Regression Modeling Strategies

Springer Series in Statistics

Frank E. Harrell, Jr.

Regression Modeling Strategies

With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis

Second Edition

Springer Series in Statistics

Advisors: P. Bickel, P. Diggle, S.E. Feinberg, U. Gather, I. Olkin, S. Zeger

More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/692

Frank E. Harrell, Jr.

Regression Modeling Strategies

With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis

Second Edition

Frank E. Harrell, Jr. Department of Biostatistics School of Medicine Vanderbilt University Nashville, TN, USA

ISSN 0172-7397 ISSN 2197-568X (electronic) Springer Series in Statistics ISBN 978-3-319-19424-0 ISBN 978-3-319-19425-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015942921

Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London

© Springer Science+Business Media New York 2001

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.

Printed on acid-free paper

Springer International Publishing AG Switzerland is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www. springer.com)

To the memories of Frank E. Harrell, Sr., Richard Jackson, L. Richard Smith, John Burdeshaw, and Todd Nick, and with appreciation to Liana and Charlotte Harrell, two high school math teachers: Carolyn Wailes (n´ee Gaston) and Floyd Christian, two college professors: David Hurst (who advised me to choose the field of biostatistics) and Doug Stocks, and my graduate advisor P. K. Sen.

Preface

There are many books that are excellent sources of knowledge about individual statistical tools (survival models, general linear models, etc.), but the art of data analysis is about choosing and using multiple tools. In the words of Chatfield [100, p. 420] “. . . students typically know the technical details of regression for example, but not necessarily when and how to apply it. This argues the need for a better balance in the literature and in statistical teaching between techniques and problem solving strategies.” Whether analyzing risk factors, adjusting for biases in observational studies, or developing predictive models, there are common problems that few regression texts address. For example, there are missing data in the majority of datasets one is likely to encounter (other than those used in textbooks!) but most regression texts do not include methods for dealing with such data effectively, and most texts on missing data do not cover regression modeling.

This book links standard regression modeling approaches with

- methods for relaxing linearity assumptions that still allow one to easily obtain predictions and confidence limits for future observations, and to do formal hypothesis tests,

- non-additive modeling approaches not requiring the assumption that interactions are always linear × linear,

- methods for imputing missing data and for penalizing variances for incomplete data,

- methods for handling large numbers of predictors without resorting to problematic stepwise variable selection techniques,

- data reduction methods (unsupervised learning methods, some of which are based on multivariate psychometric techniques too seldom used in statistics) that help with the problem of “too many variables to analyze and not enough observations” as well as making the model more interpretable when there are predictor variables containing overlapping information,

- methods for quantifying predictive accuracy of a fitted model,

- powerful model validation techniques based on the bootstrap that allow the analyst to estimate predictive accuracy nearly unbiasedly without holding back data from the model development process, and

- graphical methods for understanding complex models.

On the last point, this text has special emphasis on what could be called “presentation graphics for fitted models” to help make regression analyses more palatable to non-statisticians. For example, nomograms have long been used to make equations portable, but they are not drawn routinely because doing so is very labor-intensive. An R function called nomogram in the package described below draws nomograms from a regression fit, and these diagrams can be used to communicate modeling results as well as to obtain predicted values manually even in the presence of complex variable transformations.

Most of the methods in this text apply to all regression models, but special emphasis is given to some of the most popular ones: multiple regression using least squares and its generalized least squares extension for serial (repeated measurement) data, the binary logistic model, models for ordinal responses, parametric survival regression models, and the Cox semiparametric survival model. There is also a chapter on nonparametric transform-both-sides regression. Emphasis is given to detailed case studies for these methods as well as for data reduction, imputation, model simplification, and other tasks. Except for the case study on survival of Titanic passengers, all examples are from biomedical research. However, the methods presented here have broad application to other areas including economics, epidemiology, sociology, psychology, engineering, and predicting consumer behavior and other business outcomes.

This text is intended for Masters or PhD level graduate students who have had a general introductory probability and statistics course and who are well versed in ordinary multiple regression and intermediate algebra. The book is also intended to serve as a reference for data analysts and statistical methodologists. Readers without a strong background in applied statistics may wish to first study one of the many introductory applied statistics and regression texts that are available. The author’s course notes Biostatistics for Biomedical Research on the text’s web site covers basic regression and many other topics. The paper by Nick and Hardin [476] also provides a good introduction to multivariable modeling and interpretation. There are many excellent intermediate level texts on regression analysis. One of them is by Fox, which also has a companion software-based text [200, 201]. For readers interested in medical or epidemiologic research, Steyerberg’s excellent text Clinical Prediction Models [586] is an ideal companion for Regression Modeling Strategies. Steyerberg’s book provides further explanations, examples, and simulations of many of the methods presented here. And no text on regression modeling should fail to mention the seminal work of John Nelder [450].

The overall philosophy of this book is summarized by the following statements.

- Satisfaction of model assumptions improves precision and increases statistical power.

- It is more productive to make a model fit step by step (e.g., transformation estimation) than to postulate a simple model and find out what went wrong.

- Graphical methods should be married to formal inference.

- Overfitting occurs frequently, so data reduction and model validation are important.

- In most research projects, the cost of data collection far outweighs the cost of data analysis, so it is important to use the most efficient and accurate modeling techniques, to avoid categorizing continuous variables, and to not remove data from the estimation sample just to be able to validate the model.

- The bootstrap is a breakthrough for statistical modeling, and the analyst should use it for many steps of the modeling strategy, including derivation of distribution-free confidence intervals and estimation of optimism in model fit that takes into account variations caused by the modeling strategy.

- Imputation of missing data is better than discarding incomplete observations.

- Variance often dominates bias, so biased methods such as penalized maximum likelihood estimation yield models that have a greater chance of accurately predicting future observations.

- Software without multiple facilities for assessing and fixing model fit may only seem to be user-friendly.

- Carefully fitting an improper model is better than badly fitting (and overfitting) a well-chosen one.

- Methods that work for all types of regression models are the most valuable.

- Using the data to guide the data analysis is almost as dangerous as not doing so.

- There are benefits to modeling by deciding how many degrees of freedom (i.e., number of regression parameters) can be “spent,” deciding where they should be spent, and then spending them.

On the last point, the author believes that significance tests and P-values are problematic, especially when making modeling decisions. Judging by the increased emphasis on confidence intervals in scientific journals there is reason to believe that hypothesis testing is gradually being de-emphasized. Yet the reader will notice that this text contains many P-values. How does that make sense when, for example, the text recommends against simplifying a model when a test of linearity is not significant? First, some readers may wish to emphasize hypothesis testing in general, and some hypotheses have special interest, such as in pharmacology where one may be interested in whether the effect of a drug is linear in log dose. Second, many of the more interesting hypothesis tests in the text are tests of complexity (nonlinearity, interaction) of the overall model. Null hypotheses of linearity of effects in particular are frequently rejected, providing formal evidence that the analyst’s investment of time to use more than simple statistical models was warranted.

The rapid development of Bayesian modeling methods and rise in their use is exciting. Full Bayesian modeling greatly reduces the need for the approximations made for confidence intervals and distributions of test statistics, and Bayesian methods formalize the still rather ad hoc frequentist approach to penalized maximum likelihood estimation by using skeptical prior distributions to obtain well-defined posterior distributions that automatically deal with shrinkage. The Bayesian approach also provides a formal mechanism for incorporating information external to the data. Although Bayesian methods are beyond the scope of this text, the text is Bayesian in spirit by emphasizing the careful use of subject matter expertise while building statistical models.

The text emphasizes predictive modeling, but as discussed in Chapter 1, developing good predictions goes hand in hand with accurate estimation of effects and with hypothesis testing (when appropriate). Besides emphasis on multivariable modeling, the text includes a Chapter 17 introducing survival analysis and methods for analyzing various types of single and multiple events. This book does not provide examples of analyses of one common type of response variable, namely, cost and related measures of resource consumption. However, least squares modeling presented in Chapter 15.1, the robust rank-based methods presented in Chapters 13, 15, and 20, and the transform-both-sides regression models discussed in Chapter 16 are very applicable and robust for modeling economic outcomes. See [167] and [260] for example analyses of such dependent variables using, respectively, the Cox model and nonparametric additive regression. The central Web site for this book (see the Appendix) has much more material on the use of the Cox model for analyzing costs.

This text does not address some important study design issues that if not respected can doom a predictive modeling or estimation project to failure. See Laupacis, Sekar, and Stiell [378] for a list of some of these issues.

Heavy use is made of the S language used by R. R is the focus because it is an elegant object-oriented system in which it is easy to implement new statistical ideas. Many R users around the world have done so, and their work has benefited many of the procedures described here. R also has a uniform syntax for specifying statistical models (with respect to categorical predictors, interactions, etc.), no matter which type of model is being fitted [96].

The free, open-source statistical software system R has been adopted by analysts and research statisticians worldwide. Its capabilities are growing exponentially because of the involvement of an ever-growing community of statisticians who are adding new tools to the base R system through contributed packages. All of the functions used in this text are available in R. See the book’s Web site for updated information about software availability.

Readers who don’t use R or any other statistical software environment will still find the statistical methods and case studies in this text useful, and it is hoped that the code that is presented will make the statistical methods more concrete. At the very least, the code demonstrates that all of the methods presented in the text are feasible.

This text does not teach analysts how to use R. For that, the reader may wish to see reading recommendations on www.r-project.org as well as Venables and Ripley [635] (which is also an excellent companion to this text) and the many other excellent texts on R. See the Appendix for more information.

In addition to powerful features that are built into R, this text uses a package of freely available R functions called rms written by the author. rms tracks modeling details related to the expanded X or design matrix. It is a series of over 200 functions for model fitting, testing, estimation, validation, graphics, prediction, and typesetting by storing enhanced model design attributes in the fit. rms includes functions for least squares and penalized least squares multiple regression modeling in addition to functions for binary and ordinal regression, generalized least squares for analyzing serial data, quantile regression, and survival analysis that are emphasized in this text. Other freely available miscellaneous R functions used in the text are found in the Hmisc package also written by the author. Functions in Hmisc include facilities for data reduction, imputation, power and sample size calculation, advanced table making, recoding variables, importing and inspecting data, and general graphics. Consult the Appendix for information on obtaining Hmisc and rms.

The author and his colleagues have written SAS macros for fitting restricted cubic splines and for other basic operations. See the Appendix for more information. It is unfair not to mention some excellent capabilities of other statistical packages such as Stata (which has also been extended to provide regression splines and other modeling tools), but the extendability and graphics of R makes it especially attractive for all aspects of the comprehensive modeling strategy presented in this book.

Portions of Chapters 4 and 20 were published as reference [269]. Some of Chapter 13 was published as reference [272].

The author may be contacted by electronic mail at f.harrell@ vanderbilt.edu and would appreciate being informed of unclear points, errors, and omissions in this book. Suggestions for improvements and for future topics are also welcome. As described in the Web site, instructors may contact the author to obtain copies of quizzes and extra assignments (both with answers) related to much of the material in the earlier chapters, and to obtain full solutions (with graphical output) to the majority of assignments in the text.

Major changes since the first edition include the following:

- Creation of a now mature R package, rms, that replaces and greatly extends the Design library used in the first edition

- Conversion of all of the book’s code to R

- Conversion of the book source into knitr [677] reproducible documents

- All code from the text is executable and is on the web site

- Use of color graphics and use of the ggplot2 graphics package [667]

- Scanned images were re-drawn

- New text about problems with dichotomization of continuous variables and with classification (as opposed to prediction)

- Expanded material on multiple imputation and predictive mean matching and emphasis on multiple imputation (using the Hmisc aregImpute function) instead of single imputation

- Addition of redundancy analysis

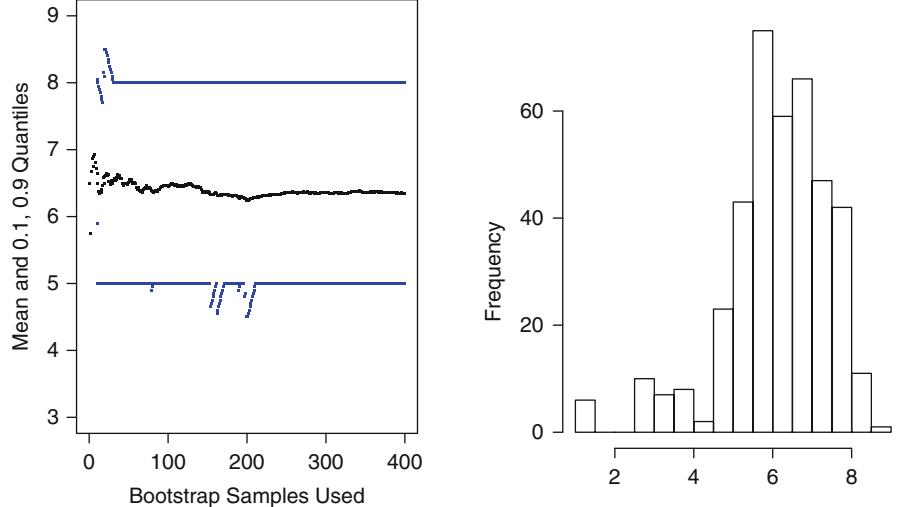

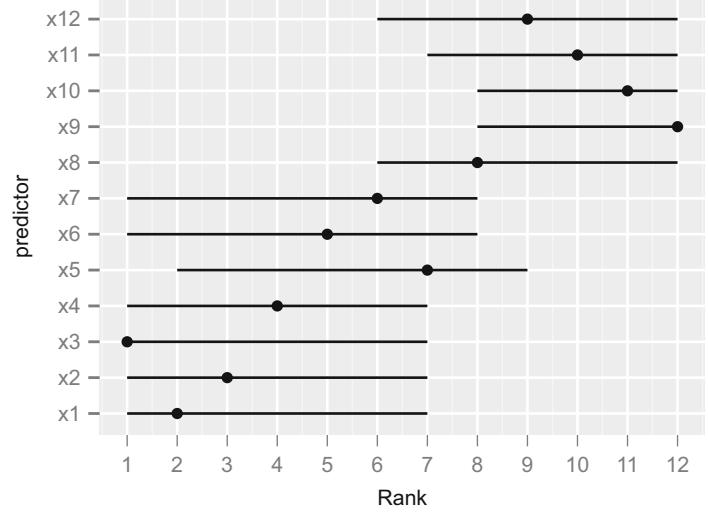

- Added a new section in Chapter 5 on bootstrap confidence intervals for rankings of predictors

- Replacement of the U.S. presidential election data with analyses of a new diabetes dataset from NHANES using ordinal and quantile regression

- More emphasis on semiparametric ordinal regression models for continuous Y , as direct competitors of ordinary multiple regression, with a detailed case study

- A new chapter on generalized least squares for analysis of serial response data

- The case study in imputation and data reduction was completely reworked and now focuses only on data reduction, with the addition of sparse principal components

- More information about indexes of predictive accuracy

- Augmentation of the chapter on maximum likelihood to include more flexible ways of testing contrasts as well as new methods for obtaining simultaneous confidence intervals

- Binary logistic regression case study 1 was completely re-worked, now providing examples of model selection and model approximation accuracy

- Single imputation was dropped from binary logistic case study 2

- The case study in transform-both-sides regression modeling has been reworked using simulated data where true transformations are known, and a new example of the smearing estimator was added

- Addition of 225 references, most of them published 2001–2014

- New guidance on minimum sample sizes needed by some of the models

Acknowledgments

A good deal of the writing of the first edition of this book was done during my 17 years on the faculty of Duke University. I wish to thank my close colleague Kerry Lee for providing many valuable ideas, fruitful collaborations, and well-organized lecture notes from which I have greatly benefited over the past years. Terry Therneau of Mayo Clinic has given me many of his wonderful ideas for many years, and has written state-of-the-art R software for survival analysis that forms the core of survival analysis software in my rms package. Michael Symons of the Department of Biostatistics of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Timothy Morgan of the Division of Public Health Sciences at Wake Forest University School of Medicine also provided course materials, some of which motivated portions of this text. My former clinical colleagues in the Cardiology Division at Duke University, Robert Califf, Phillip Harris, Mark Hlatky, Dan Mark, David Pryor, and Robert Rosati, for many years provided valuable motivation, feedback, and ideas through our interaction on clinical problems. Besides Kerry Lee, statistical colleagues L. Richard Smith, Lawrence Muhlbaier, and Elizabeth DeLong clarified my thinking and gave me new ideas on numerous occasions. Charlotte Nelson and Carlos Alzola frequently helped me debug S routines when they thought they were just analyzing data.

Former students Bercedis Peterson, James Herndon, Robert McMahon, and Yuan-Li Shen have provided many insights into logistic and survival modeling. Associations with Doug Wagner and William Knaus of the University of Virginia, Ken Offord of Mayo Clinic, David Naftel of the University of Alabama in Birmingham, Phil Miller of Washington University, and Phil Goodman of the University of Nevada Reno have provided many valuable ideas and motivations for this work, as have Michael Schemper of Vienna University, Janez Stare of Ljubljana University, Slovenia, Ewout Steyerberg of Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Karel Moons of Utrecht University, and Drew Levy of Genentech. Richard Goldstein, along with several anonymous reviewers, provided many helpful criticisms of a previous version of this manuscript that resulted in significant improvements, and critical reading by Bob Edson (VA Cooperative Studies Program, Palo Alto) resulted in many error corrections. Thanks to Brian Ripley of the University of Oxford for providing many helpful software tools and statistical insights that greatly aided in the production of this book, and to Bill Venables of CSIRO Australia for wisdom, both statistical and otherwise. This work would also not have been possible without the S environment developed by Rick Becker, John Chambers, Allan Wilks, and the R language developed by Ross Ihaka and Robert Gentleman.

Work for the second edition was done in the excellent academic environment of Vanderbilt University, where biostatistical and biomedical colleagues and graduate students provided new insights and stimulating discussions. Thanks to Nick Cox, Durham University, UK, who provided from his careful reading of the first edition a very large number of improvements and corrections that were incorporated into the second. Four anonymous reviewers of the second edition also made numerous suggestions that improved the text.

July 2015

Nashville, TN, USA Frank E. Harrell, Jr.

Contents

| Typographical Conventions . xxv |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction | 1 | ||

| 1.1 | Hypothesis Testing, Estimation, and Prediction |

1 | ||

| 1.2 | Examples of Uses of Predictive Multivariable Modeling |

3 | ||

| 1.3 | Prediction vs. Classification |

4 | ||

| 1.4 | Planning for Modeling |

6 | ||

| 1.4.1 | Emphasizing Continuous Variables |

8 | ||

| 1.5 | Choice of the Model |

8 | ||

| 1.6 | Further Reading . |

11 | ||

| 2 | General Aspects of Fitting Regression Models . |

13 | ||

| 2.1 | Notation for Multivariable Regression Models . |

13 | ||

| 2.2 | Model Formulations . |

14 | ||

| 2.3 | Interpreting Model Parameters . |

15 | ||

| 2.3.1 | Nominal Predictors . |

16 | ||

| 2.3.2 | Interactions. | 16 | ||

| 2.3.3 | Example: Inference for a Simple Model . |

17 | ||

| 2.4 | Relaxing Linearity Assumption for Continuous Predictors . . |

18 | ||

| 2.4.1 | Avoiding Categorization . |

18 | ||

| 2.4.2 | Simple Nonlinear Terms . |

21 | ||

| 2.4.3 | Splines for Estimating Shape of Regression | |||

| Function and Determining Predictor | ||||

| Transformations. | 22 | |||

| 2.4.4 | Cubic Spline Functions. | 23 | ||

| 2.4.5 | Restricted Cubic Splines . |

24 | ||

| 2.4.6 | Choosing Number and Position of Knots . |

26 | ||

| 2.4.7 | Nonparametric Regression . |

28 | ||

| 2.4.8 | Advantages of Regression Splines over | |||

| Other Methods. | 30 |

| 2.5 | Recursive Partitioning: Tree-Based Models. | 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.6 | Multiple Degree of Freedom Tests of Association . |

31 | |

| 2.7 | Assessment of Model Fit . |

33 | |

| 2.7.1 Regression Assumptions . |

33 | ||

| 2.7.2 Modeling and Testing Complex Interactions . |

36 | ||

| 2.7.3 Fitting Ordinal Predictors . |

38 | ||

| 2.7.4 Distributional Assumptions . |

39 | ||

| 2.8 | Further Reading . |

40 | |

| 2.9 | Problems . |

42 | |

| 3 | Missing Data . |

45 | |

| 3.1 | Types of Missing Data . |

45 | |

| 3.2 | Prelude to Modeling . |

46 | |

| 3.3 | Missing Values for Different Types of Response Variables . |

47 | |

| 3.4 | Problems with Simple Alternatives to Imputation . |

47 | |

| 3.5 | Strategies for Developing an Imputation Model . |

49 | |

| 3.6 | Single Conditional Mean Imputation . |

52 | |

| 3.7 | Predictive Mean Matching . |

52 | |

| 3.8 | Multiple Imputation . |

53 | |

| 3.8.1 The aregImpute and Other Chained Equations |

|||

| Approaches . |

55 | ||

| 3.9 | Diagnostics . |

56 | |

| 3.10 | Summary and Rough Guidelines. | 56 | |

| 3.11 | Further Reading . |

58 | |

| 3.12 | Problems . |

59 | |

| 4 | Multivariable Modeling Strategies . |

63 | |

| 4.1 | Prespecification of Predictor Complexity Without | ||

| Later Simplification . |

64 | ||

| 4.2 | Checking Assumptions of Multiple Predictors | ||

| Simultaneously . |

67 | ||

| 4.3 | Variable Selection . |

67 | |

| 4.4 | Sample Size, Overfitting, and Limits on Number | ||

| of Predictors . |

72 | ||

| 4.5 | Shrinkage . |

75 | |

| 4.6 | Collinearity . |

78 | |

| 4.7 | Data Reduction . |

79 | |

| 4.7.1 Redundancy Analysis . |

80 | ||

| 4.7.2 Variable Clustering . |

81 | ||

| 4.7.3 Transformation and Scaling Variables Without |

|||

| Using Y . |

81 | ||

| 4.7.4 Simultaneous Transformation and Imputation . |

83 | ||

| 4.7.5 Simple Scoring of Variable Clusters . |

85 | ||

| 4.7.6 Simplifying Cluster Scores . |

87 | ||

| 4.7.7 How Much Data Reduction Is Necessary? . |

87 | ||

| 4.8 | Other Approaches to Predictive Modeling . |

89 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.9 | Overly Influential Observations. | 90 | |

| 4.10 | Comparing Two Models . |

92 | |

| 4.11 | Improving the Practice of Multivariable Prediction . |

94 | |

| 4.12 | Summary: Possible Modeling Strategies . |

94 | |

| 4.12.1 Developing Predictive Models . |

95 | ||

| 4.12.2 Developing Models for Effect Estimation . |

98 | ||

| 4.12.3 Developing Models for Hypothesis Testing . |

99 | ||

| 4.13 | Further Reading . 100 |

||

| 4.14 | Problems . 102 |

||

| 5 | Describing, Resampling, Validating, and Simplifying | ||

| the Model . 103 |

|||

| 5.1 | Describing the Fitted Model . 103 |

||

| 5.1.1 Interpreting Effects . 103 |

|||

| 5.1.2 Indexes of Model Performance . 104 |

|||

| 5.2 | The Bootstrap . 106 |

||

| 5.3 | Model Validation . 109 |

||

| 5.3.1 Introduction . 109 |

|||

| 5.3.2 Which Quantities Should Be Used in Validation? . 110 |

|||

| 5.3.3 Data-Splitting . 111 |

|||

| 5.3.4 Improvements on Data-Splitting: Resampling . 112 |

|||

| 5.3.5 Validation Using the Bootstrap . 114 |

|||

| 5.4 | Bootstrapping Ranks of Predictors. 117 | ||

| 5.5 | Simplifying the Final Model by Approximating It. 118 | ||

| 5.5.1 Difficulties Using Full Models . 118 |

|||

| 5.5.2 Approximating the Full Model . 119 |

|||

| 5.6 | Further Reading . 121 |

||

| 5.7 | Problem . 124 |

||

| 6 | R Software . 127 |

||

| 6.1 | The R Modeling Language . 128 |

||

| 6.2 | User-Contributed Functions. 129 | ||

| 6.3 | The rms Package . 130 |

||

| 6.4 | Other Functions . 141 |

||

| 6.5 | Further Reading . 142 |

||

| 7 | Modeling Longitudinal Responses using Generalized | ||

| Least Squares . 143 |

|||

| 7.1 | Notation and Data Setup . 143 |

||

| 7.2 | Model Specification for Effects on E(Y ) . 144 |

||

| 7.3 | Modeling Within-Subject Dependence . 144 |

||

| 7.4 | Parameter Estimation Procedure . 147 |

||

| 7.5 | Common Correlation Structures . 147 |

||

| 7.6 | Checking Model Fit. 148 | ||

| 7.7 | Sample Size Considerations . 148 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 7.8 | R Software . 149 |

||

| 7.9 | Case Study . 149 |

||

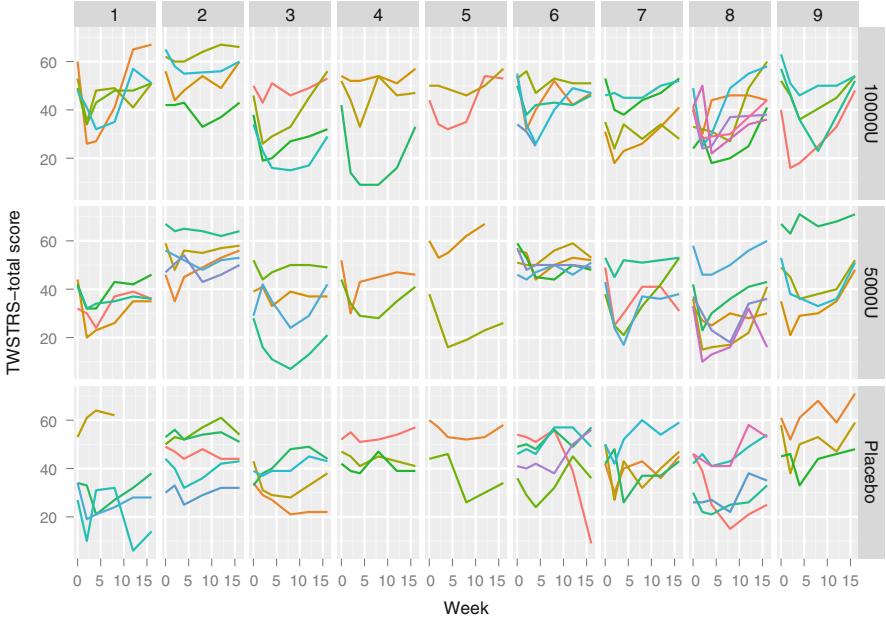

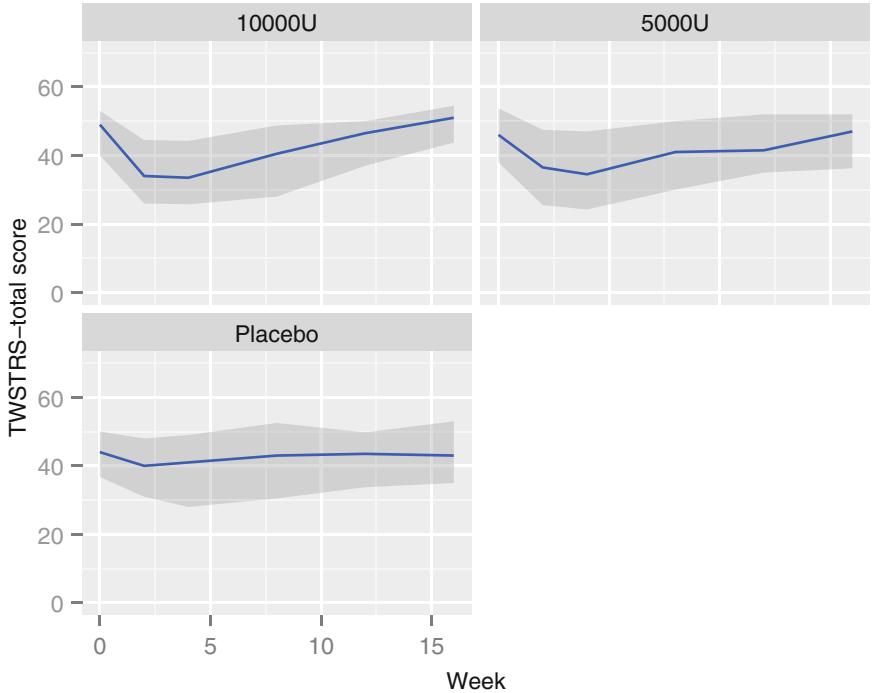

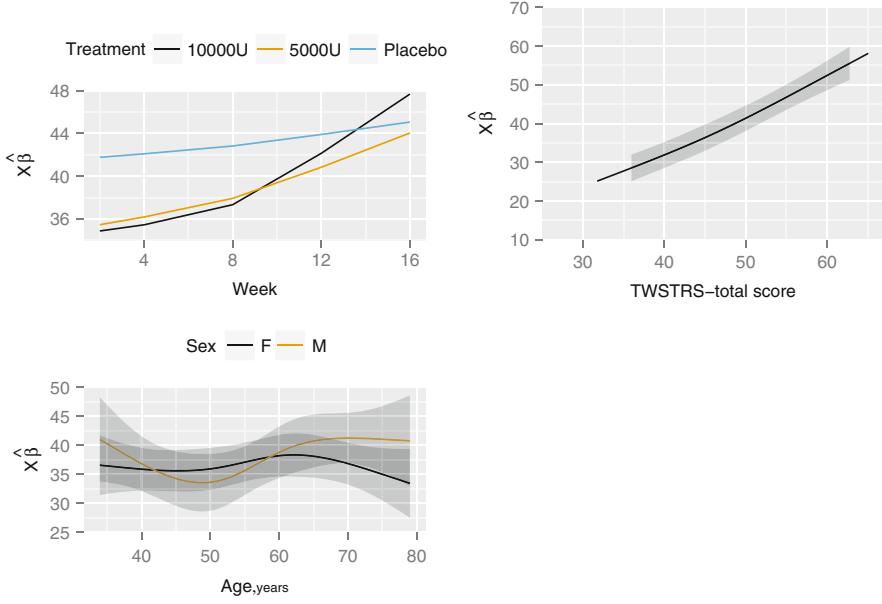

| 7.9.1 Graphical Exploration of Data . 150 |

|||

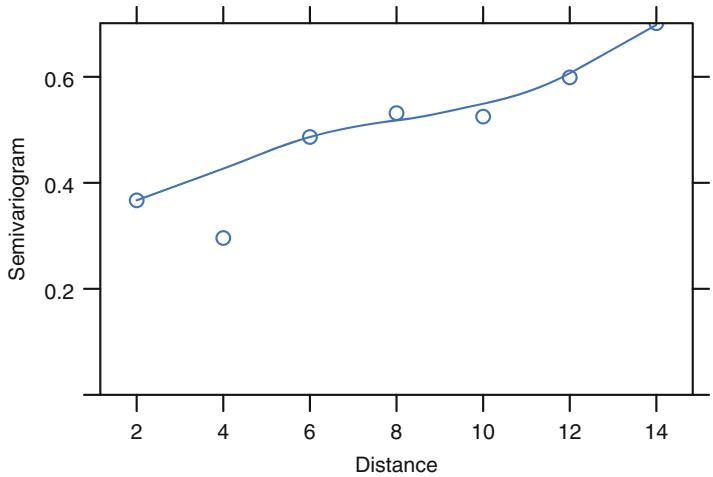

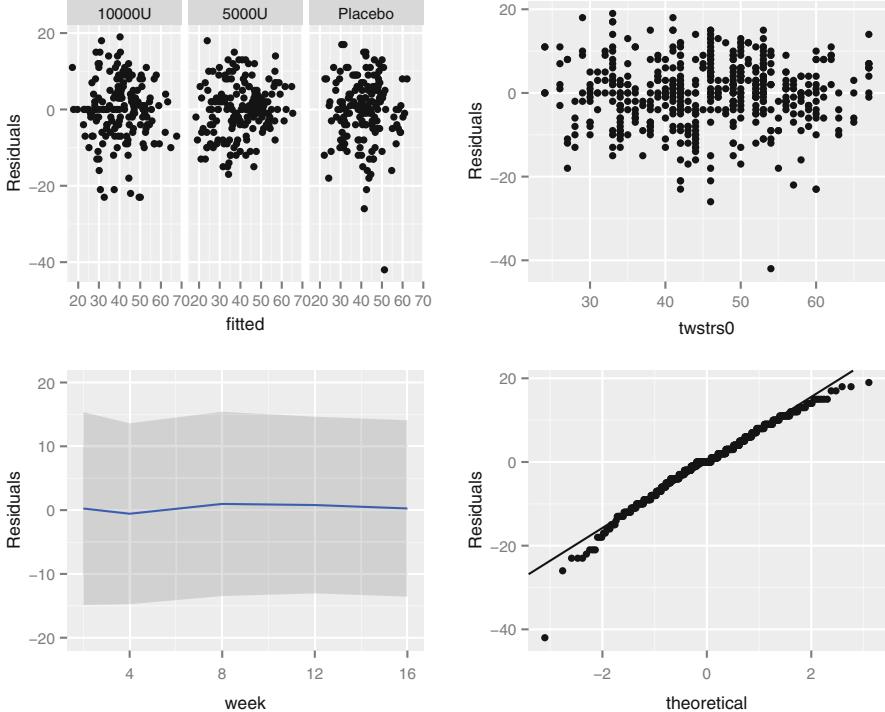

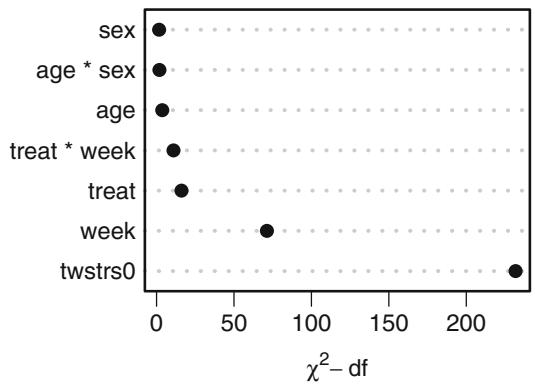

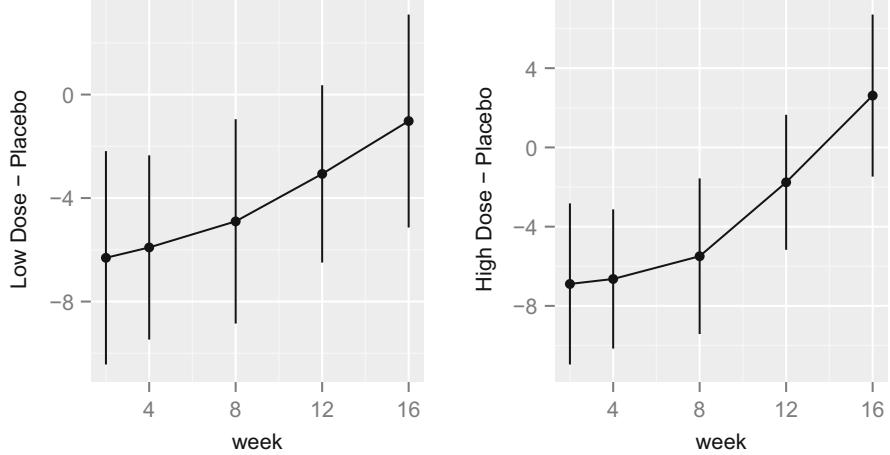

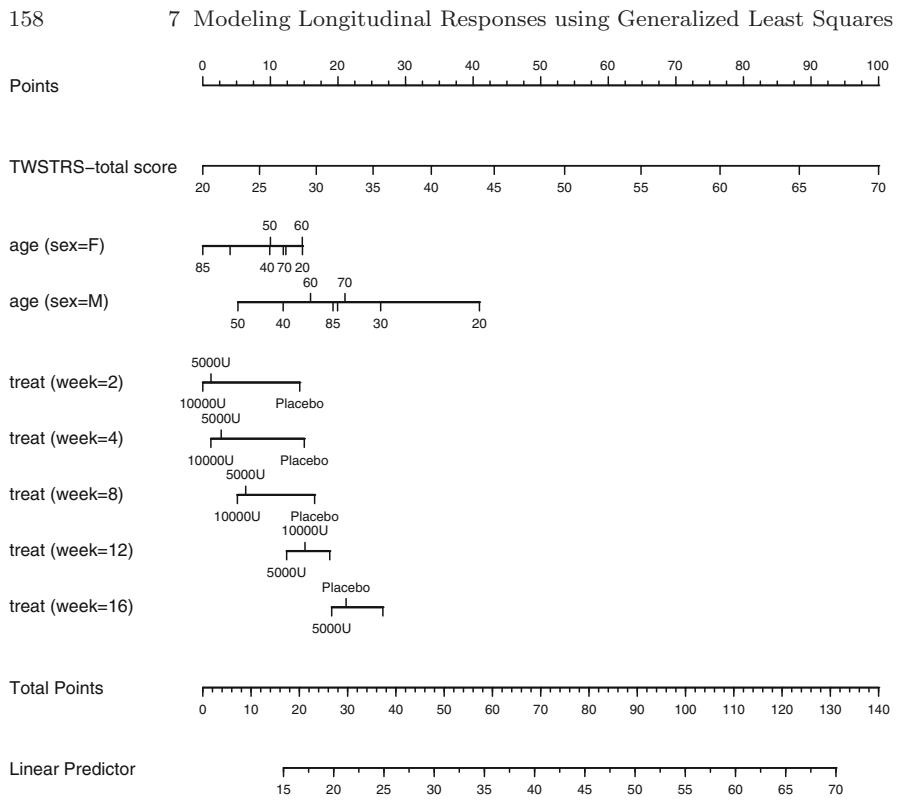

| 7.9.2 Using Generalized Least Squares . 151 |

|||

| 7.10 | Further Reading . 158 |

||

| 8 | Case Study in Data Reduction. 161 | ||

| 8.1 | Data . 161 |

||

| 8.2 | How Many Parameters Can Be Estimated? . 164 |

||

| 8.3 | Redundancy Analysis . 164 |

||

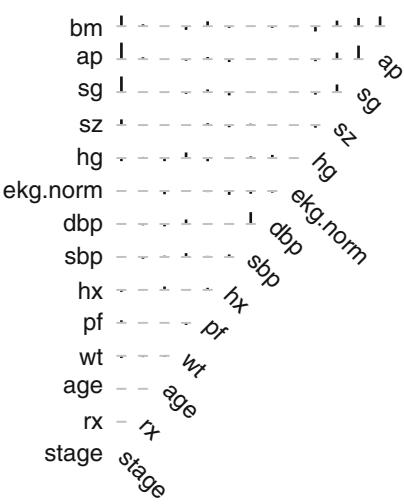

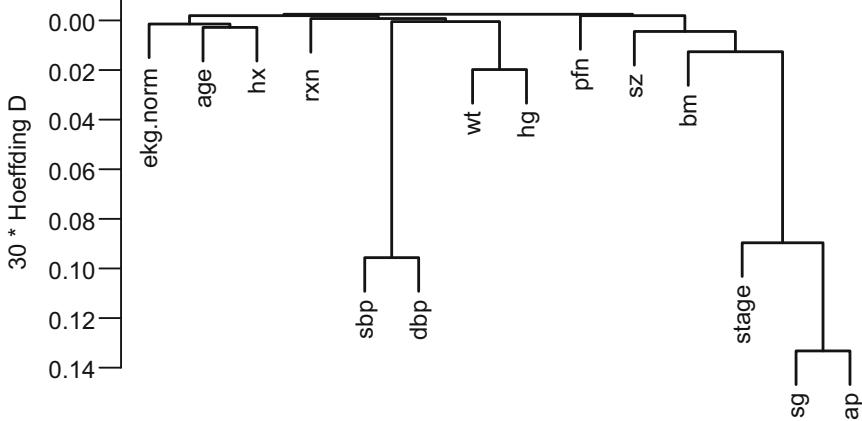

| 8.4 | Variable Clustering . 166 |

||

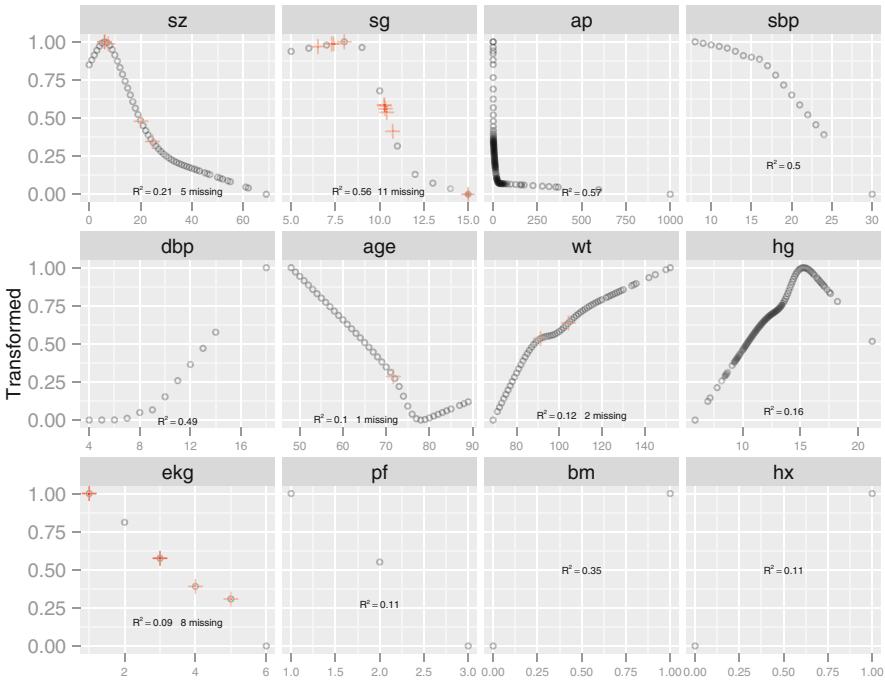

| 8.5 | Transformation and Single Imputation Using transcan. 167 |

||

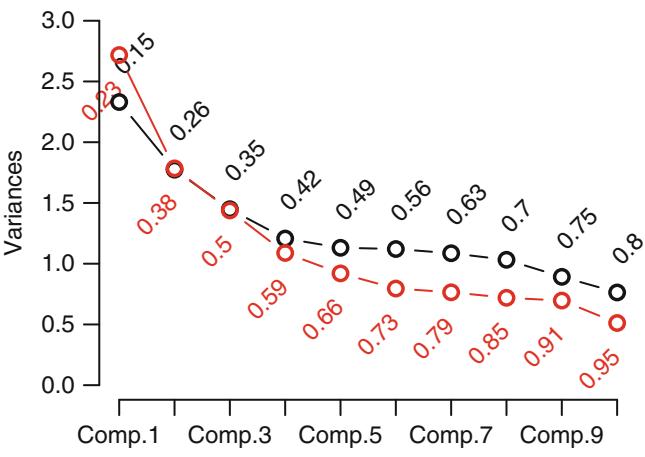

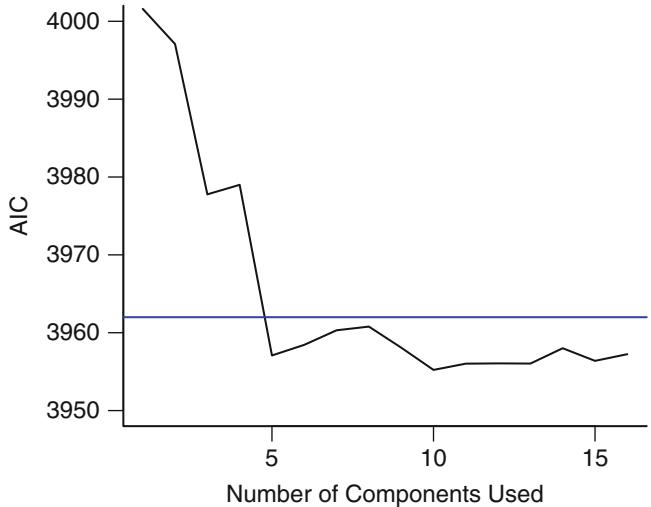

| 8.6 | Data Reduction Using Principal Components . 170 |

||

| 8.6.1 Sparse Principal Components . 175 |

|||

| 8.7 | Transformation Using Nonparametric Smoothers . 176 |

||

| 8.8 | Further Reading . 177 |

||

| 8.9 | Problems . 178 |

||

| 9 | Overview of Maximum Likelihood Estimation . 181 |

||

| 9.1 | General Notions—Simple Cases . 181 |

||

| 9.2 | Hypothesis Tests . 185 |

||

| 9.2.1 Likelihood Ratio Test . 185 |

|||

| 9.2.2 Wald Test . 186 |

|||

| 9.2.3 Score Test . 186 |

|||

| 9.2.4 Normal Distribution—One Sample . 187 |

|||

| 9.3 | General Case . 188 |

||

| 9.3.1 Global Test Statistics . 189 |

|||

| 9.3.2 Testing a Subset of the Parameters . 190 |

|||

| 9.3.3 Tests Based on Contrasts. 192 |

|||

| 9.3.4 Which Test Statistics to Use When . 193 |

|||

| 9.3.5 Example: Binomial—Comparing Two |

|||

| Proportions. 194 | |||

| 9.4 | Iterative ML Estimation . 195 |

||

| 9.5 | Robust Estimation of the Covariance Matrix . 196 |

||

| 9.6 | Wald, Score, and Likelihood-Based Confidence Intervals | . 198 | |

| 9.6.1 Simultaneous Wald Confidence Regions . 199 |

|||

| 9.7 | Bootstrap Confidence Regions. 199 | ||

| 9.8 | Further Use of the Log Likelihood . 203 |

||

| 9.8.1 Rating Two Models, Penalizing for Complexity |

. 203 | ||

| 9.8.2 Testing Whether One Model Is Better |

|||

| than Another . 204 |

|||

| 9.8.3 Unitless Index of Predictive Ability . 205 |

|||

| 9.8.4 Unitless Index of Adequacy of a Subset |

|||

| of Predictors. 207 | |||

| 9.9 | Weighted Maximum Likelihood Estimation . 208 |

||

| 9.10 | Penalized Maximum Likelihood Estimation . 209 |

| 9.11 | Further Reading . 213 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 9.12 | Problems . 216 |

||

| 10 | Binary Logistic Regression. 219 | ||

| 10.1 | Model. 219 | ||

| 10.1.1 Model Assumptions and Interpretation |

|||

| of Parameters . 221 |

|||

| 10.1.2 Odds Ratio, Risk Ratio, and Risk Difference . 224 |

|||

| 10.1.3 Detailed Example . 225 |

|||

| 10.1.4 Design Formulations . 230 |

|||

| 10.2 | Estimation . 231 |

||

| 10.2.1 Maximum Likelihood Estimates . 231 |

|||

| 10.2.2 Estimation of Odds Ratios and Probabilities . 232 |

|||

| 10.2.3 Minimum Sample Size Requirement . 233 |

|||

| 10.3 | Test Statistics. 234 | ||

| 10.4 | Residuals . 235 |

||

| 10.5 | Assessment of Model Fit . 236 |

||

| 10.6 | Collinearity . 255 |

||

| 10.7 | Overly Influential Observations. 255 | ||

| 10.8 10.9 |

Quantifying Predictive Ability . 256 Validating the Fitted Model . 259 |

||

| 10.10 Describing the Fitted Model . 264 |

|||

| 10.11 | R Functions . 269 |

||

| 10.12 Further Reading . 271 |

|||

| 10.13 Problems . 273 |

|||

| 11 | Binary Logistic Regression Case Study 1 . 275 |

||

| 11.1 | Overview . 275 |

||

| 11.2 | Background. 275 | ||

| 11.3 | Data Transformations and Single Imputation . 276 |

||

| 11.4 | Regression on Original Variables, Principal Components | ||

| and Pretransformations . 277 |

|||

| 11.5 | Description of Fitted Model. 278 | ||

| 11.6 | Backwards Step-Down . 280 |

||

| 11.7 | Model Approximation . 287 |

||

| 12 | Logistic Model Case Study 2: Survival of Titanic |

||

| Passengers . 291 |

|||

| 12.1 | Descriptive Statistics. 291 | ||

| 12.2 | Exploring Trends with Nonparametric Regression . 294 |

||

| 12.3 | Binary Logistic Model With Casewise Deletion | ||

| of Missing Values . 296 |

|||

| 12.4 | Examining Missing Data Patterns . 302 |

||

| 12.5 | Multiple Imputation . 304 |

||

| 12.6 | Summarizing the Fitted Model . 307 |

| 13 | Ordinal Logistic Regression . 311 |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 13.1 | Background. 311 | ||

| 13.2 | Ordinality Assumption . 312 |

||

| 13.3 | Proportional Odds Model. 313 | ||

| 13.3.1 Model . 313 |

|||

| 13.3.2 Assumptions and Interpretation of Parameters . 313 |

|||

| 13.3.3 Estimation . 314 |

|||

| 13.3.4 Residuals. 314 |

|||

| 13.3.5 Assessment of Model Fit . 315 |

|||

| 13.3.6 Quantifying Predictive Ability . 318 |

|||

| 13.3.7 Describing the Fitted Model . 318 |

|||

| 13.3.8 Validating the Fitted Model . 318 |

|||

| 13.3.9 R Functions. 319 |

|||

| 13.4 | Continuation Ratio Model . 319 |

||

| 13.4.1 Model . 319 |

|||

| 13.4.2 Assumptions and Interpretation of Parameters . 320 |

|||

| 13.4.3 Estimation . 320 |

|||

| 13.4.4 Residuals. 321 |

|||

| 13.4.5 Assessment of Model Fit . 321 |

|||

| 13.4.6 Extended CR Model . 321 |

|||

| 13.4.7 Role of Penalization in Extended CR Model . 322 |

|||

| 13.4.8 Validating the Fitted Model . 322 |

|||

| 13.4.9 R Functions. 323 |

|||

| 13.5 | Further Reading . 324 |

||

| 13.6 | Problems . 324 |

||

| 14 | Case Study in Ordinal Regression, Data Reduction, | ||

| and Penalization . 327 |

|||

| 14.1 | Response Variable . 328 |

||

| 14.2 | Variable Clustering . 329 |

||

| 14.3 | Developing Cluster Summary Scores . 330 |

||

| 14.4 | Assessing Ordinality of Y for each X, and Unadjusted |

||

| Checking of PO and CR Assumptions . 333 |

|||

| 14.5 | A Tentative Full Proportional Odds Model . 333 |

||

| 14.6 | Residual Plots . 336 |

||

| 14.7 | Graphical Assessment of Fit of CR Model . 338 |

||

| 14.8 | Extended Continuation Ratio Model . 340 |

||

| 14.9 | Penalized Estimation . 342 |

||

| 14.10 Using Approximations to Simplify the Model . 348 |

|||

| 14.11 Validating the Model . 353 |

|||

| 14.12 Summary . 355 |

|||

| 14.13 Further Reading . 356 |

|||

| 14.14 Problems . 357 |

| 15 | Regression Models for Continuous Y and Case Study |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in Ordinal Regression. 359 | ||||||

| 15.1 | The Linear Model . 359 |

|||||

| 15.2 | Quantile Regression. 360 | |||||

| 15.3 | Ordinal Regression Models for Continuous Y . 361 |

|||||

| 15.3.1 Minimum Sample Size Requirement . 363 |

||||||

| 15.4 | Comparison of Assumptions of Various Models . 364 |

|||||

| 15.5 | Dataset and Descriptive Statistics . 365 |

|||||

| 15.5.1 Checking Assumptions of OLS and Other Models. 368 |

||||||

| 15.6 | Ordinal Regression Applied to HbA1c . 370 |

|||||

| 15.6.1 Checking Fit for Various Models Using Age . 370 |

||||||

| 15.6.2 Examination of BMI . 374 |

||||||

| 15.6.3 Consideration of All Body Size Measurements. 375 |

||||||

| 16 | Transform-Both-Sides Regression . 389 |

|||||

| 16.1 | Background. 389 | |||||

| 16.2 | Generalized Additive Models. 390 | |||||

| 16.3 | Nonparametric Estimation of Y -Transformation . 390 |

|||||

| 16.4 | Obtaining Estimates on the Original Scale . 391 |

|||||

| 16.5 | R Functions . 392 |

|||||

| 16.6 | Case Study . 393 |

|||||

| 17 | Introduction to Survival Analysis . 399 |

|||||

| 17.1 | Background. 399 | |||||

| 17.2 | Censoring, Delayed Entry, and Truncation . 401 |

|||||

| 17.3 | Notation, Survival, and Hazard Functions . 402 |

|||||

| 17.4 | Homogeneous Failure Time Distributions . 407 |

|||||

| 17.5 | Nonparametric Estimation of S and Λ . 409 |

|||||

| 17.5.1 Kaplan–Meier Estimator . 409 |

||||||

| 17.5.2 Altschuler–Nelson Estimator . 413 |

||||||

| 17.6 | Analysis of Multiple Endpoints . 413 |

|||||

| 17.6.1 Competing Risks . 414 |

||||||

| 17.6.2 Competing Dependent Risks . 414 |

||||||

| 17.6.3 State Transitions and Multiple Types of Nonfatal Events . 416 |

||||||

| 17.6.4 Joint Analysis of Time and Severity of an Event. 417 |

||||||

| 17.6.5 Analysis of Multiple Events. 417 |

||||||

| 17.7 | R Functions . 418 |

|||||

| 17.8 | Further Reading . 420 |

|||||

| 17.9 | Problems . 421 |

|||||

| 18 | Parametric Survival Models . 423 |

|||||

| 18.1 | Homogeneous Models (No Predictors) . 423 |

|||||

| 18.1.1 Specific Models . 423 |

||||||

| 18.1.2 Estimation . 424 |

||||||

| 18.1.3 Assessment of Model Fit . 426 |

||||||

| 18.2 | Parametric Proportional Hazards Models . 427 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.2.1 Model . 427 |

||||

| 18.2.2 Model Assumptions and Interpretation |

||||

| of Parameters . 428 |

||||

| 18.2.3 Hazard Ratio, Risk Ratio, and Risk Difference |

. 430 | |||

| 18.2.4 Specific Models . 431 |

||||

| 18.2.5 Estimation . 432 |

||||

| 18.2.6 Assessment of Model Fit . 434 |

||||

| 18.3 | Accelerated Failure Time Models . 436 |

|||

| 18.3.1 Model . 436 |

||||

| 18.3.2 Model Assumptions and Interpretation |

||||

| of Parameters . 436 |

||||

| 18.3.3 Specific Models . 437 |

||||

| 18.3.4 Estimation . 438 |

||||

| 18.3.5 Residuals. 440 |

||||

| 18.3.6 Assessment of Model Fit . 440 |

||||

| 18.3.7 Validating the Fitted Model . 446 |

||||

| 18.4 | Buckley–James Regression Model . 447 |

|||

| 18.5 | Design Formulations . 447 |

|||

| 18.6 | Test Statistics. 447 | |||

| 18.7 | Quantifying Predictive Ability . 447 |

|||

| 18.8 | Time-Dependent Covariates. 447 | |||

| 18.9 | R Functions . 448 |

|||

| 18.10 Further Reading . 450 |

||||

| 18.11 Problems . 451 |

||||

| 19 | Case Study in Parametric Survival Modeling and Model | |||

| Approximation . 453 |

||||

| 19.1 | Descriptive Statistics. 453 | |||

| 19.2 | Checking Adequacy of Log-Normal Accelerated Failure | |||

| Time Model . 458 |

||||

| 19.3 | Summarizing the Fitted Model . 466 |

|||

| 19.4 | Internal Validation of the Fitted Model Using | |||

| the Bootstrap . 466 |

||||

| 19.5 | Approximating the Full Model . 469 |

|||

| 19.6 | Problems . 473 |

|||

| 20 | Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Model . 475 |

|||

| 20.1 | Model. 475 | |||

| 20.1.1 Preliminaries . 475 |

||||

| 20.1.2 Model Definition . 476 |

||||

| 20.1.3 Estimation of β . 476 |

||||

| 20.1.4 Model Assumptions and Interpretation |

||||

| of Parameters . 478 |

||||

| 20.1.5 Example . 478 |

| 20.1.6 Design Formulations . 480 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20.1.7 Extending the Model by Stratification . 481 |

|||

| 20.2 | Estimation of Survival Probability and Secondary | ||

| Parameters . 483 |

|||

| 20.3 | Sample Size Considerations . 486 |

||

| 20.4 | Test Statistics. 486 | ||

| 20.5 | Residuals . 487 |

||

| 20.6 | Assessment of Model Fit . 487 20.6.1 Regression Assumptions . 487 |

||

| 20.6.2 Proportional Hazards Assumption . 494 |

|||

| 20.7 | What to Do When PH Fails . 501 |

||

| 20.8 | Collinearity . 503 |

||

| 20.9 | Overly Influential Observations. 504 | ||

| 20.10 Quantifying Predictive Ability . 504 |

|||

| 20.11 Validating the Fitted Model . 506 |

|||

| 20.11.1 Validation of Model Calibration . 506 |

|||

| 20.11.2 Validation of Discrimination and Other Statistical | |||

| Indexes . 507 |

|||

| 20.12 Describing the Fitted Model . 509 |

|||

| 20.13 | R Functions . 513 |

||

| 20.14 Further Reading . 517 |

|||

| 21 | Case Study in Cox Regression . 521 |

||

| 21.1 | Choosing the Number of Parameters and Fitting | ||

| the Model . 521 |

|||

| 21.2 | Checking Proportional Hazards . 525 |

||

| 21.3 | Testing Interactions. 527 | ||

| 21.4 | Describing Predictor Effects . 527 |

||

| 21.5 | Validating the Model . 529 |

||

| 21.6 | Presenting the Model . 530 |

||

| 21.7 | Problems . 531 |

||

| A | Datasets, | R Packages, and Internet Resources . 535 |

|

| References | . 539 | ||

| Index | . 571 |

Typographical Conventions

Boxed numbers in the margins such as 1 correspond to numbers at the end of chapters in sections named “Further Reading.” Bracketed numbers and numeric superscripts in the text refer to the bibliography, while alphabetic superscripts indicate footnotes.

R language commands and names of R functions and packages are set in typewriter font, as are most variable names.

R code blocks are set off with a shadowbox, and R output that is not directly using LATEX appears in a box that is framed on three sides.

In the S language upon which R is based, x ← y is read “x gets the value of y.” The assignment operator ←, used in the text for aesthetic reasons (as are ≤ and ≥), is entered by the user as <-. Comments begin with #, subscripts use brackets ([ ]), and the missing value is denoted by NA (not available).

In ordinary text and mathematical expressions, [logical variable] and [logical expression] imply a value of 1 if the logical variable or expression is true, and 0 otherwise.

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.1 Hypothesis Testing, Estimation, and Prediction

Statistics comprises among other areas study design, hypothesis testing, estimation, and prediction. This text aims at the last area, by presenting methods that enable an analyst to develop models that will make accurate predictions of responses for future observations. Prediction could be considered a superset of hypothesis testing and estimation, so the methods presented here will also assist the analyst in those areas. It is worth pausing to explain how this is so.

In traditional hypothesis testing one often chooses a null hypothesis defined as the absence of some effect. For example, in testing whether a variable such as cholesterol is a risk factor for sudden death, one might test the null hypothesis that an increase in cholesterol does not increase the risk of death. Hypothesis testing can easily be done within the context of a statistical model, but a model is not required. When one only wishes to assess whether an effect is zero, P-values may be computed using permutation or rank (nonparametric) tests while making only minimal assumptions. But there are still reasons for preferring a model-based approach over techniques that only yield P-values.

- Permutation and rank tests do not easily give rise to estimates of magnitudes of effects.

- These tests cannot be readily extended to incorporate complexities such as cluster sampling or repeated measurements within subjects.

- Once the analyst is familiar with a model, that model may be used to carry out many different statistical tests; there is no need to learn specific formulas to handle the special cases. The two-sample t-test is a special case of the ordinary multiple regression model having as its sole X variable a dummy variable indicating group membership. The Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test is a special case of the proportional odds ordinal logistic

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

F.E. Harrell, Jr., Regression Modeling Strategies, Springer Series in Statistics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7 1

model.664 The analysis of variance (multiple group) test and the Kruskal– Wallis test can easily be obtained from these two regression models by using more than one dummy predictor variable.

Even without complexities such as repeated measurements, problems can arise when many hypotheses are to be tested. Testing too many hypotheses is related to fitting too many predictors in a regression model. One commonly hears the statement that “the dataset was too small to allow modeling, so we just did hypothesis tests.” It is unlikely that the resulting inferences would be reliable. If the sample size is insufficient for modeling it is often insufficient for tests or estimation. This is especially true when one desires to publish an estimate of the effect corresponding to the hypothesis yielding the smallest P-value. Ordinary point estimates are known to be badly biased when the quantity to be estimated was determined by “data dredging.” This can be remedied by the same kind of shrinkage used in multivariable modeling (Section 9.10).

Statistical estimation is usually model-based. For example, one might use a survival regression model to estimate the relative effect of increasing cholesterol from 200 to 250 mg/dl on the hazard of death. Variables other than cholesterol may also be in the regression model, to allow estimation of the effect of increasing cholesterol, holding other risk factors constant. But accurate estimation of the cholesterol effect will depend on how cholesterol as well as each of the adjustment variables is assumed to relate to the hazard of death. If linear relationships are incorrectly assumed, estimates will be inaccurate. Accurate estimation also depends on avoiding overfitting the adjustment variables. If the dataset contains 200 subjects, 30 of whom died, and if one adjusted for 15 “confounding” variables, the estimates would be “overadjusted” for the effects of the 15 variables, as some of their apparent effects would actually result from spurious associations with the response variable (time until death). The overadjustment would reduce the cholesterol effect. The resulting unreliability of estimates equals the degree to which the overall model fails to validate on an independent sample.

It is often useful to think of effect estimates as differences between two predicted values from a model. This way, one can account for nonlinearities and interactions. For example, if cholesterol is represented nonlinearly in a logistic regression model, predicted values on the “linear combination of X’s scale” are predicted log odds of an event. The increase in log odds from raising cholesterol from 200 to 250 mg/dl is the difference in predicted values, where cholesterol is set to 250 and then to 200, and all other variables are held constant. The point estimate of the 250:200 mg/dl odds ratio is the anti-log of this difference. If cholesterol is represented nonlinearly in the model, it does not matter how many terms in the model involve cholesterol as long as the overall predicted values are obtained.

Thus when one develops a reasonable multivariable predictive model, hypothesis testing and estimation of effects are byproducts of the fitted model. So predictive modeling is often desirable even when prediction is not the main goal.

1.2 Examples of Uses of Predictive Multivariable Modeling

There is an endless variety of uses for multivariable models. Predictive models have long been used in business to forecast financial performance and to model consumer purchasing and loan pay-back behavior. In ecology, regression models are used to predict the probability that a fish species will disappear from a lake. Survival models have been used to predict product life (e.g., time to burn-out of an mechanical part, time until saturation of a disposable diaper). Models are commonly used in discrimination litigation in an attempt to determine whether race or sex is used as the basis for hiring or promotion, after taking other personnel characteristics into account.

Multivariable models are used extensively in medicine, epidemiology, biostatistics, health services research, pharmaceutical research, and related fields. The author has worked primarily in these fields, so most of the examples in this text come from those areas. In medicine, two of the major areas of application are diagnosis and prognosis. There models are used to predict the probability that a certain type of patient will be shown to have a specific disease, or to predict the time course of an already diagnosed disease. In observational studies in which one desires to compare patient outcomes between two or more treatments, multivariable modeling is very important because of the biases caused by nonrandom treatment assignment. Here the simultaneous effects of several uncontrolled variables must be controlled (held constant mathematically if using a regression model) so that the effect of the factor of interest can be more purely estimated. A newer technique for more aggressively adjusting for nonrandom treatment assignment, the propensity score, 116, 530 provides yet another opportunity for multivariable modeling (see Section 10.1.4). The propensity score is merely the predicted value from a multivariable model where the response variable is the exposure or the treatment actually used. The estimated propensity score is then used in a second step as an adjustment variable in the model for the response of interest.

It is not widely recognized that multivariable modeling is extremely valuable even in well-designed randomized experiments. Such studies are often designed to make relative comparisons of two or more treatments, using odds ratios, hazard ratios, and other measures of relative effects. But to be able to estimate absolute effects one must develop a multivariable model of the response variable. This model can predict, for example, the probability that a patient on treatment A with characteristics X will survive five years, or it can predict the life expectancy for this patient. By making the same prediction for a patient on treatment B with the same characteristics, one can estimate the absolute difference in probabilities or life expectancies. This approach recognizes that low-risk patients must have less absolute benefit of treatment (lower change in outcome probability) than high-risk patients,351 a fact that has been ignored in many clinical trials. Another reason for multivariable modeling in randomized clinical trials is that when the basic response model is nonlinear (e.g., logistic, Cox, parametric survival models), the unadjusted estimate of the treatment effect is not correct if there is moderate heterogeneity of subjects, even with perfect balance of baseline characteristics across the treatment groups.a9, 24, 198, 588 So even when investigators are interested in simple comparisons of two groups’ responses, multivariable modeling can be advantageous and sometimes mandatory.

Cost-effectiveness analysis is becoming increasingly used in health care research, and the “effectiveness” (denominator of the cost-effectiveness ratio) is always a measure of absolute effectiveness. As absolute effectiveness varies dramatically with the risk profiles of subjects, it must be estimated for individual subjects using a multivariable model90, 344.

1.3 Prediction vs. Classification

For problems ranging from bioinformatics to marketing, many analysts desire to develop “classifiers” instead of developing predictive models. Consider an optimum case for classifier development, in which the response variable is binary, the two levels represent a sharp dichotomy with no gray zone (e.g., complete success vs. total failure with no possibility of a partial success), the user of the classifier is forced to make one of the two choices, the cost of misclassification is the same for every future observation, and the ratio of the cost of a false positive to that of a false negative equals the (often hidden) ratio implied by the analyst’s classification rule. Even if all of those conditions are met, classification is still inferior to probability modeling for driving the development of a predictive instrument or for estimation or hypothesis testing. It is far better to use the full information in the data to develop a probability model, then develop classification rules on the basis of estimated probabilities. At the least, this forces the analyst to use a proper accuracy score219 in finding or weighting data features.

When the dependent variable is ordinal or continuous, classification through forced up-front dichotomization in an attempt to simplify the problem results in arbitrariness and major information loss even when the optimum cut point

a For example, unadjusted odds ratios from 2 × 2 tables are different from adjusted odds ratios when there is variation in subjects’ risk factors within each treatment group, even when the distribution of the risk factors is identical between the two groups.

(the median) is used. Dichtomizing the outcome at a different point may require a many-fold increase in sample size to make up for the lost information187. In the area of medical diagnosis, it is often the case that the disease is really on a continuum, and predicting the severity of disease (rather than just its presence or absence) will greatly increase power and precision, not to mention making the result less arbitrary.

It is important to note that two-group classification represents an artificial forced choice. It is not often the case that the user of the classifier needs to be limited to two possible actions. The best option for many subjects may be to refuse to make a decision or to obtain more data (e.g., order another medical diagnostic test). A gray zone can be helpful, and predictions include gray zones automatically.

Unlike prediction (e.g., of absolute risk), classification implicitly uses utility functions (also called loss or cost functions, e.g., cost of a false positive classification). Implicit utility functions are highly problematic. First, it is well known that the utility function depends on variables that are not predictive of outcome and are not collected (e.g., subjects’ preferences) that are available only at the decision point. Second, the approach assumes every subject has the same utility functionb. Third, the analyst presumptuously assumes that the subject’s utility coincides with his own.

Formal decision analysis uses subject-specific utilities and optimum predictions based on all available data62, 74, 183, 210, 219, 642c. It follows that receiver

b Simple examples to the contrary are the less weight given to a false negative diagnosis of cancer in the elderly and the aversion of some subjects to surgery or chemotherapy.

c To make an optimal decision you need to know all relevant data about an individual (used to estimate the probability of an outcome), and the utility (cost, loss function) of making each decision. Sensitivity and specificity do not provide this information. For example, if one estimated that the probability of a disease given age, sex, and symptoms is 0.1 and the “cost”of a false positive equaled the “cost” of a false negative, one would act as if the person does not have the disease. Given other utilities, one would make different decisions. If the utilities are unknown, one gives the best estimate of the probability of the outcome to the decision maker and let her incorporate her own unspoken utilities in making an optimum decision for her.

Besides the fact that cutoffs that are not individualized do not apply to individuals, only to groups, individual decision making does not utilize sensitivity and specificity. For an individual we can compute Prob(Y = 1|X = x); we don’t care about Prob(Y = 1|X>c), and an individual having X = x would be quite puzzled if she were given Prob(X>c|future unknown Y) when she already knows X = x so X is no longer a random variable.

Even when group decision making is needed, sensitivity and specificity can be bypassed. For mass marketing, for example, one can rank order individuals by the estimated probability of buying the product, to create a lift curve. This is then used to target the k most likely buyers where k is chosen to meet total program cost constraints.

operating characteristic curve (ROCd) analysis is misleading except for the special case of mass one-time group decision making with unknown utilities 1 (e.g., launching a flu vaccination program).

An analyst’s goal should be the development of the most accurate and reliable predictive model or the best model on which to base estimation or hypothesis testing. In the vast majority of cases, classification is the task of the user of the predictive model, at the point in which utilities (costs) and preferences are known.

1.4 Planning for Modeling

When undertaking the development of a model to predict a response, one of the first questions the researcher must ask is “will this model actually be used?” Many models are never used, for several reasons522 including: (1) it was not deemed relevant to make predictions in the setting envisioned by the authors; (2) potential users of the model did not trust the relationships, weights, or variables used to make the predictions; and (3) the variables necessary to make the predictions were not routinely available.

Once the researcher convinces herself that a predictive model is worth developing, there are many study design issues to be addressed.18, 378 Models are often developed using a “convenience sample,” that is, a dataset that was not collected with such predictions in mind. The resulting models are often fraught with difficulties such as the following.

- The most important predictor or response variables may not have been collected, tempting the researchers to make do with variables that do not capture the real underlying processes.

- The subjects appearing in the dataset are ill-defined, or they are not representative of the population for which inferences are to be drawn; similarly, the data collection sites may not represent the kind of variation in the population of sites.

- Key variables are missing in large numbers of subjects.

- Data are not missing at random; for example, data may not have been collected on subjects who dropped out of a study early, or on patients who were too sick to be interviewed.

- Operational definitions of some of the key variables were never made.

- Observer variability studies may not have been done, so that the reliability of measurements is unknown, or there are other kinds of important measurement errors.

A predictive model will be more accurate, as well as useful, when data collection is planned prospectively. That way one can design data collection

d The ROC curve is a plot of sensitivity vs. one minus specificity as one varies a cutoff on a continuous predictor used to make a decision.

instruments containing the necessary variables, and all terms can be given standard definitions (for both descriptive and response variables) for use at all data collection sites. Also, steps can be taken to minimize the amount of missing data.

In the context of describing and modeling health outcomes, Iezzoni317 has an excellent discussion of the dimensions of risk that should be captured by variables included in the model. She lists these general areas that should be quantified by predictor variables:

- age,

- sex,

- acute clinical stability,

- principal diagnosis,

- severity of principal diagnosis,

- extent and severity of comorbidities,

- physical functional status,

- psychological, cognitive, and psychosocial functioning,

- cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic attributes and behaviors,

- health status and quality of life, and

- patient attitudes and preferences for outcomes.

Some baseline covariates to be sure to capture in general include

- a baseline measurement of the response variable,

- the subject’s most recent status,

- the subject’s trajectory as of time zero or past levels of a key variable,

- variables explaining much of the variation in the response, and

- more subtle predictors whose distributions strongly differ between the levels of a key variable of interest in an observational study.

Many things can go wrong in statistical modeling, including the following.

- The process generating the data is not stable.

- The model is misspecified with regard to nonlinearities or interactions, or there are predictors missing.

- The model is misspecified in terms of the transformation of the response variable or the model’s distributional assumptions.

- The model contains discontinuities (e.g., by categorizing continuous predictors or fitting regression shapes with sudden changes) that can be gamed by users.

- Correlations among subjects are not specified, or the correlation structure is misspecified, resulting in inefficient parameter estimates and overconfident inference.

- The model is overfitted, resulting in predictions that are too extreme or positive associations that are false.

- The user of the model relies on predictions obtained by extrapolating to combinations of predictor values well outside the range of the dataset used to develop the model.

- Accurate and discriminating predictions can lead to behavior changes that make future predictions inaccurate.

1.4.1 Emphasizing Continuous Variables

When designing the data collection it is important to emphasize the use of continuous variables over categorical ones. Some categorical variables are subjective and hard to standardize, and on the average they do not contain the same amount of statistical information as continuous variables. Above all, it is unwise to categorize naturally continuous variables during data collection,e as the original values can then not be recovered, and if another researcher feels that the (arbitrary) cutoff values were incorrect, other cutoffs cannot be substituted. Many researchers make the mistake of assuming that categorizing a continuous variable will result in less measurement error. This is a false assumption, for if a subject is placed in the wrong interval this will be as much as a 100% error. Thus the magnitude of the error multiplied by the 2 probability of an error is no better with categorization.

1.5 Choice of the Model

The actual method by which an underlying statistical model should be chosen by the analyst is not well developed. A. P. Dawid is quoted in Lehmann397 as saying the following.

Where do probability models come from? To judge by the resounding silence over this question on the part of most statisticians, it seems highly embarrassing. In general, the theoretician is happy to accept that his abstract probability triple (Ω, A, P) was found under a gooseberry bush, while the applied statisti-3 cian’s model “just growed”.

In biostatistics, epidemiology, economics, psychology, sociology, and many other fields it is seldom the case that subject matter knowledge exists that would allow the analyst to pre-specify a model (e.g., Weibull or log-normal survival model), a transformation for the response variable, and a structure

e An exception may be sensitive variables such as income level. Subjects may be more willing to check a box corresponding to a wide interval containing their income. It is unlikely that a reduction in the probability that a subject will inflate her income will offset the loss of precision due to categorization of income, but there will be a decrease in the number of refusals. This reduction in missing data can more than offset the lack of precision.

for how predictors appear in the model (e.g., transformations, addition of nonlinear terms, interaction terms). Indeed, some authors question whether the notion of a true model even exists in many cases.100 We are for better or worse forced to develop models empirically in the majority of cases. Fortunately, careful and objective validation of the accuracy of model predictions against observable responses can lend credence to a model, if a good validation is not merely the result of overfitting (see Section 5.3).

There are a few general guidelines that can help in choosing the basic form of the statistical model.

- The model must use the data efficiently. If, for example, one were interested in predicting the probability that a patient with a specific set of characteristics would live five years from diagnosis, an inefficient model would be a binary logistic model. A more efficient method, and one that would also allow for losses to follow-up before five years, would be a semiparametric (rank based) or parametric survival model. Such a model uses individual times of events in estimating coefficients, but it can easily be used to estimate the probability of surviving five years. As another example, if one were interested in predicting patients’ quality of life on a scale of excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor, a polytomous (multinomial) categorical response model would not be efficient as it would not make use of the ordering of responses.

- Choose a model that fits overall structures likely to be present in the data. In modeling survival time in chronic disease one might feel that the importance of most of the risk factors is constant over time. In that case, a proportional hazards model such as the Cox or Weibull model would be a good initial choice. If on the other hand one were studying acutely ill patients whose risk factors wane in importance as the patients survive longer, a model such as the log-normal or log-logistic regression model would be more appropriate.

- Choose a model that is robust to problems in the data that are difficult to check. For example, the Cox proportional hazards model and ordinal logistic models are not affected by monotonic transformations of the response variable.

- Choose a model whose mathematical form is appropriate for the response being modeled. This often has to do with minimizing the need for interaction terms that are included only to address a basic lack of fit. For example, many researchers have used ordinary linear regression models for binary responses, because of their simplicity. But such models allow predicted probabilities to be outside the interval [0, 1], and strange interactions among the predictor variables are needed to make predictions remain in the legal range.

- Choose a model that is readily extendible. The Cox model, by its use of stratification, easily allows a few of the predictors, especially if they are categorical, to violate the assumption of equal regression coefficients over

time (proportional hazards assumption). The continuation ratio ordinal logistic model can also be generalized easily to allow for varying coefficients of some of the predictors as one proceeds across categories of the response.

R. A. Fisher as quoted in Lehmann397 had these suggestions about model building: “(a) We must confine ourselves to those forms which we know how to handle,” and (b) “More or less elaborate forms will be suitable according to the volume of the data.” Ameen [100, p. 453] stated that a good model is “(a) satisfactory in performance relative to the stated objective, (b) logically sound, (c) representative, (d) questionable and subject to on-line interrogation, (e) able to accommodate external or expert information and (f) able to convey information.”

It is very typical to use the data to make decisions about the form of the model as well as about how predictors are represented in the model. Then, once a model is developed, the entire modeling process is routinely forgotten, and statistical quantities such as standard errors, confidence limits, P-values, and R2 are computed as if the resulting model were entirely prespecified. However, Faraway,186 Draper,163 Chatfield,100 Buckland et al.80 and others have written about the severe problems that result from treating an empirically derived model as if it were pre-specified and as if it were the correct model. As Chatfield states [100, p. 426]:“It is indeed strange that we often admit model uncertainty by searching for a best model but then ignore this uncertainty by making inferences and predictions as if certain that the best fitting model is actually true.”

Stepwise variable selection is one of the most widely used and abused of all data analysis techniques. Much is said about this technique later (see Section 4.3), but there are many other elements of model development that will need to be accounted for when making statistical inferences, and unfortunately it is difficult to derive quantities such as confidence limits that are properly adjusted for uncertainties such as the data-based choice between a 4 Weibull and a log-normal regression model.

Ye678 developed a general method for estimating the “generalized degrees of freedom” (GDF) for any “data mining” or model selection procedure based on least squares. The GDF is an extremely useful index of the amount of “data dredging” or overfitting that has been done in a modeling process. It is also useful for estimating the residual variance with less bias. In one example, Ye developed a regression tree using recursive partitioning involving 10 candidate predictor variables on 100 observations. The resulting tree had 19 nodes and GDF of 76. The usual way of estimating the residual variance involves dividing the pooled within-node sum of squares by 100 − 19, but Ye showed that dividing by 100 − 76 instead yielded a much less biased (and much higher) estimate of σ2. In another example, Ye considered stepwise variable selection using 20 candidate predictors and 22 observations. When there is no true association between any of the predictors and the response, Ye found that GDF = 14.1 for a strategy that selected the best five-variable 5 model.

1.6 Further Reading 11

Given that the choice of the model has been made (e.g., a log-normal model), penalized maximum likelihood estimation has major advantages in the battle between making the model fit adequately and avoiding overfitting (Sections 9.10 and 13.4.7). Penalization lessens the need for model selection.

1.6 Further Reading

1 Briggs and Zaretzki74 eloquently state the problem with ROC curves and the areas under them (AUC):

Statistics such as the AUC are not especially relevant to someone who must make a decision about a particular xc. . . . ROC curves lack or obscure several quantities that are necessary for evaluating the operational effectiveness of diagnostic tests. . . . ROC curves were first used to check how radio receivers (like radar receivers) operated over a range of frequencies. . . . This is not how must ROC curves are used now, particularly in medicine. The receiver of a diagnostic measurement . . . wants to make a decision based on some xc, and is not especially interested in how well he would have done had he used some different cutoff.

In the discussion to their paper, David Hand states

When integrating to yield the overall AUC measure, it is necessary to decide what weight to give each value in the integration. The AUC implicitly does this using a weighting derived empirically from the data. This is nonsensical. The relative importance of misclassifying a case as a noncase, compared to the reverse, cannot come from the data itself. It must come externally, from considerations of the severity one attaches to the different kinds of misclassifications.

AUC, only because it equals the concordance probability in the binary Y case, is still often useful as a predictive discrimination measure.

- 2 More severe problems caused by dichotomizing continuous variables are discussed in [13, 17, 45, 82, 185, 294, 379, 521, 597].

- 3 See the excellent editorial by Mallows434 for more about model choice. See Breiman and discussants67 for an interesting debate about the use of data models vs. algorithms. This material also covers interpretability vs. predictive accuracy and several other topics.

- 4 See [15, 80, 100, 163, 186, 415] for information about accounting for model selection in making final inferences. Faraway186 demonstrated that the bootstrap has good potential in related although somewhat simpler settings, and Buckland et al.80 developed a promising bootstrap weighting method for accounting for model uncertainty.

- 5 Tibshirani and Knight611 developed another approach to estimating the generalized degrees of freedom. Luo et al.430 developed a way to add noise of known variance to the response variable to tune the stopping rule used for variable selection. Zou et al.689 showed that the lasso, an approach that simultaneously selects variables and shrinks coefficients, has a nice property. Since it uses penalization (shrinkage), an unbiased estimate of its effective number of degrees of freedom is the number of nonzero regression coefficients in the final model.

Chapter 2 General Aspects of Fitting Regression Models

2.1 Notation for Multivariable Regression Models

The ordinary multiple linear regression model is frequently used and has parameters that are easily interpreted. In this chapter we study a general class of regression models, those stated in terms of a weighted sum of a set of independent or predictor variables. It is shown that after linearizing the model with respect to the predictor variables, the parameters in such regression models are also readily interpreted. Also, all the designs used in ordinary linear regression can be used in this general setting. These designs include analysis of variance (ANOVA) setups, interaction effects, and nonlinear effects. Besides describing and interpreting general regression models, this chapter also describes, in general terms, how the three types of assumptions of regression models can be examined.

First we introduce notation for regression models. Let Y denote the response (dependent) variable, and let X = X1, X2,…,Xp denote a list or vector of predictor variables (also called covariables or independent, descriptor, or concomitant variables). These predictor variables are assumed to be constants for a given individual or subject from the population of interest. Let β = β0, β1,…, βp denote the list of regression coefficients (parameters). β0 is an optional intercept parameter, and β1,…, βp are weights or regression coefficients corresponding to X1,…,Xp. We use matrix or vector notation to describe a weighted sum of the Xs:

\[X\beta = \beta\_0 + \beta\_1 X\_1 + \dots + \beta\_p X\_p,\tag{2.1}\]

where there is an implied X0 = 1.

A regression model is stated in terms of a connection between the predictors X and the response Y . Let C(Y |X) denote a property of the distribution of Y given X (as a function of X). For example, C(Y |X) could be E(Y |X),

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015

F.E. Harrell, Jr., Regression Modeling Strategies, Springer Series

in Statistics, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-19425-7 2

the expected value or average of Y given X, or C(Y |X) could be the probability that Y = 1 given X (where Y = 0 or 1).

2.2 Model Formulations

We define a regression function as a function that describes interesting properties of Y that may vary across individuals in the population. X describes the list of factors determining these properties. Stated mathematically, a general regression model is given by

\[C(Y|X) = g(X). \tag{2.2}\]

We restrict our attention to models that, after a certain transformation, are linear in the unknown parameters, that is, models that involve X only through a weighted sum of all the Xs. The general linear regression model is given by

\[C(Y|X) = g(X\beta). \tag{2.3}\]

For example, the ordinary linear regression model is

\[C(Y|X) = E(Y|X) = X\beta,\tag{2.4}\]

and given X, Y has a normal distribution with mean Xβ and constant variance σ2. The binary logistic regression model129, 647 is

\[C(Y|X) = \text{Prob}\{Y=1|X\} = (1 + \exp(-X\beta))^{-1},\tag{2.5}\]

where Y can take on the values 0 and 1. In general the model, when stated in terms of the property C(Y |X), may not be linear in Xβ; that is C(Y |X) = g(Xβ), where g(u) is nonlinear in u. For example, a regression model could be E(Y |X)=(Xβ).5. The model may be made linear in the unknown parameters by a transformation in the property C(Y |X):

\[h(C(Y|X)) = X\beta,\tag{2.6}\]

where h(u) = g−1(u), the inverse function of g. As an example consider the binary logistic regression model given by

\[C(Y|X) = \text{Prob}\{Y = 1|X\} = (1 + \exp(-X\beta))^{-1}.\tag{2.7}\]

If h(u) = logit(u) = log(u/(1 − u)), the transformed model becomes

\[h(\text{Prob}(Y=1|X)) = \log(\exp(X\beta)) = X\beta. \tag{2.8}\]

The transformation h(C(Y |X)) is sometimes called a link function. Let h(C(Y |X)) be denoted by C′ (Y |X). The general linear regression model then becomes

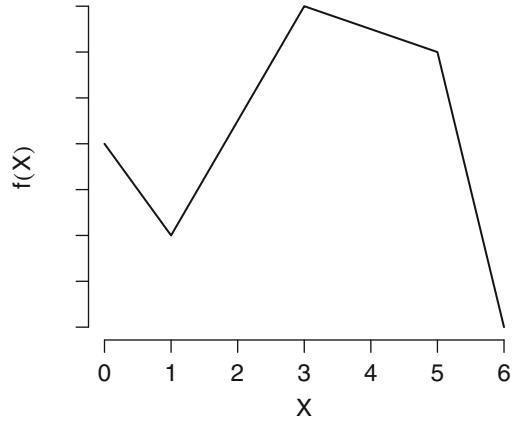

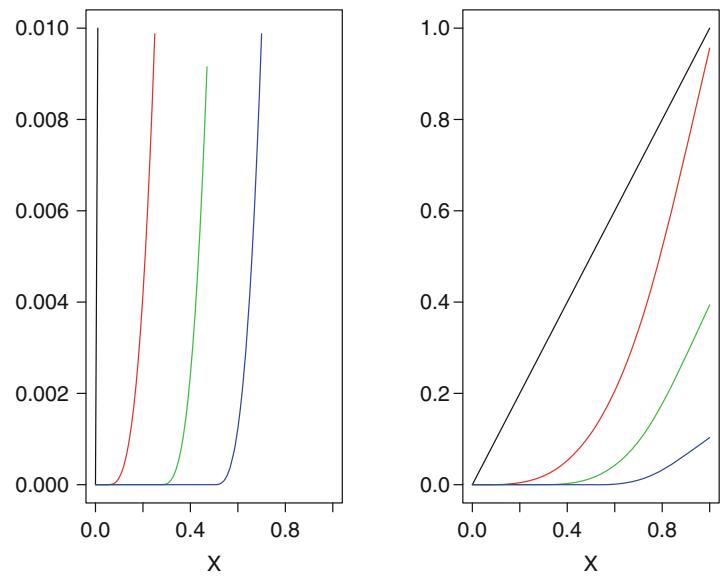

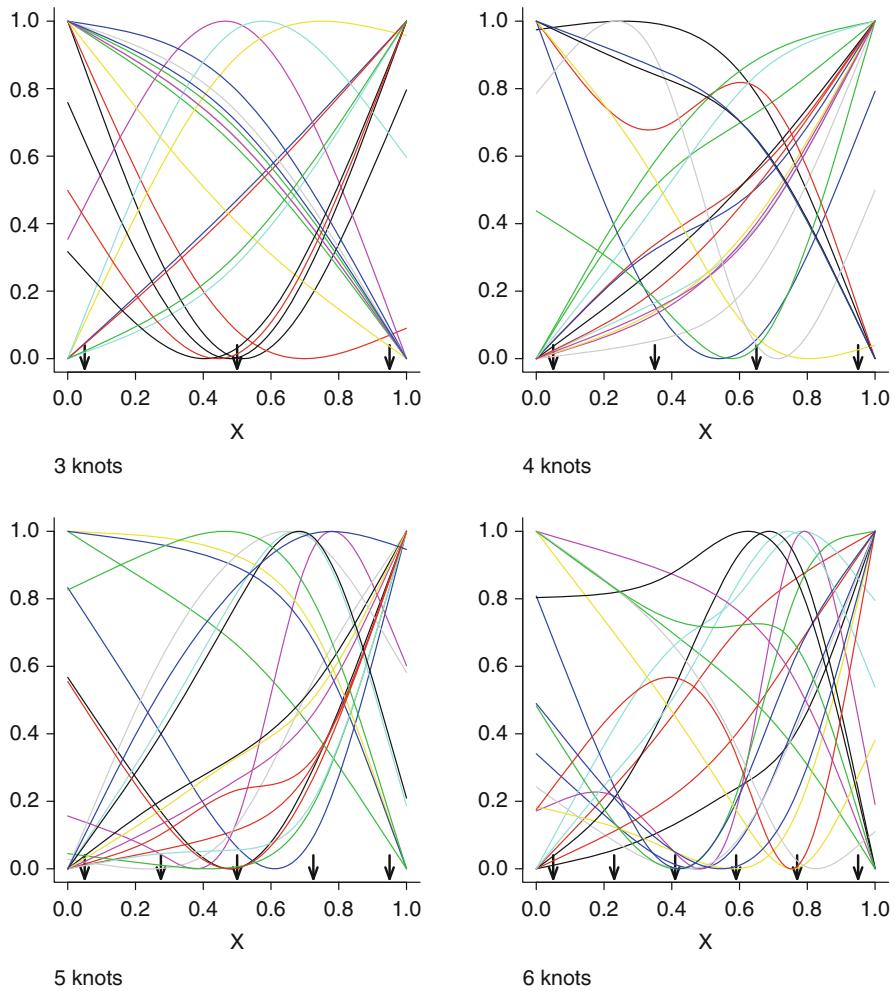

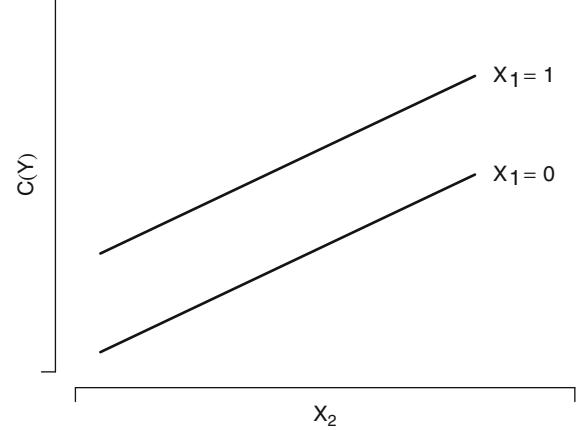

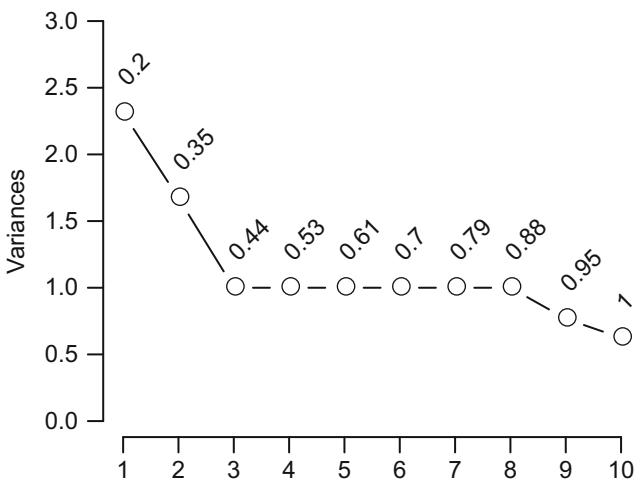

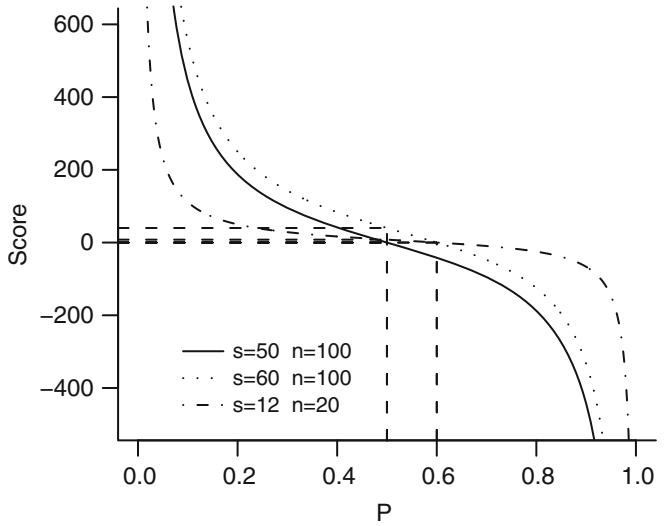

\[C'(Y|X) = X\beta. \tag{2.9}\]