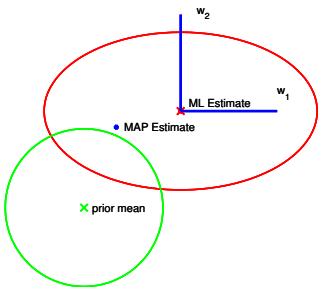

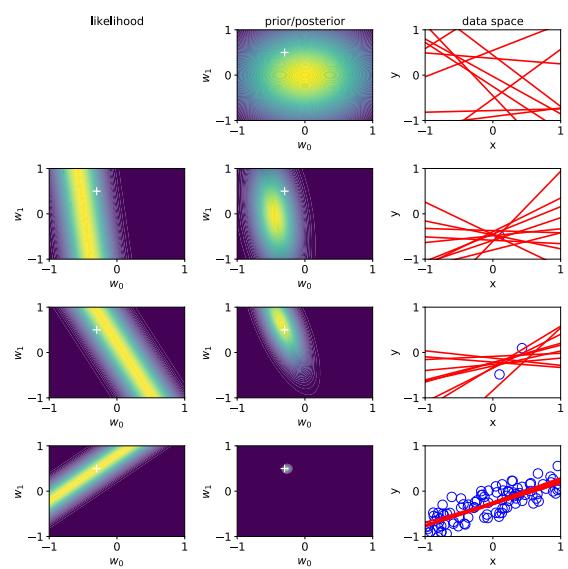

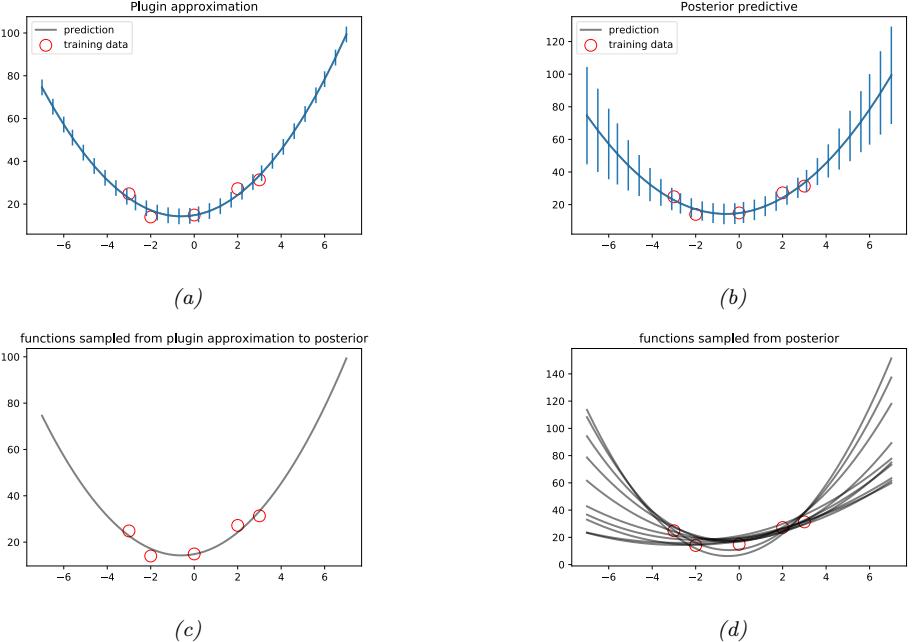

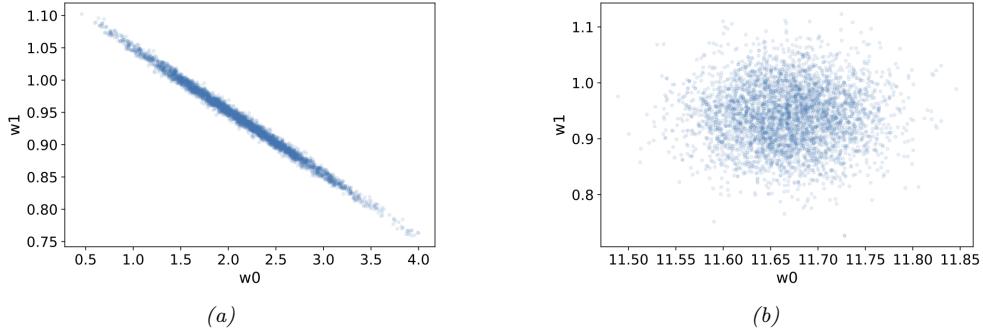

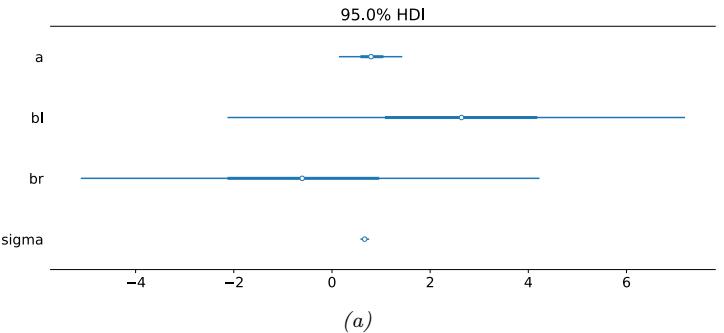

An alternative evaluation metric is to use the learned unsupervised representation as features or input to a downstream supervised learning method. If the unsupervised method has discovered useful