Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach 4th Edition

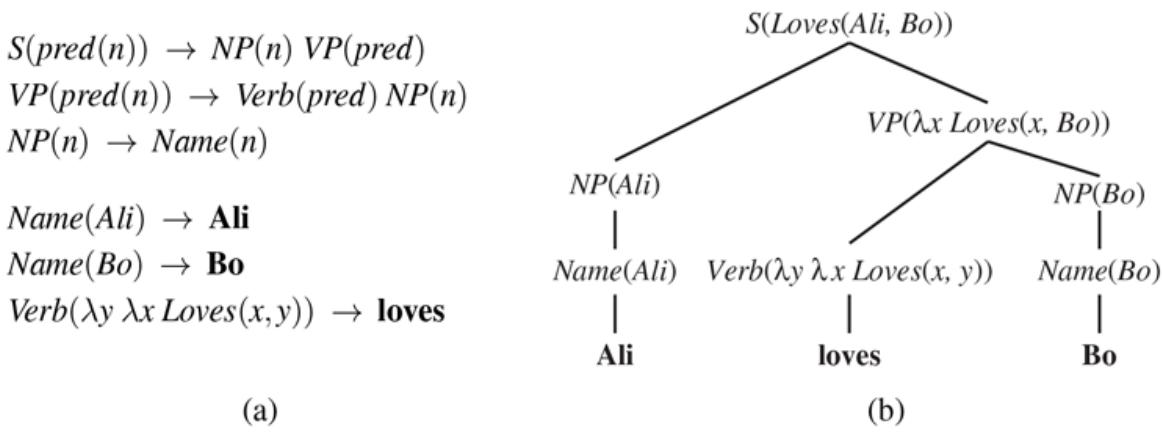

V Machine Learning

Chapter 19 Learning from Examples

In which we describe agents that can improve their behavior through diligent study of past experiences and predictions about the future.

An agent is learning if it improves its performance after making observations about the world. Learning can range from the trivial, such as jotting down a shopping list, to the profound, as when Albert Einstein inferred a new theory of the universe. When the agent is a computer, we call it machine learning: a computer observes some data, builds a model based on the data, and uses the model as both a hypothesis about the world and a piece of software that can solve problems.

Machine learning

Why would we want a machine to learn? Why not just program it the right way to begin with? There are two main reasons. First, the designers cannot anticipate all possible future situations. For example, a robot designed to navigate mazes must learn the layout of each new maze it encounters; a program for predicting stock market prices must learn to adapt when conditions change from boom to bust. Second, sometimes the designers have no idea how to program a solution themselves. Most people are good at recognizing the faces of family members, but they do it subconsciously, so even the best programmers don’t know how to program a computer to accomplish that task, except by using machine learning algorithms.

In this chapter, we interleave a discussion of various model classes—decision trees (Section 19.3 ), linear models (Section 19.6 ), nonparametric models such as nearest neighbors (Section 19.7 ), ensemble models such as random forests (Section 19.8 )—with practical

advice on building machine learning systems (Section 19.9 ), and discussion of the theory of machine learning (Sections 19.1 to 19.5 ).

19.1 Forms of Learning

Any component of an agent program can be improved by machine learning. The improvements, and the techniques used to make them, depend on these factors:

- Which component is to be improved.

- What prior knowledge the agent has, which influences the model it builds.

- What data and feedback on that data is available.

Chapter 2 described several agent designs. The components of these agents include:

- 1. A direct mapping from conditions on the current state to actions.

- 2. A means to infer relevant properties of the world from the percept sequence.

- 3. Information about the way the world evolves and about the results of possible actions the agent can take.

- 4. Utility information indicating the desirability of world states.

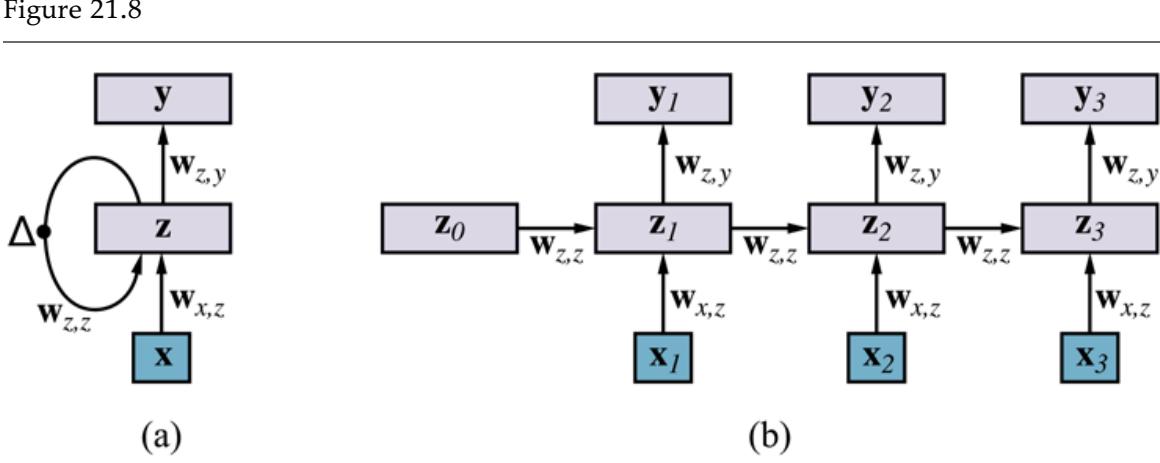

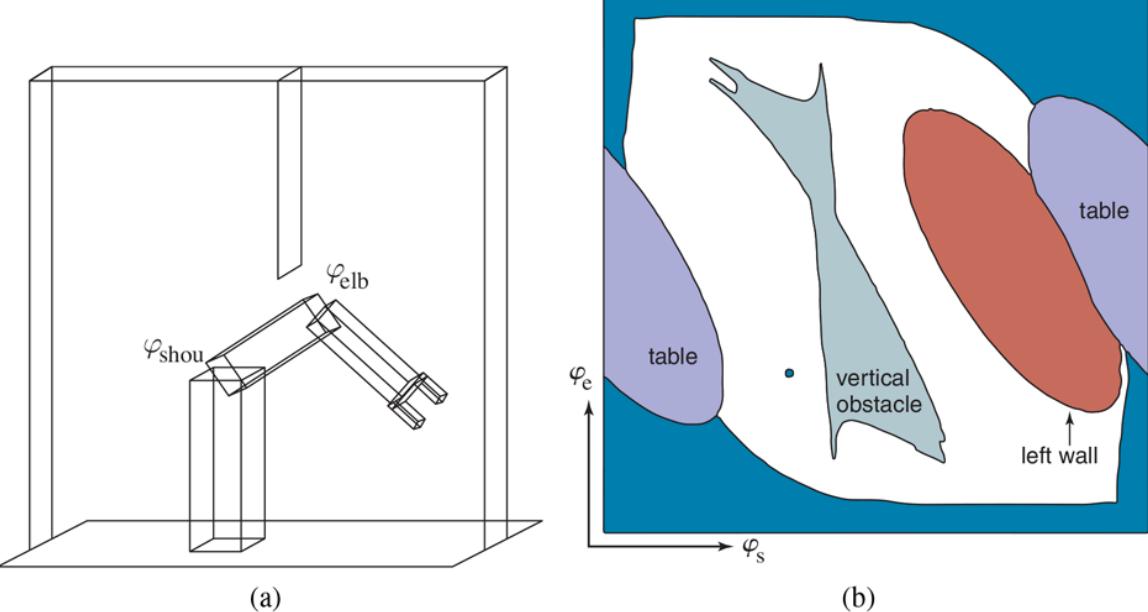

- 5. Action-value information indicating the desirability of actions.

- 6. Goals that describe the most desirable states.

- 7. A problem generator, critic, and learning element that enable the system to improve.

Each of these components can be learned. Consider a self-driving car agent that learns by observing a human driver. Every time the driver brakes, the agent might learn a condition– action rule for when to brake (component 1). By seeing many camera images that it is told contain buses, it can learn to recognize them (component 2). By trying actions and observing the results—for example, braking hard on a wet road—it can learn the effects of its actions (component 3). Then, when it receives complaints from passengers who have been thoroughly shaken up during the trip, it can learn a useful component of its overall utility function (component 4).

The technology of machine learning has become a standard part of software engineering. Any time you are building a software system, even if you don’t think of it as an AI agent, components of the system can potentially be improved with machine learning. For example, software to analyze images of galaxies under gravitational lensing was speeded up by a

factor of 10 million with a machine-learned model (Hezaveh et al., 2017), and energy use for cooling data centers was reduced by 40% with another machine-learned model (Gao, 2014). Turing Award winner David Patterson and Google AI head Jeff Dean declared the dawn of a “Golden Age” for computer architecture due to machine learning (Dean et al., 2018).

We have seen several examples of models for agent components: atomic, factored, and relational models based on logic or probability, and so on. Learning algorithms have been devised for all of these.

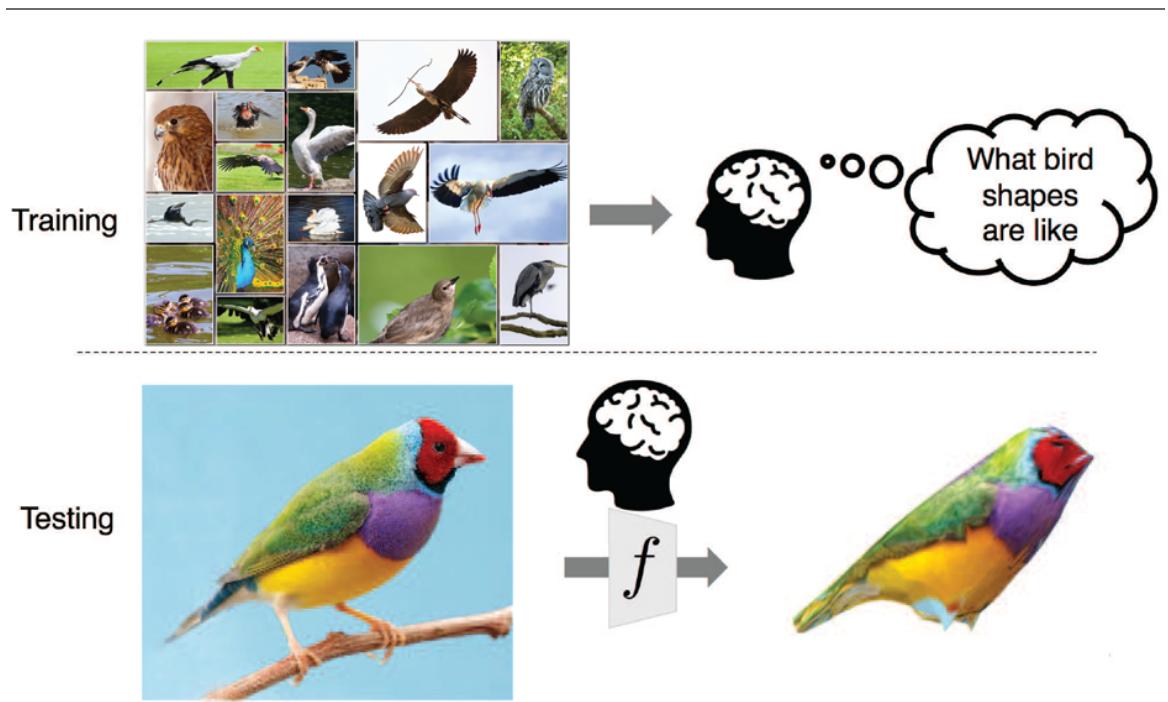

This chapter assumes little prior knowledge on the part of the agent: it starts from scratch and learns from the data. In Section 21.7.2 we consider transfer learning, in which knowledge from one domain is transferred to a new domain, so that learning can proceed faster with less data. We do assume, however, that the designer of the system chooses a model framework that can lead to effective learning.

Prior knowledge

Going from a specific set of observations to a general rule is called induction; from the observations that the sun rose every day in the past, we induce that the sun will come up tomorrow. This differs from the deduction we studied in Chapter 7 because the inductive conclusions may be incorrect, whereas deductive conclusions are guaranteed to be correct if the premises are correct.

This chapter concentrates on problems where the input is a factored representation—a vector of attribute values. It is also possible for the input to be any kind of data structure, including atomic and relational.

When the output is one of a finite set of values (such as sunny/cloudy/rainy or true/false), the learning problem is called classification. When it is a number (such as tomorrow’s temperature, measured either as an integer or a real number), the learning problem has the (admittedly obscure ) name regression. 1

1 A better name would have been function approximation or numeric prediction. But in 1886 Francis Galton wrote an influential article on the concept of regression to the mean (e.g., the children of tall parents are likely to be taller than average, but not as tall as the parents). Galton showed plots with what he called “regression lines,” and readers came to associate the word “regression” with the statistical technique of function approximation rather than with the topic of regression to the mean.

Classification

Regression

There are three types of feedback that can accompany the inputs, and that determine the three main types of learning:

In supervised learning the agent observes input-output pairs and learns a function that maps from input to output. For example, the inputs could be camera images, each one accompanied by an output saying “bus” or “pedestrian,” etc. An output like this is called a label. The agent learns a function that, when given a new image, predicts the appropriate label. In the case of braking actions (component 1 above), an input is the current state (speed and direction of the car, road condition), and an output is the distance it took to stop. In this case a set of output values can be obtained by the agent from its own percepts (after the fact); the environment is the teacher, and the agent learns a function that maps states to stopping distance.

Supervised learning

Label

In unsupervised learning the agent learns patterns in the input without any explicit feedback. The most common unsupervised learning task is clustering: detecting potentially useful clusters of input examples. For example, when shown millions of images taken from the Internet, a computer vision system can identify a large cluster of similar images which an English speaker would call “cats.”

Unsupervised learning

In reinforcement learning the agent learns from a series of reinforcements: rewards and punishments. For example, at the end of a chess game the agent is told that it has won (a reward) or lost (a punishment). It is up to the agent to decide which of the actions prior to the reinforcement were most responsible for it, and to alter its actions to aim towards more rewards in the future.

Reinforcement learning

Feedback

19.2 Supervised Learning

More formally, the task of supervised learning is this:

Given a training set of example input–output pairs

Training set

where each pair was generated by an unknown function discover a function that approximates the true function

The function is called a hypothesis about the world. It is drawn from a hypothesis space of possible functions. For example, the hypothesis space might be the set of polynomials of degree 3; or the set of Javascript functions; or the set of 3-SAT Boolean logic formulas.

Hypothesis space

With alternative vocabulary, we can say that is a model of the data, drawn from a model class or we can say a function drawn from a function class. We call the output the ground truth—the true answer we are asking our model to predict.

Model class

Ground truth

How do we choose a hypothesis space? We might have some prior knowledge about the process that generated the data. If not, we can perform exploratory data analysis: examining the data with statistical tests and visualizations—histograms, scatter plots, box plots—to get a feel for the data, and some insight into what hypothesis space might be appropriate. Or we can just try multiple hypothesis spaces and evaluate which one works best.

Exploratory data analysis

Consistent hypothesis

How do we choose a good hypothesis from within the hypothesis space? We could hope for a consistent hypothesis: and such that each in the training set has With continuous-valued outputs we can’t expect an exact match to the ground truth; instead we look for a best-fit function for which each is close to (in a way that we will formalize in Section 19.4.2 ).

The true measure of a hypothesis is not how it does on the training set, but rather how well it handles inputs it has not yet seen. We can evaluate that with a second sample of pairs called a test set. We say that generalizes well if it accurately predicts the outputs of the test set.

Test set

Generalization

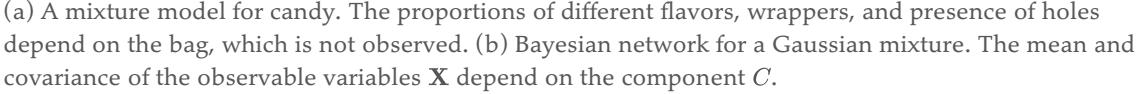

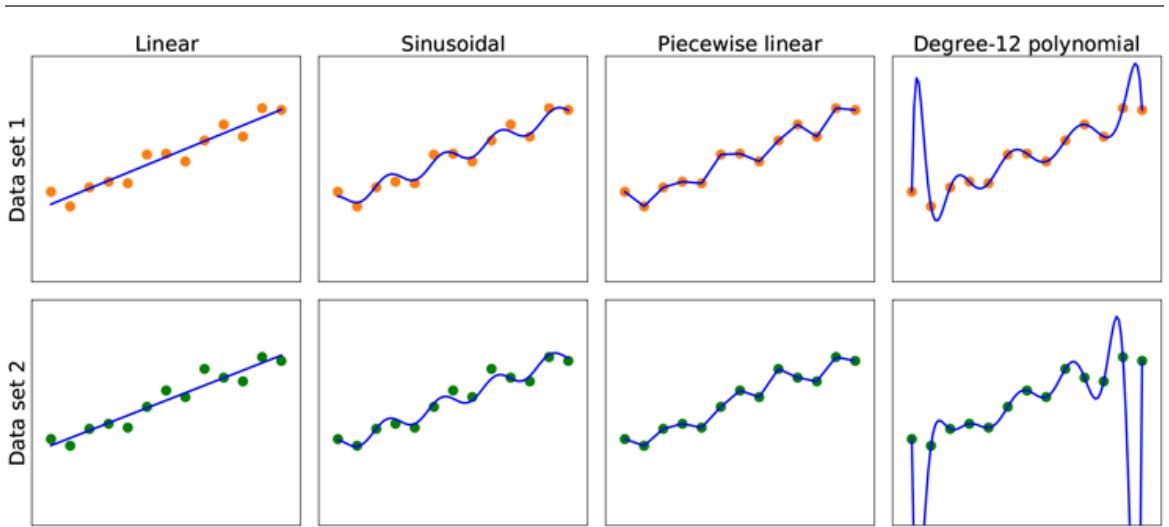

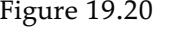

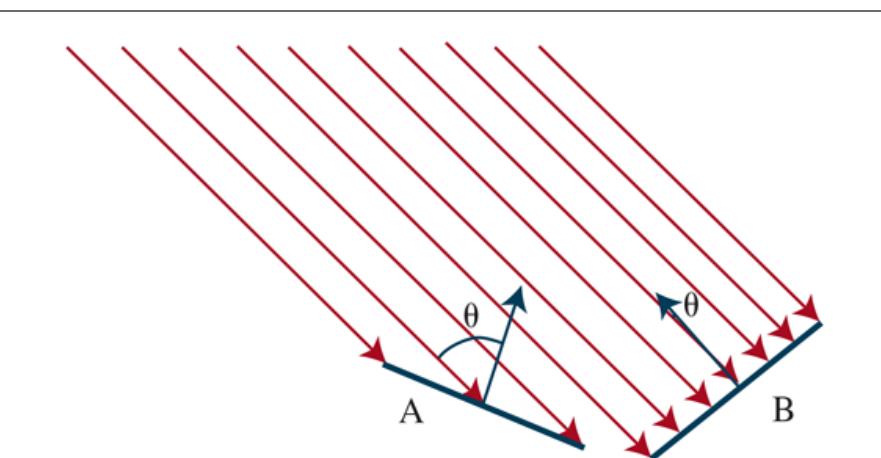

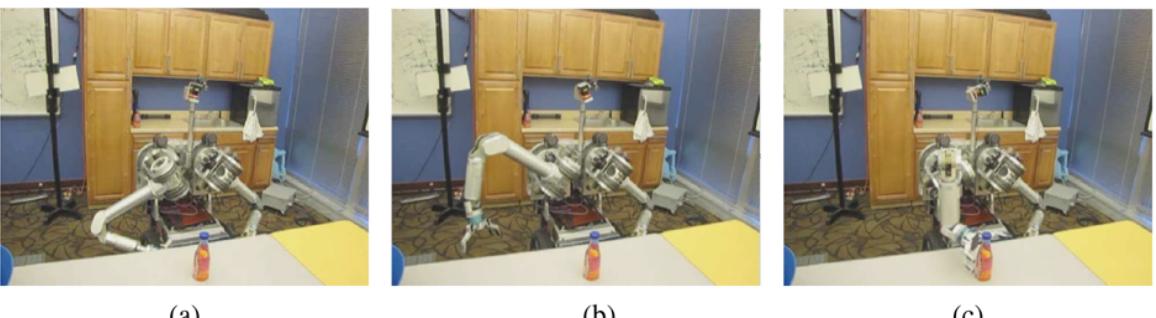

Figure 19.1 shows that the function that a learning algorithm discovers depends on the hypothesis space it considers and on the training set it is given. Each of the four plots in the top row have the same training set of 13 data points in the plane. The four plots in the bottom row have a second set of 13 data points; both sets are representative of the same unknown function Each column shows the best-fit hypothesis from a different hypothesis space:

- COLUMN 1: Straight lines; functions of the form There is no line that would be a consistent hypothesis for the data points.

- COLUMN 2: Sinusoidal functions of the form This choice is not quite consistent, but fits both data sets very well.

- COLUMN 3: Piecewise-linear functions where each line segment connects the dots from one data point to the next. These functions are always consistent.

- COLUMN 4: Degree-12 polynomials, These are consistent: we can always get a degree-12 polynomial to perfectly fit 13 distinct points. But just because the hypothesis is consistent does not mean it is a good guess.

Figure 19.1

Finding hypotheses to fit data. Top row: four plots of best-fit functions from four different hypothesis spaces trained on data set 1. Bottom row: the same four functions, but trained on a slightly different data set (sampled from the same function).

One way to analyze hypothesis spaces is by the bias they impose (regardless of the training data set) and the variance they produce (from one training set to another).

Bias

By bias we mean (loosely) the tendency of a predictive hypothesis to deviate from the expected value when averaged over different training sets. Bias often results from restrictions imposed by the hypothesis space. For example, the hypothesis space of linear functions induces a strong bias: it only allows functions consisting of straight lines. If there are any patterns in the data other than the overall slope of a line, a linear function will not be able to represent those patterns. We say that a hypothesis is underfitting when it fails to find a pattern in the data. On the other hand, the piecewise linear function has low bias; the shape of the function is driven by the data.

Underfitting

By variance we mean the amount of change in the hypothesis due to fluctuation in the training data. The two rows of Figure 19.1 represent data sets that were each sampled from the same function. The data sets turned out to be slightly different. For the first three columns, the small difference in the data set translates into a small difference in the hypothesis. We call that low variance. But the degree-12 polynomials in the fourth column have high variance: look how different the two functions are at both ends of the -axis. Clearly, at least one of these polynomials must be a poor approximation to the true We say a function is overfitting the data when it pays too much attention to the particular data set it is trained on, causing it to perform poorly on unseen data.

Variance

Overfitting

Often there is a bias–variance tradeoff: a choice between more complex, low-bias hypotheses that fit the training data well and simpler, low-variance hypotheses that may generalize better. Albert Einstein said in 1933, “the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.” In other words, Einstein recommends choosing the simplest hypothesis that matches the data. This principle can be traced further back to the 14th-century English philosopher William of Ockham. His principle that “plurality [of entities] should not be posited without necessity” is called Ockham’s razor because it is used to “shave off” dubious explanations. 2

2 The name is often misspelled as “Occam.”

Bias–variance tradeoff

Defining simplicity is not easy. It seems clear that a polynomial with only two parameters is simpler than one with thirteen parameters. We will make this intuition more precise in Section 19.3.4 . However, in Chapter 21 we will see that deep neural network models can often generalize quite well, even though they are very complex—some of them have billions of parameters. So the number of parameters by itself is not a good measure of a model’s fitness. Perhaps we should be aiming for “appropriateness,” not “simplicity” in a model class. We will consider this issue in Section 19.4.1 .

Which hypothesis is best in Figure 19.1 ? We can’t be certain. If we knew the data represented, say, the number of hits to a Web site that grows from day to day, but also cycles depending on the time of day, then we might favor the sinusoidal function. If we knew the data was definitely not cyclic but had high noise, that would favor the linear function.

In some cases, an analyst is willing to say not just that a hypothesis is possible or impossible, but rather how probable it is. Supervised learning can be done by choosing the hypothesis that is most probable given the data:

\[h^\* = \underset{h \in H}{\text{argmax}} \, P\left(h|data\right).\]

By Bayes’ rule this is equivalent to

\[h^\* = \underset{h \in H}{\text{argmax}} \, P(data \, \middle| \, h) \, P(h).\]

Then we can say that the prior probability is high for a smooth degree-1 or -2 polynomial and lower for a degree-12 polynomial with large, sharp spikes. We allow unusual-looking functions when the data say we really need them, but we discourage them by giving them a low prior probability.

Why not let be the class of all computer programs, or all Turing machines? The problem is that there is a tradeoff between the expressiveness of a hypothesis space and the computational complexity of finding a good hypothesis within that space. For example, fitting a straight line to data is an easy computation; fitting high-degree polynomials is somewhat harder; and fitting Turing machines is undecidable. A second reason to prefer simple hypothesis spaces is that presumably we will want to use after we have learned it, and computing when is a linear function is guaranteed to be fast, while computing an arbitrary Turing machine program is not even guaranteed to terminate.

For these reasons, most work on learning has focused on simple representations. In recent years there has been great interest in deep learning (Chapter 21 ), where representations are not simple but where the computation still takes only a bounded number of steps to compute with appropriate hardware.

We will see that the expressiveness–complexity tradeoff is not simple: it is often the case, as we saw with first-order logic in Chapter 8 , that an expressive language makes it possible for a simple hypothesis to fit the data, whereas restricting the expressiveness of the language means that any consistent hypothesis must be complex.

19.2.1 Example problem: Restaurant waiting

We will describe a sample supervised learning problem in detail: the problem of deciding whether to wait for a table at a restaurant. This problem will be used throughout the chapter to demonstrate different model classes. For this problem the output, is a Boolean variable that we will call WillWait; it is true for examples where we do wait for a table. The input, is a vector of ten attribute values, each of which has discrete values:

- 1. ALTERNATE: whether there is a suitable alternative restaurant nearby.

- 2. BAR: whether the restaurant has a comfortable bar area to wait in.

- 3. FRI/SAT: true on Fridays and Saturdays.

- 4. HUNGRY: whether we are hungry right now.

- 5. PATRONS: how many people are in the restaurant (values are None, Some, and Full).

- 6. PRICE: the restaurant’s price range

- 7. RAINING: whether it is raining outside.

- 8. RESERVATION: whether we made a reservation.

- 9. TYPE: the kind of restaurant (French, Italian, Thai, or burger).

- 10. WAITESTIMATE: host’s wait estimate:

A set of 12 examples, taken from the experience of one of us (SR), is shown in Figure 19.2 . Note how skimpy these data are: there are possible combinations of values for the input attributes, but we are given the correct output for only 12 of them; each of the other 9,204 could be either true or false; we don’t know. This is the essence of induction: we need to make our best guess at these missing 9,204 output values, given only the evidence of the 12 examples.

Figure 19.2

| Example | Input Attributes | Output | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt | Bar | Fri | Hun | Pat | Price | Rain | Res | Type | Est | Will Wait | |

| X1 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Some | 888 | No | Yes | French | 0-10 | = Yes V1 |

| X2 | Yes | No | No | Yes | Full | S | No | No | Thai | 30-60 | = No V2 |

| X3 | No | Yes | No | No | Some | S | No | No | Burger | 0-10 | = Yes V3 |

| X4 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Full | S | Yes | No | Thai | 10-30 | Yes V4 ll |

| X5 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Full | 888 | No | Yes | French | >60 | = No V5 |

| X6 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Some | 88 | Yes | Yes | Italian | 0-10 | = Yes V6 |

| X7 | No | Yes | No | No | None | S | Yes | No | Burger | 0-10 | No V7 == |

| X8 | No | No | No | Yes | Some | 88 | Yes | Yes | Thai | 0-10 | = Yes V8 |

| X9 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Full | S | Yes | No | Burger | >60 | = No V9 |

| X10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Full | 888 | No | Yes | Italian | 10-30 | = No V10 |

| X11 | No | No | No | No | None | S | No | No | Thai | 0-10 | = No V11 |

| X12 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Full | S | No | No | Burger | 30-60 | Yes == V12 |

Examples for the restaurant domain.

19.3 Learning Decision Trees

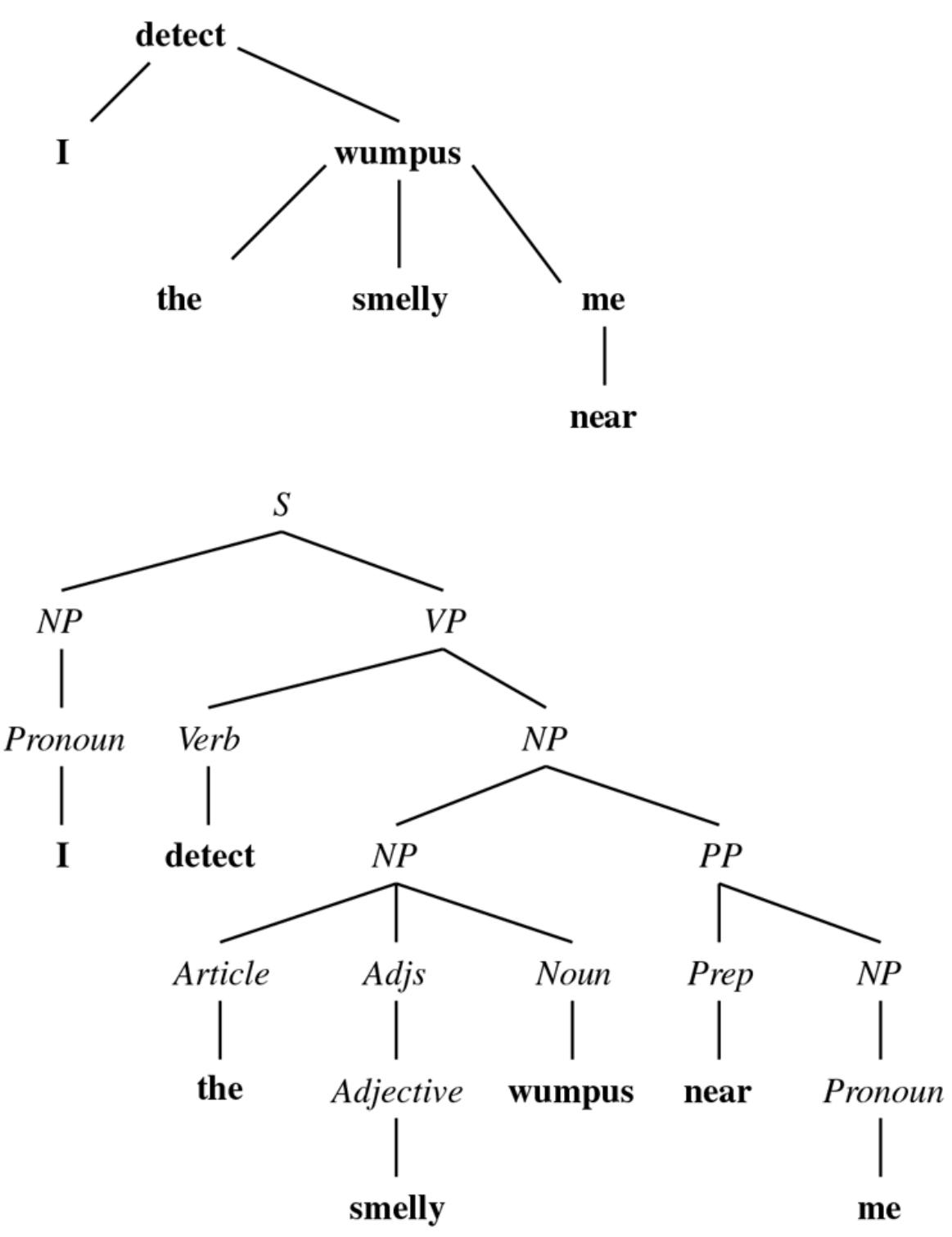

A decision tree is a representation of a function that maps a vector of attribute values to a single output value—a “decision.” A decision tree reaches its decision by performing a sequence of tests, starting at the root and following the appropriate branch until a leaf is reached. Each internal node in the tree corresponds to a test of the value of one of the input attributes, the branches from the node are labeled with the possible values of the attribute, and the leaf nodes specify what value is to be returned by the function.

Decision tree

In general, the input and output values can be discrete or continuous, but for now we will consider only inputs consisting of discrete values and outputs that are either true (a positive example) or false (a negative example). We call this Boolean classification. We will use to index the examples ( is the input vector for the th example and is the output), and for the th attribute of the th example.

Positive

Negative

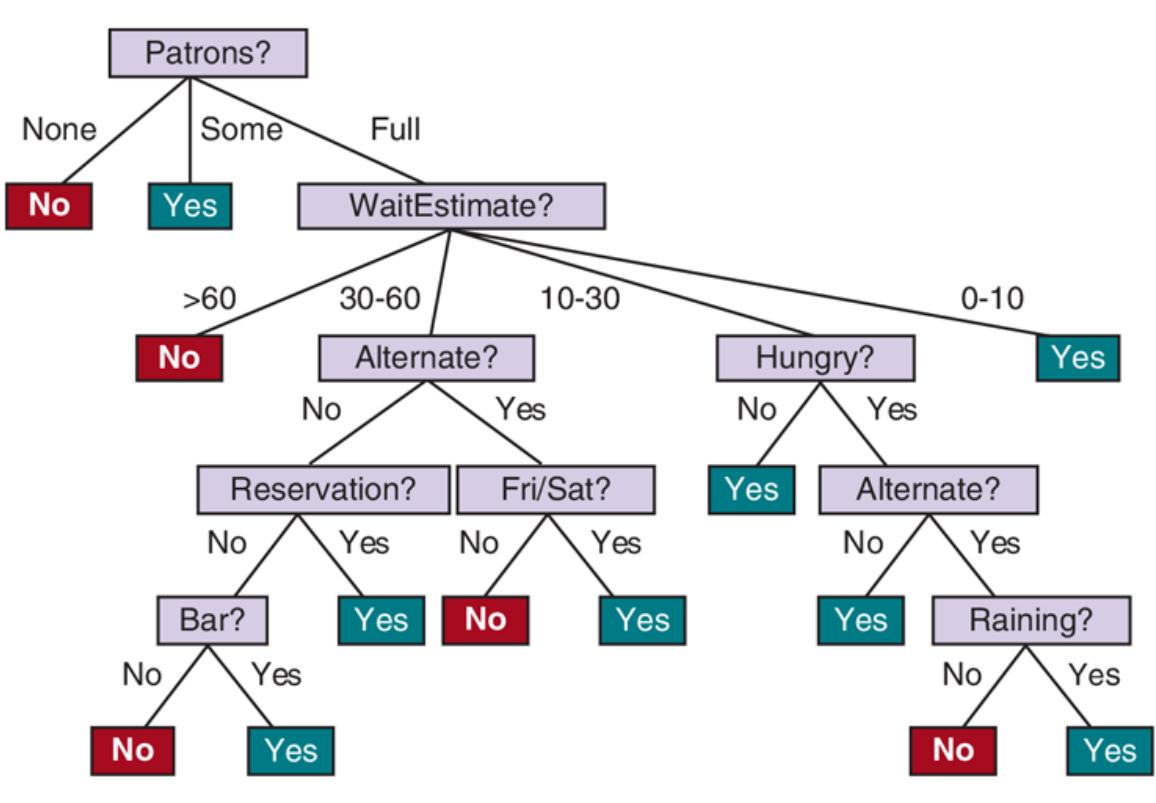

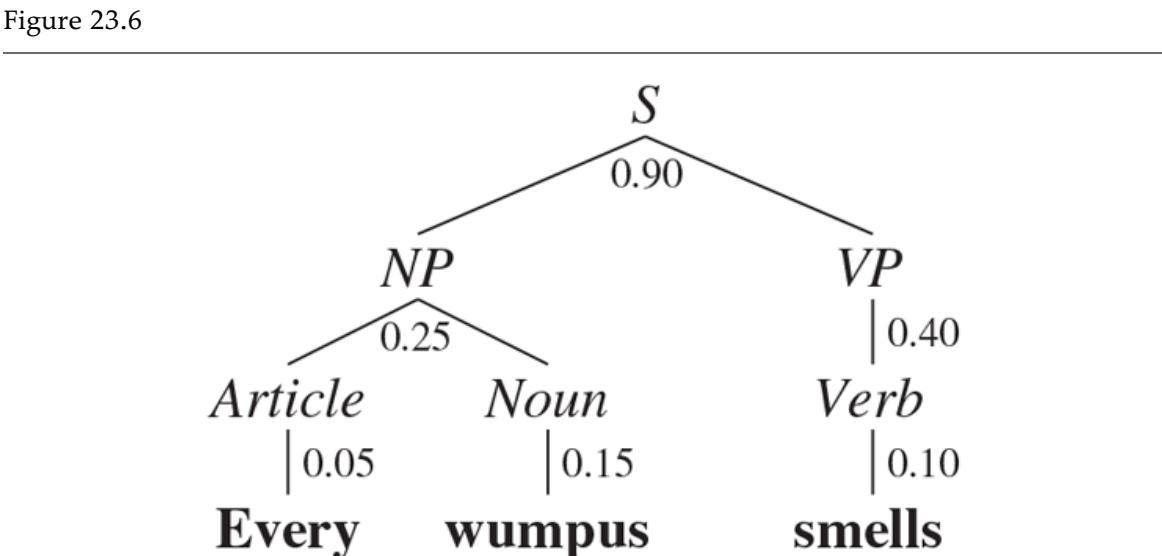

The tree representing the decision function that SR uses for the restaurant problem is shown in Figure 19.3 . Following the branches, we see that an example with and will be classified as positive (i.e., yes, we will wait for a table).

A decision tree for deciding whether to wait for a table.

19.3.1 Expressiveness of decision trees

A Boolean decision tree is equivalent to a logical statement of the form:

\[Output \iff \left(Path\_1 \lor Path\_2 \lor \cdots \right),\]

where each is a conjunction of the form of attribute-value tests corresponding to a path from the root to a true leaf. Thus, the whole expression is in disjunctive normal form, which means that any function in propositional logic can be expressed as a decision tree.

For many problems, the decision tree format yields a nice, concise, understandable result. Indeed, many “How To” manuals (e.g., for car repair) are written as decision trees. But some functions cannot be represented concisely. For example, the majority function, which returns true if and only if more than half of the inputs are true, requires an exponentially large decision tree, as does the parity function, which returns true if and only if an even number of input attributes are true. With real-valued attributes, the function is

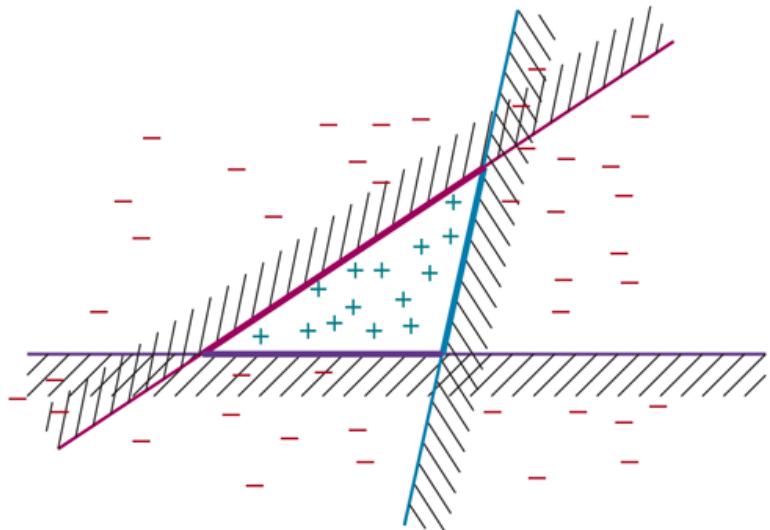

hard to represent with a decision tree because the decision boundary is a diagonal line, and all decision tree tests divide the space up into rectangular, axis-aligned boxes. We would have to stack a lot of boxes to closely approximate the diagonal line. In other words, decision trees are good for some kinds of functions and bad for others.

Is there any kind of representation that is efficient for all kinds of functions? Unfortunately, the answer is no—there are just too many functions to be able to represent them all with a small number of bits. Even just considering Boolean functions with Boolean attributes, the truth table will have rows, and each row can output true or false, so there are different functions. With 20 attributes there are functions, so if we limit ourselves to a million-bit representation, we can’t represent all these functions.

19.3.2 Learning decision trees from examples

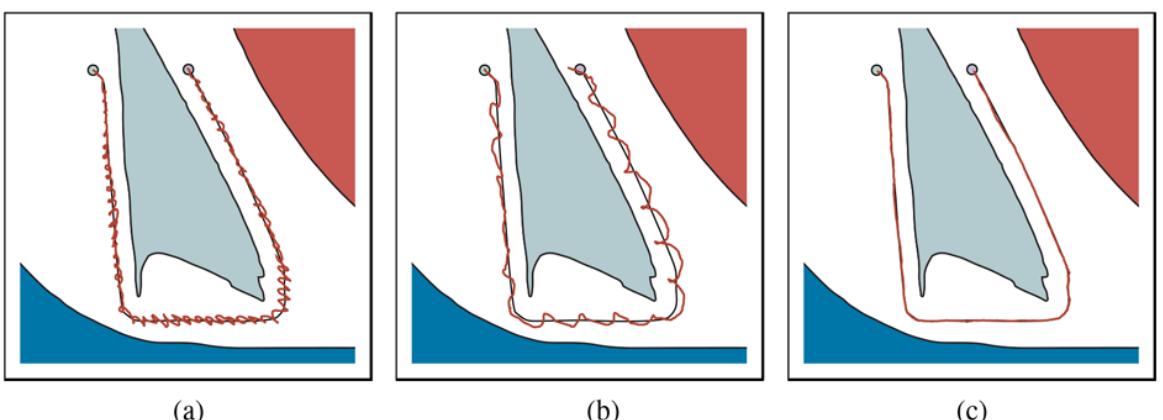

We want to find a tree that is consistent with the examples in Figure 19.2 and is as small as possible. Unfortunately, it is intractable to find a guaranteed smallest consistent tree. But with some simple heuristics, we can efficiently find one that is close to the smallest. The LEARN-DECISION-TREE algorithm adopts a greedy divide-and-conquer strategy: always test the most important attribute first, then recursively solve the smaller subproblems that are defined by the possible results of the test. By “most important attribute,” we mean the one that makes the most difference to the classification of an example. That way, we hope to get to the correct classification with a small number of tests, meaning that all paths in the tree will be short and the tree as a whole will be shallow.

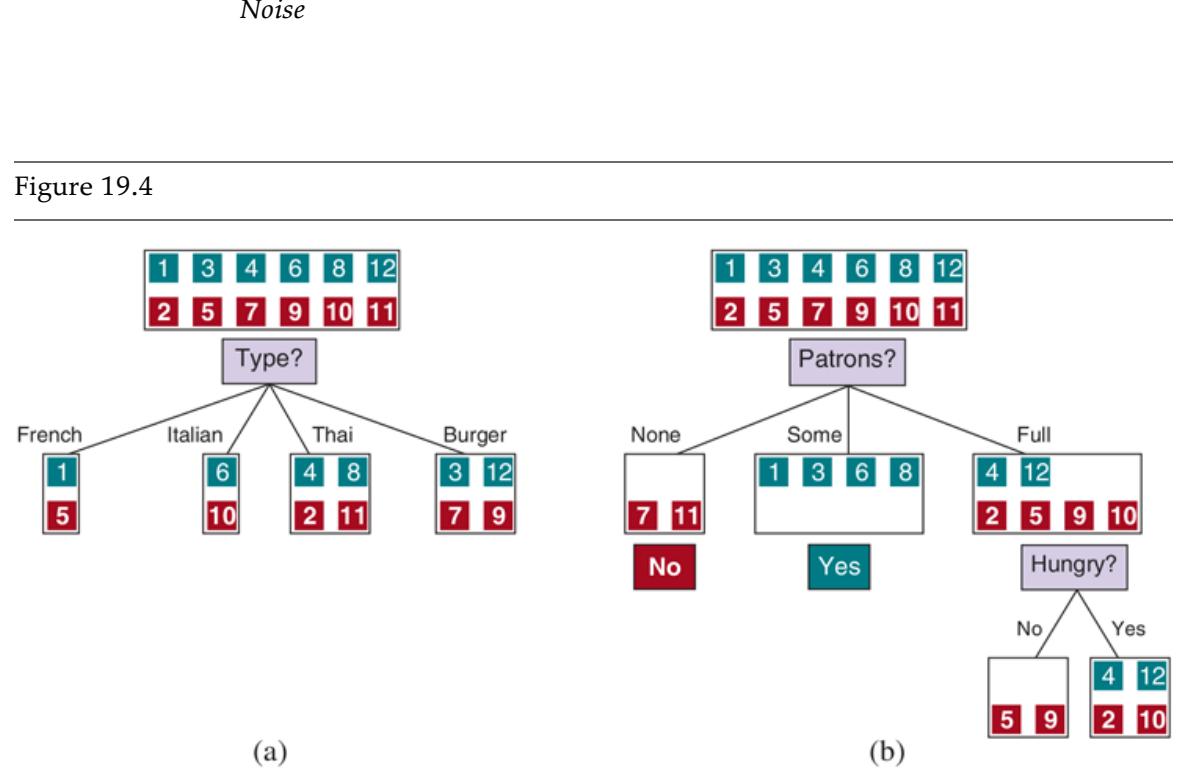

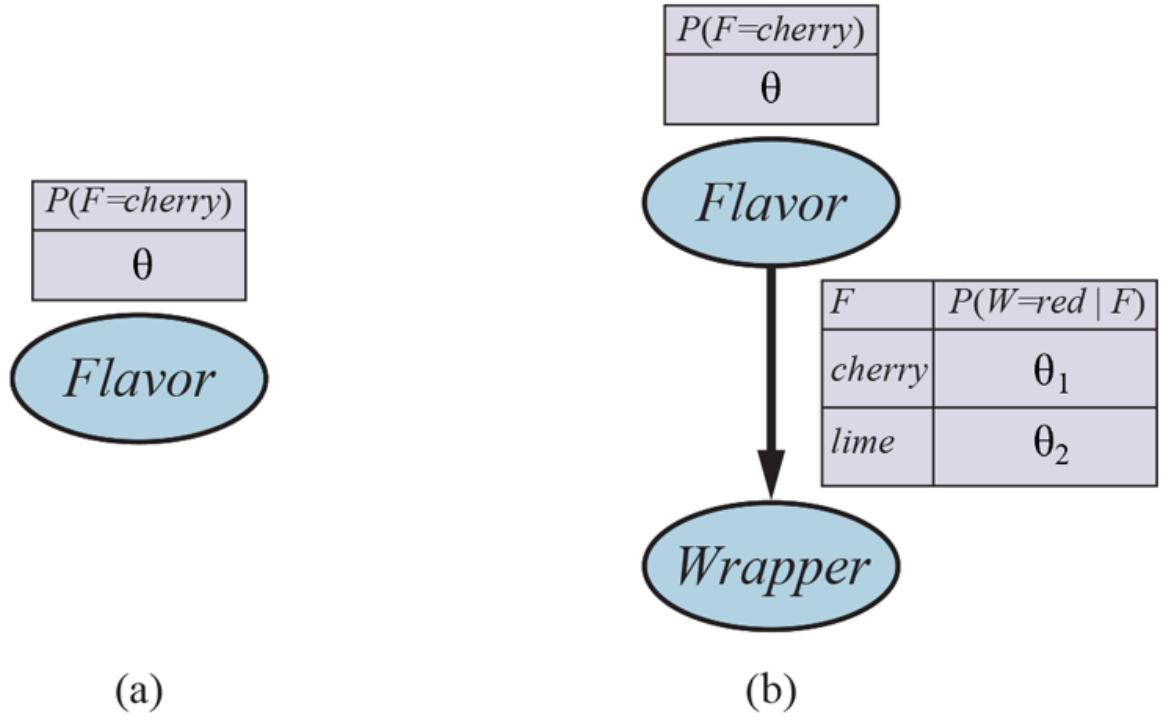

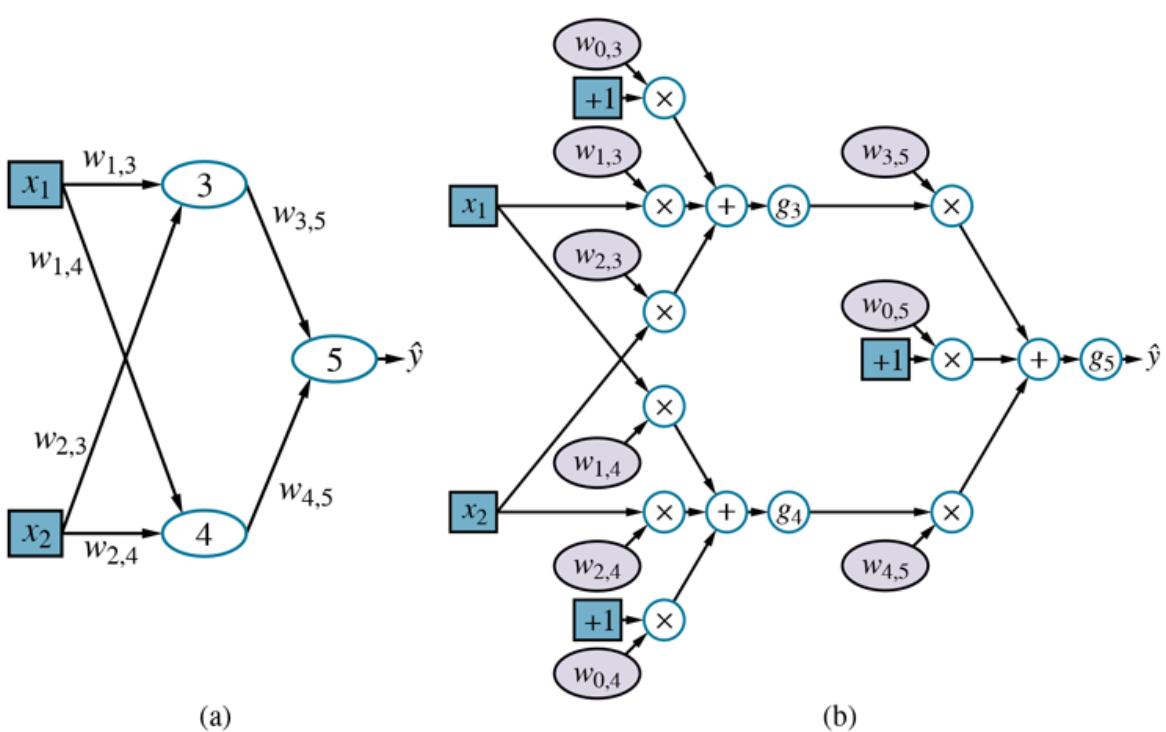

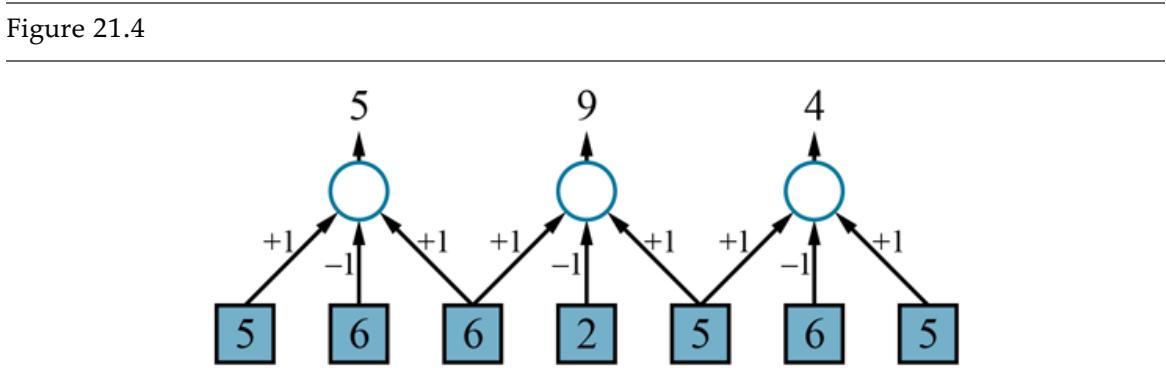

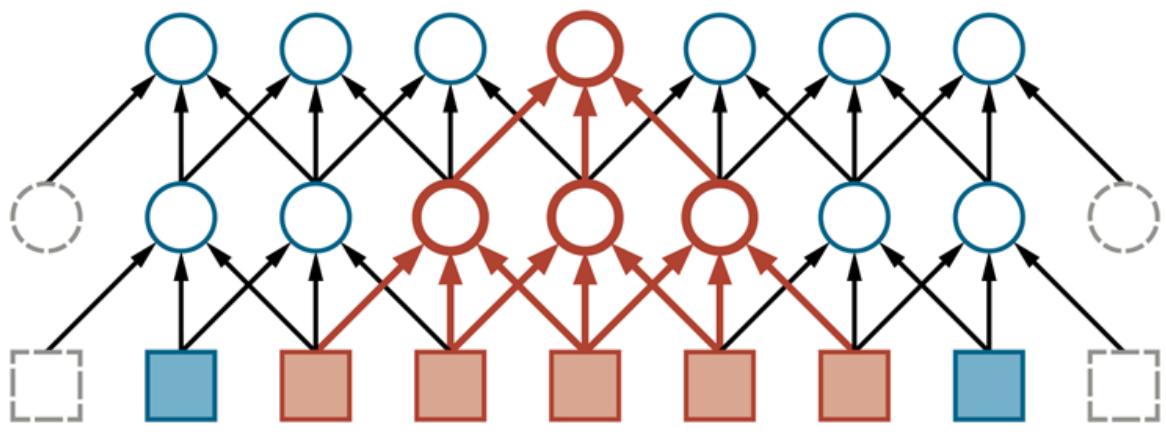

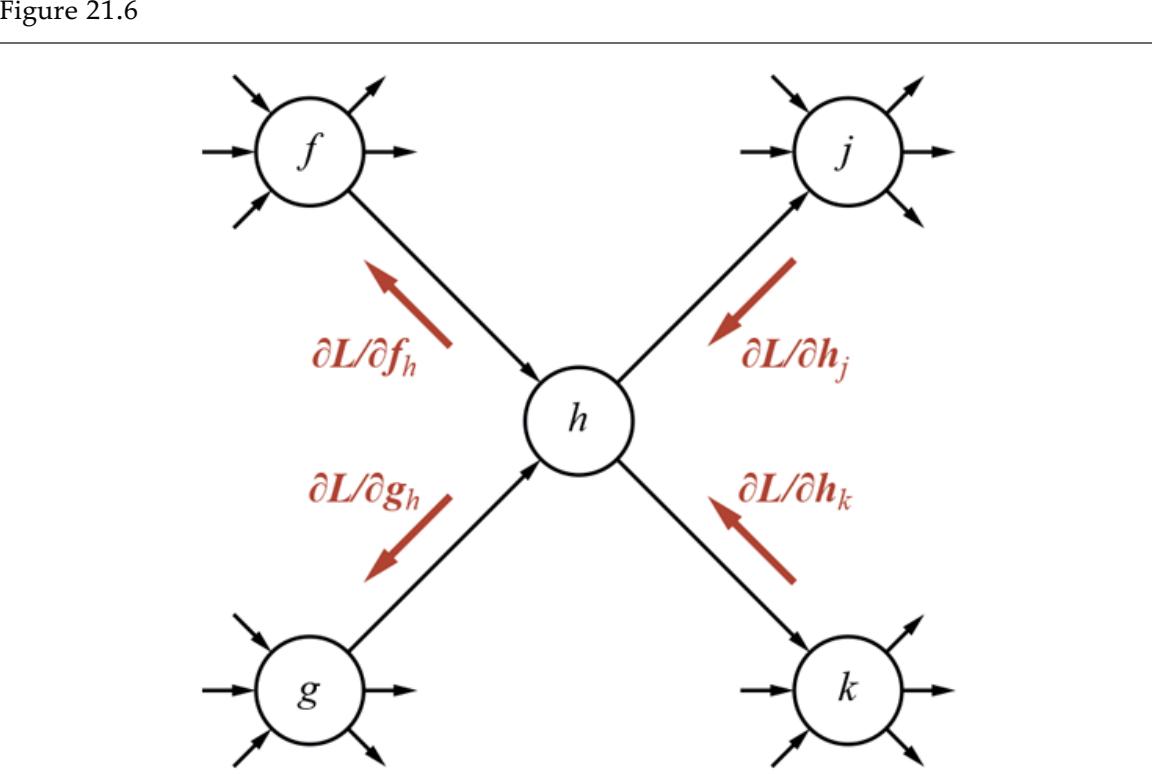

Figure 19.4(a) shows that Type is a poor attribute, because it leaves us with four possible outcomes, each of which has the same number of positive as negative examples. On the other hand, in (b) we see that Patrons is a fairly important attribute, because if the value is None or Some, then we are left with example sets for which we can answer definitively (No and Yes, respectively). If the value is Full, we are left with a mixed set of examples. There are four cases to consider for these recursive subproblems:

- 1. If the remaining examples are all positive (or all negative), then we are done: we can answer Yes or No. Figure 19.4(b) shows examples of this happening in the None and Some branches.

- 2. If there are some positive and some negative examples, then choose the best attribute to split them. Figure 19.4(b) shows Hungry being used to split the

remaining examples.

- 3. If there are no examples left, it means that no example has been observed for this combination of attribute values, and we return the most common output value from the set of examples that were used in constructing the node’s parent.

- 4. If there are no attributes left, but both positive and negative examples, it means that these examples have exactly the same description, but different classifications. This can happen because there is an error or noise in the data; because the domain is nondeterministic; or because we can’t observe an attribute that would distinguish the examples. The best we can do is return the most common output value of the remaining examples.

Splitting the examples by testing on attributes. At each node we show the positive (light boxes) and negative (dark boxes) examples remaining. (a) Splitting on Type brings us no nearer to distinguishing between positive and negative examples. (b) Splitting on Patrons does a good job of separating positive and negative examples. After splitting on Patrons, Hungry is a fairly good second test.

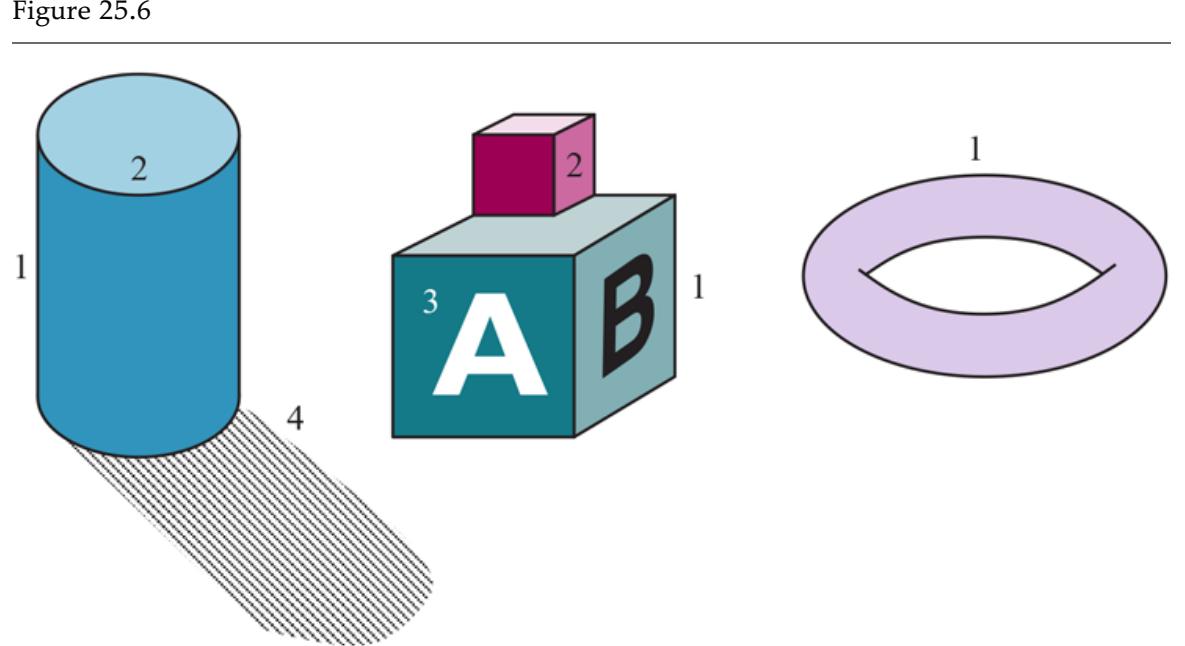

The LEARN-DECISION-TREE algorithm is shown in Figure 19.5 . Note that the set of examples is an input to the algorithm, but nowhere do the examples appear in the tree returned by the algorithm. A tree consists of tests on attributes in the interior nodes, values of attributes on

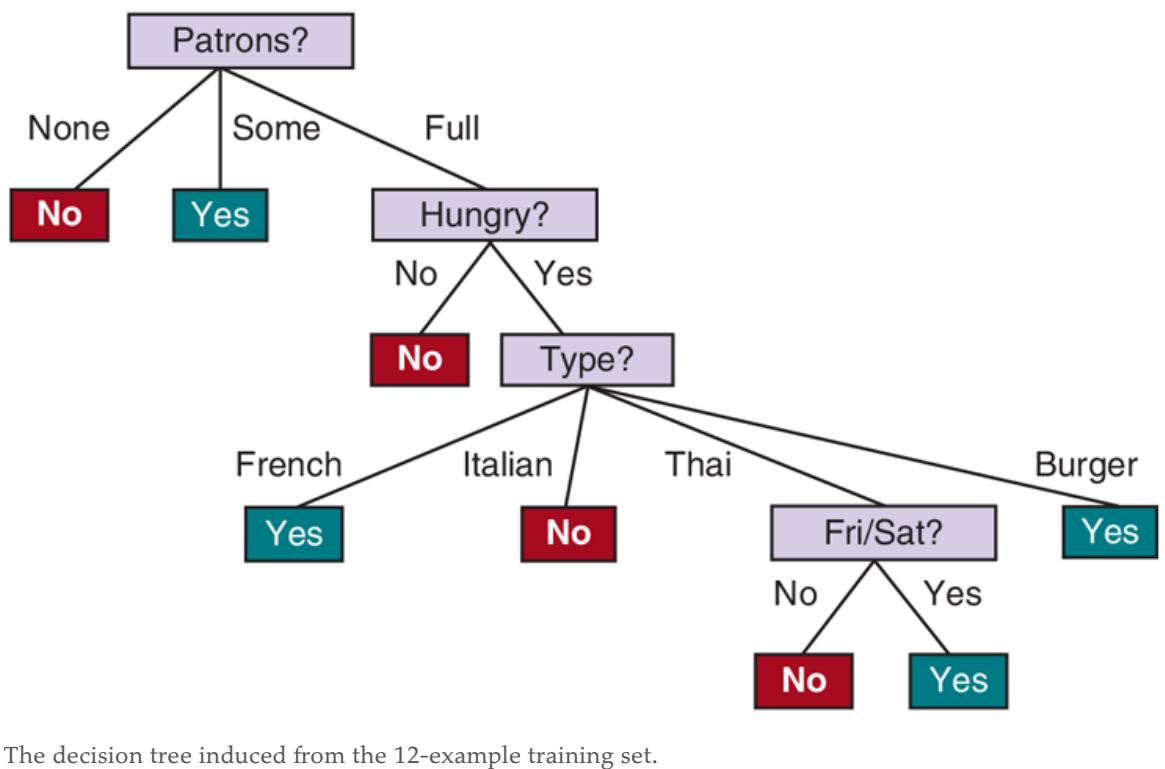

the branches, and output values on the leaf nodes. The details of the IMPORTANCE function are given in Section 19.3.3 . The output of the learning algorithm on our sample training set is shown in Figure 19.6 . The tree is clearly different from the original tree shown in Figure 19.3 . One might conclude that the learning algorithm is not doing a very good job of learning the correct function. This would be the wrong conclusion to draw, however. The learning algorithm looks at the examples, not at the correct function, and in fact, its hypothesis (see Figure 19.6 ) not only is consistent with all the examples, but is considerably simpler than the original tree! With slightly different examples the tree might be very different, but the function it represents would be similar.

Figure 19.5

The decision tree learning algorithm. The function IMPORTANCE is described in Section 19.3.3 . The function PLURALITY-VALUE selects the most common output value among a set of examples, breaking ties randomly.

Figure 19.6

The learning algorithm has no reason to include tests for Raining and Reservation, because it can classify all the examples without them. It has also detected an interesting and previously unsuspected pattern: SR will wait for Thai food on weekends. It is also bound to make some mistakes for cases where it has seen no examples. For example, it has never seen a case where the wait is 0–10 minutes but the restaurant is full. In that case it says not to wait when Hungry is false, but SR would certainly wait. With more training examples the learning program could correct this mistake.

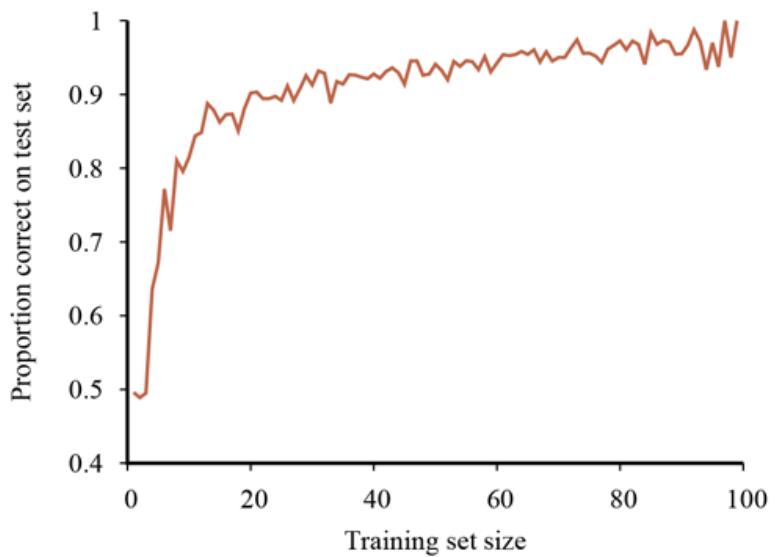

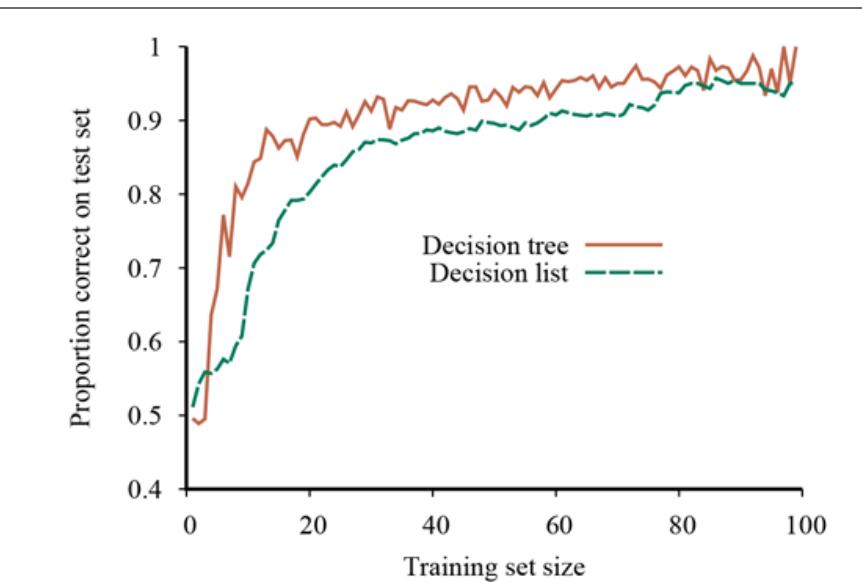

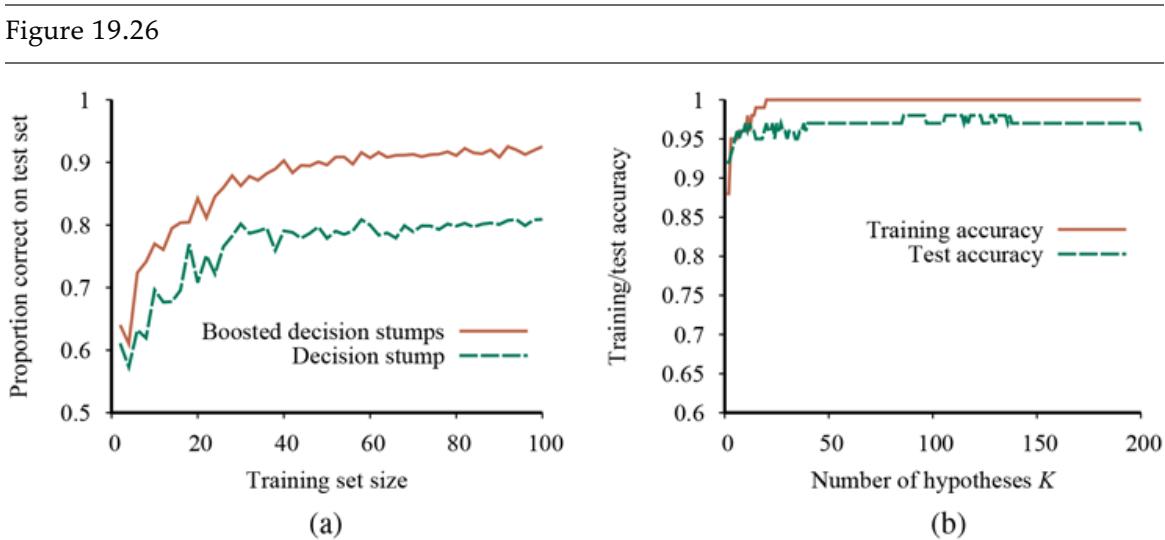

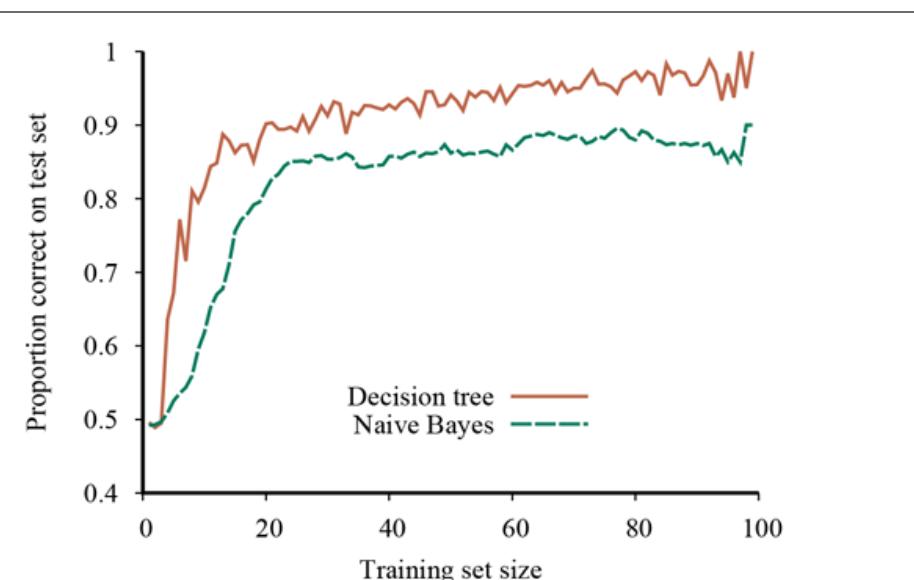

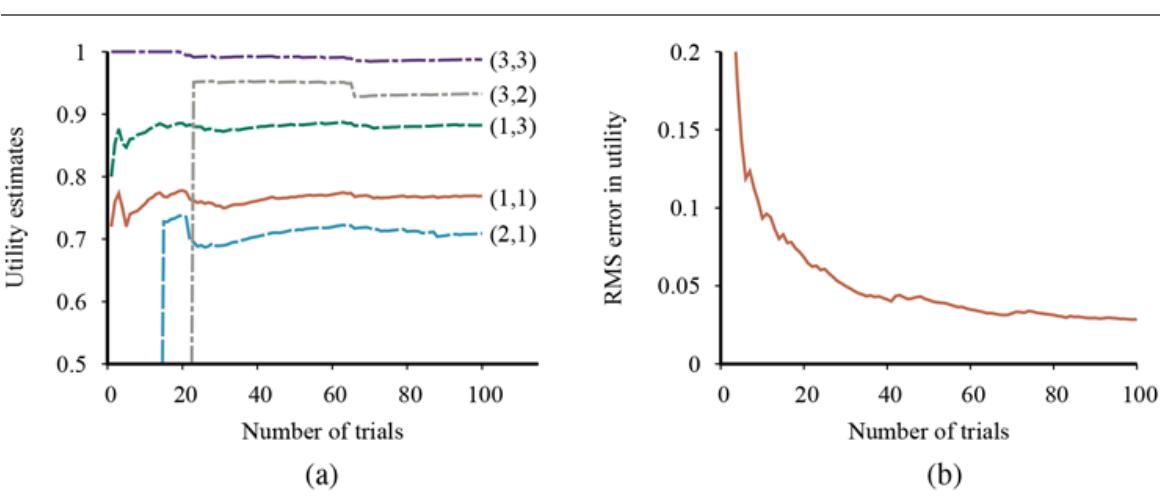

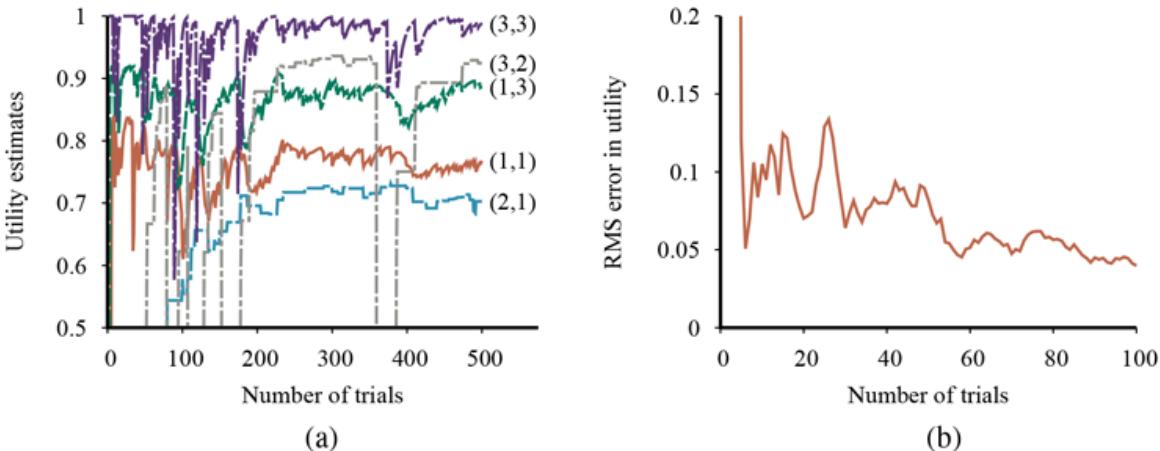

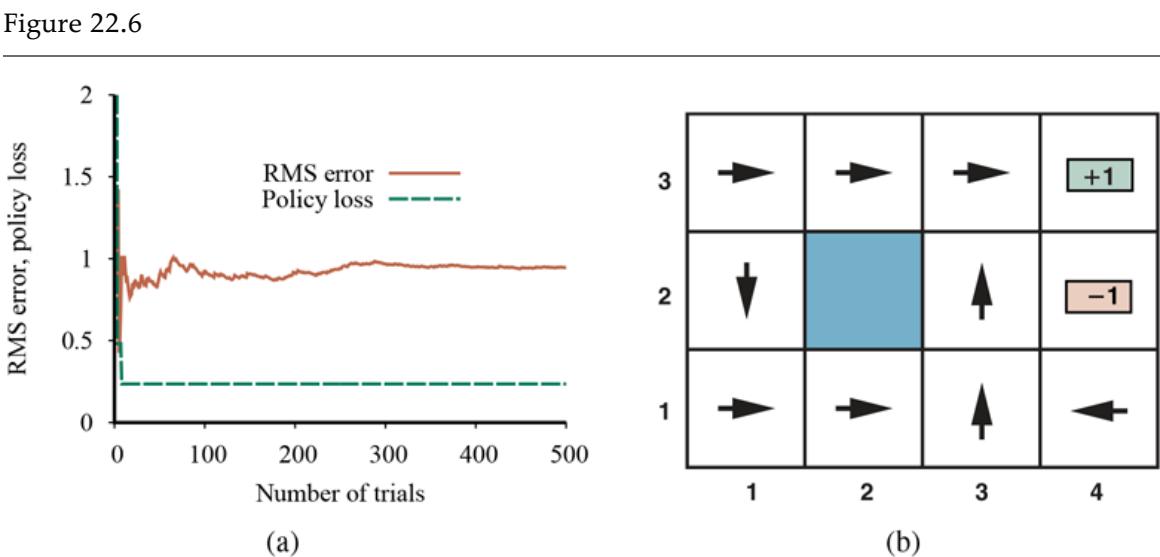

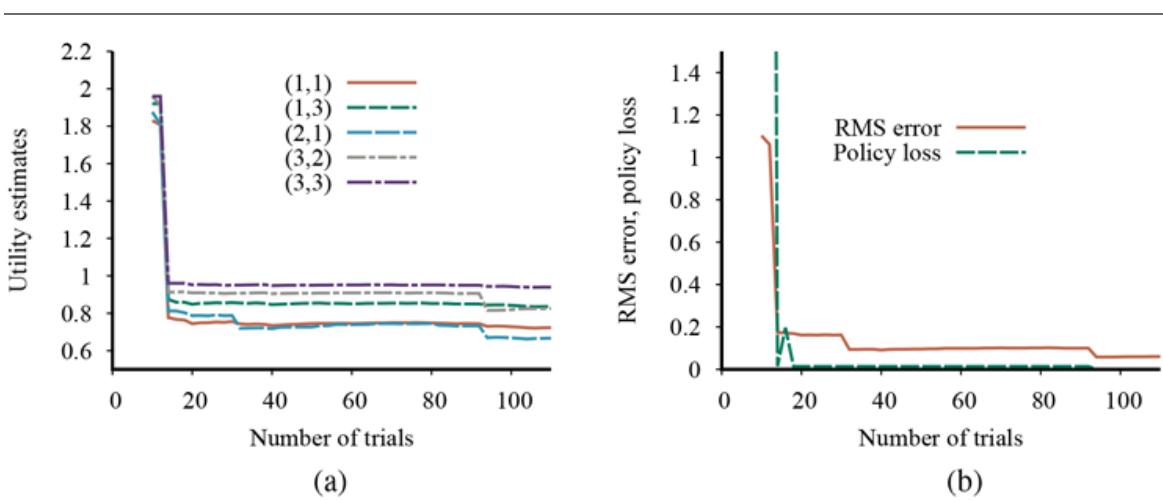

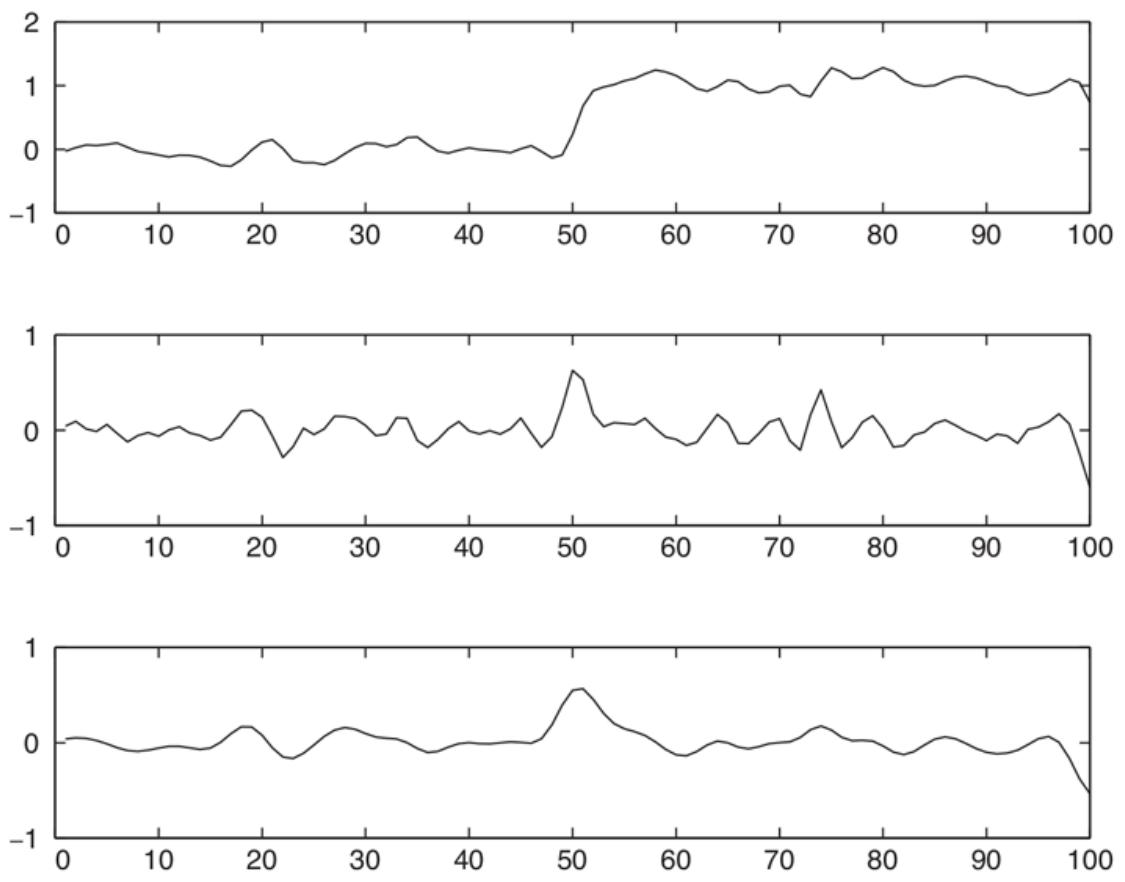

We can evaluate the performance of a learning algorithm with a learning curve, as shown in Figure 19.7 . For this figure we have 100 examples at our disposal, which we split randomly into a training set and a test set. We learn a hypothesis with the training set and measure its accuracy with the test set. We can do this starting with a training set of size 1 and increasing one at a time up to size 99. For each size, we actually repeat the process of randomly splitting into training and test sets 20 times, and average the results of the 20 trials. The curve shows that as the training set size grows, the accuracy increases. (For this reason, learning curves are also called happy graphs.) In this graph we reach 95% accuracy, and it looks as if the curve might continue to increase if we had more data.

A learning curve for the decision tree learning algorithm on 100 randomly generated examples in the restaurant domain. Each data point is the average of 20 trials.

Learning curve

Happy graphs

19.3.3 Choosing attribute tests

The decision tree learning algorithm chooses the attribute with the highest IMPORTANCE. We will now show how to measure importance, using the notion of information gain, which is defined in terms of entropy, which is the fundamental quantity in information theory (Shannon and Weaver, 1949).

Entropy

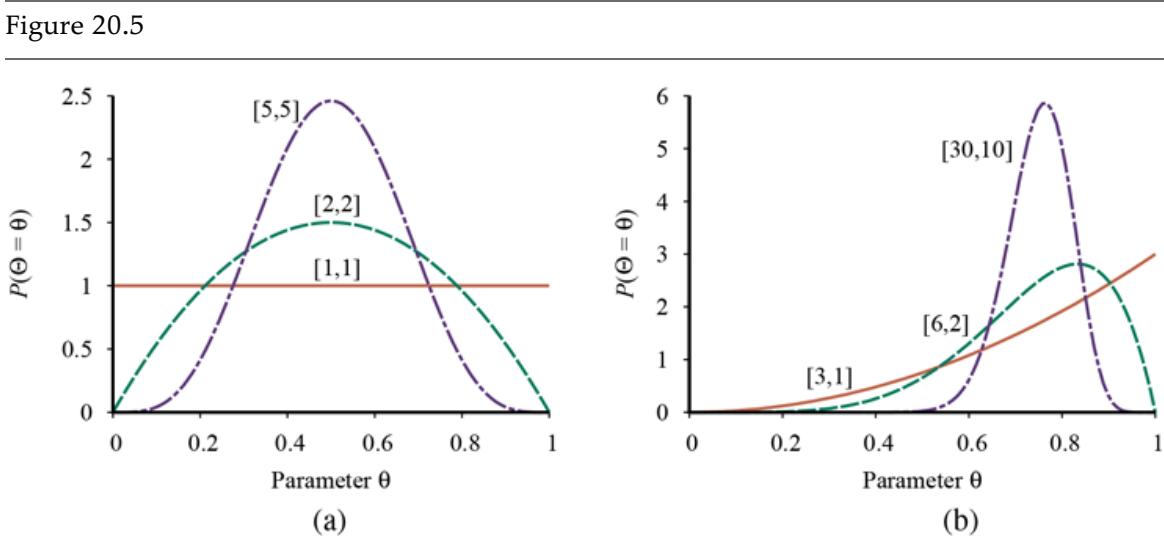

Entropy is a measure of the uncertainty of a random variable; the more information, the less entropy. A random variable with only one possible value—a coin that always comes up heads—has no uncertainty and thus its entropy is defined as zero. A fair coin is equally likely to come up heads or tails when flipped, and we will soon show that this counts as “1 bit” of entropy. The roll of a fair four-sided die has 2 bits of entropy, because there are equally probable choices. Now consider an unfair coin that comes up heads 99% of the time. Intuitively, this coin has less uncertainty than the fair coin—if we guess heads we’ll be wrong only 1% of the time—so we would like it to have an entropy measure that is close to zero, but positive. In general, the entropy of a random variable with values having probability is defined as

\[\text{Entropy:} \quad H(V) = \sum\_{k} P(v\_k) \log\_2 \frac{1}{P(v\_k)} = -\sum\_{k} P(v\_k) \log\_2 P(v\_k).\]

We can check that the entropy of a fair coin flip is indeed 1 bit:

\[H(Fair) = -(0.5\log\_2 0.5 + 0.5\log\_2 0.5) = 1\]

And of a four-sided die is 2 bits:

\[H(Die4) = -(0.25\log\_2 0.25 + 0.25\log\_2 0.25 + 0.25\log\_2 0.25 + 0.25\log\_2 0.25) = 2.5\]

For the loaded coin with 99% heads, we get

\[H(Loaded) = -(0.99\log\_2 0.99 + 0.01\log\_2 0.01) \approx 0.08 \text{ bits}.\]

It will help to define as the entropy of a Boolean random variable that is true with probability

\[B(q) = -(q\log\_2 q + (1-q)\log\_2(1-q)).\]

Thus, Now let’s get back to decision tree learning. If a training set contains positive examples and negative examples, then the entropy of the output variable on the whole set is

\[H(Output) = B\left(\frac{p}{p+n}\right).\]

The restaurant training set in Figure 19.2 has so the corresponding entropy is or exactly 1 bit. The result of a test on an attribute will give us some information, thus reducing the overall entropy by some amount. We can measure this reduction by looking at the entropy remaining after the attribute test.

An attribute with distinct values divides the training set into subsets Each subset has positive examples and negative examples, so if we go along that branch, we will need an additional bits of information to answer the question. A randomly chosen example from the training set has the th value for the attribute (i.e., is in with probability ), so the expected entropy remaining after testing attribute is

\[Remainder(A) = \sum\_{k=1}^{d} \frac{p\_k + n\_k}{p + n} B\left(\frac{p\_k}{p\_k + n\_k}\right).\]

The information gain from the attribute test on is the expected reduction in entropy:

\[Gain(A) = B\left(\frac{p}{p+n}\right) - Remainder(A).\]

Information gain

In fact is just what we need to implement the IMPORTANCE function. Returning to the attributes considered in Figure 19.4 , we have

\[\begin{aligned} Gain(Patrons) &= 1 - \left[ \frac{2}{12} B\left(\frac{0}{2}\right) + \frac{4}{12} B\left(\frac{4}{4}\right) + \frac{6}{12} B\left(\frac{2}{6}\right) \right] \approx 0.541 \text{ bits}, \\ Gain(Type) &= 1 - \left[ \frac{2}{12} B\left(\frac{1}{2}\right) + \frac{2}{12} B\left(\frac{1}{2}\right) + \frac{4}{12} B\left(\frac{2}{4}\right) + \frac{4}{12} B\left(\frac{2}{4}\right) \right] = 0 \text{ bits}, \end{aligned}\]

confirming our intuition that Patrons is a better attribute to split on first. In fact, Patrons has the maximum information gain of any of the attributes and thus would be chosen by the decision tree learning algorithm as the root.

19.3.4 Generalization and overfitting

We want our learning algorithms to find a hypothesis that fits the training data, but more importantly, we want it to generalize well for previously unseen data. In Figure 19.1 we saw that a high-degree polynomial can fit all the data, but has wild swings that are not warranted by the data: it fits but can overfit. Overfitting becomes more likely as the number of attributes grows, and less likely as we increase the number of training examples. Larger hypothesis spaces (e.g., decision trees with more nodes or polynomials with high degree) have more capacity both to fit and to overfit; some model classes are more prone to overfitting than others.

For decision trees, a technique called decision tree pruning combats overfitting. Pruning works by eliminating nodes that are not clearly relevant. We start with a full tree, as generated by LEARN-DECISION-TREE. We then look at a test node that has only leaf nodes as descendants. If the test appears to be irrelevant—detecting only noise in the data—then we eliminate the test, replacing it with a leaf node. We repeat this process, considering each test with only leaf descendants, until each one has either been pruned or accepted as is.

Decision tree pruning

The question is, how do we detect that a node is testing an irrelevant attribute? Suppose we are at a node consisting of positive and negative examples. If the attribute is irrelevant, we would expect that it would split the examples into subsets such that each subset has roughly the same proportion of positive examples as the whole set, and so the information gain will be close to zero. Thus, a low information gain is a good clue that the attribute is irrelevant. Now the question is, how large a gain should we require in order to split on a particular attribute? 3

3 The gain will be strictly positive except for the unlikely case where all the proportions are exactly the same. (See Exercise 19.NNGA.)

We can answer this question by using a statistical significance test. Such a test begins by assuming that there is no underlying pattern (the so-called null hypothesis). Then the actual data are analyzed to calculate the extent to which they deviate from a perfect absence of pattern. If the degree of deviation is statistically unlikely (usually taken to mean a 5% probability or less), then that is considered to be good evidence for the presence of a

significant pattern in the data. The probabilities are calculated from standard distributions of the amount of deviation one would expect to see in random sampling.

Significance test

Null hypothesis

In this case, the null hypothesis is that the attribute is irrelevant and, hence, that the information gain for an infinitely large sample would be zero. We need to calculate the probability that, under the null hypothesis, a sample of size would exhibit the observed deviation from the expected distribution of positive and negative examples. We can measure the deviation by comparing the actual numbers of positive and negative examples in each subset, and with the expected numbers, and assuming true irrelevance:

\[ \hat{p}\_k = p \times \frac{p\_k + n\_k}{p + n} \qquad \qquad \hat{n}\_k = n \times \frac{p\_k + n\_k}{p + n}. \]

A convenient measure of the total deviation is given by

\[ \Delta = \sum\_{k=1}^{d} \frac{(p\_k - \hat{p}\_k)^2}{\hat{p}\_k} + \frac{(n\_k - \hat{n}\_k)^2}{\hat{n}\_k}. \]

Under the null hypothesis, the value of is distributed according to the (chi-squared) distribution with degrees of freedom. We can use a statistics function to see if a particular value confirms or rejects the null hypothesis. For example, consider the restaurant Type attribute, with four values and thus three degrees of freedom. A value of or more would reject the null hypothesis at the 5% level (and a value of or more would reject at the 1% level). Values below that lead to accepting the hypothesis that the attribute is irrelevant, and thus the associated branch of the tree should be pruned away. This is known as pruning.

pruning

With pruning, noise in the examples can be tolerated. Errors in the example’s label (e.g., an example that should be ) give a linear increase in prediction error, whereas errors in the descriptions of examples (e.g., when it was actually ) have an asymptotic effect that gets worse as the tree shrinks down to smaller sets. Pruned trees perform significantly better than unpruned trees when the data contain a large amount of noise. Also, the pruned trees are often much smaller and hence easier to understand and more efficient to execute.

One final warning: You might think that pruning and information gain look similar, so why not combine them using an approach called early stopping—have the decision tree algorithm stop generating nodes when there is no good attribute to split on, rather than going to all the trouble of generating nodes and then pruning them away. The problem with early stopping is that it stops us from recognizing situations where there is no one good attribute, but there are combinations of attributes that are informative. For example, consider the XOR function of two binary attributes. If there are roughly equal numbers of examples for all four combinations of input values, then neither attribute will be informative, yet the correct thing to do is to split on one of the attributes (it doesn’t matter which one), and then at the second level we will get splits that are very informative. Early stopping would miss this, but generate-and-then-prune handles it correctly.

Early stopping

19.3.5 Broadening the applicability of decision trees

Decision trees can be made more widely useful by handling the following complications:

MISSING DATA: In many domains, not all the attribute values will be known for every example. The values might have gone unrecorded, or they might be too expensive to obtain. This gives rise to two problems: First, given a complete decision tree, how

should one classify an example that is missing one of the test attributes? Second, how should one modify the information-gain formula when some examples have unknown values for the attribute? These questions are addressed in Exercise 19.MISS.

CONTINUOUS AND MULTIVALUED INPUT ATTRIBUTES: For continuous attributes like Height, Weight, or Time, it may be that every example has a different attribute value. The information gain measure would give its highest score to such an attribute, giving us a shallow tree with this attribute at the root, and single-example subtrees for each possible value below it. But that doesn’t help when we get a new example to classify with an attribute value that we haven’t seen before.

Split point

A better way to deal with continuous values is a split point test—an inequality test on the value of an attribute. For example, at a given node in the tree, it might be the case that testing on gives the most information. Efficient methods exist for finding good split points: start by sorting the values of the attribute, and then consider only split points that are between two examples in sorted order that have different classifications, while keeping track of the running totals of positive and negative examples on each side of the split point. Splitting is the most expensive part of realworld decision tree learning applications.

For attributes that are not continuous and do not have a meaningful ordering, but have a large number of possible values (e.g., Zipcode or CreditCardNumber), a measure called the information gain ratio (see Exercise 19.GAIN) can be used to avoid splitting into lots of single-example subtrees. Another useful approach is to allow an equality test of the form For example, the test could be used to pick out a large group of people in this zip code in New York City, and to lump everyone else into the “other” subtree.

CONTINUOUS-VALUED OUTPUT ATTRIBUTE: If we are trying to predict a numerical output value, such as the price of an apartment, then we need a regression tree rather than a classification tree. A regression tree has at each leaf a linear function of some subset of numerical attributes, rather than a single output value. For example, the branch for two-bedroom apartments might end with a linear function of square

footage and number of bathrooms. The learning algorithm must decide when to stop splitting and begin applying linear regression (see Section 19.6 ) over the attributes. The name CART, standing for Classification And Regression Trees, is used to cover both classes.

Regression tree

CART

A decision tree learning system for real-world applications must be able to handle all of these problems. Handling continuous-valued variables is especially important, because both physical and financial processes provide numerical data. Several commercial packages have been built that meet these criteria, and they have been used to develop thousands of fielded systems. In many areas of industry and commerce, decision trees are the first method tried when a classification method is to be extracted from a data set.

Decision trees have a lot going for them: ease of understanding, scalability to large data sets, and versatility in handling discrete and continuous inputs as well as classification and regression. However, they can have suboptimal accuracy (largely due to the greedy search), and if trees are very deep, then getting a prediction for a new example can be expensive in run time. Decision trees are also unstable in that adding just one new example can change the test at the root, which changes the entire tree. In Section 19.8.2 we will see that the random forest model can fix some of these issues.

Unstable

19.4 Model Selection and Optimization

Our goal in machine learning is to select a hypothesis that will optimally fit future examples. To make that precise we need to define “future example” and “optimal fit.”

First we will make the assumption that the future examples will be like the past. We call this the stationarity assumption; without it, all bets are off. We assume that each example has the same prior probability distribution:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(E\_{j}\right) = \mathbf{P}\left(E\_{j+1}\right) = \mathbf{P}\left(E\_{j+2}\right) = \cdots,\]

Stationarity

and is independent of the previous examples:

\[\mathbf{P}\left(E\_j\right) = \mathbf{P}\left(E\_j|E\_{j-1}, E\_{j-2}, \dots\right).\]

Examples that satisfy these equations are independent and identically distributed or i.i.d..

I.i.d.

The next step is to define “optimal fit.” For now, we will say that the optimal fit is the hypothesis that minimizes the error rate: the proportion of times that for an example. (Later we will expand on this to allow different errors to have different costs, in effect giving partial credit for answers that are “almost” correct.) We can estimate the error rate of a hypothesis by giving it a test: measure its performance on a test set of examples. It would be cheating for a hypothesis (or a student) to peek at the test answers before taking

the test. The simplest way to ensure this doesn’t happen is to split the examples you have into two sets: a training set to create the hypothesis, and a test set to evaluate it.

Error rate

If we are only going to create one hypothesis, then this approach is sufficient. But often we will end up creating multiple hypotheses: we might want to compare two completely different machine learning models, or we might want to adjust the various “knobs” within one model. For example, we could try different thresholds for pruning of decision trees, or different degrees for polynomials. We call these “knobs” hyperparameters—parameters of the model class, not of the individual model.

Hyperparameters

Suppose a researcher generates a hypotheses for one setting of the pruning hyperparameter, measures the error rates on the test set, and then tries different hyperparameters. No individual hypothesis has peeked at the test set data, but the overall process did, through the researcher.

The way to avoid this is to really hold out the test set—lock it away until you are completely done with training, experimenting, hyperparameter-tuning, re-training, etc. That means you need three data sets:

- 1. A training set to train candidate models.

- 2. A validation set, also known as a development set or dev set, to evaluate the candidate models and choose the best one.

Validation set

3. A test set to do a final unbiased evaluation of the best model.

What if we don’t have enough data to make all three of these data sets? We can squeeze more out of the data using a technique called -fold cross-validation. The idea is that each example serves double duty—as training data and validation data—but not at the same time. First we split the data into equal subsets. We then perform rounds of learning; on each round of the data are held out as a validation set and the remaining examples are used as the training set. The average test set score of the rounds should then be a better estimate than a single score. Popular values for are 5 and 10—enough to give an estimate that is statistically likely to be accurate, at a cost of 5 to 10 times longer computation time. The extreme is also known as leave-one-out cross-validation or LOOCV. Even with cross-validation, we still need a separate test set.

K-fold cross-validation

LOOCV

In Figure 19.1 (page 654) we saw a linear function underfit the data set, and a high-degree polynomial overfit the data. We can think of the task of finding a good hypothesis as two subtasks: model selection chooses a good hypothesis space, and optimization (also called training) finds the best hypothesis within that space. 4

4 Although the name “model selection” is in common use, a better name would have been “model class selection” or “hypothesis space selection.” The word “model” has been used in the literature to refer to three different levels of specificity: a broad hypothesis space (like “polynomials”), a hypothesis space with hyperparameters filled in (like “degree-2 polynomials”), and a specific hypothesis with all parameters filled in (like ).

Model selection

Optimization

Part of model selection is qualitative and subjective: we might select polynomials rather than decision trees based on something that we know about the problem. And part is quantitative and empirical: within the class of polynomials, we might select because that value performs best on the validation data set.

19.4.1 Model selection

Figure 19.8 describes a simple MODEL-SELECTION algorithm. It takes as argument a learning algorithm, Learner (for example, it could be LEARN-DECISION-TREE). Learner takes one hyperparameter, which is named size in the figure. For decision trees it could be the number of nodes in the tree; for polynomials size would be Degree. MODEL-SELECTION starts with the smallest value of size, yielding a simple model (which will probably underfit the data) and iterates through larger values of size, considering more complex models. In the end MODEL-SELECTION selects the model that has the lowest average error rate on the held-out validation data.

Figure 19.8

An algorithm to select the model that has the lowest validation error. It builds models of increasing complexity, and choosing the one with best empirical error rate, err, on the validation data set. Learner(size,examples) returns a hypothesis whose complexity is set by the parameter size, and which is trained on examples. In CROSS-VALIDATION, each iteration of the for loop selects a different slice of the examples as the validation set, and keeps the other examples as the training set. It then returns the average validation set error over all the folds. Once we have determined which value of the size parameter is best, MODEL-SELECTION returns the model (i.e., learner/hypothesis) of that size, trained on all the training examples, along with its error rate on the held-out test examples.

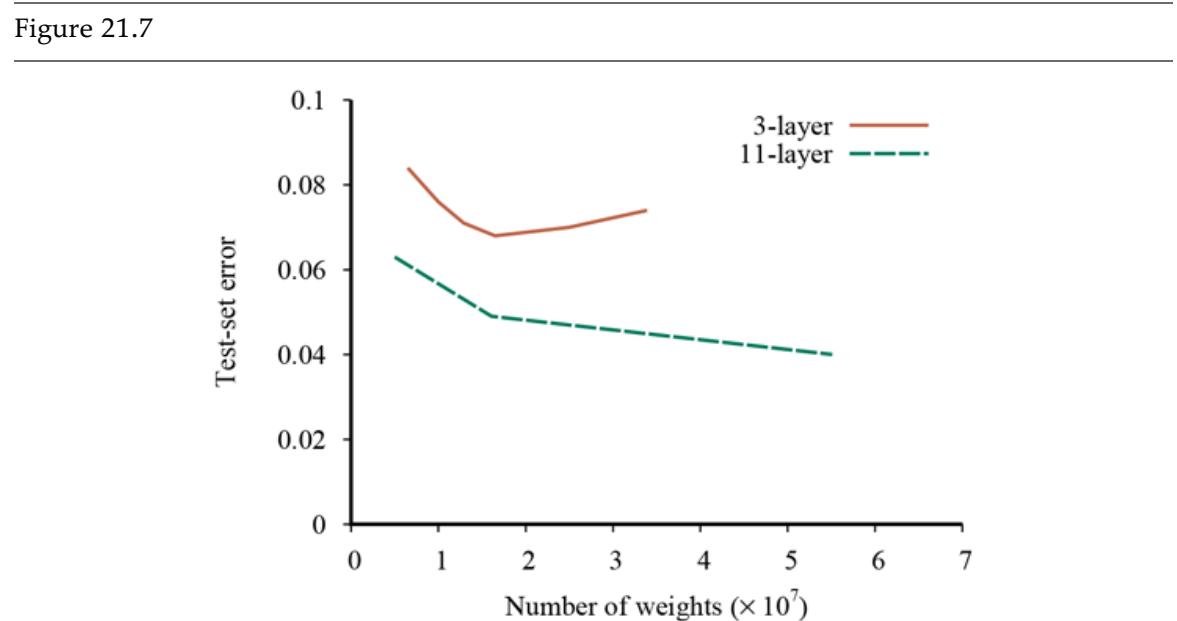

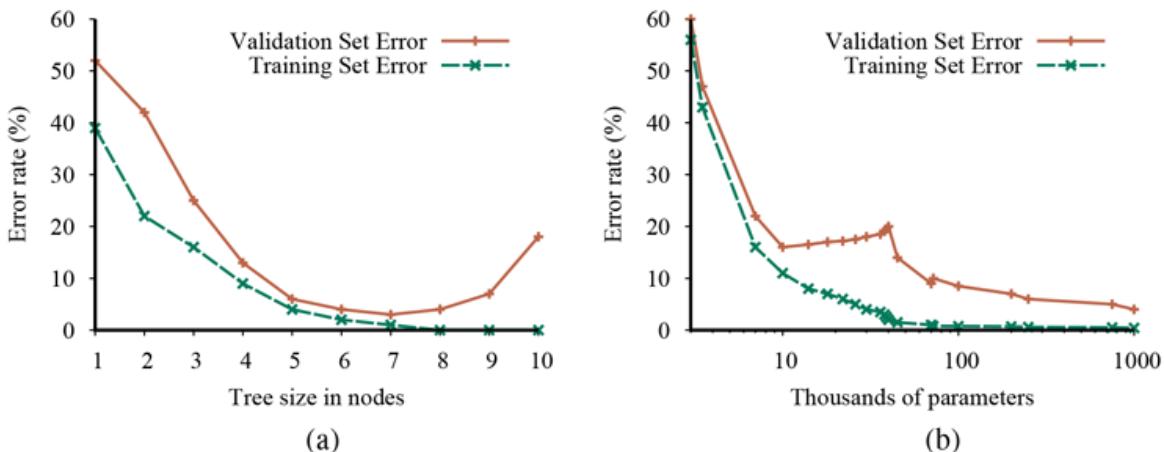

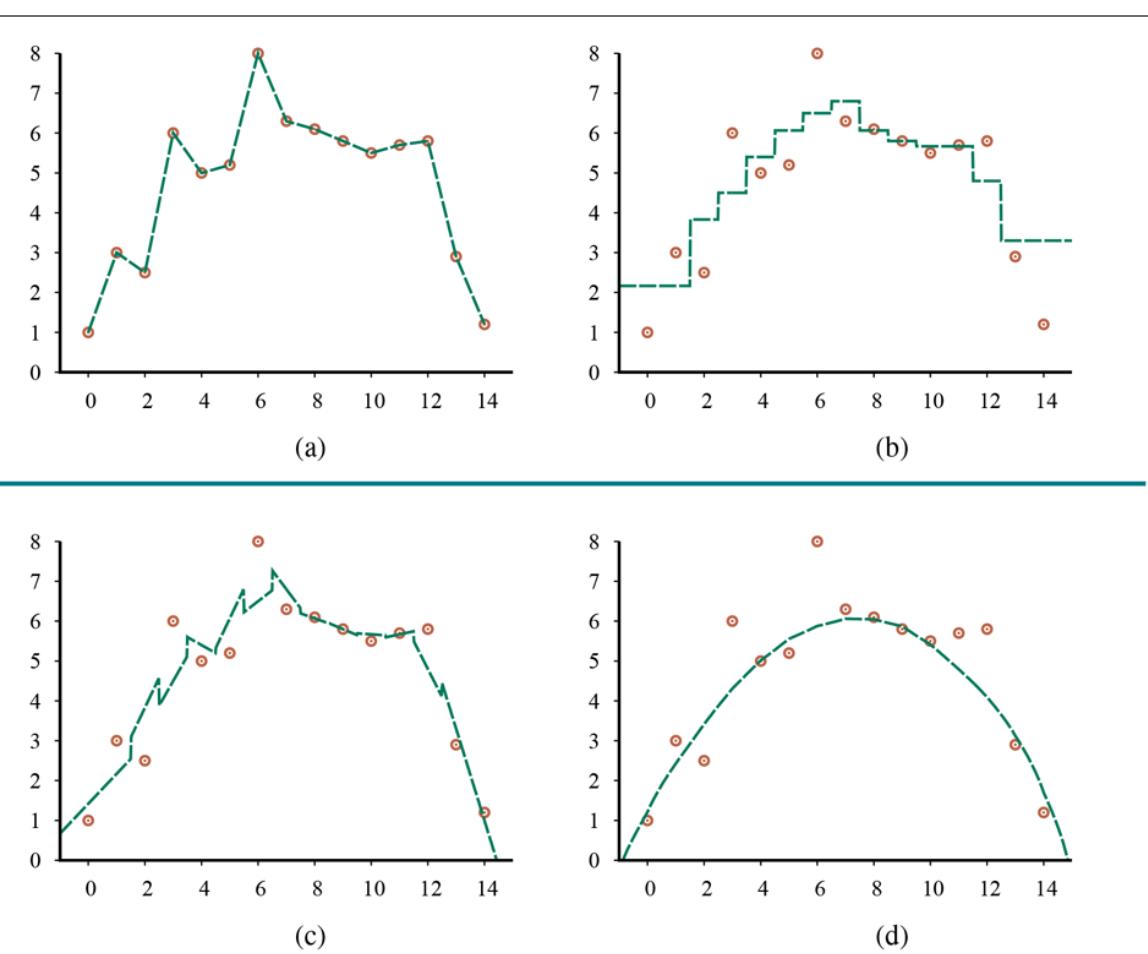

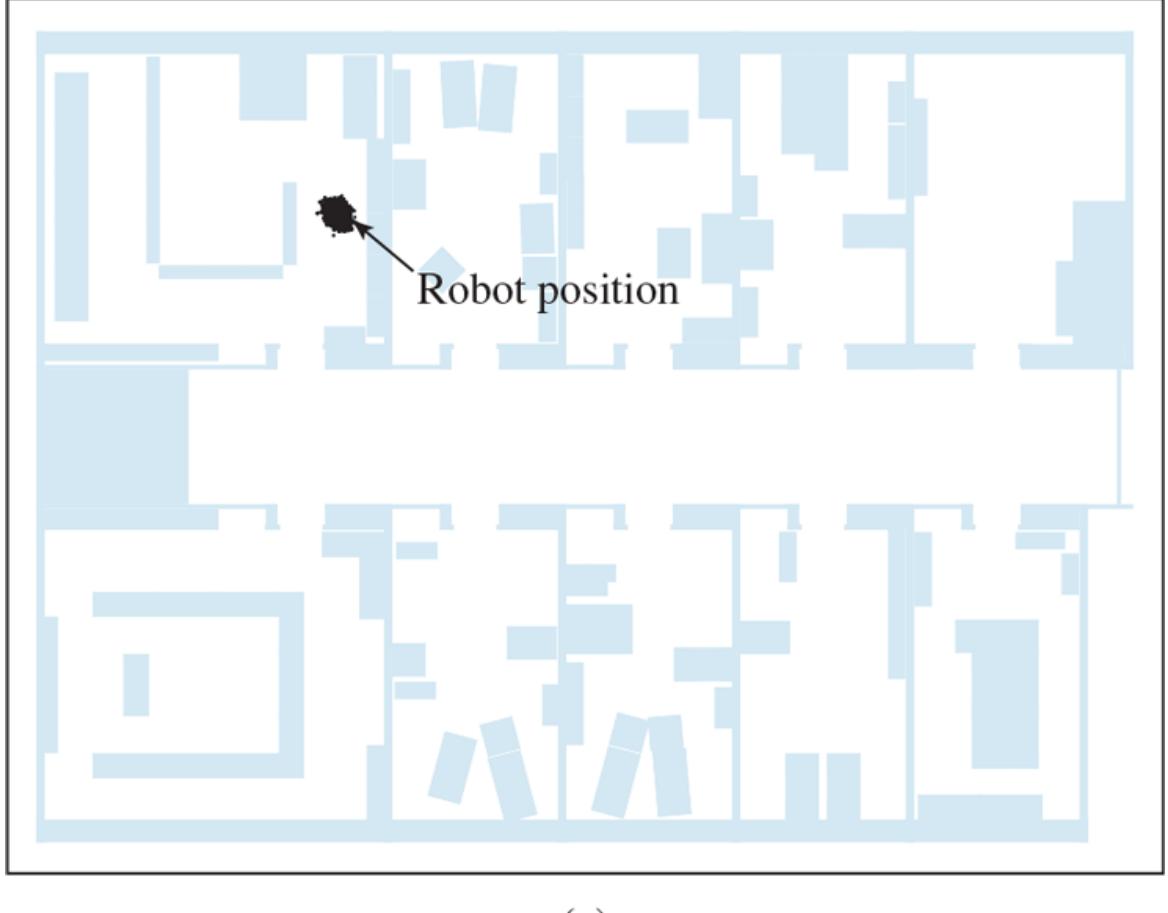

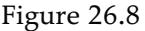

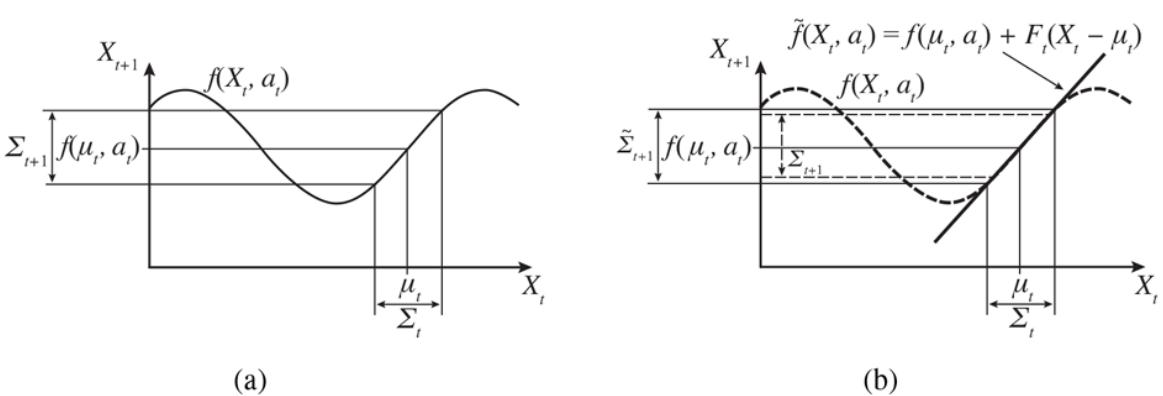

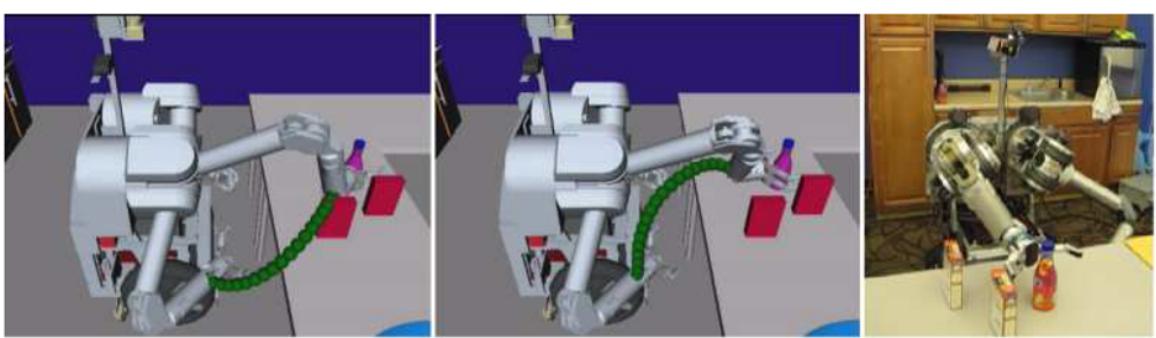

In Figure 19.9 we see two typical patterns that occur in model selection. In both (a) and (b) the training set error decreases monotonically (with slight random fluctuation) as we increase the complexity of the model. Complexity is measured by the number of decision tree nodes in (a) and by the number of neural network parameters in (b). For many model classes, the training set error reaches zero as the complexity increases.

Figure 19.9

Error rates on training data (lower, green line) and validation data (upper, orange line) for models of different complexity on two different problems. MODEL-SELECTION picks the hyperparameter value with the lowest validation-set error. In (a) the model class is decision trees and the hyperparameter is the number of nodes. The data is from a version of the restaurant problem. The optimal size is 7. In (b) the model class is convolutional neural networks (see Section 21.3 ) and the hyperparameter is the number of regular parameters in the network. The data is the MNIST data set of images of digits; the task is to identify each digit. The optimal number of parameters is 1,000,000 (note the log scale).

The two cases differ markedly in validation set error. In (a) we see a U-shaped validationerror curve: error decreases for a while as model complexity increases, but then we reach a point where the model begins to overfit, and validation error rises. MODEL-SELECTION picks the value at the bottom of the U-shaped validation-error curve: in this case a tree with size 7. This is the spot that best balances underfitting and overfitting. In (b) we see an initial Ushaped curve just as in (a) but then the validation error starts to decrease again; the lowest validation error rate is the final point in the plot, with 1,000,000 parameters.

Why are some validation-error curves like (a) and some like (b)? It comes down to how the different model classes make use of excess capacity, and how well that matches up with the problem at hand. As we add capacity to a model class, we often reach the point where all the training examples can be represented perfectly within the model. For example, given a training set with distinct examples, there is always a decision tree with leaf nodes that can represent all the examples.

Interpolated

We say that a model that exactly fits all the training data has interpolated the data. Model classes typically start to overfit as the capacity approaches the point of interpolation. That seems to be because most of the model’s capacity is concentrated on the training examples, and the capacity that remains is allocated rather randomly in a way that is not representative of the patterns in the validation data set. Some model classes never recover from this overfitting, as with the decision trees in (a). But for other model classes, adding capacity means that there are more candidate functions, and some of them are naturally well-suited to the patterns of data that are in the true function The higher the capacity, the more of these suitable representations there are, and the more likely that the optimization mechanism will be able to land on one. 5

19.4.2 From error rates to loss

So far, we have been trying to minimize error rate. This is clearly better than maximizing error rate, but it is not the full story. Consider the problem of classifying email messages as spam or non-spam. It is worse to classify non-spam as spam (and thus potentially miss an important message) than to classify spam as non-spam (and thus suffer a few seconds of annoyance). So a classifier with a 1% error rate, where almost all the errors were classifying spam as non-spam, would be better than a classifier with only a 0.5% error rate, if most of those errors were classifying non-spam as spam. We saw in Chapter 16 that decision makers should maximize expected utility, and utility is what learners should maximize as well. However, in machine learning it is traditional to express this as a negative: to minimize a loss function rather than maximize a utility function. The loss function

is defined as the amount of utility lost by predicting when the correct answer is

Loss function

This is the most general formulation of the loss function. Often a simplified version is used, that is independent of We will use the simplified version for the rest of this chapter, which means we can’t say that it is worse to misclassify a letter from Mom than it is to misclassify a letter from our annoying cousin, but we can say that it is 10 times worse to classify non-spam as spam than vice versa:

Note that is always zero; by definition there is no loss when you guess exactly right. For functions with discrete outputs, we can enumerate a loss value for each possible misclassification, but we can’t enumerate all the possibilities for real-valued data. If is 137.035999, we would be fairly happy with but just how happy should we be? In general, small errors are better than large ones; two functions that implement that idea are the absolute value of the difference (called the loss), and the square of the difference (called the loss; think “2” for square). For discrete-valued outputs, if we are content with the idea of minimizing error rate, we can use the loss function, which has a loss of 1 for an incorrect answer:

Theoretically, the learning agent maximizes its expected utility by choosing the hypothesis that minimizes expected loss over all input–output pairs it will see. To compute this expectation we need to define a prior probability distribution over examples. Let

be the set of all possible input–output examples. Then the expected generalization loss for a hypothesis (with respect to loss function ) is

\[GenLoss\_L(h) = \sum\_{(x,y)\in \varepsilon} L(y, h(x)) \, P(x, y) \,, .\]

Generalization loss

and the best hypothesis, is the one with the minimum expected generalization loss:

\[h^\* = \underset{h \in H}{\text{argmin}} \, GenLoss\_L(h).\]

Because is not known in most cases, the learning agent can only estimate generalization loss with empirical loss on a set of examples of size

\[EmpLoss\_{L,E}(h) = \sum\_{(x,y)\in E} L(y, h(x))\,\frac{1}{N} \,.\]

Empirical loss

The estimated best hypothesis is then the one with minimum empirical loss:

\[ \hat{h}^\* = \underset{h \in H}{\text{argmin }} EmpLoss\_{L,E}(h). \]

There are four reasons why may differ from the true function, unrealizability, variance, noise, and computational complexity.

First, we say that a learning problem is realizable if the hypothesis space actually contains the true function If is the set of linear functions, and the true function is a quadratic function, then no amount of data will recover the true Second, variance means that a

learning algorithm will in general return different hypotheses for different sets of examples. If the problem is realizable, then variance decreases towards zero as the number of training examples increases. Third, may be nondeterministic or noisy—it may return different values of for the same By definition, noise cannot be predicted (it can only be characterized). And finally, when is a complicated function in a large hypothesis space, it can be computationally intractable to systematically search all possibilities; in that case, a search can explore part of the space and return a reasonably good hypothesis, but can’t always guarantee the best one.

Realizable

Noise

Traditional methods in statistics and the early years of machine learning concentrated on small-scale learning, where the number of training examples ranged from dozens to the low thousands. Here the generalization loss mostly comes from the approximation error of not having the true in the hypothesis space, and from the estimation error of not having enough training examples to limit variance.

Small-scale learning

In recent years there has been more emphasis on large-scale learning, with millions of examples. Here the generalization loss may be dominated by limits of computation: there are enough data and a rich enough model that we could find an that is very close to the true but the computation to find it is complex, so we settle for an approximation.

Large-scale learning

19.4.3 Regularization

In Section 19.4.1 , we saw how to do model selection with cross-validation. An alternative approach is to search for a hypothesis that directly minimizes the weighted sum of empirical loss and the complexity of the hypothesis, which we will call the total cost:

Here is a hyperparameter, a positive number that serves as a conversion rate between loss and hypothesis complexity. If is chosen well, it nicely balances the empirical loss of a simple function against a complicated function’s tendency to overfit.

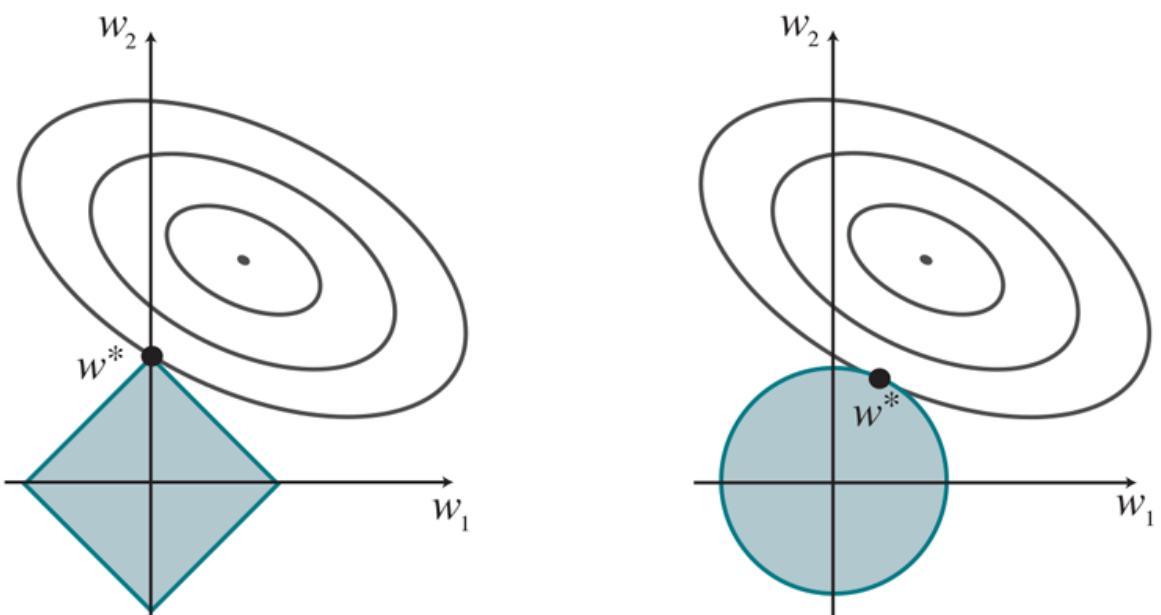

This process of explicitly penalizing complex hypotheses is called regularization: we’re looking for functions that are more regular. Note that we are now making two choices: the loss function ( or ), and the complexity measure, which is called a regularization function. The choice of regularization function depends on the hypothesis space. For example, for polynomials, a good regularization function is the sum of the squares of the coefficients—keeping the sum small would guide us away from the wiggly degree-12 polynomial in Figure 19.1 . We will show an example of this type of regularization in Section 19.6.3 .

Regularization

Regularization function

Another way to simplify models is to reduce the dimensions that the models work with. A process of feature selection can be performed to discard attributes that appear to be irrelevant. pruning is a kind of feature selection.

Feature selection

It is in fact possible to have the empirical loss and the complexity measured on the same scale, without the conversion factor they can both be measured in bits. First encode the hypothesis as a Turing machine program, and count the number of bits. Then count the number of bits required to encode the data, where a correctly predicted example costs zero bits and the cost of an incorrectly predicted example depends on how large the error is. The minimum description length or MDL hypothesis minimizes the total number of bits required. This works well in the limit, but for smaller problems the choice of encoding for the program—how best to encode a decision tree as a bit string—affects the outcome. In Chapter 20 (page 724), we describe a probabilistic interpretation of the MDL approach.

Minimum description length

19.4.4 Hyperparameter tuning

In Section 19.4.1 we showed how to select the best value of the hyperparameter size by applying cross-validation to each possible value until the validation error rate increases. That is a good approach when there is a single hyperparameter with a small number of possible values. But when there are multiple hyperparameters, or when they have continuous values, it is more difficult to choose good values.

The simplest approach to hyperparameter tuning is hand-tuning: guess some parameter values based on past experience, train a model, measure its performance on the validation data, analyze the results, and use your intuition to suggest new parameter values. Repeat

until you have satisfactory performance (or you run out of time, computing budget, or patience).

Hand-tuning

If there are only a few hyperparameters, each with a small number of possible values, then a more systematic approach called grid search is appropriate: try all combinations of values and see which performs best on the validation data. Different combinations can be run in parallel on different machines, so if you have sufficient computing resources, this need not be slow, although in some cases model selection has been known to suck up resources on thousand-computer clusters for days at a time.

Grid search

The search strategies from Chapters 3 and 4 can also come into play. For example, if two hyperparameters are independent of each other, they can be optimized separately.

If there are too many combinations of possible values, then random search samples uniformly from the set of all possible hyperparameter settings, repeating for as long as you are willing to spend the time and computational resources. Random sampling is also a good way to handle continuous values.

Random search

When each training run takes a long time, it can be helpful to get useful information out of each one. Bayesian optimization treats the task of choosing good hyperparameter values as a machine learning problem in itself. That is, think of the vector of hyperparameter values as an input, and the total loss on the validation set for the model built with those hyperparameters as an output, then we are trying to find the function that minimizes the loss Each time we do a training run we get a new pair, which we can use to update our belief about the shape of the function

Bayesian optimization

The idea is to trade off exploitation (choosing parameter values that are near to a previous good result) with exploration (trying novel parameter values). This is the same tradeoff we saw in Monte Carlo tree search (Section 5.4 ), and in fact the idea of upper confidence bounds is used here as well to minimize regret. If we make the assumption that can be approximated by a Gaussian process, then the math of updating our belief about works out nicely. Snoek et al. (2013) explain the math and give a practical guide to the approach, showing that it can outperform hand-tuning of parameters, even by experts.

Population-based training (PBT)

An alternative to Bayesian optimization is population-based training (PBT). PBT starts by using random search to train (in parallel) a population of models, each with different hyperparameter values. Then a second generation of models are trained, but they can choose hyperparameter values based on the successful values from the previous generation, as well as by random mutation, as in genetic algorithms (Section 4.1.4 ). Thus, populationbased training shares the advantage of random search that many runs can be done in parallel, and it shares the advantage of Bayesian optimization (or of hand-tuning by a clever human) that we can gain information from earlier runs to inform later ones.

19.5 The Theory of Learning

How can we be sure that our learned hypothesis will predict well for previously unseen inputs? That is, how do we know that the hypothesis is close to the target function if we don’t know what is? These questions have been pondered for centuries, by Ockham, Hume, and others. In recent decades, other questions have emerged: how many examples do we need to get a good What hypothesis space should we use? If the hypothesis space is very complex, can we even find the best or do we have to settle for a local maximum? How complex should be? How do we avoid overfitting? This section examines these questions.

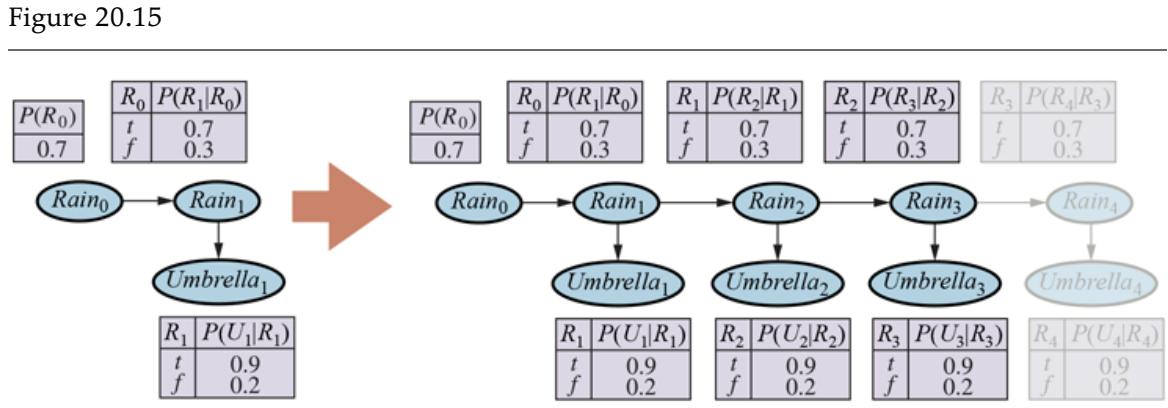

We’ll start with the question of how many examples are needed for learning. We saw from the learning curve for decision tree learning on the restaurant problem (Figure 19.7 on page 661 ) that accuracy improves with more training data. Learning curves are useful, but they are specific to a particular learning algorithm on a particular problem. Are there some more general principles governing the number of examples needed?

Questions like this are addressed by computational learning theory, which lies at the intersection of AI, statistics, and theoretical computer science. The underlying principle is that any hypothesis that is seriously wrong will almost certainly be “found out” with high probability after a small number of examples, because it will make an incorrect prediction. Thus, any hypothesis that is consistent with a sufficiently large set of training examples is unlikely to be seriously wrong: that is, it must be probably approximately correct (PAC).

Computational learning theory

Probably approximately correct (PAC)

Any learning algorithm that returns hypotheses that are probably approximately correct is called a PAC learning algorithm; we can use this approach to provide bounds on the performance of various learning algorithms.

PAC learning

PAC-learning theorems, like all theorems, are logical consequences of axioms. When a theorem (as opposed to, say, a political pundit) states something about the future based on the past, the axioms have to provide the “juice” to make that connection. For PAC learning, the juice is provided by the stationarity assumption introduced on page 665 , which says that future examples are going to be drawn from the same fixed distribution as past examples. (Note that we do not have to know what distribution that is, just that it doesn’t change.) In addition, to keep things simple, we will assume that the true function is deterministic and is a member of the hypothesis space that is being considered.

The simplest PAC theorems deal with Boolean functions, for which the 0/1 loss is appropriate. The error rate of a hypothesis defined informally earlier, is defined formally here as the expected generalization error for examples drawn from the stationary distribution:

\[\text{error}(h) = \text{GenLoss}\_{L\_{0/1}}(h) = \sum\_{x,y} L\_{0/1}(y, h(x)) \, P(x, y).\]

In other words, is the probability that misclassifies a new example. This is the same quantity being measured experimentally by the learning curves shown earlier.

A hypothesis is called approximately correct if where is a small constant. We will show that we can find an such that, after training on examples, with high probability, all consistent hypotheses will be approximately correct. One can think of an approximately correct hypothesis as being “close” to the true function in hypothesis space: it lies inside what is called the around the true function The hypothesis space outside this ball is called

We can derive a bound on the probability that a “seriously wrong” hypothesis is consistent with the first examples as follows. We know that Thus, the probability that it agrees with a given example is at most Since the examples are independent, the bound for examples is:

\[P(h\_b \text{ agrees with } N \text{ examples}) \le (1 - \epsilon)^N.\]

The probability that contains at least one consistent hypothesis is bounded by the sum of the individual probabilities:

\[P(H\_{\text{bad}} \text{ contains a consistent hypothesis}) \le |H\_{\text{bad}}| (1 - \epsilon)^N \le |H| (1 - \epsilon)^N,\]

where we have used the fact that is a subset of and thus We would like to reduce the probability of this event below some small number

\[P(H\_{\text{bad}} \text{ contains a consistent hypothesis}) \le |H|(1 - \epsilon)^N \le \delta.\]

Given that we can achieve this if we allow the algorithm to see

(19.1)

\[N \geq \frac{1}{\epsilon} \left( \ln \frac{1}{\delta} + \ln |H| \right)\]

examples. Thus, with probability at least after seeing this many examples, the learning algorithm will return a hypothesis that has error at most In other words, it is probably approximately correct. The number of required examples, as a function of and is called the sample complexity of the learning algorithm.

Sample complexity

As we saw earlier, if is the set of all Boolean functions on attributes, then Thus, the sample complexity of the space grows as Because the number of possible examples is also this suggests that PAC-learning in the class of all Boolean functions requires seeing all, or nearly all, of the possible examples. A moment’s thought reveals the reason for this: contains enough hypotheses to classify any given set of examples in all possible ways. In particular, for any set of examples, the set of hypotheses consistent with those examples contains equal numbers of hypotheses that predict to be positive and hypotheses that predict to be negative.

To obtain real generalization to unseen examples, then, it seems we need to restrict the hypothesis space in some way; but of course, if we do restrict the space, we might eliminate the true function altogether. There are three ways to escape this dilemma.

The first is to bring prior knowledge to bear on the problem.

The second, which we introduced in Section 19.4.3 , is to insist that the algorithm return not just any consistent hypothesis, but preferably a simple one (as is done in decision tree learning). In cases where finding simple consistent hypotheses is tractable, the sample complexity results are generally better than for analyses based only on consistency.

The third, which we pursue next, is to focus on learnable subsets of the entire hypothesis space of Boolean functions. This approach relies on the assumption that the restricted hypothesis space contains a hypothesis that is close enough to the true function the benefits are that the restricted hypothesis space allows for effective generalization and is typically easier to search. We now examine one such restricted hypothesis space in more detail.

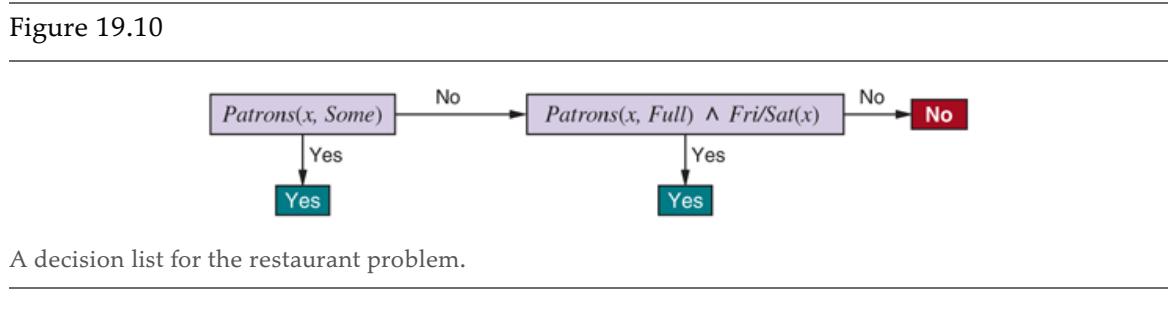

19.5.1 PAC learning example: Learning decision lists

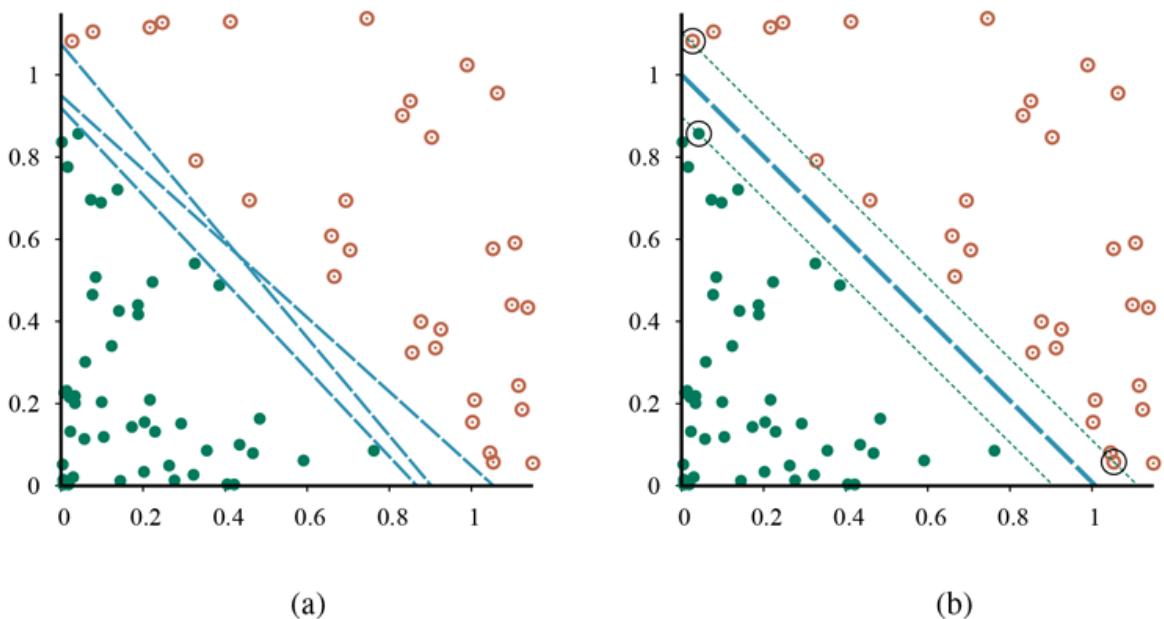

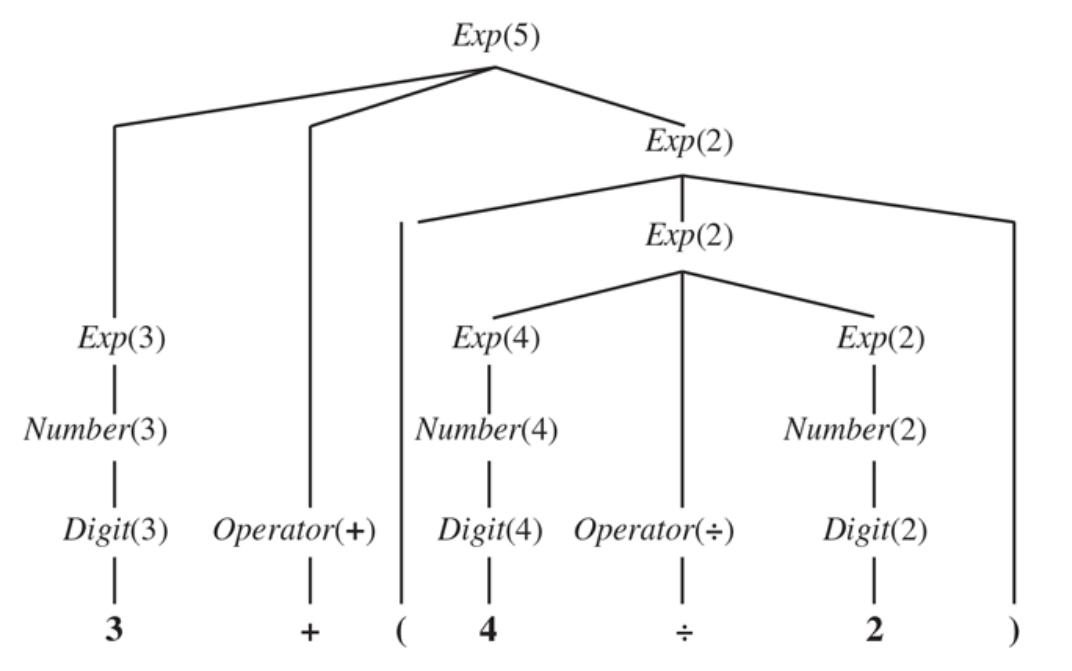

We now show how to apply PAC learning to a new hypothesis space: decision lists. A decision list consists of a series of tests, each of which is a conjunction of literals. If a test succeeds when applied to an example description, the decision list specifies the value to be returned. If the test fails, processing continues with the next test in the list. Decision lists resemble decision trees, but their overall structure is simpler: they branch only in one direction. In contrast, the individual tests are more complex. Figure 19.10 shows a decision list that represents the following hypothesis:

If we allow tests of arbitrary size, then decision lists can represent any Boolean function (Exercise 19.DLEX). On the other hand, if we restrict the size of each test to at most literals, then it is possible for the learning algorithm to generalize successfully from a small number of examples. We use the notation for a decision list with up to conjunctions. The example in Figure 19.10 is in 2-DL. It is easy to show (Exercise 19.DLEX) that includes as a subset the set of all decision trees of depth at most We will use the notation to denote a using Boolean attributes.

K-DT

The first task is to show that is learnable—that is, that any function in can be approximated accurately after training on a reasonable number of examples. To do this, we need to calculate the number of possible hypotheses. Let the set of conjunctions of at most literals using attributes be Because a decision list is constructed from tests, and because each test can be attached to either a Yes or a No outcome or can be absent from the decision list, there are at most distinct sets of component tests. Each of these sets of tests can be in any order, so

\[|k \text{-DL}(n)| \le 3^c c! \text{ where } c = |C \\ con j(n, k)|.\]

The number of conjunctions of at most literals from attributes is given by

\[\left| \operatorname{Con} j(n,k) \right| = \sum\_{i=0}^{k} \binom{2n}{i} = O(n^k).\]

Hence, after some work, we obtain

\[\left|k \operatorname{\cdotDL}(n)\right| = 2^{O(n^k \log\_2(n^k))}.\]

We can plug this into Equation (19.1) to show that the number of examples needed for PAC-learning a function is polynomial in

\[N \ge \frac{1}{\epsilon} \left( \ln \frac{1}{\delta} + O(n^k \log\_2(n^k)) \right).\]

Therefore, any algorithm that returns a consistent decision list will PAC-learn a function in a reasonable number of examples, for small

The next task is to find an efficient algorithm that returns a consistent decision list. We will use a greedy algorithm called DECISION-LIST-LEARNING that repeatedly finds a test that agrees exactly with some subset of the training set. Once it finds such a test, it adds it to the decision list under construction and removes the corresponding examples. It then constructs the remainder of the decision list, using just the remaining examples. This is repeated until there are no examples left. The algorithm is shown in Figure 19.11 .

Figure 19.11

An algorithm for learning decision lists.

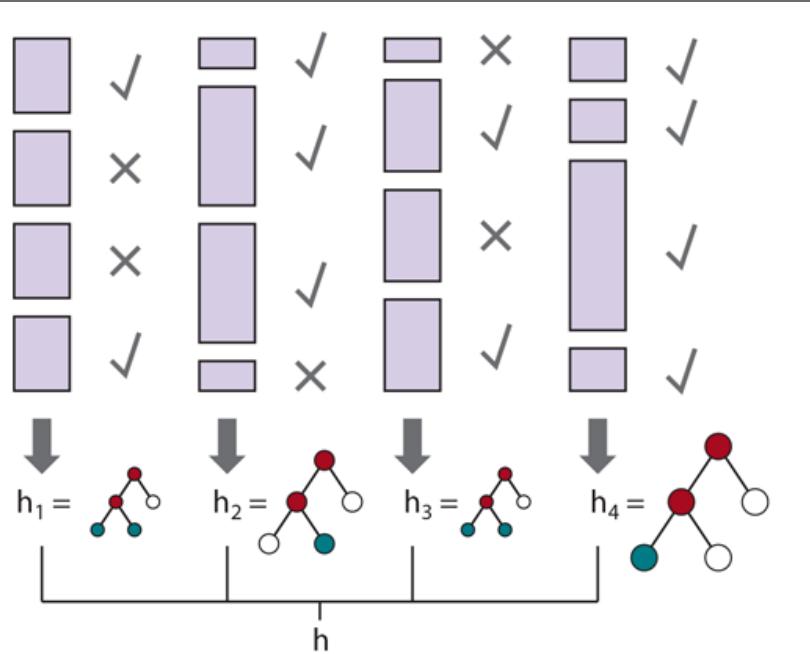

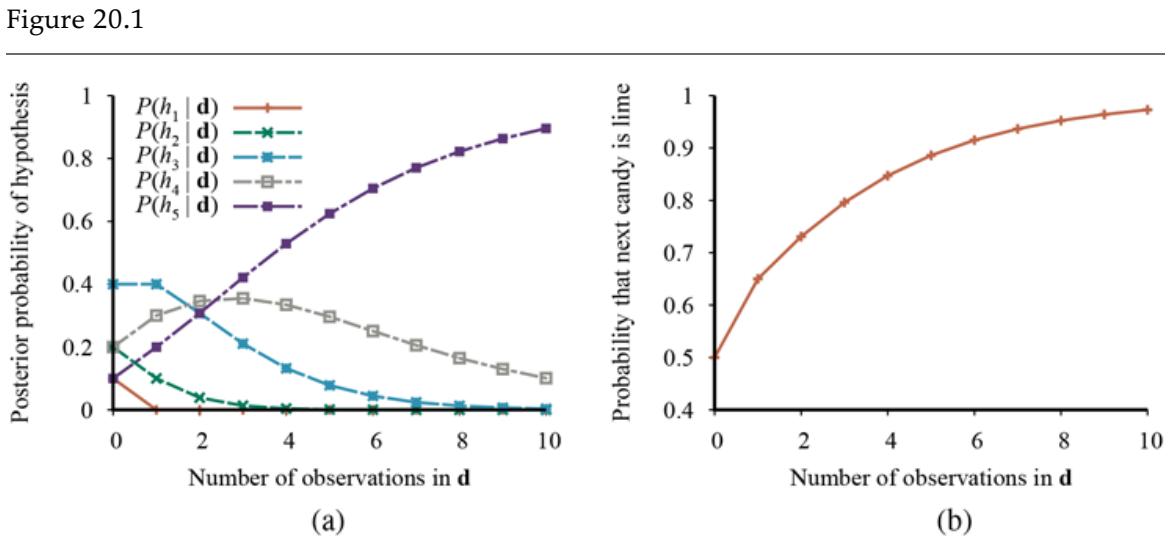

This algorithm does not specify the method for selecting the next test to add to the decision list. Although the formal results given earlier do not depend on the selection method, it would seem reasonable to prefer small tests that match large sets of uniformly classified examples, so that the overall decision list will be as compact as possible. The simplest strategy is to find the smallest test that matches any uniformly classified subset, regardless of the size of the subset. Even this approach works quite well, as Figure 19.12 suggests. For this problem, the decision tree learns a bit faster than the decision list, but has more variation. Both methods are over 90% accurate after 100 trials.

Learning curve for DECISION-LIST-LEARNING algorithm on the restaurant data. The curve for LEARN-DECISION-TREE is shown for comparison; decision trees do slightly better on this particular problem.

19.6 Linear Regression and Classification

Now it is time to move on from decision trees and lists to a different hypothesis space, one that has been used for hundreds of years: the class of linear functions of continuous-valued inputs. We’ll start with the simplest case: regression with a univariate linear function, otherwise known as “fitting a straight line.” Section 19.6.3 covers the multivariable case. Sections 19.6.4 and 19.6.5 show how to turn linear functions into classifiers by applying hard and soft thresholds.

Linear function

19.6.1 Univariate linear regression

A univariate linear function (a straight line) with input and output has the form where and are real-valued coefficients to be learned. We use the letter because we think of the coefficients as weights; the value of is changed by changing the relative weight of one term or another. We’ll define to be the vector and define the linear function with those weights as

\[h\_{\mathbf{w}}(x) = w\_1 x + w\_0.\]

Weight

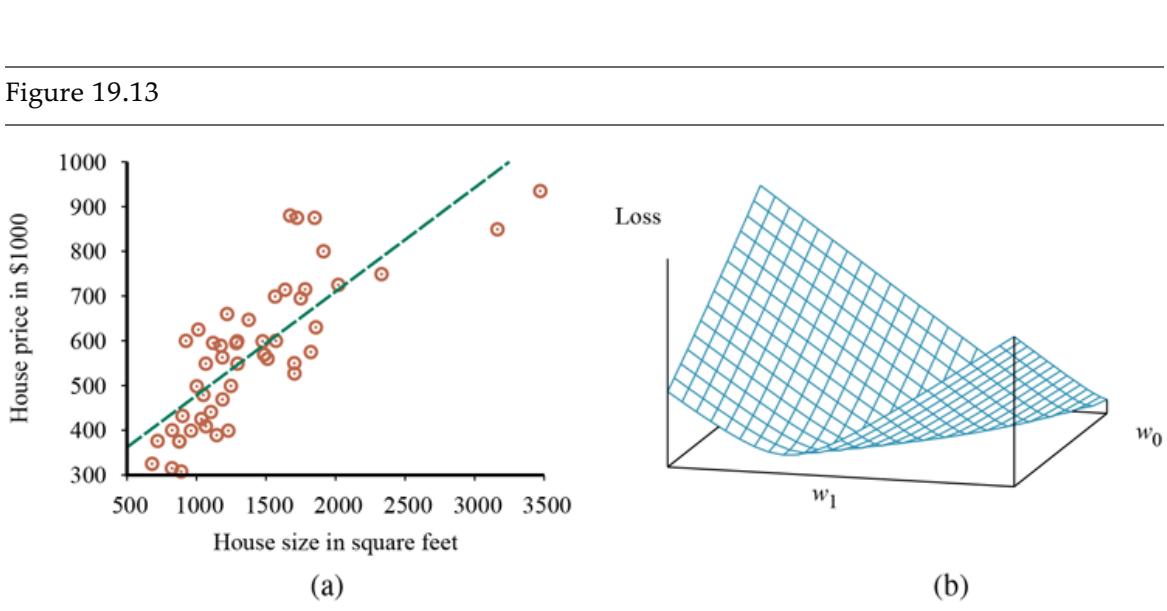

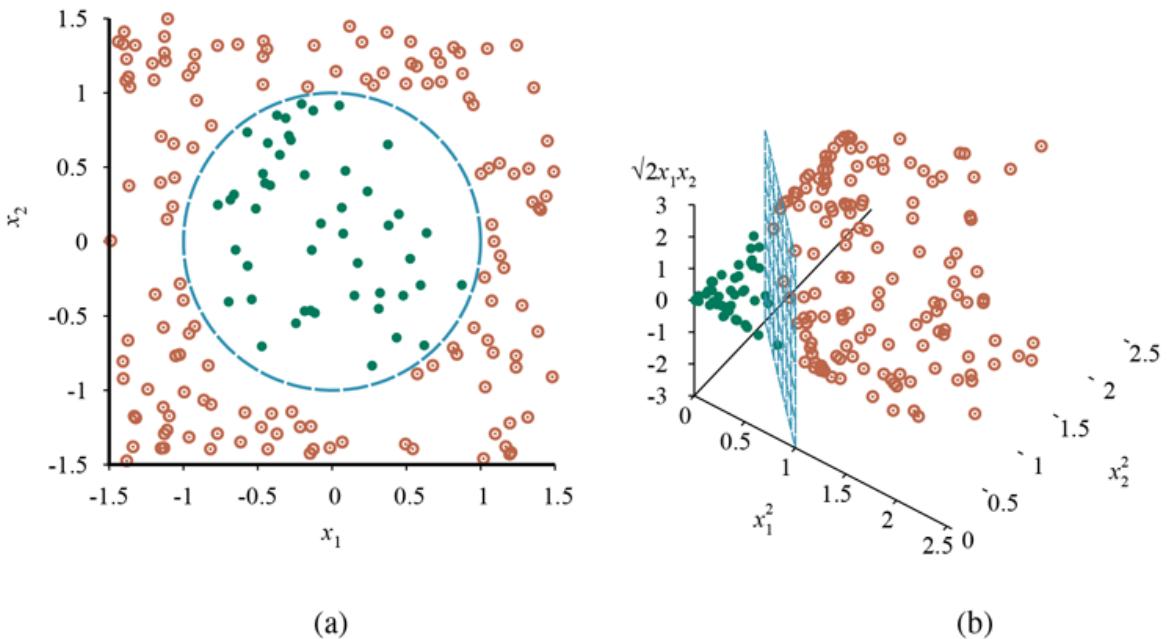

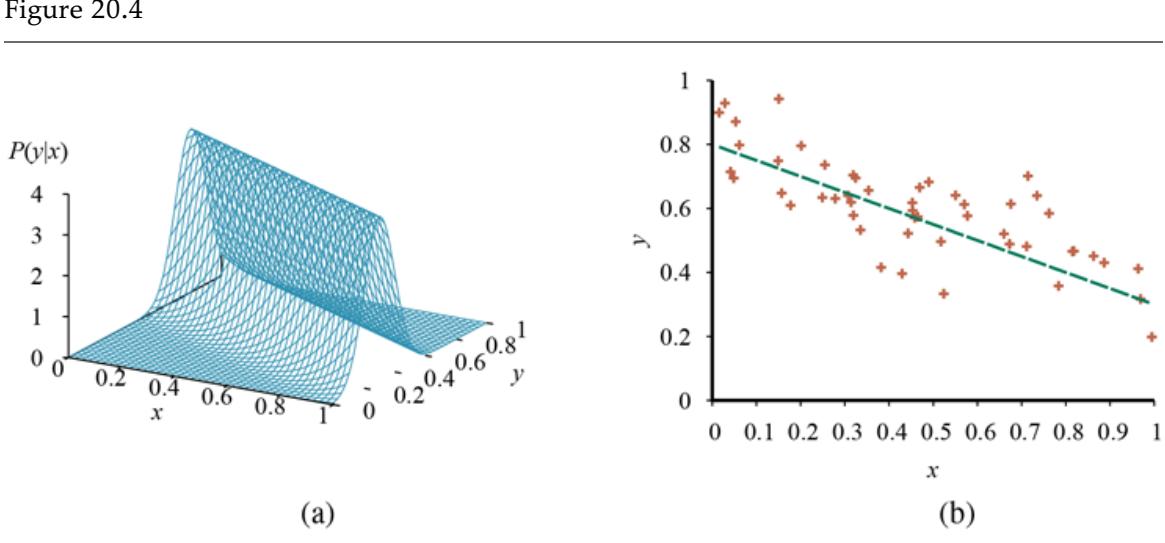

Figure 19.13(a) shows an example of a training set of points in the plane, each point representing the size in square feet and the price of a house offered for sale. The task of finding the that best fits these data is called linear regression. To fit a line to the data, all we have to do is find the values of the weights that minimize the empirical loss. It is traditional (going back to Gauss ) to use the squared-error loss function, summed over all the training examples: 6

6 Gauss showed that if the values have normally distributed noise, then the most likely values of and are obtained by using loss, minimizing the sum of the squares of the errors. (If the values have noise that follows a Laplace (double exponential) distribution, then loss is appropriate.)

\[Loss(h\_{\mathbf{w}}) = \sum\_{j=1}^{N} L\_2\left(y\_j, h\_{\mathbf{w}}\left(x\_j\right)\right) = \sum\_{j=1}^{N} \left(y\_j - h\_{\mathbf{w}}\left(x\_j\right)\right)^2 = \sum\_{j=1}^{N} \left(y\_j - \left(w\_1 x\_j + w\_0\right)\right)^2.\]

Linear regression

- Data points of price versus floor space of houses for sale in Berkeley, CA, in July 2009, along with the linear function hypothesis that minimizes squared-error loss: (b) Plot of the loss function for various values of Note that the loss function is convex, with a single global minimum.

We would like to find The sum is minimized when its partial derivatives with respect to and are zero:

(19.2)

\[\frac{\partial}{\partial w\_0} \sum\_{j=1}^N (y\_j - (w\_1 x\_j + w\_0))^2 = 0 \text{ and } \frac{\partial}{\partial w\_1} \sum\_{j=1}^N (y\_j - (w\_1 x\_j + w\_0))^2 = 0.\]

These equations have a unique solution:

(19.3)

\[w\_1 = \frac{N\left(\sum x\_j y\_j\right) - \left(\sum x\_j\right)\left(\sum y\_j\right)}{N\left(\sum x\_j^2\right) - \left(\sum x\_j\right)^2}; \qquad w\_0 = \left(\sum y\_j - w\_1\left(\sum x\_j\right)\right) / N.\]

For the example in Figure 19.13(a) , the solution is and the line with those weights is shown as a dashed line in the figure.

Many forms of learning involve adjusting weights to minimize a loss, so it helps to have a mental picture of what’s going on in weight space—the space defined by all possible settings of the weights. For univariate linear regression, the weight space defined by and is two-dimensional, so we can graph the loss as a function of and in a 3D plot (see Figure 19.13(b) ). We see that the loss function is convex, as defined on page 122; this is true for every linear regression problem with an loss function, and implies that there are no local minima. In some sense that’s the end of the story for linear models; if we need to fit lines to data, we apply Equation (19.3) . 7

7 With some caveats: the loss function is appropriate when there is normally distributed noise that is independent of all results rely on the stationarity assumption; etc.

Weight space

19.6.2 Gradient descent

The univariate linear model has the nice property that it is easy to find an optimal solution where the partial derivatives are zero. But that won’t always be the case, so we introduce here a method for minimizing loss that does not depend on solving to find zeroes of the derivatives, and can be applied to any loss function, no matter how complex.

As discussed in Section 4.2 (page 119) we can search through a continuous weight space by incrementally modifying the parameters. There we called the algorithm hill climbing, but here we are minimizing loss, not maximizing gain, so we will use the term gradient descent. We choose any starting point in weight space—here, a point in the ( ) plane and then compute an estimate of the gradient and move a small amount in the steepest downhill direction, repeating until we converge on a point in weight space with (local) minimum loss. The algorithm is as follows:

(19.4)

Gradient descent

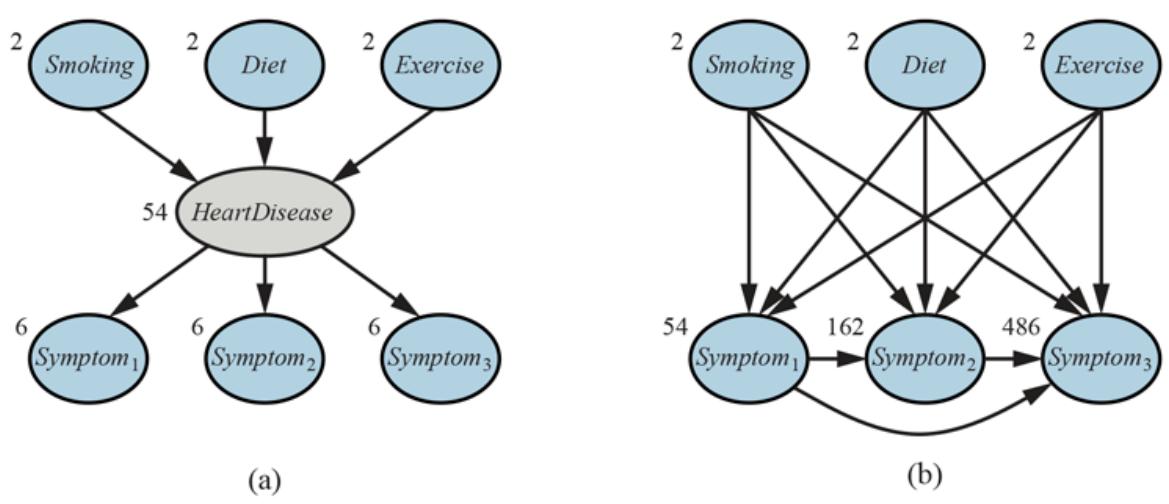

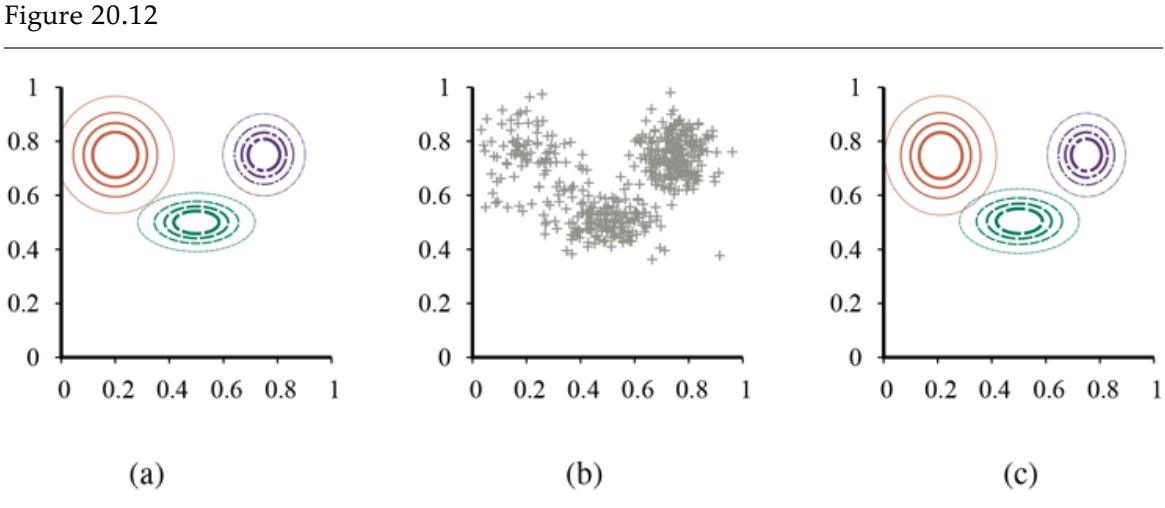

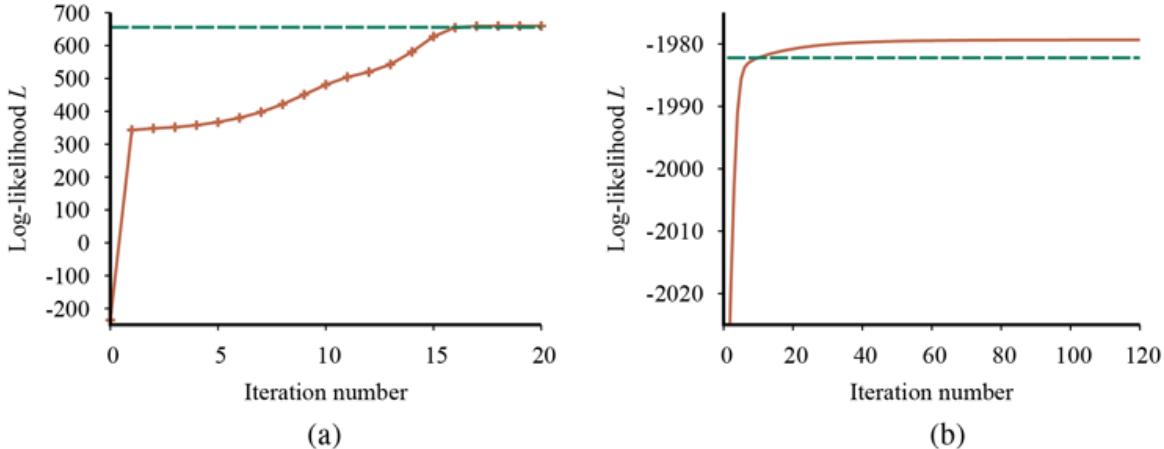

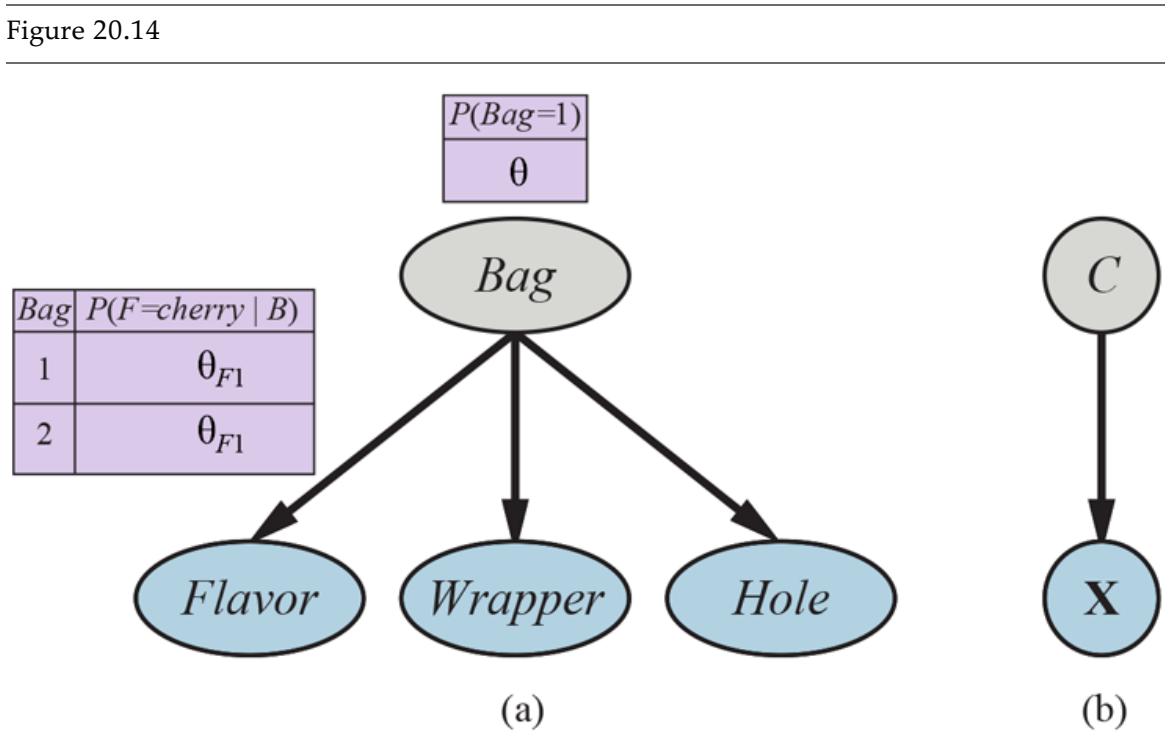

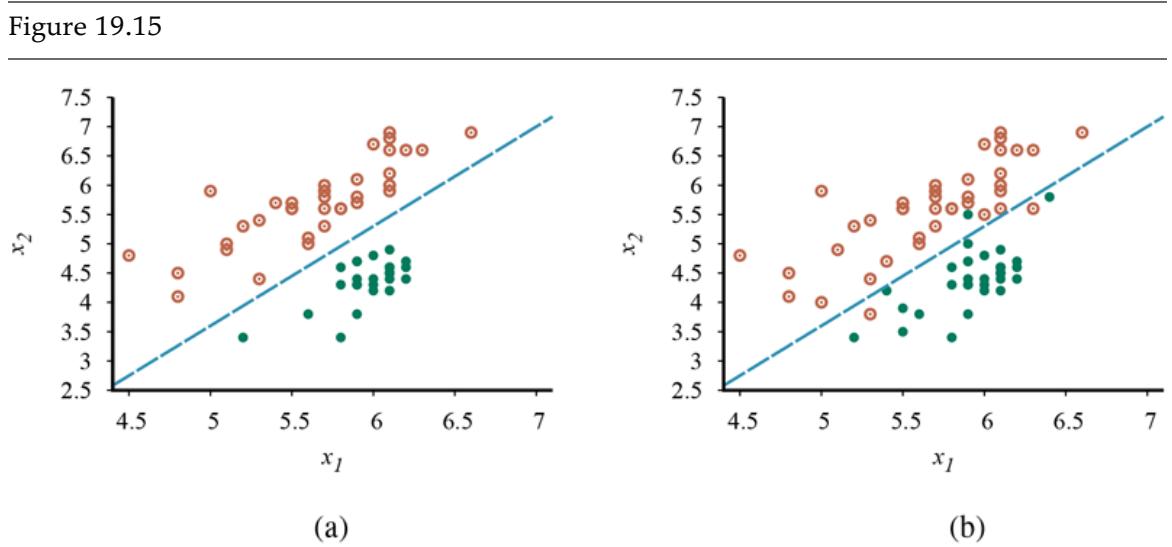

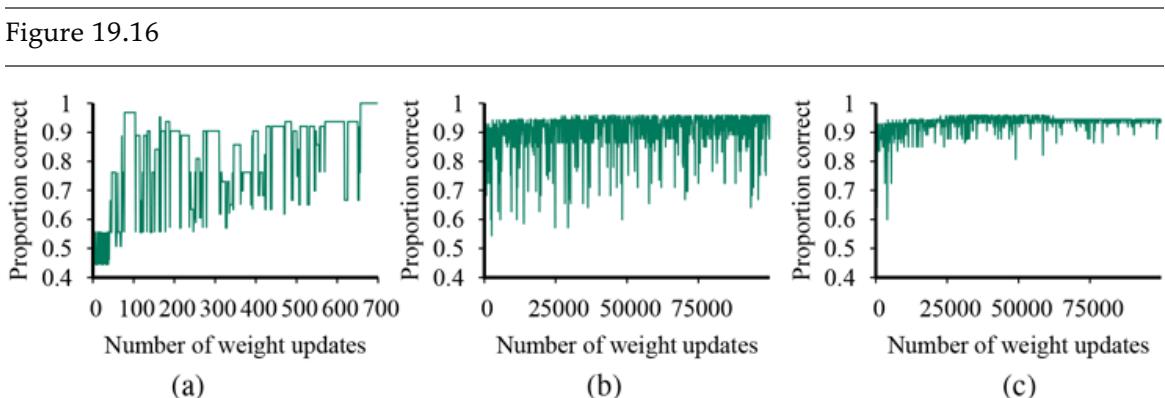

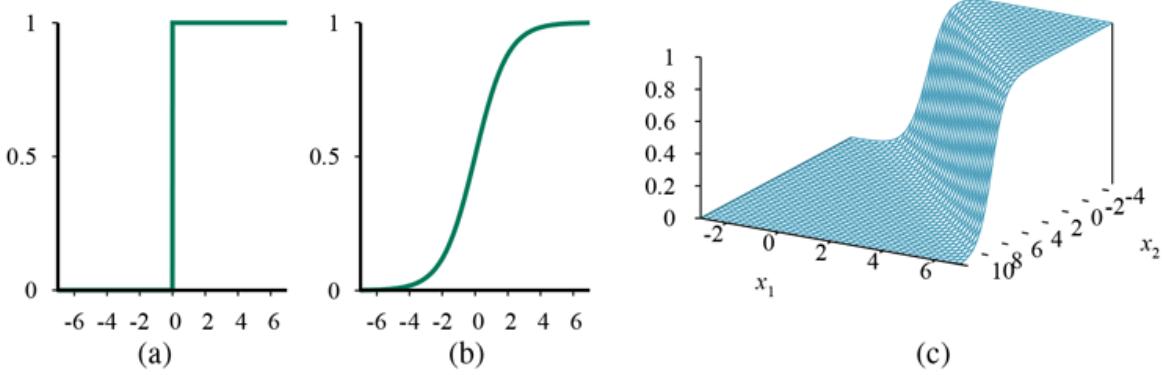

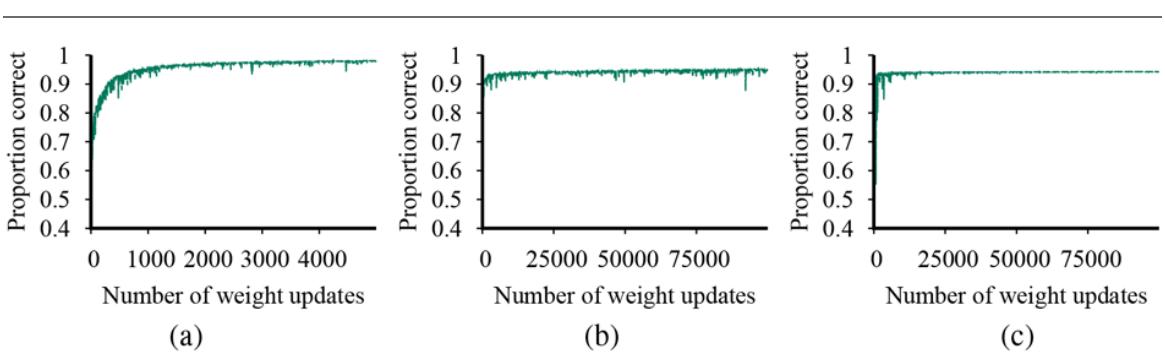

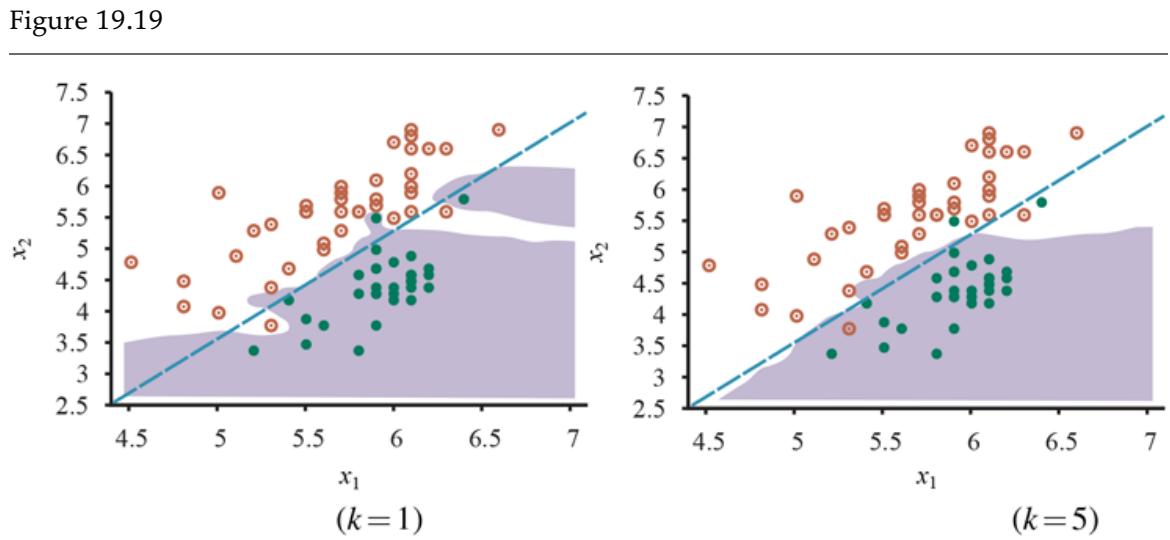

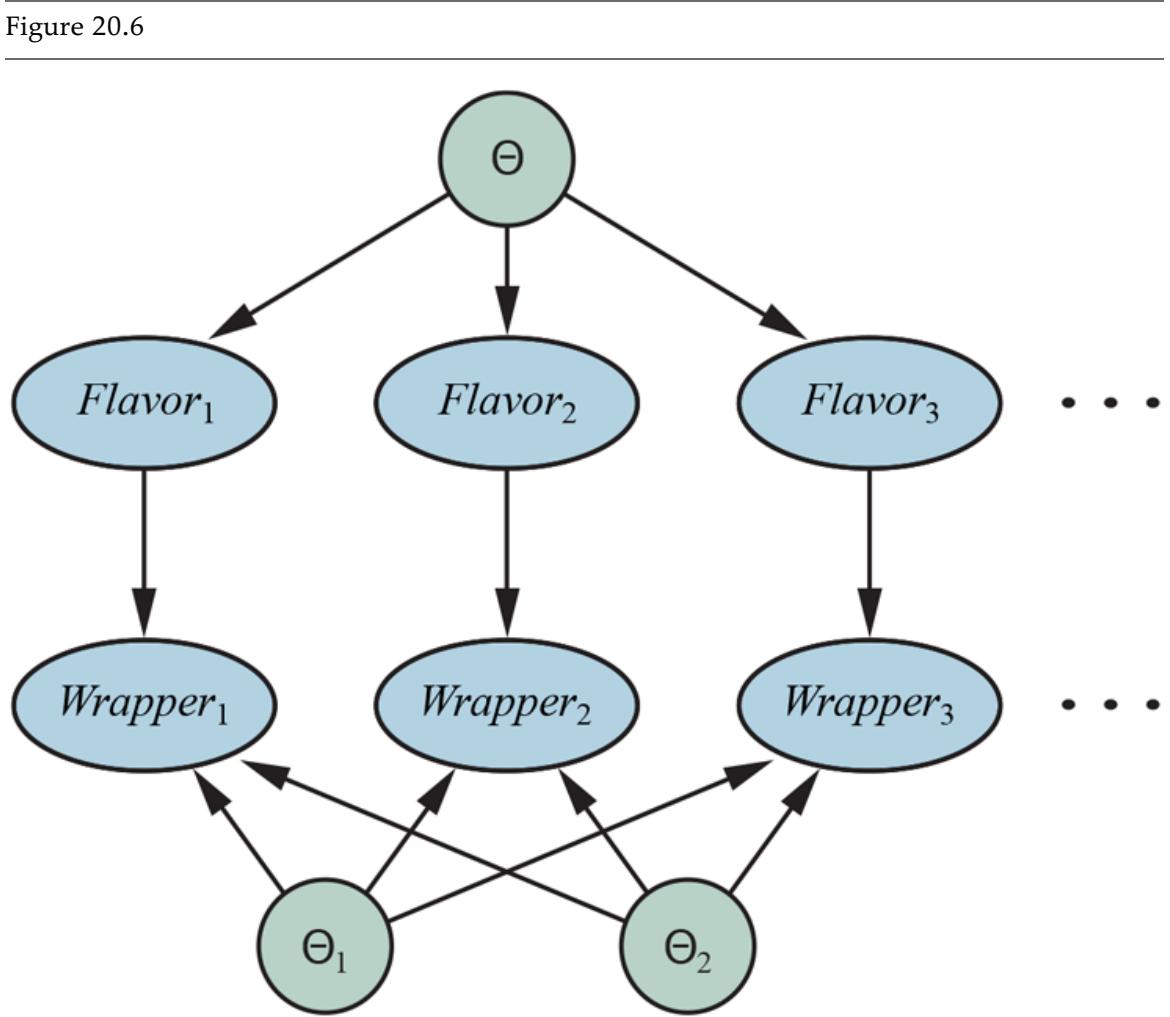

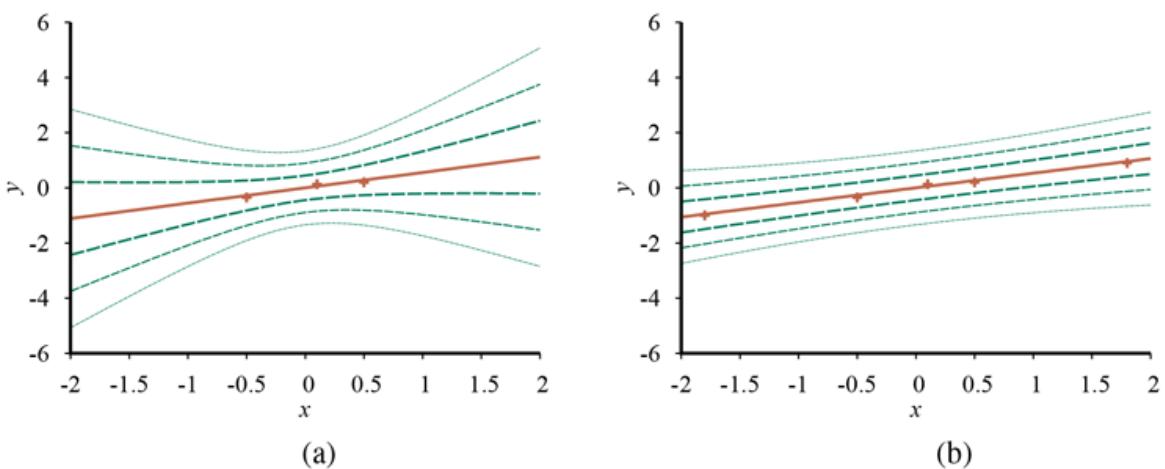

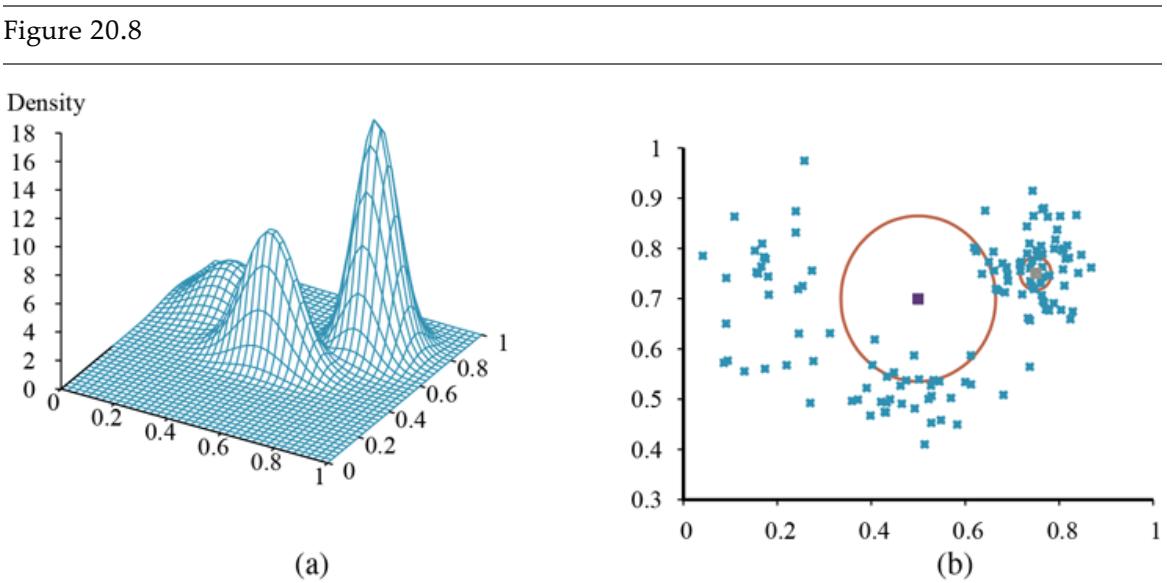

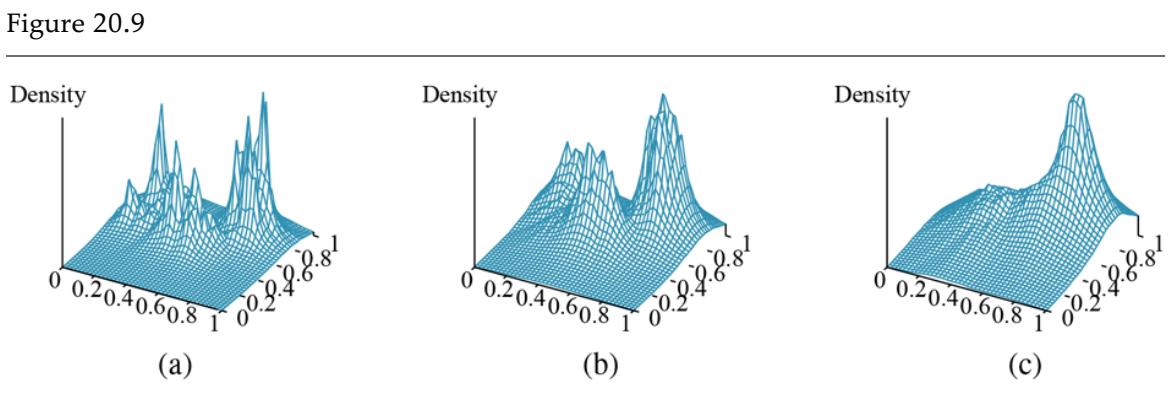

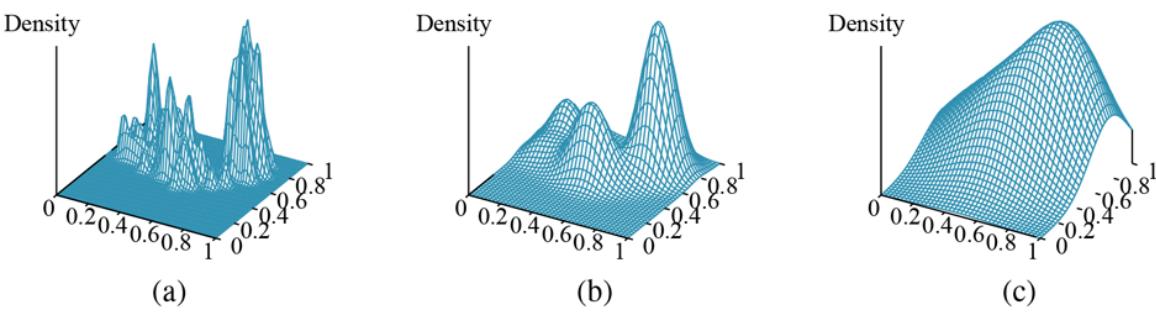

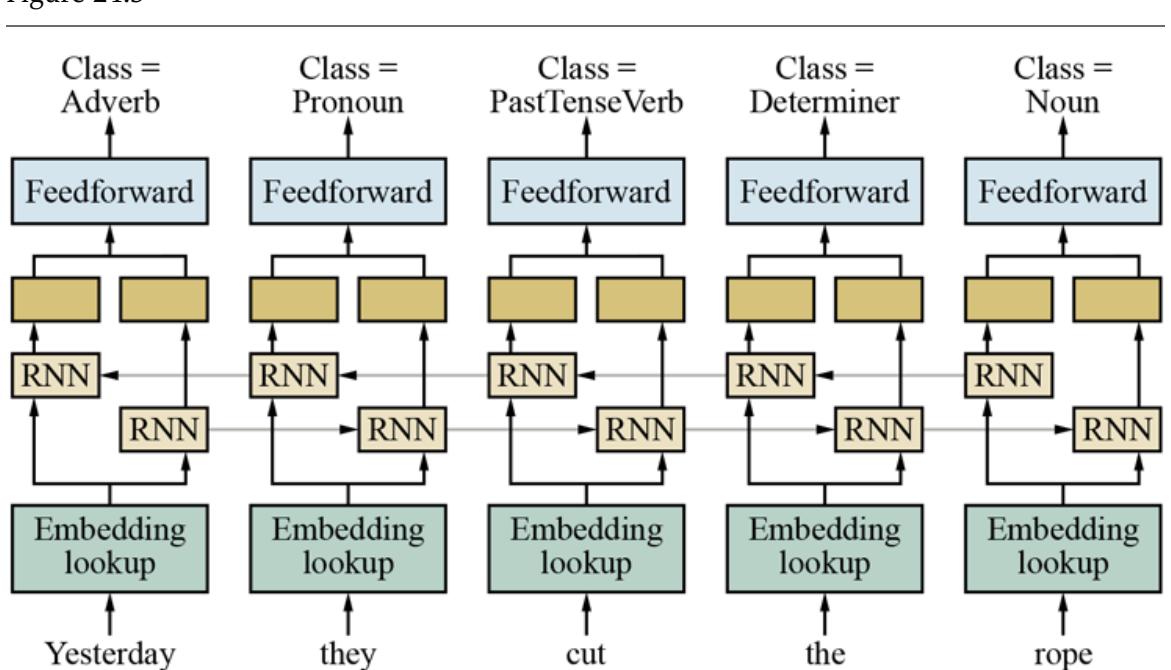

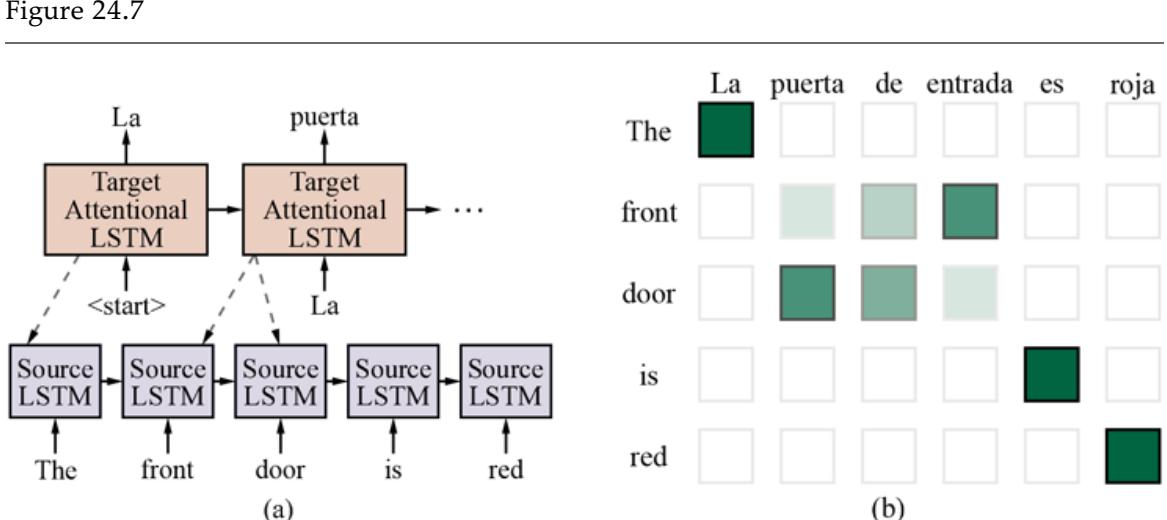

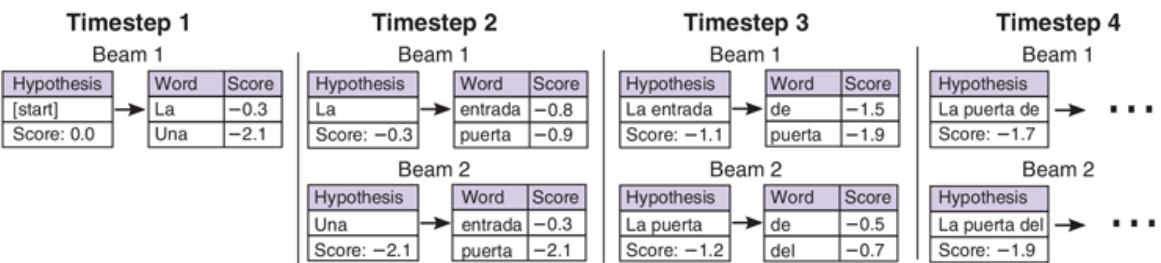

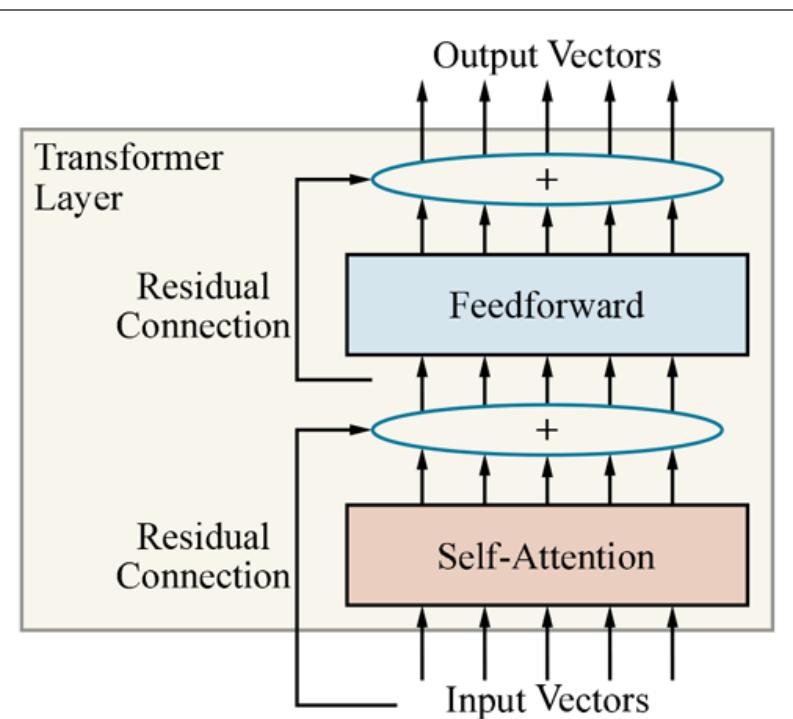

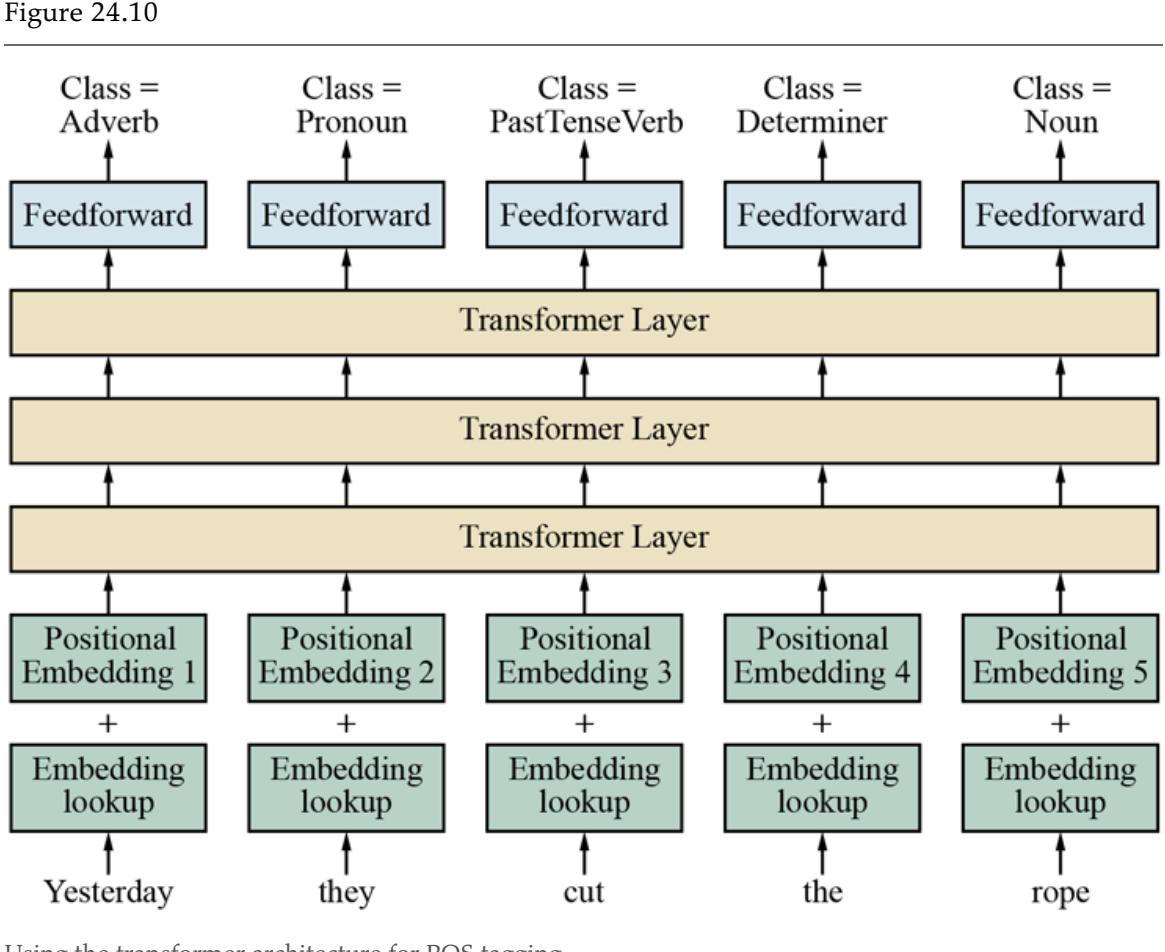

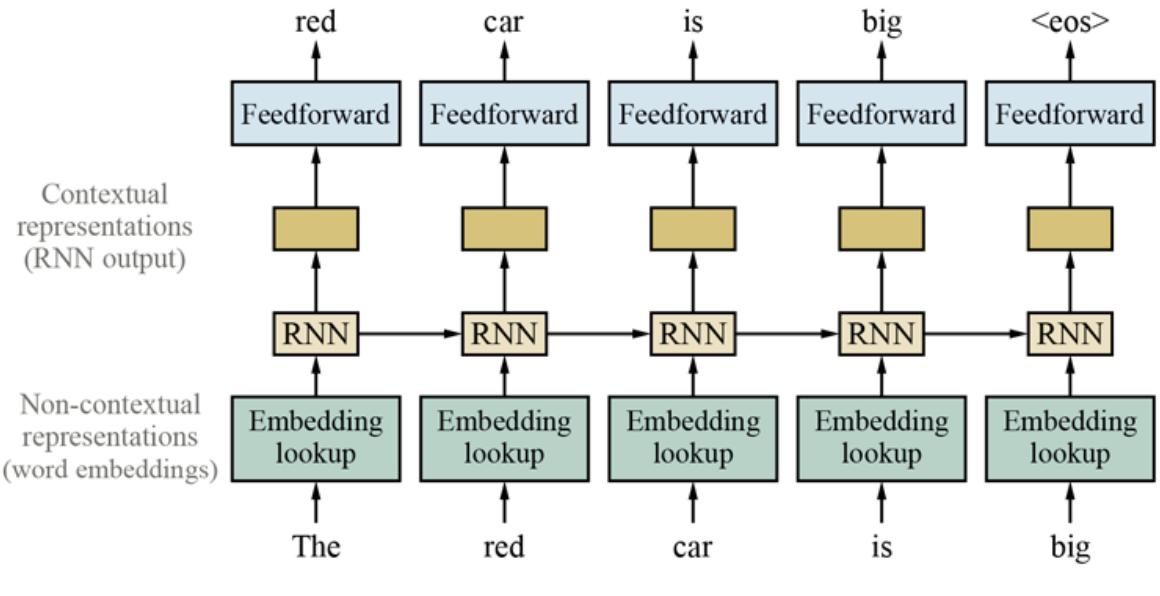

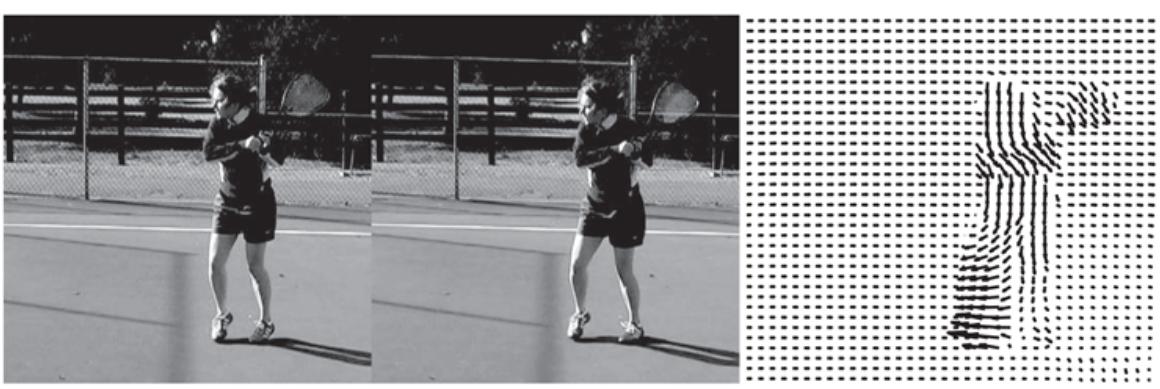

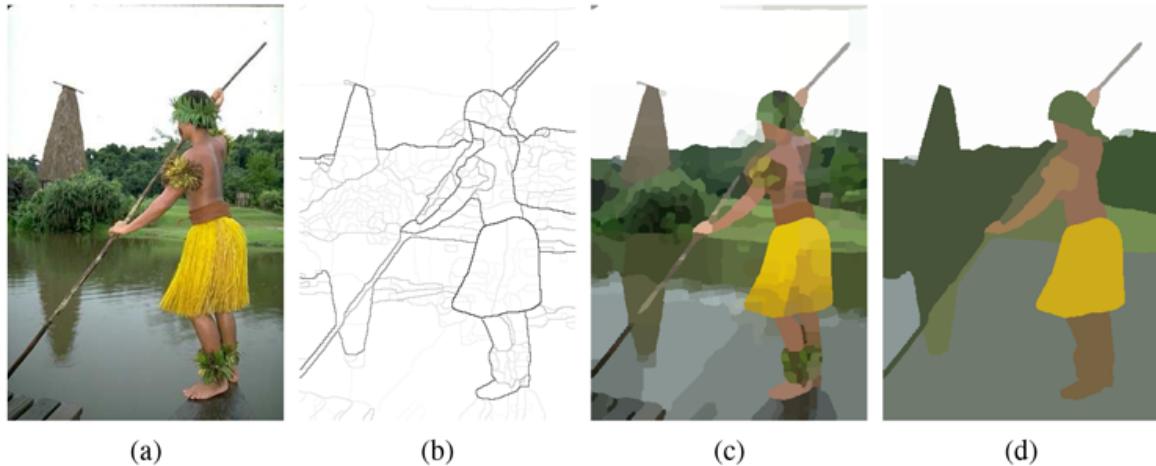

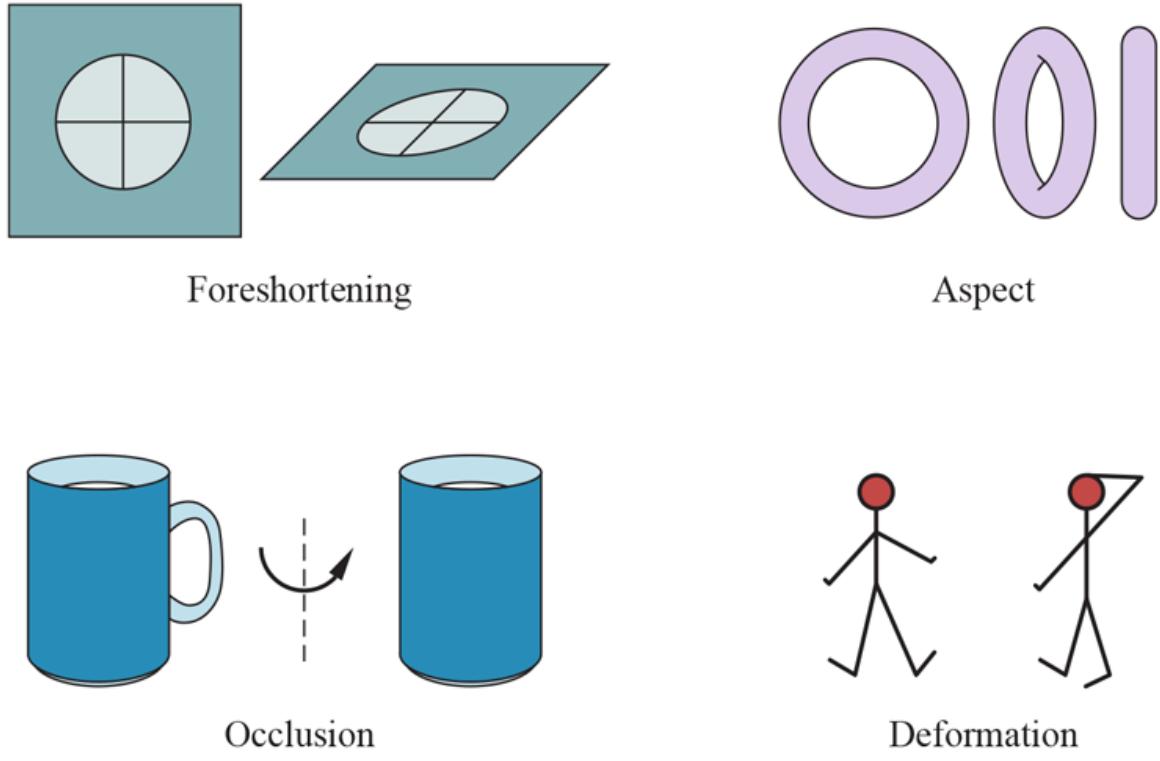

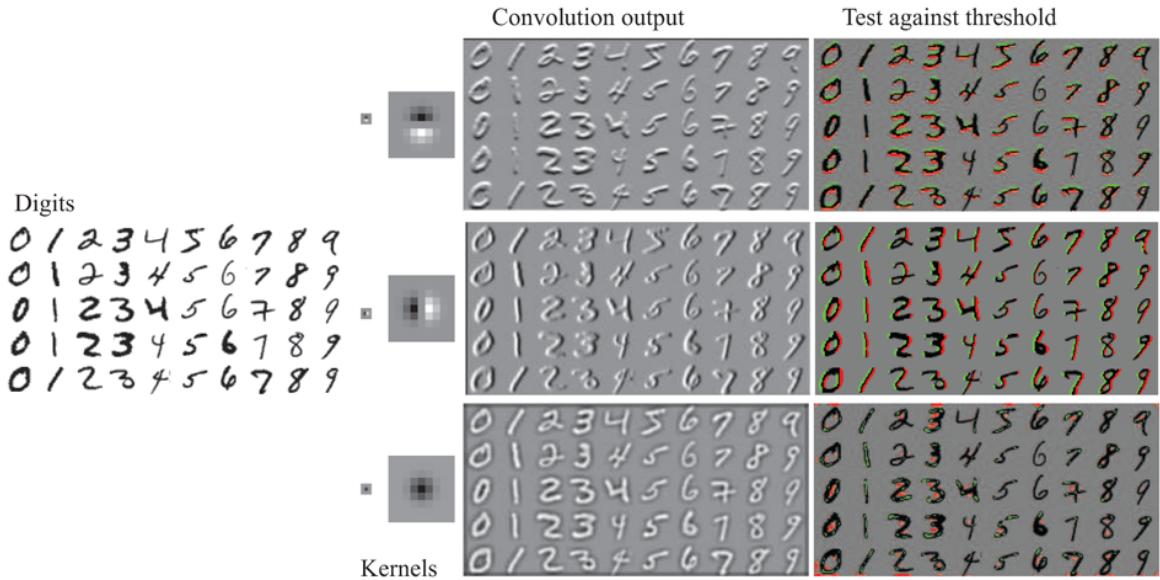

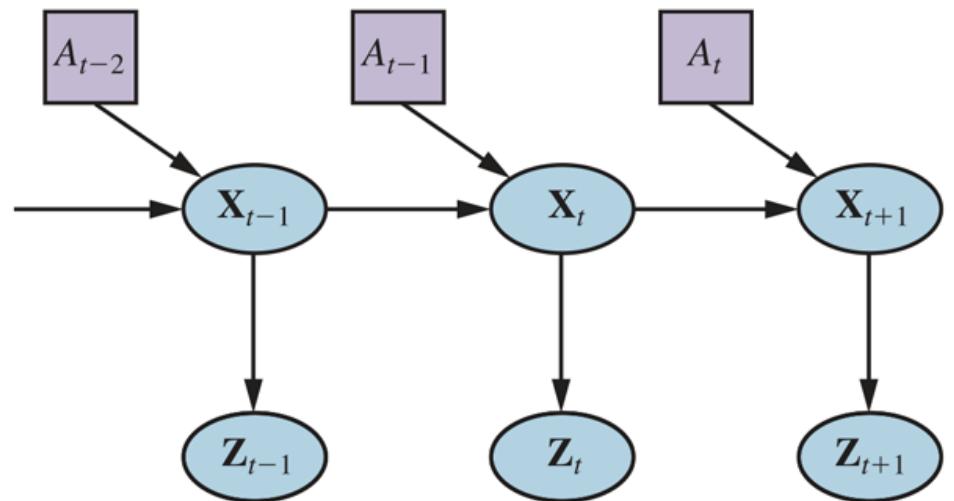

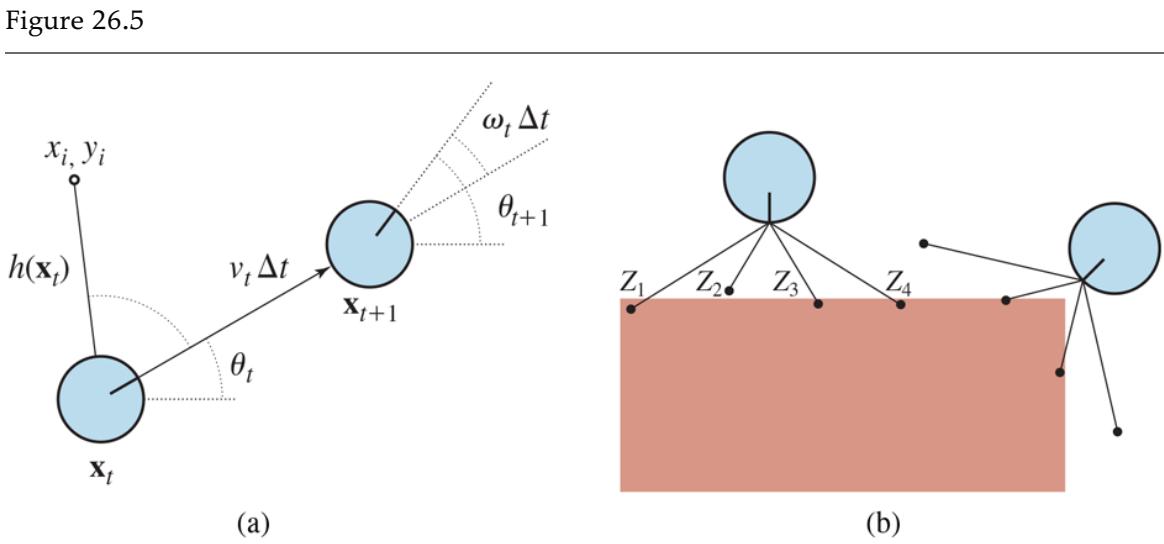

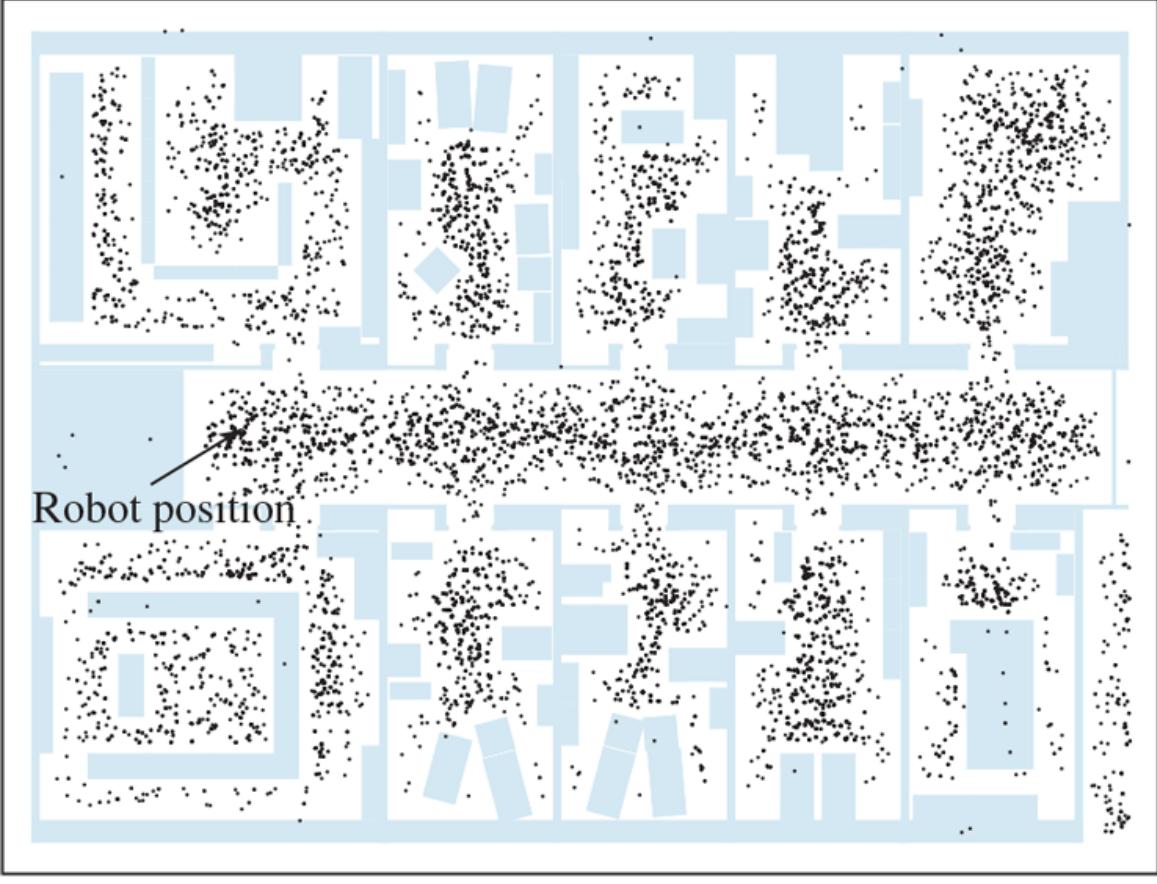

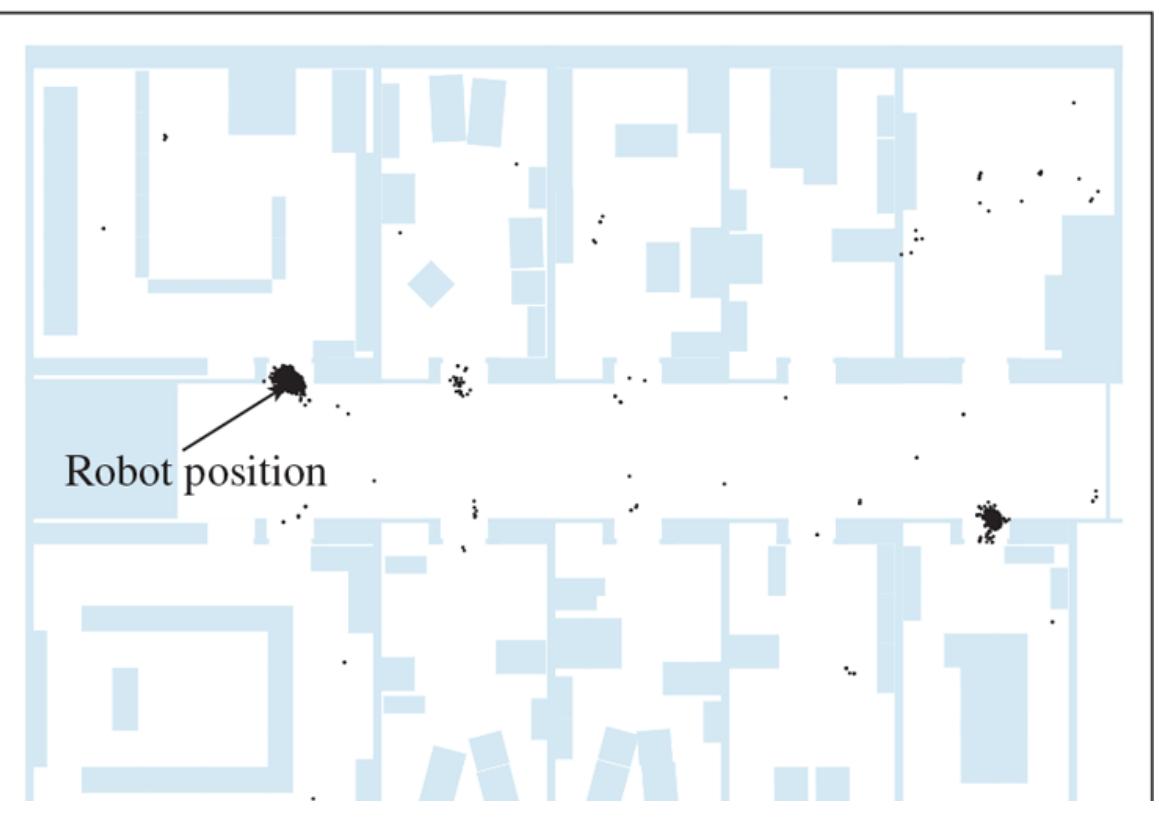

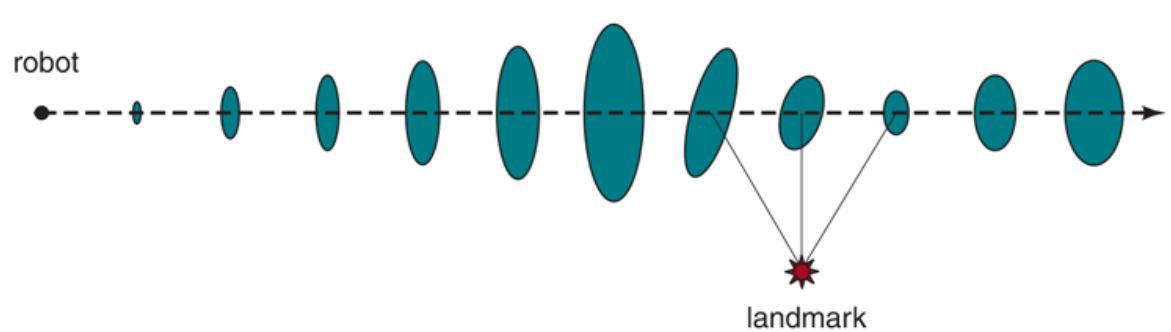

The parameter which we called the step size in Section 4.2 , is usually called the learning rate when we are trying to minimize loss in a learning problem. It can be a fixed constant, or it can decay over time as the learning process proceeds.