A Synopsis of ‘The Seven Sins of Evolutionary Psychology’

Contents

Evolutionary Psychology: An Exchange

| Jaak Panksepp/Jules B. Panksepp | 2 | A Synopsis of “The Seven Sins of Evolutionary Psychology” |

|||

| Ullica Segerstråle | 6 | Minding the Brain: The Continuing Conflict about Models and Reality |

|||

| Linda Mealey | 14 | “La plus ça change…”: Response to a Critique of Evolutionary Psychology |

|||

| Carlos Stegmann | 20 | Comments on Jaak Panksepp and Jules B. Panksepp’s Paper “The Seven Sins of Evolutionary Psychology” |

|||

| Russell Gardner, Jr. | 25 | Affective Neuroscience, Psychiatry, and Sociophysiology | |||

| Gerhard Meisenberg | 31 | Degrees of Modularity | |||

| Ian Pitchford | 39 | No Evolution. No Cognition | |||

| Scott Atran | 46 | The Case for Modularity: Sin or Salvation? | |||

| Jaak Panksepp/Jules B. Panksepp | 56 | A Continuing Critique of Evolutionary Psychology: Seven Sins for Seven Sinners, Plus or Minus Two |

General Articles

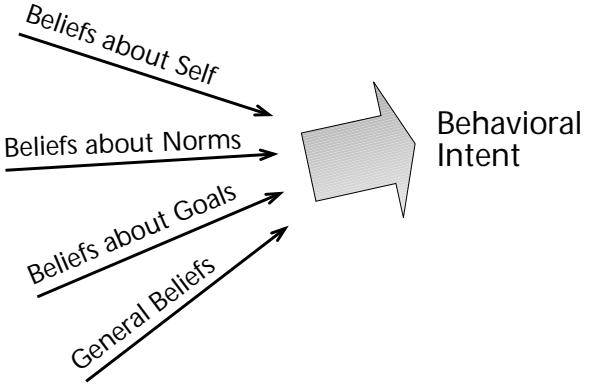

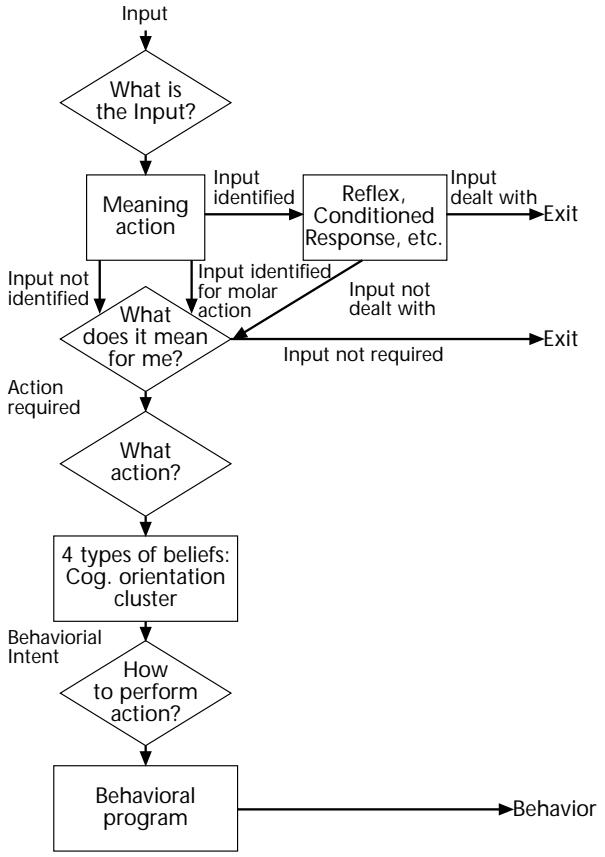

| Shulamith Kreitler | 81 | An Evolutionary Perspective on Cognitive Orientation | |||

| Chris MacDonald | 98 | Evolutionary Ethics: Value, Psychology, Strategy and Conventions |

|||

| 106 | Zusammenfassungen der Artikel in deutscher Sprache |

Impressum

Evolution and Cognition: ISSN: 0938-2623 Published by: Konrad Lorenz Institut für Evolutions- und Kognitionsforschung, Adolf-Lorenz-Gasse 2, A-3422 Altenberg/Donau. Tel.: 0043-2242-32390; Fax: 0043-2242-323904; e-mail: sec@kla.univie.ac.at; World Wide Web: http://www.univie.ac.at/evolution/kli/ Editors: Rupert Riedl, Manfred Wimmer Layout: Alexander Riegler Aim and Scope: “Evolution and Cognition” is an

interdisciplinary forum devoted to all aspects of research on cognition in animals and humans. The major emphasis of the journal is on evolutionary approaches to cognition, reflecting the fact that the cognitive capacities of organisms result from biological evolution. Empirical and theoretical work from both fields, evolutionary and cognitive science, is accepted, but particular attention is paid to interdisciplinary perspectives on the mutual relationship between evolutionary and cognitive processes. Submissions dealing with the significance of cognitive research for the theories of biological and sociocultural evolution are also welcome. “Evolution and Cognition” publishes both original papers and review articles. Period of Publication: Semi-annual Price: Annuals subscription rate (2 issues): ATS 500; DEM 70, US$ 50; SFr 60; GBP 25. Annual subscriptions are assumed to be continued automatically unless subscription orders are cancelled by written information. Single issue price: ATS 300; DEM 43; US$ 30; SFr 36; GBP 15 Publishing House: WUV-Universitätsverlag/Vienna University Press, Berggasse 5, A-1090 Wien, Tel.: 0043/1/3105356-0, Fax: 0043/1/3197050 Bank: Erste österreichische Spar-Casse, Acct.No. 073-08191 (Bank Code 20111) Advertising: Vienna University Press, Berggasse 5, A-1090 Wien. Supported by Cultural Office of the City of Vienna, Austrian Federal Ministry of Science/ Transportation and the Section Culture and Science of the Lower Austrian State Government.

A Synopsis of “The Sevens Sins of Evolutionary Psychology”

Our target article (PANKSEPP/PANKSEPP 2000) summarized some common and uncommon concerns that neuroscientifically oriented investigators of the mind/brain may have with currently fashionable versions of evolutionary psychology. Our main thesis was that an evolutionary psychology that seeks to understand “human nature” will be woefully incomplete and perhaps misguided if it does not incorporate the lessons from the past century of research on subcortical emotional and motivational systems that all mammals share. It is advisable to begin building an evolutionary viewpoint of mind based on comparative concepts that incorporate the intrinsic, evolutionarily provide systems found in all mammalian brains.

The more evangelical varieties of psycho–evolutionary thought that arose from social-science traditions have typically not been concerned with how the human mind emerges from specific brain functions. Thus, our argument was motivated by three converging and overlapping issues: (1) The failure of evolutionary psychology (e.g., BUSS 1999, and many others) to address the evolved, adaptive mechanisms in the mammalian brain that have been and are being studied by many investigators in the neurosciences. (2) The prolific tendency of evolutionary psychology to generate adaptive stories, especially with regard to human socio–emotional processes, without much apparent concern about how such presumed adaptations might be instantiated in neural systems through a great diversity of brain–environment interactions (e.g., COSMIDES/TOOBY 2000). (3) The concurrent claim that evolutionary psychology is now providing one of the most robust lines of thought for identifying the types of evolved mechanisms that actually exist in the human brain (TOOBY/COSMIDES 2000).

Our discussion was framed with the recognition that several distinct schools of thought are currently providing conceptual frameworks to help guide future empirical inquiries in the ongoing attempt to understand how evolution constructed the mind/ brain of humans and other animals. Also, our article was premised on the full acceptance that evolutionary viewpoints are essential for specifying the neuropsychological natural kinds that actually exist, as ancestral birthrights, within the brains of humans as well as other animals.

Our specific concerns were as follows:

1. Are there really Pleistocene sources of current human social adaptations? Evolutionary Psychologists seem to be backing off from this assumption as they begin to realize that neocortex is the main type of cerebral tissue that emerged two million years ago, when hominid brains diverged from the “chimp-sized” brains of our ancestral stock. Thus, the critical question is whether special-purpose programs emerged in neocortical tissues primarily through genetic changes that occurred in the human line during the past few million years. That issue probably cannot be answered unambiguously without concurrent behavioral neuroscience and molecular biology research. If such adaptations emerged, they are likely to reflect quite general information handling capacities, permitting abilities ranging from art to human languages, from thought to culture. Most evolved, special-purpose systems may be devoted to functions we still share with other animals.

2. Excessive species-centrism in Evolutionary Psychology. Completion of the human genome project has unequivocally highlighted the likelihood for genetic similarities across all mammalian species. We suggest that without a clear recognition of what we share with other animals, it will be impossible to specify what is truly unique in the intrinsic, genetically-provided capacities of the human mind/brain. The neuroanatomical and neurochemical homologies that exist in all mammalian brains presently provide the most substantive way to specify the types of evolved faculties in our own minds.

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 2 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

3. The sin of adaptationism. It is well recognized that one must always discriminate between adaptations arising from natural selection and those arising from the emergence of flexible abilities to learn new skills and strategies. The cortex obviously becomes specialized for a large number of special purpose skills and abilities during development (many of which may seem superfically “encapsulated” because most of our thoughts are constrained by primitive emotional systems that regulate our feelings), but current evolutionary psychology provides no special inroads to understanding which adaptations have truly emerged through natural selection.

4. The sin of massive modularity. From a neuroscience perspective, “modularity” is an obsolete concept, resembling the “centers” concept that was discarded by scientists doing brain research several decades ago. There are many special-purpose circuits and systems in subcortical areas of the brain, but those systems are not encapsulated and appear to interact with each other extensively. For instance, during every emotion, the activities of widespread brain areas are modified. Obviously, a critical scientific issue is the degree to which the specialized functions of higher cerebral abilities exist as birthrights and how much they reflect the operation of developmental programs.

5. On the conflation of emotions and cognitions.

The cortex mediates many specialized cognitive abilities. Most of the key systems for mammalian emotionality are subcortically organized, and the neglect of these systems can only lead to a very mistaken view of how emotionality is truly elaborated in the human brain. Disciplines that focus simply on the higher cortico–cognitive aspects of emotional processing are bound to make many mistakes about the fundamental nature of emotions and affective processes (PANKSEPP 2001).

6. The absence of credible neural perspective in Evolutionary Psychology. This is a general criticism of all mind sciences that fail to take real brain issues into consideration. Although the full potential of the mind emerges from organismic–environmental interactions, all foundational issues need to be linked to our gradually emerging understanding of how specific neural systems function. The neuroscience revolution has provided enough raw evidence for everyone to begin thinking more clearly about those underlying brain issues.

7. Anti-organic bias or the computationalist/representationalist myth. There have always been two grand perspectives for explaining the organization of mind—mind as an organic process and mind as a “spiritual” process that can exist independently of the material world. The modern computational view still tends to subscribe to a modern variant of the latter view. From a non-dualistic, materialistic perspective, that may be highly misleading. All minds are probably strongly constrained by the organic–neural processes by which they are instantiated. To neglect those issues, in preference for a strict computationalist view, is likely, we believe, to retard deep understanding. In our reply to the commentators, we highlight a recent critique by FODOR (2000), one of the great promoters of the computationalism, who now agrees that grave errors have been made during the cognitive revolution.

Our criticisms do not apply equally to all existing lines of psycho–evolutionary thought, but mainly to the rhetorically most audible social psychological variants that arose from the ashes of the contentious “sociobiology wars” of the late 1970s and early 80s. Additional issues could have been raised, such as the massive interactions of certain well-characterized brain systems (e.g., dopamine, norepinephrine, serotonin, acetylcholine, GABA and glutamate) which participate heavily in all of the processes about which evolutionary psychologists opine. Several related “sinful” tendencies could have been highlighted, but they all ultimately relate to the failure of Evolutionary Psychology to assume a deeply organic stance that fully respects the role of developmental systems in the epigenetic creation of higher mental faculties.

Our overall view is that the developmental interactions between ancient, special-purpose circuits and more recent, general-purpose brain systems, such as those found in the neocortex, can generate many of the “modularized” human abilities that Evolutionary Psychology has entertained. By simply accepting the remarkable degree of neocortical plasticity, especially during human development, genetically-dictated, sociobiological “modules” begin to resemble products of dubious human ambition rather than sound scientific inquiry. We believe that if Evolutionary Psychology attempts to construct a view of human nature based upon inclusive-fitness issues and improbable neurological assumptions, while continuing to avoid a substantive confrontation with our ancient animalian heritage, it is as likely to retard lasting scientific progress as to advance it. In short, the only place many concepts of

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 3 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

evolutionary psychology may be encapsulated are in the minds of scholars who, all too often, have little wish to immerse themselves in the essential neuroscientific and genetic issues.

We recognize that there are recent strands of thought in evolutionary psychology that take positions more congenial to our own. For instance, we admire BADCOCK’s (2000) confrontation with key biological issues, as well as his willingness to try to link evolutionary thought to earlier intellectual traditions. We especially appreciate the way he handles the possibility that cultural issues, obviously important in their own right, may be linked to some important heritability findings such as genomic imprinting. Stunning discoveries such as that of KEV-ERNE and colleagues (1996), indicating that the development of neocortex may be influenced more by maternally-imprinted genes while the development of key emotional areas such as the hypothalamus are governed more by paternally-imprinted genes, provide novel ancestral–genetic tethers over brain organization that may have profound implications for the nature–nurture controversy.

Of course, we remain as intellectually stimulated by evolutionary psychological stories as anyone. We have been especially entertained by the recent willingness of some theorists to recognize the importance of the emergence of artistic endeavors in the socio–cortical emergence of our species (MILLER 2000) and of course, the view of language as partly a social-grooming adaptation (DUNBAR 1995) which fits nicely with some animal social-systems data (PANKSEPP 1998a). However, we would again advise evolutionists to view the neocortex as the generalpurpose playground for our basic attentional, emotional and motivational systems, as opposed to their sources. Indeed, it may well be that such a generalpurpose associational spaces are the ideal playgrounds for the many dimensions of human creativity and entertainment, both abundantly serious and humorous depending on the depth of our emo-

tional personalities as much as anything else. With our neocortex we can do whatever we can imagine—and because of the mass of general purpose associational space that we possess, there are few obvious limits to our imagination. This affords us great liberties in our humanistic endeavors and helps create great havoc for our scientific ones.

We would simply note that the expansion of instincts at the turn of the previous century is now being matched by the postulation of genetically modularized cognitive functions. The “expansion of instincts” failed scientifically because they were not tethered to brain systems, and the expansion of “modularized” functions may have a comparable fate for similar reasons. A recent, and more guarded attempt to bring instinctual systems back to the forefront of our thinking (e.g., PANKSEPP 1998a) has been premised on only entertaining basic psycho– behavioral entities for which there exist robust and converging neuroscientific evidence. This also gives us considerable confidence in defining what types of systems we need to study more earnestly in humans, while preventing mere human creativity from being the major guide of what does or does not exist in the natural organization of our minds. If we carefully work out the fundamental neuro-psychological processes that we share with other animals, we will be in a better position to comprehend what is truly unique in our own mind/brains.

Our implicit aim in the target article was to strongly encourage similar constraints in evolutionary psychological thought. Obviously, there are many stories that remain to be told around this new intellectual campfire, and the likelihood that primitive forms of affective self-representation still link us to a deep animalian past may be a worthy concept for mainstream thought in evolutionary psychology (PANKSEPP 1998a,b). Indeed, this view may allow us to better understand and harmonize scientific and humanistic endeavors. We do hope that an increasing number of scholars will begin to incorporate the evolutionary passages of deep-time into their considerations of the evolved nature of human mind-flesh… most especially in ways that can lead to the deep empirical evaluation of ideas. Being inheritors of a vast and to some extent, general-purpose cerebral canopy,

References

- Badcock, C. (2000) Evolutionary Psychology: A Critical Introduction. Polity Press: Cambridge UK.

- Buss, D. M. (1999) Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. Allyn and Bacon: Boston.

- Cosmides, L./Tooby, J. (2000) Evolutionary psychology and the emotions. In: Lewis, M./Haviland, J. (eds) The Handbook of Emotions, 2nd edition. Guilford: New York, pp. 91–116.

- Dunbar, R. (1995) Grooming, Gossip and The Evolution of Language. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA.

- Fodor, J. (2000) The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way, The Scope and Limits of Computational Psychology. The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA.

- Keverne, E. B./Fundele, R., et al. (1996) Genomic imprinting and the differential roles of parental genomes in brain development. Developmental Brain Research 92: 91–100.

Miller, G. (2000) The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice

Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. William Heinemann: London UK.

- Panksepp, J. (1998a) Affective Neuroscience, The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions. Oxford University Press: New York.

- Panksepp, J. (1998b) The periconscious substrates of consciousness: Affective states and the evolutionary origins of the SELF. Journal of Consciousness Studies 5: 566–582.

- Panksepp, J. (2001) At the interface between the affective, behavioral and cognitive neurosciences. Decoding the emotional feelings of the brain. Brain and Cognition, in press.

- Panksepp, J./Panksepp, J. B. (2000) The seven sins of evolutionary psychology. Evolution and Cognition 6(2): 108– 131.

- Tooby, J./Cosmides, L. (2000) Toward mapping the evolved functional organization of mind and brain. In: Gazzaniga, M.S. (ed) The New Cognitive Neuroscience, 2nd edition. MIT Press: Cambridge MA, pp. 1167–1178.

Minding the Brain

The Continuing Conflict about Models and Reality

HERE IS THE FAMOUS joke about a traveler asking a local if he knew how far it was to a particular town. Yes, said the man. But, he added, you can’t get to there from here! This may be rather like the way Jaak and Jules PANKSEPP view the prospect of elucidating the mind with the help of evolutionarily informed cognitive neuroscience. Theirs is one of the strongest scientific objections so far to the whole enterprise of evolutionary psychology. For the PANKSEPPs, there is only one correct way to go, and that is through the field of affective neuroscience. You cannot find out about the functioning of the mind/brain by asking questions about adaptation and design, and by reconstructing the kinds of problems our Pleistocene ancestors faced, they say. Evolutionary psychologists are on the wrong track. If you want to find out about functions, you should not be looking at T

Abstract

The battle for ‘good science’, so evident in the sociobiology controversy, now continues in the realm of neuroscience. Modelers again clash with hardnosed scientific ‘realists’. From the PANKSEPPs’ point of view, in order to be scientific and ground their own enterprise, evolutionary psychologists ought to pay attention to anatomy and the evolutionary history of the mind.

Moreover, the PANKSEPPs’ criticism of cognitive neuroscience parallels traditional ethological objections to sociobiology, emphasizing not only the ultimate function, but also the development, evolutionary history, and proximate causes of behaviors. This may signal an emerging conflict between evolutionary psychology and ethology. Meanwhile, the PANKSEPPs are in good critical company with many others, such as developmentally oriented scientists, who argue that the modularity in the adult brain does not reflect a preexisting domain specificity, but is rather a product of epigenesis. Indeed, a new interdisciplinary alliance may be currently emerging, as the critics of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology, in their search for a more ‘holistic’ and ‘pluralistic’ paradigm, have recently discovered ethology!

Finally, we should not forget that evolutionary psychology is an evolving research program. Most likely we will see an eventual rapprochement between cognitive and affective neuroscience. A possible mediator could be the interdisciplinary field of nonverbal communication.

Key words

Sociobiology controversy, neuroscience, ethology, evolutionary psychology, development, nonverbal communication, human nature, modularity.

man’ as a whole). I believe that the PANKSEPPs’ stance may be reflecting something more than an opposition between a cognitive and an affective approach to neuroscience. It could be an expression of a deeper conflict between two neighboring fields: evolutionary psychology and ethology. In this commentary I note how their criticism often coincides with an ethological viewpoint and some of the objections that ethologists have typically had to sociobiology. I also find the PANKSEPPs’ views to be surprisingly in tune with those of the critics of sociobiology. Indeed, a new ‘critical syndrome’ appears to be forming in academia, bringing together researchers from different fields with different types of objections to evolutionary psychology and gene-selectionist sociobiology. Finally I discuss the role of the interdisciplinary field of nonverbal communication as a

evolutionary biology, but rather at neuroanatomy.

Lining up ‘seven deadly sins’ of evolutionary psychology, as they do, may sound a bit harsh. (Well, Konrad LORENZ listed eight deadly sins, but that was of a much broader population, ’civilized

possible mediator between cognitive and affective neuroscience, or between an information oriented and an anatomical approach.

The PANKSEPPs are convinced that the best scientific progress in elucidating the mind will be made on the basis of real, physical knowledge rather than through modeling. In the sociobiology controversy, experimentally oriented scientists voiced a similar criticism of the efforts of sociobiologists, who were perceived as constructing models which had little to do with reality. Sometimes the accusation went so far as to allege that sociobiologists actually believed in the reality of such things as average gene frequencies, rather than considering these to be mere calculations. And just in the same way in the earlier (and overlapping) IQ controversy, psychometricians had been accused by largely the same critics of ‘reifying’ a mere computation of test scores into a mysterious entity, general intelligence, g. According to the critics, since this was a mere statistical construct, it ‘could not’ exist in anyone’s head.1 For the critics, real science had to do with research at the molecular level (cf. SEGERSTRÅLE 2000, especially chapters 13 and 14).

The sociobiologists, for their part, felt perfectly justified in constructing models, as did the psychometricians in making their correlations and calculations. For them, these were quite legitimate approaches in their respective fields. They had no doubts, meanwhile, that their results, obtained by a different scientific route, would be compatible with future molecular level research.

Nowhere is the conflict clearer between a modeling and a ‘realist’ approach than in the case of the meaning of the ‘gene’. For instance, molecular biologist Gunther STENT (1977) called DAWKINS’ notion of the selfish gene ‘a heinous terminological sin’, pointing out that the ‘true’ gene was ‘unambiguously’ that unit of genetic material which encoded the amino acid sequence of a particular protein (a cistron)—and, in addition, that it was not selfish! Indeed, laboratory geneticists sometimes seemed especially displeased with sociobiological models sometimes one got the feeling that they wanted sociobiologists to go into the lab and do ‘real’ scientific research on genes (e.g., HOWE/LYNE 1992; SEG-ERSTRÅLE 2000, pp386–387).

In other words, in these controversies there was a clear dividing line in regard to what was ‘good science’. The critics felt remarkably free to accuse sociobiologists of scientific ‘error’ for holding views and using methods that these scientists themselves considered standard in their own field! Some critics went as far as using the ‘errors’ of sociobiologists as evidence that the sociobiological agenda ‘must’ be politically motivated. According to them, the sociobiologists’ scientific quest ‘could not’ be driven by scientific interest, because the only interesting science was done at the molecular level (e.g., LEWONTIN 1975; CHOROVER 1979).

Now in the case of the PANKSEPPs vs. evolutionary psychology we seem to have a similar opposition between two views of ‘good science’: a ‘hard data’ approach conflicting with a model-happy one. Take the PANKSEPPs’ criticism of the computational cognitive science models used by evolutionary psychologists. According to them, real science is done at the anatomical, physical level. PET scans and other fancy new methods for showing brain activity are at best correlational, and can easily be misleading about the true neural processes. They also point out that evolutionary psychologists, following the lead of cognitive scientists, use a digital model of mind. But the mind is analog, they protest.

In other words, the battle for good science, so evident in the sociobiology controversy, now continues in the realm of neuroscience. Modelers again clash with hardnosed scientific ‘realists’. But if the sociobiologists were criticized for telling adaptive ‘just-so’ stories about hypothetical genes ‘for’ behaviors and speculating on the basis of very little evidence, the present authors go one step further. They accuse the evolutionary psychologists of ignoring a whole body of evidence that actually exists: the findings from comparative neuroscience! And the consequences are grave, the PANKSEPPs maintain. Evolutionary psychologists feel free to postulate a system of massive modularity in the neocortex. But from the point of view of comparative neuroanatomy, such modules could not have evolved.

To rub this in, they cite TOOBY and COSMIDES’ (1992) own call for consistency across scientific fields. TOOBY and COSMIDES criticize social scientists for what they call the Standard Social Science Model, which regards the human mind as a generalpurpose machine for learning. Such a model is an evolutionary impossibility, according to them. The PANKSEPPs have no direct argument with this. Rather, they point out that when it comes to their own research, TOOBY and COSMIDES are not applying their own principle: they do not ground themselves on already existing knowledge about the brain.

The whole premise of evolutionary psychology is wrong, say the PANKSEPPs. The problem is not the assumption of modularity per se, but evolutionary psychologists are looking for modules in the wrong place. Any claim about the structure of the human mind/brain would have to take into account its evolutionary history. If routinized behaviors of the ‘module’ kind exist and confer survival value on humans, these are bound to be of a kind we share with

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 7 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

other mammals. This means we had better look for modules in older, subcortical parts of the brain, particularly those parts that deal with emotions, those important motivators for animal survival. (Here they invoke not only Paul MACLEAN’S famous ‘triune brain’ but also E. O. WILSON’s opening statements in Sociobiology). This is why, they argue, comparative, affective neuroscience cannot be ignored.

And they have an additional argument. Evolutionary psychologists have erroneously taken the most recent and particular characteristic of the human brain—our large neocortex—expecting to find modules there. They may believe they have found some modules in the adult brain, but any such modules are likely to be a product of development, they point out. In contrast to the evolutionary psychologists, the PANKSEPPs envision the individual as initially working with a type of general purpose program; it is only later during ontogenesis that more specialized modules are being formed. So for the PANKSEPPs, cognitive modules, to the extent they can be found, are actually by-products, not primary adaptations.

Here we see that the PANKSEPPs adhere to GOULD’s and LEWONTIN’s ‘spandrel’ thinking (GOULD/ LEWONTIN 1979), according to which many traits that sociobiologists see as direct adaptations may actually be mere by-products of evolution, just like some details of architecture—spandrels—are created around vaults. This would seem to put them squarely in the same camp as the ‘anti-adaptationist’ critics of sociobiology. And they in fact go a step further, arguing, with GOULD (1991), that human language, too, is likely to be an evolutionary byproduct.2 And if language is a mere spandrel, then focusing on language as the model module is obviously misdirected. (This latter point is an unnecessary piece of overkill, in my view, because the PANK-SEPPs’ argument does not hinge on the nature of language. True, if it were possible to conclusively prove that language was a mere spandrel, they would have a point. But GOULD is operating rather on the level of principle, while for many following CHOMSKY’s and PINKER’s work, the idea of a particular language module does appear persuasive. Might it not be possible to regard language as a module without taking the next step with PINKER (1994, 1997a) and argue from the modularity of language to a view of massive modularity?).

From the PANKSEPPs’ point of view, then, in order to be scientific and ground their own enterprise, evolutionary psychologists ‘ought to’ pay attention to anatomy and the evolutionary history of the mind. They are dismayed that COSMIDES and TOOBY in a recent contribution went so far as to attempt to deal with emotion without making any mention of affective neuroscience (COSMIDES/TOOBY 2000). What could be some reasons for this neglect among the leading theorists in evolutionary psychology?

In the first place, evolutionary psychologists have their hands full. They are busy fighting a multi-front battle: against cultural anthropologists and mainstream psychologists on the one hand, and against sniping critics of ‘adaptationism’ on the other. In many regards, they have inherited the mantle of sociobiology, and with this, its critics.3 Despite their attempt to emphasize universal features of humans and ‘the psychic unity of mankind’, and thus trying to fend off accusations of racism and biological determinism, they are labelled ‘ultra-DARWINIANS’ by GOULD and other critics (GOULD 1997a–b; ELDREDGE 1995; ROSE 1998). They have to create legitimacy for their field at the same time as they have to establish a viable research program.

Predictably, too, the reception of evolutionary psychology among mainstream psychologists has not been too hospitable. But there were potential allies among scholars in other fields which also deal with the mind, and whose approach is similar or at least compatible with the methods typically used in evolutionary psychology. Cognitive science seemed the natural way to go. By associating itself with cognitive science, evolutionary psychology could ride on the wave of the triumphant cognitive revolution. It could be linked to booming research fields such as artificial intelligence, and to novel methods for monitoring cognitive processes. Computational algorithms would provide the necessary theoretical rigor, while new imaging techniques would provide the physical correlates for their claims.

The PANKSEPPs are duly respectful of the cognitive revolution—it is just that they feel that the next revolution, the neuroscientific one, did not have a chance to make its mark before the surge of interest in evolutionary explanation. The new kin selection paradigm swept people off their feet, they complain. And here it becomes clear that, unlike sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists, the PANK-SEPPs are interested not only in ultimate answers about function, but also in the development, evolutionary history, and proximate causes of behaviors. In other words, they want to emphasize the importance of all of TINBERGEN’s famous ‘four questions’ (TINBERGEN 1963). As we see, they are particularly concerned about developmental aspects.

Interestingly, a very similar complaint about evolutionary explanations ‘taking over’ can be found among bona fide ethologists in their comments on the 1970’s sociobiological revolution. Just like the present authors, many ethologists felt that in the 1970s their field, too, was on the brink of making interesting discoveries and solidifying a new, complex, paradigm for the study of animal behavior (as demonstrated, e.g., by BATESON/HINDE 1976). But when the exploitable-seeming new sociobiological framework arrived, many ethologists chose to focus on only one of TINBERGEN’s four questions, the question about function, and this served to drive ethology into a narrow direction (BATESON/KLOPFER 1989). (Recently, though, the sociobiology ‘gold rush’ appears to be over, and the tide has turned back toward a more complex ethological approach, e.g., KREBS/DAVIES 1997).

But the PANKSEPPs do not only criticize evolutionary psychology on scientific grounds, they also warn the field about potential political consequences. Here it is not clear exactly what they have in mind. The political critics of sociobiology actually reasoned in a number of different ways about sociobiology. The idea of a genetically based universal human nature was anathema for them, because they saw this as connected to genetic determinism and other evils. But a further belief was that ‘bad science’ (for the critics, sociobiology and IQ research) would inevitably lead to undesirable social consequences. As I have argued (SEGERSTRÅLE 2000), there is no obvious reason why ‘bad’ science (however defined) would be particularly prone to social abuse; it seems to me that ‘good’ science in the wrong hands would actually be more dangerous. If we apply this to evolutionary psychology, there would seem to be no inherent connection between, say, belief in modularity of mind and risk of political abuse. The PANKSEPPs may simply mean that, just like sociobiology, evolutionary psychology is going to be politically attacked as a deterministic, dangerous doctrine about human nature.

If that is what they mean, that has already happened. For instance THORNHILL and PALMER’s (2000) recent book about rape created quite a stir (e.g., COYNE 2000; SHULEVITZ 2000; for a response see TOOBY/COSMIDES 2000). And recently there was a collection of critical essays on evolutionary psychology (ROSE/ROSE 2000), which was surprisingly well received in the popular press at least in the United Kingdom. I take this to mean that there is a blossoming market for this kind of moral–cum–scientific criticism both in the UK and the US—just as there is a great market for books that explain why we do what we do. Indeed, a certain symbiosis appears to prevail between the writers of popular evolutionary psychology books and their critics—a phenomenon observed already in the sociobiology controversy (SEGERSTRÅLE 2000).

Of course, evolutionary psychologists have made the situation rather difficult for political critics. Well aware of the attacks on sociobiology, they have carefully stated that they are interested in the evolved human mind, not genes, and in a universal human nature, not human differences. They do not employ population-genetic models, and do not address genetic differences between populations.4 They explicitly distance themselves from human behavioral genetics (something WILSON needed for his sociobiological approach). This makes it hard to construe evolutionary psychologists as racists—the standard move in left-wing criticism of biological theories of human nature, and one that was much employed in the sociobiology controversy (cf. SEG-ERSTRÅLE 2000, esp. ch. 2, 9, and 15). Finally, they are uninterested in IQ differences, which means they are not connectable either to the various standard accusations against psychometricians (cf. SEGER-STRÅLE 2000, esp. ch. 10, 12, 13, 14). Indeed, a recent primer in evolutionary psychology sounds remarkably ‘politically correct,’ repudiating explicitly both the notion of race and the idea of ‘general intelligence’ (COSMIDES/TOOBY 1997).

Whatever the evolutionary psychologists say, however, it is clear that the former critics of sociobiology do not like evolutionary psychology, as little as they like sociobiology (and they typically criticize these fields together). In their search for scientific and moral/political counter-arguments the opponents to evolutionary psychology have generated a plethora of different criticisms, not all necessarily compatible with one another. This is déjà vu, and one needs only look back at the sociobiology controversy. Still, the tone is now more muted, and the critique more scientific and not as personal and nasty. One reason for this more cautious approach may be that it has become harder to stir up general outrage around claims about the evolutionary basis of human behavior. At the turn of the millennium the idea of genes influencing behavior has become more acceptable to the general public. In fact, some worry that the situation has totally flip-flopped. They fear a new doctrine of ‘genetic essentialism’ will be holding genes increasingly responsible for our behavior (NELKIN/LINDEE 1995; cf. SEGERSTRÅLE 2000, ch. 19).

This is why veteran critic of sociobiology, Steven ROSE (2000), coauthor of Not In Our Genes (LEWONTIN/ROSE/KAMIN 1984), does not any longer

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 9 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

declare that nothing is in our genes. In his criticism of evolutionary psychology he now leans on a battery of other arguments, particularly well-known anti-adaptationist ones. What is interesting, however, is the remarkable convergence between the criticism coming from this long-standing critic of sociobiology (whom I have called ‘Britain’s LEWONTIN’) and the PANKSEPPs’ present critique of evolutionary psychology. One reason for this could be that ROSE is, after all, a neurospsychologist with a ‘realist’ bent. Still, in both ROSE and the PANKSEPPs, I see something like a cluster of similar critical ideas. Just like the PANKSEPPs, ROSE criticizes the evolutionary psychologists’ conception of the brain as an information processing machine. Brains/minds do not only deal with information, ROSE points out: they deal with meaning. And meanings involve emotions! ROSE goes on to question the idea that modules have evolved ‘quasi independently’ and that they are primary, that is, that they underlie proximal mechanisms such as motivation. Finally, ROSE points to the survival value of emotion and invokes recent research in ‘the emotional brain’ by people such as Antonio DAMASIO and Joseph LEDOUX.

What I perceive here is an emerging alliance between ethologists and left-wing critics of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology. It seems that the critics of sociobiology, in their resistance to geneselectionism, have grasped for a more ‘holistic’ and ‘pluralistic’ paradigm—and voilà, they have found ethology! This means that the critics of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology have come a long way from their initial position, which seemed to dismiss even the thought of an evolutionary basis for human behavior (cf. for instance, ALLEN et al. 1975). And look what more we find! Another element in the evolving new moral–cum–scientific vision of the new opposition appears to be a belief in group selection, that heretic view so irritating to adherents of gene selectionism (cf. SEGERSTRÅLE 2000, pp383– 384). This belief has certainly been stimulated by the new study of SOBER/WILSON (1998). So, here we now have ROSE, always trendy, topping off his critique of evolutionary psychology with an argument for group-selection. The PANKSEPPs, too, seem to like group selection, a way of thinking clearly compatible with a (LORENZIAN) ethological model.

But criticism of evolutionary psychology does not only come from the earlier critics of sociobiology. It comes from a number of directions: developmentally oriented biologists and psychologists (e.g., BATESON/MARTIN 2000), biological systems theorists (e.g., OYAMA 2000), a variety of researchers and theorists of cognitive processes (e.g., VAN GELDER/PORT 1995; HUTCHINS 1996), and, finally, even one type of cognitive scientists: students of developmental cognitive neuroscience (e.g., JOHNSON 1997). These critics typically argue that the computational model of the mind does not cover many important aspects of the mind and living systems, such as internal regulation, coordination, and feed-back mechanisms, or they protest that human intelligence is of a complex type that simply cannot be translated into machine language.

Not surprisingly, researchers on development have found the model used by evolutionary psychology too deterministic. Among other things they point out that many supposedly ‘innate’ competencies actually presuppose learning during an organism’s lifetime (e.g., BATESON 1987; BATESON/ MARTIN 2000). Still, it seems to me that they may be sometimes caricaturing the evolutionary psychologists’ position in order to drive home their point. It often seems unclear just how their own views differ, particularly since TOOBY and COSMIDES already in 1992 emphasized that they do not expect modules to be ‘hardwired’ but only to develop reliably. The question is what this means. Those who study development may want greater explicit recognition of the variety of phenotypes that can develop depending on environmental conditions, and of the de facto unpredictability of animal and human behavior (see SEGERSTRÅLE 2000, pp378–379)—or might they perhaps wish to suggest that organisms ‘choose’ their environments?

An interesting criticism comes from a developmental psychologist, Annette KARMILOFF-SMITH, who challenges one of the arguments used to boost nativism and modularity: the so-called ‘double dissociation’ found in WILLIAMS syndrome patients. People with this syndrome are said to be good at recognizing faces, language, and social interaction but have difficulty with spatial cognition, numbers, and problem-solving. KARMILOFF-SMITH studied more closely children and adults with this developmental disorder, and concluded that the assumption that WILLIAMS syndrome patients were otherwise normal was incorrect. In fact, WILLIAMS syndrome patients differed from controls in their dealing both with faces and with language and grammar. In regard to faces, the children instead of adopting holistic, configurational, approach put together faces feature–by–feature. This she interpreted to mean that they in ontogeny had developed a novel, compensatory strategy for dealing with information. They also followed an unusual pathway

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 10 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

in their language acquisition. According to her, this was evidence for the dynamic development of the brain and the interaction of its different parts in ontogeny (KARMILOFF-SMITH 2000, 1998, 1992).

And there is more evidence for flexibility in the developing brain. For instance, brain imaging findings of face processing (in normal infants) show increased specialization and localization of face-processing circuits during the first year of life. Language, too, shows progressive specialization of this sort: it is processed in both hemispheres until about the age of six when it (for right-handed people) goes to the left hemisphere (KARMILOFF-SMITH 2000; JOHNSON 1997).

These kinds of findings would seem to support the PANKSEPPs’ point that the modularity in the adult brain does not reflect a pre-existing domain specificity of the brain, but is rather a product of epigenesis. Although the PANKSEPPs do not elaborate on this, one would assume that they would concur with the distinction between two views of development: a ‘regulatory’ vision as opposed to a ‘mosaic’ one. While the ‘mosaic’ kind is represented by the evolutionary psychologists’ vision of ‘the mind as a Swiss army knife’ and presupposes tight genetic control on epigenesis, the regulatory model involves a probabilistic epigenesis under broad genetic control, but flexible.5 KARMILOFF-SMITH specifically suggests that there exists a number of different evolved learning mechanisms which during ontogeny may “each discover inputs from the environment that are more or less suited to their form of processing”. This is why she calls for a closer study of the Swiss army knife’s ontogenesis (KARMILOFF-SMITH 2000).

More alarming, perhaps, for evolutionary psychologists—and giving an indirect boost to the PANKSEPPs—is the recent removal of one of the cornerstones of the whole modular theory. The very father of modularity, Jerry FODOR himself (FODOR 1983), appears to have had a change of mind (pun intended!), and now seems devoted to attacking those who describe the mind as a collection of domain-specific special processing machines. This is instantiated by his new The Mind Does Not Work That Way (Fodor 2000), a direct critique of Steve PINKER’s (1997a) How The Mind Works.

Finally, the PANKSEPPs get unexpected support from someone quite sympathetic to sociobiology and a fierce critic of its critics, anthropologist Melvin KONNER. On the face of it KONNER ‘should’ be enthusiastic about evolutionary psychology, but he takes a surprisingly critical stance of PINKER’s 1997 book (KONNER 1998). One of his main complaints is

that PINKER and evolutionary psychologists in their modeling totally ignore the actual anatomical structure of the brain. One cannot make the assumption of homogenous modularity throughout the brain.

In other words, the PANKSEPPs are in good critical company.

But our authors are not intending only to be critical. In fact, they say they wish to help evolutionary psychology. What are, in fact, the possibilities of bringing cognitive and affective neuroscience together? Is there a middle ground that might be reached? In light of the criticism, it would seem prudent for evolutionary psychologists to postulate a limited number of basic modules rather than massive modularity. Plausible candidates for more or less hardwired specialized programs come from animal studies and research on neonates in humans. I believe there is enough evidence, for instance, to speak of a ‘face recognition module’, based on infant research and the demonstrated existence of ‘face neurons’ in monkeys and sheep. Moreover, imitation may be another such basic capability, as may the set of basic emotional expressions, as demonstrated by Paul EKMAN and his associates (e.g., EK-MAN/KELTNER 1997). One indication here is that we have all necessary facial muscles fully developed at birth, another that neonates—even anencephalic ones—react in predictable ways to sweet and sour substances (SEGERSTRÅLE/MOLNAR 1997, pp8–9). Interestingly, even Gerald EDELMAN, otherwise committed to a neural network, ‘constructivist’ view of the mind, believes that there do, in fact, exist a few basic inborn capabilities in humans: among these face recognition, and fundamental affect (SEGER-STRÅLE/MOLNAR 1997, p16).

Many of our basic abilities do appear to be connected to the human face and be of a nonverbal nature. It would seem that the face has important inbuilt capabilities that will later form the basis for the infant’s further emotional development and interactional skills (SEGERSTRÅLE/MOLNAR 1997, p16, see also Part III on ontogeny). Thus, one more candidate for relatively hard-wired equipment may be certain fast-moving ‘facial affect programs’ that enable us to competently send and receive nonverbal messages, identified by Swedish psychologist Ulf DIMBERG (DIMBERG 1997). In other words, nonverbal communication is an important means whereby ‘nature’ is transformed to ‘culture’. Also, recent research on language emphasizes the importance of nonverbal communication as a preparatory stage in language acquisition (VELICHKOVSKY/RUMBAUGH 1996).

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 11 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

Ullica Segerstråle

The PANKSEPPs, with MACLEAN and his triune brain, and WILSON (in Sociobiology) see emotions as primary, because of the evolutionary history of the brain. Still, nonverbal capabilities appear to be at the same time emotional and cognitive. And this may eventually help open the door for a synthesis between cognitive and affective neuroscience.

In general, then, why not relax the modularity idea, concentrate on a few indisputable ones, and postulate different degrees of hardwiredness for different human capabilities based on the best available empirical studies across a variety of fields, while leaving space also for general, undifferentiated learning programs? Also, why not keep the question open as to where exactly some of these circuits are located and how big these modules are. (Perhaps even MACLEAN’s various brains can be seen as modules?) The important thing would seem to be to be able to pool ideas from a variety of fields: cognitive and affective neuroscience, and a wide spectrum of interdisciplinary nonverbal research. That kind of approach would seem to go toward TOOBY and COSMIDES–style consistency across scientific fields, ‘consilience’ of the William WHEWELL type (simultaneous support for an idea from many fields of science) and may be even E. O. WILSON type ‘consilience’ (unity of science) (WILSON 1998).

Unfortunately there is a real obstacle to mutually beneficial cooperation between scientists from different disciplines. Interdisciplinary efforts may give them no credit—on the contrary, they may be ostracized by their ‘home’ discipline, particularly if they are regarded as breaking certain long-standing taboos.

But perhaps affective neuroscience needs to rethink its criticism somewhat. Whatever modules ‘really’ are, and how many ‘really’ exist, the basic theoretical contributions of the evolutionary psychologists are interesting and

Notes

- 1 While they sharply resisted this kind of research in cognitive abilities, the critics expressed interest in finding out about cognitive traits.

- 2 On this topic in 1997 GOULD (1997c) got himself involved in a furious dispute with Steven PINKER (1997b) on the pages of The New York Review of Books.

- 3 WILSON thinks evolutionary psychology is “the same” as sociobiology (personal communication), and so does DAWKINS.

can in principle open up new fruitful avenues of research in other fields—including affective neuroscience. This kind of importation into one field of ideas from another is a well-known device for scientific growth—after all, it was physicists rather than geneticists that created the new field of molecular biology. What the possibilities are for a field to stimulate another at a particular time is dependent on the availability of individuals and their visions and ambitions. Fields develop according to concrete opportunities perceived and particular initiatives taken—not according to how they ‘ought to’ develop from some abstract scientific point of view.

Finally, we should not forget that evolutionary psychology is an evolving research program. There are already signs that the evolutionary psychologists are backing off somewhat from their initial militancy. For instance, in COSMIDES and TOOBY’s recent primer the assumption of the Environment of Evolutionary Adaptation seems to be relaxed, the assumption of modularity looks less massive, and epigenesis is more explicitly factored in. Emotions, too, are increasingly brought in, a potential harbinger of the next step of the evolving program of evolutionary psychology. If this kind of rapprochement between the evolutionary psychologists and their critics is taking place, it is only something that is typical of science. Indeed, in the future, we may expect both (all?) sides to integrate some of their opponents’ arguments into their own explanatory frameworks—without necessarily giving their critics explicit credit. We may even see a convergence between seemingly totally opposed positions (remember the DARWINISTS and MENDELIANS

Author’s address

Ullica Segerstråle, Department of Social Sciences, Illinois Institute of Technology, Suite 116, Siegel Hall, 3301 South Dearborn Street, Chicago IL 60616, USA. Email: segerstrale@iit.edu

fighting each other only to be united in the Modern Synthesis?). But if and when this happens, we will probably not have a synthesis with big fanfare. Academia being what it is, both sides are likely to claim victory and get out.

- 4 Something that WILSON was challenged into doing by critics who said that he did not address human variation.

- 5 Note, however, that although her arguments supports that of our authors, she is actually citing data from imaging processes which the PANKSEPPs may consider unreliable!

- 6 KARMILOFF-SMITH herself believes a regulatory approach is more likely to reach the complexity required by cortical functions. She suggests, however, that a deterministic view of development could be applicable to other parts of the brain.

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 12 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

References

- Bateson, P. P. G. (1987) Biological approaches to the study of behavioral development. International Journal of Behavioral Development 10: 1–22.

- Bateson, P. P. G./Klopfer, P. H. (1989) Preface. In: Bateson, P. P. G./Klopfer, P. H. (eds) Whither Ethology? Perspectives in Ethology 8. Plenum Press: New York, London, pp. v–viii.

- Bateson, P. P. G./Martin, P. (2000) Design for A Life: How Biology and Psychology Shape Human Behavior. Touchstone Books: New York.

- Chorover, S. (1979) From Genesis to Genocide. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- Cosmides, L./Tooby, J. (1992) The psychological foundations of culture. In: Barkow, J/Cosmides, L./Tooby, J. (eds) The Adapted Mind. Oxford University Press: New York.

- Cosmides, L/Tooby, J. (1997) Evolutionary Psychology: A Primer. Retrieved on 15 Feb 2001 from the World Wide Web: http://www.psych.ucsb.edu/research/cep/primer.html

- Cosmides, L/Tooby, J. (2000) Evolutionary psychology and the emotions. In: Lewis, M./Haviland, J. (eds) The Handbook of Emotions. 2nd edition. Guilford: New York, pp. 91–116.

- Coyne, J. (2000) Of vice and men. Review of “A Natural History of Rape” by R. Thornhill and C. Palmer. New Republic 04.03.00: 27–34.

- Dimberg, U. (1997) Psychophysiological reactions to facial expressions. In: Segerstråle, U./Molnar, P. (eds) Nonverbal Communication: Where Nature Meets Culture. Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah NJ, pp. 47–60.

- Ekman, P./Keltner, D. (1997) Universal facial expressions of emotions: An old controversy and new findings. In: Segerstråle, U./Molnar, P. (eds) Nonverbal Communication: Where Nature Meets Culture. Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah NJ, pp. 27–46.

- Eldredge, N. (1995) Reinventing Darwin. The Great Debate at the High Table. John Wiley and Sons: New York.

- Fodor, J. (1983) The Modularity of Mind. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- Fodor, J. (2000) The Mind Doesn’t Work That Way. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- van Gelder, T./Port, R. F. (ed) (1995) Mind as Motion: Explorations in the Dynamics of Cognition. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- Gould, S. J. (1991) Exaptation: A crucial tool for evolutionary psychology. Journal of Social Issues 47: 43–65.

- Gould, S. J. (1997a) Darwinian fundamentalism. The New York Review of Books, June 12: 34–37.

- Gould, S. J. (1997b) Evolution: the pleasures of pluralism. The New York Review of Books, June 26: 47–52.

Gould, S. J. (1997c) Evolutionary psychology: An exchange. New York Review of Books, October 9.

- Gould, S. J./Lewontin, R. C. (1979) The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 205: 581–598.

- Howe, H./Lyne, J. (1992) Gene Talk in Sociobiology. Social Epistemology 6: 109–63.

- Hutchins, E. (1996) Cognition in the Wild. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- Johnson, M. (1997) Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience: An Introduction. Blackwell: Oxford.

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1992) Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1998) Development itself is the key to

understanding developmental disorders. Trends in Cognitive Science 2: 389–398.

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (2000) Why babies’ brains are not Swiss army knives. In: Rose, H./Rose, S. (eds) Alas, Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology. Jonathan Cape: London, pp. 144–156.

- Konner, M. (1998) A piece of your mind. Review of “How the Mind Works” by S. Pinker. Science 281: 653–654.

- Krebs, J. R./Davies, N. B. (1997) Behavioural Ecology. Fourth Edition. Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford.

- Lewontin, R. C. (1975a) Genetic aspects of intelligence. Annual Review of Genetics 9: 387–405.

- MacLean, P. D. (1990) The Triune Brain in Evolution. Plenum Press: New York.

- Nelkin, D./Lindee, M. S. (1995) The DNA Mystique. Freeman: New York.

- Oyama, S. (2000) The Ontogeny of Information: Developmental Systems and Evolution. Duke University Press: Durham NC.

- Pinker, S. (1994) The Language Instinct. HarperCollins: New York.

- Pinker, S. (1997a) How the Mind Works. W. W. Norton: New York.

- Pinker, S. (1997b) Evolutionary psychology: An exchange. New York Review of Books, October 9.

- Rose, S. (1998) Lifelines. Oxford University Press: New York.

- Rose, S. (2000) Escaping evolutionary psychology. In: Rose, H./Rose, S. (eds) Alas, Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology. Jonathan Cape: London, pp. 247–265.

- Rose, H./Rose, S. (eds) (2000) Alas, Poor Darwin: Arguments Against Evolutionary Psychology. Jonathan Cape: London.

- Segerstråle, U. (2000) Defenders of the Truth: The Battle for Science in the Sociobiology Debate and Beyond. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Segerstråle, U./Molnar, P. (eds) (1997) Nonverbal Communication: Where Nature Meets Culture. Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah NJ.

- Shulevitz, J. (2000) Evolutionary psychology teaches Rape 101. Dialogues. Slate (online magazine), January 13. Retrieved on 15 Feb 2001 from the World Wide Web: http:// slate.msn.com/code/Culturebox/

Culturebox.asp?Show=1/13/2000&idMessage=4368

- Sober, E./Wilson, D. S. (1998) Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. Harvard University Press: Cambridge MA.

- Stent, G. S. (1977) You can take ethics out of altruism but you can’t take the altruism out of ethics. Hastings Center Report 7: 33–36.

- Thornhill, R./Palmer, C. (2000) A Natural History of Rape. MIT Press: Cambridge MA.

- Tinbergen, N. (1963) On aims and methods of ethology. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 20: 410–433.

- Tooby, J./Cosmides, L. (2000) Letter to the editor of New Republic (response to Coyne). Retrieved on 15 Feb 2001 from the World Wide Web: http://www.psych.ucsb.edu/research/cep/

- Velichkovsky, B./Rumbaugh, D. (eds) (1996) Communicating Meaning: The Evolution and Development of Language. Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah NJ.

- Wilson, E. O. (1975) Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard University Press: Cambridge MA.

- Wilson, E. O. (1998) Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge. Alfred Knopf: New York.

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 13 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

“La plus ça change…”

Response to a Critique of Evolutionary Psychology

ANKSEPP & PANKSEPP are not alone in their criticisms of evolutionary psychology. In fact, controversies sparked by this ‘new’ discipline abound and have even merited front page coverage in a recent issue of the NY Times’ ‘Science Times’ (GOODE 2000). It is clear, however, that most of the critics, including P&P, are against neither evolution nor psychology—nor even the use of evolutionary approaches in psychology. Indeed many, like P&P, are themselves practitioners of what might be called evolutionary psychology without the capital E capital P P

Abstract

PANKSEPP & PANKSEPP are not alone in their criticisms of Evolutionary Psychology. It is clear, however, that most of the critics, including P&P, are against neither evolution nor psychology—nor even the use of evolutionary approaches in psychology. Criticism has, rather, focused on a particular approach taken by a very small but highly visible group of individuals who share a specific stance on a set of related issues. I share P&P’s concerns about the rigidity and doctrinal restrictiveness of “some currently fashionable versions of evolutionary psychology”. But this debate is not new, and I believe that as with most controversies in science, its sparks have propelled us more steps forward than back.

Key words

Cognition, comparative method, evolutionary psychology, modularity, philosophy of science, science studies.

(see e.g., MEALEY 1994, in press; MILLER 2000a, 2000b; THIESSEN 1998; WILSON 1994). Criticism has, rather, focused on a particular approach taken by a very small but highly visible group of individuals who share a specific stance on a set of related issues. In their target paper, P&P variously refer to this subset of theorists and their positions, respectively, as “a new breed of evolutionary psychologists” (p3) and “the most visible form of evolutionary psychology” (p30). Speaking as one who would prefer to see multidisciplinary integration rather than interdisciplinary derogation, I share P&P’s concerns about the rigidity and doctrinal restrictiveness of “some currently fashionable versions of evolutionary psychology” (p6). But this debate is not new, and I believe that as with most controversies in science, its sparks have propelled us more steps forward than back.

The Seven Sins

The environment of evolutionary adaptedness (EEA)

John TOOBY, Leda COSMIDES, David BUSS, Randy THORNHILL, and others, describe evolutionary psychology as a kind of ‘reverse engineering’ through which we try to decipher the components and workings of the human brain/mind by analyzing the types of ‘problems’ it has evolved to ‘solve’ in its ‘environment of evolutionary adaptation’ (e.g., BUSS 1995; COSMIDES/TOOBY 1997; THORNHILL 1997; TOOBY

1999; TOOBY/COSMIDES 1990, 1992). Of course, the human brain/mind has been evolving ever since there was first a neuron, and the problems that it has evolved to solve have waxed and waned and reversed and conflicted and interacted in countless ways over that immense span of time. The EEA of the human brain/mind is thus, not a single definitive environment that we might reconstruct as we might construct a museum diorama, but rather, a multidimensional hyperspace of the net vectors of every selection pressure that ever impinged upon our ancestors (DALY/WILSON 1999; MEALEY 2000).

Stated as such, the EEA is a potent concept. Unfortunately, it is a concept that has been trivialized and reduced to a much more simplistic but manageable notion, i.e., ‘the Pleistocene’, which, as a heuristic for making novel hypotheses about the brain/mind, is virtually useless. This common substitution of a

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 14 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

simple concept for a more complex one needs to be pointed out—much as does the reification of the term ‘gene’ in the commonly used phrase ‘a gene for x behavior’—but however unfortunate such substitution may be, it is a ubiquitous phenomenon in the social process that is the communication of science and spread of knowledge (see also YOUNG/PERSELL 2000). The good evolutionary psychologist might need to be more careful, but need not be damned for this sin.

Species-centrism

Lack of a true comparative foundation is, indeed, a weakness of a modern evolutionary psychology that has forgotten the word ‘ethology’ and the name ‘TINBERGEN’ (see DALY/WILSON 1999). Although comparative psychology and ethology were antagonistic disciplines through much of their early history (JAYNES 1969), most of their differences were resolved with the development and joint use of new techniques in neuroscience and neuroendocrinology (HINDE 1966); even more recently, progress in computer modeling and evolutionary taxonomy have made comparative analyses both easier and more valuable (HALL 1994; HARVEY/PURVIS 1991; LARSON/LOSOS 1996). Still, comparative psychology and human ethology seem to be undergoing major decline—or, if not decline, at least further isolation from what is now mainstream psychology: conferences and journals which once attracted and even showcased research on both human and other species now tend to specialize in one or the other. (See discussions in HIRSCH 1987 and MEALEY 2001.)

A case in point to illustrate the consequences of this neglect can be drawn from a highly visible research area: language. According to evolutionary psychologists, language is the prime exemplar of a recently-evolved, complex, but uniquely human faculty (PINKER 1994, 1997a, 1997b). Unfortunately, to many this status implies that comparative analysis is useless. Indeed, after the once-popular ape studies documented the species-specific nature of human language, comparative studies virtually disappeared. Yet the notion that our language capacity has its basis in a set of modular functions is one that absolutely begs for comparative analysis. For example, for decades psycholinguists cited the phenomenon of ‘categorical perception’ of human speech sounds as evidence for the specialness of human language (EIMAS 1985; EIMAS/MILLER 1992; WERKER/LALONDE 1988; LENNEBERG 1967; LIBERMAN/ MATTINGLY 1989; ZATORRE et al. 1992) without bothering to determine whether that particular component of language was indeed, human-specific. Comparative studies, however, show that it is not (HAUSER 1996, 2000); categorical perception is, rather, a preadaption for language that has its basis in some other feature or function of the brain. Of course, this insight does not negate the argument that human language is special and requires study of human subjects—but it does highlight P&P’s argument that evolutionary psychologists, by being too speciescentric, have ignored a tremendous resource for hypothesis-generation and hypothesis-testing, as well as a huge and valuable extant literature (e.g., HAUSER 1996, LIEBERMAN 1977).

Adaptationism

The possibility that language emerged from a set of pre-adaptations, or that language itself is a ‘spandrel’ (GOULD 1991; GOULD/LEWONTIN 1979) has been hotly debated (PINKER/BLOOM 1990). I happen to think that language is not a spandrel. But I also happen to think that others of our most complex attributes might be: specifically, our intelligence and our capacity for self-reflection, which I believe are likely to be spandrels of our Theory of Mind.

My own opinion about what is or isn’t a spandrel is not particularly relevant here, but the idea that very complex seemingly designed functions and processes might be spandrels is, as P&P claim, an idea that is not only disregarded by most evolutionary psychologists, but unfairly attacked and even mocked (e.g., ALCOCK 1998). If evolved features of the human brain/mind are likely to be modular as P&P’s brand of evolutionary psychologist claims, then indeed, the most likely place for us to search for spandrels is amongst those features that seem the most generalized and un-modular… such as the ‘g– factor’ of intelligence and the ‘binding factor’ or ‘seamless nature’ of self-awareness.

Massive modularity

Since the structure of the mind is, in some sense, dependent upon the structure of the brain that houses it, it might be the case that some functional mechanisms of the mind map directly onto certain structures of the brain. While such direct mapping is not a prerequisite for psychic modularity (FODOR 1983), it is plausible (SHALLICE 1988, 1991), and the fact that different parts of the brain do exhibit functional specialization has been known for over a hundred years. Not only are specialized structures

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 15 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

and neural circuits known to regulate such complex operations as sleep and visual–motor coordination, but the agreement of functional maps of the brain with cytoarchitectural maps and projection maps is ‘stunning’ (KOLB/WISHAW 1990) and ‘precise’ (GAZ-ZANIGA 1989). Together with evidence from comparative anatomy (e.g., PANKSEPP 1992, 1998), this suggests an evolutionary pattern of cumulative layering of new brain structures (MACLEAN 1990), rather than a single ‘general purpose’ structure.

P&P not only acknowledge, but have helped to document the existence of, extensive brain modules; their beef is not with the concept of modules, but with the unquestioned assumption of modules—especially at the cortical level, where evidence is sparse (FINLAY/DARLINGTON 1995). They further note that evolutionary psychology’s characterisation of an adaptation as compared to an exaptation or a spandrel (‘complexity, economy, efficiency, reliability, precision and functionality’: BUSS et al. 1998) can be equally applied to various non-modular, and even domain-general, processes. Modern discoveries in neuroscience—such as RAMACHANDRAN’s dramatic demonstrations of cortical rewiring of perceptual maps (RAMACHANDRAN/BLAKESLEE 1998)—raise questions about the fixity, and therefore, the supposed rigid prescription of what otherwise appear to be modular faculties.

I suspect that the delineation of ‘modular’ processes and organs from ‘non-modular’ processes and organs will never be so neat as the picture that FODOR (1983) originally laid out—even FODOR thinks that evolutionary psychologists have carried the concept too far (FODOR 2000). More likely, whether one chooses to admit a particular functional neurological pathway to the club of ‘modules’ or prefers to consider it an exaptation, a spandrel, a “fixed action pattern” (SCHLEIDT 1974), “prepared learning” (SE-LIGMAN 1970), or a case of “tinkering” (JACOB 1977) will turn out to be more a matter of personal opinion than neuropsychology. This too, is not a new debate, and the answer is not going to be of the either/or form.

Conflation of emotions and cognitions

The relationship between emotions and cognitions has also been an ongoing subject of debate. Phenomenologically, does one arise first and then trigger the other? Or are they simultaneous? If simultaneous, are they two aspects of the same thing? If so, then why do we experience them as different? Or do we? Or when do we? If different, is each thought or emotion discrete? Or do they blend? And of course, what is the underlying neurophysiology? (See DAMASIO 1994, 1999; EKMAN/DAVIDSON 1994; GRIFFITHS 1990, 1997; LAZARUS 1991; NESSE 1991, 1992a, 1992b; PANK-SEPP 1998; PLUTCHIK 1980, 1992; ROLLS 2000.)

Emotions and cognitions both serve to motivate the organism: they promote action. Indeed, the words ‘emotion’ and ‘motivation’ share the same Latin root. If emotions and cognitions share function, then it is most likely that they are designed to be experienced together—and of course, it is easy to conflate them if/when we experience them together. One of my favorite quotes on this topic comes from PLUTCHIK (1980); he suggests that:

“The whole cognitive process evolved over millions of years in order to make the evaluations of stimulus events more correct and the predictions more precise so that the emotional behavior that finally resulted would be adaptively related to the stimulus events. It is in this sense that cognitions are in the service of emotions.” (p303)

So emotions are generated first, which are honed and articulated by cognitions, and then expressed as behavior… Or do cognitions first filter and assess stimuli, then direct them to the proper emotion module for action!? No matter which came first phylogenetically, the inputs to various brain/mind structures may be directional or reciprocal, simultaneous or sequential. Which parts of this clearly joint phenomenon are labelled ‘emotion’ and which ‘cognition’ depends in large degree on the breadth of one’s sweep and the differential jargon of disciplines (MALLON/STICH 2000). We know better than to speak of nature versus nurture, and we know better than to speak of learning versus instinct; it is time we learn not to speak of emotion versus cognition (see also MILLER/KELLER 2000).

Absence of neural perspectives

As I mentioned above, whether one considers the evidence for modularity to be obvious or underwhelming is a matter of opinion, reflecting the rigidity with which one holds to which definition. Again, P&P do not decry modularity in general (pun noted but not intended); rather, they find no evidence for modularity of cognitions (‘contra’ emotions) and of cortical pathways (contra subcortical pathways).

Certainly there is less evidence for modularity at the cortical level than at the subcortical (CAMHI 1984; PANKSEPP 1998). But this too, is neither a new finding nor a new debate (POLSTER/NADEL/SCHACTER

Evolution and Cognition ❘ 16 ❘ 2001, Vol. 7, No. 1

1991), and ‘less evidence’ of cortical modularity doesn’t mean ‘no evidence’: there is room here for empirical investigation (see ARBIB/ERDI 2000 and PAGE 2000). Cortical localization of function has been documented from many studies of human brain damage (e.g., COSMIDES/TOOBY 2000; GRODZIN-SKY 2000; HART/BERNDT/CARAMAZZA 1985; KOLB/ WISHAW 1990; SACKS 1985; TRANEL/DAMASIO 1985), as well as in intact, non-human animals (e.g., KEN-DRICK/BALDWIN 1987). Whether these specialized circuits provide inputs or outputs or both, or are considered to be processing and producing affects or cognitions, are still questions that are open to debate. Is face recognition purely cognitive? Is it an input or is it an output? What about recognition of facial expressions?

Anti-organic bias

These questions inevitably lead P&P to reframe both emotions and cognitions in terms of organic, rather than computational representations. I think this is important to do. While there are likely to be truly computational processes in the brain/mind (e.g., GALLISTEL 1995), there are also likely to be analog processes (e.g., CARMAN/WELCH 1992) and truly organic ‘embodied’ representations (see HUMPHREY 1992). I suspect that the computational metaphor, though widely used by evolutionary psychologists, is likely to be just metaphor much of the time.

But even if the metaphor is literally true more often than not, computation is not sufficient. I suspect that P&P are correct when they assert that “the foun-

dations of mind are fundamentally ‘embodied’ by organic processes that are impossible to compute except in the most superficial way”. Once again, however, this is an old debate which won’t be settled any time soon (see e.g., FODOR 1981; SEARLE 1981, 1990; WELLS 1998).

What Penance?

The terms ‘environment of evolutionary adaptedness’, ‘encapsulated modules’, ‘computations’ and for that matter, ‘representations’—were put forth as short-hand notations for things that we do not yet fully understand and therefore cannot yet adequately describe. Like all metaphors and analogies, they have their limits—and while we do need to take care not to push those limits and still believe that we are speaking ‘truth’, I think that their worth must be assessed not on their ultimate ability to ‘reflect’ reality, but on their practical value. If their use encourages inquiry, they are a good thing; if they discourage inquiry, they are a bad thing.

On the whole, I think such metaphors have encouraged inquiry and that they are, therefore, useful (see e.g., MEALEY/DAOOD/KRAGE 1996; MURPHY/ STICH 2000). DARWIN’s entire book “On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection” (1859) was an analogy, and although that analogy led to several misunderstandings—including Herbert SPENCER’s ‘survival of the fittest’—we nevertheless, still find value in DARWIN’s choice of words. The concept of a gene as a ‘particulate entity’ was, too, an analogy—an analogy that may have led MENDEL to overlook the reality of linkage—but an analogy which we still use today.

Debates about terminology permeate all disciplines, including other subdisciplines of evolutionary biology (e.g., GHISELIN 1981) and psychology (e.g., WIDIGER/SANKIS 2000). As elsewhere, the metaphors of modern evolutionary psychology will

References

- Alcock, J. (1998) Unpunctuated equilibrium in the Natural History essays of Stephen J. Gould. Evolution and Human Behavior 19: 321–336.

- Arbib, M. A./Erdi, P. (2000) Precis of ‘Neural Organization: Structure, Function, and Dynamics’. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 23: 513–571.

- Buss, D. M. (1995) Evolutionary psychology: A new paradigm for psychological science. Psychological Inquiry 6: 1–30.

- Buss, D. M./Haselton, M. G./Shackelford, T. K./Bleske, A. L./ Wakefield, J. C. (1998) Adaptations, exaptations, and spandrels. American Psychologist 53: 533–548.

Camhi, J. M. (1984) Neuroethology. Sinauer: Sunderland MA.

- Carman, G. J./Welch, L. (1992) Three dimensional illusory contours and surfaces. Nature 360: 585–587.

- Cosmides, L./Tooby, J. (1997) The modular nature of human intelligence. In: Scheibel, A. B./Schopf, J. W. (eds) The Origin and Evolution of Intelligence. Jones & Bartlett: Boston MA, pp. 71–101.

- Cosmides, L./Tooby, J. (2000) Social exchange: Converging evidence for special design. Presented at the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, Amherst College, Amherst MA, June 2000.

- Daly, M./Wilson, M. (1999) Human evolutionary psychology and animal behaviour. Animal Behaviour 57: 509–519.

- Damasio, A. R. (1994) Descarte’s Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. Putnam: New York.

- Damasio, A. R. (1999) The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt Brace: New York.

- Darwin, C. (1859) On the Origin of Species by Natural Selection. John Murray: London.

- Eimas, P. D. (1985) The perception of speech in early infancy. Scientific American 252: 46–52.

- Eimas, P. D./Miller, J. L. (1992) Organization in the perception of speech by young infants. Psychological Science 3: 340–345.

- Ekman, P./Davidson, R. J. (eds) (1994) The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions. Oxford University: New York.

- Finlay, B. L./Darlington, R. B. (1995) Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science 268: 1578–1584.

- Fodor, J. A. (1981) The mind–body problem. Scientific American 244: 114–123.